User login

Cases of pediatric invasive melanoma have declined since 2002, study finds

AUSTIN – The compared with females. The risk of death is also significantly increased in black patients, other nonwhite patients, and in cases where surgery was not performed.

Those are key findings from a study that set out to investigate the incidence of pediatric melanoma over the last 2 decades and factors influencing survival. At the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, one of the study authors, Spandana Maddukuri, said that pediatric melanoma is the most common skin cancer in the pediatric population, accounting for 1-3% of all pediatric malignancies and 1%-4% of all cases of melanoma (Pediatr Surg. 2013;48[11]:2207-13).

“Nonmodifiable risk factors are similar to those in adult melanoma and include fair skin, light hair and eye color, increased number of congenital nevi, and family history of melanoma,” said Ms. Maddukuri, a third-year student at New Jersey Medical School, Newark. “Environmental risk factors are similar to those in adult melanoma and include exposure to UV radiation. About 60% of children do not meet standard ABCDE [asymmetrical, border, color, diameter, evolving] diagnosis criteria, which often leads to delayed diagnosis.”

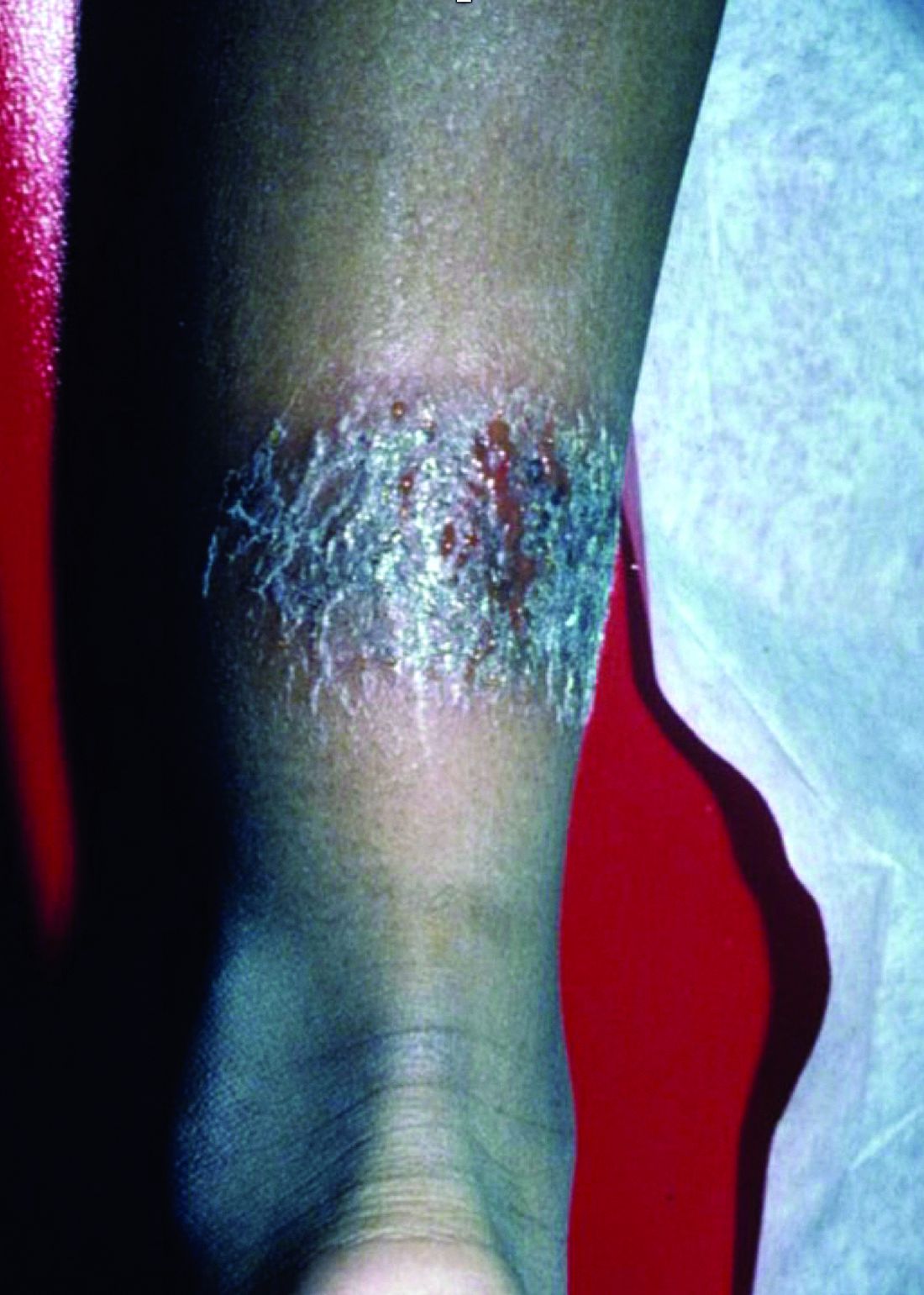

Some of the characteristics that are more commonly found in pediatric lesions include amelanosis, bleeding, uniform color, and variable diameter (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013; 68[6]:913-25).

Ms. Maddukuri and colleagues queried the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database for cases of malignant melanoma that were diagnosed in individuals aged younger than 20 years between 2002 and 2015. After excluding all cases of adult melanoma and all cases of in situ melanoma, they included 1,620 patients in the final analysis and divided them into five age groups: less than 1 year, 1-4 years, 5-9 years, 10-14 years, and 15-19 years. They calculated the overall incidence rate per 100,000 population of pediatric melanoma based on data from the 2000 U.S. Census. Age-, sex-, and race-specific incidence rates were also calculated. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses to investigate disease-specific survival and risk factors.

With each successive age group, the investigators observed that incidence rate was significantly higher than that of the previous age group (P less than .005). “However, the most striking increase in incidence occurs between the age group of 10-14 and 15-19,” she said. “Sex also influenced incidence rates. Males had an incidence rate of 0.396 per 100,000 population while females had an incidence rate of 0.579 per 100,000 population.”

Race also influenced incidence rates. White patients had the highest incidence rate of 0.605 per 100,000 population, while blacks had the lowest incident rate at 0.042 per 100,000 population. American Indian and Alaska Native patients had incidence rates of 0.046 per 100,000 population, while Asians and Pacific Islanders had an incidence rate of 0.127 per 100,000 population.

The researchers found that increased survival was associated with white race, female sex, treatment with surgical intervention, and age older than 5 years. No differences in survival were observed regarding the primary anatomic location or extent of disease. The hazard ratio of death from invasive melanoma was significantly increased in males (HR, 2.34), black patients (HR, 3.96), other nonwhite patients (HR, 3.64), and in cases where surgery was not performed (HR, 6.04).

“It is surprising that, although incidence is significantly higher in white patients and females, compared to black patients and males, respectively, the risk of dying from melanoma is much higher in black patients and males,” Ms. Maddukuri said in an interview at the meeting. “Overall, the dermatologic community is on the right track in screening and diagnosing pediatric melanoma, as seen by the decreased incidence over the last 2 decades. However, increased awareness regarding pediatric melanoma is still encouraged. I believe we were able to identify certain populations that need more attention in terms of screening, diagnosis, and treatment, which are patients less than 5 years old, black and other nonwhite patients, and males.”

She acknowledged certain shortcomings of the study, including a limited clinical history of the patient population because of the nature of the database. She also said that further studies are required to investigate the contributing factors to decreasing incidence and to evaluate the relationship of the favorable prognostic factors to increased survival. The researchers are currently working on correlating incidence rates with UV exposure and geographical location.

They reported having no financial disclosures.

AUSTIN – The compared with females. The risk of death is also significantly increased in black patients, other nonwhite patients, and in cases where surgery was not performed.

Those are key findings from a study that set out to investigate the incidence of pediatric melanoma over the last 2 decades and factors influencing survival. At the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, one of the study authors, Spandana Maddukuri, said that pediatric melanoma is the most common skin cancer in the pediatric population, accounting for 1-3% of all pediatric malignancies and 1%-4% of all cases of melanoma (Pediatr Surg. 2013;48[11]:2207-13).

