User login

CBTI Strategy Reduces Sleeping Pill Use in Canadian Seniors

A strategy developed by Canadian researchers for encouraging older patients with insomnia to wean themselves from sleeping pills and improve their sleep through behavioral techniques is effective, data suggest. If proven helpful for the millions of older Canadians who currently rely on nightly benzodiazepines (BZDs) and non-BZDs (colloquially known as Z drugs) for their sleep, it might yield an additional benefit: Reducing resource utilization.

“We know that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) works. It’s recommended as first-line therapy because it works,” study author David Gardner, PharmD, professor of psychiatry at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, told this news organization.

“We’re sharing information about sleeping pills, information that has been embedded with behavior-change techniques that lead people to second-guess or rethink their long-term use of sedative hypnotics and then bring that information to their provider or pharmacist to discuss it,” he said.

The results were published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Better Sleep, Fewer Pills

Dr. Gardner and his team created a direct-to-patient, patient-directed, multicomponent knowledge mobilization intervention called Sleepwell. It incorporates best practice– and guideline-based evidence and multiple behavioral change techniques with content and graphics. Dr. Gardner emphasized that it represents a directional shift in care that alleviates providers’ burden without removing it entirely.

To test the intervention’s effectiveness, Dr. Gardner and his team chose New Brunswick as a location for a 6-month, three-arm, open-label, randomized controlled trial; the province has one of the highest rates of sedative use and an older adult population that is vulnerable to the serious side effects of these drugs (eg, cognitive impairment, falls, and frailty). The study was called Your Answers When Needing Sleep in New Brunswick (YAWNS NB).

Eligible participants were aged ≥ 65 years, lived in the community, and had taken benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs) for ≥ 3 nights per week for 3 or more months. Participants were randomly assigned to a control group or one of the two intervention groups. The YAWNS-1 intervention group (n = 195) received a mailed package containing a cover letter, a booklet outlining how to stop sleeping pills, a booklet on how to “get your sleep back,” and a companion website. The YAWNS-2 group (n = 193) received updated versions of the booklets used in a prior trial. The control group (n = 192) was assigned treatment as usual (TAU).

A greater proportion of YAWNS-1 participants discontinued BZRAs at 6 months (26.2%) and had dose reductions (20.4%), compared with YAWNS-2 participants (20.3% and 14.4%, respectively) and TAU participants (7.5% and 12.8%, respectively). The corresponding numbers needed to mail to achieve an additional discontinuation was 5.3 YAWNS-1 packages and 7.8 YAWNS-2 packages.

At 6 months, BZRA cessation was sustained a mean 13.6 weeks for YAWNS-1, 14.3 weeks for YAWNS-2, and 16.9 weeks for TAU.

Sleep measures also improved with YAWNS-1, compared with YAWNs-2 and TAU. Sleep onset latency was reduced by 26.1 minutes among YAWNS-1 participants, compared with YAWNS-2 (P < .001), and by 27.7 minutes, compared with TAU (P < .001). Wake after sleep onset increased by 4.1 minutes in YAWNS-1, 11.1 minutes in YAWNS-2, and 7.5 minutes in TAU.

Although all participants underwent rigorous assessment before inclusion, less than half of participants receiving either intervention (36% in YAWNS-1 and 43% in YAWNS-2) contacted their provider or pharmacist to discuss BZD dose reductions. This finding may have resulted partly from limited access because of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the authors.

A Stepped-Care Model

The intervention is intended to help patients “change their approach from sleeping pills to a short-term CBTI course for long-term sleep benefits, and then speak to their provider,” said Dr. Gardner.

He pointed to a post-study follow-up of the study participants’ health providers, most of whom had moderate to extensive experience deprescribing BZRAs, which showed that 87.5%-100% fully or nearly fully agreed with or supported using the Sleepwell strategy and its content with older patients who rely on sedatives.

“Providers said that deprescribing is difficult, time-consuming, and often not a productive use of their time,” said Dr. Gardner. “I see insomnia as a health issue well set up for a stepped-care model. Self-help approaches are at the very bottom of that model and can help shift the initial burden to patients and out of the healthcare system.”

Poor uptake has prevented CBTI from demonstrating its potential, which is a challenge that Charles M. Morin, PhD, professor of psychology at Laval University in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada, attributes to two factors. “Clearly, there aren’t enough providers with this kind of expertise, and it’s not always covered by public health insurance, so people have to pay out of pocket to treat their insomnia,” he said.

“Overall, I think that this was a very nice study, well conducted, with an impressive sample size,” said Dr. Morin, who was not involved in the study. “The results are quite encouraging, telling us that even when older adults have used sleep medications for an average of 10 years, it’s still possible to reduce the medication. But this doesn’t happen alone. People need to be guided in doing that, not only to decrease medication use, but they also need an alternative,” he said.

Dr. Morin questioned how many patients agree to start with a low intensity. “Ideally, it should be a shared decision paradigm, where the physician or whoever sees the patient first presents the available options and explains the pluses and minuses of each. Some patients might choose medication because it’s a quick fix,” he said. “But some might want to do CBTI, even if it takes more work. The results are sustainable over time,” he added.

The study was jointly funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the government of New Brunswick as a Healthy Seniors Pilot Project. Dr. Gardner and Dr. Morin reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A strategy developed by Canadian researchers for encouraging older patients with insomnia to wean themselves from sleeping pills and improve their sleep through behavioral techniques is effective, data suggest. If proven helpful for the millions of older Canadians who currently rely on nightly benzodiazepines (BZDs) and non-BZDs (colloquially known as Z drugs) for their sleep, it might yield an additional benefit: Reducing resource utilization.

“We know that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) works. It’s recommended as first-line therapy because it works,” study author David Gardner, PharmD, professor of psychiatry at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, told this news organization.

“We’re sharing information about sleeping pills, information that has been embedded with behavior-change techniques that lead people to second-guess or rethink their long-term use of sedative hypnotics and then bring that information to their provider or pharmacist to discuss it,” he said.

The results were published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Better Sleep, Fewer Pills

Dr. Gardner and his team created a direct-to-patient, patient-directed, multicomponent knowledge mobilization intervention called Sleepwell. It incorporates best practice– and guideline-based evidence and multiple behavioral change techniques with content and graphics. Dr. Gardner emphasized that it represents a directional shift in care that alleviates providers’ burden without removing it entirely.

To test the intervention’s effectiveness, Dr. Gardner and his team chose New Brunswick as a location for a 6-month, three-arm, open-label, randomized controlled trial; the province has one of the highest rates of sedative use and an older adult population that is vulnerable to the serious side effects of these drugs (eg, cognitive impairment, falls, and frailty). The study was called Your Answers When Needing Sleep in New Brunswick (YAWNS NB).

Eligible participants were aged ≥ 65 years, lived in the community, and had taken benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs) for ≥ 3 nights per week for 3 or more months. Participants were randomly assigned to a control group or one of the two intervention groups. The YAWNS-1 intervention group (n = 195) received a mailed package containing a cover letter, a booklet outlining how to stop sleeping pills, a booklet on how to “get your sleep back,” and a companion website. The YAWNS-2 group (n = 193) received updated versions of the booklets used in a prior trial. The control group (n = 192) was assigned treatment as usual (TAU).

A greater proportion of YAWNS-1 participants discontinued BZRAs at 6 months (26.2%) and had dose reductions (20.4%), compared with YAWNS-2 participants (20.3% and 14.4%, respectively) and TAU participants (7.5% and 12.8%, respectively). The corresponding numbers needed to mail to achieve an additional discontinuation was 5.3 YAWNS-1 packages and 7.8 YAWNS-2 packages.

At 6 months, BZRA cessation was sustained a mean 13.6 weeks for YAWNS-1, 14.3 weeks for YAWNS-2, and 16.9 weeks for TAU.

Sleep measures also improved with YAWNS-1, compared with YAWNs-2 and TAU. Sleep onset latency was reduced by 26.1 minutes among YAWNS-1 participants, compared with YAWNS-2 (P < .001), and by 27.7 minutes, compared with TAU (P < .001). Wake after sleep onset increased by 4.1 minutes in YAWNS-1, 11.1 minutes in YAWNS-2, and 7.5 minutes in TAU.

Although all participants underwent rigorous assessment before inclusion, less than half of participants receiving either intervention (36% in YAWNS-1 and 43% in YAWNS-2) contacted their provider or pharmacist to discuss BZD dose reductions. This finding may have resulted partly from limited access because of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the authors.

A Stepped-Care Model

The intervention is intended to help patients “change their approach from sleeping pills to a short-term CBTI course for long-term sleep benefits, and then speak to their provider,” said Dr. Gardner.

He pointed to a post-study follow-up of the study participants’ health providers, most of whom had moderate to extensive experience deprescribing BZRAs, which showed that 87.5%-100% fully or nearly fully agreed with or supported using the Sleepwell strategy and its content with older patients who rely on sedatives.

“Providers said that deprescribing is difficult, time-consuming, and often not a productive use of their time,” said Dr. Gardner. “I see insomnia as a health issue well set up for a stepped-care model. Self-help approaches are at the very bottom of that model and can help shift the initial burden to patients and out of the healthcare system.”

