User login

Despite PCV, pediatric asthma patients face pneumococcal risks

Even on-time pneumococcal vaccines don’t completely protect children with asthma from developing invasive pneumococcal disease, a meta-analysis has determined.

Despite receiving pneumococcal valent 7, 10, or 13, children with asthma were still almost twice as likely to develop the disease as were children without asthma, Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, PhD, and colleagues reported in Pediatrics (2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200). None of the studies included rates for those who received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

“For the first time, this meta-analysis reveals 90% increased odds of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among [vaccinated] children with asthma,” said Dr. Castro-Rodriguez, of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, and colleagues. “If confirmed, these findings will bear clinical and public health importance,” they noted, because guidelines now recommend PPSV23 after age 2 in children with asthma only if they’re treated with prolonged high-dose oral corticosteroids.

However, because the analysis comprised only four studies, the authors cautioned that the results aren’t enough to justify changes to practice recommendations.

Asthma treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) may be driving the increased risk, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his coauthors suggested. ICS deposition in the oropharynx could boost oropharyngeal candidiasis risk by weakening the mucosal immune response, the researchers noted. And that same process may be at work with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A prior study found that children with asthma who received ICS for at least 1 month were almost four times more likely to have oropharyngeal colonization by S. pneumoniae as were those who didn’t get the drugs. Thus, a higher carrier rate of S. pneumoniae in the oropharynx, along with asthma’s impaired airway clearance, might increase the risk of pneumococcal diseases, the investigators explained.

Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and colleagues analyzed four studies with more than 4,000 cases and controls, and about 26 million person-years of follow-up.

Rates and risks of IPD in the four studies were as follows:

- Among those with IPD, 27% had asthma, with 18% of those without, an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.8.

- In a European of patients who received at least 3 doses of PCV7, IPD rates per 100,000 person-years for 5-year-olds were 11.6 for children with asthma and 7.3 for those without. For 5- to 17-year-olds with and without asthma, the rates were 2.3 and 1.6, respectively.

- In 2001, a Korean found an aOR of 2.08 for IPD in children with asthma, compared with those without. In 2010, the aOR was 3.26. No vaccine types were reported in the study.

- of IPD were 3.7 per 100,000 person-years for children with asthma, compared with 2.5 for healthy controls – an adjusted relative risk of 1.5.

The pooled estimate of the four studies revealed an aOR of 1.9 for IPD among children with asthma, compared with those without, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his team concluded.

None of the studies reported hospital admissions, mortality, length of hospital stay, intensive care admission, invasive respiratory support, or additional medication use.

One, however, did find asthma severity was significantly associated with increasing IPD treatment costs per 100,000 person-years: $72,581 for healthy controls, compared with $100,020 for children with mild asthma, $172,002 for moderate asthma, and $638,452 for severe asthma.

In addition, treating all-cause pneumonia was more expensive in children with asthma. For all-cause pneumonia, the researchers found that estimated costs per 100,000 person-years for mild, moderate, and severe asthma were $7.5 million, $14.6 million, and $46.8 million, respectively, compared with $1.7 million for healthy controls.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Castro-Rodriguez J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200.

The meta-analysis contains some important lessons for pediatricians, Tina Q. Tan, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“First, asthma remains a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal pneumonia, even in the era of widespread use of PCV,” Dr. Tan noted. “Second, it is important that all patients, especially those with asthma, are receiving their vaccinations on time and, most notably, are up to date on their pneumococcal vaccinations. This will provide the best protection against pneumococcal infections and their complications for pediatric patients with asthma.”

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) have impressively decreased rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and pneumonia in children in the United States, Dr. Tan explained. Overall, incidence dropped from 95 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1998 to only 9 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

In addition, the incidence of IPD caused by 13-valent PCV serotypes fell, from 88 cases per 100,000 in 1998 to 2 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

The threat is not over, however.

“IPD still remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide,” Dr. Tan cautioned. “In 2017, the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance network reported that there were 31,000 cases of IPD (meningitis, bacteremia, and bacteremic pneumonia) and 3,590 deaths, of which 147 cases and 9 deaths occurred in children younger than 5 years of age.”

Dr. Tan is a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. Her comments appear in Pediatrics 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3360 .

