User login

Verrucous Plaque on the Leg

Blastomycosis

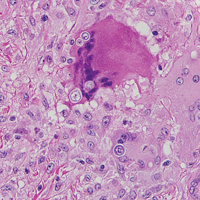

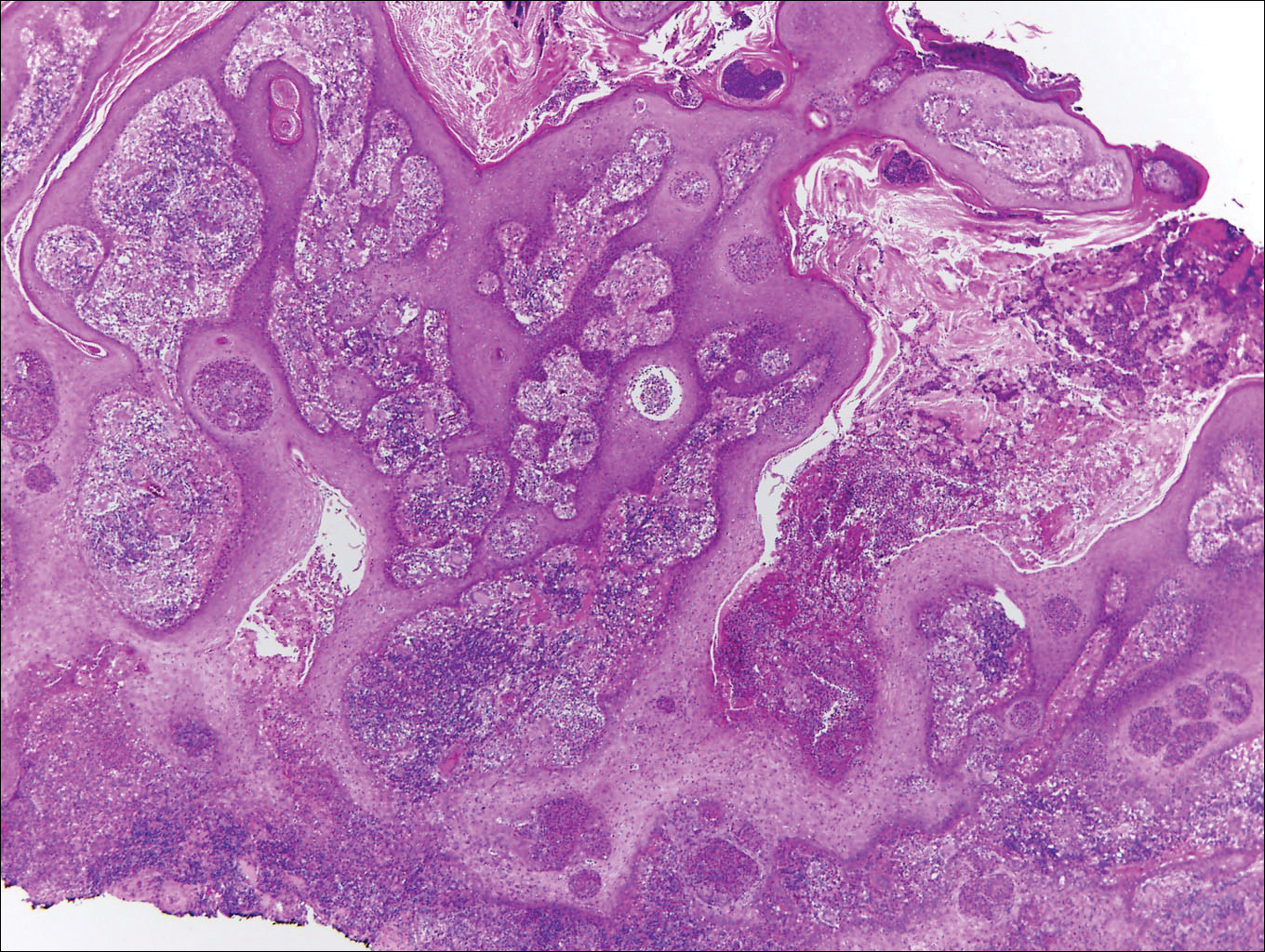

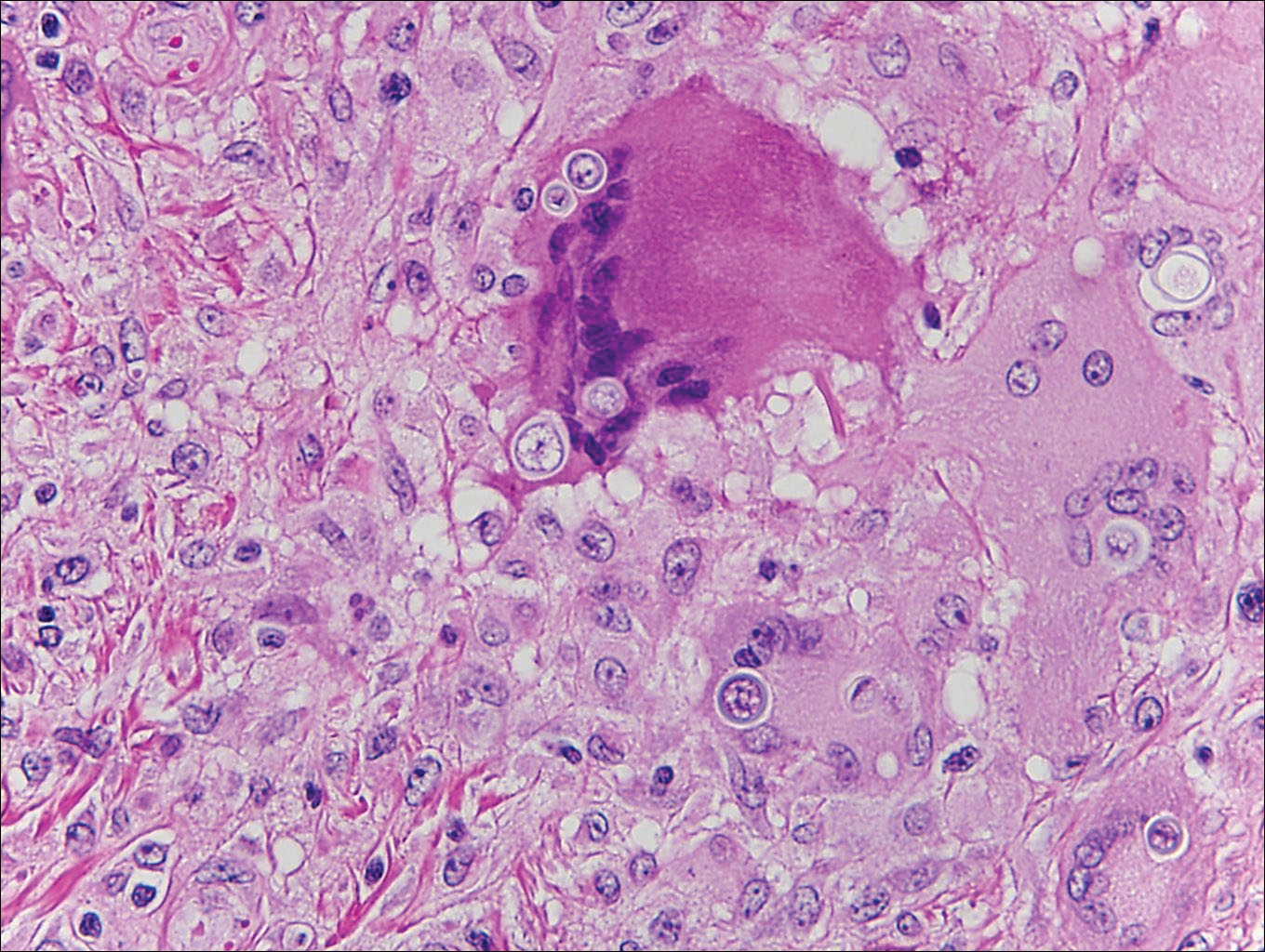

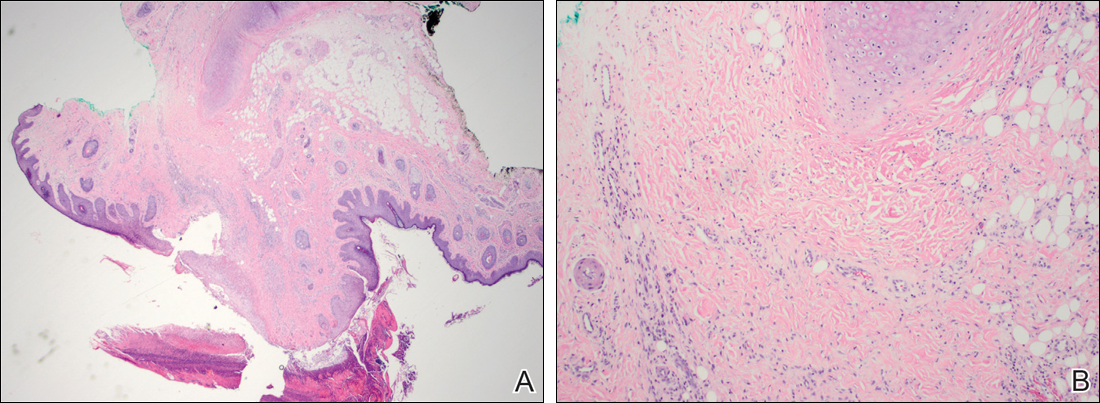

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

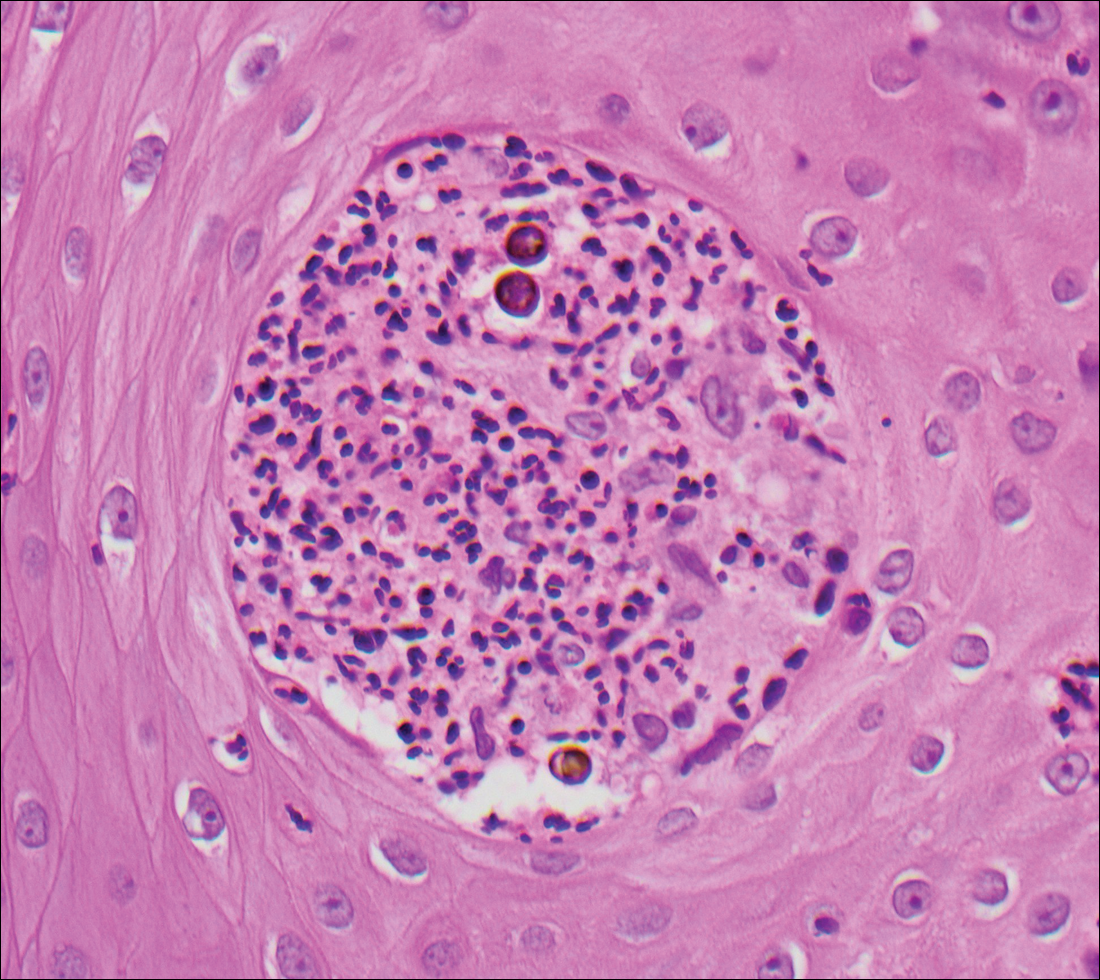

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

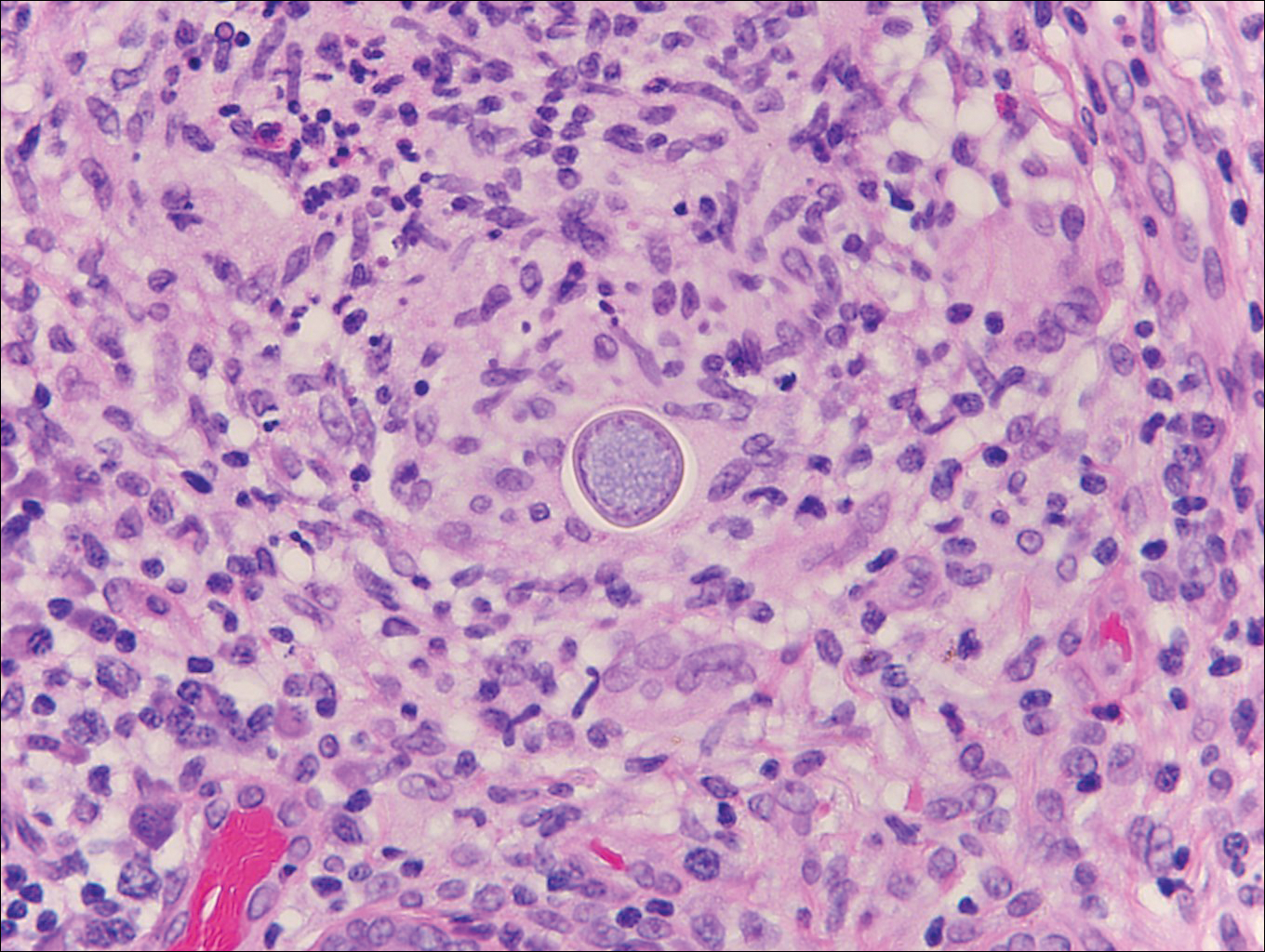

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

Aquatic Antagonists: Cutaneous Sea Urchin Spine Injury

Sea urchin injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions near both warm and cold salt water with frequent recreational water activities or fishing. Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea with approximately 600 species, of which roughly 80 are poisonous to humans.1,2 When a human comes in contact with a sea urchin, the spines of the sea urchin (made of calcium carbonate) can penetrate the skin and break off from the sea urchin, becoming embedded in the skin. Injuries from sea urchin spines are most commonly seen on the hands and feet, as the likelihood of contact with a sea urchin is greater on these sites. The severity of sea urchin spine injuries can vary widely, from minimal local trauma and pain to arthritis, synovitis, and occasionally systemic illness.1,3 It is important to recognize the wide variety of responses to sea urchin spine injuries and the impact of prompt treatment. Many published reports on injuries from sea urchin spines describe arthritis and synovitis from spines in the joints.1,2,4-6 Fewer reports discuss nonjoint injuries and the dermatologic aspects of sea urchin spine injuries.3,7,8 We pre-sent a case of a patient with a puncture injury from sea urchin spines that resulted in painful granulomas.