Poor uptake has prevented CBTI from demonstrating its potential, which is a challenge that Charles M. Morin, PhD, professor of psychology at Laval University in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada, attributes to two factors. “Clearly, there aren’t enough providers with this kind of expertise, and it’s not always covered by public health insurance, so people have to pay out of pocket to treat their insomnia,” he said.

“Overall, I think that this was a very nice study, well conducted, with an impressive sample size,” said Dr. Morin, who was not involved in the study. “The results are quite encouraging, telling us that even when older adults have used sleep medications for an average of 10 years, it’s still possible to reduce the medication. But this doesn’t happen alone. People need to be guided in doing that, not only to decrease medication use, but they also need an alternative,” he said.

Dr. Morin questioned how many patients agree to start with a low intensity. “Ideally, it should be a shared decision paradigm, where the physician or whoever sees the patient first presents the available options and explains the pluses and minuses of each. Some patients might choose medication because it’s a quick fix,” he said. “But some might want to do CBTI, even if it takes more work. The results are sustainable over time,” he added.

The study was jointly funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the government of New Brunswick as a Healthy Seniors Pilot Project. Dr. Gardner and Dr. Morin reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A strategy developed by Canadian researchers for encouraging older patients with insomnia to wean themselves from sleeping pills and improve their sleep through behavioral techniques is effective, data suggest. If proven helpful for the millions of older Canadians who currently rely on nightly benzodiazepines (BZDs) and non-BZDs (colloquially known as Z drugs) for their sleep, it might yield an additional benefit: Reducing resource utilization.

“We know that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) works. It’s recommended as first-line therapy because it works,” study author David Gardner, PharmD, professor of psychiatry at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, told this news organization.

“We’re sharing information about sleeping pills, information that has been embedded with behavior-change techniques that lead people to second-guess or rethink their long-term use of sedative hypnotics and then bring that information to their provider or pharmacist to discuss it,” he said.

The results were published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Better Sleep, Fewer Pills

Dr. Gardner and his team created a direct-to-patient, patient-directed, multicomponent knowledge mobilization intervention called Sleepwell. It incorporates best practice– and guideline-based evidence and multiple behavioral change techniques with content and graphics. Dr. Gardner emphasized that it represents a directional shift in care that alleviates providers’ burden without removing it entirely.

To test the intervention’s effectiveness, Dr. Gardner and his team chose New Brunswick as a location for a 6-month, three-arm, open-label, randomized controlled trial; the province has one of the highest rates of sedative use and an older adult population that is vulnerable to the serious side effects of these drugs (eg, cognitive impairment, falls, and frailty). The study was called Your Answers When Needing Sleep in New Brunswick (YAWNS NB).

Eligible participants were aged ≥ 65 years, lived in the community, and had taken benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs) for ≥ 3 nights per week for 3 or more months. Participants were randomly assigned to a control group or one of the two intervention groups. The YAWNS-1 intervention group (n = 195) received a mailed package containing a cover letter, a booklet outlining how to stop sleeping pills, a booklet on how to “get your sleep back,” and a companion website. The YAWNS-2 group (n = 193) received updated versions of the booklets used in a prior trial. The control group (n = 192) was assigned treatment as usual (TAU).

A greater proportion of YAWNS-1 participants discontinued BZRAs at 6 months (26.2%) and had dose reductions (20.4%), compared with YAWNS-2 participants (20.3% and 14.4%, respectively) and TAU participants (7.5% and 12.8%, respectively). The corresponding numbers needed to mail to achieve an additional discontinuation was 5.3 YAWNS-1 packages and 7.8 YAWNS-2 packages.

At 6 months, BZRA cessation was sustained a mean 13.6 weeks for YAWNS-1, 14.3 weeks for YAWNS-2, and 16.9 weeks for TAU.

Sleep measures also improved with YAWNS-1, compared with YAWNs-2 and TAU. Sleep onset latency was reduced by 26.1 minutes among YAWNS-1 participants, compared with YAWNS-2 (P < .001), and by 27.7 minutes, compared with TAU (P < .001). Wake after sleep onset increased by 4.1 minutes in YAWNS-1, 11.1 minutes in YAWNS-2, and 7.5 minutes in TAU.

Although all participants underwent rigorous assessment before inclusion, less than half of participants receiving either intervention (36% in YAWNS-1 and 43% in YAWNS-2) contacted their provider or pharmacist to discuss BZD dose reductions. This finding may have resulted partly from limited access because of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the authors.

A Stepped-Care Model

The intervention is intended to help patients “change their approach from sleeping pills to a short-term CBTI course for long-term sleep benefits, and then speak to their provider,” said Dr. Gardner.

He pointed to a post-study follow-up of the study participants’ health providers, most of whom had moderate to extensive experience deprescribing BZRAs, which showed that 87.5%-100% fully or nearly fully agreed with or supported using the Sleepwell strategy and its content with older patients who rely on sedatives.

“Providers said that deprescribing is difficult, time-consuming, and often not a productive use of their time,” said Dr. Gardner. “I see insomnia as a health issue well set up for a stepped-care model. Self-help approaches are at the very bottom of that model and can help shift the initial burden to patients and out of the healthcare system.”

Poor uptake has prevented CBTI from demonstrating its potential, which is a challenge that Charles M. Morin, PhD, professor of psychology at Laval University in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada, attributes to two factors. “Clearly, there aren’t enough providers with this kind of expertise, and it’s not always covered by public health insurance, so people have to pay out of pocket to treat their insomnia,” he said.

“Overall, I think that this was a very nice study, well conducted, with an impressive sample size,” said Dr. Morin, who was not involved in the study. “The results are quite encouraging, telling us that even when older adults have used sleep medications for an average of 10 years, it’s still possible to reduce the medication. But this doesn’t happen alone. People need to be guided in doing that, not only to decrease medication use, but they also need an alternative,” he said.

Dr. Morin questioned how many patients agree to start with a low intensity. “Ideally, it should be a shared decision paradigm, where the physician or whoever sees the patient first presents the available options and explains the pluses and minuses of each. Some patients might choose medication because it’s a quick fix,” he said. “But some might want to do CBTI, even if it takes more work. The results are sustainable over time,” he added.

The study was jointly funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the government of New Brunswick as a Healthy Seniors Pilot Project. Dr. Gardner and Dr. Morin reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Age-Friendly Health Systems Transformation: A Whole Person Approach to Support the Well-Being of Older Adults

The COVID-19 pandemic established a new normal for health care delivery, with leaders rethinking core practices to survive and thrive in a changing environment and improve the health and well-being of patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is embracing a shift in focus from “what is the matter” to “what really matters” to address pre- and postpandemic challenges through a whole health approach.1 Initially conceptualized by the VHA in 2011, whole health “is an approach to health care that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being so that they can live their life to the fullest.”1 Whole health integrates evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage pain; this includes acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, yoga, massage therapy, guided imagery, biofeedback, and clinical hypnosis.1 The VHA now recognizes well-being as a core value, helping clinicians respond to emerging challenges related to the social determinants of health (eg, access to health care, physical activity, and healthy foods) and guiding health care decision making.1,2

Well-being through empowerment—elements of whole health and Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS)—encourages health care institutions to work with employees, patients, and other stakeholders to address global challenges, clinician burnout, and social issues faced by their communities. This approach focuses on life’s purpose and meaning for individuals and inspires leaders to engage with patients, staff, and communities in new, impactful ways by focusing on wellbeing and wholeness rather than illness and disease. Having a higher sense of purpose is associated with lower all-cause mortality, reduced risk of specific diseases, better health behaviors, greater use of preventive services, and fewer hospital days of care.3

This article describes how AFHS supports the well-being of older adults and aligns with the whole health model of care. It also outlines the VHA investment to transform health care to be more person-centered by documenting what matters in the electronic health record (EHR).

AGE-FRIENDLY CARE

Given that nearly half of veterans enrolled in the VHA are aged ≥ 65 years, there is an increased need to identify models of care to support this aging population.4 This is especially critical because older veterans often have multiple chronic conditions and complex care needs that benefit from a whole person approach. The AFHS movement aims to provide evidence-based care aligned with what matters to older adults and provides a mechanism for transforming care to meet the needs of older veterans. This includes addressing age-related health concerns while promoting optimal health outcomes and quality of life. AFHS follows the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.5 The 4Ms serve as a guide for the health care of older adults in any setting, where each “M” is assessed and acted on to support what matters.5 Since 2020, > 390 teams have developed a plan to implement the 4Ms at 156 VHA facilities, demonstrating the VHA commitment to transforming health care for veterans.6

