User login

The Power of a Multidisciplinary Tumor Board: Managing Unresectable and/or High-Risk Skin Cancers

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Improved Workup and Diagnosis

One of the values of a tumor board is that it allows for patient data to be collected and assembled in a way that tells a story. The specialist from each field can then discuss and weigh the benefits and risks for each diagnostic test that should be performed for the workup in each patient. Physicians who refer their patients to the tumor board use their recommendations to both confirm the diagnosis and shift their treatment plans, depending on the information presented during the meeting.1 There may be a change in the tumor type, decision to refer for surgery, cancer staging, and list of viable options, especially after reviewing pathology and imaging.2 The discussion of the treatment plan may consider not only surgical considerations but also the patient’s quality of life. At times, noninvasive interventions are more appropriate and align with the patient’s goals of care. In addition, during the tumor board clinic there may be new tumors that are identified and biopsied, providing increased diagnosis and surveillance for patients who may have a higher risk for developing skin cancer.

Education for Residents and Providers

The multidisciplinary tumor board not only helps patients but also educates both residents and providers on the evidence-based therapeutic management of high-risk tumors.2 Research literature on cutaneous oncology is dynamic, and the weekly tumor board meetings help providers stay informed about the best and most effective treatments for their patients.3 In addition to the attending specialists, participants of the tumor board also may include residents, medical students, medical assistance staff, nurses, physician assistants, and fellows. Furthermore, the recommendations given by the tumor board serve to educate both the patient and the provider who referred them to the tumor board. Although we have access to excellent dermatology textbooks as residents, the most impactful educational experience is seeing the patients in tumor board clinic and participating in the immensely educational discussions at the weekly conferences. Through this experience, I have learned that treatment plans should be personalized to the patient. There are many factors to take into consideration when deciphering what the best course of treatment will be for a patient. Sometimes the best option is Mohs micrographic surgery, while other times it may be scheduling several sessions of palliative radiation oncology. Treatment depends on the individual patient and their condition.

Coordination of Care

During a week that I was on call, I was consulted to biopsy a patient with a giant hemorrhagic basal cell carcinoma that caused substantial cheek and nose distortion as well as anemia secondary to acute blood loss. The patient not only did not have a dermatologist but also did not have a primary care physician given he had not had contact with the health care system in more than 30 years. The reason for him not seeking care was multifactorial, but the approach to his care became multidisciplinary. We sought to connect him with the right providers to help him in any way that we could. We presented him at our multidisciplinary tumor board and started him on sonedigib, a medication that binds to and inhibits the smoothened protein.4 Through the tumor board, we were able to establish sustained contact with the patient. The tumor board created effective communication between providers to get him the referrals that he needed for dermatology, pathology, radiation oncology, hematology/oncology, and otolaryngology. The discussions centered around being cognizant of the patient’s apprehension with the health care system as well as providing medical and surgical treatment that would help his quality of life. We built a consensus on what the best plan was for the patient and his family. This consensus would have been more difficult had it not been for the combined specialties of the tumor board. In general, studies have shown that weekly tumor boards have resulted in decreased mortality rates for patients with advanced cancers.5

Final Thoughts

The multidisciplinary tumor board is a powerful resource for hospitals and the greater medical community. At these weekly conferences you realize there may still be hope that begins at the line where your expertise ends. It represents a team of providers who compassionately refuse to give up on patients when they are the last refuge.

- Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:E895.

- El Saghir NS, Charara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1:57-64.

- Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, et al. Tumor board conferences for multidisciplinary skin cancer management: a survey of US cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1209-1215.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1944-1956.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:E267-E278.

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Improved Workup and Diagnosis

One of the values of a tumor board is that it allows for patient data to be collected and assembled in a way that tells a story. The specialist from each field can then discuss and weigh the benefits and risks for each diagnostic test that should be performed for the workup in each patient. Physicians who refer their patients to the tumor board use their recommendations to both confirm the diagnosis and shift their treatment plans, depending on the information presented during the meeting.1 There may be a change in the tumor type, decision to refer for surgery, cancer staging, and list of viable options, especially after reviewing pathology and imaging.2 The discussion of the treatment plan may consider not only surgical considerations but also the patient’s quality of life. At times, noninvasive interventions are more appropriate and align with the patient’s goals of care. In addition, during the tumor board clinic there may be new tumors that are identified and biopsied, providing increased diagnosis and surveillance for patients who may have a higher risk for developing skin cancer.

Education for Residents and Providers

The multidisciplinary tumor board not only helps patients but also educates both residents and providers on the evidence-based therapeutic management of high-risk tumors.2 Research literature on cutaneous oncology is dynamic, and the weekly tumor board meetings help providers stay informed about the best and most effective treatments for their patients.3 In addition to the attending specialists, participants of the tumor board also may include residents, medical students, medical assistance staff, nurses, physician assistants, and fellows. Furthermore, the recommendations given by the tumor board serve to educate both the patient and the provider who referred them to the tumor board. Although we have access to excellent dermatology textbooks as residents, the most impactful educational experience is seeing the patients in tumor board clinic and participating in the immensely educational discussions at the weekly conferences. Through this experience, I have learned that treatment plans should be personalized to the patient. There are many factors to take into consideration when deciphering what the best course of treatment will be for a patient. Sometimes the best option is Mohs micrographic surgery, while other times it may be scheduling several sessions of palliative radiation oncology. Treatment depends on the individual patient and their condition.

Coordination of Care

During a week that I was on call, I was consulted to biopsy a patient with a giant hemorrhagic basal cell carcinoma that caused substantial cheek and nose distortion as well as anemia secondary to acute blood loss. The patient not only did not have a dermatologist but also did not have a primary care physician given he had not had contact with the health care system in more than 30 years. The reason for him not seeking care was multifactorial, but the approach to his care became multidisciplinary. We sought to connect him with the right providers to help him in any way that we could. We presented him at our multidisciplinary tumor board and started him on sonedigib, a medication that binds to and inhibits the smoothened protein.4 Through the tumor board, we were able to establish sustained contact with the patient. The tumor board created effective communication between providers to get him the referrals that he needed for dermatology, pathology, radiation oncology, hematology/oncology, and otolaryngology. The discussions centered around being cognizant of the patient’s apprehension with the health care system as well as providing medical and surgical treatment that would help his quality of life. We built a consensus on what the best plan was for the patient and his family. This consensus would have been more difficult had it not been for the combined specialties of the tumor board. In general, studies have shown that weekly tumor boards have resulted in decreased mortality rates for patients with advanced cancers.5

Final Thoughts

The multidisciplinary tumor board is a powerful resource for hospitals and the greater medical community. At these weekly conferences you realize there may still be hope that begins at the line where your expertise ends. It represents a team of providers who compassionately refuse to give up on patients when they are the last refuge.

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Improved Workup and Diagnosis

One of the values of a tumor board is that it allows for patient data to be collected and assembled in a way that tells a story. The specialist from each field can then discuss and weigh the benefits and risks for each diagnostic test that should be performed for the workup in each patient. Physicians who refer their patients to the tumor board use their recommendations to both confirm the diagnosis and shift their treatment plans, depending on the information presented during the meeting.1 There may be a change in the tumor type, decision to refer for surgery, cancer staging, and list of viable options, especially after reviewing pathology and imaging.2 The discussion of the treatment plan may consider not only surgical considerations but also the patient’s quality of life. At times, noninvasive interventions are more appropriate and align with the patient’s goals of care. In addition, during the tumor board clinic there may be new tumors that are identified and biopsied, providing increased diagnosis and surveillance for patients who may have a higher risk for developing skin cancer.

