User login

Localized Argyria With Pseudo-ochronosis

Localized cutaneous argyria often presents as asymptomatic black or blue-gray pigmented macules in areas of the skin exposed to silver-containing compounds.1 Silver may enter the skin by traumatic implantation or absorption via eccrine sweat glands.2 Our patient witnessed a gun fight several years ago while on a mission trip and sustained multiple shrapnel wounds.

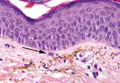

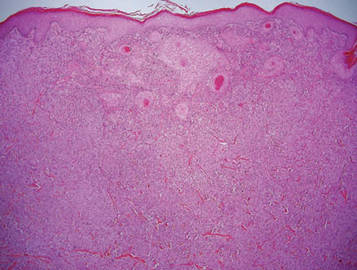

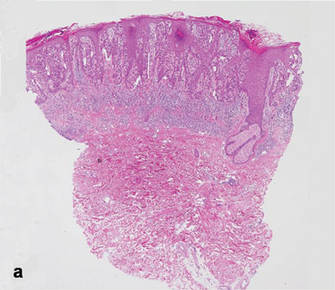

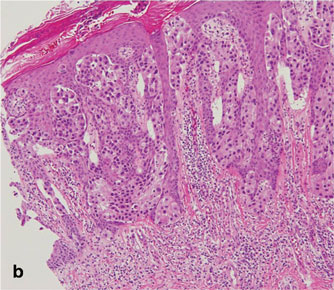

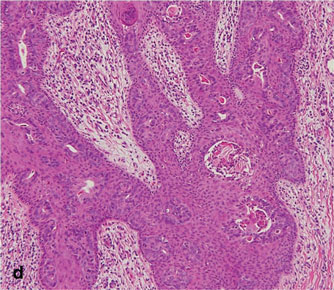

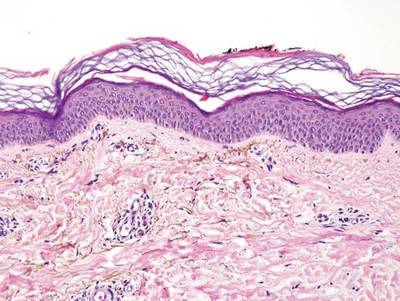

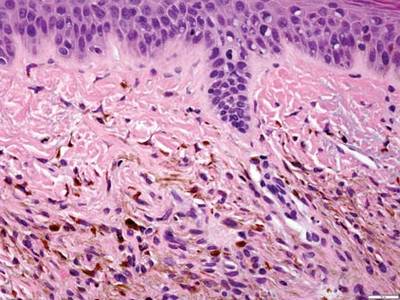

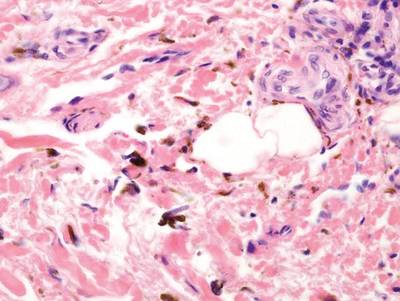

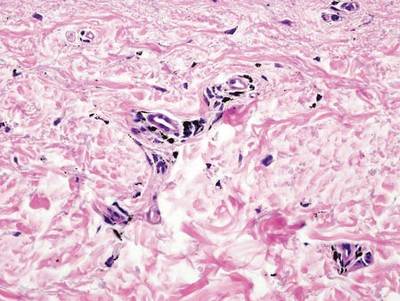

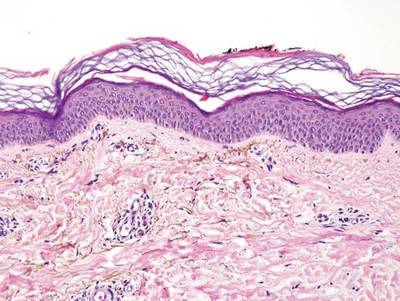

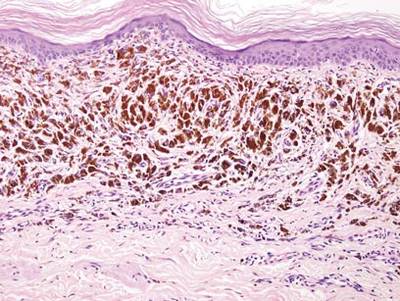

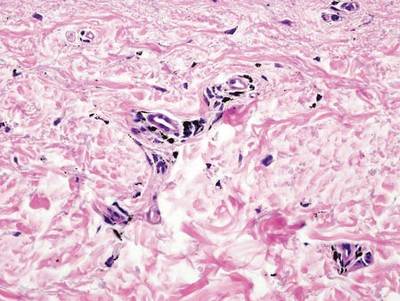

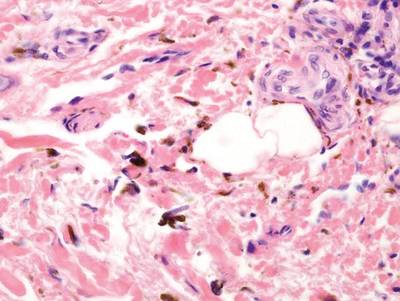

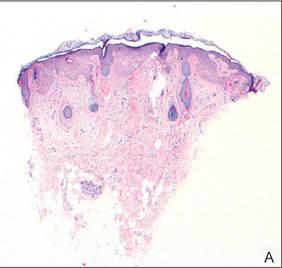

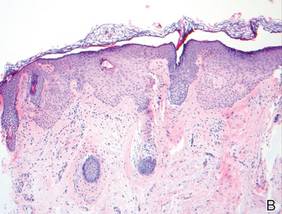

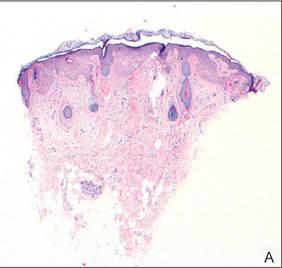

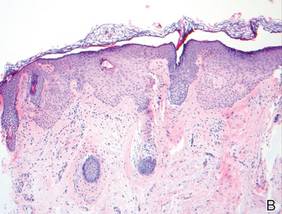

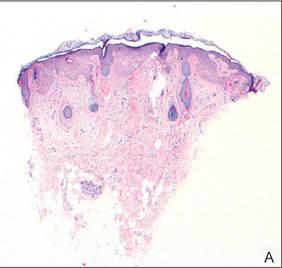

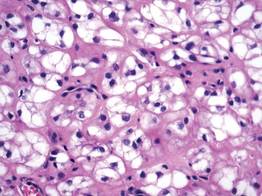

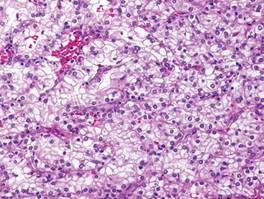

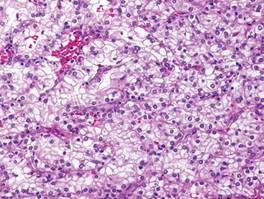

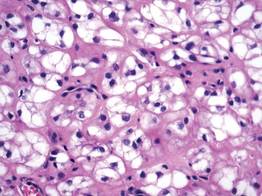

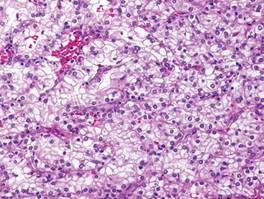

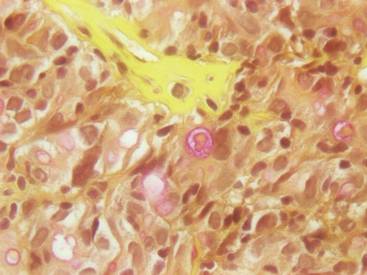

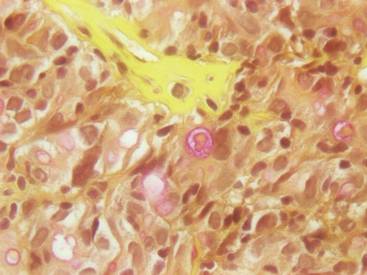

As in our patient, hyperpigmentation may appear years following initial exposure. Over time, incident light reduces colorless silver salts and compounds to black elemental silver.3 It also has been suggested that metallic silver granules stimulate tyrosine kinase activity, leading to locally increased melanin production.4 Together, these processes result in the clinical appearance of a blue-black macule. Despite its long-standing association with silver, this appearance also has been noted with deposition of other metals.5 Histologically, metal deposits can be seen as black granules surrounding eccrine glands, blood vessels, and elastic fibers on higher magnification.6 Granules also may be found in sebaceous glands and arrector pili muscle fibers. These findings do not distinguish from generalized argyria due to increased serum silver levels; however, some cases of localized cutaneous argyria have demonstrated spheroid black globules with surrounding collagen necrosis,1 which have not been reported with generalized disease. Localized cutaneous argyria also may be associated with ocher pigmentation of thickened collagen fibers, resembling changes typically found in alkaptonuria, an inherited deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase (an enzyme involved in tyrosine metabolism).7 The resulting buildup of metabolic intermediates leads to ochronosis, a deposition of ocher-pigmented intermediates in connective tissue throughout the body. In the skin, ocher pigmentation occurs in elastic fibers of the reticular dermis.1 Grossly, these changes result in a blue-gray discoloration of the skin due to a light-scattering phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect. Exogenous ochronosis also can occur, most commonly from the topical application of hydroquinone or other skin-lightening compounds.1,5 Ocher pigmentation occurring in the setting of localized cutaneous argyria is referred to as pseudo-ochronosis, a finding first described by Robinson-Bostom et al.1 The etiology of this condition is poorly understood, but Robinson-Bostom et al1 noted the appearance of dark metal granules surrounding collagen bundles and hypothesized that metal aggregates surrounding collagen bundles in pseudo-ochronosis cause a homogenized appearance under light microscopy. Yellow-brown, swollen, homogenized collagen bundles can be visualized in the reticular dermis with surrounding deposition of metal granules (Figures 1 and 2).1 Typical patterns of granule deposition in localized argyria also are present.

