User login

FDA authorizes Pfizer’s COVID booster for kids ages 5 to 11

emergency use authorization (EUA), allowing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 booster shot for children ages 5 to 11 who are at least 5 months out from their first vaccine series.

According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28.6% of children in this age group have received both initial doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and 35.3% have received their first dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine trial involving 4,500 children showed few side effects among children younger than 12 who received a booster, or third dose, according to a company statement.

Pfizer asked the FDA for an amended authorization in April, after submitting data showing that a third dose in children between 5 and 11 raised antibodies targeting the Omicron variant by 36 times.

“While it has largely been the case that COVID-19 tends to be less severe in children than adults, the omicron wave has seen more kids getting sick with the disease and being hospitalized, and children may also experience longer-term effects, even following initially mild disease,” FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, said in a news release.

A study done by the New York State Department of Health showed the effectiveness of Pfizer’s two-dose vaccine series fell from 68% to 12% 4-5 months after the second dose was given to children 5 to 11 during the Omicron surge. A CDC study published in March also showed that the Pfizer shot reduced the risk of Omicron by 31% in children 5 to 11, a significantly lower rate than for kids 12 to 15, who had a 59% risk reduction after receiving two doses.

To some experts, this data suggest an even greater need for children under 12 to be eligible for a third dose.

“Since authorizing the vaccine for children down to 5 years of age in October 2021, emerging data suggest that vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 wanes after the second dose of the vaccine in all authorized populations,” says Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The CDC still needs to sign off on the shots before they can be allowed. The agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is set to meet on May 19 to discuss boosters in this age group.

FDA advisory panels plan to meet next month to discuss allowing Pfizer’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines for children under 6 years old.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

emergency use authorization (EUA), allowing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 booster shot for children ages 5 to 11 who are at least 5 months out from their first vaccine series.

According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28.6% of children in this age group have received both initial doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and 35.3% have received their first dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine trial involving 4,500 children showed few side effects among children younger than 12 who received a booster, or third dose, according to a company statement.

Pfizer asked the FDA for an amended authorization in April, after submitting data showing that a third dose in children between 5 and 11 raised antibodies targeting the Omicron variant by 36 times.

“While it has largely been the case that COVID-19 tends to be less severe in children than adults, the omicron wave has seen more kids getting sick with the disease and being hospitalized, and children may also experience longer-term effects, even following initially mild disease,” FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, said in a news release.

A study done by the New York State Department of Health showed the effectiveness of Pfizer’s two-dose vaccine series fell from 68% to 12% 4-5 months after the second dose was given to children 5 to 11 during the Omicron surge. A CDC study published in March also showed that the Pfizer shot reduced the risk of Omicron by 31% in children 5 to 11, a significantly lower rate than for kids 12 to 15, who had a 59% risk reduction after receiving two doses.

To some experts, this data suggest an even greater need for children under 12 to be eligible for a third dose.

“Since authorizing the vaccine for children down to 5 years of age in October 2021, emerging data suggest that vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 wanes after the second dose of the vaccine in all authorized populations,” says Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The CDC still needs to sign off on the shots before they can be allowed. The agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is set to meet on May 19 to discuss boosters in this age group.

FDA advisory panels plan to meet next month to discuss allowing Pfizer’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines for children under 6 years old.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

emergency use authorization (EUA), allowing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 booster shot for children ages 5 to 11 who are at least 5 months out from their first vaccine series.

According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28.6% of children in this age group have received both initial doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and 35.3% have received their first dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine trial involving 4,500 children showed few side effects among children younger than 12 who received a booster, or third dose, according to a company statement.

Pfizer asked the FDA for an amended authorization in April, after submitting data showing that a third dose in children between 5 and 11 raised antibodies targeting the Omicron variant by 36 times.

“While it has largely been the case that COVID-19 tends to be less severe in children than adults, the omicron wave has seen more kids getting sick with the disease and being hospitalized, and children may also experience longer-term effects, even following initially mild disease,” FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, said in a news release.

A study done by the New York State Department of Health showed the effectiveness of Pfizer’s two-dose vaccine series fell from 68% to 12% 4-5 months after the second dose was given to children 5 to 11 during the Omicron surge. A CDC study published in March also showed that the Pfizer shot reduced the risk of Omicron by 31% in children 5 to 11, a significantly lower rate than for kids 12 to 15, who had a 59% risk reduction after receiving two doses.

To some experts, this data suggest an even greater need for children under 12 to be eligible for a third dose.

“Since authorizing the vaccine for children down to 5 years of age in October 2021, emerging data suggest that vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 wanes after the second dose of the vaccine in all authorized populations,” says Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The CDC still needs to sign off on the shots before they can be allowed. The agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is set to meet on May 19 to discuss boosters in this age group.

FDA advisory panels plan to meet next month to discuss allowing Pfizer’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines for children under 6 years old.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: New cases up by 50%

The latest increase in new child COVID-19 cases seems to be picking up steam, rising by 50% in the last week, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 50% week-to-week change follows increases of 17%, 44%, 12%, and 28% since the nationwide weekly total fell to its low point for the year (25,915) in the beginning of April, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Regionally, the distribution of those 93,000 COVID cases was fairly even. The Northeast, which saw the biggest jump for the week, and the Midwest were both around 25,000 new cases, while the South had about 20,000 and the West was lowest with 18,000 or so. At the state/territory level, the largest percent increases over the last 2 weeks were found in Maine and Puerto Rico, with Massachusetts and Vermont just a step behind, the AAP/CHA data show.

In cumulative terms, there have been over 13.1 million cases of COVID-19 among children in the United States, with pediatric cases representing 19.0% of all cases since the pandemic began, the two organizations reported. They also noted a number of important limitations: New York state has never reported cases by age, several states have stopped updating their online dashboards, and states apply a variety of age ranges to define children (Alabama has the smallest range, 0-14 years; South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia the largest, 0-20).

By comparison, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put the total number of cases in children aged 0-17 at 12.7 million, although that figure is based on a cumulative number of 73.4 million cases among all ages, which is well short of the reported total of almost 82.4 million as of May 16. COVID cases in children have led to 1,536 deaths so far, the CDC said.