Education for Residents and Providers

The multidisciplinary tumor board not only helps patients but also educates both residents and providers on the evidence-based therapeutic management of high-risk tumors.2 Research literature on cutaneous oncology is dynamic, and the weekly tumor board meetings help providers stay informed about the best and most effective treatments for their patients.3 In addition to the attending specialists, participants of the tumor board also may include residents, medical students, medical assistance staff, nurses, physician assistants, and fellows. Furthermore, the recommendations given by the tumor board serve to educate both the patient and the provider who referred them to the tumor board. Although we have access to excellent dermatology textbooks as residents, the most impactful educational experience is seeing the patients in tumor board clinic and participating in the immensely educational discussions at the weekly conferences. Through this experience, I have learned that treatment plans should be personalized to the patient. There are many factors to take into consideration when deciphering what the best course of treatment will be for a patient. Sometimes the best option is Mohs micrographic surgery, while other times it may be scheduling several sessions of palliative radiation oncology. Treatment depends on the individual patient and their condition.

Coordination of Care

During a week that I was on call, I was consulted to biopsy a patient with a giant hemorrhagic basal cell carcinoma that caused substantial cheek and nose distortion as well as anemia secondary to acute blood loss. The patient not only did not have a dermatologist but also did not have a primary care physician given he had not had contact with the health care system in more than 30 years. The reason for him not seeking care was multifactorial, but the approach to his care became multidisciplinary. We sought to connect him with the right providers to help him in any way that we could. We presented him at our multidisciplinary tumor board and started him on sonedigib, a medication that binds to and inhibits the smoothened protein.4 Through the tumor board, we were able to establish sustained contact with the patient. The tumor board created effective communication between providers to get him the referrals that he needed for dermatology, pathology, radiation oncology, hematology/oncology, and otolaryngology. The discussions centered around being cognizant of the patient’s apprehension with the health care system as well as providing medical and surgical treatment that would help his quality of life. We built a consensus on what the best plan was for the patient and his family. This consensus would have been more difficult had it not been for the combined specialties of the tumor board. In general, studies have shown that weekly tumor boards have resulted in decreased mortality rates for patients with advanced cancers.5

Final Thoughts

The multidisciplinary tumor board is a powerful resource for hospitals and the greater medical community. At these weekly conferences you realize there may still be hope that begins at the line where your expertise ends. It represents a team of providers who compassionately refuse to give up on patients when they are the last refuge.

- Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:E895.

- El Saghir NS, Charara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1:57-64.

- Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, et al. Tumor board conferences for multidisciplinary skin cancer management: a survey of US cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1209-1215.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1944-1956.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:E267-E278.

- Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:E895.

- El Saghir NS, Charara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1:57-64.

- Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, et al. Tumor board conferences for multidisciplinary skin cancer management: a survey of US cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1209-1215.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1944-1956.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:E267-E278.

Resident Pearl

- Participating in a multidisciplinary tumor board allows residents to learn more about how to manage and treat high-risk skin cancers. The multidisciplinary team approach provides high-quality care for challenging patients.

