User login

ASCO clinical practice guideline update incorporates Oncotype DX

In women with hormone receptor–positive, axillary node–negative breast cancer with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of less than 26, there is minimal to no benefit from chemotherapy, particularly for those greater than age 50 years, according to a clinical practice guideline update by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Furthermore, endocrine therapy alone may be offered for patients greater than age 50 years whose tumors have recurrence scores of less than 26, wrote Fabrice Andre, MD, PhD, of Paris Sud University and associates on the expert panel in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel members reviewed recently published findings from the Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx), which evaluated the clinical utility of the Oncotype DX assay in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer.

“This focused update reviews and analyzes new data regarding these recommendations while applying the same criteria of clinical utility as described in the 2016 guideline,” they wrote.

The expert panel provided recommendations on how to integrate the results of the TAILORx study into clinical practice.

“For patients age 50 years or younger with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of 16-25, clinicians may offer chemoendocrine therapy” the panel wrote. “Patients with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of greater than 30 should be considered candidates for chemoendocrine therapy.”

In addition, on the basis of consensus they recommended that chemoendocrine therapy could be offered to patients with recurrence scores of 26-30.

The panel acknowledged that relevant literature on the use of Oncotype DX in this population will be reviewed over the upcoming months to address anticipated practice deviation related to biomarker testing.

More information on the guidelines is available on the ASCO website.

The study was funded by ASCO. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and several others.

SOURCE: Andre F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00945.

In women with hormone receptor–positive, axillary node–negative breast cancer with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of less than 26, there is minimal to no benefit from chemotherapy, particularly for those greater than age 50 years, according to a clinical practice guideline update by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Furthermore, endocrine therapy alone may be offered for patients greater than age 50 years whose tumors have recurrence scores of less than 26, wrote Fabrice Andre, MD, PhD, of Paris Sud University and associates on the expert panel in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel members reviewed recently published findings from the Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx), which evaluated the clinical utility of the Oncotype DX assay in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer.

“This focused update reviews and analyzes new data regarding these recommendations while applying the same criteria of clinical utility as described in the 2016 guideline,” they wrote.

The expert panel provided recommendations on how to integrate the results of the TAILORx study into clinical practice.

“For patients age 50 years or younger with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of 16-25, clinicians may offer chemoendocrine therapy” the panel wrote. “Patients with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of greater than 30 should be considered candidates for chemoendocrine therapy.”

In addition, on the basis of consensus they recommended that chemoendocrine therapy could be offered to patients with recurrence scores of 26-30.

The panel acknowledged that relevant literature on the use of Oncotype DX in this population will be reviewed over the upcoming months to address anticipated practice deviation related to biomarker testing.

More information on the guidelines is available on the ASCO website.

The study was funded by ASCO. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and several others.

SOURCE: Andre F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00945.

In women with hormone receptor–positive, axillary node–negative breast cancer with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of less than 26, there is minimal to no benefit from chemotherapy, particularly for those greater than age 50 years, according to a clinical practice guideline update by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Furthermore, endocrine therapy alone may be offered for patients greater than age 50 years whose tumors have recurrence scores of less than 26, wrote Fabrice Andre, MD, PhD, of Paris Sud University and associates on the expert panel in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel members reviewed recently published findings from the Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx), which evaluated the clinical utility of the Oncotype DX assay in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer.

“This focused update reviews and analyzes new data regarding these recommendations while applying the same criteria of clinical utility as described in the 2016 guideline,” they wrote.

The expert panel provided recommendations on how to integrate the results of the TAILORx study into clinical practice.

“For patients age 50 years or younger with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of 16-25, clinicians may offer chemoendocrine therapy” the panel wrote. “Patients with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of greater than 30 should be considered candidates for chemoendocrine therapy.”

In addition, on the basis of consensus they recommended that chemoendocrine therapy could be offered to patients with recurrence scores of 26-30.

The panel acknowledged that relevant literature on the use of Oncotype DX in this population will be reviewed over the upcoming months to address anticipated practice deviation related to biomarker testing.

More information on the guidelines is available on the ASCO website.

The study was funded by ASCO. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and several others.

SOURCE: Andre F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00945.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux

In a 2018 guideline, the writing committee defined GER as reflux of stomach contents to the esophagus. GER is considered pathologic and, therefore, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) when it is associated with troublesome symptoms and/or complications that can include esophagitis and aspiration.

Infants

GERD is difficult to diagnose in infants. The symptoms of GERD, such as crying after feeds, regurgitation, and irritability, occur commonly in all infants and in any individual infant may not be reflective of GERD. Regurgitation is common, frequent and normal in infants up to 6 months of age. A common challenge occurs when families request treatment for infants with irritability, back arching, and/or regurgitation who are otherwise doing well. In this group of infants it is important to recognize that neither testing nor therapy is indicated unless there is difficulty with feeding, growth, acquisition of milestones, or red flag signs.

In infants with recurrent regurgitation history, physical exam is usually sufficient to distinguish uncomplicated GER from GERD and other more worrisome diagnoses. Red flag symptoms raise the possibility of a different diagnosis. Red flag symptoms include weight loss; lethargy; excessive irritability/pain; onset of vomiting for more than 6 months or persisting past 12-18 months of age; rapidly increasing head circumference; persistent forceful, nocturnal, bloody, or bilious vomiting; abdominal distention; rectal bleeding; and chronic diarrhea. GERD that starts after 6 months of age or which persists after 12 months of age warrants further evaluation, often with referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist.

When GERD is suspected, the first therapeutic steps are to institute behavioral changes. Caregivers should avoid overfeeding and modify the feeding pattern to more frequent feedings consisting of less volume at each feed. The addition of thickeners to feeds does reduce regurgitation, although it may not affect other GERD signs and symptoms. Formula can be thickened with rice cereal, which tends to be an affordable choice that doesn’t clog nipples. Enzymes present in breast milk digest cereal thickeners, so breast milk can be thickened with xanthum gum (after 1 year of age) or carob bean–based products (after 42 weeks gestation).

If these modifications do not improve symptoms, the next step is to change the type of feeds. Some infants in whom GERD is suspected actually have cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA), so a trial of cow’s milk elimination is warranted. A breastfeeding mother can eliminate all dairy from her diet including casein and whey. Caregivers can switch to an extensively hydrolyzed formula or an amino acid–based formula. The guideline do not recommend soy-based formulas because they are not available in Europe and because a significant percentage of infants with CMPA also develop allergy to soy, and they do not recommend rice hydrolysate formula because of a lack of evidence. Dairy can be reintroduced at a later point. While positional changes including elevating the head of the crib or placing the infant in the left lateral position can help decrease GERD, the American Academy of Pediatrics strongly discourages these positions because of safety concerns, so the guidelines do not recommend positional change.

If a 2-4 week trial of nonpharmacologic interventions fails, the next step is referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist. If a pediatric gastroenterologist is not available, a 4-8 week trial of acid suppressive medication may be given. No trial has shown utility of a trial of acid suppression as a diagnostic test for GERD. Medication should only be used in infants with strongly suspected GERD and, per the guidelines, “should not be used for the treatment of visible regurgitation in otherwise healthy infants.” Medications to treat GER do not have evidence of efficacy, and there is evidence of an increased risk of infection with use of acid suppression, including an increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections, sepsis, urinary tract infections, and Clostridium difficile. If used, proton-pump inhibitors are preferred over histamine-2 receptor blockers. Antacids and alginates are not recommended.

Older children

In children with heartburn or regurgitation without red flag symptoms, a trial of lifestyle changes and dietary education may be initiated. If a child is overweight, it is important to inform the patient and parents that excess body weight is associated with GERD. The head of the bed can be elevated along with left lateral positioning. The guidelines do not support any probiotics or herbal medicines.

If bothersome symptoms persist, a trial of acid-suppressing medication for 4-8 weeks is reasonable. A PPI is preferred to a histamine-2 receptor blocker. PPI safety studies are lacking, but case studies suggest an increase in infections in children taking acid-suppressing medications. Therefore, as with infants, if medications are used they should be prescribed at the lowest dose and for the shortest period of time possible. If medications are not helping, or need to be used long term, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist can be considered. Of note, the guidelines do support a 4-8 week trial of PPIs in older children as a diagnostic test; this differs from the recommendations for infants, in whom a trial for diagnostic purposes is discouraged.

