User login

Indurated Violaceous Lesions on the Face, Trunk, and Legs

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

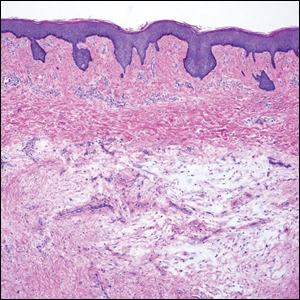

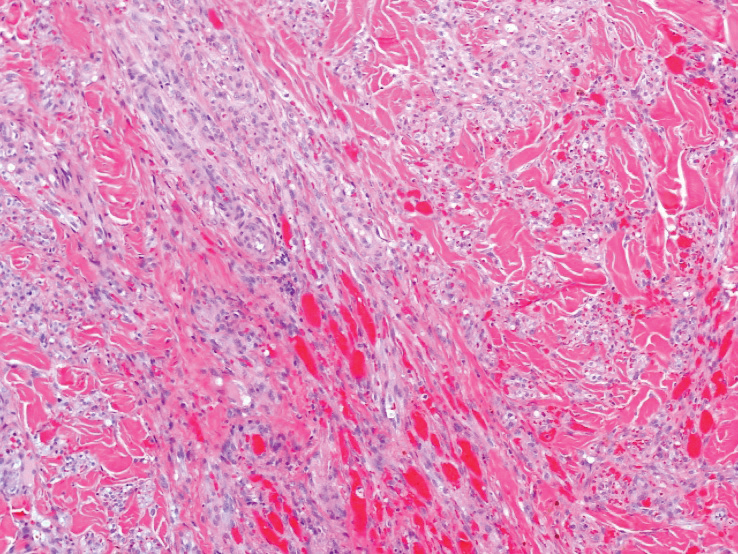

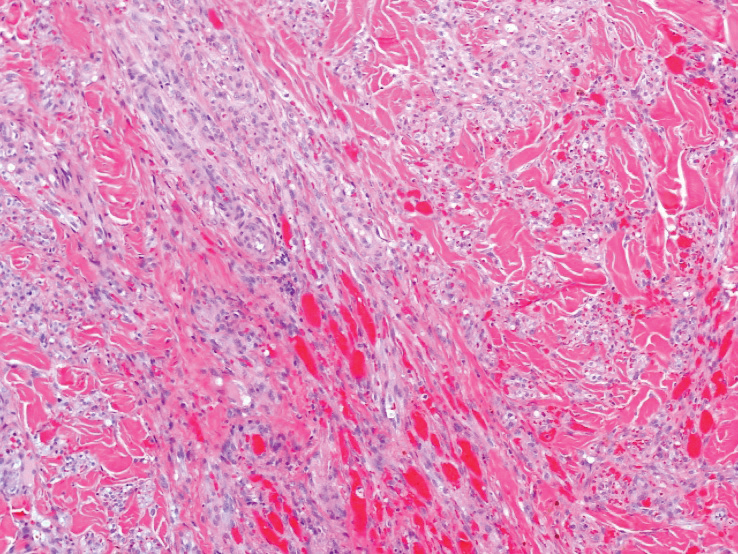

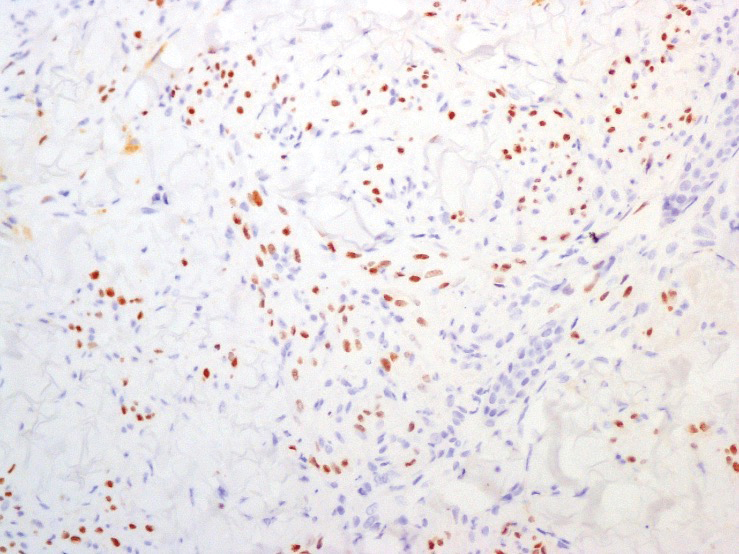

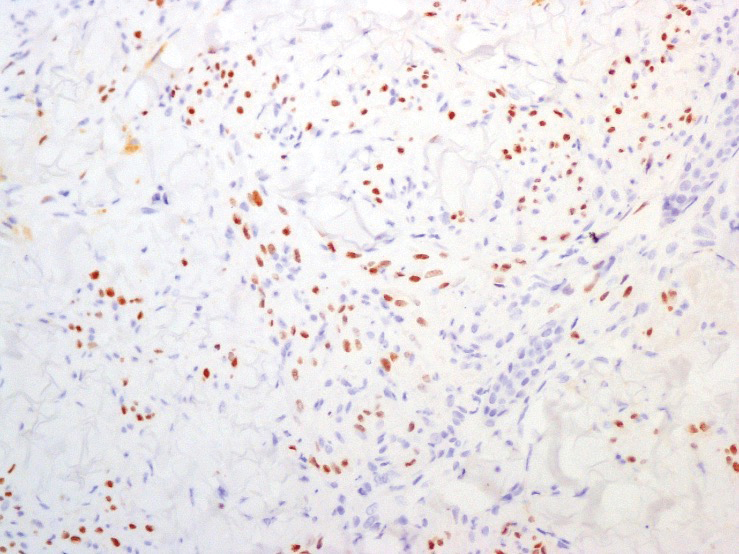

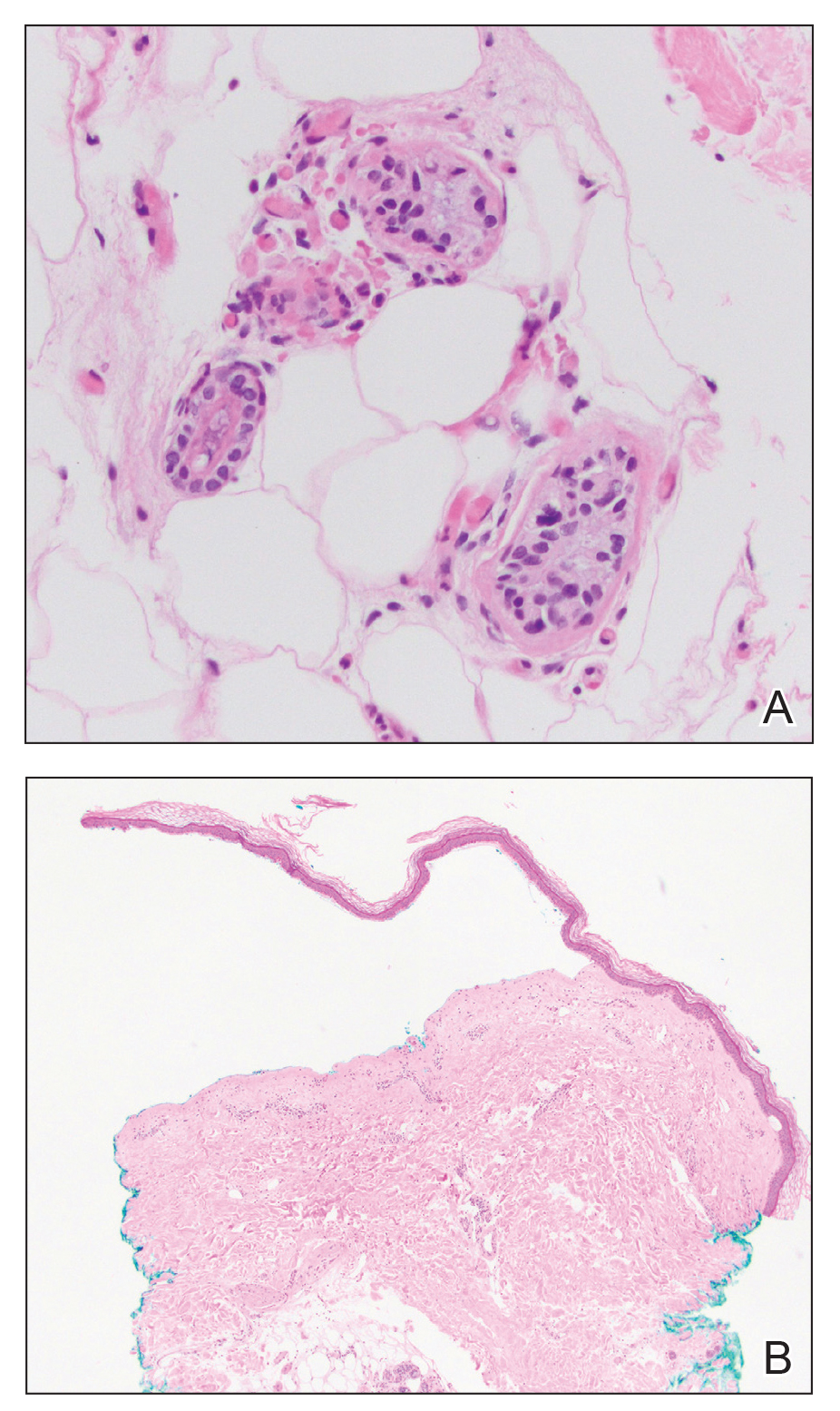

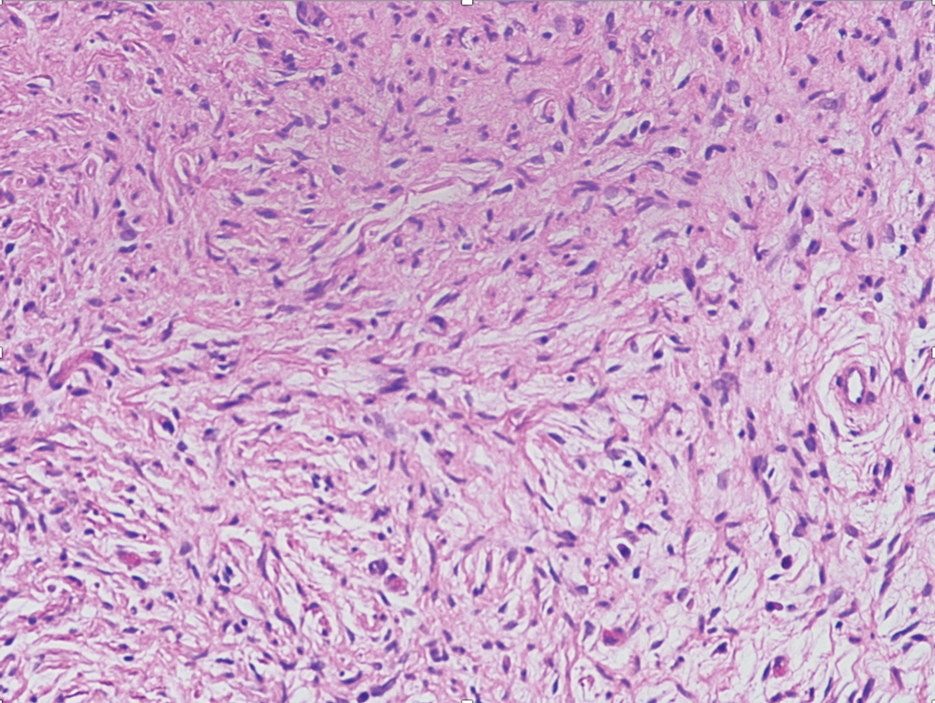

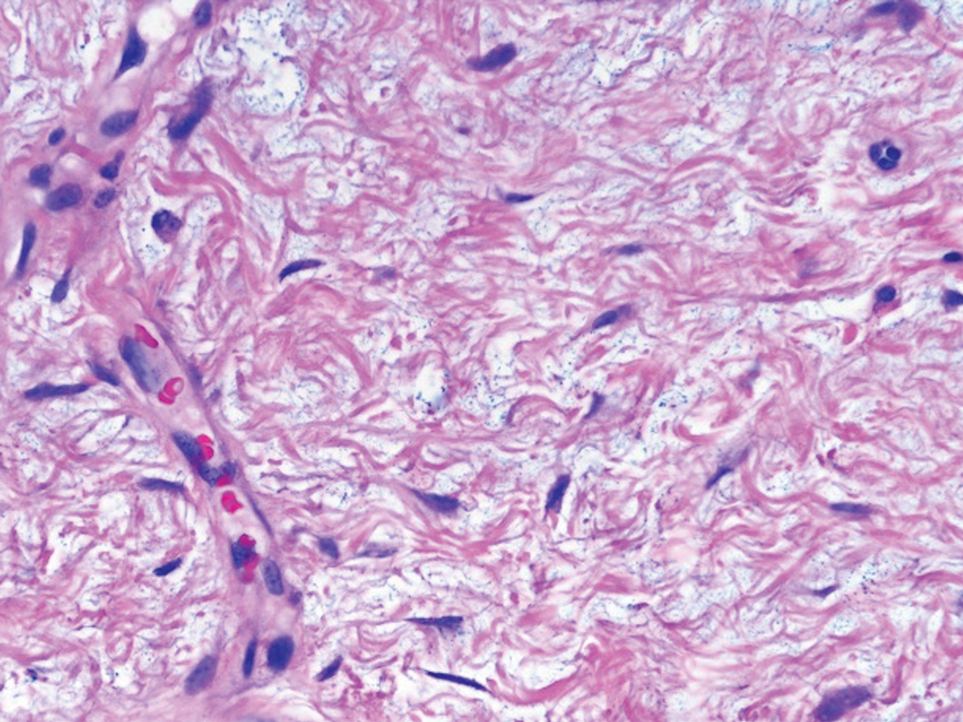

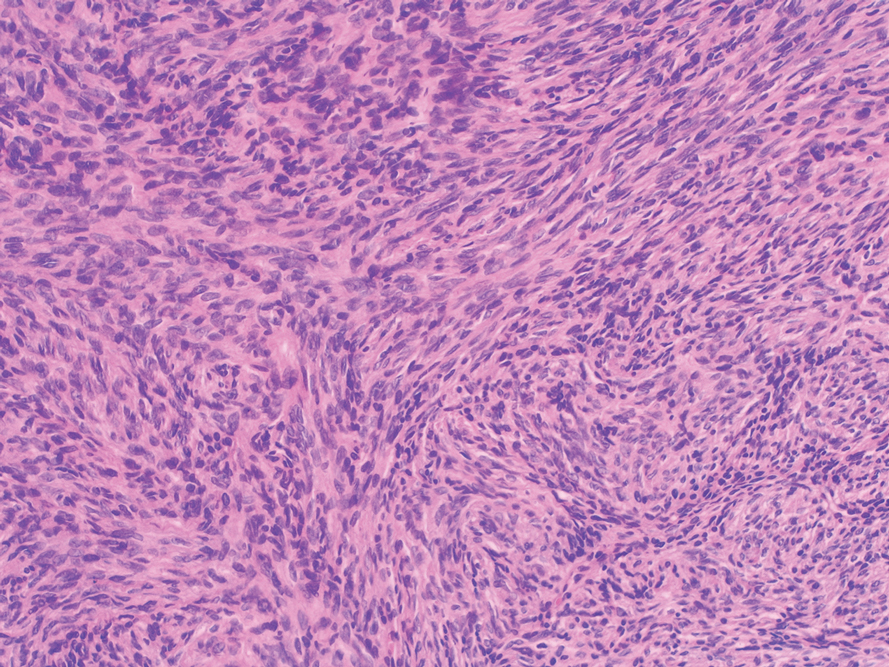

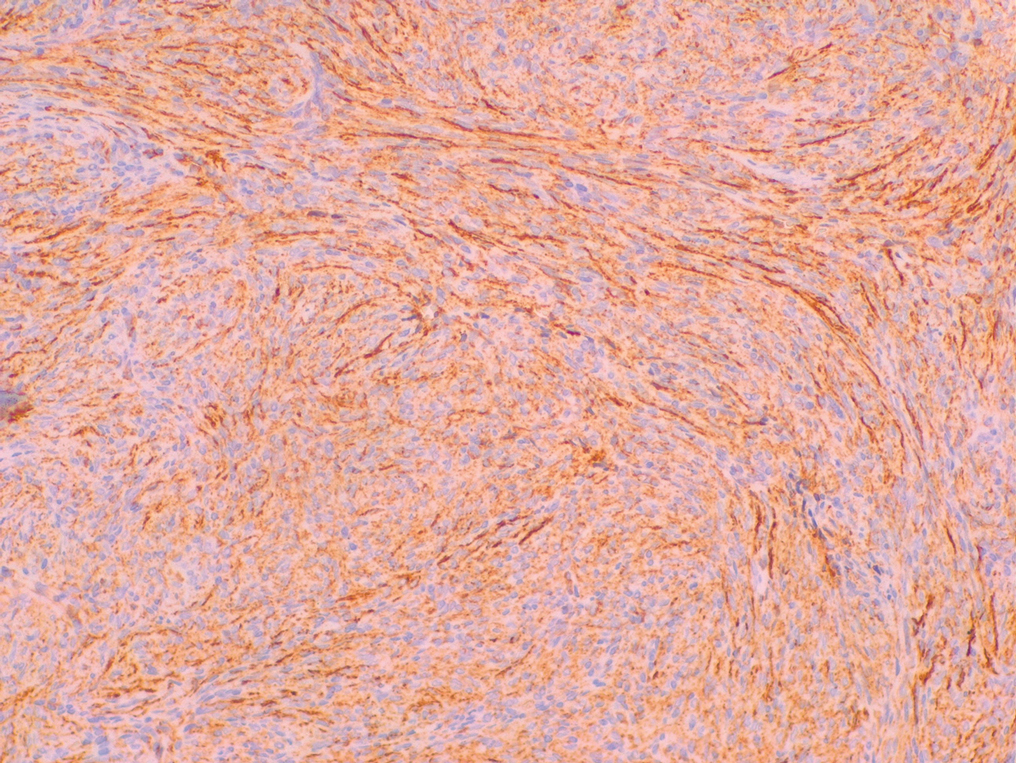

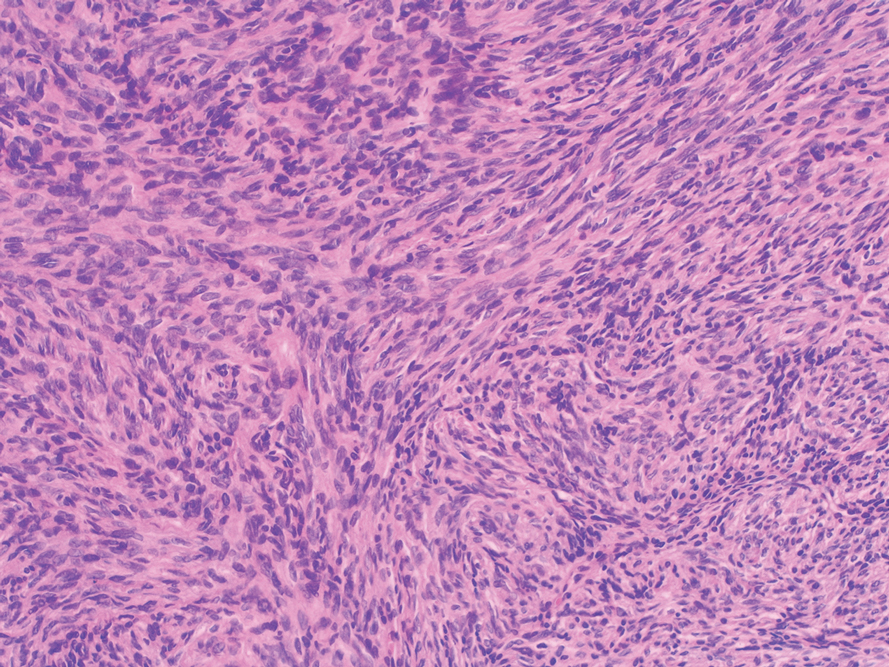

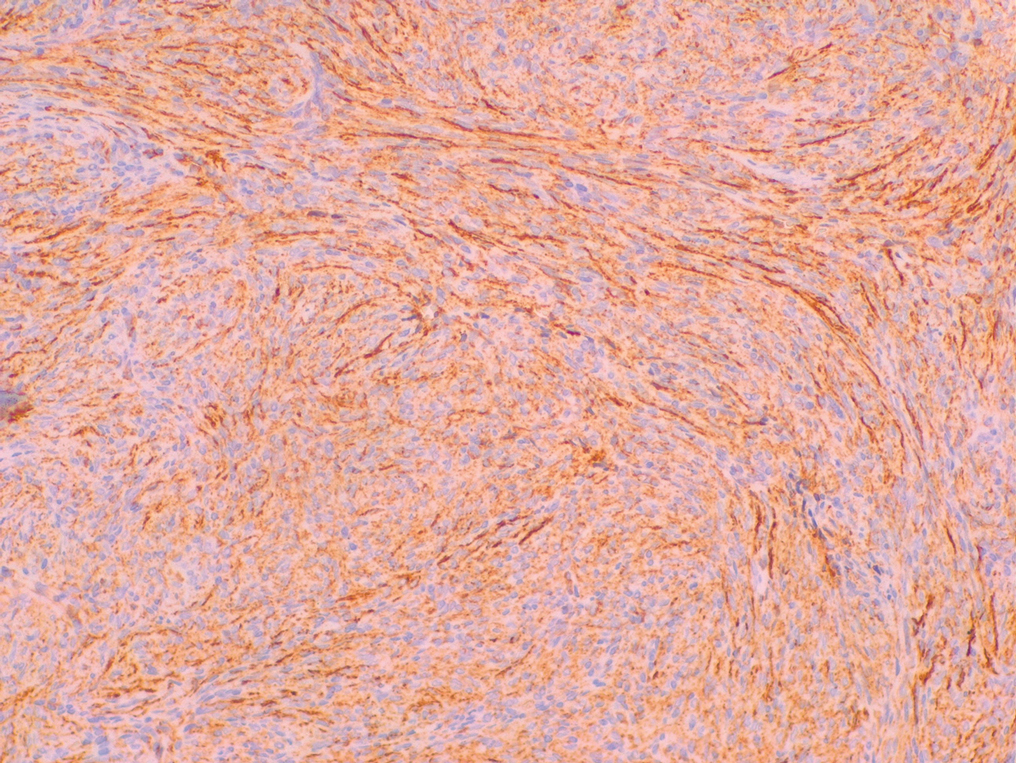

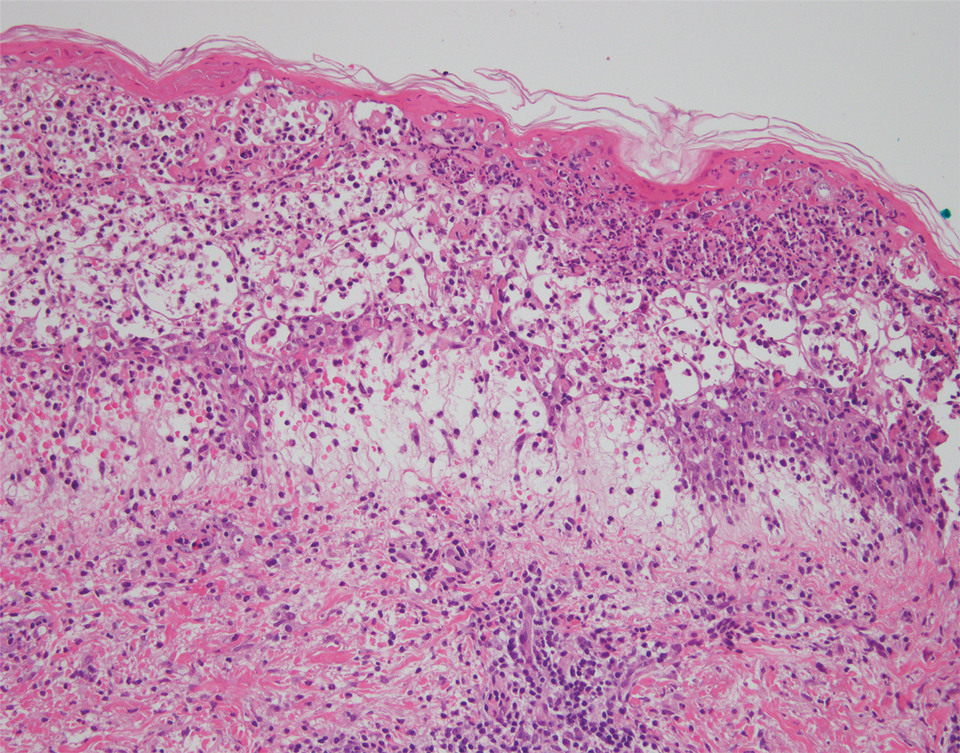

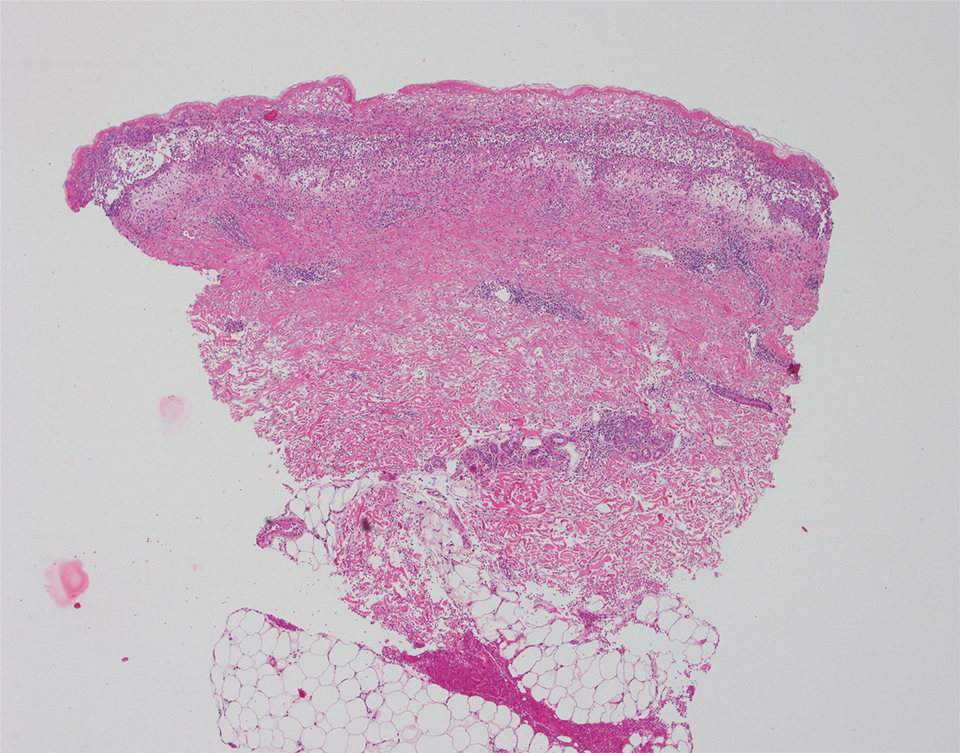