Harassment of health care workers: A survey

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

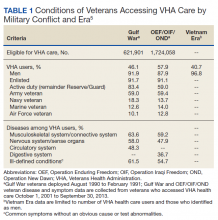

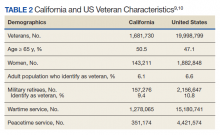

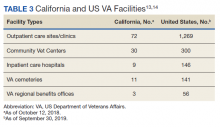

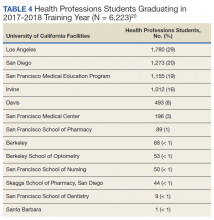

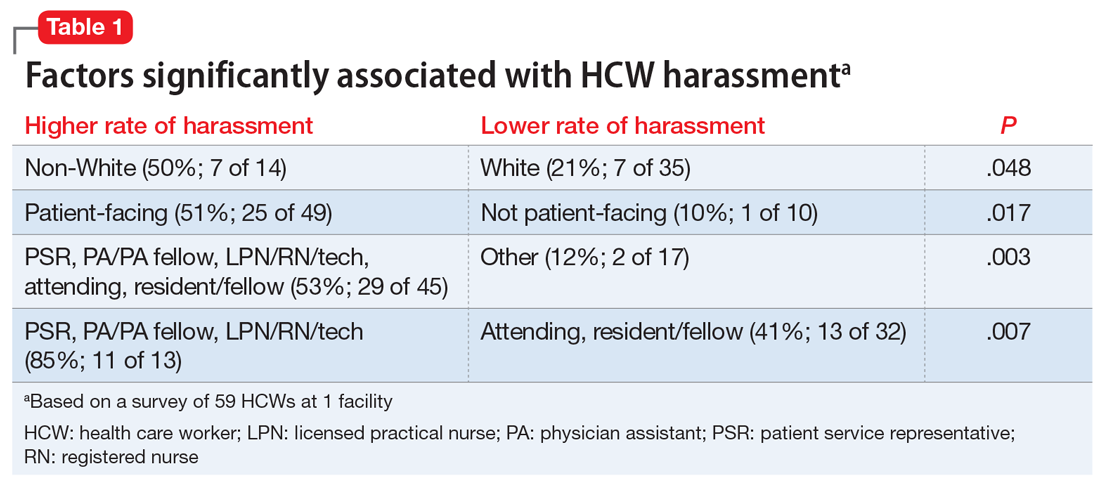

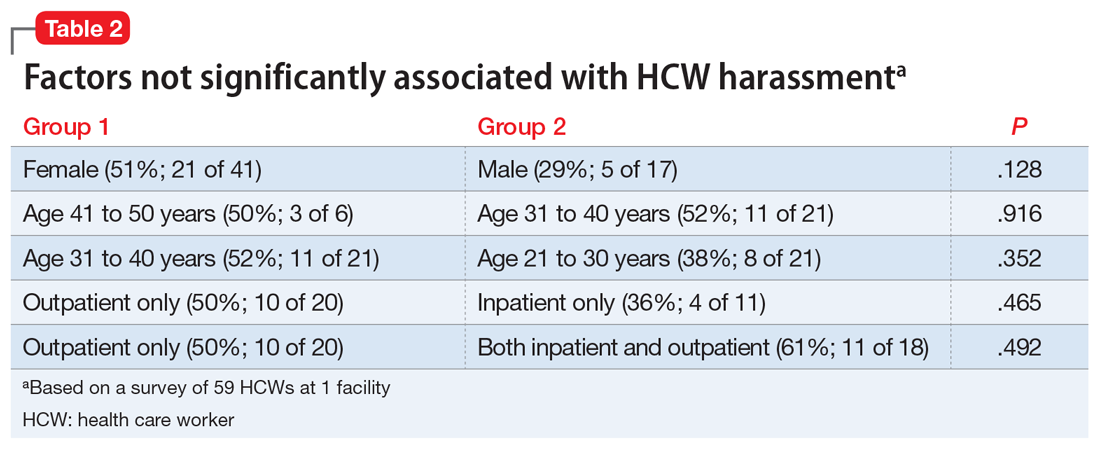

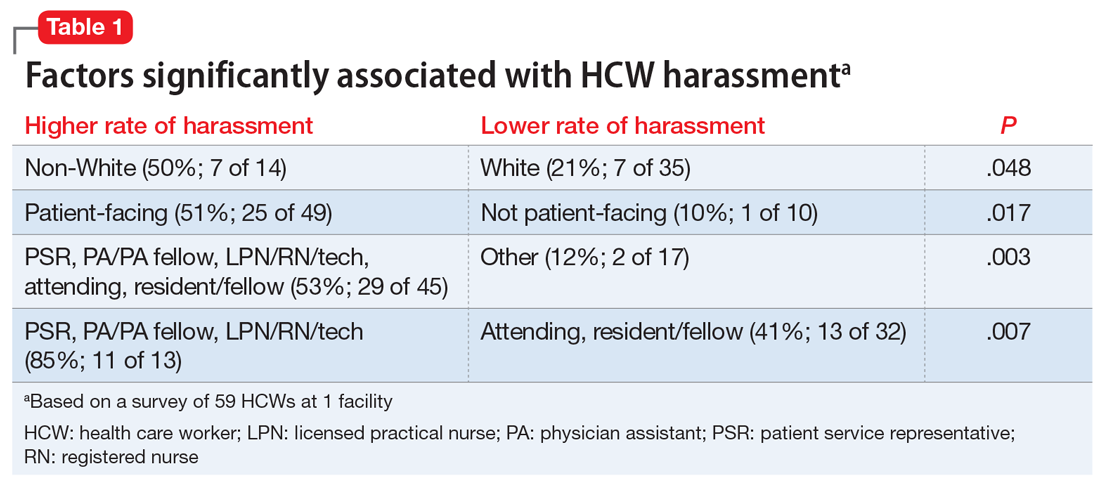

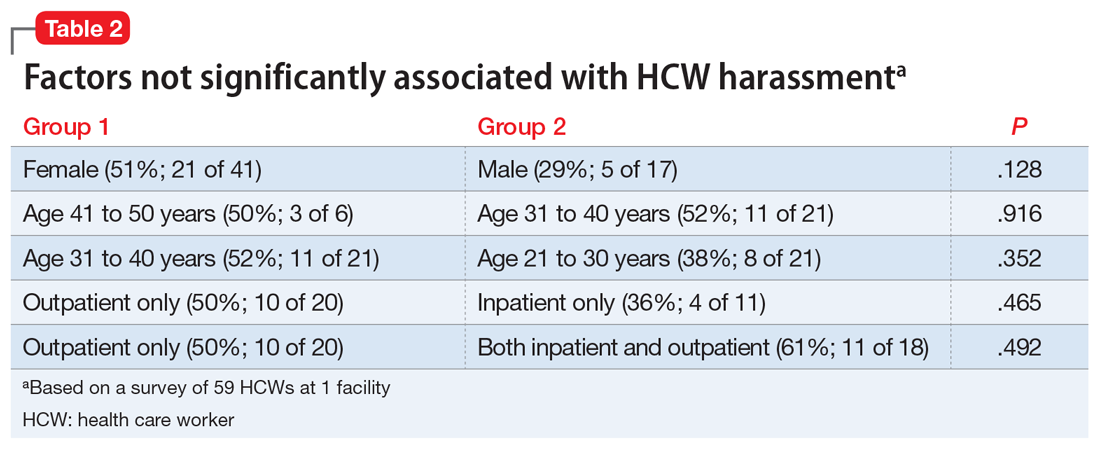

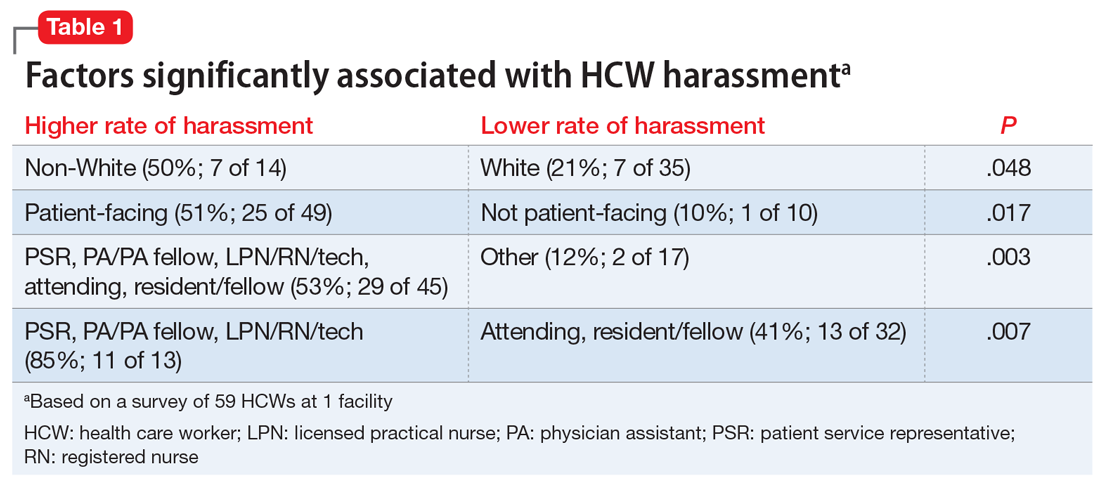

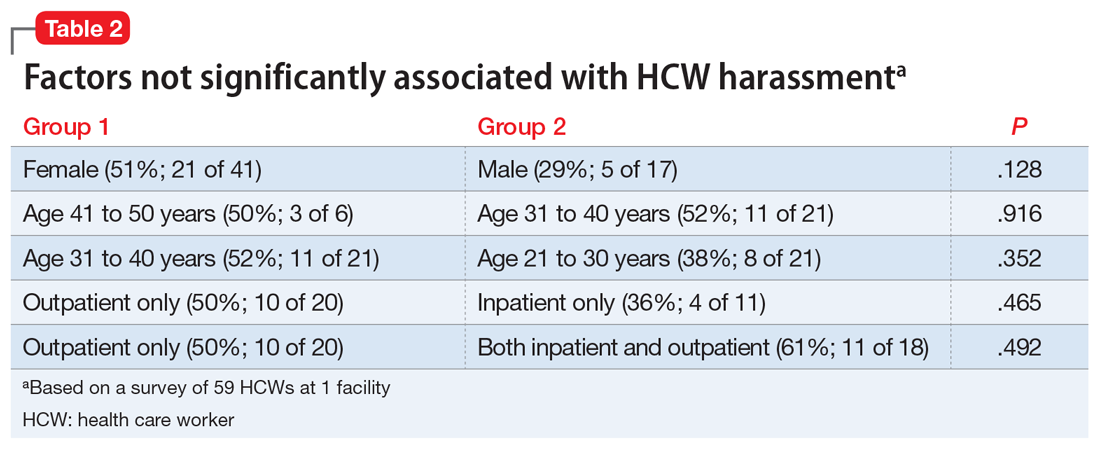

