User login

Widespread hyperpigmented plaques

The differential diagnosis included psoriasis, drug eruption, and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A drug eruption could have been due to an over-the-counter medication or supplement, so the lack of improvement from stopping the antihypertensive medication did not rule out this diagnosis. Psoriasis does not always show erythema in persons of color, but these plaques were not typical of psoriasis. (There also were some flat patches that were even less typical of psoriasis.)

The FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on one of the hyperpigmented plaques on the abdomen. A 4-mm punch biopsy is generally an ideal method for determining the cause of an unknown skin rash, and it is usually better to choose a lesion on the upper body rather than below the waist if the rash is widespread. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also prescribed a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment for symptomatic relief as this could help any of the possible diagnoses being considered. The pathology report came back as mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The patient was sent to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and treatment. Mycosis fungoides can have both patches and plaques and frequently involves the trunk more than the extremities (which was the situation in this case). It is important to consider uncommon diagnoses like this in the differential when the initial diagnosis does not appear to be responding to treatment or there is something atypical about the presentation of an expected diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The differential diagnosis included psoriasis, drug eruption, and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A drug eruption could have been due to an over-the-counter medication or supplement, so the lack of improvement from stopping the antihypertensive medication did not rule out this diagnosis. Psoriasis does not always show erythema in persons of color, but these plaques were not typical of psoriasis. (There also were some flat patches that were even less typical of psoriasis.)

The FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on one of the hyperpigmented plaques on the abdomen. A 4-mm punch biopsy is generally an ideal method for determining the cause of an unknown skin rash, and it is usually better to choose a lesion on the upper body rather than below the waist if the rash is widespread. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also prescribed a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment for symptomatic relief as this could help any of the possible diagnoses being considered. The pathology report came back as mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The patient was sent to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and treatment. Mycosis fungoides can have both patches and plaques and frequently involves the trunk more than the extremities (which was the situation in this case). It is important to consider uncommon diagnoses like this in the differential when the initial diagnosis does not appear to be responding to treatment or there is something atypical about the presentation of an expected diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The differential diagnosis included psoriasis, drug eruption, and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A drug eruption could have been due to an over-the-counter medication or supplement, so the lack of improvement from stopping the antihypertensive medication did not rule out this diagnosis. Psoriasis does not always show erythema in persons of color, but these plaques were not typical of psoriasis. (There also were some flat patches that were even less typical of psoriasis.)

The FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on one of the hyperpigmented plaques on the abdomen. A 4-mm punch biopsy is generally an ideal method for determining the cause of an unknown skin rash, and it is usually better to choose a lesion on the upper body rather than below the waist if the rash is widespread. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also prescribed a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment for symptomatic relief as this could help any of the possible diagnoses being considered. The pathology report came back as mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The patient was sent to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and treatment. Mycosis fungoides can have both patches and plaques and frequently involves the trunk more than the extremities (which was the situation in this case). It is important to consider uncommon diagnoses like this in the differential when the initial diagnosis does not appear to be responding to treatment or there is something atypical about the presentation of an expected diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Erythematous swollen ear

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

Failure to thrive in a 6-day-old neonate • intermittent retractions with inspiratory stridor • Dx?

THE CASE

A primiparous mother gave birth to a girl at 38 and 4/7 weeks via uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Prenatal labs were normal. Neonatal physical examination was normal and the child’s birth weight was in the 33rd percentile. APGAR scores were 8 and 9. The neonate was afebrile during hospitalization, with a heart rate of 120 to 150 beats/min and a respiratory rate of 30 to 48 breaths/min. Her preductal and postductal oxygen saturations were 100% and 98%, respectively. She was discharged on Day 2 of life, having lost only 3% of her birth weight.

The patient was seen in clinic on Day 6 of life for a well-child exam and was in the 17th percentile for weight. At another visit for a well-child exam on Day 14 of life, she had not fully regained her birth weight. At both visits, the mother reported no issues with breastfeeding and said she was supplementing with formula. The patient was seen again for follow-up on Days 16 and 21 of life and demonstrated no weight gain despite close follow-up with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which determined the newborn had some breastfeeding issues but seemed to be consuming adequate calories. However, WIC assessments revealed that during feeding, the child was expending too many calories and had nasal congestion. The patient was admitted to the hospital on Day 21 of life with a diagnosis of failure to thrive (FTT), at which point she was in the 12th percentile for weight.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Shortly after the infant was admitted, she showed signs of respiratory distress. On physical examination, the on-call resident noted intermittent retractions with inspiratory stridor, and the patient demonstrated intermittent severe oxygen desaturations into the 70s. She also was sucking her pacifier furiously, which appeared to provide some relief from the respiratory distress. The child’s parents noted that she had demonstrated intermittent periods of respiratory distress since shortly after birth that seemed to be increasing in frequency.

Upon careful examination, the on-call resident identified a cystic lesion at the base of the child’s tongue. The otolaryngologist on call was brought in for an urgent consultation but was unable to visualize the lesion on physical examination and did not recommend further intervention at that time. The patient continued to demonstrate respiratory distress with hypoxia and was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit for close monitoring.

