User login

Despite Good Prognosis, Early Melanoma Sparks Fear of Recurrence

Localized melanoma of the skin is highly curable with surgery, especially when the malignancy is in its early stages. Yet .

These findings come from a study of 51 patients who were treated for stage 0 (melanoma in situ) to stage IIA (Breslow thickness 1.01-2.0 mm without lymph node invasion or metastasis) disease, and who were interviewed about their experiences as survivors and their fear of recurrence.

“Consistent themes and subthemes brought up by participants included anxiety associated with follow-up skin examinations, frequent biopsy procedures attributable to screening intensity, fear of the sun, changes in sun exposure behavior, and increasing thoughts about death. Many of these experiences profoundly affected participants’ lives, despite the favorable prognosis for this group,” wrote Ayisha N. Mahama, MD, MPH, from the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin, and colleagues, in an article published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Interviews and Inventory

The investigators sought to characterize the psychological well-being of localized melanoma survivors who were treated in their practice. Participants took part in a semistructured interview and the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory short form, with a score of 13 or greater indicating potential cases of clinically significant fear of recurrence.

The mean patient age was 48.5 years, and there were twice as many women as men (34 and 17, respectively). In all, 17 of the patients were treated for stage 0 melanoma, and the remainder were treated for stage I-IIA disease.

The interviews and survey revealed four main “themes” among the patients: anxiety surrounding follow-up appointments and relief after a normal examination; concerns about intensity of melanoma surveillance, including anxiety or reassurance about frequent biopsies and worries regarding familial melanoma risk; lifestyle changes related to sun exposure, such as limiting time outdoors, using sunscreen, and wearing protective clothing; and thoughts about life and death.

On the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory short form, 38 of the 51 participants (75%) had a score of 13 or more points, indicating clinically significant fear of cancer recurrence, and when a higher threshold of 16 or more points were was applied, 34 participants (67%) still met the definition for clinically significant fear of recurrence.

Inform, Reassure, Counsel

“Given the crucial role that dermatologists play in diagnosing melanomas, there may be an opportunity to provide reassurance and support for patients to mitigate the psychological consequences of the diagnosis, by emphasizing the excellent life expectancy at a localized stage, particularly at stage 0. In addition, a referral to a mental health practitioner could be placed for patients with higher levels of anxiety and fear of recurrence,” Dr. Mahama and her coauthors wrote.

They also noted that their findings suggest that some individuals who undergo screening for melanoma might experience “psychological harms” from receiving a melanoma diagnosis “particularly given that many or most screening-detected early-stage melanomas will not progress.”

In an interview seeking objective commentary, a surgical oncologist who was not involved in the study said that anxiety about recurrence is common among patients with melanoma, many of whom may be unfamiliar with significant recent advances such as immunotherapy in the care of patients with more advanced disease.

“Often what we will do in addition to just sharing statistics, which are historical and don’t even necessarily reflect how much better we can do for patients now if the melanoma does recur or metastasize, is recommend close surveillance by their dermatologist,” said Sonia Cohen, MD, PhD, from the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston.

“The earlier we capture a recurrence the better we can help the patients. So that’s something we’ll recommend for patients to help give them a sense of control, and that they’re doing everything they can to capture current or new skin cancers,” she said.

Dr. Cohen and colleagues also instruct patients how to look for potential signs of recurrence, such as swollen lymph nodes or suspicious lesions. Patients who express extreme anxiety may also be referred to an oncology social worker or other support services, she said.

Also asked to comment on the results, Allison Dibiaso MSW, LICSW, a social worker at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, who specializes in melanoma, said that she often sees patients who have been successfully treated for early localized malignant melanoma who experience a fear of recurrence. “These patients frequently express feelings of uncertainty and worry, with the fear of another occurrence always on their mind. Managing this fear on a day-to-day basis can be challenging,” she told this news organization.

Moreover, patients with previous treatment for melanoma often experience significant anxiety before skin exams. “Some may feel anxious and worried a few days or weeks before their appointment wondering if something will reoccur and be discovered during the examination,” she said. “While some individuals develop coping skills to manage their anxiety beforehand, many still feel anxious about the possibility of recurrence until after the exam is over and results are confirmed.”

At Dana-Farber, patients with completely resected lesions are provided with individual counseling and have access to support groups specifically designed for patients with melanoma. In addition, a caregiver group is also available for those supporting patients with melanoma, and, “if needed, we provide referrals to therapists in their local community,” Ms. Dibiaso said.

The study was supported by awards/grants to senior author Adewole S. Adamson, MD, MPP from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dermatology Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and the American Cancer Society. All authors reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cohen had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Ms. Dibiaso had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Localized melanoma of the skin is highly curable with surgery, especially when the malignancy is in its early stages. Yet .

These findings come from a study of 51 patients who were treated for stage 0 (melanoma in situ) to stage IIA (Breslow thickness 1.01-2.0 mm without lymph node invasion or metastasis) disease, and who were interviewed about their experiences as survivors and their fear of recurrence.

“Consistent themes and subthemes brought up by participants included anxiety associated with follow-up skin examinations, frequent biopsy procedures attributable to screening intensity, fear of the sun, changes in sun exposure behavior, and increasing thoughts about death. Many of these experiences profoundly affected participants’ lives, despite the favorable prognosis for this group,” wrote Ayisha N. Mahama, MD, MPH, from the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin, and colleagues, in an article published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Interviews and Inventory

The investigators sought to characterize the psychological well-being of localized melanoma survivors who were treated in their practice. Participants took part in a semistructured interview and the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory short form, with a score of 13 or greater indicating potential cases of clinically significant fear of recurrence.

The mean patient age was 48.5 years, and there were twice as many women as men (34 and 17, respectively). In all, 17 of the patients were treated for stage 0 melanoma, and the remainder were treated for stage I-IIA disease.

The interviews and survey revealed four main “themes” among the patients: anxiety surrounding follow-up appointments and relief after a normal examination; concerns about intensity of melanoma surveillance, including anxiety or reassurance about frequent biopsies and worries regarding familial melanoma risk; lifestyle changes related to sun exposure, such as limiting time outdoors, using sunscreen, and wearing protective clothing; and thoughts about life and death.

On the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory short form, 38 of the 51 participants (75%) had a score of 13 or more points, indicating clinically significant fear of cancer recurrence, and when a higher threshold of 16 or more points were was applied, 34 participants (67%) still met the definition for clinically significant fear of recurrence.

Inform, Reassure, Counsel

“Given the crucial role that dermatologists play in diagnosing melanomas, there may be an opportunity to provide reassurance and support for patients to mitigate the psychological consequences of the diagnosis, by emphasizing the excellent life expectancy at a localized stage, particularly at stage 0. In addition, a referral to a mental health practitioner could be placed for patients with higher levels of anxiety and fear of recurrence,” Dr. Mahama and her coauthors wrote.

They also noted that their findings suggest that some individuals who undergo screening for melanoma might experience “psychological harms” from receiving a melanoma diagnosis “particularly given that many or most screening-detected early-stage melanomas will not progress.”

In an interview seeking objective commentary, a surgical oncologist who was not involved in the study said that anxiety about recurrence is common among patients with melanoma, many of whom may be unfamiliar with significant recent advances such as immunotherapy in the care of patients with more advanced disease.

“Often what we will do in addition to just sharing statistics, which are historical and don’t even necessarily reflect how much better we can do for patients now if the melanoma does recur or metastasize, is recommend close surveillance by their dermatologist,” said Sonia Cohen, MD, PhD, from the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston.

“The earlier we capture a recurrence the better we can help the patients. So that’s something we’ll recommend for patients to help give them a sense of control, and that they’re doing everything they can to capture current or new skin cancers,” she said.

Dr. Cohen and colleagues also instruct patients how to look for potential signs of recurrence, such as swollen lymph nodes or suspicious lesions. Patients who express extreme anxiety may also be referred to an oncology social worker or other support services, she said.