Case Report

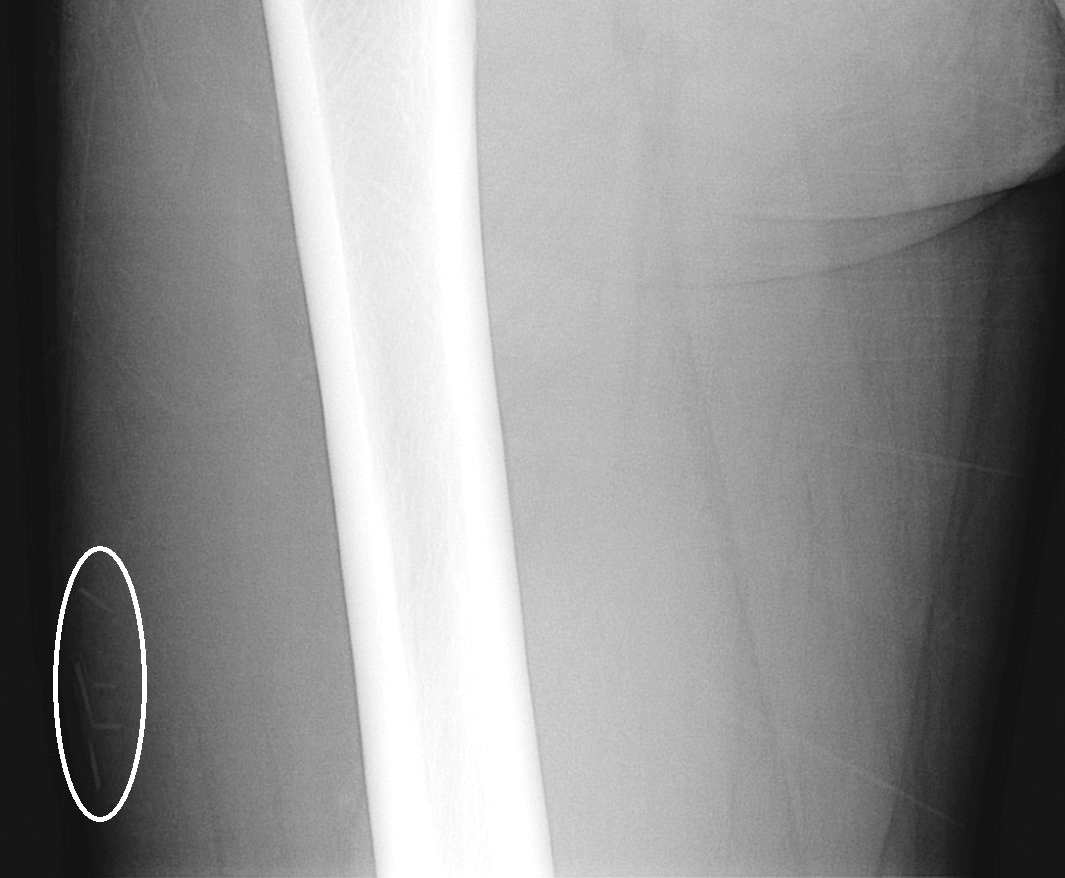

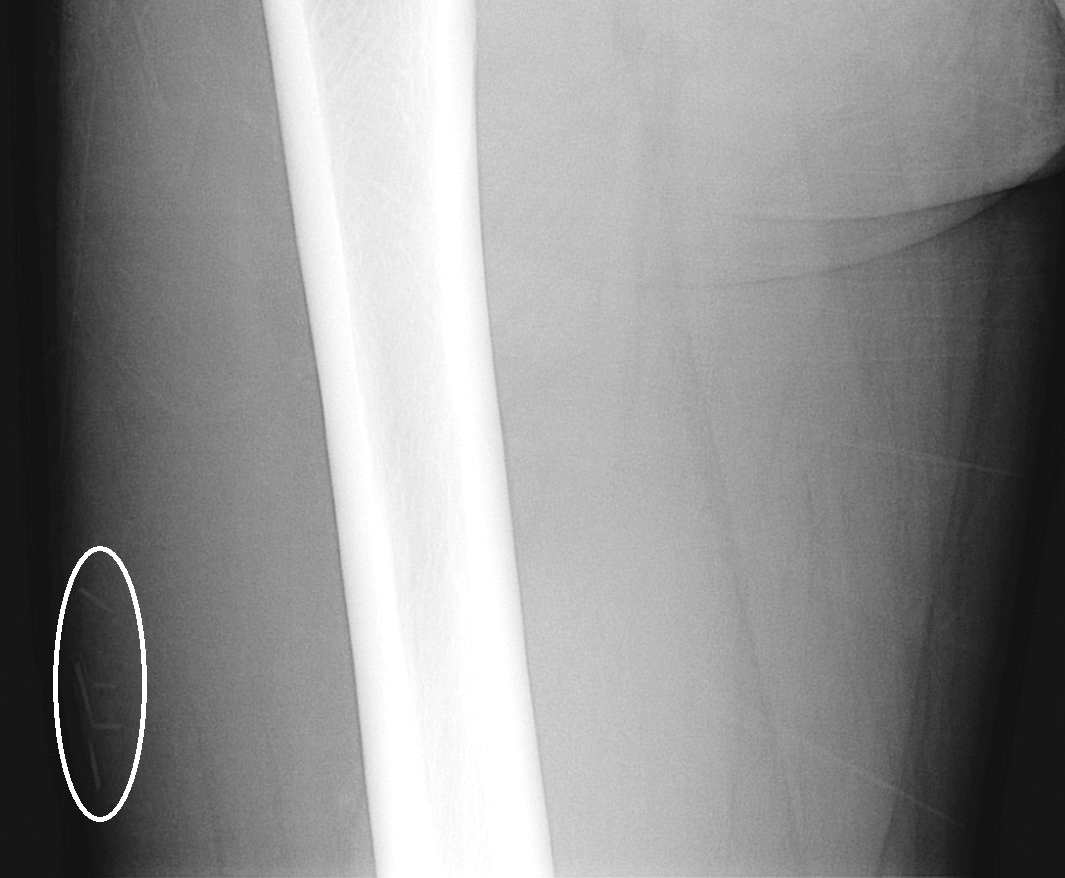

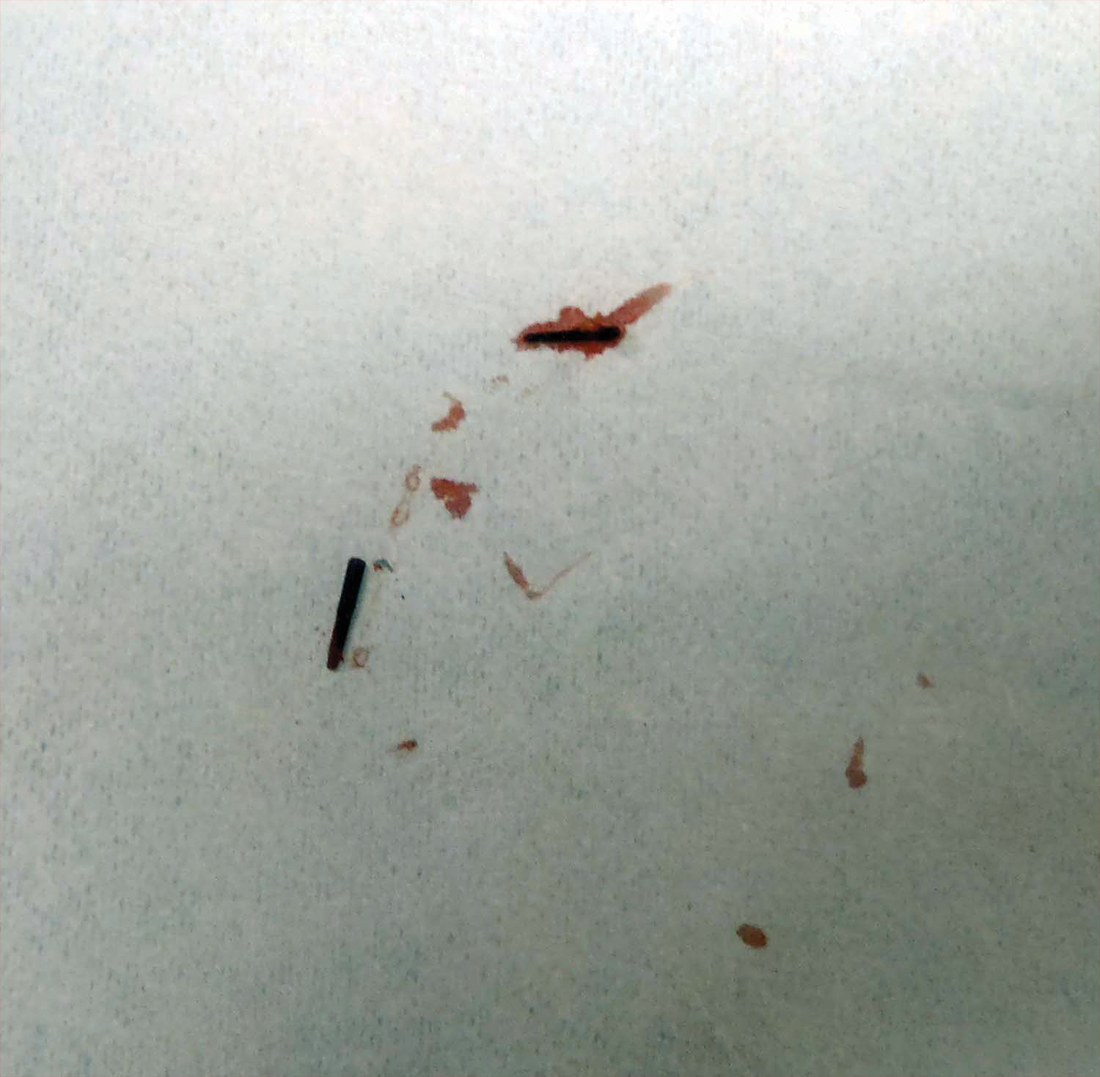

A 29-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to our dermatology clinic by the university student health center due to continued pain in the right thigh. Five weeks prior to presentation to the student health center, the patient had fallen on a sea urchin while snorkeling in Hawaii. Sea urchin spines became lodged in the right thigh, some of which were removed in a local medical clinic in Hawaii. He was given oral antibiotics prior to his return home. A plain film radiograph of the affected area ordered by the student health center showed several punctate and linear densities in the lateral aspect of the right mid thigh (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with sea urchin spines within the superficial soft tissues of the lateral thigh.

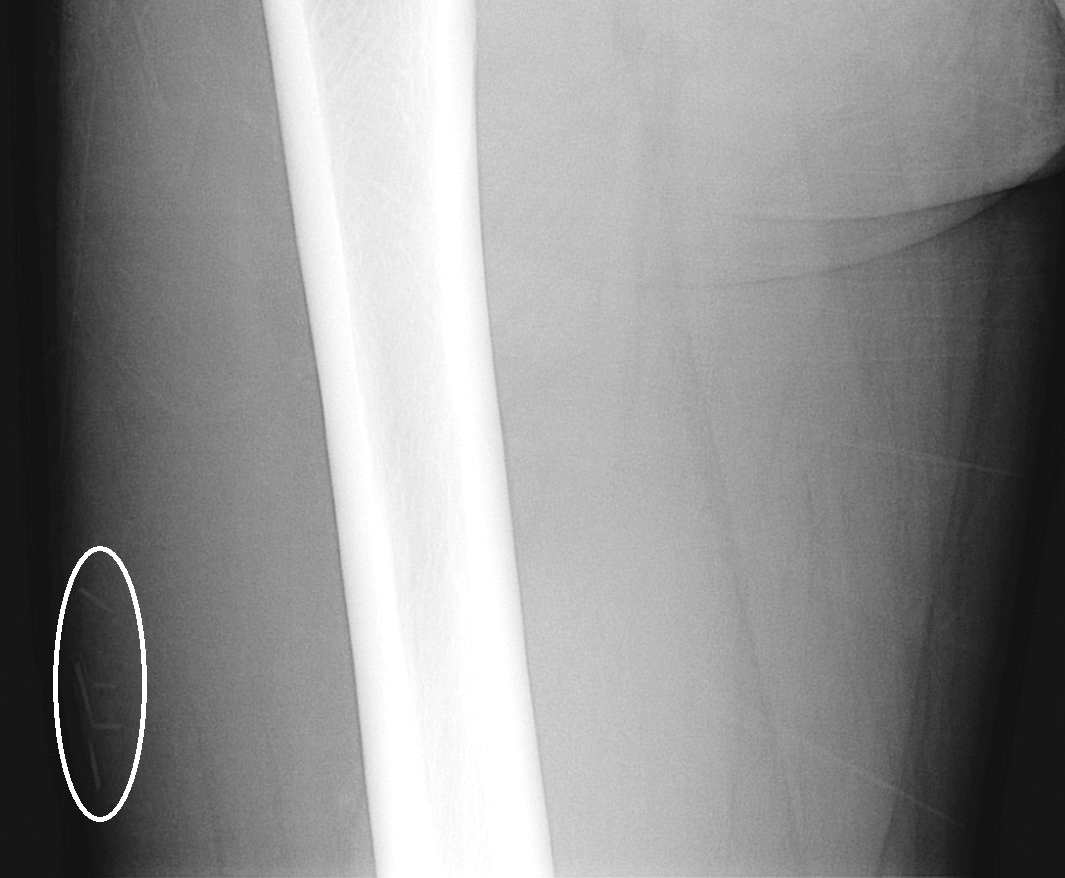

At the time of presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient reported sharp intermittent pain localized to the right thigh. The patient denied any fever, chills, or pain in the joints. On physical examination, there were several firm nodules on the right thigh, ranging from 4 to 20 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The nodules were tender to palpation with some surrounding edema. Drainage was not noted. Several scars were visible at sites of the original puncture injuries and removal of the spines.