The recent upward trend in new cases also can be seen in the CDC’s data, which show the weekly rate rising from 35 per 100,000 population on March 26 to 102 per 100,000 on May 7 in children aged 0-14 years, with commensurate increases seen among older children over the same period. In turn, the rate of new admissions for children aged 0-17 has gone from a low of 0.13 per 100,000 as late as April 10 up to 0.23 on May 13, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

One thing not going up these days is vaccinations among the youngest eligible children. The number of 5- to 11-year-olds receiving their initial dose was down to 40,000 for the week of May 5-11, the fewest since the vaccine was approved for that age group. For a change of pace, the number increased among children aged 12-17, as 37,000 got initial vaccinations that week, compared with 29,000 a week earlier, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report.

The latest increase in new child COVID-19 cases seems to be picking up steam, rising by 50% in the last week, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 50% week-to-week change follows increases of 17%, 44%, 12%, and 28% since the nationwide weekly total fell to its low point for the year (25,915) in the beginning of April, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Regionally, the distribution of those 93,000 COVID cases was fairly even. The Northeast, which saw the biggest jump for the week, and the Midwest were both around 25,000 new cases, while the South had about 20,000 and the West was lowest with 18,000 or so. At the state/territory level, the largest percent increases over the last 2 weeks were found in Maine and Puerto Rico, with Massachusetts and Vermont just a step behind, the AAP/CHA data show.

In cumulative terms, there have been over 13.1 million cases of COVID-19 among children in the United States, with pediatric cases representing 19.0% of all cases since the pandemic began, the two organizations reported. They also noted a number of important limitations: New York state has never reported cases by age, several states have stopped updating their online dashboards, and states apply a variety of age ranges to define children (Alabama has the smallest range, 0-14 years; South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia the largest, 0-20).

By comparison, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put the total number of cases in children aged 0-17 at 12.7 million, although that figure is based on a cumulative number of 73.4 million cases among all ages, which is well short of the reported total of almost 82.4 million as of May 16. COVID cases in children have led to 1,536 deaths so far, the CDC said.

The recent upward trend in new cases also can be seen in the CDC’s data, which show the weekly rate rising from 35 per 100,000 population on March 26 to 102 per 100,000 on May 7 in children aged 0-14 years, with commensurate increases seen among older children over the same period. In turn, the rate of new admissions for children aged 0-17 has gone from a low of 0.13 per 100,000 as late as April 10 up to 0.23 on May 13, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

One thing not going up these days is vaccinations among the youngest eligible children. The number of 5- to 11-year-olds receiving their initial dose was down to 40,000 for the week of May 5-11, the fewest since the vaccine was approved for that age group. For a change of pace, the number increased among children aged 12-17, as 37,000 got initial vaccinations that week, compared with 29,000 a week earlier, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report.

The latest increase in new child COVID-19 cases seems to be picking up steam, rising by 50% in the last week, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 50% week-to-week change follows increases of 17%, 44%, 12%, and 28% since the nationwide weekly total fell to its low point for the year (25,915) in the beginning of April, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Regionally, the distribution of those 93,000 COVID cases was fairly even. The Northeast, which saw the biggest jump for the week, and the Midwest were both around 25,000 new cases, while the South had about 20,000 and the West was lowest with 18,000 or so. At the state/territory level, the largest percent increases over the last 2 weeks were found in Maine and Puerto Rico, with Massachusetts and Vermont just a step behind, the AAP/CHA data show.

In cumulative terms, there have been over 13.1 million cases of COVID-19 among children in the United States, with pediatric cases representing 19.0% of all cases since the pandemic began, the two organizations reported. They also noted a number of important limitations: New York state has never reported cases by age, several states have stopped updating their online dashboards, and states apply a variety of age ranges to define children (Alabama has the smallest range, 0-14 years; South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia the largest, 0-20).

By comparison, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put the total number of cases in children aged 0-17 at 12.7 million, although that figure is based on a cumulative number of 73.4 million cases among all ages, which is well short of the reported total of almost 82.4 million as of May 16. COVID cases in children have led to 1,536 deaths so far, the CDC said.

The recent upward trend in new cases also can be seen in the CDC’s data, which show the weekly rate rising from 35 per 100,000 population on March 26 to 102 per 100,000 on May 7 in children aged 0-14 years, with commensurate increases seen among older children over the same period. In turn, the rate of new admissions for children aged 0-17 has gone from a low of 0.13 per 100,000 as late as April 10 up to 0.23 on May 13, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

One thing not going up these days is vaccinations among the youngest eligible children. The number of 5- to 11-year-olds receiving their initial dose was down to 40,000 for the week of May 5-11, the fewest since the vaccine was approved for that age group. For a change of pace, the number increased among children aged 12-17, as 37,000 got initial vaccinations that week, compared with 29,000 a week earlier, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report.

Pfizer COVID vaccine performs well in youth with rheumatic diseases

The Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty) showed a good safety profile with minimal short-term side effects and no negative impact on disease activity in a cohort of adolescents and young adults with rheumatic diseases, according to research presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance, held virtually this year.

Only 3% of patients experience a severe transient adverse event, according to Merav Heshin-Bekenstein, MD, of Dana-Dwek Children’s Hospital at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel. The findings were published in Rheumatology.

“We found that the mRNA Pfizer vaccine was immunogenic and induced an adequate humoral immune response in adolescent patients,” Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told CARRA attendees. “It was definitely comparable to healthy controls and practically all patients were seropositive following the second vaccine, except for one patient with long-standing systemic sclerosis.”

The findings were not necessarily surprising but were encouraging to Melissa S. Oliver, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of pediatric rheumatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Dr. Oliver wasn’t part of the study team.

“We know that the COVID vaccines in healthy adolescents have shown good efficacy with minimal side effects, and it’s good to see that this study showed that in those with rheumatic diseases on immunosuppressive therapy,” Dr. Oliver told this news organization.

Until now, the data on COVID-19 vaccines in teens with rheumatic illnesses has been limited, she said, so “many pediatric rheumatologists only have the data from adult studies to go on or personal experience with their own cohort of patients.”

But the high immunogenicity seen in the study was a pleasant surprise to Beth H. Rutstein, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I was both surprised and thrilled with Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein’s findings suggesting near-universal seroconversion for patients with rheumatic disease regardless of underlying diagnosis or immunomodulatory therapy regimen, as much of the adult data has suggested a poorer seroconversion rate” and lower antibody titers in adults with similar illnesses, Dr. Rutstein said in an interview.

