User login

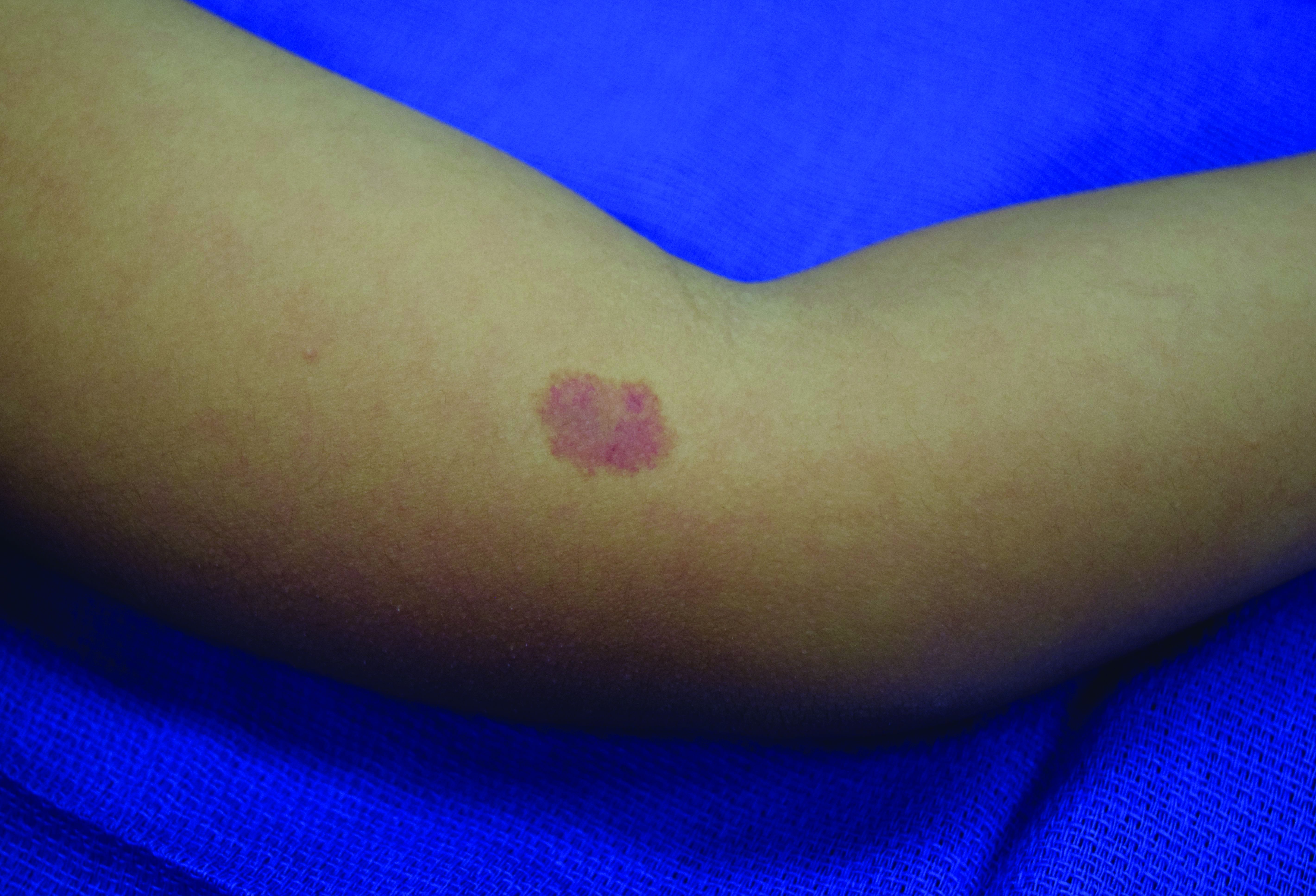

A 70-year-old presented with a 3-week history of asymptomatic violaceous papules on his feet

and named the condition multiple benign pigmented hemorrhagic sarcoma. The disease emerged again at the onset of the AIDS epidemic among homosexual men. There are five variants: HIV/AIDS–related KS, classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS (from immunosuppressive therapy or malignancies such as lymphoma).

KS is caused by human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). Patients with KS have an increased risk of developing other malignancies such as lymphomas, leukemia, and myeloma. This patient exhibited classic KS.

