User login

Mobile Apps for Professional Dermatology Education: An Objective Review

With today’s technology, it is easier than ever to access web-based tools that enrich traditional dermatology education. The literature supports the use of these innovative platforms to enhance learning at the student and trainee levels. A controlled study of pediatric residents showed that online modules effectively supplemented clinical experience with atopic dermatitis.1 In a randomized diagnostic study of medical students, practice with an image-based web application (app) that teaches rapid recognition of melanoma proved more effective than learning a rule-based algorithm.2 Given the visual nature of dermatology, pattern recognition is an essential skill that is fostered through experience and is only made more accessible with technology.

With the added benefit of convenience and accessibility, mobile apps can supplement experiential learning. Mirroring the overall growth of mobile apps, the number of available dermatology apps has increased.3 Dermatology mobile apps serve purposes ranging from quick reference tools to comprehensive modules, journals, and question banks. At an academic hospital in Taiwan, both nondermatology and dermatology trainees’ examination performance improved after 3 weeks of using a smartphone-based wallpaper learning module displaying morphologic characteristics of fungi.4 With the expansion of virtual microscopy, mobile apps also have been created as a learning tool for dermatopathology, giving trainees the flexibility and autonomy to view slides on their own time.5 Nevertheless, the literature on dermatology mobile apps designed for the education of medical students and trainees is limited, demonstrating a need for further investigation.

Prior studies have reviewed dermatology apps for patients and practicing dermatologists.6-8 Herein, we focus on mobile apps targeting students and residents learning dermatology. General dermatology reference apps and educational aid apps have grown by 33% and 32%, respectively, from 2014 to 2017.3 As with any resource meant to educate future and current medical providers, there must be an objective review process in place to ensure accurate, unbiased, evidence-based teaching.

Well-organized, comprehensive information and a user-friendly interface are additional factors of importance when selecting an educational mobile app. When discussing supplemental resources, accessibility and affordability also are priorities given the high cost of a medical education at baseline. Overall, there is a need for a standardized method to evaluate the key factors of an educational mobile app that make it appropriate for this demographic. We conducted a search of mobile apps relating to dermatology education for students and residents.

Methods

We searched for publicly available mobile apps relating to dermatology education in the App Store (Apple Inc) from September to November 2019 using the search terms dermatology education, dermoscopy education, melanoma education, skin cancer education, psoriasis education, rosacea education, acne education, eczema education, dermal fillers education, and Mohs surgery education. We excluded apps that were not in English, were created for a conference, cost more than $5 to download, or did not include a specific dermatology education section. In this way, we hoped to evaluate apps that were relevant, accessible, and affordable.

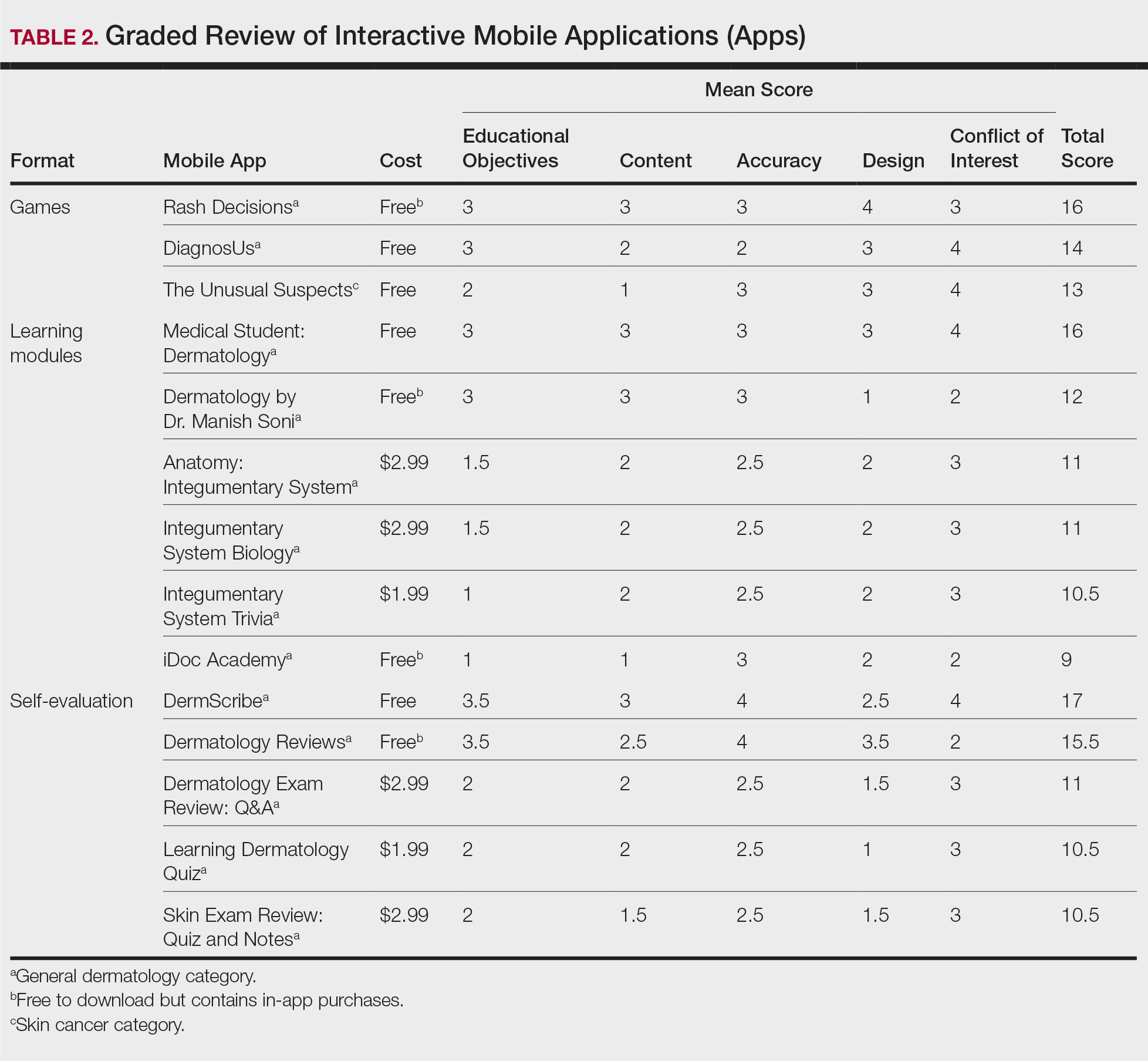

We modeled our study after a review of patient education apps performed by Masud et al6 and utilized their quantified grading rubric (scale of 1 to 4). We found their established criteria—educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest—to be equally applicable for evaluating apps designed for professional education.6 Each app earned a minimum of 1 point and a maximum of 4 points per criterion. One point was given if the app did not fulfill the criterion, 2 points for minimally fulfilling the criterion, 3 points for mostly fulfilling the criterion, and 4 points if the criterion was completely fulfilled. Two medical students (E.H. and N.C.)—one at the preclinical stage and the other at the clinical stage of medical education—reviewed the apps using the given rubric, then discussed and resolved any discrepancies in points assigned. A dermatology resident (M.A.) independently reviewed the apps using the given rubric.

The mean of the student score and the resident score was calculated for each category. The sum of the averages for each category was considered the final score for an app, determining its overall quality. Apps with a total score of 5 to 10 were considered poor and inadequate for education. A total score of 10.5 to 15 indicated that an app was somewhat adequate (ie, useful for education in some aspects but falling short in others). Apps that were considered adequate for education, across all or most criteria, received a total score ranging from 15.5 to 20.

Results

Our search generated 130 apps. After applying exclusion criteria, 42 apps were eligible for review. At the time of publication, 36 of these apps were still available. The possible range of scores based on the rubric was 5 to 20. The actual range of scores was 7 to 20. Of the 36 apps, 2 (5.6%) were poor, 16 (44.4%) were somewhat adequate, and 18 (50%) were adequate. Formats included primary resources, such as clinical decision support tools, journals, references, and a podcast (Table 1). Additionally, interactive learning tools included games, learning modules, and apps for self-evaluation (Table 2). Thirty apps covered general dermatology; others focused on skin cancer (n=5) and cosmetic dermatology (n=1). Regarding cost, 29 apps were free to download, whereas 7 charged a fee (mean price, $2.56).

Comment

In addition to the convenience of having an educational tool in their white-coat pocket, learners of dermatology have been shown to benefit from supplementing their curriculum with mobile apps, which sets the stage for formal integration of mobile apps into dermatology teaching in the future.8 Prior to widespread adoption, mobile apps must be evaluated for content and utility, starting with an objective rubric.

Without official scientific standards in place, it was unsurprising that only half of the dermatology education applications were classified as adequate in this study. Among the types of apps offered—clinical decision support tools, journals, references, podcast, games, learning modules, and self-evaluation—certain categories scored higher than others. App formats with the highest average score (16.5 out of 20) were journals and podcast.

