User login

Signals of gut microbiome interaction with experimental Alzheimer’s drug prompt new trial

LOS ANGELES – A single look at the gut microbiome of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) suggests an interaction between anti-inflammatory gut bacteria and long-term exposure to an investigational sigma 1 receptor agonist.

After up to 148 weeks treatment with Anavex 2-73, patients with stable or improved functional scores showed significantly higher levels of both Ruminococcaceae and Porphyromonadaceae, compared with patients who had declining function. Both bacterial families produce butyrate, an anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acid.

Conversely, poor response was associated with a low level of Verrucomicrobia, a mucin-degrading phylum thought to be important in gut homeostasis. These bacteria live mainly in the intestinal mucosa – the physical interface between the microbiome and the rest of the body.

The data, presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, represent the first microbiome measurements reported in a clinical trial of an investigational Alzheimer’s therapy. Because they come from a single sample taken from a small group in an extension study, without a baseline comparator, it’s impossible to know what these associations mean. But the findings are enough to nudge Anavex Life Sciences into adding microbiome changes to its new study of Anavex 2-73, according to Christopher Missling, PhD, president and chief executive officer of the company.

The study, ramping up now, aims to recruit 450 patients with mild AD. They will be randomized to high-dose or mid-dose Anavex 2-73 for 48 weeks. The primary outcomes are measures of cognition and function. Stool sampling at baseline and at the end of the study will be included as well, Dr. Missling said in an interview.

Anavex 2-73 is a sigma-1 receptor agonist. A chaperone protein, sigma-1 is activated in response to acute and chronic cellular stressors, several which are important in neurodegeneration. The sigma-1 receptor is found on neurons and glia in many areas of the central nervous system. It modulates several processes implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including glutamate and calcium activity, reaction to oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. There is some evidence that sigma-1 receptor activation can induce neuronal regrowth and functional recovery after stroke. It also appears to play a role in helping cells clear misfolded proteins – a pathway that makes it an attractive drug target in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases with aberrant proteins, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases.

Anavex 2-73’s phase 2 development started with a 5-week crossover trial of 32 patients. This was followed by a 52-week, open-label extension trial of 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/day orally, in which each patient was titrated to the maximum tolerated dose. The main endpoints were change on the Mini Mental State Exam and change on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living (ADCS-ADL) scale.

At 57 weeks, six patients had improved on the Mini Mental State Exam score: four with high plasma levels and two with low plasma levels, correlating to the dosage obtained. On the functional measure of activities of daily living, nine patients had improved, including five with high plasma levels, three with moderate levels, and one with a low level. One patient, with a moderate level, remained stable. The remaining 14 patients declined.

The company then enrolled 21 of the cohort in a 208-week extension trial, primarily because of patient request, Dr. Missling said. “They know they are doing better. Their families know they’re doing better. They did not want to give this up.”

Last fall, the company released 148-week functional and cognitive data confirming the initial findings: Patients with higher plasma levels (correlating with higher doses) declined about 2 points on the ADCS-ADL scale, compared with a mean decline of about 25 points among those with lower blood levels – an 88% difference in favor of treatment. Cognition scores showed a similar pattern, with the high-concentration group declining 64% less than the low-concentration group.

Sixteen patients consented to stool sampling. A sophisticated computer algorithm characterized the microbiome of each, measuring the relative abundance of phyla. Microbiome analysis wasn’t included as an endpoint in the original study design because, at that time, the idea of a connection between AD and the gut microbiome was barely on the research radar.

Things shifted dramatically in 2017, with a seminal paper finding that germ-free mice inoculated with stool from Parkinson’s patients developed Parkinson’s symptoms. This study was widely heralded as a breakthrough in the field – the first time any neurodegenerative disease had been conclusively linked to dysregulations in the human microbiome.

Last year, Vo Van Giau, PhD, of Gachon University, South Korea, and his colleagues published an extensive review of the data suggesting a similar link with Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Giau and his coauthors laid out a potential pathogenic pathway for this interaction.

“The microbiota is closely related to neurological dysfunction and plays a significant role in neuroinflammation through the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Changes in the homeostatic state of the microbiota lead to increased intestinal permeability, which may promote the translocation of bacteria and endotoxins across the epithelial barrier, inducing an immunological response associated with the production of proinflammatory cytokines. The activation of both enteric neurons and glial cells may result in various neurological disorders,” including Alzheimer’s, he wrote.

Dr. Missling said this paper, and smaller studies appearing at Alzheimer’s meetings, prompted the company to add the stool sampling as a follow-up measure.

“It’s something of great interest, we think, and deserves to be investigated.”

SOURCE: Missling C et al. AAIC 2019, Abstract 32260.

LOS ANGELES – A single look at the gut microbiome of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) suggests an interaction between anti-inflammatory gut bacteria and long-term exposure to an investigational sigma 1 receptor agonist.

After up to 148 weeks treatment with Anavex 2-73, patients with stable or improved functional scores showed significantly higher levels of both Ruminococcaceae and Porphyromonadaceae, compared with patients who had declining function. Both bacterial families produce butyrate, an anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acid.

Conversely, poor response was associated with a low level of Verrucomicrobia, a mucin-degrading phylum thought to be important in gut homeostasis. These bacteria live mainly in the intestinal mucosa – the physical interface between the microbiome and the rest of the body.

The data, presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, represent the first microbiome measurements reported in a clinical trial of an investigational Alzheimer’s therapy. Because they come from a single sample taken from a small group in an extension study, without a baseline comparator, it’s impossible to know what these associations mean. But the findings are enough to nudge Anavex Life Sciences into adding microbiome changes to its new study of Anavex 2-73, according to Christopher Missling, PhD, president and chief executive officer of the company.

The study, ramping up now, aims to recruit 450 patients with mild AD. They will be randomized to high-dose or mid-dose Anavex 2-73 for 48 weeks. The primary outcomes are measures of cognition and function. Stool sampling at baseline and at the end of the study will be included as well, Dr. Missling said in an interview.

Anavex 2-73 is a sigma-1 receptor agonist. A chaperone protein, sigma-1 is activated in response to acute and chronic cellular stressors, several which are important in neurodegeneration. The sigma-1 receptor is found on neurons and glia in many areas of the central nervous system. It modulates several processes implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including glutamate and calcium activity, reaction to oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. There is some evidence that sigma-1 receptor activation can induce neuronal regrowth and functional recovery after stroke. It also appears to play a role in helping cells clear misfolded proteins – a pathway that makes it an attractive drug target in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases with aberrant proteins, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases.

Anavex 2-73’s phase 2 development started with a 5-week crossover trial of 32 patients. This was followed by a 52-week, open-label extension trial of 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/day orally, in which each patient was titrated to the maximum tolerated dose. The main endpoints were change on the Mini Mental State Exam and change on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living (ADCS-ADL) scale.

At 57 weeks, six patients had improved on the Mini Mental State Exam score: four with high plasma levels and two with low plasma levels, correlating to the dosage obtained. On the functional measure of activities of daily living, nine patients had improved, including five with high plasma levels, three with moderate levels, and one with a low level. One patient, with a moderate level, remained stable. The remaining 14 patients declined.

The company then enrolled 21 of the cohort in a 208-week extension trial, primarily because of patient request, Dr. Missling said. “They know they are doing better. Their families know they’re doing better. They did not want to give this up.”

Last fall, the company released 148-week functional and cognitive data confirming the initial findings: Patients with higher plasma levels (correlating with higher doses) declined about 2 points on the ADCS-ADL scale, compared with a mean decline of about 25 points among those with lower blood levels – an 88% difference in favor of treatment. Cognition scores showed a similar pattern, with the high-concentration group declining 64% less than the low-concentration group.