The meta-analysis contains some important lessons for pediatricians, Tina Q. Tan, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“First, asthma remains a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal pneumonia, even in the era of widespread use of PCV,” Dr. Tan noted. “Second, it is important that all patients, especially those with asthma, are receiving their vaccinations on time and, most notably, are up to date on their pneumococcal vaccinations. This will provide the best protection against pneumococcal infections and their complications for pediatric patients with asthma.”

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) have impressively decreased rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and pneumonia in children in the United States, Dr. Tan explained. Overall, incidence dropped from 95 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1998 to only 9 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

In addition, the incidence of IPD caused by 13-valent PCV serotypes fell, from 88 cases per 100,000 in 1998 to 2 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

The threat is not over, however.

“IPD still remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide,” Dr. Tan cautioned. “In 2017, the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance network reported that there were 31,000 cases of IPD (meningitis, bacteremia, and bacteremic pneumonia) and 3,590 deaths, of which 147 cases and 9 deaths occurred in children younger than 5 years of age.”

Dr. Tan is a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. Her comments appear in Pediatrics 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3360 .

The meta-analysis contains some important lessons for pediatricians, Tina Q. Tan, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“First, asthma remains a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal pneumonia, even in the era of widespread use of PCV,” Dr. Tan noted. “Second, it is important that all patients, especially those with asthma, are receiving their vaccinations on time and, most notably, are up to date on their pneumococcal vaccinations. This will provide the best protection against pneumococcal infections and their complications for pediatric patients with asthma.”

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) have impressively decreased rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and pneumonia in children in the United States, Dr. Tan explained. Overall, incidence dropped from 95 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1998 to only 9 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

In addition, the incidence of IPD caused by 13-valent PCV serotypes fell, from 88 cases per 100,000 in 1998 to 2 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

The threat is not over, however.

“IPD still remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide,” Dr. Tan cautioned. “In 2017, the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance network reported that there were 31,000 cases of IPD (meningitis, bacteremia, and bacteremic pneumonia) and 3,590 deaths, of which 147 cases and 9 deaths occurred in children younger than 5 years of age.”

Dr. Tan is a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. Her comments appear in Pediatrics 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3360 .

Even on-time pneumococcal vaccines don’t completely protect children with asthma from developing invasive pneumococcal disease, a meta-analysis has determined.

Despite receiving pneumococcal valent 7, 10, or 13, children with asthma were still almost twice as likely to develop the disease as were children without asthma, Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, PhD, and colleagues reported in Pediatrics (2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200). None of the studies included rates for those who received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

“For the first time, this meta-analysis reveals 90% increased odds of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among [vaccinated] children with asthma,” said Dr. Castro-Rodriguez, of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, and colleagues. “If confirmed, these findings will bear clinical and public health importance,” they noted, because guidelines now recommend PPSV23 after age 2 in children with asthma only if they’re treated with prolonged high-dose oral corticosteroids.

However, because the analysis comprised only four studies, the authors cautioned that the results aren’t enough to justify changes to practice recommendations.

Asthma treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) may be driving the increased risk, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his coauthors suggested. ICS deposition in the oropharynx could boost oropharyngeal candidiasis risk by weakening the mucosal immune response, the researchers noted. And that same process may be at work with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A prior study found that children with asthma who received ICS for at least 1 month were almost four times more likely to have oropharyngeal colonization by S. pneumoniae as were those who didn’t get the drugs. Thus, a higher carrier rate of S. pneumoniae in the oropharynx, along with asthma’s impaired airway clearance, might increase the risk of pneumococcal diseases, the investigators explained.

Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and colleagues analyzed four studies with more than 4,000 cases and controls, and about 26 million person-years of follow-up.

Rates and risks of IPD in the four studies were as follows:

- Among those with IPD, 27% had asthma, with 18% of those without, an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.8.

- In a European of patients who received at least 3 doses of PCV7, IPD rates per 100,000 person-years for 5-year-olds were 11.6 for children with asthma and 7.3 for those without. For 5- to 17-year-olds with and without asthma, the rates were 2.3 and 1.6, respectively.

- In 2001, a Korean found an aOR of 2.08 for IPD in children with asthma, compared with those without. In 2010, the aOR was 3.26. No vaccine types were reported in the study.

- of IPD were 3.7 per 100,000 person-years for children with asthma, compared with 2.5 for healthy controls – an adjusted relative risk of 1.5.