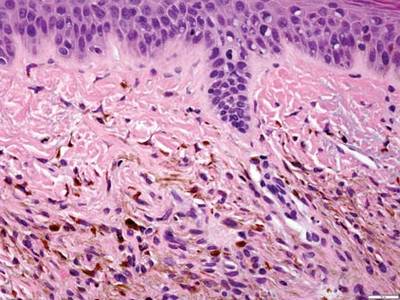

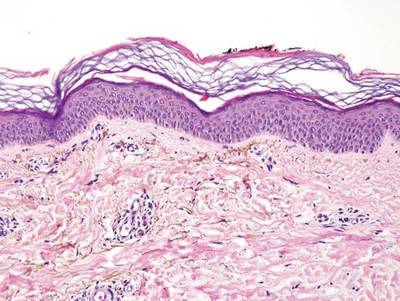

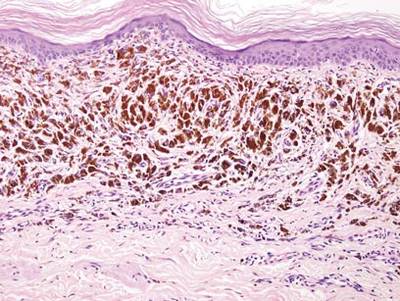

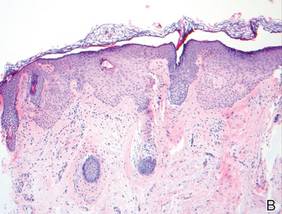

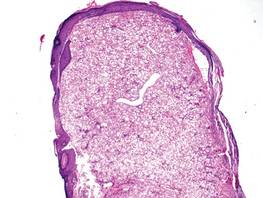

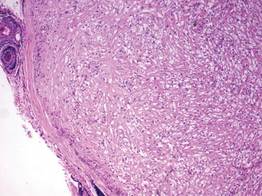

A blue nevus is a collection of proliferating dermal melanocytes. Many histologic subtypes exist and there may be extensive variability in the extent of sclerosis, cellular architecture, and tissue cellularity between each variant.8 Blue nevi commonly present as blue-black hyperpigmentation in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.9 Histologically, they are characterized by slender, bipolar, dendritic melanocytes in a sclerotic stroma (Figure 3).8 Melanocytes are highly pigmented and contain small monomorphic nuclei. Lesions are relatively homogenous and typically are restricted to the dermis with epidermal sparing.9 Dark granules and ocher fibers are absent.

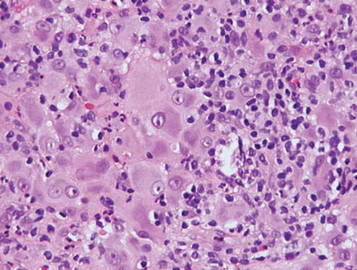

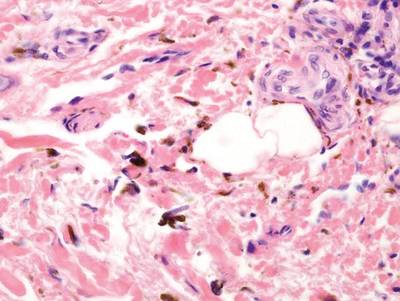

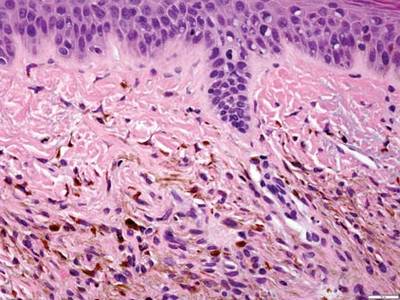

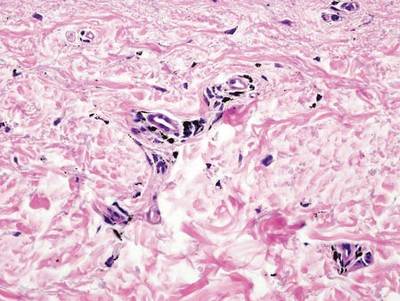

Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials may cause a macular pattern of blue-gray hyperpigmentation.10 Biopsy specimens typically reveal coarse, yellow-brown pigment granules primarily affecting the superficial dermis (Figure 4). Granules are found both extracellularly and within macrophages. Fontana-Masson silver staining may identify melanin, as hydroxychloroquine-melanin binding may contribute to patterns of hyperpigmentation.10 Hemosiderin often is present in cases of hydroxychloroquine pigmentation. Preceding ecchymosis appears to favor the deposition of hydroxychloroquine in the skin.11 The absence of dark metal granules helps distinguish hydroxychloroquine pigmentation from argyria.

Regressed melanomas may appear clinically as gray macules. These lesions arise in cases of malignant melanoma that spontaneously regress without treatment. Spontaneous regression occurs in 10% to 35% of cases depending on tumor subtype.12 Lesions can have a variable appearance based on the degree of regression. Partial regression is demonstrated by mixed melanosis and fibrosis in the dermis (Figure 5).13,14 Melanin is housed within melanophages present in a variably expanded papillary dermis. Tumors in early stages of regression can be surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate, which becomes diminished at later stages. However, a few exceptional cases have been noted with extensive inflammatory infiltrate and no residual tumor.14 Completely regressed lesions typically appear as a band of dermal melanophages in the absence of inflammation or melanocytic atypia.15 The finding of regressed melanoma should prompt further investigation including sentinel lymph node biopsy, as it may be associated with metastasis.

Tattooing occurs following traumatic penetration of the skin with impregnation of pigmented foreign material into deep dermal layers.16 Histologic examination usually reveals clumps of fine particulate material in the dermis (Figure 6). The color of the pigment depends on the agent used. For example, graphite appears as black particles that may be confused with localized cutaneous argyria. Distinction can be made using elemental identification techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.1 The intensity of the pigment in granules found in tattoos or localized cutaneous argyria will fail to diminish with the application of melanin bleach.6

- Robinson-Bostom L, Pomerantz D, Wilkel C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:222-227.

- Tajirian AL, Campbell RM, Robinson-Bostom L. Localized argyria after exposure to aerosolized solder. Cutis. 2006;78:305-308.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED, Burmeister V. Argyria: the intradermal photograph, a manifestation of passive photosensitivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:211-217.

- Buckley WR, Terhaar CJ. The skin as an excretory organ in argyria. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1973;59:39-44.

- Shimizu I, Dill SW, McBean J, et al. Metal-induced granule deposition with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:357-359.

- Rackoff EMJ, Benbenisty KM, Maize JC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria from an acupuncture needle clini-cally concerning for metastatic melanoma. Cutis. 2007;80:423-426.

- Fernandez-Canon JM, Granadino B, Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, et al. The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nat Genet. 1996;14:5-6.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, et al. Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called ‘malignant blue nevus.’ Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:316.

- Puri PK, Lountzis NI, Tyler W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced hyperpigmentation: the staining pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1134-1137.

- Jallouli M, Francès C, Piette JC, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced pigmentation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:935-940.

- Blessing K, McLaren KM. Histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: recognition, prevalence and significance. Histopathology. 1992;20:315-322.

- LeBoit PE. Melanosis and its meanings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:369-372.

- Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

- Yang CH, Yeh JT, Shen SC, et al. Regressed subungual melanoma simulating cellular blue nevus: managed with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:577-581.

- Apfelberg DB, Manchester GH. Decorative and traumatic tattoo biophysics and removal. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:243-251.

