User login

Nonpainful Ulcerations on the Nose and Forehead

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

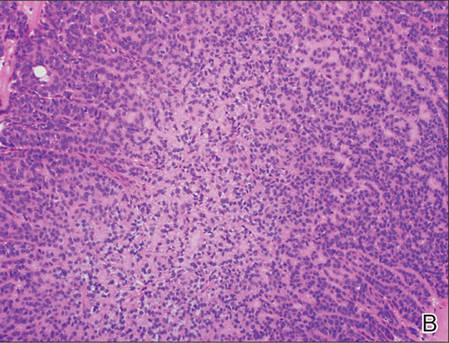

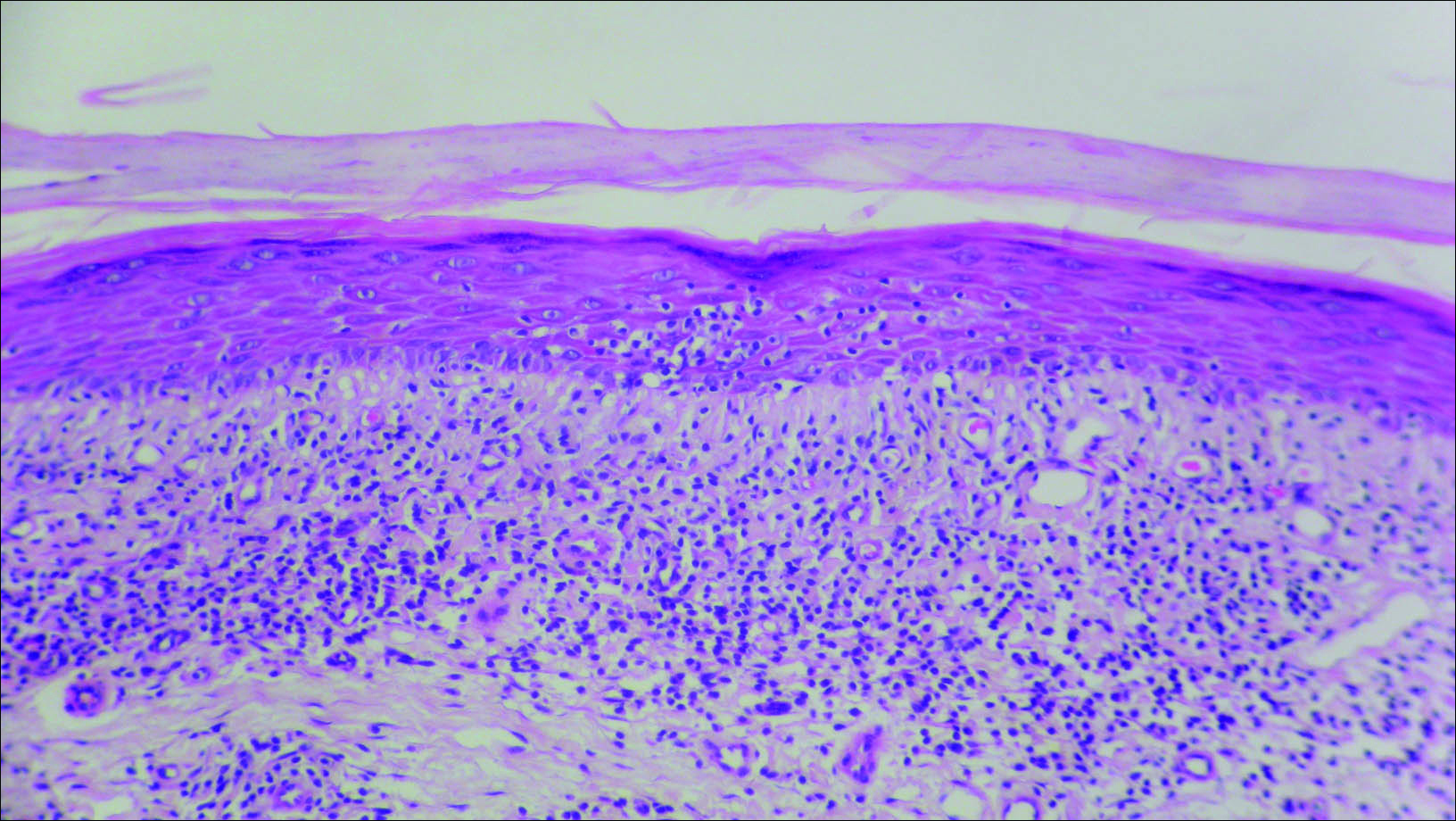

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

A 57-year-old man with a history of multiple cerebrovascular accidents was transferred from an outside hospital to our inpatient rheumatology service with nonpainful erosions of the forehead and nasal ala of 6 months’ duration. The patient reported that he initially developed a sore on the nose months prior to presentation with worsening sensations of itching and tingling on the forehead and nose. He also noted a headache and gradual loss of vision in the right eye. The patient was immunocompetent and denied arthralgia or any other skin lesions.

