User login

Monitoring effectively identifies seizures in postbypass neonates

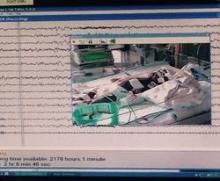

In the first report evaluating the impact of a clinical guideline that calls for the use of postoperative continuous electroencephalography (CEEG) on infants after they’ve had cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, investigators at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania validated the clinical utility of routine CEEG monitoring and found that clinical assessment for seizures without CEEG is not a reliable marker for diagnosis and treatment.

In a report online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.045]), Dr. Maryam Naim and colleagues said that CEEG identified electroencephalographic seizures in 8% of newborns after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. The study, conducted over 18 months, evaluated 172 newborns, none older than 1 month, with 161 (94%) having undergone postoperative CEEG. They had CEEG within 6 hours of their return to the cardiac intensive care unit.

The study classified electroencephalographic seizures as EEG-only (also termed nonconvulsive seizures, with no observable clinical signs either at bedside or via video) or electroclinical seizures. Dr. Naim and colleagues said the majority of seizures they identified with CEEG would not have been noticed otherwise as they had no clinically obvious signs or symptoms.

The American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) recommends that cardiac surgeons consider continuous CEEG monitoring in high-risk neonates with congenital heart disease (CHD) after bypass surgery, but Dr. Naim and coauthors raised the question of whether seizure incidence would justify routine CEEG for all neonates with CHD who’ve had bypass surgery, especially as health systems place greater emphasis on quality improvement programs and cost-effective strategies. The authors said that neonates with all types of congenital heart disease had seizures.

“In adult populations, CEEG has not been shown to significantly increase hospital costs, but cost-effectiveness analyses have not been performed in neonates with CHD,” the authors said.

So they attempted to identify at-risk populations of newborns who would benefit most from routine CEEG monitoring. In a multivariable model that the investigators used, both delayed sternal closure and longer deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) during surgery seemed predictive of seizures, but the odds ratios for both were low, “suggesting the statistically significant findings may not be very useful in focusing CEEG implementation on a high-risk group.”

Previous studies have reported that identifying and treating seizures in newborns who have had bypass surgery may reduce secondary brain injury and improve outcomes (Pediatrics 2008;121:e759-67), and the Boston Circulatory Arrest Study showed an association between postoperative seizures and lower reading and math scores and lower cognitive and functional skills later in life (Circulation 2011;124:1361-1369). The authors cited other studies that showed older, critically ill children with “high seizure burdens” have had worse outcomes. (Critical Care Medicine 2013;31:215-23; Neurology 2014;82:396-404; Brain 2014;137:1429-38). They also pointed out increased risk if the seizure is not treated. “While occurrence of a seizure is a marker of brain injury, there may also be secondary injury if the seizure activity is not terminated,” Dr. Naim and coauthors said.

The investigators concluded that postoperative CEEG to identify seizures “is warranted,” and while they found some newborns may be at greater risk of postbypass seizures than others, they advocated for “widespread” monitoring strategies.

Their work also questioned the effectiveness of non-CEEG assessment. In the study, clinicians identified bedside events indicative of seizures – what the study termed “push-button events” – in 32 newborns, or about 18% of patients, but none of the events had an EEG correlate, so they were considered nonepileptic. When the authors looked more closely at those “push-button” events, they found they ranged from abnormal body movement in 14 and hypertension in 7 to tachycardia and abnormal face movements, among other characterizations, in lesser numbers.

“Furthermore, push-button events by bedside clinicians, including abnormal movements and hypertensive episodes concerning for possible seizures, did not have any EEG correlate, indicating that bedside clinical assessment for seizures without CEEG monitoring is unreliable,” Dr. Naim and colleagues said.

As to whether identifying and treating postbypass seizures in young newborns with CHD will improve long-term neurodevelopment in these children, the authors acknowledged that further study is needed.

They reported having no financial disclosures.

The findings of Dr. Maryam Naim and coauthors show that relying on physical examination alone is no longer adequate to rule out postoperative neurologic complications, Dr. Carl L. Backer and Dr. Bradley S. Marino said in their invited commentary on the study (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.028]).

However, they noted that the level of “sophisticated monitoring” the investigators had at their disposal – 24-hour availability of EEG technologists, comprehensive 12-scalp electrode monitoring – is not available at all institutions. “What we need is a screening tool that is not as labor intensive,” Dr. Backer and Dr. Marino said – a screening CEEG monitor that would allow care teams to identify seizure activity at a minimal expense and serve as a basis for a full EEG for evaluation and avoid the expense and manpower for the vast majority of patients who do not have seizures.

Nonetheless, prevention of seizures in this newborn population is “critically important,” but that can only be achieved if the care team monitors for seizures and then assesses strategies, both during and after surgery, to eliminate development of seizures, the commentary authors said.

But the recent study points to the need for a multicenter, observational cross-sectional study using CEEG monitoring, Dr. Backer and Dr. Marino said.

Dr. Backer is a cardiovascular-thoracic surgeon and Dr. Marino is a cardiac surgeon at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

The findings of Dr. Maryam Naim and coauthors show that relying on physical examination alone is no longer adequate to rule out postoperative neurologic complications, Dr. Carl L. Backer and Dr. Bradley S. Marino said in their invited commentary on the study (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.028]).

However, they noted that the level of “sophisticated monitoring” the investigators had at their disposal – 24-hour availability of EEG technologists, comprehensive 12-scalp electrode monitoring – is not available at all institutions. “What we need is a screening tool that is not as labor intensive,” Dr. Backer and Dr. Marino said – a screening CEEG monitor that would allow care teams to identify seizure activity at a minimal expense and serve as a basis for a full EEG for evaluation and avoid the expense and manpower for the vast majority of patients who do not have seizures.

Nonetheless, prevention of seizures in this newborn population is “critically important,” but that can only be achieved if the care team monitors for seizures and then assesses strategies, both during and after surgery, to eliminate development of seizures, the commentary authors said.

But the recent study points to the need for a multicenter, observational cross-sectional study using CEEG monitoring, Dr. Backer and Dr. Marino said.

Dr. Backer is a cardiovascular-thoracic surgeon and Dr. Marino is a cardiac surgeon at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

The findings of Dr. Maryam Naim and coauthors show that relying on physical examination alone is no longer adequate to rule out postoperative neurologic complications, Dr. Carl L. Backer and Dr. Bradley S. Marino said in their invited commentary on the study (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.028]).

However, they noted that the level of “sophisticated monitoring” the investigators had at their disposal – 24-hour availability of EEG technologists, comprehensive 12-scalp electrode monitoring – is not available at all institutions. “What we need is a screening tool that is not as labor intensive,” Dr. Backer and Dr. Marino said – a screening CEEG monitor that would allow care teams to identify seizure activity at a minimal expense and serve as a basis for a full EEG for evaluation and avoid the expense and manpower for the vast majority of patients who do not have seizures.

Nonetheless, prevention of seizures in this newborn population is “critically important,” but that can only be achieved if the care team monitors for seizures and then assesses strategies, both during and after surgery, to eliminate development of seizures, the commentary authors said.

But the recent study points to the need for a multicenter, observational cross-sectional study using CEEG monitoring, Dr. Backer and Dr. Marino said.

