User login

Long-term use of prescription sleep meds unsupported by new research

a new study shows.

“While there are good data from [randomized, controlled trials] that these medications improve sleep disturbances in the short term,” few studies have examined whether they provide long-term benefits, stated the authors of the paper, which was published in BMJ Open.

“The current observational study does not support use of sleep medications over the long term, as there were no self-reported differences at 1 or 2 years of follow-up comparing sleep medication users with nonusers,” author Daniel H. Solomon, MD, MPH, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote.

Women included in the analysis were drawn from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), an ongoing multicenter, longitudinal study examining women during the menopausal transition. The average age of the women included in the cohort was 49.5 years and approximately half were White. All women reported a sleep disturbance on at least 3 nights per week during a 2-week interval. At follow up, women were asked to use a Likert scale to rate three aspects of sleep: difficulty initiating sleep, frequent awakening, and waking up early. On the scale, 1 represented having no difficulties on any nights, 3 represented having difficulties 1-2 nights per week, and 5 represented having difficulty 5-7 nights per week.

Women already using prescription sleep medication at their baseline visit were excluded from the study. Medications used included benzodiazepines, selective BZD receptor agonists, and other hypnotics.

Over the 21 years of follow-up in the SWAN study (1995-2016), Dr. Solomon and colleagues identified 238 women using sleep medication and these were compared with a cohort of 447 propensity score–matched non–sleep medication uses. Overall, the 685 women included were similar in characteristics to each other as well as to the other potentially eligible women not included in the analysis.

Sleep disturbance patterns compared

At baseline, sleep disturbance patterns were similar between the two groups. Among medication users, the mean score for difficulty initiating sleep was 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 2.5-2.9), waking frequently 3.8 (95% CI, 3.6-3.9), and waking early 2.9 (95% CI, 2.7-3.1). Among the nonusers, the baseline scores were 2.6 (95% CI, 2.5-2.7), 3.7 (95% CI, 3.6-3.8), and 2.7 (95% CI, 2.5-2.8), respectively. After 1 year, there was no statistically significant difference in scores between the two groups. The average ratings for medication users were 2.6 (95% CI, 2.3-2.8) for difficulty initiating sleep, 3.8 (95% CI, 3.6-4.0) for waking frequently, and 2.8 (95% CI, 2.6-3.0) for waking early.

Average ratings among nonusers were 2.3 (95% CI, 2.2-2.4), 3.5 (95% CI, 3.3-3.6), and 2.5 (95% CI, 2.3-2.6), respectively.

After 2 years, there were still no statistically significant reductions in sleep disturbances among those taking prescription sleep medications, compared with those not taking medication.

The researchers noted that approximately half of the women in this cohort were current or past tobacco users and that 20% were moderate to heavy alcohol users.

More work-up, not more medication, needed

The study authors acknowledged the limitations of an observational study and noted that, since participants only reported medication use and sleep disturbances at annual visits, they did not know whether patients’ medication use was intermittent or of any interim outcomes. Additionally, the authors pointed out that those classified as “nonusers” may have been using over-the-counter medication.

“Investigations should look at detailed-use patterns, on a daily or weekly basis, with frequent outcomes data,” Dr. Solomon said in an interview. “While our data shed new light on chronic use, we only had data collected on an annual basis; daily or weekly data would provide more granular information.”

Regarding clinician prescribing practices, Dr. Solomon said, “short-term, intermittent use can be helpful, but use these agents sparingly” and “educate patients that chronic regular use of medications for sleep is not associated with improvement in sleep disturbances.”

Commenting on the study, Andrea Matsumura, MD, a sleep specialist at the Oregon Clinic in Portland, echoed this sentiment: “When someone says they are having trouble sleeping this is the tip of the iceberg and it warrants an evaluation to determine if someone has a breathing disorder, a circadian disorder, a life situation, or a type of insomnia that is driving the sleeplessness.”

“I think this study supports what we all should know,” Dr. Matsumura concluded. “Sleep aids are not meant to be used long term” and should not be used for longer than 2 weeks without further work-up.

Funding for this study was provided through a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Solomon has received salary support from research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated work from AbbVie, Amgen, Corrona, Genentech and Pfizer. The other authors and Dr. Matsumura have reported no relevant financial relationships.

a new study shows.

“While there are good data from [randomized, controlled trials] that these medications improve sleep disturbances in the short term,” few studies have examined whether they provide long-term benefits, stated the authors of the paper, which was published in BMJ Open.

“The current observational study does not support use of sleep medications over the long term, as there were no self-reported differences at 1 or 2 years of follow-up comparing sleep medication users with nonusers,” author Daniel H. Solomon, MD, MPH, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote.

Women included in the analysis were drawn from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), an ongoing multicenter, longitudinal study examining women during the menopausal transition. The average age of the women included in the cohort was 49.5 years and approximately half were White. All women reported a sleep disturbance on at least 3 nights per week during a 2-week interval. At follow up, women were asked to use a Likert scale to rate three aspects of sleep: difficulty initiating sleep, frequent awakening, and waking up early. On the scale, 1 represented having no difficulties on any nights, 3 represented having difficulties 1-2 nights per week, and 5 represented having difficulty 5-7 nights per week.

Women already using prescription sleep medication at their baseline visit were excluded from the study. Medications used included benzodiazepines, selective BZD receptor agonists, and other hypnotics.

Over the 21 years of follow-up in the SWAN study (1995-2016), Dr. Solomon and colleagues identified 238 women using sleep medication and these were compared with a cohort of 447 propensity score–matched non–sleep medication uses. Overall, the 685 women included were similar in characteristics to each other as well as to the other potentially eligible women not included in the analysis.

Sleep disturbance patterns compared

At baseline, sleep disturbance patterns were similar between the two groups. Among medication users, the mean score for difficulty initiating sleep was 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 2.5-2.9), waking frequently 3.8 (95% CI, 3.6-3.9), and waking early 2.9 (95% CI, 2.7-3.1). Among the nonusers, the baseline scores were 2.6 (95% CI, 2.5-2.7), 3.7 (95% CI, 3.6-3.8), and 2.7 (95% CI, 2.5-2.8), respectively. After 1 year, there was no statistically significant difference in scores between the two groups. The average ratings for medication users were 2.6 (95% CI, 2.3-2.8) for difficulty initiating sleep, 3.8 (95% CI, 3.6-4.0) for waking frequently, and 2.8 (95% CI, 2.6-3.0) for waking early.

Average ratings among nonusers were 2.3 (95% CI, 2.2-2.4), 3.5 (95% CI, 3.3-3.6), and 2.5 (95% CI, 2.3-2.6), respectively.

After 2 years, there were still no statistically significant reductions in sleep disturbances among those taking prescription sleep medications, compared with those not taking medication.

The researchers noted that approximately half of the women in this cohort were current or past tobacco users and that 20% were moderate to heavy alcohol users.

More work-up, not more medication, needed

The study authors acknowledged the limitations of an observational study and noted that, since participants only reported medication use and sleep disturbances at annual visits, they did not know whether patients’ medication use was intermittent or of any interim outcomes. Additionally, the authors pointed out that those classified as “nonusers” may have been using over-the-counter medication.

“Investigations should look at detailed-use patterns, on a daily or weekly basis, with frequent outcomes data,” Dr. Solomon said in an interview. “While our data shed new light on chronic use, we only had data collected on an annual basis; daily or weekly data would provide more granular information.”

Regarding clinician prescribing practices, Dr. Solomon said, “short-term, intermittent use can be helpful, but use these agents sparingly” and “educate patients that chronic regular use of medications for sleep is not associated with improvement in sleep disturbances.”

Commenting on the study, Andrea Matsumura, MD, a sleep specialist at the Oregon Clinic in Portland, echoed this sentiment: “When someone says they are having trouble sleeping this is the tip of the iceberg and it warrants an evaluation to determine if someone has a breathing disorder, a circadian disorder, a life situation, or a type of insomnia that is driving the sleeplessness.”

