User login

FDA concerned about e-cigs/seizures in youth

the agency announced April 3.

Between 2010 and early 2019, the FDA and poison control centers received 35 reports of seizures that mentioned the use of e-cigarettes. Most reports involved youth or young adults, and the reports have increased slightly since June 2018, the announcement says.

“We want to be clear that we don’t yet know if there’s a direct relationship between the use of e-cigarettes and a risk of seizure,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, and Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in a statement. “We believe these 35 cases warrant scientific investigation into whether there is in fact a connection.”

In addition, the FDA is trying to determine whether any e-cigarette product-specific factors may be associated with the risk of seizures.

Seizures have been reported after a few puffs or up to 1 day after e-cigarette use and among first-time and experienced users. A few patients had a prior history of seizures or also used other substances, such as marijuana or amphetamines.

“While 35 cases may not seem like much compared to the total number of people using e-cigarettes, we are nonetheless concerned by these reported cases. We also recognized that not all of the cases may be reported,” Dr. Gottlieb and Dr. Abernethy said.

Although seizures are known side effects of nicotine toxicity and have been reported in the context of intentional or accidental swallowing of e-cigarette liquid, the voluntary reports of seizures occurring with vaping could represent a new safety issue, the FDA said.

The agency encouraged people to report cases via an online safety reporting portal. It also provided redacted case reports that involve vaping and seizures.

the agency announced April 3.

Between 2010 and early 2019, the FDA and poison control centers received 35 reports of seizures that mentioned the use of e-cigarettes. Most reports involved youth or young adults, and the reports have increased slightly since June 2018, the announcement says.

“We want to be clear that we don’t yet know if there’s a direct relationship between the use of e-cigarettes and a risk of seizure,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, and Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in a statement. “We believe these 35 cases warrant scientific investigation into whether there is in fact a connection.”

In addition, the FDA is trying to determine whether any e-cigarette product-specific factors may be associated with the risk of seizures.

Seizures have been reported after a few puffs or up to 1 day after e-cigarette use and among first-time and experienced users. A few patients had a prior history of seizures or also used other substances, such as marijuana or amphetamines.

“While 35 cases may not seem like much compared to the total number of people using e-cigarettes, we are nonetheless concerned by these reported cases. We also recognized that not all of the cases may be reported,” Dr. Gottlieb and Dr. Abernethy said.

Although seizures are known side effects of nicotine toxicity and have been reported in the context of intentional or accidental swallowing of e-cigarette liquid, the voluntary reports of seizures occurring with vaping could represent a new safety issue, the FDA said.

The agency encouraged people to report cases via an online safety reporting portal. It also provided redacted case reports that involve vaping and seizures.

the agency announced April 3.

Between 2010 and early 2019, the FDA and poison control centers received 35 reports of seizures that mentioned the use of e-cigarettes. Most reports involved youth or young adults, and the reports have increased slightly since June 2018, the announcement says.

“We want to be clear that we don’t yet know if there’s a direct relationship between the use of e-cigarettes and a risk of seizure,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, and Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in a statement. “We believe these 35 cases warrant scientific investigation into whether there is in fact a connection.”

In addition, the FDA is trying to determine whether any e-cigarette product-specific factors may be associated with the risk of seizures.

Seizures have been reported after a few puffs or up to 1 day after e-cigarette use and among first-time and experienced users. A few patients had a prior history of seizures or also used other substances, such as marijuana or amphetamines.

“While 35 cases may not seem like much compared to the total number of people using e-cigarettes, we are nonetheless concerned by these reported cases. We also recognized that not all of the cases may be reported,” Dr. Gottlieb and Dr. Abernethy said.

Although seizures are known side effects of nicotine toxicity and have been reported in the context of intentional or accidental swallowing of e-cigarette liquid, the voluntary reports of seizures occurring with vaping could represent a new safety issue, the FDA said.

The agency encouraged people to report cases via an online safety reporting portal. It also provided redacted case reports that involve vaping and seizures.

Rituximab does not improve fatigue symptoms of ME/CFS

according to results from the phase 3 RituxME trial.

“The lack of clinical effect of B-cell depletion in this trial weakens the case for an important role of B lymphocytes in ME/CFS but does not exclude an immunologic basis,” Øystein Fluge, MD, PhD, of the department of oncology and medical physics at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, and his colleagues wrote April 1 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The investigators noted that the basis for testing the effects of a B-cell–depleting intervention on clinical symptoms in patients with ME/CFS came from observations of its potential benefit in a subgroup of patients in previous studies. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues performed a three-patient case series in their own group that found benefit for patients who received rituximab for treatment of CFS (BMC Neurol. 2009 May 8;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-28). A phase 2 trial of 30 patients with CFS also performed by his own group found improved fatigue scores in 66.7% of patients in the rituximab group, compared with placebo (PLOS One. 2011 Oct 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026358).

In the double-blinded RituxME trial, 151 patients with ME/CFS from four university hospitals and one general hospital in Norway were recruited and randomized to receive infusions of rituximab (n = 77) or placebo (n = 74). The patients were aged 18-65 years old and had the disease ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Patients reported and rated their ME/CFS symptoms at baseline as well as completed forms for the SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, and modified DePaul Symptom Questionnaire out to 24 months. The rituximab group received two infusions at 500 mg/m2 across body surface area at 2 weeks apart. They then received 500-mg maintenance infusions at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months where they also self-reported changes in ME/CFS symptoms.

There were no significant differences between groups regarding fatigue score at any follow-up period, with an average between-group difference of 0.02 at 24 months (95% confidence interval, –0.27 to 0.31). The overall response rate was 26% with rituximab and 35% with placebo. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues also noted no significant differences regarding SF-36 scores, function level, and fatigue severity between groups.

Adverse event rates were higher in the rituximab group (63 patients; 82%) than in the placebo group (48 patients; 65%), and these were more often attributed to treatment for those taking rituximab (26 patients [34%]) than for placebo (12 patients [16%]). Adverse events requiring hospitalization also occurred more often among those taking rituximab (31 events in 20 patients [26%]) than for those who took placebo (16 events in 14 patients [19%]).