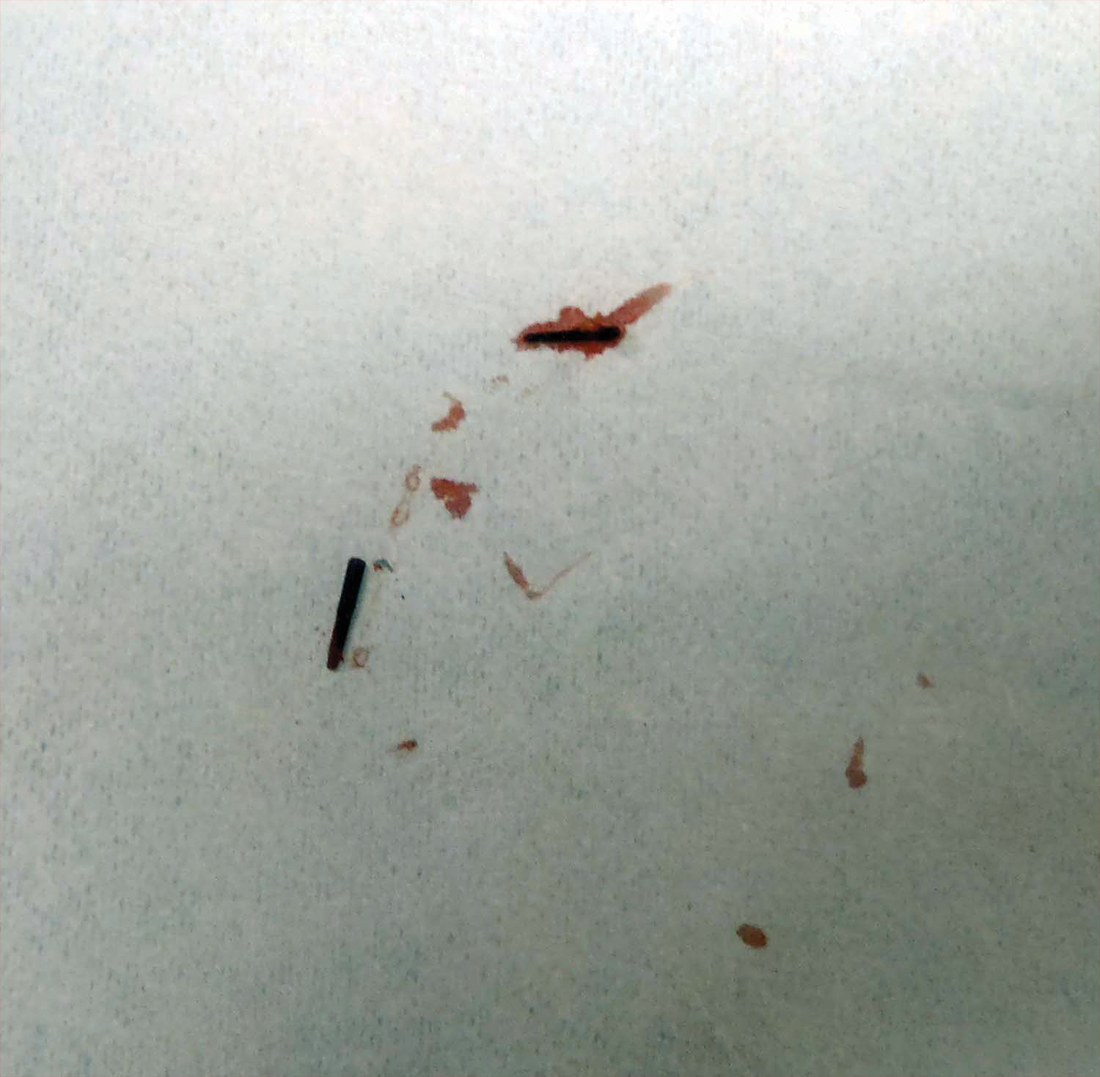

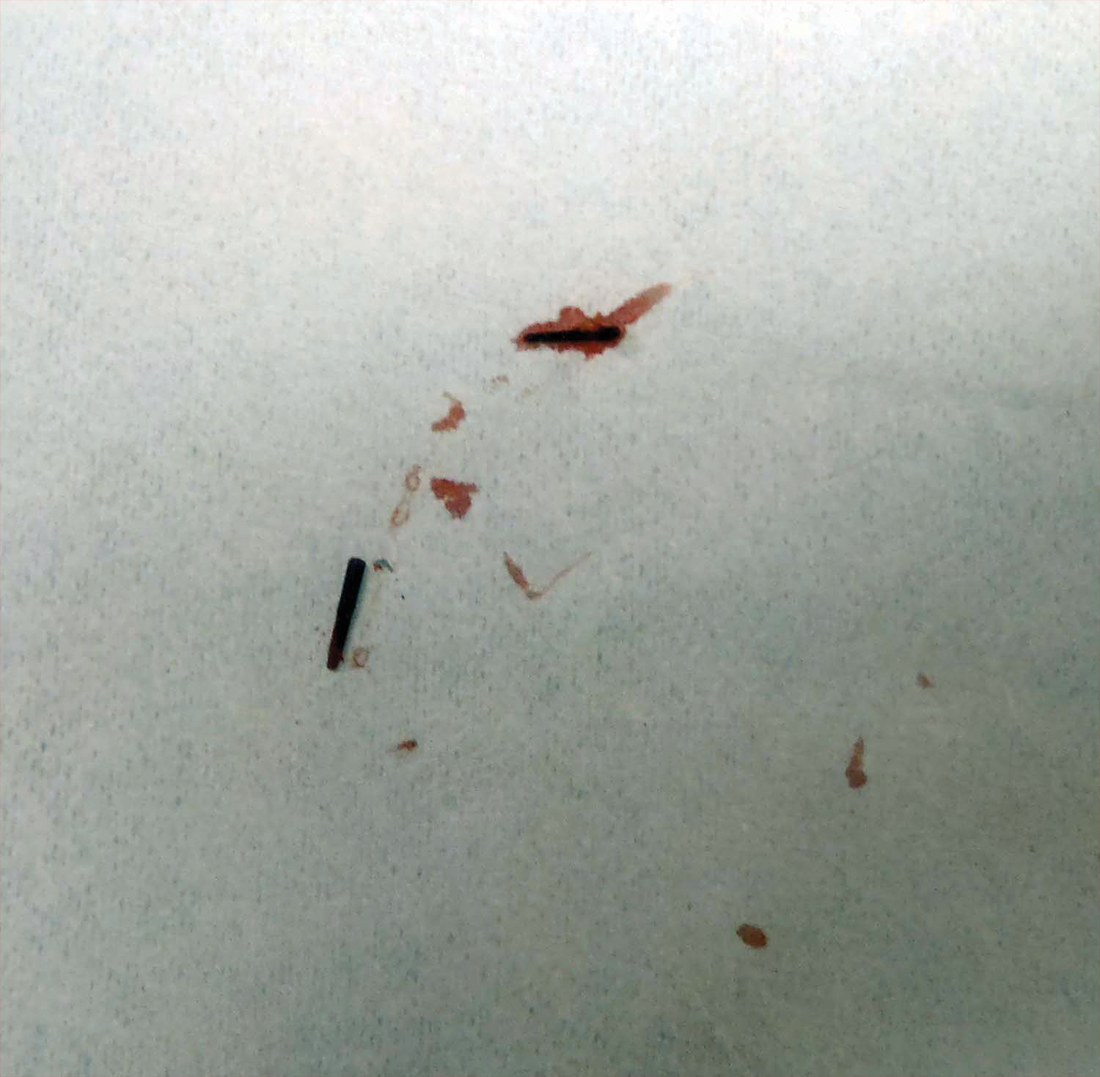

Two 6-mm punch biopsies were performed on representative nodules on the right thigh for histopathologic examination. Along with the biopsy tissue, firm, brown-black, linear foreign bodies consistent with sea urchin spines were extracted with forceps (Figure 3). Histopathologic examination revealed a dense, diffuse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis predominantly composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils. Proliferation of small vessels was noted. In one of the biopsies, small fragments of necrotic tissue were present. These findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation and granulation tissue due to a foreign body.

At the time of suture removal 2 weeks later, the biopsied areas were well healed with minimal erythema. The patient reported decreased pain in the involved areas. He was not seen in clinic again due to resolution of the nodules and associated pain.

Comment

Sea urchin spine injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions with frequent participation in recreational and occupational water activities. A wide variety of responses can be seen in sea urchin spine injuries. There generally are 2 types of cutaneous reaction patterns to sea urchin spines: a primary initial reaction and a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction. When the spines initially penetrate the skin, the primary initial reaction consists of sharp localized pain that worsens with applied pressure. In addition to pain, bleeding, erythema, edema, and myalgia can occur.3 These symptoms typically subside a few hours after complete removal of the spines from the skin.6 If some spines remain in the skin, a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction can occur, which can lead to the formation of granulomas that can manifest as nodules or papules and can be diffuse.

