User login

Black psychiatric inpatients more likely to be restrained and for longer

TOPLINE:

, new research suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study, part of a larger retrospective chart review of inpatient psychiatric electronic medical records (EMRs), included 29,739 adolescents (aged 12-17 years) and adults admitted because of severe and disruptive psychiatric illness or concerns about self-harm.

- A restraint event was defined as a physician-ordered physical or mechanical hold in which patients are unable to move their limbs, body, or head or are given medication to restrict their movement.

- Researchers used scores on the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA) at admission to assess risk for aggression among high-risk psychiatric inpatients (scores ranged from a low of 0 to a high of 7).

- From restraint event data extracted from the EMR, researchers investigated whether restraint frequency or duration was affected by “adultification,” a form of racial bias in which adolescents are perceived as being older than their actual age and are treated accordingly.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the entire cohort, 1867 (6.3%) experienced a restraint event, and 27,872 (93.7%) did not.

- Compared with White patients, restraint was 85% more likely among Black patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; P < .001) and 36% more likely among multiracial patients (aOR, 1.36; P = .006), which researchers suggest may reflect systemic racism within psychiatry and medicine, as well as an implicit or learned perception that people of color are more aggressive and dangerous.

- Lower DASA score at admission (P = .001), shorter length of stay (P < .001), adult age (P = .001), female sex (P = .042), and Black race, compared with White race (P = .001), were significantly associated with longer restraint duration, which may serve as a proxy for psychiatric symptom severity.

- Neither age group alone (adolescent or adult) nor the interaction of race and age group was significantly associated with experiencing a restraint event, suggesting no evidence of “adultification.”

IN PRACTICE:

It’s important to raise awareness about racial differences in restraint events in inpatient psychiatric settings, the authors write, adding that addressing overcrowding and investing in bias assessment and restraint education may reduce bias in the care of agitated patients and the use of restraints.

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Sonali Singal, BS, Institute of Behavioral Science, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. It was published online in Psychiatric Services.

LIMITATIONS:

The variables analyzed in the study were limited by the retrospective chart review and by the available EMR data, which may have contained entry errors. Although the investigators used DASA scores to control for differences in aggression, they could not control for symptom severity. The study could not examine the impact of race on seclusion (involuntary confinement), a variable often examined in tandem with restraint, because there were too few such events. The analysis also did not control for substance use disorder, which can influence a patient’s behavior and be related to restraint use.

DISCLOSURES:

Ms. Singal reported no relevant financial relationships. The original article has disclosures of other authors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new research suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study, part of a larger retrospective chart review of inpatient psychiatric electronic medical records (EMRs), included 29,739 adolescents (aged 12-17 years) and adults admitted because of severe and disruptive psychiatric illness or concerns about self-harm.

- A restraint event was defined as a physician-ordered physical or mechanical hold in which patients are unable to move their limbs, body, or head or are given medication to restrict their movement.

- Researchers used scores on the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA) at admission to assess risk for aggression among high-risk psychiatric inpatients (scores ranged from a low of 0 to a high of 7).

- From restraint event data extracted from the EMR, researchers investigated whether restraint frequency or duration was affected by “adultification,” a form of racial bias in which adolescents are perceived as being older than their actual age and are treated accordingly.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the entire cohort, 1867 (6.3%) experienced a restraint event, and 27,872 (93.7%) did not.

- Compared with White patients, restraint was 85% more likely among Black patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; P < .001) and 36% more likely among multiracial patients (aOR, 1.36; P = .006), which researchers suggest may reflect systemic racism within psychiatry and medicine, as well as an implicit or learned perception that people of color are more aggressive and dangerous.

- Lower DASA score at admission (P = .001), shorter length of stay (P < .001), adult age (P = .001), female sex (P = .042), and Black race, compared with White race (P = .001), were significantly associated with longer restraint duration, which may serve as a proxy for psychiatric symptom severity.

- Neither age group alone (adolescent or adult) nor the interaction of race and age group was significantly associated with experiencing a restraint event, suggesting no evidence of “adultification.”

IN PRACTICE:

It’s important to raise awareness about racial differences in restraint events in inpatient psychiatric settings, the authors write, adding that addressing overcrowding and investing in bias assessment and restraint education may reduce bias in the care of agitated patients and the use of restraints.

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Sonali Singal, BS, Institute of Behavioral Science, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. It was published online in Psychiatric Services.

LIMITATIONS:

The variables analyzed in the study were limited by the retrospective chart review and by the available EMR data, which may have contained entry errors. Although the investigators used DASA scores to control for differences in aggression, they could not control for symptom severity. The study could not examine the impact of race on seclusion (involuntary confinement), a variable often examined in tandem with restraint, because there were too few such events. The analysis also did not control for substance use disorder, which can influence a patient’s behavior and be related to restraint use.

DISCLOSURES:

Ms. Singal reported no relevant financial relationships. The original article has disclosures of other authors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new research suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study, part of a larger retrospective chart review of inpatient psychiatric electronic medical records (EMRs), included 29,739 adolescents (aged 12-17 years) and adults admitted because of severe and disruptive psychiatric illness or concerns about self-harm.

- A restraint event was defined as a physician-ordered physical or mechanical hold in which patients are unable to move their limbs, body, or head or are given medication to restrict their movement.

- Researchers used scores on the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA) at admission to assess risk for aggression among high-risk psychiatric inpatients (scores ranged from a low of 0 to a high of 7).

- From restraint event data extracted from the EMR, researchers investigated whether restraint frequency or duration was affected by “adultification,” a form of racial bias in which adolescents are perceived as being older than their actual age and are treated accordingly.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the entire cohort, 1867 (6.3%) experienced a restraint event, and 27,872 (93.7%) did not.

- Compared with White patients, restraint was 85% more likely among Black patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; P < .001) and 36% more likely among multiracial patients (aOR, 1.36; P = .006), which researchers suggest may reflect systemic racism within psychiatry and medicine, as well as an implicit or learned perception that people of color are more aggressive and dangerous.

- Lower DASA score at admission (P = .001), shorter length of stay (P < .001), adult age (P = .001), female sex (P = .042), and Black race, compared with White race (P = .001), were significantly associated with longer restraint duration, which may serve as a proxy for psychiatric symptom severity.

- Neither age group alone (adolescent or adult) nor the interaction of race and age group was significantly associated with experiencing a restraint event, suggesting no evidence of “adultification.”

IN PRACTICE:

It’s important to raise awareness about racial differences in restraint events in inpatient psychiatric settings, the authors write, adding that addressing overcrowding and investing in bias assessment and restraint education may reduce bias in the care of agitated patients and the use of restraints.

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Sonali Singal, BS, Institute of Behavioral Science, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. It was published online in Psychiatric Services.

LIMITATIONS:

The variables analyzed in the study were limited by the retrospective chart review and by the available EMR data, which may have contained entry errors. Although the investigators used DASA scores to control for differences in aggression, they could not control for symptom severity. The study could not examine the impact of race on seclusion (involuntary confinement), a variable often examined in tandem with restraint, because there were too few such events. The analysis also did not control for substance use disorder, which can influence a patient’s behavior and be related to restraint use.

DISCLOSURES:

Ms. Singal reported no relevant financial relationships. The original article has disclosures of other authors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

Black men are at higher risk of prostate cancer at younger ages, lower PSA levels

Black men are at higher risk of prostate cancer than their White counterparts at younger ages and lower prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, a large new study conducted in a Veterans Affairs health care system suggests.

The findings suggest the need for PSA biopsy thresholds that are set with better understanding of patients’ risk factors, said the authors, led by Kyung Min Lee, PhD, with VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, at Salt Lake City Health Care System.

The study, which included more than 280,000 veterans, was published online in Cancer.

Risk higher, regardless of PSA level before biopsy

The researchers found that self-identified Black men are more likely than White men to be diagnosed with prostate cancer on their first prostate biopsy after controlling for age, prebiopsy PSA count, statin use, smoking status, and several socioeconomic variables.

Among the highlighted results are that a Black man who had a PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL before biopsy “had the same risk of prostate cancer as a White man with a PSA level 3.4 times higher [13.4 ng/mL].”

The gap was even more evident at younger ages. “Among men aged 60 years or younger, a Black man with a prebiopsy PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL had the same risk of prostate cancer as a White man with PSA level 3.7 times higher,” they wrote.

Researchers also found that Black veterans sought PSA screening and underwent their first diagnostic prostate biopsy at a younger age than did their White counterparts. Logistic regression models were used to predict the likelihood of a prostate cancer diagnosis on the first biopsy for 75,295 Black and 207,658 White male veterans.

U.S. Black men have an 80% higher risk of prostate cancer that White men

Previous research has shown that, in the United States, Black men have an 80% higher risk than White men of developing prostate cancer and are 220% more likely to die from it. Rigorous early screening has been suggested to decrease deaths from prostate cancer in Black men, but because that population group is underrepresented in randomized controlled trials, evidence for this has been lacking, the authors wrote.

Different national screening guidelines reflect the lack of clarity about best protocols. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force acknowledges the higher risk but doesn’t make specific screening recommendations for Black men or those at higher risk. Conversely, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network “explicitly recommends earlier PSA screening and a shorter retest interval at lower PSA levels for populations at greater than average risk (including Black men). However, it does not otherwise recommend a different screening protocol.”

Social determinants of health may play a role

The reasons for the higher risk in Black men is unclear, the authors said, pointing out that recent studies suggest that “Black men may have higher genetic risk as assessed by polygenic scores.”

The authors wrote that nongenetic causes, such as access to care, mistrust of the health system, and environmental exposures may also be driving the association of Black race or ethnicity with higher risk of prostate cancer.

“Identifying and addressing these risk factors could further reduce racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledged that they are limited in their ability to account for socioeconomic status individually and used ZIP codes as proxies. Also, veterans generally have more comorbidities and mortality risks, compared with the general population.

The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

Black men are at higher risk of prostate cancer than their White counterparts at younger ages and lower prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, a large new study conducted in a Veterans Affairs health care system suggests.

The findings suggest the need for PSA biopsy thresholds that are set with better understanding of patients’ risk factors, said the authors, led by Kyung Min Lee, PhD, with VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, at Salt Lake City Health Care System.

The study, which included more than 280,000 veterans, was published online in Cancer.

Risk higher, regardless of PSA level before biopsy

The researchers found that self-identified Black men are more likely than White men to be diagnosed with prostate cancer on their first prostate biopsy after controlling for age, prebiopsy PSA count, statin use, smoking status, and several socioeconomic variables.

Among the highlighted results are that a Black man who had a PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL before biopsy “had the same risk of prostate cancer as a White man with a PSA level 3.4 times higher [13.4 ng/mL].”

The gap was even more evident at younger ages. “Among men aged 60 years or younger, a Black man with a prebiopsy PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL had the same risk of prostate cancer as a White man with PSA level 3.7 times higher,” they wrote.

Researchers also found that Black veterans sought PSA screening and underwent their first diagnostic prostate biopsy at a younger age than did their White counterparts. Logistic regression models were used to predict the likelihood of a prostate cancer diagnosis on the first biopsy for 75,295 Black and 207,658 White male veterans.

U.S. Black men have an 80% higher risk of prostate cancer that White men

Previous research has shown that, in the United States, Black men have an 80% higher risk than White men of developing prostate cancer and are 220% more likely to die from it. Rigorous early screening has been suggested to decrease deaths from prostate cancer in Black men, but because that population group is underrepresented in randomized controlled trials, evidence for this has been lacking, the authors wrote.