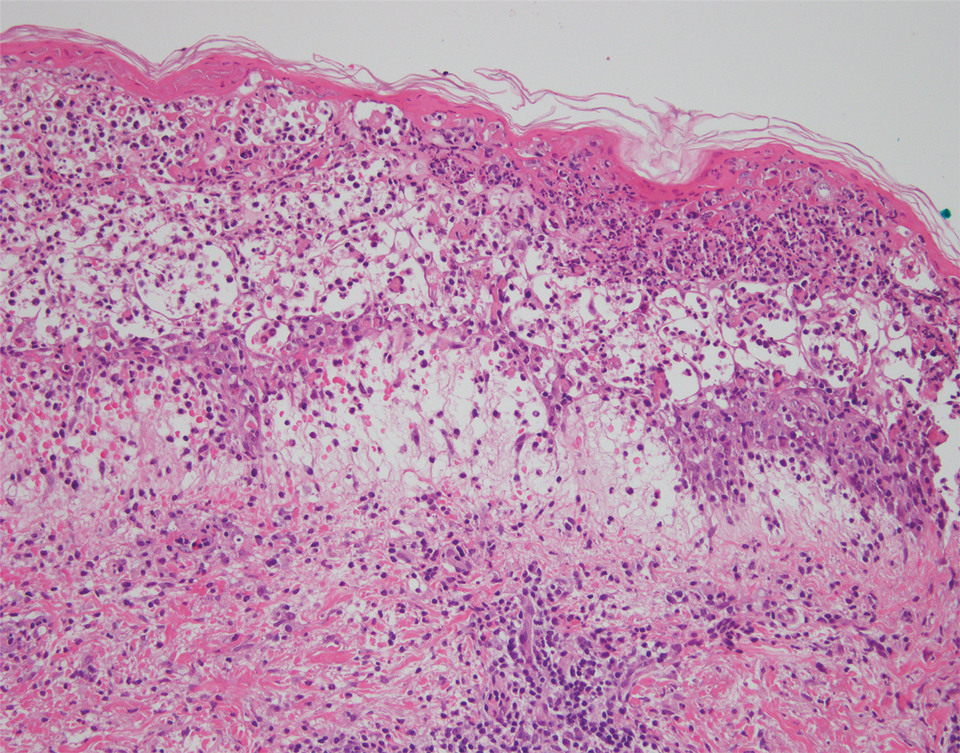

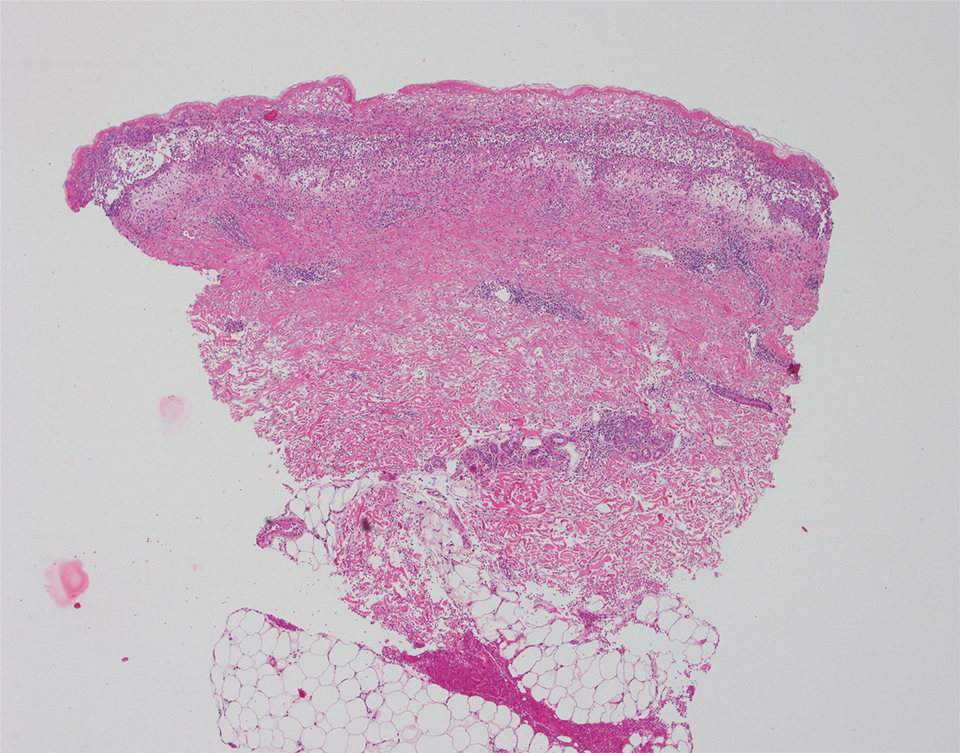

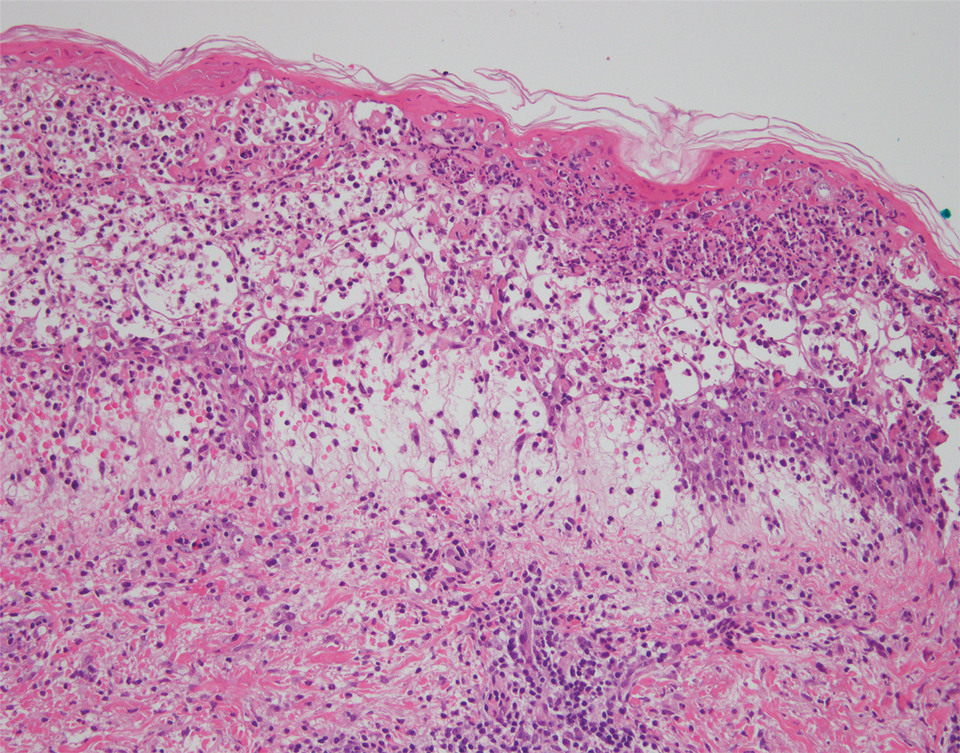

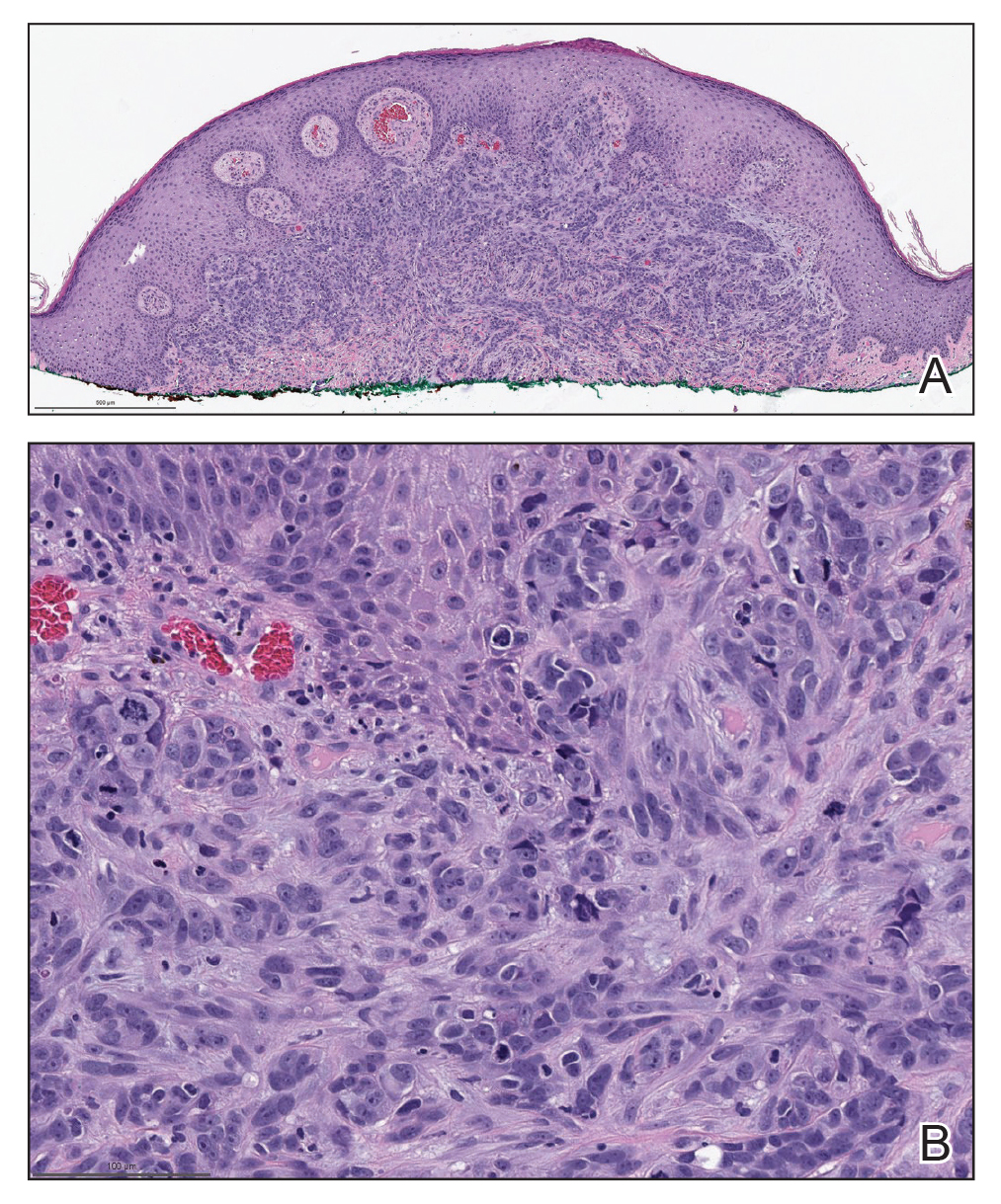

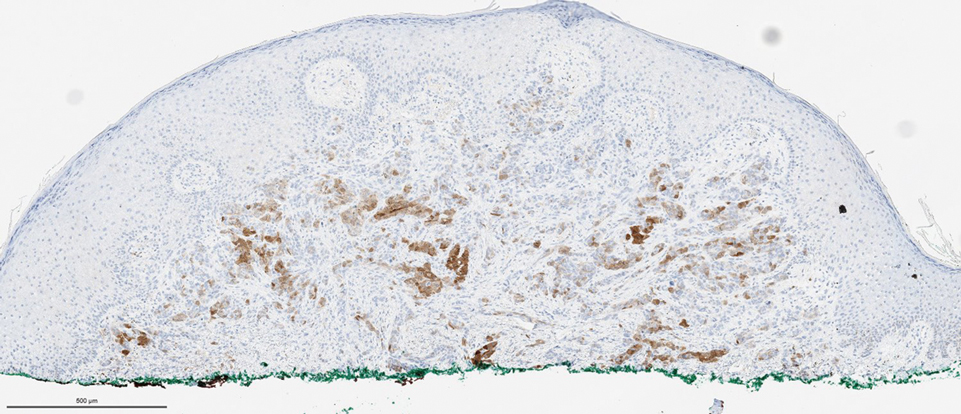

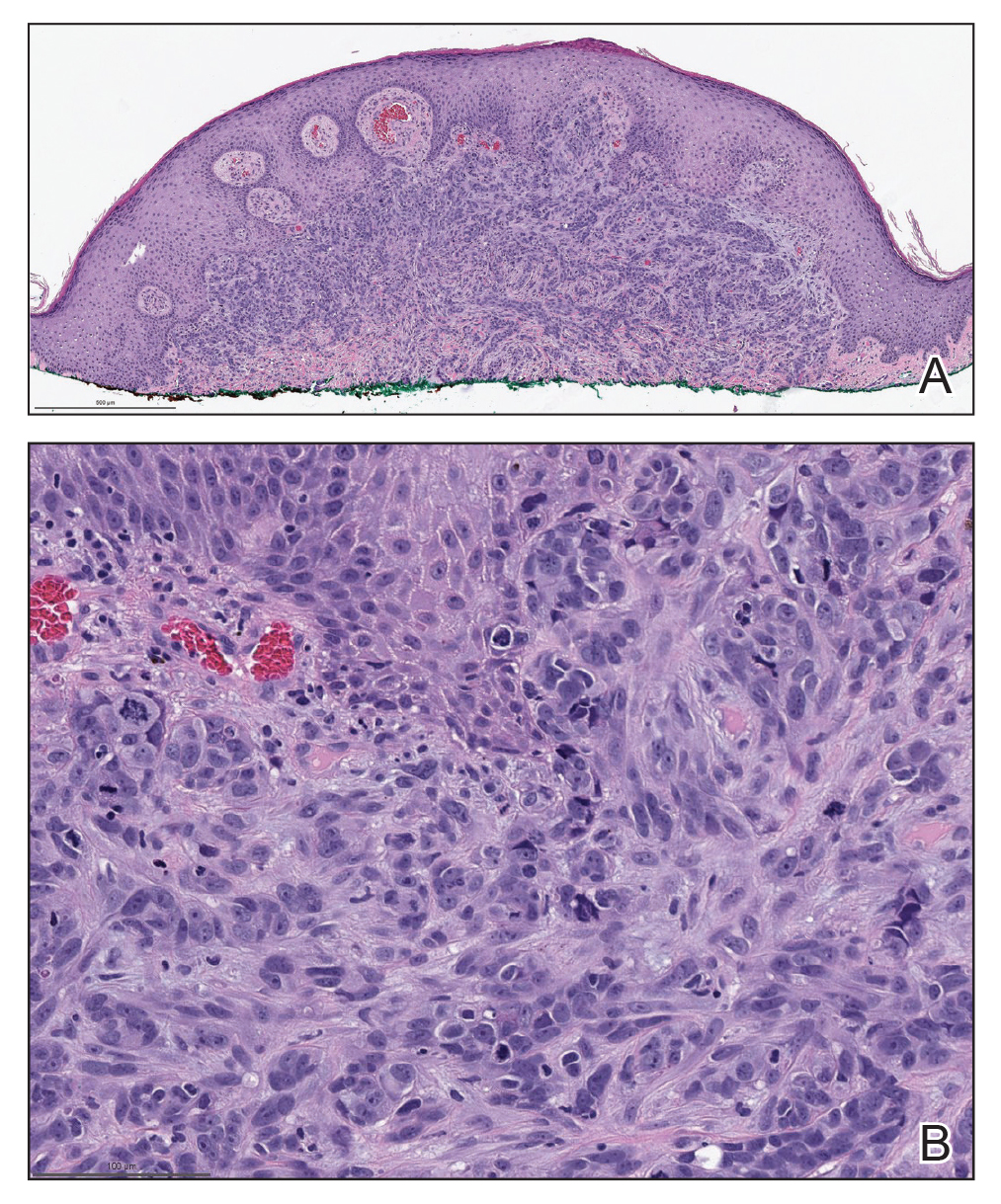

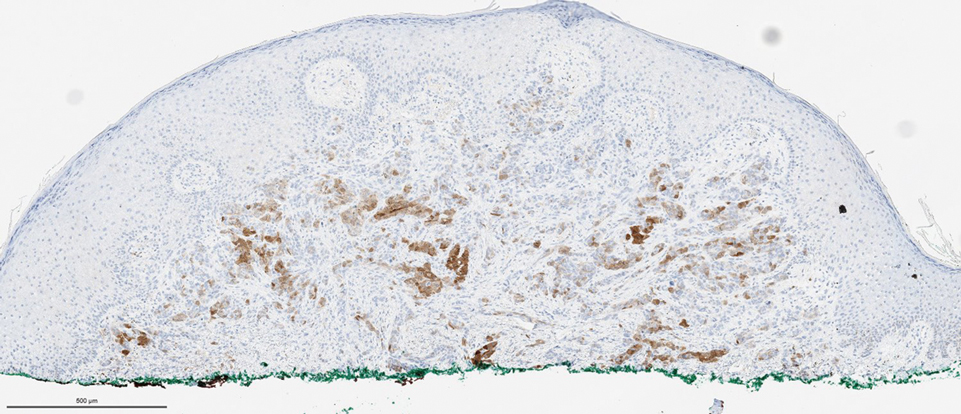

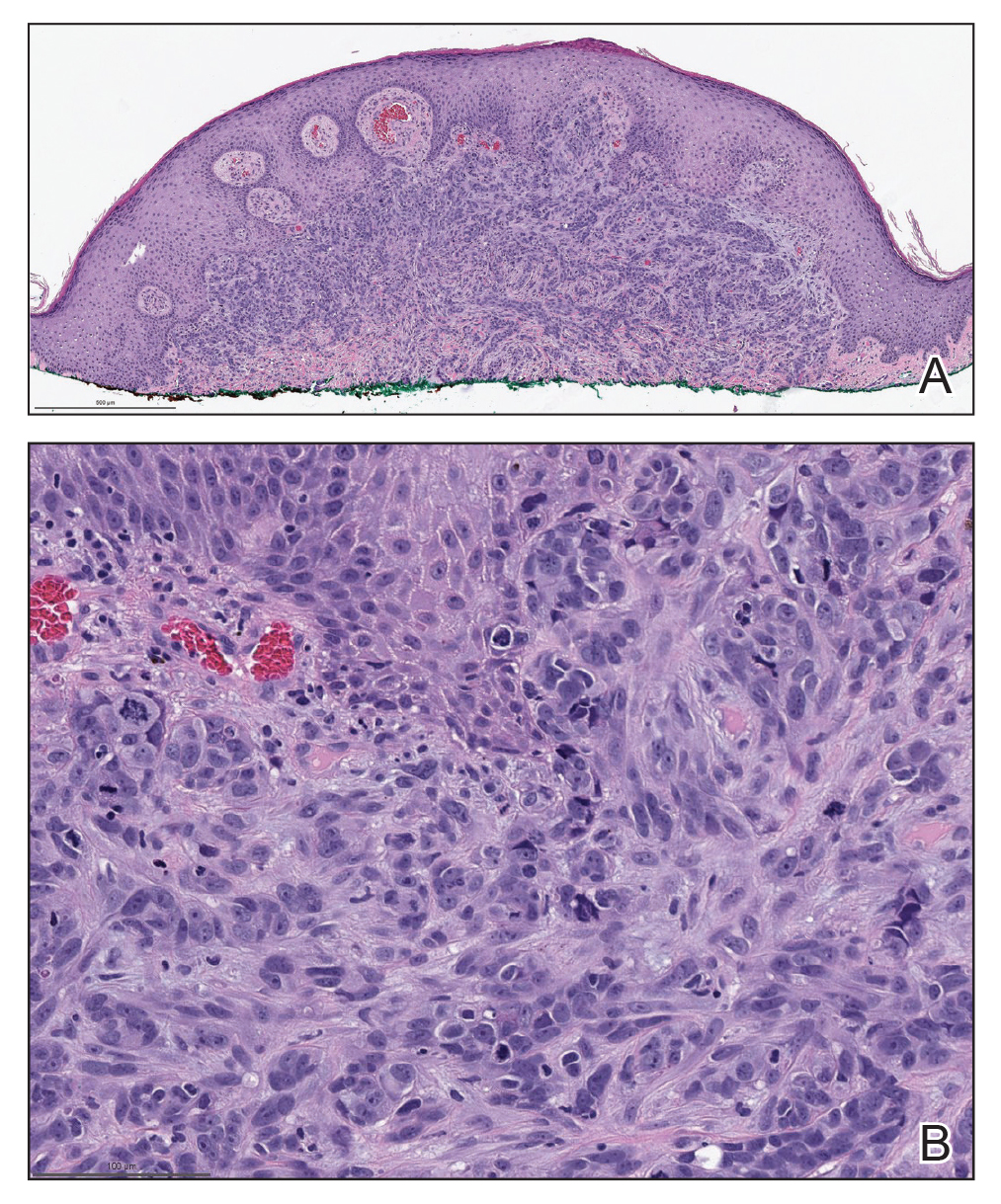

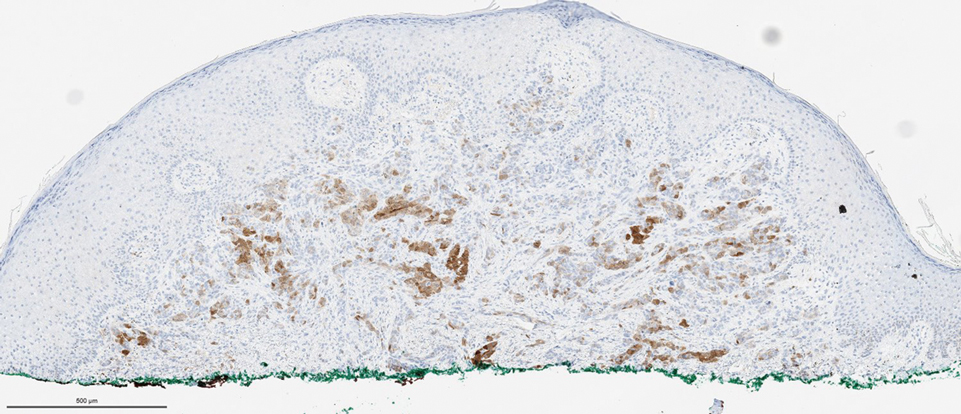

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

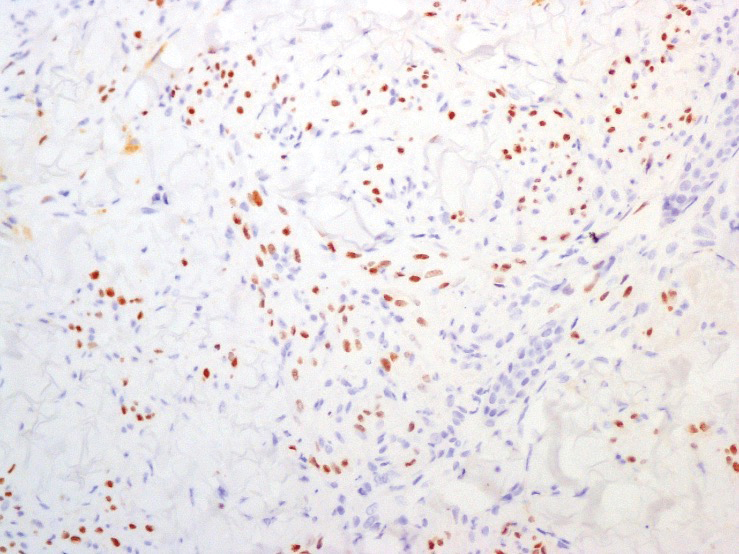

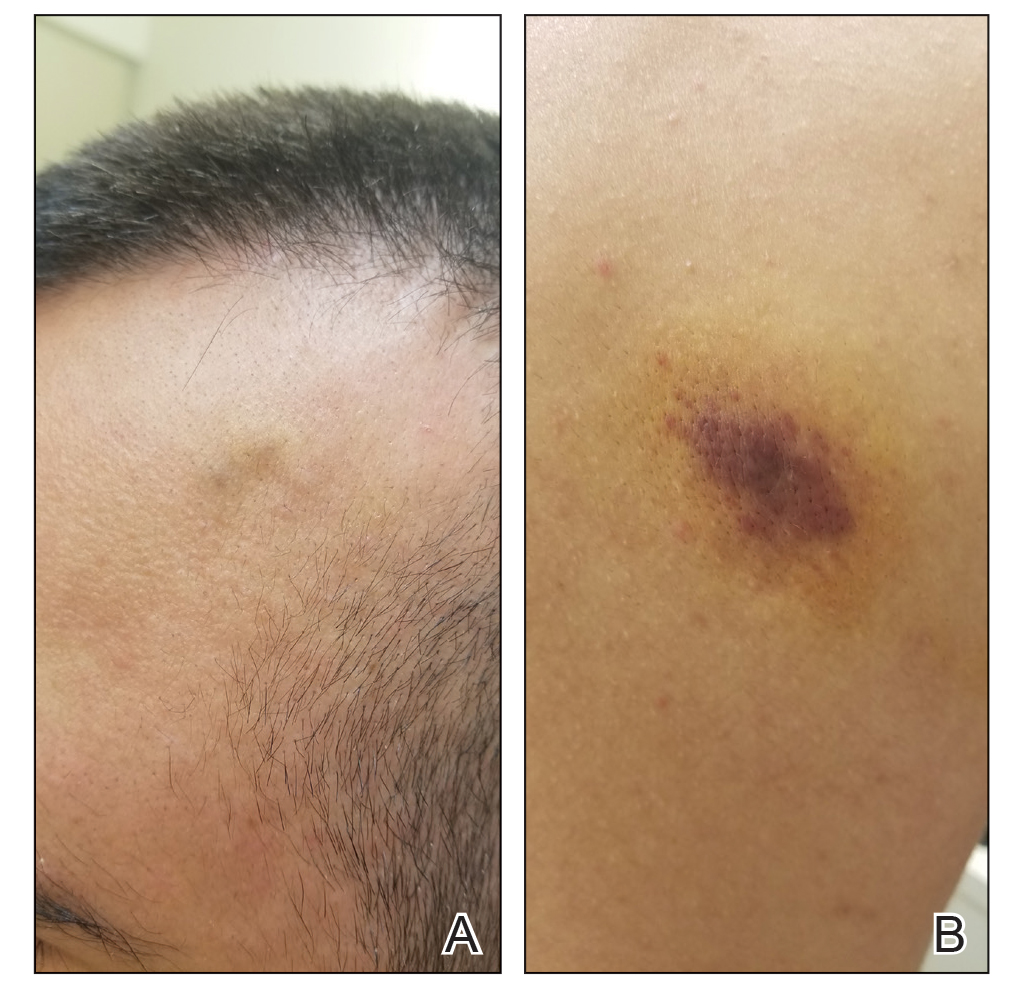

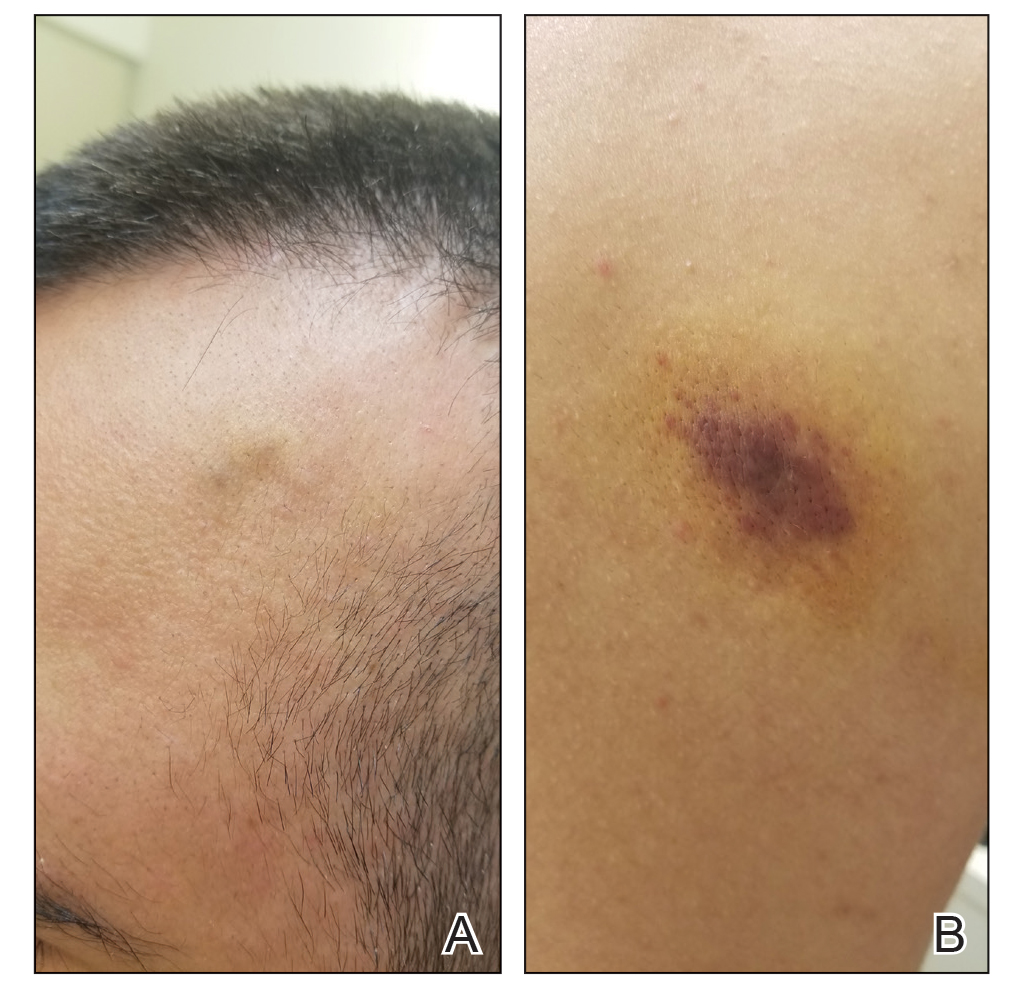

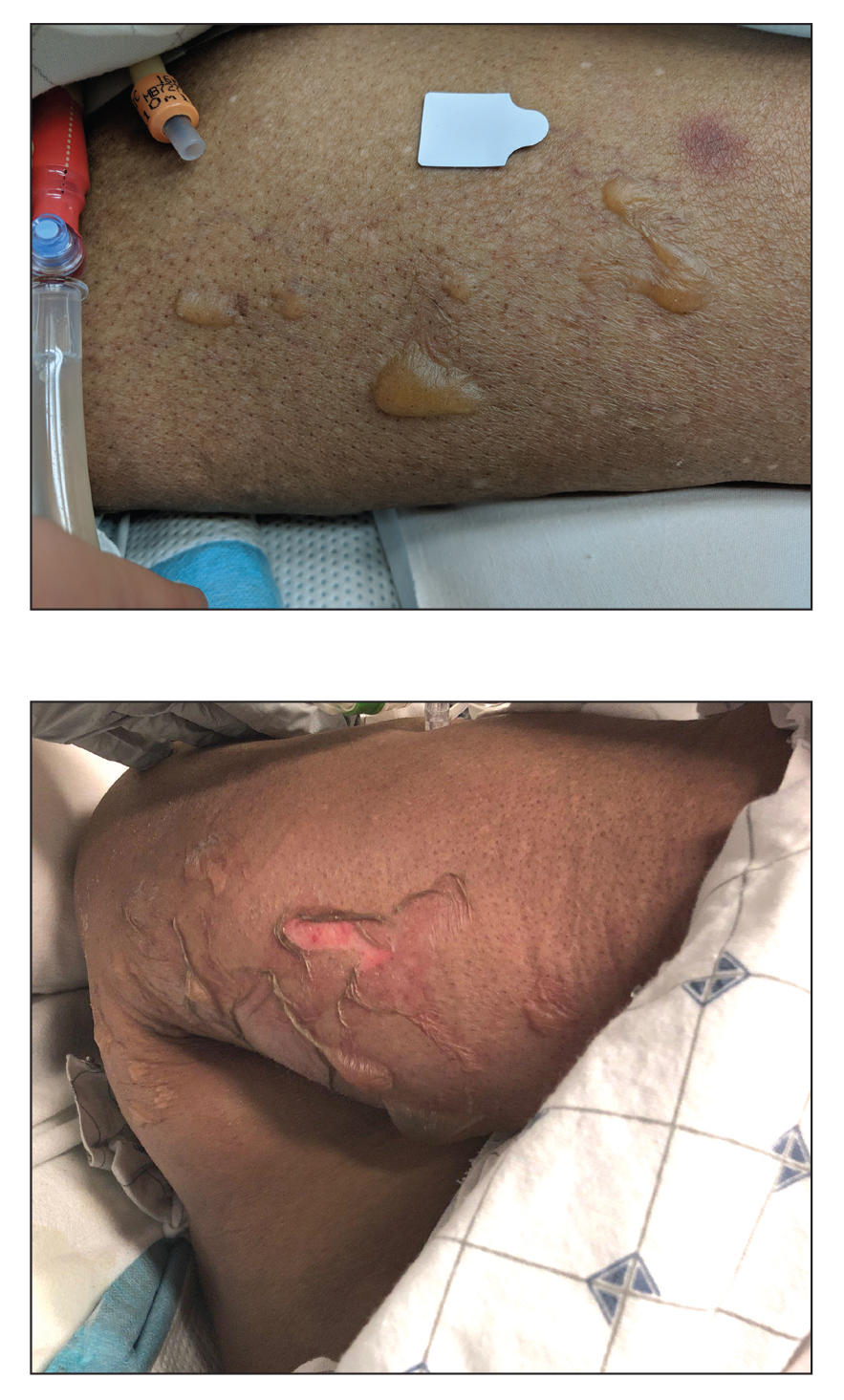

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

A 25-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with growing selfdescribed cysts on the face, trunk, and legs of 6 months’ duration. The lesions started as bruiselike discolorations and progressed to become firm nodules and inflamed masses. Some were minimally itchy and sensitive to touch, but there was no history of bleeding or drainage. The patient denied any new or recent environmental or animal exposures, use of illicit drugs, or travel correlating with the rash onset. He denied any prior treatments. He reported being in his normal state of health and was not taking any medications. Physical examination revealed indurated, violaceous, purpuric subcutaneous nodules, plaques, and masses on the forehead, cheek (top), jaw, flank, axillae (bottom), and back.

