User login

Adolescent substance use and the COVID-19 pandemic

During the past year, adolescents, families, educators, and health care providers have had to press forward through myriad challenges and stressors with flexibility and adaptability. With appropriate concern, we ask ourselves how children and youth are coping emotionally with the unprecedented changes of the past year.

Adolescent substance use represents an important area of concern. What has happened during the pandemic? Has youth substance use increased or decreased? Has access to substances increased or decreased, has monitoring and support for at-risk youth increased or decreased?

The answers to these questions are mixed. If anything, the pandemic has highlighted the heterogeneity of adolescent substance use. Now is a key time for assessment, support, and conversation with teens and families.

Monitoring the Future (MTF), a nationally representative annual survey, has provided a broad perspective on trends of adolescent substance use for decades.1 The MTF data is usually collected from February to May and was cut short in 2020 because of school closures associated with the pandemic. The sample size, though still nationally representative, was about a quarter of the typical volume. Some of the data are encouraging, including a flattening out of previous years’ stark increase in vaping of both nicotine and cannabis products (though overall numbers remain alarmingly high). Other data are more concerning including a continued increase in misuse of cough medicine, amphetamines, and inhalants among the youngest cohort surveyed (eighth graders). However, these data were largely representative of prepandemic circumstances.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected risk and protective factors for teen drug and alcohol use. Most notably, it has had a widely observed negative impact on adolescent mental health, across multiple disease categories.2 In addition, the cancellation of in-person academic and extracurricular activities such as arts and athletics markedly increased unstructured time, a known associated factor for higher-risk activities including substance use. This has also led to decreased contact with many supportive adults such as teachers and coaches. On the other hand, some adolescents now have more time with supportive parents and caregivers, more meals together, and more supervision, all of which are associated with decreased likelihood of substance use disorders.

The highly variable reasons for substance use affect highly variable pandemic-related changes in use. Understanding the impetus for use is a good place to start conversation and can help providers assess risk of escalation during the pandemic. Some teens primarily use for social enhancement while others use as a means of coping with stress or to mask or escape negative emotions. Still others continue use because of physiological dependence, craving, and other symptoms consistent with use disorders.

Highlighting the heterogeneity of this issue, one study assessing use early in the pandemic showed a decrease in the percentage of teens who use substances but an increase in frequency of use for those who are using.3 Though expected, an increase in frequency of use by oneself as compared with peers was also notable. Using substances alone is associated with more severe use disorders, carries greater risk of overdose, and can increase shame and secrecy, further fueling use disorders.

The pandemic has thus represented a protective pause for some experimental or socially motivated substance-using teens who have experienced a period of abstinence even if not fully by choice. For others, it has represented an acute amplification of risk factors and use has accelerated. This latter group includes those whose use represents an effort to cope with depression, anxiety, and loneliness or for whom isolation at home represents less monitoring, increased access, and greater exposure to substances.

Over the past year, in the treatment of adolescents struggling with substance use, many clinicians have observed a sifting effect during these unprecedented social changes. Many youth, who no longer have access to substances, have found they can “take it or leave it”. Other youth have been observed engaging in additional risk or going to greater lengths to access substances and continue their use. For both groups and everyone in between, this is an important time for screening, clinical assessment, and support.

While anticipating further research and data regarding broad substance use trends, including MTF data from 2021, recognizing that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is individual, with marked differences from adolescent to adolescent, will help us continue to act now to assess this important area of adolescent health. The first step for primary care providers is unchanged: to routinely screen for and discuss substance use in clinical settings.

Two brief, validated, easily accessible screening tools are available for primary care settings. They can both be self-administered and take less than 2 minutes to complete. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment and the Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol and other Drugs can both be used for youth aged 12-17 years.4,5 Both screens are available online at drugabuse.gov.6

Routine screening will normalize conversations about substance use and healthy choices, provide opportunities for positive reinforcement, identify adolescents at risk, increase comfort and competence in providing brief intervention, and expedite referrals for additional support and treatment.

A false assumption that a particular adolescent isn’t using substances creates a missed opportunity to offer guidance and treatment. An oft-overlooked opportunity is that of providing positive reinforcement for an adolescent who isn’t using any substances or experimenting at all. Positive reinforcement is a strong component of reinforcing health maintenance.

Parent guidance and family assessment will also be critical tools. Parents and caregivers play a primary role in substance use treatment for teens and have a contributory impact on risk through both genes and environment. Of note, research suggests a moderate overall increase in adult substance use during the pandemic, particularly substances that are widely available such as alcohol. Adolescents may thus have greater access and exposure to substance use. A remarkably high percentage, 42%, of substance-using teens surveyed early in the pandemic indicated that they were using substances with their parents.3 Parents, who have equally been challenged by the pandemic, may need guidance in balancing compassion and support for struggling youth, while setting appropriate limits and maintaining expectations of healthy activities.

Unprecedented change and uncertainty provide an opportunity to reassess risks and openly discuss substance use with youth and families. Even with much on our minds during the COVID-19 pandemic, we can maintain focus on this significant risk to adolescent health and wellness. Our efforts now, from screening to treatment for adolescent substance use should be reinforced rather than delayed.

Dr. Jackson is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

References

1. Monitoringthefuture.org

2. Jones EAK et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021;18(5):2470.

3. Dumas TM et al. J Adolesc Health, 2020;67(3):354-61.

4. Levy S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):822-8.

5. Kelly SM et al. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):819-26.

6. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Adolescent Substance Use Screening Tools. 2016 Apr 27. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/screening-tools-prevention/screening-tools-adolescent-substance-use/adolescent-substance-use-screening-tools

During the past year, adolescents, families, educators, and health care providers have had to press forward through myriad challenges and stressors with flexibility and adaptability. With appropriate concern, we ask ourselves how children and youth are coping emotionally with the unprecedented changes of the past year.

Adolescent substance use represents an important area of concern. What has happened during the pandemic? Has youth substance use increased or decreased? Has access to substances increased or decreased, has monitoring and support for at-risk youth increased or decreased?

The answers to these questions are mixed. If anything, the pandemic has highlighted the heterogeneity of adolescent substance use. Now is a key time for assessment, support, and conversation with teens and families.

Monitoring the Future (MTF), a nationally representative annual survey, has provided a broad perspective on trends of adolescent substance use for decades.1 The MTF data is usually collected from February to May and was cut short in 2020 because of school closures associated with the pandemic. The sample size, though still nationally representative, was about a quarter of the typical volume. Some of the data are encouraging, including a flattening out of previous years’ stark increase in vaping of both nicotine and cannabis products (though overall numbers remain alarmingly high). Other data are more concerning including a continued increase in misuse of cough medicine, amphetamines, and inhalants among the youngest cohort surveyed (eighth graders). However, these data were largely representative of prepandemic circumstances.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected risk and protective factors for teen drug and alcohol use. Most notably, it has had a widely observed negative impact on adolescent mental health, across multiple disease categories.2 In addition, the cancellation of in-person academic and extracurricular activities such as arts and athletics markedly increased unstructured time, a known associated factor for higher-risk activities including substance use. This has also led to decreased contact with many supportive adults such as teachers and coaches. On the other hand, some adolescents now have more time with supportive parents and caregivers, more meals together, and more supervision, all of which are associated with decreased likelihood of substance use disorders.

The highly variable reasons for substance use affect highly variable pandemic-related changes in use. Understanding the impetus for use is a good place to start conversation and can help providers assess risk of escalation during the pandemic. Some teens primarily use for social enhancement while others use as a means of coping with stress or to mask or escape negative emotions. Still others continue use because of physiological dependence, craving, and other symptoms consistent with use disorders.

