User login

Characterizing Hospitalizations for Pediatric Concussion and Trends in Care

Approximately 14% of children who sustain a concussion are admitted to the hospital,1 although admission rates reportedly vary substantially among pediatric hospitals.2 Children hospitalized for concussion may be at a higher risk for persistent postconcussive symptoms,3,4 yet little is known about this subset of children and how they are managed while in the hospital. Characterizing children hospitalized for concussion and describing the inpatient care they received will promote hypothesis generation for further inquiry into indications for admission, as well as the relationship between inpatient management and concussion recovery.

We described a cohort of children admitted to 40 pediatric hospitals primarily for concussion and detailed care delivered during hospitalization. We explored individual-level factors and their association with prolonged length of stay (LOS) and emergency department (ED) readmission. Finally, we evaluated if there had been changes in inpatient care over the 8-year study period.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

The Institutional Review Board determined that this retrospective cohort study was exempt from review.

Data Source

The Children’s Hospital Association’s Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) is an administrative database from pediatric hospitals located within 17 major metropolitan areas in the United States. Data include: service dates, patient demographics, payer type, diagnosis codes, resource utilization information (eg, medications), and hospital characteristics.1,5 De-identified data undergo reliability and validity checks prior to inclusion.1,5 We analyzed data from 40 of 43 hospitals that contributed inpatient data during our study period. 2 hospitals were excluded due to inconsistent data submission, and 1 removed their data.

Study Population

Data were extracted for children 0 to 17 years old who were admitted to an inpatient or observational unit between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2014 for traumatic brain injury (TBI). Children were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification, Ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes that denote TBI per the Centers for Disease Control (CDC): 800.0–801.9, 803.0–804.9, 850–854.1, and 959.01.6–8 To examine inpatient care for concussion, we only retained children with a primary (ie, first) concussion-related diagnosis code (850.0–850.99) for analyses. For patients with multiple visits during our study period, only the index admission was analyzed. We refined our cohort using 2 injury scores calculated from ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes using validated ICDMAP-90 injury coding software.6,10–12 The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) ranges from 1 (minor injury) to 6 (not survivable). The total Injury Severity Score (ISS) is based on 6 body regions (head/neck, face, chest, abdomen, extremity, and external) and calculated by summing the squares of the 3 worst AIS scores.13 A concussion receives a head AIS score of 2 if there is an associated loss of consciousness or a score of 1 if there is not; therefore, children were excluded if the head AIS score was >2. We also excluded children with the following features, as they may be indicative of more severe injuries that were likely the cause of admission: ISS > 6, secondary diagnosis code of skull fracture or intracranial injury, intensive care unit (ICU) or operating room (OR) charges, or a LOS > 7 days. Because some children are hospitalized for potentially abusive minor head trauma pending a safe discharge plan, we excluded children 0 to 4 years of age with child abuse, which was determined using a specific set of diagnosis codes (E960-E96820, 995.54, and 995.55) similar to previous research.14

Data Elements and Outcomes

Outcomes

Based on previous reports,1,15 a LOS ≥ 2 days distinguished a typical hospitalization from a prolonged one. ED revisit was identified when a child had a visit with a TBI-related primary diagnosis code at a PHIS hospital within 30 days of initial admission and was discharged home. We limited analyses to children discharged, as children readmitted may have had an initially missed intracranial injury.

Patient Characteristics

We examined the following patient variables: age, race, sex, presence of chronic medical condition, payer type, household income, area of residence (eg, rural versus urban), and mechanism of injury. Age was categorized to represent early childhood (0 to 4 years), school age (5 to 12 years), and adolescence (12 to 17 years). Race was grouped as white, black, or other (Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, and “other” per PHIS). Ethnicity was described as Hispanic/Latino or not Hispanic/Latino. Children with medical conditions lasting at least 12 months and comorbidities that may impact TBI recovery were identified using a subgrouping of ICD-9-CM codes for children with “complex chronic conditions”.16 Payer type was categorized as government, private, and self-pay. We extracted a PHIS variable representing the 2010 median household income for the child’s home zip code and categorized it into quartiles based on the Federal Poverty Level for a family of 4.17,18 Area of residence was defined using a Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classification system19 and grouped into large urban core, suburban area, large rural town, or small rural town/isolated rural area.17 Mechanism of injury was determined using E-codes and categorized using the CDC injury framework,20 with sports-related injuries identified using a previously described set of E-codes.1 Mechanisms of injury included fall, motor vehicle collision, other motorized transport (eg, all-terrain vehicles), sports-related, struck by or against (ie, objects), and all others (eg, cyclists).

Hospital Characteristics

Hospitals were characterized by region (Northeast, Central, South, and West) and size (small <200, medium 200–400, and large >400 beds). The trauma-level accreditation was identified with Level 1 reflecting the highest possible trauma resources.

Medical Care Variables

Care variables included medications, neuroimaging, and cost of stay. Medication classes included oral non-narcotic analgesics [acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and others (aspirin, tramadol, and naproxen)], oral narcotics (codeine, oxycodone, and narcotic–non-narcotic combinations), intravenous (IV) non-narcotics (ketorolac), IV narcotics (morphine, fentanyl, and hydromorphone), antiemetics [ondansetron, metoclopramide, and phenothiazines (prochlorperazine, chlorpromazine, and promethazine)], maintenance IV fluids (dextrose with electrolytes or 0.45% sodium chloride), and resuscitation IV fluids (0.9% sodium chloride or lactated Ringer’s solution). Receipt of neuroimaging was determined if head computed tomography (CT) had been conducted at the admitting hospital. Adjusted cost of stay was calculated using a hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratio with additional adjustments using the Center for Medicare & Medicaid’s Wage Index.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for individual, injury, and hospital, and care data elements, LOS, and ED readmissions. The number of children admitted with TBI was used as the denominator to assess the proportion of pediatric TBI admissions that were due to concussions. To identify factors associated with prolonged LOS (ie, ≥2 days) and ED readmission, we employed a mixed models approach that accounted for clustering of observations within hospitals. Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, payer type, household income, RUCA code, chronic medical condition, and injury mechanism. Models were adjusted for hospital location, size, and trauma-level accreditation. The binary distribution was specified along with a logit link function. A 2-phase process determined factors associated with each outcome. First, bivariable models were developed, followed by multivariable models that included independent variables with P values < .25 in the bivariable analysis. Backward step-wise elimination was performed, deleting variables with the highest P value one at a time. After each deletion, the percentage change in odds ratios was examined; if variable removal resulted in >10% change, the variable was retained as a potential confounder. This process was repeated until all remaining variables were significant (P < .05) with the exception of potential confounders. Finally, we examined the proportion of children receiving selected care practices annually. Descriptive and trend analyses were used to analyze adjusted median cost of stay. Analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Over 8 years, 88,526 children were admitted to 40 PHIS hospitals with a TBI-related diagnosis, among whom 13,708 had a primary diagnosis of concussion. We excluded 2,973 children with 1 or more of the following characteristics: a secondary diagnosis of intracranial injury (n = 58), head AIS score > 2 (n = 218), LOS > 7 days (n = 50), OR charges (n = 132), ICU charges (n = 1947), and ISS > 6 (n = 568). Six additional children aging 0 to 4 years were excluded due to child abuse. The remaining 10,729 children, averaging 1300 hospitalizations annually, were identified as being hospitalized primarily for concussion.