Blisters in a Comatose Elderly Woman

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

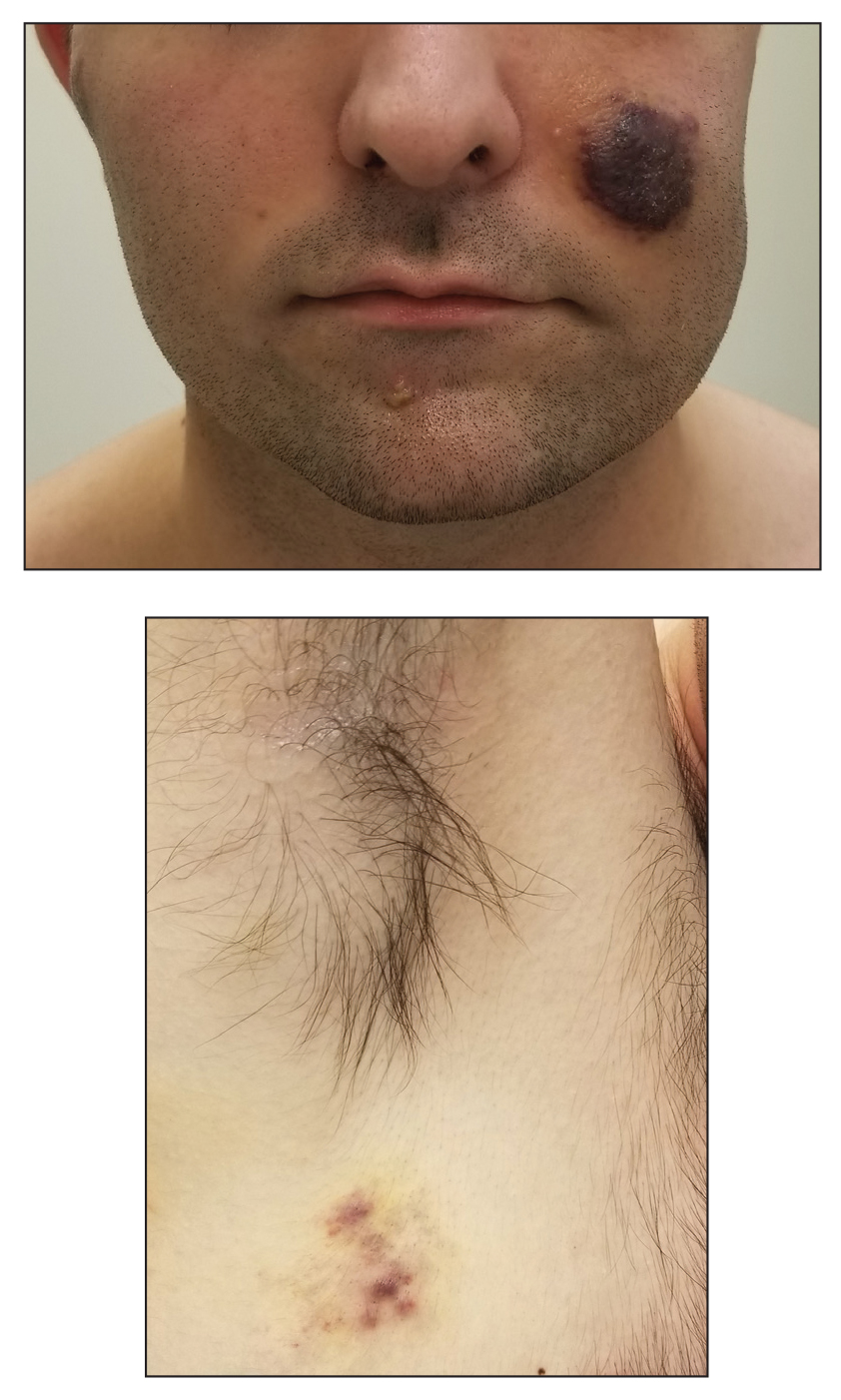

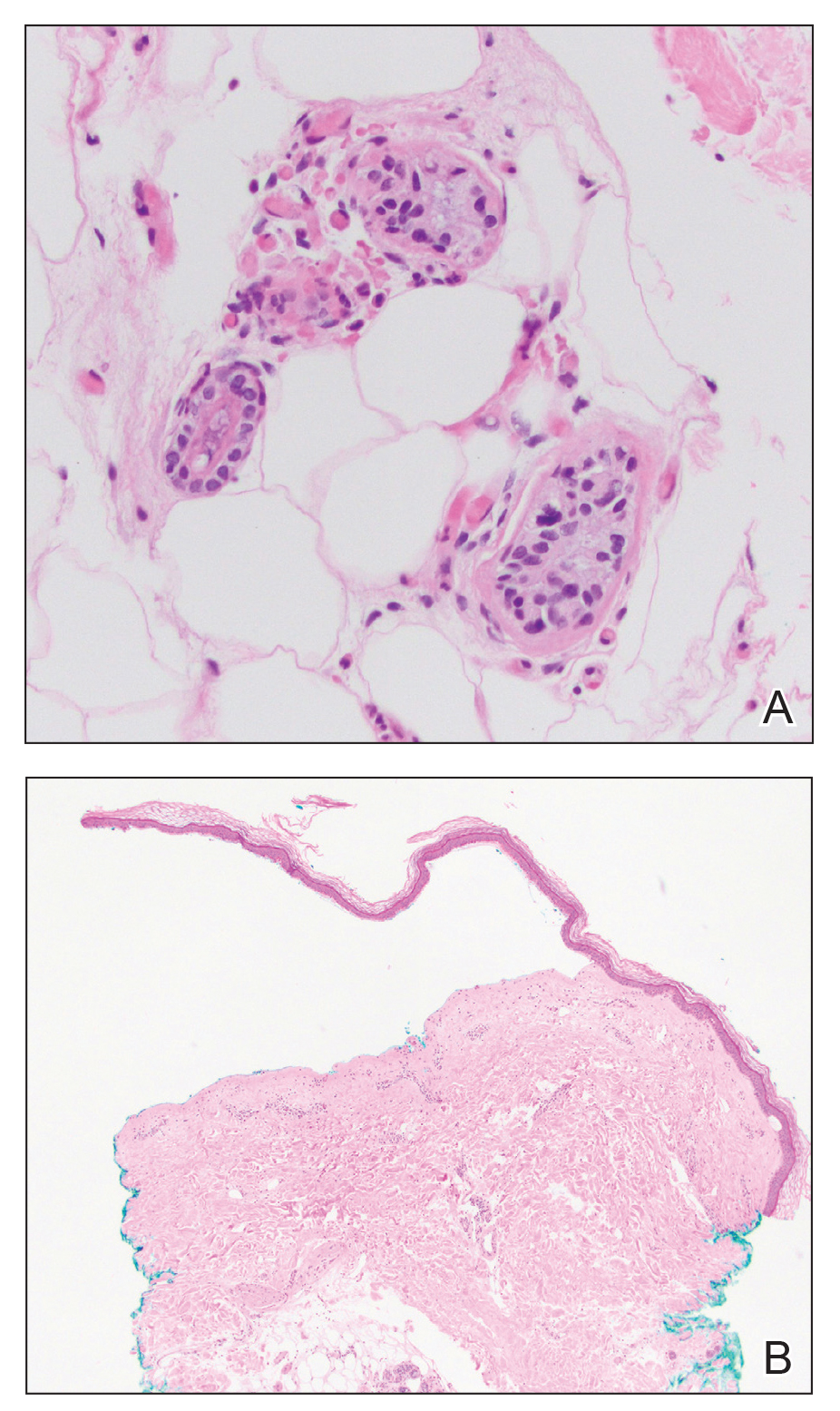

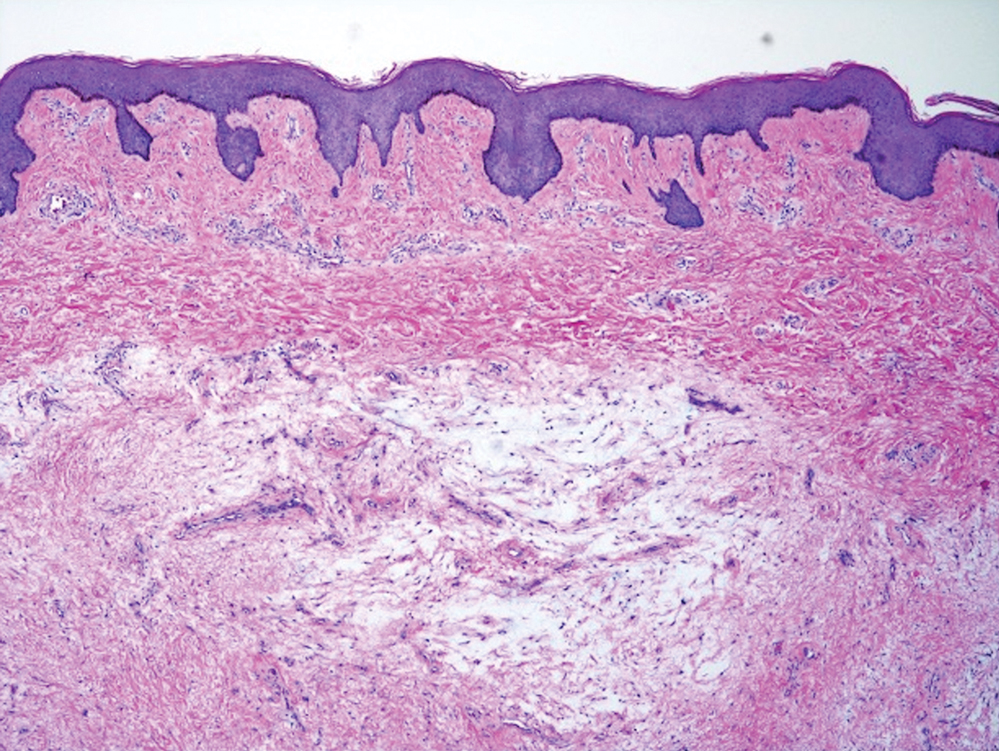

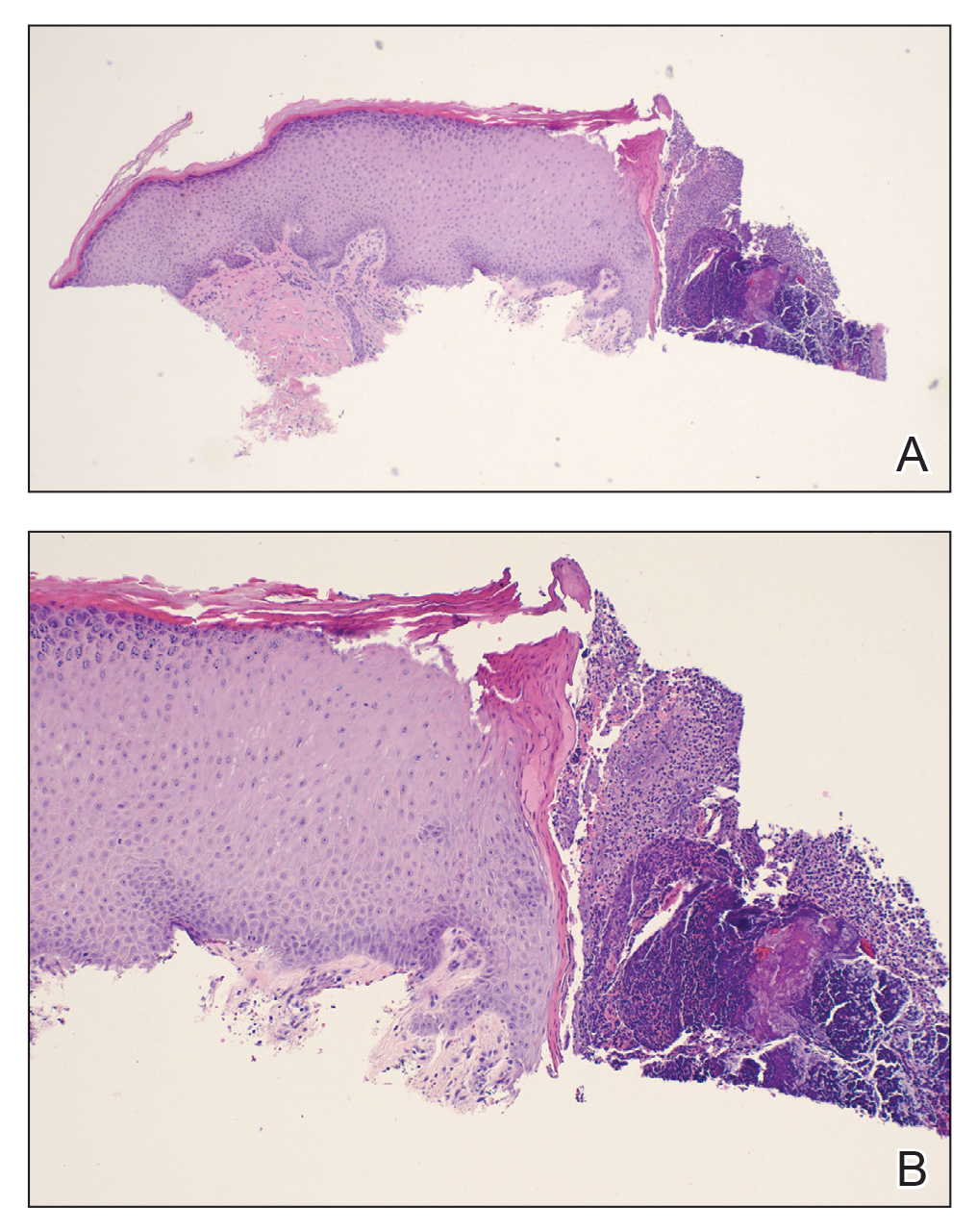

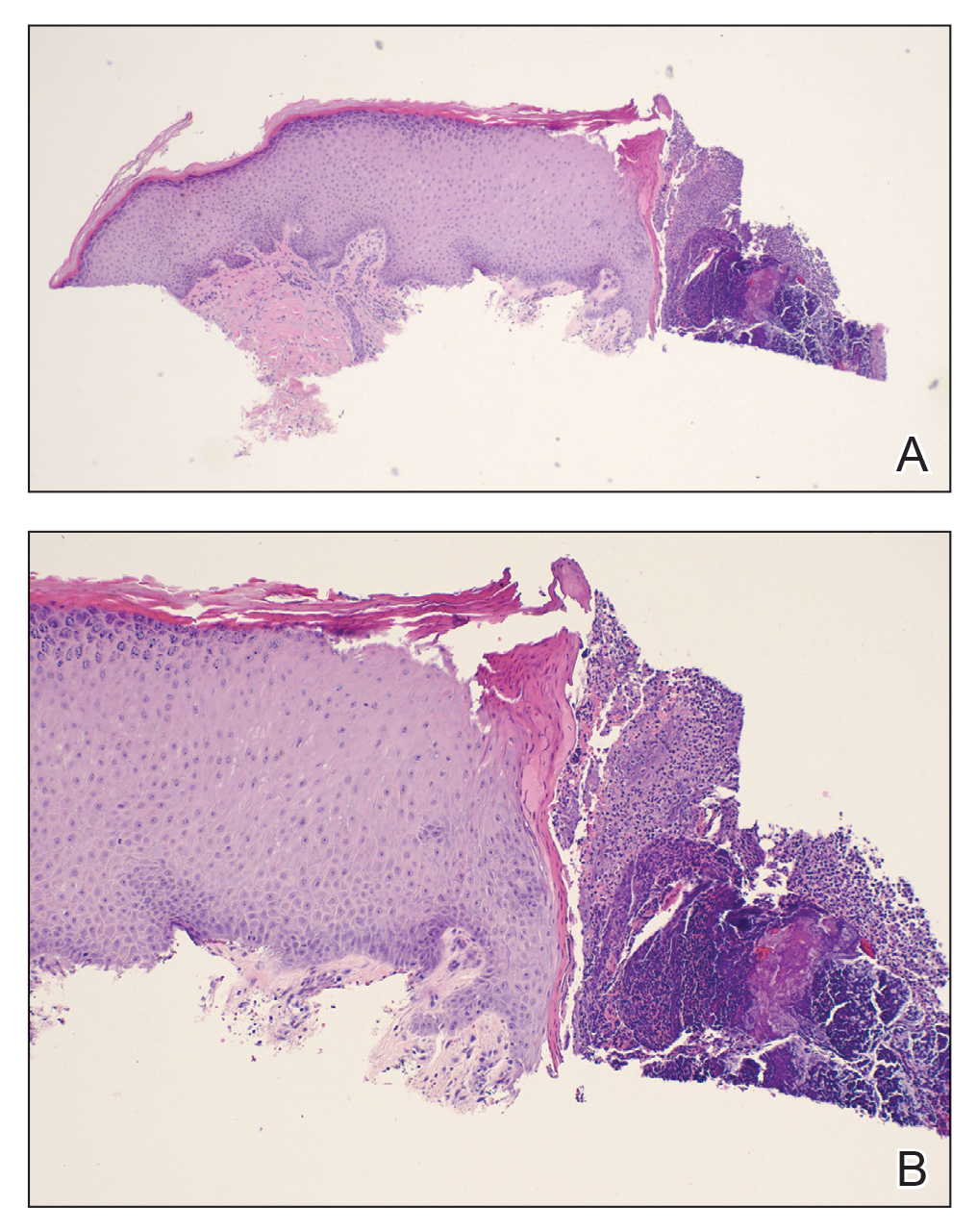

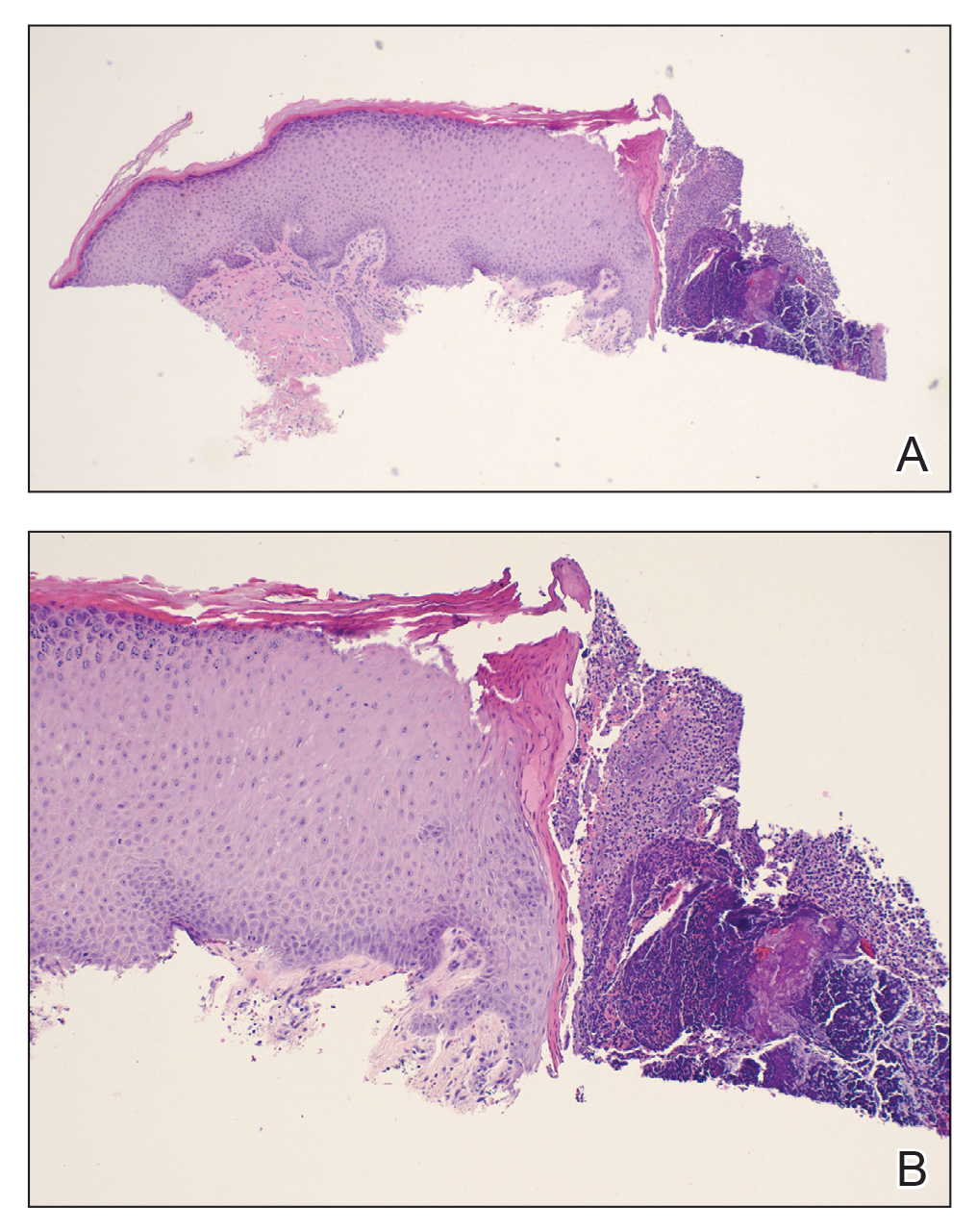

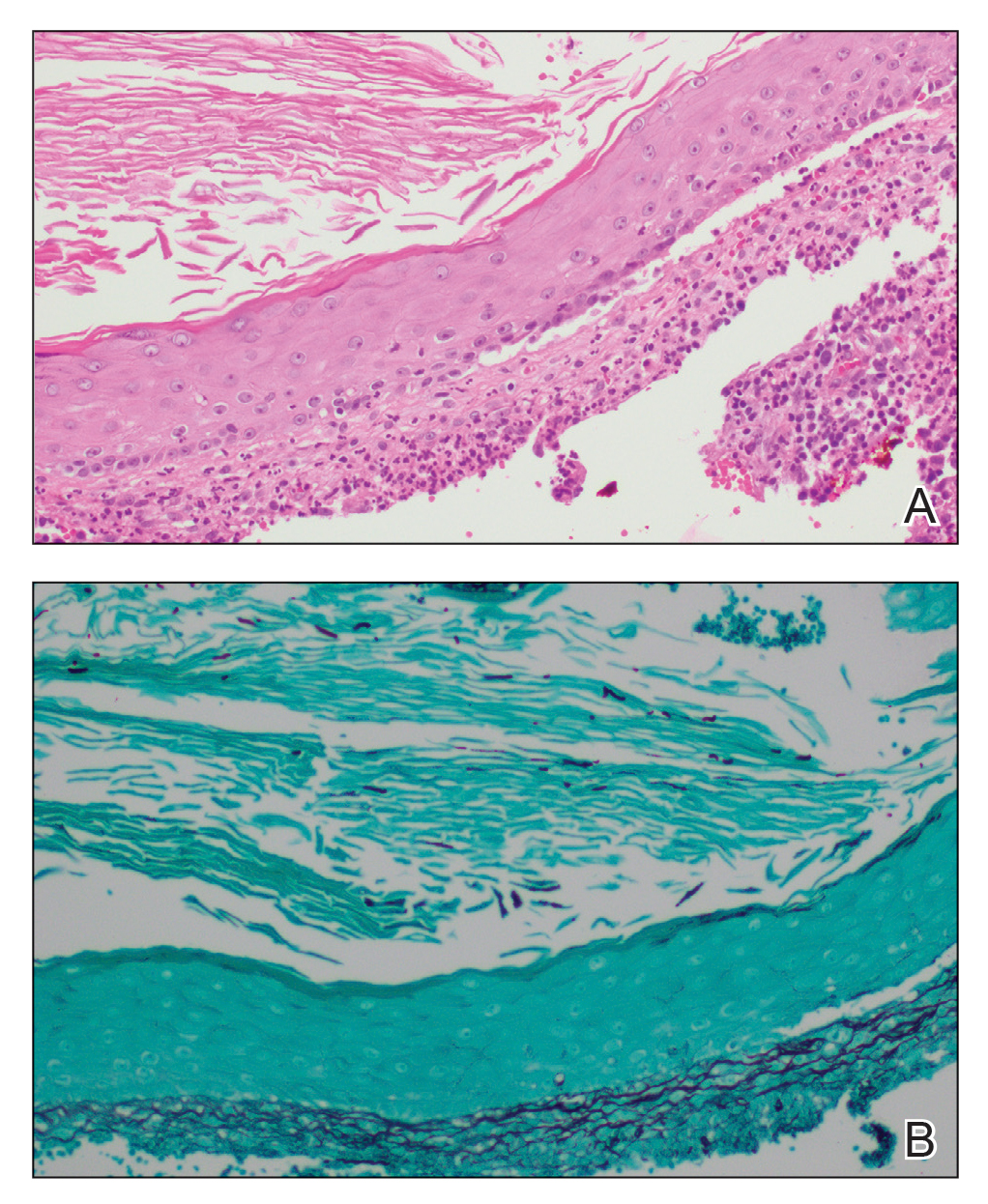

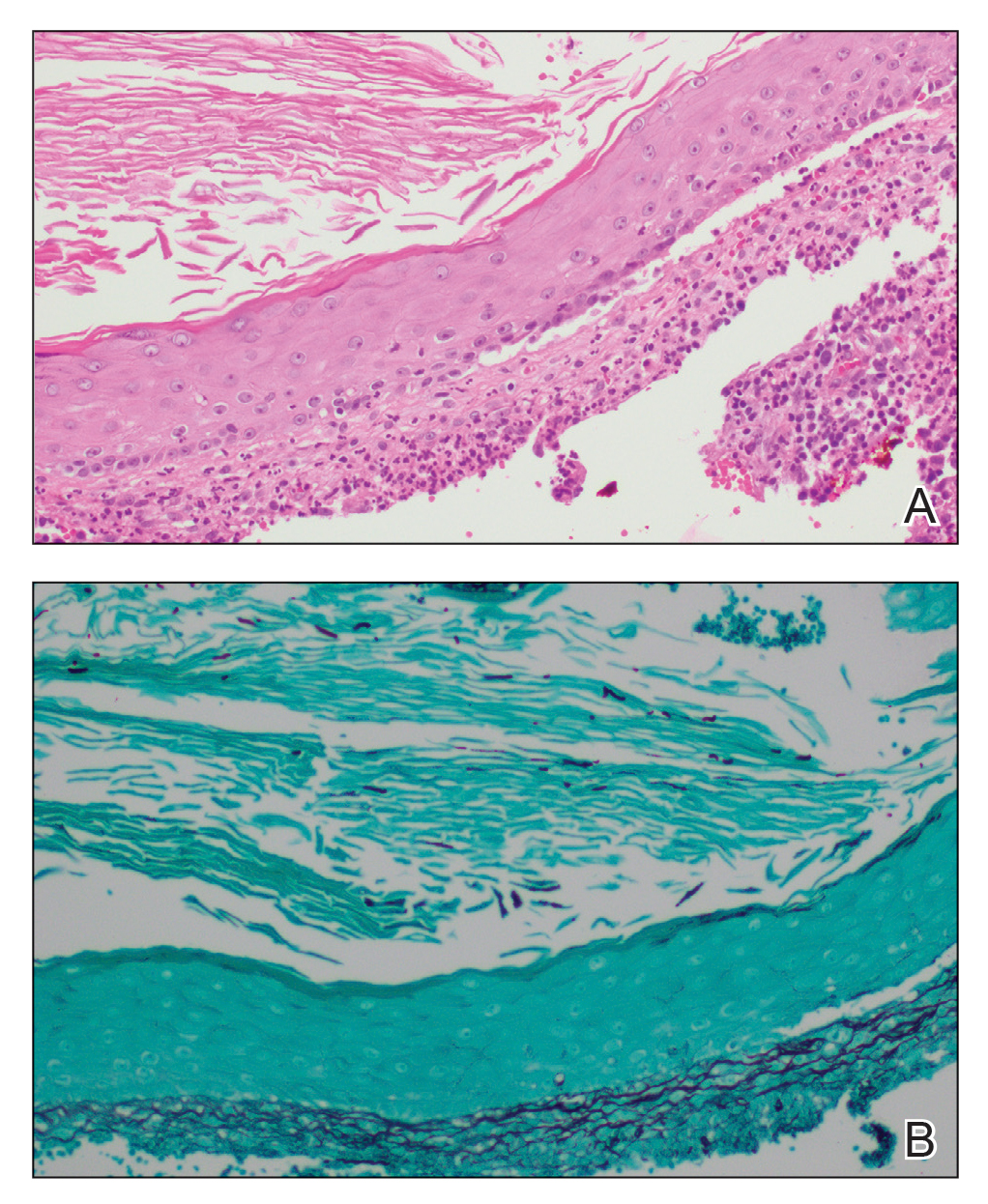

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

An 82-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after her daughter found her unconscious in the bathroom laying on her right side. Her medical history was notable for hypertension and asthma for which she was on losartan, furosemide, diltiazem, and albuterol. She recently had been prescribed lorazepam for insomnia and had started taking the medication 2 days prior. She underwent intubation and was noted to have flaccid, fluid-filled bullae on the right thigh (top) along with large areas of desquamation on the right lateral arm (bottom) with minimal surrounding erythema. There was no mucous membrane involvement. Urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and negative for all other drugs, including barbiturates.

What is the diagnosis?

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that is becoming more recognized in children. It has a variable presentation, most commonly presenting as painful, recurrent cysts, abscesses, nodules, and/or pustules in classic locations with associated scarring and sinus tract formation.

The majority of patients present with bilateral lesions found most commonly in the axillae and inguinal folds.1 There are myriad other potential sites of involvement including the inframammary folds, inner thighs, buttocks, and groin.1 Diagnosis is made based on history and physical exam. There is a standard severity classification scheme called the Hurley score, which stratifies disease severity based on the presence of sinus tracts and extent of disease.1 HS is associated with comorbid conditions such as obesity, overweight, acne, and inflammatory bowel and joint disease.2 This painful, persistent condition is well documented to have a negative impact on quality of life in adult patients, and similar impairment has been found in pediatric patients.3,4

HS may be increasing in pediatric and adolescent patients, with recent studies showing onset coinciding most commonly with the onset of puberty.1,2 There is often a period of several years between symptom onset and diagnosis.1 A recent editorial highlighted the disparities that exist in HS, with disease more common in Black children and limited information about disease prevalence in Hispanic children.5

What’s the treatment plan?

HS is a difficult disease to treat, with few patients achieving remission and a significant proportion of patients with treatment-refractory disease.1 There are limited studies of HS treatment in pediatric patients. Topical and systemic antibiotic therapy are mainstays of HS treatment, with tetracyclines and a combination of clindamycin plus rifampin commonly used in adults and children alike. Topical therapies including topical antibiotics and antibacterial solutions are frequently used as adjunctive therapy.6 Adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor receptor blocker, has been Food and Drug Administration approved for HS for ages 12 and up and is currently the only FDA-approved medication for HS in pediatric patients. Our patient was started on 100 mg doxycycline twice daily, with short-dose topical corticosteroids for symptom management of the most inflamed lesions.

What’s on the differential?

Acne conglobata

Acne conglobata is an uncommon, severe variant of acne vulgaris which arise in patients with a history of acne vulgaris and presents with comedones, cysts, abscesses, and scarring with possible drainage of pus. Lesions can present diffusely on the face, back, and body, including in the axillae, groin, and buttocks, and as such can be confused with HS.7

However, in contrast with HS, patients with acne conglobata will also develop disease in non–apocrine gland–bearing skin. This patient’s lack of preceding acne and restriction of lesions to the axillae, inguinal folds, and buttocks makes acne conglobata less likely.

Epidermal inclusion cyst

Epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC) is a common cutaneous cyst, presenting as a well-circumscribed nodule(s) with a central punctum. If not excised, lesions can sometimes become infected and painful.8 In contrast with HS, EIC presents only uncommonly as multiple lesions arising in different areas, and spontaneous drainage is uncommon. Our patient’s development of multiple draining lesions makes this diagnosis unlikely.

Furunculosis

Furunculosis is a common bacterial infection of the skin, presenting with inflammatory nodules or pustules centered around the hair follicle. Lesions may commonly present at sites of skin trauma and are found most frequently on the extremities.9 Though furunculosis lesions may drain pus and can coalesce to form larger “carbuncles,” our patient’s presence of significant scarring and lack of extremity involvement makes HS more likely.

Recurrent MRSA abscesses

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft-tissue infections are not uncommon in the pediatric population, with presentation of infection ranging from cellulitis to fluid-containing abscesses.10 Recurrent abscesses may be seen in MRSA infection, however in this patient the presence of draining, scarring lesions in multiple locations typical for HS over time is more consistent with a diagnosis of HS.

Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Ms. Appiah is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Appiah have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Liy-Wong C et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):385-91.

2. Choi E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(1):140-7.

3. Machado MO et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(8):939-45.

4. McAndrew R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):829-30.

5. Kirby JS and Zaenglein AL. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):379-80.

6. Alikhan A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):91-101.

7. Greydanus DE et al. Dis Mon. 2021;67(4):101103.

8. Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal Inclusion Cyst, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla: StatPearls Publishing, 2021.

9. Atanaskova N and Tomecki KJ. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(3):479-87.

10. Papastefan ST et al. J Surg Res. 2019;242:70-7.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that is becoming more recognized in children. It has a variable presentation, most commonly presenting as painful, recurrent cysts, abscesses, nodules, and/or pustules in classic locations with associated scarring and sinus tract formation.

The majority of patients present with bilateral lesions found most commonly in the axillae and inguinal folds.1 There are myriad other potential sites of involvement including the inframammary folds, inner thighs, buttocks, and groin.1 Diagnosis is made based on history and physical exam. There is a standard severity classification scheme called the Hurley score, which stratifies disease severity based on the presence of sinus tracts and extent of disease.1 HS is associated with comorbid conditions such as obesity, overweight, acne, and inflammatory bowel and joint disease.2 This painful, persistent condition is well documented to have a negative impact on quality of life in adult patients, and similar impairment has been found in pediatric patients.3,4

HS may be increasing in pediatric and adolescent patients, with recent studies showing onset coinciding most commonly with the onset of puberty.1,2 There is often a period of several years between symptom onset and diagnosis.1 A recent editorial highlighted the disparities that exist in HS, with disease more common in Black children and limited information about disease prevalence in Hispanic children.5

What’s the treatment plan?

HS is a difficult disease to treat, with few patients achieving remission and a significant proportion of patients with treatment-refractory disease.1 There are limited studies of HS treatment in pediatric patients. Topical and systemic antibiotic therapy are mainstays of HS treatment, with tetracyclines and a combination of clindamycin plus rifampin commonly used in adults and children alike. Topical therapies including topical antibiotics and antibacterial solutions are frequently used as adjunctive therapy.6 Adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor receptor blocker, has been Food and Drug Administration approved for HS for ages 12 and up and is currently the only FDA-approved medication for HS in pediatric patients. Our patient was started on 100 mg doxycycline twice daily, with short-dose topical corticosteroids for symptom management of the most inflamed lesions.