Highlighting the heterogeneity of this issue, one study assessing use early in the pandemic showed a decrease in the percentage of teens who use substances but an increase in frequency of use for those who are using.3 Though expected, an increase in frequency of use by oneself as compared with peers was also notable. Using substances alone is associated with more severe use disorders, carries greater risk of overdose, and can increase shame and secrecy, further fueling use disorders.

The pandemic has thus represented a protective pause for some experimental or socially motivated substance-using teens who have experienced a period of abstinence even if not fully by choice. For others, it has represented an acute amplification of risk factors and use has accelerated. This latter group includes those whose use represents an effort to cope with depression, anxiety, and loneliness or for whom isolation at home represents less monitoring, increased access, and greater exposure to substances.

Over the past year, in the treatment of adolescents struggling with substance use, many clinicians have observed a sifting effect during these unprecedented social changes. Many youth, who no longer have access to substances, have found they can “take it or leave it”. Other youth have been observed engaging in additional risk or going to greater lengths to access substances and continue their use. For both groups and everyone in between, this is an important time for screening, clinical assessment, and support.

While anticipating further research and data regarding broad substance use trends, including MTF data from 2021, recognizing that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is individual, with marked differences from adolescent to adolescent, will help us continue to act now to assess this important area of adolescent health. The first step for primary care providers is unchanged: to routinely screen for and discuss substance use in clinical settings.

Two brief, validated, easily accessible screening tools are available for primary care settings. They can both be self-administered and take less than 2 minutes to complete. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment and the Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol and other Drugs can both be used for youth aged 12-17 years.4,5 Both screens are available online at drugabuse.gov.6

Routine screening will normalize conversations about substance use and healthy choices, provide opportunities for positive reinforcement, identify adolescents at risk, increase comfort and competence in providing brief intervention, and expedite referrals for additional support and treatment.

A false assumption that a particular adolescent isn’t using substances creates a missed opportunity to offer guidance and treatment. An oft-overlooked opportunity is that of providing positive reinforcement for an adolescent who isn’t using any substances or experimenting at all. Positive reinforcement is a strong component of reinforcing health maintenance.

Parent guidance and family assessment will also be critical tools. Parents and caregivers play a primary role in substance use treatment for teens and have a contributory impact on risk through both genes and environment. Of note, research suggests a moderate overall increase in adult substance use during the pandemic, particularly substances that are widely available such as alcohol. Adolescents may thus have greater access and exposure to substance use. A remarkably high percentage, 42%, of substance-using teens surveyed early in the pandemic indicated that they were using substances with their parents.3 Parents, who have equally been challenged by the pandemic, may need guidance in balancing compassion and support for struggling youth, while setting appropriate limits and maintaining expectations of healthy activities.

Unprecedented change and uncertainty provide an opportunity to reassess risks and openly discuss substance use with youth and families. Even with much on our minds during the COVID-19 pandemic, we can maintain focus on this significant risk to adolescent health and wellness. Our efforts now, from screening to treatment for adolescent substance use should be reinforced rather than delayed.

Dr. Jackson is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

References

1. Monitoringthefuture.org

2. Jones EAK et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021;18(5):2470.

3. Dumas TM et al. J Adolesc Health, 2020;67(3):354-61.

4. Levy S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):822-8.

5. Kelly SM et al. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):819-26.

6. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Adolescent Substance Use Screening Tools. 2016 Apr 27. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/screening-tools-prevention/screening-tools-adolescent-substance-use/adolescent-substance-use-screening-tools

During the past year, adolescents, families, educators, and health care providers have had to press forward through myriad challenges and stressors with flexibility and adaptability. With appropriate concern, we ask ourselves how children and youth are coping emotionally with the unprecedented changes of the past year.

Adolescent substance use represents an important area of concern. What has happened during the pandemic? Has youth substance use increased or decreased? Has access to substances increased or decreased, has monitoring and support for at-risk youth increased or decreased?

The answers to these questions are mixed. If anything, the pandemic has highlighted the heterogeneity of adolescent substance use. Now is a key time for assessment, support, and conversation with teens and families.

Monitoring the Future (MTF), a nationally representative annual survey, has provided a broad perspective on trends of adolescent substance use for decades.1 The MTF data is usually collected from February to May and was cut short in 2020 because of school closures associated with the pandemic. The sample size, though still nationally representative, was about a quarter of the typical volume. Some of the data are encouraging, including a flattening out of previous years’ stark increase in vaping of both nicotine and cannabis products (though overall numbers remain alarmingly high). Other data are more concerning including a continued increase in misuse of cough medicine, amphetamines, and inhalants among the youngest cohort surveyed (eighth graders). However, these data were largely representative of prepandemic circumstances.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected risk and protective factors for teen drug and alcohol use. Most notably, it has had a widely observed negative impact on adolescent mental health, across multiple disease categories.2 In addition, the cancellation of in-person academic and extracurricular activities such as arts and athletics markedly increased unstructured time, a known associated factor for higher-risk activities including substance use. This has also led to decreased contact with many supportive adults such as teachers and coaches. On the other hand, some adolescents now have more time with supportive parents and caregivers, more meals together, and more supervision, all of which are associated with decreased likelihood of substance use disorders.

The highly variable reasons for substance use affect highly variable pandemic-related changes in use. Understanding the impetus for use is a good place to start conversation and can help providers assess risk of escalation during the pandemic. Some teens primarily use for social enhancement while others use as a means of coping with stress or to mask or escape negative emotions. Still others continue use because of physiological dependence, craving, and other symptoms consistent with use disorders.

Highlighting the heterogeneity of this issue, one study assessing use early in the pandemic showed a decrease in the percentage of teens who use substances but an increase in frequency of use for those who are using.3 Though expected, an increase in frequency of use by oneself as compared with peers was also notable. Using substances alone is associated with more severe use disorders, carries greater risk of overdose, and can increase shame and secrecy, further fueling use disorders.

The pandemic has thus represented a protective pause for some experimental or socially motivated substance-using teens who have experienced a period of abstinence even if not fully by choice. For others, it has represented an acute amplification of risk factors and use has accelerated. This latter group includes those whose use represents an effort to cope with depression, anxiety, and loneliness or for whom isolation at home represents less monitoring, increased access, and greater exposure to substances.

Over the past year, in the treatment of adolescents struggling with substance use, many clinicians have observed a sifting effect during these unprecedented social changes. Many youth, who no longer have access to substances, have found they can “take it or leave it”. Other youth have been observed engaging in additional risk or going to greater lengths to access substances and continue their use. For both groups and everyone in between, this is an important time for screening, clinical assessment, and support.

While anticipating further research and data regarding broad substance use trends, including MTF data from 2021, recognizing that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is individual, with marked differences from adolescent to adolescent, will help us continue to act now to assess this important area of adolescent health. The first step for primary care providers is unchanged: to routinely screen for and discuss substance use in clinical settings.

Two brief, validated, easily accessible screening tools are available for primary care settings. They can both be self-administered and take less than 2 minutes to complete. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment and the Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol and other Drugs can both be used for youth aged 12-17 years.4,5 Both screens are available online at drugabuse.gov.6

Routine screening will normalize conversations about substance use and healthy choices, provide opportunities for positive reinforcement, identify adolescents at risk, increase comfort and competence in providing brief intervention, and expedite referrals for additional support and treatment.

A false assumption that a particular adolescent isn’t using substances creates a missed opportunity to offer guidance and treatment. An oft-overlooked opportunity is that of providing positive reinforcement for an adolescent who isn’t using any substances or experimenting at all. Positive reinforcement is a strong component of reinforcing health maintenance.

Parent guidance and family assessment will also be critical tools. Parents and caregivers play a primary role in substance use treatment for teens and have a contributory impact on risk through both genes and environment. Of note, research suggests a moderate overall increase in adult substance use during the pandemic, particularly substances that are widely available such as alcohol. Adolescents may thus have greater access and exposure to substance use. A remarkably high percentage, 42%, of substance-using teens surveyed early in the pandemic indicated that they were using substances with their parents.3 Parents, who have equally been challenged by the pandemic, may need guidance in balancing compassion and support for struggling youth, while setting appropriate limits and maintaining expectations of healthy activities.

