User login

How Safe is Anti–IL-6 Therapy During Pregnancy?

TOPLINE:

The maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women treated with anti–interleukin (IL)-6 therapy for COVID-19 are largely favorable, with transient neonatal cytopenia observed in around one third of the babies being the only possible adverse outcome that could be related to anti–IL-6 therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- Despite guidance, very few pregnant women with COVID-19 are offered evidence-based therapies such as anti–IL-6 due to concerns regarding fetal safety in later pregnancy.

- In this retrospective study, researchers evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomes in 25 pregnant women with COVID-19 (mean age at admission, 33 years) treated with anti–IL-6 (tocilizumab or sarilumab) at two tertiary hospitals in London.

- Most women (n = 16) received anti–IL-6 in the third trimester of pregnancy, whereas nine received it during the second trimester.

- Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed through medical record reviews and maternal medicine networks, with follow-up for 12 months.

- The women included in the study constituted a high-risk population with severe COVID-19; 24 required level two or three critical care. All women were receiving at least three concomitant medications due to their critical illness.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 24 of 25 women treated with IL-6 receptor antibodies survived until hospital discharge.

- The sole death occurred in a woman with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis who later developed myocarditis and cardiac arrest. The physicians believed that these complications were more likely due to severe COVID-19 rather than anti–IL-6 therapy.

- All pregnancies resulted in live births; however, 16 babies had to be delivered preterm due to COVID-19 complications.

- Transient cytopenia was observed in 6 of 19 babies in whom a full blood count was performed. All the six babies were premature, with cytopenia resolving within 7 days in four babies; one baby died from complications associated with extreme prematurity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although the authors found mild, transitory cytopenia in some (6 of 19) exposed infants, most had been delivered prematurely due to progressive COVID-19–related morbidity, and distinguishing drug effects from similar prematurity-related effects is difficult,” wrote Steven L. Clark, MD, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melanie Nana, MRCP, from the Department of Obstetric Medicine, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, England. It was published online in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective in design, which may have introduced bias. The small sample size of 25 women may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study did not include a control group, which made it difficult to attribute outcomes solely to anti–IL-6 therapy. The lack of long-term follow-up data on the neonates also limited the understanding of potential long-term effects.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. Some authors, including the lead author, received speaker fees, grants, or consultancy fees from academic institutions or pharmaceutical companies or had other ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women treated with anti–interleukin (IL)-6 therapy for COVID-19 are largely favorable, with transient neonatal cytopenia observed in around one third of the babies being the only possible adverse outcome that could be related to anti–IL-6 therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- Despite guidance, very few pregnant women with COVID-19 are offered evidence-based therapies such as anti–IL-6 due to concerns regarding fetal safety in later pregnancy.

- In this retrospective study, researchers evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomes in 25 pregnant women with COVID-19 (mean age at admission, 33 years) treated with anti–IL-6 (tocilizumab or sarilumab) at two tertiary hospitals in London.

- Most women (n = 16) received anti–IL-6 in the third trimester of pregnancy, whereas nine received it during the second trimester.

- Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed through medical record reviews and maternal medicine networks, with follow-up for 12 months.

- The women included in the study constituted a high-risk population with severe COVID-19; 24 required level two or three critical care. All women were receiving at least three concomitant medications due to their critical illness.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 24 of 25 women treated with IL-6 receptor antibodies survived until hospital discharge.

- The sole death occurred in a woman with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis who later developed myocarditis and cardiac arrest. The physicians believed that these complications were more likely due to severe COVID-19 rather than anti–IL-6 therapy.

- All pregnancies resulted in live births; however, 16 babies had to be delivered preterm due to COVID-19 complications.

- Transient cytopenia was observed in 6 of 19 babies in whom a full blood count was performed. All the six babies were premature, with cytopenia resolving within 7 days in four babies; one baby died from complications associated with extreme prematurity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although the authors found mild, transitory cytopenia in some (6 of 19) exposed infants, most had been delivered prematurely due to progressive COVID-19–related morbidity, and distinguishing drug effects from similar prematurity-related effects is difficult,” wrote Steven L. Clark, MD, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melanie Nana, MRCP, from the Department of Obstetric Medicine, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, England. It was published online in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective in design, which may have introduced bias. The small sample size of 25 women may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study did not include a control group, which made it difficult to attribute outcomes solely to anti–IL-6 therapy. The lack of long-term follow-up data on the neonates also limited the understanding of potential long-term effects.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. Some authors, including the lead author, received speaker fees, grants, or consultancy fees from academic institutions or pharmaceutical companies or had other ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women treated with anti–interleukin (IL)-6 therapy for COVID-19 are largely favorable, with transient neonatal cytopenia observed in around one third of the babies being the only possible adverse outcome that could be related to anti–IL-6 therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- Despite guidance, very few pregnant women with COVID-19 are offered evidence-based therapies such as anti–IL-6 due to concerns regarding fetal safety in later pregnancy.

- In this retrospective study, researchers evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomes in 25 pregnant women with COVID-19 (mean age at admission, 33 years) treated with anti–IL-6 (tocilizumab or sarilumab) at two tertiary hospitals in London.

- Most women (n = 16) received anti–IL-6 in the third trimester of pregnancy, whereas nine received it during the second trimester.

- Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed through medical record reviews and maternal medicine networks, with follow-up for 12 months.

- The women included in the study constituted a high-risk population with severe COVID-19; 24 required level two or three critical care. All women were receiving at least three concomitant medications due to their critical illness.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 24 of 25 women treated with IL-6 receptor antibodies survived until hospital discharge.

- The sole death occurred in a woman with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis who later developed myocarditis and cardiac arrest. The physicians believed that these complications were more likely due to severe COVID-19 rather than anti–IL-6 therapy.

- All pregnancies resulted in live births; however, 16 babies had to be delivered preterm due to COVID-19 complications.

- Transient cytopenia was observed in 6 of 19 babies in whom a full blood count was performed. All the six babies were premature, with cytopenia resolving within 7 days in four babies; one baby died from complications associated with extreme prematurity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although the authors found mild, transitory cytopenia in some (6 of 19) exposed infants, most had been delivered prematurely due to progressive COVID-19–related morbidity, and distinguishing drug effects from similar prematurity-related effects is difficult,” wrote Steven L. Clark, MD, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melanie Nana, MRCP, from the Department of Obstetric Medicine, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, England. It was published online in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective in design, which may have introduced bias. The small sample size of 25 women may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study did not include a control group, which made it difficult to attribute outcomes solely to anti–IL-6 therapy. The lack of long-term follow-up data on the neonates also limited the understanding of potential long-term effects.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. Some authors, including the lead author, received speaker fees, grants, or consultancy fees from academic institutions or pharmaceutical companies or had other ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anti-Smith and Anti–Double-Stranded DNA Antibodies in a Patient With Henoch-Schönlein Purpura Following COVID-19 Vaccination

To the Editor:

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)(also known as IgA vasculitis) is a small vessel vasculitis characterized by deposition of IgA in small vessels, resulting in the development of purpura on the legs. Based on the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria,1 the patient also must have at least 1 of the following: arthritis, arthralgia, abdominal pain, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposition, or kidney involvement. The disease can be triggered by infection—with more than 75% of patients reporting an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection2—as well as medications, circulating immune complexes, certain foods, vaccines, and rarely cancer.3,4 The disease more commonly occurs in children but also can affect adults.

Several cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.5 We report a case of HSP developing days after the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster that was associated with anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies as well as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs).