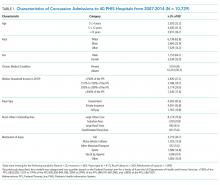

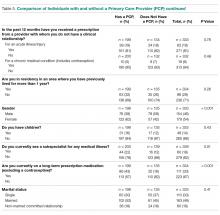

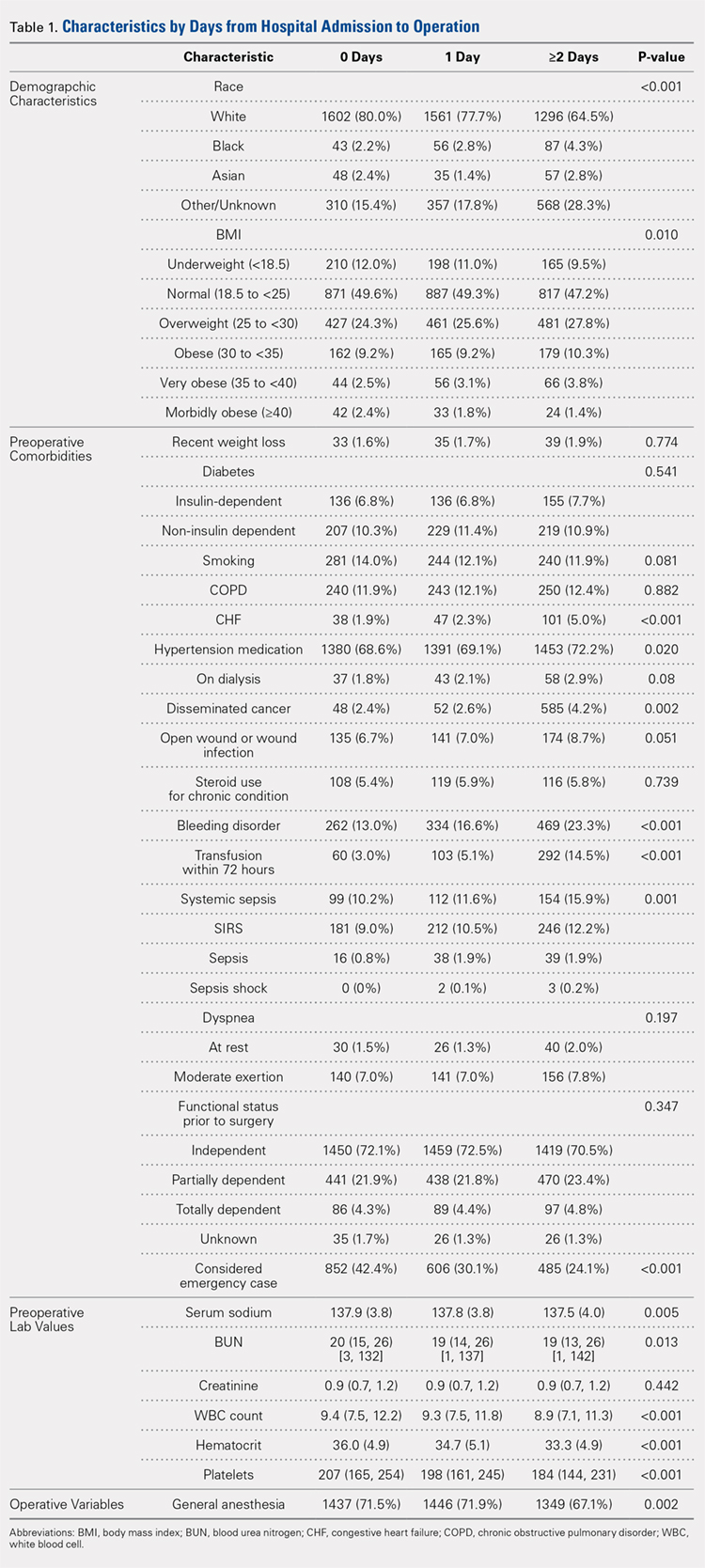

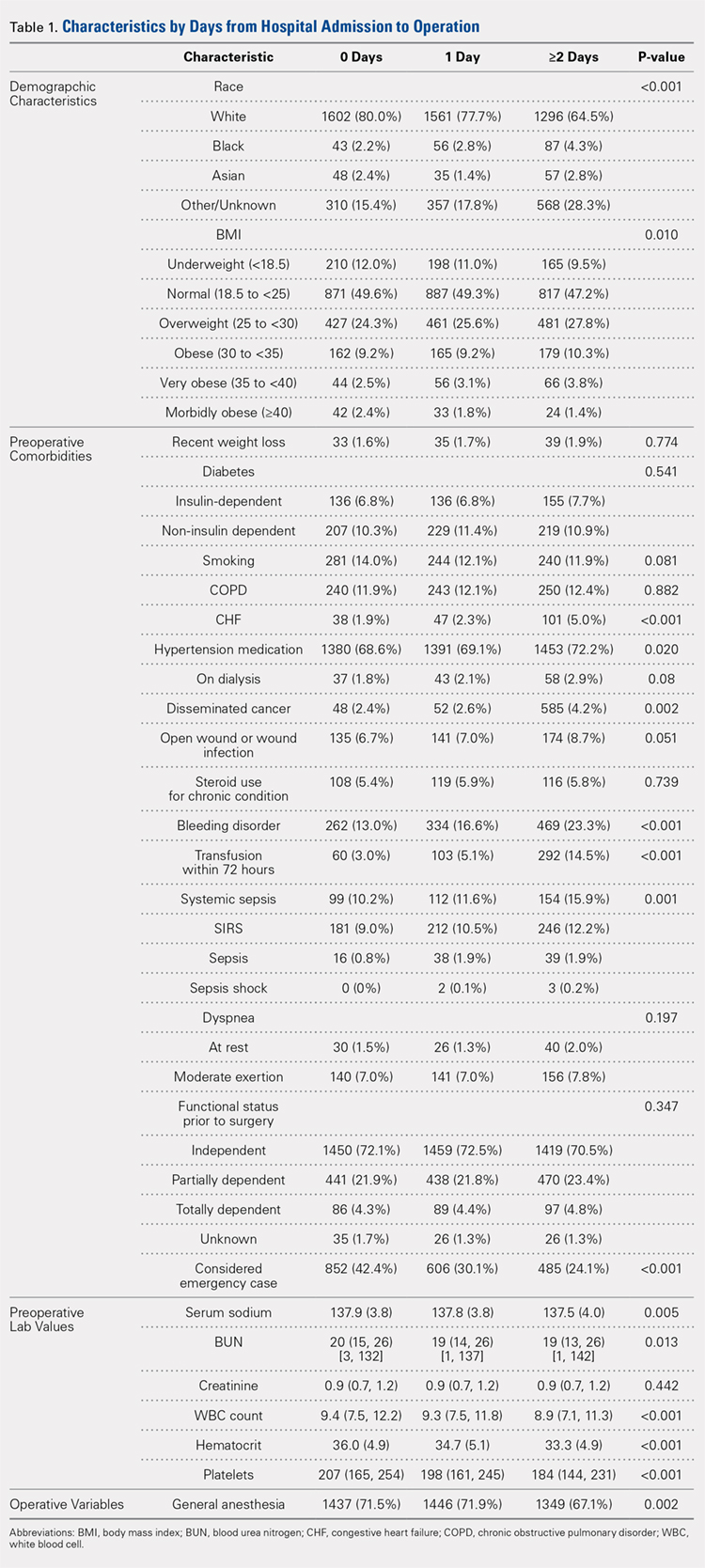

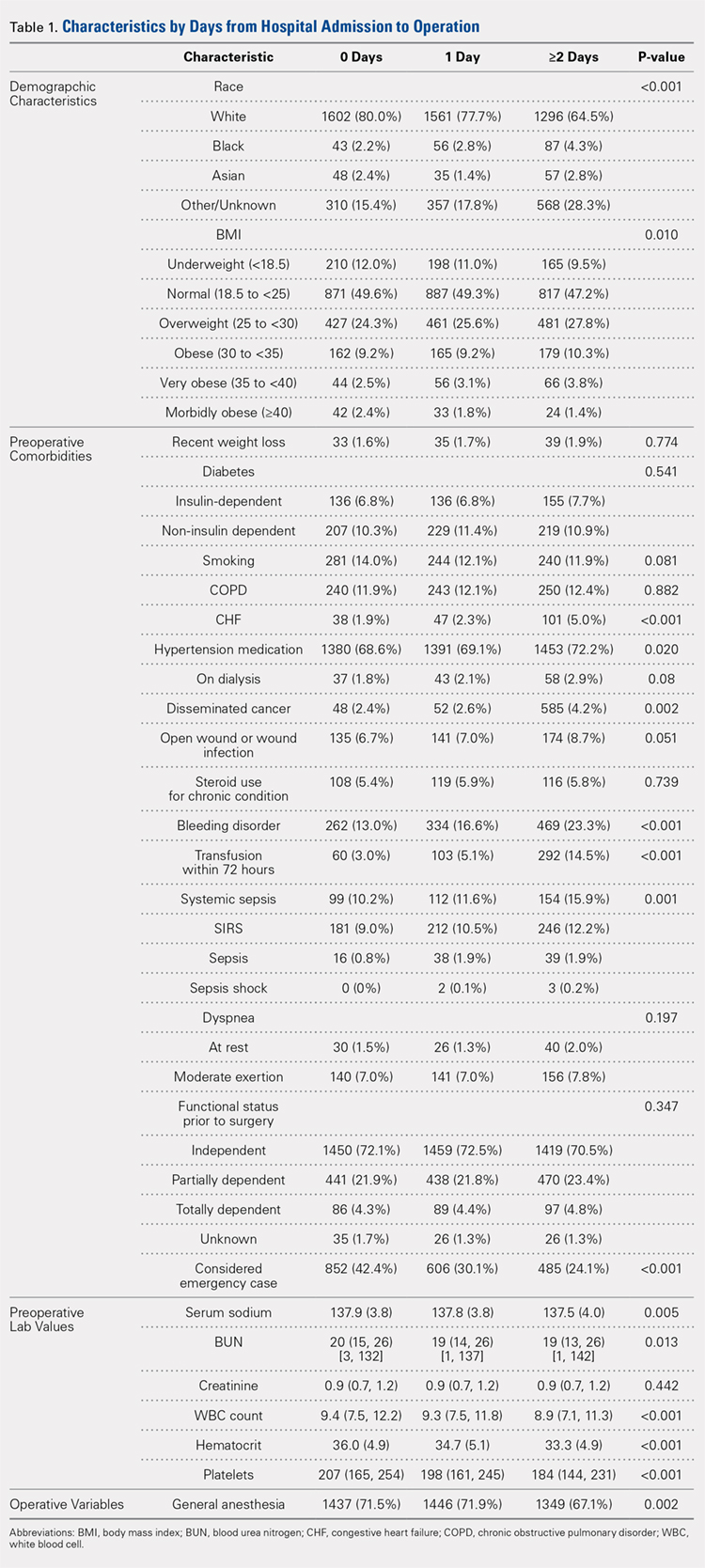

Table 1 summarizes the individual characteristics for this cohort. The average (standard deviation) age was 9.5 (5.1) years. Ethnicity was missing for 25.3% and therefore excluded from the multivariable models. Almost all children had a head AIS score of 2 (99.2%), and the majority had a total ISS ≤ 4 (73.4%). The majority of admissions were admitted to Level 1 trauma-accredited hospitals (78.7%) and medium-sized hospitals (63.9%).

