User login

High-intensity statins may cut risk of joint replacement

TORONTO – comparing nearly 180,000 statin users with an equal number of propensity-matched nonusers, Jie Wei, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Less intensive statin therapy was associated with significantly less need for joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients, but not in those with osteoarthritis, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“In summary, statins may reduce the risk of joint replacement, especially when given at high strength and in people with rheumatoid arthritis,” said Dr. Wei, an epidemiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Central South University in Changsha, Hunan, China.

She was quick to note that this study can’t be considered the final, definitive word on the topic, since other investigators’ studies of the relationship between statin usage and joint replacement surgery for arthritis have yielded conflicting results. However, given the thoroughly established super-favorable risk/benefit ratio of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, the possibility of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial addressing the joint surgery issue is for ethical reasons a train that’s left the station.

Dr. Wei presented an analysis drawn from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink for the years 1989 through mid-2017. The initial sample included the medical records of 17.1 million patients, or 26% of the total U.K. population. From that massive pool, she and her coinvestigators zeroed in on 178,467 statin users and an equal number of non–statin-user controls under the care of 718 primary care physicians, with the pairs propensity score-matched on the basis of age, gender, locality, comorbid conditions, nonstatin medications, lifestyle factors, and duration of rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. The mean age of the matched pairs was 62 years, 52% were women, and the mean prospective follow-up was 6.5 years.

The use of high-intensity statin therapy – for example, atorvastatin at 40-80 mg/day or rosuvastatin (Crestor) at 20-40 mg/day – was independently associated with a 21% reduction in the risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for osteoarthritis and a 90% reduction for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers. Notably, joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis was roughly 25-fold more common than for rheumatoid arthritis.

Statin therapy overall, including the more widely prescribed low- and intermediate-intensity regimens, was associated with a 23% reduction in joint replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers, but had no significant impact on surgery for the osteoarthritis population.

A couple of distinguished American rheumatologists in the audience rose to voice reluctance about drawing broad conclusions from this study.

“Bias, as you’ve said yourself, is a bit of a concern,” said David T. Felson, MD, professor of medicine and public health and director of clinical epidemiology at Boston University.

He was troubled that the study design was such that anyone who filled as few as two statin prescriptions during the more than 6-year study period was categorized as a statin user. That, he said, muddies the waters. Does the database contain information on duration of statin therapy, and whether joint replacement surgery was more likely to occur when patients were on or off statin therapy? he asked.

It does, Dr. Wei replied, adding that she will take that suggestion for additional analysis back to her international team of coinvestigators.

“It seems to me,” said Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, “that the major risk of potential bias is that people who were provided high-intensity statins were prescribed that because they were at risk for or had cardiac disease.”

That high cardiovascular risk might have curbed orthopedic surgeons’ enthusiasm to operate. Thus, it would be helpful to learn whether patients who underwent joint replacement were less likely to have undergone coronary revascularization or other cardiac interventions than were those without joint replacement, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Dr. Wei agreed that confounding by indication is always a possibility in an observational study such as this. Identification of a plausible mechanism by which statins might reduce the risk of joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis – something that hasn’t happened yet – would help counter such concerns.

She noted that a separate recent analysis of the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink by other investigators concluded that statin therapy started up to 5 years following total hip or knee replacement was associated with a significantly reduced risk of revision arthroplasty. Moreover, the benefit was treatment duration-dependent: Patients on statin therapy for more than 5 years were 26% less likely to undergo revision arthroplasty than were those on a statin for less than 1 year (J Rheumatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180574).

On the other hand, Swedish investigators found that statin use wasn’t associated with a reduced risk of consultation or surgery for osteoarthritis in a pooled analysis of four cohort studies totaling more than 132,000 Swedes followed for 7.5 years (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Nov;25[11]:1804-13).

Dr. Wei reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders in Hunan, China, and several British universities.

SOURCE: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

TORONTO – comparing nearly 180,000 statin users with an equal number of propensity-matched nonusers, Jie Wei, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Less intensive statin therapy was associated with significantly less need for joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients, but not in those with osteoarthritis, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“In summary, statins may reduce the risk of joint replacement, especially when given at high strength and in people with rheumatoid arthritis,” said Dr. Wei, an epidemiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Central South University in Changsha, Hunan, China.

She was quick to note that this study can’t be considered the final, definitive word on the topic, since other investigators’ studies of the relationship between statin usage and joint replacement surgery for arthritis have yielded conflicting results. However, given the thoroughly established super-favorable risk/benefit ratio of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, the possibility of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial addressing the joint surgery issue is for ethical reasons a train that’s left the station.

Dr. Wei presented an analysis drawn from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink for the years 1989 through mid-2017. The initial sample included the medical records of 17.1 million patients, or 26% of the total U.K. population. From that massive pool, she and her coinvestigators zeroed in on 178,467 statin users and an equal number of non–statin-user controls under the care of 718 primary care physicians, with the pairs propensity score-matched on the basis of age, gender, locality, comorbid conditions, nonstatin medications, lifestyle factors, and duration of rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. The mean age of the matched pairs was 62 years, 52% were women, and the mean prospective follow-up was 6.5 years.

The use of high-intensity statin therapy – for example, atorvastatin at 40-80 mg/day or rosuvastatin (Crestor) at 20-40 mg/day – was independently associated with a 21% reduction in the risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for osteoarthritis and a 90% reduction for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers. Notably, joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis was roughly 25-fold more common than for rheumatoid arthritis.

Statin therapy overall, including the more widely prescribed low- and intermediate-intensity regimens, was associated with a 23% reduction in joint replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers, but had no significant impact on surgery for the osteoarthritis population.

A couple of distinguished American rheumatologists in the audience rose to voice reluctance about drawing broad conclusions from this study.

“Bias, as you’ve said yourself, is a bit of a concern,” said David T. Felson, MD, professor of medicine and public health and director of clinical epidemiology at Boston University.

He was troubled that the study design was such that anyone who filled as few as two statin prescriptions during the more than 6-year study period was categorized as a statin user. That, he said, muddies the waters. Does the database contain information on duration of statin therapy, and whether joint replacement surgery was more likely to occur when patients were on or off statin therapy? he asked.

It does, Dr. Wei replied, adding that she will take that suggestion for additional analysis back to her international team of coinvestigators.

“It seems to me,” said Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, “that the major risk of potential bias is that people who were provided high-intensity statins were prescribed that because they were at risk for or had cardiac disease.”

That high cardiovascular risk might have curbed orthopedic surgeons’ enthusiasm to operate. Thus, it would be helpful to learn whether patients who underwent joint replacement were less likely to have undergone coronary revascularization or other cardiac interventions than were those without joint replacement, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Dr. Wei agreed that confounding by indication is always a possibility in an observational study such as this. Identification of a plausible mechanism by which statins might reduce the risk of joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis – something that hasn’t happened yet – would help counter such concerns.

She noted that a separate recent analysis of the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink by other investigators concluded that statin therapy started up to 5 years following total hip or knee replacement was associated with a significantly reduced risk of revision arthroplasty. Moreover, the benefit was treatment duration-dependent: Patients on statin therapy for more than 5 years were 26% less likely to undergo revision arthroplasty than were those on a statin for less than 1 year (J Rheumatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180574).

On the other hand, Swedish investigators found that statin use wasn’t associated with a reduced risk of consultation or surgery for osteoarthritis in a pooled analysis of four cohort studies totaling more than 132,000 Swedes followed for 7.5 years (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Nov;25[11]:1804-13).

Dr. Wei reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders in Hunan, China, and several British universities.

SOURCE: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

TORONTO – comparing nearly 180,000 statin users with an equal number of propensity-matched nonusers, Jie Wei, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Less intensive statin therapy was associated with significantly less need for joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients, but not in those with osteoarthritis, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“In summary, statins may reduce the risk of joint replacement, especially when given at high strength and in people with rheumatoid arthritis,” said Dr. Wei, an epidemiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Central South University in Changsha, Hunan, China.

She was quick to note that this study can’t be considered the final, definitive word on the topic, since other investigators’ studies of the relationship between statin usage and joint replacement surgery for arthritis have yielded conflicting results. However, given the thoroughly established super-favorable risk/benefit ratio of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, the possibility of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial addressing the joint surgery issue is for ethical reasons a train that’s left the station.

Dr. Wei presented an analysis drawn from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink for the years 1989 through mid-2017. The initial sample included the medical records of 17.1 million patients, or 26% of the total U.K. population. From that massive pool, she and her coinvestigators zeroed in on 178,467 statin users and an equal number of non–statin-user controls under the care of 718 primary care physicians, with the pairs propensity score-matched on the basis of age, gender, locality, comorbid conditions, nonstatin medications, lifestyle factors, and duration of rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. The mean age of the matched pairs was 62 years, 52% were women, and the mean prospective follow-up was 6.5 years.

The use of high-intensity statin therapy – for example, atorvastatin at 40-80 mg/day or rosuvastatin (Crestor) at 20-40 mg/day – was independently associated with a 21% reduction in the risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for osteoarthritis and a 90% reduction for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers. Notably, joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis was roughly 25-fold more common than for rheumatoid arthritis.

Statin therapy overall, including the more widely prescribed low- and intermediate-intensity regimens, was associated with a 23% reduction in joint replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers, but had no significant impact on surgery for the osteoarthritis population.

A couple of distinguished American rheumatologists in the audience rose to voice reluctance about drawing broad conclusions from this study.

“Bias, as you’ve said yourself, is a bit of a concern,” said David T. Felson, MD, professor of medicine and public health and director of clinical epidemiology at Boston University.

He was troubled that the study design was such that anyone who filled as few as two statin prescriptions during the more than 6-year study period was categorized as a statin user. That, he said, muddies the waters. Does the database contain information on duration of statin therapy, and whether joint replacement surgery was more likely to occur when patients were on or off statin therapy? he asked.

It does, Dr. Wei replied, adding that she will take that suggestion for additional analysis back to her international team of coinvestigators.

“It seems to me,” said Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, “that the major risk of potential bias is that people who were provided high-intensity statins were prescribed that because they were at risk for or had cardiac disease.”

That high cardiovascular risk might have curbed orthopedic surgeons’ enthusiasm to operate. Thus, it would be helpful to learn whether patients who underwent joint replacement were less likely to have undergone coronary revascularization or other cardiac interventions than were those without joint replacement, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Dr. Wei agreed that confounding by indication is always a possibility in an observational study such as this. Identification of a plausible mechanism by which statins might reduce the risk of joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis – something that hasn’t happened yet – would help counter such concerns.

She noted that a separate recent analysis of the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink by other investigators concluded that statin therapy started up to 5 years following total hip or knee replacement was associated with a significantly reduced risk of revision arthroplasty. Moreover, the benefit was treatment duration-dependent: Patients on statin therapy for more than 5 years were 26% less likely to undergo revision arthroplasty than were those on a statin for less than 1 year (J Rheumatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180574).

On the other hand, Swedish investigators found that statin use wasn’t associated with a reduced risk of consultation or surgery for osteoarthritis in a pooled analysis of four cohort studies totaling more than 132,000 Swedes followed for 7.5 years (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Nov;25[11]:1804-13).

Dr. Wei reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders in Hunan, China, and several British universities.

SOURCE: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

Key clinical point: High-intensity statin therapy may reduce need for joint replacement in arthritis.

Major finding: The risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis was slashed by 90%, and by 21% for osteoarthritis.

