User login

Opicapone increased on-time without dyskinesia in patients with Parkinson’s disease

PHILADELPHIA -

The 2-hour improvement was considered clinically meaningful, although the average patient in the studies had about 6 hours of off-time, said investigator Peter LeWitt, MD, of Henry Ford Hospital in West Bloomfield, Mich., and the department of neurology at Wayne State University, Detroit. Dr. LeWitt and colleagues will present the data at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“While this is a substantial improvement, it is 2 hours improvement over a total of 6 hours of off-time, which is not perfect,” Dr. LeWitt said in an interview. “So how could we do better is the challenge for all of us who are doing research.”

Opicapone is under development in the United States; it is currently approved in the European Union as adjunctive therapy to preparations of levodopa/DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors for patients with Parkinson’s disease and end-of-dose motor fluctuations.

The ability of opicapone to prolong the clinical actions of levodopa has been evaluated in BIPARK-1 and BIPARK-2. These two international phase 3 studies evaluated the third-generation COMT inhibitor against placebo and, in the case of BIPARK-1, against the COMT inhibitor entacapone as an active control. Each study was 14-15 weeks in duration and included a 1-year open-label phase.

In BIPARK-1, on-time without troublesome dyskinesia was significantly increased for opicapone 50 mg versus placebo, with an absolute increase of 1.9 versus 0.9 hours, respectively, from baseline to week 14 or 15 (P = .002), investigators said. Similarly, BIPARK-2 data showed an increase in this endpoint, at 1.7 versus 0.9 hours for opicapone and placebo, respectively (P = .025).

The 50-mg dose of opicapone was received by 115 patients in BIPARK-1 and 147 patients in BIPARK-2, while placebo was received by 120 and 135 patients in those two studies, respectively.

In the long-term extension studies, the mean change in on-time without dyskinesia from baseline to the end of the open-label endpoint was 2.0 hours for all 494 opicapone-treated patients in BIPARK-1 and 1.8 hours for all 339 opicapone-treated patients in BIPARK-2.

Dyskinesia was reported as a treatment-emergent adverse effect for 17.4% of opicapone-treated patients and 6.2% of placebo-treated patients, according to results of a pooled safety analysis of BIPARK-1 and BIPARK-2. However, only 1.9% of opicapone-treated patients and 0.4% of placebo-treated patients had treatment-emergent dyskinesia leading to discontinuation, and the dyskinesia was considered serious in 0.3% of the opicapone group and 0.0% of the placebo group, investigators added.

Neurocrine Biosciences has announced plans to file a New Drug Application for opicapone for Parkinson’s disease in the United States. That filing is expected to take place in the second quarter of 2019, according to an April 29 press release.

Dr. LeWitt disclosed that he has served as an advisor to Neurocrine Biosciences. He also provided disclosures related to Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, BioElectron Technology, Biotie, Britannia, Intec, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Merz, NeuroDerm, the Parkinson Study Group, Pfizer, Prexton, Sage, Scion, Sunovion, SynAgile, and US WorldMeds.

SOURCE: LeWitt P et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S4.003.

PHILADELPHIA -

The 2-hour improvement was considered clinically meaningful, although the average patient in the studies had about 6 hours of off-time, said investigator Peter LeWitt, MD, of Henry Ford Hospital in West Bloomfield, Mich., and the department of neurology at Wayne State University, Detroit. Dr. LeWitt and colleagues will present the data at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“While this is a substantial improvement, it is 2 hours improvement over a total of 6 hours of off-time, which is not perfect,” Dr. LeWitt said in an interview. “So how could we do better is the challenge for all of us who are doing research.”

Opicapone is under development in the United States; it is currently approved in the European Union as adjunctive therapy to preparations of levodopa/DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors for patients with Parkinson’s disease and end-of-dose motor fluctuations.

The ability of opicapone to prolong the clinical actions of levodopa has been evaluated in BIPARK-1 and BIPARK-2. These two international phase 3 studies evaluated the third-generation COMT inhibitor against placebo and, in the case of BIPARK-1, against the COMT inhibitor entacapone as an active control. Each study was 14-15 weeks in duration and included a 1-year open-label phase.

In BIPARK-1, on-time without troublesome dyskinesia was significantly increased for opicapone 50 mg versus placebo, with an absolute increase of 1.9 versus 0.9 hours, respectively, from baseline to week 14 or 15 (P = .002), investigators said. Similarly, BIPARK-2 data showed an increase in this endpoint, at 1.7 versus 0.9 hours for opicapone and placebo, respectively (P = .025).

The 50-mg dose of opicapone was received by 115 patients in BIPARK-1 and 147 patients in BIPARK-2, while placebo was received by 120 and 135 patients in those two studies, respectively.

In the long-term extension studies, the mean change in on-time without dyskinesia from baseline to the end of the open-label endpoint was 2.0 hours for all 494 opicapone-treated patients in BIPARK-1 and 1.8 hours for all 339 opicapone-treated patients in BIPARK-2.

Dyskinesia was reported as a treatment-emergent adverse effect for 17.4% of opicapone-treated patients and 6.2% of placebo-treated patients, according to results of a pooled safety analysis of BIPARK-1 and BIPARK-2. However, only 1.9% of opicapone-treated patients and 0.4% of placebo-treated patients had treatment-emergent dyskinesia leading to discontinuation, and the dyskinesia was considered serious in 0.3% of the opicapone group and 0.0% of the placebo group, investigators added.

Neurocrine Biosciences has announced plans to file a New Drug Application for opicapone for Parkinson’s disease in the United States. That filing is expected to take place in the second quarter of 2019, according to an April 29 press release.

Dr. LeWitt disclosed that he has served as an advisor to Neurocrine Biosciences. He also provided disclosures related to Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, BioElectron Technology, Biotie, Britannia, Intec, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Merz, NeuroDerm, the Parkinson Study Group, Pfizer, Prexton, Sage, Scion, Sunovion, SynAgile, and US WorldMeds.

SOURCE: LeWitt P et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S4.003.

PHILADELPHIA -

The 2-hour improvement was considered clinically meaningful, although the average patient in the studies had about 6 hours of off-time, said investigator Peter LeWitt, MD, of Henry Ford Hospital in West Bloomfield, Mich., and the department of neurology at Wayne State University, Detroit. Dr. LeWitt and colleagues will present the data at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“While this is a substantial improvement, it is 2 hours improvement over a total of 6 hours of off-time, which is not perfect,” Dr. LeWitt said in an interview. “So how could we do better is the challenge for all of us who are doing research.”

Opicapone is under development in the United States; it is currently approved in the European Union as adjunctive therapy to preparations of levodopa/DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors for patients with Parkinson’s disease and end-of-dose motor fluctuations.

The ability of opicapone to prolong the clinical actions of levodopa has been evaluated in BIPARK-1 and BIPARK-2. These two international phase 3 studies evaluated the third-generation COMT inhibitor against placebo and, in the case of BIPARK-1, against the COMT inhibitor entacapone as an active control. Each study was 14-15 weeks in duration and included a 1-year open-label phase.

In BIPARK-1, on-time without troublesome dyskinesia was significantly increased for opicapone 50 mg versus placebo, with an absolute increase of 1.9 versus 0.9 hours, respectively, from baseline to week 14 or 15 (P = .002), investigators said. Similarly, BIPARK-2 data showed an increase in this endpoint, at 1.7 versus 0.9 hours for opicapone and placebo, respectively (P = .025).

The 50-mg dose of opicapone was received by 115 patients in BIPARK-1 and 147 patients in BIPARK-2, while placebo was received by 120 and 135 patients in those two studies, respectively.

In the long-term extension studies, the mean change in on-time without dyskinesia from baseline to the end of the open-label endpoint was 2.0 hours for all 494 opicapone-treated patients in BIPARK-1 and 1.8 hours for all 339 opicapone-treated patients in BIPARK-2.

Dyskinesia was reported as a treatment-emergent adverse effect for 17.4% of opicapone-treated patients and 6.2% of placebo-treated patients, according to results of a pooled safety analysis of BIPARK-1 and BIPARK-2. However, only 1.9% of opicapone-treated patients and 0.4% of placebo-treated patients had treatment-emergent dyskinesia leading to discontinuation, and the dyskinesia was considered serious in 0.3% of the opicapone group and 0.0% of the placebo group, investigators added.