One barrier to utilization of these apps was that a subscription to the journals and podcast was required to obtain access to all available content. Students and trainees can seek out library resources at their academic institutions to take advantage of journal subscriptions available to them at no additional cost. Dermatology residents can take advantage of their complimentary membership in the American Academy of Dermatology for a free subscription to AAD Dialogues in Dermatology (otherwise $179 annually for nonresident members and $320 annually for nonmembers).

On the other hand, learning module was the lowest-rated format (average score, 11.3 out of 20), with only Medical Student: Dermatology qualifying as adequate (total score, 16). This finding is worrisome given that students and residents might look to learning modules for quick targeted lessons on specific topics.

The lowest-scoring app, a clinical decision support tool called Naturelize, received a total score of 7. Although it listed the indications and contraindications for dermal filler types to be used in different locations on the face, there was a clear conflict of interest, oversimplified design, and little evidence-based education, mirroring the current state of cosmetic dermatology training in residency, in which trainees think they are inadequately prepared for aesthetic procedures and comparative effectiveness research is lacking.9-11

At the opposite end of the spectrum, MyDermPath+ was a reference app with a total score of 20. The app cited credible authors with a medical degree (MD) and had an easy-to-use, well-designed interface, including a reference guide, differential builder, and quiz for a range of topics within dermatology. As a free download without in-app purchases or advertisements, there was no evidence of conflict of interest. The position of a dermatopathology app as the top dermatology education mobile app might reflect an increased emphasis on dermatopathology education in residency as well as a transition to digitization of slides.5

The second-highest scoring apps (total score of 19 points) were Dermatology Database and VisualDx. Both were references covering a wide range of dermatology topics. Dermatology Database was a comprehensive search tool for diseases, drugs, procedures, and terms that was simple and entirely free to use but did not cite references. VisualDx, as its name suggests, offered quality clinical images, complete guides with references, and a unique differential builder. An annual subscription is $399.99, but the process to gain free access through a participating academic institution was simple.

Games were a unique mobile app format; however, 2 of 3 games scored in the somewhat adequate range. The game DiagnosUs, which tested users’ ability to differentiate skin cancer and psoriasis from dermatitis on clinical images, would benefit from more comprehensive content as well as professional verification of true diagnoses, which earned the app 2 points in both the content and accuracy categories. The Unusual Suspects tested the ABCDE algorithm in a short learning module, followed by a simple game that involved identification of melanoma in a timed setting. Although the design was novel and interactive, the game was limited to the same 5 melanoma tumors overlaid on pictures of normal skin. The narrow scope earned 1 point for content, the redundancy in the game earned 3 points for design, and the lack of real clinical images earned 2 points for educational objectives. Although game-format mobile apps have the capability to challenge the user’s knowledge with a built-in feedback or reward system, improvements should be made to ensure that apps are equally educational as they are engaging.

AAD Dialogues in Dermatology was the only app in the form of a podcast and provided expert interviews along with disclosures, transcripts, commentary, and references. More than half the content in the app could not be accessed without a subscription, earning 2.5 points in the conflict of interest category. Additionally, several flaws resulted in a design score of 2.5, including inconsistent availability of transcripts, poor quality of sound on some episodes, difficulty distinguishing new episodes from those already played, and a glitch that removed the episode duration. Still, the app was a valuable and comprehensive resource, with clear objectives and cited references. With improvements in content, affordability, and user experience, apps in unique formats such as games and podcasts might appeal to kinesthetic and auditory learners.

An important factor to consider when discussing mobile apps for students and residents is cost. With rising prices of board examinations and preparation materials, supplementary study tools should not come with an exorbitant price tag. Therefore, we limited our evaluation to apps that were free or cost less than $5 to download. Even so, subscriptions and other in-app purchases were an obstacle in one-third of apps, ranging from $4.99 to unlock additional content in Rash Decisions to $69.99 to access most topics in Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas. The highest-rated app in our study, MyDermPath+, historically cost $19.99 to download but became free with a grant from the Sulzberger Foundation.12 An initial investment to develop quality apps for the purpose of dermatology education might pay off in the end.

To evaluate the apps from the perspective of the target demographic of this study, 2 medical students—one in the preclinical stage and the other in the clinical stage of medical education—and a dermatology resident graded the apps. Certain limitations exist in this type of study, including differing learning styles, which might influence the types of apps that evaluators found most impactful to their education. Interestingly, some apps earned a higher resident score than student score. In particular, RightSite (a reference that helps with anatomically correct labeling) and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (a clinical decision support tool to determine whether to perform Mohs surgery) each had a 3-point discrepancy (data not shown). A resident might benefit from these practical apps in day-to-day practice, but a student would be less likely to find them useful as a learning tool.

Still, by defining adequate teaching value using specific categories of educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest, we attempted to minimize the effect of personal preference on the grading process. Although we acknowledge a degree of subjectivity, we found that utilizing a previously published rubric with defined criteria was crucial in remaining unbiased.

Conclusion

Further studies should evaluate additional apps available on Apple’s iPad (tablet), as well as those on other operating systems, including Google’s Android. To ensure the existence of mobile apps as adequate education tools, they should be peer reviewed prior to publication or before widespread use by future and current providers at the minimum. To maximize free access to highly valuable resources available in the palm of their hand, students and trainees should contact the library at their academic institution.

- Craddock MF, Blondin HM, Youssef MJ, et al. Online education improves pediatric residents' understanding of atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:64-69.

- Lacy FA, Coman GC, Holliday AC, et al. Assessment of smartphone application for teaching intuitive visual diagnosis of melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:730-731.

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology--2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13.

- Liu R-F, Wang F-Y, Yen H, et al. A new mobile learning module using smartphone wallpapers in identification of medical fungi for medical students and residents. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:458-462.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Masud A, Shafi S, Rao BK. Mobile medical apps for patient education: a graded review of available dermatology apps. Cutis. 2018;101:141-144.

- Mercer JM. An array of mobile apps for dermatologists. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:295-297.

- Tongdee E, Markowitz O. Mobile app rankings in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102:252-256.

- Kirby JS, Adgerson CN, Anderson BE. A survey of dermatology resident education in cosmetic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e23-e28.

- Waldman A, Sobanko JF, Alam M. Practice and educational gaps in cosmetic dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:341-346.

- Nielson CB, Harb JN, Motaparthi K. Education in cosmetic procedural dermatology: resident experiences and perceptions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:E70-E72.

- Hanna MG, Parwani AV, Pantanowitz L, et al. Smartphone applications: a contemporary resource for dermatopathology. J Pathol Inform. 2015;6:44.

With today’s technology, it is easier than ever to access web-based tools that enrich traditional dermatology education. The literature supports the use of these innovative platforms to enhance learning at the student and trainee levels. A controlled study of pediatric residents showed that online modules effectively supplemented clinical experience with atopic dermatitis.1 In a randomized diagnostic study of medical students, practice with an image-based web application (app) that teaches rapid recognition of melanoma proved more effective than learning a rule-based algorithm.2 Given the visual nature of dermatology, pattern recognition is an essential skill that is fostered through experience and is only made more accessible with technology.

With the added benefit of convenience and accessibility, mobile apps can supplement experiential learning. Mirroring the overall growth of mobile apps, the number of available dermatology apps has increased.3 Dermatology mobile apps serve purposes ranging from quick reference tools to comprehensive modules, journals, and question banks. At an academic hospital in Taiwan, both nondermatology and dermatology trainees’ examination performance improved after 3 weeks of using a smartphone-based wallpaper learning module displaying morphologic characteristics of fungi.4 With the expansion of virtual microscopy, mobile apps also have been created as a learning tool for dermatopathology, giving trainees the flexibility and autonomy to view slides on their own time.5 Nevertheless, the literature on dermatology mobile apps designed for the education of medical students and trainees is limited, demonstrating a need for further investigation.

Prior studies have reviewed dermatology apps for patients and practicing dermatologists.6-8 Herein, we focus on mobile apps targeting students and residents learning dermatology. General dermatology reference apps and educational aid apps have grown by 33% and 32%, respectively, from 2014 to 2017.3 As with any resource meant to educate future and current medical providers, there must be an objective review process in place to ensure accurate, unbiased, evidence-based teaching.

Well-organized, comprehensive information and a user-friendly interface are additional factors of importance when selecting an educational mobile app. When discussing supplemental resources, accessibility and affordability also are priorities given the high cost of a medical education at baseline. Overall, there is a need for a standardized method to evaluate the key factors of an educational mobile app that make it appropriate for this demographic. We conducted a search of mobile apps relating to dermatology education for students and residents.

