User login

Asthma severity higher among LGBTQ+ population

HONOLULU – and asthma is especially exacerbated in SGM persons who use e-cigarettes compared with heterosexuals.

These findings come from a study of asthma severity among SGM people, with a special focus on the contribution of tobacco, reported Tugba Kaplan, MD, a resident in internal medicine at Luminis Health Anne Arundel Medical Center, Annapolis, Md.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing asthma severity among SGM people in a nationally representative longitudinal cohort study,” she said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

There has been only limited research on the health status and health needs of SGM people, and most of the studies conducted have focused on issues such as HIV/AIDS, sexual health, and substance use, not respiratory health, she said.

Following the PATH

Dr. Kaplan and colleagues drew on data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, a nationally representative longitudinal cohort study with data on approximately 46,000 adults and adolescents in the United States.

The study uses self-reported data on tobacco use patterns; perceptions of risk and attitudes toward tobacco products; tobacco initiation, cessation, and relapse; and associated health outcomes.

The investigators combined data from three waves of the PATH Study, conducted from 2015 to 2019 on nonpregnant participants aged 18 years and older, and used mixed-effect logistic regression models to look for potential associations between sexual orientation and asthma severity.

They used standard definitions of asthma severity, based on lung function impairment measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity, nighttime awakenings, use of a short-acting beta2-agonist for symptoms, interference with normal activity, and exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids.

The study also includes a sexual orientation question, asking participants, “do you consider yourself to be ...” with the options “straight, lesbian or gay, bisexual, something else, don’t know, or refused.”

Based on these responses, Dr. Kaplan and colleagues studied a total sample of 1,815 people who identify as SGM and 12,879 who identify as non-SGM.

Risks increased

In an analysis adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, tobacco use, body mass index, physical activity, and asthma medication use, the authors found that, compared with non-SGM people, SGM respondents were significantly more likely to have had asthma attacks requiring steroid use in the past years (odds ratio, 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.15), asthma interfering with daily activities in the past month (OR, 1.33; CI, 1.10-1.61), and shortness of breath in any week over the 30 days (OR, 1.82; CI, 1.32-2.51). There was no significant difference between the groups in inhaler use over the past month, however.

They also found two interactions in the logistic regression models, one between urgent care visits and respondents who reported using both regular tobacco and e-cigarettes (dual users), and between exclusive e-cigarette use and waking up at night.

Among dual users, SGM respondents had a nearly fourfold greater risk for asthma attacks requiring urgent care visits, compared with non-SGM respondents (OR, 3.89; CI, 1.99-7.63). In contrast, among those who never used tobacco, there were no significant differences between the sexual orientation groups in regard to asthma attacks requiring urgent care visits.

Among those who reported using e-cigarettes exclusively, SGM respondents were nearly eight times more likely to report night awakening, compared with non-SGM users (OR, 7.81; CI, 2.93-20.8).

Among never users, in contrast, there was no significant difference in nighttime disturbances.

Possible confounders

The data suggest that “in the context of chronic illnesses like asthma, it is crucial to offer patients the knowledge and tools required to proficiently handle their conditions,” Dr. Kaplan said, adding that the differences seen between SGM and non-SGM respondents may be caused by health care disparities among SGM people that result in nonadherence to regular follow-ups.

In an interview, Jean Bourbeau, MD, MSc, who was a moderator for the session but was not involved in the study, commented that “we have to be very careful before making any conclusions, because this population could be at high risk for different reasons, and especially, do they get the same attention in terms of the care that is provided to the general population, and do they get access to the same medication?”

Nonetheless, Dr. Bourbeau continued, “I think this study is very important, because it shows us how much awareness we need to determine differences in populations, and [sexual orientation] is probably one thing that nobody had considered before, and for the first time we are now considering these potential differences in our population.”

The authors did not report a study funding source. Dr. Kaplan and Dr. Bourbeau reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HONOLULU – and asthma is especially exacerbated in SGM persons who use e-cigarettes compared with heterosexuals.

These findings come from a study of asthma severity among SGM people, with a special focus on the contribution of tobacco, reported Tugba Kaplan, MD, a resident in internal medicine at Luminis Health Anne Arundel Medical Center, Annapolis, Md.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing asthma severity among SGM people in a nationally representative longitudinal cohort study,” she said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

There has been only limited research on the health status and health needs of SGM people, and most of the studies conducted have focused on issues such as HIV/AIDS, sexual health, and substance use, not respiratory health, she said.

Following the PATH

Dr. Kaplan and colleagues drew on data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, a nationally representative longitudinal cohort study with data on approximately 46,000 adults and adolescents in the United States.

The study uses self-reported data on tobacco use patterns; perceptions of risk and attitudes toward tobacco products; tobacco initiation, cessation, and relapse; and associated health outcomes.

The investigators combined data from three waves of the PATH Study, conducted from 2015 to 2019 on nonpregnant participants aged 18 years and older, and used mixed-effect logistic regression models to look for potential associations between sexual orientation and asthma severity.

They used standard definitions of asthma severity, based on lung function impairment measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity, nighttime awakenings, use of a short-acting beta2-agonist for symptoms, interference with normal activity, and exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids.

The study also includes a sexual orientation question, asking participants, “do you consider yourself to be ...” with the options “straight, lesbian or gay, bisexual, something else, don’t know, or refused.”

Based on these responses, Dr. Kaplan and colleagues studied a total sample of 1,815 people who identify as SGM and 12,879 who identify as non-SGM.

Risks increased

In an analysis adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, tobacco use, body mass index, physical activity, and asthma medication use, the authors found that, compared with non-SGM people, SGM respondents were significantly more likely to have had asthma attacks requiring steroid use in the past years (odds ratio, 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.15), asthma interfering with daily activities in the past month (OR, 1.33; CI, 1.10-1.61), and shortness of breath in any week over the 30 days (OR, 1.82; CI, 1.32-2.51). There was no significant difference between the groups in inhaler use over the past month, however.

They also found two interactions in the logistic regression models, one between urgent care visits and respondents who reported using both regular tobacco and e-cigarettes (dual users), and between exclusive e-cigarette use and waking up at night.