“Nonmodifiable risk factors are similar to those in adult melanoma and include fair skin, light hair and eye color, increased number of congenital nevi, and family history of melanoma,” said Ms. Maddukuri, a third-year student at New Jersey Medical School, Newark. “Environmental risk factors are similar to those in adult melanoma and include exposure to UV radiation. About 60% of children do not meet standard ABCDE [asymmetrical, border, color, diameter, evolving] diagnosis criteria, which often leads to delayed diagnosis.”

Some of the characteristics that are more commonly found in pediatric lesions include amelanosis, bleeding, uniform color, and variable diameter (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013; 68[6]:913-25).

Ms. Maddukuri and colleagues queried the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database for cases of malignant melanoma that were diagnosed in individuals aged younger than 20 years between 2002 and 2015. After excluding all cases of adult melanoma and all cases of in situ melanoma, they included 1,620 patients in the final analysis and divided them into five age groups: less than 1 year, 1-4 years, 5-9 years, 10-14 years, and 15-19 years. They calculated the overall incidence rate per 100,000 population of pediatric melanoma based on data from the 2000 U.S. Census. Age-, sex-, and race-specific incidence rates were also calculated. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses to investigate disease-specific survival and risk factors.

With each successive age group, the investigators observed that incidence rate was significantly higher than that of the previous age group (P less than .005). “However, the most striking increase in incidence occurs between the age group of 10-14 and 15-19,” she said. “Sex also influenced incidence rates. Males had an incidence rate of 0.396 per 100,000 population while females had an incidence rate of 0.579 per 100,000 population.”

Race also influenced incidence rates. White patients had the highest incidence rate of 0.605 per 100,000 population, while blacks had the lowest incident rate at 0.042 per 100,000 population. American Indian and Alaska Native patients had incidence rates of 0.046 per 100,000 population, while Asians and Pacific Islanders had an incidence rate of 0.127 per 100,000 population.

The researchers found that increased survival was associated with white race, female sex, treatment with surgical intervention, and age older than 5 years. No differences in survival were observed regarding the primary anatomic location or extent of disease. The hazard ratio of death from invasive melanoma was significantly increased in males (HR, 2.34), black patients (HR, 3.96), other nonwhite patients (HR, 3.64), and in cases where surgery was not performed (HR, 6.04).

“It is surprising that, although incidence is significantly higher in white patients and females, compared to black patients and males, respectively, the risk of dying from melanoma is much higher in black patients and males,” Ms. Maddukuri said in an interview at the meeting. “Overall, the dermatologic community is on the right track in screening and diagnosing pediatric melanoma, as seen by the decreased incidence over the last 2 decades. However, increased awareness regarding pediatric melanoma is still encouraged. I believe we were able to identify certain populations that need more attention in terms of screening, diagnosis, and treatment, which are patients less than 5 years old, black and other nonwhite patients, and males.”

She acknowledged certain shortcomings of the study, including a limited clinical history of the patient population because of the nature of the database. She also said that further studies are required to investigate the contributing factors to decreasing incidence and to evaluate the relationship of the favorable prognostic factors to increased survival. The researchers are currently working on correlating incidence rates with UV exposure and geographical location.

They reported having no financial disclosures.

AUSTIN – The compared with females. The risk of death is also significantly increased in black patients, other nonwhite patients, and in cases where surgery was not performed.

Those are key findings from a study that set out to investigate the incidence of pediatric melanoma over the last 2 decades and factors influencing survival. At the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, one of the study authors, Spandana Maddukuri, said that pediatric melanoma is the most common skin cancer in the pediatric population, accounting for 1-3% of all pediatric malignancies and 1%-4% of all cases of melanoma (Pediatr Surg. 2013;48[11]:2207-13).

“Nonmodifiable risk factors are similar to those in adult melanoma and include fair skin, light hair and eye color, increased number of congenital nevi, and family history of melanoma,” said Ms. Maddukuri, a third-year student at New Jersey Medical School, Newark. “Environmental risk factors are similar to those in adult melanoma and include exposure to UV radiation. About 60% of children do not meet standard ABCDE [asymmetrical, border, color, diameter, evolving] diagnosis criteria, which often leads to delayed diagnosis.”

Some of the characteristics that are more commonly found in pediatric lesions include amelanosis, bleeding, uniform color, and variable diameter (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013; 68[6]:913-25).

Ms. Maddukuri and colleagues queried the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database for cases of malignant melanoma that were diagnosed in individuals aged younger than 20 years between 2002 and 2015. After excluding all cases of adult melanoma and all cases of in situ melanoma, they included 1,620 patients in the final analysis and divided them into five age groups: less than 1 year, 1-4 years, 5-9 years, 10-14 years, and 15-19 years. They calculated the overall incidence rate per 100,000 population of pediatric melanoma based on data from the 2000 U.S. Census. Age-, sex-, and race-specific incidence rates were also calculated. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses to investigate disease-specific survival and risk factors.

With each successive age group, the investigators observed that incidence rate was significantly higher than that of the previous age group (P less than .005). “However, the most striking increase in incidence occurs between the age group of 10-14 and 15-19,” she said. “Sex also influenced incidence rates. Males had an incidence rate of 0.396 per 100,000 population while females had an incidence rate of 0.579 per 100,000 population.”

Race also influenced incidence rates. White patients had the highest incidence rate of 0.605 per 100,000 population, while blacks had the lowest incident rate at 0.042 per 100,000 population. American Indian and Alaska Native patients had incidence rates of 0.046 per 100,000 population, while Asians and Pacific Islanders had an incidence rate of 0.127 per 100,000 population.

The researchers found that increased survival was associated with white race, female sex, treatment with surgical intervention, and age older than 5 years. No differences in survival were observed regarding the primary anatomic location or extent of disease. The hazard ratio of death from invasive melanoma was significantly increased in males (HR, 2.34), black patients (HR, 3.96), other nonwhite patients (HR, 3.64), and in cases where surgery was not performed (HR, 6.04).

“It is surprising that, although incidence is significantly higher in white patients and females, compared to black patients and males, respectively, the risk of dying from melanoma is much higher in black patients and males,” Ms. Maddukuri said in an interview at the meeting. “Overall, the dermatologic community is on the right track in screening and diagnosing pediatric melanoma, as seen by the decreased incidence over the last 2 decades. However, increased awareness regarding pediatric melanoma is still encouraged. I believe we were able to identify certain populations that need more attention in terms of screening, diagnosis, and treatment, which are patients less than 5 years old, black and other nonwhite patients, and males.”

She acknowledged certain shortcomings of the study, including a limited clinical history of the patient population because of the nature of the database. She also said that further studies are required to investigate the contributing factors to decreasing incidence and to evaluate the relationship of the favorable prognostic factors to increased survival. The researchers are currently working on correlating incidence rates with UV exposure and geographical location.

They reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SPD 2019

Adjuvanted flu vaccine performs better than others in young children

according to an industry-funded synthesis of six studies.

The vaccine “offers significant advances over conventional inactivated influenza vaccines and presents an acceptable safety profile in children 6 months through 5 years of age,” Sanjay S. Patel, PhD, of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass., and associates wrote in the analysis, published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases. “The noteworthy increases in antibody responses and decreases in influenza cases following vaccination suggest an alternative for use in a population that is heavily impacted by influenza disease.”

Children are, of course, vulnerable to flu. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 186 children died of flu during the landmark 2017-2018 flu season. That’s the highest number of pediatric flu deaths since they became a notifiable condition in 2004 (exclusive of the 2009 pandemic, when 358 pediatric deaths were reported from April 15, 2009, to October 2, 2010).The CDC said the vaccine during that flu season had an overall effectiveness level of 40%. According to research of others, however, flu vaccines are less effective in younger children than in adolescents and adults (Vaccine. 2014;32[31]:3886-94; Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004879.pub3).

