User login

Study documents obesity-related defecation disorders

, as well as clinically significant rectocele and increased anal resting and rectal pressures.

The study, which was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology and led by Pam Chaichanavichkij, MBChB, MRCS, of Queen Mary University, London, included 1,155 patients (84% female, median age 52) who were obese (31.7%), overweight (34.8%), or of normal weight 33.5%).

“These results support the notion that rectal evacuation disorder/incomplete evacuation may be an important underlying mechanism for fecal incontinence in obese patients,” the authors wrote.

Obese patients had higher odds of fecal incontinence to liquid stools (69.9 vs. 47.8%; odds ratio, 1.96 [confidence interval, 1.43-2.70]), use of containment products (54.6% vs. 32.6%; OR, 1.81 [CI, 1.31-2.51]), fecal urgency (74.6% vs. 60.7%; OR, 1.54 [CI, 1.11-2.14]), urge fecal incontinence (63.4% vs. 47.3%, OR, 1.68 [CI, 1.23-2.29]), and vaginal digitation (18.0% vs. 9.7%; OR, 2.18 [CI, 1.26-3.86]).

Obese patients were also more likely to have functional constipation (50.3%), compared with overweight (44.8%) and normal weight patients (41.1%).

There was a positive linear association between body mass index (BMI) and anal resting pressure (beta 0.45; R2, 0.25, P = 0.0003), though the odds of anal hypertension were not significantly higher after Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Obese patients more often had a large clinically significant rectocele (34.4% vs. 20.6%; OR, 2.62 [CI, 1.51-4.55]), compared with normal BMI patients.

The data showed higher rates of gynecological surgery, cholecystectomy, diabetes, and self-reported use of opioids, antidepressants, and anticholinergic medications in the obese group, compared with the others.

In morphological differences measured by x-ray defecography, obese patients had more than two-fold higher odds of having a rectocele and even greater odds of the rectocele being large and clinically significant. Anal and rectal resting pressures were linearly related to increasing BMI, the authors report.

Because most patients in the study were female, the findings may not be generalizable to the general population or male patients. Also, diet and exercise, two factors that may affect defecation disorders, were not accounted for in this study.

Dr. Chaichanavichkij reported no disclosures. Two other authors reported financial relationships with Medtronic Inc. and MMS/Laborie.

, as well as clinically significant rectocele and increased anal resting and rectal pressures.

The study, which was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology and led by Pam Chaichanavichkij, MBChB, MRCS, of Queen Mary University, London, included 1,155 patients (84% female, median age 52) who were obese (31.7%), overweight (34.8%), or of normal weight 33.5%).

“These results support the notion that rectal evacuation disorder/incomplete evacuation may be an important underlying mechanism for fecal incontinence in obese patients,” the authors wrote.

Obese patients had higher odds of fecal incontinence to liquid stools (69.9 vs. 47.8%; odds ratio, 1.96 [confidence interval, 1.43-2.70]), use of containment products (54.6% vs. 32.6%; OR, 1.81 [CI, 1.31-2.51]), fecal urgency (74.6% vs. 60.7%; OR, 1.54 [CI, 1.11-2.14]), urge fecal incontinence (63.4% vs. 47.3%, OR, 1.68 [CI, 1.23-2.29]), and vaginal digitation (18.0% vs. 9.7%; OR, 2.18 [CI, 1.26-3.86]).

Obese patients were also more likely to have functional constipation (50.3%), compared with overweight (44.8%) and normal weight patients (41.1%).

There was a positive linear association between body mass index (BMI) and anal resting pressure (beta 0.45; R2, 0.25, P = 0.0003), though the odds of anal hypertension were not significantly higher after Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Obese patients more often had a large clinically significant rectocele (34.4% vs. 20.6%; OR, 2.62 [CI, 1.51-4.55]), compared with normal BMI patients.

The data showed higher rates of gynecological surgery, cholecystectomy, diabetes, and self-reported use of opioids, antidepressants, and anticholinergic medications in the obese group, compared with the others.

In morphological differences measured by x-ray defecography, obese patients had more than two-fold higher odds of having a rectocele and even greater odds of the rectocele being large and clinically significant. Anal and rectal resting pressures were linearly related to increasing BMI, the authors report.

Because most patients in the study were female, the findings may not be generalizable to the general population or male patients. Also, diet and exercise, two factors that may affect defecation disorders, were not accounted for in this study.

Dr. Chaichanavichkij reported no disclosures. Two other authors reported financial relationships with Medtronic Inc. and MMS/Laborie.

, as well as clinically significant rectocele and increased anal resting and rectal pressures.

The study, which was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology and led by Pam Chaichanavichkij, MBChB, MRCS, of Queen Mary University, London, included 1,155 patients (84% female, median age 52) who were obese (31.7%), overweight (34.8%), or of normal weight 33.5%).

“These results support the notion that rectal evacuation disorder/incomplete evacuation may be an important underlying mechanism for fecal incontinence in obese patients,” the authors wrote.

Obese patients had higher odds of fecal incontinence to liquid stools (69.9 vs. 47.8%; odds ratio, 1.96 [confidence interval, 1.43-2.70]), use of containment products (54.6% vs. 32.6%; OR, 1.81 [CI, 1.31-2.51]), fecal urgency (74.6% vs. 60.7%; OR, 1.54 [CI, 1.11-2.14]), urge fecal incontinence (63.4% vs. 47.3%, OR, 1.68 [CI, 1.23-2.29]), and vaginal digitation (18.0% vs. 9.7%; OR, 2.18 [CI, 1.26-3.86]).

Obese patients were also more likely to have functional constipation (50.3%), compared with overweight (44.8%) and normal weight patients (41.1%).

There was a positive linear association between body mass index (BMI) and anal resting pressure (beta 0.45; R2, 0.25, P = 0.0003), though the odds of anal hypertension were not significantly higher after Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Obese patients more often had a large clinically significant rectocele (34.4% vs. 20.6%; OR, 2.62 [CI, 1.51-4.55]), compared with normal BMI patients.

The data showed higher rates of gynecological surgery, cholecystectomy, diabetes, and self-reported use of opioids, antidepressants, and anticholinergic medications in the obese group, compared with the others.

In morphological differences measured by x-ray defecography, obese patients had more than two-fold higher odds of having a rectocele and even greater odds of the rectocele being large and clinically significant. Anal and rectal resting pressures were linearly related to increasing BMI, the authors report.

Because most patients in the study were female, the findings may not be generalizable to the general population or male patients. Also, diet and exercise, two factors that may affect defecation disorders, were not accounted for in this study.

Dr. Chaichanavichkij reported no disclosures. Two other authors reported financial relationships with Medtronic Inc. and MMS/Laborie.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Revised presentation of obesity may reduce internalized bias

a new study suggests.

In an online study, patients with obesity reported significantly less internalized weight bias and significantly enhanced perceptions of positive communication with their medical providers after watching a video of a doctor who framed obesity as a treatable medical condition, compared with a video of a doctor who emphasized willpower.

“Recent research has identified the dominant role that biology (both genetics as well as homeostatic, hedonic, and executive brain systems) and environment, rather than willpower, play in the development of obesity and the resistance to weight loss,” wrote study authors Sara English, a medical student, and Michael Vallis, MD, associate professor of family medicine, both at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S. “Yet the false narrative that ideal or goal weight can be achieved by eating less and moving more using willpower continues to dominate the public narrative.”

The findings were published in Clinical Obesity.

Medical complexity

The public discussion generally places all responsibility for the health outcomes of obesity on the patient. As a result, patients with obesity face bias and stigma from the public and the health care system, wrote the authors.

This stigmatization contributes to increased mortality and morbidity by promoting maladaptive eating behaviors and stress. It also causes mistrust of health care professionals, which, in turn, leads to worse health outcomes and increased health care costs.

