User login

When to treat, delay, or omit breast cancer therapy in the face of COVID-19

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Home-based chemo skyrockets at one U.S. center

Major organization opposes concept

In the fall of 2019, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia started a pilot program of home-based chemotherapy for two treatment regimens (one via infusion and one via injection). Six months later, the Cancer Care at Home program had treated 40 patients.

The uptake within the university’s large regional health system was acceptable but not rapid, admitted Amy Laughlin, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow involved with the program.

Then COVID-19 arrived, along with related travel restrictions.

Suddenly, in a 5-week period (March to April 7), 175 patients had been treated – a 300% increase from the first half year. Program staff jumped from 12 to 80 employees. The list of chemotherapies delivered went from two to seven, with more coming.

“We’re not the pilot anymore – we’re the standard of care,” Laughlin told Medscape Medical News.

“The impact [on patients] is amazing,” she said. “As long as you are selecting the right patients and right therapy, it is feasible and even preferable for a lot of patients.”

For example, patients with hormone-positive breast cancer who receive leuprolide (to shut down the ovaries and suppress estrogen production) ordinarily would have to visit a Penn facility for an injection every month, potentially for years. Now, a nurse can meet patients at home (or before the COVID-19 pandemic, even at their place of work) and administer the injection, saving the patient travel time and associated costs.

This home-based chemotherapy service does not appear to be offered elsewhere in the United States, and a major oncology organization – the Community Oncology Alliance – is opposed to the practice because of patient safety concerns.

The service is not offered at a sample of cancer centers queried by Medscape Medical News, including the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, the Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Moores Cancer Center, the University of California, San Diego.

Opposition because of safety concerns

On April 9, the Community Oncology Alliance (COA) issued a statement saying it “fundamentally opposes home infusion of chemotherapy, cancer immunotherapy, and cancer treatment supportive drugs because of serious patient safety concerns.”

The COA warned that “many of the side effects caused by cancer treatment can have a rapid, unpredictable onset that places patients in incredible jeopardy and can even be life-threatening.”

In contrast, in a recent communication related to COVID-19, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tacitly endorsed the concept, stating that a number of chemotherapies may potentially be administered at home, but it did not include guidelines for doing so.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that chemotherapy at home is “an issue [we] are monitoring closely,” according to a spokesperson.

What’s involved

Criteria for home-based chemotherapy at Penn include use of anticancer therapies that a patient has previously tolerated and low toxicity (that can be readily managed in the home setting). In addition, patients must be capable of following a med chart.

The chemotherapy is reconstituted at a Penn facility in a Philadelphia suburb. A courier then delivers the drug to the patient’s home, where it is administered by an oncology-trained nurse. Drugs must be stable for at least a few hours to qualify for the program.

The Penn program started with two regimens: EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) for lymphoma, and leuprolide acetate injections for either breast or prostate cancer.

The two treatments are polar opposites in terms of complexity, common usage, and time required, which was intended, said Laughlin.

Time to deliver the chemo varies from a matter of minutes with leuprolide to more than 2 hours for rituximab, a lymphoma drug that may be added to EPOCH.

The current list of at-home chemo agents in the Penn program also includes bortezomib, lanreotide, zoledronic acid, and denosumab. Soon to come are rituximab and pembrolizumab for lung cancer and head and neck cancer.

Already practiced in some European countries

Home-based chemotherapy dates from at least the 1980s in the medical literature and is practiced in some European countries.

A 2018 randomized study of adjuvant treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for stage II/III colon cancer in Denmark, where home-based care has been practiced for the past 2 years and is growing in use, concluded that “it might be a valuable alternative to treatment at an outpatient clinic.”

However, in the study, there was no difference in quality of life between the home and outpatient settings, which is somewhat surprising, inasmuch as a major appeal to receiving chemotherapy at home is that it is less disruptive compared to receiving it in a hospital or clinic, which requires travel.

Also, chemo at home “may be resource intensive” and have a “lower throughput of patients due to transportation time,” cautioned the Danish investigators, who were from Herlev and Gentofte Hospital.

A 2015 review called home chemo “a safe and patient‐centered alternative to hospital‐ and outpatient‐based service.” Jenna Evans, PhD, McMaster University, Toronto, Canada, and lead author of that review, says there are two major barriers to infusion chemotherapy in homes.

One is inadequate resources in the community, such as oncology-trained nurses to deliver treatment, and the other is perceptions of safety and quality, including among healthcare providers.

COVID-19 might prompt more chemo at home, said Evans, a health policy expert, in an email to Medscape Medical News. “It is not unusual for change of this type and scale to require a seismic event to become more mainstream,” she argued.

Reimbursement for home-based chemo is usually the same as for chemo in a free-standing infusion suite, says Cassandra Redmond, PharmD, MBA, director of pharmacy, Penn Home Infusion Therapy.

Private insurers and Medicare cover a subset of infused medications at home, but coverage is limited. “The opportunity now is to expand these initiatives ... to include other cancer therapies,” she said about coverage.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Major organization opposes concept

Major organization opposes concept

In the fall of 2019, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia started a pilot program of home-based chemotherapy for two treatment regimens (one via infusion and one via injection). Six months later, the Cancer Care at Home program had treated 40 patients.

The uptake within the university’s large regional health system was acceptable but not rapid, admitted Amy Laughlin, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow involved with the program.

Then COVID-19 arrived, along with related travel restrictions.

Suddenly, in a 5-week period (March to April 7), 175 patients had been treated – a 300% increase from the first half year. Program staff jumped from 12 to 80 employees. The list of chemotherapies delivered went from two to seven, with more coming.

“We’re not the pilot anymore – we’re the standard of care,” Laughlin told Medscape Medical News.

“The impact [on patients] is amazing,” she said. “As long as you are selecting the right patients and right therapy, it is feasible and even preferable for a lot of patients.”

For example, patients with hormone-positive breast cancer who receive leuprolide (to shut down the ovaries and suppress estrogen production) ordinarily would have to visit a Penn facility for an injection every month, potentially for years. Now, a nurse can meet patients at home (or before the COVID-19 pandemic, even at their place of work) and administer the injection, saving the patient travel time and associated costs.