Methods

We searched for publicly available mobile apps relating to dermatology education in the App Store (Apple Inc) from September to November 2019 using the search terms dermatology education, dermoscopy education, melanoma education, skin cancer education, psoriasis education, rosacea education, acne education, eczema education, dermal fillers education, and Mohs surgery education. We excluded apps that were not in English, were created for a conference, cost more than $5 to download, or did not include a specific dermatology education section. In this way, we hoped to evaluate apps that were relevant, accessible, and affordable.

We modeled our study after a review of patient education apps performed by Masud et al6 and utilized their quantified grading rubric (scale of 1 to 4). We found their established criteria—educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest—to be equally applicable for evaluating apps designed for professional education.6 Each app earned a minimum of 1 point and a maximum of 4 points per criterion. One point was given if the app did not fulfill the criterion, 2 points for minimally fulfilling the criterion, 3 points for mostly fulfilling the criterion, and 4 points if the criterion was completely fulfilled. Two medical students (E.H. and N.C.)—one at the preclinical stage and the other at the clinical stage of medical education—reviewed the apps using the given rubric, then discussed and resolved any discrepancies in points assigned. A dermatology resident (M.A.) independently reviewed the apps using the given rubric.

The mean of the student score and the resident score was calculated for each category. The sum of the averages for each category was considered the final score for an app, determining its overall quality. Apps with a total score of 5 to 10 were considered poor and inadequate for education. A total score of 10.5 to 15 indicated that an app was somewhat adequate (ie, useful for education in some aspects but falling short in others). Apps that were considered adequate for education, across all or most criteria, received a total score ranging from 15.5 to 20.

Results

Our search generated 130 apps. After applying exclusion criteria, 42 apps were eligible for review. At the time of publication, 36 of these apps were still available. The possible range of scores based on the rubric was 5 to 20. The actual range of scores was 7 to 20. Of the 36 apps, 2 (5.6%) were poor, 16 (44.4%) were somewhat adequate, and 18 (50%) were adequate. Formats included primary resources, such as clinical decision support tools, journals, references, and a podcast (Table 1). Additionally, interactive learning tools included games, learning modules, and apps for self-evaluation (Table 2). Thirty apps covered general dermatology; others focused on skin cancer (n=5) and cosmetic dermatology (n=1). Regarding cost, 29 apps were free to download, whereas 7 charged a fee (mean price, $2.56).

Comment

In addition to the convenience of having an educational tool in their white-coat pocket, learners of dermatology have been shown to benefit from supplementing their curriculum with mobile apps, which sets the stage for formal integration of mobile apps into dermatology teaching in the future.8 Prior to widespread adoption, mobile apps must be evaluated for content and utility, starting with an objective rubric.

Without official scientific standards in place, it was unsurprising that only half of the dermatology education applications were classified as adequate in this study. Among the types of apps offered—clinical decision support tools, journals, references, podcast, games, learning modules, and self-evaluation—certain categories scored higher than others. App formats with the highest average score (16.5 out of 20) were journals and podcast.

One barrier to utilization of these apps was that a subscription to the journals and podcast was required to obtain access to all available content. Students and trainees can seek out library resources at their academic institutions to take advantage of journal subscriptions available to them at no additional cost. Dermatology residents can take advantage of their complimentary membership in the American Academy of Dermatology for a free subscription to AAD Dialogues in Dermatology (otherwise $179 annually for nonresident members and $320 annually for nonmembers).

On the other hand, learning module was the lowest-rated format (average score, 11.3 out of 20), with only Medical Student: Dermatology qualifying as adequate (total score, 16). This finding is worrisome given that students and residents might look to learning modules for quick targeted lessons on specific topics.

The lowest-scoring app, a clinical decision support tool called Naturelize, received a total score of 7. Although it listed the indications and contraindications for dermal filler types to be used in different locations on the face, there was a clear conflict of interest, oversimplified design, and little evidence-based education, mirroring the current state of cosmetic dermatology training in residency, in which trainees think they are inadequately prepared for aesthetic procedures and comparative effectiveness research is lacking.9-11

At the opposite end of the spectrum, MyDermPath+ was a reference app with a total score of 20. The app cited credible authors with a medical degree (MD) and had an easy-to-use, well-designed interface, including a reference guide, differential builder, and quiz for a range of topics within dermatology. As a free download without in-app purchases or advertisements, there was no evidence of conflict of interest. The position of a dermatopathology app as the top dermatology education mobile app might reflect an increased emphasis on dermatopathology education in residency as well as a transition to digitization of slides.5

The second-highest scoring apps (total score of 19 points) were Dermatology Database and VisualDx. Both were references covering a wide range of dermatology topics. Dermatology Database was a comprehensive search tool for diseases, drugs, procedures, and terms that was simple and entirely free to use but did not cite references. VisualDx, as its name suggests, offered quality clinical images, complete guides with references, and a unique differential builder. An annual subscription is $399.99, but the process to gain free access through a participating academic institution was simple.

Games were a unique mobile app format; however, 2 of 3 games scored in the somewhat adequate range. The game DiagnosUs, which tested users’ ability to differentiate skin cancer and psoriasis from dermatitis on clinical images, would benefit from more comprehensive content as well as professional verification of true diagnoses, which earned the app 2 points in both the content and accuracy categories. The Unusual Suspects tested the ABCDE algorithm in a short learning module, followed by a simple game that involved identification of melanoma in a timed setting. Although the design was novel and interactive, the game was limited to the same 5 melanoma tumors overlaid on pictures of normal skin. The narrow scope earned 1 point for content, the redundancy in the game earned 3 points for design, and the lack of real clinical images earned 2 points for educational objectives. Although game-format mobile apps have the capability to challenge the user’s knowledge with a built-in feedback or reward system, improvements should be made to ensure that apps are equally educational as they are engaging.

AAD Dialogues in Dermatology was the only app in the form of a podcast and provided expert interviews along with disclosures, transcripts, commentary, and references. More than half the content in the app could not be accessed without a subscription, earning 2.5 points in the conflict of interest category. Additionally, several flaws resulted in a design score of 2.5, including inconsistent availability of transcripts, poor quality of sound on some episodes, difficulty distinguishing new episodes from those already played, and a glitch that removed the episode duration. Still, the app was a valuable and comprehensive resource, with clear objectives and cited references. With improvements in content, affordability, and user experience, apps in unique formats such as games and podcasts might appeal to kinesthetic and auditory learners.

An important factor to consider when discussing mobile apps for students and residents is cost. With rising prices of board examinations and preparation materials, supplementary study tools should not come with an exorbitant price tag. Therefore, we limited our evaluation to apps that were free or cost less than $5 to download. Even so, subscriptions and other in-app purchases were an obstacle in one-third of apps, ranging from $4.99 to unlock additional content in Rash Decisions to $69.99 to access most topics in Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas. The highest-rated app in our study, MyDermPath+, historically cost $19.99 to download but became free with a grant from the Sulzberger Foundation.12 An initial investment to develop quality apps for the purpose of dermatology education might pay off in the end.

To evaluate the apps from the perspective of the target demographic of this study, 2 medical students—one in the preclinical stage and the other in the clinical stage of medical education—and a dermatology resident graded the apps. Certain limitations exist in this type of study, including differing learning styles, which might influence the types of apps that evaluators found most impactful to their education. Interestingly, some apps earned a higher resident score than student score. In particular, RightSite (a reference that helps with anatomically correct labeling) and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (a clinical decision support tool to determine whether to perform Mohs surgery) each had a 3-point discrepancy (data not shown). A resident might benefit from these practical apps in day-to-day practice, but a student would be less likely to find them useful as a learning tool.

Still, by defining adequate teaching value using specific categories of educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest, we attempted to minimize the effect of personal preference on the grading process. Although we acknowledge a degree of subjectivity, we found that utilizing a previously published rubric with defined criteria was crucial in remaining unbiased.

Conclusion

Further studies should evaluate additional apps available on Apple’s iPad (tablet), as well as those on other operating systems, including Google’s Android. To ensure the existence of mobile apps as adequate education tools, they should be peer reviewed prior to publication or before widespread use by future and current providers at the minimum. To maximize free access to highly valuable resources available in the palm of their hand, students and trainees should contact the library at their academic institution.

With today’s technology, it is easier than ever to access web-based tools that enrich traditional dermatology education. The literature supports the use of these innovative platforms to enhance learning at the student and trainee levels. A controlled study of pediatric residents showed that online modules effectively supplemented clinical experience with atopic dermatitis.1 In a randomized diagnostic study of medical students, practice with an image-based web application (app) that teaches rapid recognition of melanoma proved more effective than learning a rule-based algorithm.2 Given the visual nature of dermatology, pattern recognition is an essential skill that is fostered through experience and is only made more accessible with technology.

