User login

55-year-old woman • unilateral nasal drainage • salty taste • nasal redness • recent COVID-19 nasal swabs • Dx?

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman was evaluated in a family medicine clinic for clear, right-side nasal drainage. She stated that the drainage began 5 months earlier after 2 hospitalizations for severe anxiety leading to emesis and hypokalemia. She reported 3 different COVID-19 nasal swab tests performed on the right nare. Chart review showed 2 negative COVID-19 tests, 6 days apart. Since the hospitalizations, the patient had been given antihistamines for rhinorrhea at an urgent care visit. Despite this treatment, the patient reported a constant drip from the right nare with a salty taste. She also reported experiencing occasional headaches but denied nausea/vomiting.

The patient’s history included uncontrolled hypertension, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic sinus disease (observed on computed tomography [CT] scans), and type 2 diabetes. She was on amlodipine 10 mg/d for hypertension and was not taking any medication for diabetes.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits except for an elevated blood pressure of 158/88 mm Hg. The patient had persistent clear rhinorrhea fluid draining from the right nostril that was exacerbated when she looked down. Right nasal erythema was present.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s negative COVID-19 tests, lack of improvement on antihistamines, and description of the nasal fluid as salty tasting prompted us to suspect a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. The clinical work-up included a halo (“double-ring”) sign test, a β-2 transferrin test, and a sinus x-ray.

The halo sign test was negative for CSF fluid. Sinus/skull x-ray did not show a cribriform or other fracture. However, a sample of the nasal fluid collected in a sterile container was positive for β-2 transferrin, the gold-standard laboratory test to confirm a CSF leak.

The patient was sent for a maxillofacial CT scan without contrast. Results showed a 3-mm defect over the right ethmoid roof associated with a 10 × 16–mm low-attenuation structure in the right ethmoid labyrinth, suspicious for encephalocele. This defect, in the setting of the patient’s history of chronic sinus disease, furthered our suspicion of a CSF leak secondary to COVID-19 testing. Radiology confirmed the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

CSF rhinorrhea is CSF leakage through the nasal cavity due to abnormal communication between the arachnoid membrane and nasal mucosa.1 The most commonly reported risk factors for this include female sex, middle age (fourth to fifth decade), obesity (body mass index > 40), intracranial hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.1,2

Continue to: Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea...

Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea drainage that increases at times of relatively increased intracranial pressure and has a metallic or salty taste is suspicious for CSF rhinorrhea.3 It can occur following skull‐base trauma (eg, cribriform plate, temporal bone), endoscopic sinus surgery, or neurosurgical procedures, or have a spontaneous etiology.3,4

Modalities to confirm CSF rhinorrhea include radionuclide cisternography and testing of fluid for the halo sign, glucose, and the CSF-specific proteins β‐2 transferrin and β-trace protein.3,4 High‐resolution CT is the imaging method most commonly used for localizing a CSF leak.4

Treatment is provided in the hospital

Patients with CSF rhinorrhea typically require inpatient management with bed rest, head-of-bed elevation, and frequent neurologic evaluation, as persistent CSF rhinorrhea increases the risk for meningitis, thus necessitating surgical intervention.3,5 Some cases resolve with bed rest alone. Endonasal endoscopic repair of CSF leaks has become the standard of care because of its high success rate and lower morbidity profile.4

The preferred treatment method for encephalocele is surgical removal after diagnosis is confirmed with CT or magnetic resonance imaging.6

Our patient underwent surgery to remove the encephalocele. The surgeons reported no evidence of fracture.

The final cause of her CSF leak is still uncertain. The surgeons felt confident it was due to ethmoidal encephalocele, a form of neural tube defect in which brain tissue herniates through structural weaknesses of the skull.6-8 While more common in infants, encephalocele can manifest in adulthood due to traumatic or iatrogenic causes.7,8

There is a previous report of encephalocele with CSF leak after COVID-19 testing.9 This case report suggests the possibility of a nasal swab causing trauma to a patient’s pre‐existing encephalocele—a probability in our patient’s case. It is unlikely, however, that the nasal swab itself violated the bony skull base.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case exemplifies how unexplained local symptoms, a high index of suspicion, and adequate work-up can lead to a rare diagnosis. Diagnostic strategies employed for cases of CSF rhinorrhea vary widely due to limited evidence-based guidance.4 Unilateral rhinorrhea with clear fluid that increases at times of increased intracranial pressure, such as bending over, should prompt suspicion for CSF rhinorrhea. With millions of people getting nasal swabs daily during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important to keep CSF leak in our differential diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eliana Lizeth Garcia, MD, BS, BA, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1209 University Boulevard NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131-5001; [email protected]

1. Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran RS, et al. Management of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: an institutional experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80:493-499. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676334

2. Lobo BC, Baumanis MM, Nelson RF. Surgical repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2:215-224. doi: 10.1002/lio2.75

3. Van Zele T, Dewaele F. Traumatic CSF leaks of the anterior skull base. B-ENT. 2016;suppl 26:19-27.

4. Oakley GM, Alt JA, Schlosser RJ, et al. Diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:8-16. doi: 10.1002/alr.21637

5. Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. World J Surg. 2001;25:1062-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0059-7

6. Tirumandas M, Sharma A, Gbenimacho I, et al. Nasal encephaloceles: a review of etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:739-744. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1998-z

7. Junaid M, Sobani ZU, Shamim AA, et al. Nasal encephaloceles presenting at later ages: experience of otorhinolaryngology department at a tertiary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:74-76.

8. Dhirawani RB, Gupta R, Pathak S, et al. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele: case report and review on management. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:195-197. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.147140

9. Paquin R, Ryan L, Vale FL, et al. CSF leak after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:1927-1929. doi: 10.1002/lary.29462

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman was evaluated in a family medicine clinic for clear, right-side nasal drainage. She stated that the drainage began 5 months earlier after 2 hospitalizations for severe anxiety leading to emesis and hypokalemia. She reported 3 different COVID-19 nasal swab tests performed on the right nare. Chart review showed 2 negative COVID-19 tests, 6 days apart. Since the hospitalizations, the patient had been given antihistamines for rhinorrhea at an urgent care visit. Despite this treatment, the patient reported a constant drip from the right nare with a salty taste. She also reported experiencing occasional headaches but denied nausea/vomiting.

The patient’s history included uncontrolled hypertension, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic sinus disease (observed on computed tomography [CT] scans), and type 2 diabetes. She was on amlodipine 10 mg/d for hypertension and was not taking any medication for diabetes.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits except for an elevated blood pressure of 158/88 mm Hg. The patient had persistent clear rhinorrhea fluid draining from the right nostril that was exacerbated when she looked down. Right nasal erythema was present.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s negative COVID-19 tests, lack of improvement on antihistamines, and description of the nasal fluid as salty tasting prompted us to suspect a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. The clinical work-up included a halo (“double-ring”) sign test, a β-2 transferrin test, and a sinus x-ray.

The halo sign test was negative for CSF fluid. Sinus/skull x-ray did not show a cribriform or other fracture. However, a sample of the nasal fluid collected in a sterile container was positive for β-2 transferrin, the gold-standard laboratory test to confirm a CSF leak.

The patient was sent for a maxillofacial CT scan without contrast. Results showed a 3-mm defect over the right ethmoid roof associated with a 10 × 16–mm low-attenuation structure in the right ethmoid labyrinth, suspicious for encephalocele. This defect, in the setting of the patient’s history of chronic sinus disease, furthered our suspicion of a CSF leak secondary to COVID-19 testing. Radiology confirmed the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

CSF rhinorrhea is CSF leakage through the nasal cavity due to abnormal communication between the arachnoid membrane and nasal mucosa.1 The most commonly reported risk factors for this include female sex, middle age (fourth to fifth decade), obesity (body mass index > 40), intracranial hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.1,2

Continue to: Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea...

Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea drainage that increases at times of relatively increased intracranial pressure and has a metallic or salty taste is suspicious for CSF rhinorrhea.3 It can occur following skull‐base trauma (eg, cribriform plate, temporal bone), endoscopic sinus surgery, or neurosurgical procedures, or have a spontaneous etiology.3,4

Modalities to confirm CSF rhinorrhea include radionuclide cisternography and testing of fluid for the halo sign, glucose, and the CSF-specific proteins β‐2 transferrin and β-trace protein.3,4 High‐resolution CT is the imaging method most commonly used for localizing a CSF leak.4

Treatment is provided in the hospital

Patients with CSF rhinorrhea typically require inpatient management with bed rest, head-of-bed elevation, and frequent neurologic evaluation, as persistent CSF rhinorrhea increases the risk for meningitis, thus necessitating surgical intervention.3,5 Some cases resolve with bed rest alone. Endonasal endoscopic repair of CSF leaks has become the standard of care because of its high success rate and lower morbidity profile.4

The preferred treatment method for encephalocele is surgical removal after diagnosis is confirmed with CT or magnetic resonance imaging.6

Our patient underwent surgery to remove the encephalocele. The surgeons reported no evidence of fracture.

The final cause of her CSF leak is still uncertain. The surgeons felt confident it was due to ethmoidal encephalocele, a form of neural tube defect in which brain tissue herniates through structural weaknesses of the skull.6-8 While more common in infants, encephalocele can manifest in adulthood due to traumatic or iatrogenic causes.7,8

There is a previous report of encephalocele with CSF leak after COVID-19 testing.9 This case report suggests the possibility of a nasal swab causing trauma to a patient’s pre‐existing encephalocele—a probability in our patient’s case. It is unlikely, however, that the nasal swab itself violated the bony skull base.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case exemplifies how unexplained local symptoms, a high index of suspicion, and adequate work-up can lead to a rare diagnosis. Diagnostic strategies employed for cases of CSF rhinorrhea vary widely due to limited evidence-based guidance.4 Unilateral rhinorrhea with clear fluid that increases at times of increased intracranial pressure, such as bending over, should prompt suspicion for CSF rhinorrhea. With millions of people getting nasal swabs daily during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important to keep CSF leak in our differential diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eliana Lizeth Garcia, MD, BS, BA, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1209 University Boulevard NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131-5001; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman was evaluated in a family medicine clinic for clear, right-side nasal drainage. She stated that the drainage began 5 months earlier after 2 hospitalizations for severe anxiety leading to emesis and hypokalemia. She reported 3 different COVID-19 nasal swab tests performed on the right nare. Chart review showed 2 negative COVID-19 tests, 6 days apart. Since the hospitalizations, the patient had been given antihistamines for rhinorrhea at an urgent care visit. Despite this treatment, the patient reported a constant drip from the right nare with a salty taste. She also reported experiencing occasional headaches but denied nausea/vomiting.

The patient’s history included uncontrolled hypertension, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic sinus disease (observed on computed tomography [CT] scans), and type 2 diabetes. She was on amlodipine 10 mg/d for hypertension and was not taking any medication for diabetes.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits except for an elevated blood pressure of 158/88 mm Hg. The patient had persistent clear rhinorrhea fluid draining from the right nostril that was exacerbated when she looked down. Right nasal erythema was present.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s negative COVID-19 tests, lack of improvement on antihistamines, and description of the nasal fluid as salty tasting prompted us to suspect a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. The clinical work-up included a halo (“double-ring”) sign test, a β-2 transferrin test, and a sinus x-ray.

The halo sign test was negative for CSF fluid. Sinus/skull x-ray did not show a cribriform or other fracture. However, a sample of the nasal fluid collected in a sterile container was positive for β-2 transferrin, the gold-standard laboratory test to confirm a CSF leak.

The patient was sent for a maxillofacial CT scan without contrast. Results showed a 3-mm defect over the right ethmoid roof associated with a 10 × 16–mm low-attenuation structure in the right ethmoid labyrinth, suspicious for encephalocele. This defect, in the setting of the patient’s history of chronic sinus disease, furthered our suspicion of a CSF leak secondary to COVID-19 testing. Radiology confirmed the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

CSF rhinorrhea is CSF leakage through the nasal cavity due to abnormal communication between the arachnoid membrane and nasal mucosa.1 The most commonly reported risk factors for this include female sex, middle age (fourth to fifth decade), obesity (body mass index > 40), intracranial hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.1,2

Continue to: Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea...

Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea drainage that increases at times of relatively increased intracranial pressure and has a metallic or salty taste is suspicious for CSF rhinorrhea.3 It can occur following skull‐base trauma (eg, cribriform plate, temporal bone), endoscopic sinus surgery, or neurosurgical procedures, or have a spontaneous etiology.3,4

Modalities to confirm CSF rhinorrhea include radionuclide cisternography and testing of fluid for the halo sign, glucose, and the CSF-specific proteins β‐2 transferrin and β-trace protein.3,4 High‐resolution CT is the imaging method most commonly used for localizing a CSF leak.4

Treatment is provided in the hospital

Patients with CSF rhinorrhea typically require inpatient management with bed rest, head-of-bed elevation, and frequent neurologic evaluation, as persistent CSF rhinorrhea increases the risk for meningitis, thus necessitating surgical intervention.3,5 Some cases resolve with bed rest alone. Endonasal endoscopic repair of CSF leaks has become the standard of care because of its high success rate and lower morbidity profile.4

The preferred treatment method for encephalocele is surgical removal after diagnosis is confirmed with CT or magnetic resonance imaging.6

Our patient underwent surgery to remove the encephalocele. The surgeons reported no evidence of fracture.

The final cause of her CSF leak is still uncertain. The surgeons felt confident it was due to ethmoidal encephalocele, a form of neural tube defect in which brain tissue herniates through structural weaknesses of the skull.6-8 While more common in infants, encephalocele can manifest in adulthood due to traumatic or iatrogenic causes.7,8

There is a previous report of encephalocele with CSF leak after COVID-19 testing.9 This case report suggests the possibility of a nasal swab causing trauma to a patient’s pre‐existing encephalocele—a probability in our patient’s case. It is unlikely, however, that the nasal swab itself violated the bony skull base.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case exemplifies how unexplained local symptoms, a high index of suspicion, and adequate work-up can lead to a rare diagnosis. Diagnostic strategies employed for cases of CSF rhinorrhea vary widely due to limited evidence-based guidance.4 Unilateral rhinorrhea with clear fluid that increases at times of increased intracranial pressure, such as bending over, should prompt suspicion for CSF rhinorrhea. With millions of people getting nasal swabs daily during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important to keep CSF leak in our differential diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eliana Lizeth Garcia, MD, BS, BA, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1209 University Boulevard NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131-5001; [email protected]

1. Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran RS, et al. Management of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: an institutional experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80:493-499. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676334

2. Lobo BC, Baumanis MM, Nelson RF. Surgical repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2:215-224. doi: 10.1002/lio2.75

3. Van Zele T, Dewaele F. Traumatic CSF leaks of the anterior skull base. B-ENT. 2016;suppl 26:19-27.

4. Oakley GM, Alt JA, Schlosser RJ, et al. Diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:8-16. doi: 10.1002/alr.21637

5. Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. World J Surg. 2001;25:1062-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0059-7

6. Tirumandas M, Sharma A, Gbenimacho I, et al. Nasal encephaloceles: a review of etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:739-744. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1998-z

7. Junaid M, Sobani ZU, Shamim AA, et al. Nasal encephaloceles presenting at later ages: experience of otorhinolaryngology department at a tertiary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:74-76.

8. Dhirawani RB, Gupta R, Pathak S, et al. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele: case report and review on management. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:195-197. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.147140

9. Paquin R, Ryan L, Vale FL, et al. CSF leak after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:1927-1929. doi: 10.1002/lary.29462

1. Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran RS, et al. Management of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: an institutional experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80:493-499. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676334

2. Lobo BC, Baumanis MM, Nelson RF. Surgical repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2:215-224. doi: 10.1002/lio2.75

3. Van Zele T, Dewaele F. Traumatic CSF leaks of the anterior skull base. B-ENT. 2016;suppl 26:19-27.

4. Oakley GM, Alt JA, Schlosser RJ, et al. Diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:8-16. doi: 10.1002/alr.21637

5. Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. World J Surg. 2001;25:1062-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0059-7

6. Tirumandas M, Sharma A, Gbenimacho I, et al. Nasal encephaloceles: a review of etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:739-744. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1998-z

7. Junaid M, Sobani ZU, Shamim AA, et al. Nasal encephaloceles presenting at later ages: experience of otorhinolaryngology department at a tertiary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:74-76.

