User login

Novel guidance informs plasma biomarker use for Alzheimer’s disease

SAN DIEGO – The organization has previously published recommendations for use of amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease.

The recommendations were the subject of a presentation at the 2022 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference and were published online in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

During his presentation, Oskar Hansson, MD, PhD, stressed that the document describes recommendations, not criteria, for use of blood-based biomarkers. He suggested that the recommendations will need to be updated within 9-12 months, and that criteria for blood-based biomarkers use could come within 2 years.

The new recommendations reflect the recent acceleration of progress in the field, according to Wiesje M. van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session. “It’s just growing so quickly. I think within 5 years the whole field will have transformed. By starting to use them in specialized memory clinics first, but then also local memory clinics, and then finally, I think that they may also transform primary care,” said Dr. van der Flier, who is a professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Guidance for clinical trials and memory clinics

The guidelines were created in part because blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease have become increasingly available, and there has been a call from the community for guidance, according to Dr. Hansson. There is also a hazard that widespread adoption could interfere with the field itself, especially if physicians don’t understand how to interpret the results. That’s a particularly acute problem since Alzheimer’s disease pathology can precede symptoms. “It’s important to have some guidance about regulating their use so we don’t get the problem that they are misused and get a bad reputation,” said Dr. Hansson in an interview.

The current recommendations are for use in clinical trials to identify patients likely to have Alzheimer’s disease, as well as in memory clinics, though “we’re still a bit cautious. We still need to confirm it with other biomarkers. The reason for that is we still don’t know how these will perform in the clinical reality. So it’s a bit trying it out. You can start using these blood biomarkers to some degree,” said Dr. Hansson.

However, he offered the caveat that plasma-based biomarkers should only be used while confirming that the blood-based biomarkers agree with CSF tests, ideally more than 90% of the time. “If suddenly only 60% of the plasma biomarkers agree with CSF, you have a problem and you need to stop,” said Dr. Hansson.

The authors recommend that blood-based biomarkers be used in clinical trials to help select patients and identify healthy controls. Dr. Hansson said that there is not enough evidence that blood-based biomarkers have sufficient positive predictive value to be used as the sole criteria for clinical trial admission. However, they could also be used to inform decision-making in adaptive clinical trials.

Specifically, plasma Abeta42/Abeta40 and P-tau assays using established thresholds can be used in clinical studies first-screening step for clinical trials, though they should be confirmed by PET or CSF in those with abnormal blood biomarker levels. The biomarkers could also be used in non–Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials to exclude patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease copathology.

In memory clinics, the authors recommend that BBMs be used only in patients who are symptomatic and, when possible, should be confirmed by PET or CSF.

More work to be done

Dr. Hansson noted that 50%-70% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease are misdiagnosed in primary care, showing a clear need for biomarkers that could improve diagnosis. However, he stressed that blood-based biomarkers are not yet ready for use in that setting.

Still, they could eventually become a boon. “The majority of patients now do not get any biomarker support to diagnosis. They do not have access to amyloid PET or [CSF] biomarkers, but when the blood-based biomarkers are good enough, that means that biomarker support for an Alzheimer’s diagnosis [will be] available to many patients … across the globe,” said Dr. van der Flier.

There are numerous research efforts underway to validate blood-based biomarkers in more diverse groups of patients. That’s because the retrospective studies typically used to identify and validate biomarkers tend to recruit carefully selected patients, with clearly defined cases and good CSF characterization, according to Charlotte Teunissen, PhD, who is also a coauthor of the guidelines and professor of neuropsychiatry at Amsterdam University Medical Center. “Now we want to go one step further to go real-life practice, and there are several initiatives,” she said.

Dr. Hansson, Dr. Tenuissen, and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The organization has previously published recommendations for use of amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease.

The recommendations were the subject of a presentation at the 2022 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference and were published online in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

During his presentation, Oskar Hansson, MD, PhD, stressed that the document describes recommendations, not criteria, for use of blood-based biomarkers. He suggested that the recommendations will need to be updated within 9-12 months, and that criteria for blood-based biomarkers use could come within 2 years.

The new recommendations reflect the recent acceleration of progress in the field, according to Wiesje M. van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session. “It’s just growing so quickly. I think within 5 years the whole field will have transformed. By starting to use them in specialized memory clinics first, but then also local memory clinics, and then finally, I think that they may also transform primary care,” said Dr. van der Flier, who is a professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Guidance for clinical trials and memory clinics

The guidelines were created in part because blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease have become increasingly available, and there has been a call from the community for guidance, according to Dr. Hansson. There is also a hazard that widespread adoption could interfere with the field itself, especially if physicians don’t understand how to interpret the results. That’s a particularly acute problem since Alzheimer’s disease pathology can precede symptoms. “It’s important to have some guidance about regulating their use so we don’t get the problem that they are misused and get a bad reputation,” said Dr. Hansson in an interview.

The current recommendations are for use in clinical trials to identify patients likely to have Alzheimer’s disease, as well as in memory clinics, though “we’re still a bit cautious. We still need to confirm it with other biomarkers. The reason for that is we still don’t know how these will perform in the clinical reality. So it’s a bit trying it out. You can start using these blood biomarkers to some degree,” said Dr. Hansson.

However, he offered the caveat that plasma-based biomarkers should only be used while confirming that the blood-based biomarkers agree with CSF tests, ideally more than 90% of the time. “If suddenly only 60% of the plasma biomarkers agree with CSF, you have a problem and you need to stop,” said Dr. Hansson.

The authors recommend that blood-based biomarkers be used in clinical trials to help select patients and identify healthy controls. Dr. Hansson said that there is not enough evidence that blood-based biomarkers have sufficient positive predictive value to be used as the sole criteria for clinical trial admission. However, they could also be used to inform decision-making in adaptive clinical trials.

Specifically, plasma Abeta42/Abeta40 and P-tau assays using established thresholds can be used in clinical studies first-screening step for clinical trials, though they should be confirmed by PET or CSF in those with abnormal blood biomarker levels. The biomarkers could also be used in non–Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials to exclude patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease copathology.

In memory clinics, the authors recommend that BBMs be used only in patients who are symptomatic and, when possible, should be confirmed by PET or CSF.

More work to be done

Dr. Hansson noted that 50%-70% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease are misdiagnosed in primary care, showing a clear need for biomarkers that could improve diagnosis. However, he stressed that blood-based biomarkers are not yet ready for use in that setting.

Still, they could eventually become a boon. “The majority of patients now do not get any biomarker support to diagnosis. They do not have access to amyloid PET or [CSF] biomarkers, but when the blood-based biomarkers are good enough, that means that biomarker support for an Alzheimer’s diagnosis [will be] available to many patients … across the globe,” said Dr. van der Flier.

There are numerous research efforts underway to validate blood-based biomarkers in more diverse groups of patients. That’s because the retrospective studies typically used to identify and validate biomarkers tend to recruit carefully selected patients, with clearly defined cases and good CSF characterization, according to Charlotte Teunissen, PhD, who is also a coauthor of the guidelines and professor of neuropsychiatry at Amsterdam University Medical Center. “Now we want to go one step further to go real-life practice, and there are several initiatives,” she said.

Dr. Hansson, Dr. Tenuissen, and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The organization has previously published recommendations for use of amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease.

The recommendations were the subject of a presentation at the 2022 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference and were published online in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

During his presentation, Oskar Hansson, MD, PhD, stressed that the document describes recommendations, not criteria, for use of blood-based biomarkers. He suggested that the recommendations will need to be updated within 9-12 months, and that criteria for blood-based biomarkers use could come within 2 years.

The new recommendations reflect the recent acceleration of progress in the field, according to Wiesje M. van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session. “It’s just growing so quickly. I think within 5 years the whole field will have transformed. By starting to use them in specialized memory clinics first, but then also local memory clinics, and then finally, I think that they may also transform primary care,” said Dr. van der Flier, who is a professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Guidance for clinical trials and memory clinics

The guidelines were created in part because blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease have become increasingly available, and there has been a call from the community for guidance, according to Dr. Hansson. There is also a hazard that widespread adoption could interfere with the field itself, especially if physicians don’t understand how to interpret the results. That’s a particularly acute problem since Alzheimer’s disease pathology can precede symptoms. “It’s important to have some guidance about regulating their use so we don’t get the problem that they are misused and get a bad reputation,” said Dr. Hansson in an interview.

The current recommendations are for use in clinical trials to identify patients likely to have Alzheimer’s disease, as well as in memory clinics, though “we’re still a bit cautious. We still need to confirm it with other biomarkers. The reason for that is we still don’t know how these will perform in the clinical reality. So it’s a bit trying it out. You can start using these blood biomarkers to some degree,” said Dr. Hansson.

However, he offered the caveat that plasma-based biomarkers should only be used while confirming that the blood-based biomarkers agree with CSF tests, ideally more than 90% of the time. “If suddenly only 60% of the plasma biomarkers agree with CSF, you have a problem and you need to stop,” said Dr. Hansson.

The authors recommend that blood-based biomarkers be used in clinical trials to help select patients and identify healthy controls. Dr. Hansson said that there is not enough evidence that blood-based biomarkers have sufficient positive predictive value to be used as the sole criteria for clinical trial admission. However, they could also be used to inform decision-making in adaptive clinical trials.

Specifically, plasma Abeta42/Abeta40 and P-tau assays using established thresholds can be used in clinical studies first-screening step for clinical trials, though they should be confirmed by PET or CSF in those with abnormal blood biomarker levels. The biomarkers could also be used in non–Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials to exclude patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease copathology.

In memory clinics, the authors recommend that BBMs be used only in patients who are symptomatic and, when possible, should be confirmed by PET or CSF.

More work to be done

Dr. Hansson noted that 50%-70% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease are misdiagnosed in primary care, showing a clear need for biomarkers that could improve diagnosis. However, he stressed that blood-based biomarkers are not yet ready for use in that setting.

Still, they could eventually become a boon. “The majority of patients now do not get any biomarker support to diagnosis. They do not have access to amyloid PET or [CSF] biomarkers, but when the blood-based biomarkers are good enough, that means that biomarker support for an Alzheimer’s diagnosis [will be] available to many patients … across the globe,” said Dr. van der Flier.

There are numerous research efforts underway to validate blood-based biomarkers in more diverse groups of patients. That’s because the retrospective studies typically used to identify and validate biomarkers tend to recruit carefully selected patients, with clearly defined cases and good CSF characterization, according to Charlotte Teunissen, PhD, who is also a coauthor of the guidelines and professor of neuropsychiatry at Amsterdam University Medical Center. “Now we want to go one step further to go real-life practice, and there are several initiatives,” she said.