The various forms of KS may appear different clinically. The lesions may appear as erythematous macules, small violaceous papules, large plaques, or ulcerated nodules. In classic KS, violaceous to bluish-black macules evolve to papules or plaques. Lesions are generally asymptomatic. The most common locations are the toes and soles, although other areas may be affected. Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics.

Histology reveals angular vessels lined by atypical cells. An associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells may be present in the upper dermis and perivascular areas. Nodules and plaques reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions will stain positive for HHV-8.

In patients with HIV/AIDS–related KS, highly active antiretroviral therapy is the most important and beneficial treatment. Since the introduction of HAART, the incidence of KS has greatly decreased. However, there are a proportion of HIV/AIDS–associated Kaposi’s sarcoma patients with well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads who require further treatment.

Lesions may spontaneously resolve on their own. Other treatment methods include: cryotherapy, topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon-alpha or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin or paclitaxel. Small lesions that are asymptomatic may be monitored.

This patient had no internal involvement and responded well to cryotherapy.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

and named the condition multiple benign pigmented hemorrhagic sarcoma. The disease emerged again at the onset of the AIDS epidemic among homosexual men. There are five variants: HIV/AIDS–related KS, classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS (from immunosuppressive therapy or malignancies such as lymphoma).

KS is caused by human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). Patients with KS have an increased risk of developing other malignancies such as lymphomas, leukemia, and myeloma. This patient exhibited classic KS.

The various forms of KS may appear different clinically. The lesions may appear as erythematous macules, small violaceous papules, large plaques, or ulcerated nodules. In classic KS, violaceous to bluish-black macules evolve to papules or plaques. Lesions are generally asymptomatic. The most common locations are the toes and soles, although other areas may be affected. Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics.

Histology reveals angular vessels lined by atypical cells. An associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells may be present in the upper dermis and perivascular areas. Nodules and plaques reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions will stain positive for HHV-8.

In patients with HIV/AIDS–related KS, highly active antiretroviral therapy is the most important and beneficial treatment. Since the introduction of HAART, the incidence of KS has greatly decreased. However, there are a proportion of HIV/AIDS–associated Kaposi’s sarcoma patients with well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads who require further treatment.

Lesions may spontaneously resolve on their own. Other treatment methods include: cryotherapy, topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon-alpha or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin or paclitaxel. Small lesions that are asymptomatic may be monitored.

This patient had no internal involvement and responded well to cryotherapy.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

and named the condition multiple benign pigmented hemorrhagic sarcoma. The disease emerged again at the onset of the AIDS epidemic among homosexual men. There are five variants: HIV/AIDS–related KS, classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS (from immunosuppressive therapy or malignancies such as lymphoma).

KS is caused by human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). Patients with KS have an increased risk of developing other malignancies such as lymphomas, leukemia, and myeloma. This patient exhibited classic KS.

The various forms of KS may appear different clinically. The lesions may appear as erythematous macules, small violaceous papules, large plaques, or ulcerated nodules. In classic KS, violaceous to bluish-black macules evolve to papules or plaques. Lesions are generally asymptomatic. The most common locations are the toes and soles, although other areas may be affected. Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics.

Histology reveals angular vessels lined by atypical cells. An associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells may be present in the upper dermis and perivascular areas. Nodules and plaques reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions will stain positive for HHV-8.

In patients with HIV/AIDS–related KS, highly active antiretroviral therapy is the most important and beneficial treatment. Since the introduction of HAART, the incidence of KS has greatly decreased. However, there are a proportion of HIV/AIDS–associated Kaposi’s sarcoma patients with well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads who require further treatment.

Lesions may spontaneously resolve on their own. Other treatment methods include: cryotherapy, topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon-alpha or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin or paclitaxel. Small lesions that are asymptomatic may be monitored.

This patient had no internal involvement and responded well to cryotherapy.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Photosensitivity diagnosis made simple

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Sunscreen myths, controversies continue

, according to Steven Q. Wang, MD, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Basking Ridge, N.J.