Sixteen patients consented to stool sampling. A sophisticated computer algorithm characterized the microbiome of each, measuring the relative abundance of phyla. Microbiome analysis wasn’t included as an endpoint in the original study design because, at that time, the idea of a connection between AD and the gut microbiome was barely on the research radar.

Things shifted dramatically in 2017, with a seminal paper finding that germ-free mice inoculated with stool from Parkinson’s patients developed Parkinson’s symptoms. This study was widely heralded as a breakthrough in the field – the first time any neurodegenerative disease had been conclusively linked to dysregulations in the human microbiome.

Last year, Vo Van Giau, PhD, of Gachon University, South Korea, and his colleagues published an extensive review of the data suggesting a similar link with Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Giau and his coauthors laid out a potential pathogenic pathway for this interaction.

“The microbiota is closely related to neurological dysfunction and plays a significant role in neuroinflammation through the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Changes in the homeostatic state of the microbiota lead to increased intestinal permeability, which may promote the translocation of bacteria and endotoxins across the epithelial barrier, inducing an immunological response associated with the production of proinflammatory cytokines. The activation of both enteric neurons and glial cells may result in various neurological disorders,” including Alzheimer’s, he wrote.

Dr. Missling said this paper, and smaller studies appearing at Alzheimer’s meetings, prompted the company to add the stool sampling as a follow-up measure.

“It’s something of great interest, we think, and deserves to be investigated.”

SOURCE: Missling C et al. AAIC 2019, Abstract 32260.

LOS ANGELES – A single look at the gut microbiome of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) suggests an interaction between anti-inflammatory gut bacteria and long-term exposure to an investigational sigma 1 receptor agonist.

After up to 148 weeks treatment with Anavex 2-73, patients with stable or improved functional scores showed significantly higher levels of both Ruminococcaceae and Porphyromonadaceae, compared with patients who had declining function. Both bacterial families produce butyrate, an anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acid.

Conversely, poor response was associated with a low level of Verrucomicrobia, a mucin-degrading phylum thought to be important in gut homeostasis. These bacteria live mainly in the intestinal mucosa – the physical interface between the microbiome and the rest of the body.

The data, presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, represent the first microbiome measurements reported in a clinical trial of an investigational Alzheimer’s therapy. Because they come from a single sample taken from a small group in an extension study, without a baseline comparator, it’s impossible to know what these associations mean. But the findings are enough to nudge Anavex Life Sciences into adding microbiome changes to its new study of Anavex 2-73, according to Christopher Missling, PhD, president and chief executive officer of the company.

The study, ramping up now, aims to recruit 450 patients with mild AD. They will be randomized to high-dose or mid-dose Anavex 2-73 for 48 weeks. The primary outcomes are measures of cognition and function. Stool sampling at baseline and at the end of the study will be included as well, Dr. Missling said in an interview.

Anavex 2-73 is a sigma-1 receptor agonist. A chaperone protein, sigma-1 is activated in response to acute and chronic cellular stressors, several which are important in neurodegeneration. The sigma-1 receptor is found on neurons and glia in many areas of the central nervous system. It modulates several processes implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including glutamate and calcium activity, reaction to oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. There is some evidence that sigma-1 receptor activation can induce neuronal regrowth and functional recovery after stroke. It also appears to play a role in helping cells clear misfolded proteins – a pathway that makes it an attractive drug target in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases with aberrant proteins, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases.

Anavex 2-73’s phase 2 development started with a 5-week crossover trial of 32 patients. This was followed by a 52-week, open-label extension trial of 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/day orally, in which each patient was titrated to the maximum tolerated dose. The main endpoints were change on the Mini Mental State Exam and change on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living (ADCS-ADL) scale.

At 57 weeks, six patients had improved on the Mini Mental State Exam score: four with high plasma levels and two with low plasma levels, correlating to the dosage obtained. On the functional measure of activities of daily living, nine patients had improved, including five with high plasma levels, three with moderate levels, and one with a low level. One patient, with a moderate level, remained stable. The remaining 14 patients declined.

The company then enrolled 21 of the cohort in a 208-week extension trial, primarily because of patient request, Dr. Missling said. “They know they are doing better. Their families know they’re doing better. They did not want to give this up.”

Last fall, the company released 148-week functional and cognitive data confirming the initial findings: Patients with higher plasma levels (correlating with higher doses) declined about 2 points on the ADCS-ADL scale, compared with a mean decline of about 25 points among those with lower blood levels – an 88% difference in favor of treatment. Cognition scores showed a similar pattern, with the high-concentration group declining 64% less than the low-concentration group.

Sixteen patients consented to stool sampling. A sophisticated computer algorithm characterized the microbiome of each, measuring the relative abundance of phyla. Microbiome analysis wasn’t included as an endpoint in the original study design because, at that time, the idea of a connection between AD and the gut microbiome was barely on the research radar.

Things shifted dramatically in 2017, with a seminal paper finding that germ-free mice inoculated with stool from Parkinson’s patients developed Parkinson’s symptoms. This study was widely heralded as a breakthrough in the field – the first time any neurodegenerative disease had been conclusively linked to dysregulations in the human microbiome.

Last year, Vo Van Giau, PhD, of Gachon University, South Korea, and his colleagues published an extensive review of the data suggesting a similar link with Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Giau and his coauthors laid out a potential pathogenic pathway for this interaction.

“The microbiota is closely related to neurological dysfunction and plays a significant role in neuroinflammation through the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Changes in the homeostatic state of the microbiota lead to increased intestinal permeability, which may promote the translocation of bacteria and endotoxins across the epithelial barrier, inducing an immunological response associated with the production of proinflammatory cytokines. The activation of both enteric neurons and glial cells may result in various neurological disorders,” including Alzheimer’s, he wrote.

Dr. Missling said this paper, and smaller studies appearing at Alzheimer’s meetings, prompted the company to add the stool sampling as a follow-up measure.

“It’s something of great interest, we think, and deserves to be investigated.”

SOURCE: Missling C et al. AAIC 2019, Abstract 32260.

REPORTING FROM AAIC 2019

Sleep disorder treatment tied to lower suicide attempt risk in veterans

in a large case-control matched study of patients in the Veterans Health Administration database.

However, treatment for sleep disorders was correlated to a reduced risk for suicide attempts.

Todd M. Bishop, PhD, of the Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua (N.Y.) VA Medical Center, and the department of psychiatry, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, and his colleagues wrote that suicide is the 10th most frequent cause of death in the United States, and “nowhere is the suicide rate more alarming than among military veterans, who after adjusting for age and gender, have an approximately 1.5 times greater risk for suicide as compared to the civilian population.”

Previous research has explored the link between sleep disturbances and suicide attempts. But less has been done to look at specific sleep problems, and little research has examined the role of sleep medicine interventions and suicide attempt risk.

The investigators conducted a study to establish the association between suicide attempts and specific sleep disorders, and to examine the correlation between sleep medicine treatment and suicide attempts. Their sample consisted of 60,102 veterans who had received care within the VHA between Oct. 1, 2012, and Sept. 20, 2014. Half of the sample had a documented suicide attempt in the medical record (n = 30,051) and half did not (n = 30,051). The overall sample was predominately male (87.1%) with a mean age of 48.6 years. More than half the sample identified as white (67.4%).

Suicide attempts, sleep disturbance, and medical and mental health comorbidities were identified via ICD codes and prescription records. The predominant sleep disorders studied were insomnia, sleep-related breathing disorder (SRBD), and nightmares. The first suicide attempt in the study period was determined to be the index date for the case-control matching.

