User login

Hair Disorders in the Skin of Color Population: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIDEO: Consider alopecia ‘camouflage kits’ to boost patients’ self-esteem

ORLANDO – The hair loss encounter – which can be challenging for both physicians and patients – should address the negative psychological effects of hair loss, including ways to camouflage hair loss, advised Adriana N. Schmidt, MD, a dermatologist in Santa Monica, Calif.

Dermatologists may spend so much time on the work-up – reviewing history regarding medication, lab values, and hair care practices – that they do not spend time to simply say to patients, “I want to help you feel better about yourself, and here’s how,” she said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“What we can do is offer them a way to camouflage the hair loss,” Dr. Schmidt said. She shared tips that include creating a kit to keep in the office filled with lists of reputable hairpiece vendors and tattoo specialists in the community, as well as sample wigs, cosmetic powders, and other items to show to patients during hair loss consultations. She also offers thoughts on working with new hair styles and stylists to help improve the self-esteem of alopecia patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Schmidt had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – The hair loss encounter – which can be challenging for both physicians and patients – should address the negative psychological effects of hair loss, including ways to camouflage hair loss, advised Adriana N. Schmidt, MD, a dermatologist in Santa Monica, Calif.

Dermatologists may spend so much time on the work-up – reviewing history regarding medication, lab values, and hair care practices – that they do not spend time to simply say to patients, “I want to help you feel better about yourself, and here’s how,” she said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“What we can do is offer them a way to camouflage the hair loss,” Dr. Schmidt said. She shared tips that include creating a kit to keep in the office filled with lists of reputable hairpiece vendors and tattoo specialists in the community, as well as sample wigs, cosmetic powders, and other items to show to patients during hair loss consultations. She also offers thoughts on working with new hair styles and stylists to help improve the self-esteem of alopecia patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Schmidt had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – The hair loss encounter – which can be challenging for both physicians and patients – should address the negative psychological effects of hair loss, including ways to camouflage hair loss, advised Adriana N. Schmidt, MD, a dermatologist in Santa Monica, Calif.

Dermatologists may spend so much time on the work-up – reviewing history regarding medication, lab values, and hair care practices – that they do not spend time to simply say to patients, “I want to help you feel better about yourself, and here’s how,” she said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“What we can do is offer them a way to camouflage the hair loss,” Dr. Schmidt said. She shared tips that include creating a kit to keep in the office filled with lists of reputable hairpiece vendors and tattoo specialists in the community, as well as sample wigs, cosmetic powders, and other items to show to patients during hair loss consultations. She also offers thoughts on working with new hair styles and stylists to help improve the self-esteem of alopecia patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Schmidt had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT AAD 2017

VIDEO: Working with alopecia patients’ insurers when using novel therapies

ORLANDO – Janus kinase inhibitors are “currently the most promising treatments” for alopecia areata, but they are expensive, are not approved for this indication, and so getting insurance coverage for these treatments can be difficult, Carolyn Goh, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Goh of the department of dermatology, University of California, Los Angeles, shares the latest treatment algorithms that include these novel therapies, and thoughts on how to work with patients to increase their likelihood of getting insurance coverage for these treatments. Referring to the Janus kinase inhibitors, also known as JAK inhibitors, she said, “I think they would be very helpful for all patients with alopecia areata, but really given their side effect profile and risks involved, they should be reserved for more extensive disease.”

In the interview, Dr. Goh also discusses screening for thyroid disease in this patient population.

She had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Janus kinase inhibitors are “currently the most promising treatments” for alopecia areata, but they are expensive, are not approved for this indication, and so getting insurance coverage for these treatments can be difficult, Carolyn Goh, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Goh of the department of dermatology, University of California, Los Angeles, shares the latest treatment algorithms that include these novel therapies, and thoughts on how to work with patients to increase their likelihood of getting insurance coverage for these treatments. Referring to the Janus kinase inhibitors, also known as JAK inhibitors, she said, “I think they would be very helpful for all patients with alopecia areata, but really given their side effect profile and risks involved, they should be reserved for more extensive disease.”

In the interview, Dr. Goh also discusses screening for thyroid disease in this patient population.

She had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Janus kinase inhibitors are “currently the most promising treatments” for alopecia areata, but they are expensive, are not approved for this indication, and so getting insurance coverage for these treatments can be difficult, Carolyn Goh, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Goh of the department of dermatology, University of California, Los Angeles, shares the latest treatment algorithms that include these novel therapies, and thoughts on how to work with patients to increase their likelihood of getting insurance coverage for these treatments. Referring to the Janus kinase inhibitors, also known as JAK inhibitors, she said, “I think they would be very helpful for all patients with alopecia areata, but really given their side effect profile and risks involved, they should be reserved for more extensive disease.”

In the interview, Dr. Goh also discusses screening for thyroid disease in this patient population.

She had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT AAD 17

VIDEO: Grading tools help set alopecia treatment expectations and monitor progress

ORLANDO – Two hair loss clinical grading tools can help physicians and their female androgenetic alopecia patients set medical treatment expectations, and make tracking progress both easier and more accurate, according to the dermatologist who developed the scales.

The five-point clinical grading scale helps physicians with diagnosing female pattern hair loss and grading the severity, Rodney Sinclair, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “And you can use that clinical grading scale to monitor the response to treatment” and show patients what to expect with treatment, added Dr. Sinclair, professor and chairman, department of dermatology, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne.

He also discussed a validated hair shedding scale, “a really simple and easy test to use,” with six photographs to help patients determine how much hair they are shedding on a daily basis. “Most women don’t know what’s a normal amount of hair to shed,” he said. In the interview, Dr. Sinclair explains more about the two scales, and how they can be used to obtain clinically relevant information to help guide treatment – and shares his tips for how to work with women who are anxious about their hair loss improvement.

Dr. Sinclair owns the copyrights for the Sinclair Severity Scale. He has no other relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Two hair loss clinical grading tools can help physicians and their female androgenetic alopecia patients set medical treatment expectations, and make tracking progress both easier and more accurate, according to the dermatologist who developed the scales.

The five-point clinical grading scale helps physicians with diagnosing female pattern hair loss and grading the severity, Rodney Sinclair, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “And you can use that clinical grading scale to monitor the response to treatment” and show patients what to expect with treatment, added Dr. Sinclair, professor and chairman, department of dermatology, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne.

He also discussed a validated hair shedding scale, “a really simple and easy test to use,” with six photographs to help patients determine how much hair they are shedding on a daily basis. “Most women don’t know what’s a normal amount of hair to shed,” he said. In the interview, Dr. Sinclair explains more about the two scales, and how they can be used to obtain clinically relevant information to help guide treatment – and shares his tips for how to work with women who are anxious about their hair loss improvement.

Dr. Sinclair owns the copyrights for the Sinclair Severity Scale. He has no other relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Two hair loss clinical grading tools can help physicians and their female androgenetic alopecia patients set medical treatment expectations, and make tracking progress both easier and more accurate, according to the dermatologist who developed the scales.

The five-point clinical grading scale helps physicians with diagnosing female pattern hair loss and grading the severity, Rodney Sinclair, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “And you can use that clinical grading scale to monitor the response to treatment” and show patients what to expect with treatment, added Dr. Sinclair, professor and chairman, department of dermatology, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne.

He also discussed a validated hair shedding scale, “a really simple and easy test to use,” with six photographs to help patients determine how much hair they are shedding on a daily basis. “Most women don’t know what’s a normal amount of hair to shed,” he said. In the interview, Dr. Sinclair explains more about the two scales, and how they can be used to obtain clinically relevant information to help guide treatment – and shares his tips for how to work with women who are anxious about their hair loss improvement.

Dr. Sinclair owns the copyrights for the Sinclair Severity Scale. He has no other relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT AAD 17

Lupus Erythematosus Tumidus of the Scalp Masquerading as Alopecia Areata

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a relatively rare condition but may simply be underdiagnosed in the literature. It presents as urticarialike papules and plaques in sun-exposed areas, characterized by induration and erythema. Lesions occur on the face, neck, upper extremities, and trunk and heal without scarring.1,2 Rarely, lesions can show fine scaling and associated pruritus, but most often the lesions are asymptomatic.3

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman presented with 2 asymptomatic self-described bald spots on the top of the head of 2 months’ duration. The patient denied prior treatment of the lesions and noted one patch was resolving. She reported no involvement of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and axillary and pubic hair. A review of systems was negative. The patient denied personal or family history of lupus, thyroid disease, or vitiligo.