Dr. Hansson, Dr. Tenuissen, and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAIC 2022

ICU stays linked to a doubling of dementia risk

compared with older adults who have never stayed in the ICU, new research suggests.

“ICU hospitalization may be an underrecognized risk factor for dementia in older adults,” Bryan D. James, PhD, epidemiologist with Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Chicago, said in an interview.

“Health care providers caring for older patients who have experienced a hospitalization for critical illness should be prepared to assess and monitor their patients’ cognitive status as part of their long-term care plan,” Dr. James added.

The findings were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Hidden risk factor?

ICU hospitalization as a result of critical illness has been linked to subsequent cognitive impairment in older patients. However, how ICU hospitalization relates to the long-term risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other age-related dementias is unknown.

“Given the high rate of ICU hospitalization in older persons, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical to explore this relationship, Dr. James said.

The Rush team assessed the impact of an ICU stay on dementia risk in 3,822 older adults (mean age, 77 years) without known dementia at baseline participating in five diverse epidemiologic cohorts.

Participants were checked annually for development of Alzheimer’s and all-type dementia using standardized cognitive assessments.

Over an average of 7.8 years, 1,991 (52%) adults had at least one ICU stay; 1,031 (27%) had an ICU stay before study enrollment; and 961 (25%) had an ICU stay during the study period.

In models adjusted for age, sex, education, and race, ICU hospitalization was associated with 63% higher risk of Alzheimer’s dementia (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-1.88) and 71% higher risk of all-type dementia (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.48-1.97).

In models further adjusted for other health factors such as vascular risk factors and disease, other chronic medical conditions and functional disabilities, the association was even stronger: ICU hospitalization was associated with roughly double the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia (HR 2.10; 95% CI, 1.66-2.65) and all-type dementia (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.75-2.77).

Dr. James said in an interview that it remains unclear why an ICU stay may raise the dementia risk.

“This study was not designed to assess the causes of the higher risk of dementia in persons who had ICU hospitalizations. However, researchers have looked into a number of factors that could account for this increased risk,” he explained.

One is critical illness itself that leads to hospitalization, which could result in damage to the brain; for example, severe COVID-19 has been shown to directly harm the brain, Dr. James said.

He also noted that specific events experienced during ICU stay have been shown to increase risk for cognitive impairment, including infection and severe sepsis, acute dialysis, neurologic dysfunction and delirium, and sedation.

Important work

Commenting on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical & scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said what’s interesting about the study is that it looks at individuals in the ICU, regardless of the cause.

“The study shows that having some type of health issue that results in some type of ICU stay is associated with an increased risk of declining cognition,” Dr. Snyder said.

“That’s really important,” she said, “especially given the increase in individuals, particularly those 60 and older, who did experience an ICU stay over the last couple of years and understanding how that might impact their long-term risk related to Alzheimer’s and other changes in memory.”

“If an individual has been in the ICU, that should be part of the conversation with their physician or health care provider,” Dr. Snyder advised.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. James and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with older adults who have never stayed in the ICU, new research suggests.

“ICU hospitalization may be an underrecognized risk factor for dementia in older adults,” Bryan D. James, PhD, epidemiologist with Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Chicago, said in an interview.

“Health care providers caring for older patients who have experienced a hospitalization for critical illness should be prepared to assess and monitor their patients’ cognitive status as part of their long-term care plan,” Dr. James added.

The findings were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Hidden risk factor?

ICU hospitalization as a result of critical illness has been linked to subsequent cognitive impairment in older patients. However, how ICU hospitalization relates to the long-term risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other age-related dementias is unknown.

“Given the high rate of ICU hospitalization in older persons, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical to explore this relationship, Dr. James said.

The Rush team assessed the impact of an ICU stay on dementia risk in 3,822 older adults (mean age, 77 years) without known dementia at baseline participating in five diverse epidemiologic cohorts.

Participants were checked annually for development of Alzheimer’s and all-type dementia using standardized cognitive assessments.

Over an average of 7.8 years, 1,991 (52%) adults had at least one ICU stay; 1,031 (27%) had an ICU stay before study enrollment; and 961 (25%) had an ICU stay during the study period.

In models adjusted for age, sex, education, and race, ICU hospitalization was associated with 63% higher risk of Alzheimer’s dementia (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-1.88) and 71% higher risk of all-type dementia (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.48-1.97).

In models further adjusted for other health factors such as vascular risk factors and disease, other chronic medical conditions and functional disabilities, the association was even stronger: ICU hospitalization was associated with roughly double the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia (HR 2.10; 95% CI, 1.66-2.65) and all-type dementia (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.75-2.77).

Dr. James said in an interview that it remains unclear why an ICU stay may raise the dementia risk.

“This study was not designed to assess the causes of the higher risk of dementia in persons who had ICU hospitalizations. However, researchers have looked into a number of factors that could account for this increased risk,” he explained.

One is critical illness itself that leads to hospitalization, which could result in damage to the brain; for example, severe COVID-19 has been shown to directly harm the brain, Dr. James said.

He also noted that specific events experienced during ICU stay have been shown to increase risk for cognitive impairment, including infection and severe sepsis, acute dialysis, neurologic dysfunction and delirium, and sedation.

Important work

Commenting on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical & scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said what’s interesting about the study is that it looks at individuals in the ICU, regardless of the cause.

“The study shows that having some type of health issue that results in some type of ICU stay is associated with an increased risk of declining cognition,” Dr. Snyder said.

“That’s really important,” she said, “especially given the increase in individuals, particularly those 60 and older, who did experience an ICU stay over the last couple of years and understanding how that might impact their long-term risk related to Alzheimer’s and other changes in memory.”

“If an individual has been in the ICU, that should be part of the conversation with their physician or health care provider,” Dr. Snyder advised.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. James and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with older adults who have never stayed in the ICU, new research suggests.

“ICU hospitalization may be an underrecognized risk factor for dementia in older adults,” Bryan D. James, PhD, epidemiologist with Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Chicago, said in an interview.

“Health care providers caring for older patients who have experienced a hospitalization for critical illness should be prepared to assess and monitor their patients’ cognitive status as part of their long-term care plan,” Dr. James added.

The findings were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Hidden risk factor?

ICU hospitalization as a result of critical illness has been linked to subsequent cognitive impairment in older patients. However, how ICU hospitalization relates to the long-term risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other age-related dementias is unknown.

“Given the high rate of ICU hospitalization in older persons, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical to explore this relationship, Dr. James said.

The Rush team assessed the impact of an ICU stay on dementia risk in 3,822 older adults (mean age, 77 years) without known dementia at baseline participating in five diverse epidemiologic cohorts.

Participants were checked annually for development of Alzheimer’s and all-type dementia using standardized cognitive assessments.

Over an average of 7.8 years, 1,991 (52%) adults had at least one ICU stay; 1,031 (27%) had an ICU stay before study enrollment; and 961 (25%) had an ICU stay during the study period.

In models adjusted for age, sex, education, and race, ICU hospitalization was associated with 63% higher risk of Alzheimer’s dementia (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-1.88) and 71% higher risk of all-type dementia (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.48-1.97).

In models further adjusted for other health factors such as vascular risk factors and disease, other chronic medical conditions and functional disabilities, the association was even stronger: ICU hospitalization was associated with roughly double the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia (HR 2.10; 95% CI, 1.66-2.65) and all-type dementia (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.75-2.77).

Dr. James said in an interview that it remains unclear why an ICU stay may raise the dementia risk.

“This study was not designed to assess the causes of the higher risk of dementia in persons who had ICU hospitalizations. However, researchers have looked into a number of factors that could account for this increased risk,” he explained.

One is critical illness itself that leads to hospitalization, which could result in damage to the brain; for example, severe COVID-19 has been shown to directly harm the brain, Dr. James said.

He also noted that specific events experienced during ICU stay have been shown to increase risk for cognitive impairment, including infection and severe sepsis, acute dialysis, neurologic dysfunction and delirium, and sedation.

Important work

Commenting on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical & scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said what’s interesting about the study is that it looks at individuals in the ICU, regardless of the cause.

“The study shows that having some type of health issue that results in some type of ICU stay is associated with an increased risk of declining cognition,” Dr. Snyder said.

“That’s really important,” she said, “especially given the increase in individuals, particularly those 60 and older, who did experience an ICU stay over the last couple of years and understanding how that might impact their long-term risk related to Alzheimer’s and other changes in memory.”

“If an individual has been in the ICU, that should be part of the conversation with their physician or health care provider,” Dr. Snyder advised.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. James and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAIC 2022

Is it psychosis, or an autoimmune encephalitis?

Hidden within routine presentations of first-episode psychosis is a rare subpopulation whose symptoms are mediated by an autoimmune process for which proper treatment differs significantly from standard care for typical psychotic illness. In this article, we present a hypothetical case and describe how to assess if a patient has an elevated probability of autoimmune encephalitis, determine what diagnostics or medication-induced effects to consider, and identify unresolved questions about best practices.

CASE REPORT

Bizarre behavior and isolation

Ms. L, age 21, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by her college roommate after exhibiting out-of-character behavior and gradual self-isolation over the last 2 months. Her roommate noticed that she had been spending more time isolated in her dorm room and remaining in bed into the early afternoon, though she does not appear to be asleep. Ms. L’s mother is concerned about her daughter’s uncharacteristic refusal to travel home for a family event. Ms. L expresses concern about the intentions of her research preceptor, and recalls messages from the association of colleges telling her to “change her future.” Ms. L hears voices telling her who she can and cannot trust. In the ED, she says she has a headache, experiences mild dizziness while standing, and reports having a brief upper respiratory illness at the end of last semester. Otherwise, a medical review of systems is negative.

Although the etiology of first-episode psychosis can be numerous or unknown, many psychiatrists feel comfortable with the initial diagnostic for this type of clinical presentation. However, for some clinicians, it may be challenging to feel confident in making a diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis.

Autoimmune encephalitis is a family of syndromes caused by autoantibodies targeting either intracellular or extracellular neuronal antigens. Anti-N-methyl-

In this article, we focus on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and use the term interchangeably with autoimmune encephalitis for 2 reasons. First, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis can present with psychotic symptoms as the only symptoms (prior to cognitive or neurologic manifestations) or can present with psychotic symptoms as the main indicator (with other symptoms that are more subtle and possibly missed). Second, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis often occurs in young adults, which is when it is common to see the onset of a primary psychotic illness. These 2 factors make it likely that these cases will come into the evaluative sphere of psychiatrists. We give special attention to features of cases of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis confirmed with antineuronal antibodies in the CSF, as it has emerged that antibodies in the serum can be nonspecific and nonpathogenic.2,3

What does anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis look like?