Fluad – a MF59-adjuvanted inactivated trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine – is used in adults over 65 in the United States and 29 other countries, and it is approved for children aged 6 months through 23 months in Canada.

Dr. Patel and associates examined the results of six studies – one phase 1b, three phase 2, and two phase 3 – that tested Fluad with or without other vaccines in 11,942 children aged 6 months to 5 years. The studies, mostly multicenter, were conducted in various countries, mainly in Europe and South and Central America, from 2006 to 2012.

In general, children in the intervention groups in the studies received two doses of the Fluad vaccine 4 weeks apart: two 0.25-mL doses for children aged 6-35 months and two 0.5-mL doses for those aged 3 years or older. In most of the studies, parallel control groups received nonadjuvanted trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccines.

Most participants (93%-94%) completed the studies. Solicited adverse effects were common in all groups (72% in the Fluad group vs. 67% who received IIV3 vaccines), and generally mild to moderate and resolved in 1-3 days. Unsolicited adverse effects were similar (55% and 62%, respectively) in the two flu vaccine groups. The authors wrote that “these data reflect a safety profile consistent with other licensed inactivated influenza vaccines administered to children.”

As for results, Dr. Patel and colleagues said, “HI [hemagglutination inhibition] antibody responses to both homologous and heterologous influenza strains are higher following vaccination with aIIV3, and this increase in immunogenicity is observed across all age subgroups in children aged 6 months through 5 years, and most profound in the children 6 to 36 months.”

For example, in one of the phase 3 studies when the influenza viruses were antigenically matched (homologous) for A/H1N1 among the children aged 6-35 months seroconversion was 100% for allV3 (Fluad) and 38% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4 (trivalent/quadrivalent flu vaccines); among children aged 3-5 years seroconversion was 100% for allV3 and 82% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4. For AH3N2 homologous among children aged 6-35 months, seroconversion was 98% for allV3 and 44% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4. For the B strain homologous among children aged 6-35 months, seroconversion was 88% for allV3 and 19% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4; among children aged 3-5 years seroconversion for B was 99% for allV3 and 59% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4.

In the same study when the influenza viruses were antigenically mismatched (heterologous) for A/H1N1 among children of all ages 6 months to greater than 72 months, seroconversion was 96% for allV3 (Fluad) and 44% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4; for A/H3N2 it was 98% for allV3 and 49% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4, and for the B strain it was 10% for allV3 and 3% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4.

They added that “in addition, aIIV3 had the fastest onset of immunogenicity and longest persistence of immune response, which has implications for the real-world clinical setting, where the influenza season might start earlier than expected or last longer, and second (follow-up) vaccinations may be missed.”

Dr. Patel and associates said the MF59 adjuvant in Fluad “recruits immune cells (primarily monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) at the site of injection and differentiates them into antigen-presenting cells. With an MF59-adjuvanted vaccine, more antigen is transported from the injection site to the draining lymph node, wherein MF59 leads to T-cell activation and an increased B-cell expansion and a greater number and diversity of antibodies.”

According to goodrx.com, one syringe of Fluad 0.5 mL costs $45-$74 with coupon. The same dose of Fluzone Quadrivalent, a flu vaccine recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in young children aged 6-35 months, costs $31 with coupon.

The study was funded by Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics and Seqirus (formerly part of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics). The study authors disclosed employment by Novartis and Seqirus.

SOURCE: Patel SS et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.05.009.

according to an industry-funded synthesis of six studies.

The vaccine “offers significant advances over conventional inactivated influenza vaccines and presents an acceptable safety profile in children 6 months through 5 years of age,” Sanjay S. Patel, PhD, of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass., and associates wrote in the analysis, published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases. “The noteworthy increases in antibody responses and decreases in influenza cases following vaccination suggest an alternative for use in a population that is heavily impacted by influenza disease.”

Children are, of course, vulnerable to flu. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 186 children died of flu during the landmark 2017-2018 flu season. That’s the highest number of pediatric flu deaths since they became a notifiable condition in 2004 (exclusive of the 2009 pandemic, when 358 pediatric deaths were reported from April 15, 2009, to October 2, 2010).The CDC said the vaccine during that flu season had an overall effectiveness level of 40%. According to research of others, however, flu vaccines are less effective in younger children than in adolescents and adults (Vaccine. 2014;32[31]:3886-94; Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004879.pub3).

Fluad – a MF59-adjuvanted inactivated trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine – is used in adults over 65 in the United States and 29 other countries, and it is approved for children aged 6 months through 23 months in Canada.

Dr. Patel and associates examined the results of six studies – one phase 1b, three phase 2, and two phase 3 – that tested Fluad with or without other vaccines in 11,942 children aged 6 months to 5 years. The studies, mostly multicenter, were conducted in various countries, mainly in Europe and South and Central America, from 2006 to 2012.

In general, children in the intervention groups in the studies received two doses of the Fluad vaccine 4 weeks apart: two 0.25-mL doses for children aged 6-35 months and two 0.5-mL doses for those aged 3 years or older. In most of the studies, parallel control groups received nonadjuvanted trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccines.

Most participants (93%-94%) completed the studies. Solicited adverse effects were common in all groups (72% in the Fluad group vs. 67% who received IIV3 vaccines), and generally mild to moderate and resolved in 1-3 days. Unsolicited adverse effects were similar (55% and 62%, respectively) in the two flu vaccine groups. The authors wrote that “these data reflect a safety profile consistent with other licensed inactivated influenza vaccines administered to children.”

As for results, Dr. Patel and colleagues said, “HI [hemagglutination inhibition] antibody responses to both homologous and heterologous influenza strains are higher following vaccination with aIIV3, and this increase in immunogenicity is observed across all age subgroups in children aged 6 months through 5 years, and most profound in the children 6 to 36 months.”

For example, in one of the phase 3 studies when the influenza viruses were antigenically matched (homologous) for A/H1N1 among the children aged 6-35 months seroconversion was 100% for allV3 (Fluad) and 38% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4 (trivalent/quadrivalent flu vaccines); among children aged 3-5 years seroconversion was 100% for allV3 and 82% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4. For AH3N2 homologous among children aged 6-35 months, seroconversion was 98% for allV3 and 44% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4. For the B strain homologous among children aged 6-35 months, seroconversion was 88% for allV3 and 19% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4; among children aged 3-5 years seroconversion for B was 99% for allV3 and 59% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4.

In the same study when the influenza viruses were antigenically mismatched (heterologous) for A/H1N1 among children of all ages 6 months to greater than 72 months, seroconversion was 96% for allV3 (Fluad) and 44% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4; for A/H3N2 it was 98% for allV3 and 49% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4, and for the B strain it was 10% for allV3 and 3% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4.

They added that “in addition, aIIV3 had the fastest onset of immunogenicity and longest persistence of immune response, which has implications for the real-world clinical setting, where the influenza season might start earlier than expected or last longer, and second (follow-up) vaccinations may be missed.”

Dr. Patel and associates said the MF59 adjuvant in Fluad “recruits immune cells (primarily monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) at the site of injection and differentiates them into antigen-presenting cells. With an MF59-adjuvanted vaccine, more antigen is transported from the injection site to the draining lymph node, wherein MF59 leads to T-cell activation and an increased B-cell expansion and a greater number and diversity of antibodies.”

According to goodrx.com, one syringe of Fluad 0.5 mL costs $45-$74 with coupon. The same dose of Fluzone Quadrivalent, a flu vaccine recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in young children aged 6-35 months, costs $31 with coupon.

The study was funded by Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics and Seqirus (formerly part of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics). The study authors disclosed employment by Novartis and Seqirus.

SOURCE: Patel SS et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.05.009.

according to an industry-funded synthesis of six studies.

The vaccine “offers significant advances over conventional inactivated influenza vaccines and presents an acceptable safety profile in children 6 months through 5 years of age,” Sanjay S. Patel, PhD, of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass., and associates wrote in the analysis, published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases. “The noteworthy increases in antibody responses and decreases in influenza cases following vaccination suggest an alternative for use in a population that is heavily impacted by influenza disease.”

