User login

Understanding Psychosis in a Veteran With a History of Combat and Multiple Sclerosis (FULL)

A patient with significant combat history and previous diagnoses of multiple sclerosis and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder was admitted with acute psychosis inconsistent with expected clinical presentations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated neurodegenerative disease that affects > 700,000 people in the US.1 The hallmarks of MS pathology are axonal or neuronal loss, demyelination, and astrocytic gliosis. Of these, axonal or neuronal loss is the main underlying mechanism of permanent clinical disability.

MS also has been associated with an increased prevalence of psychiatric illnesses, with mood disorders affecting up to 40% to 60% of the population, and psychosis being reported in 2% to 4% of patients.2 The link between MS and mood disorders, including bipolar disorder and depression, was documented as early as 1926,with mood disorders hypothesized to be manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation.3 More recently, inflammation-driven microglia have been hypothesized to impair hippocampal connectivity and activate glucocorticoid-insensitive inflammatory cells that then overstimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4,5

Although the prevalence of psychosis in patients with MS is significantly rarer, averaging between 2% and 4%.6 A Canadian study by Patten and colleagues reviewed data from 2.45 million residents of Alberta and found that those who identified as having MS had a 2% to 3% prevalence of psychosis compared with 0.5% to 1% in the general population.7 The connection between psychosis and MS, similar to that between mood disorders and MS, has been described as a common regional demyelination process. Supporting this, MS manifesting as psychosis has been found to present with distinct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, such as diffuse periventricular lesions.8 Still, no conclusive criteria have been developed to distinguish MS presenting as psychosis from a primary psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia.

In patients with combat history, it is possible that both neurodegenerative and psychotic symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure. When soldiers were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, they may have been exposed to multiple toxicities, including depleted uranium, dust and fumes, and numerous infectious diseases.9 Gulf War illness (GWI) or chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) encompass a cluster of symptoms, such as chronic pain, chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, dermatitis, and seizures, as well as mental health issues such as depression and anxiety experienced following exposure to these combat environments.10,11

In light of this diagnostic uncertainty, the authors detail a case of a patient with significant combat history previously diagnosed with MS and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (USS & OPD) presenting with acute psychosis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old male veteran, with a history of MS, USS & OPD, posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) was admitted to the psychiatric unit after being found by the police lying in the middle of a busy intersection, internally preoccupied. On admission, he reported a week of auditory hallucinations from birds with whom he had been communicating telepathically, and a recurrent visual hallucination of a tall man in white and purple robes. He had discontinued his antipsychotic medication, aripiprazole 10 mg, a few weeks prior for unknown reasons. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance, where he presented with disorganized thinking, tangential thought process, and active auditory and visual hallucinations. The differential diagnoses included USS & OPD, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and ruled out substance-induced psychotic disorder, and psychosis as a manifestation of MS.

The patient had 2 psychotic episodes prior to this presentation. He was hospitalized for his first psychotic break in 2015 at age 32, when he had tailed another car “to come back to reality” and ended up in a motor vehicle accident. During that admission, he reported weeks of thought broadcasting, conspiratorial delusions, and racing thoughts. Two years later, he was admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit for his second episode of severe psychosis. After several trials of different antipsychotic medications, his most recent pharmacologic regimen was aripiprazole 10 mg once daily.

His medical history was complicated by 2 TBIs, in November 2014 and January 2015, with normal computed tomography (CT) scans. He was diagnosed with MS in December 2017, when he presented with intractable emesis, left facial numbness, right upper extremity ataxia, nystagmus, and imbalance. An MRI scan revealed multifocal bilateral hypodensities in his periventricular, subcortical, and brain stem white matter. Multiple areas of hyperintensity were visualized, including in the right periatrial region and left brachium pontis. More than 5 oligoclonal bands on lumbar puncture confirmed the diagnosis.

He was treated with IV methylprednisolone followed by a 2-week prednisone taper. Within 1 week, he returned to the psychiatric unit with worsening symptoms and received a second dose of IV steroids and plasma exchange treatment. In the following months, he completed a course of rituximab infusions and physical therapy for his dysarthria, gait abnormality, and vision impairment.

His social history was notable for multiple first-degree relatives with schizophrenia. He reported a history of sexual and verbal abuse and attempted suicide once at age 13 years by hanging himself with a bathrobe. He left home at age 18 years to serve in the Marine Corps (2001-2006). His service included deployment to Afghanistan, where he received a purple heart. Upon his return, he received BA and MS degrees. He married and had 2 daughters but became estranged from his wife. By his most recent admission, he was unemployed and living with his half-sister.

On the first day of this most recent psychiatric hospitalization, he was restarted on aripiprazole 10 mg daily, and a medicine consult was sought to evaluate the progression of his MS. No new onset neurologic symptoms were noted, but he had possible residual lower extremity hyperreflexia and tandem gait incoordination. The episodes of psychotic and neurologic symptoms appeared independent, given that his psychiatric history preceded the onset of his MS.

The patient reported no visual hallucinations starting day 2, and he no longer endorsed auditory hallucinations by day 3. However, he continued to appear internally preoccupied and was noticed to be pacing around the unit. On day 4 he presented with newly pressured speech and flights of ideas, while his affect remained euthymic and his sleep stayed consistent. In combination with his ongoing pacing, his newfound symptoms were hypothesized to be possibly akathisia, an adverse effect (AE) of aripiprazole. As such, on day 5 his dose was lowered to 5 mg daily. He continued to report no hallucinations and demonstrated progressively increased emotional range. A MRI scan was done on day 6 in case a new lesion could be identified, suggesting a primary MS flare-up; however, the scan identified no enhancing lesions, indicating no ongoing demyelination. After a neurology consult corroborated this conclusion, he was discharged in stable condition on day 7.

As is the case with the majority of patients with MS-induced psychosis, he continued to have relapsing psychiatric disease even after MS treatment had been started. Unfortunately, because this patient had stopped taking his atypical antipsychotic medication several weeks prior to his hospitalization, we cannot clarify whether his psychosis stems from a primary psychiatric vs MS process.

Discussion

Presently, treatment preferences for MS-related psychosis are divided between atypical antipsychotics and glucocorticoids. Some suggest that the treatment remains similar between MS-related psychosis and primary psychotic disorders in that atypical antipsychotics are the standard of care.12 A variety of atypical antipsychotics have been used successfully in case reports, including zipradisone, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole.13,14 First-generation antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs that can precipitate extra-pyramidal AEs are not recommended given their potential additive effect to motor deficits associated with MS.12 Alternatively, several case reports have found that MS-related psychotic symptoms respond to glucocorticoids more effectively, while cautioning that glucocorticoids can precipitate psychosis and depression.15,16 One review article found that 90% of patients who received corticosteroids saw an improvement in their psychotic symptoms.2

Finally, it is possible that our patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure during his time in Afghanistan. In a pilot study of veterans with GWI, Abou-Donia and colleagues found 2-to-9 fold increase in autoantibody reactivity levels of the following neuronal and glial-specific proteins relative to healthy controls: neurofilament triplet proteins, tubulin, microtubule-associated tau proteins, microtubule-associated protein-2, myelin basic protein, myelin-associated glycoprotein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II.17,18 Many of these autoantibodies are longstanding explicit markers for neurodegenerative disorders, given that they target proteins and antigens that support axonal transport and myelination. Still Gulf War veteran status has yet to be explicitly linked to an increased risk of MS,19 making this hypothesis less likely for our patient. Future research should address the clinical and therapeutic implications of different autoantibody levels in combat veterans with psychosis.

