User login

Unleashing Our Immune Response to Quash Cancer

This article was originally published on February 10 in Eric Topol’s substack “Ground Truths.”

It’s astounding how devious cancer cells and tumor tissue can be. This week in Science we learned how certain lung cancer cells can function like “Catch Me If You Can” — changing their driver mutation and cell identity to escape targeted therapy. This histologic transformation, as seen in an experimental model, is just one of so many cancer tricks that we are learning about.

Recently, as shown by single-cell sequencing, cancer cells can steal the mitochondria from T cells, a double whammy that turbocharges cancer cells with the hijacked fuel supply and, at the same time, dismantles the immune response.

Last week, we saw how tumor cells can release a virus-like protein that unleashes a vicious autoimmune response.

And then there’s the finding that cancer cell spread predominantly is occurring while we sleep.

As I previously reviewed, the ability for cancer cells to hijack neurons and neural circuits is now well established, no less their ability to reprogram neurons to become adrenergic and stimulate tumor progression, and interfere with the immune response. Stay tuned on that for a new Ground Truths podcast with Prof Michelle Monje, a leader in cancer neuroscience, which will post soon.

Add advancing age’s immunosenescence as yet another challenge to the long and growing list of formidable ways that cancer cells, and the tumor microenvironment, evade our immune response.

An Ever-Expanding Armamentarium

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

The field of immunotherapies took off with the immune checkpoint inhibitors, first approved by the FDA in 2011, that take the brakes off of T cells, with the programmed death-1 (PD-1), PD-ligand1, and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies.

But we’re clearly learning they are not enough to prevail over cancer with common recurrences, only short term success in most patients, with some notable exceptions. Adding other immune response strategies, such as a vaccine, or antibody-drug conjugates, or engineered T cells, are showing improved chances for success.

Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

There are many therapeutic cancer vaccines in the works, as reviewed in depth here.

Here’s a list of ongoing clinical trials of cancer vaccines. You’ll note most of these are on top of a checkpoint inhibitor and use personalized neoantigens (cancer cell surface proteins) derived from sequencing (whole-exome or whole genome, RNA-sequencing and HLA-profiling) the patient’s tumor.

An example of positive findings is with the combination of an mRNA-nanoparticle vaccine with up to 34 personalized neoantigens and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) vs pembrolizumab alone in advanced melanoma after resection, with improved outcomes at 3-year follow-up, cutting death or relapse rate in half.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADC)

There is considerable excitement about antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) whereby a linker is used to attach a chemotherapy agent to the checkpoint inhibitor antibody, specifically targeting the cancer cell and facilitating entry of the chemotherapy into the cell. Akin to these are bispecific antibodies (BiTEs, binding to a tumor antigen and T cell receptor simultaneously), both of these conjugates acting as “biologic” or “guided” missiles.

A very good example of the potency of an ADC was seen in a “HER2-low” breast cancer randomized trial. The absence or very low expression or amplification of the HER2 receptor is common in breast cancer and successful treatment has been elusive. A randomized trial of an ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan) compared to physician’s choice therapy demonstrated a marked success for progression-free survival in HER2-low patients, which was characterized as “unheard-of success” by media coverage.

This strategy is being used to target some of the most difficult cancer driver mutations such as TP53 and KRAS.

Oncolytic Viruses

Modifying viruses to infect the tumor and make it more visible to the immune system, potentiating anti-tumor responses, known as oncolytic viruses, have been proposed as a way to rev up the immune response for a long time but without positive Phase 3 clinical trials.

After decades of failure, a recent trial in refractory bladder cancer showed marked success, along with others, summarized here, now providing very encouraging results. It looks like oncolytic viruses are on a comeback path.

Engineering T Cells (Chimeric Antigen Receptor [CAR-T])

As I recently reviewed, there are over 500 ongoing clinical trials to build on the success of the first CAR-T approval for leukemia 7 years ago. I won’t go through that all again here, but to reiterate most of the success to date has been in “liquid” blood (leukemia and lymphoma) cancer tumors. This week in Nature is the discovery of a T cell cancer mutation, a gene fusion CARD11-PIK3R3, from a T cell lymphoma that can potentially be used to augment CAR-T efficacy. It has pronounced and prolonged effects in the experimental model. Instead of 1 million cells needed for treatment, even 20,000 were enough to melt the tumor. This is a noteworthy discovery since CAR-T work to date has largely not exploited such naturally occurring mutations, while instead concentrating on those seen in the patient’s set of key tumor mutations.

As currently conceived, CAR-T, and what is being referred to more broadly as adoptive cell therapies, involves removing T cells from the patient’s body and engineering their activation, then reintroducing them back to the patient. This is laborious, technically difficult, and very expensive. Recently, the idea of achieving all of this via an injection of virus that specifically infects T cells and inserts the genes needed, was advanced by two biotech companies with preclinical results, one in non-human primates.

Gearing up to meet the challenge of solid tumor CAR-T intervention, there’s more work using CRISPR genome editing of T cell receptors. A.I. is increasingly being exploited to process the data from sequencing and identify optimal neoantigens.

Instead of just CAR-T, we’re seeing the emergence of CAR-macrophage and CAR-natural killer (NK) cells strategies, and rapidly expanding potential combinations of all the strategies I’ve mentioned. No less, there’s been maturation of on-off suicide switches programmed in, to limit cytokine release and promote safety of these interventions. Overall, major side effects of immunotherapies are not only cytokine release syndromes, but also include interstitial pneumonitis and neurotoxicity.

Summary

Given the multitude of ways cancer cells and tumor tissue can evade our immune response, durably successful treatment remains a daunting challenge. But the ingenuity of so many different approaches to unleash our immune response, and their combinations, provides considerable hope that we’ll increasingly meet the challenge in the years ahead. We have clearly learned that combining different immunotherapy strategies will be essential for many patients with the most resilient solid tumors.

Of concern, as noted by a recent editorial in The Lancet, entitled “Cancer Research Equity: Innovations For The Many, Not The Few,” is that these individualized, sophisticated strategies are not scalable; they will have limited reach and benefit. The movement towards “off the shelf” CAR-T and inexpensive, orally active checkpoint inhibitors may help mitigate this issue.

Notwithstanding this important concern, we’re seeing an array of diverse and potent immunotherapy strategies that are providing highly encouraging results, engendering more excitement than we’ve seen in this space for some time. These should propel substantial improvements in outcomes for patients in the years ahead. It can’t happen soon enough.

Thanks for reading this edition of Ground Truths. If you found it informative, please share it with your colleagues.

Dr. Topol has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Dexcom; Illumina; Molecular Stethoscope; Quest Diagnostics; Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Received research grant from National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was originally published on February 10 in Eric Topol’s substack “Ground Truths.”

It’s astounding how devious cancer cells and tumor tissue can be. This week in Science we learned how certain lung cancer cells can function like “Catch Me If You Can” — changing their driver mutation and cell identity to escape targeted therapy. This histologic transformation, as seen in an experimental model, is just one of so many cancer tricks that we are learning about.

Recently, as shown by single-cell sequencing, cancer cells can steal the mitochondria from T cells, a double whammy that turbocharges cancer cells with the hijacked fuel supply and, at the same time, dismantles the immune response.

Last week, we saw how tumor cells can release a virus-like protein that unleashes a vicious autoimmune response.

And then there’s the finding that cancer cell spread predominantly is occurring while we sleep.

As I previously reviewed, the ability for cancer cells to hijack neurons and neural circuits is now well established, no less their ability to reprogram neurons to become adrenergic and stimulate tumor progression, and interfere with the immune response. Stay tuned on that for a new Ground Truths podcast with Prof Michelle Monje, a leader in cancer neuroscience, which will post soon.

Add advancing age’s immunosenescence as yet another challenge to the long and growing list of formidable ways that cancer cells, and the tumor microenvironment, evade our immune response.

An Ever-Expanding Armamentarium

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

The field of immunotherapies took off with the immune checkpoint inhibitors, first approved by the FDA in 2011, that take the brakes off of T cells, with the programmed death-1 (PD-1), PD-ligand1, and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies.

