User login

Prenatal, postnatal neuroimaging IDs most Zika-related brain injuries

Prenatal ultrasound can identify most abnormalities in fetuses exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy, and neuroimaging after birth can detect infant exposure in cases that appeared normal on prenatal ultrasound, according to research published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Absence of prolonged maternal viremia did not have predictive associations with normal fetal or neonatal brain imaging,” Sarah B. Mulkey, MD, PhD, from the division of fetal and transitional medicine at Children’s National Health System, in Washington, and her colleagues wrote. “Postnatal imaging can detect changes not seen on fetal imaging, supporting the current CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] recommendation for postnatal cranial [ultrasound].”

Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort analysis of 82 pregnant women from Colombia and the United States who had clinical evidence of probable exposure to the Zika virus through travel (U.S. cases, 2 patients), physician referral, or community cases during June 2016-June 2017. Pregnant women underwent fetal MRI or ultrasound during the second or third trimesters between 4 weeks and 10 weeks after symptom onset, with infants undergoing brain MRI and cranial ultrasound after birth.

Of those 82 pregnancies, there were 80 live births, 1 case of termination because of severe fetal brain abnormalities, and 1 near-term fetal death of unknown cause. There was one death 3 days after birth and one instance of neurosurgical intervention from encephalocele. The researchers found 3 of 82 cases (4%) displayed fetal abnormalities from MRI, which consisted of 2 cases of heterotopias and malformations in cortical development and 1 case with parietal encephalocele, Chiari II malformation, and microcephaly. One infant had a normal ultrasound despite abnormalities displayed on fetal MRI.

After birth, of the 79 infants with normal ultrasound results, 53 infants underwent a postnatal brain MRI and Dr. Mulkey and her associates found 7 cases with mild abnormalities (13%). There were 57 infants who underwent cranial ultrasound, which yielded 21 cases of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, choroid plexus cysts, germinolytic/subependymal cysts, and/or calcification; these were poorly characterized by MRI.

“Normal fetal imaging had predictive associations with normal postnatal imaging or mild postnatal imaging findings unlikely to be of significant clinical consequence,” they said.

Nonetheless, “there is a need for long-term follow-up to assess the neurodevelopmental significance of these early neuroimaging findings, both normal and abnormal; such studies are in progress,” Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues said.

The researchers noted the timing of maternal infections and symptoms as well as the Zika testing, ultrasound, and MRI performance, technique during fetal MRI, and incomplete prenatal testing in the cohort as limitations in the study.

This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr. Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

While the study by Mulkey et al. adds to the body of evidence of prenatal and postnatal brain abnormalities, there are still many unanswered questions about the Zika virus and how to handle its unique diagnostic and clinical challenges, Margaret A. Honein, PhD, MPH, and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial.

For example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations state that infants with possible Zika exposure should receive an ophthalmologic and ultrasonographic examination at 1 month, and if the hearing test used otoacoustic emissions methods only, an automated auditory brainstem response test should be administered. While Mulkey et al. examined brain abnormalities in utero and in infants, it is not clear whether all CDC guidelines were followed in these cases.

In addition, because there is no reliable way to determine whether infants acquired Zika virus through the mother or through vertical transmission, assessing the proportion of congenitally infected infants or vertical-transmission infected infants who have neurodevelopmental disabilities and defects is not possible, they said. More longitudinal studies are needed to study the effects of the Zika virus and to prepare for the next outbreak.

“Zika was affecting pregnant women and their infants years before its teratogenic effect was recognized, and Zika will remain a serious risk to pregnant women and their infants until we have a safe vaccine that can fully prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” they said. “Until then, ongoing public health efforts are essential to protect mothers and babies from this threat and ensure all disabilities associated with Zika virus infection are promptly identified, so that timely interventions can be provided.”

Dr. Honein is from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Jamieson is from the department of gynecology & obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Mulkey et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4164). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

While the study by Mulkey et al. adds to the body of evidence of prenatal and postnatal brain abnormalities, there are still many unanswered questions about the Zika virus and how to handle its unique diagnostic and clinical challenges, Margaret A. Honein, PhD, MPH, and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial.

For example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations state that infants with possible Zika exposure should receive an ophthalmologic and ultrasonographic examination at 1 month, and if the hearing test used otoacoustic emissions methods only, an automated auditory brainstem response test should be administered. While Mulkey et al. examined brain abnormalities in utero and in infants, it is not clear whether all CDC guidelines were followed in these cases.

In addition, because there is no reliable way to determine whether infants acquired Zika virus through the mother or through vertical transmission, assessing the proportion of congenitally infected infants or vertical-transmission infected infants who have neurodevelopmental disabilities and defects is not possible, they said. More longitudinal studies are needed to study the effects of the Zika virus and to prepare for the next outbreak.

“Zika was affecting pregnant women and their infants years before its teratogenic effect was recognized, and Zika will remain a serious risk to pregnant women and their infants until we have a safe vaccine that can fully prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” they said. “Until then, ongoing public health efforts are essential to protect mothers and babies from this threat and ensure all disabilities associated with Zika virus infection are promptly identified, so that timely interventions can be provided.”

Dr. Honein is from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Jamieson is from the department of gynecology & obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Mulkey et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4164). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

While the study by Mulkey et al. adds to the body of evidence of prenatal and postnatal brain abnormalities, there are still many unanswered questions about the Zika virus and how to handle its unique diagnostic and clinical challenges, Margaret A. Honein, PhD, MPH, and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial.

For example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations state that infants with possible Zika exposure should receive an ophthalmologic and ultrasonographic examination at 1 month, and if the hearing test used otoacoustic emissions methods only, an automated auditory brainstem response test should be administered. While Mulkey et al. examined brain abnormalities in utero and in infants, it is not clear whether all CDC guidelines were followed in these cases.

In addition, because there is no reliable way to determine whether infants acquired Zika virus through the mother or through vertical transmission, assessing the proportion of congenitally infected infants or vertical-transmission infected infants who have neurodevelopmental disabilities and defects is not possible, they said. More longitudinal studies are needed to study the effects of the Zika virus and to prepare for the next outbreak.

“Zika was affecting pregnant women and their infants years before its teratogenic effect was recognized, and Zika will remain a serious risk to pregnant women and their infants until we have a safe vaccine that can fully prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” they said. “Until then, ongoing public health efforts are essential to protect mothers and babies from this threat and ensure all disabilities associated with Zika virus infection are promptly identified, so that timely interventions can be provided.”