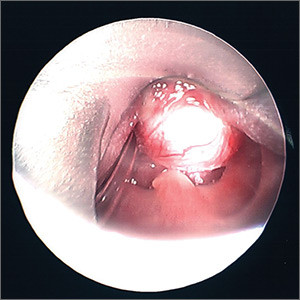

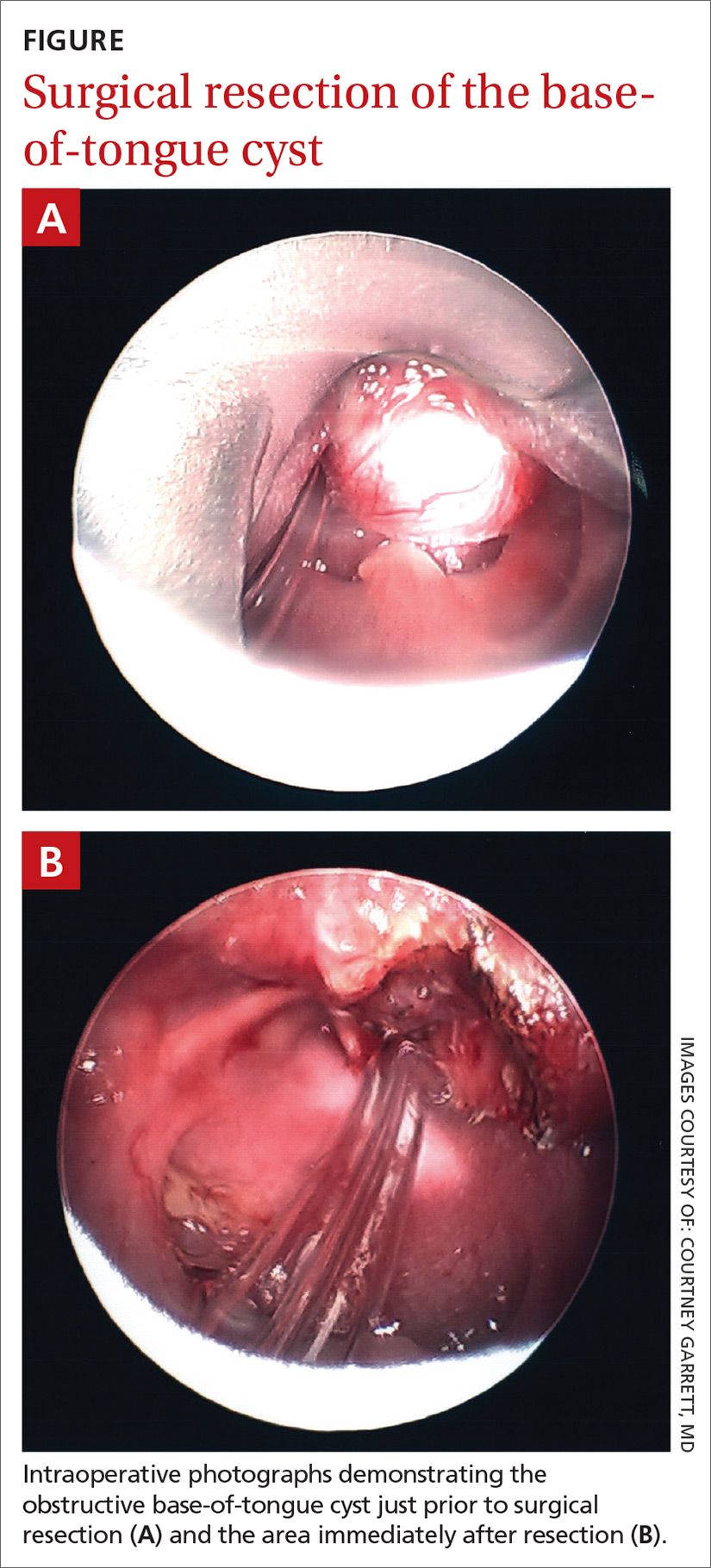

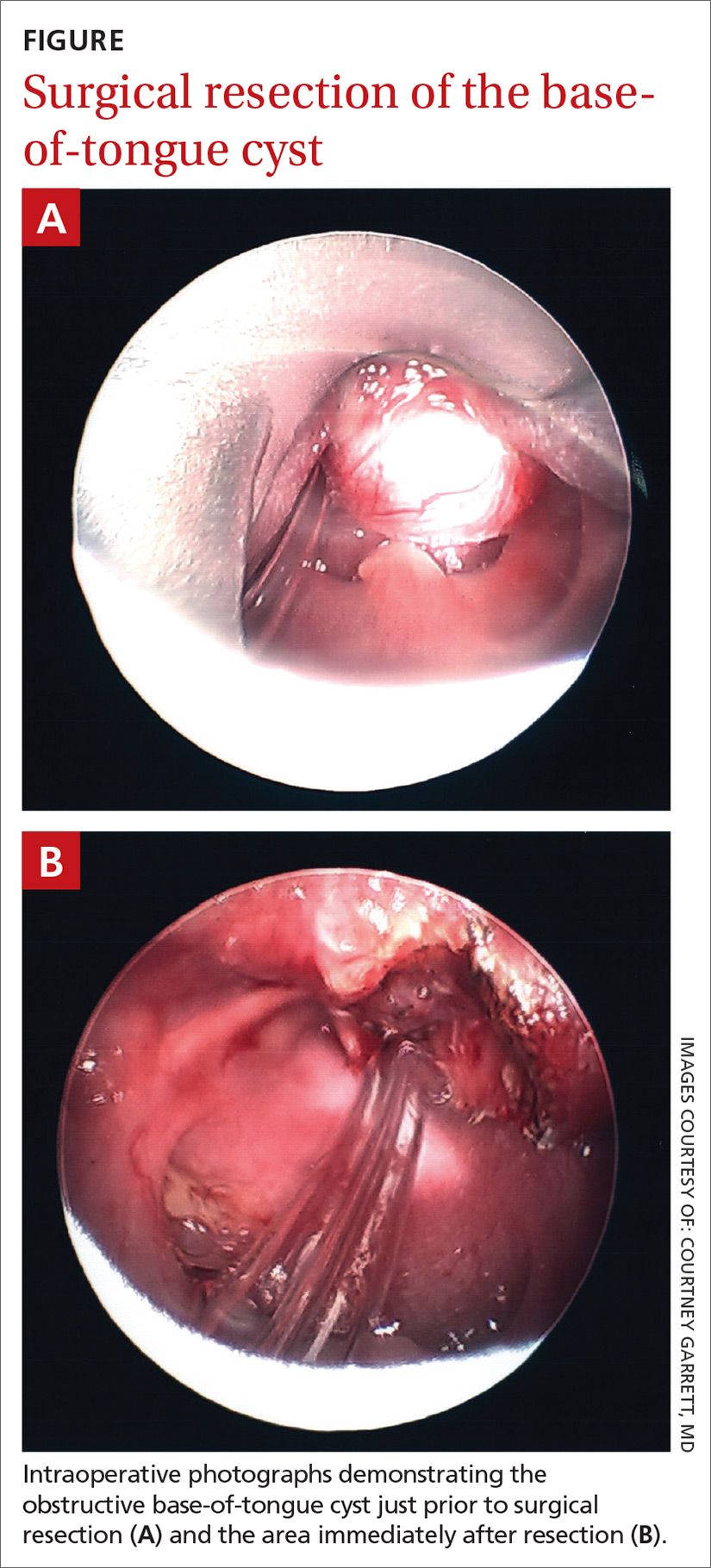

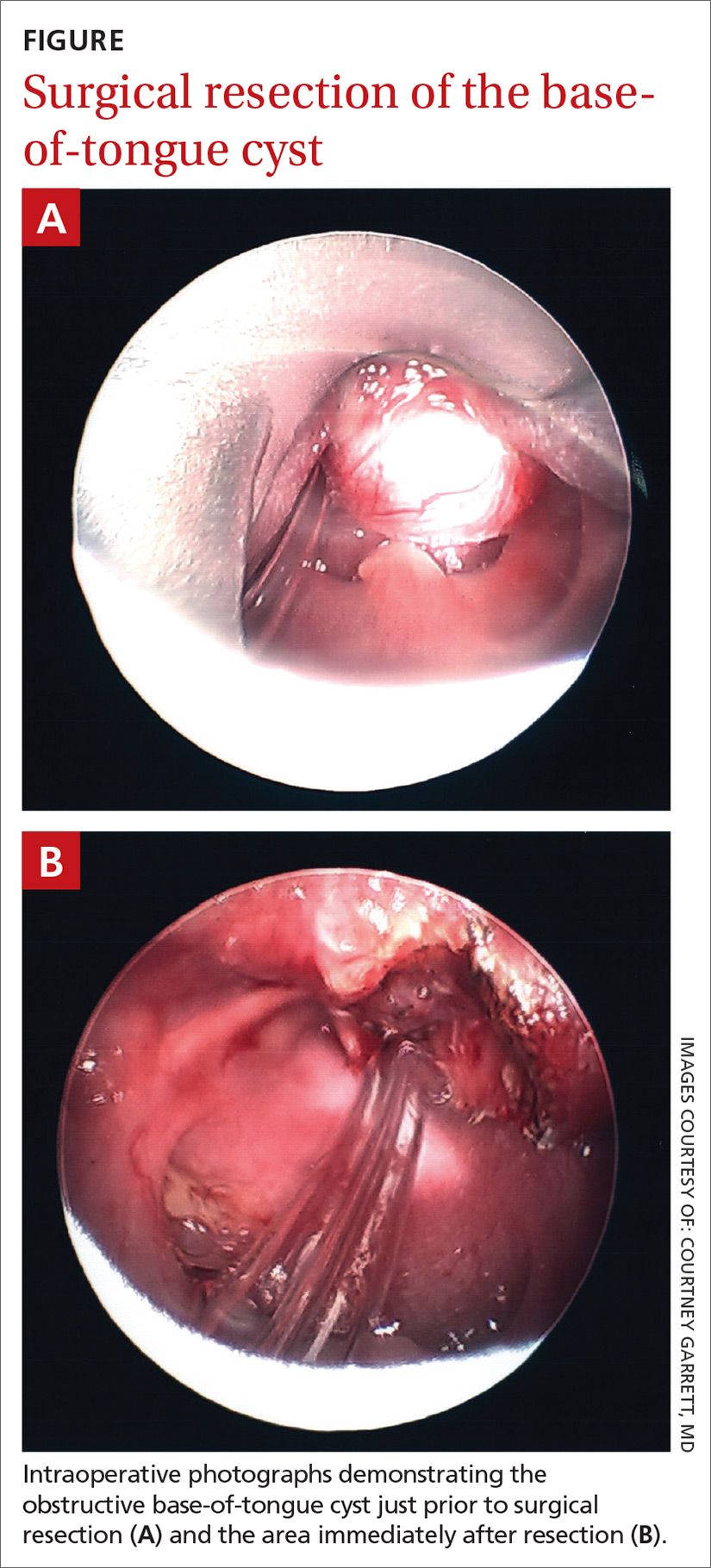

The next morning a second otolaryngology consultation was requested. A computed tomography scan of the neck demonstrated a 1.5-cm cystic-appearing mass at the base of the tongue that was obstructing the patient’s airway. Direct flexible bronchoscopy confirmed the radiographic findings. The patient underwent immediate surgical resection of the lesion using a laser. A clear and milky gray cystic fluid exuded from the cyst when the lesion was pierced. The otolaryngologist visualized a widely patent airway following excision of the lesion (FIGURE).

Pathology results revealed no evidence of malignancy. The final diagnosis was a simple base-of-tongue cyst.

DISCUSSION

Failure to thrive is common in neonates and occurs most often due to inadequate caloric intake; however, it also can be caused by systemic disease associated with inadequate gastrointestinal absorption or increased caloric expenditure, such as congenital heart disease, renal disease (eg, renal tubular acidosis), chronic pulmonary disease (eg, cystic fibrosis), laryngomalacia, malignancy, immunodeficiency, or thyroid disease.1

Continue to: Respiratory distress

Respiratory distress in neonates also is common but tends to occur shortly after birth.2 Conditions associated with respiratory distress in neonates include transient tachypnea of the newborn, respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, pneumonia, and meconium aspiration syndrome.2 Interestingly, there are additional reports in the literature of FTT and respiratory distress in neonat

Base-of-tongue cysts are rare in infants. Fewer than 50 cases were reported prior to 2011, with many being described as asymptomatic nonpainful lesions.6 Given the anatomic location of base-of-tongue cysts, the differential diagnosis should also include mucoceles, thyroglossal duct cysts, dermoid cysts, epidermoid cysts, vallecular cysts, hemangiomas, cystic hygromas, lymphangiomas, thyroid remnant cysts, teratomas, and hamartomas.4,7,8 When tongue cysts are initially discovered, inspiratory stridor, FTT, swallowing deficits, oxygen desaturation, respiratory failure, and/or acute life-threatening events have been reported.6,9,10

One important clinical observation made in our case was the use of an external apparatus to relieve the neonate’s respiratory distress. During physical examination, the on-call resident noted the patient was furiously sucking her pacifier, which seemed to reduce the respiratory difficulty and desaturations. It is known that non-nutritive sucking (NNS) can provide provisions for stress relief, improve oxygenation, and provide proprioceptive positioning of key anatomical structures within the oral cavity.11 Without the use of an external apparatus like a pacifier during restful states, neonates may develop vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome, in which the dorsum of the tongue and the soft palate adhere to the posterior pharyngeal wall and obstruct the airway.12 Our patient may have used the pacifier as an NNS task to move the tongue forward and break the glossoptosis-pharyngeal seal by sucking hard and fast during periods of respiratory distress, which reduced the potential for a vacuum-glossoptosis phenomenon that was likely created by the cyst during restful states.

Our patient was seen in clinic for follow-up after surgery on Day 35 of life. She was thriving and her weight was in the 24th percentile. She was seen again on Day 67 of life for a well-child exam and was in the 43rd percentile for weight.

THE TAKEAWAY

There is a sizeable list of possible diagnoses to consider when a neonate presents with FTT and respiratory distress. It is important to consider mechanical obstruction as a possible diagnosis and one which, if identified early, may be lifesaving. Our case demonstrates a proposed mechanism by which a mechanical obstruction such as a base-of-tongue cyst can cause the vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome; it also highlights NNS as a potential means of overcoming this phenomenon.

CORRESPONDENCE

Benjamin P. Hansen, MD, Renown Medical Group, 4796 Caughlin Pkwy, Ste 108, Reno, NV 89519; [email protected]

1. Larson-Nath C, Biank VF. Clinical review of failure to thrive in pediatric patients. Pediatr Ann. 2016;45:e46-e49.

2. Edwards MO, Kotecha SJ, Kotecha S. Respiratory distress of the term newborn infant. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2013;14:29-37.

3. Brennan T, Rastatter JC. Multilevel airway obstruction including rare tongue base mass presenting as severe croup in an infant. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:128-129.

4. Gutiérrez JP, Berkowitz RG, Robertson CF. Vallecular cysts in newborns and young infants. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;27:282-285.

5. Wong KS, Huang YH, Wu CT. A vanishing tongue-base cyst. Turk J Pediatr. 2007;49:451-452.

6. Aubin A, Lescanne E, Pondaven S, et al. Stridor and lingual thyroglossal duct cyst in a newborn. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:321-323.

7. Hur JH, Byun JS, Kim JK, et al. Mucocele in the base of the tongue mimicking a thyroglossal duct cyst: a very rare location. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13:4-7.

8. Tárrega ER, Rojas SF, Portero RG, et al. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of a cyst of the oral cavity: an unusual case of thyroglossal duct cyst located on the tongue base [published online January 21, 2016]. 2016;2016:7816306.

9. Parelkar SV, Patel JL, Sanghvi BV, et al. An unusual presentation of vallecular cyst with near fatal respiratory distress and management using conventional laparoscopic instruments. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2012;4:118-120.

10. Sands NB, Anand SM, Manoukian JJ. Series of congenital vallecular cysts: a rare yet potentially fatal cause of upper airway obstruction and failure to thrive in the newborn. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38:6-10.

11. Pinelli J, Symington A. Non-nutritive sucking for promoting physiologic stability and nutrition in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005. 2010;4:CD001071.

12. Cozzi F, Albani R, Cardi E. A common pathophysiology for sudden cot death and sleep apnoea. “the vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome.” Med Hypotheses. 1979;5:329-338.

THE CASE

A primiparous mother gave birth to a girl at 38 and 4/7 weeks via uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Prenatal labs were normal. Neonatal physical examination was normal and the child’s birth weight was in the 33rd percentile. APGAR scores were 8 and 9. The neonate was afebrile during hospitalization, with a heart rate of 120 to 150 beats/min and a respiratory rate of 30 to 48 breaths/min. Her preductal and postductal oxygen saturations were 100% and 98%, respectively. She was discharged on Day 2 of life, having lost only 3% of her birth weight.

The patient was seen in clinic on Day 6 of life for a well-child exam and was in the 17th percentile for weight. At another visit for a well-child exam on Day 14 of life, she had not fully regained her birth weight. At both visits, the mother reported no issues with breastfeeding and said she was supplementing with formula. The patient was seen again for follow-up on Days 16 and 21 of life and demonstrated no weight gain despite close follow-up with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which determined the newborn had some breastfeeding issues but seemed to be consuming adequate calories. However, WIC assessments revealed that during feeding, the child was expending too many calories and had nasal congestion. The patient was admitted to the hospital on Day 21 of life with a diagnosis of failure to thrive (FTT), at which point she was in the 12th percentile for weight.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Shortly after the infant was admitted, she showed signs of respiratory distress. On physical examination, the on-call resident noted intermittent retractions with inspiratory stridor, and the patient demonstrated intermittent severe oxygen desaturations into the 70s. She also was sucking her pacifier furiously, which appeared to provide some relief from the respiratory distress. The child’s parents noted that she had demonstrated intermittent periods of respiratory distress since shortly after birth that seemed to be increasing in frequency.

Upon careful examination, the on-call resident identified a cystic lesion at the base of the child’s tongue. The otolaryngologist on call was brought in for an urgent consultation but was unable to visualize the lesion on physical examination and did not recommend further intervention at that time. The patient continued to demonstrate respiratory distress with hypoxia and was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit for close monitoring.

The next morning a second otolaryngology consultation was requested. A computed tomography scan of the neck demonstrated a 1.5-cm cystic-appearing mass at the base of the tongue that was obstructing the patient’s airway. Direct flexible bronchoscopy confirmed the radiographic findings. The patient underwent immediate surgical resection of the lesion using a laser. A clear and milky gray cystic fluid exuded from the cyst when the lesion was pierced. The otolaryngologist visualized a widely patent airway following excision of the lesion (FIGURE).

Pathology results revealed no evidence of malignancy. The final diagnosis was a simple base-of-tongue cyst.