Among dual users, SGM respondents had a nearly fourfold greater risk for asthma attacks requiring urgent care visits, compared with non-SGM respondents (OR, 3.89; CI, 1.99-7.63). In contrast, among those who never used tobacco, there were no significant differences between the sexual orientation groups in regard to asthma attacks requiring urgent care visits.

Among those who reported using e-cigarettes exclusively, SGM respondents were nearly eight times more likely to report night awakening, compared with non-SGM users (OR, 7.81; CI, 2.93-20.8).

Among never users, in contrast, there was no significant difference in nighttime disturbances.

Possible confounders

The data suggest that “in the context of chronic illnesses like asthma, it is crucial to offer patients the knowledge and tools required to proficiently handle their conditions,” Dr. Kaplan said, adding that the differences seen between SGM and non-SGM respondents may be caused by health care disparities among SGM people that result in nonadherence to regular follow-ups.

In an interview, Jean Bourbeau, MD, MSc, who was a moderator for the session but was not involved in the study, commented that “we have to be very careful before making any conclusions, because this population could be at high risk for different reasons, and especially, do they get the same attention in terms of the care that is provided to the general population, and do they get access to the same medication?”

Nonetheless, Dr. Bourbeau continued, “I think this study is very important, because it shows us how much awareness we need to determine differences in populations, and [sexual orientation] is probably one thing that nobody had considered before, and for the first time we are now considering these potential differences in our population.”

The authors did not report a study funding source. Dr. Kaplan and Dr. Bourbeau reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HONOLULU – and asthma is especially exacerbated in SGM persons who use e-cigarettes compared with heterosexuals.

These findings come from a study of asthma severity among SGM people, with a special focus on the contribution of tobacco, reported Tugba Kaplan, MD, a resident in internal medicine at Luminis Health Anne Arundel Medical Center, Annapolis, Md.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing asthma severity among SGM people in a nationally representative longitudinal cohort study,” she said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

There has been only limited research on the health status and health needs of SGM people, and most of the studies conducted have focused on issues such as HIV/AIDS, sexual health, and substance use, not respiratory health, she said.

Following the PATH

Dr. Kaplan and colleagues drew on data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, a nationally representative longitudinal cohort study with data on approximately 46,000 adults and adolescents in the United States.

The study uses self-reported data on tobacco use patterns; perceptions of risk and attitudes toward tobacco products; tobacco initiation, cessation, and relapse; and associated health outcomes.

The investigators combined data from three waves of the PATH Study, conducted from 2015 to 2019 on nonpregnant participants aged 18 years and older, and used mixed-effect logistic regression models to look for potential associations between sexual orientation and asthma severity.

They used standard definitions of asthma severity, based on lung function impairment measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity, nighttime awakenings, use of a short-acting beta2-agonist for symptoms, interference with normal activity, and exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids.

The study also includes a sexual orientation question, asking participants, “do you consider yourself to be ...” with the options “straight, lesbian or gay, bisexual, something else, don’t know, or refused.”

Based on these responses, Dr. Kaplan and colleagues studied a total sample of 1,815 people who identify as SGM and 12,879 who identify as non-SGM.

Risks increased

In an analysis adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, tobacco use, body mass index, physical activity, and asthma medication use, the authors found that, compared with non-SGM people, SGM respondents were significantly more likely to have had asthma attacks requiring steroid use in the past years (odds ratio, 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.15), asthma interfering with daily activities in the past month (OR, 1.33; CI, 1.10-1.61), and shortness of breath in any week over the 30 days (OR, 1.82; CI, 1.32-2.51). There was no significant difference between the groups in inhaler use over the past month, however.

They also found two interactions in the logistic regression models, one between urgent care visits and respondents who reported using both regular tobacco and e-cigarettes (dual users), and between exclusive e-cigarette use and waking up at night.

Among dual users, SGM respondents had a nearly fourfold greater risk for asthma attacks requiring urgent care visits, compared with non-SGM respondents (OR, 3.89; CI, 1.99-7.63). In contrast, among those who never used tobacco, there were no significant differences between the sexual orientation groups in regard to asthma attacks requiring urgent care visits.

Among those who reported using e-cigarettes exclusively, SGM respondents were nearly eight times more likely to report night awakening, compared with non-SGM users (OR, 7.81; CI, 2.93-20.8).

Among never users, in contrast, there was no significant difference in nighttime disturbances.

Possible confounders

The data suggest that “in the context of chronic illnesses like asthma, it is crucial to offer patients the knowledge and tools required to proficiently handle their conditions,” Dr. Kaplan said, adding that the differences seen between SGM and non-SGM respondents may be caused by health care disparities among SGM people that result in nonadherence to regular follow-ups.

In an interview, Jean Bourbeau, MD, MSc, who was a moderator for the session but was not involved in the study, commented that “we have to be very careful before making any conclusions, because this population could be at high risk for different reasons, and especially, do they get the same attention in terms of the care that is provided to the general population, and do they get access to the same medication?”

Nonetheless, Dr. Bourbeau continued, “I think this study is very important, because it shows us how much awareness we need to determine differences in populations, and [sexual orientation] is probably one thing that nobody had considered before, and for the first time we are now considering these potential differences in our population.”

The authors did not report a study funding source. Dr. Kaplan and Dr. Bourbeau reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT CHEST 2023

Lack of time is damaging women’s health

Various speakers at the VII National Conference of the Onda Foundation, Italy’s National Observatory for Women and Gender’s Health, focused on this topic. The conference was dedicated to the social factors that determine health within the context of gender medicine.

In our society, housework and raising a family are responsibilities placed predominantly on the shoulders of women. These responsibilities contribute significantly to women’s daily workload. The most overburdened women are working mothers (according to ISTAT, Italy’s Office for National Statistics, 2019), who are forced to combine their professional responsibilities with family life, dedicating 8 hours and 20 minutes per day to paid and unpaid work overall, compared with the 7 hours and 29 minutes spent by working fathers. Working mothers between ages 25 and 44 years have on average 2 hours and 35 minutes of free time per day.

Stress and sleep deprivation

“Under these conditions, the risk of chronic stress is raised, and stress leads to depression. The rate of depression in the female population is double that of the male population,” said Claudio Mencacci, MD, chair of the Italian Society of Neuropsychopharmacology and the Onda Foundation. “What’s more, stress increases the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, asthma, arthritis, and autoimmune diseases.”

