User login

A complication of enoxaparin injection

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

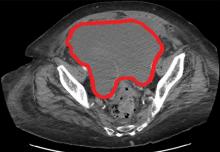

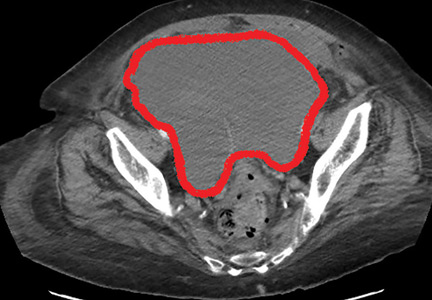

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

Q&A: Drug costs and value in cancer

Skyrocketing drug costs are a key issue facing physicians, patients, and policymakers, but an even thornier problem may be determining a drug’s value.

In this Q&A, Richard L. Schilsky, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), weighs in on the value proposition for cancer drugs and the implications for physicians.

Q: What tools exist for determining a drug’s value?

A: A number of organizations have developed tools to try to determine the value of cancer drug treatments. ASCO, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have all developed tools for this purpose.

Our tool, the ASCO Value Framework, assesses the value of new cancer drug treatments based on clinical benefit, side effects, and improvements in patient symptoms or quality of life in the context of cost. While it’s hard to directly compare frameworks – given differences in methodology and the many nuances of evaluating clinical trial results – in 2018, ASCO and ESMO published a joint analysis of our value frameworks in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2018; 37[4]:336-49).

The analysis found that the frameworks produce comparable measures of the clinical benefits of new therapies in approximately two-thirds of the more than 100 treatment comparisons that were examined. It also identified a number of factors that may contribute to the discordant scores, revealing potential ways for both of our organizations to refine our frameworks in the future.

That said, ASCO’s Value Framework is just one part of our broader, multifaceted effort to achieve high-quality, high-value care for all patients with cancer. Other efforts include ASCO’s proposed Patient-Centered Oncology Payment model, the Choosing Wisely campaign to identify low-value clinical strategies, and CancerLinQ and the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative to implement quality measurement and improvement.

Q: How can the issues around drug price and value be addressed earlier in the context of clinical trials?

A: The definition of value ultimately comes down to the price that must be paid to achieve meaningfully improved health outcomes for individual patients or the broader population of affected individuals. Optimizing the value of a new cancer drug treatment begins with an innovation to address an unmet medical need, followed by defining and achieving clinically meaningful improvements in health outcomes through well-designed and efficiently conducted clinical trials. Effectiveness research is also essential to determining how well new treatments perform compared with available alternatives and how they perform in more diverse populations than those typically included in the clinical trials used to establish efficacy.

Patient goals, preferences, and choices shape the real-world experience of a new product, and the direct and indirect costs of a treatment to patients and their families significantly affect whether it is adopted widely. Until their value is clearly established, new and costly products should be deployed judiciously and after careful consideration of the goals of treatment, available options, and the unique needs, preferences, and goals of individual patients.

More research is needed to improve how we assess the value of new cancer drug treatments. New clinical efficacy endpoints – both provider- and patient-reported ones – that accurately describe how a patient feels and functions must be developed and should reflect outcomes of value to patients other than survival, particularly in noncurative settings.

Better predictive biomarkers can transform a drug of modest efficacy in an unselected population to one of high efficacy in a biomarker-defined subgroup and thereby contribute to improving the value of a treatment.

Regulatory and policy initiatives such as adaptive licensing, value-based insurance, and indication-specific pricing that affect marketing approval, reimbursement, or price, respectively, based on treatment effectiveness, also deserve careful consideration and further research to determine their effects on aligning cost with benefit while ensuring patient access to potentially life-extending therapies and continued innovation in drug development.

Q: Aside from the policy options, what’s the role of the oncologist in discussing the value of drugs with patients when determining a treatment plan?

A: Since oncologists don’t control drug prices, our role in improving the value of cancer care involves appropriately managing how resources are used and guiding patients during discussions around the right treatment plan for their particular diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment goals.

Adopting and adhering to high-quality oncology clinical pathways is an important way to improve the quality, efficiency, and value of cancer care. High-quality oncology pathways are detailed, evidence-based treatment protocols for delivering cancer care to patients with specific disease types and stages. When properly designed and implemented, oncology pathways serve as an important tool in appropriately managing cancer care resources and improving the quality of care that patients with cancer receive, while also reducing costs.

Dr. Schilsky is the senior vice president and chief medical officer of ASCO. Formerly the chief of hematology/oncology in the department of medicine and deputy director of the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center, he is a leader in the field of clinical oncology, specializing in new drug development and the treatment of gastrointestinal cancers. Dr. Schilsky reported research funding from several pharmaceutical companies to ASCO for the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) clinical trial. He also reported travel/accommodation/expense support from Varian.