Dr. Honein is from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Jamieson is from the department of gynecology & obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Mulkey et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4164). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Prenatal ultrasound can identify most abnormalities in fetuses exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy, and neuroimaging after birth can detect infant exposure in cases that appeared normal on prenatal ultrasound, according to research published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Absence of prolonged maternal viremia did not have predictive associations with normal fetal or neonatal brain imaging,” Sarah B. Mulkey, MD, PhD, from the division of fetal and transitional medicine at Children’s National Health System, in Washington, and her colleagues wrote. “Postnatal imaging can detect changes not seen on fetal imaging, supporting the current CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] recommendation for postnatal cranial [ultrasound].”

Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort analysis of 82 pregnant women from Colombia and the United States who had clinical evidence of probable exposure to the Zika virus through travel (U.S. cases, 2 patients), physician referral, or community cases during June 2016-June 2017. Pregnant women underwent fetal MRI or ultrasound during the second or third trimesters between 4 weeks and 10 weeks after symptom onset, with infants undergoing brain MRI and cranial ultrasound after birth.

Of those 82 pregnancies, there were 80 live births, 1 case of termination because of severe fetal brain abnormalities, and 1 near-term fetal death of unknown cause. There was one death 3 days after birth and one instance of neurosurgical intervention from encephalocele. The researchers found 3 of 82 cases (4%) displayed fetal abnormalities from MRI, which consisted of 2 cases of heterotopias and malformations in cortical development and 1 case with parietal encephalocele, Chiari II malformation, and microcephaly. One infant had a normal ultrasound despite abnormalities displayed on fetal MRI.

After birth, of the 79 infants with normal ultrasound results, 53 infants underwent a postnatal brain MRI and Dr. Mulkey and her associates found 7 cases with mild abnormalities (13%). There were 57 infants who underwent cranial ultrasound, which yielded 21 cases of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, choroid plexus cysts, germinolytic/subependymal cysts, and/or calcification; these were poorly characterized by MRI.

“Normal fetal imaging had predictive associations with normal postnatal imaging or mild postnatal imaging findings unlikely to be of significant clinical consequence,” they said.

Nonetheless, “there is a need for long-term follow-up to assess the neurodevelopmental significance of these early neuroimaging findings, both normal and abnormal; such studies are in progress,” Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues said.

The researchers noted the timing of maternal infections and symptoms as well as the Zika testing, ultrasound, and MRI performance, technique during fetal MRI, and incomplete prenatal testing in the cohort as limitations in the study.

This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr. Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

Prenatal ultrasound can identify most abnormalities in fetuses exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy, and neuroimaging after birth can detect infant exposure in cases that appeared normal on prenatal ultrasound, according to research published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Absence of prolonged maternal viremia did not have predictive associations with normal fetal or neonatal brain imaging,” Sarah B. Mulkey, MD, PhD, from the division of fetal and transitional medicine at Children’s National Health System, in Washington, and her colleagues wrote. “Postnatal imaging can detect changes not seen on fetal imaging, supporting the current CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] recommendation for postnatal cranial [ultrasound].”

Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort analysis of 82 pregnant women from Colombia and the United States who had clinical evidence of probable exposure to the Zika virus through travel (U.S. cases, 2 patients), physician referral, or community cases during June 2016-June 2017. Pregnant women underwent fetal MRI or ultrasound during the second or third trimesters between 4 weeks and 10 weeks after symptom onset, with infants undergoing brain MRI and cranial ultrasound after birth.

Of those 82 pregnancies, there were 80 live births, 1 case of termination because of severe fetal brain abnormalities, and 1 near-term fetal death of unknown cause. There was one death 3 days after birth and one instance of neurosurgical intervention from encephalocele. The researchers found 3 of 82 cases (4%) displayed fetal abnormalities from MRI, which consisted of 2 cases of heterotopias and malformations in cortical development and 1 case with parietal encephalocele, Chiari II malformation, and microcephaly. One infant had a normal ultrasound despite abnormalities displayed on fetal MRI.

After birth, of the 79 infants with normal ultrasound results, 53 infants underwent a postnatal brain MRI and Dr. Mulkey and her associates found 7 cases with mild abnormalities (13%). There were 57 infants who underwent cranial ultrasound, which yielded 21 cases of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, choroid plexus cysts, germinolytic/subependymal cysts, and/or calcification; these were poorly characterized by MRI.

“Normal fetal imaging had predictive associations with normal postnatal imaging or mild postnatal imaging findings unlikely to be of significant clinical consequence,” they said.

Nonetheless, “there is a need for long-term follow-up to assess the neurodevelopmental significance of these early neuroimaging findings, both normal and abnormal; such studies are in progress,” Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues said.

The researchers noted the timing of maternal infections and symptoms as well as the Zika testing, ultrasound, and MRI performance, technique during fetal MRI, and incomplete prenatal testing in the cohort as limitations in the study.

This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr. Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In 82 pregnant women, prenatal neuroimaging identified fetal abnormalities in 3 cases, while postnatal neuroimaging in 53 of the remaining 79 cases yielded an additional 7 cases with mild abnormalities.

Study details: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 82 pregnant women with clinical evidence of probable Zika infection in Colombia and the United States.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26; doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

Gestational, umbilical cord vitamin D levels don’t predict atopic disease in offspring

according to study results published in the journal Allergy.

Áine Hennessy, PhD, from the School of Food and Nutritional Sciences at the University College Cork (Ireland), and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 1,537 women in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study who underwent measurement of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) from maternal sera followed by measurement of 25(OH)D in umbilical cord blood (1,050 cases). They then measured the prevalence of eczema, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in infants at aged 2 and 5 years.

The researchers found at 2 years old, 5% of infants had persistent eczema, 4% of infants had a food allergy and 8% of infants had aeroallergen sensitization. At age 5 years, 15% of infants had asthma, while 5% had allergic rhinitis. Mothers whose children went on to have atopy did not differ in their 25(OH)D levels at 15 weeks’ gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) or in the levels in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L).

Of the women in the cohort, 74% ranged in age from 25 to 34 years; 49% reported a personal history of allergy and 37% reported a paternal allergy. The mean birth weight of the infants was 3,458 g; infants were breastfed for mean 11.9 weeks, 73% of infants were breastfeeding by the time they left the hospital and 45% of infants were breastfeeding by age 2 months.

Limitations of the study included that parental atopy status was self-reported and that the researchers noted they did not examine genetic variants of immunoglobulin E synthesis or vitamin D receptor polymorphisms.

“To fully characterize relationships between intrauterine vitamin D exposure and allergic disease, analysis of well‐constructed, large‐scale prospective cohorts of maternal‐infant dyads, which take due consideration of an individual’s inherited risk, early‐life exposures and environmental confounders, is still needed,” Dr. Hennessy and her colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hennessy A et al. Allergy. 2018 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/all.13590.

according to study results published in the journal Allergy.