This home-based chemotherapy service does not appear to be offered elsewhere in the United States, and a major oncology organization – the Community Oncology Alliance – is opposed to the practice because of patient safety concerns.

The service is not offered at a sample of cancer centers queried by Medscape Medical News, including the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, the Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Moores Cancer Center, the University of California, San Diego.

Opposition because of safety concerns

On April 9, the Community Oncology Alliance (COA) issued a statement saying it “fundamentally opposes home infusion of chemotherapy, cancer immunotherapy, and cancer treatment supportive drugs because of serious patient safety concerns.”

The COA warned that “many of the side effects caused by cancer treatment can have a rapid, unpredictable onset that places patients in incredible jeopardy and can even be life-threatening.”

In contrast, in a recent communication related to COVID-19, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tacitly endorsed the concept, stating that a number of chemotherapies may potentially be administered at home, but it did not include guidelines for doing so.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that chemotherapy at home is “an issue [we] are monitoring closely,” according to a spokesperson.

What’s involved

Criteria for home-based chemotherapy at Penn include use of anticancer therapies that a patient has previously tolerated and low toxicity (that can be readily managed in the home setting). In addition, patients must be capable of following a med chart.

The chemotherapy is reconstituted at a Penn facility in a Philadelphia suburb. A courier then delivers the drug to the patient’s home, where it is administered by an oncology-trained nurse. Drugs must be stable for at least a few hours to qualify for the program.

The Penn program started with two regimens: EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) for lymphoma, and leuprolide acetate injections for either breast or prostate cancer.

The two treatments are polar opposites in terms of complexity, common usage, and time required, which was intended, said Laughlin.

Time to deliver the chemo varies from a matter of minutes with leuprolide to more than 2 hours for rituximab, a lymphoma drug that may be added to EPOCH.

The current list of at-home chemo agents in the Penn program also includes bortezomib, lanreotide, zoledronic acid, and denosumab. Soon to come are rituximab and pembrolizumab for lung cancer and head and neck cancer.

Already practiced in some European countries

Home-based chemotherapy dates from at least the 1980s in the medical literature and is practiced in some European countries.

A 2018 randomized study of adjuvant treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for stage II/III colon cancer in Denmark, where home-based care has been practiced for the past 2 years and is growing in use, concluded that “it might be a valuable alternative to treatment at an outpatient clinic.”

However, in the study, there was no difference in quality of life between the home and outpatient settings, which is somewhat surprising, inasmuch as a major appeal to receiving chemotherapy at home is that it is less disruptive compared to receiving it in a hospital or clinic, which requires travel.

Also, chemo at home “may be resource intensive” and have a “lower throughput of patients due to transportation time,” cautioned the Danish investigators, who were from Herlev and Gentofte Hospital.

A 2015 review called home chemo “a safe and patient‐centered alternative to hospital‐ and outpatient‐based service.” Jenna Evans, PhD, McMaster University, Toronto, Canada, and lead author of that review, says there are two major barriers to infusion chemotherapy in homes.

One is inadequate resources in the community, such as oncology-trained nurses to deliver treatment, and the other is perceptions of safety and quality, including among healthcare providers.

COVID-19 might prompt more chemo at home, said Evans, a health policy expert, in an email to Medscape Medical News. “It is not unusual for change of this type and scale to require a seismic event to become more mainstream,” she argued.

Reimbursement for home-based chemo is usually the same as for chemo in a free-standing infusion suite, says Cassandra Redmond, PharmD, MBA, director of pharmacy, Penn Home Infusion Therapy.

Private insurers and Medicare cover a subset of infused medications at home, but coverage is limited. “The opportunity now is to expand these initiatives ... to include other cancer therapies,” she said about coverage.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the fall of 2019, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia started a pilot program of home-based chemotherapy for two treatment regimens (one via infusion and one via injection). Six months later, the Cancer Care at Home program had treated 40 patients.

The uptake within the university’s large regional health system was acceptable but not rapid, admitted Amy Laughlin, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow involved with the program.

Then COVID-19 arrived, along with related travel restrictions.

Suddenly, in a 5-week period (March to April 7), 175 patients had been treated – a 300% increase from the first half year. Program staff jumped from 12 to 80 employees. The list of chemotherapies delivered went from two to seven, with more coming.

“We’re not the pilot anymore – we’re the standard of care,” Laughlin told Medscape Medical News.

“The impact [on patients] is amazing,” she said. “As long as you are selecting the right patients and right therapy, it is feasible and even preferable for a lot of patients.”

For example, patients with hormone-positive breast cancer who receive leuprolide (to shut down the ovaries and suppress estrogen production) ordinarily would have to visit a Penn facility for an injection every month, potentially for years. Now, a nurse can meet patients at home (or before the COVID-19 pandemic, even at their place of work) and administer the injection, saving the patient travel time and associated costs.

This home-based chemotherapy service does not appear to be offered elsewhere in the United States, and a major oncology organization – the Community Oncology Alliance – is opposed to the practice because of patient safety concerns.

The service is not offered at a sample of cancer centers queried by Medscape Medical News, including the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, the Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Moores Cancer Center, the University of California, San Diego.

Opposition because of safety concerns

On April 9, the Community Oncology Alliance (COA) issued a statement saying it “fundamentally opposes home infusion of chemotherapy, cancer immunotherapy, and cancer treatment supportive drugs because of serious patient safety concerns.”

The COA warned that “many of the side effects caused by cancer treatment can have a rapid, unpredictable onset that places patients in incredible jeopardy and can even be life-threatening.”

In contrast, in a recent communication related to COVID-19, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tacitly endorsed the concept, stating that a number of chemotherapies may potentially be administered at home, but it did not include guidelines for doing so.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that chemotherapy at home is “an issue [we] are monitoring closely,” according to a spokesperson.

What’s involved

Criteria for home-based chemotherapy at Penn include use of anticancer therapies that a patient has previously tolerated and low toxicity (that can be readily managed in the home setting). In addition, patients must be capable of following a med chart.

The chemotherapy is reconstituted at a Penn facility in a Philadelphia suburb. A courier then delivers the drug to the patient’s home, where it is administered by an oncology-trained nurse. Drugs must be stable for at least a few hours to qualify for the program.

The Penn program started with two regimens: EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) for lymphoma, and leuprolide acetate injections for either breast or prostate cancer.