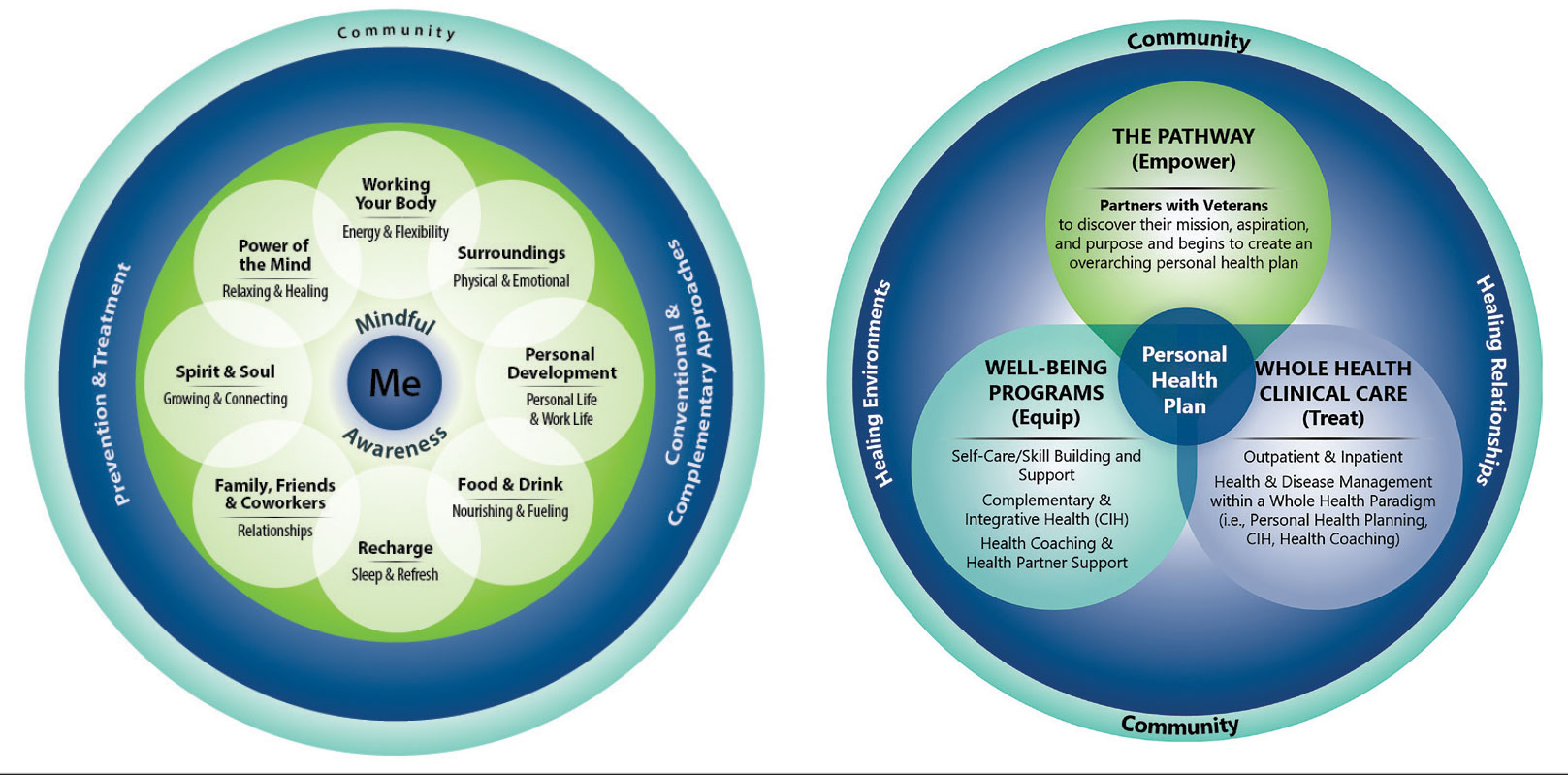

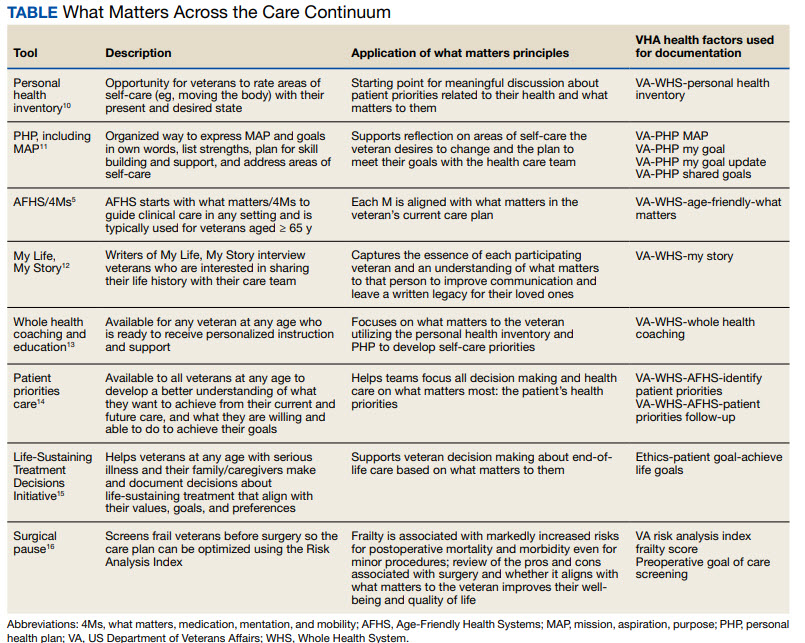

When VHA teams join the AFHS movement, they may also engage older veterans in a whole health system (WHS) (Figure). While AFHS is designed to improve care for patients aged ≥ 65 years, it also complements whole health, a person-centered approach available to all veterans enrolled in the VHA. Through the WHS and AFHS, veterans are empowered and equipped to take charge of their health and well-being through conversations about their unique goals, preferences, and health priorities.4 Clinicians are challenged to assess what matters by asking questions like, “What brings you joy?” and, “How can we help you meet your health goals?”1,5 These questions shift the conversation from disease-based treatment and enable clinicians to better understand the veteran as a person.1,5

For whole health and AFHS, conversations about what matters are anchored in the veteran’s goals and preferences, especially those facing a significant health change (ie, a new diagnosis or treatment decision).5,7 Together, the veteran’s goals and priorities serve as the foundation for developing person-centered care plans that often go beyond conventional medical treatments to address the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of health.

SYSTEM-WIDE DIRECTIVE

The WHS enhances AFHS discussions about what matters to veterans by adding a system-level lens for conceptualizing health care delivery by leveraging the 3 components of WHS: the “pathway,” well-being programs, and whole health clinical care.