The one thing that is especially damaging to physical and mental health is sleep deprivation, and working mothers get less sleep than do working fathers. “This is partially due to biological factors: hormonal changes that take place toward the end of adolescence in women during the premenstrual period are responsible for an increased rate of sleep disturbance and insomnia,” said Dr. Mencacci. “During pregnancy and the postpartum period, female sex hormones make sleep lighter, reducing time spent in the REM sleep stage. Then there’s the social aspect that plays a decisive role: by and large, it’s mothers who take care of the youngest children at night.”

According to a 2019 German study, during the first 6 years of life of the first child, a mother loses on average 44 minutes sleep per night, compared with the average time spent sleeping before pregnancy; a father loses 14 minutes.

“Another aspect to bear in mind is that, for cultural reasons, women tend to overlook the issue and not seek help, deeming sleep deprivation normal,” said Dr. Mencacci.

Caregivers at greatest risk

The negative effects of stress are evident in people continuously caring for a dependent older or disabled family member, so-called caregivers. This is, “A group predominantly made up of women aged between 45 and 55 years,” said Marina Petrini, PhD, of the Italian Health Institute’s Gender Medicine Center of Excellence. Dr. Petrini coordinated a study on stress and health in family caregivers.

“The results obtained reveal a high level of stress, especially among female caregivers, who are more exposed to the risk of severe symptoms of depression, physical disorders, especially those affecting the nervous and immune systems, and who tend to adopt irregular eating patterns and sedentary habits,” said Dr. Petrini.

Limited treatment access

Another study presented at the Onda Foundation’s conference, which shows just how much a lack of “me time” can damage your health, is the Access to Diagnostic Medicine and Treatment by Region: the Patient’s Perspective Survey, conducted by market research agency Elma Research on a sample of cancer patients requiring specialist treatment.

“Forty percent of them had to move to a different region from the one they live in to get the care they needed,” said Massimo Massagrande, CEO of Elma Research. “Of that group, 40% had to move to an area not neighboring their own. The impact of area of residence is heavy, in terms of money and logistics – so much so that a large proportion of patients interviewed were forced to turn their back on the best available treatments. For women responding to our survey, the biggest obstacle is the impossibility of reconciling the effects of a move or the prospective of a temporary transfer to another region with their responsibilities for looking after their family.”

This article was translated from Univadis Italy. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Various speakers at the VII National Conference of the Onda Foundation, Italy’s National Observatory for Women and Gender’s Health, focused on this topic. The conference was dedicated to the social factors that determine health within the context of gender medicine.

In our society, housework and raising a family are responsibilities placed predominantly on the shoulders of women. These responsibilities contribute significantly to women’s daily workload. The most overburdened women are working mothers (according to ISTAT, Italy’s Office for National Statistics, 2019), who are forced to combine their professional responsibilities with family life, dedicating 8 hours and 20 minutes per day to paid and unpaid work overall, compared with the 7 hours and 29 minutes spent by working fathers. Working mothers between ages 25 and 44 years have on average 2 hours and 35 minutes of free time per day.

Stress and sleep deprivation

“Under these conditions, the risk of chronic stress is raised, and stress leads to depression. The rate of depression in the female population is double that of the male population,” said Claudio Mencacci, MD, chair of the Italian Society of Neuropsychopharmacology and the Onda Foundation. “What’s more, stress increases the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, asthma, arthritis, and autoimmune diseases.”

The one thing that is especially damaging to physical and mental health is sleep deprivation, and working mothers get less sleep than do working fathers. “This is partially due to biological factors: hormonal changes that take place toward the end of adolescence in women during the premenstrual period are responsible for an increased rate of sleep disturbance and insomnia,” said Dr. Mencacci. “During pregnancy and the postpartum period, female sex hormones make sleep lighter, reducing time spent in the REM sleep stage. Then there’s the social aspect that plays a decisive role: by and large, it’s mothers who take care of the youngest children at night.”

According to a 2019 German study, during the first 6 years of life of the first child, a mother loses on average 44 minutes sleep per night, compared with the average time spent sleeping before pregnancy; a father loses 14 minutes.

“Another aspect to bear in mind is that, for cultural reasons, women tend to overlook the issue and not seek help, deeming sleep deprivation normal,” said Dr. Mencacci.

Caregivers at greatest risk

The negative effects of stress are evident in people continuously caring for a dependent older or disabled family member, so-called caregivers. This is, “A group predominantly made up of women aged between 45 and 55 years,” said Marina Petrini, PhD, of the Italian Health Institute’s Gender Medicine Center of Excellence. Dr. Petrini coordinated a study on stress and health in family caregivers.

“The results obtained reveal a high level of stress, especially among female caregivers, who are more exposed to the risk of severe symptoms of depression, physical disorders, especially those affecting the nervous and immune systems, and who tend to adopt irregular eating patterns and sedentary habits,” said Dr. Petrini.

Limited treatment access

Another study presented at the Onda Foundation’s conference, which shows just how much a lack of “me time” can damage your health, is the Access to Diagnostic Medicine and Treatment by Region: the Patient’s Perspective Survey, conducted by market research agency Elma Research on a sample of cancer patients requiring specialist treatment.

“Forty percent of them had to move to a different region from the one they live in to get the care they needed,” said Massimo Massagrande, CEO of Elma Research. “Of that group, 40% had to move to an area not neighboring their own. The impact of area of residence is heavy, in terms of money and logistics – so much so that a large proportion of patients interviewed were forced to turn their back on the best available treatments. For women responding to our survey, the biggest obstacle is the impossibility of reconciling the effects of a move or the prospective of a temporary transfer to another region with their responsibilities for looking after their family.”

This article was translated from Univadis Italy. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Various speakers at the VII National Conference of the Onda Foundation, Italy’s National Observatory for Women and Gender’s Health, focused on this topic. The conference was dedicated to the social factors that determine health within the context of gender medicine.

In our society, housework and raising a family are responsibilities placed predominantly on the shoulders of women. These responsibilities contribute significantly to women’s daily workload. The most overburdened women are working mothers (according to ISTAT, Italy’s Office for National Statistics, 2019), who are forced to combine their professional responsibilities with family life, dedicating 8 hours and 20 minutes per day to paid and unpaid work overall, compared with the 7 hours and 29 minutes spent by working fathers. Working mothers between ages 25 and 44 years have on average 2 hours and 35 minutes of free time per day.