Clinical examination revealed a 1.1-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia on the right vertex scalp and a 0.9-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia with moderate hair regrowth on the left vertex scalp. There was no erythema, scaling, or induration. The rest of the scalp was normal in appearance and the eyebrows and eyelashes were uninvolved. The patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata and was treated with 10 mg/mL of intralesional triamcinolone once monthly for 4 months.

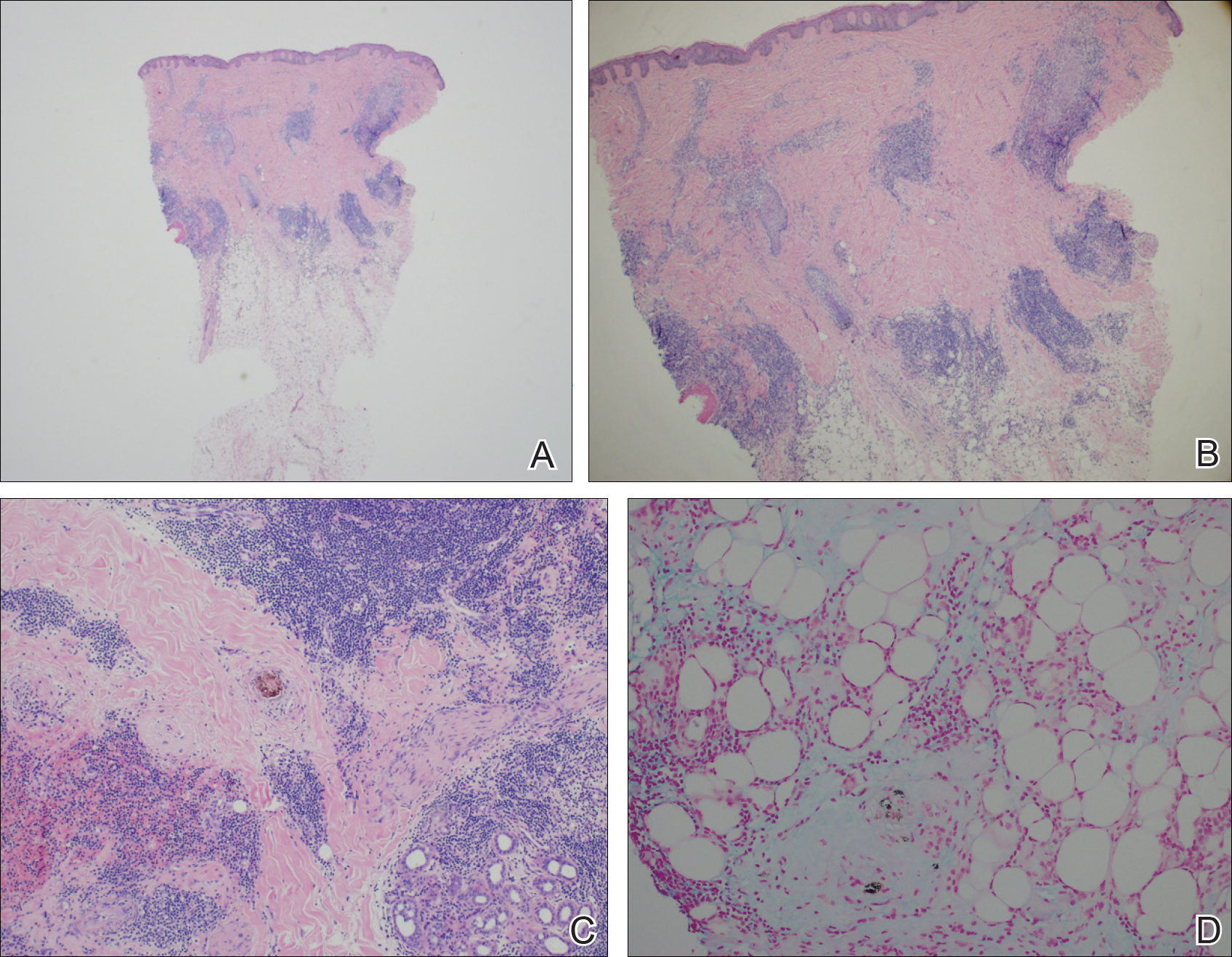

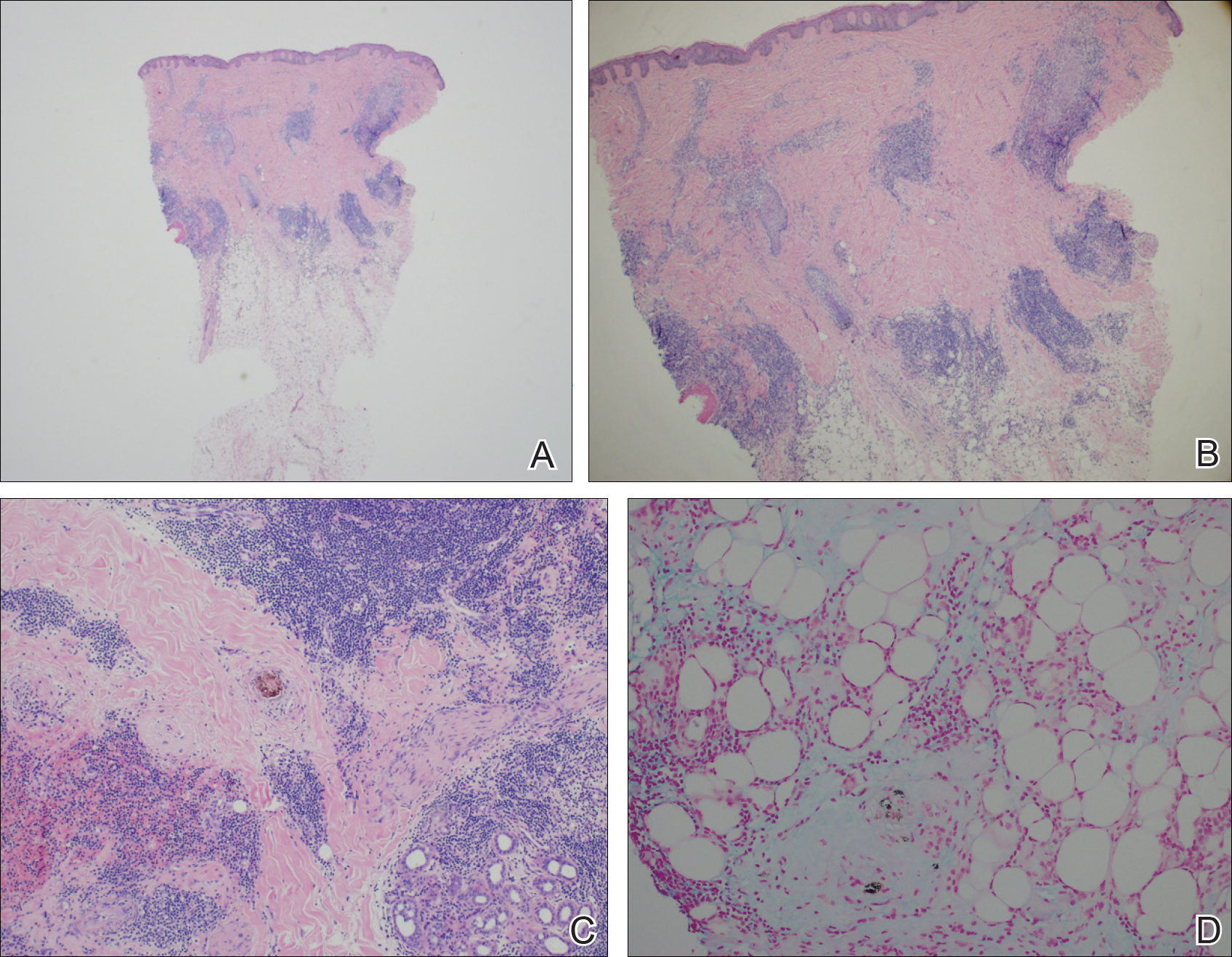

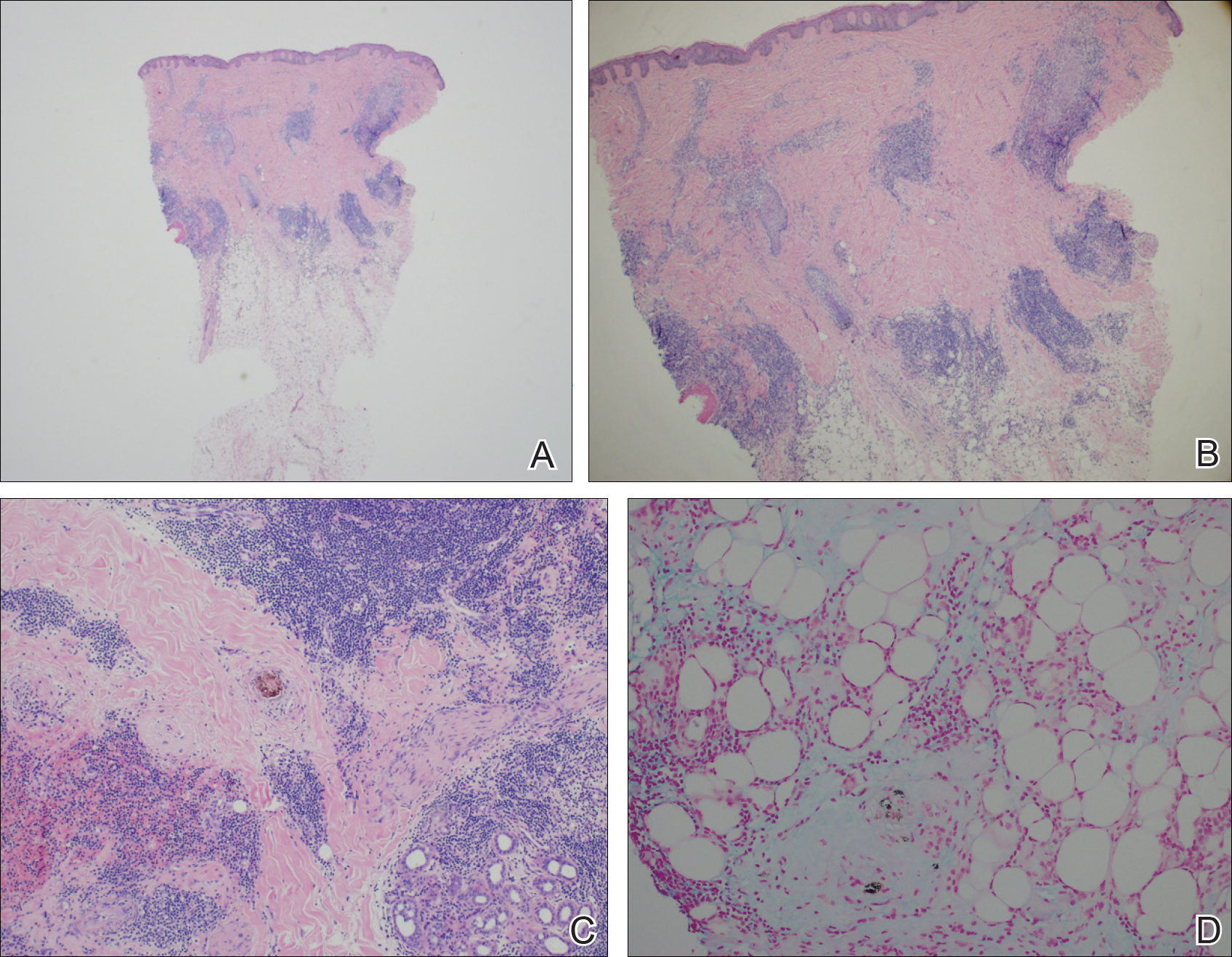

The patient initially showed improvement with moderate hair regrowth. After 4 months of treatment, she developed 3 new 1- to 1.5-cm erythematous alopecic patches on the vertex scalp and had worsening in the initial patches (Figure 1). Given the resistance to standard therapy and the onset of multiple new areas with evidence of inflammatory involvement, a punch biopsy was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a fairly unremarkable epidermis and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was present both in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The inflammatory cells, which appeared to be predominantly comprised of lymphocytes, had a predilection for the vasculature but also were observed within the interstitial dermis. Additionally, mucin appeared to be slightly increased in the deep dermis. The lymphocytic phenotype was confirmed by immunohistochemical studies for CD20 and CD3. The most likely possibilities for this reaction pattern were LET, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin (JLIS), gyrate erythema, and lymphoma; however, the immunohistochemical studies effectively ruled out lymphoma. Additionally, there was pronounced dermal mucin noted in the specimen. The patient was diagnosed with LET of the scalp based on the constellation of findings.

Comment

The classification of LET as a single unique entity or disease process sui generis has been in flux in the last decade. Its similarities to JLIS and other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) have brought debate.4-6 In 1930, Gougerot and Burnier7 documented the first case of LET in the literature, describing smooth, infiltrated, erythematous lesions with no desquamation or other superficial changes seen in 5 patients.

In 2000, interest in LET and other forms of CCLE was increasing, and reports in the literature paralleled. That year, Kuhn et al4 reported 40 cases of LET, characterizing the clinical and histological features of each case to demonstrate that LET should be separate from other forms of CCLE. Until then, it is likely that many lesions that should have been classified as LET were instead classified as various forms of CCLE. The investigators maintained that LET also should be distinct from JLIS because it is associated with UV exposure.4 Kuhn et al8 reviewed phototesting in 60 patients with LET in 2001 and confirmed this subset was the most photosensitive type of lupus erythematosus.

In general, the histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies in LET and JLIS can be quite similar. Relatively distinguishing histopathologic findings in JLIS include no evidence of epidermal atrophy, basal vacuolar change, or follicular plugging, as well as negative immunofluorescence studies. Both entities show a predominantly T-cell population with a smaller component of B cells and thus a distinction cannot be made based on relative proportions of T and B cells in lesions.2