The pooled estimate of the four studies revealed an aOR of 1.9 for IPD among children with asthma, compared with those without, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his team concluded.

None of the studies reported hospital admissions, mortality, length of hospital stay, intensive care admission, invasive respiratory support, or additional medication use.

One, however, did find asthma severity was significantly associated with increasing IPD treatment costs per 100,000 person-years: $72,581 for healthy controls, compared with $100,020 for children with mild asthma, $172,002 for moderate asthma, and $638,452 for severe asthma.

In addition, treating all-cause pneumonia was more expensive in children with asthma. For all-cause pneumonia, the researchers found that estimated costs per 100,000 person-years for mild, moderate, and severe asthma were $7.5 million, $14.6 million, and $46.8 million, respectively, compared with $1.7 million for healthy controls.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Castro-Rodriguez J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200.

Even on-time pneumococcal vaccines don’t completely protect children with asthma from developing invasive pneumococcal disease, a meta-analysis has determined.

Despite receiving pneumococcal valent 7, 10, or 13, children with asthma were still almost twice as likely to develop the disease as were children without asthma, Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, PhD, and colleagues reported in Pediatrics (2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200). None of the studies included rates for those who received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

“For the first time, this meta-analysis reveals 90% increased odds of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among [vaccinated] children with asthma,” said Dr. Castro-Rodriguez, of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, and colleagues. “If confirmed, these findings will bear clinical and public health importance,” they noted, because guidelines now recommend PPSV23 after age 2 in children with asthma only if they’re treated with prolonged high-dose oral corticosteroids.

However, because the analysis comprised only four studies, the authors cautioned that the results aren’t enough to justify changes to practice recommendations.

Asthma treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) may be driving the increased risk, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his coauthors suggested. ICS deposition in the oropharynx could boost oropharyngeal candidiasis risk by weakening the mucosal immune response, the researchers noted. And that same process may be at work with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A prior study found that children with asthma who received ICS for at least 1 month were almost four times more likely to have oropharyngeal colonization by S. pneumoniae as were those who didn’t get the drugs. Thus, a higher carrier rate of S. pneumoniae in the oropharynx, along with asthma’s impaired airway clearance, might increase the risk of pneumococcal diseases, the investigators explained.

Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and colleagues analyzed four studies with more than 4,000 cases and controls, and about 26 million person-years of follow-up.

Rates and risks of IPD in the four studies were as follows:

- Among those with IPD, 27% had asthma, with 18% of those without, an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.8.

- In a European of patients who received at least 3 doses of PCV7, IPD rates per 100,000 person-years for 5-year-olds were 11.6 for children with asthma and 7.3 for those without. For 5- to 17-year-olds with and without asthma, the rates were 2.3 and 1.6, respectively.

- In 2001, a Korean found an aOR of 2.08 for IPD in children with asthma, compared with those without. In 2010, the aOR was 3.26. No vaccine types were reported in the study.

- of IPD were 3.7 per 100,000 person-years for children with asthma, compared with 2.5 for healthy controls – an adjusted relative risk of 1.5.

The pooled estimate of the four studies revealed an aOR of 1.9 for IPD among children with asthma, compared with those without, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his team concluded.

None of the studies reported hospital admissions, mortality, length of hospital stay, intensive care admission, invasive respiratory support, or additional medication use.

One, however, did find asthma severity was significantly associated with increasing IPD treatment costs per 100,000 person-years: $72,581 for healthy controls, compared with $100,020 for children with mild asthma, $172,002 for moderate asthma, and $638,452 for severe asthma.

In addition, treating all-cause pneumonia was more expensive in children with asthma. For all-cause pneumonia, the researchers found that estimated costs per 100,000 person-years for mild, moderate, and severe asthma were $7.5 million, $14.6 million, and $46.8 million, respectively, compared with $1.7 million for healthy controls.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Castro-Rodriguez J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200.

FROM PEDIATRICS

EEG surveillance, preseizure treatment prevents TSC epilepsy, cognitive loss

BALTIMORE – Monitoring children who have tuberous sclerosis with EEG and treating them with vigabatrin (Sabril) at the first sign of preseizure abnormalities, rather than the usual practice of no surveillance and waiting until they have seizures, prevents epilepsy and cognitive decline, according to European investigators.

Early surveillance is recommended and standard practice in Europe. That’s not the case in the United States, but might be someday pending the results of the PREVENT trial (Preventing Epilepsy Using Vigabatrin In Infants With Tuberous Sclerosis Complex), an ongoing, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–funded study to confirm the European findings.