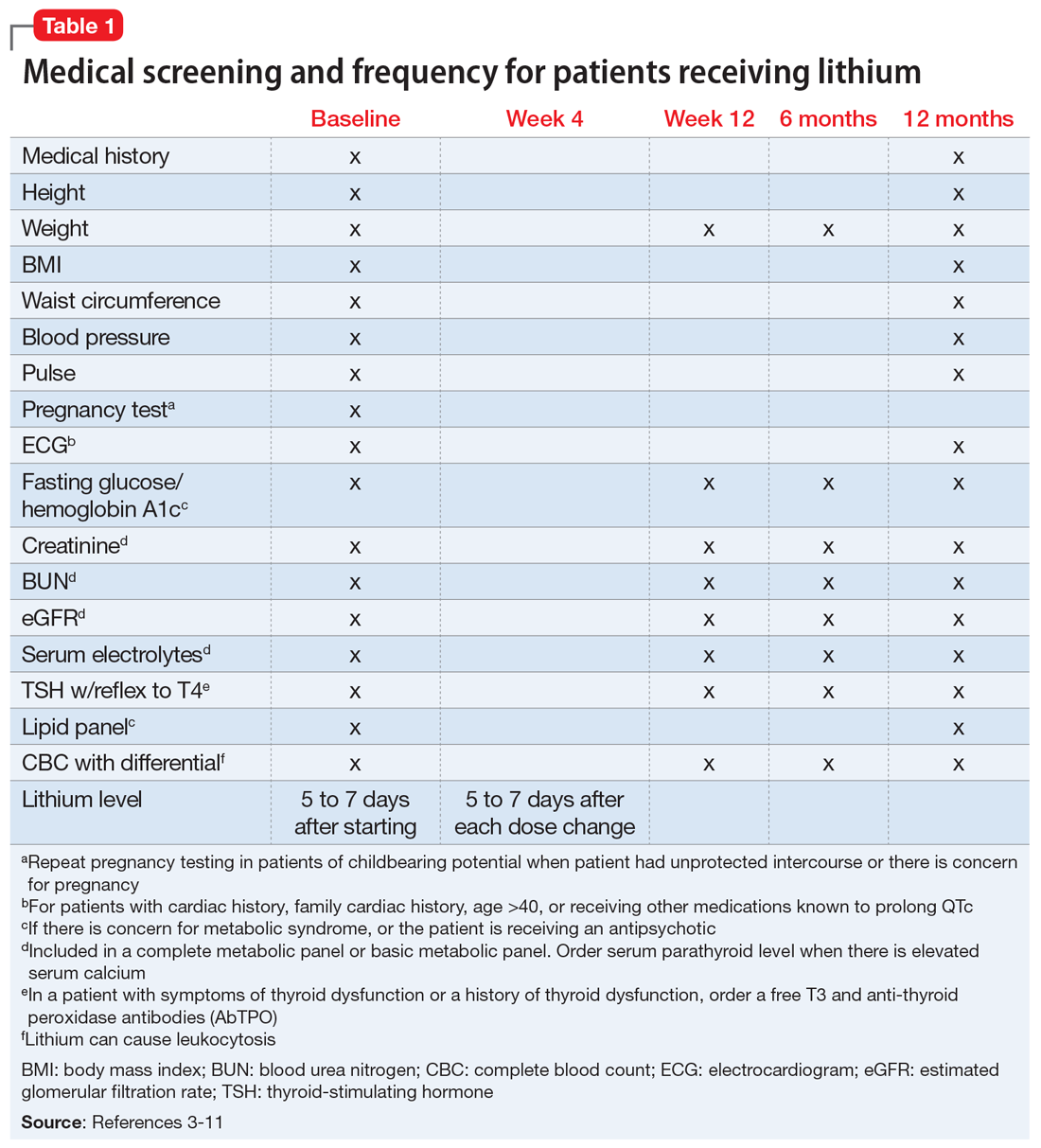

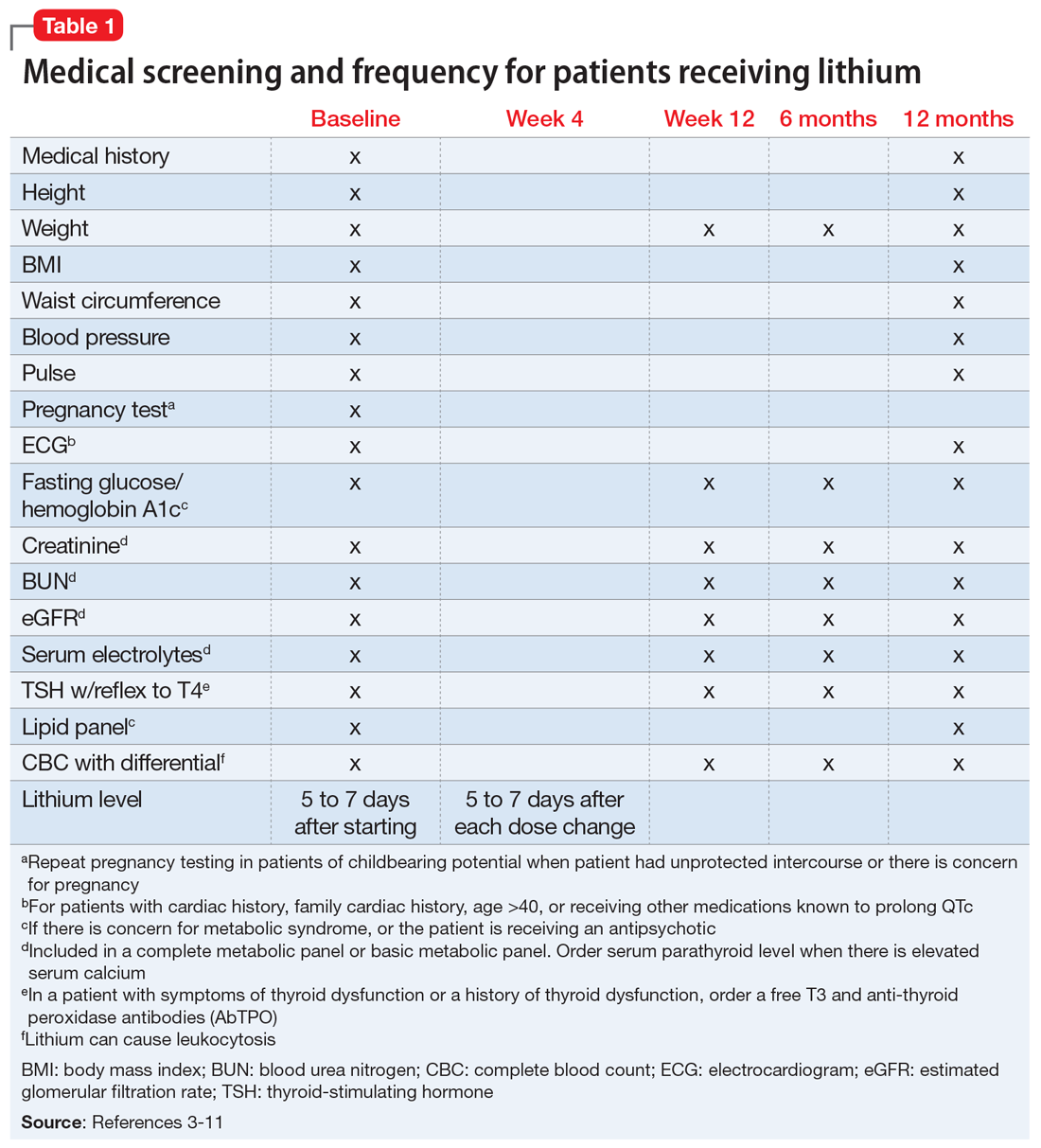

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

Private practice: The basics for psychiatry trainees

Many psychiatry trainees consider private practice as a career option or form of supplemental income. In my experience, however, residency training may provide limited introduction to the general steps involved in starting a practice. In this article, I briefly summarize what I learned while exploring the private practice option as a psychiatry resident.

A good specialty for private practice

Trainees in the earlier stages of their education should be aware that the first step toward private practice may actually occur during medical school, when they are considering which specialty to pursue. If a student is particularly interested in solo private practice, they may want to select a specialty with the potential for less overhead in an independent setting. Psychiatry typically has lower overhead costs than some other specialties. This gap widens even further with the increased popularity and acceptance of telepsychiatry.

Budgeting and finance

Once you decide to pursue private practice, you will want to consider whether you prefer solo practice or group practice, and part-time or full-time. If working for yourself, you will need to understand business planning and budgeting, including how to project revenue and expenses. When first starting in solo practice—especially if you are not taking over a previously established practice—it is useful to have secondary sources of income. This can be a part-time clinical position, working with on-demand health care companies, contracting, consulting, etc. Many new physicians begin with a full-time position and decide to initiate their private practice on a part-time basis. This approach provides a level of financial security that you otherwise would not have. However, a full-time position requires full-time energy, hours, and attention, and it can be challenging to balance full-time and part-time work. Whichever approach you decide to take, it can be most helpful to simply keep an open mind and always consider looking further into any new opportunity that interests you.

Insurance and licensing

You don’t have to wait to establish your own practice to purchase malpractice insurance. Shop around for the best rates and the coverage that most comprehensively fits your needs. If your training program allows “moonlighting,” you might need your own insurance to work at sites other than your training hospital. Many residents begin to apply for independent state licensure at the same time they begin pursuing moonlighting opportunities. It may be helpful not to wait until the last minute to do this, because the process has quite a few steps and can take a while. If your state requires letters of reference, think about which of your supervisors you can ask for one. If you plan to work in a state other than that of your training location, it may be helpful to simultaneously apply for your medical license in that state, because you will already be going through the process. Certain states offer reciprocity regarding medical licenses. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact offers an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who want to practice in multiple states.1

Marketing your practice

Potential sources for building a panel of patients include referral networks, insurance panels, professional organizations, social media, networking, directories, and word of mouth. If you plan to accept health insurance, the directories provided by insurance panels will allow potential patients to find you when searching for practitioners who accept their plan. Professional organizations offer similar directories, and some private companies also provide directories, either for free or for a fee.

Use technology to your advantage

The exciting thing about starting a private practice today is that the technology available to support a small practice has drastically improved. Many software applications can help with scheduling and billing, which minimizes the need for office staff and enables you to be more productive. These programs typically are available via an online subscription that gives you access to an electronic medical record and other features for a monthly fee. Many of these programs provide add-ons such as a website for your practice and integrated telehealth services. While these programs typically perform many of the same functions, each has a different setup and varying workflows. An online search can facilitate a side-by-side comparison of the software programs that most closely meet your needs.

Seek out mentors and consultants

Finally, try to find a private practice mentor, and reach out to as many people as possible who have worked in any type of private practice setting. A mentor can alert you to factors you might not otherwise have considered. It also may be helpful to establish some form of supervision; such opportunities can be found through professional societies and other groups for private practice clinicians. In these groups, you also can ask other clinicians to recommend private practice and practice management consultants.

Stepping into the unknown can be an intimidating experience; however, you will not know what you are capable of until you try. Fortunately, psychiatry offers the flexibility to create a hybrid career that allows you to follow your passion and maintain your level of comfort. The American Psychiatric Association offers members additional information in the practice management resources section of its website.2

1. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Information for physicians. 2020. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.imlcc.org/information-for-physicians

2. American Psychiatric Association. Online practice handbook. 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/practice-management/starting-a-practice/online-practice-handbook

Many psychiatry trainees consider private practice as a career option or form of supplemental income. In my experience, however, residency training may provide limited introduction to the general steps involved in starting a practice. In this article, I briefly summarize what I learned while exploring the private practice option as a psychiatry resident.

A good specialty for private practice

Trainees in the earlier stages of their education should be aware that the first step toward private practice may actually occur during medical school, when they are considering which specialty to pursue. If a student is particularly interested in solo private practice, they may want to select a specialty with the potential for less overhead in an independent setting. Psychiatry typically has lower overhead costs than some other specialties. This gap widens even further with the increased popularity and acceptance of telepsychiatry.

Budgeting and finance

Once you decide to pursue private practice, you will want to consider whether you prefer solo practice or group practice, and part-time or full-time. If working for yourself, you will need to understand business planning and budgeting, including how to project revenue and expenses. When first starting in solo practice—especially if you are not taking over a previously established practice—it is useful to have secondary sources of income. This can be a part-time clinical position, working with on-demand health care companies, contracting, consulting, etc. Many new physicians begin with a full-time position and decide to initiate their private practice on a part-time basis. This approach provides a level of financial security that you otherwise would not have. However, a full-time position requires full-time energy, hours, and attention, and it can be challenging to balance full-time and part-time work. Whichever approach you decide to take, it can be most helpful to simply keep an open mind and always consider looking further into any new opportunity that interests you.

Insurance and licensing

You don’t have to wait to establish your own practice to purchase malpractice insurance. Shop around for the best rates and the coverage that most comprehensively fits your needs. If your training program allows “moonlighting,” you might need your own insurance to work at sites other than your training hospital. Many residents begin to apply for independent state licensure at the same time they begin pursuing moonlighting opportunities. It may be helpful not to wait until the last minute to do this, because the process has quite a few steps and can take a while. If your state requires letters of reference, think about which of your supervisors you can ask for one. If you plan to work in a state other than that of your training location, it may be helpful to simultaneously apply for your medical license in that state, because you will already be going through the process. Certain states offer reciprocity regarding medical licenses. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact offers an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who want to practice in multiple states.1

Marketing your practice

Potential sources for building a panel of patients include referral networks, insurance panels, professional organizations, social media, networking, directories, and word of mouth. If you plan to accept health insurance, the directories provided by insurance panels will allow potential patients to find you when searching for practitioners who accept their plan. Professional organizations offer similar directories, and some private companies also provide directories, either for free or for a fee.

Use technology to your advantage

The exciting thing about starting a private practice today is that the technology available to support a small practice has drastically improved. Many software applications can help with scheduling and billing, which minimizes the need for office staff and enables you to be more productive. These programs typically are available via an online subscription that gives you access to an electronic medical record and other features for a monthly fee. Many of these programs provide add-ons such as a website for your practice and integrated telehealth services. While these programs typically perform many of the same functions, each has a different setup and varying workflows. An online search can facilitate a side-by-side comparison of the software programs that most closely meet your needs.