Diagnostic testing

Refer to a gastroenterologist for endoscopy in cases of persistent symptoms despite PPI use or failure to wean off medication. If there are no erosions, pH monitoring with pH-impedance monitoring or pH-metry can help distinguish between nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), reflux hypersensitivity, and functional heartburn. If it is performed when a child is off of PPIs, endoscopy can also diagnose PPI-responsive eosinophilic esophagitis. Barium contrast, abdominal ultrasonography, and manometry may be considered during the course of a search for an alternative diagnosis, but they should not be used to diagnose or confirm GERD.

The bottom line

Most GER is physiologic and does not need treatment. First-line treatment for GERD in infants and children is nonpharmacologic intervention.

Reference

Rosen R et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Mar;66(3):516-554.

Dr. Oh is a third year resident in the Family Medicine Residency at Abington-Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington - Jefferson Health.

In a 2018 guideline, the writing committee defined GER as reflux of stomach contents to the esophagus. GER is considered pathologic and, therefore, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) when it is associated with troublesome symptoms and/or complications that can include esophagitis and aspiration.

Infants

GERD is difficult to diagnose in infants. The symptoms of GERD, such as crying after feeds, regurgitation, and irritability, occur commonly in all infants and in any individual infant may not be reflective of GERD. Regurgitation is common, frequent and normal in infants up to 6 months of age. A common challenge occurs when families request treatment for infants with irritability, back arching, and/or regurgitation who are otherwise doing well. In this group of infants it is important to recognize that neither testing nor therapy is indicated unless there is difficulty with feeding, growth, acquisition of milestones, or red flag signs.

In infants with recurrent regurgitation history, physical exam is usually sufficient to distinguish uncomplicated GER from GERD and other more worrisome diagnoses. Red flag symptoms raise the possibility of a different diagnosis. Red flag symptoms include weight loss; lethargy; excessive irritability/pain; onset of vomiting for more than 6 months or persisting past 12-18 months of age; rapidly increasing head circumference; persistent forceful, nocturnal, bloody, or bilious vomiting; abdominal distention; rectal bleeding; and chronic diarrhea. GERD that starts after 6 months of age or which persists after 12 months of age warrants further evaluation, often with referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist.

When GERD is suspected, the first therapeutic steps are to institute behavioral changes. Caregivers should avoid overfeeding and modify the feeding pattern to more frequent feedings consisting of less volume at each feed. The addition of thickeners to feeds does reduce regurgitation, although it may not affect other GERD signs and symptoms. Formula can be thickened with rice cereal, which tends to be an affordable choice that doesn’t clog nipples. Enzymes present in breast milk digest cereal thickeners, so breast milk can be thickened with xanthum gum (after 1 year of age) or carob bean–based products (after 42 weeks gestation).

If these modifications do not improve symptoms, the next step is to change the type of feeds. Some infants in whom GERD is suspected actually have cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA), so a trial of cow’s milk elimination is warranted. A breastfeeding mother can eliminate all dairy from her diet including casein and whey. Caregivers can switch to an extensively hydrolyzed formula or an amino acid–based formula. The guideline do not recommend soy-based formulas because they are not available in Europe and because a significant percentage of infants with CMPA also develop allergy to soy, and they do not recommend rice hydrolysate formula because of a lack of evidence. Dairy can be reintroduced at a later point. While positional changes including elevating the head of the crib or placing the infant in the left lateral position can help decrease GERD, the American Academy of Pediatrics strongly discourages these positions because of safety concerns, so the guidelines do not recommend positional change.

If a 2-4 week trial of nonpharmacologic interventions fails, the next step is referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist. If a pediatric gastroenterologist is not available, a 4-8 week trial of acid suppressive medication may be given. No trial has shown utility of a trial of acid suppression as a diagnostic test for GERD. Medication should only be used in infants with strongly suspected GERD and, per the guidelines, “should not be used for the treatment of visible regurgitation in otherwise healthy infants.” Medications to treat GER do not have evidence of efficacy, and there is evidence of an increased risk of infection with use of acid suppression, including an increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections, sepsis, urinary tract infections, and Clostridium difficile. If used, proton-pump inhibitors are preferred over histamine-2 receptor blockers. Antacids and alginates are not recommended.

Older children

In children with heartburn or regurgitation without red flag symptoms, a trial of lifestyle changes and dietary education may be initiated. If a child is overweight, it is important to inform the patient and parents that excess body weight is associated with GERD. The head of the bed can be elevated along with left lateral positioning. The guidelines do not support any probiotics or herbal medicines.

If bothersome symptoms persist, a trial of acid-suppressing medication for 4-8 weeks is reasonable. A PPI is preferred to a histamine-2 receptor blocker. PPI safety studies are lacking, but case studies suggest an increase in infections in children taking acid-suppressing medications. Therefore, as with infants, if medications are used they should be prescribed at the lowest dose and for the shortest period of time possible. If medications are not helping, or need to be used long term, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist can be considered. Of note, the guidelines do support a 4-8 week trial of PPIs in older children as a diagnostic test; this differs from the recommendations for infants, in whom a trial for diagnostic purposes is discouraged.

Diagnostic testing

Refer to a gastroenterologist for endoscopy in cases of persistent symptoms despite PPI use or failure to wean off medication. If there are no erosions, pH monitoring with pH-impedance monitoring or pH-metry can help distinguish between nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), reflux hypersensitivity, and functional heartburn. If it is performed when a child is off of PPIs, endoscopy can also diagnose PPI-responsive eosinophilic esophagitis. Barium contrast, abdominal ultrasonography, and manometry may be considered during the course of a search for an alternative diagnosis, but they should not be used to diagnose or confirm GERD.

The bottom line

Most GER is physiologic and does not need treatment. First-line treatment for GERD in infants and children is nonpharmacologic intervention.

Reference

Rosen R et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Mar;66(3):516-554.

Dr. Oh is a third year resident in the Family Medicine Residency at Abington-Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington - Jefferson Health.

In a 2018 guideline, the writing committee defined GER as reflux of stomach contents to the esophagus. GER is considered pathologic and, therefore, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) when it is associated with troublesome symptoms and/or complications that can include esophagitis and aspiration.

Infants

GERD is difficult to diagnose in infants. The symptoms of GERD, such as crying after feeds, regurgitation, and irritability, occur commonly in all infants and in any individual infant may not be reflective of GERD. Regurgitation is common, frequent and normal in infants up to 6 months of age. A common challenge occurs when families request treatment for infants with irritability, back arching, and/or regurgitation who are otherwise doing well. In this group of infants it is important to recognize that neither testing nor therapy is indicated unless there is difficulty with feeding, growth, acquisition of milestones, or red flag signs.

In infants with recurrent regurgitation history, physical exam is usually sufficient to distinguish uncomplicated GER from GERD and other more worrisome diagnoses. Red flag symptoms raise the possibility of a different diagnosis. Red flag symptoms include weight loss; lethargy; excessive irritability/pain; onset of vomiting for more than 6 months or persisting past 12-18 months of age; rapidly increasing head circumference; persistent forceful, nocturnal, bloody, or bilious vomiting; abdominal distention; rectal bleeding; and chronic diarrhea. GERD that starts after 6 months of age or which persists after 12 months of age warrants further evaluation, often with referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist.

When GERD is suspected, the first therapeutic steps are to institute behavioral changes. Caregivers should avoid overfeeding and modify the feeding pattern to more frequent feedings consisting of less volume at each feed. The addition of thickeners to feeds does reduce regurgitation, although it may not affect other GERD signs and symptoms. Formula can be thickened with rice cereal, which tends to be an affordable choice that doesn’t clog nipples. Enzymes present in breast milk digest cereal thickeners, so breast milk can be thickened with xanthum gum (after 1 year of age) or carob bean–based products (after 42 weeks gestation).

If these modifications do not improve symptoms, the next step is to change the type of feeds. Some infants in whom GERD is suspected actually have cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA), so a trial of cow’s milk elimination is warranted. A breastfeeding mother can eliminate all dairy from her diet including casein and whey. Caregivers can switch to an extensively hydrolyzed formula or an amino acid–based formula. The guideline do not recommend soy-based formulas because they are not available in Europe and because a significant percentage of infants with CMPA also develop allergy to soy, and they do not recommend rice hydrolysate formula because of a lack of evidence. Dairy can be reintroduced at a later point. While positional changes including elevating the head of the crib or placing the infant in the left lateral position can help decrease GERD, the American Academy of Pediatrics strongly discourages these positions because of safety concerns, so the guidelines do not recommend positional change.