Although sunscreens are regulated as an OTC drug under the Food and Drug Administration, concerns persist about the safety of sunscreen active ingredients, including avobenzone, oxybenzone, and octocrylene, Dr. Wang said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In 2019, the FDA proposed a rule that requested additional information on sunscreen ingredients. In response, researchers examined six active ingredients used in sunscreen products. The preliminary results were published in JAMA Dermatology in 2019, with a follow-up study published in 2020 . The studies examined the effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration as a sign of absorption of sunscreen active ingredients.

High absorption

Overall, the maximum level of blood concentration went above the 0.5 ng/mL threshold for waiving nonclinical toxicology studies for all six ingredients. However, the studies had several key limitations, Dr. Wang pointed out. “The maximum usage condition applied in these studies was unrealistic,” he said. “Most people when they use a sunscreen don’t reapply and don’t use enough,” he said.

Also, just because an ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream does not mean it is toxic or harmful to humans, he said. Sunscreens have been used for 5 or 6 decades with almost zero reports of systemic toxicity, he observed.

The conclusions from the studies were that the FDA wanted additional research, but “they do not indicate that individuals should refrain from using sunscreen as a way to protect themselves from skin cancer,” Dr. Wang emphasized.

Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 to provide financial relief for individuals affected by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. “Within that act, there is a provision to reform modernized U.S. regulatory framework on OTC drug reviews,” which will add confusion to the development of a comprehensive monograph about sunscreen because the regulatory process will change, he said.

In the meantime, confusion will likely increase among patients, who may, among other strategies, attempt to make their own sunscreen products at home, as evidenced by videos of individuals making their own products that have had thousands of views, said Dr. Wang. However, these products have no UV protection, he said.

For current sunscreen products, manufacturers are likely to focus on titanium dioxide and zinc oxide products, which fall into the GRASE I category for active ingredients recognized as safe and effective. More research is needed on homosalate, avobenzone, octisalate, and octocrylene, which are currently in the GRASE III category, meaning the data are insufficient to make statements about safety, he said.

Vitamin D concerns

Another sunscreen concern is that use will block healthy vitamin D production, Dr. Wang said. Vitamin D enters the body in two ways, either through food or through the skin, and the latter requires UVB exposure, he explained. “If you started using a sunscreen with SPF 15 that blocks 93% of UVB, you can essentially shut down vitamin D production in the skin,” but that is in the laboratory setting, he said. What happens in reality is different, as people use much less than in a lab setting, and many people put on a small amount of sunscreen and then spend more time in the sun, thereby increasing exposure, Dr. Wang noted.

For example, a study published in 1988 showed that long-term sunscreen users had levels of vitamin D that were less than 50% of those seen in non–sunscreen users. However, another study published in 1995 showed that serum vitamin D levels were not significantly different between users of an SPF 17 sunscreen and a placebo over a 7-month period.

Is a higher SPF better?

Many patients believe that the difference between a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 and 60 is negligible. “People generally say that SPF 30 blocks 96.7% of UVB and SPF 60 blocks 98.3%, but that’s the wrong way of looking at it,” said Dr. Wang. Instead, consider “how much of the UV ray is able to pass through the sunscreen and reach your skin and do damage,” he said. If a product with SPF 30 allows a transmission of 3.3% and a product with SPF 60 allows a transmission of 1.7%, “the SPF 60 product has 194% better protection in preventing the UV reaching the skin,” he said.

Over a lifetime, individuals will build up more UV damage with consistent use of SPF 30, compared with SPF 60 products, so this myth is important to dispel, Dr. Wang emphasized. “It is the transmission we should focus on, not the blockage,” he said.

Also, consider that the inactive ingredients matter in sunscreens, such as water resistance and film-forming technology that helps promote full coverage, Dr. Wang said, but don’t discount features such as texture, aesthetics, smell, and color, all of which impact compliance.

“Sunscreen is very personal, and people do not want to use a product just because of the SPF value, they want to use a product based on how it makes them feel,” he said.

At the end of the day, “the best sunscreen is the one a patient will use regularly and actually enjoy using,” Dr. Wang concluded.

Dr. Wang had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, according to Steven Q. Wang, MD, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Basking Ridge, N.J.