The Pathway

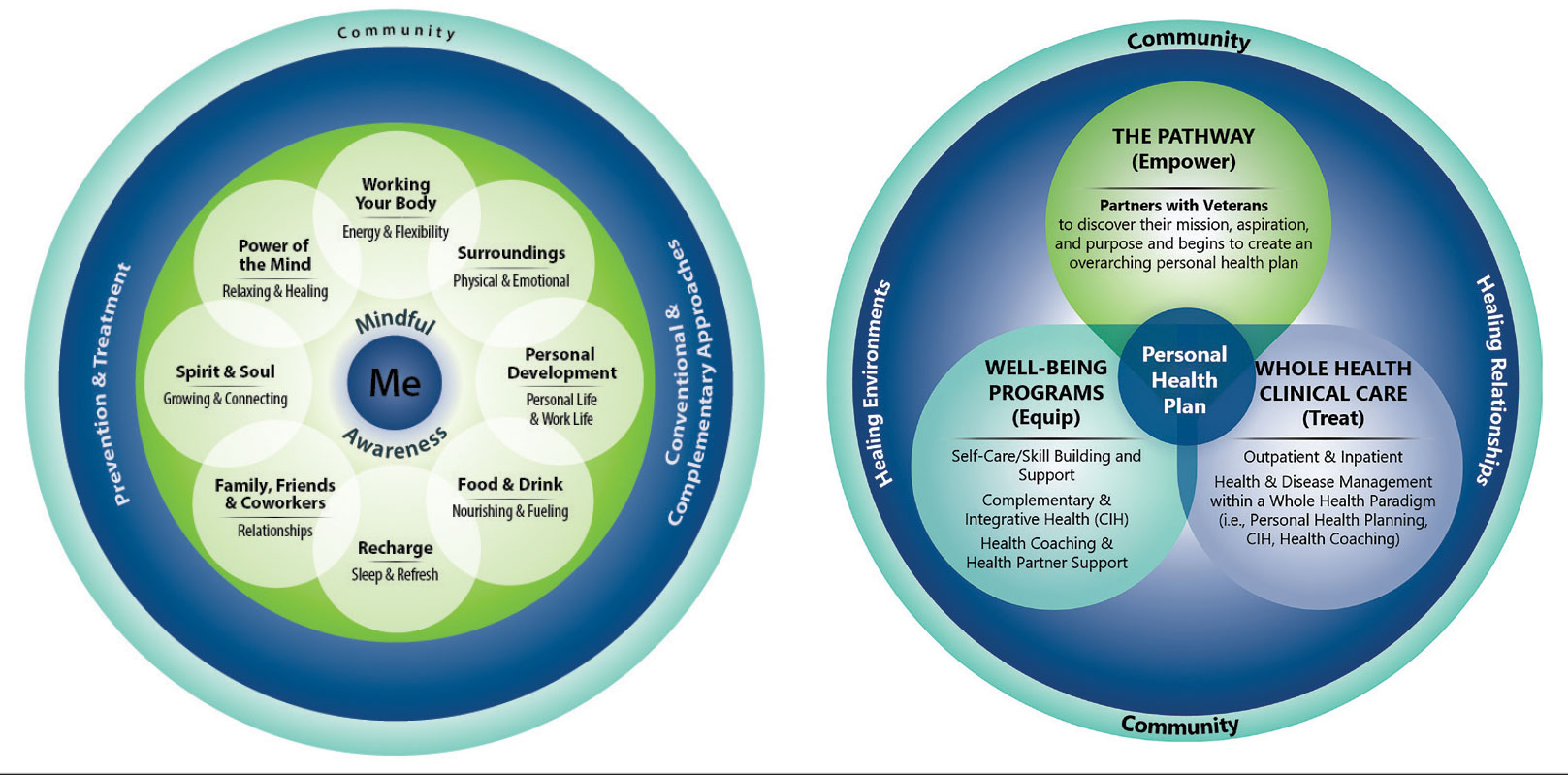

Discovering what matters, or the veteran’s “mission, aspiration, and purpose,” begins with the WHS pathway. When stepping into the pathway, veterans begin completing a personal health inventory, or “walking the circle of health,” which encourages self-reflection that focuses on components of their life that can influence health and well-being.1,8 The circle of health offers a visual representation of the 4 most important aspects of health and well-being: First, “Me” at the center as an individual who is the expert on their life, values, goals, and priorities. Only the individual can know what really matters through mindful awareness and what works for their life. Second, self-care consists of 8 areas that impact health and wellbeing: working your body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind. Third, professional care consists of prevention, conventional care, and complementary care. Finally, the community that supports the individual.

Well-Being Programs

VHA provides WHS programs that support veterans in building self-care skills and improving their quality of life, often through integrative care clinics that offer coaching and CIH therapies. For example, a veteran who prioritizes mobility when seeking care at an integrative care clinic will not only receive conventional medical treatment for their physical symptoms but may also be offered CIH therapies depending on their goals. The veteran may set a daily mobility goal with their care team that supports what matters, incorporating CIH approaches, such as yoga and tai chi into the care plan.5 These holistic approaches for moving the body can help alleviate physical symptoms, reduce stress, improve mindful awareness, and provide opportunities for self-discovery and growth, thus promote overall well-being

Whole Health Clinical Care

AFHS and the 4Ms embody the clinical care component of the WHS. Because what matters is the driver of the 4Ms, every action taken by the care team supports wellbeing and quality of life by promoting independence, connection, and support, and addressing external factors, such as social determinants of health. At a minimum, well-being includes “functioning well: the experience of positive emotions such as happiness and contentment as well as the development of one’s potential, having some control over one’s life, having a sense of purpose, and experiencing positive relationships.”9 From a system perspective, the VHA has begun to normalize focusing on what matters to veterans, using an interprofessional approach, one of the first steps to implementing AFHS.

As the programs expand, AFHS teams can learn from whole health well-being programs and increase the capacity for self-care in older veterans. Learning about the key elements included in the circle of health helps clinicians understand each veteran’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to support their self-care. From there, teams can act on the 4Ms and connect older veterans with the most appropriate programs and services at their facility, ensuring continuum of care.

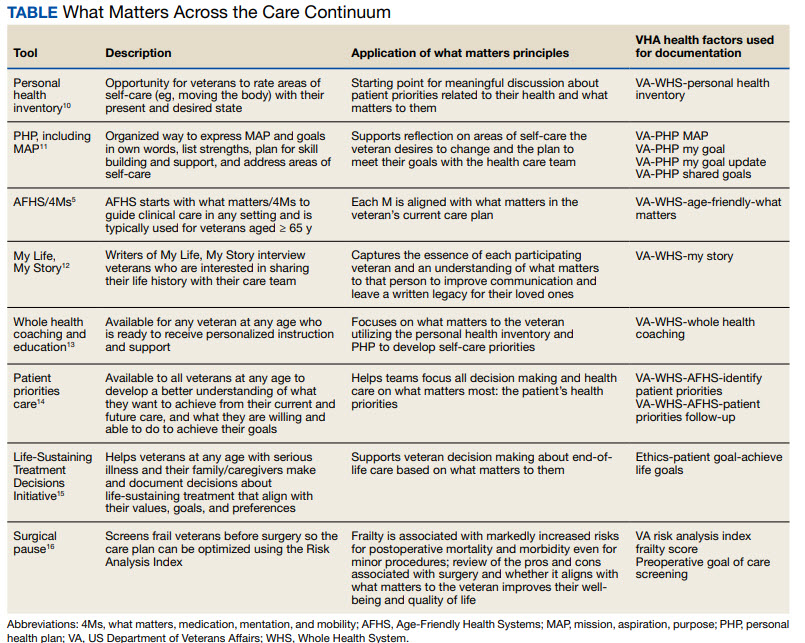

DOCUMENTATION

The VHA leverages several tools and evidence-based practices to assess and act on what matters for veterans of all ages (Table).5,10-16 The VHA EHR and associated dashboards contain a wealth of information about whole health and AFHS implementation, scale up, and spread. A national AFHS 4Ms note template contains standardized data elements called health factors, which provide a mechanism for monitoring 4Ms care via its related dashboard. This template was developed by an interprofessional workgroup of VHA staff and underwent a thorough human factors engineering review and testing process prior to its release. Although teams continue to personalize care based on what matters to the veteran, data from the standardized 4Ms note template and dashboard provide a way to establish consistent, equitable care across multiple care settings.17

Between January 2022 and December 2023, > 612,000 participants aged ≥ 65 years identified what matters to them through 1.35 million assessments. During that period, > 36,000 veterans aged ≥ 65 years participated in AFHS and had what matters conversations documented. A personalized health plan was completed by 585,270 veterans for a total of 1.1 million assessments.11 Whole health coaching has been documented for > 57,000 veterans with > 200,000 assessments completed.13 In fiscal year 2023, a total of 1,802,131 veterans participated in whole health.

When teams share information about what matters to the veteran in a clinicianfacing format in the EHR, this helps ensure that the VHA honors veteran preferences throughout transitions of care and across all phases of health care. Although the EHR captures data on what matters, measurement of the overall impact on veteran and health system outcomes is essential. Further evaluation and ongoing education are needed to ensure clinicians are accurately and efficiently capturing the care provided by completing the appropriate EHR. Additional challenges include identifying ways to balance the documentation burden, while ensuring notes include valuable patient-centered information to guide care. EHR tools and templates have helped to unlock important insights on health care delivery in the VHA; however, health systems must consider how these clinical practices support the overall well-being of patients. How leaders empower frontline clinicians in any care setting to use these data to drive meaningful change is also important.

TRANSFORMING VHA CARE DELIVERY

In Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation, the National Academy of Science proposes a framework for the transformation of health care institutions to provide better whole health to veterans.3 Transformation requires change in entire systems and leaders who mobilize people “for participation in the process of change, encouraging a sense of collective identity and collective efficacy, which in turn brings stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy,” and an enhanced sense of meaningfulness in their work and lives.18

Shifting health care approaches to equipping and empowering veterans and employees with whole health and AFHS resources is transformational and requires radically different assumptions and approaches that cannot be realized through traditional approaches. This change requires robust and multifaceted cultural transformation spanning all levels of the organization. Whole health and AFHS are facilitating this transformation by supporting documentation and data needs, tracking outcomes across settings, and accelerating spread to new facilities and care settings nationwide to support older veterans in improving their health and well-being.

Whole health and AFHS are complementary approaches to care that can work to empower veterans (as well as caregivers and clinicians) to align services with what matters most to veterans. Lessons such as standardizing person-centered assessments of what matters, creating supportive structures to better align care with veterans’ priorities, and identifying meaningful veteran and system-level outcomes to help sustain transformational change can be applied from whole health to AFHS. Together these programs have the potential to enhance overall health outcomes and quality of life for veterans.

- Kligler B, Hyde J, Gantt C, Bokhour B. The Whole Health transformation at the Veterans Health Administration: moving from “what’s the matter with you?” to “what matters to you?” Med Care. 2022;60(5):387-391. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001706

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH) at CDC. January 17, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/social-determinants-of-health.html

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. The National Academies Press; 2023. Accessed September 9, 2024. doi:10.17226/26854

- Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-friendly health systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

- Laderman M, Jackson C, Little K, Duong T, Pelton L. “What Matters” to older adults? A toolkit for health systems to design better care with older adults. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHI_Age_Friendly_What_Matters_to_Older_Adults_Toolkit.pdf

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Age-Friendly Health Systems. Updated September 4, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/age-friendly-health-systems

- Brown TT, Hurley VB, Rodriguez HP, et al. Shared dec i s i o n - m a k i n g l o w e r s m e d i c a l e x p e n d i t u re s a n d the effect is amplified in racially-ethnically concordant relationships. Med Care. 2023;61(8):528-535. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001881

- Kligler B. Whole Health in the Veterans Health Administration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:2164957X221077214.

- Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):192. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal Health Inventory. Updated May 2022. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PHI-long-May22-fillable-508.pdf doi:10.1177/2164957X221077214

- Veterans Health Administration. Personal Health Plan. Updated March 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https:// www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PersonalHealthPlan_508_03-2019.pdf

- Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: My Life, My Story. Updated March 20, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/mylifemystory/index.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole Health Library: Whole Health for Skill Building. Updated April 17, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/courses/whole-health-skill-building.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Making Decisions: Current Care Planning. Updated May 21, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/making_decisions.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI). Updated March 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/life-sustaining-treatment-decisions-initiative

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion: Surgical Pause Saving Veterans Lives. Updated September 22, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.cherp.research.va.gov/features/Surgical_Pause_Saving_Veterans_Lives.asp

- Munro S, Church K, Berner C, et al. Implementation of an agefriendly template in the Veterans Health Administration electronic health record. J Inform Nurs. 2023;8(3):6-11.

- Burns JM. Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. Grove Press; 2003.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: Circle of Health Overview. Updated May 20, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/index.asp

The COVID-19 pandemic established a new normal for health care delivery, with leaders rethinking core practices to survive and thrive in a changing environment and improve the health and well-being of patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is embracing a shift in focus from “what is the matter” to “what really matters” to address pre- and postpandemic challenges through a whole health approach.1 Initially conceptualized by the VHA in 2011, whole health “is an approach to health care that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being so that they can live their life to the fullest.”1 Whole health integrates evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage pain; this includes acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, yoga, massage therapy, guided imagery, biofeedback, and clinical hypnosis.1 The VHA now recognizes well-being as a core value, helping clinicians respond to emerging challenges related to the social determinants of health (eg, access to health care, physical activity, and healthy foods) and guiding health care decision making.1,2

Well-being through empowerment—elements of whole health and Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS)—encourages health care institutions to work with employees, patients, and other stakeholders to address global challenges, clinician burnout, and social issues faced by their communities. This approach focuses on life’s purpose and meaning for individuals and inspires leaders to engage with patients, staff, and communities in new, impactful ways by focusing on wellbeing and wholeness rather than illness and disease. Having a higher sense of purpose is associated with lower all-cause mortality, reduced risk of specific diseases, better health behaviors, greater use of preventive services, and fewer hospital days of care.3

This article describes how AFHS supports the well-being of older adults and aligns with the whole health model of care. It also outlines the VHA investment to transform health care to be more person-centered by documenting what matters in the electronic health record (EHR).

AGE-FRIENDLY CARE

Given that nearly half of veterans enrolled in the VHA are aged ≥ 65 years, there is an increased need to identify models of care to support this aging population.4 This is especially critical because older veterans often have multiple chronic conditions and complex care needs that benefit from a whole person approach. The AFHS movement aims to provide evidence-based care aligned with what matters to older adults and provides a mechanism for transforming care to meet the needs of older veterans. This includes addressing age-related health concerns while promoting optimal health outcomes and quality of life. AFHS follows the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.5 The 4Ms serve as a guide for the health care of older adults in any setting, where each “M” is assessed and acted on to support what matters.5 Since 2020, > 390 teams have developed a plan to implement the 4Ms at 156 VHA facilities, demonstrating the VHA commitment to transforming health care for veterans.6

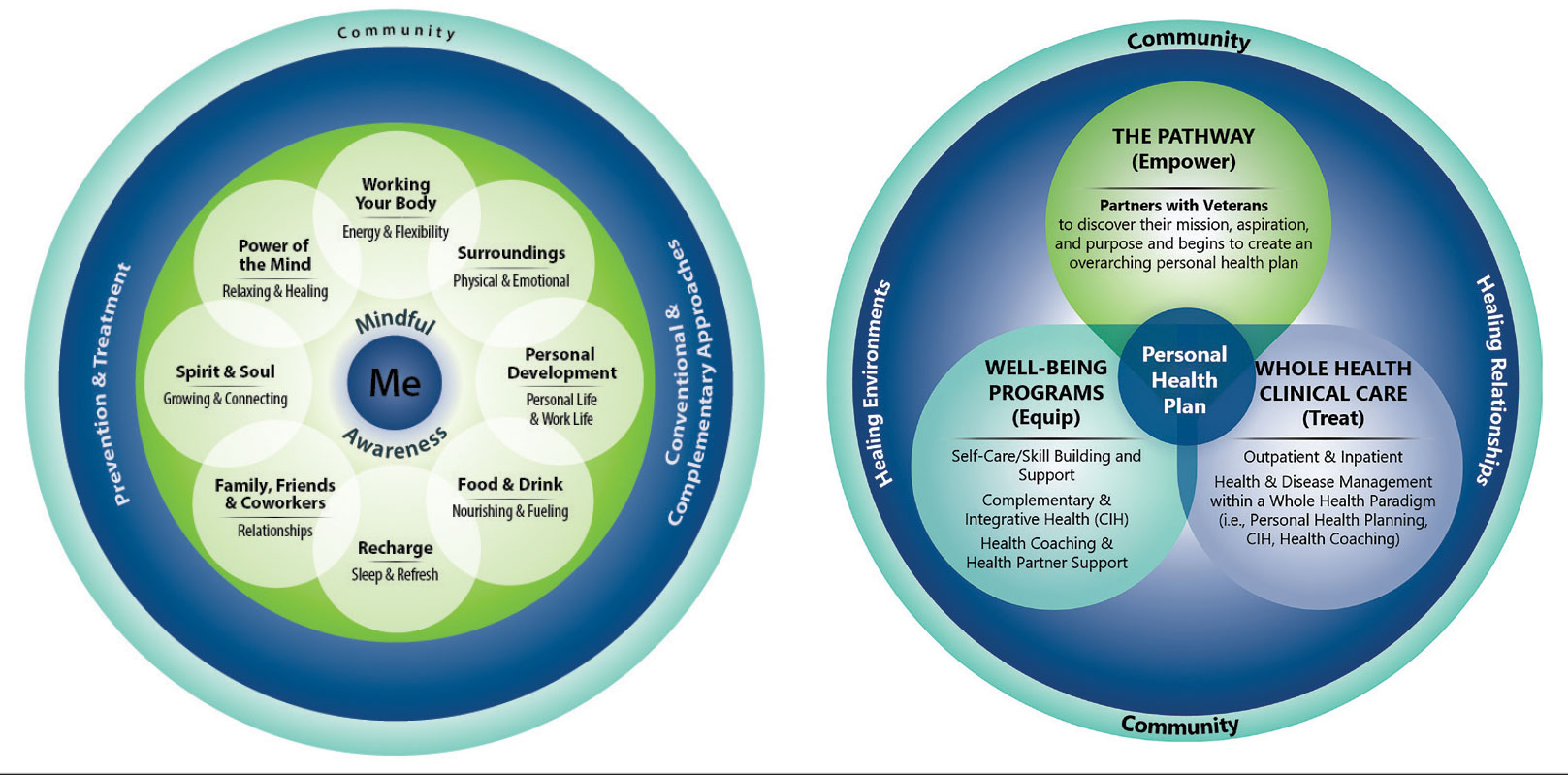

When VHA teams join the AFHS movement, they may also engage older veterans in a whole health system (WHS) (Figure). While AFHS is designed to improve care for patients aged ≥ 65 years, it also complements whole health, a person-centered approach available to all veterans enrolled in the VHA. Through the WHS and AFHS, veterans are empowered and equipped to take charge of their health and well-being through conversations about their unique goals, preferences, and health priorities.4 Clinicians are challenged to assess what matters by asking questions like, “What brings you joy?” and, “How can we help you meet your health goals?”1,5 These questions shift the conversation from disease-based treatment and enable clinicians to better understand the veteran as a person.1,5

For whole health and AFHS, conversations about what matters are anchored in the veteran’s goals and preferences, especially those facing a significant health change (ie, a new diagnosis or treatment decision).5,7 Together, the veteran’s goals and priorities serve as the foundation for developing person-centered care plans that often go beyond conventional medical treatments to address the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of health.

SYSTEM-WIDE DIRECTIVE

The WHS enhances AFHS discussions about what matters to veterans by adding a system-level lens for conceptualizing health care delivery by leveraging the 3 components of WHS: the “pathway,” well-being programs, and whole health clinical care.

The Pathway

Discovering what matters, or the veteran’s “mission, aspiration, and purpose,” begins with the WHS pathway. When stepping into the pathway, veterans begin completing a personal health inventory, or “walking the circle of health,” which encourages self-reflection that focuses on components of their life that can influence health and well-being.1,8 The circle of health offers a visual representation of the 4 most important aspects of health and well-being: First, “Me” at the center as an individual who is the expert on their life, values, goals, and priorities. Only the individual can know what really matters through mindful awareness and what works for their life. Second, self-care consists of 8 areas that impact health and wellbeing: working your body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind. Third, professional care consists of prevention, conventional care, and complementary care. Finally, the community that supports the individual.

Well-Being Programs

VHA provides WHS programs that support veterans in building self-care skills and improving their quality of life, often through integrative care clinics that offer coaching and CIH therapies. For example, a veteran who prioritizes mobility when seeking care at an integrative care clinic will not only receive conventional medical treatment for their physical symptoms but may also be offered CIH therapies depending on their goals. The veteran may set a daily mobility goal with their care team that supports what matters, incorporating CIH approaches, such as yoga and tai chi into the care plan.5 These holistic approaches for moving the body can help alleviate physical symptoms, reduce stress, improve mindful awareness, and provide opportunities for self-discovery and growth, thus promote overall well-being

Whole Health Clinical Care

AFHS and the 4Ms embody the clinical care component of the WHS. Because what matters is the driver of the 4Ms, every action taken by the care team supports wellbeing and quality of life by promoting independence, connection, and support, and addressing external factors, such as social determinants of health. At a minimum, well-being includes “functioning well: the experience of positive emotions such as happiness and contentment as well as the development of one’s potential, having some control over one’s life, having a sense of purpose, and experiencing positive relationships.”9 From a system perspective, the VHA has begun to normalize focusing on what matters to veterans, using an interprofessional approach, one of the first steps to implementing AFHS.

