User login

Vitamin D deficiency: Can we improve diagnosis?

CHICAGO – , new research suggests.

The study supports previous data suggesting that a ratio cut-off of greater than 100 is associated with the development of secondary hyperparathyroidism and the need for correction with supplementation, while a level greater than 50 suggests mild to moderate deficiency, Zhinous Shahidzadeh Yazdi, MD, noted in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society

Current Endocrine Society guidelines published in 2011 advise measurement of plasma circulating 25(OH)D levels to evaluate vitamin D status in patients at risk for deficiency, defined as < 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L). Revised guidelines are due out in early 2024.

“We don’t think measuring 25 hydroxy D is optimal because of the impact of vitamin D binding protein,” Dr. Yazdi said in an interview.

“Over 99% of all metabolites are bound to vitamin D binding protein, but only the free fraction is biologically active. By measuring total plasma 25(OH)D – as we do right now in clinic – we cannot account for the impact of vitamin D binding proteins, which vary by threefold across the population,” she added.

Thus, the total 25(OH)D deficiency cut-off of < 20 mg/mL currently recommended by the Endocrine Society may signal clinically significant vitamin D deficiency in one person but not another, noted Dr. Yazdi, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Directly measuring binding protein or the free fraction would be ideal, but “there aren’t good commercial assays for those, and it’s more difficult to do. So, as an alternative, the vitamin D metabolite ratios implicitly adjust for individual differences in vitamin D binding protein,” she explained.

The ratio that Dr. Yazdi and colleagues propose to measure is that of the vitamin D metabolites 1,25(OH)2D/24,25 (OH)2D (shortened to 1,25D/24,25D), which they say reflect the body’s homeostatic response to vitamin D levels, and which rises in the setting of deficiency. It is a measurement > 100 in this ratio that they believe means the patient should receive vitamin D supplementation.

Controversial topic, ratio proposal is “very early in the game”

The issue of vitamin D deficiency has long generated controversy, particularly since publication of findings from the VITAL study in 2022, which showed vitamin D supplements did not significantly reduce the risk of fracture among adults in midlife and older compared with placebo.

According to the senior author of the new study, Simeon I. Taylor, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, what still remains controversial after VITAL is the question: “How can you identify people who have sufficiently bad vitamin D deficiency that it’s adversely impacting their bones?”

He added that there is a suggestion that small subpopulations in VITAL really did benefit from vitamin D supplementation, but the study “wasn’t designed to look at that.”

Indeed, the authors of an editorial accompanying the publication of the VITAL study said the findings mean there is no justification for measuring 25(OH)D in the general population or for treating to a target level.

Asked to comment on Dr. Yazdi and colleagues’ ratio proposal for diagnosing vitamin D deficiency, the coauthor of the VITAL study editorial, Clifford J. Rosen, MD, said in an interview: “I do think it’s important to point out that changes in the vitamin D binding protein can have a significant impact on the level of 25 [OH] D ... People should recognize that.”

And, Dr. Rosen noted, “I like the idea that the ... [ratio] is a measure of what’s happening in the body in response to vitamin D stores. So, when you supplement, it comes back up ... In certain individuals at high risk for fractures, for example, you might want to consider a more extensive workup like they’re suggesting.”

However, Dr. Rosen, of the Rosen Musculoskeletal Laboratory at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, added: “If the 25[OH]D level is below 20 [ng/mL] you’re going to treat regardless. When we think about sensitivity, a 25[OH]D level less than 20 [ng/mL] is a good screen ... Those individuals need to be treated, especially if they have low bone mass or fractures.”

To validate the ratio for clinical use, Dr. Rosen said, larger numbers of individuals would need to be evaluated. Moreover, “you’d need to run a standard of vitamin D binding protein by mass spectrometry versus their assumed method using ratios. Ratios are always a little tricky to interpret. So, I think this is very early in the game.”

And measuring the ratio of 1,25D/24,25D “is quite expensive,” he added.

He also pointed out that “calcium intake is really critical. You can have a [25(OH)D] level of 18 ng/mL and not have any of those secondary changes because [you’re] taking adequate calcium ... So, that always is a consideration that has to be worked into the evaluation.”

Same 25(OH)D, different risk level

In their poster, Dr. Yazdi and colleagues explain that to assess vitamin D status “one needs to understand regulation of vitamin D metabolism.” 25(OH)D undergoes two alternative fates: 1α-hydroxylation in the kidney, generating 1,25D (the biologically active form) or 24-hydroxylation leading to 24,25D (a biologically inactive metabolite).

For their study, they analyzed pilot data from 11 otherwise healthy individuals who had total baseline plasma 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL, and compared 25(OH)D, 1,25D, 24,25D, and parathyroid hormone before versus after treating them with vitamin D3 supplementation of 50,000 IU per week for 4-6 weeks, aiming for a total 25D level above 30 ng/mL.

They then modeled how the body maintains 1,25D in a normal range and calculated/compared two vitamin D metabolite ratios in vitamin D deficient versus sufficient states: 25(OH)D/1,25D and 1,25D/24,25D. They then evaluated the applicability of these ratios for assessment of vitamin D status.

They explained that suppression of 24-hydroxylase is the first line of defense to maintain 1,25D levels. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is the second line of defense and occurs in severe vitamin D deficiency when the first line is maximally deployed.

Overall, there was poor correlation between 25[OH]D and 1,25D, “consistent with previous evidence that in mild to moderate vitamin D deficiency, 1,25D is maintained in the normal range, and therefore not a useful index for assessing vitamin D status,” the researchers said in their poster.

Hence, they said, the need to add the ratio of 1,25D/24,25D.

They presented a comparison of two study participants: one with a baseline 25[OH]D of 12.3 ng/mL, the other of 11.7 ng/mL. Although both would therefore be classified as deficient according to current guidelines, their 1,25D/24,25D ratios were 20 and 110, respectively.

In the first participant, the parathyroid hormone response to vitamin D supplementation was negligible, at +5%, compared with a dramatic 34% drop in the second participant.

“We think only the one with very high 1,25D/24,25D [ratio of 110] and a significant drop in parathyroid hormone after vitamin D supplementation [-34%] was vitamin D deficient,” the researchers said.

However, Dr. Taylor noted: “The diagnostic cut-offs we describe should be viewed as tentative for the time being. Additional research will be required to fully validate the optimal diagnostic criteria.”

Dr. Yazdi and Dr. Rosen have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taylor has reported being a consultant for Ionis Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO – , new research suggests.

The study supports previous data suggesting that a ratio cut-off of greater than 100 is associated with the development of secondary hyperparathyroidism and the need for correction with supplementation, while a level greater than 50 suggests mild to moderate deficiency, Zhinous Shahidzadeh Yazdi, MD, noted in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society

Current Endocrine Society guidelines published in 2011 advise measurement of plasma circulating 25(OH)D levels to evaluate vitamin D status in patients at risk for deficiency, defined as < 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L). Revised guidelines are due out in early 2024.

“We don’t think measuring 25 hydroxy D is optimal because of the impact of vitamin D binding protein,” Dr. Yazdi said in an interview.

“Over 99% of all metabolites are bound to vitamin D binding protein, but only the free fraction is biologically active. By measuring total plasma 25(OH)D – as we do right now in clinic – we cannot account for the impact of vitamin D binding proteins, which vary by threefold across the population,” she added.

Thus, the total 25(OH)D deficiency cut-off of < 20 mg/mL currently recommended by the Endocrine Society may signal clinically significant vitamin D deficiency in one person but not another, noted Dr. Yazdi, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Directly measuring binding protein or the free fraction would be ideal, but “there aren’t good commercial assays for those, and it’s more difficult to do. So, as an alternative, the vitamin D metabolite ratios implicitly adjust for individual differences in vitamin D binding protein,” she explained.

The ratio that Dr. Yazdi and colleagues propose to measure is that of the vitamin D metabolites 1,25(OH)2D/24,25 (OH)2D (shortened to 1,25D/24,25D), which they say reflect the body’s homeostatic response to vitamin D levels, and which rises in the setting of deficiency. It is a measurement > 100 in this ratio that they believe means the patient should receive vitamin D supplementation.

Controversial topic, ratio proposal is “very early in the game”

The issue of vitamin D deficiency has long generated controversy, particularly since publication of findings from the VITAL study in 2022, which showed vitamin D supplements did not significantly reduce the risk of fracture among adults in midlife and older compared with placebo.

According to the senior author of the new study, Simeon I. Taylor, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, what still remains controversial after VITAL is the question: “How can you identify people who have sufficiently bad vitamin D deficiency that it’s adversely impacting their bones?”

He added that there is a suggestion that small subpopulations in VITAL really did benefit from vitamin D supplementation, but the study “wasn’t designed to look at that.”

Indeed, the authors of an editorial accompanying the publication of the VITAL study said the findings mean there is no justification for measuring 25(OH)D in the general population or for treating to a target level.

Asked to comment on Dr. Yazdi and colleagues’ ratio proposal for diagnosing vitamin D deficiency, the coauthor of the VITAL study editorial, Clifford J. Rosen, MD, said in an interview: “I do think it’s important to point out that changes in the vitamin D binding protein can have a significant impact on the level of 25 [OH] D ... People should recognize that.”

And, Dr. Rosen noted, “I like the idea that the ... [ratio] is a measure of what’s happening in the body in response to vitamin D stores. So, when you supplement, it comes back up ... In certain individuals at high risk for fractures, for example, you might want to consider a more extensive workup like they’re suggesting.”

However, Dr. Rosen, of the Rosen Musculoskeletal Laboratory at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, added: “If the 25[OH]D level is below 20 [ng/mL] you’re going to treat regardless. When we think about sensitivity, a 25[OH]D level less than 20 [ng/mL] is a good screen ... Those individuals need to be treated, especially if they have low bone mass or fractures.”

To validate the ratio for clinical use, Dr. Rosen said, larger numbers of individuals would need to be evaluated. Moreover, “you’d need to run a standard of vitamin D binding protein by mass spectrometry versus their assumed method using ratios. Ratios are always a little tricky to interpret. So, I think this is very early in the game.”

And measuring the ratio of 1,25D/24,25D “is quite expensive,” he added.

He also pointed out that “calcium intake is really critical. You can have a [25(OH)D] level of 18 ng/mL and not have any of those secondary changes because [you’re] taking adequate calcium ... So, that always is a consideration that has to be worked into the evaluation.”

Same 25(OH)D, different risk level

In their poster, Dr. Yazdi and colleagues explain that to assess vitamin D status “one needs to understand regulation of vitamin D metabolism.” 25(OH)D undergoes two alternative fates: 1α-hydroxylation in the kidney, generating 1,25D (the biologically active form) or 24-hydroxylation leading to 24,25D (a biologically inactive metabolite).

