User login

For MD-IQ use only

What Effect Can a ‘Caring Message’ Intervention Have?

What Effect Can a ‘Caring Message’ Intervention Have?

Caring messages to veterans at risk for suicide come in many forms: cards, letters, phone calls, email, and text messages. Each message can have a major impact on the veteran’s mental health and their decision to use health care provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). A recent study outlined ways to centralize that impact, ensuring the caring message reaches those who need it most.

The study examined the impact of the VA Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) caring letters intervention among veterans at increased psychiatric risk. It focused on veterans with ≥ 2 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health service encounters within 24 months prior to VCL contact. The primary outcome was suicide-related events (SRE), including suicide attempts, intentional self-harm, and suicidal self-directed violence. Secondary outcomes included VHA health care use (all-cause inpatient and outpatient, mental health outpatient, mental health inpatient, and emergency department).

Of 186,514 VCL callers, 8.3% had a psychiatric hospitalization, 4.8% were flagged as high-risk by the REACH VET program, 6.2% had an SRE, and 12.9% met any of these criteria in the year prior to initial VCL contact. There was no association between caring letters and all-cause mortality or SRE, even though caring letters is one of the only interventions to demonstrate a reduction in suicide mortality as a randomized controlled trial.

While reducing suicide has not been the expected result, caring letters have consistently been associated with increased use of outpatient mental health services. The analysis found that veterans with and without indicators of elevated psychiatric risk were using services more. That, the researchers suggest, is more evidence that caring letters might prompt engagement with VHA care, even among veterans not identified as high risk.

Psychiatrist Jerome A. Motto, MD believed long-term supportive but nondemanding contact could reduce a suicidal person’s sense of isolation and enhance feelings of connectedness. His 1976 intervention established a plan to “exert a suicide prevention influence on high-risk persons who decline to enter the health care system.” In Motto’s 5-year follow-up study of 3,006 psychiatric inpatients, half of those who were not following their postdischarge treatment plan received calls or letters expressing interest in their well-being. Suicidal deaths were found to “diverge progressively,” leading Motto to claim the study showed “tentative evidence” that a high-risk population for suicide can be identified and that risk might be reduced through a systematic approach.

Despite those findings, the results of studies on repeated follow-up contact have been mixed. One review outlined how 5 studies showed a statistically significant reduction in suicidal behavior, 4 showed mixed results with trends toward a preventive effect, and 2 studies did not show a preventive effect.

In 2020, the VA launched an intervention for veterans who contacted the VCL. In the first 12 months, CLs were sent to > 100,000 veterans. In feedback interviews, participants described feeling appreciated, cared for, encouraged, and connected. They also said that the CLs helped them engage with community resources and made them more likely to seek VA care. Even veterans who were skeptical of the utility of the caring letters sometimes admitted keeping them.

Finding effective ways to prevent suicide among veterans has been a top priority for the VA. In 2021, then-US Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued a Call to Action that recommended using caring letters when gaps in care may exist, including following crisis line calls.

Caring messages to veterans at risk for suicide come in many forms: cards, letters, phone calls, email, and text messages. Each message can have a major impact on the veteran’s mental health and their decision to use health care provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). A recent study outlined ways to centralize that impact, ensuring the caring message reaches those who need it most.

The study examined the impact of the VA Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) caring letters intervention among veterans at increased psychiatric risk. It focused on veterans with ≥ 2 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health service encounters within 24 months prior to VCL contact. The primary outcome was suicide-related events (SRE), including suicide attempts, intentional self-harm, and suicidal self-directed violence. Secondary outcomes included VHA health care use (all-cause inpatient and outpatient, mental health outpatient, mental health inpatient, and emergency department).

Of 186,514 VCL callers, 8.3% had a psychiatric hospitalization, 4.8% were flagged as high-risk by the REACH VET program, 6.2% had an SRE, and 12.9% met any of these criteria in the year prior to initial VCL contact. There was no association between caring letters and all-cause mortality or SRE, even though caring letters is one of the only interventions to demonstrate a reduction in suicide mortality as a randomized controlled trial.

While reducing suicide has not been the expected result, caring letters have consistently been associated with increased use of outpatient mental health services. The analysis found that veterans with and without indicators of elevated psychiatric risk were using services more. That, the researchers suggest, is more evidence that caring letters might prompt engagement with VHA care, even among veterans not identified as high risk.

Psychiatrist Jerome A. Motto, MD believed long-term supportive but nondemanding contact could reduce a suicidal person’s sense of isolation and enhance feelings of connectedness. His 1976 intervention established a plan to “exert a suicide prevention influence on high-risk persons who decline to enter the health care system.” In Motto’s 5-year follow-up study of 3,006 psychiatric inpatients, half of those who were not following their postdischarge treatment plan received calls or letters expressing interest in their well-being. Suicidal deaths were found to “diverge progressively,” leading Motto to claim the study showed “tentative evidence” that a high-risk population for suicide can be identified and that risk might be reduced through a systematic approach.

Despite those findings, the results of studies on repeated follow-up contact have been mixed. One review outlined how 5 studies showed a statistically significant reduction in suicidal behavior, 4 showed mixed results with trends toward a preventive effect, and 2 studies did not show a preventive effect.

In 2020, the VA launched an intervention for veterans who contacted the VCL. In the first 12 months, CLs were sent to > 100,000 veterans. In feedback interviews, participants described feeling appreciated, cared for, encouraged, and connected. They also said that the CLs helped them engage with community resources and made them more likely to seek VA care. Even veterans who were skeptical of the utility of the caring letters sometimes admitted keeping them.

Finding effective ways to prevent suicide among veterans has been a top priority for the VA. In 2021, then-US Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued a Call to Action that recommended using caring letters when gaps in care may exist, including following crisis line calls.