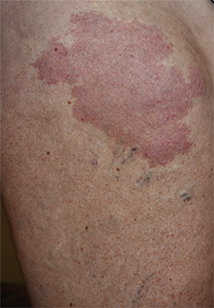

Hyperkeratotic Lesions in a Patient With Hepatitis C Virus

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

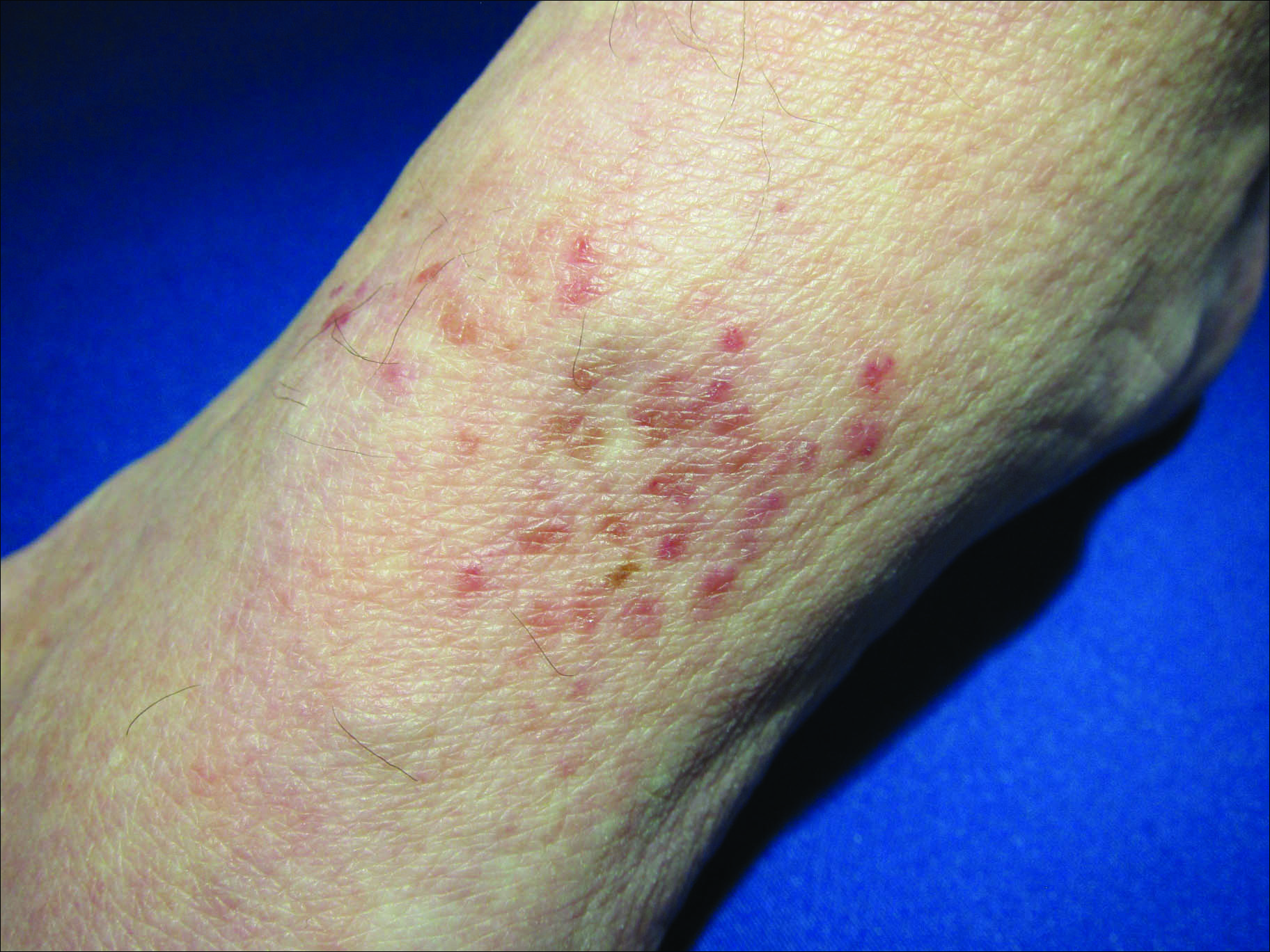

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

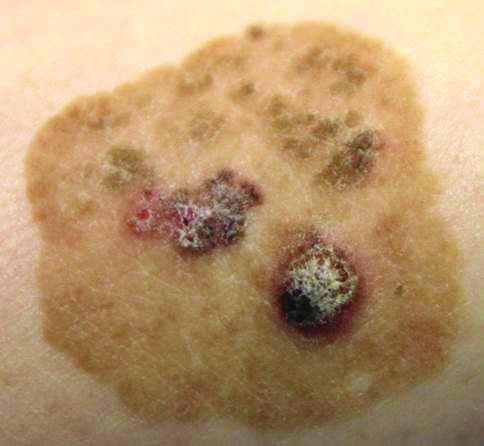

Brown Papules and a Plaque on the Calf

The Diagnosis: Irritated Seborrheic Keratosis

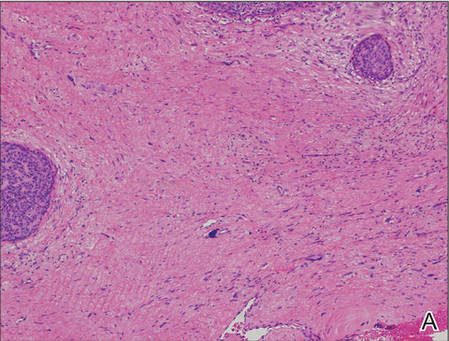

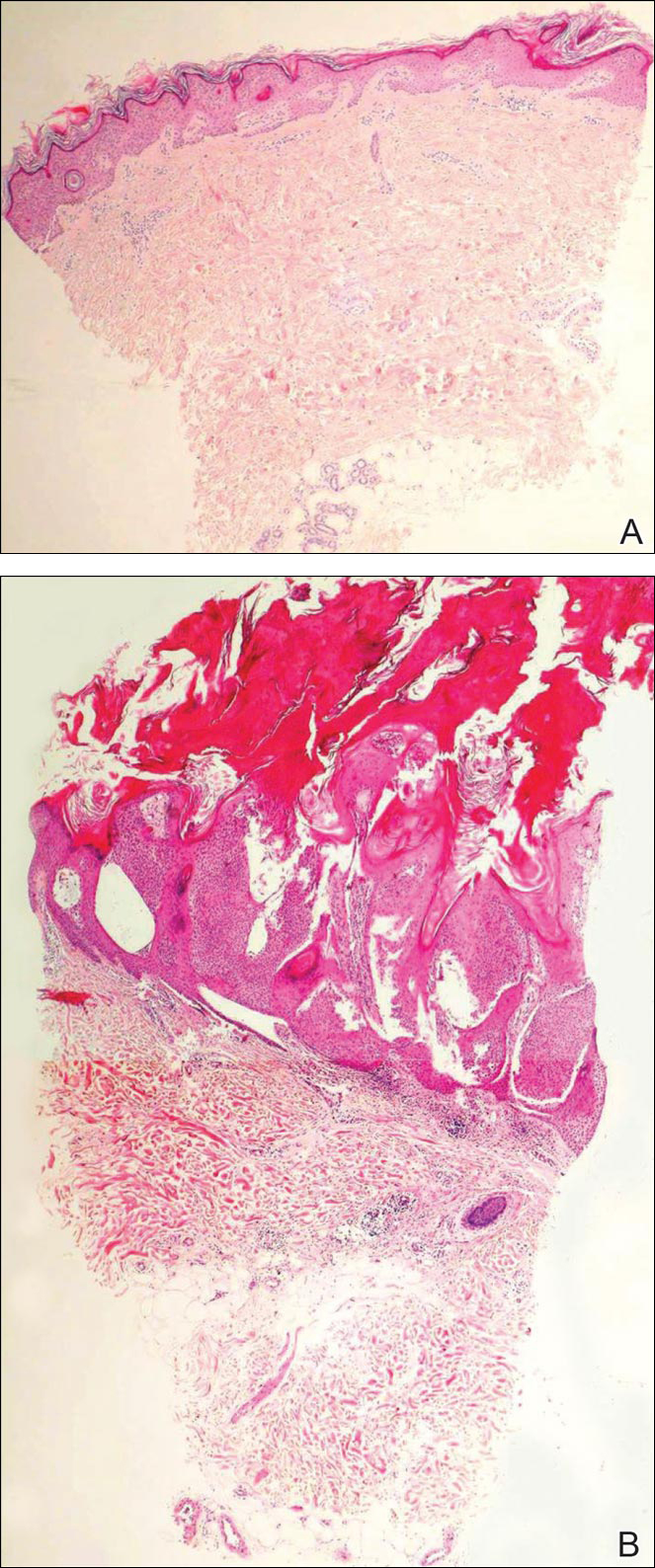

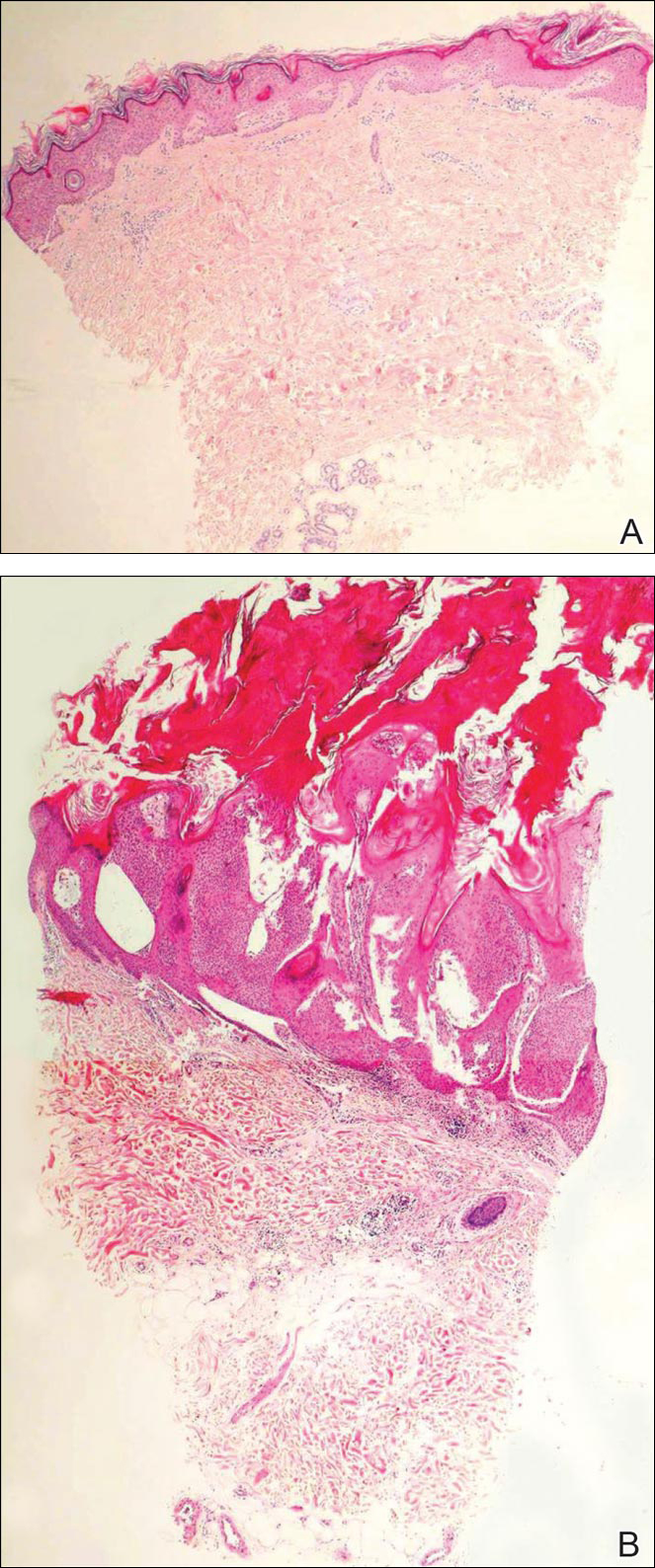

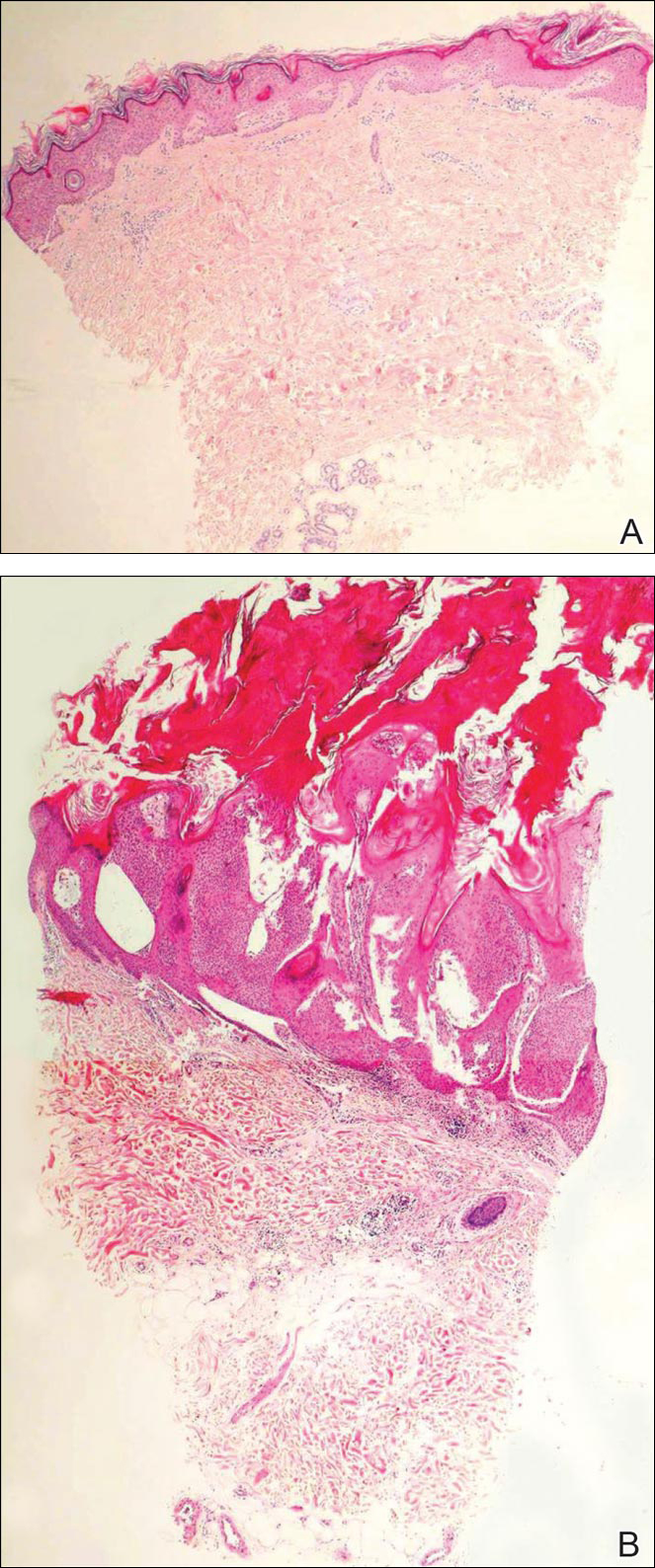

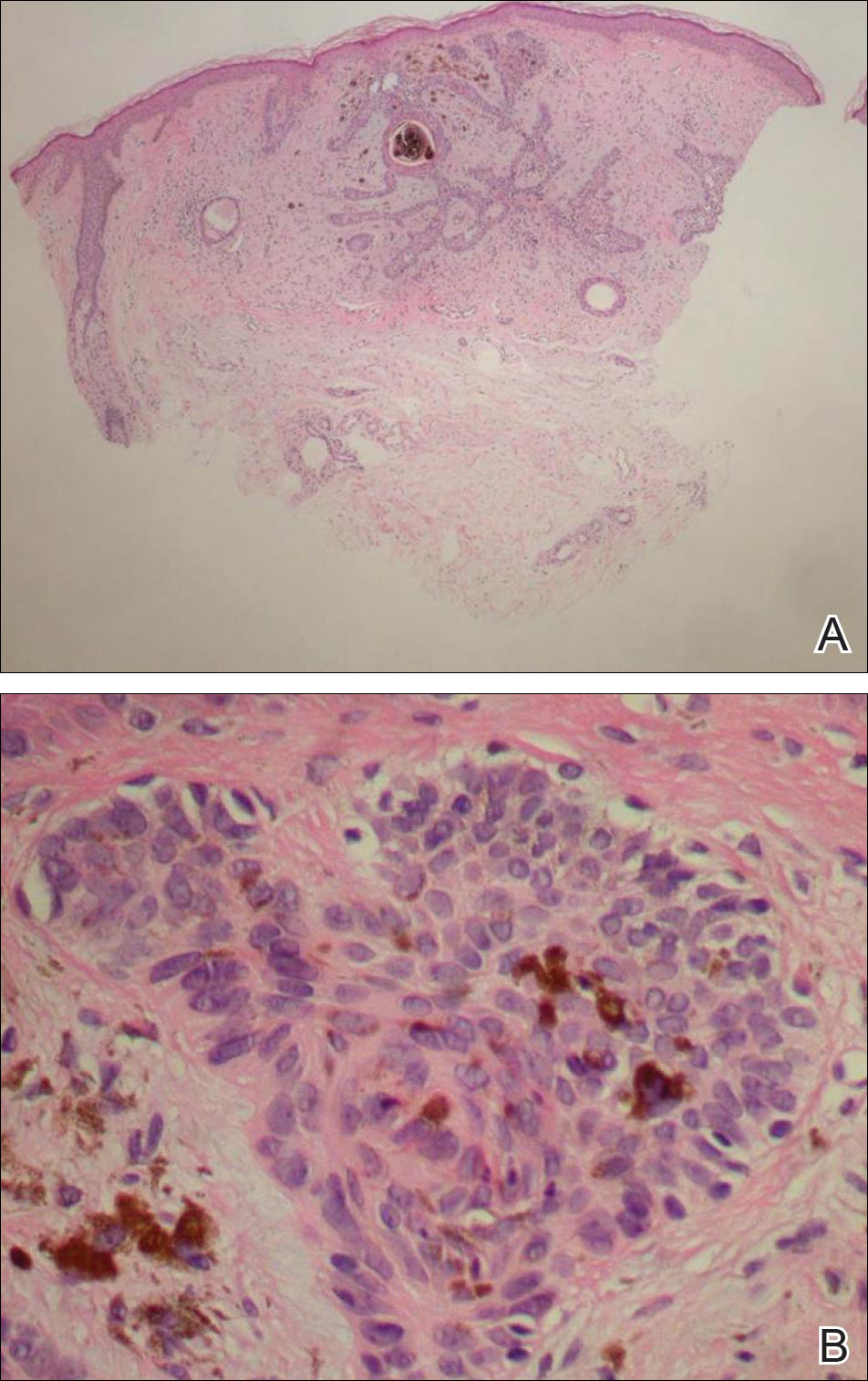

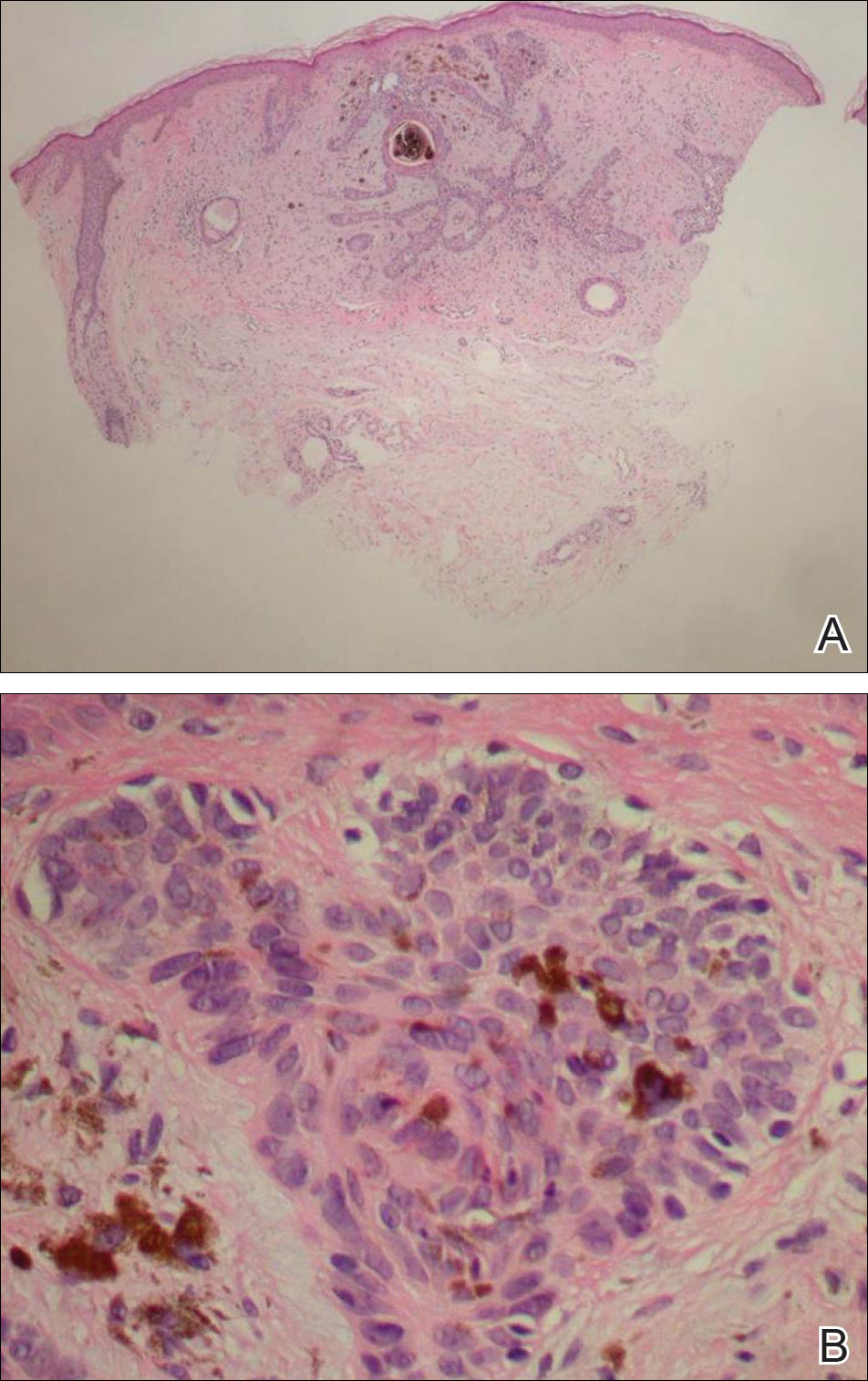

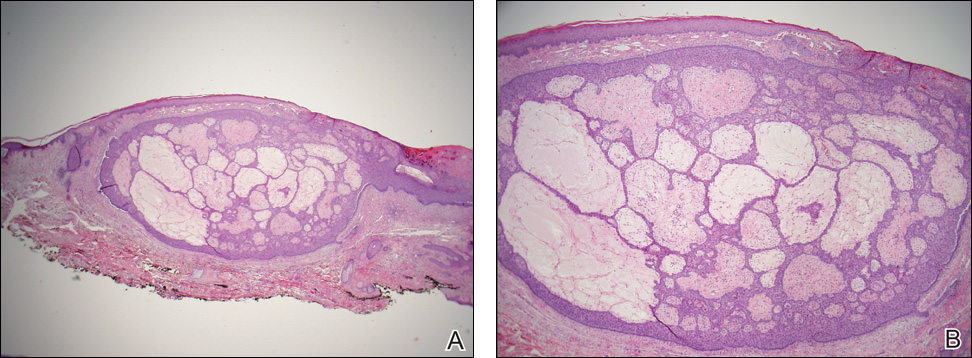

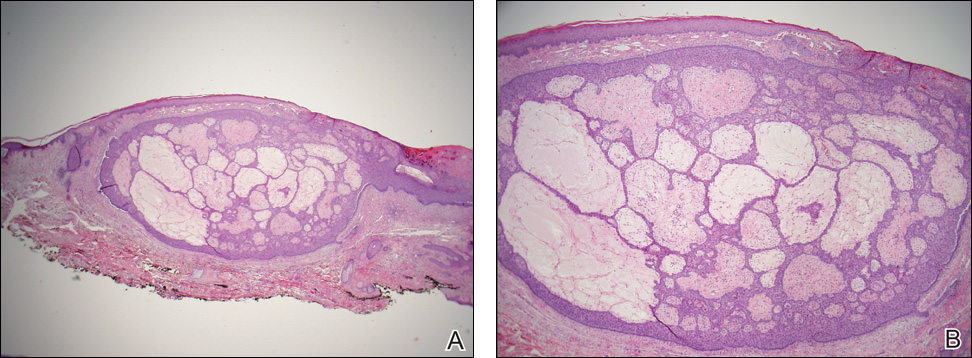

Biopsies of one of the protruding papules and the underlying plaque were performed. The specimen from the papule showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and a