With the added benefit of convenience and accessibility, mobile apps can supplement experiential learning. Mirroring the overall growth of mobile apps, the number of available dermatology apps has increased.3 Dermatology mobile apps serve purposes ranging from quick reference tools to comprehensive modules, journals, and question banks. At an academic hospital in Taiwan, both nondermatology and dermatology trainees’ examination performance improved after 3 weeks of using a smartphone-based wallpaper learning module displaying morphologic characteristics of fungi.4 With the expansion of virtual microscopy, mobile apps also have been created as a learning tool for dermatopathology, giving trainees the flexibility and autonomy to view slides on their own time.5 Nevertheless, the literature on dermatology mobile apps designed for the education of medical students and trainees is limited, demonstrating a need for further investigation.

Prior studies have reviewed dermatology apps for patients and practicing dermatologists.6-8 Herein, we focus on mobile apps targeting students and residents learning dermatology. General dermatology reference apps and educational aid apps have grown by 33% and 32%, respectively, from 2014 to 2017.3 As with any resource meant to educate future and current medical providers, there must be an objective review process in place to ensure accurate, unbiased, evidence-based teaching.

Well-organized, comprehensive information and a user-friendly interface are additional factors of importance when selecting an educational mobile app. When discussing supplemental resources, accessibility and affordability also are priorities given the high cost of a medical education at baseline. Overall, there is a need for a standardized method to evaluate the key factors of an educational mobile app that make it appropriate for this demographic. We conducted a search of mobile apps relating to dermatology education for students and residents.

Methods

We searched for publicly available mobile apps relating to dermatology education in the App Store (Apple Inc) from September to November 2019 using the search terms dermatology education, dermoscopy education, melanoma education, skin cancer education, psoriasis education, rosacea education, acne education, eczema education, dermal fillers education, and Mohs surgery education. We excluded apps that were not in English, were created for a conference, cost more than $5 to download, or did not include a specific dermatology education section. In this way, we hoped to evaluate apps that were relevant, accessible, and affordable.

We modeled our study after a review of patient education apps performed by Masud et al6 and utilized their quantified grading rubric (scale of 1 to 4). We found their established criteria—educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest—to be equally applicable for evaluating apps designed for professional education.6 Each app earned a minimum of 1 point and a maximum of 4 points per criterion. One point was given if the app did not fulfill the criterion, 2 points for minimally fulfilling the criterion, 3 points for mostly fulfilling the criterion, and 4 points if the criterion was completely fulfilled. Two medical students (E.H. and N.C.)—one at the preclinical stage and the other at the clinical stage of medical education—reviewed the apps using the given rubric, then discussed and resolved any discrepancies in points assigned. A dermatology resident (M.A.) independently reviewed the apps using the given rubric.

The mean of the student score and the resident score was calculated for each category. The sum of the averages for each category was considered the final score for an app, determining its overall quality. Apps with a total score of 5 to 10 were considered poor and inadequate for education. A total score of 10.5 to 15 indicated that an app was somewhat adequate (ie, useful for education in some aspects but falling short in others). Apps that were considered adequate for education, across all or most criteria, received a total score ranging from 15.5 to 20.

Results

Our search generated 130 apps. After applying exclusion criteria, 42 apps were eligible for review. At the time of publication, 36 of these apps were still available. The possible range of scores based on the rubric was 5 to 20. The actual range of scores was 7 to 20. Of the 36 apps, 2 (5.6%) were poor, 16 (44.4%) were somewhat adequate, and 18 (50%) were adequate. Formats included primary resources, such as clinical decision support tools, journals, references, and a podcast (Table 1). Additionally, interactive learning tools included games, learning modules, and apps for self-evaluation (Table 2). Thirty apps covered general dermatology; others focused on skin cancer (n=5) and cosmetic dermatology (n=1). Regarding cost, 29 apps were free to download, whereas 7 charged a fee (mean price, $2.56).

Comment

In addition to the convenience of having an educational tool in their white-coat pocket, learners of dermatology have been shown to benefit from supplementing their curriculum with mobile apps, which sets the stage for formal integration of mobile apps into dermatology teaching in the future.8 Prior to widespread adoption, mobile apps must be evaluated for content and utility, starting with an objective rubric.

Without official scientific standards in place, it was unsurprising that only half of the dermatology education applications were classified as adequate in this study. Among the types of apps offered—clinical decision support tools, journals, references, podcast, games, learning modules, and self-evaluation—certain categories scored higher than others. App formats with the highest average score (16.5 out of 20) were journals and podcast.

One barrier to utilization of these apps was that a subscription to the journals and podcast was required to obtain access to all available content. Students and trainees can seek out library resources at their academic institutions to take advantage of journal subscriptions available to them at no additional cost. Dermatology residents can take advantage of their complimentary membership in the American Academy of Dermatology for a free subscription to AAD Dialogues in Dermatology (otherwise $179 annually for nonresident members and $320 annually for nonmembers).

On the other hand, learning module was the lowest-rated format (average score, 11.3 out of 20), with only Medical Student: Dermatology qualifying as adequate (total score, 16). This finding is worrisome given that students and residents might look to learning modules for quick targeted lessons on specific topics.

The lowest-scoring app, a clinical decision support tool called Naturelize, received a total score of 7. Although it listed the indications and contraindications for dermal filler types to be used in different locations on the face, there was a clear conflict of interest, oversimplified design, and little evidence-based education, mirroring the current state of cosmetic dermatology training in residency, in which trainees think they are inadequately prepared for aesthetic procedures and comparative effectiveness research is lacking.9-11

At the opposite end of the spectrum, MyDermPath+ was a reference app with a total score of 20. The app cited credible authors with a medical degree (MD) and had an easy-to-use, well-designed interface, including a reference guide, differential builder, and quiz for a range of topics within dermatology. As a free download without in-app purchases or advertisements, there was no evidence of conflict of interest. The position of a dermatopathology app as the top dermatology education mobile app might reflect an increased emphasis on dermatopathology education in residency as well as a transition to digitization of slides.5

The second-highest scoring apps (total score of 19 points) were Dermatology Database and VisualDx. Both were references covering a wide range of dermatology topics. Dermatology Database was a comprehensive search tool for diseases, drugs, procedures, and terms that was simple and entirely free to use but did not cite references. VisualDx, as its name suggests, offered quality clinical images, complete guides with references, and a unique differential builder. An annual subscription is $399.99, but the process to gain free access through a participating academic institution was simple.

Games were a unique mobile app format; however, 2 of 3 games scored in the somewhat adequate range. The game DiagnosUs, which tested users’ ability to differentiate skin cancer and psoriasis from dermatitis on clinical images, would benefit from more comprehensive content as well as professional verification of true diagnoses, which earned the app 2 points in both the content and accuracy categories. The Unusual Suspects tested the ABCDE algorithm in a short learning module, followed by a simple game that involved identification of melanoma in a timed setting. Although the design was novel and interactive, the game was limited to the same 5 melanoma tumors overlaid on pictures of normal skin. The narrow scope earned 1 point for content, the redundancy in the game earned 3 points for design, and the lack of real clinical images earned 2 points for educational objectives. Although game-format mobile apps have the capability to challenge the user’s knowledge with a built-in feedback or reward system, improvements should be made to ensure that apps are equally educational as they are engaging.

AAD Dialogues in Dermatology was the only app in the form of a podcast and provided expert interviews along with disclosures, transcripts, commentary, and references. More than half the content in the app could not be accessed without a subscription, earning 2.5 points in the conflict of interest category. Additionally, several flaws resulted in a design score of 2.5, including inconsistent availability of transcripts, poor quality of sound on some episodes, difficulty distinguishing new episodes from those already played, and a glitch that removed the episode duration. Still, the app was a valuable and comprehensive resource, with clear objectives and cited references. With improvements in content, affordability, and user experience, apps in unique formats such as games and podcasts might appeal to kinesthetic and auditory learners.

An important factor to consider when discussing mobile apps for students and residents is cost. With rising prices of board examinations and preparation materials, supplementary study tools should not come with an exorbitant price tag. Therefore, we limited our evaluation to apps that were free or cost less than $5 to download. Even so, subscriptions and other in-app purchases were an obstacle in one-third of apps, ranging from $4.99 to unlock additional content in Rash Decisions to $69.99 to access most topics in Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas. The highest-rated app in our study, MyDermPath+, historically cost $19.99 to download but became free with a grant from the Sulzberger Foundation.12 An initial investment to develop quality apps for the purpose of dermatology education might pay off in the end.

To evaluate the apps from the perspective of the target demographic of this study, 2 medical students—one in the preclinical stage and the other in the clinical stage of medical education—and a dermatology resident graded the apps. Certain limitations exist in this type of study, including differing learning styles, which might influence the types of apps that evaluators found most impactful to their education. Interestingly, some apps earned a higher resident score than student score. In particular, RightSite (a reference that helps with anatomically correct labeling) and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (a clinical decision support tool to determine whether to perform Mohs surgery) each had a 3-point discrepancy (data not shown). A resident might benefit from these practical apps in day-to-day practice, but a student would be less likely to find them useful as a learning tool.