Many patients may think their painful encounter with a sea urchin was just an unfortunate event, but depending on the location of the injury, more serious extracutaneous reactions and chronic symptoms may occur. Some cases have described the development of arthritis and synovitis from the implantation of spines into joints.1,2,4-6 Other extracutaneous complications include neuropathy and paresthesia, local bone destruction, radiating pain, muscular weakness, and hypotension.3

The severity of the injury also can depend on the sea urchin species and the number of spines implanted. There are approximately 80 poisonous sea urchin species possessing toxins in venomous spines, resulting in edema and change in the leukocyte-endothelial interaction.9 Substances identified in the spines include proteins, steroids, serotonin, histamine, and glycosides.3,9 The number of spines implanted, particularly the number of venomous spines, can lead to more severe complications. Penetration of 15 or more venomous spines can commonly lead to extracutaneous symptoms.3 Another concern, irrespective of species type, is the potential for secondary infection associated with the spine penetration or implantation into the skin. Mycobacterium marinum infections have been reported in some sea urchin granulomas,10 as well as fungal infection, bacterial infection, and tetanus.3

The diagnosis of sea urchin spine injuries starts with a thorough history and physical examination. A positive history of sea urchin contact suggests the diagnosis, and radiographs can be useful to find the location of the spine(s), especially if there are no visible nodules on the skin. However, small fragments of spine may not be completely observed on plain radiographs. Any signs or symptoms of infection should prompt a culture for confirmation and guidance for management. Cutaneous biopsies can be helpful for both diagnosis confirmation and symptomatic relief. Reported cases have described granulomatous reactions in the vast majority of the histologic specimens, with necrosis an additional common finding.7,8 Sea urchin granulomas can be of varying types, the majority being foreign-body and sarcoid types.3,6,7

Treatment of sea urchin spine injuries primarily involves removal of the spines by a physician. Patients may soak the affected areas in warm water prior to the removal of the spines to aid in pain relief. Surgical removal with local anesthesia and cutaneous extraction is a common treatment method, and more extensive surgical removal of the spines is another option, especially in areas around the joints.2 The use of liquid nitrogen or skin punch biopsy also have been described as possible methods to remove the spines.11,12

Conclusion

Sea urchin spine injuries can result in a wide range of cutaneous and systemic complications. Prompt diagnosis and treatment to remove the sea urchin spines can lessen the associated pain and is important in the prevention of more serious complications.

- Liram N, Gomori M, Perouansky M. Sea urchin puncture resulting in PIP joint synovial arthritis: case report and MRI study. J Travel Med. 2000;7:43-45.

- Dahl WJ, Jebson P, Louis DS. Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:153-156.

- Rossetto AL, de Macedo Mora J, Haddad Junior V. Sea urchin granuloma. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2006;48:303-306.

- Ahmad R, McCann PA, Barakat M, et al. Sea urchin spine injuries of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:670-671.

- Schefflein J, Umans H, Ellenbogen D, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis in the foot. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1327-1331.

- Wada T, Soma T, Gaman K, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2008;33:398-401.

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Vieites B, Del Río E, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of sea urchin granulomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:550-556.

- De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. a pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223-228.

- Sciani JM, Zychar BC, Gonçalves LR, et al. Pro-inflammatory effects of the aqueous extract of Echinometra lucunter sea urchin spines. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2011;236:277-280.

- De la Torre C, Vega A, Carracedo A, et al. Identification of Mycobacterium marinum in sea-urchin granulomas. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:114-116.

- Gargus MD, Morohashi DK. A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1867-1868.

- Sjøberg T, de Weerd L. The usefulness of a skin biopsy punch to remove sea urchin spines. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:383.

Sea urchin injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions near both warm and cold salt water with frequent recreational water activities or fishing. Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea with approximately 600 species, of which roughly 80 are poisonous to humans.1,2 When a human comes in contact with a sea urchin, the spines of the sea urchin (made of calcium carbonate) can penetrate the skin and break off from the sea urchin, becoming embedded in the skin. Injuries from sea urchin spines are most commonly seen on the hands and feet, as the likelihood of contact with a sea urchin is greater on these sites. The severity of sea urchin spine injuries can vary widely, from minimal local trauma and pain to arthritis, synovitis, and occasionally systemic illness.1,3 It is important to recognize the wide variety of responses to sea urchin spine injuries and the impact of prompt treatment. Many published reports on injuries from sea urchin spines describe arthritis and synovitis from spines in the joints.1,2,4-6 Fewer reports discuss nonjoint injuries and the dermatologic aspects of sea urchin spine injuries.3,7,8 We pre-sent a case of a patient with a puncture injury from sea urchin spines that resulted in painful granulomas.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to our dermatology clinic by the university student health center due to continued pain in the right thigh. Five weeks prior to presentation to the student health center, the patient had fallen on a sea urchin while snorkeling in Hawaii. Sea urchin spines became lodged in the right thigh, some of which were removed in a local medical clinic in Hawaii. He was given oral antibiotics prior to his return home. A plain film radiograph of the affected area ordered by the student health center showed several punctate and linear densities in the lateral aspect of the right mid thigh (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with sea urchin spines within the superficial soft tissues of the lateral thigh.

At the time of presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient reported sharp intermittent pain localized to the right thigh. The patient denied any fever, chills, or pain in the joints. On physical examination, there were several firm nodules on the right thigh, ranging from 4 to 20 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The nodules were tender to palpation with some surrounding edema. Drainage was not noted. Several scars were visible at sites of the original puncture injuries and removal of the spines.

Two 6-mm punch biopsies were performed on representative nodules on the right thigh for histopathologic examination. Along with the biopsy tissue, firm, brown-black, linear foreign bodies consistent with sea urchin spines were extracted with forceps (Figure 3). Histopathologic examination revealed a dense, diffuse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis predominantly composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils. Proliferation of small vessels was noted. In one of the biopsies, small fragments of necrotic tissue were present. These findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation and granulation tissue due to a foreign body.

At the time of suture removal 2 weeks later, the biopsied areas were well healed with minimal erythema. The patient reported decreased pain in the involved areas. He was not seen in clinic again due to resolution of the nodules and associated pain.

Comment

Sea urchin spine injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions with frequent participation in recreational and occupational water activities. A wide variety of responses can be seen in sea urchin spine injuries. There generally are 2 types of cutaneous reaction patterns to sea urchin spines: a primary initial reaction and a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction. When the spines initially penetrate the skin, the primary initial reaction consists of sharp localized pain that worsens with applied pressure. In addition to pain, bleeding, erythema, edema, and myalgia can occur.3 These symptoms typically subside a few hours after complete removal of the spines from the skin.6 If some spines remain in the skin, a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction can occur, which can lead to the formation of granulomas that can manifest as nodules or papules and can be diffuse.

Many patients may think their painful encounter with a sea urchin was just an unfortunate event, but depending on the location of the injury, more serious extracutaneous reactions and chronic symptoms may occur. Some cases have described the development of arthritis and synovitis from the implantation of spines into joints.1,2,4-6 Other extracutaneous complications include neuropathy and paresthesia, local bone destruction, radiating pain, muscular weakness, and hypotension.3

The severity of the injury also can depend on the sea urchin species and the number of spines implanted. There are approximately 80 poisonous sea urchin species possessing toxins in venomous spines, resulting in edema and change in the leukocyte-endothelial interaction.9 Substances identified in the spines include proteins, steroids, serotonin, histamine, and glycosides.3,9 The number of spines implanted, particularly the number of venomous spines, can lead to more severe complications. Penetration of 15 or more venomous spines can commonly lead to extracutaneous symptoms.3 Another concern, irrespective of species type, is the potential for secondary infection associated with the spine penetration or implantation into the skin. Mycobacterium marinum infections have been reported in some sea urchin granulomas,10 as well as fungal infection, bacterial infection, and tetanus.3

The diagnosis of sea urchin spine injuries starts with a thorough history and physical examination. A positive history of sea urchin contact suggests the diagnosis, and radiographs can be useful to find the location of the spine(s), especially if there are no visible nodules on the skin. However, small fragments of spine may not be completely observed on plain radiographs. Any signs or symptoms of infection should prompt a culture for confirmation and guidance for management. Cutaneous biopsies can be helpful for both diagnosis confirmation and symptomatic relief. Reported cases have described granulomatous reactions in the vast majority of the histologic specimens, with necrosis an additional common finding.7,8 Sea urchin granulomas can be of varying types, the majority being foreign-body and sarcoid types.3,6,7

Treatment of sea urchin spine injuries primarily involves removal of the spines by a physician. Patients may soak the affected areas in warm water prior to the removal of the spines to aid in pain relief. Surgical removal with local anesthesia and cutaneous extraction is a common treatment method, and more extensive surgical removal of the spines is another option, especially in areas around the joints.2 The use of liquid nitrogen or skin punch biopsy also have been described as possible methods to remove the spines.11,12

Conclusion

Sea urchin spine injuries can result in a wide range of cutaneous and systemic complications. Prompt diagnosis and treatment to remove the sea urchin spines can lessen the associated pain and is important in the prevention of more serious complications.

Sea urchin injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions near both warm and cold salt water with frequent recreational water activities or fishing. Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea with approximately 600 species, of which roughly 80 are poisonous to humans.1,2 When a human comes in contact with a sea urchin, the spines of the sea urchin (made of calcium carbonate) can penetrate the skin and break off from the sea urchin, becoming embedded in the skin. Injuries from sea urchin spines are most commonly seen on the hands and feet, as the likelihood of contact with a sea urchin is greater on these sites. The severity of sea urchin spine injuries can vary widely, from minimal local trauma and pain to arthritis, synovitis, and occasionally systemic illness.1,3 It is important to recognize the wide variety of responses to sea urchin spine injuries and the impact of prompt treatment. Many published reports on injuries from sea urchin spines describe arthritis and synovitis from spines in the joints.1,2,4-6 Fewer reports discuss nonjoint injuries and the dermatologic aspects of sea urchin spine injuries.3,7,8 We pre-sent a case of a patient with a puncture injury from sea urchin spines that resulted in painful granulomas.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to our dermatology clinic by the university student health center due to continued pain in the right thigh. Five weeks prior to presentation to the student health center, the patient had fallen on a sea urchin while snorkeling in Hawaii. Sea urchin spines became lodged in the right thigh, some of which were removed in a local medical clinic in Hawaii. He was given oral antibiotics prior to his return home. A plain film radiograph of the affected area ordered by the student health center showed several punctate and linear densities in the lateral aspect of the right mid thigh (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with sea urchin spines within the superficial soft tissues of the lateral thigh.

