User login

CNS lymphoma guidelines stress patient fitness, not age, in choosing treatment

for the diagnosis and management of primary central nervous system diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma.

PCNSL, implicated in some 3% of all brain tumors, is complex to diagnose and treat. People with suspected PCNSL must receive quick and coordinated attention from a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, hematologist-oncologists, and ocular specialists, according to the guidelines, published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Christopher P. Fox, MD, of the Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, and his colleagues, stress the importance of early multidisciplinary attention, aggressive induction treatment, helping patients into trials, universal screening for eye involvement, attaining histological diagnoses in addition to imaging findings, and avoidance or discontinuation of any corticosteroids before biopsy, as even a short course of steroids can impede diagnosis.

The guidelines incorporate findings from studies published since the society’s last comprehensive PCNSL guideline was issued more than a decade ago.

Dr. Fox and his colleagues say definitive treatment for PCNSL – induction of remission followed by consolidation – should start within 2 weeks of diagnosis and that a treatment regimen should be chosen according to a patient’s physiological fitness, not age. The fittest patients, who have better organ function and fewer comorbidities, should be eligible for intensive combination immunochemotherapy incorporating high-dose methotrexate (optimally four cycles of HD-MTX, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab). Those deemed unfit for this regimen should be offered induction treatment with HD-MTX, rituximab and procarbazine, the guidelines’ authors say.

If patients cannot tolerate HD-MTX, oral chemotherapy and/or whole-brain radiotherapy may be offered. Response should be assessed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging.

Consolidation therapy should be initiated after induction for all patients with nonprogressive disease, and high-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant is the recommended first-line option for consolidation. Response to consolidation, again measured with contrast-enhanced MRI, should be carried out at between 1 and 2 months after therapy is completed, and patients should be referred for neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function.

Patients with relapsed or refractory disease should be approached with maximum urgency – the guidelines offer an algorithm for retreatment options – and offered clinical trial entry wherever possible.

The PCNSL guideline writing process was sponsored by the British Society for Haematology, and some coauthors, including the lead author, disclosed receiving fees from pharmaceutical manufacturers Adienne or F. Hoffman-La Roche.

SOURCE: Fox et al. Br J Haematol. 2018 Nov 23 doi: 10.1111/bjh.15661.

for the diagnosis and management of primary central nervous system diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma.

PCNSL, implicated in some 3% of all brain tumors, is complex to diagnose and treat. People with suspected PCNSL must receive quick and coordinated attention from a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, hematologist-oncologists, and ocular specialists, according to the guidelines, published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Christopher P. Fox, MD, of the Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, and his colleagues, stress the importance of early multidisciplinary attention, aggressive induction treatment, helping patients into trials, universal screening for eye involvement, attaining histological diagnoses in addition to imaging findings, and avoidance or discontinuation of any corticosteroids before biopsy, as even a short course of steroids can impede diagnosis.

The guidelines incorporate findings from studies published since the society’s last comprehensive PCNSL guideline was issued more than a decade ago.

Dr. Fox and his colleagues say definitive treatment for PCNSL – induction of remission followed by consolidation – should start within 2 weeks of diagnosis and that a treatment regimen should be chosen according to a patient’s physiological fitness, not age. The fittest patients, who have better organ function and fewer comorbidities, should be eligible for intensive combination immunochemotherapy incorporating high-dose methotrexate (optimally four cycles of HD-MTX, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab). Those deemed unfit for this regimen should be offered induction treatment with HD-MTX, rituximab and procarbazine, the guidelines’ authors say.

If patients cannot tolerate HD-MTX, oral chemotherapy and/or whole-brain radiotherapy may be offered. Response should be assessed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging.

Consolidation therapy should be initiated after induction for all patients with nonprogressive disease, and high-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant is the recommended first-line option for consolidation. Response to consolidation, again measured with contrast-enhanced MRI, should be carried out at between 1 and 2 months after therapy is completed, and patients should be referred for neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function.

Patients with relapsed or refractory disease should be approached with maximum urgency – the guidelines offer an algorithm for retreatment options – and offered clinical trial entry wherever possible.

The PCNSL guideline writing process was sponsored by the British Society for Haematology, and some coauthors, including the lead author, disclosed receiving fees from pharmaceutical manufacturers Adienne or F. Hoffman-La Roche.

SOURCE: Fox et al. Br J Haematol. 2018 Nov 23 doi: 10.1111/bjh.15661.

for the diagnosis and management of primary central nervous system diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma.

PCNSL, implicated in some 3% of all brain tumors, is complex to diagnose and treat. People with suspected PCNSL must receive quick and coordinated attention from a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, hematologist-oncologists, and ocular specialists, according to the guidelines, published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Christopher P. Fox, MD, of the Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, and his colleagues, stress the importance of early multidisciplinary attention, aggressive induction treatment, helping patients into trials, universal screening for eye involvement, attaining histological diagnoses in addition to imaging findings, and avoidance or discontinuation of any corticosteroids before biopsy, as even a short course of steroids can impede diagnosis.

The guidelines incorporate findings from studies published since the society’s last comprehensive PCNSL guideline was issued more than a decade ago.

Dr. Fox and his colleagues say definitive treatment for PCNSL – induction of remission followed by consolidation – should start within 2 weeks of diagnosis and that a treatment regimen should be chosen according to a patient’s physiological fitness, not age. The fittest patients, who have better organ function and fewer comorbidities, should be eligible for intensive combination immunochemotherapy incorporating high-dose methotrexate (optimally four cycles of HD-MTX, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab). Those deemed unfit for this regimen should be offered induction treatment with HD-MTX, rituximab and procarbazine, the guidelines’ authors say.

If patients cannot tolerate HD-MTX, oral chemotherapy and/or whole-brain radiotherapy may be offered. Response should be assessed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging.

Consolidation therapy should be initiated after induction for all patients with nonprogressive disease, and high-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant is the recommended first-line option for consolidation. Response to consolidation, again measured with contrast-enhanced MRI, should be carried out at between 1 and 2 months after therapy is completed, and patients should be referred for neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function.

Patients with relapsed or refractory disease should be approached with maximum urgency – the guidelines offer an algorithm for retreatment options – and offered clinical trial entry wherever possible.

The PCNSL guideline writing process was sponsored by the British Society for Haematology, and some coauthors, including the lead author, disclosed receiving fees from pharmaceutical manufacturers Adienne or F. Hoffman-La Roche.

SOURCE: Fox et al. Br J Haematol. 2018 Nov 23 doi: 10.1111/bjh.15661.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF HAEMATOLOGY

ASH releases new VTE guidelines

The new guidelines, released on Nov. 27, contain more than 150 individual recommendations, including sections devoted to managing venous thromboembolism (VTE) during pregnancy and in pediatric patients. Guideline highlights cited by some of the writing-panel participants included a high reliance on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) agents as the preferred treatment for many patients, reliance on the D-dimer test to rule out VTE in patients with a low pretest probability of disease, and reliance on the 4Ts score to identify patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines took more than 3 years to develop, an effort that began in 2015.

An updated set of VTE guidelines were needed because clinicians now have a “greater understanding of risk factors” for VTE as well as having “more options available for treating VTE, including new medications,” Adam C. Cuker, MD, cochair of the guideline-writing group and a hematologist and thrombosis specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said during a webcast to unveil the new guidelines.

Prevention

For preventing VTE in hospitalized medical patients the guidelines recommended initial assessment of the patient’s risk for both VTE and bleeding. Patients with a high bleeding risk who need VTE prevention should preferentially receive mechanical prophylaxis, either compression stockings or pneumatic sleeves. But in patients with a high VTE risk and an “acceptable” bleeding risk, prophylaxis with an anticoagulant is preferred over mechanical measures, said Mary Cushman, MD, professor and medical director of the thrombosis and hemostasis program at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

For prevention of VTE in medical inpatients, LMWH is preferred over unfractionated heparin because of its once-daily dosing and fewer complications, said Dr. Cushman, a member of the writing group. The panel also endorsed LMWH over a direct-acting oral anticoagulant, both during hospitalization and following discharge. The guidelines for prevention in medical patients explicitly “recommended against” using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant “over other treatments” both for hospitalized medical patients and after discharge, and the guidelines further recommend against extended prophylaxis after discharge with any other anticoagulant.