Also asked to comment on the results, Allison Dibiaso MSW, LICSW, a social worker at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, who specializes in melanoma, said that she often sees patients who have been successfully treated for early localized malignant melanoma who experience a fear of recurrence. “These patients frequently express feelings of uncertainty and worry, with the fear of another occurrence always on their mind. Managing this fear on a day-to-day basis can be challenging,” she told this news organization.

Moreover, patients with previous treatment for melanoma often experience significant anxiety before skin exams. “Some may feel anxious and worried a few days or weeks before their appointment wondering if something will reoccur and be discovered during the examination,” she said. “While some individuals develop coping skills to manage their anxiety beforehand, many still feel anxious about the possibility of recurrence until after the exam is over and results are confirmed.”

At Dana-Farber, patients with completely resected lesions are provided with individual counseling and have access to support groups specifically designed for patients with melanoma. In addition, a caregiver group is also available for those supporting patients with melanoma, and, “if needed, we provide referrals to therapists in their local community,” Ms. Dibiaso said.

The study was supported by awards/grants to senior author Adewole S. Adamson, MD, MPP from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dermatology Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and the American Cancer Society. All authors reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cohen had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Ms. Dibiaso had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Localized melanoma of the skin is highly curable with surgery, especially when the malignancy is in its early stages. Yet .

These findings come from a study of 51 patients who were treated for stage 0 (melanoma in situ) to stage IIA (Breslow thickness 1.01-2.0 mm without lymph node invasion or metastasis) disease, and who were interviewed about their experiences as survivors and their fear of recurrence.

“Consistent themes and subthemes brought up by participants included anxiety associated with follow-up skin examinations, frequent biopsy procedures attributable to screening intensity, fear of the sun, changes in sun exposure behavior, and increasing thoughts about death. Many of these experiences profoundly affected participants’ lives, despite the favorable prognosis for this group,” wrote Ayisha N. Mahama, MD, MPH, from the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin, and colleagues, in an article published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Interviews and Inventory

The investigators sought to characterize the psychological well-being of localized melanoma survivors who were treated in their practice. Participants took part in a semistructured interview and the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory short form, with a score of 13 or greater indicating potential cases of clinically significant fear of recurrence.

The mean patient age was 48.5 years, and there were twice as many women as men (34 and 17, respectively). In all, 17 of the patients were treated for stage 0 melanoma, and the remainder were treated for stage I-IIA disease.

The interviews and survey revealed four main “themes” among the patients: anxiety surrounding follow-up appointments and relief after a normal examination; concerns about intensity of melanoma surveillance, including anxiety or reassurance about frequent biopsies and worries regarding familial melanoma risk; lifestyle changes related to sun exposure, such as limiting time outdoors, using sunscreen, and wearing protective clothing; and thoughts about life and death.

On the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory short form, 38 of the 51 participants (75%) had a score of 13 or more points, indicating clinically significant fear of cancer recurrence, and when a higher threshold of 16 or more points were was applied, 34 participants (67%) still met the definition for clinically significant fear of recurrence.

Inform, Reassure, Counsel

“Given the crucial role that dermatologists play in diagnosing melanomas, there may be an opportunity to provide reassurance and support for patients to mitigate the psychological consequences of the diagnosis, by emphasizing the excellent life expectancy at a localized stage, particularly at stage 0. In addition, a referral to a mental health practitioner could be placed for patients with higher levels of anxiety and fear of recurrence,” Dr. Mahama and her coauthors wrote.

They also noted that their findings suggest that some individuals who undergo screening for melanoma might experience “psychological harms” from receiving a melanoma diagnosis “particularly given that many or most screening-detected early-stage melanomas will not progress.”

In an interview seeking objective commentary, a surgical oncologist who was not involved in the study said that anxiety about recurrence is common among patients with melanoma, many of whom may be unfamiliar with significant recent advances such as immunotherapy in the care of patients with more advanced disease.

“Often what we will do in addition to just sharing statistics, which are historical and don’t even necessarily reflect how much better we can do for patients now if the melanoma does recur or metastasize, is recommend close surveillance by their dermatologist,” said Sonia Cohen, MD, PhD, from the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston.

“The earlier we capture a recurrence the better we can help the patients. So that’s something we’ll recommend for patients to help give them a sense of control, and that they’re doing everything they can to capture current or new skin cancers,” she said.

Dr. Cohen and colleagues also instruct patients how to look for potential signs of recurrence, such as swollen lymph nodes or suspicious lesions. Patients who express extreme anxiety may also be referred to an oncology social worker or other support services, she said.

Also asked to comment on the results, Allison Dibiaso MSW, LICSW, a social worker at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, who specializes in melanoma, said that she often sees patients who have been successfully treated for early localized malignant melanoma who experience a fear of recurrence. “These patients frequently express feelings of uncertainty and worry, with the fear of another occurrence always on their mind. Managing this fear on a day-to-day basis can be challenging,” she told this news organization.

Moreover, patients with previous treatment for melanoma often experience significant anxiety before skin exams. “Some may feel anxious and worried a few days or weeks before their appointment wondering if something will reoccur and be discovered during the examination,” she said. “While some individuals develop coping skills to manage their anxiety beforehand, many still feel anxious about the possibility of recurrence until after the exam is over and results are confirmed.”

At Dana-Farber, patients with completely resected lesions are provided with individual counseling and have access to support groups specifically designed for patients with melanoma. In addition, a caregiver group is also available for those supporting patients with melanoma, and, “if needed, we provide referrals to therapists in their local community,” Ms. Dibiaso said.

The study was supported by awards/grants to senior author Adewole S. Adamson, MD, MPP from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dermatology Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and the American Cancer Society. All authors reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cohen had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Ms. Dibiaso had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Expert Hopes to Expand Ohio Model of Melanoma Case Reporting

SAN DIEGO – Soon after Brett M. Coldiron, MD, launched his Cincinnati-based dermatology and Mohs surgery practice more than 20 years ago, he reported his first three cases of thin melanomas to the Ohio Department of Health, as mandated by state law.

“I got sent reams of paperwork to fill out that I did not understand,” Dr. Coldiron, a past president of the American College of Mohs Surgery and the American Academy of Dermatology, recalled at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “Then, I got chewed out for not reporting sooner and threatened with thousands of dollars in fines if I did not promptly report the forms in the future. It was an obnoxious experience.”

About 15 years later, while testifying at the Ohio Legislature on medical reasons to restrict the use of tanning beds, a lobbyist for the tanning bed industry told him that the melanoma rates had been stable in Ohio for the previous 5 years. “It turns out they were cherry picking certain segments of data to fit their narrative,” Dr. Coldiron said. “I was stunned and it kind of deflated me. I thought about this for a long time, and thought, ‘how do we solve this issue of reporting melanoma cases without adding work to existing staff if you’re a small practice and without spending significant amounts of money? Let’s make this easier.’ ”

In addition to reducing the use of tanning beds, proper reporting of melanoma cases is important for reasons that include efforts to increase sunscreen use and to be counted in ongoing research efforts to obtain a realistic snapshot of melanoma prevalence and incidence, he said.

Quality of melanoma case reporting relies on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program, which collects data on the incidence, treatment, staging, and survival for 28% of the US population. All 50 states and US territories require melanoma to be reported to the NPCR, but while most hospital systems have reporting protocols and dedicated data registrars, private practices may not.

Also, many dermatopathology practices operate independently and do not have dedicated registrars and may not report cases. “Melanoma is unique in that it is often completely managed in outpatient settings and these melanomas may never be reported,” said Dr. Coldiron, current president of the Ohio Dermatological Foundation. “That’s the practice gap.” One study published in 2018 found that only 49% of dermatologists knew that melanoma was a reportable disease and only 34% routinely reported newly diagnosed cases to their state’s cancer registry. He characterized melanoma reporting as an unfunded mandate.

“Hospitals are doing the most of them, because they have a registrar,” he said. “Small practices have to assign someone to do this, and it can be difficult to train that person. It’s time consuming. The first time we did it, it took an hour,” but, he said, taking a 2-hour tutorial from the Ohio Department of Health helped.