Conclusion

For patients with MS, mood disorder and psychotic symptoms should warrant a MRI given the possibility of a psychiatric manifestation of MS relapse. Ultimately, our patient’s presentation was inconsistent with the expected clinical presentations of both a primary psychotic disorder and psychosis as a manifestation of MS. His late age at his first psychotic break is atypical for primary psychotic disease, and the lack of MRI imaging done at his initial psychotic episodes cannot exclude a primary MS diagnosis. Still, his lack of MRI findings at his most recent hospitalization, negative symptomatology, and strong history of schizophrenia make a primary psychotic disorder likely.

Following his future clinical course will be necessary to determine the etiology of his psychotic episodes. Future episodes of psychosis with neurologic symptoms would suggest a primary MS diagnosis and potential benefit of immunosuppressant treatment, whereas repeated psychotic breaks with minimal temporal lobe involvement or demyelination as seen on MRI would be suspicious for separate MS and psychotic disease processes. Further research on treatment regimens for patients experiencing psychosis as a manifestation of MS is still necessary.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Camara-Lemarroy CR, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Berrios-Morales I, Ionete C, Riskind P. The varieties of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:9-14.

3. Cottrel SS, Wilson SA. The affective symptomatology of disseminated sclerosis: a study of 100 cases. J Neurol Psychopathology. 1926;7(25):1-30.

4. Johansson V, Lundholm C, Hillert J, et al. Multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders: comorbidity and sibling risk in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Mult Scler. 2014;20(14):1881-1891.

5. Rossi S, Studer V, Motta C, et al. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338-1347.

6. Gilberthorpe TG, O’Connell KE, Carolan A, et al. The spectrum of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a clinical case series. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2017;13:303.

7. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Psychotic disorders in MS: population-based evidence of an association. Neurology 2005;65(7):1123-1125.

8. Kosmidis MH, Giannakou M, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P. Psychotic features associated with multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010; 22(1):55-66.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Public health: military exposures. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/. Updated April 16, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. DeBeer BB, Davidson D, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. The association between toxic exposures and chronic multisymptom illness in veterans of the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(1):54-60.

11. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

12. Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697-708.

13. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar, M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):743-744.

14. Lo Fermo S, Barone R, Patti F, et al. Outcome of psychiatric symptoms presenting at onset of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Mult Scler. 2010;16(6):742-748.

15. Enderami A, Fouladi R, Hosseini HS. First-episode psychosis as the initial presentation of multiple sclerosis: a case report. Int Medical Case Rep J. 2018;11:73-76.

16. Fragoso YD, Frota ER, Lopes JS, et al. Severe depression, suicide attempts, and ideation during the use of interferon beta by patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):312-316.

17. Abou-Donia MB, Conboy LA, Kokkotou E, et al. Screening for novel central nervous system biomarkers in veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;61:36-46.

18. Abou-Donia MB, Lieberman A, Curtis L. Neural autoantibodies in patients with neurological symptoms and histories of chemical/mold exposures. Toxicol Ind Health. 2018;34(1):44-53.

19. Wallin MT, Kurtzke JF, Culpepper WJ, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Gulf War era veterans. 2. Military deployment and risk of multiple sclerosis in the first Gulf War. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42(4):226-234.

A patient with significant combat history and previous diagnoses of multiple sclerosis and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder was admitted with acute psychosis inconsistent with expected clinical presentations.

A patient with significant combat history and previous diagnoses of multiple sclerosis and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder was admitted with acute psychosis inconsistent with expected clinical presentations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated neurodegenerative disease that affects > 700,000 people in the US.1 The hallmarks of MS pathology are axonal or neuronal loss, demyelination, and astrocytic gliosis. Of these, axonal or neuronal loss is the main underlying mechanism of permanent clinical disability.

MS also has been associated with an increased prevalence of psychiatric illnesses, with mood disorders affecting up to 40% to 60% of the population, and psychosis being reported in 2% to 4% of patients.2 The link between MS and mood disorders, including bipolar disorder and depression, was documented as early as 1926,with mood disorders hypothesized to be manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation.3 More recently, inflammation-driven microglia have been hypothesized to impair hippocampal connectivity and activate glucocorticoid-insensitive inflammatory cells that then overstimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4,5

Although the prevalence of psychosis in patients with MS is significantly rarer, averaging between 2% and 4%.6 A Canadian study by Patten and colleagues reviewed data from 2.45 million residents of Alberta and found that those who identified as having MS had a 2% to 3% prevalence of psychosis compared with 0.5% to 1% in the general population.7 The connection between psychosis and MS, similar to that between mood disorders and MS, has been described as a common regional demyelination process. Supporting this, MS manifesting as psychosis has been found to present with distinct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, such as diffuse periventricular lesions.8 Still, no conclusive criteria have been developed to distinguish MS presenting as psychosis from a primary psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia.

In patients with combat history, it is possible that both neurodegenerative and psychotic symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure. When soldiers were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, they may have been exposed to multiple toxicities, including depleted uranium, dust and fumes, and numerous infectious diseases.9 Gulf War illness (GWI) or chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) encompass a cluster of symptoms, such as chronic pain, chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, dermatitis, and seizures, as well as mental health issues such as depression and anxiety experienced following exposure to these combat environments.10,11

In light of this diagnostic uncertainty, the authors detail a case of a patient with significant combat history previously diagnosed with MS and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (USS & OPD) presenting with acute psychosis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old male veteran, with a history of MS, USS & OPD, posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) was admitted to the psychiatric unit after being found by the police lying in the middle of a busy intersection, internally preoccupied. On admission, he reported a week of auditory hallucinations from birds with whom he had been communicating telepathically, and a recurrent visual hallucination of a tall man in white and purple robes. He had discontinued his antipsychotic medication, aripiprazole 10 mg, a few weeks prior for unknown reasons. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance, where he presented with disorganized thinking, tangential thought process, and active auditory and visual hallucinations. The differential diagnoses included USS & OPD, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and ruled out substance-induced psychotic disorder, and psychosis as a manifestation of MS.

The patient had 2 psychotic episodes prior to this presentation. He was hospitalized for his first psychotic break in 2015 at age 32, when he had tailed another car “to come back to reality” and ended up in a motor vehicle accident. During that admission, he reported weeks of thought broadcasting, conspiratorial delusions, and racing thoughts. Two years later, he was admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit for his second episode of severe psychosis. After several trials of different antipsychotic medications, his most recent pharmacologic regimen was aripiprazole 10 mg once daily.

His medical history was complicated by 2 TBIs, in November 2014 and January 2015, with normal computed tomography (CT) scans. He was diagnosed with MS in December 2017, when he presented with intractable emesis, left facial numbness, right upper extremity ataxia, nystagmus, and imbalance. An MRI scan revealed multifocal bilateral hypodensities in his periventricular, subcortical, and brain stem white matter. Multiple areas of hyperintensity were visualized, including in the right periatrial region and left brachium pontis. More than 5 oligoclonal bands on lumbar puncture confirmed the diagnosis.

He was treated with IV methylprednisolone followed by a 2-week prednisone taper. Within 1 week, he returned to the psychiatric unit with worsening symptoms and received a second dose of IV steroids and plasma exchange treatment. In the following months, he completed a course of rituximab infusions and physical therapy for his dysarthria, gait abnormality, and vision impairment.

His social history was notable for multiple first-degree relatives with schizophrenia. He reported a history of sexual and verbal abuse and attempted suicide once at age 13 years by hanging himself with a bathrobe. He left home at age 18 years to serve in the Marine Corps (2001-2006). His service included deployment to Afghanistan, where he received a purple heart. Upon his return, he received BA and MS degrees. He married and had 2 daughters but became estranged from his wife. By his most recent admission, he was unemployed and living with his half-sister.