The two treatments are polar opposites in terms of complexity, common usage, and time required, which was intended, said Laughlin.

Time to deliver the chemo varies from a matter of minutes with leuprolide to more than 2 hours for rituximab, a lymphoma drug that may be added to EPOCH.

The current list of at-home chemo agents in the Penn program also includes bortezomib, lanreotide, zoledronic acid, and denosumab. Soon to come are rituximab and pembrolizumab for lung cancer and head and neck cancer.

Already practiced in some European countries

Home-based chemotherapy dates from at least the 1980s in the medical literature and is practiced in some European countries.

A 2018 randomized study of adjuvant treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for stage II/III colon cancer in Denmark, where home-based care has been practiced for the past 2 years and is growing in use, concluded that “it might be a valuable alternative to treatment at an outpatient clinic.”

However, in the study, there was no difference in quality of life between the home and outpatient settings, which is somewhat surprising, inasmuch as a major appeal to receiving chemotherapy at home is that it is less disruptive compared to receiving it in a hospital or clinic, which requires travel.

Also, chemo at home “may be resource intensive” and have a “lower throughput of patients due to transportation time,” cautioned the Danish investigators, who were from Herlev and Gentofte Hospital.

A 2015 review called home chemo “a safe and patient‐centered alternative to hospital‐ and outpatient‐based service.” Jenna Evans, PhD, McMaster University, Toronto, Canada, and lead author of that review, says there are two major barriers to infusion chemotherapy in homes.

One is inadequate resources in the community, such as oncology-trained nurses to deliver treatment, and the other is perceptions of safety and quality, including among healthcare providers.

COVID-19 might prompt more chemo at home, said Evans, a health policy expert, in an email to Medscape Medical News. “It is not unusual for change of this type and scale to require a seismic event to become more mainstream,” she argued.

Reimbursement for home-based chemo is usually the same as for chemo in a free-standing infusion suite, says Cassandra Redmond, PharmD, MBA, director of pharmacy, Penn Home Infusion Therapy.

Private insurers and Medicare cover a subset of infused medications at home, but coverage is limited. “The opportunity now is to expand these initiatives ... to include other cancer therapies,” she said about coverage.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Conducting cancer trials amid the COVID-19 pandemic

More than three-quarters of cancer clinical research programs have experienced operational changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) during a recent webinar.

The webinar included insights into how some cancer research programs have adapted to the pandemic, a review of guidance for conducting cancer trials during this time, and a discussion of how the cancer research landscape may be affected by COVID-19 going forward.

The webinar was led by Randall A. Oyer, MD, president of the ACCC and medical director of the oncology program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health in Pennsylvania.

The impact of COVID-19 on cancer research

Dr. Oyer observed that planning and implementation for COVID-19–related illness at U.S. health care institutions has had a predictable effect of limiting patient access and staff availability for nonessential services.

Coronavirus-related exposure and/or illness has relegated cancer research to a lower-level priority. As a result, ACCC institutions have made adjustments in their cancer research programs, including moving clinical research coordinators off-campus and deploying them in clinical areas.

New clinical trials have not been opened. In some cases, new accruals have been halted, particularly for registry, prevention, and symptom control trials.

Standards that have changed and those that have not

Guidance documents for conducting clinical trials during the pandemic have been developed by the Food and Drug Administration, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Central Institutional Review Board, and the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Extramural Research. Industry sponsors and parent institutions of research programs have also disseminated guidance.

Among other topics, guidance documents have addressed:

- How COVID-19-related protocol deviations will be judged at monitoring visits and audits

- Missed office visits and endpoint evaluations

- Providing investigational oral medications to patients via mail and potential issues of medication unavailability

- Processes for patients to have interim visits with providers at external institutions, including providers who may not be personally engaged in or credentialed for the research trial

- Potential delays in submitting protocol amendments for institutional review board (IRB) review

- Recommendations for patients confirmed or suspected of having a coronavirus infection.

Dr. Oyer emphasized that patient safety must remain the highest priority for patient management, on or off study. He advised continuing investigational therapy when potential benefit from treatment is anticipated and identifying alternative methods to face-to-face visits for monitoring and access to treatment.

Dr. Oyer urged programs to:

- Maintain good clinical practice standards

- Consult with sponsors and IRBs when questions arise but implement changes that affect patient safety prior to IRB review if necessary

- Document all deviations and COVID-19 related adaptations in a log or spreadsheet in anticipation of future questions from sponsors, monitors, and other entities.

New questions and considerations

In the short-term, Dr. Oyer predicts fewer available trials and a decreased rate of accrual to existing studies. This may result in delays in trial completion and the possibility of redesign for some trials.

He predicts the emergence of COVID-19-focused research questions, including those assessing the course of coronavirus infection in various malignant settings and the impact of cancer-directed treatments and supportive care interventions (e.g., treatment for graft-versus-host disease) on response to COVID-19.

To facilitate developing a clinically and research-relevant database, Dr. Oyer stressed the importance of documentation in the research record, reporting infections as serious adverse events. Documentation should specify whether the infection was confirmed or suspected coronavirus or related to another organism.

In general, when coronavirus infection is strongly suspected, Dr. Oyer said investigational treatments should be interrupted, but study-specific criteria will be forthcoming on that issue.

Looking to the future

For patients with advanced cancers, clinical trials provide an important option for hope and clinical benefit. Disrupting the conduct of clinical trials could endanger the lives of participants and delay the emergence of promising treatments and diagnostic tests.

When the coronavirus pandemic recedes, advancing knowledge and treatments for cancer will demand renewed commitment across the oncology care community.

Going forward, Dr. Oyer advised that clinical research staff protect their own health and the safety of trial participants. He encouraged programs to work with sponsors and IRBs to solve logistical problems and clarify individual issues.

He was optimistic that resumption of more normal conduct of studies will enable the successful completion of ongoing trials, enhanced by the creative solutions that were devised during the crisis and by additional prospective, clinically annotated, carefully recorded data from academic and community research sites.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

More than three-quarters of cancer clinical research programs have experienced operational changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) during a recent webinar.

The webinar included insights into how some cancer research programs have adapted to the pandemic, a review of guidance for conducting cancer trials during this time, and a discussion of how the cancer research landscape may be affected by COVID-19 going forward.