8. Dhirawani RB, Gupta R, Pathak S, et al. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele: case report and review on management. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:195-197. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.147140

9. Paquin R, Ryan L, Vale FL, et al. CSF leak after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:1927-1929. doi: 10.1002/lary.29462

► Unilateral nasal drainage

► Salty taste

► Nasal redness

► Recent COVID-19 nasal swabs

Caring for the caregiver in dementia

THE CASE

Sam C* is a 68-year-old man who presented to his family physician in a rural health clinic due to concerns about weight loss. Since his visit 8 months prior, Mr. C unintentionally had lost 20 pounds. Upon questioning, Mr. C also reported feeling irritable and having difficulty with sleep and concentration.

A review of systems did not indicate the presence of infection or other medical conditions. In the 6 years since becoming a patient to the practice, he had reported no chronic health concerns, was taking no medications, and had only been to the clinic for his annual check-up appointments. He completed a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and scored 18, indicating moderately severe depression.

Mr. C had established care with his physician when he moved to the area from out of state so that he could be closer to his parents, who were in their mid-80s at the time. Mr. C’s physician also had been the family physician for his parents for the previous 20 years. Three years prior to Mr. C’s presentation for weight loss, his mother had received a diagnosis of acute leukemia; she died a year later.

Over the past year, Mr. C had needed to take a more active role in the care of his father, who was now in his early 90s. Mr. C’s father, who was previously in excellent health, had begun to develop significant health problems, including degenerative arthritis and progressive vascular dementia. He also had ataxia, leading to poor mobility, and a neurogenic bladder requiring self-catheterization, which required Mr. C’s assistance. Mr. C lived next door to his father and provided frequent assistance with activities of daily living. However, his father, who always had been the dominant figure in the family, was determined to maintain his independence and not relinquish control to others.

The strain of caregiving activities, along with managing his father’s inflexibility, was causing increasing distress for Mr. C. As he told his family physician, “I just don’t know what to do.”

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

It is estimated that more than 11 million Americans provided more than 18 billion hours in unpaid support for individuals with dementia in 2022, averaging 30 hours of care per caregiver per week.1 As individuals with dementia progressively decline, they require increased assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs, such as bathing and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs, such as paying bills and using transportation). Most of this assistance comes from informal caregiving provided by family members and friends.

Caregiver burden can be defined as “the strain or load borne by a person who cares for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member.”2 Caregiver stress has been found to be higher for dementia caregiving than other types of caregiving.3 In particular, caring for someone with greater behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSDs) has been associated with higher caregiver burden.4-

