User login

An unexplained exacerbation of depression, anxiety, and panic

CASE Depression, anxiety, and panic attacks

At the urging of his parents Mr. P, age 33, presents to the partial hospitalization program (PHP) for worsening depression and anxiety, daily panic attacks with accompanying diaphoresis and headache, and the possibility that he may have taken an overdose of zolpidem. Mr. P denies taking an intentional overdose of zolpidem, claiming instead that he was having a sleep-walking episode and did not realize how many pills he took.

In addition to daily panic attacks, Mr. P reports having trouble falling asleep, overwhelming sadness, and daily passive suicidal ideation without a plan or active intent.

Mr. P cannot identify a specific trigger to this most recent exacerbation of depressed/anxious mood, but instead describes it as slowly building over the past 6 to 8 months. Mr. P says the panic attacks occur without warning and states, “I feel like my heart is going to jump out of my chest; I get a terrible headache, and I sweat like crazy. Sometimes I just feel like I’m about to pass out or die.” Although these episodes had been present for approximately 2 years, they now occur almost daily.

HISTORY Inconsistent adherence

For the last year, Mr. P had been taking alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, and paroxetine, 20 mg/d, and these medications provided moderate relief of his depressive/anxious symptoms. However, he stopped taking both medications approximately 3 or 4 weeks ago when he ran out. He also takes propranolol, 20 mg/d, sporadically, for hypertension. In the past, he had been prescribed carvedilol, clonidine, and lisinopril—all with varying degrees of relief of his hypertension. He denies a family history of hypertension or any other chronic or acute health problems. He reports that he has been sober from alcohol for 19 months but smokes 1 to 2 marijuana cigarettes a day.

EVALUATION Elevated blood pressure and pulse

Mr. P’s physical examination and medical review of systems are unremarkable, except for an elevated blood pressure (190/110 mm Hg) and pulse (92 beats per minute); he also has a headache. A repeat blood pressure test later in the day is 172/94 mm Hg, with a pulse of 100 beats per minute. His urine drug screen is positive only for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

[polldaddy:10558304]

The author’s observations

A CBC with differential is helpful for ruling out infection and anemia as causes of anxiety and depression.1 In Mr. P’s case, there were no concerning symptoms that pointed to anemia or infection as likely causes of his anxiety, depression, or panic attacks. A TSH level also would be reasonable, because hyperthyroidism can present as anxiety, while hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism each can present as depression.1 However, both Mr. P’s medical history and physical examination were not concerning for thyroid disease, making it unlikely that he had either of those conditions. A review of Mr. P’s medical records indicated that within the past 6 months, his primary care physician (PCP) had ordered a CBC and TSH test; the results of both were within normal limits.

Serum porphyrin tests can exclude porphyria as a contributor to Mr. P’s anxiety and depression. Porphyrias are a group of 8 inherited disorders that involve accumulation of heme precursors (porphyrins) in the CNS and subcutaneous tissue.2 Collectively, porphyrias affect approximately 1 in 200,000 people.2 Anxiety and depression are strongly associated with porphyria, but do not occur secondary to the illness; depression and anxiety appear to be intrinsic personality features in people with porphyria.3 Skin lesions and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms,3 and there is a higher incidence of hypertension in people with porphyria than in the general population.4 Mr. P does not report any heritable disorders, nor does he appear to have any CNS disturbance or unusual cutaneous lesions, which makes it unlikely that this disorder is related to his psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: A serum metanephrines test measures...

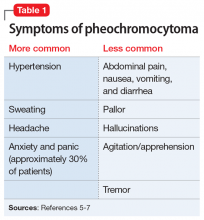

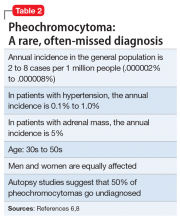

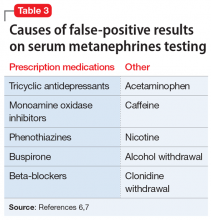

A serum metanephrines test measures the metabolites of epinephrine and norepinephrine. These catecholamines are produced in excess by an adrenal or extra-adrenal tumor seen in pheochromocytoma. The classic triad of symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic (Table 15-7). This type of tumor is rare, with an annual incidence of only 2 to 8 cases per 1 million individuals. Among people with hypertension, the annual incidence is 0.1% to 1.0%, and for those with an adrenal mass, the annual incidence is 5% (Table 26,8). Autopsy studies suggest that up to 50% of pheochromocytomas are undiagnosed.8 Left untreated, pheochromocytoma can result in hypertensive crisis, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, multisystem organ failure, and premature death.7 Table 36,7 highlights some causes of false-positive serum on metanephrines testing.

EVALUATION Metanephrines testing

Mr. P has what appears to be treatment-resistant hypertension, accompanied by the classic symptoms observed in most patients with pheochromocytoma. Because Mr. P is participating in the PHP 6 days per week for 6 hours each day, visiting his PCP would be inconvenient, so the treatment team orders the serum metanephrines test. If a positive result is found, Mr. P will be referred to his PCP for further assessment and follow-up care with endocrinology.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy to target anxiety and panic

Next, the treatment team establishes a safety plan for Mr. P, and restarts paroxetine, 20 mg/d, to target his depressed and anxious mood. Alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, is started to target anxious mood and panic symptoms, and to allow time for the anxiolytic properties of the paroxetine to become fully effective. The alprazolam will be tapered and stopped after 2 weeks. Mr. P is started on hydroxyzine, 1 to 2 25-mg tablets 2 to 3 times daily as needed for anxious mood and panic symptoms.

