User login

Omalizumab proves effective for severe pediatric atopic dermatitis

A new study has found that omalizumab (Xolair) reduced severity and improved quality of life in pediatric patients with severe atopic dermatitis.

“Future work with an even larger sample size, a longer duration, and higher-affinity versions of omalizumab would clarify the precise role of anti-IgE therapy and its ideal target population,” wrote Susan Chan, MD, of Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Pediatrics.

To determine the benefits of omalizumab in reducing immunoglobulin E levels and thereby treating severe childhood eczema, the researchers launched the Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT). This randomized clinical trial recruited 62 patients between the ages of 4 and 19 years with severe eczema, which was defined as a score over 40 on the objective Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index. They received 24 weeks of treatment with either omalizumab (n = 30) or placebo (n = 32) followed by 24 weeks of follow-up. Participants had a mean age of 10.3 years.

After 24 weeks, the adjusted mean difference in objective SCORAD index between the two groups was –6.9 (95% confidence interval, –12.2 to –1.5; P = .01) and significantly favored omalizumab therapy. The adjusted mean difference for the Eczema Area and Severity Index (–6.7; 95% CI, –13.2 to –0.1) also favored omalizumab. In regard to quality of life, after 24 weeks the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index/Dermatology Life Quality Index favored the omalizumab group with an adjusted mean difference of –3.5 (95% CI, –6.4 to –0.5).

In an accompanying editorial, Ann Chen Wu, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston noted that the results of the study from Chan et al. were promising but “more questions need to be answered before the drug can be used to treat atopic dermatitis in clinical practice” (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov. 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4509).

Her initial concern was price; she acknowledged that “omalizumab is a costly intervention” but said atopic dermatitis is also costly, raising the question as to whether the high costs of both justify treatment. In addition, omalizumab as treatment can come with both benefits and harms. Severe atopic dermatitis can decrease quality of life and, though omalizumab appears to be safe, there are adverse effects and logistical burdens to overcome.

More than anything, she recognized the need to prioritize, wondering what level of atopic dermatitis patients would truly benefit from this level of treatment. “Is using a $100,000-per-year medication for an itchy condition an overtreatment,” she asked, “or a lifesaver?”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity. The authors had numerous financial disclosures, including receiving grants from the NIHR EME Programme and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity along with active and placebo drugs from Novartis for use in the study. Dr. Wu reported receiving a grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Chan S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4476.

A new study has found that omalizumab (Xolair) reduced severity and improved quality of life in pediatric patients with severe atopic dermatitis.

“Future work with an even larger sample size, a longer duration, and higher-affinity versions of omalizumab would clarify the precise role of anti-IgE therapy and its ideal target population,” wrote Susan Chan, MD, of Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Pediatrics.

To determine the benefits of omalizumab in reducing immunoglobulin E levels and thereby treating severe childhood eczema, the researchers launched the Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT). This randomized clinical trial recruited 62 patients between the ages of 4 and 19 years with severe eczema, which was defined as a score over 40 on the objective Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index. They received 24 weeks of treatment with either omalizumab (n = 30) or placebo (n = 32) followed by 24 weeks of follow-up. Participants had a mean age of 10.3 years.

After 24 weeks, the adjusted mean difference in objective SCORAD index between the two groups was –6.9 (95% confidence interval, –12.2 to –1.5; P = .01) and significantly favored omalizumab therapy. The adjusted mean difference for the Eczema Area and Severity Index (–6.7; 95% CI, –13.2 to –0.1) also favored omalizumab. In regard to quality of life, after 24 weeks the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index/Dermatology Life Quality Index favored the omalizumab group with an adjusted mean difference of –3.5 (95% CI, –6.4 to –0.5).

In an accompanying editorial, Ann Chen Wu, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston noted that the results of the study from Chan et al. were promising but “more questions need to be answered before the drug can be used to treat atopic dermatitis in clinical practice” (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov. 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4509).

Her initial concern was price; she acknowledged that “omalizumab is a costly intervention” but said atopic dermatitis is also costly, raising the question as to whether the high costs of both justify treatment. In addition, omalizumab as treatment can come with both benefits and harms. Severe atopic dermatitis can decrease quality of life and, though omalizumab appears to be safe, there are adverse effects and logistical burdens to overcome.

More than anything, she recognized the need to prioritize, wondering what level of atopic dermatitis patients would truly benefit from this level of treatment. “Is using a $100,000-per-year medication for an itchy condition an overtreatment,” she asked, “or a lifesaver?”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity. The authors had numerous financial disclosures, including receiving grants from the NIHR EME Programme and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity along with active and placebo drugs from Novartis for use in the study. Dr. Wu reported receiving a grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Chan S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4476.

A new study has found that omalizumab (Xolair) reduced severity and improved quality of life in pediatric patients with severe atopic dermatitis.

“Future work with an even larger sample size, a longer duration, and higher-affinity versions of omalizumab would clarify the precise role of anti-IgE therapy and its ideal target population,” wrote Susan Chan, MD, of Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Pediatrics.

To determine the benefits of omalizumab in reducing immunoglobulin E levels and thereby treating severe childhood eczema, the researchers launched the Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT). This randomized clinical trial recruited 62 patients between the ages of 4 and 19 years with severe eczema, which was defined as a score over 40 on the objective Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index. They received 24 weeks of treatment with either omalizumab (n = 30) or placebo (n = 32) followed by 24 weeks of follow-up. Participants had a mean age of 10.3 years.

After 24 weeks, the adjusted mean difference in objective SCORAD index between the two groups was –6.9 (95% confidence interval, –12.2 to –1.5; P = .01) and significantly favored omalizumab therapy. The adjusted mean difference for the Eczema Area and Severity Index (–6.7; 95% CI, –13.2 to –0.1) also favored omalizumab. In regard to quality of life, after 24 weeks the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index/Dermatology Life Quality Index favored the omalizumab group with an adjusted mean difference of –3.5 (95% CI, –6.4 to –0.5).

In an accompanying editorial, Ann Chen Wu, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston noted that the results of the study from Chan et al. were promising but “more questions need to be answered before the drug can be used to treat atopic dermatitis in clinical practice” (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov. 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4509).

Her initial concern was price; she acknowledged that “omalizumab is a costly intervention” but said atopic dermatitis is also costly, raising the question as to whether the high costs of both justify treatment. In addition, omalizumab as treatment can come with both benefits and harms. Severe atopic dermatitis can decrease quality of life and, though omalizumab appears to be safe, there are adverse effects and logistical burdens to overcome.

More than anything, she recognized the need to prioritize, wondering what level of atopic dermatitis patients would truly benefit from this level of treatment. “Is using a $100,000-per-year medication for an itchy condition an overtreatment,” she asked, “or a lifesaver?”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity. The authors had numerous financial disclosures, including receiving grants from the NIHR EME Programme and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity along with active and placebo drugs from Novartis for use in the study. Dr. Wu reported receiving a grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Chan S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4476.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Naturopaths emphasize role of diet in atopic dermatitis

, based on data from a small survey of the two.

Data from previous studies show that more than half of patients with AD have used complementary and alternative medicine in addition to allopathic care, but providers may be unaware of each other’s treatment approaches and confuse patients, wrote Julie Dhossche, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and her colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatric Dermatology, the researchers assessed results of an 11-question, free-text survey of 30 allopathic providers and 21 naturopathic providers about AD. The survey included questions on patient education and evaluation, skin care, and treatment.

Overall, both allopathic and naturopathic providers recommended skin care protocols involving moisturization and “soak and seal” bathing. However, allopathic providers were more likely to prescribe topical corticosteroids for mild to moderate disease (100% vs. 19%), followed by phototherapy and systemic treatments in more severe cases. Naturopathic providers were more likely than allopathic providers to choose topical botanicals, oils, or probiotics (52% vs. 0%) for mild to moderate disease, as well stress relief and acupuncture. Naturopathic providers favored topical corticosteroids and referrals to dermatologists for second- or third-line treatment.

Of note, 85% of naturopathic providers said they thought diet had a probable or definite role in AD, compared with 3% of allopathic providers.

In addition, naturopathic providers differed in their response to an optional question on the use of additional education about food and diet. A total of 11 of 19 naturopathic providers (58%) recommended dietary changes, including “remove potential food allergens/reduce sugar” and “emphasize anti-inflammatory diet,” the researchers said.

“Confusion regarding the role of food in AD management is a common source of frustration for patients, and perhaps a consensus statement from both fields regarding the role of food allergy in AD management could be aspired toward in the name of reducing patient confusion,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the small sample size and self-selection bias, as well as the subjective nature of an open-ended survey, the researchers noted. However, the results provide evidence of differences in treatment approaches between allopathic and naturopathic providers and suggest that “respectful collaboration between allopathic and naturopathic providers will help practitioners find common ground, decrease patient confusion, and improve patient outcomes,” they concluded.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dhossche J et al. Ped Dermatol. 2019 Nov 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.14036.

, based on data from a small survey of the two.

Data from previous studies show that more than half of patients with AD have used complementary and alternative medicine in addition to allopathic care, but providers may be unaware of each other’s treatment approaches and confuse patients, wrote Julie Dhossche, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and her colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatric Dermatology, the researchers assessed results of an 11-question, free-text survey of 30 allopathic providers and 21 naturopathic providers about AD. The survey included questions on patient education and evaluation, skin care, and treatment.

Overall, both allopathic and naturopathic providers recommended skin care protocols involving moisturization and “soak and seal” bathing. However, allopathic providers were more likely to prescribe topical corticosteroids for mild to moderate disease (100% vs. 19%), followed by phototherapy and systemic treatments in more severe cases. Naturopathic providers were more likely than allopathic providers to choose topical botanicals, oils, or probiotics (52% vs. 0%) for mild to moderate disease, as well stress relief and acupuncture. Naturopathic providers favored topical corticosteroids and referrals to dermatologists for second- or third-line treatment.

Of note, 85% of naturopathic providers said they thought diet had a probable or definite role in AD, compared with 3% of allopathic providers.

In addition, naturopathic providers differed in their response to an optional question on the use of additional education about food and diet. A total of 11 of 19 naturopathic providers (58%) recommended dietary changes, including “remove potential food allergens/reduce sugar” and “emphasize anti-inflammatory diet,” the researchers said.

“Confusion regarding the role of food in AD management is a common source of frustration for patients, and perhaps a consensus statement from both fields regarding the role of food allergy in AD management could be aspired toward in the name of reducing patient confusion,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the small sample size and self-selection bias, as well as the subjective nature of an open-ended survey, the researchers noted. However, the results provide evidence of differences in treatment approaches between allopathic and naturopathic providers and suggest that “respectful collaboration between allopathic and naturopathic providers will help practitioners find common ground, decrease patient confusion, and improve patient outcomes,” they concluded.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dhossche J et al. Ped Dermatol. 2019 Nov 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.14036.

, based on data from a small survey of the two.

Data from previous studies show that more than half of patients with AD have used complementary and alternative medicine in addition to allopathic care, but providers may be unaware of each other’s treatment approaches and confuse patients, wrote Julie Dhossche, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and her colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatric Dermatology, the researchers assessed results of an 11-question, free-text survey of 30 allopathic providers and 21 naturopathic providers about AD. The survey included questions on patient education and evaluation, skin care, and treatment.

Overall, both allopathic and naturopathic providers recommended skin care protocols involving moisturization and “soak and seal” bathing. However, allopathic providers were more likely to prescribe topical corticosteroids for mild to moderate disease (100% vs. 19%), followed by phototherapy and systemic treatments in more severe cases. Naturopathic providers were more likely than allopathic providers to choose topical botanicals, oils, or probiotics (52% vs. 0%) for mild to moderate disease, as well stress relief and acupuncture. Naturopathic providers favored topical corticosteroids and referrals to dermatologists for second- or third-line treatment.

Of note, 85% of naturopathic providers said they thought diet had a probable or definite role in AD, compared with 3% of allopathic providers.

In addition, naturopathic providers differed in their response to an optional question on the use of additional education about food and diet. A total of 11 of 19 naturopathic providers (58%) recommended dietary changes, including “remove potential food allergens/reduce sugar” and “emphasize anti-inflammatory diet,” the researchers said.

“Confusion regarding the role of food in AD management is a common source of frustration for patients, and perhaps a consensus statement from both fields regarding the role of food allergy in AD management could be aspired toward in the name of reducing patient confusion,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the small sample size and self-selection bias, as well as the subjective nature of an open-ended survey, the researchers noted. However, the results provide evidence of differences in treatment approaches between allopathic and naturopathic providers and suggest that “respectful collaboration between allopathic and naturopathic providers will help practitioners find common ground, decrease patient confusion, and improve patient outcomes,” they concluded.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dhossche J et al. Ped Dermatol. 2019 Nov 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.14036.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Atopic dermatitis acts differently in certain populations

LAS VEGAS – Eczema is eczema is eczema, right? Maybe not. “Atopic dermatitis might not be one disease,” a dermatologist told colleagues, and treatments may need to be adjusted to reflect the age and ethnicity of patients.

More research is needed, Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, chair and professor of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said during a presentation at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. “We’re probably just on the tip of the iceberg of understanding the physiology of atopic dermatitis. Hopefully, it will lead to the therapeutic advances we’ve seen in psoriasis.”

As Dr. Gordon explained, there’s a , he said, “and our medicines aren’t well understood.”

As for the disease itself, he said, “you might hear a renowned [expert] say, ‘This is how it works,’ and another say, ‘This is absolutely not how it works.’ ” One camp focused on the skin barrier, he said, while another camp highlighted inflammation in AD.

“Both the barrier and inflammation are important,” he said. “There are multiple cell types and cytokines that are important, but we don’t know yet the relative importance of them all. You have this cytokine soup, and we’re still trying to figure out the driving forces.”

What is clear, Dr. Gordon said, is that AD acts differently in certain patient populations. It’s not the same in pediatric versus adult patients, he said, and it’s not the same in white versus black versus Asian patients. Research, for example, suggests that Th2, Th22, and Th17 pathways appear to be important in pediatric AD, but not Th1, he said. In contrast, the Th1 pathway plays a role in white adults – but not in black adults

Different cytokines appear to play different roles in these populations, he said. “One of the key things moving forward is going to be figuring out which patients you apply these medications to,” he noted.

Dr. Gordon has multiple disclosures including honoraria or research support from Abbvie, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and others. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Eczema is eczema is eczema, right? Maybe not. “Atopic dermatitis might not be one disease,” a dermatologist told colleagues, and treatments may need to be adjusted to reflect the age and ethnicity of patients.

More research is needed, Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, chair and professor of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said during a presentation at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. “We’re probably just on the tip of the iceberg of understanding the physiology of atopic dermatitis. Hopefully, it will lead to the therapeutic advances we’ve seen in psoriasis.”

As Dr. Gordon explained, there’s a , he said, “and our medicines aren’t well understood.”

As for the disease itself, he said, “you might hear a renowned [expert] say, ‘This is how it works,’ and another say, ‘This is absolutely not how it works.’ ” One camp focused on the skin barrier, he said, while another camp highlighted inflammation in AD.

“Both the barrier and inflammation are important,” he said. “There are multiple cell types and cytokines that are important, but we don’t know yet the relative importance of them all. You have this cytokine soup, and we’re still trying to figure out the driving forces.”

What is clear, Dr. Gordon said, is that AD acts differently in certain patient populations. It’s not the same in pediatric versus adult patients, he said, and it’s not the same in white versus black versus Asian patients. Research, for example, suggests that Th2, Th22, and Th17 pathways appear to be important in pediatric AD, but not Th1, he said. In contrast, the Th1 pathway plays a role in white adults – but not in black adults

Different cytokines appear to play different roles in these populations, he said. “One of the key things moving forward is going to be figuring out which patients you apply these medications to,” he noted.

Dr. Gordon has multiple disclosures including honoraria or research support from Abbvie, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and others. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Eczema is eczema is eczema, right? Maybe not. “Atopic dermatitis might not be one disease,” a dermatologist told colleagues, and treatments may need to be adjusted to reflect the age and ethnicity of patients.

More research is needed, Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, chair and professor of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said during a presentation at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. “We’re probably just on the tip of the iceberg of understanding the physiology of atopic dermatitis. Hopefully, it will lead to the therapeutic advances we’ve seen in psoriasis.”

As Dr. Gordon explained, there’s a , he said, “and our medicines aren’t well understood.”

As for the disease itself, he said, “you might hear a renowned [expert] say, ‘This is how it works,’ and another say, ‘This is absolutely not how it works.’ ” One camp focused on the skin barrier, he said, while another camp highlighted inflammation in AD.

“Both the barrier and inflammation are important,” he said. “There are multiple cell types and cytokines that are important, but we don’t know yet the relative importance of them all. You have this cytokine soup, and we’re still trying to figure out the driving forces.”

What is clear, Dr. Gordon said, is that AD acts differently in certain patient populations. It’s not the same in pediatric versus adult patients, he said, and it’s not the same in white versus black versus Asian patients. Research, for example, suggests that Th2, Th22, and Th17 pathways appear to be important in pediatric AD, but not Th1, he said. In contrast, the Th1 pathway plays a role in white adults – but not in black adults

Different cytokines appear to play different roles in these populations, he said. “One of the key things moving forward is going to be figuring out which patients you apply these medications to,” he noted.

Dr. Gordon has multiple disclosures including honoraria or research support from Abbvie, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and others. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

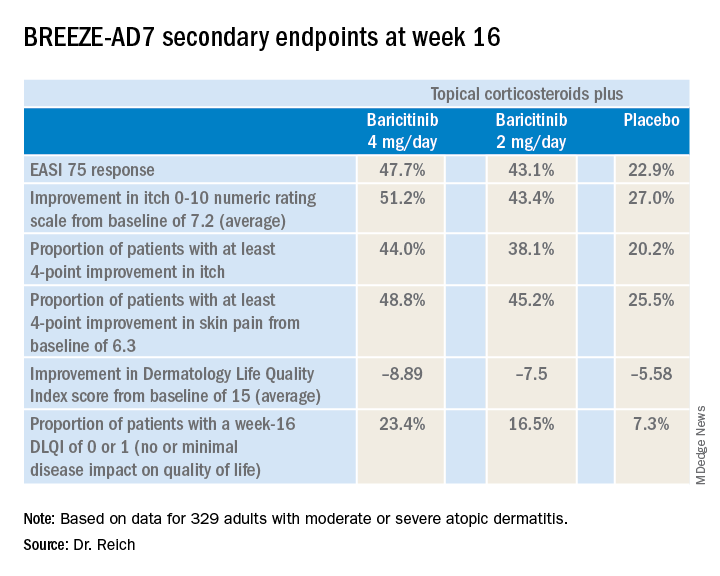

Oral baricitinib performs well in phase 3 for atopic dermatitis

MADRID – Adding the oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor baricitinib to standard atopic dermatitis therapy with low- and midpotency topical corticosteroids markedly improved disease severity and key patient-reported outcomes, compared with topical corticosteroids alone, in the phase 3, randomized, double-blind BREEZE-AD7 trial, Kristian Reich, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

in the phase 3 BREEZE-AD1 and -AD2 trials. But BREEZE-AD7 further advances the field because it’s the first phase 3 study testing the efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in combination with low- and midpotency topical steroids.

“I think this study is important because it looks into the situation that’s more like what happens in the real world, which is, as with dupilumab and other drugs, we use the systemic agent in combination with topical therapies and, in particular, with topical corticosteroids,” commented Dr. Reich, professor of dermatology at University Medical Center, Hamburg, and medical director at SCIderm, a scientific research company.

“This is what I think we can expect from existing and upcoming systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: We will use them in combination with topical corticosteroids, and hopefully this will allow patients to dramatically reduce the concomitant use of topical corticosteroids, as shown here in BREEZE-AD7,” he added.

BREEZE-AD7 was a 16-week study that included 329 adults with moderate or severe atopic dermatitis who were randomized to low- and midpotency topical corticosteroids plus either baricitinib at 2 mg once daily, baricitinib at 4 mg once daily, or placebo. The group’s mean baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score was 29. Overall, 45% of participants had a baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) of disease severity of 4 on a 0-4 scale.

The primary endpoint was achievement of an IGA of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear, along with at least a 2-point IGA improvement from baseline at week 16. This was accomplished in 30.6% of those on 4 mg/day of baricitinib, 23.9% of patients in the 2-mg group, and 14.7% of controls.

The 4-mg dose of baricitinib was statistically superior to placebo; the 2-mg dose was not. However, Dr. Reich indicated he was untroubled by this because the primary endpoint was set at a high bar, and both doses of baricitinib proved to be significantly better than topical steroids plus placebo in terms of EASI 75 response rates, as well as reductions in itch, skin pain, and sleep problems, which aren’t captured in EASI scores (see graphic).

“One of my big learnings from this year’s EADV is that we have to rethink the dimensions of atopic dermatitis. I think we have underestimated the relevance of important symptoms such as itch, the impact atopic dermatitis has on pain, and the effect it has on sleeping problems,” the dermatologist said. “My feeling is that baricitinib is strongest in reducing itch, improving sleep, and reducing pain, but it also has good effects on the clinical signs of atopic dermatitis.”

The baricitinib-treated patients’ rapidity of improvement in the various endpoints was particularly impressive. Both doses of the JAK 1/2 inhibitor showed significant separation from the control group in the first week, and the majority of improvement occurred by week 4.

A key finding was that patients on baricitinib at 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day used a mean total of 162 g and 137 g of midpotency topical steroids, respectively, during the 16 weeks, compared with 225 g in the control group. The higher-dose baricitinib group was topical corticosteroid-free on 33% of study days, compared with 25% of days for the baricitinib 2 mg patients and 17% of days for controls.

In terms of safety, there was a case of pulmonary embolism in the higher-dose baricitinib group and an opportunistic toxoplasmosis eye infection in the control population. The frequency of oral herpes and herpes simplex virus infections was 2.8% in controls, 4.6% in the baricitinib 2-mg group, and 6.3% in the 4-mg group. There was also a signal of a dose-dependent increased risk of new-onset acne, with rates of 0.9% in controls and patients on baricitinib 2 mg, climbing to 3.6% with baricitinib 4 mg.

“In phase 2 results with upadacitinib [another oral JAK inhibitor], we saw that more than 10% of patients in the highest-dose group developed what was classified as acne. I cannot explain this, but it’s something we will monitor in the future,” Dr. Reich promised.

A fuller picture of baricitinib’s safety profile in the setting of atopic dermatitis clearly requires larger and longer-term studies, he added.

Baricitinib at the 2 mg daily dose is already marketed as Olumiant for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, with labeling that includes a boxed warning about serious infections, malignancy, and thrombosis. The Food and Drug Administration did not approve the 4-mg dose after determining that its higher safety hazard outweighed the efficacy advantage over the lower dose.

The BREEZE-AD7 study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Reich reported serving as an adviser to, paid speaker for, and recipient of research grants from that pharmaceutical company and more than two dozen others.

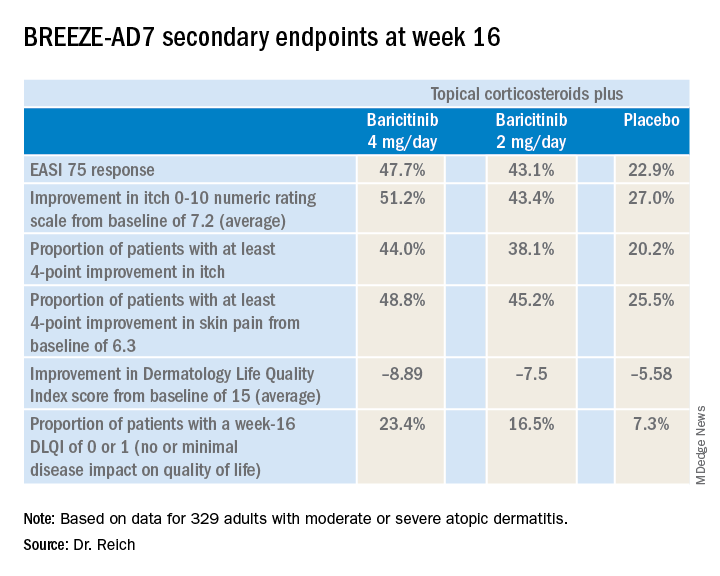

MADRID – Adding the oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor baricitinib to standard atopic dermatitis therapy with low- and midpotency topical corticosteroids markedly improved disease severity and key patient-reported outcomes, compared with topical corticosteroids alone, in the phase 3, randomized, double-blind BREEZE-AD7 trial, Kristian Reich, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

in the phase 3 BREEZE-AD1 and -AD2 trials. But BREEZE-AD7 further advances the field because it’s the first phase 3 study testing the efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in combination with low- and midpotency topical steroids.

“I think this study is important because it looks into the situation that’s more like what happens in the real world, which is, as with dupilumab and other drugs, we use the systemic agent in combination with topical therapies and, in particular, with topical corticosteroids,” commented Dr. Reich, professor of dermatology at University Medical Center, Hamburg, and medical director at SCIderm, a scientific research company.

“This is what I think we can expect from existing and upcoming systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: We will use them in combination with topical corticosteroids, and hopefully this will allow patients to dramatically reduce the concomitant use of topical corticosteroids, as shown here in BREEZE-AD7,” he added.

BREEZE-AD7 was a 16-week study that included 329 adults with moderate or severe atopic dermatitis who were randomized to low- and midpotency topical corticosteroids plus either baricitinib at 2 mg once daily, baricitinib at 4 mg once daily, or placebo. The group’s mean baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score was 29. Overall, 45% of participants had a baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) of disease severity of 4 on a 0-4 scale.

The primary endpoint was achievement of an IGA of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear, along with at least a 2-point IGA improvement from baseline at week 16. This was accomplished in 30.6% of those on 4 mg/day of baricitinib, 23.9% of patients in the 2-mg group, and 14.7% of controls.

The 4-mg dose of baricitinib was statistically superior to placebo; the 2-mg dose was not. However, Dr. Reich indicated he was untroubled by this because the primary endpoint was set at a high bar, and both doses of baricitinib proved to be significantly better than topical steroids plus placebo in terms of EASI 75 response rates, as well as reductions in itch, skin pain, and sleep problems, which aren’t captured in EASI scores (see graphic).

“One of my big learnings from this year’s EADV is that we have to rethink the dimensions of atopic dermatitis. I think we have underestimated the relevance of important symptoms such as itch, the impact atopic dermatitis has on pain, and the effect it has on sleeping problems,” the dermatologist said. “My feeling is that baricitinib is strongest in reducing itch, improving sleep, and reducing pain, but it also has good effects on the clinical signs of atopic dermatitis.”

The baricitinib-treated patients’ rapidity of improvement in the various endpoints was particularly impressive. Both doses of the JAK 1/2 inhibitor showed significant separation from the control group in the first week, and the majority of improvement occurred by week 4.

A key finding was that patients on baricitinib at 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day used a mean total of 162 g and 137 g of midpotency topical steroids, respectively, during the 16 weeks, compared with 225 g in the control group. The higher-dose baricitinib group was topical corticosteroid-free on 33% of study days, compared with 25% of days for the baricitinib 2 mg patients and 17% of days for controls.

In terms of safety, there was a case of pulmonary embolism in the higher-dose baricitinib group and an opportunistic toxoplasmosis eye infection in the control population. The frequency of oral herpes and herpes simplex virus infections was 2.8% in controls, 4.6% in the baricitinib 2-mg group, and 6.3% in the 4-mg group. There was also a signal of a dose-dependent increased risk of new-onset acne, with rates of 0.9% in controls and patients on baricitinib 2 mg, climbing to 3.6% with baricitinib 4 mg.

“In phase 2 results with upadacitinib [another oral JAK inhibitor], we saw that more than 10% of patients in the highest-dose group developed what was classified as acne. I cannot explain this, but it’s something we will monitor in the future,” Dr. Reich promised.

A fuller picture of baricitinib’s safety profile in the setting of atopic dermatitis clearly requires larger and longer-term studies, he added.

Baricitinib at the 2 mg daily dose is already marketed as Olumiant for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, with labeling that includes a boxed warning about serious infections, malignancy, and thrombosis. The Food and Drug Administration did not approve the 4-mg dose after determining that its higher safety hazard outweighed the efficacy advantage over the lower dose.

The BREEZE-AD7 study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Reich reported serving as an adviser to, paid speaker for, and recipient of research grants from that pharmaceutical company and more than two dozen others.

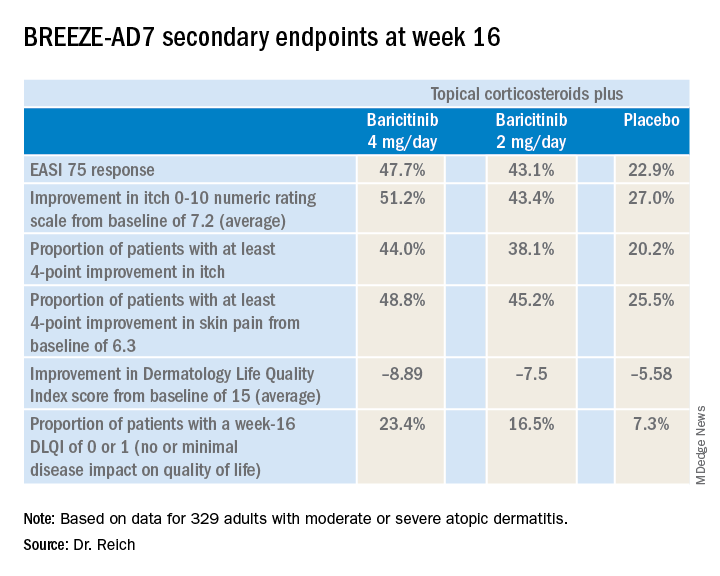

MADRID – Adding the oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor baricitinib to standard atopic dermatitis therapy with low- and midpotency topical corticosteroids markedly improved disease severity and key patient-reported outcomes, compared with topical corticosteroids alone, in the phase 3, randomized, double-blind BREEZE-AD7 trial, Kristian Reich, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

in the phase 3 BREEZE-AD1 and -AD2 trials. But BREEZE-AD7 further advances the field because it’s the first phase 3 study testing the efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in combination with low- and midpotency topical steroids.

“I think this study is important because it looks into the situation that’s more like what happens in the real world, which is, as with dupilumab and other drugs, we use the systemic agent in combination with topical therapies and, in particular, with topical corticosteroids,” commented Dr. Reich, professor of dermatology at University Medical Center, Hamburg, and medical director at SCIderm, a scientific research company.

“This is what I think we can expect from existing and upcoming systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: We will use them in combination with topical corticosteroids, and hopefully this will allow patients to dramatically reduce the concomitant use of topical corticosteroids, as shown here in BREEZE-AD7,” he added.

BREEZE-AD7 was a 16-week study that included 329 adults with moderate or severe atopic dermatitis who were randomized to low- and midpotency topical corticosteroids plus either baricitinib at 2 mg once daily, baricitinib at 4 mg once daily, or placebo. The group’s mean baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score was 29. Overall, 45% of participants had a baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) of disease severity of 4 on a 0-4 scale.

The primary endpoint was achievement of an IGA of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear, along with at least a 2-point IGA improvement from baseline at week 16. This was accomplished in 30.6% of those on 4 mg/day of baricitinib, 23.9% of patients in the 2-mg group, and 14.7% of controls.

The 4-mg dose of baricitinib was statistically superior to placebo; the 2-mg dose was not. However, Dr. Reich indicated he was untroubled by this because the primary endpoint was set at a high bar, and both doses of baricitinib proved to be significantly better than topical steroids plus placebo in terms of EASI 75 response rates, as well as reductions in itch, skin pain, and sleep problems, which aren’t captured in EASI scores (see graphic).

“One of my big learnings from this year’s EADV is that we have to rethink the dimensions of atopic dermatitis. I think we have underestimated the relevance of important symptoms such as itch, the impact atopic dermatitis has on pain, and the effect it has on sleeping problems,” the dermatologist said. “My feeling is that baricitinib is strongest in reducing itch, improving sleep, and reducing pain, but it also has good effects on the clinical signs of atopic dermatitis.”

The baricitinib-treated patients’ rapidity of improvement in the various endpoints was particularly impressive. Both doses of the JAK 1/2 inhibitor showed significant separation from the control group in the first week, and the majority of improvement occurred by week 4.

A key finding was that patients on baricitinib at 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day used a mean total of 162 g and 137 g of midpotency topical steroids, respectively, during the 16 weeks, compared with 225 g in the control group. The higher-dose baricitinib group was topical corticosteroid-free on 33% of study days, compared with 25% of days for the baricitinib 2 mg patients and 17% of days for controls.

In terms of safety, there was a case of pulmonary embolism in the higher-dose baricitinib group and an opportunistic toxoplasmosis eye infection in the control population. The frequency of oral herpes and herpes simplex virus infections was 2.8% in controls, 4.6% in the baricitinib 2-mg group, and 6.3% in the 4-mg group. There was also a signal of a dose-dependent increased risk of new-onset acne, with rates of 0.9% in controls and patients on baricitinib 2 mg, climbing to 3.6% with baricitinib 4 mg.

“In phase 2 results with upadacitinib [another oral JAK inhibitor], we saw that more than 10% of patients in the highest-dose group developed what was classified as acne. I cannot explain this, but it’s something we will monitor in the future,” Dr. Reich promised.

A fuller picture of baricitinib’s safety profile in the setting of atopic dermatitis clearly requires larger and longer-term studies, he added.

Baricitinib at the 2 mg daily dose is already marketed as Olumiant for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, with labeling that includes a boxed warning about serious infections, malignancy, and thrombosis. The Food and Drug Administration did not approve the 4-mg dose after determining that its higher safety hazard outweighed the efficacy advantage over the lower dose.

The BREEZE-AD7 study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Reich reported serving as an adviser to, paid speaker for, and recipient of research grants from that pharmaceutical company and more than two dozen others.

REPORTING FROM EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor baricitinib shows promise as a novel oral treatment for moderate or severe atopic dermatitis.

Major finding: Among atopic dermatitis patients on concomitant topical corticosteroids, a 75% improvement on Eczema Area and Severity Index at 16 weeks was achieved in 48% of those on baricitinib at 4 mg/day, 43% with baricitinib at 2 mg/day, and 23% on placebo.

Study details: BREEZE-AD7 was a phase 3, multicenter, 16-week, double-blind, three-arm study including 329 adults with moderate or severe atopic dermatitis.

Disclosures: The BREEZE-AD7 study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. The presenter reported serving as an adviser to, paid speaker for, and/or recipient of research grants from that pharmaceutical company and more than two dozen others.

Source: Reich K. EADV Congress, late breaker.

Early onset of atopic dermatitis linked to poorer control

according to a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis most commonly arises in infancy but also can emerge in later childhood and even adolescence, leading to a distinction between early- and late-onset disease, wrote Joy Wan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors.

“Early-onset, mid-onset, and late-onset AD appear to differ in the presence of active disease over time; however, whether these groups also differ in terms of the severity of AD is unknown,” they wrote.

In this observational cohort study, 8,015 individuals with childhood-onset atopic dermatitis – 53% of whom were female – were assessed twice-yearly for up to 10 years. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the group had early-onset atopic dermatitis – defined as onset before 2 years of age – while 19% had mid-onset disease (3-7 years) and 9% had late-onset disease (8-17 years).

The study found that older age of onset was associated with better control, such that for each additional year of age at the onset of disease, there was a 7% reduction in the odds of poorer control of disease. Those who had mid-onset disease had a 29% lower odds of poorer control compared with those with early-onset, while those with late-onset disease had a 49% lower odds of poorer control.

The likelihood of atopic dermatitis persisting beyond childhood also appeared to be linked to the age of onset. Those with mid-onset disease had a 55% lower odds of persistent atopic dermatitis, compared with those with early-onset disease, while those with late-onset disease had an 81% lower odds.

“In all 3 groups, the proportion of subjects reporting persistent AD generally declined with older age, and the differences among the 3 onset age groups were most pronounced from early adolescence onward,” the authors wrote.

They noted that there was considerable research currently focused on identifying distinct atopic dermatitis phenotypes and endotypes, and their evidence on the different disease course for early-, mid-, and late-onset disease supported this idea of disease subtypes.

“However, additional research is needed to understand whether and how early-, mid-, and late-onset AD differ molecularly or immunologically, and whether they respond differentially to treatment,” they wrote. They also suggested that the timing of onset could help identify patients who were at greater risk of persistent or poorly controlled disease, and who benefits from more intensive monitoring or treatment.

The study was partly supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Dermatology Foundation. Three authors declared funding, consultancies, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wan J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1292-9.

according to a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis most commonly arises in infancy but also can emerge in later childhood and even adolescence, leading to a distinction between early- and late-onset disease, wrote Joy Wan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors.

“Early-onset, mid-onset, and late-onset AD appear to differ in the presence of active disease over time; however, whether these groups also differ in terms of the severity of AD is unknown,” they wrote.

In this observational cohort study, 8,015 individuals with childhood-onset atopic dermatitis – 53% of whom were female – were assessed twice-yearly for up to 10 years. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the group had early-onset atopic dermatitis – defined as onset before 2 years of age – while 19% had mid-onset disease (3-7 years) and 9% had late-onset disease (8-17 years).

The study found that older age of onset was associated with better control, such that for each additional year of age at the onset of disease, there was a 7% reduction in the odds of poorer control of disease. Those who had mid-onset disease had a 29% lower odds of poorer control compared with those with early-onset, while those with late-onset disease had a 49% lower odds of poorer control.

The likelihood of atopic dermatitis persisting beyond childhood also appeared to be linked to the age of onset. Those with mid-onset disease had a 55% lower odds of persistent atopic dermatitis, compared with those with early-onset disease, while those with late-onset disease had an 81% lower odds.

“In all 3 groups, the proportion of subjects reporting persistent AD generally declined with older age, and the differences among the 3 onset age groups were most pronounced from early adolescence onward,” the authors wrote.

They noted that there was considerable research currently focused on identifying distinct atopic dermatitis phenotypes and endotypes, and their evidence on the different disease course for early-, mid-, and late-onset disease supported this idea of disease subtypes.

“However, additional research is needed to understand whether and how early-, mid-, and late-onset AD differ molecularly or immunologically, and whether they respond differentially to treatment,” they wrote. They also suggested that the timing of onset could help identify patients who were at greater risk of persistent or poorly controlled disease, and who benefits from more intensive monitoring or treatment.

The study was partly supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Dermatology Foundation. Three authors declared funding, consultancies, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wan J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1292-9.

according to a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis most commonly arises in infancy but also can emerge in later childhood and even adolescence, leading to a distinction between early- and late-onset disease, wrote Joy Wan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors.

“Early-onset, mid-onset, and late-onset AD appear to differ in the presence of active disease over time; however, whether these groups also differ in terms of the severity of AD is unknown,” they wrote.

In this observational cohort study, 8,015 individuals with childhood-onset atopic dermatitis – 53% of whom were female – were assessed twice-yearly for up to 10 years. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the group had early-onset atopic dermatitis – defined as onset before 2 years of age – while 19% had mid-onset disease (3-7 years) and 9% had late-onset disease (8-17 years).

The study found that older age of onset was associated with better control, such that for each additional year of age at the onset of disease, there was a 7% reduction in the odds of poorer control of disease. Those who had mid-onset disease had a 29% lower odds of poorer control compared with those with early-onset, while those with late-onset disease had a 49% lower odds of poorer control.

The likelihood of atopic dermatitis persisting beyond childhood also appeared to be linked to the age of onset. Those with mid-onset disease had a 55% lower odds of persistent atopic dermatitis, compared with those with early-onset disease, while those with late-onset disease had an 81% lower odds.

“In all 3 groups, the proportion of subjects reporting persistent AD generally declined with older age, and the differences among the 3 onset age groups were most pronounced from early adolescence onward,” the authors wrote.

They noted that there was considerable research currently focused on identifying distinct atopic dermatitis phenotypes and endotypes, and their evidence on the different disease course for early-, mid-, and late-onset disease supported this idea of disease subtypes.

“However, additional research is needed to understand whether and how early-, mid-, and late-onset AD differ molecularly or immunologically, and whether they respond differentially to treatment,” they wrote. They also suggested that the timing of onset could help identify patients who were at greater risk of persistent or poorly controlled disease, and who benefits from more intensive monitoring or treatment.

The study was partly supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Dermatology Foundation. Three authors declared funding, consultancies, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wan J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1292-9.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Skin barrier dysfunction mutations vary by race, disease persistence in children with AD

Among children with atopic dermatitis, genetic variants associated with skin barrier dysfunction vary significantly by race and by their influence on disease persistence, according to authors of a cohort study.

In the study, which was based on data from a pediatric eczema registry, The investigators remarked on “profound” differences by race in the study, which used a high-throughput sequencing method to identify FLG LoF variants, some of which were common in white children but not so frequently seen in black children.

Conversely, some variants common in black children were completely absent in the white children, according to the investigators, led by David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

These findings imply that any genetic tests developed for AD should be “inclusive,” they wrote, and shouldn’t simply rely on the most common variants associated with patients of European ancestry, namely p.R501*, c.2282del4[p.S761fs], p.S3247*, and p.R2447*.

“Relying on the classic 4 FLG LoF variants would result in approximately 8% of white children and 64% of black children with an FLG LoF variant being improperly classified,” Dr. Margolis and coinvestigators wrote.

Their comprehensive analysis of FLG LoF variants was based on a U.S. cohort of 741 children with mild to moderate AD in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), enrolled from 2005 to 2017. The mean age of onset of AD among the children was almost 2 years. Using massively parallel sequencing, the investigators identified a total of 23 FLG LoF variants in 177 children, or 23.9% of the overall cohort.

White children had a higher frequency of FLG LoF variants, according to the investigators. The prevalence of variants was 31.5% in white and 15.3% in black participants, translating into an odds ratio of 2.44 for carrying any variant in a white versus black child (95% confidence interval, 1.76-3.39).

In previous studies, FLG LoF variants are seen in 25%-30% of people with AD who have European and Asian ancestry; by contrast, they are “uncommonly” exhibited in individuals of African ancestry, the investigators wrote.

Persistent AD was more likely among children with FLG LoF variants, with an odds ratio of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.56-0.80), according to Dr. Margolis and coauthors. However, the black children in this cohort had more persistent disease, compared with white children, regardless of whether they had FLG LoF variants or not.

Exon 3 FLG LoF are known to be the most common variants linked to skin barrier dysfunction, the investigators noted.

“However, all FLG LoF variants might not confer an increased risk of AD, and further, they may not all have the same effect on the persistence of AD over time,” they added in a discussion of their results.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The PEER cohort is funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Margolis reported receiving research funding as the principal investigator via the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, and receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and Valeant; disclosures not related to the study included consulting activities primarily as a member of a data monitoring or scientific advisory boards for several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Margolis DJ et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1011/jamadermatol.2019.1946.

Among children with atopic dermatitis, genetic variants associated with skin barrier dysfunction vary significantly by race and by their influence on disease persistence, according to authors of a cohort study.

In the study, which was based on data from a pediatric eczema registry, The investigators remarked on “profound” differences by race in the study, which used a high-throughput sequencing method to identify FLG LoF variants, some of which were common in white children but not so frequently seen in black children.

Conversely, some variants common in black children were completely absent in the white children, according to the investigators, led by David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

These findings imply that any genetic tests developed for AD should be “inclusive,” they wrote, and shouldn’t simply rely on the most common variants associated with patients of European ancestry, namely p.R501*, c.2282del4[p.S761fs], p.S3247*, and p.R2447*.

“Relying on the classic 4 FLG LoF variants would result in approximately 8% of white children and 64% of black children with an FLG LoF variant being improperly classified,” Dr. Margolis and coinvestigators wrote.

Their comprehensive analysis of FLG LoF variants was based on a U.S. cohort of 741 children with mild to moderate AD in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), enrolled from 2005 to 2017. The mean age of onset of AD among the children was almost 2 years. Using massively parallel sequencing, the investigators identified a total of 23 FLG LoF variants in 177 children, or 23.9% of the overall cohort.

White children had a higher frequency of FLG LoF variants, according to the investigators. The prevalence of variants was 31.5% in white and 15.3% in black participants, translating into an odds ratio of 2.44 for carrying any variant in a white versus black child (95% confidence interval, 1.76-3.39).

In previous studies, FLG LoF variants are seen in 25%-30% of people with AD who have European and Asian ancestry; by contrast, they are “uncommonly” exhibited in individuals of African ancestry, the investigators wrote.

Persistent AD was more likely among children with FLG LoF variants, with an odds ratio of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.56-0.80), according to Dr. Margolis and coauthors. However, the black children in this cohort had more persistent disease, compared with white children, regardless of whether they had FLG LoF variants or not.

Exon 3 FLG LoF are known to be the most common variants linked to skin barrier dysfunction, the investigators noted.

“However, all FLG LoF variants might not confer an increased risk of AD, and further, they may not all have the same effect on the persistence of AD over time,” they added in a discussion of their results.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The PEER cohort is funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Margolis reported receiving research funding as the principal investigator via the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, and receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and Valeant; disclosures not related to the study included consulting activities primarily as a member of a data monitoring or scientific advisory boards for several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Margolis DJ et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1011/jamadermatol.2019.1946.

Among children with atopic dermatitis, genetic variants associated with skin barrier dysfunction vary significantly by race and by their influence on disease persistence, according to authors of a cohort study.

In the study, which was based on data from a pediatric eczema registry, The investigators remarked on “profound” differences by race in the study, which used a high-throughput sequencing method to identify FLG LoF variants, some of which were common in white children but not so frequently seen in black children.

Conversely, some variants common in black children were completely absent in the white children, according to the investigators, led by David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

These findings imply that any genetic tests developed for AD should be “inclusive,” they wrote, and shouldn’t simply rely on the most common variants associated with patients of European ancestry, namely p.R501*, c.2282del4[p.S761fs], p.S3247*, and p.R2447*.

“Relying on the classic 4 FLG LoF variants would result in approximately 8% of white children and 64% of black children with an FLG LoF variant being improperly classified,” Dr. Margolis and coinvestigators wrote.

Their comprehensive analysis of FLG LoF variants was based on a U.S. cohort of 741 children with mild to moderate AD in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), enrolled from 2005 to 2017. The mean age of onset of AD among the children was almost 2 years. Using massively parallel sequencing, the investigators identified a total of 23 FLG LoF variants in 177 children, or 23.9% of the overall cohort.

White children had a higher frequency of FLG LoF variants, according to the investigators. The prevalence of variants was 31.5% in white and 15.3% in black participants, translating into an odds ratio of 2.44 for carrying any variant in a white versus black child (95% confidence interval, 1.76-3.39).

In previous studies, FLG LoF variants are seen in 25%-30% of people with AD who have European and Asian ancestry; by contrast, they are “uncommonly” exhibited in individuals of African ancestry, the investigators wrote.

Persistent AD was more likely among children with FLG LoF variants, with an odds ratio of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.56-0.80), according to Dr. Margolis and coauthors. However, the black children in this cohort had more persistent disease, compared with white children, regardless of whether they had FLG LoF variants or not.

Exon 3 FLG LoF are known to be the most common variants linked to skin barrier dysfunction, the investigators noted.

“However, all FLG LoF variants might not confer an increased risk of AD, and further, they may not all have the same effect on the persistence of AD over time,” they added in a discussion of their results.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The PEER cohort is funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Margolis reported receiving research funding as the principal investigator via the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, and receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and Valeant; disclosures not related to the study included consulting activities primarily as a member of a data monitoring or scientific advisory boards for several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Margolis DJ et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1011/jamadermatol.2019.1946.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Symmetric hair loss across frontal and temporal scalp

The FP referred the patient to a dermatology clinic that specialized in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, physicians at the clinic suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients. Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face, and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan). Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A punch biopsy taken from the leading edge of the hair loss confirms the diagnosis of FFA and, ideally, should be reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring. In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, the following conditions must be ruled out in the differential: alopecia areata, female pattern hair loss, discoid lupus erythematosus, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and traction alopecia.

Early detection is key. In general, physicians should initiate treatment as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses. Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine also may be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.

This patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. She also was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering. These interventions decreased the patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continued to see a dermatologist annually.

This case was adapted from: Power DV, Disse M, Hordinsky M. Progressive hair loss. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:521-523.

The FP referred the patient to a dermatology clinic that specialized in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, physicians at the clinic suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients. Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face, and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan). Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A punch biopsy taken from the leading edge of the hair loss confirms the diagnosis of FFA and, ideally, should be reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring. In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, the following conditions must be ruled out in the differential: alopecia areata, female pattern hair loss, discoid lupus erythematosus, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and traction alopecia.

Early detection is key. In general, physicians should initiate treatment as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses. Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine also may be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.

This patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. She also was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering. These interventions decreased the patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continued to see a dermatologist annually.

This case was adapted from: Power DV, Disse M, Hordinsky M. Progressive hair loss. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:521-523.

The FP referred the patient to a dermatology clinic that specialized in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, physicians at the clinic suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients. Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face, and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan). Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A punch biopsy taken from the leading edge of the hair loss confirms the diagnosis of FFA and, ideally, should be reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring. In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, the following conditions must be ruled out in the differential: alopecia areata, female pattern hair loss, discoid lupus erythematosus, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and traction alopecia.

Early detection is key. In general, physicians should initiate treatment as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses. Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine also may be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.

This patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. She also was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering. These interventions decreased the patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continued to see a dermatologist annually.

This case was adapted from: Power DV, Disse M, Hordinsky M. Progressive hair loss. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:521-523.

Keeping Lesions at Arm’s Length

A 14-year-old boy presents to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic “rash” present on his arms since age 6. The condition has caught the attention of family members and teachers over the years, particularly in regard to possible contagion.

The patient is otherwise reasonably healthy, although he has asthma and seasonal allergies.

EXAMINATION

The "rash" consists of uniformly distributed and sized planar papules. Although they are tiny, averaging only 1 mm wide, they are prominent enough to be noticeable and palpable. They appear slightly lighter than the surrounding skin. Distribution is from the lower deltoid to mid-dorsal forearm, affecting both arms identically. The volar aspects and triceps of both arms are totally spared.

The patient has type IV skin.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is an almost perfect representation of lichen nitidus (LN), in terms of morphology, distribution, and configuration. Close examination of individual lesions revealed that the papules were somewhat planar (ie, flat-topped), giving their surfaces a reflective appearance that the eye interprets as white (particularly contrasted with darker skin).

LN can occur in anyone, but it is most often seen in those with darker skin. It is also frequently seen in children, many of whom are atopic, with dry, sensitive skin that is prone to eczema.

In terms of distribution, LN typically affects the extensor triceps, elbow, and forearms bilaterally. With its flat-topped and shiny appearance, LN is sometimes called "mini-lichen planus"—a condition that can demonstrate similar features. Fortunately, LN is seldom itchy and shares none of the distinct histologic characteristics of lichen planus.

LN is quite unusual, if not rare. It is also idiopathic and nearly always resolves on its own—although this can take months to years.

Emollients help to make the affected skin smoother and less visible. Class 4 steroid creams (eg, triamcinolone 0.05%) can help with itching.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen nitidus (LN) is a rare idiopathic skin condition manifesting with patches of tiny planar papules; it typically affects the elbow and dorsal forearm.

- LN has no pathologic implications and is asymptomatic and self-limited.

- The lesions of LN have a “lichenoid” appearance—ie, a shiny, flat-topped look similar to that seen with lichen planus.

- Fortunately, LN rarely requires treatment, aside from relief of mild itching.

A 14-year-old boy presents to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic “rash” present on his arms since age 6. The condition has caught the attention of family members and teachers over the years, particularly in regard to possible contagion.

The patient is otherwise reasonably healthy, although he has asthma and seasonal allergies.

EXAMINATION

The "rash" consists of uniformly distributed and sized planar papules. Although they are tiny, averaging only 1 mm wide, they are prominent enough to be noticeable and palpable. They appear slightly lighter than the surrounding skin. Distribution is from the lower deltoid to mid-dorsal forearm, affecting both arms identically. The volar aspects and triceps of both arms are totally spared.

The patient has type IV skin.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is an almost perfect representation of lichen nitidus (LN), in terms of morphology, distribution, and configuration. Close examination of individual lesions revealed that the papules were somewhat planar (ie, flat-topped), giving their surfaces a reflective appearance that the eye interprets as white (particularly contrasted with darker skin).

LN can occur in anyone, but it is most often seen in those with darker skin. It is also frequently seen in children, many of whom are atopic, with dry, sensitive skin that is prone to eczema.

In terms of distribution, LN typically affects the extensor triceps, elbow, and forearms bilaterally. With its flat-topped and shiny appearance, LN is sometimes called "mini-lichen planus"—a condition that can demonstrate similar features. Fortunately, LN is seldom itchy and shares none of the distinct histologic characteristics of lichen planus.

LN is quite unusual, if not rare. It is also idiopathic and nearly always resolves on its own—although this can take months to years.

Emollients help to make the affected skin smoother and less visible. Class 4 steroid creams (eg, triamcinolone 0.05%) can help with itching.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen nitidus (LN) is a rare idiopathic skin condition manifesting with patches of tiny planar papules; it typically affects the elbow and dorsal forearm.

- LN has no pathologic implications and is asymptomatic and self-limited.

- The lesions of LN have a “lichenoid” appearance—ie, a shiny, flat-topped look similar to that seen with lichen planus.

- Fortunately, LN rarely requires treatment, aside from relief of mild itching.

A 14-year-old boy presents to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic “rash” present on his arms since age 6. The condition has caught the attention of family members and teachers over the years, particularly in regard to possible contagion.

The patient is otherwise reasonably healthy, although he has asthma and seasonal allergies.

EXAMINATION

The "rash" consists of uniformly distributed and sized planar papules. Although they are tiny, averaging only 1 mm wide, they are prominent enough to be noticeable and palpable. They appear slightly lighter than the surrounding skin. Distribution is from the lower deltoid to mid-dorsal forearm, affecting both arms identically. The volar aspects and triceps of both arms are totally spared.

The patient has type IV skin.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is an almost perfect representation of lichen nitidus (LN), in terms of morphology, distribution, and configuration. Close examination of individual lesions revealed that the papules were somewhat planar (ie, flat-topped), giving their surfaces a reflective appearance that the eye interprets as white (particularly contrasted with darker skin).

LN can occur in anyone, but it is most often seen in those with darker skin. It is also frequently seen in children, many of whom are atopic, with dry, sensitive skin that is prone to eczema.

In terms of distribution, LN typically affects the extensor triceps, elbow, and forearms bilaterally. With its flat-topped and shiny appearance, LN is sometimes called "mini-lichen planus"—a condition that can demonstrate similar features. Fortunately, LN is seldom itchy and shares none of the distinct histologic characteristics of lichen planus.

LN is quite unusual, if not rare. It is also idiopathic and nearly always resolves on its own—although this can take months to years.

Emollients help to make the affected skin smoother and less visible. Class 4 steroid creams (eg, triamcinolone 0.05%) can help with itching.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen nitidus (LN) is a rare idiopathic skin condition manifesting with patches of tiny planar papules; it typically affects the elbow and dorsal forearm.

- LN has no pathologic implications and is asymptomatic and self-limited.

- The lesions of LN have a “lichenoid” appearance—ie, a shiny, flat-topped look similar to that seen with lichen planus.

- Fortunately, LN rarely requires treatment, aside from relief of mild itching.

Firm and tender growth in right nostril

The clinical features were consistent with a filiform wart, which is caused by human papillomavirus and common on the face. Filiform warts may occur on mucosal surfaces, including the nasal mucosa, lips, or eyelids. Most are benign and resolve within 2 years without treatment, but others can be symptomatic. Larger filiform warts may develop the clinical features of a cutaneous horn and mimic a squamous cell carcinoma.

Patients often want the wart removed for functional or cosmetic reasons. Although, there are many treatments available for warts, none have success rates that exceed about 70%. The most common options for treatment include topical salicylic acid in a liquid or plaster, cryotherapy, intralesional immunotherapy with candida antigen, excision, and topical acid.

The location of this patient’s wart limited the treatment options to cryotherapy or snip excision and cautery. The patient opted for cryotherapy. In this process, a hemostat or heavy gauge tweezer is dipped in liquid nitrogen and allowed to cool. Then, without anesthesia, the clinician pinches the lesion gently with the instrument and holds it until the freeze horizon extends to the base. This is then repeated. Each cycle may take 10 and 15 seconds. A benefit of this technique (which is also useful for skin tags and lesions close to the eye) is the ability to avoid overspray of liquid nitrogen and thus, minimize collateral tissue damage. It is also quick and bloodless.