Caring messages to veterans at risk for suicide come in many forms: cards, letters, phone calls, email, and text messages. Each message can have a major impact on the veteran’s mental health and their decision to use health care provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). A recent study outlined ways to centralize that impact, ensuring the caring message reaches those who need it most.

The study examined the impact of the VA Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) caring letters intervention among veterans at increased psychiatric risk. It focused on veterans with ≥ 2 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health service encounters within 24 months prior to VCL contact. The primary outcome was suicide-related events (SRE), including suicide attempts, intentional self-harm, and suicidal self-directed violence. Secondary outcomes included VHA health care use (all-cause inpatient and outpatient, mental health outpatient, mental health inpatient, and emergency department).

Of 186,514 VCL callers, 8.3% had a psychiatric hospitalization, 4.8% were flagged as high-risk by the REACH VET program, 6.2% had an SRE, and 12.9% met any of these criteria in the year prior to initial VCL contact. There was no association between caring letters and all-cause mortality or SRE, even though caring letters is one of the only interventions to demonstrate a reduction in suicide mortality as a randomized controlled trial.

While reducing suicide has not been the expected result, caring letters have consistently been associated with increased use of outpatient mental health services. The analysis found that veterans with and without indicators of elevated psychiatric risk were using services more. That, the researchers suggest, is more evidence that caring letters might prompt engagement with VHA care, even among veterans not identified as high risk.

Psychiatrist Jerome A. Motto, MD believed long-term supportive but nondemanding contact could reduce a suicidal person’s sense of isolation and enhance feelings of connectedness. His 1976 intervention established a plan to “exert a suicide prevention influence on high-risk persons who decline to enter the health care system.” In Motto’s 5-year follow-up study of 3,006 psychiatric inpatients, half of those who were not following their postdischarge treatment plan received calls or letters expressing interest in their well-being. Suicidal deaths were found to “diverge progressively,” leading Motto to claim the study showed “tentative evidence” that a high-risk population for suicide can be identified and that risk might be reduced through a systematic approach.

Despite those findings, the results of studies on repeated follow-up contact have been mixed. One review outlined how 5 studies showed a statistically significant reduction in suicidal behavior, 4 showed mixed results with trends toward a preventive effect, and 2 studies did not show a preventive effect.

In 2020, the VA launched an intervention for veterans who contacted the VCL. In the first 12 months, CLs were sent to > 100,000 veterans. In feedback interviews, participants described feeling appreciated, cared for, encouraged, and connected. They also said that the CLs helped them engage with community resources and made them more likely to seek VA care. Even veterans who were skeptical of the utility of the caring letters sometimes admitted keeping them.

Finding effective ways to prevent suicide among veterans has been a top priority for the VA. In 2021, then-US Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued a Call to Action that recommended using caring letters when gaps in care may exist, including following crisis line calls.

What Effect Can a ‘Caring Message’ Intervention Have?

What Effect Can a ‘Caring Message’ Intervention Have?

Military Service May Increase Risk for Early Menopause

Military Service May Increase Risk for Early Menopause

Traumatic and environmental exposures during military service may put women veterans at risk for early menopause, a recent longitudinal analysis of data from 668 women in the Gulf War Era Cohort Study found.

The study examined associations between possible early menopause (aged < 45 years) and participants’ Gulf War deployment, military environmental exposures (MEEs), Gulf War Illness, military sexual trauma (MST) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Of 384 Gulf War–deployed veterans, 63% reported MEEs and 26% reported MST during deployment. More than half (57%) of study participants (both Gulf War veterans and nondeployed veterans) met criteria for Gulf War Illness, and 23% met criteria for probable PTSD.

At follow-up, 15% of the women had possible early menopause—higher than population estimates for early menopause in the US, which range from 5% to 10%.

Gulf War deployment, Gulf War–related environmental exposures, and MST during deployment were not significantly associated with early menopause. However, both Gulf War Illness (odds ratio [OR], 1.83; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.95) and probable PTSD (OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.54 to 3.90) were strongly associated with early menopause. Women with probable PTSD at baseline had more than double the odds of possible early menopause.

Previous research suggests that deployment, MEEs, and Gulf War Illness are broadly associated with adverse reproductive health conditions in women veterans. Exposure to persistent organic pollutants and combustion byproducts (eg, from industrial processes and burn pits) have been linked to ovarian dysfunction and oocyte destruction presumed to contribute to accelerated ovarian aging.

The average age for menopause in the US is 52 years. About 5% of women go through early menopause naturally. Early and premature (< 40 years) menopause may also result from a medical or surgical cause, such as a hysterectomy. Regardless the cause, early menopause can have a profound impact on a woman’s physical, emotional, and mental health. It is associated with premature mortality, poor bone health, sexual dysfunction, a 50% increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and 2-fold increased odds of depression.

“Sometimes we talk about menopause symptoms thinking that they're just sort of 1 brief point in time, but we're also talking about things that may affect women's health and functioning for a third or half of a lifespan,” Carolyn Gibson, PhD, MPH, said at the 2024 Spotlight on Women's Health Cyberseminar Series.

Gibson, a staff psychologist at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs (VA) Women’s Mental Health Program and lead author on the recent early-menopause study, pointed to some of the chronic physical health issues that might develop, such as cardiovascular disease, but also the psychological effects.

“It's just important,” she said during the Cyberseminar Series. “To think about the number of things that women in midlife tend to be juggling and managing, all of which may turn up the volume on symptom experience, effect of vulnerability to health and mental health challenges during this period.”