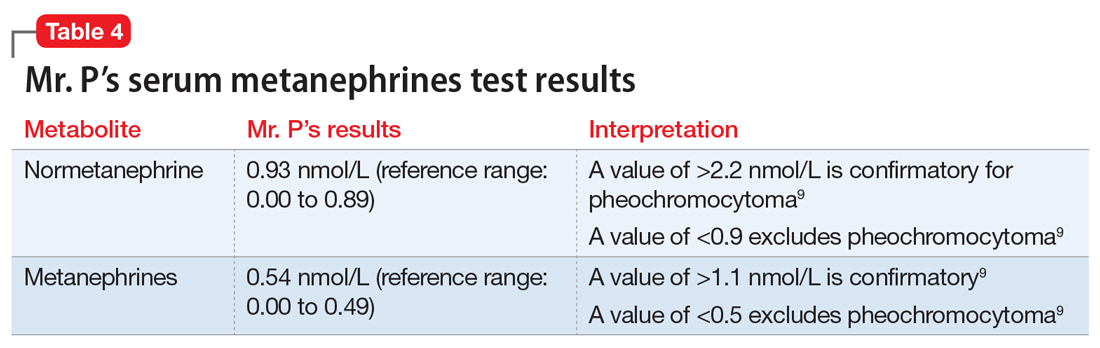

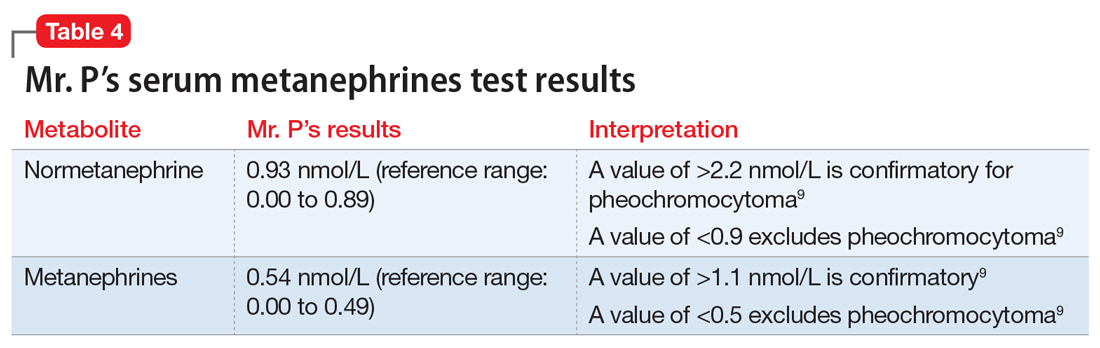

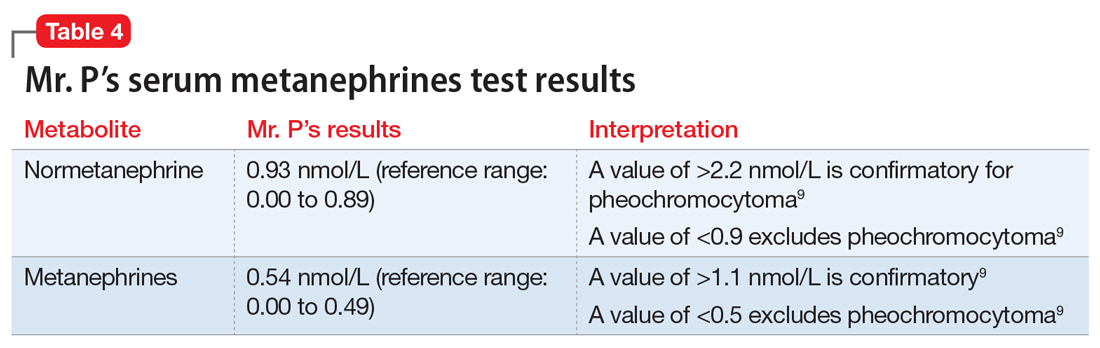

The serum metanephrines test results are equivocal, with a slight elevation of both epinephrine and norepinephrine that is too low to confirm a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma but too elevated to exclude it (Table 49). With Mr. P’s consent, the treatment team contacts his PCP and convey the results of this test. Mr. P schedules an appointment with his PCP for the following week for further assessment and confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing.

After 1 week, Mr. P remains anxious, with a slight reduction in panic attacks from multiple attacks each day to 3 or 4 attacks per week. The team considers adding an additional anxiolytic agent.

[polldaddy:10558305]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

The triad of symptoms in pheochromocytoma results directly from the intermittent release of catecholamines into systemic circulation. Surges of epinephrine and norepinephrine lead to headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, and (less commonly) gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Persistent or episodic hypertension may be present, with 13% of patients maintaining a normal blood pressure.5-7 Patients with pheochromocytoma-related anxiety typically have substantial or complete resolution of anxiety and panic attacks after tumor resection.6,8,10

Because of their ability to raise catecholamine levels, several medications, including some psychotropics, can lead to false-positive results on serum and urine metanephrines testing. Tricyclic antidepressants and beta-blockers can cause false-positive results on plasma assays, while buspirone can cause false-positives on urinalysis assays.5 Trazodone, on the other hand, exhibits no catecholaminergic activity and its alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism may actually have some benefit in pheochromocytoma.11 Alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism with doxazosin, prazosin, or terazosin is the first-line of treatment in reducing pheochromocytoma-related hypertension.7 Treatment with a beta-blocker is safe only after alpha-adrenergic blockade occurs. While beta-blockers are useful for reducing the palpitations and anxiety observed in patients with pheochromocytoma, they must not be used alone due to the risk of hypertensive crisis resulting from unopposed alpha-adrenergic agonist activated vasoconstriction.5,7

TREATMENT CBT provides benefit

Mr. P decides against receiving an additional agent for anxiety and instead decides to wait for the outcome of the confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing. He continues to take alprazolam, and both his depressed mood and anxiety improve. His panic attacks continue to lessen, and he appears to benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy provided during group therapy. Mr. P is advised by his PCP to taper and stop the alprazolam 3 to 5 days before his 24-hour urine metanephrines test because benzodiazepines can lead to false-positive results on a urinalysis assay.7

OUTCOME Remission of anxiety and depression

Mr. P has a repeat serum metanephrines test and a 24-hour urinalysis assay. Both are negative for pheochromocytoma. His PCP refers him to cardiology for management of treatment-resistant hypertension. He is discharged from the PHP and continues psychotherapy for depression and anxiety in an intensive outpatient program (IOP). Throughout his PHP and IOP treatments, he continues to take paroxetine and hydroxyzine. He achieves a successful remission of his anxiety and depression, with partial but significant remission of his panic attacks.

The author’s observations

Although Mr. P did not have pheochromocytoma, it is important to rule out this rare condition in patients who present with treatment-resistant hypertension and/or treatment-resistant anxiety.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of the adrenal gland. The classic triad of symptoms of this rare condition is hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic. Several medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, and buspirone, can lead to false-positive results on the serum and urine metanephrines testing used to diagnose pheochromocytoma.

Related Resources

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Rare Disease Database: pheochromocytoma. www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pheochromocytoma/.

- Young WF Jr. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-pheochromocytoma. Published January 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Buspirone • Buspar

Carvedilol • Coreg

Clonidine • Catapres

Doxazosin • Cardura

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal

Terazosin • Hytrin

Trazodone • Desyrel

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Morrison J. When psychological problems mask medical disorders: a guide for psychotherapists. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. American Porphyria Foundation. About porphyria. https://porphyriafoundation.org/patients/about-porphyria. Accessed May 13, 2020.

3. Millward L, Kelly P, King A, et al. Anxiety and depression in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(6):1099-1107.

4. Bonkovsky H, Maddukuri VC, Yazici C, et al. Acute porphyrias in the USA: features of 108 subjects from porphyria consortium. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1233-1241.

5. Tsirlin A, Oo Y, Sharma R, et al. Pheochromocytoma: a review. Maturitas. 2014;77(3):229-238.

6. Leung A, Zun L, Nordstrom K, et al. Psychiatric emergencies for physicians: clinical management and approach to distinguishing pheochromocytoma from psychiatric and thyrotoxic diseases in the emergency room. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(5):712-716.

7. Garg M, Kharb S, Brar KS, et al. Medical management of pheochromocytoma: role of the endocrinologist. Indian J Endocrinol and Metab. 2011;15(suppl 4):S329-S336. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.86976.

8. Zardawi I. Phaeochromocytoma masquerading as anxiety and depression. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:161-163.

9. ARUP Laboratories. Test directory. https://www.aruplab.com. Accessed February 11, 2020.

10. Sriram P, Raghavan V. Pheochromocytoma presenting as anxiety disorder: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:83-84.

11. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

CASE Depression, anxiety, and panic attacks

At the urging of his parents Mr. P, age 33, presents to the partial hospitalization program (PHP) for worsening depression and anxiety, daily panic attacks with accompanying diaphoresis and headache, and the possibility that he may have taken an overdose of zolpidem. Mr. P denies taking an intentional overdose of zolpidem, claiming instead that he was having a sleep-walking episode and did not realize how many pills he took.

In addition to daily panic attacks, Mr. P reports having trouble falling asleep, overwhelming sadness, and daily passive suicidal ideation without a plan or active intent.

Mr. P cannot identify a specific trigger to this most recent exacerbation of depressed/anxious mood, but instead describes it as slowly building over the past 6 to 8 months. Mr. P says the panic attacks occur without warning and states, “I feel like my heart is going to jump out of my chest; I get a terrible headache, and I sweat like crazy. Sometimes I just feel like I’m about to pass out or die.” Although these episodes had been present for approximately 2 years, they now occur almost daily.