Symptoms of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis resemble those of a primary psychotic disorder, which can make it challenging to differentiate between the 2 conditions, and might cause the correct diagnosis to be missed. Pollak et al4 proposed that psychiatrically confusing presentations that don’t clearly match an identifiable psychotic disorder should raise a red flag for an autoimmune etiology. However, studies often fail to describe the specific psychiatric features of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, and thus provide little practical evidence to guide diagnosis. In some of the largest studies of patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, psychiatric clinical findings are often combined into nonspecific headings such as “abnormal behavior” or “behavioral and cognitive” symptoms.5 Such groupings make this the most common clinical finding (95%)5 but make it difficult to discern particular clinical characteristics. Where available, specific symptoms identified across studies include agitation, aggression, changes in mood and/or irritability, insomnia, delusions, hallucinations, and occasionally catatonic features.6,7 Attempts to identify specific psychiatric phenotypes distinct from primary psychotic illnesses have fallen short due to contradictory findings and lack of clinical practicality.8 One exception is the presence of catatonic features, which have been found in CSF-confirmed studies.2 In contrast to the typical teaching that the hallucination modality (eg, visual or tactile) can be helpful in estimating the likelihood of a secondary psychosis (ie, drug-induced, neurodegenerative, or autoimmune), there does not appear to be a difference in hallucination modality between encephalitis and primary psychotic disorders.9

History and review of systems

Another red flag to consider is the rapidity of symptom presentation. Symptoms that progress within 3 months increase the likelihood that the patient has autoimmune encephalitis.10 Cases where collateral information indicates the psychotic episode was preceded by a long, subtle decline in school performance, social withdrawal, and attenuated psychotic symptoms typical of a schizophrenia prodrome are less likely to be an autoimmune psychosis.11 A more delayed presentation does not entirely exclude autoimmune encephalitis; however, a viral-like prodrome before the onset of psychosis increases the likelihood of autoimmune encephalitis. Such a prodrome may include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.7

Continue to: Another indication is the presence...

Another indication is the presence of new seizures within 1 year of presenting with psychotic symptoms.10 The possibility of undiagnosed seizures should be considered in a patient with psychosis who has episodes of unresponsiveness, dissociative episodes, or seizure-like activity that is thought to be psychogenic but has not been fully evaluated. Seizures in autoimmune encephalitis involve deep structures in the brain and can be present without overt epileptiform activity on EEG, but rather causing only bilateral slowing that is often described as nonspecific.12

In a young patient presenting with first-episode psychosis, a recent diagnosis of cancer or abnormal finding in the ovaries increases the likelihood of autoimmune encephalitis.4 Historically, however, this type of medical history has been irrelevant to psychosis. Although rare, any person presenting with first-episode psychosis and a history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis should be evaluated for autoimmune encephalitis because anti-NMDA receptor antibodies have been reported to be present in approximately one-third of these patients.13 Finally, the report of focal neurologic symptoms, including neck stiffness or neck pain, should raise concern, although sensory, working memory, and cognitive deficits may be difficult to fully distinguish from common somatic and cognitive symptoms in a primary psychiatric presentation.

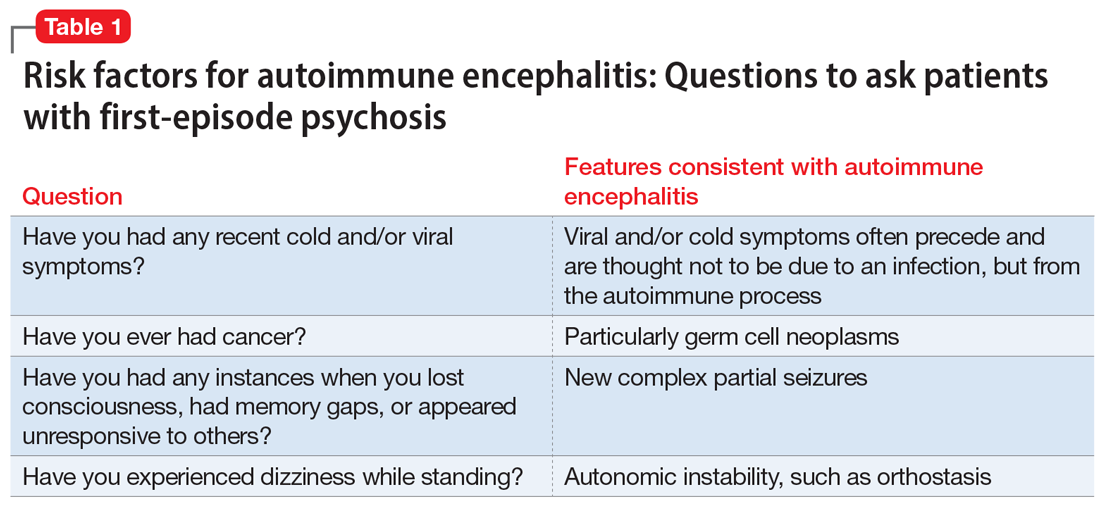

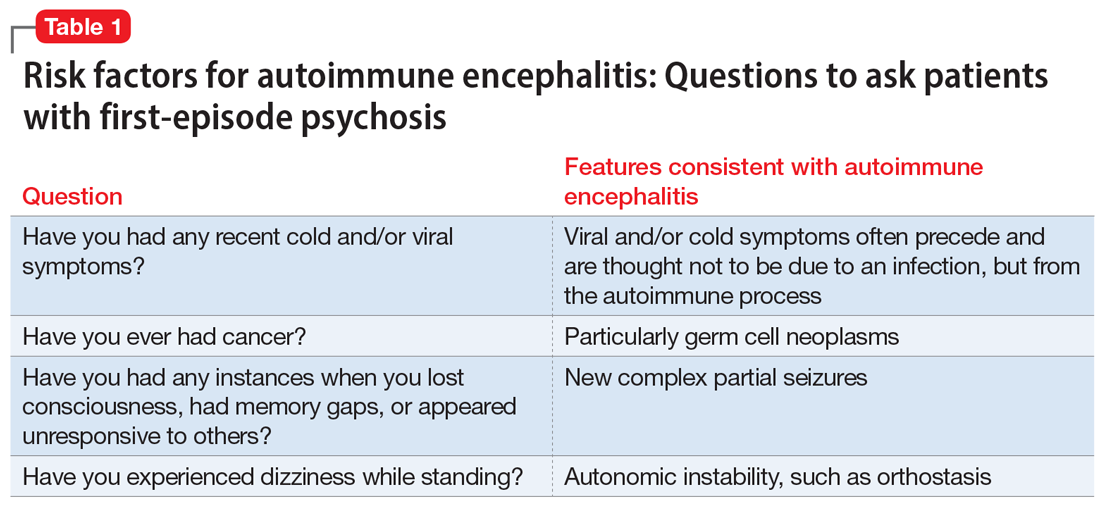

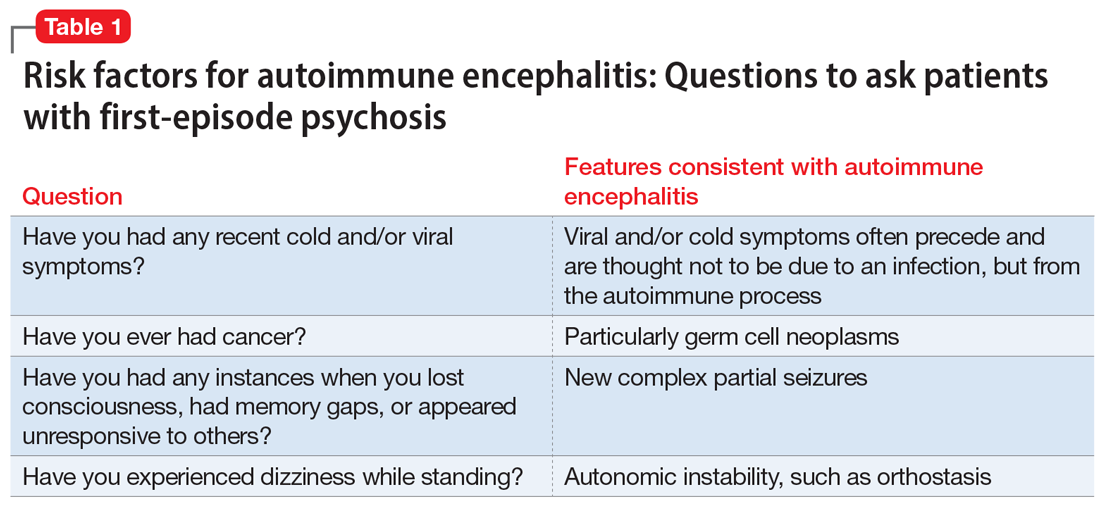

Table 1 lists 4 questions to ask patients who present with first-episode psychosis that may not usually be part of a typical evaluation.

CASE CONTINUED

Uncooperative with examination

In the ED, Ms. L’s heart rate is 101 beats per minute and her blood pressure is 102/72 mm Hg. Her body mass index (BMI) is 22, which suggests an approximate 8-pound weight loss since her BMI was last assessed. Ms. L responds to questions with 1- to 6-word sentences, without clear verbigeration. Though her speech is not pressured, it is of increased rate. Her gaze scans the room, occasionally becoming fixed for 5 to 10 seconds but is aborted by the interviewer’s comment on this behavior. Ms. L efficiently and accurately spells WORLD backwards, then asks “Why?” and refuses to engage in further cognitive testing, stating “Not doing that.” When the interviewer asks “Why not?” she responds “Not doing that.” Her cranial nerves are intact, and she refuses cerebellar testing or requests to assess tone. There are no observed stereotypies, posturing, or echopraxia.

While not necessary for a diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis, short-term memory loss is a common cognitive finding across studies.5-7 A common clinical finding from a mental status exam is speech disorders, including (but not limited to) increased rates of speech or decreased verbal output.7 Autonomic instability—including tachycardia, markedly labile blood pressures, and orthostasis—all increase the likelihood of autoimmune encephalitis.14 Interpreting a patient’s vital sign changes can be confounded if they are agitated or anxious, or if they are taking an antipsychotic that produces adverse anticholinergic effects. However, vital sign abnormalities that precede medication administration or do not correlate with fluctuations in mental status increase suspicion for an autoimmune encephalitis.

Continue to: In the absence of the adverse effect...