Still, by defining adequate teaching value using specific categories of educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest, we attempted to minimize the effect of personal preference on the grading process. Although we acknowledge a degree of subjectivity, we found that utilizing a previously published rubric with defined criteria was crucial in remaining unbiased.

Conclusion

Further studies should evaluate additional apps available on Apple’s iPad (tablet), as well as those on other operating systems, including Google’s Android. To ensure the existence of mobile apps as adequate education tools, they should be peer reviewed prior to publication or before widespread use by future and current providers at the minimum. To maximize free access to highly valuable resources available in the palm of their hand, students and trainees should contact the library at their academic institution.

- Craddock MF, Blondin HM, Youssef MJ, et al. Online education improves pediatric residents' understanding of atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:64-69.

- Lacy FA, Coman GC, Holliday AC, et al. Assessment of smartphone application for teaching intuitive visual diagnosis of melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:730-731.

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology--2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13.

- Liu R-F, Wang F-Y, Yen H, et al. A new mobile learning module using smartphone wallpapers in identification of medical fungi for medical students and residents. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:458-462.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Masud A, Shafi S, Rao BK. Mobile medical apps for patient education: a graded review of available dermatology apps. Cutis. 2018;101:141-144.

- Mercer JM. An array of mobile apps for dermatologists. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:295-297.

- Tongdee E, Markowitz O. Mobile app rankings in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102:252-256.

- Kirby JS, Adgerson CN, Anderson BE. A survey of dermatology resident education in cosmetic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e23-e28.

- Waldman A, Sobanko JF, Alam M. Practice and educational gaps in cosmetic dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:341-346.

- Nielson CB, Harb JN, Motaparthi K. Education in cosmetic procedural dermatology: resident experiences and perceptions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:E70-E72.

- Hanna MG, Parwani AV, Pantanowitz L, et al. Smartphone applications: a contemporary resource for dermatopathology. J Pathol Inform. 2015;6:44.

- Craddock MF, Blondin HM, Youssef MJ, et al. Online education improves pediatric residents' understanding of atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:64-69.

- Lacy FA, Coman GC, Holliday AC, et al. Assessment of smartphone application for teaching intuitive visual diagnosis of melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:730-731.

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology--2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13.

- Liu R-F, Wang F-Y, Yen H, et al. A new mobile learning module using smartphone wallpapers in identification of medical fungi for medical students and residents. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:458-462.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Masud A, Shafi S, Rao BK. Mobile medical apps for patient education: a graded review of available dermatology apps. Cutis. 2018;101:141-144.

- Mercer JM. An array of mobile apps for dermatologists. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:295-297.

- Tongdee E, Markowitz O. Mobile app rankings in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102:252-256.

- Kirby JS, Adgerson CN, Anderson BE. A survey of dermatology resident education in cosmetic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e23-e28.

- Waldman A, Sobanko JF, Alam M. Practice and educational gaps in cosmetic dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:341-346.

- Nielson CB, Harb JN, Motaparthi K. Education in cosmetic procedural dermatology: resident experiences and perceptions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:E70-E72.

- Hanna MG, Parwani AV, Pantanowitz L, et al. Smartphone applications: a contemporary resource for dermatopathology. J Pathol Inform. 2015;6:44.

Practice Points

- Mobile applications (apps) are a convenient way to learn dermatology, but there is no objective method to assess their quality.

- To determine which apps are most useful for education, we performed a graded review of dermatology apps targeted to students and residents.

- By applying a rubric to 36 affordable apps, we identified 18 (50%) with adequate teaching value.

Death anxiety among psychiatry trainees during COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

The far-reaching effects of death anxiety

Postgraduate psychiatry training may expose one to stressful situations with adverse psychologic consequences.1 Furthermore, when caring for patients, psychiatry trainees frequently need to face issues of death and dying in the form of suicide risk assessments, grief and bereavement processes, near-death experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psycho-oncology rotations. Because these interactions are incredibly personal, the emotions they provoke inevitably affect every interaction, theoretical discussion, diagnostic work-up, and treatment plan.

How each of us experiences death anxiety is unique. For some, it could be a fear of nonexistence, ultimate loss, disruption of the flow of life, worry about leaving loved ones behind, or fear of pain or loneliness in dying. Some might fear an untimely or violent death and subsequent judgment and retributions. The literature suggests that fear of death may be at the root of various mental health problems and, if left unaddressed, may adversely impact long-term treatment outcomes.2 Despite this, many standard treatment approaches typically do not target death anxiety, which potentially contributes to a “revolving door” of mental health problems.3

American existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom, MD, cautioned psychiatrists not to “scratch where it does not itch.”4 Yet death, according to Dr. Yalom, does itch. Violent death is that caused by human intent or negligence, and is characterized by feeling helpless and terrorized at the time of dying. It may occur as an acute incident that denies the dying individual and his/her family members the time and space to prepare for the death.5 For survivors, accommodating the mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual effects of violent death is a complex process that rarely has a conclusion. It often is accompanied by survivors’ guilt, which is replayed in the form of flashbacks and nightmares.6 With this understanding, I view COVID-19 deaths as violent deaths.

Pay close attention to countertransference

As much as we influence our patients and their families, we also are profoundly influenced by them. We need to pay attention to any feelings our clinical encounters generate within us, and to carefully use these feelings in our clinical judgment, and not just make causal inferences. For instance, if a clinician thinks that a patient with suicidal ideation would be better off dead, these feelings are a reliable indicator that the patient is, indeed, at a high risk of completing suicide.7 It is our ethical and moral responsibility towards our patients to listen to our countertransference responses. The aim is to identify countertransference and use it to inform us, not to rule us. By taking an active role in managing our emotional responses in the face of loss, we can harness the spirit of resilience. This is not always as easy as it seems. We need our peers, experienced clinicians, and supervisors to help us explore our feelings, resistances, and countertransference reactions.

Strategies to combat burnout

Psychiatric trainees must be encouraged to establish and maintain rigorous plans of self-care to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Most importantly, training programs must diversify residents’ clinical exposure by providing activities that promote mental health promotion activities, scholarly endeavors, and peer support groups. This will help trainees to restore meaning and purpose in life beyond.

1. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. What are some stressful adversities in psychiatry residency training, and how should they be managed professionally? Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):145-150.

2. Russac RJ, Gatliff C, Reece M, et al. Death anxiety across the adult years: an examination of age and gender effects. Death Stud. 2007;31(6):549-561.

3. Lisa I, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(7):580-593.

4. Yalom ID. Staring at the sun: being at peace with your own mortality. London, UK: Piatkus; 2011.

5. Rynearson EK, Johnson TA, Correa F. The horror and helplessness of violent death. In: Katz RS, Johnson TA (eds). When professionals weep: emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016:91-103.

6. Breggin PR. Guilt, shame, and anxiety: understanding and overcoming negative emotions. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books; 2014.

7. Katz RS, Johnson TA, (eds). When professionals weep: Emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

The far-reaching effects of death anxiety

Postgraduate psychiatry training may expose one to stressful situations with adverse psychologic consequences.1 Furthermore, when caring for patients, psychiatry trainees frequently need to face issues of death and dying in the form of suicide risk assessments, grief and bereavement processes, near-death experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psycho-oncology rotations. Because these interactions are incredibly personal, the emotions they provoke inevitably affect every interaction, theoretical discussion, diagnostic work-up, and treatment plan.

How each of us experiences death anxiety is unique. For some, it could be a fear of nonexistence, ultimate loss, disruption of the flow of life, worry about leaving loved ones behind, or fear of pain or loneliness in dying. Some might fear an untimely or violent death and subsequent judgment and retributions. The literature suggests that fear of death may be at the root of various mental health problems and, if left unaddressed, may adversely impact long-term treatment outcomes.2 Despite this, many standard treatment approaches typically do not target death anxiety, which potentially contributes to a “revolving door” of mental health problems.3

American existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom, MD, cautioned psychiatrists not to “scratch where it does not itch.”4 Yet death, according to Dr. Yalom, does itch. Violent death is that caused by human intent or negligence, and is characterized by feeling helpless and terrorized at the time of dying. It may occur as an acute incident that denies the dying individual and his/her family members the time and space to prepare for the death.5 For survivors, accommodating the mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual effects of violent death is a complex process that rarely has a conclusion. It often is accompanied by survivors’ guilt, which is replayed in the form of flashbacks and nightmares.6 With this understanding, I view COVID-19 deaths as violent deaths.