What’s on the differential?

Acne conglobata

Acne conglobata is an uncommon, severe variant of acne vulgaris which arise in patients with a history of acne vulgaris and presents with comedones, cysts, abscesses, and scarring with possible drainage of pus. Lesions can present diffusely on the face, back, and body, including in the axillae, groin, and buttocks, and as such can be confused with HS.7

However, in contrast with HS, patients with acne conglobata will also develop disease in non–apocrine gland–bearing skin. This patient’s lack of preceding acne and restriction of lesions to the axillae, inguinal folds, and buttocks makes acne conglobata less likely.

Epidermal inclusion cyst

Epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC) is a common cutaneous cyst, presenting as a well-circumscribed nodule(s) with a central punctum. If not excised, lesions can sometimes become infected and painful.8 In contrast with HS, EIC presents only uncommonly as multiple lesions arising in different areas, and spontaneous drainage is uncommon. Our patient’s development of multiple draining lesions makes this diagnosis unlikely.

Furunculosis

Furunculosis is a common bacterial infection of the skin, presenting with inflammatory nodules or pustules centered around the hair follicle. Lesions may commonly present at sites of skin trauma and are found most frequently on the extremities.9 Though furunculosis lesions may drain pus and can coalesce to form larger “carbuncles,” our patient’s presence of significant scarring and lack of extremity involvement makes HS more likely.

Recurrent MRSA abscesses

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft-tissue infections are not uncommon in the pediatric population, with presentation of infection ranging from cellulitis to fluid-containing abscesses.10 Recurrent abscesses may be seen in MRSA infection, however in this patient the presence of draining, scarring lesions in multiple locations typical for HS over time is more consistent with a diagnosis of HS.

Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Ms. Appiah is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Appiah have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Liy-Wong C et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):385-91.

2. Choi E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(1):140-7.

3. Machado MO et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(8):939-45.

4. McAndrew R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):829-30.

5. Kirby JS and Zaenglein AL. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):379-80.

6. Alikhan A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):91-101.

7. Greydanus DE et al. Dis Mon. 2021;67(4):101103.

8. Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal Inclusion Cyst, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla: StatPearls Publishing, 2021.

9. Atanaskova N and Tomecki KJ. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(3):479-87.

10. Papastefan ST et al. J Surg Res. 2019;242:70-7.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that is becoming more recognized in children. It has a variable presentation, most commonly presenting as painful, recurrent cysts, abscesses, nodules, and/or pustules in classic locations with associated scarring and sinus tract formation.

The majority of patients present with bilateral lesions found most commonly in the axillae and inguinal folds.1 There are myriad other potential sites of involvement including the inframammary folds, inner thighs, buttocks, and groin.1 Diagnosis is made based on history and physical exam. There is a standard severity classification scheme called the Hurley score, which stratifies disease severity based on the presence of sinus tracts and extent of disease.1 HS is associated with comorbid conditions such as obesity, overweight, acne, and inflammatory bowel and joint disease.2 This painful, persistent condition is well documented to have a negative impact on quality of life in adult patients, and similar impairment has been found in pediatric patients.3,4

HS may be increasing in pediatric and adolescent patients, with recent studies showing onset coinciding most commonly with the onset of puberty.1,2 There is often a period of several years between symptom onset and diagnosis.1 A recent editorial highlighted the disparities that exist in HS, with disease more common in Black children and limited information about disease prevalence in Hispanic children.5

What’s the treatment plan?

HS is a difficult disease to treat, with few patients achieving remission and a significant proportion of patients with treatment-refractory disease.1 There are limited studies of HS treatment in pediatric patients. Topical and systemic antibiotic therapy are mainstays of HS treatment, with tetracyclines and a combination of clindamycin plus rifampin commonly used in adults and children alike. Topical therapies including topical antibiotics and antibacterial solutions are frequently used as adjunctive therapy.6 Adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor receptor blocker, has been Food and Drug Administration approved for HS for ages 12 and up and is currently the only FDA-approved medication for HS in pediatric patients. Our patient was started on 100 mg doxycycline twice daily, with short-dose topical corticosteroids for symptom management of the most inflamed lesions.

What’s on the differential?

Acne conglobata

Acne conglobata is an uncommon, severe variant of acne vulgaris which arise in patients with a history of acne vulgaris and presents with comedones, cysts, abscesses, and scarring with possible drainage of pus. Lesions can present diffusely on the face, back, and body, including in the axillae, groin, and buttocks, and as such can be confused with HS.7

However, in contrast with HS, patients with acne conglobata will also develop disease in non–apocrine gland–bearing skin. This patient’s lack of preceding acne and restriction of lesions to the axillae, inguinal folds, and buttocks makes acne conglobata less likely.

Epidermal inclusion cyst

Epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC) is a common cutaneous cyst, presenting as a well-circumscribed nodule(s) with a central punctum. If not excised, lesions can sometimes become infected and painful.8 In contrast with HS, EIC presents only uncommonly as multiple lesions arising in different areas, and spontaneous drainage is uncommon. Our patient’s development of multiple draining lesions makes this diagnosis unlikely.

Furunculosis

Furunculosis is a common bacterial infection of the skin, presenting with inflammatory nodules or pustules centered around the hair follicle. Lesions may commonly present at sites of skin trauma and are found most frequently on the extremities.9 Though furunculosis lesions may drain pus and can coalesce to form larger “carbuncles,” our patient’s presence of significant scarring and lack of extremity involvement makes HS more likely.

Recurrent MRSA abscesses

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft-tissue infections are not uncommon in the pediatric population, with presentation of infection ranging from cellulitis to fluid-containing abscesses.10 Recurrent abscesses may be seen in MRSA infection, however in this patient the presence of draining, scarring lesions in multiple locations typical for HS over time is more consistent with a diagnosis of HS.

Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Ms. Appiah is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Appiah have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Liy-Wong C et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):385-91.

2. Choi E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(1):140-7.

3. Machado MO et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(8):939-45.

4. McAndrew R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):829-30.

5. Kirby JS and Zaenglein AL. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):379-80.

6. Alikhan A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):91-101.

7. Greydanus DE et al. Dis Mon. 2021;67(4):101103.

8. Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal Inclusion Cyst, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla: StatPearls Publishing, 2021.