At the time of presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient reported sharp intermittent pain localized to the right thigh. The patient denied any fever, chills, or pain in the joints. On physical examination, there were several firm nodules on the right thigh, ranging from 4 to 20 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The nodules were tender to palpation with some surrounding edema. Drainage was not noted. Several scars were visible at sites of the original puncture injuries and removal of the spines.

Two 6-mm punch biopsies were performed on representative nodules on the right thigh for histopathologic examination. Along with the biopsy tissue, firm, brown-black, linear foreign bodies consistent with sea urchin spines were extracted with forceps (Figure 3). Histopathologic examination revealed a dense, diffuse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis predominantly composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils. Proliferation of small vessels was noted. In one of the biopsies, small fragments of necrotic tissue were present. These findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation and granulation tissue due to a foreign body.

At the time of suture removal 2 weeks later, the biopsied areas were well healed with minimal erythema. The patient reported decreased pain in the involved areas. He was not seen in clinic again due to resolution of the nodules and associated pain.

Comment

Sea urchin spine injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions with frequent participation in recreational and occupational water activities. A wide variety of responses can be seen in sea urchin spine injuries. There generally are 2 types of cutaneous reaction patterns to sea urchin spines: a primary initial reaction and a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction. When the spines initially penetrate the skin, the primary initial reaction consists of sharp localized pain that worsens with applied pressure. In addition to pain, bleeding, erythema, edema, and myalgia can occur.3 These symptoms typically subside a few hours after complete removal of the spines from the skin.6 If some spines remain in the skin, a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction can occur, which can lead to the formation of granulomas that can manifest as nodules or papules and can be diffuse.

Many patients may think their painful encounter with a sea urchin was just an unfortunate event, but depending on the location of the injury, more serious extracutaneous reactions and chronic symptoms may occur. Some cases have described the development of arthritis and synovitis from the implantation of spines into joints.1,2,4-6 Other extracutaneous complications include neuropathy and paresthesia, local bone destruction, radiating pain, muscular weakness, and hypotension.3

The severity of the injury also can depend on the sea urchin species and the number of spines implanted. There are approximately 80 poisonous sea urchin species possessing toxins in venomous spines, resulting in edema and change in the leukocyte-endothelial interaction.9 Substances identified in the spines include proteins, steroids, serotonin, histamine, and glycosides.3,9 The number of spines implanted, particularly the number of venomous spines, can lead to more severe complications. Penetration of 15 or more venomous spines can commonly lead to extracutaneous symptoms.3 Another concern, irrespective of species type, is the potential for secondary infection associated with the spine penetration or implantation into the skin. Mycobacterium marinum infections have been reported in some sea urchin granulomas,10 as well as fungal infection, bacterial infection, and tetanus.3

The diagnosis of sea urchin spine injuries starts with a thorough history and physical examination. A positive history of sea urchin contact suggests the diagnosis, and radiographs can be useful to find the location of the spine(s), especially if there are no visible nodules on the skin. However, small fragments of spine may not be completely observed on plain radiographs. Any signs or symptoms of infection should prompt a culture for confirmation and guidance for management. Cutaneous biopsies can be helpful for both diagnosis confirmation and symptomatic relief. Reported cases have described granulomatous reactions in the vast majority of the histologic specimens, with necrosis an additional common finding.7,8 Sea urchin granulomas can be of varying types, the majority being foreign-body and sarcoid types.3,6,7

Treatment of sea urchin spine injuries primarily involves removal of the spines by a physician. Patients may soak the affected areas in warm water prior to the removal of the spines to aid in pain relief. Surgical removal with local anesthesia and cutaneous extraction is a common treatment method, and more extensive surgical removal of the spines is another option, especially in areas around the joints.2 The use of liquid nitrogen or skin punch biopsy also have been described as possible methods to remove the spines.11,12

Conclusion

Sea urchin spine injuries can result in a wide range of cutaneous and systemic complications. Prompt diagnosis and treatment to remove the sea urchin spines can lessen the associated pain and is important in the prevention of more serious complications.

- Liram N, Gomori M, Perouansky M. Sea urchin puncture resulting in PIP joint synovial arthritis: case report and MRI study. J Travel Med. 2000;7:43-45.

- Dahl WJ, Jebson P, Louis DS. Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:153-156.

- Rossetto AL, de Macedo Mora J, Haddad Junior V. Sea urchin granuloma. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2006;48:303-306.

- Ahmad R, McCann PA, Barakat M, et al. Sea urchin spine injuries of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:670-671.

- Schefflein J, Umans H, Ellenbogen D, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis in the foot. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1327-1331.

- Wada T, Soma T, Gaman K, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2008;33:398-401.

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Vieites B, Del Río E, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of sea urchin granulomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:550-556.

- De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. a pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223-228.

- Sciani JM, Zychar BC, Gonçalves LR, et al. Pro-inflammatory effects of the aqueous extract of Echinometra lucunter sea urchin spines. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2011;236:277-280.

- De la Torre C, Vega A, Carracedo A, et al. Identification of Mycobacterium marinum in sea-urchin granulomas. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:114-116.

- Gargus MD, Morohashi DK. A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1867-1868.

- Sjøberg T, de Weerd L. The usefulness of a skin biopsy punch to remove sea urchin spines. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:383.

- Liram N, Gomori M, Perouansky M. Sea urchin puncture resulting in PIP joint synovial arthritis: case report and MRI study. J Travel Med. 2000;7:43-45.

- Dahl WJ, Jebson P, Louis DS. Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:153-156.

- Rossetto AL, de Macedo Mora J, Haddad Junior V. Sea urchin granuloma. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2006;48:303-306.

- Ahmad R, McCann PA, Barakat M, et al. Sea urchin spine injuries of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:670-671.

- Schefflein J, Umans H, Ellenbogen D, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis in the foot. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1327-1331.

- Wada T, Soma T, Gaman K, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2008;33:398-401.

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Vieites B, Del Río E, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of sea urchin granulomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:550-556.

- De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. a pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223-228.

- Sciani JM, Zychar BC, Gonçalves LR, et al. Pro-inflammatory effects of the aqueous extract of Echinometra lucunter sea urchin spines. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2011;236:277-280.

- De la Torre C, Vega A, Carracedo A, et al. Identification of Mycobacterium marinum in sea-urchin granulomas. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:114-116.

- Gargus MD, Morohashi DK. A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1867-1868.

- Sjøberg T, de Weerd L. The usefulness of a skin biopsy punch to remove sea urchin spines. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:383.

Practice Points

- Radiographic imaging may aid in the identification of sea urchin spines, especially if there are no visible or palpable skin nodules.

- Treatment of sea urchin spine injuries typically involves surgical removal of the spines with local anesthesia and cutaneous extraction.

- Prompt extraction of sea urchin spines can improve pain symptoms and decrease the likelihood of granuloma formation, infection, and extracutaneous complications.

Necrotic Lesion of the Ear

The Diagnosis: Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis

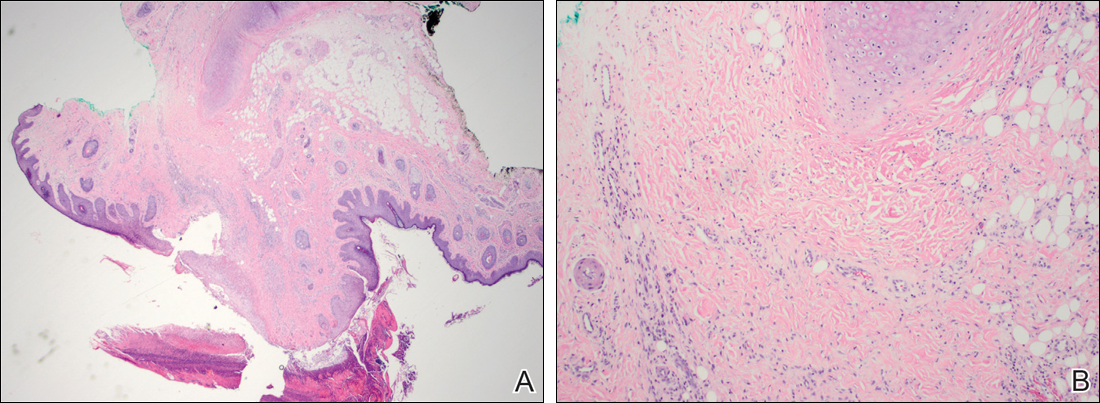

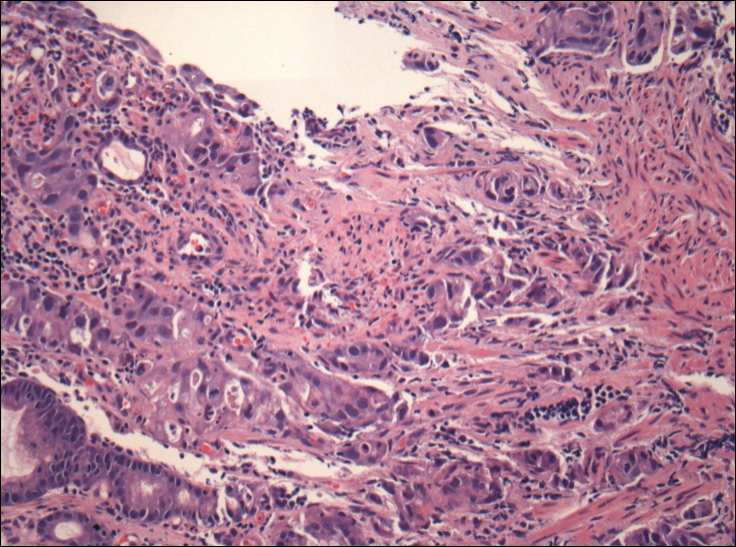

Histopathologic examination revealed focal epidermal erosion and ulceration directly overlying the hyaline cartilage with degenerative changes (Figure). The dermis was relatively noninflamed with fibroplasia of the vasculature. The blood vessels indirectly beneath the ulceration were found to be unremarkable with no indications of fibrinoid necrosis, vasculitis, or the presence of thrombi. The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which point she reported that she slept on the right side. The excisional biopsy site healed well without recurrence of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis (CNH).

Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, also known as clavus helicis, is a benign, usually solitary, painful lesion. Historically, it was first described in 1915 by Winkler1 and in the 1960s the most common documented cases were attributed to the headpieces of telephone operators and nuns.2 In the early 2000s, cell phones were determined to be a growing cause.3 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis is most commonly found on the helix with the antihelix being affected less often.4 The condition is more common in men, with a male to female ratio being reported as high as 10:1. Possible causes of this disorder stem from damage to cartilage associated with pressure, sun exposure, cold temperatures, and microvascular disease. Additionally, some researchers have hypothesized that the cartilaginous damage resulting from solar elastosis and minor trauma leaves a susceptibility to CNH. This disorder usually presents as a small, exquisitely tender nodule that may ulcerate and crust.4 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis may be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, and weathering nodules, though CNH tends to be more painful.

The diagnosis of CNH often is clinical but may require a skin biopsy. Histopathology of CNH shows a benign inflammatory lesion with an acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis that may be ulcerated. A primarily lymphocytic infiltrate usually is observed with variable presence of histiocytes and neutrophils. Cartilaginous changes range from simple perichondral thickening to notable areas of degeneration with calcification and ossification.4

Although the diagnosis of CNH often is straightforward, the remarkable necrosis present in our case made for an interesting differential diagnosis. Pernio, cryoglobulinemia, and levamisole-induced vasculopathy were all considered. Pernio, caused by cold-induced vasoconstriction and hypoxemia, classically presents as erythematous lesions with a symmetrical distribution on acral sites.5 Cryoglobulinemia involves proteins that precipitate at cold temperatures causing damage via an occlusive vasculopathy or an immune complex-mediated vasculitis. The presence of cryoglobulinemia is strongly associated with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection.6 Ulcerated and purpuric lesions of cryoglobulinemia may become necrotic. Levamisole is a veterinary antihelminthic drug and common cocaine contaminant, often added to cocaine as a cutting agent. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy favors acral sites and often is noted on the ears as purpuric patches, sometimes with necrosis.7

Several therapies for CNH have been reported with variable effectiveness.8 First-line treatments are the use of pressure-relieving devices including a doughnut-shaped pillow during sleep and intralesional corticosteroids.9 Surgical treatments including cryotherapy, simple excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, wedge resection with helical rim advancement flap, punch and graft technique, and CO2 laser have been tried.8 Photodynamic therapy and topical nitroglycerine also have shown to be of benefit.8,9

Our case of CNH is unique because of the remarkable degree of necrosis present on clinical examination. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis with such an impressive necrotic presentation is rare. We speculate that the patient's underlying hypercoagulable state may have contributed to the dramatic presentation. It is important to keep CNH in mind when evaluating any necrotic lesion on the ear.

- Winkler M. Knötcehnformige Erkrankung am helix. chondrodermatitis nodularis chronic helicis. Arch für Dermatologie und Syphilis. 1915;121:278-285.

- Barker L, Young AW, Sachs W. Chondrodermatitis of the ears: a differential study of nodules of the helix and antihelix. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:15-25.

- Elgart M. Cell phone chondrodermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Peltre B. Neural hyperplasia in chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:844-848.

- King JM, Plotner AN, Adams BB. Perniosis induced by a cold-therapy system. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1101-1102.

- Berk DR, Mallory SB, Keeffe EB, et al. Dermatologic disorders associated with chronic hepatitis C: effect of interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:142-151.

- Hennings C, Miller J. Illicit drugs: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:135-142.

- Flynn V, Chisholm C, Grimwood R. Topical nitroglycerin: a promising treatment option for chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:531-536.

- Gilaberte Y, Frias M, Pérez-Lorenz J. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1080-1082.

The Diagnosis: Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis

Histopathologic examination revealed focal epidermal erosion and ulceration directly overlying the hyaline cartilage with degenerative changes (Figure). The dermis was relatively noninflamed with fibroplasia of the vasculature. The blood vessels indirectly beneath the ulceration were found to be unremarkable with no indications of fibrinoid necrosis, vasculitis, or the presence of thrombi. The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which point she reported that she slept on the right side. The excisional biopsy site healed well without recurrence of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis (CNH).

Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, also known as clavus helicis, is a benign, usually solitary, painful lesion. Historically, it was first described in 1915 by Winkler1 and in the 1960s the most common documented cases were attributed to the headpieces of telephone operators and nuns.2 In the early 2000s, cell phones were determined to be a growing cause.3 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis is most commonly found on the helix with the antihelix being affected less often.4 The condition is more common in men, with a male to female ratio being reported as high as 10:1. Possible causes of this disorder stem from damage to cartilage associated with pressure, sun exposure, cold temperatures, and microvascular disease. Additionally, some researchers have hypothesized that the cartilaginous damage resulting from solar elastosis and minor trauma leaves a susceptibility to CNH. This disorder usually presents as a small, exquisitely tender nodule that may ulcerate and crust.4 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis may be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, and weathering nodules, though CNH tends to be more painful.

The diagnosis of CNH often is clinical but may require a skin biopsy. Histopathology of CNH shows a benign inflammatory lesion with an acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis that may be ulcerated. A primarily lymphocytic infiltrate usually is observed with variable presence of histiocytes and neutrophils. Cartilaginous changes range from simple perichondral thickening to notable areas of degeneration with calcification and ossification.4

Although the diagnosis of CNH often is straightforward, the remarkable necrosis present in our case made for an interesting differential diagnosis. Pernio, cryoglobulinemia, and levamisole-induced vasculopathy were all considered. Pernio, caused by cold-induced vasoconstriction and hypoxemia, classically presents as erythematous lesions with a symmetrical distribution on acral sites.5 Cryoglobulinemia involves proteins that precipitate at cold temperatures causing damage via an occlusive vasculopathy or an immune complex-mediated vasculitis. The presence of cryoglobulinemia is strongly associated with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection.6 Ulcerated and purpuric lesions of cryoglobulinemia may become necrotic. Levamisole is a veterinary antihelminthic drug and common cocaine contaminant, often added to cocaine as a cutting agent. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy favors acral sites and often is noted on the ears as purpuric patches, sometimes with necrosis.7

Several therapies for CNH have been reported with variable effectiveness.8 First-line treatments are the use of pressure-relieving devices including a doughnut-shaped pillow during sleep and intralesional corticosteroids.9 Surgical treatments including cryotherapy, simple excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, wedge resection with helical rim advancement flap, punch and graft technique, and CO2 laser have been tried.8 Photodynamic therapy and topical nitroglycerine also have shown to be of benefit.8,9

Our case of CNH is unique because of the remarkable degree of necrosis present on clinical examination. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis with such an impressive necrotic presentation is rare. We speculate that the patient's underlying hypercoagulable state may have contributed to the dramatic presentation. It is important to keep CNH in mind when evaluating any necrotic lesion on the ear.

The Diagnosis: Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis

Histopathologic examination revealed focal epidermal erosion and ulceration directly overlying the hyaline cartilage with degenerative changes (Figure). The dermis was relatively noninflamed with fibroplasia of the vasculature. The blood vessels indirectly beneath the ulceration were found to be unremarkable with no indications of fibrinoid necrosis, vasculitis, or the presence of thrombi. The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which point she reported that she slept on the right side. The excisional biopsy site healed well without recurrence of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis (CNH).

Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, also known as clavus helicis, is a benign, usually solitary, painful lesion. Historically, it was first described in 1915 by Winkler1 and in the 1960s the most common documented cases were attributed to the headpieces of telephone operators and nuns.2 In the early 2000s, cell phones were determined to be a growing cause.3 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis is most commonly found on the helix with the antihelix being affected less often.4 The condition is more common in men, with a male to female ratio being reported as high as 10:1. Possible causes of this disorder stem from damage to cartilage associated with pressure, sun exposure, cold temperatures, and microvascular disease. Additionally, some researchers have hypothesized that the cartilaginous damage resulting from solar elastosis and minor trauma leaves a susceptibility to CNH. This disorder usually presents as a small, exquisitely tender nodule that may ulcerate and crust.4 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis may be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, and weathering nodules, though CNH tends to be more painful.

The diagnosis of CNH often is clinical but may require a skin biopsy. Histopathology of CNH shows a benign inflammatory lesion with an acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis that may be ulcerated. A primarily lymphocytic infiltrate usually is observed with variable presence of histiocytes and neutrophils. Cartilaginous changes range from simple perichondral thickening to notable areas of degeneration with calcification and ossification.4

Although the diagnosis of CNH often is straightforward, the remarkable necrosis present in our case made for an interesting differential diagnosis. Pernio, cryoglobulinemia, and levamisole-induced vasculopathy were all considered. Pernio, caused by cold-induced vasoconstriction and hypoxemia, classically presents as erythematous lesions with a symmetrical distribution on acral sites.5 Cryoglobulinemia involves proteins that precipitate at cold temperatures causing damage via an occlusive vasculopathy or an immune complex-mediated vasculitis. The presence of cryoglobulinemia is strongly associated with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection.6 Ulcerated and purpuric lesions of cryoglobulinemia may become necrotic. Levamisole is a veterinary antihelminthic drug and common cocaine contaminant, often added to cocaine as a cutting agent. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy favors acral sites and often is noted on the ears as purpuric patches, sometimes with necrosis.7

Several therapies for CNH have been reported with variable effectiveness.8 First-line treatments are the use of pressure-relieving devices including a doughnut-shaped pillow during sleep and intralesional corticosteroids.9 Surgical treatments including cryotherapy, simple excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, wedge resection with helical rim advancement flap, punch and graft technique, and CO2 laser have been tried.8 Photodynamic therapy and topical nitroglycerine also have shown to be of benefit.8,9

Our case of CNH is unique because of the remarkable degree of necrosis present on clinical examination. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis with such an impressive necrotic presentation is rare. We speculate that the patient's underlying hypercoagulable state may have contributed to the dramatic presentation. It is important to keep CNH in mind when evaluating any necrotic lesion on the ear.

- Winkler M. Knötcehnformige Erkrankung am helix. chondrodermatitis nodularis chronic helicis. Arch für Dermatologie und Syphilis. 1915;121:278-285.

- Barker L, Young AW, Sachs W. Chondrodermatitis of the ears: a differential study of nodules of the helix and antihelix. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:15-25.

- Elgart M. Cell phone chondrodermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Peltre B. Neural hyperplasia in chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:844-848.

- King JM, Plotner AN, Adams BB. Perniosis induced by a cold-therapy system. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1101-1102.