On the first day of this most recent psychiatric hospitalization, he was restarted on aripiprazole 10 mg daily, and a medicine consult was sought to evaluate the progression of his MS. No new onset neurologic symptoms were noted, but he had possible residual lower extremity hyperreflexia and tandem gait incoordination. The episodes of psychotic and neurologic symptoms appeared independent, given that his psychiatric history preceded the onset of his MS.

The patient reported no visual hallucinations starting day 2, and he no longer endorsed auditory hallucinations by day 3. However, he continued to appear internally preoccupied and was noticed to be pacing around the unit. On day 4 he presented with newly pressured speech and flights of ideas, while his affect remained euthymic and his sleep stayed consistent. In combination with his ongoing pacing, his newfound symptoms were hypothesized to be possibly akathisia, an adverse effect (AE) of aripiprazole. As such, on day 5 his dose was lowered to 5 mg daily. He continued to report no hallucinations and demonstrated progressively increased emotional range. A MRI scan was done on day 6 in case a new lesion could be identified, suggesting a primary MS flare-up; however, the scan identified no enhancing lesions, indicating no ongoing demyelination. After a neurology consult corroborated this conclusion, he was discharged in stable condition on day 7.

As is the case with the majority of patients with MS-induced psychosis, he continued to have relapsing psychiatric disease even after MS treatment had been started. Unfortunately, because this patient had stopped taking his atypical antipsychotic medication several weeks prior to his hospitalization, we cannot clarify whether his psychosis stems from a primary psychiatric vs MS process.

Discussion

Presently, treatment preferences for MS-related psychosis are divided between atypical antipsychotics and glucocorticoids. Some suggest that the treatment remains similar between MS-related psychosis and primary psychotic disorders in that atypical antipsychotics are the standard of care.12 A variety of atypical antipsychotics have been used successfully in case reports, including zipradisone, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole.13,14 First-generation antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs that can precipitate extra-pyramidal AEs are not recommended given their potential additive effect to motor deficits associated with MS.12 Alternatively, several case reports have found that MS-related psychotic symptoms respond to glucocorticoids more effectively, while cautioning that glucocorticoids can precipitate psychosis and depression.15,16 One review article found that 90% of patients who received corticosteroids saw an improvement in their psychotic symptoms.2

Finally, it is possible that our patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure during his time in Afghanistan. In a pilot study of veterans with GWI, Abou-Donia and colleagues found 2-to-9 fold increase in autoantibody reactivity levels of the following neuronal and glial-specific proteins relative to healthy controls: neurofilament triplet proteins, tubulin, microtubule-associated tau proteins, microtubule-associated protein-2, myelin basic protein, myelin-associated glycoprotein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II.17,18 Many of these autoantibodies are longstanding explicit markers for neurodegenerative disorders, given that they target proteins and antigens that support axonal transport and myelination. Still Gulf War veteran status has yet to be explicitly linked to an increased risk of MS,19 making this hypothesis less likely for our patient. Future research should address the clinical and therapeutic implications of different autoantibody levels in combat veterans with psychosis.

Conclusion

For patients with MS, mood disorder and psychotic symptoms should warrant a MRI given the possibility of a psychiatric manifestation of MS relapse. Ultimately, our patient’s presentation was inconsistent with the expected clinical presentations of both a primary psychotic disorder and psychosis as a manifestation of MS. His late age at his first psychotic break is atypical for primary psychotic disease, and the lack of MRI imaging done at his initial psychotic episodes cannot exclude a primary MS diagnosis. Still, his lack of MRI findings at his most recent hospitalization, negative symptomatology, and strong history of schizophrenia make a primary psychotic disorder likely.

Following his future clinical course will be necessary to determine the etiology of his psychotic episodes. Future episodes of psychosis with neurologic symptoms would suggest a primary MS diagnosis and potential benefit of immunosuppressant treatment, whereas repeated psychotic breaks with minimal temporal lobe involvement or demyelination as seen on MRI would be suspicious for separate MS and psychotic disease processes. Further research on treatment regimens for patients experiencing psychosis as a manifestation of MS is still necessary.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated neurodegenerative disease that affects > 700,000 people in the US.1 The hallmarks of MS pathology are axonal or neuronal loss, demyelination, and astrocytic gliosis. Of these, axonal or neuronal loss is the main underlying mechanism of permanent clinical disability.

MS also has been associated with an increased prevalence of psychiatric illnesses, with mood disorders affecting up to 40% to 60% of the population, and psychosis being reported in 2% to 4% of patients.2 The link between MS and mood disorders, including bipolar disorder and depression, was documented as early as 1926,with mood disorders hypothesized to be manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation.3 More recently, inflammation-driven microglia have been hypothesized to impair hippocampal connectivity and activate glucocorticoid-insensitive inflammatory cells that then overstimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4,5

Although the prevalence of psychosis in patients with MS is significantly rarer, averaging between 2% and 4%.6 A Canadian study by Patten and colleagues reviewed data from 2.45 million residents of Alberta and found that those who identified as having MS had a 2% to 3% prevalence of psychosis compared with 0.5% to 1% in the general population.7 The connection between psychosis and MS, similar to that between mood disorders and MS, has been described as a common regional demyelination process. Supporting this, MS manifesting as psychosis has been found to present with distinct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, such as diffuse periventricular lesions.8 Still, no conclusive criteria have been developed to distinguish MS presenting as psychosis from a primary psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia.

In patients with combat history, it is possible that both neurodegenerative and psychotic symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure. When soldiers were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, they may have been exposed to multiple toxicities, including depleted uranium, dust and fumes, and numerous infectious diseases.9 Gulf War illness (GWI) or chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) encompass a cluster of symptoms, such as chronic pain, chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, dermatitis, and seizures, as well as mental health issues such as depression and anxiety experienced following exposure to these combat environments.10,11

In light of this diagnostic uncertainty, the authors detail a case of a patient with significant combat history previously diagnosed with MS and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (USS & OPD) presenting with acute psychosis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old male veteran, with a history of MS, USS & OPD, posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) was admitted to the psychiatric unit after being found by the police lying in the middle of a busy intersection, internally preoccupied. On admission, he reported a week of auditory hallucinations from birds with whom he had been communicating telepathically, and a recurrent visual hallucination of a tall man in white and purple robes. He had discontinued his antipsychotic medication, aripiprazole 10 mg, a few weeks prior for unknown reasons. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance, where he presented with disorganized thinking, tangential thought process, and active auditory and visual hallucinations. The differential diagnoses included USS & OPD, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and ruled out substance-induced psychotic disorder, and psychosis as a manifestation of MS.

The patient had 2 psychotic episodes prior to this presentation. He was hospitalized for his first psychotic break in 2015 at age 32, when he had tailed another car “to come back to reality” and ended up in a motor vehicle accident. During that admission, he reported weeks of thought broadcasting, conspiratorial delusions, and racing thoughts. Two years later, he was admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit for his second episode of severe psychosis. After several trials of different antipsychotic medications, his most recent pharmacologic regimen was aripiprazole 10 mg once daily.

His medical history was complicated by 2 TBIs, in November 2014 and January 2015, with normal computed tomography (CT) scans. He was diagnosed with MS in December 2017, when he presented with intractable emesis, left facial numbness, right upper extremity ataxia, nystagmus, and imbalance. An MRI scan revealed multifocal bilateral hypodensities in his periventricular, subcortical, and brain stem white matter. Multiple areas of hyperintensity were visualized, including in the right periatrial region and left brachium pontis. More than 5 oligoclonal bands on lumbar puncture confirmed the diagnosis.