The study “provides essential reassurance that vaccination against COVID-19 does not increase the risk of disease flare or worsen disease severity scores,” said Dr. Rutstein, who was not associated with the research. “Rather than speaking purely anecdotally with our patients and their families, we can refer to the science – which is always more reassuring for both our patients and ourselves.”

Study included diverse conditions and therapies

Risk factors for poor outcomes with COVID-19 in children include obesity, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and asthma, Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told CARRA attendees. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and long COVID are also potential complications of COVID-19 with less understood risk factors.

Although COVID-19 is most often mild in children, certain severe, systemic rheumatic diseases increase hospitalization risk, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and vasculitis. Evidence has also shown that COVID-19 infection increases the risk of disease flare in teens with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases, so it’s “crucial to prevent COVID-19 disease in this population,” Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein said.

Her study therefore aimed to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine for teens with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases and those taking immunomodulatory medications. The international prospective multicenter study ran from April to November 2021 at three pediatric rheumatology clinics in Israel and one in Slovenia. Endpoints included short-term side effects, vaccination impact on clinical disease activity, immunogenicity at 2-9 weeks after the second dose, and, secondarily, efficacy against COVID-19 infection.

The 91 participants included adolescents aged 12-18 and young adults aged 18-21. Nearly half of the participants (46%) had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), and 14% had SLE. Other participants’ conditions included systemic vasculitis, idiopathic uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease–related arthritis, systemic or localized scleroderma, juvenile dermatomyositis, or an autoinflammatory disease. Participants’ mean disease duration was 4.8 years.

The researchers compared the patients with a control group of 40 individuals with similar demographics but without rheumatic disease. The researchers used the LIAISON quantitative assay to assess serum IgG antibody levels against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in both groups.

Eight in 10 participants with rheumatic disease were taking an immunomodulatory medication, including a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) in 40%, a biologic DMARD in 37%, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in 32%, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in 19%, glucocorticoids in 14%, and mycophenolate in 11%. A smaller proportion were on other biologics: JAK inhibitors in 6.6%, anti-CD20 drugs in 4.4%, and an IL-6 inhibitor in 1%.

Side effects similar in both groups

None of the side effects reported by participants were statistically different between those with rheumatic disease and the control group. Localized pain was the most common side effect, reported by 73%-79% of participants after each dose. About twice as many participants with rheumatic disease experienced muscle aches and joint pains, compared with the control group, but the differences were not significant. Fever occurred more often in those with rheumatic disease (6%, five cases) than without (3%, one case). One-third of those with rheumatic disease felt tiredness, compared with 20% of the control group.

None of the healthy controls were hospitalized after vaccination, but three rheumatic patients were, including two after the first dose. Both were 17 years old, had systemic vasculitis with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and were taking rituximab (Rituxan). One patient experienced acute onset of chronic renal failure, fever, dehydration, and high C-reactive protein within hours of vaccination. The other experienced new onset of pulmonary hemorrhage a week after vaccination.

In addition, a 14-year-old female with lupus, taking only HCQ, went to the emergency department with fever, headache, vomiting, and joint pain 1 day after the second vaccine dose. She had normal inflammatory markers and no change in disease activity score, and she was discharged with low-dose steroids tapered after 2 weeks.

Immune response high in patients with rheumatic disease

Immunogenicity was similar in both groups, with 97% seropositivity in the rheumatic disease group and 100% in the control group. Average IgG titers were 242 in the rheumatic group and 388 in the control group (P < .0001). Seropositivity was 88% in those taking mycophenolate with another drug (100% with mycophenolate monotherapy), 90% with HCQ, 94% with any csDMARDs and another drug (100% with csDMARD monotherapy), and 100% for all other drugs. During 3 months’ follow-up after vaccination, there were no COVID-19 cases among the participants.

Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein noted that their results showed better immunogenicity in teens, compared with adults, for two specific drugs. Seropositivity in teens taking methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall) or rituximab was 100% in this study, compared with 84% in adults taking methotrexate and 39% in adults taking rituximab in a previous study. However, only three patients in this study were taking rituximab, and only seven were taking methotrexate.

The study’s heterogenous population was both a strength and a weakness of the study. “Due to the diversity of rheumatic diseases and medications included in this cohort, it was not possible to draw significant conclusions regarding the impact of the immunomodulatory medications and type of disease” on titers, Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told attendees.

Still, “I think as pediatric rheumatologists, we can feel reassured in recommending the COVID-19 vaccine to our patients,” Dr. Oliver said. “I will add that every patient is different, and everyone should have a conversation with their physician about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.” Dr. Oliver said she discusses vaccination, including COVID vaccination, with every patient, and it’s been challenging to address concerns in the midst of so much misinformation circulating about the vaccine.

These findings do raise questions about whether it’s still necessary to hold immunomodulatory medications to get the vaccine,” Dr. Rutstein said.

“Many families are nervous to pause their medications before and after the vaccine as is currently recommended for many therapies by the American College of Rheumatology, and I do share that concern for some of my patients with more clinically unstable disease, so I try to work with each family to decide on best timing and have delayed or deferred the series until some patients are on a steady dose of a new immunomodulatory medication if it has been recently started,” Dr. Rutstein said. “This is one of the reasons why Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein’s study is so important – we may be holding medications that can be safely continued and even further decrease the risk of disease flare.”

None of the physicians have disclosed any relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty) showed a good safety profile with minimal short-term side effects and no negative impact on disease activity in a cohort of adolescents and young adults with rheumatic diseases, according to research presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance, held virtually this year.

Only 3% of patients experience a severe transient adverse event, according to Merav Heshin-Bekenstein, MD, of Dana-Dwek Children’s Hospital at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel. The findings were published in Rheumatology.

“We found that the mRNA Pfizer vaccine was immunogenic and induced an adequate humoral immune response in adolescent patients,” Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told CARRA attendees. “It was definitely comparable to healthy controls and practically all patients were seropositive following the second vaccine, except for one patient with long-standing systemic sclerosis.”

The findings were not necessarily surprising but were encouraging to Melissa S. Oliver, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of pediatric rheumatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Dr. Oliver wasn’t part of the study team.