Skyrocketing drug costs are a key issue facing physicians, patients, and policymakers, but an even thornier problem may be determining a drug’s value.

In this Q&A, Richard L. Schilsky, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), weighs in on the value proposition for cancer drugs and the implications for physicians.

Q: What tools exist for determining a drug’s value?

A: A number of organizations have developed tools to try to determine the value of cancer drug treatments. ASCO, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have all developed tools for this purpose.

Our tool, the ASCO Value Framework, assesses the value of new cancer drug treatments based on clinical benefit, side effects, and improvements in patient symptoms or quality of life in the context of cost. While it’s hard to directly compare frameworks – given differences in methodology and the many nuances of evaluating clinical trial results – in 2018, ASCO and ESMO published a joint analysis of our value frameworks in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2018; 37[4]:336-49).

The analysis found that the frameworks produce comparable measures of the clinical benefits of new therapies in approximately two-thirds of the more than 100 treatment comparisons that were examined. It also identified a number of factors that may contribute to the discordant scores, revealing potential ways for both of our organizations to refine our frameworks in the future.

That said, ASCO’s Value Framework is just one part of our broader, multifaceted effort to achieve high-quality, high-value care for all patients with cancer. Other efforts include ASCO’s proposed Patient-Centered Oncology Payment model, the Choosing Wisely campaign to identify low-value clinical strategies, and CancerLinQ and the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative to implement quality measurement and improvement.

Q: How can the issues around drug price and value be addressed earlier in the context of clinical trials?

A: The definition of value ultimately comes down to the price that must be paid to achieve meaningfully improved health outcomes for individual patients or the broader population of affected individuals. Optimizing the value of a new cancer drug treatment begins with an innovation to address an unmet medical need, followed by defining and achieving clinically meaningful improvements in health outcomes through well-designed and efficiently conducted clinical trials. Effectiveness research is also essential to determining how well new treatments perform compared with available alternatives and how they perform in more diverse populations than those typically included in the clinical trials used to establish efficacy.

Patient goals, preferences, and choices shape the real-world experience of a new product, and the direct and indirect costs of a treatment to patients and their families significantly affect whether it is adopted widely. Until their value is clearly established, new and costly products should be deployed judiciously and after careful consideration of the goals of treatment, available options, and the unique needs, preferences, and goals of individual patients.

More research is needed to improve how we assess the value of new cancer drug treatments. New clinical efficacy endpoints – both provider- and patient-reported ones – that accurately describe how a patient feels and functions must be developed and should reflect outcomes of value to patients other than survival, particularly in noncurative settings.

Better predictive biomarkers can transform a drug of modest efficacy in an unselected population to one of high efficacy in a biomarker-defined subgroup and thereby contribute to improving the value of a treatment.

Regulatory and policy initiatives such as adaptive licensing, value-based insurance, and indication-specific pricing that affect marketing approval, reimbursement, or price, respectively, based on treatment effectiveness, also deserve careful consideration and further research to determine their effects on aligning cost with benefit while ensuring patient access to potentially life-extending therapies and continued innovation in drug development.

Q: Aside from the policy options, what’s the role of the oncologist in discussing the value of drugs with patients when determining a treatment plan?

A: Since oncologists don’t control drug prices, our role in improving the value of cancer care involves appropriately managing how resources are used and guiding patients during discussions around the right treatment plan for their particular diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment goals.

Adopting and adhering to high-quality oncology clinical pathways is an important way to improve the quality, efficiency, and value of cancer care. High-quality oncology pathways are detailed, evidence-based treatment protocols for delivering cancer care to patients with specific disease types and stages. When properly designed and implemented, oncology pathways serve as an important tool in appropriately managing cancer care resources and improving the quality of care that patients with cancer receive, while also reducing costs.

Dr. Schilsky is the senior vice president and chief medical officer of ASCO. Formerly the chief of hematology/oncology in the department of medicine and deputy director of the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center, he is a leader in the field of clinical oncology, specializing in new drug development and the treatment of gastrointestinal cancers. Dr. Schilsky reported research funding from several pharmaceutical companies to ASCO for the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) clinical trial. He also reported travel/accommodation/expense support from Varian.

Skyrocketing drug costs are a key issue facing physicians, patients, and policymakers, but an even thornier problem may be determining a drug’s value.

In this Q&A, Richard L. Schilsky, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), weighs in on the value proposition for cancer drugs and the implications for physicians.

Q: What tools exist for determining a drug’s value?

A: A number of organizations have developed tools to try to determine the value of cancer drug treatments. ASCO, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have all developed tools for this purpose.