“I think this study supports what we all should know,” Dr. Matsumura concluded. “Sleep aids are not meant to be used long term” and should not be used for longer than 2 weeks without further work-up.

Funding for this study was provided through a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Solomon has received salary support from research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated work from AbbVie, Amgen, Corrona, Genentech and Pfizer. The other authors and Dr. Matsumura have reported no relevant financial relationships.

a new study shows.

“While there are good data from [randomized, controlled trials] that these medications improve sleep disturbances in the short term,” few studies have examined whether they provide long-term benefits, stated the authors of the paper, which was published in BMJ Open.

“The current observational study does not support use of sleep medications over the long term, as there were no self-reported differences at 1 or 2 years of follow-up comparing sleep medication users with nonusers,” author Daniel H. Solomon, MD, MPH, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote.

Women included in the analysis were drawn from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), an ongoing multicenter, longitudinal study examining women during the menopausal transition. The average age of the women included in the cohort was 49.5 years and approximately half were White. All women reported a sleep disturbance on at least 3 nights per week during a 2-week interval. At follow up, women were asked to use a Likert scale to rate three aspects of sleep: difficulty initiating sleep, frequent awakening, and waking up early. On the scale, 1 represented having no difficulties on any nights, 3 represented having difficulties 1-2 nights per week, and 5 represented having difficulty 5-7 nights per week.

Women already using prescription sleep medication at their baseline visit were excluded from the study. Medications used included benzodiazepines, selective BZD receptor agonists, and other hypnotics.

Over the 21 years of follow-up in the SWAN study (1995-2016), Dr. Solomon and colleagues identified 238 women using sleep medication and these were compared with a cohort of 447 propensity score–matched non–sleep medication uses. Overall, the 685 women included were similar in characteristics to each other as well as to the other potentially eligible women not included in the analysis.

Sleep disturbance patterns compared

At baseline, sleep disturbance patterns were similar between the two groups. Among medication users, the mean score for difficulty initiating sleep was 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 2.5-2.9), waking frequently 3.8 (95% CI, 3.6-3.9), and waking early 2.9 (95% CI, 2.7-3.1). Among the nonusers, the baseline scores were 2.6 (95% CI, 2.5-2.7), 3.7 (95% CI, 3.6-3.8), and 2.7 (95% CI, 2.5-2.8), respectively. After 1 year, there was no statistically significant difference in scores between the two groups. The average ratings for medication users were 2.6 (95% CI, 2.3-2.8) for difficulty initiating sleep, 3.8 (95% CI, 3.6-4.0) for waking frequently, and 2.8 (95% CI, 2.6-3.0) for waking early.

Average ratings among nonusers were 2.3 (95% CI, 2.2-2.4), 3.5 (95% CI, 3.3-3.6), and 2.5 (95% CI, 2.3-2.6), respectively.

After 2 years, there were still no statistically significant reductions in sleep disturbances among those taking prescription sleep medications, compared with those not taking medication.

The researchers noted that approximately half of the women in this cohort were current or past tobacco users and that 20% were moderate to heavy alcohol users.

More work-up, not more medication, needed

The study authors acknowledged the limitations of an observational study and noted that, since participants only reported medication use and sleep disturbances at annual visits, they did not know whether patients’ medication use was intermittent or of any interim outcomes. Additionally, the authors pointed out that those classified as “nonusers” may have been using over-the-counter medication.

“Investigations should look at detailed-use patterns, on a daily or weekly basis, with frequent outcomes data,” Dr. Solomon said in an interview. “While our data shed new light on chronic use, we only had data collected on an annual basis; daily or weekly data would provide more granular information.”

Regarding clinician prescribing practices, Dr. Solomon said, “short-term, intermittent use can be helpful, but use these agents sparingly” and “educate patients that chronic regular use of medications for sleep is not associated with improvement in sleep disturbances.”

Commenting on the study, Andrea Matsumura, MD, a sleep specialist at the Oregon Clinic in Portland, echoed this sentiment: “When someone says they are having trouble sleeping this is the tip of the iceberg and it warrants an evaluation to determine if someone has a breathing disorder, a circadian disorder, a life situation, or a type of insomnia that is driving the sleeplessness.”

“I think this study supports what we all should know,” Dr. Matsumura concluded. “Sleep aids are not meant to be used long term” and should not be used for longer than 2 weeks without further work-up.

Funding for this study was provided through a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Solomon has received salary support from research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated work from AbbVie, Amgen, Corrona, Genentech and Pfizer. The other authors and Dr. Matsumura have reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Study points to best treatments for depression in primary care

according to a network meta-analysis (NMA) comparing either and both approaches with control conditions in the primary care setting.

The findings are important, since the majority of depressed patients are treated by primary care physicians, yet relatively few randomized trials of treatment have focused on this setting, noted senior study author Pim Cuijpers, PhD, from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and colleagues, in the paper, which was published in Annals of Family Medicine.

“The main message is that clinicians should certainly consider psychotherapy instead of pharmacotherapy, because this is preferred by most patients, and when possible, combined treatments should be the preferred choice because the outcomes are considerably better,” he said in an interview. Either way, he emphasized that “preference of patients is very important and all three treatments are better than usual care.”

The NMA included studies comparing psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, or a combination of both, with control conditions (defined as usual care, wait list, or pill placebo) in adult primary care patients with depression.

Patients could have major depression, persistent mood disorders (dysthymia), both, or high scores on self-rating depression scales. The primary outcome of the NMA was response, defined as a 50% improvement in the Hamilton Depression Rating scores (HAM-D).

A total of 58 studies met inclusion criteria, involving 9,301 patients.

Treatment options compared

Compared with usual care, both psychotherapy alone and pharmacotherapy alone had significantly better response rates, with no significant difference between them (relative risk, 1.60 and RR, 1.65, respectively). The combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was even better (RR, 2.15), whereas the wait list was less effective (RR, 0.68).

When comparing combined therapy with psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, the superiority of combination therapy over psychotherapy was only slightly statistically significant (RR, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-1.81), while pharmacotherapy was only slightly inferior (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.98-1.73).

“The significance level is not very high, which is related to statistical power,” said Dr. Cuijpers. “But the mean benefit is quite substantial in my opinion, with a 35% higher chance of response in the combined treatment, compared to psychotherapy alone.”

Looking at the outcome of remission, (normally defined as a score of 7 or less on the HAM-D), the outcomes were “comparable to those for response, with the exception that combined treatment was not significantly different from psychotherapy,” they wrote.

One important caveat is that several studies included in the NMA included patients with moderate to severe depression, a population that is different from the usual primary care population of depressed patients who have mild to moderate symptoms. Antidepressant medications are also assumed to work better against more severe symptoms, added the authors. “The inclusion of these studies might therefore have resulted in an overestimation of the effects of pharmacotherapy in the present NMA.”

Among other limitations, the authors noted that studies included mixed populations of patients with dysthymia and major depression; they also made no distinction between different types of antidepressants.

Psychotherapies unknown, but meta-analysis is still useful

Commenting on these findings, Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, said this is “an important study, confirming and extending the conclusions” of a systematic review published in 2016 as a Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians.

“Unfortunately, the authors did not specify what type of psychotherapy was studied in the meta-analysis, so we have to look elsewhere if we want to advise our patients on what type of psychotherapy to seek, since there are important differences between different types of therapy,” he said.

Still, he described the study as providing “helpful information for the practicing clinician, as it gives us solid information with which to engage and advise patients in a shared decision-making process for effective treatment of depression.”

“Some patients will choose psychotherapy, some will choose medications. They can make either choice with the confidence that both approaches are effective,” Dr. Skolnik elaborated. “In addition, if psychotherapy does not seem to be sufficiently helping we are on solid ground adding an antidepressant medication to psychotherapy, with this data showing that the combined treatment works better than psychotherapy alone.”