Pay close attention to countertransference

As much as we influence our patients and their families, we also are profoundly influenced by them. We need to pay attention to any feelings our clinical encounters generate within us, and to carefully use these feelings in our clinical judgment, and not just make causal inferences. For instance, if a clinician thinks that a patient with suicidal ideation would be better off dead, these feelings are a reliable indicator that the patient is, indeed, at a high risk of completing suicide.7 It is our ethical and moral responsibility towards our patients to listen to our countertransference responses. The aim is to identify countertransference and use it to inform us, not to rule us. By taking an active role in managing our emotional responses in the face of loss, we can harness the spirit of resilience. This is not always as easy as it seems. We need our peers, experienced clinicians, and supervisors to help us explore our feelings, resistances, and countertransference reactions.

Strategies to combat burnout

Psychiatric trainees must be encouraged to establish and maintain rigorous plans of self-care to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Most importantly, training programs must diversify residents’ clinical exposure by providing activities that promote mental health promotion activities, scholarly endeavors, and peer support groups. This will help trainees to restore meaning and purpose in life beyond.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

The far-reaching effects of death anxiety

Postgraduate psychiatry training may expose one to stressful situations with adverse psychologic consequences.1 Furthermore, when caring for patients, psychiatry trainees frequently need to face issues of death and dying in the form of suicide risk assessments, grief and bereavement processes, near-death experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psycho-oncology rotations. Because these interactions are incredibly personal, the emotions they provoke inevitably affect every interaction, theoretical discussion, diagnostic work-up, and treatment plan.

How each of us experiences death anxiety is unique. For some, it could be a fear of nonexistence, ultimate loss, disruption of the flow of life, worry about leaving loved ones behind, or fear of pain or loneliness in dying. Some might fear an untimely or violent death and subsequent judgment and retributions. The literature suggests that fear of death may be at the root of various mental health problems and, if left unaddressed, may adversely impact long-term treatment outcomes.2 Despite this, many standard treatment approaches typically do not target death anxiety, which potentially contributes to a “revolving door” of mental health problems.3

American existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom, MD, cautioned psychiatrists not to “scratch where it does not itch.”4 Yet death, according to Dr. Yalom, does itch. Violent death is that caused by human intent or negligence, and is characterized by feeling helpless and terrorized at the time of dying. It may occur as an acute incident that denies the dying individual and his/her family members the time and space to prepare for the death.5 For survivors, accommodating the mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual effects of violent death is a complex process that rarely has a conclusion. It often is accompanied by survivors’ guilt, which is replayed in the form of flashbacks and nightmares.6 With this understanding, I view COVID-19 deaths as violent deaths.

Pay close attention to countertransference

As much as we influence our patients and their families, we also are profoundly influenced by them. We need to pay attention to any feelings our clinical encounters generate within us, and to carefully use these feelings in our clinical judgment, and not just make causal inferences. For instance, if a clinician thinks that a patient with suicidal ideation would be better off dead, these feelings are a reliable indicator that the patient is, indeed, at a high risk of completing suicide.7 It is our ethical and moral responsibility towards our patients to listen to our countertransference responses. The aim is to identify countertransference and use it to inform us, not to rule us. By taking an active role in managing our emotional responses in the face of loss, we can harness the spirit of resilience. This is not always as easy as it seems. We need our peers, experienced clinicians, and supervisors to help us explore our feelings, resistances, and countertransference reactions.

Strategies to combat burnout

Psychiatric trainees must be encouraged to establish and maintain rigorous plans of self-care to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Most importantly, training programs must diversify residents’ clinical exposure by providing activities that promote mental health promotion activities, scholarly endeavors, and peer support groups. This will help trainees to restore meaning and purpose in life beyond.

1. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. What are some stressful adversities in psychiatry residency training, and how should they be managed professionally? Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):145-150.

2. Russac RJ, Gatliff C, Reece M, et al. Death anxiety across the adult years: an examination of age and gender effects. Death Stud. 2007;31(6):549-561.

3. Lisa I, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(7):580-593.

4. Yalom ID. Staring at the sun: being at peace with your own mortality. London, UK: Piatkus; 2011.

5. Rynearson EK, Johnson TA, Correa F. The horror and helplessness of violent death. In: Katz RS, Johnson TA (eds). When professionals weep: emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016:91-103.

6. Breggin PR. Guilt, shame, and anxiety: understanding and overcoming negative emotions. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books; 2014.

7. Katz RS, Johnson TA, (eds). When professionals weep: Emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016.

1. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. What are some stressful adversities in psychiatry residency training, and how should they be managed professionally? Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):145-150.

2. Russac RJ, Gatliff C, Reece M, et al. Death anxiety across the adult years: an examination of age and gender effects. Death Stud. 2007;31(6):549-561.

3. Lisa I, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(7):580-593.

4. Yalom ID. Staring at the sun: being at peace with your own mortality. London, UK: Piatkus; 2011.

5. Rynearson EK, Johnson TA, Correa F. The horror and helplessness of violent death. In: Katz RS, Johnson TA (eds). When professionals weep: emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016:91-103.

6. Breggin PR. Guilt, shame, and anxiety: understanding and overcoming negative emotions. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books; 2014.

7. Katz RS, Johnson TA, (eds). When professionals weep: Emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016.

Virtual residency/fellowship interviews: The good, the bad, and the future

As a psychiatry resident in the age of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many of my educational experiences have undergone adjustments. Now, as I interview for a fellowship, I see firsthand that recruitment activities have not been spared from shifting paradigms levied by the pandemic. To adhere to social distancing guidelines and limit trainee interpersonal exposure, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training recommended that all psychiatry residency interviews be conducted virtually for 2020/2021.1 Trainees and programs alike are embarking on a new frontier of virtual interviews, and it is important that we evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. Because uncertainty abounds regarding when a sense of normalcy might eventually return to psychiatry residency and fellowship recruitment activities, I also provide recommendations to interviewers and interviewees who may navigate virtual recruitment in the future.

Advantages of virtual interviews

An immediately significant advantage of virtual interviews is the lack of travel, which for some applicants can be cost-prohibitive. The costs of airfare, rental vehicles, and lodging in multiple cities can add up, sometimes requiring students to budget interview travel into already-high student loans. In some cases, applicants may have limited days to interview, which makes the flexibility afforded by the lack of travel advantageous. Furthermore, navigating new locations can add to preexisting interview stress. Without travel, applicants can consider a broader set of programs and accept more interviews.

Another advantage is that virtual interviews allow interviewees latitude to shift the interview’s “frame.” Rather than sitting in an interviewer’s office, interviewees can choose a more comfortable environment for themselves, imparting a “home-field advantage” that may put them at ease. During my fellowship interviews, controlling the room temperature, using a familiar chair, and wearing comfortable shoes helped to reduce the anxiety inherent to interviewing.

Disadvantages of virtual interviews

Any new or unfamiliar experience can impart challenges. For example, applicants and interviewers must adjust to and observe different sets of etiquette during virtual interviews. These include muting microphones to avoid talking over each other, maintaining consistent eye contact, avoiding multitasking, and following up to avoid miscommunication.

Another potential problem is that virtual interviews can dampen an applicant’s ability to appreciate a program’s culture. Observing informal interactions between trainees and faculty is often as important as the formal interviews in ascertaining which programs have a supportive culture. Because my virtual fellowship interviews have generally been limited to formal one-on-one interviews, assessing program culture has become more challenging. Conversely, programs may find it difficult to grasp an applicant’s temperament and interaction style.

Virtual interviewing, while undeniably convenient in many regards, may fall prey to its own convenience. There can be disparities in the quantity, duration, and frequency of interviews. For me, the number of and time allotted for interviews has varied widely, ranging from 2.5 to 8 hours. The amount of allotted break time has also differed, with some programs providing longer breaks between interviews (30 to 60 minutes) and others offering shorter (5 to 10 minutes) or no breaks. Minimal breaks may fatigue applicants, while longer breaks may seem like wasted time. While virtual interviews may require no physical travel between offices, breaks are a necessity that should be implemented thoughtfully.

Finally, a troublesome challenge I encountered surprisingly often was unreliable internet service and other technical difficulties. Several times, my interviewers’ (or my) screen froze or shut off due to connectivity issues. This is an obstacle unique to virtual interviews that requires both a backup plan as well as patience and calm to navigate during an already taxing situation.

Continue to: What's next?

What’s next?