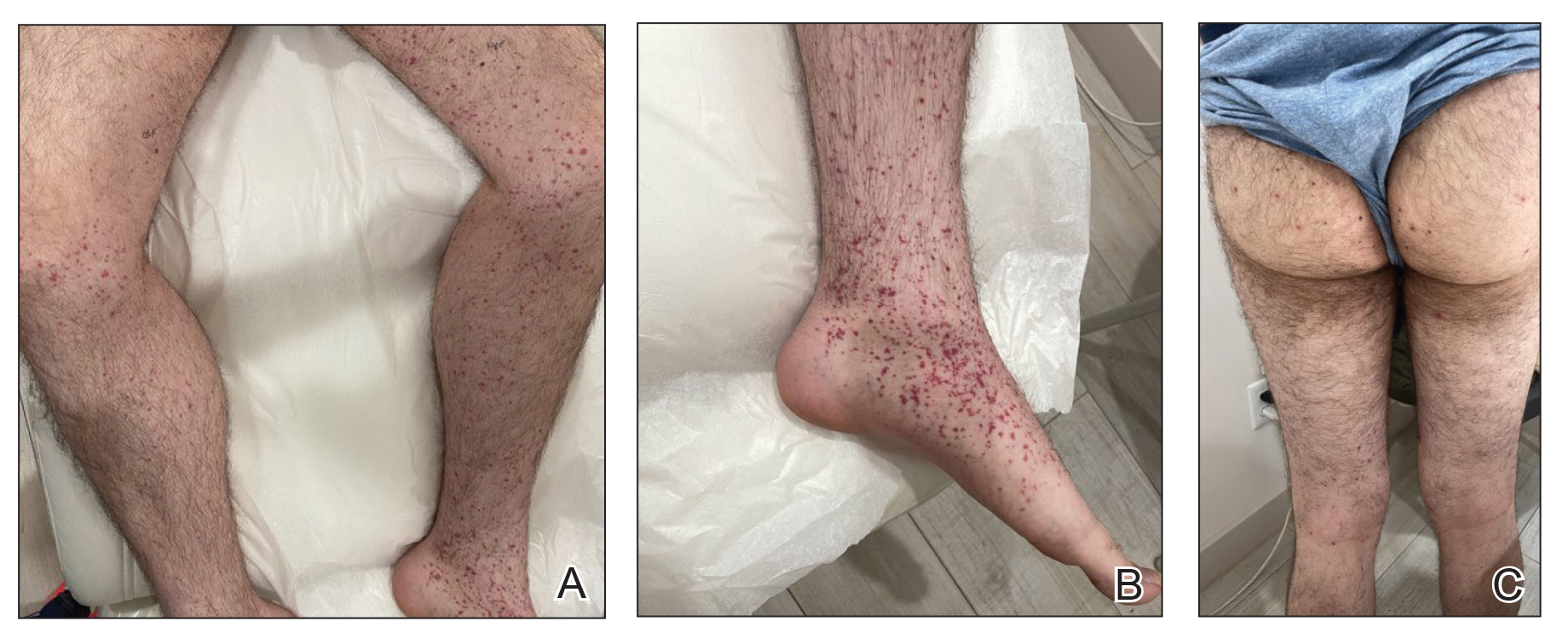

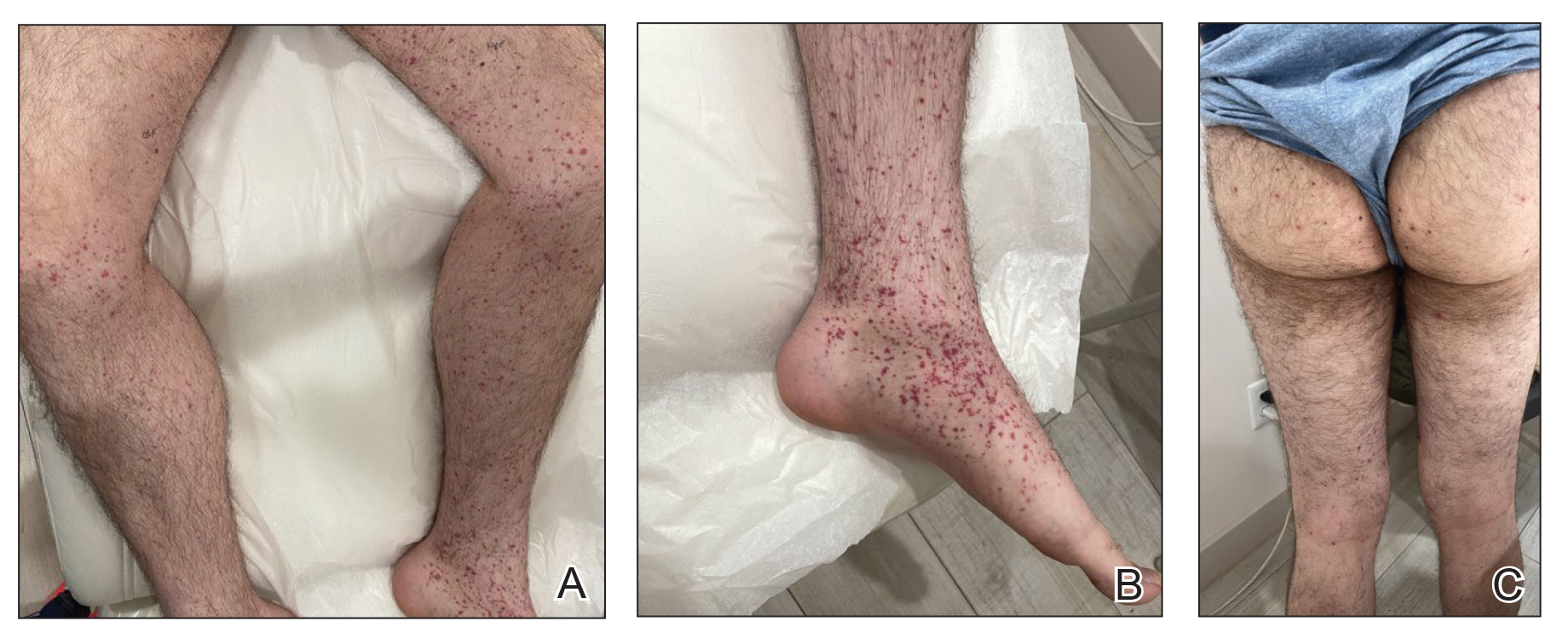

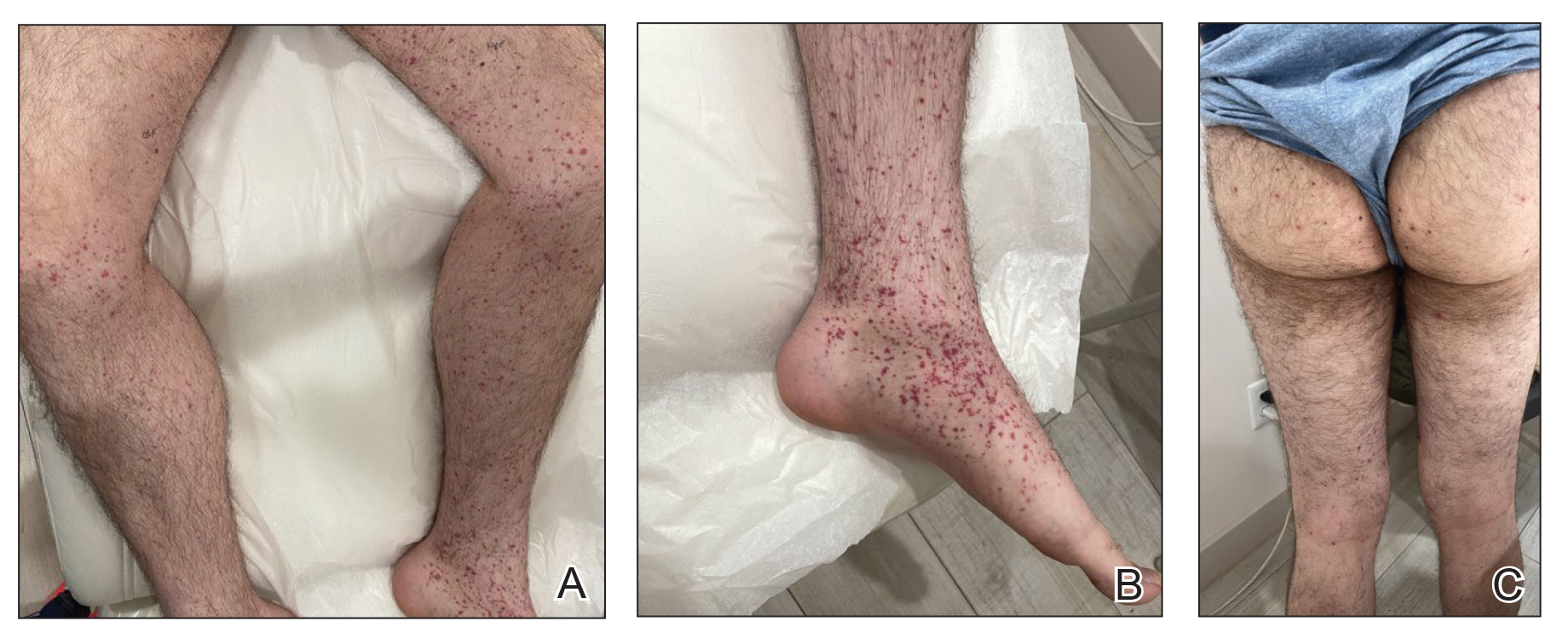

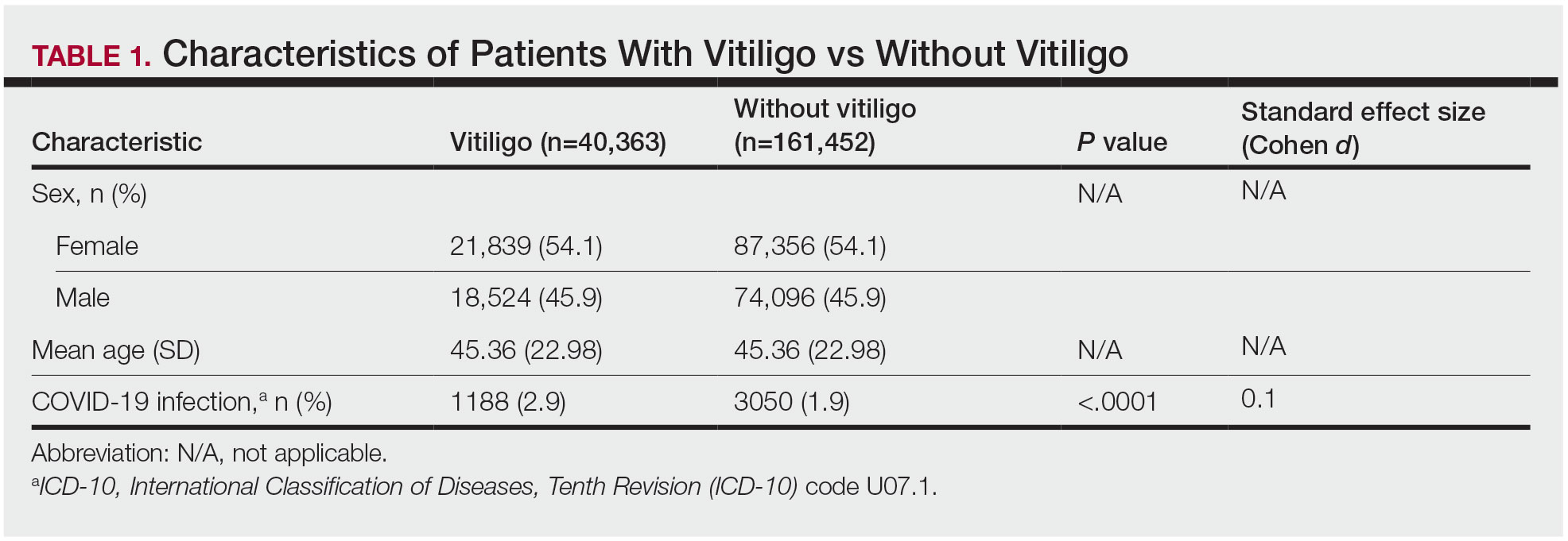

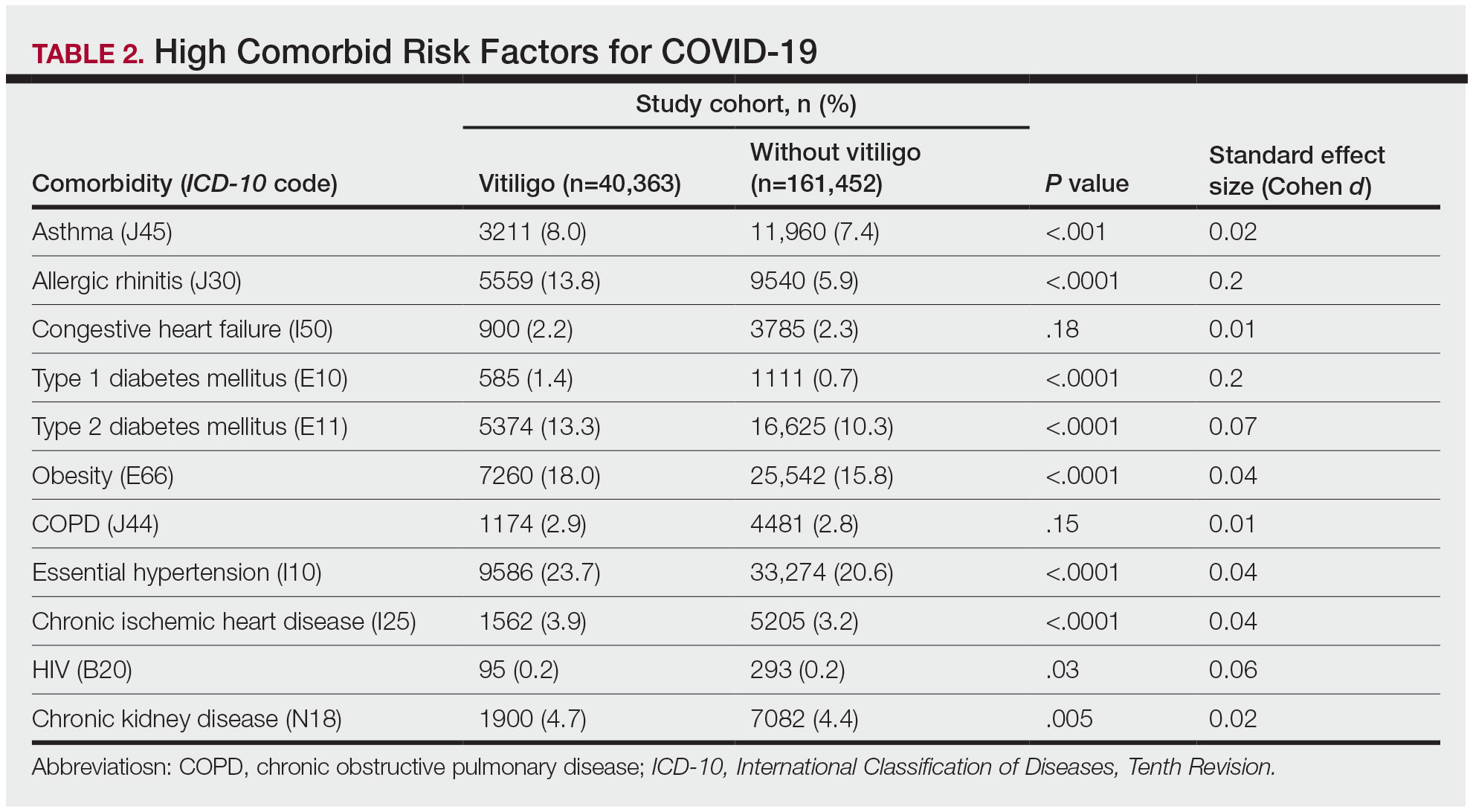

A 24-year-old man presented to dermatology with a rash of 3 weeks’ duration that first appeared 1 week after receiving his second booster of the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Physical examination revealed petechiae with nonblanching erythematous macules and papules covering the legs below the knees (Figure 1) as well as the back of the right arm. A few days later, he developed arthralgia in the knees, hands, and feet. The patient denied any recent infections as well as respiratory and urinary tract symptoms. Approximately 10 days after the rash appeared, he developed epigastric abdominal pain that gradually worsened and sought care from his primary care physician, who ordered computed tomography and referred him for endoscopy. Computed tomography with and without contrast was suspicious for colitis. Colonoscopy and endoscopy were unremarkable. Laboratory tests were notable for elevated white blood cell count (17.08×103/µL [reference range, 3.66–10.60×103/µL]), serum IgA (437 mg/dL [reference range, 70–400 mg/dL]), C-reactive protein (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, <0.5 mg/dL]), anti-Smith antibody (28.1 CU [reference range, <20 CU), positive antinuclear antibody with titer (1:160 [reference range, <1:80]), anti-dsDNA (40.4 IU/mL [reference range, <27 IU/mL]), and cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) titer (1:320 [reference range, <1:20]). Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were all within reference range. Urinalysis with microscopic examination was notable for 2 to 5 red blood cells per high-power field (reference range, 0) and proteinuria of 1+ (reference range, negative for protein).

The patient’s rash progressively worsened over the next few weeks, spreading proximally on the legs to the buttocks and the back of both elbows. A repeat complete blood cell count showed resolution of the leukocytosis. Two biopsies were taken from a lesion on the left proximal thigh: 1 for hematoxylin and eosin stain for histopathologic examination and 1 for direct immunofluorescence examination.

The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with HSP, and dermatology prescribed oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily for 5 days, which was supposed to be increased to 10 mg twice daily on the sixth day of treatment; however, the patient discontinued the medication after 4 days based on his primary care physician’s recommendation due to clotting concerns. The rash and arthralgia temporarily improved for 1 week, then relapsed.

