User login

An eConsults Program to Improve Patient Access to Specialty Care in an Academic Health System

From the Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, Orange, CA.

Abstract

Background: Orange County’s residents have difficulty accessing timely, quality, affordable specialty care services. As the county’s only academic health system, the University of California, Irvine (UCI) aimed to improve specialty care access for the communities it serves by implementing an electronic consultations (eConsults) program that allows primary care providers (PCPs) to efficiently receive specialist recommendations on referral problems that do not require an in-person evaluation.

Objective: To implement an eConsults program at the UCI that enhances access to and the delivery of coordinated specialty care for lower-complexity referral problems.

Methods: We developed custom solutions to integrate eConsults into UCI’s 2 electronic health record platforms. The impact of the eConsults program was assessed by continuously evaluating usage and outcomes. Measures used to track usage included the number of submitted eConsult requests per PCP, the number of completed responses per specialty, and the response time for eConsult requests. Outcome measures included the specialist recommendation (eg, in-office visit, consultation avoided) and physician feedback.

Results: Over 4.5 years, more than 1400 successful eConsults have been completed, and the program has expanded to 17 specialties. The average turnaround time for an eConsult response across all specialties was 1 business day. Moreover, more than 50% of the eConsults received specialty responses within the same day of the eConsult request. Most important, about 80% of eConsult requests were addressed without the need for an in-office visit with a specialist.

Conclusion: The enhanced access to and the delivery of coordinated specialty care provided by eConsults resulted in improved efficiency and specialty access, while likely reducing costs and improving patient satisfaction. The improved communication and collaboration among providers with eConsults has also led to overwhelmingly positive feedback from both PCPs and specialists.

Keywords: electronic consultation; access to care; primary care; specialty referral; telehealth.

Orange County’s growing, aging, and diverse population is driving an increased demand for health care.1 But with the county’s high cost of living and worsening shortage of physicians,1-3 many of its residents are struggling to access timely, quality, affordable care. Access to specialty care services is especially frustrating for many patients and their providers, both primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists, due to problems with the referral process. Many patients experience increased wait times for a visit with a specialist due to poor communication between providers, insufficient guidance on the information or diagnostic results needed by specialists, and lack of care coordination.4-6 One promising approach to overcome these challenges is the use of an electronic consultation, or eConsult, in place of a standard in-person referral. An eConsult is an asynchronous, non-face-to-face, provider-to-provider exchange using a secure electronic communication platform. For appropriate referral problems, the patient is able to receive timely access to specialist expertise through electronic referral by their PCP,7-9 and avoid the time and costs associated with a visit to the specialist,10,11 such as travel, missed work, co-pays, and child-care expenses. Clinical questions addressed using an eConsult system subsequently free up office visit appointment slots, improving access for patients requiring in-office evaluation.8,12

Orange County’s only academic health system, the University of California, Irvine (UCI), serves a population of 3.5 million, and its principal priority is providing the communities in the county (which is the sixth largest in United States) and the surrounding region with the highest quality health care possible. Thus, UCI aimed to improve its referral processes and provide timely access to specialty care for its patients by implementing an eConsults program that allows PCPs to efficiently receive specialist recommendations on referral problems that do not require the specialist to evaluate the patient in person. This report describes our experiences with developing and implementing a custom-built eConsults workflow in UCI’s prior electronic health record (EHR) platform, Allscripts, and subsequently transitioning our mature eConsults program to a new EHR system when UCI adopted Epic. UCI is likely the only academic medical center to have experience in successfully implementing eConsults into 2 different EHR systems.

Setting

UCI’s medical center is a 417-bed acute care hospital providing tertiary and quaternary care, ambulatory and specialty medical clinics, behavioral health care, and rehabilitation services. It is located in Orange, CA, and serves a diverse population of 3.5 million persons with broad health care needs. With more than 400 specialty and primary care physicians, UCI offers a full scope of acute and general care services. It is also the primary teaching location for UCI medical and nursing students, medical residents, and fellows, and is home to Orange County’s only adult Level I and pediatric Level II trauma centers and the regional burn center.

eConsults Program

We designed the initial eConsults program within UCI’s Allscripts EHR platform. Our information technology (IT) build team developed unique “documents-based” eConsults workflows that simplified the process of initiating requests directly from the EHR and facilitated rapid responses from participating specialties. The requesting provider’s eConsults interface was user-friendly, and referring providers were able to initiate an eConsult easily by selecting the customized eConsult icon from the Allscripts main toolbar. To ensure that all relevant information is provided to the specialists, condition-specific templates are embedded in the requesting provider’s eConsults workflow that allow PCPs to enter a focused, patient-specific clinical question and provide guidance on recommended patient information (eg, health history, laboratory results, and digital images) that may help the specialist provide an informed response. The eConsult templates were adapted from standardized forms developed by partner University of California Health Systems in an initiative funded by the University of California Center for Health Quality and Innovation.

To facilitate timely responses from specialists, an innovative notification system was created in the responding provider’s eConsults workflow to automatically send an email to participating specialists when a new eConsult is requested. The responding provider’s workflow also includes an option for the specialist to decline the eConsult if the case is deemed too complex to be addressed electronically. For every completed eConsult that does not result in an in-person patient evaluation, the requesting provider and responding specialist each receives a modest reimbursement, which was initially paid by UCI Health System funds.