Although sunscreens are regulated as an OTC drug under the Food and Drug Administration, concerns persist about the safety of sunscreen active ingredients, including avobenzone, oxybenzone, and octocrylene, Dr. Wang said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In 2019, the FDA proposed a rule that requested additional information on sunscreen ingredients. In response, researchers examined six active ingredients used in sunscreen products. The preliminary results were published in JAMA Dermatology in 2019, with a follow-up study published in 2020 . The studies examined the effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration as a sign of absorption of sunscreen active ingredients.

High absorption

Overall, the maximum level of blood concentration went above the 0.5 ng/mL threshold for waiving nonclinical toxicology studies for all six ingredients. However, the studies had several key limitations, Dr. Wang pointed out. “The maximum usage condition applied in these studies was unrealistic,” he said. “Most people when they use a sunscreen don’t reapply and don’t use enough,” he said.

Also, just because an ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream does not mean it is toxic or harmful to humans, he said. Sunscreens have been used for 5 or 6 decades with almost zero reports of systemic toxicity, he observed.

The conclusions from the studies were that the FDA wanted additional research, but “they do not indicate that individuals should refrain from using sunscreen as a way to protect themselves from skin cancer,” Dr. Wang emphasized.

Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 to provide financial relief for individuals affected by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. “Within that act, there is a provision to reform modernized U.S. regulatory framework on OTC drug reviews,” which will add confusion to the development of a comprehensive monograph about sunscreen because the regulatory process will change, he said.

In the meantime, confusion will likely increase among patients, who may, among other strategies, attempt to make their own sunscreen products at home, as evidenced by videos of individuals making their own products that have had thousands of views, said Dr. Wang. However, these products have no UV protection, he said.

For current sunscreen products, manufacturers are likely to focus on titanium dioxide and zinc oxide products, which fall into the GRASE I category for active ingredients recognized as safe and effective. More research is needed on homosalate, avobenzone, octisalate, and octocrylene, which are currently in the GRASE III category, meaning the data are insufficient to make statements about safety, he said.

Vitamin D concerns

Another sunscreen concern is that use will block healthy vitamin D production, Dr. Wang said. Vitamin D enters the body in two ways, either through food or through the skin, and the latter requires UVB exposure, he explained. “If you started using a sunscreen with SPF 15 that blocks 93% of UVB, you can essentially shut down vitamin D production in the skin,” but that is in the laboratory setting, he said. What happens in reality is different, as people use much less than in a lab setting, and many people put on a small amount of sunscreen and then spend more time in the sun, thereby increasing exposure, Dr. Wang noted.

For example, a study published in 1988 showed that long-term sunscreen users had levels of vitamin D that were less than 50% of those seen in non–sunscreen users. However, another study published in 1995 showed that serum vitamin D levels were not significantly different between users of an SPF 17 sunscreen and a placebo over a 7-month period.

Is a higher SPF better?

Many patients believe that the difference between a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 and 60 is negligible. “People generally say that SPF 30 blocks 96.7% of UVB and SPF 60 blocks 98.3%, but that’s the wrong way of looking at it,” said Dr. Wang. Instead, consider “how much of the UV ray is able to pass through the sunscreen and reach your skin and do damage,” he said. If a product with SPF 30 allows a transmission of 3.3% and a product with SPF 60 allows a transmission of 1.7%, “the SPF 60 product has 194% better protection in preventing the UV reaching the skin,” he said.

Over a lifetime, individuals will build up more UV damage with consistent use of SPF 30, compared with SPF 60 products, so this myth is important to dispel, Dr. Wang emphasized. “It is the transmission we should focus on, not the blockage,” he said.

Also, consider that the inactive ingredients matter in sunscreens, such as water resistance and film-forming technology that helps promote full coverage, Dr. Wang said, but don’t discount features such as texture, aesthetics, smell, and color, all of which impact compliance.

“Sunscreen is very personal, and people do not want to use a product just because of the SPF value, they want to use a product based on how it makes them feel,” he said.

At the end of the day, “the best sunscreen is the one a patient will use regularly and actually enjoy using,” Dr. Wang concluded.

Dr. Wang had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, according to Steven Q. Wang, MD, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Basking Ridge, N.J.

Although sunscreens are regulated as an OTC drug under the Food and Drug Administration, concerns persist about the safety of sunscreen active ingredients, including avobenzone, oxybenzone, and octocrylene, Dr. Wang said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In 2019, the FDA proposed a rule that requested additional information on sunscreen ingredients. In response, researchers examined six active ingredients used in sunscreen products. The preliminary results were published in JAMA Dermatology in 2019, with a follow-up study published in 2020 . The studies examined the effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration as a sign of absorption of sunscreen active ingredients.

High absorption

Overall, the maximum level of blood concentration went above the 0.5 ng/mL threshold for waiving nonclinical toxicology studies for all six ingredients. However, the studies had several key limitations, Dr. Wang pointed out. “The maximum usage condition applied in these studies was unrealistic,” he said. “Most people when they use a sunscreen don’t reapply and don’t use enough,” he said.

Also, just because an ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream does not mean it is toxic or harmful to humans, he said. Sunscreens have been used for 5 or 6 decades with almost zero reports of systemic toxicity, he observed.

The conclusions from the studies were that the FDA wanted additional research, but “they do not indicate that individuals should refrain from using sunscreen as a way to protect themselves from skin cancer,” Dr. Wang emphasized.

Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 to provide financial relief for individuals affected by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. “Within that act, there is a provision to reform modernized U.S. regulatory framework on OTC drug reviews,” which will add confusion to the development of a comprehensive monograph about sunscreen because the regulatory process will change, he said.

In the meantime, confusion will likely increase among patients, who may, among other strategies, attempt to make their own sunscreen products at home, as evidenced by videos of individuals making their own products that have had thousands of views, said Dr. Wang. However, these products have no UV protection, he said.

For current sunscreen products, manufacturers are likely to focus on titanium dioxide and zinc oxide products, which fall into the GRASE I category for active ingredients recognized as safe and effective. More research is needed on homosalate, avobenzone, octisalate, and octocrylene, which are currently in the GRASE III category, meaning the data are insufficient to make statements about safety, he said.

Vitamin D concerns

Another sunscreen concern is that use will block healthy vitamin D production, Dr. Wang said. Vitamin D enters the body in two ways, either through food or through the skin, and the latter requires UVB exposure, he explained. “If you started using a sunscreen with SPF 15 that blocks 93% of UVB, you can essentially shut down vitamin D production in the skin,” but that is in the laboratory setting, he said. What happens in reality is different, as people use much less than in a lab setting, and many people put on a small amount of sunscreen and then spend more time in the sun, thereby increasing exposure, Dr. Wang noted.

For example, a study published in 1988 showed that long-term sunscreen users had levels of vitamin D that were less than 50% of those seen in non–sunscreen users. However, another study published in 1995 showed that serum vitamin D levels were not significantly different between users of an SPF 17 sunscreen and a placebo over a 7-month period.

Is a higher SPF better?

Many patients believe that the difference between a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 and 60 is negligible. “People generally say that SPF 30 blocks 96.7% of UVB and SPF 60 blocks 98.3%, but that’s the wrong way of looking at it,” said Dr. Wang. Instead, consider “how much of the UV ray is able to pass through the sunscreen and reach your skin and do damage,” he said. If a product with SPF 30 allows a transmission of 3.3% and a product with SPF 60 allows a transmission of 1.7%, “the SPF 60 product has 194% better protection in preventing the UV reaching the skin,” he said.

Over a lifetime, individuals will build up more UV damage with consistent use of SPF 30, compared with SPF 60 products, so this myth is important to dispel, Dr. Wang emphasized. “It is the transmission we should focus on, not the blockage,” he said.

Also, consider that the inactive ingredients matter in sunscreens, such as water resistance and film-forming technology that helps promote full coverage, Dr. Wang said, but don’t discount features such as texture, aesthetics, smell, and color, all of which impact compliance.

“Sunscreen is very personal, and people do not want to use a product just because of the SPF value, they want to use a product based on how it makes them feel,” he said.

At the end of the day, “the best sunscreen is the one a patient will use regularly and actually enjoy using,” Dr. Wang concluded.

Dr. Wang had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Expert shares key facts about keloid therapy

although few understand what this process entails, according to Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

A key point to keep in mind about keloids is that, while they result from trauma, however slight, trauma alone does not cause them, Dr. Baldwin said in a presentation at the virtual MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In general, people with darker skin form keloids more easily and consistently than those with lighter skin, but keloids in people with darker skin are often easier to treat, Dr. Baldwin added. Also worth noting is the fact that earlobe keloids recur less frequently, she said.

Most patients with keloids are not surgical candidates, and they need convincing to pursue alternative options, Dr. Baldwin said.

However, successful management of keloids starts with sorting out what the patient wants. Some want “eradication with normal skin,” which is not realistic, versus simply flattening, lightening, or eradication of the keloid and leaving a scar, she noted. “That skin is never going to look normal,” she said. “Very often, they don’t need the whole thing gone, they just want to be better, and not itch or cause them to think about it all the time.”

Quality clinical research on the management of keloids is limited, Dr. Baldwin continued. “If you are holding out for a good randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study with a healthy ‘N,’ adequate follow-up rational conclusions, don’t hold your breath,” she said. The few literature reviews on keloids in recent decades concluded that modalities used to treat keloids are based on anecdotal evidence rather than rigorous research, she noted.

Size (and shape) matters

The decision to cut a keloid depends on several factors, including lesion size, shape, age, and location, but especially patient commitment to follow up and postsurgery care, said Dr. Baldwin.

She noted that larger keloids are no more difficult to remove than smaller ones, and patients tend to be more satisfied with the outcome with larger keloids. In terms of shape, pedunculated lesions are most amenable to surgery because of their small footprint. “Often the base does not contain keloidal tissue, and the patient gets the maximum benefit for the least risk,” she said. In addition, the residue from the removal of large keloids is often more acceptable.

Options for adjunctive therapy when excising keloids include corticosteroids, radiation, interferon, pressure dressings, dextran hydrogel scaffolding, and possibly botulinum toxin A, Dr. Baldwin said.

Adjunctive treatment alternatives

Intralesional corticosteroids can prevent the recurrence of keloids, and Dr. Baldwin recommends a 40 mg/cc injection into the base and walls of the excision site immediately postop, with repeat injections every 2 weeks for 2 months regardless of the patient’s clinical appearance. However, appearance determines the dose and concentration during 6 months of monthly follow-up, she said.

Radiation therapy, while not an effective monotherapy for keloids, can be used as an adjunct. A short radiation treatment plan may improve compliance, and no local malignancies linked to radiation therapy for keloids have been reported, she said. Dr. Baldwin also shared details of using an in-office superficial radiation therapy with the SRT-100 device, which she said has shown some ability to reduce recurrence of keloids.

Interferon, which can reduce production of collagen and increase collagenase can be used in an amount of 1.5 million units per linear cm around the base and walls of a keloid excision (maximum is 5 million units a day). Be aware that patients can develop flulike symptoms within a day or so, and warn patients to take it easy and monitor for symptoms, she said.

Studies of imiquimod for keloid recurrence have yielded mixed results, and a 2020 literature review concluded that it is not recommended as a treatment option for keloids, said Dr. Baldwin. Pressure dressings also have not shown effectiveness on existing lesions.

Botulinum toxin A has been studied as a way to prevent hypertrophic scars and keloids and potentially for preventing recurrence by injecting at the wound edges, she said. A meta-analysis showed that botulinum toxin was superior to corticosteroids for treating keloids, but “there were a lot of problems with the studies,” she said.

One other option for postexcision keloid treatment is dextran hydrogel scaffolding, which involves a triple-stranded collagen denatured by heat, with the addition of dextran to form a scaffold for fibroblasts, Dr. Baldwin said. This product, when injected prior to the final closure of surgical excision of keloids, may improve outcomes in certain areas, such as the earlobe, she said.

Dr. Baldwin concluded with comments about preventing other keloids from getting out of hand, which is extraordinarily challenging. However, treatment with dupilumab might provide an answer, although data are limited and more research is needed. She cited a case study of a male patient who had severe atopic dermatitis, with two keloids that improved after 7 months on dupilumab. The Th2 cytokines interleukin (IL)–4 and IL-13 have been implicated as key mediators in the pathogenesis of fibroproliferative disorders, which may respond to dupilumab, which targets Th2, she noted.

Dr. Baldwin had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

although few understand what this process entails, according to Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

A key point to keep in mind about keloids is that, while they result from trauma, however slight, trauma alone does not cause them, Dr. Baldwin said in a presentation at the virtual MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In general, people with darker skin form keloids more easily and consistently than those with lighter skin, but keloids in people with darker skin are often easier to treat, Dr. Baldwin added. Also worth noting is the fact that earlobe keloids recur less frequently, she said.