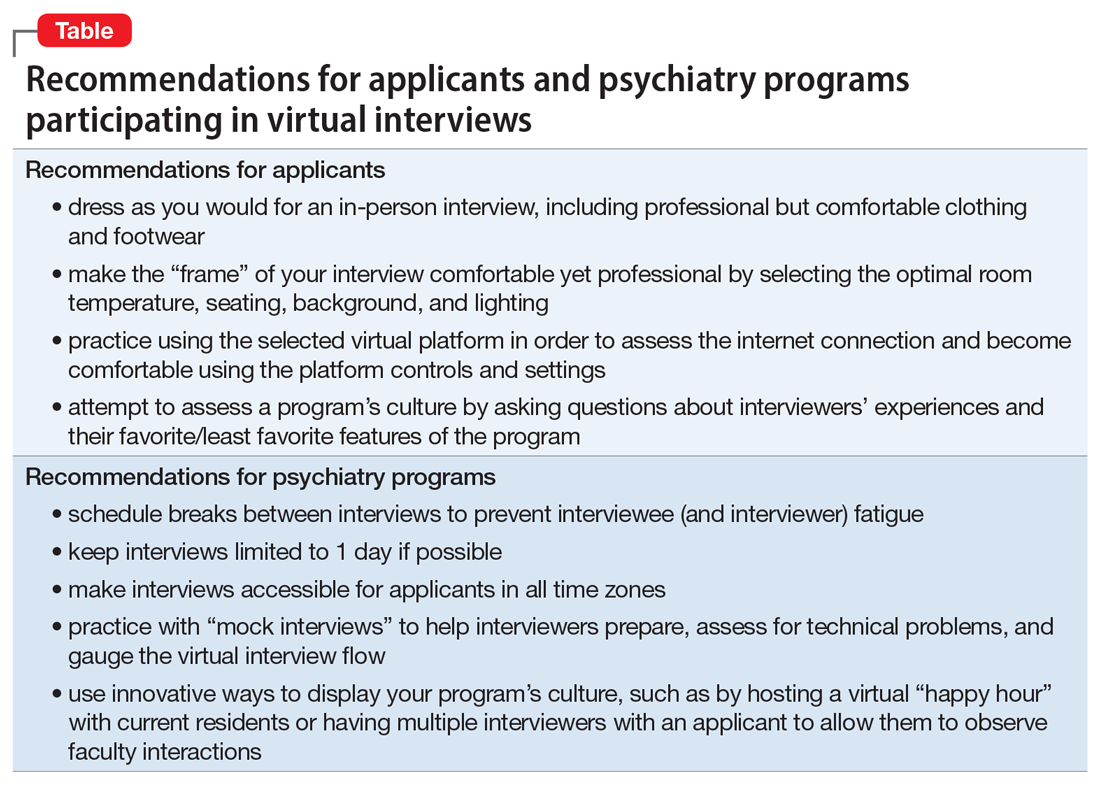

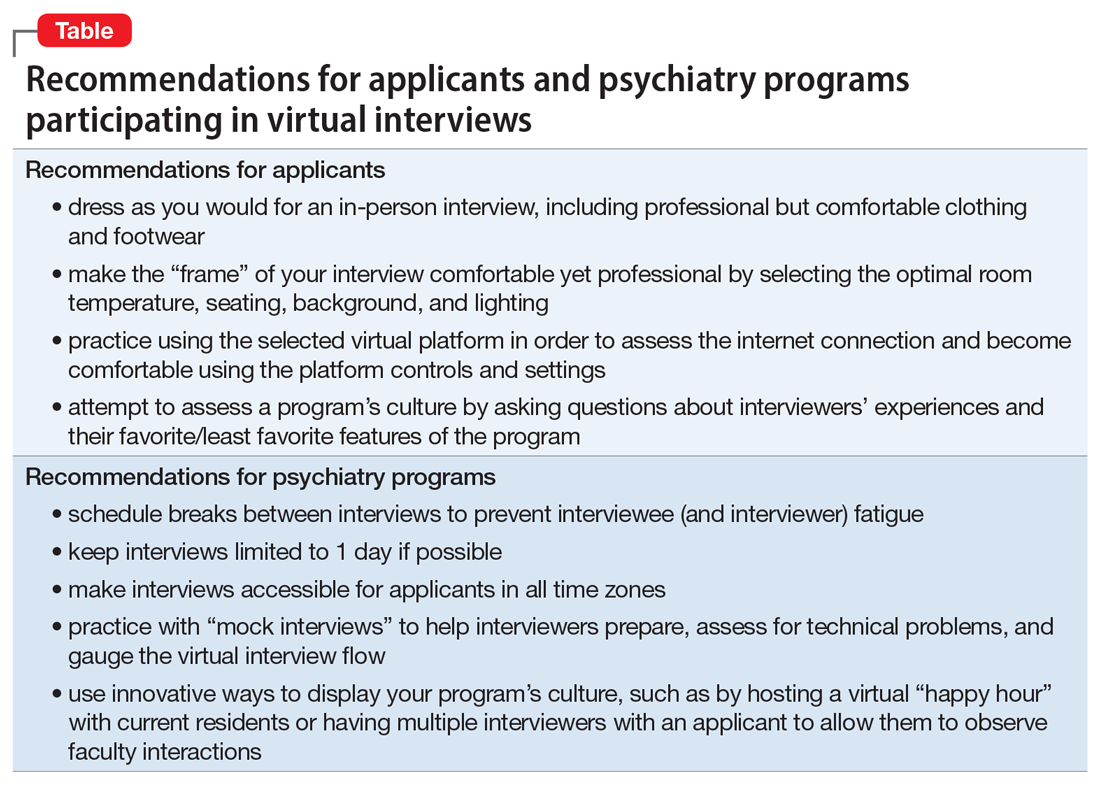

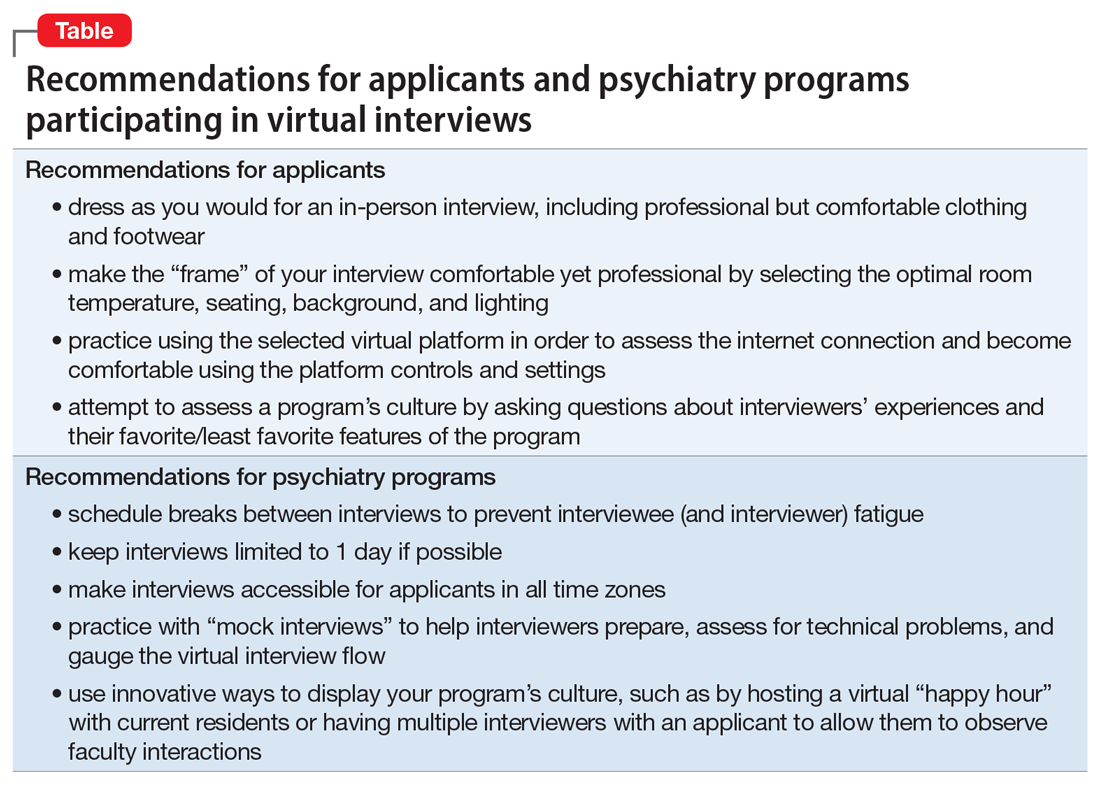

As applicants and programs adjust to the realities of virtual interviewing, this is likely an unfamiliar experience for all. While the benefits and shortcomings must be considered together, I, along with many of my peers,2 continue to prefer traditional in-person interviews. As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic makes in-person interviews difficult, applicants and programs must embrace the experience of virtual interviews. However, a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages are instrumental in preempting prospective challenges. Based on my recent experiences with virtual fellowship interviews, I have created some recommendations for applicants and psychiatry programs participating in virtual recruitment (Table).

After the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, it is conceivable that the advantages of virtual interviewing may justify its continued use. For example, applicants may be able to apply to geographically diverse programs without travel expenses. Currently, there is a paucity of evidence regarding virtual interviews specifically in psychiatry training programs, but the experiences of both applicants and psychiatry programs during this atypical time will allow us to improve the process going forward, and evaluate its utility well after COVID-19 recedes.