Some of the weaknesses of the trial included its use of self-referral and self-reported symptom scores, which might have been subject to recall bias. In commenting on the difference in outcome between the phase 3 trial and others, Dr. Fluge and his associates said the discrepancy could potentially be high expectations in the placebo group, unknown factors surrounding symptom variation in ME/CFS patients, and unknown patient selection effects.

“[T]he negative outcome of RituxME should spur research to assess patient subgroups and further elucidate disease mechanisms, of which recently disclosed impairment of energy metabolism may be important,” Dr. Fluge and his coauthors wrote.

The trial was funded by grants to the researchers from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Regional Health Trusts, the MEandYou Foundation, the Norwegian ME Association, and the legacy of Torstein Hereid.

SOURCE: Fluge Ø et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M18-1451

The RituxME trial’s results weaken the case for the use of rituximab to treat myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but there are opportunities to test other treatments targeting immunologic abnormalities in ME/CFS, Peter C. Rowe, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a related editorial.

“Persons with ME/CFS often meet criteria for several comorbid conditions, each of which could flare during a trial, possibly obscuring a true beneficial effect of an intervention,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Trials with open treatment periods, in which ME/CFS patients all receive rituximab and then are grouped based on nontargeted conditions, could be warranted to “allow better control” of these conditions. Other trial designs could include randomizing patients to continue or discontinue therapy for responders, he added.

“The profound level of impaired function of affected individuals warrants a new commitment to hypothesis-driven clinical trials that incorporate and expand on the methodological sophistication of the rituximab trial,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Dr. Rowe is with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments summarize his editorial in response to Fluge et al. (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0643). Dr. Rowe reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and is a scientific advisory board member for Solve ME/CFS, all outside the submitted work.

The RituxME trial’s results weaken the case for the use of rituximab to treat myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but there are opportunities to test other treatments targeting immunologic abnormalities in ME/CFS, Peter C. Rowe, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a related editorial.

“Persons with ME/CFS often meet criteria for several comorbid conditions, each of which could flare during a trial, possibly obscuring a true beneficial effect of an intervention,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Trials with open treatment periods, in which ME/CFS patients all receive rituximab and then are grouped based on nontargeted conditions, could be warranted to “allow better control” of these conditions. Other trial designs could include randomizing patients to continue or discontinue therapy for responders, he added.

“The profound level of impaired function of affected individuals warrants a new commitment to hypothesis-driven clinical trials that incorporate and expand on the methodological sophistication of the rituximab trial,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Dr. Rowe is with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments summarize his editorial in response to Fluge et al. (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0643). Dr. Rowe reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and is a scientific advisory board member for Solve ME/CFS, all outside the submitted work.

The RituxME trial’s results weaken the case for the use of rituximab to treat myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but there are opportunities to test other treatments targeting immunologic abnormalities in ME/CFS, Peter C. Rowe, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a related editorial.

“Persons with ME/CFS often meet criteria for several comorbid conditions, each of which could flare during a trial, possibly obscuring a true beneficial effect of an intervention,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Trials with open treatment periods, in which ME/CFS patients all receive rituximab and then are grouped based on nontargeted conditions, could be warranted to “allow better control” of these conditions. Other trial designs could include randomizing patients to continue or discontinue therapy for responders, he added.

“The profound level of impaired function of affected individuals warrants a new commitment to hypothesis-driven clinical trials that incorporate and expand on the methodological sophistication of the rituximab trial,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Dr. Rowe is with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments summarize his editorial in response to Fluge et al. (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0643). Dr. Rowe reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and is a scientific advisory board member for Solve ME/CFS, all outside the submitted work.

according to results from the phase 3 RituxME trial.

“The lack of clinical effect of B-cell depletion in this trial weakens the case for an important role of B lymphocytes in ME/CFS but does not exclude an immunologic basis,” Øystein Fluge, MD, PhD, of the department of oncology and medical physics at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, and his colleagues wrote April 1 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The investigators noted that the basis for testing the effects of a B-cell–depleting intervention on clinical symptoms in patients with ME/CFS came from observations of its potential benefit in a subgroup of patients in previous studies. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues performed a three-patient case series in their own group that found benefit for patients who received rituximab for treatment of CFS (BMC Neurol. 2009 May 8;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-28). A phase 2 trial of 30 patients with CFS also performed by his own group found improved fatigue scores in 66.7% of patients in the rituximab group, compared with placebo (PLOS One. 2011 Oct 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026358).

In the double-blinded RituxME trial, 151 patients with ME/CFS from four university hospitals and one general hospital in Norway were recruited and randomized to receive infusions of rituximab (n = 77) or placebo (n = 74). The patients were aged 18-65 years old and had the disease ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Patients reported and rated their ME/CFS symptoms at baseline as well as completed forms for the SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, and modified DePaul Symptom Questionnaire out to 24 months. The rituximab group received two infusions at 500 mg/m2 across body surface area at 2 weeks apart. They then received 500-mg maintenance infusions at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months where they also self-reported changes in ME/CFS symptoms.

There were no significant differences between groups regarding fatigue score at any follow-up period, with an average between-group difference of 0.02 at 24 months (95% confidence interval, –0.27 to 0.31). The overall response rate was 26% with rituximab and 35% with placebo. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues also noted no significant differences regarding SF-36 scores, function level, and fatigue severity between groups.

Adverse event rates were higher in the rituximab group (63 patients; 82%) than in the placebo group (48 patients; 65%), and these were more often attributed to treatment for those taking rituximab (26 patients [34%]) than for placebo (12 patients [16%]). Adverse events requiring hospitalization also occurred more often among those taking rituximab (31 events in 20 patients [26%]) than for those who took placebo (16 events in 14 patients [19%]).

Some of the weaknesses of the trial included its use of self-referral and self-reported symptom scores, which might have been subject to recall bias. In commenting on the difference in outcome between the phase 3 trial and others, Dr. Fluge and his associates said the discrepancy could potentially be high expectations in the placebo group, unknown factors surrounding symptom variation in ME/CFS patients, and unknown patient selection effects.

“[T]he negative outcome of RituxME should spur research to assess patient subgroups and further elucidate disease mechanisms, of which recently disclosed impairment of energy metabolism may be important,” Dr. Fluge and his coauthors wrote.