In 2003, Alexiades-Armenakas et al6 determined immunohistochemical criteria for LET, finding a predominance of T cells and more CD4 lymphocytes than CD8 lymphocytes with a mean ratio of roughly 3 to 1. Their study results maintained LET should be classified as a form of CCLE due to the chronicity of the lesions, the serologic profile with negative anti–double-stranded DNA, anticentromere, anti-Smith, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and anti-nuclear ribonucleoprotein antibodies and the rare association with systemic disease.6 This conclusion was further solidified by a review published that same year citing unique histopathological features when compared to subacute cutaneous LE and discoid lupus erythematosus.5

This case illustrates the importance of histologic evaluation in determining the correct diagnosis in a patient with alopecia areata recalcitrant to treatment. Including LET in the differential of alopecic patches on the scalp could prove beneficial for patients, as LET responds well to antimalarial drugs and photoprotection.9 This patient had a normal antinuclear antibody panel and no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus. It was recommended that she avoid sun exposure and begin treatment with hydroxychloroquine but she declined. At a follow-up visit 6 months later she reported the lesions had improved, but a permanent wig had been sewn over the area, so it could not be examined.

- Lee L, Werth V. Rheumatologic disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008:615-629.

- Weedon D. The lichenoid reaction pattern. In: Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:35-70.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Ruzicka T, et al. Histopathologic findings in lupus erythematosus tumidus: review of 80 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:901-908.

- Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Baldassano M, Bince B, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: criteria for classification with immunohistochemical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:494-500.

- Gougerot H, Burnier R. Lupuse rythe mateux “tumidus.” Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1930;37:1291-1292.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus tumidus—review of 60 patients. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;73:532-536.

- Cozzani E, Christana K, Rongioletti F, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical, histopathological and serological aspects and therapy response of 21 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:797-801.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a relatively rare condition but may simply be underdiagnosed in the literature. It presents as urticarialike papules and plaques in sun-exposed areas, characterized by induration and erythema. Lesions occur on the face, neck, upper extremities, and trunk and heal without scarring.1,2 Rarely, lesions can show fine scaling and associated pruritus, but most often the lesions are asymptomatic.3

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman presented with 2 asymptomatic self-described bald spots on the top of the head of 2 months’ duration. The patient denied prior treatment of the lesions and noted one patch was resolving. She reported no involvement of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and axillary and pubic hair. A review of systems was negative. The patient denied personal or family history of lupus, thyroid disease, or vitiligo.

Clinical examination revealed a 1.1-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia on the right vertex scalp and a 0.9-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia with moderate hair regrowth on the left vertex scalp. There was no erythema, scaling, or induration. The rest of the scalp was normal in appearance and the eyebrows and eyelashes were uninvolved. The patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata and was treated with 10 mg/mL of intralesional triamcinolone once monthly for 4 months.