Localized cutaneous argyria often presents as asymptomatic black or blue-gray pigmented macules in areas of the skin exposed to silver-containing compounds.1 Silver may enter the skin by traumatic implantation or absorption via eccrine sweat glands.2 Our patient witnessed a gun fight several years ago while on a mission trip and sustained multiple shrapnel wounds.

As in our patient, hyperpigmentation may appear years following initial exposure. Over time, incident light reduces colorless silver salts and compounds to black elemental silver.3 It also has been suggested that metallic silver granules stimulate tyrosine kinase activity, leading to locally increased melanin production.4 Together, these processes result in the clinical appearance of a blue-black macule. Despite its long-standing association with silver, this appearance also has been noted with deposition of other metals.5 Histologically, metal deposits can be seen as black granules surrounding eccrine glands, blood vessels, and elastic fibers on higher magnification.6 Granules also may be found in sebaceous glands and arrector pili muscle fibers. These findings do not distinguish from generalized argyria due to increased serum silver levels; however, some cases of localized cutaneous argyria have demonstrated spheroid black globules with surrounding collagen necrosis,1 which have not been reported with generalized disease. Localized cutaneous argyria also may be associated with ocher pigmentation of thickened collagen fibers, resembling changes typically found in alkaptonuria, an inherited deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase (an enzyme involved in tyrosine metabolism).7 The resulting buildup of metabolic intermediates leads to ochronosis, a deposition of ocher-pigmented intermediates in connective tissue throughout the body. In the skin, ocher pigmentation occurs in elastic fibers of the reticular dermis.1 Grossly, these changes result in a blue-gray discoloration of the skin due to a light-scattering phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect. Exogenous ochronosis also can occur, most commonly from the topical application of hydroquinone or other skin-lightening compounds.1,5 Ocher pigmentation occurring in the setting of localized cutaneous argyria is referred to as pseudo-ochronosis, a finding first described by Robinson-Bostom et al.1 The etiology of this condition is poorly understood, but Robinson-Bostom et al1 noted the appearance of dark metal granules surrounding collagen bundles and hypothesized that metal aggregates surrounding collagen bundles in pseudo-ochronosis cause a homogenized appearance under light microscopy. Yellow-brown, swollen, homogenized collagen bundles can be visualized in the reticular dermis with surrounding deposition of metal granules (Figures 1 and 2).1 Typical patterns of granule deposition in localized argyria also are present.

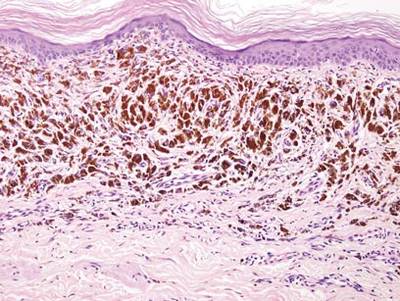

A blue nevus is a collection of proliferating dermal melanocytes. Many histologic subtypes exist and there may be extensive variability in the extent of sclerosis, cellular architecture, and tissue cellularity between each variant.8 Blue nevi commonly present as blue-black hyperpigmentation in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.9 Histologically, they are characterized by slender, bipolar, dendritic melanocytes in a sclerotic stroma (Figure 3).8 Melanocytes are highly pigmented and contain small monomorphic nuclei. Lesions are relatively homogenous and typically are restricted to the dermis with epidermal sparing.9 Dark granules and ocher fibers are absent.

Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials may cause a macular pattern of blue-gray hyperpigmentation.10 Biopsy specimens typically reveal coarse, yellow-brown pigment granules primarily affecting the superficial dermis (Figure 4). Granules are found both extracellularly and within macrophages. Fontana-Masson silver staining may identify melanin, as hydroxychloroquine-melanin binding may contribute to patterns of hyperpigmentation.10 Hemosiderin often is present in cases of hydroxychloroquine pigmentation. Preceding ecchymosis appears to favor the deposition of hydroxychloroquine in the skin.11 The absence of dark metal granules helps distinguish hydroxychloroquine pigmentation from argyria.

Regressed melanomas may appear clinically as gray macules. These lesions arise in cases of malignant melanoma that spontaneously regress without treatment. Spontaneous regression occurs in 10% to 35% of cases depending on tumor subtype.12 Lesions can have a variable appearance based on the degree of regression. Partial regression is demonstrated by mixed melanosis and fibrosis in the dermis (Figure 5).13,14 Melanin is housed within melanophages present in a variably expanded papillary dermis. Tumors in early stages of regression can be surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate, which becomes diminished at later stages. However, a few exceptional cases have been noted with extensive inflammatory infiltrate and no residual tumor.14 Completely regressed lesions typically appear as a band of dermal melanophages in the absence of inflammation or melanocytic atypia.15 The finding of regressed melanoma should prompt further investigation including sentinel lymph node biopsy, as it may be associated with metastasis.

Tattooing occurs following traumatic penetration of the skin with impregnation of pigmented foreign material into deep dermal layers.16 Histologic examination usually reveals clumps of fine particulate material in the dermis (Figure 6). The color of the pigment depends on the agent used. For example, graphite appears as black particles that may be confused with localized cutaneous argyria. Distinction can be made using elemental identification techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.1 The intensity of the pigment in granules found in tattoos or localized cutaneous argyria will fail to diminish with the application of melanin bleach.6

Localized cutaneous argyria often presents as asymptomatic black or blue-gray pigmented macules in areas of the skin exposed to silver-containing compounds.1 Silver may enter the skin by traumatic implantation or absorption via eccrine sweat glands.2 Our patient witnessed a gun fight several years ago while on a mission trip and sustained multiple shrapnel wounds.

As in our patient, hyperpigmentation may appear years following initial exposure. Over time, incident light reduces colorless silver salts and compounds to black elemental silver.3 It also has been suggested that metallic silver granules stimulate tyrosine kinase activity, leading to locally increased melanin production.4 Together, these processes result in the clinical appearance of a blue-black macule. Despite its long-standing association with silver, this appearance also has been noted with deposition of other metals.5 Histologically, metal deposits can be seen as black granules surrounding eccrine glands, blood vessels, and elastic fibers on higher magnification.6 Granules also may be found in sebaceous glands and arrector pili muscle fibers. These findings do not distinguish from generalized argyria due to increased serum silver levels; however, some cases of localized cutaneous argyria have demonstrated spheroid black globules with surrounding collagen necrosis,1 which have not been reported with generalized disease. Localized cutaneous argyria also may be associated with ocher pigmentation of thickened collagen fibers, resembling changes typically found in alkaptonuria, an inherited deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase (an enzyme involved in tyrosine metabolism).7 The resulting buildup of metabolic intermediates leads to ochronosis, a deposition of ocher-pigmented intermediates in connective tissue throughout the body. In the skin, ocher pigmentation occurs in elastic fibers of the reticular dermis.1 Grossly, these changes result in a blue-gray discoloration of the skin due to a light-scattering phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect. Exogenous ochronosis also can occur, most commonly from the topical application of hydroquinone or other skin-lightening compounds.1,5 Ocher pigmentation occurring in the setting of localized cutaneous argyria is referred to as pseudo-ochronosis, a finding first described by Robinson-Bostom et al.1 The etiology of this condition is poorly understood, but Robinson-Bostom et al1 noted the appearance of dark metal granules surrounding collagen bundles and hypothesized that metal aggregates surrounding collagen bundles in pseudo-ochronosis cause a homogenized appearance under light microscopy. Yellow-brown, swollen, homogenized collagen bundles can be visualized in the reticular dermis with surrounding deposition of metal granules (Figures 1 and 2).1 Typical patterns of granule deposition in localized argyria also are present.

A blue nevus is a collection of proliferating dermal melanocytes. Many histologic subtypes exist and there may be extensive variability in the extent of sclerosis, cellular architecture, and tissue cellularity between each variant.8 Blue nevi commonly present as blue-black hyperpigmentation in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.9 Histologically, they are characterized by slender, bipolar, dendritic melanocytes in a sclerotic stroma (Figure 3).8 Melanocytes are highly pigmented and contain small monomorphic nuclei. Lesions are relatively homogenous and typically are restricted to the dermis with epidermal sparing.9 Dark granules and ocher fibers are absent.

Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials may cause a macular pattern of blue-gray hyperpigmentation.10 Biopsy specimens typically reveal coarse, yellow-brown pigment granules primarily affecting the superficial dermis (Figure 4). Granules are found both extracellularly and within macrophages. Fontana-Masson silver staining may identify melanin, as hydroxychloroquine-melanin binding may contribute to patterns of hyperpigmentation.10 Hemosiderin often is present in cases of hydroxychloroquine pigmentation. Preceding ecchymosis appears to favor the deposition of hydroxychloroquine in the skin.11 The absence of dark metal granules helps distinguish hydroxychloroquine pigmentation from argyria.