He noted that there is a lack of awareness and clinicians think it’s the dermatopathologist’s job to report cases, “while the dermatopathologist thinks it’s the clinician’s job,” and many of the entry fields are not applicable to thinner melanomas.

There is also a “patchwork” of ways that state departments of health accept the information, not all electronically, he continued. For example, those in Arizona, Montana, West Virginia, Delaware, Vermont, and Maine accept paper copies only, “meaning you have to download a PDF, fill it out, and fax it back to them,” Dr. Coldiron said at the meeting, which was hosted by Scripps Cancer Center.

“We have them sign a HIPAA form and take the two-hour online tutorial,” he said. They download data that Ohio dermatologists have faxed to a dedicated secure HIPAA-compliant cloud-based fax line that Dr. Coldiron has set up, and the cases are then sent to the Ohio Department of Health.

Dr. Coldiron and colleagues have also partnered with the University of Cincinnati Clermont, which offers a National Cancer Registries Association–accredited certificate program — one of several nationwide. Students in this program are trained to become cancer registrars. “The university staff are gung-ho about it because they are looking for easy cases to train the students on. Also, the Ohio Department of Health staff are keen to help train the students and even help them find jobs or hire them after they complete the degree. Staff from the department of health and college faculty are fully engaged and supervising. It’s a win-win for all.”

According to Dr. Coldiron, in 2023, 8 Ohio dermatology practices were sending their reports to the fax line he set up and 7 more have signed up in recent months, making 15 practices to date. “It’s self-perpetuating at this point,” he said. “The Ohio Department of Health and the University of Cincinnati are invested in this program long-term.” The fax service costs Dr. Coldiron $42 per month — a small price to pay, he said, for being a clearinghouse for private Ohio dermatology practices looking for a practical way to report their melanoma cases. The model has increased melanoma reporting in Ohio by 2.8% in the last 2 years, “which doesn’t seem like that many, but if there are 6500 cases of melanoma, and you can increase reporting by a couple hundred cases, that’s a lot,” he said.

His goal is to expand this model to more states. “Dermatologists, surgical oncologists, and cancer center administrators should embrace this opportunity to make their practices a clearinghouse for their state,” he said. “This is an opportunity to improve state health, quality improvement projects, help providers, and gain recognition as a center of excellence. The increase in incidence of melanoma will lend great clout to public and legislative requests for prevention, treatment, and research dollars.”

In an interview, Hugh Greenway, MD, the head of Mohs and dermatologic surgery at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, also noted that cutaneous melanoma is significantly underreported in spite of individual state requirements. “As Dr. Coldiron reminds us, the main reason is that in many cases the pathology diagnosis and report come from the dermatologist’s/dermatopathologist’s office,” Dr. Greenway said. “With no hospital or large multispecialty laboratory involved, the reporting may be incomplete or not done. This is not the case with almost all other cancers where a hospital laboratory is involved.”

If widespread adoption of Dr. Coldiron’s model can occur, he added, “then we will have much better melanoma reporting data on which to both help our patients and specialty. He is to be applauded for producing a workable solution to the problem of underreporting.”

Dr. Coldiron reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Greenway reported that he conducts research for Castle Biosciences. He is also course director of the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update.

SAN DIEGO – Soon after Brett M. Coldiron, MD, launched his Cincinnati-based dermatology and Mohs surgery practice more than 20 years ago, he reported his first three cases of thin melanomas to the Ohio Department of Health, as mandated by state law.

“I got sent reams of paperwork to fill out that I did not understand,” Dr. Coldiron, a past president of the American College of Mohs Surgery and the American Academy of Dermatology, recalled at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “Then, I got chewed out for not reporting sooner and threatened with thousands of dollars in fines if I did not promptly report the forms in the future. It was an obnoxious experience.”

About 15 years later, while testifying at the Ohio Legislature on medical reasons to restrict the use of tanning beds, a lobbyist for the tanning bed industry told him that the melanoma rates had been stable in Ohio for the previous 5 years. “It turns out they were cherry picking certain segments of data to fit their narrative,” Dr. Coldiron said. “I was stunned and it kind of deflated me. I thought about this for a long time, and thought, ‘how do we solve this issue of reporting melanoma cases without adding work to existing staff if you’re a small practice and without spending significant amounts of money? Let’s make this easier.’ ”

In addition to reducing the use of tanning beds, proper reporting of melanoma cases is important for reasons that include efforts to increase sunscreen use and to be counted in ongoing research efforts to obtain a realistic snapshot of melanoma prevalence and incidence, he said.

Quality of melanoma case reporting relies on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program, which collects data on the incidence, treatment, staging, and survival for 28% of the US population. All 50 states and US territories require melanoma to be reported to the NPCR, but while most hospital systems have reporting protocols and dedicated data registrars, private practices may not.

Also, many dermatopathology practices operate independently and do not have dedicated registrars and may not report cases. “Melanoma is unique in that it is often completely managed in outpatient settings and these melanomas may never be reported,” said Dr. Coldiron, current president of the Ohio Dermatological Foundation. “That’s the practice gap.” One study published in 2018 found that only 49% of dermatologists knew that melanoma was a reportable disease and only 34% routinely reported newly diagnosed cases to their state’s cancer registry. He characterized melanoma reporting as an unfunded mandate.

“Hospitals are doing the most of them, because they have a registrar,” he said. “Small practices have to assign someone to do this, and it can be difficult to train that person. It’s time consuming. The first time we did it, it took an hour,” but, he said, taking a 2-hour tutorial from the Ohio Department of Health helped.

He noted that there is a lack of awareness and clinicians think it’s the dermatopathologist’s job to report cases, “while the dermatopathologist thinks it’s the clinician’s job,” and many of the entry fields are not applicable to thinner melanomas.

There is also a “patchwork” of ways that state departments of health accept the information, not all electronically, he continued. For example, those in Arizona, Montana, West Virginia, Delaware, Vermont, and Maine accept paper copies only, “meaning you have to download a PDF, fill it out, and fax it back to them,” Dr. Coldiron said at the meeting, which was hosted by Scripps Cancer Center.

“We have them sign a HIPAA form and take the two-hour online tutorial,” he said. They download data that Ohio dermatologists have faxed to a dedicated secure HIPAA-compliant cloud-based fax line that Dr. Coldiron has set up, and the cases are then sent to the Ohio Department of Health.

Dr. Coldiron and colleagues have also partnered with the University of Cincinnati Clermont, which offers a National Cancer Registries Association–accredited certificate program — one of several nationwide. Students in this program are trained to become cancer registrars. “The university staff are gung-ho about it because they are looking for easy cases to train the students on. Also, the Ohio Department of Health staff are keen to help train the students and even help them find jobs or hire them after they complete the degree. Staff from the department of health and college faculty are fully engaged and supervising. It’s a win-win for all.”

According to Dr. Coldiron, in 2023, 8 Ohio dermatology practices were sending their reports to the fax line he set up and 7 more have signed up in recent months, making 15 practices to date. “It’s self-perpetuating at this point,” he said. “The Ohio Department of Health and the University of Cincinnati are invested in this program long-term.” The fax service costs Dr. Coldiron $42 per month — a small price to pay, he said, for being a clearinghouse for private Ohio dermatology practices looking for a practical way to report their melanoma cases. The model has increased melanoma reporting in Ohio by 2.8% in the last 2 years, “which doesn’t seem like that many, but if there are 6500 cases of melanoma, and you can increase reporting by a couple hundred cases, that’s a lot,” he said.

His goal is to expand this model to more states. “Dermatologists, surgical oncologists, and cancer center administrators should embrace this opportunity to make their practices a clearinghouse for their state,” he said. “This is an opportunity to improve state health, quality improvement projects, help providers, and gain recognition as a center of excellence. The increase in incidence of melanoma will lend great clout to public and legislative requests for prevention, treatment, and research dollars.”