Unprecedented change and uncertainty provide an opportunity to reassess risks and openly discuss substance use with youth and families. Even with much on our minds during the COVID-19 pandemic, we can maintain focus on this significant risk to adolescent health and wellness. Our efforts now, from screening to treatment for adolescent substance use should be reinforced rather than delayed.

Dr. Jackson is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

References

1. Monitoringthefuture.org

2. Jones EAK et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021;18(5):2470.

3. Dumas TM et al. J Adolesc Health, 2020;67(3):354-61.

4. Levy S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):822-8.

5. Kelly SM et al. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):819-26.

6. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Adolescent Substance Use Screening Tools. 2016 Apr 27. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/screening-tools-prevention/screening-tools-adolescent-substance-use/adolescent-substance-use-screening-tools

I sent my suicidal teen patient to the ED: Whew?

You read “thoughts of being better off dead” on your next patient’s PHQ-9 screen results and break into a sweat. After eliciting the teen’s realistic suicide plan and intent you send him to the ED with his parent for crisis mental health evaluation. When you call the family that evening to follow-up you hear that he was discharged with a “mental health counseling” appointment next week.

Have you done enough to prevent this child from dying at his own hand? I imagine that this haunts you as it does me. It is terrifying to know that, of youth with suicidal ideation, over one-third attempt suicide, most within 1-2 years, and 20%-40% do so without having had a plan.

We now know that certain kinds of psychotherapy have evidence for preventing subsequent suicide in teens at high risk due to suicidal ideation and past attempts. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has the best evidence including its subtypes for youth with relevant histories: for both suicide and substance use (integrated, or I-CBT), trauma focused (TF-CBT), traumatic grief (CTG-CBT), and CBT-I, for the potent risk factor of insomnia. The other treatment shown to reduce risk is dialectical behavioral therapy–adolescent (DBT-A) focused on strengthening skills in interpersonal effectiveness, mindfulness, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation adapted to youth by adding family therapy and multifamily skills training. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) adapted for suicidal and self-harming adolescents (IPT-SA) also has evidence.

Some school programs have shown moderate efficacy, for example (IPT-A-IN) addresses the social and interpersonal context, and Youth Aware of Mental Health, a school curriculum to increase knowledge, help-seeking, and ways of coping with depression and suicidal behavior, that cut suicide attempts by half.

You may be able to recommend, refer to, or check to see if a youth can be provided one of the above therapies with best evidence but getting any counseling at all can be hard and some, especially minority families may decline formal interventions. Any therapy – CBT, DBT, or IPT – acceptable to the youth and family can be helpful. You can often determine if the key components are being provided by asking the teen what they are working on in therapy.

It is clear that checking in regularly with teens who have been through a suicide crisis is crucial to ensure that they continue in therapy long and consistently enough, that the family is involved in treatment, and that they are taught emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and safety planning. Warm, consistent parenting, good parent-child communication, and monitoring are protective factors but also skills that can be boosted to reduce future risk of suicide. When there is family dysfunction, conflict, or weak relationships, getting help for family relationships such as through attachment-based family therapy (ABFT) or family cognitive behavioral therapy is a priority. When bereavement or parental depression is contributing to youth suicidal thoughts, addressing these specifically can reduce suicide risk.

Sometimes family members, even with counseling, are not the best supporters for a teen in pain. When youths nominated their own support team to be informed about risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment plans and to stay in contact weekly there was a 6.6-fold lower risk of death than for nonsupported youth.

But how much of this evidence-based intervention can you ensure from your position in primary care? Refer if you can but regular supportive contacts alone reduce risk so you, trusted staff, school counselors, or even the now more available teletherapists may help. You can work with your patient to fill out a written commitment-to-safety plan (e.g. U. Colorado, CHADIS) of strategies they can use when having suicidal thoughts such as self-distractions, problem-solving, listing things they are looking forward to, things to do to get their mind off suicidal thoughts, and selecting support people to understand their situation with whom to be in regular contact. Any plan needs to take into account how understanding, supportive, and available the family is, factors you are most likely to be able to judge from your ongoing relationship, but that immediate risk may change. Contact within 48 hours, check-in within 1-2 weeks, and provision of crisis hotline information are essential actions.

Recommending home safety is part of routine anticipatory guidance but reduction of lethal means is essential in these cases. Guns are the most lethal method of suicide but discussing safe gun storage has been shown to be more effective than arguing in vain for gun removal. Medication overdose, a common means, can be reduced by not prescribing tricyclics (ineffective and more lethal), and advising parents to lock up all household medications.

You can ask about and coach teens on how to avoid the hazards of participating in online discussion groups, bullying, and cyberbullying (with risk for both perpetrator and victim), all risk factors for suicide. Managing insomnia can improve depression and is within your skills. While pediatricians can’t treat the suicide risk factors of family poverty, unemployment, or loss of culture/identity, we can refer affected families to community resources.

Repeated suicide screens can help but are imperfect, so listen to the child or parent for risk signs such as the youth having self-reported worthlessness, low self-esteem, speaking negatively about self, anhedonia, or poor emotion regulation. Children with impulsive aggression, often familial, are at special risk of suicide. This trait, while more common in ADHD, is not confined to that condition. You can help by optimizing medical management of impulsivity, when appropriate.

Most youth who attempt suicide have one or more mental health diagnoses, particularly major depressive disorder (MDD), eating disorder, ADHD, conduct, or intermittent explosive disorder. When MDD is comorbid with anxiety, suicides increase 9.5-fold. Children on the autism spectrum are more likely to have been bullied and eight times more likely to commit suicide. LGBTQ youth are five times more often bullied and are at high risk for suicide. The more common issues of school failure or substance use also confer risk. While we do our best caring for children with these conditions we may not be thinking about, screening, or monitoring for their suicide risk. It may be important for us to explain that, despite black-box warnings, rates of SSRI prescribing for depression are inversely related to suicides.

Child maltreatment is the highest risk factor for suicide (population attributed risk, or PAR, 9.6%-14.5%), particularly sexual misuse. All together, adverse childhood experiences have a PAR for suicide of 80%. Continuity allows you to monitor for developmental times when distress from past experiences often reemerges, e.g., puberty, dating onset, or divorce. Getting consent and sharing these highly sensitive but potentially triggering factors as well as prior diagnoses with a newly assigned therapist can be helpful to prioritize treatments to prevent a suicide attempt, because they may be difficult to elicit and timeliness is essential.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

References

Brent DA. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):25-35.

Cha CB et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(4):460-82.

You read “thoughts of being better off dead” on your next patient’s PHQ-9 screen results and break into a sweat. After eliciting the teen’s realistic suicide plan and intent you send him to the ED with his parent for crisis mental health evaluation. When you call the family that evening to follow-up you hear that he was discharged with a “mental health counseling” appointment next week.

Have you done enough to prevent this child from dying at his own hand? I imagine that this haunts you as it does me. It is terrifying to know that, of youth with suicidal ideation, over one-third attempt suicide, most within 1-2 years, and 20%-40% do so without having had a plan.

We now know that certain kinds of psychotherapy have evidence for preventing subsequent suicide in teens at high risk due to suicidal ideation and past attempts. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has the best evidence including its subtypes for youth with relevant histories: for both suicide and substance use (integrated, or I-CBT), trauma focused (TF-CBT), traumatic grief (CTG-CBT), and CBT-I, for the potent risk factor of insomnia. The other treatment shown to reduce risk is dialectical behavioral therapy–adolescent (DBT-A) focused on strengthening skills in interpersonal effectiveness, mindfulness, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation adapted to youth by adding family therapy and multifamily skills training. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) adapted for suicidal and self-harming adolescents (IPT-SA) also has evidence.