Implementation

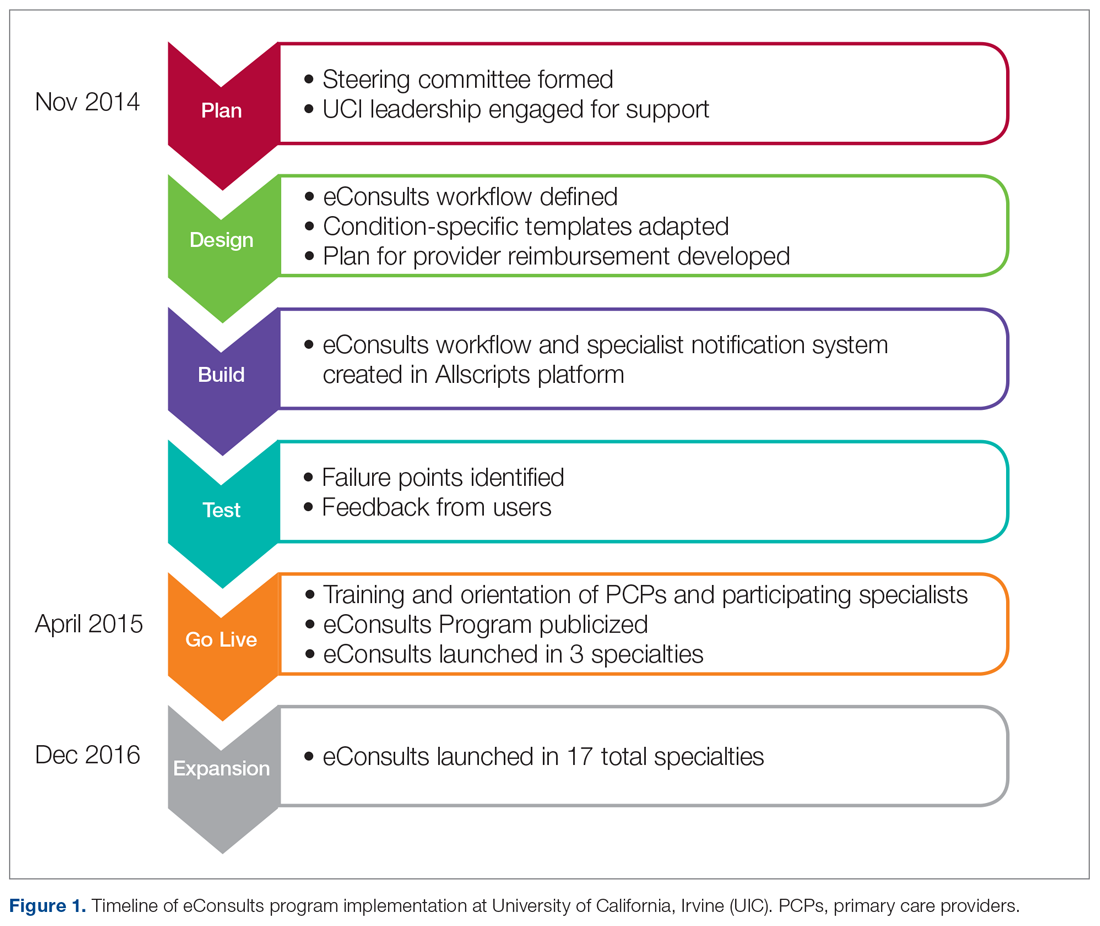

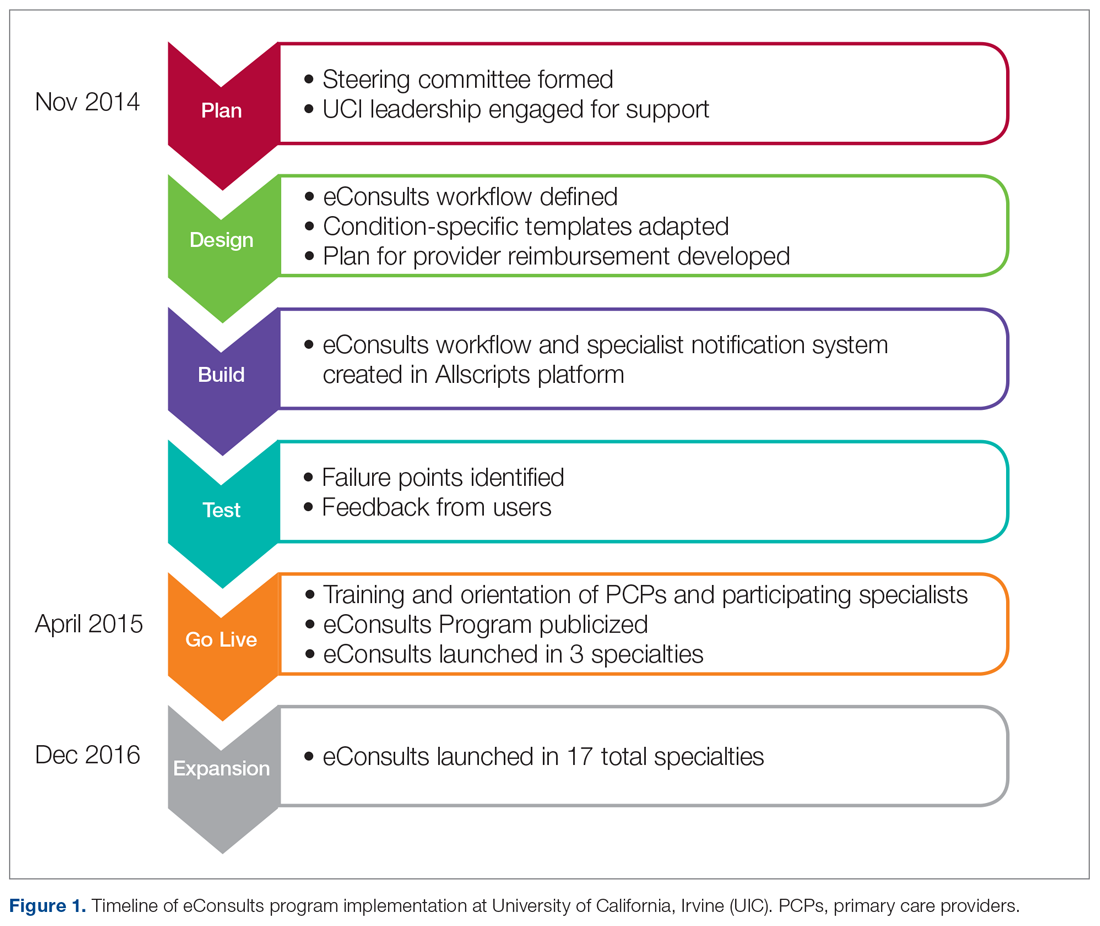

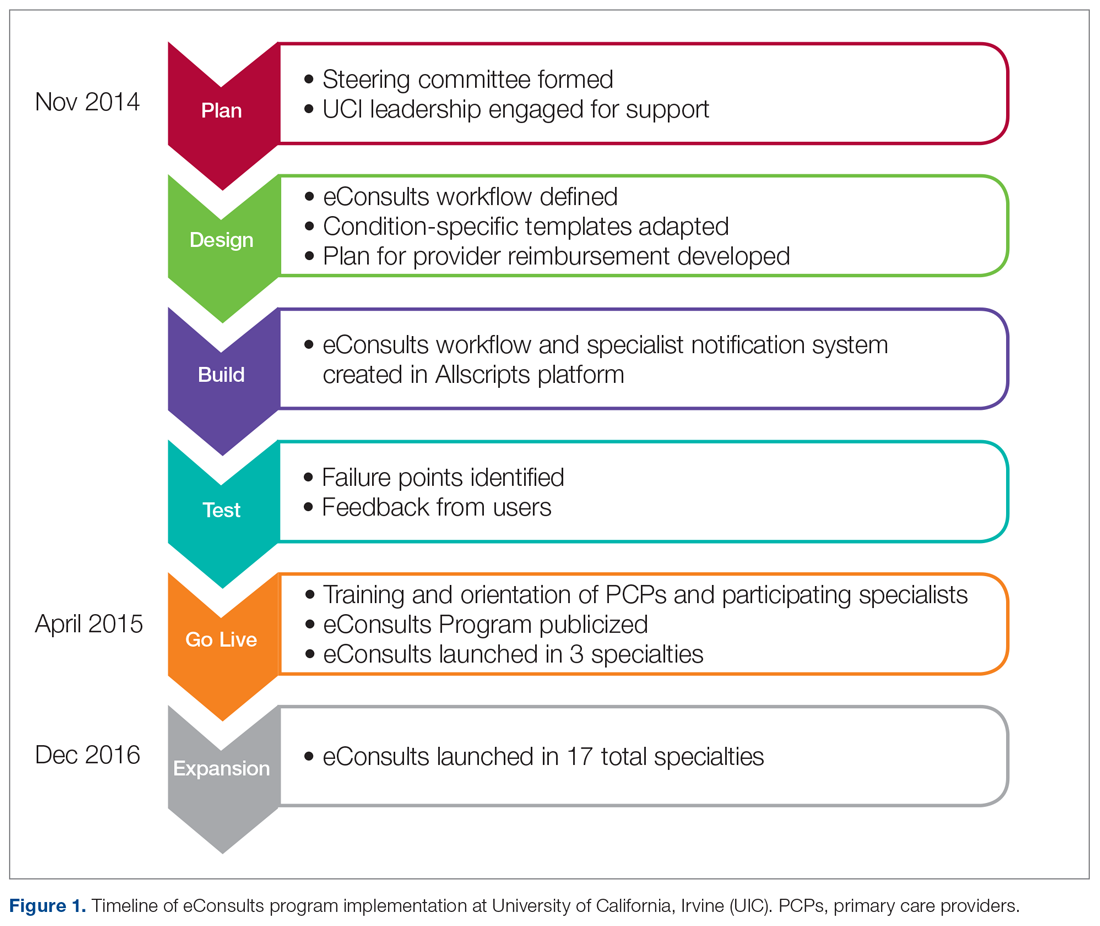

The design and implementation of the eConsults program began in November 2014, and was guided by a steering committee that included the chair of the department of medicine, chief medical information officer, primary care and specialty physician leads, IT build team, and a project manager. Early on, members of this committee engaged UCI leadership to affirm support for the program and obtain the IT resources needed to build the eConsults workflow. Regular steering committee meetings were established to discuss the design of the workflow, adapt the clinical content of the referral templates, and develop a provider reimbursement plan. After completion of the workflow build, the eConsults system was tested to identify failure points and obtain feedback from users. Prior to going live, the eConsults program was publicized by members of the steering committee through meetings with primary care groups and email communications. Committee members also hosted in-person training and orientation sessions with PCPs and participating specialists, and distributed tip sheets summarizing the steps to complete the PCP and specialist eConsult workflows.

The eConsults workflow build, testing, and launch were completed within 5 months (April 2015; Figure 1). eConsults went live in the 3 initial specialties (endocrinology, cardiology, and rheumatology) that were interested in participating in the first wave of the program. UCI’s eConsults service has subsequently expanded to 17 total specialties (allergy, cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, geriatrics, gynecology, hematology, hepatology, infectious disease, nephrology, neurology, palliative care, psychiatry, pulmonary, rheumatology, and sports medicine).

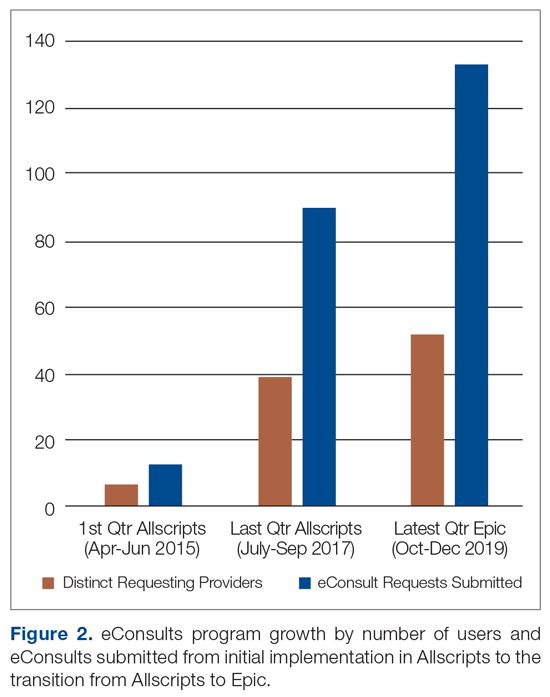

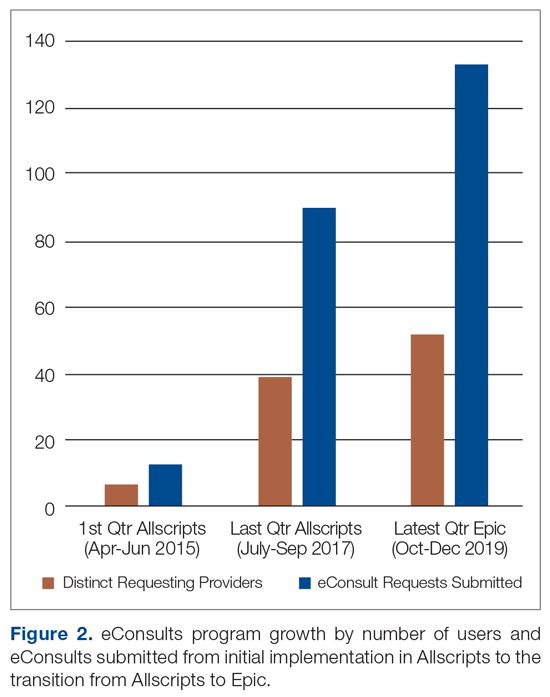

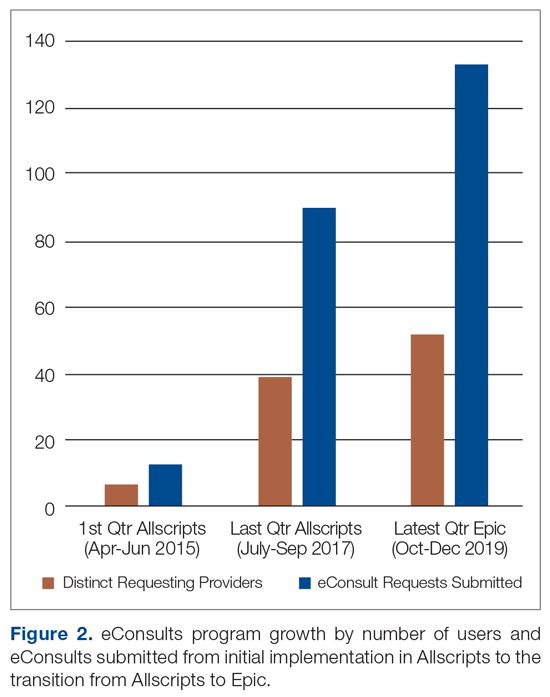

Two and half years after the eConsults program was implemented in Allscripts, UCI adopted a new EHR platform, Epic. By this time, the eConsults service had grown into a mature program with greater numbers of PCP users and submitted eConsults (Figure 2). Using our experience with the Allscripts build, our IT team was able to efficiently transition the eConsults service to the new EHR system. In contrast to the “documents-based” eConsult workflows on Allscripts, our IT team utilized an “orders-based” strategy on Epic, which followed a more traditional approach to requesting a consultation. We re-launched the service in Epic within 3 months (February 2018). However, both platforms utilized user-friendly workflows to achieve similar goals, and the program has continued to grow with respect to the number of users and eConsults.

Measurement/Analysis

The impact of the program was assessed by continuously evaluating usage and outcomes. Measures used to track usage included the number of PCP users, the number of submitted eConsult requests per PCP, and the number of requests per specialty. The response time for eConsult requests and the self-reported amount of time spent by specialists on the response were also tracked. Outcome measures included the specialist recommendation (eg, in-office visit, consultation avoided) and physician feedback. Provider satisfaction was primarily obtained by soliciting feedback from individual eConsult users.

Implementation of this eConsults program constituted a quality improvement activity and did not require Institutional Review Board review.