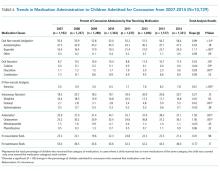

The most commonly delivered medication classes were non-narcotic oral analgesics (53.7%), dextrose-containing IV fluids (45.0%), and antiemetic medications (34.1%). IV and oral narcotic use occurred in 19.7% and 10.2% of the children, respectively. Among our cohort, 16.7% received none of these medication classes. Of the 8,940 receiving medication, 32.6% received a single medication class, 29.5% received 2 classes, 20.5% 3 classes, 11.9% 4 classes, and 5.5% received 5 or more medication classes. Approximately 15% (n = 1597) received only oral medications, among whom 91.2% (n = 1457) received only non-narcotic analgesics and 3.9% (n = 63) received only oral narcotic analgesics. The majority (69.5%) received a head CT.

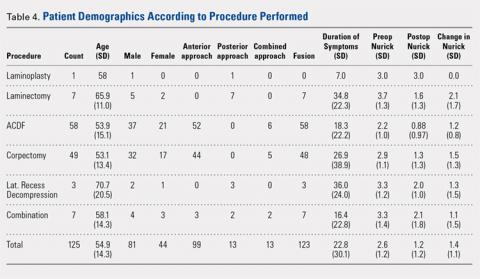

Table 4 summarizes medication administration trends over time. Oral non-narcotic administration increased significantly (slope = 0.99, P < .01) with the most pronounced change occurring in ibuprofen use (slope = 1.11, P < .001). Use of the IV non-narcotic ketorolac (slope = 0.61, P < .001) also increased significantly, as did the proportion of children receiving antiemetics (slope = 1.59, P = .001), with a substantial increase in ondansetron use (slope = 1.56, P = .001). The proportion of children receiving head CTs decreased linearly over time (slope= −1.75, P < .001), from 76.1% in 2007 to 63.7% in 2014. Median cost, adjusted for inflation, increased during our study period (P < .001) by approximately $353 each year, reaching $11,249 by 2014.

DISCUSSION

From 2007 to 2014, approximately 15% of children admitted to PHIS hospitals for TBI were admitted primarily for concussion. Since almost all children had a head AIS score of 2 and an ISS ≤ 4, our data suggest that most children had an associated loss of consciousness and that concussion was the only injury sustained, respectively. This study identified important subgroups that necessitated inpatient care but are rarely the focus of concussion research (eg, toddlers and those injured due to a motor vehicle collision). Most children (83.3%) received medications to treat common postconcussive symptoms (eg, pain and nausea), with almost half receiving 3 or more medication classes. Factors associated with the development of postconcussive syndrome (eg, female sex and adolescent age)4,21 were significantly associated with hospitalization of 2 or more days and ED revisit within 30 days of admission. In the absence of evidenced-based guidelines for inpatient concussion management, we identified significant trends in care, including increased use of specific pain [ie, oral and IV nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] and antiemetic (ie, ondansetron) medications and decreased use of head CT. Given the number of children admitted and receiving treatment for concussion symptomatology, influences on the decision to deliver specific care practices, as well as the impact and benefit of hospitalization, require closer examination.

Our study extends previous reports from the PHIS database by characterizing children admitted for concussion.1 We found that children admitted for concussion had similar characteristics to the broader population of children who sustain concussion (eg, school-aged children, male, and injured due to a fall or during sports).1,3,22 However, approximately 20% of the cohort were less than 5 years old, and less is known regarding appropriate treatment and outcomes of concussion in this age group.23 Uncertainty regarding optimal management and a young child’s inability to articulate symptoms may contribute to a physician’s decision to admit for close observation. Similar to Blinman et al., we found that a substantial proportion of children admitted with concussion were injured due to a motor vehicle collision,3 suggesting that although sports-related injuries are responsible for a significant proportion of pediatric concussions, children injured by other preventable mechanisms may also be incurring significant concussive injuries. Finally, the majority of our cohort was from an urban core, relative to a rural area, which is likely a reflection of the regionalization of trauma care, as well as variations in access to health care.

Although most children recover fully from concussion without specific interventions, 20%-30% may remain symptomatic at 1 month,3,4,21,24 and children who are hospitalized with concussion may be at higher risk for protracted symptoms. While specific individual or injury-related factors (eg, female sex, adolescent age, and injury due to motor vehicle collision) may contribute to more significant postconcussive symptoms, it is unclear how inpatient management affects recovery trajectory. Frequent sleep disruptions associated with inpatient care25 contradict current acute concussion management recommendations for physical and cognitive rest26 and could potentially impair symptom recovery. Additionally, we found widespread use of NSAIDs, although there is evidence suggesting that NSAIDs may potentially worsen concussive symptoms.26 We identified an increase in medication usage over time despite limited evidence of their effectiveness for pediatric concussion.27–29 This change may reflect improved symptom screening4,30 and/or increased awareness of specific medication safety profiles in pediatric trauma patients, especially for NSAIDs and ondansetron. Although we saw an increase in NSAID use, we did not see a proportional decrease in narcotic use. Similarly, while two-thirds of our cohort received IV medications, there is controversy about the need for IV fluids and medications for other pediatric illnesses, with research demonstrating that IV treatment may not reduce recovery time and may contribute to prolonged hospitalization and phlebitis.31,32 Thus, there is a need to understand the therapeutic effectiveness and benefits of medications and fluids on postconcussion recovery.

Neuroimaging rates for children receiving ED evaluation for concussion have been reported to be up to 60%-70%,1,22 although a more recent study spanning 2006 to 2011 found a 35-%–40% head CT rate in pediatric patients by hospital-based EDs in the United States.33 Our results appear to support decreasing head CT use over time in pediatric hospitals. Hospitalization for observation is costly1 but could decrease a child’s risk of malignancy from radiation exposure. Further work on balancing cost, risk, and shared decision-making with parents could guide decisions regarding emergent neuroimaging versus admission.

This study has limitations inherent to the use of an administrative dataset, including lack of information regarding why the child was admitted. Since the focus was to describe inpatient care of children with concussion, those discharged home from the ED were not included in this dataset. Consequently, we could not contrast the ED care of those discharged home with those who were admitted or assess trends in admission rates for concussion. Although the overall number of concussion admissions has continued to remain stable over time,1 due to a lack of prospectively collected clinical information, we are unable to determine whether observed trends in care are secondary to changes in practice or changes in concussion severity. However, there has been no research to date supporting the latter. Ethnicity was excluded due to high levels of missing data. Cost of stay was not extensively analyzed given hospital variation in designation of observational or inpatient status, which subsequently affects billing.34 Rates of neuroimaging and ED revisit may have been underestimated since children could have received care at a non-PHIS hospital. Similarly, the decrease in the proportion of children receiving neuroimaging over time may have been associated with an increase in children being transferred from a non-PHIS hospital for admission, although with increased regionalization in trauma care, we would not expect transfers of children with only concussion to have significantly increased. Finally, data were limited to the pediatric tertiary care centers participating in PHIS, thereby reducing generalizability and introducing selection bias by only including children who were able to access care at PHIS hospitals. Although the care practices we evaluated (eg, NSAIDs and head CT) are available at all hospitals, our analyses only reflect care delivered within the PHIS.

Concussion accounted for 15% of all pediatric TBI admissions during our study period. Further investigation of potential factors associated with admission and protracted recovery (eg, adolescent females needing treatment for severe symptomatology) could facilitate better understanding of how hospitalization affects recovery. Additionally, research on acute pharmacotherapies (eg, IV therapies and/or inpatient treatment until symptoms resolve) is needed to fully elucidate the acute and long-term benefits of interventions delivered to children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Colleen Mangeot: Biostatistician with extensive PHIS knowledge who contributed to database creation and statistical analysis. Yanhong (Amy) Liu: Research database programmer who developed the database, ran quality assurance measures, and cleaned all study data.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by grant R40 MC 268060102 from the Maternal and Child Health Research Program, Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. The funding source was not involved in development of the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; or in the writing of this report.