Overall, sleep disturbances were much more prevalent among cases than controls (insomnia, 46.2% vs. 12.6%), sleep-related breathing disorder (8.6% vs. 4.8%), and nightmares (7.1% vs. 1.6%). A logistic regression analysis was undertaken to examine the relationship between specific sleep disorders and suicide attempts. Insomnia, nightmares, and SRBD were each associated with increased odds of a suicide attempt with the following odds ratios: insomnia (odds ratio, 5.62; 95% confidence interval, 5.39-5.86), nightmares (OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 2.23-2.77), and sleep-related breathing disorder (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.48).

A second model included known drivers of suicide attempts (PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, medical comorbidity, and obesity). But after controlling for these factors, neither nightmares (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.85-1.09) nor sleep-related breathing disorders (OR, 0.87, 95% CI, 0.79-0.94) remained positively associated with suicide attempt, but the association of insomnia with suicide attempt was maintained (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.43-1.59).

The question of the impact of sleep medicine interventions on suicide attempts was studied with a third regression model adding the number of sleep medicine clinic visits in the 180 days prior to the suicide attempt index date as an independent variable. The variables in this model were limited to insomnia, SRBD, and nightmares. The investigators found that “for each sleep medicine clinic visit within the 6 months prior to index date the likelihood of suicide attempt is 11% less (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82-0.97).”

The limitations of the study include the lack of information on sleep treatment modalities or medications provided during the clinic visits, and the overlapping of sleep disturbance with other mental health conditions, such as alcohol dependence and PTSD. In addition, “some insomnia medications are labeled for risk of suicidal ideation and behavior, so there is some chance that the medications rather than insomnia itself were associated with the increased suicidal behavior,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to an analysis of specific types of sleep disorders associated with suicide attempts, the study showed that treatment of sleep disorders may have an important role in suicide prevention. The investigators concluded: “Identifying populations at risk for suicide prior to a first attempt is an important, but difficult task of suicide prevention. Prevention efforts can be aimed at modifiable risk factors that arise early on a patient’s trajectory toward a suicide attempt.”

The study was supported by the VISN 2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua VAMC. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bishop TM et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.07.016.

in a large case-control matched study of patients in the Veterans Health Administration database.

However, treatment for sleep disorders was correlated to a reduced risk for suicide attempts.

Todd M. Bishop, PhD, of the Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua (N.Y.) VA Medical Center, and the department of psychiatry, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, and his colleagues wrote that suicide is the 10th most frequent cause of death in the United States, and “nowhere is the suicide rate more alarming than among military veterans, who after adjusting for age and gender, have an approximately 1.5 times greater risk for suicide as compared to the civilian population.”

Previous research has explored the link between sleep disturbances and suicide attempts. But less has been done to look at specific sleep problems, and little research has examined the role of sleep medicine interventions and suicide attempt risk.

The investigators conducted a study to establish the association between suicide attempts and specific sleep disorders, and to examine the correlation between sleep medicine treatment and suicide attempts. Their sample consisted of 60,102 veterans who had received care within the VHA between Oct. 1, 2012, and Sept. 20, 2014. Half of the sample had a documented suicide attempt in the medical record (n = 30,051) and half did not (n = 30,051). The overall sample was predominately male (87.1%) with a mean age of 48.6 years. More than half the sample identified as white (67.4%).

Suicide attempts, sleep disturbance, and medical and mental health comorbidities were identified via ICD codes and prescription records. The predominant sleep disorders studied were insomnia, sleep-related breathing disorder (SRBD), and nightmares. The first suicide attempt in the study period was determined to be the index date for the case-control matching.

Overall, sleep disturbances were much more prevalent among cases than controls (insomnia, 46.2% vs. 12.6%), sleep-related breathing disorder (8.6% vs. 4.8%), and nightmares (7.1% vs. 1.6%). A logistic regression analysis was undertaken to examine the relationship between specific sleep disorders and suicide attempts. Insomnia, nightmares, and SRBD were each associated with increased odds of a suicide attempt with the following odds ratios: insomnia (odds ratio, 5.62; 95% confidence interval, 5.39-5.86), nightmares (OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 2.23-2.77), and sleep-related breathing disorder (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.48).

A second model included known drivers of suicide attempts (PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, medical comorbidity, and obesity). But after controlling for these factors, neither nightmares (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.85-1.09) nor sleep-related breathing disorders (OR, 0.87, 95% CI, 0.79-0.94) remained positively associated with suicide attempt, but the association of insomnia with suicide attempt was maintained (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.43-1.59).

The question of the impact of sleep medicine interventions on suicide attempts was studied with a third regression model adding the number of sleep medicine clinic visits in the 180 days prior to the suicide attempt index date as an independent variable. The variables in this model were limited to insomnia, SRBD, and nightmares. The investigators found that “for each sleep medicine clinic visit within the 6 months prior to index date the likelihood of suicide attempt is 11% less (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82-0.97).”

The limitations of the study include the lack of information on sleep treatment modalities or medications provided during the clinic visits, and the overlapping of sleep disturbance with other mental health conditions, such as alcohol dependence and PTSD. In addition, “some insomnia medications are labeled for risk of suicidal ideation and behavior, so there is some chance that the medications rather than insomnia itself were associated with the increased suicidal behavior,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to an analysis of specific types of sleep disorders associated with suicide attempts, the study showed that treatment of sleep disorders may have an important role in suicide prevention. The investigators concluded: “Identifying populations at risk for suicide prior to a first attempt is an important, but difficult task of suicide prevention. Prevention efforts can be aimed at modifiable risk factors that arise early on a patient’s trajectory toward a suicide attempt.”

The study was supported by the VISN 2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua VAMC. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bishop TM et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.07.016.

in a large case-control matched study of patients in the Veterans Health Administration database.

However, treatment for sleep disorders was correlated to a reduced risk for suicide attempts.

Todd M. Bishop, PhD, of the Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua (N.Y.) VA Medical Center, and the department of psychiatry, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, and his colleagues wrote that suicide is the 10th most frequent cause of death in the United States, and “nowhere is the suicide rate more alarming than among military veterans, who after adjusting for age and gender, have an approximately 1.5 times greater risk for suicide as compared to the civilian population.”

Previous research has explored the link between sleep disturbances and suicide attempts. But less has been done to look at specific sleep problems, and little research has examined the role of sleep medicine interventions and suicide attempt risk.

The investigators conducted a study to establish the association between suicide attempts and specific sleep disorders, and to examine the correlation between sleep medicine treatment and suicide attempts. Their sample consisted of 60,102 veterans who had received care within the VHA between Oct. 1, 2012, and Sept. 20, 2014. Half of the sample had a documented suicide attempt in the medical record (n = 30,051) and half did not (n = 30,051). The overall sample was predominately male (87.1%) with a mean age of 48.6 years. More than half the sample identified as white (67.4%).

Suicide attempts, sleep disturbance, and medical and mental health comorbidities were identified via ICD codes and prescription records. The predominant sleep disorders studied were insomnia, sleep-related breathing disorder (SRBD), and nightmares. The first suicide attempt in the study period was determined to be the index date for the case-control matching.

Overall, sleep disturbances were much more prevalent among cases than controls (insomnia, 46.2% vs. 12.6%), sleep-related breathing disorder (8.6% vs. 4.8%), and nightmares (7.1% vs. 1.6%). A logistic regression analysis was undertaken to examine the relationship between specific sleep disorders and suicide attempts. Insomnia, nightmares, and SRBD were each associated with increased odds of a suicide attempt with the following odds ratios: insomnia (odds ratio, 5.62; 95% confidence interval, 5.39-5.86), nightmares (OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 2.23-2.77), and sleep-related breathing disorder (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.48).

A second model included known drivers of suicide attempts (PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, medical comorbidity, and obesity). But after controlling for these factors, neither nightmares (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.85-1.09) nor sleep-related breathing disorders (OR, 0.87, 95% CI, 0.79-0.94) remained positively associated with suicide attempt, but the association of insomnia with suicide attempt was maintained (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.43-1.59).