Another important takeaway from the prevention section was a statement that combining both mechanical and medical prophylaxis was not needed for medical inpatients. And once patients are discharged, if they take a long air trip they have no need for compression stockings or aspirin if their risk for thrombosis is not elevated. People with a “substantially increased” thrombosis risk “may benefit” from compression stockings or treatment with LMWH, Dr. Cushman said.

Diagnosis

For diagnosis, Wendy Lim, MD, highlighted the need for first categorizing patients as having a low or high probability for VTE, a judgment that can aid the accuracy of the diagnosis and helps avoid unnecessary testing.

For patients with low pretest probability, the guidelines recommended the D-dimer test as the best first step. Further testing isn’t needed when the D-dimer is negative, noted Dr. Lim, a hematologist and professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The guidelines also recommended using ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) for imaging a pulmonary embolism over a CT scan, which uses more radiation. But V/Q scans are not ideal for assessing older patients or patients with lung disease, Dr. Lim cautioned.

Management

Management of VTE should occur, when feasible, through a specialized anticoagulation management service center, which can provide care that is best suited to the complexities of anticoagulation therapy. But it’s a level of care that many U.S. patients don’t currently receive and hence is an area ripe for growth, said Daniel M. Witt, PharmD, professor and vice-chair of pharmacotherapy at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The guidelines recommended against bridging therapy with LMWH for most patients who need to stop warfarin when undergoing an invasive procedure. The guidelines also called for “thoughtful” use of anticoagulant reversal agents and advised that patients who survive a major bleed while on anticoagulation should often resume the anticoagulant once they are stabilized.

For patients who develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the 4Ts score is the best way to make a more accurate diagnosis and boost the prospects for recovery, said Dr. Cuker (Blood. 2012 Nov 15;120[20]:4160-7). The guidelines cite several agents now available to treat this common complication, which affects about 1% of the 12 million Americans treated with heparin annually: argatroban, bivalirudin, danaparoid, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban.

ASH has a VTE website with links to detailed information for each of the guideline subcategories: prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, therapy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, VTE in pregnancy, and VTE in children. The website indicates that additional guidelines will soon be released on managing VTE in patients with cancer, in patients with thrombophilia, and for prophylaxis in surgical patients, as well as further information on treatment. A spokesperson for ASH said that these additional documents will post sometime in 2019.

At the time of the release, the guidelines panel published six articles in the journal Blood Advances that detailed the guidelines and their documentation.

The articles include prophylaxis of medical patients (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3198-225), diagnosis (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3226-56), anticoagulation therapy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3257-91), pediatrics (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3292-316), pregnancy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3317-59), and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3360-92).

Dr. Cushman, Dr. Lim, and Dr. Witt reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Cuker reported receiving research support from T2 Biosystems.

The new guidelines, released on Nov. 27, contain more than 150 individual recommendations, including sections devoted to managing venous thromboembolism (VTE) during pregnancy and in pediatric patients. Guideline highlights cited by some of the writing-panel participants included a high reliance on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) agents as the preferred treatment for many patients, reliance on the D-dimer test to rule out VTE in patients with a low pretest probability of disease, and reliance on the 4Ts score to identify patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines took more than 3 years to develop, an effort that began in 2015.

An updated set of VTE guidelines were needed because clinicians now have a “greater understanding of risk factors” for VTE as well as having “more options available for treating VTE, including new medications,” Adam C. Cuker, MD, cochair of the guideline-writing group and a hematologist and thrombosis specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said during a webcast to unveil the new guidelines.

Prevention

For preventing VTE in hospitalized medical patients the guidelines recommended initial assessment of the patient’s risk for both VTE and bleeding. Patients with a high bleeding risk who need VTE prevention should preferentially receive mechanical prophylaxis, either compression stockings or pneumatic sleeves. But in patients with a high VTE risk and an “acceptable” bleeding risk, prophylaxis with an anticoagulant is preferred over mechanical measures, said Mary Cushman, MD, professor and medical director of the thrombosis and hemostasis program at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

For prevention of VTE in medical inpatients, LMWH is preferred over unfractionated heparin because of its once-daily dosing and fewer complications, said Dr. Cushman, a member of the writing group. The panel also endorsed LMWH over a direct-acting oral anticoagulant, both during hospitalization and following discharge. The guidelines for prevention in medical patients explicitly “recommended against” using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant “over other treatments” both for hospitalized medical patients and after discharge, and the guidelines further recommend against extended prophylaxis after discharge with any other anticoagulant.

Another important takeaway from the prevention section was a statement that combining both mechanical and medical prophylaxis was not needed for medical inpatients. And once patients are discharged, if they take a long air trip they have no need for compression stockings or aspirin if their risk for thrombosis is not elevated. People with a “substantially increased” thrombosis risk “may benefit” from compression stockings or treatment with LMWH, Dr. Cushman said.

Diagnosis

For diagnosis, Wendy Lim, MD, highlighted the need for first categorizing patients as having a low or high probability for VTE, a judgment that can aid the accuracy of the diagnosis and helps avoid unnecessary testing.

For patients with low pretest probability, the guidelines recommended the D-dimer test as the best first step. Further testing isn’t needed when the D-dimer is negative, noted Dr. Lim, a hematologist and professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The guidelines also recommended using ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) for imaging a pulmonary embolism over a CT scan, which uses more radiation. But V/Q scans are not ideal for assessing older patients or patients with lung disease, Dr. Lim cautioned.

Management

Management of VTE should occur, when feasible, through a specialized anticoagulation management service center, which can provide care that is best suited to the complexities of anticoagulation therapy. But it’s a level of care that many U.S. patients don’t currently receive and hence is an area ripe for growth, said Daniel M. Witt, PharmD, professor and vice-chair of pharmacotherapy at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The guidelines recommended against bridging therapy with LMWH for most patients who need to stop warfarin when undergoing an invasive procedure. The guidelines also called for “thoughtful” use of anticoagulant reversal agents and advised that patients who survive a major bleed while on anticoagulation should often resume the anticoagulant once they are stabilized.

For patients who develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the 4Ts score is the best way to make a more accurate diagnosis and boost the prospects for recovery, said Dr. Cuker (Blood. 2012 Nov 15;120[20]:4160-7). The guidelines cite several agents now available to treat this common complication, which affects about 1% of the 12 million Americans treated with heparin annually: argatroban, bivalirudin, danaparoid, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban.

ASH has a VTE website with links to detailed information for each of the guideline subcategories: prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, therapy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, VTE in pregnancy, and VTE in children. The website indicates that additional guidelines will soon be released on managing VTE in patients with cancer, in patients with thrombophilia, and for prophylaxis in surgical patients, as well as further information on treatment. A spokesperson for ASH said that these additional documents will post sometime in 2019.

At the time of the release, the guidelines panel published six articles in the journal Blood Advances that detailed the guidelines and their documentation.

The articles include prophylaxis of medical patients (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3198-225), diagnosis (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3226-56), anticoagulation therapy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3257-91), pediatrics (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3292-316), pregnancy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3317-59), and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3360-92).

Dr. Cushman, Dr. Lim, and Dr. Witt reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Cuker reported receiving research support from T2 Biosystems.