In an interview, Hugh Greenway, MD, the head of Mohs and dermatologic surgery at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, also noted that cutaneous melanoma is significantly underreported in spite of individual state requirements. “As Dr. Coldiron reminds us, the main reason is that in many cases the pathology diagnosis and report come from the dermatologist’s/dermatopathologist’s office,” Dr. Greenway said. “With no hospital or large multispecialty laboratory involved, the reporting may be incomplete or not done. This is not the case with almost all other cancers where a hospital laboratory is involved.”

If widespread adoption of Dr. Coldiron’s model can occur, he added, “then we will have much better melanoma reporting data on which to both help our patients and specialty. He is to be applauded for producing a workable solution to the problem of underreporting.”

Dr. Coldiron reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Greenway reported that he conducts research for Castle Biosciences. He is also course director of the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update.

SAN DIEGO – Soon after Brett M. Coldiron, MD, launched his Cincinnati-based dermatology and Mohs surgery practice more than 20 years ago, he reported his first three cases of thin melanomas to the Ohio Department of Health, as mandated by state law.

“I got sent reams of paperwork to fill out that I did not understand,” Dr. Coldiron, a past president of the American College of Mohs Surgery and the American Academy of Dermatology, recalled at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “Then, I got chewed out for not reporting sooner and threatened with thousands of dollars in fines if I did not promptly report the forms in the future. It was an obnoxious experience.”

About 15 years later, while testifying at the Ohio Legislature on medical reasons to restrict the use of tanning beds, a lobbyist for the tanning bed industry told him that the melanoma rates had been stable in Ohio for the previous 5 years. “It turns out they were cherry picking certain segments of data to fit their narrative,” Dr. Coldiron said. “I was stunned and it kind of deflated me. I thought about this for a long time, and thought, ‘how do we solve this issue of reporting melanoma cases without adding work to existing staff if you’re a small practice and without spending significant amounts of money? Let’s make this easier.’ ”

In addition to reducing the use of tanning beds, proper reporting of melanoma cases is important for reasons that include efforts to increase sunscreen use and to be counted in ongoing research efforts to obtain a realistic snapshot of melanoma prevalence and incidence, he said.

Quality of melanoma case reporting relies on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program, which collects data on the incidence, treatment, staging, and survival for 28% of the US population. All 50 states and US territories require melanoma to be reported to the NPCR, but while most hospital systems have reporting protocols and dedicated data registrars, private practices may not.

Also, many dermatopathology practices operate independently and do not have dedicated registrars and may not report cases. “Melanoma is unique in that it is often completely managed in outpatient settings and these melanomas may never be reported,” said Dr. Coldiron, current president of the Ohio Dermatological Foundation. “That’s the practice gap.” One study published in 2018 found that only 49% of dermatologists knew that melanoma was a reportable disease and only 34% routinely reported newly diagnosed cases to their state’s cancer registry. He characterized melanoma reporting as an unfunded mandate.

“Hospitals are doing the most of them, because they have a registrar,” he said. “Small practices have to assign someone to do this, and it can be difficult to train that person. It’s time consuming. The first time we did it, it took an hour,” but, he said, taking a 2-hour tutorial from the Ohio Department of Health helped.

He noted that there is a lack of awareness and clinicians think it’s the dermatopathologist’s job to report cases, “while the dermatopathologist thinks it’s the clinician’s job,” and many of the entry fields are not applicable to thinner melanomas.

There is also a “patchwork” of ways that state departments of health accept the information, not all electronically, he continued. For example, those in Arizona, Montana, West Virginia, Delaware, Vermont, and Maine accept paper copies only, “meaning you have to download a PDF, fill it out, and fax it back to them,” Dr. Coldiron said at the meeting, which was hosted by Scripps Cancer Center.

“We have them sign a HIPAA form and take the two-hour online tutorial,” he said. They download data that Ohio dermatologists have faxed to a dedicated secure HIPAA-compliant cloud-based fax line that Dr. Coldiron has set up, and the cases are then sent to the Ohio Department of Health.

Dr. Coldiron and colleagues have also partnered with the University of Cincinnati Clermont, which offers a National Cancer Registries Association–accredited certificate program — one of several nationwide. Students in this program are trained to become cancer registrars. “The university staff are gung-ho about it because they are looking for easy cases to train the students on. Also, the Ohio Department of Health staff are keen to help train the students and even help them find jobs or hire them after they complete the degree. Staff from the department of health and college faculty are fully engaged and supervising. It’s a win-win for all.”

According to Dr. Coldiron, in 2023, 8 Ohio dermatology practices were sending their reports to the fax line he set up and 7 more have signed up in recent months, making 15 practices to date. “It’s self-perpetuating at this point,” he said. “The Ohio Department of Health and the University of Cincinnati are invested in this program long-term.” The fax service costs Dr. Coldiron $42 per month — a small price to pay, he said, for being a clearinghouse for private Ohio dermatology practices looking for a practical way to report their melanoma cases. The model has increased melanoma reporting in Ohio by 2.8% in the last 2 years, “which doesn’t seem like that many, but if there are 6500 cases of melanoma, and you can increase reporting by a couple hundred cases, that’s a lot,” he said.

His goal is to expand this model to more states. “Dermatologists, surgical oncologists, and cancer center administrators should embrace this opportunity to make their practices a clearinghouse for their state,” he said. “This is an opportunity to improve state health, quality improvement projects, help providers, and gain recognition as a center of excellence. The increase in incidence of melanoma will lend great clout to public and legislative requests for prevention, treatment, and research dollars.”

In an interview, Hugh Greenway, MD, the head of Mohs and dermatologic surgery at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, also noted that cutaneous melanoma is significantly underreported in spite of individual state requirements. “As Dr. Coldiron reminds us, the main reason is that in many cases the pathology diagnosis and report come from the dermatologist’s/dermatopathologist’s office,” Dr. Greenway said. “With no hospital or large multispecialty laboratory involved, the reporting may be incomplete or not done. This is not the case with almost all other cancers where a hospital laboratory is involved.”

If widespread adoption of Dr. Coldiron’s model can occur, he added, “then we will have much better melanoma reporting data on which to both help our patients and specialty. He is to be applauded for producing a workable solution to the problem of underreporting.”

Dr. Coldiron reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Greenway reported that he conducts research for Castle Biosciences. He is also course director of the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update.

