User login

Getting hypertension under control in the youngest of patients

Hypertension and elevated blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents correlate to hypertension in adults, insofar as complications and medical therapy increase with age.1,2 Untreated, hypertension in children and adolescents can result in multiple harmful physiologic changes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, diastolic dysfunction, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, and neurocognitive deficits.3-5

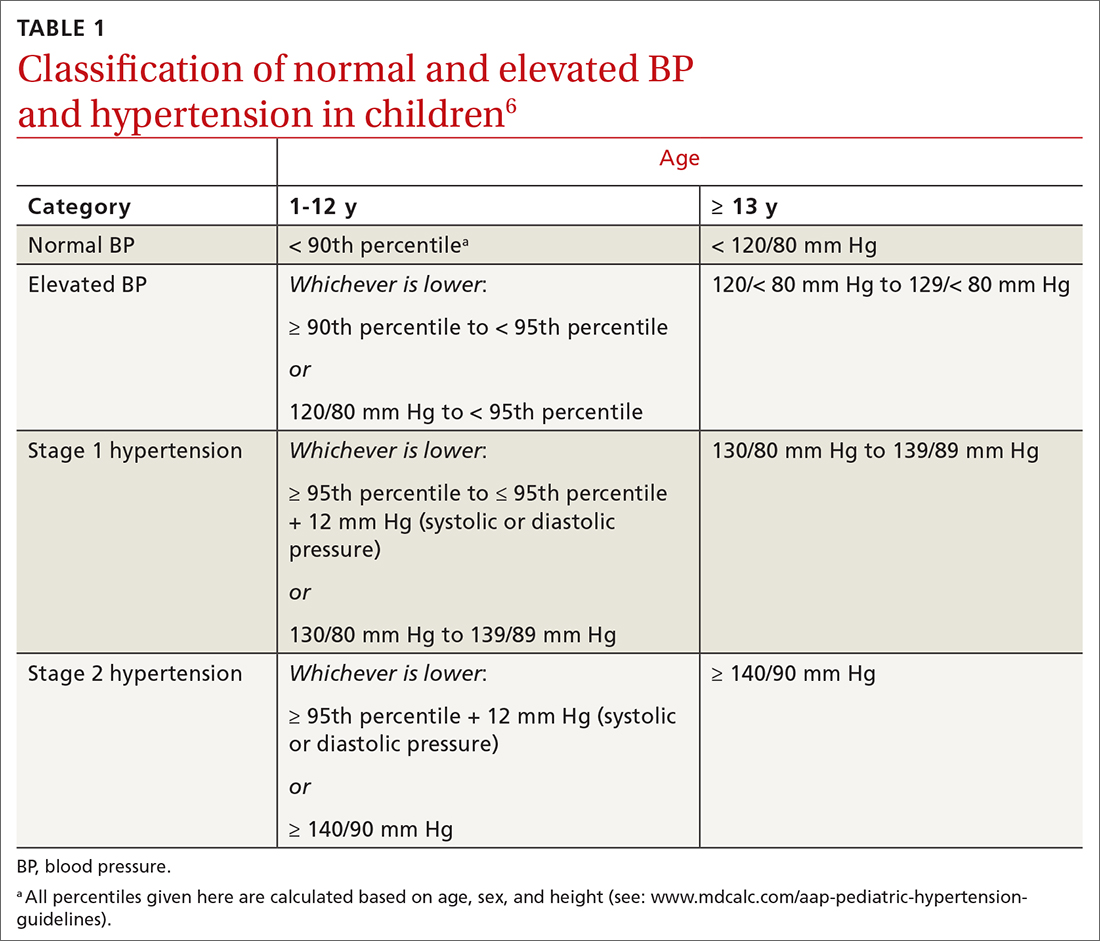

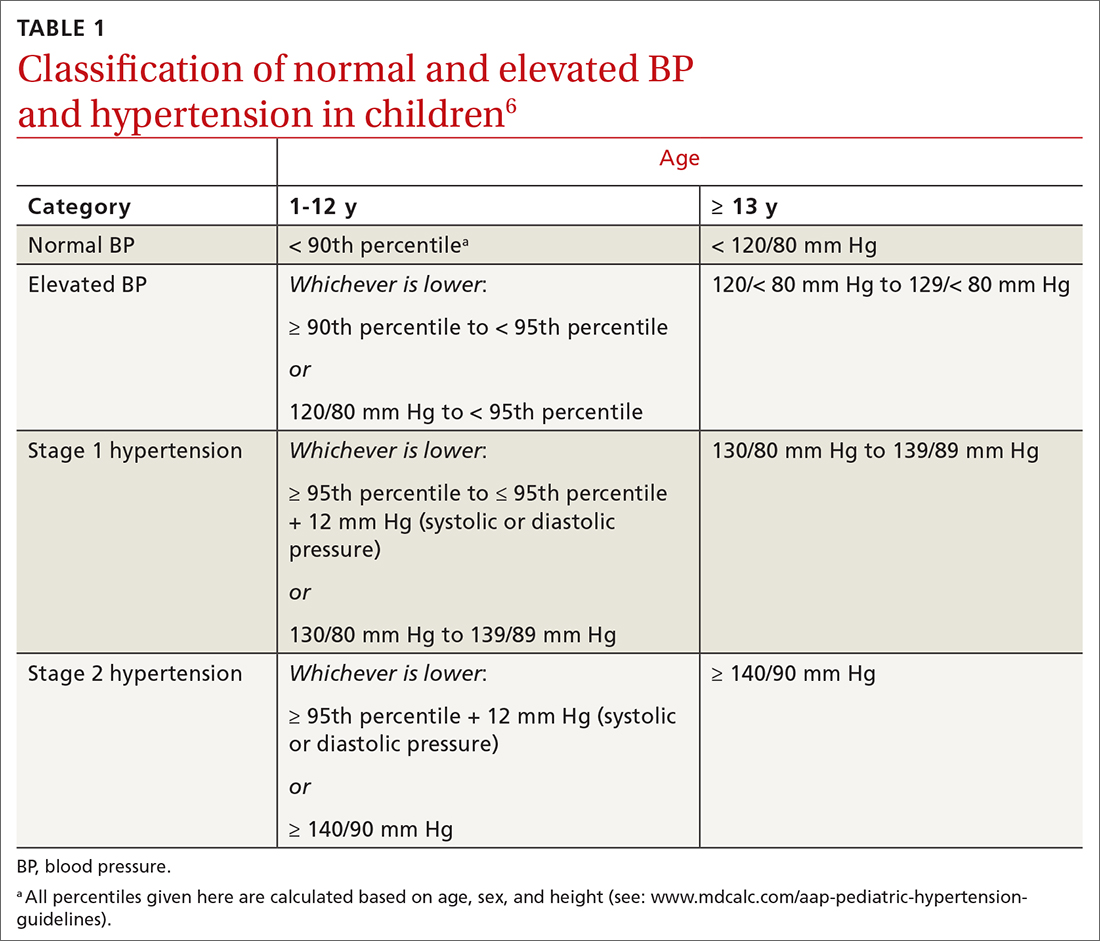

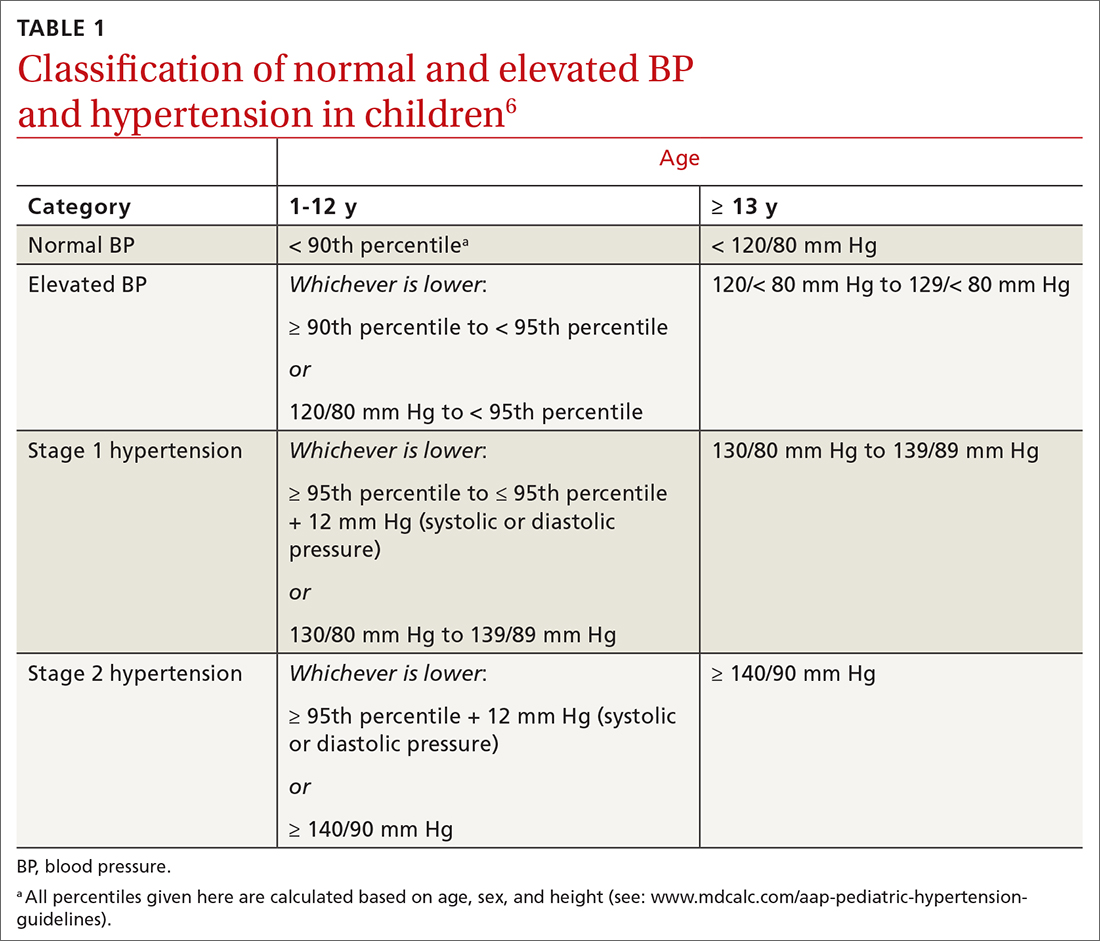

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of elevated BP and hypertension in children and adolescentsa (TABLE 16). Applying the definition of elevated BP set out in these guidelines yielded a 13% prevalence of hypertension in a cohort of subjects 10 to 18 years of age with comorbid obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). AAP guideline definitions also improved the sensitivity for identifying hypertensive end-organ damage.7

As the prevalence of hypertension increases, screening for and accurate diagnosis of this condition in children are becoming more important. Recognition and management remain a vital part of primary care. In this article, we review the updated guidance on diagnosis and treatment, including lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy.

First step: Identifying hypertension

Risk factors

Risk factors for pediatric hypertension are similar to those in adults. These include obesity (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile for age), types 1 and 2 DM, elevated sodium intake, sleep-disordered breathing, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some risk factors, such as premature birth and coarctation of the aorta, are specific to the pediatric population.8-14 Pediatric obesity strongly correlates with both pediatric and adult hypertension, and accelerated weight gain might increase the risk of elevated BP in adulthood.15,16

Intervening early to mitigate or eliminate some of these modifiable risk factors can prevent or treat hypertension.17 Alternatively, having been breastfed as an infant has been reliably shown to reduce the risk of elevated BP in children.13

Recommendations for screening and measuring BP

The optimal age to start measuring BP is not clearly defined. AAP recommends measurement:

- annually in all children ≥ 3 years of age

- at every encounter in patients who have a specific comorbid condition, including obesity, DM, renal disease, and aortic-arch abnormalities (obstruction and coarctation) and in those who are taking medication known to increase BP.6

Protocol. Measure BP in the right arm for consistency and comparison with reference values. The width of the cuff bladder should be at least 40%, and the length, 80% to 100%, of arm circumference. Position the cuff bladder midway between the olecranon and acromion. Obtain the measurement in a quiet and comfortable environment after the patient has rested for 3 to 5 minutes. The patient should be seated, preferably with feet on the floor; elbows should be supported at the level of the heart.

Continue to: When an initial reading...

When an initial reading is elevated, whether by oscillometric or auscultatory measurement, 2 more auscultatory BP measurements should be taken during the same visit; these measurements are averaged to determine the BP category.18

TABLE 16 defines BP categories based on age, sex, and height. We recommend using the free resource MD Calc (www.mdcalc.com/aap-pediatric-hypertension-guidelines) to assist in calculating the BP category.