Results

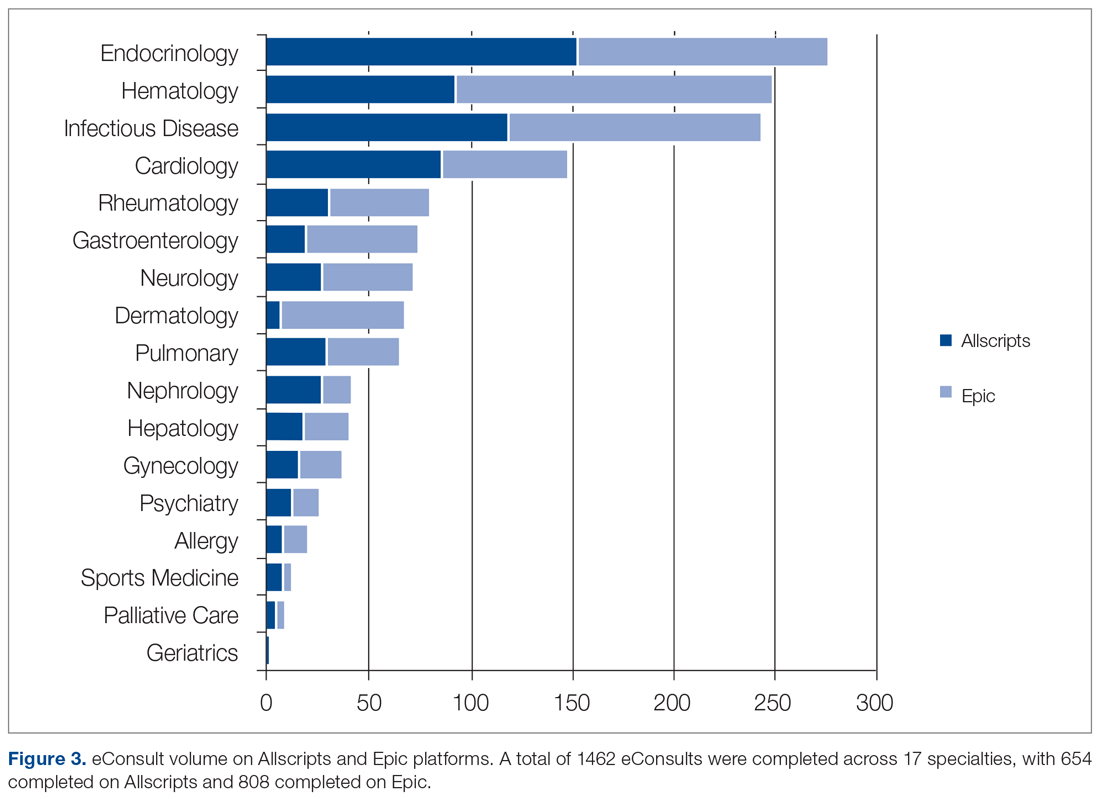

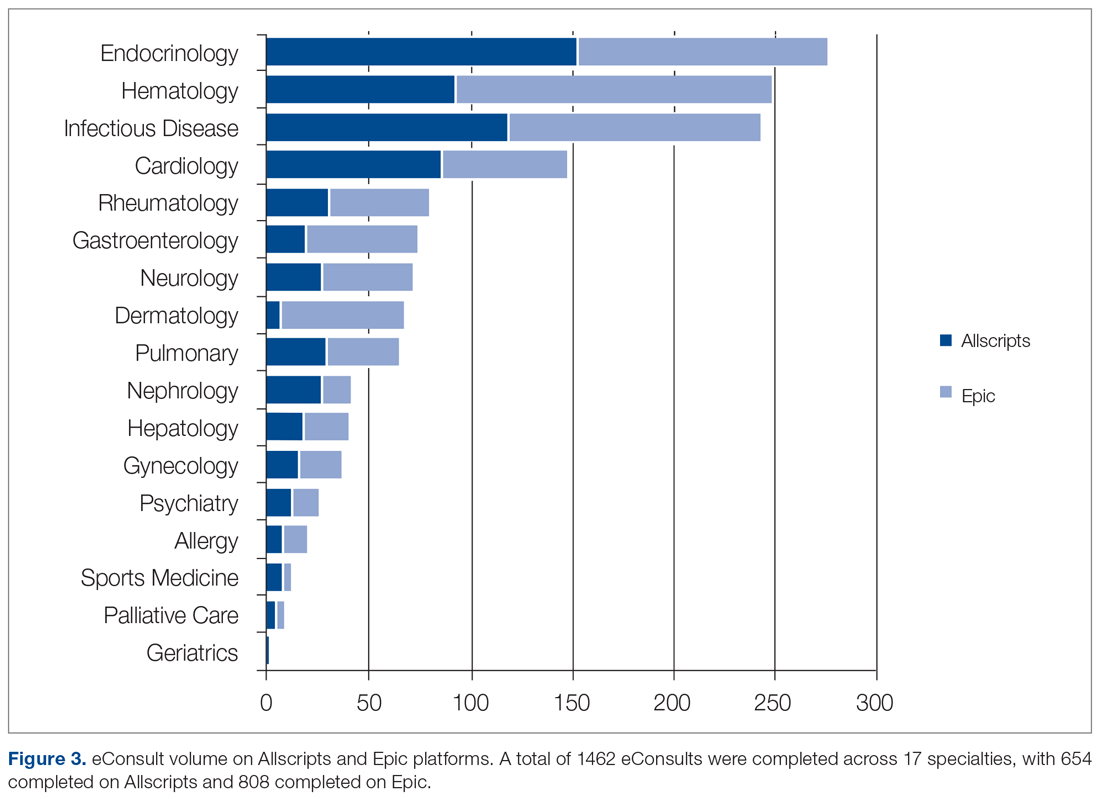

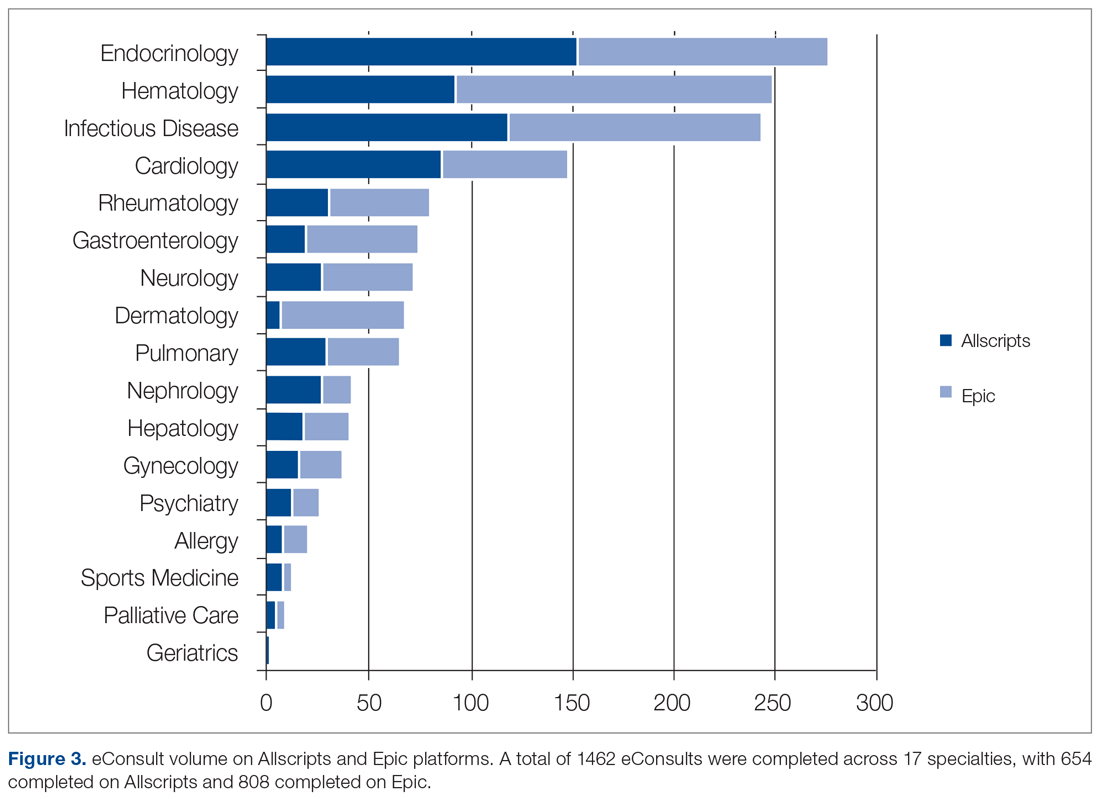

Since the program was launched in April 2015, more than 1400 eConsults have been completed across 17 specialties (Figure 3). There were 654 completed eConsults on the Allscripts platform, and 808 eConsults have been completed using the Epic platform to date. The busiest eConsult specialties were endocrinology (receiving 276, or 19%, of the eConsults requests), hematology (receiving 249 requests, or 17%), infectious disease (receiving 244 requests, or 17% ), and cardiology (receiving 148 requests, or 10%).