The webinar was led by Randall A. Oyer, MD, president of the ACCC and medical director of the oncology program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health in Pennsylvania.

The impact of COVID-19 on cancer research

Dr. Oyer observed that planning and implementation for COVID-19–related illness at U.S. health care institutions has had a predictable effect of limiting patient access and staff availability for nonessential services.

Coronavirus-related exposure and/or illness has relegated cancer research to a lower-level priority. As a result, ACCC institutions have made adjustments in their cancer research programs, including moving clinical research coordinators off-campus and deploying them in clinical areas.

New clinical trials have not been opened. In some cases, new accruals have been halted, particularly for registry, prevention, and symptom control trials.

Standards that have changed and those that have not

Guidance documents for conducting clinical trials during the pandemic have been developed by the Food and Drug Administration, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Central Institutional Review Board, and the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Extramural Research. Industry sponsors and parent institutions of research programs have also disseminated guidance.

Among other topics, guidance documents have addressed:

- How COVID-19-related protocol deviations will be judged at monitoring visits and audits

- Missed office visits and endpoint evaluations

- Providing investigational oral medications to patients via mail and potential issues of medication unavailability

- Processes for patients to have interim visits with providers at external institutions, including providers who may not be personally engaged in or credentialed for the research trial

- Potential delays in submitting protocol amendments for institutional review board (IRB) review

- Recommendations for patients confirmed or suspected of having a coronavirus infection.

Dr. Oyer emphasized that patient safety must remain the highest priority for patient management, on or off study. He advised continuing investigational therapy when potential benefit from treatment is anticipated and identifying alternative methods to face-to-face visits for monitoring and access to treatment.

Dr. Oyer urged programs to:

- Maintain good clinical practice standards

- Consult with sponsors and IRBs when questions arise but implement changes that affect patient safety prior to IRB review if necessary

- Document all deviations and COVID-19 related adaptations in a log or spreadsheet in anticipation of future questions from sponsors, monitors, and other entities.

New questions and considerations

In the short-term, Dr. Oyer predicts fewer available trials and a decreased rate of accrual to existing studies. This may result in delays in trial completion and the possibility of redesign for some trials.

He predicts the emergence of COVID-19-focused research questions, including those assessing the course of coronavirus infection in various malignant settings and the impact of cancer-directed treatments and supportive care interventions (e.g., treatment for graft-versus-host disease) on response to COVID-19.

To facilitate developing a clinically and research-relevant database, Dr. Oyer stressed the importance of documentation in the research record, reporting infections as serious adverse events. Documentation should specify whether the infection was confirmed or suspected coronavirus or related to another organism.

In general, when coronavirus infection is strongly suspected, Dr. Oyer said investigational treatments should be interrupted, but study-specific criteria will be forthcoming on that issue.

Looking to the future

For patients with advanced cancers, clinical trials provide an important option for hope and clinical benefit. Disrupting the conduct of clinical trials could endanger the lives of participants and delay the emergence of promising treatments and diagnostic tests.

When the coronavirus pandemic recedes, advancing knowledge and treatments for cancer will demand renewed commitment across the oncology care community.

Going forward, Dr. Oyer advised that clinical research staff protect their own health and the safety of trial participants. He encouraged programs to work with sponsors and IRBs to solve logistical problems and clarify individual issues.

He was optimistic that resumption of more normal conduct of studies will enable the successful completion of ongoing trials, enhanced by the creative solutions that were devised during the crisis and by additional prospective, clinically annotated, carefully recorded data from academic and community research sites.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

More than three-quarters of cancer clinical research programs have experienced operational changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) during a recent webinar.

The webinar included insights into how some cancer research programs have adapted to the pandemic, a review of guidance for conducting cancer trials during this time, and a discussion of how the cancer research landscape may be affected by COVID-19 going forward.

The webinar was led by Randall A. Oyer, MD, president of the ACCC and medical director of the oncology program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health in Pennsylvania.

The impact of COVID-19 on cancer research

Dr. Oyer observed that planning and implementation for COVID-19–related illness at U.S. health care institutions has had a predictable effect of limiting patient access and staff availability for nonessential services.

Coronavirus-related exposure and/or illness has relegated cancer research to a lower-level priority. As a result, ACCC institutions have made adjustments in their cancer research programs, including moving clinical research coordinators off-campus and deploying them in clinical areas.

New clinical trials have not been opened. In some cases, new accruals have been halted, particularly for registry, prevention, and symptom control trials.

Standards that have changed and those that have not

Guidance documents for conducting clinical trials during the pandemic have been developed by the Food and Drug Administration, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Central Institutional Review Board, and the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Extramural Research. Industry sponsors and parent institutions of research programs have also disseminated guidance.

Among other topics, guidance documents have addressed:

- How COVID-19-related protocol deviations will be judged at monitoring visits and audits

- Missed office visits and endpoint evaluations

- Providing investigational oral medications to patients via mail and potential issues of medication unavailability

- Processes for patients to have interim visits with providers at external institutions, including providers who may not be personally engaged in or credentialed for the research trial

- Potential delays in submitting protocol amendments for institutional review board (IRB) review

- Recommendations for patients confirmed or suspected of having a coronavirus infection.

Dr. Oyer emphasized that patient safety must remain the highest priority for patient management, on or off study. He advised continuing investigational therapy when potential benefit from treatment is anticipated and identifying alternative methods to face-to-face visits for monitoring and access to treatment.

Dr. Oyer urged programs to:

- Maintain good clinical practice standards

- Consult with sponsors and IRBs when questions arise but implement changes that affect patient safety prior to IRB review if necessary

- Document all deviations and COVID-19 related adaptations in a log or spreadsheet in anticipation of future questions from sponsors, monitors, and other entities.

New questions and considerations

In the short-term, Dr. Oyer predicts fewer available trials and a decreased rate of accrual to existing studies. This may result in delays in trial completion and the possibility of redesign for some trials.

He predicts the emergence of COVID-19-focused research questions, including those assessing the course of coronavirus infection in various malignant settings and the impact of cancer-directed treatments and supportive care interventions (e.g., treatment for graft-versus-host disease) on response to COVID-19.