But we’re clearly learning they are not enough to prevail over cancer with common recurrences, only short term success in most patients, with some notable exceptions. Adding other immune response strategies, such as a vaccine, or antibody-drug conjugates, or engineered T cells, are showing improved chances for success.

Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

There are many therapeutic cancer vaccines in the works, as reviewed in depth here.

Here’s a list of ongoing clinical trials of cancer vaccines. You’ll note most of these are on top of a checkpoint inhibitor and use personalized neoantigens (cancer cell surface proteins) derived from sequencing (whole-exome or whole genome, RNA-sequencing and HLA-profiling) the patient’s tumor.

An example of positive findings is with the combination of an mRNA-nanoparticle vaccine with up to 34 personalized neoantigens and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) vs pembrolizumab alone in advanced melanoma after resection, with improved outcomes at 3-year follow-up, cutting death or relapse rate in half.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADC)

There is considerable excitement about antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) whereby a linker is used to attach a chemotherapy agent to the checkpoint inhibitor antibody, specifically targeting the cancer cell and facilitating entry of the chemotherapy into the cell. Akin to these are bispecific antibodies (BiTEs, binding to a tumor antigen and T cell receptor simultaneously), both of these conjugates acting as “biologic” or “guided” missiles.

A very good example of the potency of an ADC was seen in a “HER2-low” breast cancer randomized trial. The absence or very low expression or amplification of the HER2 receptor is common in breast cancer and successful treatment has been elusive. A randomized trial of an ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan) compared to physician’s choice therapy demonstrated a marked success for progression-free survival in HER2-low patients, which was characterized as “unheard-of success” by media coverage.

This strategy is being used to target some of the most difficult cancer driver mutations such as TP53 and KRAS.

Oncolytic Viruses

Modifying viruses to infect the tumor and make it more visible to the immune system, potentiating anti-tumor responses, known as oncolytic viruses, have been proposed as a way to rev up the immune response for a long time but without positive Phase 3 clinical trials.

After decades of failure, a recent trial in refractory bladder cancer showed marked success, along with others, summarized here, now providing very encouraging results. It looks like oncolytic viruses are on a comeback path.

Engineering T Cells (Chimeric Antigen Receptor [CAR-T])

As I recently reviewed, there are over 500 ongoing clinical trials to build on the success of the first CAR-T approval for leukemia 7 years ago. I won’t go through that all again here, but to reiterate most of the success to date has been in “liquid” blood (leukemia and lymphoma) cancer tumors. This week in Nature is the discovery of a T cell cancer mutation, a gene fusion CARD11-PIK3R3, from a T cell lymphoma that can potentially be used to augment CAR-T efficacy. It has pronounced and prolonged effects in the experimental model. Instead of 1 million cells needed for treatment, even 20,000 were enough to melt the tumor. This is a noteworthy discovery since CAR-T work to date has largely not exploited such naturally occurring mutations, while instead concentrating on those seen in the patient’s set of key tumor mutations.

As currently conceived, CAR-T, and what is being referred to more broadly as adoptive cell therapies, involves removing T cells from the patient’s body and engineering their activation, then reintroducing them back to the patient. This is laborious, technically difficult, and very expensive. Recently, the idea of achieving all of this via an injection of virus that specifically infects T cells and inserts the genes needed, was advanced by two biotech companies with preclinical results, one in non-human primates.

Gearing up to meet the challenge of solid tumor CAR-T intervention, there’s more work using CRISPR genome editing of T cell receptors. A.I. is increasingly being exploited to process the data from sequencing and identify optimal neoantigens.

Instead of just CAR-T, we’re seeing the emergence of CAR-macrophage and CAR-natural killer (NK) cells strategies, and rapidly expanding potential combinations of all the strategies I’ve mentioned. No less, there’s been maturation of on-off suicide switches programmed in, to limit cytokine release and promote safety of these interventions. Overall, major side effects of immunotherapies are not only cytokine release syndromes, but also include interstitial pneumonitis and neurotoxicity.

Summary

Given the multitude of ways cancer cells and tumor tissue can evade our immune response, durably successful treatment remains a daunting challenge. But the ingenuity of so many different approaches to unleash our immune response, and their combinations, provides considerable hope that we’ll increasingly meet the challenge in the years ahead. We have clearly learned that combining different immunotherapy strategies will be essential for many patients with the most resilient solid tumors.

Of concern, as noted by a recent editorial in The Lancet, entitled “Cancer Research Equity: Innovations For The Many, Not The Few,” is that these individualized, sophisticated strategies are not scalable; they will have limited reach and benefit. The movement towards “off the shelf” CAR-T and inexpensive, orally active checkpoint inhibitors may help mitigate this issue.

Notwithstanding this important concern, we’re seeing an array of diverse and potent immunotherapy strategies that are providing highly encouraging results, engendering more excitement than we’ve seen in this space for some time. These should propel substantial improvements in outcomes for patients in the years ahead. It can’t happen soon enough.

Thanks for reading this edition of Ground Truths. If you found it informative, please share it with your colleagues.

Dr. Topol has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Dexcom; Illumina; Molecular Stethoscope; Quest Diagnostics; Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Received research grant from National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was originally published on February 10 in Eric Topol’s substack “Ground Truths.”

It’s astounding how devious cancer cells and tumor tissue can be. This week in Science we learned how certain lung cancer cells can function like “Catch Me If You Can” — changing their driver mutation and cell identity to escape targeted therapy. This histologic transformation, as seen in an experimental model, is just one of so many cancer tricks that we are learning about.

Recently, as shown by single-cell sequencing, cancer cells can steal the mitochondria from T cells, a double whammy that turbocharges cancer cells with the hijacked fuel supply and, at the same time, dismantles the immune response.

Last week, we saw how tumor cells can release a virus-like protein that unleashes a vicious autoimmune response.

And then there’s the finding that cancer cell spread predominantly is occurring while we sleep.

As I previously reviewed, the ability for cancer cells to hijack neurons and neural circuits is now well established, no less their ability to reprogram neurons to become adrenergic and stimulate tumor progression, and interfere with the immune response. Stay tuned on that for a new Ground Truths podcast with Prof Michelle Monje, a leader in cancer neuroscience, which will post soon.

Add advancing age’s immunosenescence as yet another challenge to the long and growing list of formidable ways that cancer cells, and the tumor microenvironment, evade our immune response.

An Ever-Expanding Armamentarium

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

The field of immunotherapies took off with the immune checkpoint inhibitors, first approved by the FDA in 2011, that take the brakes off of T cells, with the programmed death-1 (PD-1), PD-ligand1, and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies.

But we’re clearly learning they are not enough to prevail over cancer with common recurrences, only short term success in most patients, with some notable exceptions. Adding other immune response strategies, such as a vaccine, or antibody-drug conjugates, or engineered T cells, are showing improved chances for success.

Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

There are many therapeutic cancer vaccines in the works, as reviewed in depth here.

Here’s a list of ongoing clinical trials of cancer vaccines. You’ll note most of these are on top of a checkpoint inhibitor and use personalized neoantigens (cancer cell surface proteins) derived from sequencing (whole-exome or whole genome, RNA-sequencing and HLA-profiling) the patient’s tumor.

An example of positive findings is with the combination of an mRNA-nanoparticle vaccine with up to 34 personalized neoantigens and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) vs pembrolizumab alone in advanced melanoma after resection, with improved outcomes at 3-year follow-up, cutting death or relapse rate in half.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADC)

There is considerable excitement about antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) whereby a linker is used to attach a chemotherapy agent to the checkpoint inhibitor antibody, specifically targeting the cancer cell and facilitating entry of the chemotherapy into the cell. Akin to these are bispecific antibodies (BiTEs, binding to a tumor antigen and T cell receptor simultaneously), both of these conjugates acting as “biologic” or “guided” missiles.

A very good example of the potency of an ADC was seen in a “HER2-low” breast cancer randomized trial. The absence or very low expression or amplification of the HER2 receptor is common in breast cancer and successful treatment has been elusive. A randomized trial of an ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan) compared to physician’s choice therapy demonstrated a marked success for progression-free survival in HER2-low patients, which was characterized as “unheard-of success” by media coverage.

