User login

Transcatheter tricuspid valve repair effective and safe for regurgitation

NEW ORLEANS – In the first pivotal randomized, controlled trial of a transcatheter device for the repair of severe tricuspid regurgitation, a large reduction in valve dysfunction was associated with substantial improvement in quality of life (QOL) persisting out of 1 year of follow-up, according to results of the TRILUMINATE trial.

Based on the low procedural risks of the repair, the principal investigator, Paul Sorajja, MD, called the results “very clinically meaningful” as he presented the results at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

Conducted at 65 centers in the United States, Canada, and North America, TRILUMINATE evaluated a transcatheter end-to-end (TEER) repair performed with the TriClip G4 Delivery System (Abbott). The study included two cohorts, both of which will be followed for 5 years. One included patients with very severe tricuspid regurgitation enrolled in a single arm. Data on this cohort is expected later in 2023.

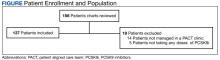

In the randomized portion of the study, 350 patients enrolled with severe tricuspid regurgitation underwent TEER with a clipping device and then were followed on the guideline-directed therapy (GDMT) for heart failure they were receiving at baseline. The control group was managed on GDMT alone.

The primary composite endpoint at 1 year was a composite of death from any cause and/or tricuspid valve surgery, hospitalization for heart failure, and quality of life as measured with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaire (KCCQ).

Benefit driven by quality of life

For the primary endpoint, the win ratio, a statistical calculation of those who did relative to those who did not benefit, was 1.48, signifying a 48% advantage (P = .02). This was driven almost entirely by the KCCQ endpoint. There was no significant difference death and/or tricuspid valve surgery, which occurred in about 10% of both groups (P = .75) or heart failure hospitalization, which was occurred in slightly more patients randomized to repair (14.9% vs. 12.1%; P = .41).

For KCCQ, the mean increase at 1 year was 12.3 points in the repair group versus 0.6 points (P < .001) in the control group. With an increase of 5-10 points typically considered to be clinically meaningful, the advantage of repair over GDMT at the threshold of 15 points or greater was highly statistically significant (49.7% vs. 26.4%; P < .0001).

This advantage was attributed to control of regurgitation. The proportion achieving moderate or less regurgitation sustained at 1 year was 87% in the repair group versus 4.8% in the GDMT group (P < .0001).

When assessed independent of treatment, KCCQ benefits at 1 year increased in a stepwise fashion as severity of regurgitation was reduced, climbing from 2 points if there was no improvement to 6 points with one grade in improvement and then to 18 points with at least a two-grade improvement.

For regurgitation, “the repair was extremely effective,” said Dr. Sorajja of Allina Health Minneapolis Heart Institute at Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis. He added that the degree of regurgitation control in the TRILUMINATE trial “is the highest ever reported.” With previous trials with other transcatheter devices in development, the improvement so far has been on the order of 70%-80%.

For enrollment in TRILUMINATE, patients were required to have at least an intermediate risk of morbidity or mortality from tricuspid valve surgery. Exclusion criteria included a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 20% and severe pulmonary hypertension.

More than 70% of patients had the highest (torrential) or second highest (massive) category of regurgitation on a five-level scale by echocardiography. Almost all the remaining were at the third level (severe).

Of those enrolled, the average age was roughly 78 years. About 55% were women. Nearly 60% were in New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure and most had significant comorbidities, including hypertension (> 80%), atrial fibrillation (about 90%), and renal disease (35%). Patients with diabetes (16%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (10%), and liver disease (7.5%) were represented in lower numbers.

Surgery is not necessarily an option

All enrolled patients were considered to be at intermediate or greater risk for mortality with surgical replacement of the tricuspid valve, but Dr. Sorajja pointed out that surgery, which involves valve replacement, is not necessarily an alternative to valve repair. Even in fit patients, the high morbidity, mortality, and extended hospital stay associated with surgical valve replacement makes this procedure unattractive.

In this trial, most patients who underwent the transcatheter procedure were discharged within a day. The safety was excellent, Dr. Sorajja said. Only three patients (1.7%) had a major adverse event. This included two cases of new-onset renal failure and one cardiovascular death. There were no cases of endocarditis requiring surgery or any other type of nonelective cardiovascular surgery, including for any device-related issue.

In the sick population enrolled, Dr. Sorajja characterized the number of adverse events over 1 year as “very low.”

These results are important, according to Kendra Grubb, MD, surgical director of the Structural Heart and Valve Center, Emory University, Atlanta. While she expressed surprise that there was no signal of benefit on hard endpoints at 1 year, she emphasized that “these patients feel terrible,” and they are frustrating to manage because surgery is often contraindicated or impractical.

“Finally, we have something for this group,” she said, noting that the mortality from valve replacement surgery even among patients who are fit enough for surgery to be considered is about 10%.

Ajay Kirtane, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, was more circumspect. He agreed that the improvement in QOL was encouraging, but cautioned that QOL is a particularly soft outcome in a nonrandomized trial in which patients may feel better just knowing that there regurgitation has been controlled. He found the lack of benefit on hard outcomes not just surprising but “disappointing.”

Still, he agreed the improvement in QOL is potentially meaningful for a procedure that appears to be relatively safe.

Dr. Sorajja reported financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Foldax. 4C Medical, Gore Medtronic, Phillips, Siemens, Shifamed, Vdyne, xDot, and Abbott Structural, which provided funding for this trial. Dr. Grubb reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Ancora Heart, Bioventrix, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, 4C Medical, JenaValve, and Medtronic. Dr. Kirtane reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Chiesi, Medtronic, Opsens, Phillips, ReCor, Regeneron, and Zoll.

NEW ORLEANS – In the first pivotal randomized, controlled trial of a transcatheter device for the repair of severe tricuspid regurgitation, a large reduction in valve dysfunction was associated with substantial improvement in quality of life (QOL) persisting out of 1 year of follow-up, according to results of the TRILUMINATE trial.

Based on the low procedural risks of the repair, the principal investigator, Paul Sorajja, MD, called the results “very clinically meaningful” as he presented the results at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

Conducted at 65 centers in the United States, Canada, and North America, TRILUMINATE evaluated a transcatheter end-to-end (TEER) repair performed with the TriClip G4 Delivery System (Abbott). The study included two cohorts, both of which will be followed for 5 years. One included patients with very severe tricuspid regurgitation enrolled in a single arm. Data on this cohort is expected later in 2023.

In the randomized portion of the study, 350 patients enrolled with severe tricuspid regurgitation underwent TEER with a clipping device and then were followed on the guideline-directed therapy (GDMT) for heart failure they were receiving at baseline. The control group was managed on GDMT alone.

The primary composite endpoint at 1 year was a composite of death from any cause and/or tricuspid valve surgery, hospitalization for heart failure, and quality of life as measured with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaire (KCCQ).

Benefit driven by quality of life

For the primary endpoint, the win ratio, a statistical calculation of those who did relative to those who did not benefit, was 1.48, signifying a 48% advantage (P = .02). This was driven almost entirely by the KCCQ endpoint. There was no significant difference death and/or tricuspid valve surgery, which occurred in about 10% of both groups (P = .75) or heart failure hospitalization, which was occurred in slightly more patients randomized to repair (14.9% vs. 12.1%; P = .41).

For KCCQ, the mean increase at 1 year was 12.3 points in the repair group versus 0.6 points (P < .001) in the control group. With an increase of 5-10 points typically considered to be clinically meaningful, the advantage of repair over GDMT at the threshold of 15 points or greater was highly statistically significant (49.7% vs. 26.4%; P < .0001).

This advantage was attributed to control of regurgitation. The proportion achieving moderate or less regurgitation sustained at 1 year was 87% in the repair group versus 4.8% in the GDMT group (P < .0001).