Neurocrine Biosciences has announced plans to file a New Drug Application for opicapone for Parkinson’s disease in the United States. That filing is expected to take place in the second quarter of 2019, according to an April 29 press release.

Dr. LeWitt disclosed that he has served as an advisor to Neurocrine Biosciences. He also provided disclosures related to Acadia, Acorda, Adamas, BioElectron Technology, Biotie, Britannia, Intec, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Merz, NeuroDerm, the Parkinson Study Group, Pfizer, Prexton, Sage, Scion, Sunovion, SynAgile, and US WorldMeds.

SOURCE: LeWitt P et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S4.003.

FROM AAN 2019

Evaluating and managing postural tachycardia syndrome

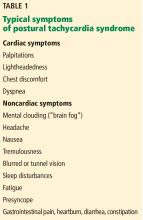

Some people, most of them relatively young women, experience lightheadedness, a racing heart, and other symptoms (but not hypotension) when they stand up, in a condition known as postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS).1 Although not known to shorten life,1 it can be physically and mentally debilitating.2,3 Therapy rarely cures it, but a multifaceted approach can substantially improve quality of life.

This review outlines the evaluation and diagnosis of POTS and provides guidance for a therapy regimen.

HOW IS POTS DEFINED?

POTS is a multifactorial syndrome rather than a specific disease. It is characterized by all of the following1,4–6:

- An increase in heart rate of ≥ 30 bpm, or ≥ 40 bpm for those under age 19, within 10 minutes of standing from a supine position

- Sustained tachycardia (> 30 seconds)

- Absence of orthostatic hypotension (a fall in blood pressure of ≥ 20/10 mm Hg)

- Frequent and chronic duration (≥ 6 months).

These features are critical to diagnosis. Hemodynamic criteria in isolation may describe postural tachycardia but are not sufficient to diagnose POTS.

The prevalence of POTS is estimated to be between 0.2% and 1.0%,7 affecting up to 3 million people in the United States. Most cases arise between ages 13 and 50, with a female-to-male ratio of 5:1.8

MANY NAMES, SAME CONDITION

In 1871, Da Costa9 described a condition he called “irritable heart syndrome” that had characteristics similar to those of POTS, including extreme fatigue and exercise intolerance. Decades later, Lewis10 and Wood11 provided more detailed descriptions of the disorder, renaming it “soldier’s heart” or “Da Costa syndrome.” As other cases were documented, more terms arose, including “effort syndrome” and “mitral valve prolapse syndrome.”

In 1982, Rosen and Cryer12 were the first to use the term “postural tachycardia syndrome” for patients with disabling tachycardia upon standing without orthostatic hypotension. In 1986, Fouad et al13 described patients with postural tachycardia, orthostatic intolerance, and a small degree of hypotension as having “idiopathic hypovolemia.”

In 1993, Schondorf and Low14 established the current definition of POTS, leading to increased awareness and research efforts to understand its pathophysiology.

MULTIFACTORIAL PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

During the last 2 decades, several often-overlapping forms of POTS have been recognized, all of which share a final common pathway of sustained orthostatic tachycardia.15–19 In addition, a number of common comorbidities were identified through review of large clinic populations of POTS.20,21

Hypovolemic POTS

Up to 70% of patients with POTS have hypovolemia. The average plasma volume deficit is about 13%, which typically causes only insignificant changes in heart rate and norepinephrine levels while a patient is supine. However, blood pooling associated with upright posture further compromises cardiac output and consequently increases sympathetic nerve activity. Abnormalities in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone volume regulation system are also suspected to impair sodium retention, contributing to hypovolemia.1,22

Neuropathic POTS

About half of patients with POTS have partial sympathetic denervation (particularly in the lower limbs) and inadequate vasoconstriction upon standing, leading to reduced venous return and stroke volume.17,23 A compensatory increase in sympathetic tone results in tachycardia to maintain cardiac output and blood pressure.

Hyperadrenergic POTS

Up to 50% of patients with POTS have high norepinephrine levels (≥ 600 pg/mL) when upright. This subtype, hyperadrenergic POTS, is characterized by an increase in systolic blood pressure of at least 10 mm Hg within 10 minutes of standing, with concomitant tachycardia that can be similar to or greater than that seen in nonhyperadrenergic POTS. Patients with hyperadrenergic POTS tend to report more prominent symptoms of sympathetic activation, such as palpitations, anxiety, and tremulousness.24,25

Norepinephrine transporter deficiency

The norepinephrine transporter (NET) is on the presynaptic cleft of sympathetic neurons and serves to clear synaptic norepinephrine. NET deficiency leads to a hyperadrenergic state and elevated sympathetic nerve activation.18 NET deficiency may be induced by common antidepressants (eg, tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) and attention-deficit disorder medications.4

Mast cell activation syndrome

The relationship between mast cell activation syndrome and POTS is poorly understood.4,26 Mast cell activation syndrome has been described in a subset of patients with POTS who have sinus tachycardia accompanied by severe episodic flushing. Patients with this subtype have a hyperadrenergic response to postural change and elevated urine methylhistamine during flushing episodes.

Patients with mast cell activation syndrome tend to have strong allergic symptoms and may also have severe gastrointestinal problems, food sensitivities, dermatographism, and neuropathy. Diagnosis can be difficult, as the condition is associated with numerous markers with varying sensitivity and specificity.

Autoimmune origin

A significant minority of patients report a viral-like illness before the onset of POTS symptoms, suggesting a possible autoimmune-mediated or inflammatory cause. Also, some autoimmune disorders (eg, Sjögren syndrome) can present with a POTS-like manifestation.

Research into the role of autoantibodies in the pathophysiology of POTS offers the potential to develop novel therapeutic targets. Autoantibodies that have been reported in POTS include those against M1 to M3 muscarinic receptors (present in over 87% of patients with POTS),27 cardiac lipid raft-associated proteins,28 adrenergic G-protein coupled receptors, alpha-1-adrenergic receptors, and beta-1- and beta-2-adrenergic receptors.29 Although commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays can assess for these antibody fragments, it is not known whether targeting the antibodies improves outcomes. At this time, antibody testing for POTS should be confined to the research setting.

LINKS TO OTHER SYNDROMES

POTS is often associated with other conditions whose symptoms cannot be explained by postural intolerance or tachycardia.

Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are a group of inherited heterogeneous disorders involving joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility, and tissue fragility.30 The hypermobile subtype is most commonly associated with POTS, with patients often having symptoms of autonomic dysregulation and autonomic test abnormalities.31–33 Patients with POTS may have a history of joint subluxations, joint pain, cervical instability, and spontaneous epidural leaks. The reason for the overlap between the two syndromes is not clear.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is characterized by persistent fatigue that does not resolve with rest and is not necessarily associated with orthostatic changes. More than 75% of patients with POTS report general fatigue as a major complaint, and up to 23% meet the full criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome.34

DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGY

A patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of POTS should first undergo a detailed history and physical examination. Other causes of sinus tachycardia should be considered.

Detailed history, symptom review

The history should focus on determining symptom burden, including tachycardia onset, frequency, severity, and triggers; the presence of syncope; and the impact of symptoms on daily function and quality of life.

Presyncope and its associated symptoms occur in less than one-third of patients with POTS, and syncope is not a principal feature.4 If syncope is the predominant complaint, alternative causes should be investigated. The usual cause of syncope in the general population is thought to be vasovagal.

In addition to orthostatic intolerance, gastrointestinal disturbances are common in POTS, presenting as abdominal pain, heartburn, irregular bowel movements, diarrhea, or constipation. Symptoms of gastroparesis are less common. Gastrointestinal symptoms tend to be prolonged, lasting hours and occurring multiple times a week. They tend not to improve in the supine position.35

POTS-associated symptoms may develop insidiously, but patients often report onset after an acute stressor such as pregnancy, major surgery, or a presumed viral illness.4 Whether these putative triggers are causative or coincidental is unknown. Symptoms of orthostatic intolerance tend to be exacerbated by dehydration, heat, alcohol, exercise, and menstruation.36,37

Consider the family history: 1 in 8 patients with POTS reports familial orthostatic intolerance,38 suggesting a genetic role in some patients. Inquire about symptoms or a previous diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and mast cell activation syndrome.