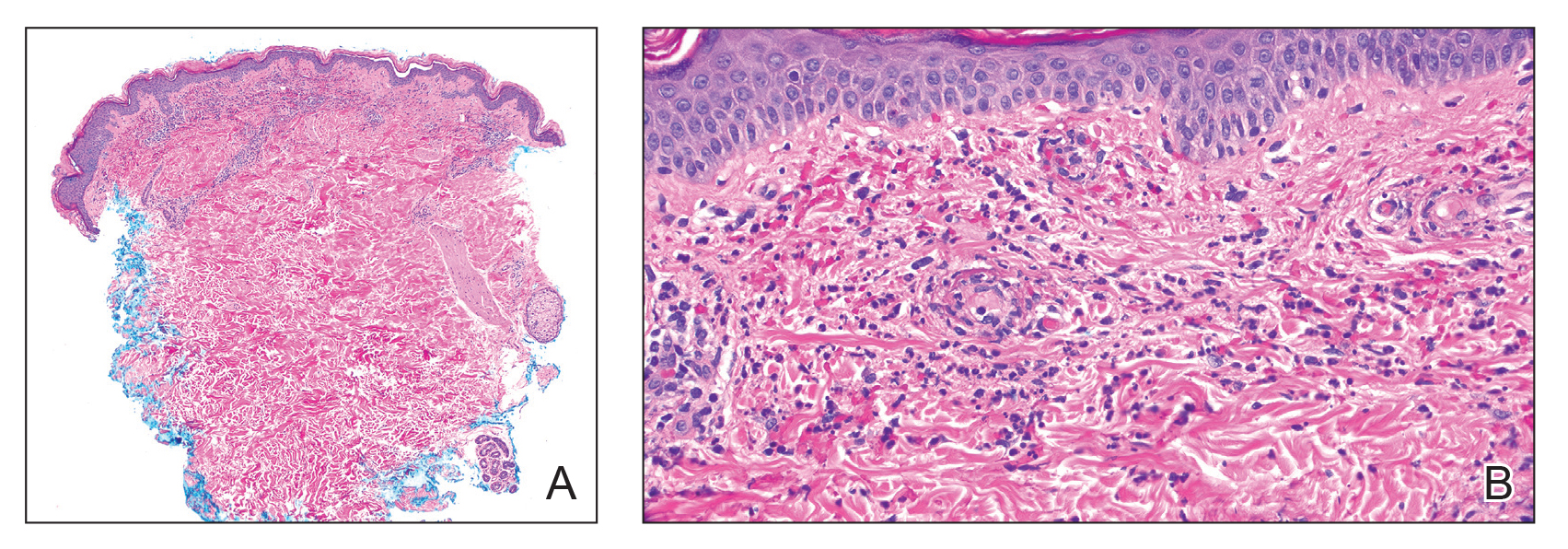

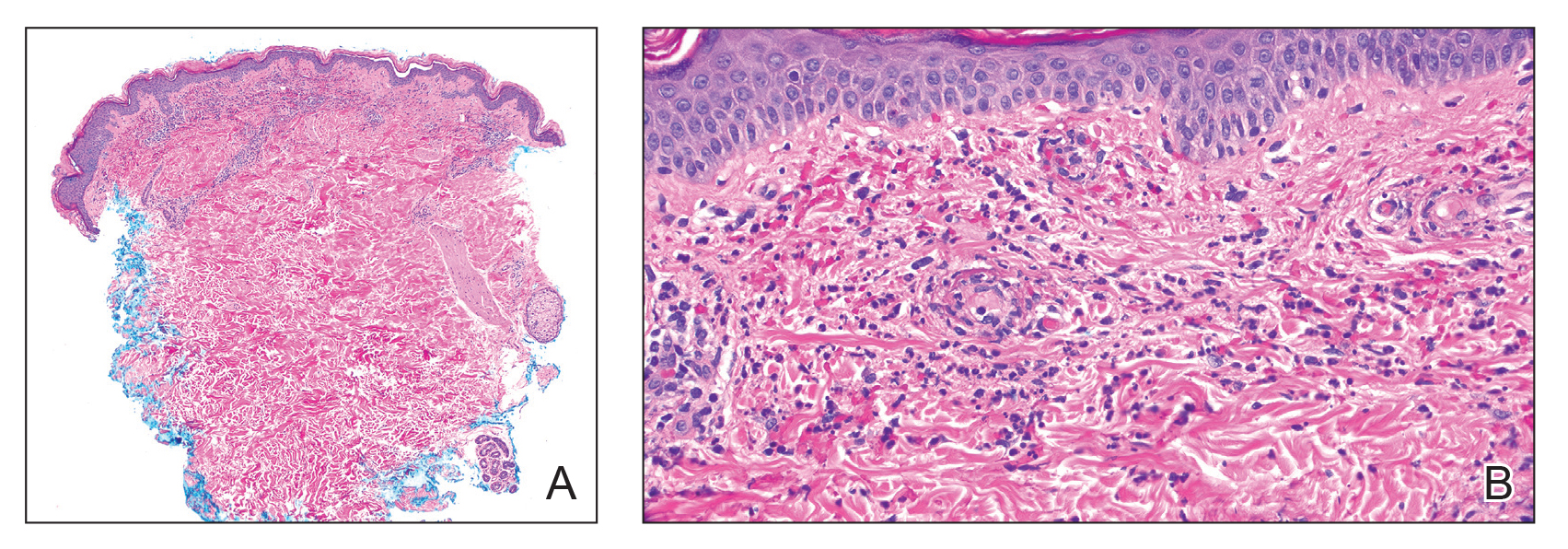

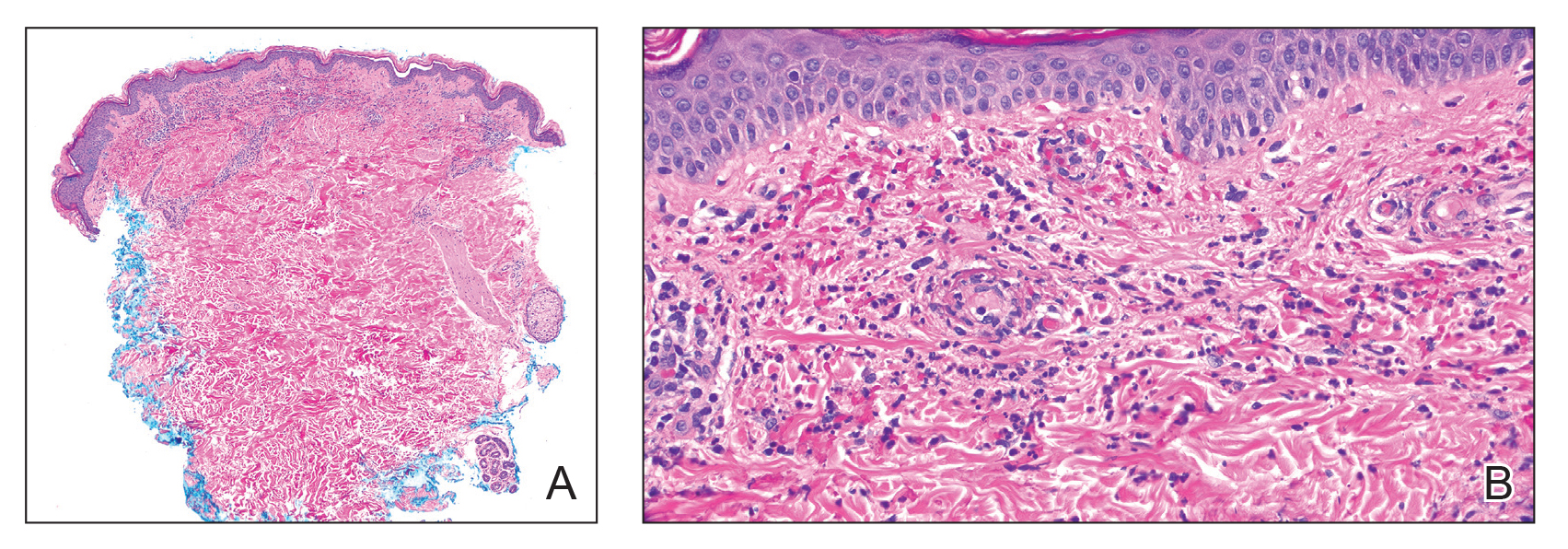

Histopathology revealed neutrophils surrounding and infiltrating small dermal blood vessel walls as well as associated neutrophilic debris and erythrocytes, consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgA antibodies. His primary care physician, in consultation with his dermatologist, then started the patient on oral prednisone 70 mg once daily for 7 days with a plan to taper. Three days after prednisone was started, the arthralgia and abdominal pain resolved, and the rash became lighter in color. After 1 week, the rash resolved completely.

Due to the unusual antibodies, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist, who repeated the blood tests approximately 1 week after the patient started prednisone. The tests were negative for anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and c-ANCA but showed an elevated atypical perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) titer of 1:80 (reference range [negative], <1:20). A repeat urinalysis was unremarkable. The patient slowly tapered the prednisone over the course of 3 months and was subsequently lost to follow-up. The rash and other symptoms had not recurred as of the patient’s last physician contact. The most recent laboratory results showed a white blood cell count of 14.0×103/µL (reference range, 3.4–10.8×103/µL), likely due to the prednisone; blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were within reference range. The urinalysis was notable for occult blood and was negative for protein. C-reactive protein was 1 mg/dL (reference range, 0–10 mg/dL); p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and atypical p-ANCA, as well as antinuclear antibody, were negative. As of his last follow-up, the patient felt well.

The major differential diagnoses for our patient included HSP, ANCA vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Although ANCA vasculitis has been reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection,6 the lack of pulmonary symptoms made this diagnosis unlikely.7 Although our patient initially had elevated anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as mild renal involvement, he fulfilled at most only 2 of the 11 criteria necessary for diagnosing lupus: malar rash, discoid rash (includes alopecia), photosensitivity, ocular ulcers, nonerosive arthritis, serositis, renal disorder (protein >500 mg/24 h, red blood cells, casts), neurologic disorder (seizures, psychosis), hematologic disorders (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia), ANA, and immunologic disorder (anti-Smith). Four of the 11 criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of lupus.8

Torraca et al7 reported a case of HSP with positive c-ANCA (1:640) in a patient lacking pulmonary symptoms who was diagnosed with HSP. Cytoplasmic ANCA is not a typical finding in HSP. However, the additional findings of anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and mildly elevated atypical p-ANCA antibodies in our patient were unexpected and could be explained by the proposed pathogenesis of HSP—an overzealous immune response resulting in aberrant antibody complex deposition with ensuing complement activation.5,9 Production of these additional antibodies could be part of the overzealous response to COVID-19 vaccination.

Of all the COVID-19 vaccines, messenger RNA–based vaccines have been associated with the majority of cutaneous reactions, including local injection-site reactions (most common), delayed local reactions, urticaria, angioedema, morbilliform eruption, herpes zoster eruption, bullous eruptions, dermal filler reactions, chilblains, and pityriasis rosea. Less common reactions have included acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet Syndrome, lichen planus, papulovesicular eruptions, pityriasis rosea–like eruptions, generalized annular lesions, facial pustular neutrophilic eruptions, and flares of underlying autoimmune skin conditions.10 Multiple cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination from all the major vaccine companies.5

In our patient, laboratory tests were repeated by a rheumatologist and were negative for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as c-ANCA, most likely because he started taking prednisone approximately 1 week prior, which may have resulted in decreased antibodies. Also, the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 week of steroid therapy. Therefore, the diagnosis is most consistent with HSP associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The clinical presentation, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria, and histopathology were consistent with the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for HSP.1

Although direct immunofluorescence typically is positive for IgA deposition on biopsies, it can be negative for IgA, especially in lesions that are biopsied more than 7 days after their appearance, as shown in our case; a negative IgA on immunofluorescence does not rule out HSP.4 Elevated serum IgA is seen in more than 50% of cases of HSP.11 Although the disease typically is self-limited, glucocorticoids are used if the disease course is prolonged or if there is evidence of kidney involvement.9 The unique combination of anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs associated with HSP with negative IgA on direct immunofluorescence has been reported with lupus.12 Clinicians should be aware of COVID-19 vaccine–associated HSP that is negative for IgA deposition and positive for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs.

Acknowledgment—We thank our patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.046300

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Casini F, Magenes VC, De Sanctis M, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following COVID-19 vaccine in a child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:158. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01351-1

- Poudel P, Adams SH, Mirchia K, et al. IgA negative immunofluorescence in diagnoses of adult-onset Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33:436-437. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1770526

- Maronese CA, Zelin E, Avallone G, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis and vasculopathy in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:996288. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.996288

- Bryant MC, Spencer LT, Yalcindag A. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a 16-year-old female following SARS-COV-2 infection and a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20:65. doi:10.1186/s12969-022-00727-1

- Torraca PFS, Castro BC, Hans Filho G. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with c-ANCA antibody in adult. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:667-669. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164181

- Agabegi SS, Agabegi ED. Step-Up to Medicine. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Ball-Burack MR, Kosowsky JM. A Case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:E62-E65. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.10.005

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Pang SM. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: a review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:178-186. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.011

- Calviño MC, Llorca J, García-Porrúa C, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from northwestern Spain: a 20-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:279-290.

- Hu P, Huang BY, Zhang DD, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a pediatric patient with lupus. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:689-690. doi:10.5114/aoms.2017.67288

To the Editor:

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)(also known as IgA vasculitis) is a small vessel vasculitis characterized by deposition of IgA in small vessels, resulting in the development of purpura on the legs. Based on the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria,1 the patient also must have at least 1 of the following: arthritis, arthralgia, abdominal pain, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposition, or kidney involvement. The disease can be triggered by infection—with more than 75% of patients reporting an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection2—as well as medications, circulating immune complexes, certain foods, vaccines, and rarely cancer.3,4 The disease more commonly occurs in children but also can affect adults.

Several cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.5 We report a case of HSP developing days after the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster that was associated with anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies as well as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs).

A 24-year-old man presented to dermatology with a rash of 3 weeks’ duration that first appeared 1 week after receiving his second booster of the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Physical examination revealed petechiae with nonblanching erythematous macules and papules covering the legs below the knees (Figure 1) as well as the back of the right arm. A few days later, he developed arthralgia in the knees, hands, and feet. The patient denied any recent infections as well as respiratory and urinary tract symptoms. Approximately 10 days after the rash appeared, he developed epigastric abdominal pain that gradually worsened and sought care from his primary care physician, who ordered computed tomography and referred him for endoscopy. Computed tomography with and without contrast was suspicious for colitis. Colonoscopy and endoscopy were unremarkable. Laboratory tests were notable for elevated white blood cell count (17.08×103/µL [reference range, 3.66–10.60×103/µL]), serum IgA (437 mg/dL [reference range, 70–400 mg/dL]), C-reactive protein (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, <0.5 mg/dL]), anti-Smith antibody (28.1 CU [reference range, <20 CU), positive antinuclear antibody with titer (1:160 [reference range, <1:80]), anti-dsDNA (40.4 IU/mL [reference range, <27 IU/mL]), and cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) titer (1:320 [reference range, <1:20]). Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were all within reference range. Urinalysis with microscopic examination was notable for 2 to 5 red blood cells per high-power field (reference range, 0) and proteinuria of 1+ (reference range, negative for protein).