“We are trying to convince doctors” in the United States and other “countries to do this. If you are not convinced to do early treatment,” at least “do surveillance with EEG. You will diagnose epilepsy earlier, and treat earlier, and children will do much better,” said Sergiusz Jozwiak, MD, PhD, head of pediatric neurology at Warsaw Medical University and recipient of an award from the U.S. Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for his pioneering work.

Some U.S. physicians are already doing preventive treatment, but it’s hit and miss. “We are talking about monitoring children below the age of 2 years,” when seizures are associated with cognitive decline, he noted at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Jozwiak presented a follow-up at the meeting to his 2011 investigation, the first prevention study in tuberous sclerosis. Fourteen infants diagnosed within 2 months of birth underwent video-EEG monitoring every 4-6 weeks until age 2 years and were treated with vigabatrin 100-150 mg/kg per day when multifocal epileptiform discharges – a sign of impending seizures – were detected. Outcomes were compared with infants treated traditionally, with no EEG monitoring and vigabatrin only after they seized.

The children are about 9 years old now; the median IQ in the prevention arm is 94 versus 46 in the control group (P less than .03). Seven of the 14 prevention children (50%) never had a clinical seizure, while all but 1 of 25 (96%) in the control arm did (P = .001). Six of 11 prevention children (55%) versus 4 of 24 in the control group (17%), were able to come off antiepileptic drugs altogether, with no seizures (P less than .03). The work was published shortly before the epilepsy meeting.

The original 2011 report, which had similarly favorable outcomes when the children were 2 years old, led directly to the EpiStop trial, conducted at 16 mostly European centers and also reported at the meeting. Dr. Jozwiak was the senior investigator.

The design was different; all of the infants had EEG monitoring every 4 weeks until month 6, then every 6 weeks until age 12 months, then every 2 months until age 2 years. At the first detection of multifocal epileptiform discharges, infants were randomized 1:1 to vigabatrin or to the control group, with further monitoring followed by vigabatrin at the first seizure on EEG or first clinical seizure. An additional group of children – the open-label arm – also had EEG monitoring, but when to start vigabatrin was left up to the study site.

Only 50 of the original 94 children completed the trial to the full 2 years; tuberous sclerosis comorbidities drove many of them out, said lead investigator Katarzyna Kotulska-Jozwiak, MD, PhD, head of neurology at Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw.

Even so, the 25 children treated preventively in the randomized and open-label cohorts were more than three times as likely to be seizure free at 2 years (P = .01), and 74% less likely to develop drug-resistant epilepsy (P = .013). None of the prevention children developed infantile spasms versus 10 controls (40%) treated at first clinical or EEG seizure.

The incidence of neurodevelopmental delay was 34%, and autism 33%, at 24 months, and did not differ between prevention and control subjects. It’s probably because even children in the control group benefited from EEG surveillance and early treatment, the investigators said.

Historically, the rate of intellectual disability with usual treatment is around 60%, Dr. Kotulska-Jozwiak noted.

Overall, Dr. Jozwiak said that European physicians are more comfortable using vigabatrin than U.S. doctors, where the drug hasn’t been on the market as long and carries a Food and Drug Administration boxed warning of visual impairment. Its indications in the United States include infantile spasms in children 1-24 months old.

Levetiracetam (Keppra) is another option, but it’s not as effective in tuberous sclerosis. The PREVENT trial is using vigabatrin, and some U.S. doctors “are changing their minds, but it takes time,” Dr. Jozwiak said.

He noted that TSC is increasingly being diagnosed in utero, which gives a leg up on early diagnosis and prevention. The giveaways are heart tumors on ECG and cortical tubers on fetal MRI.

Dr. Jozwiak thinks the prevention approach might also help in other early seizure disorders, such as Sturge-Weber syndrome.

The work was funded by the European Commission and Polish government. Dr. Jozwiak and Dr. Kotulska-Jozwiak didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCES: Jozwiak S et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.218; Kotulska-Jozwiak K et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.121.

BALTIMORE – Monitoring children who have tuberous sclerosis with EEG and treating them with vigabatrin (Sabril) at the first sign of preseizure abnormalities, rather than the usual practice of no surveillance and waiting until they have seizures, prevents epilepsy and cognitive decline, according to European investigators.