As the programs expand, AFHS teams can learn from whole health well-being programs and increase the capacity for self-care in older veterans. Learning about the key elements included in the circle of health helps clinicians understand each veteran’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to support their self-care. From there, teams can act on the 4Ms and connect older veterans with the most appropriate programs and services at their facility, ensuring continuum of care.

DOCUMENTATION

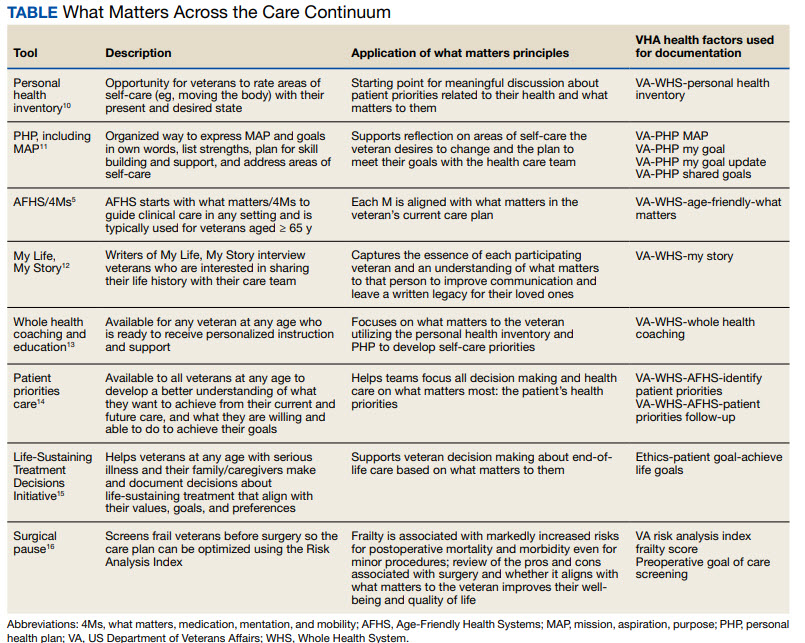

The VHA leverages several tools and evidence-based practices to assess and act on what matters for veterans of all ages (Table).5,10-16 The VHA EHR and associated dashboards contain a wealth of information about whole health and AFHS implementation, scale up, and spread. A national AFHS 4Ms note template contains standardized data elements called health factors, which provide a mechanism for monitoring 4Ms care via its related dashboard. This template was developed by an interprofessional workgroup of VHA staff and underwent a thorough human factors engineering review and testing process prior to its release. Although teams continue to personalize care based on what matters to the veteran, data from the standardized 4Ms note template and dashboard provide a way to establish consistent, equitable care across multiple care settings.17

Between January 2022 and December 2023, > 612,000 participants aged ≥ 65 years identified what matters to them through 1.35 million assessments. During that period, > 36,000 veterans aged ≥ 65 years participated in AFHS and had what matters conversations documented. A personalized health plan was completed by 585,270 veterans for a total of 1.1 million assessments.11 Whole health coaching has been documented for > 57,000 veterans with > 200,000 assessments completed.13 In fiscal year 2023, a total of 1,802,131 veterans participated in whole health.

When teams share information about what matters to the veteran in a clinicianfacing format in the EHR, this helps ensure that the VHA honors veteran preferences throughout transitions of care and across all phases of health care. Although the EHR captures data on what matters, measurement of the overall impact on veteran and health system outcomes is essential. Further evaluation and ongoing education are needed to ensure clinicians are accurately and efficiently capturing the care provided by completing the appropriate EHR. Additional challenges include identifying ways to balance the documentation burden, while ensuring notes include valuable patient-centered information to guide care. EHR tools and templates have helped to unlock important insights on health care delivery in the VHA; however, health systems must consider how these clinical practices support the overall well-being of patients. How leaders empower frontline clinicians in any care setting to use these data to drive meaningful change is also important.

TRANSFORMING VHA CARE DELIVERY

In Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation, the National Academy of Science proposes a framework for the transformation of health care institutions to provide better whole health to veterans.3 Transformation requires change in entire systems and leaders who mobilize people “for participation in the process of change, encouraging a sense of collective identity and collective efficacy, which in turn brings stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy,” and an enhanced sense of meaningfulness in their work and lives.18

Shifting health care approaches to equipping and empowering veterans and employees with whole health and AFHS resources is transformational and requires radically different assumptions and approaches that cannot be realized through traditional approaches. This change requires robust and multifaceted cultural transformation spanning all levels of the organization. Whole health and AFHS are facilitating this transformation by supporting documentation and data needs, tracking outcomes across settings, and accelerating spread to new facilities and care settings nationwide to support older veterans in improving their health and well-being.

Whole health and AFHS are complementary approaches to care that can work to empower veterans (as well as caregivers and clinicians) to align services with what matters most to veterans. Lessons such as standardizing person-centered assessments of what matters, creating supportive structures to better align care with veterans’ priorities, and identifying meaningful veteran and system-level outcomes to help sustain transformational change can be applied from whole health to AFHS. Together these programs have the potential to enhance overall health outcomes and quality of life for veterans.

The COVID-19 pandemic established a new normal for health care delivery, with leaders rethinking core practices to survive and thrive in a changing environment and improve the health and well-being of patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is embracing a shift in focus from “what is the matter” to “what really matters” to address pre- and postpandemic challenges through a whole health approach.1 Initially conceptualized by the VHA in 2011, whole health “is an approach to health care that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being so that they can live their life to the fullest.”1 Whole health integrates evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage pain; this includes acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, yoga, massage therapy, guided imagery, biofeedback, and clinical hypnosis.1 The VHA now recognizes well-being as a core value, helping clinicians respond to emerging challenges related to the social determinants of health (eg, access to health care, physical activity, and healthy foods) and guiding health care decision making.1,2

Well-being through empowerment—elements of whole health and Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS)—encourages health care institutions to work with employees, patients, and other stakeholders to address global challenges, clinician burnout, and social issues faced by their communities. This approach focuses on life’s purpose and meaning for individuals and inspires leaders to engage with patients, staff, and communities in new, impactful ways by focusing on wellbeing and wholeness rather than illness and disease. Having a higher sense of purpose is associated with lower all-cause mortality, reduced risk of specific diseases, better health behaviors, greater use of preventive services, and fewer hospital days of care.3

This article describes how AFHS supports the well-being of older adults and aligns with the whole health model of care. It also outlines the VHA investment to transform health care to be more person-centered by documenting what matters in the electronic health record (EHR).

AGE-FRIENDLY CARE

Given that nearly half of veterans enrolled in the VHA are aged ≥ 65 years, there is an increased need to identify models of care to support this aging population.4 This is especially critical because older veterans often have multiple chronic conditions and complex care needs that benefit from a whole person approach. The AFHS movement aims to provide evidence-based care aligned with what matters to older adults and provides a mechanism for transforming care to meet the needs of older veterans. This includes addressing age-related health concerns while promoting optimal health outcomes and quality of life. AFHS follows the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.5 The 4Ms serve as a guide for the health care of older adults in any setting, where each “M” is assessed and acted on to support what matters.5 Since 2020, > 390 teams have developed a plan to implement the 4Ms at 156 VHA facilities, demonstrating the VHA commitment to transforming health care for veterans.6

When VHA teams join the AFHS movement, they may also engage older veterans in a whole health system (WHS) (Figure). While AFHS is designed to improve care for patients aged ≥ 65 years, it also complements whole health, a person-centered approach available to all veterans enrolled in the VHA. Through the WHS and AFHS, veterans are empowered and equipped to take charge of their health and well-being through conversations about their unique goals, preferences, and health priorities.4 Clinicians are challenged to assess what matters by asking questions like, “What brings you joy?” and, “How can we help you meet your health goals?”1,5 These questions shift the conversation from disease-based treatment and enable clinicians to better understand the veteran as a person.1,5

For whole health and AFHS, conversations about what matters are anchored in the veteran’s goals and preferences, especially those facing a significant health change (ie, a new diagnosis or treatment decision).5,7 Together, the veteran’s goals and priorities serve as the foundation for developing person-centered care plans that often go beyond conventional medical treatments to address the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of health.

SYSTEM-WIDE DIRECTIVE

The WHS enhances AFHS discussions about what matters to veterans by adding a system-level lens for conceptualizing health care delivery by leveraging the 3 components of WHS: the “pathway,” well-being programs, and whole health clinical care.