The new guidelines, released on Nov. 27, contain more than 150 individual recommendations, including sections devoted to managing venous thromboembolism (VTE) during pregnancy and in pediatric patients. Guideline highlights cited by some of the writing-panel participants included a high reliance on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) agents as the preferred treatment for many patients, reliance on the D-dimer test to rule out VTE in patients with a low pretest probability of disease, and reliance on the 4Ts score to identify patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines took more than 3 years to develop, an effort that began in 2015.

An updated set of VTE guidelines were needed because clinicians now have a “greater understanding of risk factors” for VTE as well as having “more options available for treating VTE, including new medications,” Adam C. Cuker, MD, cochair of the guideline-writing group and a hematologist and thrombosis specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said during a webcast to unveil the new guidelines.

Prevention

For preventing VTE in hospitalized medical patients the guidelines recommended initial assessment of the patient’s risk for both VTE and bleeding. Patients with a high bleeding risk who need VTE prevention should preferentially receive mechanical prophylaxis, either compression stockings or pneumatic sleeves. But in patients with a high VTE risk and an “acceptable” bleeding risk, prophylaxis with an anticoagulant is preferred over mechanical measures, said Mary Cushman, MD, professor and medical director of the thrombosis and hemostasis program at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

For prevention of VTE in medical inpatients, LMWH is preferred over unfractionated heparin because of its once-daily dosing and fewer complications, said Dr. Cushman, a member of the writing group. The panel also endorsed LMWH over a direct-acting oral anticoagulant, both during hospitalization and following discharge. The guidelines for prevention in medical patients explicitly “recommended against” using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant “over other treatments” both for hospitalized medical patients and after discharge, and the guidelines further recommend against extended prophylaxis after discharge with any other anticoagulant.

Another important takeaway from the prevention section was a statement that combining both mechanical and medical prophylaxis was not needed for medical inpatients. And once patients are discharged, if they take a long air trip they have no need for compression stockings or aspirin if their risk for thrombosis is not elevated. People with a “substantially increased” thrombosis risk “may benefit” from compression stockings or treatment with LMWH, Dr. Cushman said.

Diagnosis

For diagnosis, Wendy Lim, MD, highlighted the need for first categorizing patients as having a low or high probability for VTE, a judgment that can aid the accuracy of the diagnosis and helps avoid unnecessary testing.

For patients with low pretest probability, the guidelines recommended the D-dimer test as the best first step. Further testing isn’t needed when the D-dimer is negative, noted Dr. Lim, a hematologist and professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The guidelines also recommended using ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) for imaging a pulmonary embolism over a CT scan, which uses more radiation. But V/Q scans are not ideal for assessing older patients or patients with lung disease, Dr. Lim cautioned.

Management

Management of VTE should occur, when feasible, through a specialized anticoagulation management service center, which can provide care that is best suited to the complexities of anticoagulation therapy. But it’s a level of care that many U.S. patients don’t currently receive and hence is an area ripe for growth, said Daniel M. Witt, PharmD, professor and vice-chair of pharmacotherapy at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The guidelines recommended against bridging therapy with LMWH for most patients who need to stop warfarin when undergoing an invasive procedure. The guidelines also called for “thoughtful” use of anticoagulant reversal agents and advised that patients who survive a major bleed while on anticoagulation should often resume the anticoagulant once they are stabilized.

For patients who develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the 4Ts score is the best way to make a more accurate diagnosis and boost the prospects for recovery, said Dr. Cuker (Blood. 2012 Nov 15;120[20]:4160-7). The guidelines cite several agents now available to treat this common complication, which affects about 1% of the 12 million Americans treated with heparin annually: argatroban, bivalirudin, danaparoid, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban.

ASH has a VTE website with links to detailed information for each of the guideline subcategories: prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, therapy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, VTE in pregnancy, and VTE in children. The website indicates that additional guidelines will soon be released on managing VTE in patients with cancer, in patients with thrombophilia, and for prophylaxis in surgical patients, as well as further information on treatment. A spokesperson for ASH said that these additional documents will post sometime in 2019.

At the time of the release, the guidelines panel published six articles in the journal Blood Advances that detailed the guidelines and their documentation.

The articles include prophylaxis of medical patients (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3198-225), diagnosis (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3226-56), anticoagulation therapy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3257-91), pediatrics (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3292-316), pregnancy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3317-59), and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3360-92).

Dr. Cushman, Dr. Lim, and Dr. Witt reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Cuker reported receiving research support from T2 Biosystems.

ADA releases guidelines for type 2 diabetes in children, youth

The American Diabetes Association’s guidelines for the evaluation and management of pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes differ from those for adults.

“Puberty-related physiologic insulin resistance, particularly in obese youth, may play a role” in the fact that youth are more insulin resistant than adults. Also, type 2 diabetes apparently is “more aggressive in youth than adults, with a faster rate of deterioration of beta-cell function and poorer response to glucose-lowering medications,” wrote Silva Arslanian, MD, from the division of pediatric endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes mellitus at the University of Pittsburgh, and her colleagues. “Even though our knowledge of youth-onset type 2 diabetes has increased tremendously over the last 2 decades, robust and evidence-based data are still limited regarding diagnostic and therapeutic approaches and prevention of complications.”

The ADA position statement by Dr. Arslanian and her colleagues outlines management of type 2 diabetes in children and youth.

Diagnosis

and repeat testing should occur at least every 3 years for these patients. Pancreatic autoantibody tests should also be considered in this patient population to rule out autoimmune type 1 diabetes, and genetic evaluation should be performed to test for monogenic diabetes, “based on clinical characteristics and presentation,” they wrote.

Use fasting plasma glucose, 2-hour fasting plasma glucose after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) to test for diabetes or prediabetes. Also consider factors like medication adherence and treatment effects when prescribing glucose-lowering or other medications for overweight or obese children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes.

Lifestyle management

With regard to lifestyle management programs, the intervention should be introduced as a part of diabetes care – aimed at reducing between 7% and 10% of body weight – and be based on a chronic care model. The intervention should include 30-60 minutes of moderate to intense physical activity for 5 days each week, strength training 3 days per week, and incorporate healthy eating plans. Dr. Arslanian and her associates noted there was limited evidence for pharmacotherapy for weight reduction in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes.

Pharmacologic therapy

Pharmacologic therapy should be started together with lifestyle therapy once a diagnosis is made, according to the recommendations.

Metformin is the preferred initial pharmacologic treatment for patients with normal renal function who are asymptomatic and with HbA1C levels of less than 8.5%.

Patients with blood glucose greater than or equal to 250 mg/dL and HbA1C greater than or equal to 8.5% with symptoms such as weight loss, polydipsia, polyuria, or nocturia should receive basal insulin during initiation and titration of metformin.

Patients with ketosis or ketoacidosis should receive intravenous insulin to address hyperglycemia. Once the acidosis is corrected, initiate metformin with subcutaneous insulin therapy. For patients who are reaching home-based glucose monitoring targets, consider tapering the dose over 2-6 weeks with a 10%-30% reduction in insulin every few days.

In patients where metformin alone is not meeting the glycemic target, consider basal insulin therapy and, if that fails to help achieve glycemic targets, more intensive approaches should be considered, such as metabolic surgery.

Jay Cohen, MD, FACE, medical director at the Endocrine Clinic in Memphis, said in an interview that he agreed with the ADA position statement except for the pharmacologic therapy recommendations.

“The pharmacology therapy is 4 years outdated,” he said. “We routinely use all of the medications that are not Food and Drug Administration [approved] for kids, but are FDA approved for adults.”

He also questioned the ADA’s recommendation to give basal insulin to patients who are insulin resistant.

“Why give insulin if these people are insulin resistant?” said Dr. Cohen, who also is a Clinical Endocrinology News editorial board member. “The oral and injectable noninsulins work fabulously with less weight gain – already a problem for these patients – and less hypoglycemia, less side effects, and better compliance.”