Dr. Backer is a cardiovascular-thoracic surgeon and Dr. Marino is a cardiac surgeon at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

In the first report evaluating the impact of a clinical guideline that calls for the use of postoperative continuous electroencephalography (CEEG) on infants after they’ve had cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, investigators at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania validated the clinical utility of routine CEEG monitoring and found that clinical assessment for seizures without CEEG is not a reliable marker for diagnosis and treatment.

In a report online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.045]), Dr. Maryam Naim and colleagues said that CEEG identified electroencephalographic seizures in 8% of newborns after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. The study, conducted over 18 months, evaluated 172 newborns, none older than 1 month, with 161 (94%) having undergone postoperative CEEG. They had CEEG within 6 hours of their return to the cardiac intensive care unit.

The study classified electroencephalographic seizures as EEG-only (also termed nonconvulsive seizures, with no observable clinical signs either at bedside or via video) or electroclinical seizures. Dr. Naim and colleagues said the majority of seizures they identified with CEEG would not have been noticed otherwise as they had no clinically obvious signs or symptoms.

The American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) recommends that cardiac surgeons consider continuous CEEG monitoring in high-risk neonates with congenital heart disease (CHD) after bypass surgery, but Dr. Naim and coauthors raised the question of whether seizure incidence would justify routine CEEG for all neonates with CHD who’ve had bypass surgery, especially as health systems place greater emphasis on quality improvement programs and cost-effective strategies. The authors said that neonates with all types of congenital heart disease had seizures.

“In adult populations, CEEG has not been shown to significantly increase hospital costs, but cost-effectiveness analyses have not been performed in neonates with CHD,” the authors said.

So they attempted to identify at-risk populations of newborns who would benefit most from routine CEEG monitoring. In a multivariable model that the investigators used, both delayed sternal closure and longer deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) during surgery seemed predictive of seizures, but the odds ratios for both were low, “suggesting the statistically significant findings may not be very useful in focusing CEEG implementation on a high-risk group.”

Previous studies have reported that identifying and treating seizures in newborns who have had bypass surgery may reduce secondary brain injury and improve outcomes (Pediatrics 2008;121:e759-67), and the Boston Circulatory Arrest Study showed an association between postoperative seizures and lower reading and math scores and lower cognitive and functional skills later in life (Circulation 2011;124:1361-1369). The authors cited other studies that showed older, critically ill children with “high seizure burdens” have had worse outcomes. (Critical Care Medicine 2013;31:215-23; Neurology 2014;82:396-404; Brain 2014;137:1429-38). They also pointed out increased risk if the seizure is not treated. “While occurrence of a seizure is a marker of brain injury, there may also be secondary injury if the seizure activity is not terminated,” Dr. Naim and coauthors said.

The investigators concluded that postoperative CEEG to identify seizures “is warranted,” and while they found some newborns may be at greater risk of postbypass seizures than others, they advocated for “widespread” monitoring strategies.

Their work also questioned the effectiveness of non-CEEG assessment. In the study, clinicians identified bedside events indicative of seizures – what the study termed “push-button events” – in 32 newborns, or about 18% of patients, but none of the events had an EEG correlate, so they were considered nonepileptic. When the authors looked more closely at those “push-button” events, they found they ranged from abnormal body movement in 14 and hypertension in 7 to tachycardia and abnormal face movements, among other characterizations, in lesser numbers.

“Furthermore, push-button events by bedside clinicians, including abnormal movements and hypertensive episodes concerning for possible seizures, did not have any EEG correlate, indicating that bedside clinical assessment for seizures without CEEG monitoring is unreliable,” Dr. Naim and colleagues said.

As to whether identifying and treating postbypass seizures in young newborns with CHD will improve long-term neurodevelopment in these children, the authors acknowledged that further study is needed.

They reported having no financial disclosures.

In the first report evaluating the impact of a clinical guideline that calls for the use of postoperative continuous electroencephalography (CEEG) on infants after they’ve had cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, investigators at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania validated the clinical utility of routine CEEG monitoring and found that clinical assessment for seizures without CEEG is not a reliable marker for diagnosis and treatment.

In a report online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.045]), Dr. Maryam Naim and colleagues said that CEEG identified electroencephalographic seizures in 8% of newborns after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. The study, conducted over 18 months, evaluated 172 newborns, none older than 1 month, with 161 (94%) having undergone postoperative CEEG. They had CEEG within 6 hours of their return to the cardiac intensive care unit.

The study classified electroencephalographic seizures as EEG-only (also termed nonconvulsive seizures, with no observable clinical signs either at bedside or via video) or electroclinical seizures. Dr. Naim and colleagues said the majority of seizures they identified with CEEG would not have been noticed otherwise as they had no clinically obvious signs or symptoms.

The American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) recommends that cardiac surgeons consider continuous CEEG monitoring in high-risk neonates with congenital heart disease (CHD) after bypass surgery, but Dr. Naim and coauthors raised the question of whether seizure incidence would justify routine CEEG for all neonates with CHD who’ve had bypass surgery, especially as health systems place greater emphasis on quality improvement programs and cost-effective strategies. The authors said that neonates with all types of congenital heart disease had seizures.

“In adult populations, CEEG has not been shown to significantly increase hospital costs, but cost-effectiveness analyses have not been performed in neonates with CHD,” the authors said.

So they attempted to identify at-risk populations of newborns who would benefit most from routine CEEG monitoring. In a multivariable model that the investigators used, both delayed sternal closure and longer deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) during surgery seemed predictive of seizures, but the odds ratios for both were low, “suggesting the statistically significant findings may not be very useful in focusing CEEG implementation on a high-risk group.”

Previous studies have reported that identifying and treating seizures in newborns who have had bypass surgery may reduce secondary brain injury and improve outcomes (Pediatrics 2008;121:e759-67), and the Boston Circulatory Arrest Study showed an association between postoperative seizures and lower reading and math scores and lower cognitive and functional skills later in life (Circulation 2011;124:1361-1369). The authors cited other studies that showed older, critically ill children with “high seizure burdens” have had worse outcomes. (Critical Care Medicine 2013;31:215-23; Neurology 2014;82:396-404; Brain 2014;137:1429-38). They also pointed out increased risk if the seizure is not treated. “While occurrence of a seizure is a marker of brain injury, there may also be secondary injury if the seizure activity is not terminated,” Dr. Naim and coauthors said.

The investigators concluded that postoperative CEEG to identify seizures “is warranted,” and while they found some newborns may be at greater risk of postbypass seizures than others, they advocated for “widespread” monitoring strategies.

Their work also questioned the effectiveness of non-CEEG assessment. In the study, clinicians identified bedside events indicative of seizures – what the study termed “push-button events” – in 32 newborns, or about 18% of patients, but none of the events had an EEG correlate, so they were considered nonepileptic. When the authors looked more closely at those “push-button” events, they found they ranged from abnormal body movement in 14 and hypertension in 7 to tachycardia and abnormal face movements, among other characterizations, in lesser numbers.

“Furthermore, push-button events by bedside clinicians, including abnormal movements and hypertensive episodes concerning for possible seizures, did not have any EEG correlate, indicating that bedside clinical assessment for seizures without CEEG monitoring is unreliable,” Dr. Naim and colleagues said.

As to whether identifying and treating postbypass seizures in young newborns with CHD will improve long-term neurodevelopment in these children, the authors acknowledged that further study is needed.

They reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Electroencephalography is more effective than clinical observation in identifying seizures in infants immediately after they’ve had cardiopulmonary bypass surgery.