This strategy is being used to target some of the most difficult cancer driver mutations such as TP53 and KRAS.

Oncolytic Viruses

Modifying viruses to infect the tumor and make it more visible to the immune system, potentiating anti-tumor responses, known as oncolytic viruses, have been proposed as a way to rev up the immune response for a long time but without positive Phase 3 clinical trials.

After decades of failure, a recent trial in refractory bladder cancer showed marked success, along with others, summarized here, now providing very encouraging results. It looks like oncolytic viruses are on a comeback path.

Engineering T Cells (Chimeric Antigen Receptor [CAR-T])

As I recently reviewed, there are over 500 ongoing clinical trials to build on the success of the first CAR-T approval for leukemia 7 years ago. I won’t go through that all again here, but to reiterate most of the success to date has been in “liquid” blood (leukemia and lymphoma) cancer tumors. This week in Nature is the discovery of a T cell cancer mutation, a gene fusion CARD11-PIK3R3, from a T cell lymphoma that can potentially be used to augment CAR-T efficacy. It has pronounced and prolonged effects in the experimental model. Instead of 1 million cells needed for treatment, even 20,000 were enough to melt the tumor. This is a noteworthy discovery since CAR-T work to date has largely not exploited such naturally occurring mutations, while instead concentrating on those seen in the patient’s set of key tumor mutations.

As currently conceived, CAR-T, and what is being referred to more broadly as adoptive cell therapies, involves removing T cells from the patient’s body and engineering their activation, then reintroducing them back to the patient. This is laborious, technically difficult, and very expensive. Recently, the idea of achieving all of this via an injection of virus that specifically infects T cells and inserts the genes needed, was advanced by two biotech companies with preclinical results, one in non-human primates.

Gearing up to meet the challenge of solid tumor CAR-T intervention, there’s more work using CRISPR genome editing of T cell receptors. A.I. is increasingly being exploited to process the data from sequencing and identify optimal neoantigens.

Instead of just CAR-T, we’re seeing the emergence of CAR-macrophage and CAR-natural killer (NK) cells strategies, and rapidly expanding potential combinations of all the strategies I’ve mentioned. No less, there’s been maturation of on-off suicide switches programmed in, to limit cytokine release and promote safety of these interventions. Overall, major side effects of immunotherapies are not only cytokine release syndromes, but also include interstitial pneumonitis and neurotoxicity.

Summary

Given the multitude of ways cancer cells and tumor tissue can evade our immune response, durably successful treatment remains a daunting challenge. But the ingenuity of so many different approaches to unleash our immune response, and their combinations, provides considerable hope that we’ll increasingly meet the challenge in the years ahead. We have clearly learned that combining different immunotherapy strategies will be essential for many patients with the most resilient solid tumors.

Of concern, as noted by a recent editorial in The Lancet, entitled “Cancer Research Equity: Innovations For The Many, Not The Few,” is that these individualized, sophisticated strategies are not scalable; they will have limited reach and benefit. The movement towards “off the shelf” CAR-T and inexpensive, orally active checkpoint inhibitors may help mitigate this issue.

Notwithstanding this important concern, we’re seeing an array of diverse and potent immunotherapy strategies that are providing highly encouraging results, engendering more excitement than we’ve seen in this space for some time. These should propel substantial improvements in outcomes for patients in the years ahead. It can’t happen soon enough.

Thanks for reading this edition of Ground Truths. If you found it informative, please share it with your colleagues.

Dr. Topol has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Dexcom; Illumina; Molecular Stethoscope; Quest Diagnostics; Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Received research grant from National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How the microbiome influences the success of cancer therapy

HAMBURG, Germany — The human microbiome comprises 39 to 44 billion microbes. That is ten times more than the number of cells in our body. Hendrik Poeck, MD, managing senior physician of internal medicine at the University Hospital Regensburg, illustrated this point at the annual meeting of the German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology. If the gut microbiome falls out of balance, then “intestinal dysbiosis potentially poses a risk for the pathogenesis of local and systemic diseases,” explained Dr. Poeck.

Cancers and their therapies can also be influenced in this way. said Dr. Poeck.

Microbial diversity could be beneficial for cancer therapy, too. The composition of the microbiome varies significantly from host to host and can mutate. These properties make it a target for precision microbiotics, which involves using the gut microbiome as a biomarker to predict various physical reactions and to develop individualized diets.

Microbiome and Pathogenesis

The body’s microbiome fulfills a barrier function, especially where the body is exposed to an external environment: at the epidermis and the internal mucous membranes, in the gastrointestinal tract, and in the lungs, chest, and urogenital system.

Association studies on humans and experimental manipulations on mouse models of cancer showed that certain microorganisms can have either protective or harmful effects on cancer development, on the progression of a malignant disease, and on the response to therapy.

A Master Regulator?

Disruptions of the microbial system in the gut, as occur during antibiotic therapy, can have significant effects on a patient’s response to immunotherapy. Taking antibiotics shortly before or after starting therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) significantly affected both overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), as reported in a recent review and meta-analysis, for example.

Proton pump inhibitors also affect the gut microbiome and reduce the response to immunotherapy; this effect was demonstrated by an analysis of data from more than 2700 cancer patients that was recently presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO).

The extent to which the gut microbiome influences the efficacy of an ICI or predicts said efficacy was examined in a retrospective analysis published in Science in 2018, which Dr. Poeck presented. Resistance to ICI correlated with the relative frequency of the bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila in the gut of patients with cancer. In mouse models, the researchers restored the efficacy of the PD-1 blockade through a stool transplant.

Predicting Immunotherapy Response

If A muciniphila is present, can the composition of the microbiome act as a predictor for an effective ICI therapy?

Laurence Zitvogel, MD, PhD, and her working group at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research in Villejuif, France, performed a prospective study in 338 patients with non–small cell lung cancer and examined the prognostic significance of the fecal bacteria A muciniphila (Akk). The “Akkerman status” (low Akk vs high Akk) in a patient’s stool correlated with an increased objective response rate and a longer OS, independently of PD-L1 expression, antibiotics, and performance status. The OS for low Akk was 13.4 months, vs 18.8 months for high Akk in first-line treatment.

These results are promising, said Dr. Poeck. But there is no one-size-fits-all solution. No conclusions can be drawn from one bacterium on the efficacy of therapies in humans, since “the entirety of the bacteria is decisive,” said Dr. Poeck. In addition to the gut microbiome, the composition of gut metabolites influences the response to immunotherapies, as shown in a study with ICI.

Therapeutic Interventions

One possible therapeutic intervention to restore the gut microbiome is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). In a phase 1 study presented by Dr. Poeck, FMT was effective in the treatment of 20 patients with melanoma with ICI in an advanced and treatment-naive stage. Seven days after the patients received FMT, the first cycle with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was initiated, with a total administration of three to four cycles. After 12 weeks, most patients were in complete or partial remission, as evidenced on imaging.

However, FMT also carries some risks. Two cases of sepsis with multiresistant Escherichia coli occurred, as well as other serious infections. Since then, there has been an FDA condition for extended screening of the donor stool, said Dr. Poeck. Nevertheless, this intervention is promising. A search of the keywords “FMT in cancer/transplant setting” reveals 46 currently clinical studies on clinicaltrials.gov.

Nutritional Interventions

Dr. Poeck advises caution about over-the-counter products. These products usually contain only a few species, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. “Over-the-counter probiotics can even delay the reconstitution of the microbiome after antibiotics,” said Dr. Poeck, according to a study. In some studies, the response rates were significantly lower after probiotic intake or led to controversial results, according to Dr. Poeck.

In contrast, Dr. Poeck said prebiotics (that is, a fiber-rich diet with indigestible carbohydrates) were promising. During digestion, prebiotics are split into short-chain fatty acids by bacterial enzymes and promote the growth of certain microbiota.

In this way, just 20 g of extremely fiber-rich food had a significant effect on PFS in 128 patients with melanoma undergoing anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. With 20 g of fiber-rich food per day, the PFS was stable over 60 months. The most significant benefit was observed in patients with a sufficient fiber intake who were not taking probiotics.

What to Recommend?

In summary, Dr. Poeck said that it is important to “budget” well, particularly with antibiotic administration, and to strive for calculated therapy with as narrow a spectrum as possible. For patients who experience complications such as cytokine release syndrome as a reaction to cell therapy, delaying the use of antibiotics is important. However, it is often difficult to differentiate this syndrome from neutropenic fever. The aim should be to avoid high-risk antibiotics, if clinically justifiable. Patients should avoid taking antibiotics for 30 days before starting immunotherapy.

Regarding nutritional interventions, Dr. Poeck referred to the recent Onkopedia recommendation for nutrition after cancer and the 10 nutritional rules of the German Nutrition Society. According to Dr. Poeck, the important aspects of these recommendations are a fiber-rich diet (> 20 g/d) from various plant products and avoiding artificial sweeteners and flavorings, as well as ultraprocessed (convenience) foods. In addition, meat should be consumed only in moderation, and as little processed meat as possible should be consumed. In addition, regular (aerobic and anaerobic) physical activity is important.

“Looking ahead into the future,” said Dr. Poeck, “we need a uniform and functional understanding and we need a randomized prediction for diagnosis.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

HAMBURG, Germany — The human microbiome comprises 39 to 44 billion microbes. That is ten times more than the number of cells in our body. Hendrik Poeck, MD, managing senior physician of internal medicine at the University Hospital Regensburg, illustrated this point at the annual meeting of the German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology. If the gut microbiome falls out of balance, then “intestinal dysbiosis potentially poses a risk for the pathogenesis of local and systemic diseases,” explained Dr. Poeck.

Cancers and their therapies can also be influenced in this way. said Dr. Poeck.

Microbial diversity could be beneficial for cancer therapy, too. The composition of the microbiome varies significantly from host to host and can mutate. These properties make it a target for precision microbiotics, which involves using the gut microbiome as a biomarker to predict various physical reactions and to develop individualized diets.

Microbiome and Pathogenesis

The body’s microbiome fulfills a barrier function, especially where the body is exposed to an external environment: at the epidermis and the internal mucous membranes, in the gastrointestinal tract, and in the lungs, chest, and urogenital system.

Association studies on humans and experimental manipulations on mouse models of cancer showed that certain microorganisms can have either protective or harmful effects on cancer development, on the progression of a malignant disease, and on the response to therapy.

A Master Regulator?

Disruptions of the microbial system in the gut, as occur during antibiotic therapy, can have significant effects on a patient’s response to immunotherapy. Taking antibiotics shortly before or after starting therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) significantly affected both overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), as reported in a recent review and meta-analysis, for example.

Proton pump inhibitors also affect the gut microbiome and reduce the response to immunotherapy; this effect was demonstrated by an analysis of data from more than 2700 cancer patients that was recently presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO).

The extent to which the gut microbiome influences the efficacy of an ICI or predicts said efficacy was examined in a retrospective analysis published in Science in 2018, which Dr. Poeck presented. Resistance to ICI correlated with the relative frequency of the bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila in the gut of patients with cancer. In mouse models, the researchers restored the efficacy of the PD-1 blockade through a stool transplant.

Predicting Immunotherapy Response

If A muciniphila is present, can the composition of the microbiome act as a predictor for an effective ICI therapy?

Laurence Zitvogel, MD, PhD, and her working group at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research in Villejuif, France, performed a prospective study in 338 patients with non–small cell lung cancer and examined the prognostic significance of the fecal bacteria A muciniphila (Akk). The “Akkerman status” (low Akk vs high Akk) in a patient’s stool correlated with an increased objective response rate and a longer OS, independently of PD-L1 expression, antibiotics, and performance status. The OS for low Akk was 13.4 months, vs 18.8 months for high Akk in first-line treatment.

These results are promising, said Dr. Poeck. But there is no one-size-fits-all solution. No conclusions can be drawn from one bacterium on the efficacy of therapies in humans, since “the entirety of the bacteria is decisive,” said Dr. Poeck. In addition to the gut microbiome, the composition of gut metabolites influences the response to immunotherapies, as shown in a study with ICI.

Therapeutic Interventions

One possible therapeutic intervention to restore the gut microbiome is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). In a phase 1 study presented by Dr. Poeck, FMT was effective in the treatment of 20 patients with melanoma with ICI in an advanced and treatment-naive stage. Seven days after the patients received FMT, the first cycle with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was initiated, with a total administration of three to four cycles. After 12 weeks, most patients were in complete or partial remission, as evidenced on imaging.

However, FMT also carries some risks. Two cases of sepsis with multiresistant Escherichia coli occurred, as well as other serious infections. Since then, there has been an FDA condition for extended screening of the donor stool, said Dr. Poeck. Nevertheless, this intervention is promising. A search of the keywords “FMT in cancer/transplant setting” reveals 46 currently clinical studies on clinicaltrials.gov.

Nutritional Interventions

Dr. Poeck advises caution about over-the-counter products. These products usually contain only a few species, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. “Over-the-counter probiotics can even delay the reconstitution of the microbiome after antibiotics,” said Dr. Poeck, according to a study. In some studies, the response rates were significantly lower after probiotic intake or led to controversial results, according to Dr. Poeck.

In contrast, Dr. Poeck said prebiotics (that is, a fiber-rich diet with indigestible carbohydrates) were promising. During digestion, prebiotics are split into short-chain fatty acids by bacterial enzymes and promote the growth of certain microbiota.

In this way, just 20 g of extremely fiber-rich food had a significant effect on PFS in 128 patients with melanoma undergoing anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. With 20 g of fiber-rich food per day, the PFS was stable over 60 months. The most significant benefit was observed in patients with a sufficient fiber intake who were not taking probiotics.

What to Recommend?

In summary, Dr. Poeck said that it is important to “budget” well, particularly with antibiotic administration, and to strive for calculated therapy with as narrow a spectrum as possible. For patients who experience complications such as cytokine release syndrome as a reaction to cell therapy, delaying the use of antibiotics is important. However, it is often difficult to differentiate this syndrome from neutropenic fever. The aim should be to avoid high-risk antibiotics, if clinically justifiable. Patients should avoid taking antibiotics for 30 days before starting immunotherapy.

Regarding nutritional interventions, Dr. Poeck referred to the recent Onkopedia recommendation for nutrition after cancer and the 10 nutritional rules of the German Nutrition Society. According to Dr. Poeck, the important aspects of these recommendations are a fiber-rich diet (> 20 g/d) from various plant products and avoiding artificial sweeteners and flavorings, as well as ultraprocessed (convenience) foods. In addition, meat should be consumed only in moderation, and as little processed meat as possible should be consumed. In addition, regular (aerobic and anaerobic) physical activity is important.

“Looking ahead into the future,” said Dr. Poeck, “we need a uniform and functional understanding and we need a randomized prediction for diagnosis.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

HAMBURG, Germany — The human microbiome comprises 39 to 44 billion microbes. That is ten times more than the number of cells in our body. Hendrik Poeck, MD, managing senior physician of internal medicine at the University Hospital Regensburg, illustrated this point at the annual meeting of the German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology. If the gut microbiome falls out of balance, then “intestinal dysbiosis potentially poses a risk for the pathogenesis of local and systemic diseases,” explained Dr. Poeck.

Cancers and their therapies can also be influenced in this way. said Dr. Poeck.

Microbial diversity could be beneficial for cancer therapy, too. The composition of the microbiome varies significantly from host to host and can mutate. These properties make it a target for precision microbiotics, which involves using the gut microbiome as a biomarker to predict various physical reactions and to develop individualized diets.

Microbiome and Pathogenesis

The body’s microbiome fulfills a barrier function, especially where the body is exposed to an external environment: at the epidermis and the internal mucous membranes, in the gastrointestinal tract, and in the lungs, chest, and urogenital system.