Consider other conditions

Pheochromocytoma causes hyperadrenergic symptoms (eg, palpitations, lightheadedness) like those in POTS, but patients with pheochromocytoma typically have these symptoms while supine. Pheochromocytoma is also characterized by plasma norepinephrine levels much higher than in POTS.4 Plasma metanephrine testing helps diagnose or rule out pheochromocytoma.5

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia, like pheochromocytoma, also has clinical features similar to those of POTS, as well as tachycardia present when supine. It involves higher sympathetic tone and lower parasympathetic tone compared with POTS; patients commonly have a daytime resting heart rate of at least 100 bpm or a 24-hour mean heart rate of at least 90 bpm.1,42 While the intrinsic heart rate is heightened in inappropriate sinus tachycardia, it is not different between POTS patients and healthy individuals.42,43 Distinguishing POTS from inappropriate sinus tachycardia is further complicated by the broad inclusion criteria of most studies of inappropriate sinus tachycardia, which failed to exclude patients with POTS.44 The Heart Rhythm Society recently adopted distinct definitions for the 2 conditions.1

Physical examination: Focus on vital signs

Dependent acrocyanosis—dark red-blue discoloration of the lower legs that is cold to the touch—occurs in about half of patients with POTS upon standing.4 Dependent acrocyanosis is associated with joint hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, so these conditions should also be considered if findings are positive.

Laboratory testing for other causes

Laboratory testing is used mainly to detect primary causes of sinus tachycardia. Tests should include:

- Complete blood cell count with hematocrit (for severe anemia)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone level (for hyperthyroidism)

- Electrolyte panel (for significant electrolyte disturbances).

Evidence is insufficient to support routinely measuring the vitamin B12 level, iron indices, and serum markers for celiac disease, although these may be done if the history or physical examination suggests related problems.4 Sicca symptoms (severe dry eye or dry mouth) should trigger evaluation for Sjögren syndrome.

Electrocardiography needed

Electrocardiography should be performed to investigate for cardiac conduction abnormalities as well as for resting markers of a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia. Extended ambulatory (Holter) monitoring may be useful to evaluate for a transient reentrant tachyarrhythmia4; however, it does not record body position, so it can be difficult to determine if detected episodes of tachycardia are related to posture.

Additional testing for select cases

Further investigation is usually not needed to diagnose POTS but should be considered in some cases. Advanced tests are typically performed at a tertiary care referral center and include:

- Quantitative sensory testing to evaluate for small-fiber neuropathy (ie, Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test, or QSART), which occurs in the neuropathic POTS subtype

- Formal autonomic function testing to characterize neurovascular responsiveness

- Supine and standing plasma norepinephrine levels (fractionated catecholamines) to characterize the net activation of the sympathetic nervous system

- Blood volume assessments to assess hypovolemia

- Formal exercise testing to objectively quantify exercise capacity.

GRADED MANAGEMENT

No single universal gold-standard therapy exists for POTS, and management should be individually determined with the primary goals of treating symptoms and restoring function. A graded approach should be used, starting with conservative nonpharmacologic therapies and adding medications as needed.

While the disease course varies substantially from patient to patient, proper management is strongly associated with eventual symptom improvement.1

NONPHARMACOLOGIC STEPS FIRST

Education

Patients should be informed of the nature of their condition and referred to appropriate healthcare personnel. POTS is a chronic illness requiring individualized coping strategies, intensive physician interaction, and support of a multidisciplinary team. Patients and family members can be reassured that most symptoms improve over time with appropriate diagnosis and treatment.1 Patients should be advised to avoid aggravating triggers and activities.

Exercise

Exercise programs are encouraged but should be introduced gradually, as physical activity can exacerbate symptoms, especially at the outset. Several studies have reported benefits from a short-term (3-month) program, in which the patient gradually progresses from non-upright exercise (eg, rowing machine, recumbent cycle, swimming) to upright endurance exercises. At the end of these programs, significant cardiac remodeling, improved quality of life, and reduced heart rate responses to standing have been reported, and benefits have been reported to persist in patients who continued exercising after the 3-month study period.46,47

Despite the benefits of exercise interventions, compliance is low.46,47 To prevent early discouragement, patients should be advised that it can take 4 to 6 weeks of continued exercise before benefits appear. Patients are encouraged to exercise every other day for 30 minutes or more. Regimens should primarily focus on aerobic conditioning, but resistance training, concentrating on thigh muscles, can also help. Exercise is a treatment and not a cure, and benefits can rapidly disappear if regular activity (at least 3 times per week) is stopped.48

Compression stockings

Compression stockings help reduce peripheral venous pooling and enhance venous return to the heart. Waist-high stockings with compression of at least 30 to 40 mm Hg offer the best results.

Diet

Increased fluid and salt intake is advisable for patients with suspected hypovolemia. At least 2 to 3 L of water accompanied by 10 to 12 g of daily sodium intake is recommended.1 This can usually be accomplished with diet and salt added to food, but salt tablets can be used if the patient prefers. The resultant plasma volume expansion may help reduce the reflex tachycardia upon standing.49

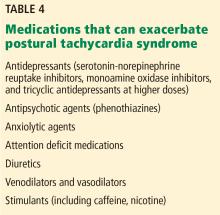

Check medications

Rescue therapy with saline infusion

Intravenous saline infusion can augment blood volume in patients who are clinically decompensated and present with severe symptoms.1 Intermittent infusion of 1 L of normal saline has been found to significantly reduce orthostatic tachycardia and related symptoms in patients with POTS, contributing to improved quality of life.51,52

Chronic saline infusions are not recommended for long-term care because of the risk of access complications and infection.1 Moak et al53 reported a high rate of bacteremia in a cohort of children with POTS with regular saline infusions, most of whom had a central line. On the other hand, Ruzieh et al54 reported significantly improved symptoms with regular saline infusions without a high rate of complications, but patients in this study received infusions for only a few months and through a peripheral intravenous catheter.

DRUG THERAPY

No medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or Health Canada specifically for treating POTS, making all pharmacologic recommendations off-label. Although the drugs discussed below have been evaluated for POTS in controlled laboratory settings, they have yet to be tested in robust clinical trials.

Blood volume expansion

Several drugs expand blood volume, which may reduce orthostatic tachycardia.

Fludrocortisone is a synthetic aldosterone analogue that enhances sodium and water retention. Although one observational study found that it normalizes hemodynamic changes in response to orthostatic stress, no high-level evidence exists for its effectiveness for POTS.55 It is generally well tolerated, although possible adverse effects include hyperkalemia, hypertension, fatigue, nausea, headache, and edema.5,56

Desmopressin is a synthetic version of a natural antidiuretic hormone that increases kidney-mediated free-water reabsorption without sodium retention. It significantly reduces upright heart rate in patients with POTS and improves symptom burden. Although potential adverse effects include edema and headache, hyponatremia is the primary concern with daily use, especially with the increased water intake advised for POTS.57 Patients should be advised to use desmopressin no more than once a week for the acute improvement of symptoms. Intermittent monitoring of serum sodium levels is recommended for safety.

Erythropoietin replacement has been suggested for treating POTS to address the significant deficit in red blood cell volume. Although erythropoietin therapy has a direct vasoconstrictive effect and largely improves red blood cell volume in patients with POTS, it does not expand plasma volume, so orthostatic tachycardia is not itself reduced.22 Nevertheless, it may significantly improve POTS symptoms refractory to more common methods of treatment, and it should be reserved for such cases. In addition to the lack of effect on orthostatic tachycardia, drawbacks to using erythropoietin include its high cost, the need for subcutaneous administration, and the risk of life-threatening complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke.58,59

Heart rate-lowering agents

Propranolol, a nonselective beta-adrenergic antagonist, can significantly reduce standing heart rate and improve symptoms at low dosages (10–20 mg). Higher dosages can further restrain orthostatic tachycardia but are not as well tolerated, mainly due to hypotension and worsening of existing symptoms such as fatigue.60 Regular-acting propranolol works for about 4 to 5 hours per dose, so full-day coverage often requires dosing 4 times per day.