The patient initially showed improvement with moderate hair regrowth. After 4 months of treatment, she developed 3 new 1- to 1.5-cm erythematous alopecic patches on the vertex scalp and had worsening in the initial patches (Figure 1). Given the resistance to standard therapy and the onset of multiple new areas with evidence of inflammatory involvement, a punch biopsy was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a fairly unremarkable epidermis and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was present both in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The inflammatory cells, which appeared to be predominantly comprised of lymphocytes, had a predilection for the vasculature but also were observed within the interstitial dermis. Additionally, mucin appeared to be slightly increased in the deep dermis. The lymphocytic phenotype was confirmed by immunohistochemical studies for CD20 and CD3. The most likely possibilities for this reaction pattern were LET, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin (JLIS), gyrate erythema, and lymphoma; however, the immunohistochemical studies effectively ruled out lymphoma. Additionally, there was pronounced dermal mucin noted in the specimen. The patient was diagnosed with LET of the scalp based on the constellation of findings.

Comment

The classification of LET as a single unique entity or disease process sui generis has been in flux in the last decade. Its similarities to JLIS and other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) have brought debate.4-6 In 1930, Gougerot and Burnier7 documented the first case of LET in the literature, describing smooth, infiltrated, erythematous lesions with no desquamation or other superficial changes seen in 5 patients.

In 2000, interest in LET and other forms of CCLE was increasing, and reports in the literature paralleled. That year, Kuhn et al4 reported 40 cases of LET, characterizing the clinical and histological features of each case to demonstrate that LET should be separate from other forms of CCLE. Until then, it is likely that many lesions that should have been classified as LET were instead classified as various forms of CCLE. The investigators maintained that LET also should be distinct from JLIS because it is associated with UV exposure.4 Kuhn et al8 reviewed phototesting in 60 patients with LET in 2001 and confirmed this subset was the most photosensitive type of lupus erythematosus.

In general, the histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies in LET and JLIS can be quite similar. Relatively distinguishing histopathologic findings in JLIS include no evidence of epidermal atrophy, basal vacuolar change, or follicular plugging, as well as negative immunofluorescence studies. Both entities show a predominantly T-cell population with a smaller component of B cells and thus a distinction cannot be made based on relative proportions of T and B cells in lesions.2

In 2003, Alexiades-Armenakas et al6 determined immunohistochemical criteria for LET, finding a predominance of T cells and more CD4 lymphocytes than CD8 lymphocytes with a mean ratio of roughly 3 to 1. Their study results maintained LET should be classified as a form of CCLE due to the chronicity of the lesions, the serologic profile with negative anti–double-stranded DNA, anticentromere, anti-Smith, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and anti-nuclear ribonucleoprotein antibodies and the rare association with systemic disease.6 This conclusion was further solidified by a review published that same year citing unique histopathological features when compared to subacute cutaneous LE and discoid lupus erythematosus.5

This case illustrates the importance of histologic evaluation in determining the correct diagnosis in a patient with alopecia areata recalcitrant to treatment. Including LET in the differential of alopecic patches on the scalp could prove beneficial for patients, as LET responds well to antimalarial drugs and photoprotection.9 This patient had a normal antinuclear antibody panel and no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus. It was recommended that she avoid sun exposure and begin treatment with hydroxychloroquine but she declined. At a follow-up visit 6 months later she reported the lesions had improved, but a permanent wig had been sewn over the area, so it could not be examined.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a relatively rare condition but may simply be underdiagnosed in the literature. It presents as urticarialike papules and plaques in sun-exposed areas, characterized by induration and erythema. Lesions occur on the face, neck, upper extremities, and trunk and heal without scarring.1,2 Rarely, lesions can show fine scaling and associated pruritus, but most often the lesions are asymptomatic.3

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman presented with 2 asymptomatic self-described bald spots on the top of the head of 2 months’ duration. The patient denied prior treatment of the lesions and noted one patch was resolving. She reported no involvement of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and axillary and pubic hair. A review of systems was negative. The patient denied personal or family history of lupus, thyroid disease, or vitiligo.

Clinical examination revealed a 1.1-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia on the right vertex scalp and a 0.9-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia with moderate hair regrowth on the left vertex scalp. There was no erythema, scaling, or induration. The rest of the scalp was normal in appearance and the eyebrows and eyelashes were uninvolved. The patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata and was treated with 10 mg/mL of intralesional triamcinolone once monthly for 4 months.

The patient initially showed improvement with moderate hair regrowth. After 4 months of treatment, she developed 3 new 1- to 1.5-cm erythematous alopecic patches on the vertex scalp and had worsening in the initial patches (Figure 1). Given the resistance to standard therapy and the onset of multiple new areas with evidence of inflammatory involvement, a punch biopsy was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a fairly unremarkable epidermis and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was present both in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The inflammatory cells, which appeared to be predominantly comprised of lymphocytes, had a predilection for the vasculature but also were observed within the interstitial dermis. Additionally, mucin appeared to be slightly increased in the deep dermis. The lymphocytic phenotype was confirmed by immunohistochemical studies for CD20 and CD3. The most likely possibilities for this reaction pattern were LET, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin (JLIS), gyrate erythema, and lymphoma; however, the immunohistochemical studies effectively ruled out lymphoma. Additionally, there was pronounced dermal mucin noted in the specimen. The patient was diagnosed with LET of the scalp based on the constellation of findings.

Comment

The classification of LET as a single unique entity or disease process sui generis has been in flux in the last decade. Its similarities to JLIS and other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) have brought debate.4-6 In 1930, Gougerot and Burnier7 documented the first case of LET in the literature, describing smooth, infiltrated, erythematous lesions with no desquamation or other superficial changes seen in 5 patients.

In 2000, interest in LET and other forms of CCLE was increasing, and reports in the literature paralleled. That year, Kuhn et al4 reported 40 cases of LET, characterizing the clinical and histological features of each case to demonstrate that LET should be separate from other forms of CCLE. Until then, it is likely that many lesions that should have been classified as LET were instead classified as various forms of CCLE. The investigators maintained that LET also should be distinct from JLIS because it is associated with UV exposure.4 Kuhn et al8 reviewed phototesting in 60 patients with LET in 2001 and confirmed this subset was the most photosensitive type of lupus erythematosus.

In general, the histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies in LET and JLIS can be quite similar. Relatively distinguishing histopathologic findings in JLIS include no evidence of epidermal atrophy, basal vacuolar change, or follicular plugging, as well as negative immunofluorescence studies. Both entities show a predominantly T-cell population with a smaller component of B cells and thus a distinction cannot be made based on relative proportions of T and B cells in lesions.2

In 2003, Alexiades-Armenakas et al6 determined immunohistochemical criteria for LET, finding a predominance of T cells and more CD4 lymphocytes than CD8 lymphocytes with a mean ratio of roughly 3 to 1. Their study results maintained LET should be classified as a form of CCLE due to the chronicity of the lesions, the serologic profile with negative anti–double-stranded DNA, anticentromere, anti-Smith, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and anti-nuclear ribonucleoprotein antibodies and the rare association with systemic disease.6 This conclusion was further solidified by a review published that same year citing unique histopathological features when compared to subacute cutaneous LE and discoid lupus erythematosus.5

This case illustrates the importance of histologic evaluation in determining the correct diagnosis in a patient with alopecia areata recalcitrant to treatment. Including LET in the differential of alopecic patches on the scalp could prove beneficial for patients, as LET responds well to antimalarial drugs and photoprotection.9 This patient had a normal antinuclear antibody panel and no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus. It was recommended that she avoid sun exposure and begin treatment with hydroxychloroquine but she declined. At a follow-up visit 6 months later she reported the lesions had improved, but a permanent wig had been sewn over the area, so it could not be examined.

- Lee L, Werth V. Rheumatologic disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008:615-629.

- Weedon D. The lichenoid reaction pattern. In: Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:35-70.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Ruzicka T, et al. Histopathologic findings in lupus erythematosus tumidus: review of 80 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:901-908.

- Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Baldassano M, Bince B, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: criteria for classification with immunohistochemical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:494-500.

- Gougerot H, Burnier R. Lupuse rythe mateux “tumidus.” Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1930;37:1291-1292.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus tumidus—review of 60 patients. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;73:532-536.

- Cozzani E, Christana K, Rongioletti F, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical, histopathological and serological aspects and therapy response of 21 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:797-801.

- Lee L, Werth V. Rheumatologic disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008:615-629.

- Weedon D. The lichenoid reaction pattern. In: Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:35-70.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Ruzicka T, et al. Histopathologic findings in lupus erythematosus tumidus: review of 80 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:901-908.

- Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Baldassano M, Bince B, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: criteria for classification with immunohistochemical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:494-500.