Our tool, the ASCO Value Framework, assesses the value of new cancer drug treatments based on clinical benefit, side effects, and improvements in patient symptoms or quality of life in the context of cost. While it’s hard to directly compare frameworks – given differences in methodology and the many nuances of evaluating clinical trial results – in 2018, ASCO and ESMO published a joint analysis of our value frameworks in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2018; 37[4]:336-49).

The analysis found that the frameworks produce comparable measures of the clinical benefits of new therapies in approximately two-thirds of the more than 100 treatment comparisons that were examined. It also identified a number of factors that may contribute to the discordant scores, revealing potential ways for both of our organizations to refine our frameworks in the future.

That said, ASCO’s Value Framework is just one part of our broader, multifaceted effort to achieve high-quality, high-value care for all patients with cancer. Other efforts include ASCO’s proposed Patient-Centered Oncology Payment model, the Choosing Wisely campaign to identify low-value clinical strategies, and CancerLinQ and the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative to implement quality measurement and improvement.

Q: How can the issues around drug price and value be addressed earlier in the context of clinical trials?

A: The definition of value ultimately comes down to the price that must be paid to achieve meaningfully improved health outcomes for individual patients or the broader population of affected individuals. Optimizing the value of a new cancer drug treatment begins with an innovation to address an unmet medical need, followed by defining and achieving clinically meaningful improvements in health outcomes through well-designed and efficiently conducted clinical trials. Effectiveness research is also essential to determining how well new treatments perform compared with available alternatives and how they perform in more diverse populations than those typically included in the clinical trials used to establish efficacy.

Patient goals, preferences, and choices shape the real-world experience of a new product, and the direct and indirect costs of a treatment to patients and their families significantly affect whether it is adopted widely. Until their value is clearly established, new and costly products should be deployed judiciously and after careful consideration of the goals of treatment, available options, and the unique needs, preferences, and goals of individual patients.

More research is needed to improve how we assess the value of new cancer drug treatments. New clinical efficacy endpoints – both provider- and patient-reported ones – that accurately describe how a patient feels and functions must be developed and should reflect outcomes of value to patients other than survival, particularly in noncurative settings.

Better predictive biomarkers can transform a drug of modest efficacy in an unselected population to one of high efficacy in a biomarker-defined subgroup and thereby contribute to improving the value of a treatment.

Regulatory and policy initiatives such as adaptive licensing, value-based insurance, and indication-specific pricing that affect marketing approval, reimbursement, or price, respectively, based on treatment effectiveness, also deserve careful consideration and further research to determine their effects on aligning cost with benefit while ensuring patient access to potentially life-extending therapies and continued innovation in drug development.

Q: Aside from the policy options, what’s the role of the oncologist in discussing the value of drugs with patients when determining a treatment plan?

A: Since oncologists don’t control drug prices, our role in improving the value of cancer care involves appropriately managing how resources are used and guiding patients during discussions around the right treatment plan for their particular diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment goals.

Adopting and adhering to high-quality oncology clinical pathways is an important way to improve the quality, efficiency, and value of cancer care. High-quality oncology pathways are detailed, evidence-based treatment protocols for delivering cancer care to patients with specific disease types and stages. When properly designed and implemented, oncology pathways serve as an important tool in appropriately managing cancer care resources and improving the quality of care that patients with cancer receive, while also reducing costs.

Dr. Schilsky is the senior vice president and chief medical officer of ASCO. Formerly the chief of hematology/oncology in the department of medicine and deputy director of the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center, he is a leader in the field of clinical oncology, specializing in new drug development and the treatment of gastrointestinal cancers. Dr. Schilsky reported research funding from several pharmaceutical companies to ASCO for the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) clinical trial. He also reported travel/accommodation/expense support from Varian.

Ongoing research aims to improve transplant outcomes in sickle cell

Researchers are leading several studies designed to improve hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), experts at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute reported during a recent webinar.

“HSCT offers a potential cure [for SCD], which may improve quantity and quality of life [for patients],” said Courtney D. Fitzhugh, MD, a Lasker Clinical Research Scholar in the Laboratory of Early Sickle Mortality Prevention at NHLBI.

Currently, HLA-matched sibling and matched unrelated donor sources provide the best outcomes for sickle cell patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, she explained. Alternative stem cell sources include umbilical cord blood and haploidentical donors.

Over the past 2 years, the majority of novel transplant techniques have been primarily aimed at improving conditioning regimens and lowering rates of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Recent evidence

A recent international survey found high survival rates in patients with SCD who underwent HLA-matched sibling HSCT during 1986-2013. At 5-years, overall- and event-free survival rates were 92.9% and 91.4%, respectively, with even higher rates (95% and 93%) seen in children aged younger than 16 years.

With respect to safety, the cumulative incidence rates of acute and chronic GVHD were 14.8% and 14.3%, Dr. Fitzhugh reported.