Ivabradine is a selective blocker of the “funny” (If) channel that reduces the sinus node firing rate without affecting blood pressure, so it slows heart rate without causing supine hypertension or orthostatic hypotension.

A retrospective case series found that 60% of patients with POTS treated with ivabradine reported symptomatic improvement, and all patients experienced reduced tachycardia with continued use.61 Ivabradine has not been compared with placebo or propranolol in a randomized controlled trial, and it has not been well studied in pregnancy and so should be avoided because of potential teratogenic effects.

When prescribing ivabradine for women of childbearing age, a negative pregnancy test may be documented prior to initiation of therapy, and the use of highly effective methods of contraception is recommended. Ivabradine should be avoided in women contemplating pregnancy. Insurance coverage can limit access to ivabradine in the United States.

Central nervous system sympatholytics

Patients with prominent hyperadrenergic features may benefit from central sympatholytic agents. However, these drugs may not be well tolerated in patients with neuropathic POTS because of the effects of reduced systemic vascular resistance5 and the possible exacerbation of drowsiness, fatigue, and mental clouding.4 Patients can be extremely sensitive to these medications, so they should initially be prescribed at the lowest dose, then gradually increased as tolerated.

Clonidine, an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist, decreases central sympathetic tone. In hyperadrenergic patients, clonidine can stabilize heart rate and blood pressure, thereby reducing orthostatic symptoms.62

Methyldopa has effects similar to those of clonidine but is easier to titrate owing to its longer half-life.63 Methyldopa is typically started at 125 mg at bedtime and increased to 125 mg twice daily, if tolerated.

Other agents

Midodrine is a prodrug. The active form, an alpha-1-adrenergic agonist, constricts peripheral veins and arteries to increase vascular resistance and venous return, thereby reducing orthostatic tachycardia.52 It is most useful in patients with impaired peripheral vasoconstriction (eg, neuropathic POTS) and may be less effective in those with hyperadrenergic POTS.64 Major limitations of midodrine include worsening supine hypertension and possible urinary retention.39

Because of midodrine’s short half-life, frequent dosing is required during daytime hours (eg, 8 AM, noon, and 4 PM), but it should not be taken within 4 to 5 hours of sleep because of the risk of supine hypertension. Midodrine is typically started at 2.5 to 5 mg per dose and can be titrated up to 15 mg per dose.

Midodrine is an FDA pregnancy category C drug (adverse effects in pregnancy seen in animal models, but evidence lacking in humans). While ideally it should be avoided, we have used it safely in pregnant women with disabling POTS symptoms.

Pyridostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, increases cardiovagal tone and possibly sympathetic tone. It has been reported to significantly reduce standing heart rate and improve symptom burden in patients with POTS.65 However, pyridostigmine increases gastrointestinal mobility, leading to severe adverse effects in over 20% of patients, including abdominal cramps, nausea, and diarrhea.66

Droxidopa, a synthetic amino acid precursor of norepinephrine, improves dizziness and fatigue in POTS with minimal effects on blood pressure.67

Modafinil, a psychostimulant, may improve POTS-associated cognitive symptoms.4 It also raises upright blood pressure without significantly worsening standing heart rate or acute orthostatic symptoms.68

EFFECTS OF COMORBID DISORDERS ON MANAGEMENT

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Pharmacologic approaches to POTS should not be altered based on the presence of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, but because many of these patients are prone to joint dislocation, exercise prescriptions may need adjusting.

A medical genetics consult is recommended for patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Although the hypermobile type (the form most commonly associated with POTS) is not associated with aortopathy, it can be confused with classical and vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, which require serial aortic screening.30

Mast cell activation syndrome

Consultation with an allergist or immunologist may help patients with severe symptoms.

Autoantibodies and autoimmunity

Treatment of the underlying disorder is recommended and can result in significantly improved POTS symptoms.

SPECIALTY CARE REFERRAL

POTS can be challenging to manage. Given the range of physiologic, emotional, and functional distress patients experience, it often requires significant physician time and multidisciplinary care. Patients with continued severe or debilitating symptoms may benefit from referral to a tertiary-care center with experience in autonomic nervous system disorders.

PROGNOSIS

Limited data are available on the long-term prognosis of POTS, and more studies are needed in pediatric and adult populations. No deaths have been reported in the handful of published cases of POTS in patients older than 50.1 Some pediatric studies suggest that some teenagers “outgrow” their POTS. However, these data are not robust, and an alternative explanation is that as they get older, they see adult physicians for their POTS symptoms and so are lost to study follow-up.6,44,69

We have not often seen POTS simply resolve without ongoing treatment. However, in our experience, most patients have improved symptoms and function with multimodal treatment (ie, exercise, salt, water, stockings, and some medications) and time.

- Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm 2015; 12(6):e41–e63. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

- Bagai K, Song Y, Ling JF, et al. Sleep disturbances and diminished quality of life in postural tachycardia syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med 2011; 7(2):204–210. pmid:21509337

- Benrud-Larson LM, Dewar MS, Sandroni P, Rummans TA, Haythornthwaite JA, Low PA. Quality of life in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 2002; 77(6):531–537. doi:10.4065/77.6.531

- Raj SR. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Circulation 2013; 127(23):2336–2342. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.144501

- Raj SR. The postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS): pathophysiology, diagnosis & management. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2006; 6(2):84–99. pmid:16943900

- Singer W, Sletten DM, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Brands CK, Fischer PR, Low PA. Postural tachycardia in children and adolescents: what is abnormal? J Pediatr 2012; 160(2):222–226. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.054

- Mar PL, Raj SR. Neuronal and hormonal perturbations in postural tachycardia syndrome. Front Physiol 2014; 5:220. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00220

- Garland EM, Raj SR, Black BK, Harris PA, Robertson D. The hemodynamic and neurohumoral phenotype of postural tachycardia syndrome. Neurology 2007; 69(8):790–798. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000267663.05398.40

- Da Costa JM. On irritable heart: a clinical study of a form of functional cardiac disorder and its consequences. Am J Med Sci 1871; 61(121):2–52.

- Lewis T. The tolerance of physical exertion, as shown by soldiers suffering from so-called “irritable heart.” Br Med J 1918; 1(2987):363–365. pmid:20768980

- Wood P. Da Costa’s syndrome (or effort syndrome): lecture I. Br Med J 1941; 1(4194):767–772. pmid:20783672

- Rosen SG, Cryer PE. Postural tachycardia syndrome. Reversal of sympathetic hyperresponsiveness and clinical improvement during sodium loading. Am J Med 1982; 72(5):847–850.

- Fouad FM, Tadena-Thome L, Bravo EL, Tarazi RC. Idiopathic hypovolemia. Ann Intern Med 1986; 104(3):298–303. pmid:3511818

- Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: an attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology 1993; 43(1):132–137. pmid:8423877

- Vernino S, Low PA, Fealey RD, Stewart JD, Farrugia G, Lennon VA. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med 2000; 343(12):847–855. doi:10.1056/NEJM200009213431204

- Raj SR, Robertson D. Blood volume perturbations in the postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Med Sci 2007; 334(1):57–60. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318063c6c0

- Jacob G, Costa F, Shannon JR, et al. The neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 343(14):1008–1014. doi:10.1056/NEJM200010053431404

- Shannon JR, Flattem NL, Jordan J, et al. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine-transporter deficiency. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(8):541–549. doi:10.1056/NEJM200002243420803

- Jones PK, Shaw BH, Raj SR. Clinical challenges in the diagnosis and management of postural tachycardia syndrome. Pract Neurol 2016; 16(6):431–438. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2016-001405

- Gunning WT, Karabin BL, Blomquist TM, Grubb BP. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is associated with platelet storage pool deficiency. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95(37):e4849. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004849

- Kanjwal K, Sheikh M, Karabin B, Kanjwal Y, Grubb BP. Neurocardiogenic syncope coexisting with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in patients suffering from orthostatic intolerance: a combined form of autonomic dysfunction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34(5):549–554. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02994.x

- Raj SR, Biaggioni I, Yamhure PC, et al. Renin-aldosterone paradox and perturbed blood volume regulation underlying postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation 2005; 111(13):1574–1582. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000160356.97313.5D

- Gibbons CH, Bonyhay I, Benson A, Wang N, Freeman R. Structural and functional small fiber abnormalities in the neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. PLoS One 2013; 8(12):e84716. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084716

- Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, Shen WK. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2009; 20(3):352–358. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01407.x

- Kanjwal K, Saeed B, Karabin B, Kanjwal Y, Grubb BP. Clinical presentation and management of patients with hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. A single center experience. Cardiol J 2011; 18(5):527–531. pmid:21947988

- Shibao C, Arzubiaga C, Roberts J, et al. Hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome in mast cell activation disorders. Hypertension 2005; 45(3):385–390. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000158259.68614.40

- Dubey D, Hopkins S, Vernino S. M1 and M2 muscarinic receptor antibodies among patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: potential disease biomarker [abstract]. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2016; 17(3):179S.