Dr. Cuijpers receives allowances for his memberships on the board of directors of Mind, Fonds Psychische Gezondheid, and Korrelatie, and for being chair of the PACO committee of the Raad voor Civiel-militaire Zorg en Onderzoek of the Dutch Ministry of Defense. He also serves as deputy editor of Depression and Anxiety and associate editor of Psychological Bulletin, and he receives royalties for books he has authored or coauthored. He received grants from the European Union, ZonMw, and PFGV. Another study author reported receiving personal fees from Mitsubishi-Tanabe, MSD, and Shionogi and a grant from Mitsubishi-Tanabe outside the submitted work. One author has received research and consultancy fees from INCiPiT (Italian Network for Paediatric Trials), CARIPLO Foundation, and Angelini Pharmam, while another reported receiving personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyowa Kirin, ASKA Pharmaceutical, and Toyota Motor Corporation outside the submitted work. The other authors and Dr. Skolnik reported no conflicts.

according to a network meta-analysis (NMA) comparing either and both approaches with control conditions in the primary care setting.

The findings are important, since the majority of depressed patients are treated by primary care physicians, yet relatively few randomized trials of treatment have focused on this setting, noted senior study author Pim Cuijpers, PhD, from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and colleagues, in the paper, which was published in Annals of Family Medicine.

“The main message is that clinicians should certainly consider psychotherapy instead of pharmacotherapy, because this is preferred by most patients, and when possible, combined treatments should be the preferred choice because the outcomes are considerably better,” he said in an interview. Either way, he emphasized that “preference of patients is very important and all three treatments are better than usual care.”

The NMA included studies comparing psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, or a combination of both, with control conditions (defined as usual care, wait list, or pill placebo) in adult primary care patients with depression.

Patients could have major depression, persistent mood disorders (dysthymia), both, or high scores on self-rating depression scales. The primary outcome of the NMA was response, defined as a 50% improvement in the Hamilton Depression Rating scores (HAM-D).

A total of 58 studies met inclusion criteria, involving 9,301 patients.

Treatment options compared

Compared with usual care, both psychotherapy alone and pharmacotherapy alone had significantly better response rates, with no significant difference between them (relative risk, 1.60 and RR, 1.65, respectively). The combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was even better (RR, 2.15), whereas the wait list was less effective (RR, 0.68).

When comparing combined therapy with psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, the superiority of combination therapy over psychotherapy was only slightly statistically significant (RR, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-1.81), while pharmacotherapy was only slightly inferior (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.98-1.73).

“The significance level is not very high, which is related to statistical power,” said Dr. Cuijpers. “But the mean benefit is quite substantial in my opinion, with a 35% higher chance of response in the combined treatment, compared to psychotherapy alone.”

Looking at the outcome of remission, (normally defined as a score of 7 or less on the HAM-D), the outcomes were “comparable to those for response, with the exception that combined treatment was not significantly different from psychotherapy,” they wrote.

One important caveat is that several studies included in the NMA included patients with moderate to severe depression, a population that is different from the usual primary care population of depressed patients who have mild to moderate symptoms. Antidepressant medications are also assumed to work better against more severe symptoms, added the authors. “The inclusion of these studies might therefore have resulted in an overestimation of the effects of pharmacotherapy in the present NMA.”

Among other limitations, the authors noted that studies included mixed populations of patients with dysthymia and major depression; they also made no distinction between different types of antidepressants.

Psychotherapies unknown, but meta-analysis is still useful

Commenting on these findings, Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, said this is “an important study, confirming and extending the conclusions” of a systematic review published in 2016 as a Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians.

“Unfortunately, the authors did not specify what type of psychotherapy was studied in the meta-analysis, so we have to look elsewhere if we want to advise our patients on what type of psychotherapy to seek, since there are important differences between different types of therapy,” he said.

Still, he described the study as providing “helpful information for the practicing clinician, as it gives us solid information with which to engage and advise patients in a shared decision-making process for effective treatment of depression.”

“Some patients will choose psychotherapy, some will choose medications. They can make either choice with the confidence that both approaches are effective,” Dr. Skolnik elaborated. “In addition, if psychotherapy does not seem to be sufficiently helping we are on solid ground adding an antidepressant medication to psychotherapy, with this data showing that the combined treatment works better than psychotherapy alone.”

Dr. Cuijpers receives allowances for his memberships on the board of directors of Mind, Fonds Psychische Gezondheid, and Korrelatie, and for being chair of the PACO committee of the Raad voor Civiel-militaire Zorg en Onderzoek of the Dutch Ministry of Defense. He also serves as deputy editor of Depression and Anxiety and associate editor of Psychological Bulletin, and he receives royalties for books he has authored or coauthored. He received grants from the European Union, ZonMw, and PFGV. Another study author reported receiving personal fees from Mitsubishi-Tanabe, MSD, and Shionogi and a grant from Mitsubishi-Tanabe outside the submitted work. One author has received research and consultancy fees from INCiPiT (Italian Network for Paediatric Trials), CARIPLO Foundation, and Angelini Pharmam, while another reported receiving personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyowa Kirin, ASKA Pharmaceutical, and Toyota Motor Corporation outside the submitted work. The other authors and Dr. Skolnik reported no conflicts.

according to a network meta-analysis (NMA) comparing either and both approaches with control conditions in the primary care setting.

The findings are important, since the majority of depressed patients are treated by primary care physicians, yet relatively few randomized trials of treatment have focused on this setting, noted senior study author Pim Cuijpers, PhD, from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and colleagues, in the paper, which was published in Annals of Family Medicine.

“The main message is that clinicians should certainly consider psychotherapy instead of pharmacotherapy, because this is preferred by most patients, and when possible, combined treatments should be the preferred choice because the outcomes are considerably better,” he said in an interview. Either way, he emphasized that “preference of patients is very important and all three treatments are better than usual care.”

The NMA included studies comparing psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, or a combination of both, with control conditions (defined as usual care, wait list, or pill placebo) in adult primary care patients with depression.

Patients could have major depression, persistent mood disorders (dysthymia), both, or high scores on self-rating depression scales. The primary outcome of the NMA was response, defined as a 50% improvement in the Hamilton Depression Rating scores (HAM-D).

A total of 58 studies met inclusion criteria, involving 9,301 patients.

Treatment options compared

Compared with usual care, both psychotherapy alone and pharmacotherapy alone had significantly better response rates, with no significant difference between them (relative risk, 1.60 and RR, 1.65, respectively). The combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was even better (RR, 2.15), whereas the wait list was less effective (RR, 0.68).

When comparing combined therapy with psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, the superiority of combination therapy over psychotherapy was only slightly statistically significant (RR, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-1.81), while pharmacotherapy was only slightly inferior (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.98-1.73).

“The significance level is not very high, which is related to statistical power,” said Dr. Cuijpers. “But the mean benefit is quite substantial in my opinion, with a 35% higher chance of response in the combined treatment, compared to psychotherapy alone.”

Looking at the outcome of remission, (normally defined as a score of 7 or less on the HAM-D), the outcomes were “comparable to those for response, with the exception that combined treatment was not significantly different from psychotherapy,” they wrote.

One important caveat is that several studies included in the NMA included patients with moderate to severe depression, a population that is different from the usual primary care population of depressed patients who have mild to moderate symptoms. Antidepressant medications are also assumed to work better against more severe symptoms, added the authors. “The inclusion of these studies might therefore have resulted in an overestimation of the effects of pharmacotherapy in the present NMA.”

Among other limitations, the authors noted that studies included mixed populations of patients with dysthymia and major depression; they also made no distinction between different types of antidepressants.

Psychotherapies unknown, but meta-analysis is still useful

Commenting on these findings, Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, said this is “an important study, confirming and extending the conclusions” of a systematic review published in 2016 as a Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians.

“Unfortunately, the authors did not specify what type of psychotherapy was studied in the meta-analysis, so we have to look elsewhere if we want to advise our patients on what type of psychotherapy to seek, since there are important differences between different types of therapy,” he said.