In the absence of the adverse effect of a medication, orthostasis is uncommon in a well-hydrated young person. Some guidelines4 suggest that symptoms of catatonia should be considered a red flag for autoimmune encephalitis. According to the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale, commonly identified features include immobility, staring, mutism, posturing, withdrawal, rigidity, and gegenhalten.15 Catatonia is common among patients with anti-NDMA receptor encephalitis, though it may not be initially present and could emerge later.2 However, there are documented cases of autoimmune encephalitis where the patient had only isolated features of catatonia, such as echolalia or mutism.2

CASE CONTINUED

History helps narrow the diagnosis

Ms. L’s parents say their daughter has not had prior contact with a therapist or psychiatrist, previous psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalizations, suicide attempts, self-injury, or binging or purging behaviors. Ms. L’s paternal grandfather was diagnosed with schizophrenia, but he is currently employed, lives alone, and has not taken medication for many years. Her mother has hypothyroidism. Ms. L was born at full term via vaginal delivery without cardiac defects or a neonatal intensive care unit stay. Her mother said she did not have postpartum depression or anxiety, a complicated pregnancy, or exposure to tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. Ms. L has no history of childhood seizures or head injury with loss of consciousness. She is an only child, born and raised in a house in a metropolitan area, walked at 13 months, did not require early intervention or speech therapy, and met normal language milestones.

She attended kindergarten at age 6 and progressed throughout public school without regressions in reading, writing, or behavioral manifestations, and did not require a 504 Plan or individualized education program. Ms. L graduated high school in the top 30% of her class, was socially active, and attended a local college. In college, she achieved honor roll, enrolled in a sorority, and was a part of a research lab. Her only medication is oral contraception. She consumes alcohol socially, and reports no cannabis, cigarette, or vaping use. Ms. L says she does not use hallucinogens, stimulants, opiates, or cocaine, and her roommate and family confirm this. She denies recent travel and is sexually active. Ms. L’s urinary and serum toxicology are unremarkable, human chorionic gonadotropin is undetectable, and her sodium level is 133 mEq/L. A measure of serum neutrophils is 6.8 x 109/L and serum lymphocytes is 1.7 x 109/L. Her parents adamantly request a Neurology consultation and further workup, including a lumbar puncture (LP), EEG, and brain imaging (MRI).

This information is useful in ruling out other potential causes of psychosis, such as substance-induced psychosis and neurodevelopmental disorders that can present with psychosis. Additionally, neurodevelopmental abnormalities and psychiatric prodromal symptoms are known precedents in individuals who develop a primary psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia.16 A family history that includes a psychotic illness may increase the likelihood of a primary psychotic disorder in offspring; however, clinicians must also consider the accuracy of diagnosis in the family, as this can often be inaccurate or influenced by historical cultural bias. We recommend further elucidating the likelihood of a genetic predisposition to a primary psychotic disorder by clarifying familial medication history and functionality.

For example, the fact that Ms. L’s grandfather has not taken medication for many years and has a high degree of functioning and/or absence of cognitive deficits would lower our suspicion for an accurate diagnosis of schizophrenia (given the typical cognitive decline with untreated illness). Another piece of family history relevant to autoimmune encephalitis includes the propensity for autoimmune disorders, but expert opinion on this matter is mixed.17 Ms. L’s mother has hypothyroidism, which is commonly caused by a prior episode of Hashimoto’s autoimmune thyroiditis. Some physicians advocate for measuring antithyroid antibodies and erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein to gauge the level of autoimmunity, but the usefulness of these measures for detecting autoimmune encephalitis is unclear. These serum markers can be useful in detecting additional important etiologies such as systemic infection or systemic inflammation, and there are conditions such as steroid-responsive encephalopathy with associated thyroiditis, which, as the name suggests, responds to steroids rather than other psychotropic medications. Other risk factors for autoimmune encephalitis include being female, being young, having viral infections (eg, HSV), prior tumor burden, and being in the postpartum period.18 Some experts also suggest the presence of neurologic symptoms 4 weeks after the first psychiatric or cognitive symptom presentation increases the likelihood of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, and a lack of neurologic symptoms would make this diagnosis less likely.6,19

Continue to: Another item of interest...

Another item of interest in Ms. L’s case is her parents’ request for a Neurology consultation and further workup, as there is an association between caregiver request for workup and eventual diagnosis.6 While the etiology of this phenomenon is unclear, the literature suggests individuals with autoimmune encephalitis who initially present to Psychiatry experience longer delays to the appropriate treatment with immunomodulatory therapy than those who first present to Neurology.20

Laboratory and diagnostic testing

Guasp et al2 recommend EEG, MRI, and serum autoimmune antibodies (ie, screening for anti-NMDA receptor antibodies) for patients who present with first-episode psychosis, even in the absence of some of the red flags previously discussed. A recent economic analysis suggested screening all patients with first-episode psychosis for serum antibodies may be cost-effective.21

For patients whose presentations include features concerning for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, an EEG and MRI are reasonable. In a review of EEG abnormalities in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, Gillinder et al23 noted that while 30% did not have initial findings, 83.6% of those with confirmed anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis demonstrated EEG abnormalities; the most common were generalized slowing, delta slowing, and focal abnormalities. Discovering an extreme delta-brush activity on EEG is specific for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, but its absence is not fully informative. Practically, slowing can be a nonspecific manifestation of encephalopathy or a medication effect, and many people who present with first-episode psychosis will have recently received antipsychotics, which alter EEG frequency. In a study of EEG changes with antipsychotics, Centorrino et al24 found that generalized background slowing into the theta range across all antipsychotics was not significantly different from control participants, while theta to delta range slowing occurred in 8.2% of those receiving antipsychotics vs 3.3% of controls. Clozapine and olanzapine may be associated with greater EEG abnormalities, while haloperidol and quetiapine contribute a lower risk.25 For young patients with first-episode psychosis without a clear alternative explanation, we advocate for further autoimmune encephalitis workup among all individuals with generalized theta or delta wave slowing.

Because these medication effects are most likely to decrease specificity but not sensitivity of EEG for autoimmune encephalitis, a normal EEG without slowing can be reassuring.26 Moreover, for patients who receive neuroimaging, an MRI may detect inflammation that is not visible on CT. The concerning findings for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis are temporal or multifocal T2 hyperintensities, though the MRI is normal in most cases and thus should not be reassuring if other concerning features are present.27

The role of lumbar puncture

Another area of active debate surrounds the usefulness and timing of LP. Guasp et al2 proposed that all individuals with first-episode psychosis and focal neurologic findings should receive LP and CSF antineuronal antibody testing. They recommend that patients with first-episode psychosis without focal neurologic findings also should receive LP and CSF testing if ≥1 of the following is present:

- slowing on EEG

- temporal or multifocal T2 hyperintensities on MRI

- positive anti-NMDA receptor antibody in the serum.2

Continue to: Evidence suggests that basic CSF parameters...

Evidence suggests that basic CSF parameters, such as elevated protein and white blood cell counts, are some of the most sensitive and specific tests for autoimmune encephalitis.2 Thus, if the patient is amenable and logistical factors are in place, it may be reasonable to pursue LP earlier in some cases without waiting for serum antibody assays to return (these results can take several weeks). CSF inflammatory changes without neuronal antibodies should lead to other diagnostic considerations (eg, systemic inflammatory disease, psychosis attributed to systemic lupus erythematosus).7 While nonspecific, serum laboratory values that may increase suspicion of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis include hyponatremia6 and an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR).28 An NLR >4 in conjunction with CSF albumin-to- serum albumin ratio >7 is associated with impaired blood brain barrier integrity and a worse prognosis for those with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.28

Additional clinical features that may sway decisions in favor of obtaining LP despite negative findings on EEG, MRI, and serum antibodies include increased adverse reactions to antipsychotics (eg, neuroleptic malignant syndrome), prodromal infectious symptoms, known tumor, or new-onset neurologic symptoms after initial evaluation.2,8