Some school programs have shown moderate efficacy, for example (IPT-A-IN) addresses the social and interpersonal context, and Youth Aware of Mental Health, a school curriculum to increase knowledge, help-seeking, and ways of coping with depression and suicidal behavior, that cut suicide attempts by half.

You may be able to recommend, refer to, or check to see if a youth can be provided one of the above therapies with best evidence but getting any counseling at all can be hard and some, especially minority families may decline formal interventions. Any therapy – CBT, DBT, or IPT – acceptable to the youth and family can be helpful. You can often determine if the key components are being provided by asking the teen what they are working on in therapy.

It is clear that checking in regularly with teens who have been through a suicide crisis is crucial to ensure that they continue in therapy long and consistently enough, that the family is involved in treatment, and that they are taught emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and safety planning. Warm, consistent parenting, good parent-child communication, and monitoring are protective factors but also skills that can be boosted to reduce future risk of suicide. When there is family dysfunction, conflict, or weak relationships, getting help for family relationships such as through attachment-based family therapy (ABFT) or family cognitive behavioral therapy is a priority. When bereavement or parental depression is contributing to youth suicidal thoughts, addressing these specifically can reduce suicide risk.

Sometimes family members, even with counseling, are not the best supporters for a teen in pain. When youths nominated their own support team to be informed about risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment plans and to stay in contact weekly there was a 6.6-fold lower risk of death than for nonsupported youth.

But how much of this evidence-based intervention can you ensure from your position in primary care? Refer if you can but regular supportive contacts alone reduce risk so you, trusted staff, school counselors, or even the now more available teletherapists may help. You can work with your patient to fill out a written commitment-to-safety plan (e.g. U. Colorado, CHADIS) of strategies they can use when having suicidal thoughts such as self-distractions, problem-solving, listing things they are looking forward to, things to do to get their mind off suicidal thoughts, and selecting support people to understand their situation with whom to be in regular contact. Any plan needs to take into account how understanding, supportive, and available the family is, factors you are most likely to be able to judge from your ongoing relationship, but that immediate risk may change. Contact within 48 hours, check-in within 1-2 weeks, and provision of crisis hotline information are essential actions.

Recommending home safety is part of routine anticipatory guidance but reduction of lethal means is essential in these cases. Guns are the most lethal method of suicide but discussing safe gun storage has been shown to be more effective than arguing in vain for gun removal. Medication overdose, a common means, can be reduced by not prescribing tricyclics (ineffective and more lethal), and advising parents to lock up all household medications.

You can ask about and coach teens on how to avoid the hazards of participating in online discussion groups, bullying, and cyberbullying (with risk for both perpetrator and victim), all risk factors for suicide. Managing insomnia can improve depression and is within your skills. While pediatricians can’t treat the suicide risk factors of family poverty, unemployment, or loss of culture/identity, we can refer affected families to community resources.

Repeated suicide screens can help but are imperfect, so listen to the child or parent for risk signs such as the youth having self-reported worthlessness, low self-esteem, speaking negatively about self, anhedonia, or poor emotion regulation. Children with impulsive aggression, often familial, are at special risk of suicide. This trait, while more common in ADHD, is not confined to that condition. You can help by optimizing medical management of impulsivity, when appropriate.

Most youth who attempt suicide have one or more mental health diagnoses, particularly major depressive disorder (MDD), eating disorder, ADHD, conduct, or intermittent explosive disorder. When MDD is comorbid with anxiety, suicides increase 9.5-fold. Children on the autism spectrum are more likely to have been bullied and eight times more likely to commit suicide. LGBTQ youth are five times more often bullied and are at high risk for suicide. The more common issues of school failure or substance use also confer risk. While we do our best caring for children with these conditions we may not be thinking about, screening, or monitoring for their suicide risk. It may be important for us to explain that, despite black-box warnings, rates of SSRI prescribing for depression are inversely related to suicides.

Child maltreatment is the highest risk factor for suicide (population attributed risk, or PAR, 9.6%-14.5%), particularly sexual misuse. All together, adverse childhood experiences have a PAR for suicide of 80%. Continuity allows you to monitor for developmental times when distress from past experiences often reemerges, e.g., puberty, dating onset, or divorce. Getting consent and sharing these highly sensitive but potentially triggering factors as well as prior diagnoses with a newly assigned therapist can be helpful to prioritize treatments to prevent a suicide attempt, because they may be difficult to elicit and timeliness is essential.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

References

Brent DA. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):25-35.

Cha CB et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(4):460-82.

You read “thoughts of being better off dead” on your next patient’s PHQ-9 screen results and break into a sweat. After eliciting the teen’s realistic suicide plan and intent you send him to the ED with his parent for crisis mental health evaluation. When you call the family that evening to follow-up you hear that he was discharged with a “mental health counseling” appointment next week.

Have you done enough to prevent this child from dying at his own hand? I imagine that this haunts you as it does me. It is terrifying to know that, of youth with suicidal ideation, over one-third attempt suicide, most within 1-2 years, and 20%-40% do so without having had a plan.

We now know that certain kinds of psychotherapy have evidence for preventing subsequent suicide in teens at high risk due to suicidal ideation and past attempts. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has the best evidence including its subtypes for youth with relevant histories: for both suicide and substance use (integrated, or I-CBT), trauma focused (TF-CBT), traumatic grief (CTG-CBT), and CBT-I, for the potent risk factor of insomnia. The other treatment shown to reduce risk is dialectical behavioral therapy–adolescent (DBT-A) focused on strengthening skills in interpersonal effectiveness, mindfulness, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation adapted to youth by adding family therapy and multifamily skills training. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) adapted for suicidal and self-harming adolescents (IPT-SA) also has evidence.

Some school programs have shown moderate efficacy, for example (IPT-A-IN) addresses the social and interpersonal context, and Youth Aware of Mental Health, a school curriculum to increase knowledge, help-seeking, and ways of coping with depression and suicidal behavior, that cut suicide attempts by half.

You may be able to recommend, refer to, or check to see if a youth can be provided one of the above therapies with best evidence but getting any counseling at all can be hard and some, especially minority families may decline formal interventions. Any therapy – CBT, DBT, or IPT – acceptable to the youth and family can be helpful. You can often determine if the key components are being provided by asking the teen what they are working on in therapy.

It is clear that checking in regularly with teens who have been through a suicide crisis is crucial to ensure that they continue in therapy long and consistently enough, that the family is involved in treatment, and that they are taught emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and safety planning. Warm, consistent parenting, good parent-child communication, and monitoring are protective factors but also skills that can be boosted to reduce future risk of suicide. When there is family dysfunction, conflict, or weak relationships, getting help for family relationships such as through attachment-based family therapy (ABFT) or family cognitive behavioral therapy is a priority. When bereavement or parental depression is contributing to youth suicidal thoughts, addressing these specifically can reduce suicide risk.

Sometimes family members, even with counseling, are not the best supporters for a teen in pain. When youths nominated their own support team to be informed about risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment plans and to stay in contact weekly there was a 6.6-fold lower risk of death than for nonsupported youth.

But how much of this evidence-based intervention can you ensure from your position in primary care? Refer if you can but regular supportive contacts alone reduce risk so you, trusted staff, school counselors, or even the now more available teletherapists may help. You can work with your patient to fill out a written commitment-to-safety plan (e.g. U. Colorado, CHADIS) of strategies they can use when having suicidal thoughts such as self-distractions, problem-solving, listing things they are looking forward to, things to do to get their mind off suicidal thoughts, and selecting support people to understand their situation with whom to be in regular contact. Any plan needs to take into account how understanding, supportive, and available the family is, factors you are most likely to be able to judge from your ongoing relationship, but that immediate risk may change. Contact within 48 hours, check-in within 1-2 weeks, and provision of crisis hotline information are essential actions.