Áine Hennessy, PhD, from the School of Food and Nutritional Sciences at the University College Cork (Ireland), and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 1,537 women in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study who underwent measurement of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) from maternal sera followed by measurement of 25(OH)D in umbilical cord blood (1,050 cases). They then measured the prevalence of eczema, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in infants at aged 2 and 5 years.

The researchers found at 2 years old, 5% of infants had persistent eczema, 4% of infants had a food allergy and 8% of infants had aeroallergen sensitization. At age 5 years, 15% of infants had asthma, while 5% had allergic rhinitis. Mothers whose children went on to have atopy did not differ in their 25(OH)D levels at 15 weeks’ gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) or in the levels in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L).

Of the women in the cohort, 74% ranged in age from 25 to 34 years; 49% reported a personal history of allergy and 37% reported a paternal allergy. The mean birth weight of the infants was 3,458 g; infants were breastfed for mean 11.9 weeks, 73% of infants were breastfeeding by the time they left the hospital and 45% of infants were breastfeeding by age 2 months.

Limitations of the study included that parental atopy status was self-reported and that the researchers noted they did not examine genetic variants of immunoglobulin E synthesis or vitamin D receptor polymorphisms.

“To fully characterize relationships between intrauterine vitamin D exposure and allergic disease, analysis of well‐constructed, large‐scale prospective cohorts of maternal‐infant dyads, which take due consideration of an individual’s inherited risk, early‐life exposures and environmental confounders, is still needed,” Dr. Hennessy and her colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hennessy A et al. Allergy. 2018 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/all.13590.

according to study results published in the journal Allergy.

Áine Hennessy, PhD, from the School of Food and Nutritional Sciences at the University College Cork (Ireland), and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 1,537 women in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study who underwent measurement of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) from maternal sera followed by measurement of 25(OH)D in umbilical cord blood (1,050 cases). They then measured the prevalence of eczema, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in infants at aged 2 and 5 years.

The researchers found at 2 years old, 5% of infants had persistent eczema, 4% of infants had a food allergy and 8% of infants had aeroallergen sensitization. At age 5 years, 15% of infants had asthma, while 5% had allergic rhinitis. Mothers whose children went on to have atopy did not differ in their 25(OH)D levels at 15 weeks’ gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) or in the levels in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L).

Of the women in the cohort, 74% ranged in age from 25 to 34 years; 49% reported a personal history of allergy and 37% reported a paternal allergy. The mean birth weight of the infants was 3,458 g; infants were breastfed for mean 11.9 weeks, 73% of infants were breastfeeding by the time they left the hospital and 45% of infants were breastfeeding by age 2 months.

Limitations of the study included that parental atopy status was self-reported and that the researchers noted they did not examine genetic variants of immunoglobulin E synthesis or vitamin D receptor polymorphisms.

“To fully characterize relationships between intrauterine vitamin D exposure and allergic disease, analysis of well‐constructed, large‐scale prospective cohorts of maternal‐infant dyads, which take due consideration of an individual’s inherited risk, early‐life exposures and environmental confounders, is still needed,” Dr. Hennessy and her colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hennessy A et al. Allergy. 2018 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/all.13590.

FROM ALLERGY

Key clinical point: There was no association between prevalence of atopic disease and vitamin D levels measured in maternal sera during pregnancy or in umbilical cord blood.

Major finding: Maternal vitamin D levels at 15 weeks of gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) and concentrations in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L) were not associated with such atopic diseases as eczema, food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis in children.

Study details: A prospective group of 1,537 women and infant pairs from the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study.

Disclosures: This study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Hennessy A et al. Allergy 2018 Aug 7. doi:10.1111/all.13590.

Frontal lobe epilepsy elevates seizure risk during pregnancy

based on a study reported by Paula E. Voinescu, MD, PhD, at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The single center study included data on 76 pregnancies in women with focal epilepsy –17 of them in patients with frontal lobe epilepsy – and 38 pregnancies in women with generalized epilepsy. Seizures were more frequent during pregnancy, compared with baseline, in 5.5% of women with generalized epilepsy, 22.6% of women with focal epilepsies, and 53.0% of women with frontal lobe epilepsy, said Dr. Voinescu, lead author of the study and a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Frontal lobe epilepsy is known to be difficult to manage in general and often resistant to therapy, but it isn’t clear why the seizures got worse among pregnant women because the levels of medication in their blood was considered adequate. Until more research provides treatment guidance, doctors should carefully monitor their pregnant patients who have focal epilepsy to see if their seizures increase despite adequate blood levels and then adjust their medication if necessary,” she advised. “As we know from other research, seizures during pregnancy can increase the risk of distress and neurodevelopmental delays for the baby, as well as the risk of miscarriage.”

For the study, Dr. Voinescu and her colleagues analyzed prospectively collected clinical data from 99 pregnant women followed at Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 2013 and 2018.

The researchers excluded patients with abortions, seizure onset during pregnancy, poorly defined preconception seizure frequency, nonepileptic seizures, antiepileptic drug (AED) noncompliance, and pregnancies that were enrolled in other studies. The investigators documented patients’ seizure types and AED regimens and recorded seizure frequency during the 9 months before conception, during pregnancy, and 9 months postpartum. The researchers summed all seizures for each individual for each interval. They defined seizure frequency worsening as any increase above the preconception baseline, and evaluated differences between focal and generalized epilepsy and between frontal lobe and other focal epilepsies.

Increased seizure activity tended to occur in women on more than one AED, according to Dr. Voinescu. In women with frontal lobe epilepsy, seizure worsening during pregnancy was most likely to begin in the second trimester.

The gap in seizure frequency between the groups narrowed in the 9-month postpartum period. Seizures were more frequent during the postpartum period, compared with baseline, in 12.12% of women with generalized epilepsy, 20.14% of women with focal epilepsies, and 20.00% of women with frontal lobe epilepsy.

Future analyses will evaluate the influence of AED type and concentration and specific timing on seizure control during pregnancy and the postpartum period, Dr. Voinescu said. Future studies should also include measures of sleep, which may be a contributory mechanism to the differences found between these epilepsy types.

Dr. Voinescu reported receiving funding from the American Brain Foundation, the American Epilepsy Society, and the Epilepsy Foundation through the Susan Spencer Clinical Research Fellowship.