Stress and sleep deprivation

“Under these conditions, the risk of chronic stress is raised, and stress leads to depression. The rate of depression in the female population is double that of the male population,” said Claudio Mencacci, MD, chair of the Italian Society of Neuropsychopharmacology and the Onda Foundation. “What’s more, stress increases the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, asthma, arthritis, and autoimmune diseases.”

The one thing that is especially damaging to physical and mental health is sleep deprivation, and working mothers get less sleep than do working fathers. “This is partially due to biological factors: hormonal changes that take place toward the end of adolescence in women during the premenstrual period are responsible for an increased rate of sleep disturbance and insomnia,” said Dr. Mencacci. “During pregnancy and the postpartum period, female sex hormones make sleep lighter, reducing time spent in the REM sleep stage. Then there’s the social aspect that plays a decisive role: by and large, it’s mothers who take care of the youngest children at night.”

According to a 2019 German study, during the first 6 years of life of the first child, a mother loses on average 44 minutes sleep per night, compared with the average time spent sleeping before pregnancy; a father loses 14 minutes.

“Another aspect to bear in mind is that, for cultural reasons, women tend to overlook the issue and not seek help, deeming sleep deprivation normal,” said Dr. Mencacci.

Caregivers at greatest risk

The negative effects of stress are evident in people continuously caring for a dependent older or disabled family member, so-called caregivers. This is, “A group predominantly made up of women aged between 45 and 55 years,” said Marina Petrini, PhD, of the Italian Health Institute’s Gender Medicine Center of Excellence. Dr. Petrini coordinated a study on stress and health in family caregivers.

“The results obtained reveal a high level of stress, especially among female caregivers, who are more exposed to the risk of severe symptoms of depression, physical disorders, especially those affecting the nervous and immune systems, and who tend to adopt irregular eating patterns and sedentary habits,” said Dr. Petrini.

Limited treatment access

Another study presented at the Onda Foundation’s conference, which shows just how much a lack of “me time” can damage your health, is the Access to Diagnostic Medicine and Treatment by Region: the Patient’s Perspective Survey, conducted by market research agency Elma Research on a sample of cancer patients requiring specialist treatment.

“Forty percent of them had to move to a different region from the one they live in to get the care they needed,” said Massimo Massagrande, CEO of Elma Research. “Of that group, 40% had to move to an area not neighboring their own. The impact of area of residence is heavy, in terms of money and logistics – so much so that a large proportion of patients interviewed were forced to turn their back on the best available treatments. For women responding to our survey, the biggest obstacle is the impossibility of reconciling the effects of a move or the prospective of a temporary transfer to another region with their responsibilities for looking after their family.”

This article was translated from Univadis Italy. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatric sleep-disordered breathing linked to multilevel risk factors

In the first study evaluating pediatric sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) from both indoor environment and neighborhood perspectives, multilevel risk factors were revealed as being associated with SDB-related symptoms. Beyond known associations with environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), .

Although it has been well known that pediatric SDB affects low socioeconomic status (SES) children disproportionately, the roles of multilevel risk factor drivers including individual health, household SES, indoor exposures to environmental tobacco smoke, pests, and neighborhood characteristics have not been well studied, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. wrote in CHEST Pulmonary.

Pediatric SDB, a known risk factor for many health, neurobehavioral, and functional outcomes, includes habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea and may contribute to health disparities. Adenotonsillar hypertrophy and obesity are the most commonly recognized risk factors for SDB in generally healthy school-aged children. A role for other risk factors, however, is suggested by the fact that Black children have a fourfold increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), compared with White children, unexplained by obesity, and have decreased response to treatment of OSA with adenotonsillectomy, compared with White children. Several studies point in the direction of neighborhood disadvantages as factors in heightened SDB prevalence or severity, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. stated.

The authors performed cross-sectional analyses on data recorded from 303 children (aged 6-12 years) enrolled in the Environmental Assessment of Sleep Youth (EASY) study from 2018 to 2022. Among them, 39% were Hispanic, Latino, Latina, or Spanish origin, 30% were Black or African American, 22% were White, and 11% were other. Maternal education attainment of a high school diploma or less was reported in 27%, and 65% of the sample lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Twenty-eight percent of children met criteria for objective SDB (Apnea-Hypopnea Index/Oxygen Desaturation Index ≥ 5/hr). Exposure documentation was informed by caregiver reports, assays of measured settled dust from the child’s bedroom, and neighborhood-level census data from which the Childhood Opportunity Index characterizing neighborhood disadvantage (ND) was derived. The study primary outcome was the SDB-related symptom burden assessed by the OSA-18 questionnaire total score.

Compared with children with no adverse indoor exposures to ETS and pests, children with such exposures had an approximately 4-12 point increase in total OSA-18 scores, and the increase among those with exposure to both ETS and pests was about 20 points (approximately a 1.3 standard deviation increase), Gueye-Ndiaye et al. reported.

In models adjusted for age, sex, minority race, and ethnicity, low maternal education was associated with a 7.55 (95% confidence interval, 3.44-11.66; P < .01) increased OSA-18 score. In models adjusted for sociodemographics including maternal education, history of asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with a 13.63 (95% CI, 9.44-17.82; P < .01) and a 6.95 (95% CI, 2.62-11.29; P < .02) increased OSA-18 score, respectively. The authors noted that prior Canadian studies have shown OSA to be three times as likely in children with mothers reporting less than a high school education than in children with university educated mothers.

Speculating on the drivers of this association, they noted that the poor air quality due to tobacco smoke and allergen exposures to rodents, mold, and cockroaches are known contributors to asthma symptoms. Despite the differing pathogenesis of OSA and asthma, they suggest overlapping risk factors. Irritants and allergens may exacerbate SDB by stimulating immune responses manifested as adenotonsillar hypertrophy and by amplifying nasopharyngeal inflammation, adversely affecting upper airway patency. While ETS was not common in the sample, it was associated strongly with SDB. Gueye-Ndiaye et al. also showed associations between pest exposure, bedroom dust, and SDB symptoms. The findings, they concluded, support the importance of household- and bedroom-environmental conditions and sleep health.