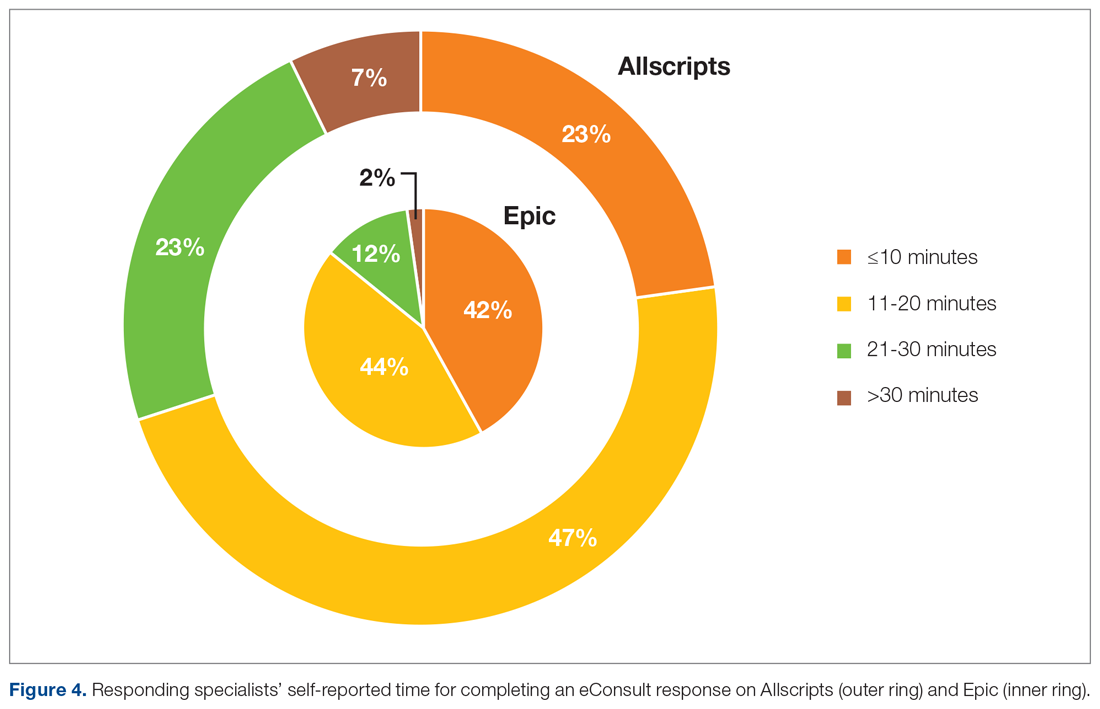

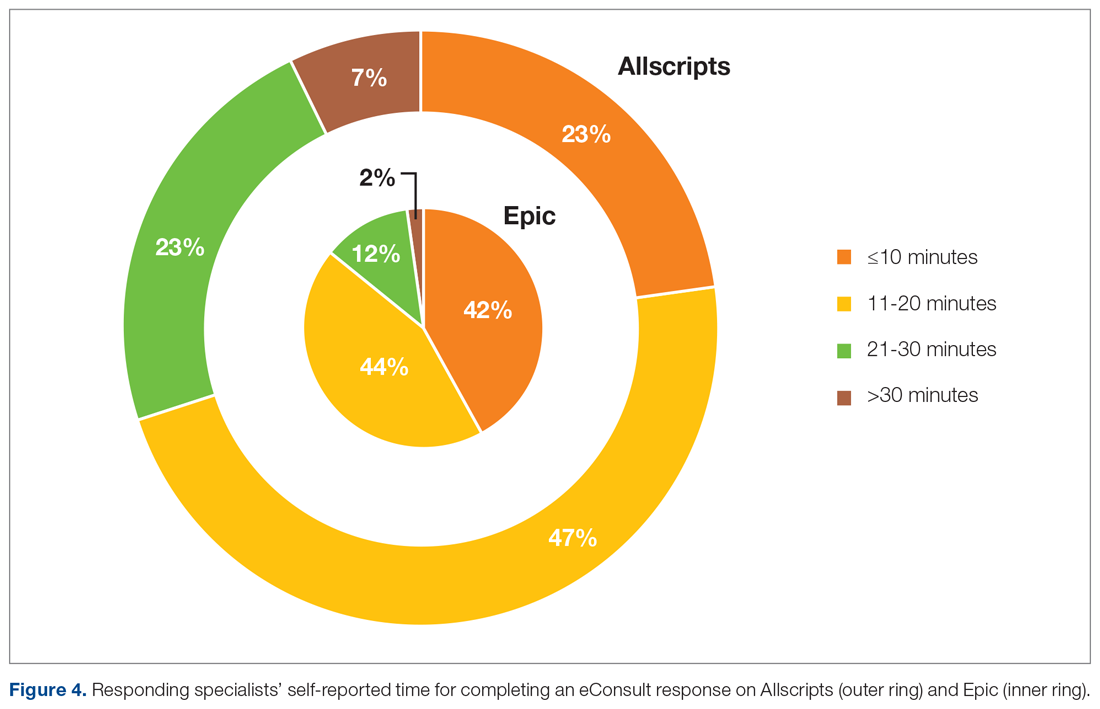

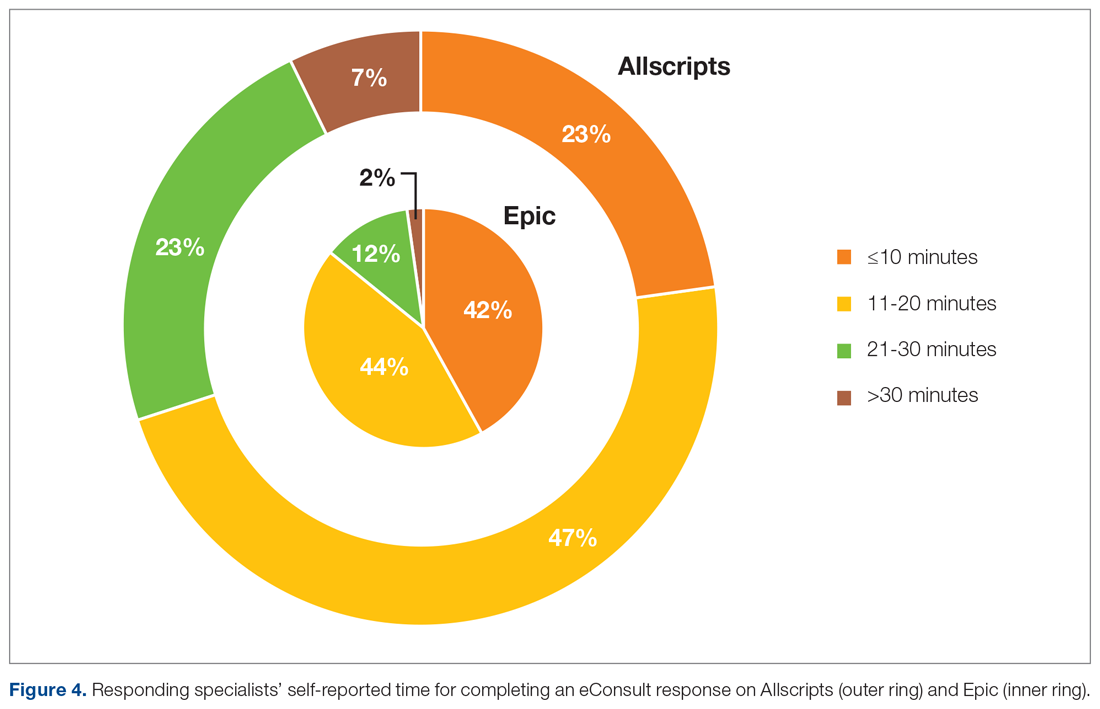

The self-reported amount of time specialists spent on the response was different between the 2 EHR systems (Figure 4). On Allscripts, specialists reported that 23% of eConsults took 10 minutes or less to complete, 47% took 11 to 20 minutes, 23% took 21 to 30 minutes, and 7% took more than 30 minutes. On Epic, specialists reported that 42% of eConsults took 10 minutes or less to complete, 44% took 11 to 20 minutes, 12% took 21 to 30 minutes, and 2% took more than 30 minutes. This difference in time spent fielding eConsults likely represents the subtle nuances between Allscripts’ “documents-based” and Epic’s “orders-based” workflows.

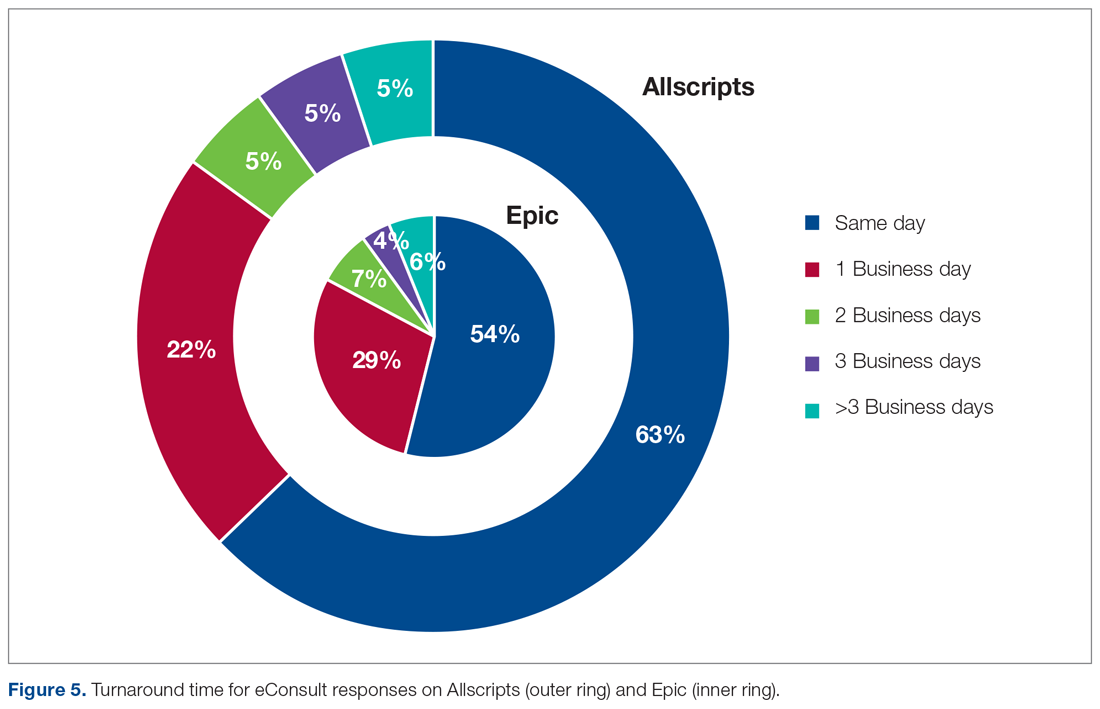

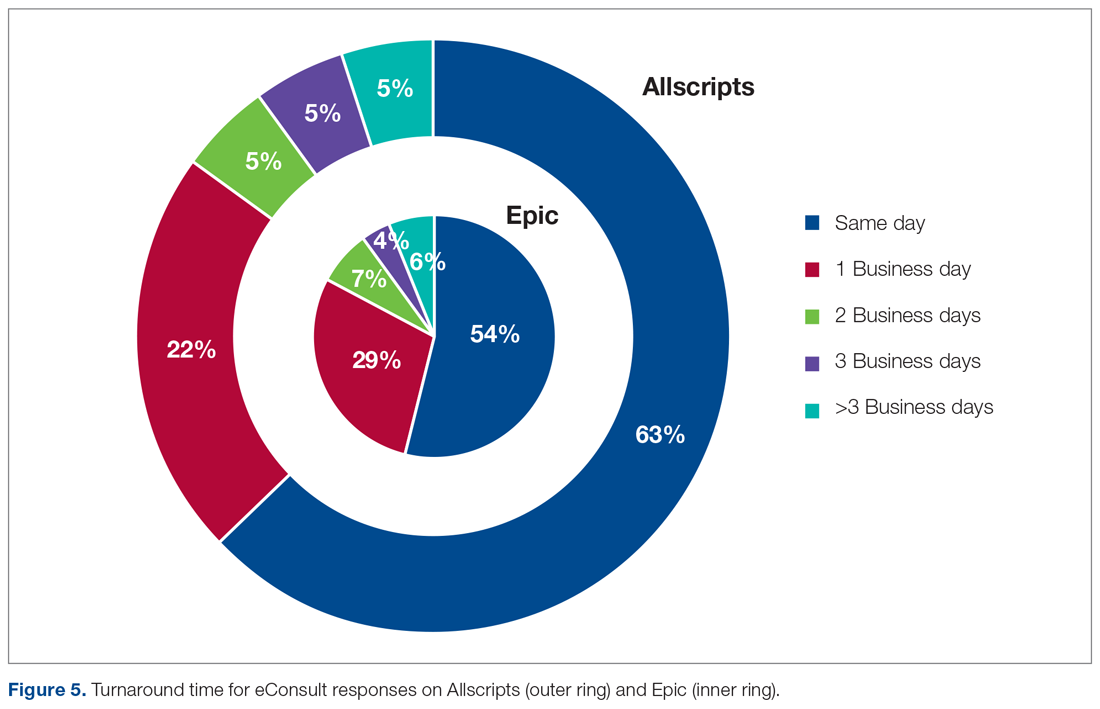

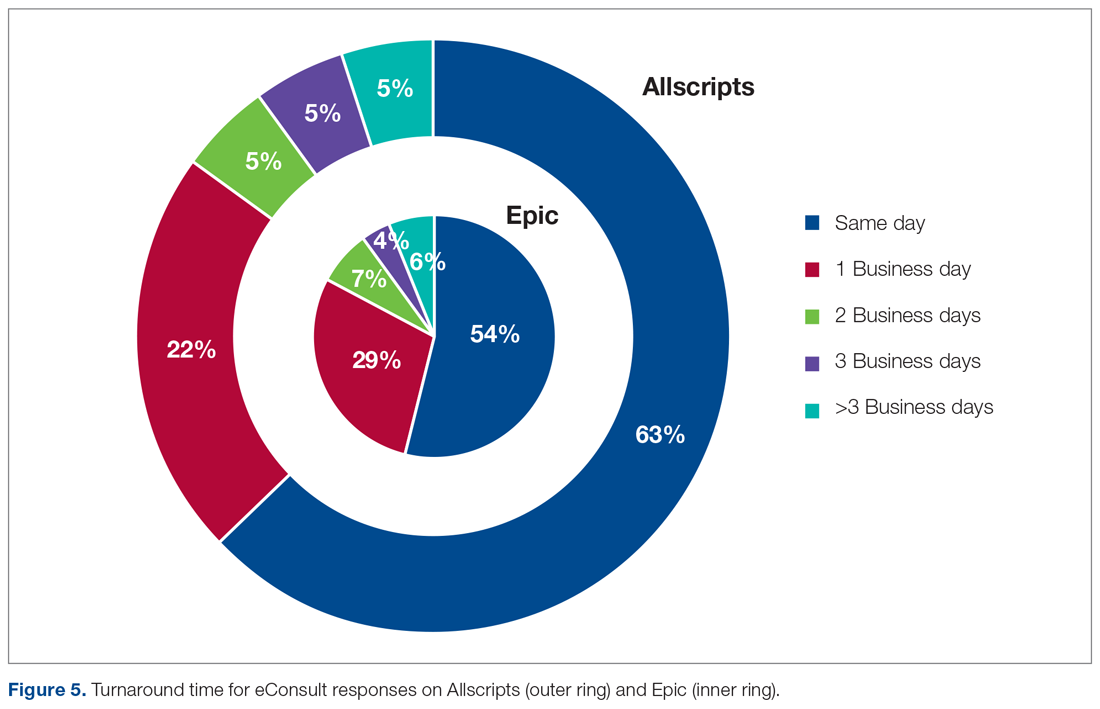

As a result of the automated notification system that was introduced early in the eConsults implementation process on Allscripts, the specialty response times were much faster than the expected 3 business days’ turnaround goal instituted by the Center for Health Quality and Innovation initiative, regardless of the EHR platform used. In fact, the average turnaround time for an eConsult response across all specialties was 1 business day, which was similar for both EHR systems (Figure 5). Furthermore, more than 50% of the eConsults on both EHR systems received specialist responses within the same day of the eConsult request (63% on Allscripts, 54% on Epic). There was a small decrease in the percentage of same-day responses when we transitioned to Epic, likely because the functionality of an automated notification email could not be restored in Epic. Regardless, the specialty response times on Epic remained expeditious, likely because the automated notifications on Allscripts instilled good practices for the specialists, and regularly checking for new eConsult requests became an ingrained behavior.

Our most important finding was that approximately 80% of eConsult requests were addressed without the need for an in-office visit with a specialist. This measure was similar for both EHR platforms (83% on Allscripts and 78% on Epic).

Provider feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. PCPs are impressed with the robust educational content of the eConsult responses, since the goal for specialists is to justify their recommendations. Specialists appreciate the convenience and efficiency that eConsults offer, as well as the improved communication and collaboration among physicians. eConsults have been especially beneficial to PCPs at UCI’s Family Health Centers, who are now able to receive subspecialty consultations from UCI specialists despite insurance barriers.

Discussion

Our eConsults program uniquely contrasts with other programs because UCI is likely the only academic medical center to have experience in successfully incorporating eConsults into 2 different EHR systems: initial development of the eConsults workflow in UCI’s existing Allscripts EHR platform, and subsequently transitioning a mature eConsults program to a new EHR system when the institution adopted Epic.