Major finding: Postoperative CEEG identified seizures in 8% of newborns with congenital heart disease after coronary bypass surgery.

Data source: Chart review involved 172 neonates from a single center. Multiple logistic regression analysis assessed seizures and clinical and predictive factors.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Elephant stent aorta repair – good outcomes, but is it too complex?

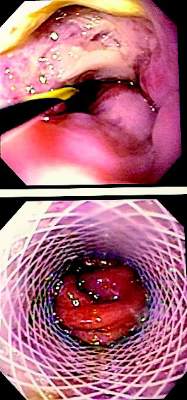

An acute aortic tear can be lethal, and more cardiac surgeons are favoring extended aortic arch replacement in these cases. Cardiac surgeons have tried many different arch replacement techniques, but en bloc repair and double- or triple-branch stent grafting carry significant risks, so a team of cardiac surgeons in Beijing has reported good 2-year results with a novel technique that combines stented elephant-trunk implantation with preservation of key vessels.

The technique accomplishes total arch replacement with the stent while preserving the autologous brachiocephalic vessels.

“This technique simplified hemostasis and anastomosis, reduced the size of the residual aortic patch wall, and preserved the autologous brachiocephalic vessels, yielding satisfactory surgical results,” wrote Dr. Li-Zhong Sun and colleagues at Beijing’s Capital Medical University (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.002]).

There are four keys to the procedure:

• The use of forceps to grasp the stent-free sewing edge of the stented elephant trunk and straightening of the spiral shaped Dacron graft to approximately 3 cm.

• Preservation of the native brachiocephalic vessels.

• Creating a residual aortic wall containing the innominate artery and LCCA that’s as small as possible.

• An end-to-side anastomosis between the left subclavian artery (LSCA) and the left common carotid artery (LCCA), a key junction in their technique.

The 20 study subjects had surgery within 2 weeks of the onset of pain. All 20 were discharged after the procedure, and in a mean follow-up period of 26 months, 18 had good outcomes while 1 patient had thoracoabdominal aortic replacement 9 months after the initial surgery (1 patient was lost to follow-up).

The researchers used computed tomography to confirm patency of the anastomosis between the LSCA and LCCA.

In 2 of the 20 patients, the aorta was normal with aortic dissection limited to the descending aorta. In the remaining patients, the investigators observed thrombus obliteration of the false lumen around the surgical graft in 16, partial thrombosis in 1 and patency in 1.

The surgical technique exposes the right axillary artery through a right subclavicular incision and a median sternotomy, then dissects and exposes the brachiocephalic vessels and the transverse arch. Dissection of the LSCA and LCCA is the key step in making the end-to-end anastomosis between the two vessels. The researchers accomplished this by partially transecting the sternocleidomastoid muscle and other cervical muscles.

Dr. Sun and coauthors said that a separated graft technique offers a number of advantages over other techniques for aortic arch reconstruction. While en bloc repair preserves the native brachiocephalic vessels and, thus, results in long-term patency, the technique carries risk for postoperative rupture of the aortic patch containing the brachiocephalic vessels. Double- or triple-branched stent grafting has resulted in shifting or kinking of the graft and eventually graft occlusion or aortic disruption.

The authors acknowledged the study’s small sample size, and that the outcomes are “preliminary.” They said long-term follow-up would be required to confirm the outcomes.

They had no disclosures to report.

The Beijing study authors’ excellent postoperative outcomes show that alternative surgical techniques for elephant-trunk implantation can be employed safely, but their technique also raises questions about the use of advanced technology, Dr. Prashanth Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Wilson Y. Szeto of the University of Pennsylvania said in their commentary on the study (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.003]).

“But does this mean we should be doing [elephant-trunk] operation on every type A dissection patient?” wrote Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto. If no primary tear appears in the aortic arch or the proximal descending thoracic aorta (DTA), “then should we empirically dissect the arch vessels and perform total arch replacement in an emergent situation?” They also questioned extensive dissection of the left subclavian artery (LSCA) by cutting into the muscles around the surgical site.

Elephant-trunk implantation is more complex than other aortic repair procedures, they noted. “So, if a total arch replacement is not required, then why do it?”

While they acknowledged advantages of total arch replacement, and elephant-trunk implantation in particular, most operations for type A dissection occur in smaller, community hospitals that are ill equipped to perform the procedure. “This raises the issue of wide clinical application of the [elephant-trunk] technique for acute type A dissection,” they said. The real issue may not be what type of anastomosis for the elephant-trunk technique surgeons should use, but rather what surgical technique – the elephant-trunk technique vs. transverse hemiarch reconstruction, they said. (Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto mentioned that their institution has advocated for the latter.)

“To address this, a more comprehensive and meticulous approach is warranted based on parameters such as patient clinical picture, acuity, malperfusion, arch and DTA anatomy, and primary tear site location,” they said. But for now, Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto said, the medical literature does not support total arch replacement over transverse hemiarch reconstruction.

Dr. Vallabhajosyula is assistant professor of surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; Dr. Szeto is associate professor of surgery in the division of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center–Penn Presbyterian Medical Center.

The Beijing study authors’ excellent postoperative outcomes show that alternative surgical techniques for elephant-trunk implantation can be employed safely, but their technique also raises questions about the use of advanced technology, Dr. Prashanth Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Wilson Y. Szeto of the University of Pennsylvania said in their commentary on the study (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.003]).

“But does this mean we should be doing [elephant-trunk] operation on every type A dissection patient?” wrote Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto. If no primary tear appears in the aortic arch or the proximal descending thoracic aorta (DTA), “then should we empirically dissect the arch vessels and perform total arch replacement in an emergent situation?” They also questioned extensive dissection of the left subclavian artery (LSCA) by cutting into the muscles around the surgical site.

Elephant-trunk implantation is more complex than other aortic repair procedures, they noted. “So, if a total arch replacement is not required, then why do it?”

While they acknowledged advantages of total arch replacement, and elephant-trunk implantation in particular, most operations for type A dissection occur in smaller, community hospitals that are ill equipped to perform the procedure. “This raises the issue of wide clinical application of the [elephant-trunk] technique for acute type A dissection,” they said. The real issue may not be what type of anastomosis for the elephant-trunk technique surgeons should use, but rather what surgical technique – the elephant-trunk technique vs. transverse hemiarch reconstruction, they said. (Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto mentioned that their institution has advocated for the latter.)

“To address this, a more comprehensive and meticulous approach is warranted based on parameters such as patient clinical picture, acuity, malperfusion, arch and DTA anatomy, and primary tear site location,” they said. But for now, Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto said, the medical literature does not support total arch replacement over transverse hemiarch reconstruction.

Dr. Vallabhajosyula is assistant professor of surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; Dr. Szeto is associate professor of surgery in the division of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center–Penn Presbyterian Medical Center.

The Beijing study authors’ excellent postoperative outcomes show that alternative surgical techniques for elephant-trunk implantation can be employed safely, but their technique also raises questions about the use of advanced technology, Dr. Prashanth Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Wilson Y. Szeto of the University of Pennsylvania said in their commentary on the study (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.003]).

“But does this mean we should be doing [elephant-trunk] operation on every type A dissection patient?” wrote Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto. If no primary tear appears in the aortic arch or the proximal descending thoracic aorta (DTA), “then should we empirically dissect the arch vessels and perform total arch replacement in an emergent situation?” They also questioned extensive dissection of the left subclavian artery (LSCA) by cutting into the muscles around the surgical site.