The patient’s rash progressively worsened over the next few weeks, spreading proximally on the legs to the buttocks and the back of both elbows. A repeat complete blood cell count showed resolution of the leukocytosis. Two biopsies were taken from a lesion on the left proximal thigh: 1 for hematoxylin and eosin stain for histopathologic examination and 1 for direct immunofluorescence examination.

The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with HSP, and dermatology prescribed oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily for 5 days, which was supposed to be increased to 10 mg twice daily on the sixth day of treatment; however, the patient discontinued the medication after 4 days based on his primary care physician’s recommendation due to clotting concerns. The rash and arthralgia temporarily improved for 1 week, then relapsed.

Histopathology revealed neutrophils surrounding and infiltrating small dermal blood vessel walls as well as associated neutrophilic debris and erythrocytes, consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgA antibodies. His primary care physician, in consultation with his dermatologist, then started the patient on oral prednisone 70 mg once daily for 7 days with a plan to taper. Three days after prednisone was started, the arthralgia and abdominal pain resolved, and the rash became lighter in color. After 1 week, the rash resolved completely.

Due to the unusual antibodies, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist, who repeated the blood tests approximately 1 week after the patient started prednisone. The tests were negative for anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and c-ANCA but showed an elevated atypical perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) titer of 1:80 (reference range [negative], <1:20). A repeat urinalysis was unremarkable. The patient slowly tapered the prednisone over the course of 3 months and was subsequently lost to follow-up. The rash and other symptoms had not recurred as of the patient’s last physician contact. The most recent laboratory results showed a white blood cell count of 14.0×103/µL (reference range, 3.4–10.8×103/µL), likely due to the prednisone; blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were within reference range. The urinalysis was notable for occult blood and was negative for protein. C-reactive protein was 1 mg/dL (reference range, 0–10 mg/dL); p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and atypical p-ANCA, as well as antinuclear antibody, were negative. As of his last follow-up, the patient felt well.

The major differential diagnoses for our patient included HSP, ANCA vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Although ANCA vasculitis has been reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection,6 the lack of pulmonary symptoms made this diagnosis unlikely.7 Although our patient initially had elevated anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as mild renal involvement, he fulfilled at most only 2 of the 11 criteria necessary for diagnosing lupus: malar rash, discoid rash (includes alopecia), photosensitivity, ocular ulcers, nonerosive arthritis, serositis, renal disorder (protein >500 mg/24 h, red blood cells, casts), neurologic disorder (seizures, psychosis), hematologic disorders (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia), ANA, and immunologic disorder (anti-Smith). Four of the 11 criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of lupus.8

Torraca et al7 reported a case of HSP with positive c-ANCA (1:640) in a patient lacking pulmonary symptoms who was diagnosed with HSP. Cytoplasmic ANCA is not a typical finding in HSP. However, the additional findings of anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and mildly elevated atypical p-ANCA antibodies in our patient were unexpected and could be explained by the proposed pathogenesis of HSP—an overzealous immune response resulting in aberrant antibody complex deposition with ensuing complement activation.5,9 Production of these additional antibodies could be part of the overzealous response to COVID-19 vaccination.

Of all the COVID-19 vaccines, messenger RNA–based vaccines have been associated with the majority of cutaneous reactions, including local injection-site reactions (most common), delayed local reactions, urticaria, angioedema, morbilliform eruption, herpes zoster eruption, bullous eruptions, dermal filler reactions, chilblains, and pityriasis rosea. Less common reactions have included acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet Syndrome, lichen planus, papulovesicular eruptions, pityriasis rosea–like eruptions, generalized annular lesions, facial pustular neutrophilic eruptions, and flares of underlying autoimmune skin conditions.10 Multiple cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination from all the major vaccine companies.5

In our patient, laboratory tests were repeated by a rheumatologist and were negative for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as c-ANCA, most likely because he started taking prednisone approximately 1 week prior, which may have resulted in decreased antibodies. Also, the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 week of steroid therapy. Therefore, the diagnosis is most consistent with HSP associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The clinical presentation, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria, and histopathology were consistent with the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for HSP.1

Although direct immunofluorescence typically is positive for IgA deposition on biopsies, it can be negative for IgA, especially in lesions that are biopsied more than 7 days after their appearance, as shown in our case; a negative IgA on immunofluorescence does not rule out HSP.4 Elevated serum IgA is seen in more than 50% of cases of HSP.11 Although the disease typically is self-limited, glucocorticoids are used if the disease course is prolonged or if there is evidence of kidney involvement.9 The unique combination of anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs associated with HSP with negative IgA on direct immunofluorescence has been reported with lupus.12 Clinicians should be aware of COVID-19 vaccine–associated HSP that is negative for IgA deposition and positive for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs.

Acknowledgment—We thank our patient for granting permission to publish this information.

To the Editor:

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)(also known as IgA vasculitis) is a small vessel vasculitis characterized by deposition of IgA in small vessels, resulting in the development of purpura on the legs. Based on the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria,1 the patient also must have at least 1 of the following: arthritis, arthralgia, abdominal pain, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposition, or kidney involvement. The disease can be triggered by infection—with more than 75% of patients reporting an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection2—as well as medications, circulating immune complexes, certain foods, vaccines, and rarely cancer.3,4 The disease more commonly occurs in children but also can affect adults.

Several cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.5 We report a case of HSP developing days after the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster that was associated with anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies as well as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs).

A 24-year-old man presented to dermatology with a rash of 3 weeks’ duration that first appeared 1 week after receiving his second booster of the messenger RNA Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Physical examination revealed petechiae with nonblanching erythematous macules and papules covering the legs below the knees (Figure 1) as well as the back of the right arm. A few days later, he developed arthralgia in the knees, hands, and feet. The patient denied any recent infections as well as respiratory and urinary tract symptoms. Approximately 10 days after the rash appeared, he developed epigastric abdominal pain that gradually worsened and sought care from his primary care physician, who ordered computed tomography and referred him for endoscopy. Computed tomography with and without contrast was suspicious for colitis. Colonoscopy and endoscopy were unremarkable. Laboratory tests were notable for elevated white blood cell count (17.08×103/µL [reference range, 3.66–10.60×103/µL]), serum IgA (437 mg/dL [reference range, 70–400 mg/dL]), C-reactive protein (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, <0.5 mg/dL]), anti-Smith antibody (28.1 CU [reference range, <20 CU), positive antinuclear antibody with titer (1:160 [reference range, <1:80]), anti-dsDNA (40.4 IU/mL [reference range, <27 IU/mL]), and cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) titer (1:320 [reference range, <1:20]). Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were all within reference range. Urinalysis with microscopic examination was notable for 2 to 5 red blood cells per high-power field (reference range, 0) and proteinuria of 1+ (reference range, negative for protein).

The patient’s rash progressively worsened over the next few weeks, spreading proximally on the legs to the buttocks and the back of both elbows. A repeat complete blood cell count showed resolution of the leukocytosis. Two biopsies were taken from a lesion on the left proximal thigh: 1 for hematoxylin and eosin stain for histopathologic examination and 1 for direct immunofluorescence examination.

The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with HSP, and dermatology prescribed oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily for 5 days, which was supposed to be increased to 10 mg twice daily on the sixth day of treatment; however, the patient discontinued the medication after 4 days based on his primary care physician’s recommendation due to clotting concerns. The rash and arthralgia temporarily improved for 1 week, then relapsed.

Histopathology revealed neutrophils surrounding and infiltrating small dermal blood vessel walls as well as associated neutrophilic debris and erythrocytes, consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgA antibodies. His primary care physician, in consultation with his dermatologist, then started the patient on oral prednisone 70 mg once daily for 7 days with a plan to taper. Three days after prednisone was started, the arthralgia and abdominal pain resolved, and the rash became lighter in color. After 1 week, the rash resolved completely.

Due to the unusual antibodies, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist, who repeated the blood tests approximately 1 week after the patient started prednisone. The tests were negative for anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and c-ANCA but showed an elevated atypical perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) titer of 1:80 (reference range [negative], <1:20). A repeat urinalysis was unremarkable. The patient slowly tapered the prednisone over the course of 3 months and was subsequently lost to follow-up. The rash and other symptoms had not recurred as of the patient’s last physician contact. The most recent laboratory results showed a white blood cell count of 14.0×103/µL (reference range, 3.4–10.8×103/µL), likely due to the prednisone; blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were within reference range. The urinalysis was notable for occult blood and was negative for protein. C-reactive protein was 1 mg/dL (reference range, 0–10 mg/dL); p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and atypical p-ANCA, as well as antinuclear antibody, were negative. As of his last follow-up, the patient felt well.

The major differential diagnoses for our patient included HSP, ANCA vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Although ANCA vasculitis has been reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection,6 the lack of pulmonary symptoms made this diagnosis unlikely.7 Although our patient initially had elevated anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as mild renal involvement, he fulfilled at most only 2 of the 11 criteria necessary for diagnosing lupus: malar rash, discoid rash (includes alopecia), photosensitivity, ocular ulcers, nonerosive arthritis, serositis, renal disorder (protein >500 mg/24 h, red blood cells, casts), neurologic disorder (seizures, psychosis), hematologic disorders (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia), ANA, and immunologic disorder (anti-Smith). Four of the 11 criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of lupus.8

Torraca et al7 reported a case of HSP with positive c-ANCA (1:640) in a patient lacking pulmonary symptoms who was diagnosed with HSP. Cytoplasmic ANCA is not a typical finding in HSP. However, the additional findings of anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, and mildly elevated atypical p-ANCA antibodies in our patient were unexpected and could be explained by the proposed pathogenesis of HSP—an overzealous immune response resulting in aberrant antibody complex deposition with ensuing complement activation.5,9 Production of these additional antibodies could be part of the overzealous response to COVID-19 vaccination.