We measured the impact of the eConsults program on access to care by the response time for eConsult requests and the percentage of eConsults that averted an in-office visit with a specialist. We found that the eConsults program at UCI provided our PCPs access to specialist consultations in a timely manner, with much shorter response times than standard in-person referrals. The average turnaround time for an eConsult response we reported is consistent with findings from other studies.12-15 Additionally, our program was able to address about 80% of its eConsults electronically, helping to reduce unnecessary in-person specialist referrals. In the literature, the percentage of eConsults that avoided an in-person specialist visit varies widely.8,12-16

We reported very positive feedback from both PCPs and specialists on UCI’s eConsults service. Similarly, other studies described PCP satisfaction with their respective eConsults programs to be uniformly high,8,9,13,14,17-19 though some reported that the level of satisfaction among specialists was more varied.18-21

Lessons Learned

The successful design and implementation of our eConsults program began with assembling the right clinical champions and technology partners for our steering committee. Establishing regular steering committee meetings helped maintain an appropriate timeline for completion of different aspects of the project. Engaging support from UCI’s leadership also provided us with a dedicated IT team that helped us with the build, training resources, troubleshooting issues, and reporting for the project.

Our experience with implementing the eConsults program on 2 different EHR systems highlighted the importance of creating efficient, user-friendly workflows to foster provider adoption and achieve sustainability. Allscripts’ open platform gave our IT team the ability to create a homegrown solution to implementing an eConsult model that was simple and easy to use. The Epic platform’s interoperability allowed us to leverage our learnings from the Allscripts build to efficiently implement eConsults in Epic.

We also found that providing modest incentive payments or reimbursements to both PCPs and specialists for each completed eConsult helps with both adoption and program sustainability. Initially, credit for the eConsult work was paid by internal UCI Health System funds. Two payers, UC Care (a preferred provider organization plan created just for the University of California) and more recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, have agreed to reimburse for outpatient eConsults. Securing additional payers for reimbursement of the eConsult service will not only ensure the program’s long-term sustainability, but also represents an acknowledgment of the value of eConsults in supporting access to care.

Applicability

Other health care settings that are experiencing issues with specialty care access can successfully implement their own eConsults program by employing strategies similar to those described in this report—assembling the right team, creating user-friendly workflows, and providing incentives. Our advice for successful implementation is to clearly communicate your goals to all involved, including primary care, specialists, leadership, and IT partners, and establish with these stakeholders the appropriate support and resources needed to facilitate the development of the program and overcome any barriers to adoption.

Current Status and Future Directions

Our future plans include continuing to optimize the Epic eConsult backend build and workflows using our experience in Allscripts. We have implemented eConsult workflows for use by graduate medical education trainees and advanced practice providers, with attending supervision. Further work is in progress to optimize these workflows, which will allow for appropriate education and supervision without delaying care. Furthermore, we plan to expand the program to include inpatient-to-inpatient and emergency department-to-inpatient eConsults. We will continue to expand the eConsults program by offering additional specialties, engage providers to encourage ongoing participation, and maximize PCP use by continuing to market the program through regular newsletters and email communications. Finally, the eConsults has served as an effective, important resource in the current era of COVID-19 in several ways: it allows for optimization of specialty input in patient care delivery without subjecting more health care workers to unnecessary exposure; saves on utilization of precious personal protective equipment; and enhances our ability to deal with a potential surge by providing access to specialists remotely and electronically all hours of the day, thus expanding care to the evening and weekend hours.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank our steering committee members (Dr. Ralph Cygan, Dr. Andrew Reikes, Dr. Byron Allen, Dr. George Lawry) and IT build team (Lori Bocchicchio, Meghan van Witsen, Jaymee Zillgitt, Tanya Sickles, Dennis Hoang, Jeanette Lisak-Phillips) for their contributions in the design and implementation of our eConsults program. We also thank additional team members Kurt McArthur and Neaktisia Lee for their assistance with generating reports, and Kathy LaPierre, Jennifer Rios, and Debra Webb Torres for their guidance with compliance and billing issues.

Corresponding author: Alpesh N. Amin, MD, MBA, University of California, Irvine, 101 The City Drive South, Building 26, Room 1000, ZC-4076H, Orange, CA 92868; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. County of Orange, Health Care Agency, Public Health Services. Orange County Health Profile 2013.

2. Coffman JM, Fix M Ko, M. California physician supply and distribution: headed for a drought? California Health Care Foundation, June 2018.

3. Spetz J, Coffman J, Geyn I. California’s primary care workforce: forecasted supply, demand, and pipeline of trainees, 2016-2030. Healthforce Center at the University of California, San Francisco, August 2017.

4. Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M, et al. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:626-631.

5. McPhee SJ, Lo B, Saika GY, Meltzer R. How good is communication between primary care physicians and subspecialty consultants? Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1265-1268.

6. Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011;89:39-68.

7. Wrenn K, Catschegn S, Cruz M, et al. Analysis of an electronic consultation program at an academic medical centre: Primary care provider questions, specialist responses, and primary care provider actions. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23: 217-224.

8. Gleason N, Prasad PA, Ackerman S, et al. Adoption and impact of an eConsult system in a fee-for-service setting. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5(1-2):40-45.

9. Stoves J, Connolly J, Cheung CK, et al. Electronic consultation as an alternative to hospital referral for patients with chronic kidney disease: a novel application for networked electronic health records to improve the accessibility and efficiency of healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19: e54.

10. Datta SK, Warshaw EM, Edison KE, et al. Cost and utility analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology referral system: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1323-1329.

11. Liddy C, Drosinis P, Deri Armstrong C, et al. What are the cost savings associated with providing access to specialist care through the Champlain BASE eConsult service? A costing evaluation. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010920.

12. Barnett ML, Yee HF Jr, Mehrotra A, Giboney P. Los Angeles safety-net program eConsult system was rapidly adopted and decreased wait times to see specialists. Health Aff. 2017;36:492-499.

13. Malagrino GD, Chaudhry R, Gardner M, et al. A study of 6,000 electronic specialty consultations for person-centered care at The Mayo Clinic. Int J Person Centered Med. 2012;2:458-466.

14. Keely E, Liddy C, Afkham A. Utilization, benefits, and impact of an e-consultation service across diverse specialties and primary care providers. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:733-738.

15. Scherpbier-de Haan ND, van Gelder VA, Van Weel C, et al. Initial implementation of a web-based consultation process for patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:151-156.

16. Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case-control study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:65.

17. Liddy C, Afkham A, Drosinis P, et al. Impact of and satisfaction with a new eConsult service: a mixed methods study of primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:394-403.

18. Angstman KB, Adamson SC, Furst JW, et al. Provider satisfaction with virtual specialist consultations in a family medicine department. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2009;28:14-18.

19. McAdams M, Cannavo L, Orlander JD. A medical specialty e-consult program in a VA health care system. Fed Pract. 2014; 31:26–31.

20. Keely E, Williams R, Epstein G, et al. Specialist perspectives on Ontario Provincial electronic consultation services. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25:3-10.

21. Kim-Hwang JE, Chen AH, Bell DS, et al. Evaluating electronic referrals for specialty care at a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1123-1128.

From the Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, Orange, CA.

Abstract

Background: Orange County’s residents have difficulty accessing timely, quality, affordable specialty care services. As the county’s only academic health system, the University of California, Irvine (UCI) aimed to improve specialty care access for the communities it serves by implementing an electronic consultations (eConsults) program that allows primary care providers (PCPs) to efficiently receive specialist recommendations on referral problems that do not require an in-person evaluation.

Objective: To implement an eConsults program at the UCI that enhances access to and the delivery of coordinated specialty care for lower-complexity referral problems.

Methods: We developed custom solutions to integrate eConsults into UCI’s 2 electronic health record platforms. The impact of the eConsults program was assessed by continuously evaluating usage and outcomes. Measures used to track usage included the number of submitted eConsult requests per PCP, the number of completed responses per specialty, and the response time for eConsult requests. Outcome measures included the specialist recommendation (eg, in-office visit, consultation avoided) and physician feedback.

Results: Over 4.5 years, more than 1400 successful eConsults have been completed, and the program has expanded to 17 specialties. The average turnaround time for an eConsult response across all specialties was 1 business day. Moreover, more than 50% of the eConsults received specialty responses within the same day of the eConsult request. Most important, about 80% of eConsult requests were addressed without the need for an in-office visit with a specialist.

Conclusion: The enhanced access to and the delivery of coordinated specialty care provided by eConsults resulted in improved efficiency and specialty access, while likely reducing costs and improving patient satisfaction. The improved communication and collaboration among providers with eConsults has also led to overwhelmingly positive feedback from both PCPs and specialists.

Keywords: electronic consultation; access to care; primary care; specialty referral; telehealth.

Orange County’s growing, aging, and diverse population is driving an increased demand for health care.1 But with the county’s high cost of living and worsening shortage of physicians,1-3 many of its residents are struggling to access timely, quality, affordable care. Access to specialty care services is especially frustrating for many patients and their providers, both primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists, due to problems with the referral process. Many patients experience increased wait times for a visit with a specialist due to poor communication between providers, insufficient guidance on the information or diagnostic results needed by specialists, and lack of care coordination.4-6 One promising approach to overcome these challenges is the use of an electronic consultation, or eConsult, in place of a standard in-person referral. An eConsult is an asynchronous, non-face-to-face, provider-to-provider exchange using a secure electronic communication platform. For appropriate referral problems, the patient is able to receive timely access to specialist expertise through electronic referral by their PCP,7-9 and avoid the time and costs associated with a visit to the specialist,10,11 such as travel, missed work, co-pays, and child-care expenses. Clinical questions addressed using an eConsult system subsequently free up office visit appointment slots, improving access for patients requiring in-office evaluation.8,12

Orange County’s only academic health system, the University of California, Irvine (UCI), serves a population of 3.5 million, and its principal priority is providing the communities in the county (which is the sixth largest in United States) and the surrounding region with the highest quality health care possible. Thus, UCI aimed to improve its referral processes and provide timely access to specialty care for its patients by implementing an eConsults program that allows PCPs to efficiently receive specialist recommendations on referral problems that do not require the specialist to evaluate the patient in person. This report describes our experiences with developing and implementing a custom-built eConsults workflow in UCI’s prior electronic health record (EHR) platform, Allscripts, and subsequently transitioning our mature eConsults program to a new EHR system when UCI adopted Epic. UCI is likely the only academic medical center to have experience in successfully implementing eConsults into 2 different EHR systems.

Setting

UCI’s medical center is a 417-bed acute care hospital providing tertiary and quaternary care, ambulatory and specialty medical clinics, behavioral health care, and rehabilitation services. It is located in Orange, CA, and serves a diverse population of 3.5 million persons with broad health care needs. With more than 400 specialty and primary care physicians, UCI offers a full scope of acute and general care services. It is also the primary teaching location for UCI medical and nursing students, medical residents, and fellows, and is home to Orange County’s only adult Level I and pediatric Level II trauma centers and the regional burn center.

eConsults Program

We designed the initial eConsults program within UCI’s Allscripts EHR platform. Our information technology (IT) build team developed unique “documents-based” eConsults workflows that simplified the process of initiating requests directly from the EHR and facilitated rapid responses from participating specialties. The requesting provider’s eConsults interface was user-friendly, and referring providers were able to initiate an eConsult easily by selecting the customized eConsult icon from the Allscripts main toolbar. To ensure that all relevant information is provided to the specialists, condition-specific templates are embedded in the requesting provider’s eConsults workflow that allow PCPs to enter a focused, patient-specific clinical question and provide guidance on recommended patient information (eg, health history, laboratory results, and digital images) that may help the specialist provide an informed response. The eConsult templates were adapted from standardized forms developed by partner University of California Health Systems in an initiative funded by the University of California Center for Health Quality and Innovation.

To facilitate timely responses from specialists, an innovative notification system was created in the responding provider’s eConsults workflow to automatically send an email to participating specialists when a new eConsult is requested. The responding provider’s workflow also includes an option for the specialist to decline the eConsult if the case is deemed too complex to be addressed electronically. For every completed eConsult that does not result in an in-person patient evaluation, the requesting provider and responding specialist each receives a modest reimbursement, which was initially paid by UCI Health System funds.