The 2020 Canadian clinical practice guidelines for obesity management in adults emphasize that obesity is complex and that nonbehavioral factors strongly influence it. They recommend that treatment focus on improving patient-centered health outcomes and address the root causes of obesity, instead of focusing on weight loss alone.

In the present study, Ms. English and Dr. Vallis evaluated how presenting obesity as a treatable medical condition affected participants’ internalized weight bias and their perceived relationship with their health care provider. They asked 61 patients with obesity (average age, 49 years; average body mass index, 41 kg/m2) to watch two videos, the first showing a doctor endorsing the traditional “eat less, move more approach,” and the second showing a doctor describing obesity as a chronic, treatable medical condition.

Nearly half (49.5%) of participants reported that their health care provider rarely or never discusses weight loss, and almost two-thirds of participants (64%) reported feeling stigmatized by their health care provider because of their weight at least some of the time.

After having watched each video, participants were asked to imagine that they were being treated by the corresponding doctor and to complete two measures: the Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS), which measures the degree to which a respondent believes the negative stereotypes about obese people, and the Patient-Health Care Provider Communication Scale (PHCPCS), which assesses the quality of patient–health care provider communication.

Virtually all participants preferred the care provider in the video with the revised presentation of obesity. Only one preferred the traditional video. The video with the revised presentation was associated with significant reductions in internalized weight bias. Participants’ WBIS total score decreased from 4.49 to 3.36 (P < .001). The revised narrative video also had a positive effect on patients’ perception of their health care providers. The PHCPCS total score increased from 2.65 to 4.20 (P < .001).

A chronic disease

In a comment, Yoni Freedhoff, MD, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa, said: “If you’re asking me if it is a good idea to treat obesity like a chronic disease, the answer would be yes, we absolutely should. It is a chronic disease, and it shouldn’t have a treatment paradigm different from the other chronic diseases.” Dr. Freedhoff did not participate in the study.

“We certainly don’t blame patients for having other chronic conditions,” Dr. Freedhoff added. “We don’t have a narrative that, in order for them to qualify for medication or other treatment options, they have to audition for them by failing lifestyle approaches first. And yet, I’d say at least 85% of chronic noncommunicable diseases have lifestyle factors, but obesity is the only one where we consider that there is a necessity for these lifestyle changes, as if there have been studies demonstrating durable and reproducible outcomes for lifestyle in obesity. There have not.”

Telling patients and doctors that obesity is a chronic disease driven by biology, not a failure of willpower, is going to reduce stigma, “which is what this study was able to demonstrate to some degree,” Dr. Freedhoff said.

“What is more stigmatizing? Being told that if you just try hard enough, you’ll succeed, and if you don’t succeed, the corollary, of course, is that you did not try hard enough? Versus, you’ve got a medical condition where you’ve got biological drivers beyond your locus of control, affecting behaviors that, in turn, contribute to your adiposity? I’m pretty sure the second statement will have far less impact on a person’s internalized weight bias than what we’ve unfortunately been doing up until now with the focus on willpower,” Dr. Freedhoff said.

No funding for the study was reported. Ms. English and Dr. Vallis reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Freedhoff reported receiving clinical grants from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new study suggests.

In an online study, patients with obesity reported significantly less internalized weight bias and significantly enhanced perceptions of positive communication with their medical providers after watching a video of a doctor who framed obesity as a treatable medical condition, compared with a video of a doctor who emphasized willpower.

“Recent research has identified the dominant role that biology (both genetics as well as homeostatic, hedonic, and executive brain systems) and environment, rather than willpower, play in the development of obesity and the resistance to weight loss,” wrote study authors Sara English, a medical student, and Michael Vallis, MD, associate professor of family medicine, both at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S. “Yet the false narrative that ideal or goal weight can be achieved by eating less and moving more using willpower continues to dominate the public narrative.”

The findings were published in Clinical Obesity.

Medical complexity

The public discussion generally places all responsibility for the health outcomes of obesity on the patient. As a result, patients with obesity face bias and stigma from the public and the health care system, wrote the authors.

This stigmatization contributes to increased mortality and morbidity by promoting maladaptive eating behaviors and stress. It also causes mistrust of health care professionals, which, in turn, leads to worse health outcomes and increased health care costs.

The 2020 Canadian clinical practice guidelines for obesity management in adults emphasize that obesity is complex and that nonbehavioral factors strongly influence it. They recommend that treatment focus on improving patient-centered health outcomes and address the root causes of obesity, instead of focusing on weight loss alone.

In the present study, Ms. English and Dr. Vallis evaluated how presenting obesity as a treatable medical condition affected participants’ internalized weight bias and their perceived relationship with their health care provider. They asked 61 patients with obesity (average age, 49 years; average body mass index, 41 kg/m2) to watch two videos, the first showing a doctor endorsing the traditional “eat less, move more approach,” and the second showing a doctor describing obesity as a chronic, treatable medical condition.

Nearly half (49.5%) of participants reported that their health care provider rarely or never discusses weight loss, and almost two-thirds of participants (64%) reported feeling stigmatized by their health care provider because of their weight at least some of the time.

After having watched each video, participants were asked to imagine that they were being treated by the corresponding doctor and to complete two measures: the Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS), which measures the degree to which a respondent believes the negative stereotypes about obese people, and the Patient-Health Care Provider Communication Scale (PHCPCS), which assesses the quality of patient–health care provider communication.

Virtually all participants preferred the care provider in the video with the revised presentation of obesity. Only one preferred the traditional video. The video with the revised presentation was associated with significant reductions in internalized weight bias. Participants’ WBIS total score decreased from 4.49 to 3.36 (P < .001). The revised narrative video also had a positive effect on patients’ perception of their health care providers. The PHCPCS total score increased from 2.65 to 4.20 (P < .001).

A chronic disease

In a comment, Yoni Freedhoff, MD, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa, said: “If you’re asking me if it is a good idea to treat obesity like a chronic disease, the answer would be yes, we absolutely should. It is a chronic disease, and it shouldn’t have a treatment paradigm different from the other chronic diseases.” Dr. Freedhoff did not participate in the study.

“We certainly don’t blame patients for having other chronic conditions,” Dr. Freedhoff added. “We don’t have a narrative that, in order for them to qualify for medication or other treatment options, they have to audition for them by failing lifestyle approaches first. And yet, I’d say at least 85% of chronic noncommunicable diseases have lifestyle factors, but obesity is the only one where we consider that there is a necessity for these lifestyle changes, as if there have been studies demonstrating durable and reproducible outcomes for lifestyle in obesity. There have not.”

Telling patients and doctors that obesity is a chronic disease driven by biology, not a failure of willpower, is going to reduce stigma, “which is what this study was able to demonstrate to some degree,” Dr. Freedhoff said.

“What is more stigmatizing? Being told that if you just try hard enough, you’ll succeed, and if you don’t succeed, the corollary, of course, is that you did not try hard enough? Versus, you’ve got a medical condition where you’ve got biological drivers beyond your locus of control, affecting behaviors that, in turn, contribute to your adiposity? I’m pretty sure the second statement will have far less impact on a person’s internalized weight bias than what we’ve unfortunately been doing up until now with the focus on willpower,” Dr. Freedhoff said.

No funding for the study was reported. Ms. English and Dr. Vallis reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Freedhoff reported receiving clinical grants from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new study suggests.

In an online study, patients with obesity reported significantly less internalized weight bias and significantly enhanced perceptions of positive communication with their medical providers after watching a video of a doctor who framed obesity as a treatable medical condition, compared with a video of a doctor who emphasized willpower.

“Recent research has identified the dominant role that biology (both genetics as well as homeostatic, hedonic, and executive brain systems) and environment, rather than willpower, play in the development of obesity and the resistance to weight loss,” wrote study authors Sara English, a medical student, and Michael Vallis, MD, associate professor of family medicine, both at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S. “Yet the false narrative that ideal or goal weight can be achieved by eating less and moving more using willpower continues to dominate the public narrative.”