Elephant-trunk implantation is more complex than other aortic repair procedures, they noted. “So, if a total arch replacement is not required, then why do it?”

While they acknowledged advantages of total arch replacement, and elephant-trunk implantation in particular, most operations for type A dissection occur in smaller, community hospitals that are ill equipped to perform the procedure. “This raises the issue of wide clinical application of the [elephant-trunk] technique for acute type A dissection,” they said. The real issue may not be what type of anastomosis for the elephant-trunk technique surgeons should use, but rather what surgical technique – the elephant-trunk technique vs. transverse hemiarch reconstruction, they said. (Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto mentioned that their institution has advocated for the latter.)

“To address this, a more comprehensive and meticulous approach is warranted based on parameters such as patient clinical picture, acuity, malperfusion, arch and DTA anatomy, and primary tear site location,” they said. But for now, Dr. Vallabhajosyula and Dr. Szeto said, the medical literature does not support total arch replacement over transverse hemiarch reconstruction.

Dr. Vallabhajosyula is assistant professor of surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; Dr. Szeto is associate professor of surgery in the division of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center–Penn Presbyterian Medical Center.

An acute aortic tear can be lethal, and more cardiac surgeons are favoring extended aortic arch replacement in these cases. Cardiac surgeons have tried many different arch replacement techniques, but en bloc repair and double- or triple-branch stent grafting carry significant risks, so a team of cardiac surgeons in Beijing has reported good 2-year results with a novel technique that combines stented elephant-trunk implantation with preservation of key vessels.

The technique accomplishes total arch replacement with the stent while preserving the autologous brachiocephalic vessels.

“This technique simplified hemostasis and anastomosis, reduced the size of the residual aortic patch wall, and preserved the autologous brachiocephalic vessels, yielding satisfactory surgical results,” wrote Dr. Li-Zhong Sun and colleagues at Beijing’s Capital Medical University (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.002]).

There are four keys to the procedure:

• The use of forceps to grasp the stent-free sewing edge of the stented elephant trunk and straightening of the spiral shaped Dacron graft to approximately 3 cm.

• Preservation of the native brachiocephalic vessels.

• Creating a residual aortic wall containing the innominate artery and LCCA that’s as small as possible.

• An end-to-side anastomosis between the left subclavian artery (LSCA) and the left common carotid artery (LCCA), a key junction in their technique.

The 20 study subjects had surgery within 2 weeks of the onset of pain. All 20 were discharged after the procedure, and in a mean follow-up period of 26 months, 18 had good outcomes while 1 patient had thoracoabdominal aortic replacement 9 months after the initial surgery (1 patient was lost to follow-up).

The researchers used computed tomography to confirm patency of the anastomosis between the LSCA and LCCA.

In 2 of the 20 patients, the aorta was normal with aortic dissection limited to the descending aorta. In the remaining patients, the investigators observed thrombus obliteration of the false lumen around the surgical graft in 16, partial thrombosis in 1 and patency in 1.

The surgical technique exposes the right axillary artery through a right subclavicular incision and a median sternotomy, then dissects and exposes the brachiocephalic vessels and the transverse arch. Dissection of the LSCA and LCCA is the key step in making the end-to-end anastomosis between the two vessels. The researchers accomplished this by partially transecting the sternocleidomastoid muscle and other cervical muscles.

Dr. Sun and coauthors said that a separated graft technique offers a number of advantages over other techniques for aortic arch reconstruction. While en bloc repair preserves the native brachiocephalic vessels and, thus, results in long-term patency, the technique carries risk for postoperative rupture of the aortic patch containing the brachiocephalic vessels. Double- or triple-branched stent grafting has resulted in shifting or kinking of the graft and eventually graft occlusion or aortic disruption.

The authors acknowledged the study’s small sample size, and that the outcomes are “preliminary.” They said long-term follow-up would be required to confirm the outcomes.

They had no disclosures to report.

An acute aortic tear can be lethal, and more cardiac surgeons are favoring extended aortic arch replacement in these cases. Cardiac surgeons have tried many different arch replacement techniques, but en bloc repair and double- or triple-branch stent grafting carry significant risks, so a team of cardiac surgeons in Beijing has reported good 2-year results with a novel technique that combines stented elephant-trunk implantation with preservation of key vessels.

The technique accomplishes total arch replacement with the stent while preserving the autologous brachiocephalic vessels.

“This technique simplified hemostasis and anastomosis, reduced the size of the residual aortic patch wall, and preserved the autologous brachiocephalic vessels, yielding satisfactory surgical results,” wrote Dr. Li-Zhong Sun and colleagues at Beijing’s Capital Medical University (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.002]).

There are four keys to the procedure:

• The use of forceps to grasp the stent-free sewing edge of the stented elephant trunk and straightening of the spiral shaped Dacron graft to approximately 3 cm.

• Preservation of the native brachiocephalic vessels.

• Creating a residual aortic wall containing the innominate artery and LCCA that’s as small as possible.

• An end-to-side anastomosis between the left subclavian artery (LSCA) and the left common carotid artery (LCCA), a key junction in their technique.

The 20 study subjects had surgery within 2 weeks of the onset of pain. All 20 were discharged after the procedure, and in a mean follow-up period of 26 months, 18 had good outcomes while 1 patient had thoracoabdominal aortic replacement 9 months after the initial surgery (1 patient was lost to follow-up).

The researchers used computed tomography to confirm patency of the anastomosis between the LSCA and LCCA.

In 2 of the 20 patients, the aorta was normal with aortic dissection limited to the descending aorta. In the remaining patients, the investigators observed thrombus obliteration of the false lumen around the surgical graft in 16, partial thrombosis in 1 and patency in 1.

The surgical technique exposes the right axillary artery through a right subclavicular incision and a median sternotomy, then dissects and exposes the brachiocephalic vessels and the transverse arch. Dissection of the LSCA and LCCA is the key step in making the end-to-end anastomosis between the two vessels. The researchers accomplished this by partially transecting the sternocleidomastoid muscle and other cervical muscles.

Dr. Sun and coauthors said that a separated graft technique offers a number of advantages over other techniques for aortic arch reconstruction. While en bloc repair preserves the native brachiocephalic vessels and, thus, results in long-term patency, the technique carries risk for postoperative rupture of the aortic patch containing the brachiocephalic vessels. Double- or triple-branched stent grafting has resulted in shifting or kinking of the graft and eventually graft occlusion or aortic disruption.

The authors acknowledged the study’s small sample size, and that the outcomes are “preliminary.” They said long-term follow-up would be required to confirm the outcomes.

They had no disclosures to report.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Total aortic arch replacement with implantation of an elephant-trunk stent avoids risks of other more conventional approaches.

Major finding: Among 20 patients who had the elephant-trunk procedure, 18 had good results at a mean of 26 months after the operation (one had thoracoabdominal aortic arch replacement at 9 months and one was lost to follow-up).

Data source: Retrospective review of 20 patients with acute type A dissection who had total arch replacement at a single center.

Disclosures: The study authors reported having no financial disclosures.