- Gougerot H, Burnier R. Lupuse rythe mateux “tumidus.” Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1930;37:1291-1292.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus tumidus—review of 60 patients. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;73:532-536.

- Cozzani E, Christana K, Rongioletti F, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical, histopathological and serological aspects and therapy response of 21 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:797-801.

Practice Points

- Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) of the scalp can mimic alopecia areata on clinical presentation.

- A unique variant of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, LET presents in sun-exposed areas without any corresponding systemic signs.

- Lupus erythematosus tumidus may respond well to antimalarial drugs.

Pediatric Nail Diseases: Clinical Pearls

Our dermatology department recently sponsored a pediatric dermatology lecture series for the pediatric residency program. Within this series, Antonella Tosti, MD, a professor at the University of Miami Health System, Florida, and a renowned expert in nail disorders and allergic contact dermatitis, presented her clinical expertise on the presentation and management of common pediatric nail diseases. This article highlights pearls from her unique and enlightening lecture.

Pearl: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is a recognized trigger for onychomadesis

An arrest in nail matrix activity is responsible for onychomadesis, or shedding of the nail. Its presentation in children can be further divided based upon the degree of involvement. If a few nails are affected, trauma should be implicated. In contrast, if all nails are involved, a systemic etiology should be suspected. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a trigger for onychomadesis in school-aged children. Onychomadesis presents with characteristic proximal nail detachment (Figure 1). The association of HFMD with onychomadesis and Beau lines was first reported in 2000. Five patients who resided within close proximity and shared a physician-diagnosed case of HFMD presented with representative nail findings 4 weeks after illness.1 Hypotheses for these changes include viral-induced nail pathology, inflammation from cutaneous lesions of HFMD, and systemic effects from the disease.2 Given the prevalence of HFMD and benign outcome, clinicians should be cognizant of this unique cutaneous manifestation.

Pearl: Management of pediatric melanonychia can take a wait-and-see approach

Melanonychia is the presence of a longitudinal brown-black band extending from the proximal nail fold. The cause of melanonychia can be due to either activation or hyperplasia. Activation is the less common etiology in children; however, if present, activation can be due to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome or trauma such as onychotillomania. Melanonychia in children usually is the result of hyperplasia of melanocytes and can manifest as a lentigo, nevus, or more rarely melanoma. Nail matrix nevi are typically exhibited on the fingernails, particularly the thumb, and frequently are junctional nevi (Figure 2). Spontaneous fading of nevi is expected with time due to decreased melanin production. Therapeutic options for melanonychia include regular clinical monitoring, biopsy, or excision. Dr. Tosti explained that one must be wary when pursuing a biopsy, as it can result in a false-negative finding due to missed pathology. If clinically indicated, a shave biopsy of the nail matrix can be performed to best analyze the lesion. She noted that if more than 3 mm of the matrix is removed, a resultant scar will ensue. Conservative management is recommended given the indolent clinical behavior of the majority of cases of melanonychia in children.3

Pearl: Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds can be treated with tape

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds is relatively common in children and normally improves with age. Koilonychia may also occur simultaneously and can be viewed as a physiologic process in this age group. The etiology of the underlying disorder is due to anomalous periungual soft-tissue changes of the bilateral halluces; the resulting overgrowth can partially cover the nail plate. Although usually a self-limiting condition, the changes can cause inflammation and discomfort due to an ingrown nail.4 Dr. Tosti advised that by simply taping and retracting the bilateral overgrowth, the condition can be more readily resolved. This simple treatment can be demonstrated in the office and subsequently performed at home.

Pearl: Onychomycosis is uncommon in children

Onychomycosis occurs in less than 1% of children.5 Several factors are responsible for this decreased prevalence. More rapid nail growth and smaller nail surface area decreases the ability of the fungi to penetrate the nail plate.6 Furthermore, children have a diminished rate of tinea pedis, leading to less neighboring infection. When onychomycosis does affect this patient population, it commonly presents as distal subungual onychomycosis and favors the fingernails over the toenails. Treatment options usually parallel those of the adult population; however, all medications for children are considered off-label use by the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Tosti explained that oral granules of terbinafine can be sprinkled on food to help with pediatric ingestion. Topical therapies should also be considered; children usually respond better than their adult counterparts due to their thinner nails, which grant enhanced drug delivery and penetration.6

Pearl: Acute paronychia can be due to nail-biting and sucking

Acute paronychia is inflammation of the proximal nail fold. In children, it frequently is a result of mixed flora induced by nail-biting and sucking. Management involves culturing the affected lesions and is effectively treated with warm soaks alone. Dr. Tosti highlighted that Candida in the subungual space is a common colonizer and is typically self-limiting in nature if isolated. Candida can be cultured more readily in premature infants, immunosuppressed patients, and those with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis can exhibit periungual inflammation involving several digits. The differential can include nail psoriasis, as both can demonstrate dystrophic changes. The differential for localized paronychia includes herpetic whitlow and can manifest as vesicles under the proximal nail fold.

Final Thoughts

These clinical pearls are shared to help deliver utmost care to our pediatric patients presenting with nail pathology. For example, a child exhibiting melanonychia can cause alarm due to the possibility of underlying melanoma; given the rarity of neoplasia in these patients, a conservative approach is favored to help avoid unnecessary biopsies and subsequent scarring. Similarly, it is important to be aware of the common colonizers of the subungual area, particularly Candida, to avoid unessential medications with potential side effects. The examples demonstrated help shed light on the management of pediatric nail diseases.

Acknowledgment

This article is possible thanks to the help of Antonella Tosti, MD (Miami, Florida), who contributed her time and expertise at the University of Miami Pediatric Grand Rounds to expand the foundation and knowledge of pediatric nail diseases.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Yuksel S, Evrengul H, Ozhan B, et al. Onychomadesis-a late complication of hand-foot-mouth disease [published online May 2, 2016]. J Pediatr. 2016;174:274.

- Cooper C, Arva NC, Lee C, et al. A clinical, histopathologic, and outcome study of melanonychia striata in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:773-779.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Totri CR, Feldstein S, Admani S, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of onychomycosis in the San Diego pediatric population [published online October 4, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:46-49.

- Feldstein S, Totri C, Friedlander SF. Antifungal therapy for onychomycosis in children. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:333-339.

Our dermatology department recently sponsored a pediatric dermatology lecture series for the pediatric residency program. Within this series, Antonella Tosti, MD, a professor at the University of Miami Health System, Florida, and a renowned expert in nail disorders and allergic contact dermatitis, presented her clinical expertise on the presentation and management of common pediatric nail diseases. This article highlights pearls from her unique and enlightening lecture.

Pearl: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is a recognized trigger for onychomadesis

An arrest in nail matrix activity is responsible for onychomadesis, or shedding of the nail. Its presentation in children can be further divided based upon the degree of involvement. If a few nails are affected, trauma should be implicated. In contrast, if all nails are involved, a systemic etiology should be suspected. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a trigger for onychomadesis in school-aged children. Onychomadesis presents with characteristic proximal nail detachment (Figure 1). The association of HFMD with onychomadesis and Beau lines was first reported in 2000. Five patients who resided within close proximity and shared a physician-diagnosed case of HFMD presented with representative nail findings 4 weeks after illness.1 Hypotheses for these changes include viral-induced nail pathology, inflammation from cutaneous lesions of HFMD, and systemic effects from the disease.2 Given the prevalence of HFMD and benign outcome, clinicians should be cognizant of this unique cutaneous manifestation.

Pearl: Management of pediatric melanonychia can take a wait-and-see approach

Melanonychia is the presence of a longitudinal brown-black band extending from the proximal nail fold. The cause of melanonychia can be due to either activation or hyperplasia. Activation is the less common etiology in children; however, if present, activation can be due to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome or trauma such as onychotillomania. Melanonychia in children usually is the result of hyperplasia of melanocytes and can manifest as a lentigo, nevus, or more rarely melanoma. Nail matrix nevi are typically exhibited on the fingernails, particularly the thumb, and frequently are junctional nevi (Figure 2). Spontaneous fading of nevi is expected with time due to decreased melanin production. Therapeutic options for melanonychia include regular clinical monitoring, biopsy, or excision. Dr. Tosti explained that one must be wary when pursuing a biopsy, as it can result in a false-negative finding due to missed pathology. If clinically indicated, a shave biopsy of the nail matrix can be performed to best analyze the lesion. She noted that if more than 3 mm of the matrix is removed, a resultant scar will ensue. Conservative management is recommended given the indolent clinical behavior of the majority of cases of melanonychia in children.3

Pearl: Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds can be treated with tape

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds is relatively common in children and normally improves with age. Koilonychia may also occur simultaneously and can be viewed as a physiologic process in this age group. The etiology of the underlying disorder is due to anomalous periungual soft-tissue changes of the bilateral halluces; the resulting overgrowth can partially cover the nail plate. Although usually a self-limiting condition, the changes can cause inflammation and discomfort due to an ingrown nail.4 Dr. Tosti advised that by simply taping and retracting the bilateral overgrowth, the condition can be more readily resolved. This simple treatment can be demonstrated in the office and subsequently performed at home.