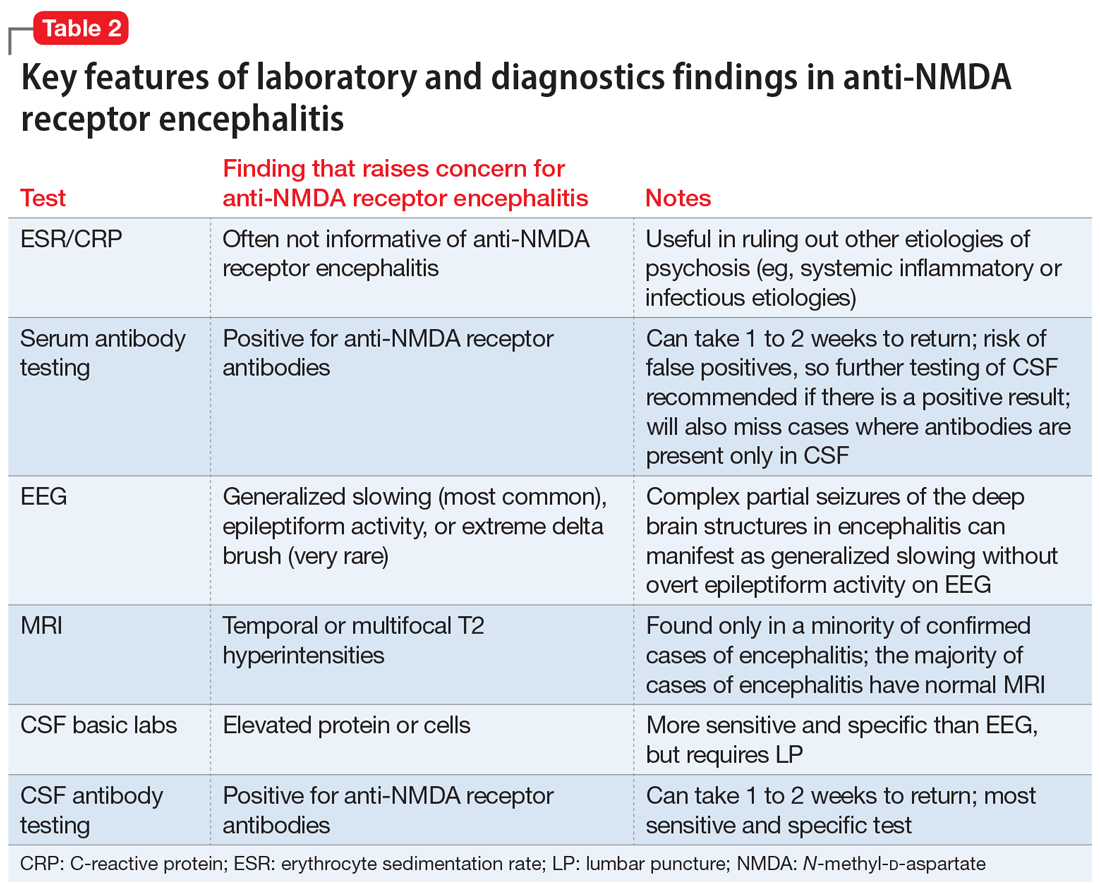

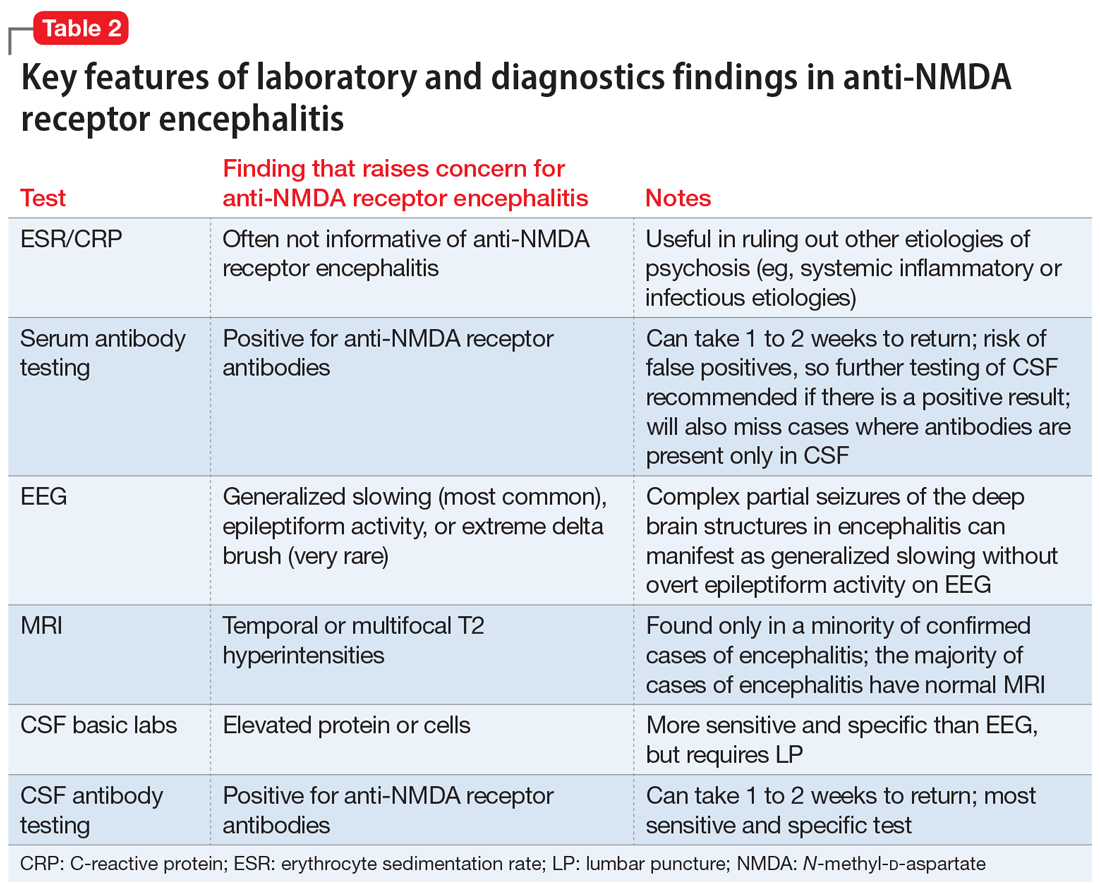

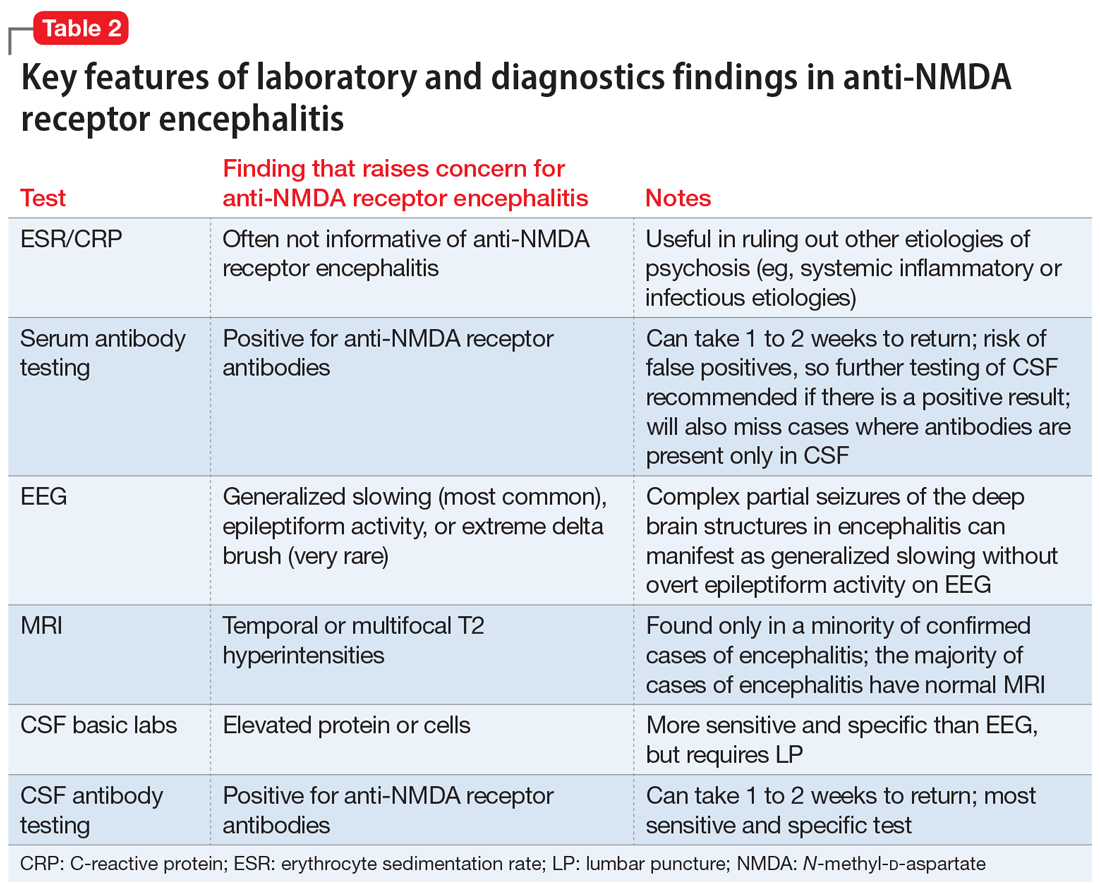

Table 2 summarizes key features of laboratory and diagnostic findings in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

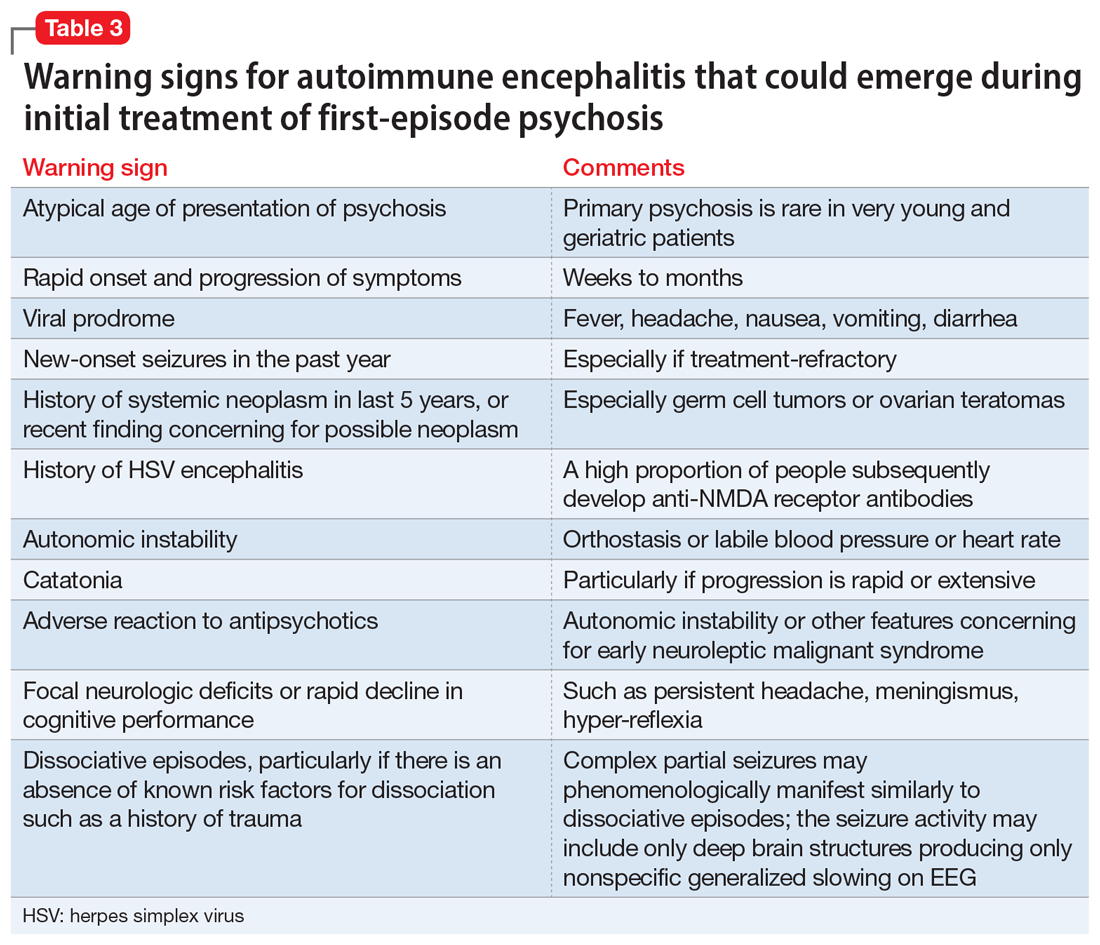

When should you pursue a more extensive workup?