Of all the COVID-19 vaccines, messenger RNA–based vaccines have been associated with the majority of cutaneous reactions, including local injection-site reactions (most common), delayed local reactions, urticaria, angioedema, morbilliform eruption, herpes zoster eruption, bullous eruptions, dermal filler reactions, chilblains, and pityriasis rosea. Less common reactions have included acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet Syndrome, lichen planus, papulovesicular eruptions, pityriasis rosea–like eruptions, generalized annular lesions, facial pustular neutrophilic eruptions, and flares of underlying autoimmune skin conditions.10 Multiple cases of HSP have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination from all the major vaccine companies.5

In our patient, laboratory tests were repeated by a rheumatologist and were negative for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as c-ANCA, most likely because he started taking prednisone approximately 1 week prior, which may have resulted in decreased antibodies. Also, the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 week of steroid therapy. Therefore, the diagnosis is most consistent with HSP associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The clinical presentation, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria, and histopathology were consistent with the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for HSP.1

Although direct immunofluorescence typically is positive for IgA deposition on biopsies, it can be negative for IgA, especially in lesions that are biopsied more than 7 days after their appearance, as shown in our case; a negative IgA on immunofluorescence does not rule out HSP.4 Elevated serum IgA is seen in more than 50% of cases of HSP.11 Although the disease typically is self-limited, glucocorticoids are used if the disease course is prolonged or if there is evidence of kidney involvement.9 The unique combination of anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs associated with HSP with negative IgA on direct immunofluorescence has been reported with lupus.12 Clinicians should be aware of COVID-19 vaccine–associated HSP that is negative for IgA deposition and positive for anti-Smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as ANCAs.

Acknowledgment—We thank our patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.046300

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Casini F, Magenes VC, De Sanctis M, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following COVID-19 vaccine in a child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:158. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01351-1

- Poudel P, Adams SH, Mirchia K, et al. IgA negative immunofluorescence in diagnoses of adult-onset Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33:436-437. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1770526

- Maronese CA, Zelin E, Avallone G, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis and vasculopathy in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:996288. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.996288

- Bryant MC, Spencer LT, Yalcindag A. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a 16-year-old female following SARS-COV-2 infection and a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20:65. doi:10.1186/s12969-022-00727-1

- Torraca PFS, Castro BC, Hans Filho G. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with c-ANCA antibody in adult. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:667-669. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164181

- Agabegi SS, Agabegi ED. Step-Up to Medicine. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Ball-Burack MR, Kosowsky JM. A Case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:E62-E65. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.10.005

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Pang SM. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: a review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:178-186. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.011

- Calviño MC, Llorca J, García-Porrúa C, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from northwestern Spain: a 20-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:279-290.

- Hu P, Huang BY, Zhang DD, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a pediatric patient with lupus. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:689-690. doi:10.5114/aoms.2017.67288

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.046300

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Casini F, Magenes VC, De Sanctis M, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura following COVID-19 vaccine in a child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:158. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01351-1

- Poudel P, Adams SH, Mirchia K, et al. IgA negative immunofluorescence in diagnoses of adult-onset Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33:436-437. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1770526

- Maronese CA, Zelin E, Avallone G, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis and vasculopathy in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:996288. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.996288

- Bryant MC, Spencer LT, Yalcindag A. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a 16-year-old female following SARS-COV-2 infection and a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20:65. doi:10.1186/s12969-022-00727-1

- Torraca PFS, Castro BC, Hans Filho G. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with c-ANCA antibody in adult. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:667-669. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164181

- Agabegi SS, Agabegi ED. Step-Up to Medicine. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Ball-Burack MR, Kosowsky JM. A Case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:E62-E65. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.10.005

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Pang SM. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: a review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:178-186. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.011

- Calviño MC, Llorca J, García-Porrúa C, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from northwestern Spain: a 20-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:279-290.

- Hu P, Huang BY, Zhang DD, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a pediatric patient with lupus. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:689-690. doi:10.5114/aoms.2017.67288

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be vigilant for Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) despite negative direct immunofluorescence of IgA deposition and unusual antibodies.

- Messenger RNA–based COVID-19 vaccines are associated with various cutaneous reactions, including HSP.

- Anti-Smith and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies typically are not associated with HSP but may be seen in patients with coexisting systemic lupus erythematosus.

Pediatric Studies Produce Mixed Messages on Relationship Between COVID and Asthma

In one of several recently published studies on the relationship between COVID-19 infection and asthma, according to data drawn from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

The inverse correlation between symptoms and vaccination was strong and statistically significant, according to investigators led by Matthew M. Davis, MD, Physician in Chief and Chief Scientific Officer, Nemours Children’s Health, Wilmington, Delaware.

“With each increase of 10 percentage points in COVID-19 vaccination coverage, the parent-reported child asthma symptoms prevalence decreased by 0.36 percentage points (P < .05),” Dr. Davis and his coinvestigators reported in a research letter published in JAMA Network Open.

Studies Explore Relationship of COVID and Asthma

The reduced risk of asthma symptoms with COVID-19 vaccination in children at the population level is just one of several recently published studies exploring the interaction between COVID-19 infection and asthma, but two studies that posed the same question did not reach the same conclusion.

In one, COVID-19 infection in children was not found to be a trigger for new-onset asthma, but the second found that it was. In a third study, the preponderance of evidence from a meta-analysis found that patients with asthma – whether children or adults – did not necessarily experience a more severe course of COVID-19 infection than in those without asthma.

The NSCH database study calculated state-level change in scores for patient-reported childhood asthma symptoms in the years in the years 2018-2019, which preceded the pandemic and the years 2020-2021, when the pandemic began. The hypothesis was that the proportion of the population 5 years of age or older who completed the COVID-19 primary vaccination would be inversely related to asthma symptom prevalence.

Relative to the 2018-2019 years, the mean rate of parent-reported asthma symptoms was 0.85% lower (6.93% vs 7.77%; P < .001) in 2020-2021, when the mean primary series COVID-19 vaccination rate was 72.3%.

The study was not able to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 vaccination specifically in children with asthma, because history of asthma is not captured in the NSCH data, but Dr. Davis contended that the reduction in symptomatic asthma among children with increased vaccination offers validation for the state-level findings.

“Moreover, the absence of an association of COVID-19 vaccination administered predominantly in 2021 with population-level COVID-19 mortality in 2020 serves as a negative control,” he and his colleagues wrote in their research letter.

Protection from Respiratory Viruses Seen for Asthma Patients

In an interview, Dr. Davis reported that these data are consistent with previous evidence that immunization against influenza also reduces risk of asthma symptoms. In a meta-analysis published in 2017, it was estimated that live vaccines reduced risk of influenza by 81% and prevented 59%-72% of asthma attacks leading to hospitalizations or emergency room visits.

“The similarity of our findings regarding COVID-19 vaccination to prior data regarding influenza vaccination underscores the importance of preventing viral illnesses in individuals with a history of asthma,” Dr. Davis said. It is not yet clear if this is true of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Because of the short time that the RSV vaccine has been available, it is too soon to conduct an analysis.

One message from this study is that “clinicians should continue to encourage COVID-19 vaccination for children because of its general benefits in preventing coronavirus-related illness and the apparent specific benefits for children with a history of asthma,” he said.

While vaccination appears to reduce asthmatic symptoms related to COVID-19 infection, one study suggests that COVID-19 does not trigger new-onset asthma. In a retrospective study published in Pediatrics, no association between COVID-19 infection and new-onset asthma could be made in an analysis of 27,423 children (ages, 1-16 years) from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Care Network.

Across all the pediatric age groups evaluated, the consistent finding was “SARS-CoV-2 positivity does not confer an additional risk for asthma diagnosis at least within the first 18 months after a [polymerase chain reaction] test,” concluded the investigators, led by David A. Hill, MD, PhD, Division of Allergy and Immunology, CHOP, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Risk of Asthma Doubled After COVID-19 Infection

However, the opposite conclusion was reached by investigators evaluating data from two cohorts of children ages 5-18 drawn from the TriNetX database, a global health research network with data on more than 250 million individuals. Cohort 1 included more than 250,000 children. These children had never received COVID-19 vaccination. The 50,000 patients in cohort 2 had all received COVID19 vaccination.

To compare the impact of COVID-19 infection on new-onset asthma, the patients who were infected with COVID-19 were compared with those who were not infected after propensity score matching over 18 months of follow-up.

In cohort 1, the rate of new onset asthma was more than twofold greater among those with COVID-19 infection (4.7% vs 2.0%). The hazard ratio (HR) of 2.25 had tight confidence intervals (95% CI, 2.158-2.367).

In cohort 2, the risk of new-onset asthma at 18 months among those who had a COVID-19 infection relative to those without was even greater (8.3% vs 3.1%). The relative risk approached a 3-fold increase (HR 2.745; 95% CI, 2.521-2.99).

The conclusion of these investigators, led by Chia-Chi Lung, PhD, Department of Public Health, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung City, Taiwan, was that there is “a critical need for ongoing monitoring and customized healthcare strategies to mitigate the long-term respiratory impacts of COVID-19 in children.”

These health risks might not be as significant as once feared. In the recently published study from Environmental Health Insights, the goal of a meta-analysis was to determine if patients with asthma relative to those without asthma face a higher risk of serious disease from COVID-19 infection. The meta-analysis included studies of children and adults. The answer, according an in-depth analysis of 21 articles in a “scoping review,” was a qualified no.

Of the 21 articles, 4 concluded that asthma is a risk factor for serious COVID-19 infection, but 17 did not, according to Chukwudi S. Ubah, PhD, Department of Public Health, Brody School of Medicine, East Caroline University, Greenville, North Carolina.

None of These Questions are Fully Resolved

However, given the disparity in the results and the fact that many of the studies included in this analysis had small sample sizes, Dr. Ubah called for larger studies and studies with better controls. He noted, for example, that the studies did not consistently evaluate mitigating factors, such as used of inhaled or oral corticosteroids, which might affect risk of the severity of a COVID-19 infection.

Rather, “our findings pointed out that the type of medication prescribed for asthma may have implications for the severity of COVID-19 infection in these patients,” Dr. Ubah said in an interview.