Different national screening guidelines reflect the lack of clarity about best protocols. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force acknowledges the higher risk but doesn’t make specific screening recommendations for Black men or those at higher risk. Conversely, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network “explicitly recommends earlier PSA screening and a shorter retest interval at lower PSA levels for populations at greater than average risk (including Black men). However, it does not otherwise recommend a different screening protocol.”

Social determinants of health may play a role

The reasons for the higher risk in Black men is unclear, the authors said, pointing out that recent studies suggest that “Black men may have higher genetic risk as assessed by polygenic scores.”

The authors wrote that nongenetic causes, such as access to care, mistrust of the health system, and environmental exposures may also be driving the association of Black race or ethnicity with higher risk of prostate cancer.

“Identifying and addressing these risk factors could further reduce racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledged that they are limited in their ability to account for socioeconomic status individually and used ZIP codes as proxies. Also, veterans generally have more comorbidities and mortality risks, compared with the general population.

The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

Black men are at higher risk of prostate cancer than their White counterparts at younger ages and lower prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, a large new study conducted in a Veterans Affairs health care system suggests.

The findings suggest the need for PSA biopsy thresholds that are set with better understanding of patients’ risk factors, said the authors, led by Kyung Min Lee, PhD, with VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, at Salt Lake City Health Care System.

The study, which included more than 280,000 veterans, was published online in Cancer.

Risk higher, regardless of PSA level before biopsy

The researchers found that self-identified Black men are more likely than White men to be diagnosed with prostate cancer on their first prostate biopsy after controlling for age, prebiopsy PSA count, statin use, smoking status, and several socioeconomic variables.

Among the highlighted results are that a Black man who had a PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL before biopsy “had the same risk of prostate cancer as a White man with a PSA level 3.4 times higher [13.4 ng/mL].”

The gap was even more evident at younger ages. “Among men aged 60 years or younger, a Black man with a prebiopsy PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL had the same risk of prostate cancer as a White man with PSA level 3.7 times higher,” they wrote.

Researchers also found that Black veterans sought PSA screening and underwent their first diagnostic prostate biopsy at a younger age than did their White counterparts. Logistic regression models were used to predict the likelihood of a prostate cancer diagnosis on the first biopsy for 75,295 Black and 207,658 White male veterans.

U.S. Black men have an 80% higher risk of prostate cancer that White men

Previous research has shown that, in the United States, Black men have an 80% higher risk than White men of developing prostate cancer and are 220% more likely to die from it. Rigorous early screening has been suggested to decrease deaths from prostate cancer in Black men, but because that population group is underrepresented in randomized controlled trials, evidence for this has been lacking, the authors wrote.

Different national screening guidelines reflect the lack of clarity about best protocols. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force acknowledges the higher risk but doesn’t make specific screening recommendations for Black men or those at higher risk. Conversely, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network “explicitly recommends earlier PSA screening and a shorter retest interval at lower PSA levels for populations at greater than average risk (including Black men). However, it does not otherwise recommend a different screening protocol.”

Social determinants of health may play a role

The reasons for the higher risk in Black men is unclear, the authors said, pointing out that recent studies suggest that “Black men may have higher genetic risk as assessed by polygenic scores.”

The authors wrote that nongenetic causes, such as access to care, mistrust of the health system, and environmental exposures may also be driving the association of Black race or ethnicity with higher risk of prostate cancer.

“Identifying and addressing these risk factors could further reduce racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledged that they are limited in their ability to account for socioeconomic status individually and used ZIP codes as proxies. Also, veterans generally have more comorbidities and mortality risks, compared with the general population.

The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM CANCER

Race-specific lung-function values may skew IPF testing

HONOLULU – Old habits die hard, especially when it comes to pulmonary function testing in a diverse population of patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Specifically, pulmonary care clinicians may be habitually relying on outdated and inaccurate race-specific reference values when evaluating respiratory impairment in persons of African and Hispanic/Latino ancestry, which can result in underrecognition, underdiagnosis, and undertreatment, reported Ayodeji Adegunsoye, MD, from the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Our results make a compelling case for re-evaluating the use of race as a physiological variable, and highlight the need to offer equitable and optimal care for all patients, regardless of their race or ethnicity,” Dr. Adegunsoye said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Flawed assumptions

In an interview, Dr. Adegunsoye noted that race-specific notions, such as the automatic assumption that Black people have less lung capacity than White people, are baked into clinical practice and passed on as clinical wisdom from one generation of clinicians to the next.

Pulmonary function reference values that are used to make a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Black or Hispanic/Latino patients “appear flawed when we use race-specific values. And beyond the diagnosis, it also appears to impact eligibility for key interventional strategies for managing the disease itself,” he said.

The use of race-specific equations can falsely inflate percent-predicted pulmonary function values in non-White patients, and make it seem as if a patient has normal lung function when in fact he may be have impaired function.

For example, using race-based reference values a Black patient and a White patient may appear to have the same absolute forced vital capacity readings, but different FVC percent predicted (FVCpp), which can mean a missed diagnosis.

Investigators who studied the association between self-identified race and visually identified emphysema among 2,674 participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study found that using standard equations to adjust for racial differences in lung-function measures appeared to miss emphysema in a significant proportion of Black patients.

PF registry study

In the current study, to see whether the use of race-neutral equations for evaluating FVCpp could change access to health care in patients with ILD, Dr. Adegunsoye and colleagues used both race-specific and race-neutral equations to calculate FVCpp values among separate cohorts of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and White patients enrolled in the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry who had pulmonary functions test within about 90 days of enrollment.

The race-specific equations used to calculate FVCpp was that published in 1999 by Hankinson and colleagues in American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. The race-neutral Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) equations by Bowerman and colleagues were developed in 2022 and published in March 2023 in the same journal.

The investigators defined access to care as enrollment in ILD clinical trials for patients with FVCpp greater than 45% but less than 90%, and US payer access to antifibrotic therapy for patients with FVCpp of greater than 55% but less than 82%.

They found that 22% of Black patients were misclassified in their eligibility for clinical trials in each of two scenarios – those who would be excluded from trials using the 1999 criteria but included using the 2022 criteria, and vice versa, that is included with 1999 criteria but excluded by the 2022 GLI criteria. In contrast, 14% of Hispanic Latino patients and 12% of White patients were misclassified.

Using the 1999 criteria to exclude patients because their values were ostensibly higher than the upper cutoff meant that 10.3% of Black patients who might benefit would be ineligible for clinical trial, compared with 0% of Hispanic/Latinos and 0.1% of Whites.

Similarly, 11.5% of Black patients but no Hispanic/Latino or White patients would be considered eligible for clinical trials using the old criteria but ineligible under the new criteria.

Regarding antifibrotic therapy eligibility, the respective misclassification rates were 21%, 17%, and 19%.

“Our study showed that use of race-specific equations may confound lung function tests, potentially leading to misclassification, delayed diagnosis, and inadequate treatment provision. While our study suggests potential disparities in access to health care for patients with interstitial lung disease facilitated by race-specific equations, further research is required to fully comprehend the implications,” the investigators wrote.

ATS statement

In an interview, Juan Wisnievsky, MD, DrPh, from Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, who also chairs the Health Equity and Diversity Committee for the American Thoracic Society, pointed to a recent ATS statement he coauthored citing evidence for replacing race and ethnicity-specific equations with race-neutral average reference equations.

“This use of race and ethnicity may contribute to health disparities by norming differences in pulmonary function. In the United States and globally, race serves as a social construct that is based on appearance and reflects social values, structures, and practices. Classification of people into racial and ethnic groups differs geographically and temporally. These considerations challenge the notion that racial and ethnic categories have biological meaning and question the use of race in PFT interpretation,” the statement authors wrote.

“There is some agreement that race-based equations shouldn’t be used, but all the potential consequences of doing that and which equations would be the best ones to use to replace them is a bit unclear,” Dr. Wisnievsky said.

He was not involved in the study by Dr. Adegunsoye and colleagues.

Data used in the study were derived from research sponsored by F. Hoffman–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Adegunsoye disclosed consultancy fees from AbbVie, Inogen, F. Hoffman–La Roche, Medscape, and PatientMpower; speaking/advisory fees from Boehringer Ingelheim; and grants/award from the CHEST Foundation, Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wisnievsky had no relevant disclosures.

HONOLULU – Old habits die hard, especially when it comes to pulmonary function testing in a diverse population of patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Specifically, pulmonary care clinicians may be habitually relying on outdated and inaccurate race-specific reference values when evaluating respiratory impairment in persons of African and Hispanic/Latino ancestry, which can result in underrecognition, underdiagnosis, and undertreatment, reported Ayodeji Adegunsoye, MD, from the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Our results make a compelling case for re-evaluating the use of race as a physiological variable, and highlight the need to offer equitable and optimal care for all patients, regardless of their race or ethnicity,” Dr. Adegunsoye said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Flawed assumptions

In an interview, Dr. Adegunsoye noted that race-specific notions, such as the automatic assumption that Black people have less lung capacity than White people, are baked into clinical practice and passed on as clinical wisdom from one generation of clinicians to the next.

Pulmonary function reference values that are used to make a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Black or Hispanic/Latino patients “appear flawed when we use race-specific values. And beyond the diagnosis, it also appears to impact eligibility for key interventional strategies for managing the disease itself,” he said.

The use of race-specific equations can falsely inflate percent-predicted pulmonary function values in non-White patients, and make it seem as if a patient has normal lung function when in fact he may be have impaired function.

For example, using race-based reference values a Black patient and a White patient may appear to have the same absolute forced vital capacity readings, but different FVC percent predicted (FVCpp), which can mean a missed diagnosis.

Investigators who studied the association between self-identified race and visually identified emphysema among 2,674 participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study found that using standard equations to adjust for racial differences in lung-function measures appeared to miss emphysema in a significant proportion of Black patients.

PF registry study

In the current study, to see whether the use of race-neutral equations for evaluating FVCpp could change access to health care in patients with ILD, Dr. Adegunsoye and colleagues used both race-specific and race-neutral equations to calculate FVCpp values among separate cohorts of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and White patients enrolled in the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry who had pulmonary functions test within about 90 days of enrollment.

The race-specific equations used to calculate FVCpp was that published in 1999 by Hankinson and colleagues in American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. The race-neutral Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) equations by Bowerman and colleagues were developed in 2022 and published in March 2023 in the same journal.

The investigators defined access to care as enrollment in ILD clinical trials for patients with FVCpp greater than 45% but less than 90%, and US payer access to antifibrotic therapy for patients with FVCpp of greater than 55% but less than 82%.

They found that 22% of Black patients were misclassified in their eligibility for clinical trials in each of two scenarios – those who would be excluded from trials using the 1999 criteria but included using the 2022 criteria, and vice versa, that is included with 1999 criteria but excluded by the 2022 GLI criteria. In contrast, 14% of Hispanic Latino patients and 12% of White patients were misclassified.

Using the 1999 criteria to exclude patients because their values were ostensibly higher than the upper cutoff meant that 10.3% of Black patients who might benefit would be ineligible for clinical trial, compared with 0% of Hispanic/Latinos and 0.1% of Whites.

Similarly, 11.5% of Black patients but no Hispanic/Latino or White patients would be considered eligible for clinical trials using the old criteria but ineligible under the new criteria.

Regarding antifibrotic therapy eligibility, the respective misclassification rates were 21%, 17%, and 19%.

“Our study showed that use of race-specific equations may confound lung function tests, potentially leading to misclassification, delayed diagnosis, and inadequate treatment provision. While our study suggests potential disparities in access to health care for patients with interstitial lung disease facilitated by race-specific equations, further research is required to fully comprehend the implications,” the investigators wrote.