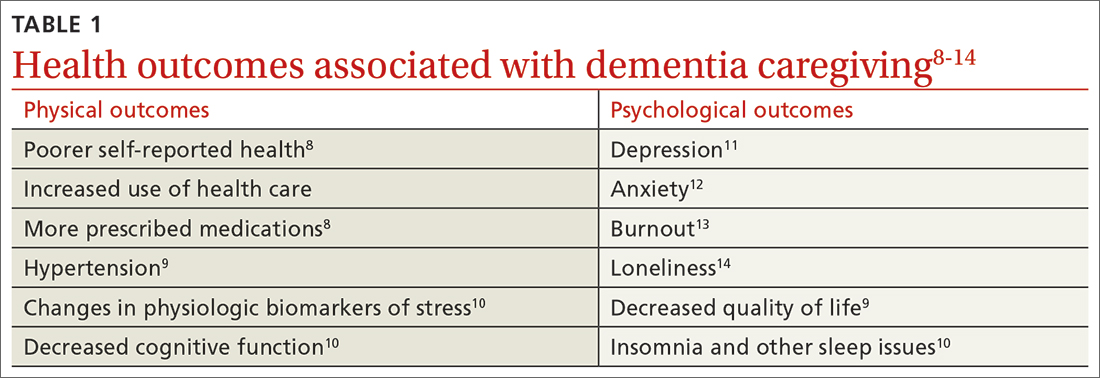

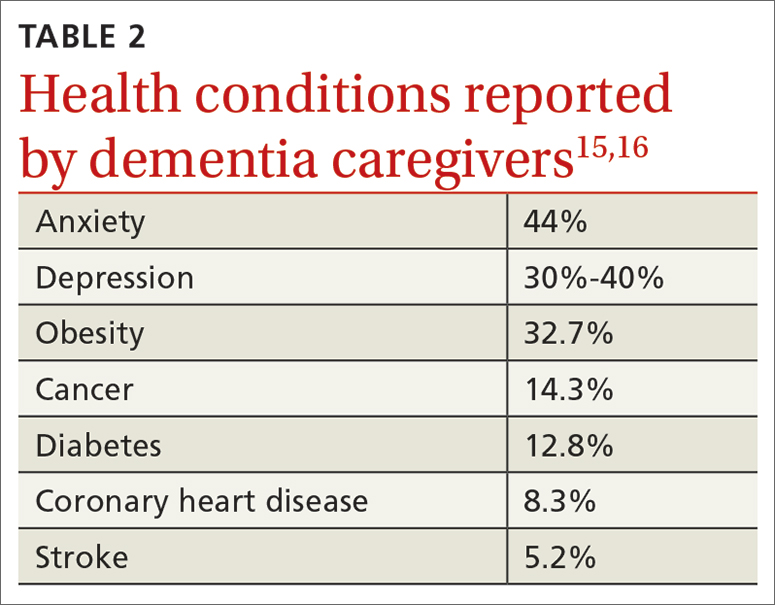

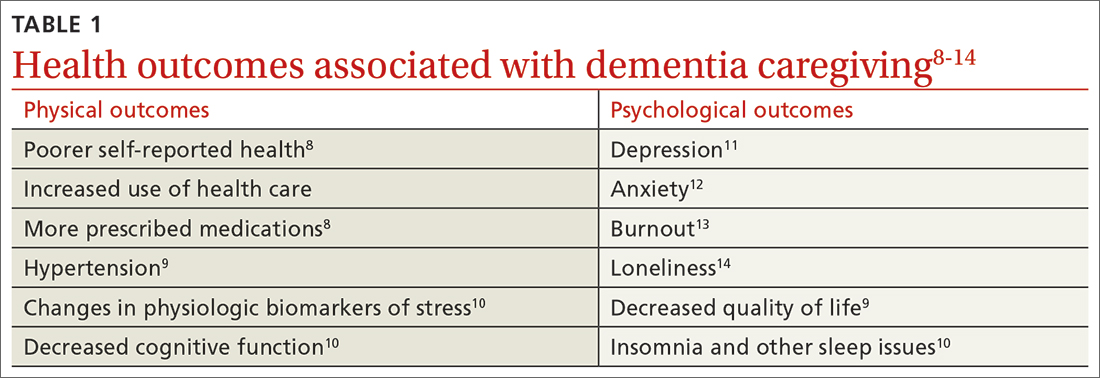

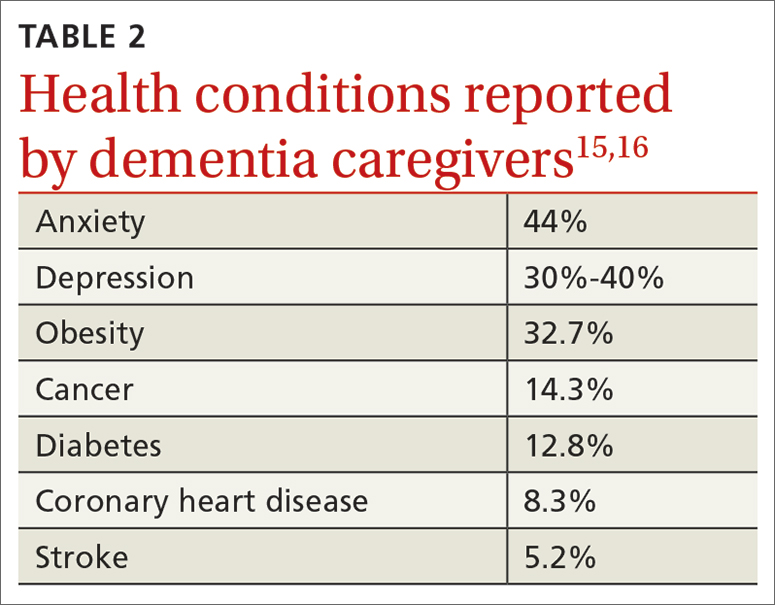

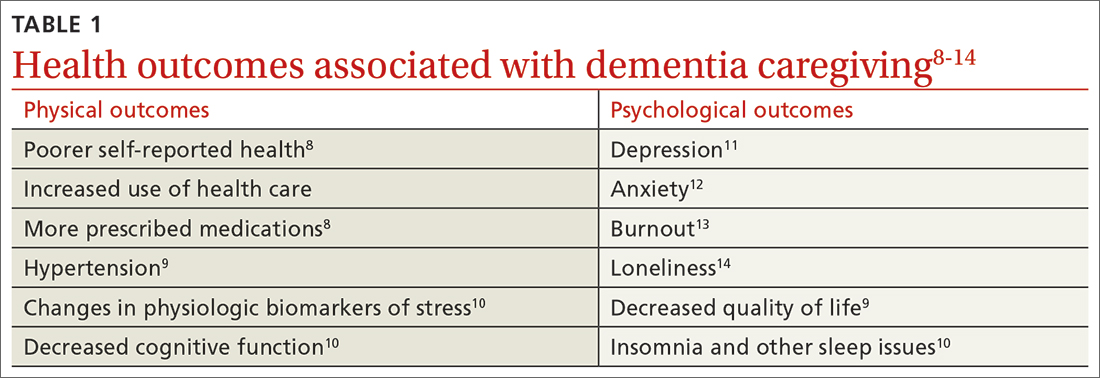

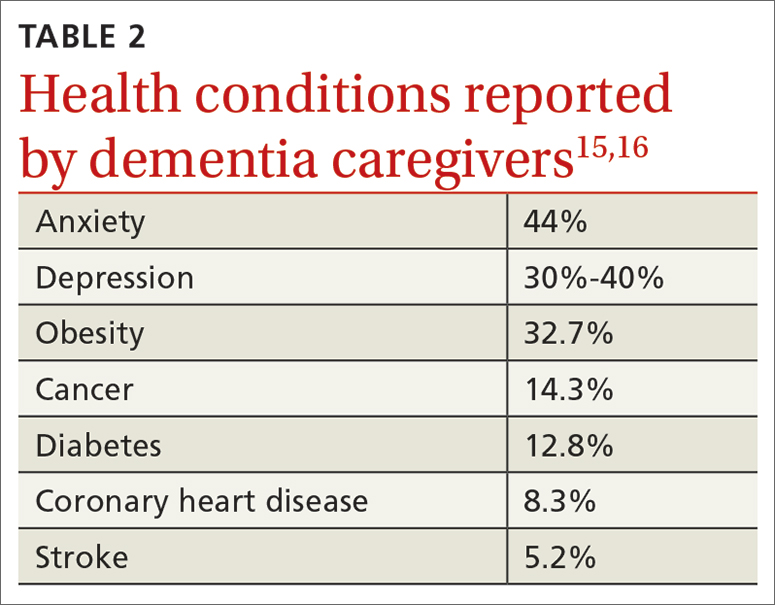

Beyond the subjective burden of caregiving, there are other potential negative consequences for dementia caregivers (see TABLE 18-14 and TABLE 215,16). In addition, caregiver distress is related to a number of care recipient outcomes, including earlier institutionalization, more hospitalizations, more BPSDs, poorer quality of life, and greater likelihood of experiencing elder abuse.17

Assessment, reassessment are key to meeting needs

Numerous factors can foster caregiver well-being, including feelings of accomplishment and contribution, a strengthening of the relationship with the care recipient, and feeling supported by friends, family, and formal care systems.18,19 Family physicians can play an important role by assessing and supporting patients with dementia and their caregivers. Ideally, the individual with dementia and the caregiver will be assessed both together and separately.

A thorough assessment includes gathering information about the context and quality of the caregiving relationship; caregiver perception of the care recipient’s health and functional status; caregiver values and preferences; caregiver well-being (including mental health assessment); caregiver skills, abilities, and knowledge about caregiving; and positive and negative consequences of caregiving.20 Caregiver needs—including informational, care support, emotional, physical, and social needs—also should be assessed.

Continue to: Tools are available...

Tools are available to facilitate caregiver assessment. For example, the Zarit Burden Interview is a 22-item self-report measure that can be given to the caregiver21; shorter versions (4 and 12 items) are also available.22 Another resource available for caregiver assessment guidance is a toolkit developed by the Family Caregiver Alliance.20

Continually assess for changing needs

As the condition of the individual with dementia progresses, it will be important to reassess the caregiver, as stressors and needs will change over the course of the caregiving relationship. Support should be adapted accordingly.

In the early stage of dementia, caregivers may need information on disease progression and dementia care planning, ways to navigate the health care system, financial planning, and useful resources. Caregivers also may need emotional support to help them adapt to the role of caregiver, deal with denial, and manage their stress.23,24

With dementia progression, caregivers may need support related to increased decision-making responsibility, managing challenging behaviors, assisting with ADLs and IADLs, and identifying opportunities to meet personal social and well-being needs. They also may need support to accept the changes they are seeing in the individual with dementia and the shifts they are experiencing in their relationship with him or her.23,25

In late-stage dementia, caregiver needs tend to shift to determining the need for long-term care placement vs staying at home, end-of-life planning, loneliness, and anticipatory grief.23,26 Support with managing changing and accumulating stress typically remains a primary need throughout the progression of dementia.27

Continue to: Specific populations have distinct needs

Specific populations have distinct needs. Some caregivers, including members of the LGBTQ+ community and different racial and ethnic groups, as well as caregivers of people with younger-onset dementia, may have additional support needs.28

For example, African American and Latino caregivers tend to have caregiving relationships of longer duration, requiring more time-intensive care, but use fewer formal support services than White caregivers.29 Caregivers from non-White racial and ethnic groups also are more likely to experience discrimination when interacting with health care services on behalf of care recipients.30

Having an awareness of potential specialized needs may help to prevent or address potential care disparities, and cultural humility may help to improve caregiver experiences with primary care physicians.

Resources to support caregivers

Family physicians are well situated to provide informational and emotional support for both patients with dementia and their informal care providers.31 Given the variability of caregiver concerns, multicomponent interventions addressing informational, self-care, social support, and financial needs often are needed.31 Supportive counseling and psychoeducation can help dementia caregivers with stress management, self-care, coping, and skills training—supporting the development of self-efficacy.32,33

Outside resources. Although significant caregiver support can be provided directly by the physician, caregivers should be connected with outside resources, including support groups, counselors, psychotherapists, financial and legal support, and formal care services

Continue to: Psychosocial and complementary interventions

Psychosocial and complementary interventions. Various psychosocial interventions (eg, psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, support groups) have been found to be beneficial in alleviating caregiver symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and improving well-being, perceived burden, and quality of life. However, systematic reviews have found variability in the degree of helpfulness of these interventions.35,36

Some caregivers and care recipients may benefit from complementary and integrative medicine referrals. Mind–body therapies such as mindfulness, yoga, and Tai Chi have shown some beneficial effects.37

Online resources. Caregivers also can be directed to online resources from organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org), the National Institutes of Health (www.alzheimers.gov), and the Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org).

In rural settings, such as the one in which this case took place, online resources may decrease some barriers to supporting caregivers.38 Internet-based interventions also have been found to have some benefit for dementia caregivers.31,39

However, some rural locations continue to have limited reliable Internet services.40 In affected areas, a strong relationship with a primary care physician may be even more important to the well-being of caregivers, since other support services may be less accessible.41

Continue to: Impacts of the pandemic

Impacts of the pandemic. Although our case took place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to acknowledge ways the pandemic has impacted informal dementia caregiving.

Caregiver stress, depression, and anxiety increased during the pandemic, and the need for greater home confinement and social distancing amplified the negative impact of social isolation, including loneliness, on caregivers.42,43 Caregivers often needed to increase their caregiving responsibilities and had more difficulty with care coordination due to limited access to in-person resources.43 The pandemic led to increased reliance on technology and telehealth in the support of dementia caregivers.43

THE CASE

The physician prescribed mirtazapine for Mr. C, titrating the dose as needed to address depressive symptoms and promote weight gain. The physician connected Mr. C’s father with home health services, including physical therapy for fall risk reduction. Mr. C also hired part-time support to provide additional assistance with ADLs and IADLs, allowing Mr. C to have time to attend to his own needs. Though provided with information about a local caregiver support group, Mr. C chose not to attend. The physician also assisted the family with advanced directives.