Most patients with keloids are not surgical candidates, and they need convincing to pursue alternative options, Dr. Baldwin said.

However, successful management of keloids starts with sorting out what the patient wants. Some want “eradication with normal skin,” which is not realistic, versus simply flattening, lightening, or eradication of the keloid and leaving a scar, she noted. “That skin is never going to look normal,” she said. “Very often, they don’t need the whole thing gone, they just want to be better, and not itch or cause them to think about it all the time.”

Quality clinical research on the management of keloids is limited, Dr. Baldwin continued. “If you are holding out for a good randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study with a healthy ‘N,’ adequate follow-up rational conclusions, don’t hold your breath,” she said. The few literature reviews on keloids in recent decades concluded that modalities used to treat keloids are based on anecdotal evidence rather than rigorous research, she noted.

Size (and shape) matters

The decision to cut a keloid depends on several factors, including lesion size, shape, age, and location, but especially patient commitment to follow up and postsurgery care, said Dr. Baldwin.

She noted that larger keloids are no more difficult to remove than smaller ones, and patients tend to be more satisfied with the outcome with larger keloids. In terms of shape, pedunculated lesions are most amenable to surgery because of their small footprint. “Often the base does not contain keloidal tissue, and the patient gets the maximum benefit for the least risk,” she said. In addition, the residue from the removal of large keloids is often more acceptable.

Options for adjunctive therapy when excising keloids include corticosteroids, radiation, interferon, pressure dressings, dextran hydrogel scaffolding, and possibly botulinum toxin A, Dr. Baldwin said.

Adjunctive treatment alternatives

Intralesional corticosteroids can prevent the recurrence of keloids, and Dr. Baldwin recommends a 40 mg/cc injection into the base and walls of the excision site immediately postop, with repeat injections every 2 weeks for 2 months regardless of the patient’s clinical appearance. However, appearance determines the dose and concentration during 6 months of monthly follow-up, she said.

Radiation therapy, while not an effective monotherapy for keloids, can be used as an adjunct. A short radiation treatment plan may improve compliance, and no local malignancies linked to radiation therapy for keloids have been reported, she said. Dr. Baldwin also shared details of using an in-office superficial radiation therapy with the SRT-100 device, which she said has shown some ability to reduce recurrence of keloids.

Interferon, which can reduce production of collagen and increase collagenase can be used in an amount of 1.5 million units per linear cm around the base and walls of a keloid excision (maximum is 5 million units a day). Be aware that patients can develop flulike symptoms within a day or so, and warn patients to take it easy and monitor for symptoms, she said.

Studies of imiquimod for keloid recurrence have yielded mixed results, and a 2020 literature review concluded that it is not recommended as a treatment option for keloids, said Dr. Baldwin. Pressure dressings also have not shown effectiveness on existing lesions.

Botulinum toxin A has been studied as a way to prevent hypertrophic scars and keloids and potentially for preventing recurrence by injecting at the wound edges, she said. A meta-analysis showed that botulinum toxin was superior to corticosteroids for treating keloids, but “there were a lot of problems with the studies,” she said.

One other option for postexcision keloid treatment is dextran hydrogel scaffolding, which involves a triple-stranded collagen denatured by heat, with the addition of dextran to form a scaffold for fibroblasts, Dr. Baldwin said. This product, when injected prior to the final closure of surgical excision of keloids, may improve outcomes in certain areas, such as the earlobe, she said.

Dr. Baldwin concluded with comments about preventing other keloids from getting out of hand, which is extraordinarily challenging. However, treatment with dupilumab might provide an answer, although data are limited and more research is needed. She cited a case study of a male patient who had severe atopic dermatitis, with two keloids that improved after 7 months on dupilumab. The Th2 cytokines interleukin (IL)–4 and IL-13 have been implicated as key mediators in the pathogenesis of fibroproliferative disorders, which may respond to dupilumab, which targets Th2, she noted.

Dr. Baldwin had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

although few understand what this process entails, according to Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

A key point to keep in mind about keloids is that, while they result from trauma, however slight, trauma alone does not cause them, Dr. Baldwin said in a presentation at the virtual MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In general, people with darker skin form keloids more easily and consistently than those with lighter skin, but keloids in people with darker skin are often easier to treat, Dr. Baldwin added. Also worth noting is the fact that earlobe keloids recur less frequently, she said.