The trial was funded by grants to the researchers from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Regional Health Trusts, the MEandYou Foundation, the Norwegian ME Association, and the legacy of Torstein Hereid.

SOURCE: Fluge Ø et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M18-1451

according to results from the phase 3 RituxME trial.

“The lack of clinical effect of B-cell depletion in this trial weakens the case for an important role of B lymphocytes in ME/CFS but does not exclude an immunologic basis,” Øystein Fluge, MD, PhD, of the department of oncology and medical physics at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, and his colleagues wrote April 1 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The investigators noted that the basis for testing the effects of a B-cell–depleting intervention on clinical symptoms in patients with ME/CFS came from observations of its potential benefit in a subgroup of patients in previous studies. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues performed a three-patient case series in their own group that found benefit for patients who received rituximab for treatment of CFS (BMC Neurol. 2009 May 8;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-28). A phase 2 trial of 30 patients with CFS also performed by his own group found improved fatigue scores in 66.7% of patients in the rituximab group, compared with placebo (PLOS One. 2011 Oct 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026358).

In the double-blinded RituxME trial, 151 patients with ME/CFS from four university hospitals and one general hospital in Norway were recruited and randomized to receive infusions of rituximab (n = 77) or placebo (n = 74). The patients were aged 18-65 years old and had the disease ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Patients reported and rated their ME/CFS symptoms at baseline as well as completed forms for the SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, and modified DePaul Symptom Questionnaire out to 24 months. The rituximab group received two infusions at 500 mg/m2 across body surface area at 2 weeks apart. They then received 500-mg maintenance infusions at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months where they also self-reported changes in ME/CFS symptoms.

There were no significant differences between groups regarding fatigue score at any follow-up period, with an average between-group difference of 0.02 at 24 months (95% confidence interval, –0.27 to 0.31). The overall response rate was 26% with rituximab and 35% with placebo. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues also noted no significant differences regarding SF-36 scores, function level, and fatigue severity between groups.

Adverse event rates were higher in the rituximab group (63 patients; 82%) than in the placebo group (48 patients; 65%), and these were more often attributed to treatment for those taking rituximab (26 patients [34%]) than for placebo (12 patients [16%]). Adverse events requiring hospitalization also occurred more often among those taking rituximab (31 events in 20 patients [26%]) than for those who took placebo (16 events in 14 patients [19%]).

Some of the weaknesses of the trial included its use of self-referral and self-reported symptom scores, which might have been subject to recall bias. In commenting on the difference in outcome between the phase 3 trial and others, Dr. Fluge and his associates said the discrepancy could potentially be high expectations in the placebo group, unknown factors surrounding symptom variation in ME/CFS patients, and unknown patient selection effects.

“[T]he negative outcome of RituxME should spur research to assess patient subgroups and further elucidate disease mechanisms, of which recently disclosed impairment of energy metabolism may be important,” Dr. Fluge and his coauthors wrote.

The trial was funded by grants to the researchers from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Regional Health Trusts, the MEandYou Foundation, the Norwegian ME Association, and the legacy of Torstein Hereid.

SOURCE: Fluge Ø et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M18-1451

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

FDA approves Mavenclad for treatment of relapsing MS

including relapsing/remitting and active secondary progressive disease.

The drug’s manufacturer, EMD Serono, said in a press release that cladribine is the first short-course oral therapy for such patients, and its use is generally recommended for patients who have had an inadequate response to, or are unable to tolerate, an alternate drug indicated for the treatment of MS. Cladribine is not recommended for use in patients with clinically isolated syndrome.

The agency’s decision is based on results from a clinical trial of 1,326 patients with relapsing MS who had experienced at least one relapse in the previous 12 months. Patients who received cladribine had significantly fewer relapses than did those who received placebo; the progression of disability was also significantly reduced in the cladribine group, compared with placebo, according to the FDA’s announcement.

The most common adverse events associated with cladribine include upper respiratory tract infections, headache, and decreased lymphocyte counts. In addition, the medication must be dispensed with a patient medication guide because the label includes a boxed warning for increased risk of malignancy and fetal harm. Other warnings include a risk for decreased lymphocyte count, hematologic toxicity and bone marrow suppression, and graft-versus-host-disease.

“We are committed to supporting the development of safe and effective treatments for patients with multiple sclerosis. The approval of Mavenclad represents an additional option for patients who have tried another treatment without success,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the division of neurology products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the announcement.

The approved dose of cladribine is 3.5 mg/kg body weight over 2 years, administered as one treatment course of 1.75 mg/kg per year, each consisting of 2 treatment weeks. Additional courses of cladribine are not to be administered because retreatment with cladribine during years 3 and 4 may further increase the risk of malignancy. The safety and efficacy of reinitiating cladribine more than 2 years after completing two treatment courses has not been studied, according to EMD Serono.

Cladribine is approved in more than 50 other countries and was approved for use in the European Union in August 2017.

including relapsing/remitting and active secondary progressive disease.

The drug’s manufacturer, EMD Serono, said in a press release that cladribine is the first short-course oral therapy for such patients, and its use is generally recommended for patients who have had an inadequate response to, or are unable to tolerate, an alternate drug indicated for the treatment of MS. Cladribine is not recommended for use in patients with clinically isolated syndrome.

The agency’s decision is based on results from a clinical trial of 1,326 patients with relapsing MS who had experienced at least one relapse in the previous 12 months. Patients who received cladribine had significantly fewer relapses than did those who received placebo; the progression of disability was also significantly reduced in the cladribine group, compared with placebo, according to the FDA’s announcement.

The most common adverse events associated with cladribine include upper respiratory tract infections, headache, and decreased lymphocyte counts. In addition, the medication must be dispensed with a patient medication guide because the label includes a boxed warning for increased risk of malignancy and fetal harm. Other warnings include a risk for decreased lymphocyte count, hematologic toxicity and bone marrow suppression, and graft-versus-host-disease.

“We are committed to supporting the development of safe and effective treatments for patients with multiple sclerosis. The approval of Mavenclad represents an additional option for patients who have tried another treatment without success,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the division of neurology products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the announcement.