For their study, they analyzed pilot data from 11 otherwise healthy individuals who had total baseline plasma 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL, and compared 25(OH)D, 1,25D, 24,25D, and parathyroid hormone before versus after treating them with vitamin D3 supplementation of 50,000 IU per week for 4-6 weeks, aiming for a total 25D level above 30 ng/mL.

They then modeled how the body maintains 1,25D in a normal range and calculated/compared two vitamin D metabolite ratios in vitamin D deficient versus sufficient states: 25(OH)D/1,25D and 1,25D/24,25D. They then evaluated the applicability of these ratios for assessment of vitamin D status.

They explained that suppression of 24-hydroxylase is the first line of defense to maintain 1,25D levels. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is the second line of defense and occurs in severe vitamin D deficiency when the first line is maximally deployed.

Overall, there was poor correlation between 25[OH]D and 1,25D, “consistent with previous evidence that in mild to moderate vitamin D deficiency, 1,25D is maintained in the normal range, and therefore not a useful index for assessing vitamin D status,” the researchers said in their poster.

Hence, they said, the need to add the ratio of 1,25D/24,25D.

They presented a comparison of two study participants: one with a baseline 25[OH]D of 12.3 ng/mL, the other of 11.7 ng/mL. Although both would therefore be classified as deficient according to current guidelines, their 1,25D/24,25D ratios were 20 and 110, respectively.

In the first participant, the parathyroid hormone response to vitamin D supplementation was negligible, at +5%, compared with a dramatic 34% drop in the second participant.

“We think only the one with very high 1,25D/24,25D [ratio of 110] and a significant drop in parathyroid hormone after vitamin D supplementation [-34%] was vitamin D deficient,” the researchers said.

However, Dr. Taylor noted: “The diagnostic cut-offs we describe should be viewed as tentative for the time being. Additional research will be required to fully validate the optimal diagnostic criteria.”

Dr. Yazdi and Dr. Rosen have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taylor has reported being a consultant for Ionis Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO – , new research suggests.

The study supports previous data suggesting that a ratio cut-off of greater than 100 is associated with the development of secondary hyperparathyroidism and the need for correction with supplementation, while a level greater than 50 suggests mild to moderate deficiency, Zhinous Shahidzadeh Yazdi, MD, noted in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society

Current Endocrine Society guidelines published in 2011 advise measurement of plasma circulating 25(OH)D levels to evaluate vitamin D status in patients at risk for deficiency, defined as < 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L). Revised guidelines are due out in early 2024.

“We don’t think measuring 25 hydroxy D is optimal because of the impact of vitamin D binding protein,” Dr. Yazdi said in an interview.

“Over 99% of all metabolites are bound to vitamin D binding protein, but only the free fraction is biologically active. By measuring total plasma 25(OH)D – as we do right now in clinic – we cannot account for the impact of vitamin D binding proteins, which vary by threefold across the population,” she added.

Thus, the total 25(OH)D deficiency cut-off of < 20 mg/mL currently recommended by the Endocrine Society may signal clinically significant vitamin D deficiency in one person but not another, noted Dr. Yazdi, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Directly measuring binding protein or the free fraction would be ideal, but “there aren’t good commercial assays for those, and it’s more difficult to do. So, as an alternative, the vitamin D metabolite ratios implicitly adjust for individual differences in vitamin D binding protein,” she explained.

The ratio that Dr. Yazdi and colleagues propose to measure is that of the vitamin D metabolites 1,25(OH)2D/24,25 (OH)2D (shortened to 1,25D/24,25D), which they say reflect the body’s homeostatic response to vitamin D levels, and which rises in the setting of deficiency. It is a measurement > 100 in this ratio that they believe means the patient should receive vitamin D supplementation.

Controversial topic, ratio proposal is “very early in the game”

The issue of vitamin D deficiency has long generated controversy, particularly since publication of findings from the VITAL study in 2022, which showed vitamin D supplements did not significantly reduce the risk of fracture among adults in midlife and older compared with placebo.

According to the senior author of the new study, Simeon I. Taylor, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, what still remains controversial after VITAL is the question: “How can you identify people who have sufficiently bad vitamin D deficiency that it’s adversely impacting their bones?”

He added that there is a suggestion that small subpopulations in VITAL really did benefit from vitamin D supplementation, but the study “wasn’t designed to look at that.”

Indeed, the authors of an editorial accompanying the publication of the VITAL study said the findings mean there is no justification for measuring 25(OH)D in the general population or for treating to a target level.

Asked to comment on Dr. Yazdi and colleagues’ ratio proposal for diagnosing vitamin D deficiency, the coauthor of the VITAL study editorial, Clifford J. Rosen, MD, said in an interview: “I do think it’s important to point out that changes in the vitamin D binding protein can have a significant impact on the level of 25 [OH] D ... People should recognize that.”

And, Dr. Rosen noted, “I like the idea that the ... [ratio] is a measure of what’s happening in the body in response to vitamin D stores. So, when you supplement, it comes back up ... In certain individuals at high risk for fractures, for example, you might want to consider a more extensive workup like they’re suggesting.”

However, Dr. Rosen, of the Rosen Musculoskeletal Laboratory at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, added: “If the 25[OH]D level is below 20 [ng/mL] you’re going to treat regardless. When we think about sensitivity, a 25[OH]D level less than 20 [ng/mL] is a good screen ... Those individuals need to be treated, especially if they have low bone mass or fractures.”

To validate the ratio for clinical use, Dr. Rosen said, larger numbers of individuals would need to be evaluated. Moreover, “you’d need to run a standard of vitamin D binding protein by mass spectrometry versus their assumed method using ratios. Ratios are always a little tricky to interpret. So, I think this is very early in the game.”

And measuring the ratio of 1,25D/24,25D “is quite expensive,” he added.

He also pointed out that “calcium intake is really critical. You can have a [25(OH)D] level of 18 ng/mL and not have any of those secondary changes because [you’re] taking adequate calcium ... So, that always is a consideration that has to be worked into the evaluation.”

Same 25(OH)D, different risk level

In their poster, Dr. Yazdi and colleagues explain that to assess vitamin D status “one needs to understand regulation of vitamin D metabolism.” 25(OH)D undergoes two alternative fates: 1α-hydroxylation in the kidney, generating 1,25D (the biologically active form) or 24-hydroxylation leading to 24,25D (a biologically inactive metabolite).

For their study, they analyzed pilot data from 11 otherwise healthy individuals who had total baseline plasma 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL, and compared 25(OH)D, 1,25D, 24,25D, and parathyroid hormone before versus after treating them with vitamin D3 supplementation of 50,000 IU per week for 4-6 weeks, aiming for a total 25D level above 30 ng/mL.

They then modeled how the body maintains 1,25D in a normal range and calculated/compared two vitamin D metabolite ratios in vitamin D deficient versus sufficient states: 25(OH)D/1,25D and 1,25D/24,25D. They then evaluated the applicability of these ratios for assessment of vitamin D status.

They explained that suppression of 24-hydroxylase is the first line of defense to maintain 1,25D levels. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is the second line of defense and occurs in severe vitamin D deficiency when the first line is maximally deployed.

Overall, there was poor correlation between 25[OH]D and 1,25D, “consistent with previous evidence that in mild to moderate vitamin D deficiency, 1,25D is maintained in the normal range, and therefore not a useful index for assessing vitamin D status,” the researchers said in their poster.

Hence, they said, the need to add the ratio of 1,25D/24,25D.

They presented a comparison of two study participants: one with a baseline 25[OH]D of 12.3 ng/mL, the other of 11.7 ng/mL. Although both would therefore be classified as deficient according to current guidelines, their 1,25D/24,25D ratios were 20 and 110, respectively.

In the first participant, the parathyroid hormone response to vitamin D supplementation was negligible, at +5%, compared with a dramatic 34% drop in the second participant.

“We think only the one with very high 1,25D/24,25D [ratio of 110] and a significant drop in parathyroid hormone after vitamin D supplementation [-34%] was vitamin D deficient,” the researchers said.

However, Dr. Taylor noted: “The diagnostic cut-offs we describe should be viewed as tentative for the time being. Additional research will be required to fully validate the optimal diagnostic criteria.”

Dr. Yazdi and Dr. Rosen have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taylor has reported being a consultant for Ionis Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ENDO 2023

64-year-old woman • hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, and palpitations • daily headaches • history of hypertension • Dx?

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman sought care after having hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, palpitations, and daily headaches for 1 month. She had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d but over the previous month, it had become more difficult to control. Her blood pressure remained elevated to 150/100 mm Hg despite the addition of lisinopril 40 mg/d and amlodipine 10 mg/d, indicating resistant hypertension. She had no family history of hypertension, diabetes, or obesity or any other pertinent medical or surgical history. Physical examination was negative for weight gain, stretch marks, or muscle weakness.