1. Arbuckle M, Kerlek A, Kovach J, et al. Consensus statement from the Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry (ADMSEP) and the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) on the 2020-21 Residency Application Cycle. https://www.aadprt.org/application/files/8816/0017/8240/admsep_aadprt_statement_9-14-20_Rev.pdf. Published May 18, 2020. Accessed November 20, 2020.

2. Seifi A, Mirahmadizadeh A, Eslami V. Perception of medical students and residents about virtual interviews for residency applications in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0238239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238239.

As a psychiatry resident in the age of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many of my educational experiences have undergone adjustments. Now, as I interview for a fellowship, I see firsthand that recruitment activities have not been spared from shifting paradigms levied by the pandemic. To adhere to social distancing guidelines and limit trainee interpersonal exposure, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training recommended that all psychiatry residency interviews be conducted virtually for 2020/2021.1 Trainees and programs alike are embarking on a new frontier of virtual interviews, and it is important that we evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. Because uncertainty abounds regarding when a sense of normalcy might eventually return to psychiatry residency and fellowship recruitment activities, I also provide recommendations to interviewers and interviewees who may navigate virtual recruitment in the future.

Advantages of virtual interviews

An immediately significant advantage of virtual interviews is the lack of travel, which for some applicants can be cost-prohibitive. The costs of airfare, rental vehicles, and lodging in multiple cities can add up, sometimes requiring students to budget interview travel into already-high student loans. In some cases, applicants may have limited days to interview, which makes the flexibility afforded by the lack of travel advantageous. Furthermore, navigating new locations can add to preexisting interview stress. Without travel, applicants can consider a broader set of programs and accept more interviews.

Another advantage is that virtual interviews allow interviewees latitude to shift the interview’s “frame.” Rather than sitting in an interviewer’s office, interviewees can choose a more comfortable environment for themselves, imparting a “home-field advantage” that may put them at ease. During my fellowship interviews, controlling the room temperature, using a familiar chair, and wearing comfortable shoes helped to reduce the anxiety inherent to interviewing.

Disadvantages of virtual interviews

Any new or unfamiliar experience can impart challenges. For example, applicants and interviewers must adjust to and observe different sets of etiquette during virtual interviews. These include muting microphones to avoid talking over each other, maintaining consistent eye contact, avoiding multitasking, and following up to avoid miscommunication.

Another potential problem is that virtual interviews can dampen an applicant’s ability to appreciate a program’s culture. Observing informal interactions between trainees and faculty is often as important as the formal interviews in ascertaining which programs have a supportive culture. Because my virtual fellowship interviews have generally been limited to formal one-on-one interviews, assessing program culture has become more challenging. Conversely, programs may find it difficult to grasp an applicant’s temperament and interaction style.

Virtual interviewing, while undeniably convenient in many regards, may fall prey to its own convenience. There can be disparities in the quantity, duration, and frequency of interviews. For me, the number of and time allotted for interviews has varied widely, ranging from 2.5 to 8 hours. The amount of allotted break time has also differed, with some programs providing longer breaks between interviews (30 to 60 minutes) and others offering shorter (5 to 10 minutes) or no breaks. Minimal breaks may fatigue applicants, while longer breaks may seem like wasted time. While virtual interviews may require no physical travel between offices, breaks are a necessity that should be implemented thoughtfully.

Finally, a troublesome challenge I encountered surprisingly often was unreliable internet service and other technical difficulties. Several times, my interviewers’ (or my) screen froze or shut off due to connectivity issues. This is an obstacle unique to virtual interviews that requires both a backup plan as well as patience and calm to navigate during an already taxing situation.

Continue to: What's next?

What’s next?

As applicants and programs adjust to the realities of virtual interviewing, this is likely an unfamiliar experience for all. While the benefits and shortcomings must be considered together, I, along with many of my peers,2 continue to prefer traditional in-person interviews. As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic makes in-person interviews difficult, applicants and programs must embrace the experience of virtual interviews. However, a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages are instrumental in preempting prospective challenges. Based on my recent experiences with virtual fellowship interviews, I have created some recommendations for applicants and psychiatry programs participating in virtual recruitment (Table).

After the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, it is conceivable that the advantages of virtual interviewing may justify its continued use. For example, applicants may be able to apply to geographically diverse programs without travel expenses. Currently, there is a paucity of evidence regarding virtual interviews specifically in psychiatry training programs, but the experiences of both applicants and psychiatry programs during this atypical time will allow us to improve the process going forward, and evaluate its utility well after COVID-19 recedes.

As a psychiatry resident in the age of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many of my educational experiences have undergone adjustments. Now, as I interview for a fellowship, I see firsthand that recruitment activities have not been spared from shifting paradigms levied by the pandemic. To adhere to social distancing guidelines and limit trainee interpersonal exposure, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training recommended that all psychiatry residency interviews be conducted virtually for 2020/2021.1 Trainees and programs alike are embarking on a new frontier of virtual interviews, and it is important that we evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. Because uncertainty abounds regarding when a sense of normalcy might eventually return to psychiatry residency and fellowship recruitment activities, I also provide recommendations to interviewers and interviewees who may navigate virtual recruitment in the future.

Advantages of virtual interviews

An immediately significant advantage of virtual interviews is the lack of travel, which for some applicants can be cost-prohibitive. The costs of airfare, rental vehicles, and lodging in multiple cities can add up, sometimes requiring students to budget interview travel into already-high student loans. In some cases, applicants may have limited days to interview, which makes the flexibility afforded by the lack of travel advantageous. Furthermore, navigating new locations can add to preexisting interview stress. Without travel, applicants can consider a broader set of programs and accept more interviews.

Another advantage is that virtual interviews allow interviewees latitude to shift the interview’s “frame.” Rather than sitting in an interviewer’s office, interviewees can choose a more comfortable environment for themselves, imparting a “home-field advantage” that may put them at ease. During my fellowship interviews, controlling the room temperature, using a familiar chair, and wearing comfortable shoes helped to reduce the anxiety inherent to interviewing.

Disadvantages of virtual interviews

Any new or unfamiliar experience can impart challenges. For example, applicants and interviewers must adjust to and observe different sets of etiquette during virtual interviews. These include muting microphones to avoid talking over each other, maintaining consistent eye contact, avoiding multitasking, and following up to avoid miscommunication.

Another potential problem is that virtual interviews can dampen an applicant’s ability to appreciate a program’s culture. Observing informal interactions between trainees and faculty is often as important as the formal interviews in ascertaining which programs have a supportive culture. Because my virtual fellowship interviews have generally been limited to formal one-on-one interviews, assessing program culture has become more challenging. Conversely, programs may find it difficult to grasp an applicant’s temperament and interaction style.

Virtual interviewing, while undeniably convenient in many regards, may fall prey to its own convenience. There can be disparities in the quantity, duration, and frequency of interviews. For me, the number of and time allotted for interviews has varied widely, ranging from 2.5 to 8 hours. The amount of allotted break time has also differed, with some programs providing longer breaks between interviews (30 to 60 minutes) and others offering shorter (5 to 10 minutes) or no breaks. Minimal breaks may fatigue applicants, while longer breaks may seem like wasted time. While virtual interviews may require no physical travel between offices, breaks are a necessity that should be implemented thoughtfully.

Finally, a troublesome challenge I encountered surprisingly often was unreliable internet service and other technical difficulties. Several times, my interviewers’ (or my) screen froze or shut off due to connectivity issues. This is an obstacle unique to virtual interviews that requires both a backup plan as well as patience and calm to navigate during an already taxing situation.

Continue to: What's next?

What’s next?

As applicants and programs adjust to the realities of virtual interviewing, this is likely an unfamiliar experience for all. While the benefits and shortcomings must be considered together, I, along with many of my peers,2 continue to prefer traditional in-person interviews. As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic makes in-person interviews difficult, applicants and programs must embrace the experience of virtual interviews. However, a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages are instrumental in preempting prospective challenges. Based on my recent experiences with virtual fellowship interviews, I have created some recommendations for applicants and psychiatry programs participating in virtual recruitment (Table).

After the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, it is conceivable that the advantages of virtual interviewing may justify its continued use. For example, applicants may be able to apply to geographically diverse programs without travel expenses. Currently, there is a paucity of evidence regarding virtual interviews specifically in psychiatry training programs, but the experiences of both applicants and psychiatry programs during this atypical time will allow us to improve the process going forward, and evaluate its utility well after COVID-19 recedes.

1. Arbuckle M, Kerlek A, Kovach J, et al. Consensus statement from the Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry (ADMSEP) and the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) on the 2020-21 Residency Application Cycle. https://www.aadprt.org/application/files/8816/0017/8240/admsep_aadprt_statement_9-14-20_Rev.pdf. Published May 18, 2020. Accessed November 20, 2020.