Children are, of course, vulnerable to flu. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 186 children died of flu during the landmark 2017-2018 flu season. That’s the highest number of pediatric flu deaths since they became a notifiable condition in 2004 (exclusive of the 2009 pandemic, when 358 pediatric deaths were reported from April 15, 2009, to October 2, 2010).The CDC said the vaccine during that flu season had an overall effectiveness level of 40%. According to research of others, however, flu vaccines are less effective in younger children than in adolescents and adults (Vaccine. 2014;32[31]:3886-94; Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004879.pub3).

Fluad – a MF59-adjuvanted inactivated trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine – is used in adults over 65 in the United States and 29 other countries, and it is approved for children aged 6 months through 23 months in Canada.

Dr. Patel and associates examined the results of six studies – one phase 1b, three phase 2, and two phase 3 – that tested Fluad with or without other vaccines in 11,942 children aged 6 months to 5 years. The studies, mostly multicenter, were conducted in various countries, mainly in Europe and South and Central America, from 2006 to 2012.

In general, children in the intervention groups in the studies received two doses of the Fluad vaccine 4 weeks apart: two 0.25-mL doses for children aged 6-35 months and two 0.5-mL doses for those aged 3 years or older. In most of the studies, parallel control groups received nonadjuvanted trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccines.

Most participants (93%-94%) completed the studies. Solicited adverse effects were common in all groups (72% in the Fluad group vs. 67% who received IIV3 vaccines), and generally mild to moderate and resolved in 1-3 days. Unsolicited adverse effects were similar (55% and 62%, respectively) in the two flu vaccine groups. The authors wrote that “these data reflect a safety profile consistent with other licensed inactivated influenza vaccines administered to children.”

As for results, Dr. Patel and colleagues said, “HI [hemagglutination inhibition] antibody responses to both homologous and heterologous influenza strains are higher following vaccination with aIIV3, and this increase in immunogenicity is observed across all age subgroups in children aged 6 months through 5 years, and most profound in the children 6 to 36 months.”

For example, in one of the phase 3 studies when the influenza viruses were antigenically matched (homologous) for A/H1N1 among the children aged 6-35 months seroconversion was 100% for allV3 (Fluad) and 38% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4 (trivalent/quadrivalent flu vaccines); among children aged 3-5 years seroconversion was 100% for allV3 and 82% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4. For AH3N2 homologous among children aged 6-35 months, seroconversion was 98% for allV3 and 44% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4. For the B strain homologous among children aged 6-35 months, seroconversion was 88% for allV3 and 19% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4; among children aged 3-5 years seroconversion for B was 99% for allV3 and 59% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4.

In the same study when the influenza viruses were antigenically mismatched (heterologous) for A/H1N1 among children of all ages 6 months to greater than 72 months, seroconversion was 96% for allV3 (Fluad) and 44% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4; for A/H3N2 it was 98% for allV3 and 49% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4, and for the B strain it was 10% for allV3 and 3% for IIV3-1/IIV3-4.

They added that “in addition, aIIV3 had the fastest onset of immunogenicity and longest persistence of immune response, which has implications for the real-world clinical setting, where the influenza season might start earlier than expected or last longer, and second (follow-up) vaccinations may be missed.”

Dr. Patel and associates said the MF59 adjuvant in Fluad “recruits immune cells (primarily monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) at the site of injection and differentiates them into antigen-presenting cells. With an MF59-adjuvanted vaccine, more antigen is transported from the injection site to the draining lymph node, wherein MF59 leads to T-cell activation and an increased B-cell expansion and a greater number and diversity of antibodies.”

According to goodrx.com, one syringe of Fluad 0.5 mL costs $45-$74 with coupon. The same dose of Fluzone Quadrivalent, a flu vaccine recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in young children aged 6-35 months, costs $31 with coupon.

The study was funded by Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics and Seqirus (formerly part of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics). The study authors disclosed employment by Novartis and Seqirus.

SOURCE: Patel SS et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.05.009.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Adjuvanted influenza vaccine appears safe for at-risk children

according to a study in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Sanjay S. Patel, PhD, of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis on an integrated dataset that drew from six randomized clinical trials comparing aIIV3 with nonadjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3). The dataset comprised 10,794 patients aged 6 months through 5 years, of whom 373 (3%) were deemed at risk of influenza complications after review of their medical history for conditions such as heart disease, asthma, and endocrine disorders.

The rates of solicited adverse events (such as erythema, diarrhea, fever, and localized swelling) were 74% in the aIIV3 group and 73% in the IIV3 group. The rates for any unsolicited adverse events (such as upper respiratory tract infection) for aIIV3 and IIV3 were 54% and 59%, respectively (Int J Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.04.023).

One of the six studies included in the dataset randomized 2,655 children for immunogenicity analyses, of whom 103 (4%) were deemed at risk. Hemagglutination inhibition assay geometric mean titers against homologous A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strains 21 days after the second of two doses of vaccines were two to three times higher in the aIIV3 than in the IIV3 group, which suggests that aIIV3 is more immunogenic than IIV3. As the investigators noted, this is likely because the adjuvanted vaccine induces a greater magnitude of immune response to the vaccine, something already lower in children than in adults, as well as more breadth of response, meaning the response goes beyond strains included in the vaccines.

The small number of at-risk children in the study poses a limitation on its findings. Dr. Patel and associates said that, regardless, the results of immunogenicity analyses were strong. “Overall, this analysis indicates that aIIV3 has a similar safety profile in young children with underlying medical conditions, consistent with other licensed inactivated influenza vaccines.”

Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics originally funded the study, but was later acquired by CSL Group and now operates as Seqirus, which continued funding for the study. The authors were employees of one or the other of these companies.

according to a study in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Sanjay S. Patel, PhD, of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis on an integrated dataset that drew from six randomized clinical trials comparing aIIV3 with nonadjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3). The dataset comprised 10,794 patients aged 6 months through 5 years, of whom 373 (3%) were deemed at risk of influenza complications after review of their medical history for conditions such as heart disease, asthma, and endocrine disorders.

The rates of solicited adverse events (such as erythema, diarrhea, fever, and localized swelling) were 74% in the aIIV3 group and 73% in the IIV3 group. The rates for any unsolicited adverse events (such as upper respiratory tract infection) for aIIV3 and IIV3 were 54% and 59%, respectively (Int J Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.04.023).

One of the six studies included in the dataset randomized 2,655 children for immunogenicity analyses, of whom 103 (4%) were deemed at risk. Hemagglutination inhibition assay geometric mean titers against homologous A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strains 21 days after the second of two doses of vaccines were two to three times higher in the aIIV3 than in the IIV3 group, which suggests that aIIV3 is more immunogenic than IIV3. As the investigators noted, this is likely because the adjuvanted vaccine induces a greater magnitude of immune response to the vaccine, something already lower in children than in adults, as well as more breadth of response, meaning the response goes beyond strains included in the vaccines.

The small number of at-risk children in the study poses a limitation on its findings. Dr. Patel and associates said that, regardless, the results of immunogenicity analyses were strong. “Overall, this analysis indicates that aIIV3 has a similar safety profile in young children with underlying medical conditions, consistent with other licensed inactivated influenza vaccines.”

Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics originally funded the study, but was later acquired by CSL Group and now operates as Seqirus, which continued funding for the study. The authors were employees of one or the other of these companies.

according to a study in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Sanjay S. Patel, PhD, of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis on an integrated dataset that drew from six randomized clinical trials comparing aIIV3 with nonadjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3). The dataset comprised 10,794 patients aged 6 months through 5 years, of whom 373 (3%) were deemed at risk of influenza complications after review of their medical history for conditions such as heart disease, asthma, and endocrine disorders.

The rates of solicited adverse events (such as erythema, diarrhea, fever, and localized swelling) were 74% in the aIIV3 group and 73% in the IIV3 group. The rates for any unsolicited adverse events (such as upper respiratory tract infection) for aIIV3 and IIV3 were 54% and 59%, respectively (Int J Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.04.023).