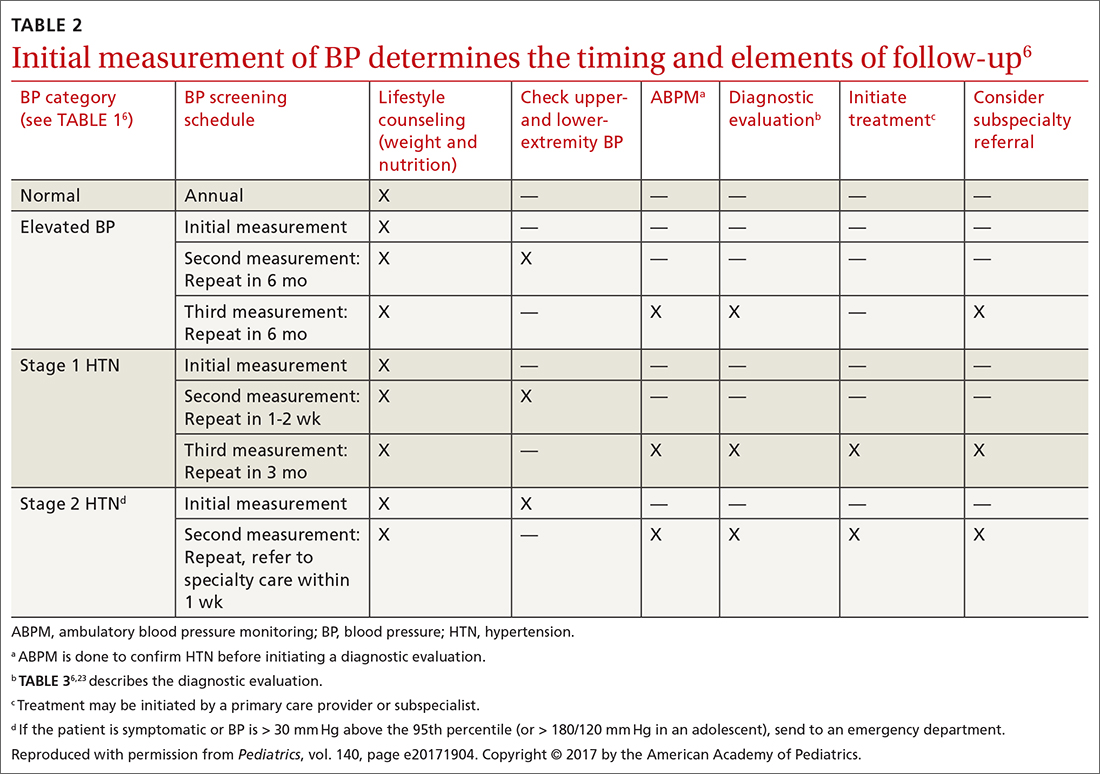

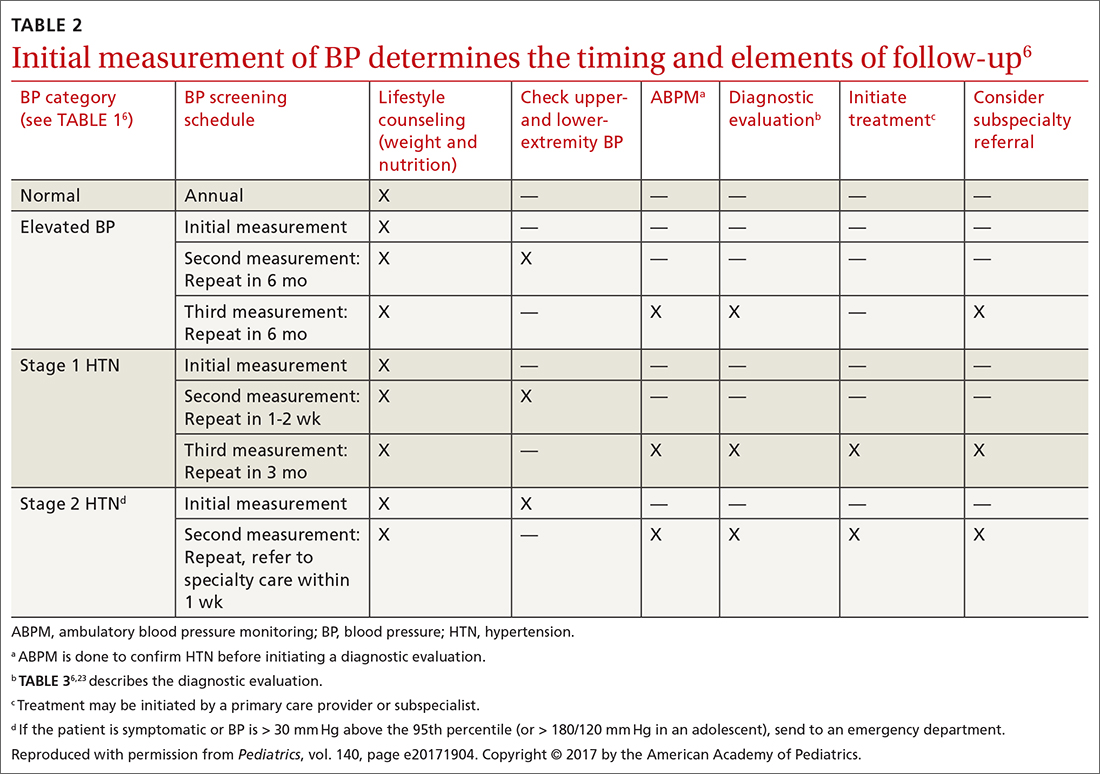

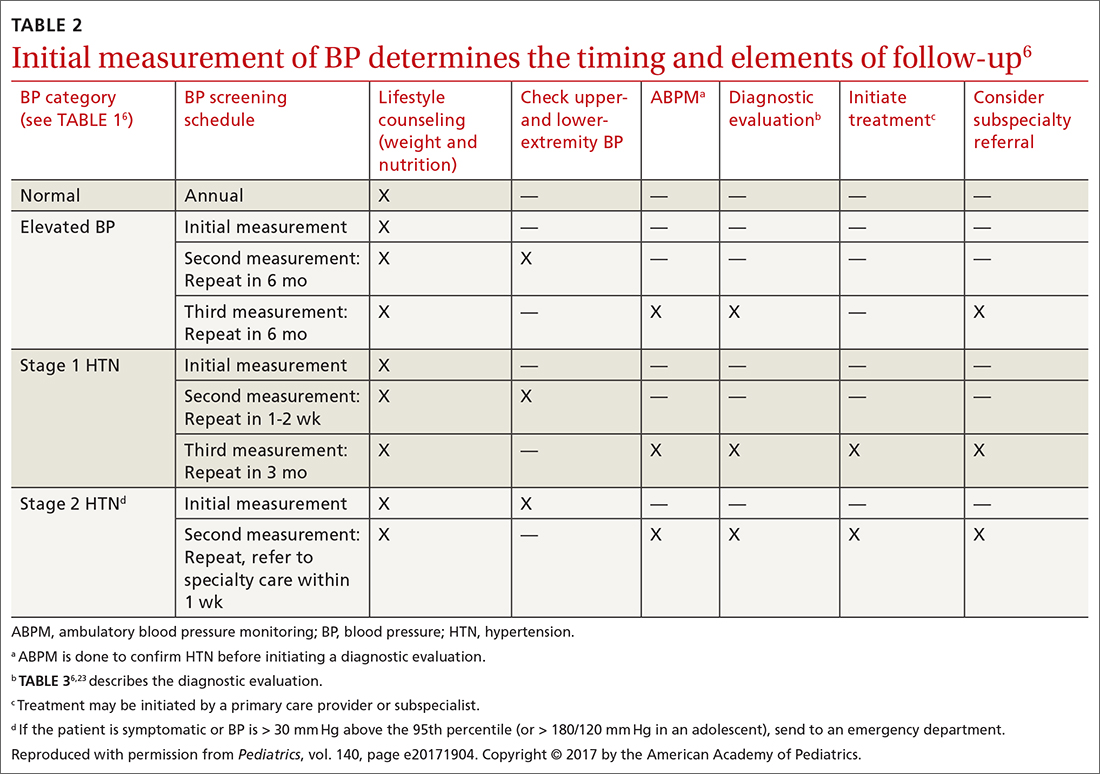

TABLE 26 describes the timing of follow-up based on the initial BP reading and diagnosis.

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is a validated device that measures BP every 20 to 30 minutes throughout the day and night. ABPM should be performed initially in all patients with persistently elevated BP and routinely in children and adolescents with a high-risk comorbidity (TABLE 26). Note: Insurance coverage of ABPM is limited.

ABPM is also used to diagnose so-called white-coat hypertension, defined as BP ≥ 95th percentile for age, sex, and height in the clinic setting but < 95th percentile during ABPM. This phenomenon can be challenging to diagnose.

Continue to: Home monitoring

Home monitoring. Do not use home BP monitoring to establish a diagnosis of hypertension, although one of these devices can be used as an adjunct to office and ambulatory BP monitoring after the diagnosis has been made.6

Evaluating hypertension in children and adolescents

Once a diagnosis of hypertension has been made, undertake a thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing to evaluate for possible causes, comorbidities, and any evidence of end-organ damage.

Comprehensive history. Pertinent aspects include perinatal, nutritional, physical activity, psychosocial, family, medication—and of course, medical—histories.6

Maternal elevated BP or hypertension is related to an offspring’s elevated BP in childhood and adolescence.19 Other pertinent aspects of the perinatal history include complications of pregnancy, gestational age, birth weight, and neonatal complications.6

Nutritional and physical activity histories can highlight contributing factors in the development of hypertension and can be a guide to recommending lifestyle modifications.6 Sodium intake, which influences BP, should be part of the nutritional history.20

Continue to: Important aspects...

Important aspects of the psychosocial history include feelings of depression or anxiety, bullying, and body perception. Children older than 10 years should be asked about smoking, alcohol, and other substance use.

The family history should include notation of first- and second-degree relatives with hypertension.6

Inquire about medications that can raise BP, including oral contraceptives, which are commonly prescribed in this population.21,22

The physical exam should include measured height and weight, with calculation of the body mass index percentile for age; of note, obesity is strongly associated with hypertension, and poor growth might signal underlying chronic disease. Once elevated BP has been confirmed, the exam should include measurement of BP in both arms and in a leg (TABLE 26). BP that is lower in the leg than in the arms (in any given patient, BP readings in the legs are usually higher than in the arms), or weak or absent femoral pulses, suggest coarctation of the aorta.6

Focus the balance of the physical exam on physical findings that suggest secondary causes of hypertension or evidence of end-organ damage.