The question of the impact of sleep medicine interventions on suicide attempts was studied with a third regression model adding the number of sleep medicine clinic visits in the 180 days prior to the suicide attempt index date as an independent variable. The variables in this model were limited to insomnia, SRBD, and nightmares. The investigators found that “for each sleep medicine clinic visit within the 6 months prior to index date the likelihood of suicide attempt is 11% less (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82-0.97).”

The limitations of the study include the lack of information on sleep treatment modalities or medications provided during the clinic visits, and the overlapping of sleep disturbance with other mental health conditions, such as alcohol dependence and PTSD. In addition, “some insomnia medications are labeled for risk of suicidal ideation and behavior, so there is some chance that the medications rather than insomnia itself were associated with the increased suicidal behavior,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to an analysis of specific types of sleep disorders associated with suicide attempts, the study showed that treatment of sleep disorders may have an important role in suicide prevention. The investigators concluded: “Identifying populations at risk for suicide prior to a first attempt is an important, but difficult task of suicide prevention. Prevention efforts can be aimed at modifiable risk factors that arise early on a patient’s trajectory toward a suicide attempt.”

The study was supported by the VISN 2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua VAMC. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bishop TM et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.07.016.

REPORTING FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

Sleep aids and dementia: Studies find both risks and benefits

LOS ANGELES – While a large number of older adults take prescription and nonprescription medications to help them sleep, the effect of these medications on dementia risk is unclear, with most researchers advocating a cautious and conservative approach to prescribing.

Research is increasingly revealing a bidirectional relationship between sleep and dementia. Poor sleep – especially from insomnia, sleep deprivation, or obstructive sleep apnea – is known to increase dementia risk. Dementias, meanwhile, are associated with serious circadian rhythm disturbances, leading to nighttime sleep loss and increasing the likelihood of institutionalization.

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, researchers presented findings assessing the links between sleep medication use and dementia and also what agents or approaches might safely improve sleep in people with sleep disorders who are at risk for dementia or who have been diagnosed with dementia.

Sex- and race-based differences in risk

Yue Leng, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, reported a link between frequent sleep medication use and later dementia – but only in white adults. Dr. Leng presented findings from the National Institutes of Health–funded Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, which recruited 3,068 subjects aged 70-79 and followed them for 15 years. At baseline, 2.7% of African Americans and 7.7% of whites in the study reported taking sleep medications “often” or “almost always.”

Dr. Leng and her colleagues found that white subjects who reported taking sleep aids five or more times a month at baseline had a nearly 80% higher risk of developing dementia during the course of the study (hazard ratio, 1.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.66), compared with people who reported never taking sleep aids or taking them less frequently.

The researchers saw no between-sex differences for this finding, and adjusted for a variety of genetic and lifestyle confounders. Importantly, no significant increase in dementia risk was seen for black subjects, who made up more than one-third of the cohort.

Dr. Leng told the conference that the researchers could not explain why black participants did not see similarly increased dementia risk. Also, she noted, researchers did not have information on the specific sleep medications people used: benzodiazepines, antihistamines, antidepressants, or other types of drugs. Nonetheless, she told the conference, the findings ratified the cautious approach many dementia experts are already stressing.

“Do we really need to prescribe so many sleep meds to older adults who are already at risk for cognitive impairment?” Dr. Leng said, adding: “I am a big advocate of behavioral sleep interventions.” People with clinical sleep problems “should be referred to sleep centers” for a fuller assessment before medication is prescribed, she said.

Findings from another cohort study, meanwhile, suggest that there could be sex-related differences in how sleep aids affect dementia risk. Investigators at Utah State University in Logan used data from some 3,656 older adults in the Cache County Study on Memory and Aging, an NIH-backed cohort study of white adults in Utah without dementia at baseline who were followed for 12 years.

The investigators, led by doctoral student Elizabeth Vernon, found that men reporting use of sleep medication saw more than threefold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than did men who did not use sleep aids (HR, 3.604; P = .0001).

Women who did not report having sleep disturbance but used sleep-inducing medications were at nearly fourfold greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 3.916; P = .0001). Women who self-reported sleep disturbances at baseline, meanwhile, saw a reduction in Alzheimer’s risk of about one-third associated with the use of sleep medications.

Ms. Vernon told the conference that, despite the finding of risk reduction for this particular group of women, caution in prescribing sleep aids was warranted.

Common sleep drugs linked to cognitive aging

Chris Fox, MD, a researcher at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, and his colleagues demonstrated in 2018 that long-term exposure to anticholinergic drugs, a class that includes some antidepressants and antihistamines used to promote sleep, was associated with a higher risk of dementia, while use of benzodiazepines, a class of sedatives used commonly in older people as sleep aids, was not. (Whether benzodiazepine exposure relates to dementia remains controversial.)

At AAIC 2019, Dr. Fox presented findings from a study of 337 brains in a U.K. brain bank, of which 17% and 21% came from users of benzodiazepines and anticholinergic drugs, whose usage history was well documented. Dr. Fox and his colleagues found that, while neither anticholinergic nor benzodiazepine exposure was associated with brain pathology specific to that seen in Alzheimer’s disease, both classes of drugs were associated with “slight signals in neuronal loss” in one brain region, the nucleus basalis of Meynert. Dr. Fox described the drugs as causing “an increase in cognitive aging” which could bear on Alzheimer’s risk without being directly causative.

Newer sleep drugs may help Alzheimer’s patients

Scientists working for drug manufacturers presented findings on agents to counter the circadian rhythm disturbances seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Margaret Moline, PhD, of Eisai in Woodcliff Lake, N.J., showed some results from a phase 2, dose-ranging, placebo-controlled study of the experimental agent lemborexant in 62 subjects aged 60-90 with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and sleep disturbances. (Lemborexant, an orexin receptor agonist that acts to regulate wakefulness, is being investigated in a broad range of sleep disorders.) Patients were randomized to one of four doses of lemborexant or placebo and wore a device for sleep monitoring. Nighttime activity indicating arousal was significantly lower for people in two dosage arms, 5 mg and 10 mg, compared with placebo, and treatment groups saw trends toward less sleep fragmentation and higher total sleep time, Dr. Moline told the conference.

Suvorexant (Belsomra), the only orexin receptor antagonist currently licensed as a sleep aid, is also being tested in people with Alzheimer’s disease. At AAIC 2019, Joseph Herring, MD, PhD, of Merck in Kenilworth, N.J., presented results from a placebo-controlled trial of 277 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and insomnia, and reported that treatment with 10 or 20 mg of suvorexant over 4 weeks was associated with about an extra half hour of total nightly sleep, with a 73-minute mean increase from baseline, compared with 45 minutes for patients receiving placebo (95% CI, 11-45; P less than .005).

Trazodone linked to slower cognitive decline

An inexpensive antidepressant used in low doses as a sleep aid, including in people with Alzheimer’s disease, was associated with a delay in cognitive decline in older adults, according to results from a retrospective study. Elissaios Karageorgiou, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the Neurological Institute of Athens presented results derived from two cohorts: patients enrolled at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center and women enrolled in the Study for Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) in Women. The investigators were able to identify trazodone users in the studies (with two or more contiguous study visits reporting trazodone use) and match them with control patients from the same cohorts who did not use trazodone.

Trazodone was studied because previous research suggests it increases total sleep time in patients with Alzheimer’s disease without affecting next-day cognitive performance.

Trazodone-using patients in the UCSF cohort (n = 25) saw significantly less decline in Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores over 4 years, compared with nonusers (0.27 vs. 0.70 points per year; P = .023), an effect that remained statistically significant even after adjusting for sedative and stimulant use and the expected progression of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Importantly, the slower decline was seen only among subjects with sleep complaints at baseline and especially those whose sleep improved over time, suggesting that the cognitive benefit was mediated by improved sleep.