The findings were published in Clinical Obesity.

Medical complexity

The public discussion generally places all responsibility for the health outcomes of obesity on the patient. As a result, patients with obesity face bias and stigma from the public and the health care system, wrote the authors.

This stigmatization contributes to increased mortality and morbidity by promoting maladaptive eating behaviors and stress. It also causes mistrust of health care professionals, which, in turn, leads to worse health outcomes and increased health care costs.

The 2020 Canadian clinical practice guidelines for obesity management in adults emphasize that obesity is complex and that nonbehavioral factors strongly influence it. They recommend that treatment focus on improving patient-centered health outcomes and address the root causes of obesity, instead of focusing on weight loss alone.

In the present study, Ms. English and Dr. Vallis evaluated how presenting obesity as a treatable medical condition affected participants’ internalized weight bias and their perceived relationship with their health care provider. They asked 61 patients with obesity (average age, 49 years; average body mass index, 41 kg/m2) to watch two videos, the first showing a doctor endorsing the traditional “eat less, move more approach,” and the second showing a doctor describing obesity as a chronic, treatable medical condition.

Nearly half (49.5%) of participants reported that their health care provider rarely or never discusses weight loss, and almost two-thirds of participants (64%) reported feeling stigmatized by their health care provider because of their weight at least some of the time.

After having watched each video, participants were asked to imagine that they were being treated by the corresponding doctor and to complete two measures: the Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS), which measures the degree to which a respondent believes the negative stereotypes about obese people, and the Patient-Health Care Provider Communication Scale (PHCPCS), which assesses the quality of patient–health care provider communication.

Virtually all participants preferred the care provider in the video with the revised presentation of obesity. Only one preferred the traditional video. The video with the revised presentation was associated with significant reductions in internalized weight bias. Participants’ WBIS total score decreased from 4.49 to 3.36 (P < .001). The revised narrative video also had a positive effect on patients’ perception of their health care providers. The PHCPCS total score increased from 2.65 to 4.20 (P < .001).

A chronic disease

In a comment, Yoni Freedhoff, MD, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa, said: “If you’re asking me if it is a good idea to treat obesity like a chronic disease, the answer would be yes, we absolutely should. It is a chronic disease, and it shouldn’t have a treatment paradigm different from the other chronic diseases.” Dr. Freedhoff did not participate in the study.

“We certainly don’t blame patients for having other chronic conditions,” Dr. Freedhoff added. “We don’t have a narrative that, in order for them to qualify for medication or other treatment options, they have to audition for them by failing lifestyle approaches first. And yet, I’d say at least 85% of chronic noncommunicable diseases have lifestyle factors, but obesity is the only one where we consider that there is a necessity for these lifestyle changes, as if there have been studies demonstrating durable and reproducible outcomes for lifestyle in obesity. There have not.”

Telling patients and doctors that obesity is a chronic disease driven by biology, not a failure of willpower, is going to reduce stigma, “which is what this study was able to demonstrate to some degree,” Dr. Freedhoff said.

“What is more stigmatizing? Being told that if you just try hard enough, you’ll succeed, and if you don’t succeed, the corollary, of course, is that you did not try hard enough? Versus, you’ve got a medical condition where you’ve got biological drivers beyond your locus of control, affecting behaviors that, in turn, contribute to your adiposity? I’m pretty sure the second statement will have far less impact on a person’s internalized weight bias than what we’ve unfortunately been doing up until now with the focus on willpower,” Dr. Freedhoff said.

No funding for the study was reported. Ms. English and Dr. Vallis reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Freedhoff reported receiving clinical grants from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL OBESITY

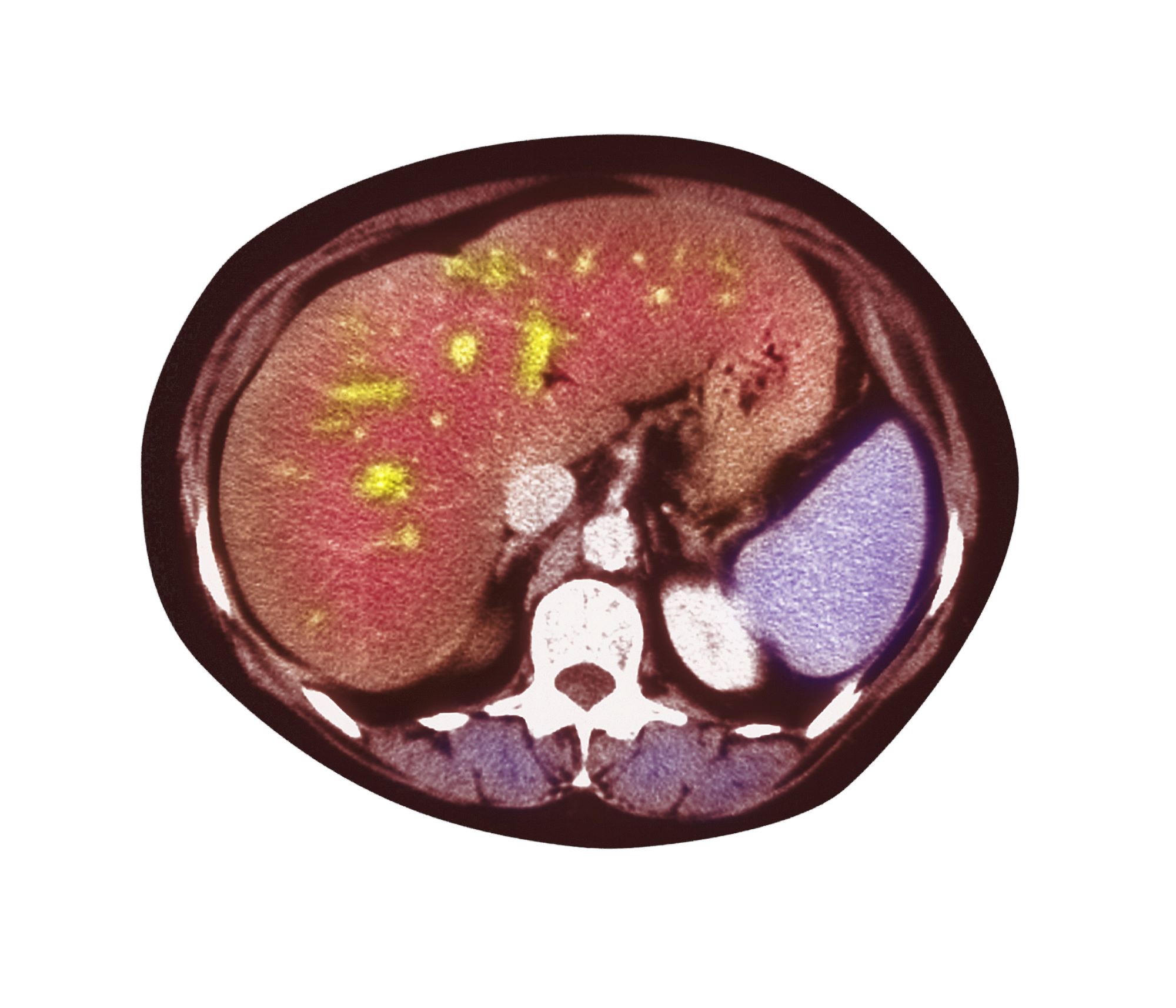

Pain in upper right abdomen

The patient's history, symptomatology, and assessments suggest a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The primary care physician recommends referral to a hepatologist for evaluation and possible liver biopsy.

NAFLD involves an accumulation of triglycerides and other fats in the liver (unrelated to alcohol consumption and other liver disease), with the presence of hepatic steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes. NAFLD affects 25% to 35% of the general population, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease. The rate increases among patients with obesity, 80% of whom are affected by NAFLD.