If a 2-4 week trial of nonpharmacologic interventions fails, the next step is referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist. If a pediatric gastroenterologist is not available, a 4-8 week trial of acid suppressive medication may be given. No trial has shown utility of a trial of acid suppression as a diagnostic test for GERD. Medication should only be used in infants with strongly suspected GERD and, per the guidelines, “should not be used for the treatment of visible regurgitation in otherwise healthy infants.” Medications to treat GER do not have evidence of efficacy, and there is evidence of an increased risk of infection with use of acid suppression, including an increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections, sepsis, urinary tract infections, and Clostridium difficile. If used, proton-pump inhibitors are preferred over histamine-2 receptor blockers. Antacids and alginates are not recommended.

Older children

In children with heartburn or regurgitation without red flag symptoms, a trial of lifestyle changes and dietary education may be initiated. If a child is overweight, it is important to inform the patient and parents that excess body weight is associated with GERD. The head of the bed can be elevated along with left lateral positioning. The guidelines do not support any probiotics or herbal medicines.

If bothersome symptoms persist, a trial of acid-suppressing medication for 4-8 weeks is reasonable. A PPI is preferred to a histamine-2 receptor blocker. PPI safety studies are lacking, but case studies suggest an increase in infections in children taking acid-suppressing medications. Therefore, as with infants, if medications are used they should be prescribed at the lowest dose and for the shortest period of time possible. If medications are not helping, or need to be used long term, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist can be considered. Of note, the guidelines do support a 4-8 week trial of PPIs in older children as a diagnostic test; this differs from the recommendations for infants, in whom a trial for diagnostic purposes is discouraged.

Diagnostic testing

Refer to a gastroenterologist for endoscopy in cases of persistent symptoms despite PPI use or failure to wean off medication. If there are no erosions, pH monitoring with pH-impedance monitoring or pH-metry can help distinguish between nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), reflux hypersensitivity, and functional heartburn. If it is performed when a child is off of PPIs, endoscopy can also diagnose PPI-responsive eosinophilic esophagitis. Barium contrast, abdominal ultrasonography, and manometry may be considered during the course of a search for an alternative diagnosis, but they should not be used to diagnose or confirm GERD.

The bottom line

Most GER is physiologic and does not need treatment. First-line treatment for GERD in infants and children is nonpharmacologic intervention.

Reference

Rosen R et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Mar;66(3):516-554.

Dr. Oh is a third year resident in the Family Medicine Residency at Abington-Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington - Jefferson Health.

NCCN publishes pediatric ALL guidelines

“The cure rate for pediatric ALL in the U.S. has risen from 0% in the 1960s to nearly 90% today. This is among the most profound medical success stories in history,” Patrick Brown, MD, of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a statement announcing the guidelines. Dr. Brown chairs the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines for adult and pediatric ALL.

“Pediatric ALL survivors live a long time; we have to consider long-term effects as well,” Hiroto Inaba, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, and vice chair of the guidelines committee, said in the statement.

The new recommendations highlight the importance of supportive care interventions in an effort to reduce the chances of patients experiencing severe adverse effects.

The pediatric ALL guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations about optimal treatment strategies for ALL to prolong survival in children affected, with a focus on treatment outside of clinical trials (Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. NCCN.org, Version 1.2019, published May 30, 2019).

While treatment for ALL often includes long-term chemotherapy regimens that involve multiple stages, several novel treatment strategies are summarized in the guidelines, including various types of immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

The guidelines are intended to accompany the NCCN Guidelines for Adult ALL and integrate treatment recommendations for patients in overlapping age categories. The recommendations are organized based on risk level, which may also be associated with age.

“The highest risk [is] associated with those diagnosed within the first 12 months of life or between the ages 10 and 21 years old,” the guideline authors wrote.

Another unique aspect of the guidelines is the recognition of vulnerable populations, such as young infants or children with Down syndrome, who face distinct treatment challenges. The authors provide guidance on the best supportive care measures for these patients.

The NCCN is currently expanding the collection of clinical practice guidelines for additional pediatric malignancies. At present, they are planning to undertake a minimum of 90% of all incident pediatric cancers.

Upcoming guidelines include treatment recommendations for pediatric Burkitt lymphoma, and are scheduled for release later in 2019.

Future efforts include modifying the guidelines for use in low- and middle-income countries, with the goal of providing direction in resource-limited environments.

“We know that many, many children can be cured with inexpensive and widely-available therapies,” Dr. Brown said. “With the increasing global reach of the NCCN Guidelines, we can really pave the way for increasing the cure rates throughout the world.”

“The cure rate for pediatric ALL in the U.S. has risen from 0% in the 1960s to nearly 90% today. This is among the most profound medical success stories in history,” Patrick Brown, MD, of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a statement announcing the guidelines. Dr. Brown chairs the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines for adult and pediatric ALL.

“Pediatric ALL survivors live a long time; we have to consider long-term effects as well,” Hiroto Inaba, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, and vice chair of the guidelines committee, said in the statement.

The new recommendations highlight the importance of supportive care interventions in an effort to reduce the chances of patients experiencing severe adverse effects.

The pediatric ALL guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations about optimal treatment strategies for ALL to prolong survival in children affected, with a focus on treatment outside of clinical trials (Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. NCCN.org, Version 1.2019, published May 30, 2019).

While treatment for ALL often includes long-term chemotherapy regimens that involve multiple stages, several novel treatment strategies are summarized in the guidelines, including various types of immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

The guidelines are intended to accompany the NCCN Guidelines for Adult ALL and integrate treatment recommendations for patients in overlapping age categories. The recommendations are organized based on risk level, which may also be associated with age.

“The highest risk [is] associated with those diagnosed within the first 12 months of life or between the ages 10 and 21 years old,” the guideline authors wrote.

Another unique aspect of the guidelines is the recognition of vulnerable populations, such as young infants or children with Down syndrome, who face distinct treatment challenges. The authors provide guidance on the best supportive care measures for these patients.

The NCCN is currently expanding the collection of clinical practice guidelines for additional pediatric malignancies. At present, they are planning to undertake a minimum of 90% of all incident pediatric cancers.

Upcoming guidelines include treatment recommendations for pediatric Burkitt lymphoma, and are scheduled for release later in 2019.

Future efforts include modifying the guidelines for use in low- and middle-income countries, with the goal of providing direction in resource-limited environments.

“We know that many, many children can be cured with inexpensive and widely-available therapies,” Dr. Brown said. “With the increasing global reach of the NCCN Guidelines, we can really pave the way for increasing the cure rates throughout the world.”

“The cure rate for pediatric ALL in the U.S. has risen from 0% in the 1960s to nearly 90% today. This is among the most profound medical success stories in history,” Patrick Brown, MD, of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a statement announcing the guidelines. Dr. Brown chairs the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines for adult and pediatric ALL.

“Pediatric ALL survivors live a long time; we have to consider long-term effects as well,” Hiroto Inaba, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, and vice chair of the guidelines committee, said in the statement.

The new recommendations highlight the importance of supportive care interventions in an effort to reduce the chances of patients experiencing severe adverse effects.

The pediatric ALL guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations about optimal treatment strategies for ALL to prolong survival in children affected, with a focus on treatment outside of clinical trials (Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. NCCN.org, Version 1.2019, published May 30, 2019).

While treatment for ALL often includes long-term chemotherapy regimens that involve multiple stages, several novel treatment strategies are summarized in the guidelines, including various types of immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

The guidelines are intended to accompany the NCCN Guidelines for Adult ALL and integrate treatment recommendations for patients in overlapping age categories. The recommendations are organized based on risk level, which may also be associated with age.

“The highest risk [is] associated with those diagnosed within the first 12 months of life or between the ages 10 and 21 years old,” the guideline authors wrote.

Another unique aspect of the guidelines is the recognition of vulnerable populations, such as young infants or children with Down syndrome, who face distinct treatment challenges. The authors provide guidance on the best supportive care measures for these patients.

The NCCN is currently expanding the collection of clinical practice guidelines for additional pediatric malignancies. At present, they are planning to undertake a minimum of 90% of all incident pediatric cancers.

