User login

FDA approves first two-drug tablet for HIV

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the first two-drug, fixed-dose, complete regimen for HIV-infected adults, according to an FDA press announcement.

Dovato (dolutegravir and lamivudine), a product of ViiV Healthcare, is intended to serve “as a complete regimen” for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults who have had no previous antiretroviral treatment and who have an infection with no known or suspected genetic substitutions associated with resistance to the individual components of Dovato.

“With this approval, patients who have never been treated have the option of taking a two-drug regimen in a single tablet while eliminating additional toxicity and potential drug interactions from a third drug,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Antiviral Products.

The Dovato labeling includes a Boxed Warning that patients infected with both HIV and hepatitis B should add additional treatment for their HBV or consider a different drug regimen. The most common adverse reactions with Dovato were headache, diarrhea, nausea, insomnia, and fatigue. In addition, the FDA warned that, as there is a known risk for neural tube defects with dolutegravir, patients are advised to avoid use of Dovato at the time of conception through the first trimester of pregnancy.

[email protected]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the first two-drug, fixed-dose, complete regimen for HIV-infected adults, according to an FDA press announcement.

Dovato (dolutegravir and lamivudine), a product of ViiV Healthcare, is intended to serve “as a complete regimen” for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults who have had no previous antiretroviral treatment and who have an infection with no known or suspected genetic substitutions associated with resistance to the individual components of Dovato.

“With this approval, patients who have never been treated have the option of taking a two-drug regimen in a single tablet while eliminating additional toxicity and potential drug interactions from a third drug,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Antiviral Products.

The Dovato labeling includes a Boxed Warning that patients infected with both HIV and hepatitis B should add additional treatment for their HBV or consider a different drug regimen. The most common adverse reactions with Dovato were headache, diarrhea, nausea, insomnia, and fatigue. In addition, the FDA warned that, as there is a known risk for neural tube defects with dolutegravir, patients are advised to avoid use of Dovato at the time of conception through the first trimester of pregnancy.

[email protected]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the first two-drug, fixed-dose, complete regimen for HIV-infected adults, according to an FDA press announcement.

Dovato (dolutegravir and lamivudine), a product of ViiV Healthcare, is intended to serve “as a complete regimen” for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults who have had no previous antiretroviral treatment and who have an infection with no known or suspected genetic substitutions associated with resistance to the individual components of Dovato.

“With this approval, patients who have never been treated have the option of taking a two-drug regimen in a single tablet while eliminating additional toxicity and potential drug interactions from a third drug,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Antiviral Products.

The Dovato labeling includes a Boxed Warning that patients infected with both HIV and hepatitis B should add additional treatment for their HBV or consider a different drug regimen. The most common adverse reactions with Dovato were headache, diarrhea, nausea, insomnia, and fatigue. In addition, the FDA warned that, as there is a known risk for neural tube defects with dolutegravir, patients are advised to avoid use of Dovato at the time of conception through the first trimester of pregnancy.

[email protected]

Cigna, Express Scripts to offer $25 cap on 30-day insulin supply

Cigna and Express Scripts have announced

The new program, open to Cigna members who are covered in commercial plans, would cap out-of-pocket costs for a 30-day supply of insulin at $25. For plan members, the only eligibility requirement is having an out-of-pocket cost higher than $25, according to a press release.

For a member to participate in the program, the plan administrator at the member’s place of employment has to opt in to it. There are no eligibility requirements imposed on the employer, other than a willingness to opt in.

A spokeswoman for Express Scripts said that there is no charge to sign up for the program, and most plans will not see an additional cost to get the copayment to $25 for the patient.

The announcement comes in the wake of the first of two hearings by the House Committee on Energy & Commerce aimed at understanding why insulin prices have spiked in recent years. The first hearing, held on April 2, examined the impact that the high list price of insulin is having on patients, and how out-of-pocket expenses are limiting access to this life-saving drug. The second hearing, expected to occur during the week of April 8 (the date had not been scheduled as of press time), will bring together various players in the supply chain, including the three major manufacturers of insulin.

“We are confident that our new program will remove cost as a barrier for people in participating plans who need insulin,” Steve Miller, MD, executive vice president and chief clinical officer at Cigna, said in a statement.

The Express Scripts spokeswoman noted that there were more than 700,000 people in a commercially insured plan across Cigna and Express Scripts who had a claim for insulin in 2018. The average out-of-pocket cost of a 30-day supply of insulin in 2018 across this population was $41.50.

Cigna and Express Scripts have announced

The new program, open to Cigna members who are covered in commercial plans, would cap out-of-pocket costs for a 30-day supply of insulin at $25. For plan members, the only eligibility requirement is having an out-of-pocket cost higher than $25, according to a press release.

For a member to participate in the program, the plan administrator at the member’s place of employment has to opt in to it. There are no eligibility requirements imposed on the employer, other than a willingness to opt in.

A spokeswoman for Express Scripts said that there is no charge to sign up for the program, and most plans will not see an additional cost to get the copayment to $25 for the patient.

The announcement comes in the wake of the first of two hearings by the House Committee on Energy & Commerce aimed at understanding why insulin prices have spiked in recent years. The first hearing, held on April 2, examined the impact that the high list price of insulin is having on patients, and how out-of-pocket expenses are limiting access to this life-saving drug. The second hearing, expected to occur during the week of April 8 (the date had not been scheduled as of press time), will bring together various players in the supply chain, including the three major manufacturers of insulin.

“We are confident that our new program will remove cost as a barrier for people in participating plans who need insulin,” Steve Miller, MD, executive vice president and chief clinical officer at Cigna, said in a statement.

The Express Scripts spokeswoman noted that there were more than 700,000 people in a commercially insured plan across Cigna and Express Scripts who had a claim for insulin in 2018. The average out-of-pocket cost of a 30-day supply of insulin in 2018 across this population was $41.50.

Cigna and Express Scripts have announced

The new program, open to Cigna members who are covered in commercial plans, would cap out-of-pocket costs for a 30-day supply of insulin at $25. For plan members, the only eligibility requirement is having an out-of-pocket cost higher than $25, according to a press release.

For a member to participate in the program, the plan administrator at the member’s place of employment has to opt in to it. There are no eligibility requirements imposed on the employer, other than a willingness to opt in.

A spokeswoman for Express Scripts said that there is no charge to sign up for the program, and most plans will not see an additional cost to get the copayment to $25 for the patient.

The announcement comes in the wake of the first of two hearings by the House Committee on Energy & Commerce aimed at understanding why insulin prices have spiked in recent years. The first hearing, held on April 2, examined the impact that the high list price of insulin is having on patients, and how out-of-pocket expenses are limiting access to this life-saving drug. The second hearing, expected to occur during the week of April 8 (the date had not been scheduled as of press time), will bring together various players in the supply chain, including the three major manufacturers of insulin.

“We are confident that our new program will remove cost as a barrier for people in participating plans who need insulin,” Steve Miller, MD, executive vice president and chief clinical officer at Cigna, said in a statement.

The Express Scripts spokeswoman noted that there were more than 700,000 people in a commercially insured plan across Cigna and Express Scripts who had a claim for insulin in 2018. The average out-of-pocket cost of a 30-day supply of insulin in 2018 across this population was $41.50.

Aspirin for primary prevention: USPSTF recommendations for CVD and colorectal cancer

Which patients are likely to benefit from using aspirin for primary prevention? In this article, we review the evidence to date, summarized for primary care settings in guidelines issued by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). We supplement this summary with a rundown of the risks associated with aspirin use. And then we wrap up by identifying a clinical decision tool that is available to help make personalized decisions in a busy clinic setting, where determining an individual’s potential cardiovascular benefits and bleeding risk can be challenging.

The “roadmap” from the guidelines. In 2014, after performing a review of the literature, the US Food and Drug Administration recommended against the routine use of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 In 2016, the USPSTF published 4 separate systematic reviews along with a decision analysis using a microsimulation model, which informed their position statement on aspirin for primary prevention.2-6 These USPSTF reviews and recommendations incorporated both CVD and colorectal cancer (CRC) benefits with the bleeding risks from aspirin. Generally, for individuals 50 to 59 years old, the benefits are deemed to outweigh the harms; shared decision making is advised with those 60 to 69 years of age. For patients younger than 50 or 70 and older, evidence is inconclusive.