Seek out mentors and consultants

Finally, try to find a private practice mentor, and reach out to as many people as possible who have worked in any type of private practice setting. A mentor can alert you to factors you might not otherwise have considered. It also may be helpful to establish some form of supervision; such opportunities can be found through professional societies and other groups for private practice clinicians. In these groups, you also can ask other clinicians to recommend private practice and practice management consultants.

Stepping into the unknown can be an intimidating experience; however, you will not know what you are capable of until you try. Fortunately, psychiatry offers the flexibility to create a hybrid career that allows you to follow your passion and maintain your level of comfort. The American Psychiatric Association offers members additional information in the practice management resources section of its website.2

Many psychiatry trainees consider private practice as a career option or form of supplemental income. In my experience, however, residency training may provide limited introduction to the general steps involved in starting a practice. In this article, I briefly summarize what I learned while exploring the private practice option as a psychiatry resident.

A good specialty for private practice

Trainees in the earlier stages of their education should be aware that the first step toward private practice may actually occur during medical school, when they are considering which specialty to pursue. If a student is particularly interested in solo private practice, they may want to select a specialty with the potential for less overhead in an independent setting. Psychiatry typically has lower overhead costs than some other specialties. This gap widens even further with the increased popularity and acceptance of telepsychiatry.

Budgeting and finance

Once you decide to pursue private practice, you will want to consider whether you prefer solo practice or group practice, and part-time or full-time. If working for yourself, you will need to understand business planning and budgeting, including how to project revenue and expenses. When first starting in solo practice—especially if you are not taking over a previously established practice—it is useful to have secondary sources of income. This can be a part-time clinical position, working with on-demand health care companies, contracting, consulting, etc. Many new physicians begin with a full-time position and decide to initiate their private practice on a part-time basis. This approach provides a level of financial security that you otherwise would not have. However, a full-time position requires full-time energy, hours, and attention, and it can be challenging to balance full-time and part-time work. Whichever approach you decide to take, it can be most helpful to simply keep an open mind and always consider looking further into any new opportunity that interests you.

Insurance and licensing

You don’t have to wait to establish your own practice to purchase malpractice insurance. Shop around for the best rates and the coverage that most comprehensively fits your needs. If your training program allows “moonlighting,” you might need your own insurance to work at sites other than your training hospital. Many residents begin to apply for independent state licensure at the same time they begin pursuing moonlighting opportunities. It may be helpful not to wait until the last minute to do this, because the process has quite a few steps and can take a while. If your state requires letters of reference, think about which of your supervisors you can ask for one. If you plan to work in a state other than that of your training location, it may be helpful to simultaneously apply for your medical license in that state, because you will already be going through the process. Certain states offer reciprocity regarding medical licenses. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact offers an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who want to practice in multiple states.1

Marketing your practice

Potential sources for building a panel of patients include referral networks, insurance panels, professional organizations, social media, networking, directories, and word of mouth. If you plan to accept health insurance, the directories provided by insurance panels will allow potential patients to find you when searching for practitioners who accept their plan. Professional organizations offer similar directories, and some private companies also provide directories, either for free or for a fee.

Use technology to your advantage

The exciting thing about starting a private practice today is that the technology available to support a small practice has drastically improved. Many software applications can help with scheduling and billing, which minimizes the need for office staff and enables you to be more productive. These programs typically are available via an online subscription that gives you access to an electronic medical record and other features for a monthly fee. Many of these programs provide add-ons such as a website for your practice and integrated telehealth services. While these programs typically perform many of the same functions, each has a different setup and varying workflows. An online search can facilitate a side-by-side comparison of the software programs that most closely meet your needs.

Seek out mentors and consultants

Finally, try to find a private practice mentor, and reach out to as many people as possible who have worked in any type of private practice setting. A mentor can alert you to factors you might not otherwise have considered. It also may be helpful to establish some form of supervision; such opportunities can be found through professional societies and other groups for private practice clinicians. In these groups, you also can ask other clinicians to recommend private practice and practice management consultants.

Stepping into the unknown can be an intimidating experience; however, you will not know what you are capable of until you try. Fortunately, psychiatry offers the flexibility to create a hybrid career that allows you to follow your passion and maintain your level of comfort. The American Psychiatric Association offers members additional information in the practice management resources section of its website.2

1. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Information for physicians. 2020. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.imlcc.org/information-for-physicians

2. American Psychiatric Association. Online practice handbook. 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/practice-management/starting-a-practice/online-practice-handbook

1. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Information for physicians. 2020. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.imlcc.org/information-for-physicians

2. American Psychiatric Association. Online practice handbook. 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/practice-management/starting-a-practice/online-practice-handbook

Canned diabetes prevention and a haunted COVID castle

Lower blood sugar with sardines

If you’ve ever turned your nose up at someone eating sardines straight from the can, you could be the one missing out on a good way to boost your own health.

New research from Open University of Catalonia (Spain) has found that eating two cans of whole sardines a week can help prevent people from developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now you might be thinking: That’s a lot of fish, can’t I just take a supplement pill? Actually, no.

“Nutrients can play an essential role in the prevention and treatment of many different pathologies, but their effect is usually caused by the synergy that exists between them and the food that they are contained in,” study coauthor Diana Rizzolo, PhD, said in a written statement. See, we told you.

In a study of 152 patients with prediabetes, each participant was put on a specific diet to reduce their chances of developing T2D. Among the patients who were not given sardines each week, the proportion considered to be at the highest risk fell from 27% to 22% after 1 year, but for those who did get the sardines, the size of the high-risk group shrank from 37% to just 8%.

Suggesting sardines during checkups could make eating them more widely accepted, Dr. Rizzolo and associates said. Sardines are cheap, easy to find, and also have the benefits of other oily fish, like boosting insulin resistance and increasing good cholesterol.

So why not have a can with a couple of saltine crackers for lunch? Your blood sugar will thank you. Just please avoid indulging on a plane or in your office, where workers are slowly returning – no need to give them another excuse to avoid their cubicle.

Come for the torture, stay for the vaccine

Bran Castle. Home of Dracula and Vlad the Impaler (at least in pop culture’s eyes). A moody Gothic structure atop a hill. You can practically hear the ancient screams of thousands of tortured souls as you wander the grounds and its cursed halls. Naturally, it’s a major tourist destination.

Unfortunately for Romania, the pandemic has rather put a damper on tourism. The restrictions have done their damage, but here’s a quick LOTME theory: Perhaps people don’t want to be reminded of medieval tortures when we’ve got plenty of modern-day ones right now.

The management of Bran Castle has developed a new gimmick to drum up attendance – come to Bran Castle and get your COVID vaccine. Anyone can come and get jabbed with the Pfizer vaccine on all weekends in May, and when they do, they gain free admittance to the castle and the exhibit within, home to 52 medieval torture instruments. “The idea … was to show how people got jabbed 500-600 years ago in Europe,” the castle’s marketing director said.

While it may not be kind of the jabbing ole Vladdy got his name for – fully impaling people on hundreds of wooden stakes while you eat a nice dinner isn’t exactly smiled upon in today’s world – we’re sure he’d approve of this more limited but ultimately beneficial version. Jabbing people while helping them really is the dream.

Fuzzy little COVID detectors

Before we get started, we need a moment to get our deep, movie trailer announcer-type voice ready. Okay, here goes.