HISTORY Inconsistent adherence

For the last year, Mr. P had been taking alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, and paroxetine, 20 mg/d, and these medications provided moderate relief of his depressive/anxious symptoms. However, he stopped taking both medications approximately 3 or 4 weeks ago when he ran out. He also takes propranolol, 20 mg/d, sporadically, for hypertension. In the past, he had been prescribed carvedilol, clonidine, and lisinopril—all with varying degrees of relief of his hypertension. He denies a family history of hypertension or any other chronic or acute health problems. He reports that he has been sober from alcohol for 19 months but smokes 1 to 2 marijuana cigarettes a day.

EVALUATION Elevated blood pressure and pulse

Mr. P’s physical examination and medical review of systems are unremarkable, except for an elevated blood pressure (190/110 mm Hg) and pulse (92 beats per minute); he also has a headache. A repeat blood pressure test later in the day is 172/94 mm Hg, with a pulse of 100 beats per minute. His urine drug screen is positive only for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

[polldaddy:10558304]

The author’s observations

A CBC with differential is helpful for ruling out infection and anemia as causes of anxiety and depression.1 In Mr. P’s case, there were no concerning symptoms that pointed to anemia or infection as likely causes of his anxiety, depression, or panic attacks. A TSH level also would be reasonable, because hyperthyroidism can present as anxiety, while hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism each can present as depression.1 However, both Mr. P’s medical history and physical examination were not concerning for thyroid disease, making it unlikely that he had either of those conditions. A review of Mr. P’s medical records indicated that within the past 6 months, his primary care physician (PCP) had ordered a CBC and TSH test; the results of both were within normal limits.

Serum porphyrin tests can exclude porphyria as a contributor to Mr. P’s anxiety and depression. Porphyrias are a group of 8 inherited disorders that involve accumulation of heme precursors (porphyrins) in the CNS and subcutaneous tissue.2 Collectively, porphyrias affect approximately 1 in 200,000 people.2 Anxiety and depression are strongly associated with porphyria, but do not occur secondary to the illness; depression and anxiety appear to be intrinsic personality features in people with porphyria.3 Skin lesions and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms,3 and there is a higher incidence of hypertension in people with porphyria than in the general population.4 Mr. P does not report any heritable disorders, nor does he appear to have any CNS disturbance or unusual cutaneous lesions, which makes it unlikely that this disorder is related to his psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: A serum metanephrines test measures...

A serum metanephrines test measures the metabolites of epinephrine and norepinephrine. These catecholamines are produced in excess by an adrenal or extra-adrenal tumor seen in pheochromocytoma. The classic triad of symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic (Table 15-7). This type of tumor is rare, with an annual incidence of only 2 to 8 cases per 1 million individuals. Among people with hypertension, the annual incidence is 0.1% to 1.0%, and for those with an adrenal mass, the annual incidence is 5% (Table 26,8). Autopsy studies suggest that up to 50% of pheochromocytomas are undiagnosed.8 Left untreated, pheochromocytoma can result in hypertensive crisis, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, multisystem organ failure, and premature death.7 Table 36,7 highlights some causes of false-positive serum on metanephrines testing.

EVALUATION Metanephrines testing

Mr. P has what appears to be treatment-resistant hypertension, accompanied by the classic symptoms observed in most patients with pheochromocytoma. Because Mr. P is participating in the PHP 6 days per week for 6 hours each day, visiting his PCP would be inconvenient, so the treatment team orders the serum metanephrines test. If a positive result is found, Mr. P will be referred to his PCP for further assessment and follow-up care with endocrinology.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy to target anxiety and panic

Next, the treatment team establishes a safety plan for Mr. P, and restarts paroxetine, 20 mg/d, to target his depressed and anxious mood. Alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, is started to target anxious mood and panic symptoms, and to allow time for the anxiolytic properties of the paroxetine to become fully effective. The alprazolam will be tapered and stopped after 2 weeks. Mr. P is started on hydroxyzine, 1 to 2 25-mg tablets 2 to 3 times daily as needed for anxious mood and panic symptoms.

The serum metanephrines test results are equivocal, with a slight elevation of both epinephrine and norepinephrine that is too low to confirm a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma but too elevated to exclude it (Table 49). With Mr. P’s consent, the treatment team contacts his PCP and convey the results of this test. Mr. P schedules an appointment with his PCP for the following week for further assessment and confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing.

After 1 week, Mr. P remains anxious, with a slight reduction in panic attacks from multiple attacks each day to 3 or 4 attacks per week. The team considers adding an additional anxiolytic agent.

[polldaddy:10558305]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

The triad of symptoms in pheochromocytoma results directly from the intermittent release of catecholamines into systemic circulation. Surges of epinephrine and norepinephrine lead to headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, and (less commonly) gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Persistent or episodic hypertension may be present, with 13% of patients maintaining a normal blood pressure.5-7 Patients with pheochromocytoma-related anxiety typically have substantial or complete resolution of anxiety and panic attacks after tumor resection.6,8,10

Because of their ability to raise catecholamine levels, several medications, including some psychotropics, can lead to false-positive results on serum and urine metanephrines testing. Tricyclic antidepressants and beta-blockers can cause false-positive results on plasma assays, while buspirone can cause false-positives on urinalysis assays.5 Trazodone, on the other hand, exhibits no catecholaminergic activity and its alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism may actually have some benefit in pheochromocytoma.11 Alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism with doxazosin, prazosin, or terazosin is the first-line of treatment in reducing pheochromocytoma-related hypertension.7 Treatment with a beta-blocker is safe only after alpha-adrenergic blockade occurs. While beta-blockers are useful for reducing the palpitations and anxiety observed in patients with pheochromocytoma, they must not be used alone due to the risk of hypertensive crisis resulting from unopposed alpha-adrenergic agonist activated vasoconstriction.5,7

TREATMENT CBT provides benefit

Mr. P decides against receiving an additional agent for anxiety and instead decides to wait for the outcome of the confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing. He continues to take alprazolam, and both his depressed mood and anxiety improve. His panic attacks continue to lessen, and he appears to benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy provided during group therapy. Mr. P is advised by his PCP to taper and stop the alprazolam 3 to 5 days before his 24-hour urine metanephrines test because benzodiazepines can lead to false-positive results on a urinalysis assay.7

OUTCOME Remission of anxiety and depression

Mr. P has a repeat serum metanephrines test and a 24-hour urinalysis assay. Both are negative for pheochromocytoma. His PCP refers him to cardiology for management of treatment-resistant hypertension. He is discharged from the PHP and continues psychotherapy for depression and anxiety in an intensive outpatient program (IOP). Throughout his PHP and IOP treatments, he continues to take paroxetine and hydroxyzine. He achieves a successful remission of his anxiety and depression, with partial but significant remission of his panic attacks.

The author’s observations

Although Mr. P did not have pheochromocytoma, it is important to rule out this rare condition in patients who present with treatment-resistant hypertension and/or treatment-resistant anxiety.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of the adrenal gland. The classic triad of symptoms of this rare condition is hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic. Several medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, and buspirone, can lead to false-positive results on the serum and urine metanephrines testing used to diagnose pheochromocytoma.

Related Resources

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Rare Disease Database: pheochromocytoma. www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pheochromocytoma/.