The benefits of primary prevention with aspirin

Cardiovascular disease

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration was one of the first meta-analyses that addressed the benefit-to-harm balance and called into question the routine use of aspirin for primary prevention.7 The USPSTF systematic review included the studies from the ATT Collaboration as well as trials performed after its publication, bringing the total number of eligible randomized controlled trials reviewed to 11.2

The benefit of aspirin for primary prevention of nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) has been shown in multiple randomized controlled trials. The USPSTF systematic review showed a statistically significant relative risk reduction of 17% in patients taking low-dose aspirin (≤ 100 mg; relative risk [RR] = 0.83; confidence interval [95% CI], 0.74-0.94), although the heterogeneity of the studies was high. The same low dose of aspirin showed a statistically significant reduction in nonfatal stroke (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.98), although the same benefit was not observed when all doses of aspirin were included. Cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality were not statistically different for patients taking low-dose aspirin when compared with placebo (RR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.85-1.10 for CVD mortality; RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-1.01 for all-cause mortality).2

One study of more than 14,000 older (≥ 60 years) Japanese patients showed a statistically significant reduction in nonfatal MI (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.91, P = .02) and nonfatal strokes (HR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.32-0.99; P = .04). The study was stopped early because at 5 years of follow-up there was no statistically significant difference in a composite primary outcome, which included death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (HR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.77-1.15; P = .54).8

Several recent landmark studies have called into question the benefit of aspirin for cardiovascular primary prevention, especially in obese individuals, patients with diabetes, and the elderly. A meta-analysis of 10 trials showed that the effectiveness of aspirin doses between 75 mg and 100 mg for primary prevention decreased as weight increased; patients weighing 70 kg or more received no benefit.9 The ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) trial included more than 15,000 patients with diabetes but no cardiovascular disease. Patients randomized to receive the low-dose aspirin did have fewer serious vascular events (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97; P = .01), but they also had high risk of major bleeding events (IRR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.09-1.52; P = .003).10 The ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial included more than 19,000 patients ages 70 years and older with no cardiovascular disease and compared low-dose aspirin to placebo. There was no statistically significant cardiovascular benefit, although there was an increase of major hemorrhage (HR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.62; P < .001).11 The ARRIVE (A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management) trial included 12,546 moderate atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk patients. Although a per-protocol analysis showed a decrease in rates of fatal and nonfatal MI (HR = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.79; P = .0014), the more reliable intention-to-treat analysis showed no improvement for any outcomes.12

[polldaddy:10286821]

Colorectal cancer

The literature base on prevention of cancer has been growing rapidly. However, the deluge of findings over the past 2 decades of trials and analyses has also introduced ambiguity and, often, conflicting results. The first journal article suggesting aspirin for primary prevention of cancer, published in 1988, was a case-control study wherein a population with CRC was matched to controls to look for potential protective factors.13 The most notable finding was the CRC risk reduction for those taking aspirin or aspirin-containing medications. Since then numerous studies and analyses have explored aspirin’s potential in primary prevention of many types of cancer, with overall unclear findings as denoted in the 2016 USPSTF systemic reviews and recommendations.

Continue to: One major limiting factor...

One major limiting factor is that most data come from CVD prevention trials, and only a limited number of trials have focused specifically on cancer prevention. For the USPSTF, these data showed no statistically significant risk reduction in overall cancer mortality (RR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.87-1.06) or in total cancer incidence (RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.04).4 Other ongoing trials may yield more definitive data.14

The particular interest in CRC was due to it being the first cancer found to be preventable with aspirin therapy. The USPSTF, while acknowledging the homogeneous nature of supporting studies, noted that their significant number and resulting evidence made CRC the only cancer warranting evaluation. Population studies have now shown more benefit than the few randomized control trials. The Women’s Health Study and the Physicians’ Health Study were both limited by their duration. But such studies conducted over a longer period revealed notable benefits in the second decade of use, with a statistically significant lower CRC incidence (RR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76). Additionally, CRC mortality at 20 years was decreased in patients taking aspirin regularly (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.52-0.86).4 Multiple studies are in progress to better establish aspirin’s CRC benefit.

While not directly applicable to the general population, use of aspirin for patients with Lynch syndrome to prevent CRC has strong supporting evidence.15 Beyond CRC, there is nascent evidence from limited observational studies that aspirin may have a preventive effect on melanoma and ovarian and pancreatic cancers.16-18 Further studies or compilations of data would be needed to draw more significant conclusions on other types of cancers. Larger studies would prove more difficult to do, given the smaller incidences of these cancers.

Interestingly, a recent study showed that for individuals 70 years and older, aspirin might increase the risk for all-cause mortality, primarily due to increased cancer mortality across all types.19 Although this result was unexpected, caution should be used when prescribing aspirin particularly for patients 70 or older with active cancer.

A look at the harms associated with aspirin use

Aspirin has long been known to cause clinically significant bleeding. Aspirin inhibits platelet-derived cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), a potent vasoconstrictor, and thereby decreases platelet aggregation, reducing thromboembolic potential and prolonging bleeding time. These effects can confer health benefits but also carry the potential for risks. A decision to initiate aspirin therapy for primary prevention relies on an understanding of the benefit-to-harm balance.

Continue to: Initial aspirin studies...

Initial aspirin studies did not show a statistically significant increase in bleeding, likely due to too few events and inadequate powering. Subsequent meta-analyses from multiple evaluations have consistently shown bleeding to be a risk.3,7 The risk for bleeding with aspirin has also been examined in multiple cohort studies, which has helped elucidate the risk in greater detail.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Epidemiologic data show that among patients who do not use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the rate of upper gastrointestinal (GI) complications is 1 case per 1000 patient-years.20 Multiple studies have consistently shown that aspirin use increases the rate of significant upper GI bleeding over baseline risk (odds ratio [OR] = 1.54-1.58).3,21,22 Interestingly, these increases seem not to be influenced by other factors, such as comorbidities that increase the risk for ASCVD. Analysis of cancer prevention studies showed similar epidemiologic trends, with aspirin use exceeding a baseline bleeding risk of 0.7 cases of upper GI complications per 1000 patient-years (