DISCUSSION

Failure to thrive is common in neonates and occurs most often due to inadequate caloric intake; however, it also can be caused by systemic disease associated with inadequate gastrointestinal absorption or increased caloric expenditure, such as congenital heart disease, renal disease (eg, renal tubular acidosis), chronic pulmonary disease (eg, cystic fibrosis), laryngomalacia, malignancy, immunodeficiency, or thyroid disease.1

Continue to: Respiratory distress

Respiratory distress in neonates also is common but tends to occur shortly after birth.2 Conditions associated with respiratory distress in neonates include transient tachypnea of the newborn, respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, pneumonia, and meconium aspiration syndrome.2 Interestingly, there are additional reports in the literature of FTT and respiratory distress in neonat

Base-of-tongue cysts are rare in infants. Fewer than 50 cases were reported prior to 2011, with many being described as asymptomatic nonpainful lesions.6 Given the anatomic location of base-of-tongue cysts, the differential diagnosis should also include mucoceles, thyroglossal duct cysts, dermoid cysts, epidermoid cysts, vallecular cysts, hemangiomas, cystic hygromas, lymphangiomas, thyroid remnant cysts, teratomas, and hamartomas.4,7,8 When tongue cysts are initially discovered, inspiratory stridor, FTT, swallowing deficits, oxygen desaturation, respiratory failure, and/or acute life-threatening events have been reported.6,9,10

One important clinical observation made in our case was the use of an external apparatus to relieve the neonate’s respiratory distress. During physical examination, the on-call resident noted the patient was furiously sucking her pacifier, which seemed to reduce the respiratory difficulty and desaturations. It is known that non-nutritive sucking (NNS) can provide provisions for stress relief, improve oxygenation, and provide proprioceptive positioning of key anatomical structures within the oral cavity.11 Without the use of an external apparatus like a pacifier during restful states, neonates may develop vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome, in which the dorsum of the tongue and the soft palate adhere to the posterior pharyngeal wall and obstruct the airway.12 Our patient may have used the pacifier as an NNS task to move the tongue forward and break the glossoptosis-pharyngeal seal by sucking hard and fast during periods of respiratory distress, which reduced the potential for a vacuum-glossoptosis phenomenon that was likely created by the cyst during restful states.

Our patient was seen in clinic for follow-up after surgery on Day 35 of life. She was thriving and her weight was in the 24th percentile. She was seen again on Day 67 of life for a well-child exam and was in the 43rd percentile for weight.

THE TAKEAWAY

There is a sizeable list of possible diagnoses to consider when a neonate presents with FTT and respiratory distress. It is important to consider mechanical obstruction as a possible diagnosis and one which, if identified early, may be lifesaving. Our case demonstrates a proposed mechanism by which a mechanical obstruction such as a base-of-tongue cyst can cause the vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome; it also highlights NNS as a potential means of overcoming this phenomenon.

CORRESPONDENCE

Benjamin P. Hansen, MD, Renown Medical Group, 4796 Caughlin Pkwy, Ste 108, Reno, NV 89519; [email protected]

THE CASE

A primiparous mother gave birth to a girl at 38 and 4/7 weeks via uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Prenatal labs were normal. Neonatal physical examination was normal and the child’s birth weight was in the 33rd percentile. APGAR scores were 8 and 9. The neonate was afebrile during hospitalization, with a heart rate of 120 to 150 beats/min and a respiratory rate of 30 to 48 breaths/min. Her preductal and postductal oxygen saturations were 100% and 98%, respectively. She was discharged on Day 2 of life, having lost only 3% of her birth weight.

The patient was seen in clinic on Day 6 of life for a well-child exam and was in the 17th percentile for weight. At another visit for a well-child exam on Day 14 of life, she had not fully regained her birth weight. At both visits, the mother reported no issues with breastfeeding and said she was supplementing with formula. The patient was seen again for follow-up on Days 16 and 21 of life and demonstrated no weight gain despite close follow-up with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which determined the newborn had some breastfeeding issues but seemed to be consuming adequate calories. However, WIC assessments revealed that during feeding, the child was expending too many calories and had nasal congestion. The patient was admitted to the hospital on Day 21 of life with a diagnosis of failure to thrive (FTT), at which point she was in the 12th percentile for weight.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Shortly after the infant was admitted, she showed signs of respiratory distress. On physical examination, the on-call resident noted intermittent retractions with inspiratory stridor, and the patient demonstrated intermittent severe oxygen desaturations into the 70s. She also was sucking her pacifier furiously, which appeared to provide some relief from the respiratory distress. The child’s parents noted that she had demonstrated intermittent periods of respiratory distress since shortly after birth that seemed to be increasing in frequency.

Upon careful examination, the on-call resident identified a cystic lesion at the base of the child’s tongue. The otolaryngologist on call was brought in for an urgent consultation but was unable to visualize the lesion on physical examination and did not recommend further intervention at that time. The patient continued to demonstrate respiratory distress with hypoxia and was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit for close monitoring.

The next morning a second otolaryngology consultation was requested. A computed tomography scan of the neck demonstrated a 1.5-cm cystic-appearing mass at the base of the tongue that was obstructing the patient’s airway. Direct flexible bronchoscopy confirmed the radiographic findings. The patient underwent immediate surgical resection of the lesion using a laser. A clear and milky gray cystic fluid exuded from the cyst when the lesion was pierced. The otolaryngologist visualized a widely patent airway following excision of the lesion (FIGURE).

Pathology results revealed no evidence of malignancy. The final diagnosis was a simple base-of-tongue cyst.

DISCUSSION

Failure to thrive is common in neonates and occurs most often due to inadequate caloric intake; however, it also can be caused by systemic disease associated with inadequate gastrointestinal absorption or increased caloric expenditure, such as congenital heart disease, renal disease (eg, renal tubular acidosis), chronic pulmonary disease (eg, cystic fibrosis), laryngomalacia, malignancy, immunodeficiency, or thyroid disease.1

Continue to: Respiratory distress

Respiratory distress in neonates also is common but tends to occur shortly after birth.2 Conditions associated with respiratory distress in neonates include transient tachypnea of the newborn, respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, pneumonia, and meconium aspiration syndrome.2 Interestingly, there are additional reports in the literature of FTT and respiratory distress in neonat

Base-of-tongue cysts are rare in infants. Fewer than 50 cases were reported prior to 2011, with many being described as asymptomatic nonpainful lesions.6 Given the anatomic location of base-of-tongue cysts, the differential diagnosis should also include mucoceles, thyroglossal duct cysts, dermoid cysts, epidermoid cysts, vallecular cysts, hemangiomas, cystic hygromas, lymphangiomas, thyroid remnant cysts, teratomas, and hamartomas.4,7,8 When tongue cysts are initially discovered, inspiratory stridor, FTT, swallowing deficits, oxygen desaturation, respiratory failure, and/or acute life-threatening events have been reported.6,9,10

One important clinical observation made in our case was the use of an external apparatus to relieve the neonate’s respiratory distress. During physical examination, the on-call resident noted the patient was furiously sucking her pacifier, which seemed to reduce the respiratory difficulty and desaturations. It is known that non-nutritive sucking (NNS) can provide provisions for stress relief, improve oxygenation, and provide proprioceptive positioning of key anatomical structures within the oral cavity.11 Without the use of an external apparatus like a pacifier during restful states, neonates may develop vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome, in which the dorsum of the tongue and the soft palate adhere to the posterior pharyngeal wall and obstruct the airway.12 Our patient may have used the pacifier as an NNS task to move the tongue forward and break the glossoptosis-pharyngeal seal by sucking hard and fast during periods of respiratory distress, which reduced the potential for a vacuum-glossoptosis phenomenon that was likely created by the cyst during restful states.

Our patient was seen in clinic for follow-up after surgery on Day 35 of life. She was thriving and her weight was in the 24th percentile. She was seen again on Day 67 of life for a well-child exam and was in the 43rd percentile for weight.

THE TAKEAWAY

There is a sizeable list of possible diagnoses to consider when a neonate presents with FTT and respiratory distress. It is important to consider mechanical obstruction as a possible diagnosis and one which, if identified early, may be lifesaving. Our case demonstrates a proposed mechanism by which a mechanical obstruction such as a base-of-tongue cyst can cause the vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome; it also highlights NNS as a potential means of overcoming this phenomenon.

CORRESPONDENCE

Benjamin P. Hansen, MD, Renown Medical Group, 4796 Caughlin Pkwy, Ste 108, Reno, NV 89519; [email protected]

1. Larson-Nath C, Biank VF. Clinical review of failure to thrive in pediatric patients. Pediatr Ann. 2016;45:e46-e49.

2. Edwards MO, Kotecha SJ, Kotecha S. Respiratory distress of the term newborn infant. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2013;14:29-37.

3. Brennan T, Rastatter JC. Multilevel airway obstruction including rare tongue base mass presenting as severe croup in an infant. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:128-129.

4. Gutiérrez JP, Berkowitz RG, Robertson CF. Vallecular cysts in newborns and young infants. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;27:282-285.

5. Wong KS, Huang YH, Wu CT. A vanishing tongue-base cyst. Turk J Pediatr. 2007;49:451-452.

6. Aubin A, Lescanne E, Pondaven S, et al. Stridor and lingual thyroglossal duct cyst in a newborn. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:321-323.

7. Hur JH, Byun JS, Kim JK, et al. Mucocele in the base of the tongue mimicking a thyroglossal duct cyst: a very rare location. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13:4-7.

8. Tárrega ER, Rojas SF, Portero RG, et al. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of a cyst of the oral cavity: an unusual case of thyroglossal duct cyst located on the tongue base [published online January 21, 2016]. 2016;2016:7816306.

9. Parelkar SV, Patel JL, Sanghvi BV, et al. An unusual presentation of vallecular cyst with near fatal respiratory distress and management using conventional laparoscopic instruments. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2012;4:118-120.

10. Sands NB, Anand SM, Manoukian JJ. Series of congenital vallecular cysts: a rare yet potentially fatal cause of upper airway obstruction and failure to thrive in the newborn. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38:6-10.

11. Pinelli J, Symington A. Non-nutritive sucking for promoting physiologic stability and nutrition in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005. 2010;4:CD001071.

12. Cozzi F, Albani R, Cardi E. A common pathophysiology for sudden cot death and sleep apnoea. “the vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome.” Med Hypotheses. 1979;5:329-338.

1. Larson-Nath C, Biank VF. Clinical review of failure to thrive in pediatric patients. Pediatr Ann. 2016;45:e46-e49.

2. Edwards MO, Kotecha SJ, Kotecha S. Respiratory distress of the term newborn infant. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2013;14:29-37.

3. Brennan T, Rastatter JC. Multilevel airway obstruction including rare tongue base mass presenting as severe croup in an infant. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:128-129.

4. Gutiérrez JP, Berkowitz RG, Robertson CF. Vallecular cysts in newborns and young infants. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;27:282-285.

5. Wong KS, Huang YH, Wu CT. A vanishing tongue-base cyst. Turk J Pediatr. 2007;49:451-452.

6. Aubin A, Lescanne E, Pondaven S, et al. Stridor and lingual thyroglossal duct cyst in a newborn. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:321-323.

7. Hur JH, Byun JS, Kim JK, et al. Mucocele in the base of the tongue mimicking a thyroglossal duct cyst: a very rare location. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13:4-7.

8. Tárrega ER, Rojas SF, Portero RG, et al. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of a cyst of the oral cavity: an unusual case of thyroglossal duct cyst located on the tongue base [published online January 21, 2016]. 2016;2016:7816306.

9. Parelkar SV, Patel JL, Sanghvi BV, et al. An unusual presentation of vallecular cyst with near fatal respiratory distress and management using conventional laparoscopic instruments. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2012;4:118-120.

10. Sands NB, Anand SM, Manoukian JJ. Series of congenital vallecular cysts: a rare yet potentially fatal cause of upper airway obstruction and failure to thrive in the newborn. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38:6-10.

11. Pinelli J, Symington A. Non-nutritive sucking for promoting physiologic stability and nutrition in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005. 2010;4:CD001071.

12. Cozzi F, Albani R, Cardi E. A common pathophysiology for sudden cot death and sleep apnoea. “the vacuum-glossoptosis syndrome.” Med Hypotheses. 1979;5:329-338.