SOURCE: Voinescu PE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.236.

based on a study reported by Paula E. Voinescu, MD, PhD, at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The single center study included data on 76 pregnancies in women with focal epilepsy –17 of them in patients with frontal lobe epilepsy – and 38 pregnancies in women with generalized epilepsy. Seizures were more frequent during pregnancy, compared with baseline, in 5.5% of women with generalized epilepsy, 22.6% of women with focal epilepsies, and 53.0% of women with frontal lobe epilepsy, said Dr. Voinescu, lead author of the study and a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Frontal lobe epilepsy is known to be difficult to manage in general and often resistant to therapy, but it isn’t clear why the seizures got worse among pregnant women because the levels of medication in their blood was considered adequate. Until more research provides treatment guidance, doctors should carefully monitor their pregnant patients who have focal epilepsy to see if their seizures increase despite adequate blood levels and then adjust their medication if necessary,” she advised. “As we know from other research, seizures during pregnancy can increase the risk of distress and neurodevelopmental delays for the baby, as well as the risk of miscarriage.”

For the study, Dr. Voinescu and her colleagues analyzed prospectively collected clinical data from 99 pregnant women followed at Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 2013 and 2018.

The researchers excluded patients with abortions, seizure onset during pregnancy, poorly defined preconception seizure frequency, nonepileptic seizures, antiepileptic drug (AED) noncompliance, and pregnancies that were enrolled in other studies. The investigators documented patients’ seizure types and AED regimens and recorded seizure frequency during the 9 months before conception, during pregnancy, and 9 months postpartum. The researchers summed all seizures for each individual for each interval. They defined seizure frequency worsening as any increase above the preconception baseline, and evaluated differences between focal and generalized epilepsy and between frontal lobe and other focal epilepsies.

Increased seizure activity tended to occur in women on more than one AED, according to Dr. Voinescu. In women with frontal lobe epilepsy, seizure worsening during pregnancy was most likely to begin in the second trimester.

The gap in seizure frequency between the groups narrowed in the 9-month postpartum period. Seizures were more frequent during the postpartum period, compared with baseline, in 12.12% of women with generalized epilepsy, 20.14% of women with focal epilepsies, and 20.00% of women with frontal lobe epilepsy.

Future analyses will evaluate the influence of AED type and concentration and specific timing on seizure control during pregnancy and the postpartum period, Dr. Voinescu said. Future studies should also include measures of sleep, which may be a contributory mechanism to the differences found between these epilepsy types.

Dr. Voinescu reported receiving funding from the American Brain Foundation, the American Epilepsy Society, and the Epilepsy Foundation through the Susan Spencer Clinical Research Fellowship.

SOURCE: Voinescu PE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.236.

based on a study reported by Paula E. Voinescu, MD, PhD, at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The single center study included data on 76 pregnancies in women with focal epilepsy –17 of them in patients with frontal lobe epilepsy – and 38 pregnancies in women with generalized epilepsy. Seizures were more frequent during pregnancy, compared with baseline, in 5.5% of women with generalized epilepsy, 22.6% of women with focal epilepsies, and 53.0% of women with frontal lobe epilepsy, said Dr. Voinescu, lead author of the study and a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Frontal lobe epilepsy is known to be difficult to manage in general and often resistant to therapy, but it isn’t clear why the seizures got worse among pregnant women because the levels of medication in their blood was considered adequate. Until more research provides treatment guidance, doctors should carefully monitor their pregnant patients who have focal epilepsy to see if their seizures increase despite adequate blood levels and then adjust their medication if necessary,” she advised. “As we know from other research, seizures during pregnancy can increase the risk of distress and neurodevelopmental delays for the baby, as well as the risk of miscarriage.”

For the study, Dr. Voinescu and her colleagues analyzed prospectively collected clinical data from 99 pregnant women followed at Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 2013 and 2018.

The researchers excluded patients with abortions, seizure onset during pregnancy, poorly defined preconception seizure frequency, nonepileptic seizures, antiepileptic drug (AED) noncompliance, and pregnancies that were enrolled in other studies. The investigators documented patients’ seizure types and AED regimens and recorded seizure frequency during the 9 months before conception, during pregnancy, and 9 months postpartum. The researchers summed all seizures for each individual for each interval. They defined seizure frequency worsening as any increase above the preconception baseline, and evaluated differences between focal and generalized epilepsy and between frontal lobe and other focal epilepsies.

Increased seizure activity tended to occur in women on more than one AED, according to Dr. Voinescu. In women with frontal lobe epilepsy, seizure worsening during pregnancy was most likely to begin in the second trimester.

The gap in seizure frequency between the groups narrowed in the 9-month postpartum period. Seizures were more frequent during the postpartum period, compared with baseline, in 12.12% of women with generalized epilepsy, 20.14% of women with focal epilepsies, and 20.00% of women with frontal lobe epilepsy.

Future analyses will evaluate the influence of AED type and concentration and specific timing on seizure control during pregnancy and the postpartum period, Dr. Voinescu said. Future studies should also include measures of sleep, which may be a contributory mechanism to the differences found between these epilepsy types.

Dr. Voinescu reported receiving funding from the American Brain Foundation, the American Epilepsy Society, and the Epilepsy Foundation through the Susan Spencer Clinical Research Fellowship.

SOURCE: Voinescu PE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.236.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: Women with focal epilepsy, especially frontal lobe epilepsy, may need closer monitoring during pregnancy.

Major finding: Compared with baseline, seizures were more frequent during pregnancy in 53% of women with frontal lobe epilepsy.

Study details: An analysis of prospectively collected data from 114 pregnancies.

Disclosures: Dr. Voinescu reported receiving funding from the American Brain Foundation, the American Epilepsy Society, and the Epilepsy Foundation through the Susan Spencer Clinical Research Fellowship.

Source: Voinescu PE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.236.