“We know that the COVID vaccines in healthy adolescents have shown good efficacy with minimal side effects, and it’s good to see that this study showed that in those with rheumatic diseases on immunosuppressive therapy,” Dr. Oliver told this news organization.

Until now, the data on COVID-19 vaccines in teens with rheumatic illnesses has been limited, she said, so “many pediatric rheumatologists only have the data from adult studies to go on or personal experience with their own cohort of patients.”

But the high immunogenicity seen in the study was a pleasant surprise to Beth H. Rutstein, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I was both surprised and thrilled with Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein’s findings suggesting near-universal seroconversion for patients with rheumatic disease regardless of underlying diagnosis or immunomodulatory therapy regimen, as much of the adult data has suggested a poorer seroconversion rate” and lower antibody titers in adults with similar illnesses, Dr. Rutstein said in an interview.

The study “provides essential reassurance that vaccination against COVID-19 does not increase the risk of disease flare or worsen disease severity scores,” said Dr. Rutstein, who was not associated with the research. “Rather than speaking purely anecdotally with our patients and their families, we can refer to the science – which is always more reassuring for both our patients and ourselves.”

Study included diverse conditions and therapies

Risk factors for poor outcomes with COVID-19 in children include obesity, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and asthma, Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told CARRA attendees. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and long COVID are also potential complications of COVID-19 with less understood risk factors.

Although COVID-19 is most often mild in children, certain severe, systemic rheumatic diseases increase hospitalization risk, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and vasculitis. Evidence has also shown that COVID-19 infection increases the risk of disease flare in teens with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases, so it’s “crucial to prevent COVID-19 disease in this population,” Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein said.

Her study therefore aimed to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine for teens with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases and those taking immunomodulatory medications. The international prospective multicenter study ran from April to November 2021 at three pediatric rheumatology clinics in Israel and one in Slovenia. Endpoints included short-term side effects, vaccination impact on clinical disease activity, immunogenicity at 2-9 weeks after the second dose, and, secondarily, efficacy against COVID-19 infection.

The 91 participants included adolescents aged 12-18 and young adults aged 18-21. Nearly half of the participants (46%) had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), and 14% had SLE. Other participants’ conditions included systemic vasculitis, idiopathic uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease–related arthritis, systemic or localized scleroderma, juvenile dermatomyositis, or an autoinflammatory disease. Participants’ mean disease duration was 4.8 years.

The researchers compared the patients with a control group of 40 individuals with similar demographics but without rheumatic disease. The researchers used the LIAISON quantitative assay to assess serum IgG antibody levels against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in both groups.

Eight in 10 participants with rheumatic disease were taking an immunomodulatory medication, including a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) in 40%, a biologic DMARD in 37%, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in 32%, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in 19%, glucocorticoids in 14%, and mycophenolate in 11%. A smaller proportion were on other biologics: JAK inhibitors in 6.6%, anti-CD20 drugs in 4.4%, and an IL-6 inhibitor in 1%.

Side effects similar in both groups

None of the side effects reported by participants were statistically different between those with rheumatic disease and the control group. Localized pain was the most common side effect, reported by 73%-79% of participants after each dose. About twice as many participants with rheumatic disease experienced muscle aches and joint pains, compared with the control group, but the differences were not significant. Fever occurred more often in those with rheumatic disease (6%, five cases) than without (3%, one case). One-third of those with rheumatic disease felt tiredness, compared with 20% of the control group.

None of the healthy controls were hospitalized after vaccination, but three rheumatic patients were, including two after the first dose. Both were 17 years old, had systemic vasculitis with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and were taking rituximab (Rituxan). One patient experienced acute onset of chronic renal failure, fever, dehydration, and high C-reactive protein within hours of vaccination. The other experienced new onset of pulmonary hemorrhage a week after vaccination.

In addition, a 14-year-old female with lupus, taking only HCQ, went to the emergency department with fever, headache, vomiting, and joint pain 1 day after the second vaccine dose. She had normal inflammatory markers and no change in disease activity score, and she was discharged with low-dose steroids tapered after 2 weeks.

Immune response high in patients with rheumatic disease

Immunogenicity was similar in both groups, with 97% seropositivity in the rheumatic disease group and 100% in the control group. Average IgG titers were 242 in the rheumatic group and 388 in the control group (P < .0001). Seropositivity was 88% in those taking mycophenolate with another drug (100% with mycophenolate monotherapy), 90% with HCQ, 94% with any csDMARDs and another drug (100% with csDMARD monotherapy), and 100% for all other drugs. During 3 months’ follow-up after vaccination, there were no COVID-19 cases among the participants.

Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein noted that their results showed better immunogenicity in teens, compared with adults, for two specific drugs. Seropositivity in teens taking methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall) or rituximab was 100% in this study, compared with 84% in adults taking methotrexate and 39% in adults taking rituximab in a previous study. However, only three patients in this study were taking rituximab, and only seven were taking methotrexate.

The study’s heterogenous population was both a strength and a weakness of the study. “Due to the diversity of rheumatic diseases and medications included in this cohort, it was not possible to draw significant conclusions regarding the impact of the immunomodulatory medications and type of disease” on titers, Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told attendees.

Still, “I think as pediatric rheumatologists, we can feel reassured in recommending the COVID-19 vaccine to our patients,” Dr. Oliver said. “I will add that every patient is different, and everyone should have a conversation with their physician about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.” Dr. Oliver said she discusses vaccination, including COVID vaccination, with every patient, and it’s been challenging to address concerns in the midst of so much misinformation circulating about the vaccine.

These findings do raise questions about whether it’s still necessary to hold immunomodulatory medications to get the vaccine,” Dr. Rutstein said.

“Many families are nervous to pause their medications before and after the vaccine as is currently recommended for many therapies by the American College of Rheumatology, and I do share that concern for some of my patients with more clinically unstable disease, so I try to work with each family to decide on best timing and have delayed or deferred the series until some patients are on a steady dose of a new immunomodulatory medication if it has been recently started,” Dr. Rutstein said. “This is one of the reasons why Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein’s study is so important – we may be holding medications that can be safely continued and even further decrease the risk of disease flare.”