Association studies on humans and experimental manipulations on mouse models of cancer showed that certain microorganisms can have either protective or harmful effects on cancer development, on the progression of a malignant disease, and on the response to therapy.

A Master Regulator?

Disruptions of the microbial system in the gut, as occur during antibiotic therapy, can have significant effects on a patient’s response to immunotherapy. Taking antibiotics shortly before or after starting therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) significantly affected both overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), as reported in a recent review and meta-analysis, for example.

Proton pump inhibitors also affect the gut microbiome and reduce the response to immunotherapy; this effect was demonstrated by an analysis of data from more than 2700 cancer patients that was recently presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO).

The extent to which the gut microbiome influences the efficacy of an ICI or predicts said efficacy was examined in a retrospective analysis published in Science in 2018, which Dr. Poeck presented. Resistance to ICI correlated with the relative frequency of the bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila in the gut of patients with cancer. In mouse models, the researchers restored the efficacy of the PD-1 blockade through a stool transplant.

Predicting Immunotherapy Response

If A muciniphila is present, can the composition of the microbiome act as a predictor for an effective ICI therapy?

Laurence Zitvogel, MD, PhD, and her working group at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research in Villejuif, France, performed a prospective study in 338 patients with non–small cell lung cancer and examined the prognostic significance of the fecal bacteria A muciniphila (Akk). The “Akkerman status” (low Akk vs high Akk) in a patient’s stool correlated with an increased objective response rate and a longer OS, independently of PD-L1 expression, antibiotics, and performance status. The OS for low Akk was 13.4 months, vs 18.8 months for high Akk in first-line treatment.

These results are promising, said Dr. Poeck. But there is no one-size-fits-all solution. No conclusions can be drawn from one bacterium on the efficacy of therapies in humans, since “the entirety of the bacteria is decisive,” said Dr. Poeck. In addition to the gut microbiome, the composition of gut metabolites influences the response to immunotherapies, as shown in a study with ICI.

Therapeutic Interventions

One possible therapeutic intervention to restore the gut microbiome is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). In a phase 1 study presented by Dr. Poeck, FMT was effective in the treatment of 20 patients with melanoma with ICI in an advanced and treatment-naive stage. Seven days after the patients received FMT, the first cycle with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was initiated, with a total administration of three to four cycles. After 12 weeks, most patients were in complete or partial remission, as evidenced on imaging.

However, FMT also carries some risks. Two cases of sepsis with multiresistant Escherichia coli occurred, as well as other serious infections. Since then, there has been an FDA condition for extended screening of the donor stool, said Dr. Poeck. Nevertheless, this intervention is promising. A search of the keywords “FMT in cancer/transplant setting” reveals 46 currently clinical studies on clinicaltrials.gov.

Nutritional Interventions

Dr. Poeck advises caution about over-the-counter products. These products usually contain only a few species, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. “Over-the-counter probiotics can even delay the reconstitution of the microbiome after antibiotics,” said Dr. Poeck, according to a study. In some studies, the response rates were significantly lower after probiotic intake or led to controversial results, according to Dr. Poeck.

In contrast, Dr. Poeck said prebiotics (that is, a fiber-rich diet with indigestible carbohydrates) were promising. During digestion, prebiotics are split into short-chain fatty acids by bacterial enzymes and promote the growth of certain microbiota.

In this way, just 20 g of extremely fiber-rich food had a significant effect on PFS in 128 patients with melanoma undergoing anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. With 20 g of fiber-rich food per day, the PFS was stable over 60 months. The most significant benefit was observed in patients with a sufficient fiber intake who were not taking probiotics.

What to Recommend?

In summary, Dr. Poeck said that it is important to “budget” well, particularly with antibiotic administration, and to strive for calculated therapy with as narrow a spectrum as possible. For patients who experience complications such as cytokine release syndrome as a reaction to cell therapy, delaying the use of antibiotics is important. However, it is often difficult to differentiate this syndrome from neutropenic fever. The aim should be to avoid high-risk antibiotics, if clinically justifiable. Patients should avoid taking antibiotics for 30 days before starting immunotherapy.

Regarding nutritional interventions, Dr. Poeck referred to the recent Onkopedia recommendation for nutrition after cancer and the 10 nutritional rules of the German Nutrition Society. According to Dr. Poeck, the important aspects of these recommendations are a fiber-rich diet (> 20 g/d) from various plant products and avoiding artificial sweeteners and flavorings, as well as ultraprocessed (convenience) foods. In addition, meat should be consumed only in moderation, and as little processed meat as possible should be consumed. In addition, regular (aerobic and anaerobic) physical activity is important.

“Looking ahead into the future,” said Dr. Poeck, “we need a uniform and functional understanding and we need a randomized prediction for diagnosis.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

What We Have Learned About Combining a Ketogenic Diet and Chemoimmunotherapy: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Originally developed for the treatment of refractory epilepsy, the ketogenic diet is distinguished by its high-fat, moderate-protein, and low-carbohydrate food program. Preclinical models provide emerging evidence that a ketogenic diet can have therapeutic potential for a broad range of cancers. The Warburg effect is a condition where cancer cells increase the uptake and fermentation of glucose to produce lactate for their metabolism, which is called aerobic glycolysis. Lactate is the key driver of cancer angiogenesis and proliferation.1,2

The ketogenic diet promotes a metabolic shift from glycolysis to mitochondrial metabolism in normal cells while cancer cells have dysfunction in their mitochondria due to damage in cellular respiration. The ketogenic diet creates a metabolic state whereby blood glucose levels are reduced, and blood ketone bodies (D-β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate) are elevated. In normal cells, the ketogenic diet causes a decrease in glucose intake for glycolysis, which makes them unable to produce enough substrate to enter the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. Fatty acid oxidation plays a key role in ketone body synthesis as a “super fuel” that enter the TCA cycle as an alternative pathway to generate ATP. On the other hand, cancer cells are unable to use ketone bodies to produce ATP for energy and metabolism due to mitochondrial defects. Lack of energy subsequently leads to the inhibition of proliferation and survival of cancer cells.3,4

We previously published a safety and feasibility study of the Modified Atkins Diet in metastatic cancer patients after failure of chemotherapy at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pittsburgh Healthcare System.1 None of the patients were on chemotherapy at the time of enrollment. The Modified Atkins Diet consists of 60% fat, 30% protein, and 10% carbohydrates and is more tolerable than the ketogenic diet due to higher amounts of protein. Six of 11 patients (54%) had stable disease and partial response on positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). Our study showed that patients who lost at least 10% of their body weight had improvement in quality of life (QOL) and cancer response.1 Here we present a case of a veteran with extensive metastatic colon cancer on concurrent ketogenic diet and chemotherapy subsequently followed by concurrent ketogenic diet and immunotherapy at Veterans Affairs Central California Health Care Systems (VACCHCS) in Fresno.

CASE PRESENTATION

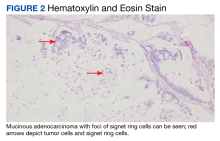

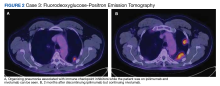

A 69-year-old veteran had iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL) about 5 years previously. He underwent a colonoscopy that revealed a near circumferential ulcerated mass measuring 7 cm in the transverse colon. Biopsy results showed mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon with a foci of signet ring cells (Figure 2).

The patient received adjuvant treatment with FOLFOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, and oxaliplatin), but within several months he developed pancreatic and worsening omental metastasis seen on PET/CT. He was then started on FOLFIRI (fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, and irinotecan hydrochloride) plus bevacizumab 16 months after his initial diagnosis. He underwent a pancreatic mastectomy that confirmed adenocarcinoma 9 months later. Afterward, he briefly resumed FOLFIRI and bevacizumab. Next-generation sequencing testing with Foundation One CDx revealed a wild-type (WT) KRAS with a high degree of tumor mutation burden of 37 muts/Mb, BRAF V600E mutation, and high microsatellite instability (MSI-H).