FDA approves congenital CMV diagnostic test

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

Infant mortality generally unchanged in 2016

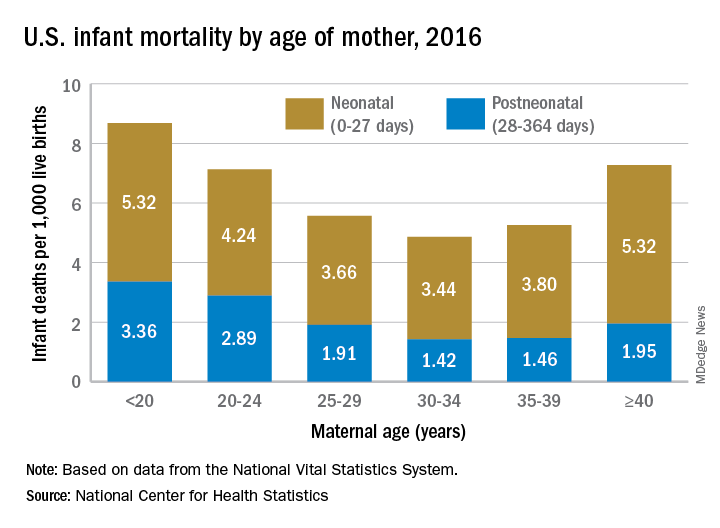

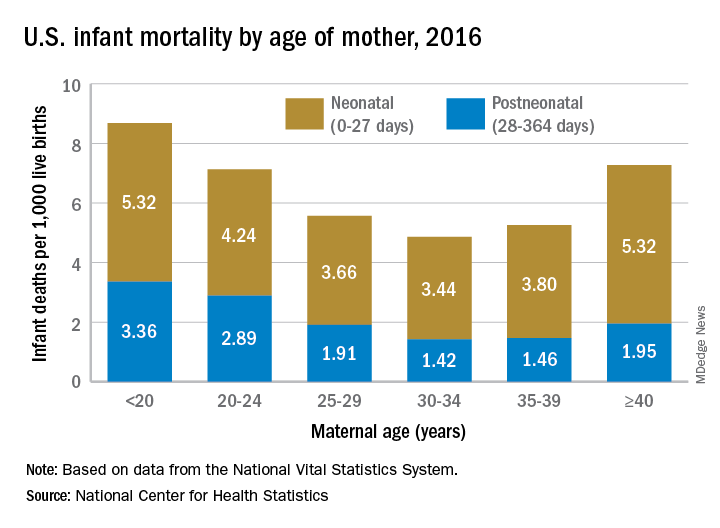

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

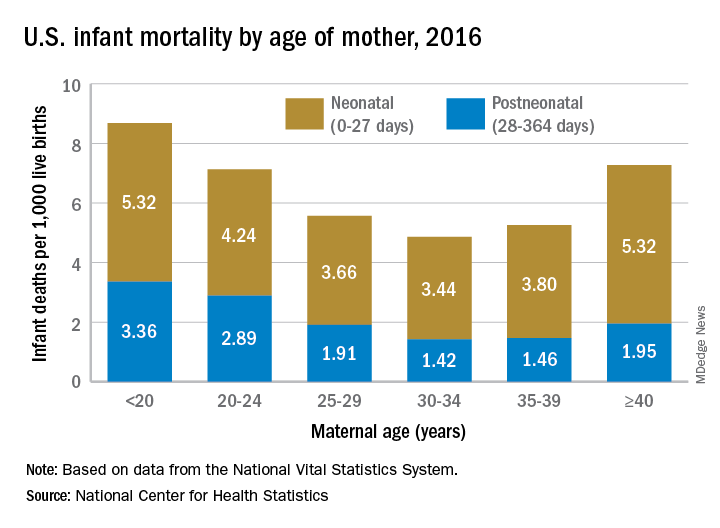

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

Evidence coming on best preeclampsia treatment threshold

CHICAGO – It’s clear that there’s a dose-dependent relationship between hypertension in pregnancy and poor outcomes, but, even so, treatment usually doesn’t begin until women hit 160/105 mm Hg or higher, according to Mark Santillan, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology – maternal fetal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

That might soon change. The National Institutes of Health–funded CHAPS (Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy) trial is testing whether earlier intervention improves outcomes, and it hopes to define proper treatment targets, which are uncertain at this point. Results are expected as soon as 2020.

What’s already changed is that the old treatment standby – methyldopa – has fallen out of favor for labetalol and nifedipine, which have been shown to work better. “Sometimes, we will throw on hydrochlorothiazide after we max out our beta- and calcium channel blockers,” Dr. Santillan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 1;10:CD002252).

For severe hypertension, “most of the time we start off with IV hydralazine or IV labetalol” in the hospital. “You give a dose and check blood pressure in 10 or 20 minutes,” he said. If it hasn’t dropped, “give another dose until you reach your max dose.” When intravenous access is an issue, oral nifedipine is a good option (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;129[4]:e90-e95).

Delivery date is key; babies exposed to chronic hypertension are more likely to be stillborn. For hypertension without symptoms, delivery is at around 38 weeks. For mild preeclampsia – hypertension with only minor symptoms – it’s at 37 weeks.

In more severe cases – hypertension with pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and other problems – “the general gestalt is to stabilize and deliver when you can. See if you can get up to at least 34 weeks,” Dr. Santillan said. However, when women “have full-on HELLP syndrome [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count], we often just deliver [immediately] because there’s not a lot of stabilization” that can be done. “We give magnesium after delivery to help decrease the risk of seizure,” he added.

Guidelines still use 140/90 mm Hg to define hypertension in pregnancy. When that level is reached, “you don’t need proteinuria anymore to diagnose preeclampsia. You need to have hypertension and something that looks like HELLP,” such as impaired liver function or neurologic symptoms, he said. Onset before 34 weeks portends more severe disease.

Daily baby aspirin 81 mg is known to help prevent preeclampsia, if only a little bit, so anyone with a history of preeclampsia or twin pregnancy, chronic hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or autoimmune disease should automatically be put on aspirin prophylaxis. Women with two or more moderate risk factors – first pregnancy, obesity, preeclamptic family history, or aged 35 years or older – also should also get baby aspirin. Vitamin C, bed rest, and other preventative measures haven’t panned out in trials.

Investigators are looking for better predictors of preeclampsia; uterine artery blood flow is among the promising markers. However, it and other options are “expensive ventures” if you’re just going to end up in the same place, giving baby aspirin, Dr. Santillan said.

Dr. Santillan reported that he holds three patents; two on copeptin to predict preeclampsia and one on vasopressin receptor antagonists to treat it.

CHICAGO – It’s clear that there’s a dose-dependent relationship between hypertension in pregnancy and poor outcomes, but, even so, treatment usually doesn’t begin until women hit 160/105 mm Hg or higher, according to Mark Santillan, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology – maternal fetal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

That might soon change. The National Institutes of Health–funded CHAPS (Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy) trial is testing whether earlier intervention improves outcomes, and it hopes to define proper treatment targets, which are uncertain at this point. Results are expected as soon as 2020.

What’s already changed is that the old treatment standby – methyldopa – has fallen out of favor for labetalol and nifedipine, which have been shown to work better. “Sometimes, we will throw on hydrochlorothiazide after we max out our beta- and calcium channel blockers,” Dr. Santillan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 1;10:CD002252).