Continue to: Testing

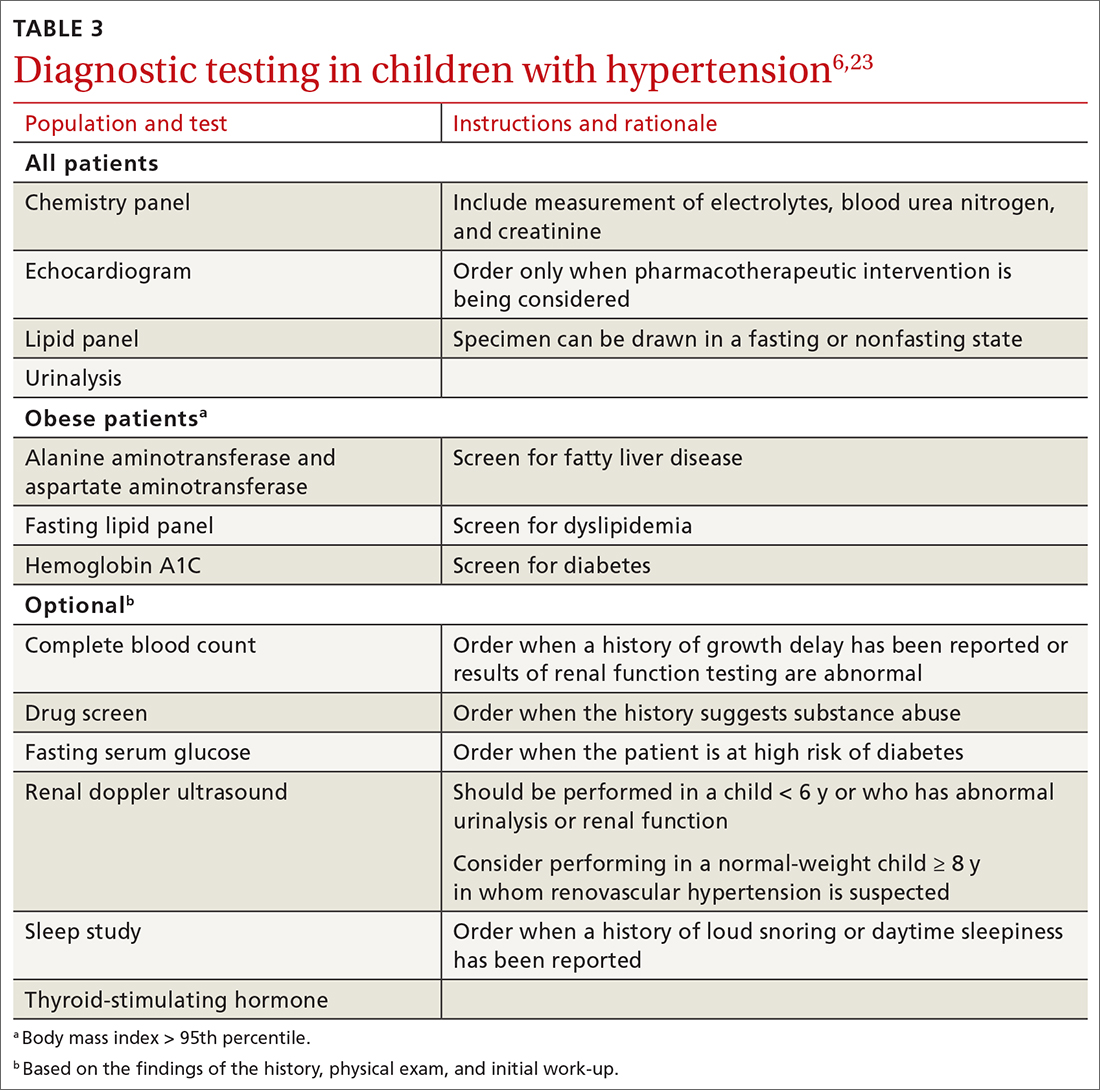

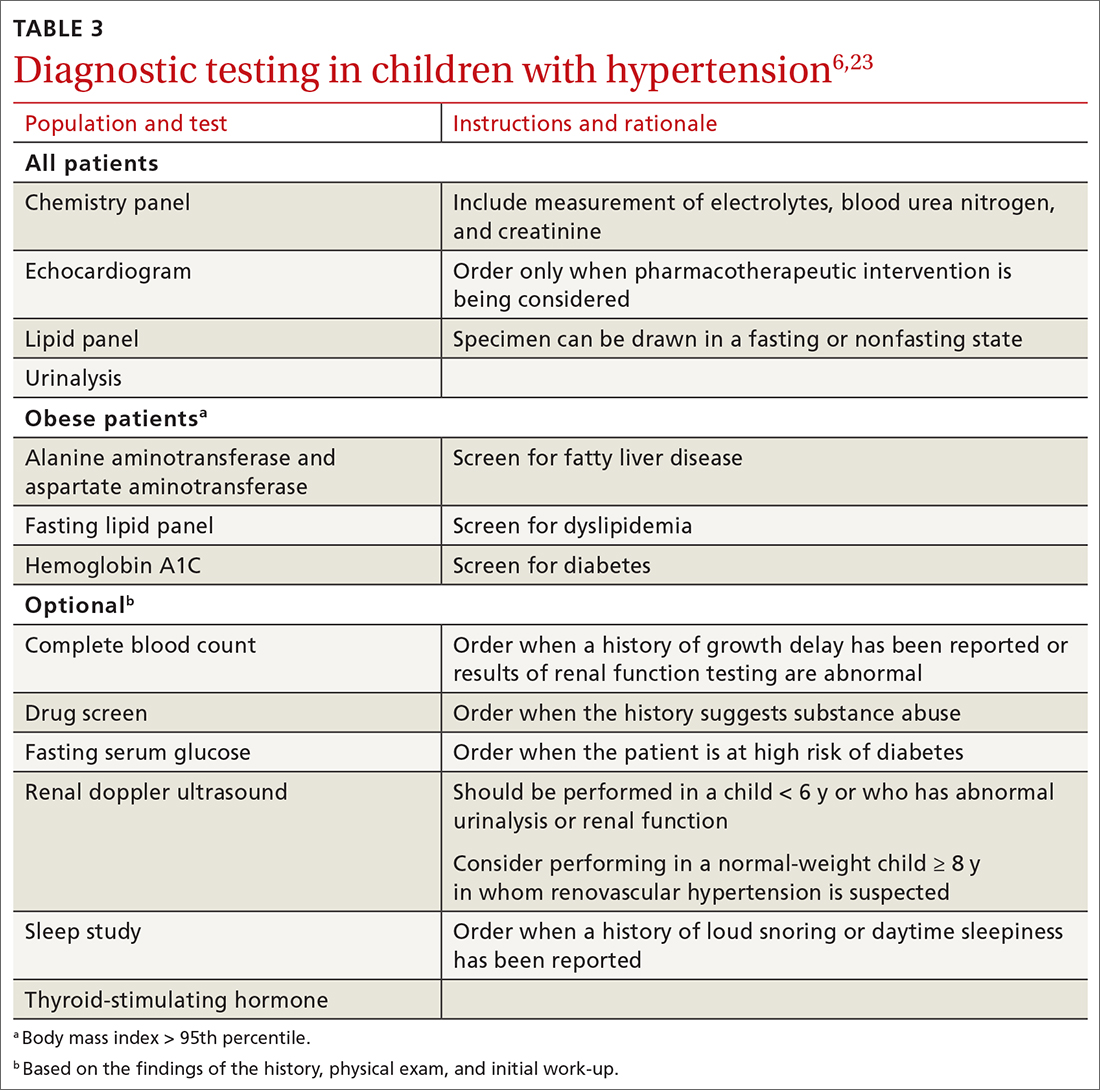

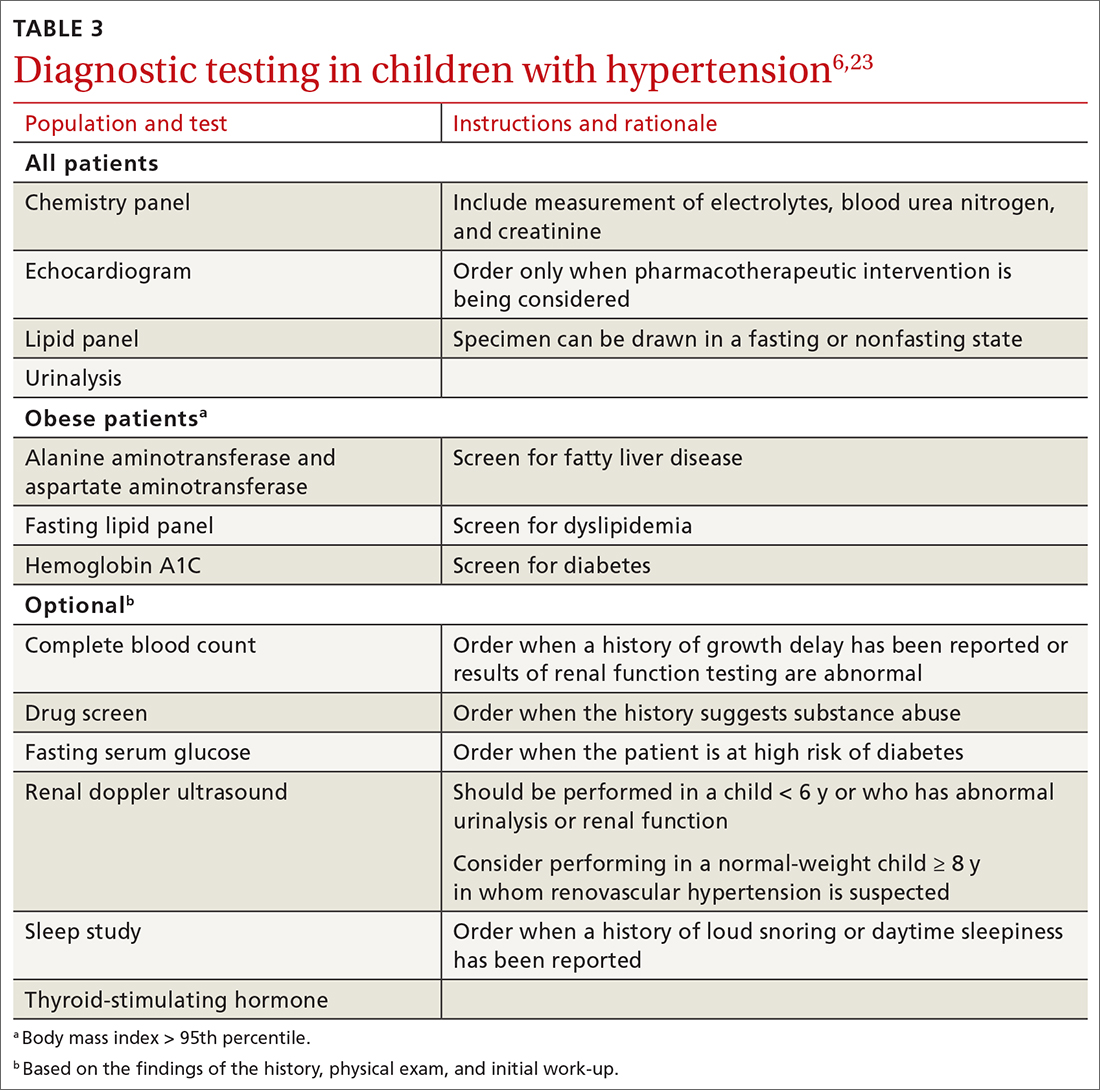

Testing. TABLE 36,23 summarizes the diagnostic testing recommended for all children and for specific populations; TABLE 26 indicates when to obtain diagnostic testing.