Implementation

The design and implementation of the eConsults program began in November 2014, and was guided by a steering committee that included the chair of the department of medicine, chief medical information officer, primary care and specialty physician leads, IT build team, and a project manager. Early on, members of this committee engaged UCI leadership to affirm support for the program and obtain the IT resources needed to build the eConsults workflow. Regular steering committee meetings were established to discuss the design of the workflow, adapt the clinical content of the referral templates, and develop a provider reimbursement plan. After completion of the workflow build, the eConsults system was tested to identify failure points and obtain feedback from users. Prior to going live, the eConsults program was publicized by members of the steering committee through meetings with primary care groups and email communications. Committee members also hosted in-person training and orientation sessions with PCPs and participating specialists, and distributed tip sheets summarizing the steps to complete the PCP and specialist eConsult workflows.

The eConsults workflow build, testing, and launch were completed within 5 months (April 2015; Figure 1). eConsults went live in the 3 initial specialties (endocrinology, cardiology, and rheumatology) that were interested in participating in the first wave of the program. UCI’s eConsults service has subsequently expanded to 17 total specialties (allergy, cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, geriatrics, gynecology, hematology, hepatology, infectious disease, nephrology, neurology, palliative care, psychiatry, pulmonary, rheumatology, and sports medicine).

Two and half years after the eConsults program was implemented in Allscripts, UCI adopted a new EHR platform, Epic. By this time, the eConsults service had grown into a mature program with greater numbers of PCP users and submitted eConsults (Figure 2). Using our experience with the Allscripts build, our IT team was able to efficiently transition the eConsults service to the new EHR system. In contrast to the “documents-based” eConsult workflows on Allscripts, our IT team utilized an “orders-based” strategy on Epic, which followed a more traditional approach to requesting a consultation. We re-launched the service in Epic within 3 months (February 2018). However, both platforms utilized user-friendly workflows to achieve similar goals, and the program has continued to grow with respect to the number of users and eConsults.

Measurement/Analysis

The impact of the program was assessed by continuously evaluating usage and outcomes. Measures used to track usage included the number of PCP users, the number of submitted eConsult requests per PCP, and the number of requests per specialty. The response time for eConsult requests and the self-reported amount of time spent by specialists on the response were also tracked. Outcome measures included the specialist recommendation (eg, in-office visit, consultation avoided) and physician feedback. Provider satisfaction was primarily obtained by soliciting feedback from individual eConsult users.

Implementation of this eConsults program constituted a quality improvement activity and did not require Institutional Review Board review.

Results

Since the program was launched in April 2015, more than 1400 eConsults have been completed across 17 specialties (Figure 3). There were 654 completed eConsults on the Allscripts platform, and 808 eConsults have been completed using the Epic platform to date. The busiest eConsult specialties were endocrinology (receiving 276, or 19%, of the eConsults requests), hematology (receiving 249 requests, or 17%), infectious disease (receiving 244 requests, or 17% ), and cardiology (receiving 148 requests, or 10%).

The self-reported amount of time specialists spent on the response was different between the 2 EHR systems (Figure 4). On Allscripts, specialists reported that 23% of eConsults took 10 minutes or less to complete, 47% took 11 to 20 minutes, 23% took 21 to 30 minutes, and 7% took more than 30 minutes. On Epic, specialists reported that 42% of eConsults took 10 minutes or less to complete, 44% took 11 to 20 minutes, 12% took 21 to 30 minutes, and 2% took more than 30 minutes. This difference in time spent fielding eConsults likely represents the subtle nuances between Allscripts’ “documents-based” and Epic’s “orders-based” workflows.

As a result of the automated notification system that was introduced early in the eConsults implementation process on Allscripts, the specialty response times were much faster than the expected 3 business days’ turnaround goal instituted by the Center for Health Quality and Innovation initiative, regardless of the EHR platform used. In fact, the average turnaround time for an eConsult response across all specialties was 1 business day, which was similar for both EHR systems (Figure 5). Furthermore, more than 50% of the eConsults on both EHR systems received specialist responses within the same day of the eConsult request (63% on Allscripts, 54% on Epic). There was a small decrease in the percentage of same-day responses when we transitioned to Epic, likely because the functionality of an automated notification email could not be restored in Epic. Regardless, the specialty response times on Epic remained expeditious, likely because the automated notifications on Allscripts instilled good practices for the specialists, and regularly checking for new eConsult requests became an ingrained behavior.

Our most important finding was that approximately 80% of eConsult requests were addressed without the need for an in-office visit with a specialist. This measure was similar for both EHR platforms (83% on Allscripts and 78% on Epic).

Provider feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. PCPs are impressed with the robust educational content of the eConsult responses, since the goal for specialists is to justify their recommendations. Specialists appreciate the convenience and efficiency that eConsults offer, as well as the improved communication and collaboration among physicians. eConsults have been especially beneficial to PCPs at UCI’s Family Health Centers, who are now able to receive subspecialty consultations from UCI specialists despite insurance barriers.

Discussion

Our eConsults program uniquely contrasts with other programs because UCI is likely the only academic medical center to have experience in successfully incorporating eConsults into 2 different EHR systems: initial development of the eConsults workflow in UCI’s existing Allscripts EHR platform, and subsequently transitioning a mature eConsults program to a new EHR system when the institution adopted Epic.

We measured the impact of the eConsults program on access to care by the response time for eConsult requests and the percentage of eConsults that averted an in-office visit with a specialist. We found that the eConsults program at UCI provided our PCPs access to specialist consultations in a timely manner, with much shorter response times than standard in-person referrals. The average turnaround time for an eConsult response we reported is consistent with findings from other studies.12-15 Additionally, our program was able to address about 80% of its eConsults electronically, helping to reduce unnecessary in-person specialist referrals. In the literature, the percentage of eConsults that avoided an in-person specialist visit varies widely.8,12-16

We reported very positive feedback from both PCPs and specialists on UCI’s eConsults service. Similarly, other studies described PCP satisfaction with their respective eConsults programs to be uniformly high,8,9,13,14,17-19 though some reported that the level of satisfaction among specialists was more varied.18-21

Lessons Learned

The successful design and implementation of our eConsults program began with assembling the right clinical champions and technology partners for our steering committee. Establishing regular steering committee meetings helped maintain an appropriate timeline for completion of different aspects of the project. Engaging support from UCI’s leadership also provided us with a dedicated IT team that helped us with the build, training resources, troubleshooting issues, and reporting for the project.

Our experience with implementing the eConsults program on 2 different EHR systems highlighted the importance of creating efficient, user-friendly workflows to foster provider adoption and achieve sustainability. Allscripts’ open platform gave our IT team the ability to create a homegrown solution to implementing an eConsult model that was simple and easy to use. The Epic platform’s interoperability allowed us to leverage our learnings from the Allscripts build to efficiently implement eConsults in Epic.

We also found that providing modest incentive payments or reimbursements to both PCPs and specialists for each completed eConsult helps with both adoption and program sustainability. Initially, credit for the eConsult work was paid by internal UCI Health System funds. Two payers, UC Care (a preferred provider organization plan created just for the University of California) and more recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, have agreed to reimburse for outpatient eConsults. Securing additional payers for reimbursement of the eConsult service will not only ensure the program’s long-term sustainability, but also represents an acknowledgment of the value of eConsults in supporting access to care.

Applicability

Other health care settings that are experiencing issues with specialty care access can successfully implement their own eConsults program by employing strategies similar to those described in this report—assembling the right team, creating user-friendly workflows, and providing incentives. Our advice for successful implementation is to clearly communicate your goals to all involved, including primary care, specialists, leadership, and IT partners, and establish with these stakeholders the appropriate support and resources needed to facilitate the development of the program and overcome any barriers to adoption.

Current Status and Future Directions

Our future plans include continuing to optimize the Epic eConsult backend build and workflows using our experience in Allscripts. We have implemented eConsult workflows for use by graduate medical education trainees and advanced practice providers, with attending supervision. Further work is in progress to optimize these workflows, which will allow for appropriate education and supervision without delaying care. Furthermore, we plan to expand the program to include inpatient-to-inpatient and emergency department-to-inpatient eConsults. We will continue to expand the eConsults program by offering additional specialties, engage providers to encourage ongoing participation, and maximize PCP use by continuing to market the program through regular newsletters and email communications. Finally, the eConsults has served as an effective, important resource in the current era of COVID-19 in several ways: it allows for optimization of specialty input in patient care delivery without subjecting more health care workers to unnecessary exposure; saves on utilization of precious personal protective equipment; and enhances our ability to deal with a potential surge by providing access to specialists remotely and electronically all hours of the day, thus expanding care to the evening and weekend hours.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank our steering committee members (Dr. Ralph Cygan, Dr. Andrew Reikes, Dr. Byron Allen, Dr. George Lawry) and IT build team (Lori Bocchicchio, Meghan van Witsen, Jaymee Zillgitt, Tanya Sickles, Dennis Hoang, Jeanette Lisak-Phillips) for their contributions in the design and implementation of our eConsults program. We also thank additional team members Kurt McArthur and Neaktisia Lee for their assistance with generating reports, and Kathy LaPierre, Jennifer Rios, and Debra Webb Torres for their guidance with compliance and billing issues.

Corresponding author: Alpesh N. Amin, MD, MBA, University of California, Irvine, 101 The City Drive South, Building 26, Room 1000, ZC-4076H, Orange, CA 92868; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, Orange, CA.

Abstract

Background: Orange County’s residents have difficulty accessing timely, quality, affordable specialty care services. As the county’s only academic health system, the University of California, Irvine (UCI) aimed to improve specialty care access for the communities it serves by implementing an electronic consultations (eConsults) program that allows primary care providers (PCPs) to efficiently receive specialist recommendations on referral problems that do not require an in-person evaluation.

Objective: To implement an eConsults program at the UCI that enhances access to and the delivery of coordinated specialty care for lower-complexity referral problems.

Methods: We developed custom solutions to integrate eConsults into UCI’s 2 electronic health record platforms. The impact of the eConsults program was assessed by continuously evaluating usage and outcomes. Measures used to track usage included the number of submitted eConsult requests per PCP, the number of completed responses per specialty, and the response time for eConsult requests. Outcome measures included the specialist recommendation (eg, in-office visit, consultation avoided) and physician feedback.

Results: Over 4.5 years, more than 1400 successful eConsults have been completed, and the program has expanded to 17 specialties. The average turnaround time for an eConsult response across all specialties was 1 business day. Moreover, more than 50% of the eConsults received specialty responses within the same day of the eConsult request. Most important, about 80% of eConsult requests were addressed without the need for an in-office visit with a specialist.

Conclusion: The enhanced access to and the delivery of coordinated specialty care provided by eConsults resulted in improved efficiency and specialty access, while likely reducing costs and improving patient satisfaction. The improved communication and collaboration among providers with eConsults has also led to overwhelmingly positive feedback from both PCPs and specialists.

Keywords: electronic consultation; access to care; primary care; specialty referral; telehealth.

Orange County’s growing, aging, and diverse population is driving an increased demand for health care.1 But with the county’s high cost of living and worsening shortage of physicians,1-3 many of its residents are struggling to access timely, quality, affordable care. Access to specialty care services is especially frustrating for many patients and their providers, both primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists, due to problems with the referral process. Many patients experience increased wait times for a visit with a specialist due to poor communication between providers, insufficient guidance on the information or diagnostic results needed by specialists, and lack of care coordination.4-6 One promising approach to overcome these challenges is the use of an electronic consultation, or eConsult, in place of a standard in-person referral. An eConsult is an asynchronous, non-face-to-face, provider-to-provider exchange using a secure electronic communication platform. For appropriate referral problems, the patient is able to receive timely access to specialist expertise through electronic referral by their PCP,7-9 and avoid the time and costs associated with a visit to the specialist,10,11 such as travel, missed work, co-pays, and child-care expenses. Clinical questions addressed using an eConsult system subsequently free up office visit appointment slots, improving access for patients requiring in-office evaluation.8,12

Orange County’s only academic health system, the University of California, Irvine (UCI), serves a population of 3.5 million, and its principal priority is providing the communities in the county (which is the sixth largest in United States) and the surrounding region with the highest quality health care possible. Thus, UCI aimed to improve its referral processes and provide timely access to specialty care for its patients by implementing an eConsults program that allows PCPs to efficiently receive specialist recommendations on referral problems that do not require the specialist to evaluate the patient in person. This report describes our experiences with developing and implementing a custom-built eConsults workflow in UCI’s prior electronic health record (EHR) platform, Allscripts, and subsequently transitioning our mature eConsults program to a new EHR system when UCI adopted Epic. UCI is likely the only academic medical center to have experience in successfully implementing eConsults into 2 different EHR systems.