ATS statement

In an interview, Juan Wisnievsky, MD, DrPh, from Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, who also chairs the Health Equity and Diversity Committee for the American Thoracic Society, pointed to a recent ATS statement he coauthored citing evidence for replacing race and ethnicity-specific equations with race-neutral average reference equations.

“This use of race and ethnicity may contribute to health disparities by norming differences in pulmonary function. In the United States and globally, race serves as a social construct that is based on appearance and reflects social values, structures, and practices. Classification of people into racial and ethnic groups differs geographically and temporally. These considerations challenge the notion that racial and ethnic categories have biological meaning and question the use of race in PFT interpretation,” the statement authors wrote.

“There is some agreement that race-based equations shouldn’t be used, but all the potential consequences of doing that and which equations would be the best ones to use to replace them is a bit unclear,” Dr. Wisnievsky said.

He was not involved in the study by Dr. Adegunsoye and colleagues.

Data used in the study were derived from research sponsored by F. Hoffman–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Adegunsoye disclosed consultancy fees from AbbVie, Inogen, F. Hoffman–La Roche, Medscape, and PatientMpower; speaking/advisory fees from Boehringer Ingelheim; and grants/award from the CHEST Foundation, Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wisnievsky had no relevant disclosures.

HONOLULU – Old habits die hard, especially when it comes to pulmonary function testing in a diverse population of patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Specifically, pulmonary care clinicians may be habitually relying on outdated and inaccurate race-specific reference values when evaluating respiratory impairment in persons of African and Hispanic/Latino ancestry, which can result in underrecognition, underdiagnosis, and undertreatment, reported Ayodeji Adegunsoye, MD, from the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Our results make a compelling case for re-evaluating the use of race as a physiological variable, and highlight the need to offer equitable and optimal care for all patients, regardless of their race or ethnicity,” Dr. Adegunsoye said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Flawed assumptions

In an interview, Dr. Adegunsoye noted that race-specific notions, such as the automatic assumption that Black people have less lung capacity than White people, are baked into clinical practice and passed on as clinical wisdom from one generation of clinicians to the next.

Pulmonary function reference values that are used to make a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Black or Hispanic/Latino patients “appear flawed when we use race-specific values. And beyond the diagnosis, it also appears to impact eligibility for key interventional strategies for managing the disease itself,” he said.

The use of race-specific equations can falsely inflate percent-predicted pulmonary function values in non-White patients, and make it seem as if a patient has normal lung function when in fact he may be have impaired function.

For example, using race-based reference values a Black patient and a White patient may appear to have the same absolute forced vital capacity readings, but different FVC percent predicted (FVCpp), which can mean a missed diagnosis.

Investigators who studied the association between self-identified race and visually identified emphysema among 2,674 participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study found that using standard equations to adjust for racial differences in lung-function measures appeared to miss emphysema in a significant proportion of Black patients.

PF registry study

In the current study, to see whether the use of race-neutral equations for evaluating FVCpp could change access to health care in patients with ILD, Dr. Adegunsoye and colleagues used both race-specific and race-neutral equations to calculate FVCpp values among separate cohorts of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and White patients enrolled in the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry who had pulmonary functions test within about 90 days of enrollment.

The race-specific equations used to calculate FVCpp was that published in 1999 by Hankinson and colleagues in American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. The race-neutral Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) equations by Bowerman and colleagues were developed in 2022 and published in March 2023 in the same journal.

The investigators defined access to care as enrollment in ILD clinical trials for patients with FVCpp greater than 45% but less than 90%, and US payer access to antifibrotic therapy for patients with FVCpp of greater than 55% but less than 82%.

They found that 22% of Black patients were misclassified in their eligibility for clinical trials in each of two scenarios – those who would be excluded from trials using the 1999 criteria but included using the 2022 criteria, and vice versa, that is included with 1999 criteria but excluded by the 2022 GLI criteria. In contrast, 14% of Hispanic Latino patients and 12% of White patients were misclassified.

Using the 1999 criteria to exclude patients because their values were ostensibly higher than the upper cutoff meant that 10.3% of Black patients who might benefit would be ineligible for clinical trial, compared with 0% of Hispanic/Latinos and 0.1% of Whites.

Similarly, 11.5% of Black patients but no Hispanic/Latino or White patients would be considered eligible for clinical trials using the old criteria but ineligible under the new criteria.

Regarding antifibrotic therapy eligibility, the respective misclassification rates were 21%, 17%, and 19%.

“Our study showed that use of race-specific equations may confound lung function tests, potentially leading to misclassification, delayed diagnosis, and inadequate treatment provision. While our study suggests potential disparities in access to health care for patients with interstitial lung disease facilitated by race-specific equations, further research is required to fully comprehend the implications,” the investigators wrote.

ATS statement

In an interview, Juan Wisnievsky, MD, DrPh, from Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, who also chairs the Health Equity and Diversity Committee for the American Thoracic Society, pointed to a recent ATS statement he coauthored citing evidence for replacing race and ethnicity-specific equations with race-neutral average reference equations.

“This use of race and ethnicity may contribute to health disparities by norming differences in pulmonary function. In the United States and globally, race serves as a social construct that is based on appearance and reflects social values, structures, and practices. Classification of people into racial and ethnic groups differs geographically and temporally. These considerations challenge the notion that racial and ethnic categories have biological meaning and question the use of race in PFT interpretation,” the statement authors wrote.

“There is some agreement that race-based equations shouldn’t be used, but all the potential consequences of doing that and which equations would be the best ones to use to replace them is a bit unclear,” Dr. Wisnievsky said.

He was not involved in the study by Dr. Adegunsoye and colleagues.

Data used in the study were derived from research sponsored by F. Hoffman–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Adegunsoye disclosed consultancy fees from AbbVie, Inogen, F. Hoffman–La Roche, Medscape, and PatientMpower; speaking/advisory fees from Boehringer Ingelheim; and grants/award from the CHEST Foundation, Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wisnievsky had no relevant disclosures.

AT CHEST 2023

Attitudes Toward Utilization of Minimally Invasive Cosmetic Procedures in Black Women: Results of a Cross-sectional Survey

Beauty has been a topic of interest for centuries. Treatments and technologies have advanced, and more women are utilizing cosmetic procedures than ever before, especially neuromodulators, minimally invasive procedures, and topical treatments.1 Over the last decade, there was a 99% increase in minimally invasive cosmetic procedures in the United States.2 There also has been an observable increase in the utilization of cosmetic procedures by Black patients in recent years; the American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported that the number of cosmetic plastic surgery procedures performed on “ethnic patients” (referring to Asian, Black, or Hispanic patients) increased 243% from 2000 to 2013,3 possibly attributed to increased accessibility, awareness of procedures due to social media, cultural acceptance, and affordability. Minimally invasive procedures are considerably less expensive than major surgical procedures and are becoming progressively more affordable, with numerous financing options available.2 Additionally, neuromodulators and fillers are now commonly administered by nonaesthetic health professionals including dentists and nurses, which has increased accessibility of these procedures among patients who typically may not seek out a consultation with a plastic surgeon or dermatologist.4

When examining the most common cosmetic procedures collectively sought out by patients with skin of color (SOC), it has been found that an even skin tone is a highly desirable feature that impacts the selection of products and procedures in this particular patient population.5 Black, Hispanic, and Asian women report fewer signs of facial aging compared to White women in the glabellar lines, crow’s-feet, oral commissures, perioral lines, and lips.6 Increased melanocytes in darker skin types help prevent photoaging but also increase susceptibility to dyschromia. Prior studies have reported the most common concerns by patients with SOC are dyschromic disorders such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, and melasma.7 Common minimally invasive cosmetic procedures utilized by the SOC population include chemical peels, laser treatments, and injectables. Fillers are utilized more for volume loss in SOC patients rather than for the deep furrows and rhytides commonly seen in the lower face of White patients.8

We conducted a survey among Black women currently residing in the United States to better understand attitudes toward beauty and aging as well as the utilization of minimally invasive cosmetic procedures in this patient population.

Methods

An in-depth questionnaire comprised of 17 questions was created for this cross-sectional observational study. The study was submitted to and deemed exempt by the institutional review board at the University of Miami (Miami, Florida)(IRB #20211184). Survey participants primarily were recruited via social media posts on personal profiles of Black dermatologists, medical residents, and medicalstudents, including the authors, targeting Black women in the United States. Utilizing a method called snowball sampling, whereby study participants are used to recruit future participants, individuals were instructed to share the survey with their social network to assist with survey distribution. After participants provided informed consent, data were captured using the REDCap secure online data collection software. The questionnaire was structured to include a sociodemographic profile of respondents, attitudes toward beauty and aging, current usage of beauty products, prior utilization of cosmetic procedures, and intentions to use cosmetic procedures in the future. Surveys with incomplete consent forms, incomplete responses, and duplicate responses, as well as surveys from participants who were not residing in the United States at the time of survey completion, were excluded.

Data characteristics were summarized by frequency and percentage. A χ2 test was performed to compare participants’ age demographics with their attitudes toward beauty and aging, utilization of cosmetic procedures, and intention to try cosmetic procedures in the future. The Fisher exact test was used instead of the χ2 test when the expected cell count was less than 5. For all tests, P<.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 28.