To facilitate developing a clinically and research-relevant database, Dr. Oyer stressed the importance of documentation in the research record, reporting infections as serious adverse events. Documentation should specify whether the infection was confirmed or suspected coronavirus or related to another organism.

In general, when coronavirus infection is strongly suspected, Dr. Oyer said investigational treatments should be interrupted, but study-specific criteria will be forthcoming on that issue.

Looking to the future

For patients with advanced cancers, clinical trials provide an important option for hope and clinical benefit. Disrupting the conduct of clinical trials could endanger the lives of participants and delay the emergence of promising treatments and diagnostic tests.

When the coronavirus pandemic recedes, advancing knowledge and treatments for cancer will demand renewed commitment across the oncology care community.

Going forward, Dr. Oyer advised that clinical research staff protect their own health and the safety of trial participants. He encouraged programs to work with sponsors and IRBs to solve logistical problems and clarify individual issues.

He was optimistic that resumption of more normal conduct of studies will enable the successful completion of ongoing trials, enhanced by the creative solutions that were devised during the crisis and by additional prospective, clinically annotated, carefully recorded data from academic and community research sites.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Evaluating and managing the patient with nipple discharge

CASE Young woman with discharge from one nipple

A 26-year-old African American woman presents with a 10-month history of left nipple discharge. The patient describes the discharge as spontaneous, colored dark brown to yellow, and occurring from a single opening in the nipple. The discharge is associated with left breast pain and fullness, without a palpable lump. The patient has no family or personal history of breast cancer.

Nipple discharge is the third most common breast-related symptom (after palpable masses and breast pain), with an estimated prevalence of 5% to 8% among premenopausal women.1 While most causes of nipple discharge reflect benign issues, approximately 5% to 12% of breast cancers have nipple discharge as the only symptom.2 Not surprisingly, nipple discharge creates anxiety for both patients and clinicians.

In this article, we—a breast imaging radiologist, gynecologist, and breast surgeon—outline key steps for evaluating and managing patients with nipple discharge.

Two types of nipple discharge

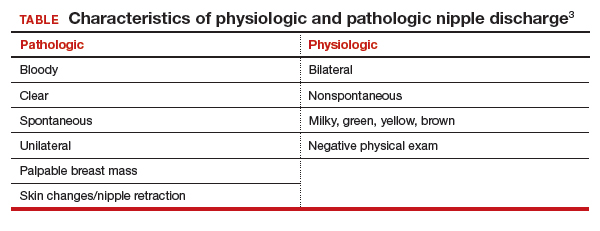

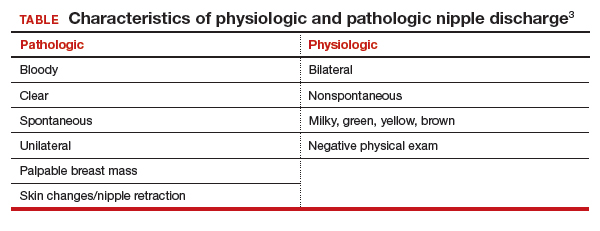

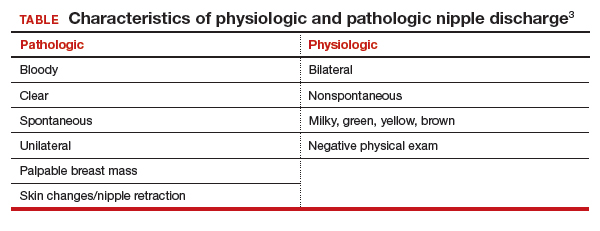

Nipple discharge can be characterized as physiologic or pathologic. The distinction is based on the patient’s history in conjunction with the clinical breast exam.

Physiologic nipple discharge often is bilateral, nonspontaneous, and white, yellow, green, or brown (TABLE).3 It often is due to nipple stimulation, and the patient can elicit discharge by manually manipulating the breast. Usually, multiple ducts are involved. Galactorrhea refers specifically to milky discharge and occurs most commonly during pregnancy or lactation.2 Galactorrhea that is not associated with pregnancy or lactation often is related to elevated prolactin or thyroid-stimulating hormone levels or to medications. One study reported that no cancers were found when discharge was nonspontaneous and colored or milky.4

Pathologic nipple discharge is defined as a spontaneous, bloody, clear, or single-duct discharge. A palpable mass in the same breast automatically increases the suspicion of the discharge, regardless of its color or spontaneity.2 The most common cause of pathologic nipple discharge is an intraductal papilloma, a benign epithelial tumor, which accounts for approximately 57% of cases.5

Although the risk of malignancy is low for all patients with nipple discharge, increasing age is associated with increased risk of breast cancer. One study demonstrated that among women aged 40 to 60 years presenting with nipple discharge, the prevalence of invasive cancer is 10%, and the percentage jumps to 32% among women older than 60.6

Breast exam. For any patient with nonlactational nipple discharge, we recommend a thorough breast examination. Deep palpation of all quadrants of the symptomatic breast, especially near the nipple areolar complex, should elicit nipple discharge without any direct squeezing of the nipple. If the patient’s history and physical exam are consistent with physiologic discharge, no further workup is needed. Reassure the patient and recommend appropriate breast cancer screening. Encourage the patient to decrease stimulation or manual manipulation of the nipples if the discharge bothers her.

Continue to: CASE Continued: Workup...

CASE Continued: Workup

On physical exam, the patient’s breasts are noted to be cup size DDD and asymmetric, with the left breast larger than the right; there is no contour deformity. There is no skin or nipple retraction, skin rash, swelling, or nipple changes bilaterally. No dominant masses are appreciated bilaterally. Manual compression elicits no nipple discharge.

Although the discharge is nonbloody, its spontaneity, unilaterality, and single-duct/orifice origin suggest a pathologic cause. The patient is referred for breast imaging.