Study details: This study included nearly 180,000 statin users propensity score-matched to an equal number of nonusers and prospectively followed for a mean of 6.5 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders at Central South University in Hunan, China, and by several British universities. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

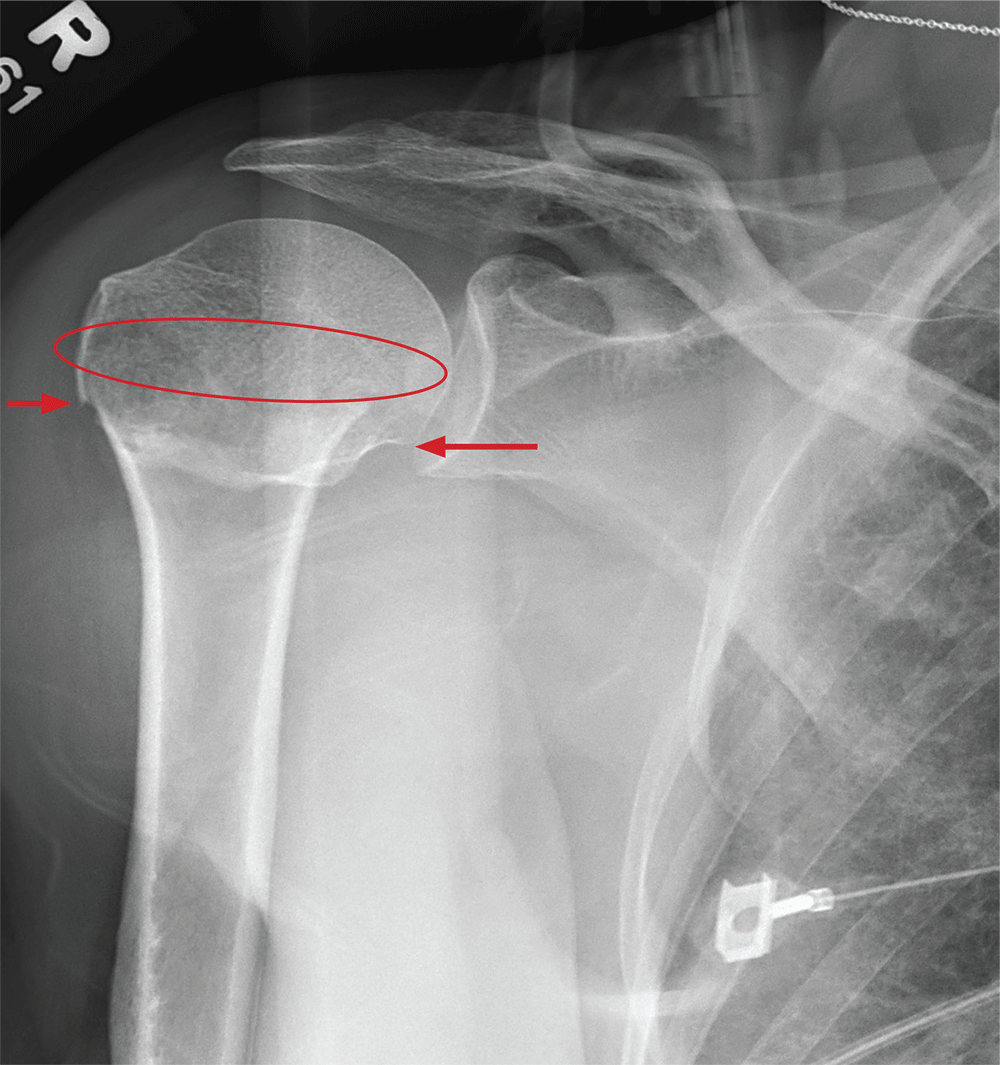

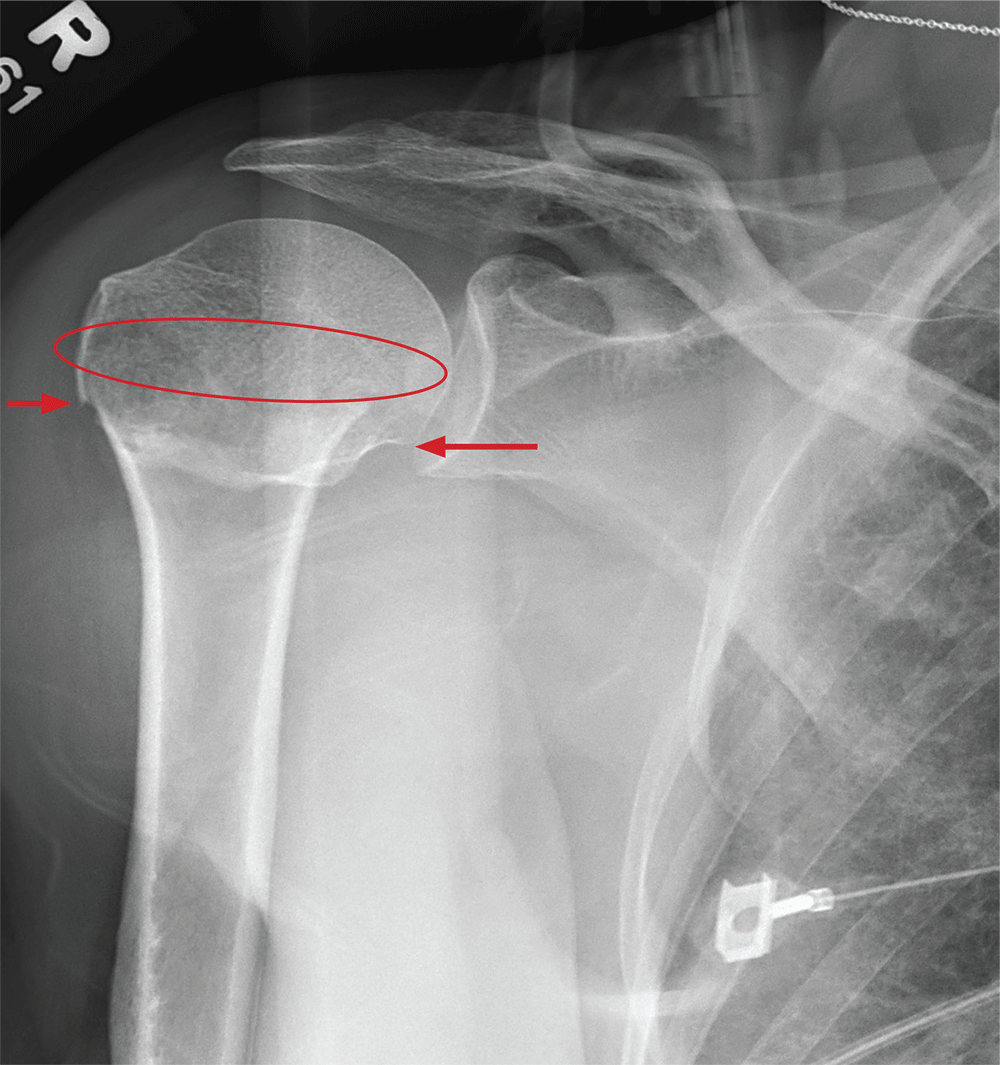

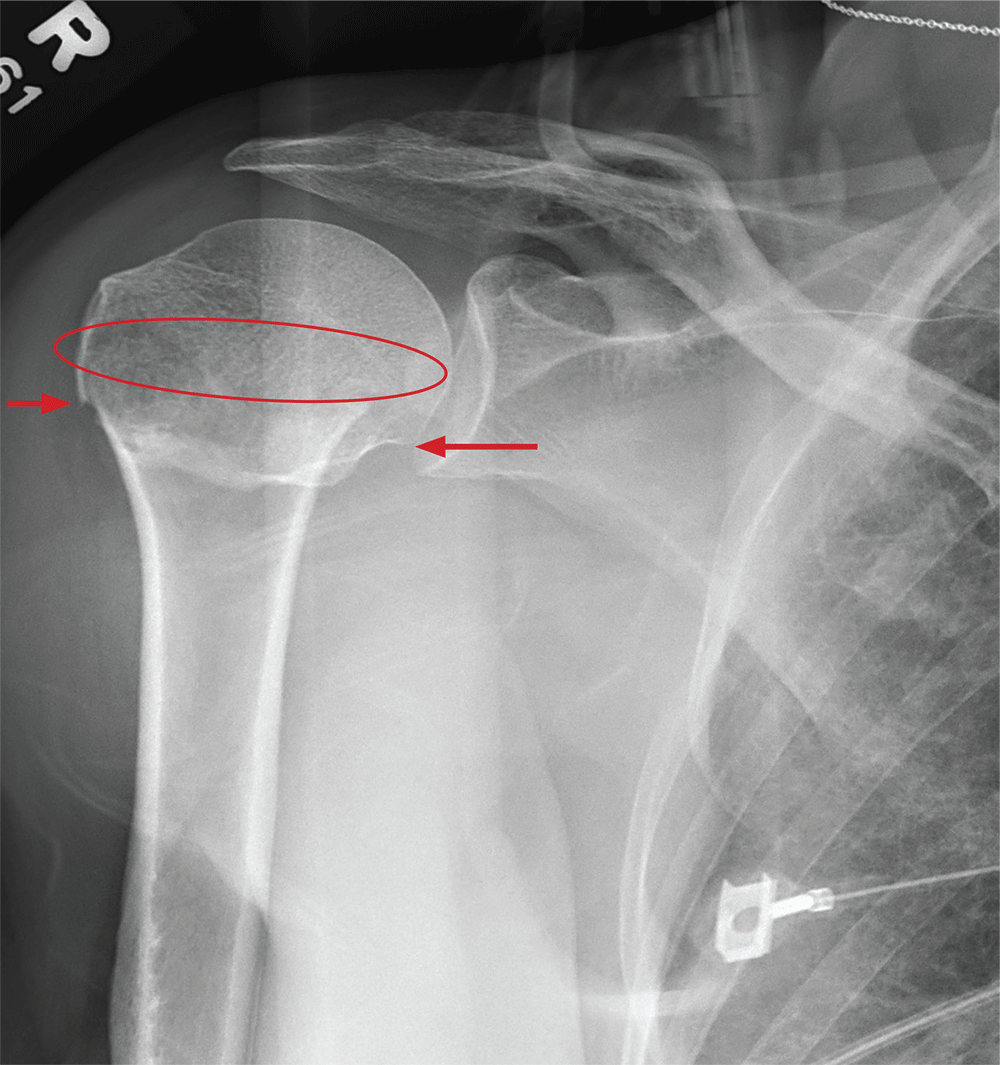

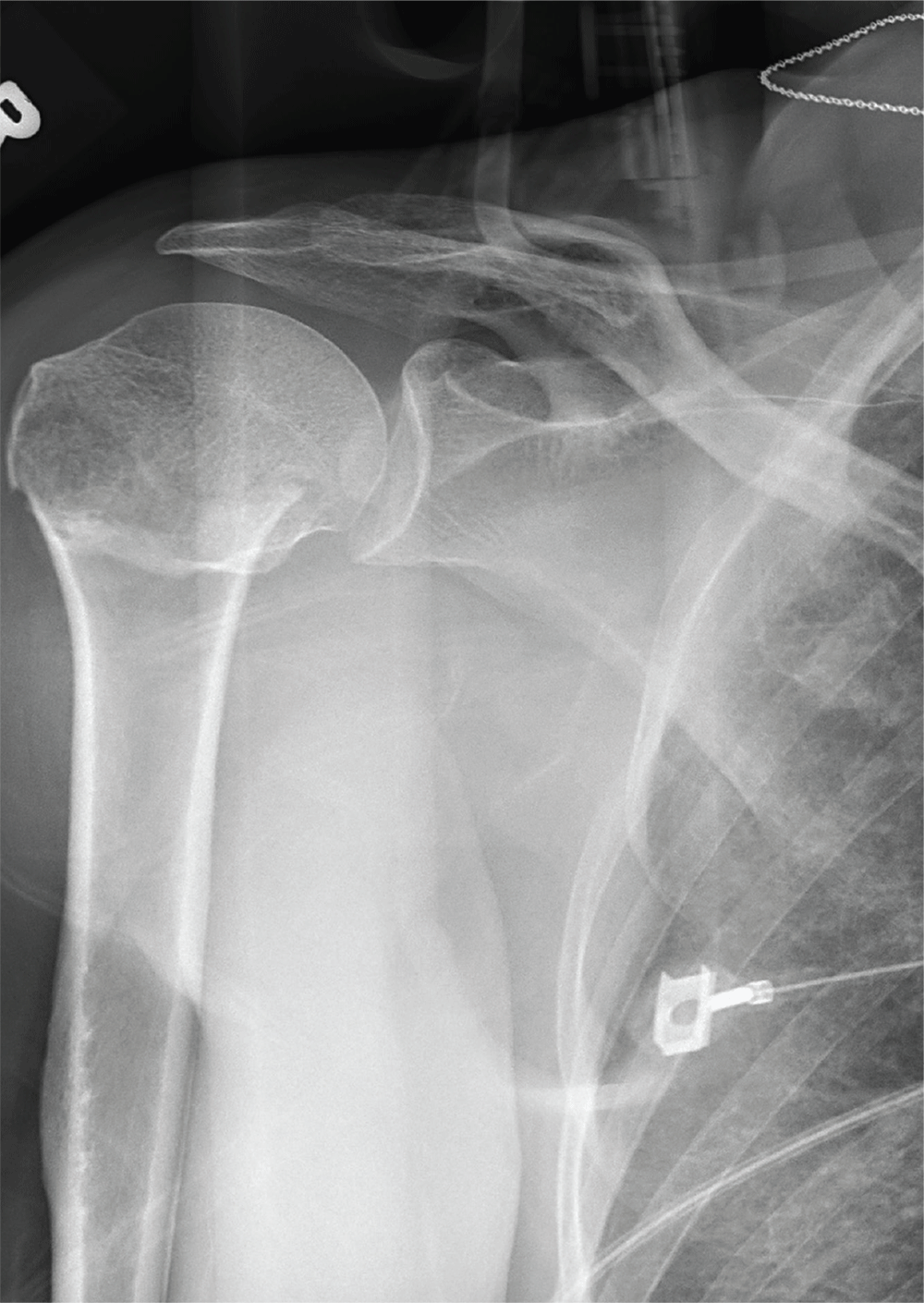

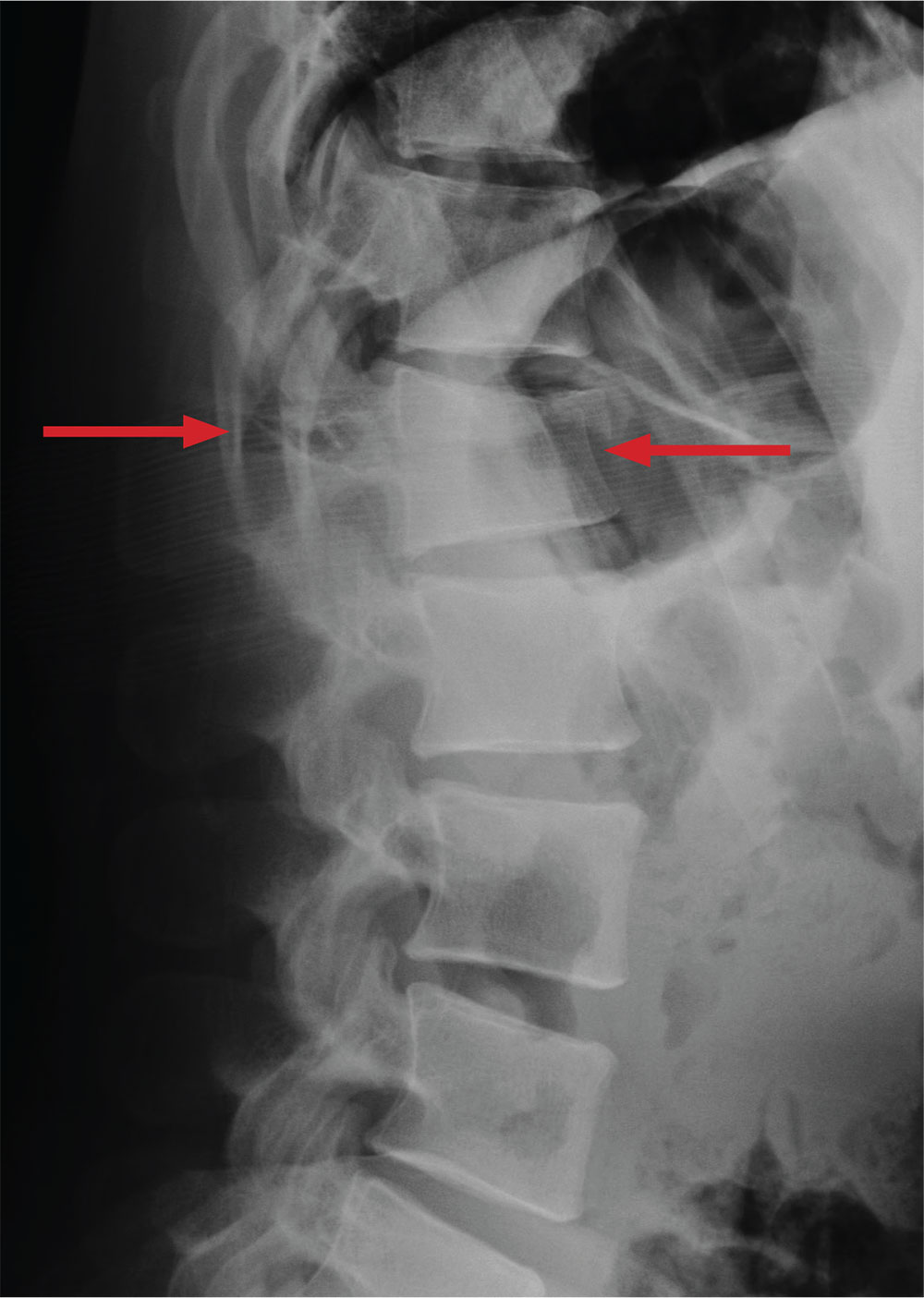

Give Her a Shoulder to Cry on

ANSWER

