User login

A saliva test for diagnosing endometriosis?

A French research team has developed a microRNA (miRNA) signature for diagnosing endometriosis through a simple saliva test. Its validation in a larger cohort could soon allow doctors to have a cheap, noninvasive, and accurate tool to use in diagnosing a disease that, for the time being, is difficult to identify with any certainty. The researchers suggest that their methodology could be used as a blueprint to investigate other pathologies, both benign and malignant.

ENDO-miRNA study

miRNAs regulate as much as 60% of gene expression at the posttranscriptional level. In the setting of endometriosis, several authors have evaluated the relevance of a blood-based miRNA signature, but the results are discordant because of methodological and control group issues. Other researchers have also sought to develop a miRNA saliva test. A French team wanted to determine whether it was possible to define a saliva-based diagnostic miRNome signature that would allow patients with and without endometriosis to be differentiated and, from there, develop the first specific diagnostic test for the disease.

The prospective ENDO-miRNA study included saliva samples obtained from women with chronic pelvic pain suggestive of endometriosis. Exploratory procedures were performed to look for lesions. All the patients underwent either a laparoscopic procedure (therapeutic or diagnostic laparoscopy) and/or MRI imaging. For the patients who underwent laparoscopy, diagnosis was confirmed by histology. For the patients diagnosed with endometriosis without laparoscopic evaluation, all had MRI imaging with features of deep endometriosis.

One part of the study involved the identification of a biomarker based on genomewide miRNA expression profiling by small RNA sequencing using next-generation sequencing. The second part involved the development of a saliva-based miRNA diagnostic signature according to expression and accuracy profiling using a random forest algorithm.

High sensitivity, specificity

Among the 200 patients (mean age, 31 years) enrolled in the study, 76.5% (n = 153) were diagnosed with endometriosis. On average, their pain was statistically more severe than that of the women in the control group. The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores were, respectively: dysmenorrhea 6 versus 5.0 (P < .001), dyspareunia 5.28 versus 4.95 (P < .001), and urinary pain during menstruation 4.35 versus 2.84 (P < .001).

Next-generation sequencing identified an average of 2,561 expressed miRNAs in the saliva samples. The feature selection method generated a subset of 109 miRNAs composing the endometriosis diagnostic signature. Among those miRNAs, 29 were associated with the main signaling pathways of endometriosis: PI3K/AKT, PTEN, Wnt/beta-catenin, HIF1-alpha/NF kappa B, and YAP/TAZ/EGFR.

The accuracy and reproducibility of the signature were tested on several data sets randomly composed of the same proportion of controls and patients with endometriosis. The respective sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve for the diagnostic miRNA signature were 96.7%, 100%, and 98.3%, respectively.

The study’s results support the use of a saliva-based miRNA signature for diagnosing whether a patient is discordant/complex (chronic pelvic pain suggestive of endometriosis and both negative clinical examination and imaging findings) or has early-stage or advanced-stage endometriosis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A French research team has developed a microRNA (miRNA) signature for diagnosing endometriosis through a simple saliva test. Its validation in a larger cohort could soon allow doctors to have a cheap, noninvasive, and accurate tool to use in diagnosing a disease that, for the time being, is difficult to identify with any certainty. The researchers suggest that their methodology could be used as a blueprint to investigate other pathologies, both benign and malignant.

ENDO-miRNA study

miRNAs regulate as much as 60% of gene expression at the posttranscriptional level. In the setting of endometriosis, several authors have evaluated the relevance of a blood-based miRNA signature, but the results are discordant because of methodological and control group issues. Other researchers have also sought to develop a miRNA saliva test. A French team wanted to determine whether it was possible to define a saliva-based diagnostic miRNome signature that would allow patients with and without endometriosis to be differentiated and, from there, develop the first specific diagnostic test for the disease.

The prospective ENDO-miRNA study included saliva samples obtained from women with chronic pelvic pain suggestive of endometriosis. Exploratory procedures were performed to look for lesions. All the patients underwent either a laparoscopic procedure (therapeutic or diagnostic laparoscopy) and/or MRI imaging. For the patients who underwent laparoscopy, diagnosis was confirmed by histology. For the patients diagnosed with endometriosis without laparoscopic evaluation, all had MRI imaging with features of deep endometriosis.

One part of the study involved the identification of a biomarker based on genomewide miRNA expression profiling by small RNA sequencing using next-generation sequencing. The second part involved the development of a saliva-based miRNA diagnostic signature according to expression and accuracy profiling using a random forest algorithm.

High sensitivity, specificity

Among the 200 patients (mean age, 31 years) enrolled in the study, 76.5% (n = 153) were diagnosed with endometriosis. On average, their pain was statistically more severe than that of the women in the control group. The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores were, respectively: dysmenorrhea 6 versus 5.0 (P < .001), dyspareunia 5.28 versus 4.95 (P < .001), and urinary pain during menstruation 4.35 versus 2.84 (P < .001).

Next-generation sequencing identified an average of 2,561 expressed miRNAs in the saliva samples. The feature selection method generated a subset of 109 miRNAs composing the endometriosis diagnostic signature. Among those miRNAs, 29 were associated with the main signaling pathways of endometriosis: PI3K/AKT, PTEN, Wnt/beta-catenin, HIF1-alpha/NF kappa B, and YAP/TAZ/EGFR.

The accuracy and reproducibility of the signature were tested on several data sets randomly composed of the same proportion of controls and patients with endometriosis. The respective sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve for the diagnostic miRNA signature were 96.7%, 100%, and 98.3%, respectively.

The study’s results support the use of a saliva-based miRNA signature for diagnosing whether a patient is discordant/complex (chronic pelvic pain suggestive of endometriosis and both negative clinical examination and imaging findings) or has early-stage or advanced-stage endometriosis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A French research team has developed a microRNA (miRNA) signature for diagnosing endometriosis through a simple saliva test. Its validation in a larger cohort could soon allow doctors to have a cheap, noninvasive, and accurate tool to use in diagnosing a disease that, for the time being, is difficult to identify with any certainty. The researchers suggest that their methodology could be used as a blueprint to investigate other pathologies, both benign and malignant.

ENDO-miRNA study

miRNAs regulate as much as 60% of gene expression at the posttranscriptional level. In the setting of endometriosis, several authors have evaluated the relevance of a blood-based miRNA signature, but the results are discordant because of methodological and control group issues. Other researchers have also sought to develop a miRNA saliva test. A French team wanted to determine whether it was possible to define a saliva-based diagnostic miRNome signature that would allow patients with and without endometriosis to be differentiated and, from there, develop the first specific diagnostic test for the disease.

The prospective ENDO-miRNA study included saliva samples obtained from women with chronic pelvic pain suggestive of endometriosis. Exploratory procedures were performed to look for lesions. All the patients underwent either a laparoscopic procedure (therapeutic or diagnostic laparoscopy) and/or MRI imaging. For the patients who underwent laparoscopy, diagnosis was confirmed by histology. For the patients diagnosed with endometriosis without laparoscopic evaluation, all had MRI imaging with features of deep endometriosis.

One part of the study involved the identification of a biomarker based on genomewide miRNA expression profiling by small RNA sequencing using next-generation sequencing. The second part involved the development of a saliva-based miRNA diagnostic signature according to expression and accuracy profiling using a random forest algorithm.

High sensitivity, specificity

Among the 200 patients (mean age, 31 years) enrolled in the study, 76.5% (n = 153) were diagnosed with endometriosis. On average, their pain was statistically more severe than that of the women in the control group. The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores were, respectively: dysmenorrhea 6 versus 5.0 (P < .001), dyspareunia 5.28 versus 4.95 (P < .001), and urinary pain during menstruation 4.35 versus 2.84 (P < .001).

Next-generation sequencing identified an average of 2,561 expressed miRNAs in the saliva samples. The feature selection method generated a subset of 109 miRNAs composing the endometriosis diagnostic signature. Among those miRNAs, 29 were associated with the main signaling pathways of endometriosis: PI3K/AKT, PTEN, Wnt/beta-catenin, HIF1-alpha/NF kappa B, and YAP/TAZ/EGFR.

The accuracy and reproducibility of the signature were tested on several data sets randomly composed of the same proportion of controls and patients with endometriosis. The respective sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve for the diagnostic miRNA signature were 96.7%, 100%, and 98.3%, respectively.

