User login

Diffuse Pruritic Eruption in an Immunocompromised Patient

The Diagnosis: Scabies Infestation

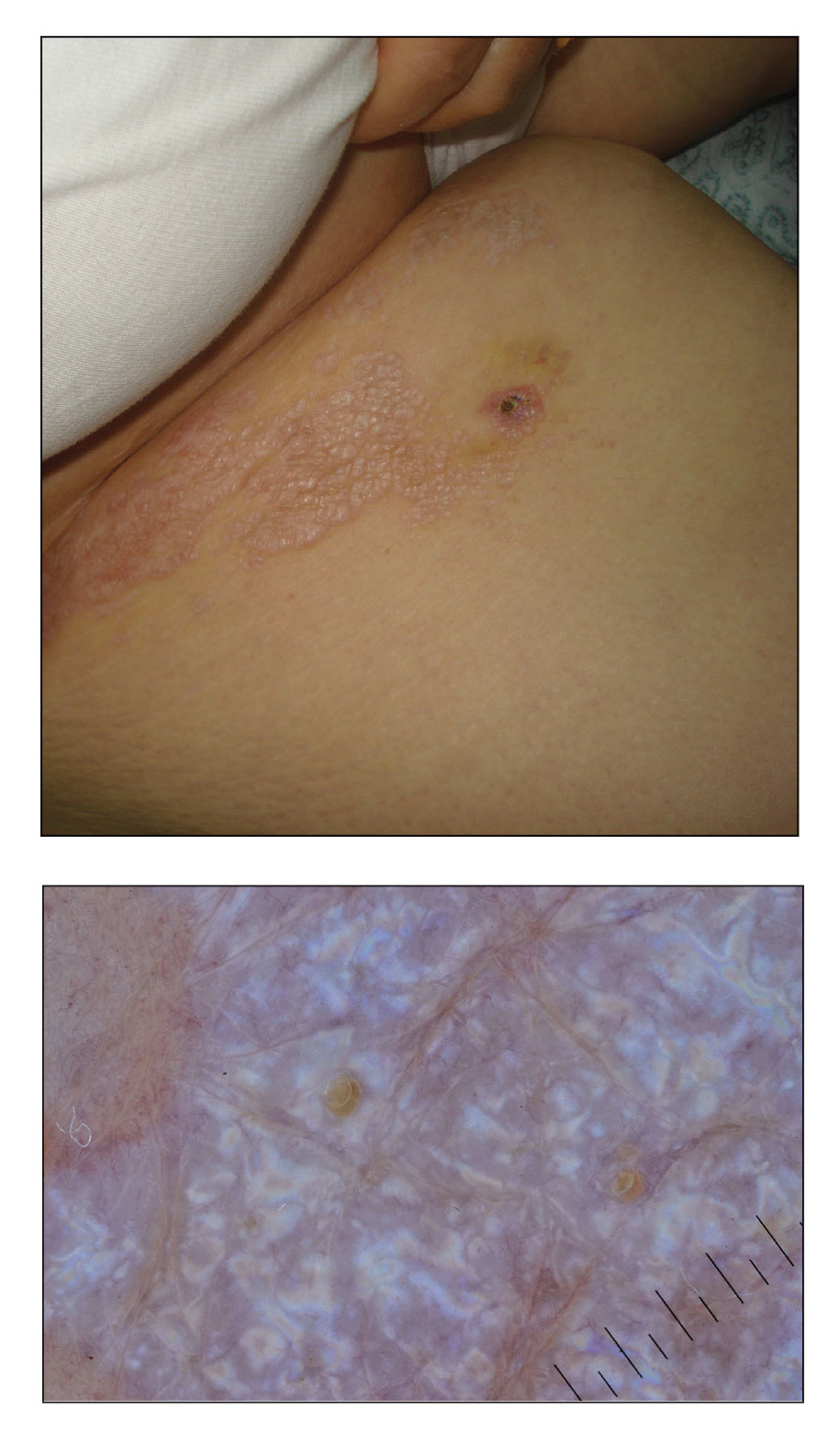

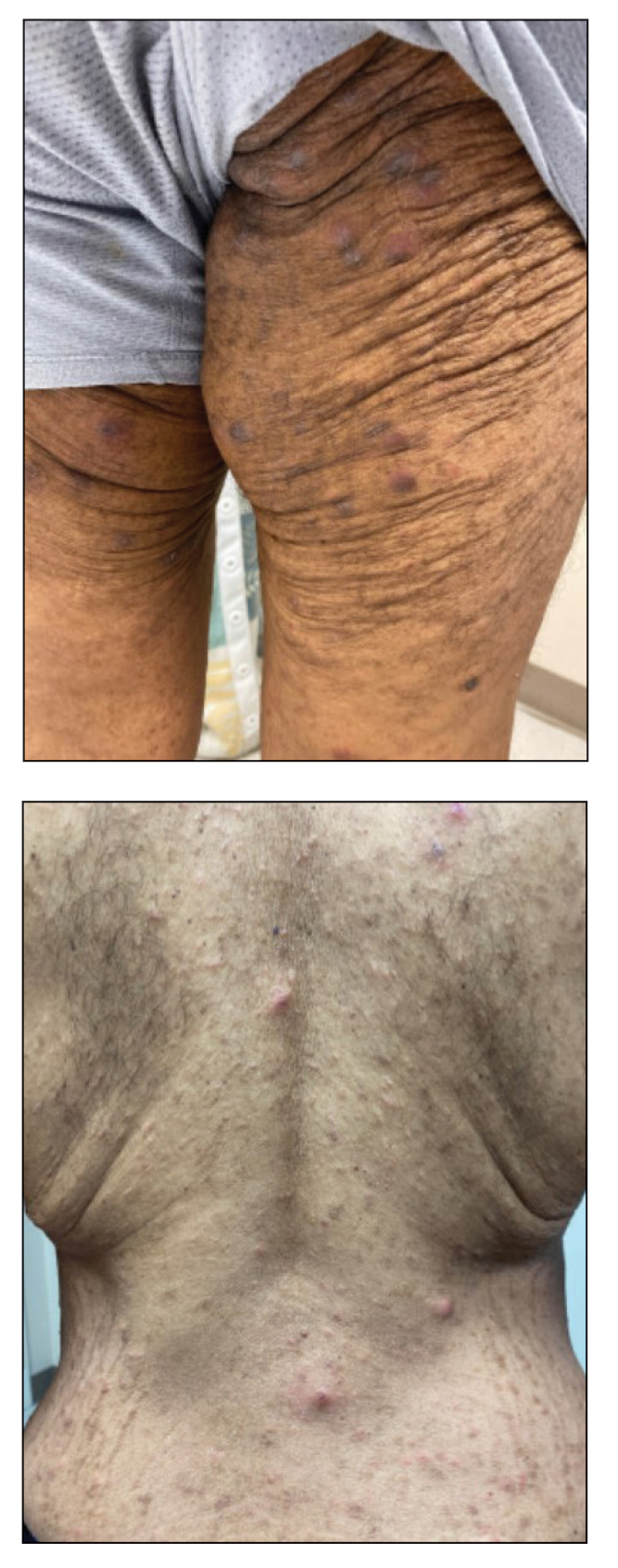

Direct microscopy revealed the presence of a live scabies mite and numerous eggs (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of a scabies infestation. Scabies, caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mite, characteristically presents in adults as pruritic hyperkeratotic plaques of the interdigital web spaces of the hands, flexor surfaces of the wrists and elbows, axillae, male genitalia, and breasts; however, an atypical presentation is common in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, such as our patient. In children, the palms, soles, and head (ie, face, scalp, neck) are common sites of involvement. Although dermatologists generally are familiar with severe atypical presentations such as Norwegian crusted scabies or bullous scabies, it is important that they are aware of other atypical presentations, such as the diffuse papulonodular variant observed in our patient.1 As such, a low threshold of suspicion for scabies infestations should be employed in immunocompromised patients with new-onset pruritic eruptions.

Direct microscopy is widely accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of scabies infestations; it is a fast and low-cost diagnostic tool. However, this technique displays variable sensitivity in clinical practice, requiring experience and a skilled hand.1,2 Other more sensitive diagnostic options for suspected scabies infestations include histopathology, serology, and molecular-based techniques such as DNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction. Although these tests do demonstrate greater sensitivity, they also are more invasive, time intensive, and costly.2 Therefore, they typically are not the first choice for a suspected scabies infestation. Dermoscopy has emerged as another tool to aid in the diagnosis of a suspected scabies infestation, enabling visualization of scaly burrows, eggs, and live mites. Classically, findings resembling a delta wing with contrail are seen on dermoscopic examination. The delta wing represents the brown triangular structure of the pigmented scabies mite head and anterior legs; the contrail is the lighter linear structures streaming behind the scabies mite (similar to visible vapor streams occurring behind flying jets), representing the burrow of the mite.