Treatment goals

The HbA1C goal for children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes is less than 7% when treated with oral agents alone. HbA1C should be tested every 3 months and should be individualized, according to the ADA recommendations. In some patients, such as those with a shorter diabetes duration, lesser degrees of beta-cell dysfunction, and those who achieve significant weight improvement through lifestyle changes or taking metformin, consider lowering the HbA1C goal to less than 6.5%.

Give individualized care with regard to home self-monitoring of blood glucose. Also provide patients and their families with “culturally competent” diabetes self-management tools and lifestyle programs. Consider social factors such as housing stability, food insecurity, and financial barriers when making treatment decisions.

Screening for complications

To screen for nephropathy, take BP measurements at every visit and promote lifestyle management to reduce risk of diabetic kidney disease and improve weight loss. After 6 months, if a patient’s BP remains greater than the 95th percentile for their age, gender, and height, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers are initial therapeutic options, according to the position statement. Other BP-lowering treatments may be added as necessary.

Also monitor protein intake (0.8 g/kg per day) as well as urine albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) annually. Patients with diabetes and hypertension who are not pregnant should receive an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker if their UACR is modestly elevated (30-299 mg/g creatinine). Such a regimen is strongly recommended if their UACR is above 300 mg/g creatinine and/or if their eGFR is less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Screening issues

When considering diabetes distress and mental or behavioral health in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, use standardized and validated tools to assess symptoms such as depression and disordered eating behaviors. Regularly screen for smoking and alcohol use and provide preconception counseling for female patients of child-bearing age.

Screen for neuropathy, retinopathy, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease annually and for obstructive sleep apnea at each visit. Lipid testing should be performed annually once patients have achieved glycemic control. Polycystic ovary syndrome should be considered in female patients with type 2 diabetes and treated with metformin together with lifestyle changes to address menstrual cyclicity and hyperandrogenism, the authors recommended.

Dr. Arslanian is on a data monitoring committee for AstraZeneca; data safety monitoring board for Boehringer Ingelheim; and advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi-Aventis; and has received research grants from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Other authors reported various relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Arslanian S et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 Nov 13. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0052.

The American Diabetes Association’s guidelines for the evaluation and management of pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes differ from those for adults.

“Puberty-related physiologic insulin resistance, particularly in obese youth, may play a role” in the fact that youth are more insulin resistant than adults. Also, type 2 diabetes apparently is “more aggressive in youth than adults, with a faster rate of deterioration of beta-cell function and poorer response to glucose-lowering medications,” wrote Silva Arslanian, MD, from the division of pediatric endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes mellitus at the University of Pittsburgh, and her colleagues. “Even though our knowledge of youth-onset type 2 diabetes has increased tremendously over the last 2 decades, robust and evidence-based data are still limited regarding diagnostic and therapeutic approaches and prevention of complications.”

The ADA position statement by Dr. Arslanian and her colleagues outlines management of type 2 diabetes in children and youth.

Diagnosis

and repeat testing should occur at least every 3 years for these patients. Pancreatic autoantibody tests should also be considered in this patient population to rule out autoimmune type 1 diabetes, and genetic evaluation should be performed to test for monogenic diabetes, “based on clinical characteristics and presentation,” they wrote.

Use fasting plasma glucose, 2-hour fasting plasma glucose after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) to test for diabetes or prediabetes. Also consider factors like medication adherence and treatment effects when prescribing glucose-lowering or other medications for overweight or obese children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes.

Lifestyle management

With regard to lifestyle management programs, the intervention should be introduced as a part of diabetes care – aimed at reducing between 7% and 10% of body weight – and be based on a chronic care model. The intervention should include 30-60 minutes of moderate to intense physical activity for 5 days each week, strength training 3 days per week, and incorporate healthy eating plans. Dr. Arslanian and her associates noted there was limited evidence for pharmacotherapy for weight reduction in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes.

Pharmacologic therapy

Pharmacologic therapy should be started together with lifestyle therapy once a diagnosis is made, according to the recommendations.

Metformin is the preferred initial pharmacologic treatment for patients with normal renal function who are asymptomatic and with HbA1C levels of less than 8.5%.

Patients with blood glucose greater than or equal to 250 mg/dL and HbA1C greater than or equal to 8.5% with symptoms such as weight loss, polydipsia, polyuria, or nocturia should receive basal insulin during initiation and titration of metformin.

Patients with ketosis or ketoacidosis should receive intravenous insulin to address hyperglycemia. Once the acidosis is corrected, initiate metformin with subcutaneous insulin therapy. For patients who are reaching home-based glucose monitoring targets, consider tapering the dose over 2-6 weeks with a 10%-30% reduction in insulin every few days.

In patients where metformin alone is not meeting the glycemic target, consider basal insulin therapy and, if that fails to help achieve glycemic targets, more intensive approaches should be considered, such as metabolic surgery.

Jay Cohen, MD, FACE, medical director at the Endocrine Clinic in Memphis, said in an interview that he agreed with the ADA position statement except for the pharmacologic therapy recommendations.

“The pharmacology therapy is 4 years outdated,” he said. “We routinely use all of the medications that are not Food and Drug Administration [approved] for kids, but are FDA approved for adults.”

He also questioned the ADA’s recommendation to give basal insulin to patients who are insulin resistant.

“Why give insulin if these people are insulin resistant?” said Dr. Cohen, who also is a Clinical Endocrinology News editorial board member. “The oral and injectable noninsulins work fabulously with less weight gain – already a problem for these patients – and less hypoglycemia, less side effects, and better compliance.”

Treatment goals

The HbA1C goal for children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes is less than 7% when treated with oral agents alone. HbA1C should be tested every 3 months and should be individualized, according to the ADA recommendations. In some patients, such as those with a shorter diabetes duration, lesser degrees of beta-cell dysfunction, and those who achieve significant weight improvement through lifestyle changes or taking metformin, consider lowering the HbA1C goal to less than 6.5%.

Give individualized care with regard to home self-monitoring of blood glucose. Also provide patients and their families with “culturally competent” diabetes self-management tools and lifestyle programs. Consider social factors such as housing stability, food insecurity, and financial barriers when making treatment decisions.

Screening for complications

To screen for nephropathy, take BP measurements at every visit and promote lifestyle management to reduce risk of diabetic kidney disease and improve weight loss. After 6 months, if a patient’s BP remains greater than the 95th percentile for their age, gender, and height, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers are initial therapeutic options, according to the position statement. Other BP-lowering treatments may be added as necessary.

Also monitor protein intake (0.8 g/kg per day) as well as urine albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) annually. Patients with diabetes and hypertension who are not pregnant should receive an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker if their UACR is modestly elevated (30-299 mg/g creatinine). Such a regimen is strongly recommended if their UACR is above 300 mg/g creatinine and/or if their eGFR is less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Screening issues

When considering diabetes distress and mental or behavioral health in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, use standardized and validated tools to assess symptoms such as depression and disordered eating behaviors. Regularly screen for smoking and alcohol use and provide preconception counseling for female patients of child-bearing age.

Screen for neuropathy, retinopathy, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease annually and for obstructive sleep apnea at each visit. Lipid testing should be performed annually once patients have achieved glycemic control. Polycystic ovary syndrome should be considered in female patients with type 2 diabetes and treated with metformin together with lifestyle changes to address menstrual cyclicity and hyperandrogenism, the authors recommended.

Dr. Arslanian is on a data monitoring committee for AstraZeneca; data safety monitoring board for Boehringer Ingelheim; and advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi-Aventis; and has received research grants from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Other authors reported various relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Arslanian S et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 Nov 13. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0052.

The American Diabetes Association’s guidelines for the evaluation and management of pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes differ from those for adults.

“Puberty-related physiologic insulin resistance, particularly in obese youth, may play a role” in the fact that youth are more insulin resistant than adults. Also, type 2 diabetes apparently is “more aggressive in youth than adults, with a faster rate of deterioration of beta-cell function and poorer response to glucose-lowering medications,” wrote Silva Arslanian, MD, from the division of pediatric endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes mellitus at the University of Pittsburgh, and her colleagues. “Even though our knowledge of youth-onset type 2 diabetes has increased tremendously over the last 2 decades, robust and evidence-based data are still limited regarding diagnostic and therapeutic approaches and prevention of complications.”