Regressed melanomas may appear clinically as gray macules. These lesions arise in cases of malignant melanoma that spontaneously regress without treatment. Spontaneous regression occurs in 10% to 35% of cases depending on tumor subtype.12 Lesions can have a variable appearance based on the degree of regression. Partial regression is demonstrated by mixed melanosis and fibrosis in the dermis (Figure 5).13,14 Melanin is housed within melanophages present in a variably expanded papillary dermis. Tumors in early stages of regression can be surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate, which becomes diminished at later stages. However, a few exceptional cases have been noted with extensive inflammatory infiltrate and no residual tumor.14 Completely regressed lesions typically appear as a band of dermal melanophages in the absence of inflammation or melanocytic atypia.15 The finding of regressed melanoma should prompt further investigation including sentinel lymph node biopsy, as it may be associated with metastasis.

Tattooing occurs following traumatic penetration of the skin with impregnation of pigmented foreign material into deep dermal layers.16 Histologic examination usually reveals clumps of fine particulate material in the dermis (Figure 6). The color of the pigment depends on the agent used. For example, graphite appears as black particles that may be confused with localized cutaneous argyria. Distinction can be made using elemental identification techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.1 The intensity of the pigment in granules found in tattoos or localized cutaneous argyria will fail to diminish with the application of melanin bleach.6

- Robinson-Bostom L, Pomerantz D, Wilkel C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:222-227.

- Tajirian AL, Campbell RM, Robinson-Bostom L. Localized argyria after exposure to aerosolized solder. Cutis. 2006;78:305-308.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED, Burmeister V. Argyria: the intradermal photograph, a manifestation of passive photosensitivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:211-217.

- Buckley WR, Terhaar CJ. The skin as an excretory organ in argyria. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1973;59:39-44.

- Shimizu I, Dill SW, McBean J, et al. Metal-induced granule deposition with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:357-359.

- Rackoff EMJ, Benbenisty KM, Maize JC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria from an acupuncture needle clini-cally concerning for metastatic melanoma. Cutis. 2007;80:423-426.

- Fernandez-Canon JM, Granadino B, Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, et al. The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nat Genet. 1996;14:5-6.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, et al. Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called ‘malignant blue nevus.’ Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:316.

- Puri PK, Lountzis NI, Tyler W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced hyperpigmentation: the staining pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1134-1137.

- Jallouli M, Francès C, Piette JC, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced pigmentation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:935-940.

- Blessing K, McLaren KM. Histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: recognition, prevalence and significance. Histopathology. 1992;20:315-322.

- LeBoit PE. Melanosis and its meanings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:369-372.

- Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

- Yang CH, Yeh JT, Shen SC, et al. Regressed subungual melanoma simulating cellular blue nevus: managed with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:577-581.

- Apfelberg DB, Manchester GH. Decorative and traumatic tattoo biophysics and removal. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:243-251.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Pomerantz D, Wilkel C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:222-227.

- Tajirian AL, Campbell RM, Robinson-Bostom L. Localized argyria after exposure to aerosolized solder. Cutis. 2006;78:305-308.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED, Burmeister V. Argyria: the intradermal photograph, a manifestation of passive photosensitivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:211-217.

- Buckley WR, Terhaar CJ. The skin as an excretory organ in argyria. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1973;59:39-44.

- Shimizu I, Dill SW, McBean J, et al. Metal-induced granule deposition with pseudo-ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:357-359.

- Rackoff EMJ, Benbenisty KM, Maize JC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria from an acupuncture needle clini-cally concerning for metastatic melanoma. Cutis. 2007;80:423-426.

- Fernandez-Canon JM, Granadino B, Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, et al. The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nat Genet. 1996;14:5-6.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, et al. Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called ‘malignant blue nevus.’ Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:316.

- Puri PK, Lountzis NI, Tyler W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced hyperpigmentation: the staining pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1134-1137.

- Jallouli M, Francès C, Piette JC, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-induced pigmentation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:935-940.

- Blessing K, McLaren KM. Histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: recognition, prevalence and significance. Histopathology. 1992;20:315-322.

- LeBoit PE. Melanosis and its meanings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:369-372.

- Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

- Yang CH, Yeh JT, Shen SC, et al. Regressed subungual melanoma simulating cellular blue nevus: managed with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:577-581.

- Apfelberg DB, Manchester GH. Decorative and traumatic tattoo biophysics and removal. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:243-251.

Autosomal-Dominant Familial Angiolipomatosis

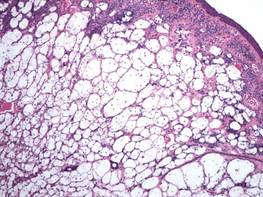

Angiolipomas are benign subcutaneous tumors that usually present on the arms, legs, and trunk in young men. Angiolipomas typically range in size from 1 to 4 cm in diameter, and multiple lesions often are present. Tenderness or mild pain may be elicited with palpation, particularly during the initial growth period. Grossly they appear as yellow, firm, circumscribed tumors. Histologic examination generally is characterized by mature adipose tissue with an admixture of capillaries that often contain fibrin thrombi.

Angiolipomas most often occur sporadically, but in a minority of cases a family history can be identified. Although the exact incidence of familial cases has not been identified in the literature, it is estimated to be 5% to 10%.1 This rare condition has been classified as familial angiolipomatosis, which may be inherited in either an autosomal-recessive or autosomal-dominant fashion, the former being far more prevalent.2 We report the case of a 31-year-old man with multiple angiolipomas who served as a proband for an evaluation of familial angiolipomatosis transmitted in an autosomal-dominant fashion among several male family members.

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented with a history of fatty tumors on the bilateral upper extremities. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for allergy to dogs and cats, as confirmed by positive skin testing, which was treated with hydroxyzine and albuterol. Physical examination was unremarkable, except for the subcutaneous nodules on both arms and forearms. Laboratory results from a complete blood cell count and a comprehensive metabolic panel including total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoproteins were all within reference range. A family history revealed that the patient’s brother, father, and 3 paternal uncles had a history of similar fatty tumors, as well as 2 of his paternal grandmother’s brothers (Figure 1). At the time of presentation, clinical examination revealed multiple tumors distributed on the upper and lower left arm as well as on the posterior and anterior aspect of the right forearm and upper arm. The patient did not report antecedent trauma to these areas.

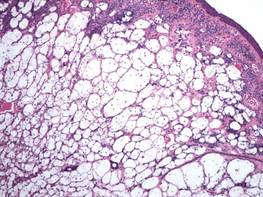

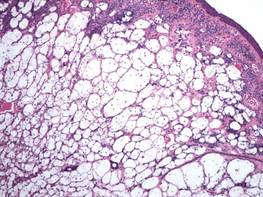

During surgical evaluation several months later, the subcutaneous nodules were preliminarily diagnosed by the surgeon as lipomas. Following surgical excision of all 5 lesions, gross examination revealed tan-yellow, circumscribed, soft-tissue nodules measuring 0.6 to 2.1 cm. Histologic examination revealed circumscribed nodules surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule. The lesions were composed of mature fat cells and benign vessels arranged in lobules of various sizes divided by fibrous septa. The vascular component ranged from 10% to approximately 50% of the lesion and was predominantly composed of capillary-sized vessels with scattered intraluminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 2). The histologic findings were considered a classic presentation of angiolipoma. Unfortunately, the patient was not able to provide pathology results pertaining to the lesions of his relatives, which he referred to as fatty tumors. At follow-up 13 months after excision, the patient developed new lesions and was planning to return for further excisions.

Comment

|

Angiolipomas are benign mesenchymal neoplasms composed of adipose tissue and blood vessels. They usually present subcutaneously but have been documented in other areas including the spinal region in rare instances.3 The most common locations include the forearms, upper arms, and trunk.4 Our case demonstrates a classic presentation of angiolipomatosis manifesting as multiple subcutaneous nodules on the upper arms of a young man. Although lipomas were clinically suspected, histologic examination revealed that the lesions were in fact angiolipomas.

Angiolipomas account for approximately 17% of all fatty tumors and are characterized by mature adipose tissue with an admixture of capillaries that often contain fibrin thrombi.4 Histologic variants of angiolipomas including cellular angiolipomas and angiomyxolipomas rarely are encountered.5-7 Cellular angiolipomas are composed almost entirely of small vessels (>95% of the lesion).5,6 In addition to the classic presentation, cellular angiolipomas also have been documented in unusual locations. Kahng et al8 reported a 73-year-old woman with abnormal mammographic findings who was found to have a cellular angiolipoma of the breast. Cellular angiolipoma with lymph node involvement was reported in a 67-year-old man with adenocarcinoma of the prostate who underwent a radical retropubic prostatectomy.9 Due to their prominent vascular component, cellular angiolipomas must be differentiated from spindle cell lipomas, Kaposi sarcoma, and other vascular tumors. Kaposi sarcomas usually have slitlike vascular spaces, contain globules in the cytoplasm of some cells that are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining, display immunoreactivity for human herpesvirus 8, and lack microthrombi. Angiomyxolipomas also are rare. This variant of angiolipomas contains mature adipose tissue, extensive myxoid stroma, and numerous blood vessels.7 The differential diagnosis for angiomyxolipomas includes myxoid liposarcomas and other adipocytic lesions (eg, myxolipomas, myxoid spindle cell lipomas).