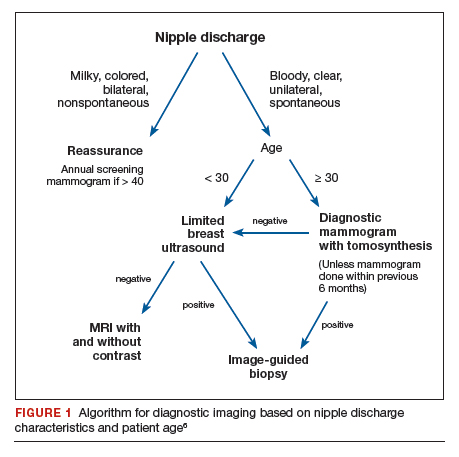

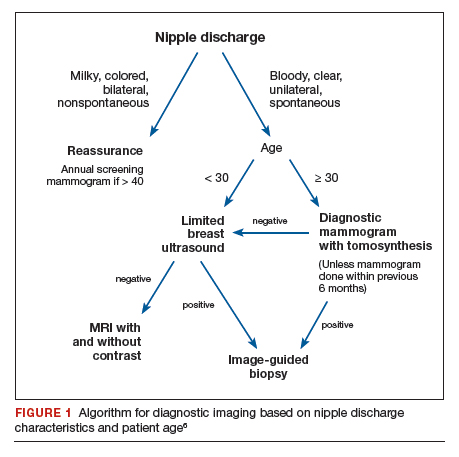

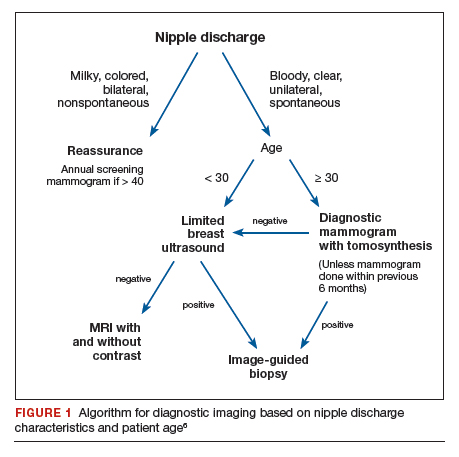

Imaging workup for pathologic discharge

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria is a useful tool that provides an evidence-based, easy-to-use algorithm for breast imaging in the patient with pathologic nipple discharge (FIGURE 1).6 The algorithm is categorized by patient age, with diagnostic mammography recommended for women aged 30 and older.6 Diagnostic mammography is recommended if the patient has not had a mammogram study in the last 6 months.6 For patients with no prior mammograms, we recommend bilateral diagnostic mammography to compare symmetry of the breasts.

Currently, no studies show that digital breast tomosynthesis (3-D mammography) has a benefit compared with standard 2-D mammography in women with pathologic nipple discharge.6 Given the increased sensitivity of digital breast tomosynthesis for cancer detection, however, in our practice it is standard to use tomosynthesis in the diagnostic evaluation of most patients.

Mammography

On mammography, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) usually presents as calcifications. Both the morphology and distribution of calcifications are used to characterize them as suspicious or, typically, benign. DCIS usually presents as fine pleomorphic or fine linear branching calcifications in a segmental or linear distribution. In patients with pathologic nipple discharge and no other symptoms, the radiologist must closely examine the retroareolar region of the breast to assess for faint calcifications. Magnification views also can be performed to better characterize calcifications.

The sensitivity of mammography for nipple discharge varies in the literature, ranging from approximately 15% to 68%, with a specificity range of 38% to 98%.6 This results in a relatively low positive predictive value but a high negative predictive value of 90%.7 Mammographic sensitivity largely is limited by increased breast density. As more data emerge on the utility of digital breast tomosynthesis in dense breasts, mammographic sensitivity for nipple discharge will likely increase.

Ultrasonography

As an adjunct to mammography, the ACR Appropriateness Criteria recommends targeted (or “limited”) ultrasonography of the retroareolar region of the affected breast for patients aged 30 and older. Ultrasonography is useful to assess for intraductal masses and architectural distortion, and it has higher sensitivity but lower specificity than mammography. The sensitivity of ultrasonography for detecting breast cancer in patients presenting with nipple discharge is reported to be 56% to 80%.6 Ultrasonography can identify lesions not visible mammographically in 63% to 69% of cases.8 Although DCIS usually presents as calcifications, it also can present as an intraductal mass on ultrasonography.

The ACR recommends targeted ultrasonography for patients with nipple discharge and a negative mammogram, or to evaluate a suspicious mammographic abnormality such as architectural distortion, focal asymmetry, or a mass.6 For patient comfort, ultrasonography is the preferred modality for image-guided biopsy.

For women younger than 30 years, targeted ultrasonography is the initial imaging study of choice, according to the ACR criteria.6 Women younger than 30 years with pathologic nipple discharge have a very low risk of breast cancer and tend to have higher breast density, making mammography less useful. Although the radiation dose from mammography is negligible given technological improvements and dose-reduction techniques, ultrasonography remains the preferred initial imaging modality in young women, not only for nipple discharge but also for palpable lumps and focal breast pain.

Mammography is used as an adjunct to ultrasonography in women younger than 30 years when a suspicious abnormality is detected on ultrasonography, such as an intraductal mass or architectural distortion. In these cases, mammography can be used to assess for extent of disease or to visualize suspicious calcifications not well seen on ultrasonography.

For practical purposes regarding which imaging study to order for a patient, it is most efficient to order both a diagnostic mammogram (with tomosynthesis, if possible) and a targeted ultrasound scan of the affected breast. Even if both orders are not needed, having them available increases efficiency for both the radiologist and the ordering physician.

Continue to: CASE Continued: Imaging findings...