FROM MELANOMA 2024

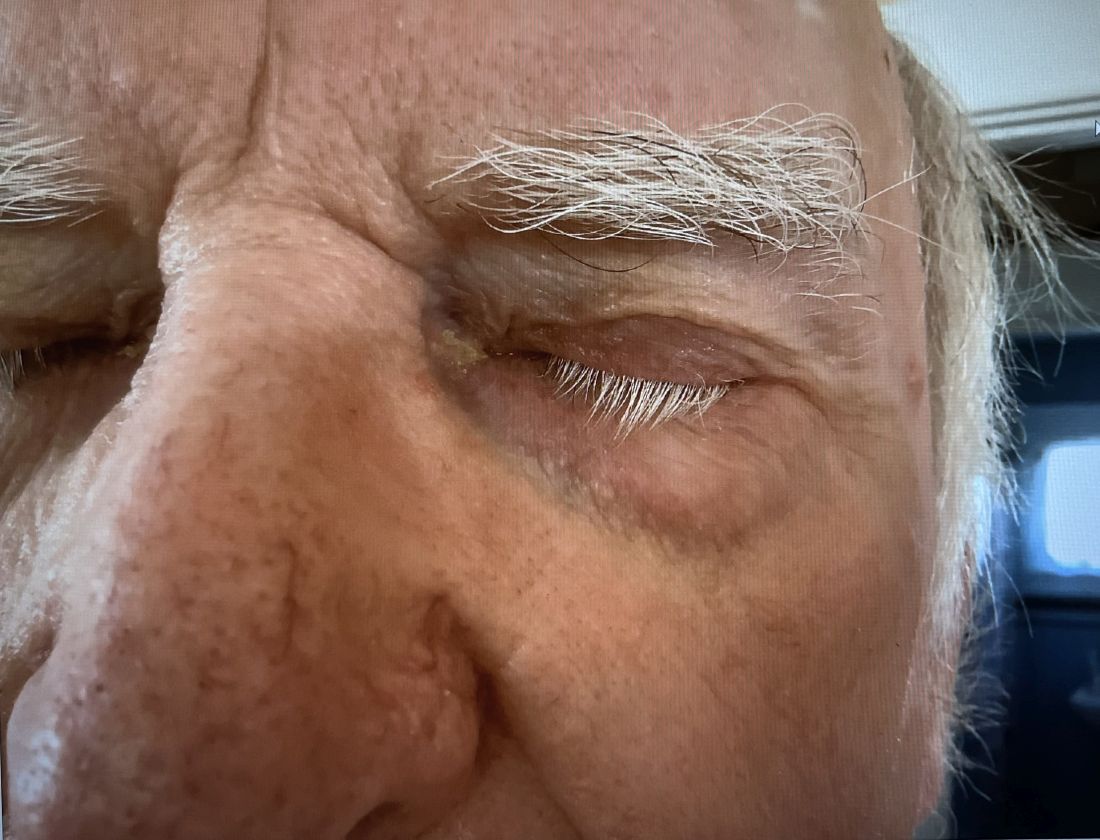

A 74-year-old White male presented with a 1-year history of depigmented patches on the hands, arms, and face, as well as white eyelashes and eyebrows

This patient showed no evidence of recurrence in the scar where the melanoma was excised, and had no enlarged lymph nodes on palpation. His complete blood count and liver function tests were normal. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan was ordered by Dr. Nasser that revealed hypermetabolic right paratracheal, right hilar, and subcarinal lymph nodes, highly suspicious for malignant lymph nodes. The patient was referred to oncology for metastatic melanoma treatment and has been doing well on ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Vitiligo is an autoimmune condition characterized by the progressive destruction of melanocytes resulting in hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin. Vitiligo has been associated with cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma-associated leukoderma occurs in a portion of patients with melanoma and is correlated with a favorable prognosis. Additionally, leukoderma has been described as a side effect of melanoma treatment itself. However, cases such as this one have also been reported of vitiligo-like depigmentation presenting prior to the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma.

Melanoma, like vitiligo, is considered highly immunogenic, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) can recognize antigens in melanoma. Furthermore, studies have shown a vitiligo-like halo around melanoma tumors, likely caused by T-cell recruitment, and this may lead to tumor destruction, but rarely total clearance. It seems that the CTL infiltrate in both diseases is similar, but regulatory T cells are decreased in vitiligo, whereas they are present in melanomas and may contribute to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment found at the margin of these lesions.

Leukoderma is also associated with melanoma immunotherapy which may be described as drug-induced leukoderma. Additionally, the frequency of recognition of melanoma cells by CTLs leading to hypopigmentation appears to be higher in those with metastatic disease. High immune infiltrate with CTLs and interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) expression by type 1 T helper cells is associated with favorable prognosis. Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has shown promise in treatment augmentation for melanoma, but not all patients fully respond to therapy. Nonetheless, development of leukoderma with these treatments has been significantly associated with good therapeutic response. Depigmentation of hair and retinal epithelium has also been reported. However, drug-induced leukoderma and vitiligo seem to have clinical and biological differences, including family history of disease and serum chemokine levels. Vaccines are in production to aid in the treatment of melanoma, but researchers must first identify the appropriate antigen(s) to include.

Conversely, vitiligo-like depigmentation has been reported as a harbinger of metastatic melanoma. Patients with previous excision of primary melanoma have presented months or years later with depigmentation and, upon further evaluation, have been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma. The prevalence of depigmentation in melanoma patients is about 3%-6%, and is estimated to be 7-10 times more common in those with melanoma than in the general population. In most cases, hypopigmentation follows the diagnosis of melanoma, with an average of 4.8 years after the initial diagnosis and 1-2 years after lymph node or distant metastases. It is unclear whether hypopigmentation occurs before or after the growth of metastatic lesions, but this clinical finding in a patient with previous melanoma may serve as an important clue to conduct further investigation for metastasis.

This case and the photos were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Natalie Y. Nasser, MD, Kaiser Permanente Riverside Medical Center; Riverside, California. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Cerci FB et al. Cutis. 2017 Jun;99(6):E1-E2. PMID: 28686764.

Cho EA et al. Ann Dermatol. 2009 May;21(2):178-181.

Failla CM et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 15;20(22):5731.

This patient showed no evidence of recurrence in the scar where the melanoma was excised, and had no enlarged lymph nodes on palpation. His complete blood count and liver function tests were normal. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan was ordered by Dr. Nasser that revealed hypermetabolic right paratracheal, right hilar, and subcarinal lymph nodes, highly suspicious for malignant lymph nodes. The patient was referred to oncology for metastatic melanoma treatment and has been doing well on ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Vitiligo is an autoimmune condition characterized by the progressive destruction of melanocytes resulting in hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin. Vitiligo has been associated with cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma-associated leukoderma occurs in a portion of patients with melanoma and is correlated with a favorable prognosis. Additionally, leukoderma has been described as a side effect of melanoma treatment itself. However, cases such as this one have also been reported of vitiligo-like depigmentation presenting prior to the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma.

Melanoma, like vitiligo, is considered highly immunogenic, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) can recognize antigens in melanoma. Furthermore, studies have shown a vitiligo-like halo around melanoma tumors, likely caused by T-cell recruitment, and this may lead to tumor destruction, but rarely total clearance. It seems that the CTL infiltrate in both diseases is similar, but regulatory T cells are decreased in vitiligo, whereas they are present in melanomas and may contribute to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment found at the margin of these lesions.

Leukoderma is also associated with melanoma immunotherapy which may be described as drug-induced leukoderma. Additionally, the frequency of recognition of melanoma cells by CTLs leading to hypopigmentation appears to be higher in those with metastatic disease. High immune infiltrate with CTLs and interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) expression by type 1 T helper cells is associated with favorable prognosis. Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has shown promise in treatment augmentation for melanoma, but not all patients fully respond to therapy. Nonetheless, development of leukoderma with these treatments has been significantly associated with good therapeutic response. Depigmentation of hair and retinal epithelium has also been reported. However, drug-induced leukoderma and vitiligo seem to have clinical and biological differences, including family history of disease and serum chemokine levels. Vaccines are in production to aid in the treatment of melanoma, but researchers must first identify the appropriate antigen(s) to include.

Conversely, vitiligo-like depigmentation has been reported as a harbinger of metastatic melanoma. Patients with previous excision of primary melanoma have presented months or years later with depigmentation and, upon further evaluation, have been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma. The prevalence of depigmentation in melanoma patients is about 3%-6%, and is estimated to be 7-10 times more common in those with melanoma than in the general population. In most cases, hypopigmentation follows the diagnosis of melanoma, with an average of 4.8 years after the initial diagnosis and 1-2 years after lymph node or distant metastases. It is unclear whether hypopigmentation occurs before or after the growth of metastatic lesions, but this clinical finding in a patient with previous melanoma may serve as an important clue to conduct further investigation for metastasis.

This case and the photos were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Natalie Y. Nasser, MD, Kaiser Permanente Riverside Medical Center; Riverside, California. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Cerci FB et al. Cutis. 2017 Jun;99(6):E1-E2. PMID: 28686764.

Cho EA et al. Ann Dermatol. 2009 May;21(2):178-181.

Failla CM et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 15;20(22):5731.