The Pathway

Discovering what matters, or the veteran’s “mission, aspiration, and purpose,” begins with the WHS pathway. When stepping into the pathway, veterans begin completing a personal health inventory, or “walking the circle of health,” which encourages self-reflection that focuses on components of their life that can influence health and well-being.1,8 The circle of health offers a visual representation of the 4 most important aspects of health and well-being: First, “Me” at the center as an individual who is the expert on their life, values, goals, and priorities. Only the individual can know what really matters through mindful awareness and what works for their life. Second, self-care consists of 8 areas that impact health and wellbeing: working your body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind. Third, professional care consists of prevention, conventional care, and complementary care. Finally, the community that supports the individual.

Well-Being Programs

VHA provides WHS programs that support veterans in building self-care skills and improving their quality of life, often through integrative care clinics that offer coaching and CIH therapies. For example, a veteran who prioritizes mobility when seeking care at an integrative care clinic will not only receive conventional medical treatment for their physical symptoms but may also be offered CIH therapies depending on their goals. The veteran may set a daily mobility goal with their care team that supports what matters, incorporating CIH approaches, such as yoga and tai chi into the care plan.5 These holistic approaches for moving the body can help alleviate physical symptoms, reduce stress, improve mindful awareness, and provide opportunities for self-discovery and growth, thus promote overall well-being

Whole Health Clinical Care

AFHS and the 4Ms embody the clinical care component of the WHS. Because what matters is the driver of the 4Ms, every action taken by the care team supports wellbeing and quality of life by promoting independence, connection, and support, and addressing external factors, such as social determinants of health. At a minimum, well-being includes “functioning well: the experience of positive emotions such as happiness and contentment as well as the development of one’s potential, having some control over one’s life, having a sense of purpose, and experiencing positive relationships.”9 From a system perspective, the VHA has begun to normalize focusing on what matters to veterans, using an interprofessional approach, one of the first steps to implementing AFHS.

As the programs expand, AFHS teams can learn from whole health well-being programs and increase the capacity for self-care in older veterans. Learning about the key elements included in the circle of health helps clinicians understand each veteran’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to support their self-care. From there, teams can act on the 4Ms and connect older veterans with the most appropriate programs and services at their facility, ensuring continuum of care.

DOCUMENTATION

The VHA leverages several tools and evidence-based practices to assess and act on what matters for veterans of all ages (Table).5,10-16 The VHA EHR and associated dashboards contain a wealth of information about whole health and AFHS implementation, scale up, and spread. A national AFHS 4Ms note template contains standardized data elements called health factors, which provide a mechanism for monitoring 4Ms care via its related dashboard. This template was developed by an interprofessional workgroup of VHA staff and underwent a thorough human factors engineering review and testing process prior to its release. Although teams continue to personalize care based on what matters to the veteran, data from the standardized 4Ms note template and dashboard provide a way to establish consistent, equitable care across multiple care settings.17

Between January 2022 and December 2023, > 612,000 participants aged ≥ 65 years identified what matters to them through 1.35 million assessments. During that period, > 36,000 veterans aged ≥ 65 years participated in AFHS and had what matters conversations documented. A personalized health plan was completed by 585,270 veterans for a total of 1.1 million assessments.11 Whole health coaching has been documented for > 57,000 veterans with > 200,000 assessments completed.13 In fiscal year 2023, a total of 1,802,131 veterans participated in whole health.

When teams share information about what matters to the veteran in a clinicianfacing format in the EHR, this helps ensure that the VHA honors veteran preferences throughout transitions of care and across all phases of health care. Although the EHR captures data on what matters, measurement of the overall impact on veteran and health system outcomes is essential. Further evaluation and ongoing education are needed to ensure clinicians are accurately and efficiently capturing the care provided by completing the appropriate EHR. Additional challenges include identifying ways to balance the documentation burden, while ensuring notes include valuable patient-centered information to guide care. EHR tools and templates have helped to unlock important insights on health care delivery in the VHA; however, health systems must consider how these clinical practices support the overall well-being of patients. How leaders empower frontline clinicians in any care setting to use these data to drive meaningful change is also important.

TRANSFORMING VHA CARE DELIVERY

In Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation, the National Academy of Science proposes a framework for the transformation of health care institutions to provide better whole health to veterans.3 Transformation requires change in entire systems and leaders who mobilize people “for participation in the process of change, encouraging a sense of collective identity and collective efficacy, which in turn brings stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy,” and an enhanced sense of meaningfulness in their work and lives.18

Shifting health care approaches to equipping and empowering veterans and employees with whole health and AFHS resources is transformational and requires radically different assumptions and approaches that cannot be realized through traditional approaches. This change requires robust and multifaceted cultural transformation spanning all levels of the organization. Whole health and AFHS are facilitating this transformation by supporting documentation and data needs, tracking outcomes across settings, and accelerating spread to new facilities and care settings nationwide to support older veterans in improving their health and well-being.

Whole health and AFHS are complementary approaches to care that can work to empower veterans (as well as caregivers and clinicians) to align services with what matters most to veterans. Lessons such as standardizing person-centered assessments of what matters, creating supportive structures to better align care with veterans’ priorities, and identifying meaningful veteran and system-level outcomes to help sustain transformational change can be applied from whole health to AFHS. Together these programs have the potential to enhance overall health outcomes and quality of life for veterans.

- Kligler B, Hyde J, Gantt C, Bokhour B. The Whole Health transformation at the Veterans Health Administration: moving from “what’s the matter with you?” to “what matters to you?” Med Care. 2022;60(5):387-391. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001706

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH) at CDC. January 17, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/social-determinants-of-health.html

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. The National Academies Press; 2023. Accessed September 9, 2024. doi:10.17226/26854

- Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-friendly health systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

- Laderman M, Jackson C, Little K, Duong T, Pelton L. “What Matters” to older adults? A toolkit for health systems to design better care with older adults. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHI_Age_Friendly_What_Matters_to_Older_Adults_Toolkit.pdf

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Age-Friendly Health Systems. Updated September 4, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/age-friendly-health-systems

- Brown TT, Hurley VB, Rodriguez HP, et al. Shared dec i s i o n - m a k i n g l o w e r s m e d i c a l e x p e n d i t u re s a n d the effect is amplified in racially-ethnically concordant relationships. Med Care. 2023;61(8):528-535. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001881

- Kligler B. Whole Health in the Veterans Health Administration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:2164957X221077214.

- Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):192. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal Health Inventory. Updated May 2022. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PHI-long-May22-fillable-508.pdf doi:10.1177/2164957X221077214

- Veterans Health Administration. Personal Health Plan. Updated March 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https:// www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PersonalHealthPlan_508_03-2019.pdf

- Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: My Life, My Story. Updated March 20, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/mylifemystory/index.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole Health Library: Whole Health for Skill Building. Updated April 17, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/courses/whole-health-skill-building.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Making Decisions: Current Care Planning. Updated May 21, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/making_decisions.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI). Updated March 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/life-sustaining-treatment-decisions-initiative

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion: Surgical Pause Saving Veterans Lives. Updated September 22, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.cherp.research.va.gov/features/Surgical_Pause_Saving_Veterans_Lives.asp

- Munro S, Church K, Berner C, et al. Implementation of an agefriendly template in the Veterans Health Administration electronic health record. J Inform Nurs. 2023;8(3):6-11.

- Burns JM. Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. Grove Press; 2003.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: Circle of Health Overview. Updated May 20, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/index.asp

- Kligler B, Hyde J, Gantt C, Bokhour B. The Whole Health transformation at the Veterans Health Administration: moving from “what’s the matter with you?” to “what matters to you?” Med Care. 2022;60(5):387-391. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001706

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH) at CDC. January 17, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/social-determinants-of-health.html

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. The National Academies Press; 2023. Accessed September 9, 2024. doi:10.17226/26854

- Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-friendly health systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

- Laderman M, Jackson C, Little K, Duong T, Pelton L. “What Matters” to older adults? A toolkit for health systems to design better care with older adults. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHI_Age_Friendly_What_Matters_to_Older_Adults_Toolkit.pdf

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Age-Friendly Health Systems. Updated September 4, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/age-friendly-health-systems

- Brown TT, Hurley VB, Rodriguez HP, et al. Shared dec i s i o n - m a k i n g l o w e r s m e d i c a l e x p e n d i t u re s a n d the effect is amplified in racially-ethnically concordant relationships. Med Care. 2023;61(8):528-535. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001881

- Kligler B. Whole Health in the Veterans Health Administration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:2164957X221077214.

- Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):192. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal Health Inventory. Updated May 2022. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PHI-long-May22-fillable-508.pdf doi:10.1177/2164957X221077214

- Veterans Health Administration. Personal Health Plan. Updated March 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https:// www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PersonalHealthPlan_508_03-2019.pdf

- Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: My Life, My Story. Updated March 20, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/mylifemystory/index.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole Health Library: Whole Health for Skill Building. Updated April 17, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/courses/whole-health-skill-building.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Making Decisions: Current Care Planning. Updated May 21, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/making_decisions.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI). Updated March 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/life-sustaining-treatment-decisions-initiative

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion: Surgical Pause Saving Veterans Lives. Updated September 22, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.cherp.research.va.gov/features/Surgical_Pause_Saving_Veterans_Lives.asp

- Munro S, Church K, Berner C, et al. Implementation of an agefriendly template in the Veterans Health Administration electronic health record. J Inform Nurs. 2023;8(3):6-11.