A particular challenge that occurred during care for the family was addressing Mr. C’s father’s driving capacity, considering his strong need for independence. To address this concern, a family meeting was held with Mr. C, his father, and his siblings from out of town. Although Mr. C’s father was not willing to relinquish his driver’s license during that meeting, he agreed to complete a functional driving assessment.

The physician continued to meet with Mr. C and his father together, as well as with Mr. C individually, to provide supportive counseling as needed. As the father’s dementia progressed and it became more difficult to complete office appointments, the physician transitioned to home visits to provide care until the father’s death.

After the death of Mr. C’s father, the physician continued to serve as Mr. C’s primary care provider.

Keeping the “family”in family medicine

Through longitudinal assessment, needs identification, and provision of relevant information, emotional support, and resources, family physicians can provide care that can improve the quality of life and well-being and help alleviate burden experienced by dementia caregivers. Family physicians also are positioned to provide treatments that can address the negative physical and psychological health outcomes associated with informal dementia caregiving. By building relationships with multiple family members across generations, family physicians can understand the context of caregiving dynamics and work together with individuals with dementia and their caregivers throughout disease progression, providing consistent support to the family unit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathleen M. Young, PhD, MPH, Novant Health Family Medicine Wilmington, 2523 Delaney Avenue, Wilmington, NC 28403; [email protected]

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 202319:1598-1695. doi: 10.1002/alz.13016

2. Liu Z, Heffernan C, Tan J. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. Int J of Nurs Sci. 2020;7:448-435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.012

3. Ory MG, Hoffman RR III, Yee JL, et al. Prevalence and impacts of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist. 1999;39:177-185. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.177

4. Baharudin AD, Din NC, Subramaniam P, et al. The associations between behavioral-psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and coping strategy, burden of care and personality style among low-income caregivers of patients with dementia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(suppl 4):447. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6868-0

5. Cheng S-T. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2

6. Reed C, Belger M, Andrews JS, et al. Factors associated with long-term impact on informal caregivers during Alzheimer’s disease dementia progression: 36-month results from GERAS. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:267-277. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000425

7. Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly MLM, Sullivan MP, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:106. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8

8. Haley WE, Levine EG, Brown SL, et al. Psychological, social, and health consequences of caring for a relative with senile dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:405-411.

9. Bom J, Bakx P, Schut F, et al. The impact of informal caregiving for older adults on the health of various types of caregivers: a systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2019;59:e629-e642. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny137

10. Fonareva I, Oken BS. Physiological and functional consequences of caregiving for relatives with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:725-747. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000039

11. Del-Pino-Casado R, Rodriguez Cardosa M, Lopez-Martinez C, et al. The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217648

12. Del-Pino-Casado R, Priego-Cubero E, Lopez-Martinez C, et al. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;16:e0247143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247143

13. De Souza Alves LC, Quirino Montiero D, Ricarte Bento S, et al. Burnout syndrome in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: a systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2019;13:415-421. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642018dn13-040008

14. Victor CR, Rippon I, Quinn C, et al. The prevalence and predictors of loneliness in caregivers of people with dementia: findings from the IDEAL programme. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:1232-1238. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1753014

15. Sallim AB, Sayampanathan AA, Cuttilan A, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:1034-1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007

16. Unpublished data from the 2015, 2016 2017, 2020, and 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey, analyzed by and provided to the Alzheimer’s Association by the Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Program (AD+HP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

17. Stall NM, Kim SJ, Hardacre KA, et al. Association of informal caregiver distress with health outcomes of community-dwelling dementia care recipients: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;00:1-9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15690

18. Lindeza P, Rodrigues M, Costa J, et al. Impact of dementia on informal care: a systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;bmjspcare-2020-002242. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242

19. Lethin C, Guiteras AR, Zwakhalen S, et al. Psychological well-being over time among informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home. Aging and Ment Health. 2017; 21:1138-1146. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1211621

20. Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregivers Count Too! A Toolkit to Help Practitioners Assess the Needs of Family Caregivers. Family Caregiver Alliance; 2006. Accessed May 16, 2023. www.caregiver.org/uploads/legacy/pdfs/Assessment_Toolkit_20060802.pdf

21. Zarit SH, Zarit JM. Instructions for the Burden Interview. Pennsylvania State University; 1987.

22. University of Wisconsin. Zarit Burden Interview: assessing caregiver burden. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://wai.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1129/2021/11/Zarit-Caregiver-Burden-Assessment-Instruments.pdf

23. Gallagher-Thompson D, Bilbrey AC, Apesoa-Varano EC, et al. Conceptual framework to guide intervention research across the trajectory of dementia caregiving. Gerontologist. 2020;60:S29-S40. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz157

24. Queluz FNFR, Kervin E, Wozney L, et al. Understanding the needs of caregivers of persons with dementia: a scoping review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:35-52. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000243

25. McCabe M, You E, Tatangelo G. Hearing their voice: a systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. Gerontologist. 2016;56:e70-e88. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw07

26. Zwaanswijk M, Peeters JM, van Beek AP, et al. Informal caregivers of people with dementia: problems, needs and support in the initial stage and in subsequent stages of dementia: a questionnaire survey. Open Nurs J. 2013;7:6-13. doi: 10.2174/1874434601307010006

27. Jennings LA, Palimaru A, Corona MG, et al. Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:685-693. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1471-7

28. Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:217-228. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty

29. Rote SM, Angel JL, Moon H, et al. Caregiving across diverse populations: new evidence from the national study of caregiving and Hispanic EPESE. Innovation in Aging. 2019;3:1-11. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz033

30. Alzheimer’s Association. 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease facts and figures. Special report—race, ethnicity, and Alzheimer’s in America. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:70-104. doi: 10.1002/alz.12328

31. Swartz K, Collins LG. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:699-706.

32. Cheng ST, Au A, Losada A, et al. Psychological interventions for dementia caregivers: what we have achieved, what we have learned. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:59. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1045-9

33. Jennings LA, Reuben DB, Everston LC, et al. Unmet needs of caregivers of patients referred to a dementia care program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:282-289. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13251

34. Soong A, Au ST, Kyaw BM, et al. Information needs and information seeking behaviour of people with dementia and their non-professional caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20:61. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1454-y

35. Cheng S-T, Zhang F. A comprehensive meta-review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on nonpharmacological interventions for informal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20:137. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01547-2

36. Wiegelmann H, Speller S, Verhaert LM, et al. Psychosocial interventions to support the mental health of informal caregivers of persons living with dementia—a systematic literature review. BMC Geriatrics. 2021;21:94. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02020-4

37. Nguyen SA, Oughli HA, Lavretsky H. Complementary and integrative medicine for neurocognitive disorders and caregiver health. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2022;24:469-480. doi: 10.1007/s11920-022-01355-y

38. Gibson A, Holmes SD, Fields NL, et al. Providing care for persons with dementia in rural communities: informal caregivers’ perceptions of supports and services. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:630-648. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2019.1636332

39. Leng M, Zhao Y, Xiau H, et al. Internet-based supportive interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19468. doi: 10.2196/19468

40. Ruggiano N, Brown EL, Li J, et al. Rural dementia caregivers and technology. What is the evidence? Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11:216-224. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20180628-04

41. Shuffler J, Lee K, Fields, et al. Challenges experienced by rural informal caregivers of older adults in the United States: a scoping review. J Evid Based Soc Work. Published online 24 February 24, 2023. doi:10.1080/26408066.2023.2183102

42. Hughes MC, Liu Y, Baumbach A. Impact of COVID-19 on the health and well-being of informal caregivers of people with dementia: a rapid systematic review. Gerontol Geriatric Med. 2021;7:1-8. doi: 10.1177/2333721421102164

43. Paplickar A, Rajagopalan J, Alladi S. Care for dementia patients and caregivers amid COVID-19 pandemic. Cereb Circ Cogn Behav. 2022;3:100040. doi: 10.1016/j.cccb.2022.100040

THE CASE

Sam C* is a 68-year-old man who presented to his family physician in a rural health clinic due to concerns about weight loss. Since his visit 8 months prior, Mr. C unintentionally had lost 20 pounds. Upon questioning, Mr. C also reported feeling irritable and having difficulty with sleep and concentration.

A review of systems did not indicate the presence of infection or other medical conditions. In the 6 years since becoming a patient to the practice, he had reported no chronic health concerns, was taking no medications, and had only been to the clinic for his annual check-up appointments. He completed a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and scored 18, indicating moderately severe depression.