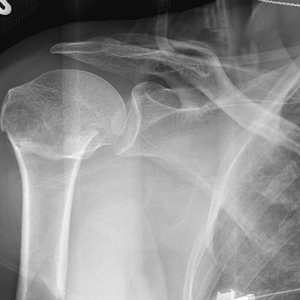

The radiograph demonstrates an acute horizontal fracture through the humeral neck. There is some slight lateral displacement of the fracture fragment.

The patient’s right arm was placed in a sling. Prompt orthopedic consultation was then obtained.

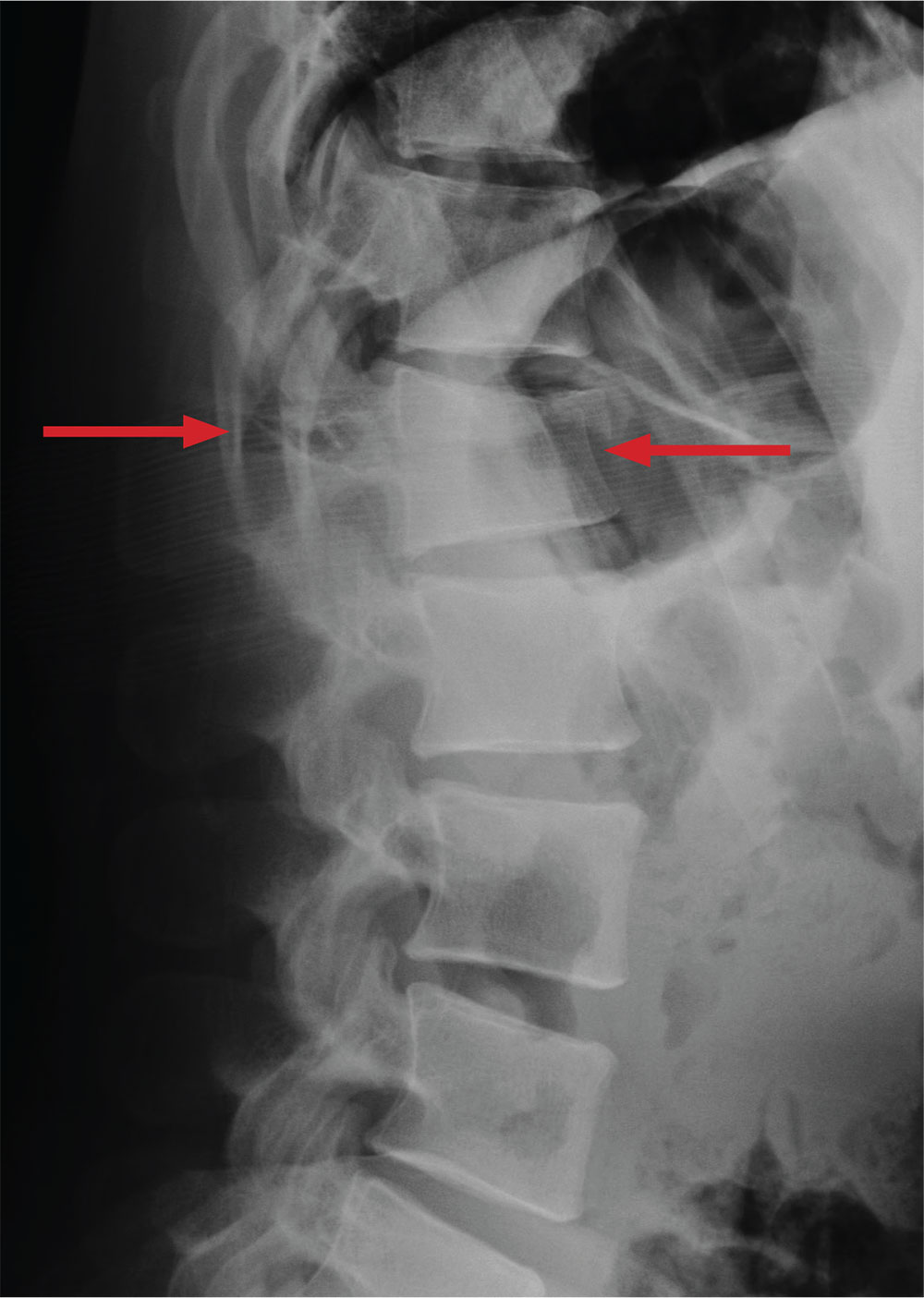

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates an acute horizontal fracture through the humeral neck. There is some slight lateral displacement of the fracture fragment.

The patient’s right arm was placed in a sling. Prompt orthopedic consultation was then obtained.

