User login

Dark Brown Hyperkeratotic Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Seborrheic Keratosis-like Melanoma

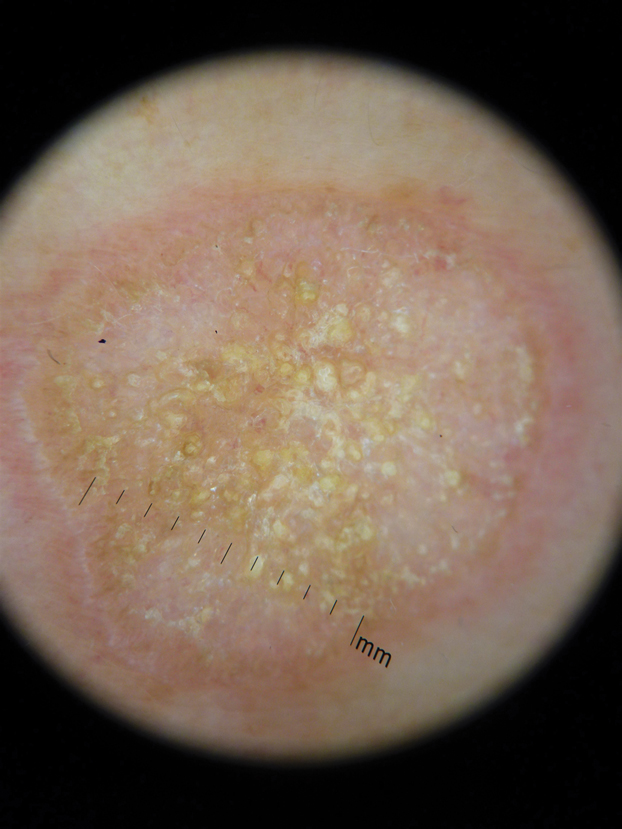

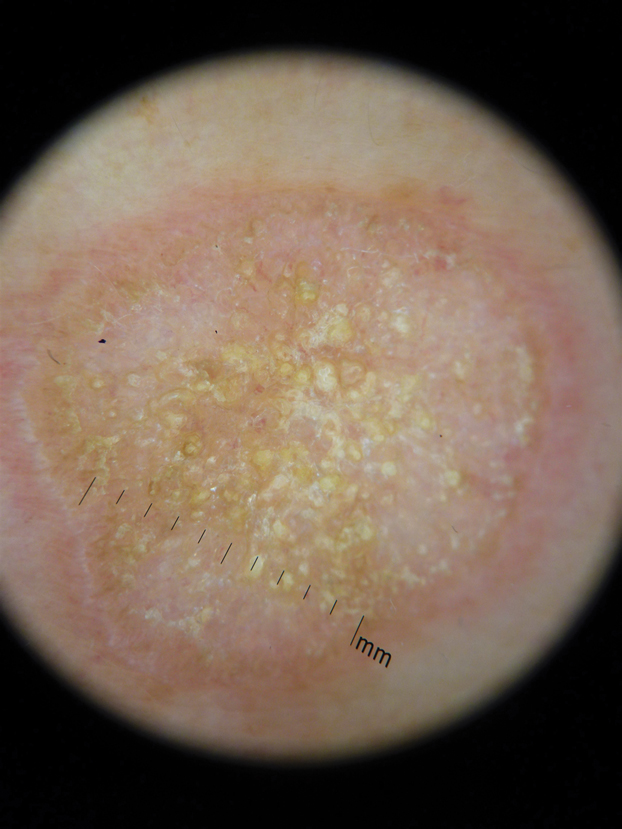

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign neoplasm commonly encountered on the skin and frequently diagnosed by clinical examination alone. Seborrheic keratosis-like melanomas are melanomas that clinically or dermatoscopically resemble SKs and thus can be challenging to accurately diagnose. Melanomas can have a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance1-3 and can even exhibit dermatoscopic and microscopic features that are found in SKs such as comedolike openings and milialike cysts as well as acanthosis and pseudohorn cysts, respectively.2