None of the physicians have disclosed any relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty) showed a good safety profile with minimal short-term side effects and no negative impact on disease activity in a cohort of adolescents and young adults with rheumatic diseases, according to research presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance, held virtually this year.

Only 3% of patients experience a severe transient adverse event, according to Merav Heshin-Bekenstein, MD, of Dana-Dwek Children’s Hospital at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel. The findings were published in Rheumatology.

“We found that the mRNA Pfizer vaccine was immunogenic and induced an adequate humoral immune response in adolescent patients,” Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told CARRA attendees. “It was definitely comparable to healthy controls and practically all patients were seropositive following the second vaccine, except for one patient with long-standing systemic sclerosis.”

The findings were not necessarily surprising but were encouraging to Melissa S. Oliver, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of pediatric rheumatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Dr. Oliver wasn’t part of the study team.

“We know that the COVID vaccines in healthy adolescents have shown good efficacy with minimal side effects, and it’s good to see that this study showed that in those with rheumatic diseases on immunosuppressive therapy,” Dr. Oliver told this news organization.

Until now, the data on COVID-19 vaccines in teens with rheumatic illnesses has been limited, she said, so “many pediatric rheumatologists only have the data from adult studies to go on or personal experience with their own cohort of patients.”

But the high immunogenicity seen in the study was a pleasant surprise to Beth H. Rutstein, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I was both surprised and thrilled with Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein’s findings suggesting near-universal seroconversion for patients with rheumatic disease regardless of underlying diagnosis or immunomodulatory therapy regimen, as much of the adult data has suggested a poorer seroconversion rate” and lower antibody titers in adults with similar illnesses, Dr. Rutstein said in an interview.

The study “provides essential reassurance that vaccination against COVID-19 does not increase the risk of disease flare or worsen disease severity scores,” said Dr. Rutstein, who was not associated with the research. “Rather than speaking purely anecdotally with our patients and their families, we can refer to the science – which is always more reassuring for both our patients and ourselves.”

Study included diverse conditions and therapies

Risk factors for poor outcomes with COVID-19 in children include obesity, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and asthma, Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told CARRA attendees. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and long COVID are also potential complications of COVID-19 with less understood risk factors.

Although COVID-19 is most often mild in children, certain severe, systemic rheumatic diseases increase hospitalization risk, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and vasculitis. Evidence has also shown that COVID-19 infection increases the risk of disease flare in teens with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases, so it’s “crucial to prevent COVID-19 disease in this population,” Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein said.

Her study therefore aimed to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine for teens with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases and those taking immunomodulatory medications. The international prospective multicenter study ran from April to November 2021 at three pediatric rheumatology clinics in Israel and one in Slovenia. Endpoints included short-term side effects, vaccination impact on clinical disease activity, immunogenicity at 2-9 weeks after the second dose, and, secondarily, efficacy against COVID-19 infection.

The 91 participants included adolescents aged 12-18 and young adults aged 18-21. Nearly half of the participants (46%) had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), and 14% had SLE. Other participants’ conditions included systemic vasculitis, idiopathic uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease–related arthritis, systemic or localized scleroderma, juvenile dermatomyositis, or an autoinflammatory disease. Participants’ mean disease duration was 4.8 years.

The researchers compared the patients with a control group of 40 individuals with similar demographics but without rheumatic disease. The researchers used the LIAISON quantitative assay to assess serum IgG antibody levels against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in both groups.

Eight in 10 participants with rheumatic disease were taking an immunomodulatory medication, including a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) in 40%, a biologic DMARD in 37%, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in 32%, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in 19%, glucocorticoids in 14%, and mycophenolate in 11%. A smaller proportion were on other biologics: JAK inhibitors in 6.6%, anti-CD20 drugs in 4.4%, and an IL-6 inhibitor in 1%.

Side effects similar in both groups

None of the side effects reported by participants were statistically different between those with rheumatic disease and the control group. Localized pain was the most common side effect, reported by 73%-79% of participants after each dose. About twice as many participants with rheumatic disease experienced muscle aches and joint pains, compared with the control group, but the differences were not significant. Fever occurred more often in those with rheumatic disease (6%, five cases) than without (3%, one case). One-third of those with rheumatic disease felt tiredness, compared with 20% of the control group.

None of the healthy controls were hospitalized after vaccination, but three rheumatic patients were, including two after the first dose. Both were 17 years old, had systemic vasculitis with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and were taking rituximab (Rituxan). One patient experienced acute onset of chronic renal failure, fever, dehydration, and high C-reactive protein within hours of vaccination. The other experienced new onset of pulmonary hemorrhage a week after vaccination.

In addition, a 14-year-old female with lupus, taking only HCQ, went to the emergency department with fever, headache, vomiting, and joint pain 1 day after the second vaccine dose. She had normal inflammatory markers and no change in disease activity score, and she was discharged with low-dose steroids tapered after 2 weeks.

Immune response high in patients with rheumatic disease

Immunogenicity was similar in both groups, with 97% seropositivity in the rheumatic disease group and 100% in the control group. Average IgG titers were 242 in the rheumatic group and 388 in the control group (P < .0001). Seropositivity was 88% in those taking mycophenolate with another drug (100% with mycophenolate monotherapy), 90% with HCQ, 94% with any csDMARDs and another drug (100% with csDMARD monotherapy), and 100% for all other drugs. During 3 months’ follow-up after vaccination, there were no COVID-19 cases among the participants.

Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein noted that their results showed better immunogenicity in teens, compared with adults, for two specific drugs. Seropositivity in teens taking methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall) or rituximab was 100% in this study, compared with 84% in adults taking methotrexate and 39% in adults taking rituximab in a previous study. However, only three patients in this study were taking rituximab, and only seven were taking methotrexate.

The study’s heterogenous population was both a strength and a weakness of the study. “Due to the diversity of rheumatic diseases and medications included in this cohort, it was not possible to draw significant conclusions regarding the impact of the immunomodulatory medications and type of disease” on titers, Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein told attendees.

Still, “I think as pediatric rheumatologists, we can feel reassured in recommending the COVID-19 vaccine to our patients,” Dr. Oliver said. “I will add that every patient is different, and everyone should have a conversation with their physician about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.” Dr. Oliver said she discusses vaccination, including COVID vaccination, with every patient, and it’s been challenging to address concerns in the midst of so much misinformation circulating about the vaccine.