Results

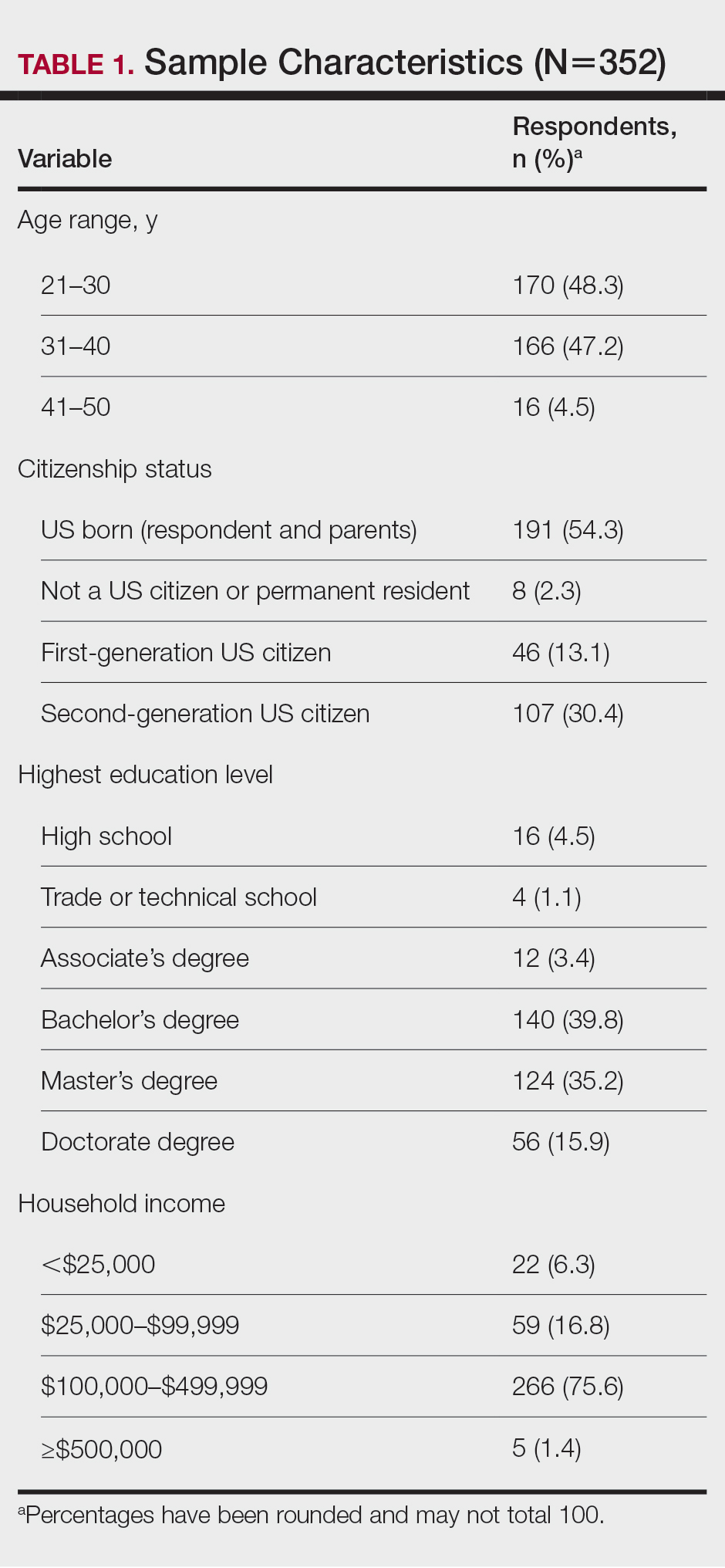

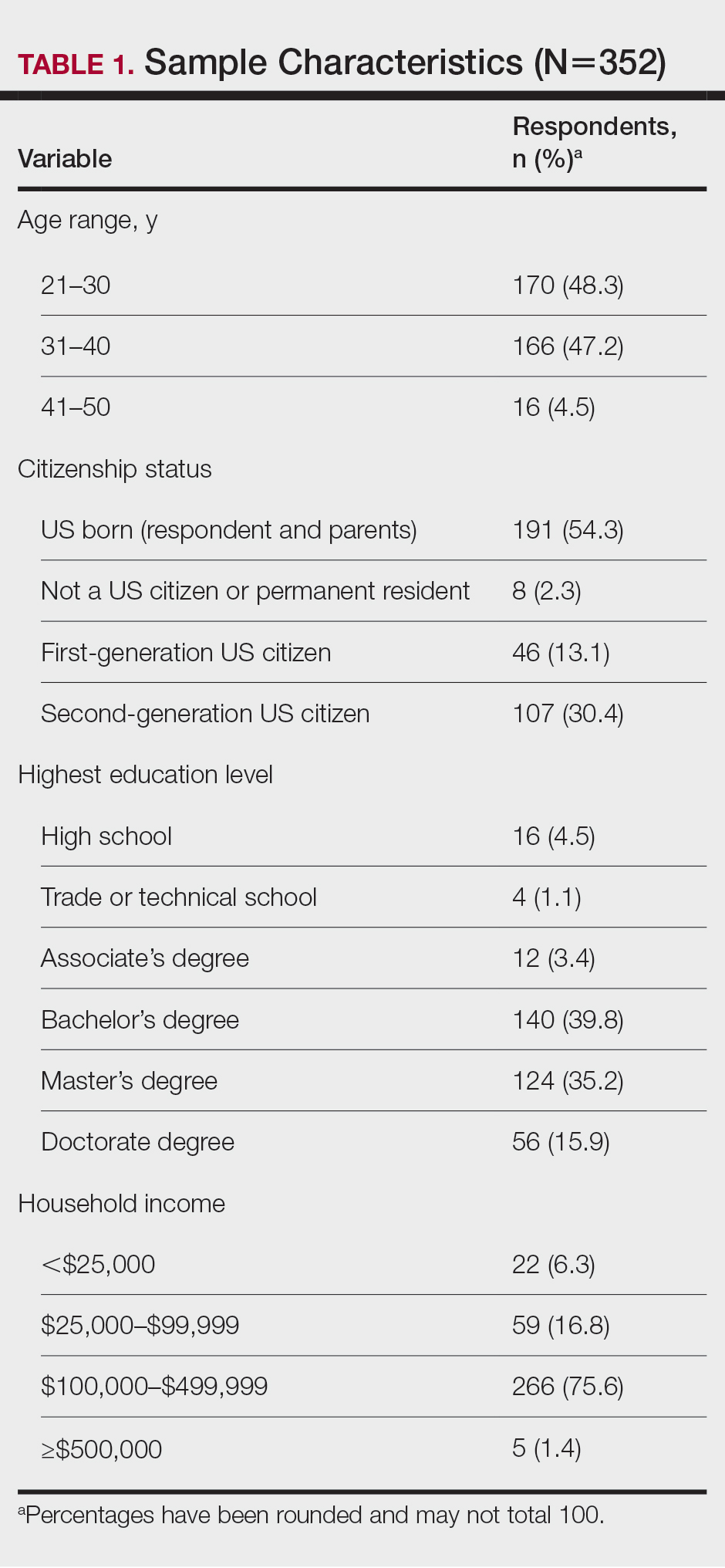

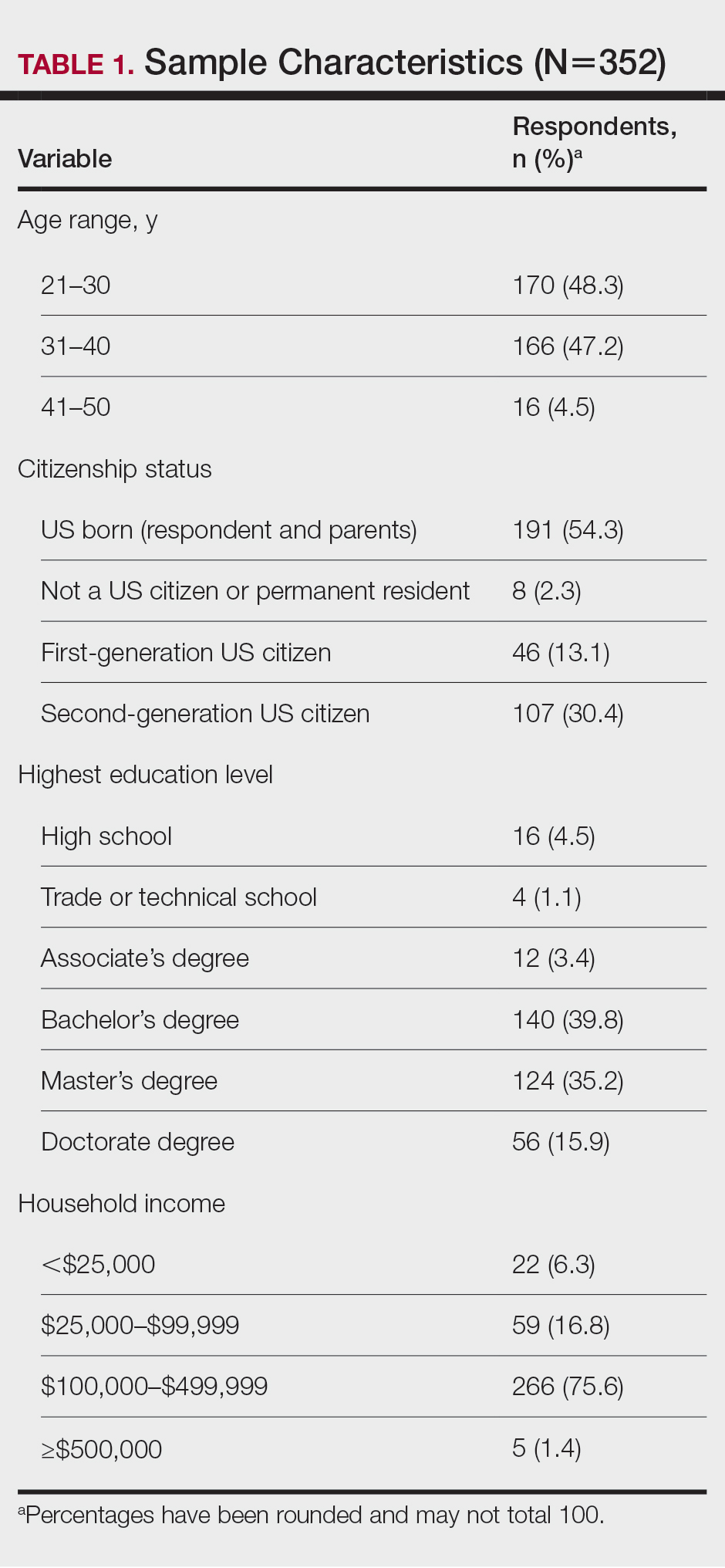

General Characteristics of Participants—A sample of 475 self-identified Black women aged 21 to 70 years participated in the study, and 352 eligible participants were included in the final analysis. Of the 352 eligible participants, 48.3% were aged 21 to 30 years, 47.2% were aged 31 to 40 years, and 4.5% were aged 41 to 50 years. All survey participants identified their race as Black; among them, 4% specified Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and 9% indicated that they held multiracial identities including White/Caucasian, Asian, and Native American backgrounds. Regarding the participants’ citizenship status, 54.3% reported that both they and their parents were born in the United States; 2.3% were not US citizens or permanent residents, 13.1% identified as first-generation Americans (born outside of the United States), and 30.4% identified as second-generation Americans (one or both parents born outside of the United States). Participant education levels (based on highest level) varied greatly: 4.5% were high school graduates, 1.1% attended trade or technical schools, 3.4% had associate’s degrees, 39.8% had bachelor’s degrees, 35.2% had master’s degrees, and 15.9% had doctorate degrees. Regarding household income, 6.3% earned less than $25,000 per year, 16.8% earned from $25,000 to $99,999, 75.6% earned from $100,000 to $499,999, and 1.4% earned $500,000 or more. Patient demographics are provided in Table 1.