When assessed independent of treatment, KCCQ benefits at 1 year increased in a stepwise fashion as severity of regurgitation was reduced, climbing from 2 points if there was no improvement to 6 points with one grade in improvement and then to 18 points with at least a two-grade improvement.

For regurgitation, “the repair was extremely effective,” said Dr. Sorajja of Allina Health Minneapolis Heart Institute at Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis. He added that the degree of regurgitation control in the TRILUMINATE trial “is the highest ever reported.” With previous trials with other transcatheter devices in development, the improvement so far has been on the order of 70%-80%.

For enrollment in TRILUMINATE, patients were required to have at least an intermediate risk of morbidity or mortality from tricuspid valve surgery. Exclusion criteria included a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 20% and severe pulmonary hypertension.

More than 70% of patients had the highest (torrential) or second highest (massive) category of regurgitation on a five-level scale by echocardiography. Almost all the remaining were at the third level (severe).

Of those enrolled, the average age was roughly 78 years. About 55% were women. Nearly 60% were in New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure and most had significant comorbidities, including hypertension (> 80%), atrial fibrillation (about 90%), and renal disease (35%). Patients with diabetes (16%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (10%), and liver disease (7.5%) were represented in lower numbers.

Surgery is not necessarily an option

All enrolled patients were considered to be at intermediate or greater risk for mortality with surgical replacement of the tricuspid valve, but Dr. Sorajja pointed out that surgery, which involves valve replacement, is not necessarily an alternative to valve repair. Even in fit patients, the high morbidity, mortality, and extended hospital stay associated with surgical valve replacement makes this procedure unattractive.

In this trial, most patients who underwent the transcatheter procedure were discharged within a day. The safety was excellent, Dr. Sorajja said. Only three patients (1.7%) had a major adverse event. This included two cases of new-onset renal failure and one cardiovascular death. There were no cases of endocarditis requiring surgery or any other type of nonelective cardiovascular surgery, including for any device-related issue.

In the sick population enrolled, Dr. Sorajja characterized the number of adverse events over 1 year as “very low.”

These results are important, according to Kendra Grubb, MD, surgical director of the Structural Heart and Valve Center, Emory University, Atlanta. While she expressed surprise that there was no signal of benefit on hard endpoints at 1 year, she emphasized that “these patients feel terrible,” and they are frustrating to manage because surgery is often contraindicated or impractical.

“Finally, we have something for this group,” she said, noting that the mortality from valve replacement surgery even among patients who are fit enough for surgery to be considered is about 10%.

Ajay Kirtane, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, was more circumspect. He agreed that the improvement in QOL was encouraging, but cautioned that QOL is a particularly soft outcome in a nonrandomized trial in which patients may feel better just knowing that there regurgitation has been controlled. He found the lack of benefit on hard outcomes not just surprising but “disappointing.”

Still, he agreed the improvement in QOL is potentially meaningful for a procedure that appears to be relatively safe.

Dr. Sorajja reported financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Foldax. 4C Medical, Gore Medtronic, Phillips, Siemens, Shifamed, Vdyne, xDot, and Abbott Structural, which provided funding for this trial. Dr. Grubb reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Ancora Heart, Bioventrix, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, 4C Medical, JenaValve, and Medtronic. Dr. Kirtane reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Chiesi, Medtronic, Opsens, Phillips, ReCor, Regeneron, and Zoll.

NEW ORLEANS – In the first pivotal randomized, controlled trial of a transcatheter device for the repair of severe tricuspid regurgitation, a large reduction in valve dysfunction was associated with substantial improvement in quality of life (QOL) persisting out of 1 year of follow-up, according to results of the TRILUMINATE trial.

Based on the low procedural risks of the repair, the principal investigator, Paul Sorajja, MD, called the results “very clinically meaningful” as he presented the results at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

Conducted at 65 centers in the United States, Canada, and North America, TRILUMINATE evaluated a transcatheter end-to-end (TEER) repair performed with the TriClip G4 Delivery System (Abbott). The study included two cohorts, both of which will be followed for 5 years. One included patients with very severe tricuspid regurgitation enrolled in a single arm. Data on this cohort is expected later in 2023.

In the randomized portion of the study, 350 patients enrolled with severe tricuspid regurgitation underwent TEER with a clipping device and then were followed on the guideline-directed therapy (GDMT) for heart failure they were receiving at baseline. The control group was managed on GDMT alone.

The primary composite endpoint at 1 year was a composite of death from any cause and/or tricuspid valve surgery, hospitalization for heart failure, and quality of life as measured with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaire (KCCQ).

Benefit driven by quality of life

For the primary endpoint, the win ratio, a statistical calculation of those who did relative to those who did not benefit, was 1.48, signifying a 48% advantage (P = .02). This was driven almost entirely by the KCCQ endpoint. There was no significant difference death and/or tricuspid valve surgery, which occurred in about 10% of both groups (P = .75) or heart failure hospitalization, which was occurred in slightly more patients randomized to repair (14.9% vs. 12.1%; P = .41).

For KCCQ, the mean increase at 1 year was 12.3 points in the repair group versus 0.6 points (P < .001) in the control group. With an increase of 5-10 points typically considered to be clinically meaningful, the advantage of repair over GDMT at the threshold of 15 points or greater was highly statistically significant (49.7% vs. 26.4%; P < .0001).

This advantage was attributed to control of regurgitation. The proportion achieving moderate or less regurgitation sustained at 1 year was 87% in the repair group versus 4.8% in the GDMT group (P < .0001).

When assessed independent of treatment, KCCQ benefits at 1 year increased in a stepwise fashion as severity of regurgitation was reduced, climbing from 2 points if there was no improvement to 6 points with one grade in improvement and then to 18 points with at least a two-grade improvement.

For regurgitation, “the repair was extremely effective,” said Dr. Sorajja of Allina Health Minneapolis Heart Institute at Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis. He added that the degree of regurgitation control in the TRILUMINATE trial “is the highest ever reported.” With previous trials with other transcatheter devices in development, the improvement so far has been on the order of 70%-80%.

For enrollment in TRILUMINATE, patients were required to have at least an intermediate risk of morbidity or mortality from tricuspid valve surgery. Exclusion criteria included a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 20% and severe pulmonary hypertension.

More than 70% of patients had the highest (torrential) or second highest (massive) category of regurgitation on a five-level scale by echocardiography. Almost all the remaining were at the third level (severe).

Of those enrolled, the average age was roughly 78 years. About 55% were women. Nearly 60% were in New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure and most had significant comorbidities, including hypertension (> 80%), atrial fibrillation (about 90%), and renal disease (35%). Patients with diabetes (16%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (10%), and liver disease (7.5%) were represented in lower numbers.

Surgery is not necessarily an option

All enrolled patients were considered to be at intermediate or greater risk for mortality with surgical replacement of the tricuspid valve, but Dr. Sorajja pointed out that surgery, which involves valve replacement, is not necessarily an alternative to valve repair. Even in fit patients, the high morbidity, mortality, and extended hospital stay associated with surgical valve replacement makes this procedure unattractive.

In this trial, most patients who underwent the transcatheter procedure were discharged within a day. The safety was excellent, Dr. Sorajja said. Only three patients (1.7%) had a major adverse event. This included two cases of new-onset renal failure and one cardiovascular death. There were no cases of endocarditis requiring surgery or any other type of nonelective cardiovascular surgery, including for any device-related issue.

In the sick population enrolled, Dr. Sorajja characterized the number of adverse events over 1 year as “very low.”

These results are important, according to Kendra Grubb, MD, surgical director of the Structural Heart and Valve Center, Emory University, Atlanta. While she expressed surprise that there was no signal of benefit on hard endpoints at 1 year, she emphasized that “these patients feel terrible,” and they are frustrating to manage because surgery is often contraindicated or impractical.