- Wang XL, Ling TY, Charlesworth MC, et al. Autoimmunoreactive IgGs against cardiac lipid raft-associated proteins in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Transl Res 2013; 162(1):34–44. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2013.03.002

- Li H, Yu X, Liles C, et al. Autoimmune basis for postural tachycardia syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3(1):e000755. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000755

- Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2017; 175(1):8–26. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31552

- Wallman D, Weinberg J, Hohler AD. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and postural tachycardia syndrome: a relationship study. J Neurol Sci 2014; 340(1-2):99–102. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2014.03.002

- De Wandele I, Calders P, Peersman W, et al. Autonomic symptom burden in the hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a comparative study with two other EDS types, fibromyalgia, and healthy controls. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 44(3):353–361. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.013

- Gazit Y, Nahir AM, Grahame R, Jacob G. Dysautonomia in the joint hypermobility syndrome. Am J Med 2003; 115(1):33–40. pmid:12867232

- Okamoto LE, Raj SR, Peltier A, et al. Neurohumoral and haemodynamic profile in postural tachycardia and chronic fatigue syndromes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012; 122(4):183–192. doi:10.1042/CS20110200

- Wang LB, Culbertson CJ, Deb A, Morgenshtern K, Huang H, Hohler AD. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in postural tachycardia syndrome. J Neurol Sci 2015; 359(1-2):193–196. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.10.052

- Raj S, Sheldon R. Management of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia and vasovagal syncope. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2016; 5(2):122–129. doi:10.15420/AER.2016.7.2

- Peggs KJ, Nguyen H, Enayat D, Keller NR, Al-Hendy A, Raj SR. Gynecologic disorders and menstrual cycle lightheadedness in postural tachycardia syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012; 118(3):242–246. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.04.014

- Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82(3):308–313. doi:10.4065/82.3.308

- Deb A, Morgenshtern K, Culbertson CJ, Wang LB, Hohler AD. A survey-based analysis of symptoms in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 28(7):157–159. pmid:25829642

- Ertek S, Cicero AF. Hyperthyroidism and cardiovascular complications: a narrative review on the basis of pathophysiology. Arch Med Sci 2013; 9(5):944–952. doi:10.5114/aoms.2013.38685

- Rangno RE, Langlois S. Comparison of withdrawal phenomena after propranolol, metoprolol and pindolol. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 13(suppl 2):345S–351S. pmid:6125187

- Nwazue VC, Paranjape SY, Black BK, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome and inappropriate sinus tachycardia: role of autonomic modulation and sinus node automaticity. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3(2):e000700. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000700

- Morillo CA, Klein GJ, Thakur RK, Li H, Zardini M, Yee R. Mechanism of “inappropriate” sinus tachycardia. Role of sympathovagal balance. Circulation 1994; 90(2):873–877. pmid:7913886

- Grubb BP. Postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation 2008; 117(21):2814–2817. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.761643

- Bhatia R, Kizilbash SJ, Ahrens SP, et al. Outcomes of adolescent-onset postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Pediatr 2016; 173:149–153. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.035

- George SA, Bivens TB, Howden EJ, et al. The international POTS registry: evaluating the efficacy of an exercise training intervention in a community setting. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13(4):943–950. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.12.012

- Fu Q, VanGundy TB, Galbreath MM, et al. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55(25):2858–2868. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.043

- Raj SR. Row, row, row your way to treating postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13(4):951–952. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.12.039

- Celedonio JE, Garland EM, Nwazue VC, et al. Effects of high sodium intake on blood volume and catecholamines in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome and healthy females [abstract]. Clin Auton Res 2014; 24:211.

- Garland EM, Celedonio JE, Raj SR. Postural tachycardia syndrome: beyond orthostatic intolerance. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2015; 15(9):60. doi:10.1007/s11910-015-0583-8

- Gordon VM, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Novak V, Low PA. Hemodynamic and symptomatic effects of acute interventions on tilt in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res 2000; 10:29–33. pmid:10750641

- Jacob G, Shannon JR, Black B, et al. Effects of volume loading and pressor agents in idiopathic orthostatic tachycardia. Circulation 1997; 96(2):575–580. pmid:9244228

- Moak JP, Leong D, Fabian R, et al. Intravenous hydration for management of medication-resistant orthostatic intolerance in the adolescent and young adult. Pediatr Cardiol 2016; 37(2):278–282. doi:10.1007/s00246-015-1274-6

- Ruzieh M, Baugh A, Dasa O, et al. Effects of intermittent intravenous saline infusions in patients with medication-refractory postural tachycardia syndrome. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2017; 48(3):255–260. doi:10.1007/s10840-017-0225-y

- Freitas J, Santos R, Azevedo E, Costa O, Carvalho M, de Freitas AF. Clinical improvement in patients with orthostatic intolerance after treatment with bisoprolol and fludrocortisone. Clin Auton Res 2000; 10(5):293–299. pmid:11198485

- Lee AK, Krahn AD. Evaluation of syncope: focus on diagnosis and treatment of neurally mediated syncope. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2016; 14(6):725–736. doi:10.1586/14779072.2016.1164034

- Coffin ST, Black BK, Biaggioni I, et al. Desmopressin acutely decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9(9):1484–1490. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.05.002

- Kanjwal K, Saeed B, Karabin B, Kanjwal Y, Sheikh M, Grubb BP. Erythropoietin in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Am J Ther 2012; 19(2):92–95. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181ef621a

- Hoeldtke RD, Horvath GG, Bryner KD. Treatment of orthostatic tachycardia with erythropoietin. Am J Med 1995; 99(5):525–529. pmid:7485211

- Raj SR, Black BK, Biaggioni I, et al. Propranolol decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome: less is more. Circulation 2009; 120(9):725–734. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846501

- McDonald C, Frith J, Newton JL. Single centre experience of ivabradine in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Europace 2011; 13(3):427–430. doi:10.1093/europace/euq390

- Gaffney FA, Lane LB, Pettinger W, Blomqvist G. Effects of long-term clonidine administration on the hemodynamic and neuroendocrine postural responses of patients with dysautonomia. Chest 1983; 83(suppl 2):436–438. pmid:6295714

- Jacob G, Biaggioni I. Idiopathic orthostatic intolerance and postural tachycardia syndromes. Am J Med Sci 1999; 317(2):88–101. pmid:10037112

- Ross AJ, Ocon AJ, Medow MS, Stewart JM. A double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study of the vascular effects of midodrine in neuropathic compared with hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014; 126(4):289–296. doi:10.1042/CS20130222

- Raj SR, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Harris PA, Robertson D. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition improves tachycardia in postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation 2005; 111(21):2734–2340. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.497594

- Kanjwal K, Karabin B, Sheikh M, et al. Pyridostigmine in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia: A single-center experience. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34(6):750–755. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03047.x

- Ruzieh M, Dasa O, Pacenta A, Karabin B, Grubb B. Droxidopa in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Am J Ther 2017; 24(2):e157–e161. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000468

- Kpaeyeh AG Jr, Mar PL, Raj V, et al. Hemodynamic profiles and tolerability of modafinil in the treatment of POTS: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014; 34(6):738–741. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000221

- Lai CC, Fischer PR, Brands CK, et al. Outcomes in adolescents with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome treated with midodrine and beta-blockers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2009; 32(2):234–238. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.02207.x

Some people, most of them relatively young women, experience lightheadedness, a racing heart, and other symptoms (but not hypotension) when they stand up, in a condition known as postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS).1 Although not known to shorten life,1 it can be physically and mentally debilitating.2,3 Therapy rarely cures it, but a multifaceted approach can substantially improve quality of life.