Although treatment of scabies infestations typically can be accomplished with permethrin cream 5%, the diffuse nature of our patient’s lesions in combination with his immunocompromised state made oral therapy a more appropriate choice. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations, the patient received 2 doses of oral weight-based ivermectin (200 μg/kg per dose) administered 1 week apart.1,3 The initial dose at day 1 serves to eliminate any scabies mites that are present, while the second dose 1 week later eliminates any residual eggs. Our patient experienced complete resolution of the symptoms following this treatment regimen.

It was important to differentiate our patient’s scabies infestation from other intensely pruritic conditions and morphologic mimics including papular urticaria, lichenoid drug eruptions, tinea corporis, and prurigo nodularis. Papular urticaria is an intensely pruritic hypersensitivity reaction to insect bites that commonly affects the extremities or other exposed areas. Visible puncta may be present.4 Our patient’s lesion distribution involved areas covered by clothing, no puncta were present, and he had no history of a recent arthropod assault, making the diagnosis of papular urticaria less likely.

Lichenoid drug eruptions classically present with symmetric, diffuse, pruritic, violaceous, scaling papules and plaques that present 2 to 3 months after exposure to an offending agent.5 Our patient’s eruption was papulonodular with no violaceous plaques, and he did not report changes to his medications, making a lichenoid drug eruption less likely.

Tinea corporis is another intensely pruritic condition that should be considered, especially in immunocompromised patients. It is caused by dermatophytes and classically presents as erythematous pruritic plaques with an annular, advancing, scaling border.6 Although immunocompromised patients may display extensive involvement, our patient’s lesions were papulonodular with no annular morphology or scale, rendering tinea corporis less likely.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition characterized by pruritic, violaceous, dome-shaped, smooth or crusted nodules secondary to repeated scratching or pressure. Although prurigo nodules can develop as a secondary change due to chronic excoriations in scabies infestations, prurigo nodules usually do not develop in areas such as the midline of the back that are not easily reached by the fingernails,7 which made prurigo nodularis less likely in our patient.

This case describes a unique papulonodular variant of scabies presenting in an immunocompromised cancer patient. Timely recognition and diagnosis of atypical scabies infestations can decrease morbidity and improve the quality of life of these patients.

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Siddig EE, Hay R. Laboratory-based diagnosis of scabies: a review of the current status. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116:4-9. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trab049

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites—scabies. medications. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ scabies/health_professionals/meds.html

- Örnek S, Zuberbier T, Kocatürk E. Annular urticarial lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:480-504. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol .2021.12.010

- Cheraghlou S, Levy LL. Fixed drug eruptions, bullous drug eruptions, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:679-692. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.06.010

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6. doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- Kwon CD, Khanna R, Williams KA, et al. Diagnostic workup and evaluation of patients with prurigo nodularis. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:97. doi:10.3390/medicines6040097

The Diagnosis: Scabies Infestation

Direct microscopy revealed the presence of a live scabies mite and numerous eggs (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of a scabies infestation. Scabies, caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mite, characteristically presents in adults as pruritic hyperkeratotic plaques of the interdigital web spaces of the hands, flexor surfaces of the wrists and elbows, axillae, male genitalia, and breasts; however, an atypical presentation is common in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, such as our patient. In children, the palms, soles, and head (ie, face, scalp, neck) are common sites of involvement. Although dermatologists generally are familiar with severe atypical presentations such as Norwegian crusted scabies or bullous scabies, it is important that they are aware of other atypical presentations, such as the diffuse papulonodular variant observed in our patient.1 As such, a low threshold of suspicion for scabies infestations should be employed in immunocompromised patients with new-onset pruritic eruptions.

Direct microscopy is widely accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of scabies infestations; it is a fast and low-cost diagnostic tool. However, this technique displays variable sensitivity in clinical practice, requiring experience and a skilled hand.1,2 Other more sensitive diagnostic options for suspected scabies infestations include histopathology, serology, and molecular-based techniques such as DNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction. Although these tests do demonstrate greater sensitivity, they also are more invasive, time intensive, and costly.2 Therefore, they typically are not the first choice for a suspected scabies infestation. Dermoscopy has emerged as another tool to aid in the diagnosis of a suspected scabies infestation, enabling visualization of scaly burrows, eggs, and live mites. Classically, findings resembling a delta wing with contrail are seen on dermoscopic examination. The delta wing represents the brown triangular structure of the pigmented scabies mite head and anterior legs; the contrail is the lighter linear structures streaming behind the scabies mite (similar to visible vapor streams occurring behind flying jets), representing the burrow of the mite.

Although treatment of scabies infestations typically can be accomplished with permethrin cream 5%, the diffuse nature of our patient’s lesions in combination with his immunocompromised state made oral therapy a more appropriate choice. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations, the patient received 2 doses of oral weight-based ivermectin (200 μg/kg per dose) administered 1 week apart.1,3 The initial dose at day 1 serves to eliminate any scabies mites that are present, while the second dose 1 week later eliminates any residual eggs. Our patient experienced complete resolution of the symptoms following this treatment regimen.

It was important to differentiate our patient’s scabies infestation from other intensely pruritic conditions and morphologic mimics including papular urticaria, lichenoid drug eruptions, tinea corporis, and prurigo nodularis. Papular urticaria is an intensely pruritic hypersensitivity reaction to insect bites that commonly affects the extremities or other exposed areas. Visible puncta may be present.4 Our patient’s lesion distribution involved areas covered by clothing, no puncta were present, and he had no history of a recent arthropod assault, making the diagnosis of papular urticaria less likely.

Lichenoid drug eruptions classically present with symmetric, diffuse, pruritic, violaceous, scaling papules and plaques that present 2 to 3 months after exposure to an offending agent.5 Our patient’s eruption was papulonodular with no violaceous plaques, and he did not report changes to his medications, making a lichenoid drug eruption less likely.

Tinea corporis is another intensely pruritic condition that should be considered, especially in immunocompromised patients. It is caused by dermatophytes and classically presents as erythematous pruritic plaques with an annular, advancing, scaling border.6 Although immunocompromised patients may display extensive involvement, our patient’s lesions were papulonodular with no annular morphology or scale, rendering tinea corporis less likely.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition characterized by pruritic, violaceous, dome-shaped, smooth or crusted nodules secondary to repeated scratching or pressure. Although prurigo nodules can develop as a secondary change due to chronic excoriations in scabies infestations, prurigo nodules usually do not develop in areas such as the midline of the back that are not easily reached by the fingernails,7 which made prurigo nodularis less likely in our patient.

This case describes a unique papulonodular variant of scabies presenting in an immunocompromised cancer patient. Timely recognition and diagnosis of atypical scabies infestations can decrease morbidity and improve the quality of life of these patients.

The Diagnosis: Scabies Infestation

Direct microscopy revealed the presence of a live scabies mite and numerous eggs (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of a scabies infestation. Scabies, caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mite, characteristically presents in adults as pruritic hyperkeratotic plaques of the interdigital web spaces of the hands, flexor surfaces of the wrists and elbows, axillae, male genitalia, and breasts; however, an atypical presentation is common in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, such as our patient. In children, the palms, soles, and head (ie, face, scalp, neck) are common sites of involvement. Although dermatologists generally are familiar with severe atypical presentations such as Norwegian crusted scabies or bullous scabies, it is important that they are aware of other atypical presentations, such as the diffuse papulonodular variant observed in our patient.1 As such, a low threshold of suspicion for scabies infestations should be employed in immunocompromised patients with new-onset pruritic eruptions.

Direct microscopy is widely accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of scabies infestations; it is a fast and low-cost diagnostic tool. However, this technique displays variable sensitivity in clinical practice, requiring experience and a skilled hand.1,2 Other more sensitive diagnostic options for suspected scabies infestations include histopathology, serology, and molecular-based techniques such as DNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction. Although these tests do demonstrate greater sensitivity, they also are more invasive, time intensive, and costly.2 Therefore, they typically are not the first choice for a suspected scabies infestation. Dermoscopy has emerged as another tool to aid in the diagnosis of a suspected scabies infestation, enabling visualization of scaly burrows, eggs, and live mites. Classically, findings resembling a delta wing with contrail are seen on dermoscopic examination. The delta wing represents the brown triangular structure of the pigmented scabies mite head and anterior legs; the contrail is the lighter linear structures streaming behind the scabies mite (similar to visible vapor streams occurring behind flying jets), representing the burrow of the mite.