Mr. C had established care with his physician when he moved to the area from out of state so that he could be closer to his parents, who were in their mid-80s at the time. Mr. C’s physician also had been the family physician for his parents for the previous 20 years. Three years prior to Mr. C’s presentation for weight loss, his mother had received a diagnosis of acute leukemia; she died a year later.

Over the past year, Mr. C had needed to take a more active role in the care of his father, who was now in his early 90s. Mr. C’s father, who was previously in excellent health, had begun to develop significant health problems, including degenerative arthritis and progressive vascular dementia. He also had ataxia, leading to poor mobility, and a neurogenic bladder requiring self-catheterization, which required Mr. C’s assistance. Mr. C lived next door to his father and provided frequent assistance with activities of daily living. However, his father, who always had been the dominant figure in the family, was determined to maintain his independence and not relinquish control to others.

The strain of caregiving activities, along with managing his father’s inflexibility, was causing increasing distress for Mr. C. As he told his family physician, “I just don’t know what to do.”

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

It is estimated that more than 11 million Americans provided more than 18 billion hours in unpaid support for individuals with dementia in 2022, averaging 30 hours of care per caregiver per week.1 As individuals with dementia progressively decline, they require increased assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs, such as bathing and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs, such as paying bills and using transportation). Most of this assistance comes from informal caregiving provided by family members and friends.

Caregiver burden can be defined as “the strain or load borne by a person who cares for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member.”2 Caregiver stress has been found to be higher for dementia caregiving than other types of caregiving.3 In particular, caring for someone with greater behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSDs) has been associated with higher caregiver burden.4-

Beyond the subjective burden of caregiving, there are other potential negative consequences for dementia caregivers (see TABLE 18-14 and TABLE 215,16). In addition, caregiver distress is related to a number of care recipient outcomes, including earlier institutionalization, more hospitalizations, more BPSDs, poorer quality of life, and greater likelihood of experiencing elder abuse.17

Assessment, reassessment are key to meeting needs

Numerous factors can foster caregiver well-being, including feelings of accomplishment and contribution, a strengthening of the relationship with the care recipient, and feeling supported by friends, family, and formal care systems.18,19 Family physicians can play an important role by assessing and supporting patients with dementia and their caregivers. Ideally, the individual with dementia and the caregiver will be assessed both together and separately.

A thorough assessment includes gathering information about the context and quality of the caregiving relationship; caregiver perception of the care recipient’s health and functional status; caregiver values and preferences; caregiver well-being (including mental health assessment); caregiver skills, abilities, and knowledge about caregiving; and positive and negative consequences of caregiving.20 Caregiver needs—including informational, care support, emotional, physical, and social needs—also should be assessed.

Continue to: Tools are available...

Tools are available to facilitate caregiver assessment. For example, the Zarit Burden Interview is a 22-item self-report measure that can be given to the caregiver21; shorter versions (4 and 12 items) are also available.22 Another resource available for caregiver assessment guidance is a toolkit developed by the Family Caregiver Alliance.20

Continually assess for changing needs

As the condition of the individual with dementia progresses, it will be important to reassess the caregiver, as stressors and needs will change over the course of the caregiving relationship. Support should be adapted accordingly.

In the early stage of dementia, caregivers may need information on disease progression and dementia care planning, ways to navigate the health care system, financial planning, and useful resources. Caregivers also may need emotional support to help them adapt to the role of caregiver, deal with denial, and manage their stress.23,24

With dementia progression, caregivers may need support related to increased decision-making responsibility, managing challenging behaviors, assisting with ADLs and IADLs, and identifying opportunities to meet personal social and well-being needs. They also may need support to accept the changes they are seeing in the individual with dementia and the shifts they are experiencing in their relationship with him or her.23,25

In late-stage dementia, caregiver needs tend to shift to determining the need for long-term care placement vs staying at home, end-of-life planning, loneliness, and anticipatory grief.23,26 Support with managing changing and accumulating stress typically remains a primary need throughout the progression of dementia.27

Continue to: Specific populations have distinct needs

Specific populations have distinct needs. Some caregivers, including members of the LGBTQ+ community and different racial and ethnic groups, as well as caregivers of people with younger-onset dementia, may have additional support needs.28

For example, African American and Latino caregivers tend to have caregiving relationships of longer duration, requiring more time-intensive care, but use fewer formal support services than White caregivers.29 Caregivers from non-White racial and ethnic groups also are more likely to experience discrimination when interacting with health care services on behalf of care recipients.30

Having an awareness of potential specialized needs may help to prevent or address potential care disparities, and cultural humility may help to improve caregiver experiences with primary care physicians.

Resources to support caregivers

Family physicians are well situated to provide informational and emotional support for both patients with dementia and their informal care providers.31 Given the variability of caregiver concerns, multicomponent interventions addressing informational, self-care, social support, and financial needs often are needed.31 Supportive counseling and psychoeducation can help dementia caregivers with stress management, self-care, coping, and skills training—supporting the development of self-efficacy.32,33

Outside resources. Although significant caregiver support can be provided directly by the physician, caregivers should be connected with outside resources, including support groups, counselors, psychotherapists, financial and legal support, and formal care services

Continue to: Psychosocial and complementary interventions

Psychosocial and complementary interventions. Various psychosocial interventions (eg, psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, support groups) have been found to be beneficial in alleviating caregiver symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and improving well-being, perceived burden, and quality of life. However, systematic reviews have found variability in the degree of helpfulness of these interventions.35,36

Some caregivers and care recipients may benefit from complementary and integrative medicine referrals. Mind–body therapies such as mindfulness, yoga, and Tai Chi have shown some beneficial effects.37

Online resources. Caregivers also can be directed to online resources from organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org), the National Institutes of Health (www.alzheimers.gov), and the Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org).

In rural settings, such as the one in which this case took place, online resources may decrease some barriers to supporting caregivers.38 Internet-based interventions also have been found to have some benefit for dementia caregivers.31,39

However, some rural locations continue to have limited reliable Internet services.40 In affected areas, a strong relationship with a primary care physician may be even more important to the well-being of caregivers, since other support services may be less accessible.41

Continue to: Impacts of the pandemic

Impacts of the pandemic. Although our case took place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to acknowledge ways the pandemic has impacted informal dementia caregiving.

Caregiver stress, depression, and anxiety increased during the pandemic, and the need for greater home confinement and social distancing amplified the negative impact of social isolation, including loneliness, on caregivers.42,43 Caregivers often needed to increase their caregiving responsibilities and had more difficulty with care coordination due to limited access to in-person resources.43 The pandemic led to increased reliance on technology and telehealth in the support of dementia caregivers.43

THE CASE

The physician prescribed mirtazapine for Mr. C, titrating the dose as needed to address depressive symptoms and promote weight gain. The physician connected Mr. C’s father with home health services, including physical therapy for fall risk reduction. Mr. C also hired part-time support to provide additional assistance with ADLs and IADLs, allowing Mr. C to have time to attend to his own needs. Though provided with information about a local caregiver support group, Mr. C chose not to attend. The physician also assisted the family with advanced directives.

A particular challenge that occurred during care for the family was addressing Mr. C’s father’s driving capacity, considering his strong need for independence. To address this concern, a family meeting was held with Mr. C, his father, and his siblings from out of town. Although Mr. C’s father was not willing to relinquish his driver’s license during that meeting, he agreed to complete a functional driving assessment.

The physician continued to meet with Mr. C and his father together, as well as with Mr. C individually, to provide supportive counseling as needed. As the father’s dementia progressed and it became more difficult to complete office appointments, the physician transitioned to home visits to provide care until the father’s death.

After the death of Mr. C’s father, the physician continued to serve as Mr. C’s primary care provider.

Keeping the “family”in family medicine

Through longitudinal assessment, needs identification, and provision of relevant information, emotional support, and resources, family physicians can provide care that can improve the quality of life and well-being and help alleviate burden experienced by dementia caregivers. Family physicians also are positioned to provide treatments that can address the negative physical and psychological health outcomes associated with informal dementia caregiving. By building relationships with multiple family members across generations, family physicians can understand the context of caregiving dynamics and work together with individuals with dementia and their caregivers throughout disease progression, providing consistent support to the family unit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathleen M. Young, PhD, MPH, Novant Health Family Medicine Wilmington, 2523 Delaney Avenue, Wilmington, NC 28403; [email protected]

THE CASE

Sam C* is a 68-year-old man who presented to his family physician in a rural health clinic due to concerns about weight loss. Since his visit 8 months prior, Mr. C unintentionally had lost 20 pounds. Upon questioning, Mr. C also reported feeling irritable and having difficulty with sleep and concentration.