Angiolipomas most often occur sporadically; however, family history has been identified in a minority of cases. This rare finding has been classified as familial angiolipomatosis (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 206550), which can be inherited in either anautosomal-recessive or very rarely in an autosomal-dominant fashion.2 Our patient had numerous relatives with a history of similar lesions, which supported the diagnosis of familial angiolipomatosis in an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern (Figure 1). Patients with autosomal-dominant familial angiolipomatosis also have been described to have other coincidental medical conditions, such as polycystic kidney disease.10

The clinical presentation of familial angiolipomatosis includes multiple subcutaneous tumors and a family history of similar lesions that are not associated with malignant transformation. Subcutaneous tumors and a family history with autosomal-dominant inheritance also can be seen in neurofibromatosis type I, which is associated with various benign and malignant neoplasms (eg, meningiomas, gliomas, pheochromocytomas). Therefore, in familial cases of multiple subcutaneous tumors transmitted in an autosomal-dominant pattern, histologic examination is essential to establish the correct diagnosis. Goodman and Baskin11 reported a patient with familial angiolipomatosis who initially was suspected to have neurofibromatosis. The patient also had a granular cell tumor, which occasionally can be seen in neurofibromatosis.11 Another diagnostic problem between familial angiolipomatosis and neurofibromatosis was described by Cina et al2 who documented a case of familial angiolipomatosis with Lisch nodules, which are common in neurofibromatosis but rarely are seen in patients without this condition.12 These reported parallels have prompted some investigators to suggest that similar pathogenetic mechanisms might be involved in both familial angiolipomatosis with an autosomal-dominant inheritance and neurofibromatosis type I.11 Karyotyping performed on angiolipomas has failed to reveal reproducible cytogenetic abnormalities,13 with the exception of 1 report that documented a patient in which 1 of 5 angiolipomas had a t(X;2) abnormality.14 Conversely, ordinary lipomas are associated with numerous karyotypic abnormalities.14

Angiolipomas are benign tumors, but patients with large or disfiguring angiolipomas may choose to undergo surgical excision. For neoplasms that deeply extend between muscles, tendons, and joint capsules, subtotal excision may be required to restore regular function; however, local recurrence with muscular hypotrophy and deformation of the bones near the affected joints may occur.15

Conclusion

We present the case of a 31-year-old man with a rare form of familial angiolipomatosis characterized by an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Our case emphasizes the need to obtain a detailed family history to determine the inheritance pattern in patients with multiple lesions of angiolipoma. Pathology review is essential to differentiate other diseases such as neurofibromatosis, which may present in a similar fashion. We encourage reports of further cases of familial angiolipomatosis to document the inheritance patterns.

1. Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

2. Cina SJ, Radentz SS, Smialek JE. A case of familial angiolipomatosis with Lisch nodules. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:946-948.

3. Konya D, Ozgen S, Kurtkaya O, et al. Lumbar spinal angiolipoma: case report and review of the literature [published online ahead of print September 20, 2005]. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1025-1028.

4. Howard WR, Helwig EB. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924-931.

5. Hunt SJ, Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ. Cellular angiolipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:75-81.

6. Kanik AB, Oh CH, Bhawan J. Cellular angiolipoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:312-315.

7. Lee HW, Lee DK, Lee MW, et al. Two cases of angiomyxolipoma (vascular myxolipoma) of subcutaneous tissue. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:379-382.

8. Kahng HC, Chin NW, Opitz LM, et al. Cellular angiolipoma of the breast: immunohistochemical study and review of the literature. Breast J. 2002;8:47-49.

9. Kazakov DV, Hes O, Hora M, et al. Primary intranodal cellular angiolipoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2005;13:99-101.

10. Kumar R, Pereira BJ, Sakhuja V, et al. Autosomal dominant inheritance in familial angiolipomatosis. Clin Genet. 1989;35:202-204.

11. Goodman JC, Baskin DS. Autosomal dominant familial angiolipomatosis clinically mimicking neurofibromatosis. Neurofibromatosis. 1989;2:326-31.

12. Cassiman C, Legius E, Spileers W, et al. Ophthalmological assessment of children with neurofibromatosis type 1 [published online ahead of print May 25, 2013]. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:1327-1333.

13. Sciot R, Akerman M, Dal Cin P, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of subcutaneous angiolipoma: further evidence supporting its difference from ordinary pure lipomas: a report of the CHAMP Study Group. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:441-444.

14. Mandahl N, Höglund M, Mertens F, et al. Cytogenetic aberrations in 188 benign and borderline adipose tissue tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;9:207-215.

15. Hapnes SA, Boman H, Skeie SO. Familial angiolipomatosis. Clin Genet. 1980;17:202-208.

Angiolipomas are benign subcutaneous tumors that usually present on the arms, legs, and trunk in young men. Angiolipomas typically range in size from 1 to 4 cm in diameter, and multiple lesions often are present. Tenderness or mild pain may be elicited with palpation, particularly during the initial growth period. Grossly they appear as yellow, firm, circumscribed tumors. Histologic examination generally is characterized by mature adipose tissue with an admixture of capillaries that often contain fibrin thrombi.

Angiolipomas most often occur sporadically, but in a minority of cases a family history can be identified. Although the exact incidence of familial cases has not been identified in the literature, it is estimated to be 5% to 10%.1 This rare condition has been classified as familial angiolipomatosis, which may be inherited in either an autosomal-recessive or autosomal-dominant fashion, the former being far more prevalent.2 We report the case of a 31-year-old man with multiple angiolipomas who served as a proband for an evaluation of familial angiolipomatosis transmitted in an autosomal-dominant fashion among several male family members.

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented with a history of fatty tumors on the bilateral upper extremities. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for allergy to dogs and cats, as confirmed by positive skin testing, which was treated with hydroxyzine and albuterol. Physical examination was unremarkable, except for the subcutaneous nodules on both arms and forearms. Laboratory results from a complete blood cell count and a comprehensive metabolic panel including total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoproteins were all within reference range. A family history revealed that the patient’s brother, father, and 3 paternal uncles had a history of similar fatty tumors, as well as 2 of his paternal grandmother’s brothers (Figure 1). At the time of presentation, clinical examination revealed multiple tumors distributed on the upper and lower left arm as well as on the posterior and anterior aspect of the right forearm and upper arm. The patient did not report antecedent trauma to these areas.

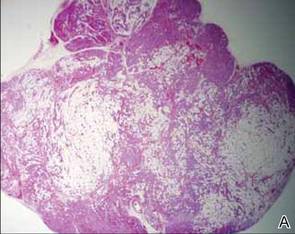

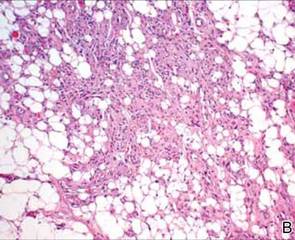

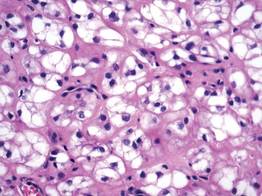

During surgical evaluation several months later, the subcutaneous nodules were preliminarily diagnosed by the surgeon as lipomas. Following surgical excision of all 5 lesions, gross examination revealed tan-yellow, circumscribed, soft-tissue nodules measuring 0.6 to 2.1 cm. Histologic examination revealed circumscribed nodules surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule. The lesions were composed of mature fat cells and benign vessels arranged in lobules of various sizes divided by fibrous septa. The vascular component ranged from 10% to approximately 50% of the lesion and was predominantly composed of capillary-sized vessels with scattered intraluminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 2). The histologic findings were considered a classic presentation of angiolipoma. Unfortunately, the patient was not able to provide pathology results pertaining to the lesions of his relatives, which he referred to as fatty tumors. At follow-up 13 months after excision, the patient developed new lesions and was planning to return for further excisions.

Comment

|

Angiolipomas are benign mesenchymal neoplasms composed of adipose tissue and blood vessels. They usually present subcutaneously but have been documented in other areas including the spinal region in rare instances.3 The most common locations include the forearms, upper arms, and trunk.4 Our case demonstrates a classic presentation of angiolipomatosis manifesting as multiple subcutaneous nodules on the upper arms of a young man. Although lipomas were clinically suspected, histologic examination revealed that the lesions were in fact angiolipomas.