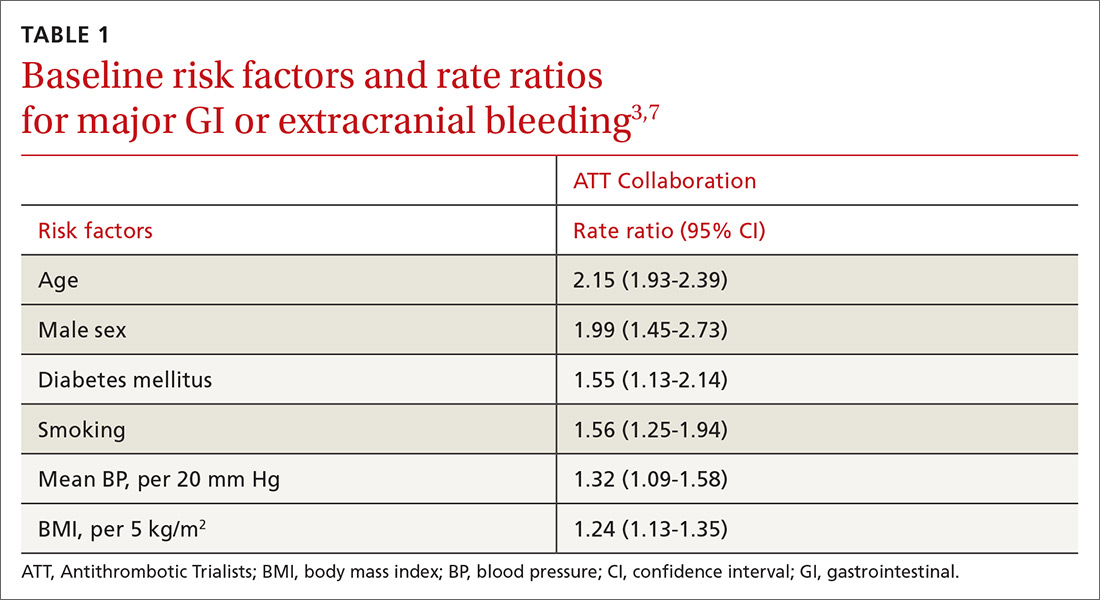

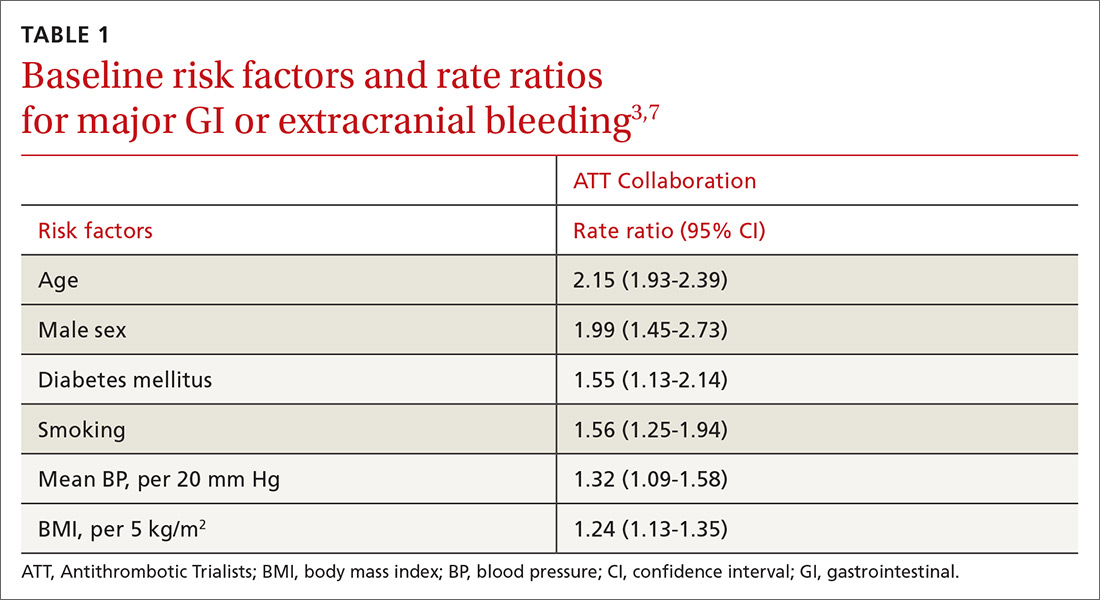

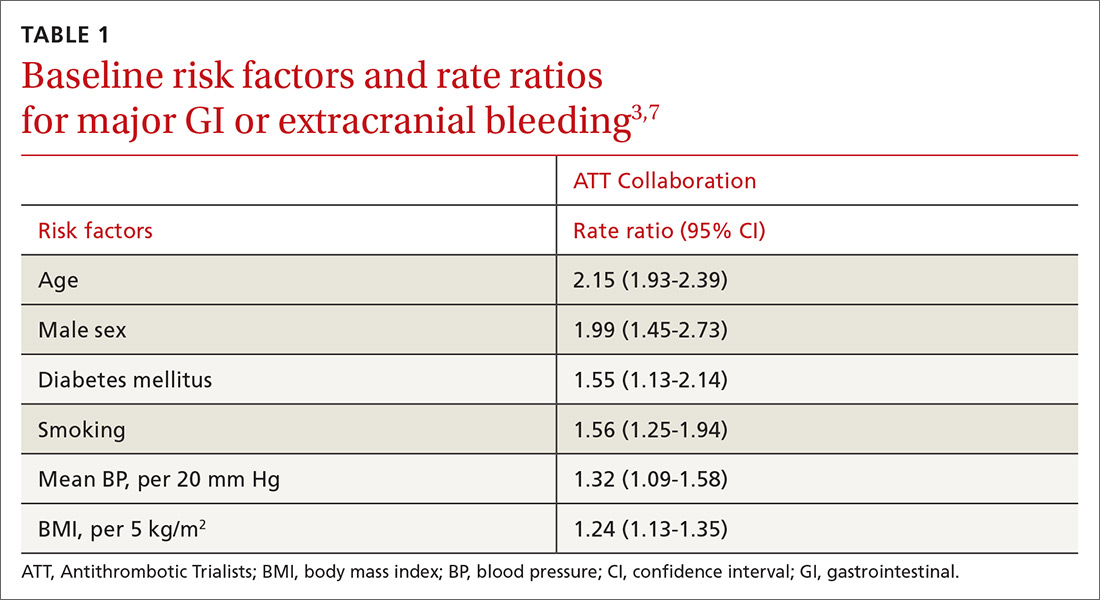

Other risk factors. Evaluation of risk factors for bleeding primarily comes from 2 studies.3,7 Most data concern the impact of individual factors on significant GI bleeding, with fewer data available for evaluating risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Initial analysis of individual prospective studies showed little or no correlation between risk for bleeding and such factors as gender, age, or history of hypertension or ASCVD.21 Subsequent analysis of meta-data and large cohorts did show statistically significant impact on rates of bleeding across several factors (TABLE 13,7).

Of note is a large heterogeneous cohort study conducted in Spain. Data showed significant increases in baseline risk for GI bleeding in older men with a history of GI bleeding and NSAID use. The absolute risk for GI bleed in this group was potentially as high as 150 cases per 1000 patient-years, well above the risk level assumed for the average patient.24 A seemingly small OR of 1.5 could dramatically increase the absolute risk for bleeding in such patients, and it suggests that a generalized risk for bleeding probably shouldn’t be applied to all patients. Individuals may be better served by a baseline risk calculation reflecting multiple factors.

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Due to the comparatively uncommon nature of ICH, fewer data are available to support definitive conclusions about its increased risk with aspirin use. Aspirin use appeared to increase the risk for ICH with ratios between 1.27 and 1.32 in meta-analyses (measured as an OR or as an RR),3,7,21 with an IRR of 1.54 in a cohort study.22 The only statistically significant factors suspected to increase the risk of ICH at baseline were smoking (RR = 2.18) and mean BP > 20 mm Hg over normal (OR = 2.18). Age, gender, and diabetes all showed a nonsignificant trend toward risk increase.7

Continue to: Risk based on dose and formulation

Risk based on dose and formulation

The effect of aspirin dose and formulation on bleeding risk is uncertain. Some studies have shown an increased risk for bleeding with daily doses of aspirin ≥ 300 mg, while others have shown no significant increase in rates for bleeding with differing doses.21,25 Enteric coating does appear to lower the rates of gastric mucosal injury, although there are few data on the effect toward reducing clinically significant bleeding.26 Currently, several prospective studies are underway to help clarify the evidence.27