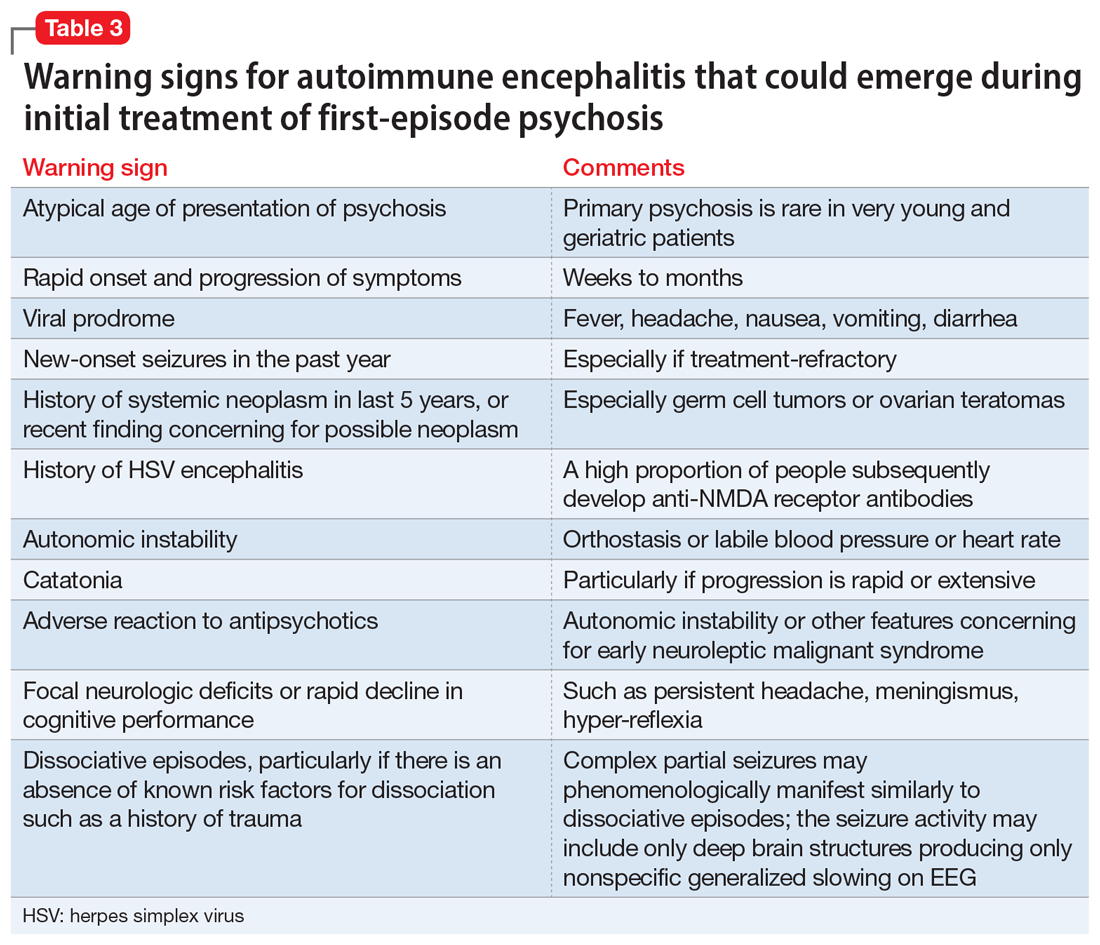

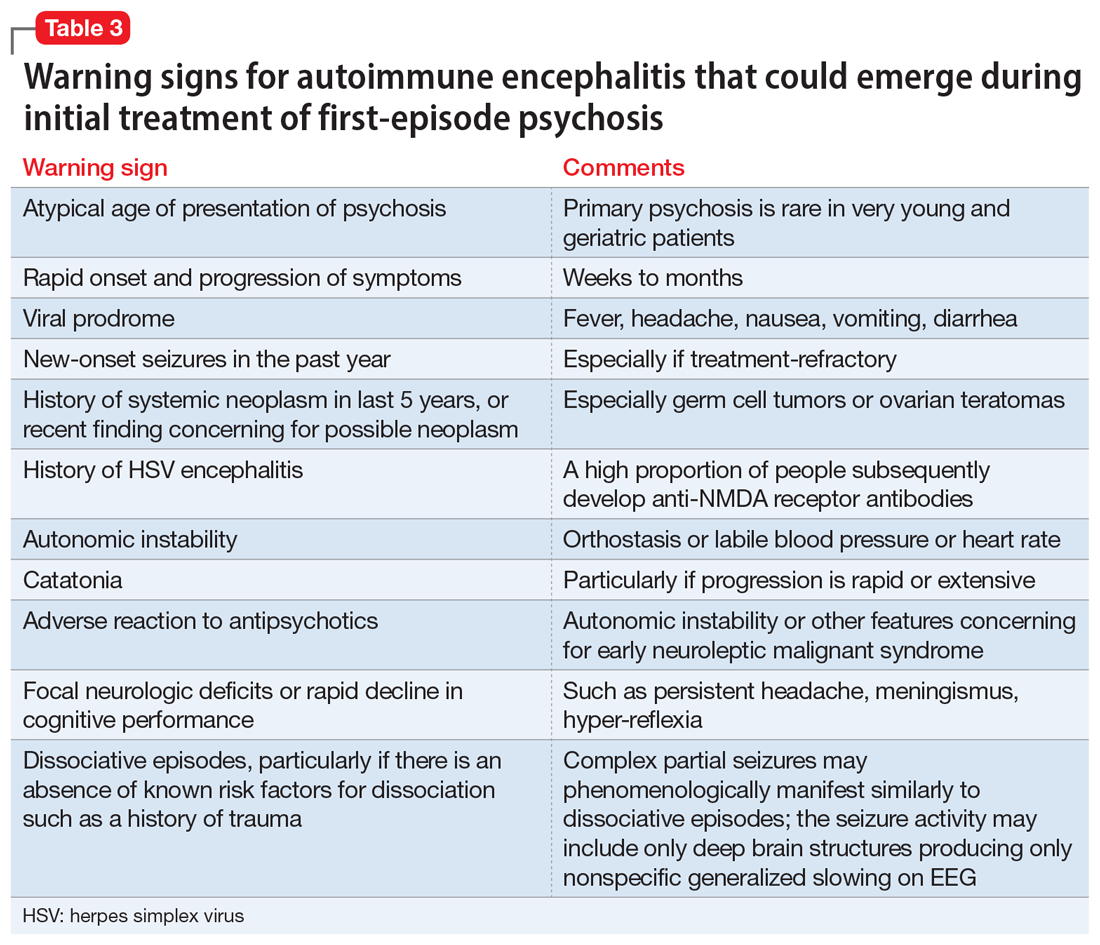

There are some practical tools and rating scales to help clinicians conceptualize risk for autoimmune encephalitis. For psychiatric purposes, however, many of these scales assume that LP, MRI, and EEG have already been completed, and thus it is challenging to incorporate them into psychiatric practice. One such tool is the Antibody Prevalence in Epilepsy and Encephalopathy scale; a score ≥4 is 98% sensitive and 78% to 84% specific for predicting antineural autoantibody positivity.10 Table 3 describes warning signs that may be useful in helping clinicians decide how urgently to pursue a more extensive workup in the possibility of autoimmune encephalitis.

The importance of catching anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is underscored by the fact that appropriate treatment is very different than for primary psychosis, and outcomes worsen with delay to appropriate treatment.20 Without treatment, severe cases may progress to autonomic instability, altered consciousness, and respiratory compromise warranting admission to an intensive care unit. While the details are beyond the scope of this review, the recommended treatment for confirmed cases of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis includes tumor removal (if indicated), reducing inflammation (steroids), removing antibodies via IV immunoglobulins, or plasma exchange.8,29 Progression of the disease may warrant consideration of rituximab or cyclophosphamide. In nonresponsive cases, third-line treatments include proteasome inhibitors or interleukin-6 receptor antagonists.8 For patients with severe catatonia, some studies have investigated the utility of electroconvulsive therapy.30 Conceptually, clinicians may consider the utility of antipsychotics as similar to recommendations for hyperactive delirium for the management of psychotic symptoms, agitation, or insomnia. However, given the risk for antipsychotic intolerance, using the lowest effective dose and vigilant screening for the emergence of extrapyramidal symptoms, fever, and autonomic instability is recommended.

CASE CONTINUED

Finally, something objective

Ms. L receives haloperidol 2 mg and undergoes an MRI without contrast. Findings are unremarkable. A spot EEG notes diffuse background slowing in the theta range, prompting lumbar puncture. Findings note 0.40 g/L, 0.2 g/L, and 3.5 for the total protein, albumin, and albumin/CSF-serum quotient (QAlb), respectively; all values are within normal limits. A mild lymphocytic pleocytosis is present as evidenced by a cell count of 35 cells/µL. The CSF is sent for qualitative examination of immunoglobulin G and electrophoresis of proteins in the CSF and serum, of which an increased concentration of restricted bands (oligoclonal bands) in the CSF but not the serum would indicate findings of oligoclonal bands. CSF is sent for detection of anti-NMDA receptor antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence, with a plan to involve an interdisciplinary team for treatment if the antibodies return positive and to manage the case symptomatically in the interim.

Bottom Line

A small subpopulation of patients who present with apparent first-episode psychosis will have symptoms caused by autoimmune encephalitis (specifically, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis). We provide 4 screening questions to determine when to pursue a workup for an autoimmune encephalitis, and describe relevant clinical symptoms and warning signs to help differentiate the 2 conditions.

Related Resources

- Askandaryan AS, Naqvi A, Varughese A, et al. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: neuropsychiatric and multidisciplinary approach to a patient not responding to first-line treatment. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e25751.

- Kayser MS, Titulaer MJ, Gresa-Arribas N, et al. Frequency and characteristics of isolated psychiatric episodes in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(9):1133-1139.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rituximab • Rituxan

1. Granerod J, Ambrose HE, Davies NW, et al; UK Health Protection Agency (HPA) Aetiology of Encephalitis Study Group. Causes of encephalitis and differences in their clinical presentations in England: a multicentre, population-based prospective study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(12):835-44. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70222-X

2. Guasp M, Giné-Servén E, Maudes E, et al. Clinical, neuroimmunologic, and CSF investigations in first episode psychosis. Neurology. 2021;97(1):e61-e75.

3. From the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR), Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE), Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (CIRA), Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT), European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR), European Stroke Organization (ESO), Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS), and World Stroke Organization (WSO), Sacks D, Baxter B, Campbell BCV, et al. Multisociety consensus quality improvement revised consensus statement for endovascular therapy of acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(6):612-632. doi:10.1177/1747493018778713

4. Pollak TA, Lennox BR, Muller S, et al. Autoimmune psychosis: an international consensus on an approach to the diagnosis and management of psychosis of suspected autoimmune origin. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(1):93-108.

5. Guasp M, Módena Y, Armangue T, et al. Clinical features of seronegative, but CSF antibody-positive, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(2):e659.