This patient showed no evidence of recurrence in the scar where the melanoma was excised, and had no enlarged lymph nodes on palpation. His complete blood count and liver function tests were normal. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan was ordered by Dr. Nasser that revealed hypermetabolic right paratracheal, right hilar, and subcarinal lymph nodes, highly suspicious for malignant lymph nodes. The patient was referred to oncology for metastatic melanoma treatment and has been doing well on ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Vitiligo is an autoimmune condition characterized by the progressive destruction of melanocytes resulting in hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin. Vitiligo has been associated with cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma-associated leukoderma occurs in a portion of patients with melanoma and is correlated with a favorable prognosis. Additionally, leukoderma has been described as a side effect of melanoma treatment itself. However, cases such as this one have also been reported of vitiligo-like depigmentation presenting prior to the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma.

Melanoma, like vitiligo, is considered highly immunogenic, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) can recognize antigens in melanoma. Furthermore, studies have shown a vitiligo-like halo around melanoma tumors, likely caused by T-cell recruitment, and this may lead to tumor destruction, but rarely total clearance. It seems that the CTL infiltrate in both diseases is similar, but regulatory T cells are decreased in vitiligo, whereas they are present in melanomas and may contribute to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment found at the margin of these lesions.

Leukoderma is also associated with melanoma immunotherapy which may be described as drug-induced leukoderma. Additionally, the frequency of recognition of melanoma cells by CTLs leading to hypopigmentation appears to be higher in those with metastatic disease. High immune infiltrate with CTLs and interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) expression by type 1 T helper cells is associated with favorable prognosis. Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has shown promise in treatment augmentation for melanoma, but not all patients fully respond to therapy. Nonetheless, development of leukoderma with these treatments has been significantly associated with good therapeutic response. Depigmentation of hair and retinal epithelium has also been reported. However, drug-induced leukoderma and vitiligo seem to have clinical and biological differences, including family history of disease and serum chemokine levels. Vaccines are in production to aid in the treatment of melanoma, but researchers must first identify the appropriate antigen(s) to include.

Conversely, vitiligo-like depigmentation has been reported as a harbinger of metastatic melanoma. Patients with previous excision of primary melanoma have presented months or years later with depigmentation and, upon further evaluation, have been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma. The prevalence of depigmentation in melanoma patients is about 3%-6%, and is estimated to be 7-10 times more common in those with melanoma than in the general population. In most cases, hypopigmentation follows the diagnosis of melanoma, with an average of 4.8 years after the initial diagnosis and 1-2 years after lymph node or distant metastases. It is unclear whether hypopigmentation occurs before or after the growth of metastatic lesions, but this clinical finding in a patient with previous melanoma may serve as an important clue to conduct further investigation for metastasis.

This case and the photos were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Natalie Y. Nasser, MD, Kaiser Permanente Riverside Medical Center; Riverside, California. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Cerci FB et al. Cutis. 2017 Jun;99(6):E1-E2. PMID: 28686764.

Cho EA et al. Ann Dermatol. 2009 May;21(2):178-181.

Failla CM et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 15;20(22):5731.

Despite An AI Assist, Imaging Study Shows Disparities in Diagnosing Different Skin Tones

When clinicians in a large-scale study viewed a series of digital images that showed skin diseases across skin tones and were asked to make a diagnosis, the accuracy was 38% among dermatologists and 19% among primary care physicians (PCPs). But when decision support from a deep learning system (DLS) was introduced, diagnostic accuracy increased by 33% among dermatologists and 69% among PCPs, results from a multicenter study showed.

However, the researchers found that across all images, diseases in dark skin (Fitzpatrick skin types 5 and 6) were diagnosed less accurately than diseases in light skin (Fitzpatrick skin types 1-4).

“,” researchers led by Matthew Groh, PhD, of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, wrote in their study, published online in Nature Medicine.

For the study, 389 board-certified dermatologists and 450 PCPs in 39 countries were presented with 364 images to view spanning 46 skin diseases and asked to submit up to four differential diagnoses. Nearly 80% of the images were of 8 diseases: atopic dermatitis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), dermatomyositis, lichen planus, Lyme disease, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and secondary syphilis.

Dermatologists and PCPs achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 38% and 19%, respectively, but both groups of clinicians were 4 percentage points less accurate for diagnosis of images of dark skin as compared with light skin. With assistance from DLS decision support, diagnostic accuracy increased by 33% among dermatologists and 69% among primary care physicians. Among dermatologists, DLS support generally increased diagnostic accuracy evenly across skin tones. However, among PCPs, DLS support increased their diagnostic accuracy more in light skin tones than in dark ones.

In the survey component of the study, when the participants were asked, “Do you feel you received sufficient training for diagnosing skin diseases in patients with skin of color (non-white patients)?” 67% of all PCPs and 33% of all dermatologists responded no. “Furthermore, we have found differences in how often BCDs [board-certified dermatologists] and PCPs refer patients with light and dark skin for biopsy,” the authors wrote. “Specifically, for CTCL (a life-threatening disease), we found that both BCDs and PCPs report that they would refer patients for biopsy significantly more often in light skin than dark skin. Moreover, for the common skin diseases atopic dermatitis and pityriasis rosea, we found that BCDs report they would refer patients for biopsy more often in dark skin than light skin, which creates an unnecessary overburden on patients with dark skin.”

In a press release about the study, Dr. Groh emphasized that he and other scientists who investigate human-computer interaction “have to find a way to incorporate underrepresented demographics in our research. That way we will be ready to accurately implement these models in the real world and build AI systems that serve as tools that are designed to avoid the kind of systematic errors we know humans and machines are prone to. Then you can update curricula, you can change norms in different fields and hopefully everyone gets better.”

Ronald Moy, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Beverly Hills, Calif., who was asked to comment on the work, said that the study contributes insights into physician-AI interaction and highlights the need for further training on diagnosing skin diseases in people with darker skin tones. “The strengths of this study include its large sample size of dermatologists and primary care physicians, use of quality-controlled images across skin tones, and thorough evaluation of diagnostic accuracy with and without AI assistance,” said Dr. Moy, who is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and the American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery.

“The study is limited to diagnosis and skin tone estimation based purely on a single image, which does not fully represent a clinical evaluation,” he added. However, “it does provide important benchmark data on diagnostic accuracy disparities across skin tones, but also demonstrates that while AI assistance can improve overall diagnostic accuracy, it may exacerbate disparities for non-specialists.”

Funding for the study was provided by MIT Media Lab consortium members and the Harold Horowitz Student Research Fund. One of the study authors, P. Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, disclosed that he has received grants, advisory fees, and/or stock from several biotechnology companies outside the scope of this work and that he is a co-inventor on several patents through Duke University. The remaining authors reported having no disclosures. Dr. Moy reported having no disclosures.

When clinicians in a large-scale study viewed a series of digital images that showed skin diseases across skin tones and were asked to make a diagnosis, the accuracy was 38% among dermatologists and 19% among primary care physicians (PCPs). But when decision support from a deep learning system (DLS) was introduced, diagnostic accuracy increased by 33% among dermatologists and 69% among PCPs, results from a multicenter study showed.

However, the researchers found that across all images, diseases in dark skin (Fitzpatrick skin types 5 and 6) were diagnosed less accurately than diseases in light skin (Fitzpatrick skin types 1-4).

“,” researchers led by Matthew Groh, PhD, of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, wrote in their study, published online in Nature Medicine.

For the study, 389 board-certified dermatologists and 450 PCPs in 39 countries were presented with 364 images to view spanning 46 skin diseases and asked to submit up to four differential diagnoses. Nearly 80% of the images were of 8 diseases: atopic dermatitis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), dermatomyositis, lichen planus, Lyme disease, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and secondary syphilis.

Dermatologists and PCPs achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 38% and 19%, respectively, but both groups of clinicians were 4 percentage points less accurate for diagnosis of images of dark skin as compared with light skin. With assistance from DLS decision support, diagnostic accuracy increased by 33% among dermatologists and 69% among primary care physicians. Among dermatologists, DLS support generally increased diagnostic accuracy evenly across skin tones. However, among PCPs, DLS support increased their diagnostic accuracy more in light skin tones than in dark ones.