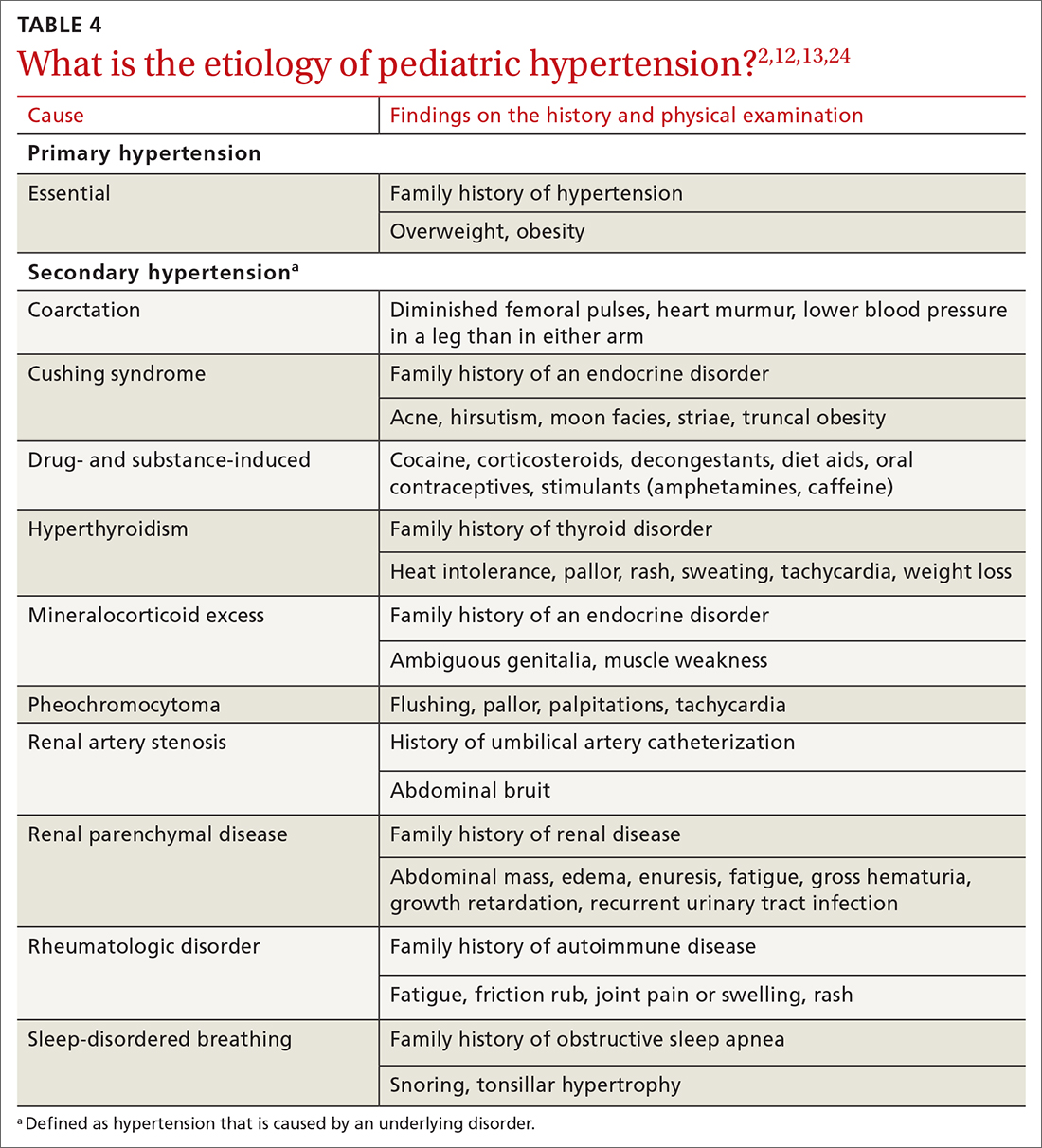

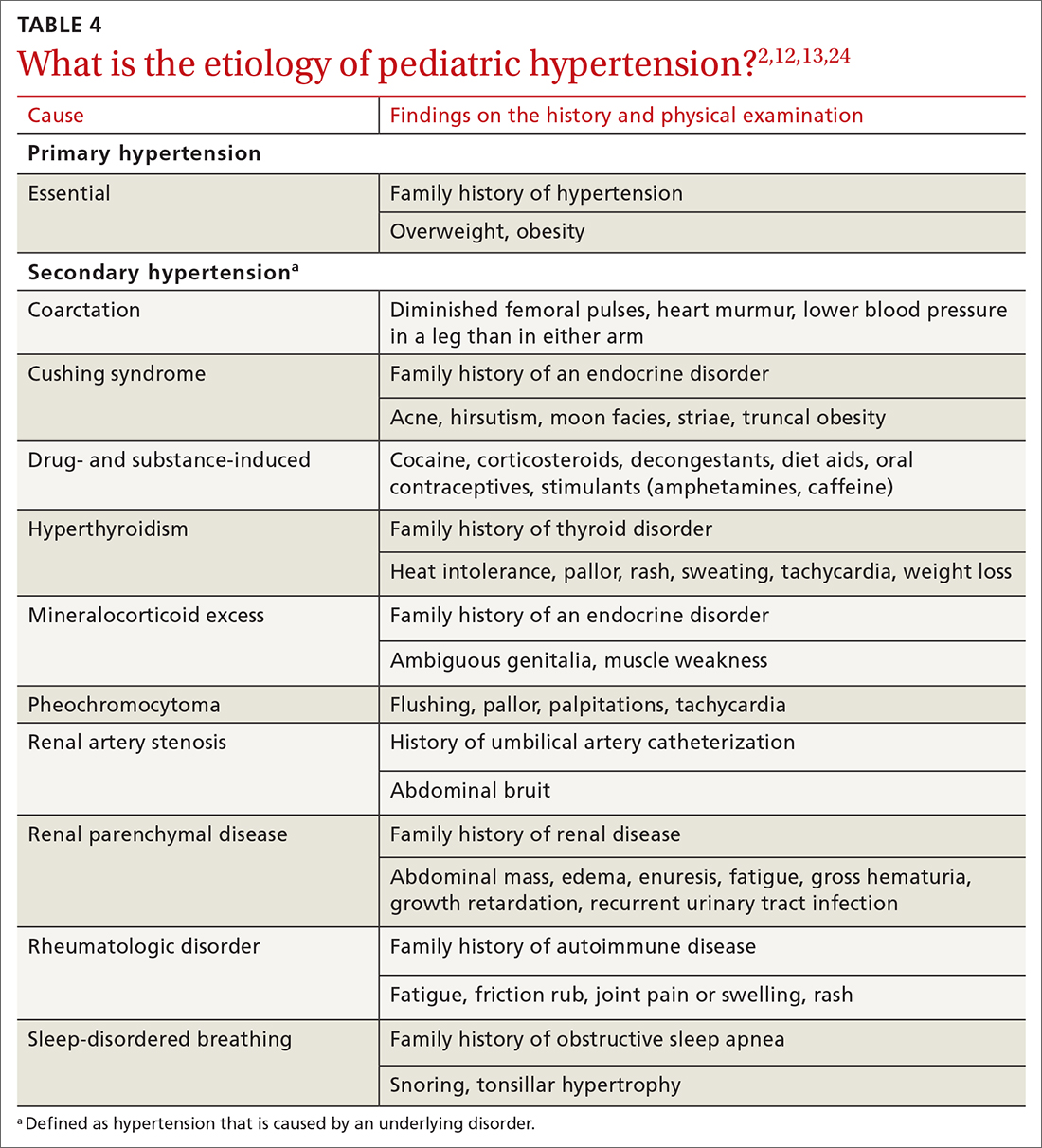

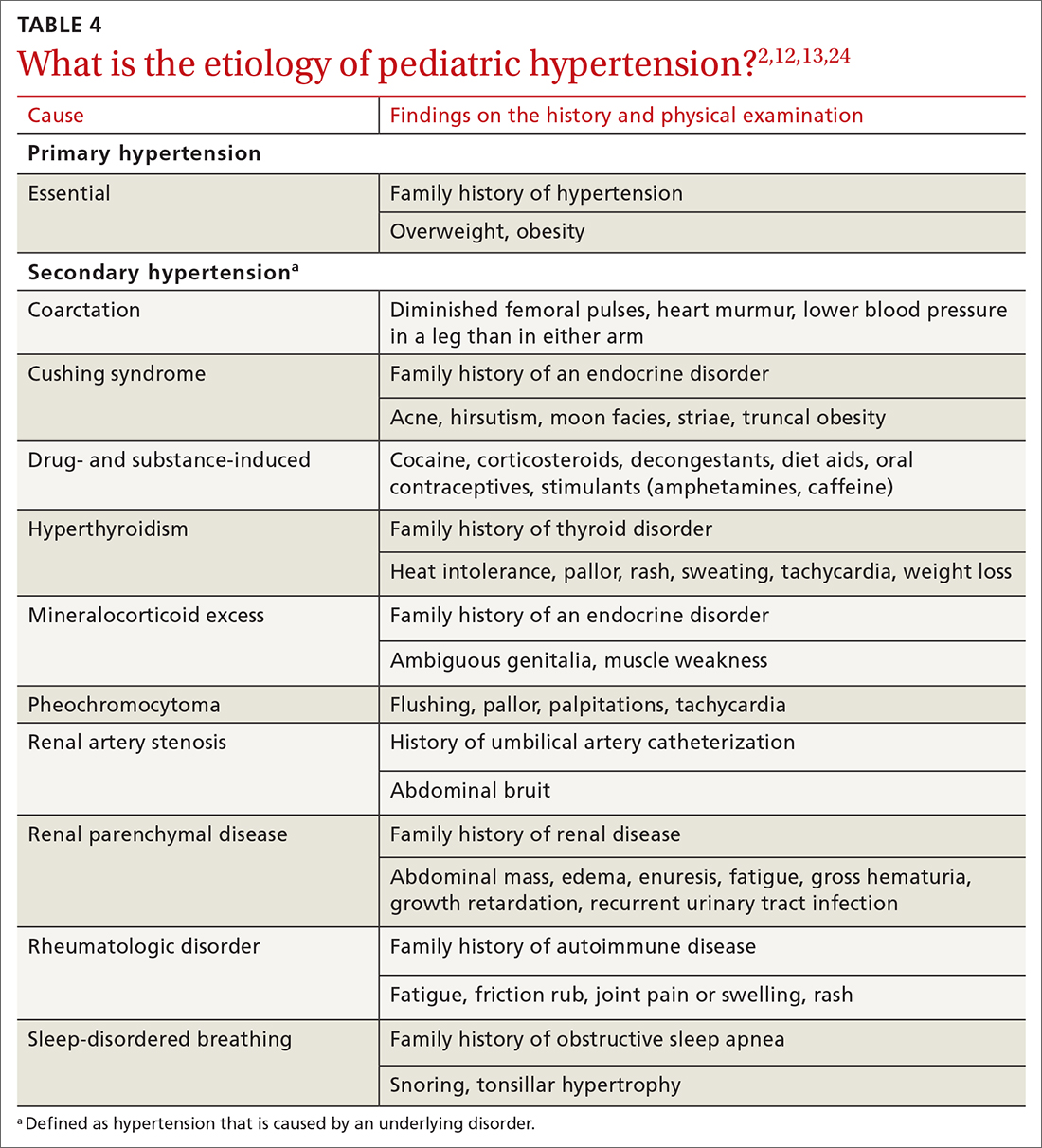

TABLE 42,12,13,24 outlines the basis of primary and of secondary hypertension and common historical and physical findings that suggest a secondary cause.

Mapping out the treatment plan

Pediatric hypertension should be treated in patients with stage 1 or higher hypertension.6 This threshold for therapy is based on evidence that reducing BP below a goal of (1) the 90th percentile (calculated based on age, sex, and height) in children up to 12 years of age or (2) of < 130/80 mm Hg for children ≥ 13 years reduces short- and long-term morbidity and mortality.5,6,25