These findings do raise questions about whether it’s still necessary to hold immunomodulatory medications to get the vaccine,” Dr. Rutstein said.

“Many families are nervous to pause their medications before and after the vaccine as is currently recommended for many therapies by the American College of Rheumatology, and I do share that concern for some of my patients with more clinically unstable disease, so I try to work with each family to decide on best timing and have delayed or deferred the series until some patients are on a steady dose of a new immunomodulatory medication if it has been recently started,” Dr. Rutstein said. “This is one of the reasons why Dr. Heshin-Bekenstein’s study is so important – we may be holding medications that can be safely continued and even further decrease the risk of disease flare.”

None of the physicians have disclosed any relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CARRA 2022

Neuropsychiatric risks of COVID-19: New data

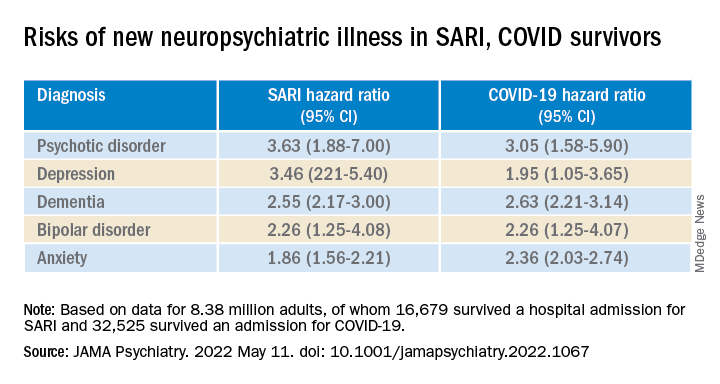

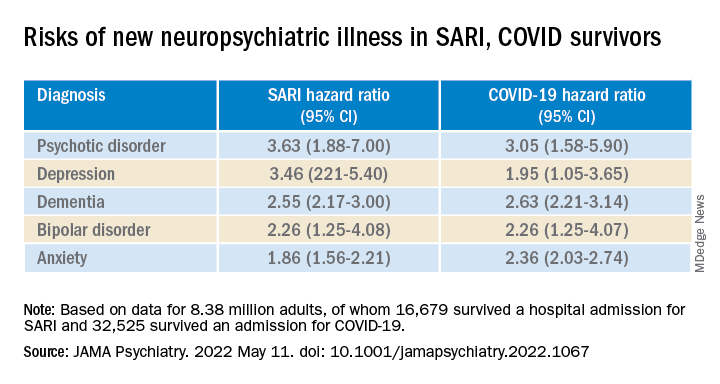

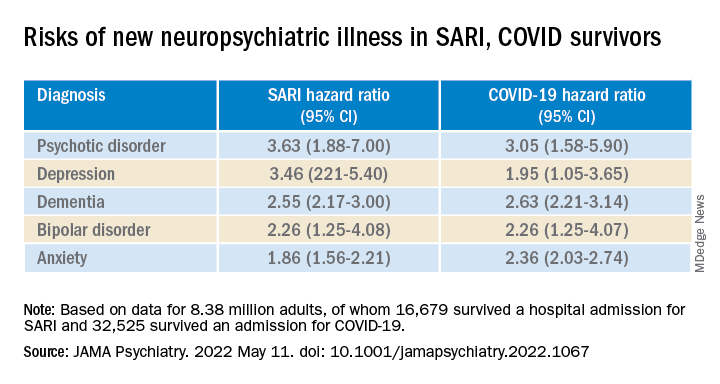

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Shielding’ status provides best indicator of COVID-19 mortality in U.K. arthritis population

Being identified as someone that was advised to stay at home and shield, or keep away from face-to-face interactions with others, during the COVID-19 pandemic was indicative of an increased risk for dying from COVID-19 within 28 days of infection, a U.K. study of inflammatory arthritis patients versus the general population suggests.

In fact, shielding status was the highest ranked of all the risk factors identified for early mortality from COVID-19, with a hazard ratio of 1.52 (95% confidence interval, 1.40-1.64) comparing people with and without inflammatory arthritis (IA) who had tested positive.

The list of risk factors associated with higher mortality in the IA patients versus the general population also included diabetes (HR, 1.38), smoking (HR, 1.27), hypertension (HR, 1.19), glucocorticoid use (HR, 1.17), and cancer (HR, 1.10), as well as increasing age (HR, 1.08) and body mass index (HR, 1.01).

Also important was the person’s prior hospitalization history, with those needing in-hospital care in the year running up to their admission for COVID-19 associated with a 34% higher risk for death, and being hospitalized previously with a serious infection was associated with a 20% higher risk.

This has more to do people’s overall vulnerability than their IA, suggested the team behind the findings, who also found that the risk of catching COVID-19 was significantly lower among patients with IA than the general population (3.5% vs. 6%), presumably because of shielding.

Examining the risks for COVID-19 in real-life practice

“COVID-19 has caused over 10 million deaths,” Roxanne Cooksey, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology. “It’s greatly affected vulnerable individuals, which includes individuals with IA, this is due to their compromised immune system and increased risk of infection and the medications that they take to manage their conditions.

“Previous studies have had mixed results about whether people with IA have an increased risk of poor outcome,” added Dr. Cooksey, who is a postdoctoral researcher in the division of infection and immunity at Cardiff (Wales) University.

“So, our research question looks to investigate inflammatory arthritis – that’s rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis – to see whether the conditions themselves or indeed their medications predispose individuals to an increased risk of contracting COVID or even more adverse outcomes.”

Dr. Cooksey and colleagues looked specifically at COVID-19 infection rates and outcomes in adults living in Wales during the first year of the pandemic (March 2020 to May 2021). As such they used routinely collected, anonymized health data from the SAIL Databank and performed a retrospective, population-based cohort study. In total, there were 1,966 people with inflammatory arthritis identified as having COVID-19 and 166,602 people without IA but who had COVID-19 in the study population.

As might be expected, people with inflammatory arthritis who tested positive for COVID-19 were older than those testing positive in the general population, at a mean of 62 years versus 46 years. They were also more likely to have been advised to shield (49.4% versus 4.6%), which in the United Kingdom constituted of receiving a letter telling them about the importance of social distancing, wearing a mask when out in public, and quarantining themselves at home whenever possible.