SVS: Four easy preop variables predict mortality in ruptured AAAs

CHICAGO – Age greater than 76 years, plus preoperative creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL, blood pH less than 7.2, and systolic pressure at any point below 70 mm Hg collectively predicted 100% mortality with open or endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, according to a new mortality risk score from Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Meeting all four criteria gives the maximum score of 4. Any one of the factors alone – a score of 1 – predicted 30% mortality with open repair and 9% with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR); a 2 predicted 80% mortality with open repair and 37% with EVAR; and a 3 predicted 82% mortality with open repair and 70% with EVAR.

Vascular surgeons at Harborview developed the system so they’d know whether to recommend transport or comfort care for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). The Level 1 trauma center serves more than a quarter of the U.S. landmass, and handles about 30-40 ruptured AAA’s annually. It’s not uncommon for patients to be flown in from Alaska.

Existing risk scores haven’t been validated for EVAR or rely on intraoperative variables, so they aren’t much help when counseling patients and referring physicians on what to do.

“Our ruptured AAA mortality risk score is based on four variables readily assessed preoperatively, allows accurate prediction of in-hospital mortality after repair of ruptured AAAs in the EVAR-first era, and does so better than any score thus published. It’s clinically relevant to the decision to transport and helps guide difficult discussions with patients and their families,” said investigator Dr. Ty Garland, chief vascular surgery resident at the University of Washington, Seattle.

When using the new risk score. “we don’t ever block transfer, but we have discussions with referring providers and in several cases with patients and their families over the telephone.” When the situation is hopeless, “we explain the data.” Twice in the past 6 months, patients have opted to spend their last hours at home with their families, Dr. Garland said at the Society for Vascular Surgery’s annual meeting.

To develop their system, the investigators culled through 37,000 variables from 303 ruptured AAA patients treated at Harborview from 2002-2013. Fifteen patients died in the emergency department, en route to surgery, or after choosing comfort care. Overall, 30-day mortality was 54% for open repair and 22% for EVAR.

On multivariate analysis, the team isolated the four preoperative variables most predictive of death. Preoperative creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL almost quadrupled the risk (odds ratio 3.7; P < .001); systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg nearly tripled it (OR 2.7; P = .002); and pH less than 7.2 (OR 2.6; P = .009) and age greater than 76 years (OR 2.1; P = .011) more than doubled it.

The investigators then checked their results against the Vascular Study Group of New England Cardiac Index, Glasgow Aneurysm Score, and Edinburgh Ruptured Aneurysm Score. “Our preoperative risk score was most predictive of death, with an area under the curve of 0.76,” Dr. Garland said.

There was no outside funding for the work and Dr. Garland has no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Age greater than 76 years, plus preoperative creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL, blood pH less than 7.2, and systolic pressure at any point below 70 mm Hg collectively predicted 100% mortality with open or endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, according to a new mortality risk score from Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Meeting all four criteria gives the maximum score of 4. Any one of the factors alone – a score of 1 – predicted 30% mortality with open repair and 9% with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR); a 2 predicted 80% mortality with open repair and 37% with EVAR; and a 3 predicted 82% mortality with open repair and 70% with EVAR.

Vascular surgeons at Harborview developed the system so they’d know whether to recommend transport or comfort care for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). The Level 1 trauma center serves more than a quarter of the U.S. landmass, and handles about 30-40 ruptured AAA’s annually. It’s not uncommon for patients to be flown in from Alaska.

Existing risk scores haven’t been validated for EVAR or rely on intraoperative variables, so they aren’t much help when counseling patients and referring physicians on what to do.

“Our ruptured AAA mortality risk score is based on four variables readily assessed preoperatively, allows accurate prediction of in-hospital mortality after repair of ruptured AAAs in the EVAR-first era, and does so better than any score thus published. It’s clinically relevant to the decision to transport and helps guide difficult discussions with patients and their families,” said investigator Dr. Ty Garland, chief vascular surgery resident at the University of Washington, Seattle.

When using the new risk score. “we don’t ever block transfer, but we have discussions with referring providers and in several cases with patients and their families over the telephone.” When the situation is hopeless, “we explain the data.” Twice in the past 6 months, patients have opted to spend their last hours at home with their families, Dr. Garland said at the Society for Vascular Surgery’s annual meeting.

To develop their system, the investigators culled through 37,000 variables from 303 ruptured AAA patients treated at Harborview from 2002-2013. Fifteen patients died in the emergency department, en route to surgery, or after choosing comfort care. Overall, 30-day mortality was 54% for open repair and 22% for EVAR.

On multivariate analysis, the team isolated the four preoperative variables most predictive of death. Preoperative creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL almost quadrupled the risk (odds ratio 3.7; P < .001); systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg nearly tripled it (OR 2.7; P = .002); and pH less than 7.2 (OR 2.6; P = .009) and age greater than 76 years (OR 2.1; P = .011) more than doubled it.

The investigators then checked their results against the Vascular Study Group of New England Cardiac Index, Glasgow Aneurysm Score, and Edinburgh Ruptured Aneurysm Score. “Our preoperative risk score was most predictive of death, with an area under the curve of 0.76,” Dr. Garland said.

There was no outside funding for the work and Dr. Garland has no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Age greater than 76 years, plus preoperative creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL, blood pH less than 7.2, and systolic pressure at any point below 70 mm Hg collectively predicted 100% mortality with open or endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, according to a new mortality risk score from Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Meeting all four criteria gives the maximum score of 4. Any one of the factors alone – a score of 1 – predicted 30% mortality with open repair and 9% with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR); a 2 predicted 80% mortality with open repair and 37% with EVAR; and a 3 predicted 82% mortality with open repair and 70% with EVAR.

Vascular surgeons at Harborview developed the system so they’d know whether to recommend transport or comfort care for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). The Level 1 trauma center serves more than a quarter of the U.S. landmass, and handles about 30-40 ruptured AAA’s annually. It’s not uncommon for patients to be flown in from Alaska.

Existing risk scores haven’t been validated for EVAR or rely on intraoperative variables, so they aren’t much help when counseling patients and referring physicians on what to do.

“Our ruptured AAA mortality risk score is based on four variables readily assessed preoperatively, allows accurate prediction of in-hospital mortality after repair of ruptured AAAs in the EVAR-first era, and does so better than any score thus published. It’s clinically relevant to the decision to transport and helps guide difficult discussions with patients and their families,” said investigator Dr. Ty Garland, chief vascular surgery resident at the University of Washington, Seattle.

When using the new risk score. “we don’t ever block transfer, but we have discussions with referring providers and in several cases with patients and their families over the telephone.” When the situation is hopeless, “we explain the data.” Twice in the past 6 months, patients have opted to spend their last hours at home with their families, Dr. Garland said at the Society for Vascular Surgery’s annual meeting.

To develop their system, the investigators culled through 37,000 variables from 303 ruptured AAA patients treated at Harborview from 2002-2013. Fifteen patients died in the emergency department, en route to surgery, or after choosing comfort care. Overall, 30-day mortality was 54% for open repair and 22% for EVAR.

On multivariate analysis, the team isolated the four preoperative variables most predictive of death. Preoperative creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL almost quadrupled the risk (odds ratio 3.7; P < .001); systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg nearly tripled it (OR 2.7; P = .002); and pH less than 7.2 (OR 2.6; P = .009) and age greater than 76 years (OR 2.1; P = .011) more than doubled it.

The investigators then checked their results against the Vascular Study Group of New England Cardiac Index, Glasgow Aneurysm Score, and Edinburgh Ruptured Aneurysm Score. “Our preoperative risk score was most predictive of death, with an area under the curve of 0.76,” Dr. Garland said.