Putting it all together

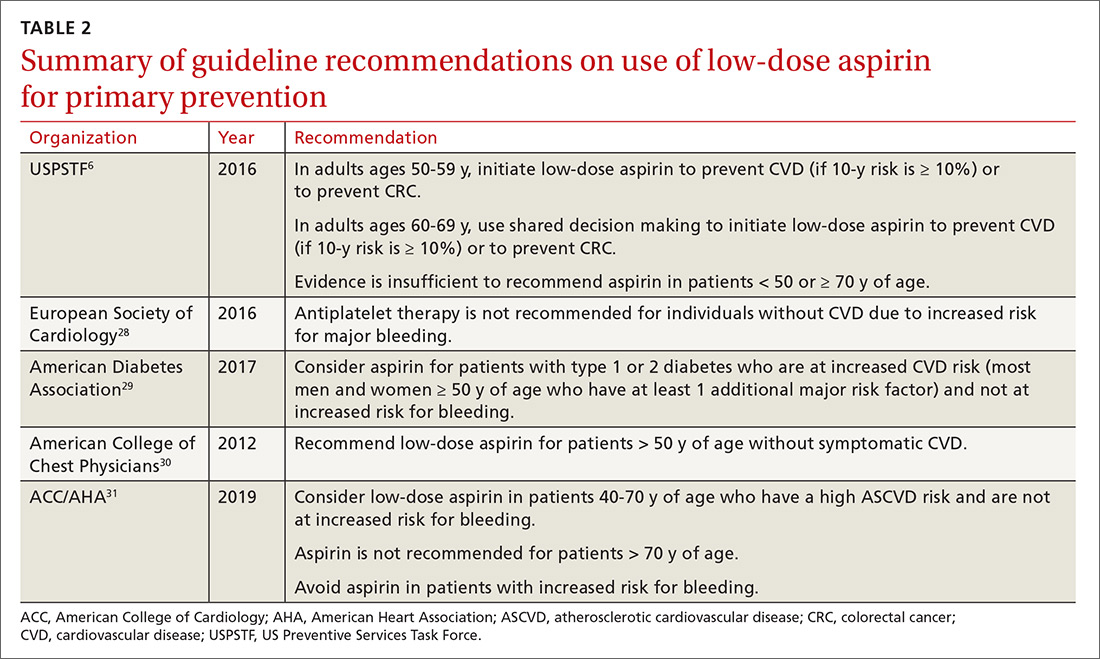

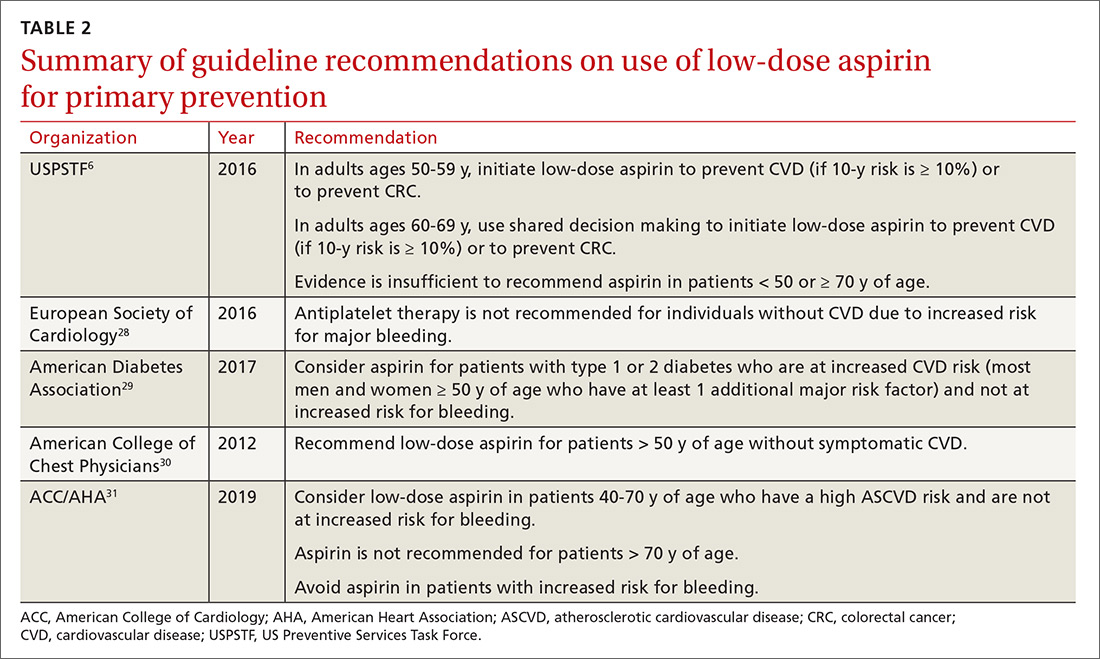

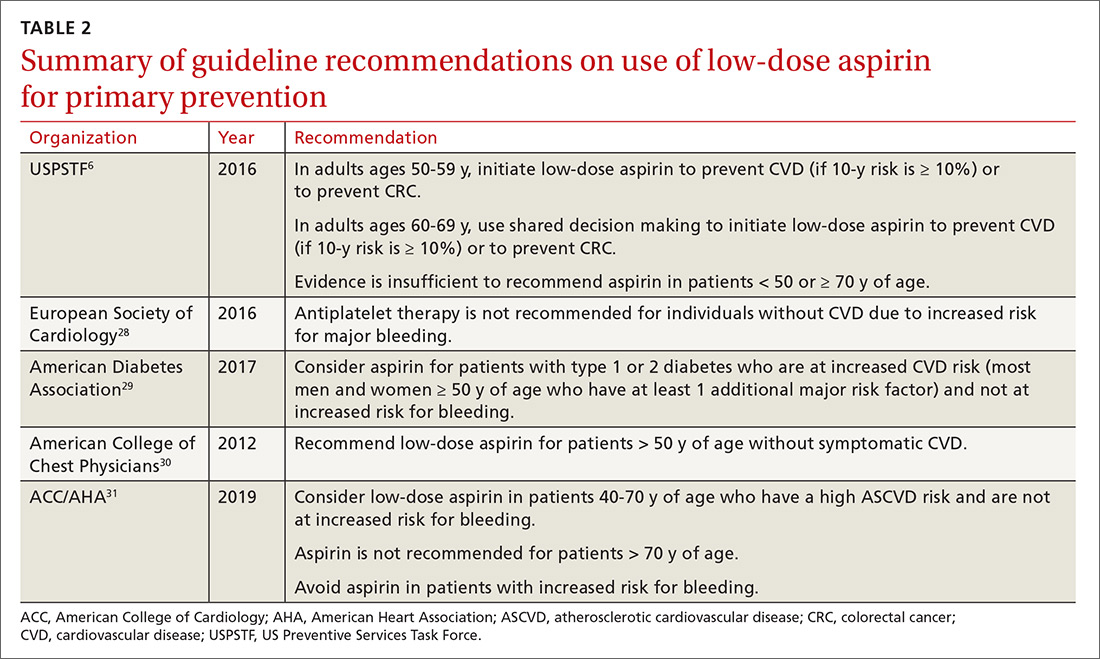

For the general population, the evidence shows that the benefits and harms of aspirin for primary prevention are relatively even. The USPSTF guidelines are the first to recommend aspirin for both CVD and cancer prevention while taking into account the bleeding risk. According to the findings of the USPSTF, the balance of benefits and harms of aspirin use is contingent on 4 factors: age, baseline CVD risk, risk for bleeding, and preferences about taking aspirin.6 The complete recommendations from the USPSTF, along with other leading organizations, are outlined in TABLE 2.6,28-31

Applying the evidence and varying guidelines in practice can feel daunting. Some practical tools have been developed to help clinicians understand patients’ bleeding risk and potential benefits with aspirin use. One such tool is highlighted below. Others are also available, and each has its own strengths and weaknesses.

Aspirin-Guide (www.aspiringuide.com) is a Web-based clinical decision support tool with an associated mobile application. It uses internal calculators (including the pooled cohort calculator prepared jointly by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association) to assess CVD risk as well as bleeding risk. This tool gives clinicians patient-specific numbers-needed-to-treat and numbers-needed-to-harm when considering starting aspirin for primary prevention. It gives specific recommendations for aspirin use based on the data entered, and it also gives providers information to help guide shared decision-making with patients.32 Unfortunately, this decision support tool and others do not take into account the data from the most recent trials, so they should be used with caution.

CORRESPONDENCE

LCDR Dustin K. Smith, DO, Naval Branch Clinic Diego Garcia, PSC 466, Box 301, FPO, AP 96595; [email protected].

1. FDA. Use of aspirin for primary prevention of heart attack and stroke. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm390574.htm. Accessed March 22, 2019.

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

3. Whitlock EP, Burda BU, Williams SB, et al. Bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention in adults: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:826-835.

4. Chubak J, Whitlock EP, Williams SB, et al. Aspirin for the prevention of cancer incidence and mortality: systematic evidence reviews for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:814-825.

5. Dehmer SP, Maciosek MV, Flottemesch TJ, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:777-786.

6. Bibbins-Domingo K. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

7. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Colins R, et al; Antithrombotic Trialists (ATT) Collaboration. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participation data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009:373:1849-1860.

8. Ikeda Y, Shimada K, Teramoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2510-2520.

9. Rothwell PM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2018;392:387-399.

10. Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al; ASCEND Study Collaborative Group. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529-1539.

11. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1509-1518.

12. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1036-1046.

13. Kune GA, Kune S, Watson LF. Colorectal cancer risk, chronic illness, operations, and medications: case control results from Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4399-4404.

14. Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, et al. Aspirin for prophylactic use in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review and overview of reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:1-253.

15. Burn J, Gerdes AM, Macrae F, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:2081-2087.

16. Gamba CA, Swetter SM, Stefanick ML, et al. Aspirin is associated with lower melanoma risk among postmenopausal Caucasian women: the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer. 2013;119:1562-1569.

17. Trabert B, Ness RB, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt431.

18. Risch H, Lu L, Streicher SA, et al. Aspirin use and reduced risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;26:68-74.

19. McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1519-1528.

20. Hernández-Díaz S, Rodríguez LA. Incidence of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding/perforation in the general population: review of epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:157-163.

21. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis no 131. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321623/. Accessed March 22, 2019.

22. De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, et al. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2012;307:2286-2294.

23. Thorat MA, Cuzick J. Prophylactic use of aspirin: systematic review of harms and approaches to mitigation in the general population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:5-18.