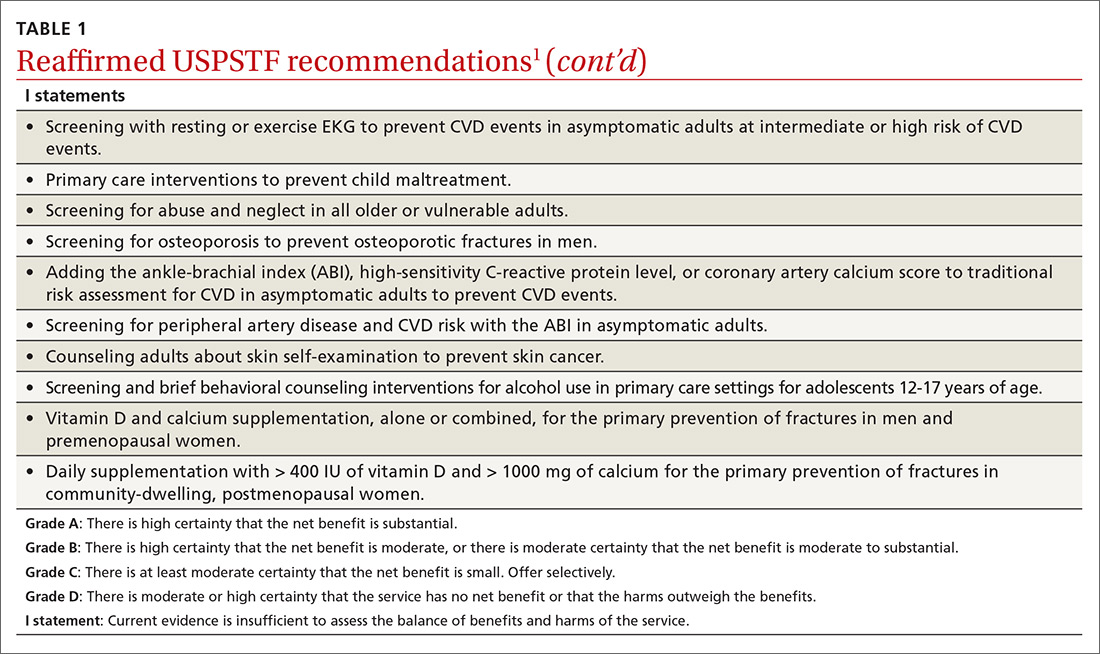

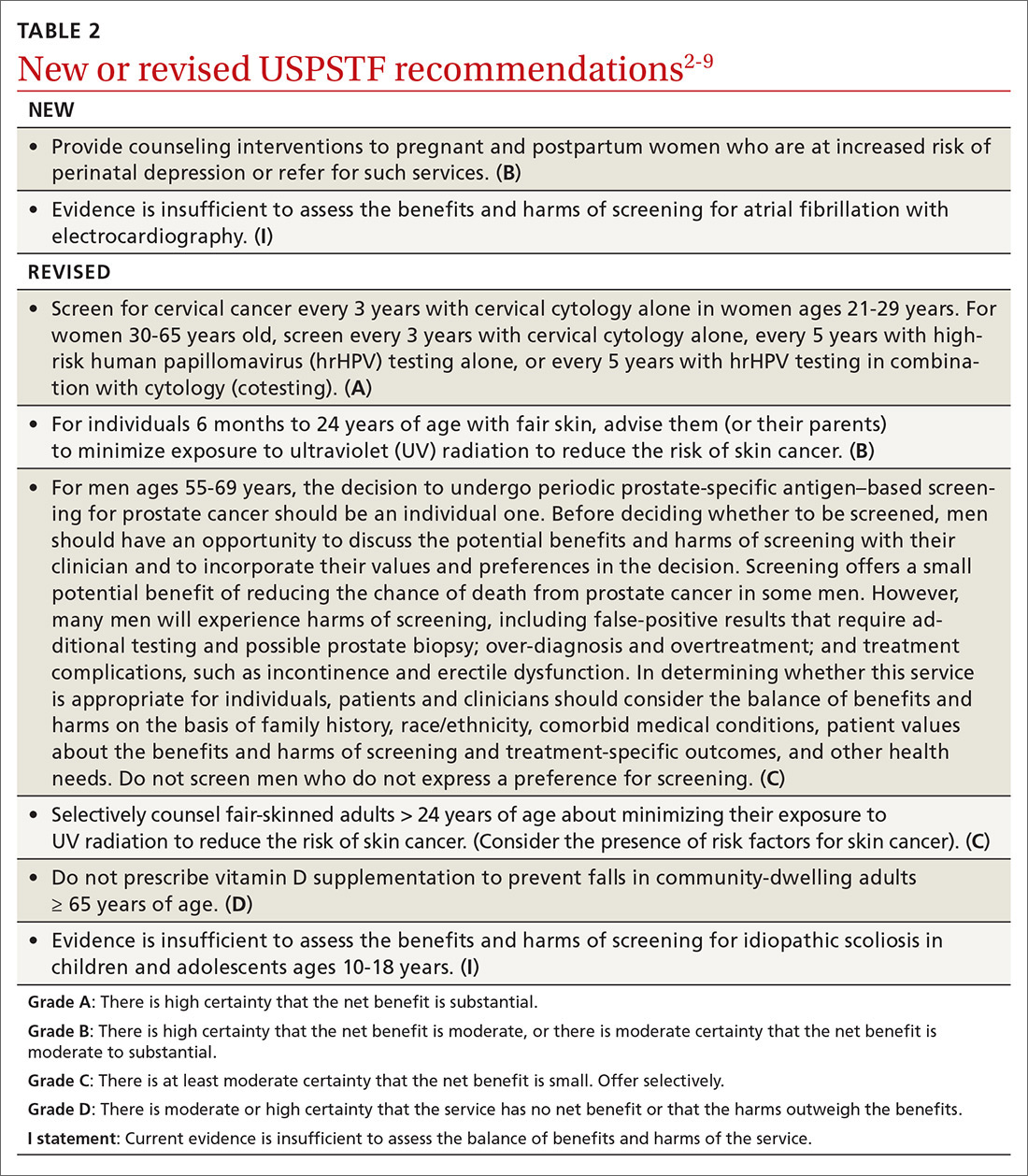

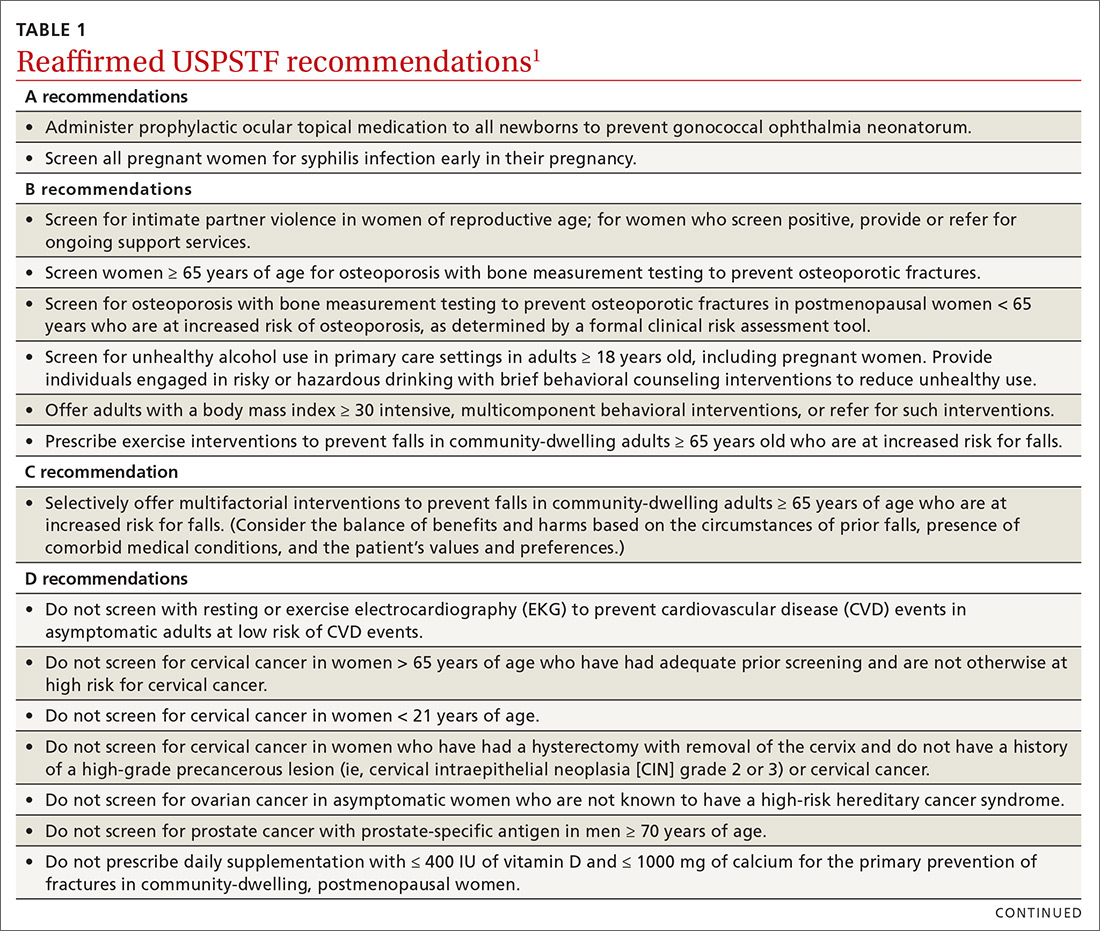

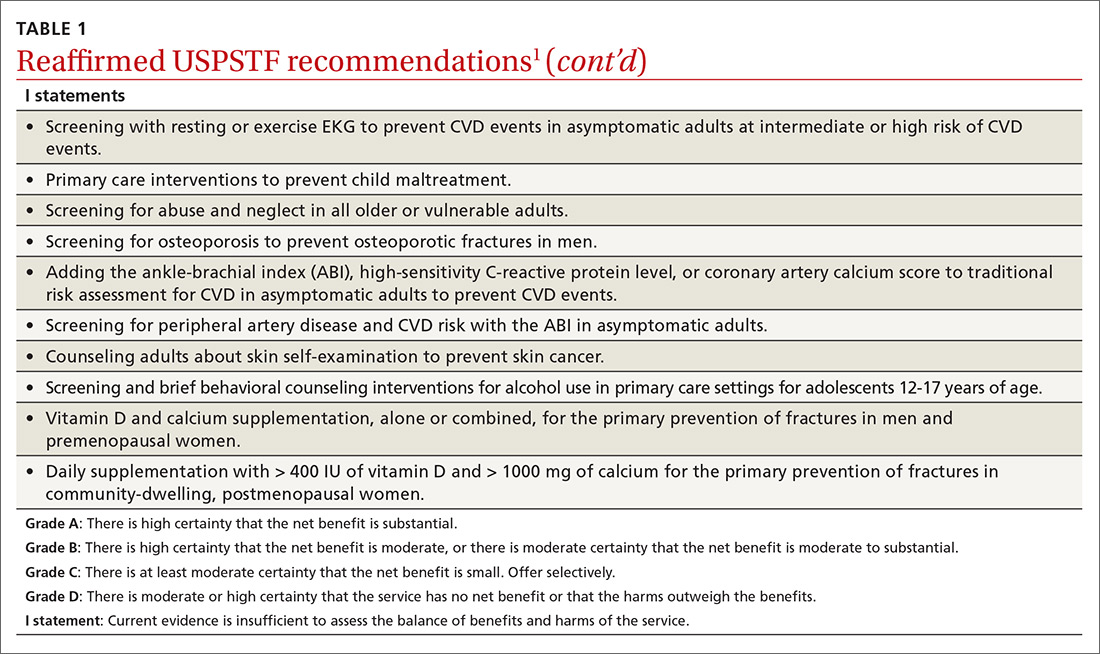

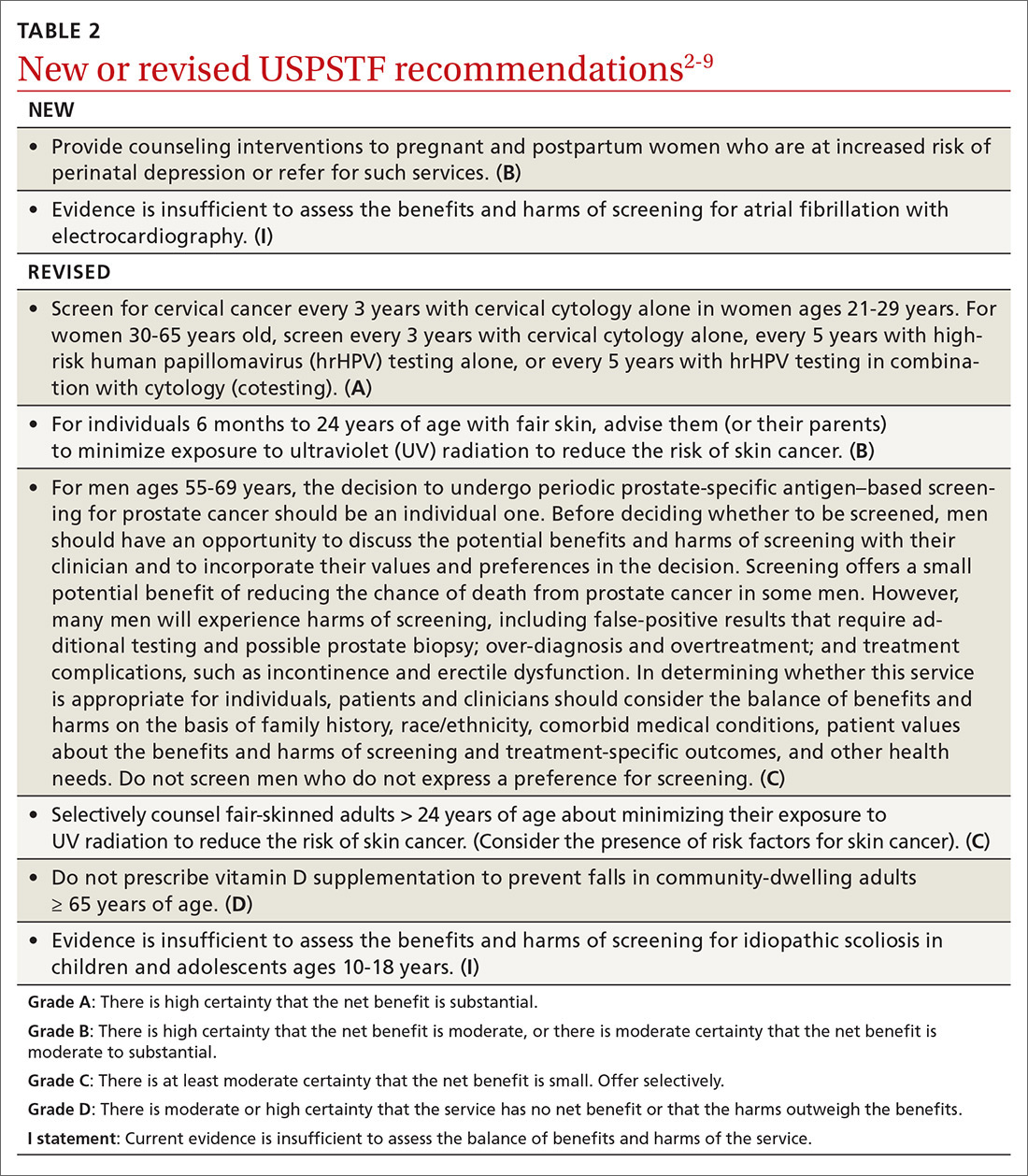

2019 USPSTF update

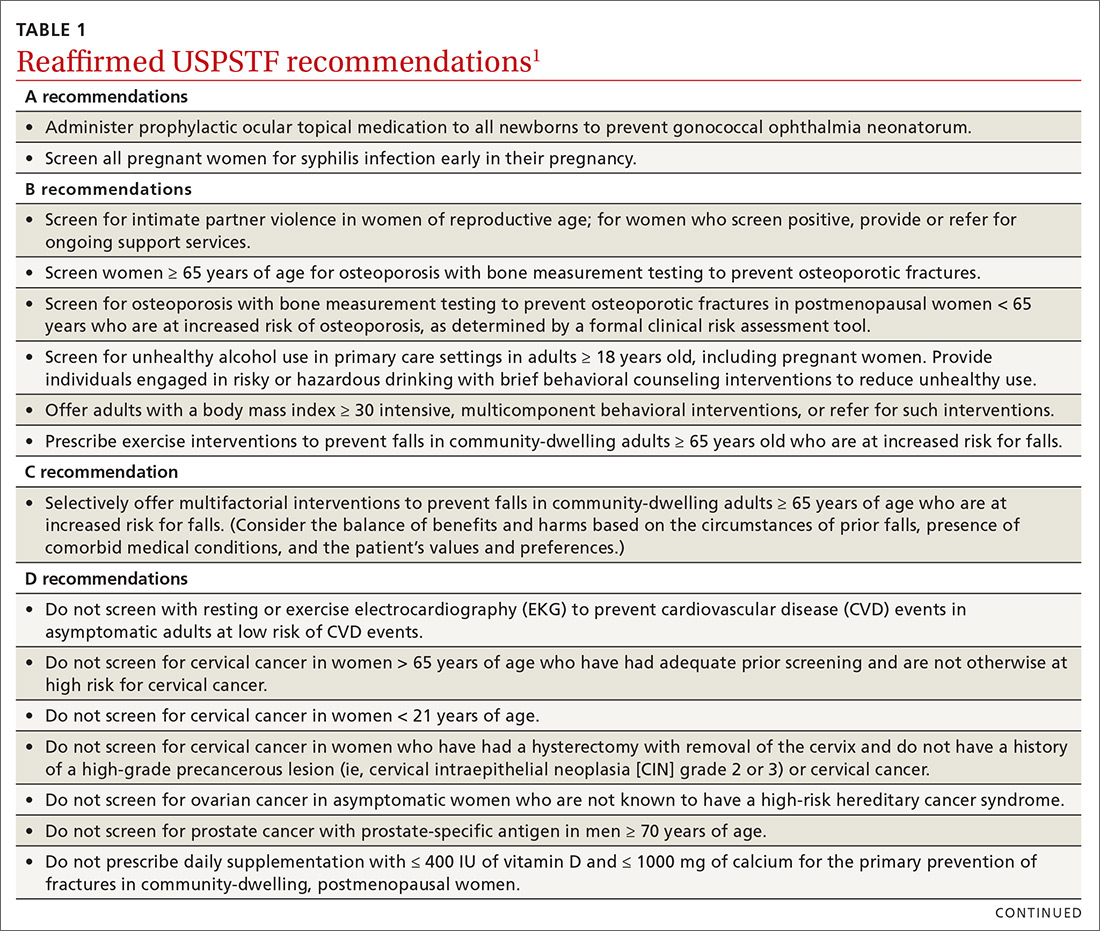

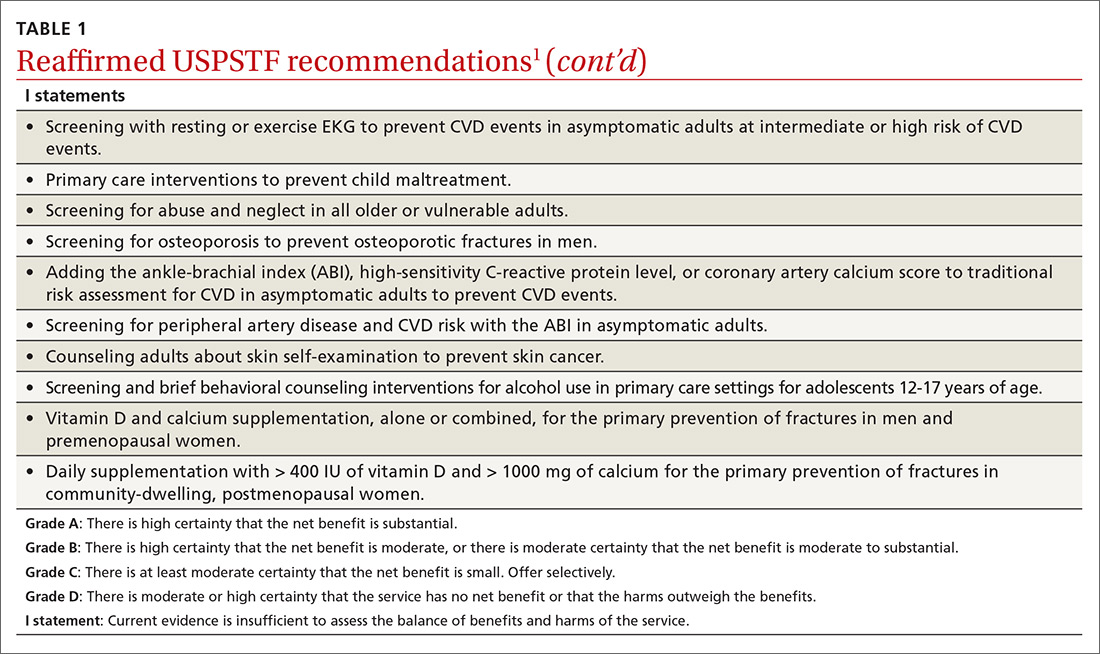

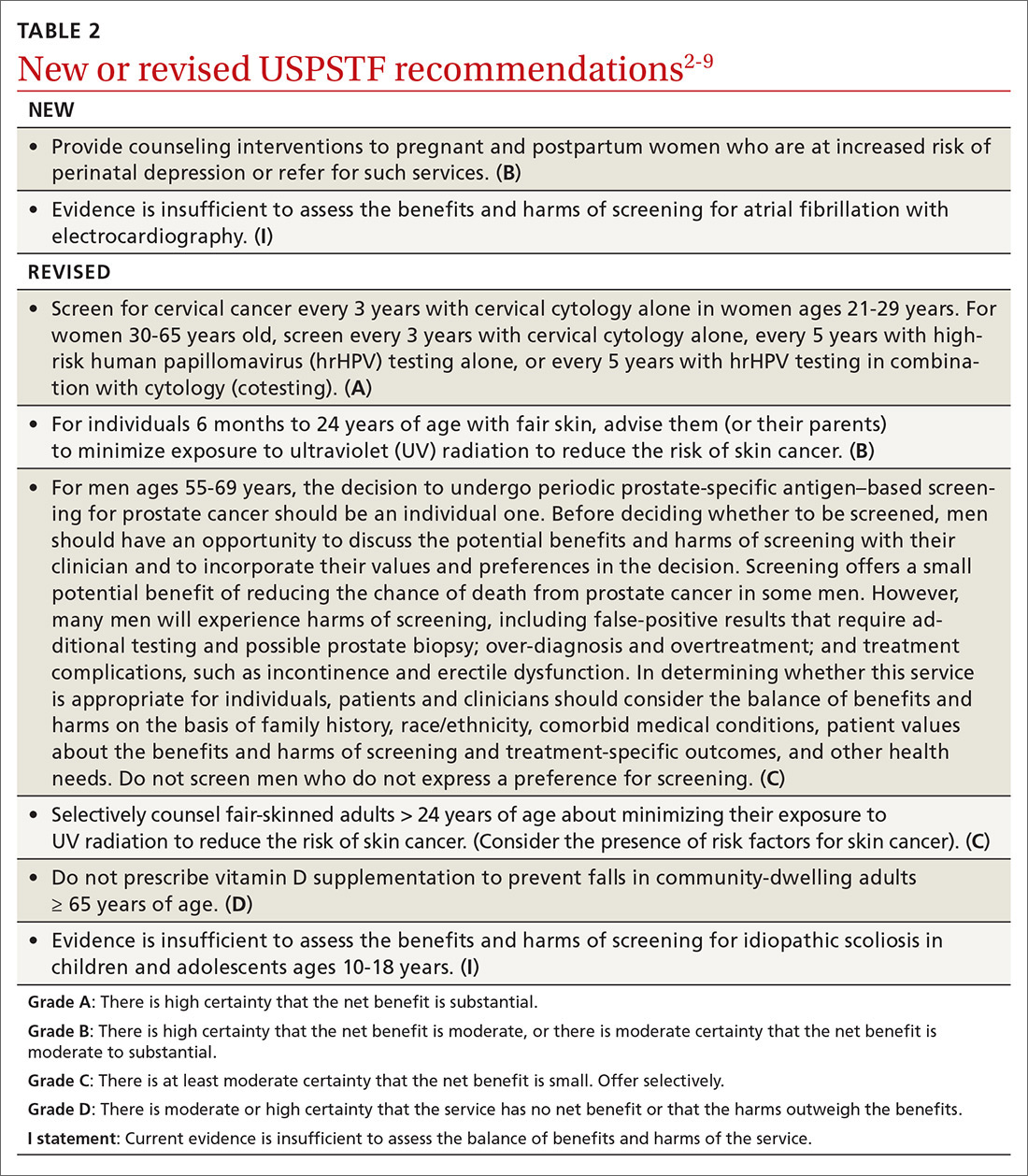

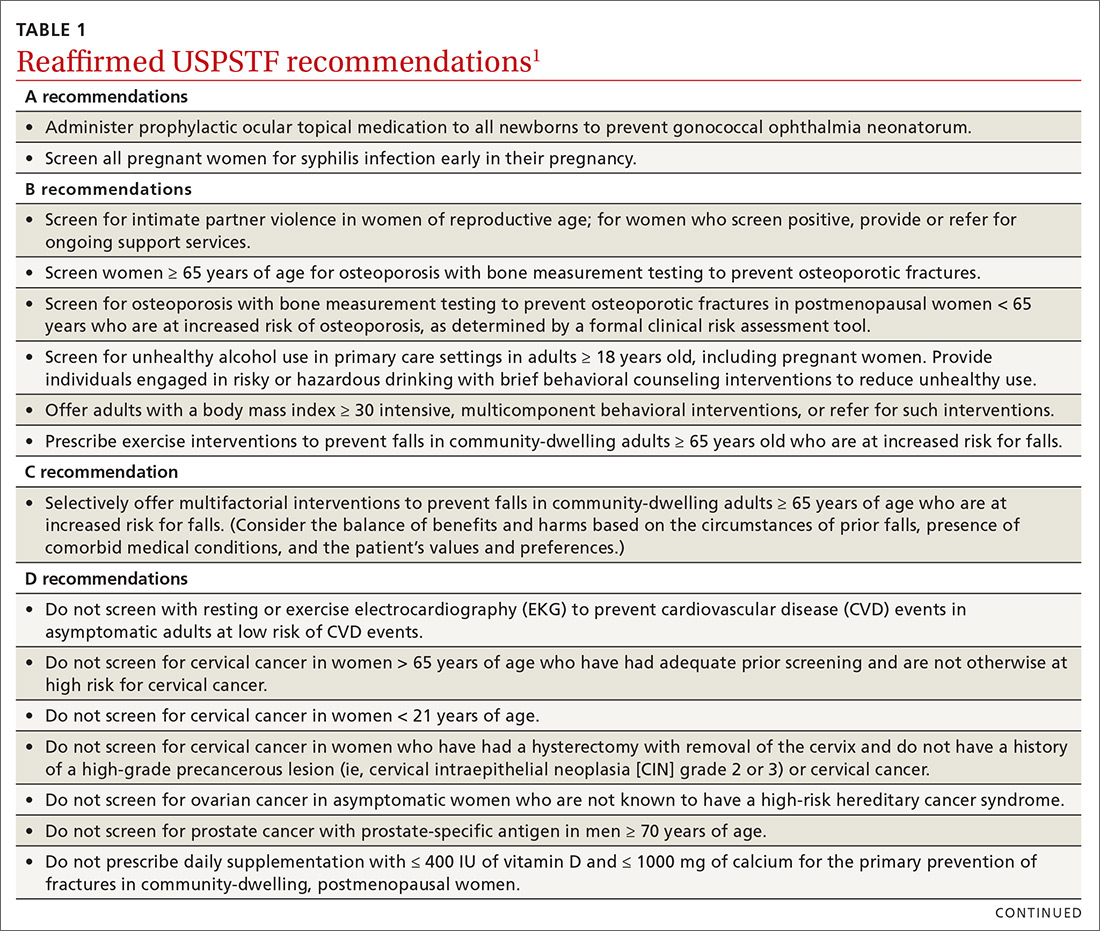

Over the past year through early 2019, the US Preventive Services Task Force made 34 recommendations on 19 different topics. Twenty-six were reaffirmations of recommendations made in previous years (TABLE 11); the Task Force attempts to reassess topics every 7 years. Two new topics were addressed with 2 new recommendations, and 6 previous recommendations were revised or reversed (TABLE 22-9).

This Practice Alert discusses the new and the changed recommendations. (In 2018, the Practice Alert podcast series covered screening for ovarian cancer [April], prostate cancer [June], and cervical cancer [October], and EKG screening for cardiovascular disease [November].) All current Task Force recommendations are available on the USPSTF Web site.1

New topics

Perinatal depression prevention

The Task Force recommends that clinicians counsel pregnant women and women in the first year postpartum who are at increased risk for perinatal depression, or refer for such services. The recommendation applies to those who are not diagnosed with depression but are at increased risk.

Perinatal depression can negatively affect both mother and child in several ways and occurs at a rate close to 9% during pregnancy and 37% during the first year postpartum.2 The interventions studied by the Task Force included cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy; most sessions were initiated in the second trimester of pregnancy and varied in number of sessions and intensity. The Task Force includes the following in the list of risks that should prompt a referral: a history of depression, current depressive symptoms that fall short of that needed for a depression diagnosis, low income, adolescent or single parenthood, recent intimate partner violence, elevated anxiety symptoms, physical or sexual abuse, or a history of significant negative life events. (See “Postpartum anxiety: More common than you think,” in the April issue.)

Atrial fibrillation

The Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of electrocardiography (EKG) to screen for atrial fibrillation (AF).3

Revisions of previous recommendations

Cervical cancer screening

Skin cancer prevention

The Task Force made 2 revisions to the 2012 recommendation on preventing skin cancer through behavioral counseling to avoid ultraviolet (UV) radiation.6 These recommendations continue to focus on those with fair skin. The first revision: The earliest age at which children (through their guardians) can benefit from counseling on UV avoidance has been lowered from age 10 years to 6 months. The second revision: Some adults older than age 24 can also benefit from such counseling if they have fair skin and other skin cancer risks such as using tanning beds, having a history of sunburns or previous skin cancer, having an increased number of nevi (moles) and atypical nevi, having human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, having received an organ transplant, or having a family history of skin cancer.

Continue to: Those at risk...

Those at risk can reduce their chances of skin cancer by using broad-spectrum sunscreens and sun-protective clothing, and by avoiding sun exposure and indoor tanning beds.

Fall prevention

In a reversal of its 2012 recommendation, the Task Force now recommends against the use of vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults 65 years or older.7 In a reanalysis of previous studies on this topic, along with new evidence, the Task Force concluded that vitamin D supplementation offers no benefit for preventing falls in adults who are not vitamin D deficient.