In the survey component of the study, when the participants were asked, “Do you feel you received sufficient training for diagnosing skin diseases in patients with skin of color (non-white patients)?” 67% of all PCPs and 33% of all dermatologists responded no. “Furthermore, we have found differences in how often BCDs [board-certified dermatologists] and PCPs refer patients with light and dark skin for biopsy,” the authors wrote. “Specifically, for CTCL (a life-threatening disease), we found that both BCDs and PCPs report that they would refer patients for biopsy significantly more often in light skin than dark skin. Moreover, for the common skin diseases atopic dermatitis and pityriasis rosea, we found that BCDs report they would refer patients for biopsy more often in dark skin than light skin, which creates an unnecessary overburden on patients with dark skin.”

In a press release about the study, Dr. Groh emphasized that he and other scientists who investigate human-computer interaction “have to find a way to incorporate underrepresented demographics in our research. That way we will be ready to accurately implement these models in the real world and build AI systems that serve as tools that are designed to avoid the kind of systematic errors we know humans and machines are prone to. Then you can update curricula, you can change norms in different fields and hopefully everyone gets better.”

Ronald Moy, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Beverly Hills, Calif., who was asked to comment on the work, said that the study contributes insights into physician-AI interaction and highlights the need for further training on diagnosing skin diseases in people with darker skin tones. “The strengths of this study include its large sample size of dermatologists and primary care physicians, use of quality-controlled images across skin tones, and thorough evaluation of diagnostic accuracy with and without AI assistance,” said Dr. Moy, who is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and the American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery.

“The study is limited to diagnosis and skin tone estimation based purely on a single image, which does not fully represent a clinical evaluation,” he added. However, “it does provide important benchmark data on diagnostic accuracy disparities across skin tones, but also demonstrates that while AI assistance can improve overall diagnostic accuracy, it may exacerbate disparities for non-specialists.”

Funding for the study was provided by MIT Media Lab consortium members and the Harold Horowitz Student Research Fund. One of the study authors, P. Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, disclosed that he has received grants, advisory fees, and/or stock from several biotechnology companies outside the scope of this work and that he is a co-inventor on several patents through Duke University. The remaining authors reported having no disclosures. Dr. Moy reported having no disclosures.

When clinicians in a large-scale study viewed a series of digital images that showed skin diseases across skin tones and were asked to make a diagnosis, the accuracy was 38% among dermatologists and 19% among primary care physicians (PCPs). But when decision support from a deep learning system (DLS) was introduced, diagnostic accuracy increased by 33% among dermatologists and 69% among PCPs, results from a multicenter study showed.

However, the researchers found that across all images, diseases in dark skin (Fitzpatrick skin types 5 and 6) were diagnosed less accurately than diseases in light skin (Fitzpatrick skin types 1-4).

“,” researchers led by Matthew Groh, PhD, of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, wrote in their study, published online in Nature Medicine.

For the study, 389 board-certified dermatologists and 450 PCPs in 39 countries were presented with 364 images to view spanning 46 skin diseases and asked to submit up to four differential diagnoses. Nearly 80% of the images were of 8 diseases: atopic dermatitis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), dermatomyositis, lichen planus, Lyme disease, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and secondary syphilis.

Dermatologists and PCPs achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 38% and 19%, respectively, but both groups of clinicians were 4 percentage points less accurate for diagnosis of images of dark skin as compared with light skin. With assistance from DLS decision support, diagnostic accuracy increased by 33% among dermatologists and 69% among primary care physicians. Among dermatologists, DLS support generally increased diagnostic accuracy evenly across skin tones. However, among PCPs, DLS support increased their diagnostic accuracy more in light skin tones than in dark ones.

In the survey component of the study, when the participants were asked, “Do you feel you received sufficient training for diagnosing skin diseases in patients with skin of color (non-white patients)?” 67% of all PCPs and 33% of all dermatologists responded no. “Furthermore, we have found differences in how often BCDs [board-certified dermatologists] and PCPs refer patients with light and dark skin for biopsy,” the authors wrote. “Specifically, for CTCL (a life-threatening disease), we found that both BCDs and PCPs report that they would refer patients for biopsy significantly more often in light skin than dark skin. Moreover, for the common skin diseases atopic dermatitis and pityriasis rosea, we found that BCDs report they would refer patients for biopsy more often in dark skin than light skin, which creates an unnecessary overburden on patients with dark skin.”

In a press release about the study, Dr. Groh emphasized that he and other scientists who investigate human-computer interaction “have to find a way to incorporate underrepresented demographics in our research. That way we will be ready to accurately implement these models in the real world and build AI systems that serve as tools that are designed to avoid the kind of systematic errors we know humans and machines are prone to. Then you can update curricula, you can change norms in different fields and hopefully everyone gets better.”

Ronald Moy, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Beverly Hills, Calif., who was asked to comment on the work, said that the study contributes insights into physician-AI interaction and highlights the need for further training on diagnosing skin diseases in people with darker skin tones. “The strengths of this study include its large sample size of dermatologists and primary care physicians, use of quality-controlled images across skin tones, and thorough evaluation of diagnostic accuracy with and without AI assistance,” said Dr. Moy, who is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and the American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery.

“The study is limited to diagnosis and skin tone estimation based purely on a single image, which does not fully represent a clinical evaluation,” he added. However, “it does provide important benchmark data on diagnostic accuracy disparities across skin tones, but also demonstrates that while AI assistance can improve overall diagnostic accuracy, it may exacerbate disparities for non-specialists.”

Funding for the study was provided by MIT Media Lab consortium members and the Harold Horowitz Student Research Fund. One of the study authors, P. Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, disclosed that he has received grants, advisory fees, and/or stock from several biotechnology companies outside the scope of this work and that he is a co-inventor on several patents through Duke University. The remaining authors reported having no disclosures. Dr. Moy reported having no disclosures.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

While Rare, Periocular Melanoma May Be Slightly Increasing

SAN DIEGO — Every year, about 4000 patients in the United States are diagnosed with periocular melanoma, according to Geva Mannor, MD, MPH.

“Though rare, the incidence is thought to be slightly increasing, while the onset tends to occur in patients over age 40 years,” Dr. Mannor, an oculofacial plastic surgeon in the division of ophthalmology at Scripps Clinic, San Diego, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “It may be more common in males and welding is a risk factor. Pain and vision loss are late symptoms, and there are amelanotic variants. Gene expression profiling and other genetic testing can predict metastasis, especially expression of BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1).”

. Extrapolating from the best available data, Dr. Mannor said that the annual incidence of choroidal melanoma in the United States is less than 2500, the annual incidence of eyelid melanoma is less than 750, and the annual incidence of conjunctival melanoma is less than 250 — much lower than for cutaneous melanomas. Put another way, the ratio between cutaneous and choroid melanoma is 80:1, the ratio between cutaneous and eyelid melanoma is 266:1, and the ratio between cutaneous and conjunctival melanoma is 800:1.

According to an article published in 2021 on the topic, risk factors for periocular melanoma include light eye color (blue/gray; relative risk, 1.75), fair skin (RR, 1.80), and inability to tan (RR, 1.64), but not blonde hair. A review of 210 patients with melanoma of the eyelid from 11 studies showed that 57% were located on the lower lid, 13% were on the upper lid (“I think because the brow protects sun exposure to the upper lid,” Dr. Mannor said), 12% were on the brow, 10% were on the lateral canthus, and 2% were on the medial canthus. In addition, 35% of the eyelid melanomas were superficial spreading cases, 31% were lentigo maligna, and 19% were nodular. The mean Breslow depth was 1.36 mm and the mortality rate was 4.9%.

Dr. Mannor said that cheek and brow melanomas can extend to the inside of the eyelid and conjunctiva. “Therefore, you want to examine the inside of upper and lower eyelids,” he said at the meeting, which was hosted by the Scripps Cancer Center. “Margin-control excision of lid melanoma is the standard treatment.”

On a related note, he said that glaucoma eye drops that contain prostaglandin F2alpha induce cutaneous and iris pigmentation with varying rates depending on the specific type of prostaglandin. “There have been case reports of these eye drops causing periocular pigmentation that masquerades as suspicious, melanoma-like skin cancer, often necessitating a skin biopsy,” he said.

