User login

Fatal pediatric melanomas diverse in presentation

results of a retrospective multicenter study showed.

“The most striking thing that we learned from this study is that pediatric melanoma can present in so many different ways, and it’s distinct from the adult population in that we see more presentations associated with congenital nevi, or spitz melanoma, which is a special class of pigmented lesions that looks a little different under the microscope,” Elena B. Hawryluk, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard University, Boston, said in an interview. Dr. Hawryluk is lead author of the study, which was published online ahead of print in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Hawryluk and colleagues at MGH and 11 other centers conducted a retrospective review of all cases of fatal pediatric melanoma among patients younger than 20 years diagnosed from late 1994 through early 2017.

They identified a total of 38 fatal cases over more than 2 decades. The cases were distinguished primarily by their heterogeneous clinical presentation and by the diversity of the patients, their precursor lesions, and the tumor histopathology, she said in an interview.

“We were surprised to find that patients with each of these presentations could end up with a fatal course, it wasn’t just all the adolescents, or all the patients with giant congenital nevi; it really presented quite diversely.”

Rare malignancy

Melanoma is far less common in the pediatric population than in adults, with an annual incidence of 18 per 1 million among adolescents aged 15-18 years, and 1 per 1 million in children under 10 years, the authors noted.

“Melanoma in children and adolescents often has distinct clinical presentations such as association with a congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), spitzoid melanoma, or amelanotic melanoma, which are more rarely observed in adult melanoma patients. Unique pediatric-specific clinical detection criteria have been proposed to highlight these differences, such as a tendency to present amelanotically,” they wrote.

Factors associated with worse prognosis, such as higher Breslow thickness and mitotic index, are more frequently present at the time of diagnosis in children compared with adults, particularly those diagnosed before age 11 years.

“It is unclear if this difference is secondary to diagnostic delays due to low clinical suspicion, atypical clinical presentations, or more rapid tumor growth rate, as many childhood melanomas are of nodular or spitzoid subtypes,” Dr. Hawryluk and her coauthors wrote.

Study details

The investigators sought to characterize the clinical and histopathologic features of fatal pediatric melanomas.

They found that 21 of the 38 patients (57%) were of White heritage, 7 (19%) were of Hispanic or Latino background, 1 (3%) was of Asian lineage, and 1 each were of Black African American or Black Hispanic background. The remaining children were classified as “other” or did not have their ethnic backgrounds recorded.

The “striking prevalence” of Hispanic patients observed in the study is consistent with surveillance reports of an increasing incidence of melanoma among children of Hispanic background, they noted.

The mean age at diagnosis was 12.7 years, and the mean age at death was 15.6 years.

Of the 16 cases with known identifiable disease subtypes, 8 (50%) were nodular, 5 (31%) were superficial spreading, and 3 (19%) were spitzoid melanomas. Of the 38 fatal melanomas, 10 were thought to have originated from congenital melanocytic nevi.

Outlook improving

Recent therapeutic breakthroughs such as targeted agents and immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors augur well for children diagnosed with melanoma, Dr. Hawryluk said.

“Fortunately, it’s not superaggressive in children at high frequency, so we generally use adult algorithms to inform treatment decisions,” she said. “It’s just important to note that melanomas that arise in congenital nevi tend to have different driver mutations than those that arise in older patients who may have lots of sun exposure.”

“Nowadays, we’re lucky to have a lot of extra tests and workups so that, if a patient does have metastatic or advance disease, they can have a better genetic profile that would guide our choice of medications,” she added.

The study was supported by a Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Study Support grant and Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Pilot award. Dr. Hawryluk is supported by the Dermatology Foundation and the Harvard Medical School Eleanor and Miles Shore Fellowship award. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hawryluk EB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1010.

results of a retrospective multicenter study showed.

“The most striking thing that we learned from this study is that pediatric melanoma can present in so many different ways, and it’s distinct from the adult population in that we see more presentations associated with congenital nevi, or spitz melanoma, which is a special class of pigmented lesions that looks a little different under the microscope,” Elena B. Hawryluk, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard University, Boston, said in an interview. Dr. Hawryluk is lead author of the study, which was published online ahead of print in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Hawryluk and colleagues at MGH and 11 other centers conducted a retrospective review of all cases of fatal pediatric melanoma among patients younger than 20 years diagnosed from late 1994 through early 2017.

They identified a total of 38 fatal cases over more than 2 decades. The cases were distinguished primarily by their heterogeneous clinical presentation and by the diversity of the patients, their precursor lesions, and the tumor histopathology, she said in an interview.

“We were surprised to find that patients with each of these presentations could end up with a fatal course, it wasn’t just all the adolescents, or all the patients with giant congenital nevi; it really presented quite diversely.”

Rare malignancy

Melanoma is far less common in the pediatric population than in adults, with an annual incidence of 18 per 1 million among adolescents aged 15-18 years, and 1 per 1 million in children under 10 years, the authors noted.

“Melanoma in children and adolescents often has distinct clinical presentations such as association with a congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), spitzoid melanoma, or amelanotic melanoma, which are more rarely observed in adult melanoma patients. Unique pediatric-specific clinical detection criteria have been proposed to highlight these differences, such as a tendency to present amelanotically,” they wrote.

Factors associated with worse prognosis, such as higher Breslow thickness and mitotic index, are more frequently present at the time of diagnosis in children compared with adults, particularly those diagnosed before age 11 years.

“It is unclear if this difference is secondary to diagnostic delays due to low clinical suspicion, atypical clinical presentations, or more rapid tumor growth rate, as many childhood melanomas are of nodular or spitzoid subtypes,” Dr. Hawryluk and her coauthors wrote.

Study details

The investigators sought to characterize the clinical and histopathologic features of fatal pediatric melanomas.

They found that 21 of the 38 patients (57%) were of White heritage, 7 (19%) were of Hispanic or Latino background, 1 (3%) was of Asian lineage, and 1 each were of Black African American or Black Hispanic background. The remaining children were classified as “other” or did not have their ethnic backgrounds recorded.

The “striking prevalence” of Hispanic patients observed in the study is consistent with surveillance reports of an increasing incidence of melanoma among children of Hispanic background, they noted.

The mean age at diagnosis was 12.7 years, and the mean age at death was 15.6 years.

Of the 16 cases with known identifiable disease subtypes, 8 (50%) were nodular, 5 (31%) were superficial spreading, and 3 (19%) were spitzoid melanomas. Of the 38 fatal melanomas, 10 were thought to have originated from congenital melanocytic nevi.

Outlook improving

Recent therapeutic breakthroughs such as targeted agents and immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors augur well for children diagnosed with melanoma, Dr. Hawryluk said.

“Fortunately, it’s not superaggressive in children at high frequency, so we generally use adult algorithms to inform treatment decisions,” she said. “It’s just important to note that melanomas that arise in congenital nevi tend to have different driver mutations than those that arise in older patients who may have lots of sun exposure.”

“Nowadays, we’re lucky to have a lot of extra tests and workups so that, if a patient does have metastatic or advance disease, they can have a better genetic profile that would guide our choice of medications,” she added.

The study was supported by a Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Study Support grant and Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Pilot award. Dr. Hawryluk is supported by the Dermatology Foundation and the Harvard Medical School Eleanor and Miles Shore Fellowship award. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hawryluk EB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1010.

results of a retrospective multicenter study showed.

“The most striking thing that we learned from this study is that pediatric melanoma can present in so many different ways, and it’s distinct from the adult population in that we see more presentations associated with congenital nevi, or spitz melanoma, which is a special class of pigmented lesions that looks a little different under the microscope,” Elena B. Hawryluk, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard University, Boston, said in an interview. Dr. Hawryluk is lead author of the study, which was published online ahead of print in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Hawryluk and colleagues at MGH and 11 other centers conducted a retrospective review of all cases of fatal pediatric melanoma among patients younger than 20 years diagnosed from late 1994 through early 2017.

They identified a total of 38 fatal cases over more than 2 decades. The cases were distinguished primarily by their heterogeneous clinical presentation and by the diversity of the patients, their precursor lesions, and the tumor histopathology, she said in an interview.

“We were surprised to find that patients with each of these presentations could end up with a fatal course, it wasn’t just all the adolescents, or all the patients with giant congenital nevi; it really presented quite diversely.”

Rare malignancy

Melanoma is far less common in the pediatric population than in adults, with an annual incidence of 18 per 1 million among adolescents aged 15-18 years, and 1 per 1 million in children under 10 years, the authors noted.

“Melanoma in children and adolescents often has distinct clinical presentations such as association with a congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), spitzoid melanoma, or amelanotic melanoma, which are more rarely observed in adult melanoma patients. Unique pediatric-specific clinical detection criteria have been proposed to highlight these differences, such as a tendency to present amelanotically,” they wrote.

Factors associated with worse prognosis, such as higher Breslow thickness and mitotic index, are more frequently present at the time of diagnosis in children compared with adults, particularly those diagnosed before age 11 years.

“It is unclear if this difference is secondary to diagnostic delays due to low clinical suspicion, atypical clinical presentations, or more rapid tumor growth rate, as many childhood melanomas are of nodular or spitzoid subtypes,” Dr. Hawryluk and her coauthors wrote.

Study details

The investigators sought to characterize the clinical and histopathologic features of fatal pediatric melanomas.

They found that 21 of the 38 patients (57%) were of White heritage, 7 (19%) were of Hispanic or Latino background, 1 (3%) was of Asian lineage, and 1 each were of Black African American or Black Hispanic background. The remaining children were classified as “other” or did not have their ethnic backgrounds recorded.

The “striking prevalence” of Hispanic patients observed in the study is consistent with surveillance reports of an increasing incidence of melanoma among children of Hispanic background, they noted.

The mean age at diagnosis was 12.7 years, and the mean age at death was 15.6 years.

Of the 16 cases with known identifiable disease subtypes, 8 (50%) were nodular, 5 (31%) were superficial spreading, and 3 (19%) were spitzoid melanomas. Of the 38 fatal melanomas, 10 were thought to have originated from congenital melanocytic nevi.

Outlook improving

Recent therapeutic breakthroughs such as targeted agents and immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors augur well for children diagnosed with melanoma, Dr. Hawryluk said.

“Fortunately, it’s not superaggressive in children at high frequency, so we generally use adult algorithms to inform treatment decisions,” she said. “It’s just important to note that melanomas that arise in congenital nevi tend to have different driver mutations than those that arise in older patients who may have lots of sun exposure.”

“Nowadays, we’re lucky to have a lot of extra tests and workups so that, if a patient does have metastatic or advance disease, they can have a better genetic profile that would guide our choice of medications,” she added.

The study was supported by a Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Study Support grant and Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Pilot award. Dr. Hawryluk is supported by the Dermatology Foundation and the Harvard Medical School Eleanor and Miles Shore Fellowship award. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hawryluk EB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1010.

FROM JAAD

Psoriasis, PsA, and pregnancy: Tailoring treatment with increasing data

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)

Many topical agents can be used during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said. Topical corticosteroids, she noted, have the most safety-affirming data of any topical medication.

Regarding oral therapies, Dr. Murase recommends against the use of apremilast (Otezla) for her patients. “It’s not contraindicated, but the animal studies don’t look promising, so I don’t use that one in women of childbearing age just in case. There’s just very little data to support the safety of this medication [in pregnancy].”

There are no therapeutic guidelines in the United States for guiding the management of psoriasis in women who are considering pregnancy. In 2012, the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation published a review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women, the “closest thing to guidelines that we’ve had,” said Dr. Murase. (Now almost a decade old, the review addresses TNF inhibitors but does not cover the anti-interleukin agents more recently approved for moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA.)

For treating PsA, rheumatologists now have the American College of Rheumatology’s first guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to reference. The 2020 guideline does not address PsA specifically, but its section on pregnancy and lactation includes recommendations on biologic and other therapies used to treat the disease.

Guidelines aside, physician-patient discussions over drug safety have the potential to be much more meaningful now that drug labels offer clinical summaries, data, and risk summaries regarding potential use in pregnancy. The labels have “more of a narrative, which is a more useful way to counsel patients and make risk-benefit decisions” than the former system of five-letter categories, said Dr. Murase. (The changes were made per the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule of 2015.)

MothertoBaby, a service of the nonprofit Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, also provides good evidence-based information to physicians and mothers, Dr. Sammaritano noted.

The use of biologic therapies

In a 2017 review of biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston; Martina L. Porter, MD, currently with the department of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston; and Stephen J. Lockwood, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, concluded that an increasing body of literature suggests that biologic agents can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Anti-TNF agents “should be considered over IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors due to the increased availability of long-term data,” they wrote.

“In general,” said Dr. Murase, “there’s more and more data coming out from gastroenterology and rheumatology to reassure patients and prescribing physicians that the TNF-blocker class is likely safe to use in pregnancy,” particularly during the first trimester and early second trimester, when the transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta is “essentially nonexistent.” In the third trimester, the active transport of IgG antibodies increases rapidly.

If possible, said Dr. Sammaritano, who served as lead author of the ACR’s reproductive health guideline, TNF inhibitors “will be stopped prior to the third trimester to avoid [the possibility of] high drug levels in the infant at birth, which raises concern for immunosuppression in the newborn. If disease is very active, however, they can be continued throughout the pregnancy.”

The TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) has the advantage of being transported only minimally across the placenta, if at all, she and Dr. Murase both explained. “To be actively carried across, antibodies need what’s called an Fc region for the placenta to grab onto,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab – a pegylated anti–binding fragment antibody – lacks this Fc region.

Two recent studies – CRIB and a UCB Pharma safety database analysis – showed “essentially no medication crossing – there were barely detectable levels,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab’s label contains this information and other clinical trial data as well as findings from safety database analyses/surveillance registries.

“Before we had much data for the biologics, I’d advise transitioning patients to light therapy from their biologics and a lot of times their psoriasis would improve, but it was more of a dance,” she said. “Now we tend to look at [certolizumab] when they’re of childbearing age and keep them on the treatment. I know that the baby is not being immunosuppressed.”

Consideration of the use of certolizumab when treatment with biologic agents is required throughout the pregnancy is a recommendation included in Dr. Kimball’s 2017 review.

As newer anti-interleukin agents – the IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors – play a growing role in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA, questions loom about their safety profile. Dr. Murase and Dr. Sammaritano are waiting for more data. “In general,” Dr. Sammaritano said, “we recommend stopping them at the time pregnancy is detected, based on a lack of data at this time.”

Small-molecule drugs are also less well studied, she noted. “Because of their low molecular weight, we anticipate they will easily cross the placenta, so we recommend avoiding use during pregnancy until more information is available.”

Postpartum care

The good news, both experts say, is that the vast majority of medications, including biologics, are safe to use during breastfeeding. Methotrexate should be avoided, Dr. Sammaritano pointed out, and the impact of novel small-molecule therapies on breast milk has not been studied.

In her 2019 review of psoriasis in women, Dr. Murase and coauthors wrote that too many dermatologists believe that breastfeeding women should either not be on biologics or are uncertain about biologic use during breastfeeding. However, “biologics are considered compatible for use while breastfeeding due to their large molecular size and the proteolytic environment in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract,” they added.

Counseling and support for breastfeeding is especially important for women with psoriasis, Dr. Murase emphasized. “Breastfeeding is very traumatizing to the skin, and psoriasis can form in skin that’s injured. I have my patients set up an office visit very soon after the pregnancy to make sure they’re doing alright with their breastfeeding and that they’re coating their nipple area with some type of moisturizer and keeping the health of their nipples in good shape.”

Timely reviews of therapy and adjustments are also a priority, she said. “We need to prepare for 6 weeks post partum” when psoriasis will often flare without treatment.

Dr. Murase disclosed that she is a consultant for Dermira, UCB Pharma, Sanofi, Ferndale, and Regeneron. She is also coeditor in chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Dr. Sammaritano reported that she has no disclosures relating to the treatment of PsA.

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)

Many topical agents can be used during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said. Topical corticosteroids, she noted, have the most safety-affirming data of any topical medication.

Regarding oral therapies, Dr. Murase recommends against the use of apremilast (Otezla) for her patients. “It’s not contraindicated, but the animal studies don’t look promising, so I don’t use that one in women of childbearing age just in case. There’s just very little data to support the safety of this medication [in pregnancy].”

There are no therapeutic guidelines in the United States for guiding the management of psoriasis in women who are considering pregnancy. In 2012, the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation published a review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women, the “closest thing to guidelines that we’ve had,” said Dr. Murase. (Now almost a decade old, the review addresses TNF inhibitors but does not cover the anti-interleukin agents more recently approved for moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA.)

For treating PsA, rheumatologists now have the American College of Rheumatology’s first guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to reference. The 2020 guideline does not address PsA specifically, but its section on pregnancy and lactation includes recommendations on biologic and other therapies used to treat the disease.

Guidelines aside, physician-patient discussions over drug safety have the potential to be much more meaningful now that drug labels offer clinical summaries, data, and risk summaries regarding potential use in pregnancy. The labels have “more of a narrative, which is a more useful way to counsel patients and make risk-benefit decisions” than the former system of five-letter categories, said Dr. Murase. (The changes were made per the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule of 2015.)

MothertoBaby, a service of the nonprofit Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, also provides good evidence-based information to physicians and mothers, Dr. Sammaritano noted.

The use of biologic therapies

In a 2017 review of biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston; Martina L. Porter, MD, currently with the department of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston; and Stephen J. Lockwood, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, concluded that an increasing body of literature suggests that biologic agents can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Anti-TNF agents “should be considered over IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors due to the increased availability of long-term data,” they wrote.

“In general,” said Dr. Murase, “there’s more and more data coming out from gastroenterology and rheumatology to reassure patients and prescribing physicians that the TNF-blocker class is likely safe to use in pregnancy,” particularly during the first trimester and early second trimester, when the transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta is “essentially nonexistent.” In the third trimester, the active transport of IgG antibodies increases rapidly.

If possible, said Dr. Sammaritano, who served as lead author of the ACR’s reproductive health guideline, TNF inhibitors “will be stopped prior to the third trimester to avoid [the possibility of] high drug levels in the infant at birth, which raises concern for immunosuppression in the newborn. If disease is very active, however, they can be continued throughout the pregnancy.”

The TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) has the advantage of being transported only minimally across the placenta, if at all, she and Dr. Murase both explained. “To be actively carried across, antibodies need what’s called an Fc region for the placenta to grab onto,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab – a pegylated anti–binding fragment antibody – lacks this Fc region.

Two recent studies – CRIB and a UCB Pharma safety database analysis – showed “essentially no medication crossing – there were barely detectable levels,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab’s label contains this information and other clinical trial data as well as findings from safety database analyses/surveillance registries.

“Before we had much data for the biologics, I’d advise transitioning patients to light therapy from their biologics and a lot of times their psoriasis would improve, but it was more of a dance,” she said. “Now we tend to look at [certolizumab] when they’re of childbearing age and keep them on the treatment. I know that the baby is not being immunosuppressed.”

Consideration of the use of certolizumab when treatment with biologic agents is required throughout the pregnancy is a recommendation included in Dr. Kimball’s 2017 review.

As newer anti-interleukin agents – the IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors – play a growing role in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA, questions loom about their safety profile. Dr. Murase and Dr. Sammaritano are waiting for more data. “In general,” Dr. Sammaritano said, “we recommend stopping them at the time pregnancy is detected, based on a lack of data at this time.”

Small-molecule drugs are also less well studied, she noted. “Because of their low molecular weight, we anticipate they will easily cross the placenta, so we recommend avoiding use during pregnancy until more information is available.”

Postpartum care

The good news, both experts say, is that the vast majority of medications, including biologics, are safe to use during breastfeeding. Methotrexate should be avoided, Dr. Sammaritano pointed out, and the impact of novel small-molecule therapies on breast milk has not been studied.

In her 2019 review of psoriasis in women, Dr. Murase and coauthors wrote that too many dermatologists believe that breastfeeding women should either not be on biologics or are uncertain about biologic use during breastfeeding. However, “biologics are considered compatible for use while breastfeeding due to their large molecular size and the proteolytic environment in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract,” they added.

Counseling and support for breastfeeding is especially important for women with psoriasis, Dr. Murase emphasized. “Breastfeeding is very traumatizing to the skin, and psoriasis can form in skin that’s injured. I have my patients set up an office visit very soon after the pregnancy to make sure they’re doing alright with their breastfeeding and that they’re coating their nipple area with some type of moisturizer and keeping the health of their nipples in good shape.”

Timely reviews of therapy and adjustments are also a priority, she said. “We need to prepare for 6 weeks post partum” when psoriasis will often flare without treatment.

Dr. Murase disclosed that she is a consultant for Dermira, UCB Pharma, Sanofi, Ferndale, and Regeneron. She is also coeditor in chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Dr. Sammaritano reported that she has no disclosures relating to the treatment of PsA.

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)

Many topical agents can be used during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said. Topical corticosteroids, she noted, have the most safety-affirming data of any topical medication.

Regarding oral therapies, Dr. Murase recommends against the use of apremilast (Otezla) for her patients. “It’s not contraindicated, but the animal studies don’t look promising, so I don’t use that one in women of childbearing age just in case. There’s just very little data to support the safety of this medication [in pregnancy].”

There are no therapeutic guidelines in the United States for guiding the management of psoriasis in women who are considering pregnancy. In 2012, the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation published a review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women, the “closest thing to guidelines that we’ve had,” said Dr. Murase. (Now almost a decade old, the review addresses TNF inhibitors but does not cover the anti-interleukin agents more recently approved for moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA.)

For treating PsA, rheumatologists now have the American College of Rheumatology’s first guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to reference. The 2020 guideline does not address PsA specifically, but its section on pregnancy and lactation includes recommendations on biologic and other therapies used to treat the disease.

Guidelines aside, physician-patient discussions over drug safety have the potential to be much more meaningful now that drug labels offer clinical summaries, data, and risk summaries regarding potential use in pregnancy. The labels have “more of a narrative, which is a more useful way to counsel patients and make risk-benefit decisions” than the former system of five-letter categories, said Dr. Murase. (The changes were made per the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule of 2015.)

MothertoBaby, a service of the nonprofit Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, also provides good evidence-based information to physicians and mothers, Dr. Sammaritano noted.

The use of biologic therapies

In a 2017 review of biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston; Martina L. Porter, MD, currently with the department of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston; and Stephen J. Lockwood, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, concluded that an increasing body of literature suggests that biologic agents can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Anti-TNF agents “should be considered over IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors due to the increased availability of long-term data,” they wrote.

“In general,” said Dr. Murase, “there’s more and more data coming out from gastroenterology and rheumatology to reassure patients and prescribing physicians that the TNF-blocker class is likely safe to use in pregnancy,” particularly during the first trimester and early second trimester, when the transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta is “essentially nonexistent.” In the third trimester, the active transport of IgG antibodies increases rapidly.

If possible, said Dr. Sammaritano, who served as lead author of the ACR’s reproductive health guideline, TNF inhibitors “will be stopped prior to the third trimester to avoid [the possibility of] high drug levels in the infant at birth, which raises concern for immunosuppression in the newborn. If disease is very active, however, they can be continued throughout the pregnancy.”

The TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) has the advantage of being transported only minimally across the placenta, if at all, she and Dr. Murase both explained. “To be actively carried across, antibodies need what’s called an Fc region for the placenta to grab onto,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab – a pegylated anti–binding fragment antibody – lacks this Fc region.

Two recent studies – CRIB and a UCB Pharma safety database analysis – showed “essentially no medication crossing – there were barely detectable levels,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab’s label contains this information and other clinical trial data as well as findings from safety database analyses/surveillance registries.

“Before we had much data for the biologics, I’d advise transitioning patients to light therapy from their biologics and a lot of times their psoriasis would improve, but it was more of a dance,” she said. “Now we tend to look at [certolizumab] when they’re of childbearing age and keep them on the treatment. I know that the baby is not being immunosuppressed.”

Consideration of the use of certolizumab when treatment with biologic agents is required throughout the pregnancy is a recommendation included in Dr. Kimball’s 2017 review.

As newer anti-interleukin agents – the IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors – play a growing role in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA, questions loom about their safety profile. Dr. Murase and Dr. Sammaritano are waiting for more data. “In general,” Dr. Sammaritano said, “we recommend stopping them at the time pregnancy is detected, based on a lack of data at this time.”

Small-molecule drugs are also less well studied, she noted. “Because of their low molecular weight, we anticipate they will easily cross the placenta, so we recommend avoiding use during pregnancy until more information is available.”

Postpartum care

The good news, both experts say, is that the vast majority of medications, including biologics, are safe to use during breastfeeding. Methotrexate should be avoided, Dr. Sammaritano pointed out, and the impact of novel small-molecule therapies on breast milk has not been studied.

In her 2019 review of psoriasis in women, Dr. Murase and coauthors wrote that too many dermatologists believe that breastfeeding women should either not be on biologics or are uncertain about biologic use during breastfeeding. However, “biologics are considered compatible for use while breastfeeding due to their large molecular size and the proteolytic environment in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract,” they added.

Counseling and support for breastfeeding is especially important for women with psoriasis, Dr. Murase emphasized. “Breastfeeding is very traumatizing to the skin, and psoriasis can form in skin that’s injured. I have my patients set up an office visit very soon after the pregnancy to make sure they’re doing alright with their breastfeeding and that they’re coating their nipple area with some type of moisturizer and keeping the health of their nipples in good shape.”

Timely reviews of therapy and adjustments are also a priority, she said. “We need to prepare for 6 weeks post partum” when psoriasis will often flare without treatment.

Dr. Murase disclosed that she is a consultant for Dermira, UCB Pharma, Sanofi, Ferndale, and Regeneron. She is also coeditor in chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Dr. Sammaritano reported that she has no disclosures relating to the treatment of PsA.

Novel Combination Therapy Rises When Occam’s Razor Falls

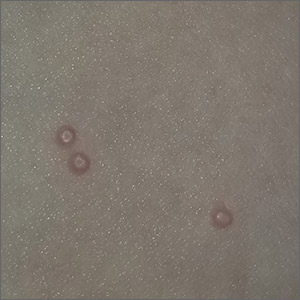

A 70-year-old veteran followed in clinic for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) was found to have a new left axillary lymph node conglomerate on routine imaging, despite stable PSA on Enzalutamide therapy. Biopsy of the axillary mass showed metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, with a differential diagnosis of small cell carcinoma of unknown primary vs. Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC). Given his prostate cancer diagnosis and the rarity of MCC, small cell differentiation of prostate cancer was initially favored. However, the patient appeared well and subsequent PET/CT only showed two subcutaneous hypermetabolic lesions. These findings would be unusual with small cell differentiation of prostate cancer. A second biopsy of a subcutaneous lesion was most consistent with MCC, confirming our diagnosis.

At time of diagnosis, staging MRI Brain revealed 3 parenchymal brain lesions, presumed to be metastatic MCC. As per a landmark trial by Nghiem et al, the patient was started on Pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every three weeks for treatment of metastatic MCC. Brain lesions were locally treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS).

Although his mCRPC was under good control with Enzalutamide, this drug is associated with increased risk of seizures in clinical trial and is not recommended for those with predisposing seizure risk. In light of MCC brain metastases, we decided to switch mCRPC therapy to Darolutamide, an androgen receptor antagonist that has lower penetration of the blood-brain barrier and less incidence of seizures. He tolerated the combination of Darolutamide with Pembrolizumab well, with only a grade 1 acneiform rash.

After just 1 cycle of Pembrolizumab, the patient’s clinically-evident MCC drastically regressed. After 8 months of treatment, his MCC continues to respond clinically and radiographically. This case emphasizes the importance of not relying on “Occam’s razor” – that one should assume a single diagnosis for multiple findings. The simplest explanation of the patient’s left axillary mass biopsy would have been small cell differentiation of prostate cancer; however, this has proved to be a synchronous MCC, which portends a much more favorable prognosis with immunotherapy treatment. We also demonstrate a successful approach to concurrent treatment of metastatic MCC and mCRPC.

A 70-year-old veteran followed in clinic for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) was found to have a new left axillary lymph node conglomerate on routine imaging, despite stable PSA on Enzalutamide therapy. Biopsy of the axillary mass showed metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, with a differential diagnosis of small cell carcinoma of unknown primary vs. Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC). Given his prostate cancer diagnosis and the rarity of MCC, small cell differentiation of prostate cancer was initially favored. However, the patient appeared well and subsequent PET/CT only showed two subcutaneous hypermetabolic lesions. These findings would be unusual with small cell differentiation of prostate cancer. A second biopsy of a subcutaneous lesion was most consistent with MCC, confirming our diagnosis.

At time of diagnosis, staging MRI Brain revealed 3 parenchymal brain lesions, presumed to be metastatic MCC. As per a landmark trial by Nghiem et al, the patient was started on Pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every three weeks for treatment of metastatic MCC. Brain lesions were locally treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS).

Although his mCRPC was under good control with Enzalutamide, this drug is associated with increased risk of seizures in clinical trial and is not recommended for those with predisposing seizure risk. In light of MCC brain metastases, we decided to switch mCRPC therapy to Darolutamide, an androgen receptor antagonist that has lower penetration of the blood-brain barrier and less incidence of seizures. He tolerated the combination of Darolutamide with Pembrolizumab well, with only a grade 1 acneiform rash.

After just 1 cycle of Pembrolizumab, the patient’s clinically-evident MCC drastically regressed. After 8 months of treatment, his MCC continues to respond clinically and radiographically. This case emphasizes the importance of not relying on “Occam’s razor” – that one should assume a single diagnosis for multiple findings. The simplest explanation of the patient’s left axillary mass biopsy would have been small cell differentiation of prostate cancer; however, this has proved to be a synchronous MCC, which portends a much more favorable prognosis with immunotherapy treatment. We also demonstrate a successful approach to concurrent treatment of metastatic MCC and mCRPC.