“Finally, we have something for this group,” she said, noting that the mortality from valve replacement surgery even among patients who are fit enough for surgery to be considered is about 10%.

Ajay Kirtane, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, was more circumspect. He agreed that the improvement in QOL was encouraging, but cautioned that QOL is a particularly soft outcome in a nonrandomized trial in which patients may feel better just knowing that there regurgitation has been controlled. He found the lack of benefit on hard outcomes not just surprising but “disappointing.”

Still, he agreed the improvement in QOL is potentially meaningful for a procedure that appears to be relatively safe.

Dr. Sorajja reported financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Foldax. 4C Medical, Gore Medtronic, Phillips, Siemens, Shifamed, Vdyne, xDot, and Abbott Structural, which provided funding for this trial. Dr. Grubb reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Ancora Heart, Bioventrix, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, 4C Medical, JenaValve, and Medtronic. Dr. Kirtane reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Chiesi, Medtronic, Opsens, Phillips, ReCor, Regeneron, and Zoll.

AT ACC 2023

Beware risk of sedatives for respiratory patients

Both asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can be challenging to diagnose, and medication-driven episodes of sedation or hypoventilation are often overlooked as causes of acute exacerbations in these conditions, according to a letter published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

write Christos V. Chalitsios, PhD, of the University of Nottingham, England, and colleagues.

The authors note that exacerbations are the main complications of both asthma and COPD, and stress the importance of identifying causes and preventive strategies.

Sedatives such as opioids have been shown to depress respiratory drive, reduce muscle tone, and increase the risk of pneumonia, they write. The authors also propose that the risk of sedative-induced aspiration or hypoventilation would be associated with medications including pregabalin, gabapentin, and amitriptyline.

Other mechanisms may be involved in the association between sedatives and exacerbations in asthma and COPD. For example, sedative medications can suppress coughing, which may promote airway mucous compaction and possible infection, the authors write.

Most research involving prevention of asthma and COPD exacerbations has not addressed the potential impact of sedatives taken for reasons outside of obstructive lung disease, the authors say.

“Although the risk of sedation and hypoventilation events are known to be increased by opioids and antipsychotic drugs, there has not been a systematic assessment of commonly prescribed medications with potential respiratory side-effects, including gabapentin, amitriptyline, and pregabalin,” they write.

Polypharmacy is increasingly common and results in many patients with asthma or COPD presenting for treatment of acute exacerbations while on a combination of gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, and opioids, the authors note; “however, there is little data or disease-specific guidance on how best to manage this problem, which often starts with a prescription in primary care,” they write. Simply stopping sedatives is not an option for many patients given the addictive nature of these drugs and the unlikely resolution of the condition for which the drugs were prescribed, the authors say. However, “cautious dose reduction” of sedatives is possible once patients understand the reason, they add.

Clinicians may be able to suggest reduced doses and alternative treatments to patients with asthma and COPD while highlighting the risk of respiratory depression and polypharmacy – “potentially reducing the number of exacerbations of obstructive lung disease,” the authors conclude.

The study received no outside funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Both asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can be challenging to diagnose, and medication-driven episodes of sedation or hypoventilation are often overlooked as causes of acute exacerbations in these conditions, according to a letter published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

write Christos V. Chalitsios, PhD, of the University of Nottingham, England, and colleagues.

The authors note that exacerbations are the main complications of both asthma and COPD, and stress the importance of identifying causes and preventive strategies.

Sedatives such as opioids have been shown to depress respiratory drive, reduce muscle tone, and increase the risk of pneumonia, they write. The authors also propose that the risk of sedative-induced aspiration or hypoventilation would be associated with medications including pregabalin, gabapentin, and amitriptyline.

Other mechanisms may be involved in the association between sedatives and exacerbations in asthma and COPD. For example, sedative medications can suppress coughing, which may promote airway mucous compaction and possible infection, the authors write.

Most research involving prevention of asthma and COPD exacerbations has not addressed the potential impact of sedatives taken for reasons outside of obstructive lung disease, the authors say.

“Although the risk of sedation and hypoventilation events are known to be increased by opioids and antipsychotic drugs, there has not been a systematic assessment of commonly prescribed medications with potential respiratory side-effects, including gabapentin, amitriptyline, and pregabalin,” they write.

Polypharmacy is increasingly common and results in many patients with asthma or COPD presenting for treatment of acute exacerbations while on a combination of gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, and opioids, the authors note; “however, there is little data or disease-specific guidance on how best to manage this problem, which often starts with a prescription in primary care,” they write. Simply stopping sedatives is not an option for many patients given the addictive nature of these drugs and the unlikely resolution of the condition for which the drugs were prescribed, the authors say. However, “cautious dose reduction” of sedatives is possible once patients understand the reason, they add.

Clinicians may be able to suggest reduced doses and alternative treatments to patients with asthma and COPD while highlighting the risk of respiratory depression and polypharmacy – “potentially reducing the number of exacerbations of obstructive lung disease,” the authors conclude.

The study received no outside funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Both asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can be challenging to diagnose, and medication-driven episodes of sedation or hypoventilation are often overlooked as causes of acute exacerbations in these conditions, according to a letter published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

write Christos V. Chalitsios, PhD, of the University of Nottingham, England, and colleagues.

The authors note that exacerbations are the main complications of both asthma and COPD, and stress the importance of identifying causes and preventive strategies.

Sedatives such as opioids have been shown to depress respiratory drive, reduce muscle tone, and increase the risk of pneumonia, they write. The authors also propose that the risk of sedative-induced aspiration or hypoventilation would be associated with medications including pregabalin, gabapentin, and amitriptyline.

Other mechanisms may be involved in the association between sedatives and exacerbations in asthma and COPD. For example, sedative medications can suppress coughing, which may promote airway mucous compaction and possible infection, the authors write.

Most research involving prevention of asthma and COPD exacerbations has not addressed the potential impact of sedatives taken for reasons outside of obstructive lung disease, the authors say.

“Although the risk of sedation and hypoventilation events are known to be increased by opioids and antipsychotic drugs, there has not been a systematic assessment of commonly prescribed medications with potential respiratory side-effects, including gabapentin, amitriptyline, and pregabalin,” they write.

Polypharmacy is increasingly common and results in many patients with asthma or COPD presenting for treatment of acute exacerbations while on a combination of gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, and opioids, the authors note; “however, there is little data or disease-specific guidance on how best to manage this problem, which often starts with a prescription in primary care,” they write. Simply stopping sedatives is not an option for many patients given the addictive nature of these drugs and the unlikely resolution of the condition for which the drugs were prescribed, the authors say. However, “cautious dose reduction” of sedatives is possible once patients understand the reason, they add.

Clinicians may be able to suggest reduced doses and alternative treatments to patients with asthma and COPD while highlighting the risk of respiratory depression and polypharmacy – “potentially reducing the number of exacerbations of obstructive lung disease,” the authors conclude.

The study received no outside funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

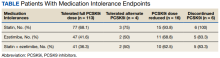

New influx of Humira biosimilars may not drive immediate change

Gastroenterologists in 2023 will have more tools in their arsenal to treat patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. As many as 8-10 adalimumab biosimilars are anticipated to come on the market this year, giving mainstay drug Humira some vigorous competition.

Three scenarios will drive adalimumab biosimilar initiation: Insurance preference for the initial treatment of a newly diagnosed condition, a change in a patient’s insurance plan, or an insurance-mandated switch, said Edward C. Oldfield IV, MD, assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School’s division of gastroenterology in Norfolk.