OSA-18 scores were also elevated by about 7-14 points with allergic rhinitis and asthma, respectively. The findings, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. stated, underscore that asthma prevention strategies can be leveraged to address SDB disparities. No amplification of pest exposure effects, however, was found for asthma or allergic rhinitis.

“This is an incredibly important study, one that adds to our understanding of the risk factors that contribute to pediatric sleep health disparities,” said assistant professor of pediatrics Anne C. Coates, MD, Tufts University, Boston. “We have previously understood risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing like adenotonsillar hypertrophy, but this adds other elements like environmental tobacco smoke, pests, and home and neighborhood factors,” she told this news organization. “One of the most important takeaways is that beyond the importance of accurate diagnosis, there is the importance of advocating for our patients to ensure that they have the healthiest homes and neighborhoods. We need to inspire our colleagues to be advocates – for example – for pest mitigation, for antismoking policies, for every policy preventing the factors that contribute to the burden of disease.”

Dr. Coates is coauthor of “Advocacy and Health Equity: The Role of the Pediatric Pulmonologist,” currently in press (Clinics in Chest Medicine), and a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

The authors noted that a study limitation was that the sample was from one geographic area (Boston). Neither the authors nor Dr. Coates listed any conflicts.

In the first study evaluating pediatric sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) from both indoor environment and neighborhood perspectives, multilevel risk factors were revealed as being associated with SDB-related symptoms. Beyond known associations with environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), .

Although it has been well known that pediatric SDB affects low socioeconomic status (SES) children disproportionately, the roles of multilevel risk factor drivers including individual health, household SES, indoor exposures to environmental tobacco smoke, pests, and neighborhood characteristics have not been well studied, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. wrote in CHEST Pulmonary.

Pediatric SDB, a known risk factor for many health, neurobehavioral, and functional outcomes, includes habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea and may contribute to health disparities. Adenotonsillar hypertrophy and obesity are the most commonly recognized risk factors for SDB in generally healthy school-aged children. A role for other risk factors, however, is suggested by the fact that Black children have a fourfold increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), compared with White children, unexplained by obesity, and have decreased response to treatment of OSA with adenotonsillectomy, compared with White children. Several studies point in the direction of neighborhood disadvantages as factors in heightened SDB prevalence or severity, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. stated.

The authors performed cross-sectional analyses on data recorded from 303 children (aged 6-12 years) enrolled in the Environmental Assessment of Sleep Youth (EASY) study from 2018 to 2022. Among them, 39% were Hispanic, Latino, Latina, or Spanish origin, 30% were Black or African American, 22% were White, and 11% were other. Maternal education attainment of a high school diploma or less was reported in 27%, and 65% of the sample lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Twenty-eight percent of children met criteria for objective SDB (Apnea-Hypopnea Index/Oxygen Desaturation Index ≥ 5/hr). Exposure documentation was informed by caregiver reports, assays of measured settled dust from the child’s bedroom, and neighborhood-level census data from which the Childhood Opportunity Index characterizing neighborhood disadvantage (ND) was derived. The study primary outcome was the SDB-related symptom burden assessed by the OSA-18 questionnaire total score.

Compared with children with no adverse indoor exposures to ETS and pests, children with such exposures had an approximately 4-12 point increase in total OSA-18 scores, and the increase among those with exposure to both ETS and pests was about 20 points (approximately a 1.3 standard deviation increase), Gueye-Ndiaye et al. reported.

In models adjusted for age, sex, minority race, and ethnicity, low maternal education was associated with a 7.55 (95% confidence interval, 3.44-11.66; P < .01) increased OSA-18 score. In models adjusted for sociodemographics including maternal education, history of asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with a 13.63 (95% CI, 9.44-17.82; P < .01) and a 6.95 (95% CI, 2.62-11.29; P < .02) increased OSA-18 score, respectively. The authors noted that prior Canadian studies have shown OSA to be three times as likely in children with mothers reporting less than a high school education than in children with university educated mothers.

Speculating on the drivers of this association, they noted that the poor air quality due to tobacco smoke and allergen exposures to rodents, mold, and cockroaches are known contributors to asthma symptoms. Despite the differing pathogenesis of OSA and asthma, they suggest overlapping risk factors. Irritants and allergens may exacerbate SDB by stimulating immune responses manifested as adenotonsillar hypertrophy and by amplifying nasopharyngeal inflammation, adversely affecting upper airway patency. While ETS was not common in the sample, it was associated strongly with SDB. Gueye-Ndiaye et al. also showed associations between pest exposure, bedroom dust, and SDB symptoms. The findings, they concluded, support the importance of household- and bedroom-environmental conditions and sleep health.

OSA-18 scores were also elevated by about 7-14 points with allergic rhinitis and asthma, respectively. The findings, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. stated, underscore that asthma prevention strategies can be leveraged to address SDB disparities. No amplification of pest exposure effects, however, was found for asthma or allergic rhinitis.

“This is an incredibly important study, one that adds to our understanding of the risk factors that contribute to pediatric sleep health disparities,” said assistant professor of pediatrics Anne C. Coates, MD, Tufts University, Boston. “We have previously understood risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing like adenotonsillar hypertrophy, but this adds other elements like environmental tobacco smoke, pests, and home and neighborhood factors,” she told this news organization. “One of the most important takeaways is that beyond the importance of accurate diagnosis, there is the importance of advocating for our patients to ensure that they have the healthiest homes and neighborhoods. We need to inspire our colleagues to be advocates – for example – for pest mitigation, for antismoking policies, for every policy preventing the factors that contribute to the burden of disease.”

Dr. Coates is coauthor of “Advocacy and Health Equity: The Role of the Pediatric Pulmonologist,” currently in press (Clinics in Chest Medicine), and a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

The authors noted that a study limitation was that the sample was from one geographic area (Boston). Neither the authors nor Dr. Coates listed any conflicts.

In the first study evaluating pediatric sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) from both indoor environment and neighborhood perspectives, multilevel risk factors were revealed as being associated with SDB-related symptoms. Beyond known associations with environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), .