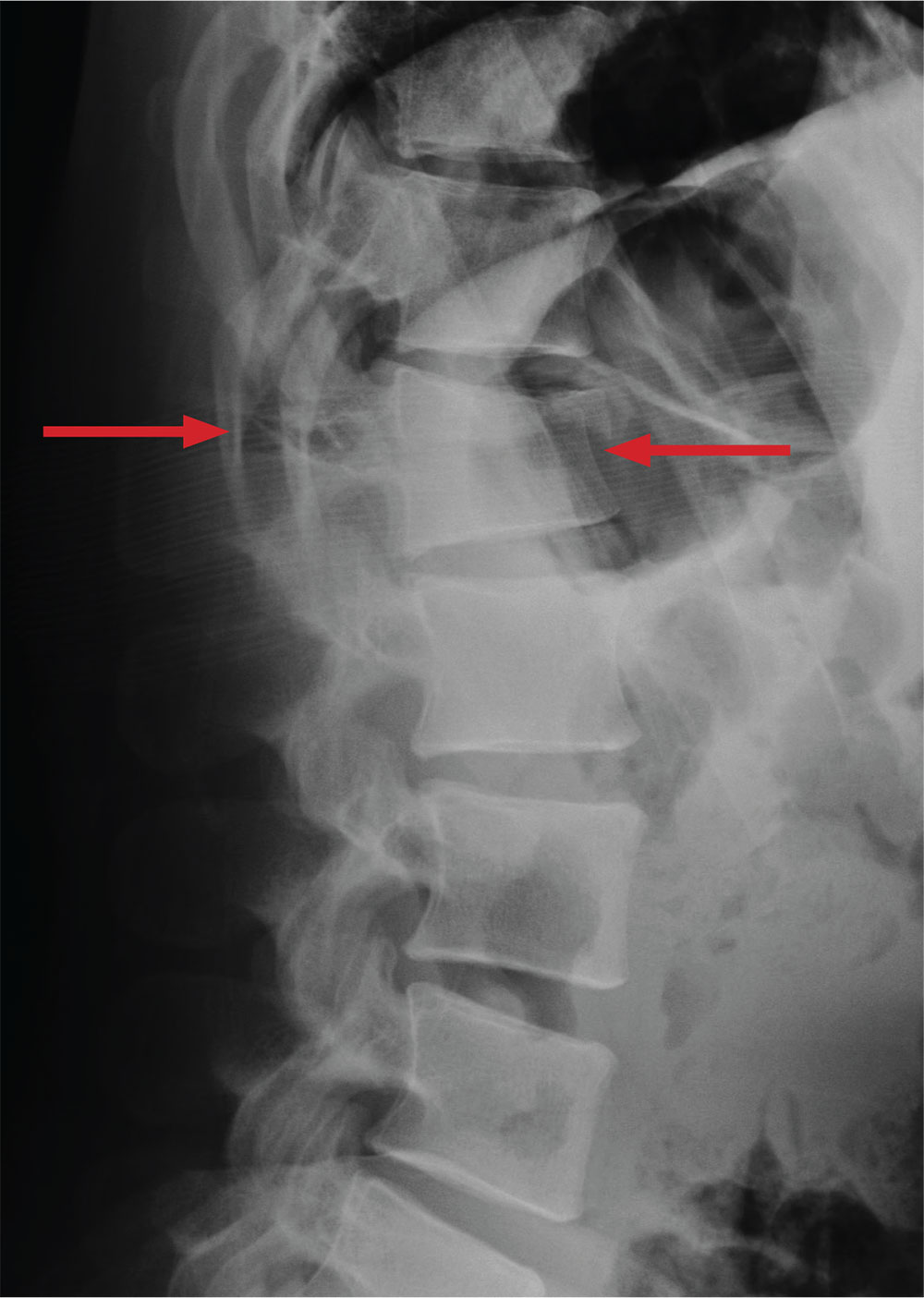

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates an acute horizontal fracture through the humeral neck. There is some slight lateral displacement of the fracture fragment.

The patient’s right arm was placed in a sling. Prompt orthopedic consultation was then obtained.