Most patients with keloids are not surgical candidates, and they need convincing to pursue alternative options, Dr. Baldwin said.

However, successful management of keloids starts with sorting out what the patient wants. Some want “eradication with normal skin,” which is not realistic, versus simply flattening, lightening, or eradication of the keloid and leaving a scar, she noted. “That skin is never going to look normal,” she said. “Very often, they don’t need the whole thing gone, they just want to be better, and not itch or cause them to think about it all the time.”

Quality clinical research on the management of keloids is limited, Dr. Baldwin continued. “If you are holding out for a good randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study with a healthy ‘N,’ adequate follow-up rational conclusions, don’t hold your breath,” she said. The few literature reviews on keloids in recent decades concluded that modalities used to treat keloids are based on anecdotal evidence rather than rigorous research, she noted.

Size (and shape) matters

The decision to cut a keloid depends on several factors, including lesion size, shape, age, and location, but especially patient commitment to follow up and postsurgery care, said Dr. Baldwin.

She noted that larger keloids are no more difficult to remove than smaller ones, and patients tend to be more satisfied with the outcome with larger keloids. In terms of shape, pedunculated lesions are most amenable to surgery because of their small footprint. “Often the base does not contain keloidal tissue, and the patient gets the maximum benefit for the least risk,” she said. In addition, the residue from the removal of large keloids is often more acceptable.

Options for adjunctive therapy when excising keloids include corticosteroids, radiation, interferon, pressure dressings, dextran hydrogel scaffolding, and possibly botulinum toxin A, Dr. Baldwin said.

Adjunctive treatment alternatives

Intralesional corticosteroids can prevent the recurrence of keloids, and Dr. Baldwin recommends a 40 mg/cc injection into the base and walls of the excision site immediately postop, with repeat injections every 2 weeks for 2 months regardless of the patient’s clinical appearance. However, appearance determines the dose and concentration during 6 months of monthly follow-up, she said.

Radiation therapy, while not an effective monotherapy for keloids, can be used as an adjunct. A short radiation treatment plan may improve compliance, and no local malignancies linked to radiation therapy for keloids have been reported, she said. Dr. Baldwin also shared details of using an in-office superficial radiation therapy with the SRT-100 device, which she said has shown some ability to reduce recurrence of keloids.

Interferon, which can reduce production of collagen and increase collagenase can be used in an amount of 1.5 million units per linear cm around the base and walls of a keloid excision (maximum is 5 million units a day). Be aware that patients can develop flulike symptoms within a day or so, and warn patients to take it easy and monitor for symptoms, she said.

Studies of imiquimod for keloid recurrence have yielded mixed results, and a 2020 literature review concluded that it is not recommended as a treatment option for keloids, said Dr. Baldwin. Pressure dressings also have not shown effectiveness on existing lesions.

Botulinum toxin A has been studied as a way to prevent hypertrophic scars and keloids and potentially for preventing recurrence by injecting at the wound edges, she said. A meta-analysis showed that botulinum toxin was superior to corticosteroids for treating keloids, but “there were a lot of problems with the studies,” she said.

One other option for postexcision keloid treatment is dextran hydrogel scaffolding, which involves a triple-stranded collagen denatured by heat, with the addition of dextran to form a scaffold for fibroblasts, Dr. Baldwin said. This product, when injected prior to the final closure of surgical excision of keloids, may improve outcomes in certain areas, such as the earlobe, she said.

Dr. Baldwin concluded with comments about preventing other keloids from getting out of hand, which is extraordinarily challenging. However, treatment with dupilumab might provide an answer, although data are limited and more research is needed. She cited a case study of a male patient who had severe atopic dermatitis, with two keloids that improved after 7 months on dupilumab. The Th2 cytokines interleukin (IL)–4 and IL-13 have been implicated as key mediators in the pathogenesis of fibroproliferative disorders, which may respond to dupilumab, which targets Th2, she noted.

Dr. Baldwin had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

GLIMMER of hope for itch in primary biliary cholangitis

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

GLIMMER of hope for itch in primary biliary cholangitis

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.