Recommending home safety is part of routine anticipatory guidance but reduction of lethal means is essential in these cases. Guns are the most lethal method of suicide but discussing safe gun storage has been shown to be more effective than arguing in vain for gun removal. Medication overdose, a common means, can be reduced by not prescribing tricyclics (ineffective and more lethal), and advising parents to lock up all household medications.

You can ask about and coach teens on how to avoid the hazards of participating in online discussion groups, bullying, and cyberbullying (with risk for both perpetrator and victim), all risk factors for suicide. Managing insomnia can improve depression and is within your skills. While pediatricians can’t treat the suicide risk factors of family poverty, unemployment, or loss of culture/identity, we can refer affected families to community resources.

Repeated suicide screens can help but are imperfect, so listen to the child or parent for risk signs such as the youth having self-reported worthlessness, low self-esteem, speaking negatively about self, anhedonia, or poor emotion regulation. Children with impulsive aggression, often familial, are at special risk of suicide. This trait, while more common in ADHD, is not confined to that condition. You can help by optimizing medical management of impulsivity, when appropriate.

Most youth who attempt suicide have one or more mental health diagnoses, particularly major depressive disorder (MDD), eating disorder, ADHD, conduct, or intermittent explosive disorder. When MDD is comorbid with anxiety, suicides increase 9.5-fold. Children on the autism spectrum are more likely to have been bullied and eight times more likely to commit suicide. LGBTQ youth are five times more often bullied and are at high risk for suicide. The more common issues of school failure or substance use also confer risk. While we do our best caring for children with these conditions we may not be thinking about, screening, or monitoring for their suicide risk. It may be important for us to explain that, despite black-box warnings, rates of SSRI prescribing for depression are inversely related to suicides.

Child maltreatment is the highest risk factor for suicide (population attributed risk, or PAR, 9.6%-14.5%), particularly sexual misuse. All together, adverse childhood experiences have a PAR for suicide of 80%. Continuity allows you to monitor for developmental times when distress from past experiences often reemerges, e.g., puberty, dating onset, or divorce. Getting consent and sharing these highly sensitive but potentially triggering factors as well as prior diagnoses with a newly assigned therapist can be helpful to prioritize treatments to prevent a suicide attempt, because they may be difficult to elicit and timeliness is essential.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

References

Brent DA. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):25-35.

Cha CB et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(4):460-82.

Hospitalization not rare for children with COVID, study says

Nearly a third of those had severe disease that required mechanical ventilation or admission to an intensive care unit, according to a new study published in JAMA Network Open on April 9.*

That means about 1 in 9 kids with COVID-19 in this cohort needed hospitalization, and about 1 in 28 had severe COVID-19.

“Although most children with COVID-19 experience mild illness, some children develop serious illness that leads to hospitalization, use of invasive mechanical ventilation, and death,” the researchers wrote.

The research team analyzed discharge data from 869 medical facilities in the Premier Healthcare Database Special COVID-19 Release. They looked for COVID-19 patients ages 18 and under who had an in-patient or emergency department visit between March and October 2020.

More than 20,700 children with COVID-19 had an in-patient or an emergency department visit, and 2,430 were hospitalized with COVID-19. Among those, 756 children had severe COVID-19 and were admitted to an intensive care unit or needed mechanical ventilation.

About 53% of the COVID-19 patients were girls, and about 54% were between ages 12-18. In addition, about 29% had at least one chronic condition.

Similar to COVID-19 studies in adults, Hispanic, Latino and Black patients were overrepresented. About 39% of the children were Hispanic or Latino, and 24% were Black. However, the researchers didn’t find an association between severe COVID-19 and race or ethnicity.

The likelihood of severe COVID-19 increased if the patient had at least one chronic condition, was male, or was between ages 2-11.

“Understanding factors associated with severe COVID-19 disease among children could help inform prevention and control strategies,” they added. “Reducing infection risk through community mitigation strategies is critical for protecting children from COVID-19 and preventing poor outcomes.”

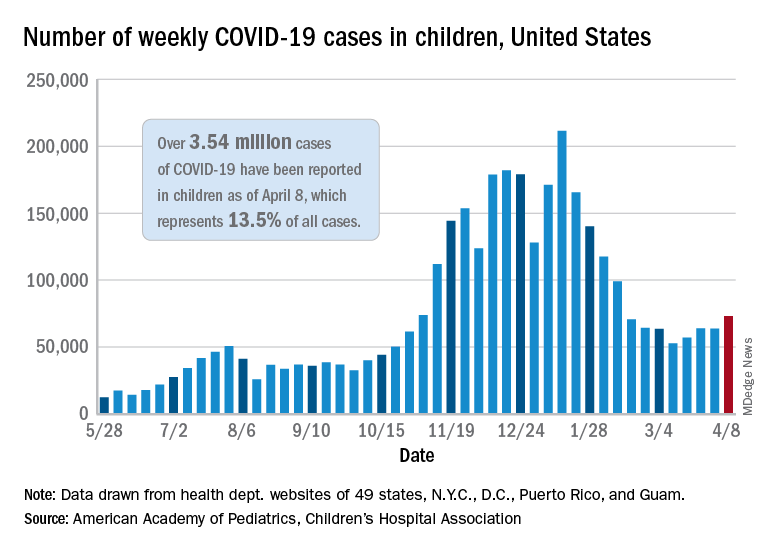

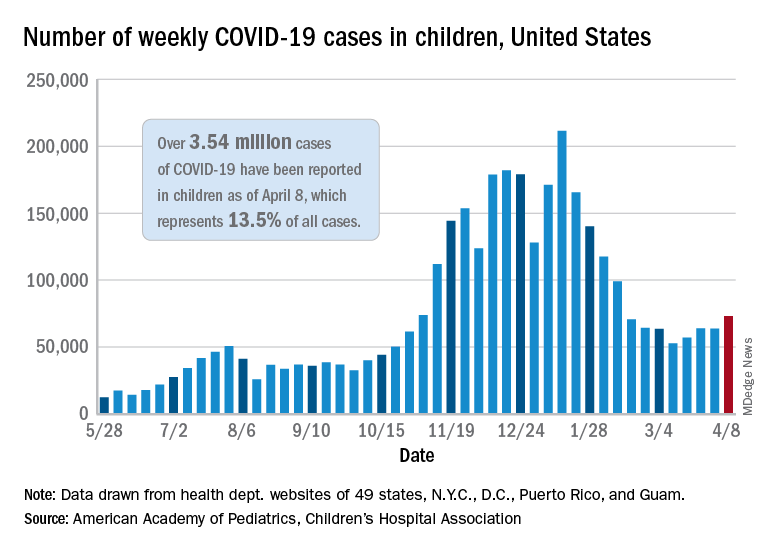

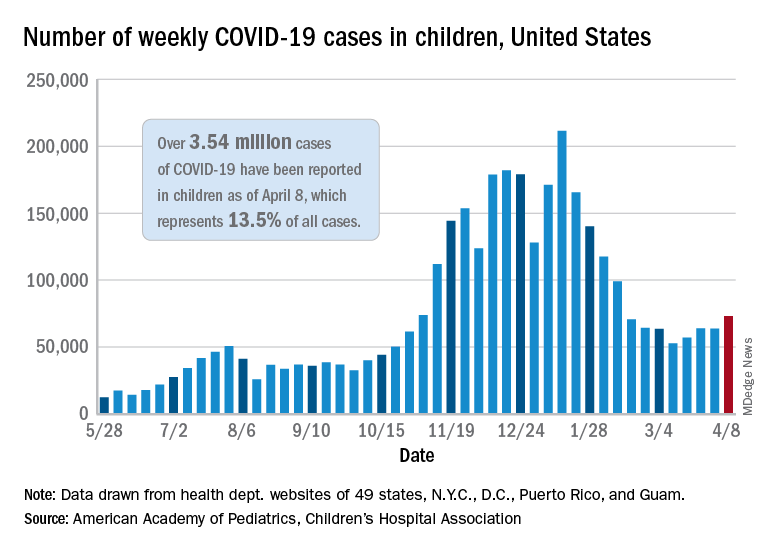

As of April 8, more than 3.54 million U.S. children have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the latest report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association. Cases among children are increasing slightly, with about 73,000 new cases reported during the first week of April.