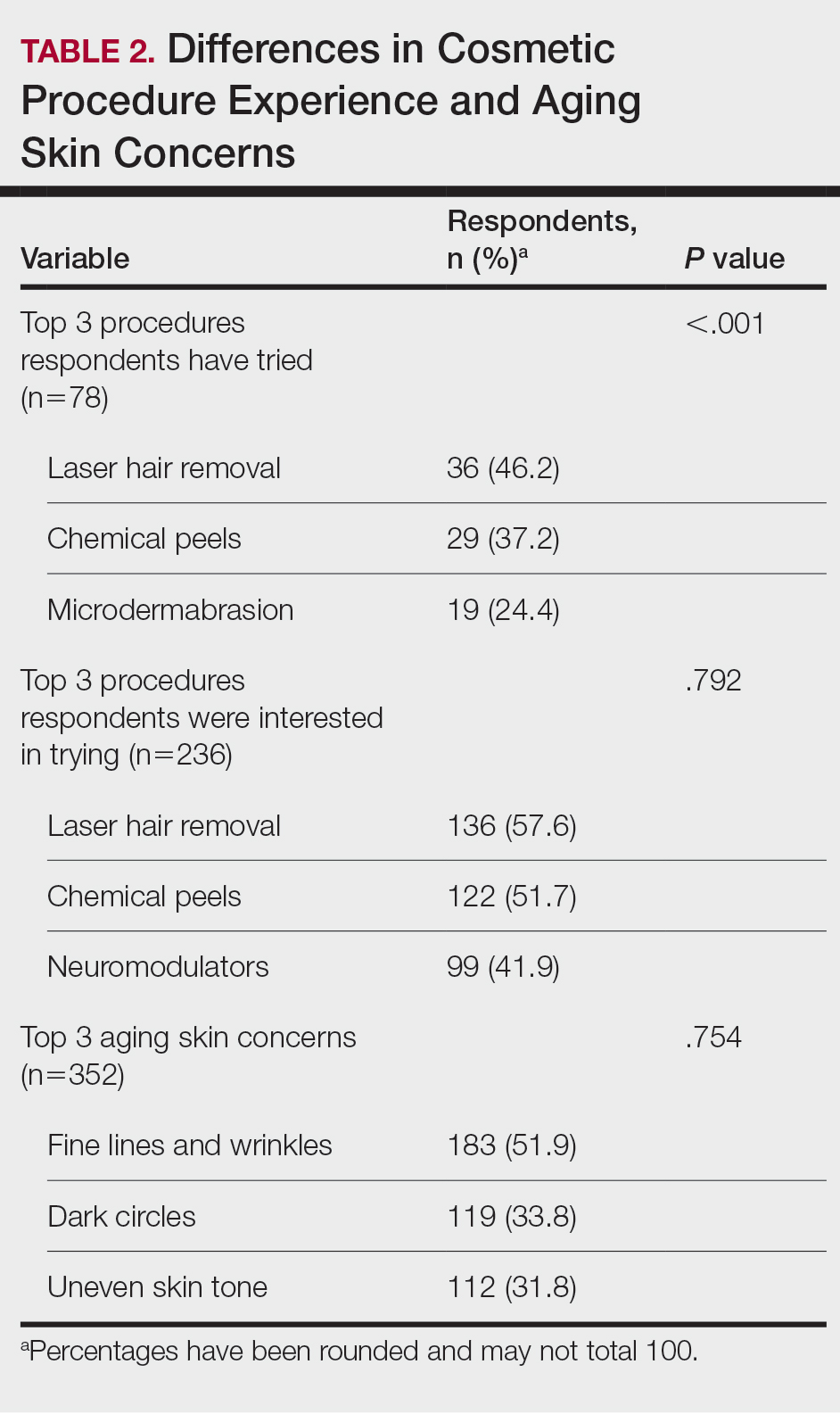

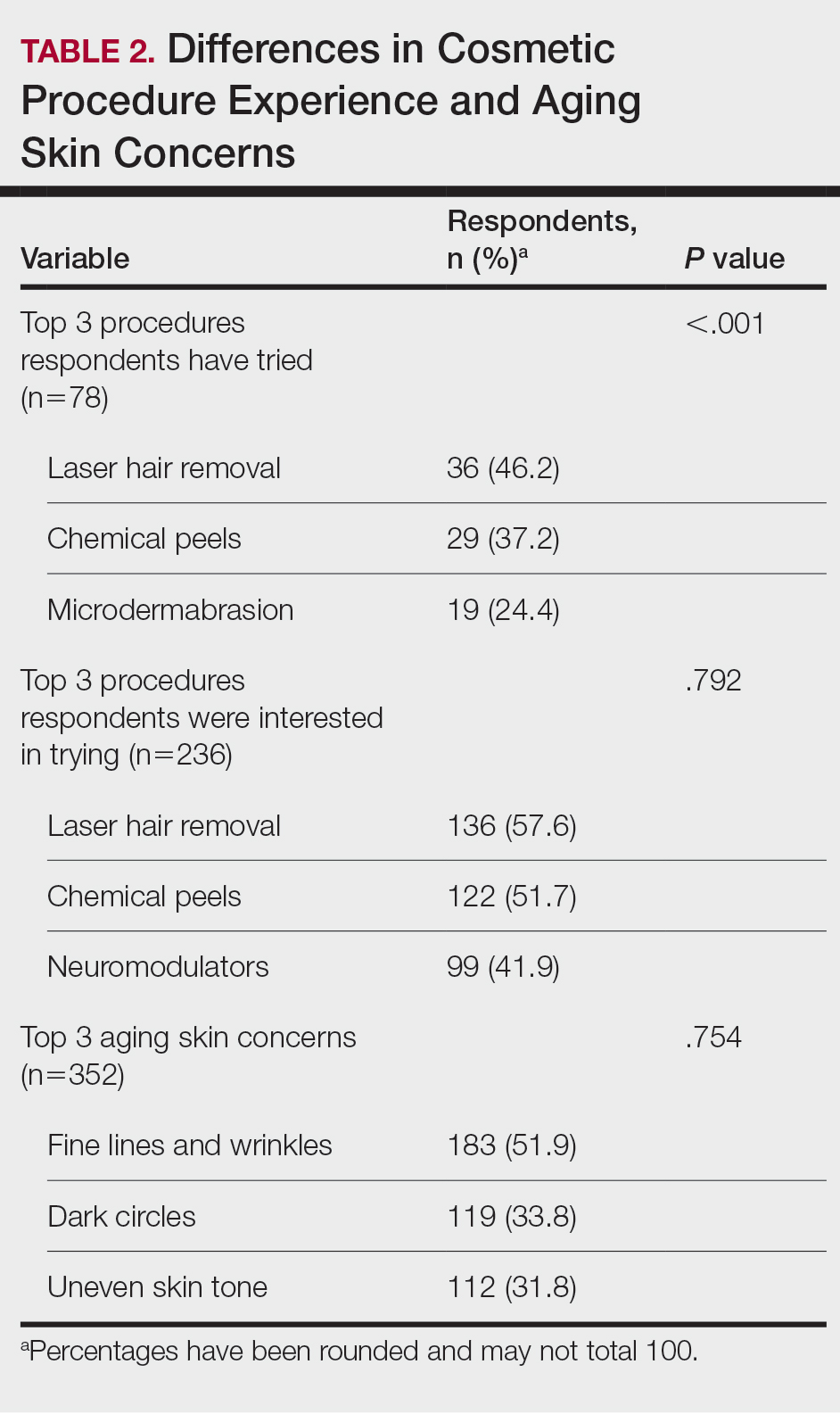

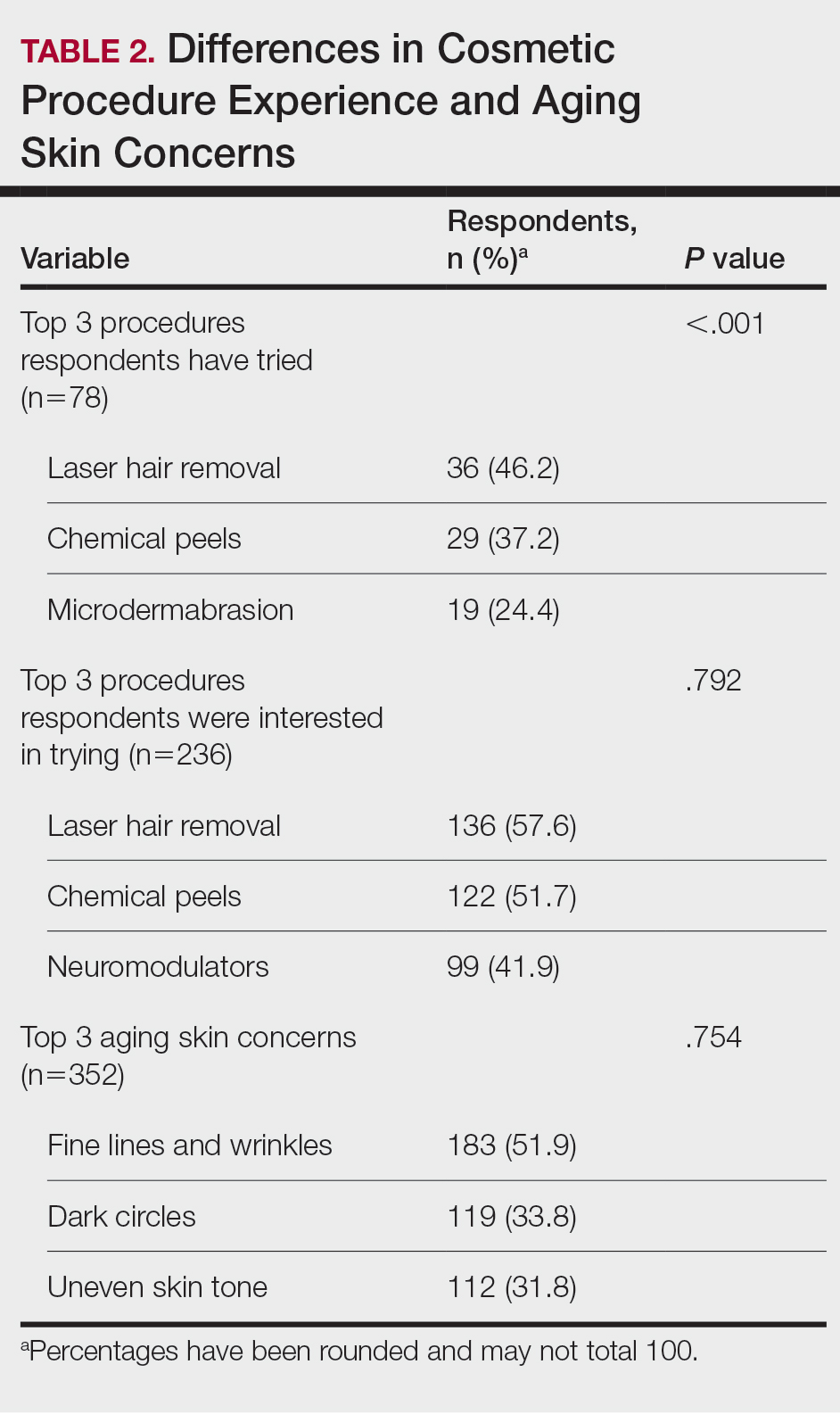

Cosmetic Skin Concerns—The top 3 aging skin concerns among participants were fine lines and wrinkles (51.9%), dark circles (33.8%), and uneven skin tone (31.8%) (Table 2). Approximately 5.4% of participants reported no desire to avoid the natural aging process. Among age groups, fine lines and wrinkles were a major concern for 51.7% of 21- to 30-year-olds, 47.6% of 31- to 40-year-olds, and 43.5% of 41- to 50-year-olds. Dark circles were a major concern for 61.3% of 21- to 30-year-olds, 44.4% of 31- to 40-year-olds, and 46.8% of 41- to 50-year-olds. Uneven skin tone was a major concern for 56.2% of 21- to 30-year-olds, 46.5% of 31- to 40-year-olds, and 31.2% of 41- to 50-year-olds. There was no statistically significant association between participants’ age and their concern with aging skin concerns.

Differences in Experience and Acceptance of Cosmetic Procedures—Regarding participants’ prior experience with cosmetic procedures, 22.3% had tried 1 or more procedures. Additionally, 67.0% reported having intentions of trying cosmetic procedures in the future, while 10.8% reported no intentions. Of those who were uninterested in trying cosmetic procedures, 78.9% (30/38) believed it unnecessary while 47.3% (18/38) reported a fear of looking unnatural. Other perceived deterrents to cosmetic procedures among this subset of participants were the need to repeat treatment for lasting results (28.9% [11/38]), too expensive (31.6% [12/38]), and fear of side effects (39.5% [15/38]). A significant difference was found between participants’ age and their experience with cosmetic procedures (P=.020). Participants aged 21 to 30 years reported they were more likely to want to try cosmetic procedures in the future. Participants aged 31 to 40 years were more likely to have already tried a cosmetic procedure. Participants aged 41 to 50 years were more likely to report no desire to try cosmetic procedures in the future. There was no significant difference in cosmetic procedure acceptance according to citizenship status, education level, or household income.