- Young WF Jr. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-pheochromocytoma. Published January 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Buspirone • Buspar

Carvedilol • Coreg

Clonidine • Catapres

Doxazosin • Cardura

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal

Terazosin • Hytrin

Trazodone • Desyrel

Zolpidem • Ambien

CASE Depression, anxiety, and panic attacks

At the urging of his parents Mr. P, age 33, presents to the partial hospitalization program (PHP) for worsening depression and anxiety, daily panic attacks with accompanying diaphoresis and headache, and the possibility that he may have taken an overdose of zolpidem. Mr. P denies taking an intentional overdose of zolpidem, claiming instead that he was having a sleep-walking episode and did not realize how many pills he took.

In addition to daily panic attacks, Mr. P reports having trouble falling asleep, overwhelming sadness, and daily passive suicidal ideation without a plan or active intent.

Mr. P cannot identify a specific trigger to this most recent exacerbation of depressed/anxious mood, but instead describes it as slowly building over the past 6 to 8 months. Mr. P says the panic attacks occur without warning and states, “I feel like my heart is going to jump out of my chest; I get a terrible headache, and I sweat like crazy. Sometimes I just feel like I’m about to pass out or die.” Although these episodes had been present for approximately 2 years, they now occur almost daily.

HISTORY Inconsistent adherence

For the last year, Mr. P had been taking alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, and paroxetine, 20 mg/d, and these medications provided moderate relief of his depressive/anxious symptoms. However, he stopped taking both medications approximately 3 or 4 weeks ago when he ran out. He also takes propranolol, 20 mg/d, sporadically, for hypertension. In the past, he had been prescribed carvedilol, clonidine, and lisinopril—all with varying degrees of relief of his hypertension. He denies a family history of hypertension or any other chronic or acute health problems. He reports that he has been sober from alcohol for 19 months but smokes 1 to 2 marijuana cigarettes a day.

EVALUATION Elevated blood pressure and pulse

Mr. P’s physical examination and medical review of systems are unremarkable, except for an elevated blood pressure (190/110 mm Hg) and pulse (92 beats per minute); he also has a headache. A repeat blood pressure test later in the day is 172/94 mm Hg, with a pulse of 100 beats per minute. His urine drug screen is positive only for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

[polldaddy:10558304]

The author’s observations

A CBC with differential is helpful for ruling out infection and anemia as causes of anxiety and depression.1 In Mr. P’s case, there were no concerning symptoms that pointed to anemia or infection as likely causes of his anxiety, depression, or panic attacks. A TSH level also would be reasonable, because hyperthyroidism can present as anxiety, while hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism each can present as depression.1 However, both Mr. P’s medical history and physical examination were not concerning for thyroid disease, making it unlikely that he had either of those conditions. A review of Mr. P’s medical records indicated that within the past 6 months, his primary care physician (PCP) had ordered a CBC and TSH test; the results of both were within normal limits.

Serum porphyrin tests can exclude porphyria as a contributor to Mr. P’s anxiety and depression. Porphyrias are a group of 8 inherited disorders that involve accumulation of heme precursors (porphyrins) in the CNS and subcutaneous tissue.2 Collectively, porphyrias affect approximately 1 in 200,000 people.2 Anxiety and depression are strongly associated with porphyria, but do not occur secondary to the illness; depression and anxiety appear to be intrinsic personality features in people with porphyria.3 Skin lesions and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms,3 and there is a higher incidence of hypertension in people with porphyria than in the general population.4 Mr. P does not report any heritable disorders, nor does he appear to have any CNS disturbance or unusual cutaneous lesions, which makes it unlikely that this disorder is related to his psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: A serum metanephrines test measures...

A serum metanephrines test measures the metabolites of epinephrine and norepinephrine. These catecholamines are produced in excess by an adrenal or extra-adrenal tumor seen in pheochromocytoma. The classic triad of symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic (Table 15-7). This type of tumor is rare, with an annual incidence of only 2 to 8 cases per 1 million individuals. Among people with hypertension, the annual incidence is 0.1% to 1.0%, and for those with an adrenal mass, the annual incidence is 5% (Table 26,8). Autopsy studies suggest that up to 50% of pheochromocytomas are undiagnosed.8 Left untreated, pheochromocytoma can result in hypertensive crisis, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, multisystem organ failure, and premature death.7 Table 36,7 highlights some causes of false-positive serum on metanephrines testing.

EVALUATION Metanephrines testing

Mr. P has what appears to be treatment-resistant hypertension, accompanied by the classic symptoms observed in most patients with pheochromocytoma. Because Mr. P is participating in the PHP 6 days per week for 6 hours each day, visiting his PCP would be inconvenient, so the treatment team orders the serum metanephrines test. If a positive result is found, Mr. P will be referred to his PCP for further assessment and follow-up care with endocrinology.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy to target anxiety and panic

Next, the treatment team establishes a safety plan for Mr. P, and restarts paroxetine, 20 mg/d, to target his depressed and anxious mood. Alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, is started to target anxious mood and panic symptoms, and to allow time for the anxiolytic properties of the paroxetine to become fully effective. The alprazolam will be tapered and stopped after 2 weeks. Mr. P is started on hydroxyzine, 1 to 2 25-mg tablets 2 to 3 times daily as needed for anxious mood and panic symptoms.

The serum metanephrines test results are equivocal, with a slight elevation of both epinephrine and norepinephrine that is too low to confirm a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma but too elevated to exclude it (Table 49). With Mr. P’s consent, the treatment team contacts his PCP and convey the results of this test. Mr. P schedules an appointment with his PCP for the following week for further assessment and confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing.

After 1 week, Mr. P remains anxious, with a slight reduction in panic attacks from multiple attacks each day to 3 or 4 attacks per week. The team considers adding an additional anxiolytic agent.

[polldaddy:10558305]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

The triad of symptoms in pheochromocytoma results directly from the intermittent release of catecholamines into systemic circulation. Surges of epinephrine and norepinephrine lead to headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, and (less commonly) gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Persistent or episodic hypertension may be present, with 13% of patients maintaining a normal blood pressure.5-7 Patients with pheochromocytoma-related anxiety typically have substantial or complete resolution of anxiety and panic attacks after tumor resection.6,8,10

Because of their ability to raise catecholamine levels, several medications, including some psychotropics, can lead to false-positive results on serum and urine metanephrines testing. Tricyclic antidepressants and beta-blockers can cause false-positive results on plasma assays, while buspirone can cause false-positives on urinalysis assays.5 Trazodone, on the other hand, exhibits no catecholaminergic activity and its alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism may actually have some benefit in pheochromocytoma.11 Alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism with doxazosin, prazosin, or terazosin is the first-line of treatment in reducing pheochromocytoma-related hypertension.7 Treatment with a beta-blocker is safe only after alpha-adrenergic blockade occurs. While beta-blockers are useful for reducing the palpitations and anxiety observed in patients with pheochromocytoma, they must not be used alone due to the risk of hypertensive crisis resulting from unopposed alpha-adrenergic agonist activated vasoconstriction.5,7

TREATMENT CBT provides benefit

Mr. P decides against receiving an additional agent for anxiety and instead decides to wait for the outcome of the confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing. He continues to take alprazolam, and both his depressed mood and anxiety improve. His panic attacks continue to lessen, and he appears to benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy provided during group therapy. Mr. P is advised by his PCP to taper and stop the alprazolam 3 to 5 days before his 24-hour urine metanephrines test because benzodiazepines can lead to false-positive results on a urinalysis assay.7

OUTCOME Remission of anxiety and depression

Mr. P has a repeat serum metanephrines test and a 24-hour urinalysis assay. Both are negative for pheochromocytoma. His PCP refers him to cardiology for management of treatment-resistant hypertension. He is discharged from the PHP and continues psychotherapy for depression and anxiety in an intensive outpatient program (IOP). Throughout his PHP and IOP treatments, he continues to take paroxetine and hydroxyzine. He achieves a successful remission of his anxiety and depression, with partial but significant remission of his panic attacks.