“Outside of these scenarios, I would encourage patients to remain on their current biologic so long as cost and accessibility remain stable,” said Dr. Oldfield.

Many factors will contribute to the success of biosimilars. Will physicians be prescribing them? How are biosimilars placed on formularies and will they be given preferred status? How will manufacturers price their biosimilars? “We have to wait and see to get the answers to these questions,” said Steven Newmark, JD, MPA, chief legal officer and director of policy, Global Healthy Living Foundation/CreakyJoints, a nonprofit advocacy organization based in New York.

Prescribing biosimilars is no different than prescribing originator biologics, so providers should know how to use them, said Mr. Newmark. “Most important will be the availability of patient-friendly resources that providers can share with their patients to provide education about and confidence in using biosimilars,” he added.

Overall, biosimilars are a good thing, said Dr. Oldfield. “In the long run they should bring down costs and increase access to medications for our patients.”

Others are skeptical that the adalimumab biosimilars will save patients much money.

Biosimilar laws were created to lower costs. However, if a patient with insurance pays only $5 a month out of pocket for Humira – a drug that normally costs $7,000 without coverage – it’s unlikely they would want to switch unless there’s comparable savings from the biosimilar, said Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, medical director of the Digestive Health Center and professor of medicine at Northwestern Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Like generics, Humira biosimilars may face some initial backlash, said Dr. Hanauer.

2023 broadens scope of adalimumab treatments

The American Gastroenterological Association describes a biosimilar as something that’s “highly similar to, but not an exact copy of, a biologic reference product already approved” by the Food and Drug Administration. Congress under the 2010 Affordable Care Act created a special, abbreviated pathway to approval for biosimilars.

AbbVie’s Humira, the global revenue for which exceeded $20 billion in 2021, has long dominated the U.S. market on injectable treatments for autoimmune diseases. The popular drug faces some competition in 2023, however, following a series of legal settlements that allowed AbbVie competitors to release their own adalimumab biosimilars.

“So far, we haven’t seen biosimilars live up to their potential in the U.S. in the inflammatory space,” said Mr. Newmark. This may change, however. Previously, biosimilars have required infusion, which demanded more time, commitment, and travel from patients. “The new set of forthcoming Humira biosimilars are injectables, an administration method preferred by patients,” he said.

The FDA will approve a biosimilar if it determines that the biological product is highly similar to the reference product, and that there are no clinically meaningful differences between the biological and reference product in terms of the safety, purity, and potency of the product.

The agency to date has approved 8 adalimumab biosimilars. These include: Idacio (adalimumab-aacf, Fresenius Kabi); Amjevita (adalimumab-atto, Amgen); Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd, Organon); Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm, Boehringer Ingelheim); Yusimry (adalimumab-aqvh from Coherus BioSciences); Hulio (adalimumab-fkjp; Mylan/Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics); Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz, Sandoz), and Abrilada (adalimumab-afzb, Pfizer).

“While FDA doesn’t formally track when products come to market, we know based on published reports that application holders for many of the currently FDA-approved biosimilars plan to market this year, starting with Amjevita being the first adalimumab biosimilar launched” in January, said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars at the agency.

At press time, two other companies (Celltrion and Alvotech/Teva) were awaiting FDA approval for their adalimumab biosimilar drugs.

Among the eight approved drugs, Cyltezo is the only one that has a designation for interchangeability with Humira.

An interchangeable biosimilar may be substituted at the pharmacy without the intervention of the prescriber – much like generics are substituted, depending on state laws, said Dr. Yim. “However, in terms of safety and effectiveness, FDA’s standards for approval mean that biosimilar or interchangeable biosimilar products can be used in place of the reference product they were compared to.”

FDA-approved biosimilars undergo a rigorous evaluation for safety, effectiveness, and quality for their approved conditions of use, she continued. “Therefore, patients and health care providers can rely on a biosimilar to be as safe and effective for its approved uses as the original biological product.”

Remicade as a yard stick

Gastroenterologists dealt with this situation once before, when Remicade (infliximab) biosimilars came on the market in 2016, noted Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

Remicade and Humira are both tumor necrosis factor inhibitors with the same mechanism of action and many of the same indications. “We already had that experience with Remicade and biosimilar switch 2 or 3 years ago. Now we’re talking about Humira,” said Dr. Regueiro.

Most GI doctors have prescribed one of the more common infliximab biosimilars (Inflectra or Renflexis), noted Dr. Oldfield.

Cardinal Health, which recently surveyed 300 gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, and dermatologists about adalimumab biosimilars, found that gastroenterologists had the highest comfort level in prescribing them. Their top concern, however, was changing a patient from adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar.

For most patients, Dr. Oldfield sees the Humira reference biologic and biosimilar as equivalent.

However, he said he would change a patient’s drug only if there were a good reason or if his hand was forced by insurance. He would not make the change for a patient who recently began induction with the reference biologic or a patient with highly active clinical disease.

“While there is limited data to support this, I would also have some qualms about changing a patient from reference biologic to a biosimilar if they previously had immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure due to antibody development with a biologic and were currently doing well on their new biologic,” he said.

Those with a new ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s diagnosis who are initiating a biologic for the first time might consider a biosimilar. If a patient is transitioning from a reference biologic to a biosimilar, “I would want to make that change during a time of stable remission and with the recognition that the switch is not a temporary switch, but a long-term switch,” he continued.

A paper that reviewed 23 observational studies of adalimumab and other biosimilars found that switching biosimilars was safe and effective. But if possible, patients should minimize the number of switches until more robust long-term data are available, added Dr. Oldfield.

If a patient is apprehensive about switching to a new therapy, “one may need to be cognizant of the ‘nocebo’ effect in which there is an unexplained or unfavorable therapeutic effect after switching,” he said.

Other gastroenterologists voiced similar reservations about switching. “I won’t use an adalimumab biosimilar unless the patient requests it, the insurance requires it, or there is a cost advantage for the patient such that they prefer it,” said Doug Wolf, MD, an Atlanta gastroenterologist.

“There is no medical treatment advantage to a biosimilar, especially if switching from Humira,” added Dr. Wolf.

Insurance will guide treatment

Once a drug is approved for use by the FDA, that drug will be available in all 50 states. “Different private insurance formularies, as well as state Medicaid formularies, might affect the actual ability of patients to receive such drugs,” said Mr. Newmark.

Patients should consult with their providers and insurance companies to see what therapies are available, he advised.

Dr. Hanauer anticipates some headaches arising for patients and doctors alike when negotiating for a specific drug.

Cyltezo may be the only biosimilar interchangeable with Humira, but the third-party pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) could negotiate for one of the noninterchangeable ones. “On a yearly basis they could switch their preference,” said Dr. Hanauer.

In the Cardinal Health survey, more than 60% of respondents said they would feel comfortable prescribing an adalimumab biosimilar only with an interchangeability designation.

A PBM may offer a patient Cyltezo if it’s cheaper than Humira. If the patient insists on staying on Humira, then they’ll have to pay more for that drug on their payer’s formulary, said Dr. Hanauer. In a worst-case scenario, a physician may have to appeal on a patient’s behalf to get Humira if the insurer offers only the biosimilar.

Taking that step to appeal is a major hassle for the physician, and leads to extra back door costs as well, said Dr. Hanauer.

Humira manufacturer AbbVie, in turn, may offer discounts and rebates to the PBMs to put Humira on their formulary. “That’s the AbbVie negotiating power. It’s not that the cost is going to be that much different. It’s going to be that there are rebates and discounts that are going to make the cost different,” he added.

As a community physician, Dr. Oldfield has specific concerns about accessibility.

The ever-increasing burden of insurance documentation and prior authorization means it can take weeks or months to get these medications approved. “The addition of new biosimilars is a welcome entrance if it can get patients the medications they need when they need it,” he said.