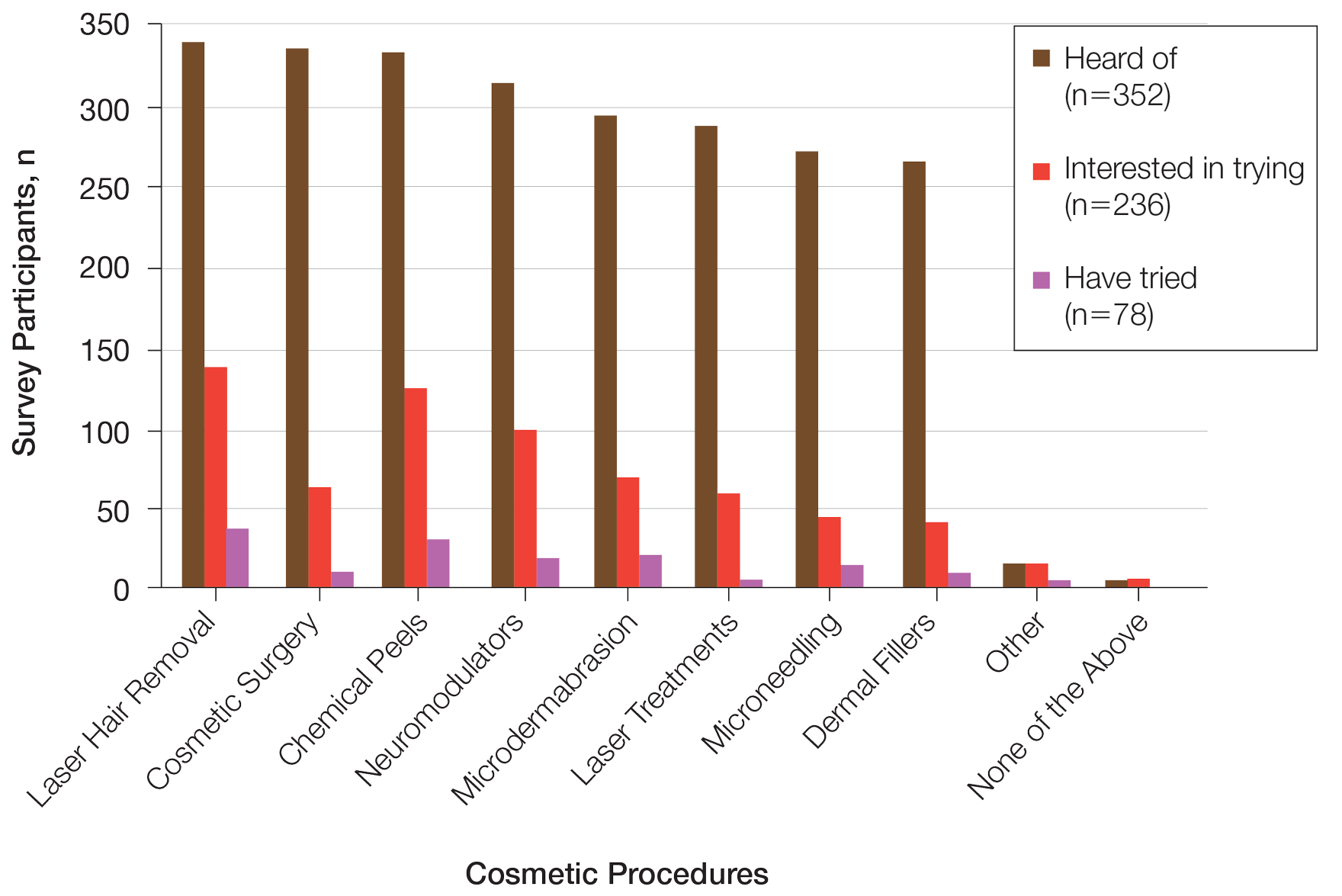

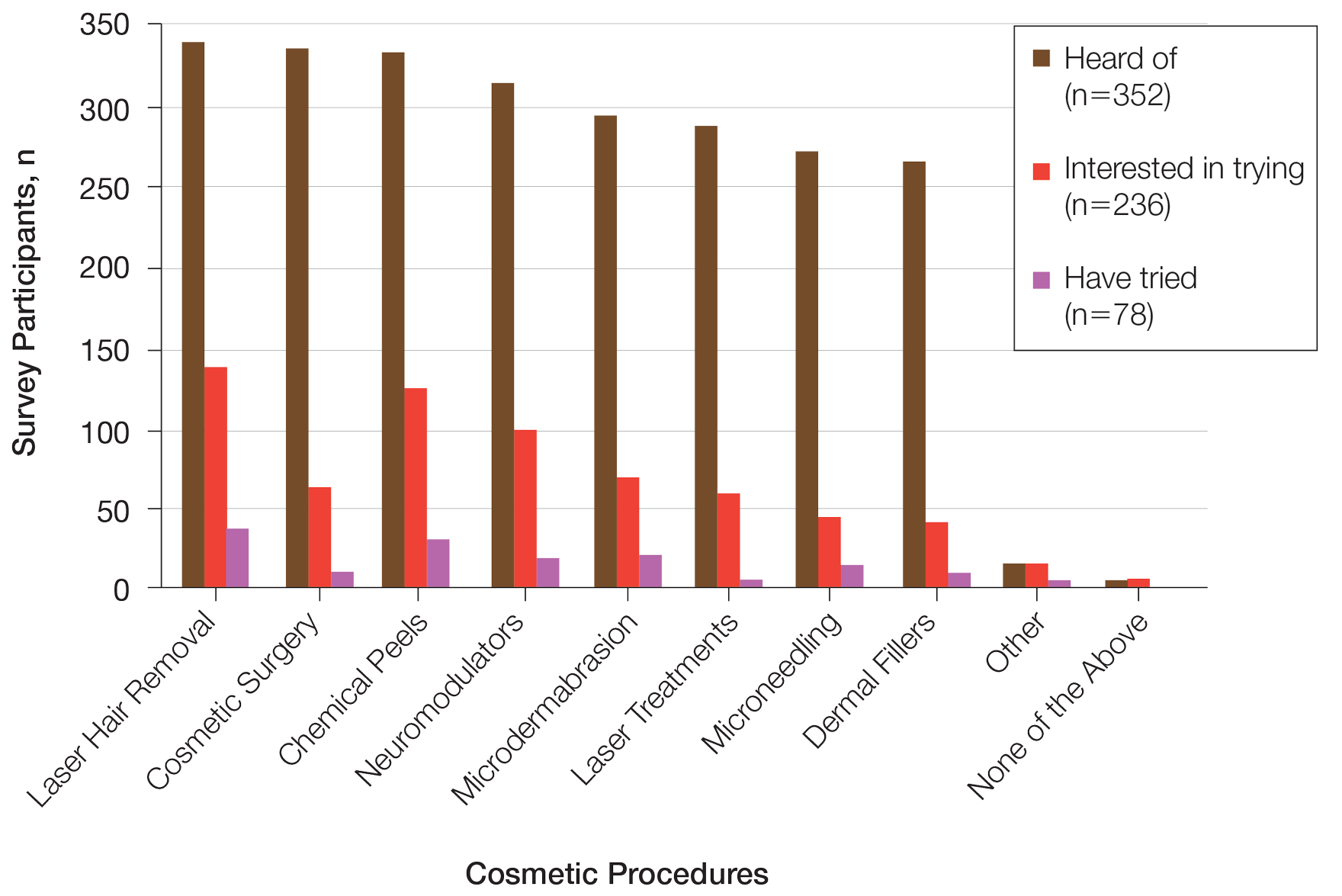

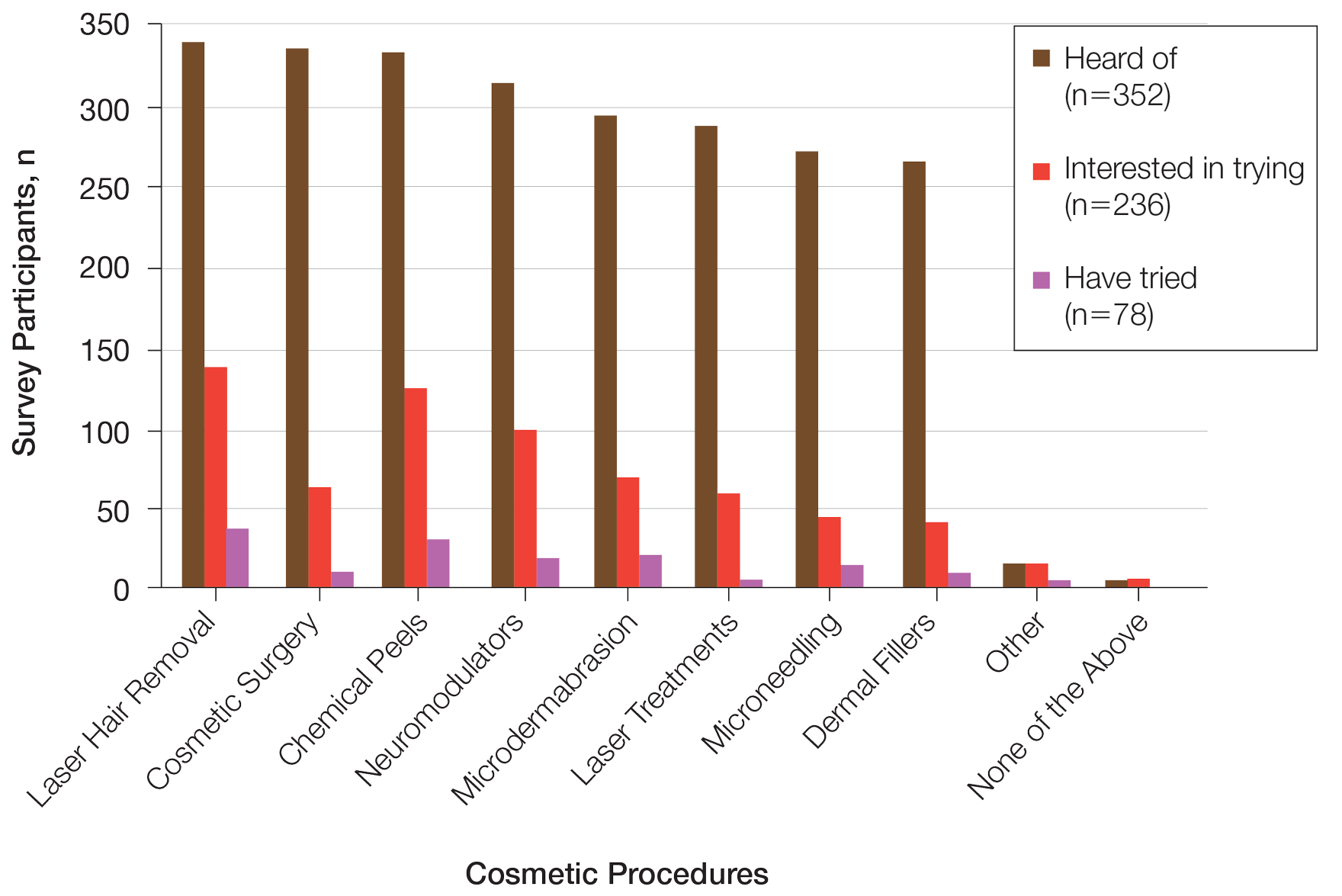

Differences in Cosmetic Procedure Experience—Study participants indicated awareness of typically practiced cosmetic procedures. Of the 78 participants who have tried cosmetic procedures (Figure 1), the most common were laser hair removal (46.2% [36/78]), chemical peels (37.2% [29/78]), and microdermabrasion (24.4% [19/78])(Table 2). Age significantly influenced the type of cosmetic procedures utilized by participants (P<.001). Laser hair removal was the most common cosmetic procedure utilized by participants aged 21 to 30 years (64.7%) and chemical peels in participants aged 31 to 40 years (47.8%); participants aged 41 to 50 years reported equal use of chemical peels (50.0%) and microdermabrasion (50.0%).