There was no outside funding for the work and Dr. Garland has no disclosures.

AT SVS 2015

Key clinical point: You can rely on preoperative variables to recommend surgery or comfort care for ruptured AAAs.

Major finding: Age greater than 76 years, plus preop creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL, blood pH less than 7.2, and systolic pressure at any point below 70 mm Hg predicted 100% mortality with open or endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Data source: More than 300 ruptured AAA patients treated at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle from 2002-2013

Disclosures: There was no outside funding for the work, and the presenting investigator has no relevant disclosures.

Older MI patients missing out on ICDs

Fewer than one in 10 elderly patients with a low ejection fraction after myocardial infarction who are eligible to receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator actually receive one within a year of their myocardial infarction, a study has found.

The retrospective observational study of 10,318 patients aged over 65 years who had experienced a myocardial infarction and had an ejection fraction of 35% or less showed only 8.1% received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) within a year of their MI, even though implantation within a year was associated with a 36% reduction in mortality at 2 years.

Those patients who did receive an ICD were more likely to have had a prior coronary artery bypass graft, had higher peak troponin levels, experienced in-hospital cardiogenic shock, or had a cardiology follow-up within 2 weeks of discharge, according to the paper published June 23 in JAMA.

“Individualized shared decision making, taking into context the patient’s quality of life, treatment goals, and preferences, is critical, because ICD therapy may shift death from a sudden event to a more gradual comorbid process,” wrote Dr. Sean D. Pokorney, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and co-authors (JAMA 2015;313:2433-40 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6409]).

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research& Quality, and Boston Scientific. Some authors declared research grants, honoraria, advisory board positions, and consultancies with private industry.

It is concerning that so few potentially ICD-eligible elderly patients are undergoing implantation, especially considering that ICDs significantly improve survival.

A possible scenario is that many of these patients did not receive an appropriate ICD simply because they fell into a crevasse of the fragmented health system in which overly burdened primary care physicians are expected to connect all the clinical and diagnostic information without the essential tools and necessary facts.

Dr. Robert G. Hauser is affiliated with the Minneapolis Heart Institute at the Abbott Northwestern Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015;313:2429-31 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6408]). No conflicts of interest were declared.

It is concerning that so few potentially ICD-eligible elderly patients are undergoing implantation, especially considering that ICDs significantly improve survival.

A possible scenario is that many of these patients did not receive an appropriate ICD simply because they fell into a crevasse of the fragmented health system in which overly burdened primary care physicians are expected to connect all the clinical and diagnostic information without the essential tools and necessary facts.

Dr. Robert G. Hauser is affiliated with the Minneapolis Heart Institute at the Abbott Northwestern Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015;313:2429-31 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6408]). No conflicts of interest were declared.

It is concerning that so few potentially ICD-eligible elderly patients are undergoing implantation, especially considering that ICDs significantly improve survival.

A possible scenario is that many of these patients did not receive an appropriate ICD simply because they fell into a crevasse of the fragmented health system in which overly burdened primary care physicians are expected to connect all the clinical and diagnostic information without the essential tools and necessary facts.

Dr. Robert G. Hauser is affiliated with the Minneapolis Heart Institute at the Abbott Northwestern Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015;313:2429-31 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6408]). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Fewer than one in 10 elderly patients with a low ejection fraction after myocardial infarction who are eligible to receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator actually receive one within a year of their myocardial infarction, a study has found.

The retrospective observational study of 10,318 patients aged over 65 years who had experienced a myocardial infarction and had an ejection fraction of 35% or less showed only 8.1% received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) within a year of their MI, even though implantation within a year was associated with a 36% reduction in mortality at 2 years.

Those patients who did receive an ICD were more likely to have had a prior coronary artery bypass graft, had higher peak troponin levels, experienced in-hospital cardiogenic shock, or had a cardiology follow-up within 2 weeks of discharge, according to the paper published June 23 in JAMA.

“Individualized shared decision making, taking into context the patient’s quality of life, treatment goals, and preferences, is critical, because ICD therapy may shift death from a sudden event to a more gradual comorbid process,” wrote Dr. Sean D. Pokorney, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and co-authors (JAMA 2015;313:2433-40 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6409]).

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research& Quality, and Boston Scientific. Some authors declared research grants, honoraria, advisory board positions, and consultancies with private industry.

Fewer than one in 10 elderly patients with a low ejection fraction after myocardial infarction who are eligible to receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator actually receive one within a year of their myocardial infarction, a study has found.

The retrospective observational study of 10,318 patients aged over 65 years who had experienced a myocardial infarction and had an ejection fraction of 35% or less showed only 8.1% received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) within a year of their MI, even though implantation within a year was associated with a 36% reduction in mortality at 2 years.

Those patients who did receive an ICD were more likely to have had a prior coronary artery bypass graft, had higher peak troponin levels, experienced in-hospital cardiogenic shock, or had a cardiology follow-up within 2 weeks of discharge, according to the paper published June 23 in JAMA.

“Individualized shared decision making, taking into context the patient’s quality of life, treatment goals, and preferences, is critical, because ICD therapy may shift death from a sudden event to a more gradual comorbid process,” wrote Dr. Sean D. Pokorney, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and co-authors (JAMA 2015;313:2433-40 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6409]).

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research& Quality, and Boston Scientific. Some authors declared research grants, honoraria, advisory board positions, and consultancies with private industry.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Many elderly patients who are eligible for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator after a myocardial infarction are not receiving them.

Major finding: Only 8.1% of older patients with an ejection fraction of less than 35% after a myocardial infarction receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Data source: Retrospective observational study of 10,318 patients aged over 65 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, and Boston Scientific. Some authors declared research grants, honoraria, advisory board positions, and consultancies with private industry.

Study establishes protocol for perioperative dabigatran discontinuation

TORONTO – In atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who must discontinue dabigatran for elective surgery, the risk of both stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting anticoagulation, according to results of a prospective study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Congress.

Among key findings presented at a press conference at the ISTH 2015 Congress, no strokes were recorded in more than 500 patients managed with the protocol, and the major bleeding rate was less than 2%, reported the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Sam Schulman, professor of hematology and thromboembolism, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Data from this study (Circulation 2015) were reported at the press conference alongside a second study of perioperative warfarin management. Both studies are potentially practice changing, because they supply evidence-based guidance for anticoagulation in patients with AF.

Based on the findings from these two studies, “it is important to get this message out” that there are now data available on which to base clinical decisions, reported Dr. Schulman, who is also president of the ISTH 2015 Congress. His data were presented alongside a study that found no benefit from heparin bridging in AF patients when warfarin was stopped 5 days in advance of surgery.

In the study presented by Dr. Schulman, 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment. The protocol provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

The primary outcome evaluated in the study was major bleeding in the first 30 days. Other outcomes of interest included thromboembolic complications, death and minor bleeding.

Major bleeding was observed in 1.8% of patients, a rate that Dr. Schulman characterized as “low and acceptable” in the context of expected background bleeding rates. There were four deaths, but all were unrelated to either bleeding or arterial thromboembolism. The only thromboembolic complication was a single transient ischemic attack. Minor bleeding occurred in 5.2%.