NAFLD should be considered in patients with unexplained elevations in serum aminotransferases (without positive viral markers or autoantibodies and no history of alcohol use) and a high risk for steatohepatitis, including obesity. The standard NAFLD assessment for biopsy specimens is the Brunt system, and disease stage is determined using the NAFLD activity score and the amount of fibrosis present.

A study of the natural history of NAFLD in patients who were followed for 3 years showed that without pharmacologic intervention, one third experienced disease progression, one third remained stable, and one third improved. An independent risk factor for progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was abnormal glucose tolerance testing. In another natural history study, a 10% higher rate of mortality over 10 years was demonstrated among those with NAFLD vs controls, with the top three causes of death being cancer, heart disease, and liver-related disease. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis has been shown to be elevated in Latino and Japanese American populations.

Patients with NAFLD should be seen regularly to assess for disease progression and receive guidance on weight management interventions and exercise. A weight loss of more than 5% has been shown to reduce liver fat and provide cardiometabolic benefits; a weight reduction of more than 10% can help reverse steatohepatitis or liver fibrosis. In addition to weight loss management strategies, physicians should discuss the importance of controlling hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and T2D with their patients and share the importance of avoiding alcohol and other hepatotoxic substances.

According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: "There are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for the treatment of NAFLD; however, some diabetes and anti-obesity medications can be beneficial. Bariatric surgery is also effective for weight loss and reducing liver fat in persons with severe obesity."

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient's history, symptomatology, and assessments suggest a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The primary care physician recommends referral to a hepatologist for evaluation and possible liver biopsy.

NAFLD involves an accumulation of triglycerides and other fats in the liver (unrelated to alcohol consumption and other liver disease), with the presence of hepatic steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes. NAFLD affects 25% to 35% of the general population, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease. The rate increases among patients with obesity, 80% of whom are affected by NAFLD.

NAFLD should be considered in patients with unexplained elevations in serum aminotransferases (without positive viral markers or autoantibodies and no history of alcohol use) and a high risk for steatohepatitis, including obesity. The standard NAFLD assessment for biopsy specimens is the Brunt system, and disease stage is determined using the NAFLD activity score and the amount of fibrosis present.

A study of the natural history of NAFLD in patients who were followed for 3 years showed that without pharmacologic intervention, one third experienced disease progression, one third remained stable, and one third improved. An independent risk factor for progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was abnormal glucose tolerance testing. In another natural history study, a 10% higher rate of mortality over 10 years was demonstrated among those with NAFLD vs controls, with the top three causes of death being cancer, heart disease, and liver-related disease. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis has been shown to be elevated in Latino and Japanese American populations.

Patients with NAFLD should be seen regularly to assess for disease progression and receive guidance on weight management interventions and exercise. A weight loss of more than 5% has been shown to reduce liver fat and provide cardiometabolic benefits; a weight reduction of more than 10% can help reverse steatohepatitis or liver fibrosis. In addition to weight loss management strategies, physicians should discuss the importance of controlling hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and T2D with their patients and share the importance of avoiding alcohol and other hepatotoxic substances.

According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: "There are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for the treatment of NAFLD; however, some diabetes and anti-obesity medications can be beneficial. Bariatric surgery is also effective for weight loss and reducing liver fat in persons with severe obesity."

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient's history, symptomatology, and assessments suggest a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The primary care physician recommends referral to a hepatologist for evaluation and possible liver biopsy.

NAFLD involves an accumulation of triglycerides and other fats in the liver (unrelated to alcohol consumption and other liver disease), with the presence of hepatic steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes. NAFLD affects 25% to 35% of the general population, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease. The rate increases among patients with obesity, 80% of whom are affected by NAFLD.

NAFLD should be considered in patients with unexplained elevations in serum aminotransferases (without positive viral markers or autoantibodies and no history of alcohol use) and a high risk for steatohepatitis, including obesity. The standard NAFLD assessment for biopsy specimens is the Brunt system, and disease stage is determined using the NAFLD activity score and the amount of fibrosis present.

A study of the natural history of NAFLD in patients who were followed for 3 years showed that without pharmacologic intervention, one third experienced disease progression, one third remained stable, and one third improved. An independent risk factor for progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was abnormal glucose tolerance testing. In another natural history study, a 10% higher rate of mortality over 10 years was demonstrated among those with NAFLD vs controls, with the top three causes of death being cancer, heart disease, and liver-related disease. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis has been shown to be elevated in Latino and Japanese American populations.

Patients with NAFLD should be seen regularly to assess for disease progression and receive guidance on weight management interventions and exercise. A weight loss of more than 5% has been shown to reduce liver fat and provide cardiometabolic benefits; a weight reduction of more than 10% can help reverse steatohepatitis or liver fibrosis. In addition to weight loss management strategies, physicians should discuss the importance of controlling hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and T2D with their patients and share the importance of avoiding alcohol and other hepatotoxic substances.

According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: "There are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for the treatment of NAFLD; however, some diabetes and anti-obesity medications can be beneficial. Bariatric surgery is also effective for weight loss and reducing liver fat in persons with severe obesity."

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 51-year-old Hispanic man presents to his primary care physician with fatigue and pain in the upper right abdomen. Physical exam reveals ascites and splenomegaly. His height is 5 ft 8 in and weight is 274 lb; his BMI is 41.7. For the past 5 years, the patient has seen his physician for routine annual exams, during which time he has consistently met the criteria for World Health Organization Class 3 overweight (BMI ≥ 40) and has taken metformin, with varying degrees of adherence, for type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now, given the patient's symptoms and the potential for uncontrolled diabetes, the physician orders laboratory studies and viral serologies for hepatitis. Results of these assessments exclude viral infection but demonstrate abnormal levels of fasting insulin and glucose, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated transaminase levels that are sixfold above normal levels, with an aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine transaminase ratio < 1:1.

‘Triple G’ agonist hits new weight loss heights

A novel triple agonist to receptors for three nutrient-stimulated hormones led to weight loss as high as 24% among people with overweight or obesity but who did not have type 2 diabetes when used at the highest tested dose for 48 weeks. The results are from a phase 2 study of retatrutide that was published in The New England Journal of Medicine (2023 Aug 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301972).

This level of weight loss is “unprecedented” for a medication administered for 48 weeks, Mary-Elizabeth Patti, MD, said in an editorial that accompanied the report.

The findings “offer further optimism ... that effective pharmacologic management of obesity and related disorders is possible,” wrote Dr. Patti, a principal investigator at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston.

The study randomly assigned 338 adults with obesity or overweight – a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 27 kg/m2 – and at least one weight-related complication to receive either weekly subcutaneous injections of retatrutide in any of six dose regimens or placebo over 48 weeks. The primary outcome was weight change from baseline after 24 weeks.

The highest dose of retatrutide safely produced an average 17.5% drop from baseline weight, compared with an average 1.6% reduction in the placebo group, after 24 weeks, a significant difference.

After 48 weeks, the highest retatrutide dose safely cut baseline weight by an average of 24.2%, compared with an average 2.1% drop among placebo control patients, Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD, and her coauthors wrote in their report. Weight loss levels after 24 and 48 weeks of retatrutide treatment followed a clear dose-response pattern.

Weight losses never before seen

“I have never seen weight loss at this level” after nearly 1 year of treatment, Dr. Jastreboff said when she discussed these findings in a press conference at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in San Diego in late June.

A separate presentation at the ADA meeting documented unprecedented weight loss levels in a study of 281 people with obesity or overweight and type 2 diabetes.

“No other medication has shown an average 17% reduction from baseline bodyweight after 36 weeks in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City, Texas, who formally presented the results from the study of retatrutide in people with type 2 diabetes at the ADA meeting.