He was treated with IV methylprednisolone followed by a 2-week prednisone taper. Within 1 week, he returned to the psychiatric unit with worsening symptoms and received a second dose of IV steroids and plasma exchange treatment. In the following months, he completed a course of rituximab infusions and physical therapy for his dysarthria, gait abnormality, and vision impairment.

His social history was notable for multiple first-degree relatives with schizophrenia. He reported a history of sexual and verbal abuse and attempted suicide once at age 13 years by hanging himself with a bathrobe. He left home at age 18 years to serve in the Marine Corps (2001-2006). His service included deployment to Afghanistan, where he received a purple heart. Upon his return, he received BA and MS degrees. He married and had 2 daughters but became estranged from his wife. By his most recent admission, he was unemployed and living with his half-sister.

On the first day of this most recent psychiatric hospitalization, he was restarted on aripiprazole 10 mg daily, and a medicine consult was sought to evaluate the progression of his MS. No new onset neurologic symptoms were noted, but he had possible residual lower extremity hyperreflexia and tandem gait incoordination. The episodes of psychotic and neurologic symptoms appeared independent, given that his psychiatric history preceded the onset of his MS.

The patient reported no visual hallucinations starting day 2, and he no longer endorsed auditory hallucinations by day 3. However, he continued to appear internally preoccupied and was noticed to be pacing around the unit. On day 4 he presented with newly pressured speech and flights of ideas, while his affect remained euthymic and his sleep stayed consistent. In combination with his ongoing pacing, his newfound symptoms were hypothesized to be possibly akathisia, an adverse effect (AE) of aripiprazole. As such, on day 5 his dose was lowered to 5 mg daily. He continued to report no hallucinations and demonstrated progressively increased emotional range. A MRI scan was done on day 6 in case a new lesion could be identified, suggesting a primary MS flare-up; however, the scan identified no enhancing lesions, indicating no ongoing demyelination. After a neurology consult corroborated this conclusion, he was discharged in stable condition on day 7.

As is the case with the majority of patients with MS-induced psychosis, he continued to have relapsing psychiatric disease even after MS treatment had been started. Unfortunately, because this patient had stopped taking his atypical antipsychotic medication several weeks prior to his hospitalization, we cannot clarify whether his psychosis stems from a primary psychiatric vs MS process.

Discussion

Presently, treatment preferences for MS-related psychosis are divided between atypical antipsychotics and glucocorticoids. Some suggest that the treatment remains similar between MS-related psychosis and primary psychotic disorders in that atypical antipsychotics are the standard of care.12 A variety of atypical antipsychotics have been used successfully in case reports, including zipradisone, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole.13,14 First-generation antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs that can precipitate extra-pyramidal AEs are not recommended given their potential additive effect to motor deficits associated with MS.12 Alternatively, several case reports have found that MS-related psychotic symptoms respond to glucocorticoids more effectively, while cautioning that glucocorticoids can precipitate psychosis and depression.15,16 One review article found that 90% of patients who received corticosteroids saw an improvement in their psychotic symptoms.2

Finally, it is possible that our patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure during his time in Afghanistan. In a pilot study of veterans with GWI, Abou-Donia and colleagues found 2-to-9 fold increase in autoantibody reactivity levels of the following neuronal and glial-specific proteins relative to healthy controls: neurofilament triplet proteins, tubulin, microtubule-associated tau proteins, microtubule-associated protein-2, myelin basic protein, myelin-associated glycoprotein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II.17,18 Many of these autoantibodies are longstanding explicit markers for neurodegenerative disorders, given that they target proteins and antigens that support axonal transport and myelination. Still Gulf War veteran status has yet to be explicitly linked to an increased risk of MS,19 making this hypothesis less likely for our patient. Future research should address the clinical and therapeutic implications of different autoantibody levels in combat veterans with psychosis.

Conclusion

For patients with MS, mood disorder and psychotic symptoms should warrant a MRI given the possibility of a psychiatric manifestation of MS relapse. Ultimately, our patient’s presentation was inconsistent with the expected clinical presentations of both a primary psychotic disorder and psychosis as a manifestation of MS. His late age at his first psychotic break is atypical for primary psychotic disease, and the lack of MRI imaging done at his initial psychotic episodes cannot exclude a primary MS diagnosis. Still, his lack of MRI findings at his most recent hospitalization, negative symptomatology, and strong history of schizophrenia make a primary psychotic disorder likely.

Following his future clinical course will be necessary to determine the etiology of his psychotic episodes. Future episodes of psychosis with neurologic symptoms would suggest a primary MS diagnosis and potential benefit of immunosuppressant treatment, whereas repeated psychotic breaks with minimal temporal lobe involvement or demyelination as seen on MRI would be suspicious for separate MS and psychotic disease processes. Further research on treatment regimens for patients experiencing psychosis as a manifestation of MS is still necessary.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Camara-Lemarroy CR, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Berrios-Morales I, Ionete C, Riskind P. The varieties of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:9-14.

3. Cottrel SS, Wilson SA. The affective symptomatology of disseminated sclerosis: a study of 100 cases. J Neurol Psychopathology. 1926;7(25):1-30.

4. Johansson V, Lundholm C, Hillert J, et al. Multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders: comorbidity and sibling risk in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Mult Scler. 2014;20(14):1881-1891.

5. Rossi S, Studer V, Motta C, et al. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338-1347.

6. Gilberthorpe TG, O’Connell KE, Carolan A, et al. The spectrum of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a clinical case series. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2017;13:303.

7. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Psychotic disorders in MS: population-based evidence of an association. Neurology 2005;65(7):1123-1125.

8. Kosmidis MH, Giannakou M, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P. Psychotic features associated with multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010; 22(1):55-66.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Public health: military exposures. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/. Updated April 16, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. DeBeer BB, Davidson D, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. The association between toxic exposures and chronic multisymptom illness in veterans of the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(1):54-60.

11. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

12. Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697-708.

13. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar, M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):743-744.

14. Lo Fermo S, Barone R, Patti F, et al. Outcome of psychiatric symptoms presenting at onset of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Mult Scler. 2010;16(6):742-748.

15. Enderami A, Fouladi R, Hosseini HS. First-episode psychosis as the initial presentation of multiple sclerosis: a case report. Int Medical Case Rep J. 2018;11:73-76.

16. Fragoso YD, Frota ER, Lopes JS, et al. Severe depression, suicide attempts, and ideation during the use of interferon beta by patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):312-316.

17. Abou-Donia MB, Conboy LA, Kokkotou E, et al. Screening for novel central nervous system biomarkers in veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;61:36-46.

18. Abou-Donia MB, Lieberman A, Curtis L. Neural autoantibodies in patients with neurological symptoms and histories of chemical/mold exposures. Toxicol Ind Health. 2018;34(1):44-53.

19. Wallin MT, Kurtzke JF, Culpepper WJ, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Gulf War era veterans. 2. Military deployment and risk of multiple sclerosis in the first Gulf War. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42(4):226-234.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Camara-Lemarroy CR, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Berrios-Morales I, Ionete C, Riskind P. The varieties of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:9-14.

3. Cottrel SS, Wilson SA. The affective symptomatology of disseminated sclerosis: a study of 100 cases. J Neurol Psychopathology. 1926;7(25):1-30.

4. Johansson V, Lundholm C, Hillert J, et al. Multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders: comorbidity and sibling risk in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Mult Scler. 2014;20(14):1881-1891.