The approved dose of cladribine is 3.5 mg/kg body weight over 2 years, administered as one treatment course of 1.75 mg/kg per year, each consisting of 2 treatment weeks. Additional courses of cladribine are not to be administered because retreatment with cladribine during years 3 and 4 may further increase the risk of malignancy. The safety and efficacy of reinitiating cladribine more than 2 years after completing two treatment courses has not been studied, according to EMD Serono.

Cladribine is approved in more than 50 other countries and was approved for use in the European Union in August 2017.

including relapsing/remitting and active secondary progressive disease.

The drug’s manufacturer, EMD Serono, said in a press release that cladribine is the first short-course oral therapy for such patients, and its use is generally recommended for patients who have had an inadequate response to, or are unable to tolerate, an alternate drug indicated for the treatment of MS. Cladribine is not recommended for use in patients with clinically isolated syndrome.

The agency’s decision is based on results from a clinical trial of 1,326 patients with relapsing MS who had experienced at least one relapse in the previous 12 months. Patients who received cladribine had significantly fewer relapses than did those who received placebo; the progression of disability was also significantly reduced in the cladribine group, compared with placebo, according to the FDA’s announcement.

The most common adverse events associated with cladribine include upper respiratory tract infections, headache, and decreased lymphocyte counts. In addition, the medication must be dispensed with a patient medication guide because the label includes a boxed warning for increased risk of malignancy and fetal harm. Other warnings include a risk for decreased lymphocyte count, hematologic toxicity and bone marrow suppression, and graft-versus-host-disease.

“We are committed to supporting the development of safe and effective treatments for patients with multiple sclerosis. The approval of Mavenclad represents an additional option for patients who have tried another treatment without success,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the division of neurology products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the announcement.

The approved dose of cladribine is 3.5 mg/kg body weight over 2 years, administered as one treatment course of 1.75 mg/kg per year, each consisting of 2 treatment weeks. Additional courses of cladribine are not to be administered because retreatment with cladribine during years 3 and 4 may further increase the risk of malignancy. The safety and efficacy of reinitiating cladribine more than 2 years after completing two treatment courses has not been studied, according to EMD Serono.

Cladribine is approved in more than 50 other countries and was approved for use in the European Union in August 2017.

Valproate, topiramate prescribed in young women despite known teratogenicity risks

results of a retrospective analysis suggest.

Topiramate, linked to increased risk of cleft palate and smaller-than-gestational-age newborns, was among the top three antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) prescribed to women 15-44 years of age in the population-based cohort study.

Valproate, linked to increases in both anatomic and behavioral teratogenicity, was less often prescribed, but nevertheless still prescribed in a considerable proportion of patients in the study, which looked at U.S. commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid claims data from 2009 to 2013.

Presence of comorbidities could be influencing whether or not a woman of childbearing age receives one of these AEDs, the investigators said. Specifically, they found valproate more often prescribed for women with epilepsy who also had mood or anxiety and dissociative disorder, while topiramate was more often prescribed in women with headaches or migraines.

Taken together, these findings suggest a lack of awareness of the teratogenic risks of valproate and topiramate, said the investigators, led by Hyunmi Kim, MD, PhD, MPH, of the department of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“To improve current practice, knowledge of the teratogenicity of certain AEDs should be disseminated to health care professionals and patients,” they wrote. The report is in JAMA Neurology.

The findings of Dr. Kim and her colleagues were based on data for 46,767 women of childbearing age: 8,003 incident (new) cases with a mean age of 27 years, and 38,764 prevalent cases with a mean age of 30 years.

Topiramate was the second- or third-most prescribed AED in the analyses, alongside levetiracetam and lamotrigine. In particular, topiramate prescriptions were found in incident cases receiving first-line monotherapy (15%), prevalent cases receiving first-line monotherapy (13%), and prevalent cases receiving polytherapy (29%).

Valproate was the fifth-most prescribed AED for incident and prevalent cases receiving first-line monotherapy (5% and 10%, respectively), and came in fourth place among prevalent cases receiving polytherapy (22%).

The somewhat lower rate of valproate prescriptions tracks with other recent analyses showing that valproate use decreased among women of childbearing age following recommendations against its use during pregnancy, according to Dr. Kim and her coauthors.

However, topiramate is another story: “Although the magnitude of risk and range of adverse reproductive outcomes associated with topiramate use appear substantially less than those associated with valproate, some reduction in the use of topiramate in this population might be expected after evidence emerged in 2008 of its association with cleft palate,” they said in their report.

UCB Pharma sponsored this study. Study authors reported disclosures related to UCB Pharma, Biogen, Eisai, SK Life Science, Brain Sentinel, UCB Pharma, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

SOURCE: Kim H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0447.

results of a retrospective analysis suggest.

Topiramate, linked to increased risk of cleft palate and smaller-than-gestational-age newborns, was among the top three antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) prescribed to women 15-44 years of age in the population-based cohort study.

Valproate, linked to increases in both anatomic and behavioral teratogenicity, was less often prescribed, but nevertheless still prescribed in a considerable proportion of patients in the study, which looked at U.S. commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid claims data from 2009 to 2013.

Presence of comorbidities could be influencing whether or not a woman of childbearing age receives one of these AEDs, the investigators said. Specifically, they found valproate more often prescribed for women with epilepsy who also had mood or anxiety and dissociative disorder, while topiramate was more often prescribed in women with headaches or migraines.

Taken together, these findings suggest a lack of awareness of the teratogenic risks of valproate and topiramate, said the investigators, led by Hyunmi Kim, MD, PhD, MPH, of the department of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“To improve current practice, knowledge of the teratogenicity of certain AEDs should be disseminated to health care professionals and patients,” they wrote. The report is in JAMA Neurology.

The findings of Dr. Kim and her colleagues were based on data for 46,767 women of childbearing age: 8,003 incident (new) cases with a mean age of 27 years, and 38,764 prevalent cases with a mean age of 30 years.

Topiramate was the second- or third-most prescribed AED in the analyses, alongside levetiracetam and lamotrigine. In particular, topiramate prescriptions were found in incident cases receiving first-line monotherapy (15%), prevalent cases receiving first-line monotherapy (13%), and prevalent cases receiving polytherapy (29%).