Still, he described the study as providing “helpful information for the practicing clinician, as it gives us solid information with which to engage and advise patients in a shared decision-making process for effective treatment of depression.”

“Some patients will choose psychotherapy, some will choose medications. They can make either choice with the confidence that both approaches are effective,” Dr. Skolnik elaborated. “In addition, if psychotherapy does not seem to be sufficiently helping we are on solid ground adding an antidepressant medication to psychotherapy, with this data showing that the combined treatment works better than psychotherapy alone.”

Dr. Cuijpers receives allowances for his memberships on the board of directors of Mind, Fonds Psychische Gezondheid, and Korrelatie, and for being chair of the PACO committee of the Raad voor Civiel-militaire Zorg en Onderzoek of the Dutch Ministry of Defense. He also serves as deputy editor of Depression and Anxiety and associate editor of Psychological Bulletin, and he receives royalties for books he has authored or coauthored. He received grants from the European Union, ZonMw, and PFGV. Another study author reported receiving personal fees from Mitsubishi-Tanabe, MSD, and Shionogi and a grant from Mitsubishi-Tanabe outside the submitted work. One author has received research and consultancy fees from INCiPiT (Italian Network for Paediatric Trials), CARIPLO Foundation, and Angelini Pharmam, while another reported receiving personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyowa Kirin, ASKA Pharmaceutical, and Toyota Motor Corporation outside the submitted work. The other authors and Dr. Skolnik reported no conflicts.

FROM ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

Outcomes Associated With Pharmacist- Led Consult Service for Opioid Tapering and Pharmacotherapy

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, an emphasis on better pain management led health care professionals (HCPs) to increase prescribing of opioids to better manage patient’s pain. In 1991, 76 million prescriptions were written for opioids in the United States, and by 2011, the number had nearly tripled to 219 million.1 Overdose rates increased as well, nearly tripling from 1999 to 2014.2 Of the 52,404 US deaths from drug overdoses in the in 2015, 63% involved an opioid.2

Opioid Safety Initiative

In response to the growing opioid epidemic, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) created the Opioid Safety Initiative in 2014.3 This comprehensive, multifaceted initiative was designed to improve the care and safety of veterans managed with opioid therapy and promote rational opioid prescribing and monitoring. In 2016 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued guidelines for opioid prescriptions, and the following year the VA and the US Department of Defense (DoD) updated the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain (VA/DoD guidelines).4,5 After the release of these guidelines, the use of opioid tapers expanded. However, due to public outcry of forced opioid tapering in 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration updated its opioid labeling requirements to provide clearer guidance on opioid tapers for tolerant patients.6,7

As a result, HCPs began to develop various strategies to balance the safety and efficacy of opioid use in patients with chronic pain. The West Palm Beach VA Medical Center (WPBVAMC) in Florida has a Pain Clinic that includes 2 pain management clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) with specialized training in pain management, who are uniquely qualified to assess and evaluate medication therapy in complex pain patient cases. These CPSs were involved in the face-to-face management of patients requiring specialized pain care and participated in a pain pharmacy electronic consult (eConsult) service to document pain management consultative recommendations for patients appropriate for management at the primary care level. This formalized process increased specialty pain care access for veterans whose pain was managed by primary care providers (PCPs).

The pain pharmacy eConsult service was initiated at the WPBVAMC in June 2013 to assist PCPs in the management of outpatients with chronic pain. The eConsult service includes evaluation of a patient’s electronic health records (EHRs) by CPSs. The eConsult service also provided PCPs with the option to engage a pharmacist who could provide recommendations for opioid dosing conversion, opioid tapering, pain pharmacotherapy, or drug screen interpretation, without the necessity for an additional patient visit.

Subsequent to the release of the 2016 CDC (and later the 2017 VA/DoD) guidelines recommending reducing morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) levels, the WPBVAMC had a large increase in pain eConsult requests for opioid tapering and opioid pharmacotherapy. A 3.4-fold increase in requests occurred in March, April, and May vs the following 9 months, and a nearly 4-fold increase in requests for opioid tapers during the same period. However, the impact of the completed eConsults was unclear. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to assess the effect of CPS services for opioid tapering and opioid pharmacotherapy by quantifying the number of recommendations accepted/implemented by PCPs. The secondary objectives included evaluating harms associated with the recommendations (eg, increase in visits to the emergency department [ED], hospitalizations, suicide attempts, or PCP visits) and provider satisfaction.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was completed to assess data of patients from the WPBVAMC and its associated community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). The project was approved by the WPBVAMC Scientific Advisory Committee as part of the facility’s performance improvement efforts.

Included patients had a pain pharmacy eConsult placed between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017. EHRs were reviewed and only eConsults for opioid pharmacotherapy recommendation or opioid tapers were evaluated. eConsults were excluded if the request was discontinued, completed by a HCP other than the pain CPS, or placed for an opioid dose conversion, nonopioid pharmacotherapy, or drug screen interpretation.

Data for analyses were entered into Microsoft Excel 2016 and were securely saved and accessible to relevant researchers. Patient protected health information used during patient care remained confidential.

Demographic data were collected, including age, gender, race, pertinent medical comorbidities (eg, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea), and mental health comorbidities. Pain scores were collected at baseline and 6-months postconsult. Pain medications used by patients were noted at baseline and 6 months postconsult, including concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine use, MEDD, and other pain medication. The duration of time needed by pain CPS to complete each eConsult and total time from eConsult entered to HCP implementation of the initial recommendation was collected. The number of actionable recommendations (eg, changes in drug therapy, urine drug screens [UDSs], and referrals to other services also were recorded and reviewed 6 months postconsult to determine the number and percentage of recommendations implemented by the HCP. The EHR was examined to determine adverse events (AEs) (eg, any documentation of suicide attempt, calls to the Veterans Crisis Line, or death 6 month postconsult). Collected data also included new eConsults, the reason for opioid tapering either by HCP or patient, and assessment of economic harms (count of the number of visits to ED, hospitalizations, or unscheduled PCP visits with uncontrolled pain as chief reason within 6 months postconsult). Last, PCPs were sent a survey to assess their satisfaction with the pain eConsult service.

Results

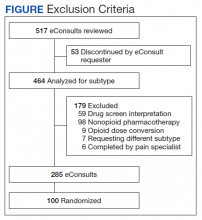

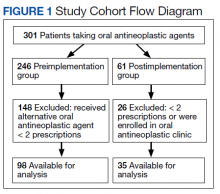

Of 517 eConsults received from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2017, 285 (55.1%) met inclusion criteria (Figure). Using a random number generator, 100 eConsults were further reviewed for outcomes of interest.

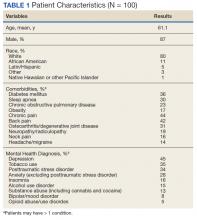

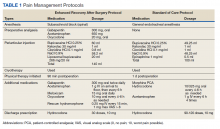

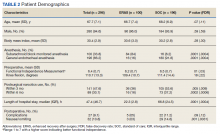

In this cohort, the mean age was 61 years, 87% were male, and 80% were White individuals. Most patients (83%) had ≥ 1 mental health comorbidity, and 53% had ≥ 2, with depressive symptoms, tobacco use, and/or posttraumatic stress disorder the most common diagnoses (Table 1). Eighty-seven percent of eConsults were for opioid tapers and the remaining 13% were for opioid pharmacotherapy.

The median pain score at time of consult was 6 on a 10-point scale, with no change at 6 months postconsult. However, 41% of patients overall had a median 3.3-point drop in pain score, 17% had no change in pain score, and 42% had a median 2.6-point increase in pain score.

At time of consult, 24% of patients had an opioid and benzodiazepine prescribed concurrently. At the time of the initial request, the mean MEDD was 177.5 mg (median, 165; range, 0-577.5). At 6 months postconsult, the average MEDD was 71 mg (median, 90; range, 0-450) for a mean 44% MEDD decrease. Eighteen percent of patients had no change in MEDD, and 5% had an increase.