9. Atanaskova N and Tomecki KJ. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(3):479-87.

10. Papastefan ST et al. J Surg Res. 2019;242:70-7.

Enlarging Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Myxoma

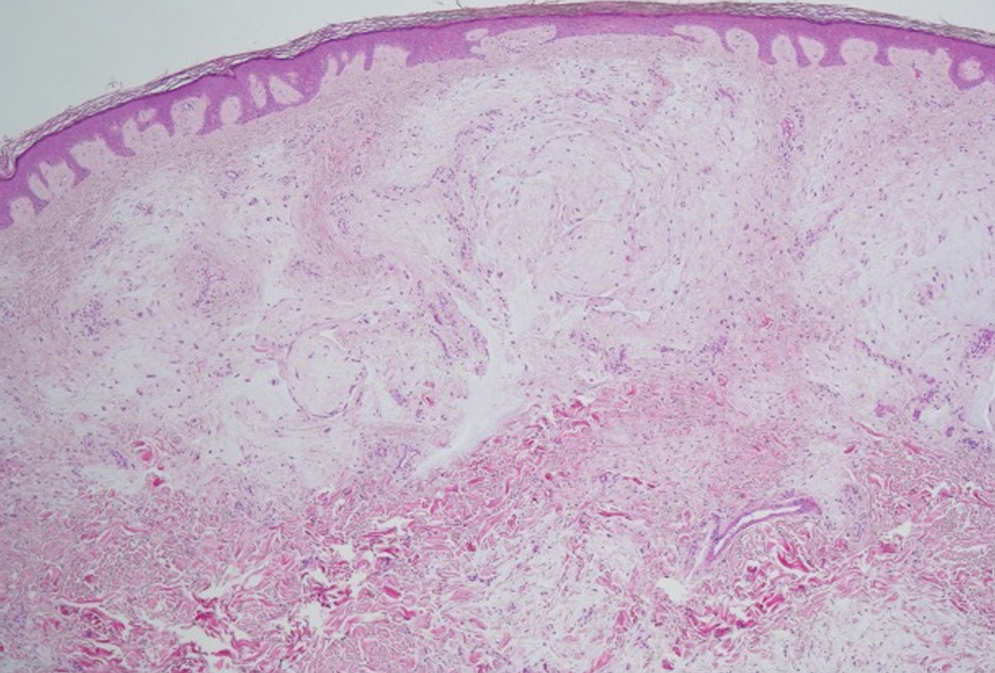

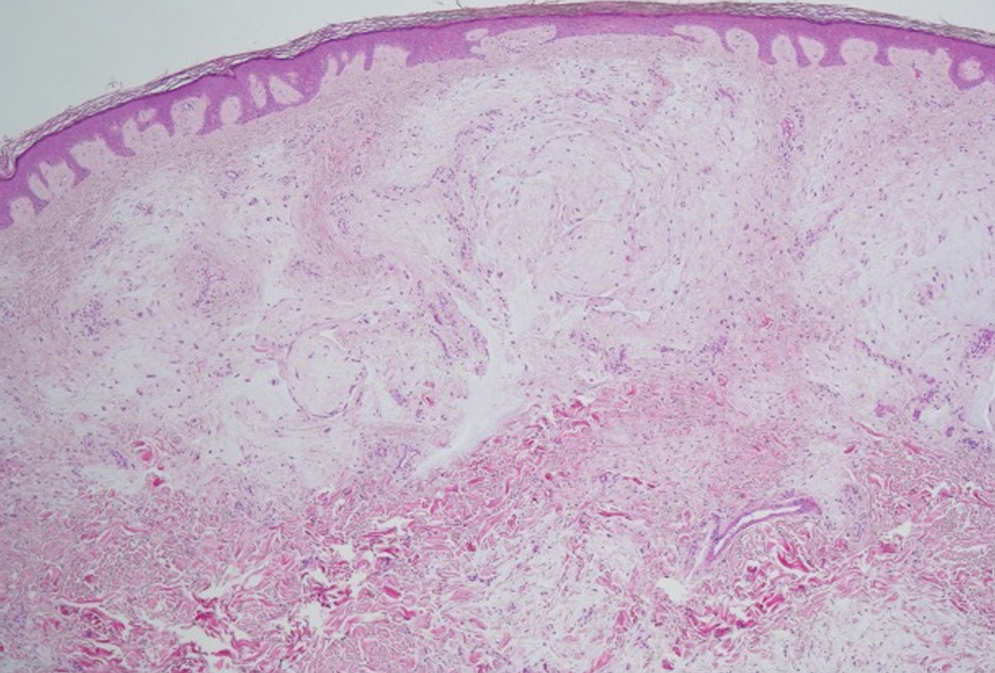

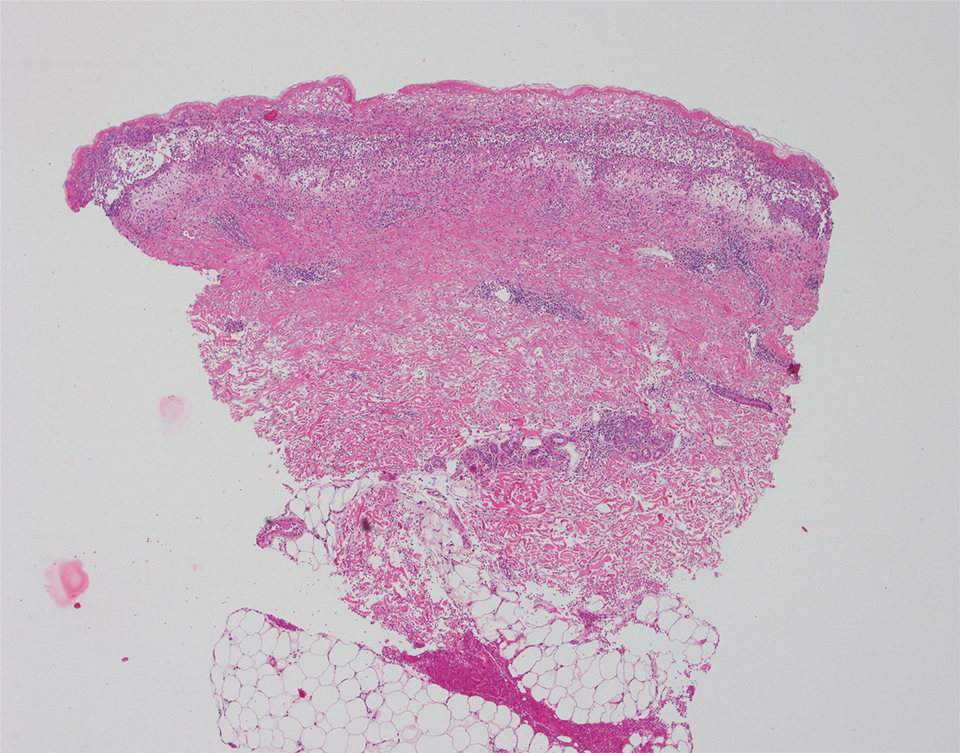

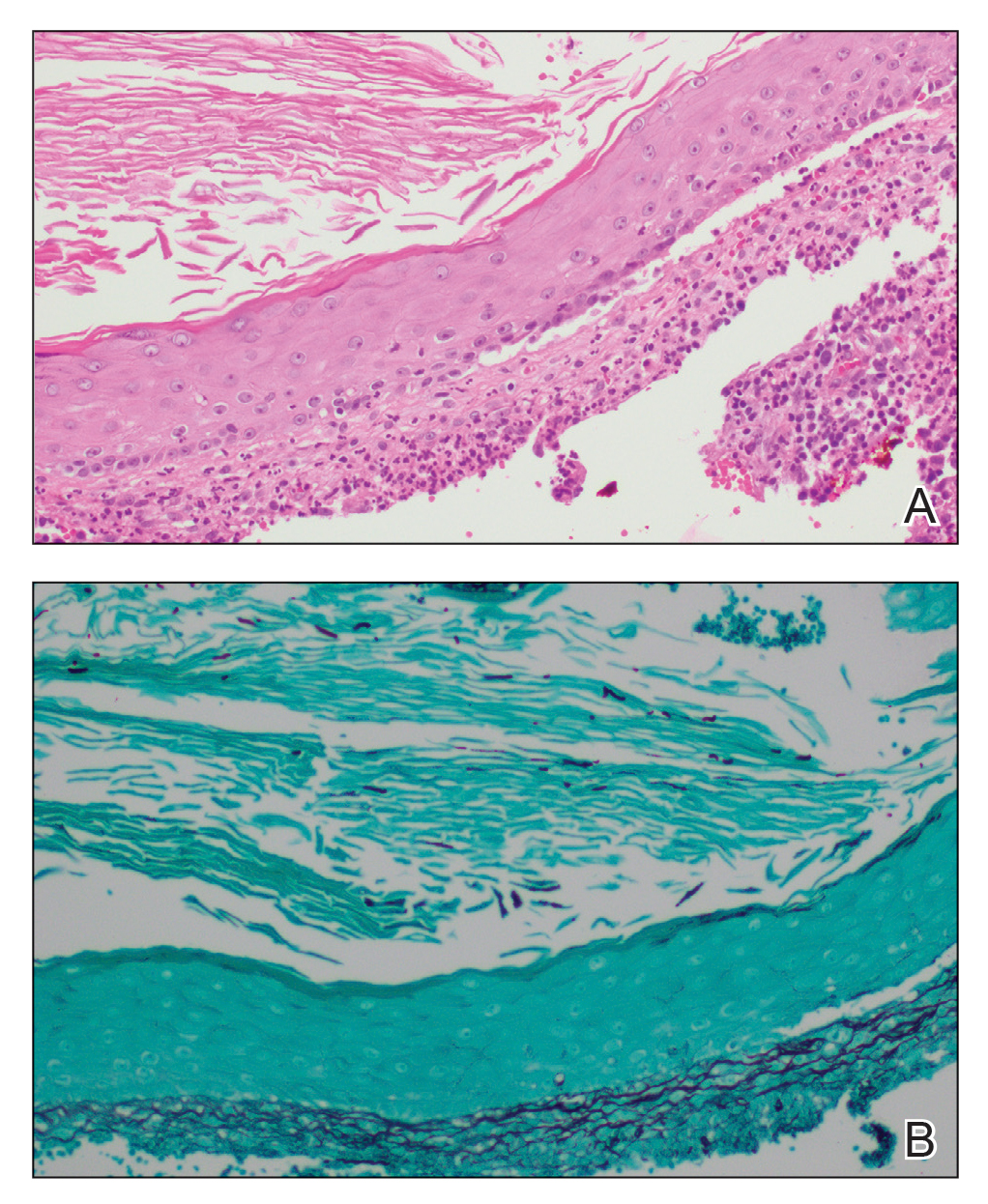

Microscopic analysis showed features of cutaneous myxoma (quiz images). The epidermis was essentially unremarkable. Stellate to spindle cells with bland nuclear chromatin were present in the dermis with abundant pools of myxoid stroma. Colloidal iron staining highlighted the markedly increased dermal mucin.

Cutaneous myxomas (also referred to as superficial angiomyxomas) are rare, well-demarcated tumors of the dermis and subcutis.1,2 They can present as solitary, fleshcolored nodules on the trunk, lower extremities, head, or neck, and they often measure between 1 and 5 cm.2,3 Histologically, cutaneous myxomas are hypocellular with some stellate fibroblasts, occasional epithelial structures, and an abundant myxoid stroma, with notable thinwalled small blood vessels.2,4 These lesions contain pools of mucin and are positive for mesenchymal mucin stains such as colloidal iron and Alcian blue.1 Moreover, perivascular neutrophils are a distinguishing characteristic of cutaneous myxomas.4

Multiple cutaneous myxomas should raise concern for Carney complex,1,5 a genodermatologic syndrome that arises due to a mutation in the protein kinase CAMP-dependent type I regulatory subunit alpha gene, PRKAR1A, on chromosome 2.1,5 Additional cutaneous manifestations include blue nevi, lentigines, and café-aulait macules.5 Carney complex also is known for endocrine overactivity and cardiac myxomas, which can cause serious embolic complications.1

Recommended management is complete excision with close follow-up, as these lesions may recur in up to one-third of cases. Although there is a potential for recurrence, metastases are uncommon.3 Even without recurrence in the presenting location, follow-up should include screening for manifestations of Carney complex.1,3

The clinical and histological differential for cutaneous myxoma may include nerve sheath myxoma or neurofibroma. A nerve sheath myxoma is a dermal tumor that manifests as a solitary, flesh-colored nodule, measuring less than 2 cm. These lesions commonly present on the head, neck, and upper body.6 Cutaneous myxomas can grow larger than 2 cm, but these two lesions have a great deal of overlap in their other features.3,6 Thus, histology can be used to distinguish them.

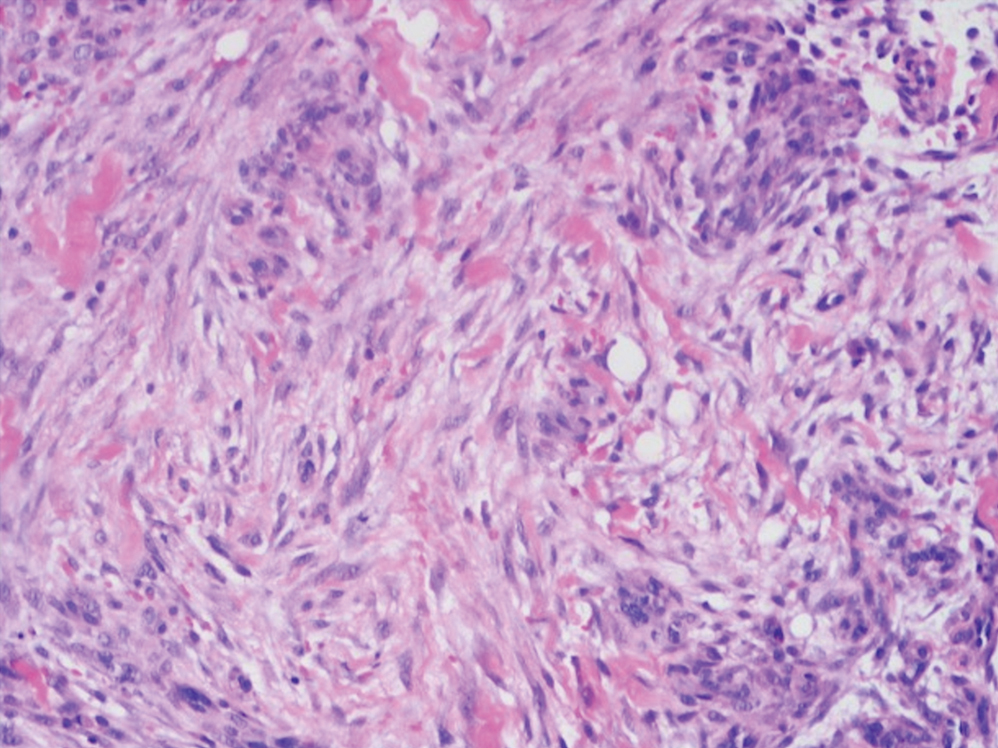

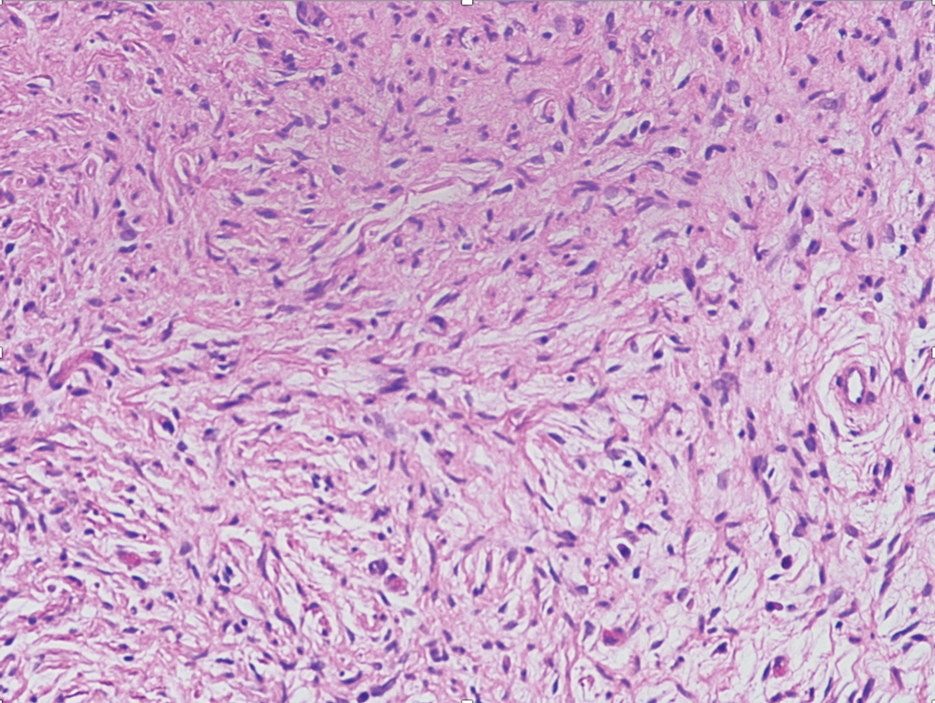

Nerve sheath myxomas are circumscribed nonencapsulated tumors of the dermis composed of multilobular aggregates of spindle to epithelioid cells in a mucinous matrix (Figure 1). Clefts often are present around the cell aggregates. Despite previously being termed myxoid neurothekeomas, nerve sheath myxomas are S-100 positive, whereas cellular neurothekeomas are S-100 negative and likely not of neural origin. Cutaneous myxomas, in contrast to nerve sheath myxomas, are S-100 negative. Nerve sheath myxomas are more cellular and lack the characteristic mucin pools compared with cutaneous myxomas.1,2,6 Neurofibromas frequently are flesh colored and pedunculated, as was the lesion in our patient, yet they are vastly different microscopically. The stroma of neurofibromas can vary, but cellularity typically is greater than a cutaneous myxoma and consists of increased numbers of bland spindle cells with wavy nuclei (Schwann cells) and fibrillar cytoplasm as well as mast cells and fibroblasts (Figure 2). Neurofibromas stain positively for S-100 and SOX-10 (Sry-related HMg-box 10).2,7 In addition to café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, optic gliomas, and positive family history, neurofibromas are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, which is linked to a defect in a tumor suppressor gene that codes for neurofibromin.7

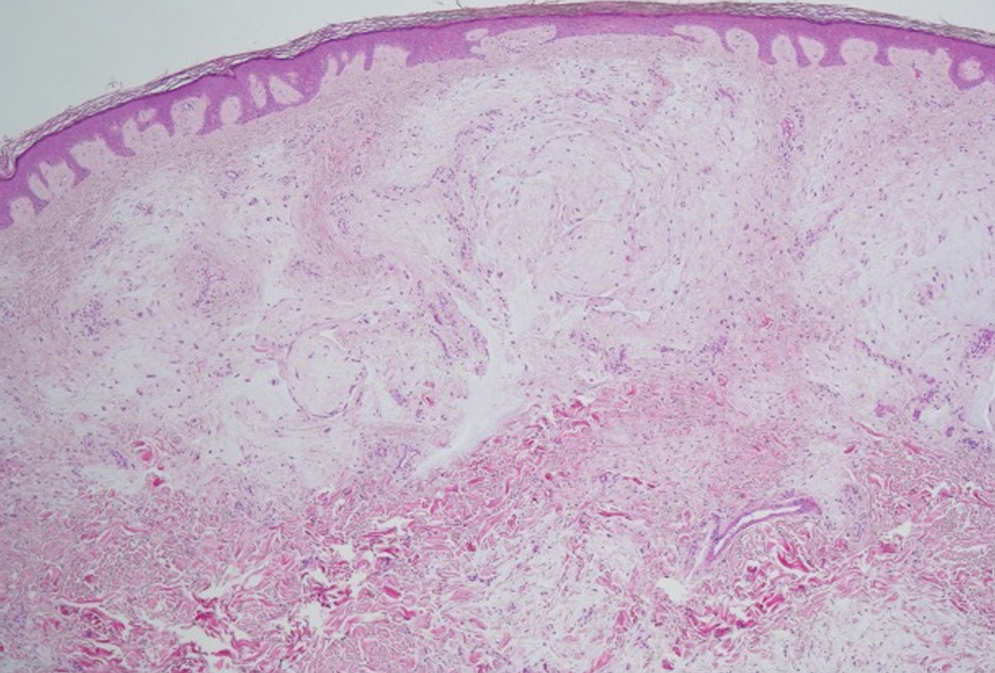

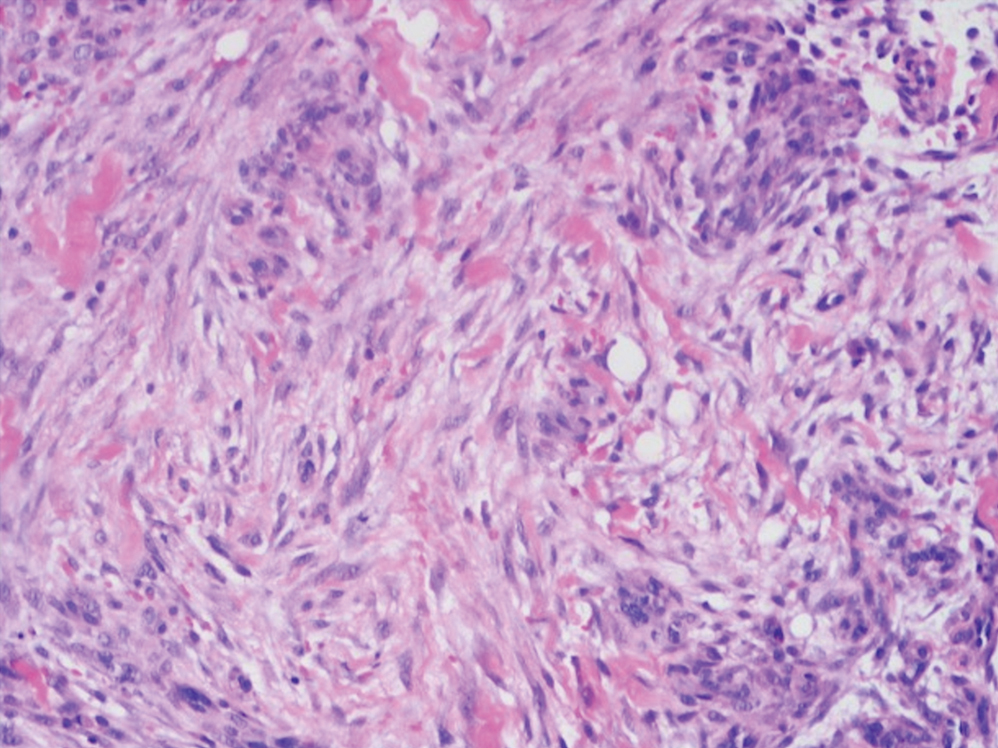

Nodular fasciitis is a self-limited myofibroblastic neoplasm that contains fusion genes, with the most common being myosin-9–ubiquitin specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, which leads to overexpression of USP6. Nodular fasciitis presents as a solitary, rapidly enlarging nodule affecting the subcutaneous tissue, muscles, or fascia.8,9 It usually presents in the third or fourth decades of life.8 The arms are the most common location in adults, while the most commonly affected site in children is the head or neck. Histopathology reveals a characteristic tissue culture pattern with a proliferation of plump spindle and stellate fibroblasts as well as myofibroblasts (Figure 3). Early lesions have haphazard spindle cells with a proliferation of small blood vessels and extravasated erythrocytes. Despite increased mitotic figures, cellular atypia is rare. The fibroblasts and myofibroblasts react positively for vimentin and muscle-specific actin.8 This lesion is highly cellular comparatively and notably lacks the perivascular neutrophils and epithelial structures that would be expected in a cutaneous myxoma.4,8