The mechanism behind retatrutide’s potent weight-loss effect seems likely tied to its action on three human receptors that naturally respond to three nutrient-stimulated hormones that control appetite, metabolism, fat mobilization, and related functions.

The three hormones that the retatrutide molecule simultaneously mimics are glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), such as agents in the class of GLP-1 agonists that includes liraglutide (Victoza/Saxenda) and semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy); the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), the receptor that is also activated by tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a dual-incretin receptor agonist that mimics both GLP-1 and GIP; and glucagon. Survodutide is a dual GLP-1 and glucagon receptor agonist in phase 2 development.

Retatrutide is currently unique among agents with reported clinical results by having agonist effects on the receptors for all three of these hormones, a property that led Dr. Patti to call retatrutide a “triple G” hormone-receptor agonist in her editorial.

Triple agonist has added effect on liver fat clearance

The glucagon-receptor agonism appears to give retatrutide added effects beyond those of the GLP-1 agonists or GLP-1/GIP dual agonists that are increasingly used in U.S. practice.

A prespecified subgroup analysis of the no diabetes/Jastreboff study (but that was not included in the NEJM report) showed that at both 8-mg and 12-mg weekly doses, 24 weeks of retatrutide produced complete resolution of excess liver fat (hepatic steatosis) in about 80% of the people eligible for the analysis (those whose liver volume was at least 10% fat at study entry).

That percentage increased to about 90% of people receiving these doses after 48 weeks, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, reported during a separate presentation at the ADA meeting.

“When you add glucagon activity, liver-fat clearance goes up tremendously,” observed Dr. Kaplan, director of the Obesity, Metabolism and Nutrition Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The average age of the participants in the new study of the use of retatrutide for those with obesity/overweight but not diabetes was 48 years. By design, 52% were men. (The study sought to enroll roughly equal numbers of men and women.) Average BMI at study entry was 37 kg/m2.

Treatment with retatrutide was also significantly associated with improvements in several cardiometabolic measures in exploratory analyses, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, A1c, fasting glucose, insulin, and some (but not all) lipids, Dr. Jastreboff, director of the Yale Obesity Research Center of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., and her coauthors reported in the NEJM article.

The safety profile of retatrutide was consistent with reported phase 1 findings for the agent among people with type 2 diabetes and resembled the safety profiles of other agents based on GLP-1 or GIP–GLP-1 mimicry for the treatment of type 2 diabetes or obesity.

The most frequently reported adverse events from retatrutide were transient, mostly mild to moderate gastrointestinal events. They occurred primarily during dose escalation. Discontinuation of retatrutide or placebo because of adverse events occurred in 6% to 16% of the participants who received retatrutide and in none of the participants who received placebo.

Lilly, the company developing retatrutide, previously announced the launch of four phase 3 trials to gather further data on retatrutide for use in a marketing-approval application to the Food and Drug Administration.

The four trials – TRIUMPH-1, TRIUMPH-2, TRIUMPH-3, and TRIUMPH-4 – are evaluating the safety and efficacy of retatrutide for chronic weight management for those with obesity or overweight, including those who also have obstructive sleep apnea, knee osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes, or cardiovascular disease.

The study was sponsored by Lilly, the company developing retatrutide. Dr. Patti has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Hanmi, and MBX. She has received funding from Dexcom and has been a monitor for a trial funded by Fractyl. Dr. Jastreboff, Dr. Kaplan, and Dr. Rosenstock have reported financial relationships with Lilly as well as other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel triple agonist to receptors for three nutrient-stimulated hormones led to weight loss as high as 24% among people with overweight or obesity but who did not have type 2 diabetes when used at the highest tested dose for 48 weeks. The results are from a phase 2 study of retatrutide that was published in The New England Journal of Medicine (2023 Aug 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301972).

This level of weight loss is “unprecedented” for a medication administered for 48 weeks, Mary-Elizabeth Patti, MD, said in an editorial that accompanied the report.

The findings “offer further optimism ... that effective pharmacologic management of obesity and related disorders is possible,” wrote Dr. Patti, a principal investigator at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston.

The study randomly assigned 338 adults with obesity or overweight – a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 27 kg/m2 – and at least one weight-related complication to receive either weekly subcutaneous injections of retatrutide in any of six dose regimens or placebo over 48 weeks. The primary outcome was weight change from baseline after 24 weeks.

The highest dose of retatrutide safely produced an average 17.5% drop from baseline weight, compared with an average 1.6% reduction in the placebo group, after 24 weeks, a significant difference.

After 48 weeks, the highest retatrutide dose safely cut baseline weight by an average of 24.2%, compared with an average 2.1% drop among placebo control patients, Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD, and her coauthors wrote in their report. Weight loss levels after 24 and 48 weeks of retatrutide treatment followed a clear dose-response pattern.

Weight losses never before seen

“I have never seen weight loss at this level” after nearly 1 year of treatment, Dr. Jastreboff said when she discussed these findings in a press conference at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in San Diego in late June.

A separate presentation at the ADA meeting documented unprecedented weight loss levels in a study of 281 people with obesity or overweight and type 2 diabetes.

“No other medication has shown an average 17% reduction from baseline bodyweight after 36 weeks in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City, Texas, who formally presented the results from the study of retatrutide in people with type 2 diabetes at the ADA meeting.

The mechanism behind retatrutide’s potent weight-loss effect seems likely tied to its action on three human receptors that naturally respond to three nutrient-stimulated hormones that control appetite, metabolism, fat mobilization, and related functions.

The three hormones that the retatrutide molecule simultaneously mimics are glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), such as agents in the class of GLP-1 agonists that includes liraglutide (Victoza/Saxenda) and semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy); the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), the receptor that is also activated by tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a dual-incretin receptor agonist that mimics both GLP-1 and GIP; and glucagon. Survodutide is a dual GLP-1 and glucagon receptor agonist in phase 2 development.

Retatrutide is currently unique among agents with reported clinical results by having agonist effects on the receptors for all three of these hormones, a property that led Dr. Patti to call retatrutide a “triple G” hormone-receptor agonist in her editorial.

Triple agonist has added effect on liver fat clearance

The glucagon-receptor agonism appears to give retatrutide added effects beyond those of the GLP-1 agonists or GLP-1/GIP dual agonists that are increasingly used in U.S. practice.

A prespecified subgroup analysis of the no diabetes/Jastreboff study (but that was not included in the NEJM report) showed that at both 8-mg and 12-mg weekly doses, 24 weeks of retatrutide produced complete resolution of excess liver fat (hepatic steatosis) in about 80% of the people eligible for the analysis (those whose liver volume was at least 10% fat at study entry).

That percentage increased to about 90% of people receiving these doses after 48 weeks, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, reported during a separate presentation at the ADA meeting.

“When you add glucagon activity, liver-fat clearance goes up tremendously,” observed Dr. Kaplan, director of the Obesity, Metabolism and Nutrition Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The average age of the participants in the new study of the use of retatrutide for those with obesity/overweight but not diabetes was 48 years. By design, 52% were men. (The study sought to enroll roughly equal numbers of men and women.) Average BMI at study entry was 37 kg/m2.

Treatment with retatrutide was also significantly associated with improvements in several cardiometabolic measures in exploratory analyses, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, A1c, fasting glucose, insulin, and some (but not all) lipids, Dr. Jastreboff, director of the Yale Obesity Research Center of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., and her coauthors reported in the NEJM article.

The safety profile of retatrutide was consistent with reported phase 1 findings for the agent among people with type 2 diabetes and resembled the safety profiles of other agents based on GLP-1 or GIP–GLP-1 mimicry for the treatment of type 2 diabetes or obesity.

The most frequently reported adverse events from retatrutide were transient, mostly mild to moderate gastrointestinal events. They occurred primarily during dose escalation. Discontinuation of retatrutide or placebo because of adverse events occurred in 6% to 16% of the participants who received retatrutide and in none of the participants who received placebo.