Dr. Mannor reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO — Every year, about 4000 patients in the United States are diagnosed with periocular melanoma, according to Geva Mannor, MD, MPH.

“Though rare, the incidence is thought to be slightly increasing, while the onset tends to occur in patients over age 40 years,” Dr. Mannor, an oculofacial plastic surgeon in the division of ophthalmology at Scripps Clinic, San Diego, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “It may be more common in males and welding is a risk factor. Pain and vision loss are late symptoms, and there are amelanotic variants. Gene expression profiling and other genetic testing can predict metastasis, especially expression of BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1).”

. Extrapolating from the best available data, Dr. Mannor said that the annual incidence of choroidal melanoma in the United States is less than 2500, the annual incidence of eyelid melanoma is less than 750, and the annual incidence of conjunctival melanoma is less than 250 — much lower than for cutaneous melanomas. Put another way, the ratio between cutaneous and choroid melanoma is 80:1, the ratio between cutaneous and eyelid melanoma is 266:1, and the ratio between cutaneous and conjunctival melanoma is 800:1.

According to an article published in 2021 on the topic, risk factors for periocular melanoma include light eye color (blue/gray; relative risk, 1.75), fair skin (RR, 1.80), and inability to tan (RR, 1.64), but not blonde hair. A review of 210 patients with melanoma of the eyelid from 11 studies showed that 57% were located on the lower lid, 13% were on the upper lid (“I think because the brow protects sun exposure to the upper lid,” Dr. Mannor said), 12% were on the brow, 10% were on the lateral canthus, and 2% were on the medial canthus. In addition, 35% of the eyelid melanomas were superficial spreading cases, 31% were lentigo maligna, and 19% were nodular. The mean Breslow depth was 1.36 mm and the mortality rate was 4.9%.

Dr. Mannor said that cheek and brow melanomas can extend to the inside of the eyelid and conjunctiva. “Therefore, you want to examine the inside of upper and lower eyelids,” he said at the meeting, which was hosted by the Scripps Cancer Center. “Margin-control excision of lid melanoma is the standard treatment.”

On a related note, he said that glaucoma eye drops that contain prostaglandin F2alpha induce cutaneous and iris pigmentation with varying rates depending on the specific type of prostaglandin. “There have been case reports of these eye drops causing periocular pigmentation that masquerades as suspicious, melanoma-like skin cancer, often necessitating a skin biopsy,” he said.

Dr. Mannor reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO — Every year, about 4000 patients in the United States are diagnosed with periocular melanoma, according to Geva Mannor, MD, MPH.

“Though rare, the incidence is thought to be slightly increasing, while the onset tends to occur in patients over age 40 years,” Dr. Mannor, an oculofacial plastic surgeon in the division of ophthalmology at Scripps Clinic, San Diego, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “It may be more common in males and welding is a risk factor. Pain and vision loss are late symptoms, and there are amelanotic variants. Gene expression profiling and other genetic testing can predict metastasis, especially expression of BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1).”

. Extrapolating from the best available data, Dr. Mannor said that the annual incidence of choroidal melanoma in the United States is less than 2500, the annual incidence of eyelid melanoma is less than 750, and the annual incidence of conjunctival melanoma is less than 250 — much lower than for cutaneous melanomas. Put another way, the ratio between cutaneous and choroid melanoma is 80:1, the ratio between cutaneous and eyelid melanoma is 266:1, and the ratio between cutaneous and conjunctival melanoma is 800:1.

According to an article published in 2021 on the topic, risk factors for periocular melanoma include light eye color (blue/gray; relative risk, 1.75), fair skin (RR, 1.80), and inability to tan (RR, 1.64), but not blonde hair. A review of 210 patients with melanoma of the eyelid from 11 studies showed that 57% were located on the lower lid, 13% were on the upper lid (“I think because the brow protects sun exposure to the upper lid,” Dr. Mannor said), 12% were on the brow, 10% were on the lateral canthus, and 2% were on the medial canthus. In addition, 35% of the eyelid melanomas were superficial spreading cases, 31% were lentigo maligna, and 19% were nodular. The mean Breslow depth was 1.36 mm and the mortality rate was 4.9%.

Dr. Mannor said that cheek and brow melanomas can extend to the inside of the eyelid and conjunctiva. “Therefore, you want to examine the inside of upper and lower eyelids,” he said at the meeting, which was hosted by the Scripps Cancer Center. “Margin-control excision of lid melanoma is the standard treatment.”

On a related note, he said that glaucoma eye drops that contain prostaglandin F2alpha induce cutaneous and iris pigmentation with varying rates depending on the specific type of prostaglandin. “There have been case reports of these eye drops causing periocular pigmentation that masquerades as suspicious, melanoma-like skin cancer, often necessitating a skin biopsy,” he said.

Dr. Mannor reported having no disclosures.

FROM MELANOMA 2024

More Than 100K New Cutaneous Melanoma Diagnoses Expected in 2024

SAN DIEGO — According to data from the

“The incidence of melanoma seems to have continued to go up since the early 1990s,” David E. Kent, MD, a dermatologist at Skin Care Physicians of Georgia, Macon, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “The death rates have been flat and may have slightly decreased.”

In 2024, the ACS estimates that about 100,640 new melanomas will be diagnosed in the United States (59,170 in men and 41,470 in women), and about 8,290 people are expected to die of melanoma (5,430 men and 2,860 women). Meanwhile, the lifetime risk of melanoma is about 3% (1 in 33) for Whites, 0.1% (1 in 1,000) for Blacks, and 0.5% (1 in 200) for Hispanics. In 2019, there were an estimated 1.4 million people in the United States living with cutaneous melanoma, and the overall 5-year survival is 93.7%.

Epidemiologic studies show an increase in melanoma incidence, primarily among White populations. “This is believed to be due to sun exposure, changes in recreational behaviors, and tanning bed exposures,” said Dr. Kent, who holds a faculty position in the department of dermatology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta. Increased surveillance and diagnosis also play a role. In the medical literature, annual increases in melanoma incidence vary from 3%-7% per year, “which means that the rate is doubling every 10-20 years,” he said, noting that annual melanoma costs are approximately $3.3 billion.

While incidence rates are lower in non-White, non-Hispanic populations, poor outcomes are disproportionately higher in persons of color, according to a 2023 paper. Black individuals present at diagnosis with more advanced stage disease and are 1.5 times more likely to die from melanoma, he said, while Hispanics are 2.4 times more likely to present with stage III disease and 3.6 times more likely to have distant metastases. Persons of color also have higher rates of mucosal, acral lentiginous, and subungual melanoma.

Risk Factors

Known genetic risk factors for melanoma include having skin types I and II, particularly those with light hair, light eyes, and freckling, and those with a family history have a twofold increased risk. Also, up to 40% of genetic cases are from inherited mutations in CDKN2A, CDK4, BAP1 and MCR1. Other genetic-related risk factors include the number and size of nevi, having atypical nevus syndrome, DNA repair defects, large congenital nevi, and a personal history of melanoma.

Dr. Kent said that genetic testing for melanoma is warranted for individuals who meet criteria for the “rule of 3s.” He defined this as three primary melanomas in an individual, or three cases of melanoma in first- or second-degree relatives, or two cases of melanoma and one pancreatic cancer or astrocytoma in first or second-degree relatives, or one case of melanoma and two of pancreatic cancer/astrocytoma in first- or second-degree relatives.

The main environmental risk factor for melanoma is exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Individuals can track their UV exposure with a variety of wearable devices and apps, including SunSense One Digital UV Tracker, the SunSense App, the UV Index Widget, the SunSmart Global UV App, the SunKnown UV light photometer, and the EPA’s UV Index Mobile App. Other environment-related risk factors include having a high socioeconomic status (SES), being immunosuppressed, as well as exposure to heavy metals, insecticides, or hormones; and ones distance from the equator.