5. Rossi S, Studer V, Motta C, et al. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338-1347.

6. Gilberthorpe TG, O’Connell KE, Carolan A, et al. The spectrum of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a clinical case series. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2017;13:303.

7. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Psychotic disorders in MS: population-based evidence of an association. Neurology 2005;65(7):1123-1125.

8. Kosmidis MH, Giannakou M, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P. Psychotic features associated with multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010; 22(1):55-66.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Public health: military exposures. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/. Updated April 16, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. DeBeer BB, Davidson D, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. The association between toxic exposures and chronic multisymptom illness in veterans of the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(1):54-60.

11. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

12. Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697-708.

13. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar, M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):743-744.

14. Lo Fermo S, Barone R, Patti F, et al. Outcome of psychiatric symptoms presenting at onset of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Mult Scler. 2010;16(6):742-748.

15. Enderami A, Fouladi R, Hosseini HS. First-episode psychosis as the initial presentation of multiple sclerosis: a case report. Int Medical Case Rep J. 2018;11:73-76.

16. Fragoso YD, Frota ER, Lopes JS, et al. Severe depression, suicide attempts, and ideation during the use of interferon beta by patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):312-316.

17. Abou-Donia MB, Conboy LA, Kokkotou E, et al. Screening for novel central nervous system biomarkers in veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;61:36-46.

18. Abou-Donia MB, Lieberman A, Curtis L. Neural autoantibodies in patients with neurological symptoms and histories of chemical/mold exposures. Toxicol Ind Health. 2018;34(1):44-53.

19. Wallin MT, Kurtzke JF, Culpepper WJ, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Gulf War era veterans. 2. Military deployment and risk of multiple sclerosis in the first Gulf War. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42(4):226-234.

Early and Accurate Identification of Parkinson Disease Among US Veterans (FULL)

Parkinson disease (PD) affects about 680,000 in the US, including > 110,000 veterans (Caroline Tanner, MD, PhD, unpublished data).1 In the next 10 years, this number is expected to double, in part because of the aging of the US population.1 Although the classic diagnostic criteria emphasize motor symptoms that include tremor, gait disturbance, and paucity of movement, there is increasing recognition that disease pathology begins decades before the development of motor impairment.2

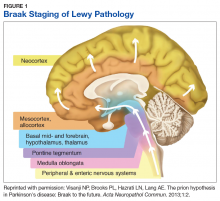

Pathologic studies confirm that by the onset of motor symptoms, at least 30% of nigrostriatal neurons are lost or dysfunctional.3-5 Similarly, the Braak staging hypothesis posits initial deposition of Lewy bodies in the olfactory bulb and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, followed by prion-like spread through the brain stem into the midbrain/substantia nigra, and finally into the cortex (Figure 1).6

The decades-long prodromal or preclinical phase represents a unique opportunity for early identification of those at highest risk for developing the motor symptoms of Parkinson disease.7 Accurate identification, ideally before the onset of manifest motor disability, would not only improve prognostic counseling of veterans and families, but also could allow for early enrollment into trials of potentially disease-modifying therapeutic agents. Thus, early and accurate identification of PD is an important goal of the care of veterans with potential PD.

Prodromal Symptoms

Prodromal PD, as defined by the International Parkinson Disease and Movement Disorders Society (MDS), focuses on nonmotor symptoms that herald the onset of manifest motor PD.8 The most commonly assessed nonmotor features include olfaction, constipation, sleep disturbance, and mood disorders.

Olfaction is impaired in > 90% of patients with motor PD at the time of diagnosis; by contrast, the prevalence of hyposmia in the general population ranges from 20% to 50%, with higher rates in older adults and in smokers.9-11 Thus, olfaction appears to be a relatively sensitive, though nonspecific, prodromal feature. Importantly, subjective report of hyposmia is poorly reliable, so a number of different tests have been developed for objective assessment of olfactory dysfunction.12 The 12-item Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT), derived from the longer University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test, is a “scratch-and-sniff” forced multiple choice test that can be self-administered by cooperative patients.13,14 The B-SIT has been validated in multiple ethnic and cultural groups and shows high discrimination between PD subjects and controls.13,15 Of note, olfactory impairment appears to be associated with risk of cognitive decline in PD, further emphasizing the need for accurate assessment to guide prognosis.16

Like hyposmia, constipation can be noted long before the diagnosis of manifest motor PD.17 After adjustment for lifestyle factors, constipated individuals have up to 4.5-fold increased odds of developing PD, and those with constipation suffer worsened disease outcomes and health-related quality of life.17-20 Some groups have demonstrated alterations in gut microbiota of those with prodromal PD, which suggests local inflammatory processes and intestinal permeability may contribute to protein misfolding and disease development.21,22 This also raises the intriguing possibility that dietary alterations may be neuroprotective or neurorestorative, although this has yet to be tested in humans.23,24

Like constipation, mood changes can precede the appearance of manifest motor PD.25,26 Case control studies suggest a higher risk of developing PD among individuals who were previously diagnosed with depression or anxiety, particularly in the 1 to 2 years prior to PD diagnosis.27-29 Both apathy and anxiety are associated with striatal dopamine dysfunction, particularly in the right caudate nucleus, which suggests that mood changes are directly related to disease pathology.30,31

Of the prodromal features, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is associated with the highest risk of conversion to motor PD.8 Up to 80% of older men with socalled idiopathic RBD develop a parkinsonian syndrome within 20 years; risk is divided about equally between idiopathic PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).32 Collateral history from a bed-partner is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis, although, this is often confounded by the prevalence of nightmares in those with posttraumatic stress disorder in the veteran population.32 Thus, in suspected cases, obtaining a polysomnogram can aid in distinguishing between idiopathic PC and DLB.33 Given the specificity of RBD as a marker of synuclein deposition and the high risk of progression to a degenerative syndrome, accurate diagnosis and counseling is imperative.

Each of the prodromal nonmotor features of PD are at best moderately sensitive or specific in isolation, but in concert, they can be used to develop a Parkinson risk score. For instance, the MDS prodromal criteria combine individual likelihood ratios into Bayesian analysis to determine a combined probability of PD, which can be further stratified to probable or possible prodromal PD (probability > 80%, > 50%, respectively).8 These criteria have been applied to several independent cohorts and demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity, especially over time.34,35 Applicability in a veteran population has yet to be determined.

Use of Imaging in Diagnosis

Although clinical diagnostic criteria and prodromal features can improve diagnostic accuracy, it can be extremely challenging to distinguish idiopathic PD from nondegenerative parkinsonism or atypical syndromes (see below). Compared with the gold standard of pathologic assessment, the clinical diagnostic accuracy for PD ranges from 73% for nonexperts to 80% for fellowship-trained movement disorders specialists.36 Thus, objective biomarkers are sought to improve diagnostic accuracy both for clinical care as well as for research purposes, such as enrollment into clinical trials.