A review of systems did not indicate the presence of infection or other medical conditions. In the 6 years since becoming a patient to the practice, he had reported no chronic health concerns, was taking no medications, and had only been to the clinic for his annual check-up appointments. He completed a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and scored 18, indicating moderately severe depression.

Mr. C had established care with his physician when he moved to the area from out of state so that he could be closer to his parents, who were in their mid-80s at the time. Mr. C’s physician also had been the family physician for his parents for the previous 20 years. Three years prior to Mr. C’s presentation for weight loss, his mother had received a diagnosis of acute leukemia; she died a year later.

Over the past year, Mr. C had needed to take a more active role in the care of his father, who was now in his early 90s. Mr. C’s father, who was previously in excellent health, had begun to develop significant health problems, including degenerative arthritis and progressive vascular dementia. He also had ataxia, leading to poor mobility, and a neurogenic bladder requiring self-catheterization, which required Mr. C’s assistance. Mr. C lived next door to his father and provided frequent assistance with activities of daily living. However, his father, who always had been the dominant figure in the family, was determined to maintain his independence and not relinquish control to others.

The strain of caregiving activities, along with managing his father’s inflexibility, was causing increasing distress for Mr. C. As he told his family physician, “I just don’t know what to do.”

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

It is estimated that more than 11 million Americans provided more than 18 billion hours in unpaid support for individuals with dementia in 2022, averaging 30 hours of care per caregiver per week.1 As individuals with dementia progressively decline, they require increased assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs, such as bathing and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs, such as paying bills and using transportation). Most of this assistance comes from informal caregiving provided by family members and friends.

Caregiver burden can be defined as “the strain or load borne by a person who cares for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member.”2 Caregiver stress has been found to be higher for dementia caregiving than other types of caregiving.3 In particular, caring for someone with greater behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSDs) has been associated with higher caregiver burden.4-

Beyond the subjective burden of caregiving, there are other potential negative consequences for dementia caregivers (see TABLE 18-14 and TABLE 215,16). In addition, caregiver distress is related to a number of care recipient outcomes, including earlier institutionalization, more hospitalizations, more BPSDs, poorer quality of life, and greater likelihood of experiencing elder abuse.17

Assessment, reassessment are key to meeting needs

Numerous factors can foster caregiver well-being, including feelings of accomplishment and contribution, a strengthening of the relationship with the care recipient, and feeling supported by friends, family, and formal care systems.18,19 Family physicians can play an important role by assessing and supporting patients with dementia and their caregivers. Ideally, the individual with dementia and the caregiver will be assessed both together and separately.

A thorough assessment includes gathering information about the context and quality of the caregiving relationship; caregiver perception of the care recipient’s health and functional status; caregiver values and preferences; caregiver well-being (including mental health assessment); caregiver skills, abilities, and knowledge about caregiving; and positive and negative consequences of caregiving.20 Caregiver needs—including informational, care support, emotional, physical, and social needs—also should be assessed.

Continue to: Tools are available...

Tools are available to facilitate caregiver assessment. For example, the Zarit Burden Interview is a 22-item self-report measure that can be given to the caregiver21; shorter versions (4 and 12 items) are also available.22 Another resource available for caregiver assessment guidance is a toolkit developed by the Family Caregiver Alliance.20

Continually assess for changing needs

As the condition of the individual with dementia progresses, it will be important to reassess the caregiver, as stressors and needs will change over the course of the caregiving relationship. Support should be adapted accordingly.

In the early stage of dementia, caregivers may need information on disease progression and dementia care planning, ways to navigate the health care system, financial planning, and useful resources. Caregivers also may need emotional support to help them adapt to the role of caregiver, deal with denial, and manage their stress.23,24

With dementia progression, caregivers may need support related to increased decision-making responsibility, managing challenging behaviors, assisting with ADLs and IADLs, and identifying opportunities to meet personal social and well-being needs. They also may need support to accept the changes they are seeing in the individual with dementia and the shifts they are experiencing in their relationship with him or her.23,25

In late-stage dementia, caregiver needs tend to shift to determining the need for long-term care placement vs staying at home, end-of-life planning, loneliness, and anticipatory grief.23,26 Support with managing changing and accumulating stress typically remains a primary need throughout the progression of dementia.27

Continue to: Specific populations have distinct needs

Specific populations have distinct needs. Some caregivers, including members of the LGBTQ+ community and different racial and ethnic groups, as well as caregivers of people with younger-onset dementia, may have additional support needs.28

For example, African American and Latino caregivers tend to have caregiving relationships of longer duration, requiring more time-intensive care, but use fewer formal support services than White caregivers.29 Caregivers from non-White racial and ethnic groups also are more likely to experience discrimination when interacting with health care services on behalf of care recipients.30

Having an awareness of potential specialized needs may help to prevent or address potential care disparities, and cultural humility may help to improve caregiver experiences with primary care physicians.

Resources to support caregivers

Family physicians are well situated to provide informational and emotional support for both patients with dementia and their informal care providers.31 Given the variability of caregiver concerns, multicomponent interventions addressing informational, self-care, social support, and financial needs often are needed.31 Supportive counseling and psychoeducation can help dementia caregivers with stress management, self-care, coping, and skills training—supporting the development of self-efficacy.32,33

Outside resources. Although significant caregiver support can be provided directly by the physician, caregivers should be connected with outside resources, including support groups, counselors, psychotherapists, financial and legal support, and formal care services

Continue to: Psychosocial and complementary interventions

Psychosocial and complementary interventions. Various psychosocial interventions (eg, psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, support groups) have been found to be beneficial in alleviating caregiver symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and improving well-being, perceived burden, and quality of life. However, systematic reviews have found variability in the degree of helpfulness of these interventions.35,36

Some caregivers and care recipients may benefit from complementary and integrative medicine referrals. Mind–body therapies such as mindfulness, yoga, and Tai Chi have shown some beneficial effects.37

Online resources. Caregivers also can be directed to online resources from organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org), the National Institutes of Health (www.alzheimers.gov), and the Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org).

In rural settings, such as the one in which this case took place, online resources may decrease some barriers to supporting caregivers.38 Internet-based interventions also have been found to have some benefit for dementia caregivers.31,39

However, some rural locations continue to have limited reliable Internet services.40 In affected areas, a strong relationship with a primary care physician may be even more important to the well-being of caregivers, since other support services may be less accessible.41

Continue to: Impacts of the pandemic

Impacts of the pandemic. Although our case took place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to acknowledge ways the pandemic has impacted informal dementia caregiving.

Caregiver stress, depression, and anxiety increased during the pandemic, and the need for greater home confinement and social distancing amplified the negative impact of social isolation, including loneliness, on caregivers.42,43 Caregivers often needed to increase their caregiving responsibilities and had more difficulty with care coordination due to limited access to in-person resources.43 The pandemic led to increased reliance on technology and telehealth in the support of dementia caregivers.43

THE CASE

The physician prescribed mirtazapine for Mr. C, titrating the dose as needed to address depressive symptoms and promote weight gain. The physician connected Mr. C’s father with home health services, including physical therapy for fall risk reduction. Mr. C also hired part-time support to provide additional assistance with ADLs and IADLs, allowing Mr. C to have time to attend to his own needs. Though provided with information about a local caregiver support group, Mr. C chose not to attend. The physician also assisted the family with advanced directives.

A particular challenge that occurred during care for the family was addressing Mr. C’s father’s driving capacity, considering his strong need for independence. To address this concern, a family meeting was held with Mr. C, his father, and his siblings from out of town. Although Mr. C’s father was not willing to relinquish his driver’s license during that meeting, he agreed to complete a functional driving assessment.

The physician continued to meet with Mr. C and his father together, as well as with Mr. C individually, to provide supportive counseling as needed. As the father’s dementia progressed and it became more difficult to complete office appointments, the physician transitioned to home visits to provide care until the father’s death.

After the death of Mr. C’s father, the physician continued to serve as Mr. C’s primary care provider.