- Berk DR, Mallory SB, Keeffe EB, et al. Dermatologic disorders associated with chronic hepatitis C: effect of interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:142-151.

- Hennings C, Miller J. Illicit drugs: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:135-142.

- Flynn V, Chisholm C, Grimwood R. Topical nitroglycerin: a promising treatment option for chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:531-536.

- Gilaberte Y, Frias M, Pérez-Lorenz J. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1080-1082.

- Winkler M. Knötcehnformige Erkrankung am helix. chondrodermatitis nodularis chronic helicis. Arch für Dermatologie und Syphilis. 1915;121:278-285.

- Barker L, Young AW, Sachs W. Chondrodermatitis of the ears: a differential study of nodules of the helix and antihelix. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:15-25.

- Elgart M. Cell phone chondrodermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Peltre B. Neural hyperplasia in chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:844-848.

- King JM, Plotner AN, Adams BB. Perniosis induced by a cold-therapy system. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1101-1102.

- Berk DR, Mallory SB, Keeffe EB, et al. Dermatologic disorders associated with chronic hepatitis C: effect of interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:142-151.

- Hennings C, Miller J. Illicit drugs: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:135-142.

- Flynn V, Chisholm C, Grimwood R. Topical nitroglycerin: a promising treatment option for chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:531-536.

- Gilaberte Y, Frias M, Pérez-Lorenz J. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1080-1082.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a painful necrotic lesion on the right ear of 1 month's duration. She denied trauma to the ear and had no other skin lesions elsewhere on the body. A course of doxycycline prior to presentation did not result in improvement. Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus, deep vein thrombosis, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. She had been taking warfarin regularly for years. She denied using recreational drugs. On physical examination, the right ear demonstrated a 6-mm necrotic area with surrounding tender erythema. Examinations of the left ear, face, and legs were normal. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Crusted Plaque in the Umbilicus

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

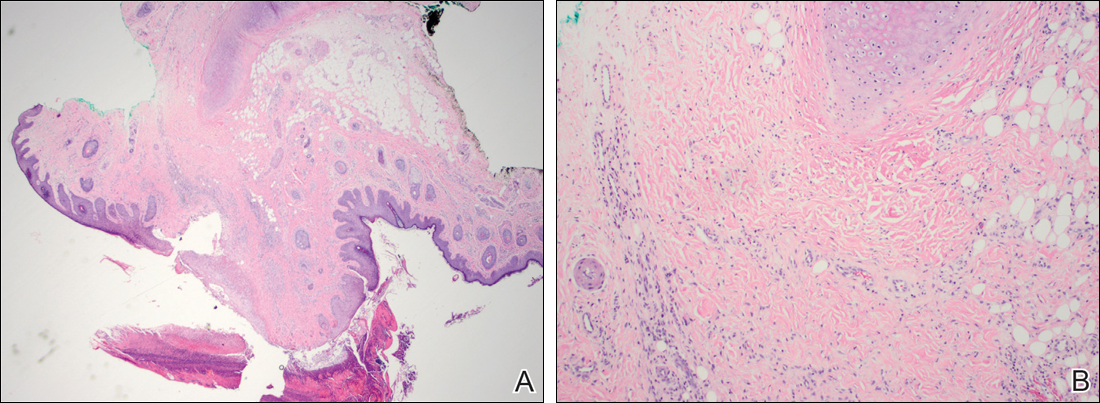

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

A 74-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic umbilical lesion of unknown duration. The patient believed the lesion was a scar resulting from a prior laparoscopic repair of an umbilical hernia. However, the patient reported epigastric abdominal pain and diarrhea of 1 month's duration that he believed was due to the stomach flu. The patient denied fever, chills, loss of appetite, or weight loss. History was remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and emphysema. The patient had a surgical history of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in addition to the laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair. The patient's medications included pantoprazole, ondansetron, diphenoxylate-atropine as needed, amlodipine, lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and aspirin. Physical examination revealed a 1×2-cm pink, nodular, firm plaque with crust at the umbilicus that was tender on palpation. A shave biopsy of the umbilicus was performed and sent for both pathological and immunohistochemical analysis.

Blaschkoid Unilateral Patch on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus (LS) is an acquired and self-limited linear inflammatory dermatosis that most frequently occurs in children and less commonly in adults.1-3 Clinically, it is characterized by the sudden onset of an eruption consisting of slightly pigmented, erythematous, flat-topped papules with minimal scaling. These papules quickly coalesce to form a linear band that extends along a limb, the trunk, or the face, within Blaschko lines.1,4 In the adult form, patients tend to experience more diffuse lesions as well as severe pruritus with higher rates of relapse. It occasionally manifests in a dermatomal manner.1

The differential diagnosis includes other linear acquired inflammatory dermatoses such as blaschkitis, lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and psoriasis. Blaschkitis has been described as a rare dermatosis that occurs along the Blaschko lines, affecting adults preferentially over children. Controversy exists whether blaschkitis and lichen striatus are the same disease or 2 separate entities.5 Clinically, both blaschkitis and lichen striatus can present with multiple linear papules and vesicles predominantly on the trunk. In blaschkitis, there is a predilection for males, with an older mean age at onset of 40 years.5 Lesions quickly resolve over months with frequent relapse compared to lichen striatus, which can persist for months to years.

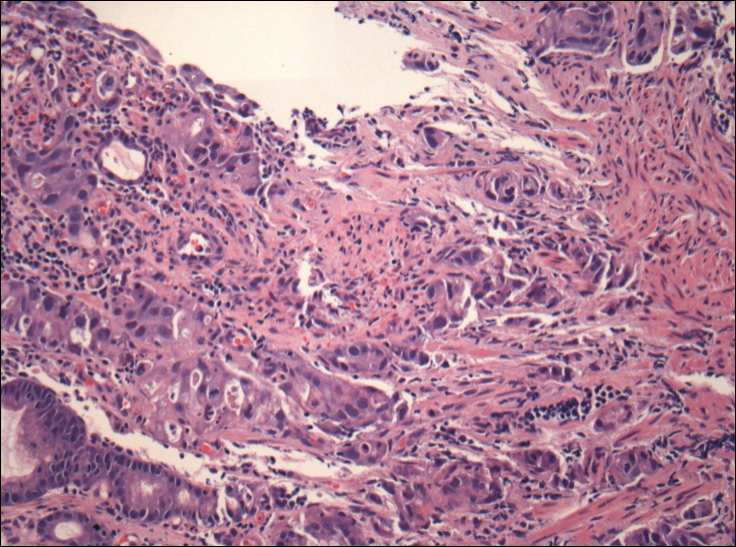

Histopathologically, blaschkitis demonstrates spongiosis, usually without involvement of the adnexal structures. Lichenoid and spongiotic changes with adnexal extension are the hallmark features of lichen striatus. In our patient, biopsy showed several dense bandlike foci of lymphohistiocytic infiltrates along the dermoepidermal junction with spongiosis, basal cell liquefactive degeneration, and pigmentary incontinence (Figure 1). The focal areas were surfaced by parakeratotic and orthohyperkeratotic scale. Deep dermal perivascular and periadnexal extension was present (Figure 2). Periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungi.

The pathogenesis of lichen striatus is not entirely understood, but it has been postulated that trauma, vaccinations, or viral infections may induce loss of immunologic tolerance to keratinocytes.1 This loss of tolerance can result in a T cell-mediated autoimmune reaction against malpighian cells, which show genetic mosaicism and are arranged along Blaschko lines.1,3 Familial cases also have been reported, suggesting that there may be an epigenetic mosaicism that contributes to this group of skin diseases.6,7

Lichen striatus tends to resolve on its own after approximately 6 to 9 months.8 Treatment typically consists of application of topical corticosteroids.1 Cases also have been successfully treated with tacrolimus and pimecrolimus.1,8 Our patient was treated with a midpotency topical steroid with improvement of the appearance but not complete resolution.

- Campanati A, Brandozzi G, Giangiacomi M, et al. Lichen striatus in adults and pimecrolimus: open, off-label clinical study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:732-736.

- Lee DY, Kim S, Kim CR, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult treated by a short course of low-dose systemic corticosteroid. J Dermatol. 2011;38:298-299.

- Hofer T. Lichen striatus in adults or "adult blaschkitis"? there is no need for a new naming. Dermatology. 2003;207:89-92.

- Shepherd V, Lun K, Strutton G. Lichen striatus in an adult following trauma. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:25-28.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Yaosaka M, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Lichen striatus affecting a mother and her son. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:352-353.

- Jackson R. The lines of Blaschko: a review and reconsideration: observations of the cause of certain unusual linear conditions of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:349-360.

- Sorgentini C, Allevato MA, Dahbar M, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult: successful treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:776-777.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus (LS) is an acquired and self-limited linear inflammatory dermatosis that most frequently occurs in children and less commonly in adults.1-3 Clinically, it is characterized by the sudden onset of an eruption consisting of slightly pigmented, erythematous, flat-topped papules with minimal scaling. These papules quickly coalesce to form a linear band that extends along a limb, the trunk, or the face, within Blaschko lines.1,4 In the adult form, patients tend to experience more diffuse lesions as well as severe pruritus with higher rates of relapse. It occasionally manifests in a dermatomal manner.1

The differential diagnosis includes other linear acquired inflammatory dermatoses such as blaschkitis, lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and psoriasis. Blaschkitis has been described as a rare dermatosis that occurs along the Blaschko lines, affecting adults preferentially over children. Controversy exists whether blaschkitis and lichen striatus are the same disease or 2 separate entities.5 Clinically, both blaschkitis and lichen striatus can present with multiple linear papules and vesicles predominantly on the trunk. In blaschkitis, there is a predilection for males, with an older mean age at onset of 40 years.5 Lesions quickly resolve over months with frequent relapse compared to lichen striatus, which can persist for months to years.

Histopathologically, blaschkitis demonstrates spongiosis, usually without involvement of the adnexal structures. Lichenoid and spongiotic changes with adnexal extension are the hallmark features of lichen striatus. In our patient, biopsy showed several dense bandlike foci of lymphohistiocytic infiltrates along the dermoepidermal junction with spongiosis, basal cell liquefactive degeneration, and pigmentary incontinence (Figure 1). The focal areas were surfaced by parakeratotic and orthohyperkeratotic scale. Deep dermal perivascular and periadnexal extension was present (Figure 2). Periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungi.