User login

This is how you get patients back for follow-up cancer testing

according to authors of a new study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Results from the clustered, randomized clinical trial indicate that systems-based interventions, such as automating reminders in electronic health records (EHRs), outreach in the form of phone calls or letters, and assistance with barriers to health care, such as housing insecurity, can increase the number of patients who complete appropriate diagnostic follow-up after an abnormal result.

Patients who received an EHR reminder, outreach call or letter, and additional calls to screen for and assist with nine barriers to health care – housing insecurity, food insecurity, paying for basic utilities, family caregiving, legal issues, transportation, financial compensation for treatment, education, and employment – completed follow-up within 120 days of study enrollment at a rate of 31.4%. The follow-up rate was 31% for those who received only an EHR reminder and outreach, 22.7% for those who received only an EHR reminder, and 22.9% for those who received usual care.

“The benefits of cancer screening won’t be fully realized without systems to ensure timely follow-up of abnormal results,” said Anna Tosteson, ScD, director of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice in Lebanon, N.H., a coauthor of the study.

Current payment incentives and quality-of-care indicators focus on getting people in for screening but should also address completion of screening – meaning timely and appropriate follow-up of results that could be indicative of cancer, Dr. Tosteson said.

“There’s a disconnect if you have screening rates that are high but once people have an abnormal result, which is potentially one step closer to a cancer diagnosis, there are no systems in place to help clinicians track them,” said study coauthor Jennifer Haas, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care Research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

In a 2016 study, researchers found that follow-up rates after abnormal cancer screenings varied widely. While 95.6% of patients with abnormal breast cancer screenings underwent timely follow-up testing, only 68.1% of patients with colorectal abnormalities and 44.8% of patients with cervical abnormalities did so.

Researchers for the new study used guideline recommendations and specialist input to create automated EHR algorithms that determined a follow-up period and diagnostic test.

They put the algorithm into practice with 11,980 patients who were part of 44 primary care practices within three health networks between August 2020 and December 2021. All patients had received abnormal test results for colorectal, breast, cervical, or lung cancer in varying risk categories.

All patients received usual care from their providers, which consisted of a “hodgepodge of whatever their clinic usually does,” Dr. Haas said. Without standards and systems in place for follow-up, the burden of testing and tracking patients with abnormal results typically falls on the primary care provider.

The researchers intervened only when patients were overdue for completion of follow-up. They then staggered the interventions sequentially.

All study participants received an automated, algorithm-triggered EHR reminder for follow-up in their patient portal along with routine health maintenance reminders. To view the reminder, patients had to log into their portal. Participants in the outreach and outreach and navigation groups also received a phone call, an EHR message, or a physical letter 2 weeks after receiving an EHR notification if they hadn’t completed follow-up. Research assistants performed the outreach after having been prompted by the algorithm.

After another 4 weeks, those in the EHR, outreach, and navigation group received a call from a patient navigator who helped them address nine barriers to health care, chiefly by providing them with referrals to free resources.

Among patients who received navigation, outcomes were not significantly better than among those who received EHR and outreach, indicating social determinants of health did not significantly affect the population studied or that the modest approach to navigation and the resources provided were insufficient, Dr. Haas said.

The complexity of an automated platform that encompasses many types of cancers, test results, and other data elements could prove difficult to apply in settings with less infrastructure, said Steven Atlas, MD, MPH, director of the Practice-Based Research and Quality Improvement Network in the division of general internal medicine at Mass General.

“I think there’s a role for the federal government to take on these initiatives,” Dr. Atlas said. Government intervention could help create “national IT systems to create standards for creating code for what an abnormal result is and how it should be followed,” he said.

While interventions improved patient follow-up, the overall rates were still low.

“What concerns me is that despite the various interventions implemented to encourage and support patients to return for follow-up testing, over 60% of patients still did not return for the recommended testing,” said Joann G. Elmore, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Elmore was not involved with the study.

The research took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have reduced follow-up, the study authors wrote. Still, given that previous research has shown that follow-up tends to be low, the rates highlight “the need to understand factors associated with not completing follow-up that go beyond reminder effort,” they wrote. These include a need for patient education about the meaning of test results and what follow-up procedures involve.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

according to authors of a new study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Results from the clustered, randomized clinical trial indicate that systems-based interventions, such as automating reminders in electronic health records (EHRs), outreach in the form of phone calls or letters, and assistance with barriers to health care, such as housing insecurity, can increase the number of patients who complete appropriate diagnostic follow-up after an abnormal result.

Patients who received an EHR reminder, outreach call or letter, and additional calls to screen for and assist with nine barriers to health care – housing insecurity, food insecurity, paying for basic utilities, family caregiving, legal issues, transportation, financial compensation for treatment, education, and employment – completed follow-up within 120 days of study enrollment at a rate of 31.4%. The follow-up rate was 31% for those who received only an EHR reminder and outreach, 22.7% for those who received only an EHR reminder, and 22.9% for those who received usual care.

“The benefits of cancer screening won’t be fully realized without systems to ensure timely follow-up of abnormal results,” said Anna Tosteson, ScD, director of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice in Lebanon, N.H., a coauthor of the study.

Current payment incentives and quality-of-care indicators focus on getting people in for screening but should also address completion of screening – meaning timely and appropriate follow-up of results that could be indicative of cancer, Dr. Tosteson said.

“There’s a disconnect if you have screening rates that are high but once people have an abnormal result, which is potentially one step closer to a cancer diagnosis, there are no systems in place to help clinicians track them,” said study coauthor Jennifer Haas, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care Research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

In a 2016 study, researchers found that follow-up rates after abnormal cancer screenings varied widely. While 95.6% of patients with abnormal breast cancer screenings underwent timely follow-up testing, only 68.1% of patients with colorectal abnormalities and 44.8% of patients with cervical abnormalities did so.

Researchers for the new study used guideline recommendations and specialist input to create automated EHR algorithms that determined a follow-up period and diagnostic test.

They put the algorithm into practice with 11,980 patients who were part of 44 primary care practices within three health networks between August 2020 and December 2021. All patients had received abnormal test results for colorectal, breast, cervical, or lung cancer in varying risk categories.

All patients received usual care from their providers, which consisted of a “hodgepodge of whatever their clinic usually does,” Dr. Haas said. Without standards and systems in place for follow-up, the burden of testing and tracking patients with abnormal results typically falls on the primary care provider.

The researchers intervened only when patients were overdue for completion of follow-up. They then staggered the interventions sequentially.

All study participants received an automated, algorithm-triggered EHR reminder for follow-up in their patient portal along with routine health maintenance reminders. To view the reminder, patients had to log into their portal. Participants in the outreach and outreach and navigation groups also received a phone call, an EHR message, or a physical letter 2 weeks after receiving an EHR notification if they hadn’t completed follow-up. Research assistants performed the outreach after having been prompted by the algorithm.

After another 4 weeks, those in the EHR, outreach, and navigation group received a call from a patient navigator who helped them address nine barriers to health care, chiefly by providing them with referrals to free resources.

Among patients who received navigation, outcomes were not significantly better than among those who received EHR and outreach, indicating social determinants of health did not significantly affect the population studied or that the modest approach to navigation and the resources provided were insufficient, Dr. Haas said.

The complexity of an automated platform that encompasses many types of cancers, test results, and other data elements could prove difficult to apply in settings with less infrastructure, said Steven Atlas, MD, MPH, director of the Practice-Based Research and Quality Improvement Network in the division of general internal medicine at Mass General.

“I think there’s a role for the federal government to take on these initiatives,” Dr. Atlas said. Government intervention could help create “national IT systems to create standards for creating code for what an abnormal result is and how it should be followed,” he said.

While interventions improved patient follow-up, the overall rates were still low.

“What concerns me is that despite the various interventions implemented to encourage and support patients to return for follow-up testing, over 60% of patients still did not return for the recommended testing,” said Joann G. Elmore, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Elmore was not involved with the study.

The research took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have reduced follow-up, the study authors wrote. Still, given that previous research has shown that follow-up tends to be low, the rates highlight “the need to understand factors associated with not completing follow-up that go beyond reminder effort,” they wrote. These include a need for patient education about the meaning of test results and what follow-up procedures involve.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

according to authors of a new study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Results from the clustered, randomized clinical trial indicate that systems-based interventions, such as automating reminders in electronic health records (EHRs), outreach in the form of phone calls or letters, and assistance with barriers to health care, such as housing insecurity, can increase the number of patients who complete appropriate diagnostic follow-up after an abnormal result.

Patients who received an EHR reminder, outreach call or letter, and additional calls to screen for and assist with nine barriers to health care – housing insecurity, food insecurity, paying for basic utilities, family caregiving, legal issues, transportation, financial compensation for treatment, education, and employment – completed follow-up within 120 days of study enrollment at a rate of 31.4%. The follow-up rate was 31% for those who received only an EHR reminder and outreach, 22.7% for those who received only an EHR reminder, and 22.9% for those who received usual care.

“The benefits of cancer screening won’t be fully realized without systems to ensure timely follow-up of abnormal results,” said Anna Tosteson, ScD, director of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice in Lebanon, N.H., a coauthor of the study.

Current payment incentives and quality-of-care indicators focus on getting people in for screening but should also address completion of screening – meaning timely and appropriate follow-up of results that could be indicative of cancer, Dr. Tosteson said.

“There’s a disconnect if you have screening rates that are high but once people have an abnormal result, which is potentially one step closer to a cancer diagnosis, there are no systems in place to help clinicians track them,” said study coauthor Jennifer Haas, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care Research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

In a 2016 study, researchers found that follow-up rates after abnormal cancer screenings varied widely. While 95.6% of patients with abnormal breast cancer screenings underwent timely follow-up testing, only 68.1% of patients with colorectal abnormalities and 44.8% of patients with cervical abnormalities did so.

Researchers for the new study used guideline recommendations and specialist input to create automated EHR algorithms that determined a follow-up period and diagnostic test.

They put the algorithm into practice with 11,980 patients who were part of 44 primary care practices within three health networks between August 2020 and December 2021. All patients had received abnormal test results for colorectal, breast, cervical, or lung cancer in varying risk categories.

All patients received usual care from their providers, which consisted of a “hodgepodge of whatever their clinic usually does,” Dr. Haas said. Without standards and systems in place for follow-up, the burden of testing and tracking patients with abnormal results typically falls on the primary care provider.

The researchers intervened only when patients were overdue for completion of follow-up. They then staggered the interventions sequentially.

All study participants received an automated, algorithm-triggered EHR reminder for follow-up in their patient portal along with routine health maintenance reminders. To view the reminder, patients had to log into their portal. Participants in the outreach and outreach and navigation groups also received a phone call, an EHR message, or a physical letter 2 weeks after receiving an EHR notification if they hadn’t completed follow-up. Research assistants performed the outreach after having been prompted by the algorithm.

After another 4 weeks, those in the EHR, outreach, and navigation group received a call from a patient navigator who helped them address nine barriers to health care, chiefly by providing them with referrals to free resources.

Among patients who received navigation, outcomes were not significantly better than among those who received EHR and outreach, indicating social determinants of health did not significantly affect the population studied or that the modest approach to navigation and the resources provided were insufficient, Dr. Haas said.

The complexity of an automated platform that encompasses many types of cancers, test results, and other data elements could prove difficult to apply in settings with less infrastructure, said Steven Atlas, MD, MPH, director of the Practice-Based Research and Quality Improvement Network in the division of general internal medicine at Mass General.

“I think there’s a role for the federal government to take on these initiatives,” Dr. Atlas said. Government intervention could help create “national IT systems to create standards for creating code for what an abnormal result is and how it should be followed,” he said.

While interventions improved patient follow-up, the overall rates were still low.

“What concerns me is that despite the various interventions implemented to encourage and support patients to return for follow-up testing, over 60% of patients still did not return for the recommended testing,” said Joann G. Elmore, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Elmore was not involved with the study.

The research took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have reduced follow-up, the study authors wrote. Still, given that previous research has shown that follow-up tends to be low, the rates highlight “the need to understand factors associated with not completing follow-up that go beyond reminder effort,” they wrote. These include a need for patient education about the meaning of test results and what follow-up procedures involve.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Higher RT doses can boost lifespan, reduce risk of death in LS-SCLC patients

SAN DIEGO – , according to a new multicenter, open-label, randomized phase III trial.

Among 224 patients in China, aged 18-70, those randomly assigned to receive volumetric-modulated arc radiotherapy of high-dose, hypofractionated thoracic radiotherapy of 54 Gy in 30 fractions had a much higher median overall survival (62.4 months) than those who received the standard dose of 45 Gy in 30 fractions (43.1 months, P = .001), reported Jiayi Yu, PhD, of Beijing University Cancer Hospital and Institute and colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

Median progression-free survival was also higher in the 54 Gy group (30.5 months vs. 16.7 months in the 45 Gy group, P = .044).

Kristin Higgins, MD, of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, provided perspective at the ASTRO session following Dr. Yu’s presentation. She noted that the study population is quite different than that of LS-SCLC patients in the United States, where patients are often older and more likely to have a history of smoking.

“We need more technical details to understand how to deliver this regimen in clinical practice, and it may not be applicable for all patients,” she said. Still, she added that “a key takeaway here is that optimizing the radiotherapy component of treatment is very important.”

Both groups received chemotherapy. “Higher-dose thoracic radiation therapy concurrently with chemotherapy is an alternative therapeutic option,” Dr. Yu said at an ASTRO presentation.

As Dr. Yu noted, twice-daily thoracic radiotherapy of 45 Gy in 30 fractions and concurrent chemotherapy has been the standard treatment for LS-SCLC for the last 20 years. Trials failed to show benefits for once-daily 66-Gy (33 fractions) or 70-Gy treatment (35 fractions), but a phase 2 trial published in 2023 did indicate that twice-daily treatment of 60 Gy (40 fractions) improved survival without boosting side effects.

For the new study, researchers tracked 224 patients from 2017 to 2021 who were previously untreated or had received specific chemotherapy treatments and had ECOG performance status scores of 0 or 1; 108 patients were randomly assigned to the 54-Gy arm and 116 to the 45-Gy arm. All were recruited at 16 public hospitals in China.

The median age in the two groups were 60 in the 54-Gy arm and 62 in the 45-Gy arm; the percentages of women were similar (45.4% and 45.7%, respectively). Most were current or former smokers (62.0% and 61.2%, respectively).

The researchers closed the trial in April 2021 because of the survival benefit in the 54-Gy arm, and patients were tracked through January 2023 for a median 45 months.

Nearly three-quarters of patients in the 54-Gy arm survived to 2 years (77.7%) vs. 53.4% in the 45-Gy arm, a 41% reduction in risk of death. Adverse events were similar between the groups, with 1 reported treatment-related death (myocardial infarction), in the 54-Gy group.

In an interview, Kenneth Rosenzweig, MD, chairman of the department of radiation oncology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, praised the study. It’s “no surprise” that higher radiation doses are well-tolerated since “our ability to shield normal tissue has improved” over the years, said Dr. Rosenzweig, who served as a moderator of the ASTRO session where the research was presented.

However, he cautioned that hypofractionation is still “intense” and may not be appropriate for certain patients. And he added that some clinics may not be set up to provide twice-daily treatments.

Information about study funding was not provided. The study authors have no disclosures. Dr. Higgins discloses relationships with AstraZeneca and Regeneron (advisory board), Jazz (funded research), and Janssen and Picture Health (consulting). Dr. Rosenzweig has no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – , according to a new multicenter, open-label, randomized phase III trial.

Among 224 patients in China, aged 18-70, those randomly assigned to receive volumetric-modulated arc radiotherapy of high-dose, hypofractionated thoracic radiotherapy of 54 Gy in 30 fractions had a much higher median overall survival (62.4 months) than those who received the standard dose of 45 Gy in 30 fractions (43.1 months, P = .001), reported Jiayi Yu, PhD, of Beijing University Cancer Hospital and Institute and colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

Median progression-free survival was also higher in the 54 Gy group (30.5 months vs. 16.7 months in the 45 Gy group, P = .044).

Kristin Higgins, MD, of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, provided perspective at the ASTRO session following Dr. Yu’s presentation. She noted that the study population is quite different than that of LS-SCLC patients in the United States, where patients are often older and more likely to have a history of smoking.

“We need more technical details to understand how to deliver this regimen in clinical practice, and it may not be applicable for all patients,” she said. Still, she added that “a key takeaway here is that optimizing the radiotherapy component of treatment is very important.”