Much of the success seen with HLA-matched sibling donors is attributable to recent data demonstrating that complete transformation of patient’s bone marrow is unnecessary to illicit a curative effect.

With donor myeloid chimerism levels of at least 20%, the sickle disease phenotype can be reversed, and there’s a reduced risk of GVHD, she said.

In mouse models, researchers have found that inclusion of sirolimus in HLA-matched pretransplant conditioning regimens leads to higher levels of donor cell engraftment. As a result, some conditioning regimens now administer sirolimus (target 10-15 ng/dL) one-day prior to transplantation.

In 55 patients transplanted using this technique, overall- and event-free survival rates of 93% and 87% have been reported, with no transplant-related mortality or evidence of GVHD. Other institutions have also begun to adopt this technique, and have reported similar findings, Dr. Fitzhugh reported.

“When you [administer high-dose] chemotherapy, you don’t expect that patients are able to have children, but we are excited to report that 8 of our patients have had 13 healthy babies post transplant,” Dr. Fitzhugh said.

As a whole, several recent studies have emphasized the importance of the conditioning regimen in successful transplantation for patients with SCD.

With HLA-matched sibling donors, myeloablative regimens that include antithymocyte globulin have demonstrated greater efficacy, she said.

In patients receiving a transplant from a matched unrelated donor, early use of alemtuzumab is linked to higher rates of GVHD, while ongoing studies are exploring whether abatacept reduces the risk of GVHD, she further explained.

With respect to haploidentical and unrelated umbilical cord donors, T-cell depletion and higher-intensity conditioning have been shown to reduce graft rejection rates, she said.

Dr. Fitzhugh acknowledged that long-term efficacy and safety of these novel conditioning regimens is largely unknown. Thus, ongoing follow-up is essential to monitor for potential late effects.

NHLBI-funded trials

Nancy L. DiFronzo, PhD, program director at NHLBI, explained that the agency has funded specific clinical studies evaluating allogeneic HSCT in patients with severe SCD.

“[Surprisingly], this treatment modality is [actually] quite rare, with [only] approximately 9,000 allogeneic transplants occurring in the United States each year,” she said.

One of the primary barriers to HSCT for SCD is a lack of compatible donors. Currently, fewer than 20% of sickle cell patients have a matched unrelated donor or HLA-matched sibling donor, she reported.

Another common barrier are the risks associated with the procedure, including treatment-related toxicities and death. Active participation in a clinical trial is one strategy that can mitigate these risks, she said.

The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) is a group of transplant centers that are recognized experts in HSCT. Dr. DiFronzo explained that the consortium is cosponsored by the National Cancer Institute and NHLBI, with the goal of improving outcomes for both pediatric and adult patients with SCD undergoing HSCT.

At present, the BMT CTN has directly funded three multicenter clinical studies for SCD, including the SCURT study, which has now been completed, as well as the STRIDE2 and Haploidentical HCT trials, both of which are currently enrolling patients.

“The goal of these new approaches [being studied in these 3 trials] is cure, where individuals can live longer with a better quality of life,” Dr. DiFronzo said. “We’ve [specifically] adjusted regimens with [this goal] in mind.”

Dr. Fitzhugh and Dr. DiFronzo did not provide information on financial disclosures.

Researchers are leading several studies designed to improve hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), experts at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute reported during a recent webinar.

“HSCT offers a potential cure [for SCD], which may improve quantity and quality of life [for patients],” said Courtney D. Fitzhugh, MD, a Lasker Clinical Research Scholar in the Laboratory of Early Sickle Mortality Prevention at NHLBI.

Currently, HLA-matched sibling and matched unrelated donor sources provide the best outcomes for sickle cell patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, she explained. Alternative stem cell sources include umbilical cord blood and haploidentical donors.

Over the past 2 years, the majority of novel transplant techniques have been primarily aimed at improving conditioning regimens and lowering rates of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Recent evidence

A recent international survey found high survival rates in patients with SCD who underwent HLA-matched sibling HSCT during 1986-2013. At 5-years, overall- and event-free survival rates were 92.9% and 91.4%, respectively, with even higher rates (95% and 93%) seen in children aged younger than 16 years.

With respect to safety, the cumulative incidence rates of acute and chronic GVHD were 14.8% and 14.3%, Dr. Fitzhugh reported.

Much of the success seen with HLA-matched sibling donors is attributable to recent data demonstrating that complete transformation of patient’s bone marrow is unnecessary to illicit a curative effect.

With donor myeloid chimerism levels of at least 20%, the sickle disease phenotype can be reversed, and there’s a reduced risk of GVHD, she said.

In mouse models, researchers have found that inclusion of sirolimus in HLA-matched pretransplant conditioning regimens leads to higher levels of donor cell engraftment. As a result, some conditioning regimens now administer sirolimus (target 10-15 ng/dL) one-day prior to transplantation.