Setting

UCI’s medical center is a 417-bed acute care hospital providing tertiary and quaternary care, ambulatory and specialty medical clinics, behavioral health care, and rehabilitation services. It is located in Orange, CA, and serves a diverse population of 3.5 million persons with broad health care needs. With more than 400 specialty and primary care physicians, UCI offers a full scope of acute and general care services. It is also the primary teaching location for UCI medical and nursing students, medical residents, and fellows, and is home to Orange County’s only adult Level I and pediatric Level II trauma centers and the regional burn center.

eConsults Program

We designed the initial eConsults program within UCI’s Allscripts EHR platform. Our information technology (IT) build team developed unique “documents-based” eConsults workflows that simplified the process of initiating requests directly from the EHR and facilitated rapid responses from participating specialties. The requesting provider’s eConsults interface was user-friendly, and referring providers were able to initiate an eConsult easily by selecting the customized eConsult icon from the Allscripts main toolbar. To ensure that all relevant information is provided to the specialists, condition-specific templates are embedded in the requesting provider’s eConsults workflow that allow PCPs to enter a focused, patient-specific clinical question and provide guidance on recommended patient information (eg, health history, laboratory results, and digital images) that may help the specialist provide an informed response. The eConsult templates were adapted from standardized forms developed by partner University of California Health Systems in an initiative funded by the University of California Center for Health Quality and Innovation.

To facilitate timely responses from specialists, an innovative notification system was created in the responding provider’s eConsults workflow to automatically send an email to participating specialists when a new eConsult is requested. The responding provider’s workflow also includes an option for the specialist to decline the eConsult if the case is deemed too complex to be addressed electronically. For every completed eConsult that does not result in an in-person patient evaluation, the requesting provider and responding specialist each receives a modest reimbursement, which was initially paid by UCI Health System funds.

Implementation

The design and implementation of the eConsults program began in November 2014, and was guided by a steering committee that included the chair of the department of medicine, chief medical information officer, primary care and specialty physician leads, IT build team, and a project manager. Early on, members of this committee engaged UCI leadership to affirm support for the program and obtain the IT resources needed to build the eConsults workflow. Regular steering committee meetings were established to discuss the design of the workflow, adapt the clinical content of the referral templates, and develop a provider reimbursement plan. After completion of the workflow build, the eConsults system was tested to identify failure points and obtain feedback from users. Prior to going live, the eConsults program was publicized by members of the steering committee through meetings with primary care groups and email communications. Committee members also hosted in-person training and orientation sessions with PCPs and participating specialists, and distributed tip sheets summarizing the steps to complete the PCP and specialist eConsult workflows.

The eConsults workflow build, testing, and launch were completed within 5 months (April 2015; Figure 1). eConsults went live in the 3 initial specialties (endocrinology, cardiology, and rheumatology) that were interested in participating in the first wave of the program. UCI’s eConsults service has subsequently expanded to 17 total specialties (allergy, cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, geriatrics, gynecology, hematology, hepatology, infectious disease, nephrology, neurology, palliative care, psychiatry, pulmonary, rheumatology, and sports medicine).

Two and half years after the eConsults program was implemented in Allscripts, UCI adopted a new EHR platform, Epic. By this time, the eConsults service had grown into a mature program with greater numbers of PCP users and submitted eConsults (Figure 2). Using our experience with the Allscripts build, our IT team was able to efficiently transition the eConsults service to the new EHR system. In contrast to the “documents-based” eConsult workflows on Allscripts, our IT team utilized an “orders-based” strategy on Epic, which followed a more traditional approach to requesting a consultation. We re-launched the service in Epic within 3 months (February 2018). However, both platforms utilized user-friendly workflows to achieve similar goals, and the program has continued to grow with respect to the number of users and eConsults.

Measurement/Analysis

The impact of the program was assessed by continuously evaluating usage and outcomes. Measures used to track usage included the number of PCP users, the number of submitted eConsult requests per PCP, and the number of requests per specialty. The response time for eConsult requests and the self-reported amount of time spent by specialists on the response were also tracked. Outcome measures included the specialist recommendation (eg, in-office visit, consultation avoided) and physician feedback. Provider satisfaction was primarily obtained by soliciting feedback from individual eConsult users.

Implementation of this eConsults program constituted a quality improvement activity and did not require Institutional Review Board review.

Results

Since the program was launched in April 2015, more than 1400 eConsults have been completed across 17 specialties (Figure 3). There were 654 completed eConsults on the Allscripts platform, and 808 eConsults have been completed using the Epic platform to date. The busiest eConsult specialties were endocrinology (receiving 276, or 19%, of the eConsults requests), hematology (receiving 249 requests, or 17%), infectious disease (receiving 244 requests, or 17% ), and cardiology (receiving 148 requests, or 10%).

The self-reported amount of time specialists spent on the response was different between the 2 EHR systems (Figure 4). On Allscripts, specialists reported that 23% of eConsults took 10 minutes or less to complete, 47% took 11 to 20 minutes, 23% took 21 to 30 minutes, and 7% took more than 30 minutes. On Epic, specialists reported that 42% of eConsults took 10 minutes or less to complete, 44% took 11 to 20 minutes, 12% took 21 to 30 minutes, and 2% took more than 30 minutes. This difference in time spent fielding eConsults likely represents the subtle nuances between Allscripts’ “documents-based” and Epic’s “orders-based” workflows.

As a result of the automated notification system that was introduced early in the eConsults implementation process on Allscripts, the specialty response times were much faster than the expected 3 business days’ turnaround goal instituted by the Center for Health Quality and Innovation initiative, regardless of the EHR platform used. In fact, the average turnaround time for an eConsult response across all specialties was 1 business day, which was similar for both EHR systems (Figure 5). Furthermore, more than 50% of the eConsults on both EHR systems received specialist responses within the same day of the eConsult request (63% on Allscripts, 54% on Epic). There was a small decrease in the percentage of same-day responses when we transitioned to Epic, likely because the functionality of an automated notification email could not be restored in Epic. Regardless, the specialty response times on Epic remained expeditious, likely because the automated notifications on Allscripts instilled good practices for the specialists, and regularly checking for new eConsult requests became an ingrained behavior.

Our most important finding was that approximately 80% of eConsult requests were addressed without the need for an in-office visit with a specialist. This measure was similar for both EHR platforms (83% on Allscripts and 78% on Epic).

Provider feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. PCPs are impressed with the robust educational content of the eConsult responses, since the goal for specialists is to justify their recommendations. Specialists appreciate the convenience and efficiency that eConsults offer, as well as the improved communication and collaboration among physicians. eConsults have been especially beneficial to PCPs at UCI’s Family Health Centers, who are now able to receive subspecialty consultations from UCI specialists despite insurance barriers.

Discussion

Our eConsults program uniquely contrasts with other programs because UCI is likely the only academic medical center to have experience in successfully incorporating eConsults into 2 different EHR systems: initial development of the eConsults workflow in UCI’s existing Allscripts EHR platform, and subsequently transitioning a mature eConsults program to a new EHR system when the institution adopted Epic.

We measured the impact of the eConsults program on access to care by the response time for eConsult requests and the percentage of eConsults that averted an in-office visit with a specialist. We found that the eConsults program at UCI provided our PCPs access to specialist consultations in a timely manner, with much shorter response times than standard in-person referrals. The average turnaround time for an eConsult response we reported is consistent with findings from other studies.12-15 Additionally, our program was able to address about 80% of its eConsults electronically, helping to reduce unnecessary in-person specialist referrals. In the literature, the percentage of eConsults that avoided an in-person specialist visit varies widely.8,12-16

We reported very positive feedback from both PCPs and specialists on UCI’s eConsults service. Similarly, other studies described PCP satisfaction with their respective eConsults programs to be uniformly high,8,9,13,14,17-19 though some reported that the level of satisfaction among specialists was more varied.18-21

Lessons Learned

The successful design and implementation of our eConsults program began with assembling the right clinical champions and technology partners for our steering committee. Establishing regular steering committee meetings helped maintain an appropriate timeline for completion of different aspects of the project. Engaging support from UCI’s leadership also provided us with a dedicated IT team that helped us with the build, training resources, troubleshooting issues, and reporting for the project.

Our experience with implementing the eConsults program on 2 different EHR systems highlighted the importance of creating efficient, user-friendly workflows to foster provider adoption and achieve sustainability. Allscripts’ open platform gave our IT team the ability to create a homegrown solution to implementing an eConsult model that was simple and easy to use. The Epic platform’s interoperability allowed us to leverage our learnings from the Allscripts build to efficiently implement eConsults in Epic.

We also found that providing modest incentive payments or reimbursements to both PCPs and specialists for each completed eConsult helps with both adoption and program sustainability. Initially, credit for the eConsult work was paid by internal UCI Health System funds. Two payers, UC Care (a preferred provider organization plan created just for the University of California) and more recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, have agreed to reimburse for outpatient eConsults. Securing additional payers for reimbursement of the eConsult service will not only ensure the program’s long-term sustainability, but also represents an acknowledgment of the value of eConsults in supporting access to care.

Applicability

Other health care settings that are experiencing issues with specialty care access can successfully implement their own eConsults program by employing strategies similar to those described in this report—assembling the right team, creating user-friendly workflows, and providing incentives. Our advice for successful implementation is to clearly communicate your goals to all involved, including primary care, specialists, leadership, and IT partners, and establish with these stakeholders the appropriate support and resources needed to facilitate the development of the program and overcome any barriers to adoption.

Current Status and Future Directions

Our future plans include continuing to optimize the Epic eConsult backend build and workflows using our experience in Allscripts. We have implemented eConsult workflows for use by graduate medical education trainees and advanced practice providers, with attending supervision. Further work is in progress to optimize these workflows, which will allow for appropriate education and supervision without delaying care. Furthermore, we plan to expand the program to include inpatient-to-inpatient and emergency department-to-inpatient eConsults. We will continue to expand the eConsults program by offering additional specialties, engage providers to encourage ongoing participation, and maximize PCP use by continuing to market the program through regular newsletters and email communications. Finally, the eConsults has served as an effective, important resource in the current era of COVID-19 in several ways: it allows for optimization of specialty input in patient care delivery without subjecting more health care workers to unnecessary exposure; saves on utilization of precious personal protective equipment; and enhances our ability to deal with a potential surge by providing access to specialists remotely and electronically all hours of the day, thus expanding care to the evening and weekend hours.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank our steering committee members (Dr. Ralph Cygan, Dr. Andrew Reikes, Dr. Byron Allen, Dr. George Lawry) and IT build team (Lori Bocchicchio, Meghan van Witsen, Jaymee Zillgitt, Tanya Sickles, Dennis Hoang, Jeanette Lisak-Phillips) for their contributions in the design and implementation of our eConsults program. We also thank additional team members Kurt McArthur and Neaktisia Lee for their assistance with generating reports, and Kathy LaPierre, Jennifer Rios, and Debra Webb Torres for their guidance with compliance and billing issues.

Corresponding author: Alpesh N. Amin, MD, MBA, University of California, Irvine, 101 The City Drive South, Building 26, Room 1000, ZC-4076H, Orange, CA 92868; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. County of Orange, Health Care Agency, Public Health Services. Orange County Health Profile 2013.

2. Coffman JM, Fix M Ko, M. California physician supply and distribution: headed for a drought? California Health Care Foundation, June 2018.