flattened dermoepidermal junction with demarcated horizontal margin, which demonstrated apparent upward growth of the epidermis. Moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis also was observed (Figure, A). The histologic findings of the plaque showed acanthosis, several pseudohorn cysts, hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, and a horizontal demarcation of the dermoepidermal junction (Figure, B).

Seborrheic keratosis is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin with variable appearance.1 It usually begins with well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan or brown patches that then grow into waxy verrucous papules.1 There are many clinicopathologic variants of SK such as common SK, stucco keratosis, and dermatosis papulosa nigra in clinical variation, as well as acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, clonal, reticulated, irritated, and melanoacanthoma subtypes based on histological variation.2,3

Seborrheic keratosis is a tumor of keratinocytic origin. Although genetics, sun exposure,4 and human papillomavirus infection5 are thought to be causative factors, the precise etiology of SK is unknown.1

The histology of SK shows monotonous basaloid tumor cells without atypia. It generally is comprised of focal acanthosis and papillomatosis with a sharp flat base. Intraepithelial horn pseudocysts are notable features of SK and increased melanin often is seen.2,6

Irritated SK is a histologic variant of SK that has been mechanically or chemically irritated or is involved in immunologic responses. Histologically, the dermis underlying an SK lesion filled with a dense lymphocytic infiltration is characteristic.1,2

For symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable lesions, complete removal of the lesion is the preferred treatment. Cryotherapy, electrodesiccation followed by curettage, curettage followed by desiccation, laser ablation, and surgical excision are effective treatments.1

- Valencia DT, Nicholas RS, Ken KL, et al. Benign epithelial tumors, hamartomas, and hyperplasias. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:1319-1336.

- Kirkharn N. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:791-850.

- Rajesh G, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ, et al. Spectrum of seborrheic keratoses in South Indians: a clinical and dermoscopic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:483-488.

- Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:411-414.

- Li YH, Chen G, Dong XP, et al. Detection of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrhoeic keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1060-1065.

- Brinster NK, Liu V, Diwan AH, et al. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

The Diagnosis: Irritated Seborrheic Keratosis

Biopsies of one of the protruding papules and the underlying plaque were performed. The specimen from the papule showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and a flattened dermoepidermal junction with demarcated horizontal margin, which demonstrated apparent upward growth of the epidermis. Moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis also was observed (Figure, A). The histologic findings of the plaque showed acanthosis, several pseudohorn cysts, hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, and a horizontal demarcation of the dermoepidermal junction (Figure, B).

Seborrheic keratosis is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin with variable appearance.1 It usually begins with well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan or brown patches that then grow into waxy verrucous papules.1 There are many clinicopathologic variants of SK such as common SK, stucco keratosis, and dermatosis papulosa nigra in clinical variation, as well as acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, clonal, reticulated, irritated, and melanoacanthoma subtypes based on histological variation.2,3

Seborrheic keratosis is a tumor of keratinocytic origin. Although genetics, sun exposure,4 and human papillomavirus infection5 are thought to be causative factors, the precise etiology of SK is unknown.1

The histology of SK shows monotonous basaloid tumor cells without atypia. It generally is comprised of focal acanthosis and papillomatosis with a sharp flat base. Intraepithelial horn pseudocysts are notable features of SK and increased melanin often is seen.2,6

Irritated SK is a histologic variant of SK that has been mechanically or chemically irritated or is involved in immunologic responses. Histologically, the dermis underlying an SK lesion filled with a dense lymphocytic infiltration is characteristic.1,2

For symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable lesions, complete removal of the lesion is the preferred treatment. Cryotherapy, electrodesiccation followed by curettage, curettage followed by desiccation, laser ablation, and surgical excision are effective treatments.1

The Diagnosis: Irritated Seborrheic Keratosis

Biopsies of one of the protruding papules and the underlying plaque were performed. The specimen from the papule showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and a flattened dermoepidermal junction with demarcated horizontal margin, which demonstrated apparent upward growth of the epidermis. Moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis also was observed (Figure, A). The histologic findings of the plaque showed acanthosis, several pseudohorn cysts, hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, and a horizontal demarcation of the dermoepidermal junction (Figure, B).

Seborrheic keratosis is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin with variable appearance.1 It usually begins with well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan or brown patches that then grow into waxy verrucous papules.1 There are many clinicopathologic variants of SK such as common SK, stucco keratosis, and dermatosis papulosa nigra in clinical variation, as well as acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, clonal, reticulated, irritated, and melanoacanthoma subtypes based on histological variation.2,3

Seborrheic keratosis is a tumor of keratinocytic origin. Although genetics, sun exposure,4 and human papillomavirus infection5 are thought to be causative factors, the precise etiology of SK is unknown.1

The histology of SK shows monotonous basaloid tumor cells without atypia. It generally is comprised of focal acanthosis and papillomatosis with a sharp flat base. Intraepithelial horn pseudocysts are notable features of SK and increased melanin often is seen.2,6

Irritated SK is a histologic variant of SK that has been mechanically or chemically irritated or is involved in immunologic responses. Histologically, the dermis underlying an SK lesion filled with a dense lymphocytic infiltration is characteristic.1,2

For symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable lesions, complete removal of the lesion is the preferred treatment. Cryotherapy, electrodesiccation followed by curettage, curettage followed by desiccation, laser ablation, and surgical excision are effective treatments.1

- Valencia DT, Nicholas RS, Ken KL, et al. Benign epithelial tumors, hamartomas, and hyperplasias. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:1319-1336.

- Kirkharn N. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:791-850.

- Rajesh G, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ, et al. Spectrum of seborrheic keratoses in South Indians: a clinical and dermoscopic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:483-488.

- Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:411-414.

- Li YH, Chen G, Dong XP, et al. Detection of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrhoeic keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1060-1065.

- Brinster NK, Liu V, Diwan AH, et al. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

- Valencia DT, Nicholas RS, Ken KL, et al. Benign epithelial tumors, hamartomas, and hyperplasias. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:1319-1336.

- Kirkharn N. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:791-850.

- Rajesh G, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ, et al. Spectrum of seborrheic keratoses in South Indians: a clinical and dermoscopic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:483-488.

- Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:411-414.

- Li YH, Chen G, Dong XP, et al. Detection of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrhoeic keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1060-1065.

- Brinster NK, Liu V, Diwan AH, et al. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

Linearly Curved, Blackish Macule on the Wrist

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

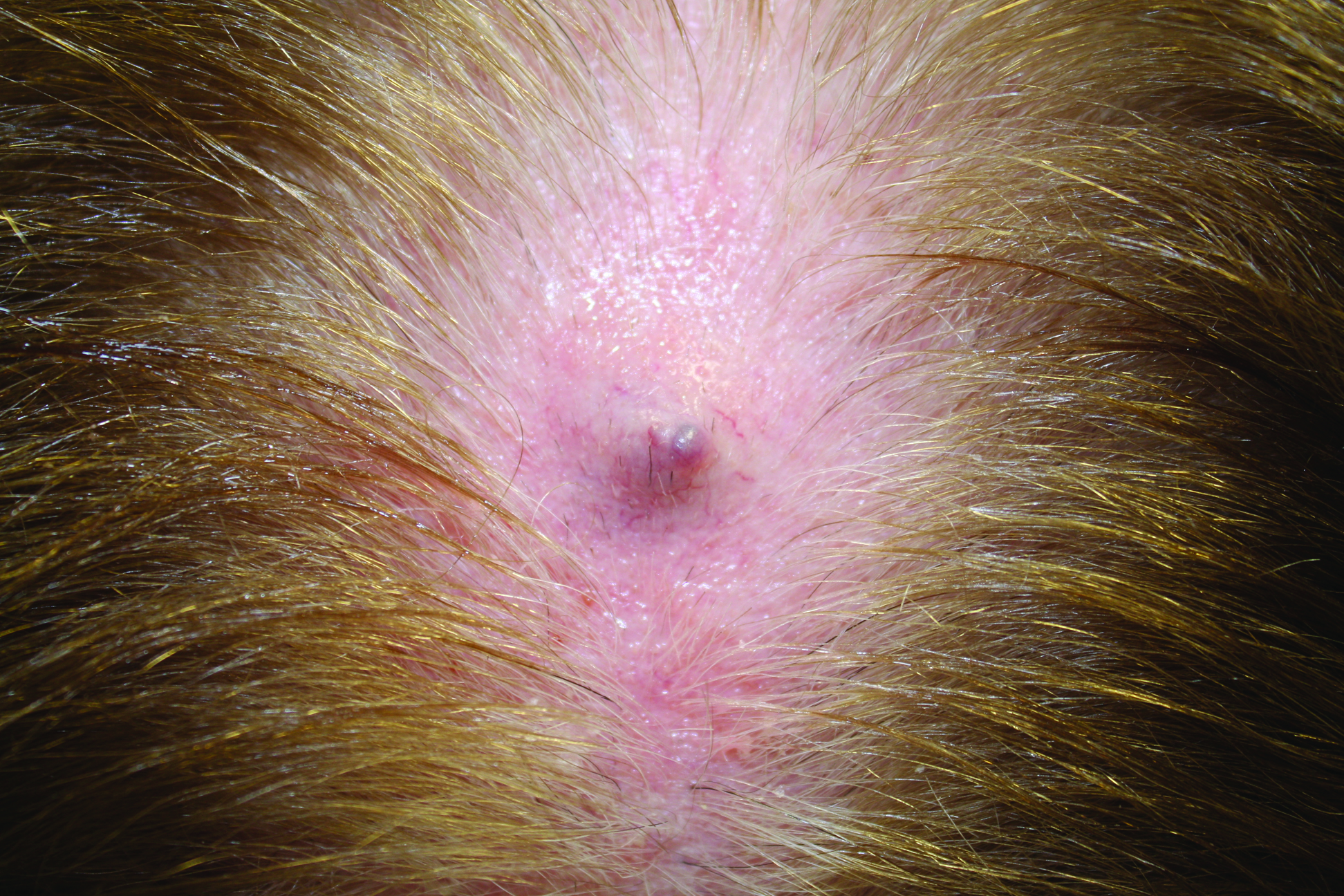

Firm Gray Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

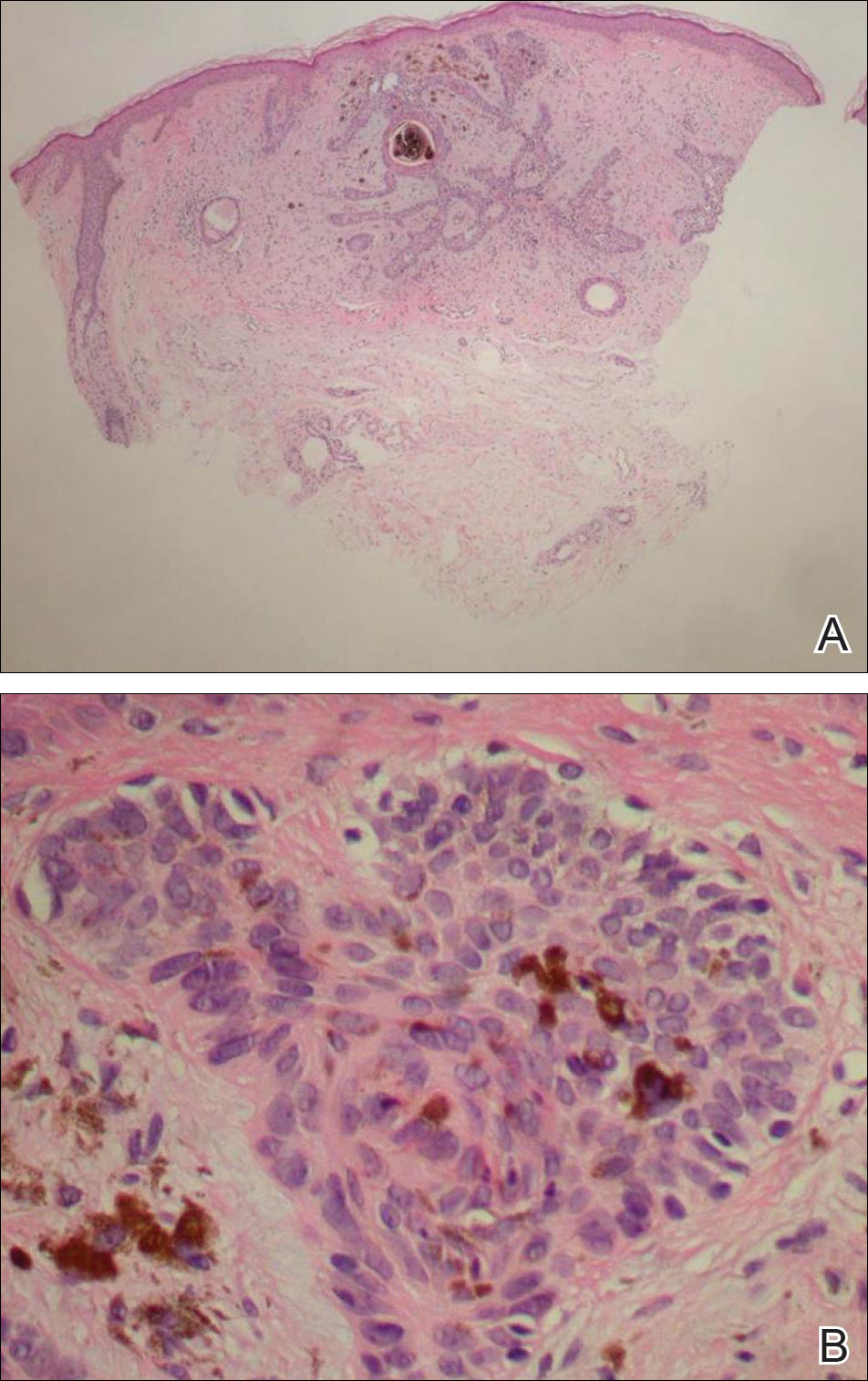

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

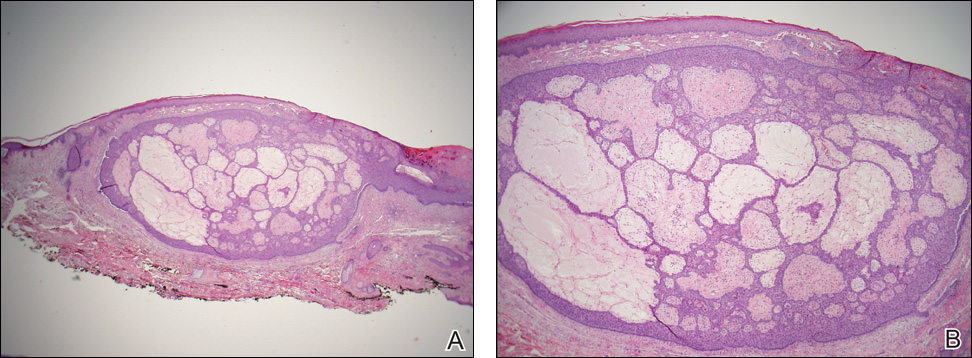

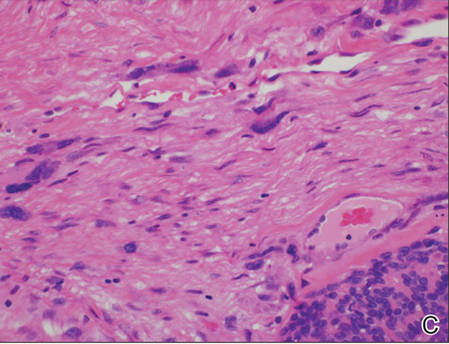

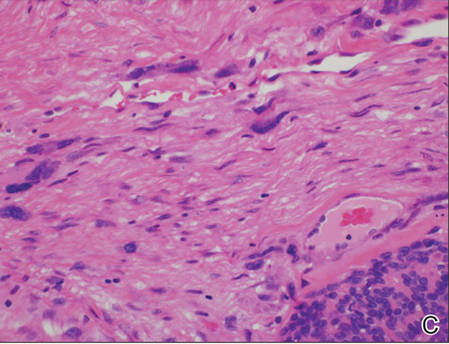

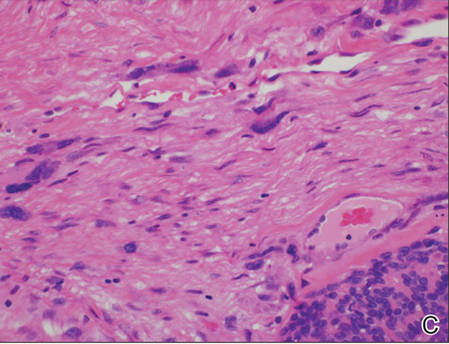

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

Growing Subcutaneous Mass on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

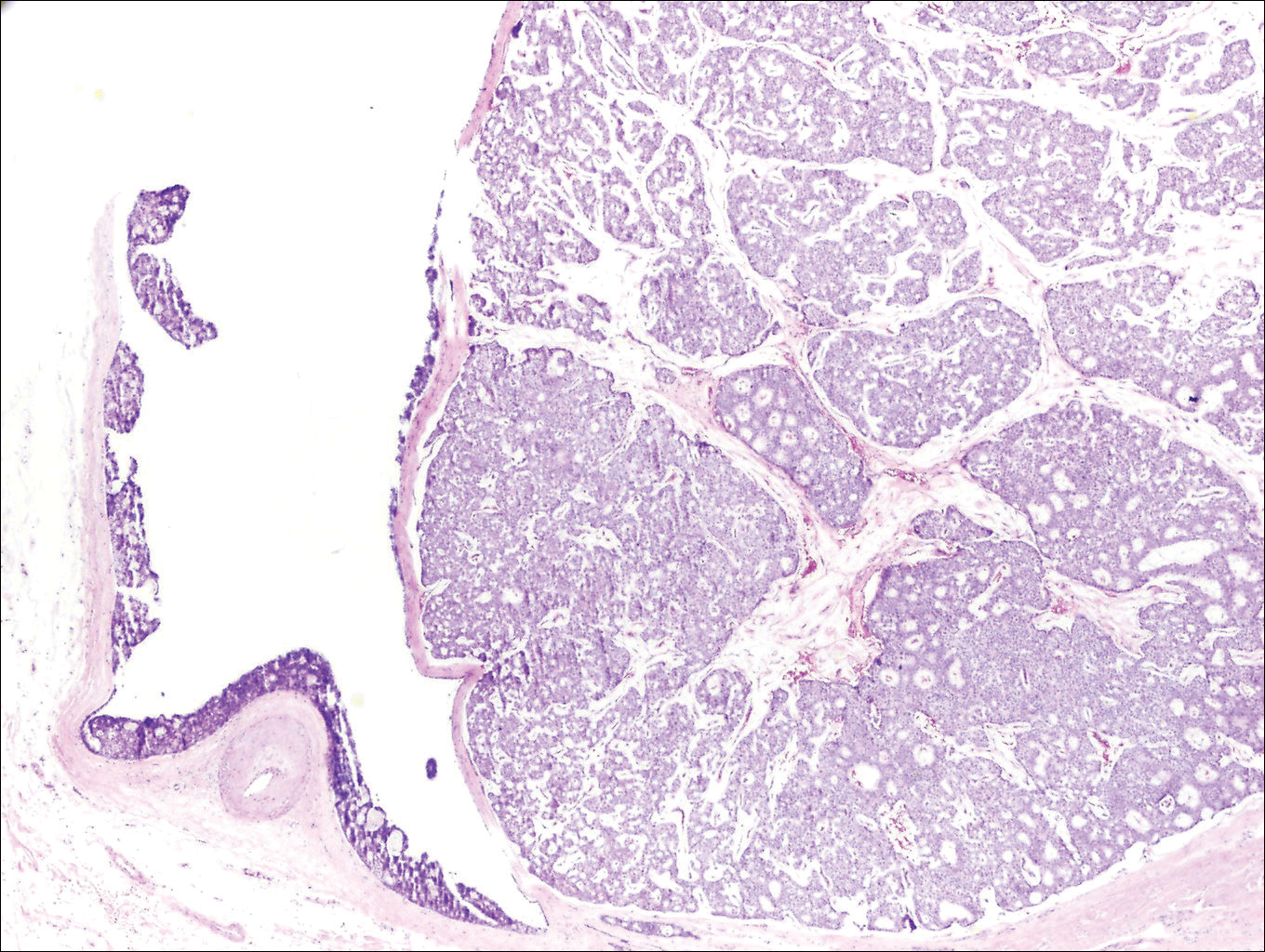

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

Erythematous Atrophic Plaque in the Inguinal Fold

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Slack Skin Disease

Initial biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered epidermotropism, papillary dermal sclerosis, and lymphocyte atypia (Figure 1). A repeat biopsy showed a lichenoid granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes and rare giant cells, superficially located in the dermis, without a deeper dense infiltration. Focal lymphocytic epidermotropism also was present (Figure 2). The infiltrate was CD3+CD4+ with a minority of cells also staining for CD8. An elastin stain demonstrated diminished elastin fibers in the superficial dermis. A clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement was identified by polymerase chain reaction. One group of pink and brown papules was present on the dorsal aspect of the right foot (Figure 3). A biopsy of this area showed similar findings. The patient was treated with a trial of carmustine 20-mg% ointment over the following year with some improvement of the mild pruritus but without notable change in the clinical findings.