In 55 patients transplanted using this technique, overall- and event-free survival rates of 93% and 87% have been reported, with no transplant-related mortality or evidence of GVHD. Other institutions have also begun to adopt this technique, and have reported similar findings, Dr. Fitzhugh reported.

“When you [administer high-dose] chemotherapy, you don’t expect that patients are able to have children, but we are excited to report that 8 of our patients have had 13 healthy babies post transplant,” Dr. Fitzhugh said.

As a whole, several recent studies have emphasized the importance of the conditioning regimen in successful transplantation for patients with SCD.

With HLA-matched sibling donors, myeloablative regimens that include antithymocyte globulin have demonstrated greater efficacy, she said.

In patients receiving a transplant from a matched unrelated donor, early use of alemtuzumab is linked to higher rates of GVHD, while ongoing studies are exploring whether abatacept reduces the risk of GVHD, she further explained.

With respect to haploidentical and unrelated umbilical cord donors, T-cell depletion and higher-intensity conditioning have been shown to reduce graft rejection rates, she said.

Dr. Fitzhugh acknowledged that long-term efficacy and safety of these novel conditioning regimens is largely unknown. Thus, ongoing follow-up is essential to monitor for potential late effects.

NHLBI-funded trials

Nancy L. DiFronzo, PhD, program director at NHLBI, explained that the agency has funded specific clinical studies evaluating allogeneic HSCT in patients with severe SCD.

“[Surprisingly], this treatment modality is [actually] quite rare, with [only] approximately 9,000 allogeneic transplants occurring in the United States each year,” she said.

One of the primary barriers to HSCT for SCD is a lack of compatible donors. Currently, fewer than 20% of sickle cell patients have a matched unrelated donor or HLA-matched sibling donor, she reported.

Another common barrier are the risks associated with the procedure, including treatment-related toxicities and death. Active participation in a clinical trial is one strategy that can mitigate these risks, she said.

The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) is a group of transplant centers that are recognized experts in HSCT. Dr. DiFronzo explained that the consortium is cosponsored by the National Cancer Institute and NHLBI, with the goal of improving outcomes for both pediatric and adult patients with SCD undergoing HSCT.

At present, the BMT CTN has directly funded three multicenter clinical studies for SCD, including the SCURT study, which has now been completed, as well as the STRIDE2 and Haploidentical HCT trials, both of which are currently enrolling patients.

“The goal of these new approaches [being studied in these 3 trials] is cure, where individuals can live longer with a better quality of life,” Dr. DiFronzo said. “We’ve [specifically] adjusted regimens with [this goal] in mind.”

Dr. Fitzhugh and Dr. DiFronzo did not provide information on financial disclosures.

Researchers are leading several studies designed to improve hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), experts at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute reported during a recent webinar.

“HSCT offers a potential cure [for SCD], which may improve quantity and quality of life [for patients],” said Courtney D. Fitzhugh, MD, a Lasker Clinical Research Scholar in the Laboratory of Early Sickle Mortality Prevention at NHLBI.

Currently, HLA-matched sibling and matched unrelated donor sources provide the best outcomes for sickle cell patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, she explained. Alternative stem cell sources include umbilical cord blood and haploidentical donors.

Over the past 2 years, the majority of novel transplant techniques have been primarily aimed at improving conditioning regimens and lowering rates of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Recent evidence

A recent international survey found high survival rates in patients with SCD who underwent HLA-matched sibling HSCT during 1986-2013. At 5-years, overall- and event-free survival rates were 92.9% and 91.4%, respectively, with even higher rates (95% and 93%) seen in children aged younger than 16 years.

With respect to safety, the cumulative incidence rates of acute and chronic GVHD were 14.8% and 14.3%, Dr. Fitzhugh reported.

Much of the success seen with HLA-matched sibling donors is attributable to recent data demonstrating that complete transformation of patient’s bone marrow is unnecessary to illicit a curative effect.

With donor myeloid chimerism levels of at least 20%, the sickle disease phenotype can be reversed, and there’s a reduced risk of GVHD, she said.

In mouse models, researchers have found that inclusion of sirolimus in HLA-matched pretransplant conditioning regimens leads to higher levels of donor cell engraftment. As a result, some conditioning regimens now administer sirolimus (target 10-15 ng/dL) one-day prior to transplantation.

In 55 patients transplanted using this technique, overall- and event-free survival rates of 93% and 87% have been reported, with no transplant-related mortality or evidence of GVHD. Other institutions have also begun to adopt this technique, and have reported similar findings, Dr. Fitzhugh reported.

“When you [administer high-dose] chemotherapy, you don’t expect that patients are able to have children, but we are excited to report that 8 of our patients have had 13 healthy babies post transplant,” Dr. Fitzhugh said.