Children represent about 13.5% of the COVID-19 cases in the country, according to the report. Among the 24 states that provide data, children represented 1% to 3% of all COVID-19 hospitalizations, and less than 2% of all child COVID-19 cases resulted in hospitalization.

“At this time, it appears that severe illness due to COVID-19 is rare among children,” the two groups wrote.

“However, there is an urgent need to collect more data on longer-term impacts of the pandemic on children, including ways the virus may harm the long-term physical health of infected children, as well as its emotional and mental health effects,” they added.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

*CORRECTION, 6/7/21 – This story has been corrected to clarify that the patient sample study reflects only those children who presented to an emergency department or received inpatient care for COVID-19 in a hospital network and were included in the Premier Healthcare Database Special COVID-19 Release. A previous version of the story incorrectly implied that 12% of all U.S. children with COVID-19 had required inpatient care.

Nearly a third of those had severe disease that required mechanical ventilation or admission to an intensive care unit, according to a new study published in JAMA Network Open on April 9.*

That means about 1 in 9 kids with COVID-19 in this cohort needed hospitalization, and about 1 in 28 had severe COVID-19.

“Although most children with COVID-19 experience mild illness, some children develop serious illness that leads to hospitalization, use of invasive mechanical ventilation, and death,” the researchers wrote.

The research team analyzed discharge data from 869 medical facilities in the Premier Healthcare Database Special COVID-19 Release. They looked for COVID-19 patients ages 18 and under who had an in-patient or emergency department visit between March and October 2020.

More than 20,700 children with COVID-19 had an in-patient or an emergency department visit, and 2,430 were hospitalized with COVID-19. Among those, 756 children had severe COVID-19 and were admitted to an intensive care unit or needed mechanical ventilation.

About 53% of the COVID-19 patients were girls, and about 54% were between ages 12-18. In addition, about 29% had at least one chronic condition.

Similar to COVID-19 studies in adults, Hispanic, Latino and Black patients were overrepresented. About 39% of the children were Hispanic or Latino, and 24% were Black. However, the researchers didn’t find an association between severe COVID-19 and race or ethnicity.

The likelihood of severe COVID-19 increased if the patient had at least one chronic condition, was male, or was between ages 2-11.

“Understanding factors associated with severe COVID-19 disease among children could help inform prevention and control strategies,” they added. “Reducing infection risk through community mitigation strategies is critical for protecting children from COVID-19 and preventing poor outcomes.”

As of April 8, more than 3.54 million U.S. children have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the latest report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association. Cases among children are increasing slightly, with about 73,000 new cases reported during the first week of April.

Children represent about 13.5% of the COVID-19 cases in the country, according to the report. Among the 24 states that provide data, children represented 1% to 3% of all COVID-19 hospitalizations, and less than 2% of all child COVID-19 cases resulted in hospitalization.

“At this time, it appears that severe illness due to COVID-19 is rare among children,” the two groups wrote.

“However, there is an urgent need to collect more data on longer-term impacts of the pandemic on children, including ways the virus may harm the long-term physical health of infected children, as well as its emotional and mental health effects,” they added.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

*CORRECTION, 6/7/21 – This story has been corrected to clarify that the patient sample study reflects only those children who presented to an emergency department or received inpatient care for COVID-19 in a hospital network and were included in the Premier Healthcare Database Special COVID-19 Release. A previous version of the story incorrectly implied that 12% of all U.S. children with COVID-19 had required inpatient care.

Nearly a third of those had severe disease that required mechanical ventilation or admission to an intensive care unit, according to a new study published in JAMA Network Open on April 9.*

That means about 1 in 9 kids with COVID-19 in this cohort needed hospitalization, and about 1 in 28 had severe COVID-19.

“Although most children with COVID-19 experience mild illness, some children develop serious illness that leads to hospitalization, use of invasive mechanical ventilation, and death,” the researchers wrote.

The research team analyzed discharge data from 869 medical facilities in the Premier Healthcare Database Special COVID-19 Release. They looked for COVID-19 patients ages 18 and under who had an in-patient or emergency department visit between March and October 2020.

More than 20,700 children with COVID-19 had an in-patient or an emergency department visit, and 2,430 were hospitalized with COVID-19. Among those, 756 children had severe COVID-19 and were admitted to an intensive care unit or needed mechanical ventilation.

About 53% of the COVID-19 patients were girls, and about 54% were between ages 12-18. In addition, about 29% had at least one chronic condition.

Similar to COVID-19 studies in adults, Hispanic, Latino and Black patients were overrepresented. About 39% of the children were Hispanic or Latino, and 24% were Black. However, the researchers didn’t find an association between severe COVID-19 and race or ethnicity.

The likelihood of severe COVID-19 increased if the patient had at least one chronic condition, was male, or was between ages 2-11.

“Understanding factors associated with severe COVID-19 disease among children could help inform prevention and control strategies,” they added. “Reducing infection risk through community mitigation strategies is critical for protecting children from COVID-19 and preventing poor outcomes.”

As of April 8, more than 3.54 million U.S. children have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the latest report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association. Cases among children are increasing slightly, with about 73,000 new cases reported during the first week of April.

Children represent about 13.5% of the COVID-19 cases in the country, according to the report. Among the 24 states that provide data, children represented 1% to 3% of all COVID-19 hospitalizations, and less than 2% of all child COVID-19 cases resulted in hospitalization.

“At this time, it appears that severe illness due to COVID-19 is rare among children,” the two groups wrote.

“However, there is an urgent need to collect more data on longer-term impacts of the pandemic on children, including ways the virus may harm the long-term physical health of infected children, as well as its emotional and mental health effects,” they added.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

*CORRECTION, 6/7/21 – This story has been corrected to clarify that the patient sample study reflects only those children who presented to an emergency department or received inpatient care for COVID-19 in a hospital network and were included in the Premier Healthcare Database Special COVID-19 Release. A previous version of the story incorrectly implied that 12% of all U.S. children with COVID-19 had required inpatient care.

Data about COVID-19-related skin manifestations in children continue to emerge

Two and stratifying children at risk for serious, systemic illness due to the virus.

In a single-center descriptive study carried out over a 9-month period, researchers in Madrid found that of 50 hospitalized children infected with COVID-19, 21 (42%) had mucocutaneous symptoms, most commonly exanthem, followed by conjunctival hyperemia without secretion and red cracked lips or strawberry tongue. In addition, 18 (36%) fulfilled criteria for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).

“Based on findings in adult patients, the skin manifestations of COVID-19 have been classified under five categories: acral pseudo-chilblain, vesicular eruptions, urticarial lesions, maculopapular eruptions, and livedo or necrosis,” David Andina-Martinez, MD, of Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online on April 2 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Chilblain lesions in healthy children and adolescents have received much attention; these lesions resolve without complications after a few weeks,” they added. “Besides, other cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in children have been the matter of case reports or small case series. Nevertheless, the mucocutaneous manifestations in hospitalized children infected with SARS-CoV-2 and their implications on the clinical course have not yet been extensively described.”

In an effort to describe the mucocutaneous manifestations in children hospitalized for COVID-19, the researchers evaluated 50 children up to 18 years of age who were admitted between March 1 and Nov. 30, 2020, to Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, which was designated as a pediatric reference center during the peak of the pandemic. The main reasons for admission were respiratory illness (40%) and MIS-C (40%).