1. Colvin JD, Thurm C, Pate BM, Newland JG, Hall M, Meehan WP. Diagnosis and acute management of patients with concussion at children’s hospitals. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(12):934-938. PubMed

2. Bourgeois FT, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM, Neuman MI. Variation in emergency department admission rates in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):539-545. PubMed

3. Blinman TA, Houseknecht E, Snyder C, Wiebe DJ, Nance ML. Postconcussive symptoms in hospitalized pediatric patients after mild traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(6):1223-1228. PubMed

4. Babcock L, Byczkowski T, Wade SL, Ho M, Mookerjee S, Bazarian JJ. Predicting postconcussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents who present to the emergency department. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(2):156-161. PubMed

5. Conway PH, Keren R. Factors associated with variability in outcomes for children hospitalized with urinary tract infection. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;154(6):789-796. PubMed

6. Services UDoHaH. International classification of diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical modification (ICD-9CM). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, Health Care Financing Administration 1989.

7. Marr AL, Coronado VG. Annual data submission standards. Central nervous system injury surveillance. In: US Department of Health and Human Services PHS, CDC, ed. Atlanta, GA 2001.

8. Organization WH. International classification of diseases: manual on the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and cause of death. In: Organization WH, ed. 9th rev. ed. Geneva, Switerland 1977.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Report to Congress on mild traumatic brain injury in the United States: steps to prevent a serious public health problem. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003.

10. Mackenzie E, Sacco WJ. ICDMAP-90 software: user’s guide. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University and Tri-Analytics. 1997:1-25.

11. MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Shankar B. Classifying trauma severity based on hospital discharge diagnoses. Validation of an ICD-9CM to AIS-85 conversion table. Med Care. 1989;27(4):412-422. PubMed

12. Fleischman RJ, Mann NC, Dai M, et al. Validating the use of ICD-9 code mapping to generate injury severity scores. J Trauma Nurs. 2017;24(1):4-14. PubMed

13. Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Jr., Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. The Journal of trauma. 1974;14(3):187-196. PubMed

14. Wood JN, Feudtner C, Medina SP, Luan X, Localio R, Rubin DM. Variation in occult injury screening for children with suspected abuse in selected US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics

15. Yang J, Phillips G, Xiang H, Allareddy V, Heiden E, Peek-Asa C. Hospitalisations for sport-related concussions in US children aged 5 to 18 years during 2000-2004. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(8):664-669. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):205-209. PubMed

17. Peltz A, Wu CL, White ML, et al. Characteristics of rural children admitted to pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5): e20153156. PubMed

18. Services UDoHaH. Annual update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register; 2016-03-14 2011.

19. Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1149-1155. PubMed

20. Proposed Matrix of E-code Groupings| WISQARS | Injury Center | CDC. 2016; http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/ecode_matrix.html.

21. Zemek RL, Farion KJ, Sampson M, McGahern C. Prognosticators of persistent symptoms following pediatric concussion: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(3):259-265. PubMed

22. Meehan WP, Mannix R. Pediatric concussions in United States emergency departments in the years 2002 to 2006. J Pediatr. 2010;157(6):889-893. PubMed

23. Davis GA, Purcell LK. The evaluation and management of acute concussion differs in young children. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(2):98-101. PubMed

24. Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014-1025. PubMed

25. Hinds PS, Hockenberry M, Rai SN, et al. Nocturnal awakenings, sleep environment interruptions, and fatigue in hospitalized children with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):393-402. PubMed

26. Patterson ZR, Holahan MR. Understanding the neuroinflammatory response following concussion to develop treatment strategies. Front Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:58. PubMed

27. Meehan WP. Medical therapies for concussion. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):115-124, ix. PubMed

28. Petraglia AL, Maroon JC, Bailes JE. From the field of play to the field of combat: a review of the pharmacological management of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(6):1520-1533. PubMed

29. Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2250-2257. PubMed

30. Barlow KM, Crawford S, Stevenson A, Sandhu SS, Belanger F, Dewey D. Epidemiology of postconcussion syndrome in pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):e374-e381. PubMed

31. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(2):120-128. PubMed

32. Hartling L, Bellemare S, Wiebe N, Russell K, Klassen TP, Craig W. Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(3):CD004390. PubMed

34. Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M, et al. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1050-1058. PubMed

33. Zonfrillo MR, Kim KH, Arbogast KB. Emergency Department Visits and Head Computed Tomography Utilization for Concussion Patients From 2006 to 2011. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):872-877. PubMed

Approximately 14% of children who sustain a concussion are admitted to the hospital,1 although admission rates reportedly vary substantially among pediatric hospitals.2 Children hospitalized for concussion may be at a higher risk for persistent postconcussive symptoms,3,4 yet little is known about this subset of children and how they are managed while in the hospital. Characterizing children hospitalized for concussion and describing the inpatient care they received will promote hypothesis generation for further inquiry into indications for admission, as well as the relationship between inpatient management and concussion recovery.

We described a cohort of children admitted to 40 pediatric hospitals primarily for concussion and detailed care delivered during hospitalization. We explored individual-level factors and their association with prolonged length of stay (LOS) and emergency department (ED) readmission. Finally, we evaluated if there had been changes in inpatient care over the 8-year study period.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

The Institutional Review Board determined that this retrospective cohort study was exempt from review.

Data Source

The Children’s Hospital Association’s Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) is an administrative database from pediatric hospitals located within 17 major metropolitan areas in the United States. Data include: service dates, patient demographics, payer type, diagnosis codes, resource utilization information (eg, medications), and hospital characteristics.1,5 De-identified data undergo reliability and validity checks prior to inclusion.1,5 We analyzed data from 40 of 43 hospitals that contributed inpatient data during our study period. 2 hospitals were excluded due to inconsistent data submission, and 1 removed their data.

Study Population

Data were extracted for children 0 to 17 years old who were admitted to an inpatient or observational unit between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2014 for traumatic brain injury (TBI). Children were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification, Ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes that denote TBI per the Centers for Disease Control (CDC): 800.0–801.9, 803.0–804.9, 850–854.1, and 959.01.6–8 To examine inpatient care for concussion, we only retained children with a primary (ie, first) concussion-related diagnosis code (850.0–850.99) for analyses. For patients with multiple visits during our study period, only the index admission was analyzed. We refined our cohort using 2 injury scores calculated from ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes using validated ICDMAP-90 injury coding software.6,10–12 The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) ranges from 1 (minor injury) to 6 (not survivable). The total Injury Severity Score (ISS) is based on 6 body regions (head/neck, face, chest, abdomen, extremity, and external) and calculated by summing the squares of the 3 worst AIS scores.13 A concussion receives a head AIS score of 2 if there is an associated loss of consciousness or a score of 1 if there is not; therefore, children were excluded if the head AIS score was >2. We also excluded children with the following features, as they may be indicative of more severe injuries that were likely the cause of admission: ISS > 6, secondary diagnosis code of skull fracture or intracranial injury, intensive care unit (ICU) or operating room (OR) charges, or a LOS > 7 days. Because some children are hospitalized for potentially abusive minor head trauma pending a safe discharge plan, we excluded children 0 to 4 years of age with child abuse, which was determined using a specific set of diagnosis codes (E960-E96820, 995.54, and 995.55) similar to previous research.14

Data Elements and Outcomes

Outcomes

Based on previous reports,1,15 a LOS ≥ 2 days distinguished a typical hospitalization from a prolonged one. ED revisit was identified when a child had a visit with a TBI-related primary diagnosis code at a PHIS hospital within 30 days of initial admission and was discharged home. We limited analyses to children discharged, as children readmitted may have had an initially missed intracranial injury.

Patient Characteristics

We examined the following patient variables: age, race, sex, presence of chronic medical condition, payer type, household income, area of residence (eg, rural versus urban), and mechanism of injury. Age was categorized to represent early childhood (0 to 4 years), school age (5 to 12 years), and adolescence (12 to 17 years). Race was grouped as white, black, or other (Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, and “other” per PHIS). Ethnicity was described as Hispanic/Latino or not Hispanic/Latino. Children with medical conditions lasting at least 12 months and comorbidities that may impact TBI recovery were identified using a subgrouping of ICD-9-CM codes for children with “complex chronic conditions”.16 Payer type was categorized as government, private, and self-pay. We extracted a PHIS variable representing the 2010 median household income for the child’s home zip code and categorized it into quartiles based on the Federal Poverty Level for a family of 4.17,18 Area of residence was defined using a Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classification system19 and grouped into large urban core, suburban area, large rural town, or small rural town/isolated rural area.17 Mechanism of injury was determined using E-codes and categorized using the CDC injury framework,20 with sports-related injuries identified using a previously described set of E-codes.1 Mechanisms of injury included fall, motor vehicle collision, other motorized transport (eg, all-terrain vehicles), sports-related, struck by or against (ie, objects), and all others (eg, cyclists).