“In a world where an organism too tiny to see brings entire economies to a standstill and pits scientists against doofuses, who can humanity turn to for help?”

How about bees? That’s right, we said bees. But not just any bees. Specially trained bees. Specially trained Dutch bees. Bees trained to sniff out our greatest nemesis. No, we’re not talking about Ted Cruz anymore. Let it go, that was just a joke. We’re talking COVID.

We’ll let Wim van der Poel, professor of virology at Wageningen (the Netherlands) University, explain the process: “We collect normal honeybees from a beekeeper, and we put the bees in harnesses.” And you thought their tulips were pretty great – the Dutch are putting harnesses on bees! (Which is much better than our previous story of bees involving a Taiwanese patient.)

The researchers presented the bees with two types of samples: COVID infected and non–COVID infected. The infected samples came with a sugary water reward and the noninfected samples did not, so the bees quickly learned to tell the difference.

The bees, then, could cut the waiting time for test results down to seconds, and at a fraction of the cost, making them an option in countries without a lot of testing infrastructure, the research team suggested.

The plan is not without its flaws, of course, but we’re convinced. More than that, we are true bee-lievers.

A little slice of … well, not heaven

If you’ve been around for the last 2 decades, you’ve seen your share of Internet trends: Remember the ice bucket challenge? Tide pod eating? We know what you’re thinking: Sigh, what could they be doing now?

Well, people are eating old meat, and before you think about the expired ground beef you got on special from the grocery store yesterday, that’s not quite what we mean. We all know expiration dates are “suggestions,” like yield signs and yellow lights. People are eating rotten, decomposing, borderline moldy meat.

They claim that the meat tastes better. We’re not so sure, but don’t worry, because it gets weirder. Some folks, apparently, are getting high from eating this meat, experiencing a feeling of euphoria. Personally, we think that rotten fumes probably knocked these people out and made them hallucinate.

Singaporean dietitian Naras Lapsys says that eating rotten meat can possibly cause a person to go into another state of consciousness, but it’s not a good thing. We don’t think you have to be a dietitian to know that.

It has not been definitively proven that eating rotting meat makes you high, but it’s definitely proven that this is disgusting … and very dangerous.

Lower blood sugar with sardines

If you’ve ever turned your nose up at someone eating sardines straight from the can, you could be the one missing out on a good way to boost your own health.

New research from Open University of Catalonia (Spain) has found that eating two cans of whole sardines a week can help prevent people from developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now you might be thinking: That’s a lot of fish, can’t I just take a supplement pill? Actually, no.

“Nutrients can play an essential role in the prevention and treatment of many different pathologies, but their effect is usually caused by the synergy that exists between them and the food that they are contained in,” study coauthor Diana Rizzolo, PhD, said in a written statement. See, we told you.

In a study of 152 patients with prediabetes, each participant was put on a specific diet to reduce their chances of developing T2D. Among the patients who were not given sardines each week, the proportion considered to be at the highest risk fell from 27% to 22% after 1 year, but for those who did get the sardines, the size of the high-risk group shrank from 37% to just 8%.

Suggesting sardines during checkups could make eating them more widely accepted, Dr. Rizzolo and associates said. Sardines are cheap, easy to find, and also have the benefits of other oily fish, like boosting insulin resistance and increasing good cholesterol.

So why not have a can with a couple of saltine crackers for lunch? Your blood sugar will thank you. Just please avoid indulging on a plane or in your office, where workers are slowly returning – no need to give them another excuse to avoid their cubicle.

Come for the torture, stay for the vaccine

Bran Castle. Home of Dracula and Vlad the Impaler (at least in pop culture’s eyes). A moody Gothic structure atop a hill. You can practically hear the ancient screams of thousands of tortured souls as you wander the grounds and its cursed halls. Naturally, it’s a major tourist destination.

Unfortunately for Romania, the pandemic has rather put a damper on tourism. The restrictions have done their damage, but here’s a quick LOTME theory: Perhaps people don’t want to be reminded of medieval tortures when we’ve got plenty of modern-day ones right now.

The management of Bran Castle has developed a new gimmick to drum up attendance – come to Bran Castle and get your COVID vaccine. Anyone can come and get jabbed with the Pfizer vaccine on all weekends in May, and when they do, they gain free admittance to the castle and the exhibit within, home to 52 medieval torture instruments. “The idea … was to show how people got jabbed 500-600 years ago in Europe,” the castle’s marketing director said.

While it may not be kind of the jabbing ole Vladdy got his name for – fully impaling people on hundreds of wooden stakes while you eat a nice dinner isn’t exactly smiled upon in today’s world – we’re sure he’d approve of this more limited but ultimately beneficial version. Jabbing people while helping them really is the dream.

Fuzzy little COVID detectors

Before we get started, we need a moment to get our deep, movie trailer announcer-type voice ready. Okay, here goes.

“In a world where an organism too tiny to see brings entire economies to a standstill and pits scientists against doofuses, who can humanity turn to for help?”

How about bees? That’s right, we said bees. But not just any bees. Specially trained bees. Specially trained Dutch bees. Bees trained to sniff out our greatest nemesis. No, we’re not talking about Ted Cruz anymore. Let it go, that was just a joke. We’re talking COVID.

We’ll let Wim van der Poel, professor of virology at Wageningen (the Netherlands) University, explain the process: “We collect normal honeybees from a beekeeper, and we put the bees in harnesses.” And you thought their tulips were pretty great – the Dutch are putting harnesses on bees! (Which is much better than our previous story of bees involving a Taiwanese patient.)

The researchers presented the bees with two types of samples: COVID infected and non–COVID infected. The infected samples came with a sugary water reward and the noninfected samples did not, so the bees quickly learned to tell the difference.

The bees, then, could cut the waiting time for test results down to seconds, and at a fraction of the cost, making them an option in countries without a lot of testing infrastructure, the research team suggested.

The plan is not without its flaws, of course, but we’re convinced. More than that, we are true bee-lievers.

A little slice of … well, not heaven

If you’ve been around for the last 2 decades, you’ve seen your share of Internet trends: Remember the ice bucket challenge? Tide pod eating? We know what you’re thinking: Sigh, what could they be doing now?

Well, people are eating old meat, and before you think about the expired ground beef you got on special from the grocery store yesterday, that’s not quite what we mean. We all know expiration dates are “suggestions,” like yield signs and yellow lights. People are eating rotten, decomposing, borderline moldy meat.

They claim that the meat tastes better. We’re not so sure, but don’t worry, because it gets weirder. Some folks, apparently, are getting high from eating this meat, experiencing a feeling of euphoria. Personally, we think that rotten fumes probably knocked these people out and made them hallucinate.

Singaporean dietitian Naras Lapsys says that eating rotten meat can possibly cause a person to go into another state of consciousness, but it’s not a good thing. We don’t think you have to be a dietitian to know that.

It has not been definitively proven that eating rotting meat makes you high, but it’s definitely proven that this is disgusting … and very dangerous.

Lower blood sugar with sardines

If you’ve ever turned your nose up at someone eating sardines straight from the can, you could be the one missing out on a good way to boost your own health.

New research from Open University of Catalonia (Spain) has found that eating two cans of whole sardines a week can help prevent people from developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now you might be thinking: That’s a lot of fish, can’t I just take a supplement pill? Actually, no.