When it comes to prescribing biologics, many physicians rely on ancillary staff for assistance. It’s a team effort to sift through all the paperwork, observed Dr. Oldfield.

“While many community GI practices have specialized staff to deal with prior authorizations, they are still a far cry from the IBD [inflammatory bowel disease] academic centers where there are often pharmacists, nursing specialists, and home-monitoring programs to check in on patients,” he explained.

Landscape on cost is uncertain

At present, little is known about the cost of the biosimilars and impact on future drug pricing, said Dr. Oldfield.

At least for Medicare, Humira biosimilars will be considered Medicare Part D drugs if used for a medically accepted indication, said a spokesperson for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Part D sponsors (pharmacy and therapeutic committees) “will make the determination as to whether Amjevita and other products will be added to their formularies,” said the spokesperson.

Patients never saw a significant cost savings with Remicade biosimilars. “I imagine the same would be true with biosimilars for Humira,” said Dr. Regueiro. Patients may see greater access to these drugs, however, because the insurance plan or the pharmacy plan will make them more readily available, he added.

The hope is that, as biosimilars are introduced, the price of the originator biologic will go down, said Mr. Newmark. “Therefore, we can expect Humira to be offered at a lower price as it faces competition. Where it will sit in comparison to the forthcoming biosimilars will depend on how much biosimilar companies drop their price and how much pressure will be on PBMs and insurers to cover the lowest list price drug,” he said.

AbbVie did not respond to several requests for comment.

Charitable patient assistance programs for biosimilars or biologics can help offset the price of copayments, Mr. Newmark offered.

Ideally, insurers will offer designated biosimilars at a reduced or even no out-of-pocket expense on their formularies. This should lead to a decreased administrative burden for approval with streamlined (or even removal) of prior authorizations for certain medications, said Dr. Oldfield.

Without insurance or medication assistance programs, the cost of biosimilars is prohibitively expensive, he added.

“Biosimilars have higher research, development, and manufacturing costs than what people conventionally think of [for] a generic medication.”

Educating, advising patients

Dr. Oldfield advised that gastroenterologists refer to biologics by the generic name rather than branded name when initiating therapy unless there is a very specific reason not to. “This approach should make the process more streamlined and less subjected to quick denials for brand-only requests as biosimilars start to assume a larger market share,” he said.

Uptake of the Humira biosimilars also will depend on proper education of physicians and patients and their comfort level with the biosimilars, said Dr. Regueiro. Cleveland Clinic uses a team approach to educate on this topic, relying on pharmacists, clinicians, and nurses to explain that there’s no real difference between the reference drug and its biosimilars, based on efficacy and safety data.

Physicians can also direct patients to patient-friendly resources, said Mr. Newmark. “By starting the conversation early, it ensures that when/if the time comes that your patient is switched to or chooses a biosimilar they will feel more confident because they have the knowledge to make decisions about their care.”

The Global Healthy Living Foundation’s podcast, Breaking Down Biosimilars , is a free resource for patients, he added.

It’s important that doctors also understand these products so they can explain to their patients what to expect, said the FDA’s Dr. Yim. The FDA provides educational materials on its website, including a comprehensive curriculum toolkit.

Dr. Hanauer has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, American College of Gastroenterology, GlaxoSmithKline, American Gastroenterological Association, Pfizer, and a host of other companies . Dr. Regueiro has served on advisory boards and as a consultant for Abbvie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Pfizer, BMS, Organon, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead, Salix, Prometheus, Lilly, Celgene, TARGET Pharma Solutions,Trellis, and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Wolf, Dr. Yim, Dr. Oldfield, and Mr. Newmark have no financial conflicts of interest.

Gastroenterologists in 2023 will have more tools in their arsenal to treat patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. As many as 8-10 adalimumab biosimilars are anticipated to come on the market this year, giving mainstay drug Humira some vigorous competition.

Three scenarios will drive adalimumab biosimilar initiation: Insurance preference for the initial treatment of a newly diagnosed condition, a change in a patient’s insurance plan, or an insurance-mandated switch, said Edward C. Oldfield IV, MD, assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School’s division of gastroenterology in Norfolk.

“Outside of these scenarios, I would encourage patients to remain on their current biologic so long as cost and accessibility remain stable,” said Dr. Oldfield.

Many factors will contribute to the success of biosimilars. Will physicians be prescribing them? How are biosimilars placed on formularies and will they be given preferred status? How will manufacturers price their biosimilars? “We have to wait and see to get the answers to these questions,” said Steven Newmark, JD, MPA, chief legal officer and director of policy, Global Healthy Living Foundation/CreakyJoints, a nonprofit advocacy organization based in New York.

Prescribing biosimilars is no different than prescribing originator biologics, so providers should know how to use them, said Mr. Newmark. “Most important will be the availability of patient-friendly resources that providers can share with their patients to provide education about and confidence in using biosimilars,” he added.

Overall, biosimilars are a good thing, said Dr. Oldfield. “In the long run they should bring down costs and increase access to medications for our patients.”

Others are skeptical that the adalimumab biosimilars will save patients much money.

Biosimilar laws were created to lower costs. However, if a patient with insurance pays only $5 a month out of pocket for Humira – a drug that normally costs $7,000 without coverage – it’s unlikely they would want to switch unless there’s comparable savings from the biosimilar, said Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, medical director of the Digestive Health Center and professor of medicine at Northwestern Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Like generics, Humira biosimilars may face some initial backlash, said Dr. Hanauer.

2023 broadens scope of adalimumab treatments

The American Gastroenterological Association describes a biosimilar as something that’s “highly similar to, but not an exact copy of, a biologic reference product already approved” by the Food and Drug Administration. Congress under the 2010 Affordable Care Act created a special, abbreviated pathway to approval for biosimilars.

AbbVie’s Humira, the global revenue for which exceeded $20 billion in 2021, has long dominated the U.S. market on injectable treatments for autoimmune diseases. The popular drug faces some competition in 2023, however, following a series of legal settlements that allowed AbbVie competitors to release their own adalimumab biosimilars.

“So far, we haven’t seen biosimilars live up to their potential in the U.S. in the inflammatory space,” said Mr. Newmark. This may change, however. Previously, biosimilars have required infusion, which demanded more time, commitment, and travel from patients. “The new set of forthcoming Humira biosimilars are injectables, an administration method preferred by patients,” he said.

The FDA will approve a biosimilar if it determines that the biological product is highly similar to the reference product, and that there are no clinically meaningful differences between the biological and reference product in terms of the safety, purity, and potency of the product.

The agency to date has approved 8 adalimumab biosimilars. These include: Idacio (adalimumab-aacf, Fresenius Kabi); Amjevita (adalimumab-atto, Amgen); Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd, Organon); Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm, Boehringer Ingelheim); Yusimry (adalimumab-aqvh from Coherus BioSciences); Hulio (adalimumab-fkjp; Mylan/Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics); Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz, Sandoz), and Abrilada (adalimumab-afzb, Pfizer).

“While FDA doesn’t formally track when products come to market, we know based on published reports that application holders for many of the currently FDA-approved biosimilars plan to market this year, starting with Amjevita being the first adalimumab biosimilar launched” in January, said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars at the agency.

At press time, two other companies (Celltrion and Alvotech/Teva) were awaiting FDA approval for their adalimumab biosimilar drugs.

Among the eight approved drugs, Cyltezo is the only one that has a designation for interchangeability with Humira.

An interchangeable biosimilar may be substituted at the pharmacy without the intervention of the prescriber – much like generics are substituted, depending on state laws, said Dr. Yim. “However, in terms of safety and effectiveness, FDA’s standards for approval mean that biosimilar or interchangeable biosimilar products can be used in place of the reference product they were compared to.”