In the SOF cohort of 46 trazodone users matched with 148 nonusers, no significant protective or negative effect related to long-term trazodone use was found using the MMSE or the Trails Making Test. In this analysis, however, baseline and longitudinal sleep quality was not captured in the group-matching process, neither was the use of other medications. The patient group was slightly older, and all patients were women.

Dr. Karageorgiou said in an interview that the link between improved sleep, trazodone, and cognition needs to be validated in prospective intervention studies. Trazodone, he said, appears to work best in people with a specific type of insomnia characterized by cortical and behavioral hyperarousal, and its cognitive effect appears limited to people whose sleep improves with treatment. “You’re not going to see long-term cognitive benefits if it’s not improving your sleep,” Dr. Karageorgiou said. “So, whether trazodone improves sleep or not in a patient after a few months can be an early indicator for the clinician to continue using it or suspend it, because it is unlikely to help their cognition otherwise.”

He stressed that physicians need to be broadly focused on improving sleep to help patients with, or at risk for, dementia by consolidating their sleep rhythms.

“Trazodone is not the magic bullet, and I don’t think we will ever have a magic bullet,” Dr. Karageorgiou said. “Because when our brain degenerates, it’s not just one chemical, or one system, it’s many. And our body changes as well. The important thing is to help the patient consolidate their rhythms, whether through light therapy, daily exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or other evidence-based interventions and their combination. The same applies for a person with dementia as for the rest of us.”

None of the investigators outside of the industry-sponsored studies had relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – While a large number of older adults take prescription and nonprescription medications to help them sleep, the effect of these medications on dementia risk is unclear, with most researchers advocating a cautious and conservative approach to prescribing.

Research is increasingly revealing a bidirectional relationship between sleep and dementia. Poor sleep – especially from insomnia, sleep deprivation, or obstructive sleep apnea – is known to increase dementia risk. Dementias, meanwhile, are associated with serious circadian rhythm disturbances, leading to nighttime sleep loss and increasing the likelihood of institutionalization.

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, researchers presented findings assessing the links between sleep medication use and dementia and also what agents or approaches might safely improve sleep in people with sleep disorders who are at risk for dementia or who have been diagnosed with dementia.

Sex- and race-based differences in risk

Yue Leng, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, reported a link between frequent sleep medication use and later dementia – but only in white adults. Dr. Leng presented findings from the National Institutes of Health–funded Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, which recruited 3,068 subjects aged 70-79 and followed them for 15 years. At baseline, 2.7% of African Americans and 7.7% of whites in the study reported taking sleep medications “often” or “almost always.”

Dr. Leng and her colleagues found that white subjects who reported taking sleep aids five or more times a month at baseline had a nearly 80% higher risk of developing dementia during the course of the study (hazard ratio, 1.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.66), compared with people who reported never taking sleep aids or taking them less frequently.

The researchers saw no between-sex differences for this finding, and adjusted for a variety of genetic and lifestyle confounders. Importantly, no significant increase in dementia risk was seen for black subjects, who made up more than one-third of the cohort.

Dr. Leng told the conference that the researchers could not explain why black participants did not see similarly increased dementia risk. Also, she noted, researchers did not have information on the specific sleep medications people used: benzodiazepines, antihistamines, antidepressants, or other types of drugs. Nonetheless, she told the conference, the findings ratified the cautious approach many dementia experts are already stressing.

“Do we really need to prescribe so many sleep meds to older adults who are already at risk for cognitive impairment?” Dr. Leng said, adding: “I am a big advocate of behavioral sleep interventions.” People with clinical sleep problems “should be referred to sleep centers” for a fuller assessment before medication is prescribed, she said.

Findings from another cohort study, meanwhile, suggest that there could be sex-related differences in how sleep aids affect dementia risk. Investigators at Utah State University in Logan used data from some 3,656 older adults in the Cache County Study on Memory and Aging, an NIH-backed cohort study of white adults in Utah without dementia at baseline who were followed for 12 years.

The investigators, led by doctoral student Elizabeth Vernon, found that men reporting use of sleep medication saw more than threefold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than did men who did not use sleep aids (HR, 3.604; P = .0001).

Women who did not report having sleep disturbance but used sleep-inducing medications were at nearly fourfold greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 3.916; P = .0001). Women who self-reported sleep disturbances at baseline, meanwhile, saw a reduction in Alzheimer’s risk of about one-third associated with the use of sleep medications.

Ms. Vernon told the conference that, despite the finding of risk reduction for this particular group of women, caution in prescribing sleep aids was warranted.

Common sleep drugs linked to cognitive aging

Chris Fox, MD, a researcher at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, and his colleagues demonstrated in 2018 that long-term exposure to anticholinergic drugs, a class that includes some antidepressants and antihistamines used to promote sleep, was associated with a higher risk of dementia, while use of benzodiazepines, a class of sedatives used commonly in older people as sleep aids, was not. (Whether benzodiazepine exposure relates to dementia remains controversial.)

At AAIC 2019, Dr. Fox presented findings from a study of 337 brains in a U.K. brain bank, of which 17% and 21% came from users of benzodiazepines and anticholinergic drugs, whose usage history was well documented. Dr. Fox and his colleagues found that, while neither anticholinergic nor benzodiazepine exposure was associated with brain pathology specific to that seen in Alzheimer’s disease, both classes of drugs were associated with “slight signals in neuronal loss” in one brain region, the nucleus basalis of Meynert. Dr. Fox described the drugs as causing “an increase in cognitive aging” which could bear on Alzheimer’s risk without being directly causative.

Newer sleep drugs may help Alzheimer’s patients

Scientists working for drug manufacturers presented findings on agents to counter the circadian rhythm disturbances seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Margaret Moline, PhD, of Eisai in Woodcliff Lake, N.J., showed some results from a phase 2, dose-ranging, placebo-controlled study of the experimental agent lemborexant in 62 subjects aged 60-90 with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and sleep disturbances. (Lemborexant, an orexin receptor agonist that acts to regulate wakefulness, is being investigated in a broad range of sleep disorders.) Patients were randomized to one of four doses of lemborexant or placebo and wore a device for sleep monitoring. Nighttime activity indicating arousal was significantly lower for people in two dosage arms, 5 mg and 10 mg, compared with placebo, and treatment groups saw trends toward less sleep fragmentation and higher total sleep time, Dr. Moline told the conference.

Suvorexant (Belsomra), the only orexin receptor antagonist currently licensed as a sleep aid, is also being tested in people with Alzheimer’s disease. At AAIC 2019, Joseph Herring, MD, PhD, of Merck in Kenilworth, N.J., presented results from a placebo-controlled trial of 277 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and insomnia, and reported that treatment with 10 or 20 mg of suvorexant over 4 weeks was associated with about an extra half hour of total nightly sleep, with a 73-minute mean increase from baseline, compared with 45 minutes for patients receiving placebo (95% CI, 11-45; P less than .005).

Trazodone linked to slower cognitive decline

An inexpensive antidepressant used in low doses as a sleep aid, including in people with Alzheimer’s disease, was associated with a delay in cognitive decline in older adults, according to results from a retrospective study. Elissaios Karageorgiou, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the Neurological Institute of Athens presented results derived from two cohorts: patients enrolled at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center and women enrolled in the Study for Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) in Women. The investigators were able to identify trazodone users in the studies (with two or more contiguous study visits reporting trazodone use) and match them with control patients from the same cohorts who did not use trazodone.

Trazodone was studied because previous research suggests it increases total sleep time in patients with Alzheimer’s disease without affecting next-day cognitive performance.