Pearl: Onychomycosis is uncommon in children

Onychomycosis occurs in less than 1% of children.5 Several factors are responsible for this decreased prevalence. More rapid nail growth and smaller nail surface area decreases the ability of the fungi to penetrate the nail plate.6 Furthermore, children have a diminished rate of tinea pedis, leading to less neighboring infection. When onychomycosis does affect this patient population, it commonly presents as distal subungual onychomycosis and favors the fingernails over the toenails. Treatment options usually parallel those of the adult population; however, all medications for children are considered off-label use by the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Tosti explained that oral granules of terbinafine can be sprinkled on food to help with pediatric ingestion. Topical therapies should also be considered; children usually respond better than their adult counterparts due to their thinner nails, which grant enhanced drug delivery and penetration.6

Pearl: Acute paronychia can be due to nail-biting and sucking

Acute paronychia is inflammation of the proximal nail fold. In children, it frequently is a result of mixed flora induced by nail-biting and sucking. Management involves culturing the affected lesions and is effectively treated with warm soaks alone. Dr. Tosti highlighted that Candida in the subungual space is a common colonizer and is typically self-limiting in nature if isolated. Candida can be cultured more readily in premature infants, immunosuppressed patients, and those with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis can exhibit periungual inflammation involving several digits. The differential can include nail psoriasis, as both can demonstrate dystrophic changes. The differential for localized paronychia includes herpetic whitlow and can manifest as vesicles under the proximal nail fold.

Final Thoughts

These clinical pearls are shared to help deliver utmost care to our pediatric patients presenting with nail pathology. For example, a child exhibiting melanonychia can cause alarm due to the possibility of underlying melanoma; given the rarity of neoplasia in these patients, a conservative approach is favored to help avoid unnecessary biopsies and subsequent scarring. Similarly, it is important to be aware of the common colonizers of the subungual area, particularly Candida, to avoid unessential medications with potential side effects. The examples demonstrated help shed light on the management of pediatric nail diseases.

Acknowledgment

This article is possible thanks to the help of Antonella Tosti, MD (Miami, Florida), who contributed her time and expertise at the University of Miami Pediatric Grand Rounds to expand the foundation and knowledge of pediatric nail diseases.

Our dermatology department recently sponsored a pediatric dermatology lecture series for the pediatric residency program. Within this series, Antonella Tosti, MD, a professor at the University of Miami Health System, Florida, and a renowned expert in nail disorders and allergic contact dermatitis, presented her clinical expertise on the presentation and management of common pediatric nail diseases. This article highlights pearls from her unique and enlightening lecture.

Pearl: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is a recognized trigger for onychomadesis

An arrest in nail matrix activity is responsible for onychomadesis, or shedding of the nail. Its presentation in children can be further divided based upon the degree of involvement. If a few nails are affected, trauma should be implicated. In contrast, if all nails are involved, a systemic etiology should be suspected. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a trigger for onychomadesis in school-aged children. Onychomadesis presents with characteristic proximal nail detachment (Figure 1). The association of HFMD with onychomadesis and Beau lines was first reported in 2000. Five patients who resided within close proximity and shared a physician-diagnosed case of HFMD presented with representative nail findings 4 weeks after illness.1 Hypotheses for these changes include viral-induced nail pathology, inflammation from cutaneous lesions of HFMD, and systemic effects from the disease.2 Given the prevalence of HFMD and benign outcome, clinicians should be cognizant of this unique cutaneous manifestation.

Pearl: Management of pediatric melanonychia can take a wait-and-see approach

Melanonychia is the presence of a longitudinal brown-black band extending from the proximal nail fold. The cause of melanonychia can be due to either activation or hyperplasia. Activation is the less common etiology in children; however, if present, activation can be due to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome or trauma such as onychotillomania. Melanonychia in children usually is the result of hyperplasia of melanocytes and can manifest as a lentigo, nevus, or more rarely melanoma. Nail matrix nevi are typically exhibited on the fingernails, particularly the thumb, and frequently are junctional nevi (Figure 2). Spontaneous fading of nevi is expected with time due to decreased melanin production. Therapeutic options for melanonychia include regular clinical monitoring, biopsy, or excision. Dr. Tosti explained that one must be wary when pursuing a biopsy, as it can result in a false-negative finding due to missed pathology. If clinically indicated, a shave biopsy of the nail matrix can be performed to best analyze the lesion. She noted that if more than 3 mm of the matrix is removed, a resultant scar will ensue. Conservative management is recommended given the indolent clinical behavior of the majority of cases of melanonychia in children.3

Pearl: Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds can be treated with tape

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds is relatively common in children and normally improves with age. Koilonychia may also occur simultaneously and can be viewed as a physiologic process in this age group. The etiology of the underlying disorder is due to anomalous periungual soft-tissue changes of the bilateral halluces; the resulting overgrowth can partially cover the nail plate. Although usually a self-limiting condition, the changes can cause inflammation and discomfort due to an ingrown nail.4 Dr. Tosti advised that by simply taping and retracting the bilateral overgrowth, the condition can be more readily resolved. This simple treatment can be demonstrated in the office and subsequently performed at home.

Pearl: Onychomycosis is uncommon in children

Onychomycosis occurs in less than 1% of children.5 Several factors are responsible for this decreased prevalence. More rapid nail growth and smaller nail surface area decreases the ability of the fungi to penetrate the nail plate.6 Furthermore, children have a diminished rate of tinea pedis, leading to less neighboring infection. When onychomycosis does affect this patient population, it commonly presents as distal subungual onychomycosis and favors the fingernails over the toenails. Treatment options usually parallel those of the adult population; however, all medications for children are considered off-label use by the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Tosti explained that oral granules of terbinafine can be sprinkled on food to help with pediatric ingestion. Topical therapies should also be considered; children usually respond better than their adult counterparts due to their thinner nails, which grant enhanced drug delivery and penetration.6

Pearl: Acute paronychia can be due to nail-biting and sucking

Acute paronychia is inflammation of the proximal nail fold. In children, it frequently is a result of mixed flora induced by nail-biting and sucking. Management involves culturing the affected lesions and is effectively treated with warm soaks alone. Dr. Tosti highlighted that Candida in the subungual space is a common colonizer and is typically self-limiting in nature if isolated. Candida can be cultured more readily in premature infants, immunosuppressed patients, and those with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis can exhibit periungual inflammation involving several digits. The differential can include nail psoriasis, as both can demonstrate dystrophic changes. The differential for localized paronychia includes herpetic whitlow and can manifest as vesicles under the proximal nail fold.

Final Thoughts

These clinical pearls are shared to help deliver utmost care to our pediatric patients presenting with nail pathology. For example, a child exhibiting melanonychia can cause alarm due to the possibility of underlying melanoma; given the rarity of neoplasia in these patients, a conservative approach is favored to help avoid unnecessary biopsies and subsequent scarring. Similarly, it is important to be aware of the common colonizers of the subungual area, particularly Candida, to avoid unessential medications with potential side effects. The examples demonstrated help shed light on the management of pediatric nail diseases.

Acknowledgment

This article is possible thanks to the help of Antonella Tosti, MD (Miami, Florida), who contributed her time and expertise at the University of Miami Pediatric Grand Rounds to expand the foundation and knowledge of pediatric nail diseases.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Yuksel S, Evrengul H, Ozhan B, et al. Onychomadesis-a late complication of hand-foot-mouth disease [published online May 2, 2016]. J Pediatr. 2016;174:274.

- Cooper C, Arva NC, Lee C, et al. A clinical, histopathologic, and outcome study of melanonychia striata in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:773-779.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Totri CR, Feldstein S, Admani S, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of onychomycosis in the San Diego pediatric population [published online October 4, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:46-49.

- Feldstein S, Totri C, Friedlander SF. Antifungal therapy for onychomycosis in children. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:333-339.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Yuksel S, Evrengul H, Ozhan B, et al. Onychomadesis-a late complication of hand-foot-mouth disease [published online May 2, 2016]. J Pediatr. 2016;174:274.