For severe hypertension, “most of the time we start off with IV hydralazine or IV labetalol” in the hospital. “You give a dose and check blood pressure in 10 or 20 minutes,” he said. If it hasn’t dropped, “give another dose until you reach your max dose.” When intravenous access is an issue, oral nifedipine is a good option (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;129[4]:e90-e95).

Delivery date is key; babies exposed to chronic hypertension are more likely to be stillborn. For hypertension without symptoms, delivery is at around 38 weeks. For mild preeclampsia – hypertension with only minor symptoms – it’s at 37 weeks.

In more severe cases – hypertension with pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and other problems – “the general gestalt is to stabilize and deliver when you can. See if you can get up to at least 34 weeks,” Dr. Santillan said. However, when women “have full-on HELLP syndrome [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count], we often just deliver [immediately] because there’s not a lot of stabilization” that can be done. “We give magnesium after delivery to help decrease the risk of seizure,” he added.

Guidelines still use 140/90 mm Hg to define hypertension in pregnancy. When that level is reached, “you don’t need proteinuria anymore to diagnose preeclampsia. You need to have hypertension and something that looks like HELLP,” such as impaired liver function or neurologic symptoms, he said. Onset before 34 weeks portends more severe disease.

Daily baby aspirin 81 mg is known to help prevent preeclampsia, if only a little bit, so anyone with a history of preeclampsia or twin pregnancy, chronic hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or autoimmune disease should automatically be put on aspirin prophylaxis. Women with two or more moderate risk factors – first pregnancy, obesity, preeclamptic family history, or aged 35 years or older – also should also get baby aspirin. Vitamin C, bed rest, and other preventative measures haven’t panned out in trials.

Investigators are looking for better predictors of preeclampsia; uterine artery blood flow is among the promising markers. However, it and other options are “expensive ventures” if you’re just going to end up in the same place, giving baby aspirin, Dr. Santillan said.

Dr. Santillan reported that he holds three patents; two on copeptin to predict preeclampsia and one on vasopressin receptor antagonists to treat it.

CHICAGO – It’s clear that there’s a dose-dependent relationship between hypertension in pregnancy and poor outcomes, but, even so, treatment usually doesn’t begin until women hit 160/105 mm Hg or higher, according to Mark Santillan, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology – maternal fetal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

That might soon change. The National Institutes of Health–funded CHAPS (Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy) trial is testing whether earlier intervention improves outcomes, and it hopes to define proper treatment targets, which are uncertain at this point. Results are expected as soon as 2020.

What’s already changed is that the old treatment standby – methyldopa – has fallen out of favor for labetalol and nifedipine, which have been shown to work better. “Sometimes, we will throw on hydrochlorothiazide after we max out our beta- and calcium channel blockers,” Dr. Santillan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 1;10:CD002252).

For severe hypertension, “most of the time we start off with IV hydralazine or IV labetalol” in the hospital. “You give a dose and check blood pressure in 10 or 20 minutes,” he said. If it hasn’t dropped, “give another dose until you reach your max dose.” When intravenous access is an issue, oral nifedipine is a good option (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;129[4]:e90-e95).

Delivery date is key; babies exposed to chronic hypertension are more likely to be stillborn. For hypertension without symptoms, delivery is at around 38 weeks. For mild preeclampsia – hypertension with only minor symptoms – it’s at 37 weeks.

In more severe cases – hypertension with pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and other problems – “the general gestalt is to stabilize and deliver when you can. See if you can get up to at least 34 weeks,” Dr. Santillan said. However, when women “have full-on HELLP syndrome [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count], we often just deliver [immediately] because there’s not a lot of stabilization” that can be done. “We give magnesium after delivery to help decrease the risk of seizure,” he added.

Guidelines still use 140/90 mm Hg to define hypertension in pregnancy. When that level is reached, “you don’t need proteinuria anymore to diagnose preeclampsia. You need to have hypertension and something that looks like HELLP,” such as impaired liver function or neurologic symptoms, he said. Onset before 34 weeks portends more severe disease.

Daily baby aspirin 81 mg is known to help prevent preeclampsia, if only a little bit, so anyone with a history of preeclampsia or twin pregnancy, chronic hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or autoimmune disease should automatically be put on aspirin prophylaxis. Women with two or more moderate risk factors – first pregnancy, obesity, preeclamptic family history, or aged 35 years or older – also should also get baby aspirin. Vitamin C, bed rest, and other preventative measures haven’t panned out in trials.

Investigators are looking for better predictors of preeclampsia; uterine artery blood flow is among the promising markers. However, it and other options are “expensive ventures” if you’re just going to end up in the same place, giving baby aspirin, Dr. Santillan said.

Dr. Santillan reported that he holds three patents; two on copeptin to predict preeclampsia and one on vasopressin receptor antagonists to treat it.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM JOINT HYPERTENSION 2018

ASH releases new VTE guidelines

The new guidelines, released on Nov. 27, contain more than 150 individual recommendations, including sections devoted to managing venous thromboembolism (VTE) during pregnancy and in pediatric patients. Guideline highlights cited by some of the writing-panel participants included a high reliance on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) agents as the preferred treatment for many patients, reliance on the D-dimer test to rule out VTE in patients with a low pretest probability of disease, and reliance on the 4Ts score to identify patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines took more than 3 years to develop, an effort that began in 2015.

An updated set of VTE guidelines were needed because clinicians now have a “greater understanding of risk factors” for VTE as well as having “more options available for treating VTE, including new medications,” Adam C. Cuker, MD, cochair of the guideline-writing group and a hematologist and thrombosis specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said during a webcast to unveil the new guidelines.

Prevention

For preventing VTE in hospitalized medical patients the guidelines recommended initial assessment of the patient’s risk for both VTE and bleeding. Patients with a high bleeding risk who need VTE prevention should preferentially receive mechanical prophylaxis, either compression stockings or pneumatic sleeves. But in patients with a high VTE risk and an “acceptable” bleeding risk, prophylaxis with an anticoagulant is preferred over mechanical measures, said Mary Cushman, MD, professor and medical director of the thrombosis and hemostasis program at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

For prevention of VTE in medical inpatients, LMWH is preferred over unfractionated heparin because of its once-daily dosing and fewer complications, said Dr. Cushman, a member of the writing group. The panel also endorsed LMWH over a direct-acting oral anticoagulant, both during hospitalization and following discharge. The guidelines for prevention in medical patients explicitly “recommended against” using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant “over other treatments” both for hospitalized medical patients and after discharge, and the guidelines further recommend against extended prophylaxis after discharge with any other anticoagulant.