The study’s results support the use of a saliva-based miRNA signature for diagnosing whether a patient is discordant/complex (chronic pelvic pain suggestive of endometriosis and both negative clinical examination and imaging findings) or has early-stage or advanced-stage endometriosis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MEDICINE

Orphenadrine recalled due to possible nitrosamine impurity

Recent tests of 13 lots of the skeletal muscle relaxant Orphenadrine Citrate 100 mg Extended Release (ER) found unacceptably high levels of a nitrosamine impurity in the tablets, leading manufacturer Sandoz (Princeton, N.J.) to announce a voluntary recall of the lots on March 21.

The nitrosamine impurity detected (N-methyl-N-nitroso-2-[(2-methylphenyl)phenylmethoxy]ethanamine [NMOA or Nitroso-Orphenadrine]) may potentially be consumed at a level higher than the Food and Drug Administration’s Acceptable Daily Intake of 26.5 ng/day. Nitrosamines have carcinogenic potency when present above the allowable exposure limits, according to Sandoz, but the company said it “has not received any reports of adverse events related to the presence of a nitrosamine impurity in the lot.”

The Orphenadrine Citrate 100 mg ER Tablets were shipped to customers from August 2019 to April 2021 and have lot numbers of JX6411, JX6413, KC0723, KC3303, KE4348, KE7169, KE4349, KL3199, KM0072, KS3939, LA7704, LA7703, and LA9243.

The lots contain 100- and 1,000-count bottles of Orphenadrine Citrate ER Tablets, which are used as an adjunct to rest, physical therapy, and other measures for the relief of discomfort associated with acute painful musculoskeletal conditions.

The recall does not apply to any other strengths of Sandoz’s Orphenadrine Citrate ER Tablets or to other lot numbers of the product.

Sandoz advises that wholesalers and distributors should “immediately stop distribution of the recalled product and quarantine and return all recalled product in their inventory.” The company advises consumers to stop taking the recalled product and immediately consult with their physicians to obtain another prescription, notifying them of any problems that may be related to taking or using the tablets.

Sandoz says that retailers and consumers should contact Sedgwick directly by phone at 844-491-7869 or email at [email protected] to return the recalled product, and report adverse reactions to Sandoz by phone at (800) 525-8747 or by email at [email protected]. Adverse reactions and quality problems can be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program either online, by regular mail, or by fax to 1-800-FDA-0178.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recent tests of 13 lots of the skeletal muscle relaxant Orphenadrine Citrate 100 mg Extended Release (ER) found unacceptably high levels of a nitrosamine impurity in the tablets, leading manufacturer Sandoz (Princeton, N.J.) to announce a voluntary recall of the lots on March 21.

The nitrosamine impurity detected (N-methyl-N-nitroso-2-[(2-methylphenyl)phenylmethoxy]ethanamine [NMOA or Nitroso-Orphenadrine]) may potentially be consumed at a level higher than the Food and Drug Administration’s Acceptable Daily Intake of 26.5 ng/day. Nitrosamines have carcinogenic potency when present above the allowable exposure limits, according to Sandoz, but the company said it “has not received any reports of adverse events related to the presence of a nitrosamine impurity in the lot.”

The Orphenadrine Citrate 100 mg ER Tablets were shipped to customers from August 2019 to April 2021 and have lot numbers of JX6411, JX6413, KC0723, KC3303, KE4348, KE7169, KE4349, KL3199, KM0072, KS3939, LA7704, LA7703, and LA9243.

The lots contain 100- and 1,000-count bottles of Orphenadrine Citrate ER Tablets, which are used as an adjunct to rest, physical therapy, and other measures for the relief of discomfort associated with acute painful musculoskeletal conditions.

The recall does not apply to any other strengths of Sandoz’s Orphenadrine Citrate ER Tablets or to other lot numbers of the product.

Sandoz advises that wholesalers and distributors should “immediately stop distribution of the recalled product and quarantine and return all recalled product in their inventory.” The company advises consumers to stop taking the recalled product and immediately consult with their physicians to obtain another prescription, notifying them of any problems that may be related to taking or using the tablets.

Sandoz says that retailers and consumers should contact Sedgwick directly by phone at 844-491-7869 or email at [email protected] to return the recalled product, and report adverse reactions to Sandoz by phone at (800) 525-8747 or by email at [email protected]. Adverse reactions and quality problems can be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program either online, by regular mail, or by fax to 1-800-FDA-0178.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recent tests of 13 lots of the skeletal muscle relaxant Orphenadrine Citrate 100 mg Extended Release (ER) found unacceptably high levels of a nitrosamine impurity in the tablets, leading manufacturer Sandoz (Princeton, N.J.) to announce a voluntary recall of the lots on March 21.

The nitrosamine impurity detected (N-methyl-N-nitroso-2-[(2-methylphenyl)phenylmethoxy]ethanamine [NMOA or Nitroso-Orphenadrine]) may potentially be consumed at a level higher than the Food and Drug Administration’s Acceptable Daily Intake of 26.5 ng/day. Nitrosamines have carcinogenic potency when present above the allowable exposure limits, according to Sandoz, but the company said it “has not received any reports of adverse events related to the presence of a nitrosamine impurity in the lot.”

The Orphenadrine Citrate 100 mg ER Tablets were shipped to customers from August 2019 to April 2021 and have lot numbers of JX6411, JX6413, KC0723, KC3303, KE4348, KE7169, KE4349, KL3199, KM0072, KS3939, LA7704, LA7703, and LA9243.

The lots contain 100- and 1,000-count bottles of Orphenadrine Citrate ER Tablets, which are used as an adjunct to rest, physical therapy, and other measures for the relief of discomfort associated with acute painful musculoskeletal conditions.

The recall does not apply to any other strengths of Sandoz’s Orphenadrine Citrate ER Tablets or to other lot numbers of the product.

Sandoz advises that wholesalers and distributors should “immediately stop distribution of the recalled product and quarantine and return all recalled product in their inventory.” The company advises consumers to stop taking the recalled product and immediately consult with their physicians to obtain another prescription, notifying them of any problems that may be related to taking or using the tablets.

Sandoz says that retailers and consumers should contact Sedgwick directly by phone at 844-491-7869 or email at [email protected] to return the recalled product, and report adverse reactions to Sandoz by phone at (800) 525-8747 or by email at [email protected]. Adverse reactions and quality problems can be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program either online, by regular mail, or by fax to 1-800-FDA-0178.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Evaluation of the Empower Veterans Program for Military Veterans With Chronic Pain

From Neurology/Chronic Pain Management Services, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore VA Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Uche), and School of Nursing, Washburn University, Topeka, KS (Drs. Jamison and Waugh).

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended the Empower Veterans Program (EVP) offered by a Veterans Administration facility in the northeastern United States.

Methods: This quality improvement project used data collected from veterans with chronic pain who completed the veterans health care facility’s EVP between August 2017 and August 2019. Pre- and post-intervention data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain catastrophizing were compared using paired t-tests.

Results: Although data were abstracted from 115 patients, the final sample included

Conclusion: Veterans with chronic high-impact noncancer pain who completed the EVP had reduced pain intensity, pain interference, pain catastrophizing as well as improved quality of life and satisfaction with their health.

Keywords: musculoskeletal pain, Veterans Affairs, complementary and integrative health, acceptance and commitment therapy, mind-body therapies, whole health, multidisciplinary pain management.

More than 100 million American adults suffer from chronic pain; costs associated with managing chronic pain are approximately $635 billion

One such program is the Empower Veterans Program (EVP). Originally developed at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System, the EVP is a CIH modality based on the biopsychosocial model of pain developed by psychiatrist George Engel in 1977.3 The biopsychosocial model of pain recognizes that pain is a complex, multidimensional, biopsychosocial experience. Under this model, the mind and body work in unison as interconnected entities. Because the model acknowledges biological, psychological, and social components of pain and illness,4 treatment focuses on all aspects of a person’s health, life, and relationships.

The EVP fits into the VHA Pain Management Stepped Care Model and is an adjunctive complement for that model.5-7 The EVP complements care at the first step, where patient/family provide self-care and where care is provided by patient-aligned primary care teams, at the second step, which includes secondary consultation with multidisciplinary pain medicine specialty teams and other specialists, and at the third step, with the addition of tertiary interdisciplinary pain centers.