Early surveillance is recommended and standard practice in Europe. That’s not the case in the United States, but might be someday pending the results of the PREVENT trial (Preventing Epilepsy Using Vigabatrin In Infants With Tuberous Sclerosis Complex), an ongoing, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–funded study to confirm the European findings.

“We are trying to convince doctors” in the United States and other “countries to do this. If you are not convinced to do early treatment,” at least “do surveillance with EEG. You will diagnose epilepsy earlier, and treat earlier, and children will do much better,” said Sergiusz Jozwiak, MD, PhD, head of pediatric neurology at Warsaw Medical University and recipient of an award from the U.S. Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for his pioneering work.

Some U.S. physicians are already doing preventive treatment, but it’s hit and miss. “We are talking about monitoring children below the age of 2 years,” when seizures are associated with cognitive decline, he noted at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Jozwiak presented a follow-up at the meeting to his 2011 investigation, the first prevention study in tuberous sclerosis. Fourteen infants diagnosed within 2 months of birth underwent video-EEG monitoring every 4-6 weeks until age 2 years and were treated with vigabatrin 100-150 mg/kg per day when multifocal epileptiform discharges – a sign of impending seizures – were detected. Outcomes were compared with infants treated traditionally, with no EEG monitoring and vigabatrin only after they seized.

The children are about 9 years old now; the median IQ in the prevention arm is 94 versus 46 in the control group (P less than .03). Seven of the 14 prevention children (50%) never had a clinical seizure, while all but 1 of 25 (96%) in the control arm did (P = .001). Six of 11 prevention children (55%) versus 4 of 24 in the control group (17%), were able to come off antiepileptic drugs altogether, with no seizures (P less than .03). The work was published shortly before the epilepsy meeting.

The original 2011 report, which had similarly favorable outcomes when the children were 2 years old, led directly to the EpiStop trial, conducted at 16 mostly European centers and also reported at the meeting. Dr. Jozwiak was the senior investigator.

The design was different; all of the infants had EEG monitoring every 4 weeks until month 6, then every 6 weeks until age 12 months, then every 2 months until age 2 years. At the first detection of multifocal epileptiform discharges, infants were randomized 1:1 to vigabatrin or to the control group, with further monitoring followed by vigabatrin at the first seizure on EEG or first clinical seizure. An additional group of children – the open-label arm – also had EEG monitoring, but when to start vigabatrin was left up to the study site.

Only 50 of the original 94 children completed the trial to the full 2 years; tuberous sclerosis comorbidities drove many of them out, said lead investigator Katarzyna Kotulska-Jozwiak, MD, PhD, head of neurology at Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw.

Even so, the 25 children treated preventively in the randomized and open-label cohorts were more than three times as likely to be seizure free at 2 years (P = .01), and 74% less likely to develop drug-resistant epilepsy (P = .013). None of the prevention children developed infantile spasms versus 10 controls (40%) treated at first clinical or EEG seizure.

The incidence of neurodevelopmental delay was 34%, and autism 33%, at 24 months, and did not differ between prevention and control subjects. It’s probably because even children in the control group benefited from EEG surveillance and early treatment, the investigators said.

Historically, the rate of intellectual disability with usual treatment is around 60%, Dr. Kotulska-Jozwiak noted.

Overall, Dr. Jozwiak said that European physicians are more comfortable using vigabatrin than U.S. doctors, where the drug hasn’t been on the market as long and carries a Food and Drug Administration boxed warning of visual impairment. Its indications in the United States include infantile spasms in children 1-24 months old.

Levetiracetam (Keppra) is another option, but it’s not as effective in tuberous sclerosis. The PREVENT trial is using vigabatrin, and some U.S. doctors “are changing their minds, but it takes time,” Dr. Jozwiak said.

He noted that TSC is increasingly being diagnosed in utero, which gives a leg up on early diagnosis and prevention. The giveaways are heart tumors on ECG and cortical tubers on fetal MRI.

Dr. Jozwiak thinks the prevention approach might also help in other early seizure disorders, such as Sturge-Weber syndrome.

The work was funded by the European Commission and Polish government. Dr. Jozwiak and Dr. Kotulska-Jozwiak didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCES: Jozwiak S et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.218; Kotulska-Jozwiak K et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.121.