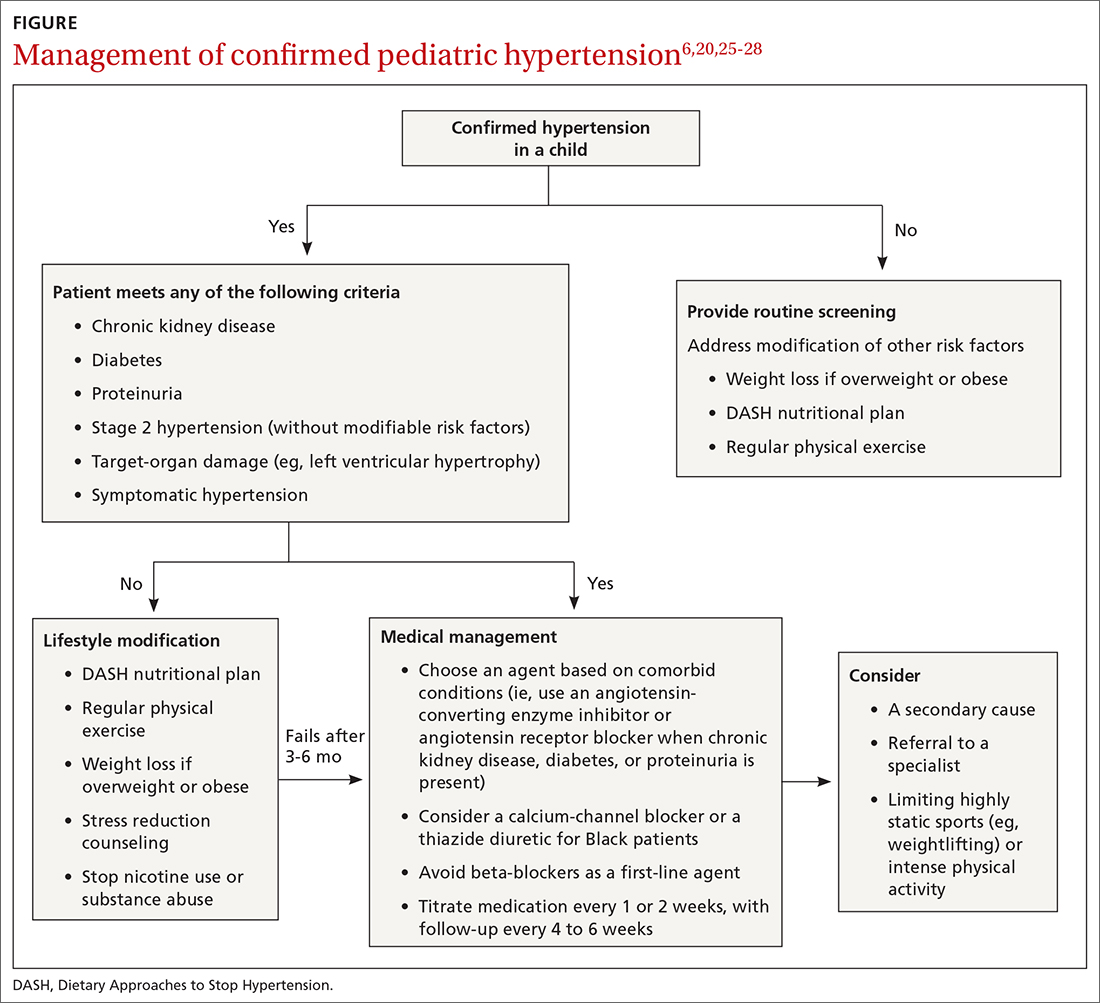

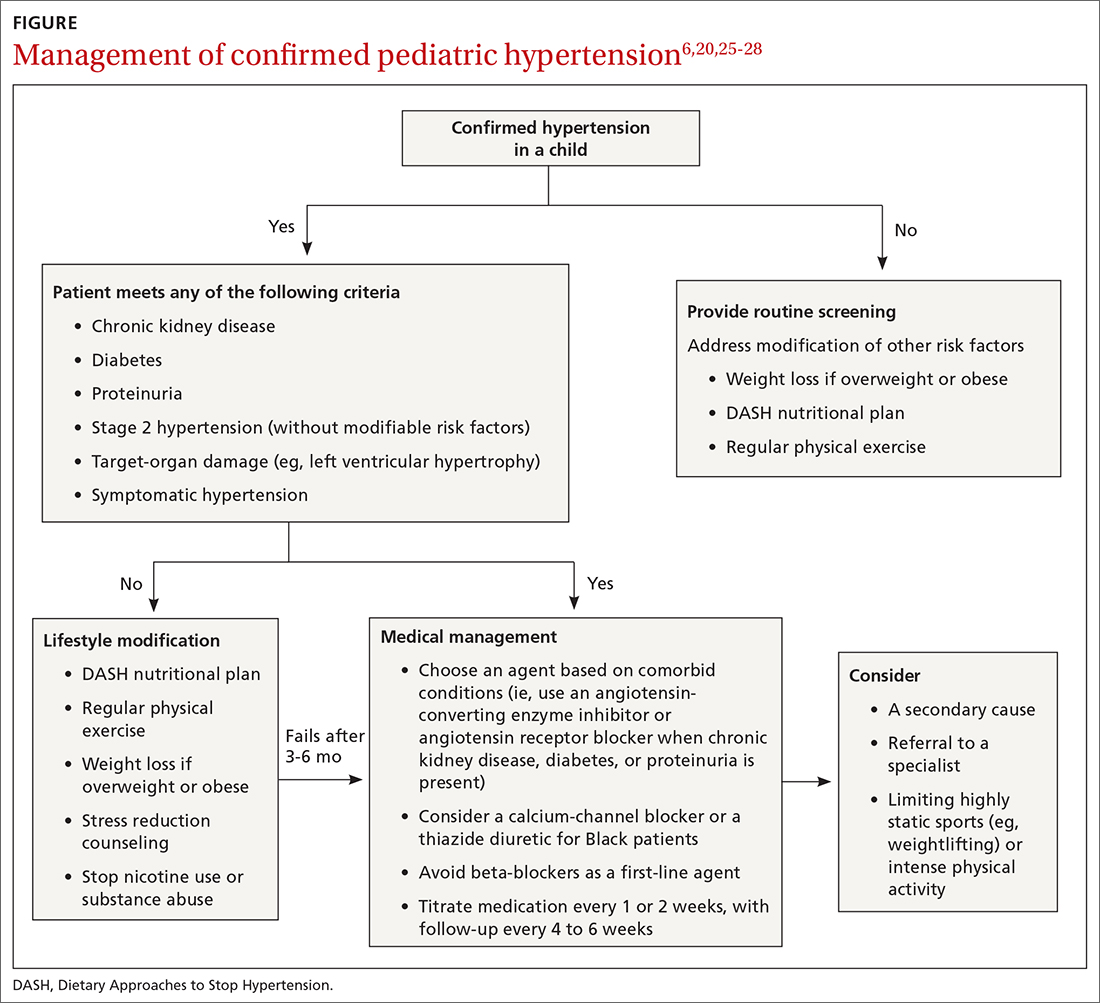

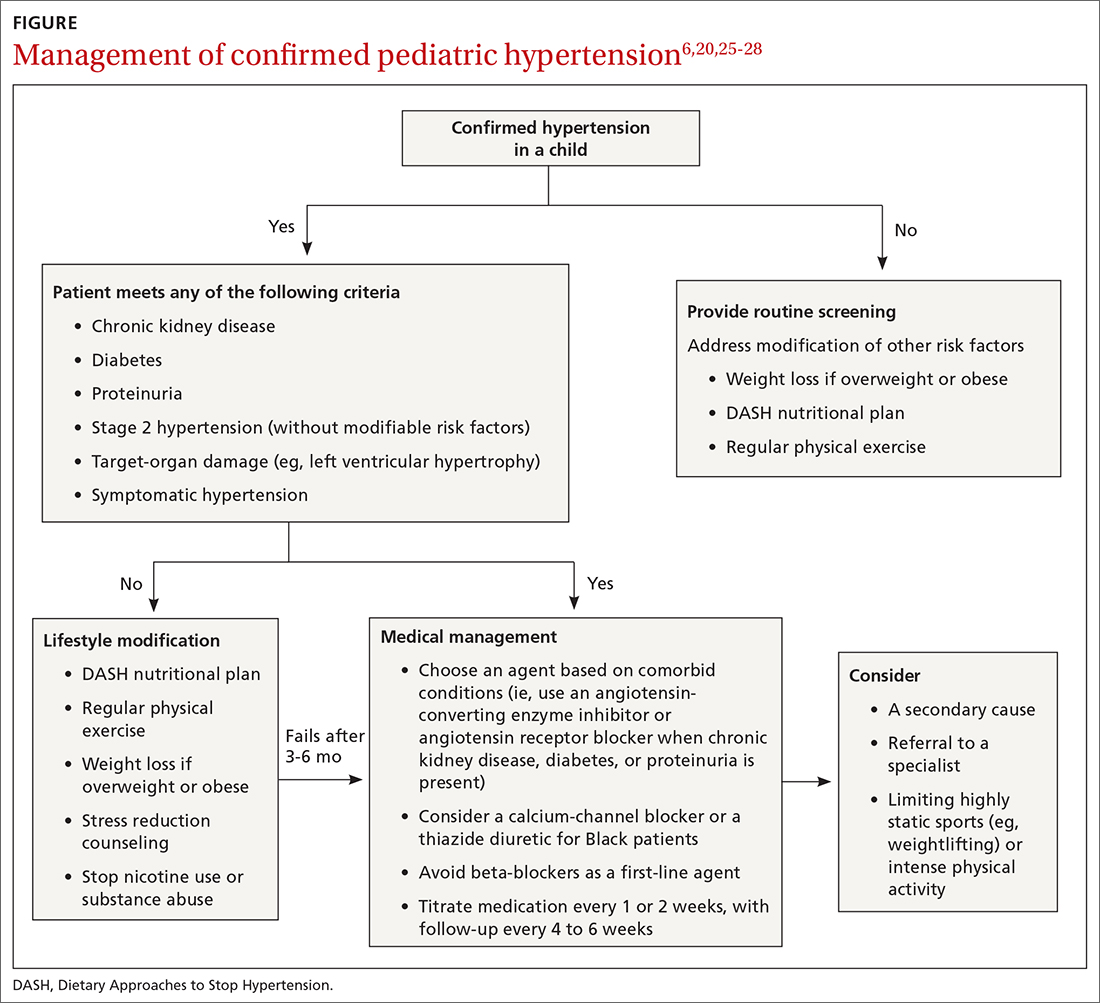

Choice of initial treatment depends on the severity of BP elevation and the presence of comorbidities (FIGURE6,20,25-28). The initial, fundamental treatment recommendation is lifestyle modification,6,29 including regular physical exercise, a change in nutritional habits, weight loss (because obesity is a common comorbid condition), elimination of tobacco and substance use, and stress reduction.25,26 Medications can be used as well, along with other treatments for specific causes of secondary hypertension.

Referral to a specialist can be considered if consultation for assistance with treatment is preferred (TABLE 26) or if the patient has:

- treatment-resistant hypertension

- stage 2 hypertension that is not quickly responsive to initial treatment

- an identified secondary cause of hypertension.

Continue to: Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Exercise. “Regular” physical exercise for children to reduce BP is defined as ≥ 30 to 60 minutes of active play daily.6,29 Studies have shown significant improvement not only in BP but also in other cardiovascular disease risk parameters with regular physical exercise.27 A study found that the reduction in systolic BP is, on average, approximately 6 mm Hg with physical activity alone.30

Nutrition. DASH—Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension—is an evidence-based program to reduce BP. This nutritional guideline focuses on a diet rich in natural foods, including fruits, vegetables, minimally processed carbohydrates and whole grains, and low-fat dairy and meats. It also emphasizes the importance of avoiding foods high in processed sugars and reducing sodium intake.31 Higher-than-recommended sodium intake, based on age and sex (and established as part of dietary recommendations for children on the US Department of Health and Human Services’ website health.gov) directly correlates with the risk of prehypertension and hypertension—especially in overweight and obese children.20,32 DASH has been shown to reliably reduce the incidence of hypertension in children; other studies have supported increased intake of fruits, vegetables, and legumes as strategies to reduce BP.33,34

Other interventions. Techniques to improve adherence to exercise and nutritional modifications for children include motivational interviewing, community programs and education, and family counseling.27,35 A recent study showed that a community-based lifestyle modification program that is focused on weight loss in obese children resulted in a significant reduction in BP values at higher stages of obesity.36 There is evidence that techniques such as controlled breathing and meditation can reduce BP.37 Last, screening and counseling to encourage tobacco and substance use discontinuation are recommended for children and adolescents to improve health outcomes.25

Proceed with pharmacotherapy when these criteria are met

Medical therapy is recommended when certain criteria are met, although this decision should be individualized and made in agreement by the treating physician, patient, and family. These criteria (FIGURE6,20,25-28) are6,29:

- once a diagnosis of stage 1 hypertension has been established, failure to meet a BP goal after 3 to 6 months of attempting lifestyle modifications

- stage 2 hypertension without a modifiable risk factor, such as obesity

- any stage of hypertension with comorbid CKD, DM, or proteinuria

- target-organ damage, such as left ventricular hypertrophy

- symptomatic hypertension.6,29

There are circumstances in which one or another specific antihypertensive agent is recommended for children; however, for most patients with primary hypertension, the following classes are recommended for first-line use6,22:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- calcium-channel blockers (CCBs)

- thiazide diuretics.

Continue to: For a child with known CKD...

For a child with known CKD, DM, or proteinuria, an ACE inhibitor or ARB is beneficial as first-line therapy.38 Because ACE inhibitors and ARBs have teratogenic effects, however, a thorough review of fertility status is recommended for female patients before any of these agents are started. CCBs and thiazides are typically recommended as first-line agents for Black patients.6,28 Beta-blockers are typically avoided in the first line because of their adverse effect profile.

Most antihypertensive medications can be titrated every 1 or 2 weeks; the patient’s BP can be monitored with a home BP cuff to track the effect of titration. In general, the patient should be seen for follow-up every 4 to 6 weeks for a BP recheck and review of medication tolerance and adverse effects. Once the treatment goal is achieved, it is reasonable to have the patient return every 3 to 6 months to reassess the treatment plan.

If the BP goal is difficult to achieve despite titration of medication and lifestyle changes, consider repeat ABPM assessment, a specialty referral, or both. It is reasonable for children who have been started on medication and have adhered to lifestyle modifications to practice a “step-down” approach to discontinuing medication; this approach can also be considered once any secondary cause has been corrected. Any target-organ abnormalities identified at diagnosis (eg, proteinuria, CKD, left ventricular hypertrophy) need to be reexamined at follow-up.6

Restrict activities—or not?

There is evidence that a child with stage 1 or well-controlled stage 2 hypertension without evidence of end-organ damage should not have restrictions on sports or activity. However, in uncontrolled stage 2 hypertension or when evidence of target end-organ damage is present, you should advise against participation in highly competitive sports and highly static sports (eg, weightlifting, wrestling), based on expert opinion6,25 (FIGURE6,20,25-28).

aAAP guidelines on the management of pediatric hypertension vary from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force. See the Practice Alert, “A review of the latest USPSTF recommendations,” in the May 2021 issue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, MD, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL, 32214; [email protected]

1. Theodore RF, Broadbent J, Nagin D, et al. Childhood to early-midlife systolic blood pressure trajectories: early-life predictors, effect modifiers, and adult cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertension. 2015;66:1108-1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05831

2. Lurbe E, Agabiti-Rosei E, Cruickshank JK, et al. 2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1887-1920. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001039

3. Weaver DJ, Mitsnefes MM. Effects of systemic hypertension on the cardiovascular system. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;41:59-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2015.11.005

4. Ippisch HM, Daniels SR. Hypertension in overweight and obese children. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;25:177-182. doi: org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2008.05.002

5. Urbina EM, Lande MB, Hooper SR, et al. Target organ abnormalities in pediatric hypertension. J Pediatr. 2018;202:14-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.026

6. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al; . Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904

7. Khoury M, Khoury PR, Dolan LM, et al. Clinical implications of the revised AAP pediatric hypertension guidelines. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20180245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0245

8. Falkner B, Gidding SS, Ramirez-Garnica G, et al. The relationship of body mass index and blood pressure in primary care pediatric patients. J Pediatr. 2006;148:195-200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.030

9. Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al; SEARCH Study Group. Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr. 2010;157:245-251.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.021

10. Shay CM, Ning H, Daniels SR, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adolescents: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005-2010. Circulation. 2013;127:1369-1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001559

11. Archbold KH, Vasquez MM, Goodwin JL, et al. Effects of sleep patterns and obesity on increases in blood pressure in a 5-year period: report from the Tucson Children’s Assessment of Sleep Apnea Study. J Pediatr. 2012;161:26-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.034

12. Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Pierce C, et al; . Blood pressure in children with chronic kidney disease: a report from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study. Hypertension. 2008;52:631-637. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110635

13. Martin RM, Ness AR, Gunnell D, et al; ALSPAC Study Team. Does breast-feeding in infancy lower blood pressure in childhood? The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Circulation. 2004;109:1259-1266. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118468.76447.CE

14. Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256-263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420407

15. Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3171-3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366

16. Sun SS, Grave GD, Siervogel RM, et al. Systolic blood pressure in childhood predicts hypertension and metabolic syndrome later in life. Pediatrics. 2007;119:237-246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2543

17. Parker ED, Sinaiko AR, Kharbanda EO, et al. Change in weight status and development of hypertension. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20151662. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1662

18. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al; . Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142-161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e

19. Staley JR, Bradley J, Silverwood RJ, et al. Associations of blood pressure in pregnancy with offspring blood pressure trajectories during childhood and adolescence: findings from a prospective study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001422. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001422

20. Yang Q, Zhang Z, Zuklina EV, et al. Sodium intake and blood pressure among US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130:611-619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3870

21. Le-Ha C, Beilin LJ, Burrows S, et al. Oral contraceptive use in girls and alcohol consumption in boys are associated with increased blood pressure in late adolescence. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:947-955. doi: 10.1177/2047487312452966

22. Samuels JA, Franco K, Wan F, Sorof JM. Effect of stimulants on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in children with ADHD: a double-blind, randomized, cross-over trial. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:92-95. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2051-1

23. Wiesen J, Adkins M, Fortune S, et al. Evaluation of pediatric patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension: yield of diagnostic testing. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e988-993. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0365

24. Kapur G, Ahmed M, Pan C, et al. Secondary hypertension in overweight and stage 1 hypertensive children: a Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium report. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:34-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00195.x

25. Anyaegbu EI, Dharnidharka VR. Hypertension in the teenager. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:131-151. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.09.011

26. Gandhi B, Cheek S, Campo JV. Anxiety in the pediatric medical setting. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:643-653. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.013

27. Farpour-Lambert NJ, Aggoun Y, Marchand LM, et al. Physical activity reduces systemic blood pressure and improves early markers of atherosclerosis in pre-pubertal obese children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2396-2406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.030

28. Li JS, Baker-Smith CM, Smith PB, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in children: a meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:315-319. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.113

29. Singer PS. Updates on hypertension and new guidelines. Adv Pediatr. 2019;66:177-187. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2019.03.009

30. Torrance B, McGuire KA, Lewanczuk R, et al. Overweight, physical activity and high blood pressure in children: a review of the literature. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:139-149.

31. DASH eating plan. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed April 26, 2021. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/dash-eating-plan

32. Nutritional goals for age-sex groups based on dietary reference intakes and dietary guidelines recommendations (Appendix 7). In: US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. December 2015;97-98. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf

33. Asghari G, Yuzbashian E, Mirmiran P, et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern is associated with reduced incidence of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016;174:178-184.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.077

34. Damasceno MMC, de Araújo MFM, de Freitas RWJF, et al. The association between blood pressure in adolescents and the consumption of fruits, vegetables and fruit juice–an exploratory study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1553-1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03608.x

35. Anderson KL. A review of the prevention and medical management of childhood obesity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27:63-76. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2017.08.003

36. Kumar S, King EC, Christison, et al; POWER Work Group. Health outcomes of youth in clinical pediatric weight management programs in POWER. J Pediatr. 2019;208:57-65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.049

37. Gregoski MJ, Barnes VA, Tingen MS, et al. Breathing awareness meditation and LifeSkills® Training programs influence upon ambulatory blood pressure and sodium excretion among African American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:59-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.019

38. Escape Trial Group; E, Trivelli A, Picca S, et al. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1639-1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902066

Hypertension and elevated blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents correlate to hypertension in adults, insofar as complications and medical therapy increase with age.1,2 Untreated, hypertension in children and adolescents can result in multiple harmful physiologic changes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, diastolic dysfunction, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, and neurocognitive deficits.3-5

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of elevated BP and hypertension in children and adolescentsa (TABLE 16). Applying the definition of elevated BP set out in these guidelines yielded a 13% prevalence of hypertension in a cohort of subjects 10 to 18 years of age with comorbid obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). AAP guideline definitions also improved the sensitivity for identifying hypertensive end-organ damage.7

As the prevalence of hypertension increases, screening for and accurate diagnosis of this condition in children are becoming more important. Recognition and management remain a vital part of primary care. In this article, we review the updated guidance on diagnosis and treatment, including lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy.