This review outlines the evaluation and diagnosis of POTS and provides guidance for a therapy regimen.

HOW IS POTS DEFINED?

POTS is a multifactorial syndrome rather than a specific disease. It is characterized by all of the following1,4–6:

- An increase in heart rate of ≥ 30 bpm, or ≥ 40 bpm for those under age 19, within 10 minutes of standing from a supine position

- Sustained tachycardia (> 30 seconds)

- Absence of orthostatic hypotension (a fall in blood pressure of ≥ 20/10 mm Hg)

- Frequent and chronic duration (≥ 6 months).

These features are critical to diagnosis. Hemodynamic criteria in isolation may describe postural tachycardia but are not sufficient to diagnose POTS.

The prevalence of POTS is estimated to be between 0.2% and 1.0%,7 affecting up to 3 million people in the United States. Most cases arise between ages 13 and 50, with a female-to-male ratio of 5:1.8

MANY NAMES, SAME CONDITION

In 1871, Da Costa9 described a condition he called “irritable heart syndrome” that had characteristics similar to those of POTS, including extreme fatigue and exercise intolerance. Decades later, Lewis10 and Wood11 provided more detailed descriptions of the disorder, renaming it “soldier’s heart” or “Da Costa syndrome.” As other cases were documented, more terms arose, including “effort syndrome” and “mitral valve prolapse syndrome.”

In 1982, Rosen and Cryer12 were the first to use the term “postural tachycardia syndrome” for patients with disabling tachycardia upon standing without orthostatic hypotension. In 1986, Fouad et al13 described patients with postural tachycardia, orthostatic intolerance, and a small degree of hypotension as having “idiopathic hypovolemia.”

In 1993, Schondorf and Low14 established the current definition of POTS, leading to increased awareness and research efforts to understand its pathophysiology.

MULTIFACTORIAL PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

During the last 2 decades, several often-overlapping forms of POTS have been recognized, all of which share a final common pathway of sustained orthostatic tachycardia.15–19 In addition, a number of common comorbidities were identified through review of large clinic populations of POTS.20,21

Hypovolemic POTS

Up to 70% of patients with POTS have hypovolemia. The average plasma volume deficit is about 13%, which typically causes only insignificant changes in heart rate and norepinephrine levels while a patient is supine. However, blood pooling associated with upright posture further compromises cardiac output and consequently increases sympathetic nerve activity. Abnormalities in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone volume regulation system are also suspected to impair sodium retention, contributing to hypovolemia.1,22

Neuropathic POTS

About half of patients with POTS have partial sympathetic denervation (particularly in the lower limbs) and inadequate vasoconstriction upon standing, leading to reduced venous return and stroke volume.17,23 A compensatory increase in sympathetic tone results in tachycardia to maintain cardiac output and blood pressure.

Hyperadrenergic POTS

Up to 50% of patients with POTS have high norepinephrine levels (≥ 600 pg/mL) when upright. This subtype, hyperadrenergic POTS, is characterized by an increase in systolic blood pressure of at least 10 mm Hg within 10 minutes of standing, with concomitant tachycardia that can be similar to or greater than that seen in nonhyperadrenergic POTS. Patients with hyperadrenergic POTS tend to report more prominent symptoms of sympathetic activation, such as palpitations, anxiety, and tremulousness.24,25

Norepinephrine transporter deficiency

The norepinephrine transporter (NET) is on the presynaptic cleft of sympathetic neurons and serves to clear synaptic norepinephrine. NET deficiency leads to a hyperadrenergic state and elevated sympathetic nerve activation.18 NET deficiency may be induced by common antidepressants (eg, tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) and attention-deficit disorder medications.4

Mast cell activation syndrome

The relationship between mast cell activation syndrome and POTS is poorly understood.4,26 Mast cell activation syndrome has been described in a subset of patients with POTS who have sinus tachycardia accompanied by severe episodic flushing. Patients with this subtype have a hyperadrenergic response to postural change and elevated urine methylhistamine during flushing episodes.

Patients with mast cell activation syndrome tend to have strong allergic symptoms and may also have severe gastrointestinal problems, food sensitivities, dermatographism, and neuropathy. Diagnosis can be difficult, as the condition is associated with numerous markers with varying sensitivity and specificity.

Autoimmune origin

A significant minority of patients report a viral-like illness before the onset of POTS symptoms, suggesting a possible autoimmune-mediated or inflammatory cause. Also, some autoimmune disorders (eg, Sjögren syndrome) can present with a POTS-like manifestation.

Research into the role of autoantibodies in the pathophysiology of POTS offers the potential to develop novel therapeutic targets. Autoantibodies that have been reported in POTS include those against M1 to M3 muscarinic receptors (present in over 87% of patients with POTS),27 cardiac lipid raft-associated proteins,28 adrenergic G-protein coupled receptors, alpha-1-adrenergic receptors, and beta-1- and beta-2-adrenergic receptors.29 Although commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays can assess for these antibody fragments, it is not known whether targeting the antibodies improves outcomes. At this time, antibody testing for POTS should be confined to the research setting.

LINKS TO OTHER SYNDROMES

POTS is often associated with other conditions whose symptoms cannot be explained by postural intolerance or tachycardia.

Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are a group of inherited heterogeneous disorders involving joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility, and tissue fragility.30 The hypermobile subtype is most commonly associated with POTS, with patients often having symptoms of autonomic dysregulation and autonomic test abnormalities.31–33 Patients with POTS may have a history of joint subluxations, joint pain, cervical instability, and spontaneous epidural leaks. The reason for the overlap between the two syndromes is not clear.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is characterized by persistent fatigue that does not resolve with rest and is not necessarily associated with orthostatic changes. More than 75% of patients with POTS report general fatigue as a major complaint, and up to 23% meet the full criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome.34

DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGY

A patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of POTS should first undergo a detailed history and physical examination. Other causes of sinus tachycardia should be considered.

Detailed history, symptom review

The history should focus on determining symptom burden, including tachycardia onset, frequency, severity, and triggers; the presence of syncope; and the impact of symptoms on daily function and quality of life.

Presyncope and its associated symptoms occur in less than one-third of patients with POTS, and syncope is not a principal feature.4 If syncope is the predominant complaint, alternative causes should be investigated. The usual cause of syncope in the general population is thought to be vasovagal.

In addition to orthostatic intolerance, gastrointestinal disturbances are common in POTS, presenting as abdominal pain, heartburn, irregular bowel movements, diarrhea, or constipation. Symptoms of gastroparesis are less common. Gastrointestinal symptoms tend to be prolonged, lasting hours and occurring multiple times a week. They tend not to improve in the supine position.35

POTS-associated symptoms may develop insidiously, but patients often report onset after an acute stressor such as pregnancy, major surgery, or a presumed viral illness.4 Whether these putative triggers are causative or coincidental is unknown. Symptoms of orthostatic intolerance tend to be exacerbated by dehydration, heat, alcohol, exercise, and menstruation.36,37

Consider the family history: 1 in 8 patients with POTS reports familial orthostatic intolerance,38 suggesting a genetic role in some patients. Inquire about symptoms or a previous diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and mast cell activation syndrome.

Consider other conditions

Pheochromocytoma causes hyperadrenergic symptoms (eg, palpitations, lightheadedness) like those in POTS, but patients with pheochromocytoma typically have these symptoms while supine. Pheochromocytoma is also characterized by plasma norepinephrine levels much higher than in POTS.4 Plasma metanephrine testing helps diagnose or rule out pheochromocytoma.5

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia, like pheochromocytoma, also has clinical features similar to those of POTS, as well as tachycardia present when supine. It involves higher sympathetic tone and lower parasympathetic tone compared with POTS; patients commonly have a daytime resting heart rate of at least 100 bpm or a 24-hour mean heart rate of at least 90 bpm.1,42 While the intrinsic heart rate is heightened in inappropriate sinus tachycardia, it is not different between POTS patients and healthy individuals.42,43 Distinguishing POTS from inappropriate sinus tachycardia is further complicated by the broad inclusion criteria of most studies of inappropriate sinus tachycardia, which failed to exclude patients with POTS.44 The Heart Rhythm Society recently adopted distinct definitions for the 2 conditions.1

Physical examination: Focus on vital signs

Dependent acrocyanosis—dark red-blue discoloration of the lower legs that is cold to the touch—occurs in about half of patients with POTS upon standing.4 Dependent acrocyanosis is associated with joint hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, so these conditions should also be considered if findings are positive.