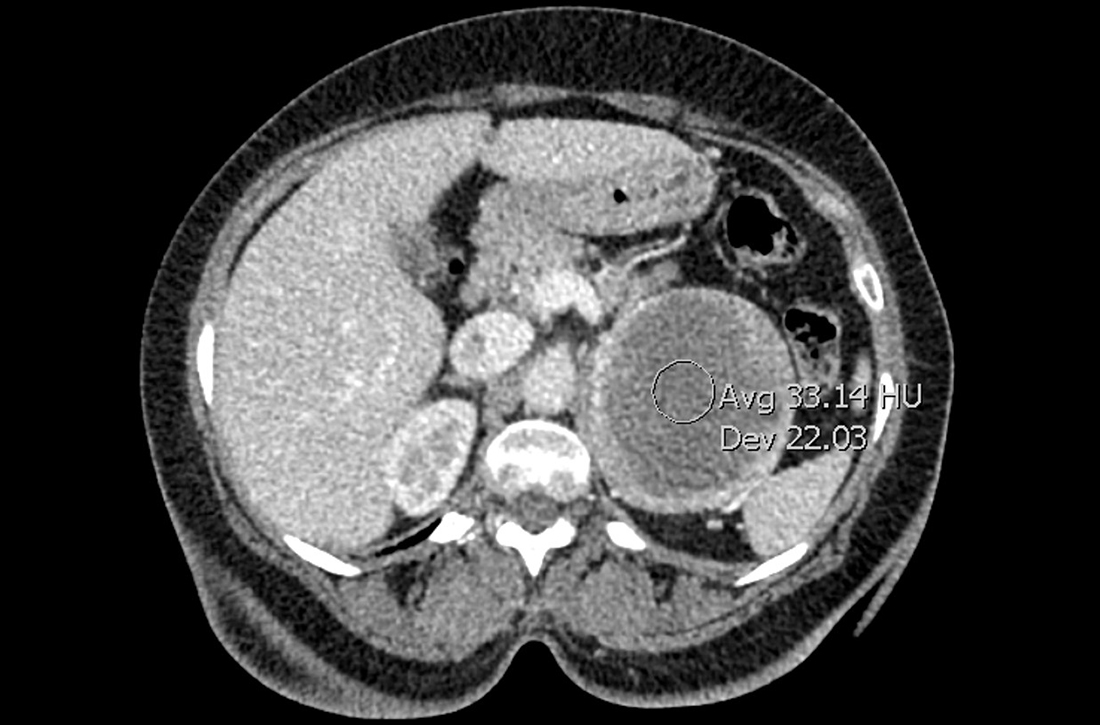

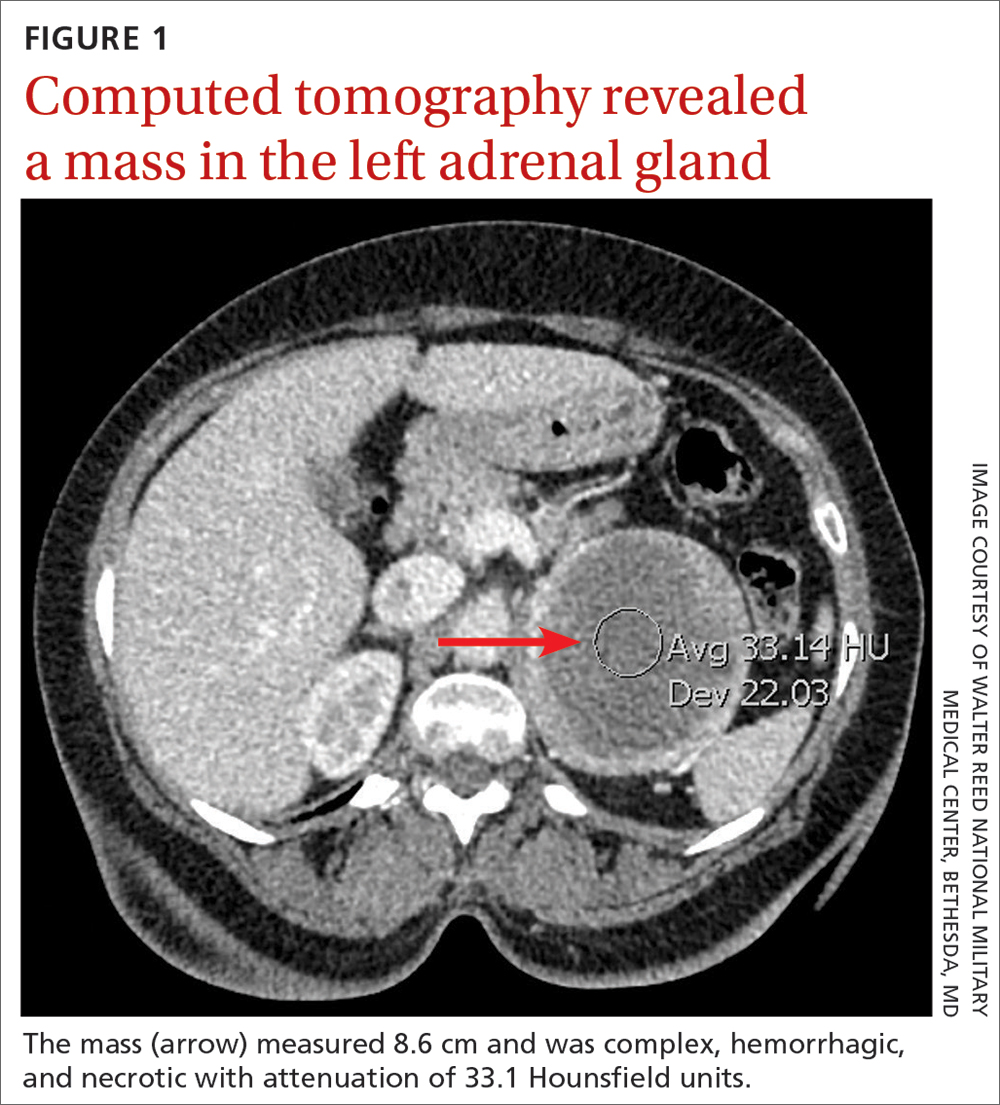

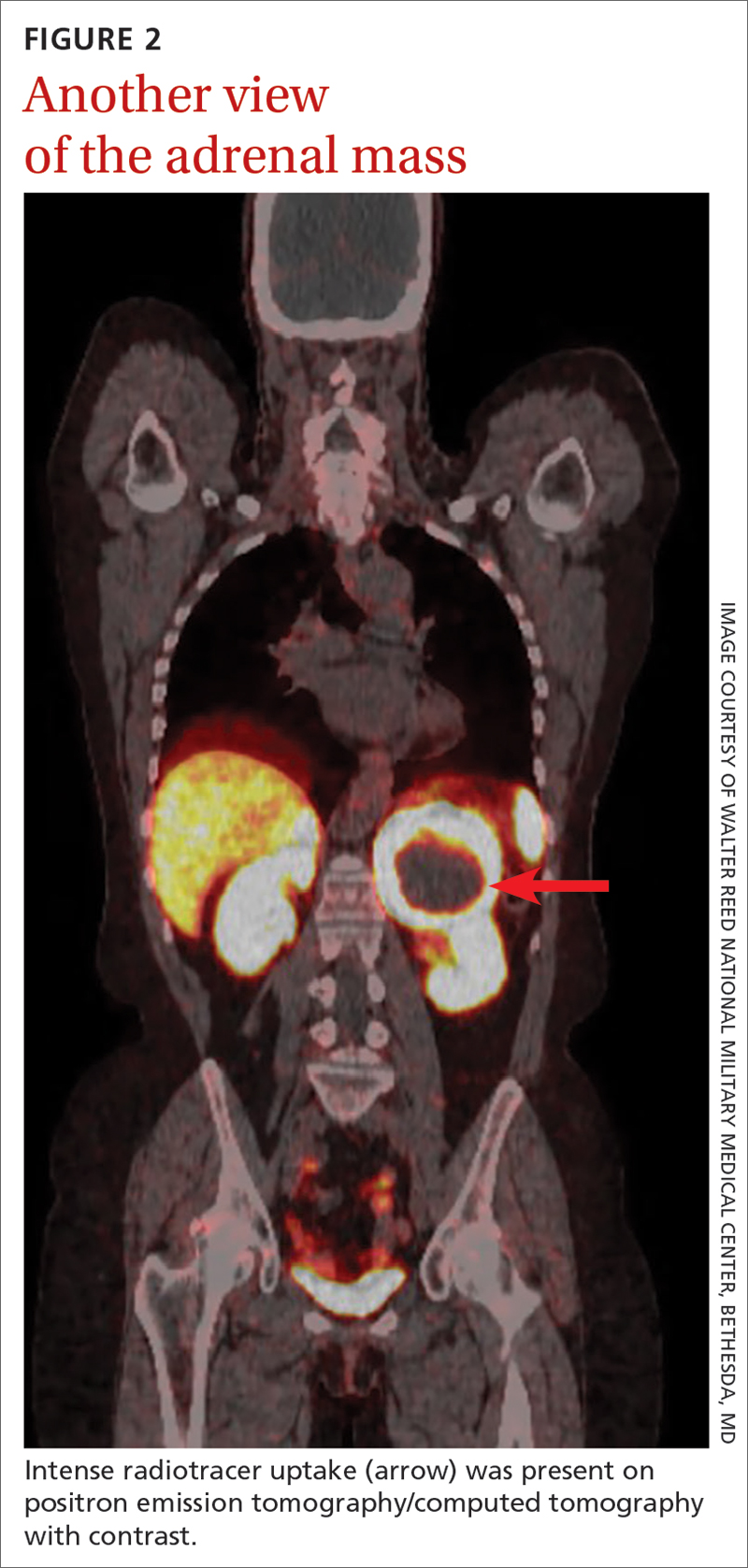

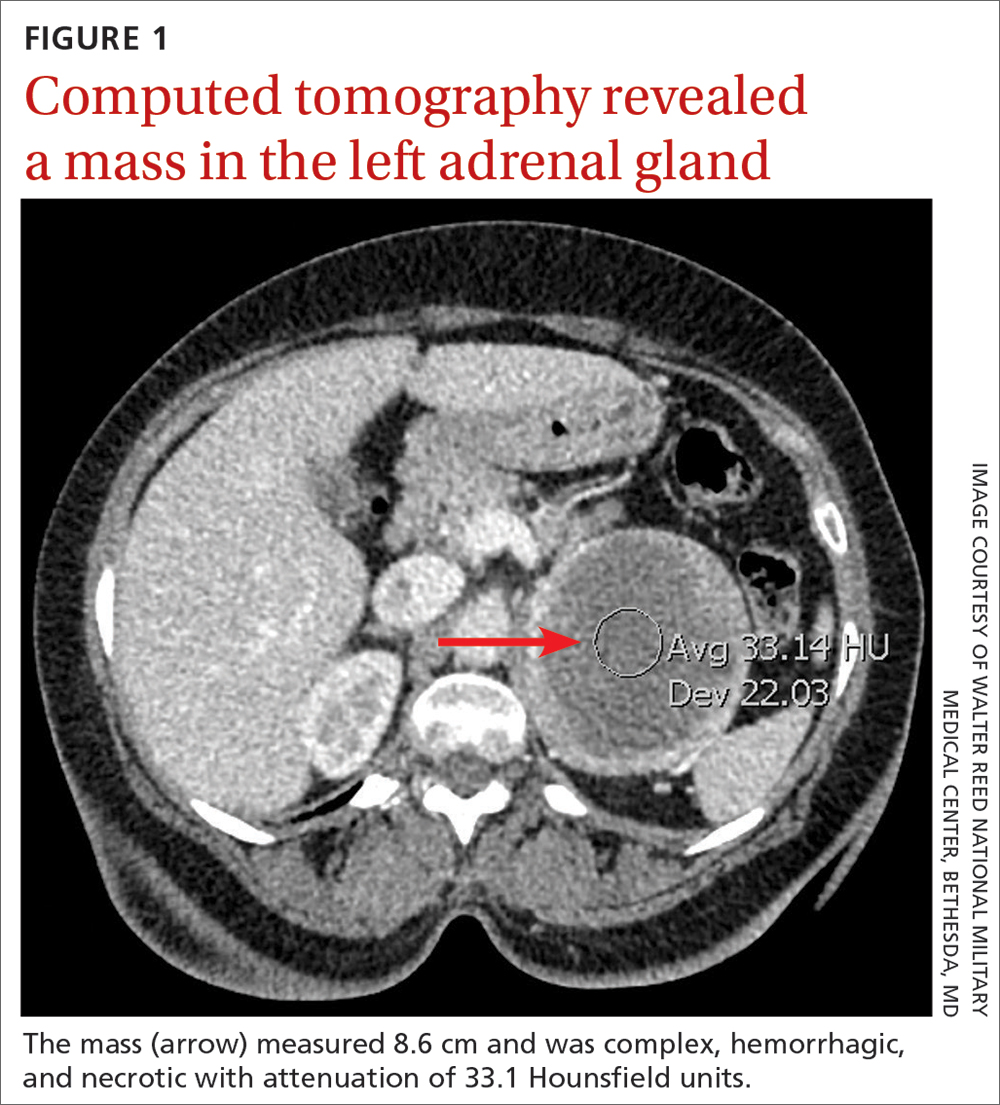

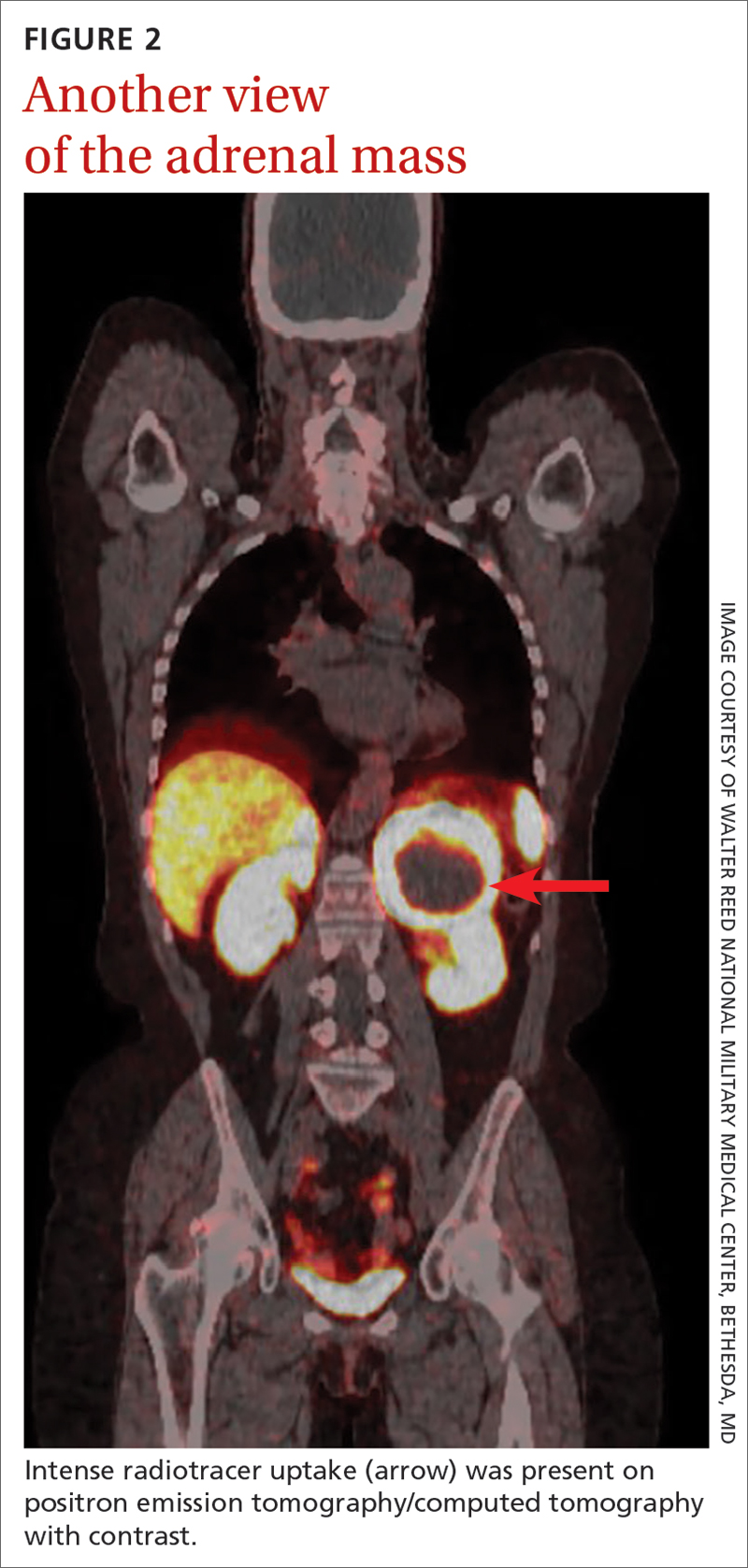

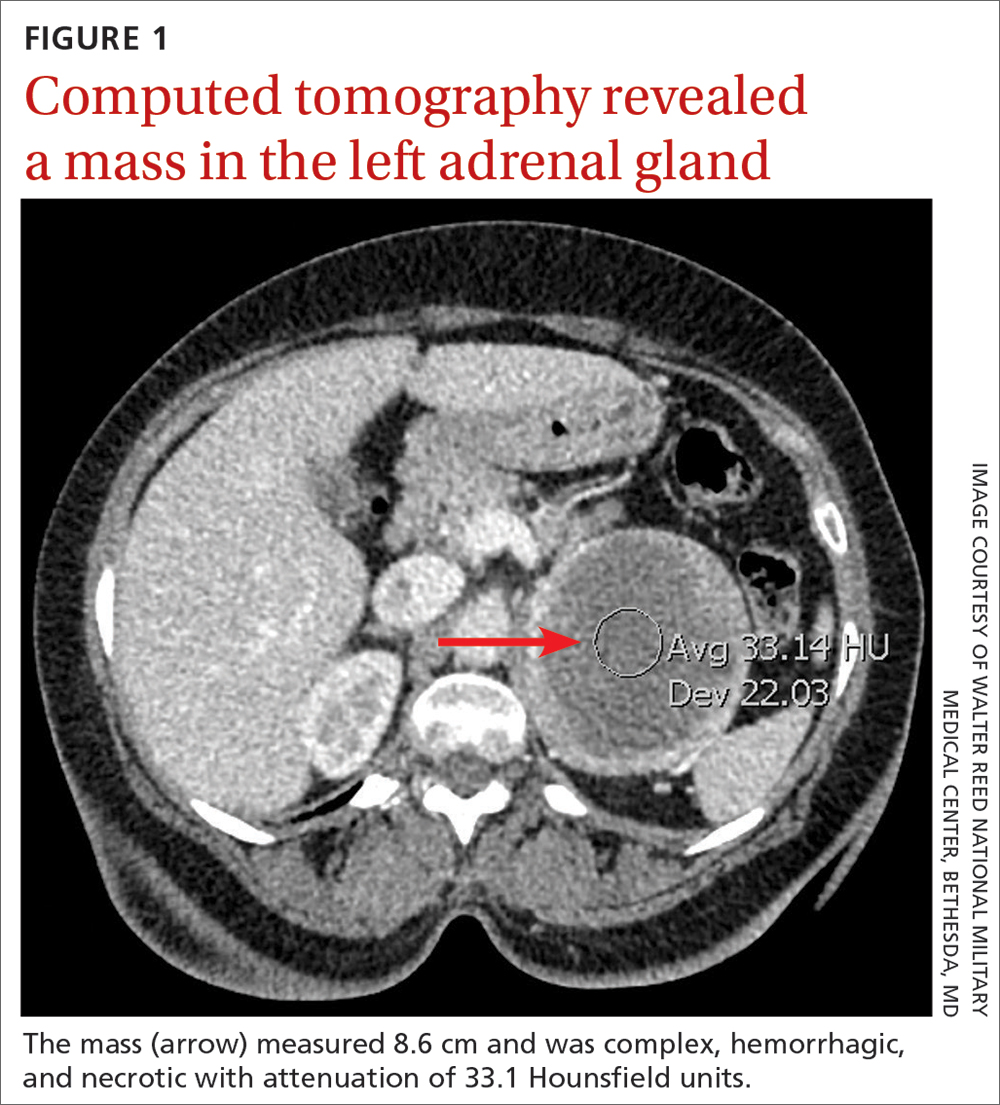

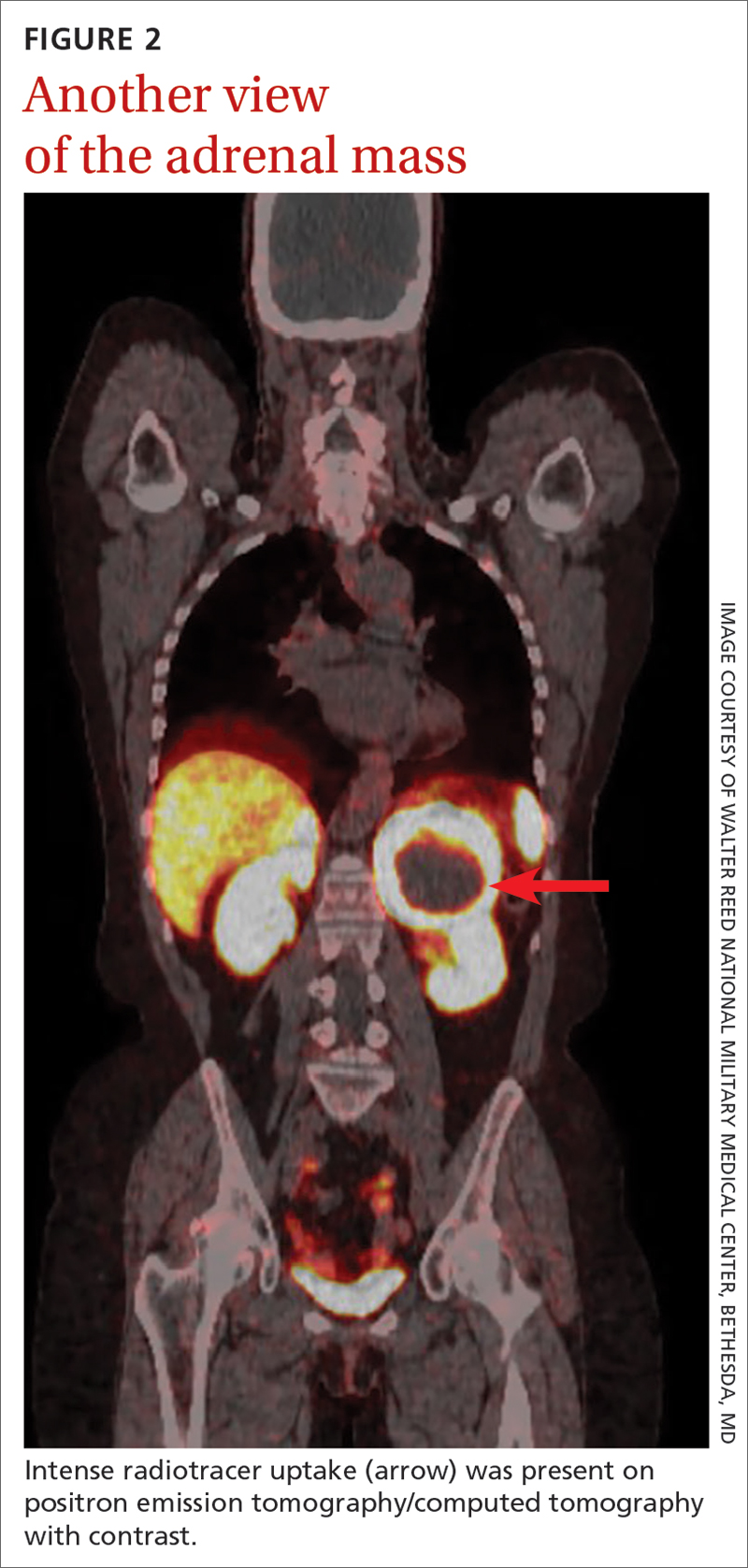

Laboratory tests revealed a normal serum aldosterone-renin ratio, renal function, and thyroid function; however, she had elevated levels of normetanephrine (2429 pg/mL; normal range, 0-145 pg/mL) and metanephrine (143 pg/mL; normal range, 0-62 pg/mL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an 8.6-cm complex, hemorrhagic, necrotic left adrenal mass with attenuation of 33.1 Hounsfield units (HU) (FIGURE 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a T2 hyperintense left adrenal mass. An evaluation for Cushing syndrome was negative, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with gallium-68 dotatate was ordered. It showed intense radiotracer uptake in the left adrenal gland, with a maximum standardized uptake value of 70.1 (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

After appropriate preparation with alpha blockade (phenoxybenzamine 20 mg twice daily for 7 days) and fluid resuscitation (normal saline run over 12 hours preoperatively), the patient underwent successful open surgical resection of the adrenal mass, during which her blood pressure was controlled with a nitroprusside infusion and boluses of esmolol and labetalol. Pathology results showed cells in a nested pattern with round to oval nuclei in a vascular background. There was no necrosis, increased mitotic figures, capsular invasion, or increased cellularity. Chromogranin immunohistochemical staining was positive. Given her resistant hypertension, clinical symptoms, and pathology results, the patient was given a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

DISCUSSION

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that is elevated above goal despite the use of 3 maximally titrated antihypertensive agents from different classes or that is well controlled with at least 4 antihypertensive medications.1 The prevalence of resistant hypertension is 12% to 18% in adults being treated for hypertension.1 Patients with resistant hypertension have a higher risk for cardiovascular events and death, are more likely to have a secondary cause of hypertension, and may benefit from special diagnostic testing or treatment approaches to control their blood pressure.1

There are many causes of resistant hypertension; primary aldosteronism is the most common cause (prevalence as high as 20%).2 Given the increased risk for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease, all patients with resistant hypertension should be screened for this condition.2 Other causes of resistant hypertension include renal parenchymal disease, renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, paraganglioma, and as seen in our case, pheochromocytoma. Although pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of resistant hypertension (0.01%-4%),1 it is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality if left untreated and may be inherited, making it an essential diagnosis to consider in all patients with resistant hypertension.1,3

Common symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension (paroxysmal or sustained), headaches, palpitations, pallor, and piloerection (or cold sweats).1 Patients with pheochromocytoma typically exhibit metanephrine levels that are more than 4 times the upper limit of normal.4 Therefore, measurement of plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines is recommended.5 Elevated metanephrine levels also are caused by obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain medications and should be ruled out.5

All pheochromocytomas are potentially malignant. Despite the existence of pathologic scoring systems6,7 and radiographic features that suggest malignancy,8,9 no single risk-stratification tool is recommended in the current literature.10 Ultimately, the only way to confirm malignancy is to see metastases where chromaffin tissue is not normally found on imaging.10

Continue to: Pathologic features to look for...

Pathologic features to look for include capsular/periadrenal adipose invasion, increased cellularity, necrosis, tumor cell spindling, increased/atypical mitotic figures, and nuclear pleomorphism. Radiographic features include larger size (≥ 4-6 cm),11 an irregular shape, necrosis, calcifications, attenuation of 10 HU or higher on noncontrast CT, absolute washout of 60% or lower, and relative washout of 40% or lower.8,12 On MRI, malignant lesions appear hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging.9 Fluorodeoxyglucose avidity on PET scan also is indicative of malignancy.8,9