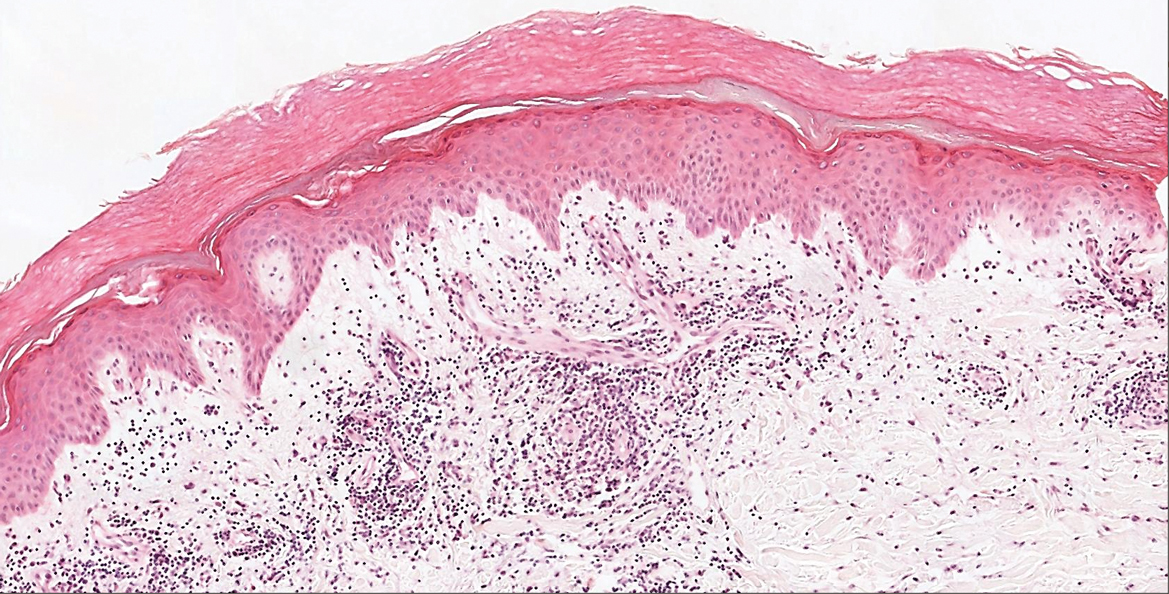

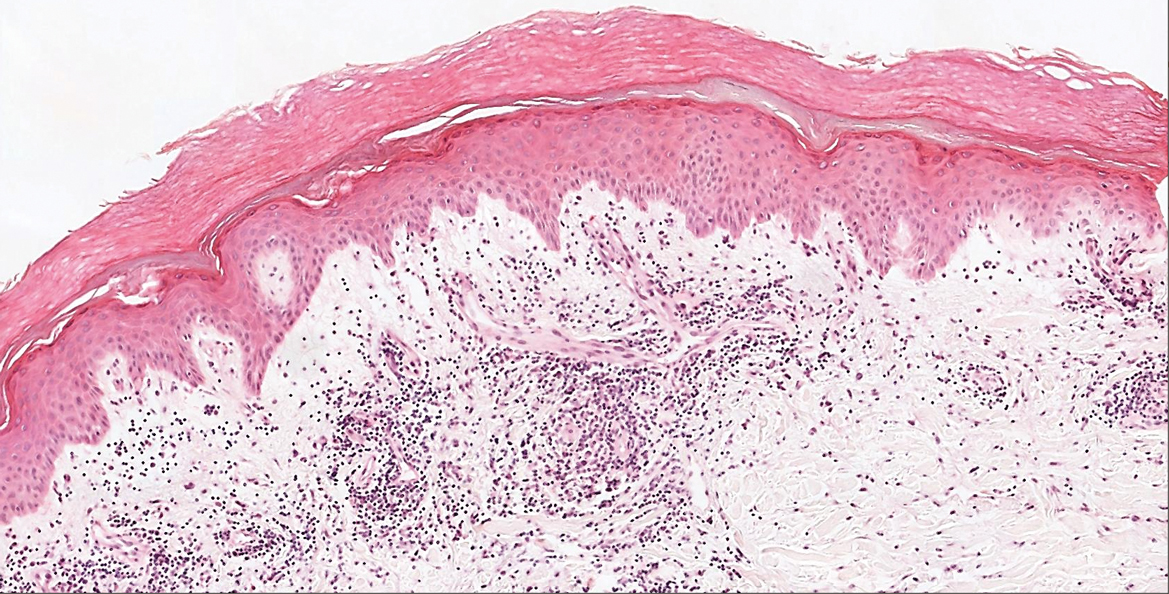

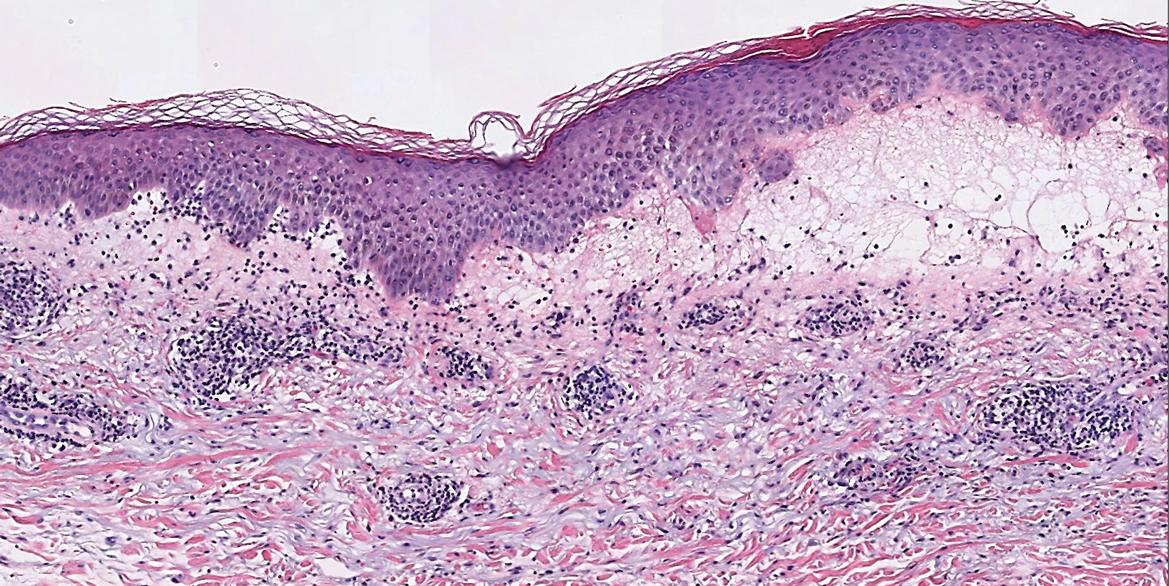

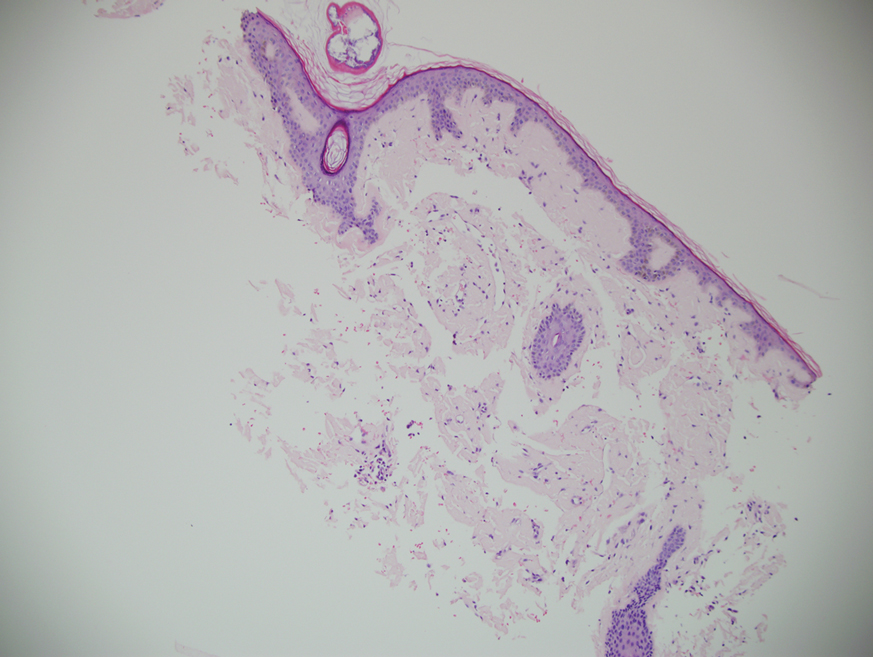

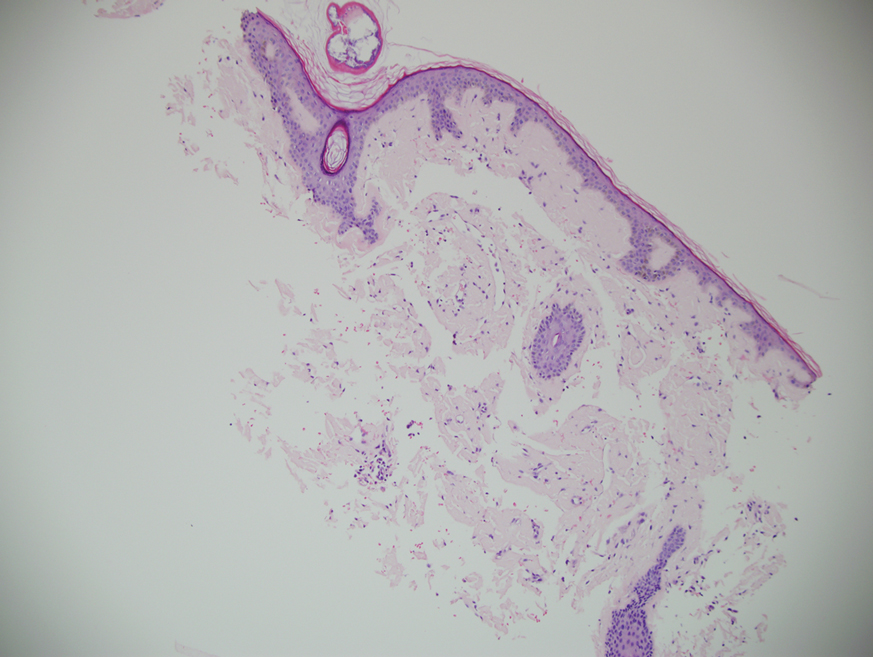

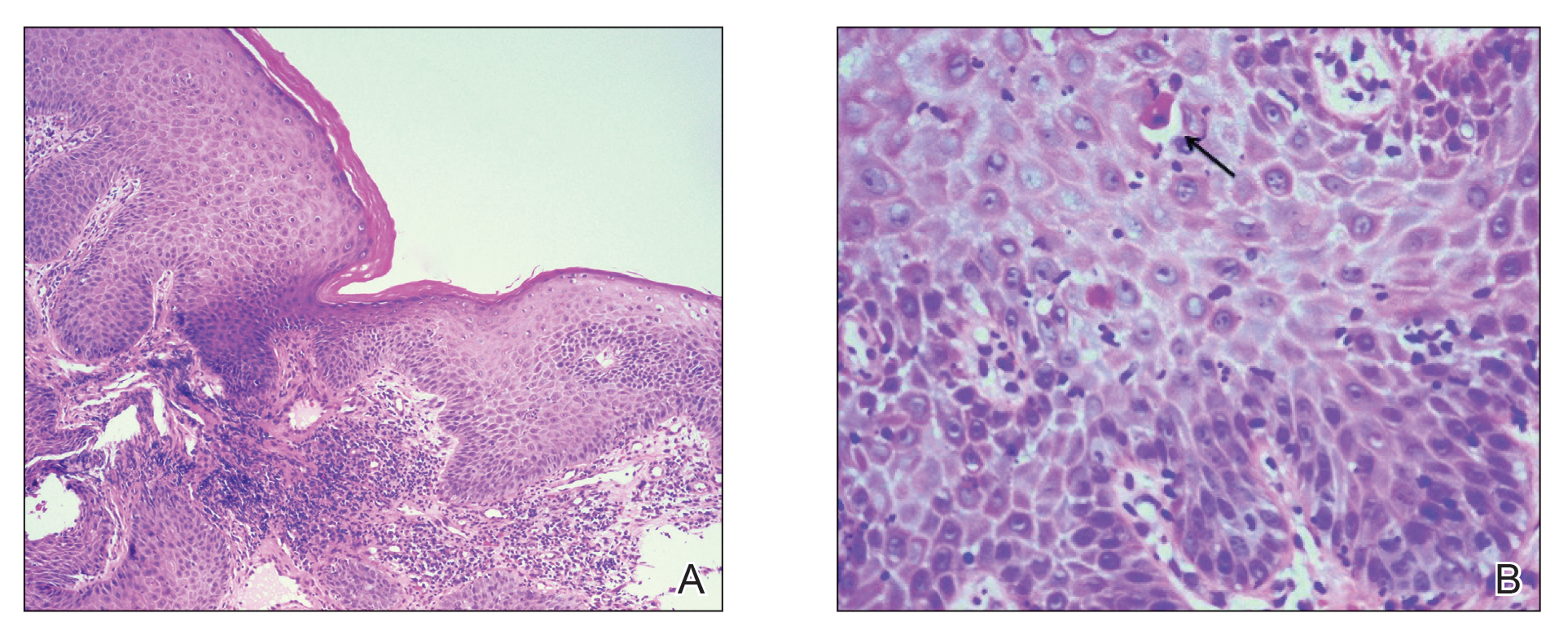

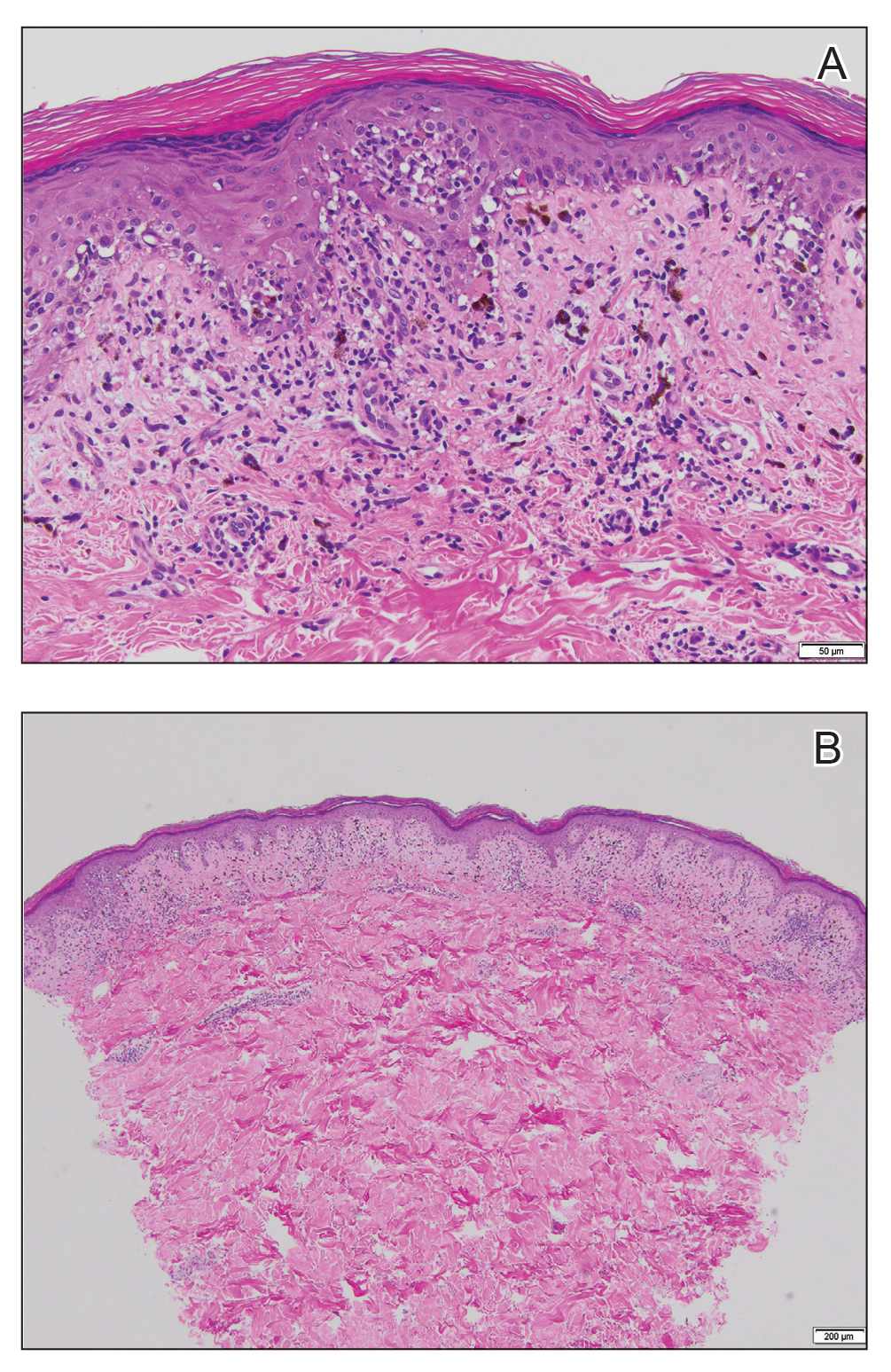

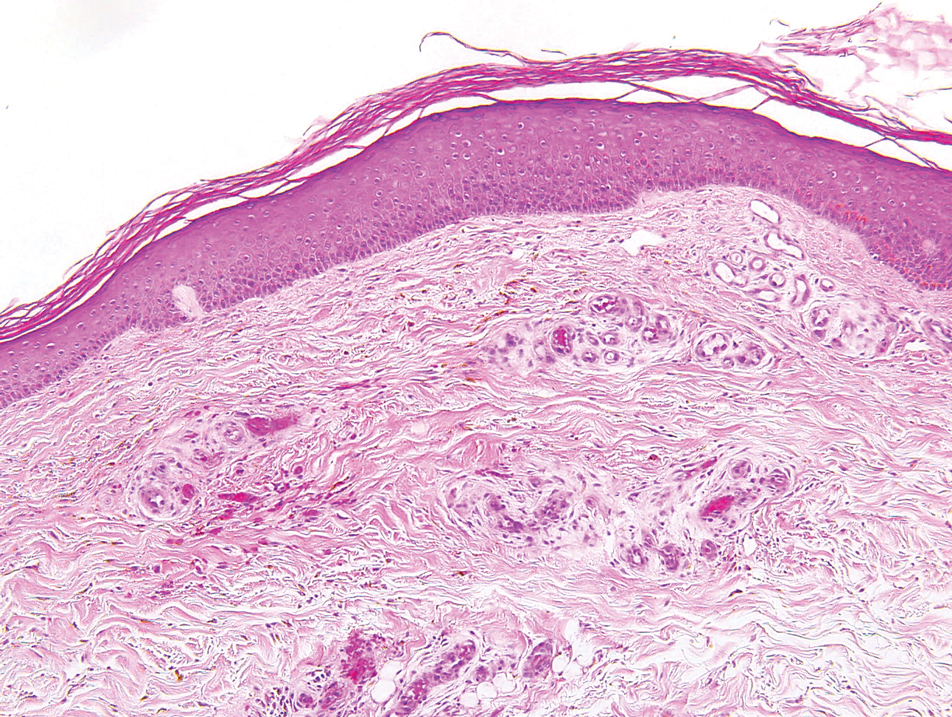

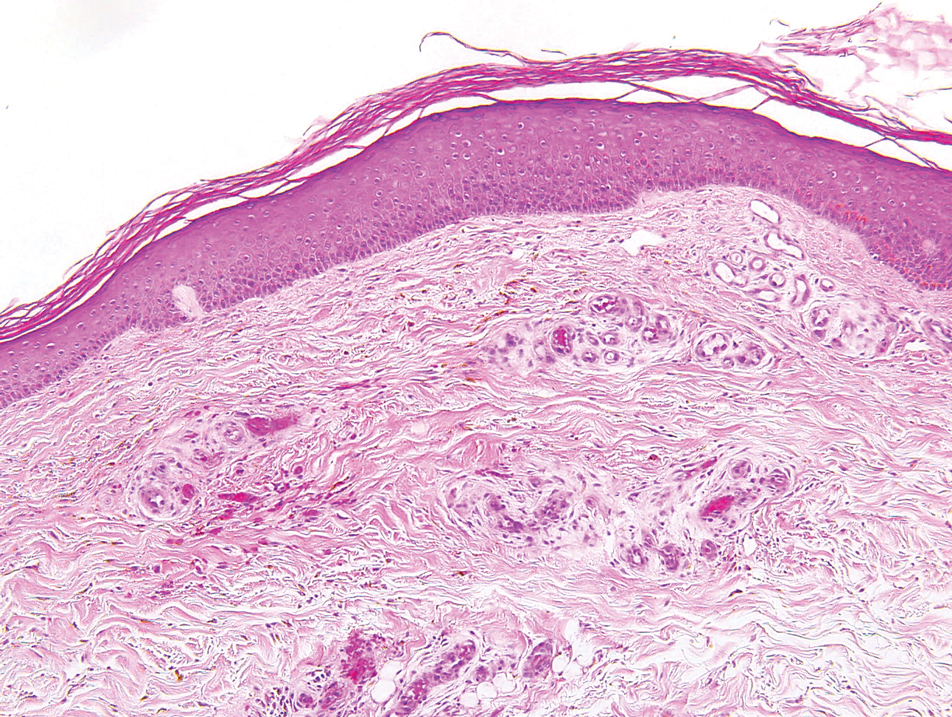

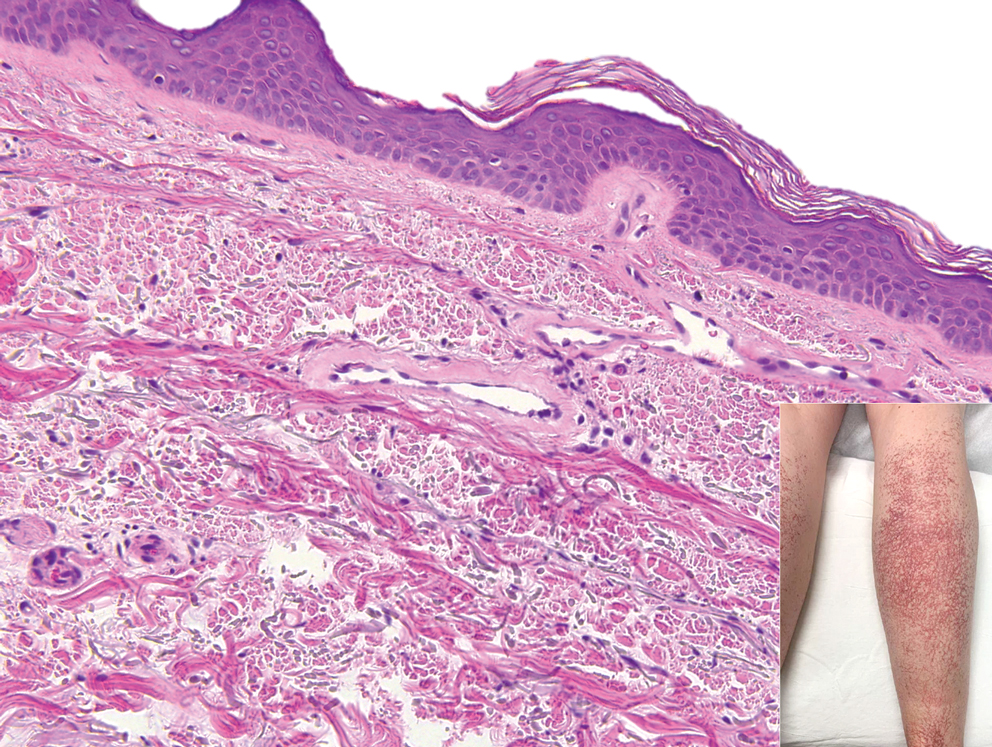

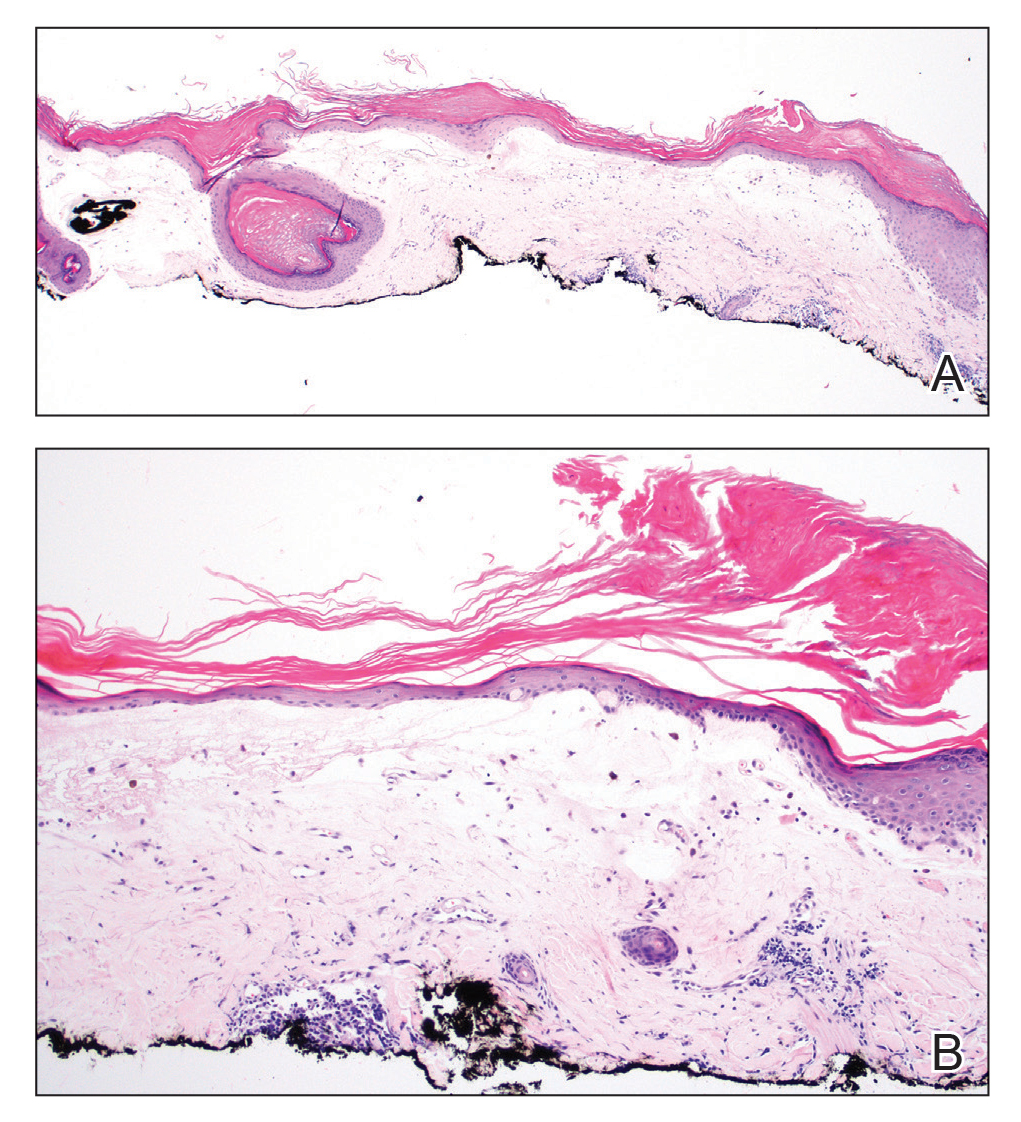

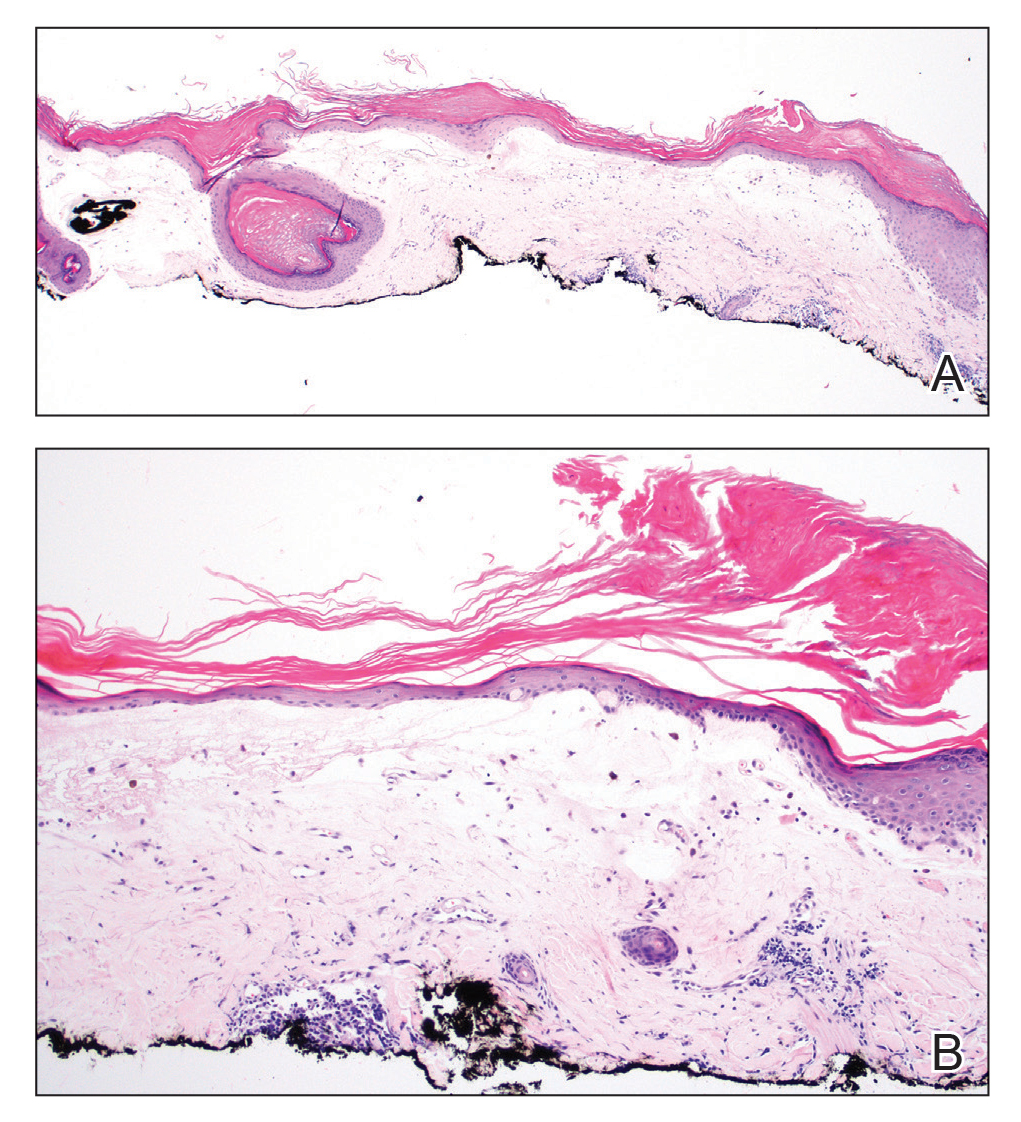

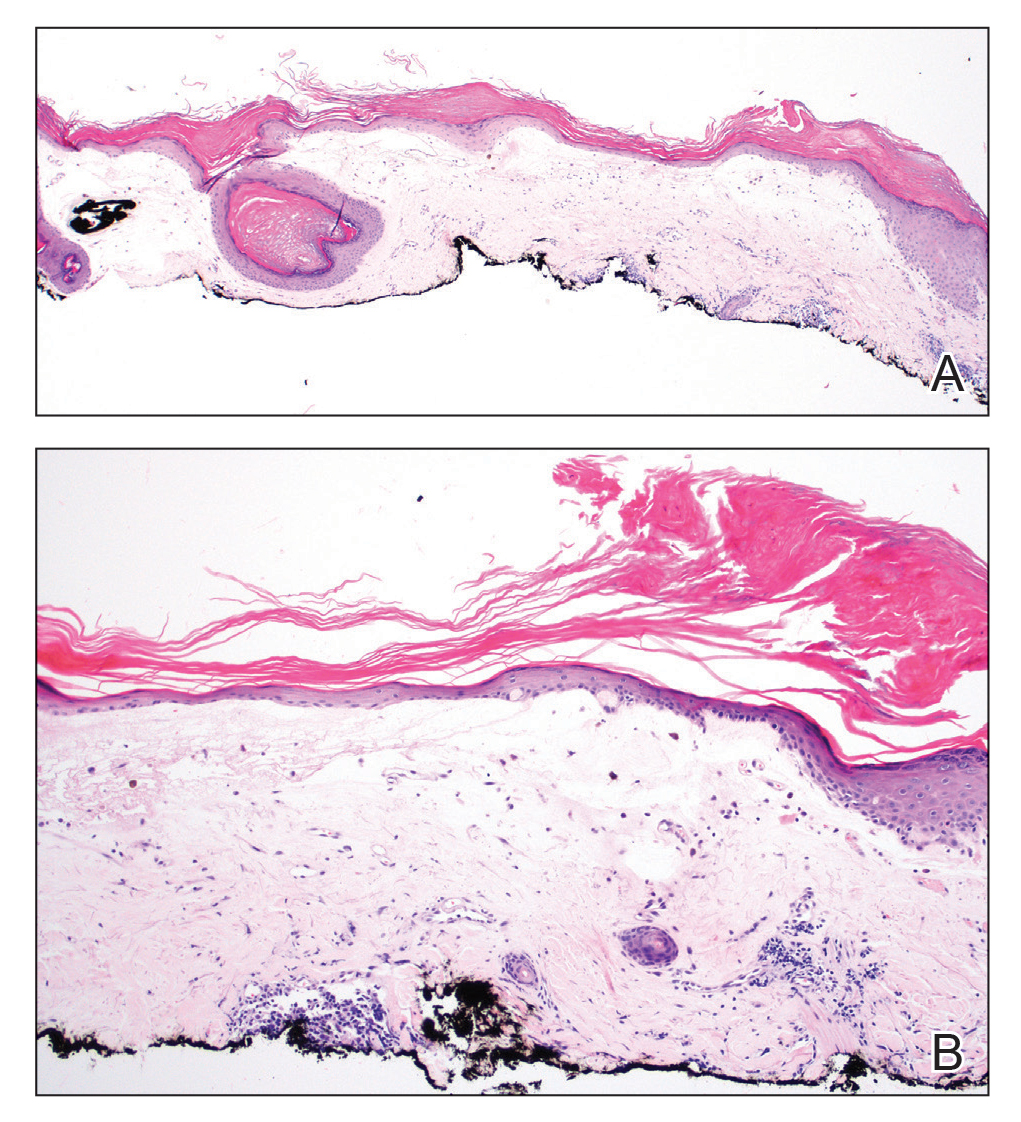

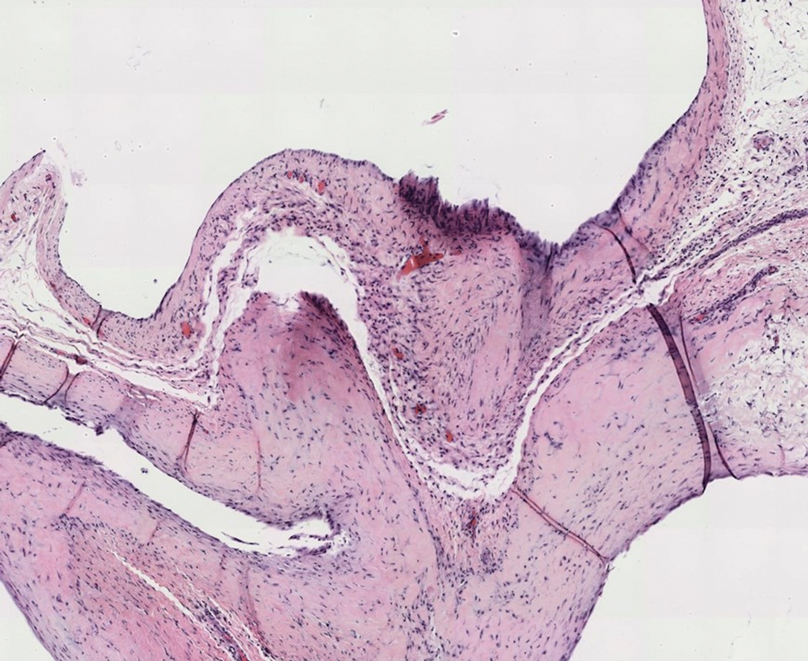

In our patient, histopathology revealed SK-like architecture with hyperorthokeratosis, papillomatosis, pseudohorn cyst formation, and basaloid acanthosis (Figure). However, within the lesion was an asymmetric proliferation of nested atypical melanocytes with melanin pigment production. The atypical melanocytes filled and expanded papillomatous projections without notable pagetoid growth and extended into the dermis. There was a background congenital nevus component. These findings were diagnostic of invasive malignant melanoma, extending to a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. A follow-up sentinel lymph node biopsy was negative for metastatic melanoma. The clinical and histologic findings did not show melanoma in the surrounding skin to suggest colonization of an SK by an adjacent melanoma. The clinical history of a long-standing lesion in conjunction with a congenital nevus component on histology favored a diagnosis of melanoma arising in association with a congenital nevus with an SK-like architecture rather than arising in a preexisting SK or de novo melanoma.

Because our patient did not have multiple widespread SKs and reported rapid growth in the lesion in the last 6 months, there was concern for a malignant neoplasm. However, in patients with numerous SKs or areas of chronically sun-damaged skin, it can be difficult to identify suspicious lesions. It is important for clinicians to remain aware of SK-like melanomas and have a lower threshold for biopsy of any changing or symptomatic lesion that clinically resembles an SK. In our case, the history of change and the markedly different clinical appearance of the lesion in comparison to our patient's SKs prompted the biopsy. Criteria have been proposed to help differentiate these entities under dermoscopy, with melanoma showing the presence of the blue-black sign, pigment network, pseudopods or streaks, and/or the blue-white veil.4

Cutaneous metastases classically present as dermal nodules, plaques, or ulcers.5,6 A rare pigmented case of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma clinically mimicking melanoma has been reported.7 There is limited literature on the dermoscopic features of cutaneous metastases, but it appears that polymorphic vascular patterns are most common.5,8 The possibility of a metastatic melanoma involving an SK is a theoretical consideration, but there was no prior history of melanoma in our patient, and the histologic findings were consistent with primary melanoma. There was no histologic evidence of pigmented metastatic breast carcinoma or metastatic lung carcinoma.

Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex and pigmented porocarcinomas are rare malignant sweat gland tumors.9-11 Their benign counterparts are the more commonly encountered hidroacanthoma simplex (intraepidermal poroma) and poroma. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex has been reported to clinically mimic an irritated SK.10 The histopathology of our case did not have features of malignant hidroacanthoma simplex or porocarcinoma. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma, and histopathology would reveal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes.12

- Saggini A, Cota C, Lora V, et al. Uncommon histopathological variants of malignant melanoma. part 2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:321-342.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:178-188.

- Tran PT, Truong AK, Munday W, et al. Verrucous melanoma masquerading as a seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt1m07k7fm.

- Carrera C, Segura S, Aguilera P. Dermoscopic clues for diagnosing melanomas that resemble seborrheic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:544-551.

- Strickley JD, Jenson AB, Jung JY. Cutaneous metastasis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:173-197.

- Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:429-433.

- Marti N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Kelati A, Gallouj S. Dermoscopy of skin metastases from breast cancer: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:273.

- Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, et al. A case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with multiple lymph node, liver and bone metastases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:227-231.

- Lee JY, Lin MH. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex mimicking irritated seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:705-708.

- Ueo T, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. Porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:500-503.

- Motta de Morais P, Schettini A, Rocha J, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

The Diagnosis: Seborrheic Keratosis-like Melanoma

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign neoplasm commonly encountered on the skin and frequently diagnosed by clinical examination alone. Seborrheic keratosis-like melanomas are melanomas that clinically or dermatoscopically resemble SKs and thus can be challenging to accurately diagnose. Melanomas can have a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance1-3 and can even exhibit dermatoscopic and microscopic features that are found in SKs such as comedolike openings and milialike cysts as well as acanthosis and pseudohorn cysts, respectively.2

In our patient, histopathology revealed SK-like architecture with hyperorthokeratosis, papillomatosis, pseudohorn cyst formation, and basaloid acanthosis (Figure). However, within the lesion was an asymmetric proliferation of nested atypical melanocytes with melanin pigment production. The atypical melanocytes filled and expanded papillomatous projections without notable pagetoid growth and extended into the dermis. There was a background congenital nevus component. These findings were diagnostic of invasive malignant melanoma, extending to a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. A follow-up sentinel lymph node biopsy was negative for metastatic melanoma. The clinical and histologic findings did not show melanoma in the surrounding skin to suggest colonization of an SK by an adjacent melanoma. The clinical history of a long-standing lesion in conjunction with a congenital nevus component on histology favored a diagnosis of melanoma arising in association with a congenital nevus with an SK-like architecture rather than arising in a preexisting SK or de novo melanoma.