First step: Identifying hypertension

Risk factors

Risk factors for pediatric hypertension are similar to those in adults. These include obesity (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile for age), types 1 and 2 DM, elevated sodium intake, sleep-disordered breathing, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some risk factors, such as premature birth and coarctation of the aorta, are specific to the pediatric population.8-14 Pediatric obesity strongly correlates with both pediatric and adult hypertension, and accelerated weight gain might increase the risk of elevated BP in adulthood.15,16

Intervening early to mitigate or eliminate some of these modifiable risk factors can prevent or treat hypertension.17 Alternatively, having been breastfed as an infant has been reliably shown to reduce the risk of elevated BP in children.13

Recommendations for screening and measuring BP

The optimal age to start measuring BP is not clearly defined. AAP recommends measurement:

- annually in all children ≥ 3 years of age

- at every encounter in patients who have a specific comorbid condition, including obesity, DM, renal disease, and aortic-arch abnormalities (obstruction and coarctation) and in those who are taking medication known to increase BP.6

Protocol. Measure BP in the right arm for consistency and comparison with reference values. The width of the cuff bladder should be at least 40%, and the length, 80% to 100%, of arm circumference. Position the cuff bladder midway between the olecranon and acromion. Obtain the measurement in a quiet and comfortable environment after the patient has rested for 3 to 5 minutes. The patient should be seated, preferably with feet on the floor; elbows should be supported at the level of the heart.

Continue to: When an initial reading...

When an initial reading is elevated, whether by oscillometric or auscultatory measurement, 2 more auscultatory BP measurements should be taken during the same visit; these measurements are averaged to determine the BP category.18

TABLE 16 defines BP categories based on age, sex, and height. We recommend using the free resource MD Calc (www.mdcalc.com/aap-pediatric-hypertension-guidelines) to assist in calculating the BP category.

TABLE 26 describes the timing of follow-up based on the initial BP reading and diagnosis.

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is a validated device that measures BP every 20 to 30 minutes throughout the day and night. ABPM should be performed initially in all patients with persistently elevated BP and routinely in children and adolescents with a high-risk comorbidity (TABLE 26). Note: Insurance coverage of ABPM is limited.

ABPM is also used to diagnose so-called white-coat hypertension, defined as BP ≥ 95th percentile for age, sex, and height in the clinic setting but < 95th percentile during ABPM. This phenomenon can be challenging to diagnose.

Continue to: Home monitoring

Home monitoring. Do not use home BP monitoring to establish a diagnosis of hypertension, although one of these devices can be used as an adjunct to office and ambulatory BP monitoring after the diagnosis has been made.6

Evaluating hypertension in children and adolescents

Once a diagnosis of hypertension has been made, undertake a thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing to evaluate for possible causes, comorbidities, and any evidence of end-organ damage.

Comprehensive history. Pertinent aspects include perinatal, nutritional, physical activity, psychosocial, family, medication—and of course, medical—histories.6

Maternal elevated BP or hypertension is related to an offspring’s elevated BP in childhood and adolescence.19 Other pertinent aspects of the perinatal history include complications of pregnancy, gestational age, birth weight, and neonatal complications.6

Nutritional and physical activity histories can highlight contributing factors in the development of hypertension and can be a guide to recommending lifestyle modifications.6 Sodium intake, which influences BP, should be part of the nutritional history.20

Continue to: Important aspects...

Important aspects of the psychosocial history include feelings of depression or anxiety, bullying, and body perception. Children older than 10 years should be asked about smoking, alcohol, and other substance use.

The family history should include notation of first- and second-degree relatives with hypertension.6

Inquire about medications that can raise BP, including oral contraceptives, which are commonly prescribed in this population.21,22

The physical exam should include measured height and weight, with calculation of the body mass index percentile for age; of note, obesity is strongly associated with hypertension, and poor growth might signal underlying chronic disease. Once elevated BP has been confirmed, the exam should include measurement of BP in both arms and in a leg (TABLE 26). BP that is lower in the leg than in the arms (in any given patient, BP readings in the legs are usually higher than in the arms), or weak or absent femoral pulses, suggest coarctation of the aorta.6

Focus the balance of the physical exam on physical findings that suggest secondary causes of hypertension or evidence of end-organ damage.

Continue to: Testing

Testing. TABLE 36,23 summarizes the diagnostic testing recommended for all children and for specific populations; TABLE 26 indicates when to obtain diagnostic testing.

TABLE 42,12,13,24 outlines the basis of primary and of secondary hypertension and common historical and physical findings that suggest a secondary cause.

Mapping out the treatment plan

Pediatric hypertension should be treated in patients with stage 1 or higher hypertension.6 This threshold for therapy is based on evidence that reducing BP below a goal of (1) the 90th percentile (calculated based on age, sex, and height) in children up to 12 years of age or (2) of < 130/80 mm Hg for children ≥ 13 years reduces short- and long-term morbidity and mortality.5,6,25

Choice of initial treatment depends on the severity of BP elevation and the presence of comorbidities (FIGURE6,20,25-28). The initial, fundamental treatment recommendation is lifestyle modification,6,29 including regular physical exercise, a change in nutritional habits, weight loss (because obesity is a common comorbid condition), elimination of tobacco and substance use, and stress reduction.25,26 Medications can be used as well, along with other treatments for specific causes of secondary hypertension.

Referral to a specialist can be considered if consultation for assistance with treatment is preferred (TABLE 26) or if the patient has:

- treatment-resistant hypertension

- stage 2 hypertension that is not quickly responsive to initial treatment

- an identified secondary cause of hypertension.

Continue to: Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Exercise. “Regular” physical exercise for children to reduce BP is defined as ≥ 30 to 60 minutes of active play daily.6,29 Studies have shown significant improvement not only in BP but also in other cardiovascular disease risk parameters with regular physical exercise.27 A study found that the reduction in systolic BP is, on average, approximately 6 mm Hg with physical activity alone.30

Nutrition. DASH—Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension—is an evidence-based program to reduce BP. This nutritional guideline focuses on a diet rich in natural foods, including fruits, vegetables, minimally processed carbohydrates and whole grains, and low-fat dairy and meats. It also emphasizes the importance of avoiding foods high in processed sugars and reducing sodium intake.31 Higher-than-recommended sodium intake, based on age and sex (and established as part of dietary recommendations for children on the US Department of Health and Human Services’ website health.gov) directly correlates with the risk of prehypertension and hypertension—especially in overweight and obese children.20,32 DASH has been shown to reliably reduce the incidence of hypertension in children; other studies have supported increased intake of fruits, vegetables, and legumes as strategies to reduce BP.33,34

Other interventions. Techniques to improve adherence to exercise and nutritional modifications for children include motivational interviewing, community programs and education, and family counseling.27,35 A recent study showed that a community-based lifestyle modification program that is focused on weight loss in obese children resulted in a significant reduction in BP values at higher stages of obesity.36 There is evidence that techniques such as controlled breathing and meditation can reduce BP.37 Last, screening and counseling to encourage tobacco and substance use discontinuation are recommended for children and adolescents to improve health outcomes.25

Proceed with pharmacotherapy when these criteria are met

Medical therapy is recommended when certain criteria are met, although this decision should be individualized and made in agreement by the treating physician, patient, and family. These criteria (FIGURE6,20,25-28) are6,29:

- once a diagnosis of stage 1 hypertension has been established, failure to meet a BP goal after 3 to 6 months of attempting lifestyle modifications

- stage 2 hypertension without a modifiable risk factor, such as obesity

- any stage of hypertension with comorbid CKD, DM, or proteinuria

- target-organ damage, such as left ventricular hypertrophy

- symptomatic hypertension.6,29

There are circumstances in which one or another specific antihypertensive agent is recommended for children; however, for most patients with primary hypertension, the following classes are recommended for first-line use6,22:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- calcium-channel blockers (CCBs)

- thiazide diuretics.

Continue to: For a child with known CKD...

For a child with known CKD, DM, or proteinuria, an ACE inhibitor or ARB is beneficial as first-line therapy.38 Because ACE inhibitors and ARBs have teratogenic effects, however, a thorough review of fertility status is recommended for female patients before any of these agents are started. CCBs and thiazides are typically recommended as first-line agents for Black patients.6,28 Beta-blockers are typically avoided in the first line because of their adverse effect profile.

Most antihypertensive medications can be titrated every 1 or 2 weeks; the patient’s BP can be monitored with a home BP cuff to track the effect of titration. In general, the patient should be seen for follow-up every 4 to 6 weeks for a BP recheck and review of medication tolerance and adverse effects. Once the treatment goal is achieved, it is reasonable to have the patient return every 3 to 6 months to reassess the treatment plan.

If the BP goal is difficult to achieve despite titration of medication and lifestyle changes, consider repeat ABPM assessment, a specialty referral, or both. It is reasonable for children who have been started on medication and have adhered to lifestyle modifications to practice a “step-down” approach to discontinuing medication; this approach can also be considered once any secondary cause has been corrected. Any target-organ abnormalities identified at diagnosis (eg, proteinuria, CKD, left ventricular hypertrophy) need to be reexamined at follow-up.6

Restrict activities—or not?

There is evidence that a child with stage 1 or well-controlled stage 2 hypertension without evidence of end-organ damage should not have restrictions on sports or activity. However, in uncontrolled stage 2 hypertension or when evidence of target end-organ damage is present, you should advise against participation in highly competitive sports and highly static sports (eg, weightlifting, wrestling), based on expert opinion6,25 (FIGURE6,20,25-28).

aAAP guidelines on the management of pediatric hypertension vary from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force. See the Practice Alert, “A review of the latest USPSTF recommendations,” in the May 2021 issue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, MD, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL, 32214; [email protected]

Hypertension and elevated blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents correlate to hypertension in adults, insofar as complications and medical therapy increase with age.1,2 Untreated, hypertension in children and adolescents can result in multiple harmful physiologic changes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, diastolic dysfunction, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, and neurocognitive deficits.3-5

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of elevated BP and hypertension in children and adolescentsa (TABLE 16). Applying the definition of elevated BP set out in these guidelines yielded a 13% prevalence of hypertension in a cohort of subjects 10 to 18 years of age with comorbid obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). AAP guideline definitions also improved the sensitivity for identifying hypertensive end-organ damage.7

As the prevalence of hypertension increases, screening for and accurate diagnosis of this condition in children are becoming more important. Recognition and management remain a vital part of primary care. In this article, we review the updated guidance on diagnosis and treatment, including lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy.

First step: Identifying hypertension

Risk factors

Risk factors for pediatric hypertension are similar to those in adults. These include obesity (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile for age), types 1 and 2 DM, elevated sodium intake, sleep-disordered breathing, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some risk factors, such as premature birth and coarctation of the aorta, are specific to the pediatric population.8-14 Pediatric obesity strongly correlates with both pediatric and adult hypertension, and accelerated weight gain might increase the risk of elevated BP in adulthood.15,16

Intervening early to mitigate or eliminate some of these modifiable risk factors can prevent or treat hypertension.17 Alternatively, having been breastfed as an infant has been reliably shown to reduce the risk of elevated BP in children.13

Recommendations for screening and measuring BP

The optimal age to start measuring BP is not clearly defined. AAP recommends measurement:

- annually in all children ≥ 3 years of age

- at every encounter in patients who have a specific comorbid condition, including obesity, DM, renal disease, and aortic-arch abnormalities (obstruction and coarctation) and in those who are taking medication known to increase BP.6

Protocol. Measure BP in the right arm for consistency and comparison with reference values. The width of the cuff bladder should be at least 40%, and the length, 80% to 100%, of arm circumference. Position the cuff bladder midway between the olecranon and acromion. Obtain the measurement in a quiet and comfortable environment after the patient has rested for 3 to 5 minutes. The patient should be seated, preferably with feet on the floor; elbows should be supported at the level of the heart.

Continue to: When an initial reading...

When an initial reading is elevated, whether by oscillometric or auscultatory measurement, 2 more auscultatory BP measurements should be taken during the same visit; these measurements are averaged to determine the BP category.18

TABLE 16 defines BP categories based on age, sex, and height. We recommend using the free resource MD Calc (www.mdcalc.com/aap-pediatric-hypertension-guidelines) to assist in calculating the BP category.

TABLE 26 describes the timing of follow-up based on the initial BP reading and diagnosis.

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is a validated device that measures BP every 20 to 30 minutes throughout the day and night. ABPM should be performed initially in all patients with persistently elevated BP and routinely in children and adolescents with a high-risk comorbidity (TABLE 26). Note: Insurance coverage of ABPM is limited.

ABPM is also used to diagnose so-called white-coat hypertension, defined as BP ≥ 95th percentile for age, sex, and height in the clinic setting but < 95th percentile during ABPM. This phenomenon can be challenging to diagnose.