One of the six studies included in the dataset randomized 2,655 children for immunogenicity analyses, of whom 103 (4%) were deemed at risk. Hemagglutination inhibition assay geometric mean titers against homologous A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strains 21 days after the second of two doses of vaccines were two to three times higher in the aIIV3 than in the IIV3 group, which suggests that aIIV3 is more immunogenic than IIV3. As the investigators noted, this is likely because the adjuvanted vaccine induces a greater magnitude of immune response to the vaccine, something already lower in children than in adults, as well as more breadth of response, meaning the response goes beyond strains included in the vaccines.

The small number of at-risk children in the study poses a limitation on its findings. Dr. Patel and associates said that, regardless, the results of immunogenicity analyses were strong. “Overall, this analysis indicates that aIIV3 has a similar safety profile in young children with underlying medical conditions, consistent with other licensed inactivated influenza vaccines.”

Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics originally funded the study, but was later acquired by CSL Group and now operates as Seqirus, which continued funding for the study. The authors were employees of one or the other of these companies.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Online ped-derm searches: What are folks looking for?

AUSTIN – After searching online for information about a suspected pediatric dermatologic condition, one in five parents and/or pediatric patients make dermatology appointments sooner than they normally would, results from a novel survey showed.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Jamie P. Schlarbaum noted that about one-third of Americans use the Internet to research their condition or symptoms prior to visiting a physician, mostly through Google. “While nearly 50% of parents look up health care information online for their children, rashes were the most common search in pediatrics in 2011,” said Mr. Schlarbaum, who is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. “However, no studies have examined the characteristics and implications of these searches; our study is the first in pediatric dermatology and also adds a new dimension to concern in an online era: How these searches influence health care behaviors.”

During February 2018–February 2019, Kristen Hook, MD, a pediatric dermatologist in Minneapolis and the study’s principal investigator, and Mr. Schlarbaum administered a survey to 220 parents/guardians and pediatric patients who had appointments in pediatric dermatology at a University of Minnesota clinic. The survey consisted of questions about demographics, search tools, search terms, and health care decisions based on this information.

Of the 220 respondents, more than half (59%) did not use an online search engine/tool prior to their appointment. Compared with parents who did not use an online search tool, those who did were slightly younger (34 vs. 36 years, respectively), more likely to be college educated (68% vs. 48%), and less likely to have the patient in question be their first child (37% vs. 52%).

Google ranked as the most common search engine used by the survey respondents (92%), followed distantly by WebMD (18%). About 15% of respondents became more concerned about the pediatric skin condition after searching online, and 20% made appointments sooner because of the information they gleaned from their searches. “Online dermatology clearly has an influence on care today,” Mr. Schlarbaum said. “As we become an even more technologically advanced and dependent society, we anticipate that both of these numbers will grow.”

The researchers also found that (33%), moles (15%), and infections (11%). “The big takeaway [from this study] is to ask your parents and teenagers if they’ve looked up information online,” Mr. Schlarbaum said. “Whether it’s photos of the ‘worst cases’ or concerning differentials that might pop up, it’s worth it to take a few seconds to ask what they’re worried about and why.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size and single-center design. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AUSTIN – After searching online for information about a suspected pediatric dermatologic condition, one in five parents and/or pediatric patients make dermatology appointments sooner than they normally would, results from a novel survey showed.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Jamie P. Schlarbaum noted that about one-third of Americans use the Internet to research their condition or symptoms prior to visiting a physician, mostly through Google. “While nearly 50% of parents look up health care information online for their children, rashes were the most common search in pediatrics in 2011,” said Mr. Schlarbaum, who is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. “However, no studies have examined the characteristics and implications of these searches; our study is the first in pediatric dermatology and also adds a new dimension to concern in an online era: How these searches influence health care behaviors.”

During February 2018–February 2019, Kristen Hook, MD, a pediatric dermatologist in Minneapolis and the study’s principal investigator, and Mr. Schlarbaum administered a survey to 220 parents/guardians and pediatric patients who had appointments in pediatric dermatology at a University of Minnesota clinic. The survey consisted of questions about demographics, search tools, search terms, and health care decisions based on this information.

Of the 220 respondents, more than half (59%) did not use an online search engine/tool prior to their appointment. Compared with parents who did not use an online search tool, those who did were slightly younger (34 vs. 36 years, respectively), more likely to be college educated (68% vs. 48%), and less likely to have the patient in question be their first child (37% vs. 52%).

Google ranked as the most common search engine used by the survey respondents (92%), followed distantly by WebMD (18%). About 15% of respondents became more concerned about the pediatric skin condition after searching online, and 20% made appointments sooner because of the information they gleaned from their searches. “Online dermatology clearly has an influence on care today,” Mr. Schlarbaum said. “As we become an even more technologically advanced and dependent society, we anticipate that both of these numbers will grow.”

The researchers also found that (33%), moles (15%), and infections (11%). “The big takeaway [from this study] is to ask your parents and teenagers if they’ve looked up information online,” Mr. Schlarbaum said. “Whether it’s photos of the ‘worst cases’ or concerning differentials that might pop up, it’s worth it to take a few seconds to ask what they’re worried about and why.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size and single-center design. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AUSTIN – After searching online for information about a suspected pediatric dermatologic condition, one in five parents and/or pediatric patients make dermatology appointments sooner than they normally would, results from a novel survey showed.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Jamie P. Schlarbaum noted that about one-third of Americans use the Internet to research their condition or symptoms prior to visiting a physician, mostly through Google. “While nearly 50% of parents look up health care information online for their children, rashes were the most common search in pediatrics in 2011,” said Mr. Schlarbaum, who is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. “However, no studies have examined the characteristics and implications of these searches; our study is the first in pediatric dermatology and also adds a new dimension to concern in an online era: How these searches influence health care behaviors.”

During February 2018–February 2019, Kristen Hook, MD, a pediatric dermatologist in Minneapolis and the study’s principal investigator, and Mr. Schlarbaum administered a survey to 220 parents/guardians and pediatric patients who had appointments in pediatric dermatology at a University of Minnesota clinic. The survey consisted of questions about demographics, search tools, search terms, and health care decisions based on this information.

Of the 220 respondents, more than half (59%) did not use an online search engine/tool prior to their appointment. Compared with parents who did not use an online search tool, those who did were slightly younger (34 vs. 36 years, respectively), more likely to be college educated (68% vs. 48%), and less likely to have the patient in question be their first child (37% vs. 52%).

Google ranked as the most common search engine used by the survey respondents (92%), followed distantly by WebMD (18%). About 15% of respondents became more concerned about the pediatric skin condition after searching online, and 20% made appointments sooner because of the information they gleaned from their searches. “Online dermatology clearly has an influence on care today,” Mr. Schlarbaum said. “As we become an even more technologically advanced and dependent society, we anticipate that both of these numbers will grow.”

The researchers also found that (33%), moles (15%), and infections (11%). “The big takeaway [from this study] is to ask your parents and teenagers if they’ve looked up information online,” Mr. Schlarbaum said. “Whether it’s photos of the ‘worst cases’ or concerning differentials that might pop up, it’s worth it to take a few seconds to ask what they’re worried about and why.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size and single-center design. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SPD 2019

Exposure to synthetic cannabinoids is associated with neuropsychiatric morbidity in adolescents

according to data published online July 8 ahead of print in Pediatrics. The results support a distinct neuropsychiatric profile of acute synthetic cannabinoid toxicity in adolescents, wrote the investigators.

Synthetic cannabinoids have become popular and accessible and primarily are used for recreation. The adverse effects of synthetic cannabinoid toxicity reported in the literature include tachycardia, cardiac ischemia, acute kidney injury, agitation, first episode of psychosis, seizures, and death. Adolescents are the largest age group presenting to the emergency department with acute synthetic cannabinoid toxicity, and this population requires more intensive care than adults with the same presentation.