6. Herken J, Prüss H. Red flags: clinical signs for identifying autoimmune encephalitis in psychiatric patients. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:25. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00025

7. Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):391-404.

8. Dalmau J, Armangue T, Planaguma J, et al. An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: mechanisms and models. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1045-1057.

9. Rattay TW, Martin P, Vittore D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients with psychotic symptoms—a retrospective analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7169.

10. Dubey D, Pittock SJ, McKeon A. Antibody prevalence in epilepsy and encephalopathy score: increased specificity and applicability. Epilepsia. 2019;60(2):367-369.

11. Maj M, van Os J, De Hert M, et al. The clinical characterization of the patient with primary psychosis aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):4-33. doi:10.1002/wps.20809

12. Caplan JP, Binius T, Lennon VA, et al. Pseudopseudoseizures: conditions that may mimic psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):501-506.

13. Armangue T, Spatola M, Vlagea A, et al. Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: a prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):760-772.

14. Takamatsu K, Nakane S. Autonomic manifestations in autoimmune encephalitis. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2022;10:130-136. doi:10.1111/ncn3.12557

15. Espinola-Nadurille M, Flores-Rivera J, Rivas-Alonso V, et al. Catatonia in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(9):574-580.

16. Keshavan M, Montrose DM, Rajarethinam R, et al. Psychopathology among offspring of parents with schizophrenia: relationship to premorbid impairments. Schizophr Res. 2008;103(1-3):114-120.

17. Jeppesen R, Benros ME. Autoimmune diseases and psychotic disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:131.

18. Bergink V, Armangue T, Titulaer MJ, et al. Autoimmune encephalitis in postpartum psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):901-908.

19. Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(12):1091-8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70224-2

20. Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157-165.

21. Ross EL, Becker JE, Linnoila JJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of routine screening for autoimmune encephalitis in patients with first-episode psychosis in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):19m13168.

22. Sonderen AV, Arends S, Tavy DLJ, et al. Predictive value of electroencephalography in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(10):1101-1106.

23. Gillinder L, Warren N, Hartel G, et al. EEG findings in NMDA encephalitis--a systematic review. Seizure. 2019;65:20-24.

24. Centorrino F, Price BH, Tuttle M, et al. EEG abnormalities during treatment with typical and atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):109-115.

25. Raymond N, Lizano P, Kelly S, et al. What can clozapine’s effect on neural oscillations tell us about its therapeutic effects? A scoping review and synthesis. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2022;6:100048.

26. Kaufman DM, Geyer H, Milstein MJ. Kaufman’s Clinical Neurology for Psychiatrists. 8th ed. Elsevier Inc; 2016.

27. Kelley BP, Patel SC, Marin HL, et al. Autoimmune encephalitis: pathophysiology and imaging review of an overlooked diagnosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(6):1070-1078.

28. Yu Y, Wu Y, Cao X, et al. The clinical features and prognosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis depends on blood brain barrier integrity. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;47:102604.

29. Dalmau J, Graus F. Antibody-mediated neuropsychiatric disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(1):37-40.

30. Warren N, Grote V, O’Gorman C, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for anti-N-methyl-daspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis: a systematic review of cases. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(2):329-334.

Hidden within routine presentations of first-episode psychosis is a rare subpopulation whose symptoms are mediated by an autoimmune process for which proper treatment differs significantly from standard care for typical psychotic illness. In this article, we present a hypothetical case and describe how to assess if a patient has an elevated probability of autoimmune encephalitis, determine what diagnostics or medication-induced effects to consider, and identify unresolved questions about best practices.

CASE REPORT

Bizarre behavior and isolation

Ms. L, age 21, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by her college roommate after exhibiting out-of-character behavior and gradual self-isolation over the last 2 months. Her roommate noticed that she had been spending more time isolated in her dorm room and remaining in bed into the early afternoon, though she does not appear to be asleep. Ms. L’s mother is concerned about her daughter’s uncharacteristic refusal to travel home for a family event. Ms. L expresses concern about the intentions of her research preceptor, and recalls messages from the association of colleges telling her to “change her future.” Ms. L hears voices telling her who she can and cannot trust. In the ED, she says she has a headache, experiences mild dizziness while standing, and reports having a brief upper respiratory illness at the end of last semester. Otherwise, a medical review of systems is negative.

Although the etiology of first-episode psychosis can be numerous or unknown, many psychiatrists feel comfortable with the initial diagnostic for this type of clinical presentation. However, for some clinicians, it may be challenging to feel confident in making a diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis.

Autoimmune encephalitis is a family of syndromes caused by autoantibodies targeting either intracellular or extracellular neuronal antigens. Anti-N-methyl-

In this article, we focus on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and use the term interchangeably with autoimmune encephalitis for 2 reasons. First, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis can present with psychotic symptoms as the only symptoms (prior to cognitive or neurologic manifestations) or can present with psychotic symptoms as the main indicator (with other symptoms that are more subtle and possibly missed). Second, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis often occurs in young adults, which is when it is common to see the onset of a primary psychotic illness. These 2 factors make it likely that these cases will come into the evaluative sphere of psychiatrists. We give special attention to features of cases of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis confirmed with antineuronal antibodies in the CSF, as it has emerged that antibodies in the serum can be nonspecific and nonpathogenic.2,3

What does anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis look like?

Symptoms of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis resemble those of a primary psychotic disorder, which can make it challenging to differentiate between the 2 conditions, and might cause the correct diagnosis to be missed. Pollak et al4 proposed that psychiatrically confusing presentations that don’t clearly match an identifiable psychotic disorder should raise a red flag for an autoimmune etiology. However, studies often fail to describe the specific psychiatric features of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, and thus provide little practical evidence to guide diagnosis. In some of the largest studies of patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, psychiatric clinical findings are often combined into nonspecific headings such as “abnormal behavior” or “behavioral and cognitive” symptoms.5 Such groupings make this the most common clinical finding (95%)5 but make it difficult to discern particular clinical characteristics. Where available, specific symptoms identified across studies include agitation, aggression, changes in mood and/or irritability, insomnia, delusions, hallucinations, and occasionally catatonic features.6,7 Attempts to identify specific psychiatric phenotypes distinct from primary psychotic illnesses have fallen short due to contradictory findings and lack of clinical practicality.8 One exception is the presence of catatonic features, which have been found in CSF-confirmed studies.2 In contrast to the typical teaching that the hallucination modality (eg, visual or tactile) can be helpful in estimating the likelihood of a secondary psychosis (ie, drug-induced, neurodegenerative, or autoimmune), there does not appear to be a difference in hallucination modality between encephalitis and primary psychotic disorders.9

History and review of systems

Another red flag to consider is the rapidity of symptom presentation. Symptoms that progress within 3 months increase the likelihood that the patient has autoimmune encephalitis.10 Cases where collateral information indicates the psychotic episode was preceded by a long, subtle decline in school performance, social withdrawal, and attenuated psychotic symptoms typical of a schizophrenia prodrome are less likely to be an autoimmune psychosis.11 A more delayed presentation does not entirely exclude autoimmune encephalitis; however, a viral-like prodrome before the onset of psychosis increases the likelihood of autoimmune encephalitis. Such a prodrome may include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.7

Continue to: Another indication is the presence...

Another indication is the presence of new seizures within 1 year of presenting with psychotic symptoms.10 The possibility of undiagnosed seizures should be considered in a patient with psychosis who has episodes of unresponsiveness, dissociative episodes, or seizure-like activity that is thought to be psychogenic but has not been fully evaluated. Seizures in autoimmune encephalitis involve deep structures in the brain and can be present without overt epileptiform activity on EEG, but rather causing only bilateral slowing that is often described as nonspecific.12

In a young patient presenting with first-episode psychosis, a recent diagnosis of cancer or abnormal finding in the ovaries increases the likelihood of autoimmune encephalitis.4 Historically, however, this type of medical history has been irrelevant to psychosis. Although rare, any person presenting with first-episode psychosis and a history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis should be evaluated for autoimmune encephalitis because anti-NMDA receptor antibodies have been reported to be present in approximately one-third of these patients.13 Finally, the report of focal neurologic symptoms, including neck stiffness or neck pain, should raise concern, although sensory, working memory, and cognitive deficits may be difficult to fully distinguish from common somatic and cognitive symptoms in a primary psychiatric presentation.

Table 1 lists 4 questions to ask patients who present with first-episode psychosis that may not usually be part of a typical evaluation.

CASE CONTINUED

Uncooperative with examination

In the ED, Ms. L’s heart rate is 101 beats per minute and her blood pressure is 102/72 mm Hg. Her body mass index (BMI) is 22, which suggests an approximate 8-pound weight loss since her BMI was last assessed. Ms. L responds to questions with 1- to 6-word sentences, without clear verbigeration. Though her speech is not pressured, it is of increased rate. Her gaze scans the room, occasionally becoming fixed for 5 to 10 seconds but is aborted by the interviewer’s comment on this behavior. Ms. L efficiently and accurately spells WORLD backwards, then asks “Why?” and refuses to engage in further cognitive testing, stating “Not doing that.” When the interviewer asks “Why not?” she responds “Not doing that.” Her cranial nerves are intact, and she refuses cerebellar testing or requests to assess tone. There are no observed stereotypies, posturing, or echopraxia.

While not necessary for a diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis, short-term memory loss is a common cognitive finding across studies.5-7 A common clinical finding from a mental status exam is speech disorders, including (but not limited to) increased rates of speech or decreased verbal output.7 Autonomic instability—including tachycardia, markedly labile blood pressures, and orthostasis—all increase the likelihood of autoimmune encephalitis.14 Interpreting a patient’s vital sign changes can be confounded if they are agitated or anxious, or if they are taking an antipsychotic that produces adverse anticholinergic effects. However, vital sign abnormalities that precede medication administration or do not correlate with fluctuations in mental status increase suspicion for an autoimmune encephalitis.

Continue to: In the absence of the adverse effect...