On the basis of the protocol, about half of the patients discontinued dabigatran 24 hours before surgery. No patient discontinued therapy more than 96 hours prior to surgery. The median time to resumption of dabigatran after surgery was 1 day, but the point at which it was restarted ranged between hours and 2 days. Bridging, which describes the injection of heparin for short-term anticoagulation, was not employed preoperatively but was used in 1.7% of cases postoperatively.

At the press conference, data also were reported from the BRIDGE study. That study, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (2015 June 22; epub ahead of print ), found that bridging was not an effective strategy in AF patients who discontinue warfarin prior to elective surgery. In the press conference, Dr. Thomas L. Ortel, hematology/oncology division, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed with Dr. Schulman that this is an area where evidence is needed to guide care.

In the absence of data, “physicians do whatever they think is best,” Dr. Schulman noted at the press conference. Referring to strategies for stopping anticoagulants for surgery in patients with AF, Dr. Schulman said, “some of them stop the blood thinner too early because they are afraid that the patient is going to bleed during surgery and instead the patient can have a stroke. Some stop too late, and the patient can have bleeding.”

The data presented at the meeting provide an evidence base for clinical decisions. Dr. Schulman suggested that these data are meaningful for guiding care.

Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

TORONTO – In atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who must discontinue dabigatran for elective surgery, the risk of both stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting anticoagulation, according to results of a prospective study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Congress.

Among key findings presented at a press conference at the ISTH 2015 Congress, no strokes were recorded in more than 500 patients managed with the protocol, and the major bleeding rate was less than 2%, reported the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Sam Schulman, professor of hematology and thromboembolism, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Data from this study (Circulation 2015) were reported at the press conference alongside a second study of perioperative warfarin management. Both studies are potentially practice changing, because they supply evidence-based guidance for anticoagulation in patients with AF.

Based on the findings from these two studies, “it is important to get this message out” that there are now data available on which to base clinical decisions, reported Dr. Schulman, who is also president of the ISTH 2015 Congress. His data were presented alongside a study that found no benefit from heparin bridging in AF patients when warfarin was stopped 5 days in advance of surgery.

In the study presented by Dr. Schulman, 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment. The protocol provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

The primary outcome evaluated in the study was major bleeding in the first 30 days. Other outcomes of interest included thromboembolic complications, death and minor bleeding.

Major bleeding was observed in 1.8% of patients, a rate that Dr. Schulman characterized as “low and acceptable” in the context of expected background bleeding rates. There were four deaths, but all were unrelated to either bleeding or arterial thromboembolism. The only thromboembolic complication was a single transient ischemic attack. Minor bleeding occurred in 5.2%.

On the basis of the protocol, about half of the patients discontinued dabigatran 24 hours before surgery. No patient discontinued therapy more than 96 hours prior to surgery. The median time to resumption of dabigatran after surgery was 1 day, but the point at which it was restarted ranged between hours and 2 days. Bridging, which describes the injection of heparin for short-term anticoagulation, was not employed preoperatively but was used in 1.7% of cases postoperatively.

At the press conference, data also were reported from the BRIDGE study. That study, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (2015 June 22; epub ahead of print ), found that bridging was not an effective strategy in AF patients who discontinue warfarin prior to elective surgery. In the press conference, Dr. Thomas L. Ortel, hematology/oncology division, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed with Dr. Schulman that this is an area where evidence is needed to guide care.

In the absence of data, “physicians do whatever they think is best,” Dr. Schulman noted at the press conference. Referring to strategies for stopping anticoagulants for surgery in patients with AF, Dr. Schulman said, “some of them stop the blood thinner too early because they are afraid that the patient is going to bleed during surgery and instead the patient can have a stroke. Some stop too late, and the patient can have bleeding.”

The data presented at the meeting provide an evidence base for clinical decisions. Dr. Schulman suggested that these data are meaningful for guiding care.

Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

TORONTO – In atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who must discontinue dabigatran for elective surgery, the risk of both stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting anticoagulation, according to results of a prospective study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Congress.

Among key findings presented at a press conference at the ISTH 2015 Congress, no strokes were recorded in more than 500 patients managed with the protocol, and the major bleeding rate was less than 2%, reported the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Sam Schulman, professor of hematology and thromboembolism, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Data from this study (Circulation 2015) were reported at the press conference alongside a second study of perioperative warfarin management. Both studies are potentially practice changing, because they supply evidence-based guidance for anticoagulation in patients with AF.

Based on the findings from these two studies, “it is important to get this message out” that there are now data available on which to base clinical decisions, reported Dr. Schulman, who is also president of the ISTH 2015 Congress. His data were presented alongside a study that found no benefit from heparin bridging in AF patients when warfarin was stopped 5 days in advance of surgery.

In the study presented by Dr. Schulman, 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment. The protocol provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

The primary outcome evaluated in the study was major bleeding in the first 30 days. Other outcomes of interest included thromboembolic complications, death and minor bleeding.

Major bleeding was observed in 1.8% of patients, a rate that Dr. Schulman characterized as “low and acceptable” in the context of expected background bleeding rates. There were four deaths, but all were unrelated to either bleeding or arterial thromboembolism. The only thromboembolic complication was a single transient ischemic attack. Minor bleeding occurred in 5.2%.

On the basis of the protocol, about half of the patients discontinued dabigatran 24 hours before surgery. No patient discontinued therapy more than 96 hours prior to surgery. The median time to resumption of dabigatran after surgery was 1 day, but the point at which it was restarted ranged between hours and 2 days. Bridging, which describes the injection of heparin for short-term anticoagulation, was not employed preoperatively but was used in 1.7% of cases postoperatively.

At the press conference, data also were reported from the BRIDGE study. That study, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (2015 June 22; epub ahead of print ), found that bridging was not an effective strategy in AF patients who discontinue warfarin prior to elective surgery. In the press conference, Dr. Thomas L. Ortel, hematology/oncology division, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed with Dr. Schulman that this is an area where evidence is needed to guide care.

In the absence of data, “physicians do whatever they think is best,” Dr. Schulman noted at the press conference. Referring to strategies for stopping anticoagulants for surgery in patients with AF, Dr. Schulman said, “some of them stop the blood thinner too early because they are afraid that the patient is going to bleed during surgery and instead the patient can have a stroke. Some stop too late, and the patient can have bleeding.”

The data presented at the meeting provide an evidence base for clinical decisions. Dr. Schulman suggested that these data are meaningful for guiding care.

Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

AT 2015 ISTH CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The risk of stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting dabigatran.

Major finding: The protocol developed provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

Data source: 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment.

Disclosures: Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

Perioperative factors influenced open TAAA repair

Open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair produced respectable early outcomes, although preoperative and intraoperative factors were found to influence risk, according to Dr. Joseph S. Coselli, who presented the results of the study he and his colleagues at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston performed at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

They analyzed data from 3,309 open TAAA repairs performed between October 1986 and December 2014.

“I have been very fortunate to have spent my entire career at Baylor College of Medicine, the epicenter of aortic surgery in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, as well as to have been mentored by Dr. E. Stanley Crawford, who was arguably the finest aortic surgeon of his era. Since transitioning from Dr. Crawford’s surgical practice to my own surgical practice, we have kept his pioneering spirit alive by developing a multimodal strategy for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair that is based on the Crawford extent of repair and our evolving investigation. We sought to describe our series of over 3,000 TAAA repairs and to identify predictors of early death and other adverse postoperative outcomes,” said Dr. Coselli.