BALTIMORE – Monitoring children who have tuberous sclerosis with EEG and treating them with vigabatrin (Sabril) at the first sign of preseizure abnormalities, rather than the usual practice of no surveillance and waiting until they have seizures, prevents epilepsy and cognitive decline, according to European investigators.

Early surveillance is recommended and standard practice in Europe. That’s not the case in the United States, but might be someday pending the results of the PREVENT trial (Preventing Epilepsy Using Vigabatrin In Infants With Tuberous Sclerosis Complex), an ongoing, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–funded study to confirm the European findings.

“We are trying to convince doctors” in the United States and other “countries to do this. If you are not convinced to do early treatment,” at least “do surveillance with EEG. You will diagnose epilepsy earlier, and treat earlier, and children will do much better,” said Sergiusz Jozwiak, MD, PhD, head of pediatric neurology at Warsaw Medical University and recipient of an award from the U.S. Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for his pioneering work.

Some U.S. physicians are already doing preventive treatment, but it’s hit and miss. “We are talking about monitoring children below the age of 2 years,” when seizures are associated with cognitive decline, he noted at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Jozwiak presented a follow-up at the meeting to his 2011 investigation, the first prevention study in tuberous sclerosis. Fourteen infants diagnosed within 2 months of birth underwent video-EEG monitoring every 4-6 weeks until age 2 years and were treated with vigabatrin 100-150 mg/kg per day when multifocal epileptiform discharges – a sign of impending seizures – were detected. Outcomes were compared with infants treated traditionally, with no EEG monitoring and vigabatrin only after they seized.

The children are about 9 years old now; the median IQ in the prevention arm is 94 versus 46 in the control group (P less than .03). Seven of the 14 prevention children (50%) never had a clinical seizure, while all but 1 of 25 (96%) in the control arm did (P = .001). Six of 11 prevention children (55%) versus 4 of 24 in the control group (17%), were able to come off antiepileptic drugs altogether, with no seizures (P less than .03). The work was published shortly before the epilepsy meeting.

The original 2011 report, which had similarly favorable outcomes when the children were 2 years old, led directly to the EpiStop trial, conducted at 16 mostly European centers and also reported at the meeting. Dr. Jozwiak was the senior investigator.

The design was different; all of the infants had EEG monitoring every 4 weeks until month 6, then every 6 weeks until age 12 months, then every 2 months until age 2 years. At the first detection of multifocal epileptiform discharges, infants were randomized 1:1 to vigabatrin or to the control group, with further monitoring followed by vigabatrin at the first seizure on EEG or first clinical seizure. An additional group of children – the open-label arm – also had EEG monitoring, but when to start vigabatrin was left up to the study site.

Only 50 of the original 94 children completed the trial to the full 2 years; tuberous sclerosis comorbidities drove many of them out, said lead investigator Katarzyna Kotulska-Jozwiak, MD, PhD, head of neurology at Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw.

Even so, the 25 children treated preventively in the randomized and open-label cohorts were more than three times as likely to be seizure free at 2 years (P = .01), and 74% less likely to develop drug-resistant epilepsy (P = .013). None of the prevention children developed infantile spasms versus 10 controls (40%) treated at first clinical or EEG seizure.

The incidence of neurodevelopmental delay was 34%, and autism 33%, at 24 months, and did not differ between prevention and control subjects. It’s probably because even children in the control group benefited from EEG surveillance and early treatment, the investigators said.

Historically, the rate of intellectual disability with usual treatment is around 60%, Dr. Kotulska-Jozwiak noted.

Overall, Dr. Jozwiak said that European physicians are more comfortable using vigabatrin than U.S. doctors, where the drug hasn’t been on the market as long and carries a Food and Drug Administration boxed warning of visual impairment. Its indications in the United States include infantile spasms in children 1-24 months old.

Levetiracetam (Keppra) is another option, but it’s not as effective in tuberous sclerosis. The PREVENT trial is using vigabatrin, and some U.S. doctors “are changing their minds, but it takes time,” Dr. Jozwiak said.

He noted that TSC is increasingly being diagnosed in utero, which gives a leg up on early diagnosis and prevention. The giveaways are heart tumors on ECG and cortical tubers on fetal MRI.

Dr. Jozwiak thinks the prevention approach might also help in other early seizure disorders, such as Sturge-Weber syndrome.