A multicenter registry analysis

To describe the neuropsychiatric presentation of adolescents to the emergency department after synthetic cannabinoid exposure, compared with that of cannabis exposure, Sarah Ann R. Anderson, MD, PhD, an adolescent medicine fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, and colleagues performed a multicenter registry analysis. They examined data collected from January 2010 through September 2018 from adolescent patients who presented to sites that participate in the Toxicology Investigators Consortium. For each patient, clinicians requested a consultation by a medical toxicologist to aid care. The exposures recorded in the case registry are reported by the patients or witnesses.

Eligible patients were between ages 13 and 19 years and presented to an emergency department with synthetic cannabinoid or cannabis exposure. Dr. Anderson and colleagues collected variables such as age, sex, reported exposures, death in hospital, location of toxicology encounter, and neuropsychiatric signs or symptoms. Patients whose exposure report came from a service outside of an emergency department and those with concomitant use of cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids were excluded. For the purpose of analysis, the investigators classified patients into the following four categories: exposure to synthetic cannabinoids alone, exposure to synthetic cannabinoids and other drugs, exposure to cannabis alone, and exposure to cannabis and other drugs.

Dr. Anderson and colleagues included 348 patients in their study. The sample included 107 patients in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group, 38 in the synthetic cannabinoid/polydrug group, 86 in the cannabis-only group, and 117 in the cannabis/polydrug group. Males predominated in all groups. The one death in the study occurred in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group.

Synthetic cannabinoid exposure increased risk for seizures

Compared with the cannabis-only group, the synthetic cannabinoid–only group had an increased risk of coma or CNS depression (odds ratio, 3.42) and seizures (OR, 3.89). The risk of agitation was significantly lower in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group, compared with the cannabis-only group (OR, 0.18). The two single-drug exposure groups did not differ in their associated risks of delirium or toxic psychosis, extrapyramidal signs, dystonia or rigidity, or hallucinations.

Exposure to synthetic cannabinoids plus other drugs was associated with increased risk of agitation (OR, 3.11) and seizures (OR, 4.8), compared with exposure to cannabis plus other drugs. Among patients exposed to synthetic cannabinoids plus other drugs, the most common class of other drug was sympathomimetics (such as synthetic cathinones, cocaine, and amphetamines). Sympathomimetics and ethanol were the two most common classes of drugs among patients exposed to cannabis plus other drugs.

Synthetic cannabinoids may have distinctive neuropsychiatric outcomes

“Findings from our study further confirm the previously described association between synthetic cannabinoid–specific overdose and severe neuropsychiatric outcomes,” wrote Dr. Anderson and colleagues. They underscore “the need for targeted public health messaging to adolescents about the dangers of using synthetic cannabinoids alone or combined with other substances.”

The investigators’ finding that patients exposed to synthetic cannabinoids alone had a lower risk of agitation than those exposed to cannabis alone is not consistent with contemporary literature on synthetic cannabinoid–associated agitation. This discordance may reflect differences in the populations studied, “with more severe toxicity prompting the emergency department presentations reported in this study,” wrote Dr. Anderson and colleagues. The current study also may be affected by selection bias, they added.

The researchers acknowledged several limitations of their study. For example, the registry lacked data for variables such as race or ethnicity, concurrent illness, previous drug use, and comorbid conditions. Another limitation was that substance exposure was patient- or witness-reported, and no testing to confirm exposure to synthetic cannabinoids was performed. Finally, the study had a relatively small sample size and lacked information about patients’ long-term outcomes.

Dr. Anderson and colleagues described future research that could address open questions. Analyzing urine to identify the synthetic cannabinoid used and correlating it with the presentation in the emergency department could illuminate specific toxidromes associated with particular compounds, they wrote. Longitudinal data on the long-term effects of adolescent exposure to synthetic cannabinoids would be valuable for understanding potential long-term neurocognitive impairments. “Lastly, additional investigations into the management of adolescent synthetic cannabinoid toxicity in the emergency department is warranted, given the health care cost burden of synthetic cannabinoid–related emergency department visits,” they concluded.

The study was not supported by external funding, and the authors had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Anderson SAR et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul 8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2690.

according to data published online July 8 ahead of print in Pediatrics. The results support a distinct neuropsychiatric profile of acute synthetic cannabinoid toxicity in adolescents, wrote the investigators.

Synthetic cannabinoids have become popular and accessible and primarily are used for recreation. The adverse effects of synthetic cannabinoid toxicity reported in the literature include tachycardia, cardiac ischemia, acute kidney injury, agitation, first episode of psychosis, seizures, and death. Adolescents are the largest age group presenting to the emergency department with acute synthetic cannabinoid toxicity, and this population requires more intensive care than adults with the same presentation.

A multicenter registry analysis

To describe the neuropsychiatric presentation of adolescents to the emergency department after synthetic cannabinoid exposure, compared with that of cannabis exposure, Sarah Ann R. Anderson, MD, PhD, an adolescent medicine fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, and colleagues performed a multicenter registry analysis. They examined data collected from January 2010 through September 2018 from adolescent patients who presented to sites that participate in the Toxicology Investigators Consortium. For each patient, clinicians requested a consultation by a medical toxicologist to aid care. The exposures recorded in the case registry are reported by the patients or witnesses.

Eligible patients were between ages 13 and 19 years and presented to an emergency department with synthetic cannabinoid or cannabis exposure. Dr. Anderson and colleagues collected variables such as age, sex, reported exposures, death in hospital, location of toxicology encounter, and neuropsychiatric signs or symptoms. Patients whose exposure report came from a service outside of an emergency department and those with concomitant use of cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids were excluded. For the purpose of analysis, the investigators classified patients into the following four categories: exposure to synthetic cannabinoids alone, exposure to synthetic cannabinoids and other drugs, exposure to cannabis alone, and exposure to cannabis and other drugs.

Dr. Anderson and colleagues included 348 patients in their study. The sample included 107 patients in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group, 38 in the synthetic cannabinoid/polydrug group, 86 in the cannabis-only group, and 117 in the cannabis/polydrug group. Males predominated in all groups. The one death in the study occurred in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group.

Synthetic cannabinoid exposure increased risk for seizures

Compared with the cannabis-only group, the synthetic cannabinoid–only group had an increased risk of coma or CNS depression (odds ratio, 3.42) and seizures (OR, 3.89). The risk of agitation was significantly lower in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group, compared with the cannabis-only group (OR, 0.18). The two single-drug exposure groups did not differ in their associated risks of delirium or toxic psychosis, extrapyramidal signs, dystonia or rigidity, or hallucinations.

Exposure to synthetic cannabinoids plus other drugs was associated with increased risk of agitation (OR, 3.11) and seizures (OR, 4.8), compared with exposure to cannabis plus other drugs. Among patients exposed to synthetic cannabinoids plus other drugs, the most common class of other drug was sympathomimetics (such as synthetic cathinones, cocaine, and amphetamines). Sympathomimetics and ethanol were the two most common classes of drugs among patients exposed to cannabis plus other drugs.

Synthetic cannabinoids may have distinctive neuropsychiatric outcomes

“Findings from our study further confirm the previously described association between synthetic cannabinoid–specific overdose and severe neuropsychiatric outcomes,” wrote Dr. Anderson and colleagues. They underscore “the need for targeted public health messaging to adolescents about the dangers of using synthetic cannabinoids alone or combined with other substances.”

The investigators’ finding that patients exposed to synthetic cannabinoids alone had a lower risk of agitation than those exposed to cannabis alone is not consistent with contemporary literature on synthetic cannabinoid–associated agitation. This discordance may reflect differences in the populations studied, “with more severe toxicity prompting the emergency department presentations reported in this study,” wrote Dr. Anderson and colleagues. The current study also may be affected by selection bias, they added.

The researchers acknowledged several limitations of their study. For example, the registry lacked data for variables such as race or ethnicity, concurrent illness, previous drug use, and comorbid conditions. Another limitation was that substance exposure was patient- or witness-reported, and no testing to confirm exposure to synthetic cannabinoids was performed. Finally, the study had a relatively small sample size and lacked information about patients’ long-term outcomes.