Lilly, the company developing retatrutide, previously announced the launch of four phase 3 trials to gather further data on retatrutide for use in a marketing-approval application to the Food and Drug Administration.

The four trials – TRIUMPH-1, TRIUMPH-2, TRIUMPH-3, and TRIUMPH-4 – are evaluating the safety and efficacy of retatrutide for chronic weight management for those with obesity or overweight, including those who also have obstructive sleep apnea, knee osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes, or cardiovascular disease.

The study was sponsored by Lilly, the company developing retatrutide. Dr. Patti has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Hanmi, and MBX. She has received funding from Dexcom and has been a monitor for a trial funded by Fractyl. Dr. Jastreboff, Dr. Kaplan, and Dr. Rosenstock have reported financial relationships with Lilly as well as other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel triple agonist to receptors for three nutrient-stimulated hormones led to weight loss as high as 24% among people with overweight or obesity but who did not have type 2 diabetes when used at the highest tested dose for 48 weeks. The results are from a phase 2 study of retatrutide that was published in The New England Journal of Medicine (2023 Aug 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301972).

This level of weight loss is “unprecedented” for a medication administered for 48 weeks, Mary-Elizabeth Patti, MD, said in an editorial that accompanied the report.

The findings “offer further optimism ... that effective pharmacologic management of obesity and related disorders is possible,” wrote Dr. Patti, a principal investigator at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston.

The study randomly assigned 338 adults with obesity or overweight – a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 27 kg/m2 – and at least one weight-related complication to receive either weekly subcutaneous injections of retatrutide in any of six dose regimens or placebo over 48 weeks. The primary outcome was weight change from baseline after 24 weeks.

The highest dose of retatrutide safely produced an average 17.5% drop from baseline weight, compared with an average 1.6% reduction in the placebo group, after 24 weeks, a significant difference.

After 48 weeks, the highest retatrutide dose safely cut baseline weight by an average of 24.2%, compared with an average 2.1% drop among placebo control patients, Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD, and her coauthors wrote in their report. Weight loss levels after 24 and 48 weeks of retatrutide treatment followed a clear dose-response pattern.

Weight losses never before seen

“I have never seen weight loss at this level” after nearly 1 year of treatment, Dr. Jastreboff said when she discussed these findings in a press conference at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in San Diego in late June.

A separate presentation at the ADA meeting documented unprecedented weight loss levels in a study of 281 people with obesity or overweight and type 2 diabetes.

“No other medication has shown an average 17% reduction from baseline bodyweight after 36 weeks in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City, Texas, who formally presented the results from the study of retatrutide in people with type 2 diabetes at the ADA meeting.

The mechanism behind retatrutide’s potent weight-loss effect seems likely tied to its action on three human receptors that naturally respond to three nutrient-stimulated hormones that control appetite, metabolism, fat mobilization, and related functions.

The three hormones that the retatrutide molecule simultaneously mimics are glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), such as agents in the class of GLP-1 agonists that includes liraglutide (Victoza/Saxenda) and semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy); the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), the receptor that is also activated by tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a dual-incretin receptor agonist that mimics both GLP-1 and GIP; and glucagon. Survodutide is a dual GLP-1 and glucagon receptor agonist in phase 2 development.

Retatrutide is currently unique among agents with reported clinical results by having agonist effects on the receptors for all three of these hormones, a property that led Dr. Patti to call retatrutide a “triple G” hormone-receptor agonist in her editorial.

Triple agonist has added effect on liver fat clearance

The glucagon-receptor agonism appears to give retatrutide added effects beyond those of the GLP-1 agonists or GLP-1/GIP dual agonists that are increasingly used in U.S. practice.

A prespecified subgroup analysis of the no diabetes/Jastreboff study (but that was not included in the NEJM report) showed that at both 8-mg and 12-mg weekly doses, 24 weeks of retatrutide produced complete resolution of excess liver fat (hepatic steatosis) in about 80% of the people eligible for the analysis (those whose liver volume was at least 10% fat at study entry).

That percentage increased to about 90% of people receiving these doses after 48 weeks, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, reported during a separate presentation at the ADA meeting.

“When you add glucagon activity, liver-fat clearance goes up tremendously,” observed Dr. Kaplan, director of the Obesity, Metabolism and Nutrition Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The average age of the participants in the new study of the use of retatrutide for those with obesity/overweight but not diabetes was 48 years. By design, 52% were men. (The study sought to enroll roughly equal numbers of men and women.) Average BMI at study entry was 37 kg/m2.

Treatment with retatrutide was also significantly associated with improvements in several cardiometabolic measures in exploratory analyses, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, A1c, fasting glucose, insulin, and some (but not all) lipids, Dr. Jastreboff, director of the Yale Obesity Research Center of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., and her coauthors reported in the NEJM article.

The safety profile of retatrutide was consistent with reported phase 1 findings for the agent among people with type 2 diabetes and resembled the safety profiles of other agents based on GLP-1 or GIP–GLP-1 mimicry for the treatment of type 2 diabetes or obesity.

The most frequently reported adverse events from retatrutide were transient, mostly mild to moderate gastrointestinal events. They occurred primarily during dose escalation. Discontinuation of retatrutide or placebo because of adverse events occurred in 6% to 16% of the participants who received retatrutide and in none of the participants who received placebo.

Lilly, the company developing retatrutide, previously announced the launch of four phase 3 trials to gather further data on retatrutide for use in a marketing-approval application to the Food and Drug Administration.

The four trials – TRIUMPH-1, TRIUMPH-2, TRIUMPH-3, and TRIUMPH-4 – are evaluating the safety and efficacy of retatrutide for chronic weight management for those with obesity or overweight, including those who also have obstructive sleep apnea, knee osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes, or cardiovascular disease.

The study was sponsored by Lilly, the company developing retatrutide. Dr. Patti has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Hanmi, and MBX. She has received funding from Dexcom and has been a monitor for a trial funded by Fractyl. Dr. Jastreboff, Dr. Kaplan, and Dr. Rosenstock have reported financial relationships with Lilly as well as other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

How newly discovered genes might fit into obesity

Identifying specific genes adds to growing evidence that biology, in part, drives obesity. Researchers hope the findings will lead to effective treatments, and in the meantime add to the understanding that there are many types of obesity that come from a mix of genes and environmental factors.

Although the study is not the first to point to specific genes, “we were quite surprised by the proposed function of some of the genes we identified,” Lena R. Kaisinger, lead study investigator and a PhD student in the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge (England), wrote in an email. For example, the genes also manage cell death and influence how cells respond to DNA damage.

The investigators are not sure why genes involved in body size perform this kind of double duty, which opens avenues for future research.

The gene sequencing study was published online in the journal Cell Genomics.

Differences between women and men

The researchers found five new genes in females and two new genes in males linked to greater body mass index (BMI): DIDO1, KIAA1109, MC4R, PTPRG and SLC12A5 in women and MC4R and SLTM in men. People who recall having obesity as a child were more likely to have rare genetic changes in two other genes, OBSCN and MADD.

“The key thing is that when you see real genes with real gene names, it really makes real the notion that genetics underlie obesity,” said Lee Kaplan, MD, PhD, director of the Obesity and Metabolism Institute in Boston, who was not affiliated with the research.

Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues found these significant genetic differences by studying genomes of about 420,000 people stored in the UK Biobank, a huge biomedical database. The researchers decided to look at genes by sex and age because these are “two areas that we still know very little about,” Ms. Kaisinger said.

“We know that different types of obesity connect to different ages,” said Dr. Kaplan, who is also past president of the Obesity Society. “But what they’ve done now is find genes that are associated with particular subtypes of obesity ... some more common in one sex and some more common in different phases of life, including early onset obesity.”

The future is already here

Treatment for obesity based on a person’s genes already exists. For example, in June 2022, the Food and Drug Administration approved setmelanotide (Imcivree) for weight management in adults and children aged over 6 years with specific genetic markers.

Even as encouraging as setmelanotide is to Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues, these are still early days for translating the current research findings into clinical obesity tests and potential treatment, she said.

The “holy grail,” Dr. Kaplan said, is a future where people get screened for a particular genetic profile and their provider can say something like, “You’re probably most susceptible to this type, so we’ll treat you with this particular drug that’s been developed for people with this phenotype.”

Dr. Kaplan added: “That’s exactly what we are trying to do.”

Moving forward, Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues plan to repeat the study in larger and more diverse populations. They also plan to reverse the usual road map for studies, which typically start in animals and then progress to humans.

“We plan to take the most promising gene candidates forward into mouse models to learn more about their function and how exactly their dysfunction results in obesity,” Ms. Kaisinger said.

Three study coauthors are employees and shareholders of Adrestia Therapeutics. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Identifying specific genes adds to growing evidence that biology, in part, drives obesity. Researchers hope the findings will lead to effective treatments, and in the meantime add to the understanding that there are many types of obesity that come from a mix of genes and environmental factors.

Although the study is not the first to point to specific genes, “we were quite surprised by the proposed function of some of the genes we identified,” Lena R. Kaisinger, lead study investigator and a PhD student in the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge (England), wrote in an email. For example, the genes also manage cell death and influence how cells respond to DNA damage.

The investigators are not sure why genes involved in body size perform this kind of double duty, which opens avenues for future research.

The gene sequencing study was published online in the journal Cell Genomics.

Differences between women and men

The researchers found five new genes in females and two new genes in males linked to greater body mass index (BMI): DIDO1, KIAA1109, MC4R, PTPRG and SLC12A5 in women and MC4R and SLTM in men. People who recall having obesity as a child were more likely to have rare genetic changes in two other genes, OBSCN and MADD.

“The key thing is that when you see real genes with real gene names, it really makes real the notion that genetics underlie obesity,” said Lee Kaplan, MD, PhD, director of the Obesity and Metabolism Institute in Boston, who was not affiliated with the research.

Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues found these significant genetic differences by studying genomes of about 420,000 people stored in the UK Biobank, a huge biomedical database. The researchers decided to look at genes by sex and age because these are “two areas that we still know very little about,” Ms. Kaisinger said.

“We know that different types of obesity connect to different ages,” said Dr. Kaplan, who is also past president of the Obesity Society. “But what they’ve done now is find genes that are associated with particular subtypes of obesity ... some more common in one sex and some more common in different phases of life, including early onset obesity.”

The future is already here

Treatment for obesity based on a person’s genes already exists. For example, in June 2022, the Food and Drug Administration approved setmelanotide (Imcivree) for weight management in adults and children aged over 6 years with specific genetic markers.

Even as encouraging as setmelanotide is to Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues, these are still early days for translating the current research findings into clinical obesity tests and potential treatment, she said.

The “holy grail,” Dr. Kaplan said, is a future where people get screened for a particular genetic profile and their provider can say something like, “You’re probably most susceptible to this type, so we’ll treat you with this particular drug that’s been developed for people with this phenotype.”

Dr. Kaplan added: “That’s exactly what we are trying to do.”

Moving forward, Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues plan to repeat the study in larger and more diverse populations. They also plan to reverse the usual road map for studies, which typically start in animals and then progress to humans.

“We plan to take the most promising gene candidates forward into mouse models to learn more about their function and how exactly their dysfunction results in obesity,” Ms. Kaisinger said.

Three study coauthors are employees and shareholders of Adrestia Therapeutics. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Identifying specific genes adds to growing evidence that biology, in part, drives obesity. Researchers hope the findings will lead to effective treatments, and in the meantime add to the understanding that there are many types of obesity that come from a mix of genes and environmental factors.

Although the study is not the first to point to specific genes, “we were quite surprised by the proposed function of some of the genes we identified,” Lena R. Kaisinger, lead study investigator and a PhD student in the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge (England), wrote in an email. For example, the genes also manage cell death and influence how cells respond to DNA damage.

The investigators are not sure why genes involved in body size perform this kind of double duty, which opens avenues for future research.

The gene sequencing study was published online in the journal Cell Genomics.

Differences between women and men

The researchers found five new genes in females and two new genes in males linked to greater body mass index (BMI): DIDO1, KIAA1109, MC4R, PTPRG and SLC12A5 in women and MC4R and SLTM in men. People who recall having obesity as a child were more likely to have rare genetic changes in two other genes, OBSCN and MADD.

“The key thing is that when you see real genes with real gene names, it really makes real the notion that genetics underlie obesity,” said Lee Kaplan, MD, PhD, director of the Obesity and Metabolism Institute in Boston, who was not affiliated with the research.

Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues found these significant genetic differences by studying genomes of about 420,000 people stored in the UK Biobank, a huge biomedical database. The researchers decided to look at genes by sex and age because these are “two areas that we still know very little about,” Ms. Kaisinger said.

“We know that different types of obesity connect to different ages,” said Dr. Kaplan, who is also past president of the Obesity Society. “But what they’ve done now is find genes that are associated with particular subtypes of obesity ... some more common in one sex and some more common in different phases of life, including early onset obesity.”

The future is already here

Treatment for obesity based on a person’s genes already exists. For example, in June 2022, the Food and Drug Administration approved setmelanotide (Imcivree) for weight management in adults and children aged over 6 years with specific genetic markers.

Even as encouraging as setmelanotide is to Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues, these are still early days for translating the current research findings into clinical obesity tests and potential treatment, she said.

The “holy grail,” Dr. Kaplan said, is a future where people get screened for a particular genetic profile and their provider can say something like, “You’re probably most susceptible to this type, so we’ll treat you with this particular drug that’s been developed for people with this phenotype.”

Dr. Kaplan added: “That’s exactly what we are trying to do.”

Moving forward, Ms. Kaisinger and colleagues plan to repeat the study in larger and more diverse populations. They also plan to reverse the usual road map for studies, which typically start in animals and then progress to humans.

“We plan to take the most promising gene candidates forward into mouse models to learn more about their function and how exactly their dysfunction results in obesity,” Ms. Kaisinger said.

Three study coauthors are employees and shareholders of Adrestia Therapeutics. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM CELL GENOMICS

Semaglutide cuts cardiovascular events in landmark trial

, in the pivotal SELECT trial, with more than 17,000 enrolled people with overweight or obesity and established cardiovascular disease (CVD), but no diabetes.

The finding should fuel improved patient access to this glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist weight-loss agent that has historically been hindered by skepticism among U.S. payers, many of whom have criticized the health benefits and cost effectiveness of this drug in people whose only indication for treatment is overweight or obesity.

According to top-line results from SELECT released by Novo Nordisk on Aug. 8, the people randomly assigned to receive weekly 2.4-mg subcutaneous injections of semaglutide showed a significant 20% reduction in their incidence of the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. The announcement added that semaglutide treatment also significantly linked with a drop in the incidence of each of these individual three endpoints; the magnitude of these reductions, however, wasn’t specified, nor was the duration of treatment and follow-up.

The results also showed a level of safety and patient tolerance for weekly 2.4-mg injections of semaglutide that were consistent with prior reports on the agent. Semaglutide as Wegovy received marketing approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for weight loss, and in 2017 for glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes, at a weekly maximum dose of 2.0 mg (for which it’s marketed as Ozempic).

SELECT began in 2018 and randomly assigned 17,604 adults aged 45 years and older at more than 800 sites in 41 countries. The company’s announcement noted that the trial had accrued a total of 1,270 study participants with a first MACE event but did not break this total down based on treatment received.