- Cooper C, Arva NC, Lee C, et al. A clinical, histopathologic, and outcome study of melanonychia striata in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:773-779.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Totri CR, Feldstein S, Admani S, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of onychomycosis in the San Diego pediatric population [published online October 4, 2016]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:46-49.

- Feldstein S, Totri C, Friedlander SF. Antifungal therapy for onychomycosis in children. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:333-339.

Essential tips to diagnose and intervene early in hair loss

MIAMI – and watch for a new trend – man bun traction alopecia.

These and other clinical pearls on hair loss come courtesy of Wendy E. Roberts, MD.

“Hair loss can be scary,” but if physicians diagnose the underlying cause and treat early, a number of existing and upcoming treatments can be effective, said Dr. Roberts, a dermatologist in private practice in Rancho Mirage, Calif. “Timing is very critical.”

A dermatology full body examination is a perfect opportunity to ask patients about their hair because “you’re checking them from head to toe,” Dr. Roberts said. She recommends asking: “How is your hair doing?” This advice prompted a bit of uproar from the ODAC audience, suggesting this may be too sensitive a subject for some to broach with patients. Dr. Roberts responded, “No, not at all. Your patients will be glad you asked.

“That simple question will open up doors of opportunity” for dermatologists, she said. The condition remains very common: About 80 million people in the United States are affected by its No. 1 cause, hereditary hair loss. An Internet search for “hair loss,” in fact, reveals an overwhelming amount of consumer interest in hair loss treatment and management, yielding approximately 35 million results.

Paying attention to hair loss is not just question of appearance or aesthetics; hair loss can also indicate declining health, Dr. Roberts said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Suggest supplements backed by science

Given the millions of online searches, it’s apparent that people continue to look for the latest solutions to treat or prevent further hair loss. But as with many “treatments” and “cures” touted online, caution is warranted – not every claim is backed by solid research, she said. “Go with supplements that do have peer review literature.”

For this reason, Dr. Roberts suggests considering the following three supplements for patients with hair loss:

• Nutrafol – “What I like about this supplement is it has ashwagandha, an Indian herb that reduces stress,” she said.

• Viviscal – This supplement has the marine extract AminoMar, which includes shark cartilage and oyster extract powder.

• Vitalize Hair – Its active ingredient, Redensyl, contains two molecules, Dr. Roberts said, one to boost metabolism of the hair follicle and the other to increase hair volume over time.

Application of platelet rich plasma is another option showing promise for hair loss. It works by activating hair bulb cells. “It kind of whispers to the hair: ‘Be young again.’ Many times it comes in at the original hair color – tell your patients to be prepared to see their hair color from childhood.” Dr. Roberts said.

Man bun alert

There is a new consideration in male hair loss based on changing hairstyles. “One thing that is trending: man bun traction alopecia. We see a lot of this in Southern California where I practice,” Dr. Roberts said. She showed meeting attendees the photo of a man with a tight hair bun whose hairline was starting to recede.

Basics to remember: differential diagnosis

When a patient presents with hair loss, things to consider in a differential diagnosis include chemical hair treatments, hairstyles that can cause traction alopecia, and behaviors such as compulsive hair pulling. Trichotillomania is on the increase. It affects approximately 2% of the population, but 90% of those are women, Dr. Roberts said. To diagnose, “look at the scalp and lower area near the nape of neck, especially in younger patients.”

She suggested that dermatologists show male patients the Norwood Scale illustrations of hair loss. The illustrations can help them understand when their hair loss is progressing over time, she added. For female patients with hair loss, the Ludwig Scale for hair loss in women can be very illustrative.

In the work-up of the patient, conduct a physical exam and consider overall health and nutritional status. Ask about family history as well, because relatives are the best window for insight into hair loss caused by genetics and aging, Dr. Roberts said.

Review patient medications. Older patients, in particular, often take multiple medications, which increases the likelihood for interactions or side effects leading to hair loss.

In addition, she had a few specific recommendations. “When you have male patient with hair loss taking Propecia [finasteride], talk to them about the dangers of exposure to a female partner and pregnancy in particular.” Also ask patients to bring in any supplements they are taking. Watch out for keratin supplements in patients with renal disease, she added, because elevated levels can be associated with kidney problems.

In terms of laboratory testing, consider checking for thyroid function, hormonal imbalance, and anemia. “The most overlooked is hemoglobin levels,” Dr. Roberts said, although anemia can cause hair loss in some patients.

Dr. Roberts is a speaker, consultant, investigator for and/or receives honoraria from Allergan, Colorescience, Galderma, Lytera, MDRejuvena, Restorsea, SkinMedica, Theraplex, Top MD Skincare, Valeant Pharmaceutical International, and Viviscal.

MIAMI – and watch for a new trend – man bun traction alopecia.

These and other clinical pearls on hair loss come courtesy of Wendy E. Roberts, MD.

“Hair loss can be scary,” but if physicians diagnose the underlying cause and treat early, a number of existing and upcoming treatments can be effective, said Dr. Roberts, a dermatologist in private practice in Rancho Mirage, Calif. “Timing is very critical.”

A dermatology full body examination is a perfect opportunity to ask patients about their hair because “you’re checking them from head to toe,” Dr. Roberts said. She recommends asking: “How is your hair doing?” This advice prompted a bit of uproar from the ODAC audience, suggesting this may be too sensitive a subject for some to broach with patients. Dr. Roberts responded, “No, not at all. Your patients will be glad you asked.

“That simple question will open up doors of opportunity” for dermatologists, she said. The condition remains very common: About 80 million people in the United States are affected by its No. 1 cause, hereditary hair loss. An Internet search for “hair loss,” in fact, reveals an overwhelming amount of consumer interest in hair loss treatment and management, yielding approximately 35 million results.

Paying attention to hair loss is not just question of appearance or aesthetics; hair loss can also indicate declining health, Dr. Roberts said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Suggest supplements backed by science

Given the millions of online searches, it’s apparent that people continue to look for the latest solutions to treat or prevent further hair loss. But as with many “treatments” and “cures” touted online, caution is warranted – not every claim is backed by solid research, she said. “Go with supplements that do have peer review literature.”

For this reason, Dr. Roberts suggests considering the following three supplements for patients with hair loss:

• Nutrafol – “What I like about this supplement is it has ashwagandha, an Indian herb that reduces stress,” she said.

• Viviscal – This supplement has the marine extract AminoMar, which includes shark cartilage and oyster extract powder.

• Vitalize Hair – Its active ingredient, Redensyl, contains two molecules, Dr. Roberts said, one to boost metabolism of the hair follicle and the other to increase hair volume over time.

Application of platelet rich plasma is another option showing promise for hair loss. It works by activating hair bulb cells. “It kind of whispers to the hair: ‘Be young again.’ Many times it comes in at the original hair color – tell your patients to be prepared to see their hair color from childhood.” Dr. Roberts said.

Man bun alert

There is a new consideration in male hair loss based on changing hairstyles. “One thing that is trending: man bun traction alopecia. We see a lot of this in Southern California where I practice,” Dr. Roberts said. She showed meeting attendees the photo of a man with a tight hair bun whose hairline was starting to recede.

Basics to remember: differential diagnosis

When a patient presents with hair loss, things to consider in a differential diagnosis include chemical hair treatments, hairstyles that can cause traction alopecia, and behaviors such as compulsive hair pulling. Trichotillomania is on the increase. It affects approximately 2% of the population, but 90% of those are women, Dr. Roberts said. To diagnose, “look at the scalp and lower area near the nape of neck, especially in younger patients.”

She suggested that dermatologists show male patients the Norwood Scale illustrations of hair loss. The illustrations can help them understand when their hair loss is progressing over time, she added. For female patients with hair loss, the Ludwig Scale for hair loss in women can be very illustrative.

In the work-up of the patient, conduct a physical exam and consider overall health and nutritional status. Ask about family history as well, because relatives are the best window for insight into hair loss caused by genetics and aging, Dr. Roberts said.

Review patient medications. Older patients, in particular, often take multiple medications, which increases the likelihood for interactions or side effects leading to hair loss.

In addition, she had a few specific recommendations. “When you have male patient with hair loss taking Propecia [finasteride], talk to them about the dangers of exposure to a female partner and pregnancy in particular.” Also ask patients to bring in any supplements they are taking. Watch out for keratin supplements in patients with renal disease, she added, because elevated levels can be associated with kidney problems.