Treatment for pheochromocytoma is surgical resection. An experienced surgical team and proper preoperative preparation are necessary because the induction of anesthesia, endotracheal intubation, and tumor manipulation can lead to a release of catecholamines, potentially resulting in an intraoperative hypertensive crisis, cardiac arrhythmias, and multiorgan failure.

Proper preoperative preparation includes taking an alpha-adrenergic blocker, such as phenoxybenzamine, prazosin, terazosin, or doxazosin, for at least 7 days to normalize the patient’s blood pressure. Patients should be counseled that they may experience nasal congestion, orthostasis, and fatigue while taking these medications. Volume expansion with intravenous fluids also should be performed and a high-salt diet considered. Beta-adrenergic blockade can be initiated once appropriate alpha-adrenergic blockade is achieved to control the patient’s heart rate; beta-blockers should never be started first because of the risk for severe hypertension. Careful hemodynamic monitoring is vital intraoperatively and postoperatively.5,13 Because metastatic lesions can occur decades after resection, long-term follow-up is critical.5,10

Following tumor resection, our patient’s blood pressure was supported with intravenous fluids and phenylephrine. She was able to discontinue all her antihypertensive medications postoperatively, and her plasma free and urinary fractionated metanephrine levels returned to within normal limits 8 weeks after surgery. Five years after surgery, she continues to have no signs of recurrence, as evidenced by annual negative plasma free metanephrines testing and abdominal/pelvic CT.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case highlights the importance of recognizing resistant hypertension and a potential secondary cause of this disease—pheochromocytoma. Although rare, pheochromocytomas confer increased risk for cardiovascular disease and death. Thus, swift recognition and proper preparation for surgical resection are necessary. Malignant lesions can be diagnosed only upon discovery of metastatic disease and can recur for decades after surgical resection, making diligent long-term follow-up imperative.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole O. Vietor, MD, Division of Endocrinology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20889; [email protected]

1. Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, et al. Resistant hypertension: detection, evaluation, and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2018;72:e53-e90. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084

2. Young WF Jr. Diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism: practical clinical perspectives. J Intern Med. 2019;285:126-148. doi: 10.1111/joim.12831

3. Young WF Jr, Calhoun DA, Lenders JWM, et al. Screening for endocrine hypertension: an Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38:103-122. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00054

4. Lenders JWM, Pacak K, Walther MM, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427-1434. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1427

5. Lenders JW, Duh Q-Y, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1915-1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498

6. Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, et al. Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:405-414. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0494

7. Thompson LDR. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:551-566. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00002

8. Vaidya A, Hamrahian A, Bancos I, et al. The evaluation of incidentally discovered adrenal masses. Endocr Pract. 2019;25:178-192. doi: 10.4158/DSCR-2018-0565

9. Young WF Jr. Conventional imaging in adrenocortical carcinoma: update and perspectives. Horm Cancer. 2011;2:341-347. doi: 10.1007/s12672-011-0089-z

10. Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:552-565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1806651

11. Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Kohlenberg JD, Delivanis DA, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and radiological characteristics of a single-center retrospective cohort of 705 large adrenal tumors. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;2:30-39. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.11.002

12. Marty M, Gaye D, Perez P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography to identify adenomas among adrenal incidentalomas in an endocrinological population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178:439-446. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-1056

13. Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4069-4079. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1720

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman sought care after having hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, palpitations, and daily headaches for 1 month. She had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d but over the previous month, it had become more difficult to control. Her blood pressure remained elevated to 150/100 mm Hg despite the addition of lisinopril 40 mg/d and amlodipine 10 mg/d, indicating resistant hypertension. She had no family history of hypertension, diabetes, or obesity or any other pertinent medical or surgical history. Physical examination was negative for weight gain, stretch marks, or muscle weakness.

Laboratory tests revealed a normal serum aldosterone-renin ratio, renal function, and thyroid function; however, she had elevated levels of normetanephrine (2429 pg/mL; normal range, 0-145 pg/mL) and metanephrine (143 pg/mL; normal range, 0-62 pg/mL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an 8.6-cm complex, hemorrhagic, necrotic left adrenal mass with attenuation of 33.1 Hounsfield units (HU) (FIGURE 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a T2 hyperintense left adrenal mass. An evaluation for Cushing syndrome was negative, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with gallium-68 dotatate was ordered. It showed intense radiotracer uptake in the left adrenal gland, with a maximum standardized uptake value of 70.1 (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

After appropriate preparation with alpha blockade (phenoxybenzamine 20 mg twice daily for 7 days) and fluid resuscitation (normal saline run over 12 hours preoperatively), the patient underwent successful open surgical resection of the adrenal mass, during which her blood pressure was controlled with a nitroprusside infusion and boluses of esmolol and labetalol. Pathology results showed cells in a nested pattern with round to oval nuclei in a vascular background. There was no necrosis, increased mitotic figures, capsular invasion, or increased cellularity. Chromogranin immunohistochemical staining was positive. Given her resistant hypertension, clinical symptoms, and pathology results, the patient was given a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

DISCUSSION

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that is elevated above goal despite the use of 3 maximally titrated antihypertensive agents from different classes or that is well controlled with at least 4 antihypertensive medications.1 The prevalence of resistant hypertension is 12% to 18% in adults being treated for hypertension.1 Patients with resistant hypertension have a higher risk for cardiovascular events and death, are more likely to have a secondary cause of hypertension, and may benefit from special diagnostic testing or treatment approaches to control their blood pressure.1

There are many causes of resistant hypertension; primary aldosteronism is the most common cause (prevalence as high as 20%).2 Given the increased risk for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease, all patients with resistant hypertension should be screened for this condition.2 Other causes of resistant hypertension include renal parenchymal disease, renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, paraganglioma, and as seen in our case, pheochromocytoma. Although pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of resistant hypertension (0.01%-4%),1 it is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality if left untreated and may be inherited, making it an essential diagnosis to consider in all patients with resistant hypertension.1,3

Common symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension (paroxysmal or sustained), headaches, palpitations, pallor, and piloerection (or cold sweats).1 Patients with pheochromocytoma typically exhibit metanephrine levels that are more than 4 times the upper limit of normal.4 Therefore, measurement of plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines is recommended.5 Elevated metanephrine levels also are caused by obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain medications and should be ruled out.5

All pheochromocytomas are potentially malignant. Despite the existence of pathologic scoring systems6,7 and radiographic features that suggest malignancy,8,9 no single risk-stratification tool is recommended in the current literature.10 Ultimately, the only way to confirm malignancy is to see metastases where chromaffin tissue is not normally found on imaging.10

Continue to: Pathologic features to look for...