Overall, the data do not support a major interaction between asthma and COVID-19, even if the data are not conclusive. Each of the senior authors of these studies called for larger and better investigations to further explore whether COVID-19 infection and preexisting asthma interact. So far, the data indicate that if COVID-19 infection poses a risk of precipitating new-onset asthma or inducing a more severe infection in children with asthma, it is low, but the degree of risk, if any, remains unresolved in subgroups defined by asthma treatment or asthma severity.

Dr. Davis, Dr. Hill, Dr. Lung, and Dr. Ubah reported no potential conflicts of interest. None of these studies received funding from commercial interests.

In one of several recently published studies on the relationship between COVID-19 infection and asthma, according to data drawn from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

The inverse correlation between symptoms and vaccination was strong and statistically significant, according to investigators led by Matthew M. Davis, MD, Physician in Chief and Chief Scientific Officer, Nemours Children’s Health, Wilmington, Delaware.

“With each increase of 10 percentage points in COVID-19 vaccination coverage, the parent-reported child asthma symptoms prevalence decreased by 0.36 percentage points (P < .05),” Dr. Davis and his coinvestigators reported in a research letter published in JAMA Network Open.

Studies Explore Relationship of COVID and Asthma

The reduced risk of asthma symptoms with COVID-19 vaccination in children at the population level is just one of several recently published studies exploring the interaction between COVID-19 infection and asthma, but two studies that posed the same question did not reach the same conclusion.

In one, COVID-19 infection in children was not found to be a trigger for new-onset asthma, but the second found that it was. In a third study, the preponderance of evidence from a meta-analysis found that patients with asthma – whether children or adults – did not necessarily experience a more severe course of COVID-19 infection than in those without asthma.

The NSCH database study calculated state-level change in scores for patient-reported childhood asthma symptoms in the years in the years 2018-2019, which preceded the pandemic and the years 2020-2021, when the pandemic began. The hypothesis was that the proportion of the population 5 years of age or older who completed the COVID-19 primary vaccination would be inversely related to asthma symptom prevalence.

Relative to the 2018-2019 years, the mean rate of parent-reported asthma symptoms was 0.85% lower (6.93% vs 7.77%; P < .001) in 2020-2021, when the mean primary series COVID-19 vaccination rate was 72.3%.

The study was not able to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 vaccination specifically in children with asthma, because history of asthma is not captured in the NSCH data, but Dr. Davis contended that the reduction in symptomatic asthma among children with increased vaccination offers validation for the state-level findings.

“Moreover, the absence of an association of COVID-19 vaccination administered predominantly in 2021 with population-level COVID-19 mortality in 2020 serves as a negative control,” he and his colleagues wrote in their research letter.

Protection from Respiratory Viruses Seen for Asthma Patients

In an interview, Dr. Davis reported that these data are consistent with previous evidence that immunization against influenza also reduces risk of asthma symptoms. In a meta-analysis published in 2017, it was estimated that live vaccines reduced risk of influenza by 81% and prevented 59%-72% of asthma attacks leading to hospitalizations or emergency room visits.

“The similarity of our findings regarding COVID-19 vaccination to prior data regarding influenza vaccination underscores the importance of preventing viral illnesses in individuals with a history of asthma,” Dr. Davis said. It is not yet clear if this is true of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Because of the short time that the RSV vaccine has been available, it is too soon to conduct an analysis.

One message from this study is that “clinicians should continue to encourage COVID-19 vaccination for children because of its general benefits in preventing coronavirus-related illness and the apparent specific benefits for children with a history of asthma,” he said.

While vaccination appears to reduce asthmatic symptoms related to COVID-19 infection, one study suggests that COVID-19 does not trigger new-onset asthma. In a retrospective study published in Pediatrics, no association between COVID-19 infection and new-onset asthma could be made in an analysis of 27,423 children (ages, 1-16 years) from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Care Network.

Across all the pediatric age groups evaluated, the consistent finding was “SARS-CoV-2 positivity does not confer an additional risk for asthma diagnosis at least within the first 18 months after a [polymerase chain reaction] test,” concluded the investigators, led by David A. Hill, MD, PhD, Division of Allergy and Immunology, CHOP, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Risk of Asthma Doubled After COVID-19 Infection

However, the opposite conclusion was reached by investigators evaluating data from two cohorts of children ages 5-18 drawn from the TriNetX database, a global health research network with data on more than 250 million individuals. Cohort 1 included more than 250,000 children. These children had never received COVID-19 vaccination. The 50,000 patients in cohort 2 had all received COVID19 vaccination.

To compare the impact of COVID-19 infection on new-onset asthma, the patients who were infected with COVID-19 were compared with those who were not infected after propensity score matching over 18 months of follow-up.

In cohort 1, the rate of new onset asthma was more than twofold greater among those with COVID-19 infection (4.7% vs 2.0%). The hazard ratio (HR) of 2.25 had tight confidence intervals (95% CI, 2.158-2.367).

In cohort 2, the risk of new-onset asthma at 18 months among those who had a COVID-19 infection relative to those without was even greater (8.3% vs 3.1%). The relative risk approached a 3-fold increase (HR 2.745; 95% CI, 2.521-2.99).

The conclusion of these investigators, led by Chia-Chi Lung, PhD, Department of Public Health, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung City, Taiwan, was that there is “a critical need for ongoing monitoring and customized healthcare strategies to mitigate the long-term respiratory impacts of COVID-19 in children.”

These health risks might not be as significant as once feared. In the recently published study from Environmental Health Insights, the goal of a meta-analysis was to determine if patients with asthma relative to those without asthma face a higher risk of serious disease from COVID-19 infection. The meta-analysis included studies of children and adults. The answer, according an in-depth analysis of 21 articles in a “scoping review,” was a qualified no.

Of the 21 articles, 4 concluded that asthma is a risk factor for serious COVID-19 infection, but 17 did not, according to Chukwudi S. Ubah, PhD, Department of Public Health, Brody School of Medicine, East Caroline University, Greenville, North Carolina.

None of These Questions are Fully Resolved

However, given the disparity in the results and the fact that many of the studies included in this analysis had small sample sizes, Dr. Ubah called for larger studies and studies with better controls. He noted, for example, that the studies did not consistently evaluate mitigating factors, such as used of inhaled or oral corticosteroids, which might affect risk of the severity of a COVID-19 infection.

Rather, “our findings pointed out that the type of medication prescribed for asthma may have implications for the severity of COVID-19 infection in these patients,” Dr. Ubah said in an interview.

Overall, the data do not support a major interaction between asthma and COVID-19, even if the data are not conclusive. Each of the senior authors of these studies called for larger and better investigations to further explore whether COVID-19 infection and preexisting asthma interact. So far, the data indicate that if COVID-19 infection poses a risk of precipitating new-onset asthma or inducing a more severe infection in children with asthma, it is low, but the degree of risk, if any, remains unresolved in subgroups defined by asthma treatment or asthma severity.

Dr. Davis, Dr. Hill, Dr. Lung, and Dr. Ubah reported no potential conflicts of interest. None of these studies received funding from commercial interests.

In one of several recently published studies on the relationship between COVID-19 infection and asthma, according to data drawn from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

The inverse correlation between symptoms and vaccination was strong and statistically significant, according to investigators led by Matthew M. Davis, MD, Physician in Chief and Chief Scientific Officer, Nemours Children’s Health, Wilmington, Delaware.

“With each increase of 10 percentage points in COVID-19 vaccination coverage, the parent-reported child asthma symptoms prevalence decreased by 0.36 percentage points (P < .05),” Dr. Davis and his coinvestigators reported in a research letter published in JAMA Network Open.

Studies Explore Relationship of COVID and Asthma

The reduced risk of asthma symptoms with COVID-19 vaccination in children at the population level is just one of several recently published studies exploring the interaction between COVID-19 infection and asthma, but two studies that posed the same question did not reach the same conclusion.

In one, COVID-19 infection in children was not found to be a trigger for new-onset asthma, but the second found that it was. In a third study, the preponderance of evidence from a meta-analysis found that patients with asthma – whether children or adults – did not necessarily experience a more severe course of COVID-19 infection than in those without asthma.

The NSCH database study calculated state-level change in scores for patient-reported childhood asthma symptoms in the years in the years 2018-2019, which preceded the pandemic and the years 2020-2021, when the pandemic began. The hypothesis was that the proportion of the population 5 years of age or older who completed the COVID-19 primary vaccination would be inversely related to asthma symptom prevalence.

Relative to the 2018-2019 years, the mean rate of parent-reported asthma symptoms was 0.85% lower (6.93% vs 7.77%; P < .001) in 2020-2021, when the mean primary series COVID-19 vaccination rate was 72.3%.

The study was not able to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 vaccination specifically in children with asthma, because history of asthma is not captured in the NSCH data, but Dr. Davis contended that the reduction in symptomatic asthma among children with increased vaccination offers validation for the state-level findings.

“Moreover, the absence of an association of COVID-19 vaccination administered predominantly in 2021 with population-level COVID-19 mortality in 2020 serves as a negative control,” he and his colleagues wrote in their research letter.

Protection from Respiratory Viruses Seen for Asthma Patients

In an interview, Dr. Davis reported that these data are consistent with previous evidence that immunization against influenza also reduces risk of asthma symptoms. In a meta-analysis published in 2017, it was estimated that live vaccines reduced risk of influenza by 81% and prevented 59%-72% of asthma attacks leading to hospitalizations or emergency room visits.

“The similarity of our findings regarding COVID-19 vaccination to prior data regarding influenza vaccination underscores the importance of preventing viral illnesses in individuals with a history of asthma,” Dr. Davis said. It is not yet clear if this is true of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Because of the short time that the RSV vaccine has been available, it is too soon to conduct an analysis.

One message from this study is that “clinicians should continue to encourage COVID-19 vaccination for children because of its general benefits in preventing coronavirus-related illness and the apparent specific benefits for children with a history of asthma,” he said.

While vaccination appears to reduce asthmatic symptoms related to COVID-19 infection, one study suggests that COVID-19 does not trigger new-onset asthma. In a retrospective study published in Pediatrics, no association between COVID-19 infection and new-onset asthma could be made in an analysis of 27,423 children (ages, 1-16 years) from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Care Network.