Laboratory testing for other causes

Laboratory testing is used mainly to detect primary causes of sinus tachycardia. Tests should include:

- Complete blood cell count with hematocrit (for severe anemia)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone level (for hyperthyroidism)

- Electrolyte panel (for significant electrolyte disturbances).

Evidence is insufficient to support routinely measuring the vitamin B12 level, iron indices, and serum markers for celiac disease, although these may be done if the history or physical examination suggests related problems.4 Sicca symptoms (severe dry eye or dry mouth) should trigger evaluation for Sjögren syndrome.

Electrocardiography needed

Electrocardiography should be performed to investigate for cardiac conduction abnormalities as well as for resting markers of a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia. Extended ambulatory (Holter) monitoring may be useful to evaluate for a transient reentrant tachyarrhythmia4; however, it does not record body position, so it can be difficult to determine if detected episodes of tachycardia are related to posture.

Additional testing for select cases

Further investigation is usually not needed to diagnose POTS but should be considered in some cases. Advanced tests are typically performed at a tertiary care referral center and include:

- Quantitative sensory testing to evaluate for small-fiber neuropathy (ie, Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test, or QSART), which occurs in the neuropathic POTS subtype

- Formal autonomic function testing to characterize neurovascular responsiveness

- Supine and standing plasma norepinephrine levels (fractionated catecholamines) to characterize the net activation of the sympathetic nervous system

- Blood volume assessments to assess hypovolemia

- Formal exercise testing to objectively quantify exercise capacity.

GRADED MANAGEMENT

No single universal gold-standard therapy exists for POTS, and management should be individually determined with the primary goals of treating symptoms and restoring function. A graded approach should be used, starting with conservative nonpharmacologic therapies and adding medications as needed.

While the disease course varies substantially from patient to patient, proper management is strongly associated with eventual symptom improvement.1

NONPHARMACOLOGIC STEPS FIRST

Education

Patients should be informed of the nature of their condition and referred to appropriate healthcare personnel. POTS is a chronic illness requiring individualized coping strategies, intensive physician interaction, and support of a multidisciplinary team. Patients and family members can be reassured that most symptoms improve over time with appropriate diagnosis and treatment.1 Patients should be advised to avoid aggravating triggers and activities.

Exercise

Exercise programs are encouraged but should be introduced gradually, as physical activity can exacerbate symptoms, especially at the outset. Several studies have reported benefits from a short-term (3-month) program, in which the patient gradually progresses from non-upright exercise (eg, rowing machine, recumbent cycle, swimming) to upright endurance exercises. At the end of these programs, significant cardiac remodeling, improved quality of life, and reduced heart rate responses to standing have been reported, and benefits have been reported to persist in patients who continued exercising after the 3-month study period.46,47

Despite the benefits of exercise interventions, compliance is low.46,47 To prevent early discouragement, patients should be advised that it can take 4 to 6 weeks of continued exercise before benefits appear. Patients are encouraged to exercise every other day for 30 minutes or more. Regimens should primarily focus on aerobic conditioning, but resistance training, concentrating on thigh muscles, can also help. Exercise is a treatment and not a cure, and benefits can rapidly disappear if regular activity (at least 3 times per week) is stopped.48

Compression stockings

Compression stockings help reduce peripheral venous pooling and enhance venous return to the heart. Waist-high stockings with compression of at least 30 to 40 mm Hg offer the best results.

Diet

Increased fluid and salt intake is advisable for patients with suspected hypovolemia. At least 2 to 3 L of water accompanied by 10 to 12 g of daily sodium intake is recommended.1 This can usually be accomplished with diet and salt added to food, but salt tablets can be used if the patient prefers. The resultant plasma volume expansion may help reduce the reflex tachycardia upon standing.49

Check medications

Rescue therapy with saline infusion

Intravenous saline infusion can augment blood volume in patients who are clinically decompensated and present with severe symptoms.1 Intermittent infusion of 1 L of normal saline has been found to significantly reduce orthostatic tachycardia and related symptoms in patients with POTS, contributing to improved quality of life.51,52

Chronic saline infusions are not recommended for long-term care because of the risk of access complications and infection.1 Moak et al53 reported a high rate of bacteremia in a cohort of children with POTS with regular saline infusions, most of whom had a central line. On the other hand, Ruzieh et al54 reported significantly improved symptoms with regular saline infusions without a high rate of complications, but patients in this study received infusions for only a few months and through a peripheral intravenous catheter.

DRUG THERAPY

No medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or Health Canada specifically for treating POTS, making all pharmacologic recommendations off-label. Although the drugs discussed below have been evaluated for POTS in controlled laboratory settings, they have yet to be tested in robust clinical trials.

Blood volume expansion

Several drugs expand blood volume, which may reduce orthostatic tachycardia.

Fludrocortisone is a synthetic aldosterone analogue that enhances sodium and water retention. Although one observational study found that it normalizes hemodynamic changes in response to orthostatic stress, no high-level evidence exists for its effectiveness for POTS.55 It is generally well tolerated, although possible adverse effects include hyperkalemia, hypertension, fatigue, nausea, headache, and edema.5,56

Desmopressin is a synthetic version of a natural antidiuretic hormone that increases kidney-mediated free-water reabsorption without sodium retention. It significantly reduces upright heart rate in patients with POTS and improves symptom burden. Although potential adverse effects include edema and headache, hyponatremia is the primary concern with daily use, especially with the increased water intake advised for POTS.57 Patients should be advised to use desmopressin no more than once a week for the acute improvement of symptoms. Intermittent monitoring of serum sodium levels is recommended for safety.

Erythropoietin replacement has been suggested for treating POTS to address the significant deficit in red blood cell volume. Although erythropoietin therapy has a direct vasoconstrictive effect and largely improves red blood cell volume in patients with POTS, it does not expand plasma volume, so orthostatic tachycardia is not itself reduced.22 Nevertheless, it may significantly improve POTS symptoms refractory to more common methods of treatment, and it should be reserved for such cases. In addition to the lack of effect on orthostatic tachycardia, drawbacks to using erythropoietin include its high cost, the need for subcutaneous administration, and the risk of life-threatening complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke.58,59

Heart rate-lowering agents

Propranolol, a nonselective beta-adrenergic antagonist, can significantly reduce standing heart rate and improve symptoms at low dosages (10–20 mg). Higher dosages can further restrain orthostatic tachycardia but are not as well tolerated, mainly due to hypotension and worsening of existing symptoms such as fatigue.60 Regular-acting propranolol works for about 4 to 5 hours per dose, so full-day coverage often requires dosing 4 times per day.

Ivabradine is a selective blocker of the “funny” (If) channel that reduces the sinus node firing rate without affecting blood pressure, so it slows heart rate without causing supine hypertension or orthostatic hypotension.

A retrospective case series found that 60% of patients with POTS treated with ivabradine reported symptomatic improvement, and all patients experienced reduced tachycardia with continued use.61 Ivabradine has not been compared with placebo or propranolol in a randomized controlled trial, and it has not been well studied in pregnancy and so should be avoided because of potential teratogenic effects.

When prescribing ivabradine for women of childbearing age, a negative pregnancy test may be documented prior to initiation of therapy, and the use of highly effective methods of contraception is recommended. Ivabradine should be avoided in women contemplating pregnancy. Insurance coverage can limit access to ivabradine in the United States.

Central nervous system sympatholytics

Patients with prominent hyperadrenergic features may benefit from central sympatholytic agents. However, these drugs may not be well tolerated in patients with neuropathic POTS because of the effects of reduced systemic vascular resistance5 and the possible exacerbation of drowsiness, fatigue, and mental clouding.4 Patients can be extremely sensitive to these medications, so they should initially be prescribed at the lowest dose, then gradually increased as tolerated.