Although treatment of scabies infestations typically can be accomplished with permethrin cream 5%, the diffuse nature of our patient’s lesions in combination with his immunocompromised state made oral therapy a more appropriate choice. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations, the patient received 2 doses of oral weight-based ivermectin (200 μg/kg per dose) administered 1 week apart.1,3 The initial dose at day 1 serves to eliminate any scabies mites that are present, while the second dose 1 week later eliminates any residual eggs. Our patient experienced complete resolution of the symptoms following this treatment regimen.

It was important to differentiate our patient’s scabies infestation from other intensely pruritic conditions and morphologic mimics including papular urticaria, lichenoid drug eruptions, tinea corporis, and prurigo nodularis. Papular urticaria is an intensely pruritic hypersensitivity reaction to insect bites that commonly affects the extremities or other exposed areas. Visible puncta may be present.4 Our patient’s lesion distribution involved areas covered by clothing, no puncta were present, and he had no history of a recent arthropod assault, making the diagnosis of papular urticaria less likely.

Lichenoid drug eruptions classically present with symmetric, diffuse, pruritic, violaceous, scaling papules and plaques that present 2 to 3 months after exposure to an offending agent.5 Our patient’s eruption was papulonodular with no violaceous plaques, and he did not report changes to his medications, making a lichenoid drug eruption less likely.

Tinea corporis is another intensely pruritic condition that should be considered, especially in immunocompromised patients. It is caused by dermatophytes and classically presents as erythematous pruritic plaques with an annular, advancing, scaling border.6 Although immunocompromised patients may display extensive involvement, our patient’s lesions were papulonodular with no annular morphology or scale, rendering tinea corporis less likely.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition characterized by pruritic, violaceous, dome-shaped, smooth or crusted nodules secondary to repeated scratching or pressure. Although prurigo nodules can develop as a secondary change due to chronic excoriations in scabies infestations, prurigo nodules usually do not develop in areas such as the midline of the back that are not easily reached by the fingernails,7 which made prurigo nodularis less likely in our patient.

This case describes a unique papulonodular variant of scabies presenting in an immunocompromised cancer patient. Timely recognition and diagnosis of atypical scabies infestations can decrease morbidity and improve the quality of life of these patients.

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Siddig EE, Hay R. Laboratory-based diagnosis of scabies: a review of the current status. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116:4-9. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trab049

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites—scabies. medications. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ scabies/health_professionals/meds.html

- Örnek S, Zuberbier T, Kocatürk E. Annular urticarial lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:480-504. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol .2021.12.010

- Cheraghlou S, Levy LL. Fixed drug eruptions, bullous drug eruptions, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:679-692. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.06.010

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6. doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- Kwon CD, Khanna R, Williams KA, et al. Diagnostic workup and evaluation of patients with prurigo nodularis. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:97. doi:10.3390/medicines6040097

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Siddig EE, Hay R. Laboratory-based diagnosis of scabies: a review of the current status. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116:4-9. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trab049

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites—scabies. medications. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ scabies/health_professionals/meds.html

- Örnek S, Zuberbier T, Kocatürk E. Annular urticarial lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:480-504. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol .2021.12.010

- Cheraghlou S, Levy LL. Fixed drug eruptions, bullous drug eruptions, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:679-692. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.06.010

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6. doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- Kwon CD, Khanna R, Williams KA, et al. Diagnostic workup and evaluation of patients with prurigo nodularis. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:97. doi:10.3390/medicines6040097

A 54-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread intensely pruritic rash of 4 weeks’ duration. Calamine lotion and oral hydroxyzine provided minimal relief. He was being treated for a myeloproliferative disorder with immunosuppressive therapy consisting of a combination of cladribine, low-dose cytarabine, and fedratinib. Physical examination revealed multiple excoriated papules and indurated nodules on the extensor and flexor surfaces of the arms and legs (top), chest, midline of the back (bottom), and groin. No lesions were noted on the volar aspect of the patient’s wrists or interdigital spaces, and no central puncta or scales were present. He denied any preceding arthropod bites, trauma, new environmental exposures, or changes to his medications. Scrapings from several representative lesions were obtained for mineral oil preparation and microscopic evaluation.

Transient Skin Rippling in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Infantile Transient Smooth Muscle Contraction of the Skin

A diagnosis of infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin (ITSMC) was made based on our patient’s clinical presentation and eliminating the diagnoses in the differential. No treatment ultimately was indicated, as episodes became less frequent over time.

The term infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin was first proposed in 2013 by Torrelo et al,1 who described 9 newborns with episodic skin rippling occasionally associated with exposure to cold or friction. The authors postulated that ITSMC was the result of a transient contraction of the arrector pili smooth muscle fibers of the skin, secondary to autonomic immaturity, primitive reflexes, or smooth muscle hypersensitivity.1 Since this first description, ITSMC has remained a rarely reported and poorly understood phenomenon with rare identified cases in the literature.2,3 Clinical history and examination of infants with intermittent transient skin rippling help to distinguish ITSMC from other diagnoses without the need for biopsy, which is particularly undesirable in the pediatric population.

Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma is a benign proliferation of mature smooth muscle that also can arise from the arrector pili muscles.4 In contrast to ITSMC, a hamartoma does not clear; rather, it persists and grows proportionally with the child and is associated with overlying hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis. The transient nature of ITSMC may be worrisome for mastocytoma; however, this condition presents as erythematous, yellow, red, or brown macules, papules, plaques, or nodules with a positive Darier sign.5 Although the differential diagnosis includes the shagreen patch characteristic of tuberous sclerosis, this irregular plaque typically is located on the lower back with overlying peau d’orange skin changes, and our patient lacked other features indicative of this condition.6 Becker nevus also remains a consideration in patients with rippled skin, but this entity typically becomes more notable at puberty and is associated with hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis and is a type of smooth muscle hamartoma.4

Our case highlighted the unusual presentation of ITSMC, a condition that can easily go unrecognized, leading to unnecessary referrals and concern. Familiarity with this benign diagnosis is essential to inform prognosis and guide management.

- Torrelo A, Moreno S, Castro C, et al. Infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:498-500. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.029

- Theodosiou G, Belfrage E, Berggård K, et al. Infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin: a case report and literature review. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:260-261. doi:10.1684/ejd.2021.3996

- Topham C, Deacon DC, Bowen A, et al. More than goosebumps: a case of marked skin dimpling in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:E71-E72. doi:10.1111/pde.13791

- Raboudi A, Litaiem N. Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF. Childhood solitary cutaneous mastocytoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2019;15:42-46. doi:10.2174/1573396315666 181120163952

- Bongiorno MA, Nathan N, Oyerinde O, et al. Clinical characteristics of connective tissue nevi in tuberous sclerosis complex with special emphasis on shagreen patches. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:660-665. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0298

The Diagnosis: Infantile Transient Smooth Muscle Contraction of the Skin

A diagnosis of infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin (ITSMC) was made based on our patient’s clinical presentation and eliminating the diagnoses in the differential. No treatment ultimately was indicated, as episodes became less frequent over time.

The term infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin was first proposed in 2013 by Torrelo et al,1 who described 9 newborns with episodic skin rippling occasionally associated with exposure to cold or friction. The authors postulated that ITSMC was the result of a transient contraction of the arrector pili smooth muscle fibers of the skin, secondary to autonomic immaturity, primitive reflexes, or smooth muscle hypersensitivity.1 Since this first description, ITSMC has remained a rarely reported and poorly understood phenomenon with rare identified cases in the literature.2,3 Clinical history and examination of infants with intermittent transient skin rippling help to distinguish ITSMC from other diagnoses without the need for biopsy, which is particularly undesirable in the pediatric population.

Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma is a benign proliferation of mature smooth muscle that also can arise from the arrector pili muscles.4 In contrast to ITSMC, a hamartoma does not clear; rather, it persists and grows proportionally with the child and is associated with overlying hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis. The transient nature of ITSMC may be worrisome for mastocytoma; however, this condition presents as erythematous, yellow, red, or brown macules, papules, plaques, or nodules with a positive Darier sign.5 Although the differential diagnosis includes the shagreen patch characteristic of tuberous sclerosis, this irregular plaque typically is located on the lower back with overlying peau d’orange skin changes, and our patient lacked other features indicative of this condition.6 Becker nevus also remains a consideration in patients with rippled skin, but this entity typically becomes more notable at puberty and is associated with hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis and is a type of smooth muscle hamartoma.4

Our case highlighted the unusual presentation of ITSMC, a condition that can easily go unrecognized, leading to unnecessary referrals and concern. Familiarity with this benign diagnosis is essential to inform prognosis and guide management.