Angiolipomas account for approximately 17% of all fatty tumors and are characterized by mature adipose tissue with an admixture of capillaries that often contain fibrin thrombi.4 Histologic variants of angiolipomas including cellular angiolipomas and angiomyxolipomas rarely are encountered.5-7 Cellular angiolipomas are composed almost entirely of small vessels (>95% of the lesion).5,6 In addition to the classic presentation, cellular angiolipomas also have been documented in unusual locations. Kahng et al8 reported a 73-year-old woman with abnormal mammographic findings who was found to have a cellular angiolipoma of the breast. Cellular angiolipoma with lymph node involvement was reported in a 67-year-old man with adenocarcinoma of the prostate who underwent a radical retropubic prostatectomy.9 Due to their prominent vascular component, cellular angiolipomas must be differentiated from spindle cell lipomas, Kaposi sarcoma, and other vascular tumors. Kaposi sarcomas usually have slitlike vascular spaces, contain globules in the cytoplasm of some cells that are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining, display immunoreactivity for human herpesvirus 8, and lack microthrombi. Angiomyxolipomas also are rare. This variant of angiolipomas contains mature adipose tissue, extensive myxoid stroma, and numerous blood vessels.7 The differential diagnosis for angiomyxolipomas includes myxoid liposarcomas and other adipocytic lesions (eg, myxolipomas, myxoid spindle cell lipomas).

Angiolipomas most often occur sporadically; however, family history has been identified in a minority of cases. This rare finding has been classified as familial angiolipomatosis (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 206550), which can be inherited in either anautosomal-recessive or very rarely in an autosomal-dominant fashion.2 Our patient had numerous relatives with a history of similar lesions, which supported the diagnosis of familial angiolipomatosis in an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern (Figure 1). Patients with autosomal-dominant familial angiolipomatosis also have been described to have other coincidental medical conditions, such as polycystic kidney disease.10

The clinical presentation of familial angiolipomatosis includes multiple subcutaneous tumors and a family history of similar lesions that are not associated with malignant transformation. Subcutaneous tumors and a family history with autosomal-dominant inheritance also can be seen in neurofibromatosis type I, which is associated with various benign and malignant neoplasms (eg, meningiomas, gliomas, pheochromocytomas). Therefore, in familial cases of multiple subcutaneous tumors transmitted in an autosomal-dominant pattern, histologic examination is essential to establish the correct diagnosis. Goodman and Baskin11 reported a patient with familial angiolipomatosis who initially was suspected to have neurofibromatosis. The patient also had a granular cell tumor, which occasionally can be seen in neurofibromatosis.11 Another diagnostic problem between familial angiolipomatosis and neurofibromatosis was described by Cina et al2 who documented a case of familial angiolipomatosis with Lisch nodules, which are common in neurofibromatosis but rarely are seen in patients without this condition.12 These reported parallels have prompted some investigators to suggest that similar pathogenetic mechanisms might be involved in both familial angiolipomatosis with an autosomal-dominant inheritance and neurofibromatosis type I.11 Karyotyping performed on angiolipomas has failed to reveal reproducible cytogenetic abnormalities,13 with the exception of 1 report that documented a patient in which 1 of 5 angiolipomas had a t(X;2) abnormality.14 Conversely, ordinary lipomas are associated with numerous karyotypic abnormalities.14

Angiolipomas are benign tumors, but patients with large or disfiguring angiolipomas may choose to undergo surgical excision. For neoplasms that deeply extend between muscles, tendons, and joint capsules, subtotal excision may be required to restore regular function; however, local recurrence with muscular hypotrophy and deformation of the bones near the affected joints may occur.15

Conclusion

We present the case of a 31-year-old man with a rare form of familial angiolipomatosis characterized by an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Our case emphasizes the need to obtain a detailed family history to determine the inheritance pattern in patients with multiple lesions of angiolipoma. Pathology review is essential to differentiate other diseases such as neurofibromatosis, which may present in a similar fashion. We encourage reports of further cases of familial angiolipomatosis to document the inheritance patterns.

Angiolipomas are benign subcutaneous tumors that usually present on the arms, legs, and trunk in young men. Angiolipomas typically range in size from 1 to 4 cm in diameter, and multiple lesions often are present. Tenderness or mild pain may be elicited with palpation, particularly during the initial growth period. Grossly they appear as yellow, firm, circumscribed tumors. Histologic examination generally is characterized by mature adipose tissue with an admixture of capillaries that often contain fibrin thrombi.

Angiolipomas most often occur sporadically, but in a minority of cases a family history can be identified. Although the exact incidence of familial cases has not been identified in the literature, it is estimated to be 5% to 10%.1 This rare condition has been classified as familial angiolipomatosis, which may be inherited in either an autosomal-recessive or autosomal-dominant fashion, the former being far more prevalent.2 We report the case of a 31-year-old man with multiple angiolipomas who served as a proband for an evaluation of familial angiolipomatosis transmitted in an autosomal-dominant fashion among several male family members.

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented with a history of fatty tumors on the bilateral upper extremities. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for allergy to dogs and cats, as confirmed by positive skin testing, which was treated with hydroxyzine and albuterol. Physical examination was unremarkable, except for the subcutaneous nodules on both arms and forearms. Laboratory results from a complete blood cell count and a comprehensive metabolic panel including total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoproteins were all within reference range. A family history revealed that the patient’s brother, father, and 3 paternal uncles had a history of similar fatty tumors, as well as 2 of his paternal grandmother’s brothers (Figure 1). At the time of presentation, clinical examination revealed multiple tumors distributed on the upper and lower left arm as well as on the posterior and anterior aspect of the right forearm and upper arm. The patient did not report antecedent trauma to these areas.

During surgical evaluation several months later, the subcutaneous nodules were preliminarily diagnosed by the surgeon as lipomas. Following surgical excision of all 5 lesions, gross examination revealed tan-yellow, circumscribed, soft-tissue nodules measuring 0.6 to 2.1 cm. Histologic examination revealed circumscribed nodules surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule. The lesions were composed of mature fat cells and benign vessels arranged in lobules of various sizes divided by fibrous septa. The vascular component ranged from 10% to approximately 50% of the lesion and was predominantly composed of capillary-sized vessels with scattered intraluminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 2). The histologic findings were considered a classic presentation of angiolipoma. Unfortunately, the patient was not able to provide pathology results pertaining to the lesions of his relatives, which he referred to as fatty tumors. At follow-up 13 months after excision, the patient developed new lesions and was planning to return for further excisions.

Comment

|

Angiolipomas are benign mesenchymal neoplasms composed of adipose tissue and blood vessels. They usually present subcutaneously but have been documented in other areas including the spinal region in rare instances.3 The most common locations include the forearms, upper arms, and trunk.4 Our case demonstrates a classic presentation of angiolipomatosis manifesting as multiple subcutaneous nodules on the upper arms of a young man. Although lipomas were clinically suspected, histologic examination revealed that the lesions were in fact angiolipomas.

Angiolipomas account for approximately 17% of all fatty tumors and are characterized by mature adipose tissue with an admixture of capillaries that often contain fibrin thrombi.4 Histologic variants of angiolipomas including cellular angiolipomas and angiomyxolipomas rarely are encountered.5-7 Cellular angiolipomas are composed almost entirely of small vessels (>95% of the lesion).5,6 In addition to the classic presentation, cellular angiolipomas also have been documented in unusual locations. Kahng et al8 reported a 73-year-old woman with abnormal mammographic findings who was found to have a cellular angiolipoma of the breast. Cellular angiolipoma with lymph node involvement was reported in a 67-year-old man with adenocarcinoma of the prostate who underwent a radical retropubic prostatectomy.9 Due to their prominent vascular component, cellular angiolipomas must be differentiated from spindle cell lipomas, Kaposi sarcoma, and other vascular tumors. Kaposi sarcomas usually have slitlike vascular spaces, contain globules in the cytoplasm of some cells that are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining, display immunoreactivity for human herpesvirus 8, and lack microthrombi. Angiomyxolipomas also are rare. This variant of angiolipomas contains mature adipose tissue, extensive myxoid stroma, and numerous blood vessels.7 The differential diagnosis for angiomyxolipomas includes myxoid liposarcomas and other adipocytic lesions (eg, myxolipomas, myxoid spindle cell lipomas).