‘A good result for patients’

“The topline results from SELECT are exciting, as preventing heart attacks and stroke with a drug that also lowers weight is very important for many patients, especially if the data also show – as I suspect they will – a meaningful improvement of quality of life for patients due to associated weight loss,” commented Naveed Sattar, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow who was not involved with the study.

Despite this lack of current clarity over the role that weight loss by itself played in driving the observed result, the SELECT findings seem poised to reset a long-standing prejudice against the medical necessity and safety of weight-loss agents when used for the sole indication of helping people lose weight.

Changing how obesity is regarded

“To date, there are no approved weight management medications proven to deliver effective weight management while also reducing the risk of heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular death,” said Martin Holst Lange, executive vice president for development at Novo Nordisk, in the company’s press release.

“SELECT is a landmark trial and has demonstrated that semaglutide 2.4 mg has the potential to change how obesity is regarded and treated.”

Several of the early medical options for aiding weight loss had substantial adverse effects, including increased MACE rates, a history that led to pervasive wariness among physicians over the safety of antiobesity agents and the wisdom of using medically aided weight loss to produce health benefits.

This attitude also helped dampen health insurance coverage of weight-loss treatments. For example, Medicare has a long-standing policy against reimbursing the cost for medications that are used for the indication of weight loss, and a 2003 U.S. law prohibited part D plans from providing this coverage.

Semaglutide belongs to the class of agents that mimic the action of the incretin GLP-1. The introduction of this class of GLP-1 agonists for weight loss began in 2014 with the FDA’s approval of liraglutide (Saxenda), a daily subcutaneous injection that marked the first step toward establishing the class as safe and effective for weight loss and launching a new era in weight-loss treatment.

According to the Novo Nordisk announcement, a full report on results from SELECT will occur “at a scientific meeting later in 2023.”

SELECT is sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets semaglutide (Wegovy). Dr. Sattar is a consultant to several companies that market GLP-1 receptor agonists, including Novo Nordisk and Lilly, but has had no involvement in SELECT.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, in the pivotal SELECT trial, with more than 17,000 enrolled people with overweight or obesity and established cardiovascular disease (CVD), but no diabetes.

The finding should fuel improved patient access to this glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist weight-loss agent that has historically been hindered by skepticism among U.S. payers, many of whom have criticized the health benefits and cost effectiveness of this drug in people whose only indication for treatment is overweight or obesity.

According to top-line results from SELECT released by Novo Nordisk on Aug. 8, the people randomly assigned to receive weekly 2.4-mg subcutaneous injections of semaglutide showed a significant 20% reduction in their incidence of the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. The announcement added that semaglutide treatment also significantly linked with a drop in the incidence of each of these individual three endpoints; the magnitude of these reductions, however, wasn’t specified, nor was the duration of treatment and follow-up.

The results also showed a level of safety and patient tolerance for weekly 2.4-mg injections of semaglutide that were consistent with prior reports on the agent. Semaglutide as Wegovy received marketing approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for weight loss, and in 2017 for glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes, at a weekly maximum dose of 2.0 mg (for which it’s marketed as Ozempic).

SELECT began in 2018 and randomly assigned 17,604 adults aged 45 years and older at more than 800 sites in 41 countries. The company’s announcement noted that the trial had accrued a total of 1,270 study participants with a first MACE event but did not break this total down based on treatment received.

‘A good result for patients’

“The topline results from SELECT are exciting, as preventing heart attacks and stroke with a drug that also lowers weight is very important for many patients, especially if the data also show – as I suspect they will – a meaningful improvement of quality of life for patients due to associated weight loss,” commented Naveed Sattar, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow who was not involved with the study.

Despite this lack of current clarity over the role that weight loss by itself played in driving the observed result, the SELECT findings seem poised to reset a long-standing prejudice against the medical necessity and safety of weight-loss agents when used for the sole indication of helping people lose weight.

Changing how obesity is regarded

“To date, there are no approved weight management medications proven to deliver effective weight management while also reducing the risk of heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular death,” said Martin Holst Lange, executive vice president for development at Novo Nordisk, in the company’s press release.

“SELECT is a landmark trial and has demonstrated that semaglutide 2.4 mg has the potential to change how obesity is regarded and treated.”

Several of the early medical options for aiding weight loss had substantial adverse effects, including increased MACE rates, a history that led to pervasive wariness among physicians over the safety of antiobesity agents and the wisdom of using medically aided weight loss to produce health benefits.

This attitude also helped dampen health insurance coverage of weight-loss treatments. For example, Medicare has a long-standing policy against reimbursing the cost for medications that are used for the indication of weight loss, and a 2003 U.S. law prohibited part D plans from providing this coverage.

Semaglutide belongs to the class of agents that mimic the action of the incretin GLP-1. The introduction of this class of GLP-1 agonists for weight loss began in 2014 with the FDA’s approval of liraglutide (Saxenda), a daily subcutaneous injection that marked the first step toward establishing the class as safe and effective for weight loss and launching a new era in weight-loss treatment.

According to the Novo Nordisk announcement, a full report on results from SELECT will occur “at a scientific meeting later in 2023.”

SELECT is sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets semaglutide (Wegovy). Dr. Sattar is a consultant to several companies that market GLP-1 receptor agonists, including Novo Nordisk and Lilly, but has had no involvement in SELECT.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, in the pivotal SELECT trial, with more than 17,000 enrolled people with overweight or obesity and established cardiovascular disease (CVD), but no diabetes.

The finding should fuel improved patient access to this glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist weight-loss agent that has historically been hindered by skepticism among U.S. payers, many of whom have criticized the health benefits and cost effectiveness of this drug in people whose only indication for treatment is overweight or obesity.

According to top-line results from SELECT released by Novo Nordisk on Aug. 8, the people randomly assigned to receive weekly 2.4-mg subcutaneous injections of semaglutide showed a significant 20% reduction in their incidence of the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. The announcement added that semaglutide treatment also significantly linked with a drop in the incidence of each of these individual three endpoints; the magnitude of these reductions, however, wasn’t specified, nor was the duration of treatment and follow-up.

The results also showed a level of safety and patient tolerance for weekly 2.4-mg injections of semaglutide that were consistent with prior reports on the agent. Semaglutide as Wegovy received marketing approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for weight loss, and in 2017 for glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes, at a weekly maximum dose of 2.0 mg (for which it’s marketed as Ozempic).

SELECT began in 2018 and randomly assigned 17,604 adults aged 45 years and older at more than 800 sites in 41 countries. The company’s announcement noted that the trial had accrued a total of 1,270 study participants with a first MACE event but did not break this total down based on treatment received.

‘A good result for patients’

“The topline results from SELECT are exciting, as preventing heart attacks and stroke with a drug that also lowers weight is very important for many patients, especially if the data also show – as I suspect they will – a meaningful improvement of quality of life for patients due to associated weight loss,” commented Naveed Sattar, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow who was not involved with the study.

Despite this lack of current clarity over the role that weight loss by itself played in driving the observed result, the SELECT findings seem poised to reset a long-standing prejudice against the medical necessity and safety of weight-loss agents when used for the sole indication of helping people lose weight.

Changing how obesity is regarded

“To date, there are no approved weight management medications proven to deliver effective weight management while also reducing the risk of heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular death,” said Martin Holst Lange, executive vice president for development at Novo Nordisk, in the company’s press release.

“SELECT is a landmark trial and has demonstrated that semaglutide 2.4 mg has the potential to change how obesity is regarded and treated.”

Several of the early medical options for aiding weight loss had substantial adverse effects, including increased MACE rates, a history that led to pervasive wariness among physicians over the safety of antiobesity agents and the wisdom of using medically aided weight loss to produce health benefits.

This attitude also helped dampen health insurance coverage of weight-loss treatments. For example, Medicare has a long-standing policy against reimbursing the cost for medications that are used for the indication of weight loss, and a 2003 U.S. law prohibited part D plans from providing this coverage.