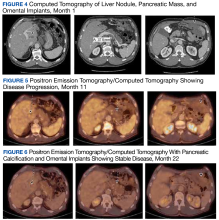

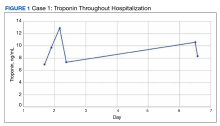

Due to disease progression, the patient’s treatment was changed to encorafenib and cetuximab for 4 months before progressing again with new liver mass and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. He then received pembrolizumab for 4 months until PET/CT showed progression and his carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) increased from 95 to 1031 ng/mL by January 2021 (Figure 4).

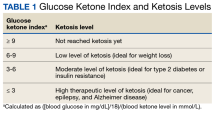

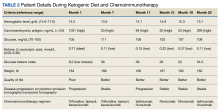

The patient was started on trifluridine/tipiracil, and bevacizumab while concurrently initiating the ketogenic diet in January 2021. Laboratory tests drawn after 1 week of strict dietary ketogenic diet adherence showed low-level ketosis with a glucose ketone index (GKI) of 8.2 (Table 1).

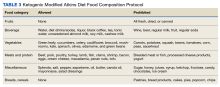

A follow-up PET/CT showed disease progression along with a CEA of 94 ng/mL after 10 months of chemotherapy plus the ketogenic diet (Table 2).

The patient continued to experience excellent QOL based on the QOL Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) core quality of life questionnaire (QLC-C30) forms, which he completed every 3 months. Twenty-two months after starting the ketogenic diet, the patient’s CEA increased to 293 ng/mL although PET/CT continues to show stable disease (Figures 4, 5, and 6).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this case report is to describe whether a patient receiving active cancer treatment was able to tolerate the ketogenic diet in conjunction with chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Most literature published on the subject evaluated the tolerability and response of the ketogenic diet after the failure of standard therapy. Our patient was diagnosed with stage III mucinous colon adenocarcinoma. He received adjuvant chemotherapy but quickly developed metastatic disease to the pancreas and omentum. We started him on encorafenib and cetuximab based on the BEACON study that showed improvement in response rate and survival when compared with standard chemotherapy for patients with BRAF V600E mutation.5 Unfortunately, his cancer quickly progressed within 4 months and again did not respond to pembrolizumab despite MSI-H, which lasted for another 4 months.

We suggested the ketogenic diet and the patient agreed. He started the diet along with trifluridine/tipiracil, and bevacizumab in January 2021. The patient’s metastatic cancer stabilized for 9 months until his disease progressed again. He was started on doublet immune checkpoint inhibitors ipilimumab and nivolumab based on his MSI-H and high tumor mutation burden with the continuation of the ketogenic diet until now. The CheckMate 142 study revealed that the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with MSI-H previously treated for metastatic colon cancer showed some benefit.6

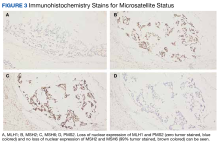

Our patient had the loss of nuclear expression of MLH1 and PMS2 (zero tumor stained) but no evidence of the loss expression of MSH2 and MSH6 genes (99% tumor stained). About 8% to 12% of patients with metastatic colon cancer have BRAF V600E mutations that are usually mucinous type, poorly differentiated, and located in the right side of the colon, which portends to a poor prognosis. Tumor DNA mismatch repair damage results in genetic hypermutability and leads to MSI that is sensitive to treatment with checkpoint inhibitors, as in our patient. Only about 3% of MSI-H tumors are due to germline mutations such as Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer). The presence of both MLH1 hypermethylation and BRAF mutation, as in our patient, is a strong indication of somatic rather than germline mutation.7

GKI, which represents the ratio of glucose to ketone, was developed to evaluate the efficacy of the ketogenic diet. This index measures the degree of metabolic stress on tumor cells through the decrease of glucose levels and increase of ketone bodies. A GKI of ≤ 1.0 has been suggested as the ideal therapeutic goal for cancer management.8 As levels of blood glucose decline, the blood levels of ketone bodies should rise. These 2 lines should eventually intersect at a certain point beyond which one enters the therapeutic zone or therapeutic ketosis zone. This is when tumor growth is expected to slow or cease.9 The patient’s ketone (β-hydroxybutyrate) level was initially high (0.71 mmol/L) with a GKI of 8.2. (low ketotic level), which meant he tolerated a rather strict diet for the first several months. This was also reflected in his 18 lb weight loss (almost 10% of body weight) and cancer stabilization, as in our previous publication.1 Unfortunately, the patient was unable to maintain high ketone and lower GKI levels due to fatigue from depleted carbohydrate intake. He added some carbohydrate snacks in between meals, which improved the fatigue. His ketone level has been < 0.5 mmol/L ever since, albeit his disease continues to be stable. The patient continues his daily work and reports a better QOL, based on the ECOG QLC-C30 form that he completed every 3 months.10 Currently, the patient is still receiving ipilimumab and nivolumab while maintaining the ketogenic diet with stable metastatic disease on PET/CT.

Ketogenic Diet and Cellular Mechanism of Action

PI3K/Akt (phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase) signaling is one of the most important intracellular pathways for tumor cells. It leads to the inhibition of apoptosis and the promotion of cell proliferation, metabolism, and angiogenesis. Deregulation of the PI3K pathway either via amplification of PI3K by tyrosine kinase growth factor receptors or inactivation of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is the negative regulator of the PI3K pathway, contributes to the development of cancer cells.11

A study by Goncalves and colleagues revealed an interesting relationship between the PI3K pathway and the benefit of the ketogenic diet to slow tumor growth. PI3K inhibitors inhibit glucose uptake into skeletal muscle and adipose tissue that activate hepatic glycogenolysis. This event results in hyperglycemia due to the pancreas releasing very high levels of insulin into the blood (hyperinsulinemia) that subsequently reactivate PI3K signaling and cause resistance to PI3K inhibitors. The ketogenic diet reportedly minimized the hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia induced by the PI3K inhibitor and enhanced the efficacy of PI3K inhibitors in tumor models. Studies combining PI3K inhibitors and ketogenic diet are underway. Hence, combining the ketogenic diet with chemotherapy or other novel treatment should be the focus of ketogenic diet trials.12,13

Ketogenic Diet and Oncology Studies

The impact of the ketogenic diet on the growth of murine pancreatic tumors was evaluated by Yang and colleagues. The ketogenic diet decreased glucose concentration that enters the TCA cycle and increased fatty acid oxidation that produces β-hydroxybutyrate. This event promotes the generation of ATP, although with only modest elevations of NADH with less impact on tumor growth. The combination of ketogenic diet and standard chemotherapy substantially raised tumor NADH and suppressed the growth of murine tumor cells, they noted.14 Furukawa and colleagues compared 10 patients with metastatic colon cancer receiving chemotherapy plus the modified medium-chain triglyceride ketogenic diet for 1 year with 14 patients receiving chemotherapy only. The ketogenic diet group exhibited a response rate of 60% with 5 patients achieving a complete response and a disease control rate of 70%, while the chemotherapy-alone group showed a response rate of only 21% with no complete response and a disease control rate of 64%.15

The ketogenic diet also reportedly stimulates cytokine and CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell production that stimulates T-cell killing activity. The ketogenic diet may overcome several immune escape mechanisms by downregulating the expression of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.16 Our patient tolerated the combination of the ketogenic diet with ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) and nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) without significant toxicities and stabilization of his disease.

Future Directions

We originally presented the abstract and poster of this case report at the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology annual meeting in San Diego, California, in September 2022.17 Based on our previous experience, we are now using a modified Atkins diet, which is a less strict diet consisting of 60% fat, 30% protein, and 10% carbohydrates combined with chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. The composition of fat to carbohydrate plus protein in the traditional ketogenic diet is usually 4:1 or 3:1, while in modified Atkins diet the ratio is 1:1 or 2:1. The benefit of the modified Atkins diet is that patients can consume more protein than a strict ketogenic diet and they can be more liberal in carbohydrate allowances. We are about to open a study protocol of combining a modified Atkin diet and chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy as a first-line treatment for veterans with all types of advanced or metastatic solid tumors at VACCHCS. The study protocol was approved by the VA Office of Research and Development and has been submitted to the VACCHCS Institutional Review Board for review. Once approved, we will start patient recruitment.

CONCLUSIONS

Cancer cells have defects in their mitochondria that prevent them from generating energy for metabolism in the absence of glucose. They also depend on the PI3K signaling pathway to survive. The ketogenic diet has the advantage of affecting cancer cell growth by exploiting these mitochondrial defects and blocking hyperglycemia. There is growing evidence that the ketogenic diet is feasible, tolerable, and reportedly inhibits cancer growth. Our case report and previous publications suggest that the ketogenic diet can be added to chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy as an adjunct to standard-of-care cancer treatment while maintaining good QOL. We are planning to open a clinical trial using the modified Atkins diet in conjunction with active cancer treatments as first-line therapy for metastatic solid tumors at the VACCHCS. We are also working closely with researchers from several veteran hospitals to do a diet collaborative study. We believe the ketogenic diet is an important part of cancer treatment and has a promising future. More research should be dedicated to this very interesting field.

Acknowledgments

We previously presented this case report in an abstract and poster at the September 2022 AVAHO meeting in San Diego, California.

1. Tan-Shalaby JL, Carrick J, Edinger K, et al. Modified Atkins diet in advanced malignancies-final results of a safety and feasibility trial within the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2016;13:52. Published 2016 Aug 12. doi:10.1186/s12986-016-0113-y

2. Talib WH, Mahmod AI, Kamal A, et al. Ketogenic diet in cancer prevention and therapy: molecular targets and therapeutic opportunities. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2021;43(2):558-589. Published 2021 Jul 3. doi:10.3390/cimb43020042

3. Tan-Shalaby J. Ketogenic diets and cancer: emerging evidence. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 1):37S-42S.

4. Cortez NE, Mackenzie GG. Ketogenic diets in pancreatic cancer and associated cachexia: cellular mechanisms and clinical perspectives. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3202. Published 2021 Sep 15. doi:10.3390/nu13093202

5. Tabernero J, Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, et al. Encorafenib plus cetuximab as a new standard of care for previously treated BRAF V600E-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: updated survival results and subgroup analyses from the BEACON study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(4):273-284. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.02088

6. André T, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, et al. Nivolumab plus low-dose ipilimumab in previously treated patients with microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer: 4-year follow-up from CheckMate 142. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(10):1052-1060. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2022.06.008

7. Grassi E, Corbelli J, Papiani G, Barbera MA, Gazzaneo F, Tamberi S. Current therapeutic strategies in BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:601722. Published 2021 Jun 23. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.601722

8. Seyfried TN, Mukherjee P, Iyikesici MS, et al. Consideration of ketogenic metabolic therapy as a complementary or alternative approach for managing breast cancer. Front Nutr. 2020;7:21. Published 2020 Mar 11. doi:10.3389/fnut.2020.00021

9. Meidenbauer JJ, Mukherjee P, Seyfried TN. The glucose ketone index calculator: a simple tool to monitor therapeutic efficacy for metabolic management of brain cancer. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2015;12:12. Published 2015 Mar 11. doi:10.1186/s12986-015-0009-2

10. Fayers P, Bottomley A; EORTC Quality of Life Group; Quality of Life Unit. Quality of life research within the EORTC-the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(suppl 4):S125-S133. doi:10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00448-8

11. Yang J, Nie J, Ma X, Wei Y, Peng Y, Wei X. Targeting PI3K in cancer: mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):26. Published 2019 Feb 19. doi:10.1186/s12943-019-0954-x

12. Goncalves MD, Hopkins BD, Cantley LC. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, growth disorders, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2052-2062. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1704560

13. Weber DD, Aminzadeh-Gohari S, Tulipan J, Catalano L, Feichtinger RG, Kofler B. Ketogenic diet in the treatment of cancer-where do we stand?. Mol Metab. 2020;33:102-121. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2019.06.026

14. Yang L, TeSlaa T, Ng S, et al. Ketogenic diet and chemotherapy combine to disrupt pancreatic cancer metabolism and growth. Med. 2022;3(2):119-136. doi:10.1016/j.medj.2021.12.008

15. Furukawa K, Shigematus K, Iwase Y, et al. Clinical effects of one year of chemotherapy with a modified medium-chain triglyceride ketogenic diet on the recurrence of stage IV colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl 15):e15709. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e15709

16. Zhang X, Li H, Lv X, et al. Impact of diets on response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) therapy against tumors. Life (Basel). 2022;12(3):409. Published 2022 Mar 11. doi:10.3390/life12030409

17. Liman, A, Hwang A, Means J, Newson J. Ketogenic diet and cancer: a case report and feasibility study at VA Central California Healthcare System. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 4):S18.

Originally developed for the treatment of refractory epilepsy, the ketogenic diet is distinguished by its high-fat, moderate-protein, and low-carbohydrate food program. Preclinical models provide emerging evidence that a ketogenic diet can have therapeutic potential for a broad range of cancers. The Warburg effect is a condition where cancer cells increase the uptake and fermentation of glucose to produce lactate for their metabolism, which is called aerobic glycolysis. Lactate is the key driver of cancer angiogenesis and proliferation.1,2

The ketogenic diet promotes a metabolic shift from glycolysis to mitochondrial metabolism in normal cells while cancer cells have dysfunction in their mitochondria due to damage in cellular respiration. The ketogenic diet creates a metabolic state whereby blood glucose levels are reduced, and blood ketone bodies (D-β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate) are elevated. In normal cells, the ketogenic diet causes a decrease in glucose intake for glycolysis, which makes them unable to produce enough substrate to enter the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. Fatty acid oxidation plays a key role in ketone body synthesis as a “super fuel” that enter the TCA cycle as an alternative pathway to generate ATP. On the other hand, cancer cells are unable to use ketone bodies to produce ATP for energy and metabolism due to mitochondrial defects. Lack of energy subsequently leads to the inhibition of proliferation and survival of cancer cells.3,4

We previously published a safety and feasibility study of the Modified Atkins Diet in metastatic cancer patients after failure of chemotherapy at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pittsburgh Healthcare System.1 None of the patients were on chemotherapy at the time of enrollment. The Modified Atkins Diet consists of 60% fat, 30% protein, and 10% carbohydrates and is more tolerable than the ketogenic diet due to higher amounts of protein. Six of 11 patients (54%) had stable disease and partial response on positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). Our study showed that patients who lost at least 10% of their body weight had improvement in quality of life (QOL) and cancer response.1 Here we present a case of a veteran with extensive metastatic colon cancer on concurrent ketogenic diet and chemotherapy subsequently followed by concurrent ketogenic diet and immunotherapy at Veterans Affairs Central California Health Care Systems (VACCHCS) in Fresno.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 69-year-old veteran had iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL) about 5 years previously. He underwent a colonoscopy that revealed a near circumferential ulcerated mass measuring 7 cm in the transverse colon. Biopsy results showed mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon with a foci of signet ring cells (Figure 2).

The patient received adjuvant treatment with FOLFOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, and oxaliplatin), but within several months he developed pancreatic and worsening omental metastasis seen on PET/CT. He was then started on FOLFIRI (fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, and irinotecan hydrochloride) plus bevacizumab 16 months after his initial diagnosis. He underwent a pancreatic mastectomy that confirmed adenocarcinoma 9 months later. Afterward, he briefly resumed FOLFIRI and bevacizumab. Next-generation sequencing testing with Foundation One CDx revealed a wild-type (WT) KRAS with a high degree of tumor mutation burden of 37 muts/Mb, BRAF V600E mutation, and high microsatellite instability (MSI-H).

Due to disease progression, the patient’s treatment was changed to encorafenib and cetuximab for 4 months before progressing again with new liver mass and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. He then received pembrolizumab for 4 months until PET/CT showed progression and his carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) increased from 95 to 1031 ng/mL by January 2021 (Figure 4).

The patient was started on trifluridine/tipiracil, and bevacizumab while concurrently initiating the ketogenic diet in January 2021. Laboratory tests drawn after 1 week of strict dietary ketogenic diet adherence showed low-level ketosis with a glucose ketone index (GKI) of 8.2 (Table 1).