Valproate was the fifth-most prescribed AED for incident and prevalent cases receiving first-line monotherapy (5% and 10%, respectively), and came in fourth place among prevalent cases receiving polytherapy (22%).

The somewhat lower rate of valproate prescriptions tracks with other recent analyses showing that valproate use decreased among women of childbearing age following recommendations against its use during pregnancy, according to Dr. Kim and her coauthors.

However, topiramate is another story: “Although the magnitude of risk and range of adverse reproductive outcomes associated with topiramate use appear substantially less than those associated with valproate, some reduction in the use of topiramate in this population might be expected after evidence emerged in 2008 of its association with cleft palate,” they said in their report.

UCB Pharma sponsored this study. Study authors reported disclosures related to UCB Pharma, Biogen, Eisai, SK Life Science, Brain Sentinel, UCB Pharma, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

SOURCE: Kim H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0447.

results of a retrospective analysis suggest.

Topiramate, linked to increased risk of cleft palate and smaller-than-gestational-age newborns, was among the top three antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) prescribed to women 15-44 years of age in the population-based cohort study.

Valproate, linked to increases in both anatomic and behavioral teratogenicity, was less often prescribed, but nevertheless still prescribed in a considerable proportion of patients in the study, which looked at U.S. commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid claims data from 2009 to 2013.

Presence of comorbidities could be influencing whether or not a woman of childbearing age receives one of these AEDs, the investigators said. Specifically, they found valproate more often prescribed for women with epilepsy who also had mood or anxiety and dissociative disorder, while topiramate was more often prescribed in women with headaches or migraines.

Taken together, these findings suggest a lack of awareness of the teratogenic risks of valproate and topiramate, said the investigators, led by Hyunmi Kim, MD, PhD, MPH, of the department of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“To improve current practice, knowledge of the teratogenicity of certain AEDs should be disseminated to health care professionals and patients,” they wrote. The report is in JAMA Neurology.

The findings of Dr. Kim and her colleagues were based on data for 46,767 women of childbearing age: 8,003 incident (new) cases with a mean age of 27 years, and 38,764 prevalent cases with a mean age of 30 years.

Topiramate was the second- or third-most prescribed AED in the analyses, alongside levetiracetam and lamotrigine. In particular, topiramate prescriptions were found in incident cases receiving first-line monotherapy (15%), prevalent cases receiving first-line monotherapy (13%), and prevalent cases receiving polytherapy (29%).

Valproate was the fifth-most prescribed AED for incident and prevalent cases receiving first-line monotherapy (5% and 10%, respectively), and came in fourth place among prevalent cases receiving polytherapy (22%).

The somewhat lower rate of valproate prescriptions tracks with other recent analyses showing that valproate use decreased among women of childbearing age following recommendations against its use during pregnancy, according to Dr. Kim and her coauthors.

However, topiramate is another story: “Although the magnitude of risk and range of adverse reproductive outcomes associated with topiramate use appear substantially less than those associated with valproate, some reduction in the use of topiramate in this population might be expected after evidence emerged in 2008 of its association with cleft palate,” they said in their report.

UCB Pharma sponsored this study. Study authors reported disclosures related to UCB Pharma, Biogen, Eisai, SK Life Science, Brain Sentinel, UCB Pharma, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

SOURCE: Kim H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0447.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Both valproate and topiramate are prescribed relatively often in women of childbearing age despite known teratogenic risks.

Major finding: Topiramate was the second- or third-most prescribed AED in the analyses. Valproate was the fifth-most prescribed AED for incident and prevalent cases receiving first-line monotherapy.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study including nearly 47,000 women of childbearing age enrolled in claims databases between 2009 and 2013.

Disclosures: UCB Pharma sponsored the study. Study authors reported disclosures related to UCB Pharma, Biogen, Eisai, SK Life Science, Brain Sentinel, UCB Pharma, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Source: Kim H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0447.

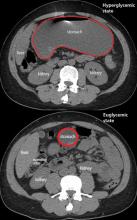

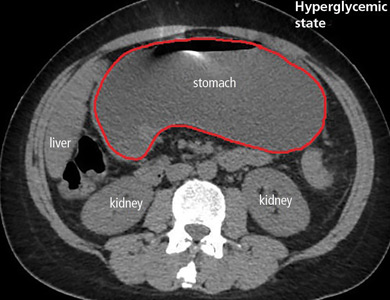

Gastroparesis in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

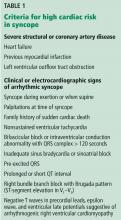

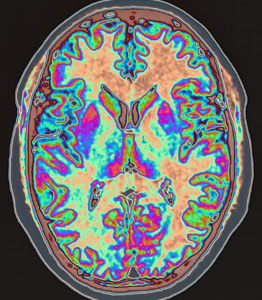

Is neuroimaging necessary to evaluate syncope?

A 40-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, who was recently started on a diuretic, presents to the emergency department after a witnessed syncopal event. She reports a prodrome of lightheadedness, nausea, and darkening of her vision that occurred a few seconds after standing, followed by loss of consciousness. She had a complete, spontaneous recovery after 10 seconds, but upon arousal she noticed she had lost bladder control.

Her blood pressure is 120/80 mm Hg supine, 110/70 mm Hg sitting, and 90/60 mm Hg standing. She has no focal neurologic deficits. The cardiac examination is normal, without murmurs, and electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia (heart rate 110 bpm) without other abnormalities. Results of laboratory testing are unremarkable.

Should you order neuroimaging to evaluate for syncope?

DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS

Syncope is an abrupt loss of consciousness due to transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, with a concomitant loss of postural tone and rapid, spontaneous recovery.1 Recovery from syncope is characterized by immediate restoration of orientation and normal behavior, although the period after recovery may be accompanied by fatigue.2

The European Society of Cardiology2 has classified syncope into 3 main categories: reflex (neurally mediated) syncope, syncope due to orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope. Determining the cause is critical, as this determines the prognosis.