Hospital Characteristics

Hospitals were characterized by region (Northeast, Central, South, and West) and size (small <200, medium 200–400, and large >400 beds). The trauma-level accreditation was identified with Level 1 reflecting the highest possible trauma resources.

Medical Care Variables

Care variables included medications, neuroimaging, and cost of stay. Medication classes included oral non-narcotic analgesics [acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and others (aspirin, tramadol, and naproxen)], oral narcotics (codeine, oxycodone, and narcotic–non-narcotic combinations), intravenous (IV) non-narcotics (ketorolac), IV narcotics (morphine, fentanyl, and hydromorphone), antiemetics [ondansetron, metoclopramide, and phenothiazines (prochlorperazine, chlorpromazine, and promethazine)], maintenance IV fluids (dextrose with electrolytes or 0.45% sodium chloride), and resuscitation IV fluids (0.9% sodium chloride or lactated Ringer’s solution). Receipt of neuroimaging was determined if head computed tomography (CT) had been conducted at the admitting hospital. Adjusted cost of stay was calculated using a hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratio with additional adjustments using the Center for Medicare & Medicaid’s Wage Index.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for individual, injury, and hospital, and care data elements, LOS, and ED readmissions. The number of children admitted with TBI was used as the denominator to assess the proportion of pediatric TBI admissions that were due to concussions. To identify factors associated with prolonged LOS (ie, ≥2 days) and ED readmission, we employed a mixed models approach that accounted for clustering of observations within hospitals. Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, payer type, household income, RUCA code, chronic medical condition, and injury mechanism. Models were adjusted for hospital location, size, and trauma-level accreditation. The binary distribution was specified along with a logit link function. A 2-phase process determined factors associated with each outcome. First, bivariable models were developed, followed by multivariable models that included independent variables with P values < .25 in the bivariable analysis. Backward step-wise elimination was performed, deleting variables with the highest P value one at a time. After each deletion, the percentage change in odds ratios was examined; if variable removal resulted in >10% change, the variable was retained as a potential confounder. This process was repeated until all remaining variables were significant (P < .05) with the exception of potential confounders. Finally, we examined the proportion of children receiving selected care practices annually. Descriptive and trend analyses were used to analyze adjusted median cost of stay. Analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Over 8 years, 88,526 children were admitted to 40 PHIS hospitals with a TBI-related diagnosis, among whom 13,708 had a primary diagnosis of concussion. We excluded 2,973 children with 1 or more of the following characteristics: a secondary diagnosis of intracranial injury (n = 58), head AIS score > 2 (n = 218), LOS > 7 days (n = 50), OR charges (n = 132), ICU charges (n = 1947), and ISS > 6 (n = 568). Six additional children aging 0 to 4 years were excluded due to child abuse. The remaining 10,729 children, averaging 1300 hospitalizations annually, were identified as being hospitalized primarily for concussion.

Table 1 summarizes the individual characteristics for this cohort. The average (standard deviation) age was 9.5 (5.1) years. Ethnicity was missing for 25.3% and therefore excluded from the multivariable models. Almost all children had a head AIS score of 2 (99.2%), and the majority had a total ISS ≤ 4 (73.4%). The majority of admissions were admitted to Level 1 trauma-accredited hospitals (78.7%) and medium-sized hospitals (63.9%).

The most commonly delivered medication classes were non-narcotic oral analgesics (53.7%), dextrose-containing IV fluids (45.0%), and antiemetic medications (34.1%). IV and oral narcotic use occurred in 19.7% and 10.2% of the children, respectively. Among our cohort, 16.7% received none of these medication classes. Of the 8,940 receiving medication, 32.6% received a single medication class, 29.5% received 2 classes, 20.5% 3 classes, 11.9% 4 classes, and 5.5% received 5 or more medication classes. Approximately 15% (n = 1597) received only oral medications, among whom 91.2% (n = 1457) received only non-narcotic analgesics and 3.9% (n = 63) received only oral narcotic analgesics. The majority (69.5%) received a head CT.

Table 4 summarizes medication administration trends over time. Oral non-narcotic administration increased significantly (slope = 0.99, P < .01) with the most pronounced change occurring in ibuprofen use (slope = 1.11, P < .001). Use of the IV non-narcotic ketorolac (slope = 0.61, P < .001) also increased significantly, as did the proportion of children receiving antiemetics (slope = 1.59, P = .001), with a substantial increase in ondansetron use (slope = 1.56, P = .001). The proportion of children receiving head CTs decreased linearly over time (slope= −1.75, P < .001), from 76.1% in 2007 to 63.7% in 2014. Median cost, adjusted for inflation, increased during our study period (P < .001) by approximately $353 each year, reaching $11,249 by 2014.

DISCUSSION

From 2007 to 2014, approximately 15% of children admitted to PHIS hospitals for TBI were admitted primarily for concussion. Since almost all children had a head AIS score of 2 and an ISS ≤ 4, our data suggest that most children had an associated loss of consciousness and that concussion was the only injury sustained, respectively. This study identified important subgroups that necessitated inpatient care but are rarely the focus of concussion research (eg, toddlers and those injured due to a motor vehicle collision). Most children (83.3%) received medications to treat common postconcussive symptoms (eg, pain and nausea), with almost half receiving 3 or more medication classes. Factors associated with the development of postconcussive syndrome (eg, female sex and adolescent age)4,21 were significantly associated with hospitalization of 2 or more days and ED revisit within 30 days of admission. In the absence of evidenced-based guidelines for inpatient concussion management, we identified significant trends in care, including increased use of specific pain [ie, oral and IV nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] and antiemetic (ie, ondansetron) medications and decreased use of head CT. Given the number of children admitted and receiving treatment for concussion symptomatology, influences on the decision to deliver specific care practices, as well as the impact and benefit of hospitalization, require closer examination.

Our study extends previous reports from the PHIS database by characterizing children admitted for concussion.1 We found that children admitted for concussion had similar characteristics to the broader population of children who sustain concussion (eg, school-aged children, male, and injured due to a fall or during sports).1,3,22 However, approximately 20% of the cohort were less than 5 years old, and less is known regarding appropriate treatment and outcomes of concussion in this age group.23 Uncertainty regarding optimal management and a young child’s inability to articulate symptoms may contribute to a physician’s decision to admit for close observation. Similar to Blinman et al., we found that a substantial proportion of children admitted with concussion were injured due to a motor vehicle collision,3 suggesting that although sports-related injuries are responsible for a significant proportion of pediatric concussions, children injured by other preventable mechanisms may also be incurring significant concussive injuries. Finally, the majority of our cohort was from an urban core, relative to a rural area, which is likely a reflection of the regionalization of trauma care, as well as variations in access to health care.

Although most children recover fully from concussion without specific interventions, 20%-30% may remain symptomatic at 1 month,3,4,21,24 and children who are hospitalized with concussion may be at higher risk for protracted symptoms. While specific individual or injury-related factors (eg, female sex, adolescent age, and injury due to motor vehicle collision) may contribute to more significant postconcussive symptoms, it is unclear how inpatient management affects recovery trajectory. Frequent sleep disruptions associated with inpatient care25 contradict current acute concussion management recommendations for physical and cognitive rest26 and could potentially impair symptom recovery. Additionally, we found widespread use of NSAIDs, although there is evidence suggesting that NSAIDs may potentially worsen concussive symptoms.26 We identified an increase in medication usage over time despite limited evidence of their effectiveness for pediatric concussion.27–29 This change may reflect improved symptom screening4,30 and/or increased awareness of specific medication safety profiles in pediatric trauma patients, especially for NSAIDs and ondansetron. Although we saw an increase in NSAID use, we did not see a proportional decrease in narcotic use. Similarly, while two-thirds of our cohort received IV medications, there is controversy about the need for IV fluids and medications for other pediatric illnesses, with research demonstrating that IV treatment may not reduce recovery time and may contribute to prolonged hospitalization and phlebitis.31,32 Thus, there is a need to understand the therapeutic effectiveness and benefits of medications and fluids on postconcussion recovery.

Neuroimaging rates for children receiving ED evaluation for concussion have been reported to be up to 60%-70%,1,22 although a more recent study spanning 2006 to 2011 found a 35-%–40% head CT rate in pediatric patients by hospital-based EDs in the United States.33 Our results appear to support decreasing head CT use over time in pediatric hospitals. Hospitalization for observation is costly1 but could decrease a child’s risk of malignancy from radiation exposure. Further work on balancing cost, risk, and shared decision-making with parents could guide decisions regarding emergent neuroimaging versus admission.

This study has limitations inherent to the use of an administrative dataset, including lack of information regarding why the child was admitted. Since the focus was to describe inpatient care of children with concussion, those discharged home from the ED were not included in this dataset. Consequently, we could not contrast the ED care of those discharged home with those who were admitted or assess trends in admission rates for concussion. Although the overall number of concussion admissions has continued to remain stable over time,1 due to a lack of prospectively collected clinical information, we are unable to determine whether observed trends in care are secondary to changes in practice or changes in concussion severity. However, there has been no research to date supporting the latter. Ethnicity was excluded due to high levels of missing data. Cost of stay was not extensively analyzed given hospital variation in designation of observational or inpatient status, which subsequently affects billing.34 Rates of neuroimaging and ED revisit may have been underestimated since children could have received care at a non-PHIS hospital. Similarly, the decrease in the proportion of children receiving neuroimaging over time may have been associated with an increase in children being transferred from a non-PHIS hospital for admission, although with increased regionalization in trauma care, we would not expect transfers of children with only concussion to have significantly increased. Finally, data were limited to the pediatric tertiary care centers participating in PHIS, thereby reducing generalizability and introducing selection bias by only including children who were able to access care at PHIS hospitals. Although the care practices we evaluated (eg, NSAIDs and head CT) are available at all hospitals, our analyses only reflect care delivered within the PHIS.

Concussion accounted for 15% of all pediatric TBI admissions during our study period. Further investigation of potential factors associated with admission and protracted recovery (eg, adolescent females needing treatment for severe symptomatology) could facilitate better understanding of how hospitalization affects recovery. Additionally, research on acute pharmacotherapies (eg, IV therapies and/or inpatient treatment until symptoms resolve) is needed to fully elucidate the acute and long-term benefits of interventions delivered to children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Colleen Mangeot: Biostatistician with extensive PHIS knowledge who contributed to database creation and statistical analysis. Yanhong (Amy) Liu: Research database programmer who developed the database, ran quality assurance measures, and cleaned all study data.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by grant R40 MC 268060102 from the Maternal and Child Health Research Program, Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. The funding source was not involved in development of the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; or in the writing of this report.

Approximately 14% of children who sustain a concussion are admitted to the hospital,1 although admission rates reportedly vary substantially among pediatric hospitals.2 Children hospitalized for concussion may be at a higher risk for persistent postconcussive symptoms,3,4 yet little is known about this subset of children and how they are managed while in the hospital. Characterizing children hospitalized for concussion and describing the inpatient care they received will promote hypothesis generation for further inquiry into indications for admission, as well as the relationship between inpatient management and concussion recovery.

We described a cohort of children admitted to 40 pediatric hospitals primarily for concussion and detailed care delivered during hospitalization. We explored individual-level factors and their association with prolonged length of stay (LOS) and emergency department (ED) readmission. Finally, we evaluated if there had been changes in inpatient care over the 8-year study period.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

The Institutional Review Board determined that this retrospective cohort study was exempt from review.

Data Source

The Children’s Hospital Association’s Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) is an administrative database from pediatric hospitals located within 17 major metropolitan areas in the United States. Data include: service dates, patient demographics, payer type, diagnosis codes, resource utilization information (eg, medications), and hospital characteristics.1,5 De-identified data undergo reliability and validity checks prior to inclusion.1,5 We analyzed data from 40 of 43 hospitals that contributed inpatient data during our study period. 2 hospitals were excluded due to inconsistent data submission, and 1 removed their data.

Study Population

Data were extracted for children 0 to 17 years old who were admitted to an inpatient or observational unit between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2014 for traumatic brain injury (TBI). Children were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification, Ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes that denote TBI per the Centers for Disease Control (CDC): 800.0–801.9, 803.0–804.9, 850–854.1, and 959.01.6–8 To examine inpatient care for concussion, we only retained children with a primary (ie, first) concussion-related diagnosis code (850.0–850.99) for analyses. For patients with multiple visits during our study period, only the index admission was analyzed. We refined our cohort using 2 injury scores calculated from ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes using validated ICDMAP-90 injury coding software.6,10–12 The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) ranges from 1 (minor injury) to 6 (not survivable). The total Injury Severity Score (ISS) is based on 6 body regions (head/neck, face, chest, abdomen, extremity, and external) and calculated by summing the squares of the 3 worst AIS scores.13 A concussion receives a head AIS score of 2 if there is an associated loss of consciousness or a score of 1 if there is not; therefore, children were excluded if the head AIS score was >2. We also excluded children with the following features, as they may be indicative of more severe injuries that were likely the cause of admission: ISS > 6, secondary diagnosis code of skull fracture or intracranial injury, intensive care unit (ICU) or operating room (OR) charges, or a LOS > 7 days. Because some children are hospitalized for potentially abusive minor head trauma pending a safe discharge plan, we excluded children 0 to 4 years of age with child abuse, which was determined using a specific set of diagnosis codes (E960-E96820, 995.54, and 995.55) similar to previous research.14

Data Elements and Outcomes

Outcomes

Based on previous reports,1,15 a LOS ≥ 2 days distinguished a typical hospitalization from a prolonged one. ED revisit was identified when a child had a visit with a TBI-related primary diagnosis code at a PHIS hospital within 30 days of initial admission and was discharged home. We limited analyses to children discharged, as children readmitted may have had an initially missed intracranial injury.

Patient Characteristics

We examined the following patient variables: age, race, sex, presence of chronic medical condition, payer type, household income, area of residence (eg, rural versus urban), and mechanism of injury. Age was categorized to represent early childhood (0 to 4 years), school age (5 to 12 years), and adolescence (12 to 17 years). Race was grouped as white, black, or other (Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, and “other” per PHIS). Ethnicity was described as Hispanic/Latino or not Hispanic/Latino. Children with medical conditions lasting at least 12 months and comorbidities that may impact TBI recovery were identified using a subgrouping of ICD-9-CM codes for children with “complex chronic conditions”.16 Payer type was categorized as government, private, and self-pay. We extracted a PHIS variable representing the 2010 median household income for the child’s home zip code and categorized it into quartiles based on the Federal Poverty Level for a family of 4.17,18 Area of residence was defined using a Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classification system19 and grouped into large urban core, suburban area, large rural town, or small rural town/isolated rural area.17 Mechanism of injury was determined using E-codes and categorized using the CDC injury framework,20 with sports-related injuries identified using a previously described set of E-codes.1 Mechanisms of injury included fall, motor vehicle collision, other motorized transport (eg, all-terrain vehicles), sports-related, struck by or against (ie, objects), and all others (eg, cyclists).

Hospital Characteristics

Hospitals were characterized by region (Northeast, Central, South, and West) and size (small <200, medium 200–400, and large >400 beds). The trauma-level accreditation was identified with Level 1 reflecting the highest possible trauma resources.

Medical Care Variables

Care variables included medications, neuroimaging, and cost of stay. Medication classes included oral non-narcotic analgesics [acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and others (aspirin, tramadol, and naproxen)], oral narcotics (codeine, oxycodone, and narcotic–non-narcotic combinations), intravenous (IV) non-narcotics (ketorolac), IV narcotics (morphine, fentanyl, and hydromorphone), antiemetics [ondansetron, metoclopramide, and phenothiazines (prochlorperazine, chlorpromazine, and promethazine)], maintenance IV fluids (dextrose with electrolytes or 0.45% sodium chloride), and resuscitation IV fluids (0.9% sodium chloride or lactated Ringer’s solution). Receipt of neuroimaging was determined if head computed tomography (CT) had been conducted at the admitting hospital. Adjusted cost of stay was calculated using a hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratio with additional adjustments using the Center for Medicare & Medicaid’s Wage Index.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for individual, injury, and hospital, and care data elements, LOS, and ED readmissions. The number of children admitted with TBI was used as the denominator to assess the proportion of pediatric TBI admissions that were due to concussions. To identify factors associated with prolonged LOS (ie, ≥2 days) and ED readmission, we employed a mixed models approach that accounted for clustering of observations within hospitals. Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, payer type, household income, RUCA code, chronic medical condition, and injury mechanism. Models were adjusted for hospital location, size, and trauma-level accreditation. The binary distribution was specified along with a logit link function. A 2-phase process determined factors associated with each outcome. First, bivariable models were developed, followed by multivariable models that included independent variables with P values < .25 in the bivariable analysis. Backward step-wise elimination was performed, deleting variables with the highest P value one at a time. After each deletion, the percentage change in odds ratios was examined; if variable removal resulted in >10% change, the variable was retained as a potential confounder. This process was repeated until all remaining variables were significant (P < .05) with the exception of potential confounders. Finally, we examined the proportion of children receiving selected care practices annually. Descriptive and trend analyses were used to analyze adjusted median cost of stay. Analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Over 8 years, 88,526 children were admitted to 40 PHIS hospitals with a TBI-related diagnosis, among whom 13,708 had a primary diagnosis of concussion. We excluded 2,973 children with 1 or more of the following characteristics: a secondary diagnosis of intracranial injury (n = 58), head AIS score > 2 (n = 218), LOS > 7 days (n = 50), OR charges (n = 132), ICU charges (n = 1947), and ISS > 6 (n = 568). Six additional children aging 0 to 4 years were excluded due to child abuse. The remaining 10,729 children, averaging 1300 hospitalizations annually, were identified as being hospitalized primarily for concussion.

Table 1 summarizes the individual characteristics for this cohort. The average (standard deviation) age was 9.5 (5.1) years. Ethnicity was missing for 25.3% and therefore excluded from the multivariable models. Almost all children had a head AIS score of 2 (99.2%), and the majority had a total ISS ≤ 4 (73.4%). The majority of admissions were admitted to Level 1 trauma-accredited hospitals (78.7%) and medium-sized hospitals (63.9%).

The most commonly delivered medication classes were non-narcotic oral analgesics (53.7%), dextrose-containing IV fluids (45.0%), and antiemetic medications (34.1%). IV and oral narcotic use occurred in 19.7% and 10.2% of the children, respectively. Among our cohort, 16.7% received none of these medication classes. Of the 8,940 receiving medication, 32.6% received a single medication class, 29.5% received 2 classes, 20.5% 3 classes, 11.9% 4 classes, and 5.5% received 5 or more medication classes. Approximately 15% (n = 1597) received only oral medications, among whom 91.2% (n = 1457) received only non-narcotic analgesics and 3.9% (n = 63) received only oral narcotic analgesics. The majority (69.5%) received a head CT.

Table 4 summarizes medication administration trends over time. Oral non-narcotic administration increased significantly (slope = 0.99, P < .01) with the most pronounced change occurring in ibuprofen use (slope = 1.11, P < .001). Use of the IV non-narcotic ketorolac (slope = 0.61, P < .001) also increased significantly, as did the proportion of children receiving antiemetics (slope = 1.59, P = .001), with a substantial increase in ondansetron use (slope = 1.56, P = .001). The proportion of children receiving head CTs decreased linearly over time (slope= −1.75, P < .001), from 76.1% in 2007 to 63.7% in 2014. Median cost, adjusted for inflation, increased during our study period (P < .001) by approximately $353 each year, reaching $11,249 by 2014.

DISCUSSION

From 2007 to 2014, approximately 15% of children admitted to PHIS hospitals for TBI were admitted primarily for concussion. Since almost all children had a head AIS score of 2 and an ISS ≤ 4, our data suggest that most children had an associated loss of consciousness and that concussion was the only injury sustained, respectively. This study identified important subgroups that necessitated inpatient care but are rarely the focus of concussion research (eg, toddlers and those injured due to a motor vehicle collision). Most children (83.3%) received medications to treat common postconcussive symptoms (eg, pain and nausea), with almost half receiving 3 or more medication classes. Factors associated with the development of postconcussive syndrome (eg, female sex and adolescent age)4,21 were significantly associated with hospitalization of 2 or more days and ED revisit within 30 days of admission. In the absence of evidenced-based guidelines for inpatient concussion management, we identified significant trends in care, including increased use of specific pain [ie, oral and IV nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] and antiemetic (ie, ondansetron) medications and decreased use of head CT. Given the number of children admitted and receiving treatment for concussion symptomatology, influences on the decision to deliver specific care practices, as well as the impact and benefit of hospitalization, require closer examination.

Our study extends previous reports from the PHIS database by characterizing children admitted for concussion.1 We found that children admitted for concussion had similar characteristics to the broader population of children who sustain concussion (eg, school-aged children, male, and injured due to a fall or during sports).1,3,22 However, approximately 20% of the cohort were less than 5 years old, and less is known regarding appropriate treatment and outcomes of concussion in this age group.23 Uncertainty regarding optimal management and a young child’s inability to articulate symptoms may contribute to a physician’s decision to admit for close observation. Similar to Blinman et al., we found that a substantial proportion of children admitted with concussion were injured due to a motor vehicle collision,3 suggesting that although sports-related injuries are responsible for a significant proportion of pediatric concussions, children injured by other preventable mechanisms may also be incurring significant concussive injuries. Finally, the majority of our cohort was from an urban core, relative to a rural area, which is likely a reflection of the regionalization of trauma care, as well as variations in access to health care.

Although most children recover fully from concussion without specific interventions, 20%-30% may remain symptomatic at 1 month,3,4,21,24 and children who are hospitalized with concussion may be at higher risk for protracted symptoms. While specific individual or injury-related factors (eg, female sex, adolescent age, and injury due to motor vehicle collision) may contribute to more significant postconcussive symptoms, it is unclear how inpatient management affects recovery trajectory. Frequent sleep disruptions associated with inpatient care25 contradict current acute concussion management recommendations for physical and cognitive rest26 and could potentially impair symptom recovery. Additionally, we found widespread use of NSAIDs, although there is evidence suggesting that NSAIDs may potentially worsen concussive symptoms.26 We identified an increase in medication usage over time despite limited evidence of their effectiveness for pediatric concussion.27–29 This change may reflect improved symptom screening4,30 and/or increased awareness of specific medication safety profiles in pediatric trauma patients, especially for NSAIDs and ondansetron. Although we saw an increase in NSAID use, we did not see a proportional decrease in narcotic use. Similarly, while two-thirds of our cohort received IV medications, there is controversy about the need for IV fluids and medications for other pediatric illnesses, with research demonstrating that IV treatment may not reduce recovery time and may contribute to prolonged hospitalization and phlebitis.31,32 Thus, there is a need to understand the therapeutic effectiveness and benefits of medications and fluids on postconcussion recovery.

Neuroimaging rates for children receiving ED evaluation for concussion have been reported to be up to 60%-70%,1,22 although a more recent study spanning 2006 to 2011 found a 35-%–40% head CT rate in pediatric patients by hospital-based EDs in the United States.33 Our results appear to support decreasing head CT use over time in pediatric hospitals. Hospitalization for observation is costly1 but could decrease a child’s risk of malignancy from radiation exposure. Further work on balancing cost, risk, and shared decision-making with parents could guide decisions regarding emergent neuroimaging versus admission.

This study has limitations inherent to the use of an administrative dataset, including lack of information regarding why the child was admitted. Since the focus was to describe inpatient care of children with concussion, those discharged home from the ED were not included in this dataset. Consequently, we could not contrast the ED care of those discharged home with those who were admitted or assess trends in admission rates for concussion. Although the overall number of concussion admissions has continued to remain stable over time,1 due to a lack of prospectively collected clinical information, we are unable to determine whether observed trends in care are secondary to changes in practice or changes in concussion severity. However, there has been no research to date supporting the latter. Ethnicity was excluded due to high levels of missing data. Cost of stay was not extensively analyzed given hospital variation in designation of observational or inpatient status, which subsequently affects billing.34 Rates of neuroimaging and ED revisit may have been underestimated since children could have received care at a non-PHIS hospital. Similarly, the decrease in the proportion of children receiving neuroimaging over time may have been associated with an increase in children being transferred from a non-PHIS hospital for admission, although with increased regionalization in trauma care, we would not expect transfers of children with only concussion to have significantly increased. Finally, data were limited to the pediatric tertiary care centers participating in PHIS, thereby reducing generalizability and introducing selection bias by only including children who were able to access care at PHIS hospitals. Although the care practices we evaluated (eg, NSAIDs and head CT) are available at all hospitals, our analyses only reflect care delivered within the PHIS.

Concussion accounted for 15% of all pediatric TBI admissions during our study period. Further investigation of potential factors associated with admission and protracted recovery (eg, adolescent females needing treatment for severe symptomatology) could facilitate better understanding of how hospitalization affects recovery. Additionally, research on acute pharmacotherapies (eg, IV therapies and/or inpatient treatment until symptoms resolve) is needed to fully elucidate the acute and long-term benefits of interventions delivered to children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Colleen Mangeot: Biostatistician with extensive PHIS knowledge who contributed to database creation and statistical analysis. Yanhong (Amy) Liu: Research database programmer who developed the database, ran quality assurance measures, and cleaned all study data.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by grant R40 MC 268060102 from the Maternal and Child Health Research Program, Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. The funding source was not involved in development of the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; or in the writing of this report.

1. Colvin JD, Thurm C, Pate BM, Newland JG, Hall M, Meehan WP. Diagnosis and acute management of patients with concussion at children’s hospitals. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(12):934-938. PubMed

2. Bourgeois FT, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM, Neuman MI. Variation in emergency department admission rates in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):539-545. PubMed

3. Blinman TA, Houseknecht E, Snyder C, Wiebe DJ, Nance ML. Postconcussive symptoms in hospitalized pediatric patients after mild traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(6):1223-1228. PubMed

4. Babcock L, Byczkowski T, Wade SL, Ho M, Mookerjee S, Bazarian JJ. Predicting postconcussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents who present to the emergency department. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(2):156-161. PubMed

5. Conway PH, Keren R. Factors associated with variability in outcomes for children hospitalized with urinary tract infection. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;154(6):789-796. PubMed

6. Services UDoHaH. International classification of diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical modification (ICD-9CM). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, Health Care Financing Administration 1989.