One concern was the number of patients whose pain management regimen consisted of either opioids as monotherapy or a combination of opioids and skeletal muscle relaxants (SMRs), which can increase the opioid overdose risk and are not indicated for long-term use (except for baclofen for spasticity). Thirty-five percent of patients were taking either opioid monotherapy or opioids and SMRs for chronic pain management at time of consult and 28% were taking opioid monotherapy or opioids and SMRs 6 months postconsult.

Electronic Consults

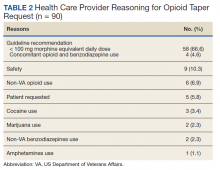

Table 2 describes the reasons eConsults were requested. The most common reason was to taper the dose to be in compliance with the CDC 2016 guideline recommendation of MEDD < 90 mg, which was later increased to 100 mg by the VA/DoD guideline.

On average, eConsults were completed within a mean of 11.5 days of the PCP request, including nights and weekends. The CPS spent a mean 66.8 minutes to complete each eConsult. Once the eConsult was completed, PCPs took a mean of 9 days to initiate the primary recommendation. This 9-day average does not include 11 eConsults with no accepted recommendations and 11 eConsults for which the PCP implemented the primary recommendation before the CPS completed the consult, most likely due to a phone call or direct contact with the CPS at the time the eConsult was ordered.

A mean 3.5 actionable recommendations were made by the CPS and a mean 1.6 recommendations were implemented within 6 months by the PCP. At least 1 recommendation was accepted/implemented for 89% of patients, with a mean 55% recommendations that were accepted/implemented. Eleven percent of the eConsult final recommendations were not accepted by PCPs and clear documentation of the reasons were not provided.

Adverse Outcomes

In the 6 months postconsult, 11 patients (7 men and 4 women) experienced 32 AEs (Table 3). Eight patients had 15 ED visits, with 3 of the visits resulting in hospitalizations, 8 patients had 9 unscheduled PCP visits, 1 patient reported suicidal ideation and 2 patients made a total of 4 calls to the Veterans Crisis Line. There were also 2 deaths; however, both were due to end-stage disease (cirrhosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and not believed to be related to eConsult recommendations.

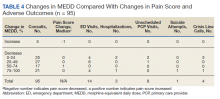

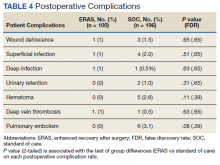

Eight patients had a history of substance use disorders (SUDs) and 8 had a history of a mood disorder or psychosis. One patient had both SUD and a mood/psychosis-related mental health disorder, including a reported suicidal attempt/ideation at an ED visit and a subsequent hospitalization. A similar number of AEs occurred in patients with decreases in MEDD of 0 to 24% compared with those that received more aggressive tapers of 75 to 100% (Table 4).

Nine patients were reconsulted, with only 1 secondary to the PCP not implementing recommendations from the initial consult. No factors were found that correlated with likelihood of a patient being reconsulted.

Surveys on PCP satisfaction with the eConsult service were completed by 29 of the 55 PCPs. PCP feedback was generally positive with nearly 90% of PCPs planning to use the service in the future as well as recommending use to other providers.

PCPs also were given the option to indicate the most important factor for overall satisfaction with eConsult service (time, access, safety, expectations or confidence). Safety was provider’s top choice with time being a close second.

Discussion

Most (89%) PCPs accepted at least 1 recommendation from the completed eConsult, and MEDDs decreased by 60%, likely reducing the patient’s risk of overdose or other AEs from opioids. There also was a slight reduction in patient’s mean pain scores; however, 41% had a decrease and 42% had an increase in pain scores. There was no clear relationship when pain scores were compared with MEDDs, likely giving credence to the idea that pain scores are largely subjective and an unreliable surrogate marker for assessing effectiveness of analgesic regimens.

Eleven patients experienced AEs, including 1 patient for whom the recommendations were not implemented by the PCP. Eight of the 11 had multiple AEs. One interesting finding was that 7 of the 11 patients with an AE tested positive for unexpected substances on routine UDS or were arrested for driving while intoxicated (DWI). However, only 3 of the 7 had an active SUD diagnosis. With 25% of the AEs coming from patients with a history of SUD, it is important that any history of SUD be documented in the EHR. Maintaining this documentation can be especially difficult if patients switch VA medical centers or receive services outside the VA. Thorough and accurate history and chart review should ideally be completed before prescribing opioids.

Guidelines

While the PCPs were following VA/DoD and CDC recommendations for opioid tapering to < 100 or 90 mg MEDD, respectively, there is weak evidence in these guidelines to support specific MEDD cutoffs. The CDC guidelines even state, “a single dosage threshold for safe opioid use could not be identified.”5 One of the largest issues when using MEDD as a cutoff is the lack of agreement on its calculation. In 2014, Nuckols and colleagues al conducted a study to compare the existing guidelines on the use of opioids for chronic pain. While 13 guidelines were considered eligible, most recommendations were supported only by observational data or expert recommendations, and there was no consensus on what constitutes a “morphine equivalent.”8 Currently there is no universally accepted opioid-conversion method, resulting in a substantial problem when calculating a MEDD.9 A survey of 8 online opioid dose conversion tools found a -55% to +242% variation.10 As Fudin and colleagues concluded in response to the large variations found in these various analyses, the studies “unequivocally disqualify the validity of embracing MEDD to assess risk in any meaningful statistical way.”11 Pharmacogenetics, drug tolerance, drug-drug interactions, body surface area, and organ function are patient- specific factors that are not taken into consideration when relying solely on a MEDD calculation. Tapering to lowest functional dose rather than a specific number or cutoff may be a more effective way to treat patients, and providers should use the guidelines as recommendations and not a hardline mandate.

At 6 months, 6 patients were receiving no pain medications from the VA, and 24 of the patients were tapered from their opiate to discontinuation. It is unclear whether patients are no longer taking opioids or switched their care to non-VA providers to receive medications, including opioids, privately. This is difficult to verify, though a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) could be used to assess patient adherence. As many of the patients that were tapered due to identification of aberrant behaviors, lack of continuity of care across health care systems may result in future patient harm.

The results of this analysis highlight the importance of checking PDMP databases and routine UDSs when prescribing opioids—there can be serious safety concerns if patients are taking other prescribed or illicit medications. However, care must be taken; there were 2 instances of patients’ chronic opioid prescriptions discontinued by their VA provider after a review of the PDMP showed they had received non-VA opioids. In both cases, the quantity and doses received were small (counts of ≤ 12) and were received more than 6 months prior to the check of the PDMP. While this constitutes a breach of the Informed Consent for long-term opioid use, if there are no other concerning behaviors, it may be more prudent to review the informed consent with the patient and discuss why the behavior is a breach to ensure that patients and PCPs continue to work as a team to manage chronic pain.

Limitations

The study population was one limitation of this project. While data suggest that chronic pain affects women more than men, this study’s population was only 13% female. Thirty percent of the women in this study had an AE compared with only 8% of the men. Additional limitations included use of problem list for comorbidities, as lists may be inaccurate or outdated, and limiting the monitoring of AE to only 6 months. As some tapers were not initiated immediately and some taper schedules can last several months to years; therefor, outcomes may have been higher if patients were followed longer. Many of the patients with AEs had increased ED visits or unscheduled primary care visits as the tapers went on and their pain worsened, but the visits were outside the 6-month time frame for data collection. An additional weakness of this review included assessing a pain score, but not functional status, which may be a better predictor of the effectiveness of a patient’s pain management regimen. This assessment is needed in future studies for more reliable data. Finally, PCP survey results also should be viewed with caution. The current survey had only 29 respondents, and the 2014 survey had only 10 respondents and did not include CBOC providers.

Conclusion

A pain eConsult service managed by CPSs specializing in pain management can assist patients and PCPs with opioid therapy recommendations in a safe and timely manner, reducing risk of overdose secondary to high dose opioid therapy and with limited harm to patients.