Continue to: Home monitoring

Home monitoring. Do not use home BP monitoring to establish a diagnosis of hypertension, although one of these devices can be used as an adjunct to office and ambulatory BP monitoring after the diagnosis has been made.6

Evaluating hypertension in children and adolescents

Once a diagnosis of hypertension has been made, undertake a thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing to evaluate for possible causes, comorbidities, and any evidence of end-organ damage.

Comprehensive history. Pertinent aspects include perinatal, nutritional, physical activity, psychosocial, family, medication—and of course, medical—histories.6

Maternal elevated BP or hypertension is related to an offspring’s elevated BP in childhood and adolescence.19 Other pertinent aspects of the perinatal history include complications of pregnancy, gestational age, birth weight, and neonatal complications.6

Nutritional and physical activity histories can highlight contributing factors in the development of hypertension and can be a guide to recommending lifestyle modifications.6 Sodium intake, which influences BP, should be part of the nutritional history.20

Continue to: Important aspects...

Important aspects of the psychosocial history include feelings of depression or anxiety, bullying, and body perception. Children older than 10 years should be asked about smoking, alcohol, and other substance use.

The family history should include notation of first- and second-degree relatives with hypertension.6

Inquire about medications that can raise BP, including oral contraceptives, which are commonly prescribed in this population.21,22

The physical exam should include measured height and weight, with calculation of the body mass index percentile for age; of note, obesity is strongly associated with hypertension, and poor growth might signal underlying chronic disease. Once elevated BP has been confirmed, the exam should include measurement of BP in both arms and in a leg (TABLE 26). BP that is lower in the leg than in the arms (in any given patient, BP readings in the legs are usually higher than in the arms), or weak or absent femoral pulses, suggest coarctation of the aorta.6

Focus the balance of the physical exam on physical findings that suggest secondary causes of hypertension or evidence of end-organ damage.

Continue to: Testing

Testing. TABLE 36,23 summarizes the diagnostic testing recommended for all children and for specific populations; TABLE 26 indicates when to obtain diagnostic testing.

TABLE 42,12,13,24 outlines the basis of primary and of secondary hypertension and common historical and physical findings that suggest a secondary cause.

Mapping out the treatment plan

Pediatric hypertension should be treated in patients with stage 1 or higher hypertension.6 This threshold for therapy is based on evidence that reducing BP below a goal of (1) the 90th percentile (calculated based on age, sex, and height) in children up to 12 years of age or (2) of < 130/80 mm Hg for children ≥ 13 years reduces short- and long-term morbidity and mortality.5,6,25

Choice of initial treatment depends on the severity of BP elevation and the presence of comorbidities (FIGURE6,20,25-28). The initial, fundamental treatment recommendation is lifestyle modification,6,29 including regular physical exercise, a change in nutritional habits, weight loss (because obesity is a common comorbid condition), elimination of tobacco and substance use, and stress reduction.25,26 Medications can be used as well, along with other treatments for specific causes of secondary hypertension.

Referral to a specialist can be considered if consultation for assistance with treatment is preferred (TABLE 26) or if the patient has:

- treatment-resistant hypertension

- stage 2 hypertension that is not quickly responsive to initial treatment

- an identified secondary cause of hypertension.

Continue to: Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Exercise. “Regular” physical exercise for children to reduce BP is defined as ≥ 30 to 60 minutes of active play daily.6,29 Studies have shown significant improvement not only in BP but also in other cardiovascular disease risk parameters with regular physical exercise.27 A study found that the reduction in systolic BP is, on average, approximately 6 mm Hg with physical activity alone.30

Nutrition. DASH—Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension—is an evidence-based program to reduce BP. This nutritional guideline focuses on a diet rich in natural foods, including fruits, vegetables, minimally processed carbohydrates and whole grains, and low-fat dairy and meats. It also emphasizes the importance of avoiding foods high in processed sugars and reducing sodium intake.31 Higher-than-recommended sodium intake, based on age and sex (and established as part of dietary recommendations for children on the US Department of Health and Human Services’ website health.gov) directly correlates with the risk of prehypertension and hypertension—especially in overweight and obese children.20,32 DASH has been shown to reliably reduce the incidence of hypertension in children; other studies have supported increased intake of fruits, vegetables, and legumes as strategies to reduce BP.33,34

Other interventions. Techniques to improve adherence to exercise and nutritional modifications for children include motivational interviewing, community programs and education, and family counseling.27,35 A recent study showed that a community-based lifestyle modification program that is focused on weight loss in obese children resulted in a significant reduction in BP values at higher stages of obesity.36 There is evidence that techniques such as controlled breathing and meditation can reduce BP.37 Last, screening and counseling to encourage tobacco and substance use discontinuation are recommended for children and adolescents to improve health outcomes.25

Proceed with pharmacotherapy when these criteria are met

Medical therapy is recommended when certain criteria are met, although this decision should be individualized and made in agreement by the treating physician, patient, and family. These criteria (FIGURE6,20,25-28) are6,29:

- once a diagnosis of stage 1 hypertension has been established, failure to meet a BP goal after 3 to 6 months of attempting lifestyle modifications

- stage 2 hypertension without a modifiable risk factor, such as obesity

- any stage of hypertension with comorbid CKD, DM, or proteinuria

- target-organ damage, such as left ventricular hypertrophy

- symptomatic hypertension.6,29

There are circumstances in which one or another specific antihypertensive agent is recommended for children; however, for most patients with primary hypertension, the following classes are recommended for first-line use6,22:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- calcium-channel blockers (CCBs)

- thiazide diuretics.

Continue to: For a child with known CKD...

For a child with known CKD, DM, or proteinuria, an ACE inhibitor or ARB is beneficial as first-line therapy.38 Because ACE inhibitors and ARBs have teratogenic effects, however, a thorough review of fertility status is recommended for female patients before any of these agents are started. CCBs and thiazides are typically recommended as first-line agents for Black patients.6,28 Beta-blockers are typically avoided in the first line because of their adverse effect profile.

Most antihypertensive medications can be titrated every 1 or 2 weeks; the patient’s BP can be monitored with a home BP cuff to track the effect of titration. In general, the patient should be seen for follow-up every 4 to 6 weeks for a BP recheck and review of medication tolerance and adverse effects. Once the treatment goal is achieved, it is reasonable to have the patient return every 3 to 6 months to reassess the treatment plan.

If the BP goal is difficult to achieve despite titration of medication and lifestyle changes, consider repeat ABPM assessment, a specialty referral, or both. It is reasonable for children who have been started on medication and have adhered to lifestyle modifications to practice a “step-down” approach to discontinuing medication; this approach can also be considered once any secondary cause has been corrected. Any target-organ abnormalities identified at diagnosis (eg, proteinuria, CKD, left ventricular hypertrophy) need to be reexamined at follow-up.6

Restrict activities—or not?

There is evidence that a child with stage 1 or well-controlled stage 2 hypertension without evidence of end-organ damage should not have restrictions on sports or activity. However, in uncontrolled stage 2 hypertension or when evidence of target end-organ damage is present, you should advise against participation in highly competitive sports and highly static sports (eg, weightlifting, wrestling), based on expert opinion6,25 (FIGURE6,20,25-28).

aAAP guidelines on the management of pediatric hypertension vary from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force. See the Practice Alert, “A review of the latest USPSTF recommendations,” in the May 2021 issue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, MD, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL, 32214; [email protected]

1. Theodore RF, Broadbent J, Nagin D, et al. Childhood to early-midlife systolic blood pressure trajectories: early-life predictors, effect modifiers, and adult cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertension. 2015;66:1108-1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05831

2. Lurbe E, Agabiti-Rosei E, Cruickshank JK, et al. 2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1887-1920. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001039

3. Weaver DJ, Mitsnefes MM. Effects of systemic hypertension on the cardiovascular system. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;41:59-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2015.11.005

4. Ippisch HM, Daniels SR. Hypertension in overweight and obese children. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;25:177-182. doi: org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2008.05.002

5. Urbina EM, Lande MB, Hooper SR, et al. Target organ abnormalities in pediatric hypertension. J Pediatr. 2018;202:14-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.026

6. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al; . Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904

7. Khoury M, Khoury PR, Dolan LM, et al. Clinical implications of the revised AAP pediatric hypertension guidelines. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20180245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0245

8. Falkner B, Gidding SS, Ramirez-Garnica G, et al. The relationship of body mass index and blood pressure in primary care pediatric patients. J Pediatr. 2006;148:195-200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.030

9. Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al; SEARCH Study Group. Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr. 2010;157:245-251.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.021

10. Shay CM, Ning H, Daniels SR, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adolescents: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005-2010. Circulation. 2013;127:1369-1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001559

11. Archbold KH, Vasquez MM, Goodwin JL, et al. Effects of sleep patterns and obesity on increases in blood pressure in a 5-year period: report from the Tucson Children’s Assessment of Sleep Apnea Study. J Pediatr. 2012;161:26-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.034

12. Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Pierce C, et al; . Blood pressure in children with chronic kidney disease: a report from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study. Hypertension. 2008;52:631-637. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110635

13. Martin RM, Ness AR, Gunnell D, et al; ALSPAC Study Team. Does breast-feeding in infancy lower blood pressure in childhood? The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Circulation. 2004;109:1259-1266. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118468.76447.CE

14. Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256-263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420407

15. Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3171-3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366

16. Sun SS, Grave GD, Siervogel RM, et al. Systolic blood pressure in childhood predicts hypertension and metabolic syndrome later in life. Pediatrics. 2007;119:237-246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2543

17. Parker ED, Sinaiko AR, Kharbanda EO, et al. Change in weight status and development of hypertension. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20151662. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1662

18. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al; . Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142-161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e

19. Staley JR, Bradley J, Silverwood RJ, et al. Associations of blood pressure in pregnancy with offspring blood pressure trajectories during childhood and adolescence: findings from a prospective study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001422. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001422

20. Yang Q, Zhang Z, Zuklina EV, et al. Sodium intake and blood pressure among US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130:611-619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3870

21. Le-Ha C, Beilin LJ, Burrows S, et al. Oral contraceptive use in girls and alcohol consumption in boys are associated with increased blood pressure in late adolescence. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:947-955. doi: 10.1177/2047487312452966

22. Samuels JA, Franco K, Wan F, Sorof JM. Effect of stimulants on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in children with ADHD: a double-blind, randomized, cross-over trial. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:92-95. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2051-1

23. Wiesen J, Adkins M, Fortune S, et al. Evaluation of pediatric patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension: yield of diagnostic testing. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e988-993. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0365

24. Kapur G, Ahmed M, Pan C, et al. Secondary hypertension in overweight and stage 1 hypertensive children: a Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium report. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:34-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00195.x

25. Anyaegbu EI, Dharnidharka VR. Hypertension in the teenager. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:131-151. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.09.011

26. Gandhi B, Cheek S, Campo JV. Anxiety in the pediatric medical setting. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:643-653. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.013

27. Farpour-Lambert NJ, Aggoun Y, Marchand LM, et al. Physical activity reduces systemic blood pressure and improves early markers of atherosclerosis in pre-pubertal obese children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2396-2406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.030

28. Li JS, Baker-Smith CM, Smith PB, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in children: a meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:315-319. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.113

29. Singer PS. Updates on hypertension and new guidelines. Adv Pediatr. 2019;66:177-187. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2019.03.009

30. Torrance B, McGuire KA, Lewanczuk R, et al. Overweight, physical activity and high blood pressure in children: a review of the literature. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:139-149.