KEYS TO THE EVALUATION

According to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the 2009 European Society of Cardiology guidelines, the evaluation of syncope should include a thorough history, taken from the patient and witnesses, and a complete physical examination. This can identify the cause of syncope in up to 50% of cases and differentiate between cardiac and noncardiac causes. Features that point to cardiac syncope include age older than 60, male sex, known heart disease, brief prodrome, syncope during exertion or when supine, first syncopal event, family history of sudden cardiac death, and abnormal physical examination.1

Features that suggest noncardiac syncope are young age; syncope only when standing; recurrent syncope; a prodrome of nausea, vomiting, and a warm sensation; and triggers such as dehydration, pain, distressful stimulus, cough, laugh micturition, defecation, and swallowing.1

Electrocardiography should follow the history and physical examination. When done at presentation, electrocardiography is diagnostic in only about 5% of cases. However, given the importance of the diagnosis, it remains an essential part of the initial evaluation of syncope.3

If a clear cause of syncope is identified at this point, no further workup is needed, and the cause of syncope should be addressed.1 If the cause is still unclear, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend further evaluation based on the clinical presentation and risk stratification.

WHEN TO PURSUE ADDITIONAL TESTING

Routine use of additional testing is costly; tests should be ordered on the basis of their potential diagnostic and prognostic value. Additional evaluation should follow a stepwise approach and can include targeted blood work, autonomic nerve evaluation, tilt-table testing, transthoracic echocardiography, stress testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and electrophysiologic testing.1

Syncope is rarely a manifestation of neurologic disease, yet 11% to 58% of patients with a first episode of uncomplicated syncope undergo extensive neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, electroencephalography (EEG), and carotid ultrasonography.4 Evidence suggests that routine neurologic testing is of limited value given its low diagnostic yield and high cost.

Epilepsy is the most common neurologic cause of loss of consciousness but is estimated to account for less than 5% of patients with syncope.5 A thorough and thoughtful neurologic history and examination is often enough to distinguish between syncope, convulsive syncope, epileptic convulsions, and pseudosyncope.

In syncope, the loss of consciousness usually occurs 30 seconds to several minutes after standing. It presents with or without a prodrome (warmth, palpitations, and diaphoresis) and can be relieved with supine positioning. True loss of consciousness usually lasts less than a minute and is accompanied by loss of postural tone, with little or no fatigue in the recovery period.6

Conversely, in convulsive syncope, the prodrome can include pallor and diaphoresis. Loss of consciousness lasts about 30 seconds but is accompanied by fixed gaze, upward eye deviation, nuchal rigidity, tonic spasms, myoclonic jerks, tonic-clonic convulsions, and oral automatisms.6

Pseudosyncope is characterized by a prodrome of lightheadedness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and tingling sensations, followed by episodes of apparent loss of consciousness that last longer than several minutes and occur multiple times a day. During these episodes, patients purposefully try to avoid trauma when they lose consciousness, and almost always keep their eyes closed, in contrast to syncopal episodes, when the eyes are open and glassy.7

ROLE OF ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

If the diagnosis remains unclear after the history and neurologic examination, EEG is recommended (class IIa, ie, reasonable, can be useful) during tilt-table testing, as it can help differentiate syncope, pseudosyncope, and epilepsy.1

In an epileptic convulsion, EEG shows epileptiform discharges, whereas in syncope, it shows diffuse brainwave slowing with delta waves and a flatline pattern. In pseudosyncope and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, EEG shows normal activity.8

Routine EEG is not recommended if there are no specific neurologic signs of epilepsy or if the history and neurologic examination indicate syncope or pseudosyncope.1

Structural brain disease does not typically present with transient global cerebral hypoperfusion resulting in syncope, so magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have a low diagnostic yield. Studies have revealed that for the 11% to 58% of patients who undergo neuroimaging, it establishes a diagnosis in only 0.2% to 1%.9 For this reason and in view of their high cost, these imaging tests should not be routinely ordered in the evaluation of syncope.4,10 Similarly, carotid artery imaging should not be routinely ordered if there is no focal neurologic finding suggesting unilateral ischemia.10

CASE CONTINUED

In our 40-year-old patient, the history suggests dehydration, as she recently started taking a diuretic. Thus, laboratory testing is reasonable.

Loss of bladder control is often interpreted as a red flag for neurologic disease, but syncope can often present with urinary incontinence. Urinary incontinence may also occur in epileptic seizure and in nonepileptic events such as syncope. A pooled analysis by Brigo et al11 determined that urinary incontinence had no value in distinguishing between epilepsy and syncope. Therefore, this physical finding should not incline the clinician to one diagnosis or the other.

Given our patient’s presentation, findings on physical examination, and absence of focal neurologic deficits, she should not undergo neuroimaging for syncope evaluation. The more likely cause of her syncope is orthostatic intolerance (orthostatic hypotension or vasovagal syncope) in the setting of intravascular volume depletion, likely secondary to diuretic use. Obtaining orthostatic vital signs is mandatory, and this confirms the diagnosis.

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(5):e39–e110. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003

- Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope; European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); Heart Failure Association (HFA); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009; 30(21):2631–2671. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

- Mehlsen J, Kaijer MN, Mehlsen AB. Autonomic and electrocardiographic changes in cardioinhibitory syncope. Europace 2008; 10(1):91–95. doi:10.1093/europace/eum237

- Goyal N, Donnino MW, Vachhani R, Bajwa R, Ahmad T, Otero R. The utility of head computed tomography in the emergency department evaluation of syncope. Intern Emerg Med 2006; 1(2):148–150. pmid:17111790

- Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Wieand S, Peterson JR, Levey GS. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. N Engl J Med 1983; 309(4):197–204. doi:10.1056/NEJM198307283090401

- Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin 2015; 33(3):377–385. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2015.04.006

- Raj V, Rowe AA, Fleisch SB, Paranjape SY, Arain AM, Nicolson SE. Psychogenic pseudosyncope: diagnosis and management. Auton Neurosci 2014; 184:66–72. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2014.05.003

- Mecarelli O, Pulitano P, Vicenzini E, Vanacore N, Accornero N, De Marinis M. Observations on EEG patterns in neurally-mediated syncope: an inspective and quantitative study. Neurophysiol Clin 2004; 34(5):203–207. doi:10.1016/j.neucli.2004.09.004