The main outcomes were hospitalizations and mortality within 28 days of COVID-19 infection. Considering the overall inflammatory arthritis population, rates of both outcomes were higher versus the general population. And when the researchers analyzed the risks according to the type of inflammatory arthritis, the associations were not statistically significant in a multivariable analysis for people with any of the inflammatory arthritis diagnoses: rheumatoid arthritis (n = 1,283), psoriatic arthritis (n = 514), or ankylosing spondylitis (n = 246). Some patients had more than one inflammatory arthritis diagnosis.

What does this all mean?

Dr. Cooksey conceded that there were lots of limitations to the data collected – from misclassification bias to data possibly not have been recorded completely or missing because of the disruption to health care services during the early stages of the pandemic. Patients may have been told to shield but not actually shielded, she observed, and maybe because a lack of testing COVID-19 cases were missed or people could have been asymptomatic or unable to be tested.

“The study supports the role of shielding in inflammatory arthritis,” Dr. Cooksey said, particularly in those with RA and the risk factors associated with an increased risk in death. However, that may not mean the entire population, she suggested, saying that “refining the criteria for shielding will help mitigate the negative effects of the entire IA population.”

Senior team member Ernest Choy, MD, added his thoughts, saying that, rather than giving generic shielding recommendations to all IA patients, not everyone has the same risk, so maybe not everyone needs to shield to the same level.

“Psoriatic arthritis patients and ankylosing spondylitis patients are younger, so they really don’t have as high a risk like patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” he said.

Dr. Choy, who is professor of rheumatology at the Cardiff Institute of Infection & Immunity, commented that it was not surprising to find that a prior serious infection was a risk for COVID-19 mortality. This risk factor was examined because of the known association between biologic use and the risk for serious infection.

Moreover, he said that, “if you have a serious comorbidity that requires you to get admitted to hospital, that is a reflection of your vulnerability.”

Dr. Cooksey and Dr. Choy had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Being identified as someone that was advised to stay at home and shield, or keep away from face-to-face interactions with others, during the COVID-19 pandemic was indicative of an increased risk for dying from COVID-19 within 28 days of infection, a U.K. study of inflammatory arthritis patients versus the general population suggests.

In fact, shielding status was the highest ranked of all the risk factors identified for early mortality from COVID-19, with a hazard ratio of 1.52 (95% confidence interval, 1.40-1.64) comparing people with and without inflammatory arthritis (IA) who had tested positive.

The list of risk factors associated with higher mortality in the IA patients versus the general population also included diabetes (HR, 1.38), smoking (HR, 1.27), hypertension (HR, 1.19), glucocorticoid use (HR, 1.17), and cancer (HR, 1.10), as well as increasing age (HR, 1.08) and body mass index (HR, 1.01).

Also important was the person’s prior hospitalization history, with those needing in-hospital care in the year running up to their admission for COVID-19 associated with a 34% higher risk for death, and being hospitalized previously with a serious infection was associated with a 20% higher risk.

This has more to do people’s overall vulnerability than their IA, suggested the team behind the findings, who also found that the risk of catching COVID-19 was significantly lower among patients with IA than the general population (3.5% vs. 6%), presumably because of shielding.

Examining the risks for COVID-19 in real-life practice

“COVID-19 has caused over 10 million deaths,” Roxanne Cooksey, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology. “It’s greatly affected vulnerable individuals, which includes individuals with IA, this is due to their compromised immune system and increased risk of infection and the medications that they take to manage their conditions.

“Previous studies have had mixed results about whether people with IA have an increased risk of poor outcome,” added Dr. Cooksey, who is a postdoctoral researcher in the division of infection and immunity at Cardiff (Wales) University.

“So, our research question looks to investigate inflammatory arthritis – that’s rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis – to see whether the conditions themselves or indeed their medications predispose individuals to an increased risk of contracting COVID or even more adverse outcomes.”

Dr. Cooksey and colleagues looked specifically at COVID-19 infection rates and outcomes in adults living in Wales during the first year of the pandemic (March 2020 to May 2021). As such they used routinely collected, anonymized health data from the SAIL Databank and performed a retrospective, population-based cohort study. In total, there were 1,966 people with inflammatory arthritis identified as having COVID-19 and 166,602 people without IA but who had COVID-19 in the study population.

As might be expected, people with inflammatory arthritis who tested positive for COVID-19 were older than those testing positive in the general population, at a mean of 62 years versus 46 years. They were also more likely to have been advised to shield (49.4% versus 4.6%), which in the United Kingdom constituted of receiving a letter telling them about the importance of social distancing, wearing a mask when out in public, and quarantining themselves at home whenever possible.

The main outcomes were hospitalizations and mortality within 28 days of COVID-19 infection. Considering the overall inflammatory arthritis population, rates of both outcomes were higher versus the general population. And when the researchers analyzed the risks according to the type of inflammatory arthritis, the associations were not statistically significant in a multivariable analysis for people with any of the inflammatory arthritis diagnoses: rheumatoid arthritis (n = 1,283), psoriatic arthritis (n = 514), or ankylosing spondylitis (n = 246). Some patients had more than one inflammatory arthritis diagnosis.

What does this all mean?

Dr. Cooksey conceded that there were lots of limitations to the data collected – from misclassification bias to data possibly not have been recorded completely or missing because of the disruption to health care services during the early stages of the pandemic. Patients may have been told to shield but not actually shielded, she observed, and maybe because a lack of testing COVID-19 cases were missed or people could have been asymptomatic or unable to be tested.

“The study supports the role of shielding in inflammatory arthritis,” Dr. Cooksey said, particularly in those with RA and the risk factors associated with an increased risk in death. However, that may not mean the entire population, she suggested, saying that “refining the criteria for shielding will help mitigate the negative effects of the entire IA population.”

Senior team member Ernest Choy, MD, added his thoughts, saying that, rather than giving generic shielding recommendations to all IA patients, not everyone has the same risk, so maybe not everyone needs to shield to the same level.

“Psoriatic arthritis patients and ankylosing spondylitis patients are younger, so they really don’t have as high a risk like patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” he said.