Upcoming guidelines include treatment recommendations for pediatric Burkitt lymphoma, and are scheduled for release later in 2019.

Future efforts include modifying the guidelines for use in low- and middle-income countries, with the goal of providing direction in resource-limited environments.

“We know that many, many children can be cured with inexpensive and widely-available therapies,” Dr. Brown said. “With the increasing global reach of the NCCN Guidelines, we can really pave the way for increasing the cure rates throughout the world.”

FROM THE NATIONAL COMPREHENSIVE CANCER NETWORK

Cholesterol guideline: Risk assessment gets personal

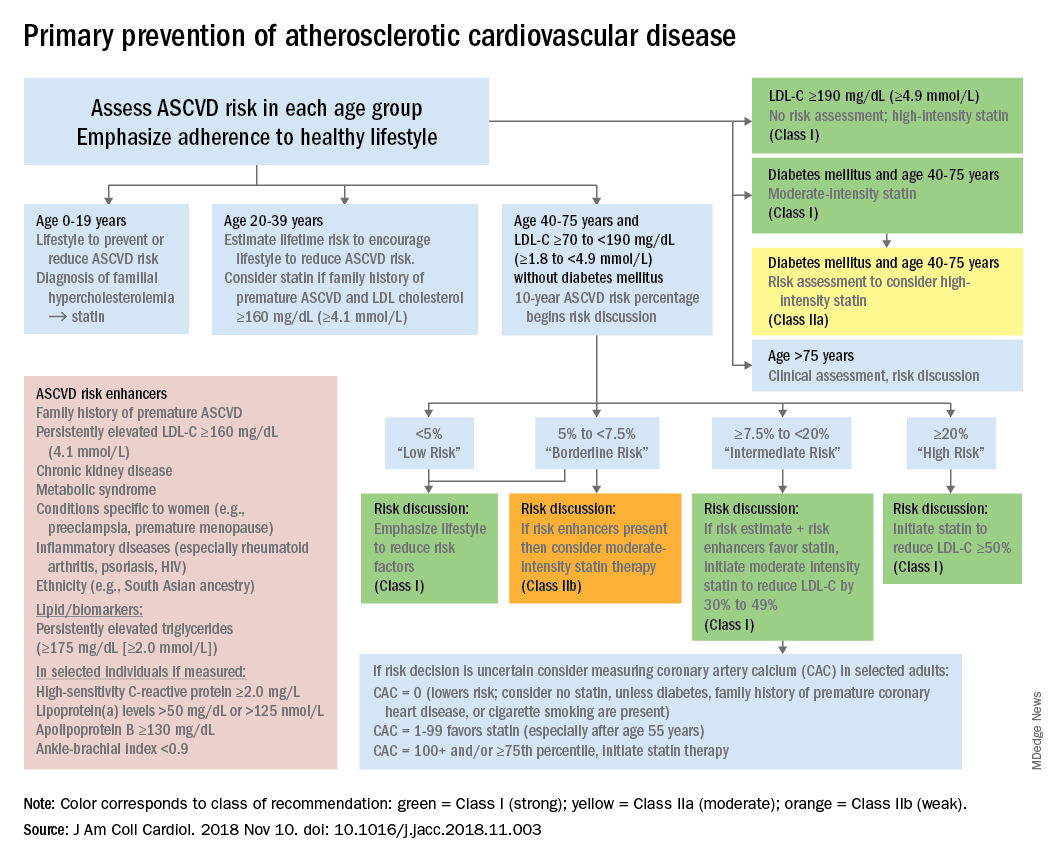

according to the 2018 update to U.S. guidelines for cholesterol management from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline also emphasizes “careful adherence to lifestyle recommendations at an early age [to] reduce risk factor burden over the lifespan and decrease the need for preventive drug therapies later in life,” Scott M. Grundy, MD, PhD, and Neil J. Stone, MD, said in a synopsis of the document in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

For primary prevention in patients aged 40-75 years, estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk – introduced in the 2013 guidelines – and stratification into one of four categories should set the stage for clinician-patient discussion. A score of less than 5% indicates low risk and should prompt a risk discussion that emphasizes lifestyle recommendations. “Statins are clinically efficacious in the latter three categories, but the higher the risk, the stronger the statin indication,” said Dr. Grundy of the University of Texas, Dallas, and Dr. Stone of Northwestern University, Chicago.

When risk status is uncertain, measurement of coronary artery calcium should be considered in patients aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol levels of 70-189 mg/dL who do no not have diabetes, they noted.

The guideline emphasizes secondary prevention with “maximally tolerated doses of statins” and the use of nonstatin drugs such as ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors for patients with very high ASCVD risk – defined as a history of multiple major events or one event and other high-risk conditions, Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone wrote.

Financial support for the Guideline Writing Committee for the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines came from the AHA and the ACC. Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Grundy SM and Stone NJ. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.7326/M19-0365.

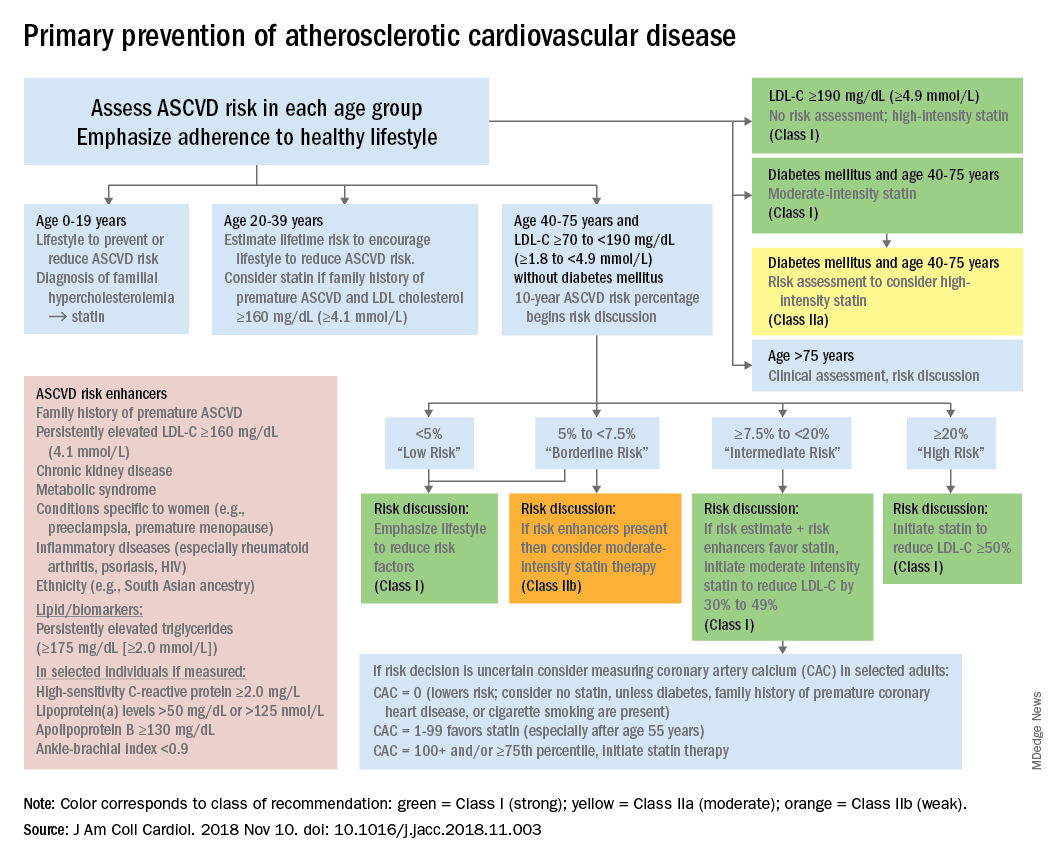

according to the 2018 update to U.S. guidelines for cholesterol management from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline also emphasizes “careful adherence to lifestyle recommendations at an early age [to] reduce risk factor burden over the lifespan and decrease the need for preventive drug therapies later in life,” Scott M. Grundy, MD, PhD, and Neil J. Stone, MD, said in a synopsis of the document in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

For primary prevention in patients aged 40-75 years, estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk – introduced in the 2013 guidelines – and stratification into one of four categories should set the stage for clinician-patient discussion. A score of less than 5% indicates low risk and should prompt a risk discussion that emphasizes lifestyle recommendations. “Statins are clinically efficacious in the latter three categories, but the higher the risk, the stronger the statin indication,” said Dr. Grundy of the University of Texas, Dallas, and Dr. Stone of Northwestern University, Chicago.