Another important takeaway from the prevention section was a statement that combining both mechanical and medical prophylaxis was not needed for medical inpatients. And once patients are discharged, if they take a long air trip they have no need for compression stockings or aspirin if their risk for thrombosis is not elevated. People with a “substantially increased” thrombosis risk “may benefit” from compression stockings or treatment with LMWH, Dr. Cushman said.

Diagnosis

For diagnosis, Wendy Lim, MD, highlighted the need for first categorizing patients as having a low or high probability for VTE, a judgment that can aid the accuracy of the diagnosis and helps avoid unnecessary testing.

For patients with low pretest probability, the guidelines recommended the D-dimer test as the best first step. Further testing isn’t needed when the D-dimer is negative, noted Dr. Lim, a hematologist and professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The guidelines also recommended using ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) for imaging a pulmonary embolism over a CT scan, which uses more radiation. But V/Q scans are not ideal for assessing older patients or patients with lung disease, Dr. Lim cautioned.

Management

Management of VTE should occur, when feasible, through a specialized anticoagulation management service center, which can provide care that is best suited to the complexities of anticoagulation therapy. But it’s a level of care that many U.S. patients don’t currently receive and hence is an area ripe for growth, said Daniel M. Witt, PharmD, professor and vice-chair of pharmacotherapy at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The guidelines recommended against bridging therapy with LMWH for most patients who need to stop warfarin when undergoing an invasive procedure. The guidelines also called for “thoughtful” use of anticoagulant reversal agents and advised that patients who survive a major bleed while on anticoagulation should often resume the anticoagulant once they are stabilized.

For patients who develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the 4Ts score is the best way to make a more accurate diagnosis and boost the prospects for recovery, said Dr. Cuker (Blood. 2012 Nov 15;120[20]:4160-7). The guidelines cite several agents now available to treat this common complication, which affects about 1% of the 12 million Americans treated with heparin annually: argatroban, bivalirudin, danaparoid, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban.

ASH has a VTE website with links to detailed information for each of the guideline subcategories: prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, therapy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, VTE in pregnancy, and VTE in children. The website indicates that additional guidelines will soon be released on managing VTE in patients with cancer, in patients with thrombophilia, and for prophylaxis in surgical patients, as well as further information on treatment. A spokesperson for ASH said that these additional documents will post sometime in 2019.

At the time of the release, the guidelines panel published six articles in the journal Blood Advances that detailed the guidelines and their documentation.

The articles include prophylaxis of medical patients (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3198-225), diagnosis (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3226-56), anticoagulation therapy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3257-91), pediatrics (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3292-316), pregnancy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3317-59), and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3360-92).

Dr. Cushman, Dr. Lim, and Dr. Witt reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Cuker reported receiving research support from T2 Biosystems.

The new guidelines, released on Nov. 27, contain more than 150 individual recommendations, including sections devoted to managing venous thromboembolism (VTE) during pregnancy and in pediatric patients. Guideline highlights cited by some of the writing-panel participants included a high reliance on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) agents as the preferred treatment for many patients, reliance on the D-dimer test to rule out VTE in patients with a low pretest probability of disease, and reliance on the 4Ts score to identify patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines took more than 3 years to develop, an effort that began in 2015.

An updated set of VTE guidelines were needed because clinicians now have a “greater understanding of risk factors” for VTE as well as having “more options available for treating VTE, including new medications,” Adam C. Cuker, MD, cochair of the guideline-writing group and a hematologist and thrombosis specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said during a webcast to unveil the new guidelines.

Prevention

For preventing VTE in hospitalized medical patients the guidelines recommended initial assessment of the patient’s risk for both VTE and bleeding. Patients with a high bleeding risk who need VTE prevention should preferentially receive mechanical prophylaxis, either compression stockings or pneumatic sleeves. But in patients with a high VTE risk and an “acceptable” bleeding risk, prophylaxis with an anticoagulant is preferred over mechanical measures, said Mary Cushman, MD, professor and medical director of the thrombosis and hemostasis program at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

For prevention of VTE in medical inpatients, LMWH is preferred over unfractionated heparin because of its once-daily dosing and fewer complications, said Dr. Cushman, a member of the writing group. The panel also endorsed LMWH over a direct-acting oral anticoagulant, both during hospitalization and following discharge. The guidelines for prevention in medical patients explicitly “recommended against” using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant “over other treatments” both for hospitalized medical patients and after discharge, and the guidelines further recommend against extended prophylaxis after discharge with any other anticoagulant.

Another important takeaway from the prevention section was a statement that combining both mechanical and medical prophylaxis was not needed for medical inpatients. And once patients are discharged, if they take a long air trip they have no need for compression stockings or aspirin if their risk for thrombosis is not elevated. People with a “substantially increased” thrombosis risk “may benefit” from compression stockings or treatment with LMWH, Dr. Cushman said.

Diagnosis

For diagnosis, Wendy Lim, MD, highlighted the need for first categorizing patients as having a low or high probability for VTE, a judgment that can aid the accuracy of the diagnosis and helps avoid unnecessary testing.

For patients with low pretest probability, the guidelines recommended the D-dimer test as the best first step. Further testing isn’t needed when the D-dimer is negative, noted Dr. Lim, a hematologist and professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The guidelines also recommended using ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) for imaging a pulmonary embolism over a CT scan, which uses more radiation. But V/Q scans are not ideal for assessing older patients or patients with lung disease, Dr. Lim cautioned.

Management

Management of VTE should occur, when feasible, through a specialized anticoagulation management service center, which can provide care that is best suited to the complexities of anticoagulation therapy. But it’s a level of care that many U.S. patients don’t currently receive and hence is an area ripe for growth, said Daniel M. Witt, PharmD, professor and vice-chair of pharmacotherapy at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The guidelines recommended against bridging therapy with LMWH for most patients who need to stop warfarin when undergoing an invasive procedure. The guidelines also called for “thoughtful” use of anticoagulant reversal agents and advised that patients who survive a major bleed while on anticoagulation should often resume the anticoagulant once they are stabilized.

For patients who develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the 4Ts score is the best way to make a more accurate diagnosis and boost the prospects for recovery, said Dr. Cuker (Blood. 2012 Nov 15;120[20]:4160-7). The guidelines cite several agents now available to treat this common complication, which affects about 1% of the 12 million Americans treated with heparin annually: argatroban, bivalirudin, danaparoid, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban.

ASH has a VTE website with links to detailed information for each of the guideline subcategories: prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, therapy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, VTE in pregnancy, and VTE in children. The website indicates that additional guidelines will soon be released on managing VTE in patients with cancer, in patients with thrombophilia, and for prophylaxis in surgical patients, as well as further information on treatment. A spokesperson for ASH said that these additional documents will post sometime in 2019.