Of the 50 patients, 44 (88%) had a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 and 6 (12%) met clinical suspicion criteria and had a negative RT-PCR with a positive IgG serology. In 34 patients (68%), a close contact with a suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19 was referred, while the source of the infection remained unknown in the remaining 16 patients (32%).

The researchers reported that 21 patients (42%) had mucocutaneous symptoms, most commonly maculopapular exanthem (86%), conjunctival hyperemia (81%), and red cracked lips or strawberry tongue (43%). In addition, 18 of the 21 patients (86%) fulfilled criteria for MIS-C.

“A tricky thing about MIS-C is that it often manifests 4-5 weeks after a child had COVID-19,” said Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who was asked to comment on the study. “MIS-C is associated with characteristic bright red lips and a red tongue that might resemble a strawberry. Such oral findings should prompt rapid evaluation for other signs and symptoms. There can be redness of the eyes or other more nonspecific skin findings (large or small areas of redness on the trunk or limbs, sometimes with surface change), but more importantly, fever, a rapid heartbeat, diarrhea, or breathing issues. The risk with MIS-C is a rapid decline in a child’s health, with admission to an intensive care unit.”

Dr. Andina-Martinez and his colleagues also contrast the skin findings of MIS-C, which are not generally on the hands or feet, with the so-called “COVID toe” or finger phenomenon, which has also been associated with SARS-CoV-2, particularly in children. “Only one of the patients in this series had skin involvement of a finger, and it only appeared after recovery from MIS-C,” Dr. Ko noted. “Distinguishing COVID toes from MIS-C is important, as COVID toes has a very good outcome, while MIS-C can have severe consequences, including protracted heart disease.”

In other findings, patients who presented with mucocutaneous signs tended to be older than those without skin signs and they presented at the emergency department with poor general status and extreme tachycardia. They also had higher C-reactive protein and D-dimer levels and lower lymphocyte counts and faced a more than a 10-fold increased risk of being admitted to the PICU, compared with patients who did not have skin signs (OR, 10.24; P = .003).

In a separate study published online on April 7 in JAMA Dermatology, Zachary E. Holcomb, MD, of the combined dermatology residency program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues presented what is believed to be the first case report of reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption (RIME) triggered by SARS-CoV-2. RIME is the preferred term for pediatric patients who present with mucositis and rash (often a scant or even absent skin eruption) triggered by various infectious agents.

The patient, a 17-year-old male, presented to the emergency department with 3 days of mouth pain and nonpainful penile erosions. “One week prior, he experienced transient anosmia and ageusia that had since spontaneously resolved,” the researchers wrote. “At that time, he was tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection via nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the results of which were positive.”

At presentation, the patient had no fever, his vital signs were normal, and the physical exam revealed shallow erosions of the vermilion lips and hard palate, circumferential erythematous erosions of the periurethral glans penis, and five small vesicles on the trunk and upper extremities. Serum analysis revealed a normal white blood cell count with mild absolute lymphopenia, slightly elevated creatinine level, normal liver function, slightly elevated C-reactive protein level, and normal ferritin level.

Dr. Holcomb and colleagues made a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2–associated RIME based on microbiological results, which revealed positive repeated SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal PCR and negative nasopharyngeal PCR testing for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, adenovirus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus, influenza A/B, parainfluenza 1 to 4, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus. In addition, titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM levels were negative, but Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG levels were elevated.

The lesions resolved with 60 mg of oral prednisone taken daily for 4 days. A recurrence of oral mucositis 3 months later responded to 80 mg oral prednisone taken daily for 6 days.

“It’s not surprising that SARS-CoV-2 is yet another trigger for RIME,” said Anna Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, chief of the division of dermatology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, who was asked to comment about the case report.

“The take-home message is for clinicians to be aware of this association and distinguish these patients from those with MIS-C, because patients with MIS-C require monitoring and urgent systemic treatment. RIME and MIS-C may potentially be distinguished clinically based on the nature of the mucositis (hemorrhagic and erosive in RIME, dry, cracked lips with ‘strawberry tongue’ in MIS-C) but more importantly patients with RIME lack laboratory evidence of severe systemic inflammation,” such as ESR, CRP, or ferritin, she said.

“A final interesting point in this article was the recurrence of mucositis in this patient, which could mean that recurrent mucositis/recurrent RIME might be yet another manifestation of ‘long-COVID’ (now called post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection) in some patients,” Dr. Kirkorian added. She noted that the American Academy of Dermatology–International League of Dermatologic Societies COVID-19 Dermatology Registry and articles like these “provide invaluable ‘hot off the presses’ information for clinicians who are facing the protean manifestations of a novel viral epidemic.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Two and stratifying children at risk for serious, systemic illness due to the virus.

In a single-center descriptive study carried out over a 9-month period, researchers in Madrid found that of 50 hospitalized children infected with COVID-19, 21 (42%) had mucocutaneous symptoms, most commonly exanthem, followed by conjunctival hyperemia without secretion and red cracked lips or strawberry tongue. In addition, 18 (36%) fulfilled criteria for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).

“Based on findings in adult patients, the skin manifestations of COVID-19 have been classified under five categories: acral pseudo-chilblain, vesicular eruptions, urticarial lesions, maculopapular eruptions, and livedo or necrosis,” David Andina-Martinez, MD, of Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online on April 2 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Chilblain lesions in healthy children and adolescents have received much attention; these lesions resolve without complications after a few weeks,” they added. “Besides, other cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in children have been the matter of case reports or small case series. Nevertheless, the mucocutaneous manifestations in hospitalized children infected with SARS-CoV-2 and their implications on the clinical course have not yet been extensively described.”

In an effort to describe the mucocutaneous manifestations in children hospitalized for COVID-19, the researchers evaluated 50 children up to 18 years of age who were admitted between March 1 and Nov. 30, 2020, to Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, which was designated as a pediatric reference center during the peak of the pandemic. The main reasons for admission were respiratory illness (40%) and MIS-C (40%).

Of the 50 patients, 44 (88%) had a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 and 6 (12%) met clinical suspicion criteria and had a negative RT-PCR with a positive IgG serology. In 34 patients (68%), a close contact with a suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19 was referred, while the source of the infection remained unknown in the remaining 16 patients (32%).

The researchers reported that 21 patients (42%) had mucocutaneous symptoms, most commonly maculopapular exanthem (86%), conjunctival hyperemia (81%), and red cracked lips or strawberry tongue (43%). In addition, 18 of the 21 patients (86%) fulfilled criteria for MIS-C.

“A tricky thing about MIS-C is that it often manifests 4-5 weeks after a child had COVID-19,” said Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who was asked to comment on the study. “MIS-C is associated with characteristic bright red lips and a red tongue that might resemble a strawberry. Such oral findings should prompt rapid evaluation for other signs and symptoms. There can be redness of the eyes or other more nonspecific skin findings (large or small areas of redness on the trunk or limbs, sometimes with surface change), but more importantly, fever, a rapid heartbeat, diarrhea, or breathing issues. The risk with MIS-C is a rapid decline in a child’s health, with admission to an intensive care unit.”

Dr. Andina-Martinez and his colleagues also contrast the skin findings of MIS-C, which are not generally on the hands or feet, with the so-called “COVID toe” or finger phenomenon, which has also been associated with SARS-CoV-2, particularly in children. “Only one of the patients in this series had skin involvement of a finger, and it only appeared after recovery from MIS-C,” Dr. Ko noted. “Distinguishing COVID toes from MIS-C is important, as COVID toes has a very good outcome, while MIS-C can have severe consequences, including protracted heart disease.”