Dr. Choy, who is professor of rheumatology at the Cardiff Institute of Infection & Immunity, commented that it was not surprising to find that a prior serious infection was a risk for COVID-19 mortality. This risk factor was examined because of the known association between biologic use and the risk for serious infection.

Moreover, he said that, “if you have a serious comorbidity that requires you to get admitted to hospital, that is a reflection of your vulnerability.”

Dr. Cooksey and Dr. Choy had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Being identified as someone that was advised to stay at home and shield, or keep away from face-to-face interactions with others, during the COVID-19 pandemic was indicative of an increased risk for dying from COVID-19 within 28 days of infection, a U.K. study of inflammatory arthritis patients versus the general population suggests.

In fact, shielding status was the highest ranked of all the risk factors identified for early mortality from COVID-19, with a hazard ratio of 1.52 (95% confidence interval, 1.40-1.64) comparing people with and without inflammatory arthritis (IA) who had tested positive.

The list of risk factors associated with higher mortality in the IA patients versus the general population also included diabetes (HR, 1.38), smoking (HR, 1.27), hypertension (HR, 1.19), glucocorticoid use (HR, 1.17), and cancer (HR, 1.10), as well as increasing age (HR, 1.08) and body mass index (HR, 1.01).

Also important was the person’s prior hospitalization history, with those needing in-hospital care in the year running up to their admission for COVID-19 associated with a 34% higher risk for death, and being hospitalized previously with a serious infection was associated with a 20% higher risk.

This has more to do people’s overall vulnerability than their IA, suggested the team behind the findings, who also found that the risk of catching COVID-19 was significantly lower among patients with IA than the general population (3.5% vs. 6%), presumably because of shielding.

Examining the risks for COVID-19 in real-life practice

“COVID-19 has caused over 10 million deaths,” Roxanne Cooksey, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology. “It’s greatly affected vulnerable individuals, which includes individuals with IA, this is due to their compromised immune system and increased risk of infection and the medications that they take to manage their conditions.

“Previous studies have had mixed results about whether people with IA have an increased risk of poor outcome,” added Dr. Cooksey, who is a postdoctoral researcher in the division of infection and immunity at Cardiff (Wales) University.

“So, our research question looks to investigate inflammatory arthritis – that’s rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis – to see whether the conditions themselves or indeed their medications predispose individuals to an increased risk of contracting COVID or even more adverse outcomes.”

Dr. Cooksey and colleagues looked specifically at COVID-19 infection rates and outcomes in adults living in Wales during the first year of the pandemic (March 2020 to May 2021). As such they used routinely collected, anonymized health data from the SAIL Databank and performed a retrospective, population-based cohort study. In total, there were 1,966 people with inflammatory arthritis identified as having COVID-19 and 166,602 people without IA but who had COVID-19 in the study population.

As might be expected, people with inflammatory arthritis who tested positive for COVID-19 were older than those testing positive in the general population, at a mean of 62 years versus 46 years. They were also more likely to have been advised to shield (49.4% versus 4.6%), which in the United Kingdom constituted of receiving a letter telling them about the importance of social distancing, wearing a mask when out in public, and quarantining themselves at home whenever possible.

The main outcomes were hospitalizations and mortality within 28 days of COVID-19 infection. Considering the overall inflammatory arthritis population, rates of both outcomes were higher versus the general population. And when the researchers analyzed the risks according to the type of inflammatory arthritis, the associations were not statistically significant in a multivariable analysis for people with any of the inflammatory arthritis diagnoses: rheumatoid arthritis (n = 1,283), psoriatic arthritis (n = 514), or ankylosing spondylitis (n = 246). Some patients had more than one inflammatory arthritis diagnosis.

What does this all mean?

Dr. Cooksey conceded that there were lots of limitations to the data collected – from misclassification bias to data possibly not have been recorded completely or missing because of the disruption to health care services during the early stages of the pandemic. Patients may have been told to shield but not actually shielded, she observed, and maybe because a lack of testing COVID-19 cases were missed or people could have been asymptomatic or unable to be tested.

“The study supports the role of shielding in inflammatory arthritis,” Dr. Cooksey said, particularly in those with RA and the risk factors associated with an increased risk in death. However, that may not mean the entire population, she suggested, saying that “refining the criteria for shielding will help mitigate the negative effects of the entire IA population.”

Senior team member Ernest Choy, MD, added his thoughts, saying that, rather than giving generic shielding recommendations to all IA patients, not everyone has the same risk, so maybe not everyone needs to shield to the same level.

“Psoriatic arthritis patients and ankylosing spondylitis patients are younger, so they really don’t have as high a risk like patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” he said.

Dr. Choy, who is professor of rheumatology at the Cardiff Institute of Infection & Immunity, commented that it was not surprising to find that a prior serious infection was a risk for COVID-19 mortality. This risk factor was examined because of the known association between biologic use and the risk for serious infection.

Moreover, he said that, “if you have a serious comorbidity that requires you to get admitted to hospital, that is a reflection of your vulnerability.”

Dr. Cooksey and Dr. Choy had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM BSR 2022

Most COVID-19 survivors return to work within 2 years

The burden of persistent COVID-19 symptoms appeared to improve over time, but a higher percentage of former patients reported poor health, compared with the general population. This suggests that some patients need more time to completely recover from COVID-19, wrote the authors of the new study, which was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Previous research has shown that the health effects of COVID-19 last for up to a year, but data from longer-term studies are limited, said Lixue Huang, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, one of the study authors, and colleagues.

Methods and results

In the new study, the researchers reviewed data from 1,192 adult patients who were discharged from the hospital after surviving COVID-19 between Jan. 7, 2020, and May 29, 2020. The researchers measured the participants’ health outcomes at 6 months, 12 months, and 2 years after their onset of symptoms. A community-based dataset of 3,383 adults with no history of COVID-19 served as controls to measure the recovery of the COVID-19 patients. The median age of the patients at the time of hospital discharge was 57 years, and 46% were women. The median follow-up time after the onset of symptoms was 185 days, 349 days, and 685 days for the 6-month, 12-month, and 2-year visits, respectively. The researchers measured health outcomes using a 6-min walking distance (6MWD) test, laboratory tests, and questionnaires about symptoms, mental health, health-related quality of life, returning to work, and health care use since leaving the hospital.