Dr. Anderson and colleagues described future research that could address open questions. Analyzing urine to identify the synthetic cannabinoid used and correlating it with the presentation in the emergency department could illuminate specific toxidromes associated with particular compounds, they wrote. Longitudinal data on the long-term effects of adolescent exposure to synthetic cannabinoids would be valuable for understanding potential long-term neurocognitive impairments. “Lastly, additional investigations into the management of adolescent synthetic cannabinoid toxicity in the emergency department is warranted, given the health care cost burden of synthetic cannabinoid–related emergency department visits,” they concluded.

The study was not supported by external funding, and the authors had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Anderson SAR et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul 8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2690.

according to data published online July 8 ahead of print in Pediatrics. The results support a distinct neuropsychiatric profile of acute synthetic cannabinoid toxicity in adolescents, wrote the investigators.

Synthetic cannabinoids have become popular and accessible and primarily are used for recreation. The adverse effects of synthetic cannabinoid toxicity reported in the literature include tachycardia, cardiac ischemia, acute kidney injury, agitation, first episode of psychosis, seizures, and death. Adolescents are the largest age group presenting to the emergency department with acute synthetic cannabinoid toxicity, and this population requires more intensive care than adults with the same presentation.

A multicenter registry analysis

To describe the neuropsychiatric presentation of adolescents to the emergency department after synthetic cannabinoid exposure, compared with that of cannabis exposure, Sarah Ann R. Anderson, MD, PhD, an adolescent medicine fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, and colleagues performed a multicenter registry analysis. They examined data collected from January 2010 through September 2018 from adolescent patients who presented to sites that participate in the Toxicology Investigators Consortium. For each patient, clinicians requested a consultation by a medical toxicologist to aid care. The exposures recorded in the case registry are reported by the patients or witnesses.

Eligible patients were between ages 13 and 19 years and presented to an emergency department with synthetic cannabinoid or cannabis exposure. Dr. Anderson and colleagues collected variables such as age, sex, reported exposures, death in hospital, location of toxicology encounter, and neuropsychiatric signs or symptoms. Patients whose exposure report came from a service outside of an emergency department and those with concomitant use of cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids were excluded. For the purpose of analysis, the investigators classified patients into the following four categories: exposure to synthetic cannabinoids alone, exposure to synthetic cannabinoids and other drugs, exposure to cannabis alone, and exposure to cannabis and other drugs.

Dr. Anderson and colleagues included 348 patients in their study. The sample included 107 patients in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group, 38 in the synthetic cannabinoid/polydrug group, 86 in the cannabis-only group, and 117 in the cannabis/polydrug group. Males predominated in all groups. The one death in the study occurred in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group.

Synthetic cannabinoid exposure increased risk for seizures

Compared with the cannabis-only group, the synthetic cannabinoid–only group had an increased risk of coma or CNS depression (odds ratio, 3.42) and seizures (OR, 3.89). The risk of agitation was significantly lower in the synthetic cannabinoid–only group, compared with the cannabis-only group (OR, 0.18). The two single-drug exposure groups did not differ in their associated risks of delirium or toxic psychosis, extrapyramidal signs, dystonia or rigidity, or hallucinations.

Exposure to synthetic cannabinoids plus other drugs was associated with increased risk of agitation (OR, 3.11) and seizures (OR, 4.8), compared with exposure to cannabis plus other drugs. Among patients exposed to synthetic cannabinoids plus other drugs, the most common class of other drug was sympathomimetics (such as synthetic cathinones, cocaine, and amphetamines). Sympathomimetics and ethanol were the two most common classes of drugs among patients exposed to cannabis plus other drugs.

Synthetic cannabinoids may have distinctive neuropsychiatric outcomes

“Findings from our study further confirm the previously described association between synthetic cannabinoid–specific overdose and severe neuropsychiatric outcomes,” wrote Dr. Anderson and colleagues. They underscore “the need for targeted public health messaging to adolescents about the dangers of using synthetic cannabinoids alone or combined with other substances.”

The investigators’ finding that patients exposed to synthetic cannabinoids alone had a lower risk of agitation than those exposed to cannabis alone is not consistent with contemporary literature on synthetic cannabinoid–associated agitation. This discordance may reflect differences in the populations studied, “with more severe toxicity prompting the emergency department presentations reported in this study,” wrote Dr. Anderson and colleagues. The current study also may be affected by selection bias, they added.

The researchers acknowledged several limitations of their study. For example, the registry lacked data for variables such as race or ethnicity, concurrent illness, previous drug use, and comorbid conditions. Another limitation was that substance exposure was patient- or witness-reported, and no testing to confirm exposure to synthetic cannabinoids was performed. Finally, the study had a relatively small sample size and lacked information about patients’ long-term outcomes.

Dr. Anderson and colleagues described future research that could address open questions. Analyzing urine to identify the synthetic cannabinoid used and correlating it with the presentation in the emergency department could illuminate specific toxidromes associated with particular compounds, they wrote. Longitudinal data on the long-term effects of adolescent exposure to synthetic cannabinoids would be valuable for understanding potential long-term neurocognitive impairments. “Lastly, additional investigations into the management of adolescent synthetic cannabinoid toxicity in the emergency department is warranted, given the health care cost burden of synthetic cannabinoid–related emergency department visits,” they concluded.

The study was not supported by external funding, and the authors had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Anderson SAR et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul 8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2690.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Mechanism does not matter for second-line biologic choice in JIA

MADRID – When biologic treatment is indicated after initial tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) has failed, the mechanism of action of the second biologic does not appear to matter, according to data presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“There appears to be no difference in effectiveness outcomes or drug survival in patients starting a second TNF inhibitor versus an alternative class of biologic,” said Lianne Kearsley-Fleet, an epidemiologist at the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England).

Indeed, at 6 months, there were no significant differences among patients who had switched from a TNF inhibitor to another TNF inhibitor or to a biologic with an alternative mechanism of action in terms of:

- The change in Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)-71 from baseline (mean score change, 7.3 with second TNF inhibitor vs. 8.5 with an alternative biologic class).

- The percentage of patients achieving an American College of Rheumatology Pediatric 90% response (22% vs. 15%).

- The proportion of patients achieving minimal disease activity (30% vs. 23%).

- The percentage reaching a minimal clinically important difference (MCID; 44% vs. 43%).

There was also no difference between switching to a TNF inhibitor or alternative biologic in terms of the duration of time patients remained treated with the second-line agent.

“After 1 year, 62% of patients remained on their biologic therapy, and when we looked at drug survival over the course of that year, there was no difference between the two cohorts,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet reported. There was no difference also in the reasons for stopping the second biologic.

“We now have a wide range of biologic therapies available; however, there is no evidence regarding which biologic should be prescribed [in JIA], and if patients switch, which order this should be,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet stated. Current NHS England guidelines recommend that most patients with JIA should start a TNF inhibitor (unless they are rheumatoid factor positive, in which case they should be treated with rituximab [Rituxan]), and if the first fails, to switch to a second TNF inhibitor rather than to change class. The evidence for this is limited, she noted, adding that adult guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis now recommended a change of class if not contraindicated.

Using data from two pediatric biologics registers – the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology Etanercept Cohort Study (BSPAR-ETN) and Biologics for Children with Rheumatic Diseases (BCRD) – Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet and her associates looked at data on 241 children and adolescents with polyarticular JIA (or oligoarticular-extended JIA) starting a second biologic. The aim was to compare the effectiveness of starting a second TNF inhibitor versus switching to an alternative class of agent, such as a B-cell depleting agent such as rituximab, in routine clinical practice.