FDA-approved biosimilars undergo a rigorous evaluation for safety, effectiveness, and quality for their approved conditions of use, she continued. “Therefore, patients and health care providers can rely on a biosimilar to be as safe and effective for its approved uses as the original biological product.”

Remicade as a yard stick

Gastroenterologists dealt with this situation once before, when Remicade (infliximab) biosimilars came on the market in 2016, noted Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

Remicade and Humira are both tumor necrosis factor inhibitors with the same mechanism of action and many of the same indications. “We already had that experience with Remicade and biosimilar switch 2 or 3 years ago. Now we’re talking about Humira,” said Dr. Regueiro.

Most GI doctors have prescribed one of the more common infliximab biosimilars (Inflectra or Renflexis), noted Dr. Oldfield.

Cardinal Health, which recently surveyed 300 gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, and dermatologists about adalimumab biosimilars, found that gastroenterologists had the highest comfort level in prescribing them. Their top concern, however, was changing a patient from adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar.

For most patients, Dr. Oldfield sees the Humira reference biologic and biosimilar as equivalent.

However, he said he would change a patient’s drug only if there were a good reason or if his hand was forced by insurance. He would not make the change for a patient who recently began induction with the reference biologic or a patient with highly active clinical disease.

“While there is limited data to support this, I would also have some qualms about changing a patient from reference biologic to a biosimilar if they previously had immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure due to antibody development with a biologic and were currently doing well on their new biologic,” he said.

Those with a new ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s diagnosis who are initiating a biologic for the first time might consider a biosimilar. If a patient is transitioning from a reference biologic to a biosimilar, “I would want to make that change during a time of stable remission and with the recognition that the switch is not a temporary switch, but a long-term switch,” he continued.

A paper that reviewed 23 observational studies of adalimumab and other biosimilars found that switching biosimilars was safe and effective. But if possible, patients should minimize the number of switches until more robust long-term data are available, added Dr. Oldfield.

If a patient is apprehensive about switching to a new therapy, “one may need to be cognizant of the ‘nocebo’ effect in which there is an unexplained or unfavorable therapeutic effect after switching,” he said.

Other gastroenterologists voiced similar reservations about switching. “I won’t use an adalimumab biosimilar unless the patient requests it, the insurance requires it, or there is a cost advantage for the patient such that they prefer it,” said Doug Wolf, MD, an Atlanta gastroenterologist.

“There is no medical treatment advantage to a biosimilar, especially if switching from Humira,” added Dr. Wolf.

Insurance will guide treatment

Once a drug is approved for use by the FDA, that drug will be available in all 50 states. “Different private insurance formularies, as well as state Medicaid formularies, might affect the actual ability of patients to receive such drugs,” said Mr. Newmark.

Patients should consult with their providers and insurance companies to see what therapies are available, he advised.

Dr. Hanauer anticipates some headaches arising for patients and doctors alike when negotiating for a specific drug.

Cyltezo may be the only biosimilar interchangeable with Humira, but the third-party pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) could negotiate for one of the noninterchangeable ones. “On a yearly basis they could switch their preference,” said Dr. Hanauer.

In the Cardinal Health survey, more than 60% of respondents said they would feel comfortable prescribing an adalimumab biosimilar only with an interchangeability designation.

A PBM may offer a patient Cyltezo if it’s cheaper than Humira. If the patient insists on staying on Humira, then they’ll have to pay more for that drug on their payer’s formulary, said Dr. Hanauer. In a worst-case scenario, a physician may have to appeal on a patient’s behalf to get Humira if the insurer offers only the biosimilar.

Taking that step to appeal is a major hassle for the physician, and leads to extra back door costs as well, said Dr. Hanauer.

Humira manufacturer AbbVie, in turn, may offer discounts and rebates to the PBMs to put Humira on their formulary. “That’s the AbbVie negotiating power. It’s not that the cost is going to be that much different. It’s going to be that there are rebates and discounts that are going to make the cost different,” he added.

As a community physician, Dr. Oldfield has specific concerns about accessibility.

The ever-increasing burden of insurance documentation and prior authorization means it can take weeks or months to get these medications approved. “The addition of new biosimilars is a welcome entrance if it can get patients the medications they need when they need it,” he said.

When it comes to prescribing biologics, many physicians rely on ancillary staff for assistance. It’s a team effort to sift through all the paperwork, observed Dr. Oldfield.

“While many community GI practices have specialized staff to deal with prior authorizations, they are still a far cry from the IBD [inflammatory bowel disease] academic centers where there are often pharmacists, nursing specialists, and home-monitoring programs to check in on patients,” he explained.

Landscape on cost is uncertain

At present, little is known about the cost of the biosimilars and impact on future drug pricing, said Dr. Oldfield.

At least for Medicare, Humira biosimilars will be considered Medicare Part D drugs if used for a medically accepted indication, said a spokesperson for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Part D sponsors (pharmacy and therapeutic committees) “will make the determination as to whether Amjevita and other products will be added to their formularies,” said the spokesperson.

Patients never saw a significant cost savings with Remicade biosimilars. “I imagine the same would be true with biosimilars for Humira,” said Dr. Regueiro. Patients may see greater access to these drugs, however, because the insurance plan or the pharmacy plan will make them more readily available, he added.

The hope is that, as biosimilars are introduced, the price of the originator biologic will go down, said Mr. Newmark. “Therefore, we can expect Humira to be offered at a lower price as it faces competition. Where it will sit in comparison to the forthcoming biosimilars will depend on how much biosimilar companies drop their price and how much pressure will be on PBMs and insurers to cover the lowest list price drug,” he said.

AbbVie did not respond to several requests for comment.

Charitable patient assistance programs for biosimilars or biologics can help offset the price of copayments, Mr. Newmark offered.

Ideally, insurers will offer designated biosimilars at a reduced or even no out-of-pocket expense on their formularies. This should lead to a decreased administrative burden for approval with streamlined (or even removal) of prior authorizations for certain medications, said Dr. Oldfield.

Without insurance or medication assistance programs, the cost of biosimilars is prohibitively expensive, he added.

“Biosimilars have higher research, development, and manufacturing costs than what people conventionally think of [for] a generic medication.”

Educating, advising patients

Dr. Oldfield advised that gastroenterologists refer to biologics by the generic name rather than branded name when initiating therapy unless there is a very specific reason not to. “This approach should make the process more streamlined and less subjected to quick denials for brand-only requests as biosimilars start to assume a larger market share,” he said.

Uptake of the Humira biosimilars also will depend on proper education of physicians and patients and their comfort level with the biosimilars, said Dr. Regueiro. Cleveland Clinic uses a team approach to educate on this topic, relying on pharmacists, clinicians, and nurses to explain that there’s no real difference between the reference drug and its biosimilars, based on efficacy and safety data.

Physicians can also direct patients to patient-friendly resources, said Mr. Newmark. “By starting the conversation early, it ensures that when/if the time comes that your patient is switched to or chooses a biosimilar they will feel more confident because they have the knowledge to make decisions about their care.”

The Global Healthy Living Foundation’s podcast, Breaking Down Biosimilars , is a free resource for patients, he added.

It’s important that doctors also understand these products so they can explain to their patients what to expect, said the FDA’s Dr. Yim. The FDA provides educational materials on its website, including a comprehensive curriculum toolkit.

Dr. Hanauer has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, American College of Gastroenterology, GlaxoSmithKline, American Gastroenterological Association, Pfizer, and a host of other companies . Dr. Regueiro has served on advisory boards and as a consultant for Abbvie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Pfizer, BMS, Organon, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead, Salix, Prometheus, Lilly, Celgene, TARGET Pharma Solutions,Trellis, and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Wolf, Dr. Yim, Dr. Oldfield, and Mr. Newmark have no financial conflicts of interest.