7. Marr AL, Coronado VG. Annual data submission standards. Central nervous system injury surveillance. In: US Department of Health and Human Services PHS, CDC, ed. Atlanta, GA 2001.

8. Organization WH. International classification of diseases: manual on the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and cause of death. In: Organization WH, ed. 9th rev. ed. Geneva, Switerland 1977.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Report to Congress on mild traumatic brain injury in the United States: steps to prevent a serious public health problem. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003.

10. Mackenzie E, Sacco WJ. ICDMAP-90 software: user’s guide. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University and Tri-Analytics. 1997:1-25.

11. MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Shankar B. Classifying trauma severity based on hospital discharge diagnoses. Validation of an ICD-9CM to AIS-85 conversion table. Med Care. 1989;27(4):412-422. PubMed

12. Fleischman RJ, Mann NC, Dai M, et al. Validating the use of ICD-9 code mapping to generate injury severity scores. J Trauma Nurs. 2017;24(1):4-14. PubMed

13. Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Jr., Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. The Journal of trauma. 1974;14(3):187-196. PubMed

14. Wood JN, Feudtner C, Medina SP, Luan X, Localio R, Rubin DM. Variation in occult injury screening for children with suspected abuse in selected US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics

15. Yang J, Phillips G, Xiang H, Allareddy V, Heiden E, Peek-Asa C. Hospitalisations for sport-related concussions in US children aged 5 to 18 years during 2000-2004. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(8):664-669. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):205-209. PubMed

17. Peltz A, Wu CL, White ML, et al. Characteristics of rural children admitted to pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5): e20153156. PubMed

18. Services UDoHaH. Annual update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register; 2016-03-14 2011.

19. Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1149-1155. PubMed

20. Proposed Matrix of E-code Groupings| WISQARS | Injury Center | CDC. 2016; http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/ecode_matrix.html.

21. Zemek RL, Farion KJ, Sampson M, McGahern C. Prognosticators of persistent symptoms following pediatric concussion: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(3):259-265. PubMed

22. Meehan WP, Mannix R. Pediatric concussions in United States emergency departments in the years 2002 to 2006. J Pediatr. 2010;157(6):889-893. PubMed

23. Davis GA, Purcell LK. The evaluation and management of acute concussion differs in young children. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(2):98-101. PubMed

24. Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014-1025. PubMed

25. Hinds PS, Hockenberry M, Rai SN, et al. Nocturnal awakenings, sleep environment interruptions, and fatigue in hospitalized children with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):393-402. PubMed

26. Patterson ZR, Holahan MR. Understanding the neuroinflammatory response following concussion to develop treatment strategies. Front Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:58. PubMed

27. Meehan WP. Medical therapies for concussion. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):115-124, ix. PubMed

28. Petraglia AL, Maroon JC, Bailes JE. From the field of play to the field of combat: a review of the pharmacological management of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(6):1520-1533. PubMed

29. Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2250-2257. PubMed

30. Barlow KM, Crawford S, Stevenson A, Sandhu SS, Belanger F, Dewey D. Epidemiology of postconcussion syndrome in pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):e374-e381. PubMed

31. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(2):120-128. PubMed

32. Hartling L, Bellemare S, Wiebe N, Russell K, Klassen TP, Craig W. Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(3):CD004390. PubMed

34. Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M, et al. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1050-1058. PubMed

33. Zonfrillo MR, Kim KH, Arbogast KB. Emergency Department Visits and Head Computed Tomography Utilization for Concussion Patients From 2006 to 2011. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):872-877. PubMed

1. Colvin JD, Thurm C, Pate BM, Newland JG, Hall M, Meehan WP. Diagnosis and acute management of patients with concussion at children’s hospitals. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(12):934-938. PubMed

2. Bourgeois FT, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM, Neuman MI. Variation in emergency department admission rates in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):539-545. PubMed

3. Blinman TA, Houseknecht E, Snyder C, Wiebe DJ, Nance ML. Postconcussive symptoms in hospitalized pediatric patients after mild traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(6):1223-1228. PubMed

4. Babcock L, Byczkowski T, Wade SL, Ho M, Mookerjee S, Bazarian JJ. Predicting postconcussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents who present to the emergency department. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(2):156-161. PubMed

5. Conway PH, Keren R. Factors associated with variability in outcomes for children hospitalized with urinary tract infection. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;154(6):789-796. PubMed

6. Services UDoHaH. International classification of diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical modification (ICD-9CM). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, Health Care Financing Administration 1989.

7. Marr AL, Coronado VG. Annual data submission standards. Central nervous system injury surveillance. In: US Department of Health and Human Services PHS, CDC, ed. Atlanta, GA 2001.

8. Organization WH. International classification of diseases: manual on the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and cause of death. In: Organization WH, ed. 9th rev. ed. Geneva, Switerland 1977.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Report to Congress on mild traumatic brain injury in the United States: steps to prevent a serious public health problem. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003.

10. Mackenzie E, Sacco WJ. ICDMAP-90 software: user’s guide. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University and Tri-Analytics. 1997:1-25.

11. MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Shankar B. Classifying trauma severity based on hospital discharge diagnoses. Validation of an ICD-9CM to AIS-85 conversion table. Med Care. 1989;27(4):412-422. PubMed

12. Fleischman RJ, Mann NC, Dai M, et al. Validating the use of ICD-9 code mapping to generate injury severity scores. J Trauma Nurs. 2017;24(1):4-14. PubMed

13. Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Jr., Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. The Journal of trauma. 1974;14(3):187-196. PubMed

14. Wood JN, Feudtner C, Medina SP, Luan X, Localio R, Rubin DM. Variation in occult injury screening for children with suspected abuse in selected US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics

15. Yang J, Phillips G, Xiang H, Allareddy V, Heiden E, Peek-Asa C. Hospitalisations for sport-related concussions in US children aged 5 to 18 years during 2000-2004. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(8):664-669. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):205-209. PubMed

17. Peltz A, Wu CL, White ML, et al. Characteristics of rural children admitted to pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5): e20153156. PubMed

18. Services UDoHaH. Annual update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register; 2016-03-14 2011.

19. Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1149-1155. PubMed

20. Proposed Matrix of E-code Groupings| WISQARS | Injury Center | CDC. 2016; http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/ecode_matrix.html.

21. Zemek RL, Farion KJ, Sampson M, McGahern C. Prognosticators of persistent symptoms following pediatric concussion: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(3):259-265. PubMed

22. Meehan WP, Mannix R. Pediatric concussions in United States emergency departments in the years 2002 to 2006. J Pediatr. 2010;157(6):889-893. PubMed

23. Davis GA, Purcell LK. The evaluation and management of acute concussion differs in young children. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(2):98-101. PubMed

24. Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014-1025. PubMed

25. Hinds PS, Hockenberry M, Rai SN, et al. Nocturnal awakenings, sleep environment interruptions, and fatigue in hospitalized children with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):393-402. PubMed

26. Patterson ZR, Holahan MR. Understanding the neuroinflammatory response following concussion to develop treatment strategies. Front Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:58. PubMed

27. Meehan WP. Medical therapies for concussion. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):115-124, ix. PubMed

28. Petraglia AL, Maroon JC, Bailes JE. From the field of play to the field of combat: a review of the pharmacological management of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(6):1520-1533. PubMed

29. Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2250-2257. PubMed

30. Barlow KM, Crawford S, Stevenson A, Sandhu SS, Belanger F, Dewey D. Epidemiology of postconcussion syndrome in pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):e374-e381. PubMed

31. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(2):120-128. PubMed

32. Hartling L, Bellemare S, Wiebe N, Russell K, Klassen TP, Craig W. Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(3):CD004390. PubMed

34. Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M, et al. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1050-1058. PubMed

33. Zonfrillo MR, Kim KH, Arbogast KB. Emergency Department Visits and Head Computed Tomography Utilization for Concussion Patients From 2006 to 2011. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):872-877. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers

Diagnostic error—defined as a failure to establish an accurate and timely explanation of the patient’s health problem—is an important source of patient harm.1 Data suggest that all patients will experience at least 1 diagnostic error in their lifetime.2-4 Not surprisingly, diagnostic errors are among the leading categories of paid malpractice claims in the United States.5

Despite diagnostic errors being morbid and sometimes deadly in the hospital,6,7 little is known about how residents and learners approach diagnostic decision making. Errors in diagnosis are believed to stem from cognitive or system failures,8 with errors in cognition believed to occur due to rapid, reflexive thinking operating in the absence of a more analytical, deliberate process. System-based problems (eg, lack of expert availability, technology barriers, and access to data) have also been cited as contributors.9 However, whether and how these apply to trainees is not known.

Therefore, we conducted a focused ethnography of inpatient medicine teams (ie, attendings, residents, interns, and medical students) in 2 affiliated teaching hospitals, aiming to (a) observe the process of diagnosis by trainees and (b) identify methods to improve the diagnostic process and prevent errors.

METHODS