31. DASH eating plan. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed April 26, 2021. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/dash-eating-plan

32. Nutritional goals for age-sex groups based on dietary reference intakes and dietary guidelines recommendations (Appendix 7). In: US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. December 2015;97-98. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf

33. Asghari G, Yuzbashian E, Mirmiran P, et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern is associated with reduced incidence of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016;174:178-184.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.077

34. Damasceno MMC, de Araújo MFM, de Freitas RWJF, et al. The association between blood pressure in adolescents and the consumption of fruits, vegetables and fruit juice–an exploratory study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1553-1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03608.x

35. Anderson KL. A review of the prevention and medical management of childhood obesity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27:63-76. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2017.08.003

36. Kumar S, King EC, Christison, et al; POWER Work Group. Health outcomes of youth in clinical pediatric weight management programs in POWER. J Pediatr. 2019;208:57-65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.049

37. Gregoski MJ, Barnes VA, Tingen MS, et al. Breathing awareness meditation and LifeSkills® Training programs influence upon ambulatory blood pressure and sodium excretion among African American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:59-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.019

38. Escape Trial Group; E, Trivelli A, Picca S, et al. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1639-1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902066

1. Theodore RF, Broadbent J, Nagin D, et al. Childhood to early-midlife systolic blood pressure trajectories: early-life predictors, effect modifiers, and adult cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertension. 2015;66:1108-1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05831

2. Lurbe E, Agabiti-Rosei E, Cruickshank JK, et al. 2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1887-1920. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001039

3. Weaver DJ, Mitsnefes MM. Effects of systemic hypertension on the cardiovascular system. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;41:59-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2015.11.005

4. Ippisch HM, Daniels SR. Hypertension in overweight and obese children. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;25:177-182. doi: org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2008.05.002

5. Urbina EM, Lande MB, Hooper SR, et al. Target organ abnormalities in pediatric hypertension. J Pediatr. 2018;202:14-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.026

6. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al; . Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904

7. Khoury M, Khoury PR, Dolan LM, et al. Clinical implications of the revised AAP pediatric hypertension guidelines. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20180245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0245

8. Falkner B, Gidding SS, Ramirez-Garnica G, et al. The relationship of body mass index and blood pressure in primary care pediatric patients. J Pediatr. 2006;148:195-200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.030

9. Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al; SEARCH Study Group. Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr. 2010;157:245-251.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.021

10. Shay CM, Ning H, Daniels SR, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adolescents: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005-2010. Circulation. 2013;127:1369-1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001559

11. Archbold KH, Vasquez MM, Goodwin JL, et al. Effects of sleep patterns and obesity on increases in blood pressure in a 5-year period: report from the Tucson Children’s Assessment of Sleep Apnea Study. J Pediatr. 2012;161:26-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.034

12. Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Pierce C, et al; . Blood pressure in children with chronic kidney disease: a report from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study. Hypertension. 2008;52:631-637. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110635

13. Martin RM, Ness AR, Gunnell D, et al; ALSPAC Study Team. Does breast-feeding in infancy lower blood pressure in childhood? The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Circulation. 2004;109:1259-1266. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118468.76447.CE

14. Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256-263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420407

15. Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3171-3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366

16. Sun SS, Grave GD, Siervogel RM, et al. Systolic blood pressure in childhood predicts hypertension and metabolic syndrome later in life. Pediatrics. 2007;119:237-246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2543

17. Parker ED, Sinaiko AR, Kharbanda EO, et al. Change in weight status and development of hypertension. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20151662. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1662

18. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al; . Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142-161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e

19. Staley JR, Bradley J, Silverwood RJ, et al. Associations of blood pressure in pregnancy with offspring blood pressure trajectories during childhood and adolescence: findings from a prospective study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001422. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001422

20. Yang Q, Zhang Z, Zuklina EV, et al. Sodium intake and blood pressure among US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130:611-619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3870

21. Le-Ha C, Beilin LJ, Burrows S, et al. Oral contraceptive use in girls and alcohol consumption in boys are associated with increased blood pressure in late adolescence. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:947-955. doi: 10.1177/2047487312452966

22. Samuels JA, Franco K, Wan F, Sorof JM. Effect of stimulants on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in children with ADHD: a double-blind, randomized, cross-over trial. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:92-95. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2051-1

23. Wiesen J, Adkins M, Fortune S, et al. Evaluation of pediatric patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension: yield of diagnostic testing. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e988-993. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0365

24. Kapur G, Ahmed M, Pan C, et al. Secondary hypertension in overweight and stage 1 hypertensive children: a Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium report. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:34-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00195.x

25. Anyaegbu EI, Dharnidharka VR. Hypertension in the teenager. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:131-151. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.09.011

26. Gandhi B, Cheek S, Campo JV. Anxiety in the pediatric medical setting. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:643-653. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.013

27. Farpour-Lambert NJ, Aggoun Y, Marchand LM, et al. Physical activity reduces systemic blood pressure and improves early markers of atherosclerosis in pre-pubertal obese children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2396-2406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.030

28. Li JS, Baker-Smith CM, Smith PB, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in children: a meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:315-319. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.113

29. Singer PS. Updates on hypertension and new guidelines. Adv Pediatr. 2019;66:177-187. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2019.03.009

30. Torrance B, McGuire KA, Lewanczuk R, et al. Overweight, physical activity and high blood pressure in children: a review of the literature. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:139-149.

31. DASH eating plan. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed April 26, 2021. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/dash-eating-plan

32. Nutritional goals for age-sex groups based on dietary reference intakes and dietary guidelines recommendations (Appendix 7). In: US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. December 2015;97-98. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf

33. Asghari G, Yuzbashian E, Mirmiran P, et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern is associated with reduced incidence of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016;174:178-184.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.077

34. Damasceno MMC, de Araújo MFM, de Freitas RWJF, et al. The association between blood pressure in adolescents and the consumption of fruits, vegetables and fruit juice–an exploratory study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1553-1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03608.x

35. Anderson KL. A review of the prevention and medical management of childhood obesity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27:63-76. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2017.08.003

36. Kumar S, King EC, Christison, et al; POWER Work Group. Health outcomes of youth in clinical pediatric weight management programs in POWER. J Pediatr. 2019;208:57-65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.049

37. Gregoski MJ, Barnes VA, Tingen MS, et al. Breathing awareness meditation and LifeSkills® Training programs influence upon ambulatory blood pressure and sodium excretion among African American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:59-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.019

38. Escape Trial Group; E, Trivelli A, Picca S, et al. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1639-1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902066

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Measure the blood pressure (BP) of all children 3 years and older annually; those who have a specific comorbid condition (eg, obesity, diabetes, renal disease, or an aortic-arch abnormality) or who are taking medication known to elevate BP should have their BP checked at every health care visit. C

› Encourage lifestyle modification as the initial treatment for elevated BP or hypertension in children. A

› Utilize pharmacotherapy for (1) children with stage 1 hypertension who have failed to meet BP goals after 3 to 6 months of lifestyle modification and (2) children with stage 2 hypertension who do not have a modifiable risk factor, such as obesity. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Prediction rule identifies low infection risk in febrile infants

A clinical prediction rule combining procalcitonin, absolute neutrophil count, and urinalysis effectively identified most febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infections, based on data from 702 individuals

The clinical prediction rule (CPR) described in 2019 in JAMA Pediatrics was developed by the Febrile Infant Working Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) to identify febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infections in order to reduce unnecessary procedures, antibiotics use, and hospitalization, according to April Clawson, MD, of Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, and colleagues.

In a poster presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, the researchers conducted an external validation of the rule via a retrospective, observational study of febrile infants aged 60 days and younger who presented to an urban pediatric ED between October 2014 and June 2019. The study population included 702 infants with an average age of 36 days. Approximately 45% were female, and 60% were White. Fever was defined as 38° C or greater. Exclusion criteria were prematurity, receipt of antibiotics in the past 48 hours, presence of an indwelling medical device, and evidence of focal infection (not including otitis media); those who were critically ill at presentation or had a previous medical condition were excluded as well, the researchers said. A serious bacterial infection (SBI) was defined as a urinary tract infection (UTI), bacteremia, or bacterial meningitis.

Based on the CPR, a patient is considered low risk for an SBI if all the following criteria are met: normal urinalysis (defined as absence of leukocyte esterase, nitrite, and 5 or less white blood cells per high power field); an absolute neutrophil count of 4,090/mL or less; and procalcitonin of 1.71 ng/mL or less.

Overall, 62 infants (8.8%) were diagnosed with an SBI, similar to the 9.3% seen in the parent study of the CPR, Dr. Clawson said.

Of these, 42 had a UTI only (6%), 10 had bacteremia only (1.4%), and 1 had meningitis only (0.1%). Another five infants had UTI with bacteremia (0.7%), and four had bacteremia and meningitis (0.6%).

According to the CPR, 432 infants met criteria for low risk and 270 were considered high risk. A total of five infants who were classified as low risk had SBIs, including two with UTIs, two with bacteremia, and one with meningitis.

“The CPR derived and validated by Kupperman et al. had a decreased sensitivity for the patients in our study and missed some SBIs,” Dr. Clawson noted. “However, it had a strong negative predictive value, so it may still be a useful CPR.”

The sensitivity for the CPR in the parent study and the current study was 97.7 and 91.9, respectively; specificity was 60 and 66.7, respectively. The negative predictive values for the parent and current studies were 99.6 and 98.8, respectively, and the positive predictive values were 20.7 and 21.1.

The results support the potential of the CPR, but more external validation is needed, they said.

PECARN rule keeps it simple

“It has always been a challenge to identify infants with fever with serious bacterial infections when they are well-appearing,” Yashas Nathani, MD, of Oklahoma University, Oklahoma City, said in an interview. “The clinical prediction rule offers a simple, step-by-step approach for pediatricians and emergency medicine physicians to stratify infants in high or low risk categories for SBIs. However, as with everything, validation of protocols, guidelines and decision-making algorithms is extremely important, especially as more clinicians start to employ this CPR to their daily practice. This study objectively puts the CPR to the test and offers an independent external validation.

“Although this study had a lower sensitivity in identifying infants with SBI using the clinical prediction rule as compared to the original study, the robust validation of negative predictive value is extremely important and not surprising,” said Dr. Nathani. “The goal of this CPR is to identify infants with low-risk for SBI and the stated NPV helps clinicians in doing just that.”

Overall, “the clinical prediction rule is a fantastic resource for physicians to identify potentially sick infants with fever, especially the ones that appear well on initial evaluation,” said Dr. Nathani. However, “it is important to acknowledge that this is merely a guideline, and not an absolute rule. Clinicians also must remain cautious, as this rule does not incorporate the presence of viral pathogens as a factor.

“It is important to continue the scientific quest to refine our approach in identifying infants with serious bacterial infections when fever is the only presentation,” Dr. Nathani noted. “Additional research is needed to continue fine-tuning this CPR and the thresholds for procalcitonin and absolute neutrophil counts to improve the sensitivity and specificity.” Research also is needed to explore whether this CPR can be extended to incorporate viral testing, “as a large number of infants with fever have viral pathogens as the primary etiology,” he concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Nathani had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A clinical prediction rule combining procalcitonin, absolute neutrophil count, and urinalysis effectively identified most febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infections, based on data from 702 individuals

The clinical prediction rule (CPR) described in 2019 in JAMA Pediatrics was developed by the Febrile Infant Working Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) to identify febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infections in order to reduce unnecessary procedures, antibiotics use, and hospitalization, according to April Clawson, MD, of Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, and colleagues.

In a poster presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, the researchers conducted an external validation of the rule via a retrospective, observational study of febrile infants aged 60 days and younger who presented to an urban pediatric ED between October 2014 and June 2019. The study population included 702 infants with an average age of 36 days. Approximately 45% were female, and 60% were White. Fever was defined as 38° C or greater. Exclusion criteria were prematurity, receipt of antibiotics in the past 48 hours, presence of an indwelling medical device, and evidence of focal infection (not including otitis media); those who were critically ill at presentation or had a previous medical condition were excluded as well, the researchers said. A serious bacterial infection (SBI) was defined as a urinary tract infection (UTI), bacteremia, or bacterial meningitis.

Based on the CPR, a patient is considered low risk for an SBI if all the following criteria are met: normal urinalysis (defined as absence of leukocyte esterase, nitrite, and 5 or less white blood cells per high power field); an absolute neutrophil count of 4,090/mL or less; and procalcitonin of 1.71 ng/mL or less.

Overall, 62 infants (8.8%) were diagnosed with an SBI, similar to the 9.3% seen in the parent study of the CPR, Dr. Clawson said.

Of these, 42 had a UTI only (6%), 10 had bacteremia only (1.4%), and 1 had meningitis only (0.1%). Another five infants had UTI with bacteremia (0.7%), and four had bacteremia and meningitis (0.6%).

According to the CPR, 432 infants met criteria for low risk and 270 were considered high risk. A total of five infants who were classified as low risk had SBIs, including two with UTIs, two with bacteremia, and one with meningitis.

“The CPR derived and validated by Kupperman et al. had a decreased sensitivity for the patients in our study and missed some SBIs,” Dr. Clawson noted. “However, it had a strong negative predictive value, so it may still be a useful CPR.”

The sensitivity for the CPR in the parent study and the current study was 97.7 and 91.9, respectively; specificity was 60 and 66.7, respectively. The negative predictive values for the parent and current studies were 99.6 and 98.8, respectively, and the positive predictive values were 20.7 and 21.1.

The results support the potential of the CPR, but more external validation is needed, they said.

PECARN rule keeps it simple

“It has always been a challenge to identify infants with fever with serious bacterial infections when they are well-appearing,” Yashas Nathani, MD, of Oklahoma University, Oklahoma City, said in an interview. “The clinical prediction rule offers a simple, step-by-step approach for pediatricians and emergency medicine physicians to stratify infants in high or low risk categories for SBIs. However, as with everything, validation of protocols, guidelines and decision-making algorithms is extremely important, especially as more clinicians start to employ this CPR to their daily practice. This study objectively puts the CPR to the test and offers an independent external validation.

“Although this study had a lower sensitivity in identifying infants with SBI using the clinical prediction rule as compared to the original study, the robust validation of negative predictive value is extremely important and not surprising,” said Dr. Nathani. “The goal of this CPR is to identify infants with low-risk for SBI and the stated NPV helps clinicians in doing just that.”

Overall, “the clinical prediction rule is a fantastic resource for physicians to identify potentially sick infants with fever, especially the ones that appear well on initial evaluation,” said Dr. Nathani. However, “it is important to acknowledge that this is merely a guideline, and not an absolute rule. Clinicians also must remain cautious, as this rule does not incorporate the presence of viral pathogens as a factor.

“It is important to continue the scientific quest to refine our approach in identifying infants with serious bacterial infections when fever is the only presentation,” Dr. Nathani noted. “Additional research is needed to continue fine-tuning this CPR and the thresholds for procalcitonin and absolute neutrophil counts to improve the sensitivity and specificity.” Research also is needed to explore whether this CPR can be extended to incorporate viral testing, “as a large number of infants with fever have viral pathogens as the primary etiology,” he concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Nathani had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A clinical prediction rule combining procalcitonin, absolute neutrophil count, and urinalysis effectively identified most febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infections, based on data from 702 individuals

The clinical prediction rule (CPR) described in 2019 in JAMA Pediatrics was developed by the Febrile Infant Working Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) to identify febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infections in order to reduce unnecessary procedures, antibiotics use, and hospitalization, according to April Clawson, MD, of Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, and colleagues.