The findings of the study have clinical implications. Midlife women veterans (aged 45 to 64 years) are the largest group of women veterans enrolled in VA health care. Early menopause brings additional age-related care considerations. The authors advise prioritizing support for routine screening for menopause status and symptoms as well as gender-sensitive training, resources, and staffing to provide comprehensive, trauma-informed, evidence-based menopause care for women at any age.

Traumatic and environmental exposures during military service may put women veterans at risk for early menopause, a recent longitudinal analysis of data from 668 women in the Gulf War Era Cohort Study found.

The study examined associations between possible early menopause (aged < 45 years) and participants’ Gulf War deployment, military environmental exposures (MEEs), Gulf War Illness, military sexual trauma (MST) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Of 384 Gulf War–deployed veterans, 63% reported MEEs and 26% reported MST during deployment. More than half (57%) of study participants (both Gulf War veterans and nondeployed veterans) met criteria for Gulf War Illness, and 23% met criteria for probable PTSD.

At follow-up, 15% of the women had possible early menopause—higher than population estimates for early menopause in the US, which range from 5% to 10%.

Gulf War deployment, Gulf War–related environmental exposures, and MST during deployment were not significantly associated with early menopause. However, both Gulf War Illness (odds ratio [OR], 1.83; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.95) and probable PTSD (OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.54 to 3.90) were strongly associated with early menopause. Women with probable PTSD at baseline had more than double the odds of possible early menopause.

Previous research suggests that deployment, MEEs, and Gulf War Illness are broadly associated with adverse reproductive health conditions in women veterans. Exposure to persistent organic pollutants and combustion byproducts (eg, from industrial processes and burn pits) have been linked to ovarian dysfunction and oocyte destruction presumed to contribute to accelerated ovarian aging.

The average age for menopause in the US is 52 years. About 5% of women go through early menopause naturally. Early and premature (< 40 years) menopause may also result from a medical or surgical cause, such as a hysterectomy. Regardless the cause, early menopause can have a profound impact on a woman’s physical, emotional, and mental health. It is associated with premature mortality, poor bone health, sexual dysfunction, a 50% increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and 2-fold increased odds of depression.

“Sometimes we talk about menopause symptoms thinking that they're just sort of 1 brief point in time, but we're also talking about things that may affect women's health and functioning for a third or half of a lifespan,” Carolyn Gibson, PhD, MPH, said at the 2024 Spotlight on Women's Health Cyberseminar Series.

Gibson, a staff psychologist at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs (VA) Women’s Mental Health Program and lead author on the recent early-menopause study, pointed to some of the chronic physical health issues that might develop, such as cardiovascular disease, but also the psychological effects.

“It's just important,” she said during the Cyberseminar Series. “To think about the number of things that women in midlife tend to be juggling and managing, all of which may turn up the volume on symptom experience, effect of vulnerability to health and mental health challenges during this period.”

The findings of the study have clinical implications. Midlife women veterans (aged 45 to 64 years) are the largest group of women veterans enrolled in VA health care. Early menopause brings additional age-related care considerations. The authors advise prioritizing support for routine screening for menopause status and symptoms as well as gender-sensitive training, resources, and staffing to provide comprehensive, trauma-informed, evidence-based menopause care for women at any age.

Traumatic and environmental exposures during military service may put women veterans at risk for early menopause, a recent longitudinal analysis of data from 668 women in the Gulf War Era Cohort Study found.

The study examined associations between possible early menopause (aged < 45 years) and participants’ Gulf War deployment, military environmental exposures (MEEs), Gulf War Illness, military sexual trauma (MST) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Of 384 Gulf War–deployed veterans, 63% reported MEEs and 26% reported MST during deployment. More than half (57%) of study participants (both Gulf War veterans and nondeployed veterans) met criteria for Gulf War Illness, and 23% met criteria for probable PTSD.

At follow-up, 15% of the women had possible early menopause—higher than population estimates for early menopause in the US, which range from 5% to 10%.

Gulf War deployment, Gulf War–related environmental exposures, and MST during deployment were not significantly associated with early menopause. However, both Gulf War Illness (odds ratio [OR], 1.83; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.95) and probable PTSD (OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.54 to 3.90) were strongly associated with early menopause. Women with probable PTSD at baseline had more than double the odds of possible early menopause.

Previous research suggests that deployment, MEEs, and Gulf War Illness are broadly associated with adverse reproductive health conditions in women veterans. Exposure to persistent organic pollutants and combustion byproducts (eg, from industrial processes and burn pits) have been linked to ovarian dysfunction and oocyte destruction presumed to contribute to accelerated ovarian aging.

The average age for menopause in the US is 52 years. About 5% of women go through early menopause naturally. Early and premature (< 40 years) menopause may also result from a medical or surgical cause, such as a hysterectomy. Regardless the cause, early menopause can have a profound impact on a woman’s physical, emotional, and mental health. It is associated with premature mortality, poor bone health, sexual dysfunction, a 50% increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and 2-fold increased odds of depression.

“Sometimes we talk about menopause symptoms thinking that they're just sort of 1 brief point in time, but we're also talking about things that may affect women's health and functioning for a third or half of a lifespan,” Carolyn Gibson, PhD, MPH, said at the 2024 Spotlight on Women's Health Cyberseminar Series.

Gibson, a staff psychologist at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs (VA) Women’s Mental Health Program and lead author on the recent early-menopause study, pointed to some of the chronic physical health issues that might develop, such as cardiovascular disease, but also the psychological effects.

“It's just important,” she said during the Cyberseminar Series. “To think about the number of things that women in midlife tend to be juggling and managing, all of which may turn up the volume on symptom experience, effect of vulnerability to health and mental health challenges during this period.”