At the time of the release, the guidelines panel published six articles in the journal Blood Advances that detailed the guidelines and their documentation.

The articles include prophylaxis of medical patients (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3198-225), diagnosis (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3226-56), anticoagulation therapy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3257-91), pediatrics (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3292-316), pregnancy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3317-59), and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3360-92).

Dr. Cushman, Dr. Lim, and Dr. Witt reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Cuker reported receiving research support from T2 Biosystems.

The new guidelines, released on Nov. 27, contain more than 150 individual recommendations, including sections devoted to managing venous thromboembolism (VTE) during pregnancy and in pediatric patients. Guideline highlights cited by some of the writing-panel participants included a high reliance on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) agents as the preferred treatment for many patients, reliance on the D-dimer test to rule out VTE in patients with a low pretest probability of disease, and reliance on the 4Ts score to identify patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines took more than 3 years to develop, an effort that began in 2015.

An updated set of VTE guidelines were needed because clinicians now have a “greater understanding of risk factors” for VTE as well as having “more options available for treating VTE, including new medications,” Adam C. Cuker, MD, cochair of the guideline-writing group and a hematologist and thrombosis specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said during a webcast to unveil the new guidelines.

Prevention

For preventing VTE in hospitalized medical patients the guidelines recommended initial assessment of the patient’s risk for both VTE and bleeding. Patients with a high bleeding risk who need VTE prevention should preferentially receive mechanical prophylaxis, either compression stockings or pneumatic sleeves. But in patients with a high VTE risk and an “acceptable” bleeding risk, prophylaxis with an anticoagulant is preferred over mechanical measures, said Mary Cushman, MD, professor and medical director of the thrombosis and hemostasis program at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

For prevention of VTE in medical inpatients, LMWH is preferred over unfractionated heparin because of its once-daily dosing and fewer complications, said Dr. Cushman, a member of the writing group. The panel also endorsed LMWH over a direct-acting oral anticoagulant, both during hospitalization and following discharge. The guidelines for prevention in medical patients explicitly “recommended against” using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant “over other treatments” both for hospitalized medical patients and after discharge, and the guidelines further recommend against extended prophylaxis after discharge with any other anticoagulant.

Another important takeaway from the prevention section was a statement that combining both mechanical and medical prophylaxis was not needed for medical inpatients. And once patients are discharged, if they take a long air trip they have no need for compression stockings or aspirin if their risk for thrombosis is not elevated. People with a “substantially increased” thrombosis risk “may benefit” from compression stockings or treatment with LMWH, Dr. Cushman said.

Diagnosis

For diagnosis, Wendy Lim, MD, highlighted the need for first categorizing patients as having a low or high probability for VTE, a judgment that can aid the accuracy of the diagnosis and helps avoid unnecessary testing.

For patients with low pretest probability, the guidelines recommended the D-dimer test as the best first step. Further testing isn’t needed when the D-dimer is negative, noted Dr. Lim, a hematologist and professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The guidelines also recommended using ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) for imaging a pulmonary embolism over a CT scan, which uses more radiation. But V/Q scans are not ideal for assessing older patients or patients with lung disease, Dr. Lim cautioned.

Management

Management of VTE should occur, when feasible, through a specialized anticoagulation management service center, which can provide care that is best suited to the complexities of anticoagulation therapy. But it’s a level of care that many U.S. patients don’t currently receive and hence is an area ripe for growth, said Daniel M. Witt, PharmD, professor and vice-chair of pharmacotherapy at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The guidelines recommended against bridging therapy with LMWH for most patients who need to stop warfarin when undergoing an invasive procedure. The guidelines also called for “thoughtful” use of anticoagulant reversal agents and advised that patients who survive a major bleed while on anticoagulation should often resume the anticoagulant once they are stabilized.

For patients who develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the 4Ts score is the best way to make a more accurate diagnosis and boost the prospects for recovery, said Dr. Cuker (Blood. 2012 Nov 15;120[20]:4160-7). The guidelines cite several agents now available to treat this common complication, which affects about 1% of the 12 million Americans treated with heparin annually: argatroban, bivalirudin, danaparoid, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban.

ASH has a VTE website with links to detailed information for each of the guideline subcategories: prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, therapy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, VTE in pregnancy, and VTE in children. The website indicates that additional guidelines will soon be released on managing VTE in patients with cancer, in patients with thrombophilia, and for prophylaxis in surgical patients, as well as further information on treatment. A spokesperson for ASH said that these additional documents will post sometime in 2019.

At the time of the release, the guidelines panel published six articles in the journal Blood Advances that detailed the guidelines and their documentation.

The articles include prophylaxis of medical patients (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3198-225), diagnosis (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3226-56), anticoagulation therapy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3257-91), pediatrics (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3292-316), pregnancy (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3317-59), and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (Blood Advances. 2018 Nov 27;2[22]:3360-92).

Dr. Cushman, Dr. Lim, and Dr. Witt reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Cuker reported receiving research support from T2 Biosystems.

Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation reduces risk of preterm birth

Taking omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of preterm birth, and also may reduce the risk of babies born at a low birth weight and risk of requiring neonatal intensive care, according to a Cochrane review of 70 randomized controlled trials.

“There are not many options for preventing premature birth, so these new findings are very important for pregnant women, babies, and the health professionals who care for them,” Philippa Middleton, MPH, PhD, of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, in Adelaide, stated in a press release. “We don’t yet fully understand the causes of premature labor, so predicting and preventing early birth has always been a challenge. This is one of the reasons omega-3 supplementation in pregnancy is of such great interest to researchers around the world.”

Dr. Middleton and her colleagues performed a search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and identified 70 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) where 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), placebo, or no omega-3.

“Many pregnant women in the UK are already taking omega-3 supplements by personal choice rather than as a result of advice from health professionals,” Dr. Middleton said in the release. “It’s worth noting though that many supplements currently on the market don’t contain the optimal dose or type of omega-3 for preventing premature birth. Our review found the optimum dose was a daily supplement containing between 500 and 1,000 milligrams of long-chain omega-3 fats (containing at least 500 mg of DHA [docosahexaenoic acid]) starting at 12 weeks of pregnancy.”

In 26 RCTs (10,304 women), the risk of preterm birth under 37 weeks was 11% lower for women who took omega-3 LCPUFA compared with women who did not take omega-3 (relative risk, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.81-0.97), while the risk for preterm birth under 34 weeks in 9 RCTs (5,204 women) was 42% lower for women compared with women who did not take omega-3 (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.77).