As a whole, several recent studies have emphasized the importance of the conditioning regimen in successful transplantation for patients with SCD.

With HLA-matched sibling donors, myeloablative regimens that include antithymocyte globulin have demonstrated greater efficacy, she said.

In patients receiving a transplant from a matched unrelated donor, early use of alemtuzumab is linked to higher rates of GVHD, while ongoing studies are exploring whether abatacept reduces the risk of GVHD, she further explained.

With respect to haploidentical and unrelated umbilical cord donors, T-cell depletion and higher-intensity conditioning have been shown to reduce graft rejection rates, she said.

Dr. Fitzhugh acknowledged that long-term efficacy and safety of these novel conditioning regimens is largely unknown. Thus, ongoing follow-up is essential to monitor for potential late effects.

NHLBI-funded trials

Nancy L. DiFronzo, PhD, program director at NHLBI, explained that the agency has funded specific clinical studies evaluating allogeneic HSCT in patients with severe SCD.

“[Surprisingly], this treatment modality is [actually] quite rare, with [only] approximately 9,000 allogeneic transplants occurring in the United States each year,” she said.

One of the primary barriers to HSCT for SCD is a lack of compatible donors. Currently, fewer than 20% of sickle cell patients have a matched unrelated donor or HLA-matched sibling donor, she reported.

Another common barrier are the risks associated with the procedure, including treatment-related toxicities and death. Active participation in a clinical trial is one strategy that can mitigate these risks, she said.

The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) is a group of transplant centers that are recognized experts in HSCT. Dr. DiFronzo explained that the consortium is cosponsored by the National Cancer Institute and NHLBI, with the goal of improving outcomes for both pediatric and adult patients with SCD undergoing HSCT.

At present, the BMT CTN has directly funded three multicenter clinical studies for SCD, including the SCURT study, which has now been completed, as well as the STRIDE2 and Haploidentical HCT trials, both of which are currently enrolling patients.

“The goal of these new approaches [being studied in these 3 trials] is cure, where individuals can live longer with a better quality of life,” Dr. DiFronzo said. “We’ve [specifically] adjusted regimens with [this goal] in mind.”

Dr. Fitzhugh and Dr. DiFronzo did not provide information on financial disclosures.

Is it safe to discharge patients with anemia?

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

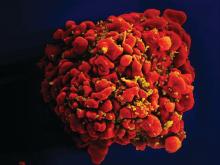

CAR T-cell therapy found safe, effective for HIV-associated lymphoma

HIV positivity does not preclude chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for patients with aggressive lymphoma, a report of two cases suggests. Both of the HIV-positive patients, one of whom had long-term psychiatric comorbidity, achieved durable remission on axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) without undue toxicity.

“To our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of CAR T-cell therapy administered to HIV-infected patients with lymphoma,” Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston and his colleagues wrote in Cancer. “Patients with HIV and AIDS, as well as those with preexisting mental illness, should not be considered disqualified from CAR T-cell therapy and deserve ongoing studies to optimize efficacy and safety in this population.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two CAR T-cell products that target the B-cell antigen CD19 for the treatment of refractory lymphoma. But their efficacy and safety in HIV-positive patients are unknown because this group has been excluded from pivotal clinical trials.

Dr. Abramson and coauthors detail the two cases of successful anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with HIV-associated, refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

The first patient was an HIV-positive man with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of germinal center B-cell subtype who was intermittently adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His comorbidities included posttraumatic stress disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

Previous treatments for DLBCL included dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (EPOCH-R), and rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (RICE). A recurrence precluded high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support.

With close multidisciplinary management, including psychiatric consultation, the patient became a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy and received axicabtagene ciloleucel. He experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome and grade 3 neurologic toxicity, both of which resolved with treatment. Imaging showed complete remission at approximately 3 months that was sustained at 1 year. Additionally, he had an undetectable HIV viral load and was psychiatrically stable.

The second patient was a man with AIDS-associated, non–germinal center B-cell, Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL who was adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His lymphoma had recurred rapidly after initially responding to dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and then was refractory to combination rituximab and lenalidomide. He previously had hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium avium complex infections.

Because of prolonged cytopenias and infectious complications after the previous lymphoma treatments, the patient was considered a poor candidate for high-dose chemotherapy. He underwent CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel and had a complete remission on day 28. Additionally, his HIV infection remained well controlled.

“Although much remains to be learned regarding CAR T-cell therapy in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies, with or without HIV infection, the cases presented herein demonstrate that patients with chemotherapy-refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma can successfully undergo autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing, and subsequently can safely tolerate CAR T-cell therapy and achieve a durable complete remission,” the researchers wrote. “These cases have further demonstrated the proactive, multidisciplinary care required to navigate a patient with high-risk lymphoma through CAR T-cell therapy with attention to significant medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Dr. Abramson reported that he has acted as a paid member of the scientific advisory board and as a paid consultant for Kite Pharma, which markets Yescarta, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Abramson JS et al. Cancer. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32411.