Angiolipomas most often occur sporadically; however, family history has been identified in a minority of cases. This rare finding has been classified as familial angiolipomatosis (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 206550), which can be inherited in either anautosomal-recessive or very rarely in an autosomal-dominant fashion.2 Our patient had numerous relatives with a history of similar lesions, which supported the diagnosis of familial angiolipomatosis in an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern (Figure 1). Patients with autosomal-dominant familial angiolipomatosis also have been described to have other coincidental medical conditions, such as polycystic kidney disease.10

The clinical presentation of familial angiolipomatosis includes multiple subcutaneous tumors and a family history of similar lesions that are not associated with malignant transformation. Subcutaneous tumors and a family history with autosomal-dominant inheritance also can be seen in neurofibromatosis type I, which is associated with various benign and malignant neoplasms (eg, meningiomas, gliomas, pheochromocytomas). Therefore, in familial cases of multiple subcutaneous tumors transmitted in an autosomal-dominant pattern, histologic examination is essential to establish the correct diagnosis. Goodman and Baskin11 reported a patient with familial angiolipomatosis who initially was suspected to have neurofibromatosis. The patient also had a granular cell tumor, which occasionally can be seen in neurofibromatosis.11 Another diagnostic problem between familial angiolipomatosis and neurofibromatosis was described by Cina et al2 who documented a case of familial angiolipomatosis with Lisch nodules, which are common in neurofibromatosis but rarely are seen in patients without this condition.12 These reported parallels have prompted some investigators to suggest that similar pathogenetic mechanisms might be involved in both familial angiolipomatosis with an autosomal-dominant inheritance and neurofibromatosis type I.11 Karyotyping performed on angiolipomas has failed to reveal reproducible cytogenetic abnormalities,13 with the exception of 1 report that documented a patient in which 1 of 5 angiolipomas had a t(X;2) abnormality.14 Conversely, ordinary lipomas are associated with numerous karyotypic abnormalities.14

Angiolipomas are benign tumors, but patients with large or disfiguring angiolipomas may choose to undergo surgical excision. For neoplasms that deeply extend between muscles, tendons, and joint capsules, subtotal excision may be required to restore regular function; however, local recurrence with muscular hypotrophy and deformation of the bones near the affected joints may occur.15

Conclusion

We present the case of a 31-year-old man with a rare form of familial angiolipomatosis characterized by an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Our case emphasizes the need to obtain a detailed family history to determine the inheritance pattern in patients with multiple lesions of angiolipoma. Pathology review is essential to differentiate other diseases such as neurofibromatosis, which may present in a similar fashion. We encourage reports of further cases of familial angiolipomatosis to document the inheritance patterns.

1. Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

2. Cina SJ, Radentz SS, Smialek JE. A case of familial angiolipomatosis with Lisch nodules. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:946-948.

3. Konya D, Ozgen S, Kurtkaya O, et al. Lumbar spinal angiolipoma: case report and review of the literature [published online ahead of print September 20, 2005]. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1025-1028.

4. Howard WR, Helwig EB. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924-931.

5. Hunt SJ, Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ. Cellular angiolipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:75-81.

6. Kanik AB, Oh CH, Bhawan J. Cellular angiolipoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:312-315.

7. Lee HW, Lee DK, Lee MW, et al. Two cases of angiomyxolipoma (vascular myxolipoma) of subcutaneous tissue. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:379-382.

8. Kahng HC, Chin NW, Opitz LM, et al. Cellular angiolipoma of the breast: immunohistochemical study and review of the literature. Breast J. 2002;8:47-49.

9. Kazakov DV, Hes O, Hora M, et al. Primary intranodal cellular angiolipoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2005;13:99-101.

10. Kumar R, Pereira BJ, Sakhuja V, et al. Autosomal dominant inheritance in familial angiolipomatosis. Clin Genet. 1989;35:202-204.

11. Goodman JC, Baskin DS. Autosomal dominant familial angiolipomatosis clinically mimicking neurofibromatosis. Neurofibromatosis. 1989;2:326-31.

12. Cassiman C, Legius E, Spileers W, et al. Ophthalmological assessment of children with neurofibromatosis type 1 [published online ahead of print May 25, 2013]. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:1327-1333.

13. Sciot R, Akerman M, Dal Cin P, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of subcutaneous angiolipoma: further evidence supporting its difference from ordinary pure lipomas: a report of the CHAMP Study Group. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:441-444.

14. Mandahl N, Höglund M, Mertens F, et al. Cytogenetic aberrations in 188 benign and borderline adipose tissue tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;9:207-215.

15. Hapnes SA, Boman H, Skeie SO. Familial angiolipomatosis. Clin Genet. 1980;17:202-208.

1. Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

2. Cina SJ, Radentz SS, Smialek JE. A case of familial angiolipomatosis with Lisch nodules. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:946-948.

3. Konya D, Ozgen S, Kurtkaya O, et al. Lumbar spinal angiolipoma: case report and review of the literature [published online ahead of print September 20, 2005]. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1025-1028.

4. Howard WR, Helwig EB. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924-931.

5. Hunt SJ, Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ. Cellular angiolipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:75-81.

6. Kanik AB, Oh CH, Bhawan J. Cellular angiolipoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:312-315.

7. Lee HW, Lee DK, Lee MW, et al. Two cases of angiomyxolipoma (vascular myxolipoma) of subcutaneous tissue. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:379-382.

8. Kahng HC, Chin NW, Opitz LM, et al. Cellular angiolipoma of the breast: immunohistochemical study and review of the literature. Breast J. 2002;8:47-49.

9. Kazakov DV, Hes O, Hora M, et al. Primary intranodal cellular angiolipoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2005;13:99-101.

10. Kumar R, Pereira BJ, Sakhuja V, et al. Autosomal dominant inheritance in familial angiolipomatosis. Clin Genet. 1989;35:202-204.

11. Goodman JC, Baskin DS. Autosomal dominant familial angiolipomatosis clinically mimicking neurofibromatosis. Neurofibromatosis. 1989;2:326-31.

12. Cassiman C, Legius E, Spileers W, et al. Ophthalmological assessment of children with neurofibromatosis type 1 [published online ahead of print May 25, 2013]. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:1327-1333.

13. Sciot R, Akerman M, Dal Cin P, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of subcutaneous angiolipoma: further evidence supporting its difference from ordinary pure lipomas: a report of the CHAMP Study Group. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:441-444.

14. Mandahl N, Höglund M, Mertens F, et al. Cytogenetic aberrations in 188 benign and borderline adipose tissue tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;9:207-215.

15. Hapnes SA, Boman H, Skeie SO. Familial angiolipomatosis. Clin Genet. 1980;17:202-208.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be familiar with the clinical and histological features of angiolipomas along with their potential inheritance patterns.

- Familial angiolipomatosis is a rare condition characterized by multiple angiolipomas that has been described as having an autosomal-recessive transmission pattern. Autosomal-dominant inheritance also may occur, as illustrated in the current case report.

- Awareness of the autosomal-dominant form of this entity is important to prevent its misdiagnosis as

neurofibromatosis type I, which has a similar family history and clinical presentation.