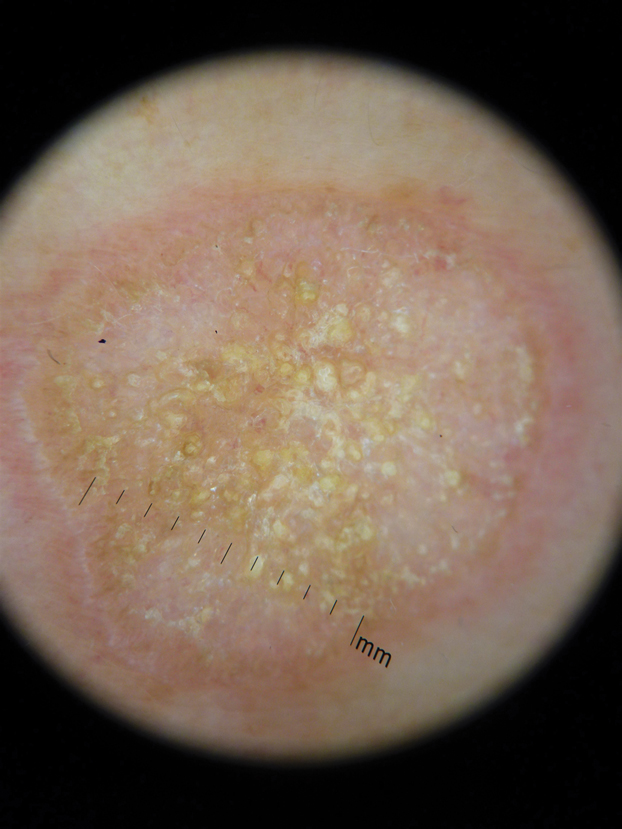

Because our patient did not have multiple widespread SKs and reported rapid growth in the lesion in the last 6 months, there was concern for a malignant neoplasm. However, in patients with numerous SKs or areas of chronically sun-damaged skin, it can be difficult to identify suspicious lesions. It is important for clinicians to remain aware of SK-like melanomas and have a lower threshold for biopsy of any changing or symptomatic lesion that clinically resembles an SK. In our case, the history of change and the markedly different clinical appearance of the lesion in comparison to our patient's SKs prompted the biopsy. Criteria have been proposed to help differentiate these entities under dermoscopy, with melanoma showing the presence of the blue-black sign, pigment network, pseudopods or streaks, and/or the blue-white veil.4

Cutaneous metastases classically present as dermal nodules, plaques, or ulcers.5,6 A rare pigmented case of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma clinically mimicking melanoma has been reported.7 There is limited literature on the dermoscopic features of cutaneous metastases, but it appears that polymorphic vascular patterns are most common.5,8 The possibility of a metastatic melanoma involving an SK is a theoretical consideration, but there was no prior history of melanoma in our patient, and the histologic findings were consistent with primary melanoma. There was no histologic evidence of pigmented metastatic breast carcinoma or metastatic lung carcinoma.

Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex and pigmented porocarcinomas are rare malignant sweat gland tumors.9-11 Their benign counterparts are the more commonly encountered hidroacanthoma simplex (intraepidermal poroma) and poroma. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex has been reported to clinically mimic an irritated SK.10 The histopathology of our case did not have features of malignant hidroacanthoma simplex or porocarcinoma. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma, and histopathology would reveal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes.12

The Diagnosis: Seborrheic Keratosis-like Melanoma

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign neoplasm commonly encountered on the skin and frequently diagnosed by clinical examination alone. Seborrheic keratosis-like melanomas are melanomas that clinically or dermatoscopically resemble SKs and thus can be challenging to accurately diagnose. Melanomas can have a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance1-3 and can even exhibit dermatoscopic and microscopic features that are found in SKs such as comedolike openings and milialike cysts as well as acanthosis and pseudohorn cysts, respectively.2

In our patient, histopathology revealed SK-like architecture with hyperorthokeratosis, papillomatosis, pseudohorn cyst formation, and basaloid acanthosis (Figure). However, within the lesion was an asymmetric proliferation of nested atypical melanocytes with melanin pigment production. The atypical melanocytes filled and expanded papillomatous projections without notable pagetoid growth and extended into the dermis. There was a background congenital nevus component. These findings were diagnostic of invasive malignant melanoma, extending to a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. A follow-up sentinel lymph node biopsy was negative for metastatic melanoma. The clinical and histologic findings did not show melanoma in the surrounding skin to suggest colonization of an SK by an adjacent melanoma. The clinical history of a long-standing lesion in conjunction with a congenital nevus component on histology favored a diagnosis of melanoma arising in association with a congenital nevus with an SK-like architecture rather than arising in a preexisting SK or de novo melanoma.

Because our patient did not have multiple widespread SKs and reported rapid growth in the lesion in the last 6 months, there was concern for a malignant neoplasm. However, in patients with numerous SKs or areas of chronically sun-damaged skin, it can be difficult to identify suspicious lesions. It is important for clinicians to remain aware of SK-like melanomas and have a lower threshold for biopsy of any changing or symptomatic lesion that clinically resembles an SK. In our case, the history of change and the markedly different clinical appearance of the lesion in comparison to our patient's SKs prompted the biopsy. Criteria have been proposed to help differentiate these entities under dermoscopy, with melanoma showing the presence of the blue-black sign, pigment network, pseudopods or streaks, and/or the blue-white veil.4

Cutaneous metastases classically present as dermal nodules, plaques, or ulcers.5,6 A rare pigmented case of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma clinically mimicking melanoma has been reported.7 There is limited literature on the dermoscopic features of cutaneous metastases, but it appears that polymorphic vascular patterns are most common.5,8 The possibility of a metastatic melanoma involving an SK is a theoretical consideration, but there was no prior history of melanoma in our patient, and the histologic findings were consistent with primary melanoma. There was no histologic evidence of pigmented metastatic breast carcinoma or metastatic lung carcinoma.

Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex and pigmented porocarcinomas are rare malignant sweat gland tumors.9-11 Their benign counterparts are the more commonly encountered hidroacanthoma simplex (intraepidermal poroma) and poroma. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex has been reported to clinically mimic an irritated SK.10 The histopathology of our case did not have features of malignant hidroacanthoma simplex or porocarcinoma. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma, and histopathology would reveal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes.12

- Saggini A, Cota C, Lora V, et al. Uncommon histopathological variants of malignant melanoma. part 2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:321-342.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:178-188.

- Tran PT, Truong AK, Munday W, et al. Verrucous melanoma masquerading as a seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt1m07k7fm.

- Carrera C, Segura S, Aguilera P. Dermoscopic clues for diagnosing melanomas that resemble seborrheic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:544-551.

- Strickley JD, Jenson AB, Jung JY. Cutaneous metastasis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:173-197.

- Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:429-433.

- Marti N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Kelati A, Gallouj S. Dermoscopy of skin metastases from breast cancer: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:273.

- Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, et al. A case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with multiple lymph node, liver and bone metastases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:227-231.

- Lee JY, Lin MH. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex mimicking irritated seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:705-708.

- Ueo T, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. Porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:500-503.

- Motta de Morais P, Schettini A, Rocha J, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Saggini A, Cota C, Lora V, et al. Uncommon histopathological variants of malignant melanoma. part 2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:321-342.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:178-188.

- Tran PT, Truong AK, Munday W, et al. Verrucous melanoma masquerading as a seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt1m07k7fm.

- Carrera C, Segura S, Aguilera P. Dermoscopic clues for diagnosing melanomas that resemble seborrheic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:544-551.

- Strickley JD, Jenson AB, Jung JY. Cutaneous metastasis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:173-197.

- Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:429-433.

- Marti N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Kelati A, Gallouj S. Dermoscopy of skin metastases from breast cancer: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:273.

- Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, et al. A case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with multiple lymph node, liver and bone metastases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:227-231.

- Lee JY, Lin MH. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex mimicking irritated seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:705-708.

- Ueo T, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. Porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:500-503.

- Motta de Morais P, Schettini A, Rocha J, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

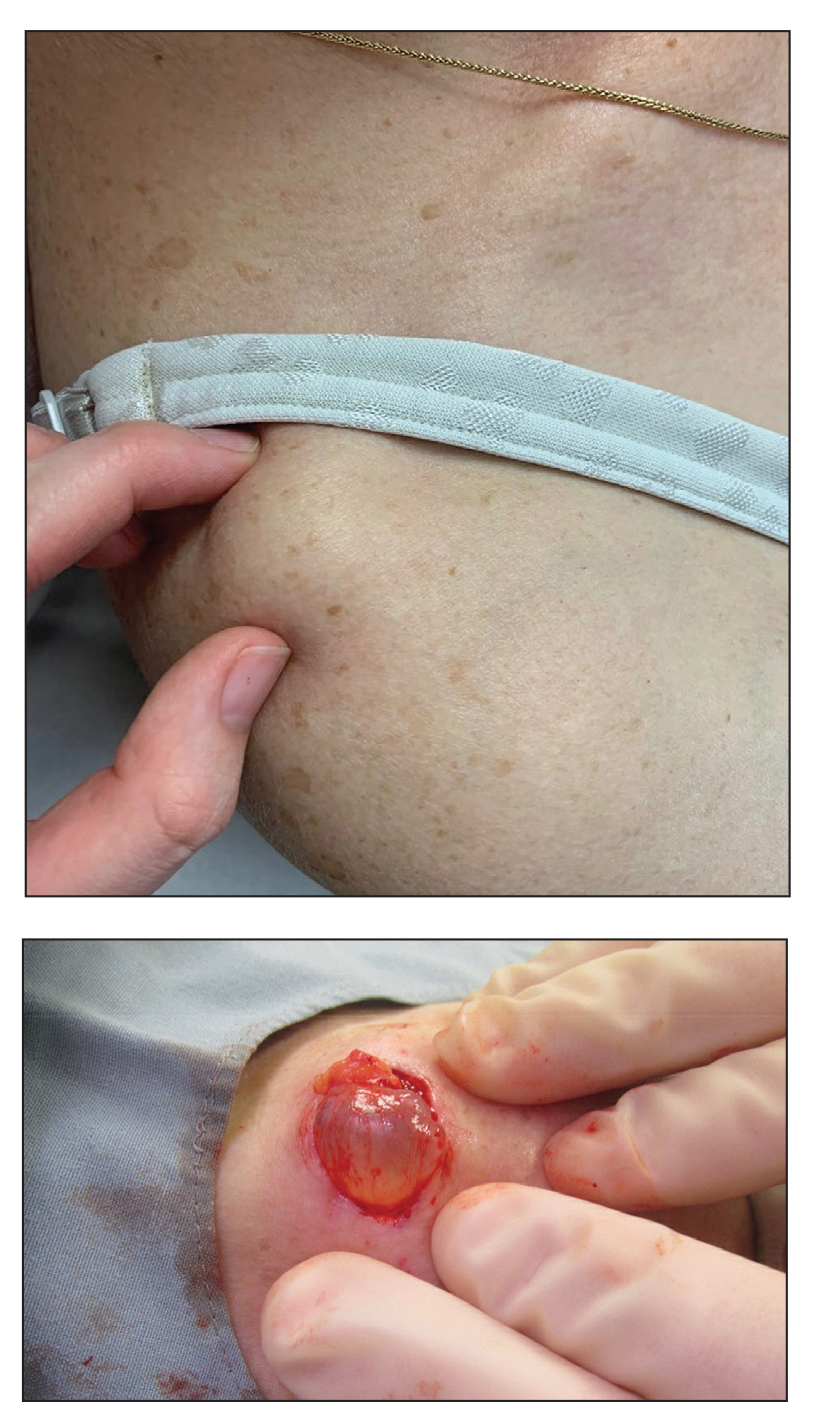

A 71-year-old woman presented with a persistent asymptomatic lesion on the right upper back that had recently increased in size and changed in color, shape, and texture. The lesion had been present for many years. Physical examination revealed a 1.5-cm, dark brown, hyperkeratotic nodule with no identifiable pigment network on dermatoscopy. The patient had no personal history of melanoma but did have a history of stage I non–small cell lung cancer. A review of systems was noncontributory. A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Tender, Diffuse, Edematous, and Erythematous Papules on the Face, Neck, Chest, and Extremities