Pathologic features to look for include capsular/periadrenal adipose invasion, increased cellularity, necrosis, tumor cell spindling, increased/atypical mitotic figures, and nuclear pleomorphism. Radiographic features include larger size (≥ 4-6 cm),11 an irregular shape, necrosis, calcifications, attenuation of 10 HU or higher on noncontrast CT, absolute washout of 60% or lower, and relative washout of 40% or lower.8,12 On MRI, malignant lesions appear hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging.9 Fluorodeoxyglucose avidity on PET scan also is indicative of malignancy.8,9

Treatment for pheochromocytoma is surgical resection. An experienced surgical team and proper preoperative preparation are necessary because the induction of anesthesia, endotracheal intubation, and tumor manipulation can lead to a release of catecholamines, potentially resulting in an intraoperative hypertensive crisis, cardiac arrhythmias, and multiorgan failure.

Proper preoperative preparation includes taking an alpha-adrenergic blocker, such as phenoxybenzamine, prazosin, terazosin, or doxazosin, for at least 7 days to normalize the patient’s blood pressure. Patients should be counseled that they may experience nasal congestion, orthostasis, and fatigue while taking these medications. Volume expansion with intravenous fluids also should be performed and a high-salt diet considered. Beta-adrenergic blockade can be initiated once appropriate alpha-adrenergic blockade is achieved to control the patient’s heart rate; beta-blockers should never be started first because of the risk for severe hypertension. Careful hemodynamic monitoring is vital intraoperatively and postoperatively.5,13 Because metastatic lesions can occur decades after resection, long-term follow-up is critical.5,10

Following tumor resection, our patient’s blood pressure was supported with intravenous fluids and phenylephrine. She was able to discontinue all her antihypertensive medications postoperatively, and her plasma free and urinary fractionated metanephrine levels returned to within normal limits 8 weeks after surgery. Five years after surgery, she continues to have no signs of recurrence, as evidenced by annual negative plasma free metanephrines testing and abdominal/pelvic CT.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case highlights the importance of recognizing resistant hypertension and a potential secondary cause of this disease—pheochromocytoma. Although rare, pheochromocytomas confer increased risk for cardiovascular disease and death. Thus, swift recognition and proper preparation for surgical resection are necessary. Malignant lesions can be diagnosed only upon discovery of metastatic disease and can recur for decades after surgical resection, making diligent long-term follow-up imperative.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole O. Vietor, MD, Division of Endocrinology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20889; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman sought care after having hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, palpitations, and daily headaches for 1 month. She had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d but over the previous month, it had become more difficult to control. Her blood pressure remained elevated to 150/100 mm Hg despite the addition of lisinopril 40 mg/d and amlodipine 10 mg/d, indicating resistant hypertension. She had no family history of hypertension, diabetes, or obesity or any other pertinent medical or surgical history. Physical examination was negative for weight gain, stretch marks, or muscle weakness.

Laboratory tests revealed a normal serum aldosterone-renin ratio, renal function, and thyroid function; however, she had elevated levels of normetanephrine (2429 pg/mL; normal range, 0-145 pg/mL) and metanephrine (143 pg/mL; normal range, 0-62 pg/mL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an 8.6-cm complex, hemorrhagic, necrotic left adrenal mass with attenuation of 33.1 Hounsfield units (HU) (FIGURE 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a T2 hyperintense left adrenal mass. An evaluation for Cushing syndrome was negative, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with gallium-68 dotatate was ordered. It showed intense radiotracer uptake in the left adrenal gland, with a maximum standardized uptake value of 70.1 (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

After appropriate preparation with alpha blockade (phenoxybenzamine 20 mg twice daily for 7 days) and fluid resuscitation (normal saline run over 12 hours preoperatively), the patient underwent successful open surgical resection of the adrenal mass, during which her blood pressure was controlled with a nitroprusside infusion and boluses of esmolol and labetalol. Pathology results showed cells in a nested pattern with round to oval nuclei in a vascular background. There was no necrosis, increased mitotic figures, capsular invasion, or increased cellularity. Chromogranin immunohistochemical staining was positive. Given her resistant hypertension, clinical symptoms, and pathology results, the patient was given a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

DISCUSSION

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that is elevated above goal despite the use of 3 maximally titrated antihypertensive agents from different classes or that is well controlled with at least 4 antihypertensive medications.1 The prevalence of resistant hypertension is 12% to 18% in adults being treated for hypertension.1 Patients with resistant hypertension have a higher risk for cardiovascular events and death, are more likely to have a secondary cause of hypertension, and may benefit from special diagnostic testing or treatment approaches to control their blood pressure.1

There are many causes of resistant hypertension; primary aldosteronism is the most common cause (prevalence as high as 20%).2 Given the increased risk for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease, all patients with resistant hypertension should be screened for this condition.2 Other causes of resistant hypertension include renal parenchymal disease, renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, paraganglioma, and as seen in our case, pheochromocytoma. Although pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of resistant hypertension (0.01%-4%),1 it is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality if left untreated and may be inherited, making it an essential diagnosis to consider in all patients with resistant hypertension.1,3

Common symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension (paroxysmal or sustained), headaches, palpitations, pallor, and piloerection (or cold sweats).1 Patients with pheochromocytoma typically exhibit metanephrine levels that are more than 4 times the upper limit of normal.4 Therefore, measurement of plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines is recommended.5 Elevated metanephrine levels also are caused by obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain medications and should be ruled out.5

All pheochromocytomas are potentially malignant. Despite the existence of pathologic scoring systems6,7 and radiographic features that suggest malignancy,8,9 no single risk-stratification tool is recommended in the current literature.10 Ultimately, the only way to confirm malignancy is to see metastases where chromaffin tissue is not normally found on imaging.10

Continue to: Pathologic features to look for...

Pathologic features to look for include capsular/periadrenal adipose invasion, increased cellularity, necrosis, tumor cell spindling, increased/atypical mitotic figures, and nuclear pleomorphism. Radiographic features include larger size (≥ 4-6 cm),11 an irregular shape, necrosis, calcifications, attenuation of 10 HU or higher on noncontrast CT, absolute washout of 60% or lower, and relative washout of 40% or lower.8,12 On MRI, malignant lesions appear hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging.9 Fluorodeoxyglucose avidity on PET scan also is indicative of malignancy.8,9

Treatment for pheochromocytoma is surgical resection. An experienced surgical team and proper preoperative preparation are necessary because the induction of anesthesia, endotracheal intubation, and tumor manipulation can lead to a release of catecholamines, potentially resulting in an intraoperative hypertensive crisis, cardiac arrhythmias, and multiorgan failure.

Proper preoperative preparation includes taking an alpha-adrenergic blocker, such as phenoxybenzamine, prazosin, terazosin, or doxazosin, for at least 7 days to normalize the patient’s blood pressure. Patients should be counseled that they may experience nasal congestion, orthostasis, and fatigue while taking these medications. Volume expansion with intravenous fluids also should be performed and a high-salt diet considered. Beta-adrenergic blockade can be initiated once appropriate alpha-adrenergic blockade is achieved to control the patient’s heart rate; beta-blockers should never be started first because of the risk for severe hypertension. Careful hemodynamic monitoring is vital intraoperatively and postoperatively.5,13 Because metastatic lesions can occur decades after resection, long-term follow-up is critical.5,10

Following tumor resection, our patient’s blood pressure was supported with intravenous fluids and phenylephrine. She was able to discontinue all her antihypertensive medications postoperatively, and her plasma free and urinary fractionated metanephrine levels returned to within normal limits 8 weeks after surgery. Five years after surgery, she continues to have no signs of recurrence, as evidenced by annual negative plasma free metanephrines testing and abdominal/pelvic CT.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case highlights the importance of recognizing resistant hypertension and a potential secondary cause of this disease—pheochromocytoma. Although rare, pheochromocytomas confer increased risk for cardiovascular disease and death. Thus, swift recognition and proper preparation for surgical resection are necessary. Malignant lesions can be diagnosed only upon discovery of metastatic disease and can recur for decades after surgical resection, making diligent long-term follow-up imperative.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole O. Vietor, MD, Division of Endocrinology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20889; [email protected]

1. Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, et al. Resistant hypertension: detection, evaluation, and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2018;72:e53-e90. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084

2. Young WF Jr. Diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism: practical clinical perspectives. J Intern Med. 2019;285:126-148. doi: 10.1111/joim.12831

3. Young WF Jr, Calhoun DA, Lenders JWM, et al. Screening for endocrine hypertension: an Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38:103-122. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00054

4. Lenders JWM, Pacak K, Walther MM, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427-1434. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1427

5. Lenders JW, Duh Q-Y, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1915-1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498

6. Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, et al. Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:405-414. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0494

7. Thompson LDR. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:551-566. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00002

8. Vaidya A, Hamrahian A, Bancos I, et al. The evaluation of incidentally discovered adrenal masses. Endocr Pract. 2019;25:178-192. doi: 10.4158/DSCR-2018-0565

9. Young WF Jr. Conventional imaging in adrenocortical carcinoma: update and perspectives. Horm Cancer. 2011;2:341-347. doi: 10.1007/s12672-011-0089-z

10. Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:552-565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1806651

11. Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Kohlenberg JD, Delivanis DA, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and radiological characteristics of a single-center retrospective cohort of 705 large adrenal tumors. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;2:30-39. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.11.002

12. Marty M, Gaye D, Perez P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography to identify adenomas among adrenal incidentalomas in an endocrinological population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178:439-446. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-1056

13. Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4069-4079. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1720

1. Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, et al. Resistant hypertension: detection, evaluation, and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2018;72:e53-e90. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084

2. Young WF Jr. Diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism: practical clinical perspectives. J Intern Med. 2019;285:126-148. doi: 10.1111/joim.12831

3. Young WF Jr, Calhoun DA, Lenders JWM, et al. Screening for endocrine hypertension: an Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38:103-122. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00054

4. Lenders JWM, Pacak K, Walther MM, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427-1434. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1427

5. Lenders JW, Duh Q-Y, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1915-1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498

6. Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, et al. Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:405-414. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0494

7. Thompson LDR. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:551-566. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00002

8. Vaidya A, Hamrahian A, Bancos I, et al. The evaluation of incidentally discovered adrenal masses. Endocr Pract. 2019;25:178-192. doi: 10.4158/DSCR-2018-0565

9. Young WF Jr. Conventional imaging in adrenocortical carcinoma: update and perspectives. Horm Cancer. 2011;2:341-347. doi: 10.1007/s12672-011-0089-z

10. Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:552-565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1806651

11. Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Kohlenberg JD, Delivanis DA, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and radiological characteristics of a single-center retrospective cohort of 705 large adrenal tumors. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;2:30-39. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.11.002

12. Marty M, Gaye D, Perez P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography to identify adenomas among adrenal incidentalomas in an endocrinological population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178:439-446. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-1056

13. Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4069-4079. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1720

► Hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, and palpitations

► Daily headaches

► History of hypertension

Hormone therapies still ‘most effective’ in treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms

Despite new options in non–hormone-based treatments,

This recommendation emerged from an updated position statement from the North American Menopause Society in its first review of the scientific literature since 2015. The statement specifically targets nonhormonal management of symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats, which occur in as many as 80% of menopausal women but are undertreated. The statement appears in the June issue of the Journal of The North American Menopause Society.

“Women with contraindications or objections to hormone treatment should be informed by professionals of evidence-based effective nonhormone treatment options,” stated a NAMS advisory panel led by Chrisandra L. Shufelt, MD, MS, professor and chair of the division of general internal medicine and associate director of the Women’s Health Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. The statement is one of multiple NAMS updates performed at regular intervals, said Dr. Shufelt, also past president of NAMS, in an interview. “But the research has changed, and we wanted to make clinicians aware of new medications. One of our interesting findings was more evidence that off-label use of the nonhormonal overactive bladder drug oxybutynin can lower the rate of hot flashes.”

Dr. Shufelt noted that many of the current update’s findings align with previous research, and stressed that the therapeutic recommendations apply specifically to VMS. “Not all menopause-related symptoms are vasomotor, however,” she said. “While a lot of the lifestyle options such as cooling techniques and exercise are not recommended for controlling hot flashes, diet and exercise changes can be beneficial for other health reasons.”

Although it’s the most effective option for VMS, hormone therapy is not suitable for women with contraindications such as a previous blood clot, an estrogen-dependent cancer, a family history of such cancers, or a personal preference against hormone use, Dr. Shufelt added, so nonhormonal alternatives are important to prevent women from wasting time and money on ineffective remedies. “Women need to know what works and what doesn’t,” she said.

Recommended nonhormonal therapies

Based on a rigorous review of the scientific evidence to date, NAMS found the following therapies to be effective: cognitive-behavioral therapy; clinical hypnosis; SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – which yield mild to moderate improvements; gabapentin – which lessens the frequency and severity of hot flashes; fezolinetant (Veozah), a novel first-in-class neurokinin B antagonist that was Food and Drug Administration–approved in May for VSM; and oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic drug, that reduces moderate to severe VMS, although long-term use in older adults may be linked to cognitive decline, weight loss, and stellate ganglion block.

Therapies that were ineffective, associated with adverse effects (AEs), or lacking adequate evidence of efficacy and thus not recommended for VMS included: paced respiration; supplemental and herbal remedies such as black cohosh, milk thistle, and evening primrose; cooling techniques; trigger avoidance; exercise and yoga; mindfulness-based intervention and relaxation; suvorexant, a dual orexin-receptor antagonist used for insomnia; soy foods, extracts, and the soy metabolite equol; cannabinoids; acupuncture; calibration of neural oscillations; chiropractics; clonidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist that is associated with significant AEs with no recent evidence of benefit over placebo; dietary modification; and pregabalin – which is associated with significant AEs and has controlled-substance prescribing restrictions.

Ultimately, clinicians should individualize menopause care to each patient. For example, “if a patient says that avoiding caffeine in the morning stops her from having hot flashes in the afternoon, that’s fine,” Dr. Shufelt said.

HT still most effective

“This statement is excellent, comprehensive, and evidence-based,” commented Jill M. Rabin MD, vice chair of education and development, obstetrics and gynecology, at Northshore University Hospital/LIJ Medical Center in Manhasset, N.Y., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y.

Dr. Rabin, coauthor of Mind Over Bladder was not involved in compiling the statement.

She agreed that hormone therapy is the most effective option for VMS and regularly prescribes it for suitable candidates in different forms depending on the type and severity of menopausal symptoms. As for nonhormonal options, Dr. Rabin added in an interview, some of those not recommended in the current NAMS statement could yet prove to be effective as more data accumulate. Suvorexant may be one to watch, for instance, but currently there are not enough data on its effectiveness.

“It’s really important to keep up on this nonhormonal research,” Dr. Rabin said. “As the population ages, more and more women will be in the peri- and postmenopausal periods and some have medical reasons for not taking hormone therapy.” It’s important to recommend nonhormonal therapies of proven benefit according to current high-level evidence, she said, “but also to keep your ear to the ground about those still under investigation.”

As for the lifestyle and alternative remedies of unproven benefit, Dr. Rabin added, there’s little harm in trying them. “As far as I know, no one’s ever died of relaxation and paced breathing.” In addition, a patient’s interaction with and sense of control over her own physiology provided by these techniques may be beneficial in themselves.

Dr. Shufelt reported grant support from the National Institutes of Health. Numerous authors reported consulting fees from and other financial ties to private-sector companies. Dr. Rabin had no relevant competing interests to disclose with regard to her comments.

Despite new options in non–hormone-based treatments,

This recommendation emerged from an updated position statement from the North American Menopause Society in its first review of the scientific literature since 2015. The statement specifically targets nonhormonal management of symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats, which occur in as many as 80% of menopausal women but are undertreated. The statement appears in the June issue of the Journal of The North American Menopause Society.

“Women with contraindications or objections to hormone treatment should be informed by professionals of evidence-based effective nonhormone treatment options,” stated a NAMS advisory panel led by Chrisandra L. Shufelt, MD, MS, professor and chair of the division of general internal medicine and associate director of the Women’s Health Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. The statement is one of multiple NAMS updates performed at regular intervals, said Dr. Shufelt, also past president of NAMS, in an interview. “But the research has changed, and we wanted to make clinicians aware of new medications. One of our interesting findings was more evidence that off-label use of the nonhormonal overactive bladder drug oxybutynin can lower the rate of hot flashes.”

Dr. Shufelt noted that many of the current update’s findings align with previous research, and stressed that the therapeutic recommendations apply specifically to VMS. “Not all menopause-related symptoms are vasomotor, however,” she said. “While a lot of the lifestyle options such as cooling techniques and exercise are not recommended for controlling hot flashes, diet and exercise changes can be beneficial for other health reasons.”

Although it’s the most effective option for VMS, hormone therapy is not suitable for women with contraindications such as a previous blood clot, an estrogen-dependent cancer, a family history of such cancers, or a personal preference against hormone use, Dr. Shufelt added, so nonhormonal alternatives are important to prevent women from wasting time and money on ineffective remedies. “Women need to know what works and what doesn’t,” she said.

Recommended nonhormonal therapies

Based on a rigorous review of the scientific evidence to date, NAMS found the following therapies to be effective: cognitive-behavioral therapy; clinical hypnosis; SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – which yield mild to moderate improvements; gabapentin – which lessens the frequency and severity of hot flashes; fezolinetant (Veozah), a novel first-in-class neurokinin B antagonist that was Food and Drug Administration–approved in May for VSM; and oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic drug, that reduces moderate to severe VMS, although long-term use in older adults may be linked to cognitive decline, weight loss, and stellate ganglion block.

Therapies that were ineffective, associated with adverse effects (AEs), or lacking adequate evidence of efficacy and thus not recommended for VMS included: paced respiration; supplemental and herbal remedies such as black cohosh, milk thistle, and evening primrose; cooling techniques; trigger avoidance; exercise and yoga; mindfulness-based intervention and relaxation; suvorexant, a dual orexin-receptor antagonist used for insomnia; soy foods, extracts, and the soy metabolite equol; cannabinoids; acupuncture; calibration of neural oscillations; chiropractics; clonidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist that is associated with significant AEs with no recent evidence of benefit over placebo; dietary modification; and pregabalin – which is associated with significant AEs and has controlled-substance prescribing restrictions.

Ultimately, clinicians should individualize menopause care to each patient. For example, “if a patient says that avoiding caffeine in the morning stops her from having hot flashes in the afternoon, that’s fine,” Dr. Shufelt said.

HT still most effective

“This statement is excellent, comprehensive, and evidence-based,” commented Jill M. Rabin MD, vice chair of education and development, obstetrics and gynecology, at Northshore University Hospital/LIJ Medical Center in Manhasset, N.Y., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y.

Dr. Rabin, coauthor of Mind Over Bladder was not involved in compiling the statement.

She agreed that hormone therapy is the most effective option for VMS and regularly prescribes it for suitable candidates in different forms depending on the type and severity of menopausal symptoms. As for nonhormonal options, Dr. Rabin added in an interview, some of those not recommended in the current NAMS statement could yet prove to be effective as more data accumulate. Suvorexant may be one to watch, for instance, but currently there are not enough data on its effectiveness.

“It’s really important to keep up on this nonhormonal research,” Dr. Rabin said. “As the population ages, more and more women will be in the peri- and postmenopausal periods and some have medical reasons for not taking hormone therapy.” It’s important to recommend nonhormonal therapies of proven benefit according to current high-level evidence, she said, “but also to keep your ear to the ground about those still under investigation.”

As for the lifestyle and alternative remedies of unproven benefit, Dr. Rabin added, there’s little harm in trying them. “As far as I know, no one’s ever died of relaxation and paced breathing.” In addition, a patient’s interaction with and sense of control over her own physiology provided by these techniques may be beneficial in themselves.