Keeping the “family”in family medicine

Through longitudinal assessment, needs identification, and provision of relevant information, emotional support, and resources, family physicians can provide care that can improve the quality of life and well-being and help alleviate burden experienced by dementia caregivers. Family physicians also are positioned to provide treatments that can address the negative physical and psychological health outcomes associated with informal dementia caregiving. By building relationships with multiple family members across generations, family physicians can understand the context of caregiving dynamics and work together with individuals with dementia and their caregivers throughout disease progression, providing consistent support to the family unit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathleen M. Young, PhD, MPH, Novant Health Family Medicine Wilmington, 2523 Delaney Avenue, Wilmington, NC 28403; [email protected]

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 202319:1598-1695. doi: 10.1002/alz.13016

2. Liu Z, Heffernan C, Tan J. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. Int J of Nurs Sci. 2020;7:448-435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.012

3. Ory MG, Hoffman RR III, Yee JL, et al. Prevalence and impacts of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist. 1999;39:177-185. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.177

4. Baharudin AD, Din NC, Subramaniam P, et al. The associations between behavioral-psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and coping strategy, burden of care and personality style among low-income caregivers of patients with dementia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(suppl 4):447. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6868-0

5. Cheng S-T. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2

6. Reed C, Belger M, Andrews JS, et al. Factors associated with long-term impact on informal caregivers during Alzheimer’s disease dementia progression: 36-month results from GERAS. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:267-277. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000425

7. Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly MLM, Sullivan MP, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:106. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8

8. Haley WE, Levine EG, Brown SL, et al. Psychological, social, and health consequences of caring for a relative with senile dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:405-411.

9. Bom J, Bakx P, Schut F, et al. The impact of informal caregiving for older adults on the health of various types of caregivers: a systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2019;59:e629-e642. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny137

10. Fonareva I, Oken BS. Physiological and functional consequences of caregiving for relatives with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:725-747. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000039

11. Del-Pino-Casado R, Rodriguez Cardosa M, Lopez-Martinez C, et al. The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217648

12. Del-Pino-Casado R, Priego-Cubero E, Lopez-Martinez C, et al. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;16:e0247143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247143

13. De Souza Alves LC, Quirino Montiero D, Ricarte Bento S, et al. Burnout syndrome in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: a systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2019;13:415-421. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642018dn13-040008

14. Victor CR, Rippon I, Quinn C, et al. The prevalence and predictors of loneliness in caregivers of people with dementia: findings from the IDEAL programme. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:1232-1238. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1753014

15. Sallim AB, Sayampanathan AA, Cuttilan A, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:1034-1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007

16. Unpublished data from the 2015, 2016 2017, 2020, and 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey, analyzed by and provided to the Alzheimer’s Association by the Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Program (AD+HP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

17. Stall NM, Kim SJ, Hardacre KA, et al. Association of informal caregiver distress with health outcomes of community-dwelling dementia care recipients: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;00:1-9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15690

18. Lindeza P, Rodrigues M, Costa J, et al. Impact of dementia on informal care: a systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;bmjspcare-2020-002242. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242

19. Lethin C, Guiteras AR, Zwakhalen S, et al. Psychological well-being over time among informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home. Aging and Ment Health. 2017; 21:1138-1146. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1211621

20. Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregivers Count Too! A Toolkit to Help Practitioners Assess the Needs of Family Caregivers. Family Caregiver Alliance; 2006. Accessed May 16, 2023. www.caregiver.org/uploads/legacy/pdfs/Assessment_Toolkit_20060802.pdf

21. Zarit SH, Zarit JM. Instructions for the Burden Interview. Pennsylvania State University; 1987.

22. University of Wisconsin. Zarit Burden Interview: assessing caregiver burden. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://wai.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1129/2021/11/Zarit-Caregiver-Burden-Assessment-Instruments.pdf

23. Gallagher-Thompson D, Bilbrey AC, Apesoa-Varano EC, et al. Conceptual framework to guide intervention research across the trajectory of dementia caregiving. Gerontologist. 2020;60:S29-S40. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz157

24. Queluz FNFR, Kervin E, Wozney L, et al. Understanding the needs of caregivers of persons with dementia: a scoping review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:35-52. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000243

25. McCabe M, You E, Tatangelo G. Hearing their voice: a systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. Gerontologist. 2016;56:e70-e88. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw07

26. Zwaanswijk M, Peeters JM, van Beek AP, et al. Informal caregivers of people with dementia: problems, needs and support in the initial stage and in subsequent stages of dementia: a questionnaire survey. Open Nurs J. 2013;7:6-13. doi: 10.2174/1874434601307010006

27. Jennings LA, Palimaru A, Corona MG, et al. Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:685-693. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1471-7

28. Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:217-228. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty

29. Rote SM, Angel JL, Moon H, et al. Caregiving across diverse populations: new evidence from the national study of caregiving and Hispanic EPESE. Innovation in Aging. 2019;3:1-11. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz033

30. Alzheimer’s Association. 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease facts and figures. Special report—race, ethnicity, and Alzheimer’s in America. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:70-104. doi: 10.1002/alz.12328

31. Swartz K, Collins LG. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:699-706.

32. Cheng ST, Au A, Losada A, et al. Psychological interventions for dementia caregivers: what we have achieved, what we have learned. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:59. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1045-9

33. Jennings LA, Reuben DB, Everston LC, et al. Unmet needs of caregivers of patients referred to a dementia care program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:282-289. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13251

34. Soong A, Au ST, Kyaw BM, et al. Information needs and information seeking behaviour of people with dementia and their non-professional caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20:61. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1454-y

35. Cheng S-T, Zhang F. A comprehensive meta-review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on nonpharmacological interventions for informal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20:137. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01547-2

36. Wiegelmann H, Speller S, Verhaert LM, et al. Psychosocial interventions to support the mental health of informal caregivers of persons living with dementia—a systematic literature review. BMC Geriatrics. 2021;21:94. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02020-4

37. Nguyen SA, Oughli HA, Lavretsky H. Complementary and integrative medicine for neurocognitive disorders and caregiver health. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2022;24:469-480. doi: 10.1007/s11920-022-01355-y

38. Gibson A, Holmes SD, Fields NL, et al. Providing care for persons with dementia in rural communities: informal caregivers’ perceptions of supports and services. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:630-648. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2019.1636332

39. Leng M, Zhao Y, Xiau H, et al. Internet-based supportive interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19468. doi: 10.2196/19468

40. Ruggiano N, Brown EL, Li J, et al. Rural dementia caregivers and technology. What is the evidence? Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11:216-224. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20180628-04

41. Shuffler J, Lee K, Fields, et al. Challenges experienced by rural informal caregivers of older adults in the United States: a scoping review. J Evid Based Soc Work. Published online 24 February 24, 2023. doi:10.1080/26408066.2023.2183102

42. Hughes MC, Liu Y, Baumbach A. Impact of COVID-19 on the health and well-being of informal caregivers of people with dementia: a rapid systematic review. Gerontol Geriatric Med. 2021;7:1-8. doi: 10.1177/2333721421102164

43. Paplickar A, Rajagopalan J, Alladi S. Care for dementia patients and caregivers amid COVID-19 pandemic. Cereb Circ Cogn Behav. 2022;3:100040. doi: 10.1016/j.cccb.2022.100040

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 202319:1598-1695. doi: 10.1002/alz.13016

2. Liu Z, Heffernan C, Tan J. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. Int J of Nurs Sci. 2020;7:448-435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.012

3. Ory MG, Hoffman RR III, Yee JL, et al. Prevalence and impacts of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist. 1999;39:177-185. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.177

4. Baharudin AD, Din NC, Subramaniam P, et al. The associations between behavioral-psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and coping strategy, burden of care and personality style among low-income caregivers of patients with dementia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(suppl 4):447. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6868-0

5. Cheng S-T. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2

6. Reed C, Belger M, Andrews JS, et al. Factors associated with long-term impact on informal caregivers during Alzheimer’s disease dementia progression: 36-month results from GERAS. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:267-277. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000425

7. Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly MLM, Sullivan MP, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:106. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8

8. Haley WE, Levine EG, Brown SL, et al. Psychological, social, and health consequences of caring for a relative with senile dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:405-411.

9. Bom J, Bakx P, Schut F, et al. The impact of informal caregiving for older adults on the health of various types of caregivers: a systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2019;59:e629-e642. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny137

10. Fonareva I, Oken BS. Physiological and functional consequences of caregiving for relatives with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:725-747. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000039