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

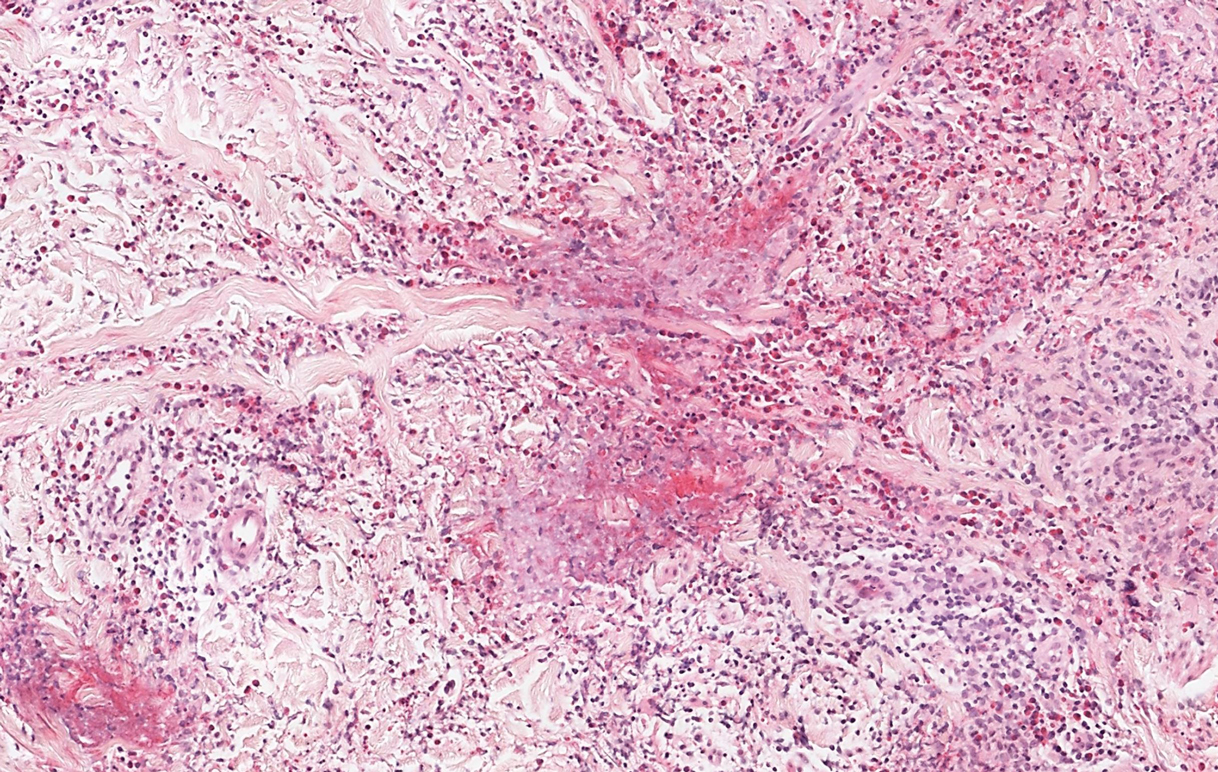

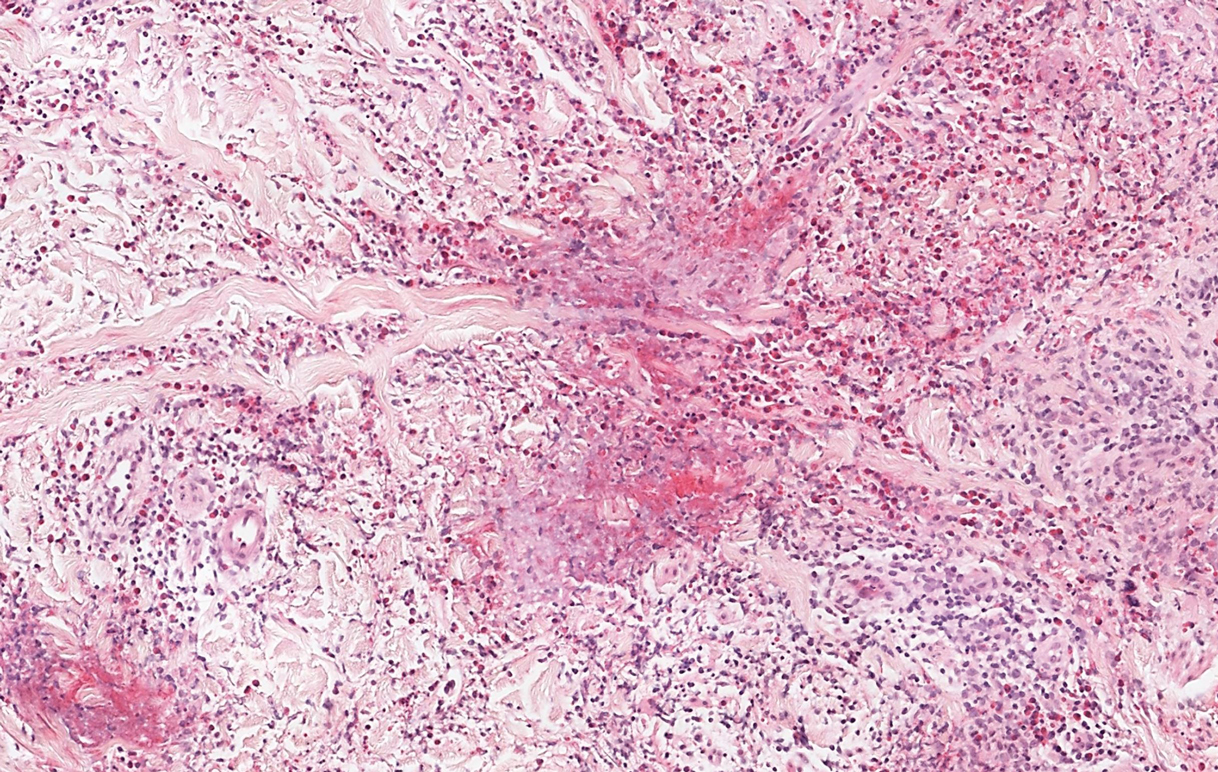

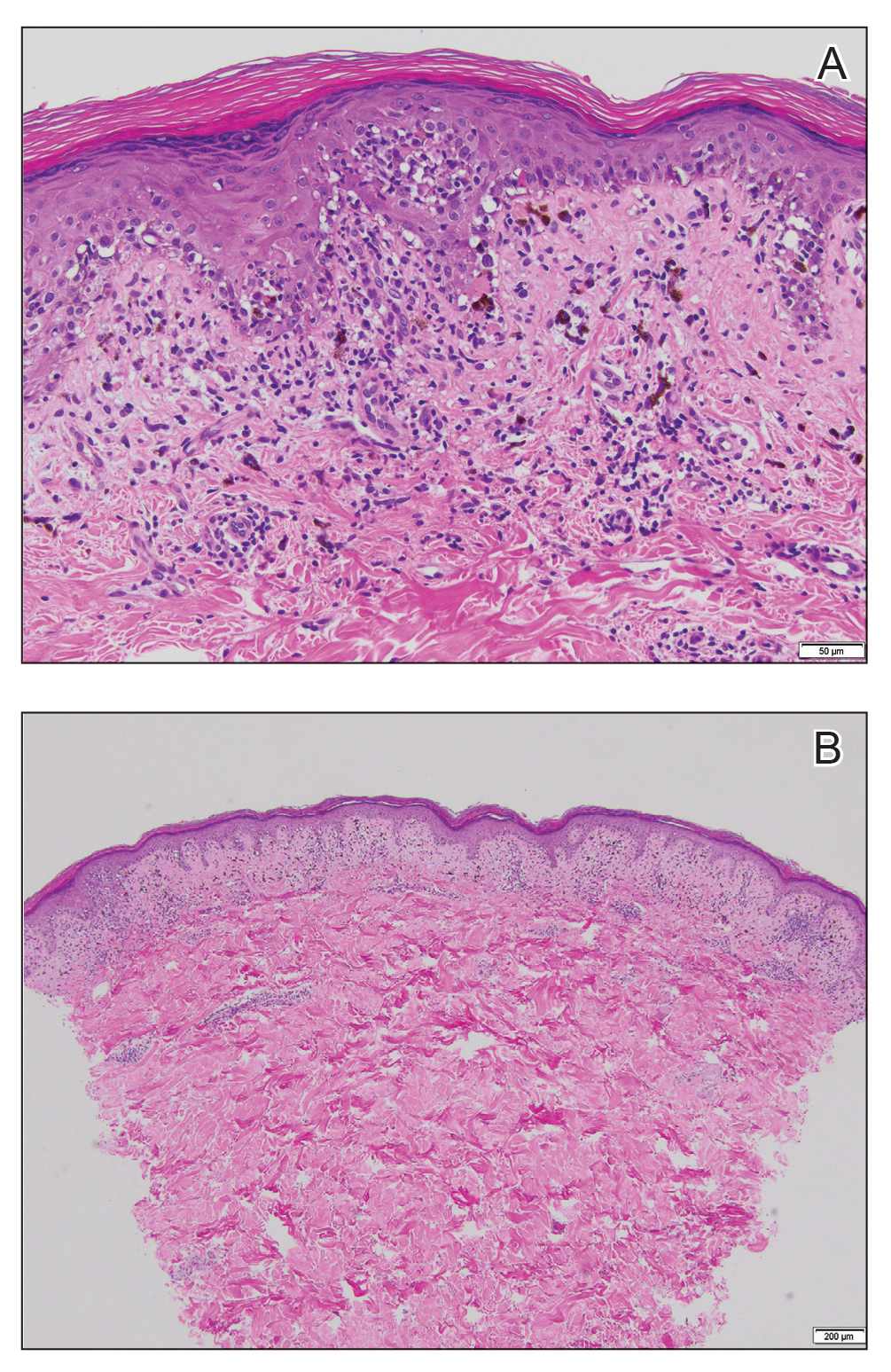

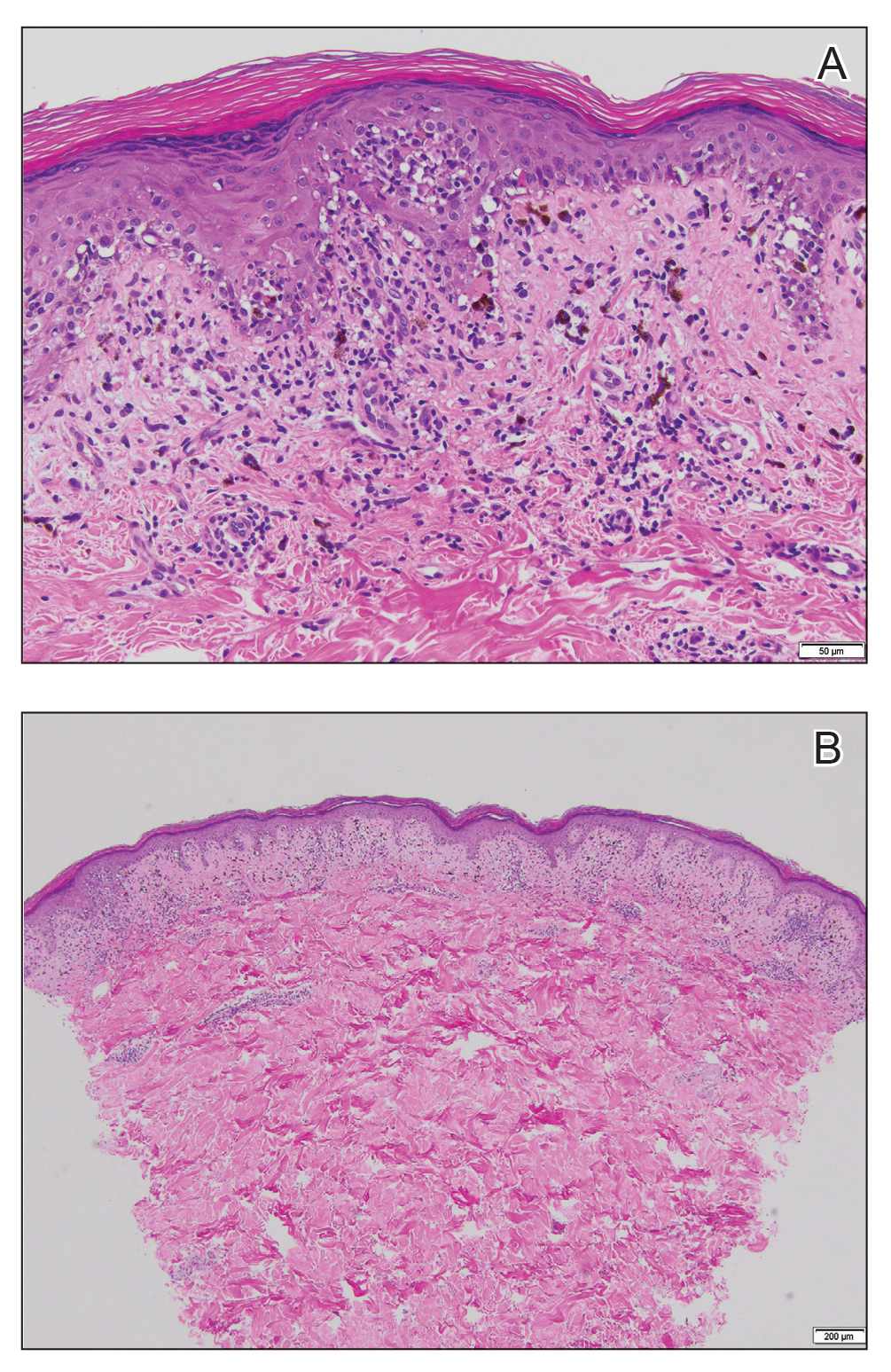

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

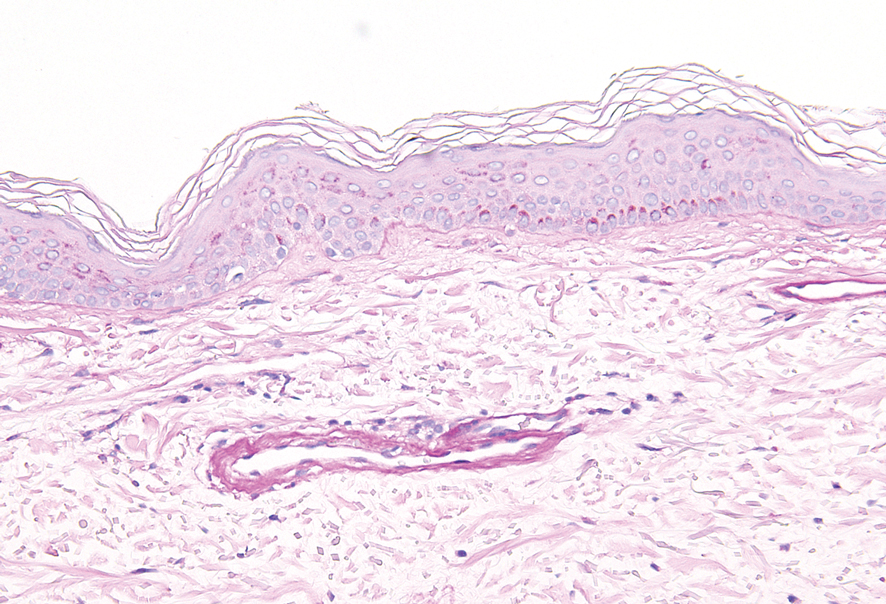

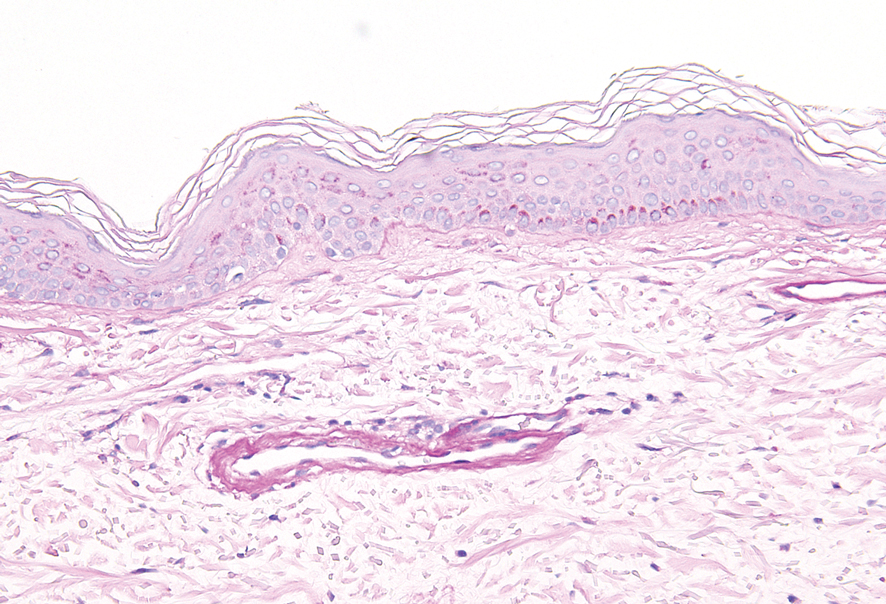

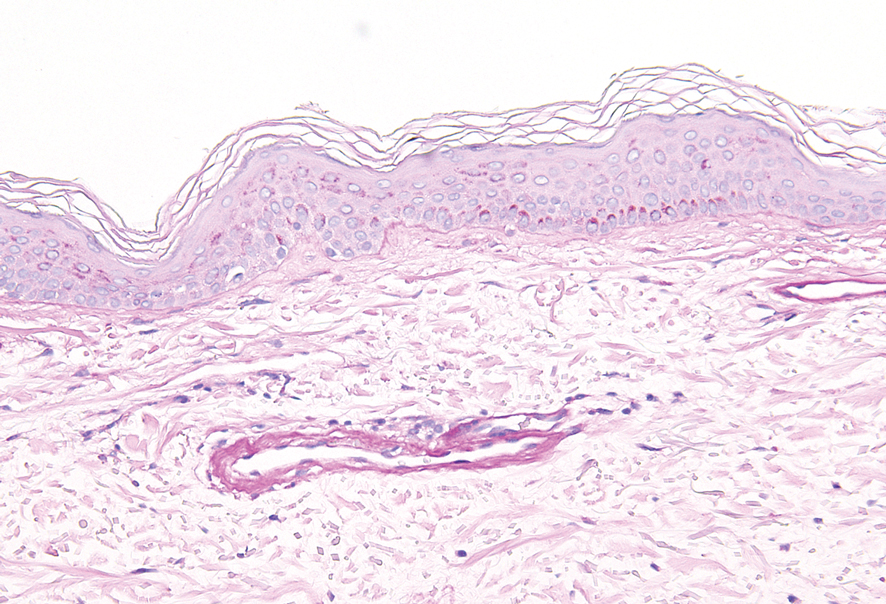

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

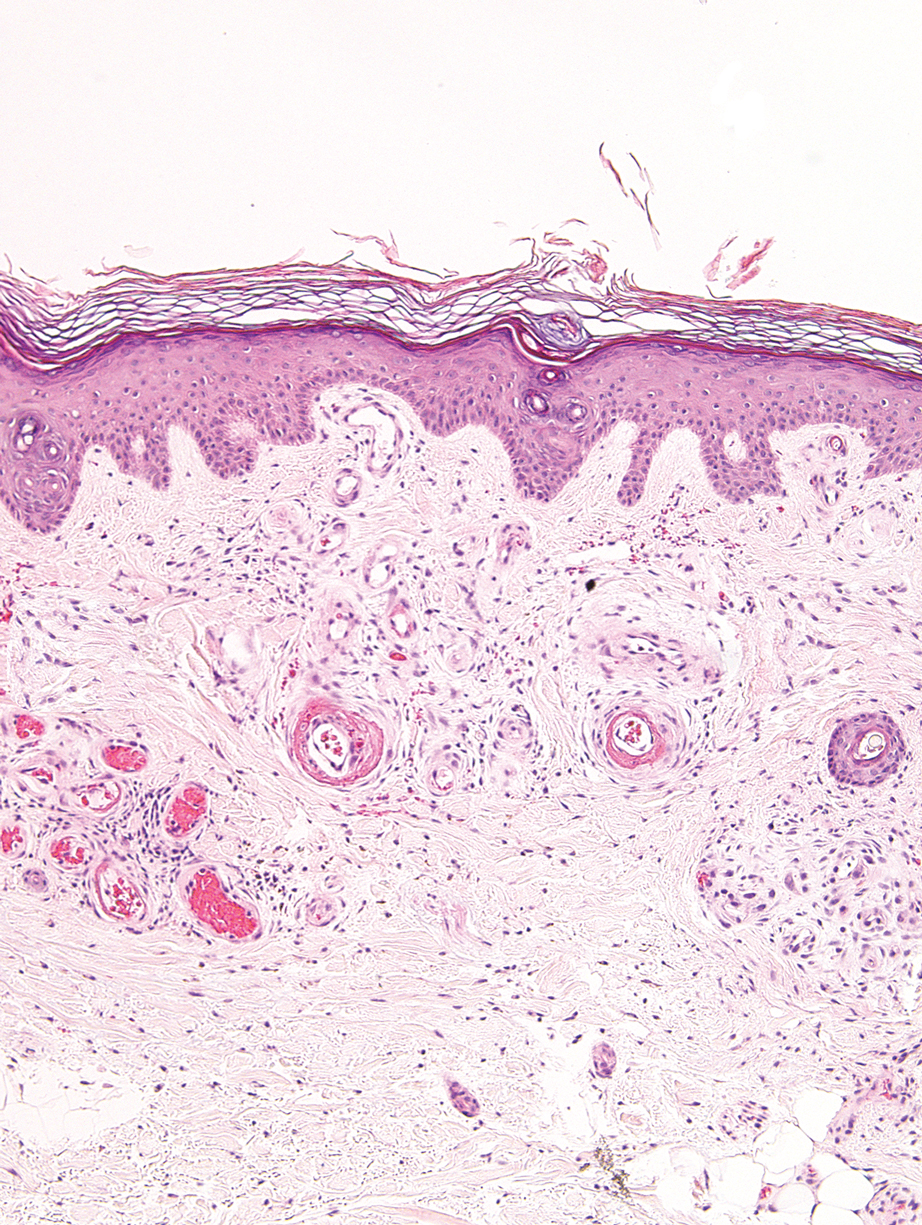

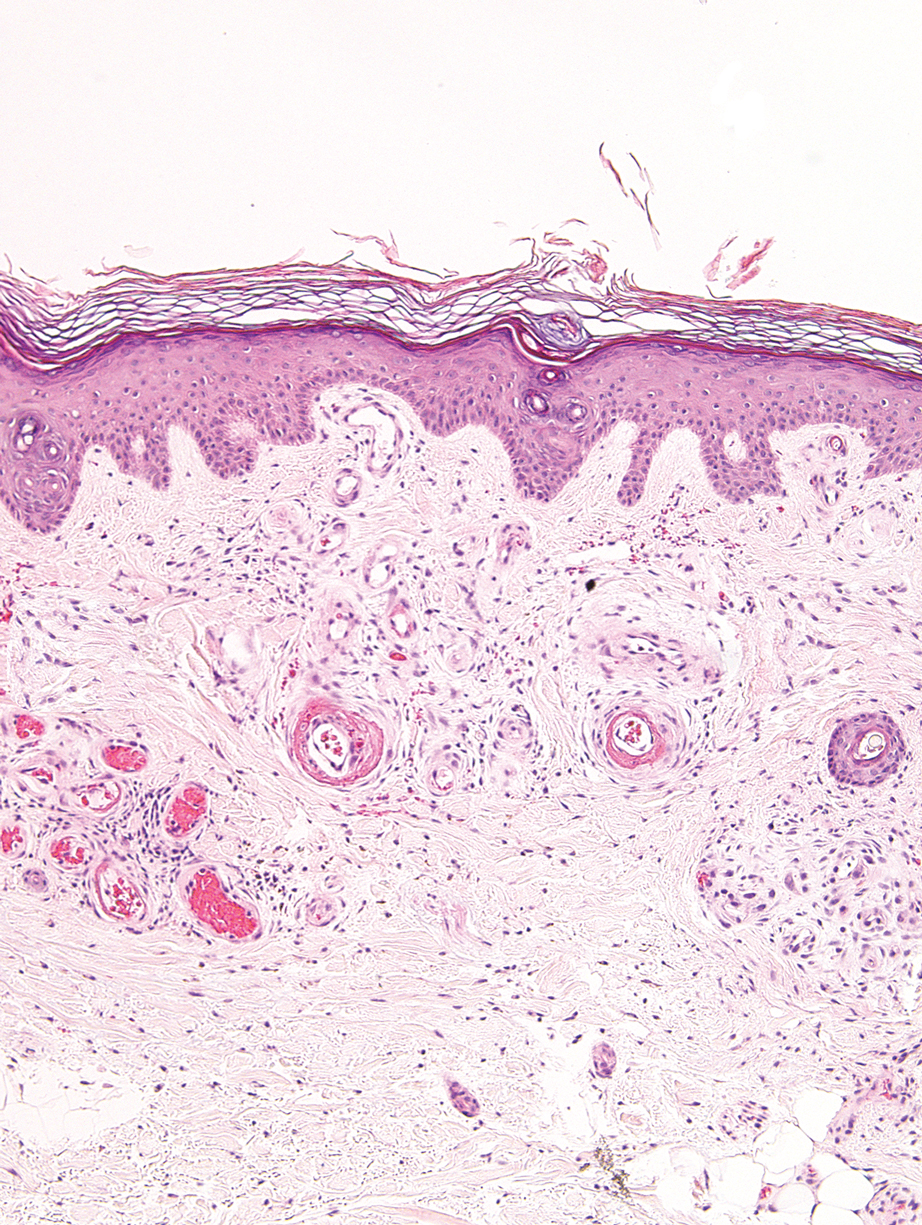

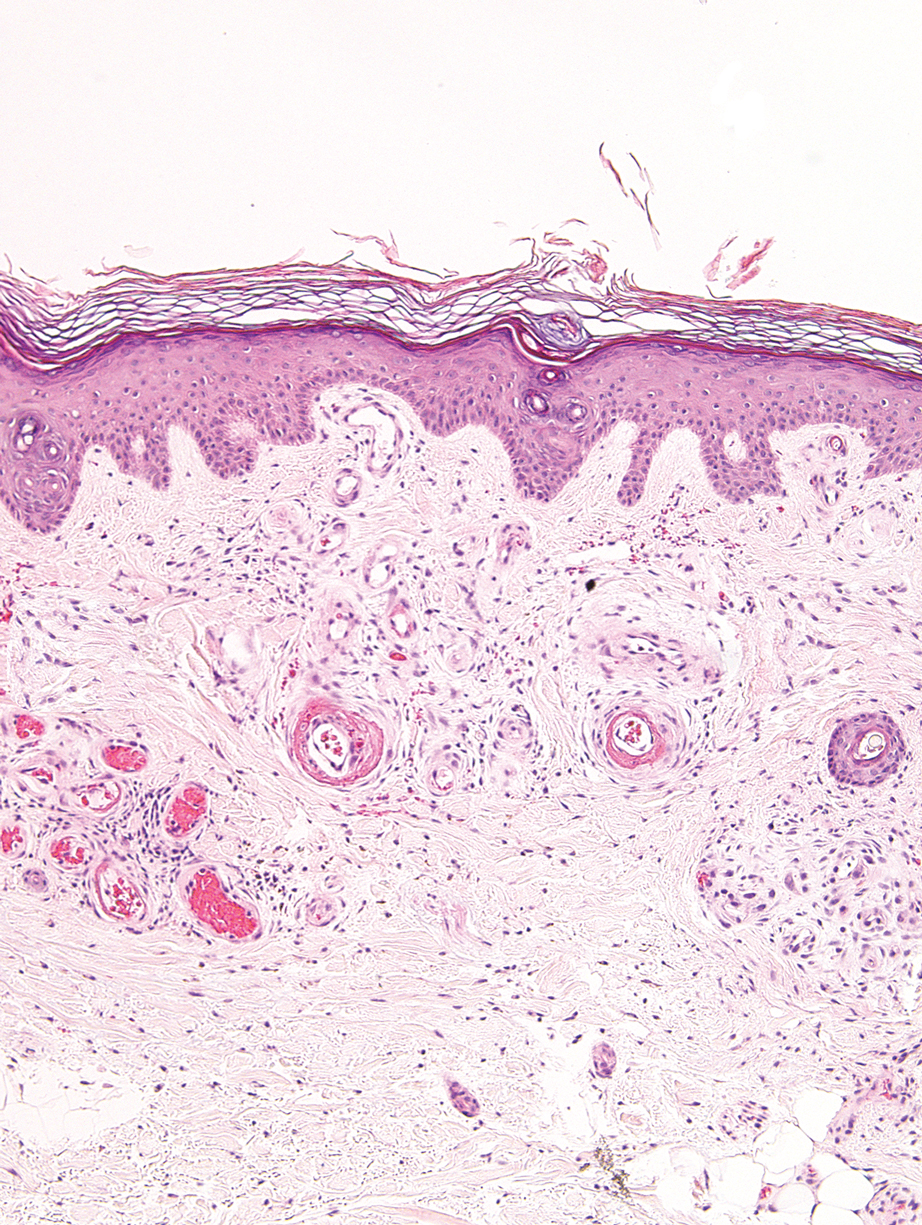

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

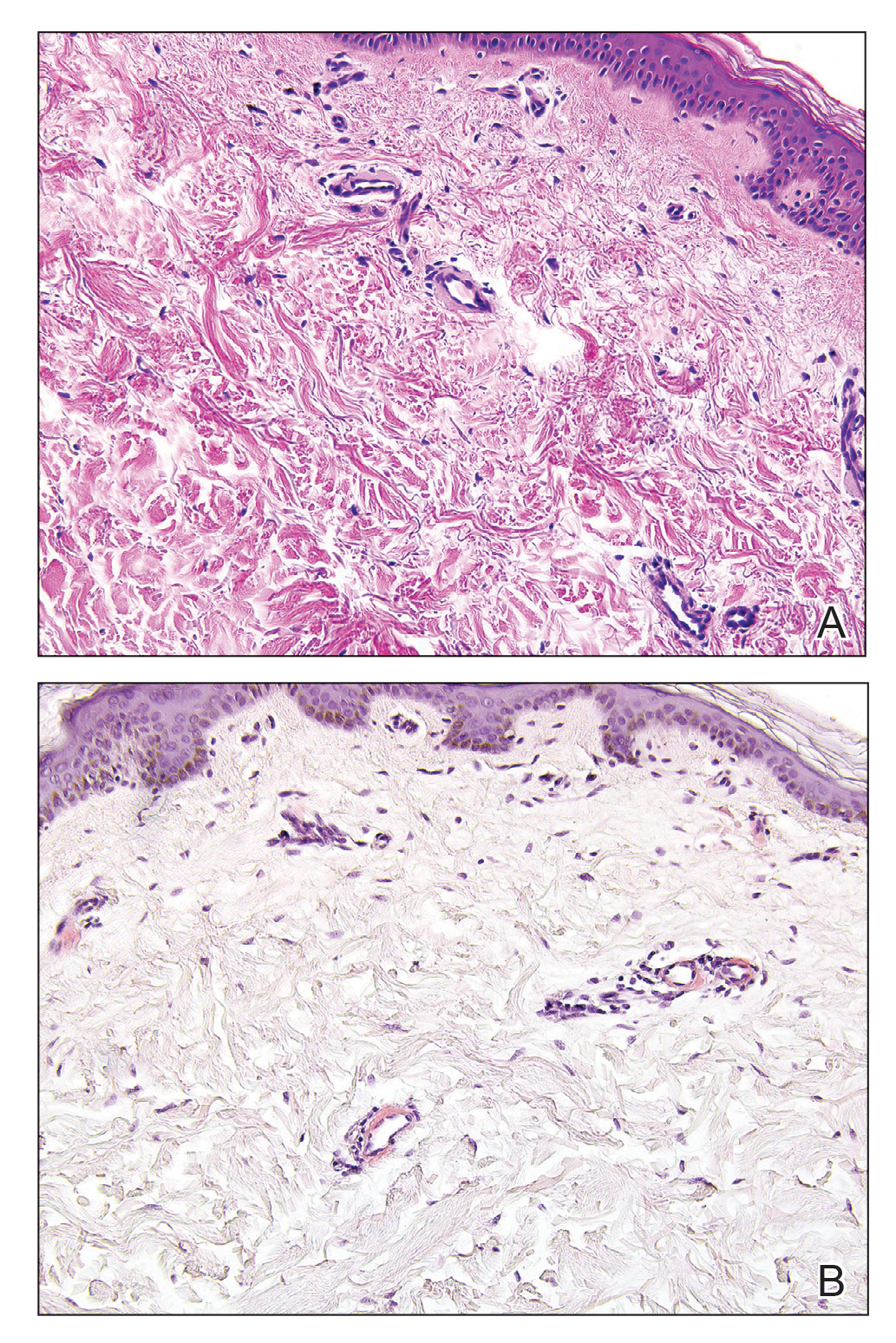

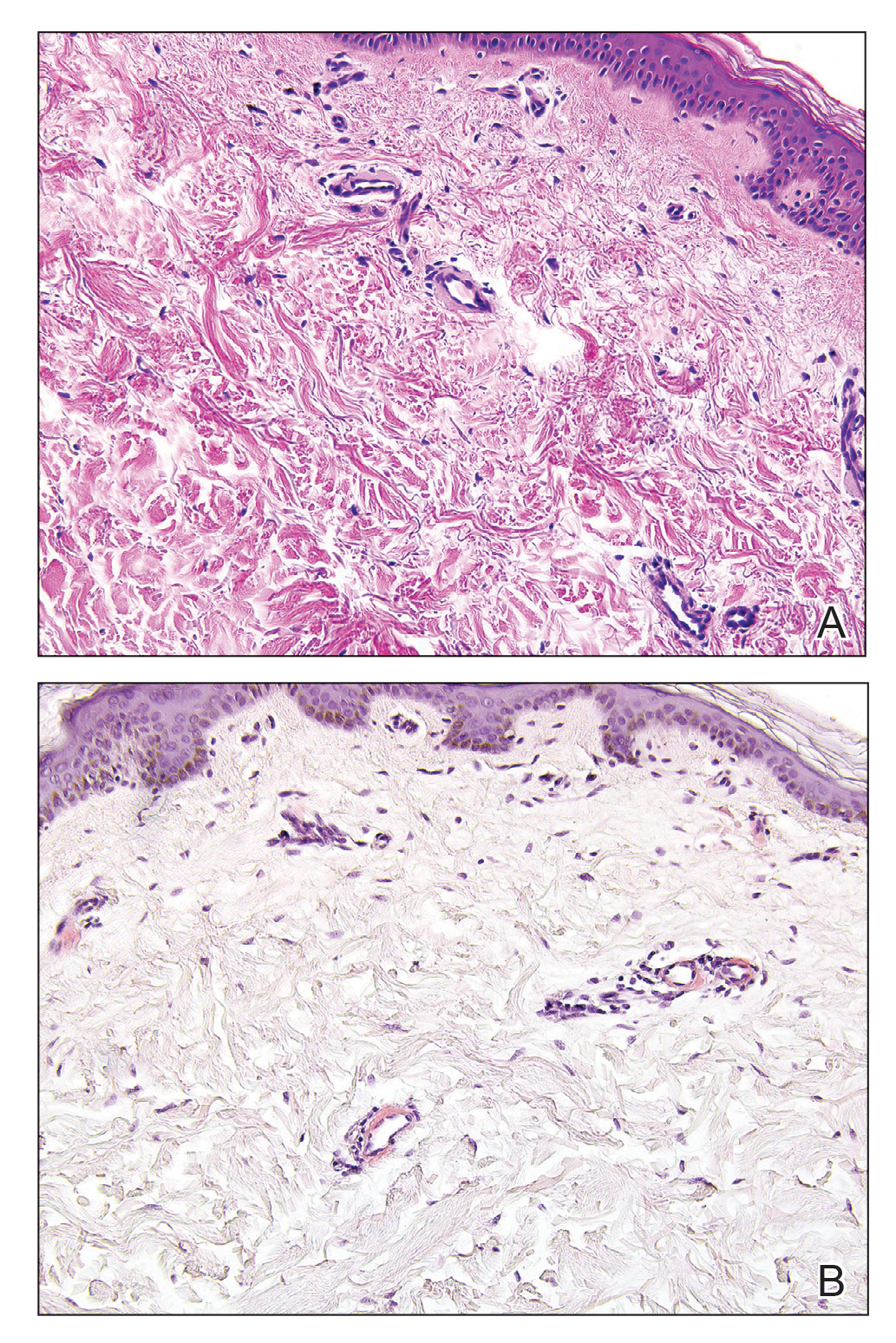

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

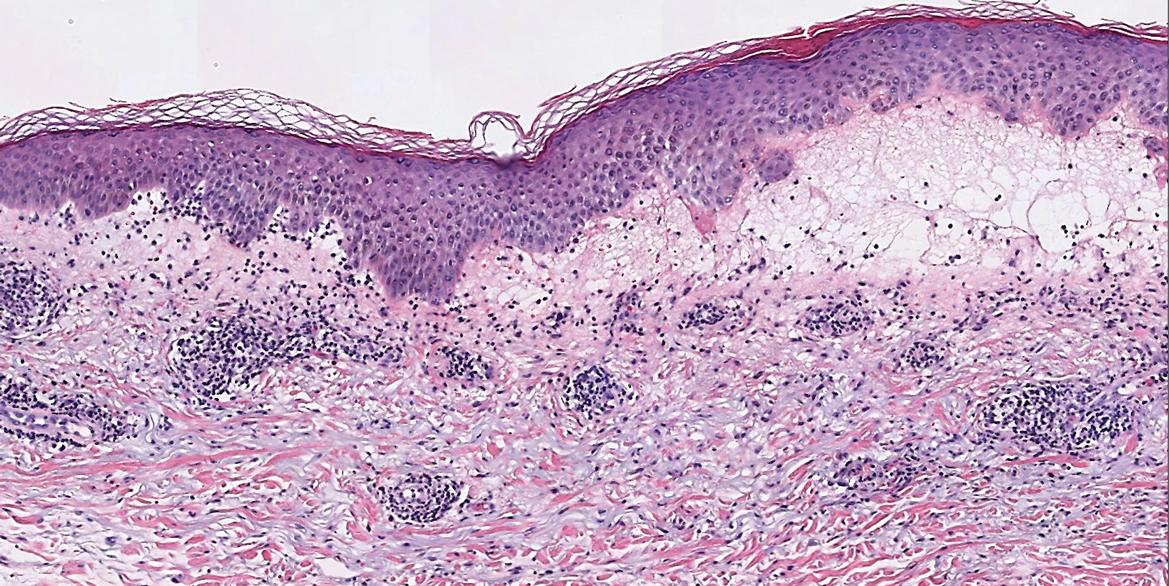

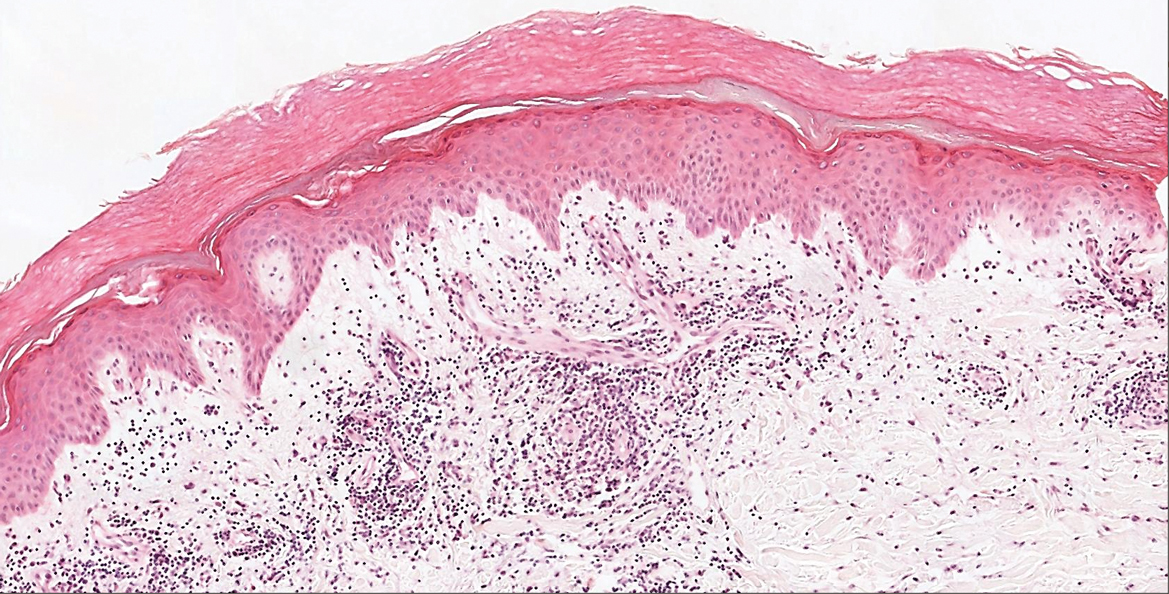

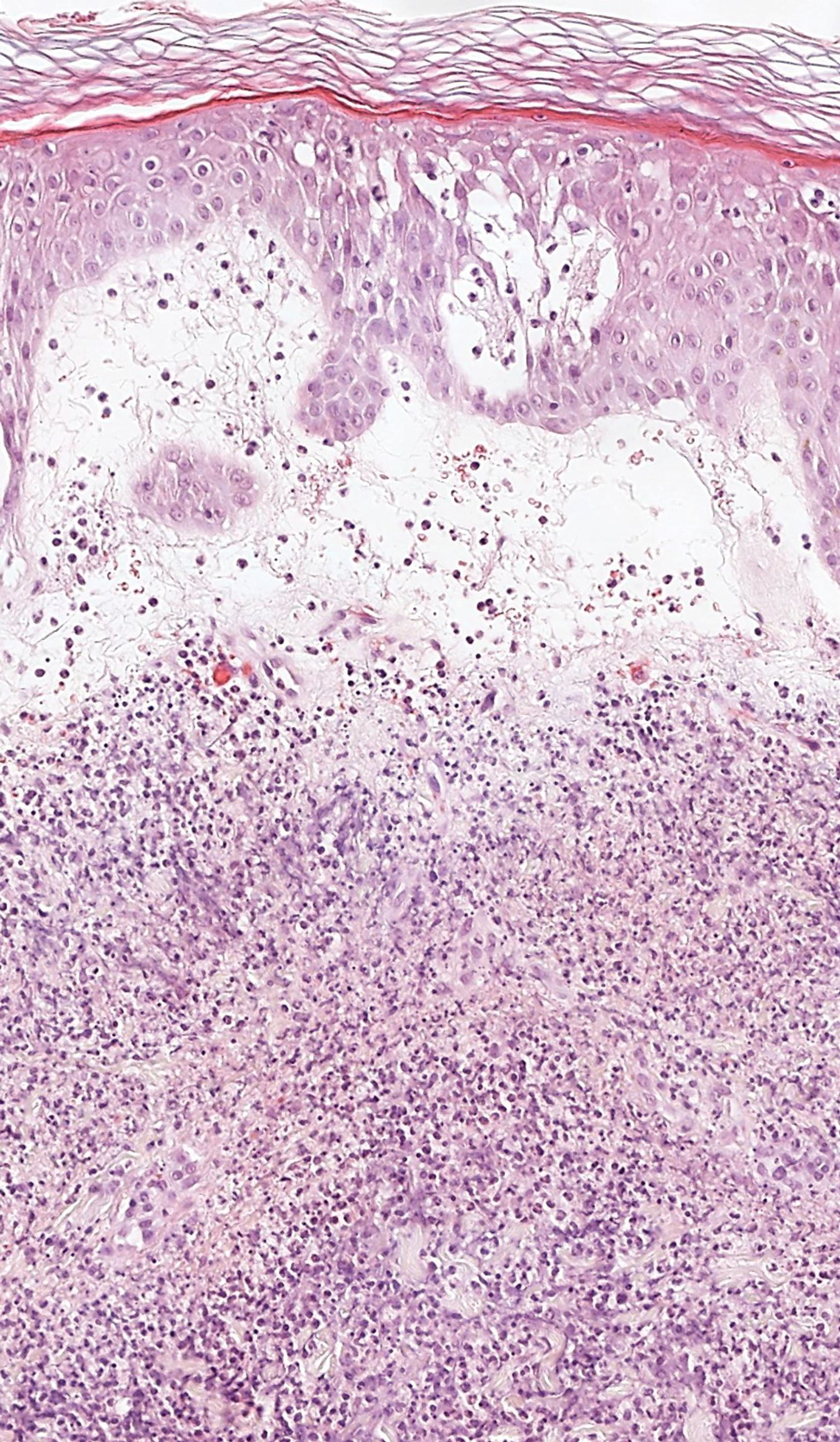

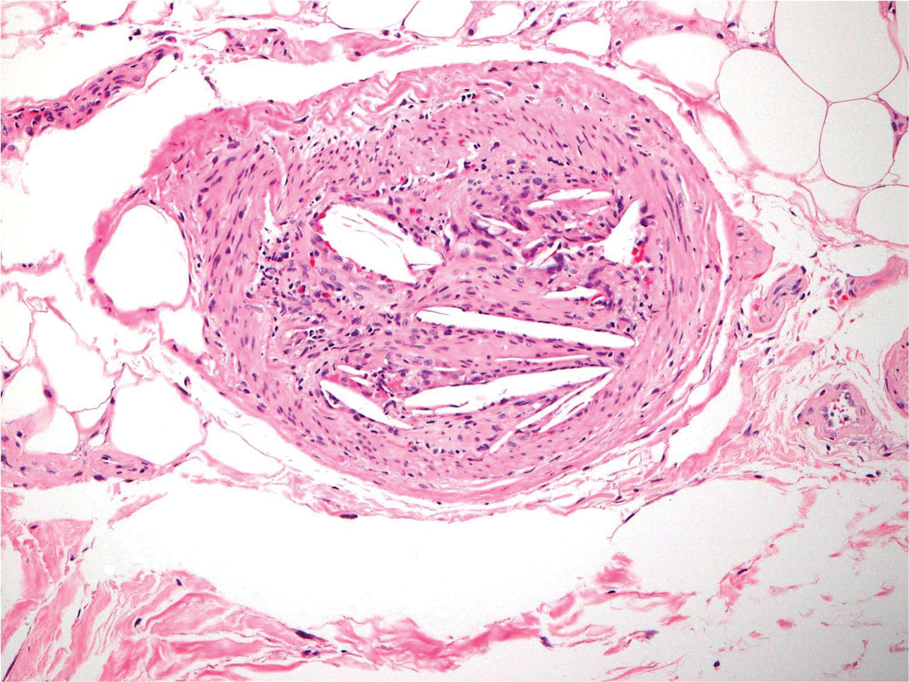

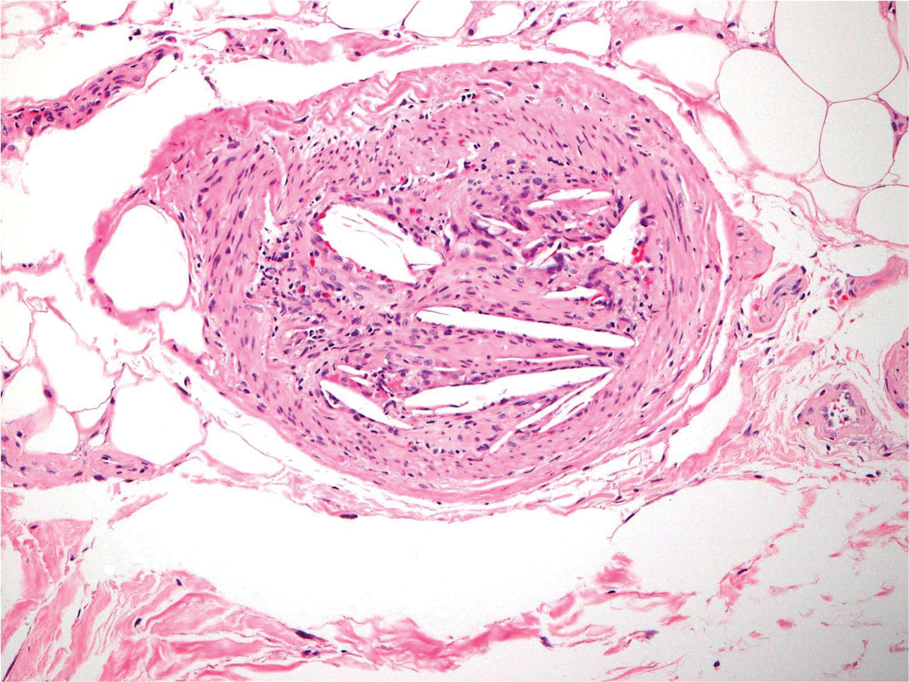

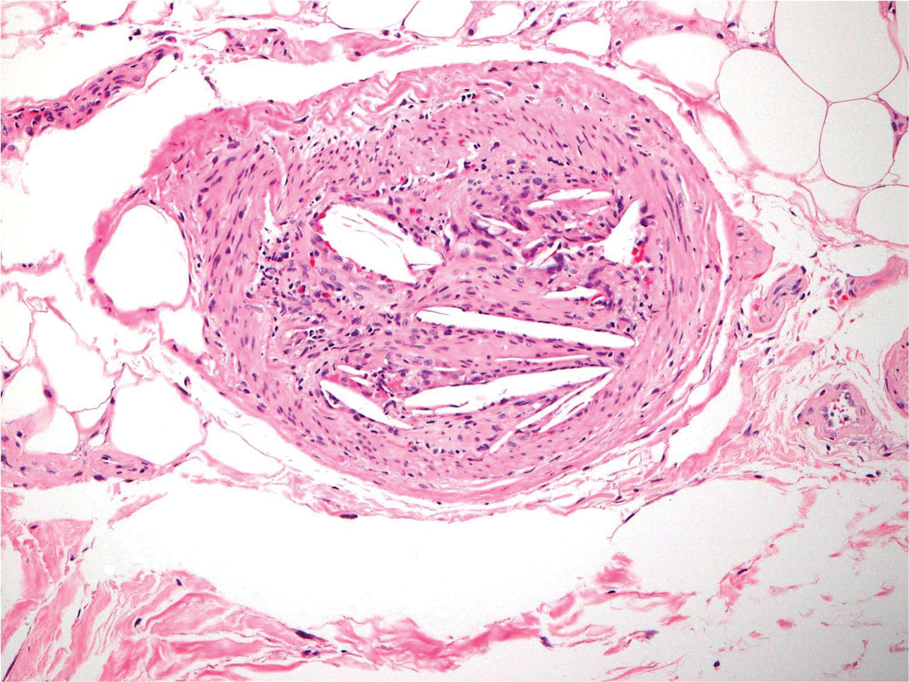

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

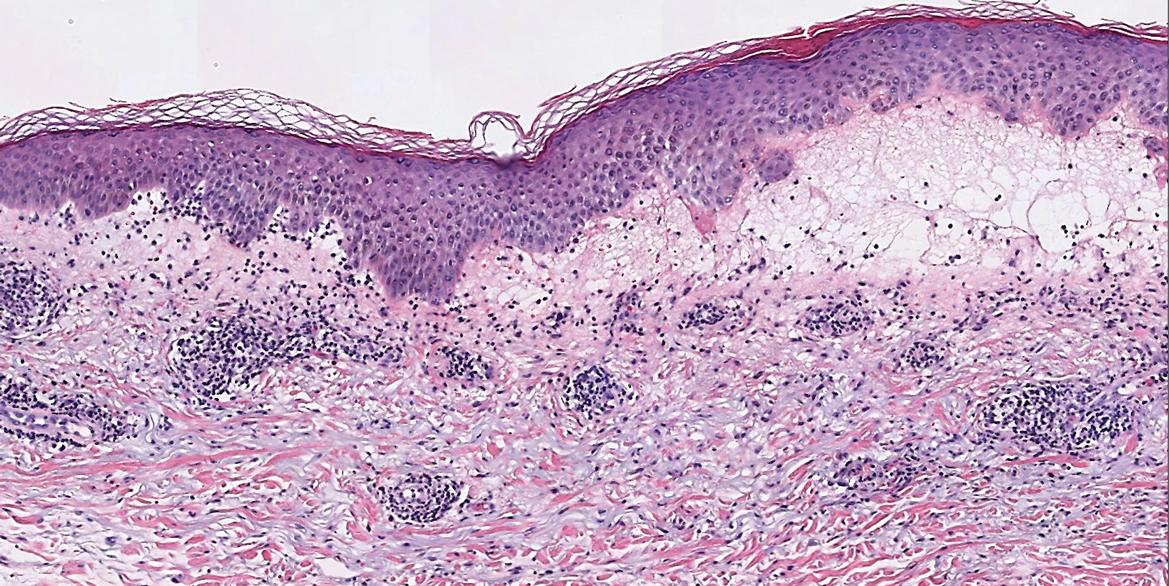

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

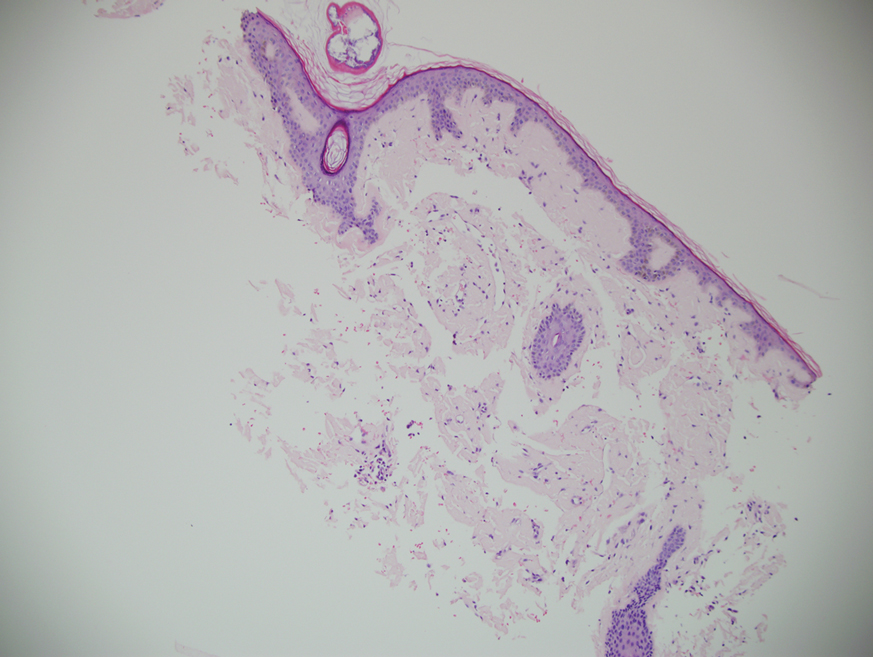

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

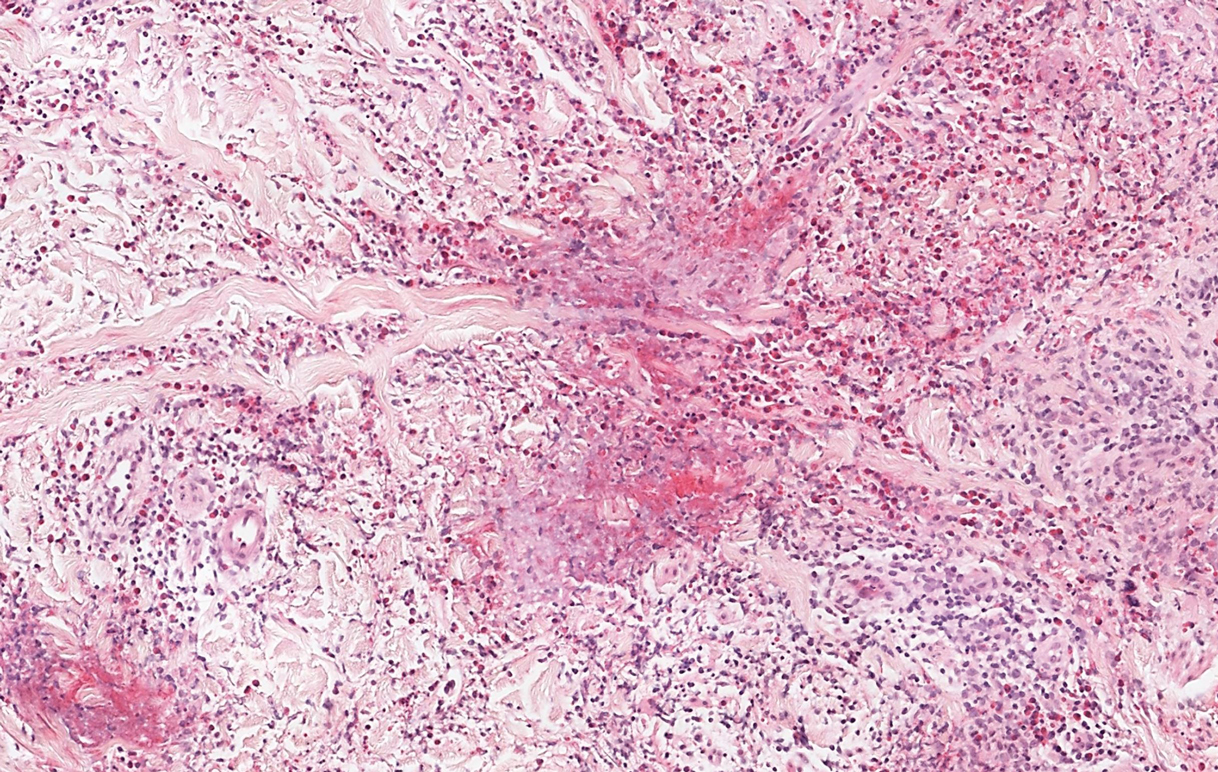

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

A 62-year-old woman presented with a tender diffuse eruption of erythematous and edematous papules and plaques on the face, neck, chest, and extremities, some appearing vesiculopustular.

Asymptomatic Hemorrhagic Lesions in an Anemic Woman

The Diagnosis: Bullous Amyloidosis

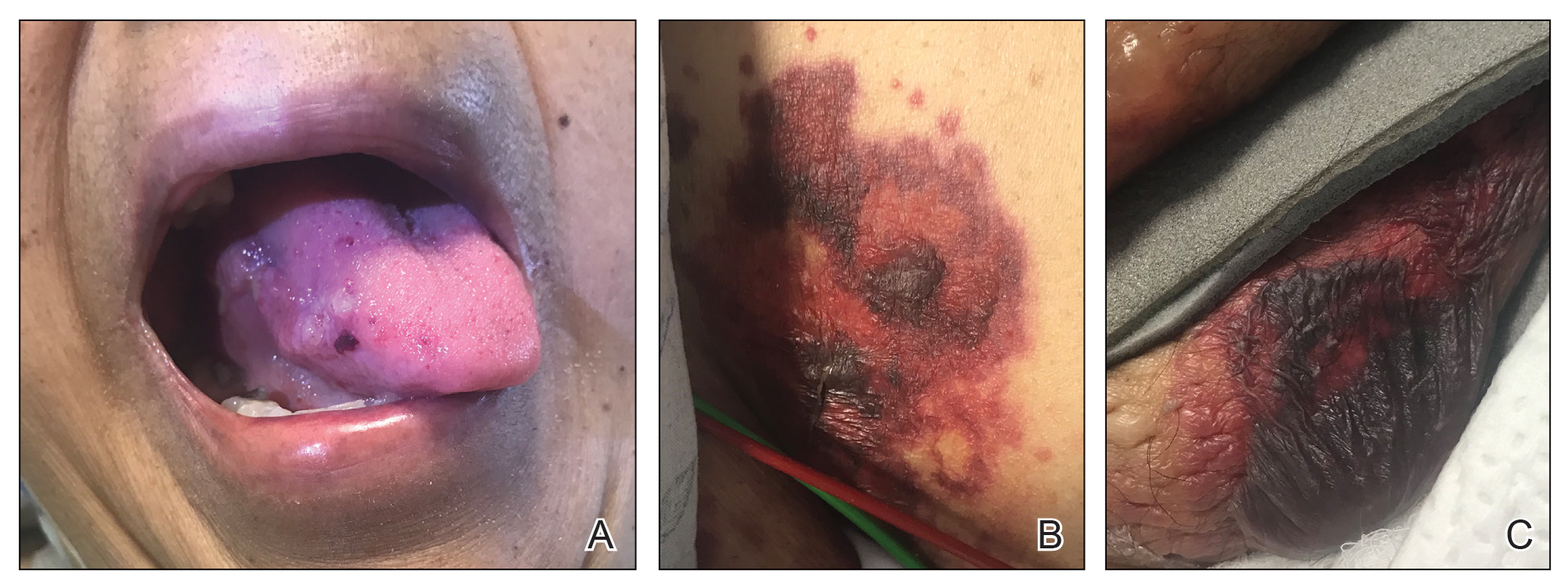

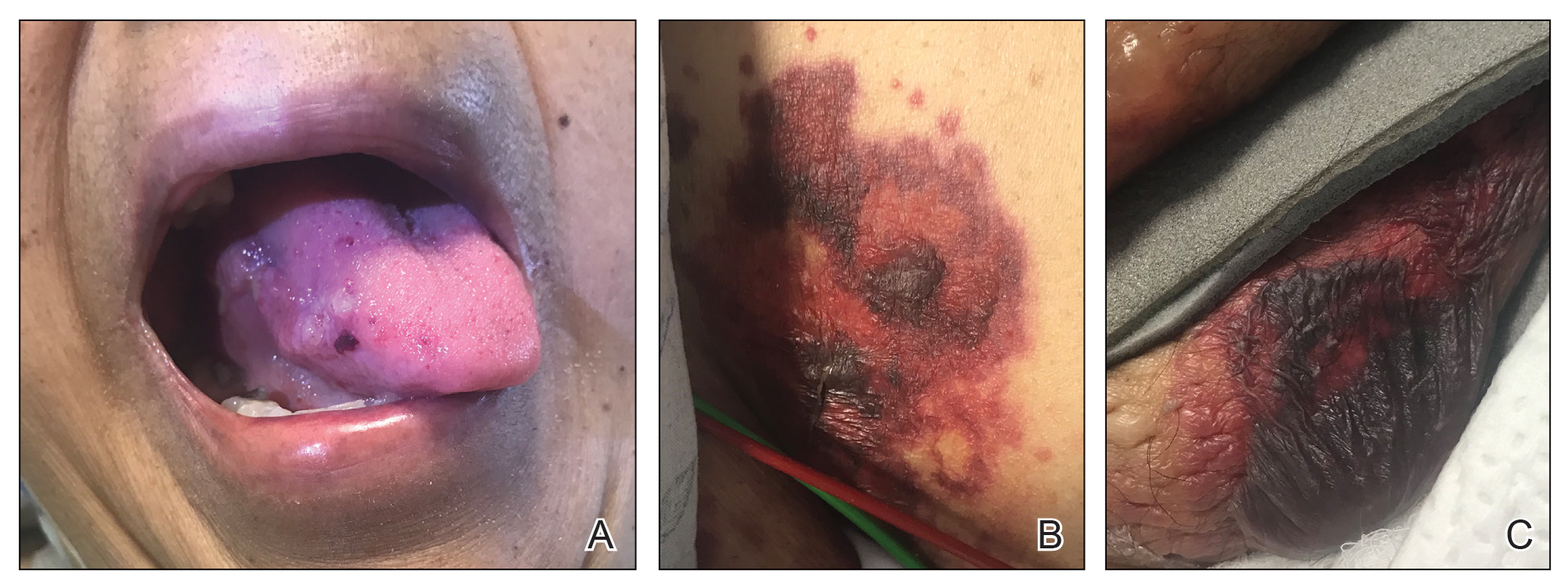

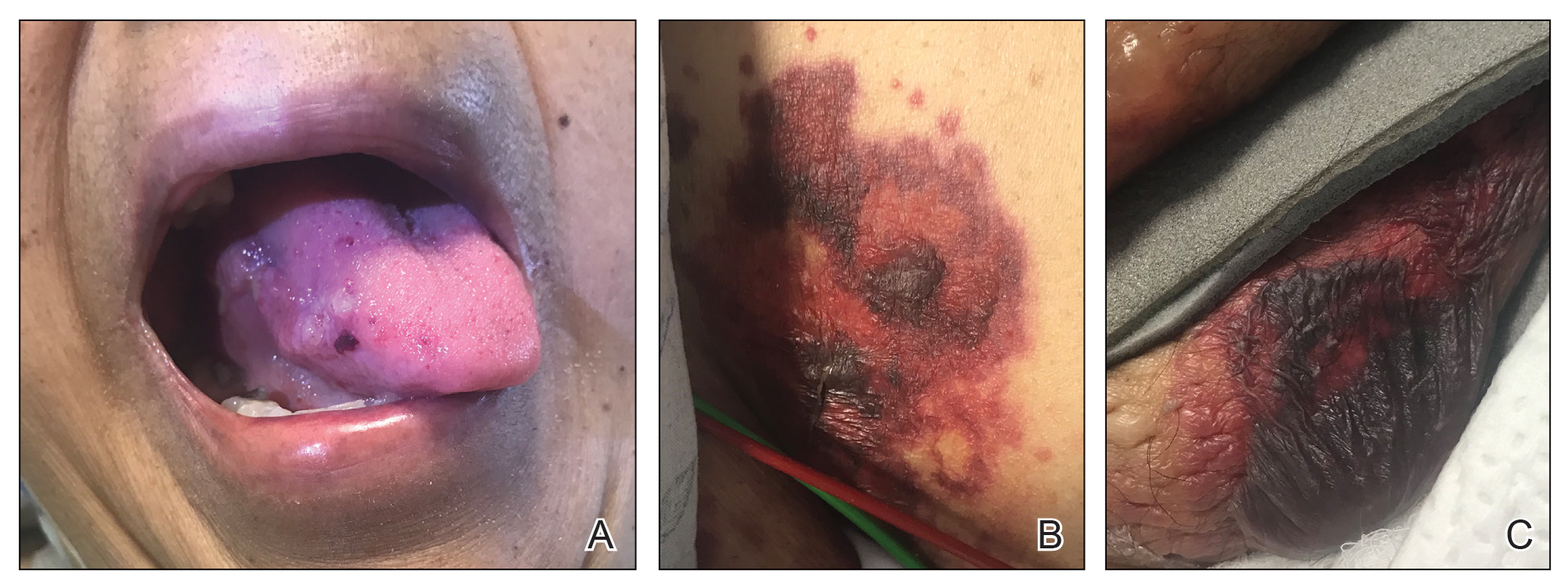

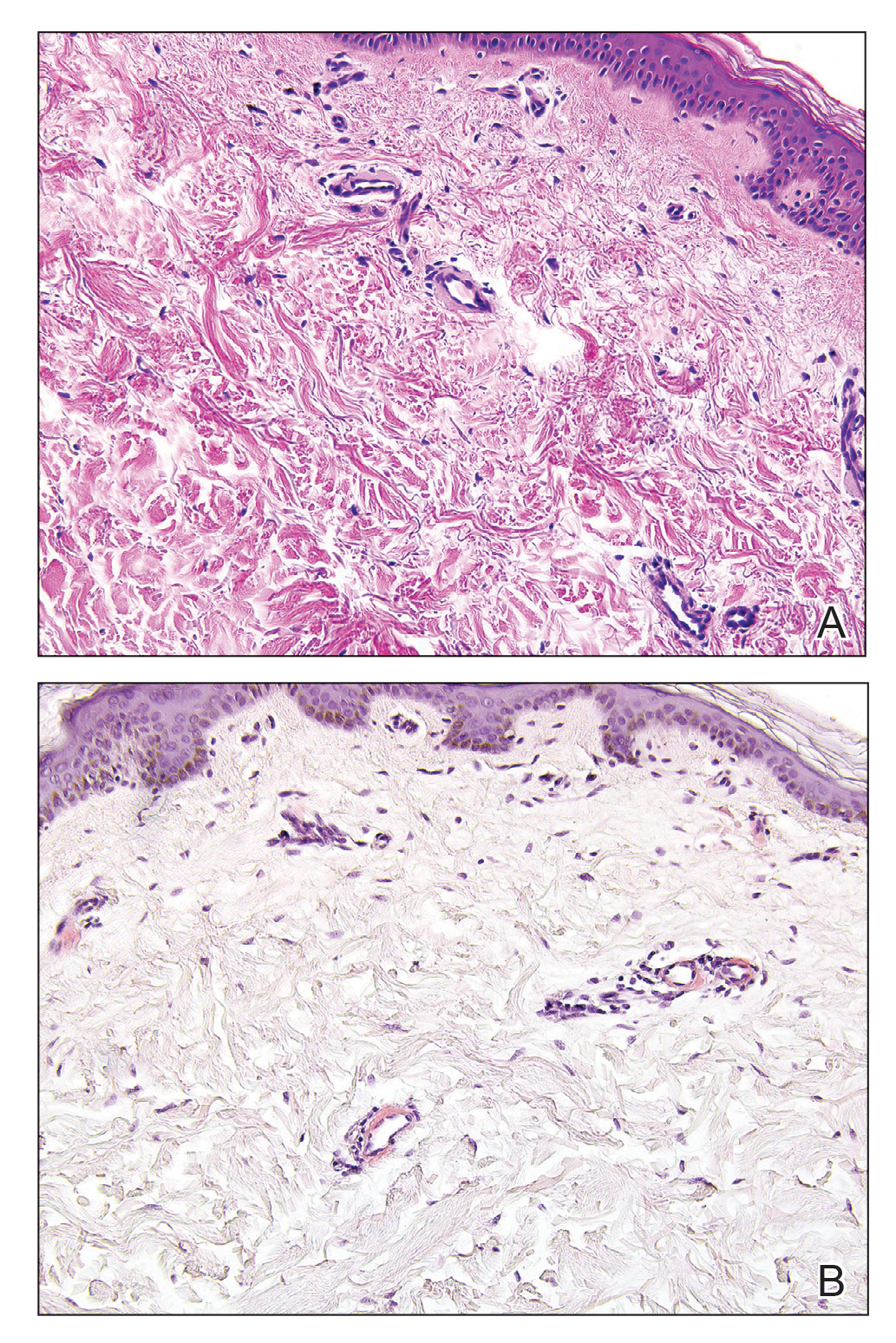

A punch biopsy from the left temple showed deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material at the tips of dermal papillae and in the papillary dermis with hemorrhage present (Figure 1). A diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed on the biopsy of the skin bulla. The low κ/λ light chain ratio and M-spike with notably elevated free λ light chains in both serum and urine were consistent with a λ light chain primary systemic amyloidosis. The patient was seen by hematology and oncology. A bone marrow biopsy demonstrated that 15% to 20% of the clonal-cell population was λ light chain restricted. Eosinophilic extracellular deposits found in the adjacent soft tissue and bone marrow space were confirmed as amyloid with apple green birefringence under polarized light on Congo red stain and metachromatic staining with crystal violet. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with λ light chain multiple myeloma and primary systemic amyloidosis.

Our patient was treated with a combination therapy of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone on 21-day cycles, with bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. She had received 3 cycles of chemotherapy before developing diarrhea, hypotension, acute on chronic heart failure, and acute renal failure requiring hospitalization. She had several related complications due to amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and subsequently died 16 days after her initial hospitalization from complications of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and septic shock.

Amyloidosis is the pathologic deposition of abnormal protein in the extracellular space of any tissue. Various soluble precursor proteins can make up amyloid, and these proteins polymerize into insoluble fibrils that damage the surrounding parenchyma. The clinical presentation of amyloidosis varies depending on the affected tissue as well as the constituent protein. The amyloidoses are divided into localized cutaneous, primary systemic, and secondary systemic variants. The initial distinction in amyloidosis is determining whether it is skin limited or systemic. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises 30% to 40% of all amyloidosis cases and is further divided into 3 main subtypes: macular, lichen, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis are composed of keratin derivatives and typically are induced by patients when rubbing or scratching the skin. Histologically, macular and lichen amyloidosis are restricted to the superficial papillary dermis.1 Nodular amyloidosis is composed of λ or κ light chain immunoglobulins, which are produced by cutaneous infiltrates of monoclonal plasma cells. Histologically, nodular amyloidosis is characterized by a diffuse dermal infiltrate of amorphous eosinophilic material.1 Primary systemic amyloidosis is associated with an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, and unlike secondary keratinocyte-derived amyloid, it can involve internal organs. Similar to nodular amyloidosis, primary systemic amyloidosis is composed of AL proteins, and it is histologically similar to nodular amyloidosis.1

Primary systemic AL amyloidosis commonly affects individuals aged 50 to 60 years. Males and females are equally affected. Macroglossia and periorbital purpura are some of the pathognomonic presentations in AL amyloidosis. The major cause of death in these patients is cardiac and renal involvement. Renal involvement commonly presents as nephrotic syndrome, and cardiac involvement can present as a restrictive cardiomyopathy with dyspnea. Other symptoms include edema, hepatosplenomegaly, bleeding diathesis, and carpal tunnel syndrome.2 An evaluation for AL amyloidosis should include a complete review of systems and physical examination with studies such as complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and electrocardiogram.

Cutaneous involvement in AL amyloidosis most commonly includes yellowish waxy papules, nodules, and plaques but also can include purpura and petechiae.2 Bullous amyloidosis, as seen in our patient, is a rare cutaneous presentation of AL amyloidosis that usually is negative for the Nikolsky sign (Figure 2). Bullae form due to weakness in amyloid-laden dermal connective tissue.3 Eighty-eight percent of cases of bullous amyloidosis have systemic involvement.1 Some cases have reported a familial linkage, suggesting there might be a genetic component to the disease.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bullous amyloidosis, bullous, amyloidosis, and amyloid revealed fewer than 35 cases of bullous amyloidosis in the English-language literature.5 Bullae can be located intradermally or subepidermally and commonly are hemorrhagic but also can be translucent, tender, and tense.

A study of electron microscopy in a patient with systemic bullous amyloidosis demonstrated amyloid and keratinocyte protrusions that perforated the dermis through the spaces in the lamina densa. The study concluded that the disintegration of the lamina densa and expansion of the intercellular spaces between keratinocytes were the causes of skin fragility as well as fluid exudation.5 Trauma or friction to the skin are local precipitating factors for blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.

Bullae can become apparent at any stage of AL amyloidosis, but they generally increase in size and number over time and are most common in intertriginous areas. Bullous amyloid lesions, especially those located in intertriginous areas, can have secondary impetiginization.6 In many cases, patients who present with bullous amyloidosis ultimately will be diagnosed with multiple myeloma or another plasma cell dyscrasia. In AL amyloidosis, only 10% to 15% of cases meet criteria for multiple myeloma, whereas 80% or more patients have a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.7

The prognosis of cutaneous amyloidosis depends on the extent of organ involvement and response to treatment. Treatment is aimed at eliminating clonal plasma cell populations to decrease the production of light chains, thereby decreasing protein burden and amyloid progression. Historically, treatment options included cytotoxic chemotherapy such as oral melphalan and dexamethasone, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant. More recent treatment options include bortezomib, thalidomide, pomalidomide, and lenalidomide.8 Our patient received a regimen of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone that is used for patients with extensive multiple myeloma.

The differential diagnosis in our patient included bullous drug eruption, which should be considered if the bullae are reoccurring at the same location and in association with the administration of a culprit drug. Bullous pemphigoid is preceded by pruritus, and biopsy demonstrates subepidermal bullae with associated eosinophilic infiltrate. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can present with milia and a linear pattern along the basement membrane zone with direct immunofluorescence. Traumatic purpura usually present with the classic shape and hue of an ecchymosis, and the patient will have a history of trauma.

Cutaneous involvement of amyloidosis can be an early clue to the diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia. Early diagnosis and treatment can portend a better prognosis and prevent progression to renal or cardiac disease.

- Heaton J, Steinhoff N, Wanner B, et al. A review of primary cutaneous amyloidosis. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. doi:10.1007/springerreference_42272

- Ventarola DJ, Schuster MW, Cohen JA, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. bullae and nodules on the legs of a 57-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1035-1037.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Suranagi VV, Siddramappa B, Bannur HB, et al. Bullous variant of familial biphasic lichen amyloidosis: a unique combination of three rare presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Antúnez-Lay A, Jaque A, González S. Hemorrhagic bullous skin lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:145-147.

- Reddy K, Hoda S, Penstein A, et al. Bullous amyloidosis complicated by cellulitis and sepsis: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:126-127.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Amyloidosis

A punch biopsy from the left temple showed deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material at the tips of dermal papillae and in the papillary dermis with hemorrhage present (Figure 1). A diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed on the biopsy of the skin bulla. The low κ/λ light chain ratio and M-spike with notably elevated free λ light chains in both serum and urine were consistent with a λ light chain primary systemic amyloidosis. The patient was seen by hematology and oncology. A bone marrow biopsy demonstrated that 15% to 20% of the clonal-cell population was λ light chain restricted. Eosinophilic extracellular deposits found in the adjacent soft tissue and bone marrow space were confirmed as amyloid with apple green birefringence under polarized light on Congo red stain and metachromatic staining with crystal violet. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with λ light chain multiple myeloma and primary systemic amyloidosis.

Our patient was treated with a combination therapy of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone on 21-day cycles, with bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. She had received 3 cycles of chemotherapy before developing diarrhea, hypotension, acute on chronic heart failure, and acute renal failure requiring hospitalization. She had several related complications due to amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and subsequently died 16 days after her initial hospitalization from complications of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and septic shock.

Amyloidosis is the pathologic deposition of abnormal protein in the extracellular space of any tissue. Various soluble precursor proteins can make up amyloid, and these proteins polymerize into insoluble fibrils that damage the surrounding parenchyma. The clinical presentation of amyloidosis varies depending on the affected tissue as well as the constituent protein. The amyloidoses are divided into localized cutaneous, primary systemic, and secondary systemic variants. The initial distinction in amyloidosis is determining whether it is skin limited or systemic. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises 30% to 40% of all amyloidosis cases and is further divided into 3 main subtypes: macular, lichen, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis are composed of keratin derivatives and typically are induced by patients when rubbing or scratching the skin. Histologically, macular and lichen amyloidosis are restricted to the superficial papillary dermis.1 Nodular amyloidosis is composed of λ or κ light chain immunoglobulins, which are produced by cutaneous infiltrates of monoclonal plasma cells. Histologically, nodular amyloidosis is characterized by a diffuse dermal infiltrate of amorphous eosinophilic material.1 Primary systemic amyloidosis is associated with an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, and unlike secondary keratinocyte-derived amyloid, it can involve internal organs. Similar to nodular amyloidosis, primary systemic amyloidosis is composed of AL proteins, and it is histologically similar to nodular amyloidosis.1

Primary systemic AL amyloidosis commonly affects individuals aged 50 to 60 years. Males and females are equally affected. Macroglossia and periorbital purpura are some of the pathognomonic presentations in AL amyloidosis. The major cause of death in these patients is cardiac and renal involvement. Renal involvement commonly presents as nephrotic syndrome, and cardiac involvement can present as a restrictive cardiomyopathy with dyspnea. Other symptoms include edema, hepatosplenomegaly, bleeding diathesis, and carpal tunnel syndrome.2 An evaluation for AL amyloidosis should include a complete review of systems and physical examination with studies such as complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and electrocardiogram.

Cutaneous involvement in AL amyloidosis most commonly includes yellowish waxy papules, nodules, and plaques but also can include purpura and petechiae.2 Bullous amyloidosis, as seen in our patient, is a rare cutaneous presentation of AL amyloidosis that usually is negative for the Nikolsky sign (Figure 2). Bullae form due to weakness in amyloid-laden dermal connective tissue.3 Eighty-eight percent of cases of bullous amyloidosis have systemic involvement.1 Some cases have reported a familial linkage, suggesting there might be a genetic component to the disease.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bullous amyloidosis, bullous, amyloidosis, and amyloid revealed fewer than 35 cases of bullous amyloidosis in the English-language literature.5 Bullae can be located intradermally or subepidermally and commonly are hemorrhagic but also can be translucent, tender, and tense.

A study of electron microscopy in a patient with systemic bullous amyloidosis demonstrated amyloid and keratinocyte protrusions that perforated the dermis through the spaces in the lamina densa. The study concluded that the disintegration of the lamina densa and expansion of the intercellular spaces between keratinocytes were the causes of skin fragility as well as fluid exudation.5 Trauma or friction to the skin are local precipitating factors for blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.

Bullae can become apparent at any stage of AL amyloidosis, but they generally increase in size and number over time and are most common in intertriginous areas. Bullous amyloid lesions, especially those located in intertriginous areas, can have secondary impetiginization.6 In many cases, patients who present with bullous amyloidosis ultimately will be diagnosed with multiple myeloma or another plasma cell dyscrasia. In AL amyloidosis, only 10% to 15% of cases meet criteria for multiple myeloma, whereas 80% or more patients have a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.7

The prognosis of cutaneous amyloidosis depends on the extent of organ involvement and response to treatment. Treatment is aimed at eliminating clonal plasma cell populations to decrease the production of light chains, thereby decreasing protein burden and amyloid progression. Historically, treatment options included cytotoxic chemotherapy such as oral melphalan and dexamethasone, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant. More recent treatment options include bortezomib, thalidomide, pomalidomide, and lenalidomide.8 Our patient received a regimen of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone that is used for patients with extensive multiple myeloma.

The differential diagnosis in our patient included bullous drug eruption, which should be considered if the bullae are reoccurring at the same location and in association with the administration of a culprit drug. Bullous pemphigoid is preceded by pruritus, and biopsy demonstrates subepidermal bullae with associated eosinophilic infiltrate. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can present with milia and a linear pattern along the basement membrane zone with direct immunofluorescence. Traumatic purpura usually present with the classic shape and hue of an ecchymosis, and the patient will have a history of trauma.

Cutaneous involvement of amyloidosis can be an early clue to the diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia. Early diagnosis and treatment can portend a better prognosis and prevent progression to renal or cardiac disease.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Amyloidosis

A punch biopsy from the left temple showed deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material at the tips of dermal papillae and in the papillary dermis with hemorrhage present (Figure 1). A diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed on the biopsy of the skin bulla. The low κ/λ light chain ratio and M-spike with notably elevated free λ light chains in both serum and urine were consistent with a λ light chain primary systemic amyloidosis. The patient was seen by hematology and oncology. A bone marrow biopsy demonstrated that 15% to 20% of the clonal-cell population was λ light chain restricted. Eosinophilic extracellular deposits found in the adjacent soft tissue and bone marrow space were confirmed as amyloid with apple green birefringence under polarized light on Congo red stain and metachromatic staining with crystal violet. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with λ light chain multiple myeloma and primary systemic amyloidosis.

Our patient was treated with a combination therapy of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone on 21-day cycles, with bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. She had received 3 cycles of chemotherapy before developing diarrhea, hypotension, acute on chronic heart failure, and acute renal failure requiring hospitalization. She had several related complications due to amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and subsequently died 16 days after her initial hospitalization from complications of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and septic shock.

Amyloidosis is the pathologic deposition of abnormal protein in the extracellular space of any tissue. Various soluble precursor proteins can make up amyloid, and these proteins polymerize into insoluble fibrils that damage the surrounding parenchyma. The clinical presentation of amyloidosis varies depending on the affected tissue as well as the constituent protein. The amyloidoses are divided into localized cutaneous, primary systemic, and secondary systemic variants. The initial distinction in amyloidosis is determining whether it is skin limited or systemic. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises 30% to 40% of all amyloidosis cases and is further divided into 3 main subtypes: macular, lichen, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis are composed of keratin derivatives and typically are induced by patients when rubbing or scratching the skin. Histologically, macular and lichen amyloidosis are restricted to the superficial papillary dermis.1 Nodular amyloidosis is composed of λ or κ light chain immunoglobulins, which are produced by cutaneous infiltrates of monoclonal plasma cells. Histologically, nodular amyloidosis is characterized by a diffuse dermal infiltrate of amorphous eosinophilic material.1 Primary systemic amyloidosis is associated with an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, and unlike secondary keratinocyte-derived amyloid, it can involve internal organs. Similar to nodular amyloidosis, primary systemic amyloidosis is composed of AL proteins, and it is histologically similar to nodular amyloidosis.1

Primary systemic AL amyloidosis commonly affects individuals aged 50 to 60 years. Males and females are equally affected. Macroglossia and periorbital purpura are some of the pathognomonic presentations in AL amyloidosis. The major cause of death in these patients is cardiac and renal involvement. Renal involvement commonly presents as nephrotic syndrome, and cardiac involvement can present as a restrictive cardiomyopathy with dyspnea. Other symptoms include edema, hepatosplenomegaly, bleeding diathesis, and carpal tunnel syndrome.2 An evaluation for AL amyloidosis should include a complete review of systems and physical examination with studies such as complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and electrocardiogram.

Cutaneous involvement in AL amyloidosis most commonly includes yellowish waxy papules, nodules, and plaques but also can include purpura and petechiae.2 Bullous amyloidosis, as seen in our patient, is a rare cutaneous presentation of AL amyloidosis that usually is negative for the Nikolsky sign (Figure 2). Bullae form due to weakness in amyloid-laden dermal connective tissue.3 Eighty-eight percent of cases of bullous amyloidosis have systemic involvement.1 Some cases have reported a familial linkage, suggesting there might be a genetic component to the disease.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bullous amyloidosis, bullous, amyloidosis, and amyloid revealed fewer than 35 cases of bullous amyloidosis in the English-language literature.5 Bullae can be located intradermally or subepidermally and commonly are hemorrhagic but also can be translucent, tender, and tense.

A study of electron microscopy in a patient with systemic bullous amyloidosis demonstrated amyloid and keratinocyte protrusions that perforated the dermis through the spaces in the lamina densa. The study concluded that the disintegration of the lamina densa and expansion of the intercellular spaces between keratinocytes were the causes of skin fragility as well as fluid exudation.5 Trauma or friction to the skin are local precipitating factors for blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.

Bullae can become apparent at any stage of AL amyloidosis, but they generally increase in size and number over time and are most common in intertriginous areas. Bullous amyloid lesions, especially those located in intertriginous areas, can have secondary impetiginization.6 In many cases, patients who present with bullous amyloidosis ultimately will be diagnosed with multiple myeloma or another plasma cell dyscrasia. In AL amyloidosis, only 10% to 15% of cases meet criteria for multiple myeloma, whereas 80% or more patients have a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.7

The prognosis of cutaneous amyloidosis depends on the extent of organ involvement and response to treatment. Treatment is aimed at eliminating clonal plasma cell populations to decrease the production of light chains, thereby decreasing protein burden and amyloid progression. Historically, treatment options included cytotoxic chemotherapy such as oral melphalan and dexamethasone, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant. More recent treatment options include bortezomib, thalidomide, pomalidomide, and lenalidomide.8 Our patient received a regimen of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone that is used for patients with extensive multiple myeloma.

The differential diagnosis in our patient included bullous drug eruption, which should be considered if the bullae are reoccurring at the same location and in association with the administration of a culprit drug. Bullous pemphigoid is preceded by pruritus, and biopsy demonstrates subepidermal bullae with associated eosinophilic infiltrate. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can present with milia and a linear pattern along the basement membrane zone with direct immunofluorescence. Traumatic purpura usually present with the classic shape and hue of an ecchymosis, and the patient will have a history of trauma.

Cutaneous involvement of amyloidosis can be an early clue to the diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia. Early diagnosis and treatment can portend a better prognosis and prevent progression to renal or cardiac disease.

- Heaton J, Steinhoff N, Wanner B, et al. A review of primary cutaneous amyloidosis. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. doi:10.1007/springerreference_42272

- Ventarola DJ, Schuster MW, Cohen JA, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. bullae and nodules on the legs of a 57-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1035-1037.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Suranagi VV, Siddramappa B, Bannur HB, et al. Bullous variant of familial biphasic lichen amyloidosis: a unique combination of three rare presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Antúnez-Lay A, Jaque A, González S. Hemorrhagic bullous skin lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:145-147.

- Reddy K, Hoda S, Penstein A, et al. Bullous amyloidosis complicated by cellulitis and sepsis: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:126-127.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Heaton J, Steinhoff N, Wanner B, et al. A review of primary cutaneous amyloidosis. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. doi:10.1007/springerreference_42272

- Ventarola DJ, Schuster MW, Cohen JA, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. bullae and nodules on the legs of a 57-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1035-1037.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Suranagi VV, Siddramappa B, Bannur HB, et al. Bullous variant of familial biphasic lichen amyloidosis: a unique combination of three rare presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Antúnez-Lay A, Jaque A, González S. Hemorrhagic bullous skin lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:145-147.

- Reddy K, Hoda S, Penstein A, et al. Bullous amyloidosis complicated by cellulitis and sepsis: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:126-127.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

A 67-year-old woman with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, unspecified leukocytosis, and anemia presented to the dermatology clinic with asymptomatic hemorrhagic bullae on the face, chest, and tongue, as well as a large, tender, tense, hemorrhagic bulla on the groin of 3 to 4 months’ duration. A review of systems was negative for fever, chills, night sweats, malaise, shortness of breath, and dyspnea on exertion. A complete blood cell count showed mild leukocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Her creatinine level was slightly elevated. Chest computed tomography showed early pulmonary fibrosis and coronary artery calcification. An echocardiogram showed diastolic dysfunction with moderate left ventricle thickening. A serum and urine electrophoresis demonstrated elevated free λ light chains with an M-spike. A punch biopsy was performed.

Isolated Perianal Erosive Lichen Planus: A Diagnostic Challenge

To the Editor:

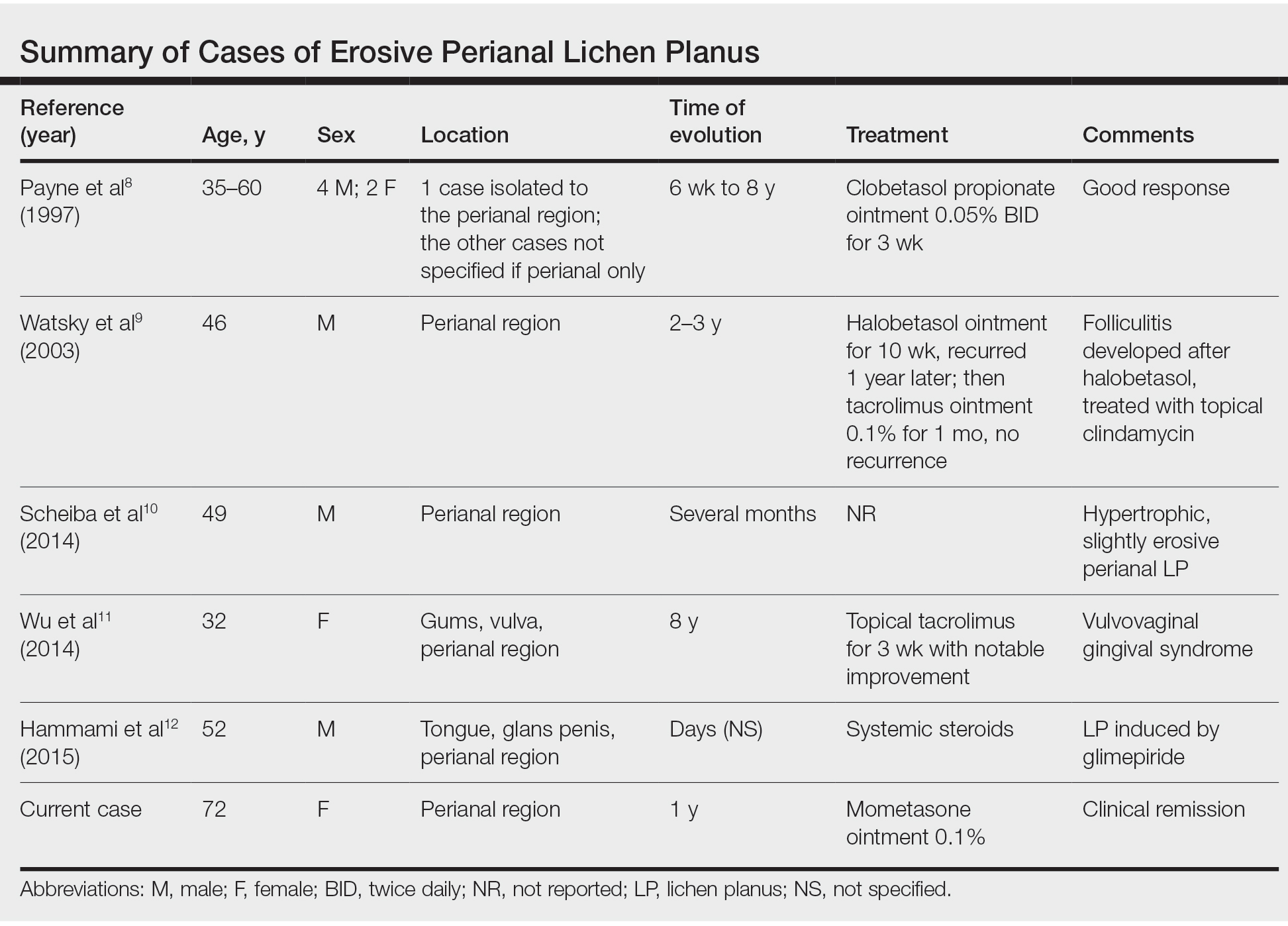

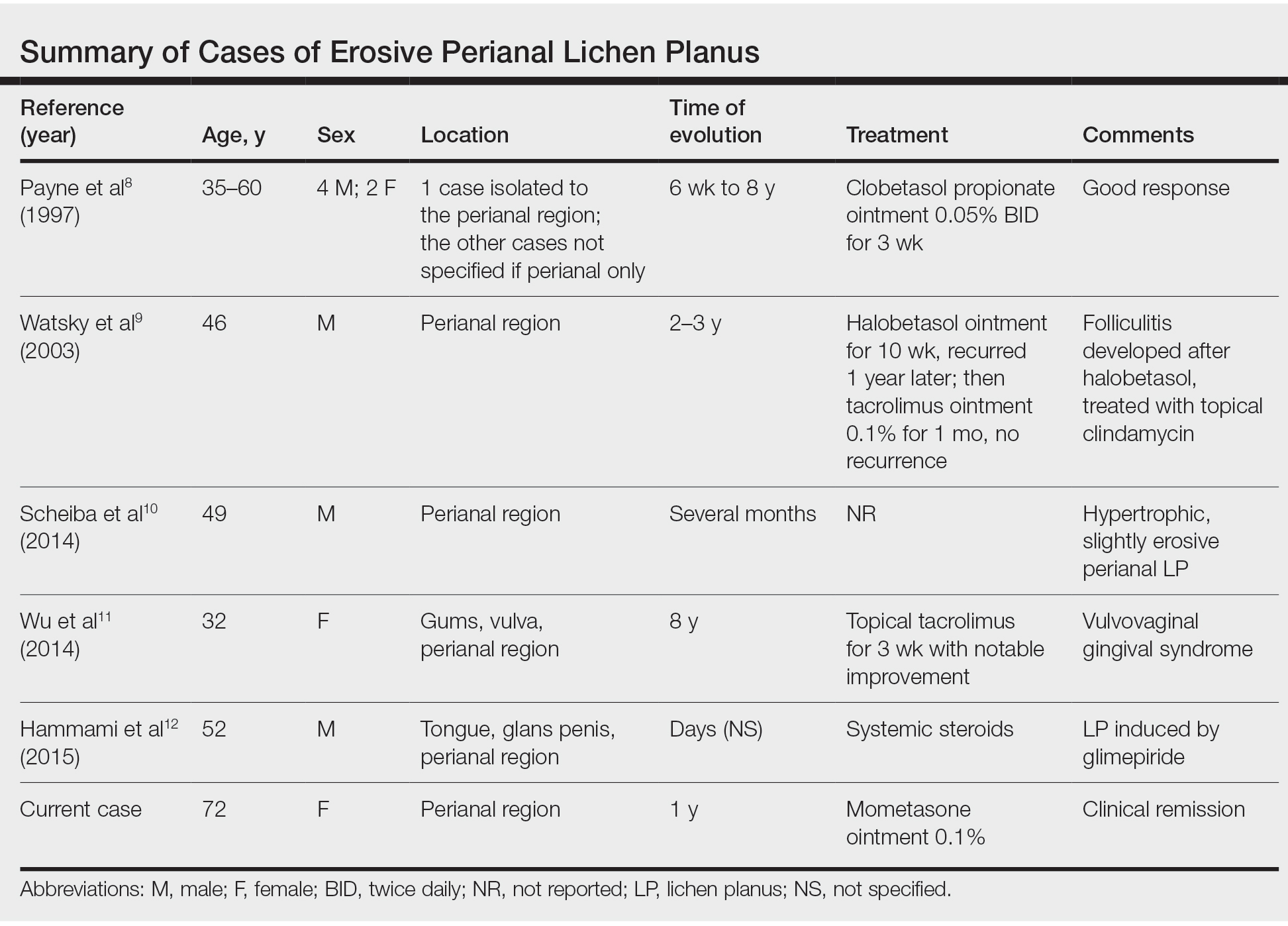

Erosive lichen planus (LP) often is painful, debilitating, and resistant to topical therapy making it both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of an elderly woman with isolated perianal erosive LP, a rare clinical manifestation. We also review cases of erosive perianal LP reported in the literature.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple pruritic and painful perianal lesions of 1 year’s duration. The lesions had remained stable since onset, with no other reported lesions elsewhere on body, including the mucosae. Her medical history was notable for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. She was taking methotrexate, folic acid, abatacept, alendronate, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. The patient reported she had been using abatacept for 3 years and lisinopril for 2 years. Her primary care physician initially treated the lesions as hemorrhoids but referred her to a gastroenterologist when they failed to improve. Gastroenterology evaluated the patient, and a colonoscopy was performed with unremarkable results. Thus, she was referred to dermatology for further evaluation.

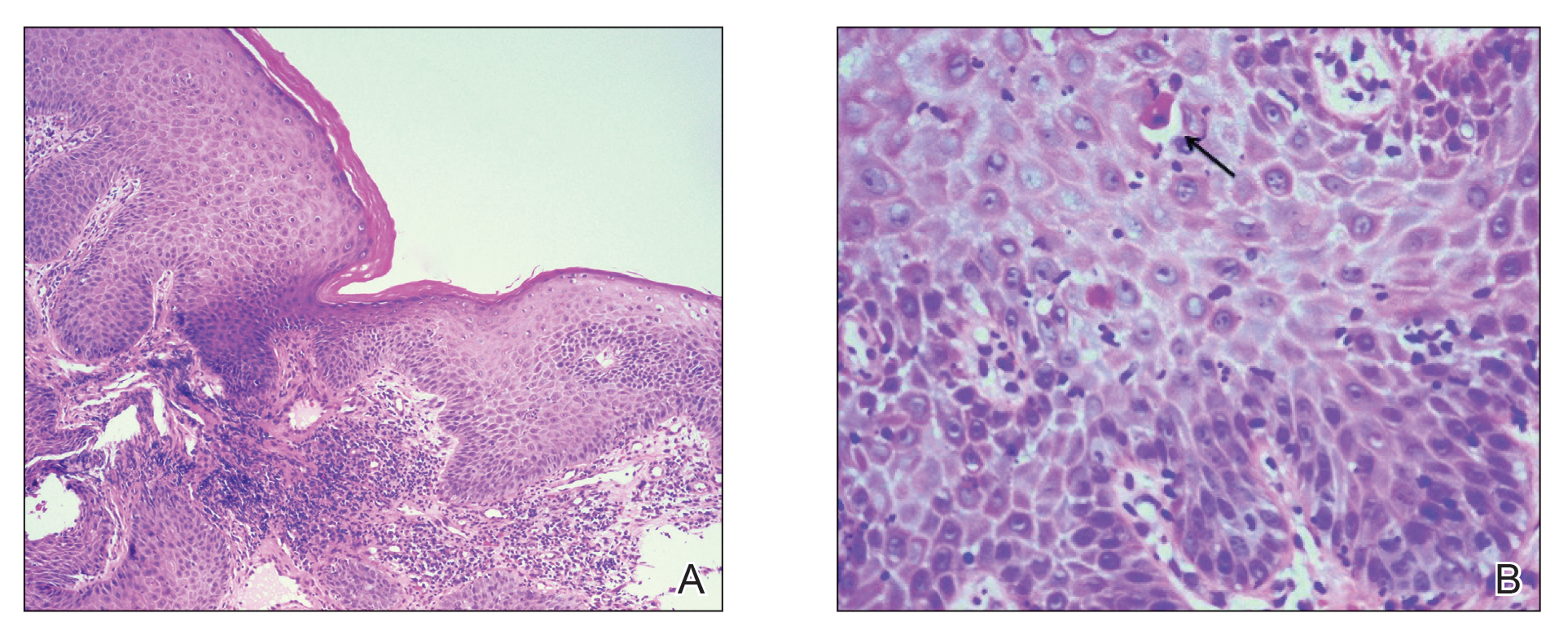

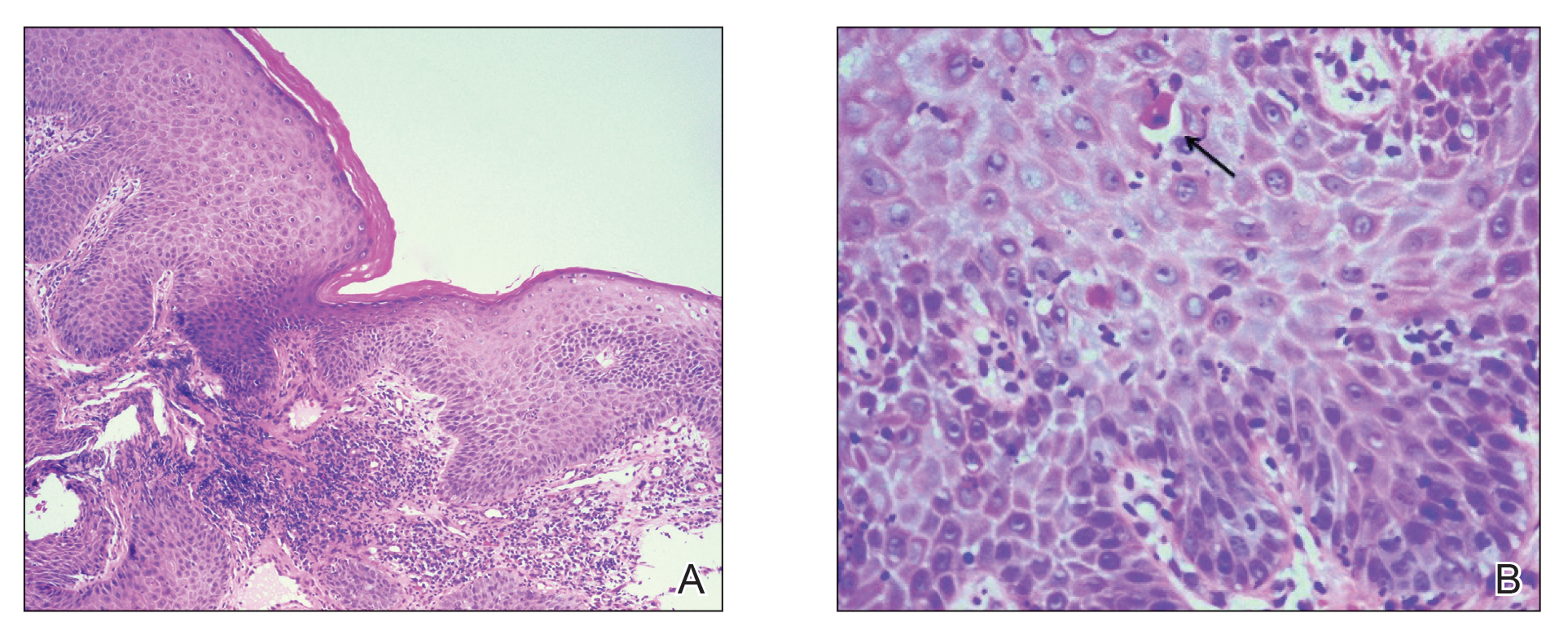

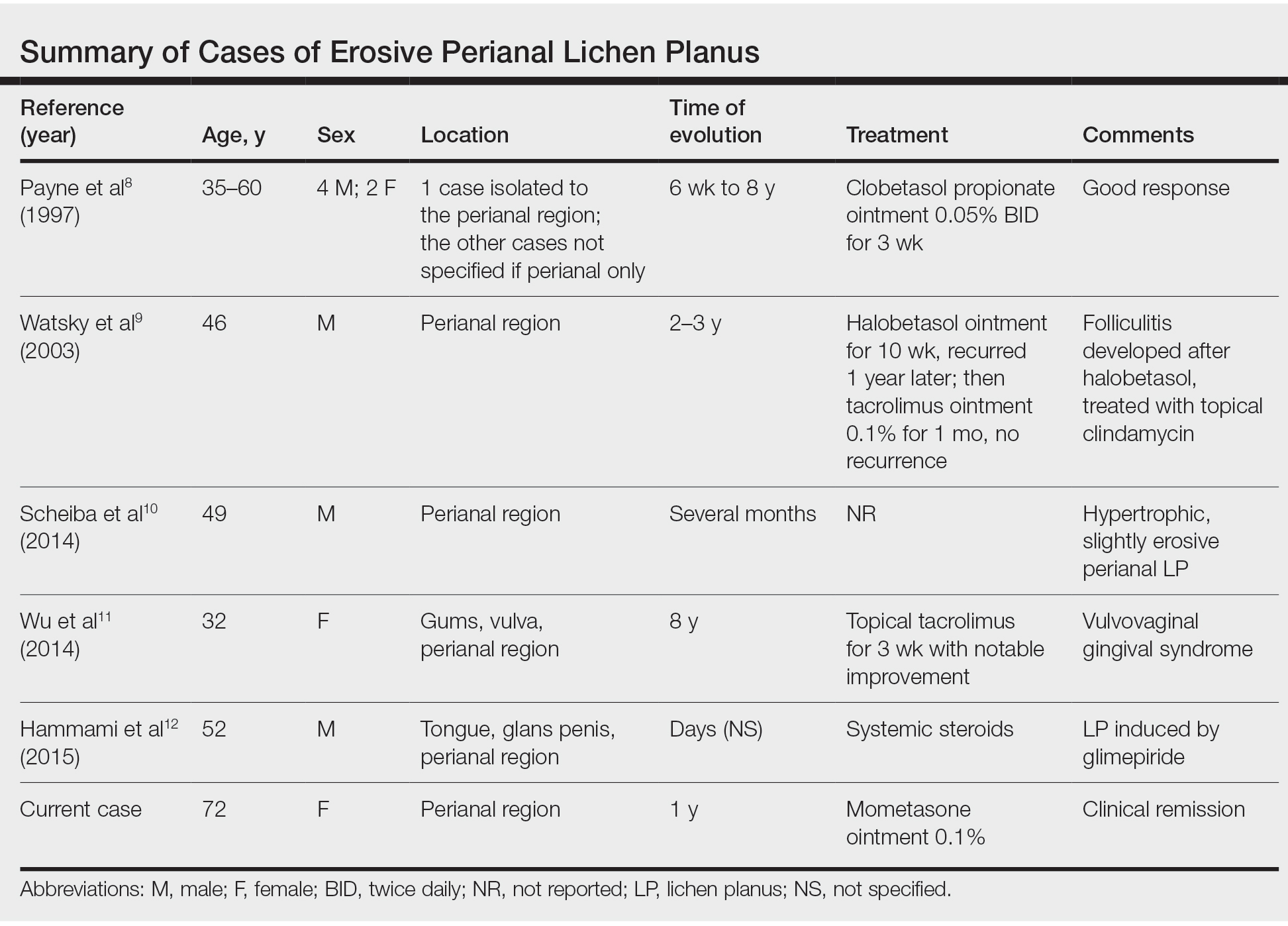

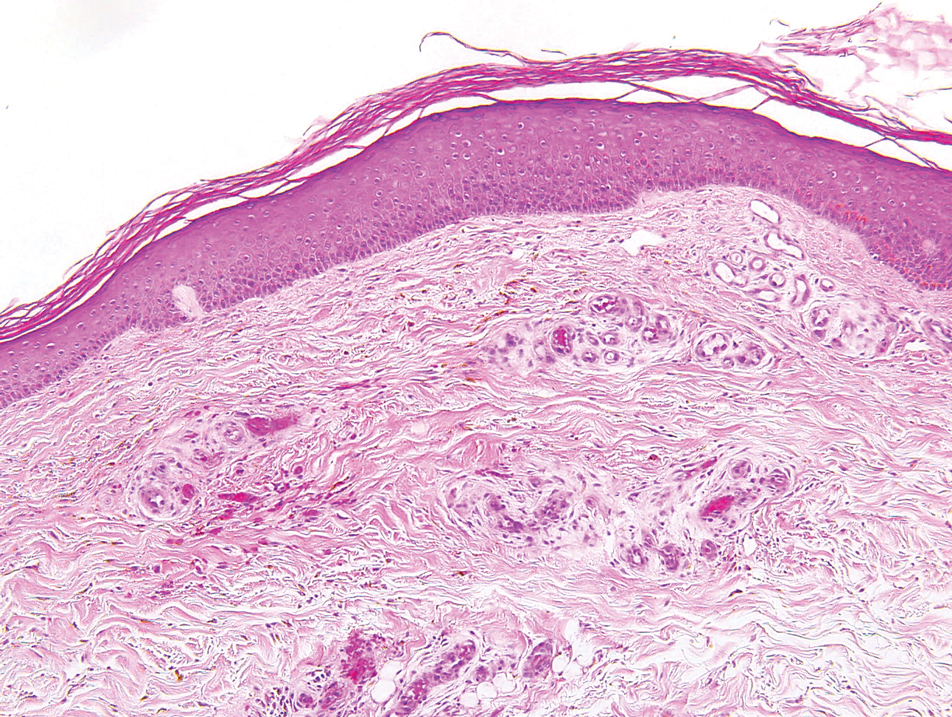

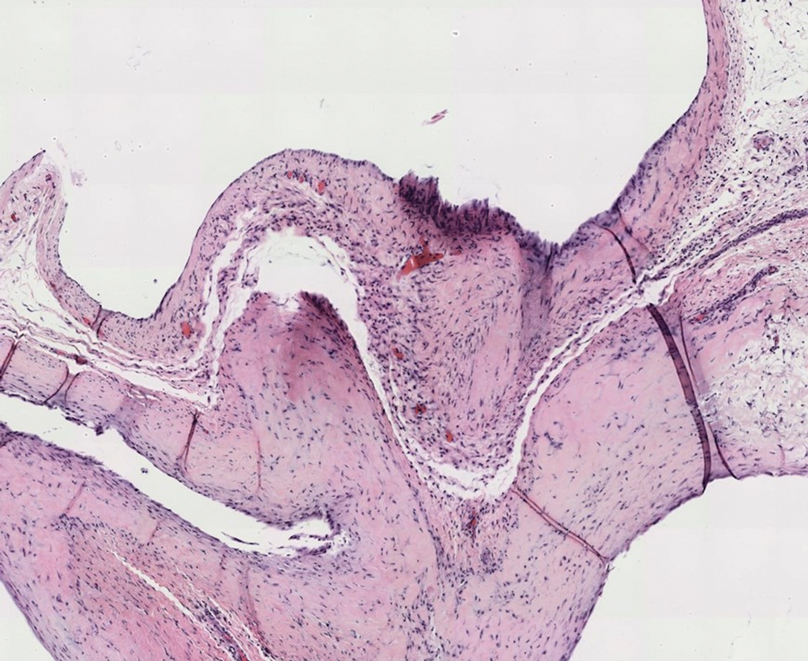

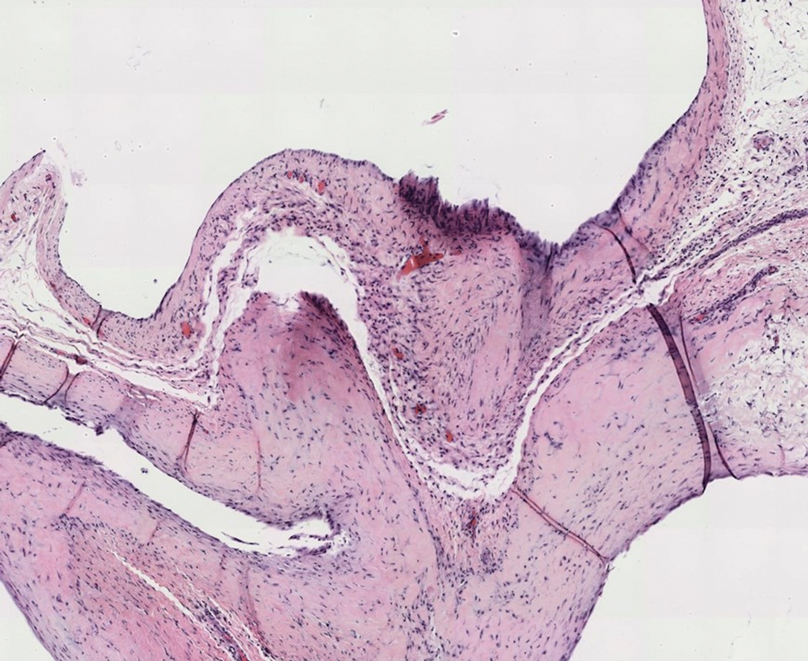

Physical examination revealed 2 tender, sharply defined, angulated erosions with irregular violaceous borders involving the perianal skin (Figure 1). A biopsy of one of the lesions was taken. Histopathologic examination revealed acanthosis of the epidermis with slight compact hyperkeratosis, scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that obliterated the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of perianal erosive LP was made. The patient was prescribed mometasone ointment 0.1% daily with notable improvement after 2 months.

Erosive LP is an extremely rare variant of LP.1 It typically manifests as chronic painful erosions that often can progress to scarring, ulceration, and tissue destruction. Although erosive LP most commonly involves the mucosal surfaces of the genitalia and oral mucosa, it also has been reported in the palmoplantar skin, lacrimal duct, external auditory meatus, and esophagus.2-7 However, isolated perianal involvement is extremely rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erosive or ulcerative and lichen planus and perianal revealed 10 cases of perianal erosive LP, and weak data exist regarding therapy (Table).8-12 Of these cases, only 3 reported isolated perianal involvement.8-10 In most reported cases, perianal involvement manifested as extremely painful and occasionally pruritic, sharply angulated erosions and ulcers arising 0.5 to 3 cm from the anus with macerated, whitish, and violaceous borders. Most of the lesions occurred unilaterally, with only 1 case of bilateral perianal involvement.10

The differential diagnosis of perianal erosions is extensive and includes cutaneous Crohn disease, extramammary Paget disease, cutaneous malignancy, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, external hemorrhoids, lichen sclerosus, Behçet disease, lichen simplex chronicus, and drug-induced lichenoid reaction, among others. It is worth emphasizing infectious processes and cutaneous malignancies in light of our patient’s immunosuppression. Perianal cytomegalovirus has been reported in the literature in association with HIV, and it is a clinically challenging diagnosis.13 Cutaneous malignancy associated with the use of methotrexate also was considered in the differential diagnosis for our patient, given the increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer with the use of immunosuppresants.14

Along with a thorough patient history and physical examination, skin biopsy and clinicopathologic correlation are key to determine the exact etiology. Histologically, LP is characterized by a lichenoid interface dermatitis with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Other distinguishing factors include irregular acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, basal cell vacuolar degeneration, and Civatte bodies. Drug-induced LP is a possibility, but it is unclear if abatacept or lisinopril may have played a role in our patient. However, absence of eosinophils and parakeratosis suggested an idiopathic rather than drug-induced etiology. In 2016, Day et al2 published a clinicopathologic review of 60 cases of perianal lichenoid dermatoses in which only 17% of lesions were LP. Of note, 90% of perianal LP lesions were of the hypertrophic variant, and none were of the erosive variant, further supporting that our case represents a rare clinical manifestation of perianal LP.

Treatment of LP varies depending on the location and subtype of the lesions and is primarily aimed at improving symptoms. Topical corticosteroids are the standard treatment of LP; however, there is limited evidence regarding their efficacy for mucosal LP. Although randomized controlled trials assessing the efficacy of different interventions on oral erosive LP are available in the literature,15 there is a paucity of studies addressing this topic for genital or perianal LP. A review of the literature regarding perianal erosive LP suggests good response to high-potency topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors with resolution of lesions within 3 to 4 weeks.11,15-18

Erosive LP is a painful variant that can cause erosions, ulcerations, and scarring. It rarely is seen in the perianal region alone and presents a diagnostic challenge. Treatment with high-potency topical steroid therapy seems to be effective in the few cases that have been reported as well as in our case. More comprehensive data from randomized controlled trials would be needed to evaluate their efficacy compared to other therapies.

- Rebora A. Erosive lichen planus: what is this? Dermatology. 2002;205:226-228; discussion 227.

- Day T, Bohl TG, Scurry J. Perianal lichen dermatoses: a review of 60 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:210-215.

- Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-883.

- Holmstrup P, Thorn JJ, Rindum J, et al. Malignant development of lichen planus-affected oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:219-225.

- Lewi, FM, Bogliatto F. Erosive vulval lichen planus—a diagnosis not to be missed: a clinical review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171:214-219.

- Webber NK, Setterfield JF, Lewis FM, et al. Lacrimal canalicular duct scarring in patients with lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:224-227.

- Martin L, Moriniere S, Machet MC, et al. Bilateral conductive deafness related to erosive lichen planus. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:365-366.

- Payne CM, McPartlin JF, Hawley PR. Ulcerative perianal lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:479.

- Watsky KL. Erosive perianal lichen planus responsive to tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:217-218.

- Scheiba N, Toberer F, Lenhard BH, et al. Erythema and erosions of the perianal region in a 49-year-old man. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:162-165.

- Wu Y, Qiao J, Fang H. Syndrome in question. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:843-844.

- Hammami S, Ksouda K, Affes H, et al. Mucosal lichenoid drug reaction associated with glimepiride: a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:2301-2302.

- Meyerle JH, Turiansky GW. Perianal ulcer in a patient with AIDS. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:877-882.

- Scott FI, Mamtani R, Brensinger CM, et al. Risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer associated with the use of immunosuppressant and biologic agents in patients with a history of autoimmune disease and nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:164-172.

- Cheng S, Kirtschig G, Cooper S, et al. Interventions for erosive lichen planus affecting mucosal sites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:Cd008092.

- Gunther S. Effect of retinoic acid in lichen planus of the genitalia and perianal region. Br J Vener Dis. 1973;49:553-554.

- Vente C, Reich K, Neumann C. Erosive mucosal lichen planus: response to topical treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:338-342.

- Lonsdale-Eccles AA, Velangi S. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of genital lichen planus: a prospective case series. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:390-394.

To the Editor:

Erosive lichen planus (LP) often is painful, debilitating, and resistant to topical therapy making it both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of an elderly woman with isolated perianal erosive LP, a rare clinical manifestation. We also review cases of erosive perianal LP reported in the literature.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple pruritic and painful perianal lesions of 1 year’s duration. The lesions had remained stable since onset, with no other reported lesions elsewhere on body, including the mucosae. Her medical history was notable for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. She was taking methotrexate, folic acid, abatacept, alendronate, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. The patient reported she had been using abatacept for 3 years and lisinopril for 2 years. Her primary care physician initially treated the lesions as hemorrhoids but referred her to a gastroenterologist when they failed to improve. Gastroenterology evaluated the patient, and a colonoscopy was performed with unremarkable results. Thus, she was referred to dermatology for further evaluation.

Physical examination revealed 2 tender, sharply defined, angulated erosions with irregular violaceous borders involving the perianal skin (Figure 1). A biopsy of one of the lesions was taken. Histopathologic examination revealed acanthosis of the epidermis with slight compact hyperkeratosis, scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that obliterated the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of perianal erosive LP was made. The patient was prescribed mometasone ointment 0.1% daily with notable improvement after 2 months.

Erosive LP is an extremely rare variant of LP.1 It typically manifests as chronic painful erosions that often can progress to scarring, ulceration, and tissue destruction. Although erosive LP most commonly involves the mucosal surfaces of the genitalia and oral mucosa, it also has been reported in the palmoplantar skin, lacrimal duct, external auditory meatus, and esophagus.2-7 However, isolated perianal involvement is extremely rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erosive or ulcerative and lichen planus and perianal revealed 10 cases of perianal erosive LP, and weak data exist regarding therapy (Table).8-12 Of these cases, only 3 reported isolated perianal involvement.8-10 In most reported cases, perianal involvement manifested as extremely painful and occasionally pruritic, sharply angulated erosions and ulcers arising 0.5 to 3 cm from the anus with macerated, whitish, and violaceous borders. Most of the lesions occurred unilaterally, with only 1 case of bilateral perianal involvement.10

The differential diagnosis of perianal erosions is extensive and includes cutaneous Crohn disease, extramammary Paget disease, cutaneous malignancy, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, external hemorrhoids, lichen sclerosus, Behçet disease, lichen simplex chronicus, and drug-induced lichenoid reaction, among others. It is worth emphasizing infectious processes and cutaneous malignancies in light of our patient’s immunosuppression. Perianal cytomegalovirus has been reported in the literature in association with HIV, and it is a clinically challenging diagnosis.13 Cutaneous malignancy associated with the use of methotrexate also was considered in the differential diagnosis for our patient, given the increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer with the use of immunosuppresants.14

Along with a thorough patient history and physical examination, skin biopsy and clinicopathologic correlation are key to determine the exact etiology. Histologically, LP is characterized by a lichenoid interface dermatitis with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Other distinguishing factors include irregular acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, basal cell vacuolar degeneration, and Civatte bodies. Drug-induced LP is a possibility, but it is unclear if abatacept or lisinopril may have played a role in our patient. However, absence of eosinophils and parakeratosis suggested an idiopathic rather than drug-induced etiology. In 2016, Day et al2 published a clinicopathologic review of 60 cases of perianal lichenoid dermatoses in which only 17% of lesions were LP. Of note, 90% of perianal LP lesions were of the hypertrophic variant, and none were of the erosive variant, further supporting that our case represents a rare clinical manifestation of perianal LP.

Treatment of LP varies depending on the location and subtype of the lesions and is primarily aimed at improving symptoms. Topical corticosteroids are the standard treatment of LP; however, there is limited evidence regarding their efficacy for mucosal LP. Although randomized controlled trials assessing the efficacy of different interventions on oral erosive LP are available in the literature,15 there is a paucity of studies addressing this topic for genital or perianal LP. A review of the literature regarding perianal erosive LP suggests good response to high-potency topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors with resolution of lesions within 3 to 4 weeks.11,15-18

Erosive LP is a painful variant that can cause erosions, ulcerations, and scarring. It rarely is seen in the perianal region alone and presents a diagnostic challenge. Treatment with high-potency topical steroid therapy seems to be effective in the few cases that have been reported as well as in our case. More comprehensive data from randomized controlled trials would be needed to evaluate their efficacy compared to other therapies.

To the Editor:

Erosive lichen planus (LP) often is painful, debilitating, and resistant to topical therapy making it both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of an elderly woman with isolated perianal erosive LP, a rare clinical manifestation. We also review cases of erosive perianal LP reported in the literature.