A majority (n = 188; 78%) of patients had etanercept (Enbrel) as their starting TNF inhibitor and those switching to a second TNF inhibitor (n = 196) were most likely to be given adalimumab (Humira; 58%). Patients starting a biologic with another mode of action (n = 45) were most likely to be given the interleukin-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (73%), followed by rituximab in 13%, and abatacept (Orencia) in 11%. The main reasons for switching to another biologic – TNF inhibitor or otherwise – were ineffectiveness (60% with a second TNF inhibitor vs. 62% with another biologic drug class) or adverse events or intolerance (19% vs. 13%, respectively).

The strength of these data are that they come from a very large cohort of children and adolescents starting biologics for JIA, with systematic follow-up and robust statistical methods, Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet said. However, she noted that JIA was rare and that only one-fifth of patients would start a biologic, and just 30% of those patients would then switch to a second biologic.

“We don’t see any reason that the guidelines should be changed,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet observed. “However, repeat analysis with a larger sample size is required to reinforce whether there is any advantage of switching or not.”

Versus Arthritis (formerly Arthritis Research UK) and The British Society for Rheumatology provided funding support. Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet had no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Kearsley-Fleet L et al. Ann Rheum Dis, Jun 2019;8(Suppl 2):74-5. Abstract OP0016. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.415.

MADRID – When biologic treatment is indicated after initial tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) has failed, the mechanism of action of the second biologic does not appear to matter, according to data presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“There appears to be no difference in effectiveness outcomes or drug survival in patients starting a second TNF inhibitor versus an alternative class of biologic,” said Lianne Kearsley-Fleet, an epidemiologist at the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England).

Indeed, at 6 months, there were no significant differences among patients who had switched from a TNF inhibitor to another TNF inhibitor or to a biologic with an alternative mechanism of action in terms of:

- The change in Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)-71 from baseline (mean score change, 7.3 with second TNF inhibitor vs. 8.5 with an alternative biologic class).

- The percentage of patients achieving an American College of Rheumatology Pediatric 90% response (22% vs. 15%).

- The proportion of patients achieving minimal disease activity (30% vs. 23%).

- The percentage reaching a minimal clinically important difference (MCID; 44% vs. 43%).

There was also no difference between switching to a TNF inhibitor or alternative biologic in terms of the duration of time patients remained treated with the second-line agent.

“After 1 year, 62% of patients remained on their biologic therapy, and when we looked at drug survival over the course of that year, there was no difference between the two cohorts,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet reported. There was no difference also in the reasons for stopping the second biologic.

“We now have a wide range of biologic therapies available; however, there is no evidence regarding which biologic should be prescribed [in JIA], and if patients switch, which order this should be,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet stated. Current NHS England guidelines recommend that most patients with JIA should start a TNF inhibitor (unless they are rheumatoid factor positive, in which case they should be treated with rituximab [Rituxan]), and if the first fails, to switch to a second TNF inhibitor rather than to change class. The evidence for this is limited, she noted, adding that adult guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis now recommended a change of class if not contraindicated.

Using data from two pediatric biologics registers – the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology Etanercept Cohort Study (BSPAR-ETN) and Biologics for Children with Rheumatic Diseases (BCRD) – Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet and her associates looked at data on 241 children and adolescents with polyarticular JIA (or oligoarticular-extended JIA) starting a second biologic. The aim was to compare the effectiveness of starting a second TNF inhibitor versus switching to an alternative class of agent, such as a B-cell depleting agent such as rituximab, in routine clinical practice.

A majority (n = 188; 78%) of patients had etanercept (Enbrel) as their starting TNF inhibitor and those switching to a second TNF inhibitor (n = 196) were most likely to be given adalimumab (Humira; 58%). Patients starting a biologic with another mode of action (n = 45) were most likely to be given the interleukin-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (73%), followed by rituximab in 13%, and abatacept (Orencia) in 11%. The main reasons for switching to another biologic – TNF inhibitor or otherwise – were ineffectiveness (60% with a second TNF inhibitor vs. 62% with another biologic drug class) or adverse events or intolerance (19% vs. 13%, respectively).

The strength of these data are that they come from a very large cohort of children and adolescents starting biologics for JIA, with systematic follow-up and robust statistical methods, Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet said. However, she noted that JIA was rare and that only one-fifth of patients would start a biologic, and just 30% of those patients would then switch to a second biologic.

“We don’t see any reason that the guidelines should be changed,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet observed. “However, repeat analysis with a larger sample size is required to reinforce whether there is any advantage of switching or not.”

Versus Arthritis (formerly Arthritis Research UK) and The British Society for Rheumatology provided funding support. Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet had no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Kearsley-Fleet L et al. Ann Rheum Dis, Jun 2019;8(Suppl 2):74-5. Abstract OP0016. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.415.

MADRID – When biologic treatment is indicated after initial tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) has failed, the mechanism of action of the second biologic does not appear to matter, according to data presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“There appears to be no difference in effectiveness outcomes or drug survival in patients starting a second TNF inhibitor versus an alternative class of biologic,” said Lianne Kearsley-Fleet, an epidemiologist at the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England).

Indeed, at 6 months, there were no significant differences among patients who had switched from a TNF inhibitor to another TNF inhibitor or to a biologic with an alternative mechanism of action in terms of:

- The change in Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)-71 from baseline (mean score change, 7.3 with second TNF inhibitor vs. 8.5 with an alternative biologic class).

- The percentage of patients achieving an American College of Rheumatology Pediatric 90% response (22% vs. 15%).

- The proportion of patients achieving minimal disease activity (30% vs. 23%).

- The percentage reaching a minimal clinically important difference (MCID; 44% vs. 43%).

There was also no difference between switching to a TNF inhibitor or alternative biologic in terms of the duration of time patients remained treated with the second-line agent.

“After 1 year, 62% of patients remained on their biologic therapy, and when we looked at drug survival over the course of that year, there was no difference between the two cohorts,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet reported. There was no difference also in the reasons for stopping the second biologic.

“We now have a wide range of biologic therapies available; however, there is no evidence regarding which biologic should be prescribed [in JIA], and if patients switch, which order this should be,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet stated. Current NHS England guidelines recommend that most patients with JIA should start a TNF inhibitor (unless they are rheumatoid factor positive, in which case they should be treated with rituximab [Rituxan]), and if the first fails, to switch to a second TNF inhibitor rather than to change class. The evidence for this is limited, she noted, adding that adult guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis now recommended a change of class if not contraindicated.

Using data from two pediatric biologics registers – the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology Etanercept Cohort Study (BSPAR-ETN) and Biologics for Children with Rheumatic Diseases (BCRD) – Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet and her associates looked at data on 241 children and adolescents with polyarticular JIA (or oligoarticular-extended JIA) starting a second biologic. The aim was to compare the effectiveness of starting a second TNF inhibitor versus switching to an alternative class of agent, such as a B-cell depleting agent such as rituximab, in routine clinical practice.

A majority (n = 188; 78%) of patients had etanercept (Enbrel) as their starting TNF inhibitor and those switching to a second TNF inhibitor (n = 196) were most likely to be given adalimumab (Humira; 58%). Patients starting a biologic with another mode of action (n = 45) were most likely to be given the interleukin-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (73%), followed by rituximab in 13%, and abatacept (Orencia) in 11%. The main reasons for switching to another biologic – TNF inhibitor or otherwise – were ineffectiveness (60% with a second TNF inhibitor vs. 62% with another biologic drug class) or adverse events or intolerance (19% vs. 13%, respectively).

The strength of these data are that they come from a very large cohort of children and adolescents starting biologics for JIA, with systematic follow-up and robust statistical methods, Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet said. However, she noted that JIA was rare and that only one-fifth of patients would start a biologic, and just 30% of those patients would then switch to a second biologic.

“We don’t see any reason that the guidelines should be changed,” Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet observed. “However, repeat analysis with a larger sample size is required to reinforce whether there is any advantage of switching or not.”

Versus Arthritis (formerly Arthritis Research UK) and The British Society for Rheumatology provided funding support. Mrs. Kearsley-Fleet had no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Kearsley-Fleet L et al. Ann Rheum Dis, Jun 2019;8(Suppl 2):74-5. Abstract OP0016. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.415.

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 Congress

The pool is closed!

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.