Across all the pediatric age groups evaluated, the consistent finding was “SARS-CoV-2 positivity does not confer an additional risk for asthma diagnosis at least within the first 18 months after a [polymerase chain reaction] test,” concluded the investigators, led by David A. Hill, MD, PhD, Division of Allergy and Immunology, CHOP, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Risk of Asthma Doubled After COVID-19 Infection

However, the opposite conclusion was reached by investigators evaluating data from two cohorts of children ages 5-18 drawn from the TriNetX database, a global health research network with data on more than 250 million individuals. Cohort 1 included more than 250,000 children. These children had never received COVID-19 vaccination. The 50,000 patients in cohort 2 had all received COVID19 vaccination.

To compare the impact of COVID-19 infection on new-onset asthma, the patients who were infected with COVID-19 were compared with those who were not infected after propensity score matching over 18 months of follow-up.

In cohort 1, the rate of new onset asthma was more than twofold greater among those with COVID-19 infection (4.7% vs 2.0%). The hazard ratio (HR) of 2.25 had tight confidence intervals (95% CI, 2.158-2.367).

In cohort 2, the risk of new-onset asthma at 18 months among those who had a COVID-19 infection relative to those without was even greater (8.3% vs 3.1%). The relative risk approached a 3-fold increase (HR 2.745; 95% CI, 2.521-2.99).

The conclusion of these investigators, led by Chia-Chi Lung, PhD, Department of Public Health, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung City, Taiwan, was that there is “a critical need for ongoing monitoring and customized healthcare strategies to mitigate the long-term respiratory impacts of COVID-19 in children.”

These health risks might not be as significant as once feared. In the recently published study from Environmental Health Insights, the goal of a meta-analysis was to determine if patients with asthma relative to those without asthma face a higher risk of serious disease from COVID-19 infection. The meta-analysis included studies of children and adults. The answer, according an in-depth analysis of 21 articles in a “scoping review,” was a qualified no.

Of the 21 articles, 4 concluded that asthma is a risk factor for serious COVID-19 infection, but 17 did not, according to Chukwudi S. Ubah, PhD, Department of Public Health, Brody School of Medicine, East Caroline University, Greenville, North Carolina.

None of These Questions are Fully Resolved

However, given the disparity in the results and the fact that many of the studies included in this analysis had small sample sizes, Dr. Ubah called for larger studies and studies with better controls. He noted, for example, that the studies did not consistently evaluate mitigating factors, such as used of inhaled or oral corticosteroids, which might affect risk of the severity of a COVID-19 infection.

Rather, “our findings pointed out that the type of medication prescribed for asthma may have implications for the severity of COVID-19 infection in these patients,” Dr. Ubah said in an interview.

Overall, the data do not support a major interaction between asthma and COVID-19, even if the data are not conclusive. Each of the senior authors of these studies called for larger and better investigations to further explore whether COVID-19 infection and preexisting asthma interact. So far, the data indicate that if COVID-19 infection poses a risk of precipitating new-onset asthma or inducing a more severe infection in children with asthma, it is low, but the degree of risk, if any, remains unresolved in subgroups defined by asthma treatment or asthma severity.

Dr. Davis, Dr. Hill, Dr. Lung, and Dr. Ubah reported no potential conflicts of interest. None of these studies received funding from commercial interests.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Chronic Absenteeism

Among the more unheralded examples of collateral damage of the COVID epidemic is chronic absenteeism. A recent NPR/Ipsos poll found that parents ranked chronic absenteeism last in a list of 12 school-related concerns. Only 5% listed it first.

This is surprising and concerning, given that In fact, in some states the chronic absenteeism rate is 40%. In 2020 8 million students were chronically absent. This number is now over 14 million. Chronic absenteeism is a metric defined as a student absent for 15 days or more, which comes out to around 10% of the school year. Chronic absenteeism has been used as a predictor of the student dropout rate.

The initial contribution of the pandemic is easily explained, as parents were understandably concerned about sending their children into an environment that might cause disease, or at least bring the disease home to a more vulnerable family member. The reasons behind the trend’s persistence are a bit more complicated.

Family schedules initially disrupted by the pandemic have settled back into a pattern that may make it more difficult for a child to get to school. Day care and work schedules may have changed, but not yet readjusted to sync with the school schedule.

In the simplest terms, children and their families may have simply fallen out of the habit of going to school. For children (and maybe their parents) who had always struggled with an unresolved separation anxiety, the time at home — or at least not in school — came as a relief. Which, in turn, meant that any gains in dealing with the anxiety have been undone. The child who was already struggling academically or socially found being at home much less challenging. It’s not surprising that he/she might resist climbing back in the academic saddle.

It is very likely that a significant contributor to the persistent trend in chronic absenteeism is what social scientists call “norm erosion.” Not just children, but families may have developed an attitude that time spent in school just isn’t as valuable as they once believed, or were at least told that it was. There seems to be more parents questioning what their children are being taught in school. The home schooling movement existed before the pandemic. Its roots may be growing under the surface in the form of general skepticism about the importance of school in the bigger scheme of things. The home schooling movement was ready to blossom when the COVID pandemic triggered school closures. We hoped and dreamed that remote learning would be just as good as in-person school. We now realize that, in most cases, that was wishful thinking.

It feels as though a “Perfect Attendance Record” may have lost the cachet it once had. During the pandemic anyone claiming to have never missed a day at school lost that gold star. Did opening your computer every day to watch a remote learning session count for anything?

The threshold for allowing a child to stay home from school may be reaching a historic low. Families seem to regard the school schedule as a guideline that can easily be ignored when planning a vacation. Take little brother out of school to attend big brother’s lacrosse playoff game, not to worry if the youngster misses school days for a trip.

Who is responsible for reversing the trend? Teachers already know it is a serious problem. They view attendance as important. Maybe educators could make school more appealing. But to whom? Sounds like this message should be targeted at the parents. Would stiff penalties for parents whose children are chronically absent help? Would demanding a note from a physician after a certain number of absences help? It might. But, are pediatricians and educators ready to take on one more task in which parents have dropped the ball?

An unknown percentage of chronically absent children are missing school because of a previously unrecognized or inadequately treated mental health condition or learning disability. Involving physicians in a community’s response to chronic absenteeism may be the first step in getting a child back on track. If socioeconomic factors are contributing to a child’s truancy, the involvement of social service agencies may be the answer.

I have a friend who is often asked to address graduating classes at both the high school and college level. One of his standard pieces of advice, whether it be about school or a workplace you may not be in love with, is to at least “show up.” The family that treats school attendance as optional is likely to produce adults who take a similarly nonchalant attitude toward their employment opportunities — with unfortunate results.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Among the more unheralded examples of collateral damage of the COVID epidemic is chronic absenteeism. A recent NPR/Ipsos poll found that parents ranked chronic absenteeism last in a list of 12 school-related concerns. Only 5% listed it first.

This is surprising and concerning, given that In fact, in some states the chronic absenteeism rate is 40%. In 2020 8 million students were chronically absent. This number is now over 14 million. Chronic absenteeism is a metric defined as a student absent for 15 days or more, which comes out to around 10% of the school year. Chronic absenteeism has been used as a predictor of the student dropout rate.

The initial contribution of the pandemic is easily explained, as parents were understandably concerned about sending their children into an environment that might cause disease, or at least bring the disease home to a more vulnerable family member. The reasons behind the trend’s persistence are a bit more complicated.

Family schedules initially disrupted by the pandemic have settled back into a pattern that may make it more difficult for a child to get to school. Day care and work schedules may have changed, but not yet readjusted to sync with the school schedule.

In the simplest terms, children and their families may have simply fallen out of the habit of going to school. For children (and maybe their parents) who had always struggled with an unresolved separation anxiety, the time at home — or at least not in school — came as a relief. Which, in turn, meant that any gains in dealing with the anxiety have been undone. The child who was already struggling academically or socially found being at home much less challenging. It’s not surprising that he/she might resist climbing back in the academic saddle.

It is very likely that a significant contributor to the persistent trend in chronic absenteeism is what social scientists call “norm erosion.” Not just children, but families may have developed an attitude that time spent in school just isn’t as valuable as they once believed, or were at least told that it was. There seems to be more parents questioning what their children are being taught in school. The home schooling movement existed before the pandemic. Its roots may be growing under the surface in the form of general skepticism about the importance of school in the bigger scheme of things. The home schooling movement was ready to blossom when the COVID pandemic triggered school closures. We hoped and dreamed that remote learning would be just as good as in-person school. We now realize that, in most cases, that was wishful thinking.

It feels as though a “Perfect Attendance Record” may have lost the cachet it once had. During the pandemic anyone claiming to have never missed a day at school lost that gold star. Did opening your computer every day to watch a remote learning session count for anything?

The threshold for allowing a child to stay home from school may be reaching a historic low. Families seem to regard the school schedule as a guideline that can easily be ignored when planning a vacation. Take little brother out of school to attend big brother’s lacrosse playoff game, not to worry if the youngster misses school days for a trip.

Who is responsible for reversing the trend? Teachers already know it is a serious problem. They view attendance as important. Maybe educators could make school more appealing. But to whom? Sounds like this message should be targeted at the parents. Would stiff penalties for parents whose children are chronically absent help? Would demanding a note from a physician after a certain number of absences help? It might. But, are pediatricians and educators ready to take on one more task in which parents have dropped the ball?

An unknown percentage of chronically absent children are missing school because of a previously unrecognized or inadequately treated mental health condition or learning disability. Involving physicians in a community’s response to chronic absenteeism may be the first step in getting a child back on track. If socioeconomic factors are contributing to a child’s truancy, the involvement of social service agencies may be the answer.

I have a friend who is often asked to address graduating classes at both the high school and college level. One of his standard pieces of advice, whether it be about school or a workplace you may not be in love with, is to at least “show up.” The family that treats school attendance as optional is likely to produce adults who take a similarly nonchalant attitude toward their employment opportunities — with unfortunate results.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Among the more unheralded examples of collateral damage of the COVID epidemic is chronic absenteeism. A recent NPR/Ipsos poll found that parents ranked chronic absenteeism last in a list of 12 school-related concerns. Only 5% listed it first.