Gastroenterologists in 2023 will have more tools in their arsenal to treat patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. As many as 8-10 adalimumab biosimilars are anticipated to come on the market this year, giving mainstay drug Humira some vigorous competition.

Three scenarios will drive adalimumab biosimilar initiation: Insurance preference for the initial treatment of a newly diagnosed condition, a change in a patient’s insurance plan, or an insurance-mandated switch, said Edward C. Oldfield IV, MD, assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School’s division of gastroenterology in Norfolk.

“Outside of these scenarios, I would encourage patients to remain on their current biologic so long as cost and accessibility remain stable,” said Dr. Oldfield.

Many factors will contribute to the success of biosimilars. Will physicians be prescribing them? How are biosimilars placed on formularies and will they be given preferred status? How will manufacturers price their biosimilars? “We have to wait and see to get the answers to these questions,” said Steven Newmark, JD, MPA, chief legal officer and director of policy, Global Healthy Living Foundation/CreakyJoints, a nonprofit advocacy organization based in New York.

Prescribing biosimilars is no different than prescribing originator biologics, so providers should know how to use them, said Mr. Newmark. “Most important will be the availability of patient-friendly resources that providers can share with their patients to provide education about and confidence in using biosimilars,” he added.

Overall, biosimilars are a good thing, said Dr. Oldfield. “In the long run they should bring down costs and increase access to medications for our patients.”

Others are skeptical that the adalimumab biosimilars will save patients much money.

Biosimilar laws were created to lower costs. However, if a patient with insurance pays only $5 a month out of pocket for Humira – a drug that normally costs $7,000 without coverage – it’s unlikely they would want to switch unless there’s comparable savings from the biosimilar, said Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, medical director of the Digestive Health Center and professor of medicine at Northwestern Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Like generics, Humira biosimilars may face some initial backlash, said Dr. Hanauer.

2023 broadens scope of adalimumab treatments

The American Gastroenterological Association describes a biosimilar as something that’s “highly similar to, but not an exact copy of, a biologic reference product already approved” by the Food and Drug Administration. Congress under the 2010 Affordable Care Act created a special, abbreviated pathway to approval for biosimilars.

AbbVie’s Humira, the global revenue for which exceeded $20 billion in 2021, has long dominated the U.S. market on injectable treatments for autoimmune diseases. The popular drug faces some competition in 2023, however, following a series of legal settlements that allowed AbbVie competitors to release their own adalimumab biosimilars.

“So far, we haven’t seen biosimilars live up to their potential in the U.S. in the inflammatory space,” said Mr. Newmark. This may change, however. Previously, biosimilars have required infusion, which demanded more time, commitment, and travel from patients. “The new set of forthcoming Humira biosimilars are injectables, an administration method preferred by patients,” he said.

The FDA will approve a biosimilar if it determines that the biological product is highly similar to the reference product, and that there are no clinically meaningful differences between the biological and reference product in terms of the safety, purity, and potency of the product.

The agency to date has approved 8 adalimumab biosimilars. These include: Idacio (adalimumab-aacf, Fresenius Kabi); Amjevita (adalimumab-atto, Amgen); Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd, Organon); Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm, Boehringer Ingelheim); Yusimry (adalimumab-aqvh from Coherus BioSciences); Hulio (adalimumab-fkjp; Mylan/Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics); Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz, Sandoz), and Abrilada (adalimumab-afzb, Pfizer).

“While FDA doesn’t formally track when products come to market, we know based on published reports that application holders for many of the currently FDA-approved biosimilars plan to market this year, starting with Amjevita being the first adalimumab biosimilar launched” in January, said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars at the agency.

At press time, two other companies (Celltrion and Alvotech/Teva) were awaiting FDA approval for their adalimumab biosimilar drugs.

Among the eight approved drugs, Cyltezo is the only one that has a designation for interchangeability with Humira.

An interchangeable biosimilar may be substituted at the pharmacy without the intervention of the prescriber – much like generics are substituted, depending on state laws, said Dr. Yim. “However, in terms of safety and effectiveness, FDA’s standards for approval mean that biosimilar or interchangeable biosimilar products can be used in place of the reference product they were compared to.”

FDA-approved biosimilars undergo a rigorous evaluation for safety, effectiveness, and quality for their approved conditions of use, she continued. “Therefore, patients and health care providers can rely on a biosimilar to be as safe and effective for its approved uses as the original biological product.”

Remicade as a yard stick

Gastroenterologists dealt with this situation once before, when Remicade (infliximab) biosimilars came on the market in 2016, noted Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

Remicade and Humira are both tumor necrosis factor inhibitors with the same mechanism of action and many of the same indications. “We already had that experience with Remicade and biosimilar switch 2 or 3 years ago. Now we’re talking about Humira,” said Dr. Regueiro.

Most GI doctors have prescribed one of the more common infliximab biosimilars (Inflectra or Renflexis), noted Dr. Oldfield.

Cardinal Health, which recently surveyed 300 gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, and dermatologists about adalimumab biosimilars, found that gastroenterologists had the highest comfort level in prescribing them. Their top concern, however, was changing a patient from adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar.

For most patients, Dr. Oldfield sees the Humira reference biologic and biosimilar as equivalent.

However, he said he would change a patient’s drug only if there were a good reason or if his hand was forced by insurance. He would not make the change for a patient who recently began induction with the reference biologic or a patient with highly active clinical disease.

“While there is limited data to support this, I would also have some qualms about changing a patient from reference biologic to a biosimilar if they previously had immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure due to antibody development with a biologic and were currently doing well on their new biologic,” he said.

Those with a new ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s diagnosis who are initiating a biologic for the first time might consider a biosimilar. If a patient is transitioning from a reference biologic to a biosimilar, “I would want to make that change during a time of stable remission and with the recognition that the switch is not a temporary switch, but a long-term switch,” he continued.

A paper that reviewed 23 observational studies of adalimumab and other biosimilars found that switching biosimilars was safe and effective. But if possible, patients should minimize the number of switches until more robust long-term data are available, added Dr. Oldfield.

If a patient is apprehensive about switching to a new therapy, “one may need to be cognizant of the ‘nocebo’ effect in which there is an unexplained or unfavorable therapeutic effect after switching,” he said.

Other gastroenterologists voiced similar reservations about switching. “I won’t use an adalimumab biosimilar unless the patient requests it, the insurance requires it, or there is a cost advantage for the patient such that they prefer it,” said Doug Wolf, MD, an Atlanta gastroenterologist.

“There is no medical treatment advantage to a biosimilar, especially if switching from Humira,” added Dr. Wolf.

Insurance will guide treatment

Once a drug is approved for use by the FDA, that drug will be available in all 50 states. “Different private insurance formularies, as well as state Medicaid formularies, might affect the actual ability of patients to receive such drugs,” said Mr. Newmark.

Patients should consult with their providers and insurance companies to see what therapies are available, he advised.

Dr. Hanauer anticipates some headaches arising for patients and doctors alike when negotiating for a specific drug.

Cyltezo may be the only biosimilar interchangeable with Humira, but the third-party pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) could negotiate for one of the noninterchangeable ones. “On a yearly basis they could switch their preference,” said Dr. Hanauer.

In the Cardinal Health survey, more than 60% of respondents said they would feel comfortable prescribing an adalimumab biosimilar only with an interchangeability designation.

A PBM may offer a patient Cyltezo if it’s cheaper than Humira. If the patient insists on staying on Humira, then they’ll have to pay more for that drug on their payer’s formulary, said Dr. Hanauer. In a worst-case scenario, a physician may have to appeal on a patient’s behalf to get Humira if the insurer offers only the biosimilar.