The ADA position statement by Dr. Arslanian and her colleagues outlines management of type 2 diabetes in children and youth.

Diagnosis

and repeat testing should occur at least every 3 years for these patients. Pancreatic autoantibody tests should also be considered in this patient population to rule out autoimmune type 1 diabetes, and genetic evaluation should be performed to test for monogenic diabetes, “based on clinical characteristics and presentation,” they wrote.

Use fasting plasma glucose, 2-hour fasting plasma glucose after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) to test for diabetes or prediabetes. Also consider factors like medication adherence and treatment effects when prescribing glucose-lowering or other medications for overweight or obese children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes.

Lifestyle management

With regard to lifestyle management programs, the intervention should be introduced as a part of diabetes care – aimed at reducing between 7% and 10% of body weight – and be based on a chronic care model. The intervention should include 30-60 minutes of moderate to intense physical activity for 5 days each week, strength training 3 days per week, and incorporate healthy eating plans. Dr. Arslanian and her associates noted there was limited evidence for pharmacotherapy for weight reduction in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes.

Pharmacologic therapy

Pharmacologic therapy should be started together with lifestyle therapy once a diagnosis is made, according to the recommendations.

Metformin is the preferred initial pharmacologic treatment for patients with normal renal function who are asymptomatic and with HbA1C levels of less than 8.5%.

Patients with blood glucose greater than or equal to 250 mg/dL and HbA1C greater than or equal to 8.5% with symptoms such as weight loss, polydipsia, polyuria, or nocturia should receive basal insulin during initiation and titration of metformin.

Patients with ketosis or ketoacidosis should receive intravenous insulin to address hyperglycemia. Once the acidosis is corrected, initiate metformin with subcutaneous insulin therapy. For patients who are reaching home-based glucose monitoring targets, consider tapering the dose over 2-6 weeks with a 10%-30% reduction in insulin every few days.

In patients where metformin alone is not meeting the glycemic target, consider basal insulin therapy and, if that fails to help achieve glycemic targets, more intensive approaches should be considered, such as metabolic surgery.

Jay Cohen, MD, FACE, medical director at the Endocrine Clinic in Memphis, said in an interview that he agreed with the ADA position statement except for the pharmacologic therapy recommendations.

“The pharmacology therapy is 4 years outdated,” he said. “We routinely use all of the medications that are not Food and Drug Administration [approved] for kids, but are FDA approved for adults.”

He also questioned the ADA’s recommendation to give basal insulin to patients who are insulin resistant.

“Why give insulin if these people are insulin resistant?” said Dr. Cohen, who also is a Clinical Endocrinology News editorial board member. “The oral and injectable noninsulins work fabulously with less weight gain – already a problem for these patients – and less hypoglycemia, less side effects, and better compliance.”

Treatment goals

The HbA1C goal for children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes is less than 7% when treated with oral agents alone. HbA1C should be tested every 3 months and should be individualized, according to the ADA recommendations. In some patients, such as those with a shorter diabetes duration, lesser degrees of beta-cell dysfunction, and those who achieve significant weight improvement through lifestyle changes or taking metformin, consider lowering the HbA1C goal to less than 6.5%.

Give individualized care with regard to home self-monitoring of blood glucose. Also provide patients and their families with “culturally competent” diabetes self-management tools and lifestyle programs. Consider social factors such as housing stability, food insecurity, and financial barriers when making treatment decisions.

Screening for complications

To screen for nephropathy, take BP measurements at every visit and promote lifestyle management to reduce risk of diabetic kidney disease and improve weight loss. After 6 months, if a patient’s BP remains greater than the 95th percentile for their age, gender, and height, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers are initial therapeutic options, according to the position statement. Other BP-lowering treatments may be added as necessary.

Also monitor protein intake (0.8 g/kg per day) as well as urine albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) annually. Patients with diabetes and hypertension who are not pregnant should receive an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker if their UACR is modestly elevated (30-299 mg/g creatinine). Such a regimen is strongly recommended if their UACR is above 300 mg/g creatinine and/or if their eGFR is less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Screening issues

When considering diabetes distress and mental or behavioral health in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, use standardized and validated tools to assess symptoms such as depression and disordered eating behaviors. Regularly screen for smoking and alcohol use and provide preconception counseling for female patients of child-bearing age.

Screen for neuropathy, retinopathy, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease annually and for obstructive sleep apnea at each visit. Lipid testing should be performed annually once patients have achieved glycemic control. Polycystic ovary syndrome should be considered in female patients with type 2 diabetes and treated with metformin together with lifestyle changes to address menstrual cyclicity and hyperandrogenism, the authors recommended.

Dr. Arslanian is on a data monitoring committee for AstraZeneca; data safety monitoring board for Boehringer Ingelheim; and advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi-Aventis; and has received research grants from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Other authors reported various relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Arslanian S et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 Nov 13. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0052.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Draft guidelines advise HIV screening for most teens and adults