Although it has been well known that pediatric SDB affects low socioeconomic status (SES) children disproportionately, the roles of multilevel risk factor drivers including individual health, household SES, indoor exposures to environmental tobacco smoke, pests, and neighborhood characteristics have not been well studied, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. wrote in CHEST Pulmonary.

Pediatric SDB, a known risk factor for many health, neurobehavioral, and functional outcomes, includes habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea and may contribute to health disparities. Adenotonsillar hypertrophy and obesity are the most commonly recognized risk factors for SDB in generally healthy school-aged children. A role for other risk factors, however, is suggested by the fact that Black children have a fourfold increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), compared with White children, unexplained by obesity, and have decreased response to treatment of OSA with adenotonsillectomy, compared with White children. Several studies point in the direction of neighborhood disadvantages as factors in heightened SDB prevalence or severity, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. stated.

The authors performed cross-sectional analyses on data recorded from 303 children (aged 6-12 years) enrolled in the Environmental Assessment of Sleep Youth (EASY) study from 2018 to 2022. Among them, 39% were Hispanic, Latino, Latina, or Spanish origin, 30% were Black or African American, 22% were White, and 11% were other. Maternal education attainment of a high school diploma or less was reported in 27%, and 65% of the sample lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Twenty-eight percent of children met criteria for objective SDB (Apnea-Hypopnea Index/Oxygen Desaturation Index ≥ 5/hr). Exposure documentation was informed by caregiver reports, assays of measured settled dust from the child’s bedroom, and neighborhood-level census data from which the Childhood Opportunity Index characterizing neighborhood disadvantage (ND) was derived. The study primary outcome was the SDB-related symptom burden assessed by the OSA-18 questionnaire total score.

Compared with children with no adverse indoor exposures to ETS and pests, children with such exposures had an approximately 4-12 point increase in total OSA-18 scores, and the increase among those with exposure to both ETS and pests was about 20 points (approximately a 1.3 standard deviation increase), Gueye-Ndiaye et al. reported.

In models adjusted for age, sex, minority race, and ethnicity, low maternal education was associated with a 7.55 (95% confidence interval, 3.44-11.66; P < .01) increased OSA-18 score. In models adjusted for sociodemographics including maternal education, history of asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with a 13.63 (95% CI, 9.44-17.82; P < .01) and a 6.95 (95% CI, 2.62-11.29; P < .02) increased OSA-18 score, respectively. The authors noted that prior Canadian studies have shown OSA to be three times as likely in children with mothers reporting less than a high school education than in children with university educated mothers.

Speculating on the drivers of this association, they noted that the poor air quality due to tobacco smoke and allergen exposures to rodents, mold, and cockroaches are known contributors to asthma symptoms. Despite the differing pathogenesis of OSA and asthma, they suggest overlapping risk factors. Irritants and allergens may exacerbate SDB by stimulating immune responses manifested as adenotonsillar hypertrophy and by amplifying nasopharyngeal inflammation, adversely affecting upper airway patency. While ETS was not common in the sample, it was associated strongly with SDB. Gueye-Ndiaye et al. also showed associations between pest exposure, bedroom dust, and SDB symptoms. The findings, they concluded, support the importance of household- and bedroom-environmental conditions and sleep health.

OSA-18 scores were also elevated by about 7-14 points with allergic rhinitis and asthma, respectively. The findings, Gueye-Ndiaye et al. stated, underscore that asthma prevention strategies can be leveraged to address SDB disparities. No amplification of pest exposure effects, however, was found for asthma or allergic rhinitis.

“This is an incredibly important study, one that adds to our understanding of the risk factors that contribute to pediatric sleep health disparities,” said assistant professor of pediatrics Anne C. Coates, MD, Tufts University, Boston. “We have previously understood risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing like adenotonsillar hypertrophy, but this adds other elements like environmental tobacco smoke, pests, and home and neighborhood factors,” she told this news organization. “One of the most important takeaways is that beyond the importance of accurate diagnosis, there is the importance of advocating for our patients to ensure that they have the healthiest homes and neighborhoods. We need to inspire our colleagues to be advocates – for example – for pest mitigation, for antismoking policies, for every policy preventing the factors that contribute to the burden of disease.”

Dr. Coates is coauthor of “Advocacy and Health Equity: The Role of the Pediatric Pulmonologist,” currently in press (Clinics in Chest Medicine), and a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

The authors noted that a study limitation was that the sample was from one geographic area (Boston). Neither the authors nor Dr. Coates listed any conflicts.

FROM CHEST PULMONARY

Pediatric psoriasis: Black children, males more likely to have palmoplantar subtype, study finds

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers reviewed data on 330 children and youths aged 0-18 years who had received a primary psoriasis diagnosis and who were seen at an academic pediatric dermatology clinic from 2012 to 2022. Among these patients, 50 cases of palmoplantar psoriasis (PP) were identified by pediatric dermatologists.

- The study population was stratified by race/ethnicity on the basis of self-identification. The cohort included White, Black, and Hispanic/Latino patients, as well as patients who identified as other; 71.5% were White persons, 59.1% were female patients.

- The researchers used a regression analysis to investigate the association between race/ethnicity and PP after controlling for multiple confounding variables, including age and gender.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black children were significantly more likely to have PP than White children (adjusted odds ratio, 6.386; P < .0001). PP was diagnosed in 41.9%, 11.5%, and 8.9% of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and White children, respectively.

- Male gender was also identified as an independent risk factor for PP (aOR, 2.241).

- Nail involvement occurred in significantly more Black and Hispanic/Latino patients than in White patients (53.2%, 50.0%, and 33.9%, respectively).

- Black patients had significantly more palm and sole involvement, compared with the other groups (P < .0001 for both); however, White children had significantly more scalp involvement, compared with the other groups (P = .04).

IN PRACTICE:

“Further research is warranted to better understand the degree to which these associations are affected by racial disparities and environmental factors,” as well as potential genetic associations, the researchers noted.

SOURCE:

The corresponding author on the study was Amy Theos, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. The study was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings were limited by the small sample size and incomplete data for some patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers reviewed data on 330 children and youths aged 0-18 years who had received a primary psoriasis diagnosis and who were seen at an academic pediatric dermatology clinic from 2012 to 2022. Among these patients, 50 cases of palmoplantar psoriasis (PP) were identified by pediatric dermatologists.