Taking that step to appeal is a major hassle for the physician, and leads to extra back door costs as well, said Dr. Hanauer.

Humira manufacturer AbbVie, in turn, may offer discounts and rebates to the PBMs to put Humira on their formulary. “That’s the AbbVie negotiating power. It’s not that the cost is going to be that much different. It’s going to be that there are rebates and discounts that are going to make the cost different,” he added.

As a community physician, Dr. Oldfield has specific concerns about accessibility.

The ever-increasing burden of insurance documentation and prior authorization means it can take weeks or months to get these medications approved. “The addition of new biosimilars is a welcome entrance if it can get patients the medications they need when they need it,” he said.

When it comes to prescribing biologics, many physicians rely on ancillary staff for assistance. It’s a team effort to sift through all the paperwork, observed Dr. Oldfield.

“While many community GI practices have specialized staff to deal with prior authorizations, they are still a far cry from the IBD [inflammatory bowel disease] academic centers where there are often pharmacists, nursing specialists, and home-monitoring programs to check in on patients,” he explained.

Landscape on cost is uncertain

At present, little is known about the cost of the biosimilars and impact on future drug pricing, said Dr. Oldfield.

At least for Medicare, Humira biosimilars will be considered Medicare Part D drugs if used for a medically accepted indication, said a spokesperson for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Part D sponsors (pharmacy and therapeutic committees) “will make the determination as to whether Amjevita and other products will be added to their formularies,” said the spokesperson.

Patients never saw a significant cost savings with Remicade biosimilars. “I imagine the same would be true with biosimilars for Humira,” said Dr. Regueiro. Patients may see greater access to these drugs, however, because the insurance plan or the pharmacy plan will make them more readily available, he added.

The hope is that, as biosimilars are introduced, the price of the originator biologic will go down, said Mr. Newmark. “Therefore, we can expect Humira to be offered at a lower price as it faces competition. Where it will sit in comparison to the forthcoming biosimilars will depend on how much biosimilar companies drop their price and how much pressure will be on PBMs and insurers to cover the lowest list price drug,” he said.

AbbVie did not respond to several requests for comment.

Charitable patient assistance programs for biosimilars or biologics can help offset the price of copayments, Mr. Newmark offered.

Ideally, insurers will offer designated biosimilars at a reduced or even no out-of-pocket expense on their formularies. This should lead to a decreased administrative burden for approval with streamlined (or even removal) of prior authorizations for certain medications, said Dr. Oldfield.

Without insurance or medication assistance programs, the cost of biosimilars is prohibitively expensive, he added.

“Biosimilars have higher research, development, and manufacturing costs than what people conventionally think of [for] a generic medication.”

Educating, advising patients

Dr. Oldfield advised that gastroenterologists refer to biologics by the generic name rather than branded name when initiating therapy unless there is a very specific reason not to. “This approach should make the process more streamlined and less subjected to quick denials for brand-only requests as biosimilars start to assume a larger market share,” he said.

Uptake of the Humira biosimilars also will depend on proper education of physicians and patients and their comfort level with the biosimilars, said Dr. Regueiro. Cleveland Clinic uses a team approach to educate on this topic, relying on pharmacists, clinicians, and nurses to explain that there’s no real difference between the reference drug and its biosimilars, based on efficacy and safety data.

Physicians can also direct patients to patient-friendly resources, said Mr. Newmark. “By starting the conversation early, it ensures that when/if the time comes that your patient is switched to or chooses a biosimilar they will feel more confident because they have the knowledge to make decisions about their care.”

The Global Healthy Living Foundation’s podcast, Breaking Down Biosimilars , is a free resource for patients, he added.

It’s important that doctors also understand these products so they can explain to their patients what to expect, said the FDA’s Dr. Yim. The FDA provides educational materials on its website, including a comprehensive curriculum toolkit.

Dr. Hanauer has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, American College of Gastroenterology, GlaxoSmithKline, American Gastroenterological Association, Pfizer, and a host of other companies . Dr. Regueiro has served on advisory boards and as a consultant for Abbvie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Pfizer, BMS, Organon, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead, Salix, Prometheus, Lilly, Celgene, TARGET Pharma Solutions,Trellis, and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Wolf, Dr. Yim, Dr. Oldfield, and Mr. Newmark have no financial conflicts of interest.

Eight-week TB treatment strategy shows potential

A strategy for the

“We found that if we use the strategy of a bedaquiline-linezolid five-drug regimen for 8 weeks and then followed patients for 96 weeks, [the regimen] was noninferior, clinically, to the standard regimen in terms of the number of people alive, free of TB disease, and not on treatment,” said lead author Nicholas Paton, MD, of the National University of Singapore, in a press conference held during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

“The total time on treatment was reduced by half – instead of 160 days, it was 85 days for the total duration.”

Commenting on the study, which was published concurrently in the New England Journal of Medicine, Richard E. Chaisson, MD, noted that, although more needs to be understood, the high number of responses is nevertheless encouraging.

“Clinicians will not feel comfortable with the short regimens at this point, but it is remarkable that so many patients did well with shorter treatments,” Dr. Chaisson, who is a professor of medicine, epidemiology, and international health and director of the Johns Hopkins University Center for Tuberculosis Research, Baltimore, said in an interview.

Importantly, the study should help push forward “future studies [that] will stratify patients according to their likelihood of responding to shorter treatments,” he said.

The current global standard for TB treatment, practiced for 4 decades, has been a 6-month rifampin-based regimen. Although the regimen performs well, curing more than 95% of cases in clinical trials, in real-world practice, the prolonged duration can be problematic, with issues of nonadherence and loss of patients to follow-up.

Previous research has shown that shorter regimens have potential, with some studies showing as many as 85% of patients cured with 3- and 4-month regimens, and some promising 2-month regimens showing efficacy specifically for those with smear-negative TB.

These efforts suggest that “the current 6-month regimen may lead to overtreatment in the majority of persons in order to prevent relapse in a minority of persons,” the authors asserted.

TRUNCATE-TB

To investigate a suitable shorter-term alternative, the authors conducted the phase 2-3, prospective, open-label TRUNCATE-TB trial, in which 674 patients with rifampin-susceptible pulmonary TB were enrolled at 18 sites in Asia and Africa.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive either the standard treatment regimen (rifampin and isoniazid for 24 weeks with pyrazinamide and ethambutol for the first 8 weeks; n = 181), or one of four novel five-drug regimens to be administered over 8 weeks, along with extended treatment for persistent clinical disease of up to 12 weeks, if needed, and a plan for retreatment in the case of relapse (n = 493).

Two of the regimens were dropped because of logistic criteria; the two remaining shorter-course groups included in the study involved either high-dose rifampin plus linezolid or bedaquiline plus linezolid, each combined with isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol.

Of the patients, 62% were male, and four withdrew or were lost to follow-up by the end of the study at a final follow-up at week 96.

Among patients assigned to the 8-week regimens, 80% stopped at exactly 8 weeks, while 9% wound up having extended treatment to 10 weeks and 3% were extended to 12 weeks.

For the primary endpoint, a composite of death, ongoing treatment, or active disease at week 96, the rate was lowest in the standard 24-week therapy group, occurring in 7 of 181 patients (3.9%), compared with 21 of 184 patients (11.4%) in the rifampin plus linezolid group (adjusted difference, 7.4 percentage points, which did not meet noninferiority criterion), and 11 of 189 (5.8%) in the group in the bedaquiline plus linezolid group (adjusted difference, 0.8 percentage points, meeting noninferiority criterion).

The mean total duration of treatment through week 96 in the standard treatment group was 180 days versus 106 days in the rifampin–linezolid group, and 85 days in the bedaquiline-linezolid group.