24. Hernández-Díaz S, García Rodríguez LA. Cardioprotective aspirin users and their excess risk of upper gastrointestinal complications. BMC Med. 2006;4:22.

25. Huang ES, Strate LL, Ho WW, et al. Long term use of aspirin and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Med. 2011:124;426-433.

26. Walker J, Robinson J, Stewart J, et al. Does enteric-coated aspirin result in a lower incidence of gastrointestinal complications compared to normal aspirin? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007:6;519-522.

27. NIH. Aspirin dosing: a patient-centric trial assessing benefits and long-term effectiveness (ADAPTABLE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02697916. Accessed March 22, 2019.

28. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315-2381.

29. ADA. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1). http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/suppl/2016/12/15/40.Supplement_1.DC1/DC_40_S1_final.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2019.

30. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl):e637S-e668S.

31. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Col Cardiol. 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010. Accessed March 22, 2019.

32. Mora S, Manson JE. Aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1195-1204.

Which patients are likely to benefit from using aspirin for primary prevention? In this article, we review the evidence to date, summarized for primary care settings in guidelines issued by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). We supplement this summary with a rundown of the risks associated with aspirin use. And then we wrap up by identifying a clinical decision tool that is available to help make personalized decisions in a busy clinic setting, where determining an individual’s potential cardiovascular benefits and bleeding risk can be challenging.

The “roadmap” from the guidelines. In 2014, after performing a review of the literature, the US Food and Drug Administration recommended against the routine use of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 In 2016, the USPSTF published 4 separate systematic reviews along with a decision analysis using a microsimulation model, which informed their position statement on aspirin for primary prevention.2-6 These USPSTF reviews and recommendations incorporated both CVD and colorectal cancer (CRC) benefits with the bleeding risks from aspirin. Generally, for individuals 50 to 59 years old, the benefits are deemed to outweigh the harms; shared decision making is advised with those 60 to 69 years of age. For patients younger than 50 or 70 and older, evidence is inconclusive.

The benefits of primary prevention with aspirin

Cardiovascular disease

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration was one of the first meta-analyses that addressed the benefit-to-harm balance and called into question the routine use of aspirin for primary prevention.7 The USPSTF systematic review included the studies from the ATT Collaboration as well as trials performed after its publication, bringing the total number of eligible randomized controlled trials reviewed to 11.2

The benefit of aspirin for primary prevention of nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) has been shown in multiple randomized controlled trials. The USPSTF systematic review showed a statistically significant relative risk reduction of 17% in patients taking low-dose aspirin (≤ 100 mg; relative risk [RR] = 0.83; confidence interval [95% CI], 0.74-0.94), although the heterogeneity of the studies was high. The same low dose of aspirin showed a statistically significant reduction in nonfatal stroke (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.98), although the same benefit was not observed when all doses of aspirin were included. Cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality were not statistically different for patients taking low-dose aspirin when compared with placebo (RR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.85-1.10 for CVD mortality; RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-1.01 for all-cause mortality).2

One study of more than 14,000 older (≥ 60 years) Japanese patients showed a statistically significant reduction in nonfatal MI (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.91, P = .02) and nonfatal strokes (HR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.32-0.99; P = .04). The study was stopped early because at 5 years of follow-up there was no statistically significant difference in a composite primary outcome, which included death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (HR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.77-1.15; P = .54).8

Several recent landmark studies have called into question the benefit of aspirin for cardiovascular primary prevention, especially in obese individuals, patients with diabetes, and the elderly. A meta-analysis of 10 trials showed that the effectiveness of aspirin doses between 75 mg and 100 mg for primary prevention decreased as weight increased; patients weighing 70 kg or more received no benefit.9 The ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) trial included more than 15,000 patients with diabetes but no cardiovascular disease. Patients randomized to receive the low-dose aspirin did have fewer serious vascular events (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97; P = .01), but they also had high risk of major bleeding events (IRR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.09-1.52; P = .003).10 The ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial included more than 19,000 patients ages 70 years and older with no cardiovascular disease and compared low-dose aspirin to placebo. There was no statistically significant cardiovascular benefit, although there was an increase of major hemorrhage (HR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.62; P < .001).11 The ARRIVE (A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management) trial included 12,546 moderate atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk patients. Although a per-protocol analysis showed a decrease in rates of fatal and nonfatal MI (HR = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.79; P = .0014), the more reliable intention-to-treat analysis showed no improvement for any outcomes.12

[polldaddy:10286821]

Colorectal cancer

The literature base on prevention of cancer has been growing rapidly. However, the deluge of findings over the past 2 decades of trials and analyses has also introduced ambiguity and, often, conflicting results. The first journal article suggesting aspirin for primary prevention of cancer, published in 1988, was a case-control study wherein a population with CRC was matched to controls to look for potential protective factors.13 The most notable finding was the CRC risk reduction for those taking aspirin or aspirin-containing medications. Since then numerous studies and analyses have explored aspirin’s potential in primary prevention of many types of cancer, with overall unclear findings as denoted in the 2016 USPSTF systemic reviews and recommendations.

Continue to: One major limiting factor...

One major limiting factor is that most data come from CVD prevention trials, and only a limited number of trials have focused specifically on cancer prevention. For the USPSTF, these data showed no statistically significant risk reduction in overall cancer mortality (RR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.87-1.06) or in total cancer incidence (RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.04).4 Other ongoing trials may yield more definitive data.14

The particular interest in CRC was due to it being the first cancer found to be preventable with aspirin therapy. The USPSTF, while acknowledging the homogeneous nature of supporting studies, noted that their significant number and resulting evidence made CRC the only cancer warranting evaluation. Population studies have now shown more benefit than the few randomized control trials. The Women’s Health Study and the Physicians’ Health Study were both limited by their duration. But such studies conducted over a longer period revealed notable benefits in the second decade of use, with a statistically significant lower CRC incidence (RR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76). Additionally, CRC mortality at 20 years was decreased in patients taking aspirin regularly (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.52-0.86).4 Multiple studies are in progress to better establish aspirin’s CRC benefit.

While not directly applicable to the general population, use of aspirin for patients with Lynch syndrome to prevent CRC has strong supporting evidence.15 Beyond CRC, there is nascent evidence from limited observational studies that aspirin may have a preventive effect on melanoma and ovarian and pancreatic cancers.16-18 Further studies or compilations of data would be needed to draw more significant conclusions on other types of cancers. Larger studies would prove more difficult to do, given the smaller incidences of these cancers.

Interestingly, a recent study showed that for individuals 70 years and older, aspirin might increase the risk for all-cause mortality, primarily due to increased cancer mortality across all types.19 Although this result was unexpected, caution should be used when prescribing aspirin particularly for patients 70 or older with active cancer.

A look at the harms associated with aspirin use

Aspirin has long been known to cause clinically significant bleeding. Aspirin inhibits platelet-derived cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), a potent vasoconstrictor, and thereby decreases platelet aggregation, reducing thromboembolic potential and prolonging bleeding time. These effects can confer health benefits but also carry the potential for risks. A decision to initiate aspirin therapy for primary prevention relies on an understanding of the benefit-to-harm balance.

Continue to: Initial aspirin studies...

Initial aspirin studies did not show a statistically significant increase in bleeding, likely due to too few events and inadequate powering. Subsequent meta-analyses from multiple evaluations have consistently shown bleeding to be a risk.3,7 The risk for bleeding with aspirin has also been examined in multiple cohort studies, which has helped elucidate the risk in greater detail.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Epidemiologic data show that among patients who do not use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the rate of upper gastrointestinal (GI) complications is 1 case per 1000 patient-years.20 Multiple studies have consistently shown that aspirin use increases the rate of significant upper GI bleeding over baseline risk (odds ratio [OR] = 1.54-1.58).3,21,22 Interestingly, these increases seem not to be influenced by other factors, such as comorbidities that increase the risk for ASCVD. Analysis of cancer prevention studies showed similar epidemiologic trends, with aspirin use exceeding a baseline bleeding risk of 0.7 cases of upper GI complications per 1000 patient-years (

Other risk factors. Evaluation of risk factors for bleeding primarily comes from 2 studies.3,7 Most data concern the impact of individual factors on significant GI bleeding, with fewer data available for evaluating risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Initial analysis of individual prospective studies showed little or no correlation between risk for bleeding and such factors as gender, age, or history of hypertension or ASCVD.21 Subsequent analysis of meta-data and large cohorts did show statistically significant impact on rates of bleeding across several factors (TABLE 13,7).