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Increased drug availability is associated with increased use and overdose. Published June 9, 2020. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/prescription-opioids-heroin/increased-drug-availability-associated-increased-use-overdose

2. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452. Published 2016 Dec 30.doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Healthcare inspection – VA patterns of dispensing take-home opioids and monitoring patients on opioid therapy. Report 14-00895-163. Published May 14, 2014. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-14-00895-163.pdf

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Version 3.0. Published December 2017. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(11):295]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49. Published 2016 Mar 18. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1.

6. US Food and Drug Administration. (2019). FDA identifies harm reported from sudden discontinuation of opioid pain medicines and requires label changes to guide prescribers on gradual, individualized tapering. Updated April 17, 2019. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-drug-safety-podcasts/fda-identifies-harm-reported-sudden-discontinuation-opioid-pain-medicines-and-requires-label-changes

7. Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R. No Shortcuts to Safer Opioid Prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2285-2287. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1904190

8. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):38-47. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-160-1-201401070-00732

9. Rennick A, Atkinson T, Cimino NM, Strassels SA, McPherson ML, Fudin J. Variability in Opioid Equivalence Calculations. Pain Med. 2016;17(5):892-898. doi:10.1111/pme.12920

10. Shaw K, Fudin J. Evaluation and comparison of online equianalgesic opioid dose conversion calculators. Pract Pain Manag. 2013;13(7):61-66.

11. Fudin J, Pratt Cleary J, Schatman ME. The MEDD myth: the impact of pseudoscience on pain research and prescribing-guideline development. J Pain Res. 2016;9:153-156. Published 2016 Mar 23. doi:10.2147/JPR.S107794

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, an emphasis on better pain management led health care professionals (HCPs) to increase prescribing of opioids to better manage patient’s pain. In 1991, 76 million prescriptions were written for opioids in the United States, and by 2011, the number had nearly tripled to 219 million.1 Overdose rates increased as well, nearly tripling from 1999 to 2014.2 Of the 52,404 US deaths from drug overdoses in the in 2015, 63% involved an opioid.2

Opioid Safety Initiative

In response to the growing opioid epidemic, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) created the Opioid Safety Initiative in 2014.3 This comprehensive, multifaceted initiative was designed to improve the care and safety of veterans managed with opioid therapy and promote rational opioid prescribing and monitoring. In 2016 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued guidelines for opioid prescriptions, and the following year the VA and the US Department of Defense (DoD) updated the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain (VA/DoD guidelines).4,5 After the release of these guidelines, the use of opioid tapers expanded. However, due to public outcry of forced opioid tapering in 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration updated its opioid labeling requirements to provide clearer guidance on opioid tapers for tolerant patients.6,7

As a result, HCPs began to develop various strategies to balance the safety and efficacy of opioid use in patients with chronic pain. The West Palm Beach VA Medical Center (WPBVAMC) in Florida has a Pain Clinic that includes 2 pain management clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) with specialized training in pain management, who are uniquely qualified to assess and evaluate medication therapy in complex pain patient cases. These CPSs were involved in the face-to-face management of patients requiring specialized pain care and participated in a pain pharmacy electronic consult (eConsult) service to document pain management consultative recommendations for patients appropriate for management at the primary care level. This formalized process increased specialty pain care access for veterans whose pain was managed by primary care providers (PCPs).

The pain pharmacy eConsult service was initiated at the WPBVAMC in June 2013 to assist PCPs in the management of outpatients with chronic pain. The eConsult service includes evaluation of a patient’s electronic health records (EHRs) by CPSs. The eConsult service also provided PCPs with the option to engage a pharmacist who could provide recommendations for opioid dosing conversion, opioid tapering, pain pharmacotherapy, or drug screen interpretation, without the necessity for an additional patient visit.

Subsequent to the release of the 2016 CDC (and later the 2017 VA/DoD) guidelines recommending reducing morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) levels, the WPBVAMC had a large increase in pain eConsult requests for opioid tapering and opioid pharmacotherapy. A 3.4-fold increase in requests occurred in March, April, and May vs the following 9 months, and a nearly 4-fold increase in requests for opioid tapers during the same period. However, the impact of the completed eConsults was unclear. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to assess the effect of CPS services for opioid tapering and opioid pharmacotherapy by quantifying the number of recommendations accepted/implemented by PCPs. The secondary objectives included evaluating harms associated with the recommendations (eg, increase in visits to the emergency department [ED], hospitalizations, suicide attempts, or PCP visits) and provider satisfaction.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was completed to assess data of patients from the WPBVAMC and its associated community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). The project was approved by the WPBVAMC Scientific Advisory Committee as part of the facility’s performance improvement efforts.

Included patients had a pain pharmacy eConsult placed between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017. EHRs were reviewed and only eConsults for opioid pharmacotherapy recommendation or opioid tapers were evaluated. eConsults were excluded if the request was discontinued, completed by a HCP other than the pain CPS, or placed for an opioid dose conversion, nonopioid pharmacotherapy, or drug screen interpretation.

Data for analyses were entered into Microsoft Excel 2016 and were securely saved and accessible to relevant researchers. Patient protected health information used during patient care remained confidential.

Demographic data were collected, including age, gender, race, pertinent medical comorbidities (eg, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea), and mental health comorbidities. Pain scores were collected at baseline and 6-months postconsult. Pain medications used by patients were noted at baseline and 6 months postconsult, including concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine use, MEDD, and other pain medication. The duration of time needed by pain CPS to complete each eConsult and total time from eConsult entered to HCP implementation of the initial recommendation was collected. The number of actionable recommendations (eg, changes in drug therapy, urine drug screens [UDSs], and referrals to other services also were recorded and reviewed 6 months postconsult to determine the number and percentage of recommendations implemented by the HCP. The EHR was examined to determine adverse events (AEs) (eg, any documentation of suicide attempt, calls to the Veterans Crisis Line, or death 6 month postconsult). Collected data also included new eConsults, the reason for opioid tapering either by HCP or patient, and assessment of economic harms (count of the number of visits to ED, hospitalizations, or unscheduled PCP visits with uncontrolled pain as chief reason within 6 months postconsult). Last, PCPs were sent a survey to assess their satisfaction with the pain eConsult service.

Results

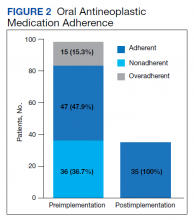

Of 517 eConsults received from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2017, 285 (55.1%) met inclusion criteria (Figure). Using a random number generator, 100 eConsults were further reviewed for outcomes of interest.

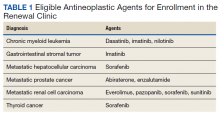

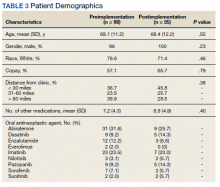

In this cohort, the mean age was 61 years, 87% were male, and 80% were White individuals. Most patients (83%) had ≥ 1 mental health comorbidity, and 53% had ≥ 2, with depressive symptoms, tobacco use, and/or posttraumatic stress disorder the most common diagnoses (Table 1). Eighty-seven percent of eConsults were for opioid tapers and the remaining 13% were for opioid pharmacotherapy.

The median pain score at time of consult was 6 on a 10-point scale, with no change at 6 months postconsult. However, 41% of patients overall had a median 3.3-point drop in pain score, 17% had no change in pain score, and 42% had a median 2.6-point increase in pain score.

At time of consult, 24% of patients had an opioid and benzodiazepine prescribed concurrently. At the time of the initial request, the mean MEDD was 177.5 mg (median, 165; range, 0-577.5). At 6 months postconsult, the average MEDD was 71 mg (median, 90; range, 0-450) for a mean 44% MEDD decrease. Eighteen percent of patients had no change in MEDD, and 5% had an increase.