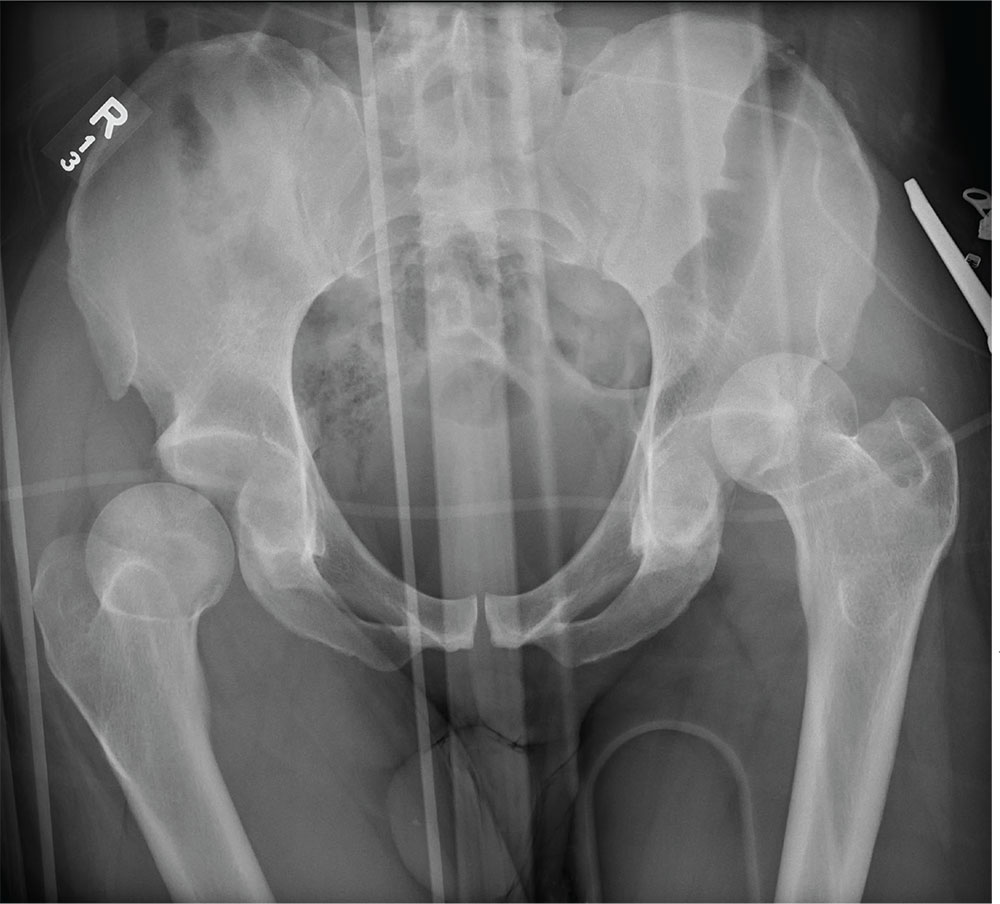

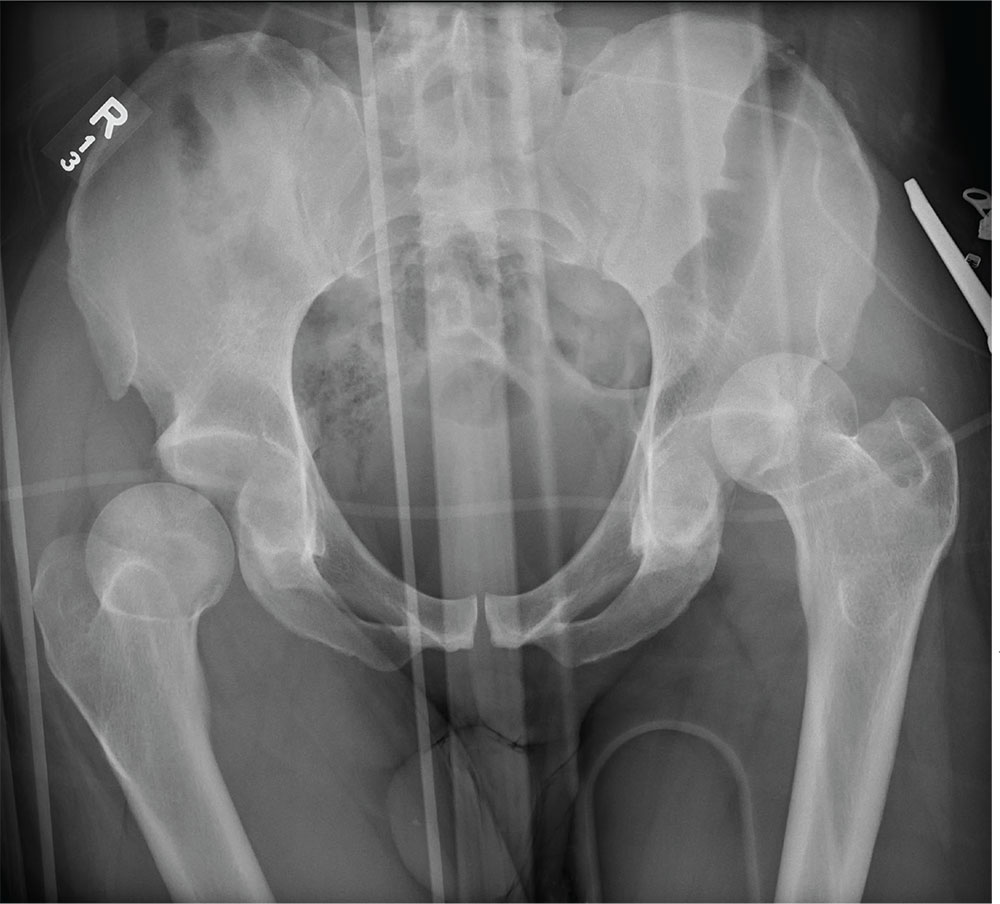

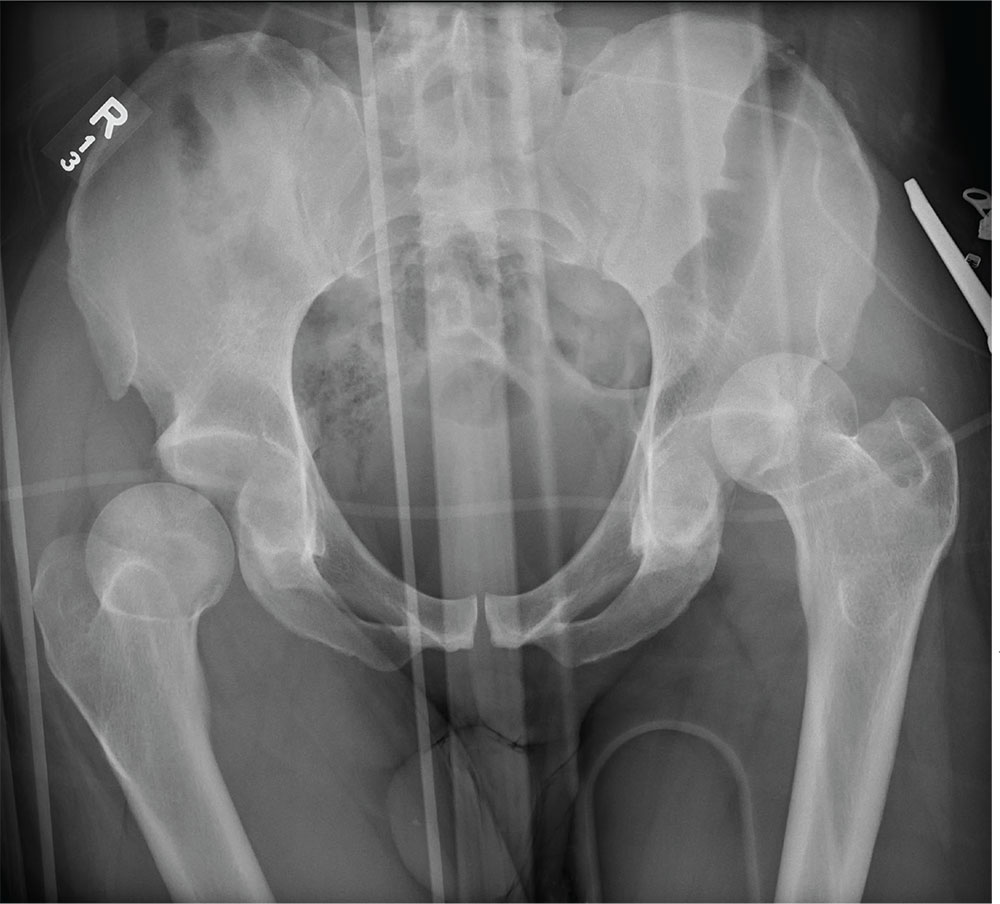

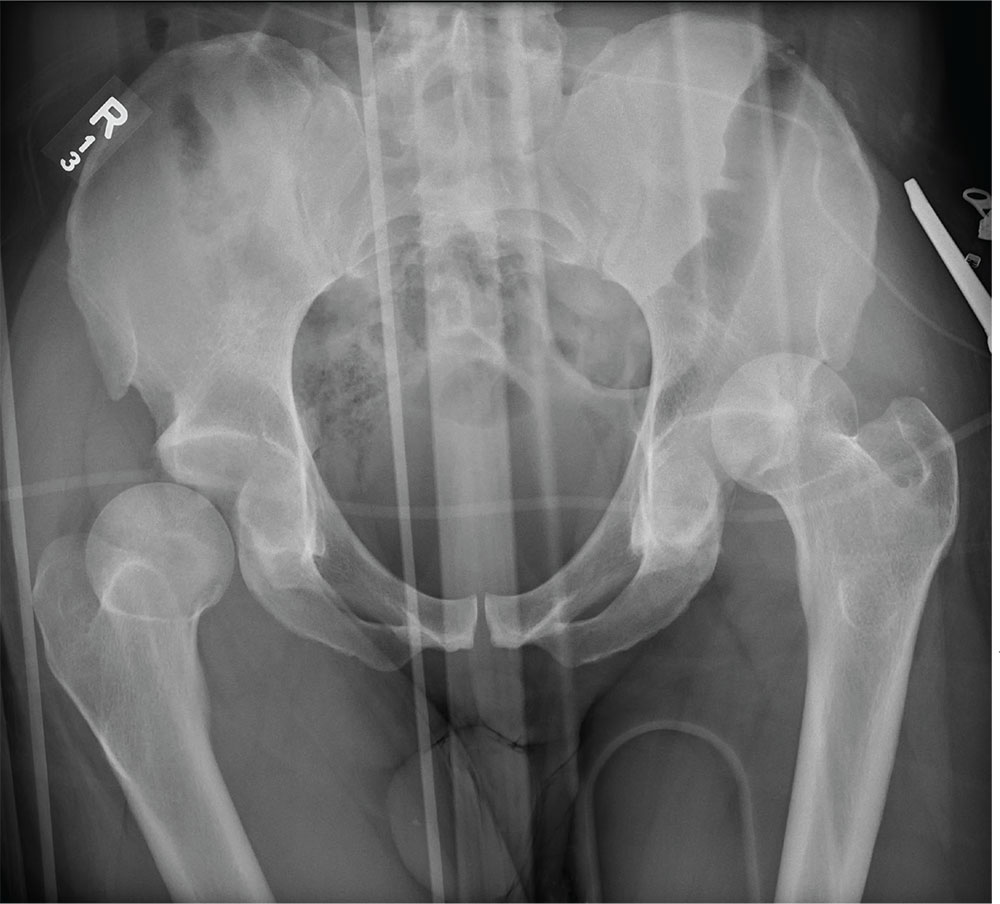

After a motor vehicle collision, a 70-year-old woman is brought to your emergency department by EMS personnel. She was a restrained driver in a vehicle crossing an intersection when she was broadsided by a tractor trailer traveling at high speed. Her airbags deployed, and she believes she briefly lost consciousness. Her biggest complaint is pain in her right shoulder.

Her medical history is significant for hypertension and hypothyroidism. On primary survey, you note an elderly woman who is in full cervical spine immobilization on a long backboard. Her Glasgow Coma Scale score is 15. She is in mild distress but has normal vital signs.

The patient has scattered abrasions and bruises on her body. Her right shoulder has mild to moderate tenderness to palpation and a decreased range of motion. Distally in that arm, she has good pulses and is neurovascularly intact.

You obtain a portable radiograph of the right shoulder (shown). What is your impression?

Good Notes Can Deter Litigation

At 11:15

While in the ED, the patient was examined and treated by a PA. At approximately 12:13

Given the lack of any positive pertinent findings, the PA irrigated the patient’s wounds and applied 1% lidocaine to all affected fingers so that pain would not mask any potential physical exam findings. He also used single-layer absorbable sutures to repair the injured digits. In addition, the PA tested the plaintiff for both distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion function and recorded normal results.

The PA discharged the patient from the ED at 5:56

The PA provided no further care or treatment to the patient following the visit to the hospital’s ED. However, the patient contended that he suffered an injury to the tendons of his right hand, which ultimately required several surgical procedures. He sued the hospital, the PA, the PA’s medical office, his supervising physician, and the physician who performed the later surgical procedures. The supervising physician and the surgeon were ultimately let out of the case by summary judgment motions. The hospital, which was named as a defendant under a respondeat superior theory, was also dismissed from the case when it was established that the PA was employed by his medical office and not by the hospital directly. The PA stipulated that he was within his course and scope of employment at the time he treated the plaintiff.

Continue to: Plaintiff's counsel contended...

Plaintiff’s counsel contended that the defendant PA was negligent in his examination and evaluation of the plaintiff’s digit lacerations and that he was negligent for failing to splint the plaintiff’s hand. Counsel also contended that the defendant was negligent for failing to refer the plaintiff to a hand surgeon (either directly or through the plaintiff’s primary care provider) and/or for failing to seek the assistance of his supervising physician, who was on site at the hospital’s ED and available for consultation.

Defense counsel argued that the defendant met the applicable standard of care at all times, in all aspects of his visit with the plaintiff in the early morning hours of September 1, 2014, and that there was nothing that he either did or did not do that was a substantial factor in causing the plaintiff’s alleged injuries and damages. The defendant claimed that upon his arrival at the patient’s bedside, the plaintiff verbally indicated to him that he could move his fingers (extension and flexion). He also claimed that he visualized the plaintiff moving his fingers while they were wrapped in the dressing that the plaintiff had placed on himself after the injury-producing event. However, the plaintiff disputed the defendant’s claim, denying ever being asked to extend and flex his fingers. The plaintiff also claimed that he never was able to make a full fist with his fingers on the night in question while in the ED, either by way of passive or active flexion.

Defense counsel noted that the defendant’s dictated ED note stated that the range of motion of all the plaintiff’s phalanges were normal, with no deficits, at all times while in the ED. The defendant testified about how he tested and evaluated the plaintiff’s DIP function. He also testified that he had the plaintiff lay his hand on the table, palm side up, and then laid his own hand across the plaintiff’s hand so as to isolate the DIP joint on each finger. He explained that he then had the plaintiff flex his fingers, which allowed him to determine whether there had been any kind of injury to the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (responsible for DIP function in the hand). The defendant claimed that he did the test for all the lacerated fingers and characterized them as active (as opposed to passive) flexion. Thus, he claimed that his physical exam findings were that the plaintiff had full range of motion (ROM) intact following the DIP function testing, which helped him conclude that the plaintiff did not have completely lacerated tendons as of that visit.

The defendant further explained that if the tendons were completely lacerated, the plaintiff would have had nonexistent DIP functioning on examination. The defendant testified that if he suspected a tendon laceration in a patient such as the plaintiff, his practice would be to notify his supervising physician in the ED and then either refer the patient to a primary care provider for an orthopedic hand surgeon referral or directly refer the patient to an orthopedic hand surgeon. He claimed that he took no such actions because there was no indication, from his perspective, that the plaintiff had suffered any tendon damage based on his physical exam findings, the plaintiff’s ability to make a fist, and the x-ray results.

Continue to: VERDICT

VERDICT

After a 5-day trial and 7 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the defendants.

COMMENTARY

As human beings, we do a lot with our hands. They are vulnerable to injury, and misdiagnosis may result in life-altering debility. The impact is even greater when one’s livelihood requires fine dexterity. Thus, tendon lacerations are relatively common and must be managed properly.

In this case, we are told that the PA documented in his notes that the plaintiff had range of motion in all phalanges and no deficits. We are also told the defendant testified regarding his procedure for hand examination. But we are not told that his note included the details of his exam—and by inference, we have reason to suspect it did not.

You might think, “The jury found in favor of the defense, so why does this matter?” Because a well-documented chart may prevent liability.

If you wish to avoid lawsuits, it is helpful to understand how they originate: An aggrieved patient contacts a plaintiff’s lawyer, insists he or she has been wronged, and asks the lawyer to take the case. Often faced with the ticking clock of statute of limitations (the absolute deadline to file), plaintiff’s counsel will review whatever records are available (which may not be all of them), looking for perceived deficiencies of care. The case may also be reviewed by a medical professional (generally a physician) prior to filing; some states require an affidavit of merit—an attestation that there is just cause to bring the action.

Whether reviewed only by plaintiff’s counsel or with the aid of an expert, a well-documented medical record may prevent a case from being filed. Medical malpractice cases are a huge gamble for plaintiff firms: They are expensive, time consuming, difficult to litigate, document heavy, and technically complex—falling outside the experience of most lawyers. They are also less likely than other cases to be settled, thanks to National Practitioner Data Bank recording requirements and (in several states) automatic medical board inquiry for potential adverse action against a medical or nursing professional following settlement. Clinicians will often fight tooth and nail to avoid an adverse recording, hospital credentialing woes, and state investigation. A medical malpractice case can be a trap for both the clinician and the plaintiff’s attorney stuck with a bad case.

Continue to: In the early stages...

In the early stages of potential litigation, before a case is filed in court, do yourself a favor: Help plaintiff’s counsel realize it will be a losing case. You actually start the process much earlier, by conducting the proper exam and documenting lavishly. This is particularly important with specialty exams, such as the hand exam in this case.

Here, simply noting “positive ROM and distal CSM [circulation, sensation, and motion] intact” is inadequate. Why? Because it is a conclusion, not evidence of the specialty examination that was diligently performed. The mechanism of injury and initial presentation roused the clinician’s suspicions sufficiently to conduct a thorough hand examination—but the mechanics of the exam were not included, only conclusions. The trouble is, those conclusions may have been based on sound medical evidence or they may have been hastily and improvidently drawn. A plaintiff’s firm deciding whether to take this case doesn’t know but will bet on the latter.

The clinician testified he performed a detailed and thorough examination of the plaintiff’s hand. Had plaintiff’s counsel been confronted with the full details of the exam—which showed the defendant PA tested all the PIPs and DIPs by isolating each finger—early on, this case may never have been filed. Thus, conduct and document specialty exams fully. If you need a cheat sheet for exams you don’t do often, use one—that is still solid practice. If you don’t do many pelvic exams or mental status exams, make sure you aren’t missing anything. Practicing medicine is an open-book exam; if you need materials, use them.

Good documentation leads to good defense, and any good defense lawyer will recommend the Jerry Maguire rule: “Help me help you.” Solid records make a case easier to defend and win at all phases of litigation. Of course, this is not a universal cure that will prevent all lawsuits. But even if the case is filed, the strength of your records may have convinced stronger, more capable medical malpractice firms to turn it down. This is something of value: It is “you helping you” and potent proof that your human head weighs more than 8 lb.

IN SUMMARY

A well-documented chart may prevent liability by showcasing the strength of your care and preventing no-win lawsuits from being filed. Help the plaintiff’s attorney realize, early on, that he or she is facing a costly uphill battle. The key word is early, when the medical records are first reviewed—not 18 months later, when the attorney hears your testimony at deposition and realizes that he or she has invested time and sweat in a case only to learn that your care was fabulous. Showcase that fabulous care early and short circuit the whole process by detailing the substance of a key exam (not just conclusions) in the record. Detailed notes may spare you from a visit by a sheriff you don’t know holding papers you don’t want.

At 11:15

While in the ED, the patient was examined and treated by a PA. At approximately 12:13

Given the lack of any positive pertinent findings, the PA irrigated the patient’s wounds and applied 1% lidocaine to all affected fingers so that pain would not mask any potential physical exam findings. He also used single-layer absorbable sutures to repair the injured digits. In addition, the PA tested the plaintiff for both distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion function and recorded normal results.

The PA discharged the patient from the ED at 5:56

The PA provided no further care or treatment to the patient following the visit to the hospital’s ED. However, the patient contended that he suffered an injury to the tendons of his right hand, which ultimately required several surgical procedures. He sued the hospital, the PA, the PA’s medical office, his supervising physician, and the physician who performed the later surgical procedures. The supervising physician and the surgeon were ultimately let out of the case by summary judgment motions. The hospital, which was named as a defendant under a respondeat superior theory, was also dismissed from the case when it was established that the PA was employed by his medical office and not by the hospital directly. The PA stipulated that he was within his course and scope of employment at the time he treated the plaintiff.

Continue to: Plaintiff's counsel contended...

Plaintiff’s counsel contended that the defendant PA was negligent in his examination and evaluation of the plaintiff’s digit lacerations and that he was negligent for failing to splint the plaintiff’s hand. Counsel also contended that the defendant was negligent for failing to refer the plaintiff to a hand surgeon (either directly or through the plaintiff’s primary care provider) and/or for failing to seek the assistance of his supervising physician, who was on site at the hospital’s ED and available for consultation.

Defense counsel argued that the defendant met the applicable standard of care at all times, in all aspects of his visit with the plaintiff in the early morning hours of September 1, 2014, and that there was nothing that he either did or did not do that was a substantial factor in causing the plaintiff’s alleged injuries and damages. The defendant claimed that upon his arrival at the patient’s bedside, the plaintiff verbally indicated to him that he could move his fingers (extension and flexion). He also claimed that he visualized the plaintiff moving his fingers while they were wrapped in the dressing that the plaintiff had placed on himself after the injury-producing event. However, the plaintiff disputed the defendant’s claim, denying ever being asked to extend and flex his fingers. The plaintiff also claimed that he never was able to make a full fist with his fingers on the night in question while in the ED, either by way of passive or active flexion.