Trazodone-using patients in the UCSF cohort (n = 25) saw significantly less decline in Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores over 4 years, compared with nonusers (0.27 vs. 0.70 points per year; P = .023), an effect that remained statistically significant even after adjusting for sedative and stimulant use and the expected progression of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Importantly, the slower decline was seen only among subjects with sleep complaints at baseline and especially those whose sleep improved over time, suggesting that the cognitive benefit was mediated by improved sleep.

In the SOF cohort of 46 trazodone users matched with 148 nonusers, no significant protective or negative effect related to long-term trazodone use was found using the MMSE or the Trails Making Test. In this analysis, however, baseline and longitudinal sleep quality was not captured in the group-matching process, neither was the use of other medications. The patient group was slightly older, and all patients were women.

Dr. Karageorgiou said in an interview that the link between improved sleep, trazodone, and cognition needs to be validated in prospective intervention studies. Trazodone, he said, appears to work best in people with a specific type of insomnia characterized by cortical and behavioral hyperarousal, and its cognitive effect appears limited to people whose sleep improves with treatment. “You’re not going to see long-term cognitive benefits if it’s not improving your sleep,” Dr. Karageorgiou said. “So, whether trazodone improves sleep or not in a patient after a few months can be an early indicator for the clinician to continue using it or suspend it, because it is unlikely to help their cognition otherwise.”

He stressed that physicians need to be broadly focused on improving sleep to help patients with, or at risk for, dementia by consolidating their sleep rhythms.

“Trazodone is not the magic bullet, and I don’t think we will ever have a magic bullet,” Dr. Karageorgiou said. “Because when our brain degenerates, it’s not just one chemical, or one system, it’s many. And our body changes as well. The important thing is to help the patient consolidate their rhythms, whether through light therapy, daily exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or other evidence-based interventions and their combination. The same applies for a person with dementia as for the rest of us.”

None of the investigators outside of the industry-sponsored studies had relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – While a large number of older adults take prescription and nonprescription medications to help them sleep, the effect of these medications on dementia risk is unclear, with most researchers advocating a cautious and conservative approach to prescribing.

Research is increasingly revealing a bidirectional relationship between sleep and dementia. Poor sleep – especially from insomnia, sleep deprivation, or obstructive sleep apnea – is known to increase dementia risk. Dementias, meanwhile, are associated with serious circadian rhythm disturbances, leading to nighttime sleep loss and increasing the likelihood of institutionalization.

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, researchers presented findings assessing the links between sleep medication use and dementia and also what agents or approaches might safely improve sleep in people with sleep disorders who are at risk for dementia or who have been diagnosed with dementia.

Sex- and race-based differences in risk

Yue Leng, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, reported a link between frequent sleep medication use and later dementia – but only in white adults. Dr. Leng presented findings from the National Institutes of Health–funded Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, which recruited 3,068 subjects aged 70-79 and followed them for 15 years. At baseline, 2.7% of African Americans and 7.7% of whites in the study reported taking sleep medications “often” or “almost always.”

Dr. Leng and her colleagues found that white subjects who reported taking sleep aids five or more times a month at baseline had a nearly 80% higher risk of developing dementia during the course of the study (hazard ratio, 1.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.66), compared with people who reported never taking sleep aids or taking them less frequently.

The researchers saw no between-sex differences for this finding, and adjusted for a variety of genetic and lifestyle confounders. Importantly, no significant increase in dementia risk was seen for black subjects, who made up more than one-third of the cohort.

Dr. Leng told the conference that the researchers could not explain why black participants did not see similarly increased dementia risk. Also, she noted, researchers did not have information on the specific sleep medications people used: benzodiazepines, antihistamines, antidepressants, or other types of drugs. Nonetheless, she told the conference, the findings ratified the cautious approach many dementia experts are already stressing.

“Do we really need to prescribe so many sleep meds to older adults who are already at risk for cognitive impairment?” Dr. Leng said, adding: “I am a big advocate of behavioral sleep interventions.” People with clinical sleep problems “should be referred to sleep centers” for a fuller assessment before medication is prescribed, she said.

Findings from another cohort study, meanwhile, suggest that there could be sex-related differences in how sleep aids affect dementia risk. Investigators at Utah State University in Logan used data from some 3,656 older adults in the Cache County Study on Memory and Aging, an NIH-backed cohort study of white adults in Utah without dementia at baseline who were followed for 12 years.

The investigators, led by doctoral student Elizabeth Vernon, found that men reporting use of sleep medication saw more than threefold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than did men who did not use sleep aids (HR, 3.604; P = .0001).

Women who did not report having sleep disturbance but used sleep-inducing medications were at nearly fourfold greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 3.916; P = .0001). Women who self-reported sleep disturbances at baseline, meanwhile, saw a reduction in Alzheimer’s risk of about one-third associated with the use of sleep medications.

Ms. Vernon told the conference that, despite the finding of risk reduction for this particular group of women, caution in prescribing sleep aids was warranted.

Common sleep drugs linked to cognitive aging

Chris Fox, MD, a researcher at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, and his colleagues demonstrated in 2018 that long-term exposure to anticholinergic drugs, a class that includes some antidepressants and antihistamines used to promote sleep, was associated with a higher risk of dementia, while use of benzodiazepines, a class of sedatives used commonly in older people as sleep aids, was not. (Whether benzodiazepine exposure relates to dementia remains controversial.)

At AAIC 2019, Dr. Fox presented findings from a study of 337 brains in a U.K. brain bank, of which 17% and 21% came from users of benzodiazepines and anticholinergic drugs, whose usage history was well documented. Dr. Fox and his colleagues found that, while neither anticholinergic nor benzodiazepine exposure was associated with brain pathology specific to that seen in Alzheimer’s disease, both classes of drugs were associated with “slight signals in neuronal loss” in one brain region, the nucleus basalis of Meynert. Dr. Fox described the drugs as causing “an increase in cognitive aging” which could bear on Alzheimer’s risk without being directly causative.

Newer sleep drugs may help Alzheimer’s patients

Scientists working for drug manufacturers presented findings on agents to counter the circadian rhythm disturbances seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Margaret Moline, PhD, of Eisai in Woodcliff Lake, N.J., showed some results from a phase 2, dose-ranging, placebo-controlled study of the experimental agent lemborexant in 62 subjects aged 60-90 with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and sleep disturbances. (Lemborexant, an orexin receptor agonist that acts to regulate wakefulness, is being investigated in a broad range of sleep disorders.) Patients were randomized to one of four doses of lemborexant or placebo and wore a device for sleep monitoring. Nighttime activity indicating arousal was significantly lower for people in two dosage arms, 5 mg and 10 mg, compared with placebo, and treatment groups saw trends toward less sleep fragmentation and higher total sleep time, Dr. Moline told the conference.

Suvorexant (Belsomra), the only orexin receptor antagonist currently licensed as a sleep aid, is also being tested in people with Alzheimer’s disease. At AAIC 2019, Joseph Herring, MD, PhD, of Merck in Kenilworth, N.J., presented results from a placebo-controlled trial of 277 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and insomnia, and reported that treatment with 10 or 20 mg of suvorexant over 4 weeks was associated with about an extra half hour of total nightly sleep, with a 73-minute mean increase from baseline, compared with 45 minutes for patients receiving placebo (95% CI, 11-45; P less than .005).

Trazodone linked to slower cognitive decline

An inexpensive antidepressant used in low doses as a sleep aid, including in people with Alzheimer’s disease, was associated with a delay in cognitive decline in older adults, according to results from a retrospective study. Elissaios Karageorgiou, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the Neurological Institute of Athens presented results derived from two cohorts: patients enrolled at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center and women enrolled in the Study for Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) in Women. The investigators were able to identify trazodone users in the studies (with two or more contiguous study visits reporting trazodone use) and match them with control patients from the same cohorts who did not use trazodone.