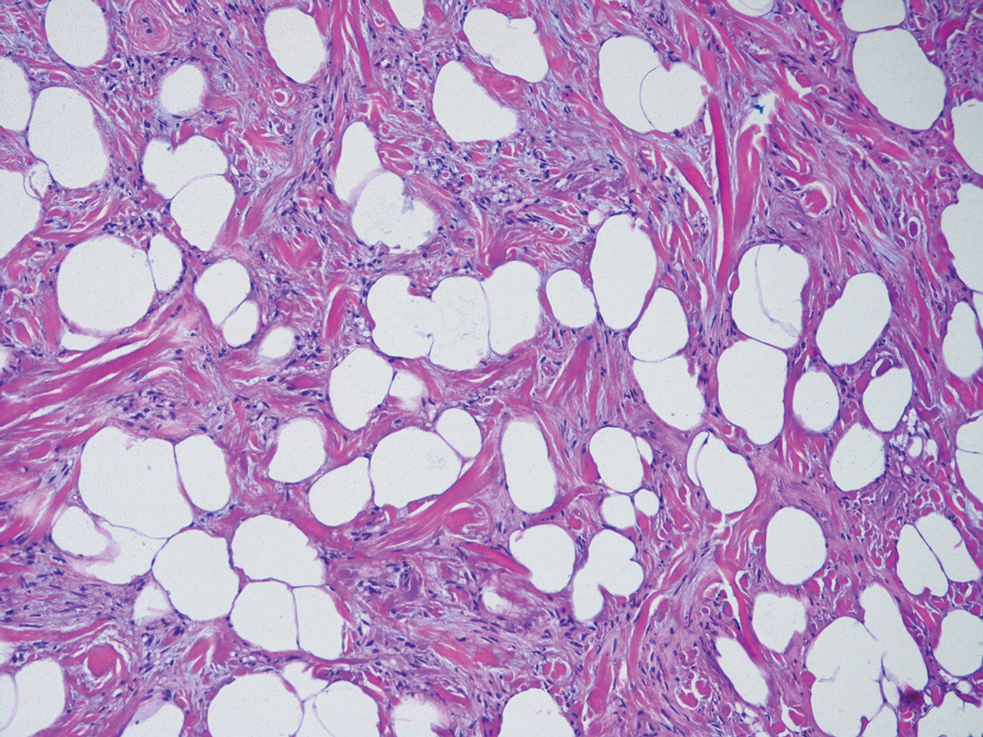

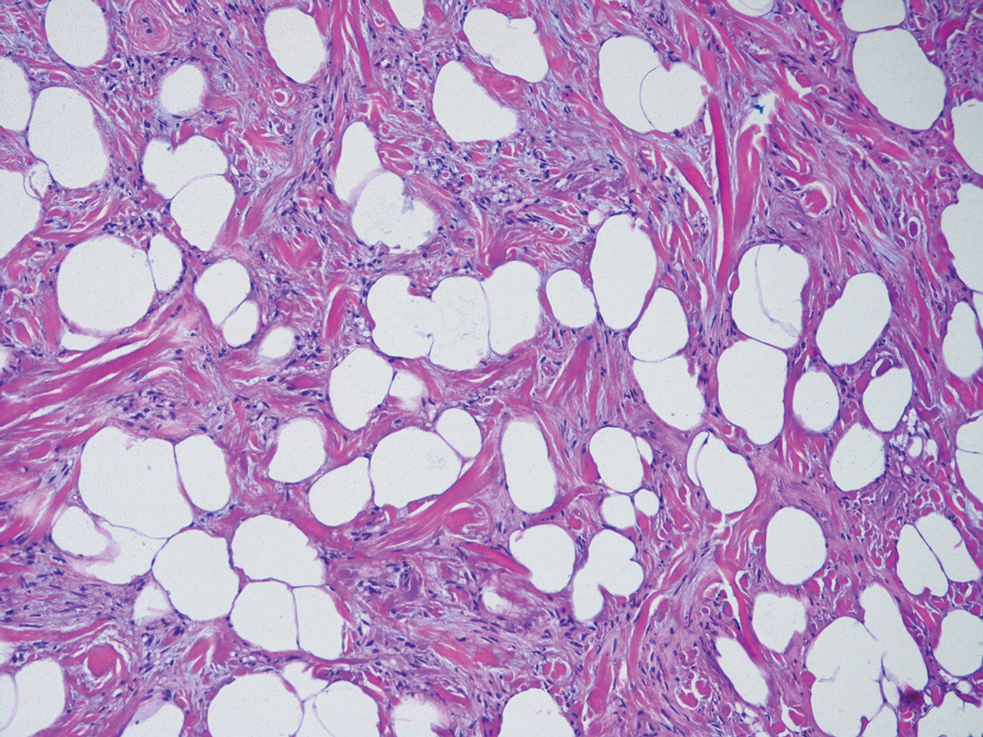

Spindle cell lipomas, solitary subcutaneous masses commonly presenting on the upper back in middle-aged men, also can mimic cutaneous myxomas.4 Histologically, these lesions may contain short bundles of spindle cells arranged in a school of fish–like pattern, mature adipocytes, or myxoid stroma and characteristic CD34 positivity (Figure 4). Spindle cell lipomas often will present with ropey collagen, which can easily distinguish them from cutaneous myxomas.4

- Lanjewar DN, Bhatia VO, Lanjewar SD, et al. Cutaneous myxoma: an important clue to Carney complex. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:460-462.

- Choi HJ, Kim YJ, Yim JH, et al. Unusual presentation of solitary cutaneous myxoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:403-404. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01881.x

- Kura MM, Jindal SR. Solitary superficial acral angiomyxoma: an infrequently reported soft tissue tumor. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:1-3. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.139893

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918.

- Sarfo A, Helm K, Flamm A. Cutaneous myxomas and a psammomatous melanotic schwannoma in a patient with Carney complex. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:93-96. doi:10.1111/cup.13385

- Gill P, Abi Daoud MS. Multiple cellular neurothekeomas in a middleaged woman including the lower extremity: a case report and review of the current literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:67-73. doi:10.1111/ cup.13366

- Ohgaki H, Kim Y, Steinbach JP. Nervous system tumors associated with familial tumor syndromes. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:583-591. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283405b5f

- Luna A, Molinari L, Bollea Garlatti LA, et al. Nodular fasciitis, a forgotten entity. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:190-193. doi:10.1111/ijd.14219

- Patel N, Chrisinger J, Demicco E, et al. USP6 activation in nodular fasciitis by promoter-swapping gene fusions. Mod Pathol. 2017; 30:1577-1588.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Myxoma

Microscopic analysis showed features of cutaneous myxoma (quiz images). The epidermis was essentially unremarkable. Stellate to spindle cells with bland nuclear chromatin were present in the dermis with abundant pools of myxoid stroma. Colloidal iron staining highlighted the markedly increased dermal mucin.

Cutaneous myxomas (also referred to as superficial angiomyxomas) are rare, well-demarcated tumors of the dermis and subcutis.1,2 They can present as solitary, fleshcolored nodules on the trunk, lower extremities, head, or neck, and they often measure between 1 and 5 cm.2,3 Histologically, cutaneous myxomas are hypocellular with some stellate fibroblasts, occasional epithelial structures, and an abundant myxoid stroma, with notable thinwalled small blood vessels.2,4 These lesions contain pools of mucin and are positive for mesenchymal mucin stains such as colloidal iron and Alcian blue.1 Moreover, perivascular neutrophils are a distinguishing characteristic of cutaneous myxomas.4

Multiple cutaneous myxomas should raise concern for Carney complex,1,5 a genodermatologic syndrome that arises due to a mutation in the protein kinase CAMP-dependent type I regulatory subunit alpha gene, PRKAR1A, on chromosome 2.1,5 Additional cutaneous manifestations include blue nevi, lentigines, and café-aulait macules.5 Carney complex also is known for endocrine overactivity and cardiac myxomas, which can cause serious embolic complications.1

Recommended management is complete excision with close follow-up, as these lesions may recur in up to one-third of cases. Although there is a potential for recurrence, metastases are uncommon.3 Even without recurrence in the presenting location, follow-up should include screening for manifestations of Carney complex.1,3

The clinical and histological differential for cutaneous myxoma may include nerve sheath myxoma or neurofibroma. A nerve sheath myxoma is a dermal tumor that manifests as a solitary, flesh-colored nodule, measuring less than 2 cm. These lesions commonly present on the head, neck, and upper body.6 Cutaneous myxomas can grow larger than 2 cm, but these two lesions have a great deal of overlap in their other features.3,6 Thus, histology can be used to distinguish them.

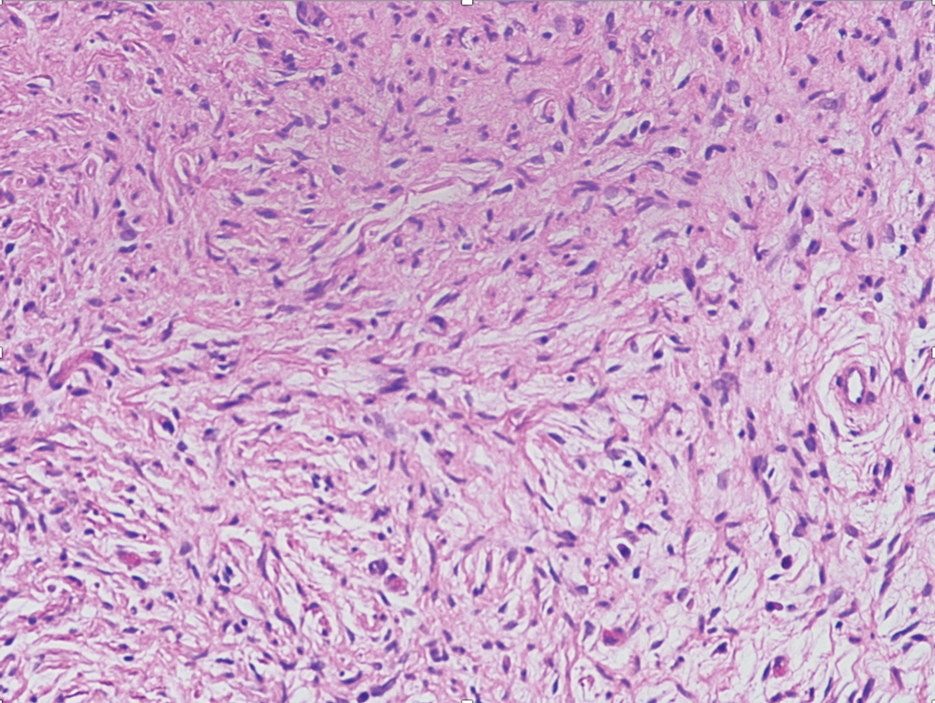

Nerve sheath myxomas are circumscribed nonencapsulated tumors of the dermis composed of multilobular aggregates of spindle to epithelioid cells in a mucinous matrix (Figure 1). Clefts often are present around the cell aggregates. Despite previously being termed myxoid neurothekeomas, nerve sheath myxomas are S-100 positive, whereas cellular neurothekeomas are S-100 negative and likely not of neural origin. Cutaneous myxomas, in contrast to nerve sheath myxomas, are S-100 negative. Nerve sheath myxomas are more cellular and lack the characteristic mucin pools compared with cutaneous myxomas.1,2,6 Neurofibromas frequently are flesh colored and pedunculated, as was the lesion in our patient, yet they are vastly different microscopically. The stroma of neurofibromas can vary, but cellularity typically is greater than a cutaneous myxoma and consists of increased numbers of bland spindle cells with wavy nuclei (Schwann cells) and fibrillar cytoplasm as well as mast cells and fibroblasts (Figure 2). Neurofibromas stain positively for S-100 and SOX-10 (Sry-related HMg-box 10).2,7 In addition to café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, optic gliomas, and positive family history, neurofibromas are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, which is linked to a defect in a tumor suppressor gene that codes for neurofibromin.7

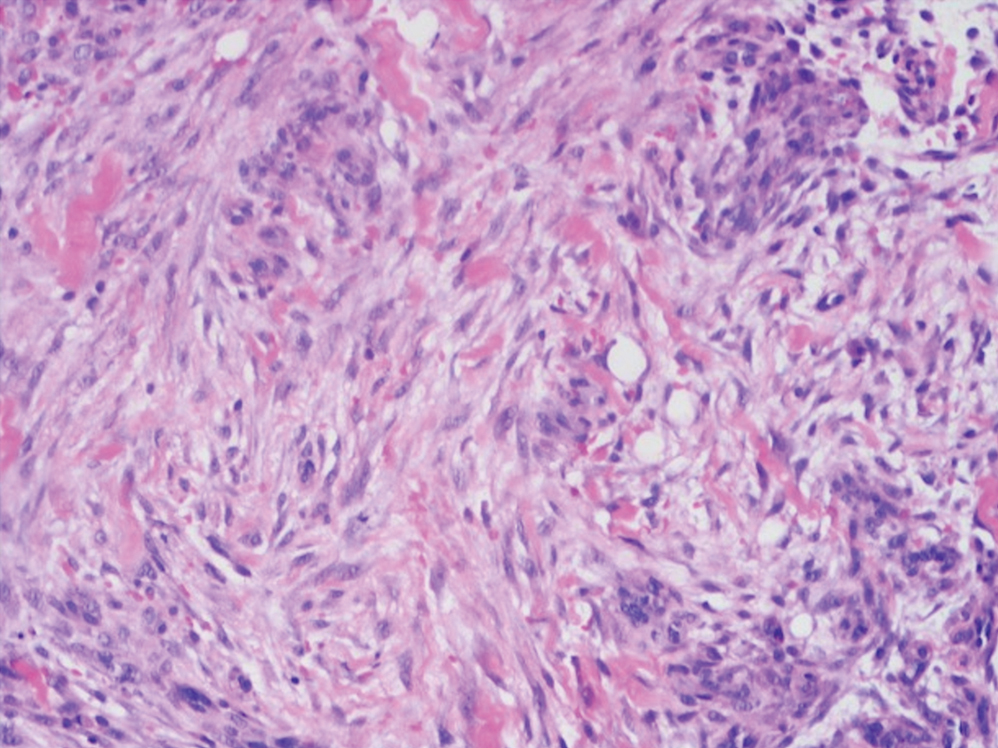

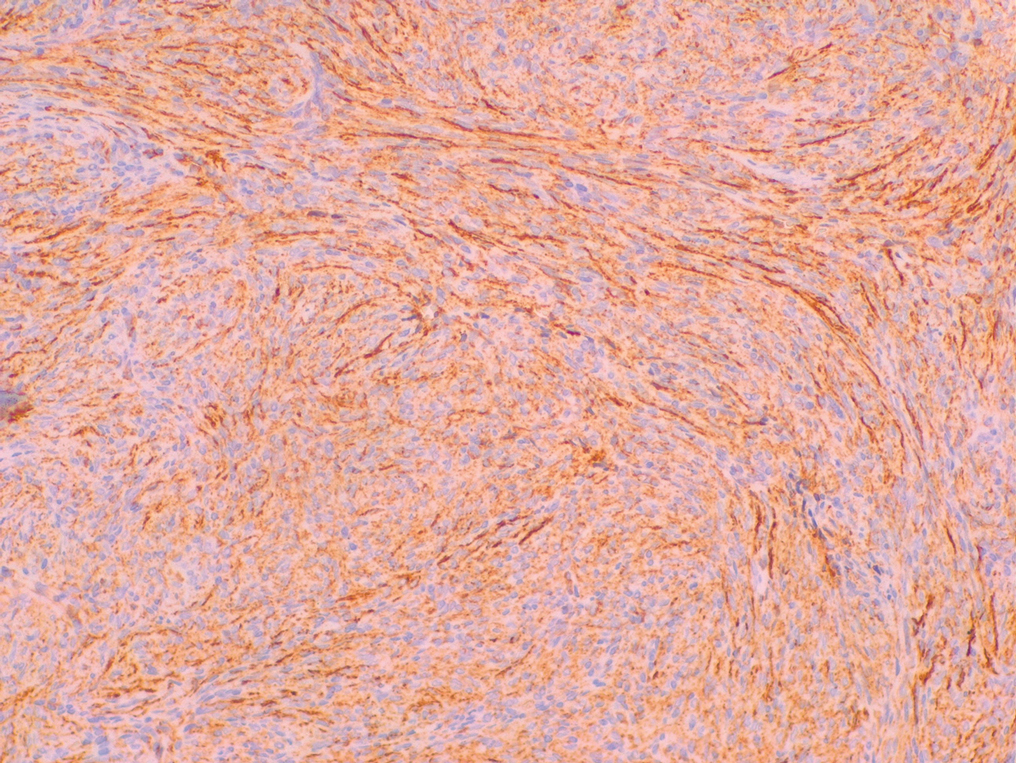

Nodular fasciitis is a self-limited myofibroblastic neoplasm that contains fusion genes, with the most common being myosin-9–ubiquitin specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, which leads to overexpression of USP6. Nodular fasciitis presents as a solitary, rapidly enlarging nodule affecting the subcutaneous tissue, muscles, or fascia.8,9 It usually presents in the third or fourth decades of life.8 The arms are the most common location in adults, while the most commonly affected site in children is the head or neck. Histopathology reveals a characteristic tissue culture pattern with a proliferation of plump spindle and stellate fibroblasts as well as myofibroblasts (Figure 3). Early lesions have haphazard spindle cells with a proliferation of small blood vessels and extravasated erythrocytes. Despite increased mitotic figures, cellular atypia is rare. The fibroblasts and myofibroblasts react positively for vimentin and muscle-specific actin.8 This lesion is highly cellular comparatively and notably lacks the perivascular neutrophils and epithelial structures that would be expected in a cutaneous myxoma.4,8

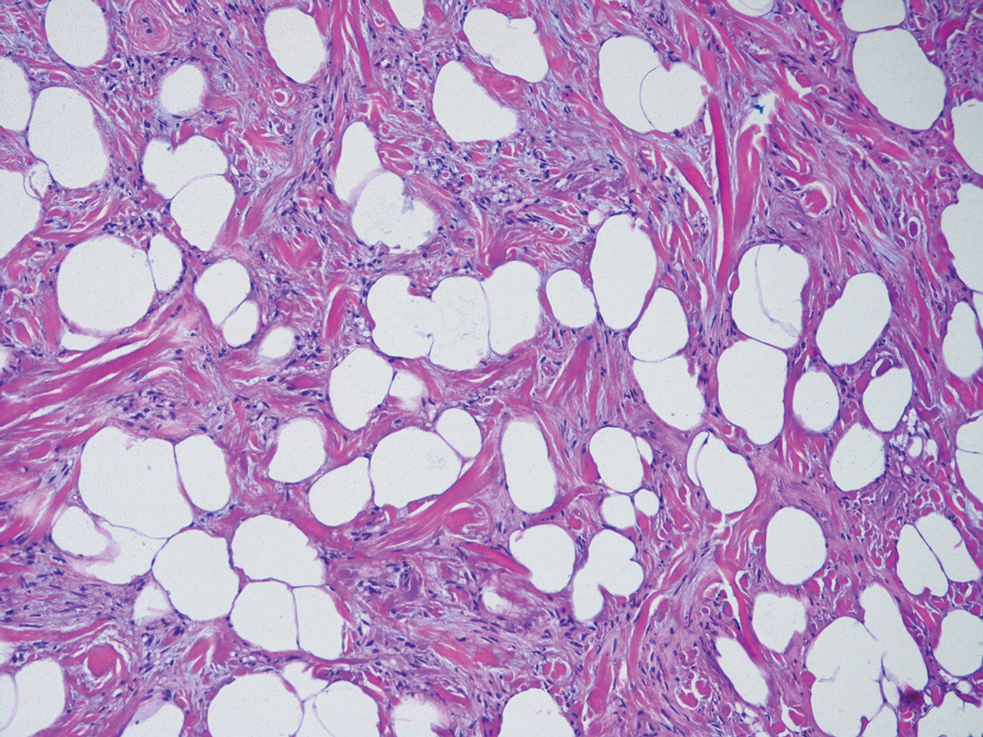

Spindle cell lipomas, solitary subcutaneous masses commonly presenting on the upper back in middle-aged men, also can mimic cutaneous myxomas.4 Histologically, these lesions may contain short bundles of spindle cells arranged in a school of fish–like pattern, mature adipocytes, or myxoid stroma and characteristic CD34 positivity (Figure 4). Spindle cell lipomas often will present with ropey collagen, which can easily distinguish them from cutaneous myxomas.4

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Myxoma

Microscopic analysis showed features of cutaneous myxoma (quiz images). The epidermis was essentially unremarkable. Stellate to spindle cells with bland nuclear chromatin were present in the dermis with abundant pools of myxoid stroma. Colloidal iron staining highlighted the markedly increased dermal mucin.

Cutaneous myxomas (also referred to as superficial angiomyxomas) are rare, well-demarcated tumors of the dermis and subcutis.1,2 They can present as solitary, fleshcolored nodules on the trunk, lower extremities, head, or neck, and they often measure between 1 and 5 cm.2,3 Histologically, cutaneous myxomas are hypocellular with some stellate fibroblasts, occasional epithelial structures, and an abundant myxoid stroma, with notable thinwalled small blood vessels.2,4 These lesions contain pools of mucin and are positive for mesenchymal mucin stains such as colloidal iron and Alcian blue.1 Moreover, perivascular neutrophils are a distinguishing characteristic of cutaneous myxomas.4

Multiple cutaneous myxomas should raise concern for Carney complex,1,5 a genodermatologic syndrome that arises due to a mutation in the protein kinase CAMP-dependent type I regulatory subunit alpha gene, PRKAR1A, on chromosome 2.1,5 Additional cutaneous manifestations include blue nevi, lentigines, and café-aulait macules.5 Carney complex also is known for endocrine overactivity and cardiac myxomas, which can cause serious embolic complications.1

Recommended management is complete excision with close follow-up, as these lesions may recur in up to one-third of cases. Although there is a potential for recurrence, metastases are uncommon.3 Even without recurrence in the presenting location, follow-up should include screening for manifestations of Carney complex.1,3

The clinical and histological differential for cutaneous myxoma may include nerve sheath myxoma or neurofibroma. A nerve sheath myxoma is a dermal tumor that manifests as a solitary, flesh-colored nodule, measuring less than 2 cm. These lesions commonly present on the head, neck, and upper body.6 Cutaneous myxomas can grow larger than 2 cm, but these two lesions have a great deal of overlap in their other features.3,6 Thus, histology can be used to distinguish them.

Nerve sheath myxomas are circumscribed nonencapsulated tumors of the dermis composed of multilobular aggregates of spindle to epithelioid cells in a mucinous matrix (Figure 1). Clefts often are present around the cell aggregates. Despite previously being termed myxoid neurothekeomas, nerve sheath myxomas are S-100 positive, whereas cellular neurothekeomas are S-100 negative and likely not of neural origin. Cutaneous myxomas, in contrast to nerve sheath myxomas, are S-100 negative. Nerve sheath myxomas are more cellular and lack the characteristic mucin pools compared with cutaneous myxomas.1,2,6 Neurofibromas frequently are flesh colored and pedunculated, as was the lesion in our patient, yet they are vastly different microscopically. The stroma of neurofibromas can vary, but cellularity typically is greater than a cutaneous myxoma and consists of increased numbers of bland spindle cells with wavy nuclei (Schwann cells) and fibrillar cytoplasm as well as mast cells and fibroblasts (Figure 2). Neurofibromas stain positively for S-100 and SOX-10 (Sry-related HMg-box 10).2,7 In addition to café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, optic gliomas, and positive family history, neurofibromas are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, which is linked to a defect in a tumor suppressor gene that codes for neurofibromin.7

Nodular fasciitis is a self-limited myofibroblastic neoplasm that contains fusion genes, with the most common being myosin-9–ubiquitin specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, which leads to overexpression of USP6. Nodular fasciitis presents as a solitary, rapidly enlarging nodule affecting the subcutaneous tissue, muscles, or fascia.8,9 It usually presents in the third or fourth decades of life.8 The arms are the most common location in adults, while the most commonly affected site in children is the head or neck. Histopathology reveals a characteristic tissue culture pattern with a proliferation of plump spindle and stellate fibroblasts as well as myofibroblasts (Figure 3). Early lesions have haphazard spindle cells with a proliferation of small blood vessels and extravasated erythrocytes. Despite increased mitotic figures, cellular atypia is rare. The fibroblasts and myofibroblasts react positively for vimentin and muscle-specific actin.8 This lesion is highly cellular comparatively and notably lacks the perivascular neutrophils and epithelial structures that would be expected in a cutaneous myxoma.4,8

Spindle cell lipomas, solitary subcutaneous masses commonly presenting on the upper back in middle-aged men, also can mimic cutaneous myxomas.4 Histologically, these lesions may contain short bundles of spindle cells arranged in a school of fish–like pattern, mature adipocytes, or myxoid stroma and characteristic CD34 positivity (Figure 4). Spindle cell lipomas often will present with ropey collagen, which can easily distinguish them from cutaneous myxomas.4

- Lanjewar DN, Bhatia VO, Lanjewar SD, et al. Cutaneous myxoma: an important clue to Carney complex. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:460-462.

- Choi HJ, Kim YJ, Yim JH, et al. Unusual presentation of solitary cutaneous myxoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:403-404. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01881.x

- Kura MM, Jindal SR. Solitary superficial acral angiomyxoma: an infrequently reported soft tissue tumor. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:1-3. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.139893

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918.

- Sarfo A, Helm K, Flamm A. Cutaneous myxomas and a psammomatous melanotic schwannoma in a patient with Carney complex. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:93-96. doi:10.1111/cup.13385

- Gill P, Abi Daoud MS. Multiple cellular neurothekeomas in a middleaged woman including the lower extremity: a case report and review of the current literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:67-73. doi:10.1111/ cup.13366

- Ohgaki H, Kim Y, Steinbach JP. Nervous system tumors associated with familial tumor syndromes. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:583-591. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283405b5f

- Luna A, Molinari L, Bollea Garlatti LA, et al. Nodular fasciitis, a forgotten entity. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:190-193. doi:10.1111/ijd.14219

- Patel N, Chrisinger J, Demicco E, et al. USP6 activation in nodular fasciitis by promoter-swapping gene fusions. Mod Pathol. 2017; 30:1577-1588.

- Lanjewar DN, Bhatia VO, Lanjewar SD, et al. Cutaneous myxoma: an important clue to Carney complex. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:460-462.

- Choi HJ, Kim YJ, Yim JH, et al. Unusual presentation of solitary cutaneous myxoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:403-404. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01881.x

- Kura MM, Jindal SR. Solitary superficial acral angiomyxoma: an infrequently reported soft tissue tumor. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:1-3. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.139893

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918.

- Sarfo A, Helm K, Flamm A. Cutaneous myxomas and a psammomatous melanotic schwannoma in a patient with Carney complex. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:93-96. doi:10.1111/cup.13385

- Gill P, Abi Daoud MS. Multiple cellular neurothekeomas in a middleaged woman including the lower extremity: a case report and review of the current literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:67-73. doi:10.1111/ cup.13366

- Ohgaki H, Kim Y, Steinbach JP. Nervous system tumors associated with familial tumor syndromes. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:583-591. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283405b5f

- Luna A, Molinari L, Bollea Garlatti LA, et al. Nodular fasciitis, a forgotten entity. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:190-193. doi:10.1111/ijd.14219

- Patel N, Chrisinger J, Demicco E, et al. USP6 activation in nodular fasciitis by promoter-swapping gene fusions. Mod Pathol. 2017; 30:1577-1588.

A 43-year-old man with an unremarkable medical history presented to our clinic with an enlarging painful nodule on the upper back that was present for years without bleeding or ulceration. He denied prior treatment or any similar lesions. Physical examination was notable for a 2×1.5-cm, pedunculated, flesh-colored nodule on the left upper back. A shave excision of the lesion was performed.

Erythematous Indurated Nodule on the Forehead

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

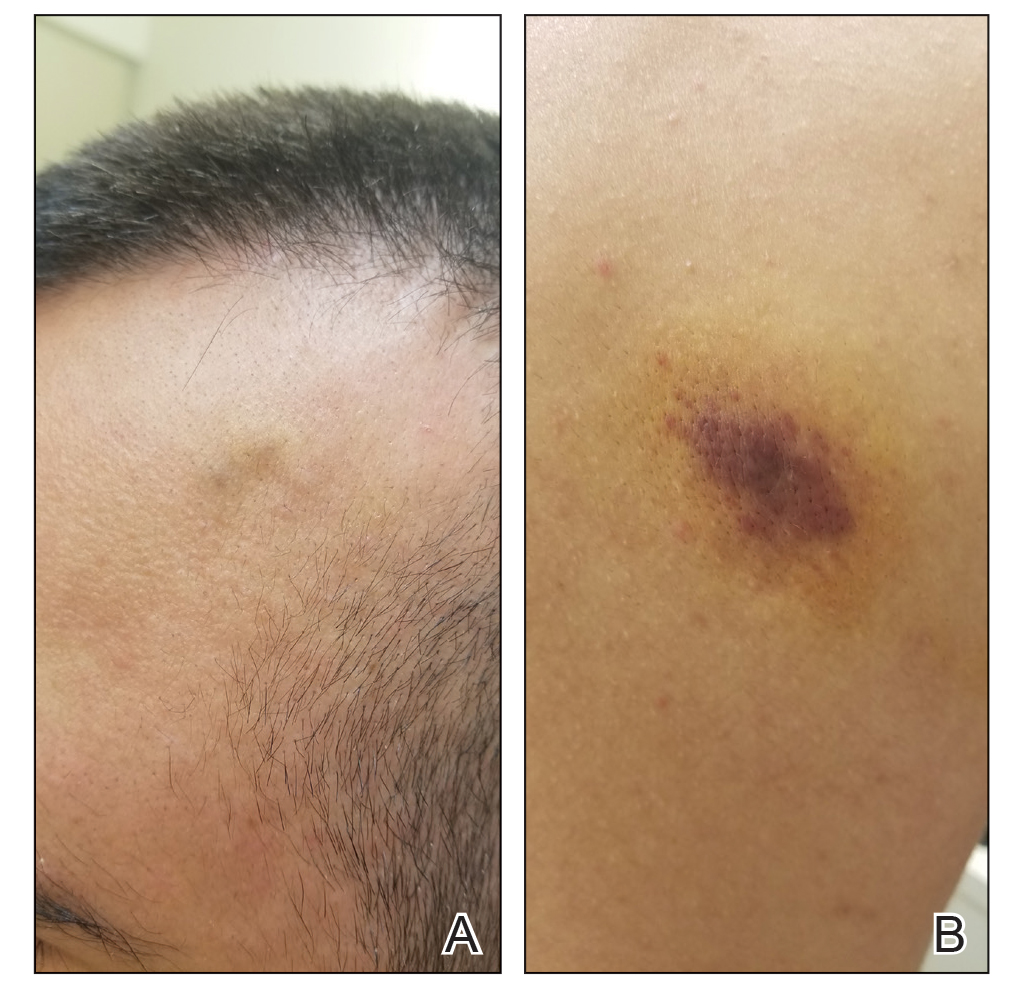

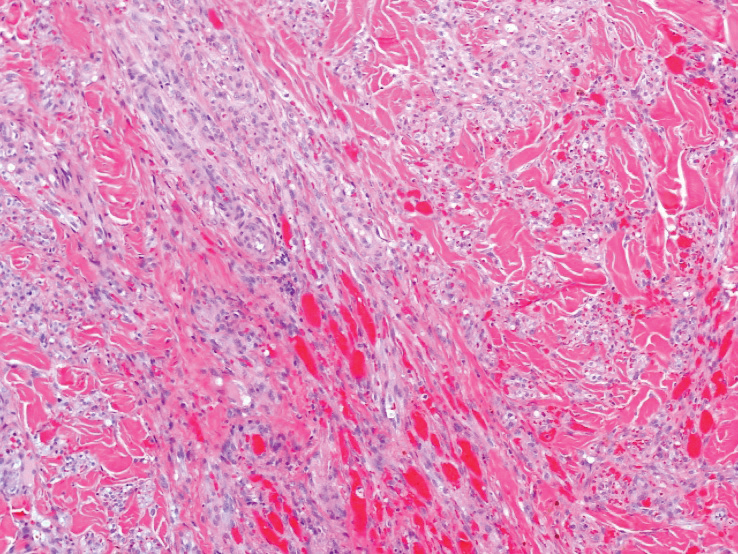

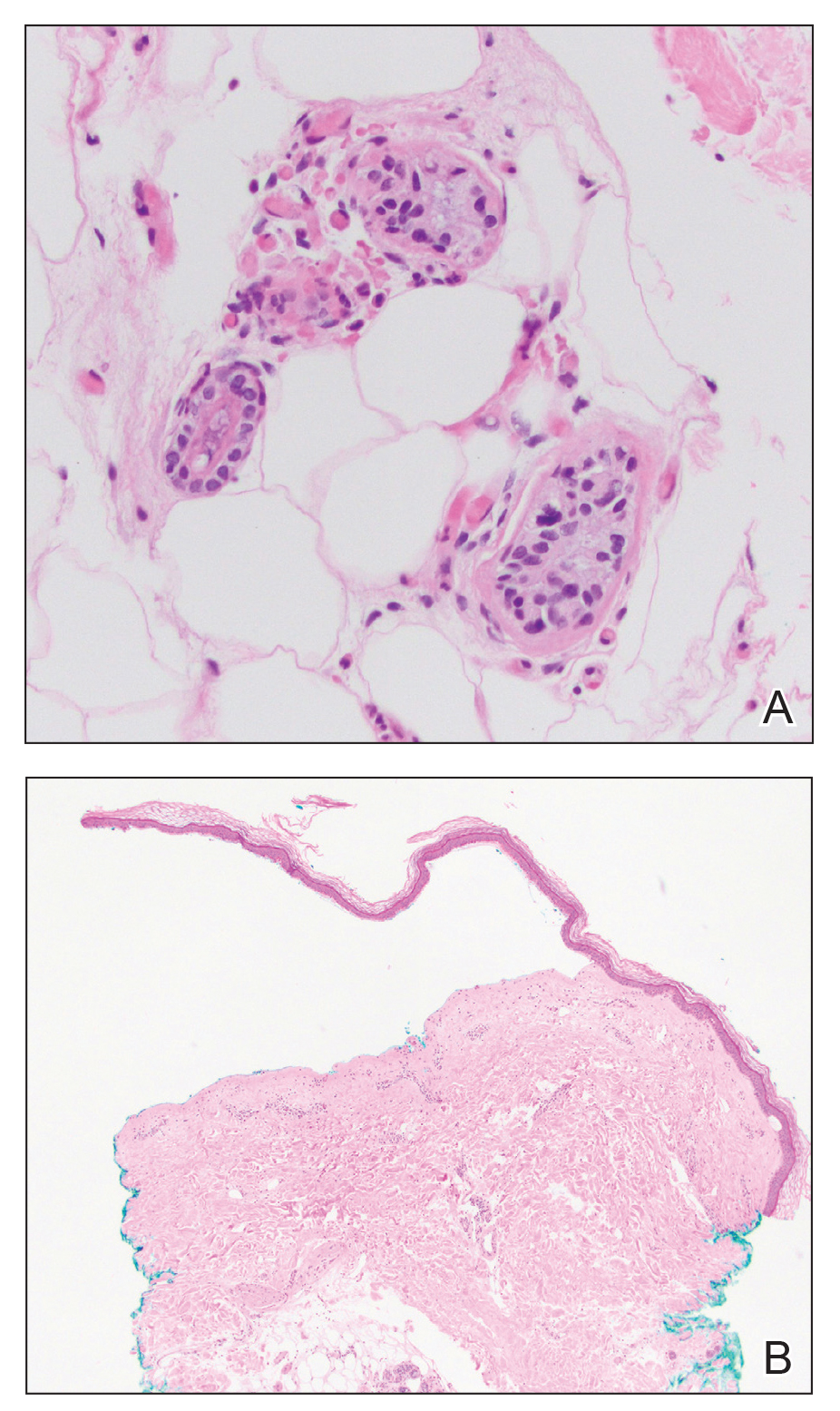

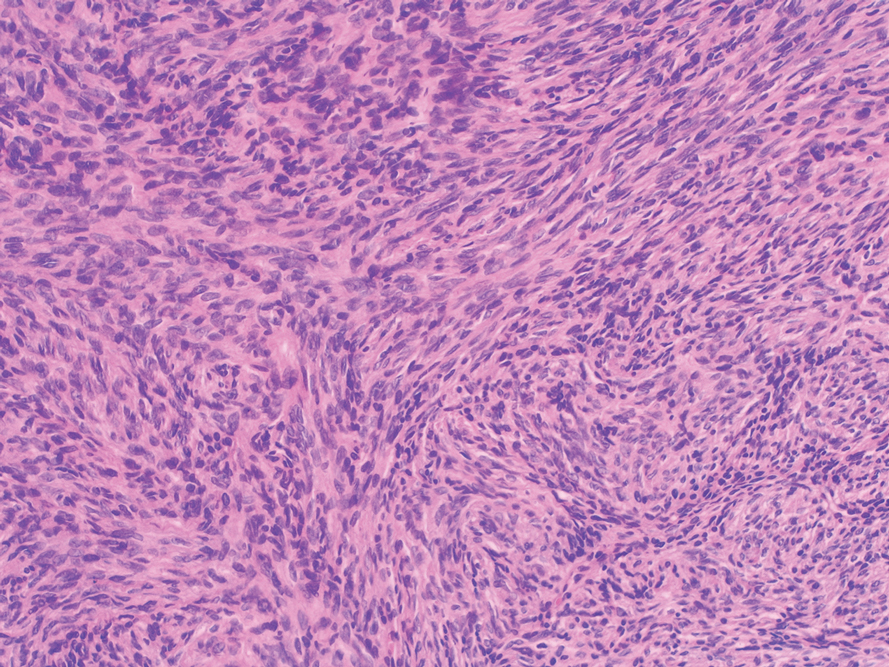

Histopathologic examination showed a dermal tumor composed of spindle cells in a storiform arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positive CD34 staining of the tumoral cells (Figure 2). Clinical review, histopathologic examination, and immunohistochemistry confirmed a diagnosis of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with clear margins after 3 stages, followed by repair with a rotation flap. No evidence of recurrence was found at 4-year follow-up.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare low-grade sarcoma of fibroblast origin with an annual incidence of 0.8 to 5 cases per million individuals.1 It typically presents in patients aged 30 to 50 years on the trunk, scalp, or proximal extremities as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored, erythematous or brown, indurated plaque or nodule.2 Due to its variable presentation, these lesions often may be misdiagnosed as lipomas or epidermoid cysts, preventing proper targeted treatment. Therefore, suspicious enlarging indurated nodules require a lower threshold for biopsy.1

A definitive diagnosis of DFSP is achieved after a biopsy and histopathologic evaluation. Hematoxylin and eosin staining typically shows diffuse infiltration of the dermis and the subcutaneous fat by densely packed, cytologic, relatively uniform, spindle-shaped tumor cells arranged in a characteristic storiform shape. Tumor cells are spread along the septae of the subcutaneous fatty tissue.3 Immunohistochemistry is characterized by positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa, with rare exceptions.

The differential diagnosis includes lipoma, epidermoid cyst, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.3 Positive CD34 immunostaining, negative S-100 staining, and a storiform pattern of spindle cells can assist in differentiating DFSP from these possible differential diagnoses; lesions of these other entities are characterized by different pathologic findings. Lipomas are composed of fat tissue, epidermoid cysts have epithelial-lined cysts filled with keratin, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors have plexiform rays of fibrous tissue extending into fat with negative CD34 staining, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors have fleshy variegated masses involving the peripheral nerve trunks with partial S-100 staining.4-7 Additional evaluation to confirm DFSP can be accomplished by analysis of tumor samples by fluorescence in situ hybridization or reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction to detect chromosomal translocations and fusion gene transcripts, as chromosomal translocations may be found in more than 90% of cases.3

Early diagnosis of DFSP is beneficial, as it can help prevent recurrence as well as metastasis. Studies have attempted to document the risk for recurrence as well as metastasis based on characteristic features and treatment strategies of DFSP. In a study of 186 patients, 3 had metastatic disease to the lungs, the most common site of metastasis.8 These 3 patients had fibrosarcomatous transformation within DFSP, emphasizing the importance of detailing this finding early in the diagnosis, as it was characterized by a higher degree of cellularity, cytologic atypia, mitotic activity, and negative CD34 immunostaining.9 In patients with suspected metastasis, lymph node ultrasonography, chest radiography, and computed tomography may be utilized.3

When treating DFSP, the goal is complete removal of the tumor with clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery, modified MMS, and wide local excision (WLE) with 2- to 4-cm margins are appropriate treatment options, though MMS is the treatment of choice. A study comparing MMS and WLE demonstrated 3% and 30.8% recurrence rates, respectively.8 In MMS, complete margin evaluation on microscopy is performed after each stage to ensure negative surgical margins. The presence of positive surgical margins elicits continued resection until the margins are clear.10,11

Other treatment modalities may be considered for patients with DFSP. Molecular therapy with imatinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting platelet-derived growth factor–regulated expression, can be utilized for inoperable tumors; however, additional clinical trials are required to ensure efficacy.3 Surgical removal of the possible remaining tumor is still recommended after molecular therapy. Radiotherapy is an additional method of treatment that may be used for inoperable tumors.3

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare lowgrade sarcoma of fibroblast origin that typically does not metastasize but often has notable subclinical extension and recurrence. Differentiating DFSP from other tumors often may be difficult. A protuberant, flesh-colored, slowgrowing, and asymptomatic lesion often may be confused with lipomas or epidermoid cysts; therefore, biopsies with immunohistostaining for suspicious lesions is required.12 Mohs micrographic surgery has evolved as the treatment of choice for this tumor, though WLE and new targeted molecular therapies still are considered. Proper diagnosis and treatment of DFSP is paramount in preventing future morbidity.

- Benoit A, Aycock J, Milam D, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead with extensive subclinical spread. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:261-264. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000604

- Khachemoune A, Barkoe D, Braun M, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the forehead and scalp with involvement of the outer calvarial plate: multistaged repair with the use of skin expanders. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:115-119. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31021

- Saiag P, Grob J-J, Lebbe C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2604-2608. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.108

- Charifa A, Badri T. Lipomas, pathology. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Cyst, epidermoid (sebaceous cyst). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138. doi:10.5858 /2007-131-1135-PFTABR

- Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, et al. Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:295-319. doi:10.1007 /s00401-012-0954-z

- Lowe GC, Onajin O, Baum CL, et al. A comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision for treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with long-term follow-up: the Mayo Clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:98-106. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000910

- Rouhani P, Fletcher CDM, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous soft tissue sarcoma incidence patterns in the U.S.: an analysis of 12,114 cases. Cancer. 2008;113:616-627. doi:10.1002/cncr.23571

- Ratner D, Thomas CO, Johnson TM, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. results of a multiinstitutional series with an analysis of the extent of microscopic spread. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:600-613. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(97)70179-8

- Buck DW, Kim JYS, Alam M, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:861-866. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.039

- Shih P-Y, Chen C-H, Kuo T-T, et al. Deep dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a pitfall in the ultrasonographic diagnosis of lipoma -like subcutaneous lesions. Dermatologica Sinica. 2010;28:32-35. doi:10.1016/S1027-8117(10)60005-5

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Histopathologic examination showed a dermal tumor composed of spindle cells in a storiform arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positive CD34 staining of the tumoral cells (Figure 2). Clinical review, histopathologic examination, and immunohistochemistry confirmed a diagnosis of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with clear margins after 3 stages, followed by repair with a rotation flap. No evidence of recurrence was found at 4-year follow-up.