When risk status is uncertain, measurement of coronary artery calcium should be considered in patients aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol levels of 70-189 mg/dL who do no not have diabetes, they noted.

The guideline emphasizes secondary prevention with “maximally tolerated doses of statins” and the use of nonstatin drugs such as ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors for patients with very high ASCVD risk – defined as a history of multiple major events or one event and other high-risk conditions, Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone wrote.

Financial support for the Guideline Writing Committee for the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines came from the AHA and the ACC. Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Grundy SM and Stone NJ. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.7326/M19-0365.

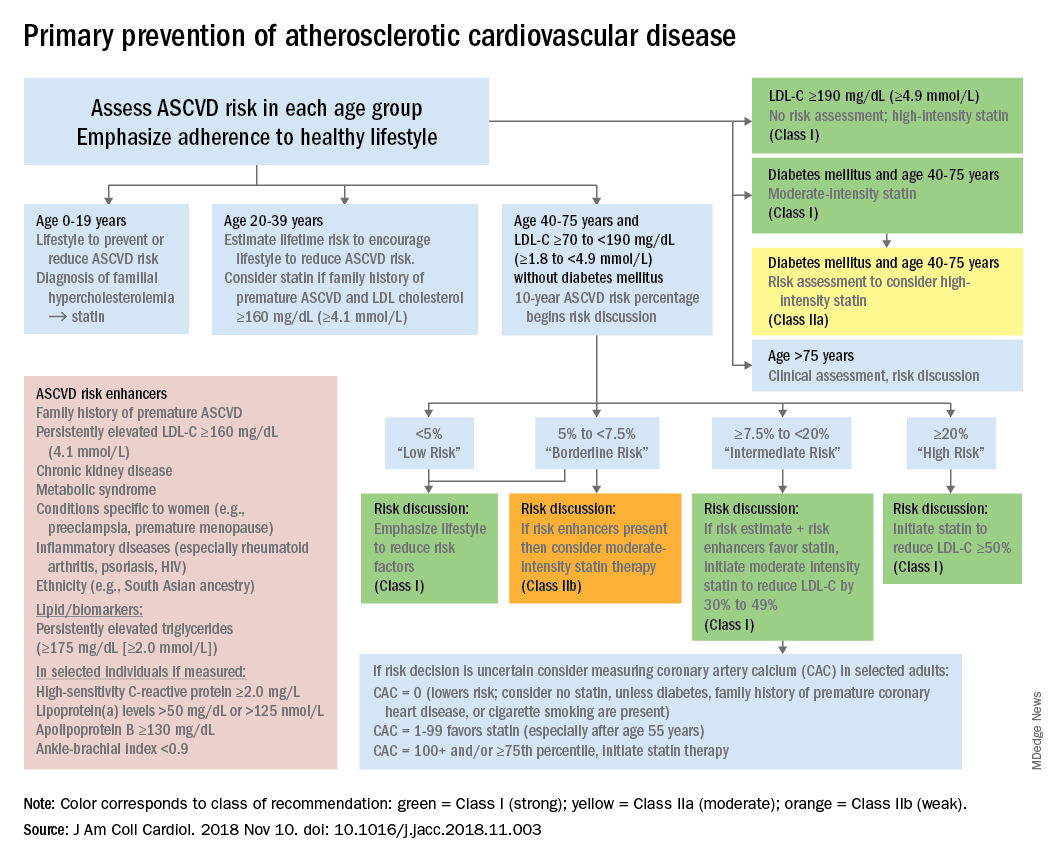

according to the 2018 update to U.S. guidelines for cholesterol management from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline also emphasizes “careful adherence to lifestyle recommendations at an early age [to] reduce risk factor burden over the lifespan and decrease the need for preventive drug therapies later in life,” Scott M. Grundy, MD, PhD, and Neil J. Stone, MD, said in a synopsis of the document in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

For primary prevention in patients aged 40-75 years, estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk – introduced in the 2013 guidelines – and stratification into one of four categories should set the stage for clinician-patient discussion. A score of less than 5% indicates low risk and should prompt a risk discussion that emphasizes lifestyle recommendations. “Statins are clinically efficacious in the latter three categories, but the higher the risk, the stronger the statin indication,” said Dr. Grundy of the University of Texas, Dallas, and Dr. Stone of Northwestern University, Chicago.

When risk status is uncertain, measurement of coronary artery calcium should be considered in patients aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol levels of 70-189 mg/dL who do no not have diabetes, they noted.

The guideline emphasizes secondary prevention with “maximally tolerated doses of statins” and the use of nonstatin drugs such as ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors for patients with very high ASCVD risk – defined as a history of multiple major events or one event and other high-risk conditions, Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone wrote.

Financial support for the Guideline Writing Committee for the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines came from the AHA and the ACC. Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Grundy SM and Stone NJ. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.7326/M19-0365.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Upcoming OA management guidelines reveal dearth of effective therapies

TORONTO – Draft guidelines for the management of OA developed by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International expose an inconvenient truth: Although a tremendous number of interventions are available for the treatment of OA, the cupboard is nearly bare when it comes to strongly recommended, evidence-based therapies.

Indeed, the sole strong, level Ia recommendation for pharmacotherapy of knee OA contained in the 2019 guidelines is for topical NSAIDs. The proposed guidelines contain no level Ia recommendations at all for nonpharmacologic treatment of knee OA. And for hip OA and polyarticular OA – the other two expressions of the disease addressed in the guidelines – there are no level Ia recommendations, pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic. The treatment recommendations for hip OA and polyarticular OA start at level Ib and drop-off in strength from there, Raveendhara R. Bannuru, MD, said at the OARSI 2019 World Congress. He and his fellow OARSI guideline panelists reviewed roughly 12,500 published abstracts before winnowing down the literature to 407 articles for data extraction. The voting panel was comprised of orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, rheumatologists, primary care physicians, and sports medicine specialists from 10 countries. Panelists employed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, resulting in guidelines which were categorized as either “strong,” that is, first-line, level Ia, a designation that required endorsement by at least 75% of panelists, or weaker “conditional” recommendations. Voting was conducted anonymously, Dr. Bannuru said in presenting highlights of the draft guidelines at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

A challenge in coming up with evidence-based guidelines for OA management is that most of the existing research is focused on patients with knee OA and no comorbid conditions, he explained. The panelists wanted to create patient-centric guidelines, so they tackled hip OA and polyarticular OA as well, despite the paucity of good-quality data. And the guidelines separately address five common comorbidity scenarios for each of the three forms of OA: GI or cardiovascular comorbidity, frailty, comorbid widespread pain disorder/depression, and OA with no major comorbid conditions.

The draft guidelines feature one category of recommendations, known as the core recommendations, which are even stronger than the level Ia recommendations. The core recommendations are defined as key treatments deemed appropriate for nearly any OA patient at all points in treatment. The core recommendations are considered standard of care – the first interventions to utilize – to be supplemented by level Ia and Ib interventions added on as needed, with lower-level recommendations available when core plus levels Ia and Ib interventions don’t achieve the desired results.

The core recommendations include arthritis education, dietary weight management, and a structured, land-based exercise program involving strengthening and/or cardiovascular exercise and/or balance training. In a major departure from previous guidelines, mind-body exercise is categorized as a core recommendation, although just for patients with knee OA.

“Mind-body exercise is comprised of tai chi and yoga only. We do not recommend other things,” according to Dr. Bannuru, director of the Center for Treatment Comparison and Integrative Analysis at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

For hip OA, mind-body exercise gets demoted to a level Ib nonpharmacologic recommendation across all five comorbidity categories, along with aquatic exercise, gait aids, and self-management programs.

Dr. Bannuru pointed out other highlights of the proposed guidelines: Opioids and acetaminophen are not recommended, duloxetine (Cymbalta) gets a conditional recommendation in OA patients with comorbid depression, and nonspecific NSAIDs are not recommended in OA patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease or frailty. When nonspecific NSAIDs are used, it should be at the lowest possible dose, for only 1-4 weeks, and in conjunction with a proton pump inhibitor, according to the draft guidelines.