Defense counsel noted that the defendant’s dictated ED note stated that the range of motion of all the plaintiff’s phalanges were normal, with no deficits, at all times while in the ED. The defendant testified about how he tested and evaluated the plaintiff’s DIP function. He also testified that he had the plaintiff lay his hand on the table, palm side up, and then laid his own hand across the plaintiff’s hand so as to isolate the DIP joint on each finger. He explained that he then had the plaintiff flex his fingers, which allowed him to determine whether there had been any kind of injury to the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (responsible for DIP function in the hand). The defendant claimed that he did the test for all the lacerated fingers and characterized them as active (as opposed to passive) flexion. Thus, he claimed that his physical exam findings were that the plaintiff had full range of motion (ROM) intact following the DIP function testing, which helped him conclude that the plaintiff did not have completely lacerated tendons as of that visit.

The defendant further explained that if the tendons were completely lacerated, the plaintiff would have had nonexistent DIP functioning on examination. The defendant testified that if he suspected a tendon laceration in a patient such as the plaintiff, his practice would be to notify his supervising physician in the ED and then either refer the patient to a primary care provider for an orthopedic hand surgeon referral or directly refer the patient to an orthopedic hand surgeon. He claimed that he took no such actions because there was no indication, from his perspective, that the plaintiff had suffered any tendon damage based on his physical exam findings, the plaintiff’s ability to make a fist, and the x-ray results.

Continue to: VERDICT

VERDICT

After a 5-day trial and 7 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the defendants.

COMMENTARY

As human beings, we do a lot with our hands. They are vulnerable to injury, and misdiagnosis may result in life-altering debility. The impact is even greater when one’s livelihood requires fine dexterity. Thus, tendon lacerations are relatively common and must be managed properly.

In this case, we are told that the PA documented in his notes that the plaintiff had range of motion in all phalanges and no deficits. We are also told the defendant testified regarding his procedure for hand examination. But we are not told that his note included the details of his exam—and by inference, we have reason to suspect it did not.

You might think, “The jury found in favor of the defense, so why does this matter?” Because a well-documented chart may prevent liability.

If you wish to avoid lawsuits, it is helpful to understand how they originate: An aggrieved patient contacts a plaintiff’s lawyer, insists he or she has been wronged, and asks the lawyer to take the case. Often faced with the ticking clock of statute of limitations (the absolute deadline to file), plaintiff’s counsel will review whatever records are available (which may not be all of them), looking for perceived deficiencies of care. The case may also be reviewed by a medical professional (generally a physician) prior to filing; some states require an affidavit of merit—an attestation that there is just cause to bring the action.

Whether reviewed only by plaintiff’s counsel or with the aid of an expert, a well-documented medical record may prevent a case from being filed. Medical malpractice cases are a huge gamble for plaintiff firms: They are expensive, time consuming, difficult to litigate, document heavy, and technically complex—falling outside the experience of most lawyers. They are also less likely than other cases to be settled, thanks to National Practitioner Data Bank recording requirements and (in several states) automatic medical board inquiry for potential adverse action against a medical or nursing professional following settlement. Clinicians will often fight tooth and nail to avoid an adverse recording, hospital credentialing woes, and state investigation. A medical malpractice case can be a trap for both the clinician and the plaintiff’s attorney stuck with a bad case.

Continue to: In the early stages...

In the early stages of potential litigation, before a case is filed in court, do yourself a favor: Help plaintiff’s counsel realize it will be a losing case. You actually start the process much earlier, by conducting the proper exam and documenting lavishly. This is particularly important with specialty exams, such as the hand exam in this case.

Here, simply noting “positive ROM and distal CSM [circulation, sensation, and motion] intact” is inadequate. Why? Because it is a conclusion, not evidence of the specialty examination that was diligently performed. The mechanism of injury and initial presentation roused the clinician’s suspicions sufficiently to conduct a thorough hand examination—but the mechanics of the exam were not included, only conclusions. The trouble is, those conclusions may have been based on sound medical evidence or they may have been hastily and improvidently drawn. A plaintiff’s firm deciding whether to take this case doesn’t know but will bet on the latter.

The clinician testified he performed a detailed and thorough examination of the plaintiff’s hand. Had plaintiff’s counsel been confronted with the full details of the exam—which showed the defendant PA tested all the PIPs and DIPs by isolating each finger—early on, this case may never have been filed. Thus, conduct and document specialty exams fully. If you need a cheat sheet for exams you don’t do often, use one—that is still solid practice. If you don’t do many pelvic exams or mental status exams, make sure you aren’t missing anything. Practicing medicine is an open-book exam; if you need materials, use them.

Good documentation leads to good defense, and any good defense lawyer will recommend the Jerry Maguire rule: “Help me help you.” Solid records make a case easier to defend and win at all phases of litigation. Of course, this is not a universal cure that will prevent all lawsuits. But even if the case is filed, the strength of your records may have convinced stronger, more capable medical malpractice firms to turn it down. This is something of value: It is “you helping you” and potent proof that your human head weighs more than 8 lb.

IN SUMMARY

A well-documented chart may prevent liability by showcasing the strength of your care and preventing no-win lawsuits from being filed. Help the plaintiff’s attorney realize, early on, that he or she is facing a costly uphill battle. The key word is early, when the medical records are first reviewed—not 18 months later, when the attorney hears your testimony at deposition and realizes that he or she has invested time and sweat in a case only to learn that your care was fabulous. Showcase that fabulous care early and short circuit the whole process by detailing the substance of a key exam (not just conclusions) in the record. Detailed notes may spare you from a visit by a sheriff you don’t know holding papers you don’t want.

At 11:15

While in the ED, the patient was examined and treated by a PA. At approximately 12:13

Given the lack of any positive pertinent findings, the PA irrigated the patient’s wounds and applied 1% lidocaine to all affected fingers so that pain would not mask any potential physical exam findings. He also used single-layer absorbable sutures to repair the injured digits. In addition, the PA tested the plaintiff for both distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion function and recorded normal results.

The PA discharged the patient from the ED at 5:56

The PA provided no further care or treatment to the patient following the visit to the hospital’s ED. However, the patient contended that he suffered an injury to the tendons of his right hand, which ultimately required several surgical procedures. He sued the hospital, the PA, the PA’s medical office, his supervising physician, and the physician who performed the later surgical procedures. The supervising physician and the surgeon were ultimately let out of the case by summary judgment motions. The hospital, which was named as a defendant under a respondeat superior theory, was also dismissed from the case when it was established that the PA was employed by his medical office and not by the hospital directly. The PA stipulated that he was within his course and scope of employment at the time he treated the plaintiff.

Continue to: Plaintiff's counsel contended...

Plaintiff’s counsel contended that the defendant PA was negligent in his examination and evaluation of the plaintiff’s digit lacerations and that he was negligent for failing to splint the plaintiff’s hand. Counsel also contended that the defendant was negligent for failing to refer the plaintiff to a hand surgeon (either directly or through the plaintiff’s primary care provider) and/or for failing to seek the assistance of his supervising physician, who was on site at the hospital’s ED and available for consultation.

Defense counsel argued that the defendant met the applicable standard of care at all times, in all aspects of his visit with the plaintiff in the early morning hours of September 1, 2014, and that there was nothing that he either did or did not do that was a substantial factor in causing the plaintiff’s alleged injuries and damages. The defendant claimed that upon his arrival at the patient’s bedside, the plaintiff verbally indicated to him that he could move his fingers (extension and flexion). He also claimed that he visualized the plaintiff moving his fingers while they were wrapped in the dressing that the plaintiff had placed on himself after the injury-producing event. However, the plaintiff disputed the defendant’s claim, denying ever being asked to extend and flex his fingers. The plaintiff also claimed that he never was able to make a full fist with his fingers on the night in question while in the ED, either by way of passive or active flexion.

Defense counsel noted that the defendant’s dictated ED note stated that the range of motion of all the plaintiff’s phalanges were normal, with no deficits, at all times while in the ED. The defendant testified about how he tested and evaluated the plaintiff’s DIP function. He also testified that he had the plaintiff lay his hand on the table, palm side up, and then laid his own hand across the plaintiff’s hand so as to isolate the DIP joint on each finger. He explained that he then had the plaintiff flex his fingers, which allowed him to determine whether there had been any kind of injury to the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (responsible for DIP function in the hand). The defendant claimed that he did the test for all the lacerated fingers and characterized them as active (as opposed to passive) flexion. Thus, he claimed that his physical exam findings were that the plaintiff had full range of motion (ROM) intact following the DIP function testing, which helped him conclude that the plaintiff did not have completely lacerated tendons as of that visit.

The defendant further explained that if the tendons were completely lacerated, the plaintiff would have had nonexistent DIP functioning on examination. The defendant testified that if he suspected a tendon laceration in a patient such as the plaintiff, his practice would be to notify his supervising physician in the ED and then either refer the patient to a primary care provider for an orthopedic hand surgeon referral or directly refer the patient to an orthopedic hand surgeon. He claimed that he took no such actions because there was no indication, from his perspective, that the plaintiff had suffered any tendon damage based on his physical exam findings, the plaintiff’s ability to make a fist, and the x-ray results.

Continue to: VERDICT

VERDICT

After a 5-day trial and 7 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the defendants.

COMMENTARY

As human beings, we do a lot with our hands. They are vulnerable to injury, and misdiagnosis may result in life-altering debility. The impact is even greater when one’s livelihood requires fine dexterity. Thus, tendon lacerations are relatively common and must be managed properly.

In this case, we are told that the PA documented in his notes that the plaintiff had range of motion in all phalanges and no deficits. We are also told the defendant testified regarding his procedure for hand examination. But we are not told that his note included the details of his exam—and by inference, we have reason to suspect it did not.

You might think, “The jury found in favor of the defense, so why does this matter?” Because a well-documented chart may prevent liability.

If you wish to avoid lawsuits, it is helpful to understand how they originate: An aggrieved patient contacts a plaintiff’s lawyer, insists he or she has been wronged, and asks the lawyer to take the case. Often faced with the ticking clock of statute of limitations (the absolute deadline to file), plaintiff’s counsel will review whatever records are available (which may not be all of them), looking for perceived deficiencies of care. The case may also be reviewed by a medical professional (generally a physician) prior to filing; some states require an affidavit of merit—an attestation that there is just cause to bring the action.

Whether reviewed only by plaintiff’s counsel or with the aid of an expert, a well-documented medical record may prevent a case from being filed. Medical malpractice cases are a huge gamble for plaintiff firms: They are expensive, time consuming, difficult to litigate, document heavy, and technically complex—falling outside the experience of most lawyers. They are also less likely than other cases to be settled, thanks to National Practitioner Data Bank recording requirements and (in several states) automatic medical board inquiry for potential adverse action against a medical or nursing professional following settlement. Clinicians will often fight tooth and nail to avoid an adverse recording, hospital credentialing woes, and state investigation. A medical malpractice case can be a trap for both the clinician and the plaintiff’s attorney stuck with a bad case.

Continue to: In the early stages...

In the early stages of potential litigation, before a case is filed in court, do yourself a favor: Help plaintiff’s counsel realize it will be a losing case. You actually start the process much earlier, by conducting the proper exam and documenting lavishly. This is particularly important with specialty exams, such as the hand exam in this case.

Here, simply noting “positive ROM and distal CSM [circulation, sensation, and motion] intact” is inadequate. Why? Because it is a conclusion, not evidence of the specialty examination that was diligently performed. The mechanism of injury and initial presentation roused the clinician’s suspicions sufficiently to conduct a thorough hand examination—but the mechanics of the exam were not included, only conclusions. The trouble is, those conclusions may have been based on sound medical evidence or they may have been hastily and improvidently drawn. A plaintiff’s firm deciding whether to take this case doesn’t know but will bet on the latter.

The clinician testified he performed a detailed and thorough examination of the plaintiff’s hand. Had plaintiff’s counsel been confronted with the full details of the exam—which showed the defendant PA tested all the PIPs and DIPs by isolating each finger—early on, this case may never have been filed. Thus, conduct and document specialty exams fully. If you need a cheat sheet for exams you don’t do often, use one—that is still solid practice. If you don’t do many pelvic exams or mental status exams, make sure you aren’t missing anything. Practicing medicine is an open-book exam; if you need materials, use them.

Good documentation leads to good defense, and any good defense lawyer will recommend the Jerry Maguire rule: “Help me help you.” Solid records make a case easier to defend and win at all phases of litigation. Of course, this is not a universal cure that will prevent all lawsuits. But even if the case is filed, the strength of your records may have convinced stronger, more capable medical malpractice firms to turn it down. This is something of value: It is “you helping you” and potent proof that your human head weighs more than 8 lb.

IN SUMMARY

A well-documented chart may prevent liability by showcasing the strength of your care and preventing no-win lawsuits from being filed. Help the plaintiff’s attorney realize, early on, that he or she is facing a costly uphill battle. The key word is early, when the medical records are first reviewed—not 18 months later, when the attorney hears your testimony at deposition and realizes that he or she has invested time and sweat in a case only to learn that your care was fabulous. Showcase that fabulous care early and short circuit the whole process by detailing the substance of a key exam (not just conclusions) in the record. Detailed notes may spare you from a visit by a sheriff you don’t know holding papers you don’t want.

A Robotic Hand Device Safety Study for People With Cervical Spinal Cord Injury (FULL)

An estimated 282,000 people in the US are living with spinal cord injury (SCI).1 Damage to the cervical spinal cord is the most prevalent. Among cervical spinal cord trauma, injury to levels C4, C5, and C6 have the highest occurrence.1 Damage to these levels has significant implications for functional status. Depending on pathology, patients’ functional status can range from requiring assistance for all activities of daily living (ADL) to potentially living independently.

Improving upper-limb function is vital to achieving independence. About half of people with tetraplegia judge hand and arm function to be the top factor that would improve quality of life (QOL).2 Persons with traumatic cervical SCI may lose the ability to use their hands from motor deficits, sensory dysfunction, proprioception problem, and/or loss of coordination. In addition, they may develop joint contracture, spasticity, pain, and other complications. Thus, their independence and ADL are affected significantly by multiple mechanisms of pathology.

Upper-extremity rehabilitation that emphasizes strengthening and maintaining functional range of motion (ROM) is fundamental to SCI rehabilitation. Rehabilitation to restore partial hand function has included ROM exercises, splinting, surgical procedures in the form of tendon transfers and various electrical stimulation devices, such as implantable neuroprostheses.2-7 These interventions improve the ability to grasp, hold, and release objects in selected individuals; however, they have not been universally accepted. Traditional modalities, such as active ROM (AROM) and passive ROM (PROM) and electrical stimulation remain highly used in upper-extremity rehabilitation. Devices have been developed to provide either PROM or electrical stimulation to improve hand function and to prevent muscle atrophy. Therapist- and caregiver-directed PROM exercises are time consuming and labor intensive. An innovative therapeutic approach that can provide all these modalities more efficiently is needed in SCI rehabilitation.

Until now, a single device that combines AROM and PROM simultaneously has not been available. A robotic system, the FES Hand Glove 200 (Robotix Hand Therapy Inc, Colorado Springs, CO), was developed to improve hand function (Figure).

Methods

This prospective safety study evaluated the occurrence of adverse effects (AEs) associated with the use of the FES Hand Glove 200. The study was performed in the Occupational Therapy Section of the Spinal Cord Injury Center at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) and approved by the JAHVH Research and Development Committee as well as the University of South Florida Investigational Review Board. For recruitment, the goals of the study as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria were presented to the Spinal Cord Injury Center health care providers. Potential candidates of the study were referred to the study team from these providers.

Screening of the referred candidates was conducted by physicians during inpatient evaluations. All subjects signed a consent form. Participants included active-duty military or veterans with traumatic SCI at levels C4 to C8 and American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) grades A, B, C, and D. Participants were aged 18 to 60 years, at least 1-month post-SCI, medically stable, and had impairments in upper-extremities strength and ROM or function, including hand.

Subjects were excluded if any of the following were present: seizure within 3 months of study; active cancer; heterotopic ossification below the shoulder; new acute hand injuries of the study limb; unhealed fractures of the study limb; myocardial infarction within 12 months; severe cognitive impairment determined by a Modified Rancho Score below VI8; severe aphasia; pregnancy; skin irritations or open wounds in the study limb; fixed contractures of > 40° of the metacarpophalangeal (MP) or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the study hand; unwillingness to perform all of the therapies and assessments required for the study; active implant device (eg, pacemaker, implanted cardiac defibrillator, neurostimulator or drug infusion device); major psychological disorder; severe residual spasticity despite maximal medical therapy; muscle power grade of more than 3+ on wrist and finger extensors and flexors of the study limb; recent or current participation in research that could influence study response; pain that prevents participation in the study; or concurrent use of transcutaneous electrical stimulation on the study arm.

The following data were documented: level of SCI, AIS-score; complete medical history; physical examination (including skin integrity); and vital signs of bilateral upper extremities. A nurse practitioner (NP) certified in Functional Independent Measure (FIM) conducted chart reviews and/or in-person interviews of each subject to establish a FIM score before and after 6 weeks of research treatment. Two experienced occupational therapists (OTs) conducted detailed hand evaluations before the research treatment interventions. An OT provided subjects with education on the use, care, and precautions of the FES Hand Glove 200. The OT adjusted the device on the subject’s hand for proper fitting, including initial available PROM, and optimal muscle stimulation.

The OT then implemented the treatment protocol using the FES Hand Glove 200 in 1 hand per the subjects’ preference. The subjects received 30 minutes of PROM only on the FES Hand Glove 200, followed by an additional 30 minutes of PROM with FES for 1 hour of therapy per session. The study participants were treated 4 times per week for 6 weeks. Before and after each session, OTs evaluated and documented any loss of skin integrity and pain. Autonomic dysreflexia occurred when systolic BP increased > 20 to 30 mm Hg with symptoms such as headache, profuse sweating, or blurred vision was reported.9 The FES Hand Glove 200 was set up for PROM to the thumb and to digits 2 to 5 and for electrical muscle stimulation of the finger extensors and flexors. No other therapeutic exercise was performed during the study period on the other extremity. Primary and secondary outcomes were collected at the end of the 6-week intervention.

Primary outcomes included complications from the use of FES Hand Glove 200, including skin integrity and any joint deformity as drawn on a figure, changes of pain level by visual analog scale (VAS), and total number of autonomic dyreflexia episodes. Secondary measured outcomes included changes in PROM and AROM of wrist, metacarpal joint and interphalangeal joints of thumbs and digits 2 to 5 ≥ 10°; hand and pinch strength decline of > 1 lb; decline in manual muscle test, and FIM score, which is a validated measurement of disability and the level of assistance required for ADL.10

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 4 (Cary, NC) to assess the degree of change in the improvement score, which was defined as the postintervention score minus the preintervention score. However, because of the large standard error due to small sample sizes, the normality assumption was not satisfied for all the outcomes considered.

Results

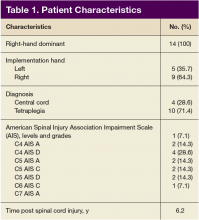

Of the 20 participants screened, 14 men aged between 19 and 66 years with cervical SCI level of C4 to C6 AIS grades A to D were enrolled in the study. Three did not complete the 6-week trial due to SCI-related medical complications, which were unrelated to the use of the FES Hand Glove 200. They continued with regular OT treatment or self-directed home exercises after they were seen by the treating physician. (Table 1)

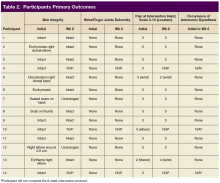

Skin integrity of all subjects was maintained throughout the study. One subject had a right-elbow wound before the intervention, which was unchanged at the end of the study. After 6 weeks of experimental intervention, there was no wrist or finger joint deformity noted and no increase in pain level except for 1 subject who reported increased pain that was unrelated to use of the device. No occurrence of autonomic dysreflexia was recorded during the use of FES Hand Glove 200 (Table 2).

For the secondary outcomes, there was no significant decrease in AROM or PROM ≥ 10° in forearm, wrist, or finger joints in any participants. There was no loss of strength > 1 lb as measured by gross grasp, pinch tip, 3-point, or lateral grip. There was no decline in motor strength per manual muscle testing. No worsening of FIM score was noted (Table 3).

Although this was not an efficacy study primarily, participants improved in several areas. Improvements included active and passive movements in the forearm, wrist, and hand. There also was significant improvement in strength of the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) muscle. Data are available on request to the authors.

Discussion

Passive ROM and AROM exercises and FES are common strategies to improve certain hand functions in people with cervical SCI. Many people, however, may experience limited duration or efficiency of rehabilitation secondary to lack of resources. Technologic advancement allowed the combination of PROM exercise and FES using the FES Hand Glove 200 device. The eventual goal of using this device is to enhance QOL by improving upper-extremity function. Because this device is not commercially available, its safety and tolerability are being tested prior to clinical use. Although 3 subjects withdrew from the study due to nondevice-related medical reasons, 11 subjects completed the study. Potential AEs included skin wounds, burns, tendon sprain or rupture, edema, and pain. At the end of the 6-week study period, there was no loss of skin integrity, no joint deformity, and no increase in hand or finger edema in all subjects. Increase in pain level at 6 weeks was noted in only 1 subject.

One concern was that overuse of such devices could potentially cause muscle fatigue, leading to decreased strength. Pinch grasp and manual muscle testing were evaluated, and no decrease in any of these parameters was noted at the end of study. Although this was not an efficacy study, there was some evidence of improved ROM of multiple wrist and finger joints as well as the EDC muscle strength.

Limitations

Limitations of the study included the duration of treatment of eight 30-minute sessions per week over a 6-week period. A longer treatment duration could result in repetition-related injuries and should be tested in future trials. Finally, the sample size of this study was relatively small. Future studies of different treatment frequency, longer duration of use and monitoring, and using a larger sample size are suggested. An efficacy study of this device using a randomized controlled design is indicated. As people with cervical SCI rank upper-extremity dysfunction as one of the top impairments that negatively impacts QOL, rehabilitation strategy to improve such functions should continue to be a research priority.2

Conclusion

This study supports the safety and tolerability of a 6-week course using FES Hand Glove 200 in traumatic SCI tetraplegic subjects. Additionally, data from this study suggest possible efficacy in enhancing ROM of various wrist and finger joints as well as certain muscle group. Further studies of efficacy with larger numbers of subjects are warranted.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. NSCISC National Spinal Cord Injury Statistic Center. 2016 annual report—public version. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/public/2016%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed March 19, 2018.

2. Ring H, Rosenthal N. Controlled study of neuroprosthetic functional electrical stimulation in sub-acute post-stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(1):32-36.

3. O’Driscoll SW, Giori NJ. Continuous passive motion (CPM): theory and principles of clinical application. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37(2):179-188.

4. Alon G, Levitt AF, McCarthy PA. Functional electrical stimulation enhancement of upper extremity functional recovery during stroke rehabilitation: a pilot study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2007;21(3):207-215.

5. de Kroon JR, Ijzerman MJ, Lankhorst GJ, Zilvold G. Electrical stimulation of the upper limb in stroke stimulation of the extensors of the hand vs. alternate stimulation of flexors and extensors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83(8):592-600.

6. Alon G, McBride K, Levitt AF. Feasibility of randomised clinical trial of early initiation and prolonged, home-base FES training to enhance upper limb functional recovery following stroke. https://www.researchgate.net /publication/237724608_Feasibility_of_randomised_clinical_trial_of_early _initiation_and_prolonged_home-based_FES_training_to_enhance_upper_limb _functional_recovery_following_stroke. Published 2004. Accessed March 21, 2018.

7. Alon G, McBride K. Persons with C5-C6 tetraplegia achieve selected functional gains using a neuroprosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(1):119-124.