- Burns JM. Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. Grove Press; 2003.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: Circle of Health Overview. Updated May 20, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/index.asp

How Psychedelic Drugs Can Aid Patients at the End of Life

Palliative care has proven to be one of the most promising fields for research on interventions with psychedelic substances. One of the most prominent researchers in this area was the American psychopharmacologist Roland Griffiths, PhD.

In 2016, Dr. Griffiths and his team at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, published one of the most relevant contributions to the field by demonstrating in a placebo-controlled study that psilocybin can reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with cancer. The study, conducted with 51 patients diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer, compared the effects of a low dose and a high dose of psilocybin, showing that the high dose resulted in improvements in mood, quality of life, and sense of life, reducing death-related anxiety.

In 2021, after a routine examination, Dr. Griffiths himself was diagnosed with advanced colon cancer. Unexpectedly, the researcher found himself in the position of his research subjects. In an interview with The New York Times in April 2023, he stated that, after some resistance, he agreed to undergo an LSD session.

In the conversation, he revealed that he had a 50% chance of being alive by Halloween. Despite the diagnosis, he showed no discouragement. “As a scientist, I feel like a kid in a candy store, considering all the research and questions that need to be answered about psychedelics and the theme of human flourishing,” he said.

In his last months of life, in the various appearances and interviews he gave, Dr. Griffiths demonstrated a perception of life uncommon in people facing death. “I’m excited to communicate, to shake off the dust and tell people: ‘Come on, wake up!’ ”

He passed away on October 16, 2023, at age 77 years, opening new horizons for clinical research with psychedelics and becoming an example of the therapeutic potential of these substances.

Innovative Treatments

“I believe this will be one of the next conditions, if not the next condition, to be considered for the designation of innovative treatment in future psilocybin regulation in the United States, where the field is more advanced,” said Lucas Maia, PhD, a psychopharmacologist and researcher affiliated with the Advanced Center for Psychedelic Medicine (CAMP) at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) and the Interdisciplinary Cooperation for Ayahuasca Research and Outreach (ICARO) at the State University of Campinas in São Paulo, Brazil.

Currently, MDMA (for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder), psilocybin (for depressive disorder), and MM120 (an LSD analogue used to treat generalized anxiety disorder) are the only psychedelic substances that have received the designation of innovative treatment by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In 2022, Dr. Maia and a colleague from ICARO, Ana Cláudia Mesquita Garcia, PhD, a professor at the School of Nursing at the Federal University of Alfenas in Brazil and leader of the Interdisciplinary Center for Studies in Palliative Care, published a systematic review in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management that evaluated the use of psychedelic-assisted treatments for symptom control in patients with serious or terminal illnesses.

Of the 20 articles reviewed, 9 (45%) used LSD, 5 (25%) psilocybin, 2 (10%) dipropyltryptamine (DPT), 1 (5%) used ketamine, and 1 (5%) used MDMA. In 10% of the studies, LSD and DPT were combined. Altogether, 347 participants (54%) received LSD, 116 (18%) psilocybin, 81 (13%) LSD and DPT, 64 (10%) DPT, 18 (3%) MDMA, and 14 (2%) ketamine.

The conclusion of the study is that psychedelics provide therapeutic effects on physical, psychological, social, and existential outcomes. They are associated with a reduction in pain and improvement in sleep. A decrease in depressive and anxiety symptoms is also observed; such symptoms are common in patients with serious diseases. In addition, interpersonal relationships become closer and more empathetic. Finally, there is a reduction in the fear of death and suffering, an increase in acceptance, and a redefinition of the disease.

In 55% of the studies, the adverse effects were mild to moderate and transient. They included nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, and fatigue, as well as anxiety, panic, and hallucinations. The researchers concluded that the scarcity and difficulty of access to professional training in psychedelic-assisted treatments represent a significant challenge for the advancement of these interventions, especially in countries in the Global South.

Another systematic review and meta-analysis published in July by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, included seven studies with 132 participants and showed significant improvements in quality of life, pain control, and anxiety relief after psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy with psilocybin. The combined effects indicated statistically significant reductions in anxiety symptoms after 4.0-4.5 months and after 6.0-6.5 months post administration, compared with the initial evaluations.

One of the most advanced research studies currently being conducted is led by Stephen Ross, MD, a psychiatrist affiliated with New York University’s Langone Medical Center, New York City. The phase 2b clinical study is randomized, double blind, and placebo controlled, and involves 300 participants. The study aims to evaluate the effects of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy on psychiatric and existential distress in patients with advanced cancer. Its expected completion date is in 2027.

“We still lack effective interventions in minimizing psychological, spiritual, and existential suffering,” said Dr. Garcia. “In this sense, respecting the contraindications of a physical nature (including pre-existing illnesses at study initiation, disease staging, patient functionality level, comorbidities, concurrent pharmacological treatments, etc) and of a psychiatric nature for the use of psychedelics, depending on the clinical picture, end-of-life patients facing existential crises and psychological suffering will likely benefit more from psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, which highlights the need for more research and the integration of this treatment into clinical practice.”

Changing Perceptions

Since 2021, the Cancer Institute of the State of São Paulo (Icesp) has been providing palliative treatment with ketamine — an atypical psychedelic — following a rigorous and carefully monitored clinical protocol. The substance is already used off label to treat refractory depressive disorder. In addition, in 2020, Brazil’s National Health Surveillance Agency approved the use of Spravato, an intranasal antidepressant based on the ketamine derivative esketamine.

Icesp has hospice beds for clinical oncology patients, and a pain management team evaluates which patients meet the inclusion criteria for ketamine use. In addition to difficult-to-control pain, it is important that the patient present emotional, existential, or spiritual symptoms that amplify that pain.

After this evaluation, a psychoeducation process takes place, in which the patient receives clear information about the treatment, its potential benefits and risks, and understands how ketamine can be a viable option for managing their symptoms. Finally, it is essential that the patient accept the referral and demonstrate a willingness to participate in the treatment, agreeing to the proposed terms.

The treatment takes place in a hospital environment, with an ambiance that aims to provide comfort and safety. Clinicians consider not only the substance dose (such as 0.5 mg/kg) but also the emotional state (“set”) and the treatment environment (“setting”). The experience is facilitated through psychological support for the patient during and after treatment.

According to Alessandro Campolina, MD, PhD, a researcher at the Center for Translational Oncology Research at Icesp, it is important to highlight that quality of life is intrinsically linked to the patient’s self-perception, including how they see themselves in terms of health and in the context in which they live.

The doctor explains that psychedelic interventions can provide a “window of opportunity,” allowing a qualified clinician to help the patient explore new perspectives based on their experiences.

“Often, although the intensity of pain remains the same, the way the patient perceives it can change significantly. For example, a patient may report that, despite the pain, they now feel less concerned about it because they were able to contemplate more significant aspects of their life,” said Dr. Campolina.

“This observation shows that treatment is not limited to addressing the pain or primary symptoms, but also addresses the associated suffering. While some patients have profound insights, many others experience more subtle changes that, under the guidance of a competent therapist, can turn into valuable clinical insights, thus improving quality of life and how they deal with their pathologies.”

Dr. Griffiths exemplified this in the interview with the Times when he reflected on his own cancer. He came to believe, as if guided an external observer, that “there is a meaning and a purpose in this [disease] that go beyond your understanding, and the way you are dealing with it is exactly how you should.”

Toshio Chiba, MD, chief physician of the Palliative Care Service at Icesp, emphasized that ketamine is already in use. “It is not feasible to wait years for the approval of psilocybin or for the FDA’s decision on MDMA, especially if the patient needs immediate care,” he said.

Furthermore, recreational and therapeutic uses are distinct. “It is essential to note that responsibilities are shared between the professional and the patient,” said Dr. Chiba. “In the therapeutic setting, there is an ethical and civil responsibility of the medical professional, as well as the patient actively engaging in treatment.”

Early palliative care can also facilitate the establishment of care goals. “I prefer to avoid terms like ‘coping’ or ‘fighting the disease,’” said Dr. Chiba. “Nowadays, dealing with cancer is more about coexisting with the disease properly, as treatments can last for years.

“Of course, there are still highly lethal tumors. However, for neoplasms like breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers, we often talk about 5, 10, or even 15 years of coexistence [with the condition]. The lack of this information [about the disease, treatments, and existential issues] can generate distress in some patients, who end up excessively worrying about the future,” he added.

But palliative treatment with psychedelics as a panacea, he said.

In addition, Marcelo Falchi, MD, medical director of CAMP at UFRN, also emphasized that psychedelics are not a risk-free intervention. Substances like LSD and psilocybin, for example, can cause increases in blood pressure and tachycardia, which, may limit their use for patients at high cardiovascular risk. Crises of anxiety or dissociative symptoms also may occur, and they require mitigation strategies such as psychological support and attention to set and setting.

“But research seems to agree that the risks can be managed effectively through a diligent process, allowing for the responsible exploration of the therapeutic potential of psychedelics,” said Dr. Falchi, who is responsible for CAMP’s postgraduate course in psychedelic therapies. The program provides training in substances used in Brazil, such as ketamine and ibogaine.