Of note is a large heterogeneous cohort study conducted in Spain. Data showed significant increases in baseline risk for GI bleeding in older men with a history of GI bleeding and NSAID use. The absolute risk for GI bleed in this group was potentially as high as 150 cases per 1000 patient-years, well above the risk level assumed for the average patient.24 A seemingly small OR of 1.5 could dramatically increase the absolute risk for bleeding in such patients, and it suggests that a generalized risk for bleeding probably shouldn’t be applied to all patients. Individuals may be better served by a baseline risk calculation reflecting multiple factors.

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Due to the comparatively uncommon nature of ICH, fewer data are available to support definitive conclusions about its increased risk with aspirin use. Aspirin use appeared to increase the risk for ICH with ratios between 1.27 and 1.32 in meta-analyses (measured as an OR or as an RR),3,7,21 with an IRR of 1.54 in a cohort study.22 The only statistically significant factors suspected to increase the risk of ICH at baseline were smoking (RR = 2.18) and mean BP > 20 mm Hg over normal (OR = 2.18). Age, gender, and diabetes all showed a nonsignificant trend toward risk increase.7

Continue to: Risk based on dose and formulation

Risk based on dose and formulation

The effect of aspirin dose and formulation on bleeding risk is uncertain. Some studies have shown an increased risk for bleeding with daily doses of aspirin ≥ 300 mg, while others have shown no significant increase in rates for bleeding with differing doses.21,25 Enteric coating does appear to lower the rates of gastric mucosal injury, although there are few data on the effect toward reducing clinically significant bleeding.26 Currently, several prospective studies are underway to help clarify the evidence.27

Putting it all together

For the general population, the evidence shows that the benefits and harms of aspirin for primary prevention are relatively even. The USPSTF guidelines are the first to recommend aspirin for both CVD and cancer prevention while taking into account the bleeding risk. According to the findings of the USPSTF, the balance of benefits and harms of aspirin use is contingent on 4 factors: age, baseline CVD risk, risk for bleeding, and preferences about taking aspirin.6 The complete recommendations from the USPSTF, along with other leading organizations, are outlined in TABLE 2.6,28-31

Applying the evidence and varying guidelines in practice can feel daunting. Some practical tools have been developed to help clinicians understand patients’ bleeding risk and potential benefits with aspirin use. One such tool is highlighted below. Others are also available, and each has its own strengths and weaknesses.

Aspirin-Guide (www.aspiringuide.com) is a Web-based clinical decision support tool with an associated mobile application. It uses internal calculators (including the pooled cohort calculator prepared jointly by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association) to assess CVD risk as well as bleeding risk. This tool gives clinicians patient-specific numbers-needed-to-treat and numbers-needed-to-harm when considering starting aspirin for primary prevention. It gives specific recommendations for aspirin use based on the data entered, and it also gives providers information to help guide shared decision-making with patients.32 Unfortunately, this decision support tool and others do not take into account the data from the most recent trials, so they should be used with caution.

CORRESPONDENCE

LCDR Dustin K. Smith, DO, Naval Branch Clinic Diego Garcia, PSC 466, Box 301, FPO, AP 96595; [email protected].

Which patients are likely to benefit from using aspirin for primary prevention? In this article, we review the evidence to date, summarized for primary care settings in guidelines issued by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). We supplement this summary with a rundown of the risks associated with aspirin use. And then we wrap up by identifying a clinical decision tool that is available to help make personalized decisions in a busy clinic setting, where determining an individual’s potential cardiovascular benefits and bleeding risk can be challenging.

The “roadmap” from the guidelines. In 2014, after performing a review of the literature, the US Food and Drug Administration recommended against the routine use of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 In 2016, the USPSTF published 4 separate systematic reviews along with a decision analysis using a microsimulation model, which informed their position statement on aspirin for primary prevention.2-6 These USPSTF reviews and recommendations incorporated both CVD and colorectal cancer (CRC) benefits with the bleeding risks from aspirin. Generally, for individuals 50 to 59 years old, the benefits are deemed to outweigh the harms; shared decision making is advised with those 60 to 69 years of age. For patients younger than 50 or 70 and older, evidence is inconclusive.

The benefits of primary prevention with aspirin

Cardiovascular disease

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration was one of the first meta-analyses that addressed the benefit-to-harm balance and called into question the routine use of aspirin for primary prevention.7 The USPSTF systematic review included the studies from the ATT Collaboration as well as trials performed after its publication, bringing the total number of eligible randomized controlled trials reviewed to 11.2

The benefit of aspirin for primary prevention of nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) has been shown in multiple randomized controlled trials. The USPSTF systematic review showed a statistically significant relative risk reduction of 17% in patients taking low-dose aspirin (≤ 100 mg; relative risk [RR] = 0.83; confidence interval [95% CI], 0.74-0.94), although the heterogeneity of the studies was high. The same low dose of aspirin showed a statistically significant reduction in nonfatal stroke (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.98), although the same benefit was not observed when all doses of aspirin were included. Cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality were not statistically different for patients taking low-dose aspirin when compared with placebo (RR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.85-1.10 for CVD mortality; RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-1.01 for all-cause mortality).2

One study of more than 14,000 older (≥ 60 years) Japanese patients showed a statistically significant reduction in nonfatal MI (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.91, P = .02) and nonfatal strokes (HR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.32-0.99; P = .04). The study was stopped early because at 5 years of follow-up there was no statistically significant difference in a composite primary outcome, which included death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (HR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.77-1.15; P = .54).8

Several recent landmark studies have called into question the benefit of aspirin for cardiovascular primary prevention, especially in obese individuals, patients with diabetes, and the elderly. A meta-analysis of 10 trials showed that the effectiveness of aspirin doses between 75 mg and 100 mg for primary prevention decreased as weight increased; patients weighing 70 kg or more received no benefit.9 The ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) trial included more than 15,000 patients with diabetes but no cardiovascular disease. Patients randomized to receive the low-dose aspirin did have fewer serious vascular events (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97; P = .01), but they also had high risk of major bleeding events (IRR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.09-1.52; P = .003).10 The ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial included more than 19,000 patients ages 70 years and older with no cardiovascular disease and compared low-dose aspirin to placebo. There was no statistically significant cardiovascular benefit, although there was an increase of major hemorrhage (HR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.62; P < .001).11 The ARRIVE (A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management) trial included 12,546 moderate atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk patients. Although a per-protocol analysis showed a decrease in rates of fatal and nonfatal MI (HR = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.79; P = .0014), the more reliable intention-to-treat analysis showed no improvement for any outcomes.12

[polldaddy:10286821]

Colorectal cancer

The literature base on prevention of cancer has been growing rapidly. However, the deluge of findings over the past 2 decades of trials and analyses has also introduced ambiguity and, often, conflicting results. The first journal article suggesting aspirin for primary prevention of cancer, published in 1988, was a case-control study wherein a population with CRC was matched to controls to look for potential protective factors.13 The most notable finding was the CRC risk reduction for those taking aspirin or aspirin-containing medications. Since then numerous studies and analyses have explored aspirin’s potential in primary prevention of many types of cancer, with overall unclear findings as denoted in the 2016 USPSTF systemic reviews and recommendations.

Continue to: One major limiting factor...

One major limiting factor is that most data come from CVD prevention trials, and only a limited number of trials have focused specifically on cancer prevention. For the USPSTF, these data showed no statistically significant risk reduction in overall cancer mortality (RR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.87-1.06) or in total cancer incidence (RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.04).4 Other ongoing trials may yield more definitive data.14

The particular interest in CRC was due to it being the first cancer found to be preventable with aspirin therapy. The USPSTF, while acknowledging the homogeneous nature of supporting studies, noted that their significant number and resulting evidence made CRC the only cancer warranting evaluation. Population studies have now shown more benefit than the few randomized control trials. The Women’s Health Study and the Physicians’ Health Study were both limited by their duration. But such studies conducted over a longer period revealed notable benefits in the second decade of use, with a statistically significant lower CRC incidence (RR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76). Additionally, CRC mortality at 20 years was decreased in patients taking aspirin regularly (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.52-0.86).4 Multiple studies are in progress to better establish aspirin’s CRC benefit.