Multiple potential imaging biomarkers for preclinical PD can aid in early diagnosis and help differentiate PD from related but distinct disorders. While beyond the scope of this review, these techniques have recently been reviewed.7 Of these, the most widely available and accurate is dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging, which uses a radioiodinated ligand that binds to DAT on striatal dopaminergic terminals; binding is detected through single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanning. Thus, a SPECT DaTscan (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Little Chalfont, England) directly assesses the integrity of the presynaptic nigrostriatal system and is well correlated with severity of motor and nonmotor parkinsonism.37,38

In individuals with suspected prodromal PD, abnormal DaTscans are associated with faster progression to manifest motor PD.39 However, it should be noted that a number of medications, several of which are commonly utilized in the veteran population, can affect the outcome of a DaTscan.40 Some of these medications only mildly affect the outcome, so the physician interpreting the scan should be made aware of their use, while others need to be held for days to weeks so as not to invalidate the DaTscan. DaTscan also do not differentiate between PD and atypical degenerative parkinsonisms such as multiple system atrophy (MSA), DLB, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), or corticobasal syndrome (CBS). Nevertheless, these scans can be used to distinguish degenerative parkinsonisms from other conditions that can be difficult to distinguish clinically from PD, including essential tremor, normal pressure hydrocephalus, vascular parkinsonism, or druginduced parkinsonism (DIP).

DIP usually is caused by blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors by antipsychotic medications, which are prescribed to as many as 1 in 4 older veterans; antiemetic agents such as metoclopramide are also potential offenders if used chronically.41 The risk of DIP appears to be associated with the D2 binding affinity of the drug. Thus, of the newer atypical antipsychotics, clozapine and quetiapine appear to have the lowest risk, while ziprasidone and aripiprazole have the highest binding affinity and therefore the highest risk.42 In many patients, parkinsonism persists even after discontinuation of the offending agent, suggesting that in at least a subset of patients, DIP may be an “unmasking” of latent PD rather than a true adverse effect of the medication. The prodromal features discussed above can be used to distinguish isolated DIP from unmasked latent PD.43 In a study we conducted in veterans at the Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, hyposmia in particular was shown to be highly predictive of an underlying dopaminergic deficit with an odds ratio of 63.44

Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis of PD are the atypical degenerative parkinsonian syndromes, formerly called Parkinson plus syndromes. These may be further divided into the synucleinopathies (MSA, DLB) or the tauopathies (PSP, CBS), depending on the predominant amyloidogenic protein. Early in the disease, the atypical syndromes and idiopathic PD may be clinically indistinguishable, although the atypical syndromes tend to progress more rapidly and often have a less robust response to levodopa.

Radiologic and fluid biomarkers for the atypical syndromes are under active investigation; at present the most accessible study is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which may show characteristic features such as degeneration of the pontocerebellar fibers in MSA or midbrain atrophy in PSP.45,46 By contrast, standard MRI sequences in idiopathic PD are usually normal, although high-resolution (7 tesla) imaging can reveal loss of neuromelanin in the substantia nigra.47 MRI also can be useful in the workup of suspected normal pressure hydrocephalus or vascular parkinsonism, which would show disproportionate ventriculomegaly with transependymal flow, or white matter lesions in the basal ganglia, respectively.

Data-Based Identification of Preclinical PD

The integration of clinical motor or prodromal features with biomarker data has led to the development of several large-scale clinical and administrative databases to identify PD. The Parkinson Progression Markers Initiative initially enrolled only de novo clinically identified people with PD, but it expanded to include a prodromal cohort who are being assessed for rates of conversion to PD.48 Similarly, metabolic imaging can be combined with prodromal symptoms, such as hyposmia or RBD, to predict risk for phenoconversion into manifest motor PD.49

The PREDICT-PD study synthesizes mood symptoms, RBD, smell testing, genotyping, and keyboard-tapping tasks to divide individuals into high-, middle-, and low-risk groups; interim analysis at 3 years of follow-up (N = 842) demonstrated a hazard ratio of 4.39 (95% CI, 1.03-18.68) for the diagnosis of PD in the highrisk group compared with the low-risk group.50 Lastly, administrative claims data for prodromal features, such as constipation, RBD, and mood symptoms, is highly predictive of eventual PD diagnosis.51 VA databases accessed through the Corporate Data Warehouse are complementary sources of information to nonveteranspecific Medicare databases; to our knowledge there has not yet been a comprehensive search of VA databases to identify veterans with preclinical PD.

Risk Factors Associated With Military Service

A number of potential environmental risk factors may increase the risk of developing Parkinson disease for veterans. Perhaps the most commonly recognized is pesticide exposure, particularly given the presumptive service connections established by the VA for Parkinson disease and exposure to Agent Orange or contaminated water at Camp Lejeune.52,53 Both dioxin, the toxic ingredient in Agent Orange, and the solvents trichloroethylene and perchloroethylene, found in the water supply at Camp Lejeune, interfere with mitochondrial function leading to oxidative stress and apoptosis of nigrostriatal neurons.54,55 Other potential exposures, which are not necessarily limited to the veteran population, include rotenone, a phytochemical used to kill fish in reservoirs, and paraquat, an herbicide that may directly promote synuclein aggregation.56,57 Veterans who have reported exposure to these or other environmental chemicals in civilian life should be carefully assessed for the presence of motor PD or prodromal features.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) also may be a risk factor for PD, which may be particularly relevant for veterans who had served in Iraq or Afghanistan. Retrospective claims data suggest a strong association between PD and recent TBI in the 5 to 10 years prior to motor PD diagnosis.58,59 A recent assessment of combat veterans with TBI found that even mild TBI was associated with a 56% increased risk of PD, while moderate-to-severe TBI was associated with an 83% higher risk of PD.60 The pathologic mechanism for this link is unclear, but post-TBI inflammatory processes may lead to the formation of reactive oxygen species and/or glutamatergic excitotoxicity, thus leading to secondary injury in the nigrostriatal pathway.61 As with prodromal symptoms, the risk of PD related to environmental risk factors may be synergistic; repetitive TBI may be more damaging than a single injury, and a combination of TBI and pesticide exposure markedly increases PD risk beyond the risk of TBI or the risk of pesticides alone.62 Recently, parkinsonism, including Parkinson disease, was recognized as a service connected condition for veterans with a servicerelated moderate or severe TBI.63

Conclusion

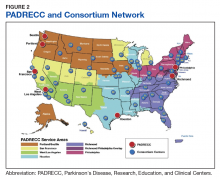

Because of the substantial impact on quality of life and disability-adjusted life years, early and accurate identification and management of veterans at risk for PD is an important priority area for the VA. The 10-year cost of PD-related benefits through the VA was estimated at $3.5 billion in fiscal year 2010, and that number is likely to rise in coming years, due to the aging population as well as synergistic effects of independent risk factors described above.64 In response, the VA has created a network of specialty care sites, known as Parkinson Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (PADRECCs) located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Richmond, Virginia; Houston, Texas; West Los Angeles and San Francisco, California; and Seattle, Washington/ Portland, Oregon (www.parkinsons.va.gov).

The PADRECCs are supplemented by a National VA PD Consortium network of VA physicians trained in PD management (Figure 2). Studies, including one investigating care of veterans with PD, have demonstrated that involvement of specialty care services early in the course of PD leads to improved patient outcomes.65,66 In addition to patient-facing resources such as support groups and specialized physical/occupational/speech therapy, PADRECCs and the consortium sites are national leaders in PD education and clinical trials and provide high-quality, multidisciplinary care for veterans with PD.67 Thus, veterans with significant risk factors or prodromal symptoms of PD should be referred into the PADRECC/Consortium network in order to maximize their quality of care and quality of life.

1. Marras C, Beck JC, Bower JH, et al; Parkinson’s Foundation P4 Group. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2018;4:21.

2. Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1591-1601.

3. Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(pt 5):2283-2301.

4. Greffard S, Verny M, Bonnet A-M, et al. Motor score of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale as a good predictor of Lewy body-associated neuronal loss in the substantia nigra. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(4):584-588.

5. Hilker R, Schweitzer K, Coburger S, et al. Nonlinear progression of Parkinson disease as determined by serial positron emission tomographic imaging of striatal fluorodopa F 18 activity. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(3):378-382.

6. Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RAI, Jansen Steur ENH, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197-211.

7. Mantri S, Morley JF, Siderowf AD. The importance of preclinical diagnostics in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018;pii:S1353-8020(18)30396-1. [Epub ahead of print]

8. Berg D, Postuma RB, Adler CH, et al. MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1600-1611.

9. Haehner A, Boesveldt S, Berendse HW, et al. Prevalence of smell loss in Parkinson’s disease – a multicenter study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(7):490-494.

10. Mullol J, Alobid I, Mariño-Sánchez F, et al. Furthering the understanding of olfaction, prevalence of loss of smell and risk factors: a population-based survey (OLFACAT study). BMJ Open. 2012;2(6).pii:e001256.

11. Doty RL, Shaman P, Applebaum SL, Giberson R, Siksorski L, Rosenberg L. Smell identification ability: changes with age. Science. 1984;226(4681):1441-1443.

12. Doty RL. Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(6):329-339.

13. Double KL, Rowe DB, Hayes M, et al. Identifying the pattern of olfactory deficits in Parkinson disease using the brief smell identification test. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(4):545-549.

14. Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 1984;32(3):489-502.

15. Morley JF, Cohen A, Silveira-Moriyama L, et al. Optimizing olfactory testing for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease: item analysis of the University of Pennsylvania smell identification test. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2018;4:2.

16. Fullard ME, Tran B, Xie SX, et al. Olfactory impairment predicts cognitive decline in early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;25:45-51.

17. Savica R, Carlin JM, Grossardt BR, et al. Medical records documentation of constipation preceding Parkinson disease: a case-control study. Neurology. 2009;73(21):1752-1758.

18. Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, et al. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57(3):456-462.

19. Stocchi F, Torti M. Constipation in Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;134:811-826.

20. Yu QJ, Yu SY, Zuo LJ, et al. Parkinson disease with constipation: clinical features and relevant factors. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):567.

21. Hill-Burns EM, Debelius JW, Morton JT, et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov Disord. 2017;32(5):739-749.

22. Mulak A, Bonaz B. Brain-gut-microbiota axis in Parkinson’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(37): 10609-10620.

23. Shah SP, Duda JE. Dietary modifications in Parkinson’s disease: a neuroprotective intervention? Med Hypotheses. 2015;85(6):1002-1005.

24. Perez-Pardo P, de Jong EM, Broersen LM, et al. Promising effects of neurorestorative diets on motor, cognitive, and gastrointestinal dysfunction after symptom development in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:57.

25. Fang F, Xu Q, Park Y, et al. Depression and the subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Mov Disord. 2010;25(9):1157-1162.

26. Leentjens AFG, Van den Akker M, Metsemakers JFM, Lousberg R, Verhey FRJ. Higher incidence of depression preceding the onset of Parkinson’s disease: a register study. Mov Disord. 2003;18(4):414-418.

27. Alonso A, Rodriguez LAG, Logroscino G, Hernán MA. Use of antidepressants and the risk of Parkinson’s disease: a prospective study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(6):671-674.

28. Weisskopf MG, Chen H, Schwarzschild MA, Kawachi I, Ascherio A. Prospective study of phobic anxiety and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2003;18(6):646-651.

29. Darweesh SK, Verlinden VJ, Stricker BH, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Ikram MA. Trajectories of prediagnostic functioning in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2017;140(2):429-441.

30. Santangelo G, Vitale C, Picillo M, et al. Apathy and striatal dopamine transporter levels in de-novo, untreated Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(5):489-493.

31. Erro R, Pappatà S, Amboni M, et al. Anxiety is associated with striatal dopamine transporter availability in newly diagnosed untreated Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(9):1034-1038.

32. Schenck CH, Boeve BF, Mahowald MW. Delayed emergence of a parkinsonian disorder or dementia in 81% of older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a 16-year update on a previously reported series. Sleep Med. 2013;14(8):

744-748.

33. Melendez J, Hesselbacher S, Sharafkhaneh A, Hirshkowitz M. Assessment of REM sleep behavior disorder in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Chest. 2011;140(4):967A.

34. Pilotto A, Heinzel S, Suenkel U, et al. Application of the movement disorder society prodromal Parkinson’s disease research criteria in 2 independent prospective cohorts. Mov Disord. 2017;32(7):1025-1034.

35. Fereshtehnejad S-M, Montplaisir JY, Pelletier A, Gagnon J-F, Berg D, Postuma RB. Validation of the MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s disease: Longitudinal assessment in a REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) cohort. Mov Disord. 2017;32(6):865-873.

36. Rizzo G, Copetti M, Arcuti S, Martino D, Fontana A, Logroscino G. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2016;86(6):566-576.

37. Moccia M, Pappatà S, Picillo M, et al. Dopamine transporter availability in motor subtypes of de novo drug-naïve Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2014;261(11):2112-2118.

38. Siepel FJ, Brønnick KS, Booij J, et al. Cognitive executive impairment and dopaminergic deficits in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(14):1802-1808.

39. Iranzo A, Valldeoriola F, Lomeña F, et al. Serial dopamine transporter imaging of nigrostriatal function in patients with idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder: a prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):797-805.

40. Booij J, Kemp P. Dopamine transporter imaging with [(123)I]FP-CIT SPECT: potential effects of drugs. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(2):424-438.

41. Gellad WF, Aspinall SL, Handler SM, et al. Use of antipsychotics among older residents in VA nursing homes. Med Care. 2012;50(11):954-960.

42. Mauri MC, Paletta S, Maffini M, et al. Clinical pharmacology of atypical antipsychotics: an update. EXCLI J. 2014;13:1163-1191.

43. Morley JF, Duda JE. Use of hyposmia and other non-motor symptoms to distinguish between drug-induced parkinsonism and Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2014;4(2):169-173.

44. Morley JF, Cheng G, Dubroff JG, Wood S, Wilkinson JR, Duda JE. Olfactory impairment predicts underlying dopaminergic deficit in presumed drug-induced parkinsonism. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2017;4(4):603-606.

45. Whitwell JL, Höglinger GU, Antonini A, et al; Movement Disorder Society-endorsed PSP Study Group. Radiological biomarkers for diagnosis in PSP: where are we and where do we need to be? Mov Disord. 2017;32(7):955-971.

46. Laurens B, Constantinescu R, Freeman R, et al. Fluid biomarkers in multiple system atrophy: A review of the MSA Biomarker Initiative. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;80:29-41.

47. Barber TR, Klein JC, Mackay CE, Hu MTM. Neuroimaging in pre-motor Parkinson’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2017;15:215-227.

48. Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative. The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI). Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95(4):629-635.

49. Meles SK, Vadasz D, Renken RJ, et al. FDG PET, dopamine transporter SPECT, and olfaction: combining biomarkers in REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2017;32(10):1482-1486.

50. Noyce AJ, R’Bibo L, Peress L, et al. PREDICT‐PD: an online approach to prospectively identify risk indicators of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2017 Feb; 32(2): 219–226.

51. Searles Nielsen S, Warden MN, Camacho-Soto A, Willis AW, Wright BA, Racette BA. A predictive model to identify Parkinson disease from administrative claims data. Neurology. 2017;89(14):1448-1456.

52. Institute of Medicine. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2012. National Academies Press: Washington, DC; 2013.

53. Department of Veterans Affairs. Diseases associated with exposure to Contaminants in the Water Supply at Camp Lejeune. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2017;82(9):4173-4185.

54. Goldman SM, Quinlan PJ, Ross GW, et al. Solvent exposures and Parkinson disease risk in twins. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):776-784.