Screening for scoliosis in adolescents

In 2004 the USPSTF recommended against screening for idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents 10 to 18 years of age. In its most recent review, the Task Force continued to find no direct evidence of the benefit of screening and inadequate evidence on the long-term benefits of reduction in spinal curvature through exercise, surgery, and bracing. However, following a reanalysis of the potential harms of these treatments and the use of a new analytic framework, the Task Force concluded it is not possible at this time to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening.8

Prostate cancer screening

In its most controversial action, the Task Force reversed its 2012 recommendation against routine prostate-specific antigen–based screening for prostate cancer in men ages 55 to 69 years and now lists this as a “C” recommendation.9 The potential benefits of screening include preventing 1.3 deaths from prostate cancer per 1000 men screened over 13 years and approximately 3 cases of metastatic prostate cancer. However, no trials have found a reduction in all-cause mortality from screening. Contrast that with the known harms of screening: 15% false positive results over 10 years; 1% hospitalization rate among those undergoing a prostate biopsy; over-diagnosis and resultant treatment of 20% to 50% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer through screening; and incontinence and erectile dysfunction in 20% and 67%, respectively, of men following prostatectomy.9

Based on these outcomes, the Task Force “does not recommend screening for prostate cancer unless men express a preference for screening after being informed of and understanding the benefits and risks.”9 The Task Force continues to recommend against screening men ages 70 years and older.

Continue to: The change in this recommendation...

The change in this recommendation and its wording present dilemmas for family physicians: whether to discuss potential screening with all men ages 55 to 69; to selectively discuss it with those at high risk (principally African Americans and those with a strong family history of prostate cancer); or to address the issue only if a patient asks about it. In addition, if a man requests screening, how often should it be performed? Most clinical trials have found equal benefit from testing less frequently than every year, with fewer harms. The Task Force provided little or no guidance on these issues.

Final advice: D recommendations

The Task Force reaffirmed that 7 services have either no benefit or cause more harm than benefit (TABLE 11). Family physicians should be familiar with these services, as well as all Task Force D recommendations, and avoid recommending them or providing them. High quality preventive care involves both providing services of proven benefit and avoiding those that do not.

1. USPSTF. Published recommendations. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations. Accessed March 25, 2019.

2. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Perinatal depression: preventive interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/perinatal-depression-preventive-interventions. Accessed March 25, 2019.

3. USPSTF. Atrial fibrillation: screening with electrocardiography. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/atrial-fibrillation-screening-with-electrocardiography. Accessed March 25, 2019.

4. USPSTF. Screening for atrial fibrillation with electrocardiography. JAMA. 2018;320:478-484.

5. USPSTF. Cervical cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 25, 2019.

6. USPSTF. Skin cancer prevention: behavioral counseling. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-counseling2. Accessed March 25, 2019.