- The study population was stratified by race/ethnicity on the basis of self-identification. The cohort included White, Black, and Hispanic/Latino patients, as well as patients who identified as other; 71.5% were White persons, 59.1% were female patients.

- The researchers used a regression analysis to investigate the association between race/ethnicity and PP after controlling for multiple confounding variables, including age and gender.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black children were significantly more likely to have PP than White children (adjusted odds ratio, 6.386; P < .0001). PP was diagnosed in 41.9%, 11.5%, and 8.9% of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and White children, respectively.

- Male gender was also identified as an independent risk factor for PP (aOR, 2.241).

- Nail involvement occurred in significantly more Black and Hispanic/Latino patients than in White patients (53.2%, 50.0%, and 33.9%, respectively).

- Black patients had significantly more palm and sole involvement, compared with the other groups (P < .0001 for both); however, White children had significantly more scalp involvement, compared with the other groups (P = .04).

IN PRACTICE:

“Further research is warranted to better understand the degree to which these associations are affected by racial disparities and environmental factors,” as well as potential genetic associations, the researchers noted.

SOURCE:

The corresponding author on the study was Amy Theos, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. The study was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings were limited by the small sample size and incomplete data for some patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers reviewed data on 330 children and youths aged 0-18 years who had received a primary psoriasis diagnosis and who were seen at an academic pediatric dermatology clinic from 2012 to 2022. Among these patients, 50 cases of palmoplantar psoriasis (PP) were identified by pediatric dermatologists.

- The study population was stratified by race/ethnicity on the basis of self-identification. The cohort included White, Black, and Hispanic/Latino patients, as well as patients who identified as other; 71.5% were White persons, 59.1% were female patients.

- The researchers used a regression analysis to investigate the association between race/ethnicity and PP after controlling for multiple confounding variables, including age and gender.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black children were significantly more likely to have PP than White children (adjusted odds ratio, 6.386; P < .0001). PP was diagnosed in 41.9%, 11.5%, and 8.9% of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and White children, respectively.

- Male gender was also identified as an independent risk factor for PP (aOR, 2.241).

- Nail involvement occurred in significantly more Black and Hispanic/Latino patients than in White patients (53.2%, 50.0%, and 33.9%, respectively).

- Black patients had significantly more palm and sole involvement, compared with the other groups (P < .0001 for both); however, White children had significantly more scalp involvement, compared with the other groups (P = .04).

IN PRACTICE:

“Further research is warranted to better understand the degree to which these associations are affected by racial disparities and environmental factors,” as well as potential genetic associations, the researchers noted.

SOURCE:

The corresponding author on the study was Amy Theos, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. The study was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings were limited by the small sample size and incomplete data for some patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Allergic contact dermatitis