The VA Maryland Health Care System (VAMHCS) implemented the EVP as part of a quality improvement project for the management of chronic pain. The objectives of the program were to reduce pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and pain interference, as well as improve functionality and quality of life among veterans with chronic high-impact noncancer pain. More than 2 years after the program was implemented, collected data had not been analyzed. The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze the previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended an EVP offered by the VAMHCS. The results of the data analysis were used to inform decisions regarding the future of the program.

Methods

This quality improvement project used the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) process.8 The first 2 phases of the PDSA cycle (Plan and Do) were completed by a team of VA employees from the VAMHCS, who donated their time to establish and implement the program at the project site. This team consisted of psychologists, a physical therapist, a social worker, and a chaplain, and included support from medical administrative staff. This team planned and implemented the EVP at the VA facility based on the model developed at the Atlanta VA Health Care System. During the “Do” phase, the team collected data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain negative cognition (catastrophizing) before the intervention and post intervention. They also collected data on program outcome (patient treatment satisfaction) post intervention. Because these employees did not have time to retrieve and analyze the data, they welcomed the opportunity to have the data analyzed by the investigators during the Study phase of the PDSA cycle. Based on the results of the analysis, recommendations for program changes were made during the Act phase of the cycle.

Intervention

The EVP was developed as a 10-week (30 hours) interdisciplinary CIH approach that coached veterans with chronic pain to live fuller lives based on their individual values and what matters to them. EVP is the “What Else” management modality for the 5% of veterans with high-impact chronic pain.9 The EVP provided functional restoration through its components of whole health, mindfulness training, coaching calls, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindful movement. It used the Wheel of Health with the 4 key components of me, self-care, professional care, and community.10,11

Veterans who had a diagnosis of chronic nonmalignant pain for 3 months or more and who agreed to participate in the EVP at this facility attended 3-hour classes every Tuesday with a cohort of 8 to 12 peers and engaged in one-on-one coaching with interdisciplinary team members. During the class sessions, veterans were coached to understand and accept their pain and commit to maintaining function despite their pain. Mindful movement by the physical therapist emphasized the pivotal place of exercise in pain management. The therapist used the mantra “Motion is Lotion.”9 The guiding principle of the EVP was that small incremental changes can have a big impact on the individual’s whole life. Emphasis was placed on increasing self-efficacy and mindful awareness for veterans with high-impact pain by giving them “Skills before Pills.”9

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI), the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL-BREF), the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), and the Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale (PTSS). Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency reliability of these measures in the sample of veterans who completed the EVP.

NPRS. The NPRS is ubiquitous as a screening tool in many health care environments and its use is mandated by the VA health care system.12 The choice of the NPRS as the tool for pain screening in the VA health care system was based on a large body of research that supports the reliability and validity of the NPRS as a single index of pain intensity or severity. Studies suggest that the NPRS is valid for use in the assessment of acute, cancer, or chronic nonmalignant pain and in varied clinical settings.13 The NPRS has 4 items, each on a scale of 0 to 10. For the purpose of this project, only 3 items were used. The 3 items assessed the worst pain, usual pain, and the current pain (right now). The higher the score, the higher the pain intensity. Cronbach alpha coefficients on the NPRS obtained from the current sample of veterans were 0.85 on both pre- and postintervention assessments.

MPI. The MPI is an easily accessible, reliable, and valid self-report questionnaire that measures the impact of pain on an individual’s life, quality of social support, and general activity.14 This instrument is a short version of the West Haven-Yale MPI.15 The MPI contains 9 items rated on a scale from 0 to 6. The higher the score, the greater pain interference a person is experiencing. The MPI produces reliable, valid information for diagnostic purposes and for therapy outcome studies.16 The MPI had a Cronbach alpha of 0.90 on pre-intervention and 0.92 on postintervention assessments in the current sample.

WHOQOL-BREF. The WHOQOL-BREF is a measure of quality of life and is an abbreviated version of the WHOQOL-100. Quality of life is defined by the World Health Organization17 “as an individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.” The WHOQOL-BREF contains 26 items. The first 2 items were examined separately; the first item asks individuals to rate their overall quality of life and the second asks individuals how satisfied they are with their health. The remaining 24 items were used to calculate the following 4 domain scores: physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environment.18 Each item is measured on a scale of 1 to 5. Higher scores denote higher or better quality of life. Domain scores have demonstrated good reliability and validity.19-21 Cronbach alpha coefficients for the domain subscales ranged from 0.63 to 0.84 in the current sample, with the lowest alphas for the 3-item Social Relationships Domain.

PCS. The PCS is a widely used measure of catastrophic thinking related to pain. Catastrophizing has been conceived by Sullivan and colleagues as “an exaggerated negative mental set brought to bear during actual or anticipated painful experience.”22 The PCS provides a total score and scores for the following subscales: rumination, magnification, and helplessness.23 It has been used in a variety of chronic pain populations and has demonstrated good reliability and validity in clinical as well as nonclinical samples.24-26 The PCS has 13 items rated on a scale of 0 to 4. Higher scores mean greater negative pain cognition (catastrophizing). In the current sample, the PCS total scale had a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.95 and 0.94 on the 2 assessments. The coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.81 to 0.90.

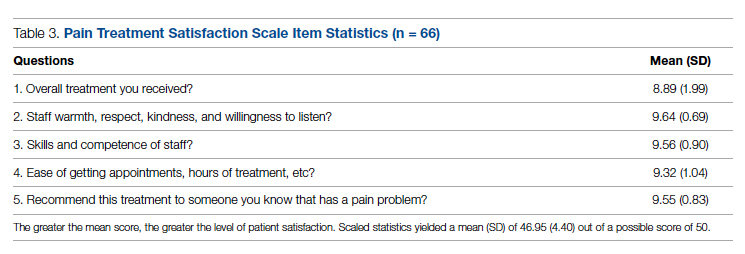

PTSS. The PTSS is a 5-item tool that measures patient satisfaction with pain treatment. It includes items that address overall satisfaction, staff warmth, staff skill level, ease of scheduling appointments, and recommendation of the program to other veterans. It was derived from the post-treatment version of The Pain Outcome Questionnaire-VA and has demonstrated reliability and validity.27 The questions are scaled from 0 to 10. High scores on the PTSS denote high patient satisfaction with the EVP. The Cronbach alpha coefficient on the PTSS obtained from the current sample was 0.80.

Data Gathering and Analysis

Prior to starting the Study phase, Washburn University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the VA IRB approved the project. The VA IRB, through its affiliate, gave a Not Human Research Determination and granted a waiver of informed consent and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization. The VA facility’s Research and Development department also approved the quality improvement project.

Once these approvals were obtained, the Study phase began with the abstraction of retrospective data obtained from veterans who participated in the VA health care facility’s EVP between

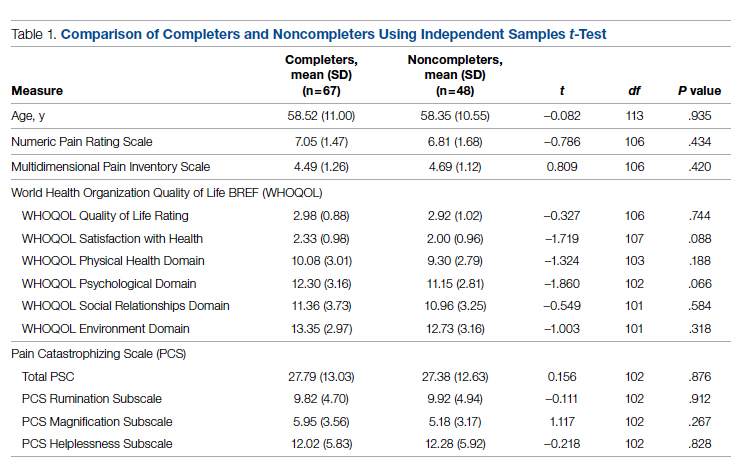

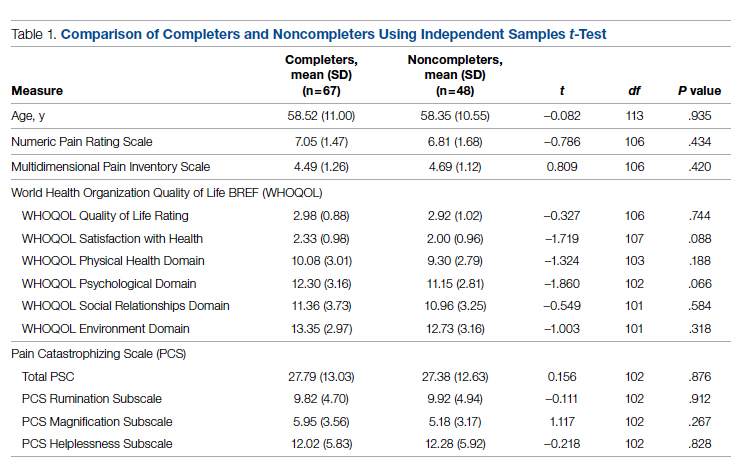

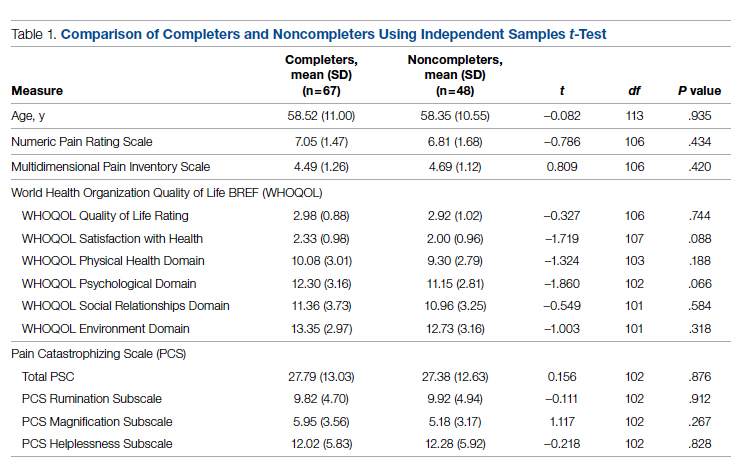

Veterans who completed the program were compared to veterans who did not complete the program on age, gender, and baseline measures. The investigators used independent samples t-tests to compare completers and noncompleters on age, pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain catastrophizing. They used the chi-square test of independence to analyze the association between gender and program completion.

Data were included in the pre- and postintervention analysis if the veteran completed the NPRS, MPI, WHOQOL-BREF, and PCS pre and post intervention. This became an important eligibility requirement as some of the tools/measures were changed towards the end of the review period in 2019. Pre- and postintervention data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, pain catastrophizing, and patient satisfaction were compared using paired samples t-test at .004 level of significance based on the Bonferroni correction.28 Data on patient satisfaction with pain treatment were collected at program completion (week 8 or 10) and were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to determine the substantive significance or magnitude of the mean differences in scores. Effect sizes (expressed as absolute values of Cohen’s d) were calculated as the mean difference divided by the standard deviation. Values of 0.2 were considered a small effect size, 0.5 a medium effect size, and 0.8 a large effect size.29

Results

Data were abstracted for 115 veterans who started the EVP. Of these, 48 left the program, leaving 67 veterans (58%) who completed the program. Completers and noncompleters were similar in age, gender, and baseline measures (Table 1). Fifty-three (79%) completers and 35 (73%) noncompleters were male. A chi-square test of independence showed no significant association between gender and program completion (χ21 [N = 115] = .595, P = .440).

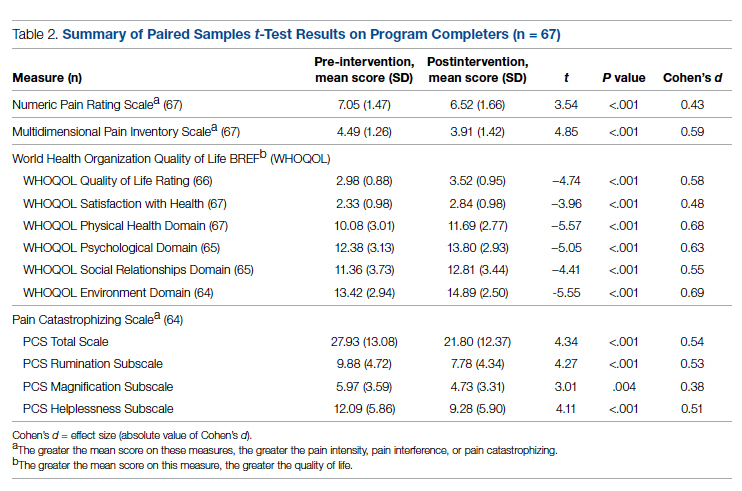

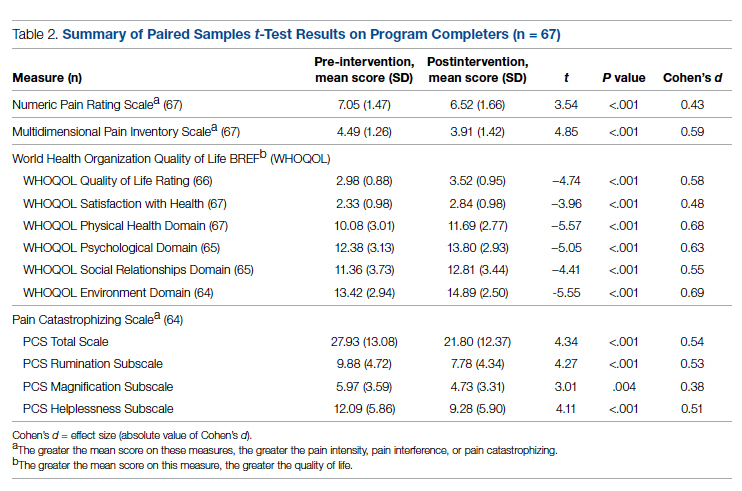

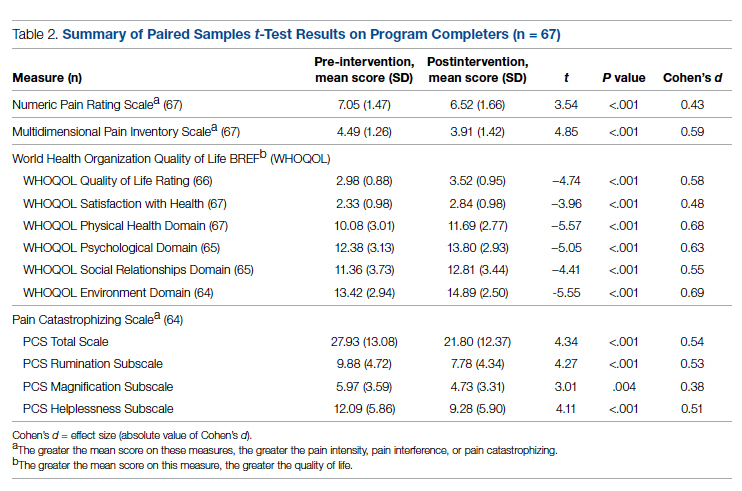

Comparison of pre-and postintervention mean scale scores resulted in statistically significant

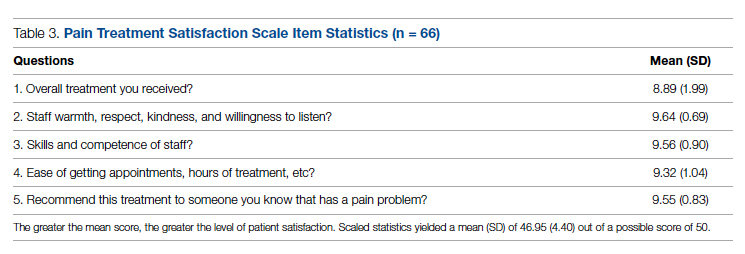

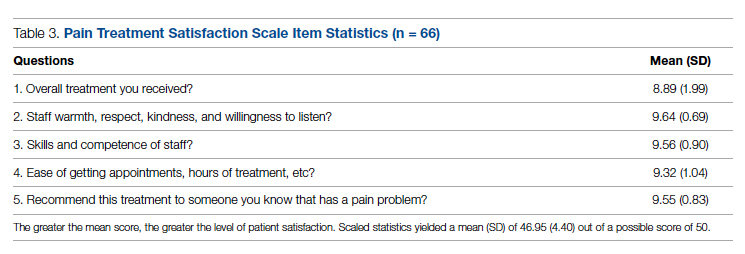

Analysis of data obtained using the PTSS yielded high mean scores for items that focused on patient satisfaction with treatment (Table 3). Scaled statistics yielded a mean (SD) of 46.95 (4.40). These results denoted overall patient satisfaction with the EVP.

Discussion

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended the EVP. Comparison of pre-intervention and postintervention data obtained from 67 veterans who completed the program revealed improvements in pain intensity, pain interference, negative cognition (catastrophizing), and quality of life. The differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful, with medium and large effect sizes. In addition, veterans reported high satisfaction with the EVP.

The EVP includes CIH approaches that have demonstrated effectiveness among veterans and other populations with chronic pain. A wealth of studies, for example, support the effectiveness of CIH approaches among veterans.30-34 Other studies focus on specific CIH approaches that are components of the EVP. Evidence supports, for example, the efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction,35-39 acceptance and commitment therapy,40-43 brief peer support intervention,44 and interdisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation.45,46

While empirical evidence supports components of the EVP, only one study focused on the outcomes of the Atlanta VA EVP among veterans with chronic pain. Results of a qualitative study conducted by Penney and Haro47 described the experience of veterans with the EVP. Those veterans reported adopting new self-care or lifestyle practices for pain management and health, accepting pain, being better able to adjust and set boundaries, feeling more in control, participating in life, and changing their medication use.

The mean baseline scores from the current sample were similar to samples of patients with chronic pain in other studies (NPRS,48 MPI,48 and PCS48-51). After converting scores on the WHOQOL-BREF from those that ranged from 4 to 20 to those that ranged from 0 to 100,18 the scores from the current sample were similar to those of other studies of patients with chronic pain.48,52,53Several strengths of the project should be noted. Data were collected using well established measurement tools that had previously demonstrated reliability and validity. All the tools used in data collection demonstrated good internal consistency reliabilities in the current sample of veterans. Weaknesses of the project include the use of a convenience sample of veterans and small sample size. Data were not available on the number of veterans who were offered participation or on how many veterans declined enrollment. The sample of veterans who chose to participate in the EVP may or may not have been representative of the population of veterans with high-impact chronic pain. As a pre- and postintervention design with no comparison group, the results are subject to multiple threats to internal validity, including the Hawthorne effect, maturation in the form of healing, and attrition. Reasons for leaving the program had not been recorded, so the investigators had no way of knowing factors that may have contributed to attrition. Also, data on when veterans left the program were unavailable. Research is needed with a control group to reduce the effect of confounding variables on the outcome measures. This project used data collected at a single VA facility, which limits its generalizability.

While completers and noncompleters of the EVP were similar on age, gender, and baseline measures, there may have been unidentified characteristics that influenced program completion. The investigators noticed the presence of more missing data among noncompleters compared to completers on the pre-intervention PCS; thus, noncompleters may have scored lower than completers on this instrument simply because there were more individual items that were unanswered/missing among this group of noncompleters.

Data were analyzed using a limited number of outcome measures that had previously been collected. Other outcome measures might include whether EVP participants reduced their use of medications, clinical resources, and personnel. Future projects, for example, could determine whether the EVP is effective in reducing opioid analgesic medication use and decreasing primary care and emergency department visits. Cost-benefit analyses could be completed to determine whether EVP is associated with financial savings.

Because no follow-up assessments were made to determine whether improvements were maintained over time, the project focus was limited to an evaluation of the short-term changes in the outcome measures. Future projects could include a follow-up assessment of the veterans 1- or 2-years post completion of the EVP.

Data for the project were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when the EVP was implemented through face-to-face meetings with participants and their peers. It is not clear how changes to the delivery of the program (such as offering it through telehealth) might impact veterans’ satisfaction with the program, willingness to complete it, and other variables of interest.

The results of this project were made available to stakeholders with recommendations for program expansion both at the current location and at other VA facilities, including the recommendation to hire additional personnel that would implement the program. As the VA network of facilities expand the EVP program and adapt it for telehealth delivery, the investigators recommended a similar analysis of data be performed following telehealth delivery. If delivery through telehealth is shown to improve outcome measures, the EVP could provide pain management treatment options for patients challenged by transportation barriers, including rural veterans.

Conclusion

This quality improvement project provided evidence of improvement in measures of pain severity, pain interference, negative cognition (catastrophizing), quality of life, and patient treatment satisfaction among veterans with chronic high-impact pain. Findings have been well received by the northeastern VA as well as the Veterans Integrated Systems Network 5. The results of the analyses were used to inform decisions regarding the future of the program.

Disclaimer: This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, Maryland. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Arianna Perra, the recent past coordinator of the Empower Veterans Program (EVP), who provided initial insights and support that motivated the decision to evaluate the program. We also thank the veterans and VA EVP clinicians who contributed data for the evaluation, and Dr. Michael Saenger (Director, TelePain-EVP: EVP) and Dr. Robert Lavin for their ongoing support, care, and concern for veteran patients. We also thank Dr. Beverly Bradley and the neurology service administrative team for their guidance in the process of obtaining necessary VA approvals for this project.

Corresponding author: Jessica U. Uche, DNP, CRNP-Family; [email protected]

doi:10.12788/jcom.0089

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. The National Academies Press (US); 2011.

2. Bastian LA, Heapy A, Becker WC, et al. Understanding pain and pain treatment for veterans: responding to the federal pain research strategy. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl_1); S1-S4. doi:10.1093/pm/pny1433

3. Engle GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

4. Bevers K, Watts L, Kishino ND, et al. The biopsychosocial model of the assessment, prevention, and treatment of chronic pain. US Neurology. 2016;12(2):98-104. doi:10.17925/USN.2016.12.02.98

5. Bair MJ, Ang D, Wu J, et al. Evaluation of stepped care for chronic pain (ESCAPE) in veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):682-689. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.97

6. Veterans Health Administration. Pain Management. VHA Directive 2009-053. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2009.https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf

7. Moore BA, Anderson D, Dorflinger L, et al. Stepped care model for pain management and quality of pain care in long-term opioid therapy. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):137-146. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.10.0254

8. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. How to improve. Accessed March 14, 2022. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

9. Saenger M. Empower Veterans Program. APA PCSS-O Webinars. Evidence CAM LBP 2016.

10. Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the Veterans Administration: How will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(S1):S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

11. Veterans Health Administration. Whole health: Circle of health. Updated April 1, 2021. Accessed March 14, 2022. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/index.asp

12. Krebs EE, Carey TS, Weinberger M. Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(10):1453-1458. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0321-2

13. Veterans Health Administration. Pain as the 5th vital sign toolkit. October 2000, revised edition. Geriatrics and Extended Care Strategic Healthcare Group, National Pain Management Coordinating Committee. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/Pain_As_the_5th_Vital_Sign_Toolkit.pdf

14. McKillop JM, Nielson WR. Improving the usefulness of the Multidimensional Pain Inventory. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16(4):239-244. doi:10.1155/2011/873424

15. Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI). Pain.1985;23(4):345-356. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1

16. Verra ML, Angst F, Staal JB, et al. Reliability of the multidimensional pain inventory and stability of the MPI classification system in chronic back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:155. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-155

17. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551-558. doi:10.1017/s0033291798006667

18. World Health Organization. Division of Mental Health. WHOQOL-BREF: introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: field trial version, December 1996. Accessed March 14, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63529

19. Guay S, Fortin C, Fikretoglu D, et al. Validation of the WHOQOL-BREF in a sample of male treatment-seeking veterans. Mil Psychol. 2015;27(2):85-92. doi:10.1037/mil0000065

20. Skevington S, Lotfy M, O’Connell K, WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(2):299-310. doi:10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00

21. Stratton KJ, Bender MC, Cameron JJ, Pickett TC. Development and evaluation of a behavioral pain management treatment program in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):263-268. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00281.

22. Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):52-64. doi:10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008

23. Sullivan JL. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: User manual. Accessed March 14, 2022. https://studylib.net/doc/8330191/the-pain-catastrophizing-scale---dr.-michael-sullivan

24. Darnall BD, Sturgeon JA, Cook KF, et al. Development and validation of a daily pain catastrophizing scale. J Pain. 2017;18(9):1139-1149. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.05.003

25. Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, et al. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J Behav Med. 1997;20(6):589-605. doi:10.1023/a:1025570508954

26. Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assessment. 1995;7(4):524-532. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524

27. Walker R, Clark M, Gironda R. Psychometric characteristics of the Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale. J Pain. 2015;6(3Suppl.):S76.

28. Emerson RW. Bonferroni correction and type I error. J Vis Impair Blind. 2020;114(1):77-78. doi:10.1177/0145482X20901378

29. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Routledge; 1988. doi:10.4324/9780203771587

30. Craner JR, Lake ES, Bancroft KA, George LL. Treatment outcomes and mechanisms for an ACT-based 10-week interdisciplinary chronic pain rehabilitation program. Pain Pract. 2020;20(1):44-54. doi:10.1111/papr.12824

31. Han L, Goulet JL, Skanderson M, et al. Evaluation of complementary and integrative health approaches among US veterans with musculoskeletal pain using propensity score methods. Pain Med. 2019;20(1):90-102. doi:10.1093/pm/pny027

32. Herman PM, Yuan AH, Cefalu MS, et al. The use of complementary and integrative health approaches for chronic musculoskeletal pain in younger US veterans: an economic evaluation. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217831. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217831

33. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Global Health; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education; Forum on Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders; Stroud C, Posey Norris SM, Bain L, eds. The Role of Nonpharmacological Approaches to Pain Management: Proceedings of a Workshop. National Academies Press (US); April 12, 2019.

34. Richmond H, Hall AM, Copsey B, et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural treatment for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134192. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134192

35. Kearney DJ, Simpson TL, Malte CA, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in addition to usual care is associated with improvements in pain, fatigue, and cognitive failures among veterans with Gulf War illness. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):204-214. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.015

36. Khoo E, Small R, Cheng W, et al. Comparative evaluation of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment and management of chronic pain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019;22(1):26-35. doi:10.1136/ebmental-2018-300062

37. Khusid MA, Vythilingam M. The emerging role of mindfulness meditation as effective self-management strategy, Part 2: clinical implications for chronic pain, substance misuse, and insomnia. Mil Med. 2016;181(9):969-975. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00678

38. la Cour P, Petersen M. Effects of mindfulness meditation on chronic pain: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2015;16(4):641-652. doi:10.1111/pme.12605

39. Zou L, Zhang Y, Yang L, et al. Are mindful exercises safe and beneficial for treating chronic lower back pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5):628. doi:10.3390/jcm8050628

40. Hughes LS, Clark J, Colclough JA, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(6):552-568. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000425

41. Kemani MK, Olsson GL, Lekander M, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and applied relaxation for longstanding pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(11):1004-1016. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000203

42. Scott W, Daly A, Yu L, McCracken LM. Treatment of chronic pain for adults 65 and over: analyses of outcomes and changes in psychological flexibility following interdisciplinary acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Pain Med. 2017;18(2):252. doi:10.1093/pm/pnw073

43. Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KMG. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016;45(1):5-31. doi:10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724

44. Matthias MS, McGuire AB, Kukla M, et al. A brief peer support intervention for veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a pilot study of feasibility and effectiveness. Pain Med. 2015;16(1):81-87. doi:10.1111/pme.12571

45. Anamkath NS, Palyo SA, Jacobs SC, et al. An interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program for veterans with chronic pain: description and initial evaluation of outcomes. Pain Res Manag. 2018;2018(3941682):1-9. doi:10.1155/2018/3941682

46. Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9: CD000963. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000963.pub3

47. Penney LS, Haro E. Qualitative evaluation of an interdisciplinary chronic pain intervention: Outcomes and barriers and facilitators to ongoing pain management. J Pain Res. 2019;12:865-878. doi:10.2147/JPR.S185652

48. Murphy JL, Cordova MJ, Dedert EA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain in veterans; Evidence for clinical effectiveness in a model program. Psychol Serv. 2022;19(1):95-102. doi:10.1037/ser0000506

49. Katz L, Patterson L, Zacharias R. Evaluation of an interdisciplinary chronic pain program and predictors of readiness for change. Can J Pain. 2019;3(1):70-78. doi:10.1080/24740527.2019.1582296

50. Majumder SMM, Ahmed S, Shazzad N, et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) into Bengali I patients with chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23:1481-1487. doi:10.1111/1756-185X.13954

51. Margiotta F, Hannigan A, Imran A, et al. Pain, perceived injustice, and pain catastrophizing in chronic pain patients in Ireland. Pain Pract. 2016;17(5):663-668. doi:10.1111/papr.12

52. Bras M, Milunovic V, Boban M, et al. Quality of live in Croatian Homeland war (1991-1995) veterans who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Health Qual Life Out. 2011;9:56. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-56

53. Liu C-H, Kung Y-Y, Lin C-L, et al. Therapeutic efficacy and the impact of the “dose” effect of acupuncture to treat sciatica: A randomized controlled pilot study. J Pain Res. 2019;12:3511-3520. doi:10.2147/JPR.S210672

From Neurology/Chronic Pain Management Services, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore VA Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Uche), and School of Nursing, Washburn University, Topeka, KS (Drs. Jamison and Waugh).

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended the Empower Veterans Program (EVP) offered by a Veterans Administration facility in the northeastern United States.

Methods: This quality improvement project used data collected from veterans with chronic pain who completed the veterans health care facility’s EVP between August 2017 and August 2019. Pre- and post-intervention data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain catastrophizing were compared using paired t-tests.

Results: Although data were abstracted from 115 patients, the final sample included

Conclusion: Veterans with chronic high-impact noncancer pain who completed the EVP had reduced pain intensity, pain interference, pain catastrophizing as well as improved quality of life and satisfaction with their health.

Keywords: musculoskeletal pain, Veterans Affairs, complementary and integrative health, acceptance and commitment therapy, mind-body therapies, whole health, multidisciplinary pain management.

More than 100 million American adults suffer from chronic pain; costs associated with managing chronic pain are approximately $635 billion

One such program is the Empower Veterans Program (EVP). Originally developed at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System, the EVP is a CIH modality based on the biopsychosocial model of pain developed by psychiatrist George Engel in 1977.3 The biopsychosocial model of pain recognizes that pain is a complex, multidimensional, biopsychosocial experience. Under this model, the mind and body work in unison as interconnected entities. Because the model acknowledges biological, psychological, and social components of pain and illness,4 treatment focuses on all aspects of a person’s health, life, and relationships.

The EVP fits into the VHA Pain Management Stepped Care Model and is an adjunctive complement for that model.5-7 The EVP complements care at the first step, where patient/family provide self-care and where care is provided by patient-aligned primary care teams, at the second step, which includes secondary consultation with multidisciplinary pain medicine specialty teams and other specialists, and at the third step, with the addition of tertiary interdisciplinary pain centers.

The VA Maryland Health Care System (VAMHCS) implemented the EVP as part of a quality improvement project for the management of chronic pain. The objectives of the program were to reduce pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and pain interference, as well as improve functionality and quality of life among veterans with chronic high-impact noncancer pain. More than 2 years after the program was implemented, collected data had not been analyzed. The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze the previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended an EVP offered by the VAMHCS. The results of the data analysis were used to inform decisions regarding the future of the program.

Methods

This quality improvement project used the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) process.8 The first 2 phases of the PDSA cycle (Plan and Do) were completed by a team of VA employees from the VAMHCS, who donated their time to establish and implement the program at the project site. This team consisted of psychologists, a physical therapist, a social worker, and a chaplain, and included support from medical administrative staff. This team planned and implemented the EVP at the VA facility based on the model developed at the Atlanta VA Health Care System. During the “Do” phase, the team collected data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain negative cognition (catastrophizing) before the intervention and post intervention. They also collected data on program outcome (patient treatment satisfaction) post intervention. Because these employees did not have time to retrieve and analyze the data, they welcomed the opportunity to have the data analyzed by the investigators during the Study phase of the PDSA cycle. Based on the results of the analysis, recommendations for program changes were made during the Act phase of the cycle.

Intervention

The EVP was developed as a 10-week (30 hours) interdisciplinary CIH approach that coached veterans with chronic pain to live fuller lives based on their individual values and what matters to them. EVP is the “What Else” management modality for the 5% of veterans with high-impact chronic pain.9 The EVP provided functional restoration through its components of whole health, mindfulness training, coaching calls, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindful movement. It used the Wheel of Health with the 4 key components of me, self-care, professional care, and community.10,11

Veterans who had a diagnosis of chronic nonmalignant pain for 3 months or more and who agreed to participate in the EVP at this facility attended 3-hour classes every Tuesday with a cohort of 8 to 12 peers and engaged in one-on-one coaching with interdisciplinary team members. During the class sessions, veterans were coached to understand and accept their pain and commit to maintaining function despite their pain. Mindful movement by the physical therapist emphasized the pivotal place of exercise in pain management. The therapist used the mantra “Motion is Lotion.”9 The guiding principle of the EVP was that small incremental changes can have a big impact on the individual’s whole life. Emphasis was placed on increasing self-efficacy and mindful awareness for veterans with high-impact pain by giving them “Skills before Pills.”9

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI), the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL-BREF), the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), and the Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale (PTSS). Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency reliability of these measures in the sample of veterans who completed the EVP.

NPRS. The NPRS is ubiquitous as a screening tool in many health care environments and its use is mandated by the VA health care system.12 The choice of the NPRS as the tool for pain screening in the VA health care system was based on a large body of research that supports the reliability and validity of the NPRS as a single index of pain intensity or severity. Studies suggest that the NPRS is valid for use in the assessment of acute, cancer, or chronic nonmalignant pain and in varied clinical settings.13 The NPRS has 4 items, each on a scale of 0 to 10. For the purpose of this project, only 3 items were used. The 3 items assessed the worst pain, usual pain, and the current pain (right now). The higher the score, the higher the pain intensity. Cronbach alpha coefficients on the NPRS obtained from the current sample of veterans were 0.85 on both pre- and postintervention assessments.

MPI. The MPI is an easily accessible, reliable, and valid self-report questionnaire that measures the impact of pain on an individual’s life, quality of social support, and general activity.14 This instrument is a short version of the West Haven-Yale MPI.15 The MPI contains 9 items rated on a scale from 0 to 6. The higher the score, the greater pain interference a person is experiencing. The MPI produces reliable, valid information for diagnostic purposes and for therapy outcome studies.16 The MPI had a Cronbach alpha of 0.90 on pre-intervention and 0.92 on postintervention assessments in the current sample.

WHOQOL-BREF. The WHOQOL-BREF is a measure of quality of life and is an abbreviated version of the WHOQOL-100. Quality of life is defined by the World Health Organization17 “as an individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.” The WHOQOL-BREF contains 26 items. The first 2 items were examined separately; the first item asks individuals to rate their overall quality of life and the second asks individuals how satisfied they are with their health. The remaining 24 items were used to calculate the following 4 domain scores: physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environment.18 Each item is measured on a scale of 1 to 5. Higher scores denote higher or better quality of life. Domain scores have demonstrated good reliability and validity.19-21 Cronbach alpha coefficients for the domain subscales ranged from 0.63 to 0.84 in the current sample, with the lowest alphas for the 3-item Social Relationships Domain.

PCS. The PCS is a widely used measure of catastrophic thinking related to pain. Catastrophizing has been conceived by Sullivan and colleagues as “an exaggerated negative mental set brought to bear during actual or anticipated painful experience.”22 The PCS provides a total score and scores for the following subscales: rumination, magnification, and helplessness.23 It has been used in a variety of chronic pain populations and has demonstrated good reliability and validity in clinical as well as nonclinical samples.24-26 The PCS has 13 items rated on a scale of 0 to 4. Higher scores mean greater negative pain cognition (catastrophizing). In the current sample, the PCS total scale had a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.95 and 0.94 on the 2 assessments. The coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.81 to 0.90.

PTSS. The PTSS is a 5-item tool that measures patient satisfaction with pain treatment. It includes items that address overall satisfaction, staff warmth, staff skill level, ease of scheduling appointments, and recommendation of the program to other veterans. It was derived from the post-treatment version of The Pain Outcome Questionnaire-VA and has demonstrated reliability and validity.27 The questions are scaled from 0 to 10. High scores on the PTSS denote high patient satisfaction with the EVP. The Cronbach alpha coefficient on the PTSS obtained from the current sample was 0.80.

Data Gathering and Analysis

Prior to starting the Study phase, Washburn University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the VA IRB approved the project. The VA IRB, through its affiliate, gave a Not Human Research Determination and granted a waiver of informed consent and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization. The VA facility’s Research and Development department also approved the quality improvement project.

Once these approvals were obtained, the Study phase began with the abstraction of retrospective data obtained from veterans who participated in the VA health care facility’s EVP between

Veterans who completed the program were compared to veterans who did not complete the program on age, gender, and baseline measures. The investigators used independent samples t-tests to compare completers and noncompleters on age, pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain catastrophizing. They used the chi-square test of independence to analyze the association between gender and program completion.

Data were included in the pre- and postintervention analysis if the veteran completed the NPRS, MPI, WHOQOL-BREF, and PCS pre and post intervention. This became an important eligibility requirement as some of the tools/measures were changed towards the end of the review period in 2019. Pre- and postintervention data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, pain catastrophizing, and patient satisfaction were compared using paired samples t-test at .004 level of significance based on the Bonferroni correction.28 Data on patient satisfaction with pain treatment were collected at program completion (week 8 or 10) and were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to determine the substantive significance or magnitude of the mean differences in scores. Effect sizes (expressed as absolute values of Cohen’s d) were calculated as the mean difference divided by the standard deviation. Values of 0.2 were considered a small effect size, 0.5 a medium effect size, and 0.8 a large effect size.29

Results

Data were abstracted for 115 veterans who started the EVP. Of these, 48 left the program, leaving 67 veterans (58%) who completed the program. Completers and noncompleters were similar in age, gender, and baseline measures (Table 1). Fifty-three (79%) completers and 35 (73%) noncompleters were male. A chi-square test of independence showed no significant association between gender and program completion (χ21 [N = 115] = .595, P = .440).

Comparison of pre-and postintervention mean scale scores resulted in statistically significant

Analysis of data obtained using the PTSS yielded high mean scores for items that focused on patient satisfaction with treatment (Table 3). Scaled statistics yielded a mean (SD) of 46.95 (4.40). These results denoted overall patient satisfaction with the EVP.

Discussion

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended the EVP. Comparison of pre-intervention and postintervention data obtained from 67 veterans who completed the program revealed improvements in pain intensity, pain interference, negative cognition (catastrophizing), and quality of life. The differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful, with medium and large effect sizes. In addition, veterans reported high satisfaction with the EVP.

The EVP includes CIH approaches that have demonstrated effectiveness among veterans and other populations with chronic pain. A wealth of studies, for example, support the effectiveness of CIH approaches among veterans.30-34 Other studies focus on specific CIH approaches that are components of the EVP. Evidence supports, for example, the efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction,35-39 acceptance and commitment therapy,40-43 brief peer support intervention,44 and interdisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation.45,46

While empirical evidence supports components of the EVP, only one study focused on the outcomes of the Atlanta VA EVP among veterans with chronic pain. Results of a qualitative study conducted by Penney and Haro47 described the experience of veterans with the EVP. Those veterans reported adopting new self-care or lifestyle practices for pain management and health, accepting pain, being better able to adjust and set boundaries, feeling more in control, participating in life, and changing their medication use.

The mean baseline scores from the current sample were similar to samples of patients with chronic pain in other studies (NPRS,48 MPI,48 and PCS48-51). After converting scores on the WHOQOL-BREF from those that ranged from 4 to 20 to those that ranged from 0 to 100,18 the scores from the current sample were similar to those of other studies of patients with chronic pain.48,52,53Several strengths of the project should be noted. Data were collected using well established measurement tools that had previously demonstrated reliability and validity. All the tools used in data collection demonstrated good internal consistency reliabilities in the current sample of veterans. Weaknesses of the project include the use of a convenience sample of veterans and small sample size. Data were not available on the number of veterans who were offered participation or on how many veterans declined enrollment. The sample of veterans who chose to participate in the EVP may or may not have been representative of the population of veterans with high-impact chronic pain. As a pre- and postintervention design with no comparison group, the results are subject to multiple threats to internal validity, including the Hawthorne effect, maturation in the form of healing, and attrition. Reasons for leaving the program had not been recorded, so the investigators had no way of knowing factors that may have contributed to attrition. Also, data on when veterans left the program were unavailable. Research is needed with a control group to reduce the effect of confounding variables on the outcome measures. This project used data collected at a single VA facility, which limits its generalizability.

While completers and noncompleters of the EVP were similar on age, gender, and baseline measures, there may have been unidentified characteristics that influenced program completion. The investigators noticed the presence of more missing data among noncompleters compared to completers on the pre-intervention PCS; thus, noncompleters may have scored lower than completers on this instrument simply because there were more individual items that were unanswered/missing among this group of noncompleters.

Data were analyzed using a limited number of outcome measures that had previously been collected. Other outcome measures might include whether EVP participants reduced their use of medications, clinical resources, and personnel. Future projects, for example, could determine whether the EVP is effective in reducing opioid analgesic medication use and decreasing primary care and emergency department visits. Cost-benefit analyses could be completed to determine whether EVP is associated with financial savings.

Because no follow-up assessments were made to determine whether improvements were maintained over time, the project focus was limited to an evaluation of the short-term changes in the outcome measures. Future projects could include a follow-up assessment of the veterans 1- or 2-years post completion of the EVP.

Data for the project were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when the EVP was implemented through face-to-face meetings with participants and their peers. It is not clear how changes to the delivery of the program (such as offering it through telehealth) might impact veterans’ satisfaction with the program, willingness to complete it, and other variables of interest.

The results of this project were made available to stakeholders with recommendations for program expansion both at the current location and at other VA facilities, including the recommendation to hire additional personnel that would implement the program. As the VA network of facilities expand the EVP program and adapt it for telehealth delivery, the investigators recommended a similar analysis of data be performed following telehealth delivery. If delivery through telehealth is shown to improve outcome measures, the EVP could provide pain management treatment options for patients challenged by transportation barriers, including rural veterans.

Conclusion

This quality improvement project provided evidence of improvement in measures of pain severity, pain interference, negative cognition (catastrophizing), quality of life, and patient treatment satisfaction among veterans with chronic high-impact pain. Findings have been well received by the northeastern VA as well as the Veterans Integrated Systems Network 5. The results of the analyses were used to inform decisions regarding the future of the program.

Disclaimer: This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, Maryland. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Arianna Perra, the recent past coordinator of the Empower Veterans Program (EVP), who provided initial insights and support that motivated the decision to evaluate the program. We also thank the veterans and VA EVP clinicians who contributed data for the evaluation, and Dr. Michael Saenger (Director, TelePain-EVP: EVP) and Dr. Robert Lavin for their ongoing support, care, and concern for veteran patients. We also thank Dr. Beverly Bradley and the neurology service administrative team for their guidance in the process of obtaining necessary VA approvals for this project.

Corresponding author: Jessica U. Uche, DNP, CRNP-Family; [email protected]

doi:10.12788/jcom.0089

From Neurology/Chronic Pain Management Services, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore VA Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Uche), and School of Nursing, Washburn University, Topeka, KS (Drs. Jamison and Waugh).

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended the Empower Veterans Program (EVP) offered by a Veterans Administration facility in the northeastern United States.

Methods: This quality improvement project used data collected from veterans with chronic pain who completed the veterans health care facility’s EVP between August 2017 and August 2019. Pre- and post-intervention data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain catastrophizing were compared using paired t-tests.

Results: Although data were abstracted from 115 patients, the final sample included

Conclusion: Veterans with chronic high-impact noncancer pain who completed the EVP had reduced pain intensity, pain interference, pain catastrophizing as well as improved quality of life and satisfaction with their health.

Keywords: musculoskeletal pain, Veterans Affairs, complementary and integrative health, acceptance and commitment therapy, mind-body therapies, whole health, multidisciplinary pain management.

More than 100 million American adults suffer from chronic pain; costs associated with managing chronic pain are approximately $635 billion

One such program is the Empower Veterans Program (EVP). Originally developed at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System, the EVP is a CIH modality based on the biopsychosocial model of pain developed by psychiatrist George Engel in 1977.3 The biopsychosocial model of pain recognizes that pain is a complex, multidimensional, biopsychosocial experience. Under this model, the mind and body work in unison as interconnected entities. Because the model acknowledges biological, psychological, and social components of pain and illness,4 treatment focuses on all aspects of a person’s health, life, and relationships.

The EVP fits into the VHA Pain Management Stepped Care Model and is an adjunctive complement for that model.5-7 The EVP complements care at the first step, where patient/family provide self-care and where care is provided by patient-aligned primary care teams, at the second step, which includes secondary consultation with multidisciplinary pain medicine specialty teams and other specialists, and at the third step, with the addition of tertiary interdisciplinary pain centers.

The VA Maryland Health Care System (VAMHCS) implemented the EVP as part of a quality improvement project for the management of chronic pain. The objectives of the program were to reduce pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and pain interference, as well as improve functionality and quality of life among veterans with chronic high-impact noncancer pain. More than 2 years after the program was implemented, collected data had not been analyzed. The purpose of this quality improvement project was to abstract and analyze the previously collected data from veterans with high-impact chronic pain who attended an EVP offered by the VAMHCS. The results of the data analysis were used to inform decisions regarding the future of the program.

Methods

This quality improvement project used the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) process.8 The first 2 phases of the PDSA cycle (Plan and Do) were completed by a team of VA employees from the VAMHCS, who donated their time to establish and implement the program at the project site. This team consisted of psychologists, a physical therapist, a social worker, and a chaplain, and included support from medical administrative staff. This team planned and implemented the EVP at the VA facility based on the model developed at the Atlanta VA Health Care System. During the “Do” phase, the team collected data on pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain negative cognition (catastrophizing) before the intervention and post intervention. They also collected data on program outcome (patient treatment satisfaction) post intervention. Because these employees did not have time to retrieve and analyze the data, they welcomed the opportunity to have the data analyzed by the investigators during the Study phase of the PDSA cycle. Based on the results of the analysis, recommendations for program changes were made during the Act phase of the cycle.

Intervention

The EVP was developed as a 10-week (30 hours) interdisciplinary CIH approach that coached veterans with chronic pain to live fuller lives based on their individual values and what matters to them. EVP is the “What Else” management modality for the 5% of veterans with high-impact chronic pain.9 The EVP provided functional restoration through its components of whole health, mindfulness training, coaching calls, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindful movement. It used the Wheel of Health with the 4 key components of me, self-care, professional care, and community.10,11

Veterans who had a diagnosis of chronic nonmalignant pain for 3 months or more and who agreed to participate in the EVP at this facility attended 3-hour classes every Tuesday with a cohort of 8 to 12 peers and engaged in one-on-one coaching with interdisciplinary team members. During the class sessions, veterans were coached to understand and accept their pain and commit to maintaining function despite their pain. Mindful movement by the physical therapist emphasized the pivotal place of exercise in pain management. The therapist used the mantra “Motion is Lotion.”9 The guiding principle of the EVP was that small incremental changes can have a big impact on the individual’s whole life. Emphasis was placed on increasing self-efficacy and mindful awareness for veterans with high-impact pain by giving them “Skills before Pills.”9

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI), the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL-BREF), the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), and the Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale (PTSS). Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency reliability of these measures in the sample of veterans who completed the EVP.

NPRS. The NPRS is ubiquitous as a screening tool in many health care environments and its use is mandated by the VA health care system.12 The choice of the NPRS as the tool for pain screening in the VA health care system was based on a large body of research that supports the reliability and validity of the NPRS as a single index of pain intensity or severity. Studies suggest that the NPRS is valid for use in the assessment of acute, cancer, or chronic nonmalignant pain and in varied clinical settings.13 The NPRS has 4 items, each on a scale of 0 to 10. For the purpose of this project, only 3 items were used. The 3 items assessed the worst pain, usual pain, and the current pain (right now). The higher the score, the higher the pain intensity. Cronbach alpha coefficients on the NPRS obtained from the current sample of veterans were 0.85 on both pre- and postintervention assessments.

MPI. The MPI is an easily accessible, reliable, and valid self-report questionnaire that measures the impact of pain on an individual’s life, quality of social support, and general activity.14 This instrument is a short version of the West Haven-Yale MPI.15 The MPI contains 9 items rated on a scale from 0 to 6. The higher the score, the greater pain interference a person is experiencing. The MPI produces reliable, valid information for diagnostic purposes and for therapy outcome studies.16 The MPI had a Cronbach alpha of 0.90 on pre-intervention and 0.92 on postintervention assessments in the current sample.

WHOQOL-BREF. The WHOQOL-BREF is a measure of quality of life and is an abbreviated version of the WHOQOL-100. Quality of life is defined by the World Health Organization17 “as an individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.” The WHOQOL-BREF contains 26 items. The first 2 items were examined separately; the first item asks individuals to rate their overall quality of life and the second asks individuals how satisfied they are with their health. The remaining 24 items were used to calculate the following 4 domain scores: physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environment.18 Each item is measured on a scale of 1 to 5. Higher scores denote higher or better quality of life. Domain scores have demonstrated good reliability and validity.19-21 Cronbach alpha coefficients for the domain subscales ranged from 0.63 to 0.84 in the current sample, with the lowest alphas for the 3-item Social Relationships Domain.