The findings of the study have clinical implications. Midlife women veterans (aged 45 to 64 years) are the largest group of women veterans enrolled in VA health care. Early menopause brings additional age-related care considerations. The authors advise prioritizing support for routine screening for menopause status and symptoms as well as gender-sensitive training, resources, and staffing to provide comprehensive, trauma-informed, evidence-based menopause care for women at any age.

Military Service May Increase Risk for Early Menopause

Military Service May Increase Risk for Early Menopause

Stay Alert to Sleep Apnea Burden in the Military

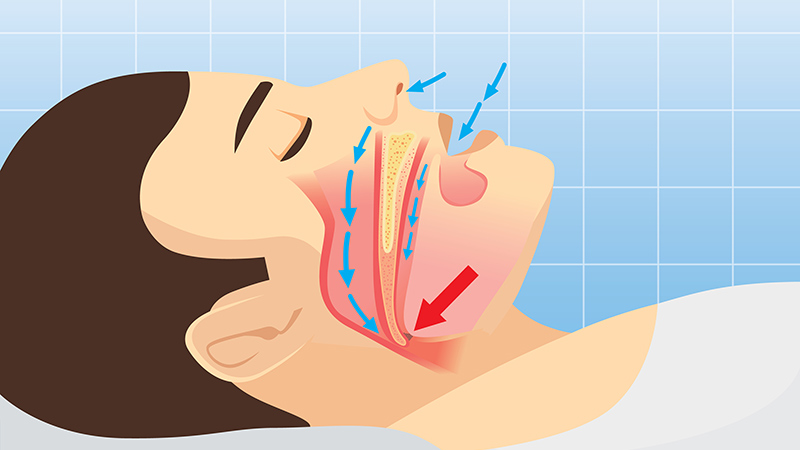

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was associated with a significantly increased risk for adverse health outcomes and health care resource use among military personnel in the US, according to data from about 120,000 active-duty service members.

OSA and other clinical sleep disorders are common among military personnel, driven in part by demanding, nontraditional work schedules that can exacerbate sleep problems, but OSA’s impact in this population has not been well-studied, Emerson M. Wickwire, PhD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and colleagues wrote in a new paper published in Chest.

In the current health economic climate of increasing costs and limited resources, the economic aspects of sleep disorders have never been more important, Wickwire said in an interview. The data in this study are the first to quantify the health and utilization burden of OSA in the US military and can support military decision-makers regarding allocation of scarce resources, he said.

To assess the burden of OSA in the military, they reviewed fully de-identified data from 59,203 active-duty military personnel with diagnoses of OSA and compared them with 59,203 active-duty military personnel without OSA. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 64 years; 7.4% were women and 64.5% were white individuals. Study outcomes included new diagnoses of physical and psychological health conditions, as well as health care resource use in the first year after the index date.

About one third of the participants were in the Army (38.7%), 25.6% were in the Air Force, 23.5% were in the Navy, 5.8% were in the Marines, 5.7% were in the Coast Guard, and 0.7% were in the Public Health Service.

Over the 1-year study period, military personnel with OSA diagnoses were significantly more likely to experience new physical and psychological adverse events than control individuals without OSA, based on proportional hazards models. The physical conditions with the greatest increased risk in the OSA group were traumatic brain injury and cardiovascular disease (which included acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease, and peripheral procedures), with hazard ratios (HRs) 3.27 and 2.32, respectively. The psychological conditions with the greatest increased risk in the OSA group vs control individuals were posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety (HR, 4.41, and HR, 3.35, respectively).

Individuals with OSA also showed increased use of healthcare resources compared with control individuals without OSA, with an additional 170,511 outpatient visits, 66 inpatient visits, and 1,852 emergency department visits.

Don’t Discount OSA in Military Personnel

“From a clinical perspective, these findings underscore the importance of recognizing OSA as a critical risk factor for a wide array of physical and psychological health outcomes,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The results highlight the need for more clinical attention to patient screening, triage, and delivery of care, but efforts are limited by the documented shortage of sleep specialists in the military health system, they noted.

Key limitations of the study include the use of an administrative claims data source, which did not include clinical information such as disease severity or daytime symptoms, and the nonrandomized, observational study design, Wickwire told this news organization.

Looking ahead, the researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, are launching a new trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telehealth visits for military beneficiaries diagnosed with OSA as a way to manage the shortage of sleep specialists in the military health system, according to a press release from the University of Maryland.

“Although the association between poor sleep and traumatic stress is well-known, present results highlight striking associations between sleep apnea and posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and musculoskeletal injuries, which are key outcomes from the military perspective,” Wickwire told this news organization.

“Our most important clinical recommendation is for healthcare providers to be on alert for signs and symptoms of OSA, including snoring, daytime sleepiness, and morning dry mouth,” said Wickwire. “Primary care and mental health providers should be especially attuned,” he added.

Results Not Surprising, but Research Gaps Remain

“The sleep health of active-duty military personnel is not only vital for optimal military performance but also impacts the health of Veterans after separation from the military,” said Q. Afifa Shamim-Uzzaman, MD, an associate professor and a sleep medicine specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, in an interview.

The current study identifies increased utilization of healthcare resources by active-duty personnel with sleep apnea, and outcomes were not surprising, said Shamim-Uzzaman, who is employed by the Veterans’ Health Administration, but was not involved in the current study.

The association between untreated OSA and medical and psychological comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mood disorders such as depression and anxiety is well-known, Shamim-Uzzaman said. “Patients with depression who also have sleep disturbances are at higher risk for suicide — the strength of this association is such that it led the Veterans’ Health Administration to mandate suicide screening for Veterans seen in its sleep clinics,” he added.