In the absence of the adverse effect of a medication, orthostasis is uncommon in a well-hydrated young person. Some guidelines4 suggest that symptoms of catatonia should be considered a red flag for autoimmune encephalitis. According to the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale, commonly identified features include immobility, staring, mutism, posturing, withdrawal, rigidity, and gegenhalten.15 Catatonia is common among patients with anti-NDMA receptor encephalitis, though it may not be initially present and could emerge later.2 However, there are documented cases of autoimmune encephalitis where the patient had only isolated features of catatonia, such as echolalia or mutism.2

CASE CONTINUED

History helps narrow the diagnosis

Ms. L’s parents say their daughter has not had prior contact with a therapist or psychiatrist, previous psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalizations, suicide attempts, self-injury, or binging or purging behaviors. Ms. L’s paternal grandfather was diagnosed with schizophrenia, but he is currently employed, lives alone, and has not taken medication for many years. Her mother has hypothyroidism. Ms. L was born at full term via vaginal delivery without cardiac defects or a neonatal intensive care unit stay. Her mother said she did not have postpartum depression or anxiety, a complicated pregnancy, or exposure to tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. Ms. L has no history of childhood seizures or head injury with loss of consciousness. She is an only child, born and raised in a house in a metropolitan area, walked at 13 months, did not require early intervention or speech therapy, and met normal language milestones.

She attended kindergarten at age 6 and progressed throughout public school without regressions in reading, writing, or behavioral manifestations, and did not require a 504 Plan or individualized education program. Ms. L graduated high school in the top 30% of her class, was socially active, and attended a local college. In college, she achieved honor roll, enrolled in a sorority, and was a part of a research lab. Her only medication is oral contraception. She consumes alcohol socially, and reports no cannabis, cigarette, or vaping use. Ms. L says she does not use hallucinogens, stimulants, opiates, or cocaine, and her roommate and family confirm this. She denies recent travel and is sexually active. Ms. L’s urinary and serum toxicology are unremarkable, human chorionic gonadotropin is undetectable, and her sodium level is 133 mEq/L. A measure of serum neutrophils is 6.8 x 109/L and serum lymphocytes is 1.7 x 109/L. Her parents adamantly request a Neurology consultation and further workup, including a lumbar puncture (LP), EEG, and brain imaging (MRI).

This information is useful in ruling out other potential causes of psychosis, such as substance-induced psychosis and neurodevelopmental disorders that can present with psychosis. Additionally, neurodevelopmental abnormalities and psychiatric prodromal symptoms are known precedents in individuals who develop a primary psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia.16 A family history that includes a psychotic illness may increase the likelihood of a primary psychotic disorder in offspring; however, clinicians must also consider the accuracy of diagnosis in the family, as this can often be inaccurate or influenced by historical cultural bias. We recommend further elucidating the likelihood of a genetic predisposition to a primary psychotic disorder by clarifying familial medication history and functionality.

For example, the fact that Ms. L’s grandfather has not taken medication for many years and has a high degree of functioning and/or absence of cognitive deficits would lower our suspicion for an accurate diagnosis of schizophrenia (given the typical cognitive decline with untreated illness). Another piece of family history relevant to autoimmune encephalitis includes the propensity for autoimmune disorders, but expert opinion on this matter is mixed.17 Ms. L’s mother has hypothyroidism, which is commonly caused by a prior episode of Hashimoto’s autoimmune thyroiditis. Some physicians advocate for measuring antithyroid antibodies and erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein to gauge the level of autoimmunity, but the usefulness of these measures for detecting autoimmune encephalitis is unclear. These serum markers can be useful in detecting additional important etiologies such as systemic infection or systemic inflammation, and there are conditions such as steroid-responsive encephalopathy with associated thyroiditis, which, as the name suggests, responds to steroids rather than other psychotropic medications. Other risk factors for autoimmune encephalitis include being female, being young, having viral infections (eg, HSV), prior tumor burden, and being in the postpartum period.18 Some experts also suggest the presence of neurologic symptoms 4 weeks after the first psychiatric or cognitive symptom presentation increases the likelihood of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, and a lack of neurologic symptoms would make this diagnosis less likely.6,19

Continue to: Another item of interest...

Another item of interest in Ms. L’s case is her parents’ request for a Neurology consultation and further workup, as there is an association between caregiver request for workup and eventual diagnosis.6 While the etiology of this phenomenon is unclear, the literature suggests individuals with autoimmune encephalitis who initially present to Psychiatry experience longer delays to the appropriate treatment with immunomodulatory therapy than those who first present to Neurology.20

Laboratory and diagnostic testing

Guasp et al2 recommend EEG, MRI, and serum autoimmune antibodies (ie, screening for anti-NMDA receptor antibodies) for patients who present with first-episode psychosis, even in the absence of some of the red flags previously discussed. A recent economic analysis suggested screening all patients with first-episode psychosis for serum antibodies may be cost-effective.21

For patients whose presentations include features concerning for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, an EEG and MRI are reasonable. In a review of EEG abnormalities in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, Gillinder et al23 noted that while 30% did not have initial findings, 83.6% of those with confirmed anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis demonstrated EEG abnormalities; the most common were generalized slowing, delta slowing, and focal abnormalities. Discovering an extreme delta-brush activity on EEG is specific for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, but its absence is not fully informative. Practically, slowing can be a nonspecific manifestation of encephalopathy or a medication effect, and many people who present with first-episode psychosis will have recently received antipsychotics, which alter EEG frequency. In a study of EEG changes with antipsychotics, Centorrino et al24 found that generalized background slowing into the theta range across all antipsychotics was not significantly different from control participants, while theta to delta range slowing occurred in 8.2% of those receiving antipsychotics vs 3.3% of controls. Clozapine and olanzapine may be associated with greater EEG abnormalities, while haloperidol and quetiapine contribute a lower risk.25 For young patients with first-episode psychosis without a clear alternative explanation, we advocate for further autoimmune encephalitis workup among all individuals with generalized theta or delta wave slowing.

Because these medication effects are most likely to decrease specificity but not sensitivity of EEG for autoimmune encephalitis, a normal EEG without slowing can be reassuring.26 Moreover, for patients who receive neuroimaging, an MRI may detect inflammation that is not visible on CT. The concerning findings for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis are temporal or multifocal T2 hyperintensities, though the MRI is normal in most cases and thus should not be reassuring if other concerning features are present.27

The role of lumbar puncture

Another area of active debate surrounds the usefulness and timing of LP. Guasp et al2 proposed that all individuals with first-episode psychosis and focal neurologic findings should receive LP and CSF antineuronal antibody testing. They recommend that patients with first-episode psychosis without focal neurologic findings also should receive LP and CSF testing if ≥1 of the following is present:

- slowing on EEG

- temporal or multifocal T2 hyperintensities on MRI

- positive anti-NMDA receptor antibody in the serum.2

Continue to: Evidence suggests that basic CSF parameters...

Evidence suggests that basic CSF parameters, such as elevated protein and white blood cell counts, are some of the most sensitive and specific tests for autoimmune encephalitis.2 Thus, if the patient is amenable and logistical factors are in place, it may be reasonable to pursue LP earlier in some cases without waiting for serum antibody assays to return (these results can take several weeks). CSF inflammatory changes without neuronal antibodies should lead to other diagnostic considerations (eg, systemic inflammatory disease, psychosis attributed to systemic lupus erythematosus).7 While nonspecific, serum laboratory values that may increase suspicion of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis include hyponatremia6 and an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR).28 An NLR >4 in conjunction with CSF albumin-to- serum albumin ratio >7 is associated with impaired blood brain barrier integrity and a worse prognosis for those with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.28

Additional clinical features that may sway decisions in favor of obtaining LP despite negative findings on EEG, MRI, and serum antibodies include increased adverse reactions to antipsychotics (eg, neuroleptic malignant syndrome), prodromal infectious symptoms, known tumor, or new-onset neurologic symptoms after initial evaluation.2,8

Table 2 summarizes key features of laboratory and diagnostic findings in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

When should you pursue a more extensive workup?

There are some practical tools and rating scales to help clinicians conceptualize risk for autoimmune encephalitis. For psychiatric purposes, however, many of these scales assume that LP, MRI, and EEG have already been completed, and thus it is challenging to incorporate them into psychiatric practice. One such tool is the Antibody Prevalence in Epilepsy and Encephalopathy scale; a score ≥4 is 98% sensitive and 78% to 84% specific for predicting antineural autoantibody positivity.10 Table 3 describes warning signs that may be useful in helping clinicians decide how urgently to pursue a more extensive workup in the possibility of autoimmune encephalitis.

The importance of catching anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is underscored by the fact that appropriate treatment is very different than for primary psychosis, and outcomes worsen with delay to appropriate treatment.20 Without treatment, severe cases may progress to autonomic instability, altered consciousness, and respiratory compromise warranting admission to an intensive care unit. While the details are beyond the scope of this review, the recommended treatment for confirmed cases of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis includes tumor removal (if indicated), reducing inflammation (steroids), removing antibodies via IV immunoglobulins, or plasma exchange.8,29 Progression of the disease may warrant consideration of rituximab or cyclophosphamide. In nonresponsive cases, third-line treatments include proteasome inhibitors or interleukin-6 receptor antagonists.8 For patients with severe catatonia, some studies have investigated the utility of electroconvulsive therapy.30 Conceptually, clinicians may consider the utility of antipsychotics as similar to recommendations for hyperactive delirium for the management of psychotic symptoms, agitation, or insomnia. However, given the risk for antipsychotic intolerance, using the lowest effective dose and vigilant screening for the emergence of extrapyramidal symptoms, fever, and autonomic instability is recommended.

CASE CONTINUED

Finally, something objective

Ms. L receives haloperidol 2 mg and undergoes an MRI without contrast. Findings are unremarkable. A spot EEG notes diffuse background slowing in the theta range, prompting lumbar puncture. Findings note 0.40 g/L, 0.2 g/L, and 3.5 for the total protein, albumin, and albumin/CSF-serum quotient (QAlb), respectively; all values are within normal limits. A mild lymphocytic pleocytosis is present as evidenced by a cell count of 35 cells/µL. The CSF is sent for qualitative examination of immunoglobulin G and electrophoresis of proteins in the CSF and serum, of which an increased concentration of restricted bands (oligoclonal bands) in the CSF but not the serum would indicate findings of oligoclonal bands. CSF is sent for detection of anti-NMDA receptor antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence, with a plan to involve an interdisciplinary team for treatment if the antibodies return positive and to manage the case symptomatically in the interim.

Bottom Line

A small subpopulation of patients who present with apparent first-episode psychosis will have symptoms caused by autoimmune encephalitis (specifically, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis). We provide 4 screening questions to determine when to pursue a workup for an autoimmune encephalitis, and describe relevant clinical symptoms and warning signs to help differentiate the 2 conditions.

Related Resources

- Askandaryan AS, Naqvi A, Varughese A, et al. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: neuropsychiatric and multidisciplinary approach to a patient not responding to first-line treatment. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e25751.

- Kayser MS, Titulaer MJ, Gresa-Arribas N, et al. Frequency and characteristics of isolated psychiatric episodes in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(9):1133-1139.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rituximab • Rituxan