55. Liu M, Shin EJ, Dang DK, et al. Trichloroethylene and Parkinson’s disease: risk assessment. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(7):6201-6214.

56. Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(12):1301-1306.

57. Manning-Bog AB, McCormack AL, Li J, Uversky VN, Fink AL, Monte DAD. The herbicide paraquat causes up-regulation and aggregation of alpha-synuclein in mice: paraquat and alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(3):1641-1644.

58. Camacho-Soto A, Warden MN, Searles Nielsen S, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the prodromal period of Parkinson’s disease: a large epidemiological study using medicare data. Ann Neurol. 2017;82(5):744-754.

59. Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, Goldman S, Tanner CM, Yaffe K. Traumatic brain injury in later life increases risk for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(6):987-995.

60. Gardner RC, Byers AL, Barnes DE, Li Y, Boscardin J, Yaffe K. Mild TBI and risk of Parkinson disease: a Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium Study. Neurology. 2018;90(20):e1771-e1779.

61. Cruz-Haces M, Tang J, Acosta G, Fernandez J, Shi R. Pathological correlations between traumatic brain injury and chronic neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener. 2017;6:20.

62. Lee PC, Bordelon Y, Bronstein J, Ritz B. Traumatic brain injury, paraquat exposure, and their relationship to Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2012;79(20):2061-2066.

63. Disabilities that are proximately due to, or aggravated by, service-connected disease or injury. 38 CFR §3.310.

64. Diseases Associated With Exposure to Certain Herbicide Agents (Hairy Cell Leukemia and Other Chronic B-Cell Leukemias, Parkinson’s Disease and Ischemic Heart Disease). Federal Regist. 2010;75(173):53202-53216. To be codified at 38 CFR §3.

65. Cheng EM, Swarztrauber K, Siderowf AD, et al. Association of specialist involvement and quality of care for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(4):515-522.

66. Qamar MA, Harington G, Trump S, Johnson J, Roberts F, Frost E. Multidisciplinary care in Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;132:511-523.

67. Pogoda TK, Cramer IE, Meterko M, et al. Patient and organizational factors related to education and support use by veterans with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24(13):1916-1924.

Parkinson disease (PD) affects about 680,000 in the US, including > 110,000 veterans (Caroline Tanner, MD, PhD, unpublished data).1 In the next 10 years, this number is expected to double, in part because of the aging of the US population.1 Although the classic diagnostic criteria emphasize motor symptoms that include tremor, gait disturbance, and paucity of movement, there is increasing recognition that disease pathology begins decades before the development of motor impairment.2

Pathologic studies confirm that by the onset of motor symptoms, at least 30% of nigrostriatal neurons are lost or dysfunctional.3-5 Similarly, the Braak staging hypothesis posits initial deposition of Lewy bodies in the olfactory bulb and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, followed by prion-like spread through the brain stem into the midbrain/substantia nigra, and finally into the cortex (Figure 1).6

The decades-long prodromal or preclinical phase represents a unique opportunity for early identification of those at highest risk for developing the motor symptoms of Parkinson disease.7 Accurate identification, ideally before the onset of manifest motor disability, would not only improve prognostic counseling of veterans and families, but also could allow for early enrollment into trials of potentially disease-modifying therapeutic agents. Thus, early and accurate identification of PD is an important goal of the care of veterans with potential PD.

Prodromal Symptoms

Prodromal PD, as defined by the International Parkinson Disease and Movement Disorders Society (MDS), focuses on nonmotor symptoms that herald the onset of manifest motor PD.8 The most commonly assessed nonmotor features include olfaction, constipation, sleep disturbance, and mood disorders.

Olfaction is impaired in > 90% of patients with motor PD at the time of diagnosis; by contrast, the prevalence of hyposmia in the general population ranges from 20% to 50%, with higher rates in older adults and in smokers.9-11 Thus, olfaction appears to be a relatively sensitive, though nonspecific, prodromal feature. Importantly, subjective report of hyposmia is poorly reliable, so a number of different tests have been developed for objective assessment of olfactory dysfunction.12 The 12-item Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT), derived from the longer University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test, is a “scratch-and-sniff” forced multiple choice test that can be self-administered by cooperative patients.13,14 The B-SIT has been validated in multiple ethnic and cultural groups and shows high discrimination between PD subjects and controls.13,15 Of note, olfactory impairment appears to be associated with risk of cognitive decline in PD, further emphasizing the need for accurate assessment to guide prognosis.16

Like hyposmia, constipation can be noted long before the diagnosis of manifest motor PD.17 After adjustment for lifestyle factors, constipated individuals have up to 4.5-fold increased odds of developing PD, and those with constipation suffer worsened disease outcomes and health-related quality of life.17-20 Some groups have demonstrated alterations in gut microbiota of those with prodromal PD, which suggests local inflammatory processes and intestinal permeability may contribute to protein misfolding and disease development.21,22 This also raises the intriguing possibility that dietary alterations may be neuroprotective or neurorestorative, although this has yet to be tested in humans.23,24

Like constipation, mood changes can precede the appearance of manifest motor PD.25,26 Case control studies suggest a higher risk of developing PD among individuals who were previously diagnosed with depression or anxiety, particularly in the 1 to 2 years prior to PD diagnosis.27-29 Both apathy and anxiety are associated with striatal dopamine dysfunction, particularly in the right caudate nucleus, which suggests that mood changes are directly related to disease pathology.30,31

Of the prodromal features, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is associated with the highest risk of conversion to motor PD.8 Up to 80% of older men with socalled idiopathic RBD develop a parkinsonian syndrome within 20 years; risk is divided about equally between idiopathic PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).32 Collateral history from a bed-partner is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis, although, this is often confounded by the prevalence of nightmares in those with posttraumatic stress disorder in the veteran population.32 Thus, in suspected cases, obtaining a polysomnogram can aid in distinguishing between idiopathic PC and DLB.33 Given the specificity of RBD as a marker of synuclein deposition and the high risk of progression to a degenerative syndrome, accurate diagnosis and counseling is imperative.

Each of the prodromal nonmotor features of PD are at best moderately sensitive or specific in isolation, but in concert, they can be used to develop a Parkinson risk score. For instance, the MDS prodromal criteria combine individual likelihood ratios into Bayesian analysis to determine a combined probability of PD, which can be further stratified to probable or possible prodromal PD (probability > 80%, > 50%, respectively).8 These criteria have been applied to several independent cohorts and demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity, especially over time.34,35 Applicability in a veteran population has yet to be determined.

Use of Imaging in Diagnosis

Although clinical diagnostic criteria and prodromal features can improve diagnostic accuracy, it can be extremely challenging to distinguish idiopathic PD from nondegenerative parkinsonism or atypical syndromes (see below). Compared with the gold standard of pathologic assessment, the clinical diagnostic accuracy for PD ranges from 73% for nonexperts to 80% for fellowship-trained movement disorders specialists.36 Thus, objective biomarkers are sought to improve diagnostic accuracy both for clinical care as well as for research purposes, such as enrollment into clinical trials.

Multiple potential imaging biomarkers for preclinical PD can aid in early diagnosis and help differentiate PD from related but distinct disorders. While beyond the scope of this review, these techniques have recently been reviewed.7 Of these, the most widely available and accurate is dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging, which uses a radioiodinated ligand that binds to DAT on striatal dopaminergic terminals; binding is detected through single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanning. Thus, a SPECT DaTscan (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Little Chalfont, England) directly assesses the integrity of the presynaptic nigrostriatal system and is well correlated with severity of motor and nonmotor parkinsonism.37,38