“We also know that untreated OSA is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, slowed reaction times, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents, all of which can contribute to sustaining injuries such as traumatic brain injury,” said Shamim-Uzzaman. “Emerging evidence also suggests that sleep disruption prior to exposure to trauma increases the risk of developing PTSD. Therefore, it is not surprising that patients with sleep apnea would have higher healthcare utilization for non-OSA conditions than those without sleep apnea,” he noted.

In clinical practice, the study underscores the importance of identifying and managing sleep health in military personnel, who frequently work nontraditional schedules with long, sustained shifts in grueling conditions not conducive to healthy sleep, Shamim-Uzzaman told this news organization. “Although the harsh work environments that our active-duty military endure come part and parcel with the job, clinicians caring for these individuals should ask specifically about their sleep and working schedules to optimize sleep as best as possible; this should include, but not be limited to, screening and testing for sleep disordered breathing and insomnia,” he said.

The current study has several limitations, including the inability to control for smoking or alcohol use, which are common in military personnel and associated with increased morbidity, said Shamim-Uzzaman. The study also did not assess the impact of other confounding factors, such as sleep duration and daytime sleepiness, that could impact the results, especially the association of OSA and traumatic brain injury, he noted. “More research is needed to assess the impact of these factors as well as the effect of treatment of OSA on comorbidities and healthcare utilization,” he said.

This study was supported by the Military Health Services Research Program.

Wickwire’s institution had received research funding from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation, Department of Defense, Merck, National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging, ResMed, the ResMed Foundation, and the SRS Foundation. Wickwire disclosed serving as a scientific consultant to Axsome Therapeutics, Dayzz, Eisai, EnsoData, Idorsia, Merck, Nox Health, Primasun, Purdue, and ResMed and is an equity shareholder in Well Tap.

Shamim-Uzzaman is an employee of the Veterans’ Health Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was associated with a significantly increased risk for adverse health outcomes and health care resource use among military personnel in the US, according to data from about 120,000 active-duty service members.

OSA and other clinical sleep disorders are common among military personnel, driven in part by demanding, nontraditional work schedules that can exacerbate sleep problems, but OSA’s impact in this population has not been well-studied, Emerson M. Wickwire, PhD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and colleagues wrote in a new paper published in Chest.

In the current health economic climate of increasing costs and limited resources, the economic aspects of sleep disorders have never been more important, Wickwire said in an interview. The data in this study are the first to quantify the health and utilization burden of OSA in the US military and can support military decision-makers regarding allocation of scarce resources, he said.

To assess the burden of OSA in the military, they reviewed fully de-identified data from 59,203 active-duty military personnel with diagnoses of OSA and compared them with 59,203 active-duty military personnel without OSA. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 64 years; 7.4% were women and 64.5% were white individuals. Study outcomes included new diagnoses of physical and psychological health conditions, as well as health care resource use in the first year after the index date.

About one third of the participants were in the Army (38.7%), 25.6% were in the Air Force, 23.5% were in the Navy, 5.8% were in the Marines, 5.7% were in the Coast Guard, and 0.7% were in the Public Health Service.

Over the 1-year study period, military personnel with OSA diagnoses were significantly more likely to experience new physical and psychological adverse events than control individuals without OSA, based on proportional hazards models. The physical conditions with the greatest increased risk in the OSA group were traumatic brain injury and cardiovascular disease (which included acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease, and peripheral procedures), with hazard ratios (HRs) 3.27 and 2.32, respectively. The psychological conditions with the greatest increased risk in the OSA group vs control individuals were posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety (HR, 4.41, and HR, 3.35, respectively).

Individuals with OSA also showed increased use of healthcare resources compared with control individuals without OSA, with an additional 170,511 outpatient visits, 66 inpatient visits, and 1,852 emergency department visits.

Don’t Discount OSA in Military Personnel

“From a clinical perspective, these findings underscore the importance of recognizing OSA as a critical risk factor for a wide array of physical and psychological health outcomes,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The results highlight the need for more clinical attention to patient screening, triage, and delivery of care, but efforts are limited by the documented shortage of sleep specialists in the military health system, they noted.

Key limitations of the study include the use of an administrative claims data source, which did not include clinical information such as disease severity or daytime symptoms, and the nonrandomized, observational study design, Wickwire told this news organization.

Looking ahead, the researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, are launching a new trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telehealth visits for military beneficiaries diagnosed with OSA as a way to manage the shortage of sleep specialists in the military health system, according to a press release from the University of Maryland.

“Although the association between poor sleep and traumatic stress is well-known, present results highlight striking associations between sleep apnea and posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and musculoskeletal injuries, which are key outcomes from the military perspective,” Wickwire told this news organization.

“Our most important clinical recommendation is for healthcare providers to be on alert for signs and symptoms of OSA, including snoring, daytime sleepiness, and morning dry mouth,” said Wickwire. “Primary care and mental health providers should be especially attuned,” he added.

Results Not Surprising, but Research Gaps Remain

“The sleep health of active-duty military personnel is not only vital for optimal military performance but also impacts the health of Veterans after separation from the military,” said Q. Afifa Shamim-Uzzaman, MD, an associate professor and a sleep medicine specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, in an interview.

The current study identifies increased utilization of healthcare resources by active-duty personnel with sleep apnea, and outcomes were not surprising, said Shamim-Uzzaman, who is employed by the Veterans’ Health Administration, but was not involved in the current study.

The association between untreated OSA and medical and psychological comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mood disorders such as depression and anxiety is well-known, Shamim-Uzzaman said. “Patients with depression who also have sleep disturbances are at higher risk for suicide — the strength of this association is such that it led the Veterans’ Health Administration to mandate suicide screening for Veterans seen in its sleep clinics,” he added.