In terms of laboratory testing, consider checking for thyroid function, hormonal imbalance, and anemia. “The most overlooked is hemoglobin levels,” Dr. Roberts said, although anemia can cause hair loss in some patients.

Dr. Roberts is a speaker, consultant, investigator for and/or receives honoraria from Allergan, Colorescience, Galderma, Lytera, MDRejuvena, Restorsea, SkinMedica, Theraplex, Top MD Skincare, Valeant Pharmaceutical International, and Viviscal.

MIAMI – and watch for a new trend – man bun traction alopecia.

These and other clinical pearls on hair loss come courtesy of Wendy E. Roberts, MD.

“Hair loss can be scary,” but if physicians diagnose the underlying cause and treat early, a number of existing and upcoming treatments can be effective, said Dr. Roberts, a dermatologist in private practice in Rancho Mirage, Calif. “Timing is very critical.”

A dermatology full body examination is a perfect opportunity to ask patients about their hair because “you’re checking them from head to toe,” Dr. Roberts said. She recommends asking: “How is your hair doing?” This advice prompted a bit of uproar from the ODAC audience, suggesting this may be too sensitive a subject for some to broach with patients. Dr. Roberts responded, “No, not at all. Your patients will be glad you asked.

“That simple question will open up doors of opportunity” for dermatologists, she said. The condition remains very common: About 80 million people in the United States are affected by its No. 1 cause, hereditary hair loss. An Internet search for “hair loss,” in fact, reveals an overwhelming amount of consumer interest in hair loss treatment and management, yielding approximately 35 million results.

Paying attention to hair loss is not just question of appearance or aesthetics; hair loss can also indicate declining health, Dr. Roberts said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Suggest supplements backed by science

Given the millions of online searches, it’s apparent that people continue to look for the latest solutions to treat or prevent further hair loss. But as with many “treatments” and “cures” touted online, caution is warranted – not every claim is backed by solid research, she said. “Go with supplements that do have peer review literature.”

For this reason, Dr. Roberts suggests considering the following three supplements for patients with hair loss:

• Nutrafol – “What I like about this supplement is it has ashwagandha, an Indian herb that reduces stress,” she said.

• Viviscal – This supplement has the marine extract AminoMar, which includes shark cartilage and oyster extract powder.

• Vitalize Hair – Its active ingredient, Redensyl, contains two molecules, Dr. Roberts said, one to boost metabolism of the hair follicle and the other to increase hair volume over time.

Application of platelet rich plasma is another option showing promise for hair loss. It works by activating hair bulb cells. “It kind of whispers to the hair: ‘Be young again.’ Many times it comes in at the original hair color – tell your patients to be prepared to see their hair color from childhood.” Dr. Roberts said.

Man bun alert

There is a new consideration in male hair loss based on changing hairstyles. “One thing that is trending: man bun traction alopecia. We see a lot of this in Southern California where I practice,” Dr. Roberts said. She showed meeting attendees the photo of a man with a tight hair bun whose hairline was starting to recede.

Basics to remember: differential diagnosis

When a patient presents with hair loss, things to consider in a differential diagnosis include chemical hair treatments, hairstyles that can cause traction alopecia, and behaviors such as compulsive hair pulling. Trichotillomania is on the increase. It affects approximately 2% of the population, but 90% of those are women, Dr. Roberts said. To diagnose, “look at the scalp and lower area near the nape of neck, especially in younger patients.”

She suggested that dermatologists show male patients the Norwood Scale illustrations of hair loss. The illustrations can help them understand when their hair loss is progressing over time, she added. For female patients with hair loss, the Ludwig Scale for hair loss in women can be very illustrative.

In the work-up of the patient, conduct a physical exam and consider overall health and nutritional status. Ask about family history as well, because relatives are the best window for insight into hair loss caused by genetics and aging, Dr. Roberts said.

Review patient medications. Older patients, in particular, often take multiple medications, which increases the likelihood for interactions or side effects leading to hair loss.

In addition, she had a few specific recommendations. “When you have male patient with hair loss taking Propecia [finasteride], talk to them about the dangers of exposure to a female partner and pregnancy in particular.” Also ask patients to bring in any supplements they are taking. Watch out for keratin supplements in patients with renal disease, she added, because elevated levels can be associated with kidney problems.

In terms of laboratory testing, consider checking for thyroid function, hormonal imbalance, and anemia. “The most overlooked is hemoglobin levels,” Dr. Roberts said, although anemia can cause hair loss in some patients.

Dr. Roberts is a speaker, consultant, investigator for and/or receives honoraria from Allergan, Colorescience, Galderma, Lytera, MDRejuvena, Restorsea, SkinMedica, Theraplex, Top MD Skincare, Valeant Pharmaceutical International, and Viviscal.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ODAC 2017

Coding Changes for 2017

All physicians will see changes in reimbursement in 2017. A new president with a new agenda makes for an interesting time ahead for health care in the United States. However, in this time of flux, there is one constant: the Final Rule, an informal term for the annual update on how the Medicare system will function and how much you will get paid for what you do.1 The document is 393 pages and outlines what is new in the Medicare system, with lots of supplements giving granular details about physician work, overhead, and supply and labor costs. In this column, I have taken the liberty of dissecting the Final Rule for you and to bring attention to its high and low points for dermatologists.

Changes in Relative Value Units

The conversion factor has gone up, meaning you will be paid a bit more this year for what you do; it is not enough to account for inflation or the increasing cost of unfunded mandates, but it is better than nothing. Although the conversion factor was $35.8043 in 2016, it increased by more than 0.2% on January 1, 2017, to $35.8887.1 How is this conversion factor calculated? We go up 0.5% due to MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act), down 0.013% due to budget neutrality, down 0.07% due to multiple procedure payment reduction changes, and down another 0.18% due to the misvalued code target.1 The misvalued code target is related to targets established by statute for 2016 to 2018 and payment rates are reduced across the board if they are not met.

If payments suffer from reductions in work value, they may not happen all at once. If the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reduce total relative value units (RVUs) by more than 20%, reductions will take place over at least 2 years with a single year drop maximum of 19%.1 Unfortunately, such limits do not apply to revised codes, which can take as big a hit as the CMS cares to make.

Changes to Global Periods

In 2015, we learned that 10- and 90-day global periods would be eliminated in 2017 and 2018, respectively, with great concern on the part of the government about the number and level of evaluation and management services embedded in these codes. The implementation of global policy elimination was prohibited by MACRA and the CMS was required to develop and implement a process to gather data on services furnished in the global period from a representative sample of physicians, which they will use to value surgical services beginningin 2019.1 The CMS decided to capture this data with a new set of time-based G codes (which would be onerous for all practicing physicians), not just the unlucky folks who were to be the sample mandated under MACRA.2 During the comment period, it became obvious to the CMS that this concept was flawed for many reasons and it decided to hold a town hall meeting at the CMS headquarters on August 25, 2016, on data collection on resources used in furnishing global services in which 90 minutes of live testimony in the morning was followed by another 90 minutes by telephone in the afternoon.3 This meeting, which I attended, resulted in the CMS changing the all-practitioner reporting program to a specified sample with others allowed to opt in. Practitioners in groups of less than 10 are exempt, and only physicians in Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nevada, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, and Rhode Island must capture data beginning in July 2017.1 These data only have to be captured on codes that are used by more than 100 practitioners and are furnished at least 10,000 times or have allowed charges of greater than $10,000,000 annually. If you are lucky enough to live in one of the testing states, you must start on July 1 but can start before July 1 if you wish. Practitioners in smaller practices or in other geographic areas are encouraged to report data if feasible but are not required to do so. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99024 will be used for reporting postoperative services rather than the proposed onerous set of G codes, and reporting will not be required for preoperative visits included in the global package or for services not related to the patient’s visit.

Changes to Chronic Care Management

There are new and modified chronic care management codes that are not of use to you unless you are the primary provider for the patient and you and the patient meet multiple stringent requirements.4 The patient must have multiple illnesses, use multiple medications, be unable to perform activities of daily living, require a caregiver, and/or have repeat admissions or emergency department visits. Typical adult patients who receive complex chronic care management services are treated with 3 or more prescription medications and may be receiving other types of therapeutic interventions (eg, physical therapy, occupational therapy). Typical pediatric patients receive 3 or more therapeutic interventions (eg, medications, nutritional support, respiratory therapy). All patients have 2 or more chronic continuous or episodic health conditions that are expected to last at least 12 months or until the death of the patient and place the patient at serious risk for death, acute exacerbation/decompensation, or functional decline.4

Changes to Moderate Sedation Codes