Dr. Shufelt reported grant support from the National Institutes of Health. Numerous authors reported consulting fees from and other financial ties to private-sector companies. Dr. Rabin had no relevant competing interests to disclose with regard to her comments.

Despite new options in non–hormone-based treatments,

This recommendation emerged from an updated position statement from the North American Menopause Society in its first review of the scientific literature since 2015. The statement specifically targets nonhormonal management of symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats, which occur in as many as 80% of menopausal women but are undertreated. The statement appears in the June issue of the Journal of The North American Menopause Society.

“Women with contraindications or objections to hormone treatment should be informed by professionals of evidence-based effective nonhormone treatment options,” stated a NAMS advisory panel led by Chrisandra L. Shufelt, MD, MS, professor and chair of the division of general internal medicine and associate director of the Women’s Health Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. The statement is one of multiple NAMS updates performed at regular intervals, said Dr. Shufelt, also past president of NAMS, in an interview. “But the research has changed, and we wanted to make clinicians aware of new medications. One of our interesting findings was more evidence that off-label use of the nonhormonal overactive bladder drug oxybutynin can lower the rate of hot flashes.”

Dr. Shufelt noted that many of the current update’s findings align with previous research, and stressed that the therapeutic recommendations apply specifically to VMS. “Not all menopause-related symptoms are vasomotor, however,” she said. “While a lot of the lifestyle options such as cooling techniques and exercise are not recommended for controlling hot flashes, diet and exercise changes can be beneficial for other health reasons.”

Although it’s the most effective option for VMS, hormone therapy is not suitable for women with contraindications such as a previous blood clot, an estrogen-dependent cancer, a family history of such cancers, or a personal preference against hormone use, Dr. Shufelt added, so nonhormonal alternatives are important to prevent women from wasting time and money on ineffective remedies. “Women need to know what works and what doesn’t,” she said.

Recommended nonhormonal therapies

Based on a rigorous review of the scientific evidence to date, NAMS found the following therapies to be effective: cognitive-behavioral therapy; clinical hypnosis; SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – which yield mild to moderate improvements; gabapentin – which lessens the frequency and severity of hot flashes; fezolinetant (Veozah), a novel first-in-class neurokinin B antagonist that was Food and Drug Administration–approved in May for VSM; and oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic drug, that reduces moderate to severe VMS, although long-term use in older adults may be linked to cognitive decline, weight loss, and stellate ganglion block.

Therapies that were ineffective, associated with adverse effects (AEs), or lacking adequate evidence of efficacy and thus not recommended for VMS included: paced respiration; supplemental and herbal remedies such as black cohosh, milk thistle, and evening primrose; cooling techniques; trigger avoidance; exercise and yoga; mindfulness-based intervention and relaxation; suvorexant, a dual orexin-receptor antagonist used for insomnia; soy foods, extracts, and the soy metabolite equol; cannabinoids; acupuncture; calibration of neural oscillations; chiropractics; clonidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist that is associated with significant AEs with no recent evidence of benefit over placebo; dietary modification; and pregabalin – which is associated with significant AEs and has controlled-substance prescribing restrictions.

Ultimately, clinicians should individualize menopause care to each patient. For example, “if a patient says that avoiding caffeine in the morning stops her from having hot flashes in the afternoon, that’s fine,” Dr. Shufelt said.

HT still most effective

“This statement is excellent, comprehensive, and evidence-based,” commented Jill M. Rabin MD, vice chair of education and development, obstetrics and gynecology, at Northshore University Hospital/LIJ Medical Center in Manhasset, N.Y., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y.

Dr. Rabin, coauthor of Mind Over Bladder was not involved in compiling the statement.

She agreed that hormone therapy is the most effective option for VMS and regularly prescribes it for suitable candidates in different forms depending on the type and severity of menopausal symptoms. As for nonhormonal options, Dr. Rabin added in an interview, some of those not recommended in the current NAMS statement could yet prove to be effective as more data accumulate. Suvorexant may be one to watch, for instance, but currently there are not enough data on its effectiveness.

“It’s really important to keep up on this nonhormonal research,” Dr. Rabin said. “As the population ages, more and more women will be in the peri- and postmenopausal periods and some have medical reasons for not taking hormone therapy.” It’s important to recommend nonhormonal therapies of proven benefit according to current high-level evidence, she said, “but also to keep your ear to the ground about those still under investigation.”

As for the lifestyle and alternative remedies of unproven benefit, Dr. Rabin added, there’s little harm in trying them. “As far as I know, no one’s ever died of relaxation and paced breathing.” In addition, a patient’s interaction with and sense of control over her own physiology provided by these techniques may be beneficial in themselves.

Dr. Shufelt reported grant support from the National Institutes of Health. Numerous authors reported consulting fees from and other financial ties to private-sector companies. Dr. Rabin had no relevant competing interests to disclose with regard to her comments.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN MENOPAUSE SOCIETY

Does weight loss surgery up the risk for bone fractures?

Currently, the two most common types of weight loss surgery performed include sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). Sleeve gastrectomy involves removing a large portion of the stomach so that its capacity is significantly decreased (to about 20%), reducing the ability to consume large quantities of food. Also, the procedure leads to marked reductions in ghrelin (an appetite-stimulating hormone), and some studies have reported increases in glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), hormones that induce satiety. Gastric bypass involves creating a small stomach pouch and rerouting the small intestine so that it bypasses much of the stomach and also the upper portion of the small intestine. This reduces the amount of food that can be consumed at any time, increases levels of GLP-1 and PYY, and reduces absorption of nutrients with resultant weight loss. Less common bariatric surgeries include gastric banding and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS). Gastric banding involves placing a ring in the upper portion of the stomach, and the size of the pouch created can be altered by injecting more or less saline through a port inserted under the skin. BPD-DS includes sleeve gastrectomy, resection of a large section of the small intestine, and diversion of the pancreatic and biliary duct to a point below the junction of the ends of the resected gut.

Weight loss surgery is currently recommended for people who have a body mass index greater than or equal to 35 regardless of obesity-related complication and may be considered for those with a BMI greater than or equal to 30. BMI is calculated by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the height (in meters). In children and adolescents, weight loss surgery should be considered in those with a BMI greater than 120% of the 95th percentile and with a major comorbidity or in those with a BMI greater than 140% of the 95th percentile.

What impact does weight loss surgery have on bone?

Multiple studies in both adults and teenagers have demonstrated that sleeve gastrectomy, RYGB, and BPD-DS (but not gastric banding) are associated with a decrease in bone density, impaired bone structure, and reduced strength estimates over time (Beavers et al; Gagnon, Schafer; Misra, Bredella). The relative risk for fracture after RYGB and BPD-DS is reported to be 1.2-2.3 (that is, 20%-130% more than normal), whereas fracture risk after sleeve gastrectomy is still under study with some conflicting results. Fracture risk starts to increase 2-3 years after surgery and peaks at 5-plus years after surgery. Most of the data for fractures come from studies in adults. With the rising use of weight loss surgery, particularly sleeve gastrectomy, in teenagers, studies are needed to determine fracture risk in this younger age group, who also seem to experience marked reductions in bone density, altered bone structure, and reduced bone strength after bariatric surgery.

What contributes to impaired bone health after weight loss surgery?

The deleterious effect of weight loss surgery on bone appears to be caused by various factors, including the massive and rapid weight loss that occurs after surgery, because body weight has a mechanical loading effect on bone and otherwise promotes bone formation. Weight loss results in mechanical unloading and thus a decrease in bone density. Further, when weight loss occurs, there is loss of both muscle and fat mass, and the reduction in muscle mass is deleterious to bone.

Other possible causes of bone density reduction include reduced absorption of certain nutrients, such as calcium and vitamin D critical for bone mineralization, and alterations in certain hormones that impact bone health. These include increases in parathyroid hormone, which increases bone loss when secreted in excess; increases in PYY (a hormone that reduces bone formation); decreases in ghrelin (a hormone that typically increases bone formation), particularly after sleeve gastrectomy; and decreases in estrone (a kind of estrogen that like other estrogens prevents bone loss). Further, age and gender may modify the bone consequences of surgery as outcomes in postmenopausal women appear to be worse than in younger women and men.

Preventing bone density loss

Given the many benefits of weight loss surgery, what can we do to prevent this decrease in bone density after surgery? It’s important for people undergoing weight loss surgery to be cognizant of this potentially negative outcome and to take appropriate precautions to mitigate this concern.

We should monitor bone density after surgery with the help of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, starting a few years after surgery, particularly in those who are at greatest risk for fracture, so that we can be proactive about addressing any severe bone loss that warrants pharmacologic intervention.

More general recommendations include optimizing intake of calcium (1,200-1,500 mg/d), vitamin D (2,000-3,000 IUs/d), and protein (60-75 g/d) via diet and/or as supplements and engaging in weight-bearing physical activity because this exerts mechanical loading effects on the skeleton leading to increased bone formation and also increases muscle mass over time, which is beneficial to bone. A progressive resistance training program has been demonstrated to have beneficial effects on bone, and measures should be taken to reduce the risk for falls, which increases after certain kinds of weight loss surgery, such as gastric bypass.

Meeting with a dietitian can help determine any other nutrients that need to be optimized.

Though many hormonal changes after surgery have been linked to reductions in bone density, there are still no recommended hormonal therapies at this time, and more work is required to determine whether specific pharmacologic therapies might help improve bone outcomes after surgery.

Dr. Misra is chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology, Mass General for Children; associate director, Harvard Catalyst Translation and Clinical Research Center; director, Pediatric Endocrine-Sports Endocrine-Neuroendocrine Lab, Mass General Hospital; and professor, department of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Currently, the two most common types of weight loss surgery performed include sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). Sleeve gastrectomy involves removing a large portion of the stomach so that its capacity is significantly decreased (to about 20%), reducing the ability to consume large quantities of food. Also, the procedure leads to marked reductions in ghrelin (an appetite-stimulating hormone), and some studies have reported increases in glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), hormones that induce satiety. Gastric bypass involves creating a small stomach pouch and rerouting the small intestine so that it bypasses much of the stomach and also the upper portion of the small intestine. This reduces the amount of food that can be consumed at any time, increases levels of GLP-1 and PYY, and reduces absorption of nutrients with resultant weight loss. Less common bariatric surgeries include gastric banding and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS). Gastric banding involves placing a ring in the upper portion of the stomach, and the size of the pouch created can be altered by injecting more or less saline through a port inserted under the skin. BPD-DS includes sleeve gastrectomy, resection of a large section of the small intestine, and diversion of the pancreatic and biliary duct to a point below the junction of the ends of the resected gut.