CASE Continued: Imaging findings

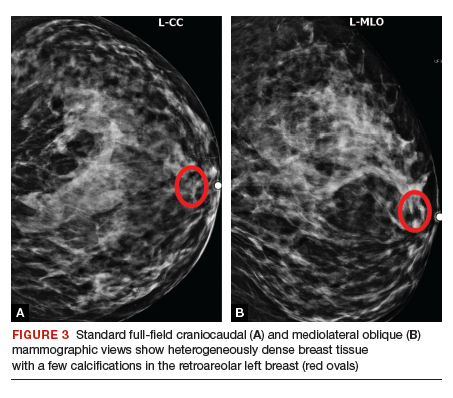

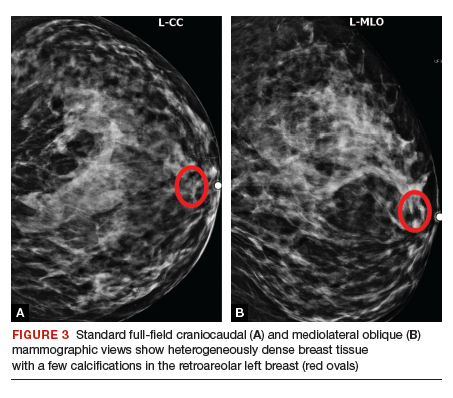

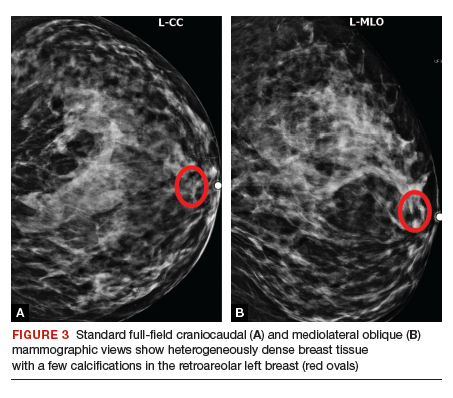

Given her age, the patient initially undergoes targeted ultrasonography. The grayscale image (FIGURE 2) demonstrates multiple mildly dilated ducts (white arrows) with surrounding hyperechogenicity of the fat (red arrows), indicating soft tissue edema. No intraductal mass is imaged. Given that the ultrasonography findings are not completely negative and are equivocal for malignancy, bilateral diagnostic mammography (FIGURE 3, left breast only) is performed. Standard full-field craniocaudal (FIGURE 3A) and mediolateral oblique (FIGURE 3B) mammographic views demonstrate a heterogeneously dense breast with a few calcifications in the retroareolar left breast (red ovals). No associated mass or architectural distortions are noted. The mammographic and sonographic findings do not reveal a definitive biopsy target.

Ductography

When a suspicious abnormality is visualized on either mammography or ultrasonography, the standard of care is to perform an image-guided biopsy of the abnormality. When the standard workup is negative or equivocal, the standard of care historically was to perform ductography.

Ductography is an invasive procedure that involves cannulating the suspicious duct with a small catheter and injecting radiopaque dye into the duct under mammographic guidance. While the sensitivity of ductography is higher than that of both mammography and ultrasonography, its specificity is lower than that of either modality.

Most cases of pathologic discharge are spontaneous and are not reproducible on the day of the procedure. If the procedural radiologist cannot visualize the duct that is producing the discharge, the procedure cannot be performed. Although most patients tolerate the procedure well, ductography produces patient discomfort from cannulation of the duct and injection of contrast.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most sensitive imaging study for evaluating pathologic nipple discharge, and it has largely replaced ductography as an adjunct to mammography and ultrasonography. MRI’s sensitivity for detecting breast cancer ranges from 93% to 100%.6 In addition, MRI allows visualization of the entire breast and areas peripheral to the field of view of a standard ductogram or ultrasound scan.9

Clinicians commonly ask, “Why not skip the mammogram and ultrasound scan and go straight to MRI, since it is so much more sensitive?” Breast MRI has several limitations, including relatively low specificity, cost, use of intravenous contrast, and patient discomfort (that is, claustrophobia, prone positioning). MRI should be utilized for pathologic discharge only when the mammogram and/or targeted ultrasound scans are negative or equivocal.

CASE Continued: Additional imaging

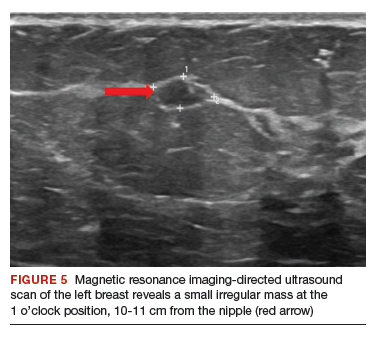

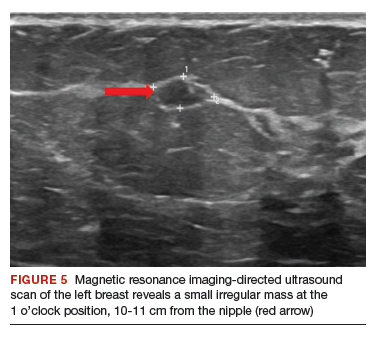

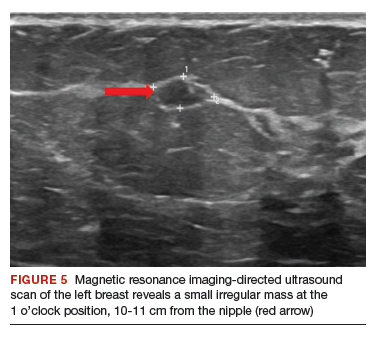

A contrast-enhanced MRI of the breasts (FIGURE 4) demonstrates a large area of non-mass enhancement (red oval) in the left breast, which involves most of the upper breast extending from the nipple to the posterior breast tissue; it measures approximately 7.3 x 14 x 9.1 cm in transverse, anteroposterior, and craniocaudal dimensions, respectively. There is no evidence of left pectoralis muscle involvement. An MRI-directed second look left breast ultrasonography (FIGURE 5) is performed, revealing a small irregular mass in the left breast 1 o’clock position, 10 to 11 cm from the nipple (red arrow). This area had not been imaged in the prior ultrasound scan due to its posterior location far from the nipple. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy is performed; moderately differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) with high-grade DCIS is found.

Continue to: When to refer for surgery...

When to refer for surgery

No surgical evaluation or intervention is needed for physiologic nipple discharge. As mentioned previously, reassure the patient and recommend appropriate breast cancer screening. In the setting of pathologic discharge, however, referral to a breast surgeon may be indicated after appropriate imaging workup has been done.

Since abnormal imaging almost always results in a recommendation for image-guided biopsy, typically the biopsy is performed prior to the surgical consultation. Once the pathology report from the biopsy is available, the radiologist makes a radiologic-pathologic concordance statement and recommends surgical consultation. This process allows the surgeon to have all the necessary information at the initial visit.

However, in the setting of pathologic nipple discharge with normal breast imaging, the surgeon and patient may opt for close observation or surgery for definitive diagnosis. Surgical options include single-duct excision when nipple discharge is localized to one duct or central duct excision when nipple discharge cannot be localized to one duct.