Two hundred thirty-six participants reported interest in trying cosmetic procedures, specifically laser hair removal (57.6%), chemical peels (51.7%), and neuromodulators (41.9%)(Table 2). Although not statistically significant, age appeared to influence interest levels in cosmetic procedures. Participants aged 21 to 30 years and 31 to 40 years were most interested in trying laser hair removal (60.7% and 58.3%, respectively). Participants aged 41 to 50 years were most interested in trying neuromodulators (36.4%). There was no significant association between age and intention to try neuromodulators, chemical peels, or laser hair removal.

Attitudes Toward Beauty—Approximately 40.6% of participants believed that peak beauty occurs when women reach their 20s, and 38.6% believed that peak beauty occurs when women reach their 30s. Participants’ strategies for maintaining beauty were assessed through their regular use of certain skin care products. The most frequently used skin care products were face wash or cleanser (92.6%), moisturizer (90.1%), lip balm (76.1%), and facial sunscreen (62.2%). Other commonly used items were serum (34.7%), toner (34.9%), topical vitamin C (33.2%), and retinol/retinoid products (33.0%). Only 2.3% of participants reported not using any skin care products regularly.

Perceptions of Aging—Concerning perceived external age, most respondents believed they looked younger than their true age (69.9%); 24.4% believed they looked their true age, and 5.7% believed they looked older. Perception of age also varied considerably by age group, though most believed they looked younger than their true age.

Comment

This survey helped to identify trends in cosmetic procedure acceptance and utilization in Black women. As expected, younger Black women were more receptive to cosmetic procedures, which was consistent with a recent finding that cosmetic procedures tend to be more widely accepted among younger generations overall.8 Participants aged 21 to 30 years had greater intentions to try a cosmetic procedure, while those aged 31 to 40 years were more likely to have tried 1 or more cosmetic procedures already, which may be because they are just beginning to see the signs of aging and are motivated to address these concerns. Additionally, women in this age group may be more likely to have a stable source of income and be able to afford these procedures. It is important to note that the population surveyed had a much higher reported household income than the average Black household income, with most respondents reporting an average annual income of $100,000 to $499,000. Our data also showed a trend toward greater acceptance and utilization of cosmetic procedures in those with higher levels of income, though the results were not statistically significant.

Respondents were most concerned about fine lines and wrinkles, followed by dark circles and uneven skin tone. One report in the literature (N=2000) indicated that the most common cosmetic concerns in women with SOC were hyperpigmentation/dark spots (86%) and blotchy or uneven skin (80%).9 Interestingly, sunscreen was one of the more commonly used products in our survey, which historically has not been the case among individuals with SOC10 and suggests that the attitudes and perceptions of SOC patients are changing to favor more frequent sunscreen use, at least among the younger generations. Because we did not specify moisturizer vs moisturizer with sun protection factor, the use of facial sunscreen may even be underestimated in our survey.

Compared to cosmetic surgery or dermal fillers, the procedures found to be most frequently utilized in our study population—microdermabrasion, chemical peels, and laser hair removal—are less invasive and fairly accessible with minimal downtime. An interesting topic for further research would be to investigate how the willingness of women to openly share their cosmetic procedure usage has changed over time. The rise of social media and influencer culture has undoubtedly had an impact on the sharing of such information. It also would have been interesting to ask participants where they receive the majority of their health/beauty information.

All skin types are susceptible to photoaging; however, melanin is known to have a natural photoprotective effect, resulting in a lesser degree and later onset of photoaging in patients with darker vs lighter skin.11 It has been reported that individuals with SOC show signs of facial aging on average a decade later than those with lighter skin tones,12 which may be why the majority of participants believed they look younger than they truly are. As expected, dyspigmentation was among the top skin concerns in our study population. Although melanin does offer some degree of protection against UVA and UVB, melanocyte lability with inflammation may make darker skin types more susceptible to pigmentary issues.13

Study Limitations—The income levels of our study population were not representative of typical Black American households, which is a limitation. Seventy-seven percent of our study population earned more than $100,000 annually, while only 18% of Black American households earned more than $100,000 in 2019.14 Another major limitation of our study was the lack of representation from older generations, as most participants were aged 21 to 40 years, which was expected, as it is the younger generation who typically is targeted by a snowball sampling method primarily shared through social media. Additionally, because participants were recruited from the social media profiles of medical professionals, followers of these accounts may be more interested in cosmetic procedures, skewing the study results. Finally, because geographic location was not captured in our initial data collection, we were unable to determine if results from a particular location within the United States were overrepresented in the data set.

Conclusion

Although the discourse around beauty and antiaging is constantly evolving, data about Black women frequently are underrepresented in the literature. The results of this study highlight the changing attitudes and perceptions of Black women regarding beauty, aging, and minimally invasive cosmetic procedures. Dermatologists should stay abreast of current trends in this population to be able to make appropriate, culturally sensitive recommendations to their Black patients—for example, pointing them to sunscreen brands that are best suited for darker skin.

- Ahn CS, Suchonwanit P, Foy CG, et al. Hair and scalp care in African American women who exercise. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:579-580.

- Prendergast TI, Ong’uti SK, Ortega G, et al. Differential trends in racial preferences for cosmetic surgery procedures. Am Surg. 2011;77:1081-1085.

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Briefing paper: plastic surgeryfor ethnic patients. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/briefing-papers/briefing-paper-plastic-surgery-for-ethnic-patients

- Small K, Kelly KM, Spinelli HM. Are nurse injectors the new norm? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:946-955.

- Quiñonez RL, Agbai ON, Burgess CM, et al. An update on cosmetic procedures in people of color. part 1: scientific background, assessment, preprocedure preparation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:715-725.

- Alexis AF, Grimes P, Boyd C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in self-assessed facial aging in women: results from a multinational study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1635-1648.

- Talakoub L, Wesley NO. Differences in perceptions of beauty and cosmetic procedures performed in ethnic patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:115-129.

- Alotaibi AS. Demographic and cultural differences in the acceptance and pursuit of cosmetic surgery: a systematic literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:E3501.

- Grimes PE. Skin and hair cosmetic issues in women of color. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:659-665.

- Buchanan Lunsford N, Berktold J, Holman DM, et al. Skin cancer knowledge, awareness, beliefs and preventive behaviors among black and Hispanic men and women. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:203-209.

- Alexis AF, Rossi, A. Photoaging in skin of color. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:367-370.

- Vashi NA, de Castro Maymone MB, Kundu RV. Aging differences in ethnic skin. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:31-38.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Tamir C, Budiman A, Noe-Bustamante L, et al. Facts about the U.S. Black population. Pew Research Center website. Published March 2, 2023. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/facts-about-the-us-black-population/

Beauty has been a topic of interest for centuries. Treatments and technologies have advanced, and more women are utilizing cosmetic procedures than ever before, especially neuromodulators, minimally invasive procedures, and topical treatments.1 Over the last decade, there was a 99% increase in minimally invasive cosmetic procedures in the United States.2 There also has been an observable increase in the utilization of cosmetic procedures by Black patients in recent years; the American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported that the number of cosmetic plastic surgery procedures performed on “ethnic patients” (referring to Asian, Black, or Hispanic patients) increased 243% from 2000 to 2013,3 possibly attributed to increased accessibility, awareness of procedures due to social media, cultural acceptance, and affordability. Minimally invasive procedures are considerably less expensive than major surgical procedures and are becoming progressively more affordable, with numerous financing options available.2 Additionally, neuromodulators and fillers are now commonly administered by nonaesthetic health professionals including dentists and nurses, which has increased accessibility of these procedures among patients who typically may not seek out a consultation with a plastic surgeon or dermatologist.4

When examining the most common cosmetic procedures collectively sought out by patients with skin of color (SOC), it has been found that an even skin tone is a highly desirable feature that impacts the selection of products and procedures in this particular patient population.5 Black, Hispanic, and Asian women report fewer signs of facial aging compared to White women in the glabellar lines, crow’s-feet, oral commissures, perioral lines, and lips.6 Increased melanocytes in darker skin types help prevent photoaging but also increase susceptibility to dyschromia. Prior studies have reported the most common concerns by patients with SOC are dyschromic disorders such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, and melasma.7 Common minimally invasive cosmetic procedures utilized by the SOC population include chemical peels, laser treatments, and injectables. Fillers are utilized more for volume loss in SOC patients rather than for the deep furrows and rhytides commonly seen in the lower face of White patients.8

We conducted a survey among Black women currently residing in the United States to better understand attitudes toward beauty and aging as well as the utilization of minimally invasive cosmetic procedures in this patient population.

Methods

An in-depth questionnaire comprised of 17 questions was created for this cross-sectional observational study. The study was submitted to and deemed exempt by the institutional review board at the University of Miami (Miami, Florida)(IRB #20211184). Survey participants primarily were recruited via social media posts on personal profiles of Black dermatologists, medical residents, and medicalstudents, including the authors, targeting Black women in the United States. Utilizing a method called snowball sampling, whereby study participants are used to recruit future participants, individuals were instructed to share the survey with their social network to assist with survey distribution. After participants provided informed consent, data were captured using the REDCap secure online data collection software. The questionnaire was structured to include a sociodemographic profile of respondents, attitudes toward beauty and aging, current usage of beauty products, prior utilization of cosmetic procedures, and intentions to use cosmetic procedures in the future. Surveys with incomplete consent forms, incomplete responses, and duplicate responses, as well as surveys from participants who were not residing in the United States at the time of survey completion, were excluded.

Data characteristics were summarized by frequency and percentage. A χ2 test was performed to compare participants’ age demographics with their attitudes toward beauty and aging, utilization of cosmetic procedures, and intention to try cosmetic procedures in the future. The Fisher exact test was used instead of the χ2 test when the expected cell count was less than 5. For all tests, P<.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 28.

Results

General Characteristics of Participants—A sample of 475 self-identified Black women aged 21 to 70 years participated in the study, and 352 eligible participants were included in the final analysis. Of the 352 eligible participants, 48.3% were aged 21 to 30 years, 47.2% were aged 31 to 40 years, and 4.5% were aged 41 to 50 years. All survey participants identified their race as Black; among them, 4% specified Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and 9% indicated that they held multiracial identities including White/Caucasian, Asian, and Native American backgrounds. Regarding the participants’ citizenship status, 54.3% reported that both they and their parents were born in the United States; 2.3% were not US citizens or permanent residents, 13.1% identified as first-generation Americans (born outside of the United States), and 30.4% identified as second-generation Americans (one or both parents born outside of the United States). Participant education levels (based on highest level) varied greatly: 4.5% were high school graduates, 1.1% attended trade or technical schools, 3.4% had associate’s degrees, 39.8% had bachelor’s degrees, 35.2% had master’s degrees, and 15.9% had doctorate degrees. Regarding household income, 6.3% earned less than $25,000 per year, 16.8% earned from $25,000 to $99,999, 75.6% earned from $100,000 to $499,999, and 1.4% earned $500,000 or more. Patient demographics are provided in Table 1.