“We also know that untreated OSA is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, slowed reaction times, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents, all of which can contribute to sustaining injuries such as traumatic brain injury,” said Shamim-Uzzaman. “Emerging evidence also suggests that sleep disruption prior to exposure to trauma increases the risk of developing PTSD. Therefore, it is not surprising that patients with sleep apnea would have higher healthcare utilization for non-OSA conditions than those without sleep apnea,” he noted.

In clinical practice, the study underscores the importance of identifying and managing sleep health in military personnel, who frequently work nontraditional schedules with long, sustained shifts in grueling conditions not conducive to healthy sleep, Shamim-Uzzaman told this news organization. “Although the harsh work environments that our active-duty military endure come part and parcel with the job, clinicians caring for these individuals should ask specifically about their sleep and working schedules to optimize sleep as best as possible; this should include, but not be limited to, screening and testing for sleep disordered breathing and insomnia,” he said.

The current study has several limitations, including the inability to control for smoking or alcohol use, which are common in military personnel and associated with increased morbidity, said Shamim-Uzzaman. The study also did not assess the impact of other confounding factors, such as sleep duration and daytime sleepiness, that could impact the results, especially the association of OSA and traumatic brain injury, he noted. “More research is needed to assess the impact of these factors as well as the effect of treatment of OSA on comorbidities and healthcare utilization,” he said.

This study was supported by the Military Health Services Research Program.

Wickwire’s institution had received research funding from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation, Department of Defense, Merck, National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging, ResMed, the ResMed Foundation, and the SRS Foundation. Wickwire disclosed serving as a scientific consultant to Axsome Therapeutics, Dayzz, Eisai, EnsoData, Idorsia, Merck, Nox Health, Primasun, Purdue, and ResMed and is an equity shareholder in Well Tap.

Shamim-Uzzaman is an employee of the Veterans’ Health Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was associated with a significantly increased risk for adverse health outcomes and health care resource use among military personnel in the US, according to data from about 120,000 active-duty service members.

OSA and other clinical sleep disorders are common among military personnel, driven in part by demanding, nontraditional work schedules that can exacerbate sleep problems, but OSA’s impact in this population has not been well-studied, Emerson M. Wickwire, PhD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and colleagues wrote in a new paper published in Chest.

In the current health economic climate of increasing costs and limited resources, the economic aspects of sleep disorders have never been more important, Wickwire said in an interview. The data in this study are the first to quantify the health and utilization burden of OSA in the US military and can support military decision-makers regarding allocation of scarce resources, he said.

To assess the burden of OSA in the military, they reviewed fully de-identified data from 59,203 active-duty military personnel with diagnoses of OSA and compared them with 59,203 active-duty military personnel without OSA. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 64 years; 7.4% were women and 64.5% were white individuals. Study outcomes included new diagnoses of physical and psychological health conditions, as well as health care resource use in the first year after the index date.

About one third of the participants were in the Army (38.7%), 25.6% were in the Air Force, 23.5% were in the Navy, 5.8% were in the Marines, 5.7% were in the Coast Guard, and 0.7% were in the Public Health Service.

Over the 1-year study period, military personnel with OSA diagnoses were significantly more likely to experience new physical and psychological adverse events than control individuals without OSA, based on proportional hazards models. The physical conditions with the greatest increased risk in the OSA group were traumatic brain injury and cardiovascular disease (which included acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease, and peripheral procedures), with hazard ratios (HRs) 3.27 and 2.32, respectively. The psychological conditions with the greatest increased risk in the OSA group vs control individuals were posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety (HR, 4.41, and HR, 3.35, respectively).

Individuals with OSA also showed increased use of healthcare resources compared with control individuals without OSA, with an additional 170,511 outpatient visits, 66 inpatient visits, and 1,852 emergency department visits.

Don’t Discount OSA in Military Personnel

“From a clinical perspective, these findings underscore the importance of recognizing OSA as a critical risk factor for a wide array of physical and psychological health outcomes,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The results highlight the need for more clinical attention to patient screening, triage, and delivery of care, but efforts are limited by the documented shortage of sleep specialists in the military health system, they noted.

Key limitations of the study include the use of an administrative claims data source, which did not include clinical information such as disease severity or daytime symptoms, and the nonrandomized, observational study design, Wickwire told this news organization.

Looking ahead, the researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, are launching a new trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telehealth visits for military beneficiaries diagnosed with OSA as a way to manage the shortage of sleep specialists in the military health system, according to a press release from the University of Maryland.

“Although the association between poor sleep and traumatic stress is well-known, present results highlight striking associations between sleep apnea and posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and musculoskeletal injuries, which are key outcomes from the military perspective,” Wickwire told this news organization.

“Our most important clinical recommendation is for healthcare providers to be on alert for signs and symptoms of OSA, including snoring, daytime sleepiness, and morning dry mouth,” said Wickwire. “Primary care and mental health providers should be especially attuned,” he added.

Results Not Surprising, but Research Gaps Remain

“The sleep health of active-duty military personnel is not only vital for optimal military performance but also impacts the health of Veterans after separation from the military,” said Q. Afifa Shamim-Uzzaman, MD, an associate professor and a sleep medicine specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, in an interview.

The current study identifies increased utilization of healthcare resources by active-duty personnel with sleep apnea, and outcomes were not surprising, said Shamim-Uzzaman, who is employed by the Veterans’ Health Administration, but was not involved in the current study.

The association between untreated OSA and medical and psychological comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mood disorders such as depression and anxiety is well-known, Shamim-Uzzaman said. “Patients with depression who also have sleep disturbances are at higher risk for suicide — the strength of this association is such that it led the Veterans’ Health Administration to mandate suicide screening for Veterans seen in its sleep clinics,” he added.