Trazodone was studied because previous research suggests it increases total sleep time in patients with Alzheimer’s disease without affecting next-day cognitive performance.

Trazodone-using patients in the UCSF cohort (n = 25) saw significantly less decline in Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores over 4 years, compared with nonusers (0.27 vs. 0.70 points per year; P = .023), an effect that remained statistically significant even after adjusting for sedative and stimulant use and the expected progression of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Importantly, the slower decline was seen only among subjects with sleep complaints at baseline and especially those whose sleep improved over time, suggesting that the cognitive benefit was mediated by improved sleep.

In the SOF cohort of 46 trazodone users matched with 148 nonusers, no significant protective or negative effect related to long-term trazodone use was found using the MMSE or the Trails Making Test. In this analysis, however, baseline and longitudinal sleep quality was not captured in the group-matching process, neither was the use of other medications. The patient group was slightly older, and all patients were women.

Dr. Karageorgiou said in an interview that the link between improved sleep, trazodone, and cognition needs to be validated in prospective intervention studies. Trazodone, he said, appears to work best in people with a specific type of insomnia characterized by cortical and behavioral hyperarousal, and its cognitive effect appears limited to people whose sleep improves with treatment. “You’re not going to see long-term cognitive benefits if it’s not improving your sleep,” Dr. Karageorgiou said. “So, whether trazodone improves sleep or not in a patient after a few months can be an early indicator for the clinician to continue using it or suspend it, because it is unlikely to help their cognition otherwise.”

He stressed that physicians need to be broadly focused on improving sleep to help patients with, or at risk for, dementia by consolidating their sleep rhythms.

“Trazodone is not the magic bullet, and I don’t think we will ever have a magic bullet,” Dr. Karageorgiou said. “Because when our brain degenerates, it’s not just one chemical, or one system, it’s many. And our body changes as well. The important thing is to help the patient consolidate their rhythms, whether through light therapy, daily exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or other evidence-based interventions and their combination. The same applies for a person with dementia as for the rest of us.”

None of the investigators outside of the industry-sponsored studies had relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM AAIC 2019