In other findings, patients who presented with mucocutaneous signs tended to be older than those without skin signs and they presented at the emergency department with poor general status and extreme tachycardia. They also had higher C-reactive protein and D-dimer levels and lower lymphocyte counts and faced a more than a 10-fold increased risk of being admitted to the PICU, compared with patients who did not have skin signs (OR, 10.24; P = .003).

In a separate study published online on April 7 in JAMA Dermatology, Zachary E. Holcomb, MD, of the combined dermatology residency program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues presented what is believed to be the first case report of reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption (RIME) triggered by SARS-CoV-2. RIME is the preferred term for pediatric patients who present with mucositis and rash (often a scant or even absent skin eruption) triggered by various infectious agents.

The patient, a 17-year-old male, presented to the emergency department with 3 days of mouth pain and nonpainful penile erosions. “One week prior, he experienced transient anosmia and ageusia that had since spontaneously resolved,” the researchers wrote. “At that time, he was tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection via nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the results of which were positive.”

At presentation, the patient had no fever, his vital signs were normal, and the physical exam revealed shallow erosions of the vermilion lips and hard palate, circumferential erythematous erosions of the periurethral glans penis, and five small vesicles on the trunk and upper extremities. Serum analysis revealed a normal white blood cell count with mild absolute lymphopenia, slightly elevated creatinine level, normal liver function, slightly elevated C-reactive protein level, and normal ferritin level.

Dr. Holcomb and colleagues made a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2–associated RIME based on microbiological results, which revealed positive repeated SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal PCR and negative nasopharyngeal PCR testing for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, adenovirus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus, influenza A/B, parainfluenza 1 to 4, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus. In addition, titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM levels were negative, but Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG levels were elevated.

The lesions resolved with 60 mg of oral prednisone taken daily for 4 days. A recurrence of oral mucositis 3 months later responded to 80 mg oral prednisone taken daily for 6 days.

“It’s not surprising that SARS-CoV-2 is yet another trigger for RIME,” said Anna Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, chief of the division of dermatology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, who was asked to comment about the case report.

“The take-home message is for clinicians to be aware of this association and distinguish these patients from those with MIS-C, because patients with MIS-C require monitoring and urgent systemic treatment. RIME and MIS-C may potentially be distinguished clinically based on the nature of the mucositis (hemorrhagic and erosive in RIME, dry, cracked lips with ‘strawberry tongue’ in MIS-C) but more importantly patients with RIME lack laboratory evidence of severe systemic inflammation,” such as ESR, CRP, or ferritin, she said.

“A final interesting point in this article was the recurrence of mucositis in this patient, which could mean that recurrent mucositis/recurrent RIME might be yet another manifestation of ‘long-COVID’ (now called post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection) in some patients,” Dr. Kirkorian added. She noted that the American Academy of Dermatology–International League of Dermatologic Societies COVID-19 Dermatology Registry and articles like these “provide invaluable ‘hot off the presses’ information for clinicians who are facing the protean manifestations of a novel viral epidemic.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Two and stratifying children at risk for serious, systemic illness due to the virus.

In a single-center descriptive study carried out over a 9-month period, researchers in Madrid found that of 50 hospitalized children infected with COVID-19, 21 (42%) had mucocutaneous symptoms, most commonly exanthem, followed by conjunctival hyperemia without secretion and red cracked lips or strawberry tongue. In addition, 18 (36%) fulfilled criteria for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).

“Based on findings in adult patients, the skin manifestations of COVID-19 have been classified under five categories: acral pseudo-chilblain, vesicular eruptions, urticarial lesions, maculopapular eruptions, and livedo or necrosis,” David Andina-Martinez, MD, of Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online on April 2 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Chilblain lesions in healthy children and adolescents have received much attention; these lesions resolve without complications after a few weeks,” they added. “Besides, other cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in children have been the matter of case reports or small case series. Nevertheless, the mucocutaneous manifestations in hospitalized children infected with SARS-CoV-2 and their implications on the clinical course have not yet been extensively described.”

In an effort to describe the mucocutaneous manifestations in children hospitalized for COVID-19, the researchers evaluated 50 children up to 18 years of age who were admitted between March 1 and Nov. 30, 2020, to Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, which was designated as a pediatric reference center during the peak of the pandemic. The main reasons for admission were respiratory illness (40%) and MIS-C (40%).

Of the 50 patients, 44 (88%) had a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 and 6 (12%) met clinical suspicion criteria and had a negative RT-PCR with a positive IgG serology. In 34 patients (68%), a close contact with a suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19 was referred, while the source of the infection remained unknown in the remaining 16 patients (32%).

The researchers reported that 21 patients (42%) had mucocutaneous symptoms, most commonly maculopapular exanthem (86%), conjunctival hyperemia (81%), and red cracked lips or strawberry tongue (43%). In addition, 18 of the 21 patients (86%) fulfilled criteria for MIS-C.

“A tricky thing about MIS-C is that it often manifests 4-5 weeks after a child had COVID-19,” said Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who was asked to comment on the study. “MIS-C is associated with characteristic bright red lips and a red tongue that might resemble a strawberry. Such oral findings should prompt rapid evaluation for other signs and symptoms. There can be redness of the eyes or other more nonspecific skin findings (large or small areas of redness on the trunk or limbs, sometimes with surface change), but more importantly, fever, a rapid heartbeat, diarrhea, or breathing issues. The risk with MIS-C is a rapid decline in a child’s health, with admission to an intensive care unit.”

Dr. Andina-Martinez and his colleagues also contrast the skin findings of MIS-C, which are not generally on the hands or feet, with the so-called “COVID toe” or finger phenomenon, which has also been associated with SARS-CoV-2, particularly in children. “Only one of the patients in this series had skin involvement of a finger, and it only appeared after recovery from MIS-C,” Dr. Ko noted. “Distinguishing COVID toes from MIS-C is important, as COVID toes has a very good outcome, while MIS-C can have severe consequences, including protracted heart disease.”

In other findings, patients who presented with mucocutaneous signs tended to be older than those without skin signs and they presented at the emergency department with poor general status and extreme tachycardia. They also had higher C-reactive protein and D-dimer levels and lower lymphocyte counts and faced a more than a 10-fold increased risk of being admitted to the PICU, compared with patients who did not have skin signs (OR, 10.24; P = .003).

In a separate study published online on April 7 in JAMA Dermatology, Zachary E. Holcomb, MD, of the combined dermatology residency program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues presented what is believed to be the first case report of reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption (RIME) triggered by SARS-CoV-2. RIME is the preferred term for pediatric patients who present with mucositis and rash (often a scant or even absent skin eruption) triggered by various infectious agents.

The patient, a 17-year-old male, presented to the emergency department with 3 days of mouth pain and nonpainful penile erosions. “One week prior, he experienced transient anosmia and ageusia that had since spontaneously resolved,” the researchers wrote. “At that time, he was tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection via nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the results of which were positive.”

At presentation, the patient had no fever, his vital signs were normal, and the physical exam revealed shallow erosions of the vermilion lips and hard palate, circumferential erythematous erosions of the periurethral glans penis, and five small vesicles on the trunk and upper extremities. Serum analysis revealed a normal white blood cell count with mild absolute lymphopenia, slightly elevated creatinine level, normal liver function, slightly elevated C-reactive protein level, and normal ferritin level.

Dr. Holcomb and colleagues made a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2–associated RIME based on microbiological results, which revealed positive repeated SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal PCR and negative nasopharyngeal PCR testing for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, adenovirus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus, influenza A/B, parainfluenza 1 to 4, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus. In addition, titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM levels were negative, but Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG levels were elevated.

The lesions resolved with 60 mg of oral prednisone taken daily for 4 days. A recurrence of oral mucositis 3 months later responded to 80 mg oral prednisone taken daily for 6 days.

“It’s not surprising that SARS-CoV-2 is yet another trigger for RIME,” said Anna Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, chief of the division of dermatology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, who was asked to comment about the case report.