The author’s observations

Although Mr. P did not have pheochromocytoma, it is important to rule out this rare condition in patients who present with treatment-resistant hypertension and/or treatment-resistant anxiety.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of the adrenal gland. The classic triad of symptoms of this rare condition is hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic. Several medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, and buspirone, can lead to false-positive results on the serum and urine metanephrines testing used to diagnose pheochromocytoma.

Related Resources

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Rare Disease Database: pheochromocytoma. www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pheochromocytoma/.

- Young WF Jr. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-pheochromocytoma. Published January 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Buspirone • Buspar

Carvedilol • Coreg

Clonidine • Catapres

Doxazosin • Cardura

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal

Terazosin • Hytrin

Trazodone • Desyrel

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Morrison J. When psychological problems mask medical disorders: a guide for psychotherapists. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. American Porphyria Foundation. About porphyria. https://porphyriafoundation.org/patients/about-porphyria. Accessed May 13, 2020.

3. Millward L, Kelly P, King A, et al. Anxiety and depression in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(6):1099-1107.

4. Bonkovsky H, Maddukuri VC, Yazici C, et al. Acute porphyrias in the USA: features of 108 subjects from porphyria consortium. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1233-1241.

5. Tsirlin A, Oo Y, Sharma R, et al. Pheochromocytoma: a review. Maturitas. 2014;77(3):229-238.

6. Leung A, Zun L, Nordstrom K, et al. Psychiatric emergencies for physicians: clinical management and approach to distinguishing pheochromocytoma from psychiatric and thyrotoxic diseases in the emergency room. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(5):712-716.

7. Garg M, Kharb S, Brar KS, et al. Medical management of pheochromocytoma: role of the endocrinologist. Indian J Endocrinol and Metab. 2011;15(suppl 4):S329-S336. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.86976.

8. Zardawi I. Phaeochromocytoma masquerading as anxiety and depression. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:161-163.

9. ARUP Laboratories. Test directory. https://www.aruplab.com. Accessed February 11, 2020.

10. Sriram P, Raghavan V. Pheochromocytoma presenting as anxiety disorder: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:83-84.

11. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

1. Morrison J. When psychological problems mask medical disorders: a guide for psychotherapists. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. American Porphyria Foundation. About porphyria. https://porphyriafoundation.org/patients/about-porphyria. Accessed May 13, 2020.

3. Millward L, Kelly P, King A, et al. Anxiety and depression in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(6):1099-1107.

4. Bonkovsky H, Maddukuri VC, Yazici C, et al. Acute porphyrias in the USA: features of 108 subjects from porphyria consortium. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1233-1241.

5. Tsirlin A, Oo Y, Sharma R, et al. Pheochromocytoma: a review. Maturitas. 2014;77(3):229-238.

6. Leung A, Zun L, Nordstrom K, et al. Psychiatric emergencies for physicians: clinical management and approach to distinguishing pheochromocytoma from psychiatric and thyrotoxic diseases in the emergency room. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(5):712-716.

7. Garg M, Kharb S, Brar KS, et al. Medical management of pheochromocytoma: role of the endocrinologist. Indian J Endocrinol and Metab. 2011;15(suppl 4):S329-S336. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.86976.

8. Zardawi I. Phaeochromocytoma masquerading as anxiety and depression. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:161-163.

9. ARUP Laboratories. Test directory. https://www.aruplab.com. Accessed February 11, 2020.

10. Sriram P, Raghavan V. Pheochromocytoma presenting as anxiety disorder: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:83-84.

11. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

COVID-19 and Mental Health Awareness Month

#howareyoureally challenge seeks to increase access to care

We are months into the COVID-19 crisis, and mental health issues are proving to be rampant. In every crisis, there is opportunity, and this one is no different. The opportunity is clear. For Mental Health Awareness Month and beyond, we must convey a powerful message that mental health is key to our well-being and must be actively addressed. Because almost everyone has felt excess anxiety these last months, we have a unique chance to engage a wider audience.

To address the urgent need, the Mental Health Coalition was formed with the understanding that the mental health crisis is fueled by a pervasive and devastating stigma, preventing millions of individuals from being able to seek the critical treatment they need. Spearheaded by social activist and fashion designer, Kenneth Cole, it is a coalition of leading mental health organizations, brands, celebrities, and advocates who have joined forces to end the stigma surrounding mental health and to change the way people talk about, and care for, mental illness. The group’s mission listed on its website states: “We must increase the conversation around mental health. We must act to end silence, reduce stigma, and engage our community to inspire hope at this essential moment.”

As most of the United States has been under stay-at-home orders, our traditional relationships have been radically disrupted. New types of relationships are forming as we are relying even more on technology to connect us. Social media seems to be on the only “social” we can now safely engage in.

The coalition’s campaign, “#howareyoureally?” is harnessing the power of social media and creating a storytelling platform to allow users to more genuinely share their feelings in these unprecedented times. Celebrities include Whoopi Goldberg, Kendall Jenner, Chris Cuomo, Deepak Chopra, Kesha, and many more have already shared their stories.

“How Are You, Really?” challenges people to answer this question using social media in an open and honest fashion while still providing hope.

The second component of the initiative is to increase access to care, and they have a long list of collaborators, including leading mental health organizations such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Anxiety and Depression Association of America, Child Mind Institute, Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services, National Alliance on Mental Illness, and many more.

We have a unique opportunity this Mental Health Awareness Month, and As a community, we must be prepared to meet the escalating needs of our population.

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach, Fla. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018) and is the founder of the Bekindr Global Initiative, a movement aimed at cultivating kindness in the world. Dr. Ritvo also is the cofounder of the Bold Beauty Project, a nonprofit group that pairs women with disabilities with photographers who create art exhibitions to raise awareness.

#howareyoureally challenge seeks to increase access to care

#howareyoureally challenge seeks to increase access to care

We are months into the COVID-19 crisis, and mental health issues are proving to be rampant. In every crisis, there is opportunity, and this one is no different. The opportunity is clear. For Mental Health Awareness Month and beyond, we must convey a powerful message that mental health is key to our well-being and must be actively addressed. Because almost everyone has felt excess anxiety these last months, we have a unique chance to engage a wider audience.

To address the urgent need, the Mental Health Coalition was formed with the understanding that the mental health crisis is fueled by a pervasive and devastating stigma, preventing millions of individuals from being able to seek the critical treatment they need. Spearheaded by social activist and fashion designer, Kenneth Cole, it is a coalition of leading mental health organizations, brands, celebrities, and advocates who have joined forces to end the stigma surrounding mental health and to change the way people talk about, and care for, mental illness. The group’s mission listed on its website states: “We must increase the conversation around mental health. We must act to end silence, reduce stigma, and engage our community to inspire hope at this essential moment.”

As most of the United States has been under stay-at-home orders, our traditional relationships have been radically disrupted. New types of relationships are forming as we are relying even more on technology to connect us. Social media seems to be on the only “social” we can now safely engage in.

The coalition’s campaign, “#howareyoureally?” is harnessing the power of social media and creating a storytelling platform to allow users to more genuinely share their feelings in these unprecedented times. Celebrities include Whoopi Goldberg, Kendall Jenner, Chris Cuomo, Deepak Chopra, Kesha, and many more have already shared their stories.

“How Are You, Really?” challenges people to answer this question using social media in an open and honest fashion while still providing hope.

The second component of the initiative is to increase access to care, and they have a long list of collaborators, including leading mental health organizations such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Anxiety and Depression Association of America, Child Mind Institute, Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services, National Alliance on Mental Illness, and many more.