7. USPSTF. Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions1. Accessed March 25, 2019.

8. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 25, 2019.

9. USPSTF. Prostate cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening1#consider. Accessed March 25, 2019.

Over the past year through early 2019, the US Preventive Services Task Force made 34 recommendations on 19 different topics. Twenty-six were reaffirmations of recommendations made in previous years (TABLE 11); the Task Force attempts to reassess topics every 7 years. Two new topics were addressed with 2 new recommendations, and 6 previous recommendations were revised or reversed (TABLE 22-9).

This Practice Alert discusses the new and the changed recommendations. (In 2018, the Practice Alert podcast series covered screening for ovarian cancer [April], prostate cancer [June], and cervical cancer [October], and EKG screening for cardiovascular disease [November].) All current Task Force recommendations are available on the USPSTF Web site.1

New topics

Perinatal depression prevention

The Task Force recommends that clinicians counsel pregnant women and women in the first year postpartum who are at increased risk for perinatal depression, or refer for such services. The recommendation applies to those who are not diagnosed with depression but are at increased risk.

Perinatal depression can negatively affect both mother and child in several ways and occurs at a rate close to 9% during pregnancy and 37% during the first year postpartum.2 The interventions studied by the Task Force included cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy; most sessions were initiated in the second trimester of pregnancy and varied in number of sessions and intensity. The Task Force includes the following in the list of risks that should prompt a referral: a history of depression, current depressive symptoms that fall short of that needed for a depression diagnosis, low income, adolescent or single parenthood, recent intimate partner violence, elevated anxiety symptoms, physical or sexual abuse, or a history of significant negative life events. (See “Postpartum anxiety: More common than you think,” in the April issue.)

Atrial fibrillation

The Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of electrocardiography (EKG) to screen for atrial fibrillation (AF).3

Revisions of previous recommendations

Cervical cancer screening

Skin cancer prevention

The Task Force made 2 revisions to the 2012 recommendation on preventing skin cancer through behavioral counseling to avoid ultraviolet (UV) radiation.6 These recommendations continue to focus on those with fair skin. The first revision: The earliest age at which children (through their guardians) can benefit from counseling on UV avoidance has been lowered from age 10 years to 6 months. The second revision: Some adults older than age 24 can also benefit from such counseling if they have fair skin and other skin cancer risks such as using tanning beds, having a history of sunburns or previous skin cancer, having an increased number of nevi (moles) and atypical nevi, having human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, having received an organ transplant, or having a family history of skin cancer.

Continue to: Those at risk...

Those at risk can reduce their chances of skin cancer by using broad-spectrum sunscreens and sun-protective clothing, and by avoiding sun exposure and indoor tanning beds.

Fall prevention

In a reversal of its 2012 recommendation, the Task Force now recommends against the use of vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults 65 years or older.7 In a reanalysis of previous studies on this topic, along with new evidence, the Task Force concluded that vitamin D supplementation offers no benefit for preventing falls in adults who are not vitamin D deficient.