Multiple Firm Pink Papules and Nodules

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

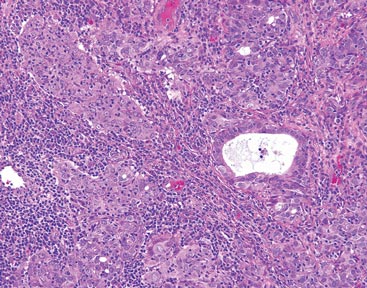

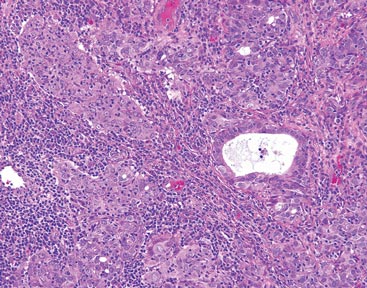

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

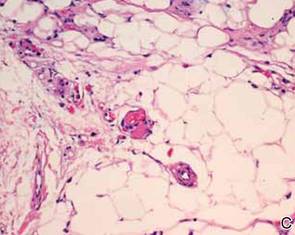

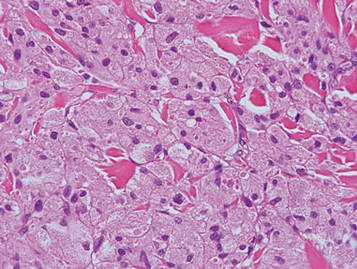

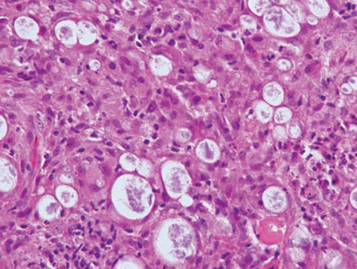

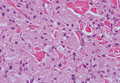

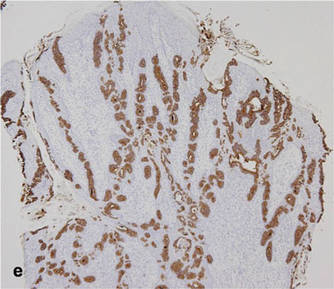

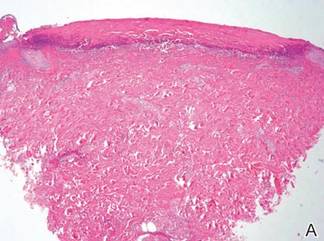

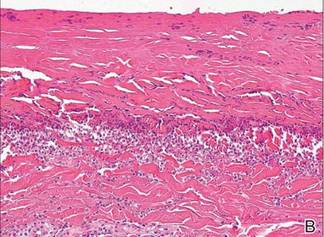

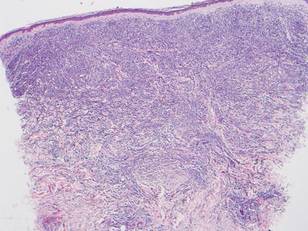

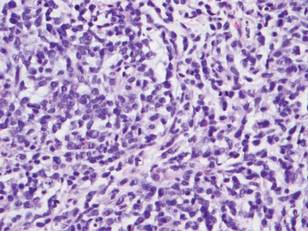

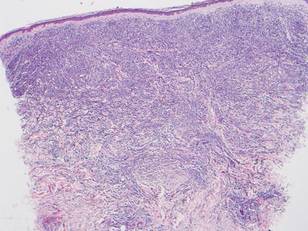

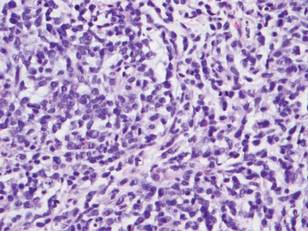

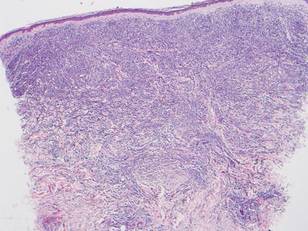

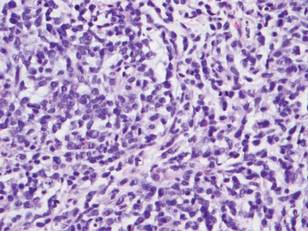

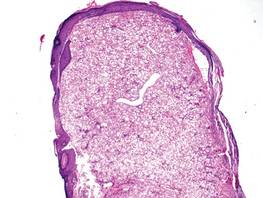

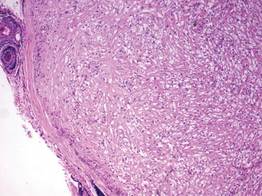

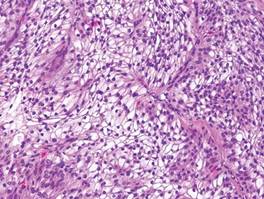

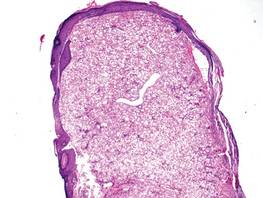

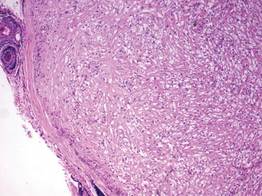

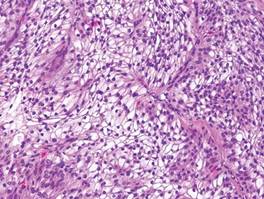

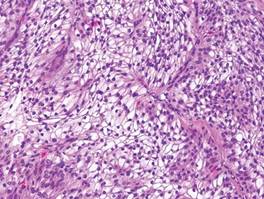

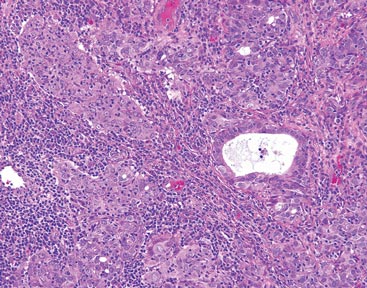

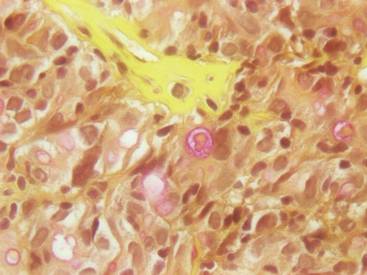

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

A 91-year-old man presented with numerous, scattered, asymptomatic, 3- to 9-mm, smooth, firm, pink papules and nodules involving the neck, trunk, and arms and legs of 1 week’s duration.

Stains and Smears: Resident Guide to Bedside Diagnostic Testing

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation

A standard in the armamentarium of a dermatologist, the KOH preparation is invaluable to diagnose fungal and yeast infections. Although there are many available preparations including varying concentrations of KOH, dimethyl sulfoxide, and various inks, the procedure is similar for all of them.1 The first step involves collecting the specimen, which can be scale from an active border of suspected cutaneous dermatophyte or Malassezia infection, debris from suspected candidiasis, or hair shafts plucked from an area of alopecia of presumed tinea capitis. A no. 15 blade can be used to scrape the specimen onto a microscope slide, though a second microscope slide can be used in lieu of a blade in patients who will not remain still, and then a coverslip is placed. Two drops of the KOH solution of your choice are then placed on opposite ends of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to spread the stain evenly. A paper towel can be folded in half and pushed down on the surface of the coverslip to spread the stain and soak up any excess, and this pressure also can help the KOH solution digest the keratin in the specimen. Briefly heating the underside of the slide (below boiling point) will help digest the keratin; this step is not necessary when you are using a KOH preparation with dimethyl sulfoxide. Although many dermatologists view the slide almost immediately, ideally at least 5 minutes should pass before it is read. Particularly thick specimens may require additional digestion time, so setting them aside for later review may help visualize infectious agents. In a busy clinic where an immediate diagnosis may not be requisite and a prescription can be called in pending the result, waiting to review the slide may be feasible.

Tzanck Smear

The Tzanck smear is a useful cytopathologic test in the rapid diagnosis of herpetic lesions, though it cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and varicella-zoster virus. It also has shown utility for rapid diagnosis of protean other dermatologic conditions including autoimmune blistering disorders, cutaneous malignancies, and other infectious processes, though it has been superseded by histopathology in most cases.2 An ideal sample is collected by scraping the base of a fresh blister with a no. 15 blade or a second microscope slide. The scrapings then are smeared onto another microscope slide and allowed to air-dry briefly. Then, Wright-Giemsa stain is dispensed to cover the sample and allowed to sit for 15 minutes before being washed off with sterile water. After air-drying, the sample is examined for the presence of clumped multinucleated giant cells, a feature that confirms herpetic infection and allows rapid initiation of antiviral medication.3

Mineral Oil Preparation

A mineral oil preparation has utility in diagnosing ectoparasitic infestation. In the case of scabies, a positive microscopic examination is diagnostic and requires no further testing, allowing for rapid initiation of therapy. This technique also is useful in diagnosing rosacea related to Demodex, which requires a treatment algorithm that differs from the classic papulopustular rosacea which it mimics.4

Mineral oil preparations can be rapidly performed and interpreted. Several drops of mineral oil are placed onto a microscope slide and a no. 15 blade is dipped into this oil prior to scraping the sample lesion. For scabies, a burrow is scraped repeatedly with the blade, and the debris is collected in the mineral oil. Occasionally, the mite can be dermoscopically visualized as a jet plane or arrowhead at the leading edge of a burrow; scraping should be focused in the vicinity of the mite.5 A coverslip is applied to the microscope slide and examination for the mite, egg casings, and scybala can be performed with microscopy.6 For Demodex infestation, a facial pustule can be expressed or several eyelash hairs can be plucked and suspended in mineral oil. Examination of this specimen is identical to scabies.

Gram Stain

The Gram stain is invaluable in classifying bacteria, and a properly performed test can narrow the identification of a causative organism based on cellular morphology. Although it is more technically complex than other bedside diagnostic maneuvers, it can be rapidly performed once the sequence of stains is mastered. The collected sample is smeared onto a glass slide and then briefly passed over a flame several times to heat-fix the specimen. Caution should be taken to avoid direct or prolonged flame contact with the underside of the slide. After fixation, the staining can be performed. First, crystal violet is instilled onto the slide and remains on for 30 seconds before being rinsed off with sink water. Then, Gram iodine is used for 30 seconds, followed by another rinse in water. Next, pour the decolorizer solution over the slide until the runoff is clear, and then rinse in water. Finally, flood with safranin counterstain for 30 seconds and give the slide a final rinse. After air-drying, it is ready to be interpreted.7

Final Thoughts

Although the modern dermatologist has access to biopsies, cultures, and sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is important to remember these useful bedside tests. The ability to rapidly pin a diagnosis is particularly useful on the consultative service where critically ill patients can benefit from identification of a causative pathogen sooner rather than later. Residents should master these stains in their training, as this knowledge may prove to be invaluable in their careers.

1. Trozak DJ, Tennenhouse DJ, Russell JJ. Dermatology Skills for Primary Care: An Illustrated Guide. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006.

2. Kelly B, Shimoni T. Reintroducing the Tzanck smear. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:141-152.

3. Singhi M, Gupta L. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295.

4. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504.

5. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

6. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology Essentials. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

7. Ruocco E, Baroni A, Donnarumma G, et al. Diagnostic procedures in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:548-556.

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation