User login

FDA Clears AI-Powered Device for Noninvasive Skin Cancer Testing

The handheld wireless tool, which was developed by Miami-based DermaSensor Inc., operates on battery power, uses spectroscopy and algorithms to evaluate skin lesions for potential cancer in a matter of seconds, and is intended for use by primary care physicians. After the device completes the scan of a lesion, a result of “investigate further” (positive result) suggests further evaluation through a referral to a dermatologist, while “monitor” (negative result) suggests that there is no immediate need for a referral to a dermatologist.

In a pivotal trial of the device that evaluated 224 high risk lesions at 18 primary care study sites in the United States and 4 in Australia, the device had an overall sensitivity of 95.5% for detecting malignancy.

In a more recent validation study funded by DermaSensor, investigators tested 333 lesions at four U.S. dermatology offices and found that the overall device sensitivity was 97.04%, with subgroup sensitivity of 96.67% for melanoma, 97.22% for basal cell carcinoma, and 97.01% for squamous cell carcinoma. Overall specificity of the device was 26.22%.

The study authors, led by Tallahassee, Fla.–based dermatologist Armand B. Cognetta Jr., MD, concluded that DermaSensor’s rapid clinical analysis of lesions “allows for its easy integration into clinical practice infrastructures. Proper use of this device may aid in the reduction of morbidity and mortality associated with skin cancer through expedited and enhanced detection and intervention.”

According to marketing material from the DermaSensor website, the device’s AI algorithm was developed and validated with more than 20,000 scans, composed of more than 4,000 benign and malignant lesions. In a statement about the clearance, the FDA emphasized that the device “should not be used as the sole diagnostic criterion nor to confirm a diagnosis of skin cancer.” The agency is requiring that the manufacturer “conduct additional post-market clinical validation performance testing of the DermaSensor device in patients from demographic groups representative of the U.S. population, including populations who had limited representation of melanomas in the premarket studies, due to their having a relatively low incidence of the disease.”

According to a spokesperson for DermaSensor, pricing for the device is based on a subscription model: $199 per month for five patients or $399 per month for unlimited use. DermaSensor is currently commercially available in Europe and Australia.

Asked to comment, Vishal A. Patel, MD, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington Cancer Center, Washington, said that the FDA clearance of DermaSensor highlights the growing appreciation of AI-driven diagnostic support for primary care providers and dermatologists. "Skin cancers are a growing epidemic in the US and the ability to accurately identify potential suspicious lesions without immediately reaching for the scalpel is invaluable," Patel told this news organization. He was not involved with DermSensor studies.

"Furthermore, this tool can help address the shortage of dermatologists and long wait times by helping primary care providers accurately risk-stratify patients and identify those who need to be seen immediately for potential biopsy and expert care," he added. "However, just like with any new technology, we must use caution to not overutilize this tool," which he said, could "lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of early or innocuous lesions that are better managed with empiric field treatments."

Dr. Cognetta was a paid investigator for the study.

Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI.

The handheld wireless tool, which was developed by Miami-based DermaSensor Inc., operates on battery power, uses spectroscopy and algorithms to evaluate skin lesions for potential cancer in a matter of seconds, and is intended for use by primary care physicians. After the device completes the scan of a lesion, a result of “investigate further” (positive result) suggests further evaluation through a referral to a dermatologist, while “monitor” (negative result) suggests that there is no immediate need for a referral to a dermatologist.

In a pivotal trial of the device that evaluated 224 high risk lesions at 18 primary care study sites in the United States and 4 in Australia, the device had an overall sensitivity of 95.5% for detecting malignancy.

In a more recent validation study funded by DermaSensor, investigators tested 333 lesions at four U.S. dermatology offices and found that the overall device sensitivity was 97.04%, with subgroup sensitivity of 96.67% for melanoma, 97.22% for basal cell carcinoma, and 97.01% for squamous cell carcinoma. Overall specificity of the device was 26.22%.

The study authors, led by Tallahassee, Fla.–based dermatologist Armand B. Cognetta Jr., MD, concluded that DermaSensor’s rapid clinical analysis of lesions “allows for its easy integration into clinical practice infrastructures. Proper use of this device may aid in the reduction of morbidity and mortality associated with skin cancer through expedited and enhanced detection and intervention.”

According to marketing material from the DermaSensor website, the device’s AI algorithm was developed and validated with more than 20,000 scans, composed of more than 4,000 benign and malignant lesions. In a statement about the clearance, the FDA emphasized that the device “should not be used as the sole diagnostic criterion nor to confirm a diagnosis of skin cancer.” The agency is requiring that the manufacturer “conduct additional post-market clinical validation performance testing of the DermaSensor device in patients from demographic groups representative of the U.S. population, including populations who had limited representation of melanomas in the premarket studies, due to their having a relatively low incidence of the disease.”

According to a spokesperson for DermaSensor, pricing for the device is based on a subscription model: $199 per month for five patients or $399 per month for unlimited use. DermaSensor is currently commercially available in Europe and Australia.

Asked to comment, Vishal A. Patel, MD, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington Cancer Center, Washington, said that the FDA clearance of DermaSensor highlights the growing appreciation of AI-driven diagnostic support for primary care providers and dermatologists. "Skin cancers are a growing epidemic in the US and the ability to accurately identify potential suspicious lesions without immediately reaching for the scalpel is invaluable," Patel told this news organization. He was not involved with DermSensor studies.

"Furthermore, this tool can help address the shortage of dermatologists and long wait times by helping primary care providers accurately risk-stratify patients and identify those who need to be seen immediately for potential biopsy and expert care," he added. "However, just like with any new technology, we must use caution to not overutilize this tool," which he said, could "lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of early or innocuous lesions that are better managed with empiric field treatments."

Dr. Cognetta was a paid investigator for the study.

Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI.

The handheld wireless tool, which was developed by Miami-based DermaSensor Inc., operates on battery power, uses spectroscopy and algorithms to evaluate skin lesions for potential cancer in a matter of seconds, and is intended for use by primary care physicians. After the device completes the scan of a lesion, a result of “investigate further” (positive result) suggests further evaluation through a referral to a dermatologist, while “monitor” (negative result) suggests that there is no immediate need for a referral to a dermatologist.

In a pivotal trial of the device that evaluated 224 high risk lesions at 18 primary care study sites in the United States and 4 in Australia, the device had an overall sensitivity of 95.5% for detecting malignancy.

In a more recent validation study funded by DermaSensor, investigators tested 333 lesions at four U.S. dermatology offices and found that the overall device sensitivity was 97.04%, with subgroup sensitivity of 96.67% for melanoma, 97.22% for basal cell carcinoma, and 97.01% for squamous cell carcinoma. Overall specificity of the device was 26.22%.

The study authors, led by Tallahassee, Fla.–based dermatologist Armand B. Cognetta Jr., MD, concluded that DermaSensor’s rapid clinical analysis of lesions “allows for its easy integration into clinical practice infrastructures. Proper use of this device may aid in the reduction of morbidity and mortality associated with skin cancer through expedited and enhanced detection and intervention.”

According to marketing material from the DermaSensor website, the device’s AI algorithm was developed and validated with more than 20,000 scans, composed of more than 4,000 benign and malignant lesions. In a statement about the clearance, the FDA emphasized that the device “should not be used as the sole diagnostic criterion nor to confirm a diagnosis of skin cancer.” The agency is requiring that the manufacturer “conduct additional post-market clinical validation performance testing of the DermaSensor device in patients from demographic groups representative of the U.S. population, including populations who had limited representation of melanomas in the premarket studies, due to their having a relatively low incidence of the disease.”

According to a spokesperson for DermaSensor, pricing for the device is based on a subscription model: $199 per month for five patients or $399 per month for unlimited use. DermaSensor is currently commercially available in Europe and Australia.

Asked to comment, Vishal A. Patel, MD, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington Cancer Center, Washington, said that the FDA clearance of DermaSensor highlights the growing appreciation of AI-driven diagnostic support for primary care providers and dermatologists. "Skin cancers are a growing epidemic in the US and the ability to accurately identify potential suspicious lesions without immediately reaching for the scalpel is invaluable," Patel told this news organization. He was not involved with DermSensor studies.

"Furthermore, this tool can help address the shortage of dermatologists and long wait times by helping primary care providers accurately risk-stratify patients and identify those who need to be seen immediately for potential biopsy and expert care," he added. "However, just like with any new technology, we must use caution to not overutilize this tool," which he said, could "lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of early or innocuous lesions that are better managed with empiric field treatments."

Dr. Cognetta was a paid investigator for the study.

Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI.

Coming Soon: The First mRNA Vaccine for Melanoma?

Moderna and Merck have presented promising results from their phase 2b clinical trial that investigated a combination of a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine and a cancer drug for the treatment of melanoma.

Is mRNA set to shake up the world of cancer treatment? This is certainly what Moderna seems to think; the pharmaceutical company has published the results of a phase 2b trial combining its mRNA vaccine (mRNA-4157 [V940]) with Merck’s cancer drug KEYTRUDA. While these are not the final results but rather mid-term data from the 3-year follow-up, they are somewhat promising. The randomized KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 clinical trial involves patients with high-risk (stage III/IV) melanoma following complete resection.

Relapse Risk Halved

Treatment with mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with pembrolizumab led to a clinically meaningful improvement in recurrence-free survival, reducing the risk for recurrence or death by 49%, compared with pembrolizumab alone. T, reducing the risk of developing distant metastasis or death by 62%. “The KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study was the first demonstration of efficacy for an investigational mRNA cancer treatment in a randomized clinical trial and the first combination therapy to show a significant benefit over pembrolizumab alone in adjuvant melanoma,” said Kyle Holen, MD, Moderna’s senior vice president, after presenting these results.

Side Effects

The combined treatment also did not demonstrate more significant side effects than pembrolizumab alone. The number of patients reporting treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater was similar between the arms (25% for mRNA-4157 [V940] with pembrolizumab vs 20% for KEYTRUDA alone). The most common adverse events of any grade attributed to mRNA-4157 (V940) were fatigue (60.6%), injection site pain (56.7%), and chills (49%). Based on data from the phase 2b KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study, the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency granted breakthrough therapy designation and recognition under the the Priority Medicines scheme, respectively, for mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with KEYTRUDA for the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk melanoma.

Phase 3 Trial

In July, Moderna and Merck announced the launch of a phase 3 trial, assessing “mRNA-4157 [V940] in combination with pembrolizumab as adjuvant treatment in patients with high-risk resected melanoma [stages IIB-IV].” Stéphane Bancel, Moderna’s director general, believes that an mRNA vaccine for melanoma could be available in 2025.

Other Cancer Vaccines

Moderna is not the only laboratory to set its sights on developing a vaccine for cancer. In May, BioNTech, in partnership with Roche, proposed a phase 1 clinical trial of a vaccine targeting pancreatic cancer in Nature. In June, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology›s conference, Transgene presented its conclusions concerning its viral vector vaccines against ENT and papillomavirus-linked cancers. And in September, Ose Immunotherapeutics made headlines with its vaccine for advanced lung cancer.

This article was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Moderna and Merck have presented promising results from their phase 2b clinical trial that investigated a combination of a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine and a cancer drug for the treatment of melanoma.

Is mRNA set to shake up the world of cancer treatment? This is certainly what Moderna seems to think; the pharmaceutical company has published the results of a phase 2b trial combining its mRNA vaccine (mRNA-4157 [V940]) with Merck’s cancer drug KEYTRUDA. While these are not the final results but rather mid-term data from the 3-year follow-up, they are somewhat promising. The randomized KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 clinical trial involves patients with high-risk (stage III/IV) melanoma following complete resection.

Relapse Risk Halved

Treatment with mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with pembrolizumab led to a clinically meaningful improvement in recurrence-free survival, reducing the risk for recurrence or death by 49%, compared with pembrolizumab alone. T, reducing the risk of developing distant metastasis or death by 62%. “The KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study was the first demonstration of efficacy for an investigational mRNA cancer treatment in a randomized clinical trial and the first combination therapy to show a significant benefit over pembrolizumab alone in adjuvant melanoma,” said Kyle Holen, MD, Moderna’s senior vice president, after presenting these results.

Side Effects

The combined treatment also did not demonstrate more significant side effects than pembrolizumab alone. The number of patients reporting treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater was similar between the arms (25% for mRNA-4157 [V940] with pembrolizumab vs 20% for KEYTRUDA alone). The most common adverse events of any grade attributed to mRNA-4157 (V940) were fatigue (60.6%), injection site pain (56.7%), and chills (49%). Based on data from the phase 2b KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study, the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency granted breakthrough therapy designation and recognition under the the Priority Medicines scheme, respectively, for mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with KEYTRUDA for the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk melanoma.

Phase 3 Trial

In July, Moderna and Merck announced the launch of a phase 3 trial, assessing “mRNA-4157 [V940] in combination with pembrolizumab as adjuvant treatment in patients with high-risk resected melanoma [stages IIB-IV].” Stéphane Bancel, Moderna’s director general, believes that an mRNA vaccine for melanoma could be available in 2025.

Other Cancer Vaccines

Moderna is not the only laboratory to set its sights on developing a vaccine for cancer. In May, BioNTech, in partnership with Roche, proposed a phase 1 clinical trial of a vaccine targeting pancreatic cancer in Nature. In June, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology›s conference, Transgene presented its conclusions concerning its viral vector vaccines against ENT and papillomavirus-linked cancers. And in September, Ose Immunotherapeutics made headlines with its vaccine for advanced lung cancer.

This article was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Moderna and Merck have presented promising results from their phase 2b clinical trial that investigated a combination of a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine and a cancer drug for the treatment of melanoma.

Is mRNA set to shake up the world of cancer treatment? This is certainly what Moderna seems to think; the pharmaceutical company has published the results of a phase 2b trial combining its mRNA vaccine (mRNA-4157 [V940]) with Merck’s cancer drug KEYTRUDA. While these are not the final results but rather mid-term data from the 3-year follow-up, they are somewhat promising. The randomized KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 clinical trial involves patients with high-risk (stage III/IV) melanoma following complete resection.

Relapse Risk Halved

Treatment with mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with pembrolizumab led to a clinically meaningful improvement in recurrence-free survival, reducing the risk for recurrence or death by 49%, compared with pembrolizumab alone. T, reducing the risk of developing distant metastasis or death by 62%. “The KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study was the first demonstration of efficacy for an investigational mRNA cancer treatment in a randomized clinical trial and the first combination therapy to show a significant benefit over pembrolizumab alone in adjuvant melanoma,” said Kyle Holen, MD, Moderna’s senior vice president, after presenting these results.

Side Effects

The combined treatment also did not demonstrate more significant side effects than pembrolizumab alone. The number of patients reporting treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater was similar between the arms (25% for mRNA-4157 [V940] with pembrolizumab vs 20% for KEYTRUDA alone). The most common adverse events of any grade attributed to mRNA-4157 (V940) were fatigue (60.6%), injection site pain (56.7%), and chills (49%). Based on data from the phase 2b KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study, the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency granted breakthrough therapy designation and recognition under the the Priority Medicines scheme, respectively, for mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with KEYTRUDA for the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk melanoma.

Phase 3 Trial

In July, Moderna and Merck announced the launch of a phase 3 trial, assessing “mRNA-4157 [V940] in combination with pembrolizumab as adjuvant treatment in patients with high-risk resected melanoma [stages IIB-IV].” Stéphane Bancel, Moderna’s director general, believes that an mRNA vaccine for melanoma could be available in 2025.

Other Cancer Vaccines

Moderna is not the only laboratory to set its sights on developing a vaccine for cancer. In May, BioNTech, in partnership with Roche, proposed a phase 1 clinical trial of a vaccine targeting pancreatic cancer in Nature. In June, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology›s conference, Transgene presented its conclusions concerning its viral vector vaccines against ENT and papillomavirus-linked cancers. And in September, Ose Immunotherapeutics made headlines with its vaccine for advanced lung cancer.

This article was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

PRAME Expression in Melanocytic Proliferations in Special Sites

The assessment and diagnosis of melanocytic lesions can present a formidable challenge to even a seasoned pathologist, which is especially true when dealing with the subset of nevi occurring at special sites—where baseline variations inherent to particular locations on the body can preclude the use of features routinely used to diagnose malignancy elsewhere. These so-called special-site nevi previously have been described in the literature along with suggested criteria for differentiating malignant lesions from their benign counterparts.1 Locations generally considered to be special sites include the acral skin, anogenital region, breast, ear, and flexural regions.1,2

When evaluating non–special-site melanocytic lesions, general characteristics associated with a malignant diagnosis include confluence or pagetoid spread of melanocytes, nuclear pleomorphism, cytologic atypia, and irregular architecture3; however, these features can be compatible with a benign diagnosis in special-site nevi depending on their extent and the site in question. Although they can be atypical, special-site nevi tend to have the bulk of their architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in the center of the lesion as opposed to the edges.1 If a given lesion is from a special site but lacks this reassuring feature, special care should be taken to rule out malignancy.

Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) is an antigen first identified in tumor-reactive T-cell populations in patients with malignant melanoma. It is the product of an oncogene that frequently is overexpressed in melanomas, lung squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, and acute leukemias.4 It functions as an antagonist of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, which normally serves to induce further cell differentiation, senescence, or apoptosis.5 PRAME inhibits retinoid signaling by forming a complex with both the ligand-bound retinoic acid holoreceptor and the polycomb protein EZH2, which blocks retinoid-dependent gene expression by encouraging chromatin condensation at the RARβ promoter site5; therefore, expressing PRAME allows lesional cells a substantial growth advantage.

PRAME expression has been extensively characterized in non–special-site nevi and has filled the need for a rather specific marker of melanoma.6-10 Although PRAME has been studied in acral nevi,11 the expression pattern in nevi of special sites has yet to be elucidated. Herein, we present a dataset characterizing PRAME expression in these challenging lesions.

Methods

We performed a retrospective case review at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia) and collected a panel of 36 special-site nevi that previously were diagnosed as benign by a trained dermatopathologist from January 2020 through December 2022. Special-site nevi were identified using a natural language filter for the following terms: acral, palm, sole, ear, auricular, lip, axilla, armpit, breast, groin, labia, vulva, umbilicus, and penis. This study was approved by the University of Virginia institutional review board.

The original hematoxylin and eosin slides used for primary diagnosis were re-examined to verify the prior diagnosis of benign nevus at a special site. We performed a detailed microscopic examination of all benign nevi in our cohort to determine the frequency of various characteristics at each special site. Sections were prepared from the formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and stained with a commercial PRAME antibody (#219650 [Abcam] at a 1:50 dilution) and counterstain. A trained dermatopathologist (S.S.R.) examined the stained sections and recorded the percentage of tumor cells with nuclear PRAME staining. We reported our results using previously established criteria for scoring PRAME immunohistochemistry7: 0 for no expression, 1+ for 1% to 25% expression, 2+ for 26% to 50% expression, 3+ for 51% to 75% expression, and 4+ for diffuse or 76% to 100% expression. Only strong clonal expression within a population of cells was graded.

Data handling and statistical testing were performed using the R Project for Statistical Computing (https://www.r-project.org/). Significance testing was performed using the Fisher exact test. Plot construction was performed using ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/).

Results

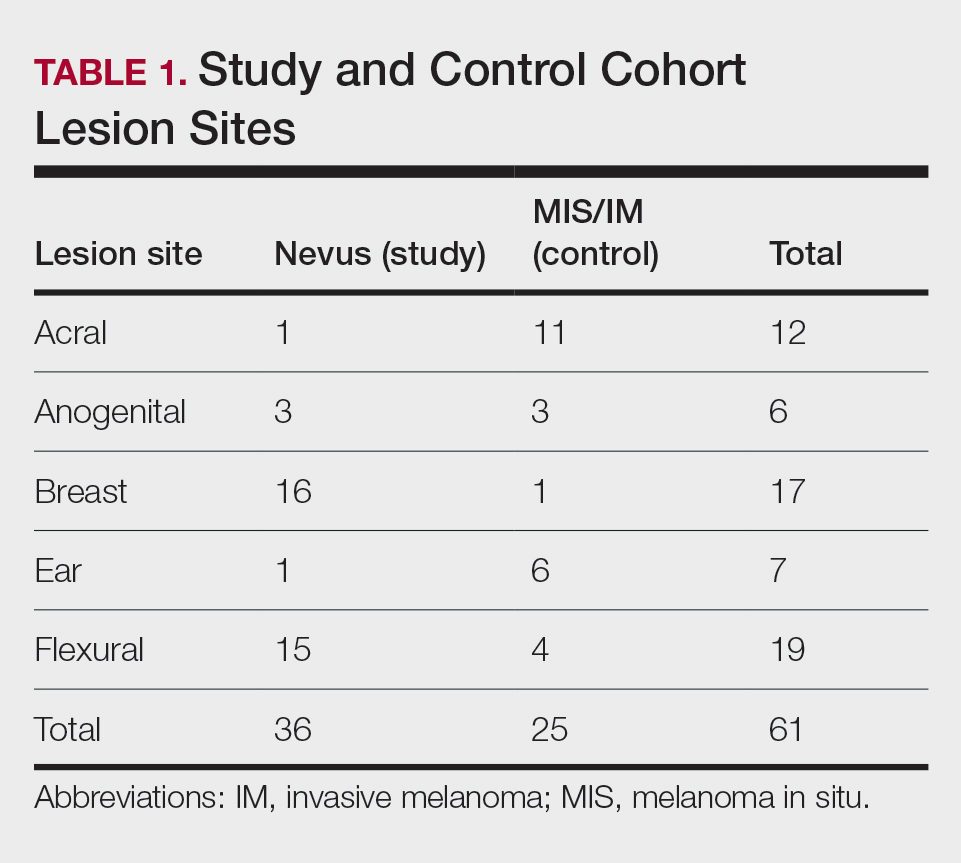

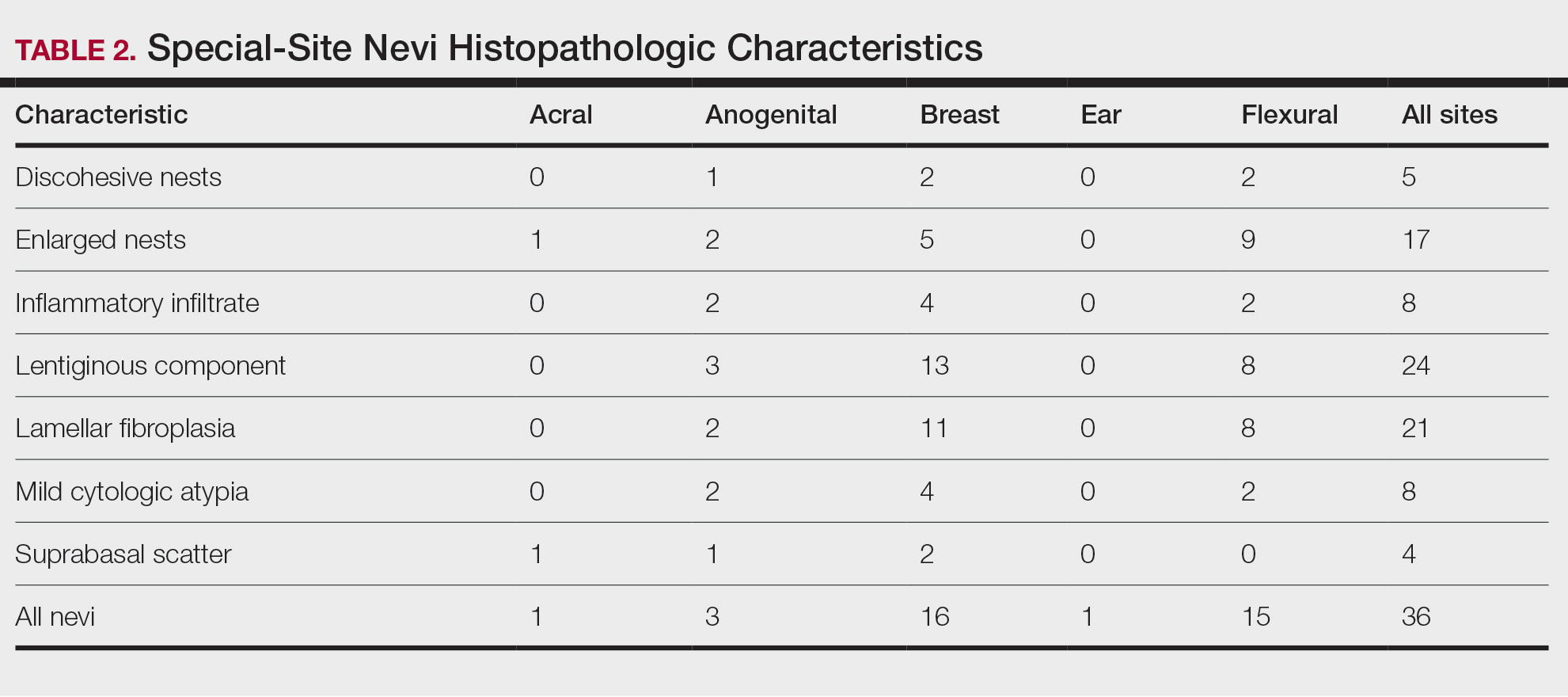

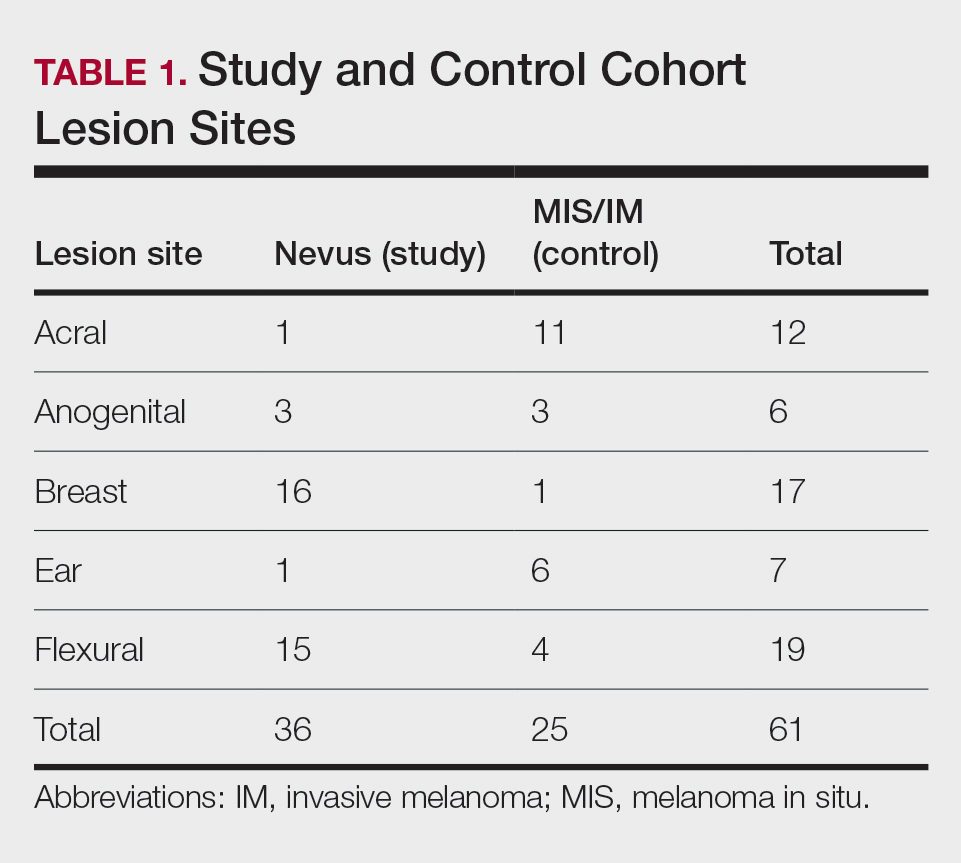

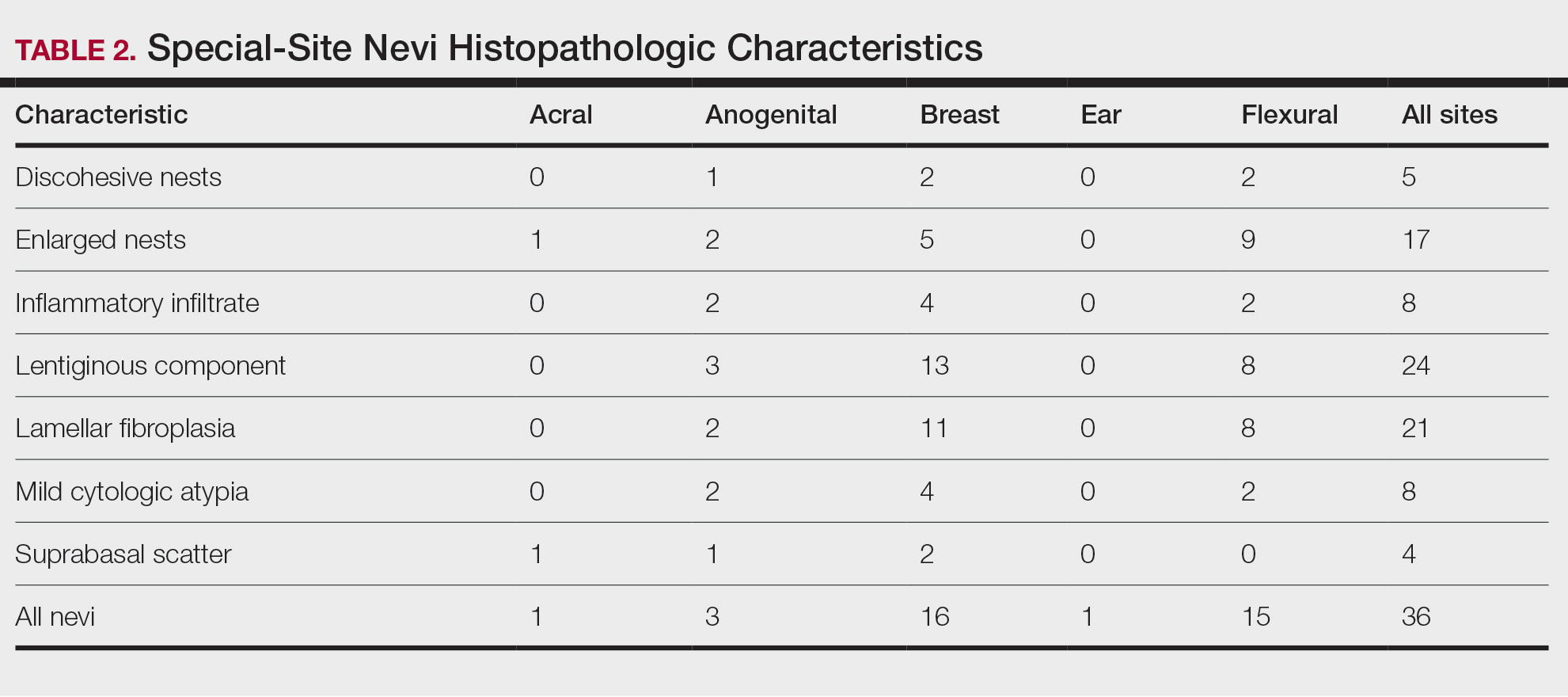

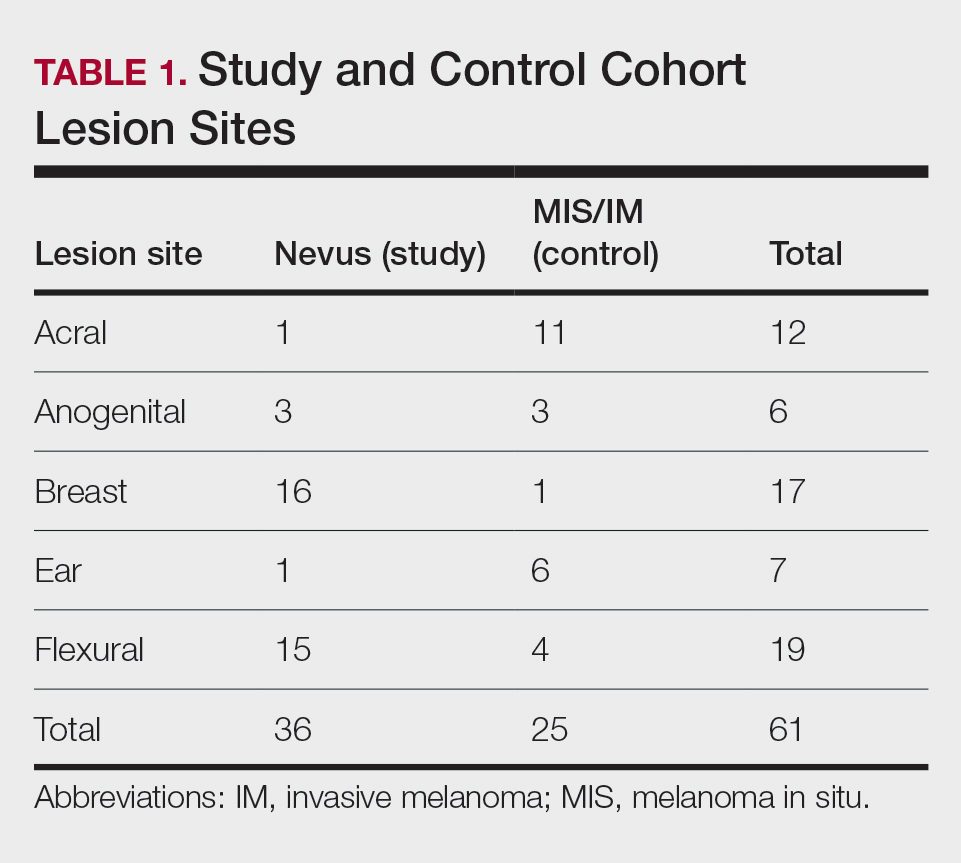

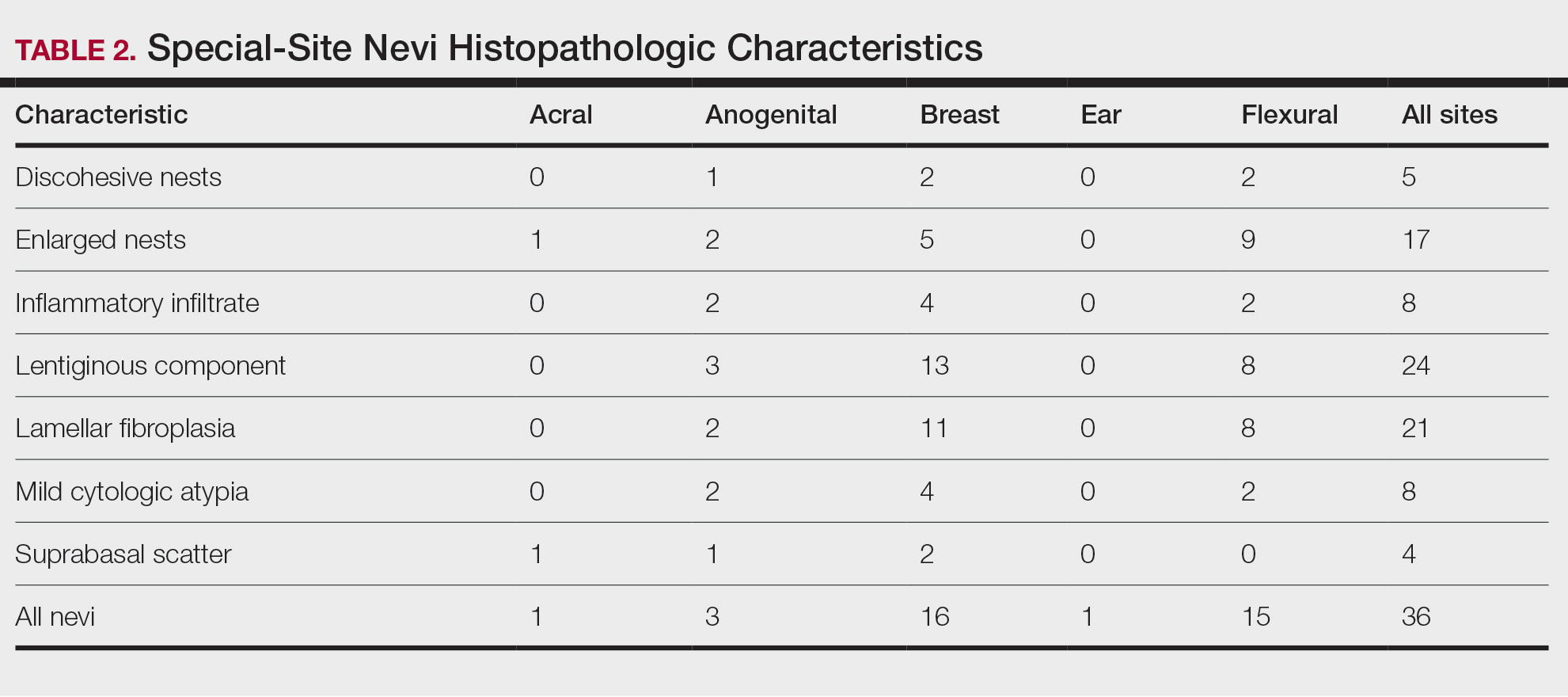

Our study cohort included 36 special-site nevi, and the control cohort comprised 25 melanoma in situ (MIS) or invasive melanoma (IM) lesions occurring at special sites. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the study and control cohorts by lesion site. Table 2 details the results of our microscopic examination, describing frequency of various characteristics of special-site nevi stratified by site.

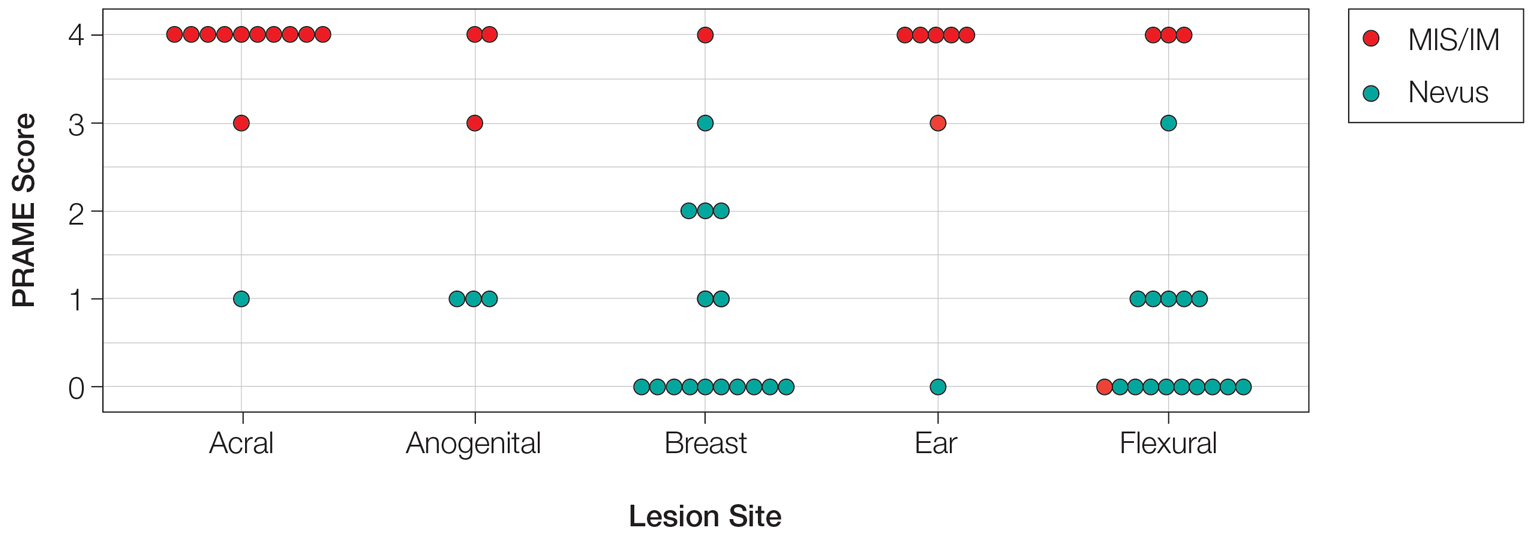

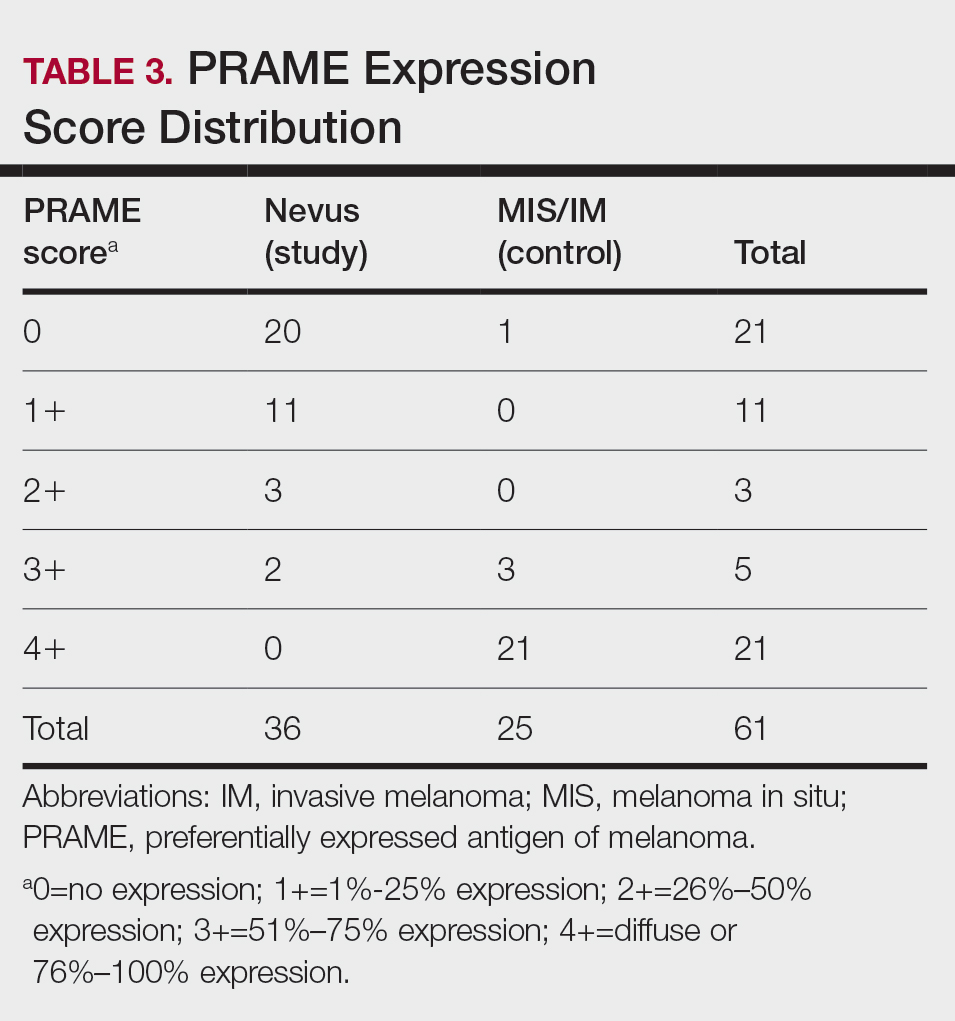

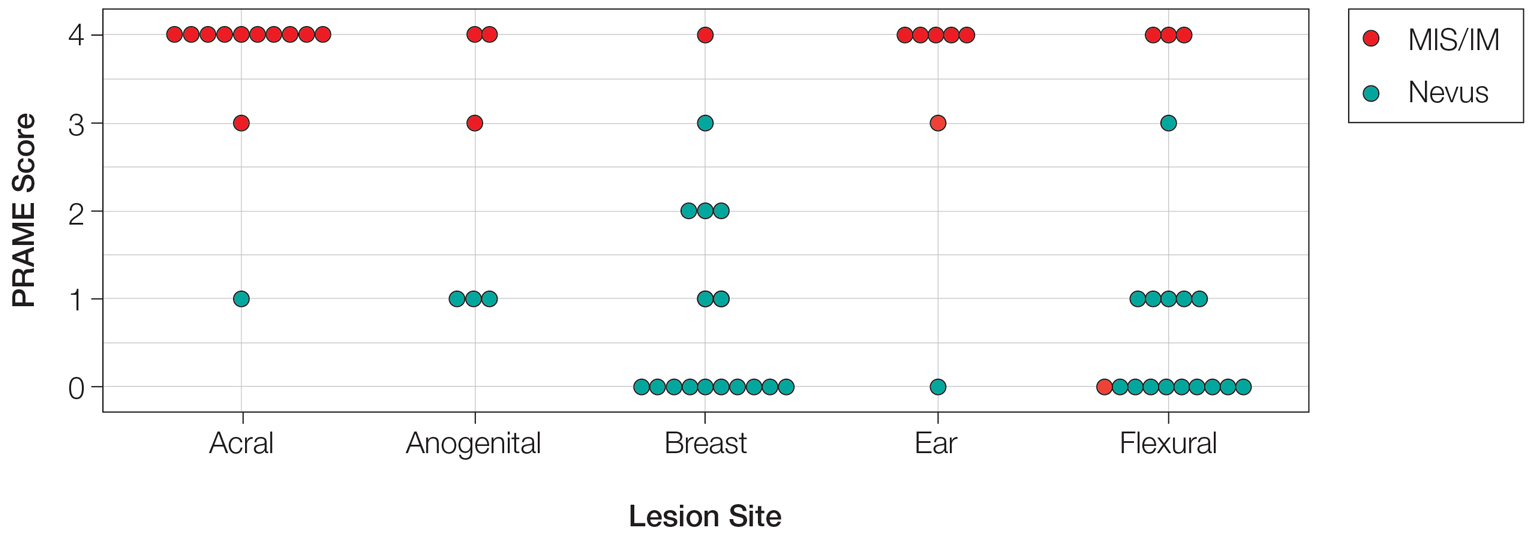

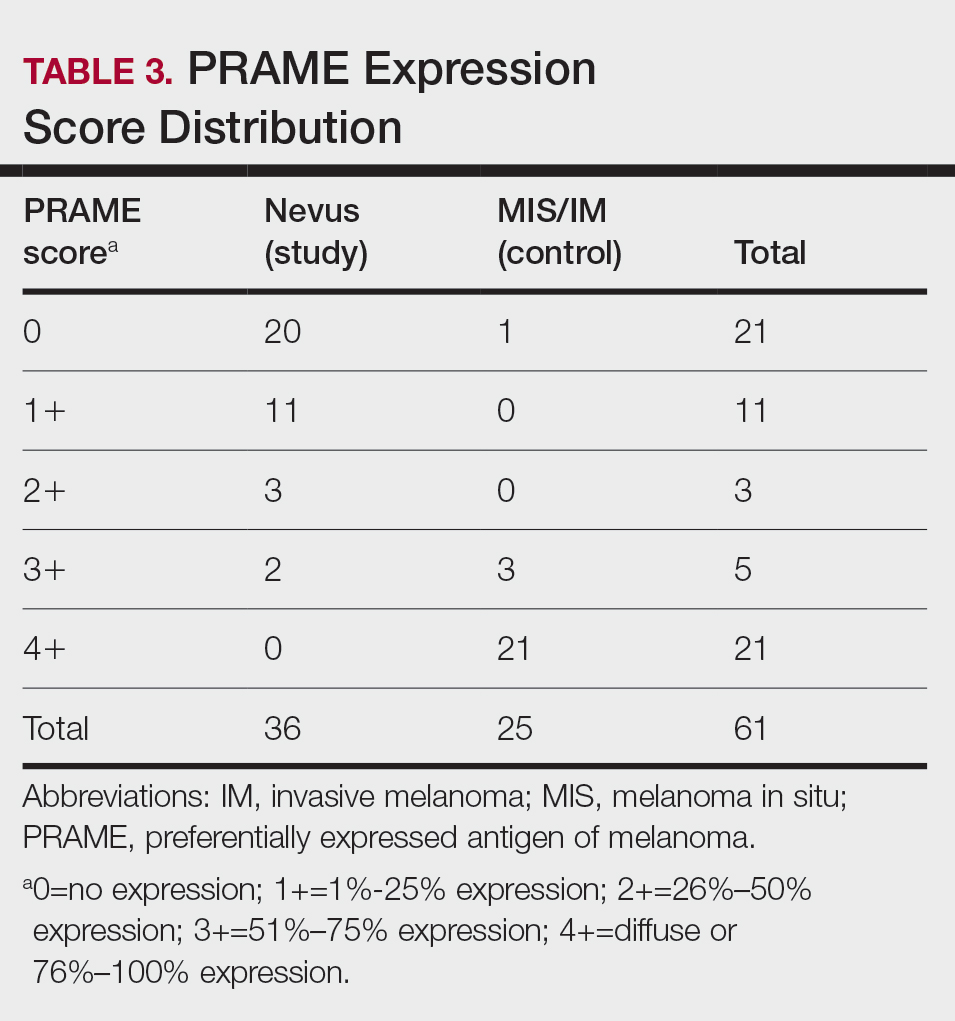

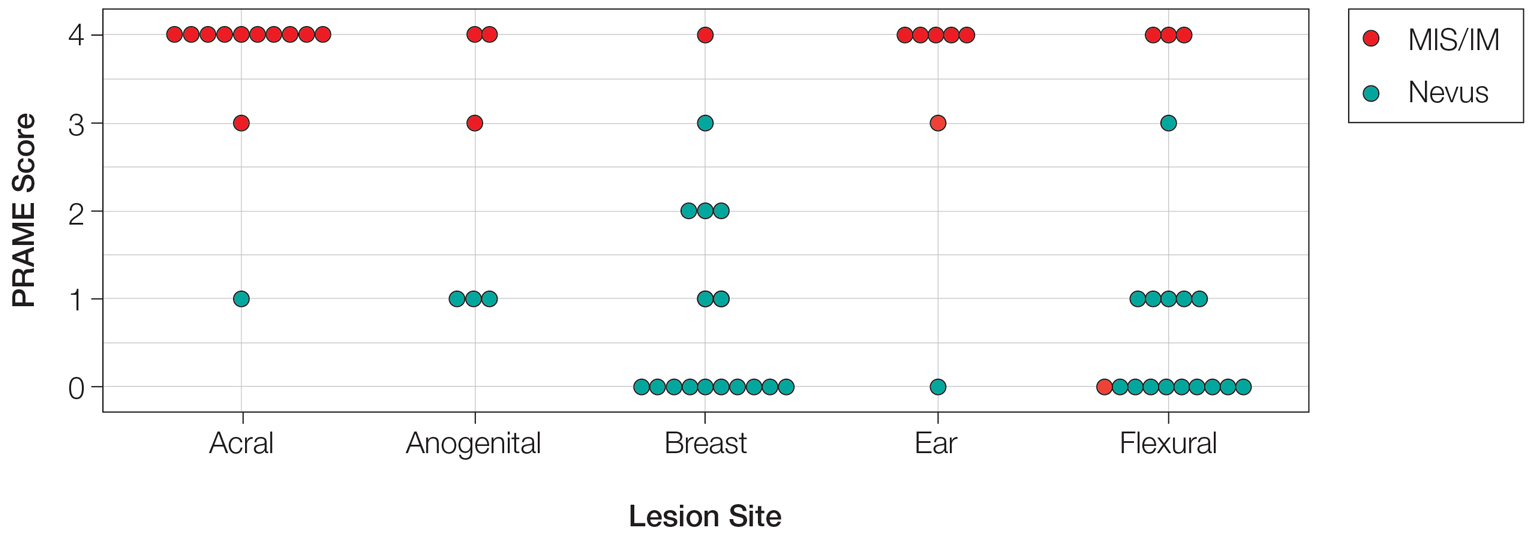

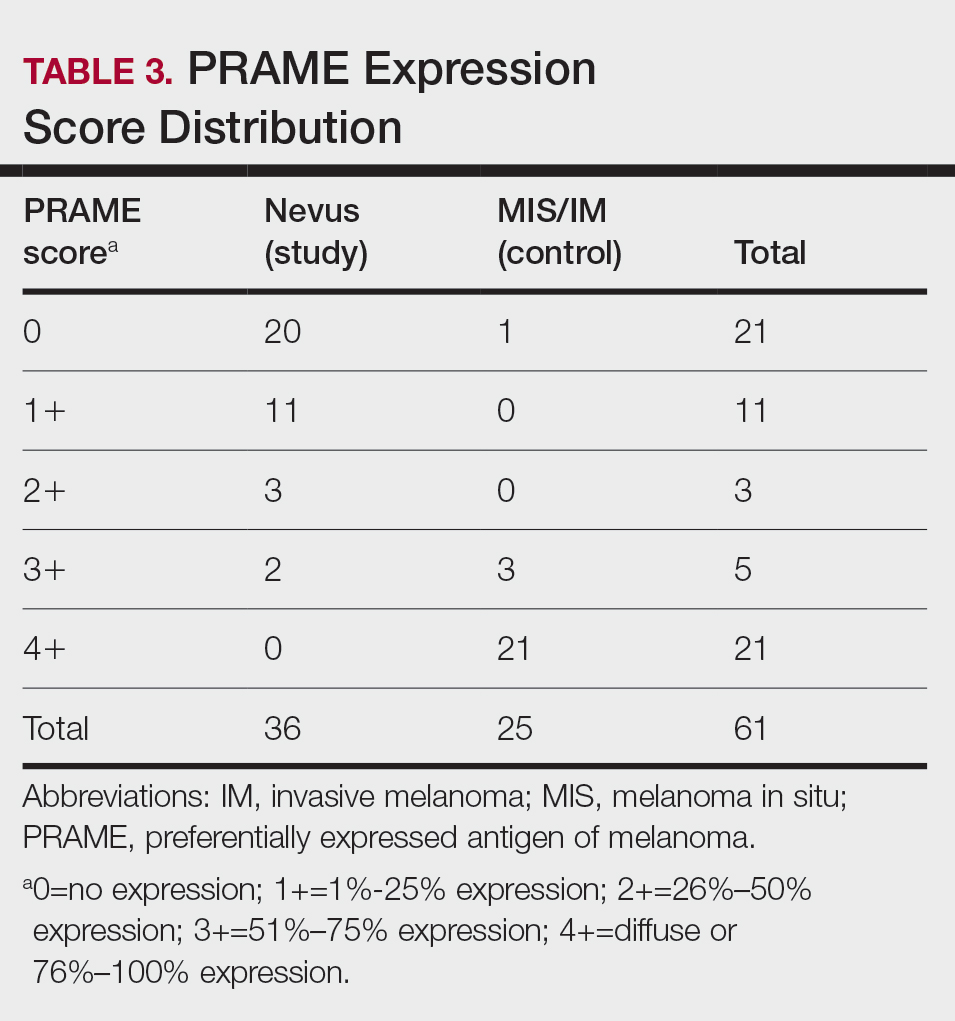

Of the 36 special-site nevi in our cohort, 20 (56%) had no staining (0) for PRAME, 11 (31%) demonstrated 1+ PRAME expression, 3 (8%) demonstrated 2+ PRAME expression, and 2 (6%) demonstrated 3+ PRAME expression. No nevi showed 4+ expression. In the control cohort, 24 of 25 (96%) MIS and IM showed 3+ or 4+ expression, with 21 (84%) demonstrating diffuse/4+ expression. One control case (4%) demonstrated 0 PRAME expression. These data are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 1. There is a significant difference in diffuse (4+) PRAME expression between special-site nevi and MIS/IM occurring at special sites (P=1.039×10-12).

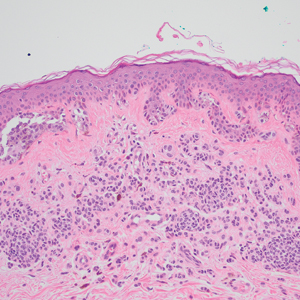

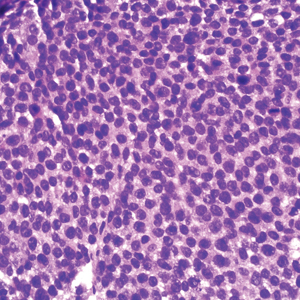

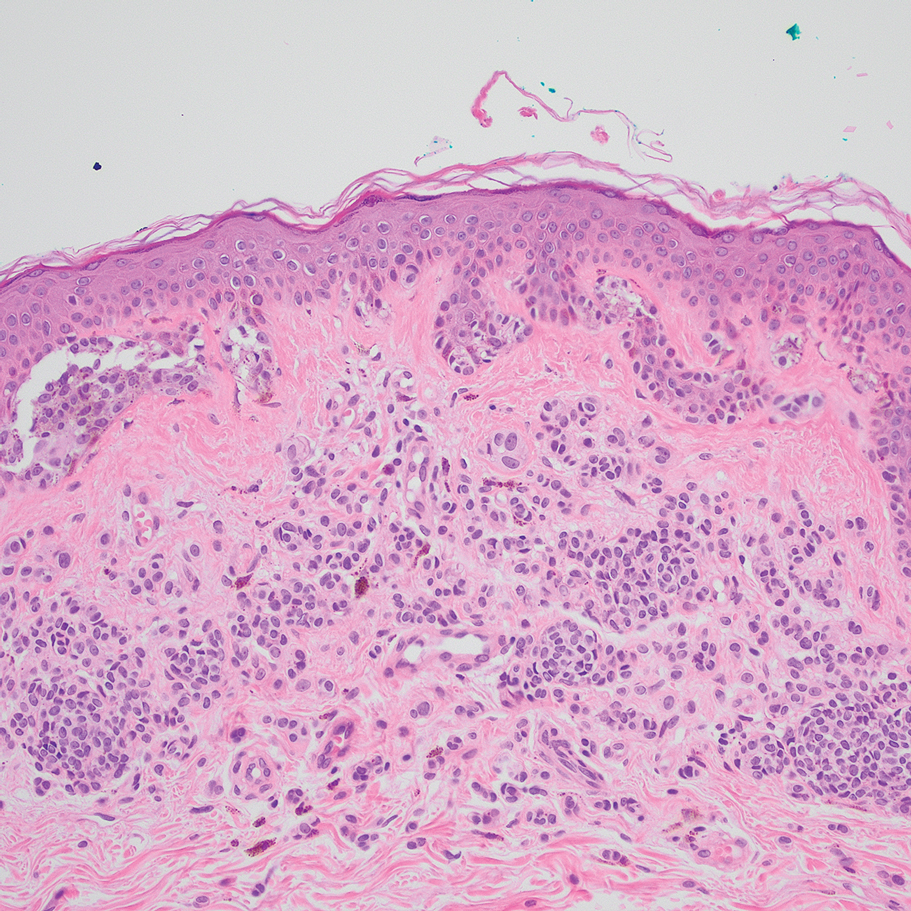

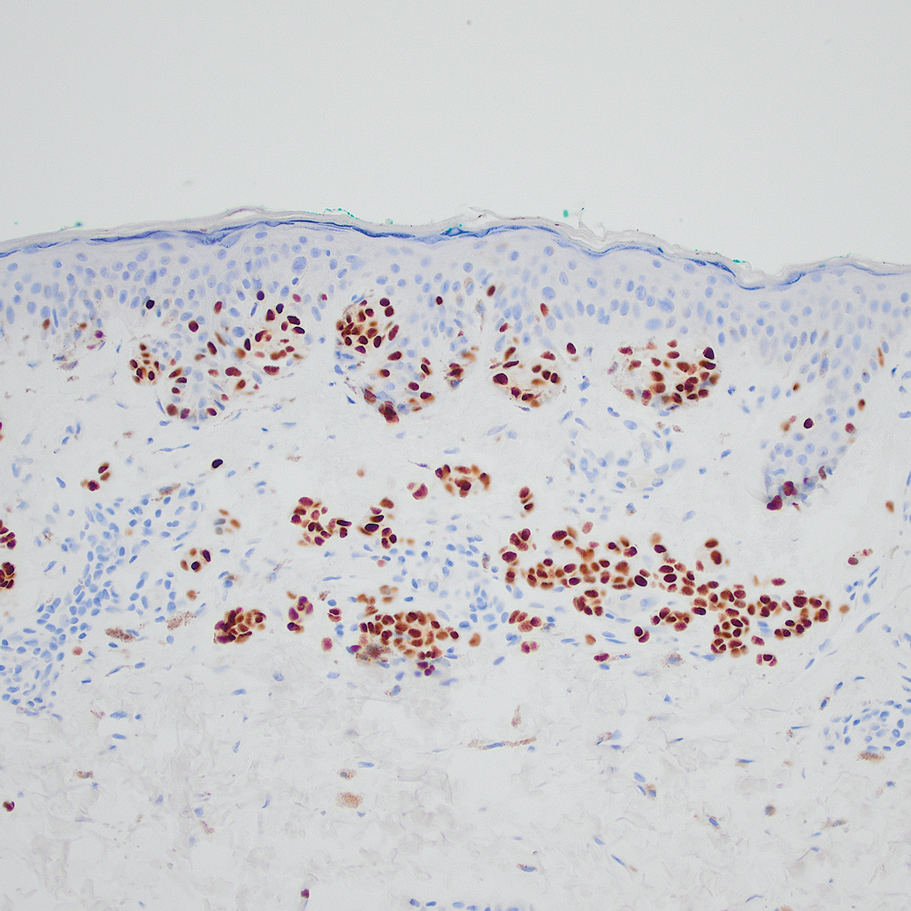

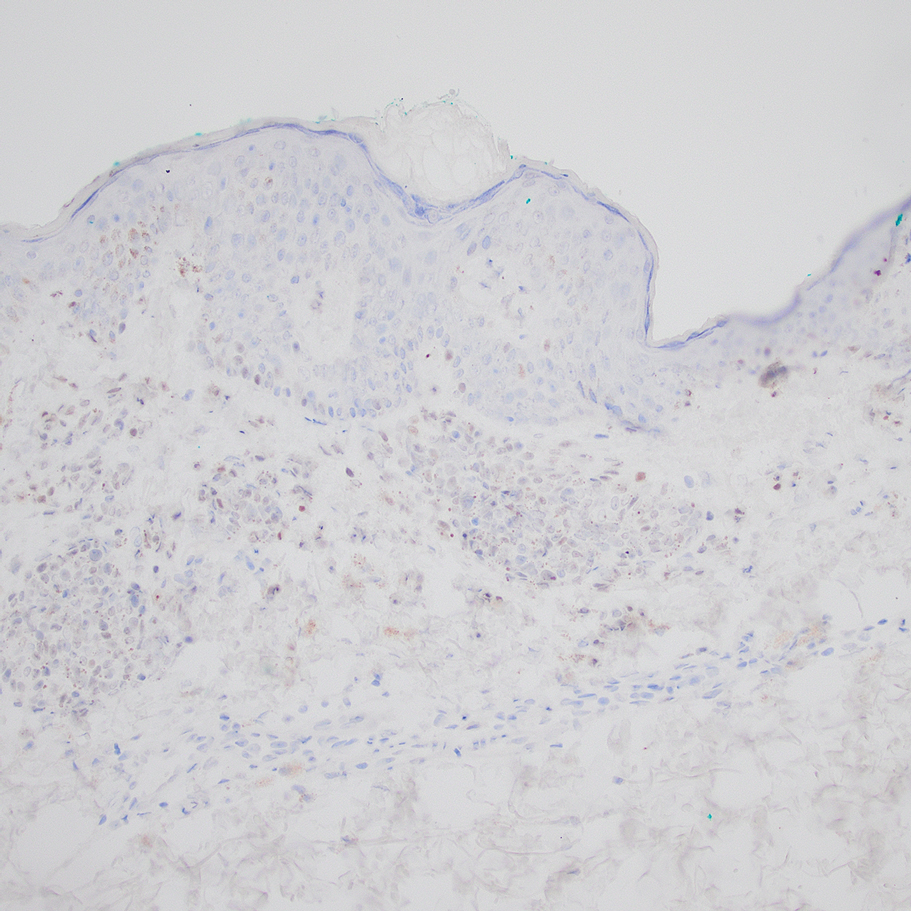

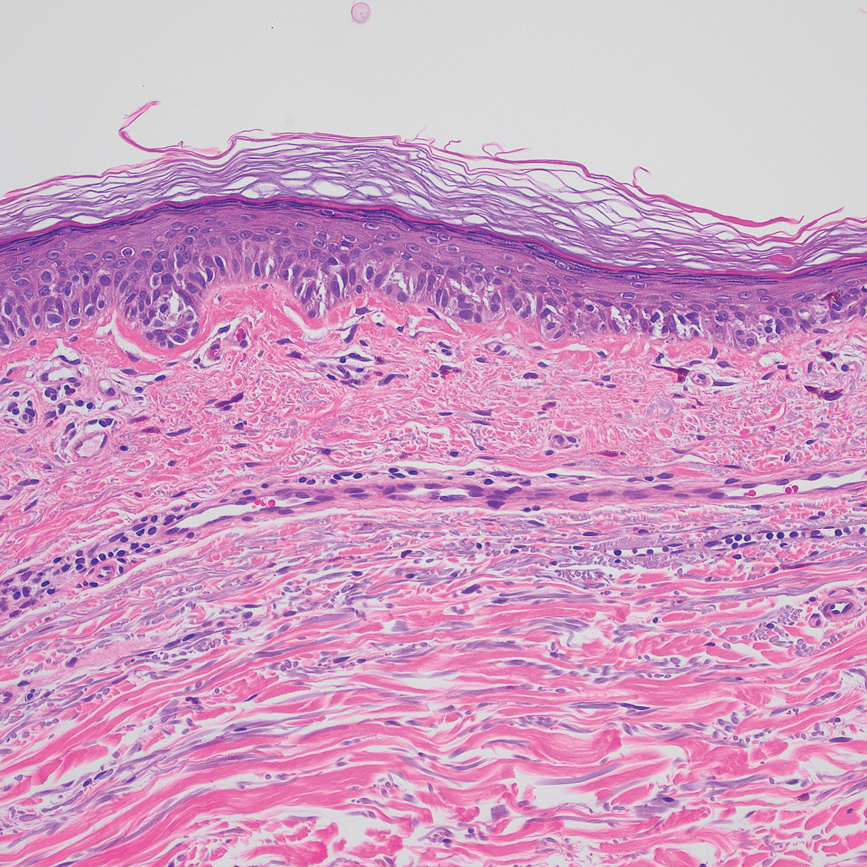

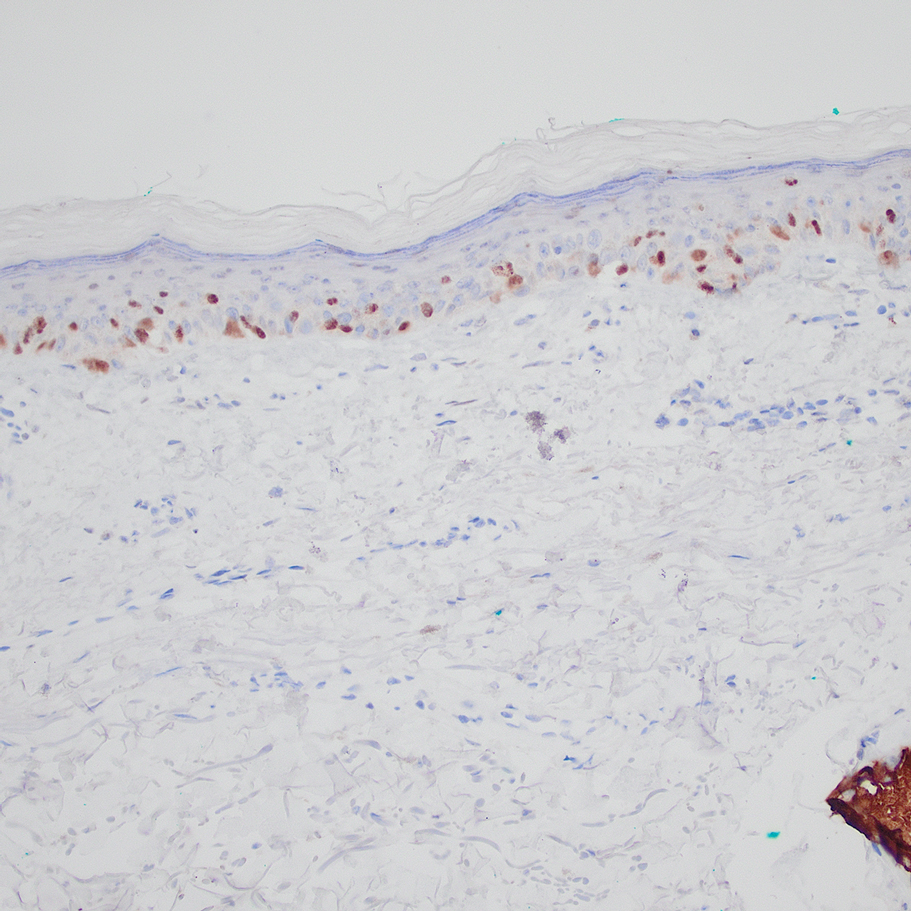

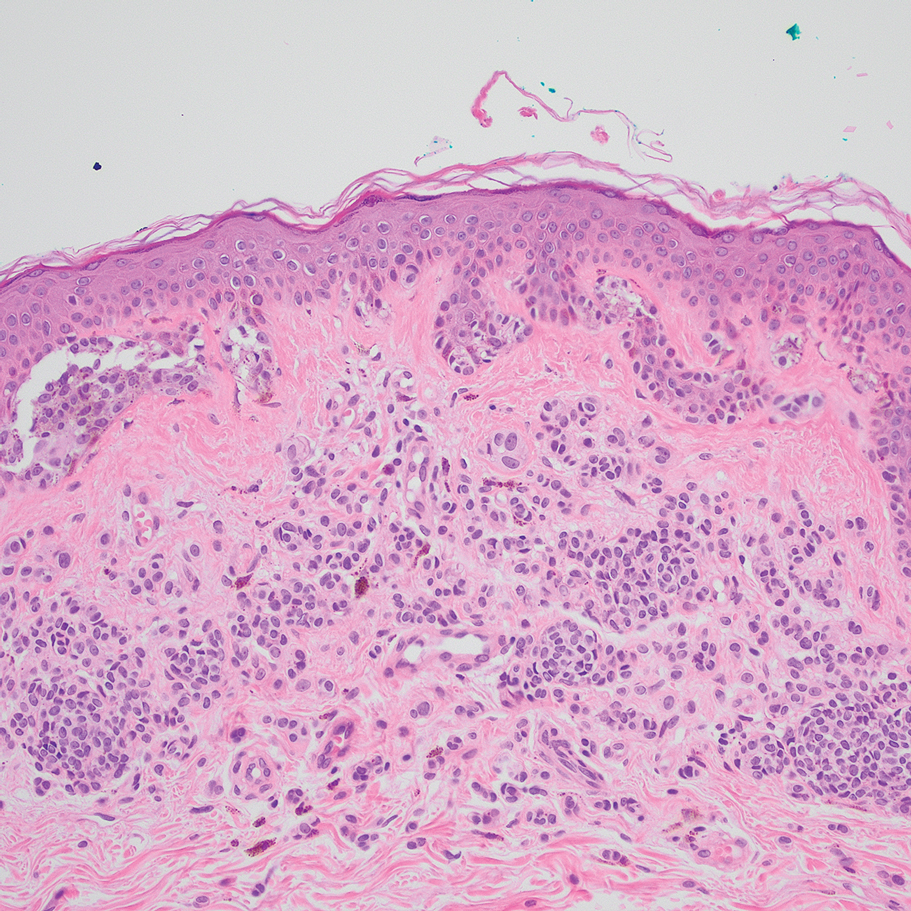

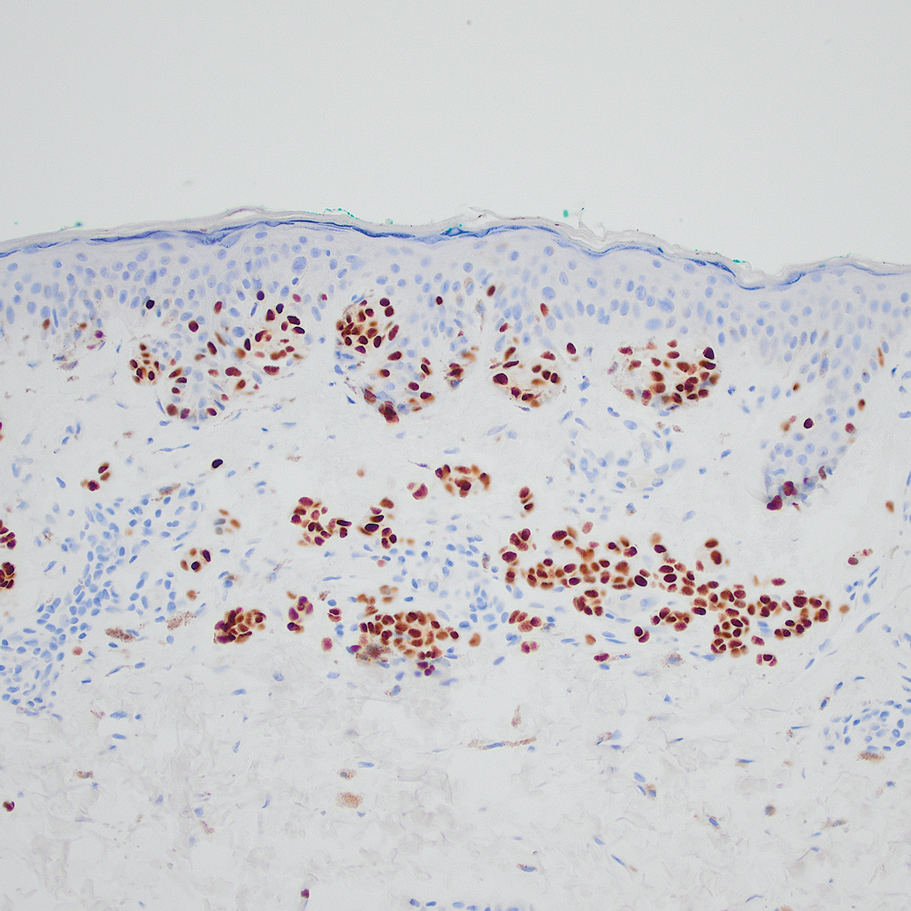

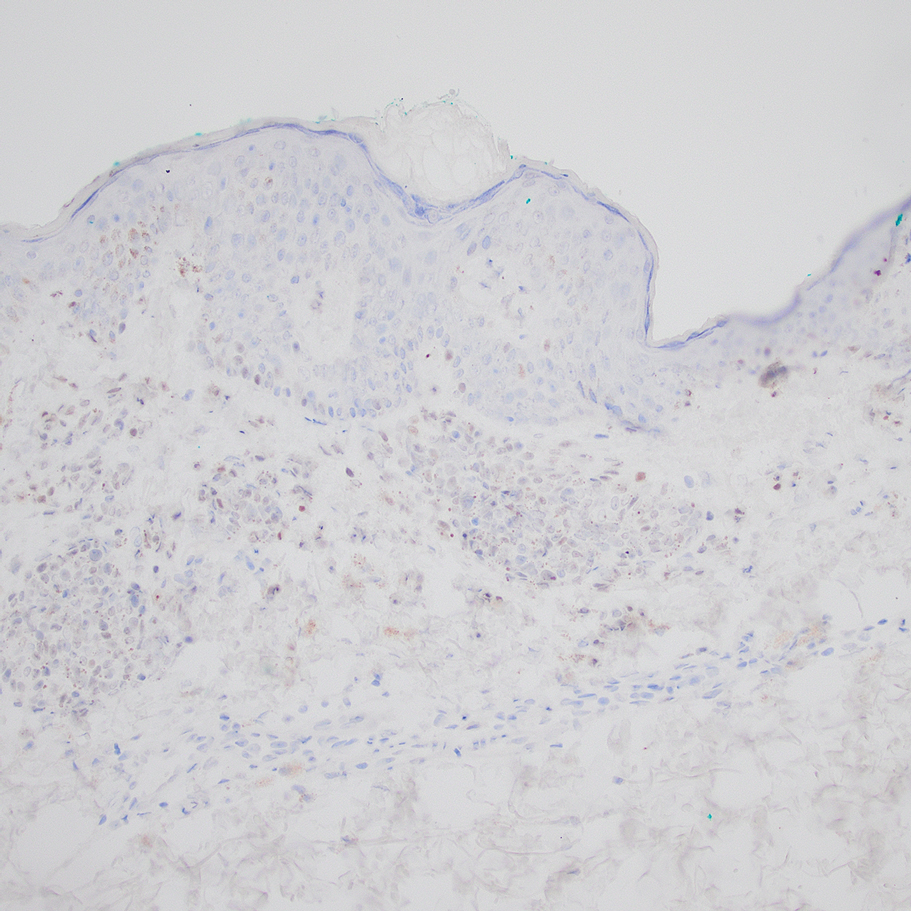

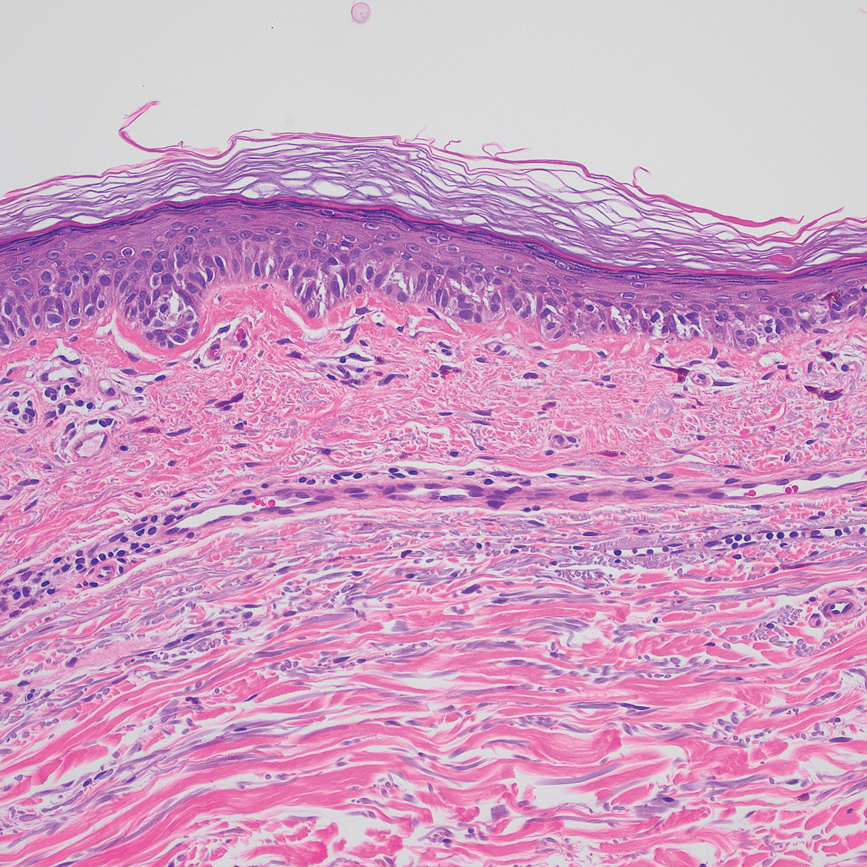

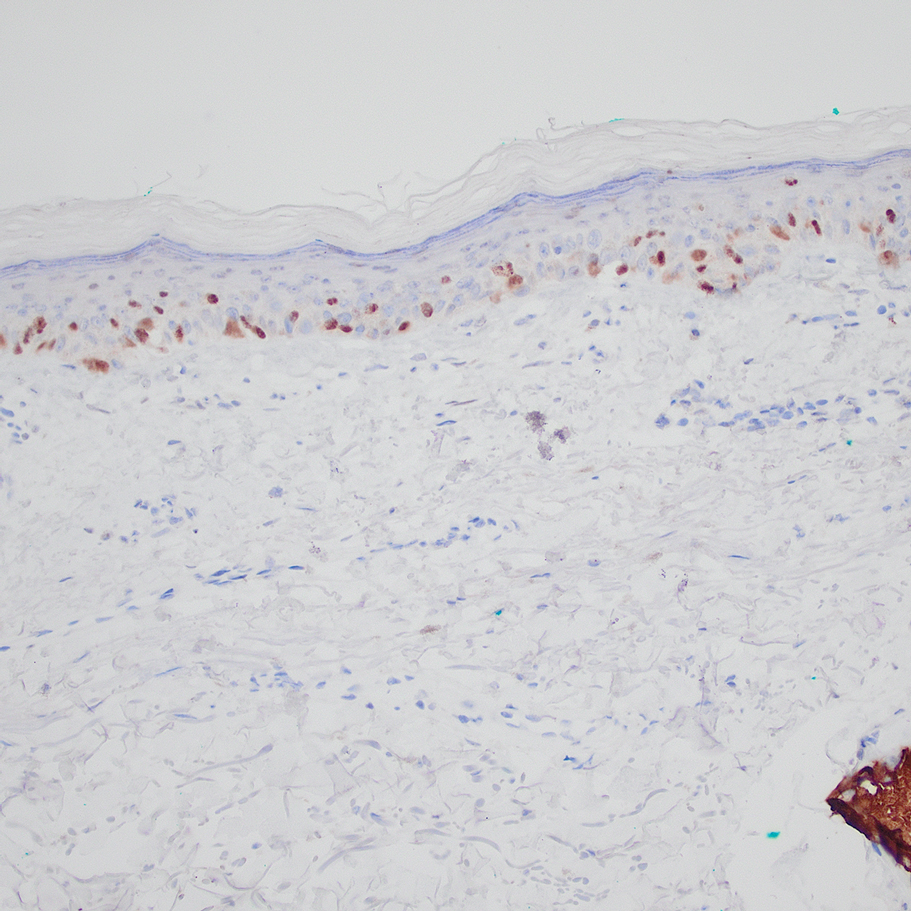

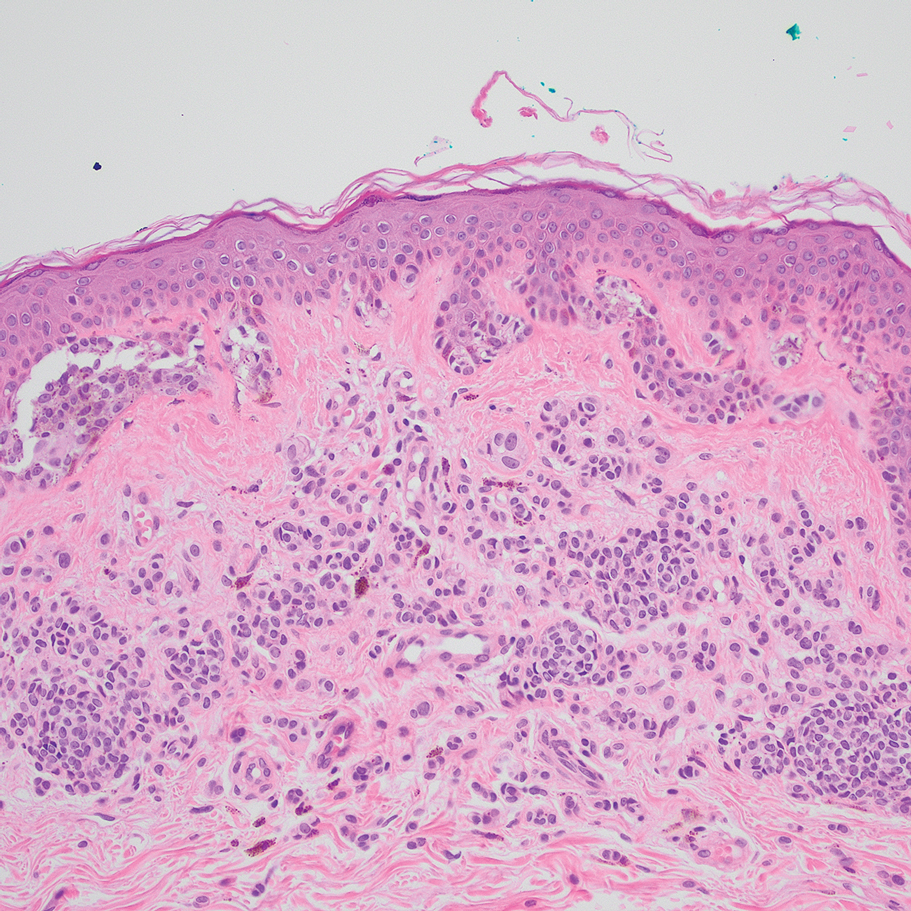

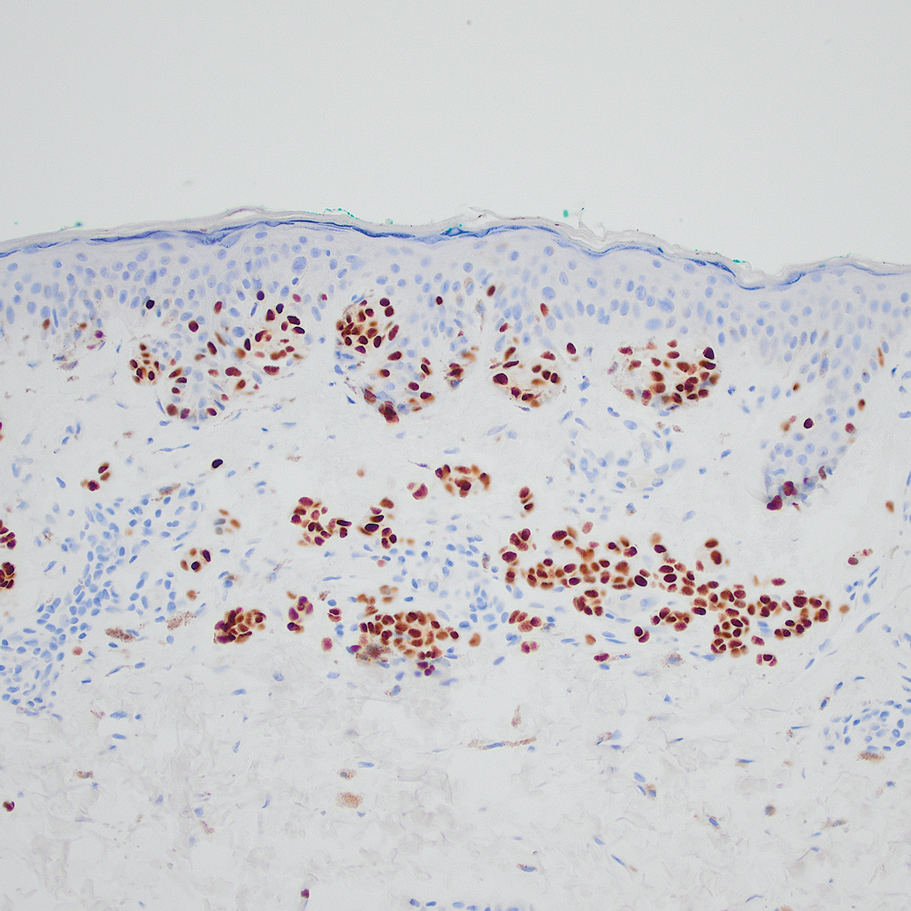

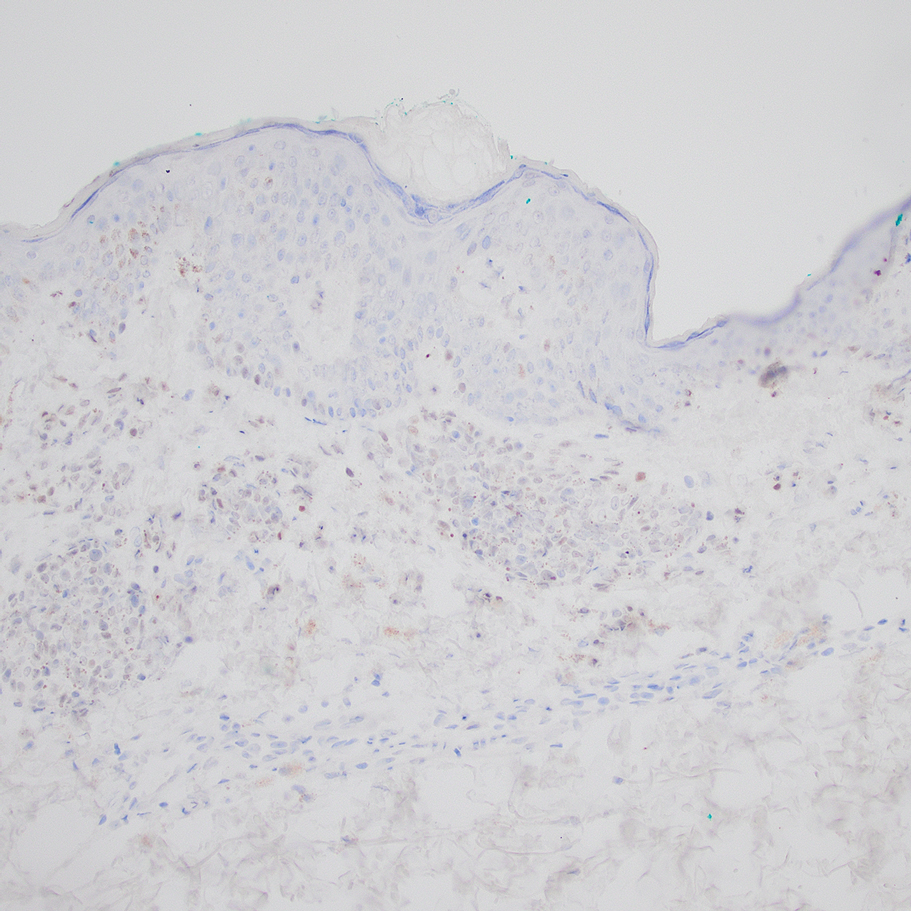

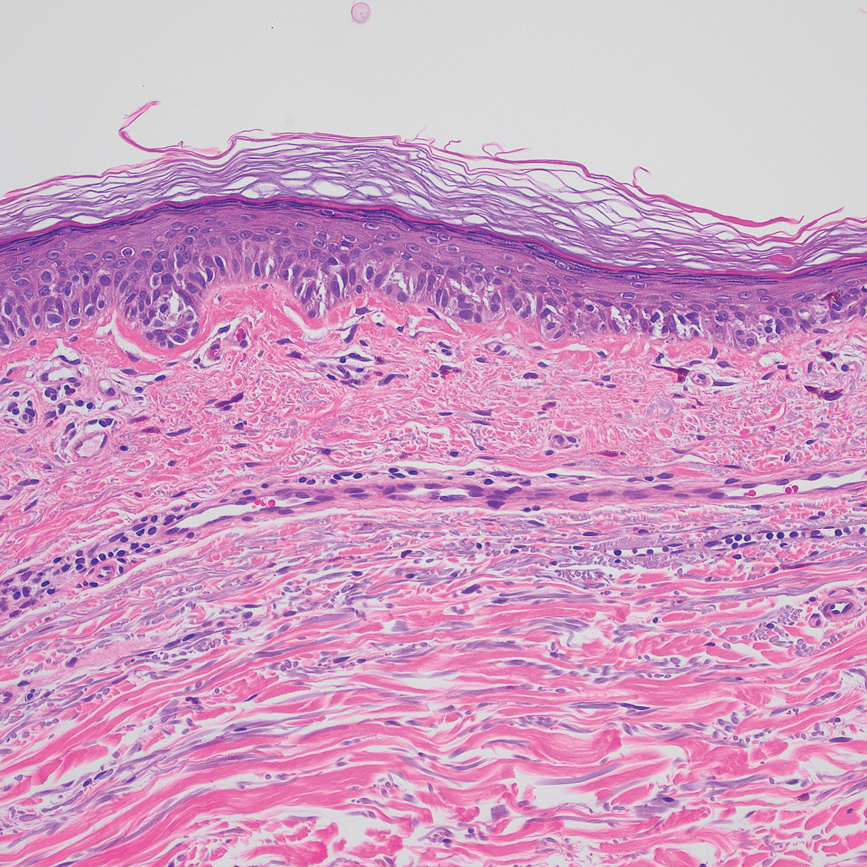

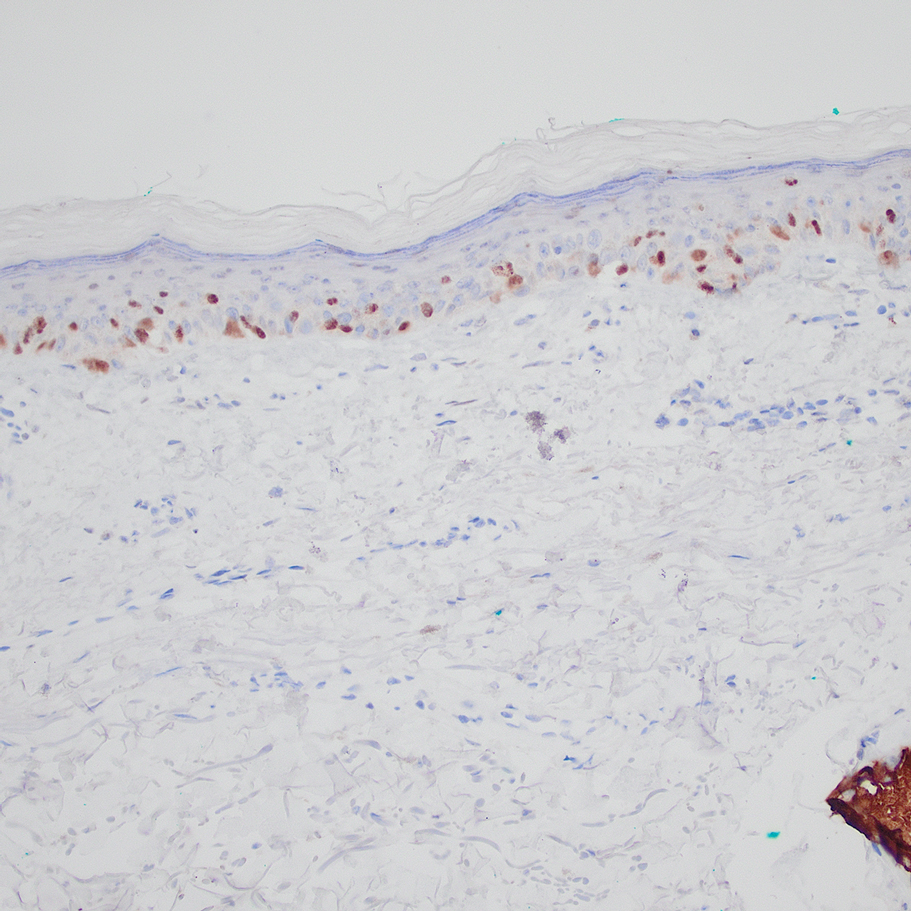

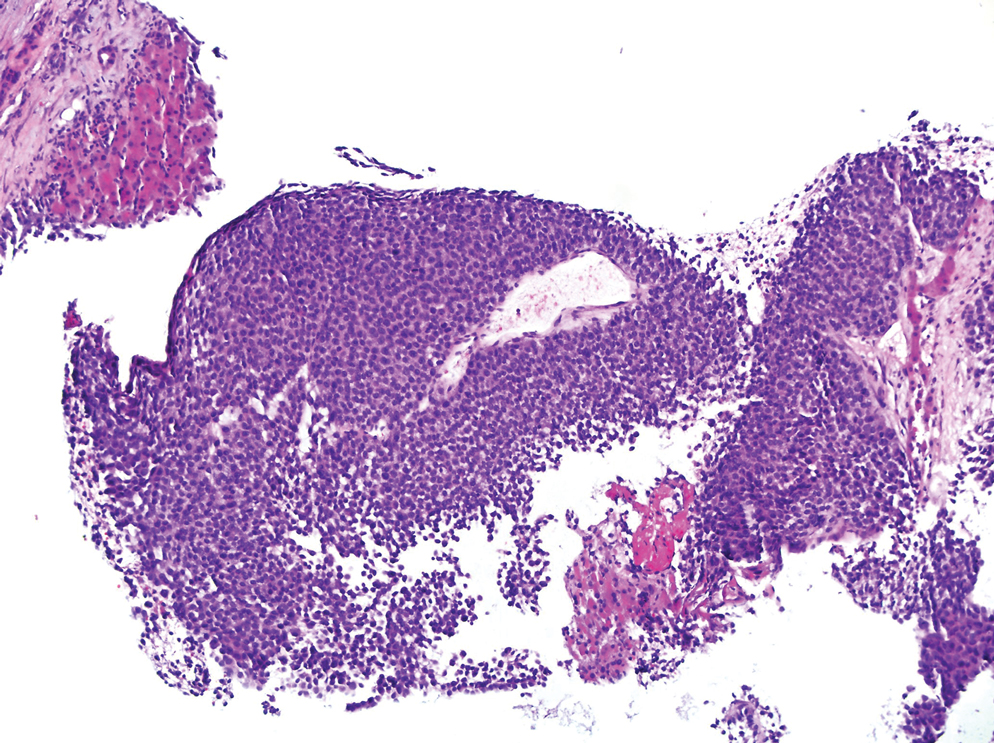

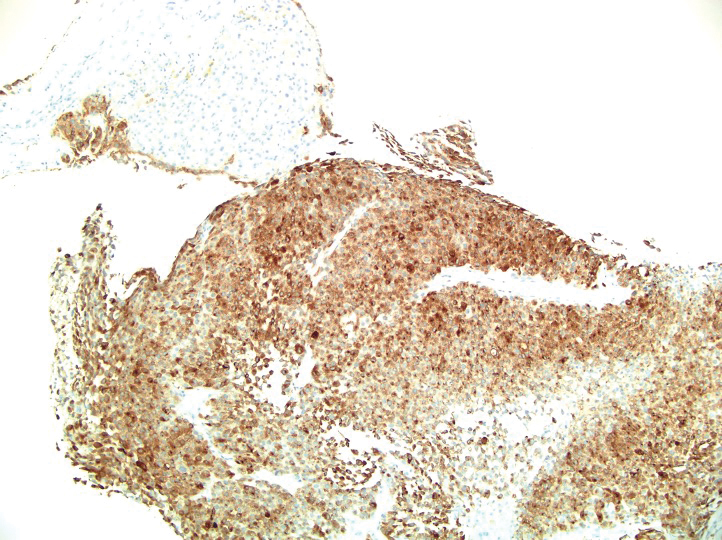

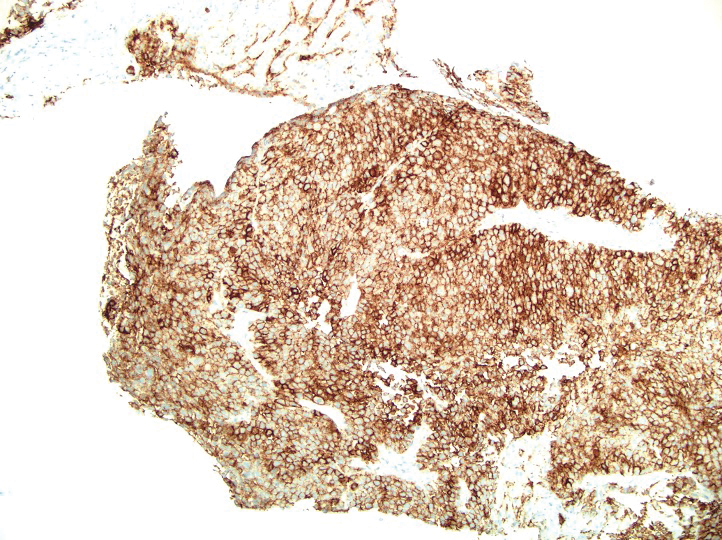

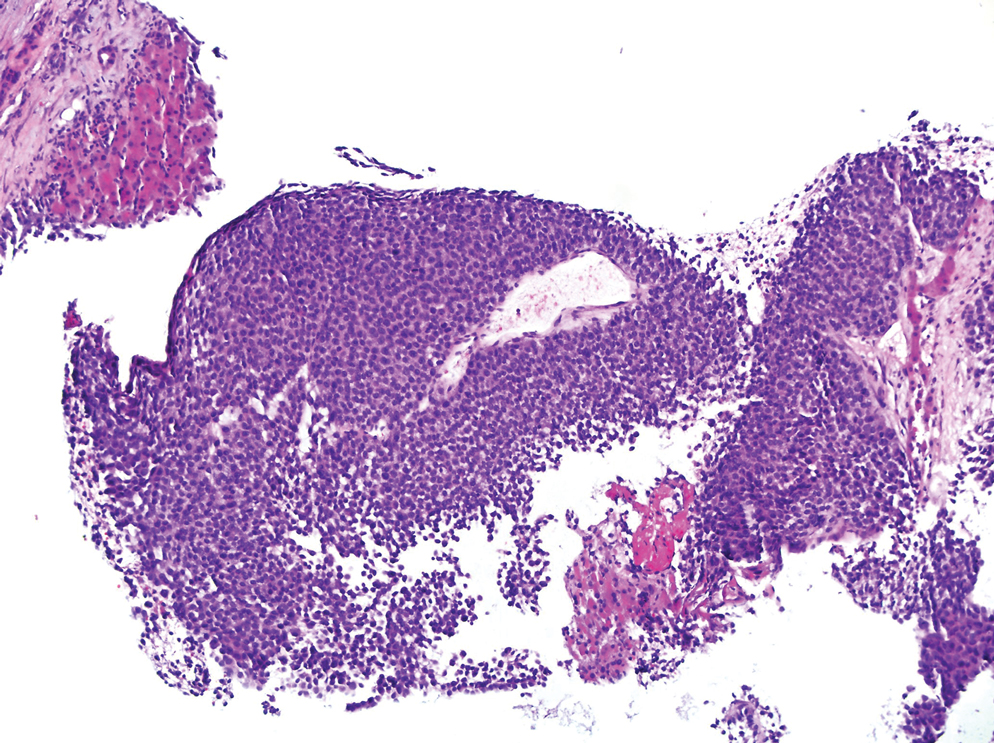

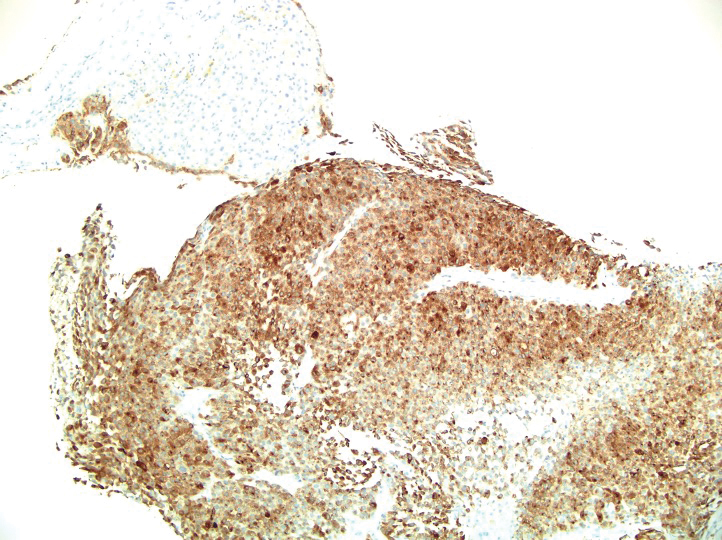

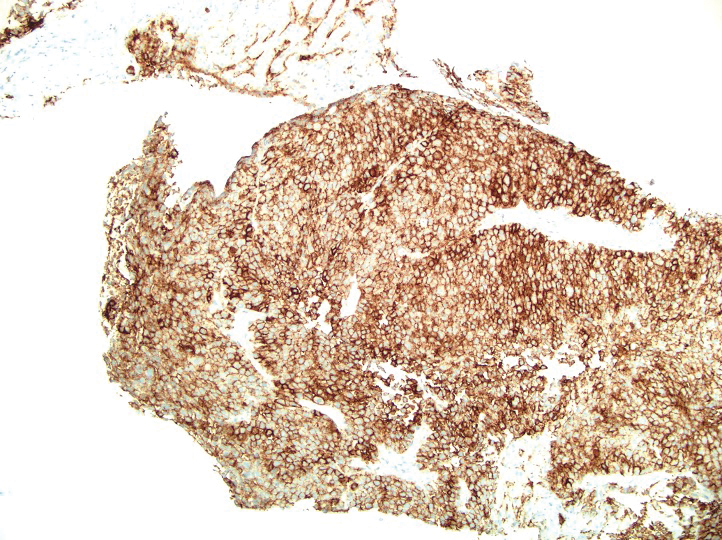

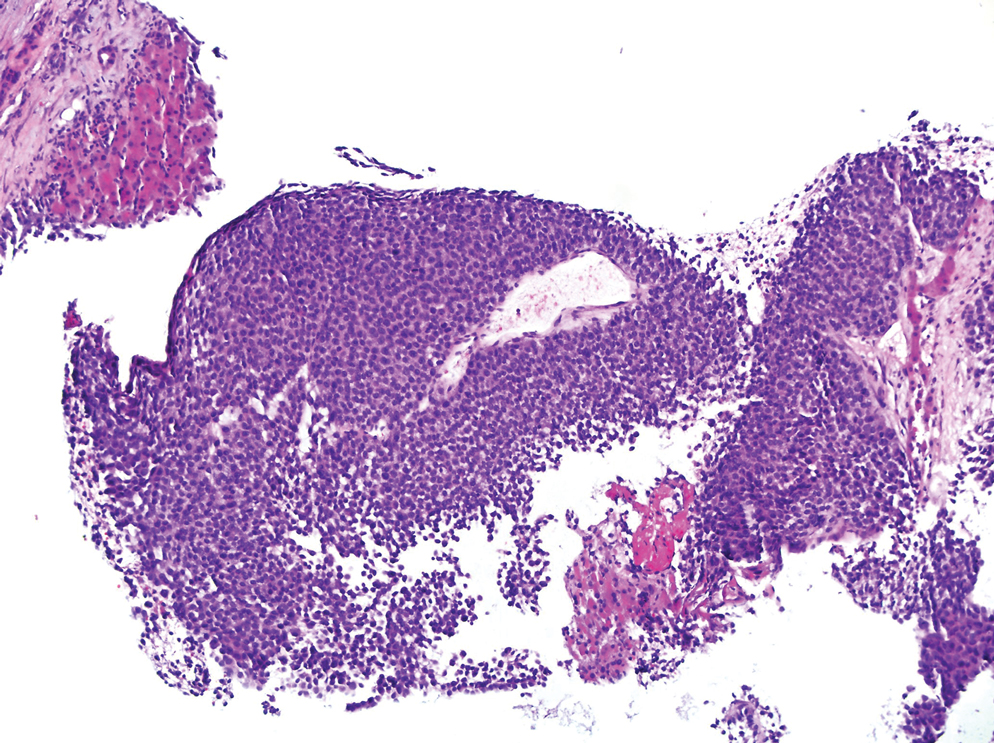

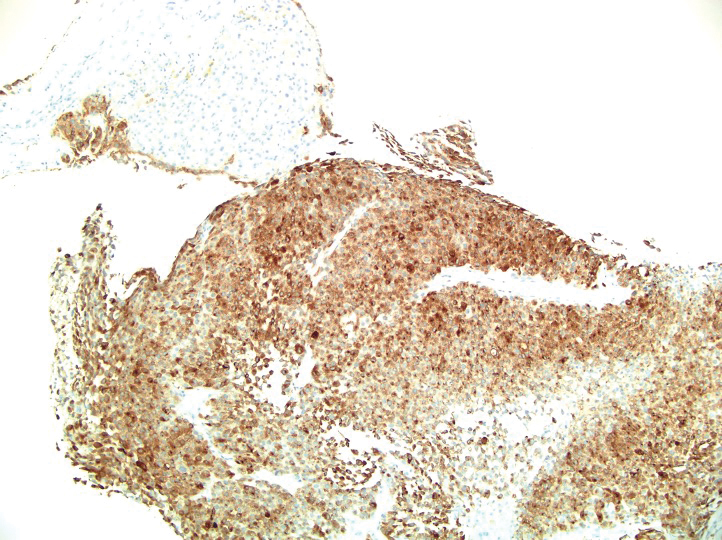

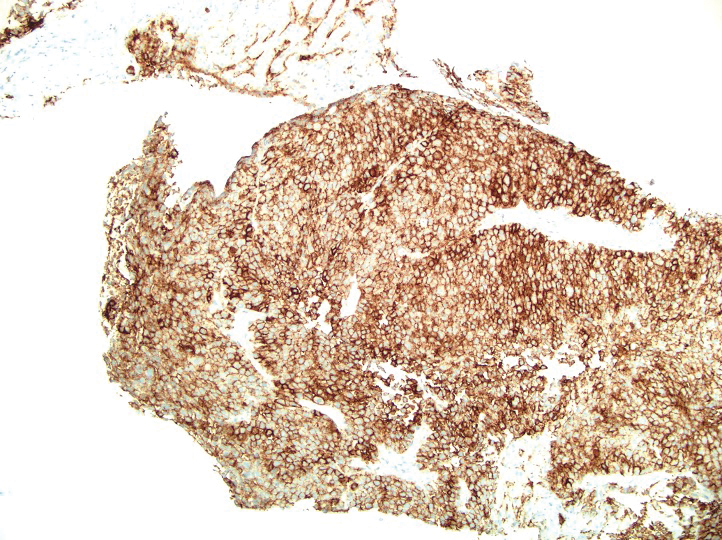

Based on our cohort, a positivity threshold of 3+ for PRAME expression for the diagnosis of melanoma in a special-site lesion would have a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 94%, while a positivity threshold of 4+ for PRAME expression would have a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 100%. Figures 2 through 4 show photomicrographs of a special-site nevus of the breast, which appropriately does not stain for PRAME; Figures 5 and 6 show an MIS at a special site that appropriately stains for PRAME.

Comment

The distinction between benign and malignant pigmented lesions at special sites presents a fair challenge for pathologists due to the larger degree of leniency for architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in benign lesions at these sites. The presence of architectural distortion or cytologic atypia at the lesion’s edge makes rendering a benign diagnosis especially difficult, and the need for a validated immunohistochemical stain is apparent. In our cohort, strong clonal PRAME expression provided a reliable immunohistochemical marker, allowing for the distinction of malignant lesions from benign nevi at special sites. Diffuse faint PRAME expression was present in several benign nevi within our cohort, and these lesions were considered negative (0) in our analysis.

Given the described test characteristics, we support the implementation of PRAME immunohistochemistry with a positivity threshold of 4+ expression as an ancillary test supporting the diagnosis of IM or MIS in special sites, which would allow clinicians to leverage the high specificity of 4+ PRAME expression to distinguish an IM or MIS from a benign nevus occurring at a special site. We do not recommend the use of 4+ PRAME expression as a screening test for melanoma or MIS among special-site nevi due to its comparatively low sensitivity; however, no one marker is always reliable, and we recommend continued clinicopathologic correlation for all cases.

Although our case series included nevi and MIS/IM from all special sites, we were limited in the number of acrogenital and ear nevi included due to a relative paucity of biopsied benign nevi from these locations at the University of Virginia. Additionally, although the magnitude of the difference in PRAME expression between the study and control groups is sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, the overall strength of our argument would be increased with a larger study group. We were limited by the number of cases available at our institution, which did not utilize PRAME during the initial diagnosis of the case; including these cases in the study group would have undermined the integrity of our argument because the differentiation of benign vs malignant initially was made using PRAME immunohistochemistry.

Conclusion

Due to their atypical features, special-site nevi can be challenging to assess. In this study, we showed that PRAME expression can be a reliable marker to distinguish benign from malignant lesions. Our results showed that 100% of benign special-site nevi demonstrated 3+ expression or less, with 56% (20/36) demonstrating no expression at all. The presence of diffuse PRAME expression (4+ PRAME staining) appears to be a specific indicator of a malignant lesion, but results should always be interpreted with respect to the patient’s clinical history and the lesion’s histomorphologic features. Further study of a larger sample size would allow refinement of the sensitivity and specificity of diffuse PRAME expression in the determination of malignancy for special-site lesions.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank the pathologistsat the University of Virginia Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (Charlottesville, Virginia) for their skill and expertise in performing immunohistochemical staining for this study.

- VandenBoom T, Gerami P. Melanocytic nevi of special sites. In: Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:90-100. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-37457-6.00007-9

- Hosler GA, Moresi JM, Barrett TL. Nevi with site-related atypia: a review of melanocytic nevi with atypical histologic features based on anatomic site. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:889-898. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01041.x.

- Brenn T. Melanocytic lesions—staying out of trouble. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;37:91-102. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.09.010

- Ikeda H, Lethé B, Lehmann F, et al. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6:199-208. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80426-4

- Epping MT, Wang L, Edel MJ, et al. The human tumor antigen PRAME is a dominant repressor of retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cell. 2005;122:835-847. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.003

- Alomari AK, Tharp AW, Umphress B, et al. The utility of PRAME immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of challenging melanocytic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1115-1123. doi:10.1111/cup.14000

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001134

- Gill P, Prieto VG, Austin MT, et al. Diagnostic utility of PRAME in distinguishing proliferative nodules from melanoma in giant congenital melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1410-1415. doi:10.1111/cup.14091

- Googe PB, Flanigan KL, Miedema JR. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma immunostaining in a series of melanocytic neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43):794-800. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001885

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131. doi:10.1111/cup.13818

- McBride JD, McAfee JL, Piliang M, et al. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma and p16 expression in acral melanocytic neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:220-230. doi:10.1111/cup.14130

The assessment and diagnosis of melanocytic lesions can present a formidable challenge to even a seasoned pathologist, which is especially true when dealing with the subset of nevi occurring at special sites—where baseline variations inherent to particular locations on the body can preclude the use of features routinely used to diagnose malignancy elsewhere. These so-called special-site nevi previously have been described in the literature along with suggested criteria for differentiating malignant lesions from their benign counterparts.1 Locations generally considered to be special sites include the acral skin, anogenital region, breast, ear, and flexural regions.1,2

When evaluating non–special-site melanocytic lesions, general characteristics associated with a malignant diagnosis include confluence or pagetoid spread of melanocytes, nuclear pleomorphism, cytologic atypia, and irregular architecture3; however, these features can be compatible with a benign diagnosis in special-site nevi depending on their extent and the site in question. Although they can be atypical, special-site nevi tend to have the bulk of their architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in the center of the lesion as opposed to the edges.1 If a given lesion is from a special site but lacks this reassuring feature, special care should be taken to rule out malignancy.

Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) is an antigen first identified in tumor-reactive T-cell populations in patients with malignant melanoma. It is the product of an oncogene that frequently is overexpressed in melanomas, lung squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, and acute leukemias.4 It functions as an antagonist of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, which normally serves to induce further cell differentiation, senescence, or apoptosis.5 PRAME inhibits retinoid signaling by forming a complex with both the ligand-bound retinoic acid holoreceptor and the polycomb protein EZH2, which blocks retinoid-dependent gene expression by encouraging chromatin condensation at the RARβ promoter site5; therefore, expressing PRAME allows lesional cells a substantial growth advantage.