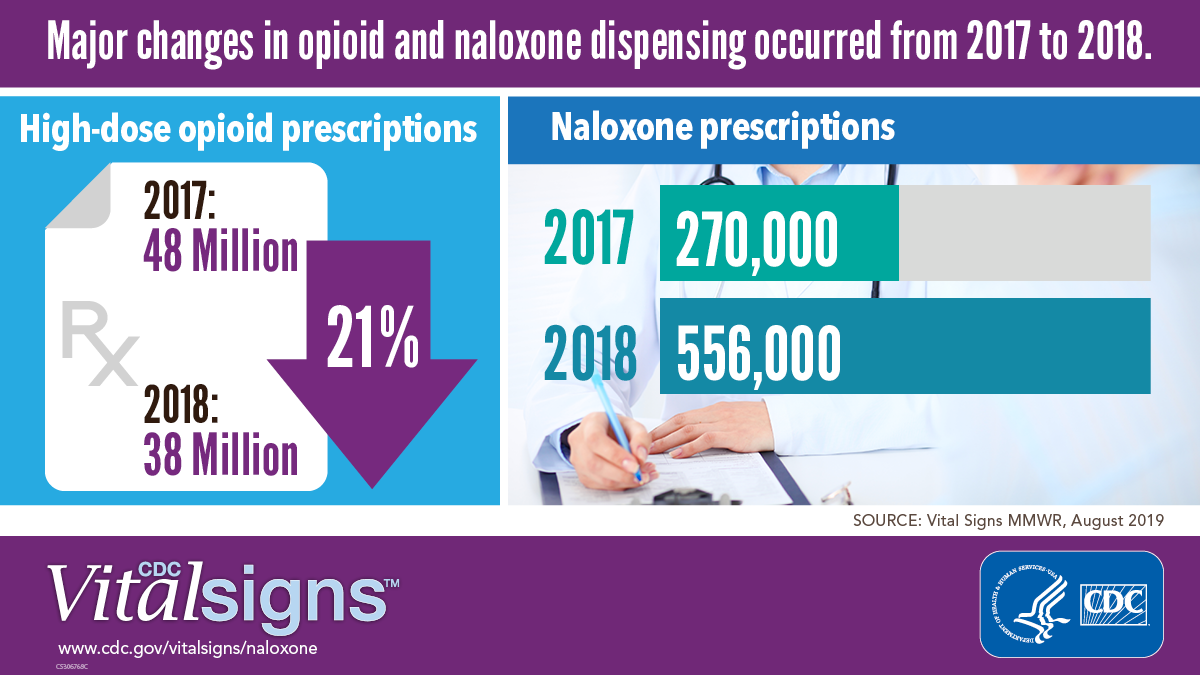

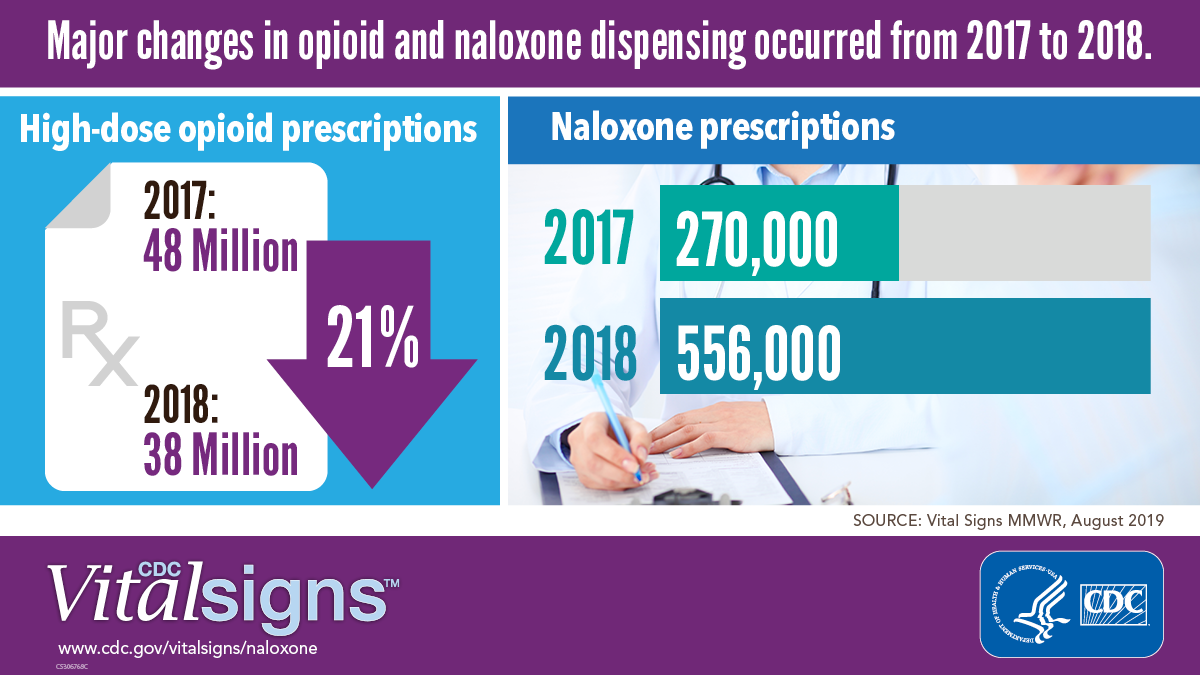

CDC finds that too little naloxone is dispensed

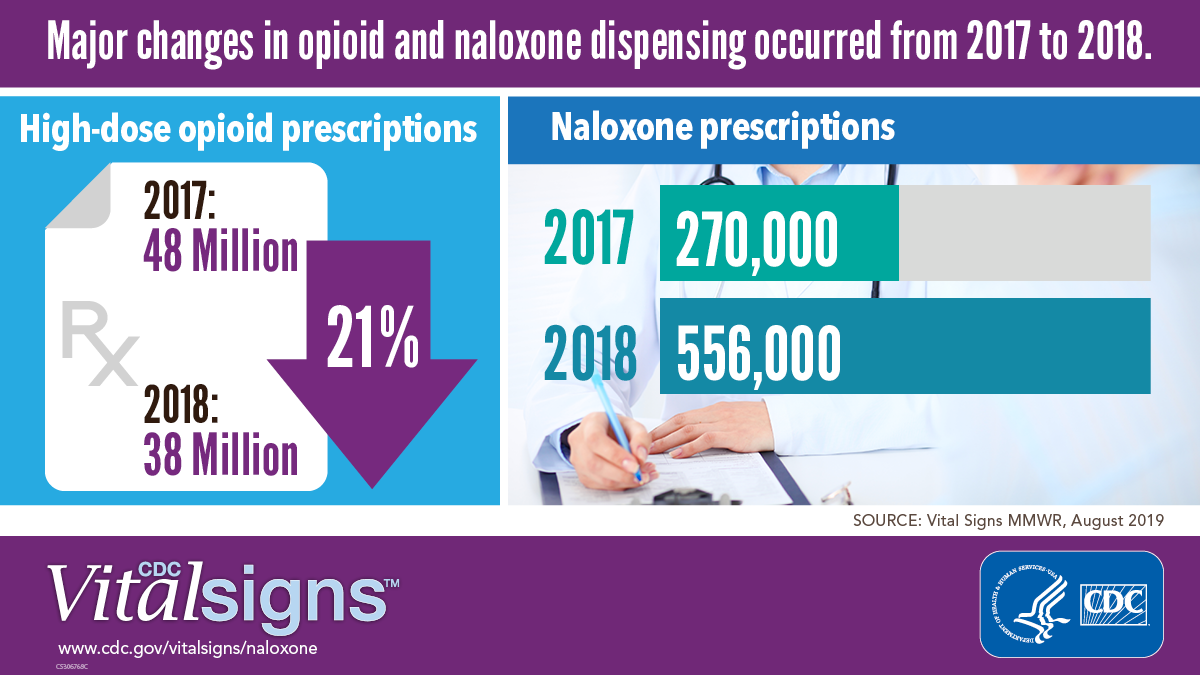

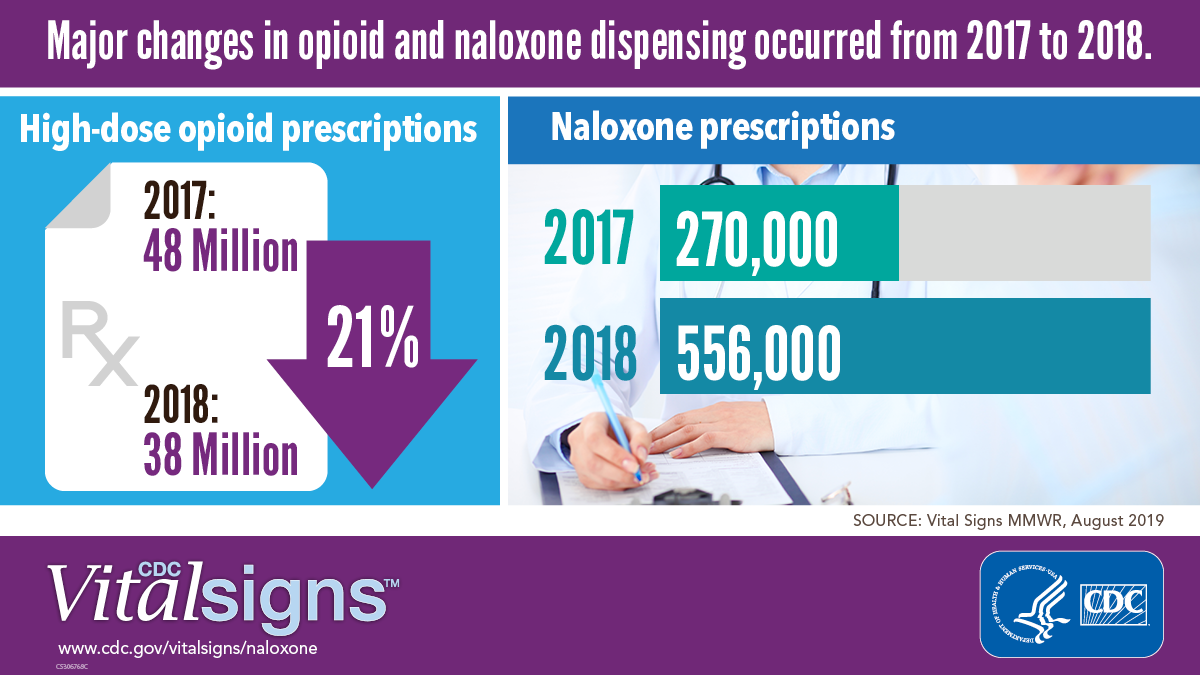

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

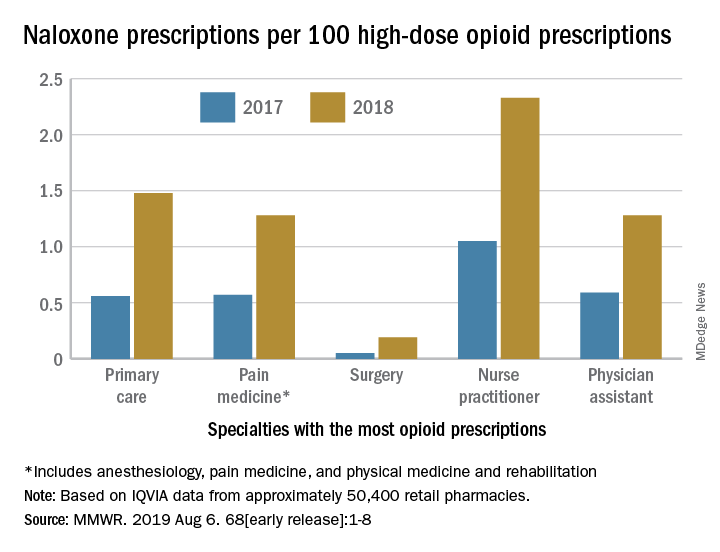

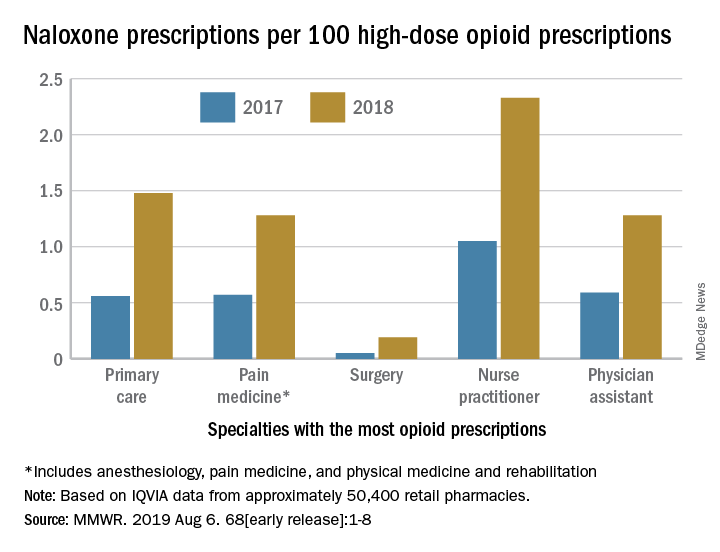

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Vaccination is not associated with increased risk of MS