One concern was the number of patients whose pain management regimen consisted of either opioids as monotherapy or a combination of opioids and skeletal muscle relaxants (SMRs), which can increase the opioid overdose risk and are not indicated for long-term use (except for baclofen for spasticity). Thirty-five percent of patients were taking either opioid monotherapy or opioids and SMRs for chronic pain management at time of consult and 28% were taking opioid monotherapy or opioids and SMRs 6 months postconsult.

Electronic Consults

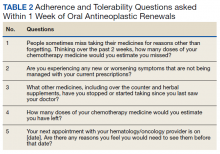

Table 2 describes the reasons eConsults were requested. The most common reason was to taper the dose to be in compliance with the CDC 2016 guideline recommendation of MEDD < 90 mg, which was later increased to 100 mg by the VA/DoD guideline.

On average, eConsults were completed within a mean of 11.5 days of the PCP request, including nights and weekends. The CPS spent a mean 66.8 minutes to complete each eConsult. Once the eConsult was completed, PCPs took a mean of 9 days to initiate the primary recommendation. This 9-day average does not include 11 eConsults with no accepted recommendations and 11 eConsults for which the PCP implemented the primary recommendation before the CPS completed the consult, most likely due to a phone call or direct contact with the CPS at the time the eConsult was ordered.

A mean 3.5 actionable recommendations were made by the CPS and a mean 1.6 recommendations were implemented within 6 months by the PCP. At least 1 recommendation was accepted/implemented for 89% of patients, with a mean 55% recommendations that were accepted/implemented. Eleven percent of the eConsult final recommendations were not accepted by PCPs and clear documentation of the reasons were not provided.

Adverse Outcomes

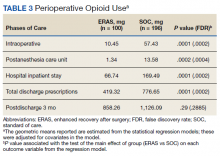

In the 6 months postconsult, 11 patients (7 men and 4 women) experienced 32 AEs (Table 3). Eight patients had 15 ED visits, with 3 of the visits resulting in hospitalizations, 8 patients had 9 unscheduled PCP visits, 1 patient reported suicidal ideation and 2 patients made a total of 4 calls to the Veterans Crisis Line. There were also 2 deaths; however, both were due to end-stage disease (cirrhosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and not believed to be related to eConsult recommendations.

Eight patients had a history of substance use disorders (SUDs) and 8 had a history of a mood disorder or psychosis. One patient had both SUD and a mood/psychosis-related mental health disorder, including a reported suicidal attempt/ideation at an ED visit and a subsequent hospitalization. A similar number of AEs occurred in patients with decreases in MEDD of 0 to 24% compared with those that received more aggressive tapers of 75 to 100% (Table 4).

Nine patients were reconsulted, with only 1 secondary to the PCP not implementing recommendations from the initial consult. No factors were found that correlated with likelihood of a patient being reconsulted.

Surveys on PCP satisfaction with the eConsult service were completed by 29 of the 55 PCPs. PCP feedback was generally positive with nearly 90% of PCPs planning to use the service in the future as well as recommending use to other providers.

PCPs also were given the option to indicate the most important factor for overall satisfaction with eConsult service (time, access, safety, expectations or confidence). Safety was provider’s top choice with time being a close second.

Discussion

Most (89%) PCPs accepted at least 1 recommendation from the completed eConsult, and MEDDs decreased by 60%, likely reducing the patient’s risk of overdose or other AEs from opioids. There also was a slight reduction in patient’s mean pain scores; however, 41% had a decrease and 42% had an increase in pain scores. There was no clear relationship when pain scores were compared with MEDDs, likely giving credence to the idea that pain scores are largely subjective and an unreliable surrogate marker for assessing effectiveness of analgesic regimens.

Eleven patients experienced AEs, including 1 patient for whom the recommendations were not implemented by the PCP. Eight of the 11 had multiple AEs. One interesting finding was that 7 of the 11 patients with an AE tested positive for unexpected substances on routine UDS or were arrested for driving while intoxicated (DWI). However, only 3 of the 7 had an active SUD diagnosis. With 25% of the AEs coming from patients with a history of SUD, it is important that any history of SUD be documented in the EHR. Maintaining this documentation can be especially difficult if patients switch VA medical centers or receive services outside the VA. Thorough and accurate history and chart review should ideally be completed before prescribing opioids.

Guidelines

While the PCPs were following VA/DoD and CDC recommendations for opioid tapering to < 100 or 90 mg MEDD, respectively, there is weak evidence in these guidelines to support specific MEDD cutoffs. The CDC guidelines even state, “a single dosage threshold for safe opioid use could not be identified.”5 One of the largest issues when using MEDD as a cutoff is the lack of agreement on its calculation. In 2014, Nuckols and colleagues al conducted a study to compare the existing guidelines on the use of opioids for chronic pain. While 13 guidelines were considered eligible, most recommendations were supported only by observational data or expert recommendations, and there was no consensus on what constitutes a “morphine equivalent.”8 Currently there is no universally accepted opioid-conversion method, resulting in a substantial problem when calculating a MEDD.9 A survey of 8 online opioid dose conversion tools found a -55% to +242% variation.10 As Fudin and colleagues concluded in response to the large variations found in these various analyses, the studies “unequivocally disqualify the validity of embracing MEDD to assess risk in any meaningful statistical way.”11 Pharmacogenetics, drug tolerance, drug-drug interactions, body surface area, and organ function are patient- specific factors that are not taken into consideration when relying solely on a MEDD calculation. Tapering to lowest functional dose rather than a specific number or cutoff may be a more effective way to treat patients, and providers should use the guidelines as recommendations and not a hardline mandate.

At 6 months, 6 patients were receiving no pain medications from the VA, and 24 of the patients were tapered from their opiate to discontinuation. It is unclear whether patients are no longer taking opioids or switched their care to non-VA providers to receive medications, including opioids, privately. This is difficult to verify, though a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) could be used to assess patient adherence. As many of the patients that were tapered due to identification of aberrant behaviors, lack of continuity of care across health care systems may result in future patient harm.

The results of this analysis highlight the importance of checking PDMP databases and routine UDSs when prescribing opioids—there can be serious safety concerns if patients are taking other prescribed or illicit medications. However, care must be taken; there were 2 instances of patients’ chronic opioid prescriptions discontinued by their VA provider after a review of the PDMP showed they had received non-VA opioids. In both cases, the quantity and doses received were small (counts of ≤ 12) and were received more than 6 months prior to the check of the PDMP. While this constitutes a breach of the Informed Consent for long-term opioid use, if there are no other concerning behaviors, it may be more prudent to review the informed consent with the patient and discuss why the behavior is a breach to ensure that patients and PCPs continue to work as a team to manage chronic pain.

Limitations

The study population was one limitation of this project. While data suggest that chronic pain affects women more than men, this study’s population was only 13% female. Thirty percent of the women in this study had an AE compared with only 8% of the men. Additional limitations included use of problem list for comorbidities, as lists may be inaccurate or outdated, and limiting the monitoring of AE to only 6 months. As some tapers were not initiated immediately and some taper schedules can last several months to years; therefor, outcomes may have been higher if patients were followed longer. Many of the patients with AEs had increased ED visits or unscheduled primary care visits as the tapers went on and their pain worsened, but the visits were outside the 6-month time frame for data collection. An additional weakness of this review included assessing a pain score, but not functional status, which may be a better predictor of the effectiveness of a patient’s pain management regimen. This assessment is needed in future studies for more reliable data. Finally, PCP survey results also should be viewed with caution. The current survey had only 29 respondents, and the 2014 survey had only 10 respondents and did not include CBOC providers.