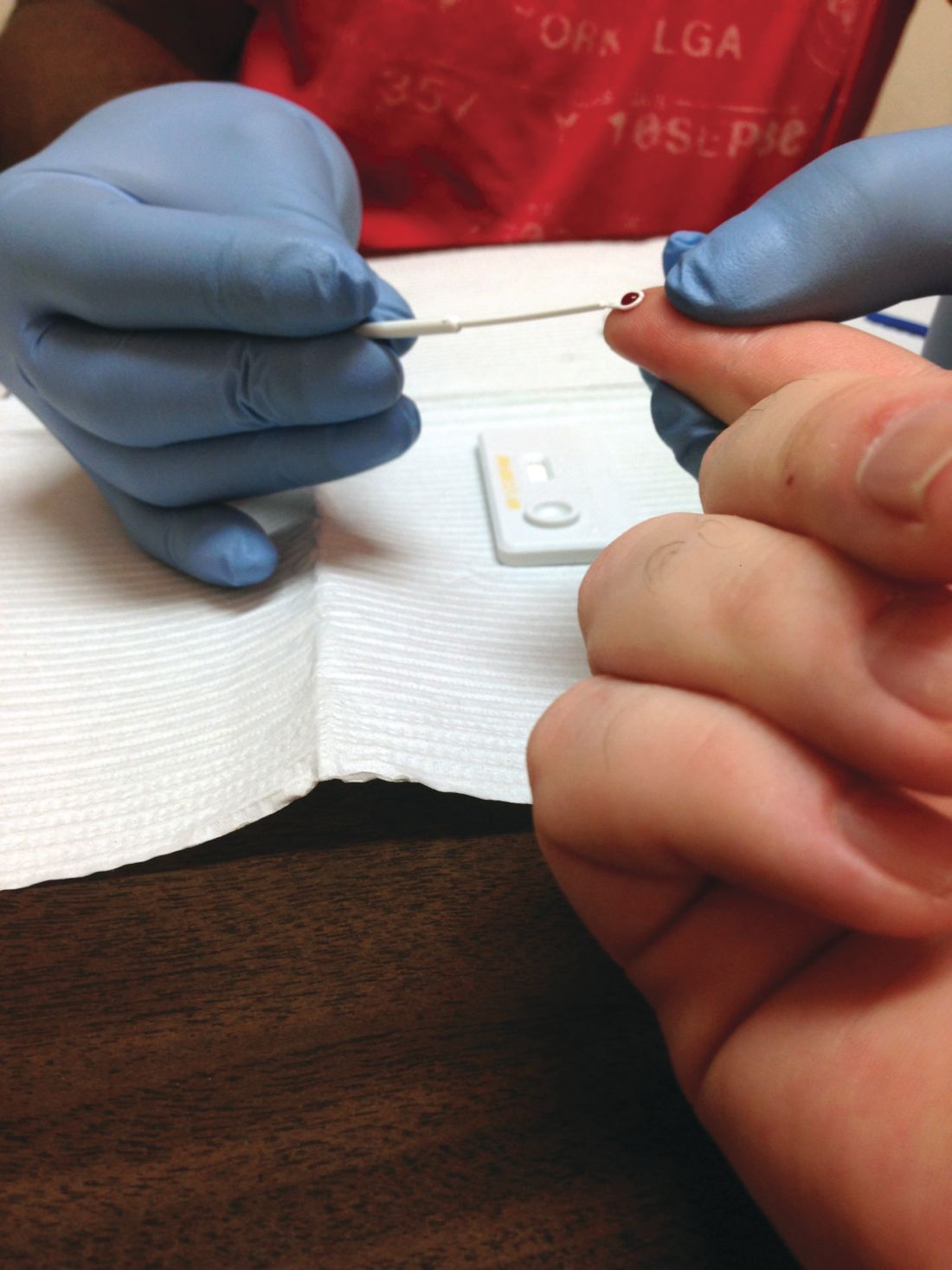

Individuals aged 15-65 years, including pregnant women, should be screened for HIV infection, and those at risk should be given prophylaxis, according to draft recommendations issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The screening recommendation extends to younger adolescents and older adults at increased risk for HIV infection. The recommendations are level A.

HIV remains a significant public health issue in the United States, with rates rising among individuals aged 25-29 years, although the overall number of cases has dropped slightly, according to the USPSTF report.

HIV prevention is a multistep process that includes not only screening but also wearing condoms during sex and using clean needles and syringes if injecting drugs, the researchers noted.

However, those at high risk for HIV, such as intravenous drug users, can help reduce their risk by taking a daily pill, the researchers wrote.

In an evidence report submitted to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, researchers reviewed the Cochrane databases, MEDLINE, and Embase for studies up to June 2018. Based on data from 11 trials, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consisting of antiretroviral therapy was associated with decreased risk of HIV infection, compared with placebo or no PrEP, with consistent effects across risk categories, the investigators noted.

The most common HIV risk factors include man-to-man sexual contact, injection drug use, having sex without a condom, exchanging sex for drugs or money, and having sex with an HIV-infected partner, according to the USPSTF report.

Although PrEP was associated with renal and gastrointestinal adverse effects, most were mild and resolved when the therapy either ended or continued long term. The use of PrEP does not absolve high-risk individuals from observing safety in sex activity and intravenous drug use, the researchers noted.

The Task Force’s draft recommendation statements and draft evidence reviews are available for public comment and are posted on the Task Force website at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Comments can be submitted from Nov. 20, 2018, to Dec. 26, 2018, at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

Individuals aged 15-65 years, including pregnant women, should be screened for HIV infection, and those at risk should be given prophylaxis, according to draft recommendations issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The screening recommendation extends to younger adolescents and older adults at increased risk for HIV infection. The recommendations are level A.

HIV remains a significant public health issue in the United States, with rates rising among individuals aged 25-29 years, although the overall number of cases has dropped slightly, according to the USPSTF report.

HIV prevention is a multistep process that includes not only screening but also wearing condoms during sex and using clean needles and syringes if injecting drugs, the researchers noted.

However, those at high risk for HIV, such as intravenous drug users, can help reduce their risk by taking a daily pill, the researchers wrote.

In an evidence report submitted to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, researchers reviewed the Cochrane databases, MEDLINE, and Embase for studies up to June 2018. Based on data from 11 trials, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consisting of antiretroviral therapy was associated with decreased risk of HIV infection, compared with placebo or no PrEP, with consistent effects across risk categories, the investigators noted.

The most common HIV risk factors include man-to-man sexual contact, injection drug use, having sex without a condom, exchanging sex for drugs or money, and having sex with an HIV-infected partner, according to the USPSTF report.

Although PrEP was associated with renal and gastrointestinal adverse effects, most were mild and resolved when the therapy either ended or continued long term. The use of PrEP does not absolve high-risk individuals from observing safety in sex activity and intravenous drug use, the researchers noted.

The Task Force’s draft recommendation statements and draft evidence reviews are available for public comment and are posted on the Task Force website at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Comments can be submitted from Nov. 20, 2018, to Dec. 26, 2018, at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

Individuals aged 15-65 years, including pregnant women, should be screened for HIV infection, and those at risk should be given prophylaxis, according to draft recommendations issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The screening recommendation extends to younger adolescents and older adults at increased risk for HIV infection. The recommendations are level A.

HIV remains a significant public health issue in the United States, with rates rising among individuals aged 25-29 years, although the overall number of cases has dropped slightly, according to the USPSTF report.

HIV prevention is a multistep process that includes not only screening but also wearing condoms during sex and using clean needles and syringes if injecting drugs, the researchers noted.

However, those at high risk for HIV, such as intravenous drug users, can help reduce their risk by taking a daily pill, the researchers wrote.

In an evidence report submitted to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, researchers reviewed the Cochrane databases, MEDLINE, and Embase for studies up to June 2018. Based on data from 11 trials, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consisting of antiretroviral therapy was associated with decreased risk of HIV infection, compared with placebo or no PrEP, with consistent effects across risk categories, the investigators noted.

The most common HIV risk factors include man-to-man sexual contact, injection drug use, having sex without a condom, exchanging sex for drugs or money, and having sex with an HIV-infected partner, according to the USPSTF report.

Although PrEP was associated with renal and gastrointestinal adverse effects, most were mild and resolved when the therapy either ended or continued long term. The use of PrEP does not absolve high-risk individuals from observing safety in sex activity and intravenous drug use, the researchers noted.

The Task Force’s draft recommendation statements and draft evidence reviews are available for public comment and are posted on the Task Force website at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Comments can be submitted from Nov. 20, 2018, to Dec. 26, 2018, at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

Monitoring limited in stage 3 chronic kidney disease

SAN DIEGO – Fewer than a quarter of patients with signs of stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) underwent follow-up testing within 1 year, even though most of these patients underwent repeat cholesterol screening during the same time.

Considering that CKD can be asymptomatic until the late stages, “this is a lost opportunity to get a proper evaluation by a nephrologist,” study coauthor and nephrologist Barbara S. Gillespie, MD, MMS, of Covance, the drug development business of LabCorp, said in an interview. Dr. Gillespie and her colleagues presented their findings at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

More than 90% of patients with stages 1-3 CKD didn’t know they had the condition, based on 2013-2016 data gathered by the United States Renal Data System . Just 57% of those with stage 4 CKD were aware of their disease.

For the retrospective study, the researchers identified 4.9 million patients (58% were women; mean age was 71) who had estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) results below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from 2011 to 2018, based on serum creatinine tests performed at least twice and at least 3 months apart by LabCorp. The researchers tracked the patients for a median 26 months.

Based on the initial results, 92% of the patients had stage 3 CKD, 6% had stage 4, and 2% had stage 5. However, at 1 year, the percentages of overall patients who underwent urine albumin/creatinine ratio, serum phosphorus, and plasma parathyroid hormone were 24%, 12%, and 17%, respectively, lead author Jennifer Ennis, MD, of LabCorp, said in an interview.

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines from 2012 recommend “assessments of GFR and albuminuria at least annually ... and more often for individuals at higher risk of progression, and/or where measurement will impact therapeutic decisions” (Ann Intern Med. 2013 Jun 4;158[11]:825-30).

Yet 76% of these patients also underwent annual LDL cholesterol screening. “This suggests that the patients were receiving evaluation and treatment for other common conditions, but that CKD may not have been specifically addressed,” Dr. Ennis said.