THE COMPARISON

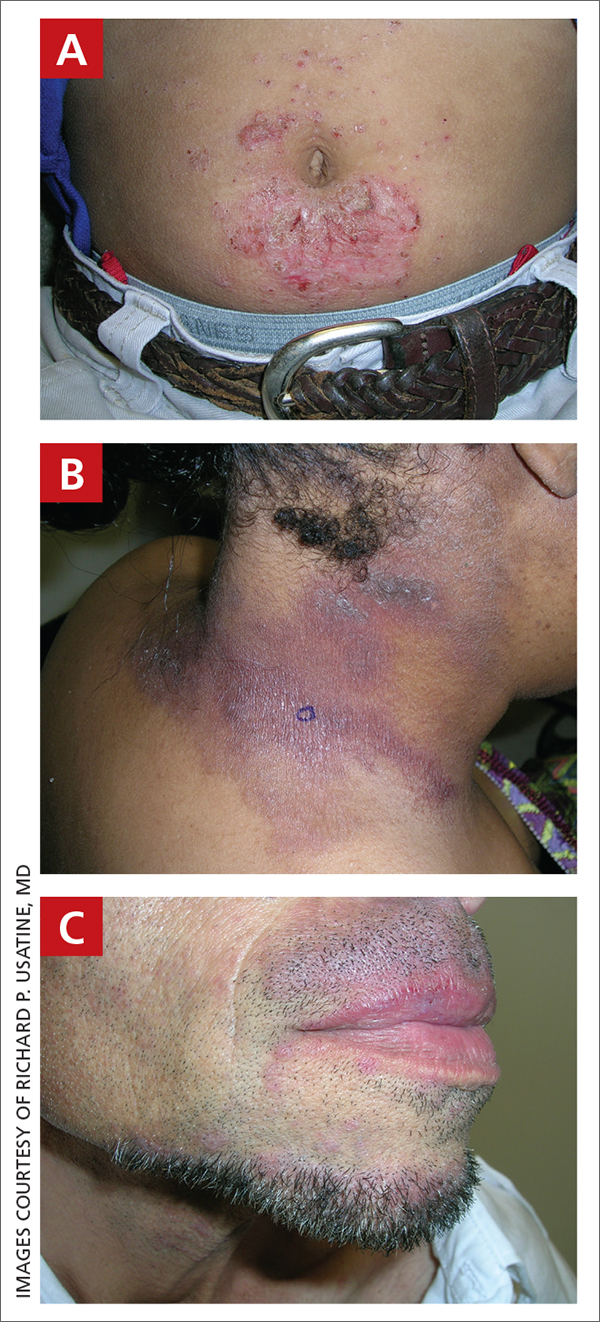

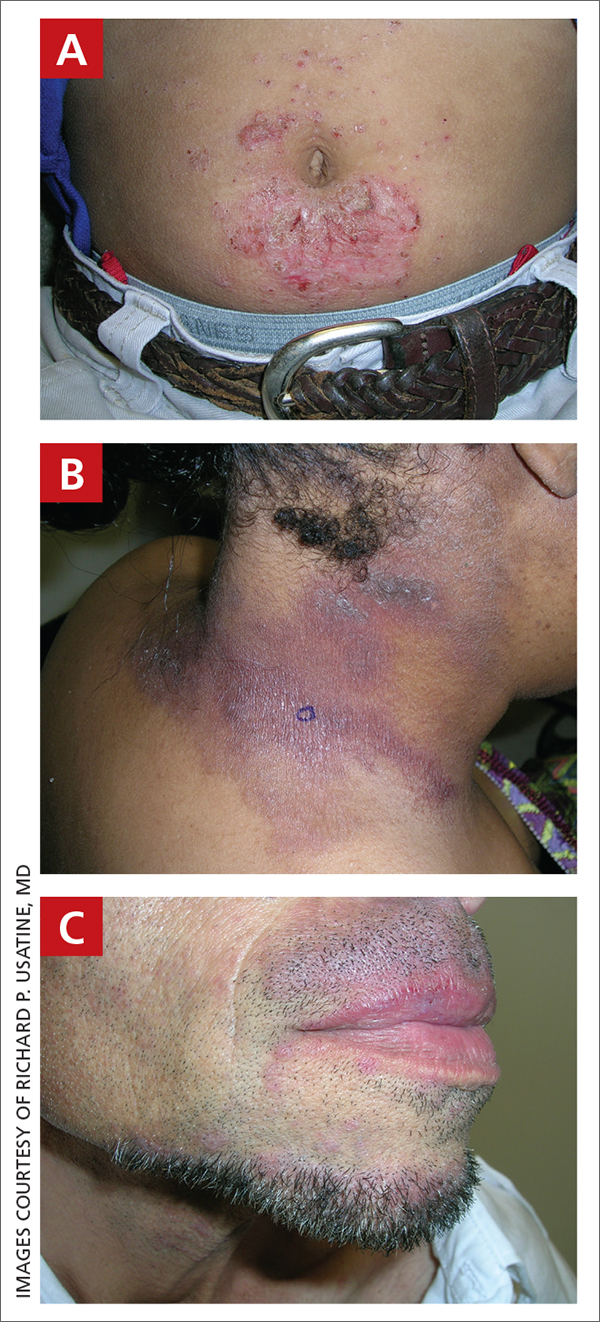

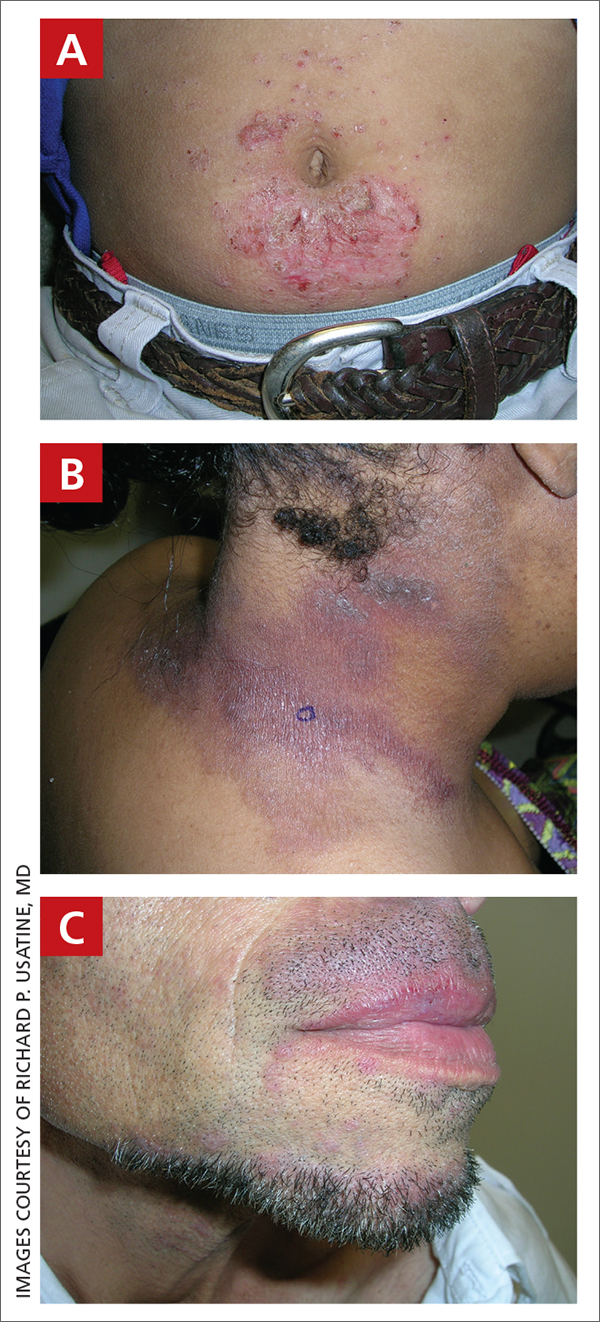

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas of the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to 1 or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is re-exposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 ACD is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

Continue to: The underrepresentation of patients...

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%-23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area, including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N = 19,457); 92.9% of these patients were White and only 7.1% were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

ACD is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (FIGURE A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (FIGURE B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD; a common component of hair dye) (FIGURE C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative; 9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Continue to: Ethnicity and cultural practices...

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. ACD due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on Day 1 and covered. Then, on Day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around Days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Continue to: Furthermore, Scott et al...

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N = 1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children ages 0-12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P < .0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23 The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

1. Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

2. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

3. Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0342

4. Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

5. Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi: 10.1007/s11882-023- 01070-5

6. Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06415.x

7. Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

8. Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi: 10.1016/ j.phrs.2020.105282

9. Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediatedand cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

10. Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi: 10.1111/cod.13119

11. DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998-2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi: 10.1097/ DER.0000000000000220

12. Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi: 10.1016/j jaad.2020.10.003

13. Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi: 10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

14. DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

15. Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0292

16. Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi: 10.1111/ pde.14578

17. Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. Stat- Pearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

18. Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

19. Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000581

20. Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

21. Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

22. Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031

23. Kadyk DL, Hall S, Belsito DV. Quality of life of patients with allergic contact dermatitis: an exploratory analysis by gender, ethnicity, age, and occupation. Dermatitis. 2004;15:117-124.

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas of the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to 1 or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is re-exposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 ACD is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

Continue to: The underrepresentation of patients...

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%-23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area, including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N = 19,457); 92.9% of these patients were White and only 7.1% were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

ACD is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (FIGURE A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (FIGURE B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD; a common component of hair dye) (FIGURE C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative; 9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Continue to: Ethnicity and cultural practices...

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. ACD due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on Day 1 and covered. Then, on Day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around Days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Continue to: Furthermore, Scott et al...

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N = 1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children ages 0-12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P < .0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23 The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas of the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).