Cosmetic Skin Concerns—The top 3 aging skin concerns among participants were fine lines and wrinkles (51.9%), dark circles (33.8%), and uneven skin tone (31.8%) (Table 2). Approximately 5.4% of participants reported no desire to avoid the natural aging process. Among age groups, fine lines and wrinkles were a major concern for 51.7% of 21- to 30-year-olds, 47.6% of 31- to 40-year-olds, and 43.5% of 41- to 50-year-olds. Dark circles were a major concern for 61.3% of 21- to 30-year-olds, 44.4% of 31- to 40-year-olds, and 46.8% of 41- to 50-year-olds. Uneven skin tone was a major concern for 56.2% of 21- to 30-year-olds, 46.5% of 31- to 40-year-olds, and 31.2% of 41- to 50-year-olds. There was no statistically significant association between participants’ age and their concern with aging skin concerns.

Differences in Experience and Acceptance of Cosmetic Procedures—Regarding participants’ prior experience with cosmetic procedures, 22.3% had tried 1 or more procedures. Additionally, 67.0% reported having intentions of trying cosmetic procedures in the future, while 10.8% reported no intentions. Of those who were uninterested in trying cosmetic procedures, 78.9% (30/38) believed it unnecessary while 47.3% (18/38) reported a fear of looking unnatural. Other perceived deterrents to cosmetic procedures among this subset of participants were the need to repeat treatment for lasting results (28.9% [11/38]), too expensive (31.6% [12/38]), and fear of side effects (39.5% [15/38]). A significant difference was found between participants’ age and their experience with cosmetic procedures (P=.020). Participants aged 21 to 30 years reported they were more likely to want to try cosmetic procedures in the future. Participants aged 31 to 40 years were more likely to have already tried a cosmetic procedure. Participants aged 41 to 50 years were more likely to report no desire to try cosmetic procedures in the future. There was no significant difference in cosmetic procedure acceptance according to citizenship status, education level, or household income.

Differences in Cosmetic Procedure Experience—Study participants indicated awareness of typically practiced cosmetic procedures. Of the 78 participants who have tried cosmetic procedures (Figure 1), the most common were laser hair removal (46.2% [36/78]), chemical peels (37.2% [29/78]), and microdermabrasion (24.4% [19/78])(Table 2). Age significantly influenced the type of cosmetic procedures utilized by participants (P<.001). Laser hair removal was the most common cosmetic procedure utilized by participants aged 21 to 30 years (64.7%) and chemical peels in participants aged 31 to 40 years (47.8%); participants aged 41 to 50 years reported equal use of chemical peels (50.0%) and microdermabrasion (50.0%).

Two hundred thirty-six participants reported interest in trying cosmetic procedures, specifically laser hair removal (57.6%), chemical peels (51.7%), and neuromodulators (41.9%)(Table 2). Although not statistically significant, age appeared to influence interest levels in cosmetic procedures. Participants aged 21 to 30 years and 31 to 40 years were most interested in trying laser hair removal (60.7% and 58.3%, respectively). Participants aged 41 to 50 years were most interested in trying neuromodulators (36.4%). There was no significant association between age and intention to try neuromodulators, chemical peels, or laser hair removal.

Attitudes Toward Beauty—Approximately 40.6% of participants believed that peak beauty occurs when women reach their 20s, and 38.6% believed that peak beauty occurs when women reach their 30s. Participants’ strategies for maintaining beauty were assessed through their regular use of certain skin care products. The most frequently used skin care products were face wash or cleanser (92.6%), moisturizer (90.1%), lip balm (76.1%), and facial sunscreen (62.2%). Other commonly used items were serum (34.7%), toner (34.9%), topical vitamin C (33.2%), and retinol/retinoid products (33.0%). Only 2.3% of participants reported not using any skin care products regularly.

Perceptions of Aging—Concerning perceived external age, most respondents believed they looked younger than their true age (69.9%); 24.4% believed they looked their true age, and 5.7% believed they looked older. Perception of age also varied considerably by age group, though most believed they looked younger than their true age.

Comment

This survey helped to identify trends in cosmetic procedure acceptance and utilization in Black women. As expected, younger Black women were more receptive to cosmetic procedures, which was consistent with a recent finding that cosmetic procedures tend to be more widely accepted among younger generations overall.8 Participants aged 21 to 30 years had greater intentions to try a cosmetic procedure, while those aged 31 to 40 years were more likely to have tried 1 or more cosmetic procedures already, which may be because they are just beginning to see the signs of aging and are motivated to address these concerns. Additionally, women in this age group may be more likely to have a stable source of income and be able to afford these procedures. It is important to note that the population surveyed had a much higher reported household income than the average Black household income, with most respondents reporting an average annual income of $100,000 to $499,000. Our data also showed a trend toward greater acceptance and utilization of cosmetic procedures in those with higher levels of income, though the results were not statistically significant.

Respondents were most concerned about fine lines and wrinkles, followed by dark circles and uneven skin tone. One report in the literature (N=2000) indicated that the most common cosmetic concerns in women with SOC were hyperpigmentation/dark spots (86%) and blotchy or uneven skin (80%).9 Interestingly, sunscreen was one of the more commonly used products in our survey, which historically has not been the case among individuals with SOC10 and suggests that the attitudes and perceptions of SOC patients are changing to favor more frequent sunscreen use, at least among the younger generations. Because we did not specify moisturizer vs moisturizer with sun protection factor, the use of facial sunscreen may even be underestimated in our survey.

Compared to cosmetic surgery or dermal fillers, the procedures found to be most frequently utilized in our study population—microdermabrasion, chemical peels, and laser hair removal—are less invasive and fairly accessible with minimal downtime. An interesting topic for further research would be to investigate how the willingness of women to openly share their cosmetic procedure usage has changed over time. The rise of social media and influencer culture has undoubtedly had an impact on the sharing of such information. It also would have been interesting to ask participants where they receive the majority of their health/beauty information.

All skin types are susceptible to photoaging; however, melanin is known to have a natural photoprotective effect, resulting in a lesser degree and later onset of photoaging in patients with darker vs lighter skin.11 It has been reported that individuals with SOC show signs of facial aging on average a decade later than those with lighter skin tones,12 which may be why the majority of participants believed they look younger than they truly are. As expected, dyspigmentation was among the top skin concerns in our study population. Although melanin does offer some degree of protection against UVA and UVB, melanocyte lability with inflammation may make darker skin types more susceptible to pigmentary issues.13

Study Limitations—The income levels of our study population were not representative of typical Black American households, which is a limitation. Seventy-seven percent of our study population earned more than $100,000 annually, while only 18% of Black American households earned more than $100,000 in 2019.14 Another major limitation of our study was the lack of representation from older generations, as most participants were aged 21 to 40 years, which was expected, as it is the younger generation who typically is targeted by a snowball sampling method primarily shared through social media. Additionally, because participants were recruited from the social media profiles of medical professionals, followers of these accounts may be more interested in cosmetic procedures, skewing the study results. Finally, because geographic location was not captured in our initial data collection, we were unable to determine if results from a particular location within the United States were overrepresented in the data set.

Conclusion

Although the discourse around beauty and antiaging is constantly evolving, data about Black women frequently are underrepresented in the literature. The results of this study highlight the changing attitudes and perceptions of Black women regarding beauty, aging, and minimally invasive cosmetic procedures. Dermatologists should stay abreast of current trends in this population to be able to make appropriate, culturally sensitive recommendations to their Black patients—for example, pointing them to sunscreen brands that are best suited for darker skin.

Beauty has been a topic of interest for centuries. Treatments and technologies have advanced, and more women are utilizing cosmetic procedures than ever before, especially neuromodulators, minimally invasive procedures, and topical treatments.1 Over the last decade, there was a 99% increase in minimally invasive cosmetic procedures in the United States.2 There also has been an observable increase in the utilization of cosmetic procedures by Black patients in recent years; the American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported that the number of cosmetic plastic surgery procedures performed on “ethnic patients” (referring to Asian, Black, or Hispanic patients) increased 243% from 2000 to 2013,3 possibly attributed to increased accessibility, awareness of procedures due to social media, cultural acceptance, and affordability. Minimally invasive procedures are considerably less expensive than major surgical procedures and are becoming progressively more affordable, with numerous financing options available.2 Additionally, neuromodulators and fillers are now commonly administered by nonaesthetic health professionals including dentists and nurses, which has increased accessibility of these procedures among patients who typically may not seek out a consultation with a plastic surgeon or dermatologist.4

When examining the most common cosmetic procedures collectively sought out by patients with skin of color (SOC), it has been found that an even skin tone is a highly desirable feature that impacts the selection of products and procedures in this particular patient population.5 Black, Hispanic, and Asian women report fewer signs of facial aging compared to White women in the glabellar lines, crow’s-feet, oral commissures, perioral lines, and lips.6 Increased melanocytes in darker skin types help prevent photoaging but also increase susceptibility to dyschromia. Prior studies have reported the most common concerns by patients with SOC are dyschromic disorders such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, and melasma.7 Common minimally invasive cosmetic procedures utilized by the SOC population include chemical peels, laser treatments, and injectables. Fillers are utilized more for volume loss in SOC patients rather than for the deep furrows and rhytides commonly seen in the lower face of White patients.8

We conducted a survey among Black women currently residing in the United States to better understand attitudes toward beauty and aging as well as the utilization of minimally invasive cosmetic procedures in this patient population.

Methods

An in-depth questionnaire comprised of 17 questions was created for this cross-sectional observational study. The study was submitted to and deemed exempt by the institutional review board at the University of Miami (Miami, Florida)(IRB #20211184). Survey participants primarily were recruited via social media posts on personal profiles of Black dermatologists, medical residents, and medicalstudents, including the authors, targeting Black women in the United States. Utilizing a method called snowball sampling, whereby study participants are used to recruit future participants, individuals were instructed to share the survey with their social network to assist with survey distribution. After participants provided informed consent, data were captured using the REDCap secure online data collection software. The questionnaire was structured to include a sociodemographic profile of respondents, attitudes toward beauty and aging, current usage of beauty products, prior utilization of cosmetic procedures, and intentions to use cosmetic procedures in the future. Surveys with incomplete consent forms, incomplete responses, and duplicate responses, as well as surveys from participants who were not residing in the United States at the time of survey completion, were excluded.

Data characteristics were summarized by frequency and percentage. A χ2 test was performed to compare participants’ age demographics with their attitudes toward beauty and aging, utilization of cosmetic procedures, and intention to try cosmetic procedures in the future. The Fisher exact test was used instead of the χ2 test when the expected cell count was less than 5. For all tests, P<.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 28.

Results

General Characteristics of Participants—A sample of 475 self-identified Black women aged 21 to 70 years participated in the study, and 352 eligible participants were included in the final analysis. Of the 352 eligible participants, 48.3% were aged 21 to 30 years, 47.2% were aged 31 to 40 years, and 4.5% were aged 41 to 50 years. All survey participants identified their race as Black; among them, 4% specified Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and 9% indicated that they held multiracial identities including White/Caucasian, Asian, and Native American backgrounds. Regarding the participants’ citizenship status, 54.3% reported that both they and their parents were born in the United States; 2.3% were not US citizens or permanent residents, 13.1% identified as first-generation Americans (born outside of the United States), and 30.4% identified as second-generation Americans (one or both parents born outside of the United States). Participant education levels (based on highest level) varied greatly: 4.5% were high school graduates, 1.1% attended trade or technical schools, 3.4% had associate’s degrees, 39.8% had bachelor’s degrees, 35.2% had master’s degrees, and 15.9% had doctorate degrees. Regarding household income, 6.3% earned less than $25,000 per year, 16.8% earned from $25,000 to $99,999, 75.6% earned from $100,000 to $499,999, and 1.4% earned $500,000 or more. Patient demographics are provided in Table 1.