Screening for scoliosis in adolescents

In 2004 the USPSTF recommended against screening for idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents 10 to 18 years of age. In its most recent review, the Task Force continued to find no direct evidence of the benefit of screening and inadequate evidence on the long-term benefits of reduction in spinal curvature through exercise, surgery, and bracing. However, following a reanalysis of the potential harms of these treatments and the use of a new analytic framework, the Task Force concluded it is not possible at this time to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening.8

Prostate cancer screening

In its most controversial action, the Task Force reversed its 2012 recommendation against routine prostate-specific antigen–based screening for prostate cancer in men ages 55 to 69 years and now lists this as a “C” recommendation.9 The potential benefits of screening include preventing 1.3 deaths from prostate cancer per 1000 men screened over 13 years and approximately 3 cases of metastatic prostate cancer. However, no trials have found a reduction in all-cause mortality from screening. Contrast that with the known harms of screening: 15% false positive results over 10 years; 1% hospitalization rate among those undergoing a prostate biopsy; over-diagnosis and resultant treatment of 20% to 50% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer through screening; and incontinence and erectile dysfunction in 20% and 67%, respectively, of men following prostatectomy.9

Based on these outcomes, the Task Force “does not recommend screening for prostate cancer unless men express a preference for screening after being informed of and understanding the benefits and risks.”9 The Task Force continues to recommend against screening men ages 70 years and older.

Continue to: The change in this recommendation...

The change in this recommendation and its wording present dilemmas for family physicians: whether to discuss potential screening with all men ages 55 to 69; to selectively discuss it with those at high risk (principally African Americans and those with a strong family history of prostate cancer); or to address the issue only if a patient asks about it. In addition, if a man requests screening, how often should it be performed? Most clinical trials have found equal benefit from testing less frequently than every year, with fewer harms. The Task Force provided little or no guidance on these issues.

Final advice: D recommendations

The Task Force reaffirmed that 7 services have either no benefit or cause more harm than benefit (TABLE 11). Family physicians should be familiar with these services, as well as all Task Force D recommendations, and avoid recommending them or providing them. High quality preventive care involves both providing services of proven benefit and avoiding those that do not.

Over the past year through early 2019, the US Preventive Services Task Force made 34 recommendations on 19 different topics. Twenty-six were reaffirmations of recommendations made in previous years (TABLE 11); the Task Force attempts to reassess topics every 7 years. Two new topics were addressed with 2 new recommendations, and 6 previous recommendations were revised or reversed (TABLE 22-9).

This Practice Alert discusses the new and the changed recommendations. (In 2018, the Practice Alert podcast series covered screening for ovarian cancer [April], prostate cancer [June], and cervical cancer [October], and EKG screening for cardiovascular disease [November].) All current Task Force recommendations are available on the USPSTF Web site.1

New topics

Perinatal depression prevention

The Task Force recommends that clinicians counsel pregnant women and women in the first year postpartum who are at increased risk for perinatal depression, or refer for such services. The recommendation applies to those who are not diagnosed with depression but are at increased risk.

Perinatal depression can negatively affect both mother and child in several ways and occurs at a rate close to 9% during pregnancy and 37% during the first year postpartum.2 The interventions studied by the Task Force included cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy; most sessions were initiated in the second trimester of pregnancy and varied in number of sessions and intensity. The Task Force includes the following in the list of risks that should prompt a referral: a history of depression, current depressive symptoms that fall short of that needed for a depression diagnosis, low income, adolescent or single parenthood, recent intimate partner violence, elevated anxiety symptoms, physical or sexual abuse, or a history of significant negative life events. (See “Postpartum anxiety: More common than you think,” in the April issue.)

Atrial fibrillation

The Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of electrocardiography (EKG) to screen for atrial fibrillation (AF).3

Revisions of previous recommendations

Cervical cancer screening

Skin cancer prevention

The Task Force made 2 revisions to the 2012 recommendation on preventing skin cancer through behavioral counseling to avoid ultraviolet (UV) radiation.6 These recommendations continue to focus on those with fair skin. The first revision: The earliest age at which children (through their guardians) can benefit from counseling on UV avoidance has been lowered from age 10 years to 6 months. The second revision: Some adults older than age 24 can also benefit from such counseling if they have fair skin and other skin cancer risks such as using tanning beds, having a history of sunburns or previous skin cancer, having an increased number of nevi (moles) and atypical nevi, having human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, having received an organ transplant, or having a family history of skin cancer.

Continue to: Those at risk...

Those at risk can reduce their chances of skin cancer by using broad-spectrum sunscreens and sun-protective clothing, and by avoiding sun exposure and indoor tanning beds.

Fall prevention

In a reversal of its 2012 recommendation, the Task Force now recommends against the use of vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults 65 years or older.7 In a reanalysis of previous studies on this topic, along with new evidence, the Task Force concluded that vitamin D supplementation offers no benefit for preventing falls in adults who are not vitamin D deficient.

Screening for scoliosis in adolescents

In 2004 the USPSTF recommended against screening for idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents 10 to 18 years of age. In its most recent review, the Task Force continued to find no direct evidence of the benefit of screening and inadequate evidence on the long-term benefits of reduction in spinal curvature through exercise, surgery, and bracing. However, following a reanalysis of the potential harms of these treatments and the use of a new analytic framework, the Task Force concluded it is not possible at this time to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening.8

Prostate cancer screening

In its most controversial action, the Task Force reversed its 2012 recommendation against routine prostate-specific antigen–based screening for prostate cancer in men ages 55 to 69 years and now lists this as a “C” recommendation.9 The potential benefits of screening include preventing 1.3 deaths from prostate cancer per 1000 men screened over 13 years and approximately 3 cases of metastatic prostate cancer. However, no trials have found a reduction in all-cause mortality from screening. Contrast that with the known harms of screening: 15% false positive results over 10 years; 1% hospitalization rate among those undergoing a prostate biopsy; over-diagnosis and resultant treatment of 20% to 50% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer through screening; and incontinence and erectile dysfunction in 20% and 67%, respectively, of men following prostatectomy.9

Based on these outcomes, the Task Force “does not recommend screening for prostate cancer unless men express a preference for screening after being informed of and understanding the benefits and risks.”9 The Task Force continues to recommend against screening men ages 70 years and older.

Continue to: The change in this recommendation...

The change in this recommendation and its wording present dilemmas for family physicians: whether to discuss potential screening with all men ages 55 to 69; to selectively discuss it with those at high risk (principally African Americans and those with a strong family history of prostate cancer); or to address the issue only if a patient asks about it. In addition, if a man requests screening, how often should it be performed? Most clinical trials have found equal benefit from testing less frequently than every year, with fewer harms. The Task Force provided little or no guidance on these issues.

Final advice: D recommendations

The Task Force reaffirmed that 7 services have either no benefit or cause more harm than benefit (TABLE 11). Family physicians should be familiar with these services, as well as all Task Force D recommendations, and avoid recommending them or providing them. High quality preventive care involves both providing services of proven benefit and avoiding those that do not.

1. USPSTF. Published recommendations. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations. Accessed March 25, 2019.

2. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Perinatal depression: preventive interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/perinatal-depression-preventive-interventions. Accessed March 25, 2019.

3. USPSTF. Atrial fibrillation: screening with electrocardiography. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/atrial-fibrillation-screening-with-electrocardiography. Accessed March 25, 2019.

4. USPSTF. Screening for atrial fibrillation with electrocardiography. JAMA. 2018;320:478-484.

5. USPSTF. Cervical cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 25, 2019.

6. USPSTF. Skin cancer prevention: behavioral counseling. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-counseling2. Accessed March 25, 2019.

7. USPSTF. Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions1. Accessed March 25, 2019.

8. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 25, 2019.

9. USPSTF. Prostate cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening1#consider. Accessed March 25, 2019.

1. USPSTF. Published recommendations. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations. Accessed March 25, 2019.

2. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Perinatal depression: preventive interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/perinatal-depression-preventive-interventions. Accessed March 25, 2019.

3. USPSTF. Atrial fibrillation: screening with electrocardiography. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/atrial-fibrillation-screening-with-electrocardiography. Accessed March 25, 2019.

4. USPSTF. Screening for atrial fibrillation with electrocardiography. JAMA. 2018;320:478-484.

5. USPSTF. Cervical cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 25, 2019.

6. USPSTF. Skin cancer prevention: behavioral counseling. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-counseling2. Accessed March 25, 2019.

7. USPSTF. Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions1. Accessed March 25, 2019.

8. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 25, 2019.

9. USPSTF. Prostate cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening1#consider. Accessed March 25, 2019.

A practical guide to the care of ingrown toenails

CASE

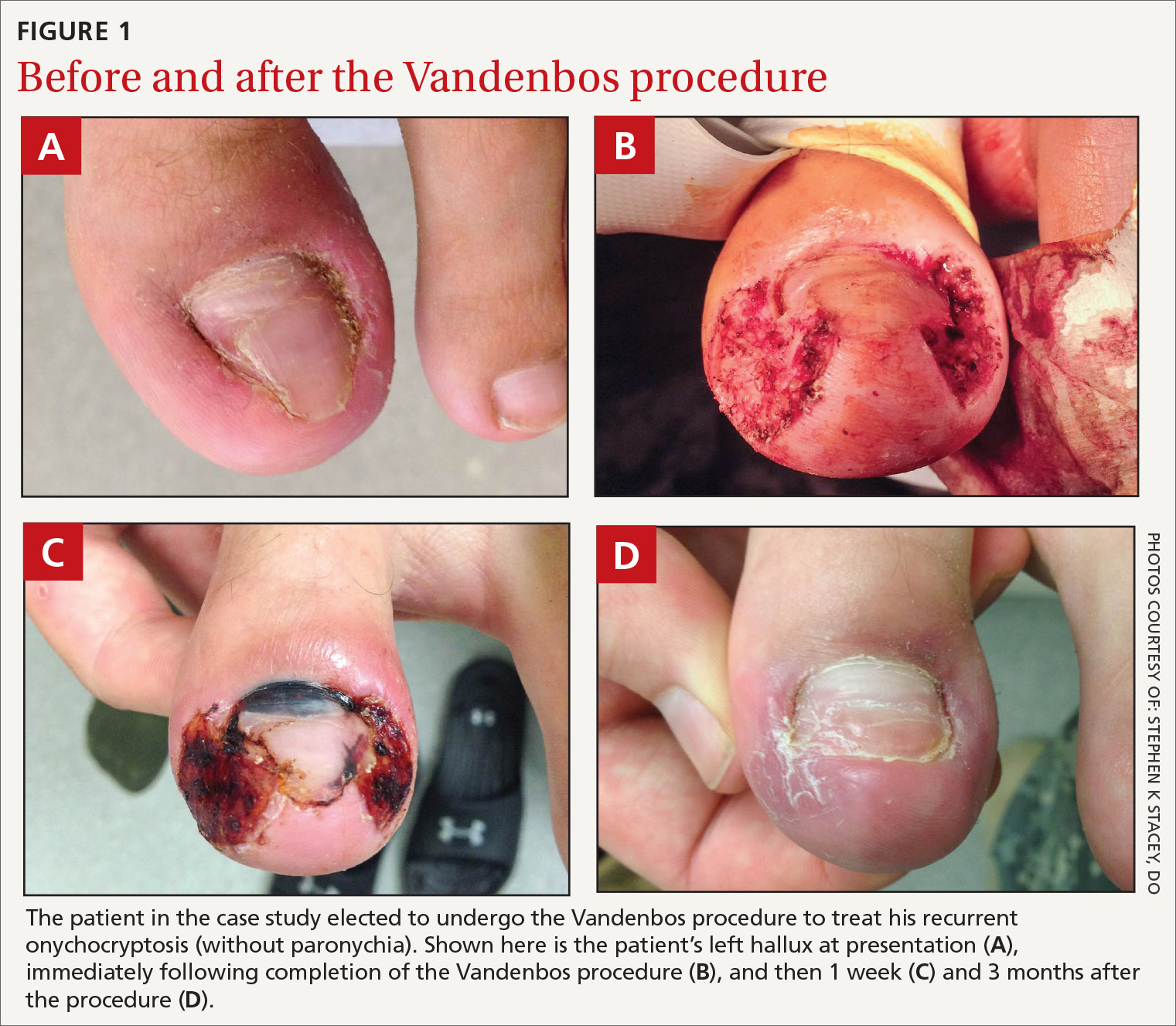

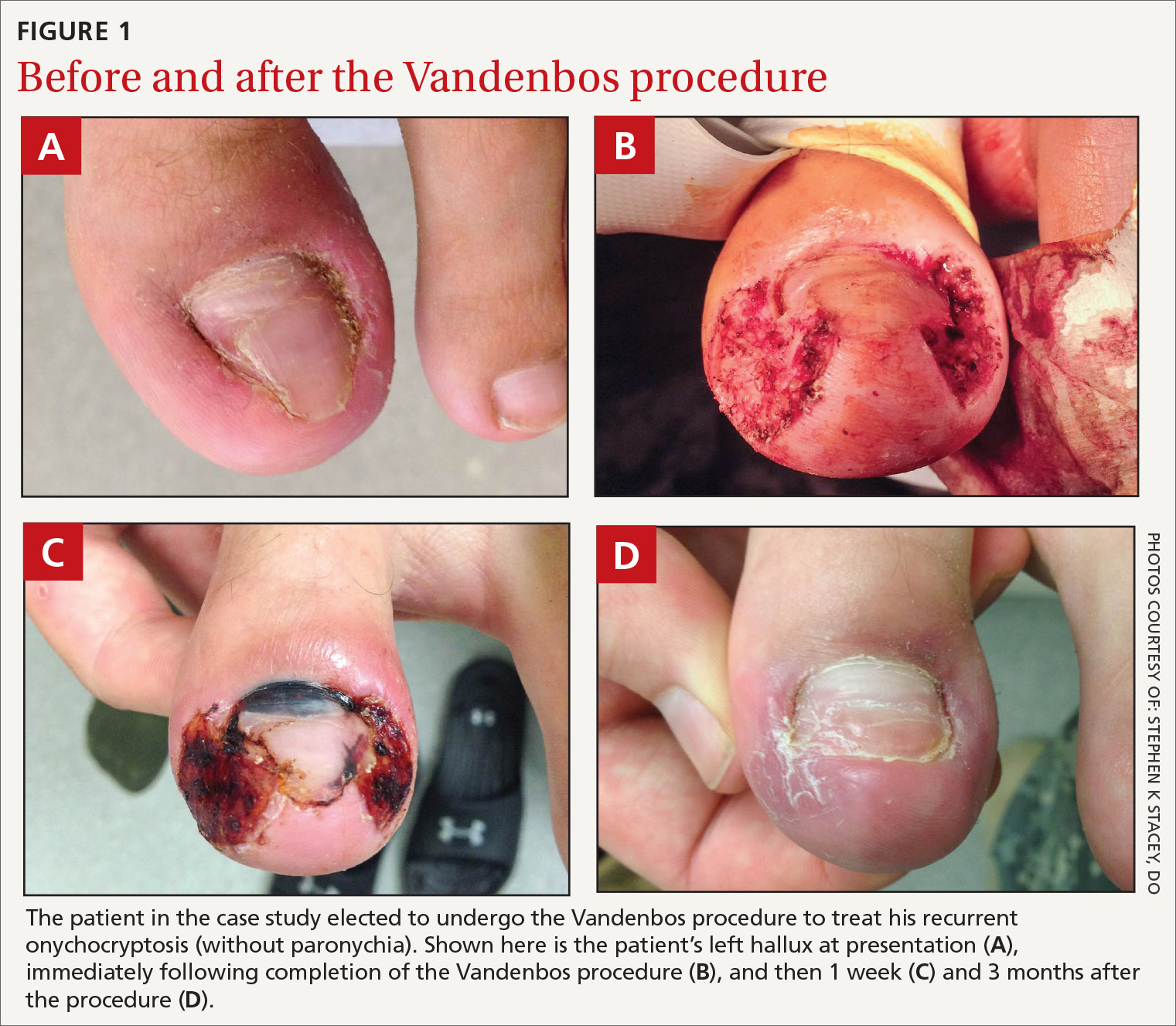

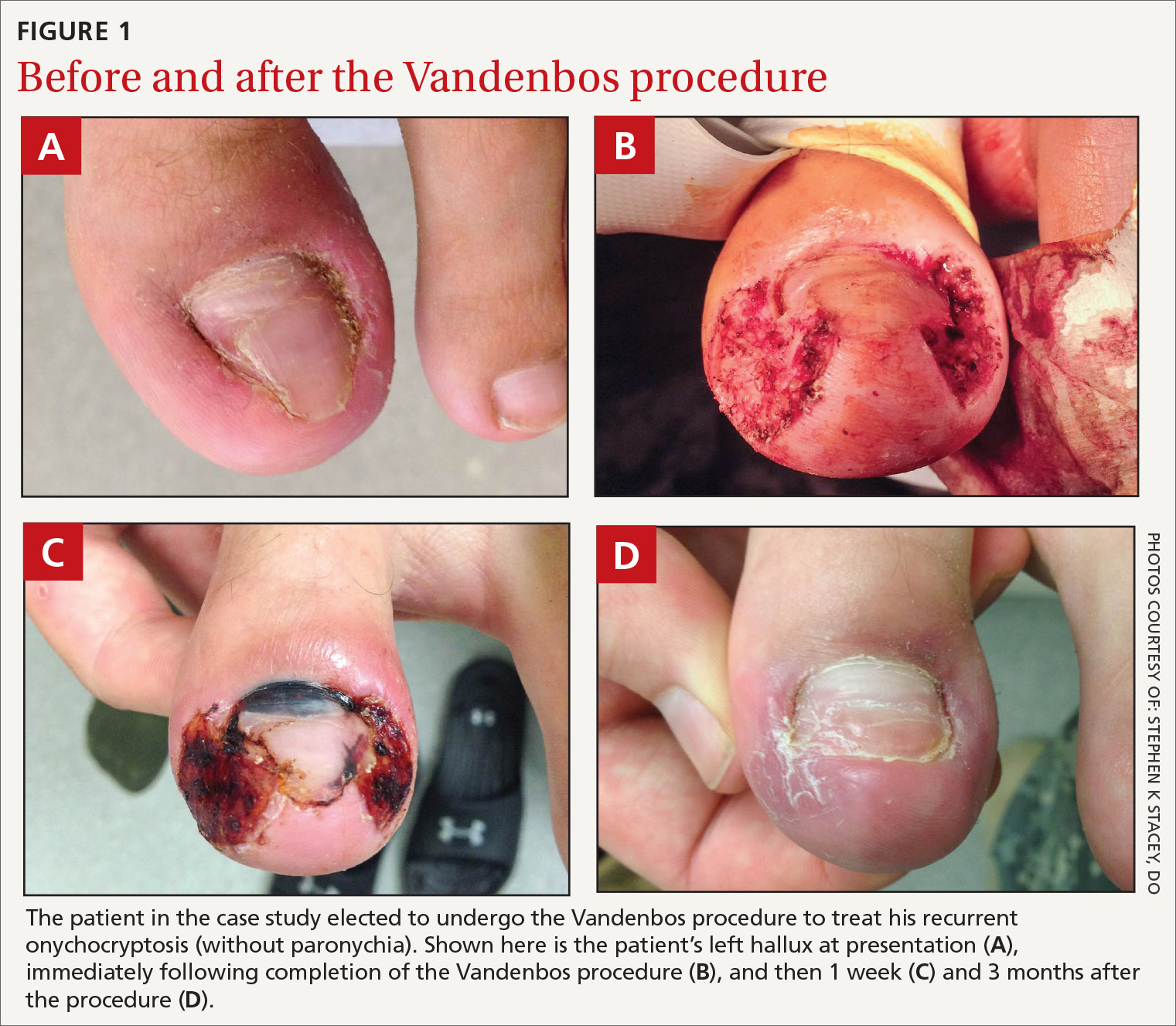

A 22-year-old active-duty man presented with left hallux pain, which he had experienced for several years due to an “ingrown toenail.” During the 3 to 4 months prior to presentation, his pain had progressed to the point that he had difficulty with weight-bearing activities. Several weeks prior to evaluation, he tried removing a portion of the nail himself with nail clippers and a pocket knife, but the symptoms persisted.

A skin exam revealed inflamed hypertrophic skin on the medial and lateral border of the toenail without exudate (FIGURE 1A). The patient was given a diagnosis of recurrent onychocryptosis without paronychia. He reported having a similar occurrence 1 to 2 years earlier, which had been treated by his primary care physician via total nail avulsion.

How would you proceed with his care?

Onychocryptosis, also known as an ingrown toenail, is a relatively common condition that can be treated with several nonsurgical and surgical approaches. It occurs when the nail plate punctures the periungual skin, usually on the hallux. Onychocryptosis may be caused by close-trimmed nails with a free edge that are allowed to enter the lateral nail fold. This results in a cascade of inflammatory and infectious processes and may result in paronychia. The inflamed toe skin will often grow over the lateral nail, which further exacerbates the condition. Mild to moderate lesions have limited pain, redness, and swelling with little or no discharge. Moderate to severe lesions have significant pain, redness, swelling, discharge, and/or persistent symptoms despite appropriate conservative therapies.

The condition may manifest at any age, although it is more common in adolescents and young adults. Onychocryptosis is slightly more common in males.1 It may present as a chief complaint, although many cases will likely be discovered incidentally on a skin exam. Although there is no firm evidence of causative factors, possible risk factors include tight-fitting shoes, repetitive activities/sports, poor foot hygiene, hyperhidrosis, genetic predisposition, obesity, and lower-extremity edema.2 Patients often exacerbate the problem with home treatments designed to trim the nail as short as possible. Comparison of symptomatic vs control patients has failed to demonstrate any systematic difference between the nails themselves. This suggests that treatment may not be effective if it is simply directed at controlling nail abnormalities.3,4

Conservative therapy

Conservative therapy should be considered first-line treatment for mild to moderate cases of onychocryptosis. The following are conservative therapy options.5

Proper nail trimming. Advise the patient to allow the nail to grow past the lateral nail fold and to keep it trimmed long so that the overgrowing toe skin cannot encroach on the free edge of the nail. The growth rate of the toenail is approximately 1.62 mm/month—something you may want to mention to the patient so that he or she will have a sense of the estimated duration of therapy.6 Also, the patient may need to implement the following other measures, while the nail is allowed to grow.

Continue to: Skin-softening techniques

Skin-softening techniques. Encourage the patient to apply warm compresses or to soak the toe in warm water for 10 to 20 minutes a day.

Barriers may be inserted between the nail and the periungual skin. Daily intermittent barriers may be used to lift the nail away from the lateral nail fold during regular hygiene activities. Tell the patient that a continuous barrier may be created using gauze or any variety of dental floss placed between the nail and the lateral nail fold, then secured in place with tape and changed daily.

Gutter splint. The gutter splint consists of a plastic tube that has been slit longitudinally from bottom to top with iris scissors or a scalpel. One end is then cut diagonally for smooth insertion between the nail edge and the periungual skin. When placed, the gutter splint lies longitudinally along the edge of the nail, providing a barrier to protect the toe during nail growth. The tube may be obtained by trimming a sterilized vinyl intravenous drip infusion, the catheter from an 18-gauge or larger needle (with the needle removed), or a filter straw. This tube can be affixed with adhesive tape, sutures, or cyanoacrylate.7

Patient-controlled taping. An adhesive tape such as 1-inch silk tape is placed on the symptomatic edge of the lateral nail fold and traction is applied. The tape is then wrapped around the toe and affixed such that the lateral nail fold is pulled away from the nail.8

Medications. Many practitioners use high-potency topical steroids, although evidence for their effectiveness is lacking. Oral antibiotics are unnecessary.

Continue to: One disadvantage of conservative therapy is...

One disadvantage of conservative therapy is that the patient must wait for nail growth before symptom resolution is achieved. In cases where the patient requires immediate symptom resolution, surgical therapies can be used (such as nail edge excision).

Surgical therapy

Surgery is more effective than nonsurgical therapies in preventing recurrence2,9 and is indicated for severe cases of onychocryptosis or for patients who do not respond to a trial of at least 3 months of conservative care.

While there are no universally accepted contraindications to surgical toenail procedures, caution should be taken with patients who have poor healing potential of the feet (eg, chronic vasculopathy or neuropathy). That said, when patients with diabetes have undergone surgical toenail procedures, the research indicates that they have not had worse outcomes.10,11