A 70-year-old veteran followed in clinic for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) was found to have a new left axillary lymph node conglomerate on routine imaging, despite stable PSA on Enzalutamide therapy. Biopsy of the axillary mass showed metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, with a differential diagnosis of small cell carcinoma of unknown primary vs. Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC). Given his prostate cancer diagnosis and the rarity of MCC, small cell differentiation of prostate cancer was initially favored. However, the patient appeared well and subsequent PET/CT only showed two subcutaneous hypermetabolic lesions. These findings would be unusual with small cell differentiation of prostate cancer. A second biopsy of a subcutaneous lesion was most consistent with MCC, confirming our diagnosis.

At time of diagnosis, staging MRI Brain revealed 3 parenchymal brain lesions, presumed to be metastatic MCC. As per a landmark trial by Nghiem et al, the patient was started on Pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every three weeks for treatment of metastatic MCC. Brain lesions were locally treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS).

Although his mCRPC was under good control with Enzalutamide, this drug is associated with increased risk of seizures in clinical trial and is not recommended for those with predisposing seizure risk. In light of MCC brain metastases, we decided to switch mCRPC therapy to Darolutamide, an androgen receptor antagonist that has lower penetration of the blood-brain barrier and less incidence of seizures. He tolerated the combination of Darolutamide with Pembrolizumab well, with only a grade 1 acneiform rash.

After just 1 cycle of Pembrolizumab, the patient’s clinically-evident MCC drastically regressed. After 8 months of treatment, his MCC continues to respond clinically and radiographically. This case emphasizes the importance of not relying on “Occam’s razor” – that one should assume a single diagnosis for multiple findings. The simplest explanation of the patient’s left axillary mass biopsy would have been small cell differentiation of prostate cancer; however, this has proved to be a synchronous MCC, which portends a much more favorable prognosis with immunotherapy treatment. We also demonstrate a successful approach to concurrent treatment of metastatic MCC and mCRPC.

The long road to a PsA prevention trial

About one-third of all patients with psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition that comes with a host of vague symptoms and no definitive blood test for diagnosis. Prevention trials could help to identify higher-risk groups for PsA, with a goal to catch disease early and improve outcomes. The challenge is finding enough participants in a disease that lacks a clear clinical profile, then tracking them for long periods of time to generate any significant data.

Researchers have been taking several approaches to improve outcomes in PsA, Christopher Ritchlin, MD, MPH, chief of the allergy/immunology and rheumatology division at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “We are in the process of identifying biomarkers and imaging findings that characterize psoriasis patients at high risk to develop PsA.”

The next step would be to design an interventional trial to treat high-risk patients before they develop musculoskeletal inflammation, with a goal to delay onset, attenuate severity, or completely prevent arthritis. The issue now is “we don’t know which agents would be most effective in this prevention effort,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Biologics that target specific pathways significant in PsA pathogenesis are an appealing prospect. However, “it may be that alternative therapies such as methotrexate or ultraviolet A radiation therapy, for example, may help arrest the development of joint inflammation.”

Underdiagnosis impedes research

Several factors may undermine this important research.

For one, psoriasis patients are often unaware that they have PsA. “Many times they are diagnosed incorrectly by nonspecialists. As a consequence, they do not get access to appropriate medications,” said Lihi Eder, MD, PhD, staff rheumatologist and director of the psoriatic arthritis research program at the University of Toronto’s Women’s College Research Institute.

The condition also lacks a good diagnostic tool, Dr. Eder said. There’s no blood test that identifies this condition in the same manner as RA and lupus, for example. For these conditions, a general practitioner such as a family physician may conduct a blood test, and if positive, refer them to a rheumatologist. Such a system doesn’t exist for PsA. “Instead, nonspecialists are ordering tests and when they’re negative, they assume wrongly that these patients don’t have a rheumatic condition,” she explained.

Many clinicians aren’t that well versed in PsA, although dermatology has taken steps to become better educated. As a result, more dermatologists are referring patients to rheumatologists for PsA. Despite this small step forward, the heterogeneous clinical presentation of this condition makes diagnosis especially difficult. Unlike RA, which presents with inflammation in the joints, PsA can present as back or joint pain, “which makes our life as rheumatologists much more complex,” Dr. Eder said.

Defining a risk group

Most experts agree that the presence of psoriasis isn’t sufficient to conduct a prevention trial. Ideally, the goal of a prevention study would be to identify a critical subgroup of psoriasis patients at high risk of developing PsA.

However, this presents a challenging task, Dr. Eder said. Psoriasis is a risk factor for PsA, but most patients with psoriasis won’t actually develop it. Given that there’s an incidence rate of 2.7% a year, “you would need to recruit many hundreds of psoriasis patients and follow them for a long period of time until you have enough events.”

Moving forward with prevention studies calls for a better definition of the PsA risk group, according to Georg Schett, MD, chair of internal medicine in the department of internal medicine, rheumatology, and immunology at Friedrich‐Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany. “That’s very important, because you need to define such a group to make a prevention trial feasible. The whole benefit of such an approach is to catch the disease early, to say that psoriasis is a biomarker that’s linked to psoriatic arthritis.”

Indicators of risk other than psoriasis, such as pain, inflammation seen in ultrasound or MRI, and other specificities of psoriasis, could be used to define a population where interception can take place, Dr. Schett added. Although it’s not always clinically recognized, the combination of pain and structural lesions can be an indicator for developing PsA.