While not directly applicable to the general population, use of aspirin for patients with Lynch syndrome to prevent CRC has strong supporting evidence.15 Beyond CRC, there is nascent evidence from limited observational studies that aspirin may have a preventive effect on melanoma and ovarian and pancreatic cancers.16-18 Further studies or compilations of data would be needed to draw more significant conclusions on other types of cancers. Larger studies would prove more difficult to do, given the smaller incidences of these cancers.

Interestingly, a recent study showed that for individuals 70 years and older, aspirin might increase the risk for all-cause mortality, primarily due to increased cancer mortality across all types.19 Although this result was unexpected, caution should be used when prescribing aspirin particularly for patients 70 or older with active cancer.

A look at the harms associated with aspirin use

Aspirin has long been known to cause clinically significant bleeding. Aspirin inhibits platelet-derived cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), a potent vasoconstrictor, and thereby decreases platelet aggregation, reducing thromboembolic potential and prolonging bleeding time. These effects can confer health benefits but also carry the potential for risks. A decision to initiate aspirin therapy for primary prevention relies on an understanding of the benefit-to-harm balance.

Continue to: Initial aspirin studies...

Initial aspirin studies did not show a statistically significant increase in bleeding, likely due to too few events and inadequate powering. Subsequent meta-analyses from multiple evaluations have consistently shown bleeding to be a risk.3,7 The risk for bleeding with aspirin has also been examined in multiple cohort studies, which has helped elucidate the risk in greater detail.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Epidemiologic data show that among patients who do not use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the rate of upper gastrointestinal (GI) complications is 1 case per 1000 patient-years.20 Multiple studies have consistently shown that aspirin use increases the rate of significant upper GI bleeding over baseline risk (odds ratio [OR] = 1.54-1.58).3,21,22 Interestingly, these increases seem not to be influenced by other factors, such as comorbidities that increase the risk for ASCVD. Analysis of cancer prevention studies showed similar epidemiologic trends, with aspirin use exceeding a baseline bleeding risk of 0.7 cases of upper GI complications per 1000 patient-years (

Other risk factors. Evaluation of risk factors for bleeding primarily comes from 2 studies.3,7 Most data concern the impact of individual factors on significant GI bleeding, with fewer data available for evaluating risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Initial analysis of individual prospective studies showed little or no correlation between risk for bleeding and such factors as gender, age, or history of hypertension or ASCVD.21 Subsequent analysis of meta-data and large cohorts did show statistically significant impact on rates of bleeding across several factors (TABLE 13,7).

Of note is a large heterogeneous cohort study conducted in Spain. Data showed significant increases in baseline risk for GI bleeding in older men with a history of GI bleeding and NSAID use. The absolute risk for GI bleed in this group was potentially as high as 150 cases per 1000 patient-years, well above the risk level assumed for the average patient.24 A seemingly small OR of 1.5 could dramatically increase the absolute risk for bleeding in such patients, and it suggests that a generalized risk for bleeding probably shouldn’t be applied to all patients. Individuals may be better served by a baseline risk calculation reflecting multiple factors.

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Due to the comparatively uncommon nature of ICH, fewer data are available to support definitive conclusions about its increased risk with aspirin use. Aspirin use appeared to increase the risk for ICH with ratios between 1.27 and 1.32 in meta-analyses (measured as an OR or as an RR),3,7,21 with an IRR of 1.54 in a cohort study.22 The only statistically significant factors suspected to increase the risk of ICH at baseline were smoking (RR = 2.18) and mean BP > 20 mm Hg over normal (OR = 2.18). Age, gender, and diabetes all showed a nonsignificant trend toward risk increase.7

Continue to: Risk based on dose and formulation

Risk based on dose and formulation

The effect of aspirin dose and formulation on bleeding risk is uncertain. Some studies have shown an increased risk for bleeding with daily doses of aspirin ≥ 300 mg, while others have shown no significant increase in rates for bleeding with differing doses.21,25 Enteric coating does appear to lower the rates of gastric mucosal injury, although there are few data on the effect toward reducing clinically significant bleeding.26 Currently, several prospective studies are underway to help clarify the evidence.27

Putting it all together

For the general population, the evidence shows that the benefits and harms of aspirin for primary prevention are relatively even. The USPSTF guidelines are the first to recommend aspirin for both CVD and cancer prevention while taking into account the bleeding risk. According to the findings of the USPSTF, the balance of benefits and harms of aspirin use is contingent on 4 factors: age, baseline CVD risk, risk for bleeding, and preferences about taking aspirin.6 The complete recommendations from the USPSTF, along with other leading organizations, are outlined in TABLE 2.6,28-31

Applying the evidence and varying guidelines in practice can feel daunting. Some practical tools have been developed to help clinicians understand patients’ bleeding risk and potential benefits with aspirin use. One such tool is highlighted below. Others are also available, and each has its own strengths and weaknesses.

Aspirin-Guide (www.aspiringuide.com) is a Web-based clinical decision support tool with an associated mobile application. It uses internal calculators (including the pooled cohort calculator prepared jointly by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association) to assess CVD risk as well as bleeding risk. This tool gives clinicians patient-specific numbers-needed-to-treat and numbers-needed-to-harm when considering starting aspirin for primary prevention. It gives specific recommendations for aspirin use based on the data entered, and it also gives providers information to help guide shared decision-making with patients.32 Unfortunately, this decision support tool and others do not take into account the data from the most recent trials, so they should be used with caution.

CORRESPONDENCE

LCDR Dustin K. Smith, DO, Naval Branch Clinic Diego Garcia, PSC 466, Box 301, FPO, AP 96595; [email protected].

1. FDA. Use of aspirin for primary prevention of heart attack and stroke. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm390574.htm. Accessed March 22, 2019.

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

3. Whitlock EP, Burda BU, Williams SB, et al. Bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention in adults: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:826-835.

4. Chubak J, Whitlock EP, Williams SB, et al. Aspirin for the prevention of cancer incidence and mortality: systematic evidence reviews for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:814-825.

5. Dehmer SP, Maciosek MV, Flottemesch TJ, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:777-786.

6. Bibbins-Domingo K. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

7. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Colins R, et al; Antithrombotic Trialists (ATT) Collaboration. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participation data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009:373:1849-1860.

8. Ikeda Y, Shimada K, Teramoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2510-2520.

9. Rothwell PM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2018;392:387-399.

10. Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al; ASCEND Study Collaborative Group. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529-1539.

11. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1509-1518.

12. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1036-1046.

13. Kune GA, Kune S, Watson LF. Colorectal cancer risk, chronic illness, operations, and medications: case control results from Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4399-4404.

14. Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, et al. Aspirin for prophylactic use in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review and overview of reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:1-253.

15. Burn J, Gerdes AM, Macrae F, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:2081-2087.

16. Gamba CA, Swetter SM, Stefanick ML, et al. Aspirin is associated with lower melanoma risk among postmenopausal Caucasian women: the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer. 2013;119:1562-1569.

17. Trabert B, Ness RB, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt431.

18. Risch H, Lu L, Streicher SA, et al. Aspirin use and reduced risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;26:68-74.

19. McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1519-1528.

20. Hernández-Díaz S, Rodríguez LA. Incidence of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding/perforation in the general population: review of epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:157-163.

21. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis no 131. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321623/. Accessed March 22, 2019.

22. De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, et al. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2012;307:2286-2294.

23. Thorat MA, Cuzick J. Prophylactic use of aspirin: systematic review of harms and approaches to mitigation in the general population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:5-18.

24. Hernández-Díaz S, García Rodríguez LA. Cardioprotective aspirin users and their excess risk of upper gastrointestinal complications. BMC Med. 2006;4:22.

25. Huang ES, Strate LL, Ho WW, et al. Long term use of aspirin and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Med. 2011:124;426-433.

26. Walker J, Robinson J, Stewart J, et al. Does enteric-coated aspirin result in a lower incidence of gastrointestinal complications compared to normal aspirin? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007:6;519-522.

27. NIH. Aspirin dosing: a patient-centric trial assessing benefits and long-term effectiveness (ADAPTABLE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02697916. Accessed March 22, 2019.

28. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315-2381.

29. ADA. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1). http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/suppl/2016/12/15/40.Supplement_1.DC1/DC_40_S1_final.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2019.

30. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl):e637S-e668S.

31. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Col Cardiol. 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010. Accessed March 22, 2019.