Patient representatives asked the guideline panelists specifically about a number of interventions for OA popular in some circles but which the panel members are strongly opposed to because of unfavorable efficacy and safety profiles. The resulting “forget-about-it” list included colchicine, collagen, diacerein, doxycycline, dextrose prolotherapy, electrical stimulation, and electroacupuncture, with explanations provided as to why they deserve to be rejected.

The OA guidelines project was funded by the Arthritis Foundation, Versus Arthritis, and ReumaNederlands, with no industry funding.

TORONTO – Draft guidelines for the management of OA developed by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International expose an inconvenient truth: Although a tremendous number of interventions are available for the treatment of OA, the cupboard is nearly bare when it comes to strongly recommended, evidence-based therapies.

Indeed, the sole strong, level Ia recommendation for pharmacotherapy of knee OA contained in the 2019 guidelines is for topical NSAIDs. The proposed guidelines contain no level Ia recommendations at all for nonpharmacologic treatment of knee OA. And for hip OA and polyarticular OA – the other two expressions of the disease addressed in the guidelines – there are no level Ia recommendations, pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic. The treatment recommendations for hip OA and polyarticular OA start at level Ib and drop-off in strength from there, Raveendhara R. Bannuru, MD, said at the OARSI 2019 World Congress. He and his fellow OARSI guideline panelists reviewed roughly 12,500 published abstracts before winnowing down the literature to 407 articles for data extraction. The voting panel was comprised of orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, rheumatologists, primary care physicians, and sports medicine specialists from 10 countries. Panelists employed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, resulting in guidelines which were categorized as either “strong,” that is, first-line, level Ia, a designation that required endorsement by at least 75% of panelists, or weaker “conditional” recommendations. Voting was conducted anonymously, Dr. Bannuru said in presenting highlights of the draft guidelines at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

A challenge in coming up with evidence-based guidelines for OA management is that most of the existing research is focused on patients with knee OA and no comorbid conditions, he explained. The panelists wanted to create patient-centric guidelines, so they tackled hip OA and polyarticular OA as well, despite the paucity of good-quality data. And the guidelines separately address five common comorbidity scenarios for each of the three forms of OA: GI or cardiovascular comorbidity, frailty, comorbid widespread pain disorder/depression, and OA with no major comorbid conditions.

The draft guidelines feature one category of recommendations, known as the core recommendations, which are even stronger than the level Ia recommendations. The core recommendations are defined as key treatments deemed appropriate for nearly any OA patient at all points in treatment. The core recommendations are considered standard of care – the first interventions to utilize – to be supplemented by level Ia and Ib interventions added on as needed, with lower-level recommendations available when core plus levels Ia and Ib interventions don’t achieve the desired results.

The core recommendations include arthritis education, dietary weight management, and a structured, land-based exercise program involving strengthening and/or cardiovascular exercise and/or balance training. In a major departure from previous guidelines, mind-body exercise is categorized as a core recommendation, although just for patients with knee OA.

“Mind-body exercise is comprised of tai chi and yoga only. We do not recommend other things,” according to Dr. Bannuru, director of the Center for Treatment Comparison and Integrative Analysis at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

For hip OA, mind-body exercise gets demoted to a level Ib nonpharmacologic recommendation across all five comorbidity categories, along with aquatic exercise, gait aids, and self-management programs.

Dr. Bannuru pointed out other highlights of the proposed guidelines: Opioids and acetaminophen are not recommended, duloxetine (Cymbalta) gets a conditional recommendation in OA patients with comorbid depression, and nonspecific NSAIDs are not recommended in OA patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease or frailty. When nonspecific NSAIDs are used, it should be at the lowest possible dose, for only 1-4 weeks, and in conjunction with a proton pump inhibitor, according to the draft guidelines.

Patient representatives asked the guideline panelists specifically about a number of interventions for OA popular in some circles but which the panel members are strongly opposed to because of unfavorable efficacy and safety profiles. The resulting “forget-about-it” list included colchicine, collagen, diacerein, doxycycline, dextrose prolotherapy, electrical stimulation, and electroacupuncture, with explanations provided as to why they deserve to be rejected.

The OA guidelines project was funded by the Arthritis Foundation, Versus Arthritis, and ReumaNederlands, with no industry funding.

TORONTO – Draft guidelines for the management of OA developed by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International expose an inconvenient truth: Although a tremendous number of interventions are available for the treatment of OA, the cupboard is nearly bare when it comes to strongly recommended, evidence-based therapies.

Indeed, the sole strong, level Ia recommendation for pharmacotherapy of knee OA contained in the 2019 guidelines is for topical NSAIDs. The proposed guidelines contain no level Ia recommendations at all for nonpharmacologic treatment of knee OA. And for hip OA and polyarticular OA – the other two expressions of the disease addressed in the guidelines – there are no level Ia recommendations, pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic. The treatment recommendations for hip OA and polyarticular OA start at level Ib and drop-off in strength from there, Raveendhara R. Bannuru, MD, said at the OARSI 2019 World Congress. He and his fellow OARSI guideline panelists reviewed roughly 12,500 published abstracts before winnowing down the literature to 407 articles for data extraction. The voting panel was comprised of orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, rheumatologists, primary care physicians, and sports medicine specialists from 10 countries. Panelists employed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, resulting in guidelines which were categorized as either “strong,” that is, first-line, level Ia, a designation that required endorsement by at least 75% of panelists, or weaker “conditional” recommendations. Voting was conducted anonymously, Dr. Bannuru said in presenting highlights of the draft guidelines at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

A challenge in coming up with evidence-based guidelines for OA management is that most of the existing research is focused on patients with knee OA and no comorbid conditions, he explained. The panelists wanted to create patient-centric guidelines, so they tackled hip OA and polyarticular OA as well, despite the paucity of good-quality data. And the guidelines separately address five common comorbidity scenarios for each of the three forms of OA: GI or cardiovascular comorbidity, frailty, comorbid widespread pain disorder/depression, and OA with no major comorbid conditions.

The draft guidelines feature one category of recommendations, known as the core recommendations, which are even stronger than the level Ia recommendations. The core recommendations are defined as key treatments deemed appropriate for nearly any OA patient at all points in treatment. The core recommendations are considered standard of care – the first interventions to utilize – to be supplemented by level Ia and Ib interventions added on as needed, with lower-level recommendations available when core plus levels Ia and Ib interventions don’t achieve the desired results.

The core recommendations include arthritis education, dietary weight management, and a structured, land-based exercise program involving strengthening and/or cardiovascular exercise and/or balance training. In a major departure from previous guidelines, mind-body exercise is categorized as a core recommendation, although just for patients with knee OA.

“Mind-body exercise is comprised of tai chi and yoga only. We do not recommend other things,” according to Dr. Bannuru, director of the Center for Treatment Comparison and Integrative Analysis at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

For hip OA, mind-body exercise gets demoted to a level Ib nonpharmacologic recommendation across all five comorbidity categories, along with aquatic exercise, gait aids, and self-management programs.

Dr. Bannuru pointed out other highlights of the proposed guidelines: Opioids and acetaminophen are not recommended, duloxetine (Cymbalta) gets a conditional recommendation in OA patients with comorbid depression, and nonspecific NSAIDs are not recommended in OA patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease or frailty. When nonspecific NSAIDs are used, it should be at the lowest possible dose, for only 1-4 weeks, and in conjunction with a proton pump inhibitor, according to the draft guidelines.

Patient representatives asked the guideline panelists specifically about a number of interventions for OA popular in some circles but which the panel members are strongly opposed to because of unfavorable efficacy and safety profiles. The resulting “forget-about-it” list included colchicine, collagen, diacerein, doxycycline, dextrose prolotherapy, electrical stimulation, and electroacupuncture, with explanations provided as to why they deserve to be rejected.

The OA guidelines project was funded by the Arthritis Foundation, Versus Arthritis, and ReumaNederlands, with no industry funding.

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

Stroke policy recommendations incorporate advances in endovascular therapy

Stroke centers need to collaborate within their regions to assure best practices and optimal access to comprehensive stroke centers as well as newly-designated thrombectomy-capable stroke centers, according to an updated policy statement from the American Stroke Association published in Stroke.

Opeolu Adeoye, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine and neurosurgery at the University of Cincinnati – and chair of the policy statement writing group – and coauthors updated the ASA’s 2005 recommendations for policy makers and public health care agencies to reflect current evidence, the increased availability of endovascular therapy, and new stroke center certifications.

“We have seen monumental advancements in acute stroke care over the past 14 years, and our concept of a comprehensive stroke system of care has evolved as a result,” Dr. Adeoye said in a news release.

While a recommendation to support the initiation of stroke prevention regimens remains unchanged from the 2005 recommendations, the 2019 update emphasizes a need to support long-term adherence to such regimens. To that end, researchers should examine the potential benefits of stroke prevention efforts that incorporate social media, gamification, and other technologies and principles to promote healthy behavior, the authors suggested. Furthermore, technology may allow for the passive surveillance of baseline behaviors and enable researchers to track changes in behavior over time.

Thrombectomy-capable centers

Thrombectomy-capable stroke centers, which have capabilities between those of primary stroke centers and comprehensive stroke centers, provide a relatively new level of acute stroke care. In communities that do not otherwise have access to thrombectomy, these centers play a clear role. In communities with comprehensive stroke centers, their role “is more controversial, and routing plans for patients with a suspected LVO [large vessel occlusion] should always seek the center of highest capability when travel time differences are short,” the statement says.

Timely parenchymal and arterial imaging via CT or MRI are needed to identify the subset of patients who may benefit from thrombectomy. All centers managing stroke patients should develop a plan for the definitive identification and treatment of these patients. Imaging techniques that assess penumbral patterns to identify candidates for endovascular therapy between 6 and 24 hours after patients were last known to be normal “merit broader adoption,” the statement says.

Hospitals without thrombectomy capability should have transfer protocols to allow the rapid treatment of these patients to hospitals with the appropriate level of care. In rural facilities that lack 24/7 imaging and radiology capabilities, this may mean rapid transfer of patients with clinically suspected LVO to hospitals where their work-up may be expedited.

To improve process, centers providing thrombectomy should rigorously track patient flow at all time points from presentation to imaging to intervention. Reperfusion rates, procedural complications, and patient clinical outcomes must be tracked and reported.

Travel times

Triage paradigms and protocols should be developed to ensure that emergency medical service (EMS) providers are able to rapidly identify all patients with a known or suspected stroke and to assess them with a validated and standardized instrument for stroke screening such as FAST (Face, Arm, Speech, Time), Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen, or Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale.

In prehospital patients who screen positive for suspected stroke, a standard prehospital stroke severity assessment tool such as the Cincinnati Stroke Triage Assessment Tool, Rapid Arterial Occlusion Evaluation, Los Angeles Motor Scale, or Field Assessment Stroke Triage for Emergency Destination should be used. “Further research is needed to establish the most effective prehospital stroke severity triage scale,” the authors noted. In all cases, EMS should notify hospitals that a stroke patient is en route.

“When there are several intravenous alteplase–capable hospitals in a well-defined geographic region, extra transportation times to reach a facility capable of endovascular thrombectomy should be limited to no more than 15 minutes in patients with a prehospital stroke severity score suggestive of LVO,” according to the recommendations. “When several hospital options exist within similar travel times, EMS should seek care at the facility capable of offering the highest level of stroke care. Further research is needed to establish travel time parameters for hospital bypass in cases of prehospital suspicion of LVO.”

Outcomes and discharge

Centers should track various treatment and patient outcomes, and all patients discharged to their homes should have appropriate follow-up with specialized stroke services and primary care and be screened for postacute complications.

Government institutions should standardize the organization of stroke care, ensure that stroke patients receive timely care at appropriate hospitals, and facilitate access to secondary prevention and rehabilitation resources after stroke, the authors wrote.

“Programs geared at further improving the knowledge of the public, encouraging primordial and primary prevention, advancing and facilitating acute therapy, improving secondary prevention and recovery from stroke, and reducing disparities in stroke care should be actively developed in a coordinated and collaborative fashion by providers and policymakers at the local, state, and national levels,” the authors concluded. “Such efforts will continue to mitigate the effects of stroke on society.”

Dr. Adeoye had no disclosures. Some coauthors reported research grants and consultant or advisory board positions.

SOURCE: Adeoye O et al. Stroke. 2019 May 20. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000173.

When determining where to transport a patient with stroke, uncertainty about the patient’s diagnosis and eligibility for thrombectomy is a necessary consideration, said Robert A. Harrington, MD, of Stanford University (Calif.), in an accompanying editorial.

In lieu of better data, stroke systems should follow the recommendation of the Mission: Lifeline Severity-based Stroke Triage Algorithm for emergency medical services to avoid more than 15 minutes of additional travel time to transport a patient to a center that can perform endovascular therapy when the patient may be eligible for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), said Dr. Harrington.

Delays in initiating tPA could lead to some patients not receiving treatment. “Some patients with suspected LVO [large vessel occlusion] either will not have thrombectomy or will not be eligible for it, and they also run the risk of not receiving any acute reperfusion therapy. Consequently, transport algorithms and models must take into account the uncertainty in prehospital diagnosis when considering the most appropriate facility,” he said.

Forthcoming acute stroke guidelines “will recommend intravenous tPA for all eligible subjects” because administration of tPA before endovascular thrombectomy does not appear to be harmful, Dr. Harrington noted.

Ultimately, approaches to routing patients may vary by region. “It is up to local and regional communities ... to define how best to implement these elements into a stroke system of care that meets their needs and resources and to define the types of hospitals that should qualify as points of entry for patients with suspected LVO strokes,” Dr. Harrington said.

A group convened by the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association is drafting further guiding principles for stroke systems of care in various regional settings.

Dr. Harrington is president-elect of the American Heart Association. He reported receiving research grants from AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

When determining where to transport a patient with stroke, uncertainty about the patient’s diagnosis and eligibility for thrombectomy is a necessary consideration, said Robert A. Harrington, MD, of Stanford University (Calif.), in an accompanying editorial.

In lieu of better data, stroke systems should follow the recommendation of the Mission: Lifeline Severity-based Stroke Triage Algorithm for emergency medical services to avoid more than 15 minutes of additional travel time to transport a patient to a center that can perform endovascular therapy when the patient may be eligible for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), said Dr. Harrington.

Delays in initiating tPA could lead to some patients not receiving treatment. “Some patients with suspected LVO [large vessel occlusion] either will not have thrombectomy or will not be eligible for it, and they also run the risk of not receiving any acute reperfusion therapy. Consequently, transport algorithms and models must take into account the uncertainty in prehospital diagnosis when considering the most appropriate facility,” he said.

Forthcoming acute stroke guidelines “will recommend intravenous tPA for all eligible subjects” because administration of tPA before endovascular thrombectomy does not appear to be harmful, Dr. Harrington noted.

Ultimately, approaches to routing patients may vary by region. “It is up to local and regional communities ... to define how best to implement these elements into a stroke system of care that meets their needs and resources and to define the types of hospitals that should qualify as points of entry for patients with suspected LVO strokes,” Dr. Harrington said.

A group convened by the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association is drafting further guiding principles for stroke systems of care in various regional settings.

Dr. Harrington is president-elect of the American Heart Association. He reported receiving research grants from AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

When determining where to transport a patient with stroke, uncertainty about the patient’s diagnosis and eligibility for thrombectomy is a necessary consideration, said Robert A. Harrington, MD, of Stanford University (Calif.), in an accompanying editorial.

In lieu of better data, stroke systems should follow the recommendation of the Mission: Lifeline Severity-based Stroke Triage Algorithm for emergency medical services to avoid more than 15 minutes of additional travel time to transport a patient to a center that can perform endovascular therapy when the patient may be eligible for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), said Dr. Harrington.

Delays in initiating tPA could lead to some patients not receiving treatment. “Some patients with suspected LVO [large vessel occlusion] either will not have thrombectomy or will not be eligible for it, and they also run the risk of not receiving any acute reperfusion therapy. Consequently, transport algorithms and models must take into account the uncertainty in prehospital diagnosis when considering the most appropriate facility,” he said.

Forthcoming acute stroke guidelines “will recommend intravenous tPA for all eligible subjects” because administration of tPA before endovascular thrombectomy does not appear to be harmful, Dr. Harrington noted.

Ultimately, approaches to routing patients may vary by region. “It is up to local and regional communities ... to define how best to implement these elements into a stroke system of care that meets their needs and resources and to define the types of hospitals that should qualify as points of entry for patients with suspected LVO strokes,” Dr. Harrington said.

A group convened by the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association is drafting further guiding principles for stroke systems of care in various regional settings.