A follow-up PET/CT showed disease progression along with a CEA of 94 ng/mL after 10 months of chemotherapy plus the ketogenic diet (Table 2).

The patient continued to experience excellent QOL based on the QOL Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) core quality of life questionnaire (QLC-C30) forms, which he completed every 3 months. Twenty-two months after starting the ketogenic diet, the patient’s CEA increased to 293 ng/mL although PET/CT continues to show stable disease (Figures 4, 5, and 6).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this case report is to describe whether a patient receiving active cancer treatment was able to tolerate the ketogenic diet in conjunction with chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Most literature published on the subject evaluated the tolerability and response of the ketogenic diet after the failure of standard therapy. Our patient was diagnosed with stage III mucinous colon adenocarcinoma. He received adjuvant chemotherapy but quickly developed metastatic disease to the pancreas and omentum. We started him on encorafenib and cetuximab based on the BEACON study that showed improvement in response rate and survival when compared with standard chemotherapy for patients with BRAF V600E mutation.5 Unfortunately, his cancer quickly progressed within 4 months and again did not respond to pembrolizumab despite MSI-H, which lasted for another 4 months.

We suggested the ketogenic diet and the patient agreed. He started the diet along with trifluridine/tipiracil, and bevacizumab in January 2021. The patient’s metastatic cancer stabilized for 9 months until his disease progressed again. He was started on doublet immune checkpoint inhibitors ipilimumab and nivolumab based on his MSI-H and high tumor mutation burden with the continuation of the ketogenic diet until now. The CheckMate 142 study revealed that the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with MSI-H previously treated for metastatic colon cancer showed some benefit.6

Our patient had the loss of nuclear expression of MLH1 and PMS2 (zero tumor stained) but no evidence of the loss expression of MSH2 and MSH6 genes (99% tumor stained). About 8% to 12% of patients with metastatic colon cancer have BRAF V600E mutations that are usually mucinous type, poorly differentiated, and located in the right side of the colon, which portends to a poor prognosis. Tumor DNA mismatch repair damage results in genetic hypermutability and leads to MSI that is sensitive to treatment with checkpoint inhibitors, as in our patient. Only about 3% of MSI-H tumors are due to germline mutations such as Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer). The presence of both MLH1 hypermethylation and BRAF mutation, as in our patient, is a strong indication of somatic rather than germline mutation.7

GKI, which represents the ratio of glucose to ketone, was developed to evaluate the efficacy of the ketogenic diet. This index measures the degree of metabolic stress on tumor cells through the decrease of glucose levels and increase of ketone bodies. A GKI of ≤ 1.0 has been suggested as the ideal therapeutic goal for cancer management.8 As levels of blood glucose decline, the blood levels of ketone bodies should rise. These 2 lines should eventually intersect at a certain point beyond which one enters the therapeutic zone or therapeutic ketosis zone. This is when tumor growth is expected to slow or cease.9 The patient’s ketone (β-hydroxybutyrate) level was initially high (0.71 mmol/L) with a GKI of 8.2. (low ketotic level), which meant he tolerated a rather strict diet for the first several months. This was also reflected in his 18 lb weight loss (almost 10% of body weight) and cancer stabilization, as in our previous publication.1 Unfortunately, the patient was unable to maintain high ketone and lower GKI levels due to fatigue from depleted carbohydrate intake. He added some carbohydrate snacks in between meals, which improved the fatigue. His ketone level has been < 0.5 mmol/L ever since, albeit his disease continues to be stable. The patient continues his daily work and reports a better QOL, based on the ECOG QLC-C30 form that he completed every 3 months.10 Currently, the patient is still receiving ipilimumab and nivolumab while maintaining the ketogenic diet with stable metastatic disease on PET/CT.

Ketogenic Diet and Cellular Mechanism of Action

PI3K/Akt (phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase) signaling is one of the most important intracellular pathways for tumor cells. It leads to the inhibition of apoptosis and the promotion of cell proliferation, metabolism, and angiogenesis. Deregulation of the PI3K pathway either via amplification of PI3K by tyrosine kinase growth factor receptors or inactivation of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is the negative regulator of the PI3K pathway, contributes to the development of cancer cells.11

A study by Goncalves and colleagues revealed an interesting relationship between the PI3K pathway and the benefit of the ketogenic diet to slow tumor growth. PI3K inhibitors inhibit glucose uptake into skeletal muscle and adipose tissue that activate hepatic glycogenolysis. This event results in hyperglycemia due to the pancreas releasing very high levels of insulin into the blood (hyperinsulinemia) that subsequently reactivate PI3K signaling and cause resistance to PI3K inhibitors. The ketogenic diet reportedly minimized the hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia induced by the PI3K inhibitor and enhanced the efficacy of PI3K inhibitors in tumor models. Studies combining PI3K inhibitors and ketogenic diet are underway. Hence, combining the ketogenic diet with chemotherapy or other novel treatment should be the focus of ketogenic diet trials.12,13

Ketogenic Diet and Oncology Studies

The impact of the ketogenic diet on the growth of murine pancreatic tumors was evaluated by Yang and colleagues. The ketogenic diet decreased glucose concentration that enters the TCA cycle and increased fatty acid oxidation that produces β-hydroxybutyrate. This event promotes the generation of ATP, although with only modest elevations of NADH with less impact on tumor growth. The combination of ketogenic diet and standard chemotherapy substantially raised tumor NADH and suppressed the growth of murine tumor cells, they noted.14 Furukawa and colleagues compared 10 patients with metastatic colon cancer receiving chemotherapy plus the modified medium-chain triglyceride ketogenic diet for 1 year with 14 patients receiving chemotherapy only. The ketogenic diet group exhibited a response rate of 60% with 5 patients achieving a complete response and a disease control rate of 70%, while the chemotherapy-alone group showed a response rate of only 21% with no complete response and a disease control rate of 64%.15

The ketogenic diet also reportedly stimulates cytokine and CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell production that stimulates T-cell killing activity. The ketogenic diet may overcome several immune escape mechanisms by downregulating the expression of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.16 Our patient tolerated the combination of the ketogenic diet with ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) and nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) without significant toxicities and stabilization of his disease.

Future Directions

We originally presented the abstract and poster of this case report at the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology annual meeting in San Diego, California, in September 2022.17 Based on our previous experience, we are now using a modified Atkins diet, which is a less strict diet consisting of 60% fat, 30% protein, and 10% carbohydrates combined with chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. The composition of fat to carbohydrate plus protein in the traditional ketogenic diet is usually 4:1 or 3:1, while in modified Atkins diet the ratio is 1:1 or 2:1. The benefit of the modified Atkins diet is that patients can consume more protein than a strict ketogenic diet and they can be more liberal in carbohydrate allowances. We are about to open a study protocol of combining a modified Atkin diet and chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy as a first-line treatment for veterans with all types of advanced or metastatic solid tumors at VACCHCS. The study protocol was approved by the VA Office of Research and Development and has been submitted to the VACCHCS Institutional Review Board for review. Once approved, we will start patient recruitment.

CONCLUSIONS

Cancer cells have defects in their mitochondria that prevent them from generating energy for metabolism in the absence of glucose. They also depend on the PI3K signaling pathway to survive. The ketogenic diet has the advantage of affecting cancer cell growth by exploiting these mitochondrial defects and blocking hyperglycemia. There is growing evidence that the ketogenic diet is feasible, tolerable, and reportedly inhibits cancer growth. Our case report and previous publications suggest that the ketogenic diet can be added to chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy as an adjunct to standard-of-care cancer treatment while maintaining good QOL. We are planning to open a clinical trial using the modified Atkins diet in conjunction with active cancer treatments as first-line therapy for metastatic solid tumors at the VACCHCS. We are also working closely with researchers from several veteran hospitals to do a diet collaborative study. We believe the ketogenic diet is an important part of cancer treatment and has a promising future. More research should be dedicated to this very interesting field.

Acknowledgments

We previously presented this case report in an abstract and poster at the September 2022 AVAHO meeting in San Diego, California.