- Johnson PC, Ammar H, Zohdy W, Fouda R, Govindu R. Yield of diagnostic tests and its impact on cost in adult patients with syncope presenting to a community hospital. South Med J 2014; 107(11):707–714. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000184

- Sclafani JJ, My J, Zacher LL, Eckart RE. Intensive education on evidence-based evaluation of syncope increases sudden death risk stratification but fails to reduce use of neuroimaging. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(13):1150–1154. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.205

- Brigo F, Nardone R Ausserer H, et al. The diagnostic value of urinary incontinence in the differential diagnosis of seizures. Seizure 2013; 22(2):85–90. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2012.10.011

A 40-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, who was recently started on a diuretic, presents to the emergency department after a witnessed syncopal event. She reports a prodrome of lightheadedness, nausea, and darkening of her vision that occurred a few seconds after standing, followed by loss of consciousness. She had a complete, spontaneous recovery after 10 seconds, but upon arousal she noticed she had lost bladder control.

Her blood pressure is 120/80 mm Hg supine, 110/70 mm Hg sitting, and 90/60 mm Hg standing. She has no focal neurologic deficits. The cardiac examination is normal, without murmurs, and electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia (heart rate 110 bpm) without other abnormalities. Results of laboratory testing are unremarkable.

Should you order neuroimaging to evaluate for syncope?

DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS

Syncope is an abrupt loss of consciousness due to transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, with a concomitant loss of postural tone and rapid, spontaneous recovery.1 Recovery from syncope is characterized by immediate restoration of orientation and normal behavior, although the period after recovery may be accompanied by fatigue.2

The European Society of Cardiology2 has classified syncope into 3 main categories: reflex (neurally mediated) syncope, syncope due to orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope. Determining the cause is critical, as this determines the prognosis.

KEYS TO THE EVALUATION

According to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the 2009 European Society of Cardiology guidelines, the evaluation of syncope should include a thorough history, taken from the patient and witnesses, and a complete physical examination. This can identify the cause of syncope in up to 50% of cases and differentiate between cardiac and noncardiac causes. Features that point to cardiac syncope include age older than 60, male sex, known heart disease, brief prodrome, syncope during exertion or when supine, first syncopal event, family history of sudden cardiac death, and abnormal physical examination.1

Features that suggest noncardiac syncope are young age; syncope only when standing; recurrent syncope; a prodrome of nausea, vomiting, and a warm sensation; and triggers such as dehydration, pain, distressful stimulus, cough, laugh micturition, defecation, and swallowing.1

Electrocardiography should follow the history and physical examination. When done at presentation, electrocardiography is diagnostic in only about 5% of cases. However, given the importance of the diagnosis, it remains an essential part of the initial evaluation of syncope.3

If a clear cause of syncope is identified at this point, no further workup is needed, and the cause of syncope should be addressed.1 If the cause is still unclear, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend further evaluation based on the clinical presentation and risk stratification.

WHEN TO PURSUE ADDITIONAL TESTING

Routine use of additional testing is costly; tests should be ordered on the basis of their potential diagnostic and prognostic value. Additional evaluation should follow a stepwise approach and can include targeted blood work, autonomic nerve evaluation, tilt-table testing, transthoracic echocardiography, stress testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and electrophysiologic testing.1

Syncope is rarely a manifestation of neurologic disease, yet 11% to 58% of patients with a first episode of uncomplicated syncope undergo extensive neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, electroencephalography (EEG), and carotid ultrasonography.4 Evidence suggests that routine neurologic testing is of limited value given its low diagnostic yield and high cost.

Epilepsy is the most common neurologic cause of loss of consciousness but is estimated to account for less than 5% of patients with syncope.5 A thorough and thoughtful neurologic history and examination is often enough to distinguish between syncope, convulsive syncope, epileptic convulsions, and pseudosyncope.

In syncope, the loss of consciousness usually occurs 30 seconds to several minutes after standing. It presents with or without a prodrome (warmth, palpitations, and diaphoresis) and can be relieved with supine positioning. True loss of consciousness usually lasts less than a minute and is accompanied by loss of postural tone, with little or no fatigue in the recovery period.6

Conversely, in convulsive syncope, the prodrome can include pallor and diaphoresis. Loss of consciousness lasts about 30 seconds but is accompanied by fixed gaze, upward eye deviation, nuchal rigidity, tonic spasms, myoclonic jerks, tonic-clonic convulsions, and oral automatisms.6

Pseudosyncope is characterized by a prodrome of lightheadedness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and tingling sensations, followed by episodes of apparent loss of consciousness that last longer than several minutes and occur multiple times a day. During these episodes, patients purposefully try to avoid trauma when they lose consciousness, and almost always keep their eyes closed, in contrast to syncopal episodes, when the eyes are open and glassy.7

ROLE OF ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

If the diagnosis remains unclear after the history and neurologic examination, EEG is recommended (class IIa, ie, reasonable, can be useful) during tilt-table testing, as it can help differentiate syncope, pseudosyncope, and epilepsy.1

In an epileptic convulsion, EEG shows epileptiform discharges, whereas in syncope, it shows diffuse brainwave slowing with delta waves and a flatline pattern. In pseudosyncope and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, EEG shows normal activity.8

Routine EEG is not recommended if there are no specific neurologic signs of epilepsy or if the history and neurologic examination indicate syncope or pseudosyncope.1

Structural brain disease does not typically present with transient global cerebral hypoperfusion resulting in syncope, so magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have a low diagnostic yield. Studies have revealed that for the 11% to 58% of patients who undergo neuroimaging, it establishes a diagnosis in only 0.2% to 1%.9 For this reason and in view of their high cost, these imaging tests should not be routinely ordered in the evaluation of syncope.4,10 Similarly, carotid artery imaging should not be routinely ordered if there is no focal neurologic finding suggesting unilateral ischemia.10

CASE CONTINUED

In our 40-year-old patient, the history suggests dehydration, as she recently started taking a diuretic. Thus, laboratory testing is reasonable.