Conclusion

A pain eConsult service managed by CPSs specializing in pain management can assist patients and PCPs with opioid therapy recommendations in a safe and timely manner, reducing risk of overdose secondary to high dose opioid therapy and with limited harm to patients.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, an emphasis on better pain management led health care professionals (HCPs) to increase prescribing of opioids to better manage patient’s pain. In 1991, 76 million prescriptions were written for opioids in the United States, and by 2011, the number had nearly tripled to 219 million.1 Overdose rates increased as well, nearly tripling from 1999 to 2014.2 Of the 52,404 US deaths from drug overdoses in the in 2015, 63% involved an opioid.2

Opioid Safety Initiative

In response to the growing opioid epidemic, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) created the Opioid Safety Initiative in 2014.3 This comprehensive, multifaceted initiative was designed to improve the care and safety of veterans managed with opioid therapy and promote rational opioid prescribing and monitoring. In 2016 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued guidelines for opioid prescriptions, and the following year the VA and the US Department of Defense (DoD) updated the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain (VA/DoD guidelines).4,5 After the release of these guidelines, the use of opioid tapers expanded. However, due to public outcry of forced opioid tapering in 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration updated its opioid labeling requirements to provide clearer guidance on opioid tapers for tolerant patients.6,7

As a result, HCPs began to develop various strategies to balance the safety and efficacy of opioid use in patients with chronic pain. The West Palm Beach VA Medical Center (WPBVAMC) in Florida has a Pain Clinic that includes 2 pain management clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) with specialized training in pain management, who are uniquely qualified to assess and evaluate medication therapy in complex pain patient cases. These CPSs were involved in the face-to-face management of patients requiring specialized pain care and participated in a pain pharmacy electronic consult (eConsult) service to document pain management consultative recommendations for patients appropriate for management at the primary care level. This formalized process increased specialty pain care access for veterans whose pain was managed by primary care providers (PCPs).

The pain pharmacy eConsult service was initiated at the WPBVAMC in June 2013 to assist PCPs in the management of outpatients with chronic pain. The eConsult service includes evaluation of a patient’s electronic health records (EHRs) by CPSs. The eConsult service also provided PCPs with the option to engage a pharmacist who could provide recommendations for opioid dosing conversion, opioid tapering, pain pharmacotherapy, or drug screen interpretation, without the necessity for an additional patient visit.

Subsequent to the release of the 2016 CDC (and later the 2017 VA/DoD) guidelines recommending reducing morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) levels, the WPBVAMC had a large increase in pain eConsult requests for opioid tapering and opioid pharmacotherapy. A 3.4-fold increase in requests occurred in March, April, and May vs the following 9 months, and a nearly 4-fold increase in requests for opioid tapers during the same period. However, the impact of the completed eConsults was unclear. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to assess the effect of CPS services for opioid tapering and opioid pharmacotherapy by quantifying the number of recommendations accepted/implemented by PCPs. The secondary objectives included evaluating harms associated with the recommendations (eg, increase in visits to the emergency department [ED], hospitalizations, suicide attempts, or PCP visits) and provider satisfaction.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was completed to assess data of patients from the WPBVAMC and its associated community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). The project was approved by the WPBVAMC Scientific Advisory Committee as part of the facility’s performance improvement efforts.

Included patients had a pain pharmacy eConsult placed between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017. EHRs were reviewed and only eConsults for opioid pharmacotherapy recommendation or opioid tapers were evaluated. eConsults were excluded if the request was discontinued, completed by a HCP other than the pain CPS, or placed for an opioid dose conversion, nonopioid pharmacotherapy, or drug screen interpretation.

Data for analyses were entered into Microsoft Excel 2016 and were securely saved and accessible to relevant researchers. Patient protected health information used during patient care remained confidential.

Demographic data were collected, including age, gender, race, pertinent medical comorbidities (eg, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea), and mental health comorbidities. Pain scores were collected at baseline and 6-months postconsult. Pain medications used by patients were noted at baseline and 6 months postconsult, including concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine use, MEDD, and other pain medication. The duration of time needed by pain CPS to complete each eConsult and total time from eConsult entered to HCP implementation of the initial recommendation was collected. The number of actionable recommendations (eg, changes in drug therapy, urine drug screens [UDSs], and referrals to other services also were recorded and reviewed 6 months postconsult to determine the number and percentage of recommendations implemented by the HCP. The EHR was examined to determine adverse events (AEs) (eg, any documentation of suicide attempt, calls to the Veterans Crisis Line, or death 6 month postconsult). Collected data also included new eConsults, the reason for opioid tapering either by HCP or patient, and assessment of economic harms (count of the number of visits to ED, hospitalizations, or unscheduled PCP visits with uncontrolled pain as chief reason within 6 months postconsult). Last, PCPs were sent a survey to assess their satisfaction with the pain eConsult service.

Results

Of 517 eConsults received from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2017, 285 (55.1%) met inclusion criteria (Figure). Using a random number generator, 100 eConsults were further reviewed for outcomes of interest.

In this cohort, the mean age was 61 years, 87% were male, and 80% were White individuals. Most patients (83%) had ≥ 1 mental health comorbidity, and 53% had ≥ 2, with depressive symptoms, tobacco use, and/or posttraumatic stress disorder the most common diagnoses (Table 1). Eighty-seven percent of eConsults were for opioid tapers and the remaining 13% were for opioid pharmacotherapy.

The median pain score at time of consult was 6 on a 10-point scale, with no change at 6 months postconsult. However, 41% of patients overall had a median 3.3-point drop in pain score, 17% had no change in pain score, and 42% had a median 2.6-point increase in pain score.

At time of consult, 24% of patients had an opioid and benzodiazepine prescribed concurrently. At the time of the initial request, the mean MEDD was 177.5 mg (median, 165; range, 0-577.5). At 6 months postconsult, the average MEDD was 71 mg (median, 90; range, 0-450) for a mean 44% MEDD decrease. Eighteen percent of patients had no change in MEDD, and 5% had an increase.

One concern was the number of patients whose pain management regimen consisted of either opioids as monotherapy or a combination of opioids and skeletal muscle relaxants (SMRs), which can increase the opioid overdose risk and are not indicated for long-term use (except for baclofen for spasticity). Thirty-five percent of patients were taking either opioid monotherapy or opioids and SMRs for chronic pain management at time of consult and 28% were taking opioid monotherapy or opioids and SMRs 6 months postconsult.

Electronic Consults

Table 2 describes the reasons eConsults were requested. The most common reason was to taper the dose to be in compliance with the CDC 2016 guideline recommendation of MEDD < 90 mg, which was later increased to 100 mg by the VA/DoD guideline.

On average, eConsults were completed within a mean of 11.5 days of the PCP request, including nights and weekends. The CPS spent a mean 66.8 minutes to complete each eConsult. Once the eConsult was completed, PCPs took a mean of 9 days to initiate the primary recommendation. This 9-day average does not include 11 eConsults with no accepted recommendations and 11 eConsults for which the PCP implemented the primary recommendation before the CPS completed the consult, most likely due to a phone call or direct contact with the CPS at the time the eConsult was ordered.

A mean 3.5 actionable recommendations were made by the CPS and a mean 1.6 recommendations were implemented within 6 months by the PCP. At least 1 recommendation was accepted/implemented for 89% of patients, with a mean 55% recommendations that were accepted/implemented. Eleven percent of the eConsult final recommendations were not accepted by PCPs and clear documentation of the reasons were not provided.

Adverse Outcomes

In the 6 months postconsult, 11 patients (7 men and 4 women) experienced 32 AEs (Table 3). Eight patients had 15 ED visits, with 3 of the visits resulting in hospitalizations, 8 patients had 9 unscheduled PCP visits, 1 patient reported suicidal ideation and 2 patients made a total of 4 calls to the Veterans Crisis Line. There were also 2 deaths; however, both were due to end-stage disease (cirrhosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and not believed to be related to eConsult recommendations.

Eight patients had a history of substance use disorders (SUDs) and 8 had a history of a mood disorder or psychosis. One patient had both SUD and a mood/psychosis-related mental health disorder, including a reported suicidal attempt/ideation at an ED visit and a subsequent hospitalization. A similar number of AEs occurred in patients with decreases in MEDD of 0 to 24% compared with those that received more aggressive tapers of 75 to 100% (Table 4).

Nine patients were reconsulted, with only 1 secondary to the PCP not implementing recommendations from the initial consult. No factors were found that correlated with likelihood of a patient being reconsulted.