“Nutrients can play an essential role in the prevention and treatment of many different pathologies, but their effect is usually caused by the synergy that exists between them and the food that they are contained in,” study coauthor Diana Rizzolo, PhD, said in a written statement. See, we told you.

In a study of 152 patients with prediabetes, each participant was put on a specific diet to reduce their chances of developing T2D. Among the patients who were not given sardines each week, the proportion considered to be at the highest risk fell from 27% to 22% after 1 year, but for those who did get the sardines, the size of the high-risk group shrank from 37% to just 8%.

Suggesting sardines during checkups could make eating them more widely accepted, Dr. Rizzolo and associates said. Sardines are cheap, easy to find, and also have the benefits of other oily fish, like boosting insulin resistance and increasing good cholesterol.

So why not have a can with a couple of saltine crackers for lunch? Your blood sugar will thank you. Just please avoid indulging on a plane or in your office, where workers are slowly returning – no need to give them another excuse to avoid their cubicle.

Come for the torture, stay for the vaccine

Bran Castle. Home of Dracula and Vlad the Impaler (at least in pop culture’s eyes). A moody Gothic structure atop a hill. You can practically hear the ancient screams of thousands of tortured souls as you wander the grounds and its cursed halls. Naturally, it’s a major tourist destination.

Unfortunately for Romania, the pandemic has rather put a damper on tourism. The restrictions have done their damage, but here’s a quick LOTME theory: Perhaps people don’t want to be reminded of medieval tortures when we’ve got plenty of modern-day ones right now.

The management of Bran Castle has developed a new gimmick to drum up attendance – come to Bran Castle and get your COVID vaccine. Anyone can come and get jabbed with the Pfizer vaccine on all weekends in May, and when they do, they gain free admittance to the castle and the exhibit within, home to 52 medieval torture instruments. “The idea … was to show how people got jabbed 500-600 years ago in Europe,” the castle’s marketing director said.

While it may not be kind of the jabbing ole Vladdy got his name for – fully impaling people on hundreds of wooden stakes while you eat a nice dinner isn’t exactly smiled upon in today’s world – we’re sure he’d approve of this more limited but ultimately beneficial version. Jabbing people while helping them really is the dream.

Fuzzy little COVID detectors

Before we get started, we need a moment to get our deep, movie trailer announcer-type voice ready. Okay, here goes.

“In a world where an organism too tiny to see brings entire economies to a standstill and pits scientists against doofuses, who can humanity turn to for help?”

How about bees? That’s right, we said bees. But not just any bees. Specially trained bees. Specially trained Dutch bees. Bees trained to sniff out our greatest nemesis. No, we’re not talking about Ted Cruz anymore. Let it go, that was just a joke. We’re talking COVID.

We’ll let Wim van der Poel, professor of virology at Wageningen (the Netherlands) University, explain the process: “We collect normal honeybees from a beekeeper, and we put the bees in harnesses.” And you thought their tulips were pretty great – the Dutch are putting harnesses on bees! (Which is much better than our previous story of bees involving a Taiwanese patient.)

The researchers presented the bees with two types of samples: COVID infected and non–COVID infected. The infected samples came with a sugary water reward and the noninfected samples did not, so the bees quickly learned to tell the difference.

The bees, then, could cut the waiting time for test results down to seconds, and at a fraction of the cost, making them an option in countries without a lot of testing infrastructure, the research team suggested.

The plan is not without its flaws, of course, but we’re convinced. More than that, we are true bee-lievers.

A little slice of … well, not heaven

If you’ve been around for the last 2 decades, you’ve seen your share of Internet trends: Remember the ice bucket challenge? Tide pod eating? We know what you’re thinking: Sigh, what could they be doing now?

Well, people are eating old meat, and before you think about the expired ground beef you got on special from the grocery store yesterday, that’s not quite what we mean. We all know expiration dates are “suggestions,” like yield signs and yellow lights. People are eating rotten, decomposing, borderline moldy meat.

They claim that the meat tastes better. We’re not so sure, but don’t worry, because it gets weirder. Some folks, apparently, are getting high from eating this meat, experiencing a feeling of euphoria. Personally, we think that rotten fumes probably knocked these people out and made them hallucinate.

Singaporean dietitian Naras Lapsys says that eating rotten meat can possibly cause a person to go into another state of consciousness, but it’s not a good thing. We don’t think you have to be a dietitian to know that.

It has not been definitively proven that eating rotting meat makes you high, but it’s definitely proven that this is disgusting … and very dangerous.

Systemic trauma in the Black community: My perspective as an Asian American

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.

In these individuals, I saw people who looked and lived just like the patients I chose to serve. But during this time, I did not see myself as the healer, but part of the system that brought pain and distress. As an Asian American, I identified with Tou Thao—the Asian American police officer involved in George Floyd’s death. In the medical community with which I identified, I found that ever-rising cases of COVID-19 were disproportionately affecting lower-income minority communities. In a polarizing world, I felt my Asian American identity prevented me from experiencing the pain and suffering Black communities faced. This was not my fight, and if it was, I was more immersed in the side that brought trauma to my patients. From a purely rational perspective, I had no right to feel sad. Intellectually, I felt unqualified to share in their pain, yet here I was, crying in my room.

An evolving transformation

As much as I wanted to take a break, training did not stop. A transformation occurred from an emerging awareness of the unique environment within which I was training and the intersection of who I knew myself to be. Serving in an urban program, I was given the opportunity for candid conversations with health professionals of color. I was humbled when Black colleagues proactively reached out to educate me about the historical context of these events and help me process them. I asked hard questions of my fellow residents who were Black, and listened to their answers and personal stories, which was difficult.

With my patients, I began to listen more intently and think about the systemic issues I had previously written off. One patient missed their appointment because public transportation was closed due to COVID-19. Another patient who was homeless was helped immensely by assistance with housing when he could no longer sleep at his place of residence. Really listening to him revealed that his street had become a common route for protests. With my therapy patient who experienced panic attacks listening to the news, I simply sat and grieved with them. I chose these interactions not because I was uniquely qualified, intelligent, or had any ability to change the trajectory of our country, but because they grew from me simply working in the context I chose and seeking the relationships I naturally sought.

How I define myself

As doctors, we accept the burden of caring for society’s ailments with the ultimate hope of celebrating triumph over the adversity of psychiatric illness. However, superseding our profession is the social system in which we live. I am part of a system that has historically caused trauma to some while benefitting others. Thus, between the calling of my practice and the country I practice in, I found a divergence. Once I accepted the truth of this system and the very personal way it affects me, my colleagues, and patients I serve, I was able to internally reconcile and rediscover hope. While I cannot change my experiences, advantages, or privilege, these facts do not change the reality that I am a citizen of the globe and human first. This realization is the silver lining of these perilous times; training among people of color who graciously included me in their experiences, and my willingness to listen and self-reflect. I now choose to define myself by what makes me similar to my patients instead of what isolates me from them. The tangible results of this deliberate step toward authenticity are renewed inspiration and joy.

For those of you who may have found yourself with no “ethnic home team” (or a desire for a new one), I leave you with this simple charge: Let your emotional reactions guide you to truth, and challenge yourself to process them with someone who doesn’t look like you. Leave your title at the door and embrace humility. You might be pleasantly surprised at the human you find when you look in the mirror.

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.