32. Mora S, Manson JE. Aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1195-1204.

1. FDA. Use of aspirin for primary prevention of heart attack and stroke. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm390574.htm. Accessed March 22, 2019.

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

3. Whitlock EP, Burda BU, Williams SB, et al. Bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention in adults: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:826-835.

4. Chubak J, Whitlock EP, Williams SB, et al. Aspirin for the prevention of cancer incidence and mortality: systematic evidence reviews for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:814-825.

5. Dehmer SP, Maciosek MV, Flottemesch TJ, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:777-786.

6. Bibbins-Domingo K. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

7. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Colins R, et al; Antithrombotic Trialists (ATT) Collaboration. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participation data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009:373:1849-1860.

8. Ikeda Y, Shimada K, Teramoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2510-2520.

9. Rothwell PM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2018;392:387-399.

10. Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al; ASCEND Study Collaborative Group. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529-1539.

11. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1509-1518.

12. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1036-1046.

13. Kune GA, Kune S, Watson LF. Colorectal cancer risk, chronic illness, operations, and medications: case control results from Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4399-4404.

14. Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, et al. Aspirin for prophylactic use in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review and overview of reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:1-253.

15. Burn J, Gerdes AM, Macrae F, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:2081-2087.

16. Gamba CA, Swetter SM, Stefanick ML, et al. Aspirin is associated with lower melanoma risk among postmenopausal Caucasian women: the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer. 2013;119:1562-1569.

17. Trabert B, Ness RB, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt431.

18. Risch H, Lu L, Streicher SA, et al. Aspirin use and reduced risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;26:68-74.

19. McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1519-1528.

20. Hernández-Díaz S, Rodríguez LA. Incidence of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding/perforation in the general population: review of epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:157-163.

21. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis no 131. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321623/. Accessed March 22, 2019.

22. De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, et al. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2012;307:2286-2294.

23. Thorat MA, Cuzick J. Prophylactic use of aspirin: systematic review of harms and approaches to mitigation in the general population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:5-18.

24. Hernández-Díaz S, García Rodríguez LA. Cardioprotective aspirin users and their excess risk of upper gastrointestinal complications. BMC Med. 2006;4:22.

25. Huang ES, Strate LL, Ho WW, et al. Long term use of aspirin and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Med. 2011:124;426-433.

26. Walker J, Robinson J, Stewart J, et al. Does enteric-coated aspirin result in a lower incidence of gastrointestinal complications compared to normal aspirin? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007:6;519-522.

27. NIH. Aspirin dosing: a patient-centric trial assessing benefits and long-term effectiveness (ADAPTABLE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02697916. Accessed March 22, 2019.

28. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315-2381.

29. ADA. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1). http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/suppl/2016/12/15/40.Supplement_1.DC1/DC_40_S1_final.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2019.

30. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl):e637S-e668S.

31. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Col Cardiol. 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010. Accessed March 22, 2019.

32. Mora S, Manson JE. Aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1195-1204.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider aspirin for patients 50 to 59 years of age who have a 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk of ≥ 10% and low bleeding risk. C

› Discuss prophylactic aspirin (using a shared decision-making model) with patients 60 to 69 years of age who have a 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 10% and low bleeding risk. C

› Avoid using aspirin for primary prevention in patients ≥ 70 years of age. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Addressing insulin price spikes will require supply chain reform

WASHINGTON – panelists said at a House Committee on Energy & Commerce hearing on insulin affordability.

“Each member of the supply chain has a responsibility to help solve this problem,” said Alvin C. Powers, MD, director of the Vanderbilt Diabetes Center at Vanderbilt University, who was speaking on behalf of the Endocrine Society during the April 2 hearing of the committee’s oversight & investigations subcommittee.

Dr. Powers identified all members – manufacturers, payers, pharmacy benefit managers, patients, providers, and Congress – as having a role in developing a solution that will encourage more access to the treatment.

The hearing was the first of two in a series specifically examining the price of insulin. This one focused on the role pricing issues play in terms of access to insulin and patient outcomes.

To highlight the pricing issues, it was noted that a vial of Humalog (insulin lispro) cost $21 when it was launched by Eli Lilly in 1996. It now costs $275 even though it has gone through no changes in formulation or innovation during that time.

Kasia Lipska, MD, of Yale University School of Medicine noted that a summer 2017 survey conducted by the Yale Diabetes Center found that one in four patients took less than the prescribed dose of insulin specifically because of the cost of insulin.

William Cefalu, MD, chief scientific, medical, and mission officer at the American Diabetes Association, echoed comments from Dr. Powers about pricing and suggested that simply going after list price is not a complete solution.

“There is also no guarantee that if the list price drops there [will] be substantive changes throughout the supply chain,” Dr. Cefalu said, adding that there needs to be a move away from a system based on high list prices and rebates and toward a system that ensures that any negotiated rebate or discount will find its way to the patient at the pharmacy counter.

“That’s what is not happening now,” Dr. Cefalu added. “Unless you can control what happens downstream in the intermediaries and what happens to the patient, there is no guarantee that just dropping list prices ... is going to get the job done.”

Aaron Kowalski, PhD, chief mission officer of JDRF, an organization that funds research into type 1 diabetes, also called out insurers as a part of the problem.

“What we are seeing in the community is people being switched [from their prescribed insulin for nonmedical reasons] by their insurance companies, not by the choice of their physician or the patient, which is just not the right way to practice medicine.”

He relayed an anecdote about a woman who went from having her blood sugar well controlled to dealing with severe cases of hyperglycemia because of changes in the medical coverage of her insulin. It took 8 hours on the phone with the insurance company, not to mention countless hours spent by the physician, to get the situation corrected and to get the proper insulin covered.

“This is a broken part of the system,” Dr. Kowalski said.

Dr. Cefalu noted that data are needed on the medical impact of switching for nonmedical reasons, such as changes to insurance coverage.

Christel Marchand Aprigliano, chief executive officer of the Diabetes Patient Advocacy Coalition, also relayed an anecdote of a friend who had suffered medical consequences of nonmedical switching of his insulin and then having to deal with his insurer’s fail-first policy before they would cover his original, medically effective insulin.

“Insurance has been denied twice because they believe that insulins are interchangeable, which they aren’t,” she said.

Michael Burgess, MD, (R-Texas) asked rhetorically during the hearing whether it would make sense for payers to simply provide insulin at no cost to patients, given the cost of medical complications resulting from lack of proper use as a result of pricing likely is much higher than covering insulin completely.

While specific legislative proposals were not discussed during the hearing, one thing that the panelists agreed would help to clarify all the factors that are contributing to the pricing increases is clear, transparent information about the finances surrounding the insulin as the product moves through the supply chain.

The Food and Drug Administration is also doing its part. Although the agency was not a participant in the hearing, the agency’s commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, MD, released a statement on the same day as the hearing in which he touted efforts in the biosimilar space that could spur competition.

“Once an interchangeable insulin product is approved and available on the market, it can be substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy, potentially leading to increased access [to insulin] and lower costs for patients,” he said in the statement. “The FDA anticipates that biosimilar and interchangeable insulin products will bring the competition that’s needed to help [deliver] affordable treatment options to patients.”

Dr Gottlieb did not say when a biosimilar insulin might be available on the market.

The second hearing in this series has not been scheduled, but is expected to take place the week of April 8 and will feature representatives from three insulin manufacturers and other participants in the supply chain.

WASHINGTON – panelists said at a House Committee on Energy & Commerce hearing on insulin affordability.

“Each member of the supply chain has a responsibility to help solve this problem,” said Alvin C. Powers, MD, director of the Vanderbilt Diabetes Center at Vanderbilt University, who was speaking on behalf of the Endocrine Society during the April 2 hearing of the committee’s oversight & investigations subcommittee.

Dr. Powers identified all members – manufacturers, payers, pharmacy benefit managers, patients, providers, and Congress – as having a role in developing a solution that will encourage more access to the treatment.

The hearing was the first of two in a series specifically examining the price of insulin. This one focused on the role pricing issues play in terms of access to insulin and patient outcomes.

To highlight the pricing issues, it was noted that a vial of Humalog (insulin lispro) cost $21 when it was launched by Eli Lilly in 1996. It now costs $275 even though it has gone through no changes in formulation or innovation during that time.

Kasia Lipska, MD, of Yale University School of Medicine noted that a summer 2017 survey conducted by the Yale Diabetes Center found that one in four patients took less than the prescribed dose of insulin specifically because of the cost of insulin.