The Diagnosis: Infantile Transient Smooth Muscle Contraction of the Skin

A diagnosis of infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin (ITSMC) was made based on our patient’s clinical presentation and eliminating the diagnoses in the differential. No treatment ultimately was indicated, as episodes became less frequent over time.

The term infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin was first proposed in 2013 by Torrelo et al,1 who described 9 newborns with episodic skin rippling occasionally associated with exposure to cold or friction. The authors postulated that ITSMC was the result of a transient contraction of the arrector pili smooth muscle fibers of the skin, secondary to autonomic immaturity, primitive reflexes, or smooth muscle hypersensitivity.1 Since this first description, ITSMC has remained a rarely reported and poorly understood phenomenon with rare identified cases in the literature.2,3 Clinical history and examination of infants with intermittent transient skin rippling help to distinguish ITSMC from other diagnoses without the need for biopsy, which is particularly undesirable in the pediatric population.

Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma is a benign proliferation of mature smooth muscle that also can arise from the arrector pili muscles.4 In contrast to ITSMC, a hamartoma does not clear; rather, it persists and grows proportionally with the child and is associated with overlying hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis. The transient nature of ITSMC may be worrisome for mastocytoma; however, this condition presents as erythematous, yellow, red, or brown macules, papules, plaques, or nodules with a positive Darier sign.5 Although the differential diagnosis includes the shagreen patch characteristic of tuberous sclerosis, this irregular plaque typically is located on the lower back with overlying peau d’orange skin changes, and our patient lacked other features indicative of this condition.6 Becker nevus also remains a consideration in patients with rippled skin, but this entity typically becomes more notable at puberty and is associated with hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis and is a type of smooth muscle hamartoma.4

Our case highlighted the unusual presentation of ITSMC, a condition that can easily go unrecognized, leading to unnecessary referrals and concern. Familiarity with this benign diagnosis is essential to inform prognosis and guide management.

- Torrelo A, Moreno S, Castro C, et al. Infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:498-500. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.029

- Theodosiou G, Belfrage E, Berggård K, et al. Infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin: a case report and literature review. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:260-261. doi:10.1684/ejd.2021.3996

- Topham C, Deacon DC, Bowen A, et al. More than goosebumps: a case of marked skin dimpling in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:E71-E72. doi:10.1111/pde.13791

- Raboudi A, Litaiem N. Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF. Childhood solitary cutaneous mastocytoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2019;15:42-46. doi:10.2174/1573396315666 181120163952

- Bongiorno MA, Nathan N, Oyerinde O, et al. Clinical characteristics of connective tissue nevi in tuberous sclerosis complex with special emphasis on shagreen patches. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:660-665. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0298

- Torrelo A, Moreno S, Castro C, et al. Infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:498-500. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.029

- Theodosiou G, Belfrage E, Berggård K, et al. Infantile transient smooth muscle contraction of the skin: a case report and literature review. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:260-261. doi:10.1684/ejd.2021.3996

- Topham C, Deacon DC, Bowen A, et al. More than goosebumps: a case of marked skin dimpling in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:E71-E72. doi:10.1111/pde.13791

- Raboudi A, Litaiem N. Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF. Childhood solitary cutaneous mastocytoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2019;15:42-46. doi:10.2174/1573396315666 181120163952

- Bongiorno MA, Nathan N, Oyerinde O, et al. Clinical characteristics of connective tissue nevi in tuberous sclerosis complex with special emphasis on shagreen patches. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:660-665. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0298

A healthy, full-term, 5-month-old infant boy presented to dermatology for evaluation of an intermittent, asymptomatic, rippled skin texture of the left thigh that resolved completely between flares. The parents noted fewer than 10 intermittent flares prior to the initial presentation at 5 months. Physical examination of the patient’s skin revealed no epidermal abnormalities, dermatographism, or subcutaneous nodules, and there was no positive Darier sign. A subsequent flare at 9 months of age occurred concurrently with fevers up to 39.4 °C (103 °F), and a corresponding photograph (quiz image) provided by the parents due to the intermittent and transient nature of the condition demonstrated an ill-defined, raised, rippled plaque on the left lateral thigh.

Disseminated Papules and Nodules on the Skin and Oral Mucosa in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Congenital Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

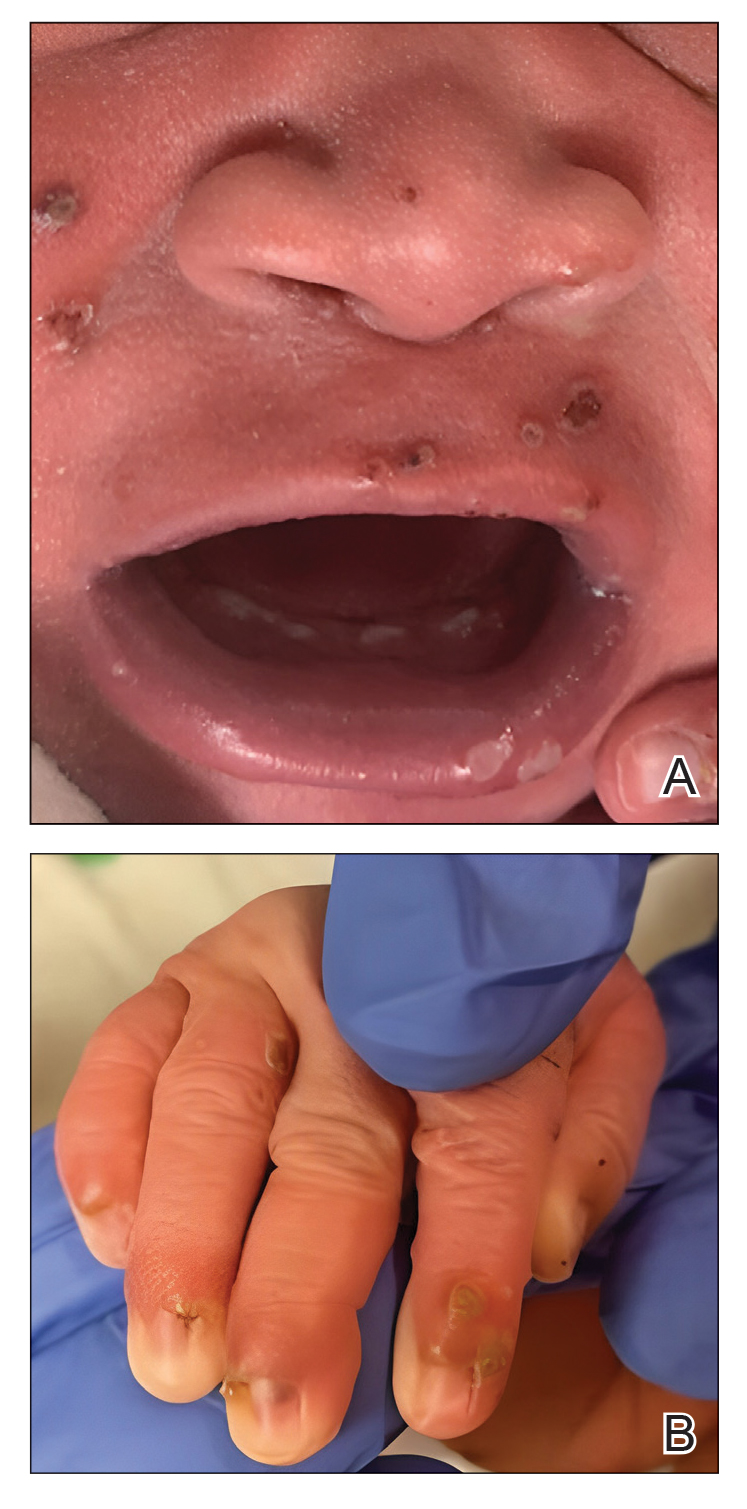

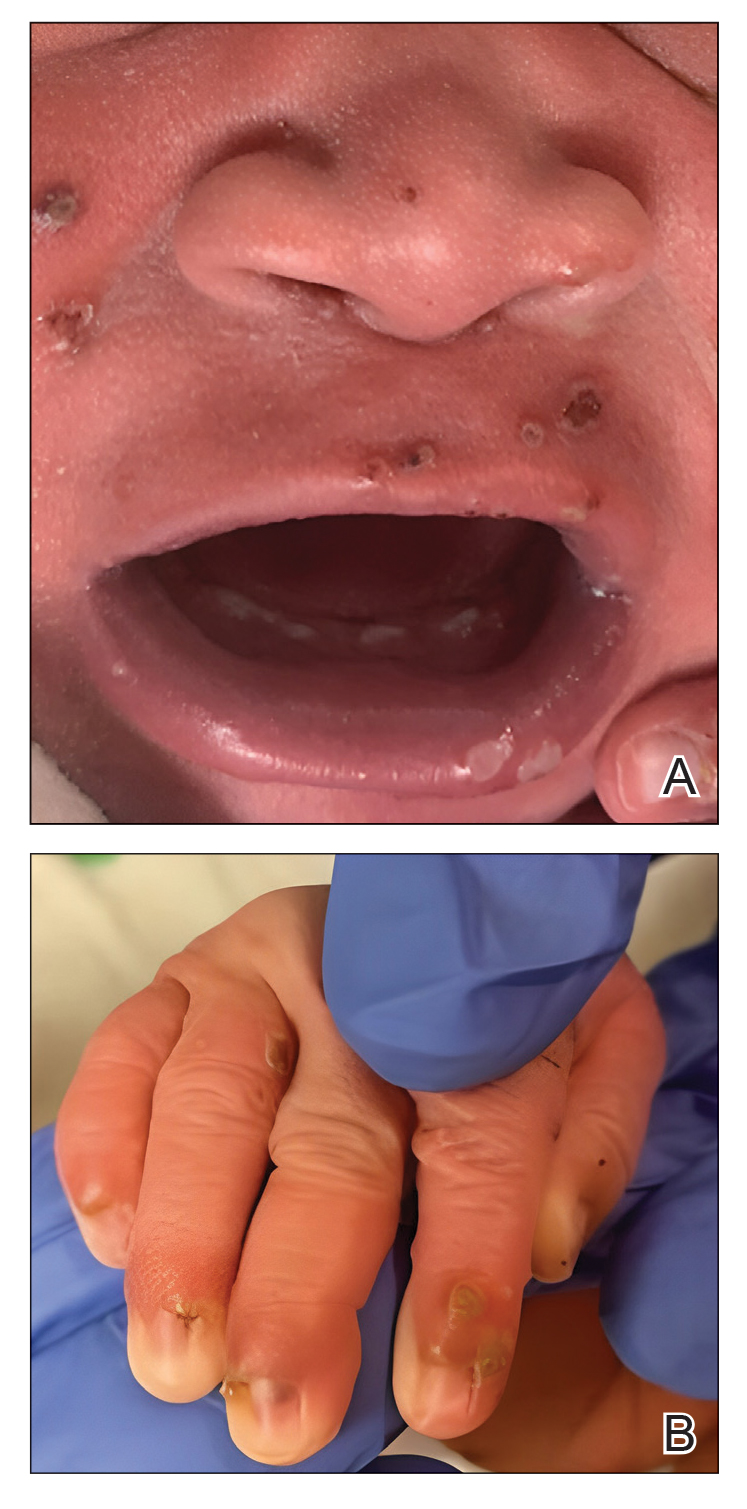

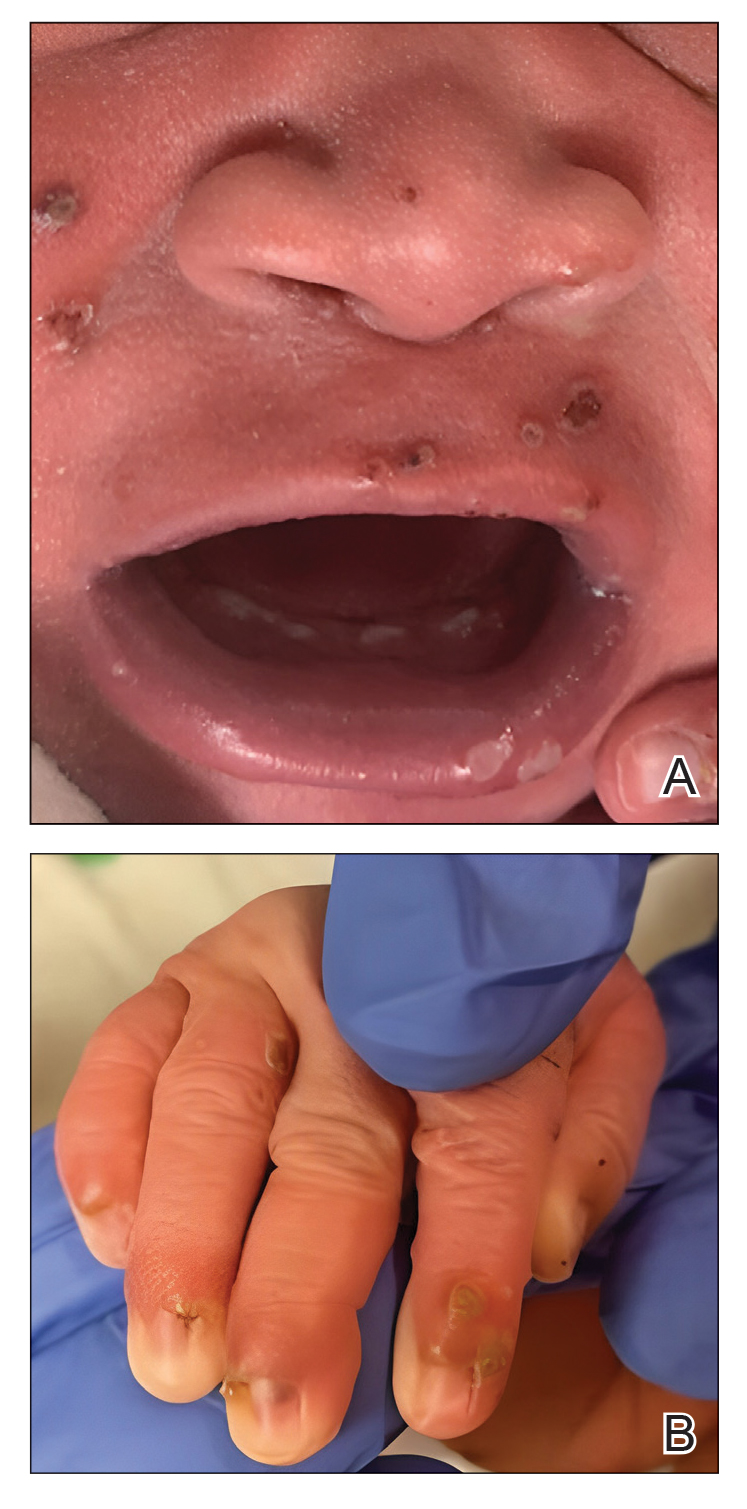

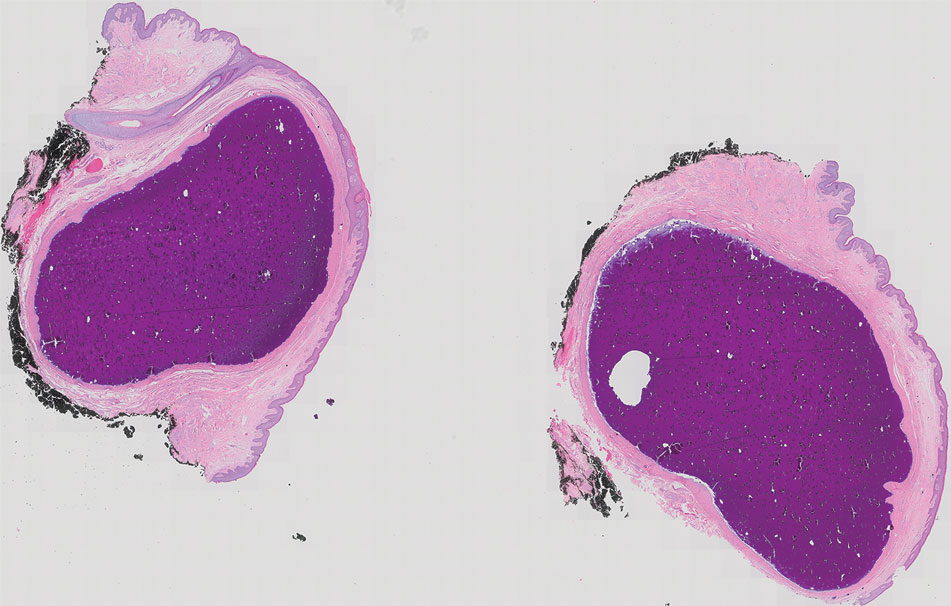

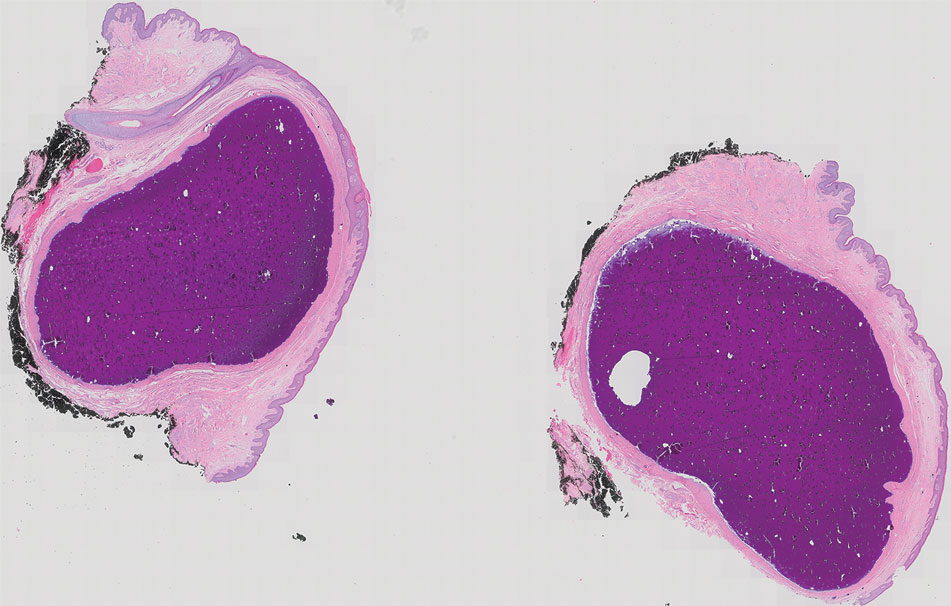

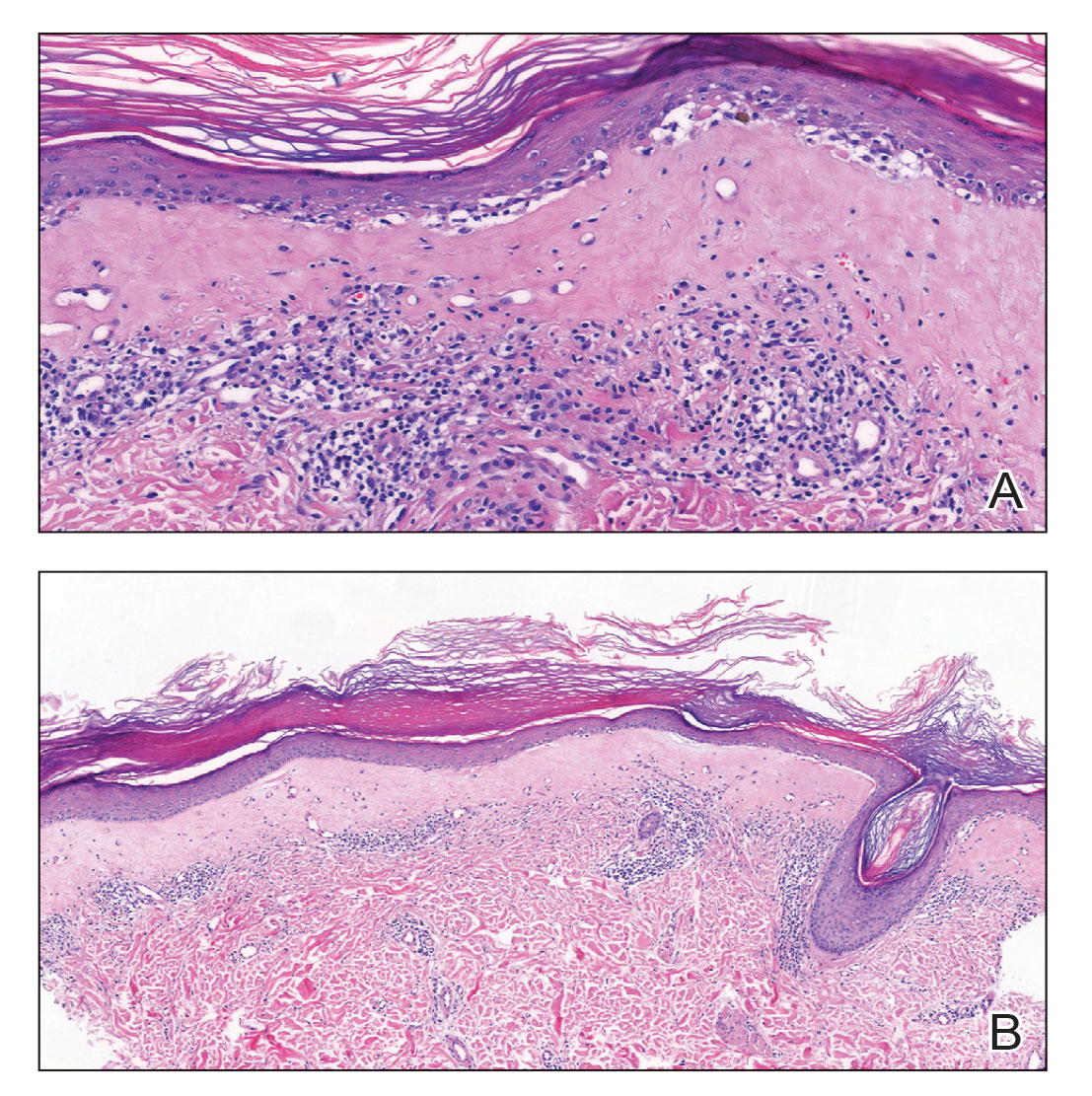

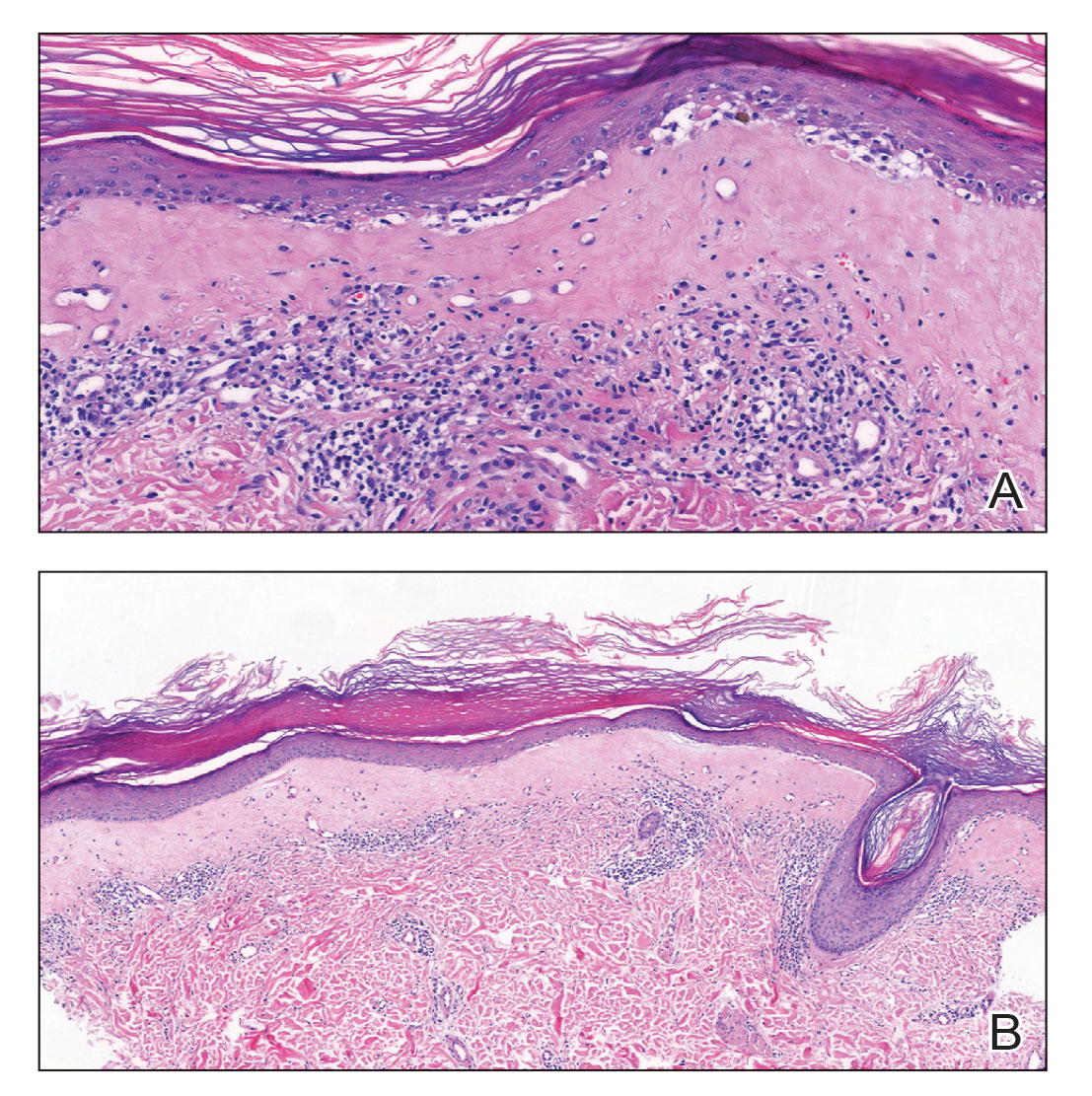

Although the infectious workup was positive for herpes simplex virus type 1 and cytomegalovirus antibodies, serologies for the rest of the TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents [syphilis, hepatitis B virus], rubella, cytomegalovirus) group of infections, as well as other bacterial, fungal, and viral infections, were negative. A skin biopsy from the right fifth toe showed a dense infiltrate of CD1a+ histiocytic cells with folded or kidney-shaped nuclei mixed with eosinophils, which was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (Figure 1). Skin lesions were treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% and progressively faded over a few weeks.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disorder with a variable clinical presentation depending on the sites affected and the extent of involvement. It can involve multiple organ systems, most commonly the skeletal system and the skin. Organ involvement is characterized by histiocyte infiltration. Acute disseminated multisystem disease most commonly is seen in children younger than 3 years.1

Congenital cutaneous LCH presents with variable skin lesions ranging from papules to vesicles, pustules, and ulcers, with onset at birth or in the neonatal period. Various morphologic traits of skin lesions have been described; the most common presentation is multiple red to yellow-brown, crusted papules with accompanying hemorrhage or erosion.1 Other cases have described an eczematous, seborrheic, diffuse eruption or erosive intertrigo. One case of a child with a solitary necrotic nodule on the scalp has been reported.2

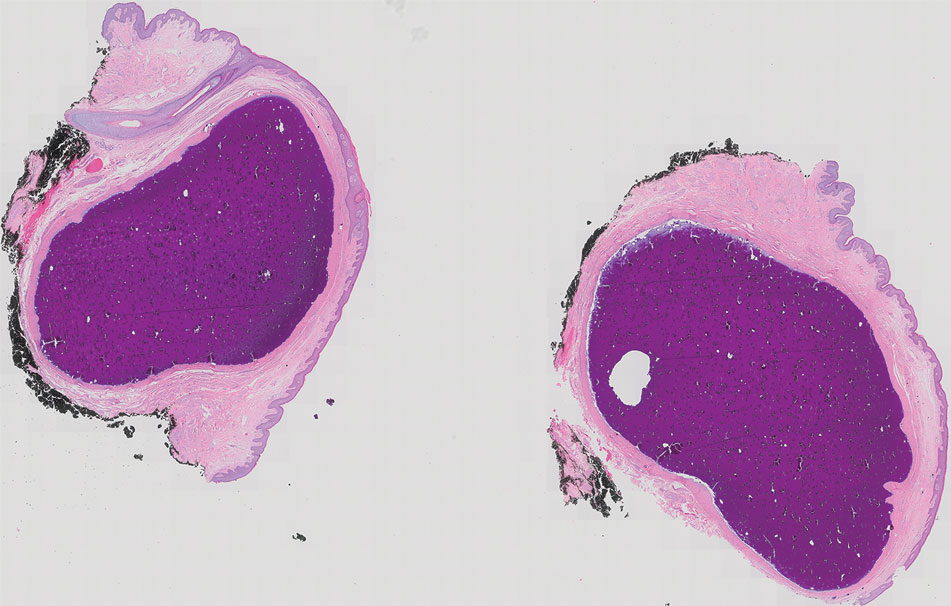

Our patient presented with disseminated, nonblanching, purple to dark red papules and nodules of the skin and oral mucosa, as well as nail dystrophy (Figure 2). However, LCH in a neonate can mimic other causes of congenital papulonodular eruptions. Red-brown papules and nodules with or without crusting in a newborn can be mistaken for erythema toxicum neonatorum, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, congenital leukemia cutis, neonatal erythropoiesis, disseminated neonatal hemangiomatosis, infantile acropustulosis, or congenital TORCH infections such as rubella or syphilis. When LCH presents as vesicles or eroded papules or nodules in a newborn, the differential diagnosis includes incontinentia pigmenti and hereditary epidermolysis bullosa.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis may even present with a classic blueberry muffin rash that can lead clinicians to consider cutaneous metastasis from various hematologic malignancies or the more common TORCH infections. Several diagnostic tests can be performed to clarify the diagnosis, including bacterial and viral cultures and stains, serology, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, bone marrow aspiration, or skin biopsy.3 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is diagnosed with a combination of histology, immunohistochemistry, and clinical presentation; however, a skin biopsy is crucial. Tissue should be taken from the most easily accessible yet representative lesion. The characteristic appearance of LCH lesions is described as a dense infiltrate of histiocytic cells mixed with numerous eosinophils in the dermis.1 Histiocytes usually have folded nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm or kidney-shaped nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Positive CD1a and/or CD207 (Langerin) staining of the cells is required for definitive diagnosis.4 After diagnosis, it is important to obtain baseline laboratory and radiographic studies to determine the extent of systemic involvement.

Treatment of congenital LCH is tailored to the extent of organ involvement. The dermatologic manifestations resolve without medications in many cases. However, true self-resolving LCH can only be diagnosed retrospectively after a full evaluation for other sites of disease. Disseminated disease can be life-threatening and requires more active management. In cases of skin-limited disease, therapies include topical steroids, nitrogen mustard, or imiquimod; surgical resection of isolated lesions; phototherapy; or systemic therapies such as methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, vinblastine/vincristine, cladribine, and/or cytarabine. Symptomatic patients initially are treated with methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine.5 Asymptomatic infants with skin-limited involvement can be managed with topical treatments.

Our patient had skin-limited disease. Abdominal ultrasonography, skeletal survey, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed no abnormalities. The patient’s family was advised to monitor him for reoccurrence of the skin lesions and to continue close follow-up with hematology and dermatology. Although congenital LCH often is self-resolving, extensive skin involvement increases the risk for internal organ involvement for several years.6 These patients require long-term follow-up for potential musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, endocrine, hepatic, and/or pulmonary disease.

- Pan Y, Zeng X, Ge J, et al. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis: clinical and pathological characteristics. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2275-2278.

- Morren MA, Vanden Broecke K, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse cutaneous presentations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:486-492. doi:10.1002/pbc.25834

- Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment, sequelae, and standardized follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1047-1056. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.060

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

- Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:26-35. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-12-569301

- Jezierska M, Stefanowicz J, Romanowicz G, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children—a disease with many faces. recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnostic examinations and treatment. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2018;35:6-17. doi:10.5114/pdia.2017.67095

The Diagnosis: Congenital Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Although the infectious workup was positive for herpes simplex virus type 1 and cytomegalovirus antibodies, serologies for the rest of the TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents [syphilis, hepatitis B virus], rubella, cytomegalovirus) group of infections, as well as other bacterial, fungal, and viral infections, were negative. A skin biopsy from the right fifth toe showed a dense infiltrate of CD1a+ histiocytic cells with folded or kidney-shaped nuclei mixed with eosinophils, which was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (Figure 1). Skin lesions were treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% and progressively faded over a few weeks.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disorder with a variable clinical presentation depending on the sites affected and the extent of involvement. It can involve multiple organ systems, most commonly the skeletal system and the skin. Organ involvement is characterized by histiocyte infiltration. Acute disseminated multisystem disease most commonly is seen in children younger than 3 years.1

Congenital cutaneous LCH presents with variable skin lesions ranging from papules to vesicles, pustules, and ulcers, with onset at birth or in the neonatal period. Various morphologic traits of skin lesions have been described; the most common presentation is multiple red to yellow-brown, crusted papules with accompanying hemorrhage or erosion.1 Other cases have described an eczematous, seborrheic, diffuse eruption or erosive intertrigo. One case of a child with a solitary necrotic nodule on the scalp has been reported.2

Our patient presented with disseminated, nonblanching, purple to dark red papules and nodules of the skin and oral mucosa, as well as nail dystrophy (Figure 2). However, LCH in a neonate can mimic other causes of congenital papulonodular eruptions. Red-brown papules and nodules with or without crusting in a newborn can be mistaken for erythema toxicum neonatorum, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, congenital leukemia cutis, neonatal erythropoiesis, disseminated neonatal hemangiomatosis, infantile acropustulosis, or congenital TORCH infections such as rubella or syphilis. When LCH presents as vesicles or eroded papules or nodules in a newborn, the differential diagnosis includes incontinentia pigmenti and hereditary epidermolysis bullosa.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis may even present with a classic blueberry muffin rash that can lead clinicians to consider cutaneous metastasis from various hematologic malignancies or the more common TORCH infections. Several diagnostic tests can be performed to clarify the diagnosis, including bacterial and viral cultures and stains, serology, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, bone marrow aspiration, or skin biopsy.3 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is diagnosed with a combination of histology, immunohistochemistry, and clinical presentation; however, a skin biopsy is crucial. Tissue should be taken from the most easily accessible yet representative lesion. The characteristic appearance of LCH lesions is described as a dense infiltrate of histiocytic cells mixed with numerous eosinophils in the dermis.1 Histiocytes usually have folded nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm or kidney-shaped nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Positive CD1a and/or CD207 (Langerin) staining of the cells is required for definitive diagnosis.4 After diagnosis, it is important to obtain baseline laboratory and radiographic studies to determine the extent of systemic involvement.

Treatment of congenital LCH is tailored to the extent of organ involvement. The dermatologic manifestations resolve without medications in many cases. However, true self-resolving LCH can only be diagnosed retrospectively after a full evaluation for other sites of disease. Disseminated disease can be life-threatening and requires more active management. In cases of skin-limited disease, therapies include topical steroids, nitrogen mustard, or imiquimod; surgical resection of isolated lesions; phototherapy; or systemic therapies such as methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, vinblastine/vincristine, cladribine, and/or cytarabine. Symptomatic patients initially are treated with methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine.5 Asymptomatic infants with skin-limited involvement can be managed with topical treatments.

Our patient had skin-limited disease. Abdominal ultrasonography, skeletal survey, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed no abnormalities. The patient’s family was advised to monitor him for reoccurrence of the skin lesions and to continue close follow-up with hematology and dermatology. Although congenital LCH often is self-resolving, extensive skin involvement increases the risk for internal organ involvement for several years.6 These patients require long-term follow-up for potential musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, endocrine, hepatic, and/or pulmonary disease.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Although the infectious workup was positive for herpes simplex virus type 1 and cytomegalovirus antibodies, serologies for the rest of the TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents [syphilis, hepatitis B virus], rubella, cytomegalovirus) group of infections, as well as other bacterial, fungal, and viral infections, were negative. A skin biopsy from the right fifth toe showed a dense infiltrate of CD1a+ histiocytic cells with folded or kidney-shaped nuclei mixed with eosinophils, which was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (Figure 1). Skin lesions were treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% and progressively faded over a few weeks.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disorder with a variable clinical presentation depending on the sites affected and the extent of involvement. It can involve multiple organ systems, most commonly the skeletal system and the skin. Organ involvement is characterized by histiocyte infiltration. Acute disseminated multisystem disease most commonly is seen in children younger than 3 years.1

Congenital cutaneous LCH presents with variable skin lesions ranging from papules to vesicles, pustules, and ulcers, with onset at birth or in the neonatal period. Various morphologic traits of skin lesions have been described; the most common presentation is multiple red to yellow-brown, crusted papules with accompanying hemorrhage or erosion.1 Other cases have described an eczematous, seborrheic, diffuse eruption or erosive intertrigo. One case of a child with a solitary necrotic nodule on the scalp has been reported.2

Our patient presented with disseminated, nonblanching, purple to dark red papules and nodules of the skin and oral mucosa, as well as nail dystrophy (Figure 2). However, LCH in a neonate can mimic other causes of congenital papulonodular eruptions. Red-brown papules and nodules with or without crusting in a newborn can be mistaken for erythema toxicum neonatorum, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, congenital leukemia cutis, neonatal erythropoiesis, disseminated neonatal hemangiomatosis, infantile acropustulosis, or congenital TORCH infections such as rubella or syphilis. When LCH presents as vesicles or eroded papules or nodules in a newborn, the differential diagnosis includes incontinentia pigmenti and hereditary epidermolysis bullosa.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis may even present with a classic blueberry muffin rash that can lead clinicians to consider cutaneous metastasis from various hematologic malignancies or the more common TORCH infections. Several diagnostic tests can be performed to clarify the diagnosis, including bacterial and viral cultures and stains, serology, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, bone marrow aspiration, or skin biopsy.3 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is diagnosed with a combination of histology, immunohistochemistry, and clinical presentation; however, a skin biopsy is crucial. Tissue should be taken from the most easily accessible yet representative lesion. The characteristic appearance of LCH lesions is described as a dense infiltrate of histiocytic cells mixed with numerous eosinophils in the dermis.1 Histiocytes usually have folded nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm or kidney-shaped nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Positive CD1a and/or CD207 (Langerin) staining of the cells is required for definitive diagnosis.4 After diagnosis, it is important to obtain baseline laboratory and radiographic studies to determine the extent of systemic involvement.

Treatment of congenital LCH is tailored to the extent of organ involvement. The dermatologic manifestations resolve without medications in many cases. However, true self-resolving LCH can only be diagnosed retrospectively after a full evaluation for other sites of disease. Disseminated disease can be life-threatening and requires more active management. In cases of skin-limited disease, therapies include topical steroids, nitrogen mustard, or imiquimod; surgical resection of isolated lesions; phototherapy; or systemic therapies such as methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, vinblastine/vincristine, cladribine, and/or cytarabine. Symptomatic patients initially are treated with methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine.5 Asymptomatic infants with skin-limited involvement can be managed with topical treatments.

Our patient had skin-limited disease. Abdominal ultrasonography, skeletal survey, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed no abnormalities. The patient’s family was advised to monitor him for reoccurrence of the skin lesions and to continue close follow-up with hematology and dermatology. Although congenital LCH often is self-resolving, extensive skin involvement increases the risk for internal organ involvement for several years.6 These patients require long-term follow-up for potential musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, endocrine, hepatic, and/or pulmonary disease.

- Pan Y, Zeng X, Ge J, et al. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis: clinical and pathological characteristics. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2275-2278.

- Morren MA, Vanden Broecke K, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse cutaneous presentations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:486-492. doi:10.1002/pbc.25834

- Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment, sequelae, and standardized follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1047-1056. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.060

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

- Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:26-35. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-12-569301

- Jezierska M, Stefanowicz J, Romanowicz G, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children—a disease with many faces. recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnostic examinations and treatment. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2018;35:6-17. doi:10.5114/pdia.2017.67095

- Pan Y, Zeng X, Ge J, et al. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis: clinical and pathological characteristics. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2275-2278.

- Morren MA, Vanden Broecke K, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse cutaneous presentations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:486-492. doi:10.1002/pbc.25834

- Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment, sequelae, and standardized follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1047-1056. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.060

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

- Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:26-35. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-12-569301

- Jezierska M, Stefanowicz J, Romanowicz G, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children—a disease with many faces. recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnostic examinations and treatment. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2018;35:6-17. doi:10.5114/pdia.2017.67095

A 38-week-old infant boy presented at birth with disseminated, nonblanching, purple to dark red papules and nodules on the skin and oral mucosa. He was born spontaneously after an uncomplicated pregnancy. The mother experienced an episode of oral herpes simplex virus during pregnancy. The infant was otherwise healthy. Laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count and routine serum biochemical analyses were within reference range; however, an infectious workup was positive for herpes simplex virus type 1 and cytomegalovirus antibodies. Ophthalmologic and auditory screenings were normal.

Raised Linear Plaques on the Back

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

A 77-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a new rash of 2 days’ duration. He trialed a previously prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1% without improvement. The patient denied any recent travel, as well as fever, nausea, vomiting, or changes in bowel habits. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, raised, linear plaques on the mid to lower back.

Diffuse Annular Plaques in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

- Derdulska JM, Rudnicka L, Szykut-Badaczewska A, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus—practical guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:529-538. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0543

- Wu J, Berk-Krauss J, Glick SA. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:590. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0041

- Hon KL, Leung AK. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:301274. doi:10.1155/2012/301274

- Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, et al. Neonatal tinea corporis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:201. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.6274

- Ang-Tiu CU, Nicolas ME. Erythema multiforme in a 25-day old neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E118-E120. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2012.01873.x

- Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Annular skin lesions in infancy [published online February 3, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:505-512. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.12.011

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.