8. Hagen C, Malkmus D, Durham P. Rancho Los Amigos Cognitive Scale. http://file .lacounty.gov/SDSInter/dhs/218118_RLOCFProfessionalReferenceCard-English .pdf. Published 1979. Accessed March 19, 2018.

9. Teasell RW, Arnold JM, Krassioukov A, Delaney GA. Cardiovascular consequences of loss of supraspinal control of the sympathetic nervous system after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(4):506-516.

10. Grey N, Kennedy P. The Functional Independence Measure: a comparative study of clinician and self rating. Paraplegia. 1993;31(7):457-461.

An estimated 282,000 people in the US are living with spinal cord injury (SCI).1 Damage to the cervical spinal cord is the most prevalent. Among cervical spinal cord trauma, injury to levels C4, C5, and C6 have the highest occurrence.1 Damage to these levels has significant implications for functional status. Depending on pathology, patients’ functional status can range from requiring assistance for all activities of daily living (ADL) to potentially living independently.

Improving upper-limb function is vital to achieving independence. About half of people with tetraplegia judge hand and arm function to be the top factor that would improve quality of life (QOL).2 Persons with traumatic cervical SCI may lose the ability to use their hands from motor deficits, sensory dysfunction, proprioception problem, and/or loss of coordination. In addition, they may develop joint contracture, spasticity, pain, and other complications. Thus, their independence and ADL are affected significantly by multiple mechanisms of pathology.

Upper-extremity rehabilitation that emphasizes strengthening and maintaining functional range of motion (ROM) is fundamental to SCI rehabilitation. Rehabilitation to restore partial hand function has included ROM exercises, splinting, surgical procedures in the form of tendon transfers and various electrical stimulation devices, such as implantable neuroprostheses.2-7 These interventions improve the ability to grasp, hold, and release objects in selected individuals; however, they have not been universally accepted. Traditional modalities, such as active ROM (AROM) and passive ROM (PROM) and electrical stimulation remain highly used in upper-extremity rehabilitation. Devices have been developed to provide either PROM or electrical stimulation to improve hand function and to prevent muscle atrophy. Therapist- and caregiver-directed PROM exercises are time consuming and labor intensive. An innovative therapeutic approach that can provide all these modalities more efficiently is needed in SCI rehabilitation.

Until now, a single device that combines AROM and PROM simultaneously has not been available. A robotic system, the FES Hand Glove 200 (Robotix Hand Therapy Inc, Colorado Springs, CO), was developed to improve hand function (Figure).

Methods

This prospective safety study evaluated the occurrence of adverse effects (AEs) associated with the use of the FES Hand Glove 200. The study was performed in the Occupational Therapy Section of the Spinal Cord Injury Center at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) and approved by the JAHVH Research and Development Committee as well as the University of South Florida Investigational Review Board. For recruitment, the goals of the study as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria were presented to the Spinal Cord Injury Center health care providers. Potential candidates of the study were referred to the study team from these providers.

Screening of the referred candidates was conducted by physicians during inpatient evaluations. All subjects signed a consent form. Participants included active-duty military or veterans with traumatic SCI at levels C4 to C8 and American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) grades A, B, C, and D. Participants were aged 18 to 60 years, at least 1-month post-SCI, medically stable, and had impairments in upper-extremities strength and ROM or function, including hand.

Subjects were excluded if any of the following were present: seizure within 3 months of study; active cancer; heterotopic ossification below the shoulder; new acute hand injuries of the study limb; unhealed fractures of the study limb; myocardial infarction within 12 months; severe cognitive impairment determined by a Modified Rancho Score below VI8; severe aphasia; pregnancy; skin irritations or open wounds in the study limb; fixed contractures of > 40° of the metacarpophalangeal (MP) or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the study hand; unwillingness to perform all of the therapies and assessments required for the study; active implant device (eg, pacemaker, implanted cardiac defibrillator, neurostimulator or drug infusion device); major psychological disorder; severe residual spasticity despite maximal medical therapy; muscle power grade of more than 3+ on wrist and finger extensors and flexors of the study limb; recent or current participation in research that could influence study response; pain that prevents participation in the study; or concurrent use of transcutaneous electrical stimulation on the study arm.

The following data were documented: level of SCI, AIS-score; complete medical history; physical examination (including skin integrity); and vital signs of bilateral upper extremities. A nurse practitioner (NP) certified in Functional Independent Measure (FIM) conducted chart reviews and/or in-person interviews of each subject to establish a FIM score before and after 6 weeks of research treatment. Two experienced occupational therapists (OTs) conducted detailed hand evaluations before the research treatment interventions. An OT provided subjects with education on the use, care, and precautions of the FES Hand Glove 200. The OT adjusted the device on the subject’s hand for proper fitting, including initial available PROM, and optimal muscle stimulation.

The OT then implemented the treatment protocol using the FES Hand Glove 200 in 1 hand per the subjects’ preference. The subjects received 30 minutes of PROM only on the FES Hand Glove 200, followed by an additional 30 minutes of PROM with FES for 1 hour of therapy per session. The study participants were treated 4 times per week for 6 weeks. Before and after each session, OTs evaluated and documented any loss of skin integrity and pain. Autonomic dysreflexia occurred when systolic BP increased > 20 to 30 mm Hg with symptoms such as headache, profuse sweating, or blurred vision was reported.9 The FES Hand Glove 200 was set up for PROM to the thumb and to digits 2 to 5 and for electrical muscle stimulation of the finger extensors and flexors. No other therapeutic exercise was performed during the study period on the other extremity. Primary and secondary outcomes were collected at the end of the 6-week intervention.

Primary outcomes included complications from the use of FES Hand Glove 200, including skin integrity and any joint deformity as drawn on a figure, changes of pain level by visual analog scale (VAS), and total number of autonomic dyreflexia episodes. Secondary measured outcomes included changes in PROM and AROM of wrist, metacarpal joint and interphalangeal joints of thumbs and digits 2 to 5 ≥ 10°; hand and pinch strength decline of > 1 lb; decline in manual muscle test, and FIM score, which is a validated measurement of disability and the level of assistance required for ADL.10

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 4 (Cary, NC) to assess the degree of change in the improvement score, which was defined as the postintervention score minus the preintervention score. However, because of the large standard error due to small sample sizes, the normality assumption was not satisfied for all the outcomes considered.

Results

Of the 20 participants screened, 14 men aged between 19 and 66 years with cervical SCI level of C4 to C6 AIS grades A to D were enrolled in the study. Three did not complete the 6-week trial due to SCI-related medical complications, which were unrelated to the use of the FES Hand Glove 200. They continued with regular OT treatment or self-directed home exercises after they were seen by the treating physician. (Table 1)

Skin integrity of all subjects was maintained throughout the study. One subject had a right-elbow wound before the intervention, which was unchanged at the end of the study. After 6 weeks of experimental intervention, there was no wrist or finger joint deformity noted and no increase in pain level except for 1 subject who reported increased pain that was unrelated to use of the device. No occurrence of autonomic dysreflexia was recorded during the use of FES Hand Glove 200 (Table 2).

For the secondary outcomes, there was no significant decrease in AROM or PROM ≥ 10° in forearm, wrist, or finger joints in any participants. There was no loss of strength > 1 lb as measured by gross grasp, pinch tip, 3-point, or lateral grip. There was no decline in motor strength per manual muscle testing. No worsening of FIM score was noted (Table 3).

Although this was not an efficacy study primarily, participants improved in several areas. Improvements included active and passive movements in the forearm, wrist, and hand. There also was significant improvement in strength of the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) muscle. Data are available on request to the authors.

Discussion

Passive ROM and AROM exercises and FES are common strategies to improve certain hand functions in people with cervical SCI. Many people, however, may experience limited duration or efficiency of rehabilitation secondary to lack of resources. Technologic advancement allowed the combination of PROM exercise and FES using the FES Hand Glove 200 device. The eventual goal of using this device is to enhance QOL by improving upper-extremity function. Because this device is not commercially available, its safety and tolerability are being tested prior to clinical use. Although 3 subjects withdrew from the study due to nondevice-related medical reasons, 11 subjects completed the study. Potential AEs included skin wounds, burns, tendon sprain or rupture, edema, and pain. At the end of the 6-week study period, there was no loss of skin integrity, no joint deformity, and no increase in hand or finger edema in all subjects. Increase in pain level at 6 weeks was noted in only 1 subject.

One concern was that overuse of such devices could potentially cause muscle fatigue, leading to decreased strength. Pinch grasp and manual muscle testing were evaluated, and no decrease in any of these parameters was noted at the end of study. Although this was not an efficacy study, there was some evidence of improved ROM of multiple wrist and finger joints as well as the EDC muscle strength.

Limitations

Limitations of the study included the duration of treatment of eight 30-minute sessions per week over a 6-week period. A longer treatment duration could result in repetition-related injuries and should be tested in future trials. Finally, the sample size of this study was relatively small. Future studies of different treatment frequency, longer duration of use and monitoring, and using a larger sample size are suggested. An efficacy study of this device using a randomized controlled design is indicated. As people with cervical SCI rank upper-extremity dysfunction as one of the top impairments that negatively impacts QOL, rehabilitation strategy to improve such functions should continue to be a research priority.2

Conclusion

This study supports the safety and tolerability of a 6-week course using FES Hand Glove 200 in traumatic SCI tetraplegic subjects. Additionally, data from this study suggest possible efficacy in enhancing ROM of various wrist and finger joints as well as certain muscle group. Further studies of efficacy with larger numbers of subjects are warranted.

Click here to read the digital edition.

An estimated 282,000 people in the US are living with spinal cord injury (SCI).1 Damage to the cervical spinal cord is the most prevalent. Among cervical spinal cord trauma, injury to levels C4, C5, and C6 have the highest occurrence.1 Damage to these levels has significant implications for functional status. Depending on pathology, patients’ functional status can range from requiring assistance for all activities of daily living (ADL) to potentially living independently.

Improving upper-limb function is vital to achieving independence. About half of people with tetraplegia judge hand and arm function to be the top factor that would improve quality of life (QOL).2 Persons with traumatic cervical SCI may lose the ability to use their hands from motor deficits, sensory dysfunction, proprioception problem, and/or loss of coordination. In addition, they may develop joint contracture, spasticity, pain, and other complications. Thus, their independence and ADL are affected significantly by multiple mechanisms of pathology.

Upper-extremity rehabilitation that emphasizes strengthening and maintaining functional range of motion (ROM) is fundamental to SCI rehabilitation. Rehabilitation to restore partial hand function has included ROM exercises, splinting, surgical procedures in the form of tendon transfers and various electrical stimulation devices, such as implantable neuroprostheses.2-7 These interventions improve the ability to grasp, hold, and release objects in selected individuals; however, they have not been universally accepted. Traditional modalities, such as active ROM (AROM) and passive ROM (PROM) and electrical stimulation remain highly used in upper-extremity rehabilitation. Devices have been developed to provide either PROM or electrical stimulation to improve hand function and to prevent muscle atrophy. Therapist- and caregiver-directed PROM exercises are time consuming and labor intensive. An innovative therapeutic approach that can provide all these modalities more efficiently is needed in SCI rehabilitation.

Until now, a single device that combines AROM and PROM simultaneously has not been available. A robotic system, the FES Hand Glove 200 (Robotix Hand Therapy Inc, Colorado Springs, CO), was developed to improve hand function (Figure).

Methods

This prospective safety study evaluated the occurrence of adverse effects (AEs) associated with the use of the FES Hand Glove 200. The study was performed in the Occupational Therapy Section of the Spinal Cord Injury Center at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) and approved by the JAHVH Research and Development Committee as well as the University of South Florida Investigational Review Board. For recruitment, the goals of the study as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria were presented to the Spinal Cord Injury Center health care providers. Potential candidates of the study were referred to the study team from these providers.

Screening of the referred candidates was conducted by physicians during inpatient evaluations. All subjects signed a consent form. Participants included active-duty military or veterans with traumatic SCI at levels C4 to C8 and American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) grades A, B, C, and D. Participants were aged 18 to 60 years, at least 1-month post-SCI, medically stable, and had impairments in upper-extremities strength and ROM or function, including hand.