“These results suggest that guideline recommendations for monitoring of CKD are not well implemented in the primary care setting, which is where the majority of this testing took place,” she added. “There are possibly many reasons for this, including lack of guideline awareness, familiarity, or agreement; inertia; or other external barriers such as time constraints and the burden of having to remember numerous guidelines for a single patient with multiple conditions.”

Dr. Gillespie said the findings may help to explain why so many patients with CKD are unaware of their condition and “crash into dialysis” within 24 hours of winding up in the emergency department with kidney failure. “Often they note they did not know they had kidney disease,” she said, “or did not know how bad it was.”

The authors disclosed employment by LabCorp, which funded the study.

SOURCE: Ennis JL et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract PUB111.

SAN DIEGO – Fewer than a quarter of patients with signs of stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) underwent follow-up testing within 1 year, even though most of these patients underwent repeat cholesterol screening during the same time.

Considering that CKD can be asymptomatic until the late stages, “this is a lost opportunity to get a proper evaluation by a nephrologist,” study coauthor and nephrologist Barbara S. Gillespie, MD, MMS, of Covance, the drug development business of LabCorp, said in an interview. Dr. Gillespie and her colleagues presented their findings at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

More than 90% of patients with stages 1-3 CKD didn’t know they had the condition, based on 2013-2016 data gathered by the United States Renal Data System . Just 57% of those with stage 4 CKD were aware of their disease.

For the retrospective study, the researchers identified 4.9 million patients (58% were women; mean age was 71) who had estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) results below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from 2011 to 2018, based on serum creatinine tests performed at least twice and at least 3 months apart by LabCorp. The researchers tracked the patients for a median 26 months.

Based on the initial results, 92% of the patients had stage 3 CKD, 6% had stage 4, and 2% had stage 5. However, at 1 year, the percentages of overall patients who underwent urine albumin/creatinine ratio, serum phosphorus, and plasma parathyroid hormone were 24%, 12%, and 17%, respectively, lead author Jennifer Ennis, MD, of LabCorp, said in an interview.

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines from 2012 recommend “assessments of GFR and albuminuria at least annually ... and more often for individuals at higher risk of progression, and/or where measurement will impact therapeutic decisions” (Ann Intern Med. 2013 Jun 4;158[11]:825-30).

Yet 76% of these patients also underwent annual LDL cholesterol screening. “This suggests that the patients were receiving evaluation and treatment for other common conditions, but that CKD may not have been specifically addressed,” Dr. Ennis said.

“These results suggest that guideline recommendations for monitoring of CKD are not well implemented in the primary care setting, which is where the majority of this testing took place,” she added. “There are possibly many reasons for this, including lack of guideline awareness, familiarity, or agreement; inertia; or other external barriers such as time constraints and the burden of having to remember numerous guidelines for a single patient with multiple conditions.”

Dr. Gillespie said the findings may help to explain why so many patients with CKD are unaware of their condition and “crash into dialysis” within 24 hours of winding up in the emergency department with kidney failure. “Often they note they did not know they had kidney disease,” she said, “or did not know how bad it was.”

The authors disclosed employment by LabCorp, which funded the study.

SOURCE: Ennis JL et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract PUB111.

SAN DIEGO – Fewer than a quarter of patients with signs of stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) underwent follow-up testing within 1 year, even though most of these patients underwent repeat cholesterol screening during the same time.

Considering that CKD can be asymptomatic until the late stages, “this is a lost opportunity to get a proper evaluation by a nephrologist,” study coauthor and nephrologist Barbara S. Gillespie, MD, MMS, of Covance, the drug development business of LabCorp, said in an interview. Dr. Gillespie and her colleagues presented their findings at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

More than 90% of patients with stages 1-3 CKD didn’t know they had the condition, based on 2013-2016 data gathered by the United States Renal Data System . Just 57% of those with stage 4 CKD were aware of their disease.

For the retrospective study, the researchers identified 4.9 million patients (58% were women; mean age was 71) who had estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) results below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from 2011 to 2018, based on serum creatinine tests performed at least twice and at least 3 months apart by LabCorp. The researchers tracked the patients for a median 26 months.

Based on the initial results, 92% of the patients had stage 3 CKD, 6% had stage 4, and 2% had stage 5. However, at 1 year, the percentages of overall patients who underwent urine albumin/creatinine ratio, serum phosphorus, and plasma parathyroid hormone were 24%, 12%, and 17%, respectively, lead author Jennifer Ennis, MD, of LabCorp, said in an interview.

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines from 2012 recommend “assessments of GFR and albuminuria at least annually ... and more often for individuals at higher risk of progression, and/or where measurement will impact therapeutic decisions” (Ann Intern Med. 2013 Jun 4;158[11]:825-30).

Yet 76% of these patients also underwent annual LDL cholesterol screening. “This suggests that the patients were receiving evaluation and treatment for other common conditions, but that CKD may not have been specifically addressed,” Dr. Ennis said.

“These results suggest that guideline recommendations for monitoring of CKD are not well implemented in the primary care setting, which is where the majority of this testing took place,” she added. “There are possibly many reasons for this, including lack of guideline awareness, familiarity, or agreement; inertia; or other external barriers such as time constraints and the burden of having to remember numerous guidelines for a single patient with multiple conditions.”

Dr. Gillespie said the findings may help to explain why so many patients with CKD are unaware of their condition and “crash into dialysis” within 24 hours of winding up in the emergency department with kidney failure. “Often they note they did not know they had kidney disease,” she said, “or did not know how bad it was.”

The authors disclosed employment by LabCorp, which funded the study.

SOURCE: Ennis JL et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract PUB111.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Physicians often ignore blood test results that indicate chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: Over 1 year, 24% of patients with signs of CKD underwent a recommended follow-up test, even though about 76% had cholesterol screening.

Study details: Retrospective study of 4.9 million U.S. patients who had signs of CKD based on LabCorp blood tests during 2011-2018.

Disclosures: The authors disclosed employment by LabCorp, which funded the study.

Source: Ennis JL et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract PUB111.

Revised U.S. cholesterol guidelines promote personalized risk assessment

CHICAGO – The latest cholesterol management guideline for U.S. practice has a core treatment principal that propels the field from its long-held focus on “know your cholesterol number,” that then became “know your risk” with the 2013 guideline, to what is now “personalize your risk.”

“The new guideline put special focus not just on risk, but on risk assessment that uses ‘enhancing factors’ to help patients understand their risk in a personal way and decide whether statin treatment is right for them” Neil J. Stone, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Other novel features of the 2018 edition of the cholesterol management guideline included: specification of the role for two types of drugs other than statins – ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors (including mention of the cost-value consideration when prescribing an expensive PCSK9 inhibitor); inclusion of coronary artery calcium (CAC) score assessment for patients with intermediate risk who are unsure whether statin treatment is right for them; and acknowledgment that nonfasting measurement of blood cholesterol levels is fine for most screening circumstances.

“Nonfasting is okay for many situations,” said Dr. Stone, a professor of medicine at Northwestern University here, and vice-chair of the writing panel for the guidelines, released by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and 10 additional endorsing societies (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003)

But among the changes in the 2018 guideline that distinguish it from the preceding, 2013 version (Circulation. 2014 June 24;129[25, suppl 2]:S1-S45), the expanded approach to risk assessment in the primary-prevention setting stood out as the biggest shift.

“In 2013 we said calculate a person’s risk” for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. “Now that is much more fleshed out,” said Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, a member of the guideline-writing group who helped develop the risk assessment tools used by the guideline.*

“The risk equations now are the same as we introduced in 2013,” he noted, and research done by Dr. Lloyd-Jones and others since that introduction showed that the “pooled cohort equations” are “well calibrated” for estimating a person’s 10-year risk for a cardiovascular event, especially at a risk level around 7.5%, which serves as the threshold for identifying a person with enough risk to warrant statin treatment. “But there are subgroups where the risk calculator clearly over- or under-estimates risk,” and that’s why the new guideline introduced the concept of risk enhancers--additional features not included in the basic risk calculation that enhance risk: family history; metabolic syndrome; chronic kidney disease; chronic inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, or HIV infection; a history of premature menopause or preeclampsia, certain ethnicity, or high levels of Lp(a) or apolipoprotein B.