Loss of bladder control is often interpreted as a red flag for neurologic disease, but syncope can often present with urinary incontinence. Urinary incontinence may also occur in epileptic seizure and in nonepileptic events such as syncope. A pooled analysis by Brigo et al11 determined that urinary incontinence had no value in distinguishing between epilepsy and syncope. Therefore, this physical finding should not incline the clinician to one diagnosis or the other.

Given our patient’s presentation, findings on physical examination, and absence of focal neurologic deficits, she should not undergo neuroimaging for syncope evaluation. The more likely cause of her syncope is orthostatic intolerance (orthostatic hypotension or vasovagal syncope) in the setting of intravascular volume depletion, likely secondary to diuretic use. Obtaining orthostatic vital signs is mandatory, and this confirms the diagnosis.

A 40-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, who was recently started on a diuretic, presents to the emergency department after a witnessed syncopal event. She reports a prodrome of lightheadedness, nausea, and darkening of her vision that occurred a few seconds after standing, followed by loss of consciousness. She had a complete, spontaneous recovery after 10 seconds, but upon arousal she noticed she had lost bladder control.

Her blood pressure is 120/80 mm Hg supine, 110/70 mm Hg sitting, and 90/60 mm Hg standing. She has no focal neurologic deficits. The cardiac examination is normal, without murmurs, and electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia (heart rate 110 bpm) without other abnormalities. Results of laboratory testing are unremarkable.

Should you order neuroimaging to evaluate for syncope?

DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS

Syncope is an abrupt loss of consciousness due to transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, with a concomitant loss of postural tone and rapid, spontaneous recovery.1 Recovery from syncope is characterized by immediate restoration of orientation and normal behavior, although the period after recovery may be accompanied by fatigue.2

The European Society of Cardiology2 has classified syncope into 3 main categories: reflex (neurally mediated) syncope, syncope due to orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope. Determining the cause is critical, as this determines the prognosis.

KEYS TO THE EVALUATION

According to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the 2009 European Society of Cardiology guidelines, the evaluation of syncope should include a thorough history, taken from the patient and witnesses, and a complete physical examination. This can identify the cause of syncope in up to 50% of cases and differentiate between cardiac and noncardiac causes. Features that point to cardiac syncope include age older than 60, male sex, known heart disease, brief prodrome, syncope during exertion or when supine, first syncopal event, family history of sudden cardiac death, and abnormal physical examination.1

Features that suggest noncardiac syncope are young age; syncope only when standing; recurrent syncope; a prodrome of nausea, vomiting, and a warm sensation; and triggers such as dehydration, pain, distressful stimulus, cough, laugh micturition, defecation, and swallowing.1

Electrocardiography should follow the history and physical examination. When done at presentation, electrocardiography is diagnostic in only about 5% of cases. However, given the importance of the diagnosis, it remains an essential part of the initial evaluation of syncope.3

If a clear cause of syncope is identified at this point, no further workup is needed, and the cause of syncope should be addressed.1 If the cause is still unclear, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend further evaluation based on the clinical presentation and risk stratification.

WHEN TO PURSUE ADDITIONAL TESTING

Routine use of additional testing is costly; tests should be ordered on the basis of their potential diagnostic and prognostic value. Additional evaluation should follow a stepwise approach and can include targeted blood work, autonomic nerve evaluation, tilt-table testing, transthoracic echocardiography, stress testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and electrophysiologic testing.1

Syncope is rarely a manifestation of neurologic disease, yet 11% to 58% of patients with a first episode of uncomplicated syncope undergo extensive neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, electroencephalography (EEG), and carotid ultrasonography.4 Evidence suggests that routine neurologic testing is of limited value given its low diagnostic yield and high cost.

Epilepsy is the most common neurologic cause of loss of consciousness but is estimated to account for less than 5% of patients with syncope.5 A thorough and thoughtful neurologic history and examination is often enough to distinguish between syncope, convulsive syncope, epileptic convulsions, and pseudosyncope.

In syncope, the loss of consciousness usually occurs 30 seconds to several minutes after standing. It presents with or without a prodrome (warmth, palpitations, and diaphoresis) and can be relieved with supine positioning. True loss of consciousness usually lasts less than a minute and is accompanied by loss of postural tone, with little or no fatigue in the recovery period.6

Conversely, in convulsive syncope, the prodrome can include pallor and diaphoresis. Loss of consciousness lasts about 30 seconds but is accompanied by fixed gaze, upward eye deviation, nuchal rigidity, tonic spasms, myoclonic jerks, tonic-clonic convulsions, and oral automatisms.6

Pseudosyncope is characterized by a prodrome of lightheadedness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and tingling sensations, followed by episodes of apparent loss of consciousness that last longer than several minutes and occur multiple times a day. During these episodes, patients purposefully try to avoid trauma when they lose consciousness, and almost always keep their eyes closed, in contrast to syncopal episodes, when the eyes are open and glassy.7

ROLE OF ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

If the diagnosis remains unclear after the history and neurologic examination, EEG is recommended (class IIa, ie, reasonable, can be useful) during tilt-table testing, as it can help differentiate syncope, pseudosyncope, and epilepsy.1

In an epileptic convulsion, EEG shows epileptiform discharges, whereas in syncope, it shows diffuse brainwave slowing with delta waves and a flatline pattern. In pseudosyncope and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, EEG shows normal activity.8

Routine EEG is not recommended if there are no specific neurologic signs of epilepsy or if the history and neurologic examination indicate syncope or pseudosyncope.1

Structural brain disease does not typically present with transient global cerebral hypoperfusion resulting in syncope, so magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have a low diagnostic yield. Studies have revealed that for the 11% to 58% of patients who undergo neuroimaging, it establishes a diagnosis in only 0.2% to 1%.9 For this reason and in view of their high cost, these imaging tests should not be routinely ordered in the evaluation of syncope.4,10 Similarly, carotid artery imaging should not be routinely ordered if there is no focal neurologic finding suggesting unilateral ischemia.10

CASE CONTINUED

In our 40-year-old patient, the history suggests dehydration, as she recently started taking a diuretic. Thus, laboratory testing is reasonable.