We have a unique opportunity this Mental Health Awareness Month, and As a community, we must be prepared to meet the escalating needs of our population.

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach, Fla. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018) and is the founder of the Bekindr Global Initiative, a movement aimed at cultivating kindness in the world. Dr. Ritvo also is the cofounder of the Bold Beauty Project, a nonprofit group that pairs women with disabilities with photographers who create art exhibitions to raise awareness.

We are months into the COVID-19 crisis, and mental health issues are proving to be rampant. In every crisis, there is opportunity, and this one is no different. The opportunity is clear. For Mental Health Awareness Month and beyond, we must convey a powerful message that mental health is key to our well-being and must be actively addressed. Because almost everyone has felt excess anxiety these last months, we have a unique chance to engage a wider audience.

To address the urgent need, the Mental Health Coalition was formed with the understanding that the mental health crisis is fueled by a pervasive and devastating stigma, preventing millions of individuals from being able to seek the critical treatment they need. Spearheaded by social activist and fashion designer, Kenneth Cole, it is a coalition of leading mental health organizations, brands, celebrities, and advocates who have joined forces to end the stigma surrounding mental health and to change the way people talk about, and care for, mental illness. The group’s mission listed on its website states: “We must increase the conversation around mental health. We must act to end silence, reduce stigma, and engage our community to inspire hope at this essential moment.”

As most of the United States has been under stay-at-home orders, our traditional relationships have been radically disrupted. New types of relationships are forming as we are relying even more on technology to connect us. Social media seems to be on the only “social” we can now safely engage in.

The coalition’s campaign, “#howareyoureally?” is harnessing the power of social media and creating a storytelling platform to allow users to more genuinely share their feelings in these unprecedented times. Celebrities include Whoopi Goldberg, Kendall Jenner, Chris Cuomo, Deepak Chopra, Kesha, and many more have already shared their stories.

“How Are You, Really?” challenges people to answer this question using social media in an open and honest fashion while still providing hope.

The second component of the initiative is to increase access to care, and they have a long list of collaborators, including leading mental health organizations such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Anxiety and Depression Association of America, Child Mind Institute, Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services, National Alliance on Mental Illness, and many more.

We have a unique opportunity this Mental Health Awareness Month, and As a community, we must be prepared to meet the escalating needs of our population.

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach, Fla. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018) and is the founder of the Bekindr Global Initiative, a movement aimed at cultivating kindness in the world. Dr. Ritvo also is the cofounder of the Bold Beauty Project, a nonprofit group that pairs women with disabilities with photographers who create art exhibitions to raise awareness.

COVID-19: Delirium first, depression, anxiety, insomnia later?

Severe COVID-19 may cause delirium in the acute stage of illness, followed by the possibility of depression, anxiety, fatigue, insomnia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) over the longer term, new research suggests.

Results from “the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychiatric consequences of coronavirus infection” showed that previous coronavirus epidemics were associated with a significant psychiatric burden in both the acute and post-illness stages.

“Most people with COVID-19 will not develop any mental health problems, even among those with severe cases requiring hospitalization, but given the huge numbers of people getting sick, the global impact on mental health could be considerable,” co–lead investigator Jonathan Rogers, MRCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, University College London, United Kingdom, said in a news release.

The study was published online May 18 in Lancet Psychiatry.

Need for Monitoring, Support

The researchers analyzed 65 peer-reviewed studies and seven preprint articles with data on acute and post-illness psychiatric and neuropsychiatric features of patients who had been hospitalized with COVID-19, as well as two other diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), in 2002–2004, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), in 2012.

“Our main findings are that signs suggestive of delirium are common in the acute stage of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19; there is evidence of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and post-traumatic stress disorder in the post-illness stage of previous coronavirus epidemics, but there are few data yet on COVID-19,” the investigators write.

The data show that among patients acutely ill with SARS and MERS, 28% experienced confusion, 33% had depressed mood, 36% had anxiety, 34% suffered from impaired memory, and 42% had insomnia.

After recovery from SARS and MERS, sleep disorder, frequent recall of traumatic memories, emotional lability, impaired concentration, fatigue, and impaired memory were reported in more than 15% of patients during a follow-up period that ranged from 6 weeks to 39 months.

In a meta-analysis, the point prevalence in the post-illness stage was 32% for PTSD and about 15% for depression and anxiety.

In patients acutely ill with severe COVID-19, available data suggest that 65% experience delirium, 69% have agitation after withdrawal of sedation, and 21% have altered consciousness.

In one study, 33% of patients had a dysexecutive syndrome at discharge, characterized by symptoms such as inattention, disorientation, or poorly organized movements in response to command. Currently, data are very limited regarding patients who have recovered from COVID-19, the investigators caution.

“, and monitored after they recover to ensure they do not develop mental illnesses, and are able to access treatment if needed,” senior author Anthony David, FMedSci, from UCL Institute of Mental Health, said in a news release.

“While most people with COVID-19 will recover without experiencing mental illness, we need to research which factors may contribute to enduring mental health problems, and develop interventions to prevent and treat them,” he added.

Be Prepared

The coauthors of a linked commentary say it makes sense, from a biological perspective, to merge data on these three coronavirus diseases, given the degree to which they resemble each other.

They caution, however, that treatment of COVID-19 seems to be different from treatment of SARS and MERS. In addition, the social and economic situation of COVID-19 survivors’ return is completely different from that of SARS and MERS survivors.

Findings from previous coronavirus outbreaks are “useful, but might not be exact predictors of prevalences of psychiatric complications for patients with COVID-19,” write Iris Sommer, MD, PhD, from University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, and P. Roberto Bakker, MD, PhD, from Maastricht University Medical Center, the Netherlands.

“The warning from [this study] that we should prepare to treat large numbers of patients with COVID-19 who go on to develop delirium, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression is an important message for the psychiatric community,” they add.

Sommer and Bakker also say the reported estimates of prevalence in this study should be interpreted with caution, “as true numbers of both acute and long-term psychiatric disorders for patients with COVID-19 might be considerably higher.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Wellcome Trust, the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the UK Medical Research Council, the NIHR Biomedical Research Center at the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and the University College London. The authors of the study and the commentary have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Severe COVID-19 may cause delirium in the acute stage of illness, followed by the possibility of depression, anxiety, fatigue, insomnia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) over the longer term, new research suggests.

Results from “the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychiatric consequences of coronavirus infection” showed that previous coronavirus epidemics were associated with a significant psychiatric burden in both the acute and post-illness stages.

“Most people with COVID-19 will not develop any mental health problems, even among those with severe cases requiring hospitalization, but given the huge numbers of people getting sick, the global impact on mental health could be considerable,” co–lead investigator Jonathan Rogers, MRCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, University College London, United Kingdom, said in a news release.

The study was published online May 18 in Lancet Psychiatry.

Need for Monitoring, Support

The researchers analyzed 65 peer-reviewed studies and seven preprint articles with data on acute and post-illness psychiatric and neuropsychiatric features of patients who had been hospitalized with COVID-19, as well as two other diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), in 2002–2004, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), in 2012.

“Our main findings are that signs suggestive of delirium are common in the acute stage of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19; there is evidence of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and post-traumatic stress disorder in the post-illness stage of previous coronavirus epidemics, but there are few data yet on COVID-19,” the investigators write.

The data show that among patients acutely ill with SARS and MERS, 28% experienced confusion, 33% had depressed mood, 36% had anxiety, 34% suffered from impaired memory, and 42% had insomnia.

After recovery from SARS and MERS, sleep disorder, frequent recall of traumatic memories, emotional lability, impaired concentration, fatigue, and impaired memory were reported in more than 15% of patients during a follow-up period that ranged from 6 weeks to 39 months.

In a meta-analysis, the point prevalence in the post-illness stage was 32% for PTSD and about 15% for depression and anxiety.

In patients acutely ill with severe COVID-19, available data suggest that 65% experience delirium, 69% have agitation after withdrawal of sedation, and 21% have altered consciousness.

In one study, 33% of patients had a dysexecutive syndrome at discharge, characterized by symptoms such as inattention, disorientation, or poorly organized movements in response to command. Currently, data are very limited regarding patients who have recovered from COVID-19, the investigators caution.

“, and monitored after they recover to ensure they do not develop mental illnesses, and are able to access treatment if needed,” senior author Anthony David, FMedSci, from UCL Institute of Mental Health, said in a news release.

“While most people with COVID-19 will recover without experiencing mental illness, we need to research which factors may contribute to enduring mental health problems, and develop interventions to prevent and treat them,” he added.

Be Prepared

The coauthors of a linked commentary say it makes sense, from a biological perspective, to merge data on these three coronavirus diseases, given the degree to which they resemble each other.

They caution, however, that treatment of COVID-19 seems to be different from treatment of SARS and MERS. In addition, the social and economic situation of COVID-19 survivors’ return is completely different from that of SARS and MERS survivors.

Findings from previous coronavirus outbreaks are “useful, but might not be exact predictors of prevalences of psychiatric complications for patients with COVID-19,” write Iris Sommer, MD, PhD, from University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, and P. Roberto Bakker, MD, PhD, from Maastricht University Medical Center, the Netherlands.

“The warning from [this study] that we should prepare to treat large numbers of patients with COVID-19 who go on to develop delirium, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression is an important message for the psychiatric community,” they add.

Sommer and Bakker also say the reported estimates of prevalence in this study should be interpreted with caution, “as true numbers of both acute and long-term psychiatric disorders for patients with COVID-19 might be considerably higher.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Wellcome Trust, the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the UK Medical Research Council, the NIHR Biomedical Research Center at the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and the University College London. The authors of the study and the commentary have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Severe COVID-19 may cause delirium in the acute stage of illness, followed by the possibility of depression, anxiety, fatigue, insomnia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) over the longer term, new research suggests.

Results from “the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychiatric consequences of coronavirus infection” showed that previous coronavirus epidemics were associated with a significant psychiatric burden in both the acute and post-illness stages.

“Most people with COVID-19 will not develop any mental health problems, even among those with severe cases requiring hospitalization, but given the huge numbers of people getting sick, the global impact on mental health could be considerable,” co–lead investigator Jonathan Rogers, MRCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, University College London, United Kingdom, said in a news release.

The study was published online May 18 in Lancet Psychiatry.

Need for Monitoring, Support

The researchers analyzed 65 peer-reviewed studies and seven preprint articles with data on acute and post-illness psychiatric and neuropsychiatric features of patients who had been hospitalized with COVID-19, as well as two other diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), in 2002–2004, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), in 2012.

“Our main findings are that signs suggestive of delirium are common in the acute stage of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19; there is evidence of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and post-traumatic stress disorder in the post-illness stage of previous coronavirus epidemics, but there are few data yet on COVID-19,” the investigators write.

The data show that among patients acutely ill with SARS and MERS, 28% experienced confusion, 33% had depressed mood, 36% had anxiety, 34% suffered from impaired memory, and 42% had insomnia.

After recovery from SARS and MERS, sleep disorder, frequent recall of traumatic memories, emotional lability, impaired concentration, fatigue, and impaired memory were reported in more than 15% of patients during a follow-up period that ranged from 6 weeks to 39 months.

In a meta-analysis, the point prevalence in the post-illness stage was 32% for PTSD and about 15% for depression and anxiety.

In patients acutely ill with severe COVID-19, available data suggest that 65% experience delirium, 69% have agitation after withdrawal of sedation, and 21% have altered consciousness.

In one study, 33% of patients had a dysexecutive syndrome at discharge, characterized by symptoms such as inattention, disorientation, or poorly organized movements in response to command. Currently, data are very limited regarding patients who have recovered from COVID-19, the investigators caution.

“, and monitored after they recover to ensure they do not develop mental illnesses, and are able to access treatment if needed,” senior author Anthony David, FMedSci, from UCL Institute of Mental Health, said in a news release.

“While most people with COVID-19 will recover without experiencing mental illness, we need to research which factors may contribute to enduring mental health problems, and develop interventions to prevent and treat them,” he added.

Be Prepared

The coauthors of a linked commentary say it makes sense, from a biological perspective, to merge data on these three coronavirus diseases, given the degree to which they resemble each other.

They caution, however, that treatment of COVID-19 seems to be different from treatment of SARS and MERS. In addition, the social and economic situation of COVID-19 survivors’ return is completely different from that of SARS and MERS survivors.

Findings from previous coronavirus outbreaks are “useful, but might not be exact predictors of prevalences of psychiatric complications for patients with COVID-19,” write Iris Sommer, MD, PhD, from University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, and P. Roberto Bakker, MD, PhD, from Maastricht University Medical Center, the Netherlands.

“The warning from [this study] that we should prepare to treat large numbers of patients with COVID-19 who go on to develop delirium, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression is an important message for the psychiatric community,” they add.

Sommer and Bakker also say the reported estimates of prevalence in this study should be interpreted with caution, “as true numbers of both acute and long-term psychiatric disorders for patients with COVID-19 might be considerably higher.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Wellcome Trust, the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the UK Medical Research Council, the NIHR Biomedical Research Center at the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and the University College London. The authors of the study and the commentary have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 exacerbating challenges for Latino patients

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.

“The COVID pandemic has highlighted the structural inequities that affect the Latino population [both] immigrant and nonimmigrant,” said Dr. Montano, a board member of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry and the officer of infrastructure and advocacy for the Hispanic Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association. “This includes income inequality, poor nutrition, history of trauma and discrimination, employment issues, quality education, access to technology, and overall access to appropriate cultural linguistic health care.”

Navigating challenges

For mental health professionals treating Latino patients, COVID-19 and the pandemic response have generated a range of treatment obstacles.

The transition to telehealth for example, has not been easy for some patients, said Jacqueline Posada, MD, consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow at the Inova Fairfax Hospital–George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and an APA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration minority fellow. Some patients lack Internet services, others forget virtual visits, and some do not have working phones, she said.

“I’ve had to be very flexible,” she said in an interview. “Ideally, I’d love to see everybody via video chat, but a lot of people either don’t have a stable Internet connection or Internet, so I meet the patient where they are. Whatever they have available, that’s what I’m going to use. If they don’t answer on the first call, I will call again at least three to five times in the first 15 minutes to make sure I’m giving them an opportunity to pick up the phone.”

In addition, Dr. Posada has encountered disconnected phones when calling patients for appointments. In such cases, Dr. Posada contacts the patient’s primary care physician to relay medication recommendations in case the patient resurfaces at the clinic.

In other instances, patients are not familiar with video technology, or they must travel to a friend or neighbor’s house to access the technology, said Hector Colón-Rivera, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and medical director of the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha Behavioral Health Program, a nonprofit organization based in the Philadelphia area. Telehealth visits frequently include appearances by children, family members, barking dogs, and other distractions, said Dr. Colón-Rivera, president of the APA Hispanic Caucus.

“We’re seeing things that we didn’t used to see when they came to our office – for good or for bad,” said Dr. Colón-Rivera, an attending telemedicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “It could be a good chance to meet our patient in a different way. Of course, it creates different stressors. If you have five kids on top of you and you’re the only one at home, it’s hard to do therapy.”