“We didn’t need new risk scores; we needed to understand how to use the scores better, and the new guideline goes a long way toward helping clinicians do that,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said in an interview.

Another aspect of this new, more nuanced approach to individualized risk assessment is the introduction of the CAC score as a possible tie breaker when a person who is otherwise a candidate for statin treatment for primary prevention is unsure about committing to possibly decades of daily statin treatment.

The guideline does not endorse obtaining a person’s CAC score for everyone as screening, stressed Dr. Stone, but this score, obtained by noncontrast CT with a radiation dose of about 1 mSv – comparable to a mammography exam, received a IIa rating” – is reasonable” for helping patients decide. Dr. Stone and others cited the importance of a CAC score of zero for patients on the fence for statin treatment as a strong indicator for many people that they can safely defer treatment.

As a result of this new endorsement for selectively obtaining CAC scores, “I think the number of tests will increase, probably fairly substantially,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University here. He also expressed hope that this acknowledgment of an evidenced-based role for selected CAC score imaging may prompt health insurers to start coving this expense, something they don’t now do. Patients generally pay out-of-pocket from $50 to $300 for CAC score imaging. “I hope they will start paying for this,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said.

The guidelines also deal, at least in passing, with another financial issue that has loomed large for cholesterol treatment, the role of the notoriously expensive PCSK9 inhibitors, alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha). For secondary prevention patients or for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia who do not reach their LDL cholesterol goal on statin treatment alone, the guideline recommended treatment first with generic ezetimibe. If the goal remains elusive, the next step is prescribing a PCSK9 inhibitor. The guideline also noted the poor cost-benefit ratio for the PCSK9 inhibitors at the U.S. list prices that existed in mid-2018, about $14,000 a year.

The guideline writers noted that this is one of the first times that cost considerations found their way into cardiology guidelines. Clinicians “need to be attuned to prescribing PCSK9 inhibitors only in those settings when it provides good value to patients,” explained Mark A. Hlatky, MD, a professor of medicine, cardiologist, and health policy specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. The guideline “focuses on patient selection for PCSK9 inhibitors, limiting it to patients who get the most benefit,” said Dr. Hlatky, another member of the writing panel.

Although 10 medical groups joined the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association in endorsing the guideline, conspicuously absent were the two largest U.S. societies representing primary care physicians, the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Practitioners. The guideline’s organizers invited both these societies to participate in the process and they declined, said Sidney C. Smith, Jr., MD, a member of the guideline committee.

Dr. Stone and Dr. Lloyd-Jones had no financial disclosures. The writing committee members’ disclosures can be found at jaccjacc.acc.org/Clinical_Document/Cholesterol_GL_Au_Comp_RWI.pdf.

*Correction, 11/13/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones.

SOURCE: AHA 2018 and Grundy S et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003.

CHICAGO – The latest cholesterol management guideline for U.S. practice has a core treatment principal that propels the field from its long-held focus on “know your cholesterol number,” that then became “know your risk” with the 2013 guideline, to what is now “personalize your risk.”

“The new guideline put special focus not just on risk, but on risk assessment that uses ‘enhancing factors’ to help patients understand their risk in a personal way and decide whether statin treatment is right for them” Neil J. Stone, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Other novel features of the 2018 edition of the cholesterol management guideline included: specification of the role for two types of drugs other than statins – ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors (including mention of the cost-value consideration when prescribing an expensive PCSK9 inhibitor); inclusion of coronary artery calcium (CAC) score assessment for patients with intermediate risk who are unsure whether statin treatment is right for them; and acknowledgment that nonfasting measurement of blood cholesterol levels is fine for most screening circumstances.

“Nonfasting is okay for many situations,” said Dr. Stone, a professor of medicine at Northwestern University here, and vice-chair of the writing panel for the guidelines, released by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and 10 additional endorsing societies (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003)

But among the changes in the 2018 guideline that distinguish it from the preceding, 2013 version (Circulation. 2014 June 24;129[25, suppl 2]:S1-S45), the expanded approach to risk assessment in the primary-prevention setting stood out as the biggest shift.

“In 2013 we said calculate a person’s risk” for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. “Now that is much more fleshed out,” said Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, a member of the guideline-writing group who helped develop the risk assessment tools used by the guideline.*

“The risk equations now are the same as we introduced in 2013,” he noted, and research done by Dr. Lloyd-Jones and others since that introduction showed that the “pooled cohort equations” are “well calibrated” for estimating a person’s 10-year risk for a cardiovascular event, especially at a risk level around 7.5%, which serves as the threshold for identifying a person with enough risk to warrant statin treatment. “But there are subgroups where the risk calculator clearly over- or under-estimates risk,” and that’s why the new guideline introduced the concept of risk enhancers--additional features not included in the basic risk calculation that enhance risk: family history; metabolic syndrome; chronic kidney disease; chronic inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, or HIV infection; a history of premature menopause or preeclampsia, certain ethnicity, or high levels of Lp(a) or apolipoprotein B.

“We didn’t need new risk scores; we needed to understand how to use the scores better, and the new guideline goes a long way toward helping clinicians do that,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said in an interview.

Another aspect of this new, more nuanced approach to individualized risk assessment is the introduction of the CAC score as a possible tie breaker when a person who is otherwise a candidate for statin treatment for primary prevention is unsure about committing to possibly decades of daily statin treatment.

The guideline does not endorse obtaining a person’s CAC score for everyone as screening, stressed Dr. Stone, but this score, obtained by noncontrast CT with a radiation dose of about 1 mSv – comparable to a mammography exam, received a IIa rating” – is reasonable” for helping patients decide. Dr. Stone and others cited the importance of a CAC score of zero for patients on the fence for statin treatment as a strong indicator for many people that they can safely defer treatment.

As a result of this new endorsement for selectively obtaining CAC scores, “I think the number of tests will increase, probably fairly substantially,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University here. He also expressed hope that this acknowledgment of an evidenced-based role for selected CAC score imaging may prompt health insurers to start coving this expense, something they don’t now do. Patients generally pay out-of-pocket from $50 to $300 for CAC score imaging. “I hope they will start paying for this,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said.

The guidelines also deal, at least in passing, with another financial issue that has loomed large for cholesterol treatment, the role of the notoriously expensive PCSK9 inhibitors, alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha). For secondary prevention patients or for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia who do not reach their LDL cholesterol goal on statin treatment alone, the guideline recommended treatment first with generic ezetimibe. If the goal remains elusive, the next step is prescribing a PCSK9 inhibitor. The guideline also noted the poor cost-benefit ratio for the PCSK9 inhibitors at the U.S. list prices that existed in mid-2018, about $14,000 a year.

The guideline writers noted that this is one of the first times that cost considerations found their way into cardiology guidelines. Clinicians “need to be attuned to prescribing PCSK9 inhibitors only in those settings when it provides good value to patients,” explained Mark A. Hlatky, MD, a professor of medicine, cardiologist, and health policy specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. The guideline “focuses on patient selection for PCSK9 inhibitors, limiting it to patients who get the most benefit,” said Dr. Hlatky, another member of the writing panel.

Although 10 medical groups joined the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association in endorsing the guideline, conspicuously absent were the two largest U.S. societies representing primary care physicians, the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Practitioners. The guideline’s organizers invited both these societies to participate in the process and they declined, said Sidney C. Smith, Jr., MD, a member of the guideline committee.

Dr. Stone and Dr. Lloyd-Jones had no financial disclosures. The writing committee members’ disclosures can be found at jaccjacc.acc.org/Clinical_Document/Cholesterol_GL_Au_Comp_RWI.pdf.