CASE Continued: Follow-up

The patient was referred to a breast surgeon. Given the extent of disease in the left breast, breast conservation was not possible. The patient underwent left breast simple mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy and prophylactic right simple mastectomy. Final pathology results revealed stage IA IDC with DCIS. Sentinel lymph nodes were negative for malignancy. The patient underwent adjuvant left chest wall radiation, endocrine therapy with tamoxifen, and implant reconstruction. After 2 years of follow-up, she is disease free.

In summary

Nipple discharge can be classified as physiologic or pathologic. For pathologic discharge, a thorough physical examination should be performed with subsequent imaging evaluation. First-line tools, based on patient age, include diagnostic mammography and targeted ultrasonography. Contrast-enhanced MRI is then recommended for negative or equivocal cases. All patients with pathologic nipple discharge should be referred to a breast surgeon following appropriate imaging evaluation. ●

- Alcock C, Layer GT. Predicting occult malignancy in nipple discharge. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:646-649.

- Patel BK, Falcon S, Drukteinis J. Management of nipple discharge and the associated imaging findings. Am J Med. 2015;128:353-360.

- Mazzarello S, Arnaout A. Five things to know about nipple discharge. CMAJ. 2015;187:599.

- Goksel HA, Yagmurdur MC, Demirhan B, et al. Management strategies for patients with nipple discharge. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:52-58.

- Vargas HI, Vargas MP, Eldrageely K, et al. Outcomes of clinical and surgical assessment of women with pathological nipple discharge. Am Surg. 2006;72:124-128.

- Expert Panel on Breast Imaging; Lee S, Tikha S, Moy L, et al. American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria: Evaluation of nipple discharge. https://acsearch.acr.org /docs/3099312/Narrative/. Accessed February 2, 2020.

- Cabioglu N, Hunt KK, Singletary SE, et al. Surgical decision making and factors determining a diagnosis of breast carcinoma in women presenting with nipple discharge. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:354-364.

- Morrogh M, Park A, Elkin EB, et al. Lessons learned from 416 cases of nipple discharge of the breast. Am J Surg. 2010;200:73-80.

- Morrogh M, Morris EA, Liberman L, et al. The predictive value of ductography and magnetic resonance imaging in the management of nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3369-3377.

CASE Young woman with discharge from one nipple

A 26-year-old African American woman presents with a 10-month history of left nipple discharge. The patient describes the discharge as spontaneous, colored dark brown to yellow, and occurring from a single opening in the nipple. The discharge is associated with left breast pain and fullness, without a palpable lump. The patient has no family or personal history of breast cancer.

Nipple discharge is the third most common breast-related symptom (after palpable masses and breast pain), with an estimated prevalence of 5% to 8% among premenopausal women.1 While most causes of nipple discharge reflect benign issues, approximately 5% to 12% of breast cancers have nipple discharge as the only symptom.2 Not surprisingly, nipple discharge creates anxiety for both patients and clinicians.

In this article, we—a breast imaging radiologist, gynecologist, and breast surgeon—outline key steps for evaluating and managing patients with nipple discharge.

Two types of nipple discharge

Nipple discharge can be characterized as physiologic or pathologic. The distinction is based on the patient’s history in conjunction with the clinical breast exam.

Physiologic nipple discharge often is bilateral, nonspontaneous, and white, yellow, green, or brown (TABLE).3 It often is due to nipple stimulation, and the patient can elicit discharge by manually manipulating the breast. Usually, multiple ducts are involved. Galactorrhea refers specifically to milky discharge and occurs most commonly during pregnancy or lactation.2 Galactorrhea that is not associated with pregnancy or lactation often is related to elevated prolactin or thyroid-stimulating hormone levels or to medications. One study reported that no cancers were found when discharge was nonspontaneous and colored or milky.4

Pathologic nipple discharge is defined as a spontaneous, bloody, clear, or single-duct discharge. A palpable mass in the same breast automatically increases the suspicion of the discharge, regardless of its color or spontaneity.2 The most common cause of pathologic nipple discharge is an intraductal papilloma, a benign epithelial tumor, which accounts for approximately 57% of cases.5

Although the risk of malignancy is low for all patients with nipple discharge, increasing age is associated with increased risk of breast cancer. One study demonstrated that among women aged 40 to 60 years presenting with nipple discharge, the prevalence of invasive cancer is 10%, and the percentage jumps to 32% among women older than 60.6

Breast exam. For any patient with nonlactational nipple discharge, we recommend a thorough breast examination. Deep palpation of all quadrants of the symptomatic breast, especially near the nipple areolar complex, should elicit nipple discharge without any direct squeezing of the nipple. If the patient’s history and physical exam are consistent with physiologic discharge, no further workup is needed. Reassure the patient and recommend appropriate breast cancer screening. Encourage the patient to decrease stimulation or manual manipulation of the nipples if the discharge bothers her.

Continue to: CASE Continued: Workup...

CASE Continued: Workup

On physical exam, the patient’s breasts are noted to be cup size DDD and asymmetric, with the left breast larger than the right; there is no contour deformity. There is no skin or nipple retraction, skin rash, swelling, or nipple changes bilaterally. No dominant masses are appreciated bilaterally. Manual compression elicits no nipple discharge.

Although the discharge is nonbloody, its spontaneity, unilaterality, and single-duct/orifice origin suggest a pathologic cause. The patient is referred for breast imaging.

Imaging workup for pathologic discharge

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria is a useful tool that provides an evidence-based, easy-to-use algorithm for breast imaging in the patient with pathologic nipple discharge (FIGURE 1).6 The algorithm is categorized by patient age, with diagnostic mammography recommended for women aged 30 and older.6 Diagnostic mammography is recommended if the patient has not had a mammogram study in the last 6 months.6 For patients with no prior mammograms, we recommend bilateral diagnostic mammography to compare symmetry of the breasts.

Currently, no studies show that digital breast tomosynthesis (3-D mammography) has a benefit compared with standard 2-D mammography in women with pathologic nipple discharge.6 Given the increased sensitivity of digital breast tomosynthesis for cancer detection, however, in our practice it is standard to use tomosynthesis in the diagnostic evaluation of most patients.

Mammography