PRAME expression has been extensively characterized in non–special-site nevi and has filled the need for a rather specific marker of melanoma.6-10 Although PRAME has been studied in acral nevi,11 the expression pattern in nevi of special sites has yet to be elucidated. Herein, we present a dataset characterizing PRAME expression in these challenging lesions.

Methods

We performed a retrospective case review at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia) and collected a panel of 36 special-site nevi that previously were diagnosed as benign by a trained dermatopathologist from January 2020 through December 2022. Special-site nevi were identified using a natural language filter for the following terms: acral, palm, sole, ear, auricular, lip, axilla, armpit, breast, groin, labia, vulva, umbilicus, and penis. This study was approved by the University of Virginia institutional review board.

The original hematoxylin and eosin slides used for primary diagnosis were re-examined to verify the prior diagnosis of benign nevus at a special site. We performed a detailed microscopic examination of all benign nevi in our cohort to determine the frequency of various characteristics at each special site. Sections were prepared from the formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and stained with a commercial PRAME antibody (#219650 [Abcam] at a 1:50 dilution) and counterstain. A trained dermatopathologist (S.S.R.) examined the stained sections and recorded the percentage of tumor cells with nuclear PRAME staining. We reported our results using previously established criteria for scoring PRAME immunohistochemistry7: 0 for no expression, 1+ for 1% to 25% expression, 2+ for 26% to 50% expression, 3+ for 51% to 75% expression, and 4+ for diffuse or 76% to 100% expression. Only strong clonal expression within a population of cells was graded.

Data handling and statistical testing were performed using the R Project for Statistical Computing (https://www.r-project.org/). Significance testing was performed using the Fisher exact test. Plot construction was performed using ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/).

Results

Our study cohort included 36 special-site nevi, and the control cohort comprised 25 melanoma in situ (MIS) or invasive melanoma (IM) lesions occurring at special sites. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the study and control cohorts by lesion site. Table 2 details the results of our microscopic examination, describing frequency of various characteristics of special-site nevi stratified by site.

Of the 36 special-site nevi in our cohort, 20 (56%) had no staining (0) for PRAME, 11 (31%) demonstrated 1+ PRAME expression, 3 (8%) demonstrated 2+ PRAME expression, and 2 (6%) demonstrated 3+ PRAME expression. No nevi showed 4+ expression. In the control cohort, 24 of 25 (96%) MIS and IM showed 3+ or 4+ expression, with 21 (84%) demonstrating diffuse/4+ expression. One control case (4%) demonstrated 0 PRAME expression. These data are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 1. There is a significant difference in diffuse (4+) PRAME expression between special-site nevi and MIS/IM occurring at special sites (P=1.039×10-12).

Based on our cohort, a positivity threshold of 3+ for PRAME expression for the diagnosis of melanoma in a special-site lesion would have a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 94%, while a positivity threshold of 4+ for PRAME expression would have a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 100%. Figures 2 through 4 show photomicrographs of a special-site nevus of the breast, which appropriately does not stain for PRAME; Figures 5 and 6 show an MIS at a special site that appropriately stains for PRAME.

Comment

The distinction between benign and malignant pigmented lesions at special sites presents a fair challenge for pathologists due to the larger degree of leniency for architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in benign lesions at these sites. The presence of architectural distortion or cytologic atypia at the lesion’s edge makes rendering a benign diagnosis especially difficult, and the need for a validated immunohistochemical stain is apparent. In our cohort, strong clonal PRAME expression provided a reliable immunohistochemical marker, allowing for the distinction of malignant lesions from benign nevi at special sites. Diffuse faint PRAME expression was present in several benign nevi within our cohort, and these lesions were considered negative (0) in our analysis.

Given the described test characteristics, we support the implementation of PRAME immunohistochemistry with a positivity threshold of 4+ expression as an ancillary test supporting the diagnosis of IM or MIS in special sites, which would allow clinicians to leverage the high specificity of 4+ PRAME expression to distinguish an IM or MIS from a benign nevus occurring at a special site. We do not recommend the use of 4+ PRAME expression as a screening test for melanoma or MIS among special-site nevi due to its comparatively low sensitivity; however, no one marker is always reliable, and we recommend continued clinicopathologic correlation for all cases.

Although our case series included nevi and MIS/IM from all special sites, we were limited in the number of acrogenital and ear nevi included due to a relative paucity of biopsied benign nevi from these locations at the University of Virginia. Additionally, although the magnitude of the difference in PRAME expression between the study and control groups is sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, the overall strength of our argument would be increased with a larger study group. We were limited by the number of cases available at our institution, which did not utilize PRAME during the initial diagnosis of the case; including these cases in the study group would have undermined the integrity of our argument because the differentiation of benign vs malignant initially was made using PRAME immunohistochemistry.

Conclusion

Due to their atypical features, special-site nevi can be challenging to assess. In this study, we showed that PRAME expression can be a reliable marker to distinguish benign from malignant lesions. Our results showed that 100% of benign special-site nevi demonstrated 3+ expression or less, with 56% (20/36) demonstrating no expression at all. The presence of diffuse PRAME expression (4+ PRAME staining) appears to be a specific indicator of a malignant lesion, but results should always be interpreted with respect to the patient’s clinical history and the lesion’s histomorphologic features. Further study of a larger sample size would allow refinement of the sensitivity and specificity of diffuse PRAME expression in the determination of malignancy for special-site lesions.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank the pathologistsat the University of Virginia Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (Charlottesville, Virginia) for their skill and expertise in performing immunohistochemical staining for this study.

The assessment and diagnosis of melanocytic lesions can present a formidable challenge to even a seasoned pathologist, which is especially true when dealing with the subset of nevi occurring at special sites—where baseline variations inherent to particular locations on the body can preclude the use of features routinely used to diagnose malignancy elsewhere. These so-called special-site nevi previously have been described in the literature along with suggested criteria for differentiating malignant lesions from their benign counterparts.1 Locations generally considered to be special sites include the acral skin, anogenital region, breast, ear, and flexural regions.1,2

When evaluating non–special-site melanocytic lesions, general characteristics associated with a malignant diagnosis include confluence or pagetoid spread of melanocytes, nuclear pleomorphism, cytologic atypia, and irregular architecture3; however, these features can be compatible with a benign diagnosis in special-site nevi depending on their extent and the site in question. Although they can be atypical, special-site nevi tend to have the bulk of their architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in the center of the lesion as opposed to the edges.1 If a given lesion is from a special site but lacks this reassuring feature, special care should be taken to rule out malignancy.

Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) is an antigen first identified in tumor-reactive T-cell populations in patients with malignant melanoma. It is the product of an oncogene that frequently is overexpressed in melanomas, lung squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, and acute leukemias.4 It functions as an antagonist of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, which normally serves to induce further cell differentiation, senescence, or apoptosis.5 PRAME inhibits retinoid signaling by forming a complex with both the ligand-bound retinoic acid holoreceptor and the polycomb protein EZH2, which blocks retinoid-dependent gene expression by encouraging chromatin condensation at the RARβ promoter site5; therefore, expressing PRAME allows lesional cells a substantial growth advantage.

PRAME expression has been extensively characterized in non–special-site nevi and has filled the need for a rather specific marker of melanoma.6-10 Although PRAME has been studied in acral nevi,11 the expression pattern in nevi of special sites has yet to be elucidated. Herein, we present a dataset characterizing PRAME expression in these challenging lesions.

Methods

We performed a retrospective case review at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia) and collected a panel of 36 special-site nevi that previously were diagnosed as benign by a trained dermatopathologist from January 2020 through December 2022. Special-site nevi were identified using a natural language filter for the following terms: acral, palm, sole, ear, auricular, lip, axilla, armpit, breast, groin, labia, vulva, umbilicus, and penis. This study was approved by the University of Virginia institutional review board.

The original hematoxylin and eosin slides used for primary diagnosis were re-examined to verify the prior diagnosis of benign nevus at a special site. We performed a detailed microscopic examination of all benign nevi in our cohort to determine the frequency of various characteristics at each special site. Sections were prepared from the formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and stained with a commercial PRAME antibody (#219650 [Abcam] at a 1:50 dilution) and counterstain. A trained dermatopathologist (S.S.R.) examined the stained sections and recorded the percentage of tumor cells with nuclear PRAME staining. We reported our results using previously established criteria for scoring PRAME immunohistochemistry7: 0 for no expression, 1+ for 1% to 25% expression, 2+ for 26% to 50% expression, 3+ for 51% to 75% expression, and 4+ for diffuse or 76% to 100% expression. Only strong clonal expression within a population of cells was graded.

Data handling and statistical testing were performed using the R Project for Statistical Computing (https://www.r-project.org/). Significance testing was performed using the Fisher exact test. Plot construction was performed using ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/).

Results

Our study cohort included 36 special-site nevi, and the control cohort comprised 25 melanoma in situ (MIS) or invasive melanoma (IM) lesions occurring at special sites. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the study and control cohorts by lesion site. Table 2 details the results of our microscopic examination, describing frequency of various characteristics of special-site nevi stratified by site.

Of the 36 special-site nevi in our cohort, 20 (56%) had no staining (0) for PRAME, 11 (31%) demonstrated 1+ PRAME expression, 3 (8%) demonstrated 2+ PRAME expression, and 2 (6%) demonstrated 3+ PRAME expression. No nevi showed 4+ expression. In the control cohort, 24 of 25 (96%) MIS and IM showed 3+ or 4+ expression, with 21 (84%) demonstrating diffuse/4+ expression. One control case (4%) demonstrated 0 PRAME expression. These data are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 1. There is a significant difference in diffuse (4+) PRAME expression between special-site nevi and MIS/IM occurring at special sites (P=1.039×10-12).

Based on our cohort, a positivity threshold of 3+ for PRAME expression for the diagnosis of melanoma in a special-site lesion would have a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 94%, while a positivity threshold of 4+ for PRAME expression would have a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 100%. Figures 2 through 4 show photomicrographs of a special-site nevus of the breast, which appropriately does not stain for PRAME; Figures 5 and 6 show an MIS at a special site that appropriately stains for PRAME.

Comment

The distinction between benign and malignant pigmented lesions at special sites presents a fair challenge for pathologists due to the larger degree of leniency for architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in benign lesions at these sites. The presence of architectural distortion or cytologic atypia at the lesion’s edge makes rendering a benign diagnosis especially difficult, and the need for a validated immunohistochemical stain is apparent. In our cohort, strong clonal PRAME expression provided a reliable immunohistochemical marker, allowing for the distinction of malignant lesions from benign nevi at special sites. Diffuse faint PRAME expression was present in several benign nevi within our cohort, and these lesions were considered negative (0) in our analysis.

Given the described test characteristics, we support the implementation of PRAME immunohistochemistry with a positivity threshold of 4+ expression as an ancillary test supporting the diagnosis of IM or MIS in special sites, which would allow clinicians to leverage the high specificity of 4+ PRAME expression to distinguish an IM or MIS from a benign nevus occurring at a special site. We do not recommend the use of 4+ PRAME expression as a screening test for melanoma or MIS among special-site nevi due to its comparatively low sensitivity; however, no one marker is always reliable, and we recommend continued clinicopathologic correlation for all cases.

Although our case series included nevi and MIS/IM from all special sites, we were limited in the number of acrogenital and ear nevi included due to a relative paucity of biopsied benign nevi from these locations at the University of Virginia. Additionally, although the magnitude of the difference in PRAME expression between the study and control groups is sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, the overall strength of our argument would be increased with a larger study group. We were limited by the number of cases available at our institution, which did not utilize PRAME during the initial diagnosis of the case; including these cases in the study group would have undermined the integrity of our argument because the differentiation of benign vs malignant initially was made using PRAME immunohistochemistry.

Conclusion

Due to their atypical features, special-site nevi can be challenging to assess. In this study, we showed that PRAME expression can be a reliable marker to distinguish benign from malignant lesions. Our results showed that 100% of benign special-site nevi demonstrated 3+ expression or less, with 56% (20/36) demonstrating no expression at all. The presence of diffuse PRAME expression (4+ PRAME staining) appears to be a specific indicator of a malignant lesion, but results should always be interpreted with respect to the patient’s clinical history and the lesion’s histomorphologic features. Further study of a larger sample size would allow refinement of the sensitivity and specificity of diffuse PRAME expression in the determination of malignancy for special-site lesions.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank the pathologistsat the University of Virginia Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (Charlottesville, Virginia) for their skill and expertise in performing immunohistochemical staining for this study.

- VandenBoom T, Gerami P. Melanocytic nevi of special sites. In: Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:90-100. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-37457-6.00007-9

- Hosler GA, Moresi JM, Barrett TL. Nevi with site-related atypia: a review of melanocytic nevi with atypical histologic features based on anatomic site. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:889-898. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01041.x.

- Brenn T. Melanocytic lesions—staying out of trouble. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;37:91-102. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.09.010

- Ikeda H, Lethé B, Lehmann F, et al. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6:199-208. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80426-4

- Epping MT, Wang L, Edel MJ, et al. The human tumor antigen PRAME is a dominant repressor of retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cell. 2005;122:835-847. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.003

- Alomari AK, Tharp AW, Umphress B, et al. The utility of PRAME immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of challenging melanocytic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1115-1123. doi:10.1111/cup.14000

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001134

- Gill P, Prieto VG, Austin MT, et al. Diagnostic utility of PRAME in distinguishing proliferative nodules from melanoma in giant congenital melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1410-1415. doi:10.1111/cup.14091

- Googe PB, Flanigan KL, Miedema JR. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma immunostaining in a series of melanocytic neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43):794-800. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001885

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131. doi:10.1111/cup.13818

- McBride JD, McAfee JL, Piliang M, et al. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma and p16 expression in acral melanocytic neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:220-230. doi:10.1111/cup.14130

- VandenBoom T, Gerami P. Melanocytic nevi of special sites. In: Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:90-100. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-37457-6.00007-9

- Hosler GA, Moresi JM, Barrett TL. Nevi with site-related atypia: a review of melanocytic nevi with atypical histologic features based on anatomic site. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:889-898. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01041.x.

- Brenn T. Melanocytic lesions—staying out of trouble. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;37:91-102. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.09.010

- Ikeda H, Lethé B, Lehmann F, et al. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6:199-208. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80426-4

- Epping MT, Wang L, Edel MJ, et al. The human tumor antigen PRAME is a dominant repressor of retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cell. 2005;122:835-847. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.003

- Alomari AK, Tharp AW, Umphress B, et al. The utility of PRAME immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of challenging melanocytic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1115-1123. doi:10.1111/cup.14000

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001134

- Gill P, Prieto VG, Austin MT, et al. Diagnostic utility of PRAME in distinguishing proliferative nodules from melanoma in giant congenital melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1410-1415. doi:10.1111/cup.14091

- Googe PB, Flanigan KL, Miedema JR. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma immunostaining in a series of melanocytic neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43):794-800. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001885

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131. doi:10.1111/cup.13818

- McBride JD, McAfee JL, Piliang M, et al. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma and p16 expression in acral melanocytic neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:220-230. doi:10.1111/cup.14130

Practice Points

- Special-site nevi are benign melanocytic proliferations at special anatomic sites. Although cytologic atypia and architectural distortion may be present, they are centrally located and should not be present at the borders of the lesion.

- Strong expression of the preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) via immunohistochemistry provides a reliable indicator for benignity in differentiating a special-site nevus from a malignant melanoma occurring at a special site.

New Therapies in Melanoma: Current Trends, Evolving Paradigms, and Future Perspectives

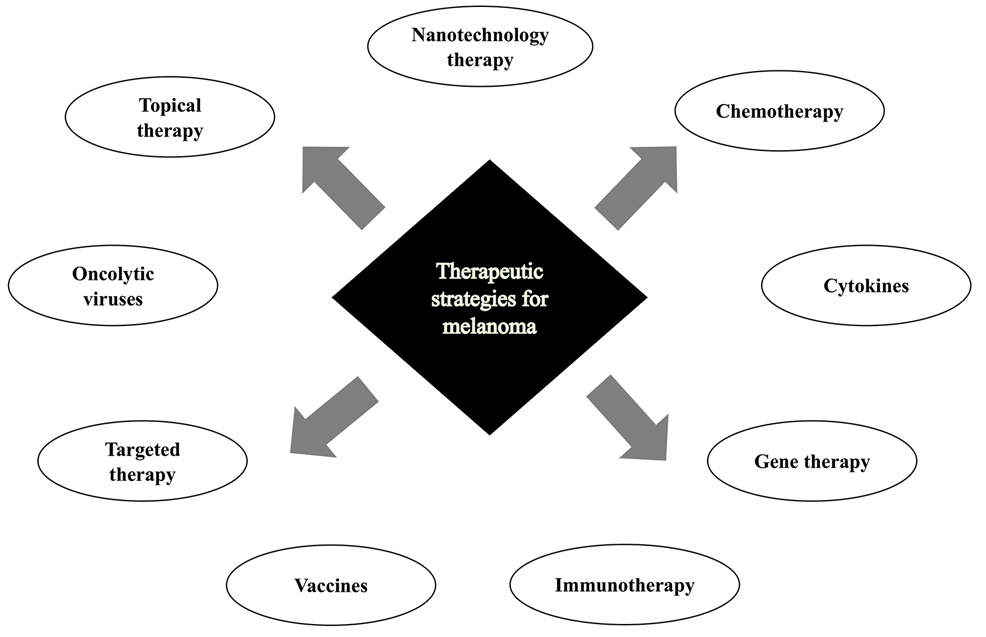

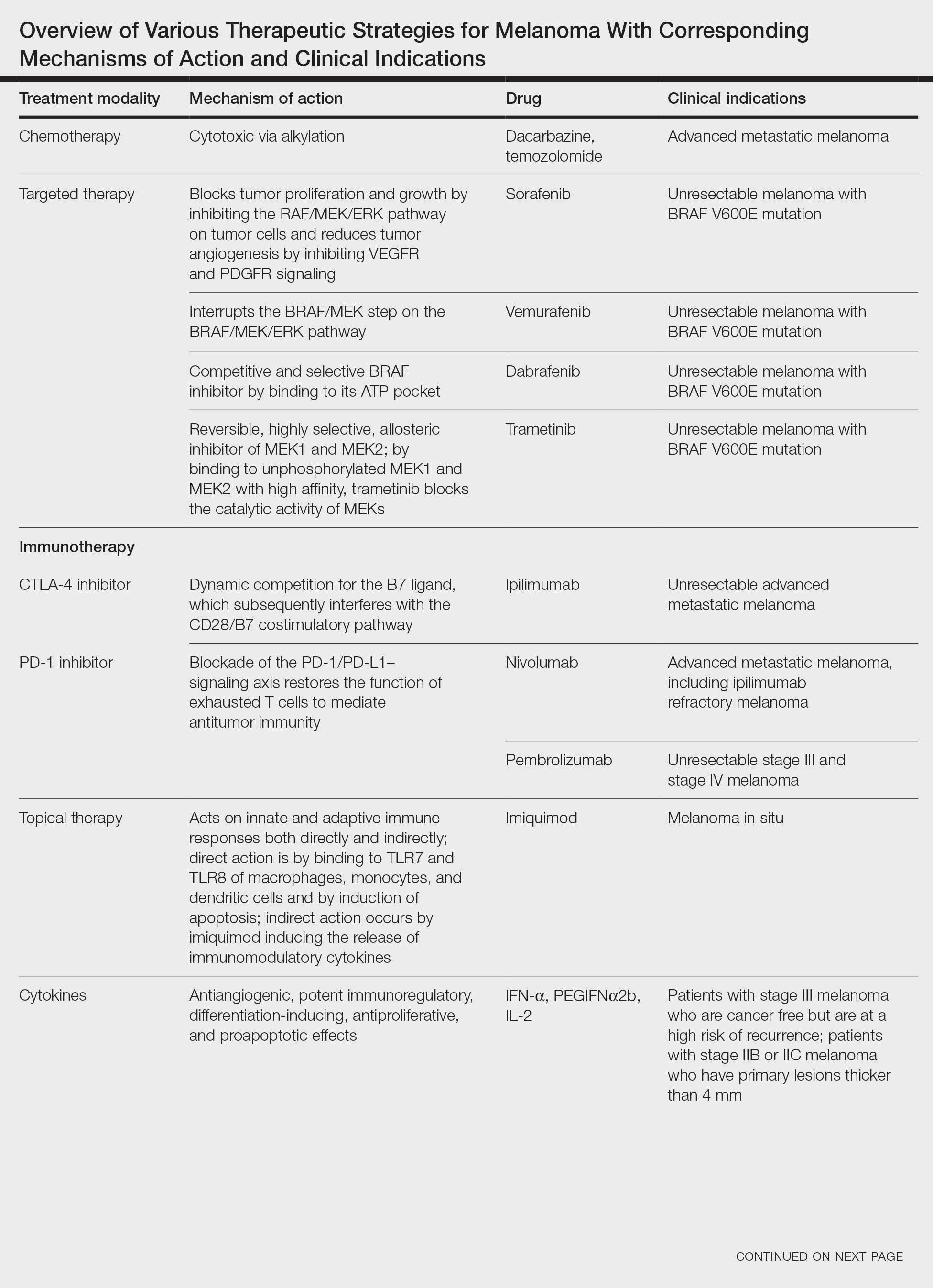

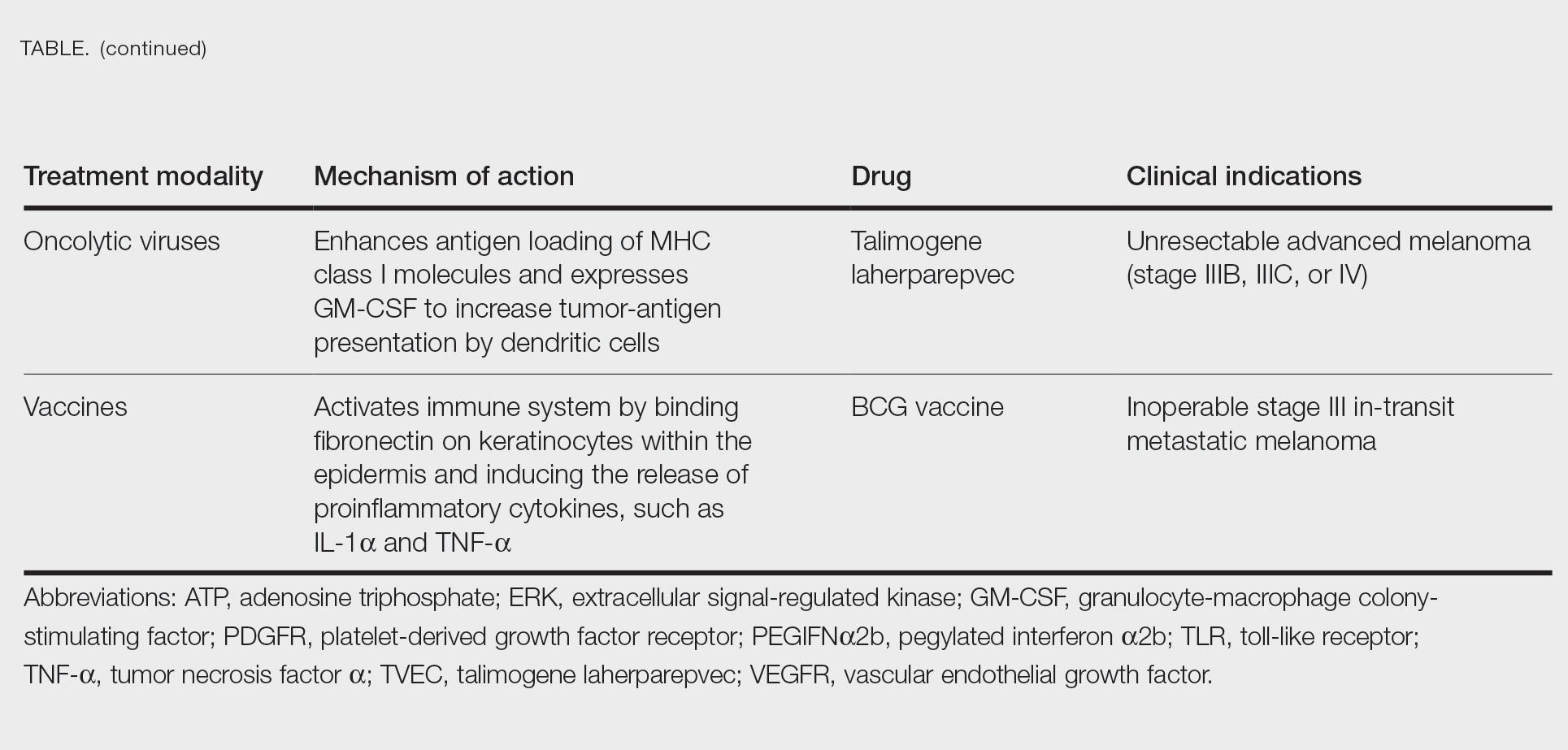

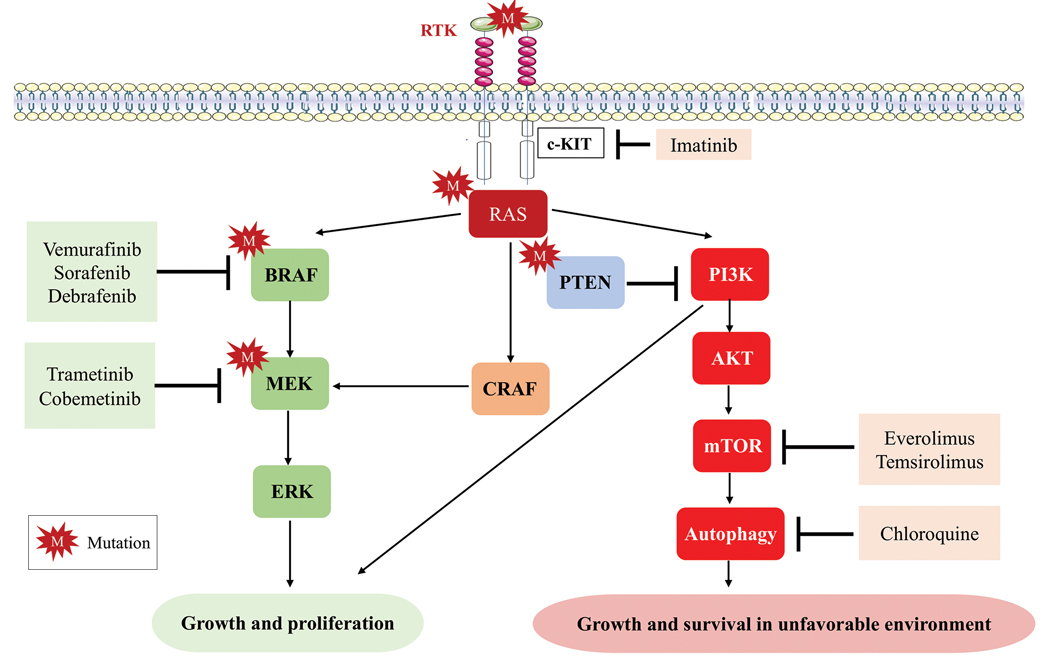

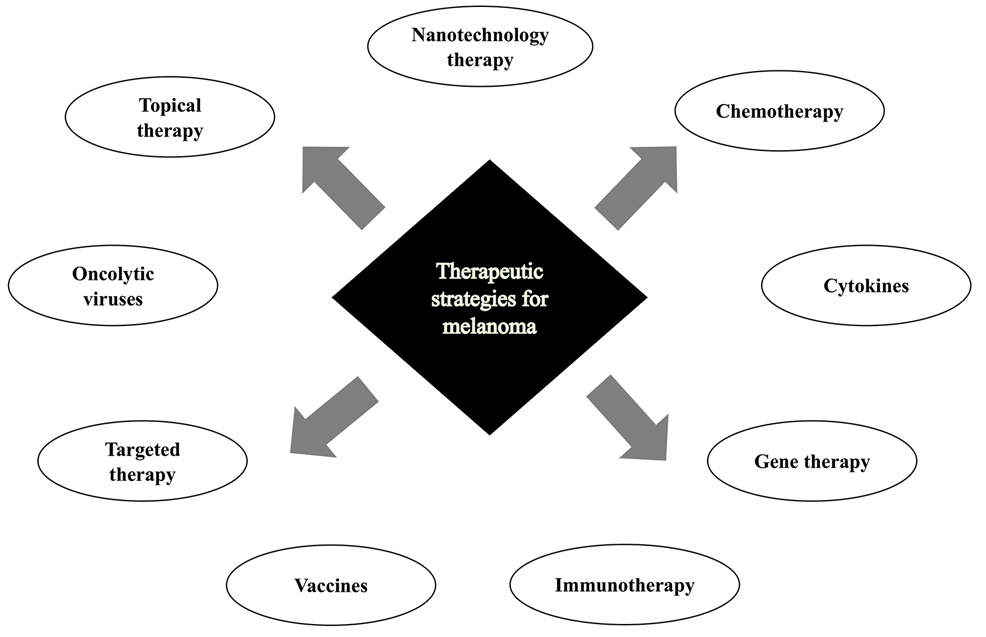

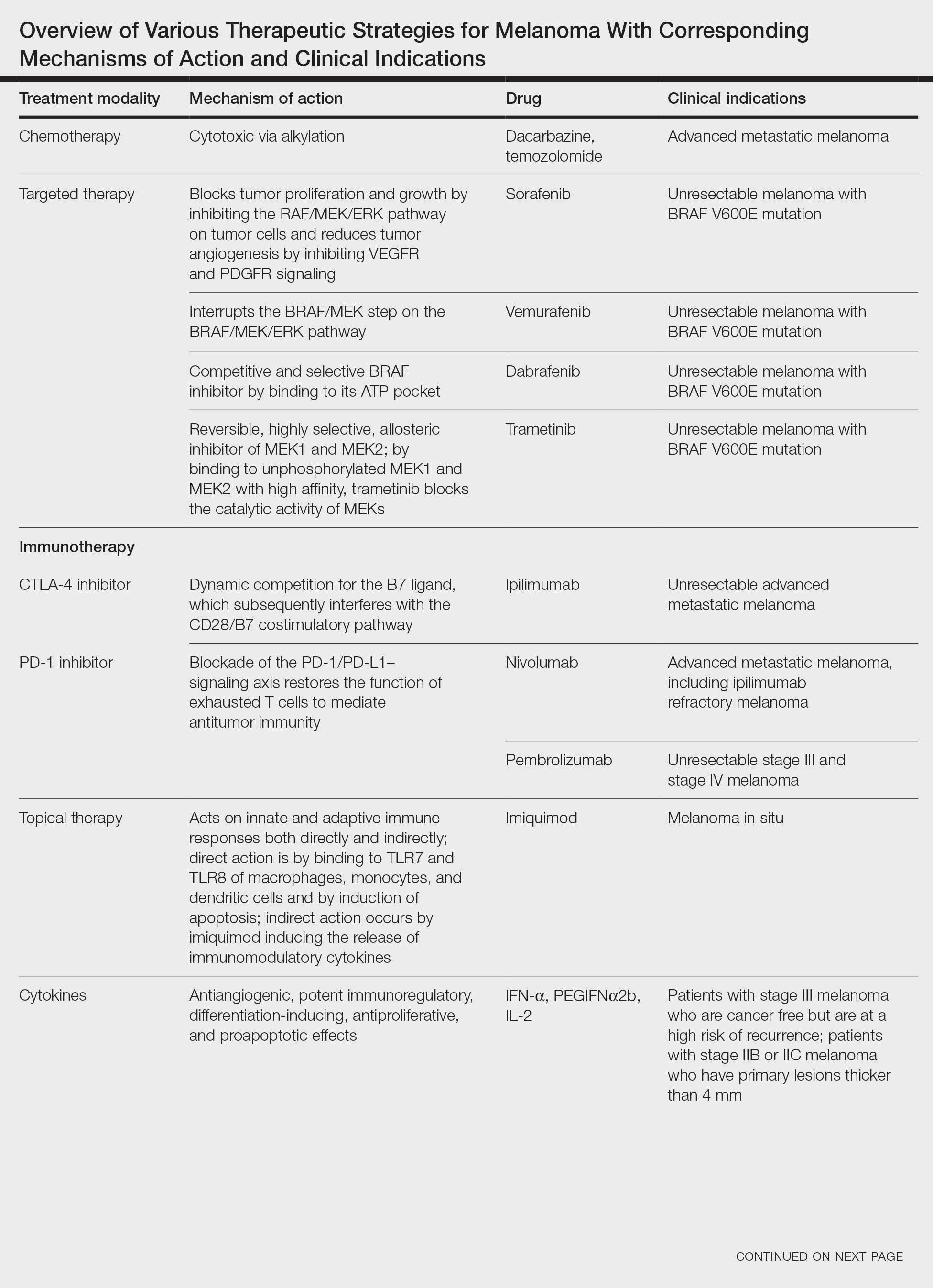

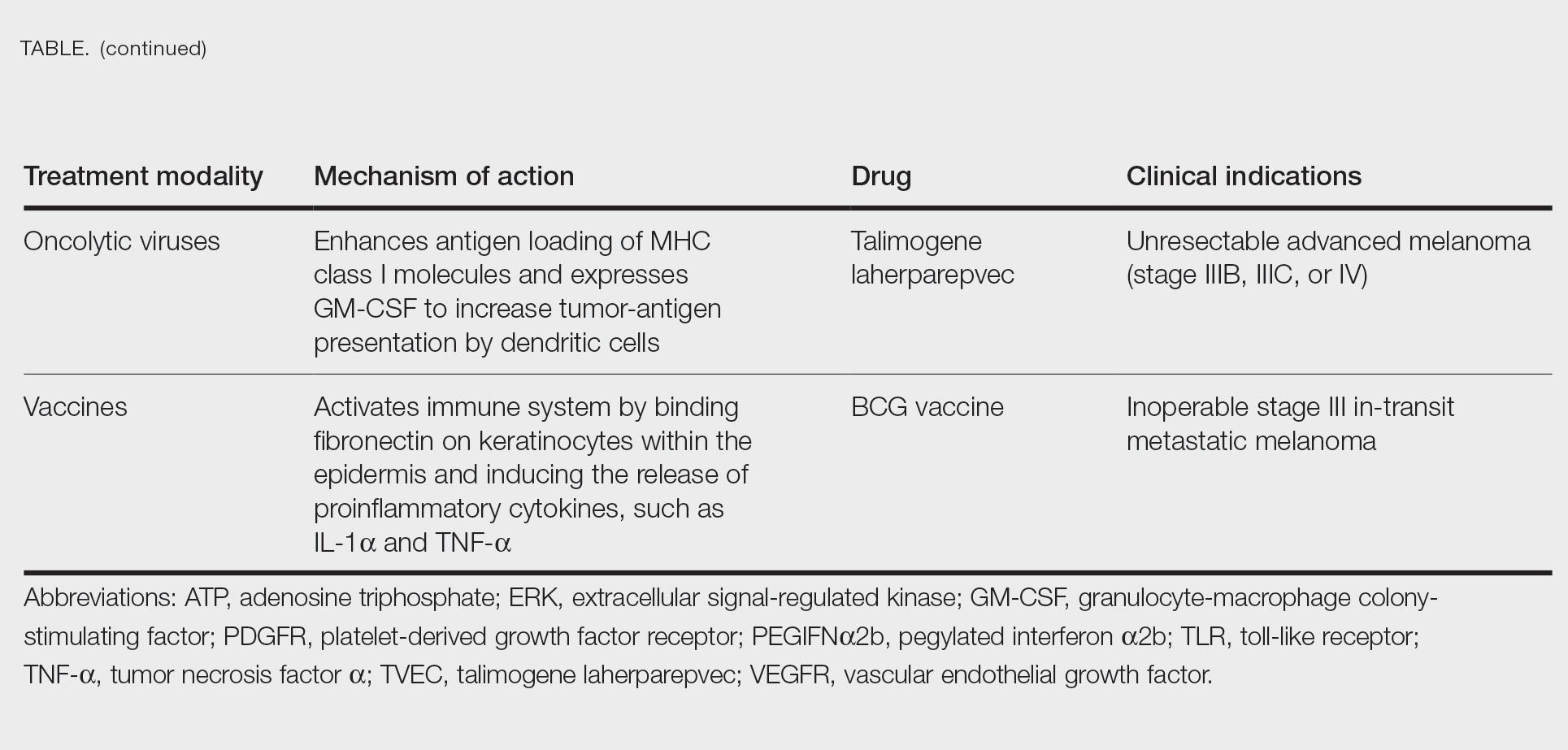

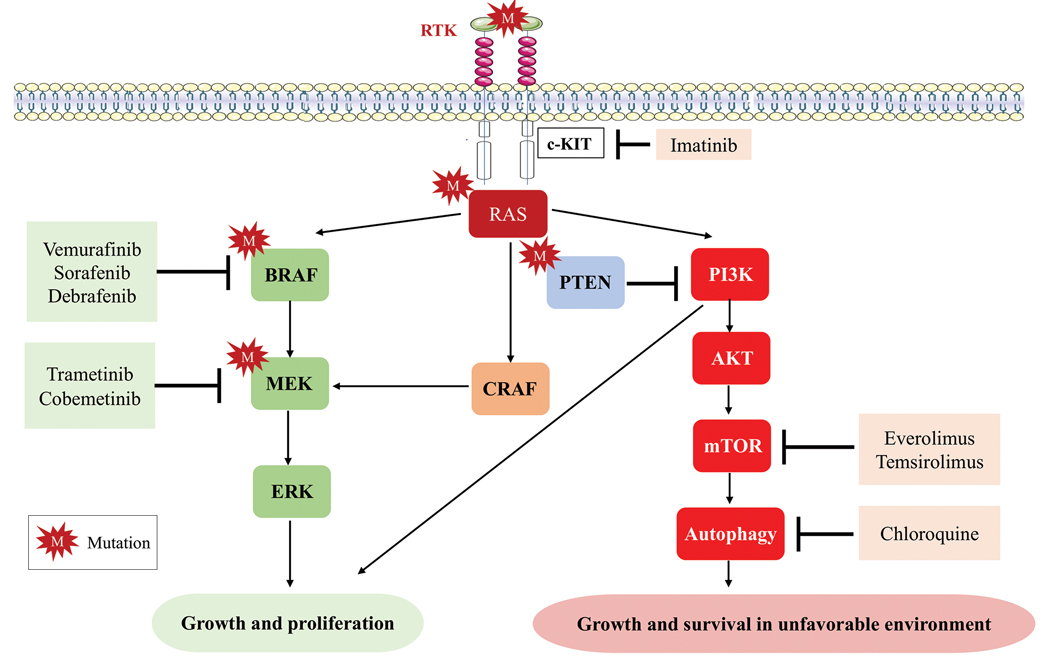

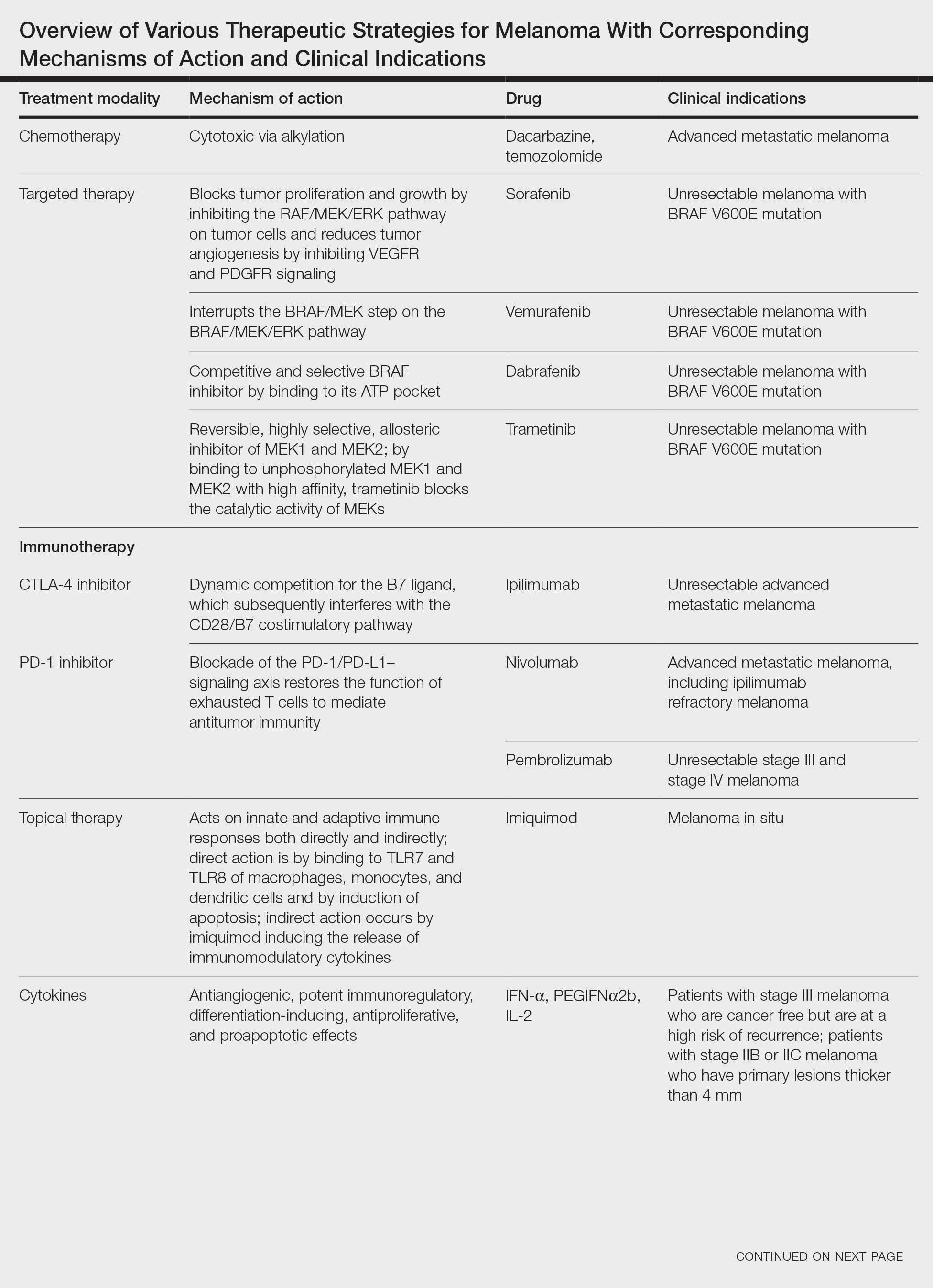

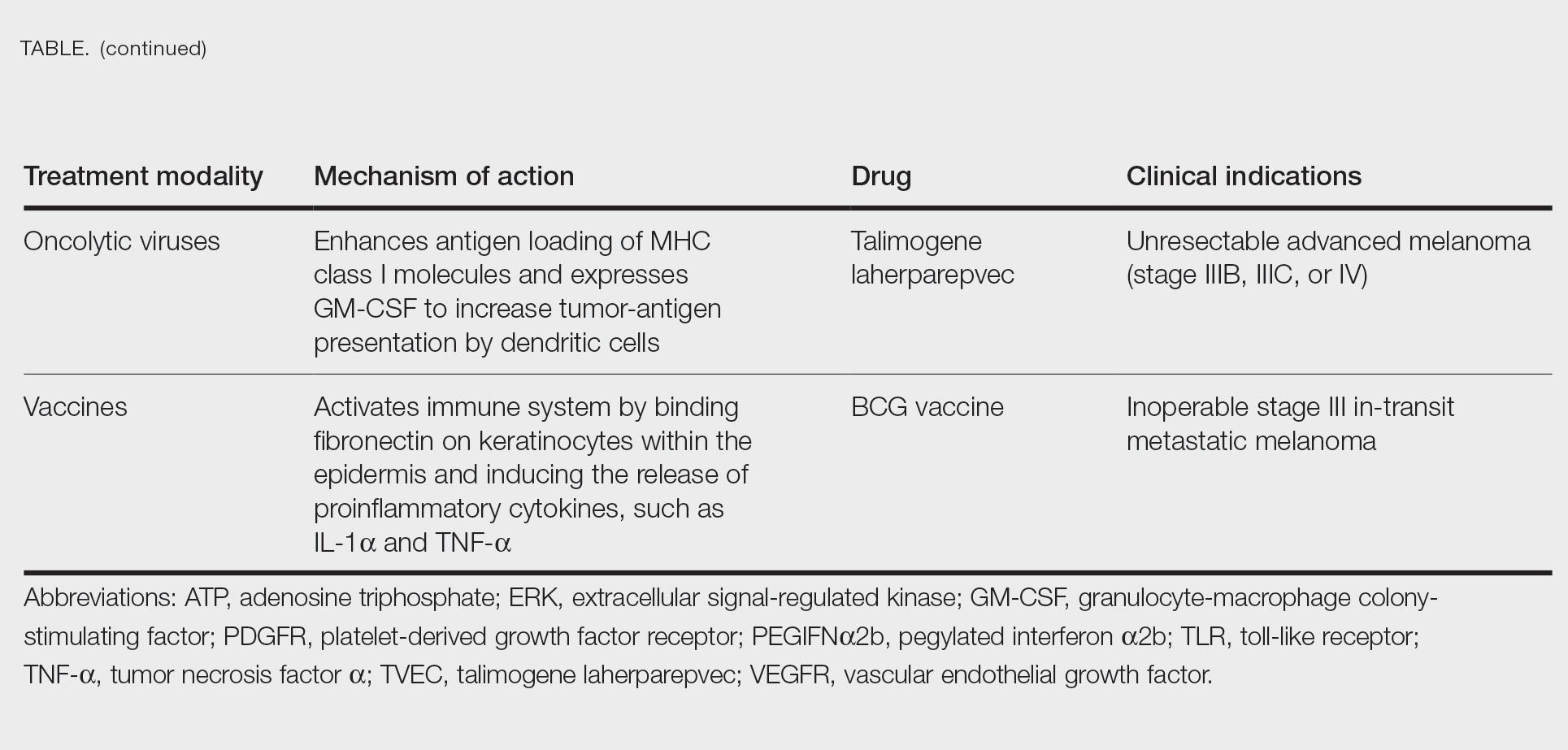

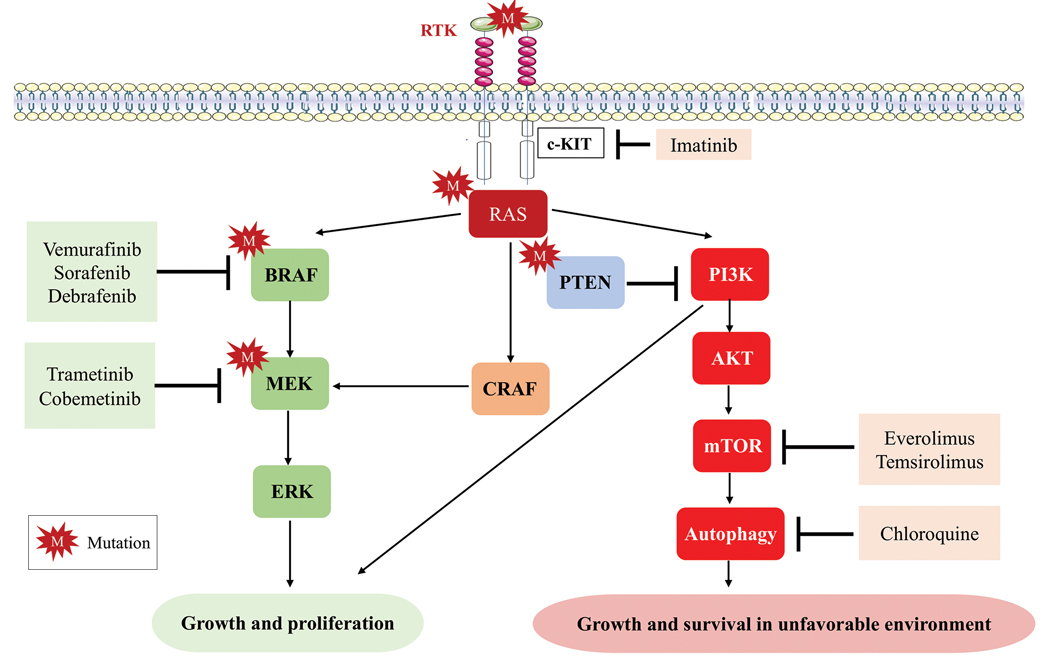

Cutaneous malignant melanoma represents an aggressive form of skin cancer, with 132,000 new cases of melanoma and 50,000 melanoma-related deaths diagnosed worldwide each year.1 In recent decades, major progress has been made in the treatment of melanoma, especially metastatic and advanced-stage disease. Approval of new treatments, such as immunotherapy with anti–PD-1 (pembrolizumab and nivolumab) and anti–CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) antibodies, has revolutionized therapeutic strategies (Figure 1). Molecularly, melanoma has the highest mutational burden among solid tumors. Approximately 40% of melanomas harbor the BRAF V600 mutation, leading to constitutive activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway.2 The other described genomic subtypes are mutated RAS (accounting for approximately 28% of cases), mutated NF1 (approximately 14% of cases), and triple wild type, though these other subtypes have not been as successfully targeted with therapy to date.3 Dual inhibition of this pathway using combination therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors confers high response rates and survival benefit, though efficacy in metastatic patients often is limited by development of resistance. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 combinations of targeted therapy in unresectable tumors: dabrafenib and trametinib, vemurafenib and cobimetinib, and encorafenib and binimetinib. The oncolytic herpesvirus talimogene laherparepvec also has received FDA approval for local treatment of unresectable cutaneous, subcutaneous, and nodal lesions in patients with recurrent melanoma after initial surgery.2

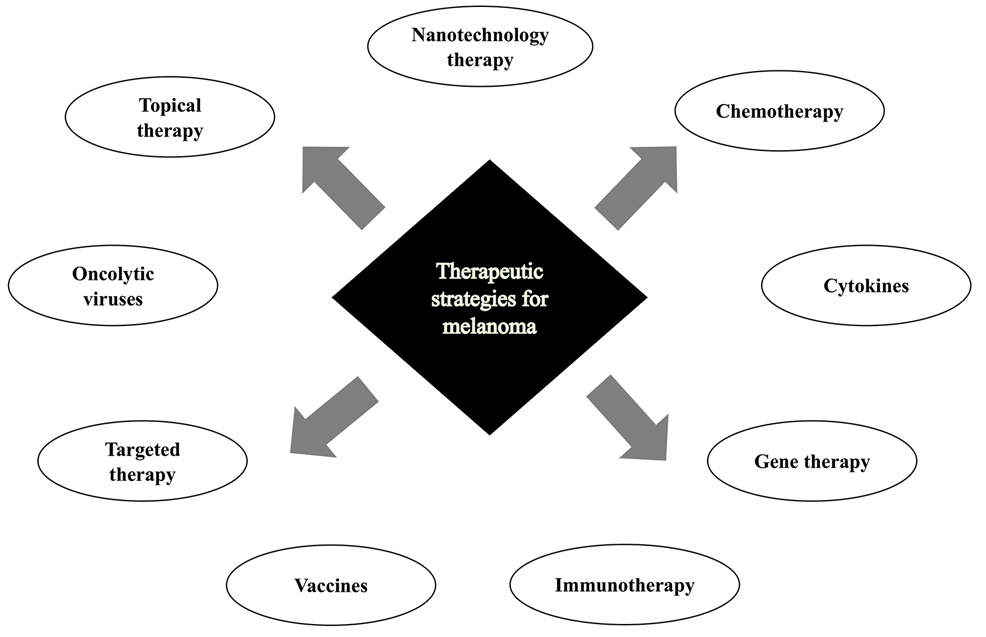

In this review, we explore new therapeutic agents and novel combinations that are being tested in early-phase clinical trials (Table). We discuss newer promising tools such as nanotechnology to develop nanosystems that act as drug carriers and/or light absorbents to potentially improve therapy outcomes. Finally, we highlight challenges such as management after resistance and intervention with novel immunotherapies and the lack of predictive biomarkers to stratify patients to targeted treatments after primary treatment failure.

Targeted Therapies

Vemurafenib was approved by the FDA in 2011 and was the first BRAF-targeted therapy approved for the treatment of melanoma based on a 48% response rate and a 63% reduction in the risk for death vs dacarbazine chemotherapy.4 Despite a rapid and clinically significant initial response, progression-free survival (PFS) was only 5.3 months, which is indicative of the rapid development of resistance with monotherapy through MAPK reactivation. As a result, combined BRAF and MEK inhibition was introduced and is now the standard of care for targeted therapy in melanoma. Treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib, vemurafenib and cobimetinib, or encorafenib and binimetinib is associated with prolonged PFS and overall survival (OS) compared to BRAF inhibitor monotherapy, with response rates exceeding 60% and a complete response rate of 10% to 18%.5 Recently, combining atezolizumab with vemurafenib and cobimetinib was shown to improve PFS compared to combined targeted therapy.6 Targeted therapy usually is given as first-line treatment to symptomatic patients with a high tumor burden because the response may be more rapid than the response to immunotherapy. Ultimately, most patients with advanced BRAF-mutated melanoma receive both targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

Mutations of KIT (encoding proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase) activate intracellular MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways (Figure 2).7 KIT mutations are found in mucosal and acral melanomas as well as chronically sun-damaged skin, with frequencies of 39%, 36%, and 28%, respectively. Imatinib was associated with a 53% response rate and PFS of 3.9 months among patients with KIT-mutated melanoma but failed to cause regression in melanomas with KIT amplification.8

Anti–CTLA-4 Immune Checkpoint Inhibition

CTLA-4 is a protein found on T cells that binds with another protein, B7, preventing T cells from killing cancer cells. Hence, blockade of CTLA-4 antibody avoids the immunosuppressive state of lymphocytes, strengthening their antitumor action.9 Ipilimumab, an anti–CTLA-4 antibody, demonstrated improvement in median OS for management of unresectable or metastatic stage IV melanoma, resulting in its FDA approval.8 A combination of ipilimumab with dacarbazine in stage IV melanoma showed notable improvement of OS.10 Similarly, tremelimumab showed evidence of tumor regression in a phase 1 trial but with more severe immune-related side effects compared with ipilimumab.11 A second study on patients with stage IV melanoma treated with tremelimumab as first-line therapy in comparison with dacarbazine demonstrated differences in OS that were not statistically significant, though there was a longer duration of an objective response in patients treated with tremelimumab (35.8 months) compared with patients responding to dacarbazine (13.7 months).12

Anti–PD-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibition

PD-1 is a transmembrane protein with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory signaling, identified as an apoptosis-associated molecule.13 Upon activation, it is expressed on the cell surface of CD4, CD8, B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells.14 PD-L1, the ligand of PD-1, is constitutively expressed on different hematopoietic cells, as well as on fibroblasts, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, neurons, and keratinocytes.15,16 Reactivation of effector T lymphocytes by PD-1:PD-L1 pathway inhibition has shown clinically significant therapeutic relevance.17 The PD-1:PD-L1 interaction is active only in the presence of T- or B-cell antigen receptor cross-link. This interaction prevents PI3K/AKT signaling and MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway activation with the net result of lymphocytic functional exhaustion.18,19 PD-L1 blockade is shown to have better clinical benefit and minor toxicity compared to anti–CTLA-4 therapy. Treatment with anti-PD1 nivolumab in a phase 1b clinical trial (N=107) demonstrated highly specific action, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in 32% of patients with advanced melanoma.20 These promising results led to the FDA approval of nivolumab for the treatment of patients with advanced and unresponsive melanoma. A recent clinical trial combining ipilimumab and nivolumab resulted in an impressive increase of PFS compared with ipilimumab monotherapy (11.5 months vs 2.9 months).21 Similarly, treatment with pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma demonstrated improvement in PFS and OS compared with anti–CTLA-4 therapy,22,23 which resulted in FDA approval of pembrolizumab for the treatment of advanced melanoma in patients previously treated with ipilimumab or BRAF inhibitors in BRAF V600 mutation–positive patients.24

Lymphocyte-Activated Gene 3–Targeted Therapies

Nanotechnology in Melanoma Therapy

The use of nanotechnology represents one of the newer alternative therapies employed for treatment of melanoma and is especially gaining interest due to reduced adverse effects in comparison with other conventional treatments for melanoma. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems precisely target tumor cells and improve the effect of both the conventional and innovative antineoplastic treatment.27,31 Tumor vasculature differs from normal tissues by being discontinuous and having interspersed small gaps/holes that allow nanoparticles to exit the circulation and enter and accumulate in the tumor tissue, leading to enhanced and targeted release of the antineoplastic drug to tumor cells.32 This mechanism is called the enhanced permeability and retention effect.33

Another mechanism by which nanoparticles work is ligand-based targeting in which ligands such as monoclonal antibodies, peptides, and nucleic acids located on the surface of nanoparticles can bind to receptors on the plasma membrane of tumor cells and lead to targeted delivery of the drug.34 Nanomaterials used for melanoma treatment include vesicular systems such as liposomes and niosomes, polymeric nanoparticles, noble metal-based nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, dendrimers, solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructures, lipid carriers, and microneedles. In melanoma, nanoparticles can be used to enhance targeted delivery of drugs, including immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Cai et al35 described usage of scaffolds in delivery systems. Tumor-associated antigens, adjuvant drugs, and chemical agents that influence the tumor microenvironment can be loaded onto these scaffolding agents. In a study by Zhu et al,36 photosensitizer chlorin e6 and immunoadjuvant aluminum hydroxide were used as a novel nanosystem that effectively destroyed tumor cells and induced a strong systemic antitumor response. IL-2 is a cytokine produced by B or T lymphocytes. Its use in melanoma has been limited by a severe adverse effect profile and lack of complete response in most patients. Cytokine-containing nanogels have been found to selectively release IL-2 in response to activation of T-cell receptors, and a mouse model in melanoma showed better response compared to free IL-1 and no adverse systemic effects.37

Nanovaccines represent another interesting novel immunotherapy modality. A study by Conniot et al38 showed that nanoparticles can be used in the treatment of melanoma. Nanoparticles made of biodegradable polymer were loaded with Melan-A/MART-1 (26–35 A27L) MHC class I-restricted peptide (MHC class I antigen), and the limited peptide MHC class II Melan-A/MART-1 51–73 (MHC class II antigen) and grafted with mannose that was then combined with an anti–PD-L1 antibody and injected into mouse models. This combination resulted in T-cell infiltration at early stages and increased infiltration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Ibrutinib, a myeloid-derived suppressor cell inhibitor, was added and demonstrated marked tumor remission and prolonged survival.38

Overexpression of certain microRNAs (miRNAs), especially miR-204-5p and miR-199b-5p, has been shown to inhibit growth of melanoma cells in vitro, both alone and in combination with MAPK inhibitors, but these miRNAs are easily degradable in body fluids. Lipid nanoparticles can bind these miRNAs and have been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation and improve efficacy of BRAF and MEK inhibitors.39

Triple-Combination Therapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–PD-1 or anti–CTLA-4 drugs have become the standard of care in treatment of advanced melanoma. Approximately 40% to 50% of cases of melanoma harbor BRAF mutations, and patients with these mutations could benefit from BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Data from clinical trials on BRAF and MEK inhibitors even showed initial high objective response rates, but the response was short-lived, and there was frequent acquired resistance.40 With ICIs, the major limitation was primary resistance, with only 50% of patients initially responding.41 Studies on murine models demonstrated that BRAF-mutated tumors had decreased expression of IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor α, and CD40 ligand on CD4+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and increased accumulation of regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, leading to a protumor microenvironment. BRAF and MEK pathway inhibition were found to improve intratumoral CD4+ T-cell activity, leading to improved antitumor T-cell responses.42 Because of this enhanced immune response by BRAF and MEK inhibitors, it was hypothesized and later supported by clinical research that a combination of these targeted treatments and ICIs can have a synergistic effect, leading to increased antitumor activity.43 A randomized phase 2 clinical trial (KEYNOTE-022) in which the treatment group was given pembrolizumab, dabrafenib, and trametinib and the control group was treated with dabrafenib and trametinib showed increased medial OS in the treatment group vs the control group (46.3 months vs 26.3 months) and more frequent complete response in the treatment group vs the control group (20% vs 15%).44 In the IMspire150 phase 3 clinical trial, patients with advanced stage IIIC to IV BRAF-mutant melanoma were treated with either a triple combination of the PDL-1 inhibitor atezolizumab, vemurafenib, and cobimetinib or vemurafenib and cobimetinib. Although the objective response rate was similar in both groups, the median duration of response was longer in the triplet group compared with the doublet group (21 months vs 12.6 months). Given these results, the FDA approved the triple-combination therapy with atezolizumab, vemurafenib, and cobimetinib. Although triple-combination therapy has shown promising results, it is expected that there will be an increase in the frequency of treatment-related adverse effects. In the phase 3 COMBi-I study, patients with advanced stage IIIC to IV BRAF V600E mutant cutaneous melanoma were treated with either a combination of spartalizumab, dabrafenib, and trametinib or just dabrafenib and trametinib. Although the objective response rates were not significantly different (69% vs 64%), there was increased frequency of treatment-related adverse effects in patients receiving triple-combination therapy.43 As more follow-up data come out of these ongoing clinical trials, benefits of triple-combination therapy and its adverse effect profile will be more definitely established.

Challenges and Future Perspectives

One of the major roadblocks in the treatment of melanoma is the failure of response to ICI with CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in a large patient population, which has resulted in the need for new biomarkers that can act as potential therapeutic targets. Further, the main underlying factor for both adjuvant and neoadjuvant approaches remains the selection of patients, optimizing therapeutic outcomes while minimizing the number of patients exposed to potentially toxic treatments without gaining clinical benefit. Clinical and pathological factors (eg, Breslow thickness, ulceration, the number of positive lymph nodes) play a role in stratifying patients as per risk of recurrence.45 Similarly, peripheral blood biomarkers have been proposed as prognostic tools for high-risk stage II and III melanoma, including markers of systemic inflammation previously explored in the metastatic setting.46 However, the use of these parameters has not been validated for clinical practice. Currently, despite promising results of BRAF and MEK inhibitors and therapeutic ICIs, as well as IL-2 or interferon alfa, treatment options in metastatic melanoma are limited because of its high heterogeneity, problematic patient stratification, and high genetic mutational rate. Recently, the role of epigenetic modifications andmiRNAs in melanoma progression and metastatic spread has been described. Silencing of CDKN2A locus and encoding for p16INK4A and p14ARF by DNA methylation are noted in 27% and 57% of metastatic melanomas, respectively, which enables melanoma cells to escape from growth arrest and apoptosis generated by Rb protein and p53 pathways.47 Demethylation of these and other tumor suppressor genes with proapoptotic function (eg, RASSF1A and tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand) can restore cell death pathways, though future clinical studies in melanoma are warranted.48

- Geller AC, Clapp RW, Sober AJ, et al. Melanoma epidemic: an analysis of six decades of data from the Connecticut Tumor Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4172-4178.

- Moreira A, Heinzerling L, Bhardwaj N, et al. Current melanoma treatments: where do we stand? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:221.

- Watson IR, Wu C-J, Zou L, et al. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Res. 2015;75(15 Suppl):2972.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Hamid O, Cowey CL, Offner M, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of approved combination BRAF and MEK inhibitor regimens for BRAF-mutant melanoma. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:1642.

- Gutzmer R, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Atezolizumab, vemurafenib, and cobimetinib as first-line treatment for unresectable advanced BRAFV600 mutation-positive melanoma (IMspire150): primary analysis of the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1835-1844.

- Reddy BY, Miller DM, Tsao H. Somatic driver mutations in melanoma. Cancer. 2017;123(suppl 11):2104-2117.

- Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3182-3190.

- Teft WA, Kirchhof MG, Madrenas J. A molecular perspective of CTLA-4 function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:65-97.

- Maverakis E, Cornelius LA, Bowen GM, et al. Metastatic melanoma—a review of current and future treatment options. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:516-524.

- Ribas A, Chesney JA, Gordon MS, et al. Safety profile and pharmacokinetic analyses of the anti-CTLA4 antibody tremelimumab administered as a one hour infusion. J Transl Med. 2012;10:1-6.

- Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:908-918.

- BG Neel, Gu H, Pao L. The ‘Shp’ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:284-293.

- Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, et al. Induced expression of PD‐1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11:3887-3895.

- Yamazaki T, Akiba H, Iwai H, et al. Expression of programmed death 1 ligands by murine T cells and APC. J Immunol. 2002;169:5538-5545.

- Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ et al. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677-704.

- Blank C, Kuball J, Voelkl S, et al. Blockade of PD‐L1 (B7‐H1) augments human tumor‐specific T cell responses in vitro. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:317-327.

- Parry RV, Chemnitz JM, Frauwirth KA, et al. CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9543-9553.

- Patsoukis N, Brown J, Petkova V, et al. Selective effects of PD-1 on Akt and Ras pathways regulate molecular components of the cell cycle and inhibit T cell proliferation. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra46.

- Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1020-1030.

- Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375-384.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

- Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006-2017.

- Burns MC, O’Donnell A, Puzanov I. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Exp Opin Orphan Drugs. 2016;4:867-873.

- F Triebel. LAG-3: a regulator of T-cell and DC responses and its use in therapeutic vaccination. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:619-622.

- Maruhashi T, Sugiura D, Okazaki I-M, et al. LAG-3: from molecular functions to clinical applications. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e001014.

- Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, et al. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:20-37.

- Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, et al. Relatlimab and nivolumab versus nivolumab in untreated advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:24-34.

- US Food and Drug Administration approves first LAG-3-blocking antibody combination, Opdualag™ (nivolumab and relatlimab-rmbw), as treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Press release. Bristol Myers Squibb. March 18, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://news.bms.com/news/details/2022/U.S.-Food-and-Drug-Administration-Approves-First-LAG-3-Blocking-Antibody-Combination-Opdualag-nivolumab-and-relatlimab-rmbw-as-Treatment-for-Patients-with-Unresectable-or-Metastatic-Melanoma/default.aspx

- Zhao B-W, Zhang F-Y, Wang Y, et al. LAG3-PD1 or CTLA4-PD1 inhibition in advanced melanoma: indirect cross comparisons of the CheckMate-067 and RELATIVITY-047 trials. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:4975.

- Jin C, Wang K, Oppong-Gyebi A, et al. Application of nanotechnology in cancer diagnosis and therapy-a mini-review. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:2964-2973.

- Maeda H. Toward a full understanding of the EPR effect in primary and metastatic tumors as well as issues related to its heterogeneity. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2015;91:3-6.

- Iyer AK, Khaled G, Fang J, et al. Exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention effect for tumor targeting. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:812-818.

- Beiu C, Giurcaneanu C, Grumezescu AM, et al. Nanosystems for improved targeted therapies in melanoma. J Clin Med. 2020;9:318.

- Cai L, Xu J, Yang Z, et al. Engineered biomaterials for cancer immunotherapy. MedComm. 2020;1:35-46.

- Zhu Y, Xue J, Chen W, et al. Albumin-biomineralized nanoparticles to synergize phototherapy and immunotherapy against melanoma. J Control Release. 2020;322:300-311.

- Zhang Y, Li N, Suh H, et al. Nanoparticle anchoring targets immune agonists to tumors enabling anti-cancer immunity without systemic toxicity. Nat Commun. 2018;9:6.

- Conniot J, Scomparin A, Peres C, et al. Immunization with mannosylated nanovaccines and inhibition of the immune-suppressing microenvironment sensitizes melanoma to immune checkpoint modulators. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14:891-901.

- Fattore L, Campani V, Ruggiero CF, et al. In vitro biophysical and biological characterization of lipid nanoparticles co-encapsulating oncosuppressors miR-199b-5p and miR-204-5p as potentiators of target therapy in metastatic melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1930.

- Welti M, Dimitriou F, Gutzmer R, et al. Triple combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and BRAF/MEK inhibitors in BRAF V600 melanoma: current status and future perspectives. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5489.

- Khair DO, Bax HJ, Mele S, et al. Combining immune checkpoint inhibitors: established and emerging targets and strategies to improve outcomes in melanoma. Front Immunol. 2019;10:453.

- Ho P-C, Meeth KM, Tsui Y-C, et al. Immune-based antitumor effects of BRAF inhibitors rely on signaling by CD40L and IFNγBRAF inhibitor-induced antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3205-3217.

- Dummer R, Sandhu SK, Miller WH, et al. A phase II, multicenter study of encorafenib/binimetinib followed by a rational triple-combination after progression in patients with advanced BRAF V600-mutated melanoma (LOGIC2). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15 suppl):10022.

- Ferrucci PF, Di Giacomo AM, Del Vecchio M, et al. KEYNOTE-022 part 3: a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 study of pembrolizumab, dabrafenib, and trametinib in BRAF-mutant melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e001806.

- Madu MF, Schopman JH, Berger DM, et al. Clinical prognostic markers in stage IIIC melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:244-251.

- Davis JL, Langan RC, Panageas KS, et al. Elevated blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: a readily available biomarker associated with death due to disease in high risk nonmetastatic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1989-1996.

- Freedberg DE, Rigas SH, Russak J, et al. Frequent p16-independent inactivation of p14ARF in human melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:784-795.