Dr. Harrington is president-elect of the American Heart Association. He reported receiving research grants from AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Stroke centers need to collaborate within their regions to assure best practices and optimal access to comprehensive stroke centers as well as newly-designated thrombectomy-capable stroke centers, according to an updated policy statement from the American Stroke Association published in Stroke.

Opeolu Adeoye, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine and neurosurgery at the University of Cincinnati – and chair of the policy statement writing group – and coauthors updated the ASA’s 2005 recommendations for policy makers and public health care agencies to reflect current evidence, the increased availability of endovascular therapy, and new stroke center certifications.

“We have seen monumental advancements in acute stroke care over the past 14 years, and our concept of a comprehensive stroke system of care has evolved as a result,” Dr. Adeoye said in a news release.

While a recommendation to support the initiation of stroke prevention regimens remains unchanged from the 2005 recommendations, the 2019 update emphasizes a need to support long-term adherence to such regimens. To that end, researchers should examine the potential benefits of stroke prevention efforts that incorporate social media, gamification, and other technologies and principles to promote healthy behavior, the authors suggested. Furthermore, technology may allow for the passive surveillance of baseline behaviors and enable researchers to track changes in behavior over time.

Thrombectomy-capable centers

Thrombectomy-capable stroke centers, which have capabilities between those of primary stroke centers and comprehensive stroke centers, provide a relatively new level of acute stroke care. In communities that do not otherwise have access to thrombectomy, these centers play a clear role. In communities with comprehensive stroke centers, their role “is more controversial, and routing plans for patients with a suspected LVO [large vessel occlusion] should always seek the center of highest capability when travel time differences are short,” the statement says.

Timely parenchymal and arterial imaging via CT or MRI are needed to identify the subset of patients who may benefit from thrombectomy. All centers managing stroke patients should develop a plan for the definitive identification and treatment of these patients. Imaging techniques that assess penumbral patterns to identify candidates for endovascular therapy between 6 and 24 hours after patients were last known to be normal “merit broader adoption,” the statement says.

Hospitals without thrombectomy capability should have transfer protocols to allow the rapid treatment of these patients to hospitals with the appropriate level of care. In rural facilities that lack 24/7 imaging and radiology capabilities, this may mean rapid transfer of patients with clinically suspected LVO to hospitals where their work-up may be expedited.

To improve process, centers providing thrombectomy should rigorously track patient flow at all time points from presentation to imaging to intervention. Reperfusion rates, procedural complications, and patient clinical outcomes must be tracked and reported.

Travel times

Triage paradigms and protocols should be developed to ensure that emergency medical service (EMS) providers are able to rapidly identify all patients with a known or suspected stroke and to assess them with a validated and standardized instrument for stroke screening such as FAST (Face, Arm, Speech, Time), Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen, or Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale.

In prehospital patients who screen positive for suspected stroke, a standard prehospital stroke severity assessment tool such as the Cincinnati Stroke Triage Assessment Tool, Rapid Arterial Occlusion Evaluation, Los Angeles Motor Scale, or Field Assessment Stroke Triage for Emergency Destination should be used. “Further research is needed to establish the most effective prehospital stroke severity triage scale,” the authors noted. In all cases, EMS should notify hospitals that a stroke patient is en route.

“When there are several intravenous alteplase–capable hospitals in a well-defined geographic region, extra transportation times to reach a facility capable of endovascular thrombectomy should be limited to no more than 15 minutes in patients with a prehospital stroke severity score suggestive of LVO,” according to the recommendations. “When several hospital options exist within similar travel times, EMS should seek care at the facility capable of offering the highest level of stroke care. Further research is needed to establish travel time parameters for hospital bypass in cases of prehospital suspicion of LVO.”

Outcomes and discharge

Centers should track various treatment and patient outcomes, and all patients discharged to their homes should have appropriate follow-up with specialized stroke services and primary care and be screened for postacute complications.

Government institutions should standardize the organization of stroke care, ensure that stroke patients receive timely care at appropriate hospitals, and facilitate access to secondary prevention and rehabilitation resources after stroke, the authors wrote.

“Programs geared at further improving the knowledge of the public, encouraging primordial and primary prevention, advancing and facilitating acute therapy, improving secondary prevention and recovery from stroke, and reducing disparities in stroke care should be actively developed in a coordinated and collaborative fashion by providers and policymakers at the local, state, and national levels,” the authors concluded. “Such efforts will continue to mitigate the effects of stroke on society.”

Dr. Adeoye had no disclosures. Some coauthors reported research grants and consultant or advisory board positions.

SOURCE: Adeoye O et al. Stroke. 2019 May 20. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000173.

Stroke centers need to collaborate within their regions to assure best practices and optimal access to comprehensive stroke centers as well as newly-designated thrombectomy-capable stroke centers, according to an updated policy statement from the American Stroke Association published in Stroke.

Opeolu Adeoye, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine and neurosurgery at the University of Cincinnati – and chair of the policy statement writing group – and coauthors updated the ASA’s 2005 recommendations for policy makers and public health care agencies to reflect current evidence, the increased availability of endovascular therapy, and new stroke center certifications.

“We have seen monumental advancements in acute stroke care over the past 14 years, and our concept of a comprehensive stroke system of care has evolved as a result,” Dr. Adeoye said in a news release.

While a recommendation to support the initiation of stroke prevention regimens remains unchanged from the 2005 recommendations, the 2019 update emphasizes a need to support long-term adherence to such regimens. To that end, researchers should examine the potential benefits of stroke prevention efforts that incorporate social media, gamification, and other technologies and principles to promote healthy behavior, the authors suggested. Furthermore, technology may allow for the passive surveillance of baseline behaviors and enable researchers to track changes in behavior over time.

Thrombectomy-capable centers

Thrombectomy-capable stroke centers, which have capabilities between those of primary stroke centers and comprehensive stroke centers, provide a relatively new level of acute stroke care. In communities that do not otherwise have access to thrombectomy, these centers play a clear role. In communities with comprehensive stroke centers, their role “is more controversial, and routing plans for patients with a suspected LVO [large vessel occlusion] should always seek the center of highest capability when travel time differences are short,” the statement says.

Timely parenchymal and arterial imaging via CT or MRI are needed to identify the subset of patients who may benefit from thrombectomy. All centers managing stroke patients should develop a plan for the definitive identification and treatment of these patients. Imaging techniques that assess penumbral patterns to identify candidates for endovascular therapy between 6 and 24 hours after patients were last known to be normal “merit broader adoption,” the statement says.

Hospitals without thrombectomy capability should have transfer protocols to allow the rapid treatment of these patients to hospitals with the appropriate level of care. In rural facilities that lack 24/7 imaging and radiology capabilities, this may mean rapid transfer of patients with clinically suspected LVO to hospitals where their work-up may be expedited.

To improve process, centers providing thrombectomy should rigorously track patient flow at all time points from presentation to imaging to intervention. Reperfusion rates, procedural complications, and patient clinical outcomes must be tracked and reported.

Travel times

Triage paradigms and protocols should be developed to ensure that emergency medical service (EMS) providers are able to rapidly identify all patients with a known or suspected stroke and to assess them with a validated and standardized instrument for stroke screening such as FAST (Face, Arm, Speech, Time), Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen, or Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale.

In prehospital patients who screen positive for suspected stroke, a standard prehospital stroke severity assessment tool such as the Cincinnati Stroke Triage Assessment Tool, Rapid Arterial Occlusion Evaluation, Los Angeles Motor Scale, or Field Assessment Stroke Triage for Emergency Destination should be used. “Further research is needed to establish the most effective prehospital stroke severity triage scale,” the authors noted. In all cases, EMS should notify hospitals that a stroke patient is en route.

“When there are several intravenous alteplase–capable hospitals in a well-defined geographic region, extra transportation times to reach a facility capable of endovascular thrombectomy should be limited to no more than 15 minutes in patients with a prehospital stroke severity score suggestive of LVO,” according to the recommendations. “When several hospital options exist within similar travel times, EMS should seek care at the facility capable of offering the highest level of stroke care. Further research is needed to establish travel time parameters for hospital bypass in cases of prehospital suspicion of LVO.”

Outcomes and discharge

Centers should track various treatment and patient outcomes, and all patients discharged to their homes should have appropriate follow-up with specialized stroke services and primary care and be screened for postacute complications.