User login

Solitary Angiokeratoma of the Vulva Mimicking Malignant Melanoma

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

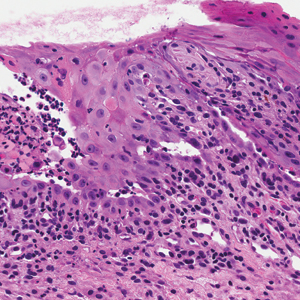

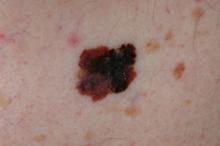

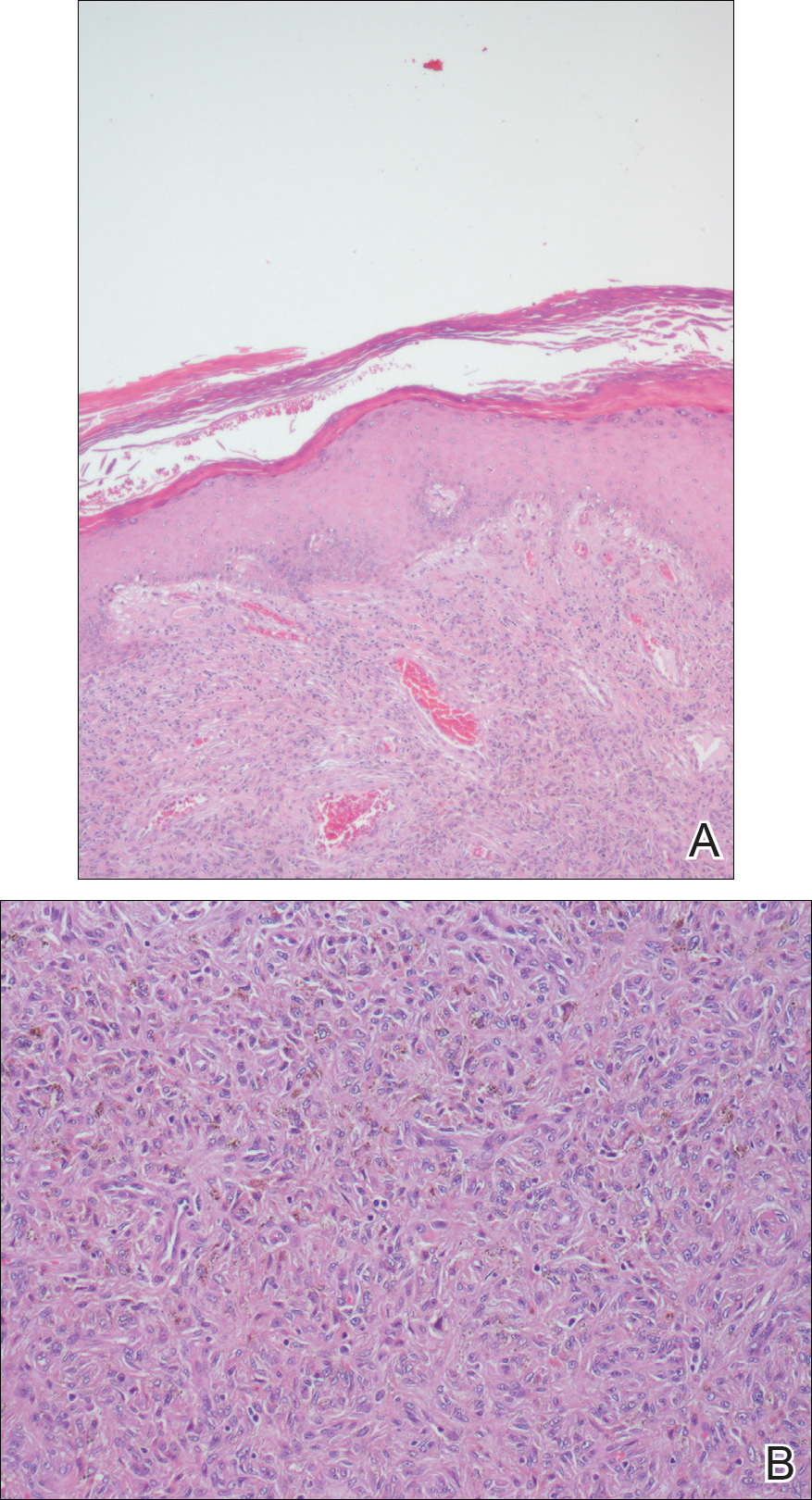

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. part I. hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

- Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

- Gomi H, Eriyama Y, Horikawa E, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma. J Dermatol. 1988;15:349-350.

- Yamazaki M, Hiruma M, Irie H, et al. Angiokeratoma of the clitoris: a subtype of angiokeratoma vulvae. J Dermatol. 1992;19:553-555.

- Cohen PR, Young AW Jr, Tovell HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:339-346.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:296-301.

- De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:127-133.

- Novick NL. Angiokeratoma vulvae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:561-563.

- Yigiter M, Arda IS, Tosun E, et al. Angiokeratoma of clitoris: a rare lesion in an adolescent girl. Urology. 2008;71:604-606.

- Zaballos P, Daufi C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. part I. hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

- Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

- Gomi H, Eriyama Y, Horikawa E, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma. J Dermatol. 1988;15:349-350.

- Yamazaki M, Hiruma M, Irie H, et al. Angiokeratoma of the clitoris: a subtype of angiokeratoma vulvae. J Dermatol. 1992;19:553-555.

- Cohen PR, Young AW Jr, Tovell HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:339-346.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:296-301.

- De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:127-133.

- Novick NL. Angiokeratoma vulvae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:561-563.

- Yigiter M, Arda IS, Tosun E, et al. Angiokeratoma of clitoris: a rare lesion in an adolescent girl. Urology. 2008;71:604-606.

- Zaballos P, Daufi C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. part I. hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

- Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

- Gomi H, Eriyama Y, Horikawa E, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma. J Dermatol. 1988;15:349-350.

- Yamazaki M, Hiruma M, Irie H, et al. Angiokeratoma of the clitoris: a subtype of angiokeratoma vulvae. J Dermatol. 1992;19:553-555.

- Cohen PR, Young AW Jr, Tovell HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:339-346.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:296-301.

- De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:127-133.

- Novick NL. Angiokeratoma vulvae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:561-563.

- Yigiter M, Arda IS, Tosun E, et al. Angiokeratoma of clitoris: a rare lesion in an adolescent girl. Urology. 2008;71:604-606.

- Zaballos P, Daufi C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

Practice Points

- Solitary angiokeratoma of the vulva often is misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma due to its rapid growth and dark color.

- Dermoscopy is a valuable tool for diagnosing vulvar angiokeratoma to avoid unnecessary excisions.

VIDEO: Skin exam crucial in rheumatic diseases, expert says

SANDESTIN, FLA. – Even when you know a patient’s serology and hear their symptoms and think you have a bead on their rheumatic disease, you might not. It’s vital to check the skin in patients with rheumatic disease to be sure the right disease is being treated and that they don’t actually have a more severe condition that might progress suddenly if left unchecked, said Alisa Femia, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at the annual Congress of Clinical Rheumatology.

In a session filled with pearls for rheumatologists on what to look for on their patients’ skin to help guide diagnosis and treatment, she told the story of a woman whom a rheumatologist colleague had correctly diagnosed with dermatomyositis. She was started on prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil, but her skin disease did not clear.

After examining her skin, Dr. Femia became immediately concerned.

“Despite prednisone, despite mycophenolate, here not only does she have Gottron’s papules, but she has erosions within her Gottron’s papules,” Dr. Femia said. The woman also had erosions within papules on her palms.

These were telltale signs of MDA5-associated dermatomyositis, which studies have found to be linked with interstitial lung disease (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jul;65[1]:25-34). Under her care, these patients ideally undergo lung monitoring every 3 months, Dr. Femia said.

“That is a form of dermatomyositis that you cannot miss,” she said.

The effects of discoid lupus are another reason to take special care in skin examination. Once the disease, which involves a scaling of the skin, is obvious, there can be permanent aesthetic effects that could have been avoided with earlier detection and treatment, Dr. Femia said.

Clinicians should also be on the lookout for volume loss, or contour change, in discoid lupus patients, because that’s a sign of lupus panniculitis, which involves deeper lesions mainly to fatty areas such as the cheeks or thighs. The disease can progress fast, with sudden, massive loss of body volume, so therapy should be escalated quickly, she said.

“We want to treat these patients aggressively in order to avoid this.”

SOURCE: Femia A. CCR 2018.

SANDESTIN, FLA. – Even when you know a patient’s serology and hear their symptoms and think you have a bead on their rheumatic disease, you might not. It’s vital to check the skin in patients with rheumatic disease to be sure the right disease is being treated and that they don’t actually have a more severe condition that might progress suddenly if left unchecked, said Alisa Femia, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at the annual Congress of Clinical Rheumatology.

In a session filled with pearls for rheumatologists on what to look for on their patients’ skin to help guide diagnosis and treatment, she told the story of a woman whom a rheumatologist colleague had correctly diagnosed with dermatomyositis. She was started on prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil, but her skin disease did not clear.

After examining her skin, Dr. Femia became immediately concerned.

“Despite prednisone, despite mycophenolate, here not only does she have Gottron’s papules, but she has erosions within her Gottron’s papules,” Dr. Femia said. The woman also had erosions within papules on her palms.

These were telltale signs of MDA5-associated dermatomyositis, which studies have found to be linked with interstitial lung disease (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jul;65[1]:25-34). Under her care, these patients ideally undergo lung monitoring every 3 months, Dr. Femia said.

“That is a form of dermatomyositis that you cannot miss,” she said.

The effects of discoid lupus are another reason to take special care in skin examination. Once the disease, which involves a scaling of the skin, is obvious, there can be permanent aesthetic effects that could have been avoided with earlier detection and treatment, Dr. Femia said.

Clinicians should also be on the lookout for volume loss, or contour change, in discoid lupus patients, because that’s a sign of lupus panniculitis, which involves deeper lesions mainly to fatty areas such as the cheeks or thighs. The disease can progress fast, with sudden, massive loss of body volume, so therapy should be escalated quickly, she said.

“We want to treat these patients aggressively in order to avoid this.”

SOURCE: Femia A. CCR 2018.

SANDESTIN, FLA. – Even when you know a patient’s serology and hear their symptoms and think you have a bead on their rheumatic disease, you might not. It’s vital to check the skin in patients with rheumatic disease to be sure the right disease is being treated and that they don’t actually have a more severe condition that might progress suddenly if left unchecked, said Alisa Femia, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at the annual Congress of Clinical Rheumatology.

In a session filled with pearls for rheumatologists on what to look for on their patients’ skin to help guide diagnosis and treatment, she told the story of a woman whom a rheumatologist colleague had correctly diagnosed with dermatomyositis. She was started on prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil, but her skin disease did not clear.

After examining her skin, Dr. Femia became immediately concerned.

“Despite prednisone, despite mycophenolate, here not only does she have Gottron’s papules, but she has erosions within her Gottron’s papules,” Dr. Femia said. The woman also had erosions within papules on her palms.

These were telltale signs of MDA5-associated dermatomyositis, which studies have found to be linked with interstitial lung disease (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jul;65[1]:25-34). Under her care, these patients ideally undergo lung monitoring every 3 months, Dr. Femia said.

“That is a form of dermatomyositis that you cannot miss,” she said.

The effects of discoid lupus are another reason to take special care in skin examination. Once the disease, which involves a scaling of the skin, is obvious, there can be permanent aesthetic effects that could have been avoided with earlier detection and treatment, Dr. Femia said.

Clinicians should also be on the lookout for volume loss, or contour change, in discoid lupus patients, because that’s a sign of lupus panniculitis, which involves deeper lesions mainly to fatty areas such as the cheeks or thighs. The disease can progress fast, with sudden, massive loss of body volume, so therapy should be escalated quickly, she said.

“We want to treat these patients aggressively in order to avoid this.”

SOURCE: Femia A. CCR 2018.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT CCR 18

Progressive Widespread Telangiectasias

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

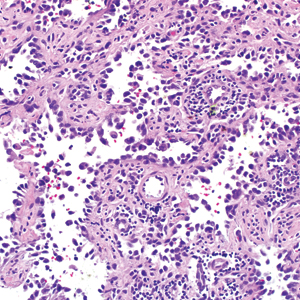

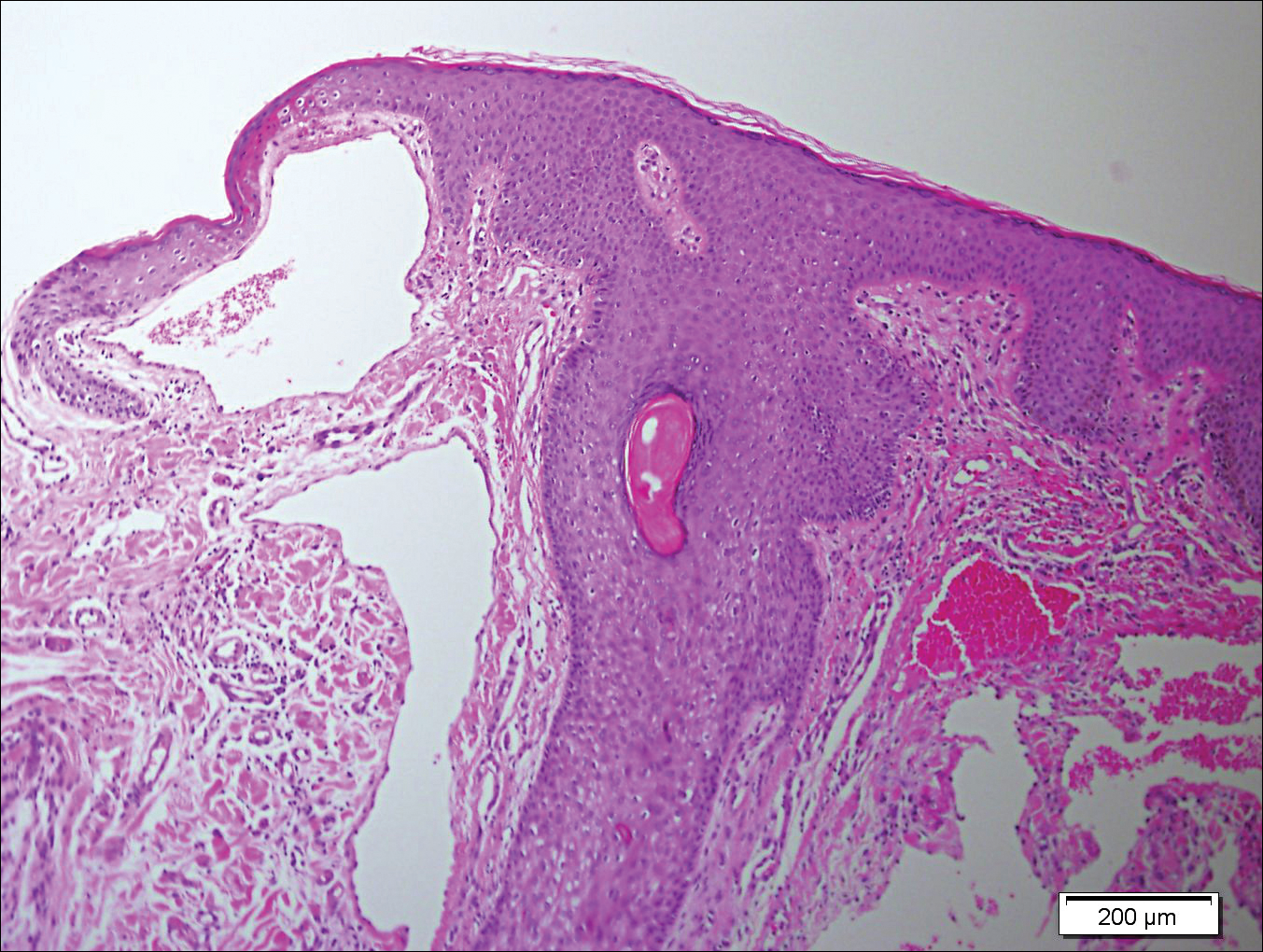

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.

A 55-year-old woman presented for evaluation of widespread asymptomatic telangiectasias of several years' duration that first appeared on the legs and steadily progressed to involve the trunk and arms. A review of systems was remarkable for episodic glossitis and oral erosions that developed at the same time as the eruption. The patient had no history of bleeding diasthesis, and her family history was unremarkable. A laboratory workup (including autoimmune screening) and a malignancy workup were negative. Physical examination revealed confluent sheets of erythematous and purple blanching telangiectasias scattered symmetrically on the trunk, bilateral arms and legs, buttocks, and dorsal aspects of the feet with sparing of the palms, soles, and head and neck regions. A small, shallow erosion was present on the lateral aspect of the tongue. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a thigh lesion revealed ectatic blood vessels with hyalinized walls.

Perianal Extramammary Paget Disease Treated With Topical Imiquimod and Oral Cimetidine

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Resident Pearls

- Topical imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine can be a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with perianal extramammary Paget disease (EMPD).

- Its antineoplastic and immunomodulatory properties may suggest a role for oral cimetidine as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of perianal EMPD.

Painful Mouth Ulcers

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.