3. Spetz J, Coffman J, Geyn I. California’s primary care workforce: forecasted supply, demand, and pipeline of trainees, 2016-2030. Healthforce Center at the University of California, San Francisco, August 2017.

4. Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M, et al. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:626-631.

5. McPhee SJ, Lo B, Saika GY, Meltzer R. How good is communication between primary care physicians and subspecialty consultants? Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1265-1268.

6. Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011;89:39-68.

7. Wrenn K, Catschegn S, Cruz M, et al. Analysis of an electronic consultation program at an academic medical centre: Primary care provider questions, specialist responses, and primary care provider actions. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23: 217-224.

8. Gleason N, Prasad PA, Ackerman S, et al. Adoption and impact of an eConsult system in a fee-for-service setting. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5(1-2):40-45.

9. Stoves J, Connolly J, Cheung CK, et al. Electronic consultation as an alternative to hospital referral for patients with chronic kidney disease: a novel application for networked electronic health records to improve the accessibility and efficiency of healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19: e54.

10. Datta SK, Warshaw EM, Edison KE, et al. Cost and utility analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology referral system: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1323-1329.

11. Liddy C, Drosinis P, Deri Armstrong C, et al. What are the cost savings associated with providing access to specialist care through the Champlain BASE eConsult service? A costing evaluation. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010920.

12. Barnett ML, Yee HF Jr, Mehrotra A, Giboney P. Los Angeles safety-net program eConsult system was rapidly adopted and decreased wait times to see specialists. Health Aff. 2017;36:492-499.

13. Malagrino GD, Chaudhry R, Gardner M, et al. A study of 6,000 electronic specialty consultations for person-centered care at The Mayo Clinic. Int J Person Centered Med. 2012;2:458-466.

14. Keely E, Liddy C, Afkham A. Utilization, benefits, and impact of an e-consultation service across diverse specialties and primary care providers. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:733-738.

15. Scherpbier-de Haan ND, van Gelder VA, Van Weel C, et al. Initial implementation of a web-based consultation process for patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:151-156.

16. Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case-control study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:65.

17. Liddy C, Afkham A, Drosinis P, et al. Impact of and satisfaction with a new eConsult service: a mixed methods study of primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:394-403.

18. Angstman KB, Adamson SC, Furst JW, et al. Provider satisfaction with virtual specialist consultations in a family medicine department. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2009;28:14-18.

19. McAdams M, Cannavo L, Orlander JD. A medical specialty e-consult program in a VA health care system. Fed Pract. 2014; 31:26–31.

20. Keely E, Williams R, Epstein G, et al. Specialist perspectives on Ontario Provincial electronic consultation services. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25:3-10.

21. Kim-Hwang JE, Chen AH, Bell DS, et al. Evaluating electronic referrals for specialty care at a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1123-1128.

1. County of Orange, Health Care Agency, Public Health Services. Orange County Health Profile 2013.

2. Coffman JM, Fix M Ko, M. California physician supply and distribution: headed for a drought? California Health Care Foundation, June 2018.

3. Spetz J, Coffman J, Geyn I. California’s primary care workforce: forecasted supply, demand, and pipeline of trainees, 2016-2030. Healthforce Center at the University of California, San Francisco, August 2017.

4. Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M, et al. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:626-631.

5. McPhee SJ, Lo B, Saika GY, Meltzer R. How good is communication between primary care physicians and subspecialty consultants? Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1265-1268.

6. Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011;89:39-68.

7. Wrenn K, Catschegn S, Cruz M, et al. Analysis of an electronic consultation program at an academic medical centre: Primary care provider questions, specialist responses, and primary care provider actions. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23: 217-224.

8. Gleason N, Prasad PA, Ackerman S, et al. Adoption and impact of an eConsult system in a fee-for-service setting. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5(1-2):40-45.

9. Stoves J, Connolly J, Cheung CK, et al. Electronic consultation as an alternative to hospital referral for patients with chronic kidney disease: a novel application for networked electronic health records to improve the accessibility and efficiency of healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19: e54.

10. Datta SK, Warshaw EM, Edison KE, et al. Cost and utility analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology referral system: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1323-1329.

11. Liddy C, Drosinis P, Deri Armstrong C, et al. What are the cost savings associated with providing access to specialist care through the Champlain BASE eConsult service? A costing evaluation. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010920.

12. Barnett ML, Yee HF Jr, Mehrotra A, Giboney P. Los Angeles safety-net program eConsult system was rapidly adopted and decreased wait times to see specialists. Health Aff. 2017;36:492-499.

13. Malagrino GD, Chaudhry R, Gardner M, et al. A study of 6,000 electronic specialty consultations for person-centered care at The Mayo Clinic. Int J Person Centered Med. 2012;2:458-466.

14. Keely E, Liddy C, Afkham A. Utilization, benefits, and impact of an e-consultation service across diverse specialties and primary care providers. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:733-738.

15. Scherpbier-de Haan ND, van Gelder VA, Van Weel C, et al. Initial implementation of a web-based consultation process for patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:151-156.

16. Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case-control study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:65.

17. Liddy C, Afkham A, Drosinis P, et al. Impact of and satisfaction with a new eConsult service: a mixed methods study of primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:394-403.

18. Angstman KB, Adamson SC, Furst JW, et al. Provider satisfaction with virtual specialist consultations in a family medicine department. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2009;28:14-18.

19. McAdams M, Cannavo L, Orlander JD. A medical specialty e-consult program in a VA health care system. Fed Pract. 2014; 31:26–31.

20. Keely E, Williams R, Epstein G, et al. Specialist perspectives on Ontario Provincial electronic consultation services. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25:3-10.

21. Kim-Hwang JE, Chen AH, Bell DS, et al. Evaluating electronic referrals for specialty care at a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1123-1128.

Framingham risk score may also predict cognitive decline

“In the absence of effective treatments for dementia, we need to monitor and control cardiovascular risk burden as a way to maintain patient’s cognitive health as they age,” said Weili Xu, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, China, in a press release.

“Given the progressive increase in the number of dementia cases worldwide, our findings have both clinical and public health relevance.”

Dr. Xu and first author Ruixue Song, MSc, also from Tianjin Medical University, published their findings online ahead of print May 18 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The World Health Organization projects that up to 82 million people will have dementia by 2050. Given the lack of effective treatments for dementia, identifying modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and aggressively managing them is an increasingly appealing strategy.

Assessing cardiovascular risk and cognition

The researchers followed 1,588 dementia-free participants from the Rush Memory and Aging Project for 21 years (median, 5.8 years). FGCRS was assessed at baseline and categorized into tertiles (lowest, middle, and highest). Mean age of the studied population was 79.5 years, 75.8% of participants were female, and mean Framingham score was 15.6 (range, 4 to 28).

Annual evaluations included assessment of episodic memory (memory of everyday events), semantic memory (long-term memory), working memory (short-term memory), visuospatial ability (capacity to identify visual and spatial relationships among objects), and perceptual speed (ability to accurately and completely compare letters, numbers, objects, pictures, or patterns) using 19 tests to derive a composite score.

A subsample (n = 378) of participants underwent MRI, and structural total and regional brain volumes were estimated.

Linear regression was used to estimate beta-coefficients for the relationship between cardiovascular risk burden at baseline and longitudinally. If the beta-coefficient is negative, the interpretation is that for every 1-unit increase in the predictor variable (FGCRS), the outcome variable (cognitive function) will decrease by the beta-coefficient value.

At baseline, higher FGCRS was related to small but consistent (although not usually statistically significant) decreases in hippocampal volume, gray matter, and total brain volume.

Considered longitudinally, participants in the highest-risk tertile of FGCRS experienced faster decline in global cognition (beta = −0.019), episodic memory (beta = −0.023), working memory (beta = −0.021), and perceptual speed (beta = −0.027) during follow-up (P < .05 for all) than those in the lowest-risk tertile.

The declines in semantic memory (beta = –0.012) and visuospatial ability (beta = –0.010) did not reach statistical significance.

Bringing dementia prevention into the exam room early

Commenting on the research, Costantino Iadecola, MD, director of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, said the study has immediate clinical usefulness.

“The link between the cardiovascular risk factors and dementia is well known, but in your doctor’s office, that link is not seen. If your GP or cardiologist sees you with high blood pressure, he’s not immediately going to think about the risk of dementia 20 years later,” said Dr. Iadecola.

“What this study does is it directly links a simple score that’s commonly used to assess cardiovascular risk to dementia risk, which can be used to counsel patients and, hopefully, reduce the risk of both cardiovascular disease and cognitive disorders.”

Dr. Iadecola wrote an editorial together with Neal S. Parikh, MD, MS, also from Weill Cornell Medicine, that accompanied the findings of the trial.

Even neurologists sometimes fail to make the connection between vascular risk and dementia, he said. “They think that by making a stroke patient move their hand better, they’re treating them, but 30% of stroke patients get dementia 6 or 8 months later and they’re missing this link between cerebrovascular pathology and dementia.

Dr. Iadecola is one of 26 experts who authored the recent Berlin Manifesto, an effort led by Vladimir Hachinski, MD, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Western University in Ontario, Canada, to raise awareness of the link between cardiovascular and brain health.

Dr. Hachinski coined the term “brain attack” and devised the Hachinski Ischemic Score that remains the standard for identifying a vascular component of cognitive impairment.

The current study has some strengths and limitations, noted Dr. Iadecola. The average age of participants was 80 years, which is appropriate given the high risk for cognitive decline at this age, but the generalizability of the study may be limited given that most participants were white women.

Going forward, he said, rigorous studies are needed to confirm these findings and to determine how to best prevent dementia through treatment of individual cardiovascular risk factors.

Dr. Xu has received grants from nonindustry entities, including the Swedish Research Council and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The study was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 320230 research and innovation program. Dr. Iadecola is a member of the scientific advisory board for Broadview Ventures.

This article appeared on Medscape.com.

“In the absence of effective treatments for dementia, we need to monitor and control cardiovascular risk burden as a way to maintain patient’s cognitive health as they age,” said Weili Xu, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, China, in a press release.

“Given the progressive increase in the number of dementia cases worldwide, our findings have both clinical and public health relevance.”

Dr. Xu and first author Ruixue Song, MSc, also from Tianjin Medical University, published their findings online ahead of print May 18 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The World Health Organization projects that up to 82 million people will have dementia by 2050. Given the lack of effective treatments for dementia, identifying modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and aggressively managing them is an increasingly appealing strategy.

Assessing cardiovascular risk and cognition

The researchers followed 1,588 dementia-free participants from the Rush Memory and Aging Project for 21 years (median, 5.8 years). FGCRS was assessed at baseline and categorized into tertiles (lowest, middle, and highest). Mean age of the studied population was 79.5 years, 75.8% of participants were female, and mean Framingham score was 15.6 (range, 4 to 28).

Annual evaluations included assessment of episodic memory (memory of everyday events), semantic memory (long-term memory), working memory (short-term memory), visuospatial ability (capacity to identify visual and spatial relationships among objects), and perceptual speed (ability to accurately and completely compare letters, numbers, objects, pictures, or patterns) using 19 tests to derive a composite score.

A subsample (n = 378) of participants underwent MRI, and structural total and regional brain volumes were estimated.

Linear regression was used to estimate beta-coefficients for the relationship between cardiovascular risk burden at baseline and longitudinally. If the beta-coefficient is negative, the interpretation is that for every 1-unit increase in the predictor variable (FGCRS), the outcome variable (cognitive function) will decrease by the beta-coefficient value.

At baseline, higher FGCRS was related to small but consistent (although not usually statistically significant) decreases in hippocampal volume, gray matter, and total brain volume.

Considered longitudinally, participants in the highest-risk tertile of FGCRS experienced faster decline in global cognition (beta = −0.019), episodic memory (beta = −0.023), working memory (beta = −0.021), and perceptual speed (beta = −0.027) during follow-up (P < .05 for all) than those in the lowest-risk tertile.

The declines in semantic memory (beta = –0.012) and visuospatial ability (beta = –0.010) did not reach statistical significance.

Bringing dementia prevention into the exam room early

Commenting on the research, Costantino Iadecola, MD, director of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, said the study has immediate clinical usefulness.