Psychiatrists are also seeing prior health conditions in patients exacerbated by COVID-19 fears and new health problems arising from the current pandemic environment. Dr. Posada recalls a patient whom she successfully treated for premenstrual dysphoric disorder who recently descended into severe clinical depression. The patient, from Colombia, was attending school in the United States on a student visa and supporting herself through child care jobs.

“So much of her depression was based on her social circumstance,” Dr. Posada said. “She had lost her job, her sister had lost her job so they were scraping by on her sister’s husband’s income, and the thing that brought her joy, which was going to school and studying so she could make a different life for herself than what her parents had in Colombia, also seemed like it was out of reach.”

Dr. Colón-Rivera recently received a call from a hospital where one of his patients was admitted after becoming delusional and psychotic. The patient was correctly taking medication prescribed by Dr. Colón-Rivera, but her diabetes had become uncontrolled because she was unable to reach her primary care doctor and couldn’t access the pharmacy. Her blood sugar level became elevated, leading to the delusions.

“A patient that was perfectly stable now is unstable,” he said. “Her diet has not been good enough through the pandemic, exacerbating her diabetes. She was admitted to the hospital for delirium.

Compounding of traumas

For many Latino patients, the adverse impacts of the pandemic comes on top of multiple prior traumas, such as violence exposures, discrimination, and economic issues, said Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, MDiv, chief of psychiatry and vice chair at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A 2017 analysis found that nearly four in five Latino youth face at least one traumatic childhood experience, like poverty or abuse, and that about 29% of Latino youth experience four or more of these traumas.

Immigrants in particular, may have faced trauma in their home country and/or immigration trauma, Dr. Fortuna added. A 2013 study on immigrant Latino adolescents for example, found that 29% of foreign-born adolescents and 34% of foreign-born parents experienced trauma during the migration process (Int Migr Rev. 2013 Dec;47(4):10).

“All of these things are cumulative,” Dr. Fortuna said. “Then when you’re hit with a pandemic, all of the disparities that you already have and all the stress that you already have are compounded. This is for the kids, too, who have been exposed to a lot of stressors and now maybe have family members that have been ill or have died. All of these things definitely put people at risk for increased depression [and] the worsening of any preexisting posttraumatic stress disorder. We’ve seen this in previous disasters, and I expect that’s what we’re going to see more of with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At the same time, a central cultural value of many Latinos is family unity, Dr. Montano said, a foundation that is now being strained by social distancing and severed connections.

“This has separated many families,” she said. “There has been a lot of loneliness and grief.”

Mistrust and fear toward the government, public agencies, and even the health system itself act as further hurdles for some Latinos in the face of COVID-19. In areas with large immigrant populations such as San Francisco, Dr. Fortuna noted, it’s not uncommon for undocumented patients to avoid accessing medical care and social services, or visiting emergency departments for needed care for fear of drawing attention to themselves or possible detainment.

“The fact that so many people showed up at our hospital so ill and ended up in the ICU – that could be a combination of factors. Because the population has high rates of diabetes and hypertension, that might have put people at increased risk for severe illness,” she said. “But some people may have been holding out for care because they wanted to avoid being in places out of fear of immigration scrutiny.”

Overcoming language barriers

Compounding the challenging pandemic landscape for Latino patients is the fact that many state resources about COVID-19 have not been translated to Spanish, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. He was troubled recently when he went to several state websites and found limited to no information in Spanish about the coronavirus. Some data about COVID-19 from the federal government were not translated to Spanish until officials received pushback, he added. Even now, press releases and other information disseminated by the federal government about the virus appear to be translated by an automated service – and lack sense and context.

The state agencies in Pennsylvania have been alerted to the absence of Spanish information, but change has been slow, he noted.

“In Philadelphia, 23% speaks a language other than English,” he said. “So we missed a lot of critical information that could have helped to avoid spreading the illness and access support.”

Dr. Fortuna said that California has done better with providing COVID-19–related information in Spanish, compared with some other states, but misinformation about the virus and lingering myths have still been a problem among the Latino community. The University of California, San Francisco, recently launched a Latino Task Force resource website for the Latino community that includes information in English, Spanish, and Yucatec Maya about COVID-19, health and wellness tips, and resources for various assistance needs.

The concerning lack of COVID-19 information translated to Spanish led Dr. Montano to start a Facebook page in Spanish about mental health tips and guidance for managing COVID-19–related issues. She and her team of clinicians share information, videos, relaxation exercises, and community resources on the page, among other posts. “There is also general info and recommendations about COVID-19 that I think can be useful for the community,” she said. “The idea is that patients, the general community, and providers can have share information, hope messages, and ask questions in Spanish.”

Feeling ‘helpless’

A central part of caring for Latino patients during the COVID-19 crisis has been referring them to outside agencies and social services, psychiatrists say. But finding the right resources amid a pandemic and ensuring that patients connect with the correct aid has been an uphill battle.

“We sometimes feel like our hands are tied,” Dr. Colón-Rivera said. “Sometimes, we need to call a place to bring food. Some of the state agencies and nonprofits don’t have delivery systems, so the patient has to go pick up for food or medication. Some of our patients don’t want to go outside. Some do not have cars.”

As a clinician, it can be easy to feel helpless when trying to navigate new challenges posed by the pandemic in addition to other longstanding barriers, Dr. Posada said.

“Already, mental health disorders are so influenced by social situations like poverty, job insecurity, or family issues, and now it just seems those obstacles are even more insurmountable,” she said. “At the end of the day, I can feel like: ‘Did I make a difference?’ That’s a big struggle.”

Dr. Montano’s team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, have come to rely on virtual debriefings to vent, express frustrations, and support one another, she said. She also recently joined a virtual mind-body skills group as a participant.

“I recognize the importance of getting additional support and ways to alleviate burnout,” she said. “We need to take care of ourselves or we won’t be able to help others.”

Focusing on resilience during the current crisis can be beneficial for both patients and providers in coping and drawing strength, Dr. Posada said.

“When it comes to fostering resilience during times of hardship, I think it’s most helpful to reflect on what skills or attributes have helped during past crises and apply those now – whether it’s turning to comfort from close relationships, looking to religion and spirituality, practicing self-care like rest or exercise, or really tapping into one’s purpose and reason for practicing psychiatry and being a physician,” she said. “The same advice goes for clinicians: We’ve all been through hard times in the past, it’s part of the human condition and we’ve also witnessed a lot of suffering in our patients, so now is the time to practice those skills that have gotten us through hard times in the past.”

Learning lessons from COVID-19

Despite the challenges with moving to telehealth, Dr. Fortuna said the tool has proved beneficial overall for mental health care. For Dr. Fortuna’s team for example, telehealth by phone has decreased the no-show rate, compared with clinic visits, and improved care access.

“We need to figure out how to maintain that,” she said. “If we can build ways for equity and access to Internet, especially equipment, I think that’s going to help.”

In addition, more data are needed about the ways in which COVID-19 is affecting Latino patients, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. Mortality statistics have been published, but information is needed about the rates of infection and manifestation of illness.

Most importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has emphasized the critical need to address and improve the underlying inequity issues among Latino patients, psychiatrists say.

“We really need to think about how there can be partnerships, in terms of community-based Latino business and leaders, multisector resources, trying to think about how we can improve conditions both work and safety for Latinos,” Dr. Fortuna said. “How can schools get support in integrating mental health and support for families, especially now after COVID-19? And really looking at some of these underlying inequities that are the underpinnings of why people were at risk for the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.