HIV positivity does not preclude chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for patients with aggressive lymphoma, a report of two cases suggests. Both of the HIV-positive patients, one of whom had long-term psychiatric comorbidity, achieved durable remission on axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) without undue toxicity.

“To our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of CAR T-cell therapy administered to HIV-infected patients with lymphoma,” Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston and his colleagues wrote in Cancer. “Patients with HIV and AIDS, as well as those with preexisting mental illness, should not be considered disqualified from CAR T-cell therapy and deserve ongoing studies to optimize efficacy and safety in this population.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two CAR T-cell products that target the B-cell antigen CD19 for the treatment of refractory lymphoma. But their efficacy and safety in HIV-positive patients are unknown because this group has been excluded from pivotal clinical trials.

Dr. Abramson and coauthors detail the two cases of successful anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with HIV-associated, refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

The first patient was an HIV-positive man with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of germinal center B-cell subtype who was intermittently adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His comorbidities included posttraumatic stress disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

Previous treatments for DLBCL included dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (EPOCH-R), and rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (RICE). A recurrence precluded high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support.

With close multidisciplinary management, including psychiatric consultation, the patient became a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy and received axicabtagene ciloleucel. He experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome and grade 3 neurologic toxicity, both of which resolved with treatment. Imaging showed complete remission at approximately 3 months that was sustained at 1 year. Additionally, he had an undetectable HIV viral load and was psychiatrically stable.

The second patient was a man with AIDS-associated, non–germinal center B-cell, Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL who was adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His lymphoma had recurred rapidly after initially responding to dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and then was refractory to combination rituximab and lenalidomide. He previously had hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium avium complex infections.

Because of prolonged cytopenias and infectious complications after the previous lymphoma treatments, the patient was considered a poor candidate for high-dose chemotherapy. He underwent CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel and had a complete remission on day 28. Additionally, his HIV infection remained well controlled.

“Although much remains to be learned regarding CAR T-cell therapy in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies, with or without HIV infection, the cases presented herein demonstrate that patients with chemotherapy-refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma can successfully undergo autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing, and subsequently can safely tolerate CAR T-cell therapy and achieve a durable complete remission,” the researchers wrote. “These cases have further demonstrated the proactive, multidisciplinary care required to navigate a patient with high-risk lymphoma through CAR T-cell therapy with attention to significant medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Dr. Abramson reported that he has acted as a paid member of the scientific advisory board and as a paid consultant for Kite Pharma, which markets Yescarta, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Abramson JS et al. Cancer. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32411.

HIV positivity does not preclude chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for patients with aggressive lymphoma, a report of two cases suggests. Both of the HIV-positive patients, one of whom had long-term psychiatric comorbidity, achieved durable remission on axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) without undue toxicity.

“To our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of CAR T-cell therapy administered to HIV-infected patients with lymphoma,” Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston and his colleagues wrote in Cancer. “Patients with HIV and AIDS, as well as those with preexisting mental illness, should not be considered disqualified from CAR T-cell therapy and deserve ongoing studies to optimize efficacy and safety in this population.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two CAR T-cell products that target the B-cell antigen CD19 for the treatment of refractory lymphoma. But their efficacy and safety in HIV-positive patients are unknown because this group has been excluded from pivotal clinical trials.

Dr. Abramson and coauthors detail the two cases of successful anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with HIV-associated, refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

The first patient was an HIV-positive man with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of germinal center B-cell subtype who was intermittently adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His comorbidities included posttraumatic stress disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

Previous treatments for DLBCL included dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (EPOCH-R), and rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (RICE). A recurrence precluded high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support.

With close multidisciplinary management, including psychiatric consultation, the patient became a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy and received axicabtagene ciloleucel. He experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome and grade 3 neurologic toxicity, both of which resolved with treatment. Imaging showed complete remission at approximately 3 months that was sustained at 1 year. Additionally, he had an undetectable HIV viral load and was psychiatrically stable.

The second patient was a man with AIDS-associated, non–germinal center B-cell, Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL who was adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His lymphoma had recurred rapidly after initially responding to dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and then was refractory to combination rituximab and lenalidomide. He previously had hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium avium complex infections.

Because of prolonged cytopenias and infectious complications after the previous lymphoma treatments, the patient was considered a poor candidate for high-dose chemotherapy. He underwent CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel and had a complete remission on day 28. Additionally, his HIV infection remained well controlled.