Both groups received chemotherapy. “Higher-dose thoracic radiation therapy concurrently with chemotherapy is an alternative therapeutic option,” Dr. Yu said at an ASTRO presentation.

As Dr. Yu noted, twice-daily thoracic radiotherapy of 45 Gy in 30 fractions and concurrent chemotherapy has been the standard treatment for LS-SCLC for the last 20 years. Trials failed to show benefits for once-daily 66-Gy (33 fractions) or 70-Gy treatment (35 fractions), but a phase 2 trial published in 2023 did indicate that twice-daily treatment of 60 Gy (40 fractions) improved survival without boosting side effects.

For the new study, researchers tracked 224 patients from 2017 to 2021 who were previously untreated or had received specific chemotherapy treatments and had ECOG performance status scores of 0 or 1; 108 patients were randomly assigned to the 54-Gy arm and 116 to the 45-Gy arm. All were recruited at 16 public hospitals in China.

The median age in the two groups were 60 in the 54-Gy arm and 62 in the 45-Gy arm; the percentages of women were similar (45.4% and 45.7%, respectively). Most were current or former smokers (62.0% and 61.2%, respectively).

The researchers closed the trial in April 2021 because of the survival benefit in the 54-Gy arm, and patients were tracked through January 2023 for a median 45 months.

Nearly three-quarters of patients in the 54-Gy arm survived to 2 years (77.7%) vs. 53.4% in the 45-Gy arm, a 41% reduction in risk of death. Adverse events were similar between the groups, with 1 reported treatment-related death (myocardial infarction), in the 54-Gy group.

In an interview, Kenneth Rosenzweig, MD, chairman of the department of radiation oncology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, praised the study. It’s “no surprise” that higher radiation doses are well-tolerated since “our ability to shield normal tissue has improved” over the years, said Dr. Rosenzweig, who served as a moderator of the ASTRO session where the research was presented.

However, he cautioned that hypofractionation is still “intense” and may not be appropriate for certain patients. And he added that some clinics may not be set up to provide twice-daily treatments.

Information about study funding was not provided. The study authors have no disclosures. Dr. Higgins discloses relationships with AstraZeneca and Regeneron (advisory board), Jazz (funded research), and Janssen and Picture Health (consulting). Dr. Rosenzweig has no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – , according to a new multicenter, open-label, randomized phase III trial.

Among 224 patients in China, aged 18-70, those randomly assigned to receive volumetric-modulated arc radiotherapy of high-dose, hypofractionated thoracic radiotherapy of 54 Gy in 30 fractions had a much higher median overall survival (62.4 months) than those who received the standard dose of 45 Gy in 30 fractions (43.1 months, P = .001), reported Jiayi Yu, PhD, of Beijing University Cancer Hospital and Institute and colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

Median progression-free survival was also higher in the 54 Gy group (30.5 months vs. 16.7 months in the 45 Gy group, P = .044).

Kristin Higgins, MD, of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, provided perspective at the ASTRO session following Dr. Yu’s presentation. She noted that the study population is quite different than that of LS-SCLC patients in the United States, where patients are often older and more likely to have a history of smoking.

“We need more technical details to understand how to deliver this regimen in clinical practice, and it may not be applicable for all patients,” she said. Still, she added that “a key takeaway here is that optimizing the radiotherapy component of treatment is very important.”

Both groups received chemotherapy. “Higher-dose thoracic radiation therapy concurrently with chemotherapy is an alternative therapeutic option,” Dr. Yu said at an ASTRO presentation.

As Dr. Yu noted, twice-daily thoracic radiotherapy of 45 Gy in 30 fractions and concurrent chemotherapy has been the standard treatment for LS-SCLC for the last 20 years. Trials failed to show benefits for once-daily 66-Gy (33 fractions) or 70-Gy treatment (35 fractions), but a phase 2 trial published in 2023 did indicate that twice-daily treatment of 60 Gy (40 fractions) improved survival without boosting side effects.

For the new study, researchers tracked 224 patients from 2017 to 2021 who were previously untreated or had received specific chemotherapy treatments and had ECOG performance status scores of 0 or 1; 108 patients were randomly assigned to the 54-Gy arm and 116 to the 45-Gy arm. All were recruited at 16 public hospitals in China.

The median age in the two groups were 60 in the 54-Gy arm and 62 in the 45-Gy arm; the percentages of women were similar (45.4% and 45.7%, respectively). Most were current or former smokers (62.0% and 61.2%, respectively).

The researchers closed the trial in April 2021 because of the survival benefit in the 54-Gy arm, and patients were tracked through January 2023 for a median 45 months.

Nearly three-quarters of patients in the 54-Gy arm survived to 2 years (77.7%) vs. 53.4% in the 45-Gy arm, a 41% reduction in risk of death. Adverse events were similar between the groups, with 1 reported treatment-related death (myocardial infarction), in the 54-Gy group.

In an interview, Kenneth Rosenzweig, MD, chairman of the department of radiation oncology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, praised the study. It’s “no surprise” that higher radiation doses are well-tolerated since “our ability to shield normal tissue has improved” over the years, said Dr. Rosenzweig, who served as a moderator of the ASTRO session where the research was presented.

However, he cautioned that hypofractionation is still “intense” and may not be appropriate for certain patients. And he added that some clinics may not be set up to provide twice-daily treatments.

Information about study funding was not provided. The study authors have no disclosures. Dr. Higgins discloses relationships with AstraZeneca and Regeneron (advisory board), Jazz (funded research), and Janssen and Picture Health (consulting). Dr. Rosenzweig has no disclosures.

AT ASTRO 2023

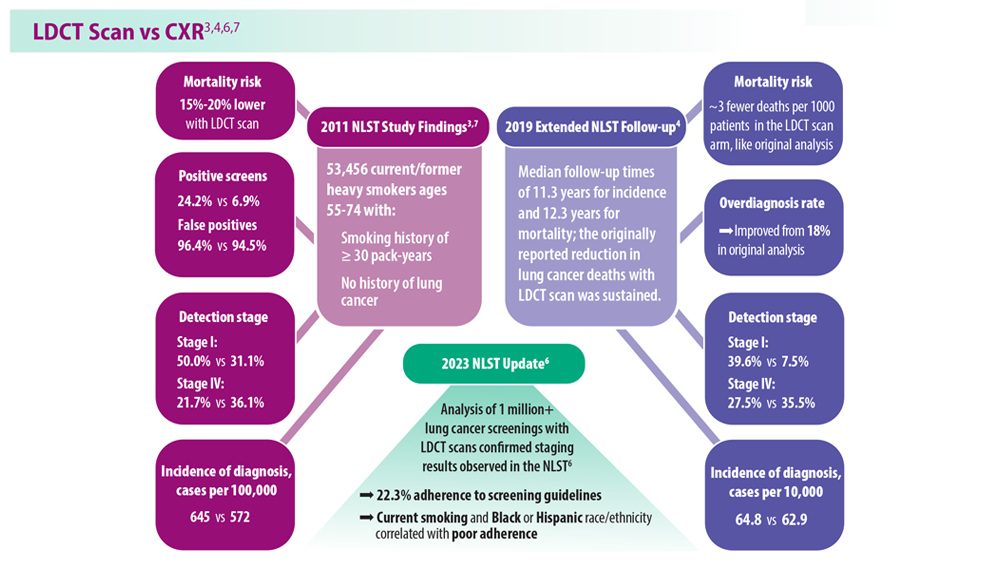

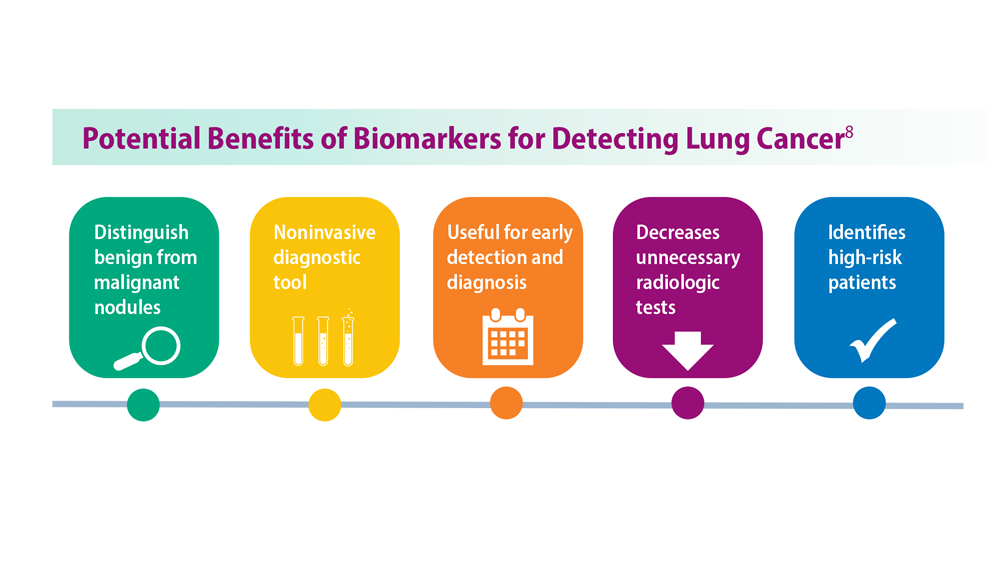

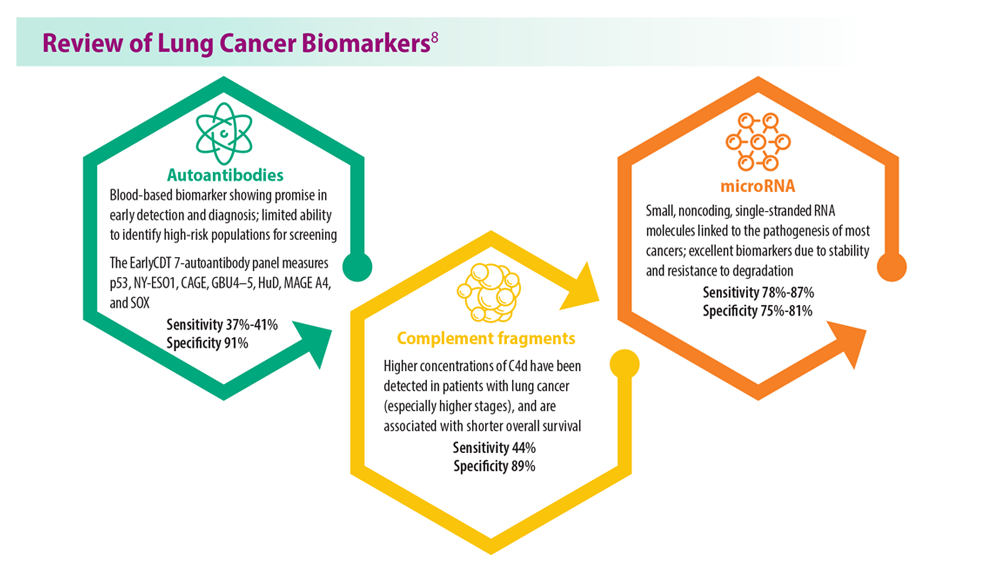

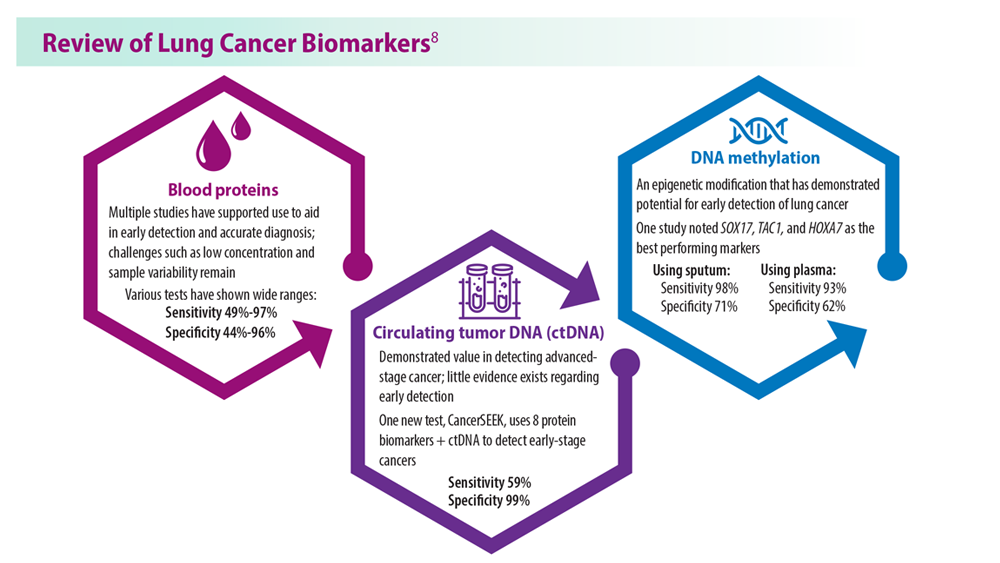

Lung Cancer Screening: A Need for Adjunctive Testing

- Naidch DP et al. Radiology. 1990;175(3):729-731. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343122

- Kaneko M et al. Radiology. 1996;201(3):798-802. doi:10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939234

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243-253. doi:10.1148/radiol.10091808

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

- Mazzone PJ et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

- Tanner NT et al. Chest. 2023;S0012-3692(23)00175-7. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.003

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395- 409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Marmor HN et al. Curr Chall Thorac Surg. 2023;5:5. doi:10.21037/ccts-20-171

- Naidch DP et al. Radiology. 1990;175(3):729-731. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343122

- Kaneko M et al. Radiology. 1996;201(3):798-802. doi:10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939234

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243-253. doi:10.1148/radiol.10091808

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

- Mazzone PJ et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

- Tanner NT et al. Chest. 2023;S0012-3692(23)00175-7. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.003

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395- 409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Marmor HN et al. Curr Chall Thorac Surg. 2023;5:5. doi:10.21037/ccts-20-171

- Naidch DP et al. Radiology. 1990;175(3):729-731. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343122

- Kaneko M et al. Radiology. 1996;201(3):798-802. doi:10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939234

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243-253. doi:10.1148/radiol.10091808

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

- Mazzone PJ et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

- Tanner NT et al. Chest. 2023;S0012-3692(23)00175-7. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.003

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395- 409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Marmor HN et al. Curr Chall Thorac Surg. 2023;5:5. doi:10.21037/ccts-20-171

Reducing cognitive impairment from SCLC brain metastases

For patients with up to 10 brain metastases from small cell lung cancer (SCLC), stereotactic radiosurgery was associated with less cognitive impairment than whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) without compromising overall survival, results of the randomized ENCEPHALON (ARO 2018-9) trial suggest.

Among 56 patients with one to 10 SCLC brain metastases, 24% of those who received WBRT demonstrated significant declines in memory function 3 months after treatment, compared with 7% of patients whose metastases were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Preliminary data showed no significant differences in overall survival between the treatment groups at 6 months of follow-up, Denise Bernhardt, MD, from the Technical University of Munich, reported at the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting.

“We propose stereotactic radiosurgery should be an option for patients with up to 10 brain metastases in small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Bernhardt said during her presentation.

Vinai Gondi, MD, who was not involved in the study, said that the primary results from the trial – while limited by the study’s small size and missing data – are notable.

Patients with brain metastases from most cancer types typically receive stereotactic radiosurgery but WBRT has remained the standard of care to control brain metastases among patients with SCLC.

“This is the first prospective trial of radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy for small cell lung cancer brain metastases, and it’s important to recognize how important this is,” said Dr. Gondi, director of Radiation Oncology and codirector of the Brain Tumor Center at Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center, Warrenville, Ill.

Prior trials that have asked the same question did not include SCLC because many of those patients received prophylactic cranial irradiation, Dr. Gondi explained. Prophylactic cranial irradiation, however, has been on the decline among patients with brain metastases from SCLC, following a study from Japan showing no difference in survival among those who received the therapy and those followed with observation as well as evidence demonstrating significant toxicities associated with the technique.

Now “with the declining use of prophylactic cranial irradiation, the emergence of brain metastases is increasing significantly in volume in the small cell lung cancer population,” said Dr. Gondi, who is principal investigator on a phase 3 trial exploring stereotactic radiosurgery versus WBRT in a similar patient population.

In a previous retrospective trial), Dr. Bernhardt and colleagues found that first-line stereotactic radiosurgery did not compromise survival, compared with WBRT, but patients receiving stereotactic radiosurgery did have a higher risk for intracranial failure.

In the current study, the investigators compared the neurocognitive responses in patients with brain metastases from SCLC treated with stereotactic radiosurgery or WBRT.

Enrolled patients had histologically confirmed extensive disease with up to 10 metastatic brain lesions and had not previously received either therapeutic or prophylactic brain irradiation. After stratifying patients by synchronous versus metachronous disease, 56 patients were randomly assigned to either WBRT, at a total dose of 30 Gy delivered in 10 fractions, or to stereotactic radiosurgery with 20 Gy, 18 Gy, or fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery with 30 Gy in 5 Gy fractions for lesions larger than 3 cm.

The primary endpoint was neurocognition after radiation therapy as defined by a decline from baseline of at least five points on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) total recall subscale at 3 months. Secondary endpoints included survival outcomes, additional neurocognitive assessments of motor skills, executive function, attention, memory, and processing as well as quality-of-life measures.

The investigators expected a high rate of study dropout and planned their statistical analysis accordingly, using a method for estimating the likely values of missing data based on observed data.

Among 26 patients who eventually underwent stereotactic radiosurgery, 18 did not meet the primary endpoint and 2 (7%) demonstrated declines on the HVLT-R subscale of 5 or more points. Data for the remaining 6 patients were missing.

Among the 25 who underwent WBRT, 13 did not meet the primary endpoint and 6 (24%) demonstrated declines of at least 5 points. Data for 6 of the remaining patients were missing.

Although more patients in the WBRT arm had significant declines in neurocognitive function, the difference between the groups was not significant, due to the high proportion of study dropouts – approximately one-fourth of patients in each arm. But the analysis suggested that the neuroprotective effect of stereotactic radiosurgery was notable, Dr. Bernhardt said.

At 6 months, the team also found no significant difference in the survival probability between the treatment groups (P = .36). The median time to death was 124 days among patients who received stereotactic radiosurgery and 131 days among patients who received WBRT.

Dr. Gondi said the data from ENCEPHALON, while promising, need to be carefully scrutinized because of the small sample sizes and the possibility for unintended bias.

ARO 2018-9 is an investigator-initiated trial funded by Accuray. Dr. Bernhardt disclosed consulting actives, fees, travel expenses, and research funding from Accuray and others. Dr. Gondi disclosed honoraria from UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with up to 10 brain metastases from small cell lung cancer (SCLC), stereotactic radiosurgery was associated with less cognitive impairment than whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) without compromising overall survival, results of the randomized ENCEPHALON (ARO 2018-9) trial suggest.

Among 56 patients with one to 10 SCLC brain metastases, 24% of those who received WBRT demonstrated significant declines in memory function 3 months after treatment, compared with 7% of patients whose metastases were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Preliminary data showed no significant differences in overall survival between the treatment groups at 6 months of follow-up, Denise Bernhardt, MD, from the Technical University of Munich, reported at the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting.

“We propose stereotactic radiosurgery should be an option for patients with up to 10 brain metastases in small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Bernhardt said during her presentation.

Vinai Gondi, MD, who was not involved in the study, said that the primary results from the trial – while limited by the study’s small size and missing data – are notable.

Patients with brain metastases from most cancer types typically receive stereotactic radiosurgery but WBRT has remained the standard of care to control brain metastases among patients with SCLC.

“This is the first prospective trial of radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy for small cell lung cancer brain metastases, and it’s important to recognize how important this is,” said Dr. Gondi, director of Radiation Oncology and codirector of the Brain Tumor Center at Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center, Warrenville, Ill.

Prior trials that have asked the same question did not include SCLC because many of those patients received prophylactic cranial irradiation, Dr. Gondi explained. Prophylactic cranial irradiation, however, has been on the decline among patients with brain metastases from SCLC, following a study from Japan showing no difference in survival among those who received the therapy and those followed with observation as well as evidence demonstrating significant toxicities associated with the technique.

Now “with the declining use of prophylactic cranial irradiation, the emergence of brain metastases is increasing significantly in volume in the small cell lung cancer population,” said Dr. Gondi, who is principal investigator on a phase 3 trial exploring stereotactic radiosurgery versus WBRT in a similar patient population.

In a previous retrospective trial), Dr. Bernhardt and colleagues found that first-line stereotactic radiosurgery did not compromise survival, compared with WBRT, but patients receiving stereotactic radiosurgery did have a higher risk for intracranial failure.

In the current study, the investigators compared the neurocognitive responses in patients with brain metastases from SCLC treated with stereotactic radiosurgery or WBRT.

Enrolled patients had histologically confirmed extensive disease with up to 10 metastatic brain lesions and had not previously received either therapeutic or prophylactic brain irradiation. After stratifying patients by synchronous versus metachronous disease, 56 patients were randomly assigned to either WBRT, at a total dose of 30 Gy delivered in 10 fractions, or to stereotactic radiosurgery with 20 Gy, 18 Gy, or fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery with 30 Gy in 5 Gy fractions for lesions larger than 3 cm.

The primary endpoint was neurocognition after radiation therapy as defined by a decline from baseline of at least five points on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) total recall subscale at 3 months. Secondary endpoints included survival outcomes, additional neurocognitive assessments of motor skills, executive function, attention, memory, and processing as well as quality-of-life measures.

The investigators expected a high rate of study dropout and planned their statistical analysis accordingly, using a method for estimating the likely values of missing data based on observed data.

Among 26 patients who eventually underwent stereotactic radiosurgery, 18 did not meet the primary endpoint and 2 (7%) demonstrated declines on the HVLT-R subscale of 5 or more points. Data for the remaining 6 patients were missing.

Among the 25 who underwent WBRT, 13 did not meet the primary endpoint and 6 (24%) demonstrated declines of at least 5 points. Data for 6 of the remaining patients were missing.

Although more patients in the WBRT arm had significant declines in neurocognitive function, the difference between the groups was not significant, due to the high proportion of study dropouts – approximately one-fourth of patients in each arm. But the analysis suggested that the neuroprotective effect of stereotactic radiosurgery was notable, Dr. Bernhardt said.

At 6 months, the team also found no significant difference in the survival probability between the treatment groups (P = .36). The median time to death was 124 days among patients who received stereotactic radiosurgery and 131 days among patients who received WBRT.

Dr. Gondi said the data from ENCEPHALON, while promising, need to be carefully scrutinized because of the small sample sizes and the possibility for unintended bias.

ARO 2018-9 is an investigator-initiated trial funded by Accuray. Dr. Bernhardt disclosed consulting actives, fees, travel expenses, and research funding from Accuray and others. Dr. Gondi disclosed honoraria from UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with up to 10 brain metastases from small cell lung cancer (SCLC), stereotactic radiosurgery was associated with less cognitive impairment than whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) without compromising overall survival, results of the randomized ENCEPHALON (ARO 2018-9) trial suggest.

Among 56 patients with one to 10 SCLC brain metastases, 24% of those who received WBRT demonstrated significant declines in memory function 3 months after treatment, compared with 7% of patients whose metastases were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Preliminary data showed no significant differences in overall survival between the treatment groups at 6 months of follow-up, Denise Bernhardt, MD, from the Technical University of Munich, reported at the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting.

“We propose stereotactic radiosurgery should be an option for patients with up to 10 brain metastases in small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Bernhardt said during her presentation.

Vinai Gondi, MD, who was not involved in the study, said that the primary results from the trial – while limited by the study’s small size and missing data – are notable.

Patients with brain metastases from most cancer types typically receive stereotactic radiosurgery but WBRT has remained the standard of care to control brain metastases among patients with SCLC.

“This is the first prospective trial of radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy for small cell lung cancer brain metastases, and it’s important to recognize how important this is,” said Dr. Gondi, director of Radiation Oncology and codirector of the Brain Tumor Center at Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center, Warrenville, Ill.

Prior trials that have asked the same question did not include SCLC because many of those patients received prophylactic cranial irradiation, Dr. Gondi explained. Prophylactic cranial irradiation, however, has been on the decline among patients with brain metastases from SCLC, following a study from Japan showing no difference in survival among those who received the therapy and those followed with observation as well as evidence demonstrating significant toxicities associated with the technique.

Now “with the declining use of prophylactic cranial irradiation, the emergence of brain metastases is increasing significantly in volume in the small cell lung cancer population,” said Dr. Gondi, who is principal investigator on a phase 3 trial exploring stereotactic radiosurgery versus WBRT in a similar patient population.

In a previous retrospective trial), Dr. Bernhardt and colleagues found that first-line stereotactic radiosurgery did not compromise survival, compared with WBRT, but patients receiving stereotactic radiosurgery did have a higher risk for intracranial failure.

In the current study, the investigators compared the neurocognitive responses in patients with brain metastases from SCLC treated with stereotactic radiosurgery or WBRT.

Enrolled patients had histologically confirmed extensive disease with up to 10 metastatic brain lesions and had not previously received either therapeutic or prophylactic brain irradiation. After stratifying patients by synchronous versus metachronous disease, 56 patients were randomly assigned to either WBRT, at a total dose of 30 Gy delivered in 10 fractions, or to stereotactic radiosurgery with 20 Gy, 18 Gy, or fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery with 30 Gy in 5 Gy fractions for lesions larger than 3 cm.

The primary endpoint was neurocognition after radiation therapy as defined by a decline from baseline of at least five points on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) total recall subscale at 3 months. Secondary endpoints included survival outcomes, additional neurocognitive assessments of motor skills, executive function, attention, memory, and processing as well as quality-of-life measures.

The investigators expected a high rate of study dropout and planned their statistical analysis accordingly, using a method for estimating the likely values of missing data based on observed data.

Among 26 patients who eventually underwent stereotactic radiosurgery, 18 did not meet the primary endpoint and 2 (7%) demonstrated declines on the HVLT-R subscale of 5 or more points. Data for the remaining 6 patients were missing.

Among the 25 who underwent WBRT, 13 did not meet the primary endpoint and 6 (24%) demonstrated declines of at least 5 points. Data for 6 of the remaining patients were missing.

Although more patients in the WBRT arm had significant declines in neurocognitive function, the difference between the groups was not significant, due to the high proportion of study dropouts – approximately one-fourth of patients in each arm. But the analysis suggested that the neuroprotective effect of stereotactic radiosurgery was notable, Dr. Bernhardt said.

At 6 months, the team also found no significant difference in the survival probability between the treatment groups (P = .36). The median time to death was 124 days among patients who received stereotactic radiosurgery and 131 days among patients who received WBRT.

Dr. Gondi said the data from ENCEPHALON, while promising, need to be carefully scrutinized because of the small sample sizes and the possibility for unintended bias.

ARO 2018-9 is an investigator-initiated trial funded by Accuray. Dr. Bernhardt disclosed consulting actives, fees, travel expenses, and research funding from Accuray and others. Dr. Gondi disclosed honoraria from UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

These adverse events linked to improved cancer prognosis

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Emerging evidence suggests that the presence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events may be linked with favorable outcomes among patients with cancer who receive ICIs.

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 23 studies and a total of 22,749 patients with cancer who received ICI treatment; studies compared outcomes among patients with and those without cutaneous immune-related adverse events.

- The major outcomes evaluated in the analysis were overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS); subgroup analyses assessed cutaneous immune-related adverse event type, cancer type, and other factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- The occurrence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events was associated with improved PFS (hazard ratio, 0.52; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 0.61; P < .001).

- In the subgroup analysis, patients with eczematous (HR, 0.69), lichenoid or lichen planus–like skin lesions (HR, 0.51), pruritus without rash (HR, 0.70), psoriasis (HR, 0.63), or vitiligo (HR, 0.30) demonstrated a significant overall survival advantage. Vitiligo was the only adverse event associated with a PFS advantage (HR, 0.28).

- Among patients with melanoma, analyses revealed a significant association between the incidence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events and improved overall survival (HR, 0.51) and PFS (HR, 0.45). The authors highlighted similar findings among patients with non–small cell lung cancer (HR, 0.50 for overall survival and 0.61 for PFS).

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that [cutaneous immune-related adverse events] may have useful prognostic value in ICI treatment,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The analysis, led by Fei Wang, MD, Zhong Da Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Most of the data came from retrospective studies, and there were limited data on specific patient subgroups. The Egger tests, used to assess potential publication bias in meta-analyses, revealed publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. The study was supported by a grant from the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Emerging evidence suggests that the presence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events may be linked with favorable outcomes among patients with cancer who receive ICIs.

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 23 studies and a total of 22,749 patients with cancer who received ICI treatment; studies compared outcomes among patients with and those without cutaneous immune-related adverse events.

- The major outcomes evaluated in the analysis were overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS); subgroup analyses assessed cutaneous immune-related adverse event type, cancer type, and other factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- The occurrence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events was associated with improved PFS (hazard ratio, 0.52; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 0.61; P < .001).

- In the subgroup analysis, patients with eczematous (HR, 0.69), lichenoid or lichen planus–like skin lesions (HR, 0.51), pruritus without rash (HR, 0.70), psoriasis (HR, 0.63), or vitiligo (HR, 0.30) demonstrated a significant overall survival advantage. Vitiligo was the only adverse event associated with a PFS advantage (HR, 0.28).

- Among patients with melanoma, analyses revealed a significant association between the incidence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events and improved overall survival (HR, 0.51) and PFS (HR, 0.45). The authors highlighted similar findings among patients with non–small cell lung cancer (HR, 0.50 for overall survival and 0.61 for PFS).

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that [cutaneous immune-related adverse events] may have useful prognostic value in ICI treatment,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The analysis, led by Fei Wang, MD, Zhong Da Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Most of the data came from retrospective studies, and there were limited data on specific patient subgroups. The Egger tests, used to assess potential publication bias in meta-analyses, revealed publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. The study was supported by a grant from the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Emerging evidence suggests that the presence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events may be linked with favorable outcomes among patients with cancer who receive ICIs.

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 23 studies and a total of 22,749 patients with cancer who received ICI treatment; studies compared outcomes among patients with and those without cutaneous immune-related adverse events.

- The major outcomes evaluated in the analysis were overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS); subgroup analyses assessed cutaneous immune-related adverse event type, cancer type, and other factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- The occurrence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events was associated with improved PFS (hazard ratio, 0.52; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 0.61; P < .001).

- In the subgroup analysis, patients with eczematous (HR, 0.69), lichenoid or lichen planus–like skin lesions (HR, 0.51), pruritus without rash (HR, 0.70), psoriasis (HR, 0.63), or vitiligo (HR, 0.30) demonstrated a significant overall survival advantage. Vitiligo was the only adverse event associated with a PFS advantage (HR, 0.28).

- Among patients with melanoma, analyses revealed a significant association between the incidence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events and improved overall survival (HR, 0.51) and PFS (HR, 0.45). The authors highlighted similar findings among patients with non–small cell lung cancer (HR, 0.50 for overall survival and 0.61 for PFS).

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that [cutaneous immune-related adverse events] may have useful prognostic value in ICI treatment,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The analysis, led by Fei Wang, MD, Zhong Da Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Most of the data came from retrospective studies, and there were limited data on specific patient subgroups. The Egger tests, used to assess potential publication bias in meta-analyses, revealed publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. The study was supported by a grant from the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Therapeutic vaccine shows promise in treating lung cancer

SINGAPORE – A few months after releasing its phase 1 and 2 data, OSE Immunotherapeutics, which is based in Nantes, France, has announced positive results for its therapeutic vaccine to treat cancer. Following its promising findings concerning early-stage melanoma, pancreatic cancer, ENT cancers, and HPV-associated anogenital cancer,

The results suggest that Tedopi is the most developmentally advanced therapeutic vaccine for cancer.

The data from Atalante-1 were presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer and were simultaneously published in Annals of Oncology.

Tedopi is composed of synthetic tumoral neo-epitopes (peptide fragments) that target five tumoral antigens, permitting the activation of tumor-specific T-lymphocytes for patients who are HLA-A2 positive. In 95% of cases, tumors express at least one of these five antigens. The aim of integrating these five antigens is to prevent immune escape. The technology uses the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, one of the keys for presenting antigens to T-lymphocytes. The vaccine is effective for patients who express the HLA-A2 gene, which is present in around half of the population. The HLA-A2 biomarker, detected via a blood test, can identify appropriate patients.

Study protocol

In the Atalante-1 trial, participants had locally advanced (unresectable and not eligible for radiotherapy) or metastatic (without alteration of the EGFR and ALK genes) non–small cell lung cancer that was resistant to previous immunotherapy. They had an HLA-A2 phenotype, as determined by a blood draw to determine whether their immune system could respond to the vaccine.

In this trial, 219 patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive the vaccine or standard-of-care chemotherapy (80% received docetaxel). The vaccine was administered subcutaneously on day 1 every 3 weeks for six cycles. After that point, the vaccine was administered every 8 weeks until 1 year of treatment and every 12 weeks thereafter. The primary endpoint was overall survival.

Secondary resistance

The plan was to enroll 363 patients in the protocol, but the study did not complete its recruitment phase because of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the study was stopped after the enrollment of 219 patients.

“It didn’t have the power we would have liked, but it helped us understand that the people who benefited the most from the vaccine were patients who had responded to immunotherapy in the past. These patients have what is called ‘secondary resistance,’ ” explained Benjamin Besse, MD, PhD, during a press conference organized by OSE Immunotherapeutics. Dr. Besse, the study’s principal investigator, is the director of clinical research at Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France.

Overall, the results weren’t significant. But the results were positive for patients who had previously responded well to immunotherapy for at least 3 months. Of the 219 patients, 118 (54%) had a positive response.

Among these patients with secondary resistance to immunotherapy, median OS was 11.1 months with Tedopi versus 7.5 months with docetaxel.

For these patients, the risk of death was reduced by 41% with the vaccine, compared with chemotherapy. Overall, 44% of patients lived for another year after receiving Tedopi, versus 27.5% with docetaxel.

“This study is a positive signal for overall survival in the selected population. In this study of 219 patients, we realized that just half of patients really benefited from the vaccine: those who had previously responded to immunotherapy,” said Dr. Besse. “The study needs confirmation from a further, larger phase 3 study in more than 300 patients with secondary resistance to immunotherapy to give us the statistical power we need to convince the regulatory authorities.”

Tolerability profile

Fewer serious adverse effects were reported with the vaccine than with chemotherapy (11.4% with Tedopi and 35.1% with docetaxel).

The vaccine also allowed patients to maintain a better quality of life. Scores from the Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, which explores several areas of daily life, were better with the vaccine. Change in patients’ overall well-being was delayed in the vaccine group: 3.3 months in the chemotherapy arm versus 9 months in the vaccine arm.

“The vaccine was well tolerated. It has benefits in terms of controlling disease symptoms and causes few side effects. Chemotherapy with docetaxel, meanwhile, is more toxic and may affect a patient’s overall well-being. It causes hair loss in practically 100% of patients, induces neuropathy, makes hands and feet swell, damages the nails, is associated with nausea and vomiting ...” noted Dr. Besse. He went on to say that after the trial, of the patients who stopped receiving the vaccine or chemotherapy (either for toxicity reasons or for disease progression), those who had been given the vaccine responded better to the subsequent chemotherapy “because their overall health was better.”

Clinical development

The clinical development of Tedopi is ongoing. Three trials are currently taking place. One study is comparing the Tedopi vaccine plus docetaxel with Tedopi plus nivolumab (immunotherapy not used as a first-line treatment) to determine whether the effects of these treatment combinations might might be enhanced for patients with previously treated lung cancer.

Another study relating to ovarian cancer is in the recruitment phase. The researchers seek to evaluate the vaccine alone or in combination with pembrolizumab for patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Results from both trials are expected in 2025.

The third trial seeks to assess FOLFIRI as maintenance therapy or FOLFIRI as maintenance plus Tedopi for patients with pancreatic cancer to improve disease management. Efficacy data are expected next year.

OSE Immunotherapeutics is simultaneously working on a companion biomarker, the HLA-A2 test.

The study was funded by OSE Immunotherapeutics. Dr. Besse disclosed the following conflicts of interest (research funding, institution): AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ellipse Pharma, EISAI, Genmab, Genzyme Corporation, Hedera Dx, Inivata, IPSEN, Janssen, MSD, Pharmamar, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi, Socar Research, Taiho Oncology, and Turning Point Therapeutics.

This article was translated from the Medscape French Edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

SINGAPORE – A few months after releasing its phase 1 and 2 data, OSE Immunotherapeutics, which is based in Nantes, France, has announced positive results for its therapeutic vaccine to treat cancer. Following its promising findings concerning early-stage melanoma, pancreatic cancer, ENT cancers, and HPV-associated anogenital cancer,

The results suggest that Tedopi is the most developmentally advanced therapeutic vaccine for cancer.

The data from Atalante-1 were presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer and were simultaneously published in Annals of Oncology.

Tedopi is composed of synthetic tumoral neo-epitopes (peptide fragments) that target five tumoral antigens, permitting the activation of tumor-specific T-lymphocytes for patients who are HLA-A2 positive. In 95% of cases, tumors express at least one of these five antigens. The aim of integrating these five antigens is to prevent immune escape. The technology uses the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, one of the keys for presenting antigens to T-lymphocytes. The vaccine is effective for patients who express the HLA-A2 gene, which is present in around half of the population. The HLA-A2 biomarker, detected via a blood test, can identify appropriate patients.

Study protocol

In the Atalante-1 trial, participants had locally advanced (unresectable and not eligible for radiotherapy) or metastatic (without alteration of the EGFR and ALK genes) non–small cell lung cancer that was resistant to previous immunotherapy. They had an HLA-A2 phenotype, as determined by a blood draw to determine whether their immune system could respond to the vaccine.

In this trial, 219 patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive the vaccine or standard-of-care chemotherapy (80% received docetaxel). The vaccine was administered subcutaneously on day 1 every 3 weeks for six cycles. After that point, the vaccine was administered every 8 weeks until 1 year of treatment and every 12 weeks thereafter. The primary endpoint was overall survival.

Secondary resistance

The plan was to enroll 363 patients in the protocol, but the study did not complete its recruitment phase because of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the study was stopped after the enrollment of 219 patients.

“It didn’t have the power we would have liked, but it helped us understand that the people who benefited the most from the vaccine were patients who had responded to immunotherapy in the past. These patients have what is called ‘secondary resistance,’ ” explained Benjamin Besse, MD, PhD, during a press conference organized by OSE Immunotherapeutics. Dr. Besse, the study’s principal investigator, is the director of clinical research at Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France.

Overall, the results weren’t significant. But the results were positive for patients who had previously responded well to immunotherapy for at least 3 months. Of the 219 patients, 118 (54%) had a positive response.

Among these patients with secondary resistance to immunotherapy, median OS was 11.1 months with Tedopi versus 7.5 months with docetaxel.

For these patients, the risk of death was reduced by 41% with the vaccine, compared with chemotherapy. Overall, 44% of patients lived for another year after receiving Tedopi, versus 27.5% with docetaxel.

“This study is a positive signal for overall survival in the selected population. In this study of 219 patients, we realized that just half of patients really benefited from the vaccine: those who had previously responded to immunotherapy,” said Dr. Besse. “The study needs confirmation from a further, larger phase 3 study in more than 300 patients with secondary resistance to immunotherapy to give us the statistical power we need to convince the regulatory authorities.”

Tolerability profile

Fewer serious adverse effects were reported with the vaccine than with chemotherapy (11.4% with Tedopi and 35.1% with docetaxel).

The vaccine also allowed patients to maintain a better quality of life. Scores from the Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, which explores several areas of daily life, were better with the vaccine. Change in patients’ overall well-being was delayed in the vaccine group: 3.3 months in the chemotherapy arm versus 9 months in the vaccine arm.

“The vaccine was well tolerated. It has benefits in terms of controlling disease symptoms and causes few side effects. Chemotherapy with docetaxel, meanwhile, is more toxic and may affect a patient’s overall well-being. It causes hair loss in practically 100% of patients, induces neuropathy, makes hands and feet swell, damages the nails, is associated with nausea and vomiting ...” noted Dr. Besse. He went on to say that after the trial, of the patients who stopped receiving the vaccine or chemotherapy (either for toxicity reasons or for disease progression), those who had been given the vaccine responded better to the subsequent chemotherapy “because their overall health was better.”

Clinical development

The clinical development of Tedopi is ongoing. Three trials are currently taking place. One study is comparing the Tedopi vaccine plus docetaxel with Tedopi plus nivolumab (immunotherapy not used as a first-line treatment) to determine whether the effects of these treatment combinations might might be enhanced for patients with previously treated lung cancer.

Another study relating to ovarian cancer is in the recruitment phase. The researchers seek to evaluate the vaccine alone or in combination with pembrolizumab for patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Results from both trials are expected in 2025.

The third trial seeks to assess FOLFIRI as maintenance therapy or FOLFIRI as maintenance plus Tedopi for patients with pancreatic cancer to improve disease management. Efficacy data are expected next year.

OSE Immunotherapeutics is simultaneously working on a companion biomarker, the HLA-A2 test.

The study was funded by OSE Immunotherapeutics. Dr. Besse disclosed the following conflicts of interest (research funding, institution): AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ellipse Pharma, EISAI, Genmab, Genzyme Corporation, Hedera Dx, Inivata, IPSEN, Janssen, MSD, Pharmamar, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi, Socar Research, Taiho Oncology, and Turning Point Therapeutics.

This article was translated from the Medscape French Edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

SINGAPORE – A few months after releasing its phase 1 and 2 data, OSE Immunotherapeutics, which is based in Nantes, France, has announced positive results for its therapeutic vaccine to treat cancer. Following its promising findings concerning early-stage melanoma, pancreatic cancer, ENT cancers, and HPV-associated anogenital cancer,

The results suggest that Tedopi is the most developmentally advanced therapeutic vaccine for cancer.

The data from Atalante-1 were presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer and were simultaneously published in Annals of Oncology.

Tedopi is composed of synthetic tumoral neo-epitopes (peptide fragments) that target five tumoral antigens, permitting the activation of tumor-specific T-lymphocytes for patients who are HLA-A2 positive. In 95% of cases, tumors express at least one of these five antigens. The aim of integrating these five antigens is to prevent immune escape. The technology uses the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, one of the keys for presenting antigens to T-lymphocytes. The vaccine is effective for patients who express the HLA-A2 gene, which is present in around half of the population. The HLA-A2 biomarker, detected via a blood test, can identify appropriate patients.

Study protocol

In the Atalante-1 trial, participants had locally advanced (unresectable and not eligible for radiotherapy) or metastatic (without alteration of the EGFR and ALK genes) non–small cell lung cancer that was resistant to previous immunotherapy. They had an HLA-A2 phenotype, as determined by a blood draw to determine whether their immune system could respond to the vaccine.

In this trial, 219 patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive the vaccine or standard-of-care chemotherapy (80% received docetaxel). The vaccine was administered subcutaneously on day 1 every 3 weeks for six cycles. After that point, the vaccine was administered every 8 weeks until 1 year of treatment and every 12 weeks thereafter. The primary endpoint was overall survival.

Secondary resistance

The plan was to enroll 363 patients in the protocol, but the study did not complete its recruitment phase because of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the study was stopped after the enrollment of 219 patients.

“It didn’t have the power we would have liked, but it helped us understand that the people who benefited the most from the vaccine were patients who had responded to immunotherapy in the past. These patients have what is called ‘secondary resistance,’ ” explained Benjamin Besse, MD, PhD, during a press conference organized by OSE Immunotherapeutics. Dr. Besse, the study’s principal investigator, is the director of clinical research at Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France.

Overall, the results weren’t significant. But the results were positive for patients who had previously responded well to immunotherapy for at least 3 months. Of the 219 patients, 118 (54%) had a positive response.

Among these patients with secondary resistance to immunotherapy, median OS was 11.1 months with Tedopi versus 7.5 months with docetaxel.

For these patients, the risk of death was reduced by 41% with the vaccine, compared with chemotherapy. Overall, 44% of patients lived for another year after receiving Tedopi, versus 27.5% with docetaxel.

“This study is a positive signal for overall survival in the selected population. In this study of 219 patients, we realized that just half of patients really benefited from the vaccine: those who had previously responded to immunotherapy,” said Dr. Besse. “The study needs confirmation from a further, larger phase 3 study in more than 300 patients with secondary resistance to immunotherapy to give us the statistical power we need to convince the regulatory authorities.”

Tolerability profile

Fewer serious adverse effects were reported with the vaccine than with chemotherapy (11.4% with Tedopi and 35.1% with docetaxel).

The vaccine also allowed patients to maintain a better quality of life. Scores from the Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, which explores several areas of daily life, were better with the vaccine. Change in patients’ overall well-being was delayed in the vaccine group: 3.3 months in the chemotherapy arm versus 9 months in the vaccine arm.

“The vaccine was well tolerated. It has benefits in terms of controlling disease symptoms and causes few side effects. Chemotherapy with docetaxel, meanwhile, is more toxic and may affect a patient’s overall well-being. It causes hair loss in practically 100% of patients, induces neuropathy, makes hands and feet swell, damages the nails, is associated with nausea and vomiting ...” noted Dr. Besse. He went on to say that after the trial, of the patients who stopped receiving the vaccine or chemotherapy (either for toxicity reasons or for disease progression), those who had been given the vaccine responded better to the subsequent chemotherapy “because their overall health was better.”

Clinical development

The clinical development of Tedopi is ongoing. Three trials are currently taking place. One study is comparing the Tedopi vaccine plus docetaxel with Tedopi plus nivolumab (immunotherapy not used as a first-line treatment) to determine whether the effects of these treatment combinations might might be enhanced for patients with previously treated lung cancer.

Another study relating to ovarian cancer is in the recruitment phase. The researchers seek to evaluate the vaccine alone or in combination with pembrolizumab for patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Results from both trials are expected in 2025.

The third trial seeks to assess FOLFIRI as maintenance therapy or FOLFIRI as maintenance plus Tedopi for patients with pancreatic cancer to improve disease management. Efficacy data are expected next year.

OSE Immunotherapeutics is simultaneously working on a companion biomarker, the HLA-A2 test.

The study was funded by OSE Immunotherapeutics. Dr. Besse disclosed the following conflicts of interest (research funding, institution): AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ellipse Pharma, EISAI, Genmab, Genzyme Corporation, Hedera Dx, Inivata, IPSEN, Janssen, MSD, Pharmamar, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi, Socar Research, Taiho Oncology, and Turning Point Therapeutics.

This article was translated from the Medscape French Edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

AT WCLC 2023

New ‘C word’: Cure should be the goal for patients with lung cancer

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hello. It’s Mark Kris from Memorial Sloan-Kettering, still musing on things I learned at ASCO 2023.

I learned that there is a new C word.

People used to be afraid to use the word “cancer,” so they would call it the C word. Hopefully we’ve gotten over that stigma, that cancer is an illness that can be fought like any other illness.

There’s a new C word now that people seem, again, afraid to use, and that word is “cure.” It’s almost a true rarity that – again, I’m talking about the lung cancer world in particular – folks use the word “cure.” I didn’t hear it at ASCO, but the truth of the matter is that’s a word we should be using and be using more.

What do our patients want? I think if you truly ask a patient what their goal of care should be, it would be to cure the illness. What I mean by “cure” is to eradicate the cancer that is in their body, keep the cancer and its effects from interfering with their ability to continue their lives, and to do it for the length of their natural life. That’s what our patients want. Yes, overall survival is important, but not as much as a life free of cancer and the burden that it puts on people having cancer in the body.

When you start thinking about cure and how to make it a goal of care, a number of issues immediately crop up. The first one is defining what is meant by “cure.” We don’t have a strict definition of cure. Again, I would probably go to the patients and ask them what they mean by it. There may be some landmark part of the definition that needs to be discussed and addressed, but again, to me it’s having your life not disturbed by cancer, and that generally comes by eradicating cancer. Living with cancer is harder than the living after cancer has been cured. But we don’t have a good definition.

We also don’t have a good way of designing clinical trials to assess whether the regimen is curative. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a trial in lung cancer that looked at the ability of any given treatment to cure patients. We need to come up with ways to design trials to do that. Now, in addition to clinical trials, we don’t have a good body of evidence to design our preclinical experiments to look for those treatments that can lead to cures, or total eradication of cancer in whatever model system might be used. If we make cure the goal, then we need to find ways preclinically to identify those strategies that could lead to that.

Also in the realm of clinical trials, we need a very clear statistical underpinning to show that one or another treatment has a better chance of cure and to show with scientific rigor that one treatment is better than the other when it comes to cure. I think there needs to be more attention to this, and as we think about revamping the clinical trial process, we need to focus more on cure.

I’m saving the most important step for last. None of this can happen unless we try to make it happen and we say cure is possible. My mentor, George Boswell, always taught us that we would, in every single patient with cancer, try to develop a curative strategy. Is there a curative strategy for this patient? If so, pursue it with all the tools and vigor that we have. We really need to think that way.