“We also know that untreated OSA is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, slowed reaction times, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents, all of which can contribute to sustaining injuries such as traumatic brain injury,” said Shamim-Uzzaman. “Emerging evidence also suggests that sleep disruption prior to exposure to trauma increases the risk of developing PTSD. Therefore, it is not surprising that patients with sleep apnea would have higher healthcare utilization for non-OSA conditions than those without sleep apnea,” he noted.

In clinical practice, the study underscores the importance of identifying and managing sleep health in military personnel, who frequently work nontraditional schedules with long, sustained shifts in grueling conditions not conducive to healthy sleep, Shamim-Uzzaman told this news organization. “Although the harsh work environments that our active-duty military endure come part and parcel with the job, clinicians caring for these individuals should ask specifically about their sleep and working schedules to optimize sleep as best as possible; this should include, but not be limited to, screening and testing for sleep disordered breathing and insomnia,” he said.

The current study has several limitations, including the inability to control for smoking or alcohol use, which are common in military personnel and associated with increased morbidity, said Shamim-Uzzaman. The study also did not assess the impact of other confounding factors, such as sleep duration and daytime sleepiness, that could impact the results, especially the association of OSA and traumatic brain injury, he noted. “More research is needed to assess the impact of these factors as well as the effect of treatment of OSA on comorbidities and healthcare utilization,” he said.

This study was supported by the Military Health Services Research Program.

Wickwire’s institution had received research funding from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation, Department of Defense, Merck, National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging, ResMed, the ResMed Foundation, and the SRS Foundation. Wickwire disclosed serving as a scientific consultant to Axsome Therapeutics, Dayzz, Eisai, EnsoData, Idorsia, Merck, Nox Health, Primasun, Purdue, and ResMed and is an equity shareholder in Well Tap.

Shamim-Uzzaman is an employee of the Veterans’ Health Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

PRACTICE POINTS

- Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of acquired hyperpigmentation and should be evaluated after metabolic or endocrine causes are ruled out.

- Belumosudil for chronic graft-vs-host disease can induce rapid-onset diffuse bronzing hyperpigmentation, even in the absence of other systemic or laboratory abnormalities.

- Treatment entails discontinuation of the offending agent and limitation of exacerbating factors such as sun exposure.

The Aftermath of Kennedy vs. Braidwood

In our June issue, I highlighted the potentially seismic clinical implications of the U.S. Supreme Court’s then-pending decision in the Kennedy vs. Braidwood Management, Inc., case. That ruling, recently released at the conclusion of the Court’s term, ultimately affirmed the Affordable Care Act’s mandate requiring insurers to cover certain preventive services, including colorectal cancer screening tests, without cost-sharing.

In doing so, however, the court determined that members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which recommends these services, are “inferior officers” appropriately appointed by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), rather than needing Senate confirmation. Thus, the decision reinforced the HHS Secretary’s authority to oversee and potentially influence USPSTF recommendations in the future. While the decision represented a victory in upholding a key provision of the ACA, it also signaled a potential threat to the scientific independence of the body charged with making those preventive care recommendations in a scientifically rigorous, unbiased manner.

As anticipated, the HHS Secretary responded to the Supreme Court’s ruling by abruptly canceling the USPSTF’s scheduled July meeting. This decision, coupled with his recent disbanding of the entire 17-member Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — the group responsible for shaping evidence-based vaccine policy — has raised serious concerns across the healthcare field. On July 9th, AGA joined a coalition of 104 health organizations in submitting a letter to the Chair and Ranking Members of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, urging them to protect the integrity of the USPSTF.

The fight to protect science-based health policy is far from over — effective advocacy necessitates that clinicians use their professional platforms to push back against the politicization of science – not only for the integrity of the medical profession, but for the health and future of the patients we serve.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

In our June issue, I highlighted the potentially seismic clinical implications of the U.S. Supreme Court’s then-pending decision in the Kennedy vs. Braidwood Management, Inc., case. That ruling, recently released at the conclusion of the Court’s term, ultimately affirmed the Affordable Care Act’s mandate requiring insurers to cover certain preventive services, including colorectal cancer screening tests, without cost-sharing.

In doing so, however, the court determined that members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which recommends these services, are “inferior officers” appropriately appointed by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), rather than needing Senate confirmation. Thus, the decision reinforced the HHS Secretary’s authority to oversee and potentially influence USPSTF recommendations in the future. While the decision represented a victory in upholding a key provision of the ACA, it also signaled a potential threat to the scientific independence of the body charged with making those preventive care recommendations in a scientifically rigorous, unbiased manner.

As anticipated, the HHS Secretary responded to the Supreme Court’s ruling by abruptly canceling the USPSTF’s scheduled July meeting. This decision, coupled with his recent disbanding of the entire 17-member Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — the group responsible for shaping evidence-based vaccine policy — has raised serious concerns across the healthcare field. On July 9th, AGA joined a coalition of 104 health organizations in submitting a letter to the Chair and Ranking Members of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, urging them to protect the integrity of the USPSTF.

The fight to protect science-based health policy is far from over — effective advocacy necessitates that clinicians use their professional platforms to push back against the politicization of science – not only for the integrity of the medical profession, but for the health and future of the patients we serve.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

In our June issue, I highlighted the potentially seismic clinical implications of the U.S. Supreme Court’s then-pending decision in the Kennedy vs. Braidwood Management, Inc., case. That ruling, recently released at the conclusion of the Court’s term, ultimately affirmed the Affordable Care Act’s mandate requiring insurers to cover certain preventive services, including colorectal cancer screening tests, without cost-sharing.