Clonidine, an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist, decreases central sympathetic tone. In hyperadrenergic patients, clonidine can stabilize heart rate and blood pressure, thereby reducing orthostatic symptoms.62

Methyldopa has effects similar to those of clonidine but is easier to titrate owing to its longer half-life.63 Methyldopa is typically started at 125 mg at bedtime and increased to 125 mg twice daily, if tolerated.

Other agents

Midodrine is a prodrug. The active form, an alpha-1-adrenergic agonist, constricts peripheral veins and arteries to increase vascular resistance and venous return, thereby reducing orthostatic tachycardia.52 It is most useful in patients with impaired peripheral vasoconstriction (eg, neuropathic POTS) and may be less effective in those with hyperadrenergic POTS.64 Major limitations of midodrine include worsening supine hypertension and possible urinary retention.39

Because of midodrine’s short half-life, frequent dosing is required during daytime hours (eg, 8 AM, noon, and 4 PM), but it should not be taken within 4 to 5 hours of sleep because of the risk of supine hypertension. Midodrine is typically started at 2.5 to 5 mg per dose and can be titrated up to 15 mg per dose.

Midodrine is an FDA pregnancy category C drug (adverse effects in pregnancy seen in animal models, but evidence lacking in humans). While ideally it should be avoided, we have used it safely in pregnant women with disabling POTS symptoms.

Pyridostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, increases cardiovagal tone and possibly sympathetic tone. It has been reported to significantly reduce standing heart rate and improve symptom burden in patients with POTS.65 However, pyridostigmine increases gastrointestinal mobility, leading to severe adverse effects in over 20% of patients, including abdominal cramps, nausea, and diarrhea.66

Droxidopa, a synthetic amino acid precursor of norepinephrine, improves dizziness and fatigue in POTS with minimal effects on blood pressure.67

Modafinil, a psychostimulant, may improve POTS-associated cognitive symptoms.4 It also raises upright blood pressure without significantly worsening standing heart rate or acute orthostatic symptoms.68

EFFECTS OF COMORBID DISORDERS ON MANAGEMENT

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Pharmacologic approaches to POTS should not be altered based on the presence of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, but because many of these patients are prone to joint dislocation, exercise prescriptions may need adjusting.

A medical genetics consult is recommended for patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Although the hypermobile type (the form most commonly associated with POTS) is not associated with aortopathy, it can be confused with classical and vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, which require serial aortic screening.30

Mast cell activation syndrome

Consultation with an allergist or immunologist may help patients with severe symptoms.

Autoantibodies and autoimmunity

Treatment of the underlying disorder is recommended and can result in significantly improved POTS symptoms.

SPECIALTY CARE REFERRAL

POTS can be challenging to manage. Given the range of physiologic, emotional, and functional distress patients experience, it often requires significant physician time and multidisciplinary care. Patients with continued severe or debilitating symptoms may benefit from referral to a tertiary-care center with experience in autonomic nervous system disorders.

PROGNOSIS

Limited data are available on the long-term prognosis of POTS, and more studies are needed in pediatric and adult populations. No deaths have been reported in the handful of published cases of POTS in patients older than 50.1 Some pediatric studies suggest that some teenagers “outgrow” their POTS. However, these data are not robust, and an alternative explanation is that as they get older, they see adult physicians for their POTS symptoms and so are lost to study follow-up.6,44,69

We have not often seen POTS simply resolve without ongoing treatment. However, in our experience, most patients have improved symptoms and function with multimodal treatment (ie, exercise, salt, water, stockings, and some medications) and time.

Some people, most of them relatively young women, experience lightheadedness, a racing heart, and other symptoms (but not hypotension) when they stand up, in a condition known as postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS).1 Although not known to shorten life,1 it can be physically and mentally debilitating.2,3 Therapy rarely cures it, but a multifaceted approach can substantially improve quality of life.

This review outlines the evaluation and diagnosis of POTS and provides guidance for a therapy regimen.

HOW IS POTS DEFINED?

POTS is a multifactorial syndrome rather than a specific disease. It is characterized by all of the following1,4–6:

- An increase in heart rate of ≥ 30 bpm, or ≥ 40 bpm for those under age 19, within 10 minutes of standing from a supine position

- Sustained tachycardia (> 30 seconds)

- Absence of orthostatic hypotension (a fall in blood pressure of ≥ 20/10 mm Hg)

- Frequent and chronic duration (≥ 6 months).

These features are critical to diagnosis. Hemodynamic criteria in isolation may describe postural tachycardia but are not sufficient to diagnose POTS.

The prevalence of POTS is estimated to be between 0.2% and 1.0%,7 affecting up to 3 million people in the United States. Most cases arise between ages 13 and 50, with a female-to-male ratio of 5:1.8

MANY NAMES, SAME CONDITION

In 1871, Da Costa9 described a condition he called “irritable heart syndrome” that had characteristics similar to those of POTS, including extreme fatigue and exercise intolerance. Decades later, Lewis10 and Wood11 provided more detailed descriptions of the disorder, renaming it “soldier’s heart” or “Da Costa syndrome.” As other cases were documented, more terms arose, including “effort syndrome” and “mitral valve prolapse syndrome.”

In 1982, Rosen and Cryer12 were the first to use the term “postural tachycardia syndrome” for patients with disabling tachycardia upon standing without orthostatic hypotension. In 1986, Fouad et al13 described patients with postural tachycardia, orthostatic intolerance, and a small degree of hypotension as having “idiopathic hypovolemia.”

In 1993, Schondorf and Low14 established the current definition of POTS, leading to increased awareness and research efforts to understand its pathophysiology.

MULTIFACTORIAL PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

During the last 2 decades, several often-overlapping forms of POTS have been recognized, all of which share a final common pathway of sustained orthostatic tachycardia.15–19 In addition, a number of common comorbidities were identified through review of large clinic populations of POTS.20,21

Hypovolemic POTS

Up to 70% of patients with POTS have hypovolemia. The average plasma volume deficit is about 13%, which typically causes only insignificant changes in heart rate and norepinephrine levels while a patient is supine. However, blood pooling associated with upright posture further compromises cardiac output and consequently increases sympathetic nerve activity. Abnormalities in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone volume regulation system are also suspected to impair sodium retention, contributing to hypovolemia.1,22

Neuropathic POTS

About half of patients with POTS have partial sympathetic denervation (particularly in the lower limbs) and inadequate vasoconstriction upon standing, leading to reduced venous return and stroke volume.17,23 A compensatory increase in sympathetic tone results in tachycardia to maintain cardiac output and blood pressure.

Hyperadrenergic POTS

Up to 50% of patients with POTS have high norepinephrine levels (≥ 600 pg/mL) when upright. This subtype, hyperadrenergic POTS, is characterized by an increase in systolic blood pressure of at least 10 mm Hg within 10 minutes of standing, with concomitant tachycardia that can be similar to or greater than that seen in nonhyperadrenergic POTS. Patients with hyperadrenergic POTS tend to report more prominent symptoms of sympathetic activation, such as palpitations, anxiety, and tremulousness.24,25

Norepinephrine transporter deficiency

The norepinephrine transporter (NET) is on the presynaptic cleft of sympathetic neurons and serves to clear synaptic norepinephrine. NET deficiency leads to a hyperadrenergic state and elevated sympathetic nerve activation.18 NET deficiency may be induced by common antidepressants (eg, tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) and attention-deficit disorder medications.4

Mast cell activation syndrome

The relationship between mast cell activation syndrome and POTS is poorly understood.4,26 Mast cell activation syndrome has been described in a subset of patients with POTS who have sinus tachycardia accompanied by severe episodic flushing. Patients with this subtype have a hyperadrenergic response to postural change and elevated urine methylhistamine during flushing episodes.

Patients with mast cell activation syndrome tend to have strong allergic symptoms and may also have severe gastrointestinal problems, food sensitivities, dermatographism, and neuropathy. Diagnosis can be difficult, as the condition is associated with numerous markers with varying sensitivity and specificity.

Autoimmune origin

A significant minority of patients report a viral-like illness before the onset of POTS symptoms, suggesting a possible autoimmune-mediated or inflammatory cause. Also, some autoimmune disorders (eg, Sjögren syndrome) can present with a POTS-like manifestation.