The median patient age was around 67 years, and the repairs involved acute or subacute aortic dissection in about 5% of the cases. Nearly 31% of the case involved chronic dissection, with nearly 22% emergent or urgent repairs and around 5% ruptured aneurysms. Connective tissue disorders were present in roughly 10% of patients. “Operatively, we tend to reserve surgical adjuncts for use in the most-extensive repairs, namely extents I and II TAAA repair; intercostal or lumbar artery reattachment was used in just over half of the repairs, left heart bypass (LHB) was used in around 45% of patients, cold renal perfusion was performed in 58%. and cerebrospinal fluid drainage (CSFD) was used in 45%,” said Dr. Coselli.

There was substantial atherosclerotic disease in older patients, and in nearly 41% of repairs, a visceral vessel procedure was performed.

Unlike many aortic centers that routinely use deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA) for extensive TAAA repair, Dr. Coselli reserved this approach for a small number of highly complex repairs (1.4%) in which the aorta could not be safely clamped.

Of the more than a thousand most extensive (i.e., Crawford extent II) repairs, intercostal/lumbar artery reattachment was used in the vast majority (88%), LHB in 82%, and CSFD in 61%. They used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of operative (30-day or in-hospital) mortality and adverse event, a composite outcome comprising operative death and permanent (present at discharge) spinal cord deficit, renal failure, or stroke, according to Dr. Coselli.

Their results showed an operative mortality rate of 7.5%, a 30-day death rate of 4.8%, with the adverse event outcome occurring in about 14% of repairs. A video of his presentation is available at the AATS website.

The statistically significant predictors of operative death were rupture; renal insufficiency, symptoms, procedures targeting visceral vessels, increasing age, and increasing clamp time, while extent IV repair (the least extensive form of TAAA repair) was inversely associated with death. Their analysis showed that the significant predictors of adverse event were use of HCA, renal insufficiency, rupture, extent II repair, visceral vessel procedures, urgent or emergent repair, increasing age, and increasing clamp time. In addition, they used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of renal failure and paraplegia.

In the 3,060 early survivors, roughly 7% had a life-altering complication at discharge: Nearly 3% of patients had renal failure necessitating dialysis, slightly more than 1% had a unresolved stroke, and about 4% had unresolved paraplegia or paraparesis. Repair failure, primarily pseudoaneurysm, or patch aneurysm, occurred after nearly 3% of repairs, said Dr. Coselli.

Outcomes differed by extent of repair, with the risk being greatest in extent II repair. Actuarial survival was 63.6% at 5 years, 36.8% at 10 years, and 18.3% at 15 years. Freedom from repair failure was nearly 98% at 5 years, around 95% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

“Along with respectable early outcomes, after repair, patients have acceptable long-term survival, and late repair failure was uncommon. Notably, there are several subgroups of patients that do exceedingly well. Paraplegia in young patients with connective tissue disorders, even in the most-extensive repair (extent II), is remarkably rare – these patients do extremely well across the board,” he concluded.

Dr. Cosselli reported that he is a principal investigator and consultant for Medtronic and W.L. Gore & Assoc., as well as being a principal investigator, consultant, and having various financial relationships with Vascutek.

Open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair produced respectable early outcomes, although preoperative and intraoperative factors were found to influence risk, according to Dr. Joseph S. Coselli, who presented the results of the study he and his colleagues at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston performed at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

They analyzed data from 3,309 open TAAA repairs performed between October 1986 and December 2014.

“I have been very fortunate to have spent my entire career at Baylor College of Medicine, the epicenter of aortic surgery in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, as well as to have been mentored by Dr. E. Stanley Crawford, who was arguably the finest aortic surgeon of his era. Since transitioning from Dr. Crawford’s surgical practice to my own surgical practice, we have kept his pioneering spirit alive by developing a multimodal strategy for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair that is based on the Crawford extent of repair and our evolving investigation. We sought to describe our series of over 3,000 TAAA repairs and to identify predictors of early death and other adverse postoperative outcomes,” said Dr. Coselli.

The median patient age was around 67 years, and the repairs involved acute or subacute aortic dissection in about 5% of the cases. Nearly 31% of the case involved chronic dissection, with nearly 22% emergent or urgent repairs and around 5% ruptured aneurysms. Connective tissue disorders were present in roughly 10% of patients. “Operatively, we tend to reserve surgical adjuncts for use in the most-extensive repairs, namely extents I and II TAAA repair; intercostal or lumbar artery reattachment was used in just over half of the repairs, left heart bypass (LHB) was used in around 45% of patients, cold renal perfusion was performed in 58%. and cerebrospinal fluid drainage (CSFD) was used in 45%,” said Dr. Coselli.

There was substantial atherosclerotic disease in older patients, and in nearly 41% of repairs, a visceral vessel procedure was performed.

Unlike many aortic centers that routinely use deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA) for extensive TAAA repair, Dr. Coselli reserved this approach for a small number of highly complex repairs (1.4%) in which the aorta could not be safely clamped.

Of the more than a thousand most extensive (i.e., Crawford extent II) repairs, intercostal/lumbar artery reattachment was used in the vast majority (88%), LHB in 82%, and CSFD in 61%. They used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of operative (30-day or in-hospital) mortality and adverse event, a composite outcome comprising operative death and permanent (present at discharge) spinal cord deficit, renal failure, or stroke, according to Dr. Coselli.

Their results showed an operative mortality rate of 7.5%, a 30-day death rate of 4.8%, with the adverse event outcome occurring in about 14% of repairs. A video of his presentation is available at the AATS website.

The statistically significant predictors of operative death were rupture; renal insufficiency, symptoms, procedures targeting visceral vessels, increasing age, and increasing clamp time, while extent IV repair (the least extensive form of TAAA repair) was inversely associated with death. Their analysis showed that the significant predictors of adverse event were use of HCA, renal insufficiency, rupture, extent II repair, visceral vessel procedures, urgent or emergent repair, increasing age, and increasing clamp time. In addition, they used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of renal failure and paraplegia.

In the 3,060 early survivors, roughly 7% had a life-altering complication at discharge: Nearly 3% of patients had renal failure necessitating dialysis, slightly more than 1% had a unresolved stroke, and about 4% had unresolved paraplegia or paraparesis. Repair failure, primarily pseudoaneurysm, or patch aneurysm, occurred after nearly 3% of repairs, said Dr. Coselli.

Outcomes differed by extent of repair, with the risk being greatest in extent II repair. Actuarial survival was 63.6% at 5 years, 36.8% at 10 years, and 18.3% at 15 years. Freedom from repair failure was nearly 98% at 5 years, around 95% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

“Along with respectable early outcomes, after repair, patients have acceptable long-term survival, and late repair failure was uncommon. Notably, there are several subgroups of patients that do exceedingly well. Paraplegia in young patients with connective tissue disorders, even in the most-extensive repair (extent II), is remarkably rare – these patients do extremely well across the board,” he concluded.

Dr. Cosselli reported that he is a principal investigator and consultant for Medtronic and W.L. Gore & Assoc., as well as being a principal investigator, consultant, and having various financial relationships with Vascutek.

Open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair produced respectable early outcomes, although preoperative and intraoperative factors were found to influence risk, according to Dr. Joseph S. Coselli, who presented the results of the study he and his colleagues at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston performed at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

They analyzed data from 3,309 open TAAA repairs performed between October 1986 and December 2014.