The work was funded by the European Commission and Polish government. Dr. Jozwiak and Dr. Kotulska-Jozwiak didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCES: Jozwiak S et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.218; Kotulska-Jozwiak K et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.121.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Experts call to revise the Uniform Determination of Death Act

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

FDA targets flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes, but says it is not a ‘ban’

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

Down syndrome arthritis: Distinct from JIA and missed in the clinic

ATLANTA – Pediatric Down syndrome arthritis is more aggressive and severe than juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but it’s underrecognized and undertreated, according to reports at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The vast majority of parents don’t know their kids are at risk for arthritis,” and a lot of doctors don’t realize it, either. Meanwhile, children show up in the clinic a year or more into the process with irreversible joint damage, said pediatric rheumatologist Jordan Jones, DO, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and the lead investigator on a review of 36 children with Down syndrome (DS) in the national Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry.

One solution is to add routine musculoskeletal exams to American Academy of Pediatrics DS guidelines, something Dr. Jones said he and his colleagues are hoping to do.

Part of the problem is that children with DS have a hard time articulating and localizing pain, and it’s easy to attribute functional issues to DS itself. Charlene Foley, MD, PhD, from the National Centre for Paediatric Rheumatology in Dublin, said she’s seen “loads of cases” in which parents were told that their children were acting up, probably because of the DS, when they didn’t want to walk down stairs anymore or hold their parent’s hand.

She was the lead investigator on an Irish program that screened 503 DS children, about one-third of the country’s pediatric DS population, for arthritis; 33 cases were identified, including 18 new ones. Most of the children had polyarticular, rheumatoid factor–negative arthritis, and all of them were antinuclear antibody negative.

A key take-home from the work is that DS arthritis preferentially attacks the hands and wrists and was present exclusively in the hands and wrists of about one-third of the Irish cohort. “So, if you only have a second to examine a child or you can’t get them to sit still, just go straight for the hands, and have a low threshold for imaging,” Dr. Foley said.

DS arthritis is often considered a subtype of JIA, but findings from the studies call that into question and suggest the need for novel therapeutic targets, the investigators said.

The Irish team found that 42% of their subjects (14 of 33) had joint erosions, far more than the 14% of JIA children (3 of 21) who served as controls, and Dr. Foley and colleagues didn’t think that was solely because of delayed diagnosis. Also, at about 20 cases per 1,000, they estimated that arthritis was far more prevalent in DS than was JIA in the general pediatrics population.

Disease onset was at a mean of 7.1 years in Dr. Jones’ CARRA registry review, and mean delay to diagnosis was 11.5 months. The 36 children presented with an average of four affected joints. Only 22% (8 of 36) had elevated inflammatory markers; just one-third were positive for antinuclear antibody, and 17% for human leukocyte antigen B27. It means that “these kids can present with normal labs, even with very aggressive disease. The threshold of concern for arthritis has to be very high when you evaluate these children,” Dr. Jones said.

Treatment was initiated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in two-thirds of the registry children, often with a concomitant biologic, most commonly etanercept. Over half had at least one switch during a mean follow-up of 4.5 years; methotrexate was a leading culprit, frequently discontinued because of nausea and other problems, and biologics were changed for lack of effect. Active joint counts and physician assessments improved, but there were no significant changes in limited joint counts and health assessments.

In short, “the current therapies for JIA appear to be poorly tolerated, more toxic, and less effective in patients with Down syndrome. These kids don’t respond the same. They have a very high disease burden despite being treated aggressively,” Dr. Jones said.

That finding adds additional weight to the idea that DS arthritis is a distinct disease entity, with unique therapeutic targets. “Down syndrome has a lot of immunologic issues associated with it; maybe that’s it. I think in the next few years, we will be able to show that this is a different disease,” Dr. Jones said.

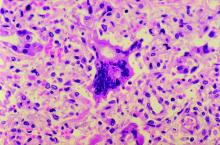

There was a boost in that direction from benchwork, also led and presented by Dr. Foley, that found significant immunologic, histologic, and genetic differences between JIA and DS arthritis, including lower CD19- and CD20-positive B-cell counts in DS arthritis and higher interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor–alpha production, greater synovial lining hyperplasia, and different minor allele frequencies.

There was no industry funding for the studies, and the investigators didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCES: Jones J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2722; Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1817; and Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 781

ATLANTA – Pediatric Down syndrome arthritis is more aggressive and severe than juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but it’s underrecognized and undertreated, according to reports at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The vast majority of parents don’t know their kids are at risk for arthritis,” and a lot of doctors don’t realize it, either. Meanwhile, children show up in the clinic a year or more into the process with irreversible joint damage, said pediatric rheumatologist Jordan Jones, DO, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and the lead investigator on a review of 36 children with Down syndrome (DS) in the national Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry.

One solution is to add routine musculoskeletal exams to American Academy of Pediatrics DS guidelines, something Dr. Jones said he and his colleagues are hoping to do.

Part of the problem is that children with DS have a hard time articulating and localizing pain, and it’s easy to attribute functional issues to DS itself. Charlene Foley, MD, PhD, from the National Centre for Paediatric Rheumatology in Dublin, said she’s seen “loads of cases” in which parents were told that their children were acting up, probably because of the DS, when they didn’t want to walk down stairs anymore or hold their parent’s hand.

She was the lead investigator on an Irish program that screened 503 DS children, about one-third of the country’s pediatric DS population, for arthritis; 33 cases were identified, including 18 new ones. Most of the children had polyarticular, rheumatoid factor–negative arthritis, and all of them were antinuclear antibody negative.

A key take-home from the work is that DS arthritis preferentially attacks the hands and wrists and was present exclusively in the hands and wrists of about one-third of the Irish cohort. “So, if you only have a second to examine a child or you can’t get them to sit still, just go straight for the hands, and have a low threshold for imaging,” Dr. Foley said.

DS arthritis is often considered a subtype of JIA, but findings from the studies call that into question and suggest the need for novel therapeutic targets, the investigators said.

The Irish team found that 42% of their subjects (14 of 33) had joint erosions, far more than the 14% of JIA children (3 of 21) who served as controls, and Dr. Foley and colleagues didn’t think that was solely because of delayed diagnosis. Also, at about 20 cases per 1,000, they estimated that arthritis was far more prevalent in DS than was JIA in the general pediatrics population.

Disease onset was at a mean of 7.1 years in Dr. Jones’ CARRA registry review, and mean delay to diagnosis was 11.5 months. The 36 children presented with an average of four affected joints. Only 22% (8 of 36) had elevated inflammatory markers; just one-third were positive for antinuclear antibody, and 17% for human leukocyte antigen B27. It means that “these kids can present with normal labs, even with very aggressive disease. The threshold of concern for arthritis has to be very high when you evaluate these children,” Dr. Jones said.

Treatment was initiated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in two-thirds of the registry children, often with a concomitant biologic, most commonly etanercept. Over half had at least one switch during a mean follow-up of 4.5 years; methotrexate was a leading culprit, frequently discontinued because of nausea and other problems, and biologics were changed for lack of effect. Active joint counts and physician assessments improved, but there were no significant changes in limited joint counts and health assessments.

In short, “the current therapies for JIA appear to be poorly tolerated, more toxic, and less effective in patients with Down syndrome. These kids don’t respond the same. They have a very high disease burden despite being treated aggressively,” Dr. Jones said.

That finding adds additional weight to the idea that DS arthritis is a distinct disease entity, with unique therapeutic targets. “Down syndrome has a lot of immunologic issues associated with it; maybe that’s it. I think in the next few years, we will be able to show that this is a different disease,” Dr. Jones said.

There was a boost in that direction from benchwork, also led and presented by Dr. Foley, that found significant immunologic, histologic, and genetic differences between JIA and DS arthritis, including lower CD19- and CD20-positive B-cell counts in DS arthritis and higher interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor–alpha production, greater synovial lining hyperplasia, and different minor allele frequencies.

There was no industry funding for the studies, and the investigators didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCES: Jones J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2722; Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1817; and Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 781

ATLANTA – Pediatric Down syndrome arthritis is more aggressive and severe than juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but it’s underrecognized and undertreated, according to reports at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The vast majority of parents don’t know their kids are at risk for arthritis,” and a lot of doctors don’t realize it, either. Meanwhile, children show up in the clinic a year or more into the process with irreversible joint damage, said pediatric rheumatologist Jordan Jones, DO, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and the lead investigator on a review of 36 children with Down syndrome (DS) in the national Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry.

One solution is to add routine musculoskeletal exams to American Academy of Pediatrics DS guidelines, something Dr. Jones said he and his colleagues are hoping to do.