One prospective study he and his colleagues conducted in 114 psoriasis patients cited structural entheseal lesions and low cortical volumetric bone mineral density as risk factors in developing PsA. Keeping these factors in mind, Dr. Schett expects to see more studies in biointervention in these populations, “with the idea to prevent the onset of PsA and also decrease pain and subcutaneous inflammation.”

Researchers are currently working to identify those high-risk patients to include in an interventional trial, Dr. Ritchlin said.

That said, there’s been a great deal of “clinical trial angst” among investigators, Dr. Ritchlin noted. Outcomes in clinical trials for a wide range of biologic agents have not demonstrated significant advances in outcomes, compared with initial studies with anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) agents 20 years ago.

Combination biologics

One approach that’s generated some interest is the use of combination biologics medications. Sequential inhibition of cytokines such as interleukin-17A and TNF-alpha is of interest given their central contribution in joint inflammation and damage. “The challenge here of course is toxicity,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Trials that combined blockade of IL-1 and TNF-alpha in a RA trial years ago resulted in significant adverse events without improving outcomes.

Comparatively, a recent study in The Lancet Rheumatology reported success in using the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) to reduce PsA symptoms. Tested on patients in the FUTURE 2 trial, investigators demonstrated that secukinumab in 300- and 150-mg doses safely reduced PsA signs and symptoms over a period of 5 years. Secukinumab also outperformed the TNF-alpha inhibitor adalimumab in 853 PsA patients in the 52-week, randomized, head-to-head, phase 3b EXCEED study, which was recently reported in The Lancet. Articular outcomes were similar between the two therapies, yet the secukinumab group did markedly better in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores, compared with the adalimumab group.

Based on these findings, “I suspect that studies examining the efficacy of combination biologics for treatment of PsA will surface in the near future,” Dr. Ritchlin said.

Yet another approach encompasses the spirit of personalized medicine. Clinicians often treat PsA patients empirically because they lack biomarkers that indicate which drug may be most effective for an individual patient, Dr. Ritchlin said. However, the technologies for investigating specific cell subsets in both the blood and tissues have advanced greatly over the last decade. “I am confident that a more precision medicine–based approach to the diagnosis and treatment of PsA is on the near horizon.”

Diet as an intervention

Other research has looked at the strong link between metabolic abnormalities and psoriasis and PsA. Some diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, show promise in improving the metabolic profile of these patients, making it a candidate as a potential intervention to reduce PsA risk. Another strategy would be to focus on limiting calories and promoting weight reduction.

One study in the British Journal of Dermatology looked at the associations between PsA and smoking, alcohol, and body mass index, identifying obesity as an important risk factor. Analyzing more than 90,000 psoriasis cases from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink between 1998 and 2014, researchers identified 1,409 PsA diagnoses. Among this cohort, researchers found an association between PsA and increased body mass index and moderate drinking. This finding underscores the need to support weight-reduction programs to reduce risk, Dr. Eder and Alexis Ogdie, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in a related editorial.

While observational studies such as this one provide further guidance for interventional trials, confounders can affect results. “Patients who lost weight could have made a positive lifestyle change (e.g., a dietary change) that was associated with the decreased risk for PsA rather than weight loss specifically, or they could have lost weight for unhealthy reasons,” Dr. Eder and Dr. Ogdie explained. Future research could address whether weight loss or other interventional factors may reduce PsA progression.

To make this work, “we would need to select patients that would benefit from diet. Secondly, we’d need to identify what kind of diet would be good for preventing PsA. And we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder further elaborated.

As with any prevention trial, the challenge is to follow patients over a long period of time, making sure they comply with the restrictions of the prescribed diet, Dr. Eder noted. “I do think it’s a really exciting type of intervention because it’s something that people are very interested in. There’s little risk of side effects, and it’s not very expensive.”

In other research on weight-loss methods, an observational study from Denmark found that bariatric surgery, especially gastric bypass, reduced the risk of developing PsA. This suggests that weight reduction by itself is important, “although we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder said.

A risk model for PsA

Dr. Eder and colleagues have been working on an algorithm that will incorporate clinical information (for example, the presence of nail lesions and the severity of psoriasis) to provide an estimated risk of developing PsA over the next 5 years. Subsequently, this information could be used to identify high-risk psoriasis patients as candidates for a prevention trial.

Other groups are looking at laboratory or imaging biomarkers to help develop PsA prediction models, she said. “Once we have these tools, we can move to next steps of prevention trials. What kinds of interventions should we apply? Are we talking biologic medications or other lifestyle interventions like diet? We are still at the early stages. However, with an improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms and risk factors we are expected to see prevention trials for PsA in the future.”

About one-third of all patients with psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition that comes with a host of vague symptoms and no definitive blood test for diagnosis. Prevention trials could help to identify higher-risk groups for PsA, with a goal to catch disease early and improve outcomes. The challenge is finding enough participants in a disease that lacks a clear clinical profile, then tracking them for long periods of time to generate any significant data.

Researchers have been taking several approaches to improve outcomes in PsA, Christopher Ritchlin, MD, MPH, chief of the allergy/immunology and rheumatology division at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “We are in the process of identifying biomarkers and imaging findings that characterize psoriasis patients at high risk to develop PsA.”