In doing so, however, the court determined that members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which recommends these services, are “inferior officers” appropriately appointed by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), rather than needing Senate confirmation. Thus, the decision reinforced the HHS Secretary’s authority to oversee and potentially influence USPSTF recommendations in the future. While the decision represented a victory in upholding a key provision of the ACA, it also signaled a potential threat to the scientific independence of the body charged with making those preventive care recommendations in a scientifically rigorous, unbiased manner.

As anticipated, the HHS Secretary responded to the Supreme Court’s ruling by abruptly canceling the USPSTF’s scheduled July meeting. This decision, coupled with his recent disbanding of the entire 17-member Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — the group responsible for shaping evidence-based vaccine policy — has raised serious concerns across the healthcare field. On July 9th, AGA joined a coalition of 104 health organizations in submitting a letter to the Chair and Ranking Members of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, urging them to protect the integrity of the USPSTF.

The fight to protect science-based health policy is far from over — effective advocacy necessitates that clinicians use their professional platforms to push back against the politicization of science – not only for the integrity of the medical profession, but for the health and future of the patients we serve.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

At-Home Alzheimer’s Testing Is Here: Are Physicians Ready?

Given the opportunity, 90% of Americans say they would take a blood biomarker test for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) — even in the absence of symptoms. Notably, 80% say they wouldn’t wait for a physician to order a test, they’d request one themselves.

The findings, from a recent nationwide survey by the Alzheimer’s Association, suggest a growing desire to predict the risk for or show evidence of AD and related dementias with a simple blood test. For consumers with the inclination and the money, that desire can now become reality.

Once limited to research settings or only available via a physician’s order, blood-based diagnostics for specific biomarkers — primarily pTau-217 and beta-amyloid 42/20 — are now offered by at least four companies in the US. Several others sell blood-based “dementia” panels without those biomarkers and screens for apolipoprotein (APOE) genes, including APOE4, a variant that confers a higher risk for AD.

The companies promote testing to all comers, not just those with a family history or concerns about cognitive symptoms. Test prices range from hundreds to thousands of dollars, depending on whether they are included in a company membership, often designed to encourage repeat testing. Blood draws are conducted at home or at certified labs. Buyers don’t need a prescription or to consult with a physician after receiving results.

Knowing results of such tests could be empowering and may encourage people to prepare for their illness, Jessica Mozersky, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the Bioethics Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis, told this news organization. A direct-to-consumer (DTC) test also eliminates potential physician-created barriers to testing, she added.

But there are also potential harms.

Based on results, individuals may interpret everyday forgetfulness — like misplacing keys — as a sign that dementia is inevitable. This can lead them to change life plans, rethink the way they spend their time, or begin viewing their future negatively. “It creates unnecessary worry and anxiety,” Mozersky said.

The growing availability of DTC tests — heralded by some experts and discouraged by others — comes as AD and dementia specialists continue to debate whether AD diagnostic and staging criteria should be based only on biomarkers or on criteria that includes both pathology and symptomology.

For many, it raises a fundamental concern: If experts haven’t reached a consensus on blood-based AD biomarker testing, how can consumers be expected to interpret at-home test results?

Growing Demand

In 2024, the number of people living with AD passed 7 million. A recent report from the Alzheimer’s Association estimates that number will nearly double by 2060.

The demand for testing also appears to be rising. Similar to the findings in the Alzheimer’s Association’s survey, a small observational study published last year showed that 90% of patients who received a cerebrospinal fluid AD biomarker test ordered by a physician said the decision to get the test was “easy.” For 82%, getting results was positive because it allowed them to plan ahead and to adopt or continue healthy behaviors such as exercise and cognitive activities.

Until now, blood biomarker tests for AD have primarily been available only through a doctor. The tests measure beta-amyloid 42/20 and pTau-217, both of which are strong biomarkers of AD. Some other blood-based biomarkers under investigation include neurofilament light chain (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

As reported by Medscape Medical News, the FDA approved the first blood-based AD diagnostic test in May. The Lumipulse G pTau 217/Beta-Amyloid 1-42 is for the early detection of amyloid plaques associated with AD in adults aged 55 years or older who show signs and symptoms of the disease. But it is only available by prescription.

Quest Diagnostics tested the DTC market in 2023, promoting a consumer-initiated test for beta-amyloid 42/40 that had previously been available only through physicians. It was not well-received by clinicians and ethicists. The company withdrew it later that year but continues to sell beta-amyloid 42/20 and pTau-217 tests through physicians, as does its competitor Labcorp.

Today, at least a handful of companies in the US market AD biomarkers directly to the public: Apollo Health, BetterBrain, Function Health, Neurogen Biomarking, and True Health Labs. None of the companies have disclosed ties to pharmaceutical or device companies or test developers.

What Can Consumers Get?

Some companies direct customers to a lab for blood sample collection, whereas others send a technician to customers’ homes. The extent of biomarker testing and posttest consultation also vary by company.

Apollo Health customers can order a “BrainScan” for $799, which includes screens for pTau-217, GFAP, and NfL. Buyers get a detailed report that explains each test, the result (in nanograms per liter) and optimal range (ng/L) and potential next steps. A pTau-217 result in the normal range, for instance, would come with a recommendation for repeat testing every 2 years. If someone receives an abnormal result, they are contacted by a health coach who can make a physician referral.

At Function Health, members pay $499 a year to have access to hundreds of tests and a written summary of results by a clinician. All of its “Brain Health” tests, including “Beta-Amyloid 42/40 Ratio,” pTau-217, APOE, MTHFR, DNA, and NfL, are available for an additional undisclosed charge.

BetterBrain has a $399 membership that covers an initial 75-minute consultation with cognitive tests, a “personalized brain health plan,” and a blood test that is a basic panel without AD biomarkers. A $499 membership includes all of that plus an APOE test. A pTau-217 test is available for an additional undisclosed fee.