“Although much remains to be learned regarding CAR T-cell therapy in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies, with or without HIV infection, the cases presented herein demonstrate that patients with chemotherapy-refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma can successfully undergo autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing, and subsequently can safely tolerate CAR T-cell therapy and achieve a durable complete remission,” the researchers wrote. “These cases have further demonstrated the proactive, multidisciplinary care required to navigate a patient with high-risk lymphoma through CAR T-cell therapy with attention to significant medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Dr. Abramson reported that he has acted as a paid member of the scientific advisory board and as a paid consultant for Kite Pharma, which markets Yescarta, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Abramson JS et al. Cancer. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32411.

FROM CANCER

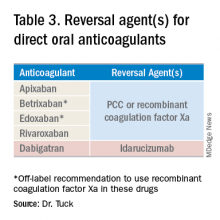

Reversal agents for direct-acting oral anticoagulants

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

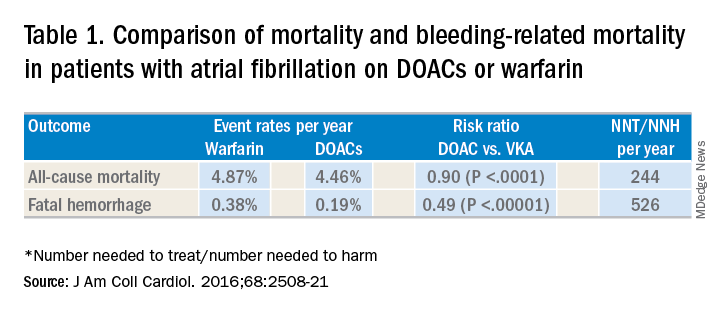

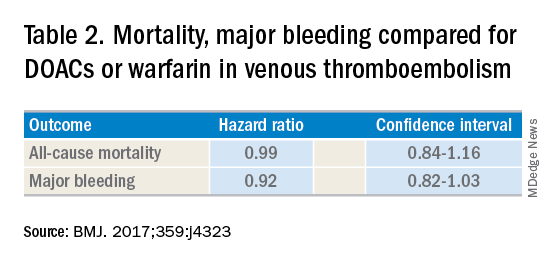

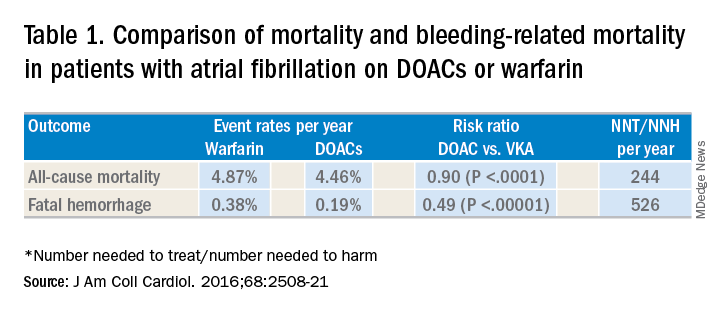

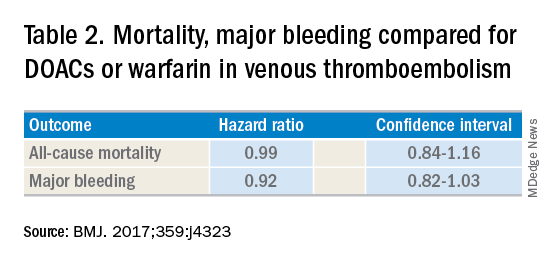

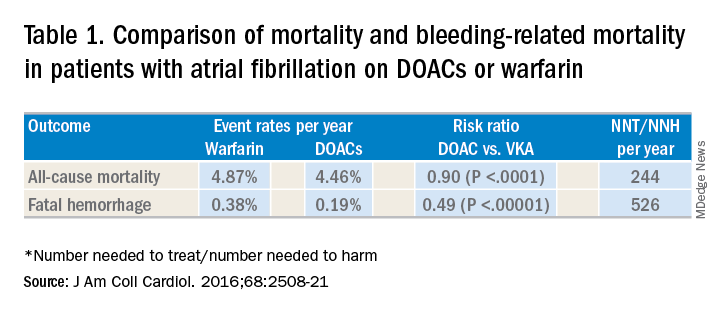

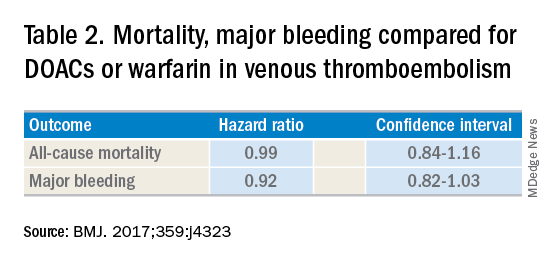

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8